User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Advocacy and Compliance Issues Impacting Dermatology in 2025

Advocacy and Compliance Issues Impacting Dermatology in 2025

The US health care system presents major administrative burdens—particularly in coding, billing, and reimbursement—that impact clinical efficiency and patient access. Dermatologists have experienced disproportionate reimbursement declines. A longitudinal review of 20 dermatologic service codes found a 10% average decline in Medicare reimbursement between 2000 and 2020.1 A recent cross-sectional study showed a 4.7% average decline in reimbursement rates from 2007 to 2021 for commonly performed dermatologic procedures, with variation across procedure categories.2 These reductions threaten practice sustainability and highlight the urgent need for comprehensive, long-term payment reform to preserve access to high-quality dermatologic care.

In dermatopathology, policy changes to reimbursement and laboratory oversight directly impact practice operations. Specialty-specific advocacy remains vital in driving policy changes. In this article, we highlight a recent advocacy win—the reversal of immunohistochemistry (IHC) stain denials—and provide updates on a new position statement on IHC guidance. We also outline regulatory changes to the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) of 1988 and College of American Pathologists (CAP) laboratory director requirements and emphasize the importance of continued legislative advocacy.

Reversal of Reimbursement Denials for IHC Stains

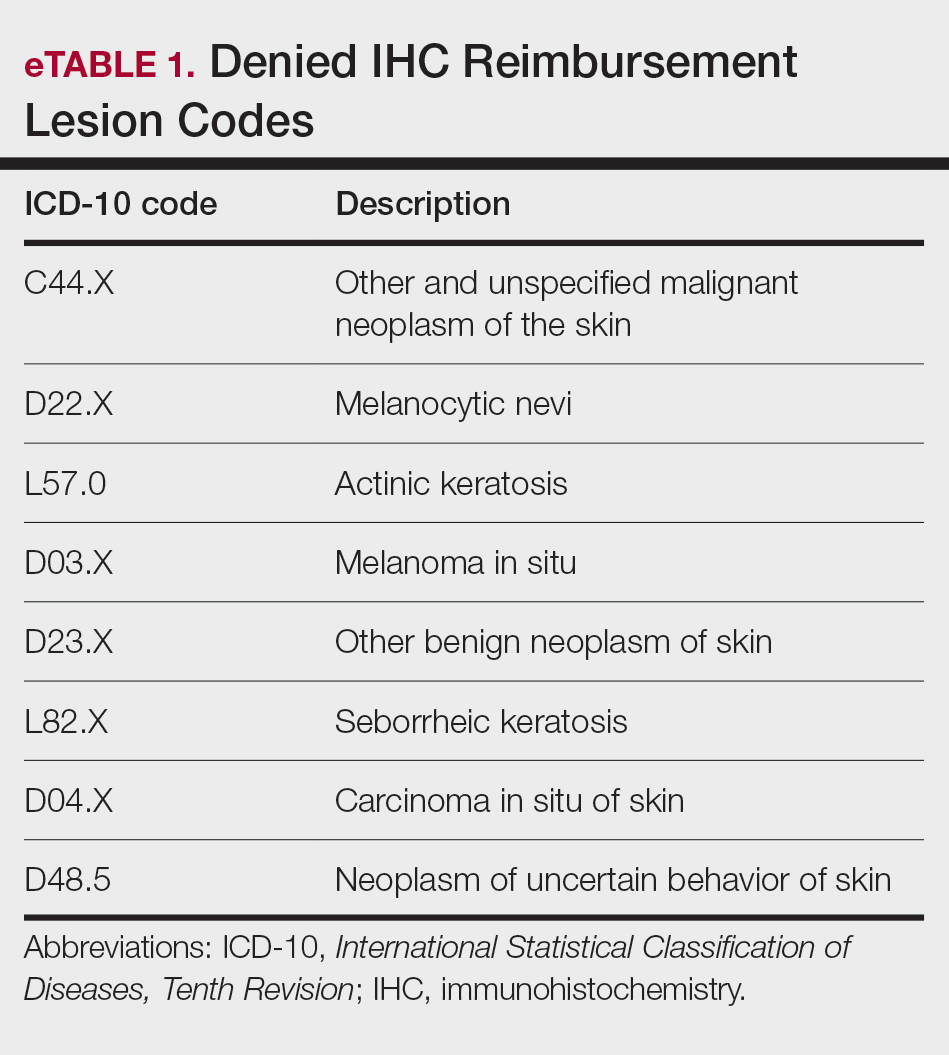

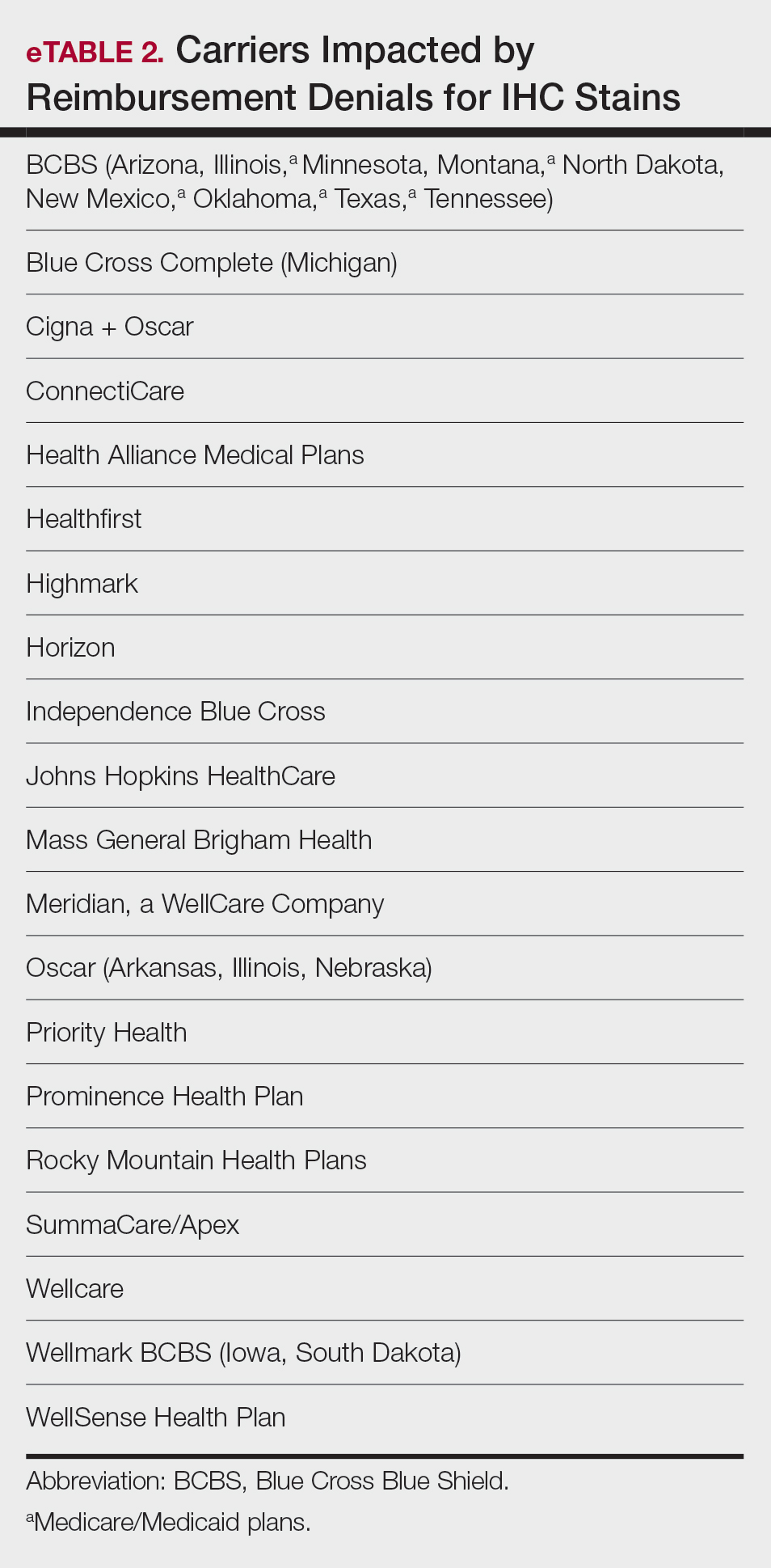

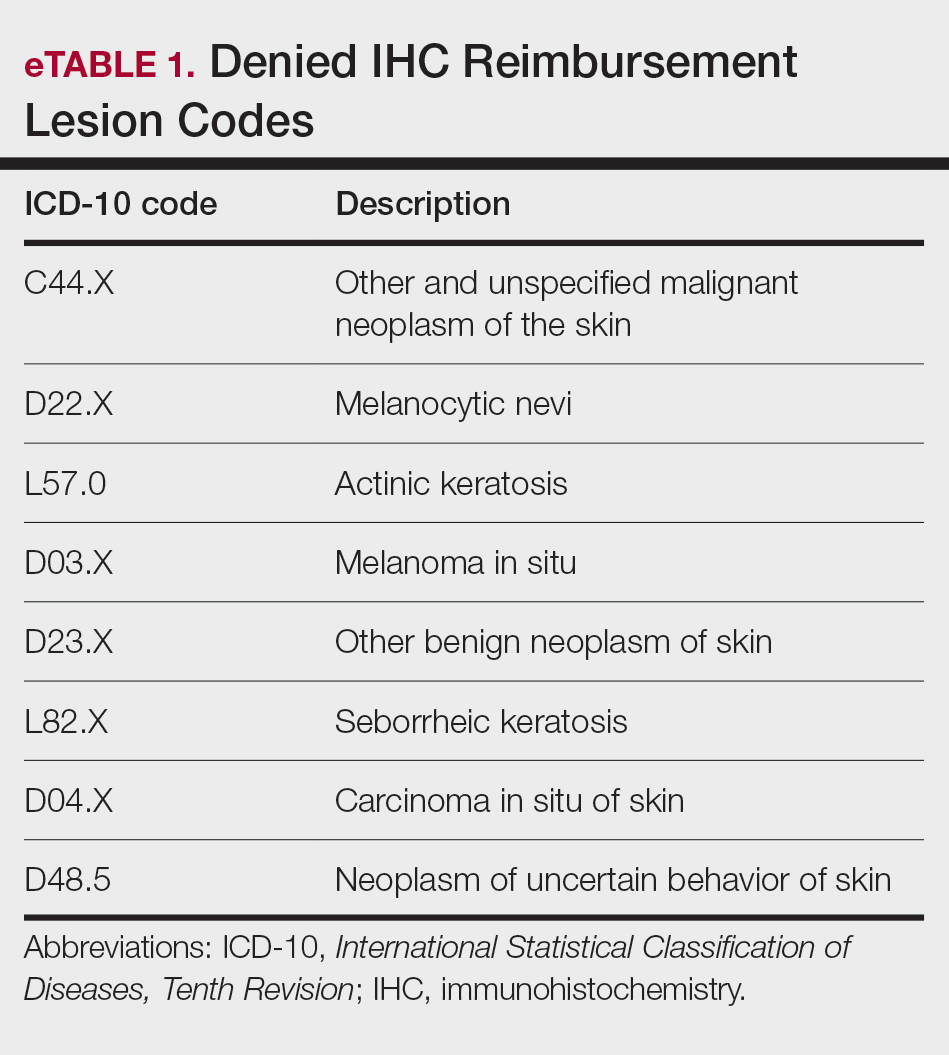

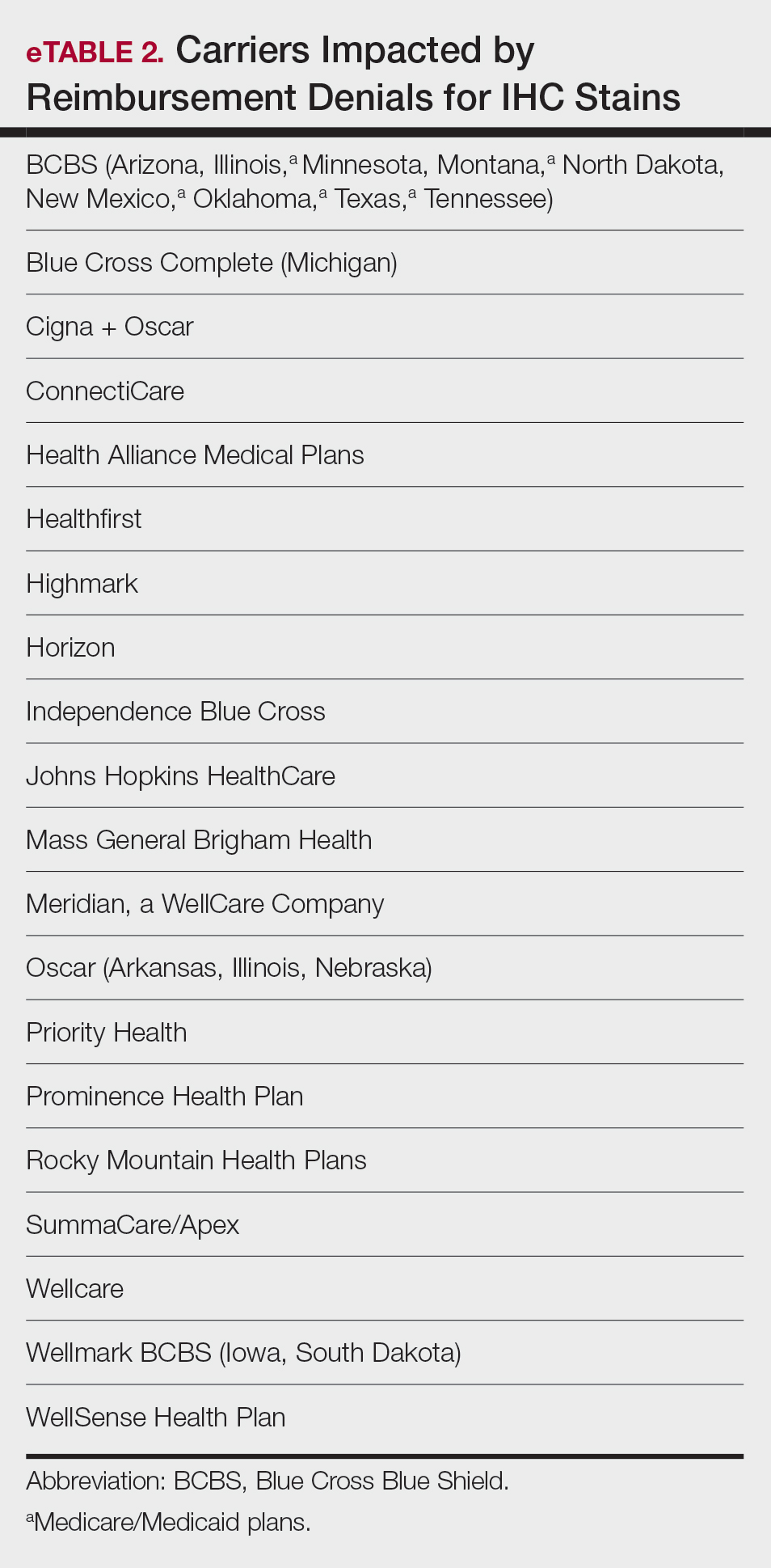

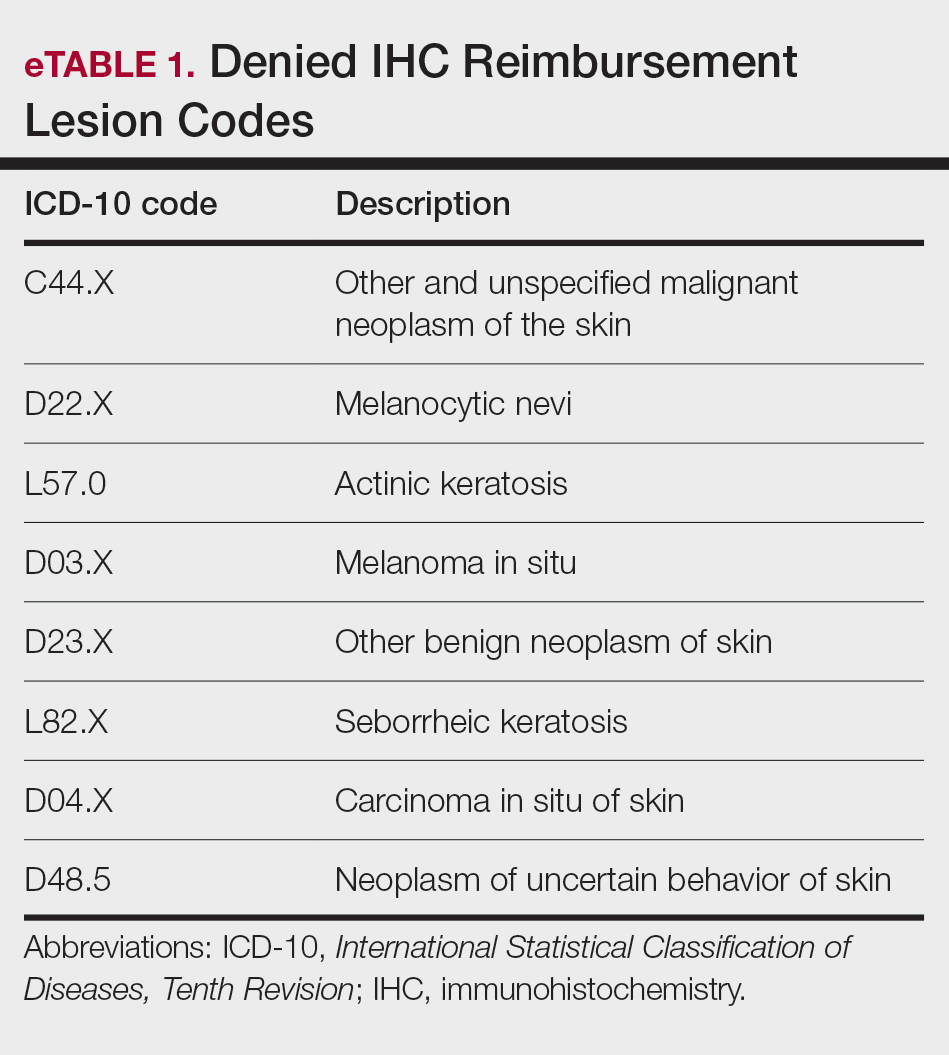

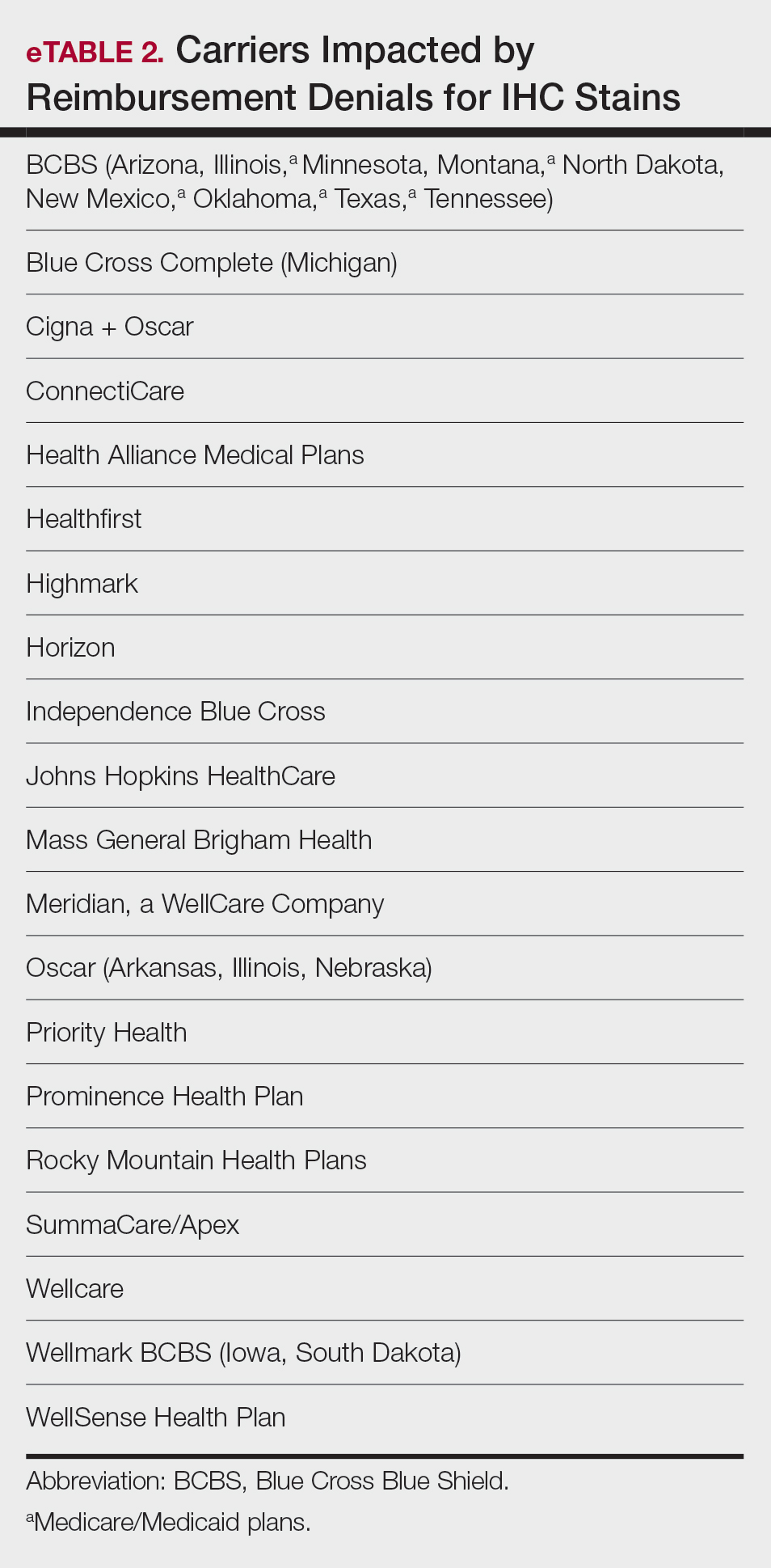

EviCore, a medical benefits management company serving over one-third of insured individuals in the United States, is hired by an extensive network of insurance companies to develop clinical and laboratory guidelines and utilization and payment integrity programs.3 EviCore’s laboratory management guidelines for 2024 denied IHC stains (Current Procedural Terminology codes 88341 and 88342) as not medically necessary when associated with specific International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, skin lesion codes (eTable 1).3-5 These policies caused major disruption to dermatopathology services nationwide, impacting both academic and private laboratories (eTable 2).5 The implementation of such blanket denials interferes with clinical decision-making, compromising diagnostic quality by restricting medically necessary and essential laboratory and pathology services. The American Academy of Dermatology Association (AADA) and CAP leadership formally objected to the policy, citing how these reimbursement denials fail to account for the importance of clinical judgment and diagnostic nuance.6

Thanks to broad advocacy efforts, EviCore updated its guidelines effective January 1, 2025. The skin-related International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, codes were removed from IHC coverage restrictions, with automatic payment reinstated retroactive to March 15, 2024. EviCore also rescinded language denying reimbursement if a diagnosis could be made without the use of IHC stains.7 While this reversal is a notable achievement, ongoing monitoring of emerging trends in claim denials remains crucial. Continued advocacy, proper documentation, and adherence to American Society of Dermatopathology (ASDP) Appropriate Use Criteria is essential to protecting clinical autonomy.

