User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Rupioid Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis in a Patient With Skin of Color

To the Editor:

A 49-year-old black woman presented with multiple hyperkeratotic papules that progressed over the last 2 months to circular plaques with central thick black crust resembling eschar. She first noticed these lesions as firm, small, black papules on the legs and continued to develop new lesions that eventually evolved into large, coin-shaped, hyperkeratotic plaques. Her medical history was notable for stage III non-Hodgkin follicular lymphoma in remission after treatment with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone 7 months earlier, and chronic hepatitis B infection being treated with entecavir. Her family history was not remarkable for psoriasis or inflammatory arthritis.

She initially was seen by internal medicine and was started on topical triamcinolone with no improvement of the lesions. At presentation to dermatology, physical examination revealed firm, small, black, hyperkeratotic papules (Figure 1A) and circular plaques with a rim of erythema and central thick, smooth, black crust resembling eschar (Figure 1B). No other skin changes were noted at the time. The bilateral metacarpophalangeal, bilateral proximal interphalangeal, left wrist, and bilateral ankle joints were remarkable for tenderness, swelling, and reduced range of motion. She noted concomitant arthralgia and stiffness but denied fever. She had no other systemic symptoms including night sweats, weight loss, fatigue, malaise, sun sensitivity, oral ulcers, or hair loss. A radiograph of the hand was negative for erosive changes but showed mild periarticular osteopenia and fusiform soft tissue swelling of the third digit. Given the central appearance of eschar in the larger lesions, the initial differential diagnosis included Sweet syndrome, invasive fungal infection, vasculitis, and recurrent lymphoma.

