User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita in Association With Mantle Cell Lymphoma

To the Editor:

A 46-year-old man presented with multiple tense bullae and denuded patches on the palms (Figure 1A) and soles (Figure 1B). The blisters first appeared 2 months prior to presentation, shortly after he was diagnosed with stage IVB mantle cell lymphoma, and waxed and waned in intensity since then. He denied antecedent trauma or friction and reported that all sites were painful. He had no family or personal history of blistering disorders.

The mantle cell lymphoma initially was treated with 4 cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) chemotherapy more than 2.5 years prior to the current presentation, which resulted in partial remission, followed by R-ICE (rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide) therapy as well as autologous stem cell transplantation; complete remission was achieved. His recovery was complicated by a necrotic small bowel leading to resection. Eighteen months following the second course of chemotherapy, a mass was noted on the neck; biopsy performed by an outside dermatologist revealed mantle cell lymphoma.

Punch biopsy revealed a subepidermal bulla. Six weeks later, biopsy of a newly developed hand lesion performed at our office revealed a subepidermal cleft with minimal dermal infiltrate (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for immunoglobulin and complement deposition. Porphyrin elevation was not detected with a 24-hour urine assay. New lesions were drained and injected with triamcinolone, which appeared to hasten healing.

Mantle cell lymphoma is a distinct lymphoproliferative disorder of B cells that represents less than 7% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases.1 The tumor cells originate in the mantle zone of the lymph nodes. Most patients present with advanced disease involving lymph nodes and other organs. The disease is characterized by male predominance and an aggressive course with a median overall survival of less than 5 years.1

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is a rare blistering disease that usually develops in adulthood. It is a subepidermal disorder characterized by the appearance of fragile tense bullae. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita can be divided into 2 subtypes: inflammatory and mechanobullous (classic EBA).2 Inflammatory EBA presents similarly to bullous pemphigoid and other subepithelial autoimmune blistering diseases. Vesiculobullous lesions predominate on the trunk and extremities and often are accompanied by intense pruritus. The less common mechanobullous noninflammatory subtype, illustrated in our case, presents in trauma-prone areas with skin fragility and tense noninflamed vesicles and bullae that rupture leaving erosions. Associated findings may include milia and scarring. Lesions appear in areas exposed to friction and trauma such as the hands, feet, elbows, knees, and lower back. The differential diagnosis includes dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, porphyria cutanea tarda, and pseudoporphyria. Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa is ruled out by family history and disease onset at birth. The lesions of porphyria cutanea tarda and pseudoporphyria occur on sun-exposed areas; porphyrin levels are elevated in the former. Direct immunofluorescence of a perilesional EBA site usually reveals IgG deposition.3 Negative direct immunofluorescence in our case could have resulted from technical error, sample location, or response to systemic immunosuppressive treatment.4

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is caused by autoantibodies against type VII collagen.2,3 After the autoantibodies bind, a complement cascade reaction is activated, leading to deposition of C3a and C5a, which recruit leukocytes and mast cells. The anchoring fibrils in the basement membrane zones of the skin and mucosa are disrupted.5,6 Injection of anti–type VII collagen antibodies into mice induces a blistering disease resembling EBA.7 In a study of 14 patients with EBA, disease severity was correlated to levels of anticollagen autoantibodies measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.8

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita has been linked to Crohn disease and approximately 30% of EBA cases occur in patients with this disease.9,10 Two case reports document an association with multiple myeloma.11,12 Treatment often proves challenging and unsatisfactory; valid controlled clinical trials are impossible given the paucity of cases. Successful therapeutic outcomes have been reported with oral prednisone,13 colchicine,14 cyclosporine,15 dapsone,16 and rituximab.17 Our patient received 2 separate courses of rituximab as part of chemotherapy for mantle cell lymphoma without measurable improvement. He was lost to follow-up after recurrence of the lymphoma and we learned from his wife that he had died.

- Hitz F, Bargetzi M, Cogliatti S, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of mantle cell lymphoma. Swiss Med Wkly. 2013;143:w13868.

- Ludwig RJ. Clinical presentation, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. ISRN Dermatol. 2013;2013:812029.

- Gupta R, Woodley DT, Chen M. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:60-69.

- Mutasim DF, Adams BB. Immunofluorescence in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:803-822.

- Woodley DT, Briggaman RA, O’Keefe EJ. Identification of the skin basement-membrane autoantigen in epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1007-1013.

- Hashimoto T, Ishii N, Ohata C, et al. Pathogenesis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, an autoimmune subepidermal bullous disease. J Pathol. 2012;228:1-7.

- Sitaru C, Chiriac MT, Mihai S, et al. Induction of complement-fixing autoantibodies against type VII collagen results in subepidermal blistering in mice. J Immunol. 2006;177:3461-3468.

- Marzano AV, Cozzani E, Fanoni D, et al. Diagnosis and disease severity assessment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita by ELISA for anti-type VII collagen autoantibodies: an Italian multicentre study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:80-84.

- Chen M, O’Toole EA, Sanghavi J, et al. The epidermolysis bullosa acquisita antigen (type VII collagen) is present in human colon and patients with Crohn’s disease have autoantibodies to type VII collagen. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:1059-1064.

- Reddy H, Shipman AR, Wojnarowska F. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and inflammatory bowel disease: a review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:225-229.

- Radfar L, Fatahzadeh M, Shahamat Y, et al. Paraneoplastic epidermolysis bullosa acquisita associated with multiple myeloma. Spec Care Dentist. 2006;26:159-163.

- Engineer L, Dow EC, Braverman IM, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and multiple myeloma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:943-946.

- Ishii N, Hamada T, Dainichi T, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: what’s new? J Dermatol. 2010;37:220-230.

- Megahed M, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita—successful treatment with colchicine. Arch Dermatol Res. 1994;286:35-46.

- Khatri ML, Benghazeil M, Shafi M. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita responsive to cyclosporin therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:182-184.

- Hughes AP, Callen JP. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita responsive to dapsone therapy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:397-399.

- Kim JH, Lee SE, Kim SC. Successful treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita with rituximab therapy. J Dermatol. 2012;39:477-479.

To the Editor:

A 46-year-old man presented with multiple tense bullae and denuded patches on the palms (Figure 1A) and soles (Figure 1B). The blisters first appeared 2 months prior to presentation, shortly after he was diagnosed with stage IVB mantle cell lymphoma, and waxed and waned in intensity since then. He denied antecedent trauma or friction and reported that all sites were painful. He had no family or personal history of blistering disorders.

The mantle cell lymphoma initially was treated with 4 cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) chemotherapy more than 2.5 years prior to the current presentation, which resulted in partial remission, followed by R-ICE (rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide) therapy as well as autologous stem cell transplantation; complete remission was achieved. His recovery was complicated by a necrotic small bowel leading to resection. Eighteen months following the second course of chemotherapy, a mass was noted on the neck; biopsy performed by an outside dermatologist revealed mantle cell lymphoma.

Punch biopsy revealed a subepidermal bulla. Six weeks later, biopsy of a newly developed hand lesion performed at our office revealed a subepidermal cleft with minimal dermal infiltrate (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for immunoglobulin and complement deposition. Porphyrin elevation was not detected with a 24-hour urine assay. New lesions were drained and injected with triamcinolone, which appeared to hasten healing.

Mantle cell lymphoma is a distinct lymphoproliferative disorder of B cells that represents less than 7% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases.1 The tumor cells originate in the mantle zone of the lymph nodes. Most patients present with advanced disease involving lymph nodes and other organs. The disease is characterized by male predominance and an aggressive course with a median overall survival of less than 5 years.1

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is a rare blistering disease that usually develops in adulthood. It is a subepidermal disorder characterized by the appearance of fragile tense bullae. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita can be divided into 2 subtypes: inflammatory and mechanobullous (classic EBA).2 Inflammatory EBA presents similarly to bullous pemphigoid and other subepithelial autoimmune blistering diseases. Vesiculobullous lesions predominate on the trunk and extremities and often are accompanied by intense pruritus. The less common mechanobullous noninflammatory subtype, illustrated in our case, presents in trauma-prone areas with skin fragility and tense noninflamed vesicles and bullae that rupture leaving erosions. Associated findings may include milia and scarring. Lesions appear in areas exposed to friction and trauma such as the hands, feet, elbows, knees, and lower back. The differential diagnosis includes dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, porphyria cutanea tarda, and pseudoporphyria. Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa is ruled out by family history and disease onset at birth. The lesions of porphyria cutanea tarda and pseudoporphyria occur on sun-exposed areas; porphyrin levels are elevated in the former. Direct immunofluorescence of a perilesional EBA site usually reveals IgG deposition.3 Negative direct immunofluorescence in our case could have resulted from technical error, sample location, or response to systemic immunosuppressive treatment.4

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is caused by autoantibodies against type VII collagen.2,3 After the autoantibodies bind, a complement cascade reaction is activated, leading to deposition of C3a and C5a, which recruit leukocytes and mast cells. The anchoring fibrils in the basement membrane zones of the skin and mucosa are disrupted.5,6 Injection of anti–type VII collagen antibodies into mice induces a blistering disease resembling EBA.7 In a study of 14 patients with EBA, disease severity was correlated to levels of anticollagen autoantibodies measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.8

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita has been linked to Crohn disease and approximately 30% of EBA cases occur in patients with this disease.9,10 Two case reports document an association with multiple myeloma.11,12 Treatment often proves challenging and unsatisfactory; valid controlled clinical trials are impossible given the paucity of cases. Successful therapeutic outcomes have been reported with oral prednisone,13 colchicine,14 cyclosporine,15 dapsone,16 and rituximab.17 Our patient received 2 separate courses of rituximab as part of chemotherapy for mantle cell lymphoma without measurable improvement. He was lost to follow-up after recurrence of the lymphoma and we learned from his wife that he had died.

