User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Painless Ulcer on the Areola

The Diagnosis: Primary Syphilitic Chancre of the Nipple

Because laboratory investigation was negative, a primary syphilitic chancre was suspected based on clinical findings, which was confirmed by a positive rapid plasma reagin with a titer of 1:32 and a positive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay. Results were negative for human immunodeficiency virus. On further inquiry, the patient acknowledged that the right areola had been traumatized during sexual activity with his regular male partner 1 month prior. In the last year he reported having had 5 different male partners. He was treated with a single dose of 2.4 million IU of intramuscular benzathine penicillin. Screening for other sexually transmitted infections revealed concomitant gonococcal infection of the pharynx and chlamydia proctitis, both of which were subsequently treated. On follow-up 2 weeks after presentation the ulcer had resolved, and he currently is undergoing serial rapid plasma reagin titer monitoring.

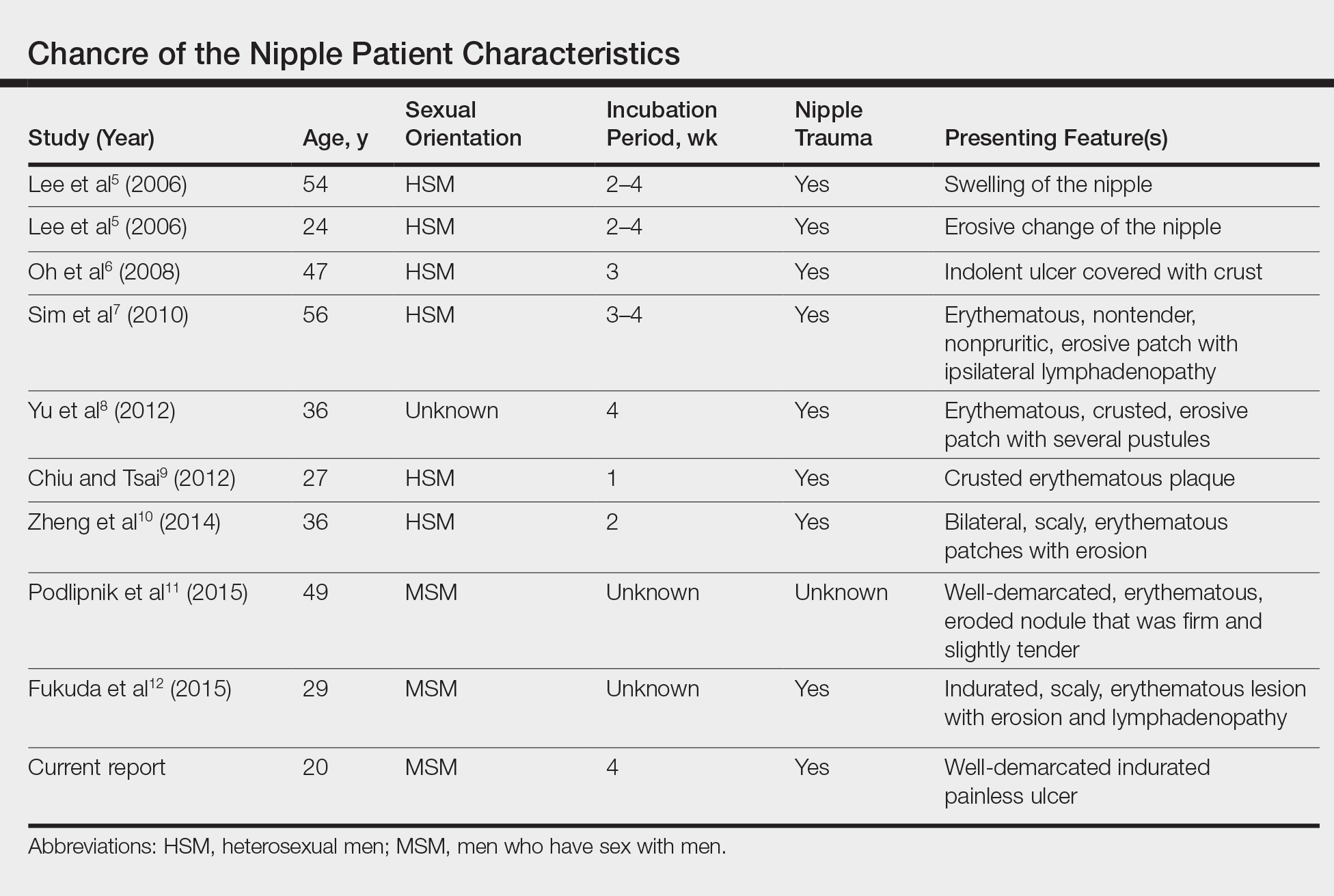

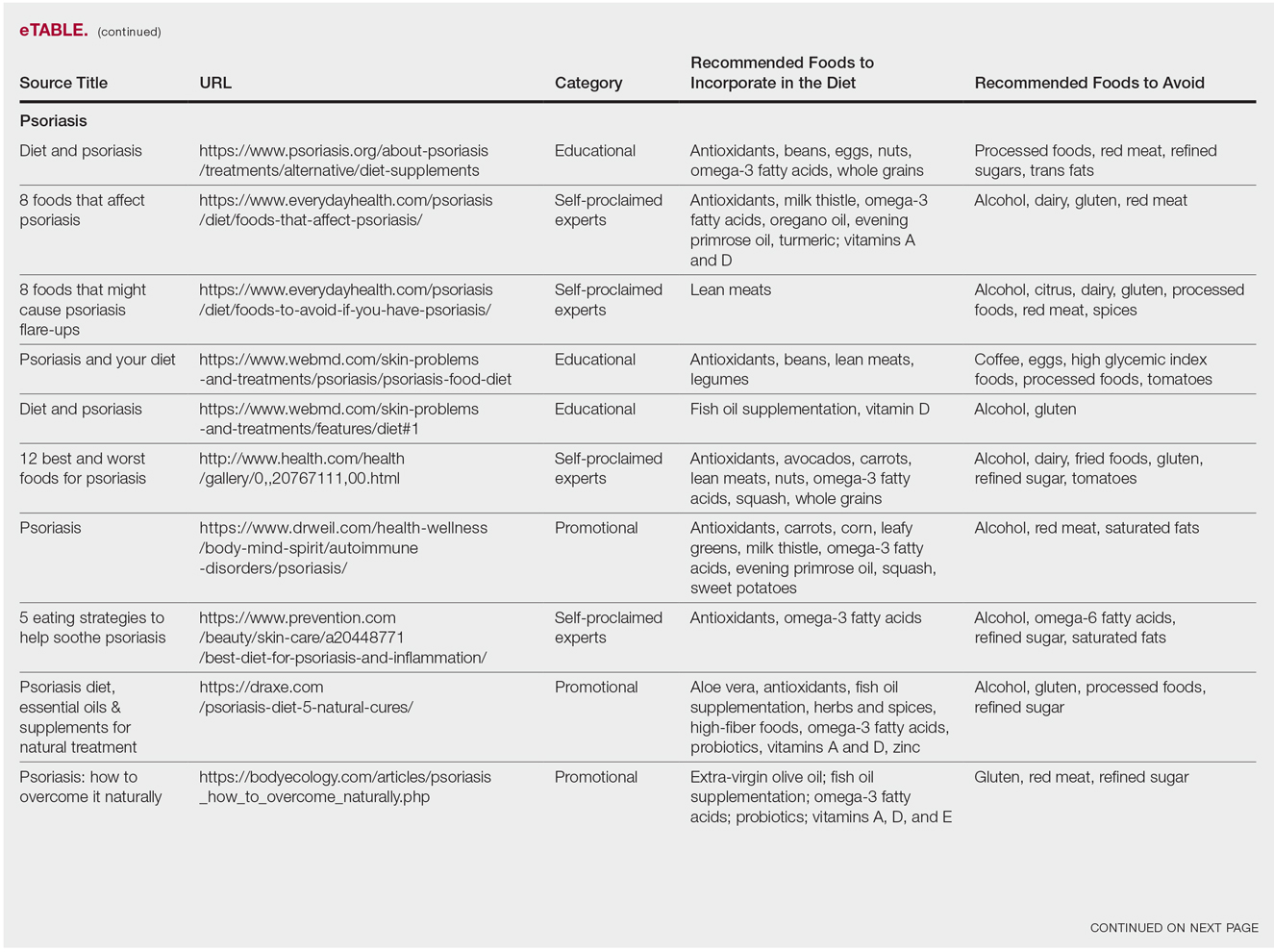

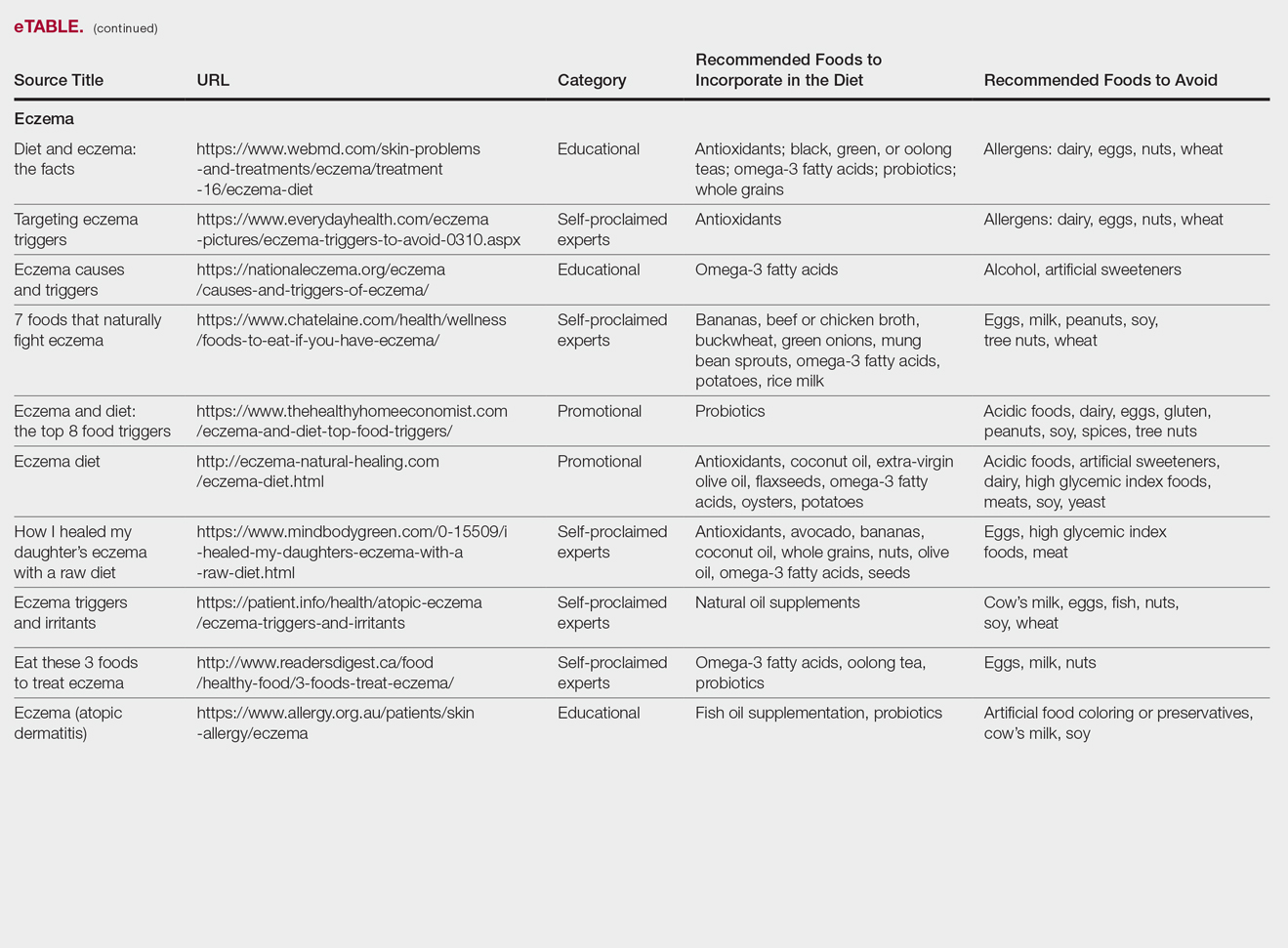

Primary syphilitic chancres can occur at any mucocutaneous site of inoculation, most frequently on the genitalia.1 Classically, after an incubation period of 9 to 90 days, a painless indurated ulcer forms2 and heals spontaneously after 3 to 6 weeks if left untreated.3 Chancres at extragenital sites are uncommon, occurring in approximately 2% of patients with primary syphilis.1 Of them, common sites include the lips and mouth (40%-70%),4 with areolar involvement rarely being reported. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms nipple and chancre revealed 9 case reports in the English-language literature, with the first 2 cases being reported by Lee et al5 in 2006. The characteristics of these cases and our patient are summarized in the Table.5-12

Oral contact or traumatization of the nipple by the patient's sexual partner was reported in all but one of these cases5-10,12; trauma was unknown in one case.11 Our patient reported a similar history of trauma to the nipple. It is known that transmission of syphilis can take place via kissing or oral contact, and it has been asserted that oral syphilitic lesions are highly infectious.13 Syphilis also can be transmitted by an already infected sexual partner sustaining minor trauma at the oral mucosa, allowing Treponema pallidum from the bloodstream to be inoculated onto the nipple. Another explanation for transmission could be the Koebner phenomenon, whereby trauma at the nipple of an already infected patient could lead to the formation of a chancre.6,8

The differential diagnosis includes erosive adenomatosis of the nipple, nipple eczema, Paget disease of the breast, and ulcerated basal cell carcinoma. Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple is a benign tumor of unilateral involvement that presents as an asymptomatic eroded/ulcerated papule. Clinically, it is similar to Paget disease of the breast. Eczema of the nipple usually is associated with pruritus and epidermal changes such as scaling.7,8 Paget disease of the breast arises from the extension of breast ductal carcinoma in situ onto the skin overlying the nipple. It can present as a unilateral nipple plaque with ulceration and bloody discharge. The diagnoses of erosive adenomatosis and Paget disease are confirmed with histologic examination. Basal cell carcinoma is the most common nonmelanoma skin cancer and can present as an ulcerated plaque, often with rolled borders, pearly edges, and overlying telangiectasia. It is known to be locally invasive. A punch biopsy and histopathologic examination would confirm the diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma.14

Extragenital chancres, especially those occurring at unusual sites, are uncommon. Therefore, a high index of suspicion is required to diagnose and initiate appropriate treatment for these patients.

