User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Skin Scores: A Review of Clinical Scoring Systems in Dermatology

The practice of dermatology is rife with bedside tools: swabs, smears, and scoring systems. First popularized in specialties such as emergency medicine and internal medicine, clinical scoring systems are now emerging in dermatology. These evidence-based scores can be calculated quickly at the bedside—often through a free smartphone app—to help guide clinical decision-making regarding diagnosis, prognosis, and management. As with any medical tool, scoring systems have limitations and should be used as a supplement, not substitute, for one’s clinical judgement. This article reviews 4 clinical scoring systems practical for dermatology residents.

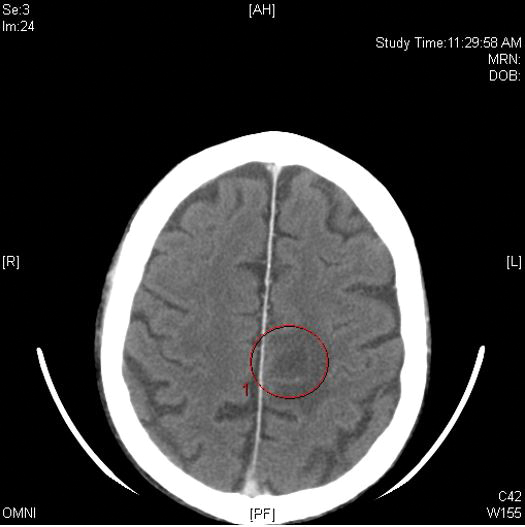

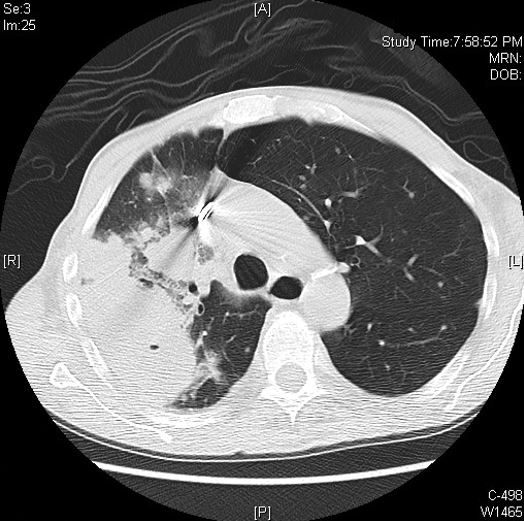

SCORTEN Prognosticates Cases of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Perhaps the best-known scoring system in dermatology, the SCORTEN is widely used to predict hospital mortality from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. The SCORTEN includes 7 variables of equal weight—age of 40 years or older, heart rate of 120 beats per minute or more, cancer/hematologic malignancy, involved body surface area (BSA) greater than 10%, serum urea greater than 10 mmol/L, serum bicarbonate less than 20 mmol/L, and serum glucose greater than 14 mmol/L—each contributing 1 point to the overall score if present.1 The involved BSA is defined as the sum of detached and detachable epidermis.1

The SCORTEN was developed and prospectively validated to be calculated at the end of the first 24 hours of admission; for this calculation, use the BSA affected at that time, and use the most abnormal values during the first 24 hours of admission for the other variables.1 In addition, a follow-up study including some of the original coauthors recommends recalculating the SCORTEN at the end of hospital day 3, having found that the score’s predictive value was better on this day than hospital days 1, 2, 4, or 5.2 Based on the original study, a SCORTEN of 0 to 1 corresponds to a mortality rate of 3.2%, 2 to 12.1%, 3 to 35.3%, 4 to 58.3%, and 5 or greater to 90.0%.1

Limitations of the SCORTEN include its ability to overestimate or underestimate mortality as demonstrated by 2 multi-institutional cohorts.3,4 Recently, the ABCD-10 score was developed as an alternative to the SCORTEN and was found to predict mortality similarly when validated in an internal cohort.5

PEST Screens for Psoriatic Arthritis

Dermatologists play an important role in screening for psoriatic arthritis, as an estimated 1 in 5 patients with psoriasis have psoriatic arthritis.6 To this end, several screening tools have been developed to help differentiate psoriatic arthritis from other arthritides. Joint guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology and the National Psoriasis Foundation acknowledge that “. . . these screening tools have tended to perform less well when tested in groups of people other than those for which they were originally developed. As such, their usefulness in routine clinical practice remains controversial.”7 Nevertheless, the guidelines state, “[b]ecause screening and early detection of inflammatory arthritis are essential to optimize patient [quality of life] and reduce morbidity, providers may consider using a formal screening tool of their choice.”7

With these limitations in mind, I have found the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) to be the most useful psoriatic arthritis screening tool. One study determined that the PEST has the best trade-off between sensitivity and specificity compared to 2 other psoriatic arthritis screening tools, the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation (PASE) and the Early Arthritis for Psoriatic Patients (EARP).8

The PEST is comprised of 5 questions: (1) Have you ever had a swollen joint (or joints)? (2) Has a doctor ever told you that you have arthritis? (3) Do your fingernails or toenails have holes or pits? (4) Have you had pain in your heel? (5) Have you had a finger or toe that was completely swollen and painful for no apparent reason? According to the PEST, a referral to a rheumatologist should be considered for patients answering yes to 3 or more questions, which is 97% sensitive and 79% specific for psoriatic arthritis.9 Patients who answer yes to fewer than 3 questions should still be referred to a rheumatologist if there is a strong clinical suspicion of psoriatic arthritis.10

The PEST can be accessed for free in 13 languages via the GRAPPA (Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis) app as well as downloaded for free from the National Psoriasis Foundation’s website (https://www.psoriasis.org/psa-screening/providers).

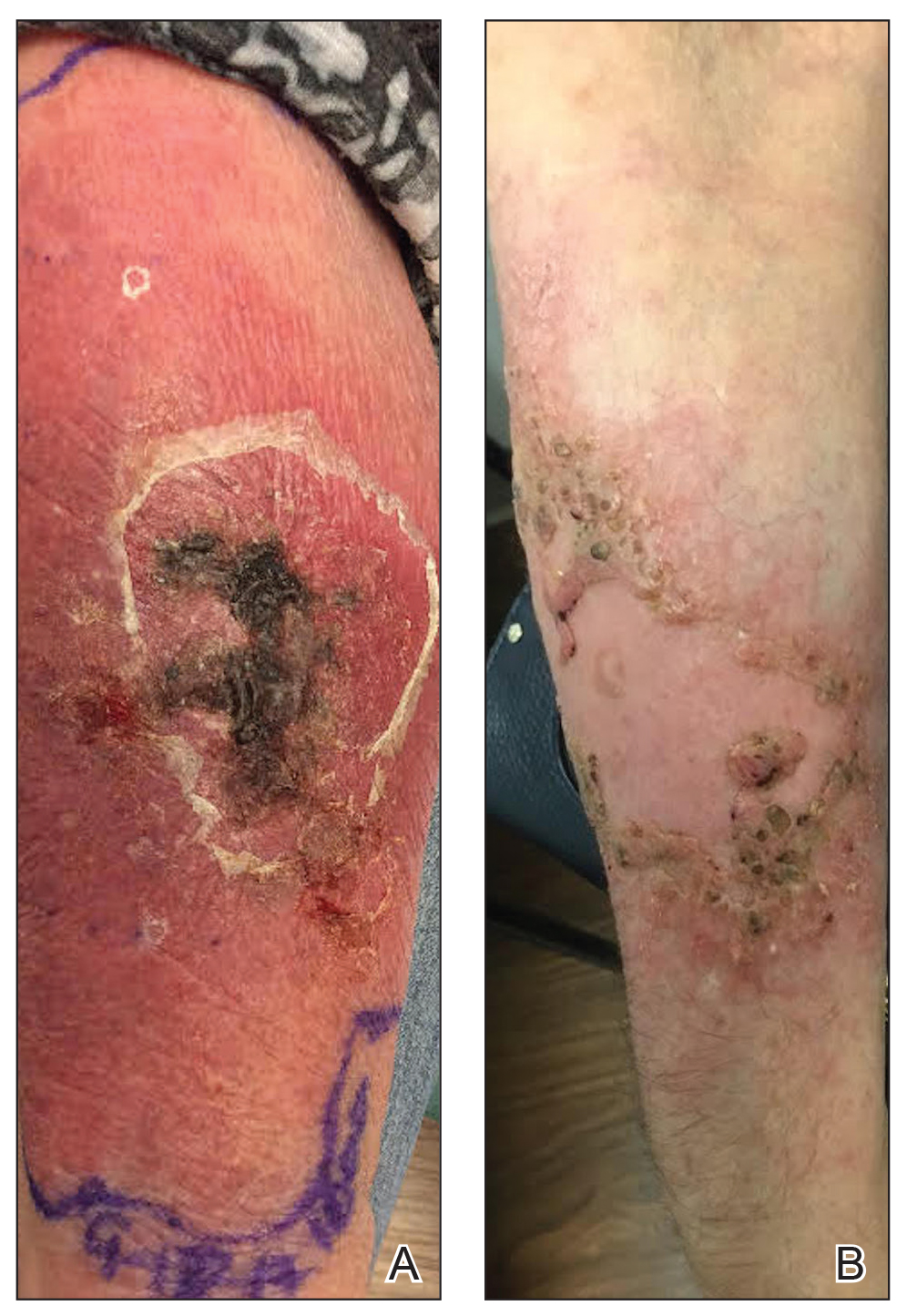

ALT-70 Differentiates Cellulitis From Pseudocellulitis

Overdiagnosing cellulitis in the United States has been estimated to result in up to 130,000 unnecessary hospitalizations and up to $515 million in avoidable health care spending.11 Dermatologists are in a unique position to help fix this issue. In one retrospective study of 1430 inpatient dermatology consultations, 74.32% of inpatients evaluated for presumed cellulitis by a dermatologist were instead diagnosed with a cellulitis mimicker (ie, pseudocellulitis), such as stasis dermatitis or contact dermatitis.12

The ALT-70 score was developed and prospectively validated to help differentiate lower extremity cellulitis from pseudocellulitis in adult patients in the emergency department (ED).13 In addition, the score has retrospectively been shown to function similarly in the inpatient setting when calculated at 24 and 48 hours after ED presentation.14 Although the ALT-70 score was designed for use by frontline clinicians prior to dermatology consultation, I also have found it helpful to calculate as a consultant, as it provides an objective measure of risk to communicate to the primary team in support of one diagnosis or another.

ALT-70 is an acronym for the score’s 4 variables: asymmetry, leukocytosis, tachycardia, and age of 70 years or older.15 If present, each variable confers a certain number of points to the final score: 3 points for asymmetry (defined as unilateral leg involvement), 1 point for leukocytosis (white blood cell count ≥10,000/μL), 1 point for tachycardia (≥90 beats per minute), and 2 points for age of 70 years or older. An ALT-70 score of 0 to 2 corresponds to an 83.3% or greater chance of pseudocellulitis, suggesting that the diagnosis of cellulitis be reconsidered. A score of 3 to 4 is indeterminate, and additional information such as a dermatology consultation should be pursued. A score of 5 to 7 corresponds to an 82.2% or greater chance of cellulitis, signifying that empiric treatment with antibiotics be considered.15

The ALT-70 score does not apply to cases involving areas other than the lower extremities; intravenous antibiotic use within 48 hours before ED presentation; surgery within the last 30 days; abscess; penetrating trauma; burn; or known history of osteomyelitis, diabetic ulcer, or indwelling hardware at the site of infection.15 The ALT-70 score is available for free via the MDCalc app and website (https://www.mdcalc.com/alt-70-score-cellulitis).