To the Editor:

A 46-year-old man presented with multiple tense bullae and denuded patches on the palms (Figure 1A) and soles (Figure 1B). The blisters first appeared 2 months prior to presentation, shortly after he was diagnosed with stage IVB mantle cell lymphoma, and waxed and waned in intensity since then. He denied antecedent trauma or friction and reported that all sites were painful. He had no family or personal history of blistering disorders.

The mantle cell lymphoma initially was treated with 4 cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) chemotherapy more than 2.5 years prior to the current presentation, which resulted in partial remission, followed by R-ICE (rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide) therapy as well as autologous stem cell transplantation; complete remission was achieved. His recovery was complicated by a necrotic small bowel leading to resection. Eighteen months following the second course of chemotherapy, a mass was noted on the neck; biopsy performed by an outside dermatologist revealed mantle cell lymphoma.

Punch biopsy revealed a subepidermal bulla. Six weeks later, biopsy of a newly developed hand lesion performed at our office revealed a subepidermal cleft with minimal dermal infiltrate (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for immunoglobulin and complement deposition. Porphyrin elevation was not detected with a 24-hour urine assay. New lesions were drained and injected with triamcinolone, which appeared to hasten healing.

Mantle cell lymphoma is a distinct lymphoproliferative disorder of B cells that represents less than 7% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases.1 The tumor cells originate in the mantle zone of the lymph nodes. Most patients present with advanced disease involving lymph nodes and other organs. The disease is characterized by male predominance and an aggressive course with a median overall survival of less than 5 years.1

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is a rare blistering disease that usually develops in adulthood. It is a subepidermal disorder characterized by the appearance of fragile tense bullae. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita can be divided into 2 subtypes: inflammatory and mechanobullous (classic EBA).2 Inflammatory EBA presents similarly to bullous pemphigoid and other subepithelial autoimmune blistering diseases. Vesiculobullous lesions predominate on the trunk and extremities and often are accompanied by intense pruritus. The less common mechanobullous noninflammatory subtype, illustrated in our case, presents in trauma-prone areas with skin fragility and tense noninflamed vesicles and bullae that rupture leaving erosions. Associated findings may include milia and scarring. Lesions appear in areas exposed to friction and trauma such as the hands, feet, elbows, knees, and lower back. The differential diagnosis includes dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, porphyria cutanea tarda, and pseudoporphyria. Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa is ruled out by family history and disease onset at birth. The lesions of porphyria cutanea tarda and pseudoporphyria occur on sun-exposed areas; porphyrin levels are elevated in the former. Direct immunofluorescence of a perilesional EBA site usually reveals IgG deposition.3 Negative direct immunofluorescence in our case could have resulted from technical error, sample location, or response to systemic immunosuppressive treatment.4

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is caused by autoantibodies against type VII collagen.2,3 After the autoantibodies bind, a complement cascade reaction is activated, leading to deposition of C3a and C5a, which recruit leukocytes and mast cells. The anchoring fibrils in the basement membrane zones of the skin and mucosa are disrupted.5,6 Injection of anti–type VII collagen antibodies into mice induces a blistering disease resembling EBA.7 In a study of 14 patients with EBA, disease severity was correlated to levels of anticollagen autoantibodies measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.8

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita has been linked to Crohn disease and approximately 30% of EBA cases occur in patients with this disease.9,10 Two case reports document an association with multiple myeloma.11,12 Treatment often proves challenging and unsatisfactory; valid controlled clinical trials are impossible given the paucity of cases. Successful therapeutic outcomes have been reported with oral prednisone,13 colchicine,14 cyclosporine,15 dapsone,16 and rituximab.17 Our patient received 2 separate courses of rituximab as part of chemotherapy for mantle cell lymphoma without measurable improvement. He was lost to follow-up after recurrence of the lymphoma and we learned from his wife that he had died.

- Hitz F, Bargetzi M, Cogliatti S, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of mantle cell lymphoma. Swiss Med Wkly. 2013;143:w13868.

- Ludwig RJ. Clinical presentation, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. ISRN Dermatol. 2013;2013:812029.

- Gupta R, Woodley DT, Chen M. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:60-69.

- Mutasim DF, Adams BB. Immunofluorescence in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:803-822.

- Woodley DT, Briggaman RA, O’Keefe EJ. Identification of the skin basement-membrane autoantigen in epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1007-1013.

- Hashimoto T, Ishii N, Ohata C, et al. Pathogenesis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, an autoimmune subepidermal bullous disease. J Pathol. 2012;228:1-7.

- Sitaru C, Chiriac MT, Mihai S, et al. Induction of complement-fixing autoantibodies against type VII collagen results in subepidermal blistering in mice. J Immunol. 2006;177:3461-3468.

- Marzano AV, Cozzani E, Fanoni D, et al. Diagnosis and disease severity assessment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita by ELISA for anti-type VII collagen autoantibodies: an Italian multicentre study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:80-84.

- Chen M, O’Toole EA, Sanghavi J, et al. The epidermolysis bullosa acquisita antigen (type VII collagen) is present in human colon and patients with Crohn’s disease have autoantibodies to type VII collagen. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:1059-1064.

- Reddy H, Shipman AR, Wojnarowska F. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and inflammatory bowel disease: a review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:225-229.

- Radfar L, Fatahzadeh M, Shahamat Y, et al. Paraneoplastic epidermolysis bullosa acquisita associated with multiple myeloma. Spec Care Dentist. 2006;26:159-163.

- Engineer L, Dow EC, Braverman IM, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and multiple myeloma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:943-946.

- Ishii N, Hamada T, Dainichi T, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: what’s new? J Dermatol. 2010;37:220-230.

- Megahed M, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita—successful treatment with colchicine. Arch Dermatol Res. 1994;286:35-46.

- Khatri ML, Benghazeil M, Shafi M. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita responsive to cyclosporin therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:182-184.

- Hughes AP, Callen JP. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita responsive to dapsone therapy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:397-399.

- Kim JH, Lee SE, Kim SC. Successful treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita with rituximab therapy. J Dermatol. 2012;39:477-479.

- Hitz F, Bargetzi M, Cogliatti S, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of mantle cell lymphoma. Swiss Med Wkly. 2013;143:w13868.

- Ludwig RJ. Clinical presentation, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. ISRN Dermatol. 2013;2013:812029.

- Gupta R, Woodley DT, Chen M. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:60-69.

- Mutasim DF, Adams BB. Immunofluorescence in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:803-822.

- Woodley DT, Briggaman RA, O’Keefe EJ. Identification of the skin basement-membrane autoantigen in epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1007-1013.

- Hashimoto T, Ishii N, Ohata C, et al. Pathogenesis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, an autoimmune subepidermal bullous disease. J Pathol. 2012;228:1-7.

- Sitaru C, Chiriac MT, Mihai S, et al. Induction of complement-fixing autoantibodies against type VII collagen results in subepidermal blistering in mice. J Immunol. 2006;177:3461-3468.

- Marzano AV, Cozzani E, Fanoni D, et al. Diagnosis and disease severity assessment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita by ELISA for anti-type VII collagen autoantibodies: an Italian multicentre study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:80-84.

- Chen M, O’Toole EA, Sanghavi J, et al. The epidermolysis bullosa acquisita antigen (type VII collagen) is present in human colon and patients with Crohn’s disease have autoantibodies to type VII collagen. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:1059-1064.

- Reddy H, Shipman AR, Wojnarowska F. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and inflammatory bowel disease: a review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:225-229.

- Radfar L, Fatahzadeh M, Shahamat Y, et al. Paraneoplastic epidermolysis bullosa acquisita associated with multiple myeloma. Spec Care Dentist. 2006;26:159-163.

- Engineer L, Dow EC, Braverman IM, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and multiple myeloma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:943-946.

- Ishii N, Hamada T, Dainichi T, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: what’s new? J Dermatol. 2010;37:220-230.

