User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Cutaneous Id Reaction After Using Cyanoacrylate for Wound Closure

To the Editor:

In 1998, 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate (2-CA) tissue adhesive gained US Food and Drug Administration approval for topical application to easily hold closed approximated skin edges from surgical excisions and simple trauma-induced lacerations.1 It has since been employed for a number of off-label indications, including sutureless circumcision,2 skin graft fixation,3 pericatheter leakage,4 and intracorporeal use to control air leaks during lung resection.5 Animal investigations additionally have attempted to elucidate potential future uses of 2-CA for procedures such as inguinal hernia repair,6 bowel anastomosis,7 incisional hernia repair with mesh,8 and microvascular anastomosis.9 Compared to sutures, 2-CA offers ease and rapidity of application, a water-resistant barrier, and equivalent cosmetic results, as well as eliminates the need for suture removal.10 As 2-CA is used with increasing frequency across a variety of settings, there arises a greater need to be mindful of the potential complications of its use, such as irritant contact dermatitis (ICD), allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), and cutaneous id reaction.

A 14-year-old adolescent boy with no notable medical history and no known allergies underwent a minimally invasive Nuss procedure11 (performed by P.L.G.) for the repair of severe pectus excavatum. Two 4-cm incisions were made—one in each lateral chest wall at the approximately eighth intercostal space—to facilitate the introduction of the Nuss bar. The surgical wounds were closed with 2 layers of running polyglactin 910 suture before 2-CA was applied topically to the incision sites. The surgery was well tolerated, and the patient’s wounds healed without incident. When the patient was evaluated for Nuss bar removal 3 years later, incision sites were noted to be well healed, and he exhibited no other skin lesions. The original incision sites (bilateral chest walls) were utilized to facilitate surgical Nuss bar removal. The wounds were closed in 4 layers and 2-CA was again applied topically to the incision sites. There were no intraoperative complications; no devices, drains, or tissue implants were left in the patient at the conclusion of the procedure.

One week later, via text message and digital photographs, the patient reported intense pruritus at the bilateral chest wall incision sites, which were now surrounded by symmetric 1-cm erythematous plaques and associated sparse erythematous satellite papules (Figure 1). The patient denied any fevers, pain, swelling, or purulent discharge from the wounds. He was started on hydrocortisone cream 1% twice daily as well as oral diphenhydramine 25 mg at bedtime with initial good effect.

Three days later, the patient sent digital photographs of a morphologically similar–appearing rash that had progressed beyond the lateral chest walls to include the central chest and bilateral upper and lower extremities (Figure 2). He continued to deny any local or systemic signs of infection. Dermatology was consulted, and a diagnosis of ACD with cutaneous id reaction was made. The patient’s medication regimen was modified to include triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% applied twice daily to the rash away from the wounds, clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% applied twice daily to the rash at the wound sites, oral levocetirizine 5 mg once daily, and oral hydroxyzine 25 to 50 mg every 6 hours as needed for pruritus. Additional recommendations included the use of a fragrance-free soap and application of an over-the-counter anti-itch lotion containing menthol and camphor applied as needed. Within 24 hours of starting this modified treatment regimen, the patient began to notice an improvement in symptoms, with full resolution over the course of the ensuing 2 weeks. The patient was counseled to inform his physicians—present and future—of his allergy to 2-CA.

Contact dermatitis associated with the use of 2-CA has been described in the literature.12-15 We report progression to an id reaction, which is characterized by the diffuse symmetric spread of a cutaneous eruption at a site distant from the primary localized dermatitis that develops within a few days of the primary lesion and exhibits the same morphologic and histopathologic findings.16,17 In our patient, pruritic erythematous papules and plaques symmetrically distributed on the arms, legs, and chest appeared 3 days after he first reported a similar eruption at the 2-CA application sites. It is theorized that id reactions develop when the sensitization phase of a type IV hypersensitivity reaction generates a population of T cells that not only recognizes a hapten but also recognizes keratinocyte-derived epitopes.16 A hapten is a small molecule (<500 Da) that is capable of penetrating the stratum corneum and binding skin components. A contact allergen is a hapten that has bound epidermal proteins to create a new antigenic determinant.18 The secondary dermatitis that characterizes id reactions results from an abnormal autoimmune response. Id reactions associated with exposure to adhesive material are rare.19

Allergic contact dermatitis is a type IV hypersensitivity reaction that appears after initial sensitization to an allergen followed by re-exposure. Our patient presented with symmetric erythematous plaques at the surgical incision sites 1 week after 2-CA had been applied. During this interval, sensitization to the inciting allergen occurred. The allergen is taken up by antigen-presenting cells, which then migrate to lymph nodes where they encounter naïve T lymphocytes that subsequently undergo clonal expansion to produce a cohort of T cells that are capable of recognizing the allergen. If subsequent exposure to the specific allergen takes place, an elicitation phase occurs in which primed T cells are incited to release mediators of inflammation that engender the manifestations of ACD within 24 to 72 hours.18,20 Sensitization may be promoted by skin barrier impairments such as dermatitis or a frank wound.12,20 In most cases, the patient is unaware that sensitization has occurred, though a primary ACD within 5 to 15 days after initial exposure to the inciting allergen rarely may be observed.18 Although our patient had 2-CA applied to his surgical wounds at 14 years of age, it was unlikely that sensitization took place at that time, as it was 1 week rather than 1 to 3 days before he experienced the cutaneous eruption associated with his second 2-CA exposure at 17 years of age.

Cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive also may cause ICD resulting from histotoxic degradation products such as formaldehyde and cyanoacetate that are capable of compromising cutaneous barrier function. Keratinocytes that have had their membranes disturbed release proinflammatory cytokines, which recruit cells of the innate immune system as well as T lymphocytes to the site of insult to facilitate the inflammatory response. The manifestations of ICD include erythema, edema, and local necrosis that can compromise wound healing.20 The speed at which a given cyanoacrylate adhesive degrades is proportional to the length of its carbon side chain. Those with shorter side chains—ethyl and methyl cyanoacrylate—degrade more rapidly into formaldehyde and cyanoacetate; 2-CA possesses a longer side chain and therefore degrades more slowly, which should, in theory, lessen its potential to cause ICD.20 Because it may take 7 to 14 days before 2-CA will spontaneously peel from the application site, however, its potential to evoke ICD nevertheless exists.

Treatment of ICD entails removing the irritant while concurrently working to restore the skin’s barrier with emollients. Although topical corticosteroids often are reflexively prescribed to treat rashes, some believe that their use should be avoided in cases of ICD, as their inhibitory effects on epidermal lipid synthesis may further impair the skin’s barrier.21 For cases of ACD, with or without an accompanying id reaction, topical corticosteroids are the mainstay of therapy. It is customary to start with a higher-potency topical steroid such as clobetasol and taper to lower-potency steroids as the patient’s condition improves. Steroid ointments are petroleum based and are capable of causing 2-CA to separate from the skin.10 As a result, they should be used with care when being applied to an area where 2-CA is maintaining dermal closure. Systemic corticosteroids may be warranted in cases with involvement of more than 20% of the body surface area and should start to provide relief within 12 to 24 hours.22 Oral antihistamines and cold water compresses can be added to help address pruritus and discomfort in both ACD and ICD.

Instances of contact dermatitis caused by 2-CA are rare, and progression to an id reaction is rarer still. Physicians should be aware of the possibility of encountering a patient that manifests one or both of these complications whenever 2-CA is employed for skin closure. Physicians who employ 2-CA for skin closure should first ask patients about prior cutaneous reactions to cyanoacrylates including 2-CA and other commonly encountered acrylate-containing products including adhesive wound dressings, dental cements and prostheses, superglue, artificial nails, and adhesives for wigs and false eyelashes. Still, many patients who exhibit acrylate-induced contact dermatitis, with or without an associated id reaction, will not attest to a history of adverse reactions; they simply may not recognize acrylate as the inciting agent. Practitioners across a range of specialties outside of dermatology—surgeons, emergency physicians, and primary care providers—should be prepared to both recognize contact dermatitis and id reaction arising from the use of 2-CA and implement a basic treatment plan that will bring the patient relief without compromising wound closure.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Premarket approval (PMA). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpma/pma.cfm?id=p960052. Accessed March 4, 2020.

- Elmore JM, Smith EA, Kirsch AJ. Sutureless circumcision using 2-octyl cyanoacrylate (Dermabond): appraisal after 18-month experience. Urology. 2007;70:803-806.

- Kilic A, Ozdengil E. Skin graft fixation by applying cyanoacrylate without any complication. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:370-371.

- Gurnaney H, Kraemer FW, Ganesh A. Dermabond decreases pericatheter local anesthetic leakage after continuous perineural infusions. Anesth Analg. 2011;113:206.

- Carr JA. The intracorporeal use of 2-octyl cyanoacrylate resin to control air leaks after lung resection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;39:579-583.

- Miyano G, Yamataka A, Kato Y, et al. Laparoscopic injection of Dermabond tissue adhesive for the repair of inguinal hernia: short- and long-term follow-up. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:1867-1870.

- Paral J, Subrt Z, Lochman P, et al. Suture-free anastomosis of the colon. experimental comparison of two cyanoacrylate adhesives. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:451-459.

- Birch DW, Park A. Octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive as an alternative to mechanical fixation of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene prosthesis. Am Surg. 2001;67:974-978.

- Ang ES, Tan KC, Tan LH, et al. 2-octylcyanoacrylate-assisted microvascular anastomosis: comparison with a conventional suture technique in rat femoral arteries. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2001;17:193-201.

- Bruns TB, Worthington JM. Using tissue adhesive for wound repair: a practical guide to Dermabond. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61:1383-1388.

- Nuss D, Kelly RE Jr, Croitoru DP, et al. A 10-year review of a minimally invasive technique for the correction of pectus excavatum. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:545-552.

- Hivnor CM, Hudkins ML. Allergic contact dermatitis after postsurgical repair with 2-octylcyanoacrylate. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:814-815.

- Howard BK, Downey SE. Contact dermatitis from Dermabond. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:E252-E253.

- Perry AW, Sosin M. Severe allergic reaction to Dermabond. Aesthet Surg J. 2009;29:314-316.

- Sachse MM, Junghans T, Rose C, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by topical 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;68:317-319.