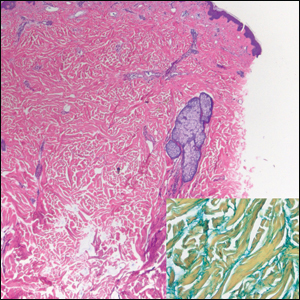

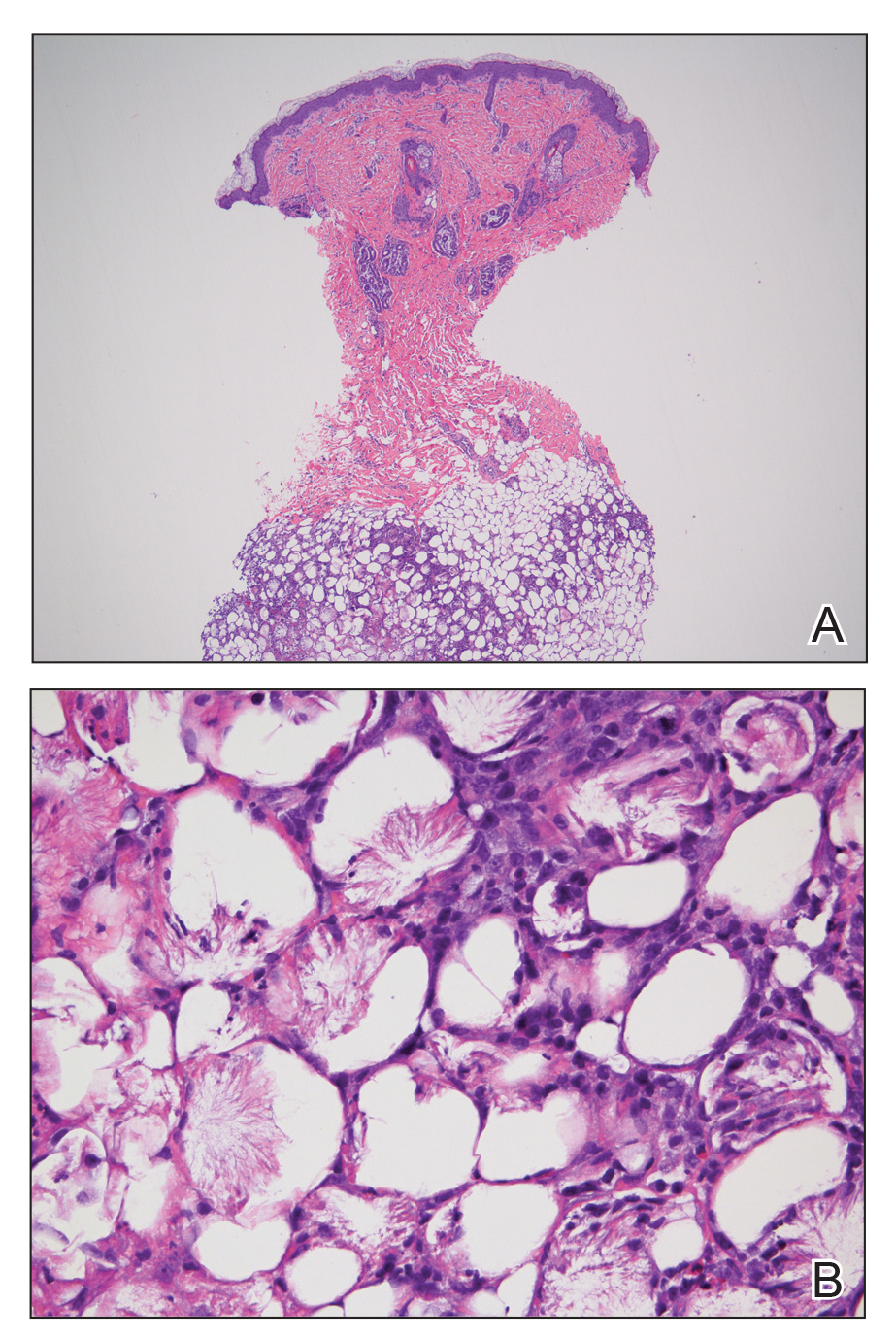

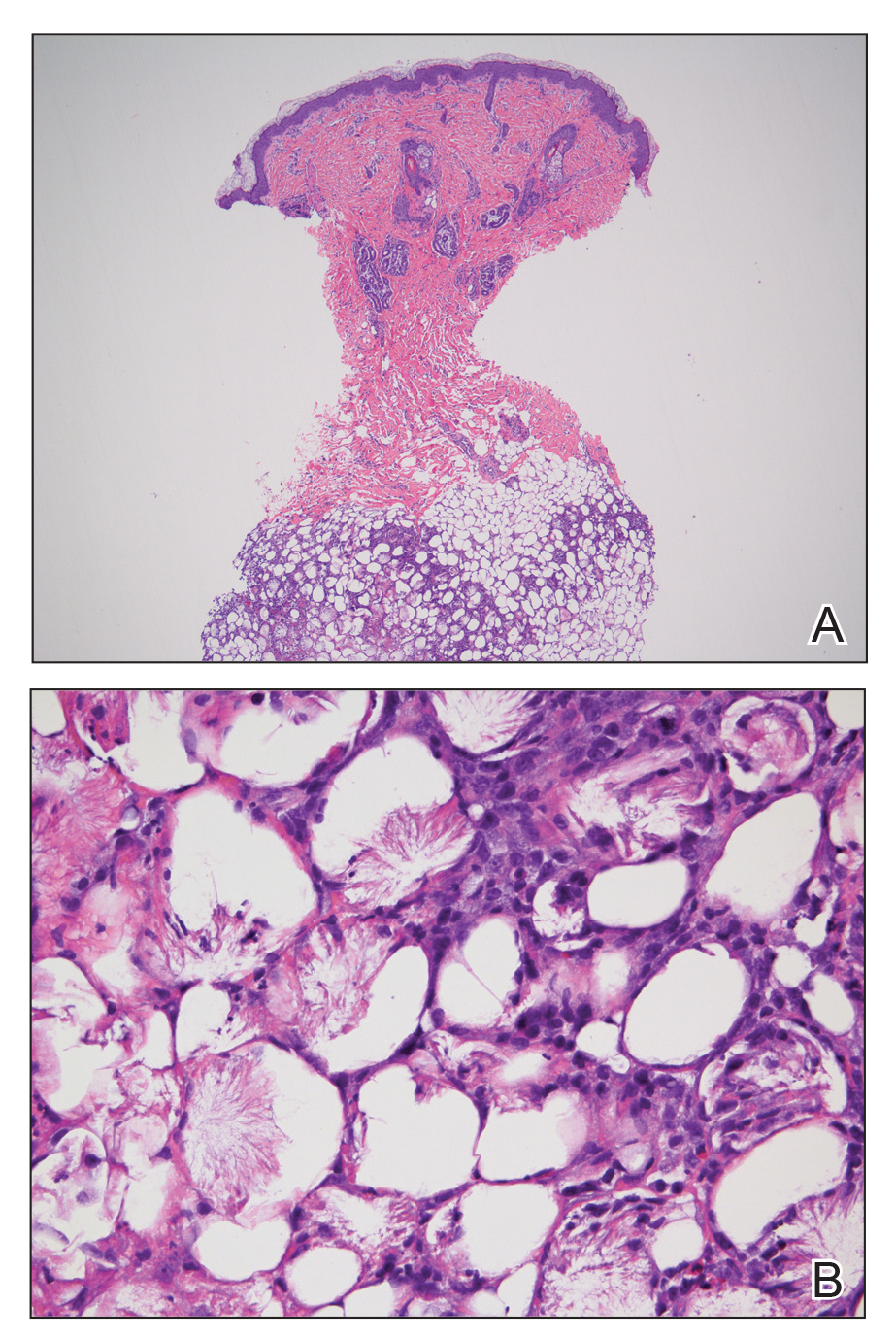

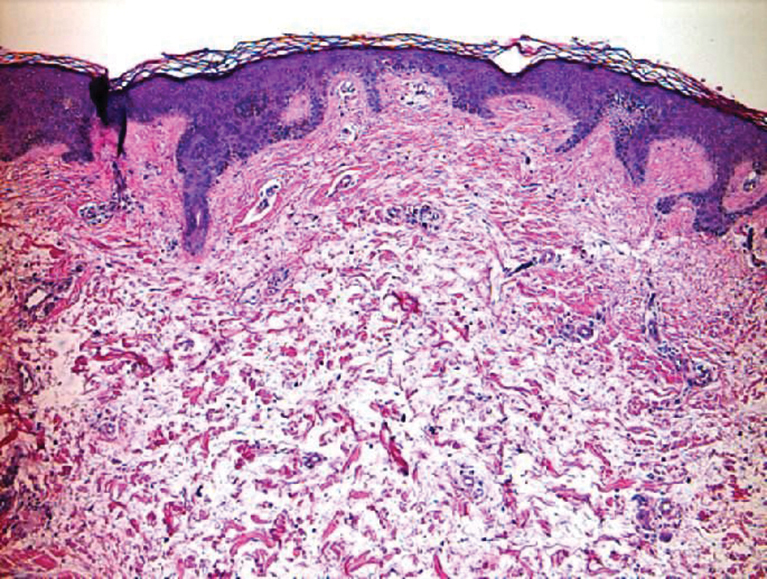

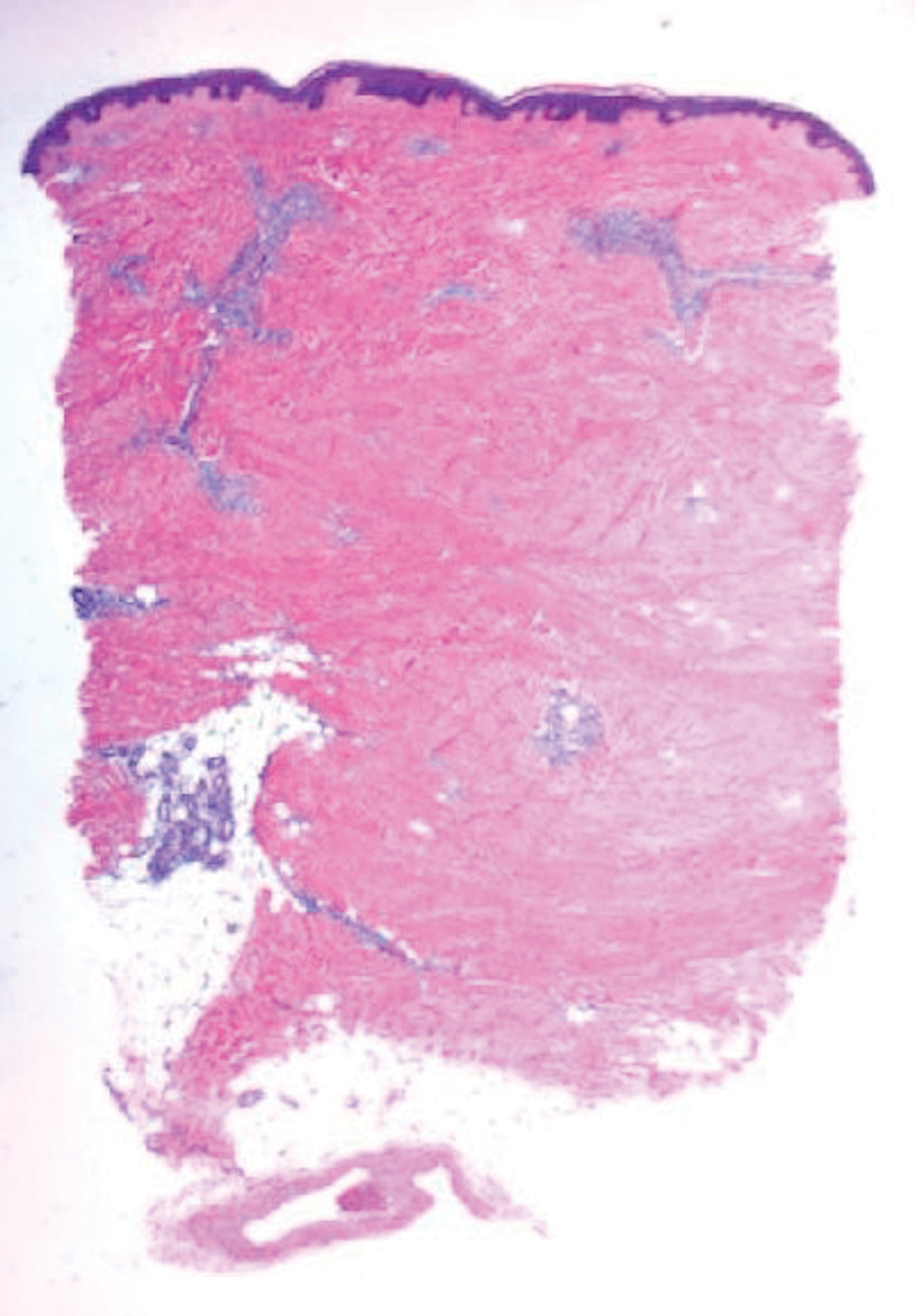

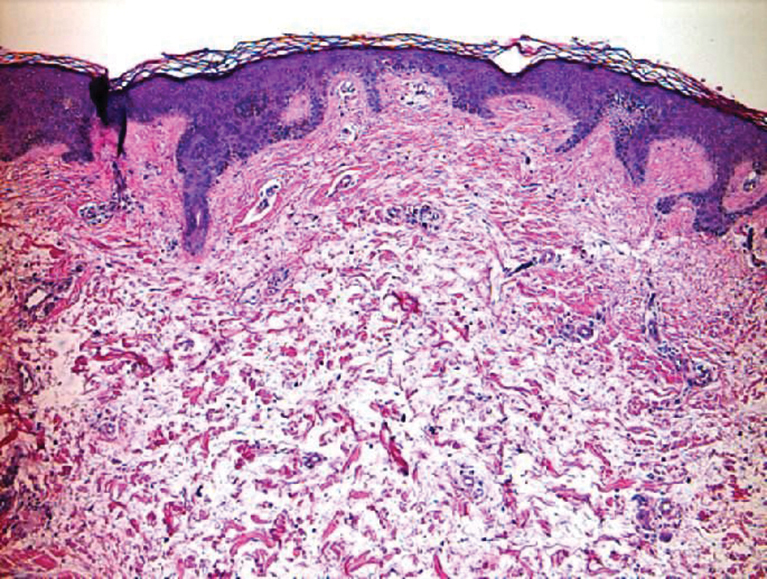

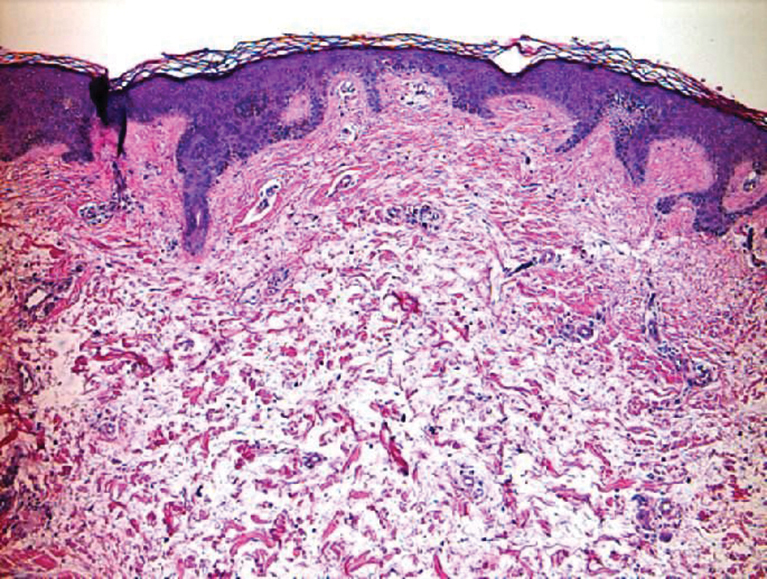

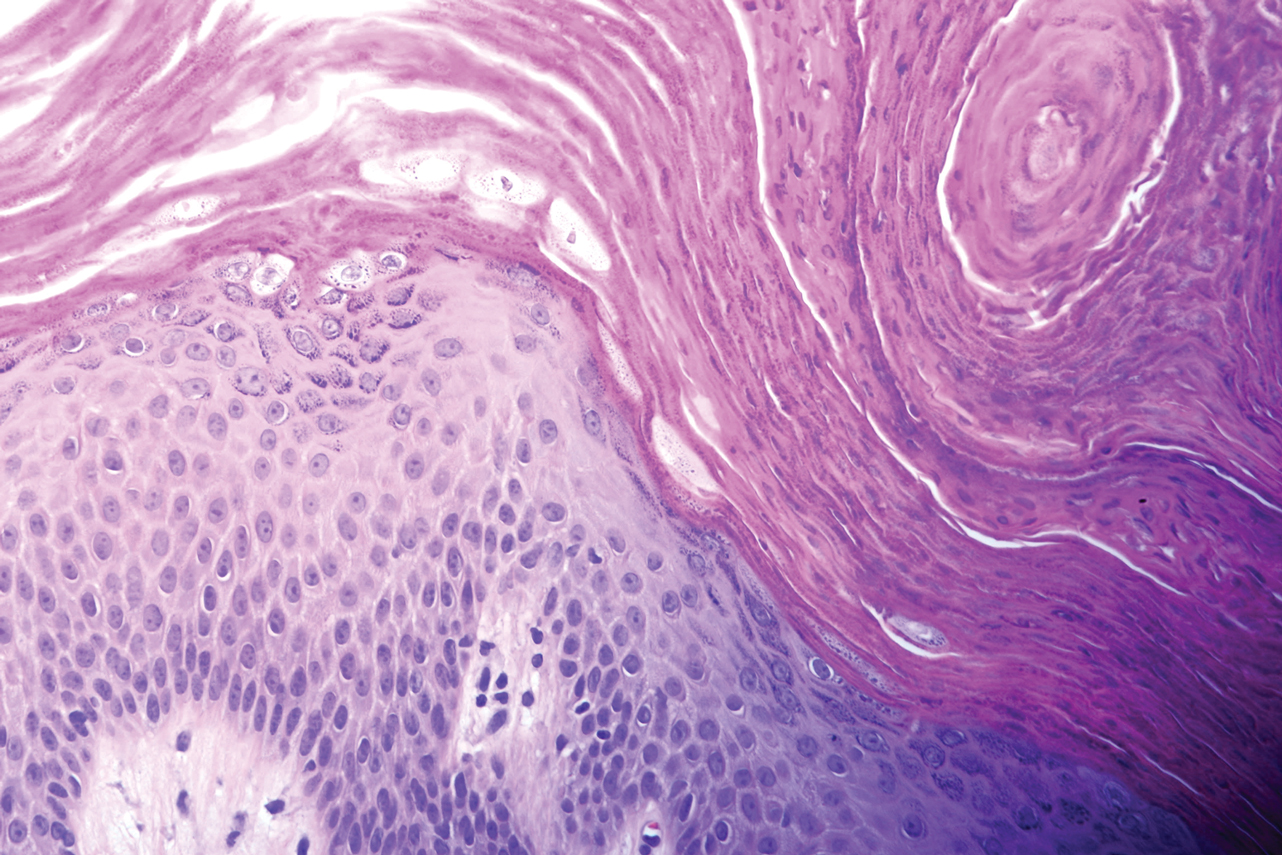

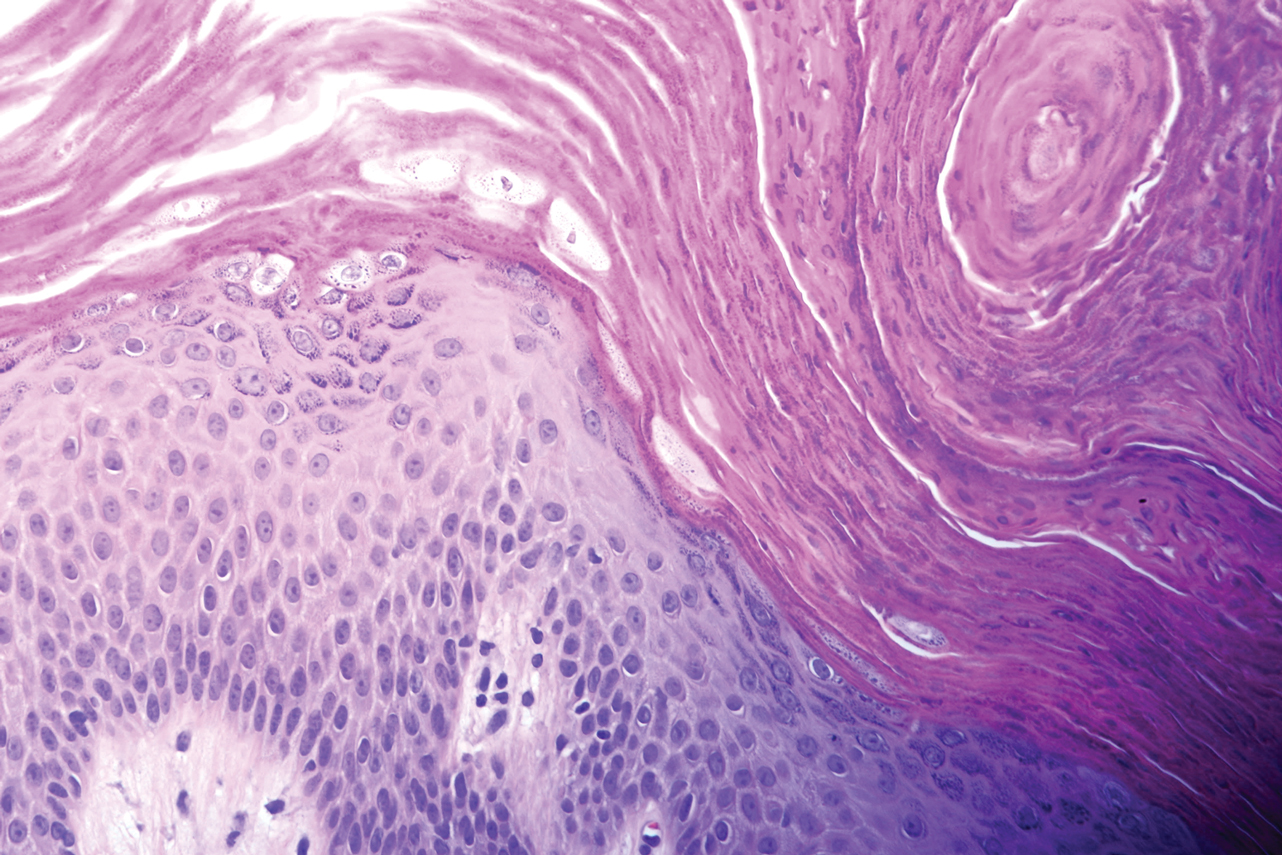

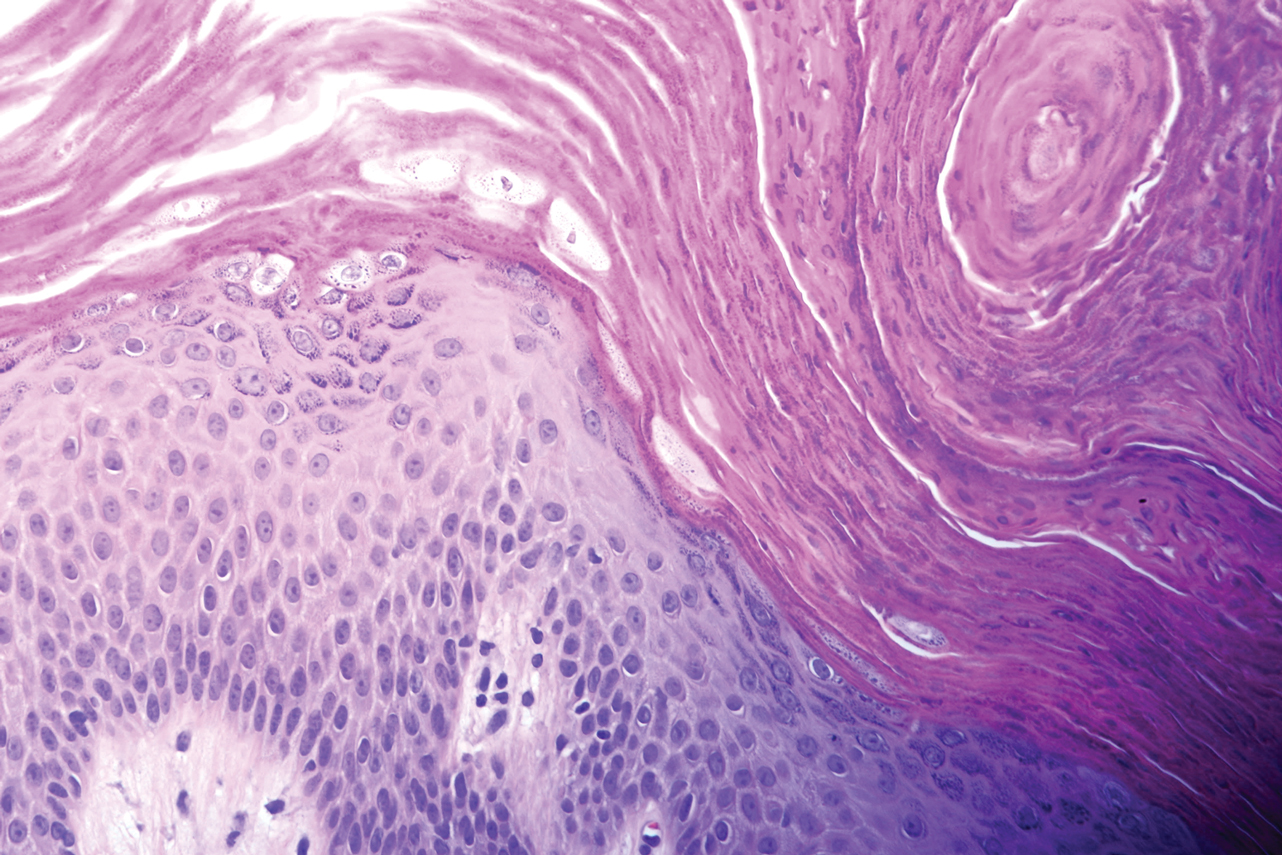

A 4-mm punch biopsy specimen of a representative lesion on the right leg revealed psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, parakeratosis, neutrophils in the stratum corneum and spinosum, elongation of the rete ridges, and superficial vascular ectasia, which favored a diagnosis of psoriasis (Figure 2). A periodic acid-Schiff stain was negative for fungal hyphae. Fungal culture, bacterial tissue culture, and acid-fast bacilli smear were negative. Absence of deep dermal inflammation precluded a diagnosis of Sweet syndrome. Further notable laboratory studies included negative human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody, rapid plasma reagin, hepatitis C antibody, and rheumatoid factor.

At follow-up 2 weeks later, the initial lesions were still present, and she had developed new widespread, well-demarcated, erythematous plaques with silver scale along the scalp, back, chest, and abdomen that were more typical of psoriasis. Oil spots were noted on several fingernails and toenails. Based on the clinicopathologic findings, nail changes, and asymmetric inflammatory arthritis, a diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) was established. Treatment with clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily to active lesions was started. Initiation of systemic therapy with a steroid-sparing agent was deferred in anticipation of care coordination with rheumatology, hepatology, and hematology/oncology due to the patient's history of follicular lymphoma and chronic hepatitis B. Although attempts were made to avoid systemic corticosteroids due to the risk for a psoriasis flare upon discontinuation, because of the severity of arthralgia she was started on oral prednisone 20 mg daily by rheumatology with plans for a slow taper once an alternative systemic agent was started.1

At 10-week follow-up, the patient had marked improvement of psoriatic plaques with no active lesions while only on prednisone 20 mg daily. In consultation with her care team, she subsequently was started on methotrexate 10 mg weekly for 2 weeks followed by titration to 15 mg weekly. Plans were to start a prednisone taper after a month of methotrexate to allow her new treatment time for therapeutic effect. Notably, the patient chose to discontinue prednisone 2 weeks into methotrexate therapy after only two 10-mg doses of methotrexate weekly and well before therapeutic levels were achieved. Despite stopping prednisone early and without a taper, she did not experience a relapse in psoriatic skin lesions. Three months following initiation of methotrexate, she sustained resolution of the cutaneous lesions with only residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory skin disorder with multiple clinical presentations. There are several variants of psoriasis that are classified by their morphologic appearance including chronic plaque, guttate, erythrodermic, and pustular, with more than 90% of cases representing the plaque variant. Less common clinical presentations of psoriasis include rupioid, ostraceous, inverse, elephantine, and HIV associated.2 Rupioid psoriasis is a rare variant that presents with cone-shaped, limpetlike lesions.3,4 Similar to the limited epidemiological and clinical data pertaining to psoriasis in nonwhite racial groups, there also is a paucity of documented reports of rupioid psoriasis in skin of color.

Rupioid comes from the Greek word rhupos, meaning dirt or filth, and is used to describe well-demarcated lesions with thick, yellow, dirty-appearing, adherent crusts resembling oyster shells with a surrounding rim of erythema.5 Rupioid psoriasis initially was reported in 1948 and remains an uncommon and infrequently reported variant.6 The majority of reported cases have been associated with arthropathy, similar to our patient.3,4 Rupioid lesions also have been observed in an array of other diseases, such as secondary syphilis, crusted scabies, disseminated histoplasmosis, HIV, reactive arthritis, and aminoaciduria.7-11

Diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis can be confirmed with a skin biopsy, which demonstrates characteristic histopathologic findings of psoriasis.3 Laboratory analysis should be performed to rule out other causes of rupioid lesions, and PsA should be differentiated from rheumatoid arthritis if arthropathy is present. In our case, serum rapid plasma reagin, anti-HIV antibody, rheumatoid factor, and fungal cultures were negative. Usin0)g clinical findings, histopathology, laboratory analyses, and radiograph findings, the diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis with PsA was confirmed in our patient.

Psoriasis was not originally suspected in our patient due to the noncharacteristic lesions with smooth black crust--similar appearing to eschar--and the patient's complicated medical history. Variations in the presentation of psoriasis among white individuals and those with skin of color have been reported in the literature.12,13 Psoriatic lesions in darker skin tones may appear more violaceous or hyperpigmented with more conspicuous erythema and thicker plaques. Our patient lacked the classic rupioid appearance of concentric circular layers of dirty, yellow, oysterlike scale, and instead had thick, lamellate, black crust. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms rupioid, coral reef psoriasis, rupioides, and rhupus revealed no other cases of rupioid psoriasis reported in black patients and no cases detailing the variations of rupioid lesions in skin of color. A case of rupioid psoriasis has been reported in a Hispanic patient, but the described psoriatic lesions were more characteristic of the dirty-appearing, conic plaques previously reported.14 Our case highlights a unique example of the variable presentations of cutaneous disorders in skin of color and black patients.

Our patient's case of rupioid psoriasis with PsA presented unique challenges for systemic treatment due to her multiple comorbidities. Rupioid psoriasis most often is treated with combination topical and systemic therapy, with agents such as methotrexate and cyclosporine having prior success.3,4 This variant of psoriasis is highly responsive to treatment, and marked improvement of lesions has been achieved with topical steroids alone with proper adherence.15 Our patient was started on clobetasol ointment 0.05% while a systemic agent was debated for her PsA. Although she did not have improvement with topical therapy alone, she experienced rapid resolution of the skin lesions after initiation of low-dose prednisone 20 mg daily. Interestingly, our patient did not experience a flare of the skin lesions upon discontinuation of systemic steroids despite the lack of an appropriate taper and methotrexate not having reached therapeutic levels.

The clinical nuances of rupioid psoriasis in skin of color have not yet been described and remain an important diagnostic consideration. Our patient achieved remission of skin lesions with sequential treatment of topical clobetasol, a low-dose systemic steroid, and methotrexate. Based on available reports, rupioid psoriasis may represent a variant of psoriasis that is highly responsive to treatment.