- Megahed M, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita—successful treatment with colchicine. Arch Dermatol Res. 1994;286:35-46.

- Khatri ML, Benghazeil M, Shafi M. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita responsive to cyclosporin therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:182-184.

- Hughes AP, Callen JP. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita responsive to dapsone therapy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:397-399.

- Kim JH, Lee SE, Kim SC. Successful treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita with rituximab therapy. J Dermatol. 2012;39:477-479.

Practice Points

- Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) is an uncommon blistering disorder and few cases have been associated with malignancy.

- Diagnosis of EBA is challenging and requires exclusion of other blistering diseases.

Slow-growing, Asymptomatic, Annular Plaques on the Bilateral Palms

The Diagnosis: Circumscribed Palmar Hypokeratosis

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a rare, benign, acquired dermatosis that was first described by Pérez et al1 in 2002 and is characterized by annular plaques with an atrophic center and hyperkeratotic edges. Classically, the lesions present on the thenar and hypothenar eminences of the palms.2 The condition predominantly affects women (4:1 ratio), with a mean age of onset of 65 years.3

Although the pathogenesis of circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is unknown, local trauma generally is considered to be the causative factor. Other hypotheses include human papillomaviruses 4 and 6 infection and primary abnormal keratinization in the epidermis.3 Immunohistochemical studies have demonstrated increased expression of keratin 16 and Ki-67 in cutaneous lesions, which is postulated to be responsible for keratinocyte fragility associated with epidermal hyperproliferation. Other reported cases have shown diminished keratin 9, keratin 2e, and connexin 26 expression, which normally are abundant in the acral epidermis. Abnormal expression of antigens associated with epidermal proliferation and differentiation also have been reported,3 suggesting that there is an altered regulation of the cutaneous desquamation process.

Histologically, circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is characterized by an abrupt reduction in the stratum corneum (Figure), forming a step between the lesion and the perilesional normal skin.2,3 The clinical appearance of erythema is due to visualization of dermal blood circulation in the area of corneal thinning and is not a result of vasodilation. The dermis is uninvolved, and inflammation is absent. The differential diagnosis includes psoriasis, Bowen disease, porokeratosis, and dermatophytosis.3

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a chronic condition, and there are no known reports of development of malignancy. Treatment is not required but may include cryotherapy; topical therapy with corticosteroids, retinoids, urea, and calcipotriene; and photodynamic therapy. Circumscribed hypokeratosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of palmar lesions.

- Pérez A, Rütten A, Gold R, et al. Circumscribed palmar or plantar hypokeratosis: a distinctive epidermal malformation of the palms or soles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:21-27.

- Mitkov M, Balagula Y, Lockshin B. Case report: circumscribed plantar hypokeratosis. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E203-E205.

- Rocha L, Nico M. Circumscribed palmoplantar hypokeratosis: report of two Brazilian cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:623-626.

The Diagnosis: Circumscribed Palmar Hypokeratosis

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a rare, benign, acquired dermatosis that was first described by Pérez et al1 in 2002 and is characterized by annular plaques with an atrophic center and hyperkeratotic edges. Classically, the lesions present on the thenar and hypothenar eminences of the palms.2 The condition predominantly affects women (4:1 ratio), with a mean age of onset of 65 years.3

Although the pathogenesis of circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is unknown, local trauma generally is considered to be the causative factor. Other hypotheses include human papillomaviruses 4 and 6 infection and primary abnormal keratinization in the epidermis.3 Immunohistochemical studies have demonstrated increased expression of keratin 16 and Ki-67 in cutaneous lesions, which is postulated to be responsible for keratinocyte fragility associated with epidermal hyperproliferation. Other reported cases have shown diminished keratin 9, keratin 2e, and connexin 26 expression, which normally are abundant in the acral epidermis. Abnormal expression of antigens associated with epidermal proliferation and differentiation also have been reported,3 suggesting that there is an altered regulation of the cutaneous desquamation process.

Histologically, circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is characterized by an abrupt reduction in the stratum corneum (Figure), forming a step between the lesion and the perilesional normal skin.2,3 The clinical appearance of erythema is due to visualization of dermal blood circulation in the area of corneal thinning and is not a result of vasodilation. The dermis is uninvolved, and inflammation is absent. The differential diagnosis includes psoriasis, Bowen disease, porokeratosis, and dermatophytosis.3

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a chronic condition, and there are no known reports of development of malignancy. Treatment is not required but may include cryotherapy; topical therapy with corticosteroids, retinoids, urea, and calcipotriene; and photodynamic therapy. Circumscribed hypokeratosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of palmar lesions.

The Diagnosis: Circumscribed Palmar Hypokeratosis

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a rare, benign, acquired dermatosis that was first described by Pérez et al1 in 2002 and is characterized by annular plaques with an atrophic center and hyperkeratotic edges. Classically, the lesions present on the thenar and hypothenar eminences of the palms.2 The condition predominantly affects women (4:1 ratio), with a mean age of onset of 65 years.3

Although the pathogenesis of circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is unknown, local trauma generally is considered to be the causative factor. Other hypotheses include human papillomaviruses 4 and 6 infection and primary abnormal keratinization in the epidermis.3 Immunohistochemical studies have demonstrated increased expression of keratin 16 and Ki-67 in cutaneous lesions, which is postulated to be responsible for keratinocyte fragility associated with epidermal hyperproliferation. Other reported cases have shown diminished keratin 9, keratin 2e, and connexin 26 expression, which normally are abundant in the acral epidermis. Abnormal expression of antigens associated with epidermal proliferation and differentiation also have been reported,3 suggesting that there is an altered regulation of the cutaneous desquamation process.

Histologically, circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is characterized by an abrupt reduction in the stratum corneum (Figure), forming a step between the lesion and the perilesional normal skin.2,3 The clinical appearance of erythema is due to visualization of dermal blood circulation in the area of corneal thinning and is not a result of vasodilation. The dermis is uninvolved, and inflammation is absent. The differential diagnosis includes psoriasis, Bowen disease, porokeratosis, and dermatophytosis.3

Circumscribed palmar hypokeratosis is a chronic condition, and there are no known reports of development of malignancy. Treatment is not required but may include cryotherapy; topical therapy with corticosteroids, retinoids, urea, and calcipotriene; and photodynamic therapy. Circumscribed hypokeratosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of palmar lesions.

- Pérez A, Rütten A, Gold R, et al. Circumscribed palmar or plantar hypokeratosis: a distinctive epidermal malformation of the palms or soles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:21-27.

- Mitkov M, Balagula Y, Lockshin B. Case report: circumscribed plantar hypokeratosis. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E203-E205.

- Rocha L, Nico M. Circumscribed palmoplantar hypokeratosis: report of two Brazilian cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:623-626.

- Pérez A, Rütten A, Gold R, et al. Circumscribed palmar or plantar hypokeratosis: a distinctive epidermal malformation of the palms or soles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:21-27.

- Mitkov M, Balagula Y, Lockshin B. Case report: circumscribed plantar hypokeratosis. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E203-E205.

- Rocha L, Nico M. Circumscribed palmoplantar hypokeratosis: report of two Brazilian cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:623-626.

A 77-year-old woman presented with slow-growing, asymptomatic, annular plaques on the bilateral palms of many years' duration. There was no history of trauma or local infection. Prior treatment with over-the-counter creams was unsuccessful. A 3-mm punch biopsy of the lesion on the right palm was performed.

New Guidelines for Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer: What You Need to Know

Painful Nonhealing Vulvar and Perianal Erosions

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

A punch biopsy of the vulvar skin revealed epidermal hyperplasia with moderate spongiosis and exocytosis of lymphocytes and neutrophils in the epidermis. A brisk mixed inflammatory infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleate foreign body-type giant cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils in a granulomatous pattern also were present in the dermis (Figure). Periodic acid-Schiff and acid-fast bacillus stains were negative. Given the history of Crohn disease (CD) and the characteristic dermal noncaseating granulomas on histology, the patient was diagnosed with cutaneous CD.

Although the patient was offered a topical corticosteroid, she deferred topical therapy. Given the lack of response to adalimumab, the gastroenterology department switched the patient to a treatment of infliximab 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks. Azathioprine was discontinued and the patient was switched to intramuscular methotrexate 25 mg/mL weekly. Slow reepithelialization of the vulvar and perianal erosions occurred on this regimen.

