User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Poly-L-Lactic Acid Reconstitution Technique to Reduce Needle Obstruction

Poly-L-Lactic Acid Reconstitution Technique to Reduce Needle Obstruction

Practice Gap

Poly-L-lactic acid is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for addressing fat loss due to HAART in patients with HIV.2,3 When used as a dermal filler for correction of facial lipoatrophy, PLLA is well tolerated and has been shown to improve quality of life.2,3 Poly-L-lactic acid is available for clinical use as microparticles of lyophilized alpha hydroxy acid polymers. Once injected (after the carrier substance is absorbed), PLLA induces an inflammatory response that ultimately leads to the production of new collagen.3 Unfortunately, PLLA microparticles often obstruct needles and make the product difficult to use, potentially hindering effective injection; thus, it is in the best interest of the patient to mitigate needle obstruction during this procedure. In this article, we describe a simple and effective way to mitigate this problem by utilizing a water bath to warm the filler prior to injection.

Technique

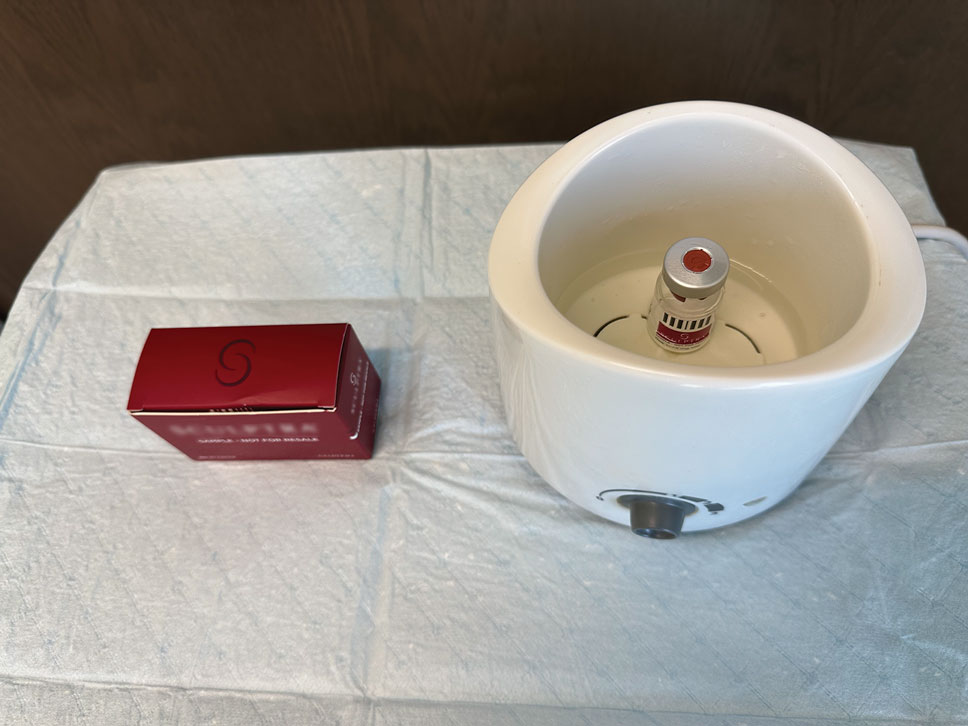

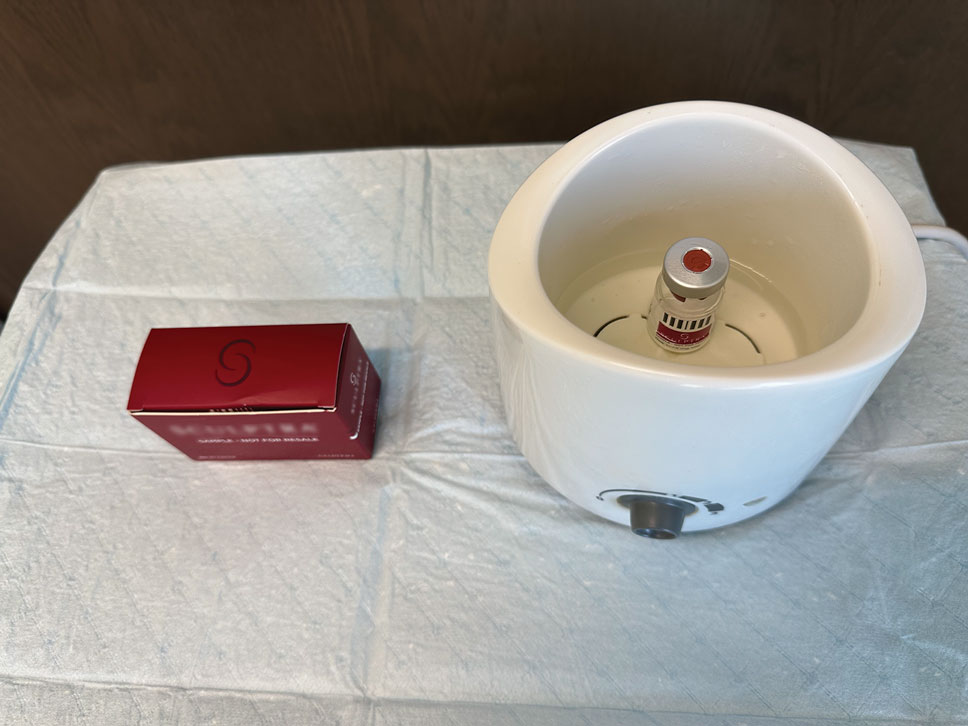

The required supplies include a thermostatic water bath, reconstituted PLLA, a syringe, and a 26-gauge injection needle. Because laboratory-grade heated water baths typically cost between $300 and $3000,4 we recommend using a more affordable, commercially available thermostatic water bath (eg, baby bottle warmer)(Figure 1) to warm the filler prior to injection, as the optimal temperature for this technique can still be achieved while remaining cost effective. Vials of PLLA reconstituted with 7 mL of sterile water and 2 mL lidocaine hydrochloride 1% should be labeled with the date of reconstitution and manually agitated for 30 seconds. The reconstituted product should be stored for 24 hours to ensure even suspension and powder saturation.5 On the day of the procedure, the vial should be placed into the water bath (heated to 100 °C) for 10 minutes prior to injection (Figure 2) and agitated again immediately before withdrawal into the syringe. The clinician then should sterilize the rubber top and draw the product from the warmed vial using the same size needle that will be used for injection. Although a larger gauge needle may make drawing up the product easier in typical practice, drawing and injecting with the same gauge needle helps prevent larger particles from clogging a smaller injection needle. Using a 26-gauge injection needle for withdrawal further reduces clogging by serving as a filter to prevent larger product particles from entering the injection syringe. The vials of PLLA can be kept in the water bath throughout the procedure between uses to keep the filler at a consistent temperature.

Practice Implications

Although many clinicians reduce needle obstructions by warming PLLA before injection, a published protocol currently is not available. One consideration when utilizing this technique is the limited data on the clinical stability and efficacy of PLLA at varying temperatures. Two studies recommend bringing the reconstituted vial to room temperature prior to injection, while others have documented an endothermic melting point in the range of 120 °C to 180

- James J, Carruthers A, Carruthers J. HIV-associated facial lipoatrophy. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:979-986. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02099.x

- Duracinsky M, Leclercq P, Herrmann S, et al. Safety of poly-L-lactic acid (New-Fill®) in the treatment of facial lipoatrophy: a large observational study among HIV-positive patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:474. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-14-474

- Sickles CK, Nassereddin A, Patel P, et al. Poly-L-lactic acid. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated February 28, 2024. Accessed October 31, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507871/

- Laboratory equipment: Water bath. Global Lab Supply. (n.d.). http://www.globallabsupply.com/Water-Bath-s/2122.htm

- Lin MJ, Dubin DP, Goldberg DJ, et al. Practices in the usage and reconstitution of poly-L-lactic acid. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:880-886.

- Vleggaar D, Fitzgerald R, Lorenc ZP, et al. Consensus recommendations on the use of injectable poly-L-lactic acid for facial and nonfacial volumization. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:s44-51.

- Sedush NG, Kalinin KT, Azarkevich PN, et al. Physicochemical characteristics and hydrolytic degradation of polylactic acid dermal fillers: a comparative study. Cosmetics. 2023;10:110. doi:10.3390/cosmetics10040110

Practice Gap

Poly-L-lactic acid is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for addressing fat loss due to HAART in patients with HIV.2,3 When used as a dermal filler for correction of facial lipoatrophy, PLLA is well tolerated and has been shown to improve quality of life.2,3 Poly-L-lactic acid is available for clinical use as microparticles of lyophilized alpha hydroxy acid polymers. Once injected (after the carrier substance is absorbed), PLLA induces an inflammatory response that ultimately leads to the production of new collagen.3 Unfortunately, PLLA microparticles often obstruct needles and make the product difficult to use, potentially hindering effective injection; thus, it is in the best interest of the patient to mitigate needle obstruction during this procedure. In this article, we describe a simple and effective way to mitigate this problem by utilizing a water bath to warm the filler prior to injection.