- Fehr BS, Takashima A, Bergstresser PR, et al. T cells reactive to keratinocyte antigens are generated during induction of contact hypersensitivity in mice. a model for autoeczematization in humans? Am J Contact Dermat. 2000;11:145-154.

- Gonzalez-Amaro R, Baranda L, Abud-Mendoza C, et al. Autoeczematization is associated with abnormal immune recognition of autologous skin antigens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:56-60.

- Vocanson M, Hennino A, Rozières A, et al. Effector and regulatory mechanisms in allergic contact dermatitis. Allergy. 2009;64:1699-1714.

- Sommer LL, Hejazi EZ, Heymann WR. An acute linear pruritic eruption following allergic contact dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:42-44.

- Rietschel RL, Fowler JF. Plastics, adhesives, and synthetic resins. In: Rietschek RL, Fowler JF, eds. Fisher’s Contact Dermatitis. Hamilton, BC: Decker Inc; 2008:542-560.

- Kao JS, Fluhr JW, Man M, et al. Short-term glucocorticoid treatment compromises both permeability barrier homeostasis and stratum corneum integrity: inhibition of epidermal lipid synthesis accounts for functional abnormalities. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:456-464.

- American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Contact dermatitis: a practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(3 suppl 2):S1-S38.

To the Editor:

In 1998, 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate (2-CA) tissue adhesive gained US Food and Drug Administration approval for topical application to easily hold closed approximated skin edges from surgical excisions and simple trauma-induced lacerations.1 It has since been employed for a number of off-label indications, including sutureless circumcision,2 skin graft fixation,3 pericatheter leakage,4 and intracorporeal use to control air leaks during lung resection.5 Animal investigations additionally have attempted to elucidate potential future uses of 2-CA for procedures such as inguinal hernia repair,6 bowel anastomosis,7 incisional hernia repair with mesh,8 and microvascular anastomosis.9 Compared to sutures, 2-CA offers ease and rapidity of application, a water-resistant barrier, and equivalent cosmetic results, as well as eliminates the need for suture removal.10 As 2-CA is used with increasing frequency across a variety of settings, there arises a greater need to be mindful of the potential complications of its use, such as irritant contact dermatitis (ICD), allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), and cutaneous id reaction.

A 14-year-old adolescent boy with no notable medical history and no known allergies underwent a minimally invasive Nuss procedure11 (performed by P.L.G.) for the repair of severe pectus excavatum. Two 4-cm incisions were made—one in each lateral chest wall at the approximately eighth intercostal space—to facilitate the introduction of the Nuss bar. The surgical wounds were closed with 2 layers of running polyglactin 910 suture before 2-CA was applied topically to the incision sites. The surgery was well tolerated, and the patient’s wounds healed without incident. When the patient was evaluated for Nuss bar removal 3 years later, incision sites were noted to be well healed, and he exhibited no other skin lesions. The original incision sites (bilateral chest walls) were utilized to facilitate surgical Nuss bar removal. The wounds were closed in 4 layers and 2-CA was again applied topically to the incision sites. There were no intraoperative complications; no devices, drains, or tissue implants were left in the patient at the conclusion of the procedure.

One week later, via text message and digital photographs, the patient reported intense pruritus at the bilateral chest wall incision sites, which were now surrounded by symmetric 1-cm erythematous plaques and associated sparse erythematous satellite papules (Figure 1). The patient denied any fevers, pain, swelling, or purulent discharge from the wounds. He was started on hydrocortisone cream 1% twice daily as well as oral diphenhydramine 25 mg at bedtime with initial good effect.

Three days later, the patient sent digital photographs of a morphologically similar–appearing rash that had progressed beyond the lateral chest walls to include the central chest and bilateral upper and lower extremities (Figure 2). He continued to deny any local or systemic signs of infection. Dermatology was consulted, and a diagnosis of ACD with cutaneous id reaction was made. The patient’s medication regimen was modified to include triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% applied twice daily to the rash away from the wounds, clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% applied twice daily to the rash at the wound sites, oral levocetirizine 5 mg once daily, and oral hydroxyzine 25 to 50 mg every 6 hours as needed for pruritus. Additional recommendations included the use of a fragrance-free soap and application of an over-the-counter anti-itch lotion containing menthol and camphor applied as needed. Within 24 hours of starting this modified treatment regimen, the patient began to notice an improvement in symptoms, with full resolution over the course of the ensuing 2 weeks. The patient was counseled to inform his physicians—present and future—of his allergy to 2-CA.

Contact dermatitis associated with the use of 2-CA has been described in the literature.12-15 We report progression to an id reaction, which is characterized by the diffuse symmetric spread of a cutaneous eruption at a site distant from the primary localized dermatitis that develops within a few days of the primary lesion and exhibits the same morphologic and histopathologic findings.16,17 In our patient, pruritic erythematous papules and plaques symmetrically distributed on the arms, legs, and chest appeared 3 days after he first reported a similar eruption at the 2-CA application sites. It is theorized that id reactions develop when the sensitization phase of a type IV hypersensitivity reaction generates a population of T cells that not only recognizes a hapten but also recognizes keratinocyte-derived epitopes.16 A hapten is a small molecule (<500 Da) that is capable of penetrating the stratum corneum and binding skin components. A contact allergen is a hapten that has bound epidermal proteins to create a new antigenic determinant.18 The secondary dermatitis that characterizes id reactions results from an abnormal autoimmune response. Id reactions associated with exposure to adhesive material are rare.19

Allergic contact dermatitis is a type IV hypersensitivity reaction that appears after initial sensitization to an allergen followed by re-exposure. Our patient presented with symmetric erythematous plaques at the surgical incision sites 1 week after 2-CA had been applied. During this interval, sensitization to the inciting allergen occurred. The allergen is taken up by antigen-presenting cells, which then migrate to lymph nodes where they encounter naïve T lymphocytes that subsequently undergo clonal expansion to produce a cohort of T cells that are capable of recognizing the allergen. If subsequent exposure to the specific allergen takes place, an elicitation phase occurs in which primed T cells are incited to release mediators of inflammation that engender the manifestations of ACD within 24 to 72 hours.18,20 Sensitization may be promoted by skin barrier impairments such as dermatitis or a frank wound.12,20 In most cases, the patient is unaware that sensitization has occurred, though a primary ACD within 5 to 15 days after initial exposure to the inciting allergen rarely may be observed.18 Although our patient had 2-CA applied to his surgical wounds at 14 years of age, it was unlikely that sensitization took place at that time, as it was 1 week rather than 1 to 3 days before he experienced the cutaneous eruption associated with his second 2-CA exposure at 17 years of age.

Cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive also may cause ICD resulting from histotoxic degradation products such as formaldehyde and cyanoacetate that are capable of compromising cutaneous barrier function. Keratinocytes that have had their membranes disturbed release proinflammatory cytokines, which recruit cells of the innate immune system as well as T lymphocytes to the site of insult to facilitate the inflammatory response. The manifestations of ICD include erythema, edema, and local necrosis that can compromise wound healing.20 The speed at which a given cyanoacrylate adhesive degrades is proportional to the length of its carbon side chain. Those with shorter side chains—ethyl and methyl cyanoacrylate—degrade more rapidly into formaldehyde and cyanoacetate; 2-CA possesses a longer side chain and therefore degrades more slowly, which should, in theory, lessen its potential to cause ICD.20 Because it may take 7 to 14 days before 2-CA will spontaneously peel from the application site, however, its potential to evoke ICD nevertheless exists.

Treatment of ICD entails removing the irritant while concurrently working to restore the skin’s barrier with emollients. Although topical corticosteroids often are reflexively prescribed to treat rashes, some believe that their use should be avoided in cases of ICD, as their inhibitory effects on epidermal lipid synthesis may further impair the skin’s barrier.21 For cases of ACD, with or without an accompanying id reaction, topical corticosteroids are the mainstay of therapy. It is customary to start with a higher-potency topical steroid such as clobetasol and taper to lower-potency steroids as the patient’s condition improves. Steroid ointments are petroleum based and are capable of causing 2-CA to separate from the skin.10 As a result, they should be used with care when being applied to an area where 2-CA is maintaining dermal closure. Systemic corticosteroids may be warranted in cases with involvement of more than 20% of the body surface area and should start to provide relief within 12 to 24 hours.22 Oral antihistamines and cold water compresses can be added to help address pruritus and discomfort in both ACD and ICD.

Instances of contact dermatitis caused by 2-CA are rare, and progression to an id reaction is rarer still. Physicians should be aware of the possibility of encountering a patient that manifests one or both of these complications whenever 2-CA is employed for skin closure. Physicians who employ 2-CA for skin closure should first ask patients about prior cutaneous reactions to cyanoacrylates including 2-CA and other commonly encountered acrylate-containing products including adhesive wound dressings, dental cements and prostheses, superglue, artificial nails, and adhesives for wigs and false eyelashes. Still, many patients who exhibit acrylate-induced contact dermatitis, with or without an associated id reaction, will not attest to a history of adverse reactions; they simply may not recognize acrylate as the inciting agent. Practitioners across a range of specialties outside of dermatology—surgeons, emergency physicians, and primary care providers—should be prepared to both recognize contact dermatitis and id reaction arising from the use of 2-CA and implement a basic treatment plan that will bring the patient relief without compromising wound closure.

To the Editor:

In 1998, 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate (2-CA) tissue adhesive gained US Food and Drug Administration approval for topical application to easily hold closed approximated skin edges from surgical excisions and simple trauma-induced lacerations.1 It has since been employed for a number of off-label indications, including sutureless circumcision,2 skin graft fixation,3 pericatheter leakage,4 and intracorporeal use to control air leaks during lung resection.5 Animal investigations additionally have attempted to elucidate potential future uses of 2-CA for procedures such as inguinal hernia repair,6 bowel anastomosis,7 incisional hernia repair with mesh,8 and microvascular anastomosis.9 Compared to sutures, 2-CA offers ease and rapidity of application, a water-resistant barrier, and equivalent cosmetic results, as well as eliminates the need for suture removal.10 As 2-CA is used with increasing frequency across a variety of settings, there arises a greater need to be mindful of the potential complications of its use, such as irritant contact dermatitis (ICD), allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), and cutaneous id reaction.