- Mrowietz U, Domm S. Systemic steroids in the treatment of psoriasis: what is fact, what is fiction? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1022-1025.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012.

- Wang JL, Yang JH. Rupioid psoriasis associated with arthropathy. J Dermatol. 1997;24:46-49.

- Murakami T, Ohtsuki M, Nakagawa H. Rupioid psoriasis with arthropathy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:409-412.

- Chung HJ, Marley-Kemp D, Keller M. Rupioid psoriasis and other skin diseases with rupioid manifestations. Cutis. 2014;94:119-121.

- Salamon M, Omulecki A, Sysa-Jedrzejowska A, et al. Psoriasisrupioides: a rare variant of a common disease. Cutis. 2011;88:135-137.

- Krase IZ, Cavanaugh K, Curiel-Lewandrowski C. A case of rupioid syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:141-143.

- Garofalo V, Saraceno R, Milana M, et al. Crusted scabies in a liver transplant patient mimicking rupioid psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2016;26:495-496.

- Corti M, Villafane MF, Palmieri O, et al. Rupioid histoplasmosis: first case reported in an AIDS patient in Argentina. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2010;52:279-280.

- Sehgal VN, Koranne RV, Shyam Prasad AL. Unusual manifestations of Reiter's disease in a child. Dermatologica. 1985;170:77-79.

- Haim S, Gilhar A, Cohen A. Cutaneous manifestations associated with aminoaciduria. report of two cases. Dermatologica. 1978;156:244-250.

- McMichael AJ, Vachiramon V, Guzman-Sanchez DA, et al. Psoriasis in African-Americans: a caregivers' survey. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:478-482.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Posligua A, Maldonado C, Gonzalez MG. Rupioid psoriasis preceded by varicella presenting as Koebner phenomenon. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5 suppl 1):AB268.

- Feldman SR, Feldman S, Brown K, et al. "Coral reef" psoriasis: a marker of resistance to topical treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:257-258.

To the Editor:

A 49-year-old black woman presented with multiple hyperkeratotic papules that progressed over the last 2 months to circular plaques with central thick black crust resembling eschar. She first noticed these lesions as firm, small, black papules on the legs and continued to develop new lesions that eventually evolved into large, coin-shaped, hyperkeratotic plaques. Her medical history was notable for stage III non-Hodgkin follicular lymphoma in remission after treatment with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone 7 months earlier, and chronic hepatitis B infection being treated with entecavir. Her family history was not remarkable for psoriasis or inflammatory arthritis.

She initially was seen by internal medicine and was started on topical triamcinolone with no improvement of the lesions. At presentation to dermatology, physical examination revealed firm, small, black, hyperkeratotic papules (Figure 1A) and circular plaques with a rim of erythema and central thick, smooth, black crust resembling eschar (Figure 1B). No other skin changes were noted at the time. The bilateral metacarpophalangeal, bilateral proximal interphalangeal, left wrist, and bilateral ankle joints were remarkable for tenderness, swelling, and reduced range of motion. She noted concomitant arthralgia and stiffness but denied fever. She had no other systemic symptoms including night sweats, weight loss, fatigue, malaise, sun sensitivity, oral ulcers, or hair loss. A radiograph of the hand was negative for erosive changes but showed mild periarticular osteopenia and fusiform soft tissue swelling of the third digit. Given the central appearance of eschar in the larger lesions, the initial differential diagnosis included Sweet syndrome, invasive fungal infection, vasculitis, and recurrent lymphoma.

A 4-mm punch biopsy specimen of a representative lesion on the right leg revealed psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, parakeratosis, neutrophils in the stratum corneum and spinosum, elongation of the rete ridges, and superficial vascular ectasia, which favored a diagnosis of psoriasis (Figure 2). A periodic acid-Schiff stain was negative for fungal hyphae. Fungal culture, bacterial tissue culture, and acid-fast bacilli smear were negative. Absence of deep dermal inflammation precluded a diagnosis of Sweet syndrome. Further notable laboratory studies included negative human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody, rapid plasma reagin, hepatitis C antibody, and rheumatoid factor.

At follow-up 2 weeks later, the initial lesions were still present, and she had developed new widespread, well-demarcated, erythematous plaques with silver scale along the scalp, back, chest, and abdomen that were more typical of psoriasis. Oil spots were noted on several fingernails and toenails. Based on the clinicopathologic findings, nail changes, and asymmetric inflammatory arthritis, a diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) was established. Treatment with clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily to active lesions was started. Initiation of systemic therapy with a steroid-sparing agent was deferred in anticipation of care coordination with rheumatology, hepatology, and hematology/oncology due to the patient's history of follicular lymphoma and chronic hepatitis B. Although attempts were made to avoid systemic corticosteroids due to the risk for a psoriasis flare upon discontinuation, because of the severity of arthralgia she was started on oral prednisone 20 mg daily by rheumatology with plans for a slow taper once an alternative systemic agent was started.1

At 10-week follow-up, the patient had marked improvement of psoriatic plaques with no active lesions while only on prednisone 20 mg daily. In consultation with her care team, she subsequently was started on methotrexate 10 mg weekly for 2 weeks followed by titration to 15 mg weekly. Plans were to start a prednisone taper after a month of methotrexate to allow her new treatment time for therapeutic effect. Notably, the patient chose to discontinue prednisone 2 weeks into methotrexate therapy after only two 10-mg doses of methotrexate weekly and well before therapeutic levels were achieved. Despite stopping prednisone early and without a taper, she did not experience a relapse in psoriatic skin lesions. Three months following initiation of methotrexate, she sustained resolution of the cutaneous lesions with only residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory skin disorder with multiple clinical presentations. There are several variants of psoriasis that are classified by their morphologic appearance including chronic plaque, guttate, erythrodermic, and pustular, with more than 90% of cases representing the plaque variant. Less common clinical presentations of psoriasis include rupioid, ostraceous, inverse, elephantine, and HIV associated.2 Rupioid psoriasis is a rare variant that presents with cone-shaped, limpetlike lesions.3,4 Similar to the limited epidemiological and clinical data pertaining to psoriasis in nonwhite racial groups, there also is a paucity of documented reports of rupioid psoriasis in skin of color.

Rupioid comes from the Greek word rhupos, meaning dirt or filth, and is used to describe well-demarcated lesions with thick, yellow, dirty-appearing, adherent crusts resembling oyster shells with a surrounding rim of erythema.5 Rupioid psoriasis initially was reported in 1948 and remains an uncommon and infrequently reported variant.6 The majority of reported cases have been associated with arthropathy, similar to our patient.3,4 Rupioid lesions also have been observed in an array of other diseases, such as secondary syphilis, crusted scabies, disseminated histoplasmosis, HIV, reactive arthritis, and aminoaciduria.7-11

Diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis can be confirmed with a skin biopsy, which demonstrates characteristic histopathologic findings of psoriasis.3 Laboratory analysis should be performed to rule out other causes of rupioid lesions, and PsA should be differentiated from rheumatoid arthritis if arthropathy is present. In our case, serum rapid plasma reagin, anti-HIV antibody, rheumatoid factor, and fungal cultures were negative. Usin0)g clinical findings, histopathology, laboratory analyses, and radiograph findings, the diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis with PsA was confirmed in our patient.

Psoriasis was not originally suspected in our patient due to the noncharacteristic lesions with smooth black crust--similar appearing to eschar--and the patient's complicated medical history. Variations in the presentation of psoriasis among white individuals and those with skin of color have been reported in the literature.12,13 Psoriatic lesions in darker skin tones may appear more violaceous or hyperpigmented with more conspicuous erythema and thicker plaques. Our patient lacked the classic rupioid appearance of concentric circular layers of dirty, yellow, oysterlike scale, and instead had thick, lamellate, black crust. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms rupioid, coral reef psoriasis, rupioides, and rhupus revealed no other cases of rupioid psoriasis reported in black patients and no cases detailing the variations of rupioid lesions in skin of color. A case of rupioid psoriasis has been reported in a Hispanic patient, but the described psoriatic lesions were more characteristic of the dirty-appearing, conic plaques previously reported.14 Our case highlights a unique example of the variable presentations of cutaneous disorders in skin of color and black patients.

Our patient's case of rupioid psoriasis with PsA presented unique challenges for systemic treatment due to her multiple comorbidities. Rupioid psoriasis most often is treated with combination topical and systemic therapy, with agents such as methotrexate and cyclosporine having prior success.3,4 This variant of psoriasis is highly responsive to treatment, and marked improvement of lesions has been achieved with topical steroids alone with proper adherence.15 Our patient was started on clobetasol ointment 0.05% while a systemic agent was debated for her PsA. Although she did not have improvement with topical therapy alone, she experienced rapid resolution of the skin lesions after initiation of low-dose prednisone 20 mg daily. Interestingly, our patient did not experience a flare of the skin lesions upon discontinuation of systemic steroids despite the lack of an appropriate taper and methotrexate not having reached therapeutic levels.

The clinical nuances of rupioid psoriasis in skin of color have not yet been described and remain an important diagnostic consideration. Our patient achieved remission of skin lesions with sequential treatment of topical clobetasol, a low-dose systemic steroid, and methotrexate. Based on available reports, rupioid psoriasis may represent a variant of psoriasis that is highly responsive to treatment.

To the Editor:

A 49-year-old black woman presented with multiple hyperkeratotic papules that progressed over the last 2 months to circular plaques with central thick black crust resembling eschar. She first noticed these lesions as firm, small, black papules on the legs and continued to develop new lesions that eventually evolved into large, coin-shaped, hyperkeratotic plaques. Her medical history was notable for stage III non-Hodgkin follicular lymphoma in remission after treatment with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone 7 months earlier, and chronic hepatitis B infection being treated with entecavir. Her family history was not remarkable for psoriasis or inflammatory arthritis.

She initially was seen by internal medicine and was started on topical triamcinolone with no improvement of the lesions. At presentation to dermatology, physical examination revealed firm, small, black, hyperkeratotic papules (Figure 1A) and circular plaques with a rim of erythema and central thick, smooth, black crust resembling eschar (Figure 1B). No other skin changes were noted at the time. The bilateral metacarpophalangeal, bilateral proximal interphalangeal, left wrist, and bilateral ankle joints were remarkable for tenderness, swelling, and reduced range of motion. She noted concomitant arthralgia and stiffness but denied fever. She had no other systemic symptoms including night sweats, weight loss, fatigue, malaise, sun sensitivity, oral ulcers, or hair loss. A radiograph of the hand was negative for erosive changes but showed mild periarticular osteopenia and fusiform soft tissue swelling of the third digit. Given the central appearance of eschar in the larger lesions, the initial differential diagnosis included Sweet syndrome, invasive fungal infection, vasculitis, and recurrent lymphoma.

A 4-mm punch biopsy specimen of a representative lesion on the right leg revealed psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, parakeratosis, neutrophils in the stratum corneum and spinosum, elongation of the rete ridges, and superficial vascular ectasia, which favored a diagnosis of psoriasis (Figure 2). A periodic acid-Schiff stain was negative for fungal hyphae. Fungal culture, bacterial tissue culture, and acid-fast bacilli smear were negative. Absence of deep dermal inflammation precluded a diagnosis of Sweet syndrome. Further notable laboratory studies included negative human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody, rapid plasma reagin, hepatitis C antibody, and rheumatoid factor.

At follow-up 2 weeks later, the initial lesions were still present, and she had developed new widespread, well-demarcated, erythematous plaques with silver scale along the scalp, back, chest, and abdomen that were more typical of psoriasis. Oil spots were noted on several fingernails and toenails. Based on the clinicopathologic findings, nail changes, and asymmetric inflammatory arthritis, a diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) was established. Treatment with clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily to active lesions was started. Initiation of systemic therapy with a steroid-sparing agent was deferred in anticipation of care coordination with rheumatology, hepatology, and hematology/oncology due to the patient's history of follicular lymphoma and chronic hepatitis B. Although attempts were made to avoid systemic corticosteroids due to the risk for a psoriasis flare upon discontinuation, because of the severity of arthralgia she was started on oral prednisone 20 mg daily by rheumatology with plans for a slow taper once an alternative systemic agent was started.1

At 10-week follow-up, the patient had marked improvement of psoriatic plaques with no active lesions while only on prednisone 20 mg daily. In consultation with her care team, she subsequently was started on methotrexate 10 mg weekly for 2 weeks followed by titration to 15 mg weekly. Plans were to start a prednisone taper after a month of methotrexate to allow her new treatment time for therapeutic effect. Notably, the patient chose to discontinue prednisone 2 weeks into methotrexate therapy after only two 10-mg doses of methotrexate weekly and well before therapeutic levels were achieved. Despite stopping prednisone early and without a taper, she did not experience a relapse in psoriatic skin lesions. Three months following initiation of methotrexate, she sustained resolution of the cutaneous lesions with only residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory skin disorder with multiple clinical presentations. There are several variants of psoriasis that are classified by their morphologic appearance including chronic plaque, guttate, erythrodermic, and pustular, with more than 90% of cases representing the plaque variant. Less common clinical presentations of psoriasis include rupioid, ostraceous, inverse, elephantine, and HIV associated.2 Rupioid psoriasis is a rare variant that presents with cone-shaped, limpetlike lesions.3,4 Similar to the limited epidemiological and clinical data pertaining to psoriasis in nonwhite racial groups, there also is a paucity of documented reports of rupioid psoriasis in skin of color.

Rupioid comes from the Greek word rhupos, meaning dirt or filth, and is used to describe well-demarcated lesions with thick, yellow, dirty-appearing, adherent crusts resembling oyster shells with a surrounding rim of erythema.5 Rupioid psoriasis initially was reported in 1948 and remains an uncommon and infrequently reported variant.6 The majority of reported cases have been associated with arthropathy, similar to our patient.3,4 Rupioid lesions also have been observed in an array of other diseases, such as secondary syphilis, crusted scabies, disseminated histoplasmosis, HIV, reactive arthritis, and aminoaciduria.7-11

Diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis can be confirmed with a skin biopsy, which demonstrates characteristic histopathologic findings of psoriasis.3 Laboratory analysis should be performed to rule out other causes of rupioid lesions, and PsA should be differentiated from rheumatoid arthritis if arthropathy is present. In our case, serum rapid plasma reagin, anti-HIV antibody, rheumatoid factor, and fungal cultures were negative. Usin0)g clinical findings, histopathology, laboratory analyses, and radiograph findings, the diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis with PsA was confirmed in our patient.

Psoriasis was not originally suspected in our patient due to the noncharacteristic lesions with smooth black crust--similar appearing to eschar--and the patient's complicated medical history. Variations in the presentation of psoriasis among white individuals and those with skin of color have been reported in the literature.12,13 Psoriatic lesions in darker skin tones may appear more violaceous or hyperpigmented with more conspicuous erythema and thicker plaques. Our patient lacked the classic rupioid appearance of concentric circular layers of dirty, yellow, oysterlike scale, and instead had thick, lamellate, black crust. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms rupioid, coral reef psoriasis, rupioides, and rhupus revealed no other cases of rupioid psoriasis reported in black patients and no cases detailing the variations of rupioid lesions in skin of color. A case of rupioid psoriasis has been reported in a Hispanic patient, but the described psoriatic lesions were more characteristic of the dirty-appearing, conic plaques previously reported.14 Our case highlights a unique example of the variable presentations of cutaneous disorders in skin of color and black patients.

Our patient's case of rupioid psoriasis with PsA presented unique challenges for systemic treatment due to her multiple comorbidities. Rupioid psoriasis most often is treated with combination topical and systemic therapy, with agents such as methotrexate and cyclosporine having prior success.3,4 This variant of psoriasis is highly responsive to treatment, and marked improvement of lesions has been achieved with topical steroids alone with proper adherence.15 Our patient was started on clobetasol ointment 0.05% while a systemic agent was debated for her PsA. Although she did not have improvement with topical therapy alone, she experienced rapid resolution of the skin lesions after initiation of low-dose prednisone 20 mg daily. Interestingly, our patient did not experience a flare of the skin lesions upon discontinuation of systemic steroids despite the lack of an appropriate taper and methotrexate not having reached therapeutic levels.

The clinical nuances of rupioid psoriasis in skin of color have not yet been described and remain an important diagnostic consideration. Our patient achieved remission of skin lesions with sequential treatment of topical clobetasol, a low-dose systemic steroid, and methotrexate. Based on available reports, rupioid psoriasis may represent a variant of psoriasis that is highly responsive to treatment.

- Mrowietz U, Domm S. Systemic steroids in the treatment of psoriasis: what is fact, what is fiction? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1022-1025.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012.

- Wang JL, Yang JH. Rupioid psoriasis associated with arthropathy. J Dermatol. 1997;24:46-49.