Technique

The required supplies include a thermostatic water bath, reconstituted PLLA, a syringe, and a 26-gauge injection needle. Because laboratory-grade heated water baths typically cost between $300 and $3000,4 we recommend using a more affordable, commercially available thermostatic water bath (eg, baby bottle warmer)(Figure 1) to warm the filler prior to injection, as the optimal temperature for this technique can still be achieved while remaining cost effective. Vials of PLLA reconstituted with 7 mL of sterile water and 2 mL lidocaine hydrochloride 1% should be labeled with the date of reconstitution and manually agitated for 30 seconds. The reconstituted product should be stored for 24 hours to ensure even suspension and powder saturation.5 On the day of the procedure, the vial should be placed into the water bath (heated to 100 °C) for 10 minutes prior to injection (Figure 2) and agitated again immediately before withdrawal into the syringe. The clinician then should sterilize the rubber top and draw the product from the warmed vial using the same size needle that will be used for injection. Although a larger gauge needle may make drawing up the product easier in typical practice, drawing and injecting with the same gauge needle helps prevent larger particles from clogging a smaller injection needle. Using a 26-gauge injection needle for withdrawal further reduces clogging by serving as a filter to prevent larger product particles from entering the injection syringe. The vials of PLLA can be kept in the water bath throughout the procedure between uses to keep the filler at a consistent temperature.

Practice Implications

Although many clinicians reduce needle obstructions by warming PLLA before injection, a published protocol currently is not available. One consideration when utilizing this technique is the limited data on the clinical stability and efficacy of PLLA at varying temperatures. Two studies recommend bringing the reconstituted vial to room temperature prior to injection, while others have documented an endothermic melting point in the range of 120 °C to 180

Practice Gap

Poly-L-lactic acid is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for addressing fat loss due to HAART in patients with HIV.2,3 When used as a dermal filler for correction of facial lipoatrophy, PLLA is well tolerated and has been shown to improve quality of life.2,3 Poly-L-lactic acid is available for clinical use as microparticles of lyophilized alpha hydroxy acid polymers. Once injected (after the carrier substance is absorbed), PLLA induces an inflammatory response that ultimately leads to the production of new collagen.3 Unfortunately, PLLA microparticles often obstruct needles and make the product difficult to use, potentially hindering effective injection; thus, it is in the best interest of the patient to mitigate needle obstruction during this procedure. In this article, we describe a simple and effective way to mitigate this problem by utilizing a water bath to warm the filler prior to injection.

Technique

The required supplies include a thermostatic water bath, reconstituted PLLA, a syringe, and a 26-gauge injection needle. Because laboratory-grade heated water baths typically cost between $300 and $3000,4 we recommend using a more affordable, commercially available thermostatic water bath (eg, baby bottle warmer)(Figure 1) to warm the filler prior to injection, as the optimal temperature for this technique can still be achieved while remaining cost effective. Vials of PLLA reconstituted with 7 mL of sterile water and 2 mL lidocaine hydrochloride 1% should be labeled with the date of reconstitution and manually agitated for 30 seconds. The reconstituted product should be stored for 24 hours to ensure even suspension and powder saturation.5 On the day of the procedure, the vial should be placed into the water bath (heated to 100 °C) for 10 minutes prior to injection (Figure 2) and agitated again immediately before withdrawal into the syringe. The clinician then should sterilize the rubber top and draw the product from the warmed vial using the same size needle that will be used for injection. Although a larger gauge needle may make drawing up the product easier in typical practice, drawing and injecting with the same gauge needle helps prevent larger particles from clogging a smaller injection needle. Using a 26-gauge injection needle for withdrawal further reduces clogging by serving as a filter to prevent larger product particles from entering the injection syringe. The vials of PLLA can be kept in the water bath throughout the procedure between uses to keep the filler at a consistent temperature.

Practice Implications

Although many clinicians reduce needle obstructions by warming PLLA before injection, a published protocol currently is not available. One consideration when utilizing this technique is the limited data on the clinical stability and efficacy of PLLA at varying temperatures. Two studies recommend bringing the reconstituted vial to room temperature prior to injection, while others have documented an endothermic melting point in the range of 120 °C to 180

- James J, Carruthers A, Carruthers J. HIV-associated facial lipoatrophy. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:979-986. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02099.x

- Duracinsky M, Leclercq P, Herrmann S, et al. Safety of poly-L-lactic acid (New-Fill®) in the treatment of facial lipoatrophy: a large observational study among HIV-positive patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:474. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-14-474

- Sickles CK, Nassereddin A, Patel P, et al. Poly-L-lactic acid. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated February 28, 2024. Accessed October 31, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507871/

- Laboratory equipment: Water bath. Global Lab Supply. (n.d.). http://www.globallabsupply.com/Water-Bath-s/2122.htm

- Lin MJ, Dubin DP, Goldberg DJ, et al. Practices in the usage and reconstitution of poly-L-lactic acid. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:880-886.

- Vleggaar D, Fitzgerald R, Lorenc ZP, et al. Consensus recommendations on the use of injectable poly-L-lactic acid for facial and nonfacial volumization. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:s44-51.

- Sedush NG, Kalinin KT, Azarkevich PN, et al. Physicochemical characteristics and hydrolytic degradation of polylactic acid dermal fillers: a comparative study. Cosmetics. 2023;10:110. doi:10.3390/cosmetics10040110

- James J, Carruthers A, Carruthers J. HIV-associated facial lipoatrophy. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:979-986. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02099.x

- Duracinsky M, Leclercq P, Herrmann S, et al. Safety of poly-L-lactic acid (New-Fill®) in the treatment of facial lipoatrophy: a large observational study among HIV-positive patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:474. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-14-474

- Sickles CK, Nassereddin A, Patel P, et al. Poly-L-lactic acid. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated February 28, 2024. Accessed October 31, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507871/

- Laboratory equipment: Water bath. Global Lab Supply. (n.d.). http://www.globallabsupply.com/Water-Bath-s/2122.htm

- Lin MJ, Dubin DP, Goldberg DJ, et al. Practices in the usage and reconstitution of poly-L-lactic acid. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:880-886.

- Vleggaar D, Fitzgerald R, Lorenc ZP, et al. Consensus recommendations on the use of injectable poly-L-lactic acid for facial and nonfacial volumization. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:s44-51.

- Sedush NG, Kalinin KT, Azarkevich PN, et al. Physicochemical characteristics and hydrolytic degradation of polylactic acid dermal fillers: a comparative study. Cosmetics. 2023;10:110. doi:10.3390/cosmetics10040110