Mohs AUC Determines the Appropriateness of Mohs Micrographic Surgery

In 2012, the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and American Society for Mohs Surgery published appropriate use criteria (AUC) to guide the decision to pursue Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) in the United States.16 Based on various tumor and patient characteristics, the Mohs AUC assign scores to 270 different clinical scenarios. A score of 1 to 3 signifies that MMS is inappropriate and generally not considered acceptable. A score 4 to 6 indicates that the appropriateness of MMS is uncertain. A score 7 to 9 means that MMS is appropriate and generally considered acceptable.16

Since publication, the Mohs AUC have been criticized for classifying most primary superficial basal cell carcinomas as appropriate for MMS17 (which an AUC coauthor18 and others19,20 have defended), excluding certain reasons for performing MMS (such as operating on multiple tumors on the same day),21 including counterintuitive scores,22 and omitting trials from Europe23 (which AUC coauthors also have defended24).

Final Thoughts

Scoring systems are emerging in dermatology as evidence-based bedside tools to help guide clinical decision-making. Despite their limitations, these scores have the potential to make a meaningful impact in dermatology as they have in other specialties.

- Bastuji-Garin S, Fouchard N, Bertocchi M, et al. SCORTEN: a severity-of-illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:149-153.

- Guegan S, Bastuji-Garin S, Poszepczynska-Guigne E, et al. Performance of the SCORTEN during the first five days of hospitalization to predict the prognosis of epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:272-276.

- Micheletti RG, Chiesa-Fuxench Z, Noe MH, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis: a multicenter retrospective study of 377 adult patients from the United States. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:2315-2321.

- Sekula P, Liss Y, Davidovici B, et al. Evaluation of SCORTEN on a cohort of patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis included in the RegiSCAR study. J Burn Care Res. 2011;32:237-245.

- Noe MH, Rosenbach M, Hubbard RA, et al. Development and validation of a risk prediction model for in-hospital mortality among patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis-ABCD-10. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:448-454.

- Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen LE, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:251-265.e219.

- Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1073-1113.

- Karreman MC, Weel A, van der Ven M, et al. Performance of screening tools for psoriatic arthritis: a cross-sectional study in primary care. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56:597-602.

- Ibrahim GH, Buch MH, Lawson C, et al. Evaluation of an existing screening tool for psoriatic arthritis in people with psoriasis and the development of a new instrument: the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) questionnaire. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27:469-474.

- Zhang A, Kurtzman DJB, Perez-Chada LM, et al. Psoriatic arthritis and the dermatologist: an approach to screening and clinical evaluation. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:551-560.

- Weng QY, Raff AB, Cohen JM, et al. Costs and consequences associated with misdiagnosed lower extremity cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:141-146.

- Strazzula L, Cotliar J, Fox LP, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultation aids diagnosis of cellulitis among hospitalized patients: a multi-institutional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:70-75.

- Li DG, Dewan AK, Xia FD, et al. The ALT-70 predictive model outperforms thermal imaging for the diagnosis of lower extremity cellulitis: a prospective evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:1076-1080.e1071.

- Singer S, Li DG, Gunasekera N, et al. The ALT-70 predictive model maintains predictive value at 24 and 48 hours after presentation [published online March 23, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.050.

- Raff AB, Weng QY, Cohen JM, et al. A predictive model for diagnosis of lower extremity cellulitis: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:618-625.e2.

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550.

- Steinman HK, Dixon A, Zachary CB. Reevaluating Mohs surgery appropriate use criteria for primary superficial basal cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:755-756.

- Montuno MA, Coldiron BM. Mohs appropriate use criteria for superficial basal cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:394-395.

- MacFarlane DF, Perlis C. Mohs appropriate use criteria for superficial basal cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:395-396.

- Kantor J. Mohs appropriate use criteria for superficial basal cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:395.

- Ruiz ES, Karia PS, Morgan FC, et al. Multiple Mohs micrographic surgery is the most common reason for divergence from the appropriate use criteria: a single institution retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:830-831.

- Croley JA, Joseph AK, Wagner RF Jr. Discrepancies in the Mohs Micrographic Surgery appropriate use criteria [published online December 23, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.064.

- Kelleners-Smeets NW, Mosterd K. Comment on 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:317-318.

- Connolly S, Baker D, Coldiron B, et al. Reply to “comment on 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery.” J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:318.

The practice of dermatology is rife with bedside tools: swabs, smears, and scoring systems. First popularized in specialties such as emergency medicine and internal medicine, clinical scoring systems are now emerging in dermatology. These evidence-based scores can be calculated quickly at the bedside—often through a free smartphone app—to help guide clinical decision-making regarding diagnosis, prognosis, and management. As with any medical tool, scoring systems have limitations and should be used as a supplement, not substitute, for one’s clinical judgement. This article reviews 4 clinical scoring systems practical for dermatology residents.

SCORTEN Prognosticates Cases of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Perhaps the best-known scoring system in dermatology, the SCORTEN is widely used to predict hospital mortality from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. The SCORTEN includes 7 variables of equal weight—age of 40 years or older, heart rate of 120 beats per minute or more, cancer/hematologic malignancy, involved body surface area (BSA) greater than 10%, serum urea greater than 10 mmol/L, serum bicarbonate less than 20 mmol/L, and serum glucose greater than 14 mmol/L—each contributing 1 point to the overall score if present.1 The involved BSA is defined as the sum of detached and detachable epidermis.1

The SCORTEN was developed and prospectively validated to be calculated at the end of the first 24 hours of admission; for this calculation, use the BSA affected at that time, and use the most abnormal values during the first 24 hours of admission for the other variables.1 In addition, a follow-up study including some of the original coauthors recommends recalculating the SCORTEN at the end of hospital day 3, having found that the score’s predictive value was better on this day than hospital days 1, 2, 4, or 5.2 Based on the original study, a SCORTEN of 0 to 1 corresponds to a mortality rate of 3.2%, 2 to 12.1%, 3 to 35.3%, 4 to 58.3%, and 5 or greater to 90.0%.1

Limitations of the SCORTEN include its ability to overestimate or underestimate mortality as demonstrated by 2 multi-institutional cohorts.3,4 Recently, the ABCD-10 score was developed as an alternative to the SCORTEN and was found to predict mortality similarly when validated in an internal cohort.5

PEST Screens for Psoriatic Arthritis

Dermatologists play an important role in screening for psoriatic arthritis, as an estimated 1 in 5 patients with psoriasis have psoriatic arthritis.6 To this end, several screening tools have been developed to help differentiate psoriatic arthritis from other arthritides. Joint guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology and the National Psoriasis Foundation acknowledge that “. . . these screening tools have tended to perform less well when tested in groups of people other than those for which they were originally developed. As such, their usefulness in routine clinical practice remains controversial.”7 Nevertheless, the guidelines state, “[b]ecause screening and early detection of inflammatory arthritis are essential to optimize patient [quality of life] and reduce morbidity, providers may consider using a formal screening tool of their choice.”7

With these limitations in mind, I have found the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) to be the most useful psoriatic arthritis screening tool. One study determined that the PEST has the best trade-off between sensitivity and specificity compared to 2 other psoriatic arthritis screening tools, the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation (PASE) and the Early Arthritis for Psoriatic Patients (EARP).8

The PEST is comprised of 5 questions: (1) Have you ever had a swollen joint (or joints)? (2) Has a doctor ever told you that you have arthritis? (3) Do your fingernails or toenails have holes or pits? (4) Have you had pain in your heel? (5) Have you had a finger or toe that was completely swollen and painful for no apparent reason? According to the PEST, a referral to a rheumatologist should be considered for patients answering yes to 3 or more questions, which is 97% sensitive and 79% specific for psoriatic arthritis.9 Patients who answer yes to fewer than 3 questions should still be referred to a rheumatologist if there is a strong clinical suspicion of psoriatic arthritis.10

The PEST can be accessed for free in 13 languages via the GRAPPA (Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis) app as well as downloaded for free from the National Psoriasis Foundation’s website (https://www.psoriasis.org/psa-screening/providers).

ALT-70 Differentiates Cellulitis From Pseudocellulitis

Overdiagnosing cellulitis in the United States has been estimated to result in up to 130,000 unnecessary hospitalizations and up to $515 million in avoidable health care spending.11 Dermatologists are in a unique position to help fix this issue. In one retrospective study of 1430 inpatient dermatology consultations, 74.32% of inpatients evaluated for presumed cellulitis by a dermatologist were instead diagnosed with a cellulitis mimicker (ie, pseudocellulitis), such as stasis dermatitis or contact dermatitis.12

The ALT-70 score was developed and prospectively validated to help differentiate lower extremity cellulitis from pseudocellulitis in adult patients in the emergency department (ED).13 In addition, the score has retrospectively been shown to function similarly in the inpatient setting when calculated at 24 and 48 hours after ED presentation.14 Although the ALT-70 score was designed for use by frontline clinicians prior to dermatology consultation, I also have found it helpful to calculate as a consultant, as it provides an objective measure of risk to communicate to the primary team in support of one diagnosis or another.

ALT-70 is an acronym for the score’s 4 variables: asymmetry, leukocytosis, tachycardia, and age of 70 years or older.15 If present, each variable confers a certain number of points to the final score: 3 points for asymmetry (defined as unilateral leg involvement), 1 point for leukocytosis (white blood cell count ≥10,000/μL), 1 point for tachycardia (≥90 beats per minute), and 2 points for age of 70 years or older. An ALT-70 score of 0 to 2 corresponds to an 83.3% or greater chance of pseudocellulitis, suggesting that the diagnosis of cellulitis be reconsidered. A score of 3 to 4 is indeterminate, and additional information such as a dermatology consultation should be pursued. A score of 5 to 7 corresponds to an 82.2% or greater chance of cellulitis, signifying that empiric treatment with antibiotics be considered.15

The ALT-70 score does not apply to cases involving areas other than the lower extremities; intravenous antibiotic use within 48 hours before ED presentation; surgery within the last 30 days; abscess; penetrating trauma; burn; or known history of osteomyelitis, diabetic ulcer, or indwelling hardware at the site of infection.15 The ALT-70 score is available for free via the MDCalc app and website (https://www.mdcalc.com/alt-70-score-cellulitis).

Mohs AUC Determines the Appropriateness of Mohs Micrographic Surgery

In 2012, the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and American Society for Mohs Surgery published appropriate use criteria (AUC) to guide the decision to pursue Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) in the United States.16 Based on various tumor and patient characteristics, the Mohs AUC assign scores to 270 different clinical scenarios. A score of 1 to 3 signifies that MMS is inappropriate and generally not considered acceptable. A score 4 to 6 indicates that the appropriateness of MMS is uncertain. A score 7 to 9 means that MMS is appropriate and generally considered acceptable.16

Since publication, the Mohs AUC have been criticized for classifying most primary superficial basal cell carcinomas as appropriate for MMS17 (which an AUC coauthor18 and others19,20 have defended), excluding certain reasons for performing MMS (such as operating on multiple tumors on the same day),21 including counterintuitive scores,22 and omitting trials from Europe23 (which AUC coauthors also have defended24).

Final Thoughts

Scoring systems are emerging in dermatology as evidence-based bedside tools to help guide clinical decision-making. Despite their limitations, these scores have the potential to make a meaningful impact in dermatology as they have in other specialties.

The practice of dermatology is rife with bedside tools: swabs, smears, and scoring systems. First popularized in specialties such as emergency medicine and internal medicine, clinical scoring systems are now emerging in dermatology. These evidence-based scores can be calculated quickly at the bedside—often through a free smartphone app—to help guide clinical decision-making regarding diagnosis, prognosis, and management. As with any medical tool, scoring systems have limitations and should be used as a supplement, not substitute, for one’s clinical judgement. This article reviews 4 clinical scoring systems practical for dermatology residents.