The AADA’s Dermatopathology Committee developed a new position statement on IHC utilization supporting the advocacy efforts with payers, who recently have tried to implement restrictive limitations.8 Immunohistochemistry is considered a valuable tool for dermatopathology diagnosis, and its utility aids in the confirmation, exclusion, or change in diagnosis.9 By clearly outlining the clinical value of IHC in dermatopathology, this statement reinforces the need to advocate against restrictive payer policies to preserve physician autonomy and promote appropriate, evidence-based use of IHC stains.8

In addition, the ASDP Standards of Practice Committee is working with the Johns Hopkins–Global Appropriateness Measures data-powered analytics platform to develop physician-led IHC benchmarks. The ASDP Appropriate Use Criteria mobile application is a valuable clinical tool for dermatopathologists, general pathologists, dermatologists, and other providers, offering case-based recommendations for test utilization grounded in current evidence.9

Legislative Advocacy: Support for H.R. 879

Physician payment cuts have reached a critical tipping point. Since 2001, physicians have experienced a 33% average reduction in Medicare reimbursement, unadjusted for inflation or rising overhead.10 In January 2025, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) imposed a further 2.83% cut, despite projecting a 3.5% increase in the Medicare Economic Index.11,12 Dermatologists and other physician groups cannot continue to absorb these reductions, as they have several consequences, including the inability to maintain practices, forcing some physicians out of business, driving health care consolidation, and limiting patient access.

The Medicare Patient Access and Practice Stabilization Act (H.R. 879)13 is bipartisan legislation that seeks to stop the 2.8% Medicare physician payment cut that went into effect in January 2025, provide physicians with an additional 2% inflation-adjusted payment increase for 2025, and help stabilize Medicare reimbursement rates.13,14 As the impact of continued cuts threatens both patient access and practice viability, member engagement is essential to advancing federal physician payment reform. To support sustainable payment reform and protect access to care, visit the AADA Advocacy Action Center online.14

2025 CLIA and CAP Laboratory Director Requirements: What’s Changing?

As of December 28, 2024, updated CLIA regulations took effect for all laboratories performing moderate- or high-complexity testing. These revisions aim to modernize outdated requirements and update regulations to incorporate technological advancements such as automation and artificial intelligence.15 New CLIA standards require laboratory directors with Doctor of Medicine or Doctor of Osteopathy degrees to be certified in anatomic and/or clinical pathology by the American Board of Pathology or the American Osteopathic Board of Pathology.15 For physicians who do not hold these board-certified qualifications, there are alternative pathways to becoming a laboratory director based on experience and education for physicians licensed to practice in the jurisdiction where the laboratory is located. For high-complexity laboratories, individuals need at least 2 years of experience directing or supervising high-complexity testing and at least 20 continuing education credit hours in laboratory practice that cover director responsibilities. For moderate-complexity laboratories, individuals need at least 1 year of experience supervising nonwaived laboratory testing and at least 20 continuing education credit hours in laboratory practice that cover director responsibilities.16