Although CD has numerous cutaneous features, cutaneous CD, also known as metastatic CD, is the rarest cutaneous manifestation of CD.1 This disease process is characterized by noncaseating granulomatous cutaneous lesions that are not contiguous with the affected gastrointestinal tract.2 The pathogenesis of cutaneous CD is unknown. Young adults tend to be more predisposed to developing cutaneous CD, likely due to the age distribution of CD.3

Cutaneous CD commonly presents in patients with a well-established history of gastrointestinal CD but occasionally can be the presenting sign of CD.1 The most common sites of involvement are the legs, vulva, penis, trunk, face, and intertriginous areas. Cutaneous CD findings can be divided into 2 subgroups: genital and nongenital lesions. Genital findings involve ulceration, erythema, edema, and fissuring of the vulva, labia, clitoris, scrotum, penis, and perineum. Nongenital cutaneous manifestations include ulcers; erythematous papules, plaques, and nodules; abscesslike lesions; and lichenoid papules.4,5 The severity of cutaneous lesions does not correlate to the severity of gastrointestinal disease; however, colon involvement is more common in patients with cutaneous CD.6

Histologically, cutaneous CD presents as noncaseating granulomatous inflammation in the papillary and reticular dermis. These granulomas consist of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells with a lymphocytic infiltrate.5

Given the rarity of cutaneous CD, treatment approach is based on anecdotal evidence from case reports and case series. For a single lesion or localized disease, topical superpotent or intralesional steroids are recommended for initial therapy.3 Oral metronidazole also is an effective treatment and can be combined with topical or intralesional steroids.7 For disseminated disease, systemic corticosteroids have shown efficacy.3 Other reported treatment options include oral corticosteroids, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, infliximab, and adalimumab. If monotherapy fails, combination therapy may be needed. Surgical debridement may be attempted if medical therapy fails but is complicated by wound dehiscence and disease recurrence.3

Although genital ulcers can be a presentation of Behçet disease and genital herpes infection, genital nodules and plaques are not typical for these 2 diseases. Also, the patient did not have oral ulcers, which is a common feature of Behçet disease. Genital sarcoidosis is extremely rare, and cutaneous CD was more likely given the patient's medical history. Finally, Jacquet dermatitis is more common in children, and patients with this condition typically have history of fecal and urinary incontinence.

- Teixeira M, Machado S, Lago P, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1074-1076.

- Stingeni L, Neve D, Bassotti G, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease successfully treated with adalimumab [published online Sep 15, 2015]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2016;30:E72-E74.

- Kurtzman DJ, Jones T, Fangru L, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review and approach to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:804-813.

- Hagen JW, Swoger JM, Grandinetti LM. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:417-431.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review [published online June 19, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Thrash B, Patel M, Shah KR, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease, part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:211.e1-211.e33.

- Abide JM. Metastatic Crohn disease: clearance with metronidazole. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:448-449.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

A punch biopsy of the vulvar skin revealed epidermal hyperplasia with moderate spongiosis and exocytosis of lymphocytes and neutrophils in the epidermis. A brisk mixed inflammatory infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleate foreign body-type giant cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils in a granulomatous pattern also were present in the dermis (Figure). Periodic acid-Schiff and acid-fast bacillus stains were negative. Given the history of Crohn disease (CD) and the characteristic dermal noncaseating granulomas on histology, the patient was diagnosed with cutaneous CD.

Although the patient was offered a topical corticosteroid, she deferred topical therapy. Given the lack of response to adalimumab, the gastroenterology department switched the patient to a treatment of infliximab 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks. Azathioprine was discontinued and the patient was switched to intramuscular methotrexate 25 mg/mL weekly. Slow reepithelialization of the vulvar and perianal erosions occurred on this regimen.

Although CD has numerous cutaneous features, cutaneous CD, also known as metastatic CD, is the rarest cutaneous manifestation of CD.1 This disease process is characterized by noncaseating granulomatous cutaneous lesions that are not contiguous with the affected gastrointestinal tract.2 The pathogenesis of cutaneous CD is unknown. Young adults tend to be more predisposed to developing cutaneous CD, likely due to the age distribution of CD.3

Cutaneous CD commonly presents in patients with a well-established history of gastrointestinal CD but occasionally can be the presenting sign of CD.1 The most common sites of involvement are the legs, vulva, penis, trunk, face, and intertriginous areas. Cutaneous CD findings can be divided into 2 subgroups: genital and nongenital lesions. Genital findings involve ulceration, erythema, edema, and fissuring of the vulva, labia, clitoris, scrotum, penis, and perineum. Nongenital cutaneous manifestations include ulcers; erythematous papules, plaques, and nodules; abscesslike lesions; and lichenoid papules.4,5 The severity of cutaneous lesions does not correlate to the severity of gastrointestinal disease; however, colon involvement is more common in patients with cutaneous CD.6

Histologically, cutaneous CD presents as noncaseating granulomatous inflammation in the papillary and reticular dermis. These granulomas consist of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells with a lymphocytic infiltrate.5

Given the rarity of cutaneous CD, treatment approach is based on anecdotal evidence from case reports and case series. For a single lesion or localized disease, topical superpotent or intralesional steroids are recommended for initial therapy.3 Oral metronidazole also is an effective treatment and can be combined with topical or intralesional steroids.7 For disseminated disease, systemic corticosteroids have shown efficacy.3 Other reported treatment options include oral corticosteroids, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, infliximab, and adalimumab. If monotherapy fails, combination therapy may be needed. Surgical debridement may be attempted if medical therapy fails but is complicated by wound dehiscence and disease recurrence.3

Although genital ulcers can be a presentation of Behçet disease and genital herpes infection, genital nodules and plaques are not typical for these 2 diseases. Also, the patient did not have oral ulcers, which is a common feature of Behçet disease. Genital sarcoidosis is extremely rare, and cutaneous CD was more likely given the patient's medical history. Finally, Jacquet dermatitis is more common in children, and patients with this condition typically have history of fecal and urinary incontinence.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

A punch biopsy of the vulvar skin revealed epidermal hyperplasia with moderate spongiosis and exocytosis of lymphocytes and neutrophils in the epidermis. A brisk mixed inflammatory infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleate foreign body-type giant cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils in a granulomatous pattern also were present in the dermis (Figure). Periodic acid-Schiff and acid-fast bacillus stains were negative. Given the history of Crohn disease (CD) and the characteristic dermal noncaseating granulomas on histology, the patient was diagnosed with cutaneous CD.

Although the patient was offered a topical corticosteroid, she deferred topical therapy. Given the lack of response to adalimumab, the gastroenterology department switched the patient to a treatment of infliximab 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks. Azathioprine was discontinued and the patient was switched to intramuscular methotrexate 25 mg/mL weekly. Slow reepithelialization of the vulvar and perianal erosions occurred on this regimen.

Although CD has numerous cutaneous features, cutaneous CD, also known as metastatic CD, is the rarest cutaneous manifestation of CD.1 This disease process is characterized by noncaseating granulomatous cutaneous lesions that are not contiguous with the affected gastrointestinal tract.2 The pathogenesis of cutaneous CD is unknown. Young adults tend to be more predisposed to developing cutaneous CD, likely due to the age distribution of CD.3

Cutaneous CD commonly presents in patients with a well-established history of gastrointestinal CD but occasionally can be the presenting sign of CD.1 The most common sites of involvement are the legs, vulva, penis, trunk, face, and intertriginous areas. Cutaneous CD findings can be divided into 2 subgroups: genital and nongenital lesions. Genital findings involve ulceration, erythema, edema, and fissuring of the vulva, labia, clitoris, scrotum, penis, and perineum. Nongenital cutaneous manifestations include ulcers; erythematous papules, plaques, and nodules; abscesslike lesions; and lichenoid papules.4,5 The severity of cutaneous lesions does not correlate to the severity of gastrointestinal disease; however, colon involvement is more common in patients with cutaneous CD.6

Histologically, cutaneous CD presents as noncaseating granulomatous inflammation in the papillary and reticular dermis. These granulomas consist of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells with a lymphocytic infiltrate.5

Given the rarity of cutaneous CD, treatment approach is based on anecdotal evidence from case reports and case series. For a single lesion or localized disease, topical superpotent or intralesional steroids are recommended for initial therapy.3 Oral metronidazole also is an effective treatment and can be combined with topical or intralesional steroids.7 For disseminated disease, systemic corticosteroids have shown efficacy.3 Other reported treatment options include oral corticosteroids, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, infliximab, and adalimumab. If monotherapy fails, combination therapy may be needed. Surgical debridement may be attempted if medical therapy fails but is complicated by wound dehiscence and disease recurrence.3

Although genital ulcers can be a presentation of Behçet disease and genital herpes infection, genital nodules and plaques are not typical for these 2 diseases. Also, the patient did not have oral ulcers, which is a common feature of Behçet disease. Genital sarcoidosis is extremely rare, and cutaneous CD was more likely given the patient's medical history. Finally, Jacquet dermatitis is more common in children, and patients with this condition typically have history of fecal and urinary incontinence.

- Teixeira M, Machado S, Lago P, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1074-1076.

- Stingeni L, Neve D, Bassotti G, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease successfully treated with adalimumab [published online Sep 15, 2015]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2016;30:E72-E74.

- Kurtzman DJ, Jones T, Fangru L, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review and approach to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:804-813.