SCORTEN Prognosticates Cases of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Perhaps the best-known scoring system in dermatology, the SCORTEN is widely used to predict hospital mortality from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. The SCORTEN includes 7 variables of equal weight—age of 40 years or older, heart rate of 120 beats per minute or more, cancer/hematologic malignancy, involved body surface area (BSA) greater than 10%, serum urea greater than 10 mmol/L, serum bicarbonate less than 20 mmol/L, and serum glucose greater than 14 mmol/L—each contributing 1 point to the overall score if present.1 The involved BSA is defined as the sum of detached and detachable epidermis.1

The SCORTEN was developed and prospectively validated to be calculated at the end of the first 24 hours of admission; for this calculation, use the BSA affected at that time, and use the most abnormal values during the first 24 hours of admission for the other variables.1 In addition, a follow-up study including some of the original coauthors recommends recalculating the SCORTEN at the end of hospital day 3, having found that the score’s predictive value was better on this day than hospital days 1, 2, 4, or 5.2 Based on the original study, a SCORTEN of 0 to 1 corresponds to a mortality rate of 3.2%, 2 to 12.1%, 3 to 35.3%, 4 to 58.3%, and 5 or greater to 90.0%.1

Limitations of the SCORTEN include its ability to overestimate or underestimate mortality as demonstrated by 2 multi-institutional cohorts.3,4 Recently, the ABCD-10 score was developed as an alternative to the SCORTEN and was found to predict mortality similarly when validated in an internal cohort.5

PEST Screens for Psoriatic Arthritis

Dermatologists play an important role in screening for psoriatic arthritis, as an estimated 1 in 5 patients with psoriasis have psoriatic arthritis.6 To this end, several screening tools have been developed to help differentiate psoriatic arthritis from other arthritides. Joint guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology and the National Psoriasis Foundation acknowledge that “. . . these screening tools have tended to perform less well when tested in groups of people other than those for which they were originally developed. As such, their usefulness in routine clinical practice remains controversial.”7 Nevertheless, the guidelines state, “[b]ecause screening and early detection of inflammatory arthritis are essential to optimize patient [quality of life] and reduce morbidity, providers may consider using a formal screening tool of their choice.”7

With these limitations in mind, I have found the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) to be the most useful psoriatic arthritis screening tool. One study determined that the PEST has the best trade-off between sensitivity and specificity compared to 2 other psoriatic arthritis screening tools, the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation (PASE) and the Early Arthritis for Psoriatic Patients (EARP).8

The PEST is comprised of 5 questions: (1) Have you ever had a swollen joint (or joints)? (2) Has a doctor ever told you that you have arthritis? (3) Do your fingernails or toenails have holes or pits? (4) Have you had pain in your heel? (5) Have you had a finger or toe that was completely swollen and painful for no apparent reason? According to the PEST, a referral to a rheumatologist should be considered for patients answering yes to 3 or more questions, which is 97% sensitive and 79% specific for psoriatic arthritis.9 Patients who answer yes to fewer than 3 questions should still be referred to a rheumatologist if there is a strong clinical suspicion of psoriatic arthritis.10

The PEST can be accessed for free in 13 languages via the GRAPPA (Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis) app as well as downloaded for free from the National Psoriasis Foundation’s website (https://www.psoriasis.org/psa-screening/providers).

ALT-70 Differentiates Cellulitis From Pseudocellulitis

Overdiagnosing cellulitis in the United States has been estimated to result in up to 130,000 unnecessary hospitalizations and up to $515 million in avoidable health care spending.11 Dermatologists are in a unique position to help fix this issue. In one retrospective study of 1430 inpatient dermatology consultations, 74.32% of inpatients evaluated for presumed cellulitis by a dermatologist were instead diagnosed with a cellulitis mimicker (ie, pseudocellulitis), such as stasis dermatitis or contact dermatitis.12

The ALT-70 score was developed and prospectively validated to help differentiate lower extremity cellulitis from pseudocellulitis in adult patients in the emergency department (ED).13 In addition, the score has retrospectively been shown to function similarly in the inpatient setting when calculated at 24 and 48 hours after ED presentation.14 Although the ALT-70 score was designed for use by frontline clinicians prior to dermatology consultation, I also have found it helpful to calculate as a consultant, as it provides an objective measure of risk to communicate to the primary team in support of one diagnosis or another.

ALT-70 is an acronym for the score’s 4 variables: asymmetry, leukocytosis, tachycardia, and age of 70 years or older.15 If present, each variable confers a certain number of points to the final score: 3 points for asymmetry (defined as unilateral leg involvement), 1 point for leukocytosis (white blood cell count ≥10,000/μL), 1 point for tachycardia (≥90 beats per minute), and 2 points for age of 70 years or older. An ALT-70 score of 0 to 2 corresponds to an 83.3% or greater chance of pseudocellulitis, suggesting that the diagnosis of cellulitis be reconsidered. A score of 3 to 4 is indeterminate, and additional information such as a dermatology consultation should be pursued. A score of 5 to 7 corresponds to an 82.2% or greater chance of cellulitis, signifying that empiric treatment with antibiotics be considered.15

The ALT-70 score does not apply to cases involving areas other than the lower extremities; intravenous antibiotic use within 48 hours before ED presentation; surgery within the last 30 days; abscess; penetrating trauma; burn; or known history of osteomyelitis, diabetic ulcer, or indwelling hardware at the site of infection.15 The ALT-70 score is available for free via the MDCalc app and website (https://www.mdcalc.com/alt-70-score-cellulitis).

Mohs AUC Determines the Appropriateness of Mohs Micrographic Surgery

In 2012, the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and American Society for Mohs Surgery published appropriate use criteria (AUC) to guide the decision to pursue Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) in the United States.16 Based on various tumor and patient characteristics, the Mohs AUC assign scores to 270 different clinical scenarios. A score of 1 to 3 signifies that MMS is inappropriate and generally not considered acceptable. A score 4 to 6 indicates that the appropriateness of MMS is uncertain. A score 7 to 9 means that MMS is appropriate and generally considered acceptable.16

Since publication, the Mohs AUC have been criticized for classifying most primary superficial basal cell carcinomas as appropriate for MMS17 (which an AUC coauthor18 and others19,20 have defended), excluding certain reasons for performing MMS (such as operating on multiple tumors on the same day),21 including counterintuitive scores,22 and omitting trials from Europe23 (which AUC coauthors also have defended24).

Final Thoughts

Scoring systems are emerging in dermatology as evidence-based bedside tools to help guide clinical decision-making. Despite their limitations, these scores have the potential to make a meaningful impact in dermatology as they have in other specialties.

- Bastuji-Garin S, Fouchard N, Bertocchi M, et al. SCORTEN: a severity-of-illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:149-153.

- Guegan S, Bastuji-Garin S, Poszepczynska-Guigne E, et al. Performance of the SCORTEN during the first five days of hospitalization to predict the prognosis of epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:272-276.

- Micheletti RG, Chiesa-Fuxench Z, Noe MH, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis: a multicenter retrospective study of 377 adult patients from the United States. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:2315-2321.

- Sekula P, Liss Y, Davidovici B, et al. Evaluation of SCORTEN on a cohort of patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis included in the RegiSCAR study. J Burn Care Res. 2011;32:237-245.

- Noe MH, Rosenbach M, Hubbard RA, et al. Development and validation of a risk prediction model for in-hospital mortality among patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis-ABCD-10. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:448-454.

- Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen LE, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:251-265.e219.

- Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1073-1113.

- Karreman MC, Weel A, van der Ven M, et al. Performance of screening tools for psoriatic arthritis: a cross-sectional study in primary care. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56:597-602.

- Ibrahim GH, Buch MH, Lawson C, et al. Evaluation of an existing screening tool for psoriatic arthritis in people with psoriasis and the development of a new instrument: the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) questionnaire. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27:469-474.

- Zhang A, Kurtzman DJB, Perez-Chada LM, et al. Psoriatic arthritis and the dermatologist: an approach to screening and clinical evaluation. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:551-560.

- Weng QY, Raff AB, Cohen JM, et al. Costs and consequences associated with misdiagnosed lower extremity cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:141-146.

- Strazzula L, Cotliar J, Fox LP, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultation aids diagnosis of cellulitis among hospitalized patients: a multi-institutional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:70-75.

- Li DG, Dewan AK, Xia FD, et al. The ALT-70 predictive model outperforms thermal imaging for the diagnosis of lower extremity cellulitis: a prospective evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:1076-1080.e1071.

- Singer S, Li DG, Gunasekera N, et al. The ALT-70 predictive model maintains predictive value at 24 and 48 hours after presentation [published online March 23, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.050.

- Raff AB, Weng QY, Cohen JM, et al. A predictive model for diagnosis of lower extremity cellulitis: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:618-625.e2.

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550.

- Steinman HK, Dixon A, Zachary CB. Reevaluating Mohs surgery appropriate use criteria for primary superficial basal cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:755-756.

- Montuno MA, Coldiron BM. Mohs appropriate use criteria for superficial basal cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:394-395.

- MacFarlane DF, Perlis C. Mohs appropriate use criteria for superficial basal cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:395-396.

- Kantor J. Mohs appropriate use criteria for superficial basal cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:395.

- Ruiz ES, Karia PS, Morgan FC, et al. Multiple Mohs micrographic surgery is the most common reason for divergence from the appropriate use criteria: a single institution retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:830-831.

- Croley JA, Joseph AK, Wagner RF Jr. Discrepancies in the Mohs Micrographic Surgery appropriate use criteria [published online December 23, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.064.

- Kelleners-Smeets NW, Mosterd K. Comment on 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:317-318.

- Connolly S, Baker D, Coldiron B, et al. Reply to “comment on 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery.” J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:318.

- Bastuji-Garin S, Fouchard N, Bertocchi M, et al. SCORTEN: a severity-of-illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:149-153.

- Guegan S, Bastuji-Garin S, Poszepczynska-Guigne E, et al. Performance of the SCORTEN during the first five days of hospitalization to predict the prognosis of epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:272-276.

- Micheletti RG, Chiesa-Fuxench Z, Noe MH, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis: a multicenter retrospective study of 377 adult patients from the United States. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:2315-2321.

- Sekula P, Liss Y, Davidovici B, et al. Evaluation of SCORTEN on a cohort of patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis included in the RegiSCAR study. J Burn Care Res. 2011;32:237-245.

- Noe MH, Rosenbach M, Hubbard RA, et al. Development and validation of a risk prediction model for in-hospital mortality among patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis-ABCD-10. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:448-454.

- Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen LE, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:251-265.e219.

- Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1073-1113.

- Karreman MC, Weel A, van der Ven M, et al. Performance of screening tools for psoriatic arthritis: a cross-sectional study in primary care. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56:597-602.

- Ibrahim GH, Buch MH, Lawson C, et al. Evaluation of an existing screening tool for psoriatic arthritis in people with psoriasis and the development of a new instrument: the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) questionnaire. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27:469-474.

- Zhang A, Kurtzman DJB, Perez-Chada LM, et al. Psoriatic arthritis and the dermatologist: an approach to screening and clinical evaluation. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:551-560.

- Weng QY, Raff AB, Cohen JM, et al. Costs and consequences associated with misdiagnosed lower extremity cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:141-146.

- Strazzula L, Cotliar J, Fox LP, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultation aids diagnosis of cellulitis among hospitalized patients: a multi-institutional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:70-75.

- Li DG, Dewan AK, Xia FD, et al. The ALT-70 predictive model outperforms thermal imaging for the diagnosis of lower extremity cellulitis: a prospective evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:1076-1080.e1071.

- Singer S, Li DG, Gunasekera N, et al. The ALT-70 predictive model maintains predictive value at 24 and 48 hours after presentation [published online March 23, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.050.