If the current laboratory director is not board certified in pathology, the new regulation will permit the grandfathering of current laboratory directors if existing laboratory directors have remained continuously employed in their current role since December 28, 2024.16 Therefore, individuals who were already employed in qualifying positions as of December 28, 2024, will be grandfathered in and will not need to meet the new educational requirements if they remain employed without interruption. All individuals qualifying after December 28, 2024, will be required to do so under the new provisions stated earlier.

The CMS updated laboratory personnel requirements, thereby impacting all CLIA-certified laboratories and those seeking CLIA certification. Likewise, laboratories seeking accreditation by the CAP must meet the new laboratory personnel requirements.17 In some cases, CAP requirements are more stringent than the CLIA regulations (CAP accreditation is more stringent in areas of quality control, personnel qualifications, proficiency testing, and in oversight of laboratory developed tests).15-17 If more stringent state or local regulations are in place for personnel qualifications, including requirements for state licensure, they must be followed.

The AADA formed an ad hoc workgroup to address the CLIA laboratory director requirements and is actively engaging CMS to amend these requirements immediately. Formal objections have been submitted, and direct dialogue with CMS leadership is under way in collaboration with the American Board of Dermatology and leading dermatology and pathology societies.

Final Thoughts

Advocacy remains essential to the future of dermatology. From payer policy reversals to laboratory compliance reforms and federal payment advocacy, physicians must remain engaged. Whether it is safeguarding diagnostic autonomy or securing financial sustainability, we must continue to put “skin in the game.”

- Pollock JR, Chen JY, Dorius DA, et al. Decreasing physician Medicare reimbursement for dermatology services. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1154-1156.

- Mazmudar RS, Sheth A, Tripathi R, et al. Inflation-adjusted trends in Medicare reimbursement for common dermatologic procedures, 2007-2021. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1355-1358.

- Miller TC, Rucker P, Armstrong D. “Not medically necessary”: inside the company helping America’s biggest health insurers deny coverage for care. ProPublica. October 23, 2024. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.propublica.org/article/evicore-health-insurance-denials-cigna-unitedhealthcare-aetna-prior-authorizations

- EviCore healthcare. Immunohistochemistry (IHC). Lab Management Guidelines v2.0.2024. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.evicore.com/sites/default/files/clinical-guidelines/2024-08/MOL.CS_.104.A_Immunohistochemistry%20%28IHC%29_V2.0.2024_eff11.01.2024_pub12.31.2024.pdf

- EviCore. Laboratory management. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.evicore.com/provider/clinical-guidelines-details?solution=laboratory%20management

- Saad AJ. College of American Pathologists. December 12, 2023. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://documents.cap.org/documents /Wellmark-Letter- https://documents.cap.org/documents/wellmarkcap-letter2023.pdf

- EviCore healthcare. Clinical Guidelines: Lab Management Program. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.evicore.com/sites/default/files/clinical-guidelines/2024-08/Cigna_LabMgmt_V1.0.2025_eff01.01.2025_pub08.22.2024_0.pdf

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Position statement on immunohistochemistry utilization. Accessed May 9, 2024. https://server.aad.org/forms/policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Immunohistochemistry%20Utilization.pdf

- Naert KA, Trotter MJ. Utilization and utility of immunohistochemistry in dermatopathology. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:74-77.

