User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Comorbidities and Lifestyle Risk Factors Associated With Scabies Infestation

Comorbidities and Lifestyle Risk Factors Associated With Scabies Infestation

To the Editor:

Scabies infestation, which has been recognized as a neglected tropical disease by the World Health Organization since 2017, is caused by the human itch mite (Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis).1 Infected individuals experience a pruritic papular rash when the mite burrows into the epidermis, where it lives and lays eggs.2,3 Infected individuals also may develop bacterial superinfections if the skin barrier becomes compromised, leading to systemic complications and considerable morbidity.3

In countries with high human development indices, scabies outbreaks are linked to densely populated living conditions, such as those found in nursing homes or prisons.3,4 Scabies also is transmitted via sexual contact in adults. Beyond immunosuppression, little is known about other comorbid conditions or lifestyle risk factors associated with scabies infestation.2 Because scabies can mimic a range of other dermatologic conditions such as folliculitis, atopic dermatitis, and arthropod bites, misdiagnosis is common and can lead to delayed treatment and increased transmission risk.4 In this study, we sought to examine comorbid conditions and/or lifestyle risk factors associated with scabies infestation.

A matched case-control study was performed using the Registered Tier dataset of the National Institutes of Health All of Us Research Program Curated Data Repository version 7, which includes more than 400,000 unique participants aged 18 years or older from across the United States. The All of Us Research Program excludes adults who are unable to consent independently as well as incarcerated populations and children younger than 18 years. Participants diagnosed with scabies were identified using SNOMED code 62752005 and compared to a control group matched 1:4 based on age, sex, and selfidentified race. SNOMED codes also were used to identify various comorbidities and lifestyle risk factors, including depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, schizophrenia, peripheral vascular disease (PVD), HIV, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), unsheltered status, tobacco use, difficulty with activities of daily living, insurance status, and any recent travel history. Logistic regression models were used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and estimate effect sizes, with statistical significance set at P<.05.

