User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Virtual Dermatology: A COVID-19 Update

The growing threat of novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), now commonly known as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has forced Americans to stay home due to quarantine, especially older individuals and those who are immunocompromised or have an underlying health problem such as pulmonary or cardiac disease. The federal government’s estimated $2 trillion CARES Act (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act)1 will provide a much-needed boost to health care and the economy; prior recent legislation approved an $8.6 billion emergency relief bill,2 HR 6074 (Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2020), which expands Medicare coverage of telehealth to patients in their home rather than having them travel to a designated site, covers both established and new patients, allows physicians to waive or reduce co-payments and cost-sharing requirements, and reimburses the same as an in-person visit.

Federal emergency legislation temporarily relaxed the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA),3,4 allowing physicians to use Facetime and Skype for Medicare patients. In addition, Medicare will reimburse telehealth services for out-of-state-providers; however, cross-state licensure is governed by the patient’s home state.5 As of March 25, 2020, emergency legislation to temporarily allow out-of-state physicians to provide care, whether or not it relates to COVID-19, was enacted in 13 states: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, and North Dakota.6 Ongoing legislation is rapidly changing; for daily updates on licensing laws, refer to the Federation of State Medical Boards website. Check your own institutional policies and malpractice provider prior to offering telehealth, as local laws and regulations may vary. Herein, we offer suggestions for using teledermatology.

Reimbursement

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 16 states—Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, Hawaii, Kentucky, Maine, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, Tennessee, Utah, and Virginia—had true payment parity laws,7 which reimbursed telehealth as a regular office visit using modifier -95. Several states have enacted emergency telehealth expansion laws to discourage COVID-19 spread8; some states such as New Jersey now prohibit co-payments or out-of-pocket deductibles from all in-network insurance plans (commercial Medicare and Medicaid).9,10 Updated legislation about COVID-19 and telemedicine can be found on the Center for Connected Health Policy website. An interactive map of laws and reimbursement policies also is available on the websites of the American Telehealth Association and the American Academy of Dermatology. The ability to charge a patient directly for telehealth services depends on the insurance provider agreement. If telehealth is a covered service, you cannot charge these patients out-of-pocket.

Teledermatology Options

For many conditions, the effectiveness and quality of teledermatology is comparable to a conventional face-to-face visit.11 There are 3 types of telehealth visits:

• Store and forward: The clinician reviews images or videos and responds asynchronously,12 similar to an email chain.

• Live interactive: The clinician uses 2-way video synchronously.12 In states with parity laws, this method is reimbursed equally to an in-person visit.

• Remote patient monitoring: Health-related data are collected and transmitted to a remote clinician, similar to remote intensive care unit management.12 Dermatologists are unlikely to utilize this modality.

The Virtual Visit

Follow these guidelines for practicing teledermatology: (1) ensure that the image or video is clear and that there is proper lighting, a monochromatic background, and a clear view of the anatomy necessary to evaluate; (2) dress in appropriate attire as if you were in clinic, such as scrubs, a white coat, or other professional attire; (3) begin the telehealth encounter by obtaining informed consent,13 according to state14 or Medicare guidelines; (4) document the location of the patient and provider; (5) for live virtual visits, document similarly to an in-person visit5; (6) for all other virtual care, document minutes spent on each task; and (7) select only 1 billing code per visit.

In some states, regulations for commercial and/or Medicaid plans require that other modifiers be added to billing codes, which vary plan-by-plan:

• Modifier GQ: For asynchronous care (store and forward).

• Modifier GT: For synchronous live telehealth visits.

• Modifier -95: In states where there are equal parity laws or if you are billing a commercial insurance payer (may vary by plan).

