User login

Clinical Psychiatry News is the online destination and multimedia properties of Clinica Psychiatry News, the independent news publication for psychiatrists. Since 1971, Clinical Psychiatry News has been the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in psychiatry as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the physician's practice.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

ketamine

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

suicide

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Neuropsychiatry affects pediatric OCD treatment

Treatment of pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) has evolved in recent years, with more attention given to some of the neuropsychiatric underpinnings of the condition and how they can affect treatment response.

At the Focus on Neuropsychiatry 2021 meeting, Jeffrey Strawn, MD, outlined some of the neuropsychiatry affecting disease and potential mechanisms to help control obsessions and behaviors, and how they may fit with some therapeutic regimens.

Dr. Strawn discussed the psychological construct of cognitive control, which can provide patients an “out” from the cycle of obsession/fear/worry and compulsion/avoidance. In the face of distress, compulsion and avoidance lead to relief, which reinforces the obsession/fear/worry; this in turn leads to more distress.

“We have an escape door for this circuit” in the form of cognitive control, said Dr. Strawn, who is an associate professor of pediatrics at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Cognitive control is linked to insight, which can in turn increase adaptive behaviors that help the patient resist the compulsion. Patients won’t eliminate distress, but they can be helped to make it more tolerable. Therapists can then help them move toward goal-directed thoughts and behaviors. Cognitive control is associated with several neural networks, but Dr. Strawn focused on two: the frontoparietal network, associated with top-down regulation; and the cingular-opercular network. Both of these are engaged during cognitive control processes, and play a role inhibitory control and error monitoring.

Dr. Strawn discussed a recent study that explored the neurofunctional basis of treatment. It compared the effects of a stress management therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in children and adults with OCD at 6 and 12 weeks. The study found similar symptom reductions in both adults and adolescents in both intervention groups.

Before initiating treatment, the researchers conducted functional MRI scans of participants while conducting an incentive flanker task, which reveals brain activity in response to cognitive control and reward processing.

A larger therapeutic response was found in the CBT group among patients who had a larger pretreatment activation within the right temporal lobe and rostral anterior cingulate cortex during cognitive control, as well as those with more activation within the medial prefrontal, orbitofrontal, lateral prefrontal, and amygdala regions during reward processing. On the other hand, within the stress management therapy group, treatment responses were better among those who had lower pretreatment activation among overlapping regions.

“There was a difference in terms of the neurofunctional predictors of treatment response. One of the key regions is the medial prefrontal cortex as well as the rostral anterior cingulate,” said Dr. Strawn, at the meeting presented by MedscapeLive. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

On the neuropharmacology side, numerous medications have been approved for OCD. Dr. Strawn highlighted some studies to illustrate general OCD treatment concepts. That included the 2004 Pediatric OCD Treatment Study, which was one of the only trials to compare placebo with an SSRI, CBT, and the combination of SSRI and CBT. It showed the best results with combination therapy, and the difference appeared early in the treatment course.

That study had aggressive dosing, which led to some issues with sertraline tolerability. Dr. Strawn showed results of a study at his institution which showed that the drug levels of pediatric patients treated with sertraline depended on CYP2C19 metabolism, which affects overall exposure and peak dose concentration. In pediatric populations, some SSRIs clear more slowly and can have high peak concentrations. SSRIs have more side effects than serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors in both anxiety disorders and OCD. A key difference between the two is that SSRI treatment is associated with greater frequency of activation, which is difficult to define, but includes restlessness and agitation and insomnia in the beginning stages of treatment.

SSRIs also lead to improvement early in the course of treatment, which was shown in a meta-analysis of nine trials. However, the same study showed that clomipramine is associated with a faster and greater magnitude of improvement, compared with SSRIs, even when the latter are dosed aggressively.

Clomipramine is a potent inhibitor of both serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake. It is recommended to monitor clomipramine levels in pediatric OCD patients, and Dr. Strawn suggested that monitoring should include both the parent drug and its primary metabolite, norclomipramine. At a given dose, there can be a great deal of variation in drug level. The clomipramine/norclomipramine ratio can provide information about the patient’s metabolic state, as well as drug adherence.

Dr. Strawn noted that peak levels occur around 1-3 hours after the dose, “and we really do want at least a 12-hour trough level.” EKGs should be performed at baseline and after any titration of clomipramine dose.

He also discussed pediatric OCD patients with OCD and tics. About one-third of Tourette syndrome patients experience OCD at some point. Tics often improve, whereas OCD more often persists. Tics that co-occur with OCD are associated with a lesser response to SSRI treatment, but not CBT treatment. Similarly, patients with hoarding tendencies are about one-third less likely to respond to SSRIs, CBT, or combination therapy.

Dr. Strawn discussed the concept of accommodation, in which family members cope with a patient’s behavior by altering routines to minimize distress and impairment. This may take the form of facilitating rituals, providing reassurance about a patient’s fears, acquiescing to demands, reducing the child’s day-to-day responsibilities, or helping the child complete tasks. Such actions are well intentioned, but they undermine cognitive control, negatively reinforce symptom engagement, and are associated with functional impairment. Reassurance is the most important behavior, occurring in more than half of patients, and it’s measurable. Parental involvement with rituals is also a concern. “This is associated with higher levels of child OCD severity, as well as parental psychopathology, and lower family cohesion. So

New developments in neurobiology and neuropsychology have changed the view of exposure. The old model emphasized the child’s fear rating as an index of corrective learning. The idea was that habituation would decrease anxiety and distress from future exposures. The new model revolves around inhibitory learning theory, which focuses on the variability of distress and aims to increase tolerance of distress. Another goal is to develop new, non-threat associations.

Finally, Dr. Strawn pointed out predictors of poor outcomes in pediatric OCD, including factors such as compulsion severity, oppositional behavior, frequent handwashing, functional impairment, lack of insight, externalizing symptoms, and possibly hoarding. Problematic family characteristics include higher levels of accommodation, parental anxiety, low family cohesion, and high levels of conflict. “The last three really represent a very concerning triad of family behaviors that may necessitate specific family work in order to facilitate the recovery of the pediatric patient,” Dr. Strawn said.

During the question-and-answer session after the talk, Dr. Strawn was asked whether there might be an inflammatory component to OCD, and whether pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcus (PANDAS) might be a prodromal condition. He noted that some studies have shown a relationship, but results have been mixed, with lots of heterogeneity within the studied populations. To be suspicious that a patient had OCD resulting from PANDAS would require a high threshold, including an acute onset of symptoms. “This is a situation also where I would tend to involve consultation with some other specialties, including neurology. And obviously there would be follow-up in terms of the general workup,” he said.

Dr. Strawn has received research funding from Allergan, Otsuka, and Myriad Genetics. He has consulted for Myriad Genetics, and is a speaker for CMEology and the Neuroscience Education Institute.

Treatment of pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) has evolved in recent years, with more attention given to some of the neuropsychiatric underpinnings of the condition and how they can affect treatment response.

At the Focus on Neuropsychiatry 2021 meeting, Jeffrey Strawn, MD, outlined some of the neuropsychiatry affecting disease and potential mechanisms to help control obsessions and behaviors, and how they may fit with some therapeutic regimens.

Dr. Strawn discussed the psychological construct of cognitive control, which can provide patients an “out” from the cycle of obsession/fear/worry and compulsion/avoidance. In the face of distress, compulsion and avoidance lead to relief, which reinforces the obsession/fear/worry; this in turn leads to more distress.