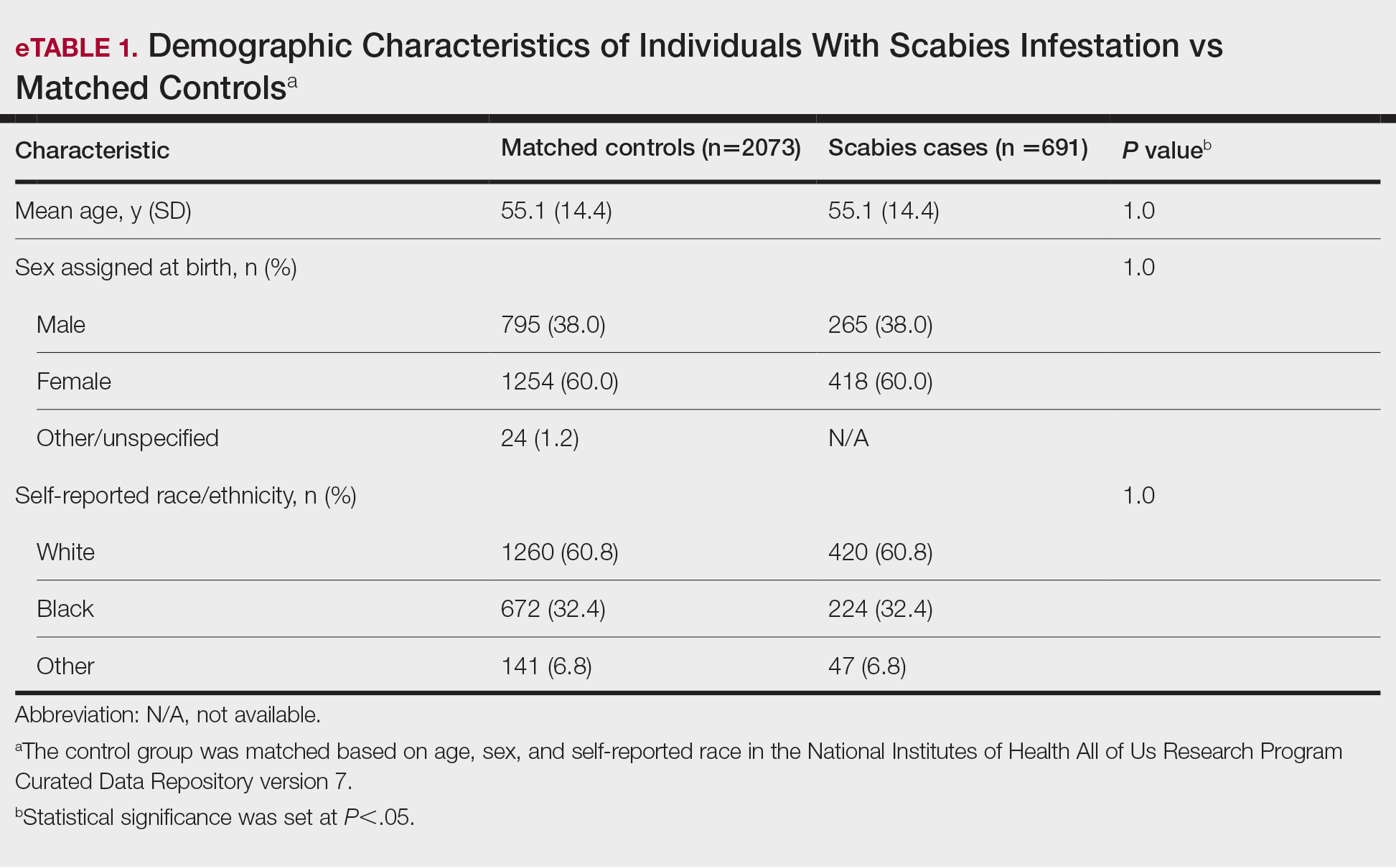

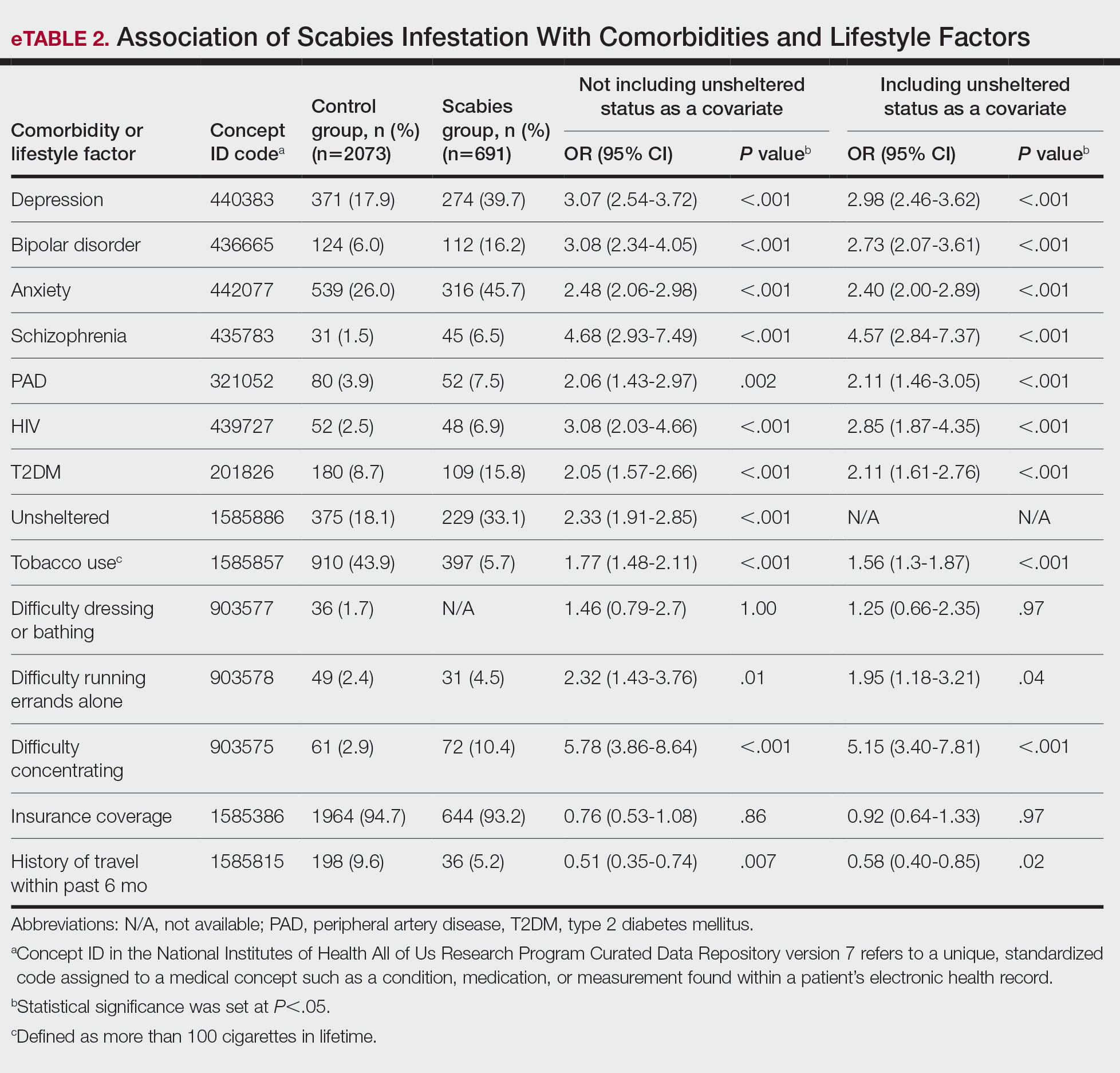

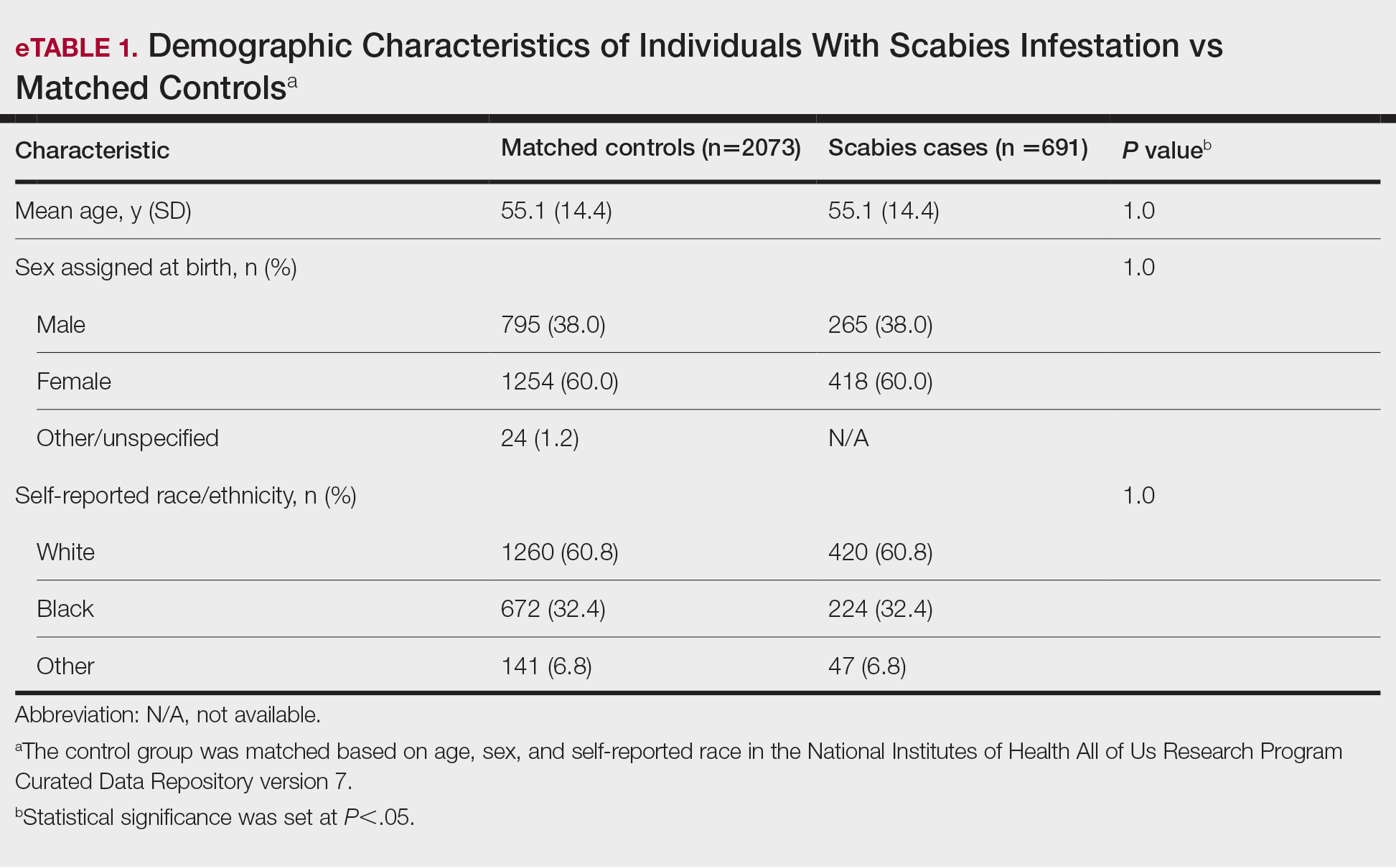

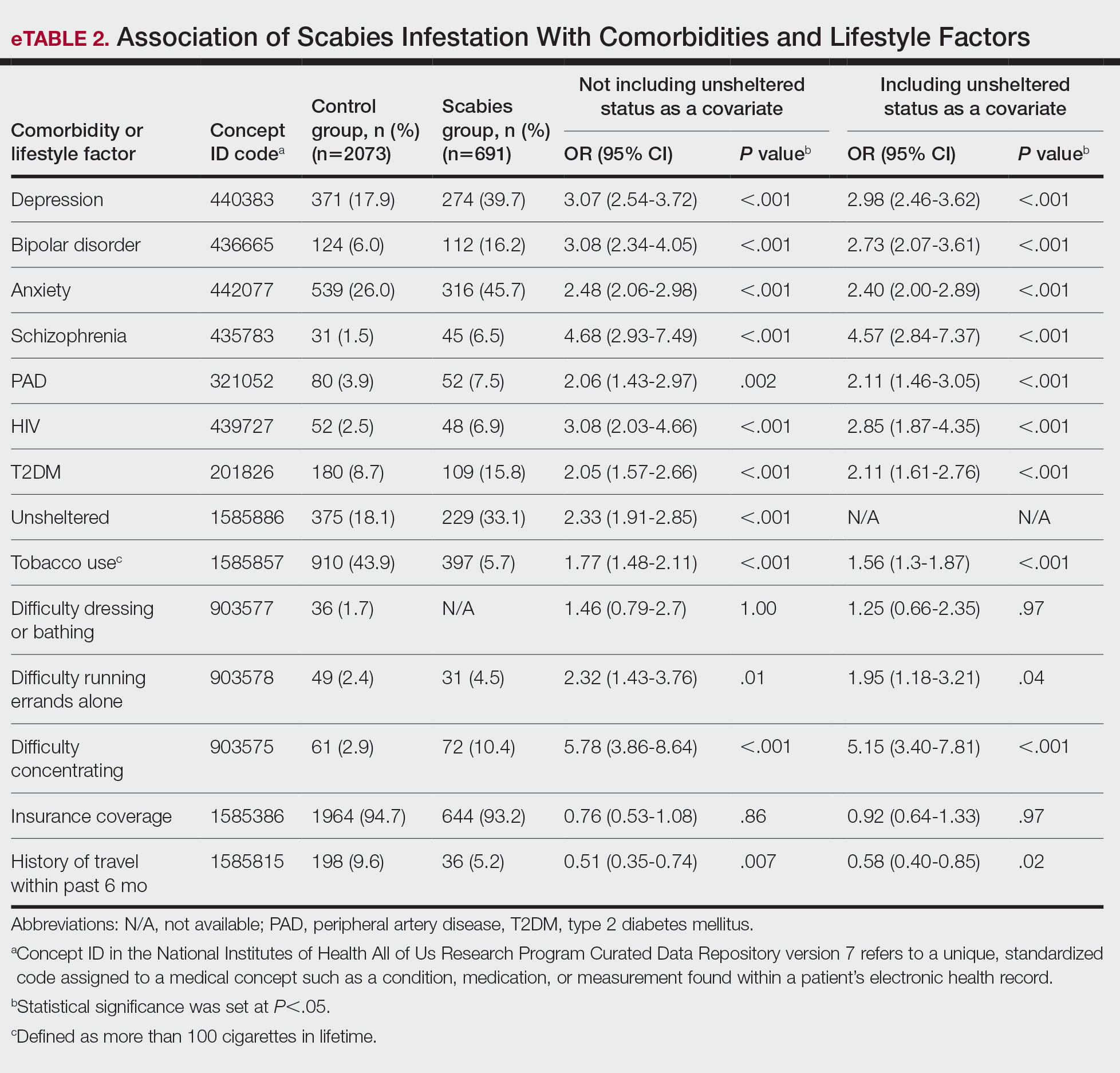

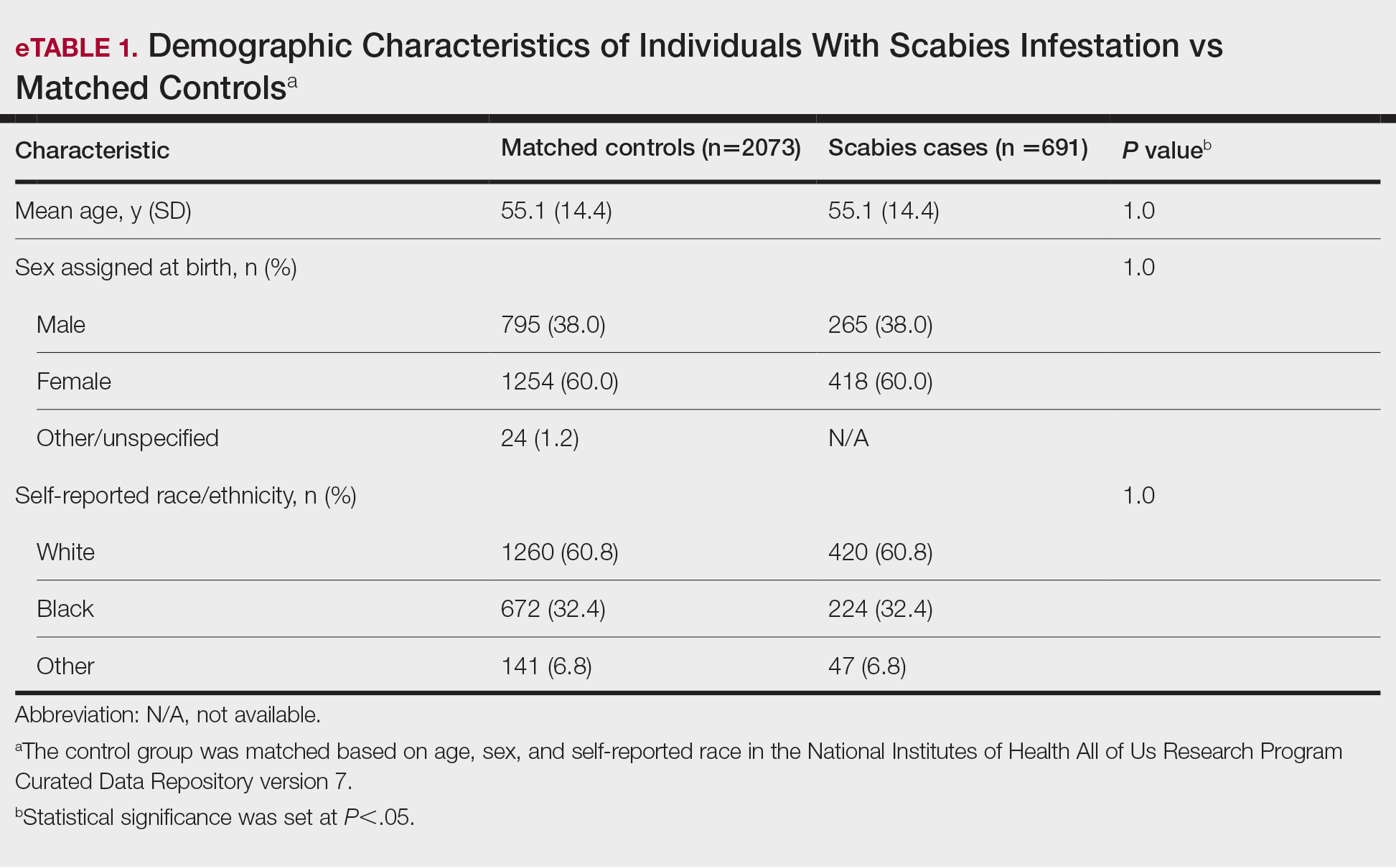

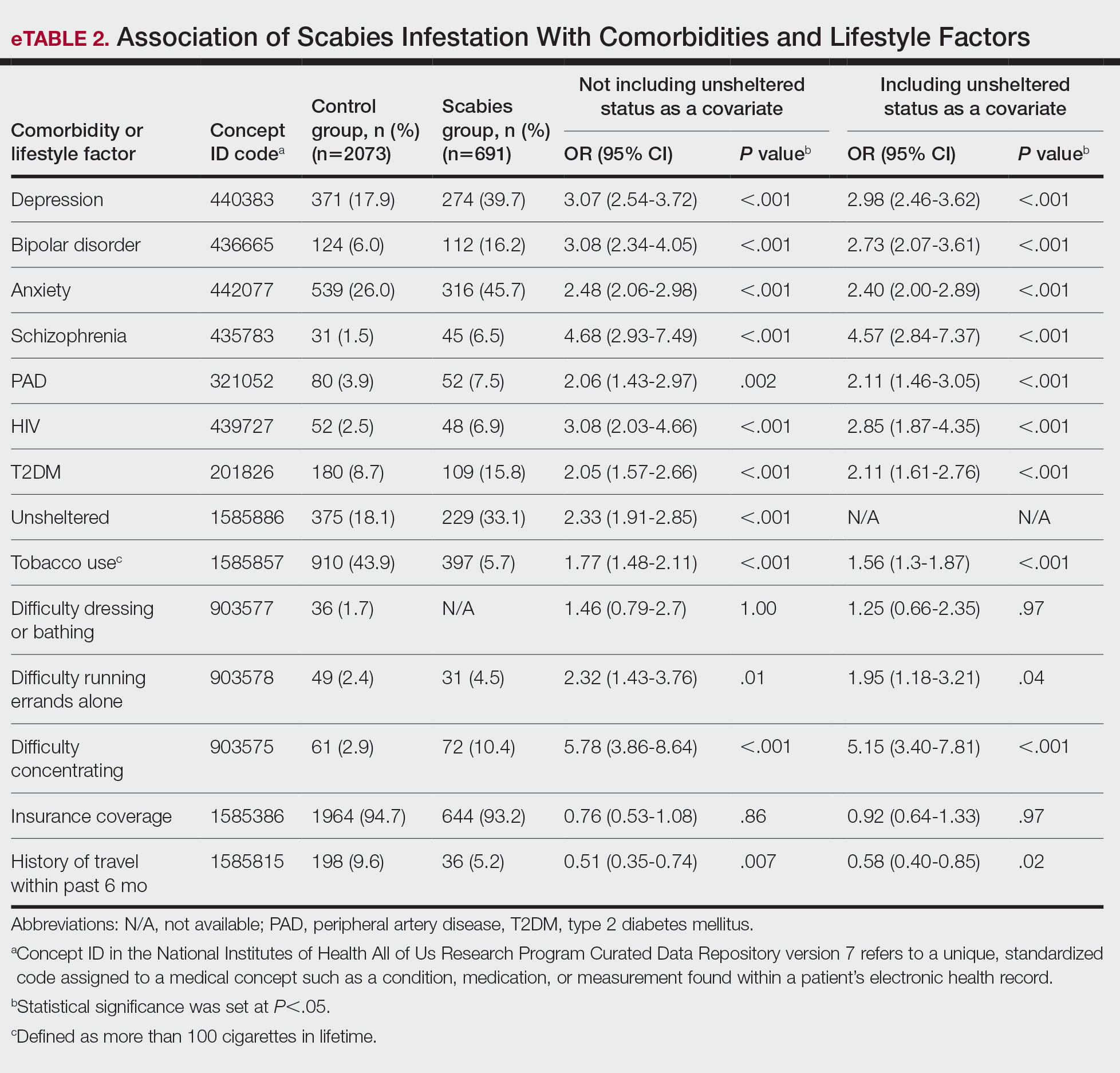

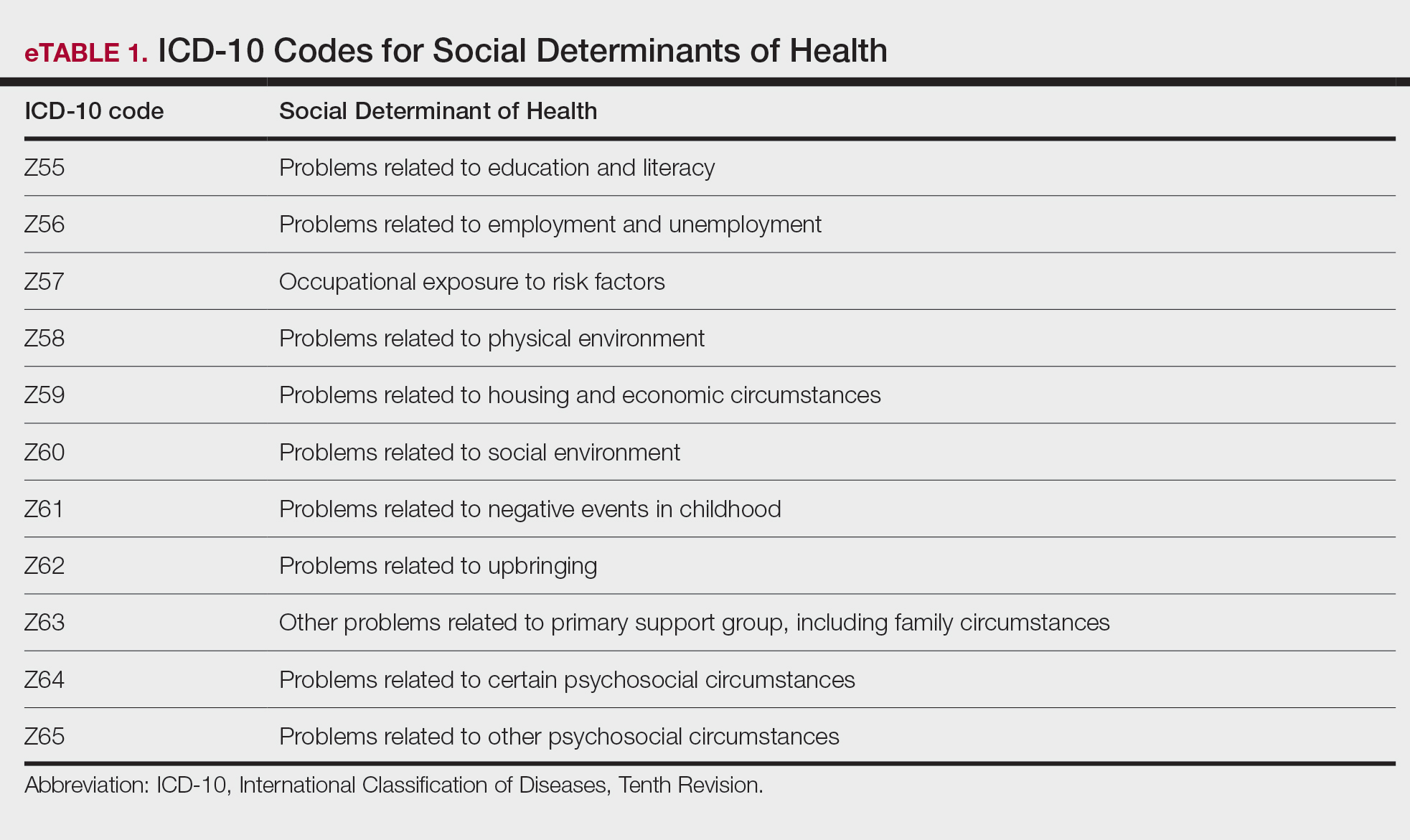

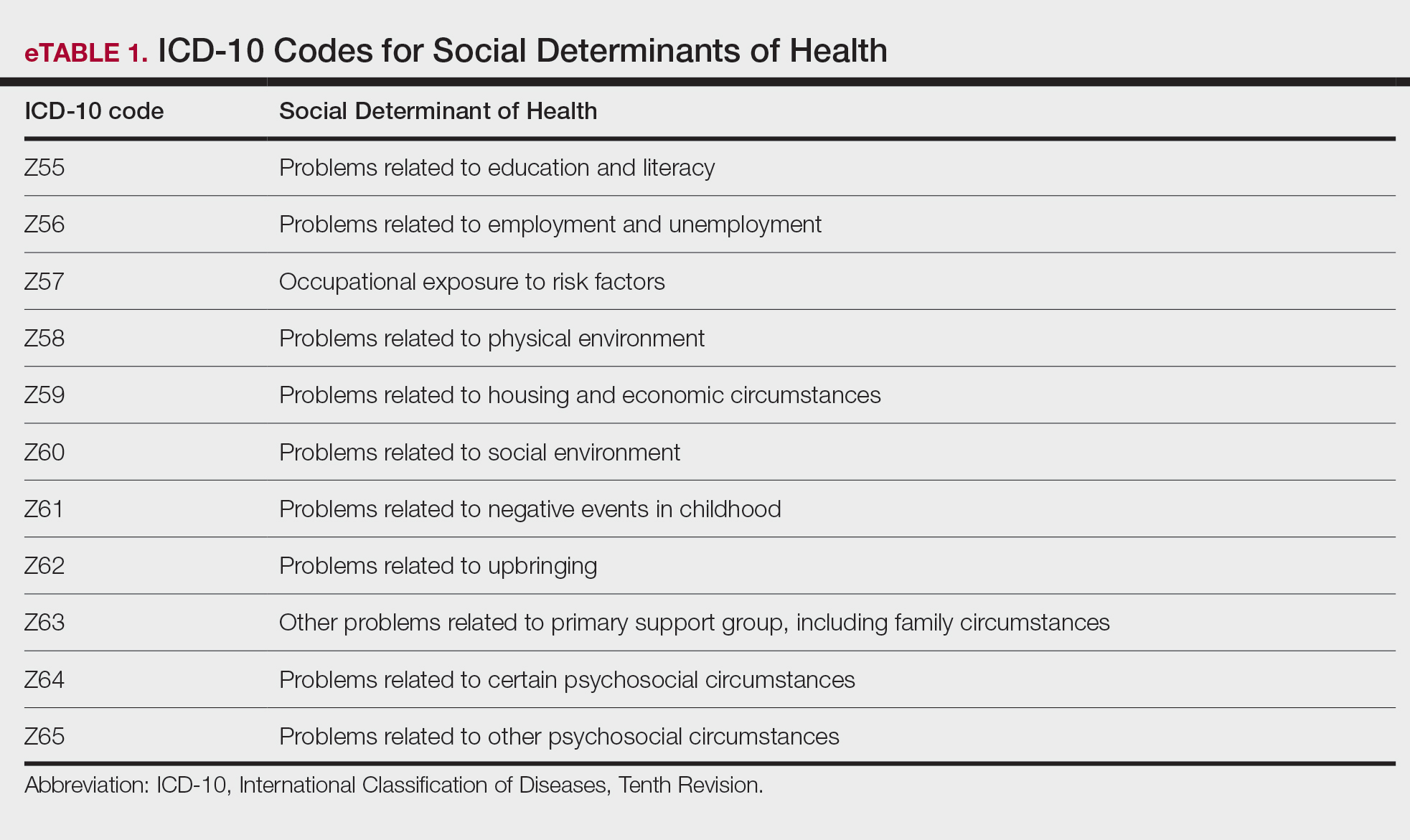

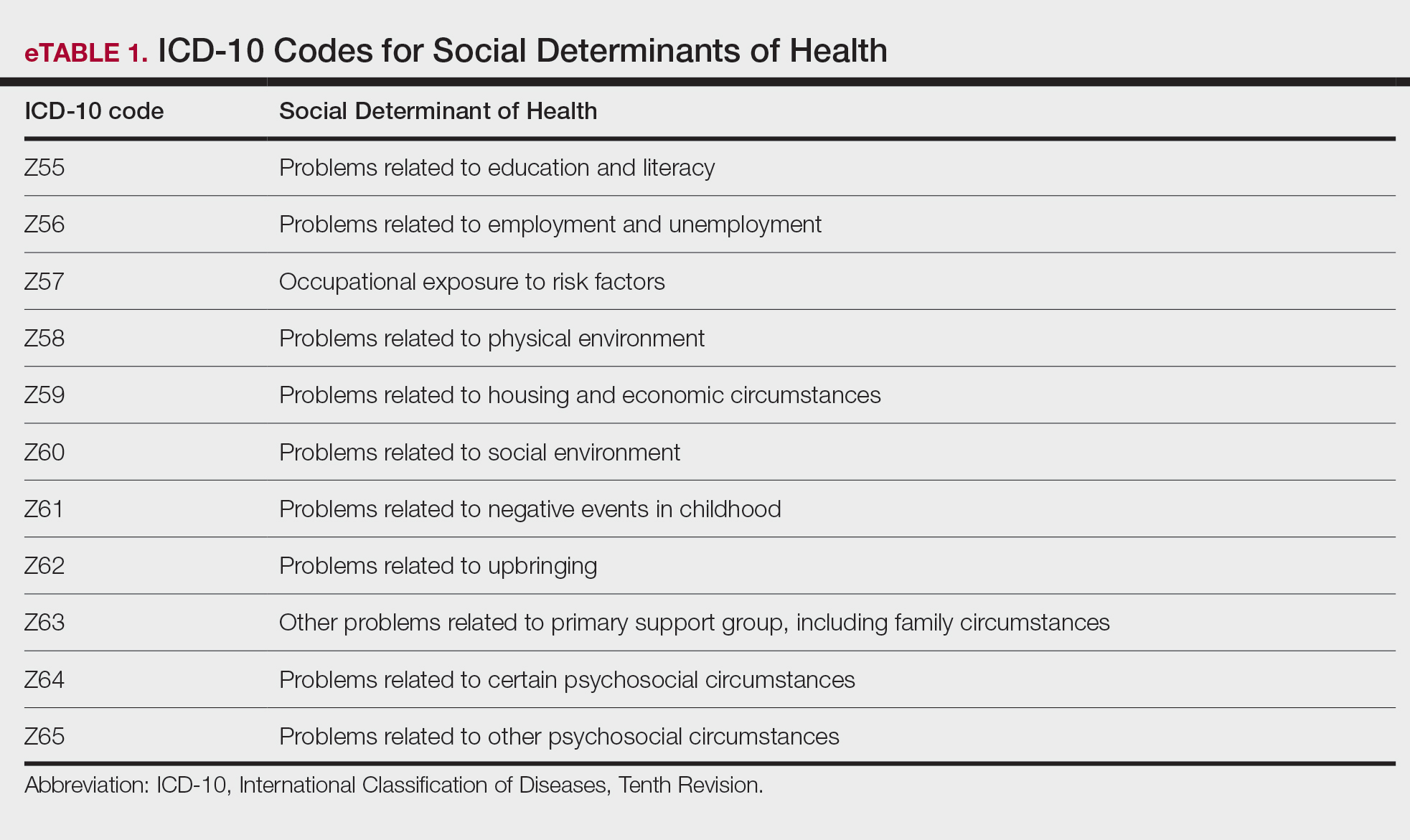

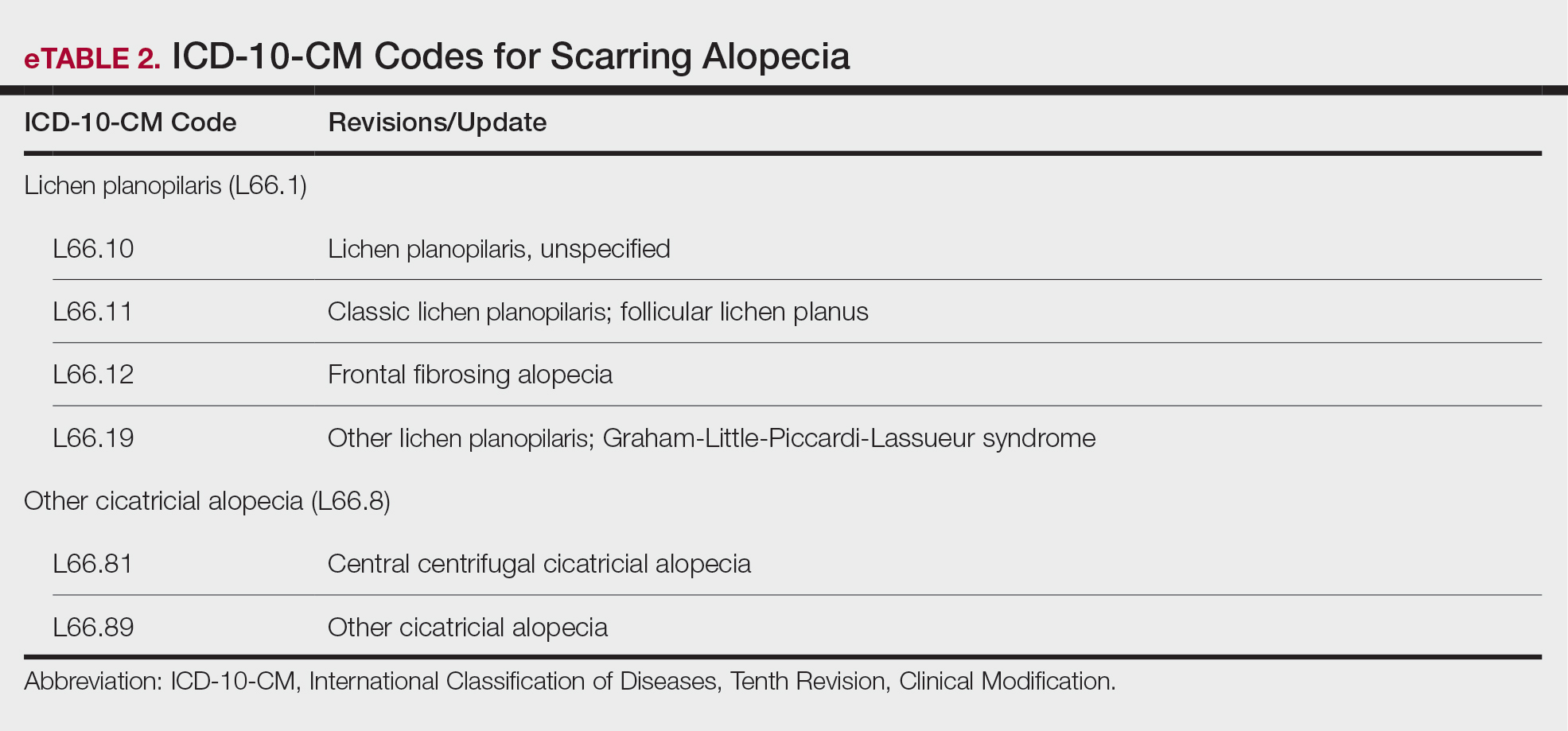

We identified 691 cases of scabies infestation and 2073 controls. The average age of the patients diagnosed with scabies was 55.1 years. Seventy percent (481/691) identified as female and 32.4% (224/491) identified as Black or African American. Matched controls were similar for all analyzed demographic characteristics (P=1.0)(eTable 1). Patients diagnosed with scabies were more likely to be unsheltered (OR, 2.33 [95% CI, 1.91-2.85]), use tobacco (OR 1.77 [95% CI, 1.48-2.11]) and have a comorbid diagnosis of HIV (OR, 3.08 [95% CI, 2.03-4.66]), T2DM (OR, 2.05 [95% CI, 1.57- 2.66]) or PVD (OR, 2.06 [95% CI, 1.43-2.97]) compared with controls (P<.001). Psychiatric comorbidities were more common in the patients diagnosed with scabies, including depression (OR, 3.07 [95% CI, 2.54-3.72]), anxiety (OR, 2.48 [95% CI, 2.06-2.98]), bipolar disorder (OR, 3.08 [95% CI, 2.34-4.05]), and schizophrenia (OR, 4.68 [95% CI, 2.93-7.49])(P<.001). Difficulties with activities of daily living, including running errands alone (OR, 2.32 [95% CI, 1.43-3.76]) and concentrating (OR, 5.78; 95% CI, 3.86-8.64), were more prevalent in the scabies group compared to controls (both P<.05). In a multivariate logistic regression model including unsheltered status as a covariate, all associations remained statistically significant (P<.05)(eTable 2).