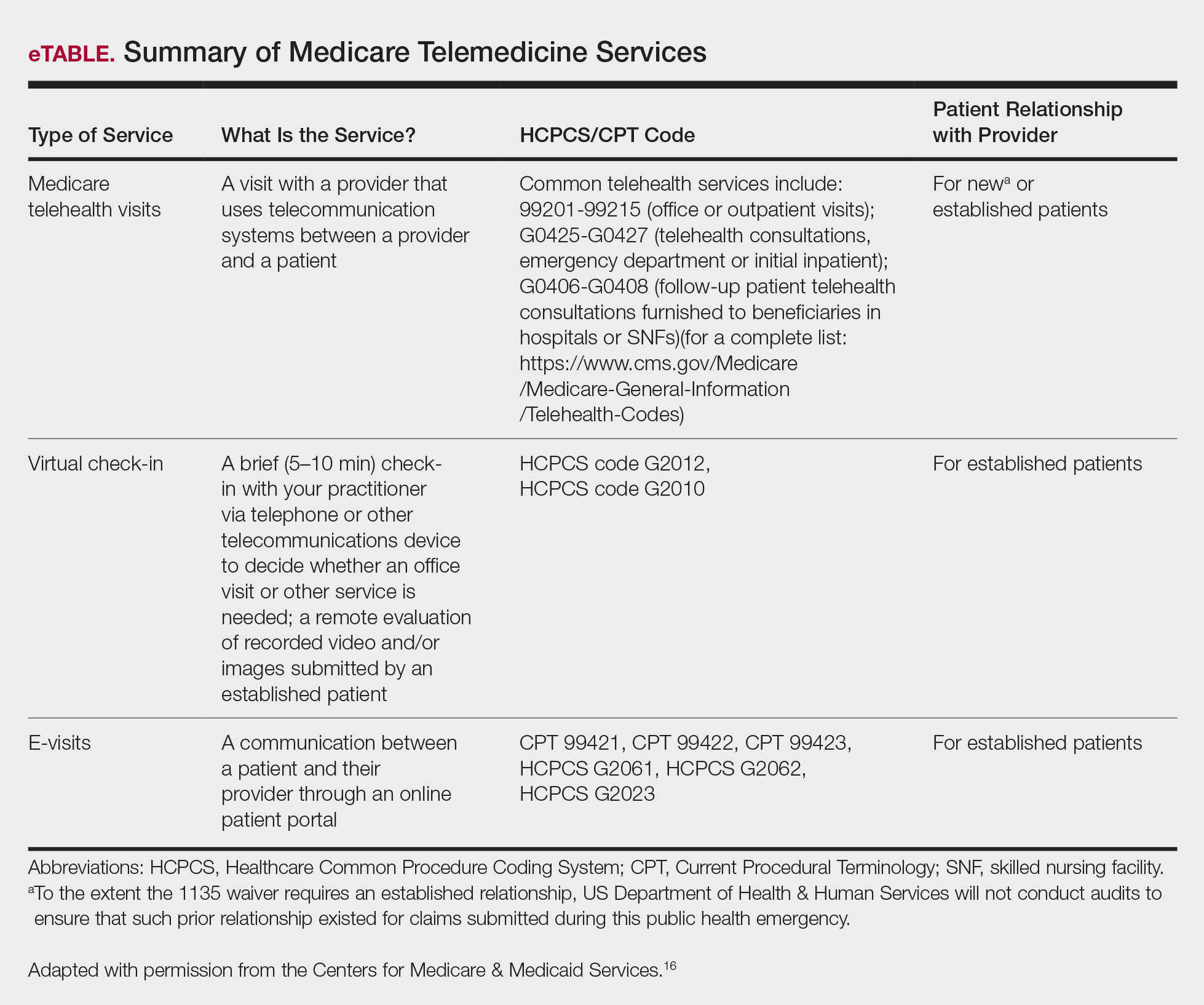

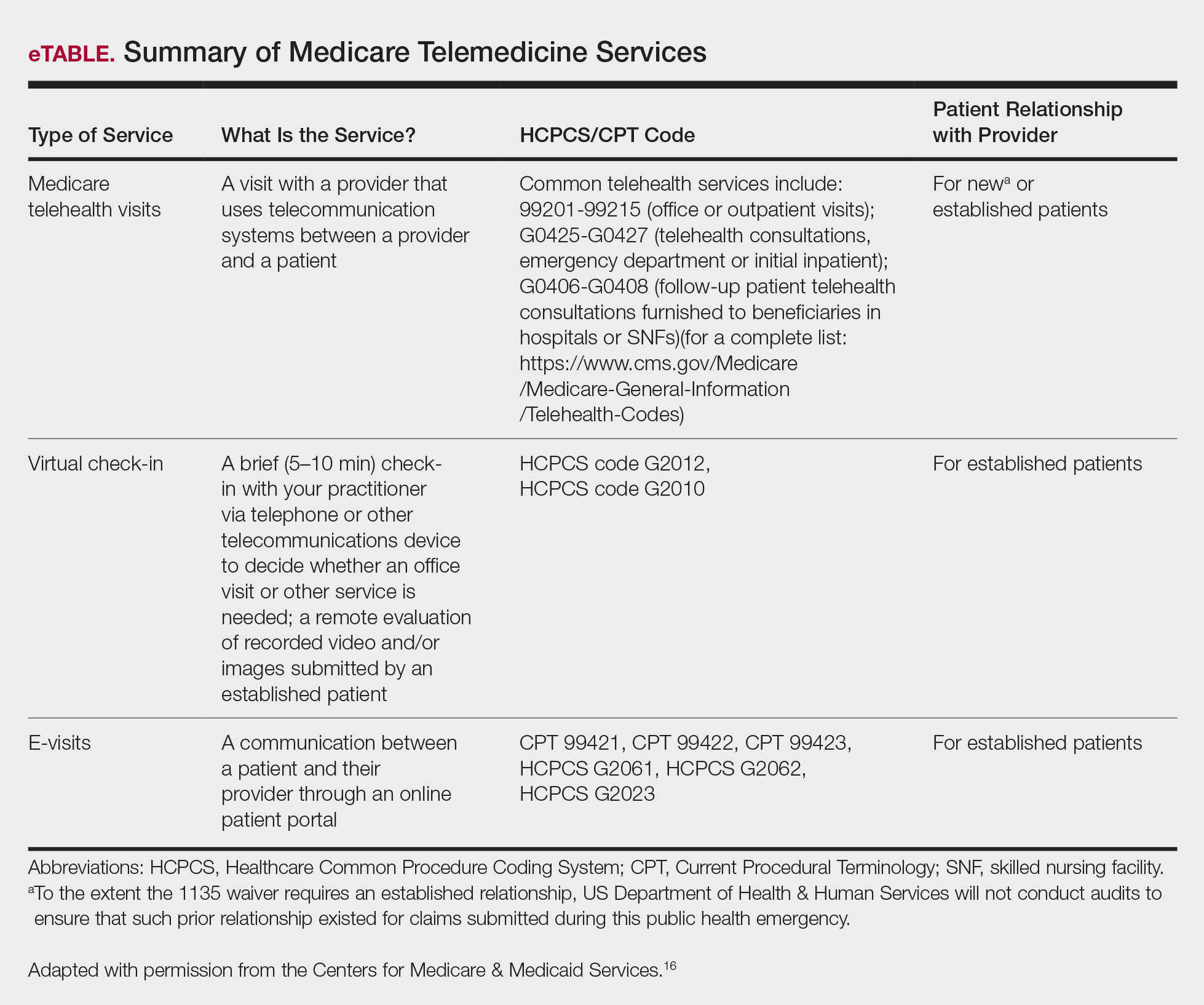

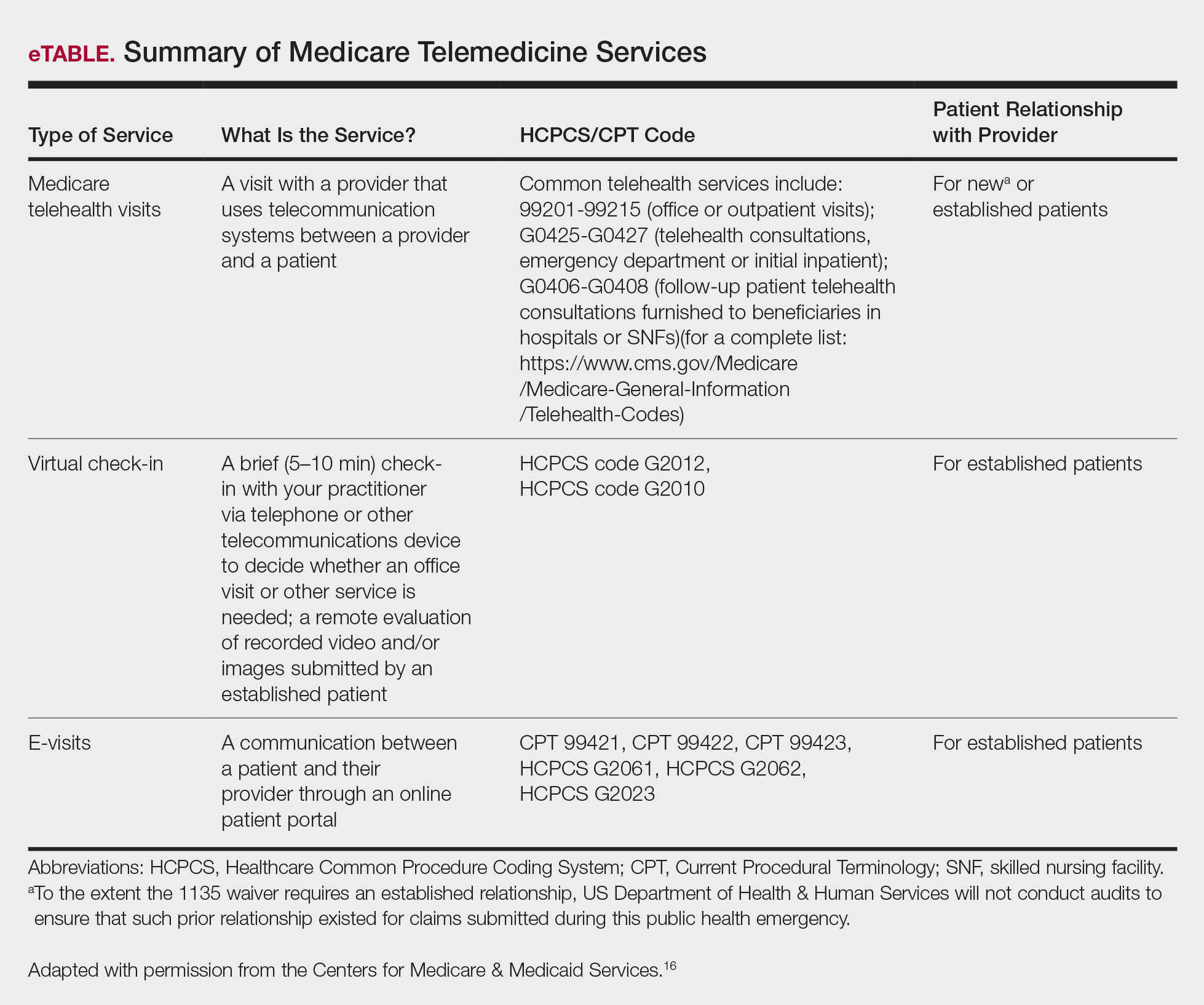

Medicare does not require any additional modifiers.15 If the plan reimburses telemedicine equally to a face-to-face visit, use regular office visit codes. The eTable16 lists billing codes and Medicare reimbursement rates.

Secure Software

Several electronic medical record systems already include secure patient communication. Other HIPAA-compliant communication options with a variety of features are available to clinicians:

• Klara allows for HIPAA-secure texting, group messaging, photograph uploads, and telephone calls.

• Doximity offers free calling and faxes.

• G Suite for health care offers HIPAA-compliant texting, emailing, and video calls through Google Voice and Google Hangouts Meet.

• Secure video chat is available on Zoom for Healthcare, VSee, Doxy.me, and other platforms.

• Multiservice platforms such as DermEngine include billing, payments, teledermatology, and teledermoscopy and allow for interprofessional consultation.

The Bottom Line

Telehealth readiness is playing a key role in containing the spread of COVID-19. In-person dermatology visits are now being limited to urgent conditions only, as per institutional guidelines.4

Acknowledgment

We thank Garfunkel Wild, P.C. (Great Neck, New York), for their expertise and assistance.

- Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, 2020. HR 748, 116th Cong, 2nd Sess (2020). https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/116/hr748. Accessed March 26, 2020.

- Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020. HR 6074, 116th Cong, 2nd Sess (2020). https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/116/hr6074/text. Accessed March 22, 2020.

- Azar AM II. Waiver or Modification of Requirements Under Section 1135 of the Social Security Act. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. https://www.phe.gov/emergency/news/healthactions

/section1135/Pages/covid19-13March20.aspx. Accessed March 25, 2020. - American Academy of Dermatology Association. Can dermatologists use telemedicine to mitigate COVID-19 outbreaks? https://www.aad.org/member/practice/telederm/toolkit. Updated March 28, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020.

- American Medical Association. AMA quick guide to telemedicine in practice. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/digital/ama-quick-guide-telemedicine-practice?utm_source=twitter&utm_medium=social_ama

&utm_term=3207044834&utm_campaign=Public+Health. Updated March 26, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020. - Federation of State Medical Boards. States waiving licensure requirements in response to COVID-19. http://www.fsmb.org/sitassets/advocacy/pdf/state-emergency-declarations-licensures-requimentscovid-19.pdf. Updated March 30, 2020. Accessed March 30, 2020.

- American Telemedicine Association. 2019 State of the States: coverage & reimbursement. https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/5096139/Files/Thought Leadership_ATA/2019 State of the States summary_final.pdf. Published July 18, 2019. Accessed March 30, 2020.

- COVID-19 related state actions. Center for Connected Health Policy website. https://www.cchpca.org/resources/covid-19-related-state-actions. Updated March 27, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020.

- Governor Murphy announces departmental actions to expand access to telehealth and tele-mental health services in response to COVID-19 [news release]. Trenton, NJ: State of New Jersey; March 22, 2020. https://www.nj.gov/governor/news/news/562020/20200322b.shtml. Accessed March 26, 2020.

- Caride M. Use of telemedicine and telehealth to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. State of New Jersey website. https://www.state.nj.us/dobi/bulletins/blt20_07.pdf. Published March 22, 2020. Accessed March 30, 2020.

- Lee JJ, English JC 3rd. Teledermatology: a review and update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:253-260.

- Tongdee E, Siegel DM, Markowitz O. New diagnostic procedure codes and reimbursement. Cutis. 2019;103:208-211.

- Telemedicine forms. American Telemedicine Association Web site. http://hub.americantelemed.org/thesource/resources/telemedicine-forms. Accessed March 22, 2020.

- State telemedicine laws, simplified. eVisit Web site. https://evisit.com/state-telemedicine-policy/. Accessed March 22, 2020.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Fee-for-Service (FFS) Response to the Public Health Emergency on the Coronavirus (COVID-19). March 20, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/se20011.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2020.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare telemedicine health care provider fact sheet. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet. Published March 17, 2020. Accessed March 20, 2020.

The growing threat of novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), now commonly known as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has forced Americans to stay home due to quarantine, especially older individuals and those who are immunocompromised or have an underlying health problem such as pulmonary or cardiac disease. The federal government’s estimated $2 trillion CARES Act (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act)1 will provide a much-needed boost to health care and the economy; prior recent legislation approved an $8.6 billion emergency relief bill,2 HR 6074 (Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2020), which expands Medicare coverage of telehealth to patients in their home rather than having them travel to a designated site, covers both established and new patients, allows physicians to waive or reduce co-payments and cost-sharing requirements, and reimburses the same as an in-person visit.

Federal emergency legislation temporarily relaxed the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA),3,4 allowing physicians to use Facetime and Skype for Medicare patients. In addition, Medicare will reimburse telehealth services for out-of-state-providers; however, cross-state licensure is governed by the patient’s home state.5 As of March 25, 2020, emergency legislation to temporarily allow out-of-state physicians to provide care, whether or not it relates to COVID-19, was enacted in 13 states: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, and North Dakota.6 Ongoing legislation is rapidly changing; for daily updates on licensing laws, refer to the Federation of State Medical Boards website. Check your own institutional policies and malpractice provider prior to offering telehealth, as local laws and regulations may vary. Herein, we offer suggestions for using teledermatology.

Reimbursement

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 16 states—Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, Hawaii, Kentucky, Maine, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, Tennessee, Utah, and Virginia—had true payment parity laws,7 which reimbursed telehealth as a regular office visit using modifier -95. Several states have enacted emergency telehealth expansion laws to discourage COVID-19 spread8; some states such as New Jersey now prohibit co-payments or out-of-pocket deductibles from all in-network insurance plans (commercial Medicare and Medicaid).9,10 Updated legislation about COVID-19 and telemedicine can be found on the Center for Connected Health Policy website. An interactive map of laws and reimbursement policies also is available on the websites of the American Telehealth Association and the American Academy of Dermatology. The ability to charge a patient directly for telehealth services depends on the insurance provider agreement. If telehealth is a covered service, you cannot charge these patients out-of-pocket.

Teledermatology Options

For many conditions, the effectiveness and quality of teledermatology is comparable to a conventional face-to-face visit.11 There are 3 types of telehealth visits:

• Store and forward: The clinician reviews images or videos and responds asynchronously,12 similar to an email chain.

• Live interactive: The clinician uses 2-way video synchronously.12 In states with parity laws, this method is reimbursed equally to an in-person visit.

• Remote patient monitoring: Health-related data are collected and transmitted to a remote clinician, similar to remote intensive care unit management.12 Dermatologists are unlikely to utilize this modality.

The Virtual Visit

Follow these guidelines for practicing teledermatology: (1) ensure that the image or video is clear and that there is proper lighting, a monochromatic background, and a clear view of the anatomy necessary to evaluate; (2) dress in appropriate attire as if you were in clinic, such as scrubs, a white coat, or other professional attire; (3) begin the telehealth encounter by obtaining informed consent,13 according to state14 or Medicare guidelines; (4) document the location of the patient and provider; (5) for live virtual visits, document similarly to an in-person visit5; (6) for all other virtual care, document minutes spent on each task; and (7) select only 1 billing code per visit.

In some states, regulations for commercial and/or Medicaid plans require that other modifiers be added to billing codes, which vary plan-by-plan:

• Modifier GQ: For asynchronous care (store and forward).

• Modifier GT: For synchronous live telehealth visits.

• Modifier -95: In states where there are equal parity laws or if you are billing a commercial insurance payer (may vary by plan).

Medicare does not require any additional modifiers.15 If the plan reimburses telemedicine equally to a face-to-face visit, use regular office visit codes. The eTable16 lists billing codes and Medicare reimbursement rates.

Secure Software

Several electronic medical record systems already include secure patient communication. Other HIPAA-compliant communication options with a variety of features are available to clinicians:

• Klara allows for HIPAA-secure texting, group messaging, photograph uploads, and telephone calls.

• Doximity offers free calling and faxes.

• G Suite for health care offers HIPAA-compliant texting, emailing, and video calls through Google Voice and Google Hangouts Meet.

• Secure video chat is available on Zoom for Healthcare, VSee, Doxy.me, and other platforms.

• Multiservice platforms such as DermEngine include billing, payments, teledermatology, and teledermoscopy and allow for interprofessional consultation.

The Bottom Line

Telehealth readiness is playing a key role in containing the spread of COVID-19. In-person dermatology visits are now being limited to urgent conditions only, as per institutional guidelines.4

Acknowledgment

We thank Garfunkel Wild, P.C. (Great Neck, New York), for their expertise and assistance.

The growing threat of novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), now commonly known as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has forced Americans to stay home due to quarantine, especially older individuals and those who are immunocompromised or have an underlying health problem such as pulmonary or cardiac disease. The federal government’s estimated $2 trillion CARES Act (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act)1 will provide a much-needed boost to health care and the economy; prior recent legislation approved an $8.6 billion emergency relief bill,2 HR 6074 (Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2020), which expands Medicare coverage of telehealth to patients in their home rather than having them travel to a designated site, covers both established and new patients, allows physicians to waive or reduce co-payments and cost-sharing requirements, and reimburses the same as an in-person visit.

Federal emergency legislation temporarily relaxed the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA),3,4 allowing physicians to use Facetime and Skype for Medicare patients. In addition, Medicare will reimburse telehealth services for out-of-state-providers; however, cross-state licensure is governed by the patient’s home state.5 As of March 25, 2020, emergency legislation to temporarily allow out-of-state physicians to provide care, whether or not it relates to COVID-19, was enacted in 13 states: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, and North Dakota.6 Ongoing legislation is rapidly changing; for daily updates on licensing laws, refer to the Federation of State Medical Boards website. Check your own institutional policies and malpractice provider prior to offering telehealth, as local laws and regulations may vary. Herein, we offer suggestions for using teledermatology.

Reimbursement

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 16 states—Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, Hawaii, Kentucky, Maine, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, Tennessee, Utah, and Virginia—had true payment parity laws,7 which reimbursed telehealth as a regular office visit using modifier -95. Several states have enacted emergency telehealth expansion laws to discourage COVID-19 spread8; some states such as New Jersey now prohibit co-payments or out-of-pocket deductibles from all in-network insurance plans (commercial Medicare and Medicaid).9,10 Updated legislation about COVID-19 and telemedicine can be found on the Center for Connected Health Policy website. An interactive map of laws and reimbursement policies also is available on the websites of the American Telehealth Association and the American Academy of Dermatology. The ability to charge a patient directly for telehealth services depends on the insurance provider agreement. If telehealth is a covered service, you cannot charge these patients out-of-pocket.

Teledermatology Options

For many conditions, the effectiveness and quality of teledermatology is comparable to a conventional face-to-face visit.11 There are 3 types of telehealth visits:

• Store and forward: The clinician reviews images or videos and responds asynchronously,12 similar to an email chain.

• Live interactive: The clinician uses 2-way video synchronously.12 In states with parity laws, this method is reimbursed equally to an in-person visit.

• Remote patient monitoring: Health-related data are collected and transmitted to a remote clinician, similar to remote intensive care unit management.12 Dermatologists are unlikely to utilize this modality.