Poly-L-Lactic Acid Reconstitution Technique to Reduce Needle Obstruction

Poly-L-Lactic Acid Reconstitution Technique to Reduce Needle Obstruction

Early Infantile Hemangioma Diagnosis Is Key in Skin of Color

Early Infantile Hemangioma Diagnosis Is Key in Skin of Color

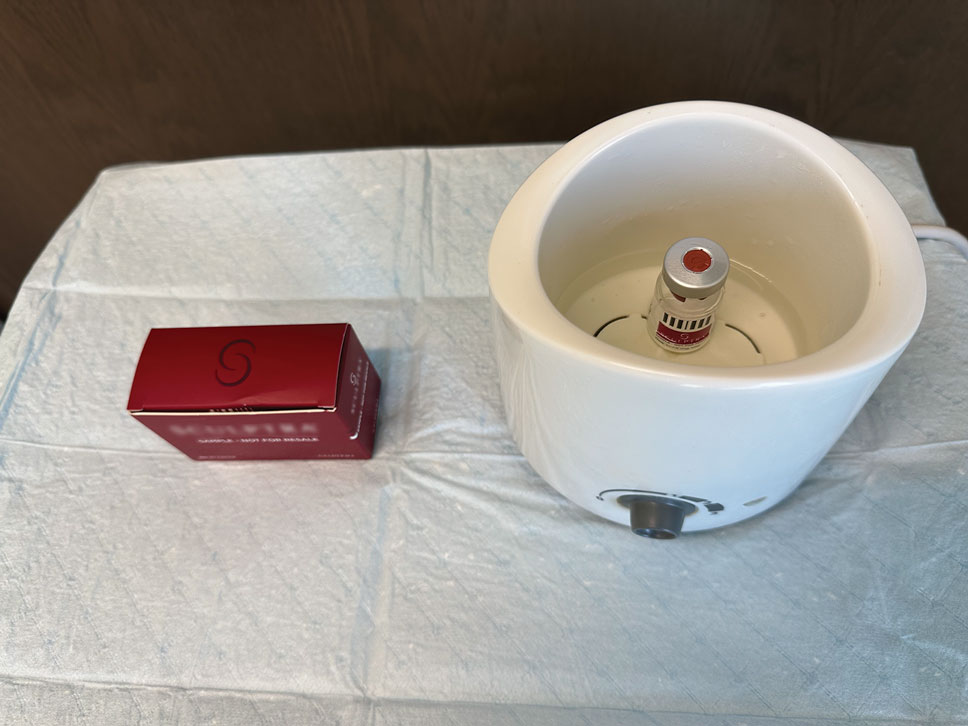

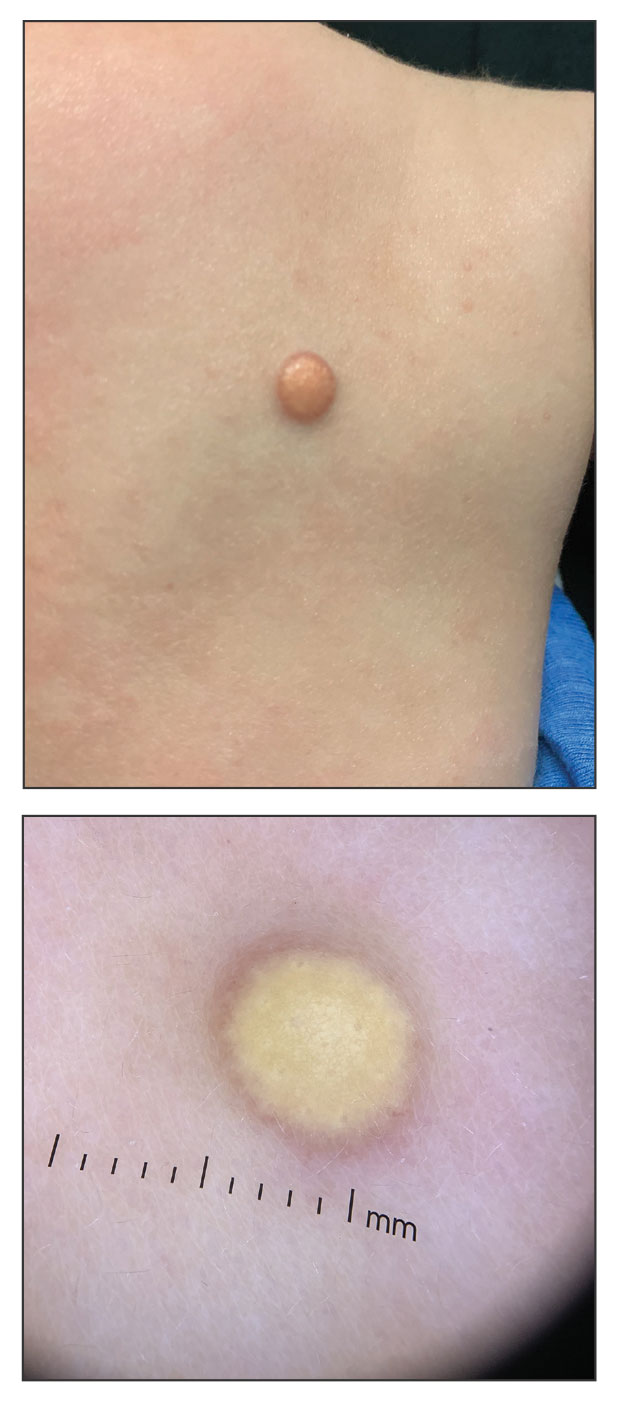

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common vascular tumor of infancy, appearing within the first few weeks of life and typically reaching peak size by age 3 to 5 months.1 It classically manifests as a raised or flat bright-red lesion in the upper dermis of the skin and/or subcutaneous tissue and can vary in number, size, shape, and location.2 It is characterized by a rapid proliferative phase, especially between 5 and 8 weeks of age, followed by gradual spontaneous regression over 1 to 10 years.1-3

Infantile hemangiomas are categorized based on depth (superficial, deep, or mixed) and distribution pattern (focal, multifocal, segmental, or indeterminate).4 In most cases, complete regression occurs by age 4 years, but there can be residual telangiectasia, fibrofatty tissue, and/or scarring.1,4 About 10% to 15% of IHs result in complications that require medical intervention (eg, visual, airway, or auditory compromise; ulceration; disfigurement); ideally, these patients should be referred to a specialist by 5 weeks of age.4 Prompt assessment of IH severity is essential to prevent or mitigate potential complications and ultimately improve outcomes.3 Social drivers of health contribute to delayed diagnosis and management of hemangiomas, leading to increased complications in some patient populations.5-7

Epidemiology

Infantile hemangiomas are estimated to manifest in 4.5% of infants in the United States.1 The most common type is superficial IH, typically found on the head or neck.5 Risk factors in infants include female sex, White race, premature birth, and low birth weight (<1000 g).1,3 Maternal risk factors include advanced gestational age (ie, >35 years), multiple gestations, family history of IH, tobacco use, use of progesterone therapy during pregnancy, and pre-eclampsia.1,3

Focal IH typically manifests as a single localized lesion that can occur anywhere on the body.2,3 In contrast, segmental IH manifests in a linear pattern and/or is distributed on a large anatomic area, most commonly on the face and less frequently the extremities and trunk.

Key Clinical Features

Superficial IH in patients with darker skin tones may appear as a dark-red or violaceous papule or plaque compared to bright red in lighter skin tones.5 Deep IH may appear as a soft, round, flesh-colored or blue-hued subcutaneous mass, the color of which may be harder to appreciate in those with darker skin tones.5

Worth Noting

Complications from IH may require imaging, close follow-up, systemic therapy, multidisciplinary care, and advanced health literacy and patient/family navigation. Multifocal IHs (≥5 lesions) are more likely to be associated with infantile hepatic hemangiomas.2,3 Large (>5 cm) segmental IHs on the face and lumbosacral area require further evaluation for PHACES (posterior fossa malformation, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, eye anomalies, and sternal raphe/cleft defects) and LUMBAR (lower-body segmental IH; urogenital anomalies and ulceration; myelopathy; bony deformities; anorectal malformations and arterial anomalies; and renal anomalies) syndromes, which are more common in patients of Hispanic ethnicity.2,3

The Infantile Hemangioma Referral Score is a recently validated tool that can assist primary care physicians in timely referral of IHs requiring early specialist intervention.4,9 It takes into account the location, number, and size of the lesions and the age of the patient; these factors help to determine which IHs may be managed conservatively vs those that may require treatment to prevent life-threatening complications.1-3

Systemic corticosteroids historically have been the primary treatment for IH; however, in the past decade, propranolol oral solution (4.28 mg/mL) has become the first-line therapy for most infants requiring systemic management.10 It is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for proliferating IH, with treatment initiation as young as 5 weeks corrected age.11 As a nonselective beta-blocker, propranolol is believed to reduce IHs through vasoconstriction or by inhibition of angiogenesis.1,4,10

For small superficial IHs, treatment options include timolol maleate ophthalmic solution 0.5% (one drop applied twice daily to the IH) or pulsed dye laser therapy.4,10 Surgical excision typically is avoided during infancy due to concerns about anesthetic risks and potential blood loss.4,10 Surgery is reserved for cases involving residual fibrofatty tissue, postinvolution scarring, obstruction of vital structures, or lesions in aesthetically sensitive areas as well as when propranolol is contraindicated.4,10

Health Disparity Highlight

Infants with skin of color and those of lower socioeconomic status (SES) face a heightened risk for delayed diagnosis and more advanced disease at the initial evaluation for IH.5,7 Access barriers such as geographic limitations to specialty services, lack of insurance, underinsurance, and language differences impact timely diagnosis and treatment.5,6 Implementation of telemedicine services in areas with limited access to specialists can facilitate early evaluation and risk stratification for IH.12

A retrospective cohort study of 804 children seen at a large academic hospital found that those of lower SES were more likely to seek care after 3 months of age than their higher-SES counterparts.6 Those who presented after 6 months of age also had higher IH severity scores compared to their counterparts with higher SES.6 Delayed access to care may cause children to miss the critical treatment window during the rapid proliferative growth phase.6,12 However, children insured through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program who participated in institutional care management programs (which assist in scheduling specialty care appointments within the institution) sought treatment earlier regardless of their SES, suggesting that such programs may help reduce disparities in timely access for children of lower SES.6

An epidemiologic study analyzing the demographics of children hospitalized across the United States demonstrated that Black infants with IH were more likely to belong to the lowest income quartile compared with White infants or those of other races. They also were 2 times older on average at initial presentation (1.8 vs 1.0 years), experienced longer hospitalizations (16.4 vs 13.8 days), and underwent more IH-related procedures than White infants and infants of other races (2.4, 1.9, and 2.1, respectively).7

These and other factors may contribute to missed windows of opportunity for timely treatment of high-risk IHs in patients with darker skin tones and/or those facing challenges stemming from social drivers of health.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Harper JI, Hoeger PH. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet. 2017;390:85-94.