This large diverse study demonstrated an association between scabies infestation and unsheltered status. Previous studies have shown that unsheltered populations are at increased risk for many dermatologic conditions, perhaps due to decreased access to health care and social support, lack of access to hygiene facilities (eg, public showers), and increased prevalence of substance use and psychiatric disorders among this population.5 In a cross-sectional analysis of hospitalized patients, 8.6% of unsheltered patients (n=197) had an ectoparasitic disease (including scabies) compared with 1.0% of patients with stable housing (n=1018), with a 9.43-fold increased risk for ectoparasitic infestation among unsheltered patients (95% CI, 3.79-23.47; P<.001).6 Increased attention to public health initiatives among unsheltered populations— including access to hygiene facilities and increased dermatologic services—are needed, as ectoparasitic infections are both preventable and treatable, and these initiatives could reduce morbidity associated with superimposed bacterial infections for which unsheltered patients are at increased risk.6

Our results also showed that individuals diagnosed with scabies were more likely than the controls to have been diagnosed with HIV, T2DM, and PVD. Our findings are similar to those of a systematic review of immunosuppressive factors associated with crusted scabies (a severe form of scabies infestation) in which 10.2% and 15.7% of patients (n=683) had comorbid HIV and T2DM, respectively.7 A functioning cell-mediated response to scabies mite antigens limits proliferation of the human itch mite; thus, infection with HIV/AIDS, which induces the destruction of CD4+ T cells, limits the immune system’s ability to mount an effective response against these antigens. The association of scabies with T2DM likely is multifactorial; for example, chronic hyperglycemia may lead to immune system impairment, and peripheral neuropathy may reduce the itch sensation, allowing scabies mites to proliferate without removal by scratching.7 In a descriptive epidemiologic study in Japan, 11.7% of patients with scabies (N=857) had comorbid PVD.8 Peripheral vascular disease can lead to the development of ulcers, gangrene, and stasis dermatitis, all of which compromise the skin barrier and increase susceptibility to infection.9 Notably, these associations remained even when unsheltered status was considered as a confounding variable. Because individuals with HIV, T2DM, and PVD may be at higher risk for serious complications of scabies infestation (eg, secondary bacterial infections, invasive group A streptococcal infections), prompt detection and treatment of scabies are crucial in curbing morbidity in these at-risk populations.

Our study also demonstrated that psychiatric comorbidities including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia were associated with scabies infestation, even when controlling for unsheltered status, which may have a bidirectional relationship with mental health disorders.10 In a cross-sectional study of 83 adult patients diagnosed with scabies, 72.2% (60/83) reported moderate to extremely large effect of scabies infestation on quality of life using the Dermatology Life Quality Index, and these scores positively correlated with increased Beck Depression Scale and Beck Anxiety Scale scores (rs=0.448 and rs=0.456 0.456, respectively; both P=.000). The results of this study suggest that scabies negatively impacts quality of life, which might increase symptoms of depression and anxiety.11

Studies are needed to assess whether patients with pre-existing depression and anxiety face increased risk for scabies infestation. In a retrospective case-control study using data from the National Health Insurance Research Database of Taiwan, 0.8% (58/7096) of patients with scabies (n=7096) and 0.4% of controls (n=28,375) were newly diagnosed with bipolar disorder over a 7-year period, indicating a 1.55-fold increased risk for bipolar disorder in patients with scabies compared to those without (95% CI, 1.12-2.09; P<.05).12 Future studies are needed to determine whether the relationship between bipolar disorder and scabies is bidirectional, with pre-existing bipolar disorder evaluated as a risk factor for subsequent scabies infestation. Increased difficulties with activities of daily living, including running errands independently and concentrating, were associated with scabies. These difficulties may reflect sequelae of psychiatric illness or pruritus associated with scabies affecting daily living.

Physician awareness of comorbidities and lifestyle risk factors associated with scabies infestation may improve diagnosis and prevent treatment delays. In a retrospective study at a single dermatology outpatient clinic, 45.3% of patients with scabies (n=428) had previously been misdiagnosed with another dermatologic condition, and the most common erroneous diagnosis was atopic dermatitis.13 Our study provides a framework of comorbidities and lifestyle risk factors associated with scabies infestation that dermatologists can use to stratify patients who may be at greater risk for this condition, allowing dermatologists to select appropriate treatment when clinical signs are ambiguous.

Limitations of our study included the potential for miscoding in the database, lack of information about treatment regimens employed (if any), and lack of information about the temporal relationship between associations.

In summary, it is recommended that patients with pruritus and other characteristic clinical findings of scabies receive appropriate workup for scabies regardless of risk factors; however, the medical and psychiatric comorbidities and lifestyle risk factors identified in this study may help to identify at-risk patients. Our study showed that unsheltered patients are at increased risk for scabies, potentially due to unique dermatologic challenges and lack of access to health care and hygiene facilities. Positive correlations between scabies and HIV, T2DM, and PVD suggest that patients with chronic immunocompromising illnesses who live in group homes or other crowded quarters and present with symptoms could be evaluated for scabies infestation to prevent widespread and difficult- to-control outbreaks in these communities. Based on our findings, scabies also should be included in the differential diagnosis for patients with psychiatric illness and suggestive symptoms. Early identification and treatment of scabies infestation could prevent misdiagnosis and treatment delays.

- World Health Organization. Scabies fact sheet. May 31, 2023. Accessed February 13, 2025. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/scabies

- Chandler DJ, Fuller LC. A review of scabies: an infestation more than skin deep. Dermatology. 2019;235:79-90. doi:10.1159/000495290

- Schneider S, Wu J, Tizek L, et al. Prevalence of scabies worldwidean updated systematic literature review in 2022. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37:1749-1757. doi:10.1111/jdv.19167

- Thomas C, Coates SJ, Engelman D, et al. Ectoparasites: Scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:533-548. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.109

- Henry T, Khachemoune A. Dermatologic conditions and risk factors in people experiencing homelessness (PEH): systematic review. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:2795-2803. doi:10.1007/s00403-023-02722-2

- Zakaria A, Amerson EH, Kim-Lim P, et al. Characterization of dermatological diagnoses among hospitalized patients experiencing homelessness. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:117-120. doi:10.1111/ced.14828

- Bergamin G, Hudson J, Currie BJ, et al. A systematic review of immunosuppressive risk factors and comorbidities associated with the development of crusted scabies. Int J Infect Dis. 2024;143:107036. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2024.107036

- Yamaguchi Y, Murata F, Maeda M, et al. Investigating the epidemiology and outbreaks of scabies in Japanese households, residential care facilities, and hospitals using claims data: the Longevity Improvement & Fair Evidence (LIFE) study. IJID Reg. 2024;11:100353. doi:10.1016 /j.ijregi.2024.03.008

- Raja A, Karch J, Shih AF, et al. Part II: Cutaneous manifestations of peripheral vascular disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:211-226. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.05.077

- Barry R, Anderson J, Tran L, et al. Prevalence of mental health disorders among individuals experiencing homelessness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024;81:691-699. doi:10.1001 /jamapsychiatry.2024.0426

- Koc Y.ld.r.m S, Demirel Og. ut N, Erbag. c. E, et al. Scabies affects quality of life in correlation with depression and anxiety. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2023;13:E2023144. doi:10.5826/dpc.1302a144

- Lin CY, Chang FW, Yang JJ, et al. Increased risk of bipolar disorder in patients with scabies: a nationwide population-based matched-cohort study. Psychiatry Res. 2017;257:14-20. doi:10.1016 /j.psychres.2017.07.013

- Anderson KL, Strowd LC. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of scabies in a dermatology office. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:78-84. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2017.01.160190

To the Editor:

Scabies infestation, which has been recognized as a neglected tropical disease by the World Health Organization since 2017, is caused by the human itch mite (Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis).1 Infected individuals experience a pruritic papular rash when the mite burrows into the epidermis, where it lives and lays eggs.2,3 Infected individuals also may develop bacterial superinfections if the skin barrier becomes compromised, leading to systemic complications and considerable morbidity.3

In countries with high human development indices, scabies outbreaks are linked to densely populated living conditions, such as those found in nursing homes or prisons.3,4 Scabies also is transmitted via sexual contact in adults. Beyond immunosuppression, little is known about other comorbid conditions or lifestyle risk factors associated with scabies infestation.2 Because scabies can mimic a range of other dermatologic conditions such as folliculitis, atopic dermatitis, and arthropod bites, misdiagnosis is common and can lead to delayed treatment and increased transmission risk.4 In this study, we sought to examine comorbid conditions and/or lifestyle risk factors associated with scabies infestation.

A matched case-control study was performed using the Registered Tier dataset of the National Institutes of Health All of Us Research Program Curated Data Repository version 7, which includes more than 400,000 unique participants aged 18 years or older from across the United States. The All of Us Research Program excludes adults who are unable to consent independently as well as incarcerated populations and children younger than 18 years. Participants diagnosed with scabies were identified using SNOMED code 62752005 and compared to a control group matched 1:4 based on age, sex, and selfidentified race. SNOMED codes also were used to identify various comorbidities and lifestyle risk factors, including depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, schizophrenia, peripheral vascular disease (PVD), HIV, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), unsheltered status, tobacco use, difficulty with activities of daily living, insurance status, and any recent travel history. Logistic regression models were used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and estimate effect sizes, with statistical significance set at P<.05.

We identified 691 cases of scabies infestation and 2073 controls. The average age of the patients diagnosed with scabies was 55.1 years. Seventy percent (481/691) identified as female and 32.4% (224/491) identified as Black or African American. Matched controls were similar for all analyzed demographic characteristics (P=1.0)(eTable 1). Patients diagnosed with scabies were more likely to be unsheltered (OR, 2.33 [95% CI, 1.91-2.85]), use tobacco (OR 1.77 [95% CI, 1.48-2.11]) and have a comorbid diagnosis of HIV (OR, 3.08 [95% CI, 2.03-4.66]), T2DM (OR, 2.05 [95% CI, 1.57- 2.66]) or PVD (OR, 2.06 [95% CI, 1.43-2.97]) compared with controls (P<.001). Psychiatric comorbidities were more common in the patients diagnosed with scabies, including depression (OR, 3.07 [95% CI, 2.54-3.72]), anxiety (OR, 2.48 [95% CI, 2.06-2.98]), bipolar disorder (OR, 3.08 [95% CI, 2.34-4.05]), and schizophrenia (OR, 4.68 [95% CI, 2.93-7.49])(P<.001). Difficulties with activities of daily living, including running errands alone (OR, 2.32 [95% CI, 1.43-3.76]) and concentrating (OR, 5.78; 95% CI, 3.86-8.64), were more prevalent in the scabies group compared to controls (both P<.05). In a multivariate logistic regression model including unsheltered status as a covariate, all associations remained statistically significant (P<.05)(eTable 2).