The Virtual Visit

Follow these guidelines for practicing teledermatology: (1) ensure that the image or video is clear and that there is proper lighting, a monochromatic background, and a clear view of the anatomy necessary to evaluate; (2) dress in appropriate attire as if you were in clinic, such as scrubs, a white coat, or other professional attire; (3) begin the telehealth encounter by obtaining informed consent,13 according to state14 or Medicare guidelines; (4) document the location of the patient and provider; (5) for live virtual visits, document similarly to an in-person visit5; (6) for all other virtual care, document minutes spent on each task; and (7) select only 1 billing code per visit.

In some states, regulations for commercial and/or Medicaid plans require that other modifiers be added to billing codes, which vary plan-by-plan:

• Modifier GQ: For asynchronous care (store and forward).

• Modifier GT: For synchronous live telehealth visits.

• Modifier -95: In states where there are equal parity laws or if you are billing a commercial insurance payer (may vary by plan).

Medicare does not require any additional modifiers.15 If the plan reimburses telemedicine equally to a face-to-face visit, use regular office visit codes. The eTable16 lists billing codes and Medicare reimbursement rates.

Secure Software

Several electronic medical record systems already include secure patient communication. Other HIPAA-compliant communication options with a variety of features are available to clinicians:

• Klara allows for HIPAA-secure texting, group messaging, photograph uploads, and telephone calls.

• Doximity offers free calling and faxes.

• G Suite for health care offers HIPAA-compliant texting, emailing, and video calls through Google Voice and Google Hangouts Meet.

• Secure video chat is available on Zoom for Healthcare, VSee, Doxy.me, and other platforms.

• Multiservice platforms such as DermEngine include billing, payments, teledermatology, and teledermoscopy and allow for interprofessional consultation.

The Bottom Line

Telehealth readiness is playing a key role in containing the spread of COVID-19. In-person dermatology visits are now being limited to urgent conditions only, as per institutional guidelines.4

Acknowledgment

We thank Garfunkel Wild, P.C. (Great Neck, New York), for their expertise and assistance.

- Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, 2020. HR 748, 116th Cong, 2nd Sess (2020). https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/116/hr748. Accessed March 26, 2020.

- Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020. HR 6074, 116th Cong, 2nd Sess (2020). https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/116/hr6074/text. Accessed March 22, 2020.

- Azar AM II. Waiver or Modification of Requirements Under Section 1135 of the Social Security Act. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. https://www.phe.gov/emergency/news/healthactions

/section1135/Pages/covid19-13March20.aspx. Accessed March 25, 2020. - American Academy of Dermatology Association. Can dermatologists use telemedicine to mitigate COVID-19 outbreaks? https://www.aad.org/member/practice/telederm/toolkit. Updated March 28, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020.

- American Medical Association. AMA quick guide to telemedicine in practice. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/digital/ama-quick-guide-telemedicine-practice?utm_source=twitter&utm_medium=social_ama

&utm_term=3207044834&utm_campaign=Public+Health. Updated March 26, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020. - Federation of State Medical Boards. States waiving licensure requirements in response to COVID-19. http://www.fsmb.org/sitassets/advocacy/pdf/state-emergency-declarations-licensures-requimentscovid-19.pdf. Updated March 30, 2020. Accessed March 30, 2020.

- American Telemedicine Association. 2019 State of the States: coverage & reimbursement. https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/5096139/Files/Thought Leadership_ATA/2019 State of the States summary_final.pdf. Published July 18, 2019. Accessed March 30, 2020.

- COVID-19 related state actions. Center for Connected Health Policy website. https://www.cchpca.org/resources/covid-19-related-state-actions. Updated March 27, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020.

- Governor Murphy announces departmental actions to expand access to telehealth and tele-mental health services in response to COVID-19 [news release]. Trenton, NJ: State of New Jersey; March 22, 2020. https://www.nj.gov/governor/news/news/562020/20200322b.shtml. Accessed March 26, 2020.

- Caride M. Use of telemedicine and telehealth to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. State of New Jersey website. https://www.state.nj.us/dobi/bulletins/blt20_07.pdf. Published March 22, 2020. Accessed March 30, 2020.

- Lee JJ, English JC 3rd. Teledermatology: a review and update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:253-260.

- Tongdee E, Siegel DM, Markowitz O. New diagnostic procedure codes and reimbursement. Cutis. 2019;103:208-211.

- Telemedicine forms. American Telemedicine Association Web site. http://hub.americantelemed.org/thesource/resources/telemedicine-forms. Accessed March 22, 2020.

- State telemedicine laws, simplified. eVisit Web site. https://evisit.com/state-telemedicine-policy/. Accessed March 22, 2020.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Fee-for-Service (FFS) Response to the Public Health Emergency on the Coronavirus (COVID-19). March 20, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/se20011.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2020.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare telemedicine health care provider fact sheet. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet. Published March 17, 2020. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, 2020. HR 748, 116th Cong, 2nd Sess (2020). https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/116/hr748. Accessed March 26, 2020.

- Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020. HR 6074, 116th Cong, 2nd Sess (2020). https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/116/hr6074/text. Accessed March 22, 2020.

- Azar AM II. Waiver or Modification of Requirements Under Section 1135 of the Social Security Act. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. https://www.phe.gov/emergency/news/healthactions

/section1135/Pages/covid19-13March20.aspx. Accessed March 25, 2020. - American Academy of Dermatology Association. Can dermatologists use telemedicine to mitigate COVID-19 outbreaks? https://www.aad.org/member/practice/telederm/toolkit. Updated March 28, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020.

- American Medical Association. AMA quick guide to telemedicine in practice. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/digital/ama-quick-guide-telemedicine-practice?utm_source=twitter&utm_medium=social_ama

&utm_term=3207044834&utm_campaign=Public+Health. Updated March 26, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020. - Federation of State Medical Boards. States waiving licensure requirements in response to COVID-19. http://www.fsmb.org/sitassets/advocacy/pdf/state-emergency-declarations-licensures-requimentscovid-19.pdf. Updated March 30, 2020. Accessed March 30, 2020.

- American Telemedicine Association. 2019 State of the States: coverage & reimbursement. https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/5096139/Files/Thought Leadership_ATA/2019 State of the States summary_final.pdf. Published July 18, 2019. Accessed March 30, 2020.

- COVID-19 related state actions. Center for Connected Health Policy website. https://www.cchpca.org/resources/covid-19-related-state-actions. Updated March 27, 2020. Accessed March 26, 2020.

- Governor Murphy announces departmental actions to expand access to telehealth and tele-mental health services in response to COVID-19 [news release]. Trenton, NJ: State of New Jersey; March 22, 2020. https://www.nj.gov/governor/news/news/562020/20200322b.shtml. Accessed March 26, 2020.

- Caride M. Use of telemedicine and telehealth to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. State of New Jersey website. https://www.state.nj.us/dobi/bulletins/blt20_07.pdf. Published March 22, 2020. Accessed March 30, 2020.

- Lee JJ, English JC 3rd. Teledermatology: a review and update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:253-260.

- Tongdee E, Siegel DM, Markowitz O. New diagnostic procedure codes and reimbursement. Cutis. 2019;103:208-211.

- Telemedicine forms. American Telemedicine Association Web site. http://hub.americantelemed.org/thesource/resources/telemedicine-forms. Accessed March 22, 2020.

- State telemedicine laws, simplified. eVisit Web site. https://evisit.com/state-telemedicine-policy/. Accessed March 22, 2020.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Fee-for-Service (FFS) Response to the Public Health Emergency on the Coronavirus (COVID-19). March 20, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/se20011.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2020.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare telemedicine health care provider fact sheet. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet. Published March 17, 2020. Accessed March 20, 2020.

