User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Follicular Traction Urticaria Induced by Electric Epilation

To the Editor:

A 33-year-old woman who was otherwise healthy presented with itchy wheals that developed within 15 to 20 minutes of removing leg hair with an electric epilator. Furthermore, she reported that small hives often developed after waxing the legs with warm wax. All lesions spontaneously disappeared within 3 hours; depilatory creams and shaving did not trigger urticarial lesions. She had no history of atopy or prior episodes of spontaneous urticaria. Symptomatic dermographism also was not reported. Classic physical stimuli that could be associated with the use of an electric epilator, such as heat, vibration, and pressure, did not elicit lesions.

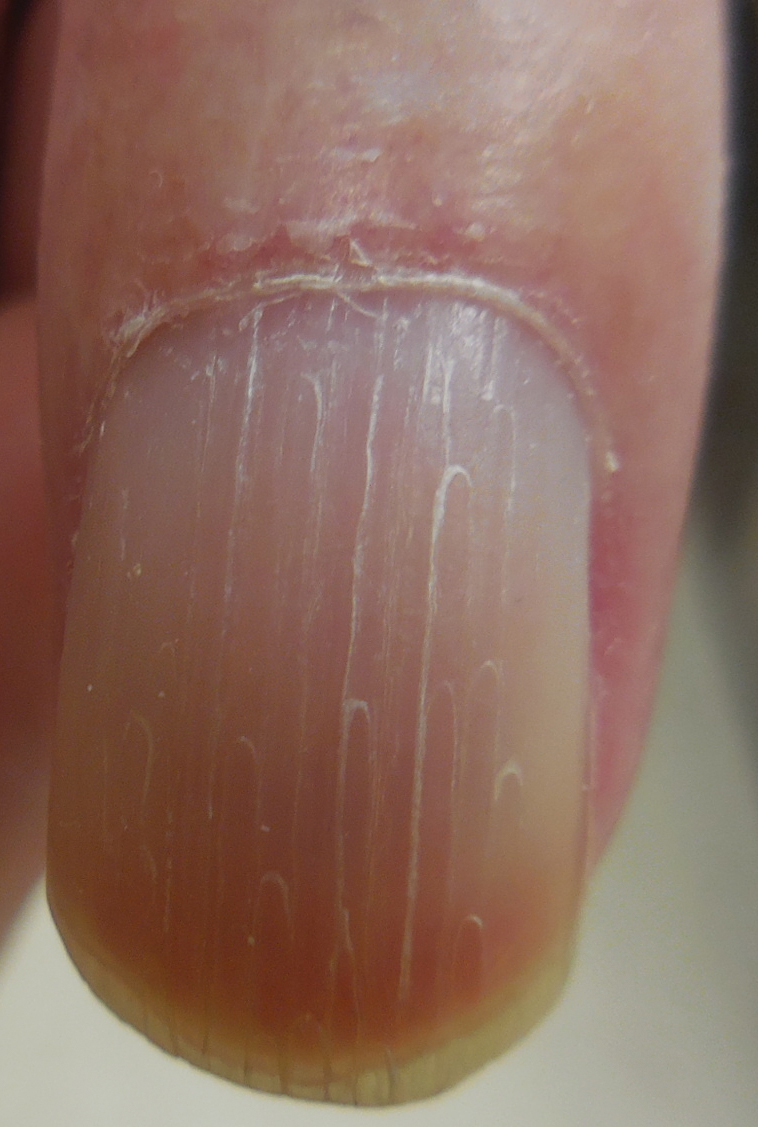

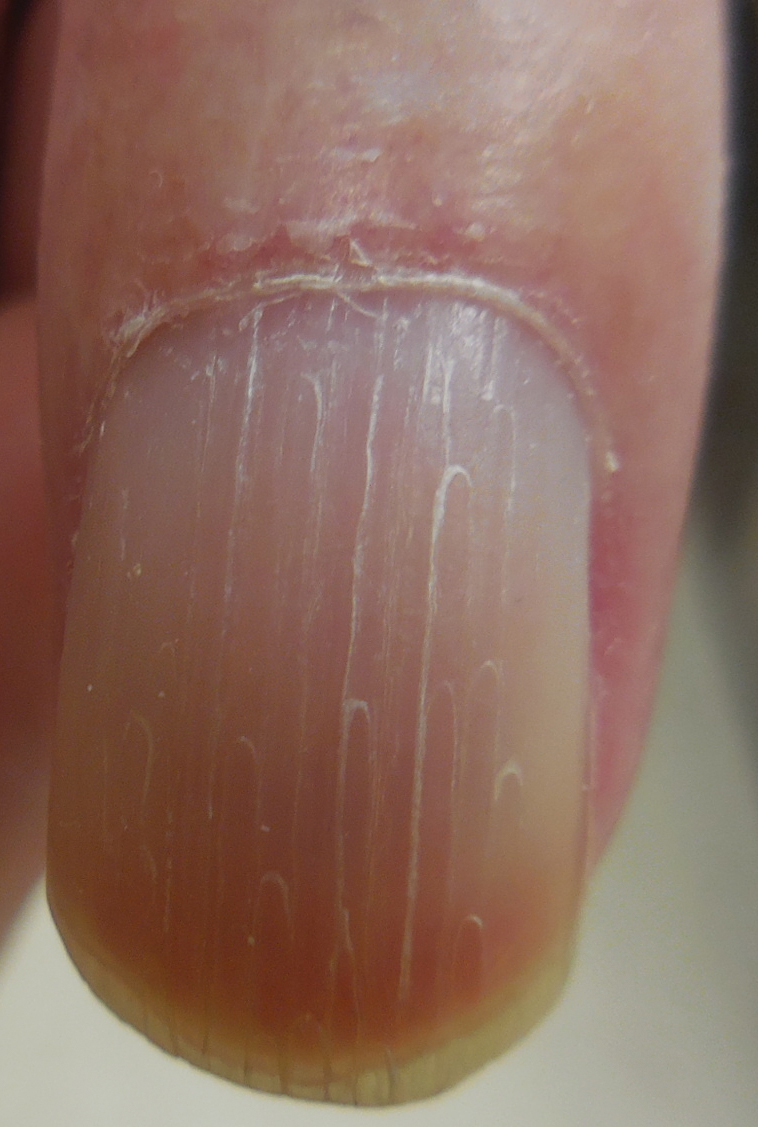

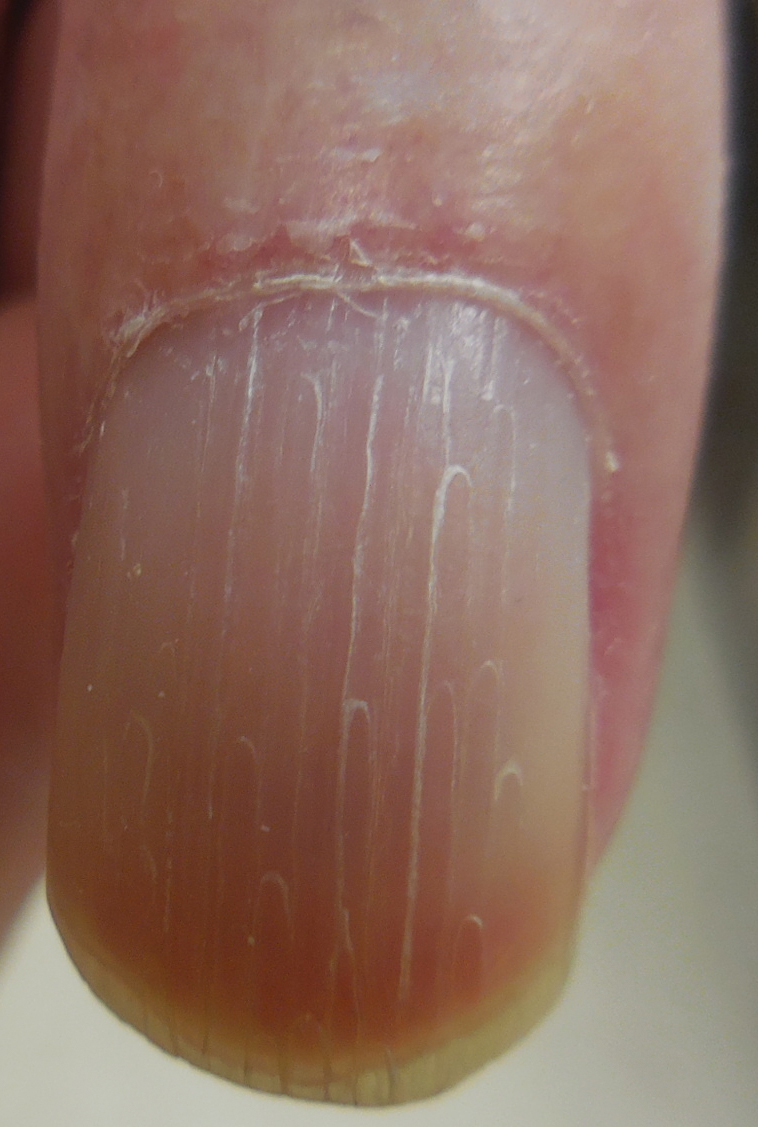

Physical examination showed no active lesions. Dermographism was not inducible by stroking the patient’s skin with a blunt object. She brought personal photographs that showed erythematous follicular hives measuring 1 to 3 mm in diameter located on the distal legs (Figure). In accordance with these findings, she was diagnosed with an unusual form of physical urticaria likely resulting from hair traction and was prescribed oral H1 antihistamines to be taken a few days before and after hair removal.

Physical urticaria are characterized by the presence of reddish, edematous, and pruritic wheals developing in response to a variety of exogenous physical stimuli such as heat, cold, vibration, dermographism, and pressure. These variants are widely described; nonetheless, follicular traction urticaria has been proposed as a new form of physical urticaria elicited by traction of hair, which would cause tension on and around hair follicles on a secondary basis.1 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term traction urticaria revealed 6 other cases. In 3 cases, hives were triggered by waxing or using an electric epilator.1-3 In 1 case, urticaria was elicited by shaving with a wet straight razor,whereas the other 2 cases were induced by the removal of patch tests.4-6 Sheraz et al7 investigated the role of dermographism in erythematous reactions during patch testing and concluded that some of these reactions might be caused by traction urticaria instead of being a form of dermographism.

Özkaya and Yazganog˘lu1 proposed that follicular dermographism should be differentiated from physical urticaria. This variant of dermographism is characterized by discrete urticarial papules appearing at the location of hair follicles after having stroked the skin with a blunt object.1,8 These lesions usually disappear within 30 minutes.8 Given that none of the reported cases presented dermographism on examination tests, we agree with Özkaya and Yazganog˘lu1 that this phenomenon of traction urticaria likely is a different condition than follicular dermographism, even though intraindividual variability sometimes can be seen in dermographism skin tests.7

We present a unique form of urticaria that easily can be misdiagnosed as pseudofolliculitis, which tends to be more commonly associated with the use of electric epilators.

- Özkaya E, Yazganog˘lu KD. Follicular traction urticaria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E234-E236.

- Duman H, Topal IO, Kocaturk E. Follicular traction urticaria. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:64-65.

- Raison-Peyron N, Reymann V, Bessis D. Follicular traction urticaria: a new form of chronic inducible urticaria? Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:522-523.

- Patel SS, Lockey RF. Follicular traction urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:1383.

- Gallo R, Fausti V, Parodi A. Traction urticaria. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;61:301-302.

- Özkaya E. Follicular traction urticaria: an occult case diagnosed by patch testing. Dermatitis. 2019;30:171-173.

- Sheraz A, Simms MJ, White IR, et al. Erythematous reactions on removal of Scanpor® tape in patch testing are not necessarily caused by dermographism. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:62-64.

- Bhute D, Doshi B, Pande S, et al. Dermatographism. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:177-179.

To the Editor:

A 33-year-old woman who was otherwise healthy presented with itchy wheals that developed within 15 to 20 minutes of removing leg hair with an electric epilator. Furthermore, she reported that small hives often developed after waxing the legs with warm wax. All lesions spontaneously disappeared within 3 hours; depilatory creams and shaving did not trigger urticarial lesions. She had no history of atopy or prior episodes of spontaneous urticaria. Symptomatic dermographism also was not reported. Classic physical stimuli that could be associated with the use of an electric epilator, such as heat, vibration, and pressure, did not elicit lesions.

Physical examination showed no active lesions. Dermographism was not inducible by stroking the patient’s skin with a blunt object. She brought personal photographs that showed erythematous follicular hives measuring 1 to 3 mm in diameter located on the distal legs (Figure). In accordance with these findings, she was diagnosed with an unusual form of physical urticaria likely resulting from hair traction and was prescribed oral H1 antihistamines to be taken a few days before and after hair removal.

Physical urticaria are characterized by the presence of reddish, edematous, and pruritic wheals developing in response to a variety of exogenous physical stimuli such as heat, cold, vibration, dermographism, and pressure. These variants are widely described; nonetheless, follicular traction urticaria has been proposed as a new form of physical urticaria elicited by traction of hair, which would cause tension on and around hair follicles on a secondary basis.1 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term traction urticaria revealed 6 other cases. In 3 cases, hives were triggered by waxing or using an electric epilator.1-3 In 1 case, urticaria was elicited by shaving with a wet straight razor,whereas the other 2 cases were induced by the removal of patch tests.4-6 Sheraz et al7 investigated the role of dermographism in erythematous reactions during patch testing and concluded that some of these reactions might be caused by traction urticaria instead of being a form of dermographism.

Özkaya and Yazganog˘lu1 proposed that follicular dermographism should be differentiated from physical urticaria. This variant of dermographism is characterized by discrete urticarial papules appearing at the location of hair follicles after having stroked the skin with a blunt object.1,8 These lesions usually disappear within 30 minutes.8 Given that none of the reported cases presented dermographism on examination tests, we agree with Özkaya and Yazganog˘lu1 that this phenomenon of traction urticaria likely is a different condition than follicular dermographism, even though intraindividual variability sometimes can be seen in dermographism skin tests.7

We present a unique form of urticaria that easily can be misdiagnosed as pseudofolliculitis, which tends to be more commonly associated with the use of electric epilators.

To the Editor:

A 33-year-old woman who was otherwise healthy presented with itchy wheals that developed within 15 to 20 minutes of removing leg hair with an electric epilator. Furthermore, she reported that small hives often developed after waxing the legs with warm wax. All lesions spontaneously disappeared within 3 hours; depilatory creams and shaving did not trigger urticarial lesions. She had no history of atopy or prior episodes of spontaneous urticaria. Symptomatic dermographism also was not reported. Classic physical stimuli that could be associated with the use of an electric epilator, such as heat, vibration, and pressure, did not elicit lesions.

Physical examination showed no active lesions. Dermographism was not inducible by stroking the patient’s skin with a blunt object. She brought personal photographs that showed erythematous follicular hives measuring 1 to 3 mm in diameter located on the distal legs (Figure). In accordance with these findings, she was diagnosed with an unusual form of physical urticaria likely resulting from hair traction and was prescribed oral H1 antihistamines to be taken a few days before and after hair removal.

Physical urticaria are characterized by the presence of reddish, edematous, and pruritic wheals developing in response to a variety of exogenous physical stimuli such as heat, cold, vibration, dermographism, and pressure. These variants are widely described; nonetheless, follicular traction urticaria has been proposed as a new form of physical urticaria elicited by traction of hair, which would cause tension on and around hair follicles on a secondary basis.1 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term traction urticaria revealed 6 other cases. In 3 cases, hives were triggered by waxing or using an electric epilator.1-3 In 1 case, urticaria was elicited by shaving with a wet straight razor,whereas the other 2 cases were induced by the removal of patch tests.4-6 Sheraz et al7 investigated the role of dermographism in erythematous reactions during patch testing and concluded that some of these reactions might be caused by traction urticaria instead of being a form of dermographism.

Özkaya and Yazganog˘lu1 proposed that follicular dermographism should be differentiated from physical urticaria. This variant of dermographism is characterized by discrete urticarial papules appearing at the location of hair follicles after having stroked the skin with a blunt object.1,8 These lesions usually disappear within 30 minutes.8 Given that none of the reported cases presented dermographism on examination tests, we agree with Özkaya and Yazganog˘lu1 that this phenomenon of traction urticaria likely is a different condition than follicular dermographism, even though intraindividual variability sometimes can be seen in dermographism skin tests.7

We present a unique form of urticaria that easily can be misdiagnosed as pseudofolliculitis, which tends to be more commonly associated with the use of electric epilators.