- Murakami T, Ohtsuki M, Nakagawa H. Rupioid psoriasis with arthropathy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:409-412.

- Chung HJ, Marley-Kemp D, Keller M. Rupioid psoriasis and other skin diseases with rupioid manifestations. Cutis. 2014;94:119-121.

- Salamon M, Omulecki A, Sysa-Jedrzejowska A, et al. Psoriasisrupioides: a rare variant of a common disease. Cutis. 2011;88:135-137.

- Krase IZ, Cavanaugh K, Curiel-Lewandrowski C. A case of rupioid syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:141-143.

- Garofalo V, Saraceno R, Milana M, et al. Crusted scabies in a liver transplant patient mimicking rupioid psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2016;26:495-496.

- Corti M, Villafane MF, Palmieri O, et al. Rupioid histoplasmosis: first case reported in an AIDS patient in Argentina. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2010;52:279-280.

- Sehgal VN, Koranne RV, Shyam Prasad AL. Unusual manifestations of Reiter's disease in a child. Dermatologica. 1985;170:77-79.

- Haim S, Gilhar A, Cohen A. Cutaneous manifestations associated with aminoaciduria. report of two cases. Dermatologica. 1978;156:244-250.

- McMichael AJ, Vachiramon V, Guzman-Sanchez DA, et al. Psoriasis in African-Americans: a caregivers' survey. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:478-482.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Posligua A, Maldonado C, Gonzalez MG. Rupioid psoriasis preceded by varicella presenting as Koebner phenomenon. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5 suppl 1):AB268.

- Feldman SR, Feldman S, Brown K, et al. "Coral reef" psoriasis: a marker of resistance to topical treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:257-258.

- Mrowietz U, Domm S. Systemic steroids in the treatment of psoriasis: what is fact, what is fiction? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1022-1025.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012.

- Wang JL, Yang JH. Rupioid psoriasis associated with arthropathy. J Dermatol. 1997;24:46-49.

- Murakami T, Ohtsuki M, Nakagawa H. Rupioid psoriasis with arthropathy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:409-412.

- Chung HJ, Marley-Kemp D, Keller M. Rupioid psoriasis and other skin diseases with rupioid manifestations. Cutis. 2014;94:119-121.

- Salamon M, Omulecki A, Sysa-Jedrzejowska A, et al. Psoriasisrupioides: a rare variant of a common disease. Cutis. 2011;88:135-137.

- Krase IZ, Cavanaugh K, Curiel-Lewandrowski C. A case of rupioid syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:141-143.

- Garofalo V, Saraceno R, Milana M, et al. Crusted scabies in a liver transplant patient mimicking rupioid psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2016;26:495-496.

- Corti M, Villafane MF, Palmieri O, et al. Rupioid histoplasmosis: first case reported in an AIDS patient in Argentina. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2010;52:279-280.

- Sehgal VN, Koranne RV, Shyam Prasad AL. Unusual manifestations of Reiter's disease in a child. Dermatologica. 1985;170:77-79.

- Haim S, Gilhar A, Cohen A. Cutaneous manifestations associated with aminoaciduria. report of two cases. Dermatologica. 1978;156:244-250.

- McMichael AJ, Vachiramon V, Guzman-Sanchez DA, et al. Psoriasis in African-Americans: a caregivers' survey. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:478-482.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Posligua A, Maldonado C, Gonzalez MG. Rupioid psoriasis preceded by varicella presenting as Koebner phenomenon. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5 suppl 1):AB268.

- Feldman SR, Feldman S, Brown K, et al. "Coral reef" psoriasis: a marker of resistance to topical treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:257-258.

Practice Points

- Rupioid psoriasis in skin of color may present a diagnostic challenge for health care providers.

- Rupioid psoriasis may represent a psoriasis variant that is highly responsive to treatment.

PD-1 Signaling in Extramammary Paget Disease

Primary extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is an adnexal carcinoma of the apocrine gland ducts that presents as an erythematous patch on cutaneous sites rich with apocrine glands.1 Primary EMPD can be in situ or invasive with the potential to become metastatic.2 Treatment of primary EMPD is challenging due to the difficulty of achieving clear surgical margins, as the tumor has microscopic spread throughout the epidermis in a skipping fashion.3 Mohs micrographic surgery is the treatment of choice; however, there is a clinical need to identify additional treatment modalities, especially for patients with unresectable, invasive, or metastatic primary EMPD,4 which partly is due to lack of data to understand the pathogenesis of primary EMPD. Recently, there have been studies investigating the genetic characteristics of EMPD tumors. The interaction between the programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) is one of the pathways recently studied and has been reported to be a potential target in EMPD.5-7 Programmed cell death receptor 1 signaling constitutes an immune checkpoint pathway that regulates the activation of tumor-specific T cells.8 In several malignancies, cancer cells express PD-L1 on their surface to activate PD-1 signaling in T cells as a mechanism to dampen the tumor-specific immune response and evade antitumor immunity.9 Thus, blocking PD-1 signaling widely is used to activate tumor-specific T cells and decrease tumor burden.10 Given the advances of immunotherapy in many neoplasms and the paucity of effective agents to treat EMPD, this article serves to shed light on recent data studying PD-1 signaling in EMPD and highlights the potential clinical use of immunotherapy for EMPD.

EMPD and Its Subtypes

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare adenocarcinoma typically affecting older patients (age >60 years) in cutaneous sites with abundant apocrine glands such as the genital and perianal skin.3 Extramammary Paget disease presents as an erythematous patch and frequently is treated initially as a skin dermatosis, resulting in a delay in diagnosis. Histologically, EMPD is characterized by the presence of single cells or a nest of cells having abundant pale cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei distributed in the epidermis in a pagetoid fashion.11

Extramammary Paget disease can be primary or secondary; the 2 subtypes behave differently both clinically and prognostically. Although primary EMPD is considered to be an adnexal carcinoma of the apocrine gland ducts, secondary EMPD is considered to be an intraepithelial extension of malignant cells from an underlying internal neoplasm.12 The underlying malignancies usually are located within dermal adnexal glands or organs in the vicinity of the cutaneous lesion, such as the colon in the case of perianal EMPD. Histologically, primary and secondary EMPD can be differentiated based on their immunophenotypic staining profiles. Although all cases of EMPD show positive immunohistochemistry staining for cytokeratin 7, carcinoembryonic antigen, and epithelial membrane antigen, only primary EMPD will additionally stain for GCDFP-15 (gross cystic disease fluid protein 15) and GATA.11 Regardless of the immunohistochemistry stains, every patient newly diagnosed with EMPD deserves a full workup for malignancy screening, including a colonoscopy, cystoscopy, mammography and Papanicolaou test in women, pelvic ultrasound, and computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis.13

The first-line treatment of EMPD is surgery; however, obtaining clear surgical margins can be a challenge, with high recurrence rates due to the microscopic spread of the disease throughout the epidermis.4 In addition, anatomic location affects the surgical approach and patient survival. Recent studies on EMPD mortality outcomes in women show that mortality is higher in patients with vaginal EMPD than in those with vulvar/labial EMPD, partly due to the sensitive location that makes it difficult to perform wide local excisions.13,14 Assessing the entire margins with tissue preservation using Mohs micrographic surgery has been shown to be successful in decreasing the recurrence rate, especially when coupled with the use of cytokeratin 7 immunohistochemistry.4 Other treatment modalities include radiation, topical imiquimod, and photodynamic therapy.15,16 Regardless of treatment modality, EMPD requires long‐term follow-up to monitor for disease recurrence, regional lymphadenopathy, distant metastasis, or development of an internal malignancy.

The pathogenesis of primary EMPD remains unclear. The tumor is thought to be derived from Toker cells, which are pluripotent adnexal stem cells located in the epidermis that normally give rise to apocrine glands.17 There have been few studies investigating the genetic characteristics of EMPD lesions in an attempt to understand pathogenesis as well as to find druggable targets. Current data for targeted therapy have focused on HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) hormone receptor expression,18 ERBB (erythroblastic oncogene B) amplification,19 CDK4 (cyclin-dependent kinase 4)–cyclin D1 signaling,20 and most recently PD-1/PD-L1 pathway.5-7

PD-1 Expression in EMPD: Implication for Immunotherapy

Most tumors display novel antigens that are recognized by the host immune system and thus stimulate cell-mediated and humoral pathways. The immune system naturally provides regulatory immune checkpoints to T cell–mediated immune responses. One of these checkpoints involves the interaction between PD-1 on T cells and its ligand PD-L1 on tumor cells.21 When PD-1 binds to PD-L1 on tumor cells, there is inhibition of T-cell proliferation, a decrease in cytokine production, and induction of T-cell cytolysis.22 The Figure summarizes the dynamics for T-cell regulation.

Naturally, tumor-infiltrating T cells trigger their own inhibition by binding to PD-L1. However, certain tumor cells constitutively upregulate the expression of PD-L1. With that, the tumor cells gain the ability to suppress T cells and avoid T cell–mediated cytotoxicity,23 which is known as the adoptive immune resistance mechanism. There have been several studies in the literature investigating the PD-1 signaling pathway in EMPD as a way to determine if EMPD would be susceptible to immune checkpoint blockade. The success of checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy generally correlates with increased PD-L1 expression by tumor cells.

One study evaluated the expression of PD-L1 in tumor cells and tumor-infiltrating T cells in 18 cases of EMPD.6 The authors identified that even though tumor cell PD-L1 expression was detected in only 3 (17%) cases, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes expressed PD-L1 in the majority of the cases analyzed and in all of the cases positive for tumor cell PD-L1.6

Another study evaluated PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in EMPD tumor cells and tumor-associated immune infiltrate.5 They found that PD-1 was expressed heavily by the tumor-associated immune infiltrate in all EMPD cases analyzed. Similar to the previously mentioned study,6 PD-L1 was expressed by tumor cells in a few cases only. Interestingly, they found that the density of CD3 in the tumor-associated immune infiltrate was significantly (P=.049) higher in patients who were alive than in those who died, suggesting the importance of an exuberant T-cell response for survival in EMPD.5

A third study investigated protein expression of the B7 family members as well as PD-1 and PD-L1/2 in 55 EMPD samples. In this study the authors also found that tumor cell PD-L1 was minimal. Interestingly, they also found that tumor cells expressed B7 proteins in the majority of the cases.7

Finally, another study examined activity levels of T cells in EMPD by measuring the number and expression levels of cytotoxic T-cell cytokines.24 The authors first found that EMPD tumors had a significantly higher number of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes compared to peripheral blood (P<.01). These CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes also had a significantly higher expression of PD-1 (P<.01). They also found that tumor cells produced an immunosuppressive molecule called indoleamine 2,3-dyoxygenae that functions by suppressing T-cell activity levels. They concluded that in EMPD, tumor-specific T lymphocytes have an exhausted phenotype due to PD-1 activation as well as indoleamine 2,3-dyoxygenase release to the tumor microenvironment.24

These studies highlight that restoring the effector functions of tumor-specific T lymphocytes could be an effective treatment strategy for EMPD. In fact, immunotherapy has been used with success for EMPD in the form of topical immunomodulators such as imiquimod.16,25 More than 40 cases of EMPD treated with imiquimod 5% have been published; of these, only 6 were considered nonresponders,5 which suggests that EMPD may respond to other immunotherapies such as checkpoint inhibitors. It is an exciting time for immunotherapy as more checkpoint inhibitors are being developed. Among the newer agents is cemiplimab, which is a PD-1 inhibitor now US Food and Drug Administration approved for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in patients who are not candidates for curative surgery or curative radiation.26 Programmed cell death receptor 1 signaling can serve as a potential target in EMPD, and further studies need to be performed to test the clinical efficacy, especially in unresectable or invasive/metastatic EMPD. As the PD-1 pathway is more studied in EMPD, and as more PD-1 inhibitors get developed, it would be a clinical need to establish clinical studies for PD-1 inhibitors in EMPD.

- Ito T, Kaku-Ito Y, Furue M. The diagnosis and management of extramammary Paget’s disease. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018;18:543-553.

- van der Zwan JM, Siesling S, Blokx WAM, et al. Invasive extramammary Paget’s disease and the risk for secondary tumours in Europe. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:214-221.

- Simonds RM, Segal RJ, Sharma A. Extramammary Paget’s disease: a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:871-879.

- Wollina U, Goldman A, Bieneck A, et al. Surgical treatment for extramammary Paget’s disease. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19:27.

- Mauzo SH, Tetzlaff MT, Milton DR, et al. Expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 in extramammary Paget disease: implications for immune-targeted therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:754.

- Fowler MR, Flanigan KL, Googe PB. PD-L1 expression in extramammary Paget disease [published online March 6, 2020]. Am J Dermatopathol. doi:10.1097/dad.0000000000001622.

- Pourmaleki M, Young JH, Socci ND, et al. Extramammary Paget disease shows differential expression of B7 family members B7-H3, B7-H4, PD-L1, PD-L2 and cancer/testis antigens NY-ESO-1 and MAGE-A. Oncotarget. 2019;10:6152-6167.

- Mahoney KM, Freeman GJ, McDermott DF. The next immune-checkpoint inhibitors: PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in melanoma. Clin Ther. 2015;37:764-782.

- Dany M, Nganga R, Chidiac A, et al. Advances in immunotherapy for melanoma management. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2016;12:2501-2511.

- Richter MD, Hughes GC, Chung SH, et al. Immunologic adverse events from immune checkpoint therapy [published online April 13, 2020]. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2020.101511.

- Kang Z, Zhang Q, Zhang Q, et al. Clinical and pathological characteristics of extramammary Paget’s disease: report of 246 Chinese male patients. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:13233-13240.

- Ohara K, Fujisawa Y, Yoshino K, et al. A proposal for a TNM staging system for extramammary Paget disease: retrospective analysis of 301 patients with invasive primary tumors. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;83:234-239.

- Hatta N. Prognostic factors of extramammary Paget’s disease. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19:47.

- Yao H, Xie M, Fu S, et al. Survival analysis of patients with invasive extramammary Paget disease: implications of anatomic sites. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:403.

- Herrel LA, Weiss AD, Goodman M, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease in males: survival outcomes in 495 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1625-1630.

- Sanderson P, Innamaa A, Palmer J, et al. Imiquimod therapy for extramammary Paget’s disease of the vulva: a viable non-surgical alternative. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33:479-483.

- Smith AA. Pre-Paget cells: evidence of keratinocyte origin of extramammary Paget’s disease. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2019;8:203-205.

- Garganese G, Inzani F, Mantovani G, et al. The vulvar immunohistochemical panel (VIP) project: molecular profiles of vulvar Paget’s disease. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2019;145:2211-2225.

- Dias-Santagata D, Lam Q, Bergethon K, et al. A potential role for targeted therapy in a subset of metastasizing adnexal carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:974-982.

- Cohen JM, Granter SR, Werchniak AE. Risk stratification in extramammary Paget disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:473-478.

- Wei SC, Duffy CR, Allison JP. Fundamental mechanisms of immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:1069-1086.

- Shi Y. Regulatory mechanisms of PD-L1 expression in cancer cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2018;67:1481-1489.

- Cui C, Yu B, Jiang Q, et al. The roles of PD-1/PD-L1 and its signalling pathway in gastrointestinal tract cancers. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2019;46:3-10.

- Iga N, Otsuka A, Yamamoto Y, et al. Accumulation of exhausted CD8+ T cells in extramammary Paget’s disease. PLoS One. 2019;14:E0211135.

- Frances L, Pascual JC, Leiva-Salinas M, et al. Extramammary Paget disease successfully treated with topical imiquimod 5% and tazarotene. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:19-20.

- Lee A, Duggan S, Deeks ED. Cemiplimab: a review in advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Drugs. 2020;80:813-819.

Primary extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is an adnexal carcinoma of the apocrine gland ducts that presents as an erythematous patch on cutaneous sites rich with apocrine glands.1 Primary EMPD can be in situ or invasive with the potential to become metastatic.2 Treatment of primary EMPD is challenging due to the difficulty of achieving clear surgical margins, as the tumor has microscopic spread throughout the epidermis in a skipping fashion.3 Mohs micrographic surgery is the treatment of choice; however, there is a clinical need to identify additional treatment modalities, especially for patients with unresectable, invasive, or metastatic primary EMPD,4 which partly is due to lack of data to understand the pathogenesis of primary EMPD. Recently, there have been studies investigating the genetic characteristics of EMPD tumors. The interaction between the programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) is one of the pathways recently studied and has been reported to be a potential target in EMPD.5-7 Programmed cell death receptor 1 signaling constitutes an immune checkpoint pathway that regulates the activation of tumor-specific T cells.8 In several malignancies, cancer cells express PD-L1 on their surface to activate PD-1 signaling in T cells as a mechanism to dampen the tumor-specific immune response and evade antitumor immunity.9 Thus, blocking PD-1 signaling widely is used to activate tumor-specific T cells and decrease tumor burden.10 Given the advances of immunotherapy in many neoplasms and the paucity of effective agents to treat EMPD, this article serves to shed light on recent data studying PD-1 signaling in EMPD and highlights the potential clinical use of immunotherapy for EMPD.