Translucent Periorbital Papules

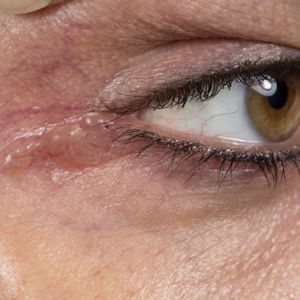

The Diagnosis: Apocrine Hidrocystoma

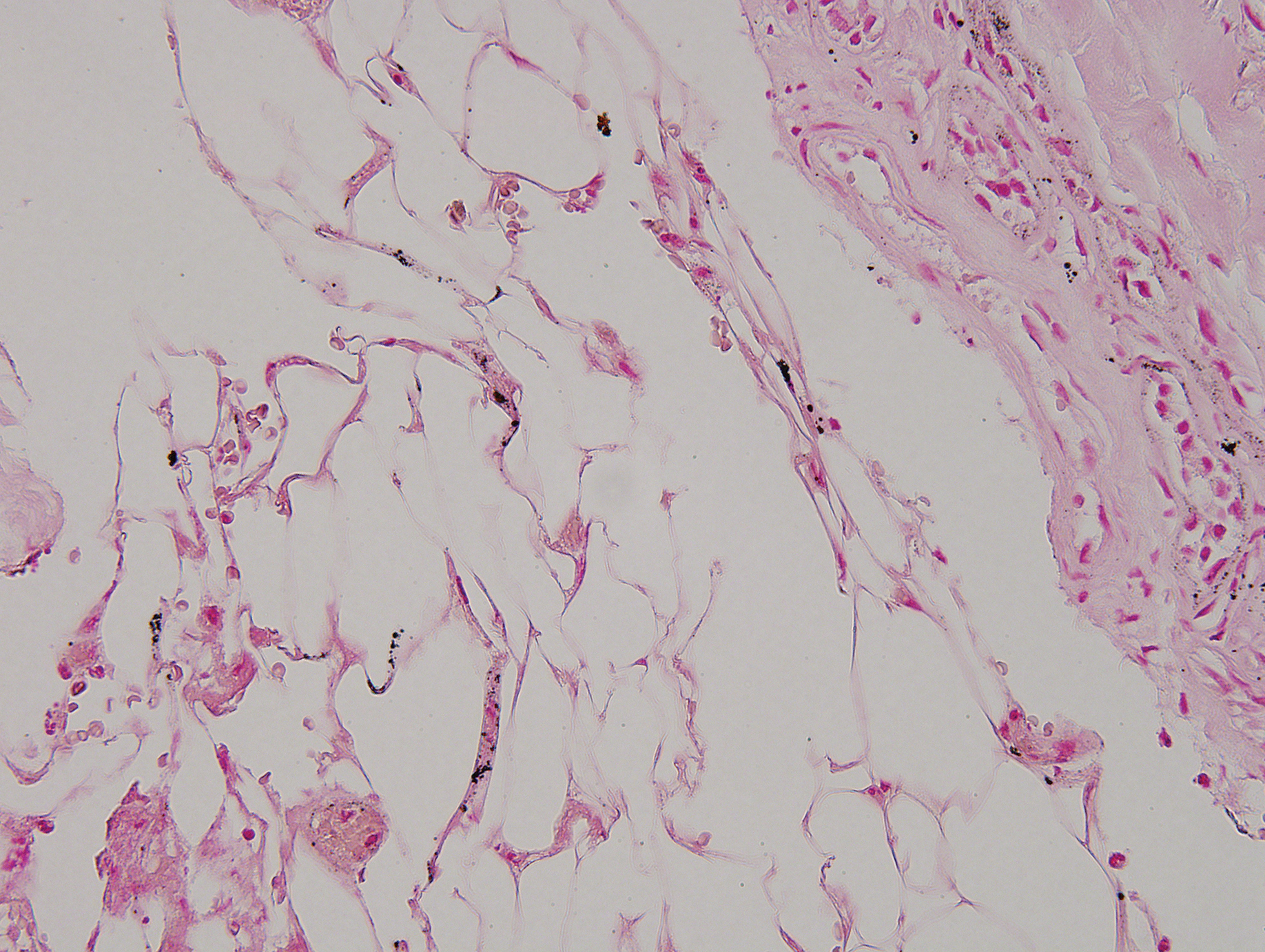

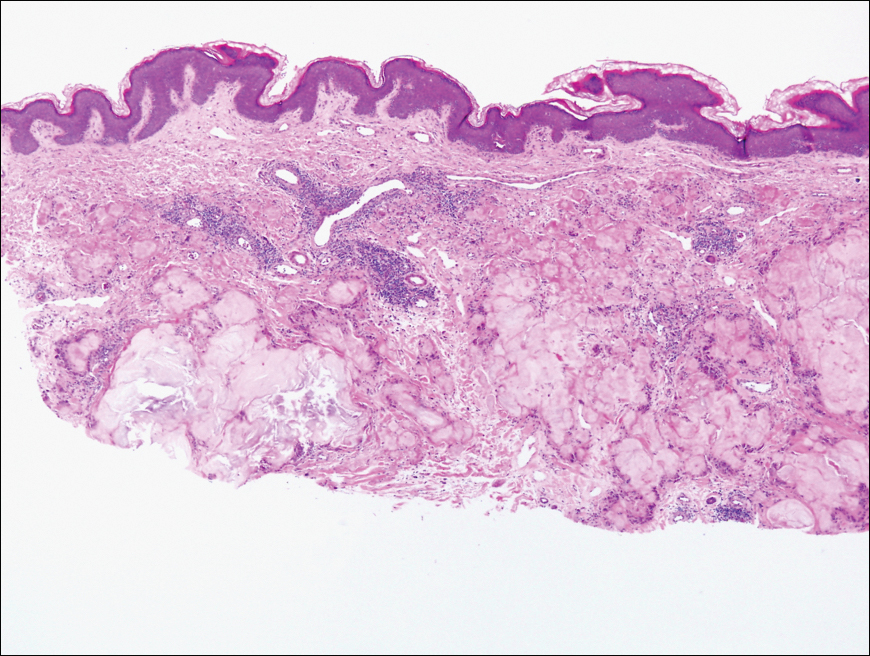

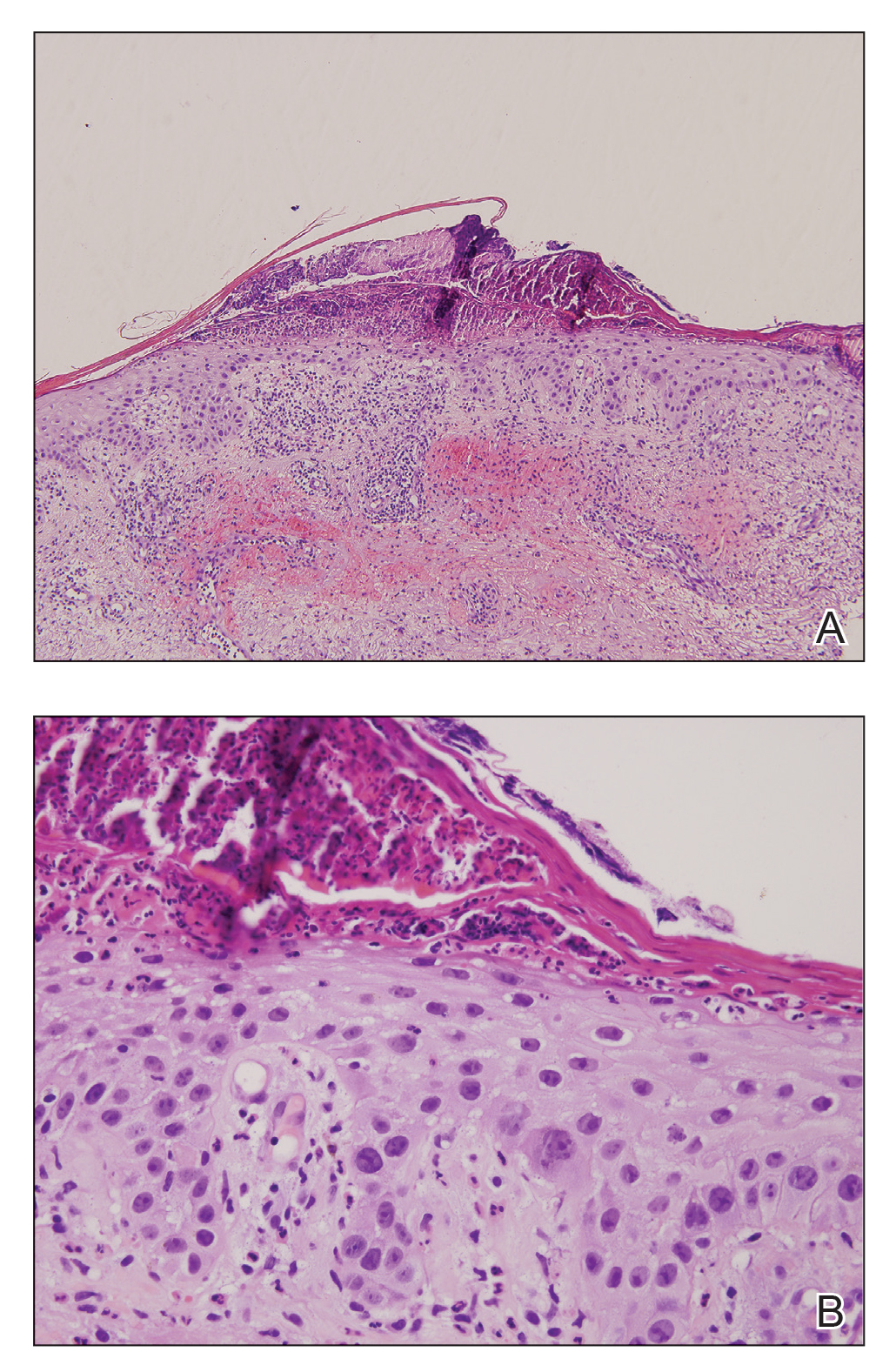

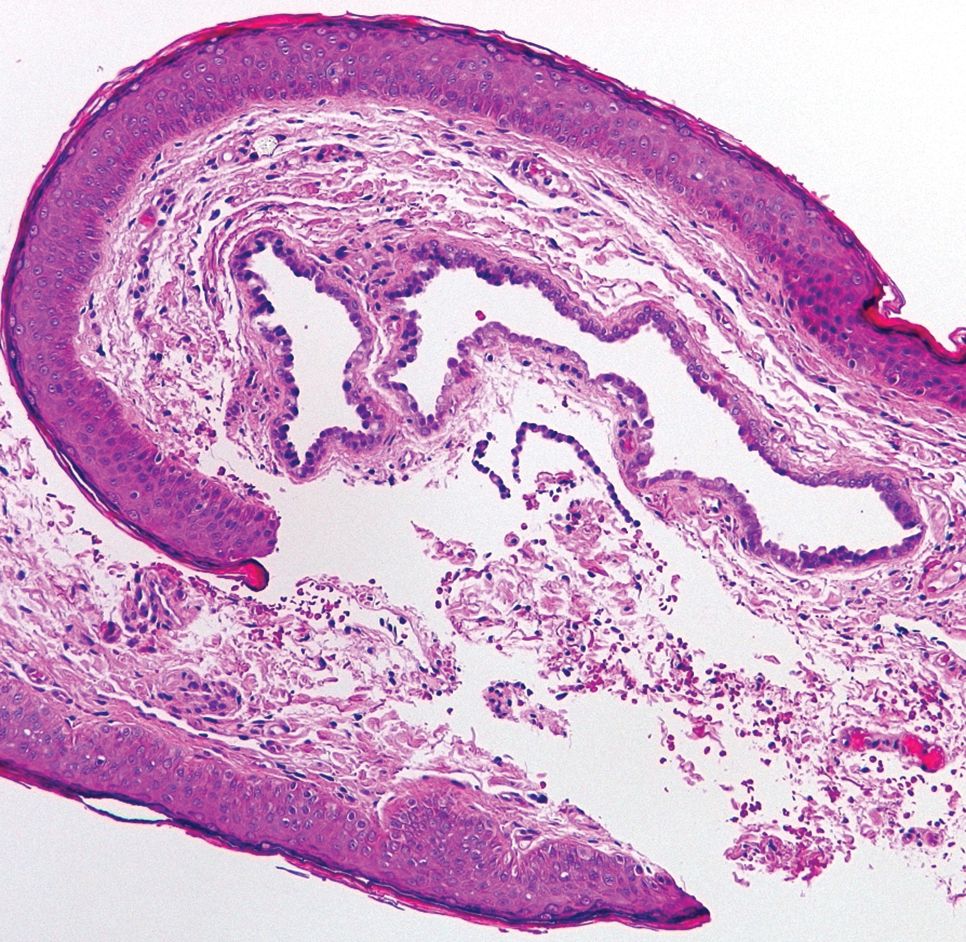

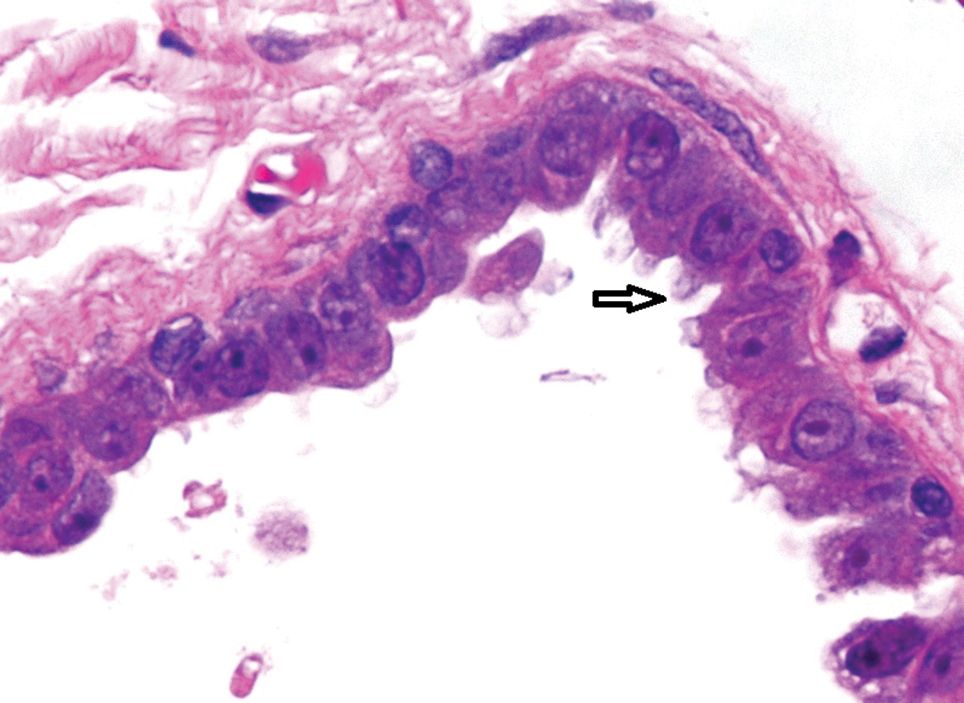

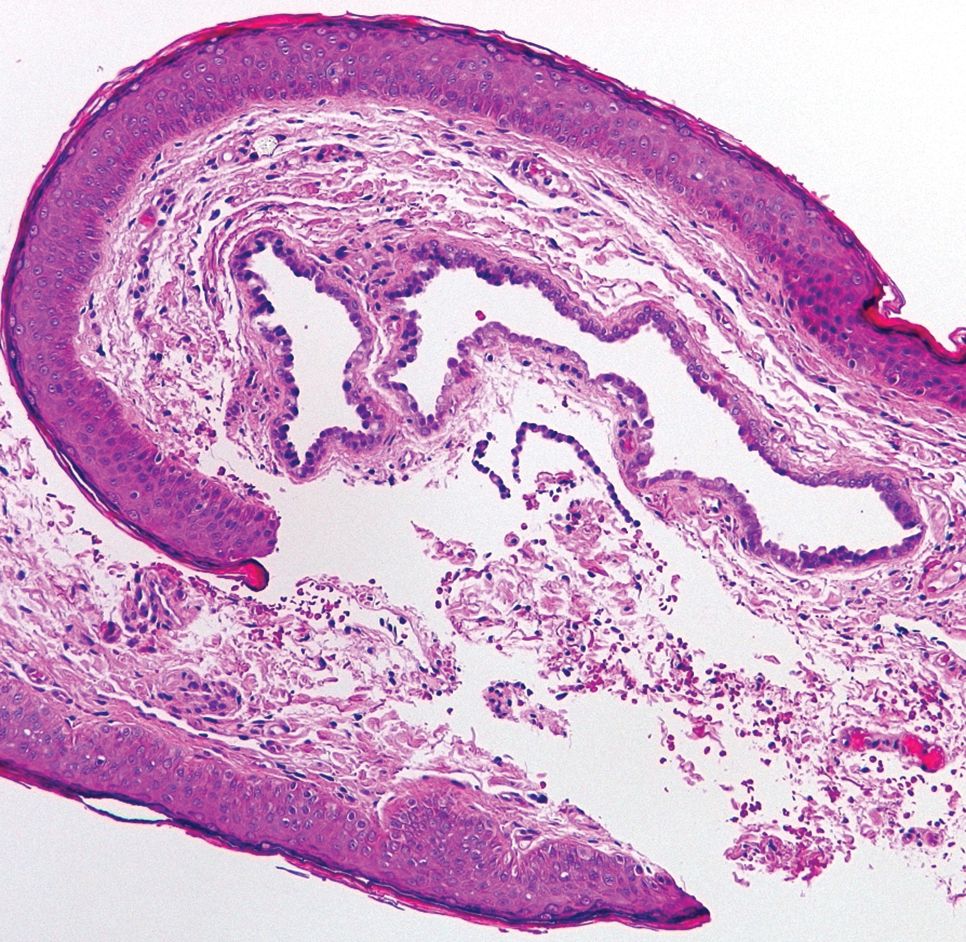

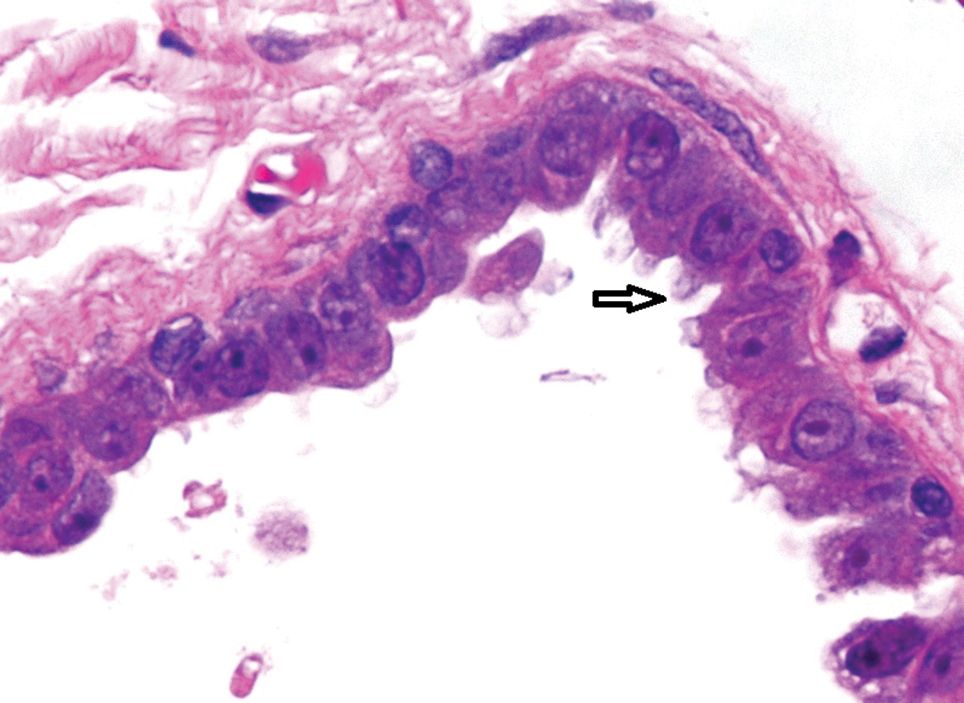

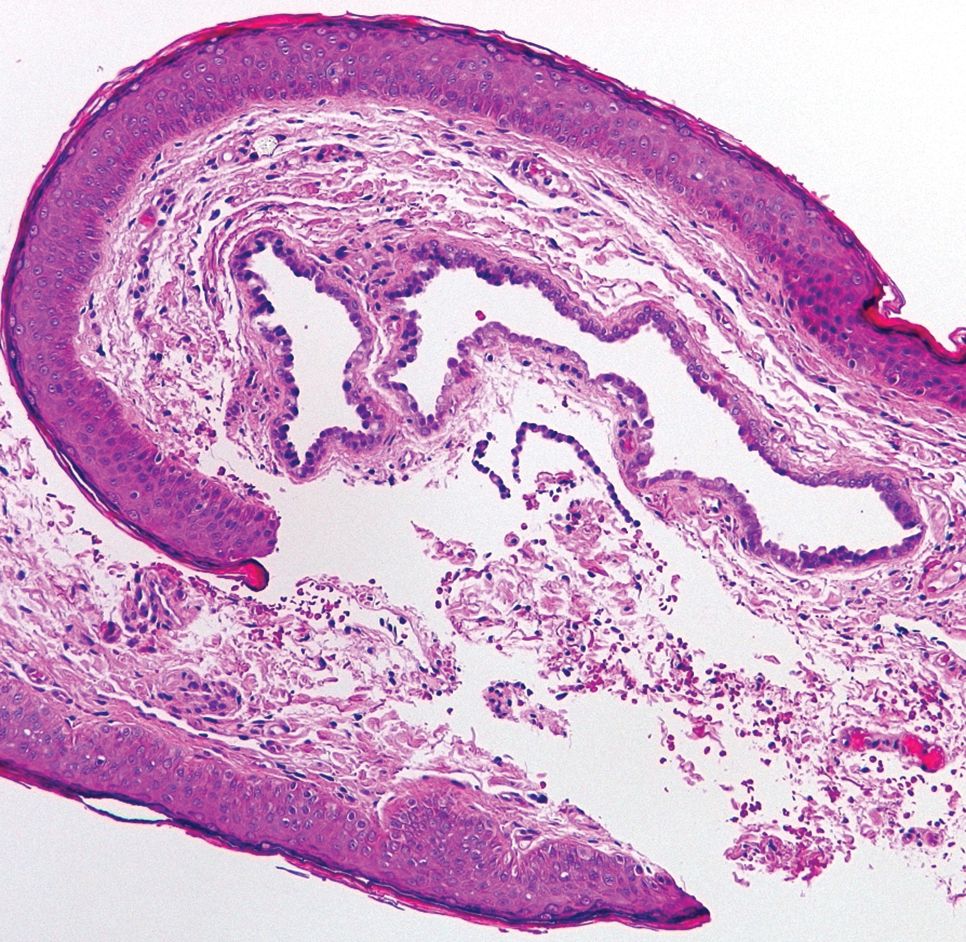

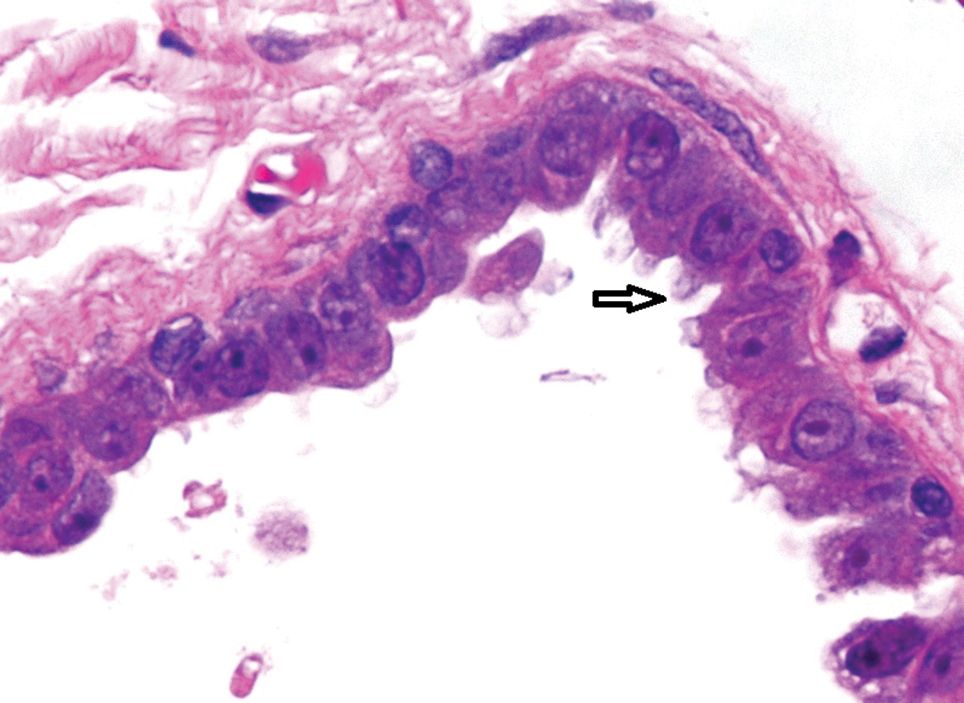

Histopathologic examination of one of the papules revealed cystic cavities located within the dermis (Figure 1) lined by a cuboidal epithelium demonstrating decapitation secretion (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of apocrine hidrocystomas. The presence of multiple lesions prompted further examination for an underlying genetic disorder; however, the patient's hair, nails, and teeth were normal. There also was no evidence of palmoplantar keratoderma or blaschkoid dermatosis.

Hidrocystomas are benign cysts of the sudoriferous apparatus that can be subdivided based on histogenesis (apocrine vs eccrine) or lesion count (single vs multiple).1 Multiple lesions may be associated with disorders of ectodermal dysplasia, including Goltz syndrome and Schopf-Schulz-Passarge syndrome. Apocrine hidrocystomas tend to present as solitary, translucent, flesh-colored to bluish facial papules, and the occurrence of multiple lesions is rare in contrast to its eccrine counterpart.2 Various extrafacial sites have been described including the trunk, axillae, umbilicus, genitalia, and digits.3 Apocrine hidrocystomas do not demonstrate aggravation with exposure to heat, unlike their eccrine counterparts.2

A review of 107 patients with 215 histologically proven hidrocystomas demonstrated a preponderance for women in their mid 50s; 74.8% of patients had unilateral disease, and 69.8% of all lesions affected either the lower eyelid or lateral canthus. Recurrence following conventional surgical excision was observed in 2.3% of lesions.1

A review from Japan recounted an incidence of 5 cases per year from 1999 to 2003.4 Patients ranged in age from 30 to 70 years, but there was no gender predilection. Individual apocrine hidrocystomas were mostly less than 2 cm and varied from flesh colored to light red, brown, blue, or purple; 61% of lesions arose periorbitally. Within their cohort, patients with multiple lesions were uncommon, with only 2 cases presenting with 2 lesions simultaneously.4

Apocrine hidrocystomas are thought to result from a cystic proliferation of the secretory component of apocrine sweat glands, though the exact pathogenesis still is unclear.3 Histologic features include a unilocular or multilocular cystic cavity within the dermis lined by columnar cells demonstrating decapitation secretion, followed by a peripheral rim of flattened myoepithelial cells.

Treatment of apocrine hidrocystomas includes topical anticholinergics, surgical excision, electrodesiccation, 1450-nm diode or CO2 lasers, and trichloroacetic acid.2 The novel use of cryotherapy,5 botulinum toxin,2 and intralesional injections of 50% glucose (as a sclerosant)6 also have been reported. Caution should be exercised when managing digital lesions, as digital papillary carcinoma has been described as a clinical and histopathologic mimicker.7

Lipoid proteinosis is a rare autosomal-recessive disorder. Cutaneous lesions manifest in 2 overlapping stages, typically within the first 2 years of life. The first stage consists of vesicles and hemorrhagic crusts on the face and extremities and intraorally, which may heal with scarring. In the second stage, the skin becomes diffusely thickened and waxy, with the appearance of papules, nodules, or plaques along the eyelid margins (moniliform blepharosis), face, axillae, or scrotum. Verrucous lesions also may develop on the knee or elbow extensors.8

Lymphangioma circumscriptum represents microcystic lymphatic malformations that can arise anywhere on the skin or oral mucosa. They present as clusters of clear or hemorrhagic vesicles of variable size and number favoring the proximal extremities and chest. Histologically, dilated lymphatic channels are seen in the upper dermis.8

Syringomas are common benign tumors of the sweat ducts characterized histologically by superficial dermal proliferations of small comma-shaped ducts set in a fibrotic stroma. Clinically, syringomas appear as small, firm, flesh-colored papules with a predilection for the periorbital area. An eruptive onset may be observed, most commonly affecting the trunk. Syringomas may be associated with Down syndrome, while the clear cell variant may be associated with diabetes mellitus.8