This large diverse study demonstrated an association between scabies infestation and unsheltered status. Previous studies have shown that unsheltered populations are at increased risk for many dermatologic conditions, perhaps due to decreased access to health care and social support, lack of access to hygiene facilities (eg, public showers), and increased prevalence of substance use and psychiatric disorders among this population.5 In a cross-sectional analysis of hospitalized patients, 8.6% of unsheltered patients (n=197) had an ectoparasitic disease (including scabies) compared with 1.0% of patients with stable housing (n=1018), with a 9.43-fold increased risk for ectoparasitic infestation among unsheltered patients (95% CI, 3.79-23.47; P<.001).6 Increased attention to public health initiatives among unsheltered populations— including access to hygiene facilities and increased dermatologic services—are needed, as ectoparasitic infections are both preventable and treatable, and these initiatives could reduce morbidity associated with superimposed bacterial infections for which unsheltered patients are at increased risk.6

Our results also showed that individuals diagnosed with scabies were more likely than the controls to have been diagnosed with HIV, T2DM, and PVD. Our findings are similar to those of a systematic review of immunosuppressive factors associated with crusted scabies (a severe form of scabies infestation) in which 10.2% and 15.7% of patients (n=683) had comorbid HIV and T2DM, respectively.7 A functioning cell-mediated response to scabies mite antigens limits proliferation of the human itch mite; thus, infection with HIV/AIDS, which induces the destruction of CD4+ T cells, limits the immune system’s ability to mount an effective response against these antigens. The association of scabies with T2DM likely is multifactorial; for example, chronic hyperglycemia may lead to immune system impairment, and peripheral neuropathy may reduce the itch sensation, allowing scabies mites to proliferate without removal by scratching.7 In a descriptive epidemiologic study in Japan, 11.7% of patients with scabies (N=857) had comorbid PVD.8 Peripheral vascular disease can lead to the development of ulcers, gangrene, and stasis dermatitis, all of which compromise the skin barrier and increase susceptibility to infection.9 Notably, these associations remained even when unsheltered status was considered as a confounding variable. Because individuals with HIV, T2DM, and PVD may be at higher risk for serious complications of scabies infestation (eg, secondary bacterial infections, invasive group A streptococcal infections), prompt detection and treatment of scabies are crucial in curbing morbidity in these at-risk populations.

Our study also demonstrated that psychiatric comorbidities including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia were associated with scabies infestation, even when controlling for unsheltered status, which may have a bidirectional relationship with mental health disorders.10 In a cross-sectional study of 83 adult patients diagnosed with scabies, 72.2% (60/83) reported moderate to extremely large effect of scabies infestation on quality of life using the Dermatology Life Quality Index, and these scores positively correlated with increased Beck Depression Scale and Beck Anxiety Scale scores (rs=0.448 and rs=0.456 0.456, respectively; both P=.000). The results of this study suggest that scabies negatively impacts quality of life, which might increase symptoms of depression and anxiety.11

Studies are needed to assess whether patients with pre-existing depression and anxiety face increased risk for scabies infestation. In a retrospective case-control study using data from the National Health Insurance Research Database of Taiwan, 0.8% (58/7096) of patients with scabies (n=7096) and 0.4% of controls (n=28,375) were newly diagnosed with bipolar disorder over a 7-year period, indicating a 1.55-fold increased risk for bipolar disorder in patients with scabies compared to those without (95% CI, 1.12-2.09; P<.05).12 Future studies are needed to determine whether the relationship between bipolar disorder and scabies is bidirectional, with pre-existing bipolar disorder evaluated as a risk factor for subsequent scabies infestation. Increased difficulties with activities of daily living, including running errands independently and concentrating, were associated with scabies. These difficulties may reflect sequelae of psychiatric illness or pruritus associated with scabies affecting daily living.

Physician awareness of comorbidities and lifestyle risk factors associated with scabies infestation may improve diagnosis and prevent treatment delays. In a retrospective study at a single dermatology outpatient clinic, 45.3% of patients with scabies (n=428) had previously been misdiagnosed with another dermatologic condition, and the most common erroneous diagnosis was atopic dermatitis.13 Our study provides a framework of comorbidities and lifestyle risk factors associated with scabies infestation that dermatologists can use to stratify patients who may be at greater risk for this condition, allowing dermatologists to select appropriate treatment when clinical signs are ambiguous.

Limitations of our study included the potential for miscoding in the database, lack of information about treatment regimens employed (if any), and lack of information about the temporal relationship between associations.

In summary, it is recommended that patients with pruritus and other characteristic clinical findings of scabies receive appropriate workup for scabies regardless of risk factors; however, the medical and psychiatric comorbidities and lifestyle risk factors identified in this study may help to identify at-risk patients. Our study showed that unsheltered patients are at increased risk for scabies, potentially due to unique dermatologic challenges and lack of access to health care and hygiene facilities. Positive correlations between scabies and HIV, T2DM, and PVD suggest that patients with chronic immunocompromising illnesses who live in group homes or other crowded quarters and present with symptoms could be evaluated for scabies infestation to prevent widespread and difficult- to-control outbreaks in these communities. Based on our findings, scabies also should be included in the differential diagnosis for patients with psychiatric illness and suggestive symptoms. Early identification and treatment of scabies infestation could prevent misdiagnosis and treatment delays.

To the Editor:

Scabies infestation, which has been recognized as a neglected tropical disease by the World Health Organization since 2017, is caused by the human itch mite (Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis).1 Infected individuals experience a pruritic papular rash when the mite burrows into the epidermis, where it lives and lays eggs.2,3 Infected individuals also may develop bacterial superinfections if the skin barrier becomes compromised, leading to systemic complications and considerable morbidity.3

In countries with high human development indices, scabies outbreaks are linked to densely populated living conditions, such as those found in nursing homes or prisons.3,4 Scabies also is transmitted via sexual contact in adults. Beyond immunosuppression, little is known about other comorbid conditions or lifestyle risk factors associated with scabies infestation.2 Because scabies can mimic a range of other dermatologic conditions such as folliculitis, atopic dermatitis, and arthropod bites, misdiagnosis is common and can lead to delayed treatment and increased transmission risk.4 In this study, we sought to examine comorbid conditions and/or lifestyle risk factors associated with scabies infestation.

A matched case-control study was performed using the Registered Tier dataset of the National Institutes of Health All of Us Research Program Curated Data Repository version 7, which includes more than 400,000 unique participants aged 18 years or older from across the United States. The All of Us Research Program excludes adults who are unable to consent independently as well as incarcerated populations and children younger than 18 years. Participants diagnosed with scabies were identified using SNOMED code 62752005 and compared to a control group matched 1:4 based on age, sex, and selfidentified race. SNOMED codes also were used to identify various comorbidities and lifestyle risk factors, including depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, schizophrenia, peripheral vascular disease (PVD), HIV, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), unsheltered status, tobacco use, difficulty with activities of daily living, insurance status, and any recent travel history. Logistic regression models were used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and estimate effect sizes, with statistical significance set at P<.05.

We identified 691 cases of scabies infestation and 2073 controls. The average age of the patients diagnosed with scabies was 55.1 years. Seventy percent (481/691) identified as female and 32.4% (224/491) identified as Black or African American. Matched controls were similar for all analyzed demographic characteristics (P=1.0)(eTable 1). Patients diagnosed with scabies were more likely to be unsheltered (OR, 2.33 [95% CI, 1.91-2.85]), use tobacco (OR 1.77 [95% CI, 1.48-2.11]) and have a comorbid diagnosis of HIV (OR, 3.08 [95% CI, 2.03-4.66]), T2DM (OR, 2.05 [95% CI, 1.57- 2.66]) or PVD (OR, 2.06 [95% CI, 1.43-2.97]) compared with controls (P<.001). Psychiatric comorbidities were more common in the patients diagnosed with scabies, including depression (OR, 3.07 [95% CI, 2.54-3.72]), anxiety (OR, 2.48 [95% CI, 2.06-2.98]), bipolar disorder (OR, 3.08 [95% CI, 2.34-4.05]), and schizophrenia (OR, 4.68 [95% CI, 2.93-7.49])(P<.001). Difficulties with activities of daily living, including running errands alone (OR, 2.32 [95% CI, 1.43-3.76]) and concentrating (OR, 5.78; 95% CI, 3.86-8.64), were more prevalent in the scabies group compared to controls (both P<.05). In a multivariate logistic regression model including unsheltered status as a covariate, all associations remained statistically significant (P<.05)(eTable 2).

This large diverse study demonstrated an association between scabies infestation and unsheltered status. Previous studies have shown that unsheltered populations are at increased risk for many dermatologic conditions, perhaps due to decreased access to health care and social support, lack of access to hygiene facilities (eg, public showers), and increased prevalence of substance use and psychiatric disorders among this population.5 In a cross-sectional analysis of hospitalized patients, 8.6% of unsheltered patients (n=197) had an ectoparasitic disease (including scabies) compared with 1.0% of patients with stable housing (n=1018), with a 9.43-fold increased risk for ectoparasitic infestation among unsheltered patients (95% CI, 3.79-23.47; P<.001).6 Increased attention to public health initiatives among unsheltered populations— including access to hygiene facilities and increased dermatologic services—are needed, as ectoparasitic infections are both preventable and treatable, and these initiatives could reduce morbidity associated with superimposed bacterial infections for which unsheltered patients are at increased risk.6

Our results also showed that individuals diagnosed with scabies were more likely than the controls to have been diagnosed with HIV, T2DM, and PVD. Our findings are similar to those of a systematic review of immunosuppressive factors associated with crusted scabies (a severe form of scabies infestation) in which 10.2% and 15.7% of patients (n=683) had comorbid HIV and T2DM, respectively.7 A functioning cell-mediated response to scabies mite antigens limits proliferation of the human itch mite; thus, infection with HIV/AIDS, which induces the destruction of CD4+ T cells, limits the immune system’s ability to mount an effective response against these antigens. The association of scabies with T2DM likely is multifactorial; for example, chronic hyperglycemia may lead to immune system impairment, and peripheral neuropathy may reduce the itch sensation, allowing scabies mites to proliferate without removal by scratching.7 In a descriptive epidemiologic study in Japan, 11.7% of patients with scabies (N=857) had comorbid PVD.8 Peripheral vascular disease can lead to the development of ulcers, gangrene, and stasis dermatitis, all of which compromise the skin barrier and increase susceptibility to infection.9 Notably, these associations remained even when unsheltered status was considered as a confounding variable. Because individuals with HIV, T2DM, and PVD may be at higher risk for serious complications of scabies infestation (eg, secondary bacterial infections, invasive group A streptococcal infections), prompt detection and treatment of scabies are crucial in curbing morbidity in these at-risk populations.

Our study also demonstrated that psychiatric comorbidities including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia were associated with scabies infestation, even when controlling for unsheltered status, which may have a bidirectional relationship with mental health disorders.10 In a cross-sectional study of 83 adult patients diagnosed with scabies, 72.2% (60/83) reported moderate to extremely large effect of scabies infestation on quality of life using the Dermatology Life Quality Index, and these scores positively correlated with increased Beck Depression Scale and Beck Anxiety Scale scores (rs=0.448 and rs=0.456 0.456, respectively; both P=.000). The results of this study suggest that scabies negatively impacts quality of life, which might increase symptoms of depression and anxiety.11

Studies are needed to assess whether patients with pre-existing depression and anxiety face increased risk for scabies infestation. In a retrospective case-control study using data from the National Health Insurance Research Database of Taiwan, 0.8% (58/7096) of patients with scabies (n=7096) and 0.4% of controls (n=28,375) were newly diagnosed with bipolar disorder over a 7-year period, indicating a 1.55-fold increased risk for bipolar disorder in patients with scabies compared to those without (95% CI, 1.12-2.09; P<.05).12 Future studies are needed to determine whether the relationship between bipolar disorder and scabies is bidirectional, with pre-existing bipolar disorder evaluated as a risk factor for subsequent scabies infestation. Increased difficulties with activities of daily living, including running errands independently and concentrating, were associated with scabies. These difficulties may reflect sequelae of psychiatric illness or pruritus associated with scabies affecting daily living.

Physician awareness of comorbidities and lifestyle risk factors associated with scabies infestation may improve diagnosis and prevent treatment delays. In a retrospective study at a single dermatology outpatient clinic, 45.3% of patients with scabies (n=428) had previously been misdiagnosed with another dermatologic condition, and the most common erroneous diagnosis was atopic dermatitis.13 Our study provides a framework of comorbidities and lifestyle risk factors associated with scabies infestation that dermatologists can use to stratify patients who may be at greater risk for this condition, allowing dermatologists to select appropriate treatment when clinical signs are ambiguous.

Limitations of our study included the potential for miscoding in the database, lack of information about treatment regimens employed (if any), and lack of information about the temporal relationship between associations.

In summary, it is recommended that patients with pruritus and other characteristic clinical findings of scabies receive appropriate workup for scabies regardless of risk factors; however, the medical and psychiatric comorbidities and lifestyle risk factors identified in this study may help to identify at-risk patients. Our study showed that unsheltered patients are at increased risk for scabies, potentially due to unique dermatologic challenges and lack of access to health care and hygiene facilities. Positive correlations between scabies and HIV, T2DM, and PVD suggest that patients with chronic immunocompromising illnesses who live in group homes or other crowded quarters and present with symptoms could be evaluated for scabies infestation to prevent widespread and difficult- to-control outbreaks in these communities. Based on our findings, scabies also should be included in the differential diagnosis for patients with psychiatric illness and suggestive symptoms. Early identification and treatment of scabies infestation could prevent misdiagnosis and treatment delays.