“We have an escape door for this circuit” in the form of cognitive control, said Dr. Strawn, who is an associate professor of pediatrics at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Cognitive control is linked to insight, which can in turn increase adaptive behaviors that help the patient resist the compulsion. Patients won’t eliminate distress, but they can be helped to make it more tolerable. Therapists can then help them move toward goal-directed thoughts and behaviors. Cognitive control is associated with several neural networks, but Dr. Strawn focused on two: the frontoparietal network, associated with top-down regulation; and the cingular-opercular network. Both of these are engaged during cognitive control processes, and play a role inhibitory control and error monitoring.

Dr. Strawn discussed a recent study that explored the neurofunctional basis of treatment. It compared the effects of a stress management therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in children and adults with OCD at 6 and 12 weeks. The study found similar symptom reductions in both adults and adolescents in both intervention groups.

Before initiating treatment, the researchers conducted functional MRI scans of participants while conducting an incentive flanker task, which reveals brain activity in response to cognitive control and reward processing.

A larger therapeutic response was found in the CBT group among patients who had a larger pretreatment activation within the right temporal lobe and rostral anterior cingulate cortex during cognitive control, as well as those with more activation within the medial prefrontal, orbitofrontal, lateral prefrontal, and amygdala regions during reward processing. On the other hand, within the stress management therapy group, treatment responses were better among those who had lower pretreatment activation among overlapping regions.

“There was a difference in terms of the neurofunctional predictors of treatment response. One of the key regions is the medial prefrontal cortex as well as the rostral anterior cingulate,” said Dr. Strawn, at the meeting presented by MedscapeLive. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

On the neuropharmacology side, numerous medications have been approved for OCD. Dr. Strawn highlighted some studies to illustrate general OCD treatment concepts. That included the 2004 Pediatric OCD Treatment Study, which was one of the only trials to compare placebo with an SSRI, CBT, and the combination of SSRI and CBT. It showed the best results with combination therapy, and the difference appeared early in the treatment course.

That study had aggressive dosing, which led to some issues with sertraline tolerability. Dr. Strawn showed results of a study at his institution which showed that the drug levels of pediatric patients treated with sertraline depended on CYP2C19 metabolism, which affects overall exposure and peak dose concentration. In pediatric populations, some SSRIs clear more slowly and can have high peak concentrations. SSRIs have more side effects than serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors in both anxiety disorders and OCD. A key difference between the two is that SSRI treatment is associated with greater frequency of activation, which is difficult to define, but includes restlessness and agitation and insomnia in the beginning stages of treatment.

SSRIs also lead to improvement early in the course of treatment, which was shown in a meta-analysis of nine trials. However, the same study showed that clomipramine is associated with a faster and greater magnitude of improvement, compared with SSRIs, even when the latter are dosed aggressively.

Clomipramine is a potent inhibitor of both serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake. It is recommended to monitor clomipramine levels in pediatric OCD patients, and Dr. Strawn suggested that monitoring should include both the parent drug and its primary metabolite, norclomipramine. At a given dose, there can be a great deal of variation in drug level. The clomipramine/norclomipramine ratio can provide information about the patient’s metabolic state, as well as drug adherence.

Dr. Strawn noted that peak levels occur around 1-3 hours after the dose, “and we really do want at least a 12-hour trough level.” EKGs should be performed at baseline and after any titration of clomipramine dose.

He also discussed pediatric OCD patients with OCD and tics. About one-third of Tourette syndrome patients experience OCD at some point. Tics often improve, whereas OCD more often persists. Tics that co-occur with OCD are associated with a lesser response to SSRI treatment, but not CBT treatment. Similarly, patients with hoarding tendencies are about one-third less likely to respond to SSRIs, CBT, or combination therapy.

Dr. Strawn discussed the concept of accommodation, in which family members cope with a patient’s behavior by altering routines to minimize distress and impairment. This may take the form of facilitating rituals, providing reassurance about a patient’s fears, acquiescing to demands, reducing the child’s day-to-day responsibilities, or helping the child complete tasks. Such actions are well intentioned, but they undermine cognitive control, negatively reinforce symptom engagement, and are associated with functional impairment. Reassurance is the most important behavior, occurring in more than half of patients, and it’s measurable. Parental involvement with rituals is also a concern. “This is associated with higher levels of child OCD severity, as well as parental psychopathology, and lower family cohesion. So

New developments in neurobiology and neuropsychology have changed the view of exposure. The old model emphasized the child’s fear rating as an index of corrective learning. The idea was that habituation would decrease anxiety and distress from future exposures. The new model revolves around inhibitory learning theory, which focuses on the variability of distress and aims to increase tolerance of distress. Another goal is to develop new, non-threat associations.

Finally, Dr. Strawn pointed out predictors of poor outcomes in pediatric OCD, including factors such as compulsion severity, oppositional behavior, frequent handwashing, functional impairment, lack of insight, externalizing symptoms, and possibly hoarding. Problematic family characteristics include higher levels of accommodation, parental anxiety, low family cohesion, and high levels of conflict. “The last three really represent a very concerning triad of family behaviors that may necessitate specific family work in order to facilitate the recovery of the pediatric patient,” Dr. Strawn said.

During the question-and-answer session after the talk, Dr. Strawn was asked whether there might be an inflammatory component to OCD, and whether pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcus (PANDAS) might be a prodromal condition. He noted that some studies have shown a relationship, but results have been mixed, with lots of heterogeneity within the studied populations. To be suspicious that a patient had OCD resulting from PANDAS would require a high threshold, including an acute onset of symptoms. “This is a situation also where I would tend to involve consultation with some other specialties, including neurology. And obviously there would be follow-up in terms of the general workup,” he said.

Dr. Strawn has received research funding from Allergan, Otsuka, and Myriad Genetics. He has consulted for Myriad Genetics, and is a speaker for CMEology and the Neuroscience Education Institute.

Treatment of pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) has evolved in recent years, with more attention given to some of the neuropsychiatric underpinnings of the condition and how they can affect treatment response.

At the Focus on Neuropsychiatry 2021 meeting, Jeffrey Strawn, MD, outlined some of the neuropsychiatry affecting disease and potential mechanisms to help control obsessions and behaviors, and how they may fit with some therapeutic regimens.

Dr. Strawn discussed the psychological construct of cognitive control, which can provide patients an “out” from the cycle of obsession/fear/worry and compulsion/avoidance. In the face of distress, compulsion and avoidance lead to relief, which reinforces the obsession/fear/worry; this in turn leads to more distress.

“We have an escape door for this circuit” in the form of cognitive control, said Dr. Strawn, who is an associate professor of pediatrics at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Cognitive control is linked to insight, which can in turn increase adaptive behaviors that help the patient resist the compulsion. Patients won’t eliminate distress, but they can be helped to make it more tolerable. Therapists can then help them move toward goal-directed thoughts and behaviors. Cognitive control is associated with several neural networks, but Dr. Strawn focused on two: the frontoparietal network, associated with top-down regulation; and the cingular-opercular network. Both of these are engaged during cognitive control processes, and play a role inhibitory control and error monitoring.

Dr. Strawn discussed a recent study that explored the neurofunctional basis of treatment. It compared the effects of a stress management therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in children and adults with OCD at 6 and 12 weeks. The study found similar symptom reductions in both adults and adolescents in both intervention groups.

Before initiating treatment, the researchers conducted functional MRI scans of participants while conducting an incentive flanker task, which reveals brain activity in response to cognitive control and reward processing.

A larger therapeutic response was found in the CBT group among patients who had a larger pretreatment activation within the right temporal lobe and rostral anterior cingulate cortex during cognitive control, as well as those with more activation within the medial prefrontal, orbitofrontal, lateral prefrontal, and amygdala regions during reward processing. On the other hand, within the stress management therapy group, treatment responses were better among those who had lower pretreatment activation among overlapping regions.