- Mitra R, Fitzsimons HL, Hale T, et al. Recent advances in understanding the molecular basis of infantile haemangioma development. Br J Dermatol. 2024;191:661-669.

- Rodríguez Bandera AI, Sebaratnam DF, Wargon O, et al. Infantile hemangioma. part 1: epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1379-1392.

- Sebaratnam DF, Rodríguez Bandera AL, Wong LCF, et al. Infantile hemangioma. part 2: management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1395-1404.

- Taye ME, Shah J, Seiverling EV, et al. Diagnosis of vascular anomalies in patients with skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17:54-62.

- Lie E, Psoter KJ, Püttgen KB. Lower socioeconomic status is associated with delayed access to care for infantile hemangioma: a cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:E221-E230.

- Kumar KD, Desai AD, Shah VP, et al. Racial discrepancies in presentation of hospitalized infantile hemangioma cases using the Kids’ Inpatient Database. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6:E1092.

- Chiller KG, Passaro D, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy: clinical characteristics, morphologic subtypes, and their relationship to race, ethnicity, and sex. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1567.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Baselga Torres E, Weibel L, et al. The infantile hemangioma referral score: a validated tool for physicians. Pediatrics. 2020;145:E20191628.

- Macca L, Altavilla D, Di Bartolomeo L, et al. Update on treatment of infantile hemangiomas: what’s new in the last five years? Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:879602.

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019;143:E20183475.

- Frieden IJ, Püttgen KB, Drolet BA, et al. Management of infantile hemangiomas during the COVID pandemic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:412-418.

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common vascular tumor of infancy, appearing within the first few weeks of life and typically reaching peak size by age 3 to 5 months.1 It classically manifests as a raised or flat bright-red lesion in the upper dermis of the skin and/or subcutaneous tissue and can vary in number, size, shape, and location.2 It is characterized by a rapid proliferative phase, especially between 5 and 8 weeks of age, followed by gradual spontaneous regression over 1 to 10 years.1-3

Infantile hemangiomas are categorized based on depth (superficial, deep, or mixed) and distribution pattern (focal, multifocal, segmental, or indeterminate).4 In most cases, complete regression occurs by age 4 years, but there can be residual telangiectasia, fibrofatty tissue, and/or scarring.1,4 About 10% to 15% of IHs result in complications that require medical intervention (eg, visual, airway, or auditory compromise; ulceration; disfigurement); ideally, these patients should be referred to a specialist by 5 weeks of age.4 Prompt assessment of IH severity is essential to prevent or mitigate potential complications and ultimately improve outcomes.3 Social drivers of health contribute to delayed diagnosis and management of hemangiomas, leading to increased complications in some patient populations.5-7

Epidemiology

Infantile hemangiomas are estimated to manifest in 4.5% of infants in the United States.1 The most common type is superficial IH, typically found on the head or neck.5 Risk factors in infants include female sex, White race, premature birth, and low birth weight (<1000 g).1,3 Maternal risk factors include advanced gestational age (ie, >35 years), multiple gestations, family history of IH, tobacco use, use of progesterone therapy during pregnancy, and pre-eclampsia.1,3

Focal IH typically manifests as a single localized lesion that can occur anywhere on the body.2,3 In contrast, segmental IH manifests in a linear pattern and/or is distributed on a large anatomic area, most commonly on the face and less frequently the extremities and trunk.

Key Clinical Features

Superficial IH in patients with darker skin tones may appear as a dark-red or violaceous papule or plaque compared to bright red in lighter skin tones.5 Deep IH may appear as a soft, round, flesh-colored or blue-hued subcutaneous mass, the color of which may be harder to appreciate in those with darker skin tones.5

Worth Noting

Complications from IH may require imaging, close follow-up, systemic therapy, multidisciplinary care, and advanced health literacy and patient/family navigation. Multifocal IHs (≥5 lesions) are more likely to be associated with infantile hepatic hemangiomas.2,3 Large (>5 cm) segmental IHs on the face and lumbosacral area require further evaluation for PHACES (posterior fossa malformation, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, eye anomalies, and sternal raphe/cleft defects) and LUMBAR (lower-body segmental IH; urogenital anomalies and ulceration; myelopathy; bony deformities; anorectal malformations and arterial anomalies; and renal anomalies) syndromes, which are more common in patients of Hispanic ethnicity.2,3

The Infantile Hemangioma Referral Score is a recently validated tool that can assist primary care physicians in timely referral of IHs requiring early specialist intervention.4,9 It takes into account the location, number, and size of the lesions and the age of the patient; these factors help to determine which IHs may be managed conservatively vs those that may require treatment to prevent life-threatening complications.1-3

Systemic corticosteroids historically have been the primary treatment for IH; however, in the past decade, propranolol oral solution (4.28 mg/mL) has become the first-line therapy for most infants requiring systemic management.10 It is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for proliferating IH, with treatment initiation as young as 5 weeks corrected age.11 As a nonselective beta-blocker, propranolol is believed to reduce IHs through vasoconstriction or by inhibition of angiogenesis.1,4,10

For small superficial IHs, treatment options include timolol maleate ophthalmic solution 0.5% (one drop applied twice daily to the IH) or pulsed dye laser therapy.4,10 Surgical excision typically is avoided during infancy due to concerns about anesthetic risks and potential blood loss.4,10 Surgery is reserved for cases involving residual fibrofatty tissue, postinvolution scarring, obstruction of vital structures, or lesions in aesthetically sensitive areas as well as when propranolol is contraindicated.4,10

Health Disparity Highlight

Infants with skin of color and those of lower socioeconomic status (SES) face a heightened risk for delayed diagnosis and more advanced disease at the initial evaluation for IH.5,7 Access barriers such as geographic limitations to specialty services, lack of insurance, underinsurance, and language differences impact timely diagnosis and treatment.5,6 Implementation of telemedicine services in areas with limited access to specialists can facilitate early evaluation and risk stratification for IH.12

A retrospective cohort study of 804 children seen at a large academic hospital found that those of lower SES were more likely to seek care after 3 months of age than their higher-SES counterparts.6 Those who presented after 6 months of age also had higher IH severity scores compared to their counterparts with higher SES.6 Delayed access to care may cause children to miss the critical treatment window during the rapid proliferative growth phase.6,12 However, children insured through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program who participated in institutional care management programs (which assist in scheduling specialty care appointments within the institution) sought treatment earlier regardless of their SES, suggesting that such programs may help reduce disparities in timely access for children of lower SES.6

An epidemiologic study analyzing the demographics of children hospitalized across the United States demonstrated that Black infants with IH were more likely to belong to the lowest income quartile compared with White infants or those of other races. They also were 2 times older on average at initial presentation (1.8 vs 1.0 years), experienced longer hospitalizations (16.4 vs 13.8 days), and underwent more IH-related procedures than White infants and infants of other races (2.4, 1.9, and 2.1, respectively).7

These and other factors may contribute to missed windows of opportunity for timely treatment of high-risk IHs in patients with darker skin tones and/or those facing challenges stemming from social drivers of health.

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common vascular tumor of infancy, appearing within the first few weeks of life and typically reaching peak size by age 3 to 5 months.1 It classically manifests as a raised or flat bright-red lesion in the upper dermis of the skin and/or subcutaneous tissue and can vary in number, size, shape, and location.2 It is characterized by a rapid proliferative phase, especially between 5 and 8 weeks of age, followed by gradual spontaneous regression over 1 to 10 years.1-3

Infantile hemangiomas are categorized based on depth (superficial, deep, or mixed) and distribution pattern (focal, multifocal, segmental, or indeterminate).4 In most cases, complete regression occurs by age 4 years, but there can be residual telangiectasia, fibrofatty tissue, and/or scarring.1,4 About 10% to 15% of IHs result in complications that require medical intervention (eg, visual, airway, or auditory compromise; ulceration; disfigurement); ideally, these patients should be referred to a specialist by 5 weeks of age.4 Prompt assessment of IH severity is essential to prevent or mitigate potential complications and ultimately improve outcomes.3 Social drivers of health contribute to delayed diagnosis and management of hemangiomas, leading to increased complications in some patient populations.5-7

Epidemiology

Infantile hemangiomas are estimated to manifest in 4.5% of infants in the United States.1 The most common type is superficial IH, typically found on the head or neck.5 Risk factors in infants include female sex, White race, premature birth, and low birth weight (<1000 g).1,3 Maternal risk factors include advanced gestational age (ie, >35 years), multiple gestations, family history of IH, tobacco use, use of progesterone therapy during pregnancy, and pre-eclampsia.1,3

Focal IH typically manifests as a single localized lesion that can occur anywhere on the body.2,3 In contrast, segmental IH manifests in a linear pattern and/or is distributed on a large anatomic area, most commonly on the face and less frequently the extremities and trunk.