- Mindel A, Tovey SJ, Timmins DJ, et al. Primary and secondary syphilis, 20 years' experience. 2. clinical features. Genitourin Med. 1989;65:1-3.

- Goh B. Syphilis in adults. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:448-452.

- Katz KA. Syphilis. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2012:2471-2492.

- Singh AE, Romanowski B. Syphilis: review with emphasis on clinical, epidemiologic, and some biologic features. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:187-209.

- Lee JY, Lin MH, Jung YC. Extragenital syphilitic chancre manifesting as a solitary nodule of the nipple. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:886-887.

- Oh Y, Ahn S, Hong SP, et al. A case of extragenital chancre on a nipple from a human bite during sexual intercourse. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:978-980.

- Sim JH, Lee MG, In SI, et al. Erythematous erosive patch on the left nipple--quiz case. diagnosis: extragenital syphilitic chancres. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:81-86.

- Yu M, Lee HR, Han TY, et al. A solitary erosive patch on the left nipple. extragenital syphilitic chancres. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:27-28.

- Chiu HY, Tsai TF. A crusted plaque on the right nipple. JAMA. 2012;308:403-404.

- Zheng S, Liu J, Xu XG, et al. Primary syphilis presenting as bilateral nipple-areola eczematoid lesions. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:617-618.

- Podlipnik S, Giavedoni P, Alsina M, et al. An erythematous nodule on the nipple: an unusual presentation of primary syphilis. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:239-243.

- Fukuda H, Takahashi M, Kato K, et al. Multiple primary syphilis on the lip, nipple-areola and penis: an immunohistochemical examination of Treponema pallidum localization using an anti-T. pallidum antibody. J Dermatol. 2015;42:515-517.

- Yu X, Zheng H. Syphilitic chancre of the lips transmitted by kissing. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:E3303.

- Carucci JA, Leffell DJ, Pettersen JS. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2012:1294-1303.

The Diagnosis: Primary Syphilitic Chancre of the Nipple

Because laboratory investigation was negative, a primary syphilitic chancre was suspected based on clinical findings, which was confirmed by a positive rapid plasma reagin with a titer of 1:32 and a positive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay. Results were negative for human immunodeficiency virus. On further inquiry, the patient acknowledged that the right areola had been traumatized during sexual activity with his regular male partner 1 month prior. In the last year he reported having had 5 different male partners. He was treated with a single dose of 2.4 million IU of intramuscular benzathine penicillin. Screening for other sexually transmitted infections revealed concomitant gonococcal infection of the pharynx and chlamydia proctitis, both of which were subsequently treated. On follow-up 2 weeks after presentation the ulcer had resolved, and he currently is undergoing serial rapid plasma reagin titer monitoring.

Primary syphilitic chancres can occur at any mucocutaneous site of inoculation, most frequently on the genitalia.1 Classically, after an incubation period of 9 to 90 days, a painless indurated ulcer forms2 and heals spontaneously after 3 to 6 weeks if left untreated.3 Chancres at extragenital sites are uncommon, occurring in approximately 2% of patients with primary syphilis.1 Of them, common sites include the lips and mouth (40%-70%),4 with areolar involvement rarely being reported. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms nipple and chancre revealed 9 case reports in the English-language literature, with the first 2 cases being reported by Lee et al5 in 2006. The characteristics of these cases and our patient are summarized in the Table.5-12

Oral contact or traumatization of the nipple by the patient's sexual partner was reported in all but one of these cases5-10,12; trauma was unknown in one case.11 Our patient reported a similar history of trauma to the nipple. It is known that transmission of syphilis can take place via kissing or oral contact, and it has been asserted that oral syphilitic lesions are highly infectious.13 Syphilis also can be transmitted by an already infected sexual partner sustaining minor trauma at the oral mucosa, allowing Treponema pallidum from the bloodstream to be inoculated onto the nipple. Another explanation for transmission could be the Koebner phenomenon, whereby trauma at the nipple of an already infected patient could lead to the formation of a chancre.6,8

The differential diagnosis includes erosive adenomatosis of the nipple, nipple eczema, Paget disease of the breast, and ulcerated basal cell carcinoma. Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple is a benign tumor of unilateral involvement that presents as an asymptomatic eroded/ulcerated papule. Clinically, it is similar to Paget disease of the breast. Eczema of the nipple usually is associated with pruritus and epidermal changes such as scaling.7,8 Paget disease of the breast arises from the extension of breast ductal carcinoma in situ onto the skin overlying the nipple. It can present as a unilateral nipple plaque with ulceration and bloody discharge. The diagnoses of erosive adenomatosis and Paget disease are confirmed with histologic examination. Basal cell carcinoma is the most common nonmelanoma skin cancer and can present as an ulcerated plaque, often with rolled borders, pearly edges, and overlying telangiectasia. It is known to be locally invasive. A punch biopsy and histopathologic examination would confirm the diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma.14

Extragenital chancres, especially those occurring at unusual sites, are uncommon. Therefore, a high index of suspicion is required to diagnose and initiate appropriate treatment for these patients.

The Diagnosis: Primary Syphilitic Chancre of the Nipple

Because laboratory investigation was negative, a primary syphilitic chancre was suspected based on clinical findings, which was confirmed by a positive rapid plasma reagin with a titer of 1:32 and a positive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay. Results were negative for human immunodeficiency virus. On further inquiry, the patient acknowledged that the right areola had been traumatized during sexual activity with his regular male partner 1 month prior. In the last year he reported having had 5 different male partners. He was treated with a single dose of 2.4 million IU of intramuscular benzathine penicillin. Screening for other sexually transmitted infections revealed concomitant gonococcal infection of the pharynx and chlamydia proctitis, both of which were subsequently treated. On follow-up 2 weeks after presentation the ulcer had resolved, and he currently is undergoing serial rapid plasma reagin titer monitoring.

Primary syphilitic chancres can occur at any mucocutaneous site of inoculation, most frequently on the genitalia.1 Classically, after an incubation period of 9 to 90 days, a painless indurated ulcer forms2 and heals spontaneously after 3 to 6 weeks if left untreated.3 Chancres at extragenital sites are uncommon, occurring in approximately 2% of patients with primary syphilis.1 Of them, common sites include the lips and mouth (40%-70%),4 with areolar involvement rarely being reported. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms nipple and chancre revealed 9 case reports in the English-language literature, with the first 2 cases being reported by Lee et al5 in 2006. The characteristics of these cases and our patient are summarized in the Table.5-12

Oral contact or traumatization of the nipple by the patient's sexual partner was reported in all but one of these cases5-10,12; trauma was unknown in one case.11 Our patient reported a similar history of trauma to the nipple. It is known that transmission of syphilis can take place via kissing or oral contact, and it has been asserted that oral syphilitic lesions are highly infectious.13 Syphilis also can be transmitted by an already infected sexual partner sustaining minor trauma at the oral mucosa, allowing Treponema pallidum from the bloodstream to be inoculated onto the nipple. Another explanation for transmission could be the Koebner phenomenon, whereby trauma at the nipple of an already infected patient could lead to the formation of a chancre.6,8

The differential diagnosis includes erosive adenomatosis of the nipple, nipple eczema, Paget disease of the breast, and ulcerated basal cell carcinoma. Erosive adenomatosis of the nipple is a benign tumor of unilateral involvement that presents as an asymptomatic eroded/ulcerated papule. Clinically, it is similar to Paget disease of the breast. Eczema of the nipple usually is associated with pruritus and epidermal changes such as scaling.7,8 Paget disease of the breast arises from the extension of breast ductal carcinoma in situ onto the skin overlying the nipple. It can present as a unilateral nipple plaque with ulceration and bloody discharge. The diagnoses of erosive adenomatosis and Paget disease are confirmed with histologic examination. Basal cell carcinoma is the most common nonmelanoma skin cancer and can present as an ulcerated plaque, often with rolled borders, pearly edges, and overlying telangiectasia. It is known to be locally invasive. A punch biopsy and histopathologic examination would confirm the diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma.14

Extragenital chancres, especially those occurring at unusual sites, are uncommon. Therefore, a high index of suspicion is required to diagnose and initiate appropriate treatment for these patients.

- Mindel A, Tovey SJ, Timmins DJ, et al. Primary and secondary syphilis, 20 years' experience. 2. clinical features. Genitourin Med. 1989;65:1-3.

- Goh B. Syphilis in adults. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:448-452.

- Katz KA. Syphilis. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2012:2471-2492.

- Singh AE, Romanowski B. Syphilis: review with emphasis on clinical, epidemiologic, and some biologic features. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:187-209.

- Lee JY, Lin MH, Jung YC. Extragenital syphilitic chancre manifesting as a solitary nodule of the nipple. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:886-887.

- Oh Y, Ahn S, Hong SP, et al. A case of extragenital chancre on a nipple from a human bite during sexual intercourse. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:978-980.

- Sim JH, Lee MG, In SI, et al. Erythematous erosive patch on the left nipple--quiz case. diagnosis: extragenital syphilitic chancres. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:81-86.

- Yu M, Lee HR, Han TY, et al. A solitary erosive patch on the left nipple. extragenital syphilitic chancres. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:27-28.

- Chiu HY, Tsai TF. A crusted plaque on the right nipple. JAMA. 2012;308:403-404.

- Zheng S, Liu J, Xu XG, et al. Primary syphilis presenting as bilateral nipple-areola eczematoid lesions. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:617-618.

- Podlipnik S, Giavedoni P, Alsina M, et al. An erythematous nodule on the nipple: an unusual presentation of primary syphilis. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:239-243.

- Fukuda H, Takahashi M, Kato K, et al. Multiple primary syphilis on the lip, nipple-areola and penis: an immunohistochemical examination of Treponema pallidum localization using an anti-T. pallidum antibody. J Dermatol. 2015;42:515-517.

- Yu X, Zheng H. Syphilitic chancre of the lips transmitted by kissing. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:E3303.

- Carucci JA, Leffell DJ, Pettersen JS. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2012:1294-1303.

- Mindel A, Tovey SJ, Timmins DJ, et al. Primary and secondary syphilis, 20 years' experience. 2. clinical features. Genitourin Med. 1989;65:1-3.

- Goh B. Syphilis in adults. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:448-452.

- Katz KA. Syphilis. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2012:2471-2492.

- Singh AE, Romanowski B. Syphilis: review with emphasis on clinical, epidemiologic, and some biologic features. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:187-209.

- Lee JY, Lin MH, Jung YC. Extragenital syphilitic chancre manifesting as a solitary nodule of the nipple. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:886-887.

- Oh Y, Ahn S, Hong SP, et al. A case of extragenital chancre on a nipple from a human bite during sexual intercourse. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:978-980.

- Sim JH, Lee MG, In SI, et al. Erythematous erosive patch on the left nipple--quiz case. diagnosis: extragenital syphilitic chancres. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:81-86.

- Yu M, Lee HR, Han TY, et al. A solitary erosive patch on the left nipple. extragenital syphilitic chancres. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:27-28.

- Chiu HY, Tsai TF. A crusted plaque on the right nipple. JAMA. 2012;308:403-404.

- Zheng S, Liu J, Xu XG, et al. Primary syphilis presenting as bilateral nipple-areola eczematoid lesions. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:617-618.