“There was a difference in terms of the neurofunctional predictors of treatment response. One of the key regions is the medial prefrontal cortex as well as the rostral anterior cingulate,” said Dr. Strawn, at the meeting presented by MedscapeLive. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

On the neuropharmacology side, numerous medications have been approved for OCD. Dr. Strawn highlighted some studies to illustrate general OCD treatment concepts. That included the 2004 Pediatric OCD Treatment Study, which was one of the only trials to compare placebo with an SSRI, CBT, and the combination of SSRI and CBT. It showed the best results with combination therapy, and the difference appeared early in the treatment course.

That study had aggressive dosing, which led to some issues with sertraline tolerability. Dr. Strawn showed results of a study at his institution which showed that the drug levels of pediatric patients treated with sertraline depended on CYP2C19 metabolism, which affects overall exposure and peak dose concentration. In pediatric populations, some SSRIs clear more slowly and can have high peak concentrations. SSRIs have more side effects than serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors in both anxiety disorders and OCD. A key difference between the two is that SSRI treatment is associated with greater frequency of activation, which is difficult to define, but includes restlessness and agitation and insomnia in the beginning stages of treatment.

SSRIs also lead to improvement early in the course of treatment, which was shown in a meta-analysis of nine trials. However, the same study showed that clomipramine is associated with a faster and greater magnitude of improvement, compared with SSRIs, even when the latter are dosed aggressively.

Clomipramine is a potent inhibitor of both serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake. It is recommended to monitor clomipramine levels in pediatric OCD patients, and Dr. Strawn suggested that monitoring should include both the parent drug and its primary metabolite, norclomipramine. At a given dose, there can be a great deal of variation in drug level. The clomipramine/norclomipramine ratio can provide information about the patient’s metabolic state, as well as drug adherence.

Dr. Strawn noted that peak levels occur around 1-3 hours after the dose, “and we really do want at least a 12-hour trough level.” EKGs should be performed at baseline and after any titration of clomipramine dose.

He also discussed pediatric OCD patients with OCD and tics. About one-third of Tourette syndrome patients experience OCD at some point. Tics often improve, whereas OCD more often persists. Tics that co-occur with OCD are associated with a lesser response to SSRI treatment, but not CBT treatment. Similarly, patients with hoarding tendencies are about one-third less likely to respond to SSRIs, CBT, or combination therapy.

Dr. Strawn discussed the concept of accommodation, in which family members cope with a patient’s behavior by altering routines to minimize distress and impairment. This may take the form of facilitating rituals, providing reassurance about a patient’s fears, acquiescing to demands, reducing the child’s day-to-day responsibilities, or helping the child complete tasks. Such actions are well intentioned, but they undermine cognitive control, negatively reinforce symptom engagement, and are associated with functional impairment. Reassurance is the most important behavior, occurring in more than half of patients, and it’s measurable. Parental involvement with rituals is also a concern. “This is associated with higher levels of child OCD severity, as well as parental psychopathology, and lower family cohesion. So

New developments in neurobiology and neuropsychology have changed the view of exposure. The old model emphasized the child’s fear rating as an index of corrective learning. The idea was that habituation would decrease anxiety and distress from future exposures. The new model revolves around inhibitory learning theory, which focuses on the variability of distress and aims to increase tolerance of distress. Another goal is to develop new, non-threat associations.

Finally, Dr. Strawn pointed out predictors of poor outcomes in pediatric OCD, including factors such as compulsion severity, oppositional behavior, frequent handwashing, functional impairment, lack of insight, externalizing symptoms, and possibly hoarding. Problematic family characteristics include higher levels of accommodation, parental anxiety, low family cohesion, and high levels of conflict. “The last three really represent a very concerning triad of family behaviors that may necessitate specific family work in order to facilitate the recovery of the pediatric patient,” Dr. Strawn said.

During the question-and-answer session after the talk, Dr. Strawn was asked whether there might be an inflammatory component to OCD, and whether pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcus (PANDAS) might be a prodromal condition. He noted that some studies have shown a relationship, but results have been mixed, with lots of heterogeneity within the studied populations. To be suspicious that a patient had OCD resulting from PANDAS would require a high threshold, including an acute onset of symptoms. “This is a situation also where I would tend to involve consultation with some other specialties, including neurology. And obviously there would be follow-up in terms of the general workup,” he said.

Dr. Strawn has received research funding from Allergan, Otsuka, and Myriad Genetics. He has consulted for Myriad Genetics, and is a speaker for CMEology and the Neuroscience Education Institute.