A 14-year-old adolescent boy with no notable medical history and no known allergies underwent a minimally invasive Nuss procedure11 (performed by P.L.G.) for the repair of severe pectus excavatum. Two 4-cm incisions were made—one in each lateral chest wall at the approximately eighth intercostal space—to facilitate the introduction of the Nuss bar. The surgical wounds were closed with 2 layers of running polyglactin 910 suture before 2-CA was applied topically to the incision sites. The surgery was well tolerated, and the patient’s wounds healed without incident. When the patient was evaluated for Nuss bar removal 3 years later, incision sites were noted to be well healed, and he exhibited no other skin lesions. The original incision sites (bilateral chest walls) were utilized to facilitate surgical Nuss bar removal. The wounds were closed in 4 layers and 2-CA was again applied topically to the incision sites. There were no intraoperative complications; no devices, drains, or tissue implants were left in the patient at the conclusion of the procedure.

One week later, via text message and digital photographs, the patient reported intense pruritus at the bilateral chest wall incision sites, which were now surrounded by symmetric 1-cm erythematous plaques and associated sparse erythematous satellite papules (Figure 1). The patient denied any fevers, pain, swelling, or purulent discharge from the wounds. He was started on hydrocortisone cream 1% twice daily as well as oral diphenhydramine 25 mg at bedtime with initial good effect.

Three days later, the patient sent digital photographs of a morphologically similar–appearing rash that had progressed beyond the lateral chest walls to include the central chest and bilateral upper and lower extremities (Figure 2). He continued to deny any local or systemic signs of infection. Dermatology was consulted, and a diagnosis of ACD with cutaneous id reaction was made. The patient’s medication regimen was modified to include triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% applied twice daily to the rash away from the wounds, clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% applied twice daily to the rash at the wound sites, oral levocetirizine 5 mg once daily, and oral hydroxyzine 25 to 50 mg every 6 hours as needed for pruritus. Additional recommendations included the use of a fragrance-free soap and application of an over-the-counter anti-itch lotion containing menthol and camphor applied as needed. Within 24 hours of starting this modified treatment regimen, the patient began to notice an improvement in symptoms, with full resolution over the course of the ensuing 2 weeks. The patient was counseled to inform his physicians—present and future—of his allergy to 2-CA.

Contact dermatitis associated with the use of 2-CA has been described in the literature.12-15 We report progression to an id reaction, which is characterized by the diffuse symmetric spread of a cutaneous eruption at a site distant from the primary localized dermatitis that develops within a few days of the primary lesion and exhibits the same morphologic and histopathologic findings.16,17 In our patient, pruritic erythematous papules and plaques symmetrically distributed on the arms, legs, and chest appeared 3 days after he first reported a similar eruption at the 2-CA application sites. It is theorized that id reactions develop when the sensitization phase of a type IV hypersensitivity reaction generates a population of T cells that not only recognizes a hapten but also recognizes keratinocyte-derived epitopes.16 A hapten is a small molecule (<500 Da) that is capable of penetrating the stratum corneum and binding skin components. A contact allergen is a hapten that has bound epidermal proteins to create a new antigenic determinant.18 The secondary dermatitis that characterizes id reactions results from an abnormal autoimmune response. Id reactions associated with exposure to adhesive material are rare.19

Allergic contact dermatitis is a type IV hypersensitivity reaction that appears after initial sensitization to an allergen followed by re-exposure. Our patient presented with symmetric erythematous plaques at the surgical incision sites 1 week after 2-CA had been applied. During this interval, sensitization to the inciting allergen occurred. The allergen is taken up by antigen-presenting cells, which then migrate to lymph nodes where they encounter naïve T lymphocytes that subsequently undergo clonal expansion to produce a cohort of T cells that are capable of recognizing the allergen. If subsequent exposure to the specific allergen takes place, an elicitation phase occurs in which primed T cells are incited to release mediators of inflammation that engender the manifestations of ACD within 24 to 72 hours.18,20 Sensitization may be promoted by skin barrier impairments such as dermatitis or a frank wound.12,20 In most cases, the patient is unaware that sensitization has occurred, though a primary ACD within 5 to 15 days after initial exposure to the inciting allergen rarely may be observed.18 Although our patient had 2-CA applied to his surgical wounds at 14 years of age, it was unlikely that sensitization took place at that time, as it was 1 week rather than 1 to 3 days before he experienced the cutaneous eruption associated with his second 2-CA exposure at 17 years of age.

Cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive also may cause ICD resulting from histotoxic degradation products such as formaldehyde and cyanoacetate that are capable of compromising cutaneous barrier function. Keratinocytes that have had their membranes disturbed release proinflammatory cytokines, which recruit cells of the innate immune system as well as T lymphocytes to the site of insult to facilitate the inflammatory response. The manifestations of ICD include erythema, edema, and local necrosis that can compromise wound healing.20 The speed at which a given cyanoacrylate adhesive degrades is proportional to the length of its carbon side chain. Those with shorter side chains—ethyl and methyl cyanoacrylate—degrade more rapidly into formaldehyde and cyanoacetate; 2-CA possesses a longer side chain and therefore degrades more slowly, which should, in theory, lessen its potential to cause ICD.20 Because it may take 7 to 14 days before 2-CA will spontaneously peel from the application site, however, its potential to evoke ICD nevertheless exists.

Treatment of ICD entails removing the irritant while concurrently working to restore the skin’s barrier with emollients. Although topical corticosteroids often are reflexively prescribed to treat rashes, some believe that their use should be avoided in cases of ICD, as their inhibitory effects on epidermal lipid synthesis may further impair the skin’s barrier.21 For cases of ACD, with or without an accompanying id reaction, topical corticosteroids are the mainstay of therapy. It is customary to start with a higher-potency topical steroid such as clobetasol and taper to lower-potency steroids as the patient’s condition improves. Steroid ointments are petroleum based and are capable of causing 2-CA to separate from the skin.10 As a result, they should be used with care when being applied to an area where 2-CA is maintaining dermal closure. Systemic corticosteroids may be warranted in cases with involvement of more than 20% of the body surface area and should start to provide relief within 12 to 24 hours.22 Oral antihistamines and cold water compresses can be added to help address pruritus and discomfort in both ACD and ICD.

Instances of contact dermatitis caused by 2-CA are rare, and progression to an id reaction is rarer still. Physicians should be aware of the possibility of encountering a patient that manifests one or both of these complications whenever 2-CA is employed for skin closure. Physicians who employ 2-CA for skin closure should first ask patients about prior cutaneous reactions to cyanoacrylates including 2-CA and other commonly encountered acrylate-containing products including adhesive wound dressings, dental cements and prostheses, superglue, artificial nails, and adhesives for wigs and false eyelashes. Still, many patients who exhibit acrylate-induced contact dermatitis, with or without an associated id reaction, will not attest to a history of adverse reactions; they simply may not recognize acrylate as the inciting agent. Practitioners across a range of specialties outside of dermatology—surgeons, emergency physicians, and primary care providers—should be prepared to both recognize contact dermatitis and id reaction arising from the use of 2-CA and implement a basic treatment plan that will bring the patient relief without compromising wound closure.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Premarket approval (PMA). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpma/pma.cfm?id=p960052. Accessed March 4, 2020.

- Elmore JM, Smith EA, Kirsch AJ. Sutureless circumcision using 2-octyl cyanoacrylate (Dermabond): appraisal after 18-month experience. Urology. 2007;70:803-806.

- Kilic A, Ozdengil E. Skin graft fixation by applying cyanoacrylate without any complication. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:370-371.

- Gurnaney H, Kraemer FW, Ganesh A. Dermabond decreases pericatheter local anesthetic leakage after continuous perineural infusions. Anesth Analg. 2011;113:206.

- Carr JA. The intracorporeal use of 2-octyl cyanoacrylate resin to control air leaks after lung resection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;39:579-583.

- Miyano G, Yamataka A, Kato Y, et al. Laparoscopic injection of Dermabond tissue adhesive for the repair of inguinal hernia: short- and long-term follow-up. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:1867-1870.

- Paral J, Subrt Z, Lochman P, et al. Suture-free anastomosis of the colon. experimental comparison of two cyanoacrylate adhesives. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:451-459.

- Birch DW, Park A. Octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive as an alternative to mechanical fixation of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene prosthesis. Am Surg. 2001;67:974-978.

- Ang ES, Tan KC, Tan LH, et al. 2-octylcyanoacrylate-assisted microvascular anastomosis: comparison with a conventional suture technique in rat femoral arteries. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2001;17:193-201.

- Bruns TB, Worthington JM. Using tissue adhesive for wound repair: a practical guide to Dermabond. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61:1383-1388.

- Nuss D, Kelly RE Jr, Croitoru DP, et al. A 10-year review of a minimally invasive technique for the correction of pectus excavatum. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:545-552.

- Hivnor CM, Hudkins ML. Allergic contact dermatitis after postsurgical repair with 2-octylcyanoacrylate. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:814-815.

- Howard BK, Downey SE. Contact dermatitis from Dermabond. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:E252-E253.

- Perry AW, Sosin M. Severe allergic reaction to Dermabond. Aesthet Surg J. 2009;29:314-316.

- Sachse MM, Junghans T, Rose C, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by topical 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;68:317-319.

- Fehr BS, Takashima A, Bergstresser PR, et al. T cells reactive to keratinocyte antigens are generated during induction of contact hypersensitivity in mice. a model for autoeczematization in humans? Am J Contact Dermat. 2000;11:145-154.

- Gonzalez-Amaro R, Baranda L, Abud-Mendoza C, et al. Autoeczematization is associated with abnormal immune recognition of autologous skin antigens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:56-60.

- Vocanson M, Hennino A, Rozières A, et al. Effector and regulatory mechanisms in allergic contact dermatitis. Allergy. 2009;64:1699-1714.

- Sommer LL, Hejazi EZ, Heymann WR. An acute linear pruritic eruption following allergic contact dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:42-44.

- Rietschel RL, Fowler JF. Plastics, adhesives, and synthetic resins. In: Rietschek RL, Fowler JF, eds. Fisher’s Contact Dermatitis. Hamilton, BC: Decker Inc; 2008:542-560.