- Hagen JW, Swoger JM, Grandinetti LM. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:417-431.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review [published online June 19, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Thrash B, Patel M, Shah KR, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease, part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:211.e1-211.e33.

- Abide JM. Metastatic Crohn disease: clearance with metronidazole. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:448-449.

- Teixeira M, Machado S, Lago P, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1074-1076.

- Stingeni L, Neve D, Bassotti G, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease successfully treated with adalimumab [published online Sep 15, 2015]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2016;30:E72-E74.

- Kurtzman DJ, Jones T, Fangru L, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review and approach to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:804-813.

- Hagen JW, Swoger JM, Grandinetti LM. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:417-431.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review [published online June 19, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Thrash B, Patel M, Shah KR, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease, part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:211.e1-211.e33.

- Abide JM. Metastatic Crohn disease: clearance with metronidazole. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:448-449.

A 38-year-old woman with a history of Crohn disease presented with painful nonhealing vulvar and perianal erosions of 6 months' duration. The erosions developed 4 months after discontinuing adalimumab for a planned surgery. During this time, the patient also had an exacerbation of Crohn colitis and developed an anal fistula. Prior to this break in adalimumab, the patient's Crohn disease was well controlled on adalimumab 40 mg every 2 weeks, azathioprine 100 mg daily, and mesalamine 4.8 g daily. Despite restarting adalimumab and therapy with multiple antibiotics (ie, metronidazole, ciprofloxacin), the erosions persisted. On physical examination erythematous plaques and nodules were present at the vulvar (top) and perianal (bottom) skin. In addition, well-demarcated erosions measuring 20 mm and 80 mm were present on the vulvar and perianal skin, respectively. Human immunodeficiency virus screening and rapid plasma reagin were negative.

Polypoid Melanoma: An Aggressive Variant of Nodular Melanoma

To the Editor:

An 81-year-old man presented with a nodular polypoid lesion that developed on a flat lesion on the back of 2 years’ duration. The lesion grew progressively over the course of 3 months prior to presentation. The patient had a history of melanoma in situ on the forehead that was treated with conventional surgery with clear surgical margins 6 years prior to the current presentation.

On physical examination the patient had a 4×2-cm ulcerated polypoid lesion on the back. The lesion was pink with a pigmented base. Additionally, 2 pink papules with superficial telangiectases were observed around the main lesion (Figure 1).