FROM FOCUS ON NEUROPSYCHIATRY 2021

EDs saw more benzodiazepine overdoses, but fewer patients overall, in 2020

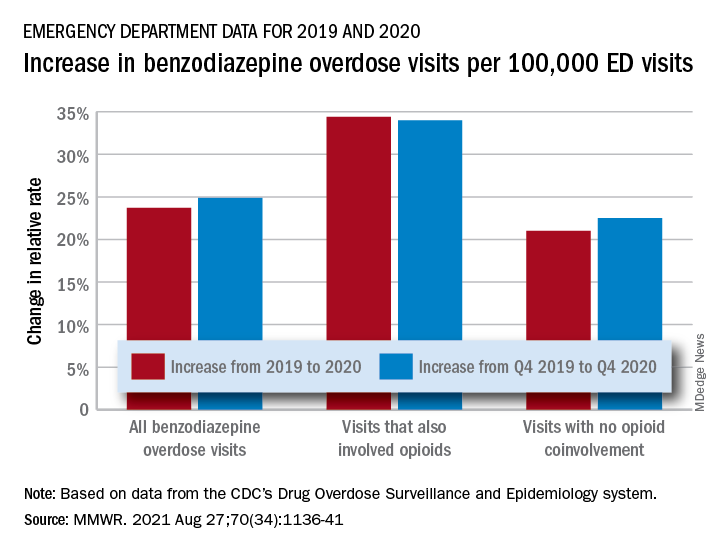

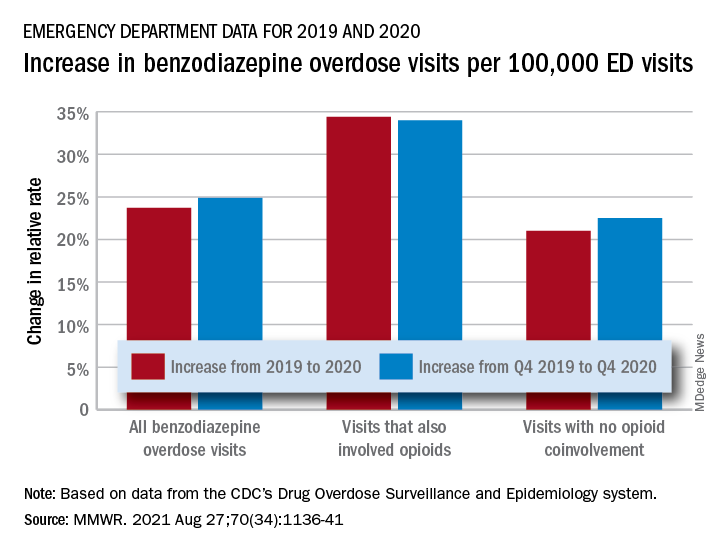

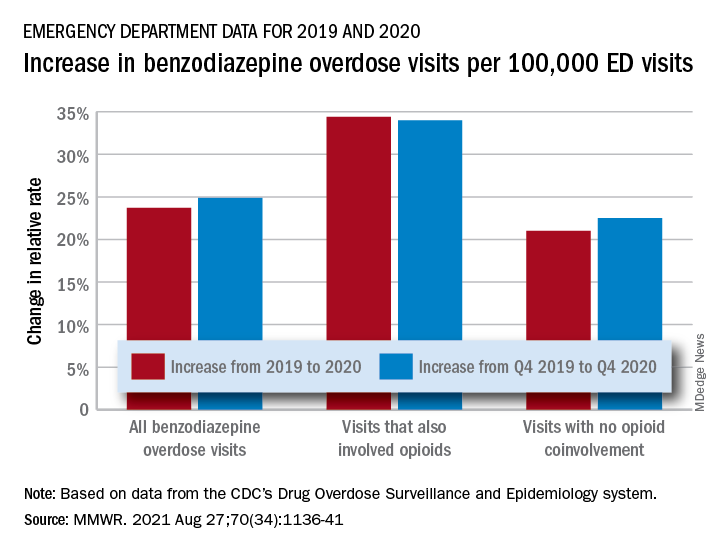

In a year when emergency department visits dropped by almost 18%, visits for benzodiazepine overdoses did the opposite, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The actual increase in the number of overdose visits for benzodiazepine overdoses was quite small – from 15,547 in 2019 to 15,830 in 2020 (1.8%) – but the 11 million fewer ED visits magnified its effect, Stephen Liu, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The rate of benzodiazepine overdose visits to all visits increased by 23.7% from 2019 (24.22 per 100,000 ED visits) to 2020 (29.97 per 100,000), with the larger share going to those involving opioids, which were up by 34.4%, compared with overdose visits not involving opioids (21.0%), the investigators said, based on data reported by 32 states and the District of Columbia to the CDC’s Drug Overdose Surveillance and Epidemiology system. All of the rate changes are statistically significant.

The number of overdose visits without opioid coinvolvement actually dropped, from 2019 (12,276) to 2020 (12,218), but not by enough to offset the decline in total visits, noted Dr. Liu, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control and associates.

The number of deaths from benzodiazepine overdose, on the other hand, did not drop in 2020. Those data, coming from 23 states participating in the CDC’s State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System, were available only for the first half of the year.

In those 6 months, The first quarter of 2020 also showed an increase, but exact numbers were not provided in the report. Overdose deaths rose by 22% for prescription forms of benzodiazepine and 520% for illicit forms in Q2 of 2020, compared with 2019, the researchers said.

Almost all of the benzodiazepine deaths (93%) in the first half of 2020 also involved opioids, mostly in the form of illicitly manufactured fentanyls (67% of all deaths). Between Q2 of 2019 and Q2 of 2020, involvement of illicit fentanyls in benzodiazepine overdose deaths increased from almost 57% to 71%, Dr. Liu and associates reported.

“Despite progress in reducing coprescribing [of opioids and benzodiazepines] before 2019, this study suggests a reversal in the decline in benzodiazepine deaths from 2017 to 2019, driven in part by increasing involvement of [illicitly manufactured fentanyls] in benzodiazepine deaths and influxes of illicit benzodiazepines,” they wrote.

In a year when emergency department visits dropped by almost 18%, visits for benzodiazepine overdoses did the opposite, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The actual increase in the number of overdose visits for benzodiazepine overdoses was quite small – from 15,547 in 2019 to 15,830 in 2020 (1.8%) – but the 11 million fewer ED visits magnified its effect, Stephen Liu, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The rate of benzodiazepine overdose visits to all visits increased by 23.7% from 2019 (24.22 per 100,000 ED visits) to 2020 (29.97 per 100,000), with the larger share going to those involving opioids, which were up by 34.4%, compared with overdose visits not involving opioids (21.0%), the investigators said, based on data reported by 32 states and the District of Columbia to the CDC’s Drug Overdose Surveillance and Epidemiology system. All of the rate changes are statistically significant.

The number of overdose visits without opioid coinvolvement actually dropped, from 2019 (12,276) to 2020 (12,218), but not by enough to offset the decline in total visits, noted Dr. Liu, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control and associates.

The number of deaths from benzodiazepine overdose, on the other hand, did not drop in 2020. Those data, coming from 23 states participating in the CDC’s State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System, were available only for the first half of the year.

In those 6 months, The first quarter of 2020 also showed an increase, but exact numbers were not provided in the report. Overdose deaths rose by 22% for prescription forms of benzodiazepine and 520% for illicit forms in Q2 of 2020, compared with 2019, the researchers said.

Almost all of the benzodiazepine deaths (93%) in the first half of 2020 also involved opioids, mostly in the form of illicitly manufactured fentanyls (67% of all deaths). Between Q2 of 2019 and Q2 of 2020, involvement of illicit fentanyls in benzodiazepine overdose deaths increased from almost 57% to 71%, Dr. Liu and associates reported.

“Despite progress in reducing coprescribing [of opioids and benzodiazepines] before 2019, this study suggests a reversal in the decline in benzodiazepine deaths from 2017 to 2019, driven in part by increasing involvement of [illicitly manufactured fentanyls] in benzodiazepine deaths and influxes of illicit benzodiazepines,” they wrote.

In a year when emergency department visits dropped by almost 18%, visits for benzodiazepine overdoses did the opposite, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The actual increase in the number of overdose visits for benzodiazepine overdoses was quite small – from 15,547 in 2019 to 15,830 in 2020 (1.8%) – but the 11 million fewer ED visits magnified its effect, Stephen Liu, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The rate of benzodiazepine overdose visits to all visits increased by 23.7% from 2019 (24.22 per 100,000 ED visits) to 2020 (29.97 per 100,000), with the larger share going to those involving opioids, which were up by 34.4%, compared with overdose visits not involving opioids (21.0%), the investigators said, based on data reported by 32 states and the District of Columbia to the CDC’s Drug Overdose Surveillance and Epidemiology system. All of the rate changes are statistically significant.

The number of overdose visits without opioid coinvolvement actually dropped, from 2019 (12,276) to 2020 (12,218), but not by enough to offset the decline in total visits, noted Dr. Liu, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control and associates.

The number of deaths from benzodiazepine overdose, on the other hand, did not drop in 2020. Those data, coming from 23 states participating in the CDC’s State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System, were available only for the first half of the year.

In those 6 months, The first quarter of 2020 also showed an increase, but exact numbers were not provided in the report. Overdose deaths rose by 22% for prescription forms of benzodiazepine and 520% for illicit forms in Q2 of 2020, compared with 2019, the researchers said.

Almost all of the benzodiazepine deaths (93%) in the first half of 2020 also involved opioids, mostly in the form of illicitly manufactured fentanyls (67% of all deaths). Between Q2 of 2019 and Q2 of 2020, involvement of illicit fentanyls in benzodiazepine overdose deaths increased from almost 57% to 71%, Dr. Liu and associates reported.

“Despite progress in reducing coprescribing [of opioids and benzodiazepines] before 2019, this study suggests a reversal in the decline in benzodiazepine deaths from 2017 to 2019, driven in part by increasing involvement of [illicitly manufactured fentanyls] in benzodiazepine deaths and influxes of illicit benzodiazepines,” they wrote.

FROM MMWR

Number of global deaths by suicide increased over 30 years

The overall global number of deaths by suicide increased by almost 20,000 during the past 30 years, new research shows.

The increase occurred despite a significant decrease in age-specific suicide rates from 1990 through 2019, according to data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.

Population growth, population aging, and changes in population age structure may explain the increase in number of suicide deaths, the investigators note.

“As suicide rates are highest among the elderly (70 years or above) for both genders in almost all regions of the world, the rapidly aging population globally will pose huge challenges for the reduction in the number of suicide deaths in the future,” write the researchers, led by Paul Siu Fai Yip, PhD, of the HKJC Center for Suicide Research and Prevention, University of Hong Kong, China.

The findings were published online Aug. 16 in Injury Prevention.

Global public health concern

Around the world, approximately 800,000 individuals die by suicide each year, while many others attempt suicide. Yet suicide has not received the same level of attention as other global public health concerns, such as HIV/AIDS and cancer, the investigators write.