Key Clinical Features

Superficial IH in patients with darker skin tones may appear as a dark-red or violaceous papule or plaque compared to bright red in lighter skin tones.5 Deep IH may appear as a soft, round, flesh-colored or blue-hued subcutaneous mass, the color of which may be harder to appreciate in those with darker skin tones.5

Worth Noting

Complications from IH may require imaging, close follow-up, systemic therapy, multidisciplinary care, and advanced health literacy and patient/family navigation. Multifocal IHs (≥5 lesions) are more likely to be associated with infantile hepatic hemangiomas.2,3 Large (>5 cm) segmental IHs on the face and lumbosacral area require further evaluation for PHACES (posterior fossa malformation, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, eye anomalies, and sternal raphe/cleft defects) and LUMBAR (lower-body segmental IH; urogenital anomalies and ulceration; myelopathy; bony deformities; anorectal malformations and arterial anomalies; and renal anomalies) syndromes, which are more common in patients of Hispanic ethnicity.2,3

The Infantile Hemangioma Referral Score is a recently validated tool that can assist primary care physicians in timely referral of IHs requiring early specialist intervention.4,9 It takes into account the location, number, and size of the lesions and the age of the patient; these factors help to determine which IHs may be managed conservatively vs those that may require treatment to prevent life-threatening complications.1-3

Systemic corticosteroids historically have been the primary treatment for IH; however, in the past decade, propranolol oral solution (4.28 mg/mL) has become the first-line therapy for most infants requiring systemic management.10 It is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for proliferating IH, with treatment initiation as young as 5 weeks corrected age.11 As a nonselective beta-blocker, propranolol is believed to reduce IHs through vasoconstriction or by inhibition of angiogenesis.1,4,10

For small superficial IHs, treatment options include timolol maleate ophthalmic solution 0.5% (one drop applied twice daily to the IH) or pulsed dye laser therapy.4,10 Surgical excision typically is avoided during infancy due to concerns about anesthetic risks and potential blood loss.4,10 Surgery is reserved for cases involving residual fibrofatty tissue, postinvolution scarring, obstruction of vital structures, or lesions in aesthetically sensitive areas as well as when propranolol is contraindicated.4,10

Health Disparity Highlight

Infants with skin of color and those of lower socioeconomic status (SES) face a heightened risk for delayed diagnosis and more advanced disease at the initial evaluation for IH.5,7 Access barriers such as geographic limitations to specialty services, lack of insurance, underinsurance, and language differences impact timely diagnosis and treatment.5,6 Implementation of telemedicine services in areas with limited access to specialists can facilitate early evaluation and risk stratification for IH.12

A retrospective cohort study of 804 children seen at a large academic hospital found that those of lower SES were more likely to seek care after 3 months of age than their higher-SES counterparts.6 Those who presented after 6 months of age also had higher IH severity scores compared to their counterparts with higher SES.6 Delayed access to care may cause children to miss the critical treatment window during the rapid proliferative growth phase.6,12 However, children insured through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program who participated in institutional care management programs (which assist in scheduling specialty care appointments within the institution) sought treatment earlier regardless of their SES, suggesting that such programs may help reduce disparities in timely access for children of lower SES.6

An epidemiologic study analyzing the demographics of children hospitalized across the United States demonstrated that Black infants with IH were more likely to belong to the lowest income quartile compared with White infants or those of other races. They also were 2 times older on average at initial presentation (1.8 vs 1.0 years), experienced longer hospitalizations (16.4 vs 13.8 days), and underwent more IH-related procedures than White infants and infants of other races (2.4, 1.9, and 2.1, respectively).7

These and other factors may contribute to missed windows of opportunity for timely treatment of high-risk IHs in patients with darker skin tones and/or those facing challenges stemming from social drivers of health.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Harper JI, Hoeger PH. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet. 2017;390:85-94.

- Mitra R, Fitzsimons HL, Hale T, et al. Recent advances in understanding the molecular basis of infantile haemangioma development. Br J Dermatol. 2024;191:661-669.

- Rodríguez Bandera AI, Sebaratnam DF, Wargon O, et al. Infantile hemangioma. part 1: epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1379-1392.

- Sebaratnam DF, Rodríguez Bandera AL, Wong LCF, et al. Infantile hemangioma. part 2: management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1395-1404.

- Taye ME, Shah J, Seiverling EV, et al. Diagnosis of vascular anomalies in patients with skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17:54-62.

- Lie E, Psoter KJ, Püttgen KB. Lower socioeconomic status is associated with delayed access to care for infantile hemangioma: a cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:E221-E230.

- Kumar KD, Desai AD, Shah VP, et al. Racial discrepancies in presentation of hospitalized infantile hemangioma cases using the Kids’ Inpatient Database. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6:E1092.

- Chiller KG, Passaro D, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy: clinical characteristics, morphologic subtypes, and their relationship to race, ethnicity, and sex. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1567.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Baselga Torres E, Weibel L, et al. The infantile hemangioma referral score: a validated tool for physicians. Pediatrics. 2020;145:E20191628.

- Macca L, Altavilla D, Di Bartolomeo L, et al. Update on treatment of infantile hemangiomas: what’s new in the last five years? Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:879602.

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019;143:E20183475.

- Frieden IJ, Püttgen KB, Drolet BA, et al. Management of infantile hemangiomas during the COVID pandemic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:412-418.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Harper JI, Hoeger PH. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet. 2017;390:85-94.

- Mitra R, Fitzsimons HL, Hale T, et al. Recent advances in understanding the molecular basis of infantile haemangioma development. Br J Dermatol. 2024;191:661-669.

- Rodríguez Bandera AI, Sebaratnam DF, Wargon O, et al. Infantile hemangioma. part 1: epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1379-1392.

- Sebaratnam DF, Rodríguez Bandera AL, Wong LCF, et al. Infantile hemangioma. part 2: management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1395-1404.

- Taye ME, Shah J, Seiverling EV, et al. Diagnosis of vascular anomalies in patients with skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17:54-62.

- Lie E, Psoter KJ, Püttgen KB. Lower socioeconomic status is associated with delayed access to care for infantile hemangioma: a cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:E221-E230.

- Kumar KD, Desai AD, Shah VP, et al. Racial discrepancies in presentation of hospitalized infantile hemangioma cases using the Kids’ Inpatient Database. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6:E1092.

- Chiller KG, Passaro D, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy: clinical characteristics, morphologic subtypes, and their relationship to race, ethnicity, and sex. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1567.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Baselga Torres E, Weibel L, et al. The infantile hemangioma referral score: a validated tool for physicians. Pediatrics. 2020;145:E20191628.

- Macca L, Altavilla D, Di Bartolomeo L, et al. Update on treatment of infantile hemangiomas: what’s new in the last five years? Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:879602.

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019;143:E20183475.

- Frieden IJ, Püttgen KB, Drolet BA, et al. Management of infantile hemangiomas during the COVID pandemic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:412-418.

Early Infantile Hemangioma Diagnosis Is Key in Skin of Color

Early Infantile Hemangioma Diagnosis Is Key in Skin of Color

Cost Analysis of Dermatology Residency Applications From 2021 to 2024 Using the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency Database

Cost Analysis of Dermatology Residency Applications From 2021 to 2024 Using the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency Database

To the Editor:

Residency applicants, especially in competitive specialties such as dermatology, face major financial barriers due to the high costs of applications, interviews, and away rotations.1 While several studies have examined application costs of other specialties, few have analyzed expenses associated with dermatology applications.1,2 There are no data examining costs following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020; thus, our study evaluated dermatology application cost trends from 2021 to 2024 and compared them to other specialties to identify strategies to reduce the financial burden on applicants.

Self-reported total application costs, application fees, interview expenses, and away rotation costs from 2021 to 2024 were collected from the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency (STAR) database powered by the UT Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, Texas).3 The mean total application expenses per year were compared among specialties, and an analysis of variance was used to determine if the differences were statistically significant.

The number of applicants who recorded information in the Texas STAR database was 110 in 2021, 163 in 2022, 136 in 2023, and 129 in 2024.3 The total dermatology application expenses increased from $2805 in 2021 to $6231 in 2024; interview costs increased from $404 in 2021 to $911 in 2024; and away rotation costs increased from $850 in 2021 to $3812 in 2024 (all P<.05)(Table). There was no significant change in application fees during the study period ($2176 in 2021 to $2125 in 2024 [P=.58]). Dermatology had the fourth highest average total cost over the study period compared to all other specialties, increasing from $2250 in 2021 to $5250 in 2024, following orthopedic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $6750 in 2024), plastic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $9750 in 2024), and neurosurgery ($1750 in 2021 to $11,250 in 2024).