- Özkaya E, Yazganog˘lu KD. Follicular traction urticaria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E234-E236.

- Duman H, Topal IO, Kocaturk E. Follicular traction urticaria. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:64-65.

- Raison-Peyron N, Reymann V, Bessis D. Follicular traction urticaria: a new form of chronic inducible urticaria? Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:522-523.

- Patel SS, Lockey RF. Follicular traction urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:1383.

- Gallo R, Fausti V, Parodi A. Traction urticaria. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;61:301-302.

- Özkaya E. Follicular traction urticaria: an occult case diagnosed by patch testing. Dermatitis. 2019;30:171-173.

- Sheraz A, Simms MJ, White IR, et al. Erythematous reactions on removal of Scanpor® tape in patch testing are not necessarily caused by dermographism. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:62-64.

- Bhute D, Doshi B, Pande S, et al. Dermatographism. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:177-179.

- Özkaya E, Yazganog˘lu KD. Follicular traction urticaria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E234-E236.

- Duman H, Topal IO, Kocaturk E. Follicular traction urticaria. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:64-65.

- Raison-Peyron N, Reymann V, Bessis D. Follicular traction urticaria: a new form of chronic inducible urticaria? Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:522-523.

- Patel SS, Lockey RF. Follicular traction urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:1383.

- Gallo R, Fausti V, Parodi A. Traction urticaria. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;61:301-302.

- Özkaya E. Follicular traction urticaria: an occult case diagnosed by patch testing. Dermatitis. 2019;30:171-173.

- Sheraz A, Simms MJ, White IR, et al. Erythematous reactions on removal of Scanpor® tape in patch testing are not necessarily caused by dermographism. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:62-64.

- Bhute D, Doshi B, Pande S, et al. Dermatographism. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:177-179.

Practice Points

- Follicular traction urticaria is an unusual form of chronic inducible urticaria.

- Follicular traction urticaria consists of follicular hives that develop after being triggered by hair traction.

Making the World's Skin Crawl: Dermatologic Implications of COVID-19

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are among the most common causes of the common cold but also can lead to severe respiratory disease.1 In recent years, CoVs have been responsible for outbreaks of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), caused by SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, respectively. Severe acute respiratory syndrome emerged from China in 2002, and MERS started in Saudi Arabia in 2012. In December 2019, several cases of unexplained pneumonia were reported in Wuhan, China.1 A novel CoV--SARS-CoV-2--was isolated in these patients and is now known to cause coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19).1 Coronavirus disease 19 can cause acute respiratory distress and multiorgan failure.1,2 It spread quickly throughout the world and was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020. According to the Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html), there were approximately 14,500 COVID-19 cases diagnosed worldwide on February 1, 2020; by May 22, 2020, there were more than 5,159,600 cases. Thus, heightened measures for infection prevention and control were put in place around the globe in an attempt to slow the spread of disease.1

In this article, we describe the dermatologic implications of COVID-19, including the clinical manifestations of the disease, risk reduction techniques for patients and providers, personal protective equipment-associated adverse reactions, and the financial impact on dermatologists.

Clinical Manifestations

At the start of the COVID-19 outbreak, little was known about the skin manifestations of the disease. Providers speculated that COVID-19 could have nonspecific skin findings similar to many other viral illnesses.3,4 Research throughout the pandemic has found many cutaneous manifestations of the disease.3-6 A case report from Thailand described a patient who presented with petechiae in addition to fever and thrombocytopenia, which led to an initial misdiagnosis of Dengue fever; however, when the patient began having respiratory symptoms, the diagnosis of COVID-19 was discovered.5 Furthermore, a study from Italy (N=88) showed dermatologic findings in 20.4% (18/88) of patients, including erythematous rash (77.8% [14/18]), widespread urticaria (16.7% [3/18]), and chickenpoxlike vesicles (5.6% [1/18]). A recent study from Spain (N=375) found 5 cutaneous patterns associated with COVID-19: pseudochilblain--acral areas of erythema with vesicles and/or pustules--lesions (19%), vesicular eruptions (9%), urticarial lesions (19%), maculopapular eruptions (47%), and livedoid/necrotic lesions (6%).6 Pseudochilblain lesions appeared in younger patients, occurred later in the disease course, and were associated with less severe disease. Vesicular lesions often were found in middle-aged patients prior to the onset of other COVID-19 symptoms, and they were associated with intermediate disease severity. Urticarial and maculopapular lesions typically paralleled other COVID-19 symptoms in timing and were associated with more severe disease. Likewise, livedoid and necrotic lesions were associated with more severe disease; they occurred more frequently in older patients.6 Clinicians at Cleveland Clinic found similar cutaneous lesions in COVID-19 patients, including morbilliform rashes, acral purpura resembling perniosis, and livedoid lesions.3 Initial biopsies of these lesions pointed to viral exanthema and thrombotic vasculopathy as potential etiologies of morbilliform and livedoid lesions, respectively. Interestingly, patients may present with multiple cutaneous morphologies of the disease at the same time.3 The acral lesions ("COVID toes") have been popularized throughout the media and thus may be the best-known cutaneous manifestation of the disease at this time. New findings continuously arise, and further research is warranted as lesions that develop in hospitalized COVID-19 patients could be virus related or secondary to hospital-induced skin irritation, stressors, or medications.3 Importantly, clinicians should be aware of these cutaneous signs of COVID-19, especially when triaging patients.

Risk Reduction

The current health crisis could have a drastic impact on dermatology patients and providers. One factor that may increase COVID-19 risk in dermatology patients is immunosuppression. Many patients are on immunomodulators and biologics for skin conditions, which can cause immunosuppression directly and indirectly. Immunosuppression is a risk factor for severe disease in patients with COVID-19, so this population is at higher risk for serious infection.7 Telemedicine for nonemergent cases and follow-ups should be considered to decrease traffic in high-risk hospitals; to limit the number of people in waiting rooms; and to protect staff, providers, and patients alike.1 Recommendations for teledermatology consultation during this time include the following: First, have patients take photographs of their skin lesions and send them remotely to the consulting physician. If the lesion is easily recognizable, treatment recommendations can be made remotely; if the diagnosis is ambiguous, the dermatologist can set up an in-person appointment.1

Personal Protective Equipment

Moreover, the current need to wear personal protective equipment (PPE) and wash hands frequently may lead to skin disease among health care providers. Facial rashes may arise from wearing masks and goggles, and repeated handwashing and wearing gloves may lead to hand dermatitis.8 One study examined adverse skin reactions among health care workers (N=322) during the SARS outbreak in 2003. More than one-third (35.5%) of staff members who wore masks regularly during the outbreak reported adverse skin reactions, including acne (59.6%), facial itching (51.4%), and rash (35.8%).8 The acne etiology likely is multifactorial. Masks increase heat and humidity in the covered facial region, which can cause acne flare-ups due to increased sebum production and Cutibacterium acnes growth.8 Additionally, tight N95 masks may occlude the pilosebaceous glands, causing acne to flare. In the SARS study, facial itchiness and rashes likely were due to irritant contact dermatitis to the N95 masks. All of the respondents with adverse skin reactions from masks developed them after using N95 masks; those who wore surgical masks did not report reactions.8 Because N95 masks are recommended for health care workers caring for patients with highly transmissible respiratory infections such as SARS and COVID-19, it will be difficult to avoid wearing them during the current crisis. For this reason, topical retinoids and topical benzoyl peroxide should be the first-line treatment of mask-induced acne, and moisturization and topical corticosteroids should be used for facial erythema. Additionally, 21.4% of respondents reported adverse skin reactions from latex gloves during the SARS outbreak, including dry skin, itchiness, rash, and wheals.8 These skin reactions may have been type I IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions or irritant contact dermatitis due to latex sensitization and frequent handwashing. No respondents reported skin reactions to plastic gloves.8 For this reason, health care providers should consider wearing plastic gloves in lieu of or under latex gloves to prevent hand dermatitis during this time. Moisturization, barrier creams, and topical corticosteroids also can help treat hand dermatitis. Frequently changing PPE may help prevent skin disease among the frontline health care workers,8 which posed a problem at the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak as there was a PPE shortage. With industry and individuals coming together to make and donate PPE, it is now more widely available for our frontline providers.

Financial Impact

Finally, the pandemic is having an immense financial impact on dermatology.9 At the onset of the outbreak, our role as health care providers was to help slow the spread of COVID-19; for this reason, most elective procedures were cancelled, and many outpatient clinics closed. Both elective procedures and outpatient visits are central to dermatology, so many dermatologists worked less or not at all during this time, leading to a loss of revenue. The goals of these measures were to reduce transmissibility of the disease, to prevent the health care system from being overwhelmed with critical COVID-19 cases, and to allocate resources to the frontline providers.9 Although these measures were beneficial for slowing the spread of disease, they were detrimental to some providers' and practices' financial stability. Many dermatology practices have begun to reopen with COVID-19 precautions in place. For example, practices are limiting the number of patients that can be in the office at one time, mandating temperature readings upon check-in, and requiring masks be worn throughout the entire visit. With continued recommendations for individuals to stay at home as much as possible, the number of patients being seen in dermatology clinics on a daily basis remains less than normal. One potential solution is telemedicine, which would allow patients' concerns to be addressed while keeping providers practicing with a normal patient volume during this time.9 Keeping providers financially afloat is vital for private practices to continue operating after the pandemic. Dermatology appointments are in high demand with long waiting lists during nonpandemic times; without dermatologists practicing at full capacity, there will be an accumulation of patients with dermatologic conditions with even longer waiting times after the pandemic. Telemedicine may help reduce this potential accumulation of patients and allow patients to be treated in a more timely manner while alleviating financial pressures for providers.

Final Thoughts

The COVID-19 pandemic has spread across the world, infecting millions of people. Although the trends have slowed, more than 106,100 cases are still being diagnosed daily according to the Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html). Patients with COVID-19 may present with a variety of cutaneous lesions. Wearing PPE to take care of COVID-19 patients may lead to skin irritation, so care should be taken to address these adverse skin reactions to maintain the safety of providers. Finally, dermatologists should consider telemedicine during this time to protect high-risk patients, prevent a postpandemic surge of patients, and alleviate financial stressors caused by COVID-19.

- Tao J, Song Z, Yang L, et al. Emergency management for preventing and controlling nosocomial infection of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for the dermatology department [published online March 5, 2020]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.19011.

- Lippi G, Plebani M, Michael HB. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: a meta-analysis [published online March 13, 2020]. Clin Chim Acta. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.022.

- Young S, Fernandez AP. Skin manifestations of COVID-19 [published online May 14, 2020]. Cleve Clin J Med. doi:10.3949/ccjm.87a.ccc031.

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective [published online March 26, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.16387.

- Joob B, Wiwanitkit V. COVID-19 can present with a rash and be mistaken for Dengue [published online March 22, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.036.

- Casas CG, Catalá A, Hernández GC, et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases [published online April 29, 2020]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.19163.

- Conforti C, Giuffrida R, Dianzani C, et al. COVID-19 and psoriasis: is it time to limited treatment with immunosuppressants? a call for action [published online March 11, 2020]. Dermatol Ther. doi:10.1111/dth.13298.

- Foo CC, Goon AT, Leow YH, et al. Adverse skin reactions to personal protective equipment against severe respiratory syndrome--a descriptive study in Singapore. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;55:291-294.

- Heymann WR. The profound dermatological manifestations of COVID-19 [published online March 18, 2020]. Dermatology World Insights and Inquiries. https://www.aad.org/dw/dw-insights-and-inquiries/2020-archive/march/dermatological-manifestations-covid-19. Accessed May 21, 2020.

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are among the most common causes of the common cold but also can lead to severe respiratory disease.1 In recent years, CoVs have been responsible for outbreaks of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), caused by SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, respectively. Severe acute respiratory syndrome emerged from China in 2002, and MERS started in Saudi Arabia in 2012. In December 2019, several cases of unexplained pneumonia were reported in Wuhan, China.1 A novel CoV--SARS-CoV-2--was isolated in these patients and is now known to cause coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19).1 Coronavirus disease 19 can cause acute respiratory distress and multiorgan failure.1,2 It spread quickly throughout the world and was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020. According to the Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html), there were approximately 14,500 COVID-19 cases diagnosed worldwide on February 1, 2020; by May 22, 2020, there were more than 5,159,600 cases. Thus, heightened measures for infection prevention and control were put in place around the globe in an attempt to slow the spread of disease.1

In this article, we describe the dermatologic implications of COVID-19, including the clinical manifestations of the disease, risk reduction techniques for patients and providers, personal protective equipment-associated adverse reactions, and the financial impact on dermatologists.

Clinical Manifestations

At the start of the COVID-19 outbreak, little was known about the skin manifestations of the disease. Providers speculated that COVID-19 could have nonspecific skin findings similar to many other viral illnesses.3,4 Research throughout the pandemic has found many cutaneous manifestations of the disease.3-6 A case report from Thailand described a patient who presented with petechiae in addition to fever and thrombocytopenia, which led to an initial misdiagnosis of Dengue fever; however, when the patient began having respiratory symptoms, the diagnosis of COVID-19 was discovered.5 Furthermore, a study from Italy (N=88) showed dermatologic findings in 20.4% (18/88) of patients, including erythematous rash (77.8% [14/18]), widespread urticaria (16.7% [3/18]), and chickenpoxlike vesicles (5.6% [1/18]). A recent study from Spain (N=375) found 5 cutaneous patterns associated with COVID-19: pseudochilblain--acral areas of erythema with vesicles and/or pustules--lesions (19%), vesicular eruptions (9%), urticarial lesions (19%), maculopapular eruptions (47%), and livedoid/necrotic lesions (6%).6 Pseudochilblain lesions appeared in younger patients, occurred later in the disease course, and were associated with less severe disease. Vesicular lesions often were found in middle-aged patients prior to the onset of other COVID-19 symptoms, and they were associated with intermediate disease severity. Urticarial and maculopapular lesions typically paralleled other COVID-19 symptoms in timing and were associated with more severe disease. Likewise, livedoid and necrotic lesions were associated with more severe disease; they occurred more frequently in older patients.6 Clinicians at Cleveland Clinic found similar cutaneous lesions in COVID-19 patients, including morbilliform rashes, acral purpura resembling perniosis, and livedoid lesions.3 Initial biopsies of these lesions pointed to viral exanthema and thrombotic vasculopathy as potential etiologies of morbilliform and livedoid lesions, respectively. Interestingly, patients may present with multiple cutaneous morphologies of the disease at the same time.3 The acral lesions ("COVID toes") have been popularized throughout the media and thus may be the best-known cutaneous manifestation of the disease at this time. New findings continuously arise, and further research is warranted as lesions that develop in hospitalized COVID-19 patients could be virus related or secondary to hospital-induced skin irritation, stressors, or medications.3 Importantly, clinicians should be aware of these cutaneous signs of COVID-19, especially when triaging patients.