- American Medical Association. Medicare physician payment continues to fall further behind practice cost inflation. Accessed April 23, 2025. https:// www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2025-medicare-updates-inflation-chart.pdf

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Calendar year (CY) 2025 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule final rule. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/calendar-year-cy-2025-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-final-rule

- American Medical Association. The Medicare Economic Index. Accessed April 23 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/medicare-basics-medicare-economic-index.pdf

- Medicare Patient Access and Practice Stabilization Act, HR 879, 119th Cong (2025). Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/house-bill/879

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. AADA advocacy action center. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aad.org/member/advocacy/take-action

- Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA) fees; histocompatibility, personnel, and alternative sanctions for certificate of waiver laboratories. Fed Regist. 2023;88:89976-90044.

- College of American Pathologists. CAP accreditation checklists – 2024 edition. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://documents.cap.org/documents/2024-Checklist-Summary.pdf?_gl=1*1b4rei9*_ga*NDc0NjYwNjM5LjE3NDQ3NTI4NjA.*_ga_97ZFJSQQ0X*MTc0NDc2OTc3My40LjEuMTc0NDc2OTgyOC4wLjAuMA

- Bennett SA, Conn CM, Gill HE, et al. Regulatory requirements for laboratory developed tests in the United States. J Immunol Methods. 2025;537:113813.

The US health care system presents major administrative burdens—particularly in coding, billing, and reimbursement—that impact clinical efficiency and patient access. Dermatologists have experienced disproportionate reimbursement declines. A longitudinal review of 20 dermatologic service codes found a 10% average decline in Medicare reimbursement between 2000 and 2020.1 A recent cross-sectional study showed a 4.7% average decline in reimbursement rates from 2007 to 2021 for commonly performed dermatologic procedures, with variation across procedure categories.2 These reductions threaten practice sustainability and highlight the urgent need for comprehensive, long-term payment reform to preserve access to high-quality dermatologic care.

In dermatopathology, policy changes to reimbursement and laboratory oversight directly impact practice operations. Specialty-specific advocacy remains vital in driving policy changes. In this article, we highlight a recent advocacy win—the reversal of immunohistochemistry (IHC) stain denials—and provide updates on a new position statement on IHC guidance. We also outline regulatory changes to the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) of 1988 and College of American Pathologists (CAP) laboratory director requirements and emphasize the importance of continued legislative advocacy.

Reversal of Reimbursement Denials for IHC Stains

EviCore, a medical benefits management company serving over one-third of insured individuals in the United States, is hired by an extensive network of insurance companies to develop clinical and laboratory guidelines and utilization and payment integrity programs.3 EviCore’s laboratory management guidelines for 2024 denied IHC stains (Current Procedural Terminology codes 88341 and 88342) as not medically necessary when associated with specific International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, skin lesion codes (eTable 1).3-5 These policies caused major disruption to dermatopathology services nationwide, impacting both academic and private laboratories (eTable 2).5 The implementation of such blanket denials interferes with clinical decision-making, compromising diagnostic quality by restricting medically necessary and essential laboratory and pathology services. The American Academy of Dermatology Association (AADA) and CAP leadership formally objected to the policy, citing how these reimbursement denials fail to account for the importance of clinical judgment and diagnostic nuance.6

Thanks to broad advocacy efforts, EviCore updated its guidelines effective January 1, 2025. The skin-related International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, codes were removed from IHC coverage restrictions, with automatic payment reinstated retroactive to March 15, 2024. EviCore also rescinded language denying reimbursement if a diagnosis could be made without the use of IHC stains.7 While this reversal is a notable achievement, ongoing monitoring of emerging trends in claim denials remains crucial. Continued advocacy, proper documentation, and adherence to American Society of Dermatopathology (ASDP) Appropriate Use Criteria is essential to protecting clinical autonomy.

The AADA’s Dermatopathology Committee developed a new position statement on IHC utilization supporting the advocacy efforts with payers, who recently have tried to implement restrictive limitations.8 Immunohistochemistry is considered a valuable tool for dermatopathology diagnosis, and its utility aids in the confirmation, exclusion, or change in diagnosis.9 By clearly outlining the clinical value of IHC in dermatopathology, this statement reinforces the need to advocate against restrictive payer policies to preserve physician autonomy and promote appropriate, evidence-based use of IHC stains.8

In addition, the ASDP Standards of Practice Committee is working with the Johns Hopkins–Global Appropriateness Measures data-powered analytics platform to develop physician-led IHC benchmarks. The ASDP Appropriate Use Criteria mobile application is a valuable clinical tool for dermatopathologists, general pathologists, dermatologists, and other providers, offering case-based recommendations for test utilization grounded in current evidence.9

Legislative Advocacy: Support for H.R. 879

Physician payment cuts have reached a critical tipping point. Since 2001, physicians have experienced a 33% average reduction in Medicare reimbursement, unadjusted for inflation or rising overhead.10 In January 2025, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) imposed a further 2.83% cut, despite projecting a 3.5% increase in the Medicare Economic Index.11,12 Dermatologists and other physician groups cannot continue to absorb these reductions, as they have several consequences, including the inability to maintain practices, forcing some physicians out of business, driving health care consolidation, and limiting patient access.

The Medicare Patient Access and Practice Stabilization Act (H.R. 879)13 is bipartisan legislation that seeks to stop the 2.8% Medicare physician payment cut that went into effect in January 2025, provide physicians with an additional 2% inflation-adjusted payment increase for 2025, and help stabilize Medicare reimbursement rates.13,14 As the impact of continued cuts threatens both patient access and practice viability, member engagement is essential to advancing federal physician payment reform. To support sustainable payment reform and protect access to care, visit the AADA Advocacy Action Center online.14

2025 CLIA and CAP Laboratory Director Requirements: What’s Changing?

As of December 28, 2024, updated CLIA regulations took effect for all laboratories performing moderate- or high-complexity testing. These revisions aim to modernize outdated requirements and update regulations to incorporate technological advancements such as automation and artificial intelligence.15 New CLIA standards require laboratory directors with Doctor of Medicine or Doctor of Osteopathy degrees to be certified in anatomic and/or clinical pathology by the American Board of Pathology or the American Osteopathic Board of Pathology.15 For physicians who do not hold these board-certified qualifications, there are alternative pathways to becoming a laboratory director based on experience and education for physicians licensed to practice in the jurisdiction where the laboratory is located. For high-complexity laboratories, individuals need at least 2 years of experience directing or supervising high-complexity testing and at least 20 continuing education credit hours in laboratory practice that cover director responsibilities. For moderate-complexity laboratories, individuals need at least 1 year of experience supervising nonwaived laboratory testing and at least 20 continuing education credit hours in laboratory practice that cover director responsibilities.16

If the current laboratory director is not board certified in pathology, the new regulation will permit the grandfathering of current laboratory directors if existing laboratory directors have remained continuously employed in their current role since December 28, 2024.16 Therefore, individuals who were already employed in qualifying positions as of December 28, 2024, will be grandfathered in and will not need to meet the new educational requirements if they remain employed without interruption. All individuals qualifying after December 28, 2024, will be required to do so under the new provisions stated earlier.

The CMS updated laboratory personnel requirements, thereby impacting all CLIA-certified laboratories and those seeking CLIA certification. Likewise, laboratories seeking accreditation by the CAP must meet the new laboratory personnel requirements.17 In some cases, CAP requirements are more stringent than the CLIA regulations (CAP accreditation is more stringent in areas of quality control, personnel qualifications, proficiency testing, and in oversight of laboratory developed tests).15-17 If more stringent state or local regulations are in place for personnel qualifications, including requirements for state licensure, they must be followed.

The AADA formed an ad hoc workgroup to address the CLIA laboratory director requirements and is actively engaging CMS to amend these requirements immediately. Formal objections have been submitted, and direct dialogue with CMS leadership is under way in collaboration with the American Board of Dermatology and leading dermatology and pathology societies.

Final Thoughts

Advocacy remains essential to the future of dermatology. From payer policy reversals to laboratory compliance reforms and federal payment advocacy, physicians must remain engaged. Whether it is safeguarding diagnostic autonomy or securing financial sustainability, we must continue to put “skin in the game.”

The US health care system presents major administrative burdens—particularly in coding, billing, and reimbursement—that impact clinical efficiency and patient access. Dermatologists have experienced disproportionate reimbursement declines. A longitudinal review of 20 dermatologic service codes found a 10% average decline in Medicare reimbursement between 2000 and 2020.1 A recent cross-sectional study showed a 4.7% average decline in reimbursement rates from 2007 to 2021 for commonly performed dermatologic procedures, with variation across procedure categories.2 These reductions threaten practice sustainability and highlight the urgent need for comprehensive, long-term payment reform to preserve access to high-quality dermatologic care.

In dermatopathology, policy changes to reimbursement and laboratory oversight directly impact practice operations. Specialty-specific advocacy remains vital in driving policy changes. In this article, we highlight a recent advocacy win—the reversal of immunohistochemistry (IHC) stain denials—and provide updates on a new position statement on IHC guidance. We also outline regulatory changes to the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) of 1988 and College of American Pathologists (CAP) laboratory director requirements and emphasize the importance of continued legislative advocacy.