- Raff AB, Weng QY, Cohen JM, et al. A predictive model for diagnosis of lower extremity cellulitis: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:618-625.e2.

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550.

- Steinman HK, Dixon A, Zachary CB. Reevaluating Mohs surgery appropriate use criteria for primary superficial basal cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:755-756.

- Montuno MA, Coldiron BM. Mohs appropriate use criteria for superficial basal cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:394-395.

- MacFarlane DF, Perlis C. Mohs appropriate use criteria for superficial basal cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:395-396.

- Kantor J. Mohs appropriate use criteria for superficial basal cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:395.

- Ruiz ES, Karia PS, Morgan FC, et al. Multiple Mohs micrographic surgery is the most common reason for divergence from the appropriate use criteria: a single institution retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:830-831.

- Croley JA, Joseph AK, Wagner RF Jr. Discrepancies in the Mohs Micrographic Surgery appropriate use criteria [published online December 23, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.064.

- Kelleners-Smeets NW, Mosterd K. Comment on 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:317-318.

- Connolly S, Baker D, Coldiron B, et al. Reply to “comment on 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery.” J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:318.

Resident Pearls

- Mortality from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis can be estimated by calculating the SCORTEN at the end of days 1 and 3 of hospitalization.

- The Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) assists with triaging which patients with psoriasis should be evaluated for psoriatic arthritis by a rheumatologist.

- The ALT-70 score is helpful to support one’s diagnosis of cellulitis or pseudocellulitis.

- The Mohs appropriate use criteria (AUC) score 270 different clinical scenarios as appropriate, uncertain, or inappropriate for Mohs micrographic surgery.

Guttate Psoriasis Following Presumed Coxsackievirus A

There are 4 variants of psoriasis: plaque, guttate, pustular, and erythroderma (in order of prevalence).2 Guttate psoriasis is characterized by small, 2- to 10-mm, raindroplike lesions on the skin.1 It accounts for approximately 2% of total psoriasis cases and is commonly triggered by group A streptococcal pharyngitis or tonsillitis.3,4

Hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) is an illness most commonly caused by a coxsackievirus A infection but also can be caused by other enteroviruses.5,6 Coxsackievirus is a serotype of the Enterovirus species within the Picornaviridae family.7 Hand-foot-and-mouth disease is characterized by a brief fever and vesicular rashes on the palms, soles, or buttocks, as well as oropharyngeal ulcers.8 Typically, the rash is benign and short-lived.9 In rare cases, neurologic complications develop. There have been no reported cases of guttate psoriasis following a coxsackievirus A infection.

The involvement of coxsackievirus B in the etiopathogenesis of psoriasis has been previously reported.10 We report the case of guttate psoriasis following presumed coxsackievirus A HFMD.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman presented with a vesicular rash on the hands, feet, and lips. The patient reported having a sore throat that started around the same time that the rash developed. The severity of the sore throat was rated as moderate. No fever was reported. One day prior, the patient’s primary care physician prescribed a tapered course of prednisone for the rash. The patient reported a medical history of herpes zoster virus, sunburn, and genital herpes. She was taking clonazepam and had a known allergy to penicillin.

Physical examination revealed erythematous vesicular and papular lesions on the extensor surfaces of the hands and feet. Vesicles also were noted on the vermilion border of the lip. Examination of the patient’s mouth showed blisters and shallow ulcerations in the oral cavity. A clinical diagnosis of coxsackievirus A HFMD was made, and the treatment plan included triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.025% applied twice daily for 2 weeks and oral valacyclovir hydrochloride 1 g taken 3 times daily for 7 days. A topical emollient also was recommended for the lips when necessary. The lesions all resolved within a 2-week period with no sequela.

The patient returned 1 month later, citing newer red abdominal skin lesions. Fever was denied. She reported that both prescribed treatments had not been helping for the newer lesions. She noticed similar lesions on the groin and brought them to the attention of her gynecologist. Physical examination revealed salmon pink papules and plaques with silvery scaling involving the abdomen, bilateral upper extremities and ears, and scalp. The patient was then clinically diagnosed with guttate psoriasis. A shave biopsy of a representative lesion on the abdomen was performed. The treatment plan included betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05% applied twice daily for 2 weeks, clobetasol propionate solution 0.05% applied twice daily for 14 days (for the scalp), and hydrocortisone valerate cream 0.2% applied twice daily for 14 days (for the groin).