EMPD and Its Subtypes

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare adenocarcinoma typically affecting older patients (age >60 years) in cutaneous sites with abundant apocrine glands such as the genital and perianal skin.3 Extramammary Paget disease presents as an erythematous patch and frequently is treated initially as a skin dermatosis, resulting in a delay in diagnosis. Histologically, EMPD is characterized by the presence of single cells or a nest of cells having abundant pale cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei distributed in the epidermis in a pagetoid fashion.11

Extramammary Paget disease can be primary or secondary; the 2 subtypes behave differently both clinically and prognostically. Although primary EMPD is considered to be an adnexal carcinoma of the apocrine gland ducts, secondary EMPD is considered to be an intraepithelial extension of malignant cells from an underlying internal neoplasm.12 The underlying malignancies usually are located within dermal adnexal glands or organs in the vicinity of the cutaneous lesion, such as the colon in the case of perianal EMPD. Histologically, primary and secondary EMPD can be differentiated based on their immunophenotypic staining profiles. Although all cases of EMPD show positive immunohistochemistry staining for cytokeratin 7, carcinoembryonic antigen, and epithelial membrane antigen, only primary EMPD will additionally stain for GCDFP-15 (gross cystic disease fluid protein 15) and GATA.11 Regardless of the immunohistochemistry stains, every patient newly diagnosed with EMPD deserves a full workup for malignancy screening, including a colonoscopy, cystoscopy, mammography and Papanicolaou test in women, pelvic ultrasound, and computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis.13

The first-line treatment of EMPD is surgery; however, obtaining clear surgical margins can be a challenge, with high recurrence rates due to the microscopic spread of the disease throughout the epidermis.4 In addition, anatomic location affects the surgical approach and patient survival. Recent studies on EMPD mortality outcomes in women show that mortality is higher in patients with vaginal EMPD than in those with vulvar/labial EMPD, partly due to the sensitive location that makes it difficult to perform wide local excisions.13,14 Assessing the entire margins with tissue preservation using Mohs micrographic surgery has been shown to be successful in decreasing the recurrence rate, especially when coupled with the use of cytokeratin 7 immunohistochemistry.4 Other treatment modalities include radiation, topical imiquimod, and photodynamic therapy.15,16 Regardless of treatment modality, EMPD requires long‐term follow-up to monitor for disease recurrence, regional lymphadenopathy, distant metastasis, or development of an internal malignancy.

The pathogenesis of primary EMPD remains unclear. The tumor is thought to be derived from Toker cells, which are pluripotent adnexal stem cells located in the epidermis that normally give rise to apocrine glands.17 There have been few studies investigating the genetic characteristics of EMPD lesions in an attempt to understand pathogenesis as well as to find druggable targets. Current data for targeted therapy have focused on HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) hormone receptor expression,18 ERBB (erythroblastic oncogene B) amplification,19 CDK4 (cyclin-dependent kinase 4)–cyclin D1 signaling,20 and most recently PD-1/PD-L1 pathway.5-7

PD-1 Expression in EMPD: Implication for Immunotherapy

Most tumors display novel antigens that are recognized by the host immune system and thus stimulate cell-mediated and humoral pathways. The immune system naturally provides regulatory immune checkpoints to T cell–mediated immune responses. One of these checkpoints involves the interaction between PD-1 on T cells and its ligand PD-L1 on tumor cells.21 When PD-1 binds to PD-L1 on tumor cells, there is inhibition of T-cell proliferation, a decrease in cytokine production, and induction of T-cell cytolysis.22 The Figure summarizes the dynamics for T-cell regulation.

Naturally, tumor-infiltrating T cells trigger their own inhibition by binding to PD-L1. However, certain tumor cells constitutively upregulate the expression of PD-L1. With that, the tumor cells gain the ability to suppress T cells and avoid T cell–mediated cytotoxicity,23 which is known as the adoptive immune resistance mechanism. There have been several studies in the literature investigating the PD-1 signaling pathway in EMPD as a way to determine if EMPD would be susceptible to immune checkpoint blockade. The success of checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy generally correlates with increased PD-L1 expression by tumor cells.

One study evaluated the expression of PD-L1 in tumor cells and tumor-infiltrating T cells in 18 cases of EMPD.6 The authors identified that even though tumor cell PD-L1 expression was detected in only 3 (17%) cases, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes expressed PD-L1 in the majority of the cases analyzed and in all of the cases positive for tumor cell PD-L1.6

Another study evaluated PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in EMPD tumor cells and tumor-associated immune infiltrate.5 They found that PD-1 was expressed heavily by the tumor-associated immune infiltrate in all EMPD cases analyzed. Similar to the previously mentioned study,6 PD-L1 was expressed by tumor cells in a few cases only. Interestingly, they found that the density of CD3 in the tumor-associated immune infiltrate was significantly (P=.049) higher in patients who were alive than in those who died, suggesting the importance of an exuberant T-cell response for survival in EMPD.5

A third study investigated protein expression of the B7 family members as well as PD-1 and PD-L1/2 in 55 EMPD samples. In this study the authors also found that tumor cell PD-L1 was minimal. Interestingly, they also found that tumor cells expressed B7 proteins in the majority of the cases.7

Finally, another study examined activity levels of T cells in EMPD by measuring the number and expression levels of cytotoxic T-cell cytokines.24 The authors first found that EMPD tumors had a significantly higher number of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes compared to peripheral blood (P<.01). These CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes also had a significantly higher expression of PD-1 (P<.01). They also found that tumor cells produced an immunosuppressive molecule called indoleamine 2,3-dyoxygenae that functions by suppressing T-cell activity levels. They concluded that in EMPD, tumor-specific T lymphocytes have an exhausted phenotype due to PD-1 activation as well as indoleamine 2,3-dyoxygenase release to the tumor microenvironment.24

These studies highlight that restoring the effector functions of tumor-specific T lymphocytes could be an effective treatment strategy for EMPD. In fact, immunotherapy has been used with success for EMPD in the form of topical immunomodulators such as imiquimod.16,25 More than 40 cases of EMPD treated with imiquimod 5% have been published; of these, only 6 were considered nonresponders,5 which suggests that EMPD may respond to other immunotherapies such as checkpoint inhibitors. It is an exciting time for immunotherapy as more checkpoint inhibitors are being developed. Among the newer agents is cemiplimab, which is a PD-1 inhibitor now US Food and Drug Administration approved for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in patients who are not candidates for curative surgery or curative radiation.26 Programmed cell death receptor 1 signaling can serve as a potential target in EMPD, and further studies need to be performed to test the clinical efficacy, especially in unresectable or invasive/metastatic EMPD. As the PD-1 pathway is more studied in EMPD, and as more PD-1 inhibitors get developed, it would be a clinical need to establish clinical studies for PD-1 inhibitors in EMPD.

Primary extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is an adnexal carcinoma of the apocrine gland ducts that presents as an erythematous patch on cutaneous sites rich with apocrine glands.1 Primary EMPD can be in situ or invasive with the potential to become metastatic.2 Treatment of primary EMPD is challenging due to the difficulty of achieving clear surgical margins, as the tumor has microscopic spread throughout the epidermis in a skipping fashion.3 Mohs micrographic surgery is the treatment of choice; however, there is a clinical need to identify additional treatment modalities, especially for patients with unresectable, invasive, or metastatic primary EMPD,4 which partly is due to lack of data to understand the pathogenesis of primary EMPD. Recently, there have been studies investigating the genetic characteristics of EMPD tumors. The interaction between the programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) is one of the pathways recently studied and has been reported to be a potential target in EMPD.5-7 Programmed cell death receptor 1 signaling constitutes an immune checkpoint pathway that regulates the activation of tumor-specific T cells.8 In several malignancies, cancer cells express PD-L1 on their surface to activate PD-1 signaling in T cells as a mechanism to dampen the tumor-specific immune response and evade antitumor immunity.9 Thus, blocking PD-1 signaling widely is used to activate tumor-specific T cells and decrease tumor burden.10 Given the advances of immunotherapy in many neoplasms and the paucity of effective agents to treat EMPD, this article serves to shed light on recent data studying PD-1 signaling in EMPD and highlights the potential clinical use of immunotherapy for EMPD.

EMPD and Its Subtypes

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare adenocarcinoma typically affecting older patients (age >60 years) in cutaneous sites with abundant apocrine glands such as the genital and perianal skin.3 Extramammary Paget disease presents as an erythematous patch and frequently is treated initially as a skin dermatosis, resulting in a delay in diagnosis. Histologically, EMPD is characterized by the presence of single cells or a nest of cells having abundant pale cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei distributed in the epidermis in a pagetoid fashion.11

Extramammary Paget disease can be primary or secondary; the 2 subtypes behave differently both clinically and prognostically. Although primary EMPD is considered to be an adnexal carcinoma of the apocrine gland ducts, secondary EMPD is considered to be an intraepithelial extension of malignant cells from an underlying internal neoplasm.12 The underlying malignancies usually are located within dermal adnexal glands or organs in the vicinity of the cutaneous lesion, such as the colon in the case of perianal EMPD. Histologically, primary and secondary EMPD can be differentiated based on their immunophenotypic staining profiles. Although all cases of EMPD show positive immunohistochemistry staining for cytokeratin 7, carcinoembryonic antigen, and epithelial membrane antigen, only primary EMPD will additionally stain for GCDFP-15 (gross cystic disease fluid protein 15) and GATA.11 Regardless of the immunohistochemistry stains, every patient newly diagnosed with EMPD deserves a full workup for malignancy screening, including a colonoscopy, cystoscopy, mammography and Papanicolaou test in women, pelvic ultrasound, and computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis.13

The first-line treatment of EMPD is surgery; however, obtaining clear surgical margins can be a challenge, with high recurrence rates due to the microscopic spread of the disease throughout the epidermis.4 In addition, anatomic location affects the surgical approach and patient survival. Recent studies on EMPD mortality outcomes in women show that mortality is higher in patients with vaginal EMPD than in those with vulvar/labial EMPD, partly due to the sensitive location that makes it difficult to perform wide local excisions.13,14 Assessing the entire margins with tissue preservation using Mohs micrographic surgery has been shown to be successful in decreasing the recurrence rate, especially when coupled with the use of cytokeratin 7 immunohistochemistry.4 Other treatment modalities include radiation, topical imiquimod, and photodynamic therapy.15,16 Regardless of treatment modality, EMPD requires long‐term follow-up to monitor for disease recurrence, regional lymphadenopathy, distant metastasis, or development of an internal malignancy.

The pathogenesis of primary EMPD remains unclear. The tumor is thought to be derived from Toker cells, which are pluripotent adnexal stem cells located in the epidermis that normally give rise to apocrine glands.17 There have been few studies investigating the genetic characteristics of EMPD lesions in an attempt to understand pathogenesis as well as to find druggable targets. Current data for targeted therapy have focused on HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) hormone receptor expression,18 ERBB (erythroblastic oncogene B) amplification,19 CDK4 (cyclin-dependent kinase 4)–cyclin D1 signaling,20 and most recently PD-1/PD-L1 pathway.5-7

PD-1 Expression in EMPD: Implication for Immunotherapy

Most tumors display novel antigens that are recognized by the host immune system and thus stimulate cell-mediated and humoral pathways. The immune system naturally provides regulatory immune checkpoints to T cell–mediated immune responses. One of these checkpoints involves the interaction between PD-1 on T cells and its ligand PD-L1 on tumor cells.21 When PD-1 binds to PD-L1 on tumor cells, there is inhibition of T-cell proliferation, a decrease in cytokine production, and induction of T-cell cytolysis.22 The Figure summarizes the dynamics for T-cell regulation.

Naturally, tumor-infiltrating T cells trigger their own inhibition by binding to PD-L1. However, certain tumor cells constitutively upregulate the expression of PD-L1. With that, the tumor cells gain the ability to suppress T cells and avoid T cell–mediated cytotoxicity,23 which is known as the adoptive immune resistance mechanism. There have been several studies in the literature investigating the PD-1 signaling pathway in EMPD as a way to determine if EMPD would be susceptible to immune checkpoint blockade. The success of checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy generally correlates with increased PD-L1 expression by tumor cells.

One study evaluated the expression of PD-L1 in tumor cells and tumor-infiltrating T cells in 18 cases of EMPD.6 The authors identified that even though tumor cell PD-L1 expression was detected in only 3 (17%) cases, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes expressed PD-L1 in the majority of the cases analyzed and in all of the cases positive for tumor cell PD-L1.6

Another study evaluated PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in EMPD tumor cells and tumor-associated immune infiltrate.5 They found that PD-1 was expressed heavily by the tumor-associated immune infiltrate in all EMPD cases analyzed. Similar to the previously mentioned study,6 PD-L1 was expressed by tumor cells in a few cases only. Interestingly, they found that the density of CD3 in the tumor-associated immune infiltrate was significantly (P=.049) higher in patients who were alive than in those who died, suggesting the importance of an exuberant T-cell response for survival in EMPD.5

A third study investigated protein expression of the B7 family members as well as PD-1 and PD-L1/2 in 55 EMPD samples. In this study the authors also found that tumor cell PD-L1 was minimal. Interestingly, they also found that tumor cells expressed B7 proteins in the majority of the cases.7

Finally, another study examined activity levels of T cells in EMPD by measuring the number and expression levels of cytotoxic T-cell cytokines.24 The authors first found that EMPD tumors had a significantly higher number of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes compared to peripheral blood (P<.01). These CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes also had a significantly higher expression of PD-1 (P<.01). They also found that tumor cells produced an immunosuppressive molecule called indoleamine 2,3-dyoxygenae that functions by suppressing T-cell activity levels. They concluded that in EMPD, tumor-specific T lymphocytes have an exhausted phenotype due to PD-1 activation as well as indoleamine 2,3-dyoxygenase release to the tumor microenvironment.24

These studies highlight that restoring the effector functions of tumor-specific T lymphocytes could be an effective treatment strategy for EMPD. In fact, immunotherapy has been used with success for EMPD in the form of topical immunomodulators such as imiquimod.16,25 More than 40 cases of EMPD treated with imiquimod 5% have been published; of these, only 6 were considered nonresponders,5 which suggests that EMPD may respond to other immunotherapies such as checkpoint inhibitors. It is an exciting time for immunotherapy as more checkpoint inhibitors are being developed. Among the newer agents is cemiplimab, which is a PD-1 inhibitor now US Food and Drug Administration approved for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in patients who are not candidates for curative surgery or curative radiation.26 Programmed cell death receptor 1 signaling can serve as a potential target in EMPD, and further studies need to be performed to test the clinical efficacy, especially in unresectable or invasive/metastatic EMPD. As the PD-1 pathway is more studied in EMPD, and as more PD-1 inhibitors get developed, it would be a clinical need to establish clinical studies for PD-1 inhibitors in EMPD.

- Ito T, Kaku-Ito Y, Furue M. The diagnosis and management of extramammary Paget’s disease. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018;18:543-553.

- van der Zwan JM, Siesling S, Blokx WAM, et al. Invasive extramammary Paget’s disease and the risk for secondary tumours in Europe. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:214-221.

- Simonds RM, Segal RJ, Sharma A. Extramammary Paget’s disease: a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:871-879.

- Wollina U, Goldman A, Bieneck A, et al. Surgical treatment for extramammary Paget’s disease. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19:27.

- Mauzo SH, Tetzlaff MT, Milton DR, et al. Expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 in extramammary Paget disease: implications for immune-targeted therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:754.

- Fowler MR, Flanigan KL, Googe PB. PD-L1 expression in extramammary Paget disease [published online March 6, 2020]. Am J Dermatopathol. doi:10.1097/dad.0000000000001622.

- Pourmaleki M, Young JH, Socci ND, et al. Extramammary Paget disease shows differential expression of B7 family members B7-H3, B7-H4, PD-L1, PD-L2 and cancer/testis antigens NY-ESO-1 and MAGE-A. Oncotarget. 2019;10:6152-6167.

- Mahoney KM, Freeman GJ, McDermott DF. The next immune-checkpoint inhibitors: PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in melanoma. Clin Ther. 2015;37:764-782.

- Dany M, Nganga R, Chidiac A, et al. Advances in immunotherapy for melanoma management. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2016;12:2501-2511.

- Richter MD, Hughes GC, Chung SH, et al. Immunologic adverse events from immune checkpoint therapy [published online April 13, 2020]. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2020.101511.

- Kang Z, Zhang Q, Zhang Q, et al. Clinical and pathological characteristics of extramammary Paget’s disease: report of 246 Chinese male patients. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:13233-13240.