Primary systemic amyloidosis may present with a variety of systemic manifestations. Skin involvement can present as waxy, translucent, or purpuric papulonodules or plaques characteristically affecting the periorbital region. Other mucocutaneous signs include macroglossia with or without translucent to hemorrhagic papulovesicles; bruising, especially on the eyelids, neck, axillae, or anogenital area; vesiculobullous skin lesions; or diffuse cutaneous infiltration imparting a sclerodermoid appearance.8

- Maeng M, Petrakos P, Zhou M, et al. Bi-institutional retrospective study on the demographics and basic clinical presentation of hidrocystomas. Orbit. 2017;36:433-435.

- Bordelon JR, Tang N, Elston D, et al. Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas successfully treated with botulinum toxin A. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:488-490.

- Hafsi W, Badri T. Apocrine hidrocystoma. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2017.

- Anzai S, Goto M, Fujiwara S, et al. Apocrine hidrocystoma: a case report and analysis of 167 Japanese cases. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:702-703.

- Panagiotopoulos A, Vasalou V, Sgontzou T, et al. Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas successfully treated with cryotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:993-995.

- Osaki TH, Osaki MH, Osaki T, et al. A minimally invasive approach for apocrine hidrocystomas of the eyelid. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:134-136.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Llamas-Velasco M, Rütten A, et al. 'Apocrine hidrocystoma and cystadenoma'-like tumor of the digits or toes: a potential diagnostic pitfall of digital papillary adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:410-418.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

The Diagnosis: Apocrine Hidrocystoma

Histopathologic examination of one of the papules revealed cystic cavities located within the dermis (Figure 1) lined by a cuboidal epithelium demonstrating decapitation secretion (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of apocrine hidrocystomas. The presence of multiple lesions prompted further examination for an underlying genetic disorder; however, the patient's hair, nails, and teeth were normal. There also was no evidence of palmoplantar keratoderma or blaschkoid dermatosis.

Hidrocystomas are benign cysts of the sudoriferous apparatus that can be subdivided based on histogenesis (apocrine vs eccrine) or lesion count (single vs multiple).1 Multiple lesions may be associated with disorders of ectodermal dysplasia, including Goltz syndrome and Schopf-Schulz-Passarge syndrome. Apocrine hidrocystomas tend to present as solitary, translucent, flesh-colored to bluish facial papules, and the occurrence of multiple lesions is rare in contrast to its eccrine counterpart.2 Various extrafacial sites have been described including the trunk, axillae, umbilicus, genitalia, and digits.3 Apocrine hidrocystomas do not demonstrate aggravation with exposure to heat, unlike their eccrine counterparts.2

A review of 107 patients with 215 histologically proven hidrocystomas demonstrated a preponderance for women in their mid 50s; 74.8% of patients had unilateral disease, and 69.8% of all lesions affected either the lower eyelid or lateral canthus. Recurrence following conventional surgical excision was observed in 2.3% of lesions.1

A review from Japan recounted an incidence of 5 cases per year from 1999 to 2003.4 Patients ranged in age from 30 to 70 years, but there was no gender predilection. Individual apocrine hidrocystomas were mostly less than 2 cm and varied from flesh colored to light red, brown, blue, or purple; 61% of lesions arose periorbitally. Within their cohort, patients with multiple lesions were uncommon, with only 2 cases presenting with 2 lesions simultaneously.4

Apocrine hidrocystomas are thought to result from a cystic proliferation of the secretory component of apocrine sweat glands, though the exact pathogenesis still is unclear.3 Histologic features include a unilocular or multilocular cystic cavity within the dermis lined by columnar cells demonstrating decapitation secretion, followed by a peripheral rim of flattened myoepithelial cells.