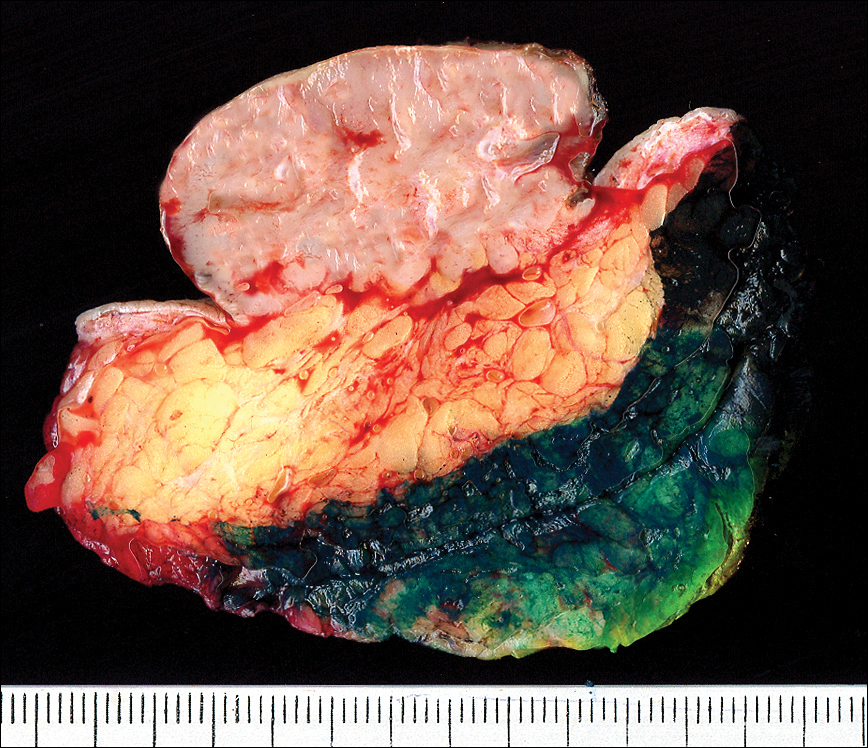

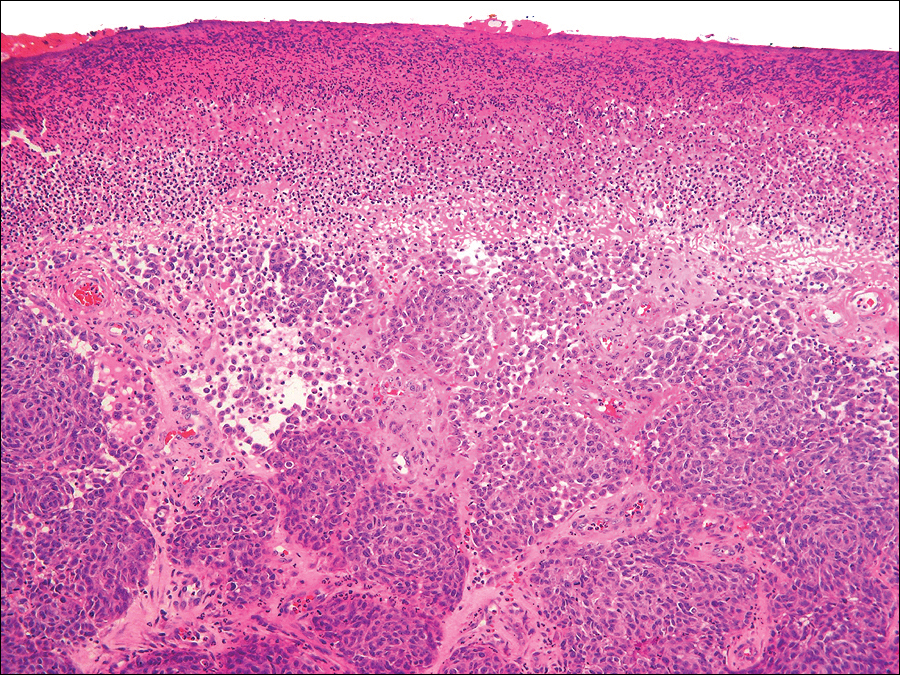

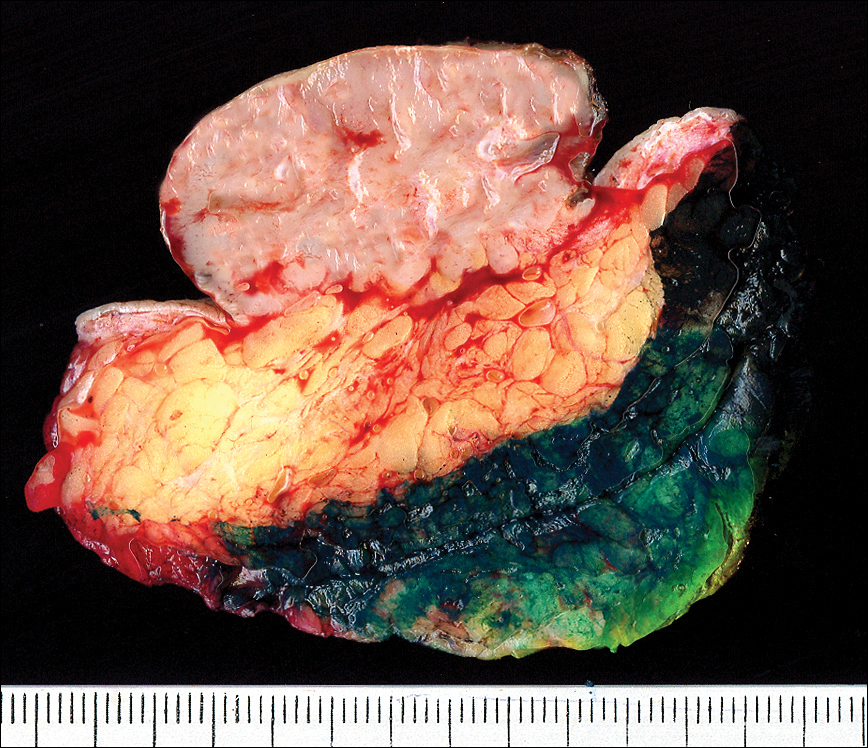

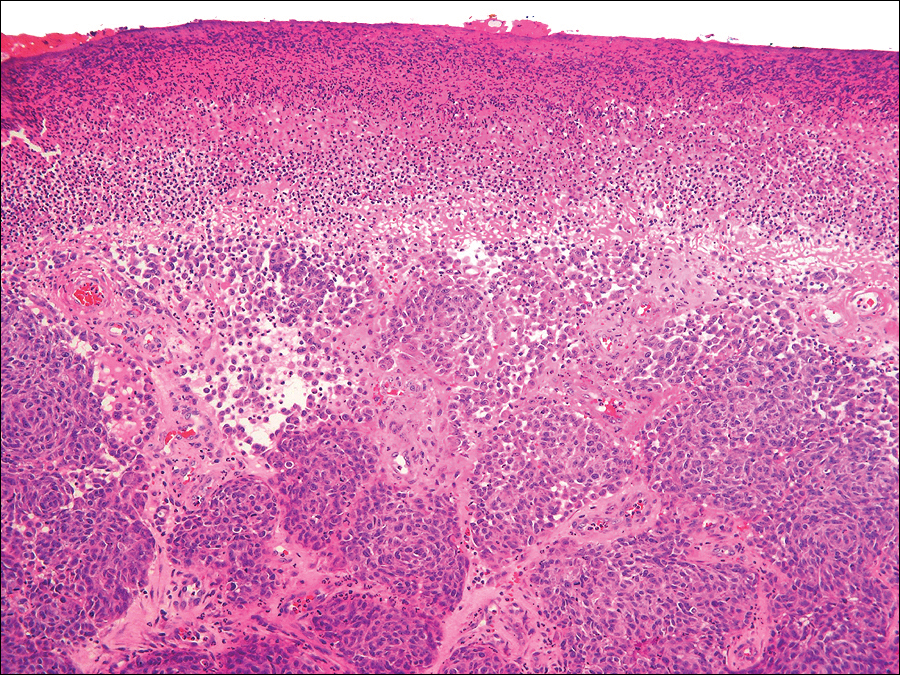

The gross section showed an exophytic tumor largely growing above the skin surface (Figure 2). Histopathologic analysis revealed an ulcerated lesion consisting of confluent nest and sheets of epithelioid and spindle atypical cells with numerous mitotic figures and necrotic foci (Figure 3). The thickness of the lesion was 2200 µm, and the mitotic count was 28 mitoses/mm2. There also was peritumoral vascular invasion and satellite metastasis within the perilesional hypodermis measuring 0.4 mm. Immunohistochemistry staining for S-100, human melanoma black 45 (HMB-45)(Figure 4), and Melan-A was positive in neoplastic cells.

The dissemination study revealed multiple mediastinal and axillary lymphadenopathies and lesions with metastatic appearance in the brain, liver, pancreas, and muscle, together with peritoneal carcinomatosis. The patient was lost to follow-up and did not follow coadjuvant therapy with interferon alfa.

Polypoid melanoma initially was described as a type of melanoma characterized by an exophytic growth in which most of the tumor is located on the cutaneous surface, together with ulceration.1 It usually occurs in patients aged 20 to 39 years,2 and the reported incidence ranges from 1.9% to 43.3%.1 It more commonly affects mucosae, including the upper respiratory tract, esophagus, and vagina. Polypoid melanoma has a rapid progression and a poor prognosis.3 Polypoid melanoma involving the skin primarily affects the back and has a 5-year survival rate of 32% to 42%.4 Poor prognosis has been attributed to the high risk for vascular embolization under the lesion.5 Histologically, there is marked cell atypia with nuclear and cellular pleomorphism and a high mitotic count. The tumor rarely involves the reticular dermis.1,2

Polypoid melanomas are rare; however, reported frequency rates cover a wide range. These frequency rates may be due to the definition of polypoid melanoma used by the pathologist issuing the report. One of the most accepted definitions at present is a pigmented macule that progresses in months with a rapid vertical growth, invading the epidermis and the papillary dermis.2 The differential diagnosis includes pyogenic granuloma, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, soft tissue sarcomas, and hemangioma.

Although our patient had a history of melanoma and the polypoid lesion developed from a flat lesion, he was late to seek medical care. The diagnosis of melanoma is made on increasingly smaller lesions with better prognosis, but there still are reports of larger melanomas. This case highlights the role dermatologists serve in the education of patients on their diagnoses and risk factors so that we may be able to diagnose non–life-threatening small lesions. It is important to remember this morphologic variety of melanoma and highlight its rapid progression and poor prognosis.

- Knezević F, Duancić V, Sitić S, et al. Histological types of polypoid cutaneous melanoma II. Coll Antropol. 2007;31:1049-1053.

- Dini M, Quercioli F, Caldarella V, et al. Head and neck polypoid melanoma. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:E23-E25.

- Plotnick H, Rachmaninoff N, VandenBerg HJ Jr. Polypoid melanoma: a virulent variant of nodular melanoma. report of three cases and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(5, pt 1):880-884.

- Manci EA, Balch CM, Murad TM, et al. Polypoid melanoma, a virulent variant of the nodular growth pattern. Am J Clin Pathol. 1981;75:810-815.

- De Giorgi V, Massi D, Gerlini G, et al. Immediate local and regional recurrence after the excision of a polypoid melanoma: tumor dormancy or tumor activation? Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:664-667.

To the Editor:

An 81-year-old man presented with a nodular polypoid lesion that developed on a flat lesion on the back of 2 years’ duration. The lesion grew progressively over the course of 3 months prior to presentation. The patient had a history of melanoma in situ on the forehead that was treated with conventional surgery with clear surgical margins 6 years prior to the current presentation.

On physical examination the patient had a 4×2-cm ulcerated polypoid lesion on the back. The lesion was pink with a pigmented base. Additionally, 2 pink papules with superficial telangiectases were observed around the main lesion (Figure 1).

The gross section showed an exophytic tumor largely growing above the skin surface (Figure 2). Histopathologic analysis revealed an ulcerated lesion consisting of confluent nest and sheets of epithelioid and spindle atypical cells with numerous mitotic figures and necrotic foci (Figure 3). The thickness of the lesion was 2200 µm, and the mitotic count was 28 mitoses/mm2. There also was peritumoral vascular invasion and satellite metastasis within the perilesional hypodermis measuring 0.4 mm. Immunohistochemistry staining for S-100, human melanoma black 45 (HMB-45)(Figure 4), and Melan-A was positive in neoplastic cells.

The dissemination study revealed multiple mediastinal and axillary lymphadenopathies and lesions with metastatic appearance in the brain, liver, pancreas, and muscle, together with peritoneal carcinomatosis. The patient was lost to follow-up and did not follow coadjuvant therapy with interferon alfa.

Polypoid melanoma initially was described as a type of melanoma characterized by an exophytic growth in which most of the tumor is located on the cutaneous surface, together with ulceration.1 It usually occurs in patients aged 20 to 39 years,2 and the reported incidence ranges from 1.9% to 43.3%.1 It more commonly affects mucosae, including the upper respiratory tract, esophagus, and vagina. Polypoid melanoma has a rapid progression and a poor prognosis.3 Polypoid melanoma involving the skin primarily affects the back and has a 5-year survival rate of 32% to 42%.4 Poor prognosis has been attributed to the high risk for vascular embolization under the lesion.5 Histologically, there is marked cell atypia with nuclear and cellular pleomorphism and a high mitotic count. The tumor rarely involves the reticular dermis.1,2

Polypoid melanomas are rare; however, reported frequency rates cover a wide range. These frequency rates may be due to the definition of polypoid melanoma used by the pathologist issuing the report. One of the most accepted definitions at present is a pigmented macule that progresses in months with a rapid vertical growth, invading the epidermis and the papillary dermis.2 The differential diagnosis includes pyogenic granuloma, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, soft tissue sarcomas, and hemangioma.

Although our patient had a history of melanoma and the polypoid lesion developed from a flat lesion, he was late to seek medical care. The diagnosis of melanoma is made on increasingly smaller lesions with better prognosis, but there still are reports of larger melanomas. This case highlights the role dermatologists serve in the education of patients on their diagnoses and risk factors so that we may be able to diagnose non–life-threatening small lesions. It is important to remember this morphologic variety of melanoma and highlight its rapid progression and poor prognosis.

To the Editor:

An 81-year-old man presented with a nodular polypoid lesion that developed on a flat lesion on the back of 2 years’ duration. The lesion grew progressively over the course of 3 months prior to presentation. The patient had a history of melanoma in situ on the forehead that was treated with conventional surgery with clear surgical margins 6 years prior to the current presentation.

On physical examination the patient had a 4×2-cm ulcerated polypoid lesion on the back. The lesion was pink with a pigmented base. Additionally, 2 pink papules with superficial telangiectases were observed around the main lesion (Figure 1).

The gross section showed an exophytic tumor largely growing above the skin surface (Figure 2). Histopathologic analysis revealed an ulcerated lesion consisting of confluent nest and sheets of epithelioid and spindle atypical cells with numerous mitotic figures and necrotic foci (Figure 3). The thickness of the lesion was 2200 µm, and the mitotic count was 28 mitoses/mm2. There also was peritumoral vascular invasion and satellite metastasis within the perilesional hypodermis measuring 0.4 mm. Immunohistochemistry staining for S-100, human melanoma black 45 (HMB-45)(Figure 4), and Melan-A was positive in neoplastic cells.