- Kao JS, Fluhr JW, Man M, et al. Short-term glucocorticoid treatment compromises both permeability barrier homeostasis and stratum corneum integrity: inhibition of epidermal lipid synthesis accounts for functional abnormalities. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:456-464.

- American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Contact dermatitis: a practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(3 suppl 2):S1-S38.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Premarket approval (PMA). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpma/pma.cfm?id=p960052. Accessed March 4, 2020.

- Elmore JM, Smith EA, Kirsch AJ. Sutureless circumcision using 2-octyl cyanoacrylate (Dermabond): appraisal after 18-month experience. Urology. 2007;70:803-806.

- Kilic A, Ozdengil E. Skin graft fixation by applying cyanoacrylate without any complication. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:370-371.

- Gurnaney H, Kraemer FW, Ganesh A. Dermabond decreases pericatheter local anesthetic leakage after continuous perineural infusions. Anesth Analg. 2011;113:206.

- Carr JA. The intracorporeal use of 2-octyl cyanoacrylate resin to control air leaks after lung resection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;39:579-583.

- Miyano G, Yamataka A, Kato Y, et al. Laparoscopic injection of Dermabond tissue adhesive for the repair of inguinal hernia: short- and long-term follow-up. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:1867-1870.

- Paral J, Subrt Z, Lochman P, et al. Suture-free anastomosis of the colon. experimental comparison of two cyanoacrylate adhesives. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:451-459.

- Birch DW, Park A. Octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive as an alternative to mechanical fixation of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene prosthesis. Am Surg. 2001;67:974-978.

- Ang ES, Tan KC, Tan LH, et al. 2-octylcyanoacrylate-assisted microvascular anastomosis: comparison with a conventional suture technique in rat femoral arteries. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2001;17:193-201.

- Bruns TB, Worthington JM. Using tissue adhesive for wound repair: a practical guide to Dermabond. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61:1383-1388.

- Nuss D, Kelly RE Jr, Croitoru DP, et al. A 10-year review of a minimally invasive technique for the correction of pectus excavatum. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:545-552.

- Hivnor CM, Hudkins ML. Allergic contact dermatitis after postsurgical repair with 2-octylcyanoacrylate. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:814-815.

- Howard BK, Downey SE. Contact dermatitis from Dermabond. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:E252-E253.

- Perry AW, Sosin M. Severe allergic reaction to Dermabond. Aesthet Surg J. 2009;29:314-316.

- Sachse MM, Junghans T, Rose C, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by topical 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;68:317-319.

- Fehr BS, Takashima A, Bergstresser PR, et al. T cells reactive to keratinocyte antigens are generated during induction of contact hypersensitivity in mice. a model for autoeczematization in humans? Am J Contact Dermat. 2000;11:145-154.

- Gonzalez-Amaro R, Baranda L, Abud-Mendoza C, et al. Autoeczematization is associated with abnormal immune recognition of autologous skin antigens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:56-60.

- Vocanson M, Hennino A, Rozières A, et al. Effector and regulatory mechanisms in allergic contact dermatitis. Allergy. 2009;64:1699-1714.

- Sommer LL, Hejazi EZ, Heymann WR. An acute linear pruritic eruption following allergic contact dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:42-44.

- Rietschel RL, Fowler JF. Plastics, adhesives, and synthetic resins. In: Rietschek RL, Fowler JF, eds. Fisher’s Contact Dermatitis. Hamilton, BC: Decker Inc; 2008:542-560.

- Kao JS, Fluhr JW, Man M, et al. Short-term glucocorticoid treatment compromises both permeability barrier homeostasis and stratum corneum integrity: inhibition of epidermal lipid synthesis accounts for functional abnormalities. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:456-464.

- American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Contact dermatitis: a practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(3 suppl 2):S1-S38.

Practice Points

- 2-Octyl-cyanoacrylate (2-CA) tissue adhesive has been reported to cause contact dermatitis when applied topically for surgical site closure.

- Id reactions resulting from the use of 2-CA tissue adhesive are possible, though less commonly observed.

- Id reactions caused by 2-CA tissue adhesive respond well to treatment with a combination of topical steroids and oral antihistamines. Systemic corticosteroids may be warranted in cases involving greater than 20% body surface area.

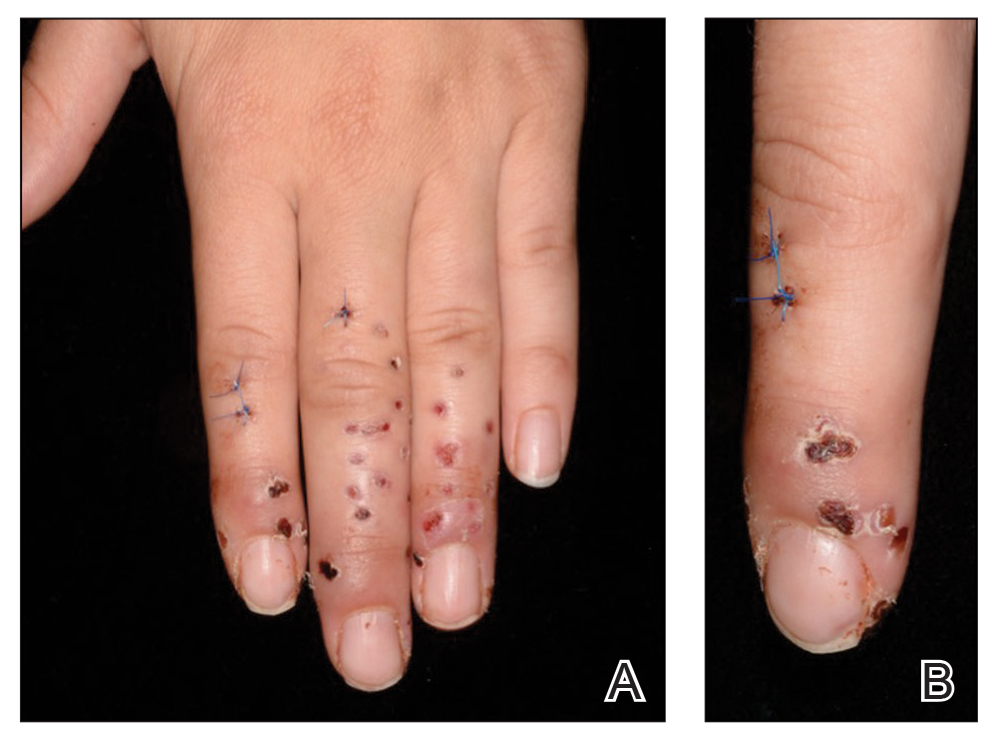

Tense Bullae on the Hands

The Diagnosis: Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) is a rare autoimmune blistering disorder characterized by tense bullae, skin fragility, atrophic scarring, and milia formation.1 Blisters occur on a noninflammatory base in the classic variant and are trauma induced, hence the predilection for the extensor surfaces.2 Mucosal involvement also has been described.1 The characteristic findings in EBA are IgG autoantibodies directed at the N-terminal collagenous domain of type VII collagen, which composes the anchoring fibrils in the basement membrane zone.1 Differentiating EBA from other subepidermal bullous diseases, especially bullous pemphigoid (BP), can be difficult, necessitating specialized tests.

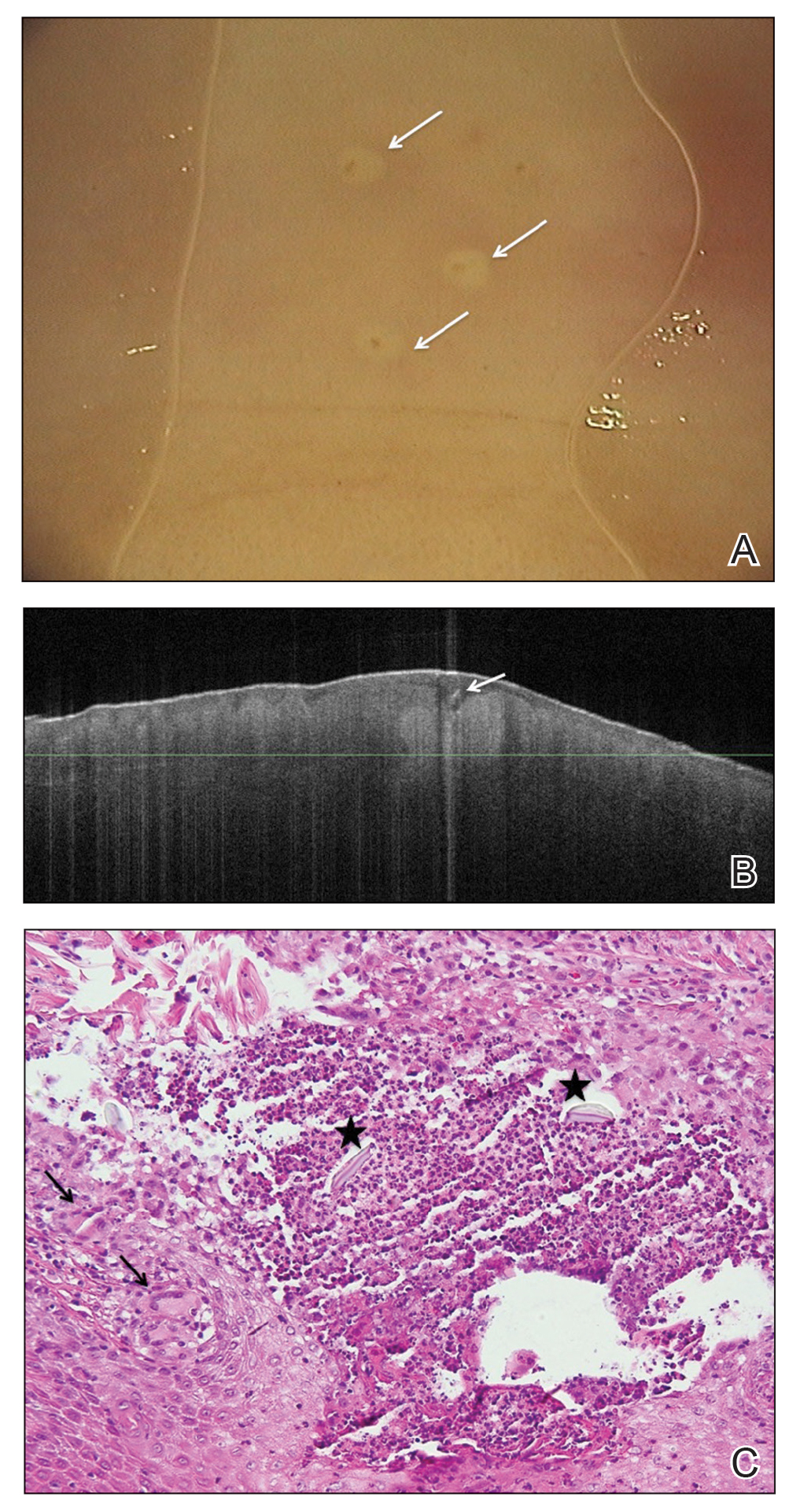

Biopsy of the perilesional skin can help identify the location of the blister formation. Our patient's biopsy showed a subepidermal blister with granulocytes. The differential diagnosis of a subepidermal blister includes BP, herpes gestationis, cicatricial pemphigoid, EBA, bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatitis herpetiformis, linear IgA disease, and porphyria cutanea tarda.