- Podlipnik S, Giavedoni P, Alsina M, et al. An erythematous nodule on the nipple: an unusual presentation of primary syphilis. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:239-243.

- Fukuda H, Takahashi M, Kato K, et al. Multiple primary syphilis on the lip, nipple-areola and penis: an immunohistochemical examination of Treponema pallidum localization using an anti-T. pallidum antibody. J Dermatol. 2015;42:515-517.

- Yu X, Zheng H. Syphilitic chancre of the lips transmitted by kissing. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:E3303.

- Carucci JA, Leffell DJ, Pettersen JS. Basal cell carcinoma. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2012:1294-1303.

A previously healthy 20-year-old Chinese man presented to our dermatology outpatient clinic with a solitary painless ulcer on the right areola of 1 week's duration. Examination showed a small, slightly indurated ulcer with well-defined borders. No lesions were noted elsewhere. Swabs for pyogenic culture and herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction tests were sent, and he was treated empirically with oral cephalexin and tetracycline ointment 3%. At 1-week follow-up the ulcer had dried up and begun to heal, and results from the laboratory investigations were negative.

Deep Soft Tissue Mass of the Knee

The Diagnosis: Nodular Fasciitis

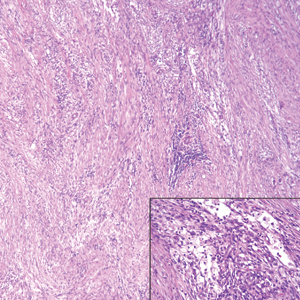

The diagnosis of spindle cell tumors can be challenging; however, by using a variety of immunoperoxidase stains and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) testing in conjunction with histology, it often is possible to arrive at a definitive diagnosis. For this case, the histologic features in conjunction with the immunoperoxidase stains and FISH were consistent with a diagnosis of nodular fasciitis.

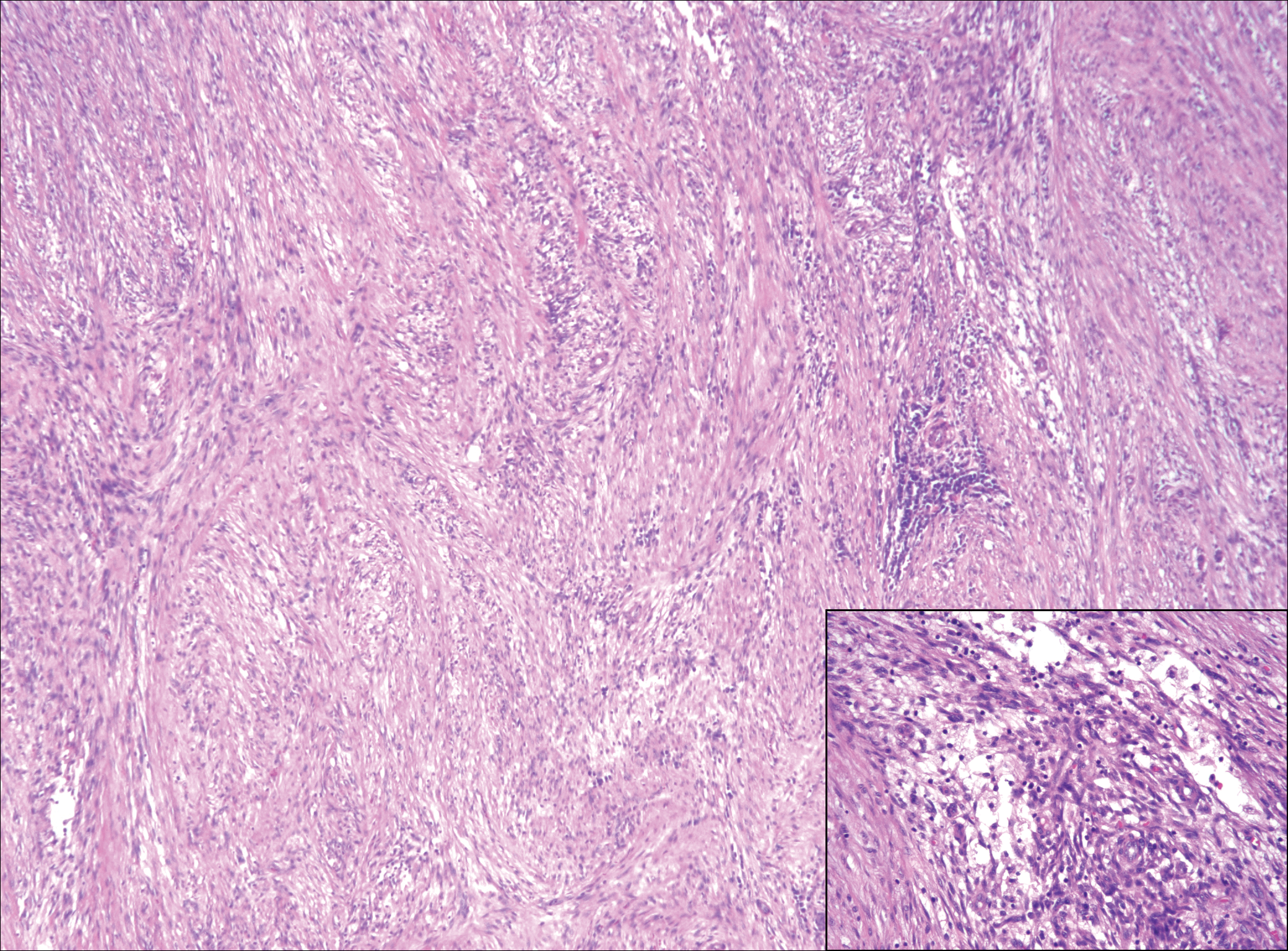

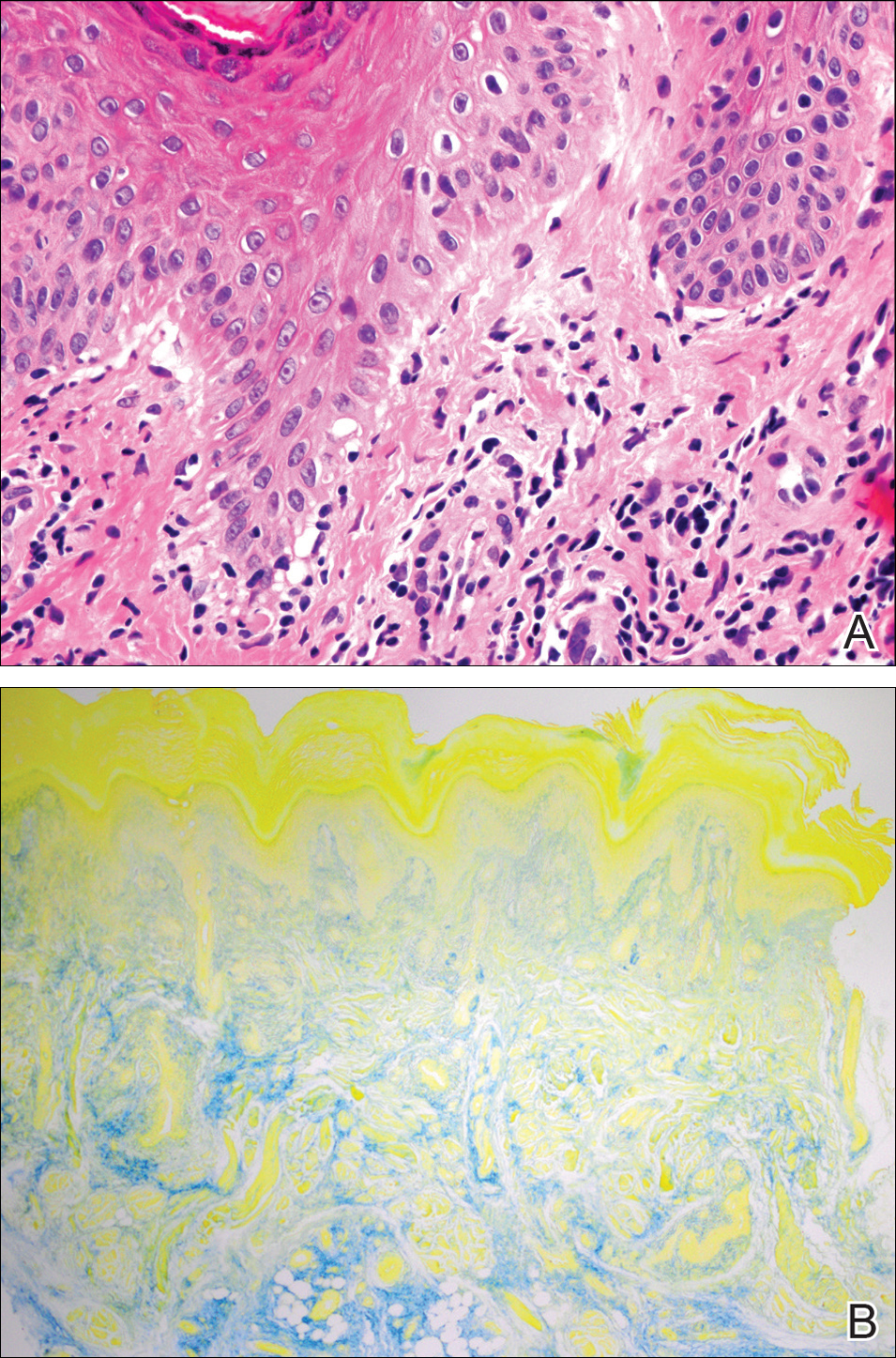

Nodular fasciitis is a benign, self-limiting, myofibroblastic, soft-tissue proliferation typically found in the subcutaneous tissue.1 It can be found anywhere on the body but most commonly on the upper arms and trunk. It most often is seen in young adults, and many cases have been reported in association with a history of trauma to the area.1,2 It typically measures less than 2 cm in diameter.3 The diagnosis of nodular fasciitis is particularly challenging because it mimics sarcoma, both in presentation and in histologic findings with rapid growth, high mitotic activity, and increased cellularity.1,4-7 In contrast to malignancy, nodular fasciitis has no atypical mitoses and little cytologic atypia.8,9 Rather, it contains plump myofibroblasts loosely arranged in a myxoid or fibrous stroma that also may contain lymphocytes, extravasated erythrocytes, and osteoclastlike giant cells distributed throughout.5,10,11 In this case, lymphocytes, extravasated red blood cells, and myxoid change are present, suggesting the diagnosis of nodular fasciitis. In other cases, however, these features may be much more limited, making the diagnosis more challenging. The spindle cells are arranged in poorly defined short fascicles. The tumor cells do not infiltrate between individual adipocytes. There is no notable cytologic atypia.

Because of the difficulty in making the diagnosis, overtreatment of this benign condition can be a problem, causing increased morbidity.1 Erickson-Johnson et al12 identified the role of an ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6, USP6, gene rearrangement on chromosome 17p13 in 92% (44/48) of cases of nodular fasciitis. The USP6 gene most often is rearranged with the myosin heavy chain 9 gene, MYH9, on chromosome 22q12.3. With this rearrangement, the MYH9 promoter leads to the overexpression of USP6, causing tumor formation.2,13 The use of multiple immunoperoxidase stains can be important in the identification of nodular fasciitis. Nodular fasciitis stains negative for S-100, epithelial membrane antigen, CD34, β-catenin, and cytokeratin, but typically stains positive for smooth muscle actin.9