- World Health Organization. Scabies fact sheet. May 31, 2023. Accessed February 13, 2025. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/scabies

- Chandler DJ, Fuller LC. A review of scabies: an infestation more than skin deep. Dermatology. 2019;235:79-90. doi:10.1159/000495290

- Schneider S, Wu J, Tizek L, et al. Prevalence of scabies worldwidean updated systematic literature review in 2022. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37:1749-1757. doi:10.1111/jdv.19167

- Thomas C, Coates SJ, Engelman D, et al. Ectoparasites: Scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:533-548. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.109

- Henry T, Khachemoune A. Dermatologic conditions and risk factors in people experiencing homelessness (PEH): systematic review. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:2795-2803. doi:10.1007/s00403-023-02722-2

- Zakaria A, Amerson EH, Kim-Lim P, et al. Characterization of dermatological diagnoses among hospitalized patients experiencing homelessness. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:117-120. doi:10.1111/ced.14828

- Bergamin G, Hudson J, Currie BJ, et al. A systematic review of immunosuppressive risk factors and comorbidities associated with the development of crusted scabies. Int J Infect Dis. 2024;143:107036. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2024.107036

- Yamaguchi Y, Murata F, Maeda M, et al. Investigating the epidemiology and outbreaks of scabies in Japanese households, residential care facilities, and hospitals using claims data: the Longevity Improvement & Fair Evidence (LIFE) study. IJID Reg. 2024;11:100353. doi:10.1016 /j.ijregi.2024.03.008

- Raja A, Karch J, Shih AF, et al. Part II: Cutaneous manifestations of peripheral vascular disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:211-226. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.05.077

- Barry R, Anderson J, Tran L, et al. Prevalence of mental health disorders among individuals experiencing homelessness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024;81:691-699. doi:10.1001 /jamapsychiatry.2024.0426

- Koc Y.ld.r.m S, Demirel Og. ut N, Erbag. c. E, et al. Scabies affects quality of life in correlation with depression and anxiety. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2023;13:E2023144. doi:10.5826/dpc.1302a144

- Lin CY, Chang FW, Yang JJ, et al. Increased risk of bipolar disorder in patients with scabies: a nationwide population-based matched-cohort study. Psychiatry Res. 2017;257:14-20. doi:10.1016 /j.psychres.2017.07.013

- Anderson KL, Strowd LC. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of scabies in a dermatology office. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:78-84. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2017.01.160190

- World Health Organization. Scabies fact sheet. May 31, 2023. Accessed February 13, 2025. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/scabies

- Chandler DJ, Fuller LC. A review of scabies: an infestation more than skin deep. Dermatology. 2019;235:79-90. doi:10.1159/000495290

- Schneider S, Wu J, Tizek L, et al. Prevalence of scabies worldwidean updated systematic literature review in 2022. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37:1749-1757. doi:10.1111/jdv.19167

- Thomas C, Coates SJ, Engelman D, et al. Ectoparasites: Scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:533-548. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.109

- Henry T, Khachemoune A. Dermatologic conditions and risk factors in people experiencing homelessness (PEH): systematic review. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:2795-2803. doi:10.1007/s00403-023-02722-2

- Zakaria A, Amerson EH, Kim-Lim P, et al. Characterization of dermatological diagnoses among hospitalized patients experiencing homelessness. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:117-120. doi:10.1111/ced.14828

- Bergamin G, Hudson J, Currie BJ, et al. A systematic review of immunosuppressive risk factors and comorbidities associated with the development of crusted scabies. Int J Infect Dis. 2024;143:107036. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2024.107036

- Yamaguchi Y, Murata F, Maeda M, et al. Investigating the epidemiology and outbreaks of scabies in Japanese households, residential care facilities, and hospitals using claims data: the Longevity Improvement & Fair Evidence (LIFE) study. IJID Reg. 2024;11:100353. doi:10.1016 /j.ijregi.2024.03.008

- Raja A, Karch J, Shih AF, et al. Part II: Cutaneous manifestations of peripheral vascular disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:211-226. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.05.077

- Barry R, Anderson J, Tran L, et al. Prevalence of mental health disorders among individuals experiencing homelessness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024;81:691-699. doi:10.1001 /jamapsychiatry.2024.0426

- Koc Y.ld.r.m S, Demirel Og. ut N, Erbag. c. E, et al. Scabies affects quality of life in correlation with depression and anxiety. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2023;13:E2023144. doi:10.5826/dpc.1302a144

- Lin CY, Chang FW, Yang JJ, et al. Increased risk of bipolar disorder in patients with scabies: a nationwide population-based matched-cohort study. Psychiatry Res. 2017;257:14-20. doi:10.1016 /j.psychres.2017.07.013

- Anderson KL, Strowd LC. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of scabies in a dermatology office. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:78-84. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2017.01.160190

Comorbidities and Lifestyle Risk Factors Associated With Scabies Infestation

Comorbidities and Lifestyle Risk Factors Associated With Scabies Infestation

PRACTICE POINTS

- Scabies infestation is caused by the human itch mite (Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis) and can be spread via sexual contact in adults.

- Crowded living conditions are associated with scabies infestation in countries with high human development indices, such as the United States.

- Patients with certain comorbid conditions or lifestyle risk factors should be screened for scabies infestation when presenting with pruritus and other characteristic clinical findings.

Emerging Insights in Vitiligo Therapeutics: A Focus on Oral and Topical JAK Inhibitors

Emerging Insights in Vitiligo Therapeutics: A Focus on Oral and Topical JAK Inhibitors

Vitiligo is a common autoimmune disorder characterized by cutaneous depigmentation that has a substantial impact on patient quality of life.1 Vitiligo affects approximately 28.5 million individuals globally, with the highest lifetime prevalence occurring in Central Europe and South Asia.2 In the United States, Asian American and Hispanic/Latine populations most commonly are affected.3 The accompanying psychosocial burdens of vitiligo are particularly substantial among individuals with darker skin types, as evidenced by higher rates of concomitant anxiety and depression in these patients.4 Despite this, patients with skin of color are underrepresented in vitiligo research.2

Treatment algorithms developed based on worldwide expert consensus recommendations provide valuable insights into the management of segmental and nonsegmental vitiligo.5 The mainstay therapeutics include topical and oral corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and phototherapy. While vitiligo pathogenesis is not completely understood, recent advances have focused on the role of the Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway. Interferon gamma drives vitiligo pathogenesis through this pathway, upregulating C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 and promoting CD8+ T-cell recruitment, resulting in targeted melanocyte destruction.6 The emergence of targeted therapeutics may address equity and inclusion gaps. Herein, we highlight innovations in vitiligo treatment with a focus on oral and topical JAK inhibitors.

Oral JAK Inhibitors for Vitiligo

The therapeutic potential of JAK inhibitors for vitiligo was first reported when patients with alopecia areata and comorbid vitiligo experienced repigmentation of the skin following administration of oral ruxolitinib.7 Since this discovery, other oral JAK inhibitors have been investigated for vitiligo treatment. A phase 2b randomized clinical trial (RCT) of 364 patients examined oral ritlecitinib, a JAK3 inhibitor, and found it to be effective in treating active nonsegmental vitiligo.8 Patients aged 18 to 65 years with active nonsegmental vitiligo that had been present for 3 months or more as well as 4% to 50% body surface area (BSA) affected excluding acral surfaces and at least 0.25% facial involvement were included. Treatment groups received 50 mg (with or without a 100- or 200- mg loading dose), 30 mg, or 10 mg daily for 24 weeks. The primary endpoint measured the percentage change in Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI) score. Significant differences in F-VASI percentage change compared with placebo occurred for those in the 50-mg group who received a loading dose (-21.2 vs 2.1 [P<.001]) and those who did not receive a loading dose (–18.5 vs 2.1 [P<.001]) as well as the 30-mg group (-14.6 vs 2.1 [P=.01]). Continued repigmentation of the skin was observed in the 24-week extension period, indicating that longer treatment periods may be necessary for optimal repigmentation results. Ritlecitinib generally was well tolerated, and the most common treatment-emergent adverse events were nasopharyngitis (15.9%), upper respiratory tract infection (11.5%), and headache (8.8%). Most patients identified as White (67.6%), with 23.6% identifying as Asian and 2.7% identifying as Black. The authors stated that continued improvement was observed in the extension period across all skin types; however, the data were not reported.8

Upadacitnib, an oral selective JAK1 inhibitor, also has demonstrated efficacy in nonsegmental vitiligo in a phase 2 RCT.9 Adult patients (N=185) with nonsegmental vitiligo were randomized to receive upadacitinib 6 mg, 11 mg, or 22 mg or placebo (the placebo group subsequently was switched to upadacitinib 11 mg or 22 mg after 24 weeks). The primary endpoint measured the percentage change in F-VASI score at 24 weeks. The higher doses of upadacitinib resulted in significant changes in F-VASI scored compared with placebo (6 mg: -7.60 [95% CI, -22.18 to 6.97][P=.30]; 11 mg: -21.27 [95% CI, -36.02 to -6.52][P=.01]; 22 mg: -19.60 [95% CI, -35.04 to –4.16][P=.01]). As with ritlecitinib, continued repigmentation was observed beyond the initial 24-week period. Of the 185 participants, 5.9% identified as Black and 13.5% identified as Asian. The investigators reported that the percentage change in F-VASI score was consistent across skin types.9 The results of these phase 2 RCTs are encouraging, and we anticipate the findings of 2 phase 3 RCTs for ritlecitinib and upadacitinib that currently are underway (Clinicaltrials.gov identifiers NCT05583526 and NCT06118411).

Topical JAK Inhibitors for Vitiligo

Tofacitinib cream 2%, a selective JAK3 inhibitor, has shown therapeutic potential for treatment of vitiligo. One of the earliest pilot studies on topical tofacitinib examined the efficacy of tofacitinib cream 2% applied twice daily combined with narrowband UVB therapy 3 times weekly for facial vitiligo. The investigators reported repigmentation of the skin in all 11 patients (which included 4 Asian patients and 1 Hispanic patient), with a mean improvement of 70% in F-VASI score (range, 50%-87%).10 In a nonrandomized cohort study of 16 patients later that year, twice-daily application of tofacitinib cream 2% on facial and nonfacial vitiligo lesions resulted in partial repigmentation in 81.3% of patients: 4 (25%) achieved greater than 90% improvement, 5 (31.3%) achieved improvement of 25% to 75%, and 4 (25%) achieved 5% to 15% improvement.11 The researchers also found that tofacitinib cream 2% was significantly more effective in facial than nonfacial lesions (P=.02).

While tofacitinib has shown promise in early studies, recent advancements have led to US Food and Drug Administration approval of ruxolitinib cream 1.5%, another topical JAK inhibitor that has undergone robust clinical testing for vitiligo.12-14 Ruxolitinib, a JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 inhibitor, is the first and only US Food and Drug Administration–approved topical JAK inhibitor for vitiligo.14,15 Two phase 3, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trials of identical design conducted across 101 centers in North America and Europe (TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2) assessed the efficacy of ruxolitinib cream 1.5% in 674 patients aged 12 years and older with nonsegmental vitiligo covering 10% or lower total BSA.13 In both trials, twice-daily application of topical ruxolitinib resulted in greater facial repigmentation and improvement in F-VASI75 score (ie, a reduction of at least 75% from baseline) at 24 weeks in 29.9% (66/221) and 30.1% (69/222) of patients in TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2, respectively. Continued application through 52 weeks resulted in F-VASI75 response in 52.6% (91/173) and 48.0% (85/177) of patients in TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2, respectively. The most frequently reported adverse events were acne (6.3% [14/221] and 6.6% [15/228]), nasopharyngitis (5.4% [12/221] and 6.1% [14/228]), and pruritus (5.4% [12/221] and 5.3% [12/228]). These findings align with prior subgroup analyses of an earlier phase 2 double- blind RCT of ruxolitinib cream 1.5% that indicated similar improvement in vitiligo among patients with differing skin tones.17

There are no additional large-scale RCTs examining topical JAK inhibitors with intentional subanalysis of diverse skin tones.16,17,18 Studies examining topical JAK inhibitors have expanded to be more inclusive, providing hope for the future of topical vitiligo therapeutics for all patients.

Final Thoughts

It is imperative to increase racial/ethnic and skin type diversity in research on JAK inhibitors for vitiligo. While the studies mentioned here are inclusive of an array of races and skin tones, it is crucial that future research continue to expand the number of diverse participants, especially given the increased psychosocial burdens of vitiligo in patients with darker skin types.4 Intentional subgroup analyses across skin tones are vital to characterize and unmask potential differences between lighter and darker skin types. This point was exemplified by a 2024 RCT that investigated ritlecitinib efficacy with biomarker analysis across skin types.19 For patients receiving ritlecitinib 50 mg, IL-9 and IL-22 expression were decreased in darker vs lighter skin tones (P<.05). This intentional and inclusive analysis revealed a potential immunologic mechanism for why darker skin tones respond to JAK inhibitor therapy earlier than lighter skin tones.19

In the expanding landscape of oral and topical JAK inhibitors for vitiligo, continued efforts to assess these therapies across a range of skin tones and racial/ ethnic groups are critical. The efficacy of JAK inhibitors in other populations, including pediatric patients and patients with refractory segmental disease, have been reported.20,21 As larger studies are developed based on the success of individual cases, researchers should investigate the efficacy of JAK inhibitors for various vitiligo subtypes (eg, segmental, nonsegmental) and recalcitrant disease and conduct direct comparisons with traditional treatments across diverse skin tones and racial/ethnic subgroup analyses to ensure broad therapeutic applicability.