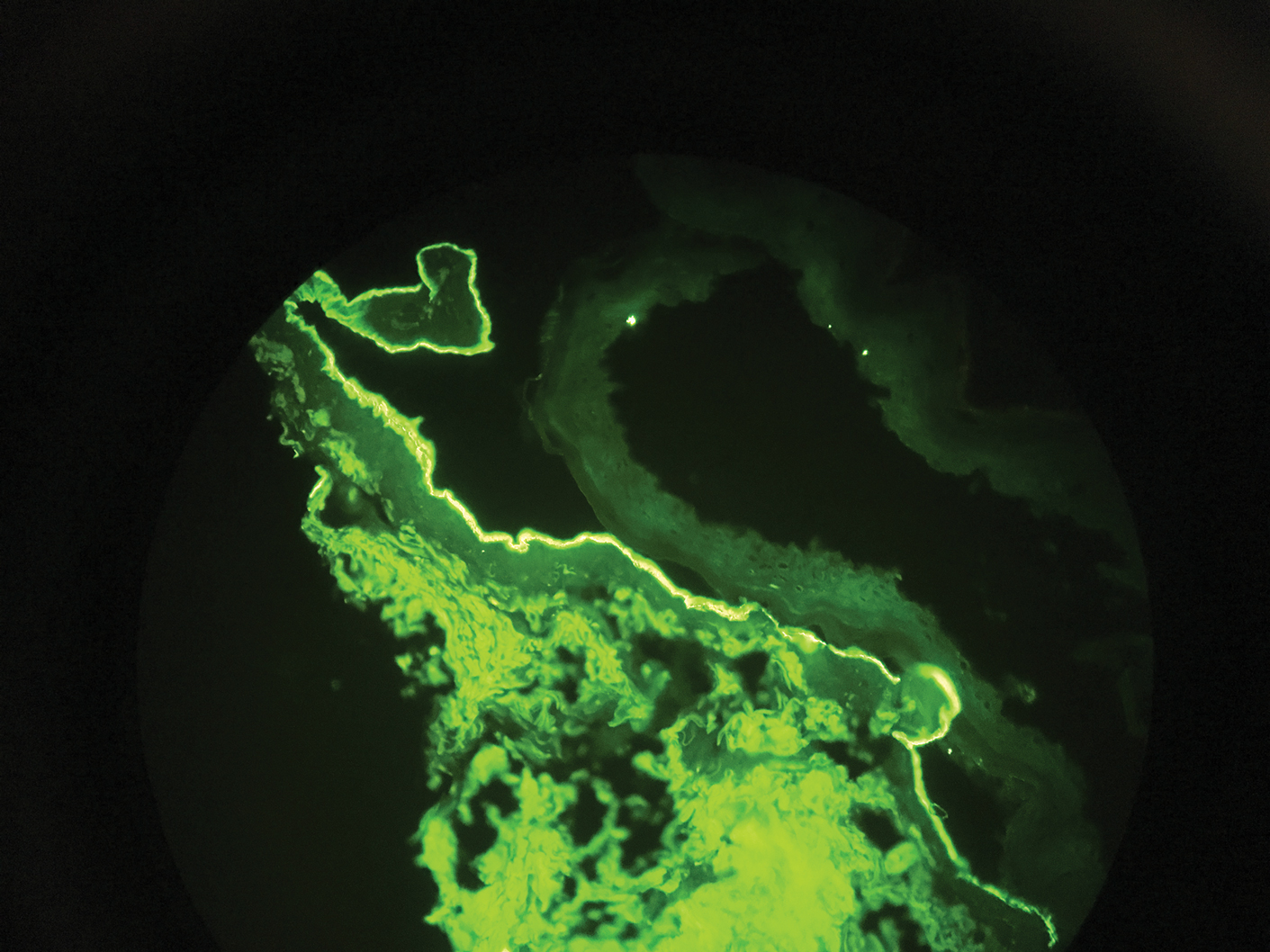

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was performed on the biopsy from our patient, which showed linear/particulate IgG, C3, and IgA deposits in the basement membrane zone, narrowing the differential diagnosis to BP or EBA. To differentiate EBA from BP, DIF of perilesional skin using a salt-split preparation was performed. This test distinguishes the location of the immunoreactants at the basement membrane zone. The antibody complexes in BP are found on the epidermal side of the split, while the antibody complexes in EBA are found on the dermal side of the split. Indirect immunofluorescence on salt-split skin also has been used to distinguish EBA from BP but is only conclusive if there are circulating autoantibodies to the basement membrane zone in the serum, which occurs in approximately 50% of patients with EBA and 15% of patients with BP.3 The immune complexes in our patient were found to be on the dermal side of the split after DIF on salt-split skin, confirming the diagnosis of EBA (Figure).

Differentiating EBA from BP has great value, as the diagnosis affects treatment options. Bullous pemphigoid is fairly easy to treat, with most patients responding to prednisone.3 Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita usually is resistant to therapy. The disease course is chronic with exacerbations and remissions. Dapsone often is used to control the disease, though this therapy for EBA is not currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. The recommended initial dose of dapsone is 50 mg daily and should be increased by 50 mg each week until remission, usually 100 to 250 mg.4 We prescribed dapsone for our patient upon clinical suspicion of EBA before the DIF on salt-split skin was completed. A trial of prednisone may be warranted for EBA if there is no response to dapsone or colchicine, but the response is unpredictable. Cyclosporine usually results in a quick response and may be considered if there is clinically severe disease and other treatment alternatives have failed.4

- Ishii N, Hamada T, Dainichi T, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: what's new. J Dermatol. 2010;37:220-230.

- Lehman JS, Camilleri MJ, Gibsom LE. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: concise review and practical considerations. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:227-236.

- Woodley D. Immunofluorescence on the salt-split skin for the diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:229-231.

- Mutasim DF. Bullous diseases. In: Kellerman RD, Rakel DP, eds. Conn's Current Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:978-982.

The Diagnosis: Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) is a rare autoimmune blistering disorder characterized by tense bullae, skin fragility, atrophic scarring, and milia formation.1 Blisters occur on a noninflammatory base in the classic variant and are trauma induced, hence the predilection for the extensor surfaces.2 Mucosal involvement also has been described.1 The characteristic findings in EBA are IgG autoantibodies directed at the N-terminal collagenous domain of type VII collagen, which composes the anchoring fibrils in the basement membrane zone.1 Differentiating EBA from other subepidermal bullous diseases, especially bullous pemphigoid (BP), can be difficult, necessitating specialized tests.

Biopsy of the perilesional skin can help identify the location of the blister formation. Our patient's biopsy showed a subepidermal blister with granulocytes. The differential diagnosis of a subepidermal blister includes BP, herpes gestationis, cicatricial pemphigoid, EBA, bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatitis herpetiformis, linear IgA disease, and porphyria cutanea tarda.

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was performed on the biopsy from our patient, which showed linear/particulate IgG, C3, and IgA deposits in the basement membrane zone, narrowing the differential diagnosis to BP or EBA. To differentiate EBA from BP, DIF of perilesional skin using a salt-split preparation was performed. This test distinguishes the location of the immunoreactants at the basement membrane zone. The antibody complexes in BP are found on the epidermal side of the split, while the antibody complexes in EBA are found on the dermal side of the split. Indirect immunofluorescence on salt-split skin also has been used to distinguish EBA from BP but is only conclusive if there are circulating autoantibodies to the basement membrane zone in the serum, which occurs in approximately 50% of patients with EBA and 15% of patients with BP.3 The immune complexes in our patient were found to be on the dermal side of the split after DIF on salt-split skin, confirming the diagnosis of EBA (Figure).

Differentiating EBA from BP has great value, as the diagnosis affects treatment options. Bullous pemphigoid is fairly easy to treat, with most patients responding to prednisone.3 Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita usually is resistant to therapy. The disease course is chronic with exacerbations and remissions. Dapsone often is used to control the disease, though this therapy for EBA is not currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. The recommended initial dose of dapsone is 50 mg daily and should be increased by 50 mg each week until remission, usually 100 to 250 mg.4 We prescribed dapsone for our patient upon clinical suspicion of EBA before the DIF on salt-split skin was completed. A trial of prednisone may be warranted for EBA if there is no response to dapsone or colchicine, but the response is unpredictable. Cyclosporine usually results in a quick response and may be considered if there is clinically severe disease and other treatment alternatives have failed.4

The Diagnosis: Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) is a rare autoimmune blistering disorder characterized by tense bullae, skin fragility, atrophic scarring, and milia formation.1 Blisters occur on a noninflammatory base in the classic variant and are trauma induced, hence the predilection for the extensor surfaces.2 Mucosal involvement also has been described.1 The characteristic findings in EBA are IgG autoantibodies directed at the N-terminal collagenous domain of type VII collagen, which composes the anchoring fibrils in the basement membrane zone.1 Differentiating EBA from other subepidermal bullous diseases, especially bullous pemphigoid (BP), can be difficult, necessitating specialized tests.

Biopsy of the perilesional skin can help identify the location of the blister formation. Our patient's biopsy showed a subepidermal blister with granulocytes. The differential diagnosis of a subepidermal blister includes BP, herpes gestationis, cicatricial pemphigoid, EBA, bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatitis herpetiformis, linear IgA disease, and porphyria cutanea tarda.