The dissemination study revealed multiple mediastinal and axillary lymphadenopathies and lesions with metastatic appearance in the brain, liver, pancreas, and muscle, together with peritoneal carcinomatosis. The patient was lost to follow-up and did not follow coadjuvant therapy with interferon alfa.

Polypoid melanoma initially was described as a type of melanoma characterized by an exophytic growth in which most of the tumor is located on the cutaneous surface, together with ulceration.1 It usually occurs in patients aged 20 to 39 years,2 and the reported incidence ranges from 1.9% to 43.3%.1 It more commonly affects mucosae, including the upper respiratory tract, esophagus, and vagina. Polypoid melanoma has a rapid progression and a poor prognosis.3 Polypoid melanoma involving the skin primarily affects the back and has a 5-year survival rate of 32% to 42%.4 Poor prognosis has been attributed to the high risk for vascular embolization under the lesion.5 Histologically, there is marked cell atypia with nuclear and cellular pleomorphism and a high mitotic count. The tumor rarely involves the reticular dermis.1,2

Polypoid melanomas are rare; however, reported frequency rates cover a wide range. These frequency rates may be due to the definition of polypoid melanoma used by the pathologist issuing the report. One of the most accepted definitions at present is a pigmented macule that progresses in months with a rapid vertical growth, invading the epidermis and the papillary dermis.2 The differential diagnosis includes pyogenic granuloma, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, soft tissue sarcomas, and hemangioma.

Although our patient had a history of melanoma and the polypoid lesion developed from a flat lesion, he was late to seek medical care. The diagnosis of melanoma is made on increasingly smaller lesions with better prognosis, but there still are reports of larger melanomas. This case highlights the role dermatologists serve in the education of patients on their diagnoses and risk factors so that we may be able to diagnose non–life-threatening small lesions. It is important to remember this morphologic variety of melanoma and highlight its rapid progression and poor prognosis.

- Knezević F, Duancić V, Sitić S, et al. Histological types of polypoid cutaneous melanoma II. Coll Antropol. 2007;31:1049-1053.

- Dini M, Quercioli F, Caldarella V, et al. Head and neck polypoid melanoma. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:E23-E25.

- Plotnick H, Rachmaninoff N, VandenBerg HJ Jr. Polypoid melanoma: a virulent variant of nodular melanoma. report of three cases and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(5, pt 1):880-884.

- Manci EA, Balch CM, Murad TM, et al. Polypoid melanoma, a virulent variant of the nodular growth pattern. Am J Clin Pathol. 1981;75:810-815.

- De Giorgi V, Massi D, Gerlini G, et al. Immediate local and regional recurrence after the excision of a polypoid melanoma: tumor dormancy or tumor activation? Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:664-667.

- Knezević F, Duancić V, Sitić S, et al. Histological types of polypoid cutaneous melanoma II. Coll Antropol. 2007;31:1049-1053.

- Dini M, Quercioli F, Caldarella V, et al. Head and neck polypoid melanoma. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:E23-E25.

- Plotnick H, Rachmaninoff N, VandenBerg HJ Jr. Polypoid melanoma: a virulent variant of nodular melanoma. report of three cases and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(5, pt 1):880-884.

- Manci EA, Balch CM, Murad TM, et al. Polypoid melanoma, a virulent variant of the nodular growth pattern. Am J Clin Pathol. 1981;75:810-815.

- De Giorgi V, Massi D, Gerlini G, et al. Immediate local and regional recurrence after the excision of a polypoid melanoma: tumor dormancy or tumor activation? Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:664-667.

Practice Points

- The differential diagnosis of polypoid melanoma includes pyogenic granuloma and squamous cell carcinoma.

- Polypoid melanoma has a poor prognosis because of its thickness and ulceration at the time of diagnosis and the risk of vascular embolization.

Scaly Annular and Concentric Plaques

The Diagnosis: Annular Psoriasis

Because the patient's history was nonconcordant with the clinical appearance, a 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from a lesion on the left hip. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections demonstrated mild irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with discrete mounds of parakeratin (Figure 1A). Higher power revealed numerous neutrophils entrapped within focal scale crusts (Figure 1B). Periodic acid-Schiff stain for fungus demonstrated no hyphal elements or yeast forms in the stratum corneum. These histopathology findings were consistent with the diagnosis of annular psoriasis.

The manifestation of psoriasis may take many forms, ranging from classic plaques to pustular eruptions--either annular or generalized--and erythroderma. Primarily annular plaque-type psoriasis without pustules, however, remains an uncommon finding.1 Psoriatic plaques may become annular or arcuate with central clearing from partial treatment with topical medications, though our patient reported annular plaques prior to any treatment. His presentation was notably different than annular pustular psoriasis in that there were no pustules in the leading edge, and there was no trailing scale, which is typical of annular pustular psoriasis.

Topical triamcinolone prescribed at the initial presentation to the dermatology department helped with pruritus, but due to the large body surface area involved, methotrexate later was initiated. After a 10-mg test dose of methotrexate and titration to 15 mg weekly, dramatic improvement in the rash was noted after 8 weeks. As the rash resolved, only faint hyperpigmented patches remained (Figure 2).

Erythema gyratum repens is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome that presents with annular scaly plaques with concentric circles with a wood grain-like appearance. The borders can advance up to 1 cm daily and show nonspecific findings on histopathology.2 Due to the observation that approximately 80% of cases of erythema gyratum repens were associated with an underlying malignancy, most often of the lung,3 this diagnosis was entertained given our patient's clinical presentation.

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) historically has been divided into 2 forms: superficial and deep.4 Both present with slowly expanding, annular, pink plaques. Superficial EAC demonstrates parakeratosis and trailing scale and has not been proven to be associated with other systemic diseases, while deep EAC has infiltrated borders without scale, and many cases of EAC may represent annular forms of tumid lupus.4 Inflammatory cells may cuff vessels tightly, resulting in so-called coat sleeve infiltrate in superficial EAC. Along with trailing scale, this finding suggests the diagnosis. It has been argued that EAC is not an entity on its own and should prompt evaluation for lupus erythematosus, dermatitis, hypersensitivity to tinea pedis, and Lyme disease in appropriate circumstances.5

Tinea corporis always should be considered when evaluating annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Diagnosis and treatment are straightforward when hyphae are found on microscopy of skin scrapings or seen on periodic acid-Schiff stains of formalin-fixed tissue. Tinea imbricata presents with an interesting morphology and appears more ornate or cerebriform than tinea corporis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. It is caused by infection with Trichophyton circumscriptum and occurs in certain regions in the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America, making the diagnosis within the United States unlikely for a patient who has not traveled to these areas.6

Erythema chronicum migrans is diagnostic of Lyme disease infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, and solitary lesions occur surrounding the site of a tick bite in the majority of patients. Only 20% of patients will develop multiple lesions consistent with erythema chronicum migrans due to multiple tick bites, spirochetemia, or lymphatic spread.7 Up to one-third of patients are unaware that they were bitten by a tick. In endemic areas, this diagnosis must be entertained in any patient presenting with an annular rash, as treatment may prevent notable morbidity.

- Guill C, Hoang M, Carder K. Primary annular plaque-type psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:15-18.

- Boyd A, Neldner K, Menter A. Erythema gyratum repens: a paraneoplastic eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:757-762.

- Kawakami T, Saito R. Erythema gyratum repens unassociated with underlying malignancy. J Dermatol. 1995;22:587-589.

- Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

- Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does notrepresent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

- Bonifaz A, Vázquez-González D. Tinea imbricata in the Americas. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:106-111.

- Müllegger R, Glatz M. Skin manifestations of Lyme borreliosis: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:355-368.

The Diagnosis: Annular Psoriasis

Because the patient's history was nonconcordant with the clinical appearance, a 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from a lesion on the left hip. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections demonstrated mild irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with discrete mounds of parakeratin (Figure 1A). Higher power revealed numerous neutrophils entrapped within focal scale crusts (Figure 1B). Periodic acid-Schiff stain for fungus demonstrated no hyphal elements or yeast forms in the stratum corneum. These histopathology findings were consistent with the diagnosis of annular psoriasis.

The manifestation of psoriasis may take many forms, ranging from classic plaques to pustular eruptions--either annular or generalized--and erythroderma. Primarily annular plaque-type psoriasis without pustules, however, remains an uncommon finding.1 Psoriatic plaques may become annular or arcuate with central clearing from partial treatment with topical medications, though our patient reported annular plaques prior to any treatment. His presentation was notably different than annular pustular psoriasis in that there were no pustules in the leading edge, and there was no trailing scale, which is typical of annular pustular psoriasis.