They examined data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 to assess how demographic and epidemiologic factors contributed to the number of suicide deaths during the past 30 years.

The researchers also analyzed relationships between population growth, population age structure, income level, and gender- and age-specific suicide rates.

The Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 includes information from 204 countries about 369 diseases and injuries by age and gender. The dataset also includes population estimates for each year by location, age group, and gender.

In their analysis, the investigators looked at changes in suicide rates and the number of suicide deaths from 1990 to 2019 by gender and age group in the four income level regions defined by the World Bank. These categories include low-income, lower-middle–income, upper-middle–income, and high-income regions.

Number of deaths versus suicide rates

The number of deaths was 738,799 in 1990 and 758,696 in 2019.

The largest increase in deaths occurred in the lower-middle–income region, where the number of suicide deaths increased by 72,550 (from 232,340 to 304,890).

Population growth (300,942; 1,512.5%) was the major contributor to the overall increase in total number of suicide deaths. The second largest contributor was population age structure (189,512; 952.4%).

However, the effects of these factors were offset to a large extent by the effect of reduction in overall suicide rates (−470,556; −2,364.9%).

Interestingly, the overall suicide rate per 100,000 population decreased from 13.8 in 1990 to 9.8 in 2019.

The upper-middle–income region had the largest decline (−6.25 per 100,000), and the high-income region had the smallest decline (−1.77 per 100,000). Suicide rates also decreased in lower-middle–income (−2.51 per 100,000) and low-income regions (−1.96 per 100,000).

Reasons for the declines across all regions “have yet to be determined,” write the investigators. International efforts coordinated by the United Nations and World Health Organization likely contributed to these declines, they add.

‘Imbalance of resources’

The overall reduction in suicide rate of −4.01 per 100,000 “was mainly due” to reduction in age-specific suicide rates (−6.09; 152%), the researchers report.

This effect was partly offset, however, by the effect of the changing population age structure (2.08; −52%). In the high-income–level region, for example, the reduction in age-specific suicide rate (−3.83; 216.3%) was greater than the increase resulting from the change in population age structure (2.06; −116.3%).

“The overall contribution of population age structure mainly came from the 45-64 (565.2%) and 65+ (528.7%) age groups,” the investigators write. “This effect was observed in middle-income– as well as high-income–level regions, reflecting the global effect of population aging.”

They add that world populations will “experience pronounced and historically unprecedented aging in the coming decades” because of increasing life expectancy and declining fertility.

Men, but not women, had a notable increase in total number of suicide deaths. The significant effect of male population growth (177,128; 890.2% vs. 123,814; 622.3% for women) and male population age structure (120,186; 604.0% vs. 69,325; 348.4%) were the main factors that explained this increase, the investigators note.

However, from 1990 to 2019, the overall suicide rate per 100,000 men decreased from 16.6 to 13.5 (–3.09). The decline in overall suicide rate was even greater for women, from 11.0 to 6.1 (–4.91).

This finding was particularly notable in the upper-middle–income region (–8.12 women vs. –4.37 men per 100,000).

“This study highlighted the considerable imbalance of the resources in carrying out suicide prevention work, especially in low-income and middle-income countries,” the investigators write.

“It is time to revisit this situation to ensure that sufficient resources can be redeployed globally to meet the future challenges,” they add.

The study was funded by a Humanities and Social Sciences Prestigious Fellowship, which Dr. Yip received. He declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The overall global number of deaths by suicide increased by almost 20,000 during the past 30 years, new research shows.

The increase occurred despite a significant decrease in age-specific suicide rates from 1990 through 2019, according to data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.

Population growth, population aging, and changes in population age structure may explain the increase in number of suicide deaths, the investigators note.

“As suicide rates are highest among the elderly (70 years or above) for both genders in almost all regions of the world, the rapidly aging population globally will pose huge challenges for the reduction in the number of suicide deaths in the future,” write the researchers, led by Paul Siu Fai Yip, PhD, of the HKJC Center for Suicide Research and Prevention, University of Hong Kong, China.

The findings were published online Aug. 16 in Injury Prevention.

Global public health concern

Around the world, approximately 800,000 individuals die by suicide each year, while many others attempt suicide. Yet suicide has not received the same level of attention as other global public health concerns, such as HIV/AIDS and cancer, the investigators write.

They examined data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 to assess how demographic and epidemiologic factors contributed to the number of suicide deaths during the past 30 years.

The researchers also analyzed relationships between population growth, population age structure, income level, and gender- and age-specific suicide rates.

The Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 includes information from 204 countries about 369 diseases and injuries by age and gender. The dataset also includes population estimates for each year by location, age group, and gender.

In their analysis, the investigators looked at changes in suicide rates and the number of suicide deaths from 1990 to 2019 by gender and age group in the four income level regions defined by the World Bank. These categories include low-income, lower-middle–income, upper-middle–income, and high-income regions.

Number of deaths versus suicide rates

The number of deaths was 738,799 in 1990 and 758,696 in 2019.

The largest increase in deaths occurred in the lower-middle–income region, where the number of suicide deaths increased by 72,550 (from 232,340 to 304,890).

Population growth (300,942; 1,512.5%) was the major contributor to the overall increase in total number of suicide deaths. The second largest contributor was population age structure (189,512; 952.4%).

However, the effects of these factors were offset to a large extent by the effect of reduction in overall suicide rates (−470,556; −2,364.9%).

Interestingly, the overall suicide rate per 100,000 population decreased from 13.8 in 1990 to 9.8 in 2019.

The upper-middle–income region had the largest decline (−6.25 per 100,000), and the high-income region had the smallest decline (−1.77 per 100,000). Suicide rates also decreased in lower-middle–income (−2.51 per 100,000) and low-income regions (−1.96 per 100,000).

Reasons for the declines across all regions “have yet to be determined,” write the investigators. International efforts coordinated by the United Nations and World Health Organization likely contributed to these declines, they add.

‘Imbalance of resources’

The overall reduction in suicide rate of −4.01 per 100,000 “was mainly due” to reduction in age-specific suicide rates (−6.09; 152%), the researchers report.

This effect was partly offset, however, by the effect of the changing population age structure (2.08; −52%). In the high-income–level region, for example, the reduction in age-specific suicide rate (−3.83; 216.3%) was greater than the increase resulting from the change in population age structure (2.06; −116.3%).

“The overall contribution of population age structure mainly came from the 45-64 (565.2%) and 65+ (528.7%) age groups,” the investigators write. “This effect was observed in middle-income– as well as high-income–level regions, reflecting the global effect of population aging.”

They add that world populations will “experience pronounced and historically unprecedented aging in the coming decades” because of increasing life expectancy and declining fertility.

Men, but not women, had a notable increase in total number of suicide deaths. The significant effect of male population growth (177,128; 890.2% vs. 123,814; 622.3% for women) and male population age structure (120,186; 604.0% vs. 69,325; 348.4%) were the main factors that explained this increase, the investigators note.

However, from 1990 to 2019, the overall suicide rate per 100,000 men decreased from 16.6 to 13.5 (–3.09). The decline in overall suicide rate was even greater for women, from 11.0 to 6.1 (–4.91).

This finding was particularly notable in the upper-middle–income region (–8.12 women vs. –4.37 men per 100,000).

“This study highlighted the considerable imbalance of the resources in carrying out suicide prevention work, especially in low-income and middle-income countries,” the investigators write.

“It is time to revisit this situation to ensure that sufficient resources can be redeployed globally to meet the future challenges,” they add.

The study was funded by a Humanities and Social Sciences Prestigious Fellowship, which Dr. Yip received. He declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The overall global number of deaths by suicide increased by almost 20,000 during the past 30 years, new research shows.