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was performed on the biopsy from our patient, which showed linear/particulate IgG, C3, and IgA deposits in the basement membrane zone, narrowing the differential diagnosis to BP or EBA. To differentiate EBA from BP, DIF of perilesional skin using a salt-split preparation was performed. This test distinguishes the location of the immunoreactants at the basement membrane zone. The antibody complexes in BP are found on the epidermal side of the split, while the antibody complexes in EBA are found on the dermal side of the split. Indirect immunofluorescence on salt-split skin also has been used to distinguish EBA from BP but is only conclusive if there are circulating autoantibodies to the basement membrane zone in the serum, which occurs in approximately 50% of patients with EBA and 15% of patients with BP.3 The immune complexes in our patient were found to be on the dermal side of the split after DIF on salt-split skin, confirming the diagnosis of EBA (Figure).

Differentiating EBA from BP has great value, as the diagnosis affects treatment options. Bullous pemphigoid is fairly easy to treat, with most patients responding to prednisone.3 Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita usually is resistant to therapy. The disease course is chronic with exacerbations and remissions. Dapsone often is used to control the disease, though this therapy for EBA is not currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. The recommended initial dose of dapsone is 50 mg daily and should be increased by 50 mg each week until remission, usually 100 to 250 mg.4 We prescribed dapsone for our patient upon clinical suspicion of EBA before the DIF on salt-split skin was completed. A trial of prednisone may be warranted for EBA if there is no response to dapsone or colchicine, but the response is unpredictable. Cyclosporine usually results in a quick response and may be considered if there is clinically severe disease and other treatment alternatives have failed.4

- Ishii N, Hamada T, Dainichi T, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: what's new. J Dermatol. 2010;37:220-230.

- Lehman JS, Camilleri MJ, Gibsom LE. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: concise review and practical considerations. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:227-236.

- Woodley D. Immunofluorescence on the salt-split skin for the diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:229-231.

- Mutasim DF. Bullous diseases. In: Kellerman RD, Rakel DP, eds. Conn's Current Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:978-982.

- Ishii N, Hamada T, Dainichi T, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: what's new. J Dermatol. 2010;37:220-230.

- Lehman JS, Camilleri MJ, Gibsom LE. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: concise review and practical considerations. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:227-236.

- Woodley D. Immunofluorescence on the salt-split skin for the diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:229-231.

- Mutasim DF. Bullous diseases. In: Kellerman RD, Rakel DP, eds. Conn's Current Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:978-982.

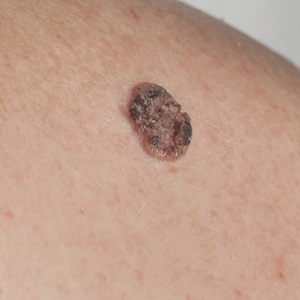

A 75-year-old man presented to our clinic with nonpainful, nonpruritic, tense bullae and erosions on the dorsal aspects of the hands and extensor surfaces of the elbows of 1 month's duration. The patient also had erythematous erosions and crusted papules on the left cheek and surrounding the left eye. He denied any new medications, history of liver or kidney disease, or history of hepatitis or human immunodeficiency virus. There were no obvious exacerbating factors, including exposure to sunlight. Direct immunofluorescence using a salt-split preparation was performed on a biopsy of the perilesional skin.

Rapid Development of Perifolliculitis Following Mesotherapy

To the Editor:

Mesotherapy, also known as intradermotherapy, is a cosmetic procedure in which multiple intradermal or subcutaneous injections of homeopathic substances, vitamins, chemicals, and plant extracts are administered.1 First conceived in Europe, mesotherapy is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration but is gaining popularity in the United States as an alternative cosmetic procedure for various purposes, including lipolysis, body contouring, stretch marks, acne scars, actinic damage, and skin rejuvenation.1,2 We report a case of a healthy woman who developed perifolliculitis, transaminitis, and neutropenia 2 weeks after mesotherapy administration to the face, neck, and chest. We also review other potential side effects of this procedure.

A 36-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the emergency department with a worsening pruritic and painful rash on the face, chest, and neck of 2 weeks’ duration. The rash had developed 3 days after the patient received mesotherapy with an unknown substance for cosmetic rejuvenation; the rash was localized only to the injection sites. She did not note any fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, arthralgia, or upper respiratory tract symptoms. She further denied starting any new medications, herbal products, or topical therapies apart from the procedure she had received 2 weeks prior.

The patient was found to be in no acute distress and vital signs were stable. Laboratory testing was remarkable for elevations in alanine aminotransferase (62 U/L [reference range, 10–40 U/L]) and aspartate aminotransferase (72 U/L [reference range 10–30 U/L]). Moreover, she had an absolute neutrophil count of 0.5×103 cells/µL (reference range 1.8–8.0×103 cells/µL). An electrolyte panel, creatinine level, and urinalysis were normal. Physical examination revealed numerous 4- to 5-mm erythematous papules in a gridlike distribution across the face, neck, and chest (Figure 1). No pustules or nodules were present. There was no discharge, crust, excoriations, or secondary lesions. Additionally, there was no lymphadenopathy and no mucous membrane or ocular involvement.

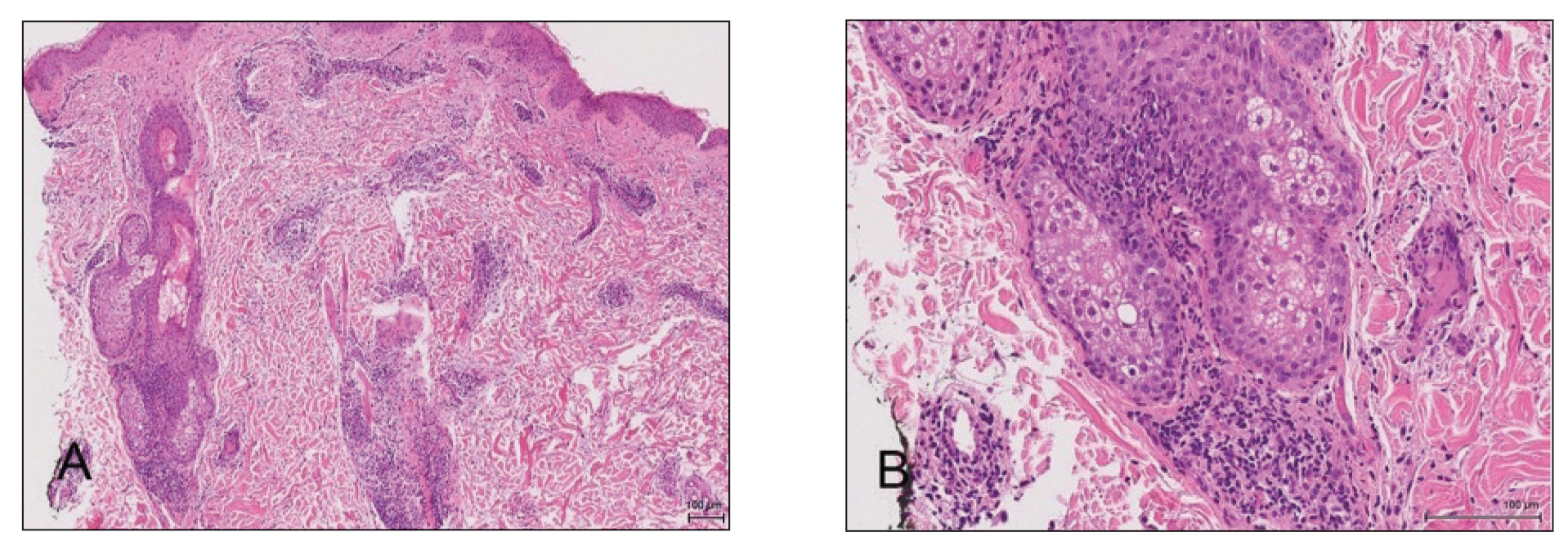

A 4-mm punch biopsy from a representative papule on the right lateral aspect of the neck demonstrated a perifollicular and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with some focal granulomatous changes. No polarizable foreign body material was found (Figure 2). Bacterial, fungal, mycobacterial, and skin cultures were obtained, and results were all negative after several weeks.

A diagnosis of perifolliculitis from the mesotherapy procedure was on the top of the differential vs a fast-growing mycobacterial or granulomatous reaction. The patient was started on a prednisone taper at 40 mg once daily tapered down completely over 3 weeks in addition to triamcinolone cream 0.1% applied 2 to 4 times daily as needed. Although she did not return to our outpatient clinic for follow-up, she informed us that her rash had improved 1 month after starting the prednisone taper. She was later lost to follow-up. It is unclear if the transaminitis and neutropenia were related to the materials injected during the mesotherapy procedure or from long-standing health issues.