- Ohara K, Fujisawa Y, Yoshino K, et al. A proposal for a TNM staging system for extramammary Paget disease: retrospective analysis of 301 patients with invasive primary tumors. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;83:234-239.

- Hatta N. Prognostic factors of extramammary Paget’s disease. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19:47.

- Yao H, Xie M, Fu S, et al. Survival analysis of patients with invasive extramammary Paget disease: implications of anatomic sites. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:403.

- Herrel LA, Weiss AD, Goodman M, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease in males: survival outcomes in 495 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1625-1630.

- Sanderson P, Innamaa A, Palmer J, et al. Imiquimod therapy for extramammary Paget’s disease of the vulva: a viable non-surgical alternative. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33:479-483.

- Smith AA. Pre-Paget cells: evidence of keratinocyte origin of extramammary Paget’s disease. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2019;8:203-205.

- Garganese G, Inzani F, Mantovani G, et al. The vulvar immunohistochemical panel (VIP) project: molecular profiles of vulvar Paget’s disease. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2019;145:2211-2225.

- Dias-Santagata D, Lam Q, Bergethon K, et al. A potential role for targeted therapy in a subset of metastasizing adnexal carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:974-982.

- Cohen JM, Granter SR, Werchniak AE. Risk stratification in extramammary Paget disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:473-478.

- Wei SC, Duffy CR, Allison JP. Fundamental mechanisms of immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:1069-1086.

- Shi Y. Regulatory mechanisms of PD-L1 expression in cancer cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2018;67:1481-1489.

- Cui C, Yu B, Jiang Q, et al. The roles of PD-1/PD-L1 and its signalling pathway in gastrointestinal tract cancers. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2019;46:3-10.

- Iga N, Otsuka A, Yamamoto Y, et al. Accumulation of exhausted CD8+ T cells in extramammary Paget’s disease. PLoS One. 2019;14:E0211135.

- Frances L, Pascual JC, Leiva-Salinas M, et al. Extramammary Paget disease successfully treated with topical imiquimod 5% and tazarotene. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:19-20.

- Lee A, Duggan S, Deeks ED. Cemiplimab: a review in advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Drugs. 2020;80:813-819.

- Ito T, Kaku-Ito Y, Furue M. The diagnosis and management of extramammary Paget’s disease. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018;18:543-553.

- van der Zwan JM, Siesling S, Blokx WAM, et al. Invasive extramammary Paget’s disease and the risk for secondary tumours in Europe. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:214-221.

- Simonds RM, Segal RJ, Sharma A. Extramammary Paget’s disease: a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:871-879.

- Wollina U, Goldman A, Bieneck A, et al. Surgical treatment for extramammary Paget’s disease. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19:27.

- Mauzo SH, Tetzlaff MT, Milton DR, et al. Expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 in extramammary Paget disease: implications for immune-targeted therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:754.

- Fowler MR, Flanigan KL, Googe PB. PD-L1 expression in extramammary Paget disease [published online March 6, 2020]. Am J Dermatopathol. doi:10.1097/dad.0000000000001622.

- Pourmaleki M, Young JH, Socci ND, et al. Extramammary Paget disease shows differential expression of B7 family members B7-H3, B7-H4, PD-L1, PD-L2 and cancer/testis antigens NY-ESO-1 and MAGE-A. Oncotarget. 2019;10:6152-6167.

- Mahoney KM, Freeman GJ, McDermott DF. The next immune-checkpoint inhibitors: PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in melanoma. Clin Ther. 2015;37:764-782.

- Dany M, Nganga R, Chidiac A, et al. Advances in immunotherapy for melanoma management. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2016;12:2501-2511.

- Richter MD, Hughes GC, Chung SH, et al. Immunologic adverse events from immune checkpoint therapy [published online April 13, 2020]. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2020.101511.

- Kang Z, Zhang Q, Zhang Q, et al. Clinical and pathological characteristics of extramammary Paget’s disease: report of 246 Chinese male patients. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:13233-13240.

- Ohara K, Fujisawa Y, Yoshino K, et al. A proposal for a TNM staging system for extramammary Paget disease: retrospective analysis of 301 patients with invasive primary tumors. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;83:234-239.

- Hatta N. Prognostic factors of extramammary Paget’s disease. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19:47.

- Yao H, Xie M, Fu S, et al. Survival analysis of patients with invasive extramammary Paget disease: implications of anatomic sites. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:403.

- Herrel LA, Weiss AD, Goodman M, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease in males: survival outcomes in 495 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1625-1630.

- Sanderson P, Innamaa A, Palmer J, et al. Imiquimod therapy for extramammary Paget’s disease of the vulva: a viable non-surgical alternative. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33:479-483.

- Smith AA. Pre-Paget cells: evidence of keratinocyte origin of extramammary Paget’s disease. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2019;8:203-205.

- Garganese G, Inzani F, Mantovani G, et al. The vulvar immunohistochemical panel (VIP) project: molecular profiles of vulvar Paget’s disease. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2019;145:2211-2225.

- Dias-Santagata D, Lam Q, Bergethon K, et al. A potential role for targeted therapy in a subset of metastasizing adnexal carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:974-982.

- Cohen JM, Granter SR, Werchniak AE. Risk stratification in extramammary Paget disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:473-478.

- Wei SC, Duffy CR, Allison JP. Fundamental mechanisms of immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:1069-1086.

- Shi Y. Regulatory mechanisms of PD-L1 expression in cancer cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2018;67:1481-1489.

- Cui C, Yu B, Jiang Q, et al. The roles of PD-1/PD-L1 and its signalling pathway in gastrointestinal tract cancers. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2019;46:3-10.

- Iga N, Otsuka A, Yamamoto Y, et al. Accumulation of exhausted CD8+ T cells in extramammary Paget’s disease. PLoS One. 2019;14:E0211135.

- Frances L, Pascual JC, Leiva-Salinas M, et al. Extramammary Paget disease successfully treated with topical imiquimod 5% and tazarotene. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:19-20.

- Lee A, Duggan S, Deeks ED. Cemiplimab: a review in advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Drugs. 2020;80:813-819.

Resident Pearls

- Primary extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is an adnexal carcinoma of the apocrine gland ducts, while secondary EMPD is an extension of malignant cells from an underlying internal neoplasm.

- Surgical margin clearance in EMPD often is problematic, with high recurrence rates indicating the need for additional treatment modalities.

- Programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1) signaling can serve as a potential target in EMPD. Further studies and clinical trials are needed to test the efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors in unresectable or invasive/metastatic EMPD.