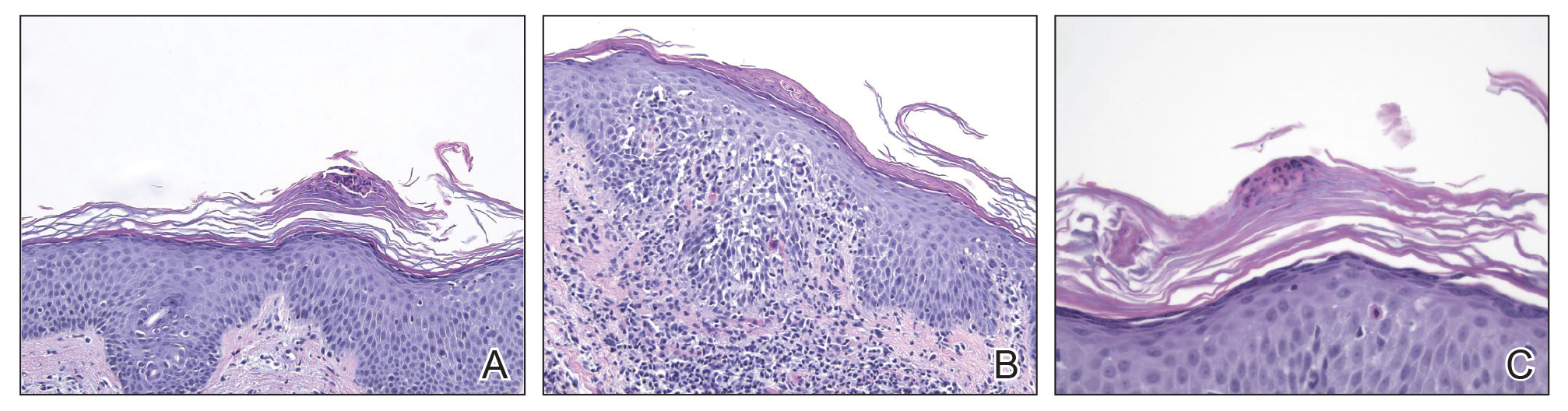

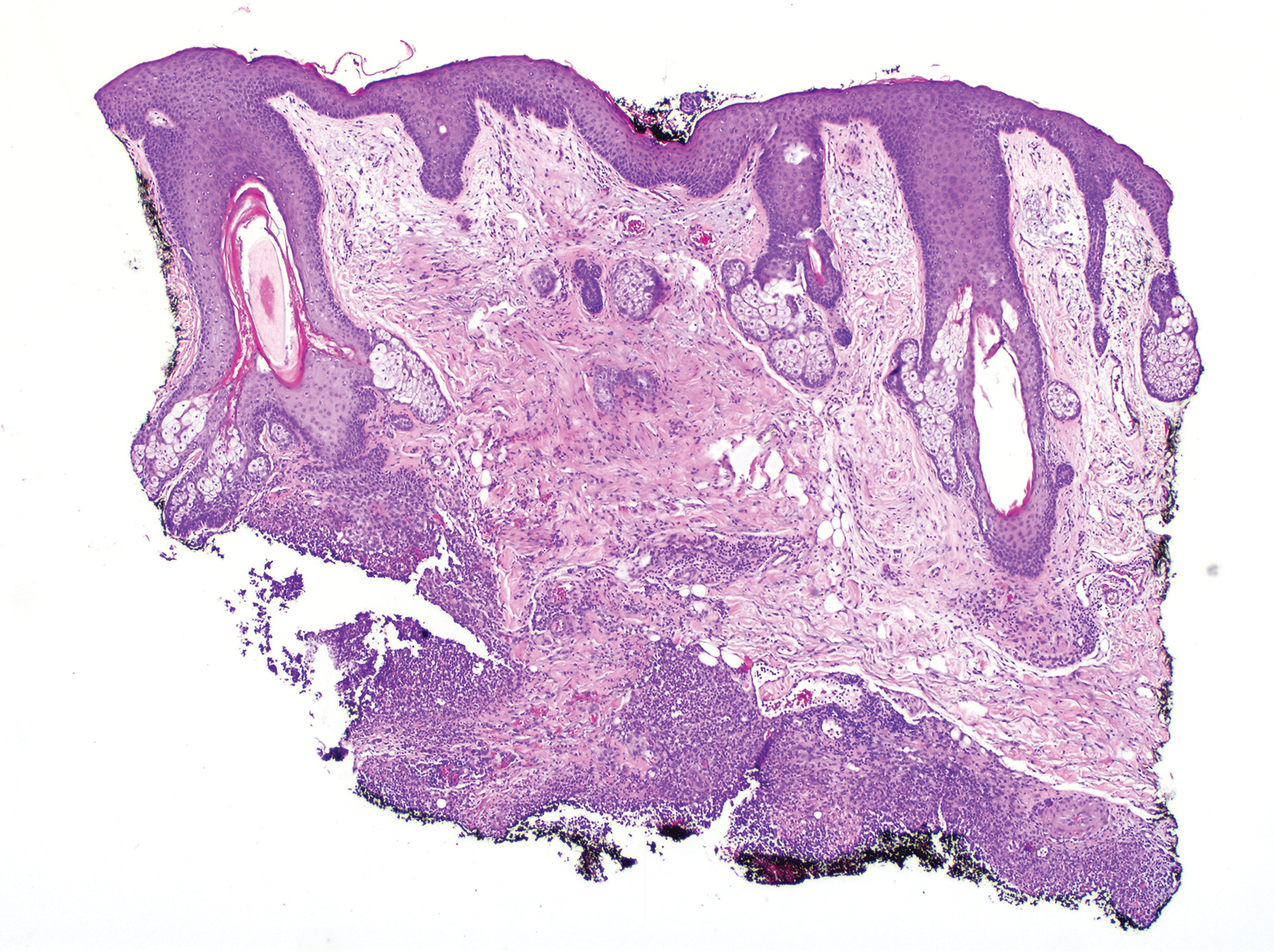

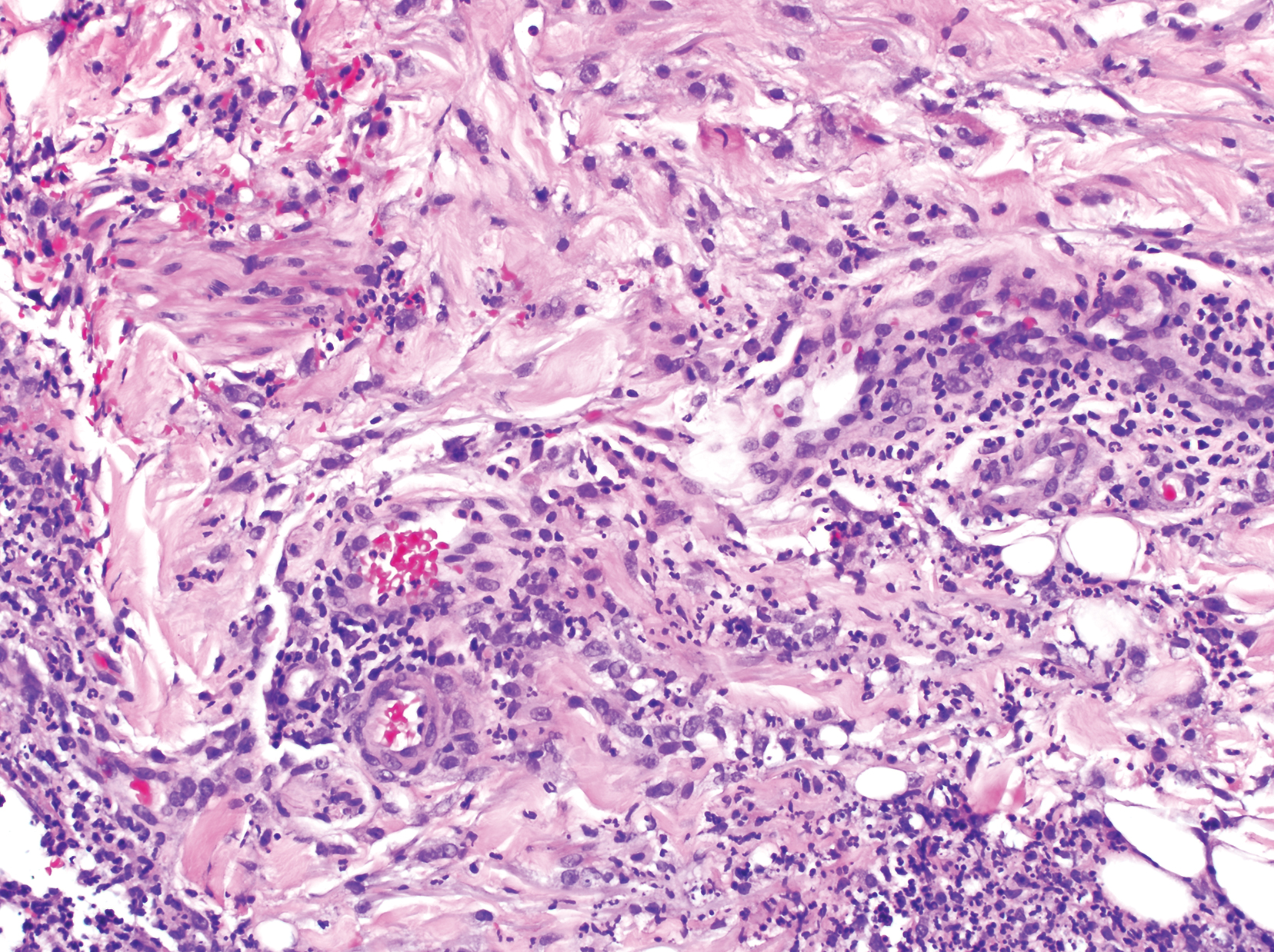

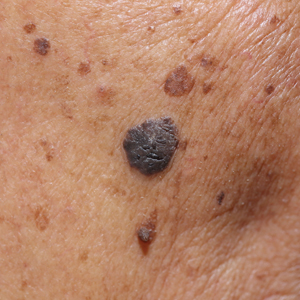

The skin biopsy shown in the Figure was received in 10% buffered formalin, measuring 5×4×1 mm of skin. Sections showed an acanthotic epidermis with foci of spongiosis and hypergranulosis covered by mounds of parakeratosis infiltrated by neutrophils. Superficial perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic inflammation was present. Tortuous blood vessels within the papillary dermis also were present. Results showed psoriasiform dermatitis with mild spongiosis. Periodic acid–Schiff stain did not reveal any fungal organisms. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of guttate psoriasis.

The patient then returned 1 month later mentioning continued flare-ups of the scalp as well as newer patches on the arms and hands that were less eruptive and faded more quickly. The plaques in the groin area had resolved. Physical examination showed fewer pink papules and plaques with silvery scaling on the abdomen, bilateral upper extremities and ears, and scalp. Topical medications were continued, and possible apremilast therapy for the psoriasis was discussed.

Comment

Enterovirus-derived HFMD likely is caused by coxsackie-virus A. Current evidence supports the theory that guttate psoriasis can be environmentally triggered in genetically susceptible individuals, often but not exclusively by a streptococcal infection. The causative agent elicits a T-cell–mediated reaction leading to increased type 1 helper T cells, IFN-γ, and IL-2 cytokine levels. HLA-Cw∗0602–positive patients are considered genetically susceptible and more likely to develop guttate psoriasis following an environmental trigger. Based on the coincidence in timing of both diagnoses, this reported case of guttate psoriasis may have been triggered by a coxsackievirus A infection.

- Langley RG, Krueger GG, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(suppl 2):ii18-ii23.

- Sarac G, Koca TT, Baglan T. A brief summary of clinical types of psoriasis. North Clin Istanb. 2016;1:79-82.

- Prinz JC. Psoriasis vulgaris—a sterile antibacterial skin reaction mediated by cross-reactive T cells? an immunological view of the pathophysiology of psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:326-332.

- Telfer N, Chalmers RJ, Whale K, et al. The role of streptococcal infection in the initiation of guttate psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:39-42.

- Cabrerizo M, Tarragó D, Muñoz-Almagro C, et al. Molecular epidemiology of enterovirus 71, coxsackievirus A16 and A6 associated with hand, foot and mouth disease in Spain. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:O150-O156.

- Li Y, Chang Z, Wu P, et al. Emerging enteroviruses causing hand, foot and mouth disease, China, 2010-2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:1902-1906.

- Seitsonen J, Shakeel S, Susi P, et al. Structural analysis of coxsackievirus A7 reveals conformational changes associated with uncoating. J Virol. 2012;86:7207-7215.

- Wu Y, Yeo A, Phoon M, et al. The largest outbreak of hand; foot and mouth disease in Singapore in 2008: the role of enterovirus 71 and coxsackievirus A strains. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:E1076-E1081.

- Tesini BL. Hand-foot-and-mouth-disease (HFMD). May 2018. https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/infectious-diseases/enteroviruses/hand-foot-and-mouth-disease-hfmd. Accessed September 25, 2019.

- Korzhova TP, Shyrobokov VP, Koliadenko VH, et al. Coxsackie B viral infection in the etiology and clinical pathogenesis of psoriasis [in Ukrainian]. Lik Sprava. 2001:54-58.

There are 4 variants of psoriasis: plaque, guttate, pustular, and erythroderma (in order of prevalence).2 Guttate psoriasis is characterized by small, 2- to 10-mm, raindroplike lesions on the skin.1 It accounts for approximately 2% of total psoriasis cases and is commonly triggered by group A streptococcal pharyngitis or tonsillitis.3,4

Hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) is an illness most commonly caused by a coxsackievirus A infection but also can be caused by other enteroviruses.5,6 Coxsackievirus is a serotype of the Enterovirus species within the Picornaviridae family.7 Hand-foot-and-mouth disease is characterized by a brief fever and vesicular rashes on the palms, soles, or buttocks, as well as oropharyngeal ulcers.8 Typically, the rash is benign and short-lived.9 In rare cases, neurologic complications develop. There have been no reported cases of guttate psoriasis following a coxsackievirus A infection.

The involvement of coxsackievirus B in the etiopathogenesis of psoriasis has been previously reported.10 We report the case of guttate psoriasis following presumed coxsackievirus A HFMD.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman presented with a vesicular rash on the hands, feet, and lips. The patient reported having a sore throat that started around the same time that the rash developed. The severity of the sore throat was rated as moderate. No fever was reported. One day prior, the patient’s primary care physician prescribed a tapered course of prednisone for the rash. The patient reported a medical history of herpes zoster virus, sunburn, and genital herpes. She was taking clonazepam and had a known allergy to penicillin.

Physical examination revealed erythematous vesicular and papular lesions on the extensor surfaces of the hands and feet. Vesicles also were noted on the vermilion border of the lip. Examination of the patient’s mouth showed blisters and shallow ulcerations in the oral cavity. A clinical diagnosis of coxsackievirus A HFMD was made, and the treatment plan included triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.025% applied twice daily for 2 weeks and oral valacyclovir hydrochloride 1 g taken 3 times daily for 7 days. A topical emollient also was recommended for the lips when necessary. The lesions all resolved within a 2-week period with no sequela.

The patient returned 1 month later, citing newer red abdominal skin lesions. Fever was denied. She reported that both prescribed treatments had not been helping for the newer lesions. She noticed similar lesions on the groin and brought them to the attention of her gynecologist. Physical examination revealed salmon pink papules and plaques with silvery scaling involving the abdomen, bilateral upper extremities and ears, and scalp. The patient was then clinically diagnosed with guttate psoriasis. A shave biopsy of a representative lesion on the abdomen was performed. The treatment plan included betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05% applied twice daily for 2 weeks, clobetasol propionate solution 0.05% applied twice daily for 14 days (for the scalp), and hydrocortisone valerate cream 0.2% applied twice daily for 14 days (for the groin).

The skin biopsy shown in the Figure was received in 10% buffered formalin, measuring 5×4×1 mm of skin. Sections showed an acanthotic epidermis with foci of spongiosis and hypergranulosis covered by mounds of parakeratosis infiltrated by neutrophils. Superficial perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic inflammation was present. Tortuous blood vessels within the papillary dermis also were present. Results showed psoriasiform dermatitis with mild spongiosis. Periodic acid–Schiff stain did not reveal any fungal organisms. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of guttate psoriasis.

The patient then returned 1 month later mentioning continued flare-ups of the scalp as well as newer patches on the arms and hands that were less eruptive and faded more quickly. The plaques in the groin area had resolved. Physical examination showed fewer pink papules and plaques with silvery scaling on the abdomen, bilateral upper extremities and ears, and scalp. Topical medications were continued, and possible apremilast therapy for the psoriasis was discussed.

Comment

Enterovirus-derived HFMD likely is caused by coxsackie-virus A. Current evidence supports the theory that guttate psoriasis can be environmentally triggered in genetically susceptible individuals, often but not exclusively by a streptococcal infection. The causative agent elicits a T-cell–mediated reaction leading to increased type 1 helper T cells, IFN-γ, and IL-2 cytokine levels. HLA-Cw∗0602–positive patients are considered genetically susceptible and more likely to develop guttate psoriasis following an environmental trigger. Based on the coincidence in timing of both diagnoses, this reported case of guttate psoriasis may have been triggered by a coxsackievirus A infection.

There are 4 variants of psoriasis: plaque, guttate, pustular, and erythroderma (in order of prevalence).2 Guttate psoriasis is characterized by small, 2- to 10-mm, raindroplike lesions on the skin.1 It accounts for approximately 2% of total psoriasis cases and is commonly triggered by group A streptococcal pharyngitis or tonsillitis.3,4

Hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) is an illness most commonly caused by a coxsackievirus A infection but also can be caused by other enteroviruses.5,6 Coxsackievirus is a serotype of the Enterovirus species within the Picornaviridae family.7 Hand-foot-and-mouth disease is characterized by a brief fever and vesicular rashes on the palms, soles, or buttocks, as well as oropharyngeal ulcers.8 Typically, the rash is benign and short-lived.9 In rare cases, neurologic complications develop. There have been no reported cases of guttate psoriasis following a coxsackievirus A infection.

The involvement of coxsackievirus B in the etiopathogenesis of psoriasis has been previously reported.10 We report the case of guttate psoriasis following presumed coxsackievirus A HFMD.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman presented with a vesicular rash on the hands, feet, and lips. The patient reported having a sore throat that started around the same time that the rash developed. The severity of the sore throat was rated as moderate. No fever was reported. One day prior, the patient’s primary care physician prescribed a tapered course of prednisone for the rash. The patient reported a medical history of herpes zoster virus, sunburn, and genital herpes. She was taking clonazepam and had a known allergy to penicillin.

Physical examination revealed erythematous vesicular and papular lesions on the extensor surfaces of the hands and feet. Vesicles also were noted on the vermilion border of the lip. Examination of the patient’s mouth showed blisters and shallow ulcerations in the oral cavity. A clinical diagnosis of coxsackievirus A HFMD was made, and the treatment plan included triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.025% applied twice daily for 2 weeks and oral valacyclovir hydrochloride 1 g taken 3 times daily for 7 days. A topical emollient also was recommended for the lips when necessary. The lesions all resolved within a 2-week period with no sequela.