The increase occurred despite a significant decrease in age-specific suicide rates from 1990 through 2019, according to data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.

Population growth, population aging, and changes in population age structure may explain the increase in number of suicide deaths, the investigators note.

“As suicide rates are highest among the elderly (70 years or above) for both genders in almost all regions of the world, the rapidly aging population globally will pose huge challenges for the reduction in the number of suicide deaths in the future,” write the researchers, led by Paul Siu Fai Yip, PhD, of the HKJC Center for Suicide Research and Prevention, University of Hong Kong, China.

The findings were published online Aug. 16 in Injury Prevention.

Global public health concern

Around the world, approximately 800,000 individuals die by suicide each year, while many others attempt suicide. Yet suicide has not received the same level of attention as other global public health concerns, such as HIV/AIDS and cancer, the investigators write.

They examined data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 to assess how demographic and epidemiologic factors contributed to the number of suicide deaths during the past 30 years.

The researchers also analyzed relationships between population growth, population age structure, income level, and gender- and age-specific suicide rates.

The Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 includes information from 204 countries about 369 diseases and injuries by age and gender. The dataset also includes population estimates for each year by location, age group, and gender.

In their analysis, the investigators looked at changes in suicide rates and the number of suicide deaths from 1990 to 2019 by gender and age group in the four income level regions defined by the World Bank. These categories include low-income, lower-middle–income, upper-middle–income, and high-income regions.

Number of deaths versus suicide rates

The number of deaths was 738,799 in 1990 and 758,696 in 2019.

The largest increase in deaths occurred in the lower-middle–income region, where the number of suicide deaths increased by 72,550 (from 232,340 to 304,890).

Population growth (300,942; 1,512.5%) was the major contributor to the overall increase in total number of suicide deaths. The second largest contributor was population age structure (189,512; 952.4%).

However, the effects of these factors were offset to a large extent by the effect of reduction in overall suicide rates (−470,556; −2,364.9%).

Interestingly, the overall suicide rate per 100,000 population decreased from 13.8 in 1990 to 9.8 in 2019.

The upper-middle–income region had the largest decline (−6.25 per 100,000), and the high-income region had the smallest decline (−1.77 per 100,000). Suicide rates also decreased in lower-middle–income (−2.51 per 100,000) and low-income regions (−1.96 per 100,000).

Reasons for the declines across all regions “have yet to be determined,” write the investigators. International efforts coordinated by the United Nations and World Health Organization likely contributed to these declines, they add.

‘Imbalance of resources’

The overall reduction in suicide rate of −4.01 per 100,000 “was mainly due” to reduction in age-specific suicide rates (−6.09; 152%), the researchers report.

This effect was partly offset, however, by the effect of the changing population age structure (2.08; −52%). In the high-income–level region, for example, the reduction in age-specific suicide rate (−3.83; 216.3%) was greater than the increase resulting from the change in population age structure (2.06; −116.3%).

“The overall contribution of population age structure mainly came from the 45-64 (565.2%) and 65+ (528.7%) age groups,” the investigators write. “This effect was observed in middle-income– as well as high-income–level regions, reflecting the global effect of population aging.”

They add that world populations will “experience pronounced and historically unprecedented aging in the coming decades” because of increasing life expectancy and declining fertility.

Men, but not women, had a notable increase in total number of suicide deaths. The significant effect of male population growth (177,128; 890.2% vs. 123,814; 622.3% for women) and male population age structure (120,186; 604.0% vs. 69,325; 348.4%) were the main factors that explained this increase, the investigators note.

However, from 1990 to 2019, the overall suicide rate per 100,000 men decreased from 16.6 to 13.5 (–3.09). The decline in overall suicide rate was even greater for women, from 11.0 to 6.1 (–4.91).

This finding was particularly notable in the upper-middle–income region (–8.12 women vs. –4.37 men per 100,000).

“This study highlighted the considerable imbalance of the resources in carrying out suicide prevention work, especially in low-income and middle-income countries,” the investigators write.

“It is time to revisit this situation to ensure that sufficient resources can be redeployed globally to meet the future challenges,” they add.

The study was funded by a Humanities and Social Sciences Prestigious Fellowship, which Dr. Yip received. He declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Report urges complete residency overhaul

from the Graduate Medical Education Review Committee (UGRC) of the Coalition for Physician Accountability.

The 275-page report presents preliminary findings that were released in April 2021 and a long list of stakeholder comments. According to the report, the coalition will meet soon to discuss the final recommendations and consider next steps toward implementation.

The UGRC includes representatives of national medical organizations, medical schools, and residency programs. Among the organizations that participated in the report’s creation are the American Medical Association, the National Board of Medical Examiners, the American Osteopathic Association, the National Board of Osteopathic Medical Examiners, the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates, and the Association of American Medical Colleges.

The report identifies a list of challenges that affect the transition of medical students into residency programs and beyond. They include:

- Too much focus on finding and filling residency positions instead of “assuring learner competence and readiness for residency training”

- Inattention to assuring congruence between applicant goals and program missions

- Overreliance on licensure exam scores rather than “valid, trustworthy measures of students’ competence and clinical abilities”

- Increasing financial costs to students

- Individual and systemic biases in the UME-GME transition, as well as inequities related to international medical graduates

Seeking a common framework for competence

Overall, the report calls for increased standardization of how students are evaluated in medical school and how residency programs evaluate students. Less reliance should be placed on the numerical scores of the U.S. Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE), the report says, and more attention should be paid to the direct observation of student performance in clinical situations. In addition, the various organizations involved in the UME-GME transition process are asked to work better together.

To develop better methods of evaluating medical students and residents, UME and GME educators should jointly define and implement a common framework and set of competencies to apply to learners across the UME-GME transition, the report suggests.

While emphasizing the need for a broader student assessment framework, the report says, USMLE scores should also continue to be used in judging residency applicants. “Assessment information should be shared in residency applications and a postmatch learner handover. Licensing examinations should be used for their intended purpose to ensure requisite competence.”

Among the committee’s three dozen recommendations are the following:

- The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services should change the GME funding structure so that the initial residency period is calculated starting with the second year of postgraduate training. This change would allow residents to reconsider their career choices. Currently, if a resident decides to switch to another program or specialty after beginning training, the hospital may not receive full GME funding, so may be less likely to approve the change.

- Residency programs should improve recruitment practices to increase specialty-specific diversity of residents. Medical educators should also receive additional training regarding antiracism, avoiding bias, and ensuring equity.

- The self-reported demographic information of applicants to residency programs should be measured and shared with stakeholders, including the programs and medical schools, to promote equity. “A residency program that finds bias in its selection process could go back in real time to find qualified applicants who may have been missed, potentially improving outcomes,” the report notes.

- An interactive database of GME program and specialty track information should be created and made available to all applicants, medical schools, and residency programs at no cost to applicants. “Applicants and their advisors should be able to sort the information according to demographic and educational features that may significantly impact the likelihood of matching at a program.”

Less than half of applicants get in-depth reviews

The 2020 National Resident Matching Program Program Director Survey found that only 49% of applications received in-depth review. In light of this, the report suggests that the application system be updated to use modern information technology, including discrete fields for key data to expedite application reviews.

Many applications have been discarded because of various filters used to block consideration of certain applications. The report suggests that new filters be designed to ensure that each detects meaningful differences among applicants and promotes review based on mission alignment and likelihood of success in a program. Filters should be improved to decrease the likelihood of random exclusions of qualified applicants.

Specialty-specific, just-in-time training for all incoming first-year residents is also suggested to support the transition from the role of student to a physician ready to assume increased responsibility for patient care. In addition, the report urges adequate time be allowed between medical school graduation and residency to enable new residents to relocate and find homes.