Risk Reduction

The current health crisis could have a drastic impact on dermatology patients and providers. One factor that may increase COVID-19 risk in dermatology patients is immunosuppression. Many patients are on immunomodulators and biologics for skin conditions, which can cause immunosuppression directly and indirectly. Immunosuppression is a risk factor for severe disease in patients with COVID-19, so this population is at higher risk for serious infection.7 Telemedicine for nonemergent cases and follow-ups should be considered to decrease traffic in high-risk hospitals; to limit the number of people in waiting rooms; and to protect staff, providers, and patients alike.1 Recommendations for teledermatology consultation during this time include the following: First, have patients take photographs of their skin lesions and send them remotely to the consulting physician. If the lesion is easily recognizable, treatment recommendations can be made remotely; if the diagnosis is ambiguous, the dermatologist can set up an in-person appointment.1

Personal Protective Equipment

Moreover, the current need to wear personal protective equipment (PPE) and wash hands frequently may lead to skin disease among health care providers. Facial rashes may arise from wearing masks and goggles, and repeated handwashing and wearing gloves may lead to hand dermatitis.8 One study examined adverse skin reactions among health care workers (N=322) during the SARS outbreak in 2003. More than one-third (35.5%) of staff members who wore masks regularly during the outbreak reported adverse skin reactions, including acne (59.6%), facial itching (51.4%), and rash (35.8%).8 The acne etiology likely is multifactorial. Masks increase heat and humidity in the covered facial region, which can cause acne flare-ups due to increased sebum production and Cutibacterium acnes growth.8 Additionally, tight N95 masks may occlude the pilosebaceous glands, causing acne to flare. In the SARS study, facial itchiness and rashes likely were due to irritant contact dermatitis to the N95 masks. All of the respondents with adverse skin reactions from masks developed them after using N95 masks; those who wore surgical masks did not report reactions.8 Because N95 masks are recommended for health care workers caring for patients with highly transmissible respiratory infections such as SARS and COVID-19, it will be difficult to avoid wearing them during the current crisis. For this reason, topical retinoids and topical benzoyl peroxide should be the first-line treatment of mask-induced acne, and moisturization and topical corticosteroids should be used for facial erythema. Additionally, 21.4% of respondents reported adverse skin reactions from latex gloves during the SARS outbreak, including dry skin, itchiness, rash, and wheals.8 These skin reactions may have been type I IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions or irritant contact dermatitis due to latex sensitization and frequent handwashing. No respondents reported skin reactions to plastic gloves.8 For this reason, health care providers should consider wearing plastic gloves in lieu of or under latex gloves to prevent hand dermatitis during this time. Moisturization, barrier creams, and topical corticosteroids also can help treat hand dermatitis. Frequently changing PPE may help prevent skin disease among the frontline health care workers,8 which posed a problem at the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak as there was a PPE shortage. With industry and individuals coming together to make and donate PPE, it is now more widely available for our frontline providers.

Financial Impact

Finally, the pandemic is having an immense financial impact on dermatology.9 At the onset of the outbreak, our role as health care providers was to help slow the spread of COVID-19; for this reason, most elective procedures were cancelled, and many outpatient clinics closed. Both elective procedures and outpatient visits are central to dermatology, so many dermatologists worked less or not at all during this time, leading to a loss of revenue. The goals of these measures were to reduce transmissibility of the disease, to prevent the health care system from being overwhelmed with critical COVID-19 cases, and to allocate resources to the frontline providers.9 Although these measures were beneficial for slowing the spread of disease, they were detrimental to some providers' and practices' financial stability. Many dermatology practices have begun to reopen with COVID-19 precautions in place. For example, practices are limiting the number of patients that can be in the office at one time, mandating temperature readings upon check-in, and requiring masks be worn throughout the entire visit. With continued recommendations for individuals to stay at home as much as possible, the number of patients being seen in dermatology clinics on a daily basis remains less than normal. One potential solution is telemedicine, which would allow patients' concerns to be addressed while keeping providers practicing with a normal patient volume during this time.9 Keeping providers financially afloat is vital for private practices to continue operating after the pandemic. Dermatology appointments are in high demand with long waiting lists during nonpandemic times; without dermatologists practicing at full capacity, there will be an accumulation of patients with dermatologic conditions with even longer waiting times after the pandemic. Telemedicine may help reduce this potential accumulation of patients and allow patients to be treated in a more timely manner while alleviating financial pressures for providers.

Final Thoughts

The COVID-19 pandemic has spread across the world, infecting millions of people. Although the trends have slowed, more than 106,100 cases are still being diagnosed daily according to the Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html). Patients with COVID-19 may present with a variety of cutaneous lesions. Wearing PPE to take care of COVID-19 patients may lead to skin irritation, so care should be taken to address these adverse skin reactions to maintain the safety of providers. Finally, dermatologists should consider telemedicine during this time to protect high-risk patients, prevent a postpandemic surge of patients, and alleviate financial stressors caused by COVID-19.

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are among the most common causes of the common cold but also can lead to severe respiratory disease.1 In recent years, CoVs have been responsible for outbreaks of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), caused by SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, respectively. Severe acute respiratory syndrome emerged from China in 2002, and MERS started in Saudi Arabia in 2012. In December 2019, several cases of unexplained pneumonia were reported in Wuhan, China.1 A novel CoV--SARS-CoV-2--was isolated in these patients and is now known to cause coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19).1 Coronavirus disease 19 can cause acute respiratory distress and multiorgan failure.1,2 It spread quickly throughout the world and was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020. According to the Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html), there were approximately 14,500 COVID-19 cases diagnosed worldwide on February 1, 2020; by May 22, 2020, there were more than 5,159,600 cases. Thus, heightened measures for infection prevention and control were put in place around the globe in an attempt to slow the spread of disease.1

In this article, we describe the dermatologic implications of COVID-19, including the clinical manifestations of the disease, risk reduction techniques for patients and providers, personal protective equipment-associated adverse reactions, and the financial impact on dermatologists.

Clinical Manifestations

At the start of the COVID-19 outbreak, little was known about the skin manifestations of the disease. Providers speculated that COVID-19 could have nonspecific skin findings similar to many other viral illnesses.3,4 Research throughout the pandemic has found many cutaneous manifestations of the disease.3-6 A case report from Thailand described a patient who presented with petechiae in addition to fever and thrombocytopenia, which led to an initial misdiagnosis of Dengue fever; however, when the patient began having respiratory symptoms, the diagnosis of COVID-19 was discovered.5 Furthermore, a study from Italy (N=88) showed dermatologic findings in 20.4% (18/88) of patients, including erythematous rash (77.8% [14/18]), widespread urticaria (16.7% [3/18]), and chickenpoxlike vesicles (5.6% [1/18]). A recent study from Spain (N=375) found 5 cutaneous patterns associated with COVID-19: pseudochilblain--acral areas of erythema with vesicles and/or pustules--lesions (19%), vesicular eruptions (9%), urticarial lesions (19%), maculopapular eruptions (47%), and livedoid/necrotic lesions (6%).6 Pseudochilblain lesions appeared in younger patients, occurred later in the disease course, and were associated with less severe disease. Vesicular lesions often were found in middle-aged patients prior to the onset of other COVID-19 symptoms, and they were associated with intermediate disease severity. Urticarial and maculopapular lesions typically paralleled other COVID-19 symptoms in timing and were associated with more severe disease. Likewise, livedoid and necrotic lesions were associated with more severe disease; they occurred more frequently in older patients.6 Clinicians at Cleveland Clinic found similar cutaneous lesions in COVID-19 patients, including morbilliform rashes, acral purpura resembling perniosis, and livedoid lesions.3 Initial biopsies of these lesions pointed to viral exanthema and thrombotic vasculopathy as potential etiologies of morbilliform and livedoid lesions, respectively. Interestingly, patients may present with multiple cutaneous morphologies of the disease at the same time.3 The acral lesions ("COVID toes") have been popularized throughout the media and thus may be the best-known cutaneous manifestation of the disease at this time. New findings continuously arise, and further research is warranted as lesions that develop in hospitalized COVID-19 patients could be virus related or secondary to hospital-induced skin irritation, stressors, or medications.3 Importantly, clinicians should be aware of these cutaneous signs of COVID-19, especially when triaging patients.

Risk Reduction

The current health crisis could have a drastic impact on dermatology patients and providers. One factor that may increase COVID-19 risk in dermatology patients is immunosuppression. Many patients are on immunomodulators and biologics for skin conditions, which can cause immunosuppression directly and indirectly. Immunosuppression is a risk factor for severe disease in patients with COVID-19, so this population is at higher risk for serious infection.7 Telemedicine for nonemergent cases and follow-ups should be considered to decrease traffic in high-risk hospitals; to limit the number of people in waiting rooms; and to protect staff, providers, and patients alike.1 Recommendations for teledermatology consultation during this time include the following: First, have patients take photographs of their skin lesions and send them remotely to the consulting physician. If the lesion is easily recognizable, treatment recommendations can be made remotely; if the diagnosis is ambiguous, the dermatologist can set up an in-person appointment.1

Personal Protective Equipment

Moreover, the current need to wear personal protective equipment (PPE) and wash hands frequently may lead to skin disease among health care providers. Facial rashes may arise from wearing masks and goggles, and repeated handwashing and wearing gloves may lead to hand dermatitis.8 One study examined adverse skin reactions among health care workers (N=322) during the SARS outbreak in 2003. More than one-third (35.5%) of staff members who wore masks regularly during the outbreak reported adverse skin reactions, including acne (59.6%), facial itching (51.4%), and rash (35.8%).8 The acne etiology likely is multifactorial. Masks increase heat and humidity in the covered facial region, which can cause acne flare-ups due to increased sebum production and Cutibacterium acnes growth.8 Additionally, tight N95 masks may occlude the pilosebaceous glands, causing acne to flare. In the SARS study, facial itchiness and rashes likely were due to irritant contact dermatitis to the N95 masks. All of the respondents with adverse skin reactions from masks developed them after using N95 masks; those who wore surgical masks did not report reactions.8 Because N95 masks are recommended for health care workers caring for patients with highly transmissible respiratory infections such as SARS and COVID-19, it will be difficult to avoid wearing them during the current crisis. For this reason, topical retinoids and topical benzoyl peroxide should be the first-line treatment of mask-induced acne, and moisturization and topical corticosteroids should be used for facial erythema. Additionally, 21.4% of respondents reported adverse skin reactions from latex gloves during the SARS outbreak, including dry skin, itchiness, rash, and wheals.8 These skin reactions may have been type I IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions or irritant contact dermatitis due to latex sensitization and frequent handwashing. No respondents reported skin reactions to plastic gloves.8 For this reason, health care providers should consider wearing plastic gloves in lieu of or under latex gloves to prevent hand dermatitis during this time. Moisturization, barrier creams, and topical corticosteroids also can help treat hand dermatitis. Frequently changing PPE may help prevent skin disease among the frontline health care workers,8 which posed a problem at the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak as there was a PPE shortage. With industry and individuals coming together to make and donate PPE, it is now more widely available for our frontline providers.

Financial Impact

Finally, the pandemic is having an immense financial impact on dermatology.9 At the onset of the outbreak, our role as health care providers was to help slow the spread of COVID-19; for this reason, most elective procedures were cancelled, and many outpatient clinics closed. Both elective procedures and outpatient visits are central to dermatology, so many dermatologists worked less or not at all during this time, leading to a loss of revenue. The goals of these measures were to reduce transmissibility of the disease, to prevent the health care system from being overwhelmed with critical COVID-19 cases, and to allocate resources to the frontline providers.9 Although these measures were beneficial for slowing the spread of disease, they were detrimental to some providers' and practices' financial stability. Many dermatology practices have begun to reopen with COVID-19 precautions in place. For example, practices are limiting the number of patients that can be in the office at one time, mandating temperature readings upon check-in, and requiring masks be worn throughout the entire visit. With continued recommendations for individuals to stay at home as much as possible, the number of patients being seen in dermatology clinics on a daily basis remains less than normal. One potential solution is telemedicine, which would allow patients' concerns to be addressed while keeping providers practicing with a normal patient volume during this time.9 Keeping providers financially afloat is vital for private practices to continue operating after the pandemic. Dermatology appointments are in high demand with long waiting lists during nonpandemic times; without dermatologists practicing at full capacity, there will be an accumulation of patients with dermatologic conditions with even longer waiting times after the pandemic. Telemedicine may help reduce this potential accumulation of patients and allow patients to be treated in a more timely manner while alleviating financial pressures for providers.

Final Thoughts

The COVID-19 pandemic has spread across the world, infecting millions of people. Although the trends have slowed, more than 106,100 cases are still being diagnosed daily according to the Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html). Patients with COVID-19 may present with a variety of cutaneous lesions. Wearing PPE to take care of COVID-19 patients may lead to skin irritation, so care should be taken to address these adverse skin reactions to maintain the safety of providers. Finally, dermatologists should consider telemedicine during this time to protect high-risk patients, prevent a postpandemic surge of patients, and alleviate financial stressors caused by COVID-19.

- Tao J, Song Z, Yang L, et al. Emergency management for preventing and controlling nosocomial infection of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for the dermatology department [published online March 5, 2020]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.19011.

- Lippi G, Plebani M, Michael HB. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: a meta-analysis [published online March 13, 2020]. Clin Chim Acta. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.022.

- Young S, Fernandez AP. Skin manifestations of COVID-19 [published online May 14, 2020]. Cleve Clin J Med. doi:10.3949/ccjm.87a.ccc031.

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective [published online March 26, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.16387.

- Joob B, Wiwanitkit V. COVID-19 can present with a rash and be mistaken for Dengue [published online March 22, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.036.

- Casas CG, Catalá A, Hernández GC, et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases [published online April 29, 2020]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.19163.

- Conforti C, Giuffrida R, Dianzani C, et al. COVID-19 and psoriasis: is it time to limited treatment with immunosuppressants? a call for action [published online March 11, 2020]. Dermatol Ther. doi:10.1111/dth.13298.

- Foo CC, Goon AT, Leow YH, et al. Adverse skin reactions to personal protective equipment against severe respiratory syndrome--a descriptive study in Singapore. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;55:291-294.

- Heymann WR. The profound dermatological manifestations of COVID-19 [published online March 18, 2020]. Dermatology World Insights and Inquiries. https://www.aad.org/dw/dw-insights-and-inquiries/2020-archive/march/dermatological-manifestations-covid-19. Accessed May 21, 2020.

- Tao J, Song Z, Yang L, et al. Emergency management for preventing and controlling nosocomial infection of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for the dermatology department [published online March 5, 2020]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.19011.

- Lippi G, Plebani M, Michael HB. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: a meta-analysis [published online March 13, 2020]. Clin Chim Acta. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.022.

- Young S, Fernandez AP. Skin manifestations of COVID-19 [published online May 14, 2020]. Cleve Clin J Med. doi:10.3949/ccjm.87a.ccc031.

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective [published online March 26, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.16387.

- Joob B, Wiwanitkit V. COVID-19 can present with a rash and be mistaken for Dengue [published online March 22, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.036.

- Casas CG, Catalá A, Hernández GC, et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases [published online April 29, 2020]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.19163.

- Conforti C, Giuffrida R, Dianzani C, et al. COVID-19 and psoriasis: is it time to limited treatment with immunosuppressants? a call for action [published online March 11, 2020]. Dermatol Ther. doi:10.1111/dth.13298.

- Foo CC, Goon AT, Leow YH, et al. Adverse skin reactions to personal protective equipment against severe respiratory syndrome--a descriptive study in Singapore. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;55:291-294.

- Heymann WR. The profound dermatological manifestations of COVID-19 [published online March 18, 2020]. Dermatology World Insights and Inquiries. https://www.aad.org/dw/dw-insights-and-inquiries/2020-archive/march/dermatological-manifestations-covid-19. Accessed May 21, 2020.

Practice Points

- Clinicians should be aware of the skin manifesta-tions of coronavirus disease 19, especially when triaging patients.

- Health care providers may develop skin diseases from wearing the extensive personal protective equipment required during the current health crisis.

- Coronavirus disease 19 has had a substantial finan-cial impact on dermatologists, and telemedicine may be a potential solution.