The patient returned 1 month later, citing newer red abdominal skin lesions. Fever was denied. She reported that both prescribed treatments had not been helping for the newer lesions. She noticed similar lesions on the groin and brought them to the attention of her gynecologist. Physical examination revealed salmon pink papules and plaques with silvery scaling involving the abdomen, bilateral upper extremities and ears, and scalp. The patient was then clinically diagnosed with guttate psoriasis. A shave biopsy of a representative lesion on the abdomen was performed. The treatment plan included betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05% applied twice daily for 2 weeks, clobetasol propionate solution 0.05% applied twice daily for 14 days (for the scalp), and hydrocortisone valerate cream 0.2% applied twice daily for 14 days (for the groin).

The skin biopsy shown in the Figure was received in 10% buffered formalin, measuring 5×4×1 mm of skin. Sections showed an acanthotic epidermis with foci of spongiosis and hypergranulosis covered by mounds of parakeratosis infiltrated by neutrophils. Superficial perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic inflammation was present. Tortuous blood vessels within the papillary dermis also were present. Results showed psoriasiform dermatitis with mild spongiosis. Periodic acid–Schiff stain did not reveal any fungal organisms. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of guttate psoriasis.

The patient then returned 1 month later mentioning continued flare-ups of the scalp as well as newer patches on the arms and hands that were less eruptive and faded more quickly. The plaques in the groin area had resolved. Physical examination showed fewer pink papules and plaques with silvery scaling on the abdomen, bilateral upper extremities and ears, and scalp. Topical medications were continued, and possible apremilast therapy for the psoriasis was discussed.

Comment

Enterovirus-derived HFMD likely is caused by coxsackie-virus A. Current evidence supports the theory that guttate psoriasis can be environmentally triggered in genetically susceptible individuals, often but not exclusively by a streptococcal infection. The causative agent elicits a T-cell–mediated reaction leading to increased type 1 helper T cells, IFN-γ, and IL-2 cytokine levels. HLA-Cw∗0602–positive patients are considered genetically susceptible and more likely to develop guttate psoriasis following an environmental trigger. Based on the coincidence in timing of both diagnoses, this reported case of guttate psoriasis may have been triggered by a coxsackievirus A infection.

- Langley RG, Krueger GG, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(suppl 2):ii18-ii23.

- Sarac G, Koca TT, Baglan T. A brief summary of clinical types of psoriasis. North Clin Istanb. 2016;1:79-82.

- Prinz JC. Psoriasis vulgaris—a sterile antibacterial skin reaction mediated by cross-reactive T cells? an immunological view of the pathophysiology of psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:326-332.

- Telfer N, Chalmers RJ, Whale K, et al. The role of streptococcal infection in the initiation of guttate psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:39-42.

- Cabrerizo M, Tarragó D, Muñoz-Almagro C, et al. Molecular epidemiology of enterovirus 71, coxsackievirus A16 and A6 associated with hand, foot and mouth disease in Spain. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:O150-O156.

- Li Y, Chang Z, Wu P, et al. Emerging enteroviruses causing hand, foot and mouth disease, China, 2010-2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:1902-1906.

- Seitsonen J, Shakeel S, Susi P, et al. Structural analysis of coxsackievirus A7 reveals conformational changes associated with uncoating. J Virol. 2012;86:7207-7215.

- Wu Y, Yeo A, Phoon M, et al. The largest outbreak of hand; foot and mouth disease in Singapore in 2008: the role of enterovirus 71 and coxsackievirus A strains. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:E1076-E1081.

- Tesini BL. Hand-foot-and-mouth-disease (HFMD). May 2018. https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/infectious-diseases/enteroviruses/hand-foot-and-mouth-disease-hfmd. Accessed September 25, 2019.

- Korzhova TP, Shyrobokov VP, Koliadenko VH, et al. Coxsackie B viral infection in the etiology and clinical pathogenesis of psoriasis [in Ukrainian]. Lik Sprava. 2001:54-58.

- Langley RG, Krueger GG, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(suppl 2):ii18-ii23.

- Sarac G, Koca TT, Baglan T. A brief summary of clinical types of psoriasis. North Clin Istanb. 2016;1:79-82.

- Prinz JC. Psoriasis vulgaris—a sterile antibacterial skin reaction mediated by cross-reactive T cells? an immunological view of the pathophysiology of psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:326-332.

- Telfer N, Chalmers RJ, Whale K, et al. The role of streptococcal infection in the initiation of guttate psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:39-42.

- Cabrerizo M, Tarragó D, Muñoz-Almagro C, et al. Molecular epidemiology of enterovirus 71, coxsackievirus A16 and A6 associated with hand, foot and mouth disease in Spain. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:O150-O156.

- Li Y, Chang Z, Wu P, et al. Emerging enteroviruses causing hand, foot and mouth disease, China, 2010-2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:1902-1906.

- Seitsonen J, Shakeel S, Susi P, et al. Structural analysis of coxsackievirus A7 reveals conformational changes associated with uncoating. J Virol. 2012;86:7207-7215.

- Wu Y, Yeo A, Phoon M, et al. The largest outbreak of hand; foot and mouth disease in Singapore in 2008: the role of enterovirus 71 and coxsackievirus A strains. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:E1076-E1081.

- Tesini BL. Hand-foot-and-mouth-disease (HFMD). May 2018. https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/infectious-diseases/enteroviruses/hand-foot-and-mouth-disease-hfmd. Accessed September 25, 2019.

- Korzhova TP, Shyrobokov VP, Koliadenko VH, et al. Coxsackie B viral infection in the etiology and clinical pathogenesis of psoriasis [in Ukrainian]. Lik Sprava. 2001:54-58.

Practice Points

- Inquire about any illnesses preceding derma-tologic diseases.

- There may be additional microbial triggers for dermatologic diseases.

Photolichenoid Dermatitis: A Presenting Sign of Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Photolichenoid dermatitis is an uncommon eruptive dermatitis of variable clinical presentation. It has a histopathologic pattern of lichenoid inflammation and is best characterized as a photoallergic reaction.1 Photolichenoid dermatitis was first described in 1954 in association with the use of quinidine in the treatment of malaria.2 Subsequently, it has been associated with various medications, including trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, azithromycin, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.1,2 Photolichenoid dermatitis has been documented in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) with variable clinical presentations. Photolichenoid dermatitis in patients with HIV has been described both with and without an associated photosensitizing systemic agent, suggesting that HIV infection is an independent risk factor for the development of this eruption in patients with HIV.3-6

Case Report

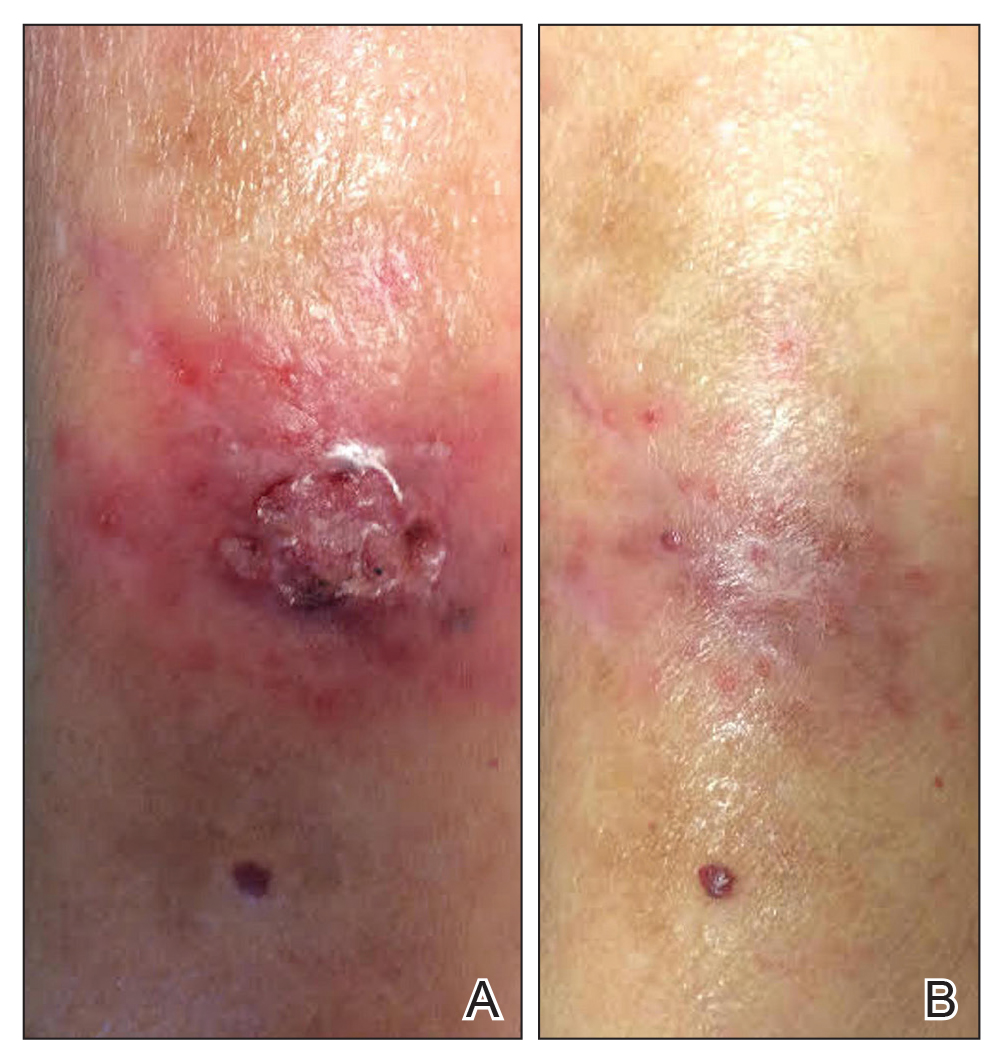

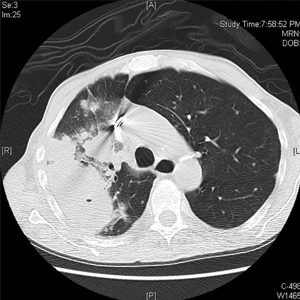

A 62-year-old African man presented for evaluation of asymptomatic hypopigmented and depigmented patches in a photodistributed pattern. The eruption began the preceding summer when he noted a pink patch on the right side of the forehead. It progressed over 2 months to involve the face, ears, neck, and arms. His medical history was negative. The only medication he was taking was hydroxychloroquine, which was prescribed by another dermatologist when the patient first developed the eruption. The patient was unsure of the indication for the medication and admitted to poor compliance. A review of systems was negative. There was no personal or family history of autoimmune disease. A detailed sexual history and illicit drug history were not obtained. Physical examination revealed hypopigmented and depigmented patches, some with overlying erythema and collarettes of fine scale. The patches were photodistributed on the face, conchal bowls, neck, dorsal aspect of the hands, and extensor forearms (Figures 1 and 2). Macules of repigmentation were noted within some of the patches. There also were large hyperpigmented patches with peripheral hypopigmentation on the legs.