Treatment of apocrine hidrocystomas includes topical anticholinergics, surgical excision, electrodesiccation, 1450-nm diode or CO2 lasers, and trichloroacetic acid.2 The novel use of cryotherapy,5 botulinum toxin,2 and intralesional injections of 50% glucose (as a sclerosant)6 also have been reported. Caution should be exercised when managing digital lesions, as digital papillary carcinoma has been described as a clinical and histopathologic mimicker.7

Lipoid proteinosis is a rare autosomal-recessive disorder. Cutaneous lesions manifest in 2 overlapping stages, typically within the first 2 years of life. The first stage consists of vesicles and hemorrhagic crusts on the face and extremities and intraorally, which may heal with scarring. In the second stage, the skin becomes diffusely thickened and waxy, with the appearance of papules, nodules, or plaques along the eyelid margins (moniliform blepharosis), face, axillae, or scrotum. Verrucous lesions also may develop on the knee or elbow extensors.8

Lymphangioma circumscriptum represents microcystic lymphatic malformations that can arise anywhere on the skin or oral mucosa. They present as clusters of clear or hemorrhagic vesicles of variable size and number favoring the proximal extremities and chest. Histologically, dilated lymphatic channels are seen in the upper dermis.8

Syringomas are common benign tumors of the sweat ducts characterized histologically by superficial dermal proliferations of small comma-shaped ducts set in a fibrotic stroma. Clinically, syringomas appear as small, firm, flesh-colored papules with a predilection for the periorbital area. An eruptive onset may be observed, most commonly affecting the trunk. Syringomas may be associated with Down syndrome, while the clear cell variant may be associated with diabetes mellitus.8

Primary systemic amyloidosis may present with a variety of systemic manifestations. Skin involvement can present as waxy, translucent, or purpuric papulonodules or plaques characteristically affecting the periorbital region. Other mucocutaneous signs include macroglossia with or without translucent to hemorrhagic papulovesicles; bruising, especially on the eyelids, neck, axillae, or anogenital area; vesiculobullous skin lesions; or diffuse cutaneous infiltration imparting a sclerodermoid appearance.8

The Diagnosis: Apocrine Hidrocystoma

Histopathologic examination of one of the papules revealed cystic cavities located within the dermis (Figure 1) lined by a cuboidal epithelium demonstrating decapitation secretion (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of apocrine hidrocystomas. The presence of multiple lesions prompted further examination for an underlying genetic disorder; however, the patient's hair, nails, and teeth were normal. There also was no evidence of palmoplantar keratoderma or blaschkoid dermatosis.

Hidrocystomas are benign cysts of the sudoriferous apparatus that can be subdivided based on histogenesis (apocrine vs eccrine) or lesion count (single vs multiple).1 Multiple lesions may be associated with disorders of ectodermal dysplasia, including Goltz syndrome and Schopf-Schulz-Passarge syndrome. Apocrine hidrocystomas tend to present as solitary, translucent, flesh-colored to bluish facial papules, and the occurrence of multiple lesions is rare in contrast to its eccrine counterpart.2 Various extrafacial sites have been described including the trunk, axillae, umbilicus, genitalia, and digits.3 Apocrine hidrocystomas do not demonstrate aggravation with exposure to heat, unlike their eccrine counterparts.2

A review of 107 patients with 215 histologically proven hidrocystomas demonstrated a preponderance for women in their mid 50s; 74.8% of patients had unilateral disease, and 69.8% of all lesions affected either the lower eyelid or lateral canthus. Recurrence following conventional surgical excision was observed in 2.3% of lesions.1

A review from Japan recounted an incidence of 5 cases per year from 1999 to 2003.4 Patients ranged in age from 30 to 70 years, but there was no gender predilection. Individual apocrine hidrocystomas were mostly less than 2 cm and varied from flesh colored to light red, brown, blue, or purple; 61% of lesions arose periorbitally. Within their cohort, patients with multiple lesions were uncommon, with only 2 cases presenting with 2 lesions simultaneously.4

Apocrine hidrocystomas are thought to result from a cystic proliferation of the secretory component of apocrine sweat glands, though the exact pathogenesis still is unclear.3 Histologic features include a unilocular or multilocular cystic cavity within the dermis lined by columnar cells demonstrating decapitation secretion, followed by a peripheral rim of flattened myoepithelial cells.

Treatment of apocrine hidrocystomas includes topical anticholinergics, surgical excision, electrodesiccation, 1450-nm diode or CO2 lasers, and trichloroacetic acid.2 The novel use of cryotherapy,5 botulinum toxin,2 and intralesional injections of 50% glucose (as a sclerosant)6 also have been reported. Caution should be exercised when managing digital lesions, as digital papillary carcinoma has been described as a clinical and histopathologic mimicker.7

Lipoid proteinosis is a rare autosomal-recessive disorder. Cutaneous lesions manifest in 2 overlapping stages, typically within the first 2 years of life. The first stage consists of vesicles and hemorrhagic crusts on the face and extremities and intraorally, which may heal with scarring. In the second stage, the skin becomes diffusely thickened and waxy, with the appearance of papules, nodules, or plaques along the eyelid margins (moniliform blepharosis), face, axillae, or scrotum. Verrucous lesions also may develop on the knee or elbow extensors.8

Lymphangioma circumscriptum represents microcystic lymphatic malformations that can arise anywhere on the skin or oral mucosa. They present as clusters of clear or hemorrhagic vesicles of variable size and number favoring the proximal extremities and chest. Histologically, dilated lymphatic channels are seen in the upper dermis.8

Syringomas are common benign tumors of the sweat ducts characterized histologically by superficial dermal proliferations of small comma-shaped ducts set in a fibrotic stroma. Clinically, syringomas appear as small, firm, flesh-colored papules with a predilection for the periorbital area. An eruptive onset may be observed, most commonly affecting the trunk. Syringomas may be associated with Down syndrome, while the clear cell variant may be associated with diabetes mellitus.8

Primary systemic amyloidosis may present with a variety of systemic manifestations. Skin involvement can present as waxy, translucent, or purpuric papulonodules or plaques characteristically affecting the periorbital region. Other mucocutaneous signs include macroglossia with or without translucent to hemorrhagic papulovesicles; bruising, especially on the eyelids, neck, axillae, or anogenital area; vesiculobullous skin lesions; or diffuse cutaneous infiltration imparting a sclerodermoid appearance.8

- Maeng M, Petrakos P, Zhou M, et al. Bi-institutional retrospective study on the demographics and basic clinical presentation of hidrocystomas. Orbit. 2017;36:433-435.

- Bordelon JR, Tang N, Elston D, et al. Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas successfully treated with botulinum toxin A. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:488-490.

- Hafsi W, Badri T. Apocrine hidrocystoma. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2017.

- Anzai S, Goto M, Fujiwara S, et al. Apocrine hidrocystoma: a case report and analysis of 167 Japanese cases. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:702-703.

- Panagiotopoulos A, Vasalou V, Sgontzou T, et al. Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas successfully treated with cryotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:993-995.

- Osaki TH, Osaki MH, Osaki T, et al. A minimally invasive approach for apocrine hidrocystomas of the eyelid. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:134-136.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Llamas-Velasco M, Rütten A, et al. 'Apocrine hidrocystoma and cystadenoma'-like tumor of the digits or toes: a potential diagnostic pitfall of digital papillary adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:410-418.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Maeng M, Petrakos P, Zhou M, et al. Bi-institutional retrospective study on the demographics and basic clinical presentation of hidrocystomas. Orbit. 2017;36:433-435.

- Bordelon JR, Tang N, Elston D, et al. Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas successfully treated with botulinum toxin A. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:488-490.

- Hafsi W, Badri T. Apocrine hidrocystoma. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2017.

- Anzai S, Goto M, Fujiwara S, et al. Apocrine hidrocystoma: a case report and analysis of 167 Japanese cases. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:702-703.

- Panagiotopoulos A, Vasalou V, Sgontzou T, et al. Multiple apocrine hidrocystomas successfully treated with cryotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:993-995.

- Osaki TH, Osaki MH, Osaki T, et al. A minimally invasive approach for apocrine hidrocystomas of the eyelid. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:134-136.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Llamas-Velasco M, Rütten A, et al. 'Apocrine hidrocystoma and cystadenoma'-like tumor of the digits or toes: a potential diagnostic pitfall of digital papillary adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:410-418.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

A 40-year-old woman was referred to dermatology for evaluation of occasionally pruritic periorbital papules that had gradually increased in size and number over the last 7 to 8 months (top). She had a similar solitary lesion on the left lower eyelid that was removed twice: 10 years and 10 months prior. She was taking an oral contraceptive (desogestrel) but otherwise had no notable medical history or drug allergies. Physical examination revealed individual and clustered translucent papules along the eyelid margins, left medial canthus, and both lateral canthi (bottom).

An Unusual Presentation of Calciphylaxis

To the Editor:

Calciphylaxis (also known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy and calcifying panniculitis) is a rare vasculopathy affecting the small vessels.1 It is characterized by cutaneous ischemia and necrosis secondary to calcification. It is most commonly seen in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and hyperparathyroidism.1-3 Histopathologic features that are consistent with the diagnosis of calciphylaxis include calcification of medium-sized vessels in the deep dermis or subcutaneous fat as well as smaller distal vessels that supply the papillary dermis and epidermis.4,5 Although it commonly presents as well-demarcated, painful, purplish lesions that evolve into necrotic eschars, calciphylaxis rarely can present with hemorrhagic or serous bullous lesions followed by ulceration, as was seen in our patient.1,5,6 We report this uncommon presentation to highlight the variety in clinical appearance of calciphylaxis and the importance of early diagnosis.

A 43-year-old woman presented to the emergency department for evaluation of chest and abdominal pain that began 1 day prior to presentation. She had a history of systemic lupus erythematosus and ESRD secondary to poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis and was currently on peritoneal dialysis. The patient was admitted for peritonitis and treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics. At the time of admission, the patient also was noted to have several painful bullae on the legs. Her medical history also was remarkable for cerebral infarction, fibromyalgia, cerebral artery occlusion with cerebral infarction, sciatica, hyperlipidemia, deep vein thrombosis, and seizures. She had no history of herpes simplex virus. Surgical history was remarkable for tubal ligation, nephrectomy and kidney transplant, parathyroidectomy, and cholecystectomy. The patient’s medications included sevelamer carbonate, prednisone, epogen, calcium carbonate, esomeprazole, ondansetron, topical gentamicin, and atorvastatin.

Skin examination was performed by the inpatient dermatology service and revealed several tense, 1- to 5-cm, nonhemorrhagic bullae on the thighs and lower legs, some that had ruptured. The lesions were notably tender to palpation. No surrounding erythema, ecchymosis, or warmth was appreciated. The Nikolsky sign was negative. The patient also was noted to have at least grade 2 to 3+ pitting edema of the bilateral legs. The oral and conjunctival mucosae were unremarkable.

Antinuclear antibody, double-stranded DNA, and anti-Smith antibody levels were negative. A punch biopsy of the left lateral thigh revealed intraepidermal vesicular dermatitis with dermal edema suggestive of edema bullae and direct immunofluorescence was negative for immune complex and complement deposition.

Conservative therapy with wound care was recommended. The patient continued to report persistent severe skin pain and developed a subcutaneous nodule on the right inner thigh 1 week later, prompting a second biopsy. Results of the excisional biopsy were nondiagnostic but were suggestive of calciphylaxis, revealing subepidermal bullae with epidermal necrosis, a scant perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, and extravasated erythrocytes. No evidence of calcification was seen within the vessels. The patient was then started on sodium thiosulfate with hemodialysis for treatment of presumed calciphylaxis.