The report also calls for a standardized process in the United States for initial licensing of doctors at entrance to residency in order to streamline the process of credentialing for both residency training and continuing practice.

Osteopathic students’ dilemma

To promote equitable treatment of applicants regardless of licensure examination requirements, comparable exams with different scales (COMLEX-USA and USMLE) should be reported within the electronic application system in a single field, the report said.

Osteopathic students, who make up 25% of U.S. medical students, must take the COMLEX-USA exam, but residency programs may filter them out if they don’t also take the USMLE exam. Thus, many osteopathic students take both exams, incurring extra time, cost, and stress.

The UGRC recommends creating a combined field in the electronic residency application service that normalizes the scores between the two exams. Residency programs could then filter applications based only on the single normalized score.

This approach makes sense from the viewpoint that it would reduce the pressure on osteopathic students to take the USMLE, Bryan Carmody, MD, an outspoken critic of various current training policies, said in an interview. But it could also have serious disadvantages.

For one thing, only osteopathic students can take the COMLEX-USA exam, he noted. If they don’t like their score, they can then take the USMLE test to get a higher score – an option that allopathic students don’t have. It’s not clear that they’d be prevented from doing this under the UGRC recommendation.

Second, he said, osteopathic students, on average, don’t do as well as allopathic students on the UMSLE exam. If they only take the COMLEX-USA test, they’re competing against other students who don’t do as well on tests as allopathic students do. If their scores were normalized with those of the USMLE test takers, they’d gain an unfair advantage against students who can only take the USMLE, including international medical graduates.

Although Dr. Carmody admitted that osteopathic students face a harder challenge than allopathic students in matching to residency programs, he said that the UGRC approach to the licensing exams might actually penalize them further. As a result of the scores of the two exams being averaged, residency program directors might discount the scores of all osteopathic students.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

from the Graduate Medical Education Review Committee (UGRC) of the Coalition for Physician Accountability.

The 275-page report presents preliminary findings that were released in April 2021 and a long list of stakeholder comments. According to the report, the coalition will meet soon to discuss the final recommendations and consider next steps toward implementation.

The UGRC includes representatives of national medical organizations, medical schools, and residency programs. Among the organizations that participated in the report’s creation are the American Medical Association, the National Board of Medical Examiners, the American Osteopathic Association, the National Board of Osteopathic Medical Examiners, the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates, and the Association of American Medical Colleges.

The report identifies a list of challenges that affect the transition of medical students into residency programs and beyond. They include:

- Too much focus on finding and filling residency positions instead of “assuring learner competence and readiness for residency training”

- Inattention to assuring congruence between applicant goals and program missions

- Overreliance on licensure exam scores rather than “valid, trustworthy measures of students’ competence and clinical abilities”

- Increasing financial costs to students

- Individual and systemic biases in the UME-GME transition, as well as inequities related to international medical graduates

Seeking a common framework for competence

Overall, the report calls for increased standardization of how students are evaluated in medical school and how residency programs evaluate students. Less reliance should be placed on the numerical scores of the U.S. Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE), the report says, and more attention should be paid to the direct observation of student performance in clinical situations. In addition, the various organizations involved in the UME-GME transition process are asked to work better together.

To develop better methods of evaluating medical students and residents, UME and GME educators should jointly define and implement a common framework and set of competencies to apply to learners across the UME-GME transition, the report suggests.

While emphasizing the need for a broader student assessment framework, the report says, USMLE scores should also continue to be used in judging residency applicants. “Assessment information should be shared in residency applications and a postmatch learner handover. Licensing examinations should be used for their intended purpose to ensure requisite competence.”

Among the committee’s three dozen recommendations are the following:

- The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services should change the GME funding structure so that the initial residency period is calculated starting with the second year of postgraduate training. This change would allow residents to reconsider their career choices. Currently, if a resident decides to switch to another program or specialty after beginning training, the hospital may not receive full GME funding, so may be less likely to approve the change.

- Residency programs should improve recruitment practices to increase specialty-specific diversity of residents. Medical educators should also receive additional training regarding antiracism, avoiding bias, and ensuring equity.

- The self-reported demographic information of applicants to residency programs should be measured and shared with stakeholders, including the programs and medical schools, to promote equity. “A residency program that finds bias in its selection process could go back in real time to find qualified applicants who may have been missed, potentially improving outcomes,” the report notes.

- An interactive database of GME program and specialty track information should be created and made available to all applicants, medical schools, and residency programs at no cost to applicants. “Applicants and their advisors should be able to sort the information according to demographic and educational features that may significantly impact the likelihood of matching at a program.”

Less than half of applicants get in-depth reviews

The 2020 National Resident Matching Program Program Director Survey found that only 49% of applications received in-depth review. In light of this, the report suggests that the application system be updated to use modern information technology, including discrete fields for key data to expedite application reviews.

Many applications have been discarded because of various filters used to block consideration of certain applications. The report suggests that new filters be designed to ensure that each detects meaningful differences among applicants and promotes review based on mission alignment and likelihood of success in a program. Filters should be improved to decrease the likelihood of random exclusions of qualified applicants.

Specialty-specific, just-in-time training for all incoming first-year residents is also suggested to support the transition from the role of student to a physician ready to assume increased responsibility for patient care. In addition, the report urges adequate time be allowed between medical school graduation and residency to enable new residents to relocate and find homes.

The report also calls for a standardized process in the United States for initial licensing of doctors at entrance to residency in order to streamline the process of credentialing for both residency training and continuing practice.

Osteopathic students’ dilemma

To promote equitable treatment of applicants regardless of licensure examination requirements, comparable exams with different scales (COMLEX-USA and USMLE) should be reported within the electronic application system in a single field, the report said.

Osteopathic students, who make up 25% of U.S. medical students, must take the COMLEX-USA exam, but residency programs may filter them out if they don’t also take the USMLE exam. Thus, many osteopathic students take both exams, incurring extra time, cost, and stress.

The UGRC recommends creating a combined field in the electronic residency application service that normalizes the scores between the two exams. Residency programs could then filter applications based only on the single normalized score.

This approach makes sense from the viewpoint that it would reduce the pressure on osteopathic students to take the USMLE, Bryan Carmody, MD, an outspoken critic of various current training policies, said in an interview. But it could also have serious disadvantages.

For one thing, only osteopathic students can take the COMLEX-USA exam, he noted. If they don’t like their score, they can then take the USMLE test to get a higher score – an option that allopathic students don’t have. It’s not clear that they’d be prevented from doing this under the UGRC recommendation.

Second, he said, osteopathic students, on average, don’t do as well as allopathic students on the UMSLE exam. If they only take the COMLEX-USA test, they’re competing against other students who don’t do as well on tests as allopathic students do. If their scores were normalized with those of the USMLE test takers, they’d gain an unfair advantage against students who can only take the USMLE, including international medical graduates.

Although Dr. Carmody admitted that osteopathic students face a harder challenge than allopathic students in matching to residency programs, he said that the UGRC approach to the licensing exams might actually penalize them further. As a result of the scores of the two exams being averaged, residency program directors might discount the scores of all osteopathic students.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

from the Graduate Medical Education Review Committee (UGRC) of the Coalition for Physician Accountability.

The 275-page report presents preliminary findings that were released in April 2021 and a long list of stakeholder comments. According to the report, the coalition will meet soon to discuss the final recommendations and consider next steps toward implementation.

The UGRC includes representatives of national medical organizations, medical schools, and residency programs. Among the organizations that participated in the report’s creation are the American Medical Association, the National Board of Medical Examiners, the American Osteopathic Association, the National Board of Osteopathic Medical Examiners, the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates, and the Association of American Medical Colleges.