Our study found that dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024, primarily driven by rising interview and away rotation expenses (both P<.05). This trend places dermatology among the most expensive fields to apply to for residency. A cross-sectional survey of dermatology residency program directors identified away rotations as one of the top 5 selection criteria, underscoring their importance in the matching process.4 In addition, a cross-sectional analysis of 345 dermatology residents found that 26.2% matched at institutions where they had mentors, including those they connected with through away rotations.5,6 Overall, the high cost of away rotations partially may reflect the competitive nature of the specialty, as building connections at programs may enhance the chances of matching. These costs also can vary based on geography, as rotating in high-cost urban centers can be more expensive than in rural areas; however, rural rotations may be less common due to limited program availability and applicant preferences. For example, nearly 50% of 2024 Electronic Residency Application Service applicants indicated a preference for urban settings, while fewer than 5% selected rural settings.7 Additionally, the high costs associated with applying to residency programs and completing away rotations can disproportionately impact students from rural backgrounds and underrepresented minorities, who may have fewer financial resources.

In our study, the lower application-related expenses in 2021 (during the pandemic) compared to those of 2024 (postpandemic) likely stem from the Association of American Medical Colleges’ recommendation to conduct virtual interviews during the pandemic.8 In 2024, some dermatology programs returned to in-person interviews, with some applicants consequently incurring higher costs related to travel, lodging, and other associated expenses.8 A cost-analysis study of 4153 dermatology applicants from 2016 to 2021 found that the average application costs were $1759 per applicant during the pandemic, when virtual interviews replaced in-person ones, whereas costs were $8476 per applicant during periods with in-person interviews and no COVID-19 restrictions.2 However, we did not observe a significant change in application fees over our study period, likely because the pandemic did not affect application numbers. A cross-sectional analysis of dermatology applicants during the pandemic similarly reported reductions in application-related expenses during the period when interviews were conducted virtually,9 supporting the trend observed in our study. Overall, our findings taken together with other studies highlight the pandemic’s role in reducing expenses and underscore the potential for exploring additional cost-saving measures.

Implementing strategies to reduce these financial burdens—including virtual interviews, increasing student funding for away rotations, and limiting the number of applications individual students can submit—could help alleviate socioeconomic disparities. The new signaling system for residency programs aims to reduce the number of applications submitted, as applicants typically receive interviews only from the limited number of programs they signal, reducing overall application costs. However, our data from the Texas STAR database suggest that application numbers remained relatively stable from 2021 to 2024, indicating that, despite signaling, many applicants still may apply broadly in hopes of improving their chances in an increasingly competitive field. Although a definitive solution to reducing the financial burden on dermatology applicants remains elusive, these strategies can raise awareness and encourage important dialogues.

Limitations of our study include the voluntary nature of the Texas STAR survey, leading to potential voluntary response bias, as well as the small sample size. Students who choose to submit cost data may differ systematically from those who do not; for example, students who match may be more likely to report their outcomes, while those who do not match may be less likely to participate, potentially introducing selection bias. In addition, general awareness of the Texas STAR survey may vary across institutions and among students, further limiting the number of students who participate. Additionally, 2021 was the only presignaling year included, making it difficult to assess longer-term trends. Despite these limitations, the Texas STAR database remains a valuable resource for analyzing general residency application expenses and trends, as it offers comprehensive data from more than 100 medical schools and includes many variables.3

In conclusion, our study found that total dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024 (all P<.05), making dermatology among the most expensive specialties for applying. This study sets the foundation for future survey-based research for applicants and program directors on strategies to alleviate financial burdens.

- Mansouri B, Walker GD, Mitchell J, et al. The cost of applying to dermatology residency: 2014 data estimates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:754-756. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.049

- Gorgy M, Shah S, Arbuiso S, et al. Comparison of cost changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic for dermatology residency applications in the USA. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:600-602. doi:10.1111/ced.15001<.li>

- UT Southwestern. Texas STAR. 2024. Accessed November 5, 2025. https://www.utsouthwestern.edu/education/medical-school/about-the-school/student-affairs/texas-star.html

- Baldwin K, Weidner Z, Ahn J, et al. Are away rotations critical for a successful match in orthopaedic surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:3340-3345. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0920-9

- Yeh C, Desai AD, Wilson BN, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of scholarly work and mentor relationships in matched dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1437-1439. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.861

- Gorouhi F, Alikhan A, Rezaei A, et al. Dermatology residency selection criteria with an emphasis on program characteristics: a national program director survey. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:692760. doi:10.1155/2014/692760

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Decoding geographic and setting preferences in residency selection. January 18, 2024. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.aamc.org/services/eras-institutions/geographic-preferences

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Virtual interviews: tips for program directors. Updated May 14, 2020. https://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/gme/program_portal/pd/pd_meet/2019-2020/8-6-20-Virtual_Interview_Tips_for_Program_Directors_05142020.pdf

- Williams GE, Zimmerman JM, Wiggins CJ, et al. The indelible marks on dermatology: impacts of COVID-19 on dermatology residency match using the Texas STAR database. Clin Dermatol. 2023;41:215-218. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.12.001

To the Editor:

Residency applicants, especially in competitive specialties such as dermatology, face major financial barriers due to the high costs of applications, interviews, and away rotations.1 While several studies have examined application costs of other specialties, few have analyzed expenses associated with dermatology applications.1,2 There are no data examining costs following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020; thus, our study evaluated dermatology application cost trends from 2021 to 2024 and compared them to other specialties to identify strategies to reduce the financial burden on applicants.

Self-reported total application costs, application fees, interview expenses, and away rotation costs from 2021 to 2024 were collected from the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency (STAR) database powered by the UT Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, Texas).3 The mean total application expenses per year were compared among specialties, and an analysis of variance was used to determine if the differences were statistically significant.

The number of applicants who recorded information in the Texas STAR database was 110 in 2021, 163 in 2022, 136 in 2023, and 129 in 2024.3 The total dermatology application expenses increased from $2805 in 2021 to $6231 in 2024; interview costs increased from $404 in 2021 to $911 in 2024; and away rotation costs increased from $850 in 2021 to $3812 in 2024 (all P<.05)(Table). There was no significant change in application fees during the study period ($2176 in 2021 to $2125 in 2024 [P=.58]). Dermatology had the fourth highest average total cost over the study period compared to all other specialties, increasing from $2250 in 2021 to $5250 in 2024, following orthopedic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $6750 in 2024), plastic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $9750 in 2024), and neurosurgery ($1750 in 2021 to $11,250 in 2024).

Our study found that dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024, primarily driven by rising interview and away rotation expenses (both P<.05). This trend places dermatology among the most expensive fields to apply to for residency. A cross-sectional survey of dermatology residency program directors identified away rotations as one of the top 5 selection criteria, underscoring their importance in the matching process.4 In addition, a cross-sectional analysis of 345 dermatology residents found that 26.2% matched at institutions where they had mentors, including those they connected with through away rotations.5,6 Overall, the high cost of away rotations partially may reflect the competitive nature of the specialty, as building connections at programs may enhance the chances of matching. These costs also can vary based on geography, as rotating in high-cost urban centers can be more expensive than in rural areas; however, rural rotations may be less common due to limited program availability and applicant preferences. For example, nearly 50% of 2024 Electronic Residency Application Service applicants indicated a preference for urban settings, while fewer than 5% selected rural settings.7 Additionally, the high costs associated with applying to residency programs and completing away rotations can disproportionately impact students from rural backgrounds and underrepresented minorities, who may have fewer financial resources.

In our study, the lower application-related expenses in 2021 (during the pandemic) compared to those of 2024 (postpandemic) likely stem from the Association of American Medical Colleges’ recommendation to conduct virtual interviews during the pandemic.8 In 2024, some dermatology programs returned to in-person interviews, with some applicants consequently incurring higher costs related to travel, lodging, and other associated expenses.8 A cost-analysis study of 4153 dermatology applicants from 2016 to 2021 found that the average application costs were $1759 per applicant during the pandemic, when virtual interviews replaced in-person ones, whereas costs were $8476 per applicant during periods with in-person interviews and no COVID-19 restrictions.2 However, we did not observe a significant change in application fees over our study period, likely because the pandemic did not affect application numbers. A cross-sectional analysis of dermatology applicants during the pandemic similarly reported reductions in application-related expenses during the period when interviews were conducted virtually,9 supporting the trend observed in our study. Overall, our findings taken together with other studies highlight the pandemic’s role in reducing expenses and underscore the potential for exploring additional cost-saving measures.

Implementing strategies to reduce these financial burdens—including virtual interviews, increasing student funding for away rotations, and limiting the number of applications individual students can submit—could help alleviate socioeconomic disparities. The new signaling system for residency programs aims to reduce the number of applications submitted, as applicants typically receive interviews only from the limited number of programs they signal, reducing overall application costs. However, our data from the Texas STAR database suggest that application numbers remained relatively stable from 2021 to 2024, indicating that, despite signaling, many applicants still may apply broadly in hopes of improving their chances in an increasingly competitive field. Although a definitive solution to reducing the financial burden on dermatology applicants remains elusive, these strategies can raise awareness and encourage important dialogues.