Reversal of Reimbursement Denials for IHC Stains

EviCore, a medical benefits management company serving over one-third of insured individuals in the United States, is hired by an extensive network of insurance companies to develop clinical and laboratory guidelines and utilization and payment integrity programs.3 EviCore’s laboratory management guidelines for 2024 denied IHC stains (Current Procedural Terminology codes 88341 and 88342) as not medically necessary when associated with specific International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, skin lesion codes (eTable 1).3-5 These policies caused major disruption to dermatopathology services nationwide, impacting both academic and private laboratories (eTable 2).5 The implementation of such blanket denials interferes with clinical decision-making, compromising diagnostic quality by restricting medically necessary and essential laboratory and pathology services. The American Academy of Dermatology Association (AADA) and CAP leadership formally objected to the policy, citing how these reimbursement denials fail to account for the importance of clinical judgment and diagnostic nuance.6

Thanks to broad advocacy efforts, EviCore updated its guidelines effective January 1, 2025. The skin-related International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, codes were removed from IHC coverage restrictions, with automatic payment reinstated retroactive to March 15, 2024. EviCore also rescinded language denying reimbursement if a diagnosis could be made without the use of IHC stains.7 While this reversal is a notable achievement, ongoing monitoring of emerging trends in claim denials remains crucial. Continued advocacy, proper documentation, and adherence to American Society of Dermatopathology (ASDP) Appropriate Use Criteria is essential to protecting clinical autonomy.

The AADA’s Dermatopathology Committee developed a new position statement on IHC utilization supporting the advocacy efforts with payers, who recently have tried to implement restrictive limitations.8 Immunohistochemistry is considered a valuable tool for dermatopathology diagnosis, and its utility aids in the confirmation, exclusion, or change in diagnosis.9 By clearly outlining the clinical value of IHC in dermatopathology, this statement reinforces the need to advocate against restrictive payer policies to preserve physician autonomy and promote appropriate, evidence-based use of IHC stains.8

In addition, the ASDP Standards of Practice Committee is working with the Johns Hopkins–Global Appropriateness Measures data-powered analytics platform to develop physician-led IHC benchmarks. The ASDP Appropriate Use Criteria mobile application is a valuable clinical tool for dermatopathologists, general pathologists, dermatologists, and other providers, offering case-based recommendations for test utilization grounded in current evidence.9

Legislative Advocacy: Support for H.R. 879

Physician payment cuts have reached a critical tipping point. Since 2001, physicians have experienced a 33% average reduction in Medicare reimbursement, unadjusted for inflation or rising overhead.10 In January 2025, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) imposed a further 2.83% cut, despite projecting a 3.5% increase in the Medicare Economic Index.11,12 Dermatologists and other physician groups cannot continue to absorb these reductions, as they have several consequences, including the inability to maintain practices, forcing some physicians out of business, driving health care consolidation, and limiting patient access.

The Medicare Patient Access and Practice Stabilization Act (H.R. 879)13 is bipartisan legislation that seeks to stop the 2.8% Medicare physician payment cut that went into effect in January 2025, provide physicians with an additional 2% inflation-adjusted payment increase for 2025, and help stabilize Medicare reimbursement rates.13,14 As the impact of continued cuts threatens both patient access and practice viability, member engagement is essential to advancing federal physician payment reform. To support sustainable payment reform and protect access to care, visit the AADA Advocacy Action Center online.14

2025 CLIA and CAP Laboratory Director Requirements: What’s Changing?

As of December 28, 2024, updated CLIA regulations took effect for all laboratories performing moderate- or high-complexity testing. These revisions aim to modernize outdated requirements and update regulations to incorporate technological advancements such as automation and artificial intelligence.15 New CLIA standards require laboratory directors with Doctor of Medicine or Doctor of Osteopathy degrees to be certified in anatomic and/or clinical pathology by the American Board of Pathology or the American Osteopathic Board of Pathology.15 For physicians who do not hold these board-certified qualifications, there are alternative pathways to becoming a laboratory director based on experience and education for physicians licensed to practice in the jurisdiction where the laboratory is located. For high-complexity laboratories, individuals need at least 2 years of experience directing or supervising high-complexity testing and at least 20 continuing education credit hours in laboratory practice that cover director responsibilities. For moderate-complexity laboratories, individuals need at least 1 year of experience supervising nonwaived laboratory testing and at least 20 continuing education credit hours in laboratory practice that cover director responsibilities.16

If the current laboratory director is not board certified in pathology, the new regulation will permit the grandfathering of current laboratory directors if existing laboratory directors have remained continuously employed in their current role since December 28, 2024.16 Therefore, individuals who were already employed in qualifying positions as of December 28, 2024, will be grandfathered in and will not need to meet the new educational requirements if they remain employed without interruption. All individuals qualifying after December 28, 2024, will be required to do so under the new provisions stated earlier.

The CMS updated laboratory personnel requirements, thereby impacting all CLIA-certified laboratories and those seeking CLIA certification. Likewise, laboratories seeking accreditation by the CAP must meet the new laboratory personnel requirements.17 In some cases, CAP requirements are more stringent than the CLIA regulations (CAP accreditation is more stringent in areas of quality control, personnel qualifications, proficiency testing, and in oversight of laboratory developed tests).15-17 If more stringent state or local regulations are in place for personnel qualifications, including requirements for state licensure, they must be followed.

The AADA formed an ad hoc workgroup to address the CLIA laboratory director requirements and is actively engaging CMS to amend these requirements immediately. Formal objections have been submitted, and direct dialogue with CMS leadership is under way in collaboration with the American Board of Dermatology and leading dermatology and pathology societies.

Final Thoughts

Advocacy remains essential to the future of dermatology. From payer policy reversals to laboratory compliance reforms and federal payment advocacy, physicians must remain engaged. Whether it is safeguarding diagnostic autonomy or securing financial sustainability, we must continue to put “skin in the game.”

- Pollock JR, Chen JY, Dorius DA, et al. Decreasing physician Medicare reimbursement for dermatology services. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1154-1156.

- Mazmudar RS, Sheth A, Tripathi R, et al. Inflation-adjusted trends in Medicare reimbursement for common dermatologic procedures, 2007-2021. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1355-1358.

- Miller TC, Rucker P, Armstrong D. “Not medically necessary”: inside the company helping America’s biggest health insurers deny coverage for care. ProPublica. October 23, 2024. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.propublica.org/article/evicore-health-insurance-denials-cigna-unitedhealthcare-aetna-prior-authorizations

- EviCore healthcare. Immunohistochemistry (IHC). Lab Management Guidelines v2.0.2024. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.evicore.com/sites/default/files/clinical-guidelines/2024-08/MOL.CS_.104.A_Immunohistochemistry%20%28IHC%29_V2.0.2024_eff11.01.2024_pub12.31.2024.pdf

- EviCore. Laboratory management. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.evicore.com/provider/clinical-guidelines-details?solution=laboratory%20management

- Saad AJ. College of American Pathologists. December 12, 2023. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://documents.cap.org/documents /Wellmark-Letter- https://documents.cap.org/documents/wellmarkcap-letter2023.pdf

- EviCore healthcare. Clinical Guidelines: Lab Management Program. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.evicore.com/sites/default/files/clinical-guidelines/2024-08/Cigna_LabMgmt_V1.0.2025_eff01.01.2025_pub08.22.2024_0.pdf

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Position statement on immunohistochemistry utilization. Accessed May 9, 2024. https://server.aad.org/forms/policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Immunohistochemistry%20Utilization.pdf

- Naert KA, Trotter MJ. Utilization and utility of immunohistochemistry in dermatopathology. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:74-77.

- American Medical Association. Medicare physician payment continues to fall further behind practice cost inflation. Accessed April 23, 2025. https:// www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2025-medicare-updates-inflation-chart.pdf

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Calendar year (CY) 2025 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule final rule. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/calendar-year-cy-2025-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-final-rule

- American Medical Association. The Medicare Economic Index. Accessed April 23 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/medicare-basics-medicare-economic-index.pdf

- Medicare Patient Access and Practice Stabilization Act, HR 879, 119th Cong (2025). Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/house-bill/879

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. AADA advocacy action center. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aad.org/member/advocacy/take-action

- Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA) fees; histocompatibility, personnel, and alternative sanctions for certificate of waiver laboratories. Fed Regist. 2023;88:89976-90044.

- College of American Pathologists. CAP accreditation checklists – 2024 edition. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://documents.cap.org/documents/2024-Checklist-Summary.pdf?_gl=1*1b4rei9*_ga*NDc0NjYwNjM5LjE3NDQ3NTI4NjA.*_ga_97ZFJSQQ0X*MTc0NDc2OTc3My40LjEuMTc0NDc2OTgyOC4wLjAuMA

- Bennett SA, Conn CM, Gill HE, et al. Regulatory requirements for laboratory developed tests in the United States. J Immunol Methods. 2025;537:113813.

- Pollock JR, Chen JY, Dorius DA, et al. Decreasing physician Medicare reimbursement for dermatology services. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1154-1156.

- Mazmudar RS, Sheth A, Tripathi R, et al. Inflation-adjusted trends in Medicare reimbursement for common dermatologic procedures, 2007-2021. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1355-1358.