The report identifies a list of challenges that affect the transition of medical students into residency programs and beyond. They include:

- Too much focus on finding and filling residency positions instead of “assuring learner competence and readiness for residency training”

- Inattention to assuring congruence between applicant goals and program missions

- Overreliance on licensure exam scores rather than “valid, trustworthy measures of students’ competence and clinical abilities”

- Increasing financial costs to students

- Individual and systemic biases in the UME-GME transition, as well as inequities related to international medical graduates

Seeking a common framework for competence

Overall, the report calls for increased standardization of how students are evaluated in medical school and how residency programs evaluate students. Less reliance should be placed on the numerical scores of the U.S. Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE), the report says, and more attention should be paid to the direct observation of student performance in clinical situations. In addition, the various organizations involved in the UME-GME transition process are asked to work better together.

To develop better methods of evaluating medical students and residents, UME and GME educators should jointly define and implement a common framework and set of competencies to apply to learners across the UME-GME transition, the report suggests.

While emphasizing the need for a broader student assessment framework, the report says, USMLE scores should also continue to be used in judging residency applicants. “Assessment information should be shared in residency applications and a postmatch learner handover. Licensing examinations should be used for their intended purpose to ensure requisite competence.”

Among the committee’s three dozen recommendations are the following:

- The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services should change the GME funding structure so that the initial residency period is calculated starting with the second year of postgraduate training. This change would allow residents to reconsider their career choices. Currently, if a resident decides to switch to another program or specialty after beginning training, the hospital may not receive full GME funding, so may be less likely to approve the change.

- Residency programs should improve recruitment practices to increase specialty-specific diversity of residents. Medical educators should also receive additional training regarding antiracism, avoiding bias, and ensuring equity.

- The self-reported demographic information of applicants to residency programs should be measured and shared with stakeholders, including the programs and medical schools, to promote equity. “A residency program that finds bias in its selection process could go back in real time to find qualified applicants who may have been missed, potentially improving outcomes,” the report notes.

- An interactive database of GME program and specialty track information should be created and made available to all applicants, medical schools, and residency programs at no cost to applicants. “Applicants and their advisors should be able to sort the information according to demographic and educational features that may significantly impact the likelihood of matching at a program.”

Less than half of applicants get in-depth reviews

The 2020 National Resident Matching Program Program Director Survey found that only 49% of applications received in-depth review. In light of this, the report suggests that the application system be updated to use modern information technology, including discrete fields for key data to expedite application reviews.

Many applications have been discarded because of various filters used to block consideration of certain applications. The report suggests that new filters be designed to ensure that each detects meaningful differences among applicants and promotes review based on mission alignment and likelihood of success in a program. Filters should be improved to decrease the likelihood of random exclusions of qualified applicants.

Specialty-specific, just-in-time training for all incoming first-year residents is also suggested to support the transition from the role of student to a physician ready to assume increased responsibility for patient care. In addition, the report urges adequate time be allowed between medical school graduation and residency to enable new residents to relocate and find homes.

The report also calls for a standardized process in the United States for initial licensing of doctors at entrance to residency in order to streamline the process of credentialing for both residency training and continuing practice.

Osteopathic students’ dilemma

To promote equitable treatment of applicants regardless of licensure examination requirements, comparable exams with different scales (COMLEX-USA and USMLE) should be reported within the electronic application system in a single field, the report said.

Osteopathic students, who make up 25% of U.S. medical students, must take the COMLEX-USA exam, but residency programs may filter them out if they don’t also take the USMLE exam. Thus, many osteopathic students take both exams, incurring extra time, cost, and stress.

The UGRC recommends creating a combined field in the electronic residency application service that normalizes the scores between the two exams. Residency programs could then filter applications based only on the single normalized score.

This approach makes sense from the viewpoint that it would reduce the pressure on osteopathic students to take the USMLE, Bryan Carmody, MD, an outspoken critic of various current training policies, said in an interview. But it could also have serious disadvantages.

For one thing, only osteopathic students can take the COMLEX-USA exam, he noted. If they don’t like their score, they can then take the USMLE test to get a higher score – an option that allopathic students don’t have. It’s not clear that they’d be prevented from doing this under the UGRC recommendation.

Second, he said, osteopathic students, on average, don’t do as well as allopathic students on the UMSLE exam. If they only take the COMLEX-USA test, they’re competing against other students who don’t do as well on tests as allopathic students do. If their scores were normalized with those of the USMLE test takers, they’d gain an unfair advantage against students who can only take the USMLE, including international medical graduates.

Although Dr. Carmody admitted that osteopathic students face a harder challenge than allopathic students in matching to residency programs, he said that the UGRC approach to the licensing exams might actually penalize them further. As a result of the scores of the two exams being averaged, residency program directors might discount the scores of all osteopathic students.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Self-described ‘assassin,’ now doctor, indicted for 1M illegal opioid doses

A according to the U.S. Department of Justice. The substances include oxycodone and morphine.

Adrian Dexter Talbot, MD, 55, of Slidell, La., is also charged with maintaining a medical clinic for the purpose of illegally distributing controlled substances, per the indictment.

Because the opioid prescriptions were filled using beneficiaries’ health insurance, Dr. Talbot is also charged with defrauding Medicare, Medicaid, and Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Louisiana of more than $5.1 million.

When contacted by this news organization for comment on the case via Twitter, Dr. Talbot or a representative responded with a link to his self-published book on Amazon. In his author bio, Dr. Talbot refers to himself as “a former assassin,” “retired military commander,” and “leader of the Medellin Cartel’s New York operations at the age of 16.” The Medellin Cartel is a notorious drug distribution empire.

Dr. Talbot is listed as the author of another book on Google Books detailing his time as a “former teenage assassin” and leader of the cartel, told as he struggles with early onset Alzheimer’s.

Dr. Talbot could spend decades in prison

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, 444 residents of the Bayou State lost their lives because of an opioid-related drug overdose in 2018. During that year, the state’s health care providers wrote more than 79.4 opioid prescriptions for every 100 persons, which puts the state in the top five in the United States in 2018, when the average U.S. rate was 51.4 prescriptions per 100 persons.

Charged with one count each of conspiracy to unlawfully distribute and dispense controlled substances and maintaining drug-involved premises and conspiracy to commit health care fraud, Dr. Talbot is also charged with four counts of unlawfully distributing and dispensing controlled substances. He is scheduled for a federal court appearance on September 10.

In addition to presigning prescriptions for individuals he didn’t meet or examine, federal officials allege Dr. Talbot hired another health care provider to similarly presign prescriptions for people who weren’t examined at a medical practice in Slidell, where Dr. Talbot was employed. The DOJ says Dr. Talbot took a full-time job in Pineville, La., and presigned prescriptions while no longer physically present at the Slidell clinic.

A speaker’s bio for Dr. Talbot indicates he worked as chief of medical services for the Alexandria Veterans Affairs Health Care System in Pineville.

According to the DOJ’s indictment, Dr. Talbot was aware that patients were filling the prescriptions that were provided outside the scope of professional practice and not for a legitimate medical purpose. This is what triggered the DOJ’s fraudulent billing claim.

Dr. Talbot faces a maximum penalty of 10 years for conspiracy to commit health care fraud and 20 years each for the other counts, if convicted.

Dr. Talbot was candidate for local coroner

In February 2015, Dr. Talbot announced his candidacy for coroner for St. Tammany Parish, about an hour’s drive south of New Orleans, reported the Times Picayune. The seat was open because the previous coroner had resigned and ultimately pleaded guilty to a federal corruption charge.

The Times Picayune reported at the time that Dr. Talbot was a U.S. Navy veteran, in addition to serving as medical director and a primary care physician at the Medical Care Center in Slidell. Among the services provided to his patients were evaluations and treatment for substance use and mental health disorders, according to a press release issued by Dr. Talbot’s campaign.