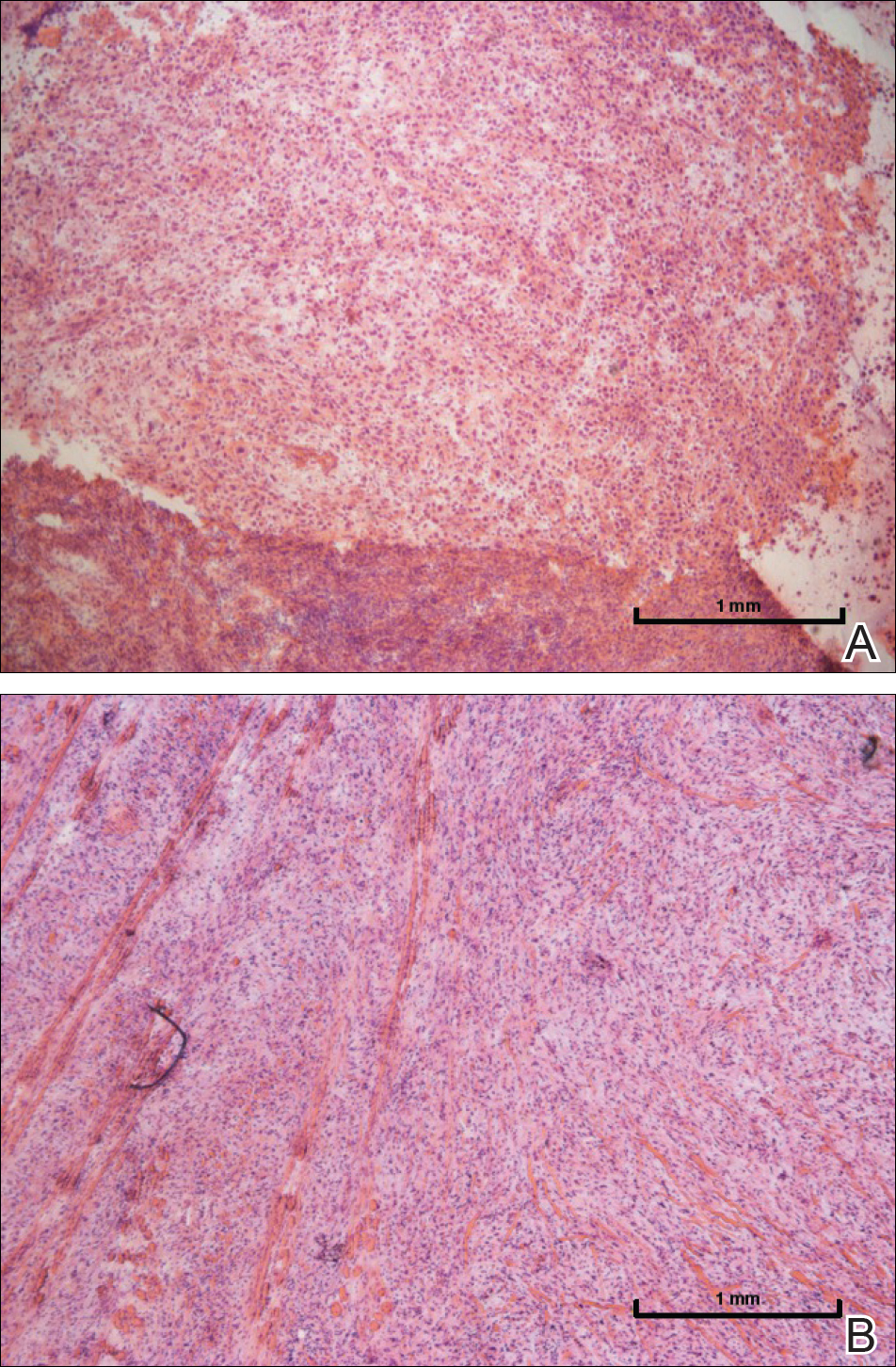

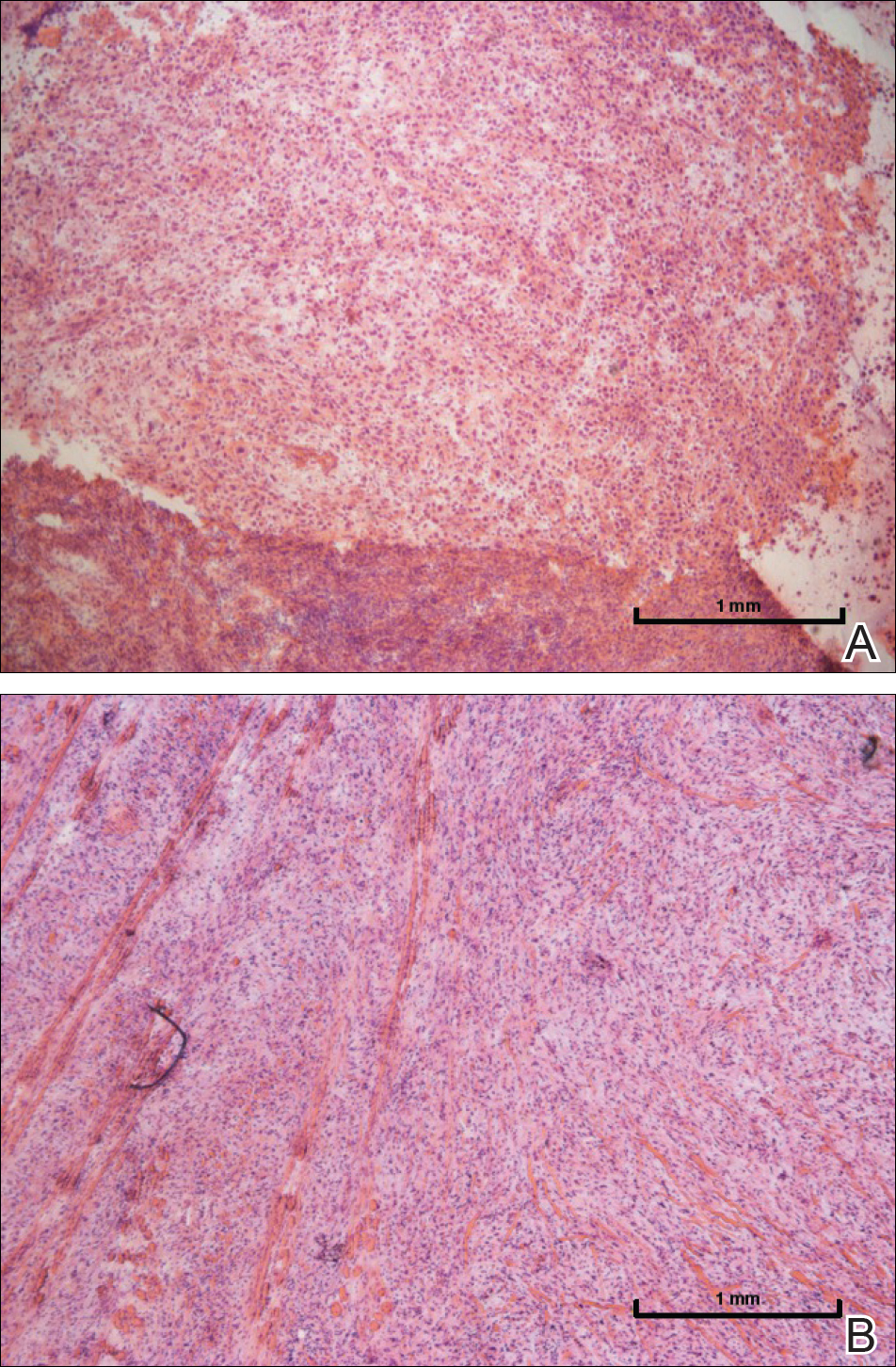

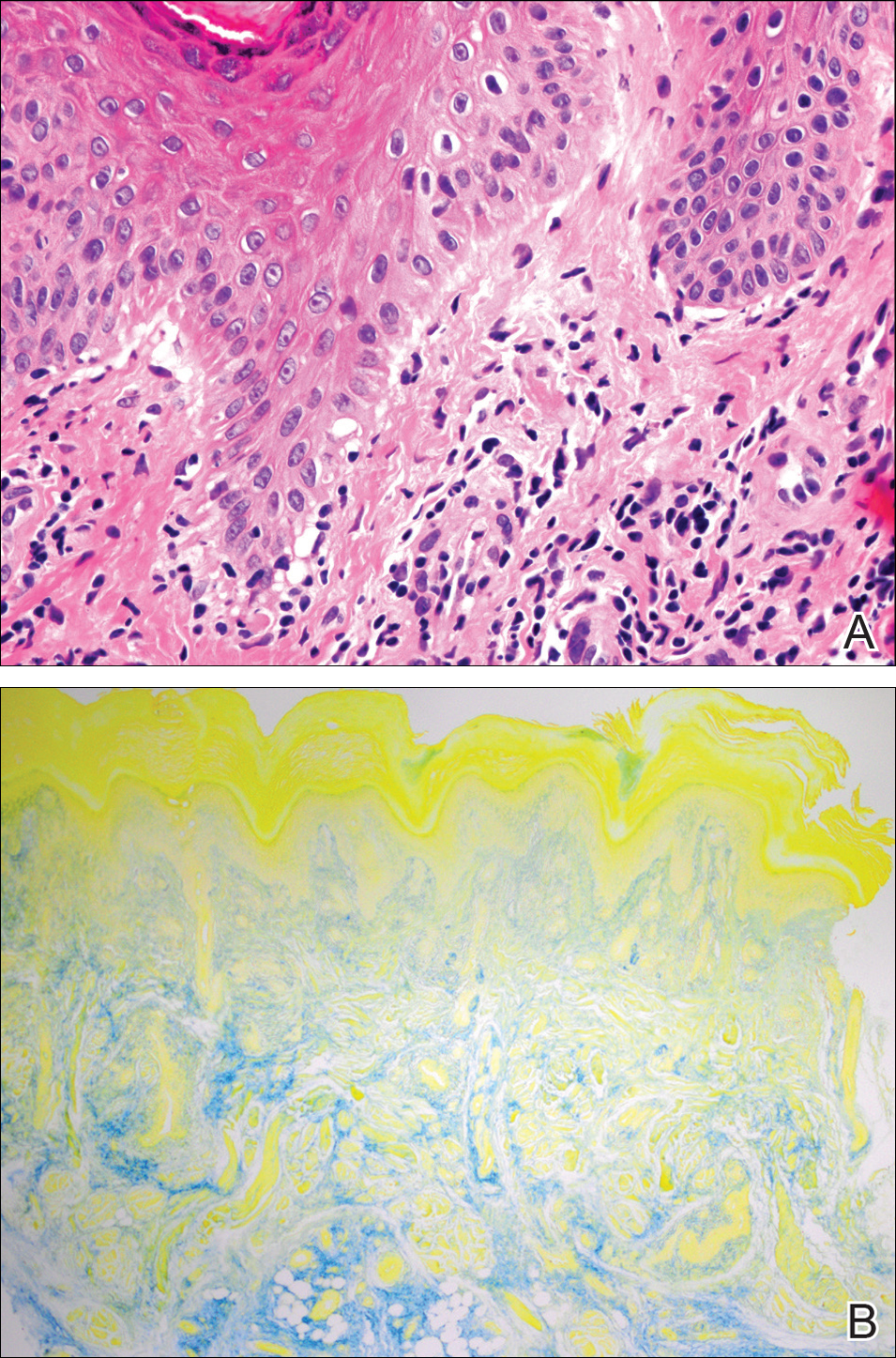

Although dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) was in the differential diagnosis, these tumors tend to have greater cellularity than nodular fasciitis. In addition, the spindle cells of DFSP typically are arranged in a storiform pattern. Another characteristic feature of DFSP is that the tumor cells will infiltrate between adipose cells creating a lacelike or honeycomblike appearance within the subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry staining and FISH testing may be useful in making a diagnosis of DFSP. These tumors typically are positive for CD34 by immunoperoxidase staining and demonstrate a translocation t(17;22)(q21;q13) between platelet-derived growth factor subunit B gene, PDGFB, and collagen type I alpha 1 chain gene, COL1A1, by FISH.