- Miller TC, Rucker P, Armstrong D. “Not medically necessary”: inside the company helping America’s biggest health insurers deny coverage for care. ProPublica. October 23, 2024. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.propublica.org/article/evicore-health-insurance-denials-cigna-unitedhealthcare-aetna-prior-authorizations

- EviCore healthcare. Immunohistochemistry (IHC). Lab Management Guidelines v2.0.2024. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.evicore.com/sites/default/files/clinical-guidelines/2024-08/MOL.CS_.104.A_Immunohistochemistry%20%28IHC%29_V2.0.2024_eff11.01.2024_pub12.31.2024.pdf

- EviCore. Laboratory management. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.evicore.com/provider/clinical-guidelines-details?solution=laboratory%20management

- Saad AJ. College of American Pathologists. December 12, 2023. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://documents.cap.org/documents /Wellmark-Letter- https://documents.cap.org/documents/wellmarkcap-letter2023.pdf

- EviCore healthcare. Clinical Guidelines: Lab Management Program. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.evicore.com/sites/default/files/clinical-guidelines/2024-08/Cigna_LabMgmt_V1.0.2025_eff01.01.2025_pub08.22.2024_0.pdf

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Position statement on immunohistochemistry utilization. Accessed May 9, 2024. https://server.aad.org/forms/policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Immunohistochemistry%20Utilization.pdf

- Naert KA, Trotter MJ. Utilization and utility of immunohistochemistry in dermatopathology. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:74-77.

- American Medical Association. Medicare physician payment continues to fall further behind practice cost inflation. Accessed April 23, 2025. https:// www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2025-medicare-updates-inflation-chart.pdf

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Calendar year (CY) 2025 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule final rule. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/calendar-year-cy-2025-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-final-rule

- American Medical Association. The Medicare Economic Index. Accessed April 23 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/medicare-basics-medicare-economic-index.pdf

- Medicare Patient Access and Practice Stabilization Act, HR 879, 119th Cong (2025). Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/house-bill/879

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. AADA advocacy action center. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aad.org/member/advocacy/take-action

- Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA) fees; histocompatibility, personnel, and alternative sanctions for certificate of waiver laboratories. Fed Regist. 2023;88:89976-90044.

- College of American Pathologists. CAP accreditation checklists – 2024 edition. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://documents.cap.org/documents/2024-Checklist-Summary.pdf?_gl=1*1b4rei9*_ga*NDc0NjYwNjM5LjE3NDQ3NTI4NjA.*_ga_97ZFJSQQ0X*MTc0NDc2OTc3My40LjEuMTc0NDc2OTgyOC4wLjAuMA

- Bennett SA, Conn CM, Gill HE, et al. Regulatory requirements for laboratory developed tests in the United States. J Immunol Methods. 2025;537:113813.

Advocacy and Compliance Issues Impacting Dermatology in 2025

Advocacy and Compliance Issues Impacting Dermatology in 2025

PRACTICE POINTS

- Recent advocacy efforts have led to the reversal of widespread insurer denials for immunohistochemistry stains; however, continued vigilance is necessary, as restrictive coverage policies may re-emerge.

- Laboratory directors must comply with updated Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 and College of American Pathologists personnel requirements effective December 28, 2024, including stricter board certification and 2 years of laboratory training or experience and 20 hours of continuing education requirements.

- The American Society of Dermatopathology Appropriate Use Criteria mobile application provides physicians with evidence-based guidance for test selection in dermatopathology.