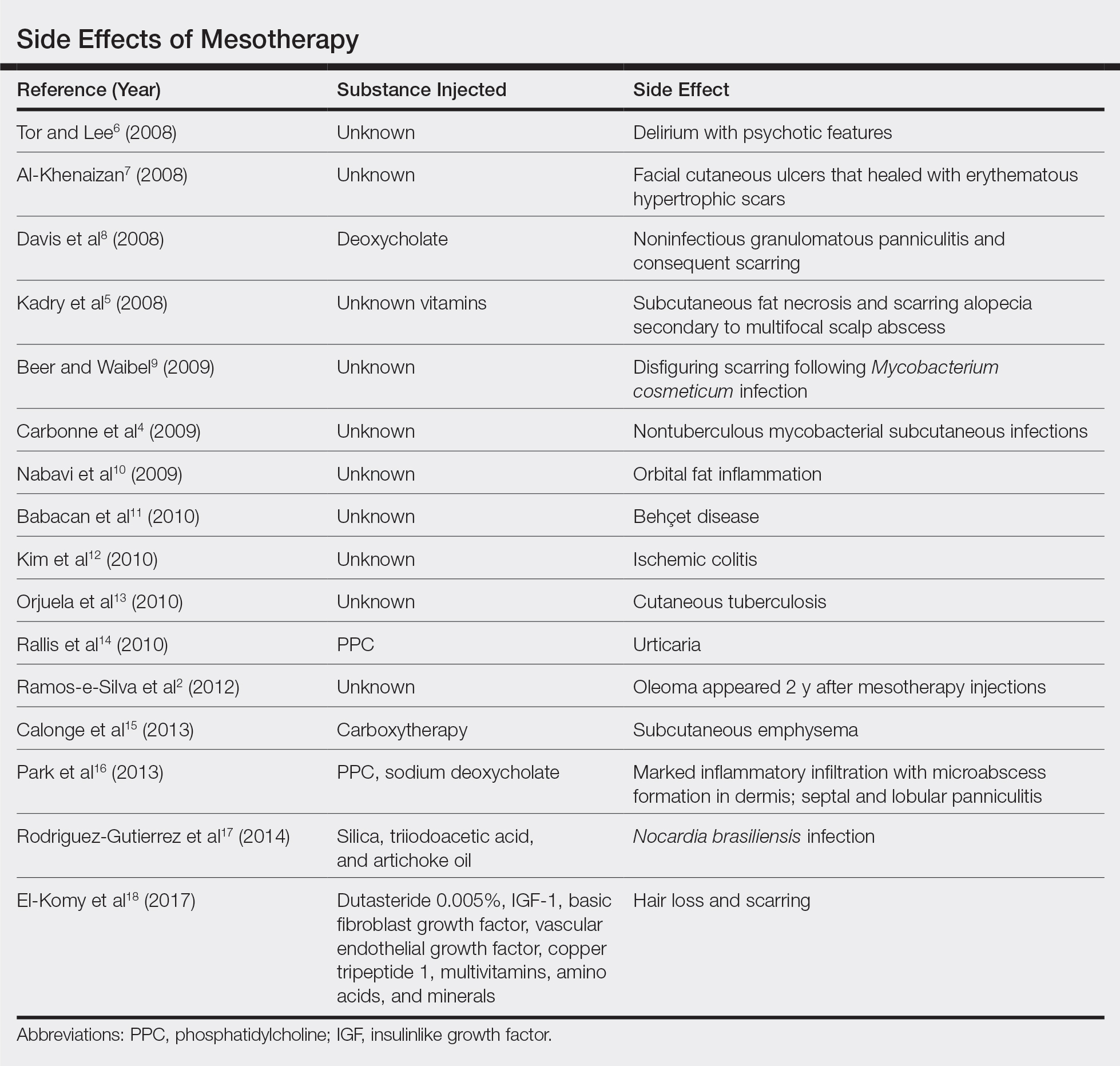

Mesotherapy promises aesthetic benefits through a minimally invasive procedure and therefore is rapidly gaining popularity in aesthetic spas and treatment centers. Due to the lack of regulation in treatment protocols and substances used, there have been numerous reported cases of adverse side effects following mesotherapy, such as pain, allergic reactions, urticaria, panniculitis, ulceration, hair loss, necrosis, paraffinoma, cutaneous tuberculosis, and rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacterial infections.1-5 More serious side effects also have been reported, such as permanent scarring, deformities, delirium, and massive subcutaneous emphysema (Table).2,4-18

Given the potential complications of mesotherapy documented in the literature, we believe clinical investigations and trials must be performed to appropriately assess the safety and efficacy of this potentially hazardous procedure. Because there currently is insufficient research showing why certain patients are developing these adverse side effects, aesthetic spas and treatment centers should inform patients of all potential side effects associated with mesotherapy for the patient to make an informed decision about the procedure. Mesotherapy should be a point of focus for both the US Food and Drug Administration and researchers to determine its efficacy, safety, and standardization of the procedure.

- Bishara AS, Ibrahim AE, Dibo SA. Cosmetic mesotherapy: between scientific evidence, science fiction, and lucrative business. Aesth Plast Surg. 2008;32:842-849.

- Ramos-e-Silva M, Pereira AL, Ramos-e-Silva S, et al. Oleoma: a rare complication of mesotherapy for cellulite. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:162-167.

- Rotunda AM, Kolodney MS. Mesotherapy and phosphatidylcholine injections: historical clarification and review. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:465-480.

- Carbonne A, Brossier F, Arnaud I, et al. Outbreak of nontuberculous mycobacterial subcutaneous infections related to multiple mesotherapy injections. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1961-1964.

- Kadry R, Hamadah I, Al-Issa A, et al. Multifocal scalp abscess with subcutaneous fat necrosis and scarring alopecia as a complication of scalp mesotherapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:72-73.

- Tor PC, Lee TS. Delirium with psychotic features possibly associated with mesotherapy. Psychosomatics. 2008;49:273-274.

- Al-Khenaizan S. Facial cutaneous ulcers following mesotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:832-834.

- Davis MD, Wright TI, Shehan JM. A complication of mesotherapy: noninfectious granulomatous panniculitis. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:808-809.

- Beer K, Waibel J. Disfiguring scarring following mesotherapy-associated Mycobacterium cosmeticum infection. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:391-393.

- Nabavi CB, Minckler DS, Tao JP. Histologic features of mesotherapy-induced orbital fat inflammation. Opthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;25:69-70.

- Babacan T, Onat AM, Pehlivan Y, et al. A case of Behçet’s disease diagnosed by the panniculitis after mesotherapy. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1657-1659.

- Kim JB, Moon W, Park SJ, et al. Ischemic colitis after mesotherapy combined with anti-obesity medications. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1537-1540.

- Orjuela D, Puerto G, Mejia G, et al. Cutaneous tuberculosis after mesotherapy: report of six cases. Biomedica. 2010;30:321-326.

- Rallis E, Kintzoglou S, Moussatou V, et al. Mesotherapy-induced urticaria. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1355-1356.

- Calonge WM, Lesbros-Pantoflickova D, Hodina M, et al. Massive subcutaneous emphysema after carbon dioxide mesotherapy. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;37:194-197.

- Park EJ, Kim HS, Kim M, et al. Histological changes after treatment for localized fat deposits with phosphatidylcholine and sodium deoxycholate. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;3:240-243.

- Rodriguez-Gutierrez G, Toussaint S, Hernandez-Castro R, et al. Norcardia brasiliensis infection: an emergent suppurative granuloma after mesotherapy. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:888-890.

- El-Komy M, Hassan A, Tawdy A, et al. Hair loss at injection sites of mesotherapy for alopecia [published online February 3, 2017]. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:E28-E30.

To the Editor:

Mesotherapy, also known as intradermotherapy, is a cosmetic procedure in which multiple intradermal or subcutaneous injections of homeopathic substances, vitamins, chemicals, and plant extracts are administered.1 First conceived in Europe, mesotherapy is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration but is gaining popularity in the United States as an alternative cosmetic procedure for various purposes, including lipolysis, body contouring, stretch marks, acne scars, actinic damage, and skin rejuvenation.1,2 We report a case of a healthy woman who developed perifolliculitis, transaminitis, and neutropenia 2 weeks after mesotherapy administration to the face, neck, and chest. We also review other potential side effects of this procedure.

A 36-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the emergency department with a worsening pruritic and painful rash on the face, chest, and neck of 2 weeks’ duration. The rash had developed 3 days after the patient received mesotherapy with an unknown substance for cosmetic rejuvenation; the rash was localized only to the injection sites. She did not note any fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, arthralgia, or upper respiratory tract symptoms. She further denied starting any new medications, herbal products, or topical therapies apart from the procedure she had received 2 weeks prior.

The patient was found to be in no acute distress and vital signs were stable. Laboratory testing was remarkable for elevations in alanine aminotransferase (62 U/L [reference range, 10–40 U/L]) and aspartate aminotransferase (72 U/L [reference range 10–30 U/L]). Moreover, she had an absolute neutrophil count of 0.5×103 cells/µL (reference range 1.8–8.0×103 cells/µL). An electrolyte panel, creatinine level, and urinalysis were normal. Physical examination revealed numerous 4- to 5-mm erythematous papules in a gridlike distribution across the face, neck, and chest (Figure 1). No pustules or nodules were present. There was no discharge, crust, excoriations, or secondary lesions. Additionally, there was no lymphadenopathy and no mucous membrane or ocular involvement.

A 4-mm punch biopsy from a representative papule on the right lateral aspect of the neck demonstrated a perifollicular and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with some focal granulomatous changes. No polarizable foreign body material was found (Figure 2). Bacterial, fungal, mycobacterial, and skin cultures were obtained, and results were all negative after several weeks.

A diagnosis of perifolliculitis from the mesotherapy procedure was on the top of the differential vs a fast-growing mycobacterial or granulomatous reaction. The patient was started on a prednisone taper at 40 mg once daily tapered down completely over 3 weeks in addition to triamcinolone cream 0.1% applied 2 to 4 times daily as needed. Although she did not return to our outpatient clinic for follow-up, she informed us that her rash had improved 1 month after starting the prednisone taper. She was later lost to follow-up. It is unclear if the transaminitis and neutropenia were related to the materials injected during the mesotherapy procedure or from long-standing health issues.

Mesotherapy promises aesthetic benefits through a minimally invasive procedure and therefore is rapidly gaining popularity in aesthetic spas and treatment centers. Due to the lack of regulation in treatment protocols and substances used, there have been numerous reported cases of adverse side effects following mesotherapy, such as pain, allergic reactions, urticaria, panniculitis, ulceration, hair loss, necrosis, paraffinoma, cutaneous tuberculosis, and rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacterial infections.1-5 More serious side effects also have been reported, such as permanent scarring, deformities, delirium, and massive subcutaneous emphysema (Table).2,4-18

Given the potential complications of mesotherapy documented in the literature, we believe clinical investigations and trials must be performed to appropriately assess the safety and efficacy of this potentially hazardous procedure. Because there currently is insufficient research showing why certain patients are developing these adverse side effects, aesthetic spas and treatment centers should inform patients of all potential side effects associated with mesotherapy for the patient to make an informed decision about the procedure. Mesotherapy should be a point of focus for both the US Food and Drug Administration and researchers to determine its efficacy, safety, and standardization of the procedure.

To the Editor:

Mesotherapy, also known as intradermotherapy, is a cosmetic procedure in which multiple intradermal or subcutaneous injections of homeopathic substances, vitamins, chemicals, and plant extracts are administered.1 First conceived in Europe, mesotherapy is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration but is gaining popularity in the United States as an alternative cosmetic procedure for various purposes, including lipolysis, body contouring, stretch marks, acne scars, actinic damage, and skin rejuvenation.1,2 We report a case of a healthy woman who developed perifolliculitis, transaminitis, and neutropenia 2 weeks after mesotherapy administration to the face, neck, and chest. We also review other potential side effects of this procedure.