Limitations of our study include the voluntary nature of the Texas STAR survey, leading to potential voluntary response bias, as well as the small sample size. Students who choose to submit cost data may differ systematically from those who do not; for example, students who match may be more likely to report their outcomes, while those who do not match may be less likely to participate, potentially introducing selection bias. In addition, general awareness of the Texas STAR survey may vary across institutions and among students, further limiting the number of students who participate. Additionally, 2021 was the only presignaling year included, making it difficult to assess longer-term trends. Despite these limitations, the Texas STAR database remains a valuable resource for analyzing general residency application expenses and trends, as it offers comprehensive data from more than 100 medical schools and includes many variables.3

In conclusion, our study found that total dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024 (all P<.05), making dermatology among the most expensive specialties for applying. This study sets the foundation for future survey-based research for applicants and program directors on strategies to alleviate financial burdens.

To the Editor:

Residency applicants, especially in competitive specialties such as dermatology, face major financial barriers due to the high costs of applications, interviews, and away rotations.1 While several studies have examined application costs of other specialties, few have analyzed expenses associated with dermatology applications.1,2 There are no data examining costs following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020; thus, our study evaluated dermatology application cost trends from 2021 to 2024 and compared them to other specialties to identify strategies to reduce the financial burden on applicants.

Self-reported total application costs, application fees, interview expenses, and away rotation costs from 2021 to 2024 were collected from the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency (STAR) database powered by the UT Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, Texas).3 The mean total application expenses per year were compared among specialties, and an analysis of variance was used to determine if the differences were statistically significant.

The number of applicants who recorded information in the Texas STAR database was 110 in 2021, 163 in 2022, 136 in 2023, and 129 in 2024.3 The total dermatology application expenses increased from $2805 in 2021 to $6231 in 2024; interview costs increased from $404 in 2021 to $911 in 2024; and away rotation costs increased from $850 in 2021 to $3812 in 2024 (all P<.05)(Table). There was no significant change in application fees during the study period ($2176 in 2021 to $2125 in 2024 [P=.58]). Dermatology had the fourth highest average total cost over the study period compared to all other specialties, increasing from $2250 in 2021 to $5250 in 2024, following orthopedic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $6750 in 2024), plastic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $9750 in 2024), and neurosurgery ($1750 in 2021 to $11,250 in 2024).

Our study found that dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024, primarily driven by rising interview and away rotation expenses (both P<.05). This trend places dermatology among the most expensive fields to apply to for residency. A cross-sectional survey of dermatology residency program directors identified away rotations as one of the top 5 selection criteria, underscoring their importance in the matching process.4 In addition, a cross-sectional analysis of 345 dermatology residents found that 26.2% matched at institutions where they had mentors, including those they connected with through away rotations.5,6 Overall, the high cost of away rotations partially may reflect the competitive nature of the specialty, as building connections at programs may enhance the chances of matching. These costs also can vary based on geography, as rotating in high-cost urban centers can be more expensive than in rural areas; however, rural rotations may be less common due to limited program availability and applicant preferences. For example, nearly 50% of 2024 Electronic Residency Application Service applicants indicated a preference for urban settings, while fewer than 5% selected rural settings.7 Additionally, the high costs associated with applying to residency programs and completing away rotations can disproportionately impact students from rural backgrounds and underrepresented minorities, who may have fewer financial resources.

In our study, the lower application-related expenses in 2021 (during the pandemic) compared to those of 2024 (postpandemic) likely stem from the Association of American Medical Colleges’ recommendation to conduct virtual interviews during the pandemic.8 In 2024, some dermatology programs returned to in-person interviews, with some applicants consequently incurring higher costs related to travel, lodging, and other associated expenses.8 A cost-analysis study of 4153 dermatology applicants from 2016 to 2021 found that the average application costs were $1759 per applicant during the pandemic, when virtual interviews replaced in-person ones, whereas costs were $8476 per applicant during periods with in-person interviews and no COVID-19 restrictions.2 However, we did not observe a significant change in application fees over our study period, likely because the pandemic did not affect application numbers. A cross-sectional analysis of dermatology applicants during the pandemic similarly reported reductions in application-related expenses during the period when interviews were conducted virtually,9 supporting the trend observed in our study. Overall, our findings taken together with other studies highlight the pandemic’s role in reducing expenses and underscore the potential for exploring additional cost-saving measures.

Implementing strategies to reduce these financial burdens—including virtual interviews, increasing student funding for away rotations, and limiting the number of applications individual students can submit—could help alleviate socioeconomic disparities. The new signaling system for residency programs aims to reduce the number of applications submitted, as applicants typically receive interviews only from the limited number of programs they signal, reducing overall application costs. However, our data from the Texas STAR database suggest that application numbers remained relatively stable from 2021 to 2024, indicating that, despite signaling, many applicants still may apply broadly in hopes of improving their chances in an increasingly competitive field. Although a definitive solution to reducing the financial burden on dermatology applicants remains elusive, these strategies can raise awareness and encourage important dialogues.

Limitations of our study include the voluntary nature of the Texas STAR survey, leading to potential voluntary response bias, as well as the small sample size. Students who choose to submit cost data may differ systematically from those who do not; for example, students who match may be more likely to report their outcomes, while those who do not match may be less likely to participate, potentially introducing selection bias. In addition, general awareness of the Texas STAR survey may vary across institutions and among students, further limiting the number of students who participate. Additionally, 2021 was the only presignaling year included, making it difficult to assess longer-term trends. Despite these limitations, the Texas STAR database remains a valuable resource for analyzing general residency application expenses and trends, as it offers comprehensive data from more than 100 medical schools and includes many variables.3

In conclusion, our study found that total dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024 (all P<.05), making dermatology among the most expensive specialties for applying. This study sets the foundation for future survey-based research for applicants and program directors on strategies to alleviate financial burdens.

- Mansouri B, Walker GD, Mitchell J, et al. The cost of applying to dermatology residency: 2014 data estimates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:754-756. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.049

- Gorgy M, Shah S, Arbuiso S, et al. Comparison of cost changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic for dermatology residency applications in the USA. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:600-602. doi:10.1111/ced.15001<.li>

- UT Southwestern. Texas STAR. 2024. Accessed November 5, 2025. https://www.utsouthwestern.edu/education/medical-school/about-the-school/student-affairs/texas-star.html

- Baldwin K, Weidner Z, Ahn J, et al. Are away rotations critical for a successful match in orthopaedic surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:3340-3345. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0920-9

- Yeh C, Desai AD, Wilson BN, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of scholarly work and mentor relationships in matched dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1437-1439. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.861

- Gorouhi F, Alikhan A, Rezaei A, et al. Dermatology residency selection criteria with an emphasis on program characteristics: a national program director survey. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:692760. doi:10.1155/2014/692760

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Decoding geographic and setting preferences in residency selection. January 18, 2024. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.aamc.org/services/eras-institutions/geographic-preferences

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Virtual interviews: tips for program directors. Updated May 14, 2020. https://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/gme/program_portal/pd/pd_meet/2019-2020/8-6-20-Virtual_Interview_Tips_for_Program_Directors_05142020.pdf

- Williams GE, Zimmerman JM, Wiggins CJ, et al. The indelible marks on dermatology: impacts of COVID-19 on dermatology residency match using the Texas STAR database. Clin Dermatol. 2023;41:215-218. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.12.001

- Mansouri B, Walker GD, Mitchell J, et al. The cost of applying to dermatology residency: 2014 data estimates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:754-756. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.049

- Gorgy M, Shah S, Arbuiso S, et al. Comparison of cost changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic for dermatology residency applications in the USA. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:600-602. doi:10.1111/ced.15001<.li>

- UT Southwestern. Texas STAR. 2024. Accessed November 5, 2025. https://www.utsouthwestern.edu/education/medical-school/about-the-school/student-affairs/texas-star.html

- Baldwin K, Weidner Z, Ahn J, et al. Are away rotations critical for a successful match in orthopaedic surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:3340-3345. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0920-9

- Yeh C, Desai AD, Wilson BN, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of scholarly work and mentor relationships in matched dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1437-1439. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.861

- Gorouhi F, Alikhan A, Rezaei A, et al. Dermatology residency selection criteria with an emphasis on program characteristics: a national program director survey. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:692760. doi:10.1155/2014/692760

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Decoding geographic and setting preferences in residency selection. January 18, 2024. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.aamc.org/services/eras-institutions/geographic-preferences

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Virtual interviews: tips for program directors. Updated May 14, 2020. https://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/gme/program_portal/pd/pd_meet/2019-2020/8-6-20-Virtual_Interview_Tips_for_Program_Directors_05142020.pdf

- Williams GE, Zimmerman JM, Wiggins CJ, et al. The indelible marks on dermatology: impacts of COVID-19 on dermatology residency match using the Texas STAR database. Clin Dermatol. 2023;41:215-218. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.12.001

Cost Analysis of Dermatology Residency Applications From 2021 to 2024 Using the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency Database

Cost Analysis of Dermatology Residency Applications From 2021 to 2024 Using the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency Database

PRACTICE POINTS

- Dermatology application costs increased from 2021 to 2024, largely due to expenses related to away rotations and, in some cases, a return to in-person interviews.