Asymptomatic Transient Lingual Hyperpigmentation

The Diagnosis: Pseudo-Black Hairy Tongue

Pseudo-black hairy tongue is a benign and painless disorder characterized by transient hyperpigmentation of the tongue with a substance that can be easily scraped off. In this case, the patient's lingual discoloration was secondary to the ingestion of bismuth salicylate. The phenomenon is thought to occur due to a reaction between bismuth and sulfur-containing compounds in the saliva, resulting in the characteristic black substance on the surface of the tongue that nestles between the lingual papillae.1 An associated feature may include black stools. Other etiologic factors involved in pseudo-black hairy tongue include food coloring, tobacco, and other drugs such antibiotics and antidepressants.2

The differential diagnosis of lingual hyperpigmentation includes lingua villosa nigra (also known as black hairy tongue), pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue, acanthosis nigricans, and oral hairy leukoplakia. Lingua villosa nigra is a similar condition in which individuals present with a black tongue; however, the tongue also appears hairy. The tongue may appear as other colors such as brown, yellow, or green. Patients additionally may have symptoms of burning, dysgeusia, halitosis, or gagging. Poor oral hygiene, xerostomia, use of tobacco or alcohol, and different medications including antibiotics and antipsychotic medications increase the risk for developing lingua villosa nigra.2,3 This condition is distinguished from pseudo-black hairy tongue by proliferation and elongation of the filiform papillae.3 Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a normal variant of tongue morphology, is more common in individuals with darker skin types, and primarily affects the lateral aspect and apex of the tongue.4 Acanthosis nigricans can appear in the oral cavity as multiple pigmented papillary lesions on the dorsal and lateral regions of the tongue and frequently involves the lips; this condition may be associated with metabolic disorders or underlying malignancy.2,3 Oral hairy leukoplakia is caused by Epstein-Barr virus infection and typically presents as white plaques on the dorsal and ventral surfaces of the tongue; this condition largely is found in immunocompromised patients.5

In our patient there was an acute onset of tongue discoloration associated with ingestion of bismuth salicylate, no hypertrophy or lengthening of the lingual papillae, and no involvement of the patient's lips, which was consistent with the diagnosis of pseudo-black hairy tongue. Pseudo-black hairy tongue is transient and treated by discontinuation of offending agents and proper hygiene practices.

- Bradley B, Singleton M, Lin Wan Po A. Bismuth toxicity--a reassessment. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1989;14:423-441.

- Gurvits GE, Tan A. Black hairy tongue syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10845-10850.

- Schlager E, St Claire C, Ashack K, et al. Black hairy tongue: predisposing factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:563-569.

- Mangold AR, Torgerson RR, Rogers RS. Diseases of the tongue. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:458-469.

- Husak R, Garbe C, Orfanos CE. Oral hairy leukoplakia in 71 HIV-seropositive patients: clinical symptoms, relation to immunologic status, and prognostic significance. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:928-934.

The Diagnosis: Pseudo-Black Hairy Tongue

Pseudo-black hairy tongue is a benign and painless disorder characterized by transient hyperpigmentation of the tongue with a substance that can be easily scraped off. In this case, the patient's lingual discoloration was secondary to the ingestion of bismuth salicylate. The phenomenon is thought to occur due to a reaction between bismuth and sulfur-containing compounds in the saliva, resulting in the characteristic black substance on the surface of the tongue that nestles between the lingual papillae.1 An associated feature may include black stools. Other etiologic factors involved in pseudo-black hairy tongue include food coloring, tobacco, and other drugs such antibiotics and antidepressants.2

The differential diagnosis of lingual hyperpigmentation includes lingua villosa nigra (also known as black hairy tongue), pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue, acanthosis nigricans, and oral hairy leukoplakia. Lingua villosa nigra is a similar condition in which individuals present with a black tongue; however, the tongue also appears hairy. The tongue may appear as other colors such as brown, yellow, or green. Patients additionally may have symptoms of burning, dysgeusia, halitosis, or gagging. Poor oral hygiene, xerostomia, use of tobacco or alcohol, and different medications including antibiotics and antipsychotic medications increase the risk for developing lingua villosa nigra.2,3 This condition is distinguished from pseudo-black hairy tongue by proliferation and elongation of the filiform papillae.3 Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a normal variant of tongue morphology, is more common in individuals with darker skin types, and primarily affects the lateral aspect and apex of the tongue.4 Acanthosis nigricans can appear in the oral cavity as multiple pigmented papillary lesions on the dorsal and lateral regions of the tongue and frequently involves the lips; this condition may be associated with metabolic disorders or underlying malignancy.2,3 Oral hairy leukoplakia is caused by Epstein-Barr virus infection and typically presents as white plaques on the dorsal and ventral surfaces of the tongue; this condition largely is found in immunocompromised patients.5

In our patient there was an acute onset of tongue discoloration associated with ingestion of bismuth salicylate, no hypertrophy or lengthening of the lingual papillae, and no involvement of the patient's lips, which was consistent with the diagnosis of pseudo-black hairy tongue. Pseudo-black hairy tongue is transient and treated by discontinuation of offending agents and proper hygiene practices.

The Diagnosis: Pseudo-Black Hairy Tongue

Pseudo-black hairy tongue is a benign and painless disorder characterized by transient hyperpigmentation of the tongue with a substance that can be easily scraped off. In this case, the patient's lingual discoloration was secondary to the ingestion of bismuth salicylate. The phenomenon is thought to occur due to a reaction between bismuth and sulfur-containing compounds in the saliva, resulting in the characteristic black substance on the surface of the tongue that nestles between the lingual papillae.1 An associated feature may include black stools. Other etiologic factors involved in pseudo-black hairy tongue include food coloring, tobacco, and other drugs such antibiotics and antidepressants.2

The differential diagnosis of lingual hyperpigmentation includes lingua villosa nigra (also known as black hairy tongue), pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue, acanthosis nigricans, and oral hairy leukoplakia. Lingua villosa nigra is a similar condition in which individuals present with a black tongue; however, the tongue also appears hairy. The tongue may appear as other colors such as brown, yellow, or green. Patients additionally may have symptoms of burning, dysgeusia, halitosis, or gagging. Poor oral hygiene, xerostomia, use of tobacco or alcohol, and different medications including antibiotics and antipsychotic medications increase the risk for developing lingua villosa nigra.2,3 This condition is distinguished from pseudo-black hairy tongue by proliferation and elongation of the filiform papillae.3 Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a normal variant of tongue morphology, is more common in individuals with darker skin types, and primarily affects the lateral aspect and apex of the tongue.4 Acanthosis nigricans can appear in the oral cavity as multiple pigmented papillary lesions on the dorsal and lateral regions of the tongue and frequently involves the lips; this condition may be associated with metabolic disorders or underlying malignancy.2,3 Oral hairy leukoplakia is caused by Epstein-Barr virus infection and typically presents as white plaques on the dorsal and ventral surfaces of the tongue; this condition largely is found in immunocompromised patients.5

In our patient there was an acute onset of tongue discoloration associated with ingestion of bismuth salicylate, no hypertrophy or lengthening of the lingual papillae, and no involvement of the patient's lips, which was consistent with the diagnosis of pseudo-black hairy tongue. Pseudo-black hairy tongue is transient and treated by discontinuation of offending agents and proper hygiene practices.

- Bradley B, Singleton M, Lin Wan Po A. Bismuth toxicity--a reassessment. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1989;14:423-441.

- Gurvits GE, Tan A. Black hairy tongue syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10845-10850.

- Schlager E, St Claire C, Ashack K, et al. Black hairy tongue: predisposing factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:563-569.

- Mangold AR, Torgerson RR, Rogers RS. Diseases of the tongue. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:458-469.

- Husak R, Garbe C, Orfanos CE. Oral hairy leukoplakia in 71 HIV-seropositive patients: clinical symptoms, relation to immunologic status, and prognostic significance. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:928-934.

- Bradley B, Singleton M, Lin Wan Po A. Bismuth toxicity--a reassessment. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1989;14:423-441.

- Gurvits GE, Tan A. Black hairy tongue syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10845-10850.

- Schlager E, St Claire C, Ashack K, et al. Black hairy tongue: predisposing factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:563-569.

- Mangold AR, Torgerson RR, Rogers RS. Diseases of the tongue. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:458-469.

- Husak R, Garbe C, Orfanos CE. Oral hairy leukoplakia in 71 HIV-seropositive patients: clinical symptoms, relation to immunologic status, and prognostic significance. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:928-934.

A 77-year-old woman incidentally was noted to have black discoloration of the tongue during a routine dermatologic examination. The patient was unaware of the tongue discoloration and reported that her tongue appeared normal the day prior. The tongue was asymptomatic. Clinical examination revealed black hyperpigmentation on the dorsal aspect of the tongue without appreciable hypertrophy or hyperkeratosis of the filiform papillae. The patient had a half-pack daily smoking habit for many years but had abstained from any smoking or tobacco use for the last 15 years. The patient endorsed good oral hygiene. Upon further questioning, the patient revealed that she had ingested 1 tablet of bismuth salicylate the prior night to relieve postprandial dyspepsia. A cotton-tipped applicator was rubbed gently against the affected area and removed some of the black pigment.

Cutaneous Metastatic Breast Adenocarcinoma

To the Editor:

Cutaneous metastases occur more often in the setting of breast carcinoma than other malignancies in women.1 Although interventions are aimed at halting disease progression, cutaneous metastases indicate widespread disease and are associated with poor prognosis. We present the case of a patient with metastatic breast adenocarcinoma who developed cutaneous metastasis on the trunk after a double mastectomy. The widespread distribution and wide range of clinical manifestations are unique.

An 81-year-old woman presented to the dermatology office for evaluation of a skin eruption that started along a mastectomy scar on the left breast a few months postoperatively. She had a history of stage IV breast adenocarcinoma metastatic to the chest wall that was treated with a double mastectomy 2 years prior. The patient denied associated pain or pruritus and mainly was concerned with the cosmetic appearance. At the time of the initial diagnosis of breast adenocarcinoma, the patient was offered chemotherapy, which she did not tolerate. The patient opted against radiation therapy, as she preferred a more natural approach, such as anticancer shakes, which she was taking from a homeopathic source. She was unaware of the ingredients used in the shakes.