Erythematous Plaque on the Back of a Newborn

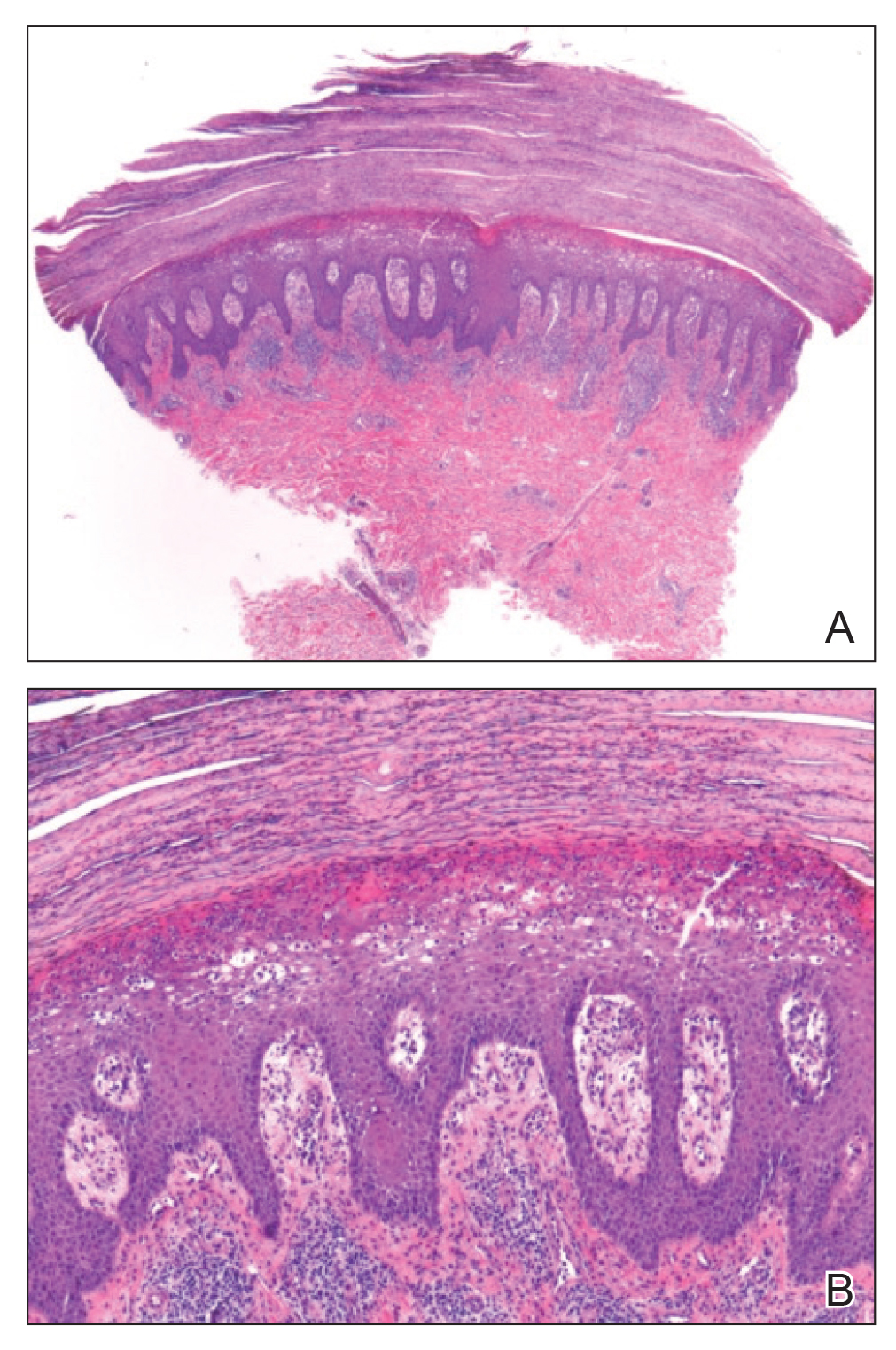

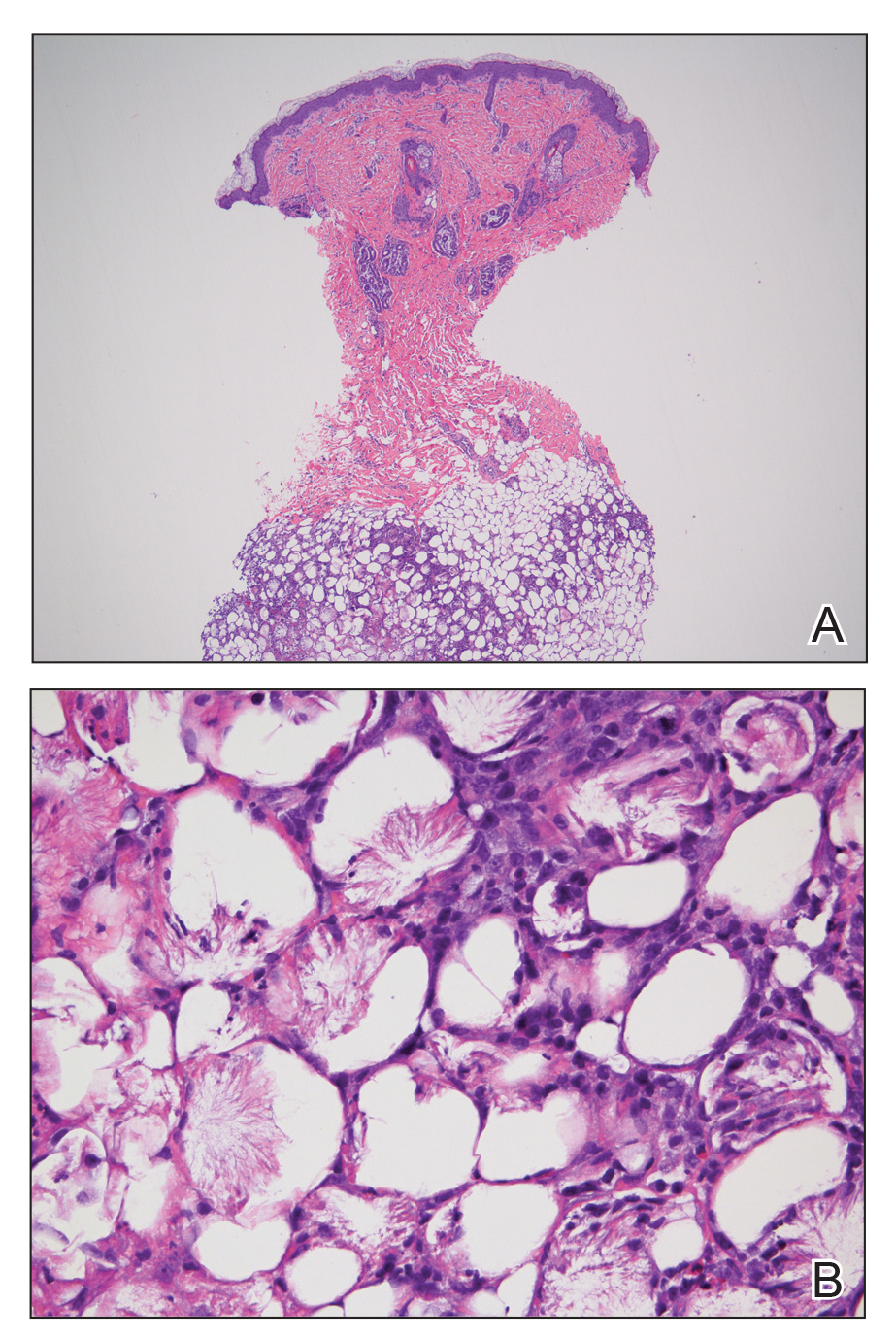

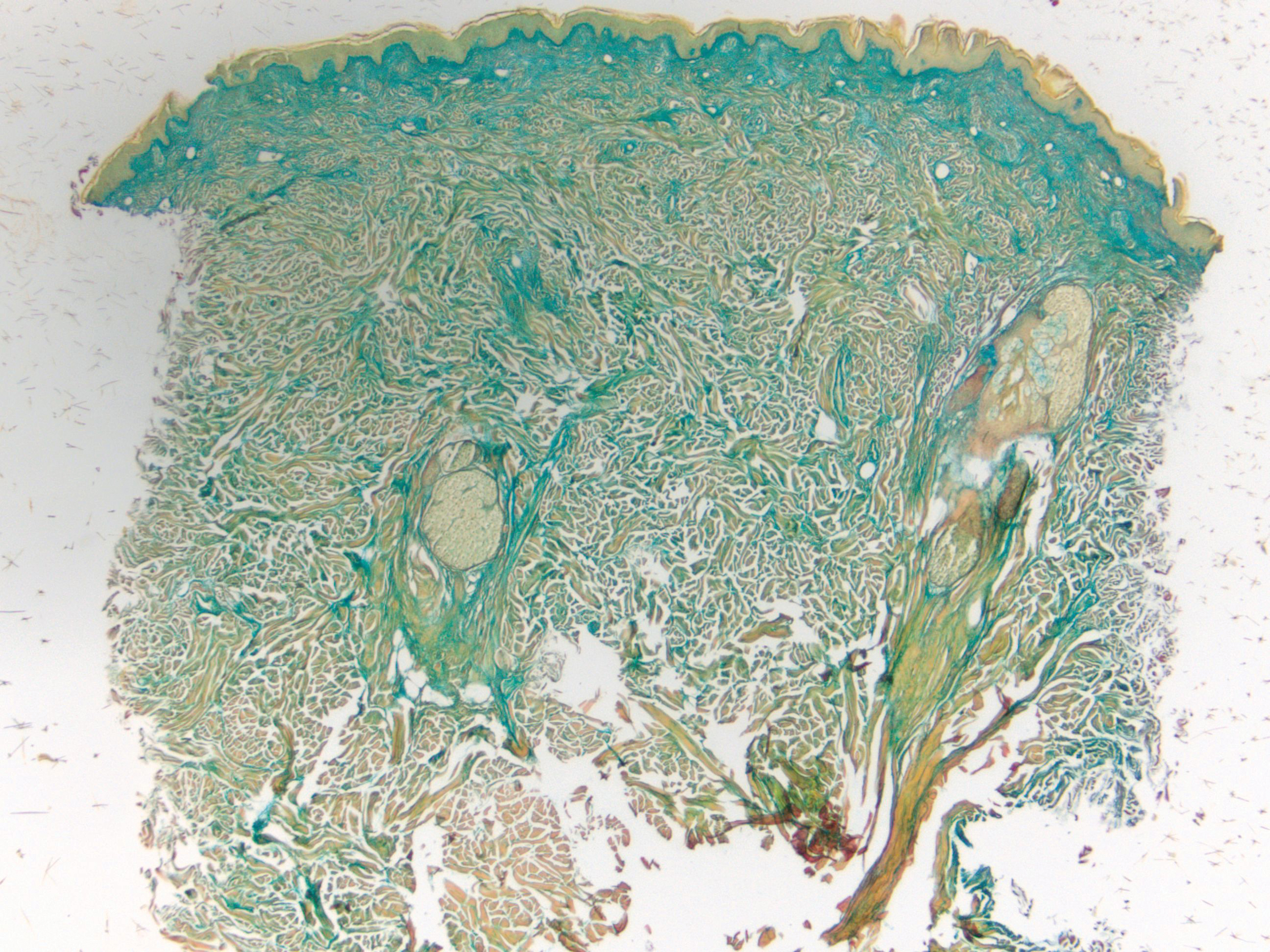

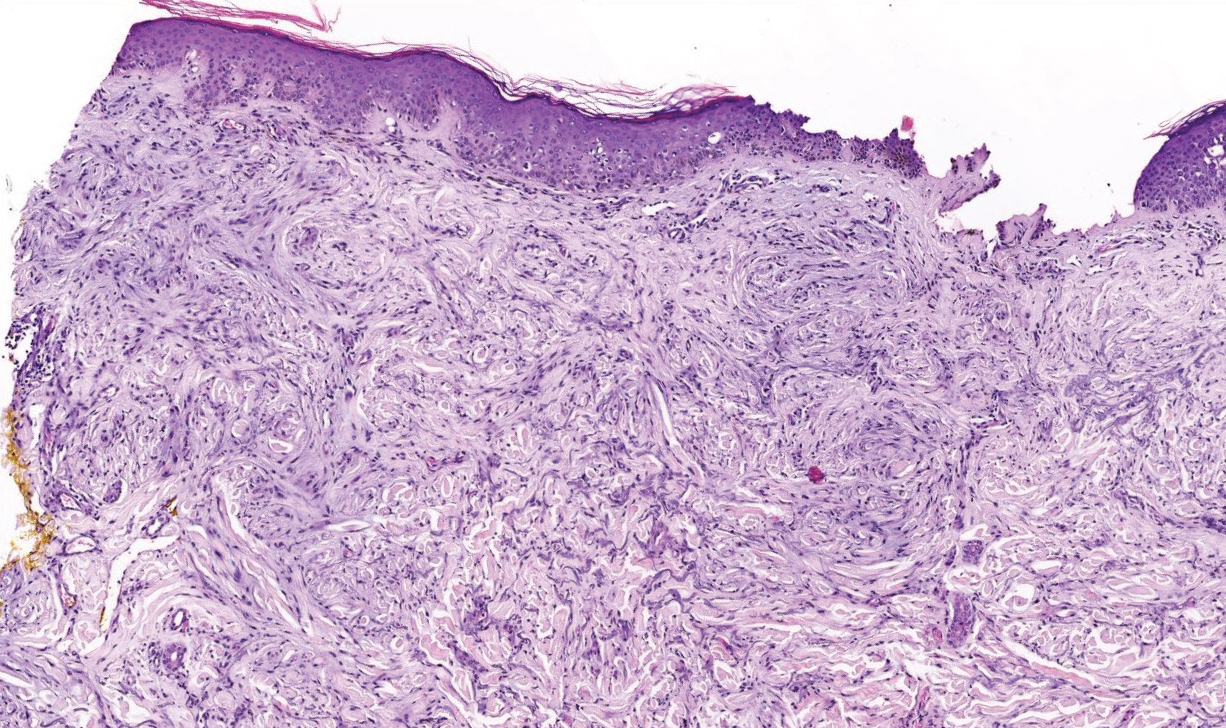

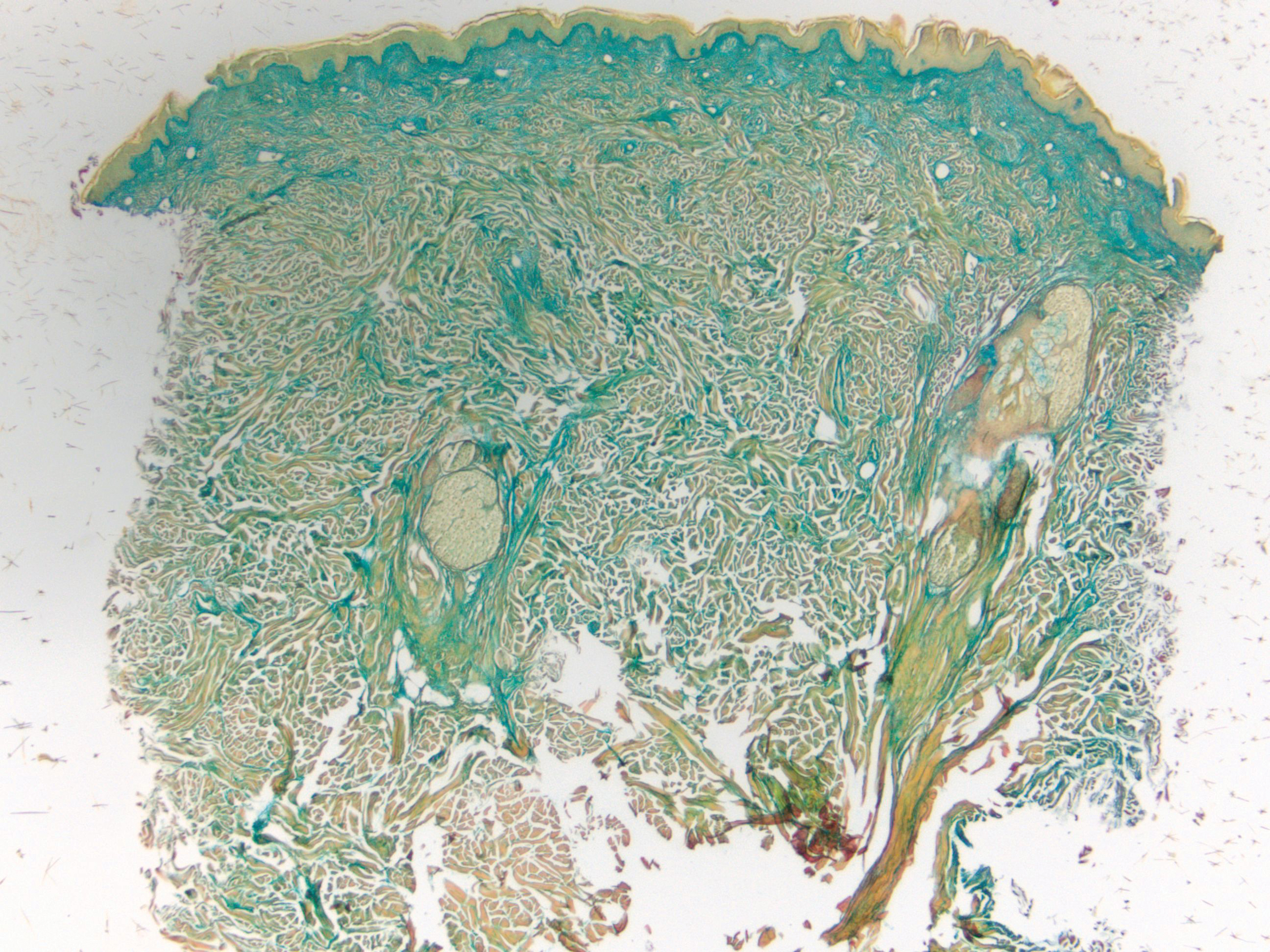

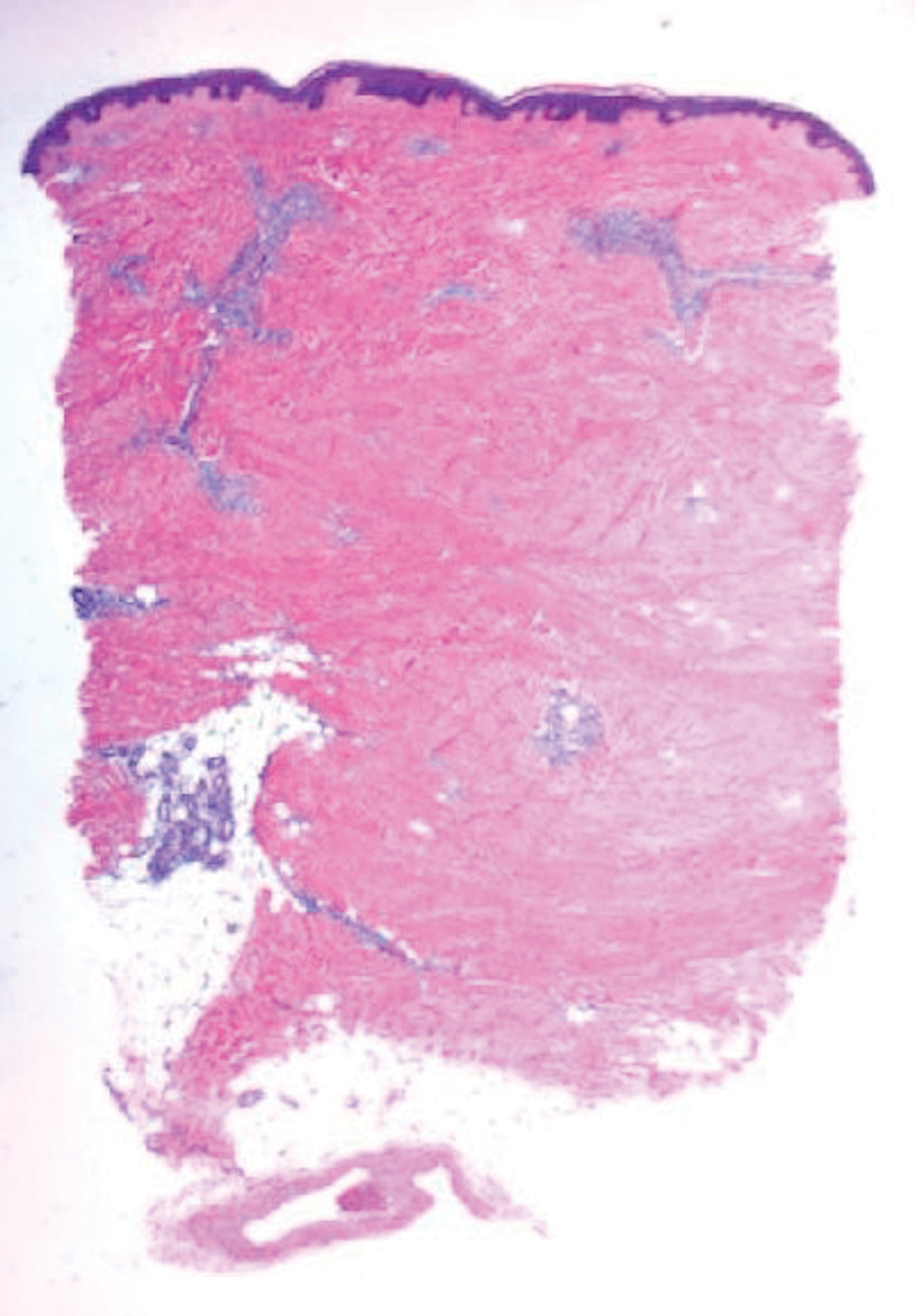

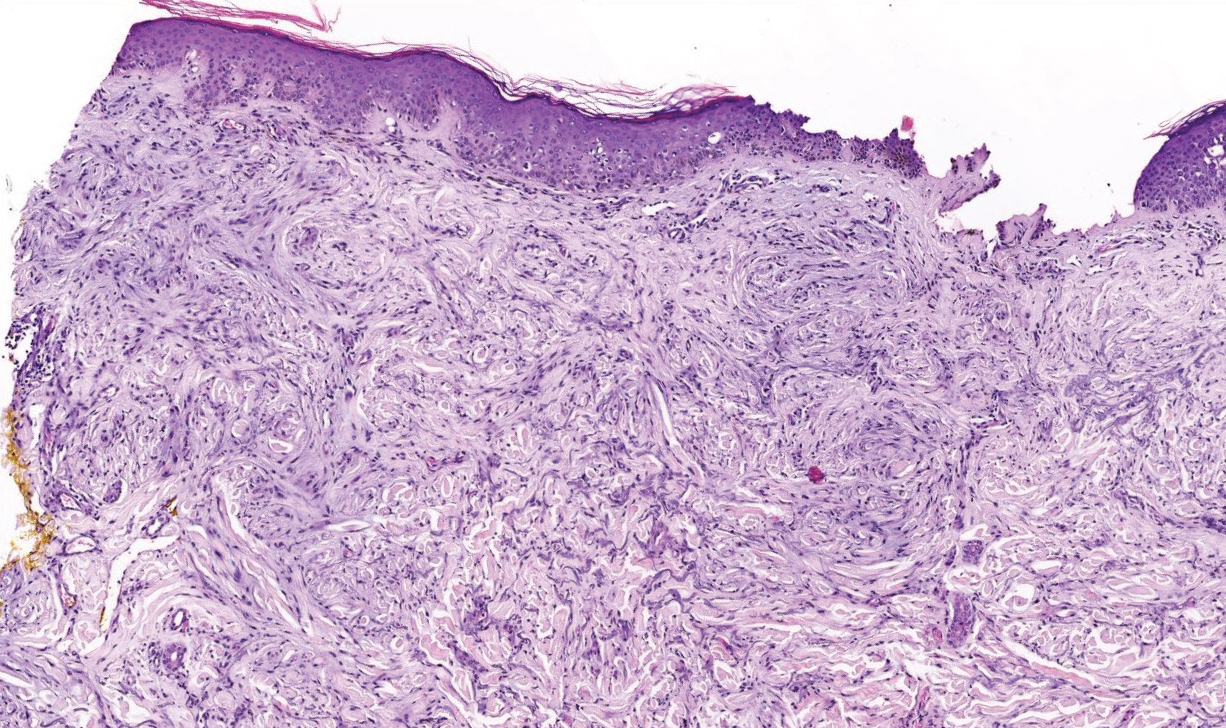

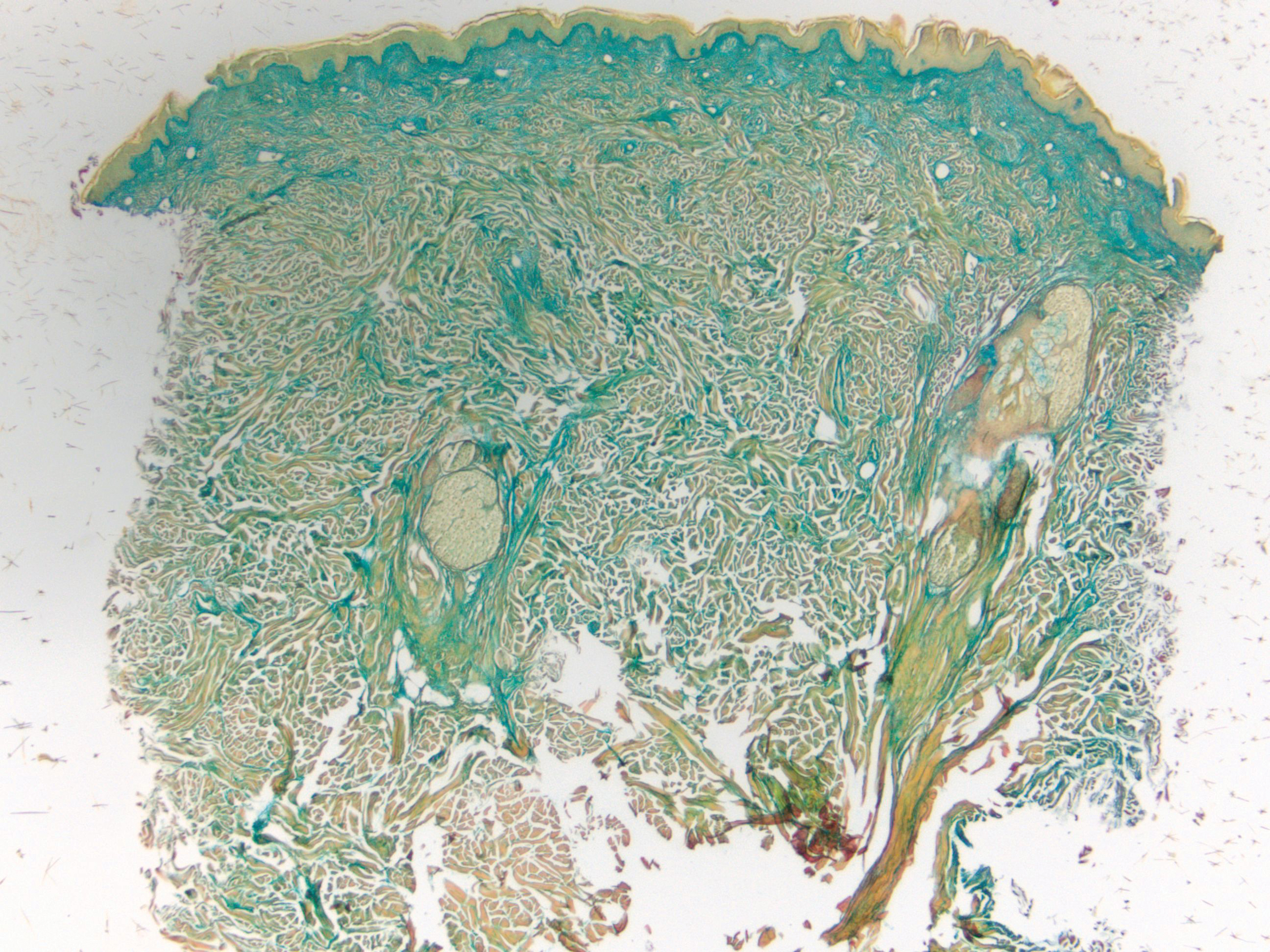

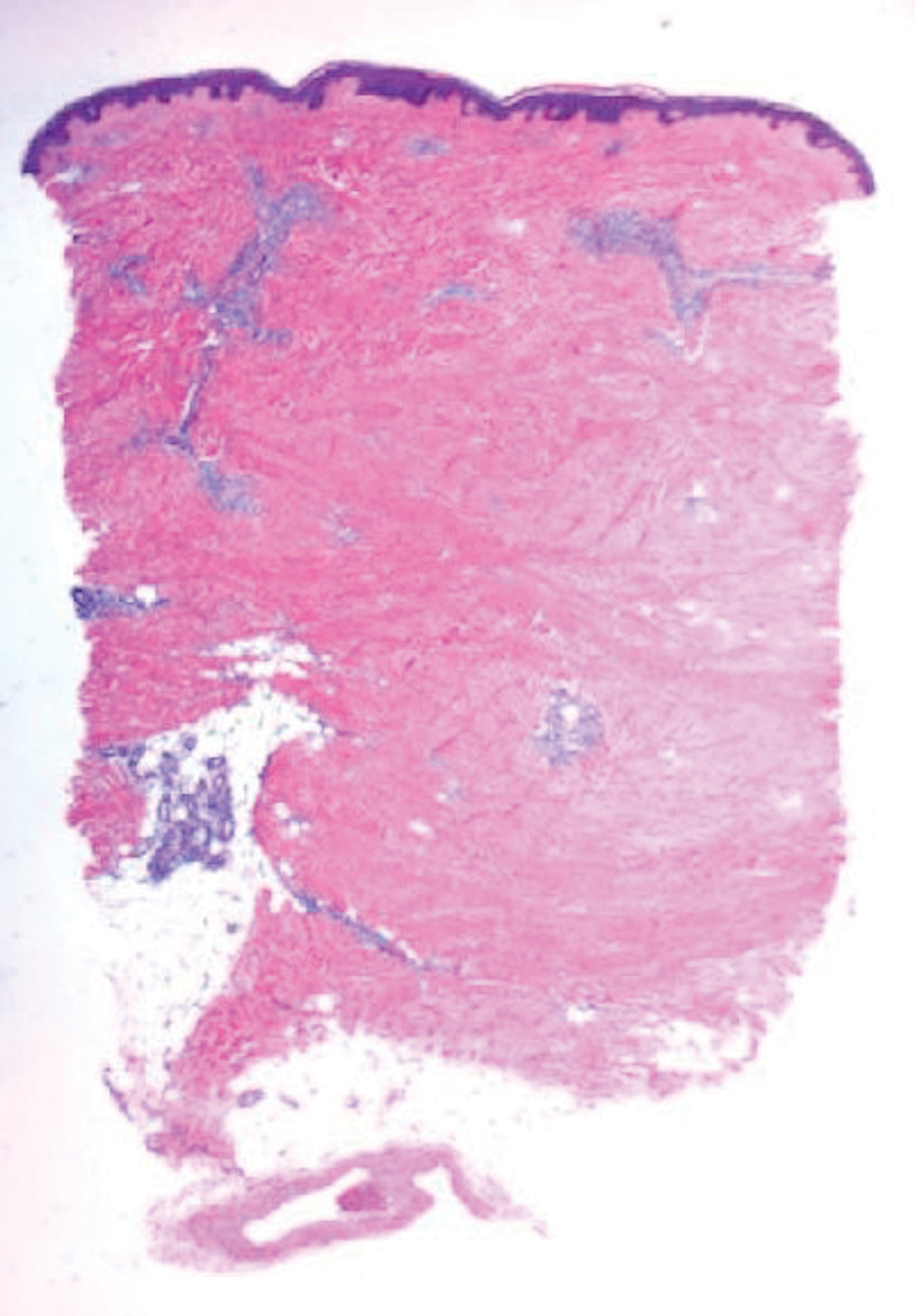

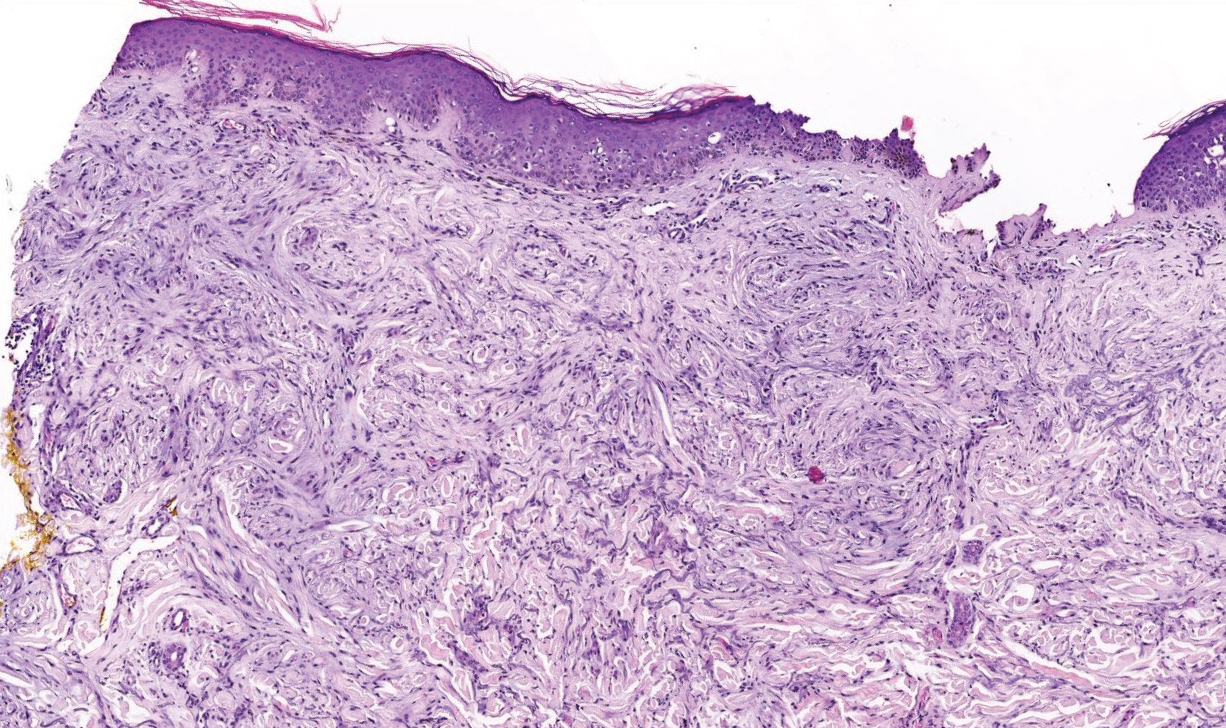

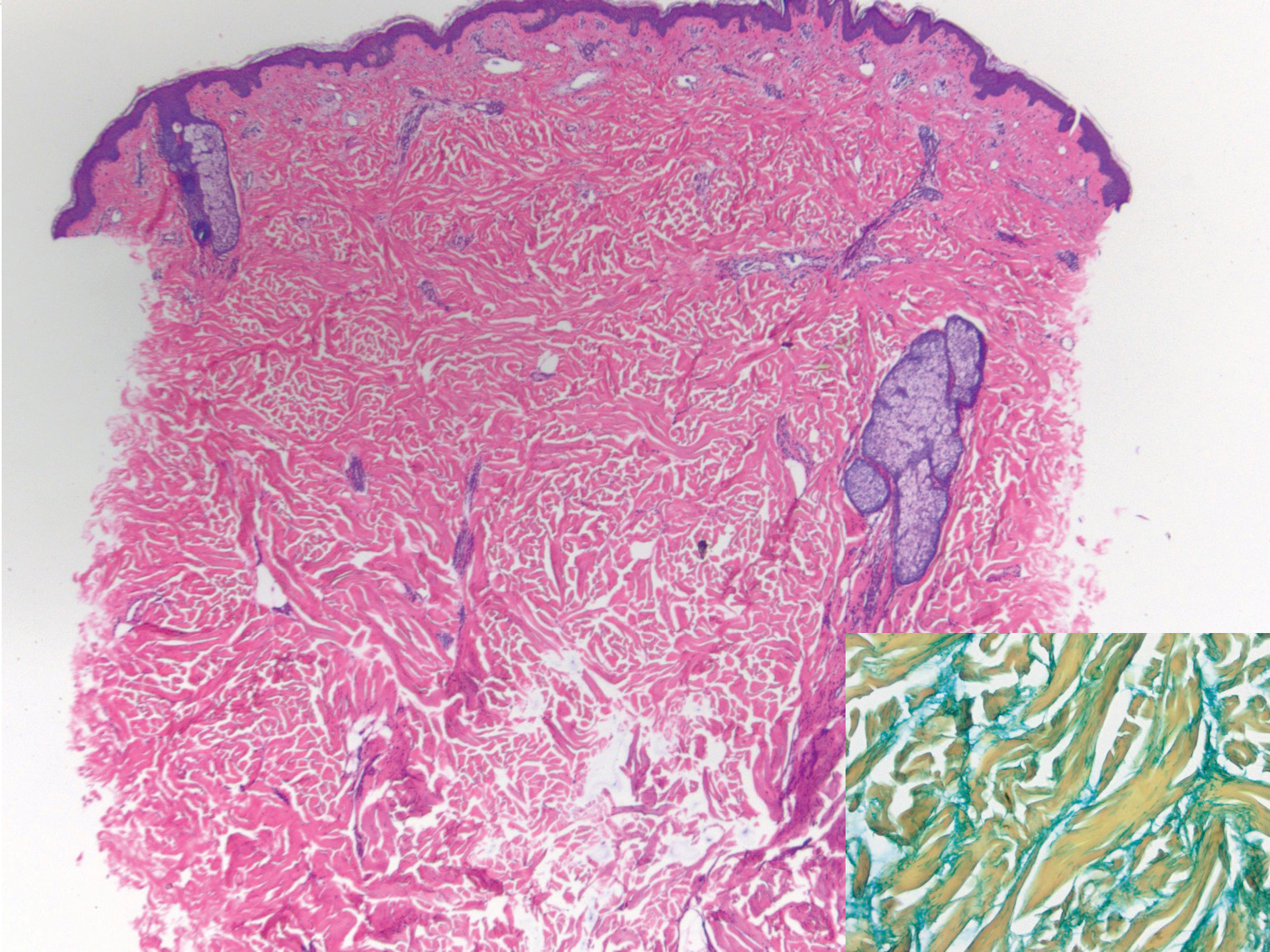

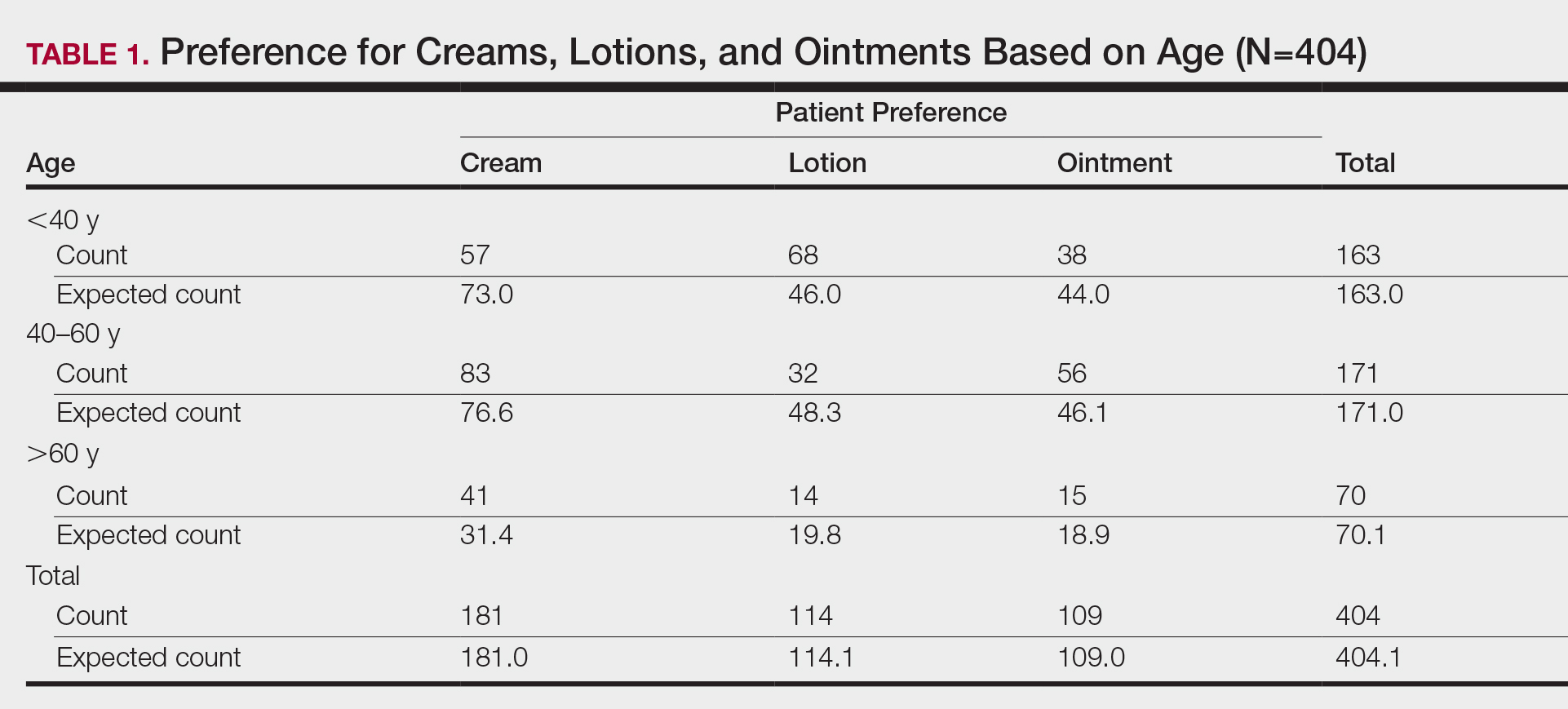

Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is a benign and self-limited condition that commonly occurs in term to postterm infants.1 However, it is an important diagnosis to recognize, as the potential exists for co-occurring metabolic derangements, most commonly hypercalcemia.1-4 Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is characterized by a panniculitis, most often on the back, shoulders, face, and buttocks. Lesions commonly present as erythematous nodules and plaques with overlying induration and can appear from birth to up to the first 6 weeks of life; calcification can be present in long-standing cases.2 Biopsy is diagnostic, showing a normal epidermis and dermis with a diffuse lobular panniculitis (Figure, A). Fat degeneration, radial crystal formation, and interstitial histiocytes also can be seen (Figure, B).

Patients with suspected subcutaneous fat necrosis should have their calcium levels checked, as up to 25% of patients may have coexisting hypercalcemia, which can contribute to morbidity and mortality.2 The hypercalcemia can occur with the onset of the lesions; however, it may be seen after they resolve completely.3 Thus, it is recommended that calcium levels be monitored for at least 1 month after lesions resolve. The exact etiology of subcutaneous fat necrosis is unknown, but it has been associated with perinatal stress and neonatal and maternal risk factors such as umbilical cord prolapse, meconium aspiration, neonatal sepsis, preeclampsia, and Rh incompatibility.1 The prognosis generally is excellent, with no treatment necessary for the skin lesions, as they resolve within a few months without subsequent sequelae or scarring.1,2 Patients with hypercalcemia should be treated appropriately with measures such as hydration and restriction of vitamin D; severe cases can be treated with bisphosphonates or loop diuretics.4