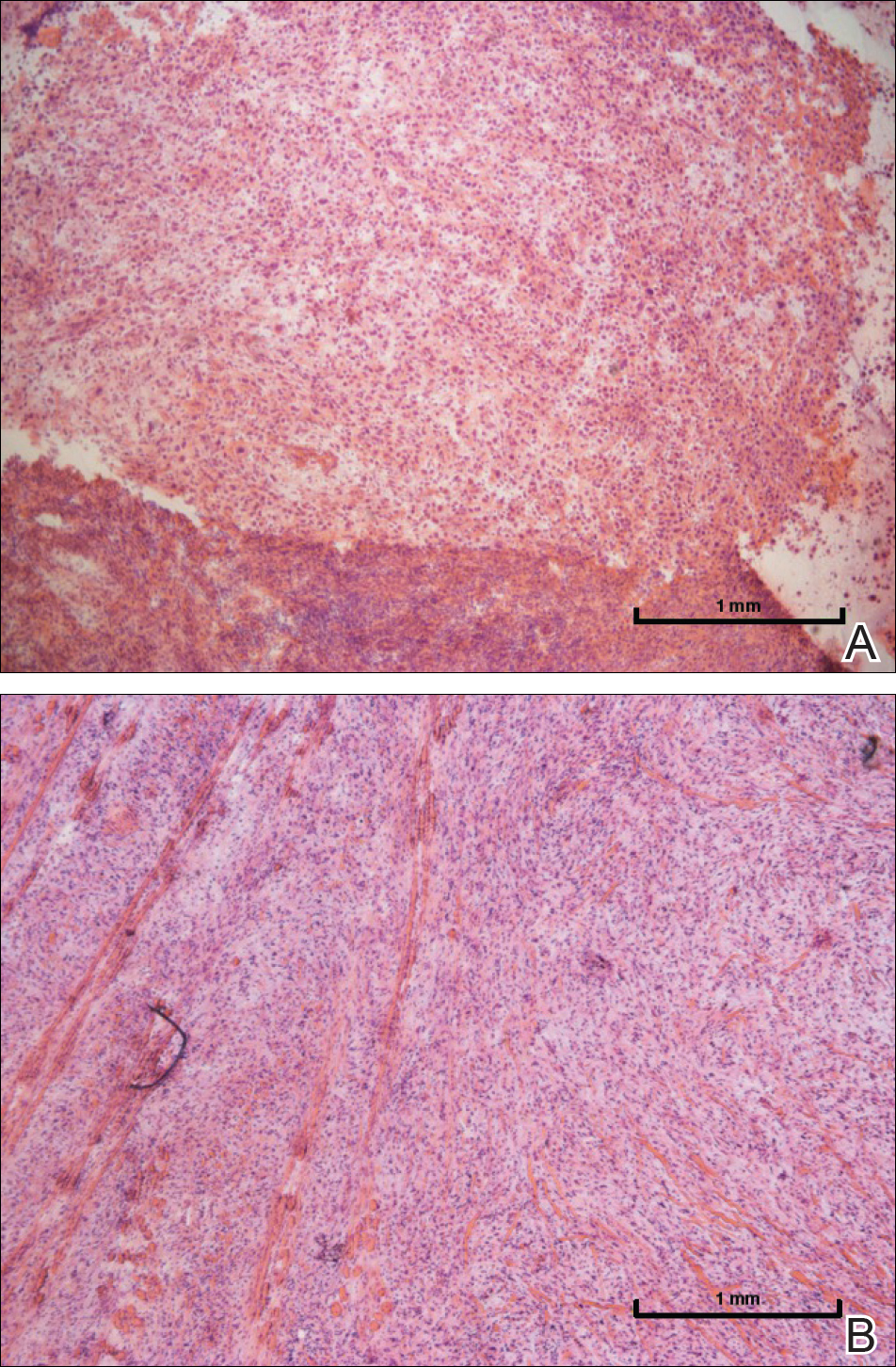

The distinction between the fibrous phase of nodular fasciitis and fibromatosis can be challenging. The size of the lesion may be helpful, with most lesions of nodular fasciitis being less than 3 cm, while lesions of fibromatosis have a mean diameter of 7 cm.5,14 Microscopically, both tumors demonstrate a fascicular growth pattern; however, the fascicles in nodular fasciitis tend to be short and irregular compared to the longer fascicles seen in fibromatosis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry staining has limited utility with only 56% (14/25) of superficial fibromatoses having positive nuclear staining for β-catenin.15

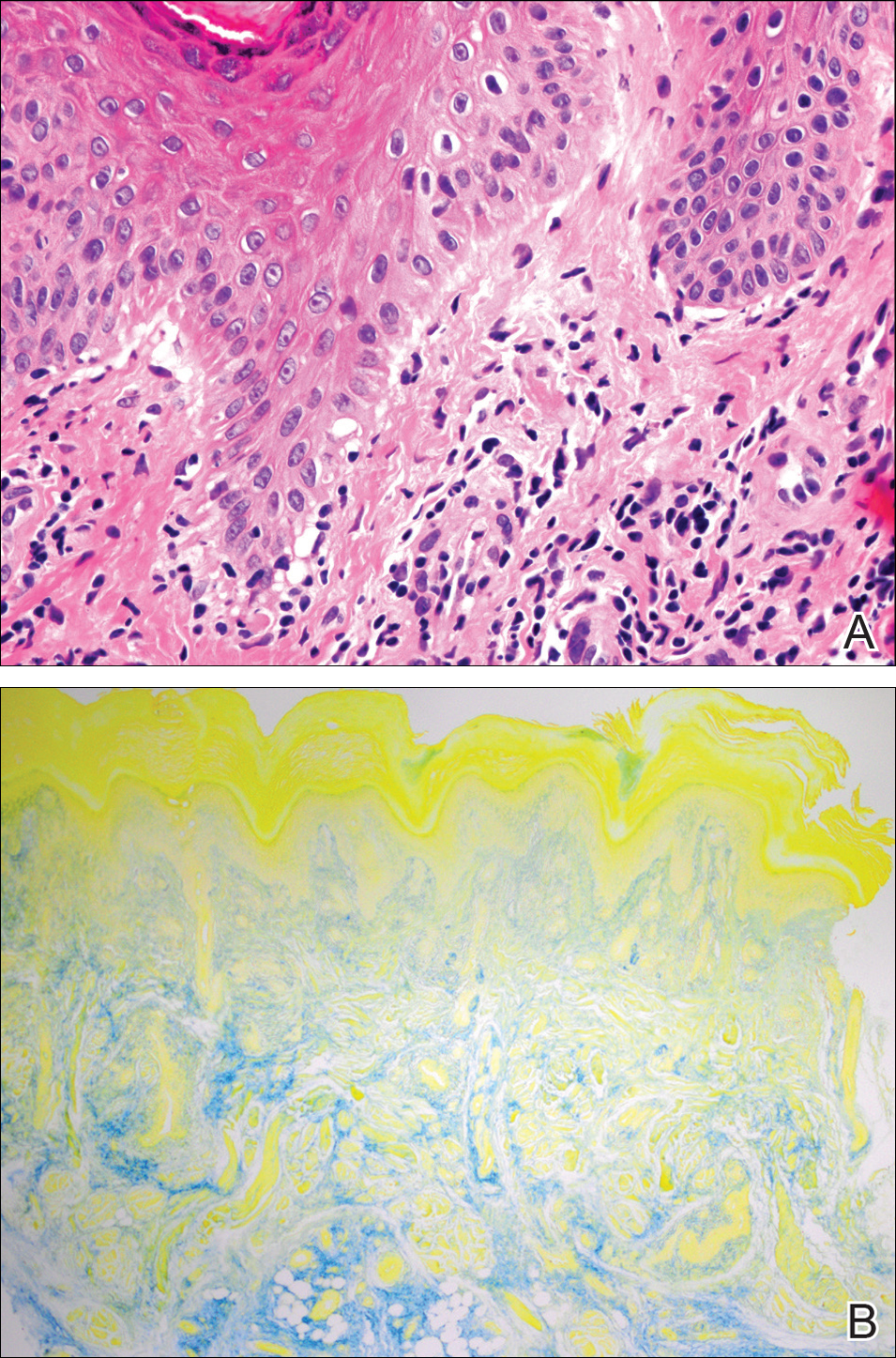

Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (LGFMS) would be unusual in this clinical scenario. Only 13% to 19% of cases present in patients younger than 18 years (mean age, 33 years).16 In LGFMS there are cytologically bland spindle cells that are typically arranged in a patternless or whorled pattern (Figure 3), though fascicular architecture may be seen. There are alternating areas of fibrous and myxoid stroma. A curvilinear vasculature network and lack of lymphocytes and extravasated red blood cells are histologic features favoring LGFMS over nodular fasciitis. Immunohistochemistry staining and FISH testing can be useful in making the diagnosis of LGFMS. These tumors are characterized by a translocation t(7;16)(q34;p11) involving the fusion in sarcoma, FUS, and cAMP responsive element binding protein 3 like 2, CREB3L2, genes.16 Positive immunohistochemistry staining for MUC4 can be seen in up to 100% of LGFMS and is absent in many other spindle cell tumors.16

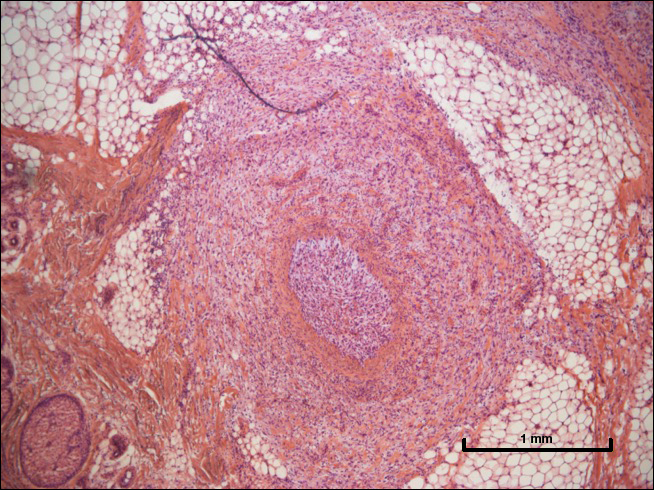

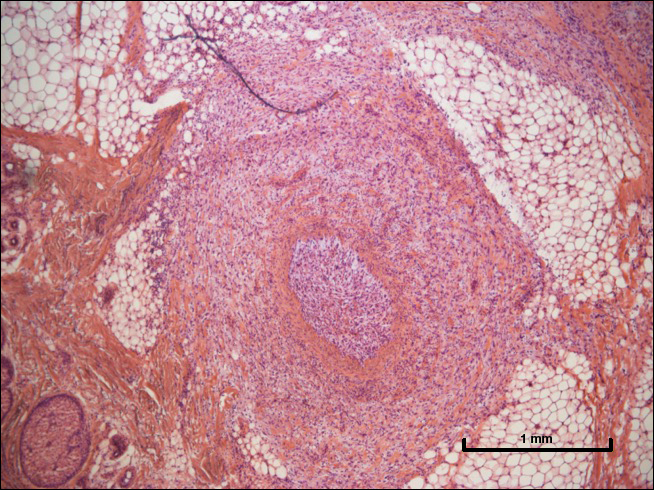

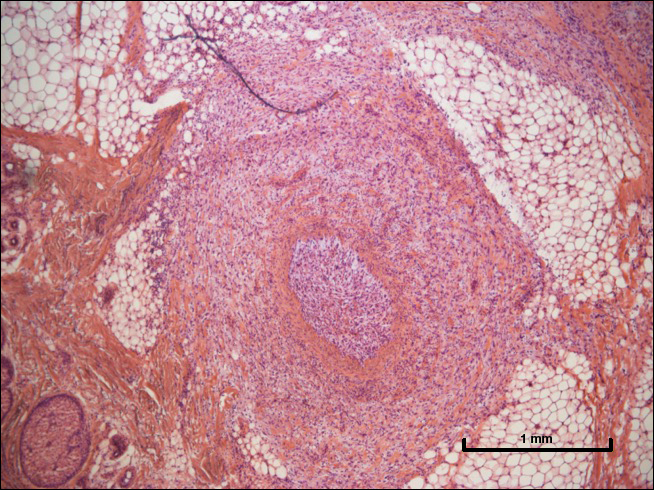

Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor (PFT) is least likely to be confused with nodular fasciitis. Histologically these tumors are characterized by multiple small nodules arranged in a plexiform pattern (Figure 4). Within the nodules, 3 cell types may be noted: spindle fibroblast-like cells, mononuclear histiocyte-like cells, and osteoclastlike cells.17 Either the spindle cells or the mononuclear cells may predominate in cases of PFT. Immunohistochemistry staining of PFT is nonspecific and there are no molecular/FISH studies that can be used to help confirm the diagnosis.

- Shin C, Low I, Ng D, et al. USP6 gene rearrangement in nodular fasciitis and histological mimics. Histopathology. 2016;69:784-791.

- Kumar E, Patel NR, Demicco EG, et al. Cutaneous nodular fasciitis with genetic analysis: a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1143-1149.

- Nishio J. Updates on the cytogenetics and molecular cytogenetics of benign and intermediate soft tissue tumors. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:12-18.

- Lin X, Wang L, Zhang Y, et al. Variable Ki67 proliferative index in 65 cases of nodular fasciitis, compared with fibrosarcoma and fibromatosis. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:50.

- Goldstein J, Cates J. Differential diagnostic considerations of desmoid-type fibromatosis. Adv Anat Pathol. 2015;22:260-266.

- Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. 4th ed. Lyons, France: IARC Press; 2013.

- Bridge JA, Cushman-Vokoun AM. Molecular diagnostics of soft tissue tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:588-601.

- Anzeljc AJ, Oliveira AM, Grossniklaus HE, et al. Nodular fasciitis of the orbit: a case report confirmed by molecular cytogenetic analysis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33(3S suppl 1):S152-S155.

- de Paula SA, Cruz AA, de Alencar VM, et al. Nodular fasciitis presenting as a large mass in the upper eyelid. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22:494-495.

- Bernstein KE, Lattes R. Nodular (pseudosarcomatous) fasciitis, a nonrecurrent lesion: clinicopathologic study of 134 cases. Cancer. 1982;49:1668-1678.

- Shimizu S, Hashimoto H, Enjoji M. Nodular fasciitis: an analysis of 250 patients. Pathology. 1984;16:161-166.

- Erickson-Johnson MR, Chou MM, Evers BR, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433.

- Amary MF, Ye H, Berisha F, et al. Detection of USP6 gene rearrangement in nodular fasciitis: an important diagnostic tool. Virchows Arch. 2013;463:97-98.

- Wirth L, Klein A, Baur-Melnyk A. Desmoid tumors of the extremity and trunk. a retrospective study of 44 patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19:2.

- Carlson JW, Fletcher CD. Immunohistochemistry for beta-catenin in the differential diagnosis of spindle cells lesions: analysis of a series and review of the literature. Histopathology. 2007;51:509-514.

- Mohamed M, Fisher C, Thway K. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: clinical, morphologic and genetic features. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2017;28:60-67.