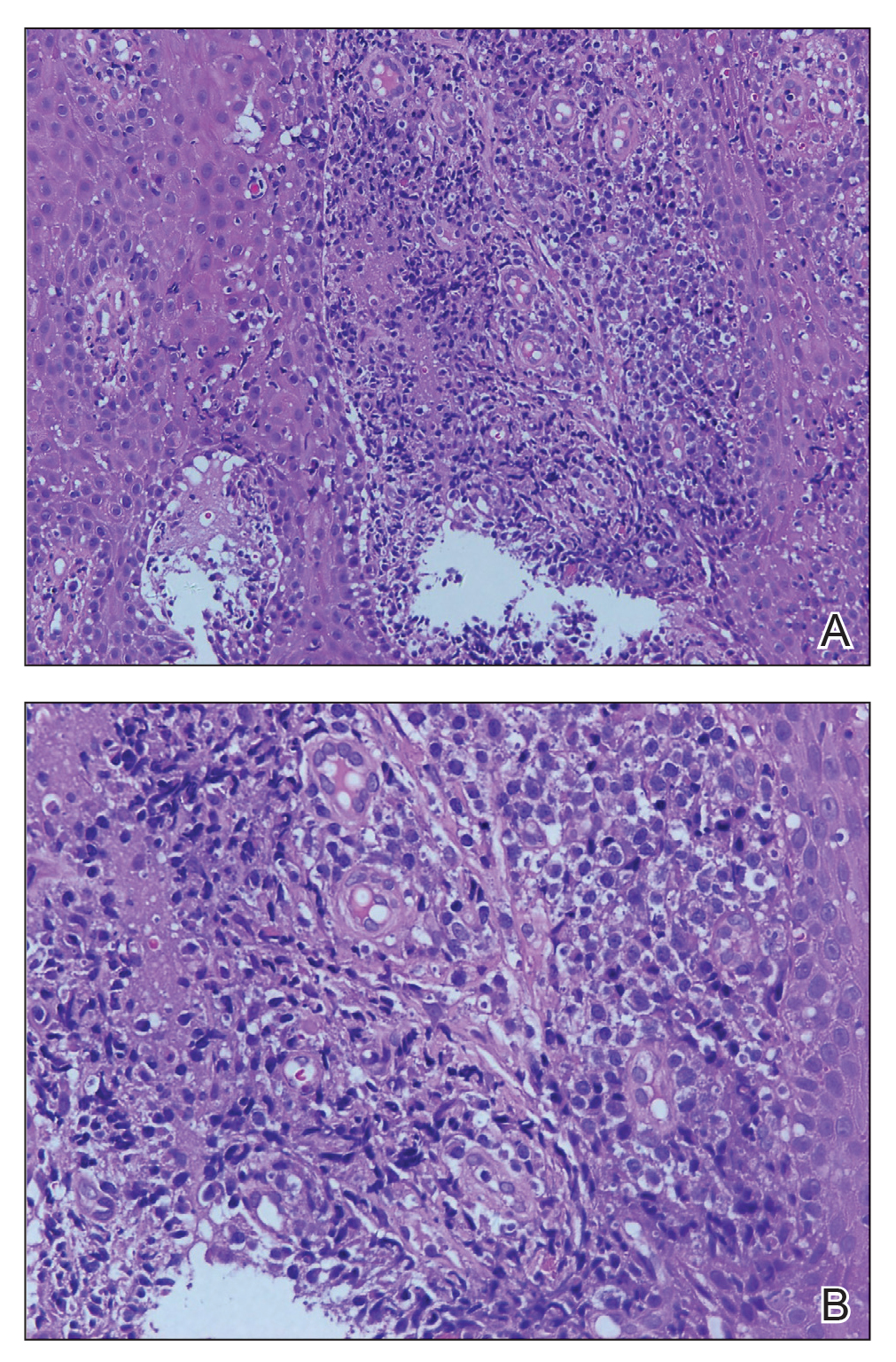

Despite meticulous wound care and treatment with sodium thiosulfate, the patient developed ulcerations with necrotic eschars on the bilateral buttocks, hips, and thighs 1 month later (Figure 1). She subsequently worsened over the next few weeks. She developed sepsis and was transferred to the intensive care unit. A third biopsy was performed, finally confirming the diagnosis of calciphylaxis. Histopathology revealed small blood vessels with basophilic granular deposits in the walls consistent with calcium in the subcutaneous tissue (highlighted with the von Kossa stain), as well as thrombi in the lumens of some vessels; early fat necrosis; focal epidermal necrosis with underlying congested blood vessels with deposits in their walls; a perivascular infiltrate predominately of lymphocytes and neutrophils with scattered nuclear dust; and thick, hyalinized, closely crowded collagen bundles in the reticular dermis and in a widened subcutaneous septum (Figures 2 and 3).

Supportive care and pain control were continued, but the overall prognosis was determined to be very poor, and the patient eventually was discharged to hospice and died.

Although calciphylaxis is commonly seen in patients with ESRD and hyperparathyroidism, patients without renal disease also may develop the condition.2,3 Prior epidemiologic studies have shown a prevalence of 1% in patients with chronic kidney disease and up to 4% in those receiving dialysis.2-5 The average age at presentation is 48 years.6,7 Although calciphylaxis has been noted to affect males and females equally, some studies have suggested a female predominance.5-8

The etiology of calciphylaxis is unknown, but ESRD requiring dialysis, primary or secondary hyperparathyroidism, obesity, diabetes mellitus, skin trauma, and/or a hypercoagulable state may put patients at increased risk for developing this disease.2,3 Other risk factors include systemic corticosteroids, liver disease, increased serum aluminum, and increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Although high calcium-phosphate product has been noted as a risk factor in prior studies, one retrospective study found that it does not reliably confirm or exclude a diagnosis of calciphylaxis.8

The pathogenesis of calciphylaxis is not well understood; however, some researchers suggest that an imbalance in calcium-phosphate homeostasis may lead to calciphylaxis; that is, elevated calcium and phosphate levels exceed their solubility and deposit in the walls of small- and medium-sized arteries, which consequently leads to ischemic necrosis and gangrene of the surrounding tissue.9

Clinically, calciphylaxis has an indolent onset and usually presents as well-demarcated, painful, purplish, mottled lesions that evolve into necrotic gray-black eschars and gangrene in adjacent tissues.1,5,6 The ischemic process may even extend to the muscle layer.5 Other common presentations include mild erythematous patches; livedo reticularis; painful nodules; necrotic ulcerating lesions; and more rarely flaccid, hemorrhagic, or serous bullous lesions followed by ulceration, as was seen in our patient.6,9,10 Lesions usually begin at sites of trauma and seem to be distributed symmetrically.5,6 The most commonly affected locations are the legs, specifically the medial thighs, as well as the abdomen and buttocks, but lesions also can be found at more distal sites such as the breasts, tongue, vulva, penis, fingers, and toes.5,6,10 The head and neck region rarely is affected. Although uncommon, calciphylaxis may affect other organs, including the lungs, stomach, kidneys, and adrenal glands.5 The accompanying systemic symptoms and findings may include muscle weakness, tenderness, or myositis with rhabdomyolysis; calcific cerebral embolism; dementia and infarction of the central nervous system; acute respiratory failure; heart disease; atrioventricular block; and calcification of the cardiac conduction system.6 Unlike other forms of peripheral vascular disease, distal pulses are present in calciphylaxis, as blood flow usually is preserved distal and deep to the areas of necrosis.5,6

A careful history and thorough physical examination are important first steps in the diagnosis of this condition.2,10 Although there are no definitive laboratory tests, elevated serum calcium, phosphorous, and calcium-phosphate product levels, as well as parathyroid hormone level, may be suggestive of calciphylaxis.2,5 Leukocytosis may occur if an infection is present.5

The most accurate method to confirm the diagnosis is a deep incisional biopsy from an erythematous, slightly purpuric area adjacent to the necrotic lesion.2,10,11 The histopathologic features used to make the diagnosis include calcification of medium-sized vessels, particularly the intimal or medial layers, in the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat in addition to lobular capillaries of the subcutaneous fat.5,10 These vessels, including the smaller distal vessels that supply the papillary dermis and epidermis, also may be thrombosed due to calcification, leading to vascular occlusion and subsequently ischemic necrosis of the overlying epidermis.10 Other findings may include pseudoxanthoma elasticum changes, panniculitis, and subcutaneous fat necrosis.4,10

The differential diagnosis for calciphylaxis includes peripheral vascular disease, vasculitis, juvenile dermatomyositis, proteins C and S deficiencies, cryofibrinogenemia, calcinosis cutis, and tumoral calcinosis.2 Polyarteritis nodosa, Sjögren syndrome, atherosclerotic peripheral vascular disease, pyoderma gangrenosum, systemic lupus erythematosus, necrotizing fasciitis, septic embolism, and necrosis secondary to warfarin and heparin may mimic calciphylaxis.5

Treatment of calciphylaxis is multidimensional but primarily is supportive.6,11 Controlling calcium and phosphate levels and secondary hyperparathyroidism through diet and phosphate binders (eg, sevelamer hydrochloride) has been shown to be effective.6 Pamidronate, a bisphosphonate, inhibits arterial calcification in animal models and has been reported to treat calciphylaxis, resulting in marked pain reduction and ulcer healing.4,6 Cinacalcet, which functions as a calcimimetic, has been implicated in the treatment of calciphylaxis. It has been used to treat primary and secondary hyperparathyroidism and to normalize serum calcium levels; it also may be used as an alternative to parathyroidectomy.4,6 Intravenous administration of sodium thiosulfate, a potent antioxidant and chelator of calcium, has been helpful in reversing signs and symptoms of calciphylaxis.6,12 It also has been shown to effectively remove extra calcium during peritoneal dialysis.6 Parathyroidectomy has been useful in patients with markedly elevated parathyroid hormone levels, as it suppresses or eliminates the sensitizing agent causing hypercalcemia, elevated calcium-phosphate product, and hyperparathyroidism.1,2,6,13

Wound care and prevention of sepsis are essential in the treatment of calciphylaxis. Management options include surgical debridement, hydrocolloid and biologic dressings, skin grafts, systemic antibiotics, oral pentoxifylline combined with maggot therapy, nutritional support, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, and revascularization and amputation when other interventions have failed. Pain control with analgesics and correction of thrombosis in the skin and blood vessels via anticoagulation therapy also are important complementary treatments.6

The clinical outcome of calciphylaxis is dependent on early diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and wound management,9 but overall, the prognosis usually is poor and has a high mortality rate. The most common causes of death are infection and sepsis.1,9 A study of 7 cases reported 100% mortality,14 but other studies have suggested a mortality rate of 60% to 80%.4,10 Female sex and obesity are poor prognostic indicators.2 A better prognosis has been appreciated in cases in which lesions occur at distal sites (eg, lower legs, hands) compared to more proximal sites (eg, abdomen), where 25% and 75% mortalities have been noted, respectively.10,14,15 In one study, the overall mortality rate was 45% in patients with calciphylaxis at 1 year.6 The rate was 41% in patients with plaques only and 67% in those who presented with ulceration. Patients who survive often experience a high degree of morbidity and prolonged hospitalization; these patients often are severely debilitated, especially in the case of limb amputation.6

Our report of calciphylaxis demonstrates the diversity in clinical presentation and emphasizes the importance of early and accurate diagnosis in reducing morbidity and mortality. In our case, the patient presented with skin pain and tense nonhemorrhagic bullae without underlying ecchymotic or erythematous lesions as the earliest sign of calciphylaxis. Physicians should have a high degree of suspicion in the setting of dialysis-dependent ESRD patients with bullae, extreme pain, and continuous decline. We hope that this case will help increase awareness of the varying presentations of this condition.

- Hanafusa T, Yamaguchi Y, Tani M, et al. Intractable wounds caused by calcific uremic arteriolopathy treated with bisphosphonates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;57:1021-1025.

- Somorin AO, Harbi AA, Subaity Y, et al. Calciphylaxis: case report and literature review. Afr J Med Sci. 2002;31:175-178.

- Barreiros HM, Goulão J, Cunha H, et al. Calciphylaxis: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2013;2:69-70.

- Vedvyas C, Winterfield LS, Vleugels RA. Calciphylaxis: a systematic review of existing and emerging therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E253-E260.

- Beitz JM. Calciphylaxis: a case study with differential diagnosis. Ostomy Wound Manag. 2003;49:28-38.

- Daudén E, Oñate M. Calciphylaxis. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:557-568.

- Oh DH, Eulau D, Tokugawa DA, et al. Five cases of calciphylaxis and a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:979-987.

- Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MDP, et al. Calciphylaxis: natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:569-578.

- Hanvesakul R, Silva MA, Hejmadi R, et al. Calciphylaxis following kidney transplantation: a case report. J Med Cases. 2009;3:9297.

- Kouba DJ, Owens NM, Barrett TL, et al. An unusual case of calciphylaxis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:19-22.

- Arch-Ferrer JE, Beenken SW, Rue LW, et al. Therapy for calciphylaxis: an outcome analysis. Surgery. 2003;134:941-945.

- Cicone JS, Petronis JB, Embert CD, et al. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:1104-1108.

- Mirza I, Chaubay D, Gunderia H, et al. An unusual presentation of calciphylaxis due to primary hyperparathyroidism. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:1351-1353.

- Alain J, Poulin YP, Cloutier RA, et al. Calciphylaxis: seven new cases. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:213-218.

- Hafner J, Keusch G, Wahl C, et al. Calciphylaxis: a syndrome of skin necrosis and acral gangrene in chronic renal failure. Vasa. 1998;27:137-143.