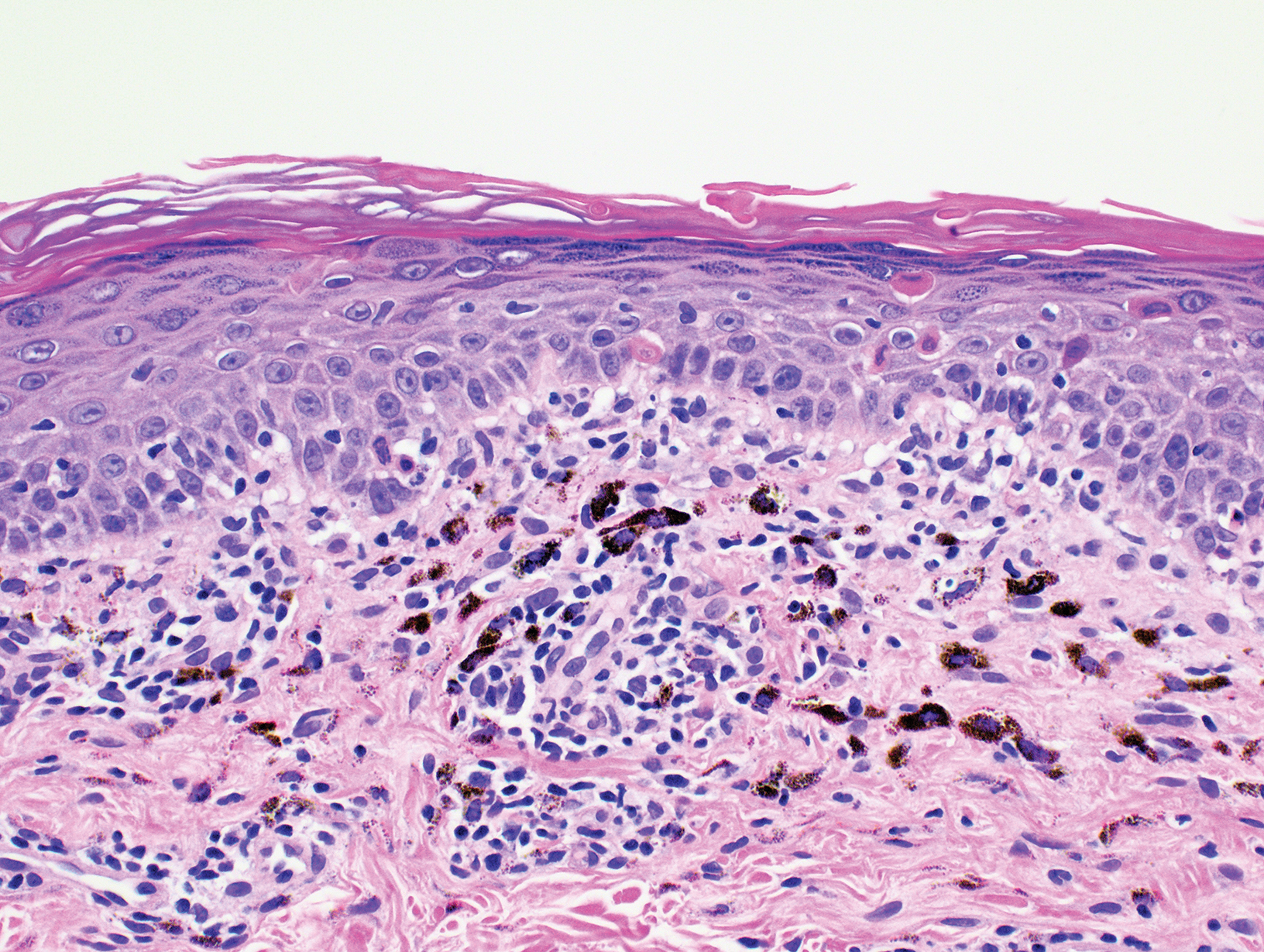

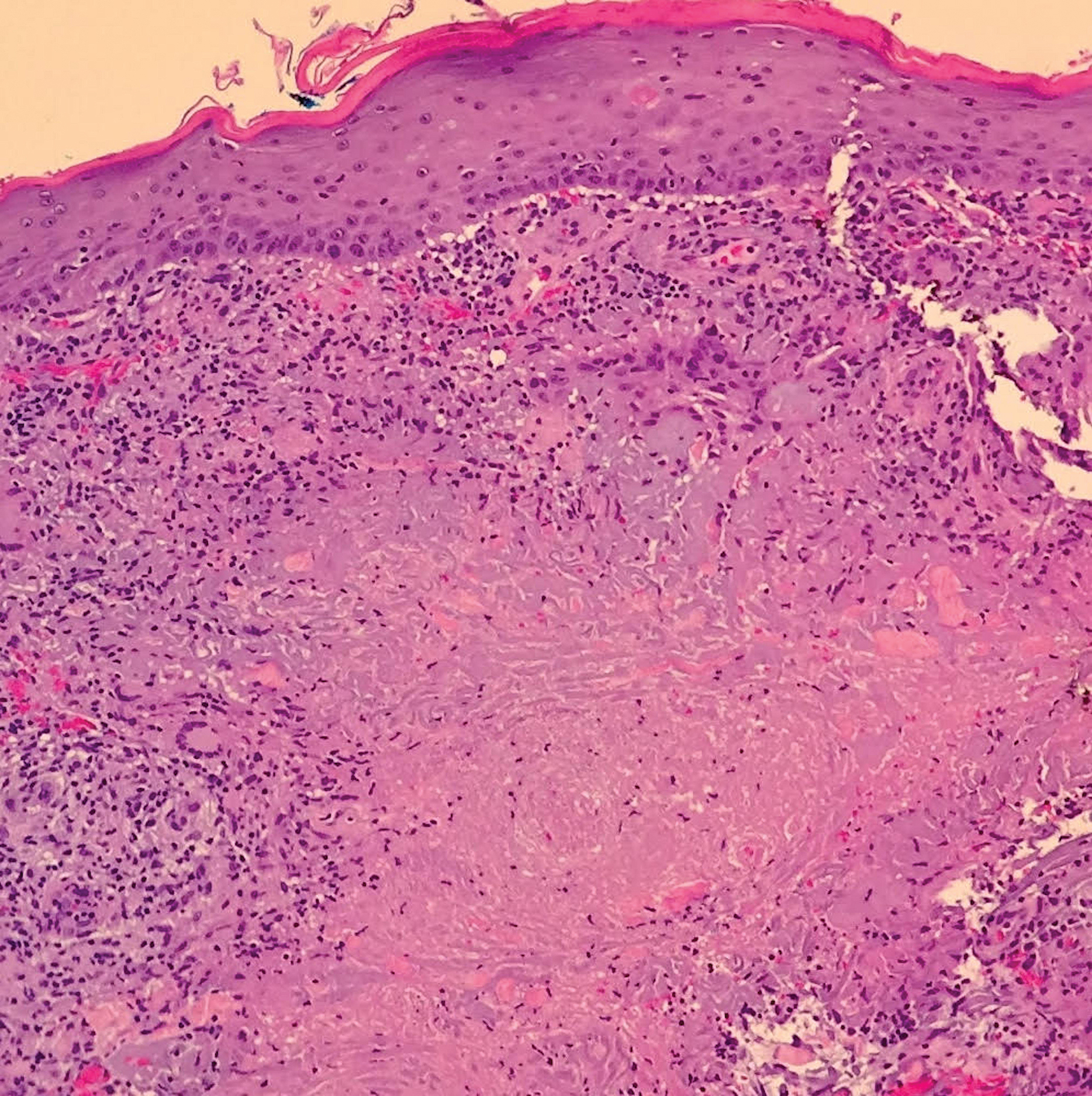

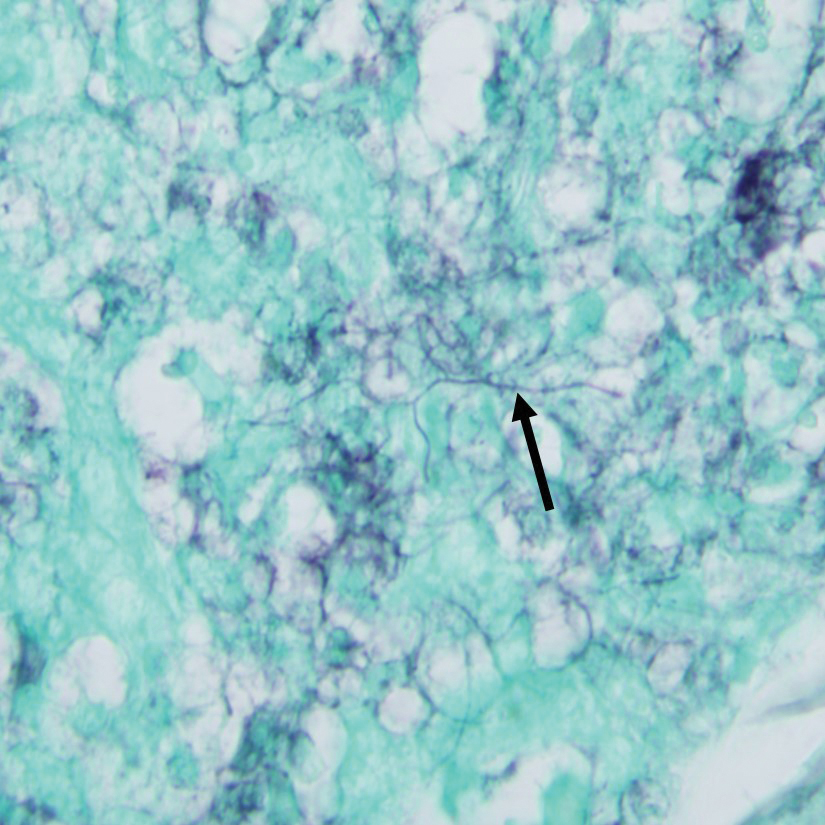

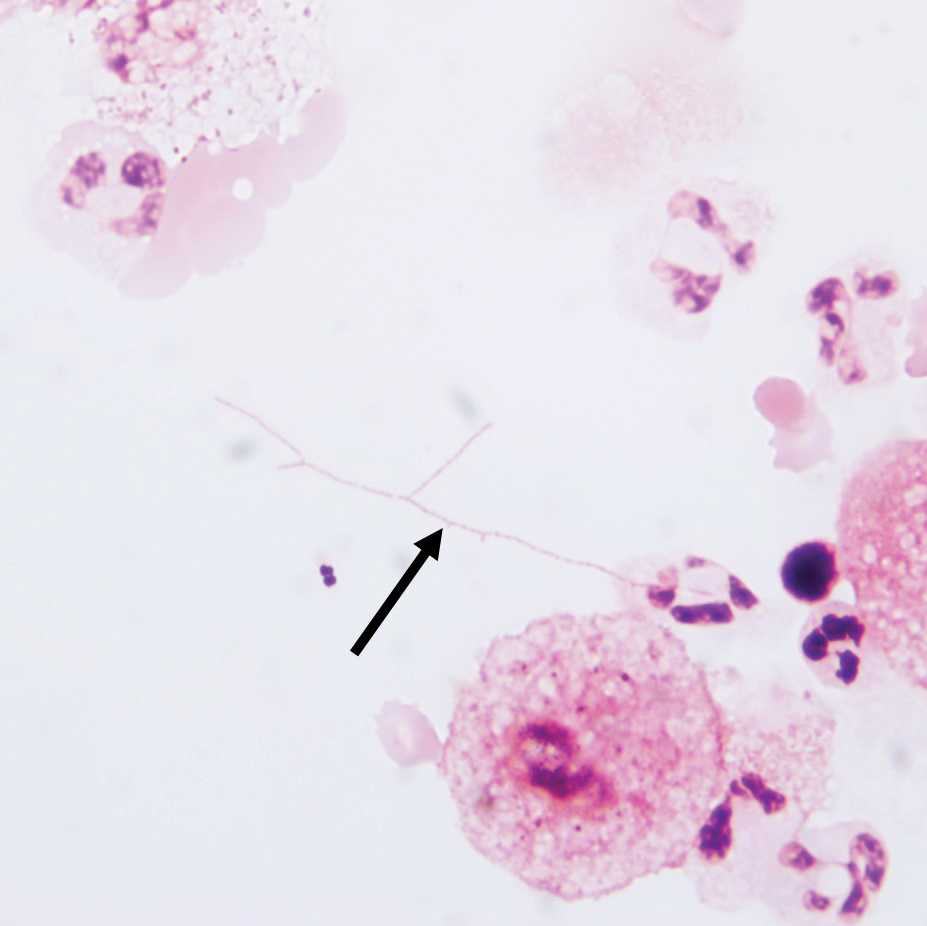

A punch biopsy taken from the left posterior neck revealed a patchy bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial dermis with lymphocytes present at the dermoepidermal junction and scattered dyskeratotic keratinocytes extending into the mid spinous layer (Figure 3). Histopathologic findings were consistent with photolichenoid dermatitis.