- Taher A, Pushpanathan C. Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor: a brief review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1135-1138.

The Diagnosis: Nodular Fasciitis

The diagnosis of spindle cell tumors can be challenging; however, by using a variety of immunoperoxidase stains and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) testing in conjunction with histology, it often is possible to arrive at a definitive diagnosis. For this case, the histologic features in conjunction with the immunoperoxidase stains and FISH were consistent with a diagnosis of nodular fasciitis.

Nodular fasciitis is a benign, self-limiting, myofibroblastic, soft-tissue proliferation typically found in the subcutaneous tissue.1 It can be found anywhere on the body but most commonly on the upper arms and trunk. It most often is seen in young adults, and many cases have been reported in association with a history of trauma to the area.1,2 It typically measures less than 2 cm in diameter.3 The diagnosis of nodular fasciitis is particularly challenging because it mimics sarcoma, both in presentation and in histologic findings with rapid growth, high mitotic activity, and increased cellularity.1,4-7 In contrast to malignancy, nodular fasciitis has no atypical mitoses and little cytologic atypia.8,9 Rather, it contains plump myofibroblasts loosely arranged in a myxoid or fibrous stroma that also may contain lymphocytes, extravasated erythrocytes, and osteoclastlike giant cells distributed throughout.5,10,11 In this case, lymphocytes, extravasated red blood cells, and myxoid change are present, suggesting the diagnosis of nodular fasciitis. In other cases, however, these features may be much more limited, making the diagnosis more challenging. The spindle cells are arranged in poorly defined short fascicles. The tumor cells do not infiltrate between individual adipocytes. There is no notable cytologic atypia.

Because of the difficulty in making the diagnosis, overtreatment of this benign condition can be a problem, causing increased morbidity.1 Erickson-Johnson et al12 identified the role of an ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6, USP6, gene rearrangement on chromosome 17p13 in 92% (44/48) of cases of nodular fasciitis. The USP6 gene most often is rearranged with the myosin heavy chain 9 gene, MYH9, on chromosome 22q12.3. With this rearrangement, the MYH9 promoter leads to the overexpression of USP6, causing tumor formation.2,13 The use of multiple immunoperoxidase stains can be important in the identification of nodular fasciitis. Nodular fasciitis stains negative for S-100, epithelial membrane antigen, CD34, β-catenin, and cytokeratin, but typically stains positive for smooth muscle actin.9

Although dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) was in the differential diagnosis, these tumors tend to have greater cellularity than nodular fasciitis. In addition, the spindle cells of DFSP typically are arranged in a storiform pattern. Another characteristic feature of DFSP is that the tumor cells will infiltrate between adipose cells creating a lacelike or honeycomblike appearance within the subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry staining and FISH testing may be useful in making a diagnosis of DFSP. These tumors typically are positive for CD34 by immunoperoxidase staining and demonstrate a translocation t(17;22)(q21;q13) between platelet-derived growth factor subunit B gene, PDGFB, and collagen type I alpha 1 chain gene, COL1A1, by FISH.

The distinction between the fibrous phase of nodular fasciitis and fibromatosis can be challenging. The size of the lesion may be helpful, with most lesions of nodular fasciitis being less than 3 cm, while lesions of fibromatosis have a mean diameter of 7 cm.5,14 Microscopically, both tumors demonstrate a fascicular growth pattern; however, the fascicles in nodular fasciitis tend to be short and irregular compared to the longer fascicles seen in fibromatosis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry staining has limited utility with only 56% (14/25) of superficial fibromatoses having positive nuclear staining for β-catenin.15

Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (LGFMS) would be unusual in this clinical scenario. Only 13% to 19% of cases present in patients younger than 18 years (mean age, 33 years).16 In LGFMS there are cytologically bland spindle cells that are typically arranged in a patternless or whorled pattern (Figure 3), though fascicular architecture may be seen. There are alternating areas of fibrous and myxoid stroma. A curvilinear vasculature network and lack of lymphocytes and extravasated red blood cells are histologic features favoring LGFMS over nodular fasciitis. Immunohistochemistry staining and FISH testing can be useful in making the diagnosis of LGFMS. These tumors are characterized by a translocation t(7;16)(q34;p11) involving the fusion in sarcoma, FUS, and cAMP responsive element binding protein 3 like 2, CREB3L2, genes.16 Positive immunohistochemistry staining for MUC4 can be seen in up to 100% of LGFMS and is absent in many other spindle cell tumors.16

Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor (PFT) is least likely to be confused with nodular fasciitis. Histologically these tumors are characterized by multiple small nodules arranged in a plexiform pattern (Figure 4). Within the nodules, 3 cell types may be noted: spindle fibroblast-like cells, mononuclear histiocyte-like cells, and osteoclastlike cells.17 Either the spindle cells or the mononuclear cells may predominate in cases of PFT. Immunohistochemistry staining of PFT is nonspecific and there are no molecular/FISH studies that can be used to help confirm the diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Nodular Fasciitis

The diagnosis of spindle cell tumors can be challenging; however, by using a variety of immunoperoxidase stains and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) testing in conjunction with histology, it often is possible to arrive at a definitive diagnosis. For this case, the histologic features in conjunction with the immunoperoxidase stains and FISH were consistent with a diagnosis of nodular fasciitis.

Nodular fasciitis is a benign, self-limiting, myofibroblastic, soft-tissue proliferation typically found in the subcutaneous tissue.1 It can be found anywhere on the body but most commonly on the upper arms and trunk. It most often is seen in young adults, and many cases have been reported in association with a history of trauma to the area.1,2 It typically measures less than 2 cm in diameter.3 The diagnosis of nodular fasciitis is particularly challenging because it mimics sarcoma, both in presentation and in histologic findings with rapid growth, high mitotic activity, and increased cellularity.1,4-7 In contrast to malignancy, nodular fasciitis has no atypical mitoses and little cytologic atypia.8,9 Rather, it contains plump myofibroblasts loosely arranged in a myxoid or fibrous stroma that also may contain lymphocytes, extravasated erythrocytes, and osteoclastlike giant cells distributed throughout.5,10,11 In this case, lymphocytes, extravasated red blood cells, and myxoid change are present, suggesting the diagnosis of nodular fasciitis. In other cases, however, these features may be much more limited, making the diagnosis more challenging. The spindle cells are arranged in poorly defined short fascicles. The tumor cells do not infiltrate between individual adipocytes. There is no notable cytologic atypia.

Because of the difficulty in making the diagnosis, overtreatment of this benign condition can be a problem, causing increased morbidity.1 Erickson-Johnson et al12 identified the role of an ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6, USP6, gene rearrangement on chromosome 17p13 in 92% (44/48) of cases of nodular fasciitis. The USP6 gene most often is rearranged with the myosin heavy chain 9 gene, MYH9, on chromosome 22q12.3. With this rearrangement, the MYH9 promoter leads to the overexpression of USP6, causing tumor formation.2,13 The use of multiple immunoperoxidase stains can be important in the identification of nodular fasciitis. Nodular fasciitis stains negative for S-100, epithelial membrane antigen, CD34, β-catenin, and cytokeratin, but typically stains positive for smooth muscle actin.9

Although dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) was in the differential diagnosis, these tumors tend to have greater cellularity than nodular fasciitis. In addition, the spindle cells of DFSP typically are arranged in a storiform pattern. Another characteristic feature of DFSP is that the tumor cells will infiltrate between adipose cells creating a lacelike or honeycomblike appearance within the subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry staining and FISH testing may be useful in making a diagnosis of DFSP. These tumors typically are positive for CD34 by immunoperoxidase staining and demonstrate a translocation t(17;22)(q21;q13) between platelet-derived growth factor subunit B gene, PDGFB, and collagen type I alpha 1 chain gene, COL1A1, by FISH.

The distinction between the fibrous phase of nodular fasciitis and fibromatosis can be challenging. The size of the lesion may be helpful, with most lesions of nodular fasciitis being less than 3 cm, while lesions of fibromatosis have a mean diameter of 7 cm.5,14 Microscopically, both tumors demonstrate a fascicular growth pattern; however, the fascicles in nodular fasciitis tend to be short and irregular compared to the longer fascicles seen in fibromatosis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry staining has limited utility with only 56% (14/25) of superficial fibromatoses having positive nuclear staining for β-catenin.15

Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (LGFMS) would be unusual in this clinical scenario. Only 13% to 19% of cases present in patients younger than 18 years (mean age, 33 years).16 In LGFMS there are cytologically bland spindle cells that are typically arranged in a patternless or whorled pattern (Figure 3), though fascicular architecture may be seen. There are alternating areas of fibrous and myxoid stroma. A curvilinear vasculature network and lack of lymphocytes and extravasated red blood cells are histologic features favoring LGFMS over nodular fasciitis. Immunohistochemistry staining and FISH testing can be useful in making the diagnosis of LGFMS. These tumors are characterized by a translocation t(7;16)(q34;p11) involving the fusion in sarcoma, FUS, and cAMP responsive element binding protein 3 like 2, CREB3L2, genes.16 Positive immunohistochemistry staining for MUC4 can be seen in up to 100% of LGFMS and is absent in many other spindle cell tumors.16

Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor (PFT) is least likely to be confused with nodular fasciitis. Histologically these tumors are characterized by multiple small nodules arranged in a plexiform pattern (Figure 4). Within the nodules, 3 cell types may be noted: spindle fibroblast-like cells, mononuclear histiocyte-like cells, and osteoclastlike cells.17 Either the spindle cells or the mononuclear cells may predominate in cases of PFT. Immunohistochemistry staining of PFT is nonspecific and there are no molecular/FISH studies that can be used to help confirm the diagnosis.

- Shin C, Low I, Ng D, et al. USP6 gene rearrangement in nodular fasciitis and histological mimics. Histopathology. 2016;69:784-791.

- Kumar E, Patel NR, Demicco EG, et al. Cutaneous nodular fasciitis with genetic analysis: a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1143-1149.

- Nishio J. Updates on the cytogenetics and molecular cytogenetics of benign and intermediate soft tissue tumors. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:12-18.

- Lin X, Wang L, Zhang Y, et al. Variable Ki67 proliferative index in 65 cases of nodular fasciitis, compared with fibrosarcoma and fibromatosis. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:50.

- Goldstein J, Cates J. Differential diagnostic considerations of desmoid-type fibromatosis. Adv Anat Pathol. 2015;22:260-266.

- Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. 4th ed. Lyons, France: IARC Press; 2013.

- Bridge JA, Cushman-Vokoun AM. Molecular diagnostics of soft tissue tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:588-601.

- Anzeljc AJ, Oliveira AM, Grossniklaus HE, et al. Nodular fasciitis of the orbit: a case report confirmed by molecular cytogenetic analysis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33(3S suppl 1):S152-S155.

- de Paula SA, Cruz AA, de Alencar VM, et al. Nodular fasciitis presenting as a large mass in the upper eyelid. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22:494-495.

- Bernstein KE, Lattes R. Nodular (pseudosarcomatous) fasciitis, a nonrecurrent lesion: clinicopathologic study of 134 cases. Cancer. 1982;49:1668-1678.

- Shimizu S, Hashimoto H, Enjoji M. Nodular fasciitis: an analysis of 250 patients. Pathology. 1984;16:161-166.

- Erickson-Johnson MR, Chou MM, Evers BR, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433.

- Amary MF, Ye H, Berisha F, et al. Detection of USP6 gene rearrangement in nodular fasciitis: an important diagnostic tool. Virchows Arch. 2013;463:97-98.

- Wirth L, Klein A, Baur-Melnyk A. Desmoid tumors of the extremity and trunk. a retrospective study of 44 patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19:2.

- Carlson JW, Fletcher CD. Immunohistochemistry for beta-catenin in the differential diagnosis of spindle cells lesions: analysis of a series and review of the literature. Histopathology. 2007;51:509-514.

- Mohamed M, Fisher C, Thway K. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: clinical, morphologic and genetic features. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2017;28:60-67.

- Taher A, Pushpanathan C. Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor: a brief review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1135-1138.

- Shin C, Low I, Ng D, et al. USP6 gene rearrangement in nodular fasciitis and histological mimics. Histopathology. 2016;69:784-791.

- Kumar E, Patel NR, Demicco EG, et al. Cutaneous nodular fasciitis with genetic analysis: a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1143-1149.

- Nishio J. Updates on the cytogenetics and molecular cytogenetics of benign and intermediate soft tissue tumors. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:12-18.

- Lin X, Wang L, Zhang Y, et al. Variable Ki67 proliferative index in 65 cases of nodular fasciitis, compared with fibrosarcoma and fibromatosis. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:50.

- Goldstein J, Cates J. Differential diagnostic considerations of desmoid-type fibromatosis. Adv Anat Pathol. 2015;22:260-266.

- Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. 4th ed. Lyons, France: IARC Press; 2013.

- Bridge JA, Cushman-Vokoun AM. Molecular diagnostics of soft tissue tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:588-601.