Scurvy in Hospitalized Patients

Scurvy in Hospitalized Patients

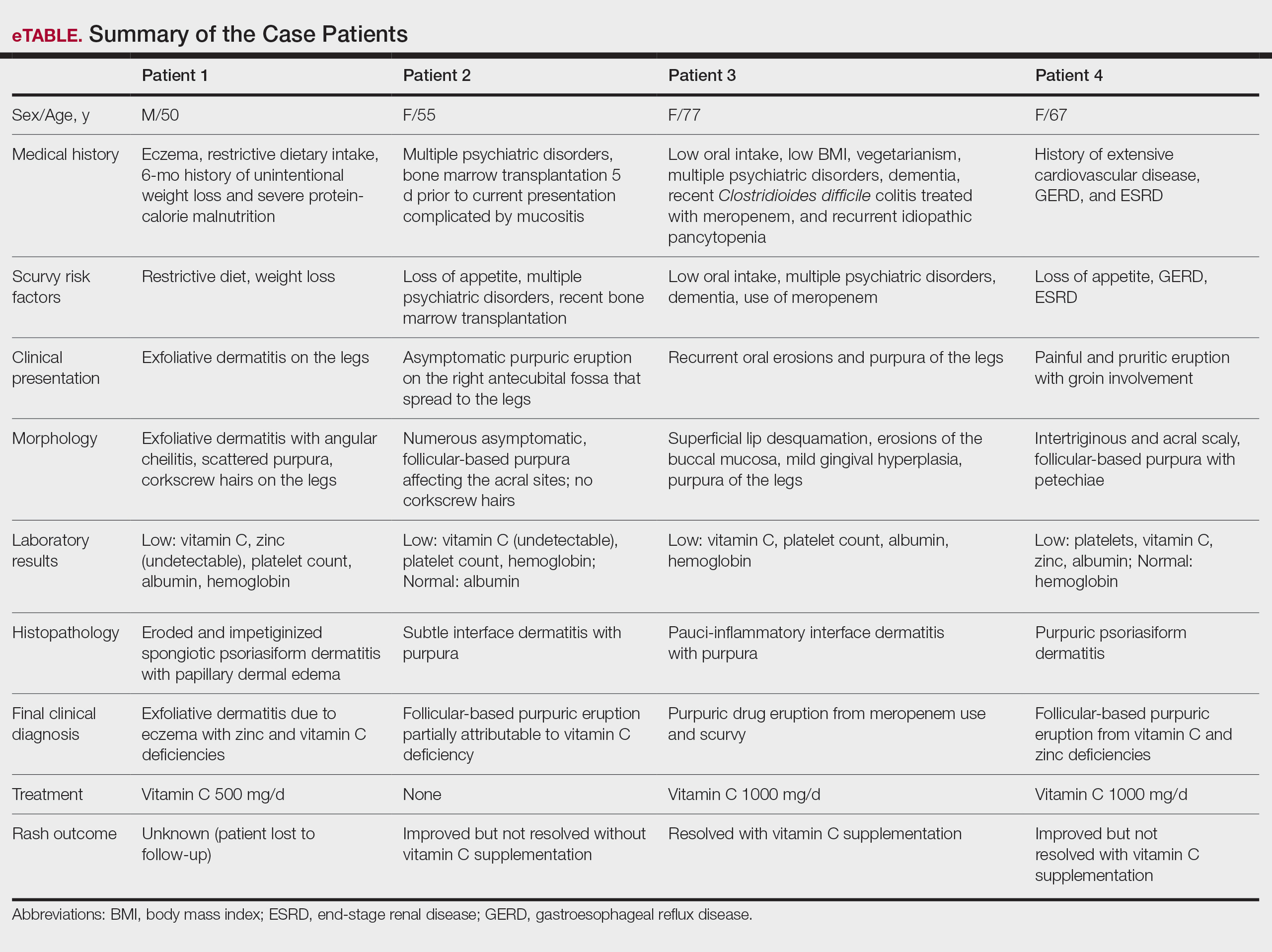

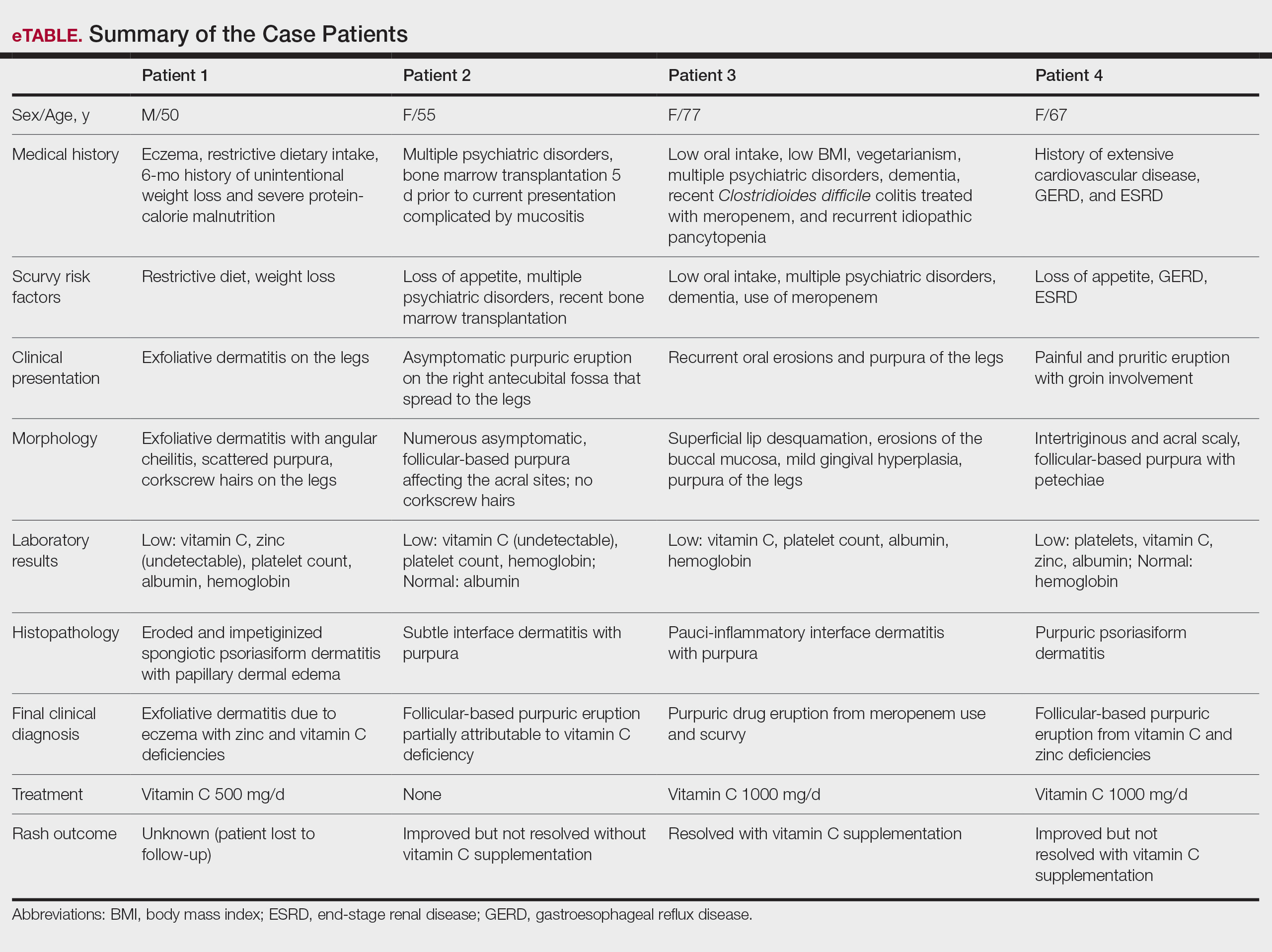

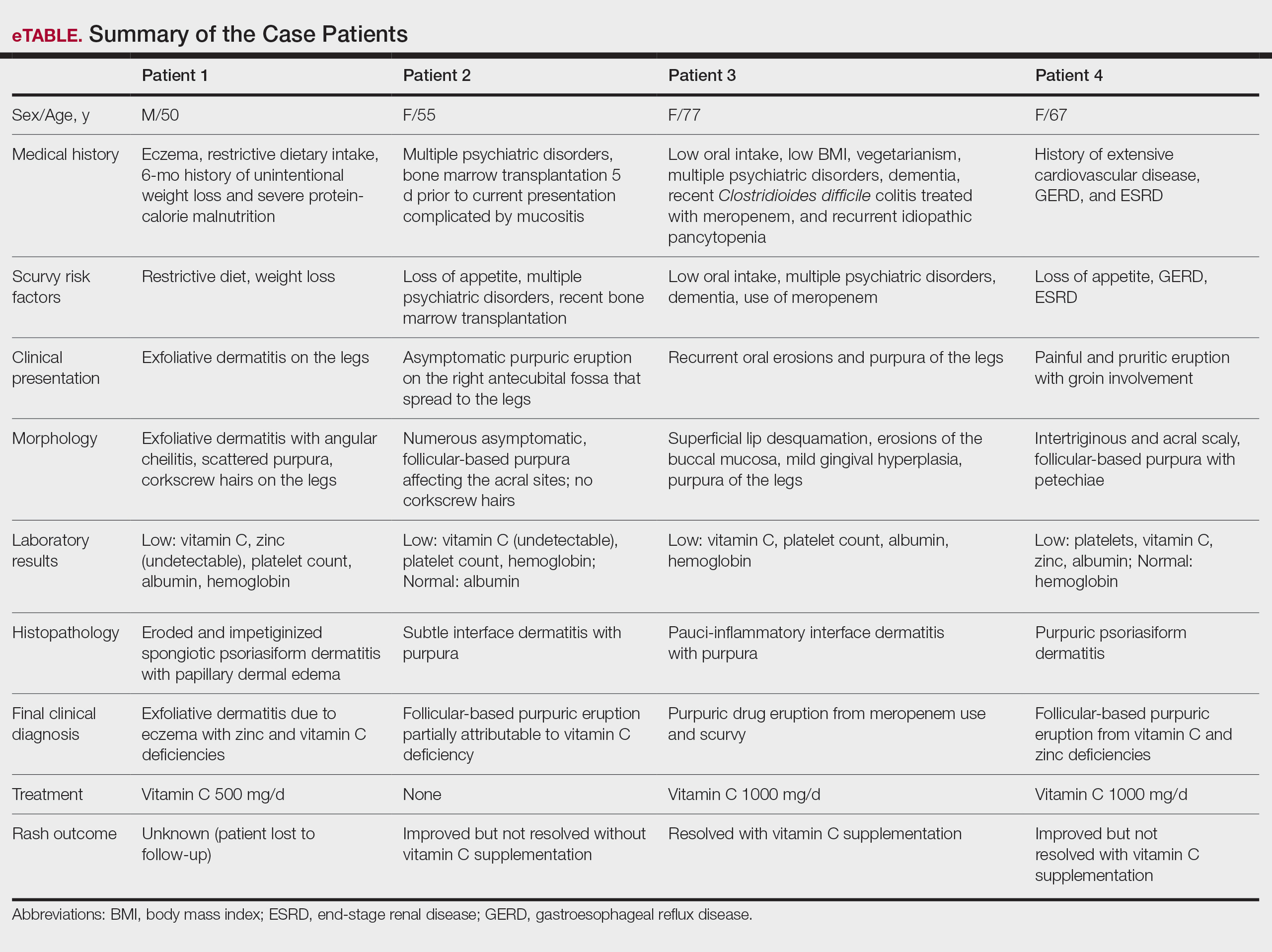

Scurvy, caused by vitamin C or ascorbic acid deficiency, historically has been associated primarily with developing nations and famine; however, specific populations in industrialized nations remain at an increased risk, particularly individuals with a history of smoking, alcohol use, restrictive diet, poor oral intake, psychiatric disorders, dementia, bone marrow transplantation, gastroesophageal reflux disease, end-stage renal disease, and hospitalization.1 Micronutrient deficiency– associated dermatoses have been linked to poor clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients.2 In this case series, we report 4 hospitalized patients with scurvy, each presenting with unique comorbidities and risk factors for vitamin C deficiency (eTable).