A 36-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the emergency department with a worsening pruritic and painful rash on the face, chest, and neck of 2 weeks’ duration. The rash had developed 3 days after the patient received mesotherapy with an unknown substance for cosmetic rejuvenation; the rash was localized only to the injection sites. She did not note any fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, arthralgia, or upper respiratory tract symptoms. She further denied starting any new medications, herbal products, or topical therapies apart from the procedure she had received 2 weeks prior.

The patient was found to be in no acute distress and vital signs were stable. Laboratory testing was remarkable for elevations in alanine aminotransferase (62 U/L [reference range, 10–40 U/L]) and aspartate aminotransferase (72 U/L [reference range 10–30 U/L]). Moreover, she had an absolute neutrophil count of 0.5×103 cells/µL (reference range 1.8–8.0×103 cells/µL). An electrolyte panel, creatinine level, and urinalysis were normal. Physical examination revealed numerous 4- to 5-mm erythematous papules in a gridlike distribution across the face, neck, and chest (Figure 1). No pustules or nodules were present. There was no discharge, crust, excoriations, or secondary lesions. Additionally, there was no lymphadenopathy and no mucous membrane or ocular involvement.

A 4-mm punch biopsy from a representative papule on the right lateral aspect of the neck demonstrated a perifollicular and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with some focal granulomatous changes. No polarizable foreign body material was found (Figure 2). Bacterial, fungal, mycobacterial, and skin cultures were obtained, and results were all negative after several weeks.

A diagnosis of perifolliculitis from the mesotherapy procedure was on the top of the differential vs a fast-growing mycobacterial or granulomatous reaction. The patient was started on a prednisone taper at 40 mg once daily tapered down completely over 3 weeks in addition to triamcinolone cream 0.1% applied 2 to 4 times daily as needed. Although she did not return to our outpatient clinic for follow-up, she informed us that her rash had improved 1 month after starting the prednisone taper. She was later lost to follow-up. It is unclear if the transaminitis and neutropenia were related to the materials injected during the mesotherapy procedure or from long-standing health issues.

Mesotherapy promises aesthetic benefits through a minimally invasive procedure and therefore is rapidly gaining popularity in aesthetic spas and treatment centers. Due to the lack of regulation in treatment protocols and substances used, there have been numerous reported cases of adverse side effects following mesotherapy, such as pain, allergic reactions, urticaria, panniculitis, ulceration, hair loss, necrosis, paraffinoma, cutaneous tuberculosis, and rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacterial infections.1-5 More serious side effects also have been reported, such as permanent scarring, deformities, delirium, and massive subcutaneous emphysema (Table).2,4-18

Given the potential complications of mesotherapy documented in the literature, we believe clinical investigations and trials must be performed to appropriately assess the safety and efficacy of this potentially hazardous procedure. Because there currently is insufficient research showing why certain patients are developing these adverse side effects, aesthetic spas and treatment centers should inform patients of all potential side effects associated with mesotherapy for the patient to make an informed decision about the procedure. Mesotherapy should be a point of focus for both the US Food and Drug Administration and researchers to determine its efficacy, safety, and standardization of the procedure.

- Bishara AS, Ibrahim AE, Dibo SA. Cosmetic mesotherapy: between scientific evidence, science fiction, and lucrative business. Aesth Plast Surg. 2008;32:842-849.

- Ramos-e-Silva M, Pereira AL, Ramos-e-Silva S, et al. Oleoma: a rare complication of mesotherapy for cellulite. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:162-167.

- Rotunda AM, Kolodney MS. Mesotherapy and phosphatidylcholine injections: historical clarification and review. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:465-480.

- Carbonne A, Brossier F, Arnaud I, et al. Outbreak of nontuberculous mycobacterial subcutaneous infections related to multiple mesotherapy injections. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1961-1964.

- Kadry R, Hamadah I, Al-Issa A, et al. Multifocal scalp abscess with subcutaneous fat necrosis and scarring alopecia as a complication of scalp mesotherapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:72-73.

- Tor PC, Lee TS. Delirium with psychotic features possibly associated with mesotherapy. Psychosomatics. 2008;49:273-274.

- Al-Khenaizan S. Facial cutaneous ulcers following mesotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:832-834.

- Davis MD, Wright TI, Shehan JM. A complication of mesotherapy: noninfectious granulomatous panniculitis. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:808-809.

- Beer K, Waibel J. Disfiguring scarring following mesotherapy-associated Mycobacterium cosmeticum infection. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:391-393.

- Nabavi CB, Minckler DS, Tao JP. Histologic features of mesotherapy-induced orbital fat inflammation. Opthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;25:69-70.

- Babacan T, Onat AM, Pehlivan Y, et al. A case of Behçet’s disease diagnosed by the panniculitis after mesotherapy. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1657-1659.

- Kim JB, Moon W, Park SJ, et al. Ischemic colitis after mesotherapy combined with anti-obesity medications. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1537-1540.

- Orjuela D, Puerto G, Mejia G, et al. Cutaneous tuberculosis after mesotherapy: report of six cases. Biomedica. 2010;30:321-326.

- Rallis E, Kintzoglou S, Moussatou V, et al. Mesotherapy-induced urticaria. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1355-1356.

- Calonge WM, Lesbros-Pantoflickova D, Hodina M, et al. Massive subcutaneous emphysema after carbon dioxide mesotherapy. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;37:194-197.

- Park EJ, Kim HS, Kim M, et al. Histological changes after treatment for localized fat deposits with phosphatidylcholine and sodium deoxycholate. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;3:240-243.

- Rodriguez-Gutierrez G, Toussaint S, Hernandez-Castro R, et al. Norcardia brasiliensis infection: an emergent suppurative granuloma after mesotherapy. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:888-890.

- El-Komy M, Hassan A, Tawdy A, et al. Hair loss at injection sites of mesotherapy for alopecia [published online February 3, 2017]. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:E28-E30.

- Bishara AS, Ibrahim AE, Dibo SA. Cosmetic mesotherapy: between scientific evidence, science fiction, and lucrative business. Aesth Plast Surg. 2008;32:842-849.

- Ramos-e-Silva M, Pereira AL, Ramos-e-Silva S, et al. Oleoma: a rare complication of mesotherapy for cellulite. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:162-167.

- Rotunda AM, Kolodney MS. Mesotherapy and phosphatidylcholine injections: historical clarification and review. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:465-480.

- Carbonne A, Brossier F, Arnaud I, et al. Outbreak of nontuberculous mycobacterial subcutaneous infections related to multiple mesotherapy injections. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1961-1964.

- Kadry R, Hamadah I, Al-Issa A, et al. Multifocal scalp abscess with subcutaneous fat necrosis and scarring alopecia as a complication of scalp mesotherapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:72-73.

- Tor PC, Lee TS. Delirium with psychotic features possibly associated with mesotherapy. Psychosomatics. 2008;49:273-274.

- Al-Khenaizan S. Facial cutaneous ulcers following mesotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:832-834.

- Davis MD, Wright TI, Shehan JM. A complication of mesotherapy: noninfectious granulomatous panniculitis. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:808-809.

- Beer K, Waibel J. Disfiguring scarring following mesotherapy-associated Mycobacterium cosmeticum infection. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:391-393.

- Nabavi CB, Minckler DS, Tao JP. Histologic features of mesotherapy-induced orbital fat inflammation. Opthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;25:69-70.

- Babacan T, Onat AM, Pehlivan Y, et al. A case of Behçet’s disease diagnosed by the panniculitis after mesotherapy. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1657-1659.

- Kim JB, Moon W, Park SJ, et al. Ischemic colitis after mesotherapy combined with anti-obesity medications. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1537-1540.

- Orjuela D, Puerto G, Mejia G, et al. Cutaneous tuberculosis after mesotherapy: report of six cases. Biomedica. 2010;30:321-326.

- Rallis E, Kintzoglou S, Moussatou V, et al. Mesotherapy-induced urticaria. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1355-1356.

- Calonge WM, Lesbros-Pantoflickova D, Hodina M, et al. Massive subcutaneous emphysema after carbon dioxide mesotherapy. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;37:194-197.

- Park EJ, Kim HS, Kim M, et al. Histological changes after treatment for localized fat deposits with phosphatidylcholine and sodium deoxycholate. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;3:240-243.

- Rodriguez-Gutierrez G, Toussaint S, Hernandez-Castro R, et al. Norcardia brasiliensis infection: an emergent suppurative granuloma after mesotherapy. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:888-890.

- El-Komy M, Hassan A, Tawdy A, et al. Hair loss at injection sites of mesotherapy for alopecia [published online February 3, 2017]. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:E28-E30.

Practice Points

- Mesotherapy—the delivery of vitamins, chemicals, and plant extracts directly into the dermis via injections—is a common procedure performed in both medical and nonmedical settings for cosmetic rejuvenation.

- Complications can occur from mesotherapy treatment.

- Patients should be advised to seek medical care with US Food and Drug Administration–approved cosmetic techniques and substances only

Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection in a Hepatitis B Virus–Positive Psoriasis Patient Treated With Ustekinumab

To the Editor:

The incidence of psoriasis in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected patients is similar to the general population, but it usually becomes more severe as immunosuppression increases. Additionally, it tends to be more resistant to conventional therapies, and the incidence and severity of psoriatic arthropathy is increased. Psoriasis often worsens at the time of HIV primary infection.1 We describe a case of a patient with hepatitis B virus (HBV) whose severe plaque psoriasis was controlled on ustekinumab; he was later diagnosed with HIV infection.

A 42-year-old man with HBV treated with entecavir (HBV DNA viral load, <20 copies/mL [inactive carrier, <2000 copies/mL]) presented to our dermatology unit with severe plaque psoriasis (psoriasis area and severity index 23) that caused notable psychologic difficulties such as anxiety and depression. Treatment was attempted with cyclosporine; acitretin; psoralen plus UVA; infliximab; adalimumab; and eventually ustekinumab (45 mg every 3 months), which controlled the condition well (psoriasis area and severity index 0) in an almost completely sustained manner.