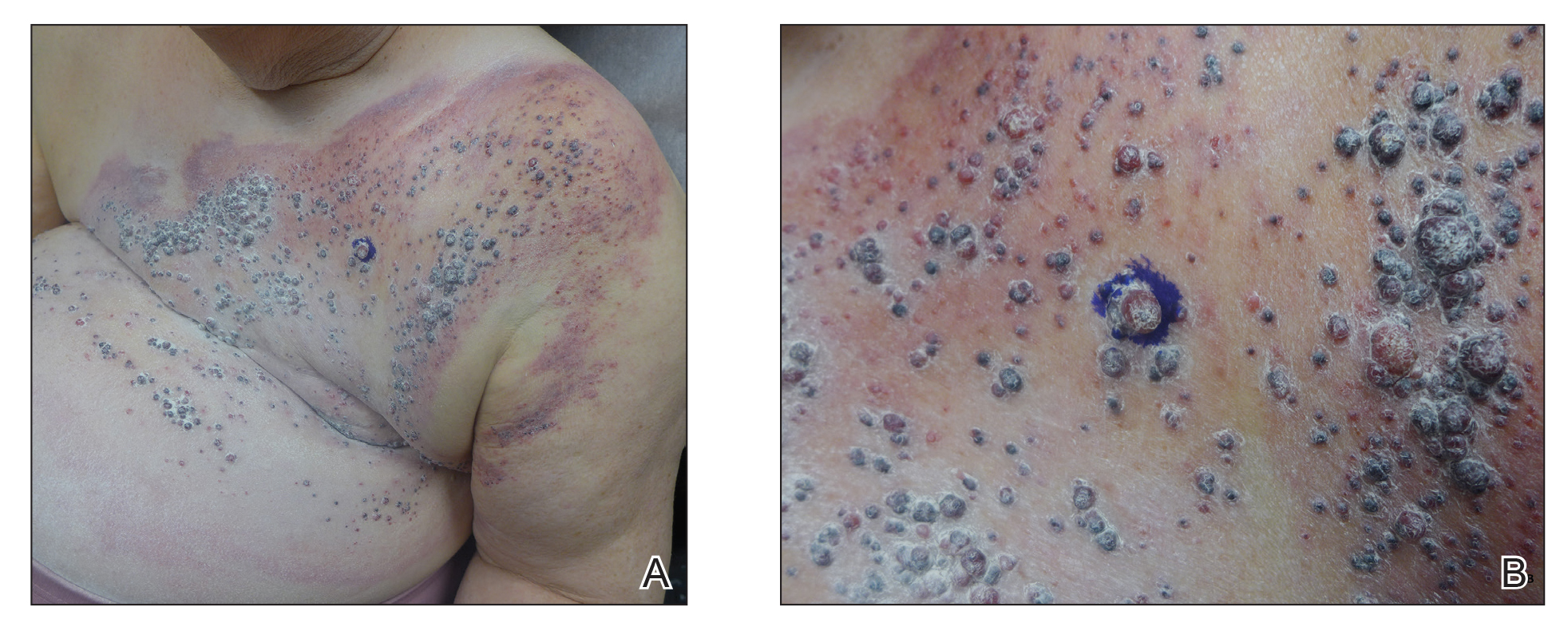

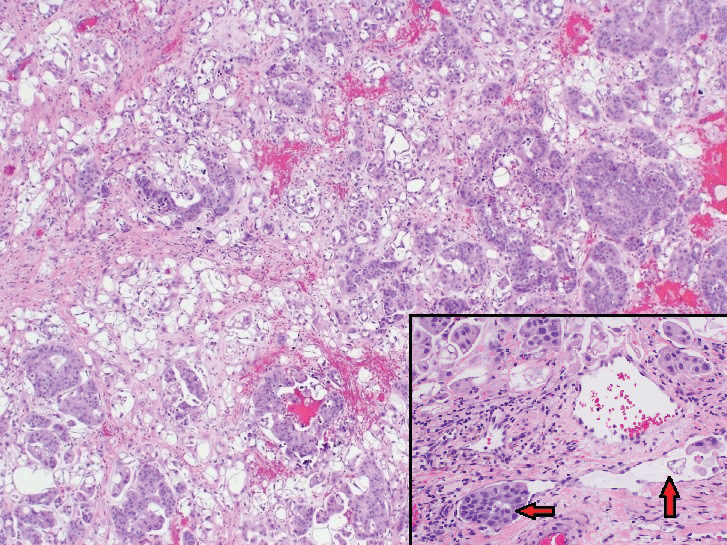

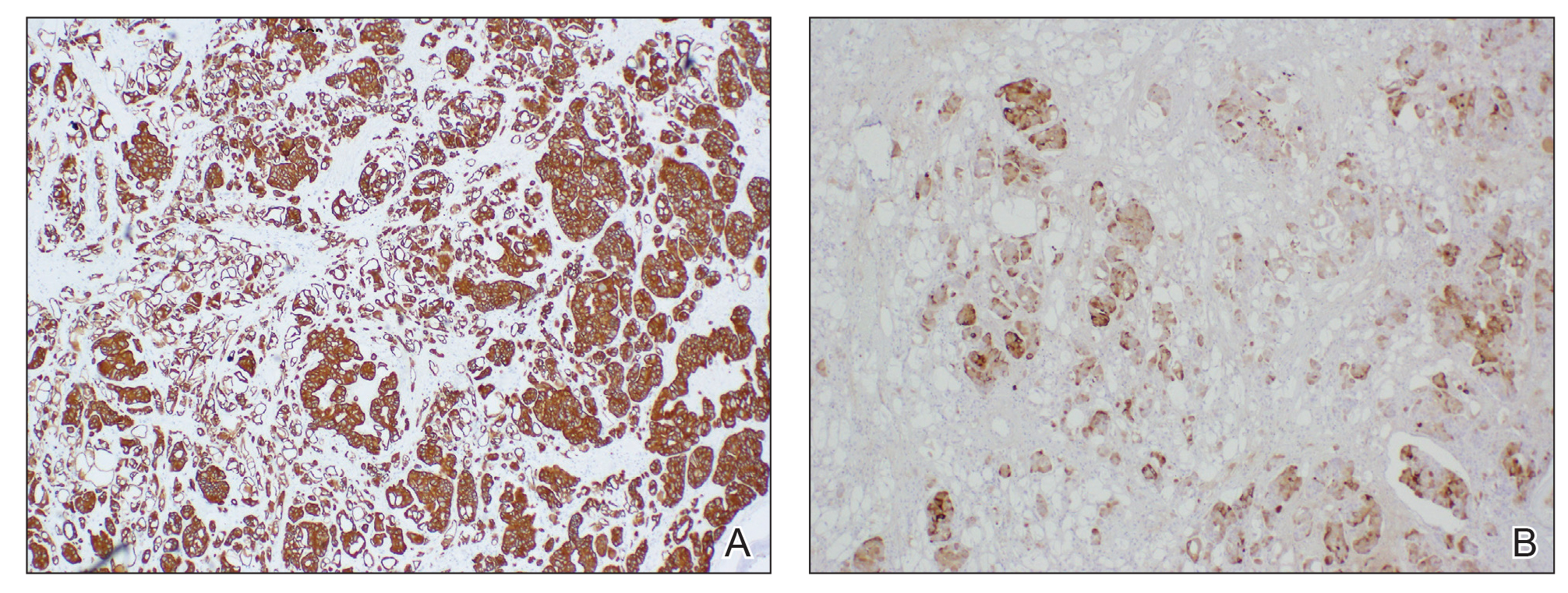

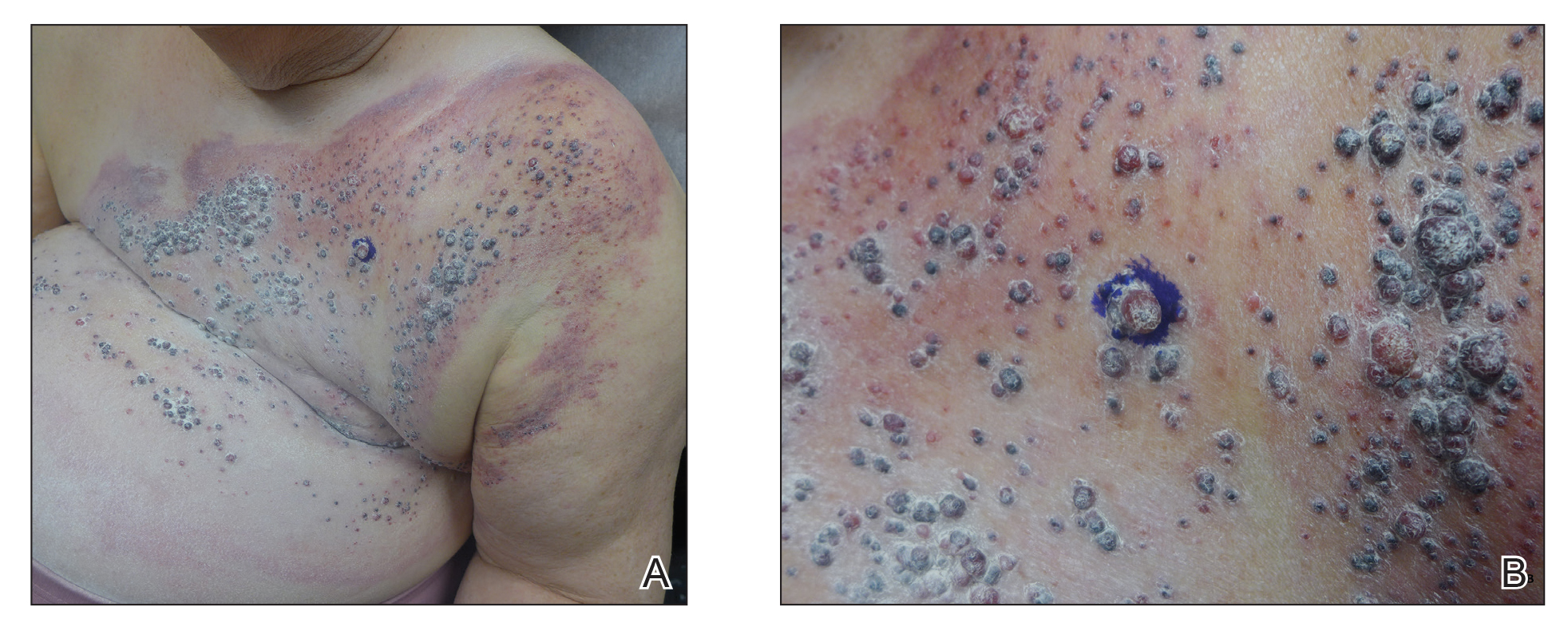

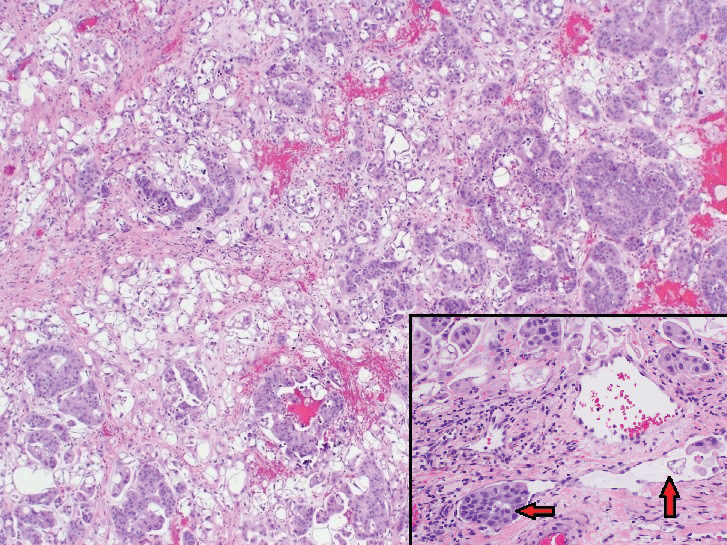

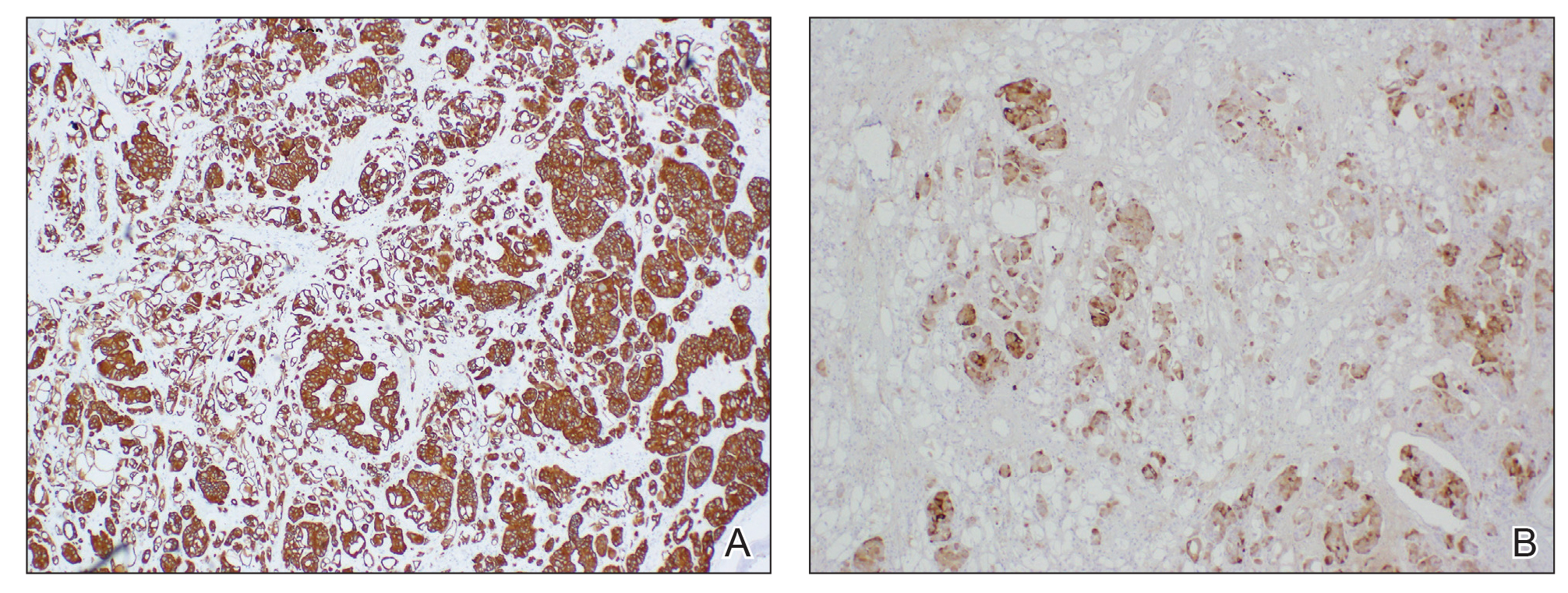

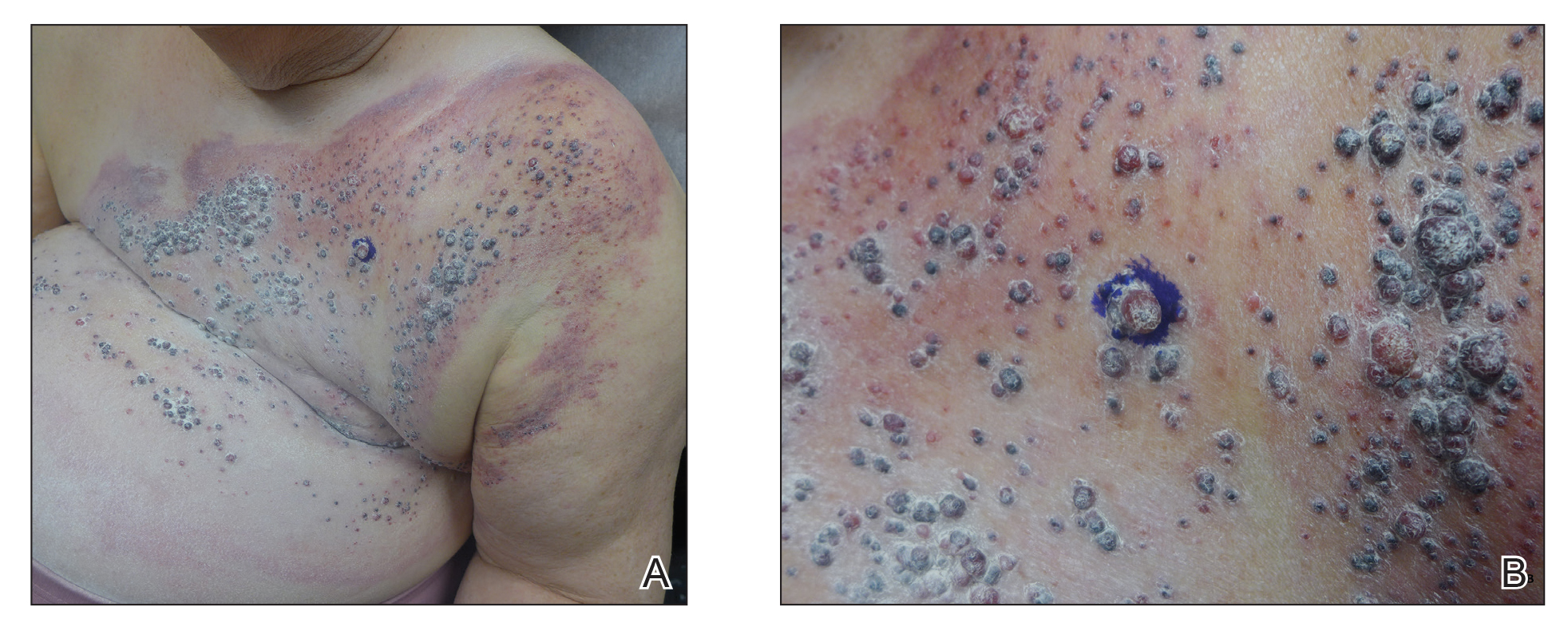

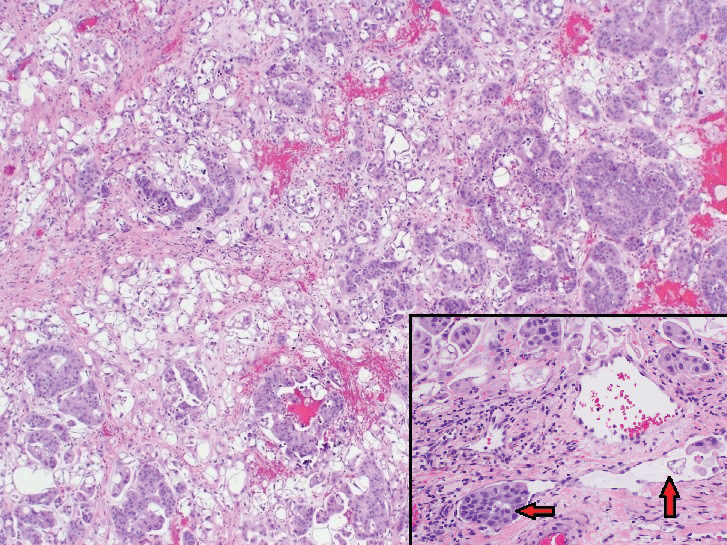

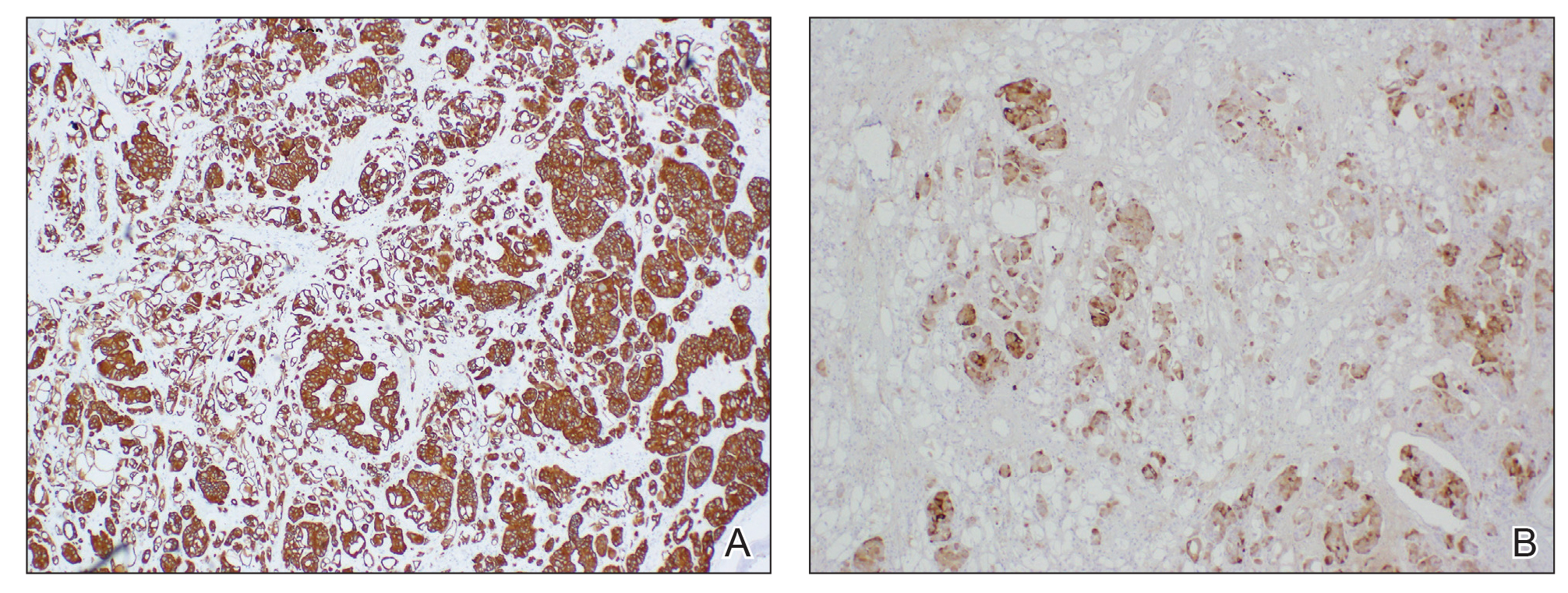

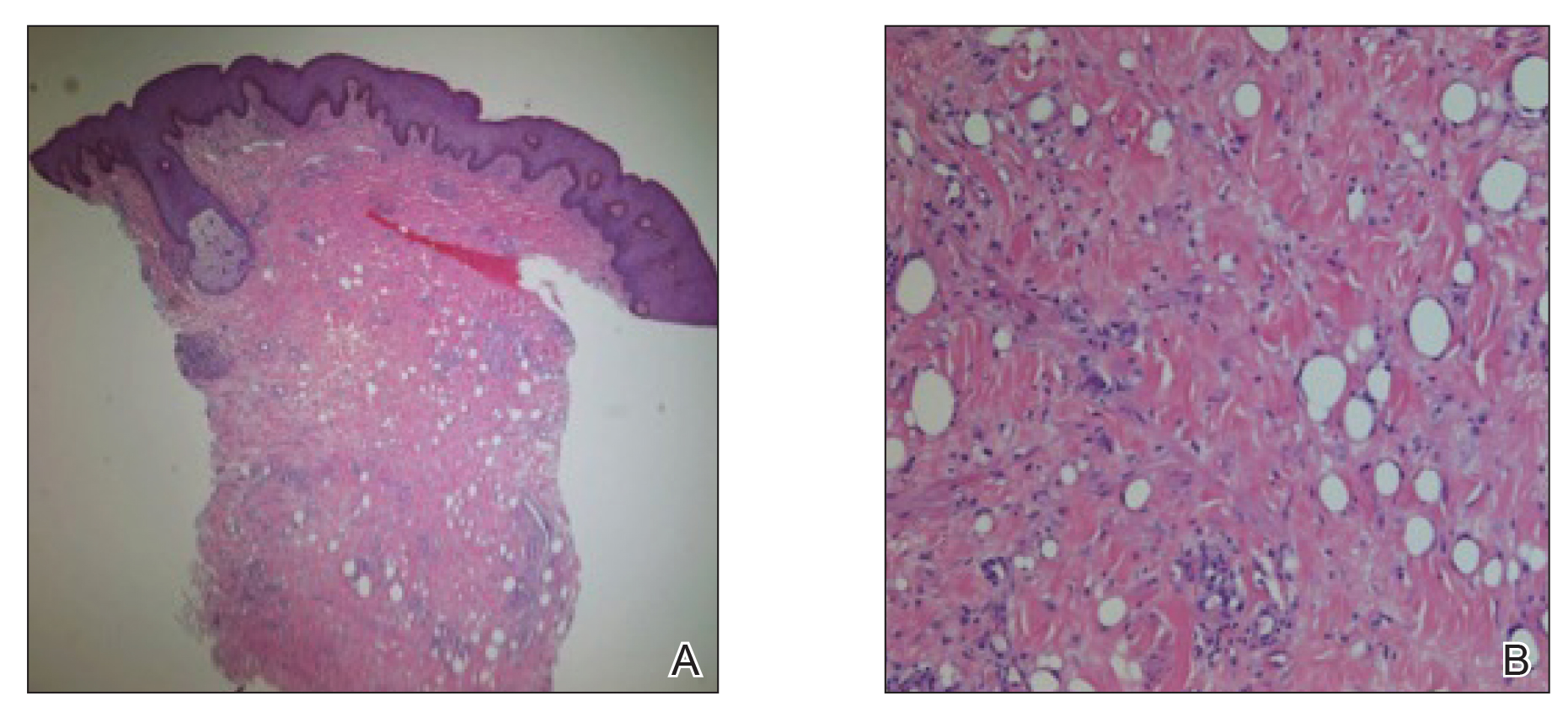

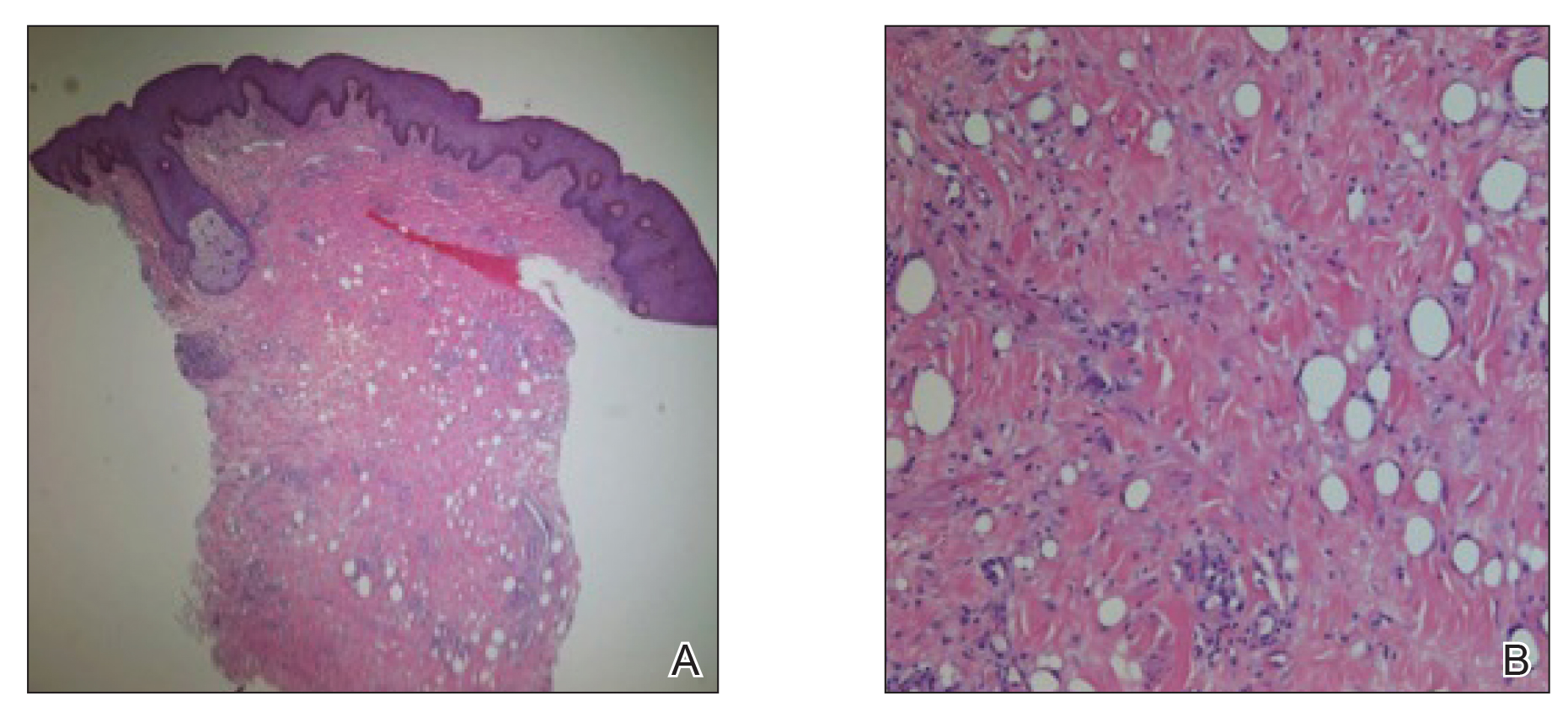

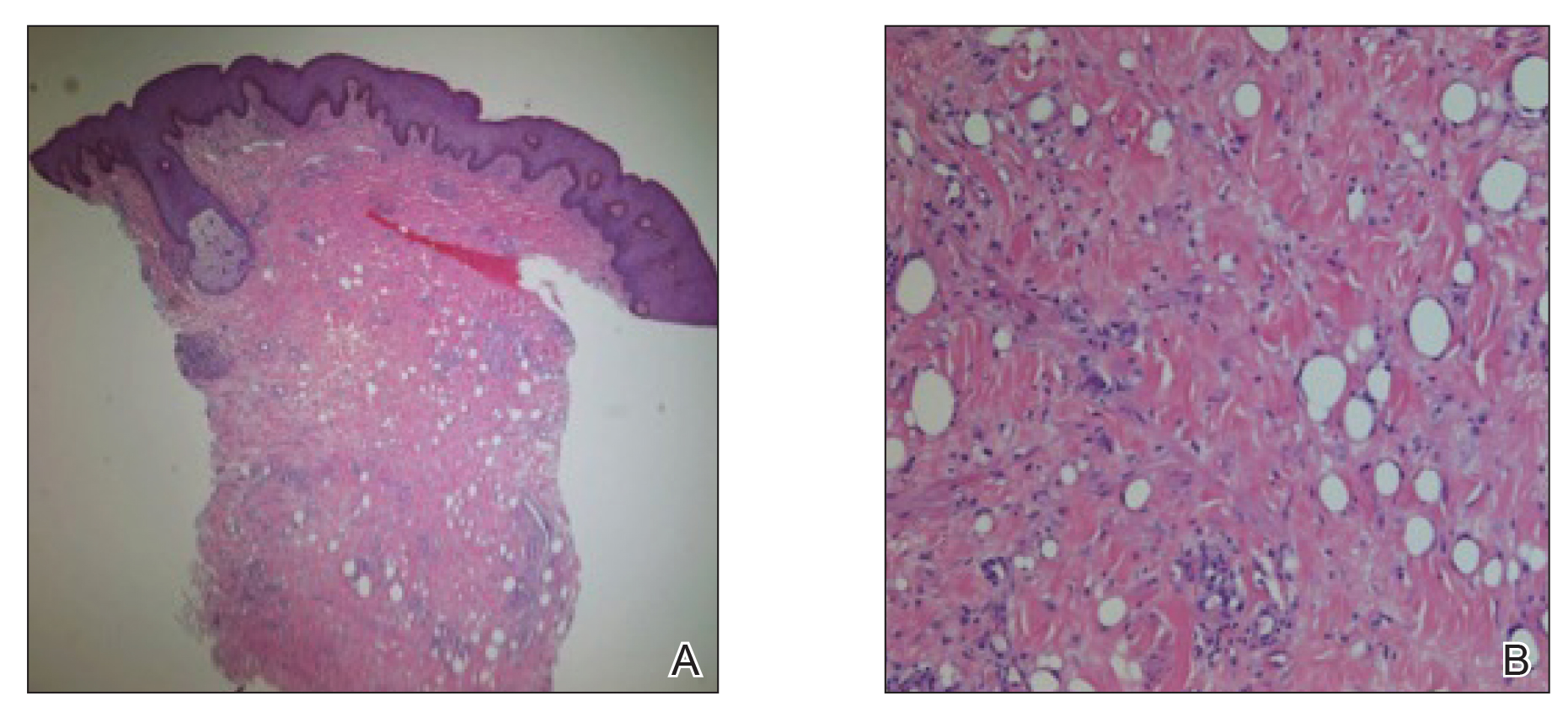

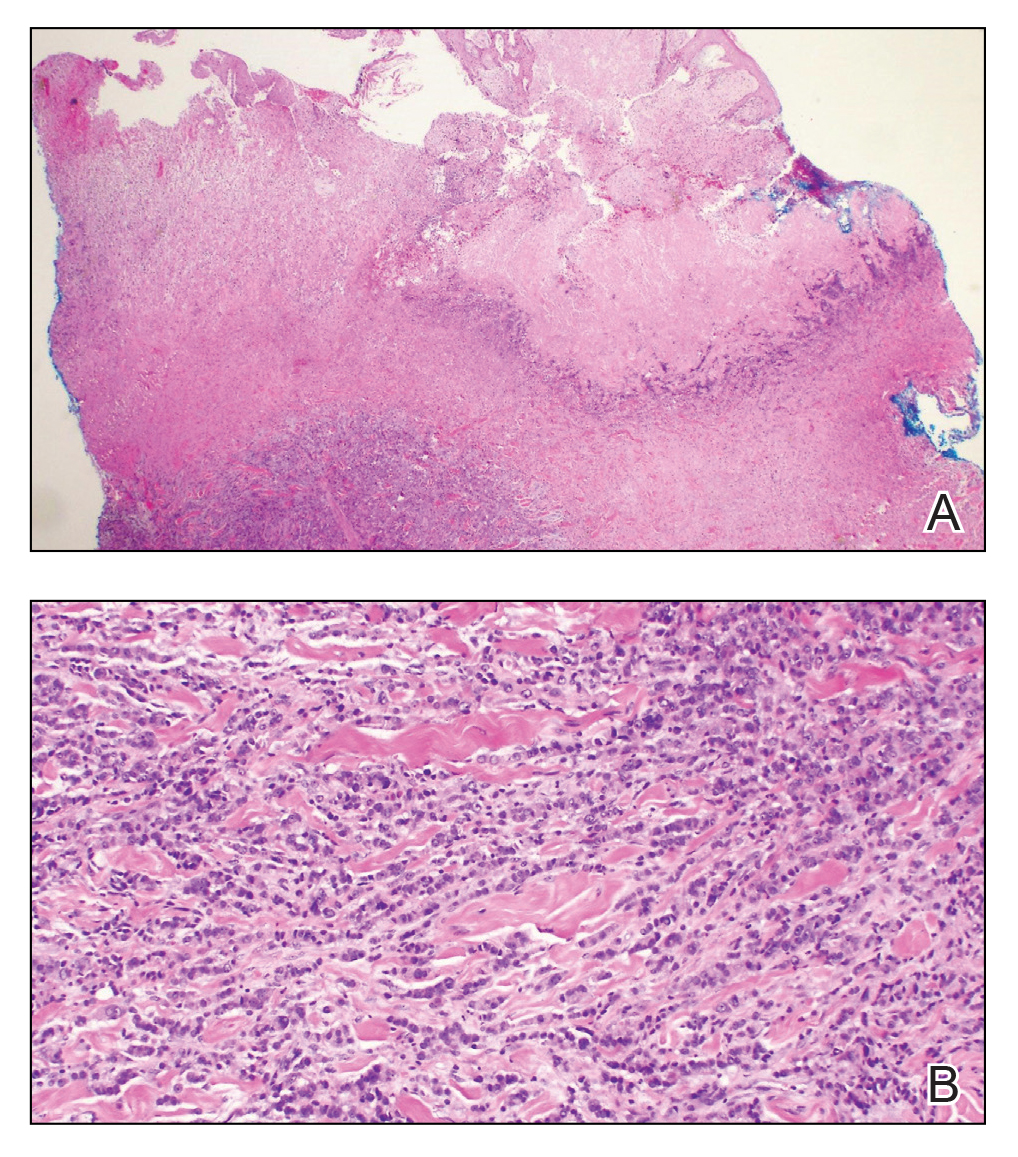

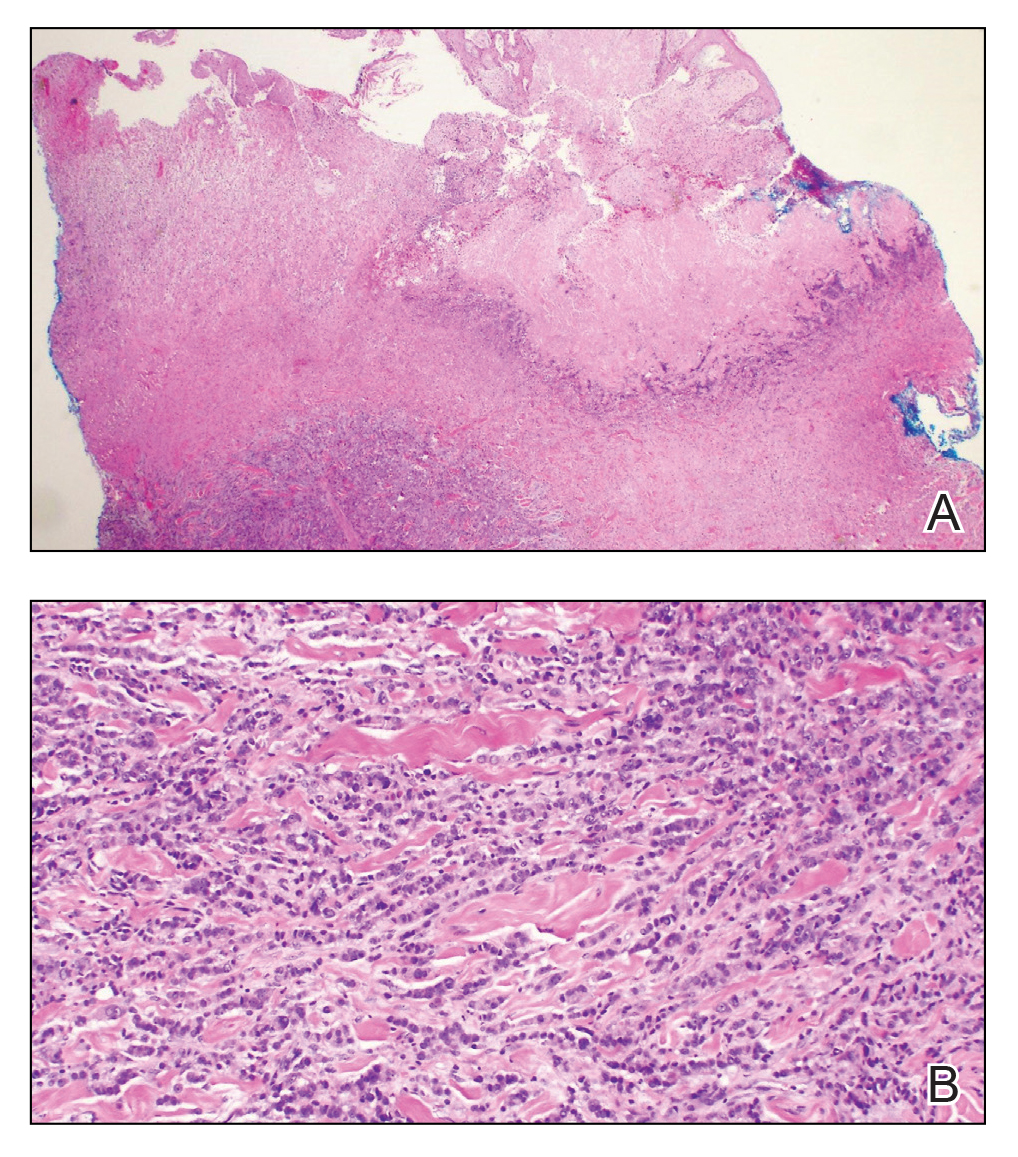

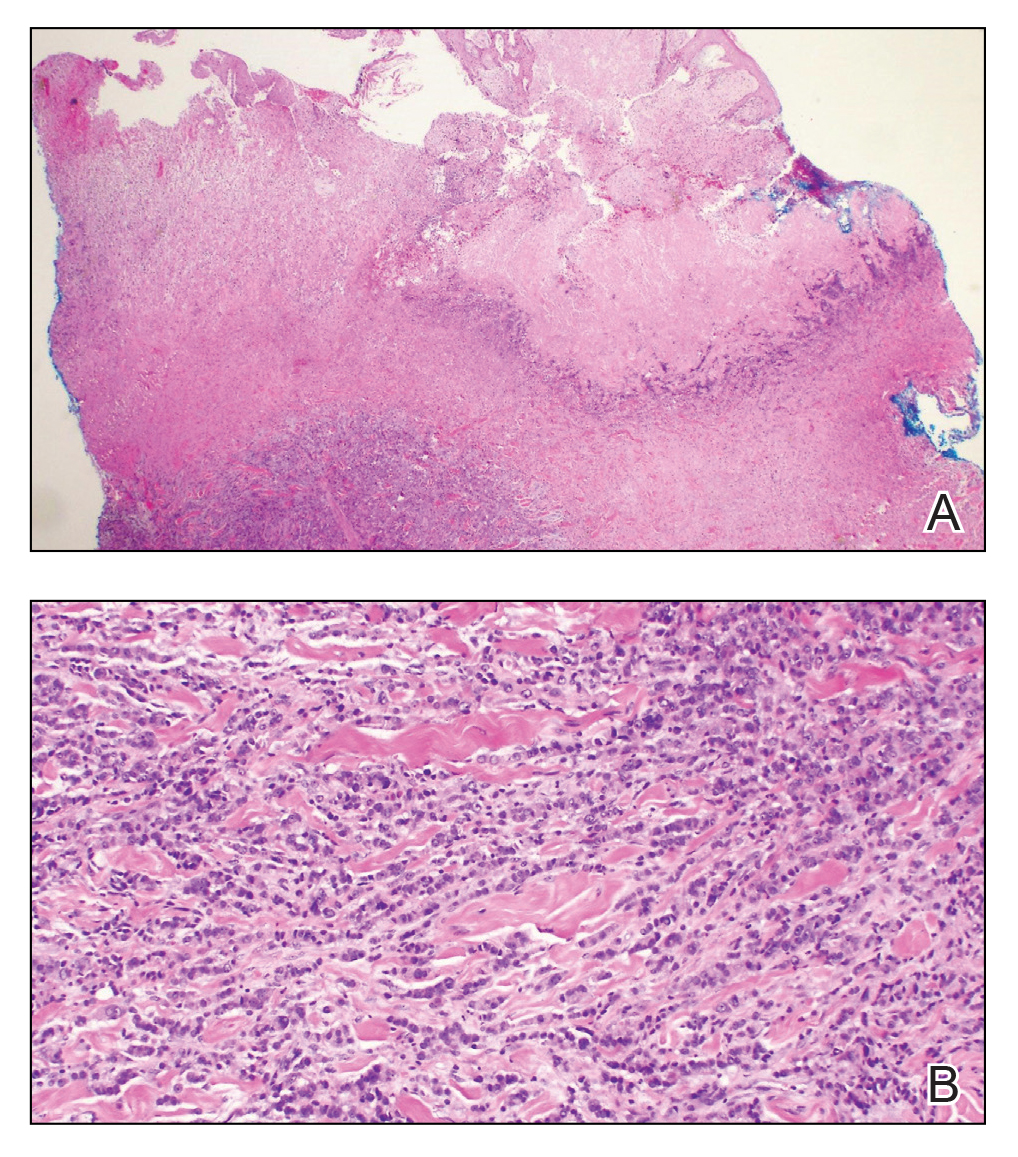

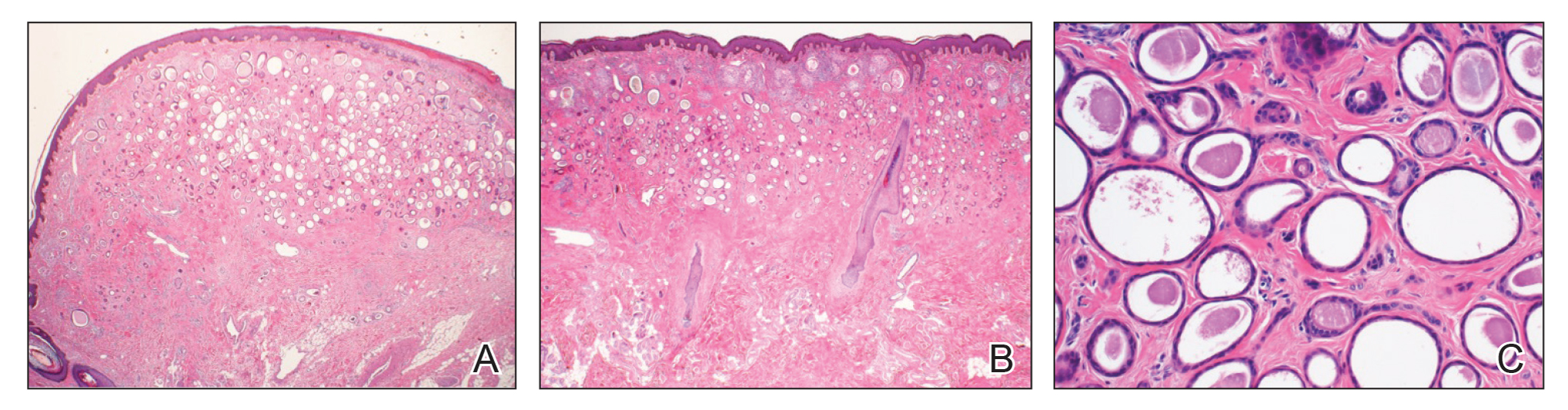

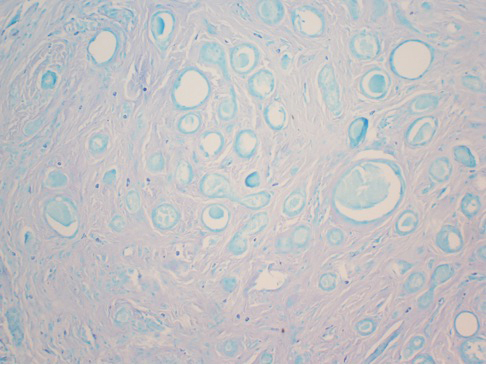

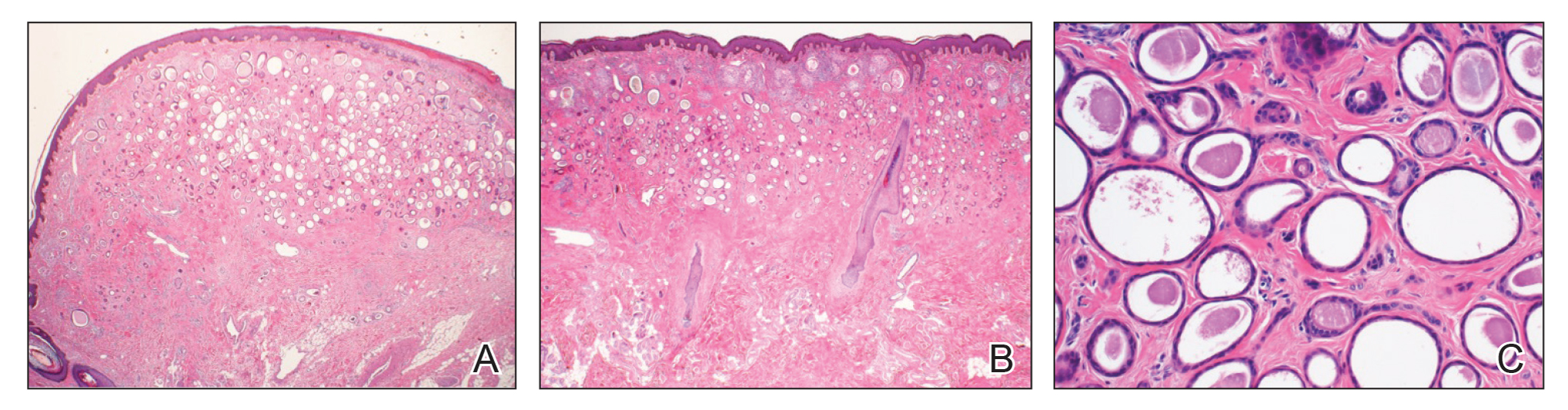

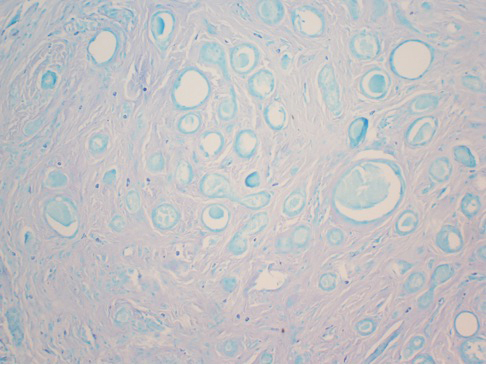

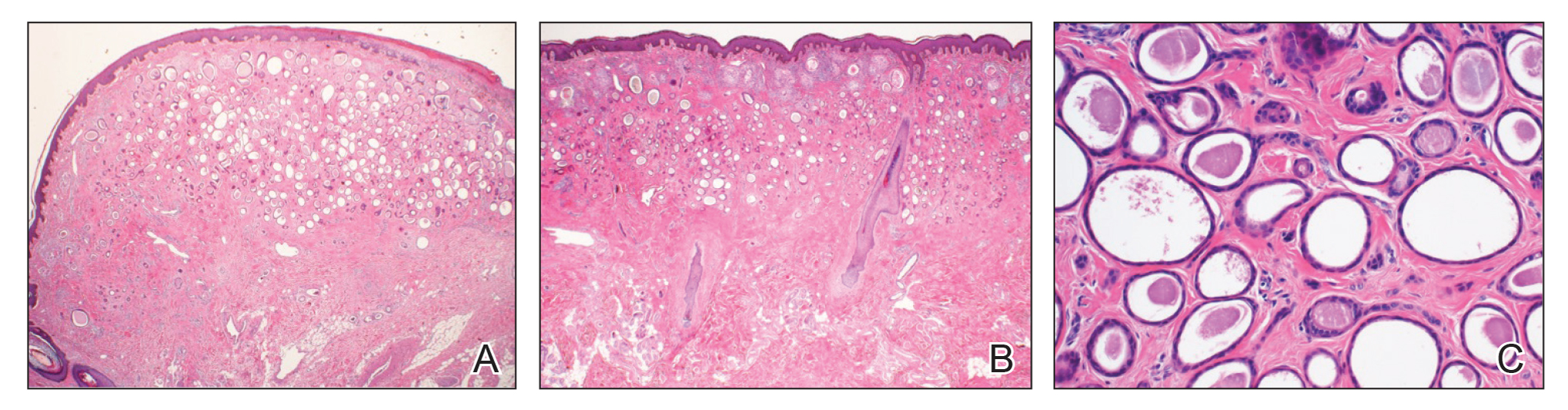

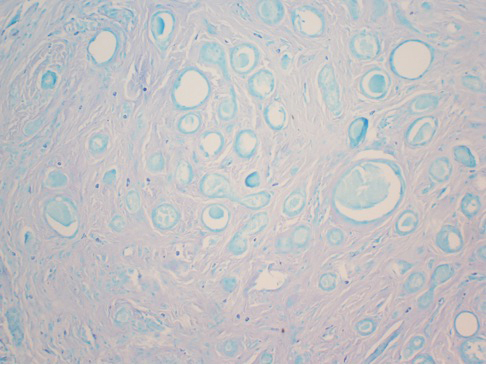

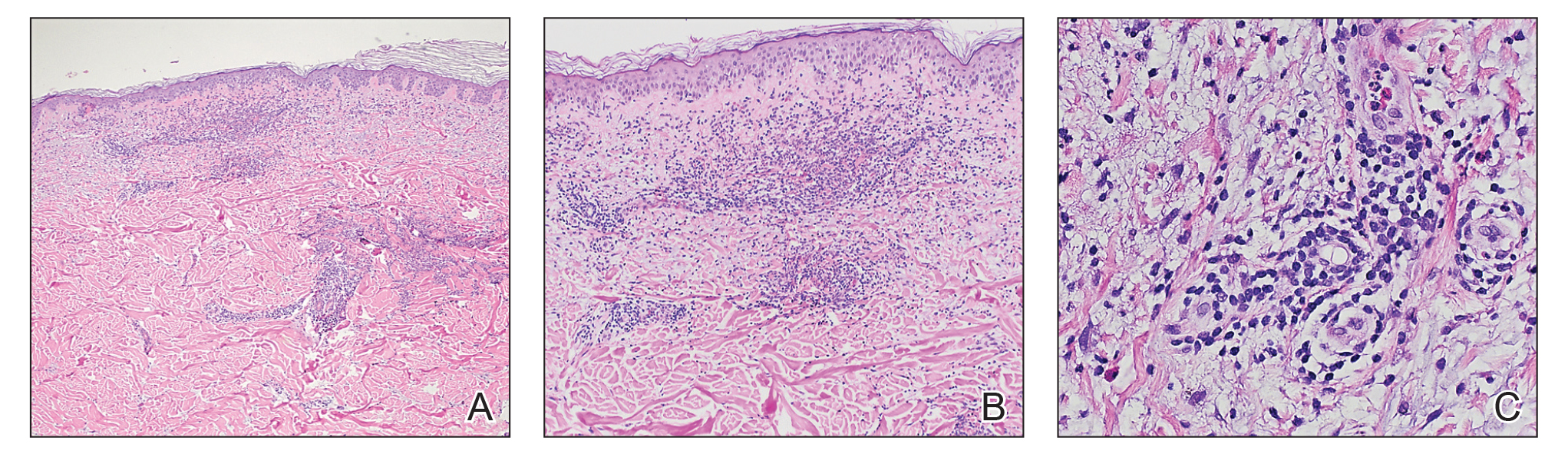

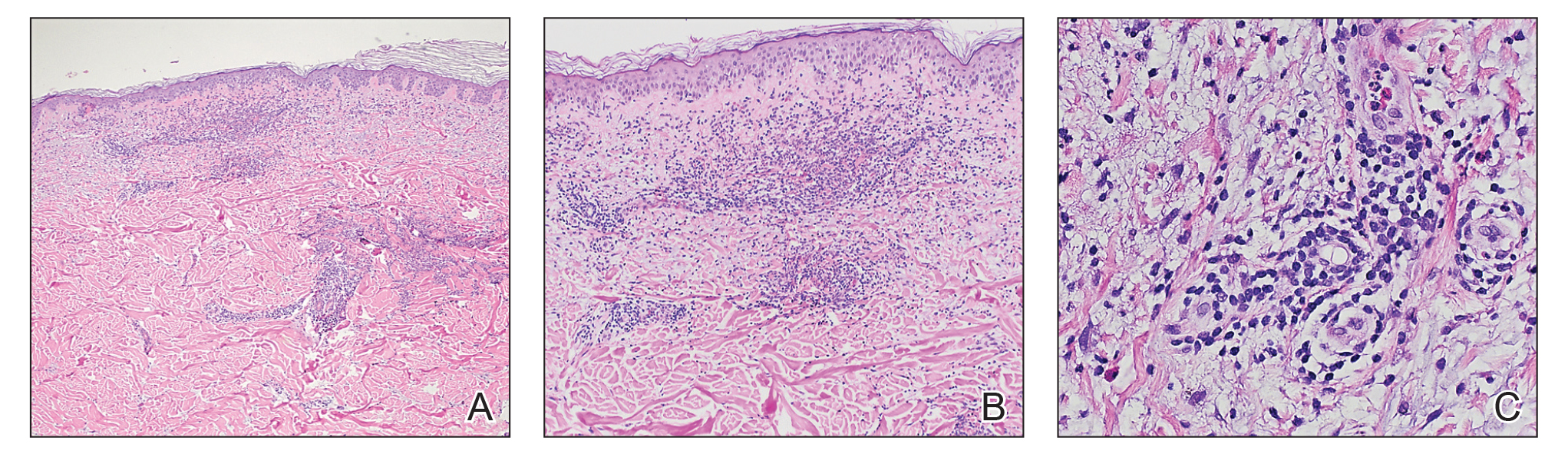

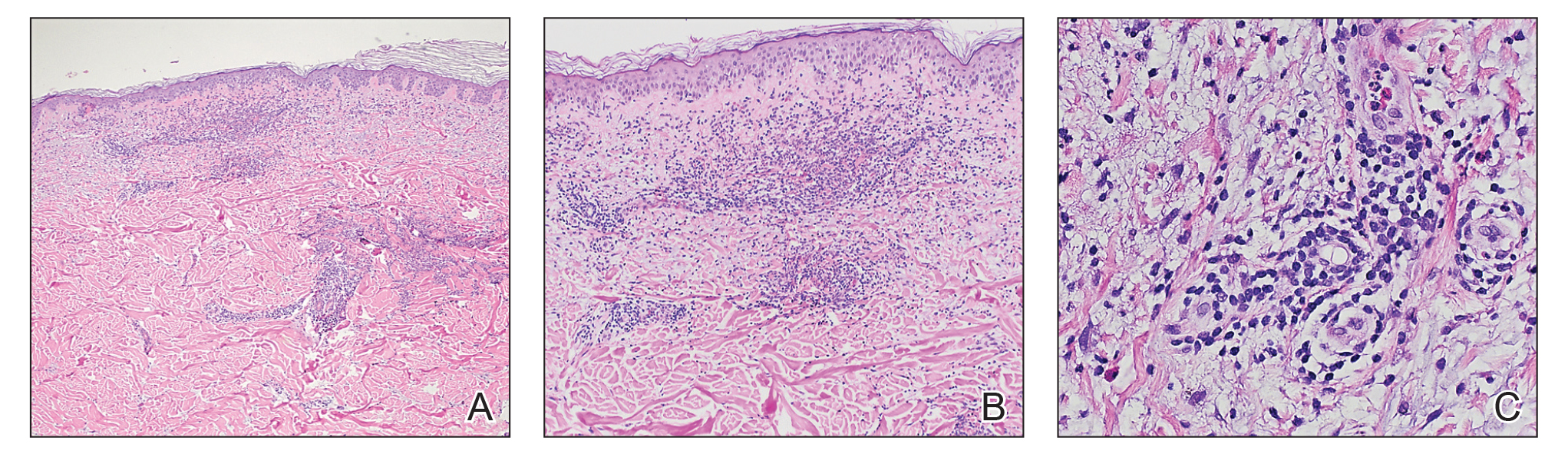

Physical examination revealed multiple grouped, firm, purpuric papules, nodules, and pseudovesicles on a background of violaceous erythema on the chest, abdomen, and flank (Figure 1). The background erythema had a mosaic pattern that extended toward the central back (Figure 2). A scoop shave biopsy of one of the purpuric nodules revealed highly atypical cells with abundant cytoplasm, large nuclei, and prominent nucleoli (Figure 3). Focally, the cells appeared to form glandular structures. Numerous atypical mitotic figures were present. Lymphatic invasion and microcalcifications were identified (Figure 3 [inset]). Immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin 7 and gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 were strongly positive (Figure 4). Based on the histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings, a diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic breast adenocarcinoma was made. The patient opted to continue the homeopathic anticancer shakes and was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies make up only 2% of all skin tumors,1 making them relatively uncommon in the dermatologic setting. However, cutaneous metastasis occurs in 23.9% of patients with breast carcinoma, making it the most common tumor after malignant melanoma to metastasize to the skin.2 The most common sites for breast carcinoma cutaneous metastasis (BCCM) are the chest wall and abdomen; other sites include the head/neck region and the extremities. The clinical presentation of BCCM varies depending on the mode of dissemination—lymphatic, hematogenous, contiguous growth, or iatrogenic implantation. The most common presentation is nodular carcinoma (47%–80%).2,3 Other presentations include carcinoma telangiectoides (8%–11%),2,3 alopecia neoplastica (2%–12%),2,3 and carcinoma erysipeloides (3%–6%).2,3 Carcinoma en cuirasse is rare.3

Nodular BCCM may present as firm solitary or grouped papules and nodules that are painless and range in color from flesh colored or pink to red-brown. Histologically, they are composed of atypical neoplastic cells arranged in small nests and cords, usually in a single-file line within the collagen bundles of the dermis.4 Carcinoma telangiectoides is characterized by its violaceous hue due to the dilated vascular channels. The lesions are purpuric papules and pseudovesicles appearing on an erythematous base, most commonly contiguous with the surgical scar. Histologically, collections of atypical tumor cells and erythrocytes are present along with dilated blood vessels in the papillary dermis.2 Alopecia neoplastica presents as singular or grouped cicatricial patches of hair loss. Lesions of carcinoma erysipeloides present as warm, erythematous, tender, well-defined patches or plaques. Carcinoma en cuirasse is characterized by an erythematous sclerodermoid plaque on the chest wall.2

Our patient’s presentation was unique due to the widespread distribution, unusual pattern, and variable clinical morphologies of the cutaneous metastases. Our patient had findings of both carcinoma telangiectoides and nodular carcinoma. The mosaic violaceous erythema extending toward the mid-back rarely is reported in the literature and indicates extensive intravascular spread of tumor cells in the dermis.