- Away rotations play a critical role in the dermatology match; however, they also contribute substantially to financial burden.

- The cost-saving impact of virtual interviews during the COVID-19 pandemic highlights a meaningful opportunity for future cost reduction.

- Further interventions are needed to meaningfully reduce financial burden and promote equity.

Therapeutic Approaches for Alopecia Areata in Children Aged 6 to 11 Years

Therapeutic Approaches for Alopecia Areata in Children Aged 6 to 11 Years

Pediatric alopecia areata (AA) is a chronic autoimmune disease of the hair follicles characterized by nonscarring hair loss. Its incidence in children in the United States ranges from 13.6 to 33.5 per 100,000 person-years, with a prevalence of 0.04% to 0.11%.1 Alopecia areata has important effects on quality of life, particularly in children. Hair loss at an early age can decrease participation in school, sports, and extracurricular activities2 and is associated with increased rates of comorbid anxiety and depression.3 Families also experience psychosocial stress, often comparable to other chronic pediatric illnesses.4 Thus, management requires not only medical therapy but also psychosocial support and school-based accommodations.

Systemic therapies for treatment of AA in adolescents and adults are increasingly available, including US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors such as baricitinib, deuruxolitinib (for adults), and ritlecitinib (for adolescents and adults); however, no systemic therapies have been approved by the FDA for children younger than 12 years. The therapeutic gap is most acute for those aged 6 to 11 years, for whom the psychosocial burden is high but treatment options are limited.3

This article highlights options and strategies for managing AA in children aged 6 to 11 years, emphasizing supportive and psychosocial care (including camouflage techniques), topical therapies, and off-label systemic approaches.

Supportive and Psychosocial Care

Treatment of AA in children extends beyond the affected child to include parents, caregivers, and even school staff (eg, teachers, principals, nurses).4 Disease-specific organizations such as the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (naaf.org) and the Children’s Alopecia Project (childrensalopeciaproject.org) provide education, support groups, and advocacy resources. These organizations assist families in navigating school accommodations, including Section 504 plans that may allow children with AA to wear hats in school to mitigate stigma. Additional resources include handouts for teachers and school nurses developed by the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.5

Psychological support for these patients is critical. Many children benefit from seeing a psychologist, particularly if anxiety, depression, and/or bullying is present.3 In clinics without embedded psychology services, dermatologists should maintain referral lists or encourage families to seek guidance from their pediatrician.

Camouflage techniques can help children cope with visible hair loss. Wigs and hairpieces are available free of charge through charitable organizations for patients younger than 17; however, young children often find adhesives uncomfortable, and they will not wear nonadherent wigs for long periods of time. Alternatives include soft hats, bonnets, scarves, and beanies. For partial hair loss, root concealers, scalp powders, or hair mascara can be useful. Temporary eyebrow tattoos are a good cosmetic approach, whereas microblading generally is not advised in children younger than 12 due to procedural risks including pain.

Topical Therapies

Topical agents remain the mainstay of treatment for AA in children aged 6 to 11 years. Potent class 1 or class 2 topical corticosteroids commonly are used, sometimes in combination with calcineurin inhibitors or topical minoxidil. Off-label compounded topical JAK inhibitors also have been tried in this population and may be helpful for eyebrow hair loss,6 though data on their efficacy for scalp AA are mixed.7 Intralesional corticosteroid injections, effective in adolescents and adults, generally are poorly tolerated by younger children and may cause considerable distress. Contact immunotherapy with squaric acid dibutyl ester or anthralin can be considered, but these agents are designed to elicit irritation, which may be intolerable for young children.8 Shared decision-making with families is essential to balance efficacy, tolerability, and treatment burden.

Systemic Therapies

Systemic therapy generally is reserved for children with extensive or refractory AA. Low-dose oral minoxidil is emerging as an off-label option. One systematic review reported that low-dose oral minoxidil was well tolerated in pediatric patients with minimal adverse effects.9 Doses of 0.01 to 0.02 mg/kg/d are reasonable starting points, achieved by cutting tablets or compounding oral solutions.10

In children with AA and concurrent atopic dermatitis, dupilumab may offer dual benefit. A real-world observational study demonstrated hair regrowth in pediatric patients with AA treated with dupilumab.11 Immunosuppressive options such as low-dose methotrexate or pulse corticosteroids (dexamethasone or prednisolone) also may be considered, although use of these agents requires careful monitoring due to increased risk for infection, clinically significant blood count and liver enzyme changes, and metabolic adverse effects related to long-term use of corticosteroids.

Clinical trials of JAK inhibitors in children aged 6 to 11 years are anticipated to begin in late 2025. Until then, off-label use of ritlecitinib, baricitinib, tofacitinib, or other JAK inhibitors may be considered in select cases with considerable disease burden and quality-of-life impairment following thorough discussion with the patient and their caregivers. Currently available pediatric data show few serious adverse events in children—the most common included upper respiratory infections (nasopharyngitis), acne, and headaches—but long-term risks remain unknown. Dosing challenges also exist for children who cannot swallow pills; currently ritlecitinib is available only as a capsule that cannot be opened while other JAK inhibitors are available in more accessible forms (baricitinib can be crushed and dissolved, and tofacitinib is available in liquid formulation for other pediatric indications). Insurance coverage is a major barrier, as these therapies are not FDA approved for AA in this age group.

Final Thoughts

Alopecia areata in children aged 6 to 11 years presents unique therapeutic challenges. While highly effective systemic therapies exist for older patients, younger children have limited options. For the 6-to-11 age group, management strategies should prioritize psychosocial support, topical therapy, and low-burden systemic alternatives such as low-dose oral minoxidil. Family education, school-based accommodations, and access to camouflage techniques are integral to holistic care. The commencement of pediatric clinical trials for JAK inhibitors offers hope for more robust treatment strategies in the near future. In the meantime, clinicians must engage in shared decision-making, tailoring therapy to the child’s disease severity, emotional well-being, and family priorities.

- Adhanom R, Ansbro B, Castelo-Soccio L. Epidemiology of pediatric alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol. 2025;42(suppl 1):12-23. doi:10.1111/pde.15803

- Paller AS, Rangel SM, Chamlin SL, et al; Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance. Stigmatization and mental health impact of chronic pediatric skin disorders. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:621-630.

- van Dalen M, Muller KS, Kasperkovitz-Oosterloo JM, et al. Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in children and adults with alopecia areata: systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:1054898.

- Yücesoy SN, Uzunçakmak TK, Selçukog?lu Ö, et al. Evaluation of quality of life scores and family impact scales in pediatric patients with alopecia areata: a cross-sectional cohort study. Int J Dermatol. 2024;63:1414-1420.

- Alopecia areata. Society for Pediatric Dermatology. Accessed November 17, 2025. https://pedsderm.net/site/assets/files/18580/spd_school_handout_1_alopecia.pdf

- Liu LY, King BA. Response to tofacitinib therapy of eyebrows and eyelashes in alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1778-1779.

- Bokhari L, Sinclair R. Treatment of alopecia universalis with topical Janus kinase inhibitors—a double blind, placebo, and active controlled pilot study. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1464-1470.

- Hill ND, Bunata K, Hebert AA. Treatment of alopecia areata with squaric acid dibutylester. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:300-304.

- Williams KN, Olukoga CTY, Tosti A. Evaluation of the safety and effectiveness of oral minoxidil in children: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024;14:1709-1727.

- Lemes LR, Melo DF, de Oliveira DS, et al. Topical and oral minoxidil for hair disorders in pediatric patients: what do we know so far? Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13950.

- David E, Shokrian N, Del Duca E, et al. Dupilumab induces hair regrowth in pediatric alopecia areata: a real-world, single-center observational study. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:487.

Pediatric alopecia areata (AA) is a chronic autoimmune disease of the hair follicles characterized by nonscarring hair loss. Its incidence in children in the United States ranges from 13.6 to 33.5 per 100,000 person-years, with a prevalence of 0.04% to 0.11%.1 Alopecia areata has important effects on quality of life, particularly in children. Hair loss at an early age can decrease participation in school, sports, and extracurricular activities2 and is associated with increased rates of comorbid anxiety and depression.3 Families also experience psychosocial stress, often comparable to other chronic pediatric illnesses.4 Thus, management requires not only medical therapy but also psychosocial support and school-based accommodations.