Topical triamcinolone prescribed at the initial presentation to the dermatology department helped with pruritus, but due to the large body surface area involved, methotrexate later was initiated. After a 10-mg test dose of methotrexate and titration to 15 mg weekly, dramatic improvement in the rash was noted after 8 weeks. As the rash resolved, only faint hyperpigmented patches remained (Figure 2).

Erythema gyratum repens is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome that presents with annular scaly plaques with concentric circles with a wood grain-like appearance. The borders can advance up to 1 cm daily and show nonspecific findings on histopathology.2 Due to the observation that approximately 80% of cases of erythema gyratum repens were associated with an underlying malignancy, most often of the lung,3 this diagnosis was entertained given our patient's clinical presentation.

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) historically has been divided into 2 forms: superficial and deep.4 Both present with slowly expanding, annular, pink plaques. Superficial EAC demonstrates parakeratosis and trailing scale and has not been proven to be associated with other systemic diseases, while deep EAC has infiltrated borders without scale, and many cases of EAC may represent annular forms of tumid lupus.4 Inflammatory cells may cuff vessels tightly, resulting in so-called coat sleeve infiltrate in superficial EAC. Along with trailing scale, this finding suggests the diagnosis. It has been argued that EAC is not an entity on its own and should prompt evaluation for lupus erythematosus, dermatitis, hypersensitivity to tinea pedis, and Lyme disease in appropriate circumstances.5

Tinea corporis always should be considered when evaluating annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Diagnosis and treatment are straightforward when hyphae are found on microscopy of skin scrapings or seen on periodic acid-Schiff stains of formalin-fixed tissue. Tinea imbricata presents with an interesting morphology and appears more ornate or cerebriform than tinea corporis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. It is caused by infection with Trichophyton circumscriptum and occurs in certain regions in the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America, making the diagnosis within the United States unlikely for a patient who has not traveled to these areas.6

Erythema chronicum migrans is diagnostic of Lyme disease infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, and solitary lesions occur surrounding the site of a tick bite in the majority of patients. Only 20% of patients will develop multiple lesions consistent with erythema chronicum migrans due to multiple tick bites, spirochetemia, or lymphatic spread.7 Up to one-third of patients are unaware that they were bitten by a tick. In endemic areas, this diagnosis must be entertained in any patient presenting with an annular rash, as treatment may prevent notable morbidity.

The Diagnosis: Annular Psoriasis

Because the patient's history was nonconcordant with the clinical appearance, a 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from a lesion on the left hip. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections demonstrated mild irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with discrete mounds of parakeratin (Figure 1A). Higher power revealed numerous neutrophils entrapped within focal scale crusts (Figure 1B). Periodic acid-Schiff stain for fungus demonstrated no hyphal elements or yeast forms in the stratum corneum. These histopathology findings were consistent with the diagnosis of annular psoriasis.

The manifestation of psoriasis may take many forms, ranging from classic plaques to pustular eruptions--either annular or generalized--and erythroderma. Primarily annular plaque-type psoriasis without pustules, however, remains an uncommon finding.1 Psoriatic plaques may become annular or arcuate with central clearing from partial treatment with topical medications, though our patient reported annular plaques prior to any treatment. His presentation was notably different than annular pustular psoriasis in that there were no pustules in the leading edge, and there was no trailing scale, which is typical of annular pustular psoriasis.

Topical triamcinolone prescribed at the initial presentation to the dermatology department helped with pruritus, but due to the large body surface area involved, methotrexate later was initiated. After a 10-mg test dose of methotrexate and titration to 15 mg weekly, dramatic improvement in the rash was noted after 8 weeks. As the rash resolved, only faint hyperpigmented patches remained (Figure 2).

Erythema gyratum repens is a rare paraneoplastic syndrome that presents with annular scaly plaques with concentric circles with a wood grain-like appearance. The borders can advance up to 1 cm daily and show nonspecific findings on histopathology.2 Due to the observation that approximately 80% of cases of erythema gyratum repens were associated with an underlying malignancy, most often of the lung,3 this diagnosis was entertained given our patient's clinical presentation.

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) historically has been divided into 2 forms: superficial and deep.4 Both present with slowly expanding, annular, pink plaques. Superficial EAC demonstrates parakeratosis and trailing scale and has not been proven to be associated with other systemic diseases, while deep EAC has infiltrated borders without scale, and many cases of EAC may represent annular forms of tumid lupus.4 Inflammatory cells may cuff vessels tightly, resulting in so-called coat sleeve infiltrate in superficial EAC. Along with trailing scale, this finding suggests the diagnosis. It has been argued that EAC is not an entity on its own and should prompt evaluation for lupus erythematosus, dermatitis, hypersensitivity to tinea pedis, and Lyme disease in appropriate circumstances.5

Tinea corporis always should be considered when evaluating annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Diagnosis and treatment are straightforward when hyphae are found on microscopy of skin scrapings or seen on periodic acid-Schiff stains of formalin-fixed tissue. Tinea imbricata presents with an interesting morphology and appears more ornate or cerebriform than tinea corporis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. It is caused by infection with Trichophyton circumscriptum and occurs in certain regions in the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America, making the diagnosis within the United States unlikely for a patient who has not traveled to these areas.6

Erythema chronicum migrans is diagnostic of Lyme disease infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, and solitary lesions occur surrounding the site of a tick bite in the majority of patients. Only 20% of patients will develop multiple lesions consistent with erythema chronicum migrans due to multiple tick bites, spirochetemia, or lymphatic spread.7 Up to one-third of patients are unaware that they were bitten by a tick. In endemic areas, this diagnosis must be entertained in any patient presenting with an annular rash, as treatment may prevent notable morbidity.

- Guill C, Hoang M, Carder K. Primary annular plaque-type psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:15-18.

- Boyd A, Neldner K, Menter A. Erythema gyratum repens: a paraneoplastic eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:757-762.

- Kawakami T, Saito R. Erythema gyratum repens unassociated with underlying malignancy. J Dermatol. 1995;22:587-589.

- Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

- Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does notrepresent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

- Bonifaz A, Vázquez-González D. Tinea imbricata in the Americas. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:106-111.

- Müllegger R, Glatz M. Skin manifestations of Lyme borreliosis: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:355-368.

- Guill C, Hoang M, Carder K. Primary annular plaque-type psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:15-18.

- Boyd A, Neldner K, Menter A. Erythema gyratum repens: a paraneoplastic eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:757-762.

- Kawakami T, Saito R. Erythema gyratum repens unassociated with underlying malignancy. J Dermatol. 1995;22:587-589.

- Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

- Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does notrepresent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

- Bonifaz A, Vázquez-González D. Tinea imbricata in the Americas. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:106-111.

- Müllegger R, Glatz M. Skin manifestations of Lyme borreliosis: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:355-368.

A healthy 23-year-old man presented for evaluation of an enlarging annular pruritic rash of 1.5 years' duration. Treatment with ciclopirox cream 0.77%, calcipotriene cream 0.005%, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, fluticasone cream 0.05%, and halobetasol cream 0.05% prescribed by an outside physician provided only modest temporary improvement. The patient reported no history of travel outside of western New York, camping, tick bites, or medications. He denied any joint swelling or morning stiffness. Physical examination revealed multiple 4- to 6-cm pink, annular, scaly plaques with central clearing on the abdomen (top) and thighs. A few 1-cm pink scaly patches were present on the back (bottom), and few 2- to 3-mm pink scaly papules were noted on the extensor aspects of the elbows and forearms. A potassium hydroxide examination revealed no hyphal elements or yeast forms.

Idiopathic Eruptive Macular Pigmentation With Papillomatosis

To the Editor:

A 13-year-old white adolescent girl presented with asymptomatic discrete hyperpigmented papules on the chest, back, arms, and upper legs of 7 months’ duration. The patient otherwise was in good health; her weight and height were on the 40th percentile on growth curves and she had no history of any medications. Treatments for the skin condition prescribed by outside dermatologists included minocycline 75 mg twice daily for 2 months, lactic acid lotion 12% daily, and ketoconazole 400 mg administered twice 1 week apart.

Physical examination revealed more than 50 scattered hyperpigmented papules on the chest, back, arms, and upper legs ranging in size from 2 to 3.5 cm (Figure 1). Stroking of lesions failed to elicit Darier sign. A potassium hydroxide preparation and fungal culture were negative for pathogenic fungal organisms. The plasma insulin level was within reference range. A punch biopsy from the abdomen was obtained and sent for histopathologic examination. Histopathology showed mild hyperkeratosis, subtle papillomatosis, and interanastomosing acanthosis comprising squamoid cells with mild basilar hyperpigmentation (Figure 2). Sparse superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and increased pigmentation was seen in the basal layer. The dermis showed a few scattered dermal melanophages. A periodic acid–Schiff with diastase stain was negative. Giemsa and Leder stains highlighted a normal number and distribution of mast cells. Based on the histologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation (IEMP).