- Alikhan Ali, Felsten LM, Daly M, et al. Vitiligo: a comprehensive overview. part I. introduction, epidemiology, quality of life, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, associations, histopathology, etiology, and work-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:473-491. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2010.11.061

- Akl J, Lee S, Ju HJ, et al. Estimating the burden of vitiligo: a systematic review and modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2024;9:E386-E396. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(24)00026-4

- Mastacouris N, Strunk A, Garg A. Incidence and prevalence of diagnosed vitiligo according to race and ethnicity, age, and sex in the US. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:986-990. doi:10.1001/jama dermatol.2023.2162

- Bibeau K, Ezzedine K, Harris JE, et al. Mental health and psychosocial quality-of-life burden among patients with vitiligo: findings from the global VALIANT study. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:1124-1128. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.2787

- van Geel N, Speeckaert R, Taïeb A, et al. Worldwide expert recommendations for the diagnosis and management of vitiligo: position statement from the International Vitiligo Task Force part 1: towards a new management algorithm. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023; 37:2173-2184. doi:10.1111/jdv.19451

- Rashighi M, Agarwal P, Richmond JM, et al. CXCL10 is critical for the progression and maintenance of depigmentation in a mouse model of vitiligo. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:223ra23. doi:10.1126 /scitranslmed.3007811

- Harris JE, Rashighi M, Nguyen N, et al. Rapid skin repigmentation on oral ruxolitinib in a patient with coexistent vitiligo and alopecia areata (AA). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:370-371. doi:10.1016/ j.jaad.2015.09.073

- Ezzedine K, Peeva E, Yamguchi Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral ritlecitinib for the treatment of active nonsegmental vitiligo: a randomized phase 2b clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:395-403. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.11.005

- Passeron T, Ezzedine K, Hamzavi I, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adults with extensive non-segmental vitiligo: a phase 2, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. EClinicalMedicine. 2024;73:102655. doi:10.1016 /j.eclinm.2024.102655

- McKesey J, Pandya AG. A pilot study of 2% tofacitinib cream with narrowband ultraviolet B for the treatment of facial vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:646-648. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.04.032

- Mobasher P, Guerra R, Li SJ, et al. Open-label pilot study of tofacitinib 2% for the treatment of refractory vitiligo. Brit J Dermatol. 2020;182:1047-1049. doi:10.1111/bjd.18606

- Rosmarin D, Pandya AG, Lebwohl M, et al. Ruxolitinib cream for treatment of vitiligo: a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2020;396:110-120. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30609-7

- Rosmarin D, Passeron T, Pandya AG, et al; TRuE-V Study Group. Two phase 3, randomized, controlled trials of ruxolitinib cream for vitiligo. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1445-1455. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2118828

- FDA. FDA approves topical treatment addressing repigmentation in vitiligo in patients aged 12 and older. Published July 19, 2022. Accessed January 30, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-topical-treatment-addressing-repigmentation-vitiligo-patients-aged-12-and-older

- Quintás-Cardama A, Vaddi K, Liu P, et al. Preclinical characterization of the selective JAK1/2 inhibitor INCB018424: therapeutic implications for the treatment of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2010;115:3109-3117. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-04-214957

- Seneschal J, Wolkerstorfer A, Desai SR, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of vitiligo by patient demographics and baseline clinical characteristics: week 52 pooled subgroup analysis from two randomized phase 3 studies. Brit J Dermatol. 2023;188 (suppl 1):ljac106.006. doi:10.1093/bjd/ljac106.006

- Hamzavi I, Rosmarin D, Harris JE, et al. Efficacy of ruxolitinib cream in vitiligo by patient characteristics and affected body areas: descriptive subgroup analyses from a phase 2, randomized, double-blind trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1398-1401. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.05.047

- Inoue S, Suzuki T, Sano S, et al. JAK inhibitors for the treatment of vitiligo. J Dermatol Sci. 2024;113:86-92. doi:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2023.12.008

- Peeva E, Yamaguchi Y, Ye Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of ritlecitinib in vitiligo patients across Fitzpatrick skin types with biomarker analyses. Exp Dermatol. 2024;33:E15177. doi:10.1111/exd.15177

- Mu Y, Pan T, Chen L. Treatment of refractory segmental vitiligo and alopecia areata in a child with upadacitinib and NB-UVB: a case report. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2024;17:1789-1792. doi:10.2147 /CCID.S467026

- Shah RR, McMichael A. Resistant vitiligo treated with tofacitinib and sustained repigmentation after discontinuation. Skinmed. 2024;22:384-385.

Vitiligo is a common autoimmune disorder characterized by cutaneous depigmentation that has a substantial impact on patient quality of life.1 Vitiligo affects approximately 28.5 million individuals globally, with the highest lifetime prevalence occurring in Central Europe and South Asia.2 In the United States, Asian American and Hispanic/Latine populations most commonly are affected.3 The accompanying psychosocial burdens of vitiligo are particularly substantial among individuals with darker skin types, as evidenced by higher rates of concomitant anxiety and depression in these patients.4 Despite this, patients with skin of color are underrepresented in vitiligo research.2

Treatment algorithms developed based on worldwide expert consensus recommendations provide valuable insights into the management of segmental and nonsegmental vitiligo.5 The mainstay therapeutics include topical and oral corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and phototherapy. While vitiligo pathogenesis is not completely understood, recent advances have focused on the role of the Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway. Interferon gamma drives vitiligo pathogenesis through this pathway, upregulating C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 and promoting CD8+ T-cell recruitment, resulting in targeted melanocyte destruction.6 The emergence of targeted therapeutics may address equity and inclusion gaps. Herein, we highlight innovations in vitiligo treatment with a focus on oral and topical JAK inhibitors.

Oral JAK Inhibitors for Vitiligo

The therapeutic potential of JAK inhibitors for vitiligo was first reported when patients with alopecia areata and comorbid vitiligo experienced repigmentation of the skin following administration of oral ruxolitinib.7 Since this discovery, other oral JAK inhibitors have been investigated for vitiligo treatment. A phase 2b randomized clinical trial (RCT) of 364 patients examined oral ritlecitinib, a JAK3 inhibitor, and found it to be effective in treating active nonsegmental vitiligo.8 Patients aged 18 to 65 years with active nonsegmental vitiligo that had been present for 3 months or more as well as 4% to 50% body surface area (BSA) affected excluding acral surfaces and at least 0.25% facial involvement were included. Treatment groups received 50 mg (with or without a 100- or 200- mg loading dose), 30 mg, or 10 mg daily for 24 weeks. The primary endpoint measured the percentage change in Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI) score. Significant differences in F-VASI percentage change compared with placebo occurred for those in the 50-mg group who received a loading dose (-21.2 vs 2.1 [P<.001]) and those who did not receive a loading dose (–18.5 vs 2.1 [P<.001]) as well as the 30-mg group (-14.6 vs 2.1 [P=.01]). Continued repigmentation of the skin was observed in the 24-week extension period, indicating that longer treatment periods may be necessary for optimal repigmentation results. Ritlecitinib generally was well tolerated, and the most common treatment-emergent adverse events were nasopharyngitis (15.9%), upper respiratory tract infection (11.5%), and headache (8.8%). Most patients identified as White (67.6%), with 23.6% identifying as Asian and 2.7% identifying as Black. The authors stated that continued improvement was observed in the extension period across all skin types; however, the data were not reported.8

Upadacitnib, an oral selective JAK1 inhibitor, also has demonstrated efficacy in nonsegmental vitiligo in a phase 2 RCT.9 Adult patients (N=185) with nonsegmental vitiligo were randomized to receive upadacitinib 6 mg, 11 mg, or 22 mg or placebo (the placebo group subsequently was switched to upadacitinib 11 mg or 22 mg after 24 weeks). The primary endpoint measured the percentage change in F-VASI score at 24 weeks. The higher doses of upadacitinib resulted in significant changes in F-VASI scored compared with placebo (6 mg: -7.60 [95% CI, -22.18 to 6.97][P=.30]; 11 mg: -21.27 [95% CI, -36.02 to -6.52][P=.01]; 22 mg: -19.60 [95% CI, -35.04 to –4.16][P=.01]). As with ritlecitinib, continued repigmentation was observed beyond the initial 24-week period. Of the 185 participants, 5.9% identified as Black and 13.5% identified as Asian. The investigators reported that the percentage change in F-VASI score was consistent across skin types.9 The results of these phase 2 RCTs are encouraging, and we anticipate the findings of 2 phase 3 RCTs for ritlecitinib and upadacitinib that currently are underway (Clinicaltrials.gov identifiers NCT05583526 and NCT06118411).

Topical JAK Inhibitors for Vitiligo

Tofacitinib cream 2%, a selective JAK3 inhibitor, has shown therapeutic potential for treatment of vitiligo. One of the earliest pilot studies on topical tofacitinib examined the efficacy of tofacitinib cream 2% applied twice daily combined with narrowband UVB therapy 3 times weekly for facial vitiligo. The investigators reported repigmentation of the skin in all 11 patients (which included 4 Asian patients and 1 Hispanic patient), with a mean improvement of 70% in F-VASI score (range, 50%-87%).10 In a nonrandomized cohort study of 16 patients later that year, twice-daily application of tofacitinib cream 2% on facial and nonfacial vitiligo lesions resulted in partial repigmentation in 81.3% of patients: 4 (25%) achieved greater than 90% improvement, 5 (31.3%) achieved improvement of 25% to 75%, and 4 (25%) achieved 5% to 15% improvement.11 The researchers also found that tofacitinib cream 2% was significantly more effective in facial than nonfacial lesions (P=.02).

While tofacitinib has shown promise in early studies, recent advancements have led to US Food and Drug Administration approval of ruxolitinib cream 1.5%, another topical JAK inhibitor that has undergone robust clinical testing for vitiligo.12-14 Ruxolitinib, a JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 inhibitor, is the first and only US Food and Drug Administration–approved topical JAK inhibitor for vitiligo.14,15 Two phase 3, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trials of identical design conducted across 101 centers in North America and Europe (TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2) assessed the efficacy of ruxolitinib cream 1.5% in 674 patients aged 12 years and older with nonsegmental vitiligo covering 10% or lower total BSA.13 In both trials, twice-daily application of topical ruxolitinib resulted in greater facial repigmentation and improvement in F-VASI75 score (ie, a reduction of at least 75% from baseline) at 24 weeks in 29.9% (66/221) and 30.1% (69/222) of patients in TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2, respectively. Continued application through 52 weeks resulted in F-VASI75 response in 52.6% (91/173) and 48.0% (85/177) of patients in TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2, respectively. The most frequently reported adverse events were acne (6.3% [14/221] and 6.6% [15/228]), nasopharyngitis (5.4% [12/221] and 6.1% [14/228]), and pruritus (5.4% [12/221] and 5.3% [12/228]). These findings align with prior subgroup analyses of an earlier phase 2 double- blind RCT of ruxolitinib cream 1.5% that indicated similar improvement in vitiligo among patients with differing skin tones.17

There are no additional large-scale RCTs examining topical JAK inhibitors with intentional subanalysis of diverse skin tones.16,17,18 Studies examining topical JAK inhibitors have expanded to be more inclusive, providing hope for the future of topical vitiligo therapeutics for all patients.

Final Thoughts

It is imperative to increase racial/ethnic and skin type diversity in research on JAK inhibitors for vitiligo. While the studies mentioned here are inclusive of an array of races and skin tones, it is crucial that future research continue to expand the number of diverse participants, especially given the increased psychosocial burdens of vitiligo in patients with darker skin types.4 Intentional subgroup analyses across skin tones are vital to characterize and unmask potential differences between lighter and darker skin types. This point was exemplified by a 2024 RCT that investigated ritlecitinib efficacy with biomarker analysis across skin types.19 For patients receiving ritlecitinib 50 mg, IL-9 and IL-22 expression were decreased in darker vs lighter skin tones (P<.05). This intentional and inclusive analysis revealed a potential immunologic mechanism for why darker skin tones respond to JAK inhibitor therapy earlier than lighter skin tones.19

In the expanding landscape of oral and topical JAK inhibitors for vitiligo, continued efforts to assess these therapies across a range of skin tones and racial/ ethnic groups are critical. The efficacy of JAK inhibitors in other populations, including pediatric patients and patients with refractory segmental disease, have been reported.20,21 As larger studies are developed based on the success of individual cases, researchers should investigate the efficacy of JAK inhibitors for various vitiligo subtypes (eg, segmental, nonsegmental) and recalcitrant disease and conduct direct comparisons with traditional treatments across diverse skin tones and racial/ethnic subgroup analyses to ensure broad therapeutic applicability.