To the Editor:

Calciphylaxis (also known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy and calcifying panniculitis) is a rare vasculopathy affecting the small vessels.1 It is characterized by cutaneous ischemia and necrosis secondary to calcification. It is most commonly seen in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and hyperparathyroidism.1-3 Histopathologic features that are consistent with the diagnosis of calciphylaxis include calcification of medium-sized vessels in the deep dermis or subcutaneous fat as well as smaller distal vessels that supply the papillary dermis and epidermis.4,5 Although it commonly presents as well-demarcated, painful, purplish lesions that evolve into necrotic eschars, calciphylaxis rarely can present with hemorrhagic or serous bullous lesions followed by ulceration, as was seen in our patient.1,5,6 We report this uncommon presentation to highlight the variety in clinical appearance of calciphylaxis and the importance of early diagnosis.

A 43-year-old woman presented to the emergency department for evaluation of chest and abdominal pain that began 1 day prior to presentation. She had a history of systemic lupus erythematosus and ESRD secondary to poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis and was currently on peritoneal dialysis. The patient was admitted for peritonitis and treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics. At the time of admission, the patient also was noted to have several painful bullae on the legs. Her medical history also was remarkable for cerebral infarction, fibromyalgia, cerebral artery occlusion with cerebral infarction, sciatica, hyperlipidemia, deep vein thrombosis, and seizures. She had no history of herpes simplex virus. Surgical history was remarkable for tubal ligation, nephrectomy and kidney transplant, parathyroidectomy, and cholecystectomy. The patient’s medications included sevelamer carbonate, prednisone, epogen, calcium carbonate, esomeprazole, ondansetron, topical gentamicin, and atorvastatin.

Skin examination was performed by the inpatient dermatology service and revealed several tense, 1- to 5-cm, nonhemorrhagic bullae on the thighs and lower legs, some that had ruptured. The lesions were notably tender to palpation. No surrounding erythema, ecchymosis, or warmth was appreciated. The Nikolsky sign was negative. The patient also was noted to have at least grade 2 to 3+ pitting edema of the bilateral legs. The oral and conjunctival mucosae were unremarkable.

Antinuclear antibody, double-stranded DNA, and anti-Smith antibody levels were negative. A punch biopsy of the left lateral thigh revealed intraepidermal vesicular dermatitis with dermal edema suggestive of edema bullae and direct immunofluorescence was negative for immune complex and complement deposition.

Conservative therapy with wound care was recommended. The patient continued to report persistent severe skin pain and developed a subcutaneous nodule on the right inner thigh 1 week later, prompting a second biopsy. Results of the excisional biopsy were nondiagnostic but were suggestive of calciphylaxis, revealing subepidermal bullae with epidermal necrosis, a scant perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, and extravasated erythrocytes. No evidence of calcification was seen within the vessels. The patient was then started on sodium thiosulfate with hemodialysis for treatment of presumed calciphylaxis.

Despite meticulous wound care and treatment with sodium thiosulfate, the patient developed ulcerations with necrotic eschars on the bilateral buttocks, hips, and thighs 1 month later (Figure 1). She subsequently worsened over the next few weeks. She developed sepsis and was transferred to the intensive care unit. A third biopsy was performed, finally confirming the diagnosis of calciphylaxis. Histopathology revealed small blood vessels with basophilic granular deposits in the walls consistent with calcium in the subcutaneous tissue (highlighted with the von Kossa stain), as well as thrombi in the lumens of some vessels; early fat necrosis; focal epidermal necrosis with underlying congested blood vessels with deposits in their walls; a perivascular infiltrate predominately of lymphocytes and neutrophils with scattered nuclear dust; and thick, hyalinized, closely crowded collagen bundles in the reticular dermis and in a widened subcutaneous septum (Figures 2 and 3).

Supportive care and pain control were continued, but the overall prognosis was determined to be very poor, and the patient eventually was discharged to hospice and died.

Although calciphylaxis is commonly seen in patients with ESRD and hyperparathyroidism, patients without renal disease also may develop the condition.2,3 Prior epidemiologic studies have shown a prevalence of 1% in patients with chronic kidney disease and up to 4% in those receiving dialysis.2-5 The average age at presentation is 48 years.6,7 Although calciphylaxis has been noted to affect males and females equally, some studies have suggested a female predominance.5-8

The etiology of calciphylaxis is unknown, but ESRD requiring dialysis, primary or secondary hyperparathyroidism, obesity, diabetes mellitus, skin trauma, and/or a hypercoagulable state may put patients at increased risk for developing this disease.2,3 Other risk factors include systemic corticosteroids, liver disease, increased serum aluminum, and increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Although high calcium-phosphate product has been noted as a risk factor in prior studies, one retrospective study found that it does not reliably confirm or exclude a diagnosis of calciphylaxis.8

The pathogenesis of calciphylaxis is not well understood; however, some researchers suggest that an imbalance in calcium-phosphate homeostasis may lead to calciphylaxis; that is, elevated calcium and phosphate levels exceed their solubility and deposit in the walls of small- and medium-sized arteries, which consequently leads to ischemic necrosis and gangrene of the surrounding tissue.9

Clinically, calciphylaxis has an indolent onset and usually presents as well-demarcated, painful, purplish, mottled lesions that evolve into necrotic gray-black eschars and gangrene in adjacent tissues.1,5,6 The ischemic process may even extend to the muscle layer.5 Other common presentations include mild erythematous patches; livedo reticularis; painful nodules; necrotic ulcerating lesions; and more rarely flaccid, hemorrhagic, or serous bullous lesions followed by ulceration, as was seen in our patient.6,9,10 Lesions usually begin at sites of trauma and seem to be distributed symmetrically.5,6 The most commonly affected locations are the legs, specifically the medial thighs, as well as the abdomen and buttocks, but lesions also can be found at more distal sites such as the breasts, tongue, vulva, penis, fingers, and toes.5,6,10 The head and neck region rarely is affected. Although uncommon, calciphylaxis may affect other organs, including the lungs, stomach, kidneys, and adrenal glands.5 The accompanying systemic symptoms and findings may include muscle weakness, tenderness, or myositis with rhabdomyolysis; calcific cerebral embolism; dementia and infarction of the central nervous system; acute respiratory failure; heart disease; atrioventricular block; and calcification of the cardiac conduction system.6 Unlike other forms of peripheral vascular disease, distal pulses are present in calciphylaxis, as blood flow usually is preserved distal and deep to the areas of necrosis.5,6

A careful history and thorough physical examination are important first steps in the diagnosis of this condition.2,10 Although there are no definitive laboratory tests, elevated serum calcium, phosphorous, and calcium-phosphate product levels, as well as parathyroid hormone level, may be suggestive of calciphylaxis.2,5 Leukocytosis may occur if an infection is present.5

The most accurate method to confirm the diagnosis is a deep incisional biopsy from an erythematous, slightly purpuric area adjacent to the necrotic lesion.2,10,11 The histopathologic features used to make the diagnosis include calcification of medium-sized vessels, particularly the intimal or medial layers, in the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat in addition to lobular capillaries of the subcutaneous fat.5,10 These vessels, including the smaller distal vessels that supply the papillary dermis and epidermis, also may be thrombosed due to calcification, leading to vascular occlusion and subsequently ischemic necrosis of the overlying epidermis.10 Other findings may include pseudoxanthoma elasticum changes, panniculitis, and subcutaneous fat necrosis.4,10

The differential diagnosis for calciphylaxis includes peripheral vascular disease, vasculitis, juvenile dermatomyositis, proteins C and S deficiencies, cryofibrinogenemia, calcinosis cutis, and tumoral calcinosis.2 Polyarteritis nodosa, Sjögren syndrome, atherosclerotic peripheral vascular disease, pyoderma gangrenosum, systemic lupus erythematosus, necrotizing fasciitis, septic embolism, and necrosis secondary to warfarin and heparin may mimic calciphylaxis.5

Treatment of calciphylaxis is multidimensional but primarily is supportive.6,11 Controlling calcium and phosphate levels and secondary hyperparathyroidism through diet and phosphate binders (eg, sevelamer hydrochloride) has been shown to be effective.6 Pamidronate, a bisphosphonate, inhibits arterial calcification in animal models and has been reported to treat calciphylaxis, resulting in marked pain reduction and ulcer healing.4,6 Cinacalcet, which functions as a calcimimetic, has been implicated in the treatment of calciphylaxis. It has been used to treat primary and secondary hyperparathyroidism and to normalize serum calcium levels; it also may be used as an alternative to parathyroidectomy.4,6 Intravenous administration of sodium thiosulfate, a potent antioxidant and chelator of calcium, has been helpful in reversing signs and symptoms of calciphylaxis.6,12 It also has been shown to effectively remove extra calcium during peritoneal dialysis.6 Parathyroidectomy has been useful in patients with markedly elevated parathyroid hormone levels, as it suppresses or eliminates the sensitizing agent causing hypercalcemia, elevated calcium-phosphate product, and hyperparathyroidism.1,2,6,13

Wound care and prevention of sepsis are essential in the treatment of calciphylaxis. Management options include surgical debridement, hydrocolloid and biologic dressings, skin grafts, systemic antibiotics, oral pentoxifylline combined with maggot therapy, nutritional support, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, and revascularization and amputation when other interventions have failed. Pain control with analgesics and correction of thrombosis in the skin and blood vessels via anticoagulation therapy also are important complementary treatments.6

The clinical outcome of calciphylaxis is dependent on early diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and wound management,9 but overall, the prognosis usually is poor and has a high mortality rate. The most common causes of death are infection and sepsis.1,9 A study of 7 cases reported 100% mortality,14 but other studies have suggested a mortality rate of 60% to 80%.4,10 Female sex and obesity are poor prognostic indicators.2 A better prognosis has been appreciated in cases in which lesions occur at distal sites (eg, lower legs, hands) compared to more proximal sites (eg, abdomen), where 25% and 75% mortalities have been noted, respectively.10,14,15 In one study, the overall mortality rate was 45% in patients with calciphylaxis at 1 year.6 The rate was 41% in patients with plaques only and 67% in those who presented with ulceration. Patients who survive often experience a high degree of morbidity and prolonged hospitalization; these patients often are severely debilitated, especially in the case of limb amputation.6

Our report of calciphylaxis demonstrates the diversity in clinical presentation and emphasizes the importance of early and accurate diagnosis in reducing morbidity and mortality. In our case, the patient presented with skin pain and tense nonhemorrhagic bullae without underlying ecchymotic or erythematous lesions as the earliest sign of calciphylaxis. Physicians should have a high degree of suspicion in the setting of dialysis-dependent ESRD patients with bullae, extreme pain, and continuous decline. We hope that this case will help increase awareness of the varying presentations of this condition.

To the Editor:

Calciphylaxis (also known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy and calcifying panniculitis) is a rare vasculopathy affecting the small vessels.1 It is characterized by cutaneous ischemia and necrosis secondary to calcification. It is most commonly seen in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and hyperparathyroidism.1-3 Histopathologic features that are consistent with the diagnosis of calciphylaxis include calcification of medium-sized vessels in the deep dermis or subcutaneous fat as well as smaller distal vessels that supply the papillary dermis and epidermis.4,5 Although it commonly presents as well-demarcated, painful, purplish lesions that evolve into necrotic eschars, calciphylaxis rarely can present with hemorrhagic or serous bullous lesions followed by ulceration, as was seen in our patient.1,5,6 We report this uncommon presentation to highlight the variety in clinical appearance of calciphylaxis and the importance of early diagnosis.

A 43-year-old woman presented to the emergency department for evaluation of chest and abdominal pain that began 1 day prior to presentation. She had a history of systemic lupus erythematosus and ESRD secondary to poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis and was currently on peritoneal dialysis. The patient was admitted for peritonitis and treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics. At the time of admission, the patient also was noted to have several painful bullae on the legs. Her medical history also was remarkable for cerebral infarction, fibromyalgia, cerebral artery occlusion with cerebral infarction, sciatica, hyperlipidemia, deep vein thrombosis, and seizures. She had no history of herpes simplex virus. Surgical history was remarkable for tubal ligation, nephrectomy and kidney transplant, parathyroidectomy, and cholecystectomy. The patient’s medications included sevelamer carbonate, prednisone, epogen, calcium carbonate, esomeprazole, ondansetron, topical gentamicin, and atorvastatin.

Skin examination was performed by the inpatient dermatology service and revealed several tense, 1- to 5-cm, nonhemorrhagic bullae on the thighs and lower legs, some that had ruptured. The lesions were notably tender to palpation. No surrounding erythema, ecchymosis, or warmth was appreciated. The Nikolsky sign was negative. The patient also was noted to have at least grade 2 to 3+ pitting edema of the bilateral legs. The oral and conjunctival mucosae were unremarkable.

Antinuclear antibody, double-stranded DNA, and anti-Smith antibody levels were negative. A punch biopsy of the left lateral thigh revealed intraepidermal vesicular dermatitis with dermal edema suggestive of edema bullae and direct immunofluorescence was negative for immune complex and complement deposition.

Conservative therapy with wound care was recommended. The patient continued to report persistent severe skin pain and developed a subcutaneous nodule on the right inner thigh 1 week later, prompting a second biopsy. Results of the excisional biopsy were nondiagnostic but were suggestive of calciphylaxis, revealing subepidermal bullae with epidermal necrosis, a scant perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, and extravasated erythrocytes. No evidence of calcification was seen within the vessels. The patient was then started on sodium thiosulfate with hemodialysis for treatment of presumed calciphylaxis.