Metastatic breast cancer is associated with a poor prognosis because it typically occurs in advanced stages and often does not respond to treatment.5 Although chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and/or radiation therapy may improve survival, the choice in regimen is guided by cancer histology as well as prior treatments. In our case, the patient chose to continue her homeopathic therapy.

- Nashan D, Meiss F, Braun-Falco M, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from internal malignancies. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:567-580.

- De Giorgi V, Grazzini M, Alfaioli B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of breast carcinoma. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:581-589.

- Mordenti C, Peris K, Concetta Fargnoli M, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Acta Dermatovenerologica. 2000;9:143-148.

- Nava G, Greer K, Patterson J, et al. Metastatic cutaneous breast carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2009;17:25-27.

- Kalmykow B, Walker S. Cutaneous metastasis in breast cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2001;15:99-101.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous metastases occur more often in the setting of breast carcinoma than other malignancies in women.1 Although interventions are aimed at halting disease progression, cutaneous metastases indicate widespread disease and are associated with poor prognosis. We present the case of a patient with metastatic breast adenocarcinoma who developed cutaneous metastasis on the trunk after a double mastectomy. The widespread distribution and wide range of clinical manifestations are unique.

An 81-year-old woman presented to the dermatology office for evaluation of a skin eruption that started along a mastectomy scar on the left breast a few months postoperatively. She had a history of stage IV breast adenocarcinoma metastatic to the chest wall that was treated with a double mastectomy 2 years prior. The patient denied associated pain or pruritus and mainly was concerned with the cosmetic appearance. At the time of the initial diagnosis of breast adenocarcinoma, the patient was offered chemotherapy, which she did not tolerate. The patient opted against radiation therapy, as she preferred a more natural approach, such as anticancer shakes, which she was taking from a homeopathic source. She was unaware of the ingredients used in the shakes.

Physical examination revealed multiple grouped, firm, purpuric papules, nodules, and pseudovesicles on a background of violaceous erythema on the chest, abdomen, and flank (Figure 1). The background erythema had a mosaic pattern that extended toward the central back (Figure 2). A scoop shave biopsy of one of the purpuric nodules revealed highly atypical cells with abundant cytoplasm, large nuclei, and prominent nucleoli (Figure 3). Focally, the cells appeared to form glandular structures. Numerous atypical mitotic figures were present. Lymphatic invasion and microcalcifications were identified (Figure 3 [inset]). Immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin 7 and gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 were strongly positive (Figure 4). Based on the histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings, a diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic breast adenocarcinoma was made. The patient opted to continue the homeopathic anticancer shakes and was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies make up only 2% of all skin tumors,1 making them relatively uncommon in the dermatologic setting. However, cutaneous metastasis occurs in 23.9% of patients with breast carcinoma, making it the most common tumor after malignant melanoma to metastasize to the skin.2 The most common sites for breast carcinoma cutaneous metastasis (BCCM) are the chest wall and abdomen; other sites include the head/neck region and the extremities. The clinical presentation of BCCM varies depending on the mode of dissemination—lymphatic, hematogenous, contiguous growth, or iatrogenic implantation. The most common presentation is nodular carcinoma (47%–80%).2,3 Other presentations include carcinoma telangiectoides (8%–11%),2,3 alopecia neoplastica (2%–12%),2,3 and carcinoma erysipeloides (3%–6%).2,3 Carcinoma en cuirasse is rare.3