Vitiligo is a common autoimmune disorder characterized by cutaneous depigmentation that has a substantial impact on patient quality of life.1 Vitiligo affects approximately 28.5 million individuals globally, with the highest lifetime prevalence occurring in Central Europe and South Asia.2 In the United States, Asian American and Hispanic/Latine populations most commonly are affected.3 The accompanying psychosocial burdens of vitiligo are particularly substantial among individuals with darker skin types, as evidenced by higher rates of concomitant anxiety and depression in these patients.4 Despite this, patients with skin of color are underrepresented in vitiligo research.2

Treatment algorithms developed based on worldwide expert consensus recommendations provide valuable insights into the management of segmental and nonsegmental vitiligo.5 The mainstay therapeutics include topical and oral corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and phototherapy. While vitiligo pathogenesis is not completely understood, recent advances have focused on the role of the Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway. Interferon gamma drives vitiligo pathogenesis through this pathway, upregulating C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 and promoting CD8+ T-cell recruitment, resulting in targeted melanocyte destruction.6 The emergence of targeted therapeutics may address equity and inclusion gaps. Herein, we highlight innovations in vitiligo treatment with a focus on oral and topical JAK inhibitors.

Oral JAK Inhibitors for Vitiligo

The therapeutic potential of JAK inhibitors for vitiligo was first reported when patients with alopecia areata and comorbid vitiligo experienced repigmentation of the skin following administration of oral ruxolitinib.7 Since this discovery, other oral JAK inhibitors have been investigated for vitiligo treatment. A phase 2b randomized clinical trial (RCT) of 364 patients examined oral ritlecitinib, a JAK3 inhibitor, and found it to be effective in treating active nonsegmental vitiligo.8 Patients aged 18 to 65 years with active nonsegmental vitiligo that had been present for 3 months or more as well as 4% to 50% body surface area (BSA) affected excluding acral surfaces and at least 0.25% facial involvement were included. Treatment groups received 50 mg (with or without a 100- or 200- mg loading dose), 30 mg, or 10 mg daily for 24 weeks. The primary endpoint measured the percentage change in Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI) score. Significant differences in F-VASI percentage change compared with placebo occurred for those in the 50-mg group who received a loading dose (-21.2 vs 2.1 [P<.001]) and those who did not receive a loading dose (–18.5 vs 2.1 [P<.001]) as well as the 30-mg group (-14.6 vs 2.1 [P=.01]). Continued repigmentation of the skin was observed in the 24-week extension period, indicating that longer treatment periods may be necessary for optimal repigmentation results. Ritlecitinib generally was well tolerated, and the most common treatment-emergent adverse events were nasopharyngitis (15.9%), upper respiratory tract infection (11.5%), and headache (8.8%). Most patients identified as White (67.6%), with 23.6% identifying as Asian and 2.7% identifying as Black. The authors stated that continued improvement was observed in the extension period across all skin types; however, the data were not reported.8

Upadacitnib, an oral selective JAK1 inhibitor, also has demonstrated efficacy in nonsegmental vitiligo in a phase 2 RCT.9 Adult patients (N=185) with nonsegmental vitiligo were randomized to receive upadacitinib 6 mg, 11 mg, or 22 mg or placebo (the placebo group subsequently was switched to upadacitinib 11 mg or 22 mg after 24 weeks). The primary endpoint measured the percentage change in F-VASI score at 24 weeks. The higher doses of upadacitinib resulted in significant changes in F-VASI scored compared with placebo (6 mg: -7.60 [95% CI, -22.18 to 6.97][P=.30]; 11 mg: -21.27 [95% CI, -36.02 to -6.52][P=.01]; 22 mg: -19.60 [95% CI, -35.04 to –4.16][P=.01]). As with ritlecitinib, continued repigmentation was observed beyond the initial 24-week period. Of the 185 participants, 5.9% identified as Black and 13.5% identified as Asian. The investigators reported that the percentage change in F-VASI score was consistent across skin types.9 The results of these phase 2 RCTs are encouraging, and we anticipate the findings of 2 phase 3 RCTs for ritlecitinib and upadacitinib that currently are underway (Clinicaltrials.gov identifiers NCT05583526 and NCT06118411).

Topical JAK Inhibitors for Vitiligo

Tofacitinib cream 2%, a selective JAK3 inhibitor, has shown therapeutic potential for treatment of vitiligo. One of the earliest pilot studies on topical tofacitinib examined the efficacy of tofacitinib cream 2% applied twice daily combined with narrowband UVB therapy 3 times weekly for facial vitiligo. The investigators reported repigmentation of the skin in all 11 patients (which included 4 Asian patients and 1 Hispanic patient), with a mean improvement of 70% in F-VASI score (range, 50%-87%).10 In a nonrandomized cohort study of 16 patients later that year, twice-daily application of tofacitinib cream 2% on facial and nonfacial vitiligo lesions resulted in partial repigmentation in 81.3% of patients: 4 (25%) achieved greater than 90% improvement, 5 (31.3%) achieved improvement of 25% to 75%, and 4 (25%) achieved 5% to 15% improvement.11 The researchers also found that tofacitinib cream 2% was significantly more effective in facial than nonfacial lesions (P=.02).

While tofacitinib has shown promise in early studies, recent advancements have led to US Food and Drug Administration approval of ruxolitinib cream 1.5%, another topical JAK inhibitor that has undergone robust clinical testing for vitiligo.12-14 Ruxolitinib, a JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 inhibitor, is the first and only US Food and Drug Administration–approved topical JAK inhibitor for vitiligo.14,15 Two phase 3, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trials of identical design conducted across 101 centers in North America and Europe (TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2) assessed the efficacy of ruxolitinib cream 1.5% in 674 patients aged 12 years and older with nonsegmental vitiligo covering 10% or lower total BSA.13 In both trials, twice-daily application of topical ruxolitinib resulted in greater facial repigmentation and improvement in F-VASI75 score (ie, a reduction of at least 75% from baseline) at 24 weeks in 29.9% (66/221) and 30.1% (69/222) of patients in TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2, respectively. Continued application through 52 weeks resulted in F-VASI75 response in 52.6% (91/173) and 48.0% (85/177) of patients in TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2, respectively. The most frequently reported adverse events were acne (6.3% [14/221] and 6.6% [15/228]), nasopharyngitis (5.4% [12/221] and 6.1% [14/228]), and pruritus (5.4% [12/221] and 5.3% [12/228]). These findings align with prior subgroup analyses of an earlier phase 2 double- blind RCT of ruxolitinib cream 1.5% that indicated similar improvement in vitiligo among patients with differing skin tones.17

There are no additional large-scale RCTs examining topical JAK inhibitors with intentional subanalysis of diverse skin tones.16,17,18 Studies examining topical JAK inhibitors have expanded to be more inclusive, providing hope for the future of topical vitiligo therapeutics for all patients.

Final Thoughts

It is imperative to increase racial/ethnic and skin type diversity in research on JAK inhibitors for vitiligo. While the studies mentioned here are inclusive of an array of races and skin tones, it is crucial that future research continue to expand the number of diverse participants, especially given the increased psychosocial burdens of vitiligo in patients with darker skin types.4 Intentional subgroup analyses across skin tones are vital to characterize and unmask potential differences between lighter and darker skin types. This point was exemplified by a 2024 RCT that investigated ritlecitinib efficacy with biomarker analysis across skin types.19 For patients receiving ritlecitinib 50 mg, IL-9 and IL-22 expression were decreased in darker vs lighter skin tones (P<.05). This intentional and inclusive analysis revealed a potential immunologic mechanism for why darker skin tones respond to JAK inhibitor therapy earlier than lighter skin tones.19

In the expanding landscape of oral and topical JAK inhibitors for vitiligo, continued efforts to assess these therapies across a range of skin tones and racial/ ethnic groups are critical. The efficacy of JAK inhibitors in other populations, including pediatric patients and patients with refractory segmental disease, have been reported.20,21 As larger studies are developed based on the success of individual cases, researchers should investigate the efficacy of JAK inhibitors for various vitiligo subtypes (eg, segmental, nonsegmental) and recalcitrant disease and conduct direct comparisons with traditional treatments across diverse skin tones and racial/ethnic subgroup analyses to ensure broad therapeutic applicability.

- Alikhan Ali, Felsten LM, Daly M, et al. Vitiligo: a comprehensive overview. part I. introduction, epidemiology, quality of life, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, associations, histopathology, etiology, and work-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:473-491. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2010.11.061

- Akl J, Lee S, Ju HJ, et al. Estimating the burden of vitiligo: a systematic review and modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2024;9:E386-E396. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(24)00026-4

- Mastacouris N, Strunk A, Garg A. Incidence and prevalence of diagnosed vitiligo according to race and ethnicity, age, and sex in the US. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:986-990. doi:10.1001/jama dermatol.2023.2162

- Bibeau K, Ezzedine K, Harris JE, et al. Mental health and psychosocial quality-of-life burden among patients with vitiligo: findings from the global VALIANT study. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:1124-1128. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.2787

- van Geel N, Speeckaert R, Taïeb A, et al. Worldwide expert recommendations for the diagnosis and management of vitiligo: position statement from the International Vitiligo Task Force part 1: towards a new management algorithm. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023; 37:2173-2184. doi:10.1111/jdv.19451

- Rashighi M, Agarwal P, Richmond JM, et al. CXCL10 is critical for the progression and maintenance of depigmentation in a mouse model of vitiligo. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:223ra23. doi:10.1126 /scitranslmed.3007811

- Harris JE, Rashighi M, Nguyen N, et al. Rapid skin repigmentation on oral ruxolitinib in a patient with coexistent vitiligo and alopecia areata (AA). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:370-371. doi:10.1016/ j.jaad.2015.09.073

- Ezzedine K, Peeva E, Yamguchi Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral ritlecitinib for the treatment of active nonsegmental vitiligo: a randomized phase 2b clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:395-403. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.11.005

- Passeron T, Ezzedine K, Hamzavi I, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adults with extensive non-segmental vitiligo: a phase 2, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. EClinicalMedicine. 2024;73:102655. doi:10.1016 /j.eclinm.2024.102655

- McKesey J, Pandya AG. A pilot study of 2% tofacitinib cream with narrowband ultraviolet B for the treatment of facial vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:646-648. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.04.032

- Mobasher P, Guerra R, Li SJ, et al. Open-label pilot study of tofacitinib 2% for the treatment of refractory vitiligo. Brit J Dermatol. 2020;182:1047-1049. doi:10.1111/bjd.18606

- Rosmarin D, Pandya AG, Lebwohl M, et al. Ruxolitinib cream for treatment of vitiligo: a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2020;396:110-120. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30609-7

- Rosmarin D, Passeron T, Pandya AG, et al; TRuE-V Study Group. Two phase 3, randomized, controlled trials of ruxolitinib cream for vitiligo. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1445-1455. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2118828

- FDA. FDA approves topical treatment addressing repigmentation in vitiligo in patients aged 12 and older. Published July 19, 2022. Accessed January 30, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-topical-treatment-addressing-repigmentation-vitiligo-patients-aged-12-and-older

- Quintás-Cardama A, Vaddi K, Liu P, et al. Preclinical characterization of the selective JAK1/2 inhibitor INCB018424: therapeutic implications for the treatment of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2010;115:3109-3117. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-04-214957

- Seneschal J, Wolkerstorfer A, Desai SR, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of vitiligo by patient demographics and baseline clinical characteristics: week 52 pooled subgroup analysis from two randomized phase 3 studies. Brit J Dermatol. 2023;188 (suppl 1):ljac106.006. doi:10.1093/bjd/ljac106.006

- Hamzavi I, Rosmarin D, Harris JE, et al. Efficacy of ruxolitinib cream in vitiligo by patient characteristics and affected body areas: descriptive subgroup analyses from a phase 2, randomized, double-blind trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1398-1401. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.05.047

- Inoue S, Suzuki T, Sano S, et al. JAK inhibitors for the treatment of vitiligo. J Dermatol Sci. 2024;113:86-92. doi:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2023.12.008

- Peeva E, Yamaguchi Y, Ye Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of ritlecitinib in vitiligo patients across Fitzpatrick skin types with biomarker analyses. Exp Dermatol. 2024;33:E15177. doi:10.1111/exd.15177

- Mu Y, Pan T, Chen L. Treatment of refractory segmental vitiligo and alopecia areata in a child with upadacitinib and NB-UVB: a case report. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2024;17:1789-1792. doi:10.2147 /CCID.S467026

- Shah RR, McMichael A. Resistant vitiligo treated with tofacitinib and sustained repigmentation after discontinuation. Skinmed. 2024;22:384-385.

- Alikhan Ali, Felsten LM, Daly M, et al. Vitiligo: a comprehensive overview. part I. introduction, epidemiology, quality of life, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, associations, histopathology, etiology, and work-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:473-491. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2010.11.061

- Akl J, Lee S, Ju HJ, et al. Estimating the burden of vitiligo: a systematic review and modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2024;9:E386-E396. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(24)00026-4

- Mastacouris N, Strunk A, Garg A. Incidence and prevalence of diagnosed vitiligo according to race and ethnicity, age, and sex in the US. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:986-990. doi:10.1001/jama dermatol.2023.2162

- Bibeau K, Ezzedine K, Harris JE, et al. Mental health and psychosocial quality-of-life burden among patients with vitiligo: findings from the global VALIANT study. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:1124-1128. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.2787