- Anzeljc AJ, Oliveira AM, Grossniklaus HE, et al. Nodular fasciitis of the orbit: a case report confirmed by molecular cytogenetic analysis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33(3S suppl 1):S152-S155.

- de Paula SA, Cruz AA, de Alencar VM, et al. Nodular fasciitis presenting as a large mass in the upper eyelid. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22:494-495.

- Bernstein KE, Lattes R. Nodular (pseudosarcomatous) fasciitis, a nonrecurrent lesion: clinicopathologic study of 134 cases. Cancer. 1982;49:1668-1678.

- Shimizu S, Hashimoto H, Enjoji M. Nodular fasciitis: an analysis of 250 patients. Pathology. 1984;16:161-166.

- Erickson-Johnson MR, Chou MM, Evers BR, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433.

- Amary MF, Ye H, Berisha F, et al. Detection of USP6 gene rearrangement in nodular fasciitis: an important diagnostic tool. Virchows Arch. 2013;463:97-98.

- Wirth L, Klein A, Baur-Melnyk A. Desmoid tumors of the extremity and trunk. a retrospective study of 44 patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19:2.

- Carlson JW, Fletcher CD. Immunohistochemistry for beta-catenin in the differential diagnosis of spindle cells lesions: analysis of a series and review of the literature. Histopathology. 2007;51:509-514.

- Mohamed M, Fisher C, Thway K. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: clinical, morphologic and genetic features. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2017;28:60-67.

- Taher A, Pushpanathan C. Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor: a brief review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1135-1138.

A 16-year-old adolescent girl presented with a bump over the left posterior knee of 1 month's duration. Her medical history was unremarkable. She denied recent trauma or injury to the area. On physical examination there was a visible and palpable tense nontender mass the size of an egg over the left posterior knee. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a lobulated mass-like focus of T2 hyperintensity centered at the subcutaneous tissues and superficial myofascial plane of the gastrocnemius on the posterior knee. Complete excision of the lesion was performed and demonstrated a 2.6.2 ×2.9.2 ×2.1-cm mass within subcutaneous adipose tissue. There was no microscopic involvement of skeletal muscle. Immunohistochemistry staining of the tumor was performed that was positive for smooth muscle actin and negative for desmin, S-100, CD34, pan-cytokeratin, and β-catenin. Fluorescent in situ hybridization testing demonstrated rearrangement of the ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6 gene, USP6, locus (17p13).

Patient Satisfaction and Quality of Care: A Prospective Study at Outpatient Dermatology Clinics

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act has increased the number of insured Americans by more than 20 million individuals.1 Approximately half of the newly insured have an income at or below 138% of the poverty level and are on average younger, sicker, and more likely to report poor to fair health compared to those individuals who already had health care coverage.2 Specialties such as dermatology are faced with the challenge of expanding access to these newly insured individuals while also improving quality of care.

Because of the complexity of defining quality in medicine, patient satisfaction is being used as a proxy for quality, with physicians evaluated and reimbursed based on patient satisfaction scores. Little research has been conducted to validate the relationship between patient satisfaction and quality; however, one study showed online reviews from patients on Yelp correlated with traditional markers of quality, such as mortality and readmission rates, lending credibility to the notion that patient satisfaction equates quality of care.3 Moreover, prospective studies have found positive correlations between patient satisfaction and compliance to therapy4,5; however, these studies may not give a complete picture of the relationship between patient satisfaction and quality of care, as other studies also have illustrated that, more often than not, factors extrinsic to actual medical care (eg, time spent in the waiting room) play a considerable role in patient satisfaction scores.6-9

When judging the quality of care that is provided, one study found that patients rate physicians based on interpersonal skills and not care delivered.8 Another important factor related to patient satisfaction is the anonymity of the surveys. Patients who have negative experiences are more likely to respond to online surveys than those who have positive experiences, skewing overall ratings.6 Additionally, because of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations, physicians often are unable to respond directly to public patient reviews, resulting in an incomplete picture of the quality of care provided.

Ultimately, even if physicians do not agree that patient satisfaction correlates with quality of care, it is increasingly being used as a marker of such. Leading health care systems are embracing this new weight on patient satisfaction by increasing transparency and publishing patient satisfaction results online, allowing patients more access to physician reviews.

In dermatology, patient satisfaction serves an even more important role, as traditional markers of quality such as mortality and hospital readmission rates are not reasonable measures of patient care in this specialty, leaving patient satisfaction as one of the most accessible markers insurance companies and prospective patients can use to evaluate dermatologists. Furthermore, treatment modalities in dermatology often aim to improve quality of life, of which patient satisfaction arguably serves as an indicator. Ideally, patient satisfaction would allow physicians to identify areas where they may be better able to meet patients’ needs. However, patient satisfaction scores rarely are used as outcome measures in studies and are notoriously difficult to ascertain, as they tend to be inaccurate and may be unreliable in correlation with physician skill and training or may be skewed by patients’ desires to please their physicians.10 There also is a lack of standardized tools and scales to quantitatively judge outcomes in procedural surgeries.

Although patient satisfaction is being used as a measure of quality of care and is particularly necessary in a field such as dermatology that has outcome measures that are subjective in nature, there is a gap in the current literature regarding patient satisfaction and dermatology. To fill this gap, we conducted a prospective study of targeted interventions administered at outpatient dermatology clinics to determine if they resulted in statistically significant increases in patient satisfaction measures, particularly among Spanish-speaking patients.

Methods

We conducted a prospective study evaluating patient satisfaction in the outpatient dermatology clinics of LAC+USC Medical Center in Los Angeles, California, spanning over 1 year. During this time period, patients were randomly selected to participate and were asked to complete the Short-Form Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ-18), which asked patients to rate their care experience on a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly agree; 5=strongly disagree). The survey was separated into the following 7 subscales or categories looking at different aspects of care: general satisfaction, technical quality, interpersonal manner, communication, financial aspects, time spent with physician, and accessibility and convenience. Patients were given this survey both before and after targeted interventions to improve patient satisfaction were implemented. The targeted interventions were created based on literature review in the factors affecting patient satisfaction. The change in relative satisfaction was then determined using statistical analysis. The study was approved by the University of Southern California Health Science institutional review board.

Results

Of 470 patients surveyed, the average age was 49 years. Fifty percent of respondents were male, 70% self-identified as Hispanic, 45% spoke Spanish as their native language, and 69% reported a mean annual household income of less than $15,000. When scores were stratified, English-speaking patients were significantly more satisfied than Spanish-speaking patients in the categories of technical quality (P.0340), financial aspects (P.0301), interpersonal manner (P.0037), and time spent with physician (P.0059). Specifically, in the time spent with physician category, the lowest scores were found in females, patients aged 18 to 29 years, and patients with a mean annual household income less than $15,000. These demographics correlate well with many of the newly insured and intimate the need for improved patient satisfaction, particularly in this subset of patients.

After analyzing baseline patient satisfaction scores, we implemented targeted interventions such as creating a call tree, developing multilingual disease-specific patient handouts, instituting quarterly nursing in-services, which judged interpersonal and occupational nursing skills, and recruiting bilingual staff. These interventions were implemented simultaneously and were selected with the goal of reducing the impact of the language barrier between physicians and patients and increasing accessibility to clinics. Following approximately 3 months of these interventions, performance on many categories increased in our demographics that were lowest performing when we collected baseline data. In Spanish-speaking respondents, improvement in several categories approached statistical significance, including general satisfaction (P.110), interpersonal skills (P.080), and time spent with physician (P.096). When stratifying by income and age, patients with a mean annual household income less than $15,000 demonstrated an improved technical quality (P.066) subscale score, and participants aged 18 to 29 years showed improvement in both accessibility and convenience (P.053) and financial aspects (P.056) subscales.

Comment

The categories where improvements were found are noteworthy and suggest that certain aspects of care are more important than others. Although it seems intuitive that clinical acumen and training should be important contributors to patient satisfaction, one study that analyzed 1000 online comments regarding patient satisfaction with dermatologists on the website DrScore.com found that most comments concerned physician personality and interpersonal skills rather than medical judgment and acumen,4 suggesting that a patient’s perception of the character of the physician directly affects patient satisfaction scores. This notion was reiterated by other studies, including one that found that a patient’s perception of the physician’s kindness and empathy skills, is the most important measure of quality of care scores.8 Although this perception can be intimidating to some physicians, as certain interpersonal skills are difficult to change, it is reassuring to note that external environment and cues, such as the clinic building and staff, also seem to affect interpersonal ratings. As seen in our study, patient ratings of a physician’s interpersonal skills increased after educational materials for staff and patients were created and more bilingual staff was recruited. Other environmental changes, such as spending a few more minutes with patients and sitting down when talking to patients, are relatively easy to administer and can improve patient satisfaction scores.8

Although some of the scores in our study approached but did not reach statistical significance, likely because of a small sample size, they suggest that targeted interventions can improve patient satisfaction. They also suggested that targeted interventions are particularly useful in Spanish-speaking patients, younger patients, and patients from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, which are all characteristics of the newly insured under the Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act.

Our study also is unique in that dermatology as a specialty is lagging in quality improvement studies. In the few studies evaluating patient satisfaction in the literature, the care provided by dermatologists was painted in a positive light.6,11 One study evaluated 45 dermatology practices and reported average patient satisfaction scores of 3.46 and 4.72 of 5 on Yelp and ZocDoc, respectively.11 Another study looking at dermatologist ratings on DrScore.com found that the majority of patients were satisfied with the care they received.6

Although these studies seem encouraging, they have several limitations. First, their results were not stratified by patient demographics and therefore may not be generalizable to low-income populations that constitute much of the newly insured. Secondly, the observational nature and limited number of studies prohibit meaningful conclusions from being drawn and leave many questions unanswered. Additionally, although the raw patient satisfaction scores seem good, dermatology is lacking compared to the patient satisfaction scores within other specialties. A study of more than 28,000 Yelp reviews of 23 specialties found that dermatology ranked second to last, ahead of only psychiatry.7 Of course, given the observational nature of this study, it is impossible to generalize, as many confounders (eg, medical comorbidities, patient age) may have skewed the dermatology ranking. Regardless, there is always room for improvement, and luckily improving patient satisfaction is not an elusive goal.

Conclusion

As dermatologists, our interventions often improve quality of life; therefore, we are positioned to be leaders in the quality improvement field. Despite the numerous limitations of using patient satisfaction as a measure for quality of care, it is used by payers to determine reimbursement and patients to select providers. Encouraging initial data from our prospective study demonstrate that small interventions can increase patient satisfaction. Continued work to maximize patient satisfaction is needed to improve outcomes for our patients, help validate the quality of care being provided, and further solidify the importance of having insurers maintain sufficient dermatologists in their networks.

- Uberoi N, Finegold K, Gee E. Health insurance coverage and the Affordable Care Act, 2010-2016. US Department of Health & Human Services website. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/187551/ACA2010-2016.pdf. Published March 3, 2016. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Shatzer A, Long SK, Zuckerman S. Who are the newly insured as of early March 2014? Urban Institute Health Policy Center website. http://hrms.urban.org/briefs/Who-Are-the-Newly-Insured.html. Published May 22, 2014. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Bardach NS, Asteria-Peñaloza R, Boscardin WJ, et al. The relationship between commercial website ratings and traditional hospital performance measures in the USA. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:194-202.

- Kincey J, Bradshaw P, Ley P. Patient satisfaction and reported acceptance of medical advice in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1975;25:558-566.

- Francis V, Korsch BM, Morris MJ. Gaps in doctor-patient communication. patients’ response to medical advice. N Engl J Med. 1969;280:535-540.

- Ali ST, Feldman SR. Patient satisfaction in dermatology: a qualitative assessment. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. pii:doj_21534.

- Internet study: highest educated & trained doctors get poorest online reviews. Vanguard Communications website. https://vanguard communications.net/best-online-doctor-reviews/. Published April 22, 2015. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Uhas AA, Camacho FT, Feldman SR, et al. The relationship between physician friendliness and caring, and patient satisfaction: findings from an internet-based survey. Patient. 2008;1:91-96.

- Anderson RT, Camacho FT, Balkrishnan R. Willing to wait?: the influence of patient wait time on satisfaction with primary care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:31.

- Maibach HI, Gorouhi F. Evidence-Based Dermatology. 2nd ed. Shelton, CT: People’s Medical Publishing House-USA; 2011.

- Smith R, Lipoff J. Evaluation of dermatology practice online reviews. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:153-157.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act has increased the number of insured Americans by more than 20 million individuals.1 Approximately half of the newly insured have an income at or below 138% of the poverty level and are on average younger, sicker, and more likely to report poor to fair health compared to those individuals who already had health care coverage.2 Specialties such as dermatology are faced with the challenge of expanding access to these newly insured individuals while also improving quality of care.