Nodular BCCM may present as firm solitary or grouped papules and nodules that are painless and range in color from flesh colored or pink to red-brown. Histologically, they are composed of atypical neoplastic cells arranged in small nests and cords, usually in a single-file line within the collagen bundles of the dermis.4 Carcinoma telangiectoides is characterized by its violaceous hue due to the dilated vascular channels. The lesions are purpuric papules and pseudovesicles appearing on an erythematous base, most commonly contiguous with the surgical scar. Histologically, collections of atypical tumor cells and erythrocytes are present along with dilated blood vessels in the papillary dermis.2 Alopecia neoplastica presents as singular or grouped cicatricial patches of hair loss. Lesions of carcinoma erysipeloides present as warm, erythematous, tender, well-defined patches or plaques. Carcinoma en cuirasse is characterized by an erythematous sclerodermoid plaque on the chest wall.2

Our patient’s presentation was unique due to the widespread distribution, unusual pattern, and variable clinical morphologies of the cutaneous metastases. Our patient had findings of both carcinoma telangiectoides and nodular carcinoma. The mosaic violaceous erythema extending toward the mid-back rarely is reported in the literature and indicates extensive intravascular spread of tumor cells in the dermis.

Metastatic breast cancer is associated with a poor prognosis because it typically occurs in advanced stages and often does not respond to treatment.5 Although chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and/or radiation therapy may improve survival, the choice in regimen is guided by cancer histology as well as prior treatments. In our case, the patient chose to continue her homeopathic therapy.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous metastases occur more often in the setting of breast carcinoma than other malignancies in women.1 Although interventions are aimed at halting disease progression, cutaneous metastases indicate widespread disease and are associated with poor prognosis. We present the case of a patient with metastatic breast adenocarcinoma who developed cutaneous metastasis on the trunk after a double mastectomy. The widespread distribution and wide range of clinical manifestations are unique.

An 81-year-old woman presented to the dermatology office for evaluation of a skin eruption that started along a mastectomy scar on the left breast a few months postoperatively. She had a history of stage IV breast adenocarcinoma metastatic to the chest wall that was treated with a double mastectomy 2 years prior. The patient denied associated pain or pruritus and mainly was concerned with the cosmetic appearance. At the time of the initial diagnosis of breast adenocarcinoma, the patient was offered chemotherapy, which she did not tolerate. The patient opted against radiation therapy, as she preferred a more natural approach, such as anticancer shakes, which she was taking from a homeopathic source. She was unaware of the ingredients used in the shakes.

Physical examination revealed multiple grouped, firm, purpuric papules, nodules, and pseudovesicles on a background of violaceous erythema on the chest, abdomen, and flank (Figure 1). The background erythema had a mosaic pattern that extended toward the central back (Figure 2). A scoop shave biopsy of one of the purpuric nodules revealed highly atypical cells with abundant cytoplasm, large nuclei, and prominent nucleoli (Figure 3). Focally, the cells appeared to form glandular structures. Numerous atypical mitotic figures were present. Lymphatic invasion and microcalcifications were identified (Figure 3 [inset]). Immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin 7 and gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 were strongly positive (Figure 4). Based on the histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings, a diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic breast adenocarcinoma was made. The patient opted to continue the homeopathic anticancer shakes and was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies make up only 2% of all skin tumors,1 making them relatively uncommon in the dermatologic setting. However, cutaneous metastasis occurs in 23.9% of patients with breast carcinoma, making it the most common tumor after malignant melanoma to metastasize to the skin.2 The most common sites for breast carcinoma cutaneous metastasis (BCCM) are the chest wall and abdomen; other sites include the head/neck region and the extremities. The clinical presentation of BCCM varies depending on the mode of dissemination—lymphatic, hematogenous, contiguous growth, or iatrogenic implantation. The most common presentation is nodular carcinoma (47%–80%).2,3 Other presentations include carcinoma telangiectoides (8%–11%),2,3 alopecia neoplastica (2%–12%),2,3 and carcinoma erysipeloides (3%–6%).2,3 Carcinoma en cuirasse is rare.3

Nodular BCCM may present as firm solitary or grouped papules and nodules that are painless and range in color from flesh colored or pink to red-brown. Histologically, they are composed of atypical neoplastic cells arranged in small nests and cords, usually in a single-file line within the collagen bundles of the dermis.4 Carcinoma telangiectoides is characterized by its violaceous hue due to the dilated vascular channels. The lesions are purpuric papules and pseudovesicles appearing on an erythematous base, most commonly contiguous with the surgical scar. Histologically, collections of atypical tumor cells and erythrocytes are present along with dilated blood vessels in the papillary dermis.2 Alopecia neoplastica presents as singular or grouped cicatricial patches of hair loss. Lesions of carcinoma erysipeloides present as warm, erythematous, tender, well-defined patches or plaques. Carcinoma en cuirasse is characterized by an erythematous sclerodermoid plaque on the chest wall.2

Our patient’s presentation was unique due to the widespread distribution, unusual pattern, and variable clinical morphologies of the cutaneous metastases. Our patient had findings of both carcinoma telangiectoides and nodular carcinoma. The mosaic violaceous erythema extending toward the mid-back rarely is reported in the literature and indicates extensive intravascular spread of tumor cells in the dermis.

Metastatic breast cancer is associated with a poor prognosis because it typically occurs in advanced stages and often does not respond to treatment.5 Although chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and/or radiation therapy may improve survival, the choice in regimen is guided by cancer histology as well as prior treatments. In our case, the patient chose to continue her homeopathic therapy.

- Nashan D, Meiss F, Braun-Falco M, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from internal malignancies. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:567-580.

- De Giorgi V, Grazzini M, Alfaioli B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of breast carcinoma. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:581-589.

- Mordenti C, Peris K, Concetta Fargnoli M, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Acta Dermatovenerologica. 2000;9:143-148.

- Nava G, Greer K, Patterson J, et al. Metastatic cutaneous breast carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2009;17:25-27.

- Kalmykow B, Walker S. Cutaneous metastasis in breast cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2001;15:99-101.

- Nashan D, Meiss F, Braun-Falco M, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from internal malignancies. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:567-580.

- De Giorgi V, Grazzini M, Alfaioli B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of breast carcinoma. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:581-589.

- Mordenti C, Peris K, Concetta Fargnoli M, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Acta Dermatovenerologica. 2000;9:143-148.

- Nava G, Greer K, Patterson J, et al. Metastatic cutaneous breast carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2009;17:25-27.