Laboratory workup revealed a normal complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel. Other negative results included antinuclear antibody, anti-Ro antibody, anti-La antibody, QuantiFERON-TB Gold, syphilis IgG antibody, and hepatitis B surface antigen and antibody. Positive results included hepatitis B antibody, hepatitis C antibody, and HIV-2 antibody. The patient denied overt symptoms suggestive of an immunocompromised status, including fever, chills, weight loss, or diarrhea. Initial treatment included mid-potency topical steroids with continued progression of the eruption. Following histopathologic and laboratory results indicating photolichenoid eruption, treatment with hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily was resumed. The patient was counseled on the importance of sun protection and was referred to an infectious disease clinic for treatment of HIV. He was ultimately lost to follow-up before further laboratory workup was obtained. Therefore, his CD4+ T-cell count and viral load were not obtained.

Comment

Prevalence of Photosensitive Eruptions

Photodermatitis is an uncommon clinical manifestation of HIV occurring in approximately 5% of patients who are HIV positive.3 Photosensitive eruptions previously described in association with HIV include porphyria cutanea tarda, pseudoporphyria, chronic actinic dermatitis, granuloma annulare, photodistributed dyspigmentation, and lichenoid photodermatitis.7 These HIV-associated photosensitive eruptions have been found to disproportionally affect patients of African and Native American descent.5,7,8 Therefore, a new photodistributed eruption in a patient of African or Native American descent should prompt evaluation of possible underlying HIV infection.

Presenting Sign of HIV Infection

We report a case of photolichenoid dermatitis presenting with loss of pigmentation as a presenting sign of HIV. The patient had no known history of HIV or prior opportunistic infections and was not taking any medications at the time of onset or presentation to clinic. Similar cases of photodistributed depigmentation with lichenoid inflammation on histopathology occurring in patients with HIV have been previously described.4-6,9 In these cases, most patients were of African descent with previously diagnosed advanced HIV and CD4 counts of less than 50 cells/mL3. The additional clinical findings of lichenoid papules and plaques were noted in several of these cases.5,6

Exposure to Photosensitizing Drugs

Photodermatitis in patients with HIV often is attributed to exposure to a photosensitizing drug. Many reported cases are retrospective and identify a temporal association between the onset of photodermatitis following the initiation of a photosensitizing drug. The most commonly implicated drugs have included nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and azithromycin. Other potential offenders may include saquinavir, dapsone, ketoconazole, and efavirenz.3,5 In cases in which temporal association with a new medication could not be identified, the photodermatitis often has been presumed to be due to polypharmacy and the potential synergistic effect of multiple photosensitizing drugs.3,5-8

Advanced HIV

There are several reported cases of photodermatitis occurring in patients who were not exposed to systemic photosensitizers. These patients had advanced HIV, meeting criteria for AIDS with a CD4 count of less than 200 cells/mL3. The majority of patients had an even lower CD4 count of less than 50 cells/mL3. Clinical presentations have included photodistributed lichenoid papules and plaques as well as depigmented patches.4,5,8,10

Evaluating HIV as a Risk Factor for Photodermatitis

Discerning the validity of the correlation between photodermatitis and HIV is difficult, as all previously reported cases are case reports and small retrospective case series.

Conclusion

This case represents an uncommon presentation of photolichenoid dermatitis as the presenting sign of HIV infection.10 Although most reported cases of photodermatitis in HIV are attributed to photosensitizing drugs, we propose that HIV may be an independent risk factor for the development of photodermatitis. We recommend consideration of HIV testing in patients who present with photodistributed depigmenting eruptions, even in the absence of a photosensitizing drug, particularly in patients of African and Native American descent.

- Collazo MH, Sanchez JL, Figueroa LD. Defining lichenoid photodermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:239-242.

- Wechsler HL. Dermatitis medicamentosa; a lichen-planus-like eruption due to quinidine. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1954;69:741-744.

- Bilu D, Mamelak AJ, Nguyen RH, et al. Clinical and epidemiologic characterization of photosensitivity in HIV-positive individuals. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2004;20:175-183.

- Philips RC, Motaparthi K, Krishnan B, et al. HIV photodermatitis presenting with widespread vitiligo-like depigmentation. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:6.

- Berger TG, Dhar A. Lichenoid photoeruptions in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:609-613.

- Tran K, Hartman R, Tzu J, et al. Photolichenoid plaques with associated vitiliginous pigmentary changes. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:13.

- Gregory N, DeLeo VA. Clinical manifestations of photosensitivity in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:630-633.

- Vin-Christian K, Epstein JH, Maurer TA, et al. Photosensitivity in HIV-infected individuals. J Dermatol. 2000;27:361-369.

- Kigonya C, Lutwama F, Colebunders R. Extensive hypopigmentation after starting antiretroviral treatment in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-seropositive African woman. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:102-103.

- Pardo RJ, Kerdel FA. Hypertrophic lichen planus and light sensitivity in an HIV-positive patient. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:642-644.

Photolichenoid dermatitis is an uncommon eruptive dermatitis of variable clinical presentation. It has a histopathologic pattern of lichenoid inflammation and is best characterized as a photoallergic reaction.1 Photolichenoid dermatitis was first described in 1954 in association with the use of quinidine in the treatment of malaria.2 Subsequently, it has been associated with various medications, including trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, azithromycin, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.1,2 Photolichenoid dermatitis has been documented in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) with variable clinical presentations. Photolichenoid dermatitis in patients with HIV has been described both with and without an associated photosensitizing systemic agent, suggesting that HIV infection is an independent risk factor for the development of this eruption in patients with HIV.3-6

Case Report

A 62-year-old African man presented for evaluation of asymptomatic hypopigmented and depigmented patches in a photodistributed pattern. The eruption began the preceding summer when he noted a pink patch on the right side of the forehead. It progressed over 2 months to involve the face, ears, neck, and arms. His medical history was negative. The only medication he was taking was hydroxychloroquine, which was prescribed by another dermatologist when the patient first developed the eruption. The patient was unsure of the indication for the medication and admitted to poor compliance. A review of systems was negative. There was no personal or family history of autoimmune disease. A detailed sexual history and illicit drug history were not obtained. Physical examination revealed hypopigmented and depigmented patches, some with overlying erythema and collarettes of fine scale. The patches were photodistributed on the face, conchal bowls, neck, dorsal aspect of the hands, and extensor forearms (Figures 1 and 2). Macules of repigmentation were noted within some of the patches. There also were large hyperpigmented patches with peripheral hypopigmentation on the legs.

A punch biopsy taken from the left posterior neck revealed a patchy bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial dermis with lymphocytes present at the dermoepidermal junction and scattered dyskeratotic keratinocytes extending into the mid spinous layer (Figure 3). Histopathologic findings were consistent with photolichenoid dermatitis.

Laboratory workup revealed a normal complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel. Other negative results included antinuclear antibody, anti-Ro antibody, anti-La antibody, QuantiFERON-TB Gold, syphilis IgG antibody, and hepatitis B surface antigen and antibody. Positive results included hepatitis B antibody, hepatitis C antibody, and HIV-2 antibody. The patient denied overt symptoms suggestive of an immunocompromised status, including fever, chills, weight loss, or diarrhea. Initial treatment included mid-potency topical steroids with continued progression of the eruption. Following histopathologic and laboratory results indicating photolichenoid eruption, treatment with hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily was resumed. The patient was counseled on the importance of sun protection and was referred to an infectious disease clinic for treatment of HIV. He was ultimately lost to follow-up before further laboratory workup was obtained. Therefore, his CD4+ T-cell count and viral load were not obtained.

Comment

Prevalence of Photosensitive Eruptions

Photodermatitis is an uncommon clinical manifestation of HIV occurring in approximately 5% of patients who are HIV positive.3 Photosensitive eruptions previously described in association with HIV include porphyria cutanea tarda, pseudoporphyria, chronic actinic dermatitis, granuloma annulare, photodistributed dyspigmentation, and lichenoid photodermatitis.7 These HIV-associated photosensitive eruptions have been found to disproportionally affect patients of African and Native American descent.5,7,8 Therefore, a new photodistributed eruption in a patient of African or Native American descent should prompt evaluation of possible underlying HIV infection.

Presenting Sign of HIV Infection

We report a case of photolichenoid dermatitis presenting with loss of pigmentation as a presenting sign of HIV. The patient had no known history of HIV or prior opportunistic infections and was not taking any medications at the time of onset or presentation to clinic. Similar cases of photodistributed depigmentation with lichenoid inflammation on histopathology occurring in patients with HIV have been previously described.4-6,9 In these cases, most patients were of African descent with previously diagnosed advanced HIV and CD4 counts of less than 50 cells/mL3. The additional clinical findings of lichenoid papules and plaques were noted in several of these cases.5,6

Exposure to Photosensitizing Drugs

Photodermatitis in patients with HIV often is attributed to exposure to a photosensitizing drug. Many reported cases are retrospective and identify a temporal association between the onset of photodermatitis following the initiation of a photosensitizing drug. The most commonly implicated drugs have included nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and azithromycin. Other potential offenders may include saquinavir, dapsone, ketoconazole, and efavirenz.3,5 In cases in which temporal association with a new medication could not be identified, the photodermatitis often has been presumed to be due to polypharmacy and the potential synergistic effect of multiple photosensitizing drugs.3,5-8

Advanced HIV

There are several reported cases of photodermatitis occurring in patients who were not exposed to systemic photosensitizers. These patients had advanced HIV, meeting criteria for AIDS with a CD4 count of less than 200 cells/mL3. The majority of patients had an even lower CD4 count of less than 50 cells/mL3. Clinical presentations have included photodistributed lichenoid papules and plaques as well as depigmented patches.4,5,8,10

Evaluating HIV as a Risk Factor for Photodermatitis

Discerning the validity of the correlation between photodermatitis and HIV is difficult, as all previously reported cases are case reports and small retrospective case series.

Conclusion

This case represents an uncommon presentation of photolichenoid dermatitis as the presenting sign of HIV infection.10 Although most reported cases of photodermatitis in HIV are attributed to photosensitizing drugs, we propose that HIV may be an independent risk factor for the development of photodermatitis. We recommend consideration of HIV testing in patients who present with photodistributed depigmenting eruptions, even in the absence of a photosensitizing drug, particularly in patients of African and Native American descent.

Photolichenoid dermatitis is an uncommon eruptive dermatitis of variable clinical presentation. It has a histopathologic pattern of lichenoid inflammation and is best characterized as a photoallergic reaction.1 Photolichenoid dermatitis was first described in 1954 in association with the use of quinidine in the treatment of malaria.2 Subsequently, it has been associated with various medications, including trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, azithromycin, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.1,2 Photolichenoid dermatitis has been documented in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) with variable clinical presentations. Photolichenoid dermatitis in patients with HIV has been described both with and without an associated photosensitizing systemic agent, suggesting that HIV infection is an independent risk factor for the development of this eruption in patients with HIV.3-6

Case Report