Because of the complexity of defining quality in medicine, patient satisfaction is being used as a proxy for quality, with physicians evaluated and reimbursed based on patient satisfaction scores. Little research has been conducted to validate the relationship between patient satisfaction and quality; however, one study showed online reviews from patients on Yelp correlated with traditional markers of quality, such as mortality and readmission rates, lending credibility to the notion that patient satisfaction equates quality of care.3 Moreover, prospective studies have found positive correlations between patient satisfaction and compliance to therapy4,5; however, these studies may not give a complete picture of the relationship between patient satisfaction and quality of care, as other studies also have illustrated that, more often than not, factors extrinsic to actual medical care (eg, time spent in the waiting room) play a considerable role in patient satisfaction scores.6-9

When judging the quality of care that is provided, one study found that patients rate physicians based on interpersonal skills and not care delivered.8 Another important factor related to patient satisfaction is the anonymity of the surveys. Patients who have negative experiences are more likely to respond to online surveys than those who have positive experiences, skewing overall ratings.6 Additionally, because of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations, physicians often are unable to respond directly to public patient reviews, resulting in an incomplete picture of the quality of care provided.

Ultimately, even if physicians do not agree that patient satisfaction correlates with quality of care, it is increasingly being used as a marker of such. Leading health care systems are embracing this new weight on patient satisfaction by increasing transparency and publishing patient satisfaction results online, allowing patients more access to physician reviews.

In dermatology, patient satisfaction serves an even more important role, as traditional markers of quality such as mortality and hospital readmission rates are not reasonable measures of patient care in this specialty, leaving patient satisfaction as one of the most accessible markers insurance companies and prospective patients can use to evaluate dermatologists. Furthermore, treatment modalities in dermatology often aim to improve quality of life, of which patient satisfaction arguably serves as an indicator. Ideally, patient satisfaction would allow physicians to identify areas where they may be better able to meet patients’ needs. However, patient satisfaction scores rarely are used as outcome measures in studies and are notoriously difficult to ascertain, as they tend to be inaccurate and may be unreliable in correlation with physician skill and training or may be skewed by patients’ desires to please their physicians.10 There also is a lack of standardized tools and scales to quantitatively judge outcomes in procedural surgeries.

Although patient satisfaction is being used as a measure of quality of care and is particularly necessary in a field such as dermatology that has outcome measures that are subjective in nature, there is a gap in the current literature regarding patient satisfaction and dermatology. To fill this gap, we conducted a prospective study of targeted interventions administered at outpatient dermatology clinics to determine if they resulted in statistically significant increases in patient satisfaction measures, particularly among Spanish-speaking patients.

Methods

We conducted a prospective study evaluating patient satisfaction in the outpatient dermatology clinics of LAC+USC Medical Center in Los Angeles, California, spanning over 1 year. During this time period, patients were randomly selected to participate and were asked to complete the Short-Form Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ-18), which asked patients to rate their care experience on a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly agree; 5=strongly disagree). The survey was separated into the following 7 subscales or categories looking at different aspects of care: general satisfaction, technical quality, interpersonal manner, communication, financial aspects, time spent with physician, and accessibility and convenience. Patients were given this survey both before and after targeted interventions to improve patient satisfaction were implemented. The targeted interventions were created based on literature review in the factors affecting patient satisfaction. The change in relative satisfaction was then determined using statistical analysis. The study was approved by the University of Southern California Health Science institutional review board.

Results

Of 470 patients surveyed, the average age was 49 years. Fifty percent of respondents were male, 70% self-identified as Hispanic, 45% spoke Spanish as their native language, and 69% reported a mean annual household income of less than $15,000. When scores were stratified, English-speaking patients were significantly more satisfied than Spanish-speaking patients in the categories of technical quality (P.0340), financial aspects (P.0301), interpersonal manner (P.0037), and time spent with physician (P.0059). Specifically, in the time spent with physician category, the lowest scores were found in females, patients aged 18 to 29 years, and patients with a mean annual household income less than $15,000. These demographics correlate well with many of the newly insured and intimate the need for improved patient satisfaction, particularly in this subset of patients.

After analyzing baseline patient satisfaction scores, we implemented targeted interventions such as creating a call tree, developing multilingual disease-specific patient handouts, instituting quarterly nursing in-services, which judged interpersonal and occupational nursing skills, and recruiting bilingual staff. These interventions were implemented simultaneously and were selected with the goal of reducing the impact of the language barrier between physicians and patients and increasing accessibility to clinics. Following approximately 3 months of these interventions, performance on many categories increased in our demographics that were lowest performing when we collected baseline data. In Spanish-speaking respondents, improvement in several categories approached statistical significance, including general satisfaction (P.110), interpersonal skills (P.080), and time spent with physician (P.096). When stratifying by income and age, patients with a mean annual household income less than $15,000 demonstrated an improved technical quality (P.066) subscale score, and participants aged 18 to 29 years showed improvement in both accessibility and convenience (P.053) and financial aspects (P.056) subscales.

Comment

The categories where improvements were found are noteworthy and suggest that certain aspects of care are more important than others. Although it seems intuitive that clinical acumen and training should be important contributors to patient satisfaction, one study that analyzed 1000 online comments regarding patient satisfaction with dermatologists on the website DrScore.com found that most comments concerned physician personality and interpersonal skills rather than medical judgment and acumen,4 suggesting that a patient’s perception of the character of the physician directly affects patient satisfaction scores. This notion was reiterated by other studies, including one that found that a patient’s perception of the physician’s kindness and empathy skills, is the most important measure of quality of care scores.8 Although this perception can be intimidating to some physicians, as certain interpersonal skills are difficult to change, it is reassuring to note that external environment and cues, such as the clinic building and staff, also seem to affect interpersonal ratings. As seen in our study, patient ratings of a physician’s interpersonal skills increased after educational materials for staff and patients were created and more bilingual staff was recruited. Other environmental changes, such as spending a few more minutes with patients and sitting down when talking to patients, are relatively easy to administer and can improve patient satisfaction scores.8

Although some of the scores in our study approached but did not reach statistical significance, likely because of a small sample size, they suggest that targeted interventions can improve patient satisfaction. They also suggested that targeted interventions are particularly useful in Spanish-speaking patients, younger patients, and patients from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, which are all characteristics of the newly insured under the Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act.

Our study also is unique in that dermatology as a specialty is lagging in quality improvement studies. In the few studies evaluating patient satisfaction in the literature, the care provided by dermatologists was painted in a positive light.6,11 One study evaluated 45 dermatology practices and reported average patient satisfaction scores of 3.46 and 4.72 of 5 on Yelp and ZocDoc, respectively.11 Another study looking at dermatologist ratings on DrScore.com found that the majority of patients were satisfied with the care they received.6

Although these studies seem encouraging, they have several limitations. First, their results were not stratified by patient demographics and therefore may not be generalizable to low-income populations that constitute much of the newly insured. Secondly, the observational nature and limited number of studies prohibit meaningful conclusions from being drawn and leave many questions unanswered. Additionally, although the raw patient satisfaction scores seem good, dermatology is lacking compared to the patient satisfaction scores within other specialties. A study of more than 28,000 Yelp reviews of 23 specialties found that dermatology ranked second to last, ahead of only psychiatry.7 Of course, given the observational nature of this study, it is impossible to generalize, as many confounders (eg, medical comorbidities, patient age) may have skewed the dermatology ranking. Regardless, there is always room for improvement, and luckily improving patient satisfaction is not an elusive goal.

Conclusion

As dermatologists, our interventions often improve quality of life; therefore, we are positioned to be leaders in the quality improvement field. Despite the numerous limitations of using patient satisfaction as a measure for quality of care, it is used by payers to determine reimbursement and patients to select providers. Encouraging initial data from our prospective study demonstrate that small interventions can increase patient satisfaction. Continued work to maximize patient satisfaction is needed to improve outcomes for our patients, help validate the quality of care being provided, and further solidify the importance of having insurers maintain sufficient dermatologists in their networks.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act has increased the number of insured Americans by more than 20 million individuals.1 Approximately half of the newly insured have an income at or below 138% of the poverty level and are on average younger, sicker, and more likely to report poor to fair health compared to those individuals who already had health care coverage.2 Specialties such as dermatology are faced with the challenge of expanding access to these newly insured individuals while also improving quality of care.

Because of the complexity of defining quality in medicine, patient satisfaction is being used as a proxy for quality, with physicians evaluated and reimbursed based on patient satisfaction scores. Little research has been conducted to validate the relationship between patient satisfaction and quality; however, one study showed online reviews from patients on Yelp correlated with traditional markers of quality, such as mortality and readmission rates, lending credibility to the notion that patient satisfaction equates quality of care.3 Moreover, prospective studies have found positive correlations between patient satisfaction and compliance to therapy4,5; however, these studies may not give a complete picture of the relationship between patient satisfaction and quality of care, as other studies also have illustrated that, more often than not, factors extrinsic to actual medical care (eg, time spent in the waiting room) play a considerable role in patient satisfaction scores.6-9

When judging the quality of care that is provided, one study found that patients rate physicians based on interpersonal skills and not care delivered.8 Another important factor related to patient satisfaction is the anonymity of the surveys. Patients who have negative experiences are more likely to respond to online surveys than those who have positive experiences, skewing overall ratings.6 Additionally, because of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations, physicians often are unable to respond directly to public patient reviews, resulting in an incomplete picture of the quality of care provided.

Ultimately, even if physicians do not agree that patient satisfaction correlates with quality of care, it is increasingly being used as a marker of such. Leading health care systems are embracing this new weight on patient satisfaction by increasing transparency and publishing patient satisfaction results online, allowing patients more access to physician reviews.

In dermatology, patient satisfaction serves an even more important role, as traditional markers of quality such as mortality and hospital readmission rates are not reasonable measures of patient care in this specialty, leaving patient satisfaction as one of the most accessible markers insurance companies and prospective patients can use to evaluate dermatologists. Furthermore, treatment modalities in dermatology often aim to improve quality of life, of which patient satisfaction arguably serves as an indicator. Ideally, patient satisfaction would allow physicians to identify areas where they may be better able to meet patients’ needs. However, patient satisfaction scores rarely are used as outcome measures in studies and are notoriously difficult to ascertain, as they tend to be inaccurate and may be unreliable in correlation with physician skill and training or may be skewed by patients’ desires to please their physicians.10 There also is a lack of standardized tools and scales to quantitatively judge outcomes in procedural surgeries.

Although patient satisfaction is being used as a measure of quality of care and is particularly necessary in a field such as dermatology that has outcome measures that are subjective in nature, there is a gap in the current literature regarding patient satisfaction and dermatology. To fill this gap, we conducted a prospective study of targeted interventions administered at outpatient dermatology clinics to determine if they resulted in statistically significant increases in patient satisfaction measures, particularly among Spanish-speaking patients.

Methods

We conducted a prospective study evaluating patient satisfaction in the outpatient dermatology clinics of LAC+USC Medical Center in Los Angeles, California, spanning over 1 year. During this time period, patients were randomly selected to participate and were asked to complete the Short-Form Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ-18), which asked patients to rate their care experience on a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly agree; 5=strongly disagree). The survey was separated into the following 7 subscales or categories looking at different aspects of care: general satisfaction, technical quality, interpersonal manner, communication, financial aspects, time spent with physician, and accessibility and convenience. Patients were given this survey both before and after targeted interventions to improve patient satisfaction were implemented. The targeted interventions were created based on literature review in the factors affecting patient satisfaction. The change in relative satisfaction was then determined using statistical analysis. The study was approved by the University of Southern California Health Science institutional review board.

Results

Of 470 patients surveyed, the average age was 49 years. Fifty percent of respondents were male, 70% self-identified as Hispanic, 45% spoke Spanish as their native language, and 69% reported a mean annual household income of less than $15,000. When scores were stratified, English-speaking patients were significantly more satisfied than Spanish-speaking patients in the categories of technical quality (P.0340), financial aspects (P.0301), interpersonal manner (P.0037), and time spent with physician (P.0059). Specifically, in the time spent with physician category, the lowest scores were found in females, patients aged 18 to 29 years, and patients with a mean annual household income less than $15,000. These demographics correlate well with many of the newly insured and intimate the need for improved patient satisfaction, particularly in this subset of patients.

After analyzing baseline patient satisfaction scores, we implemented targeted interventions such as creating a call tree, developing multilingual disease-specific patient handouts, instituting quarterly nursing in-services, which judged interpersonal and occupational nursing skills, and recruiting bilingual staff. These interventions were implemented simultaneously and were selected with the goal of reducing the impact of the language barrier between physicians and patients and increasing accessibility to clinics. Following approximately 3 months of these interventions, performance on many categories increased in our demographics that were lowest performing when we collected baseline data. In Spanish-speaking respondents, improvement in several categories approached statistical significance, including general satisfaction (P.110), interpersonal skills (P.080), and time spent with physician (P.096). When stratifying by income and age, patients with a mean annual household income less than $15,000 demonstrated an improved technical quality (P.066) subscale score, and participants aged 18 to 29 years showed improvement in both accessibility and convenience (P.053) and financial aspects (P.056) subscales.

Comment