Case Reports

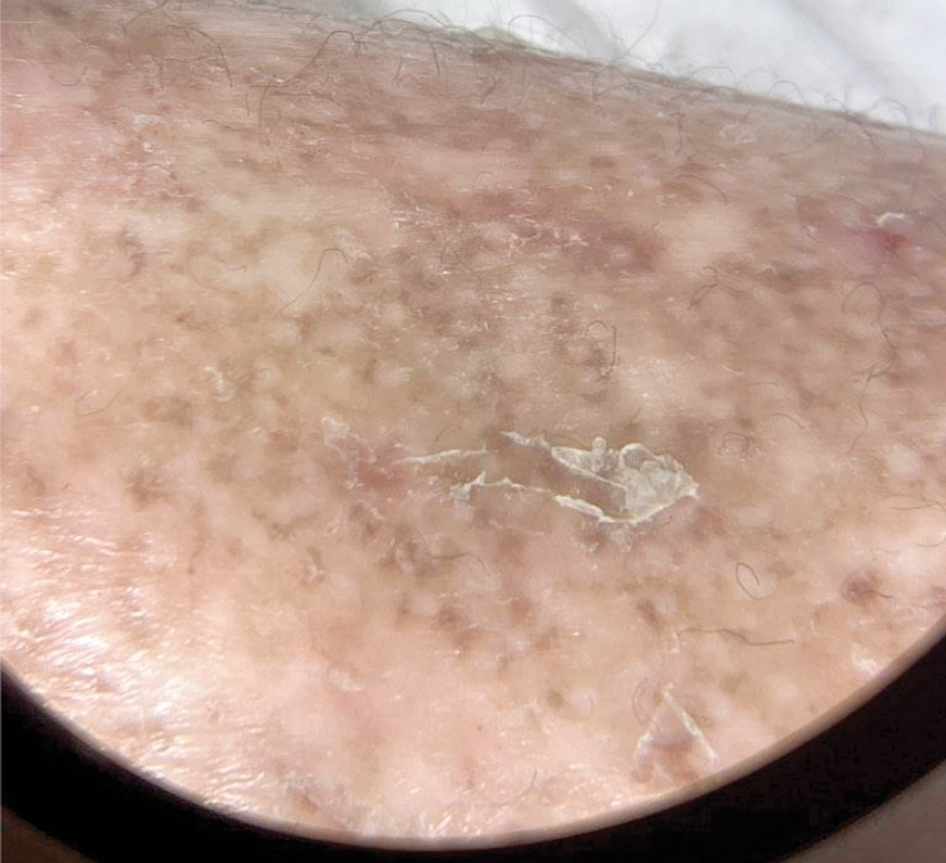

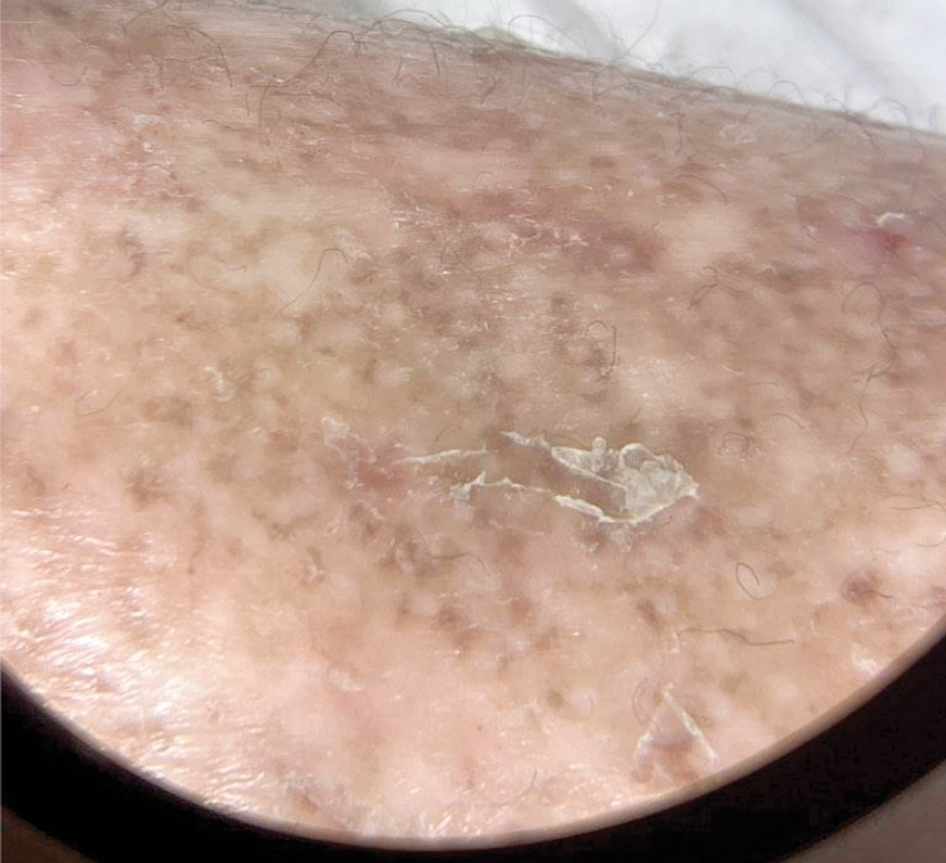

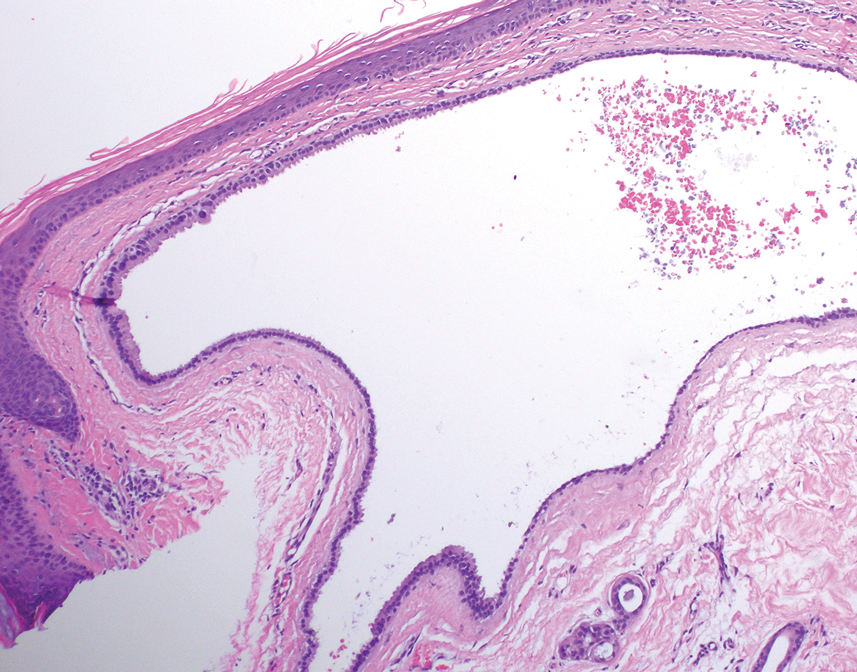

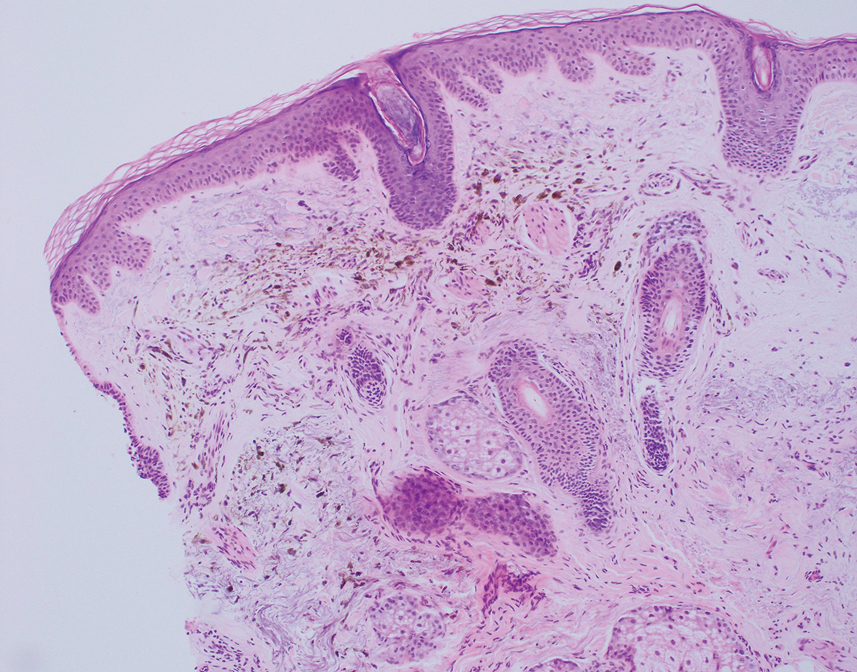

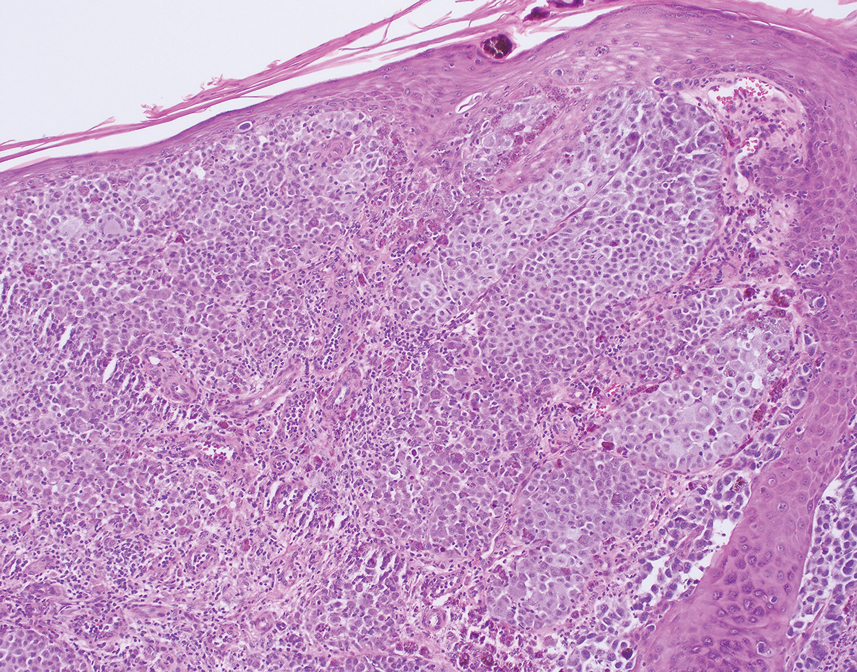

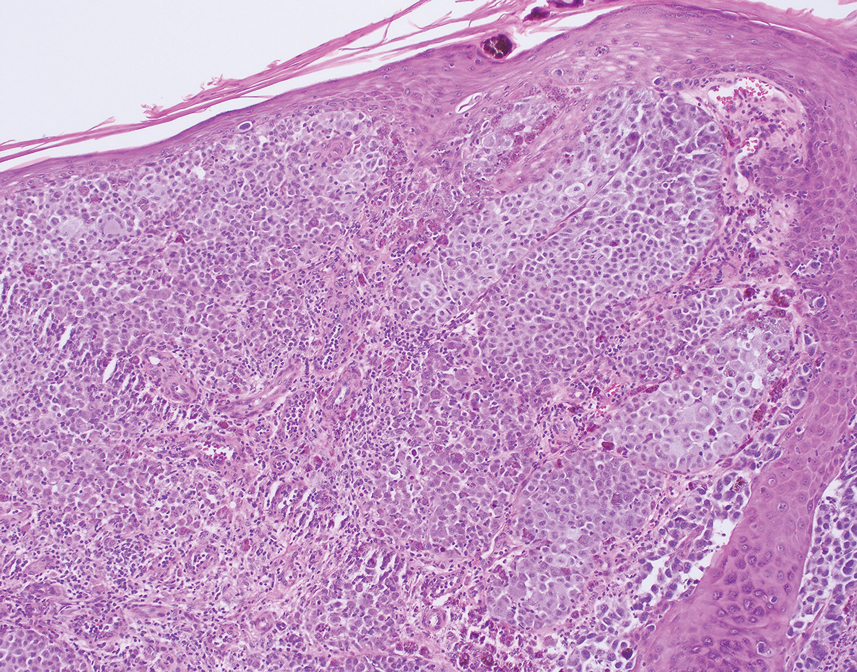

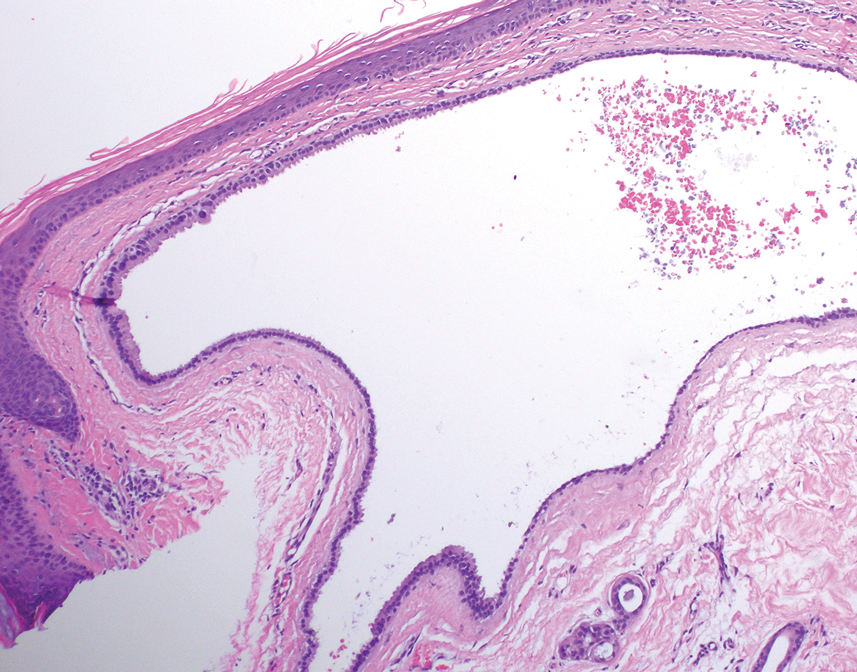

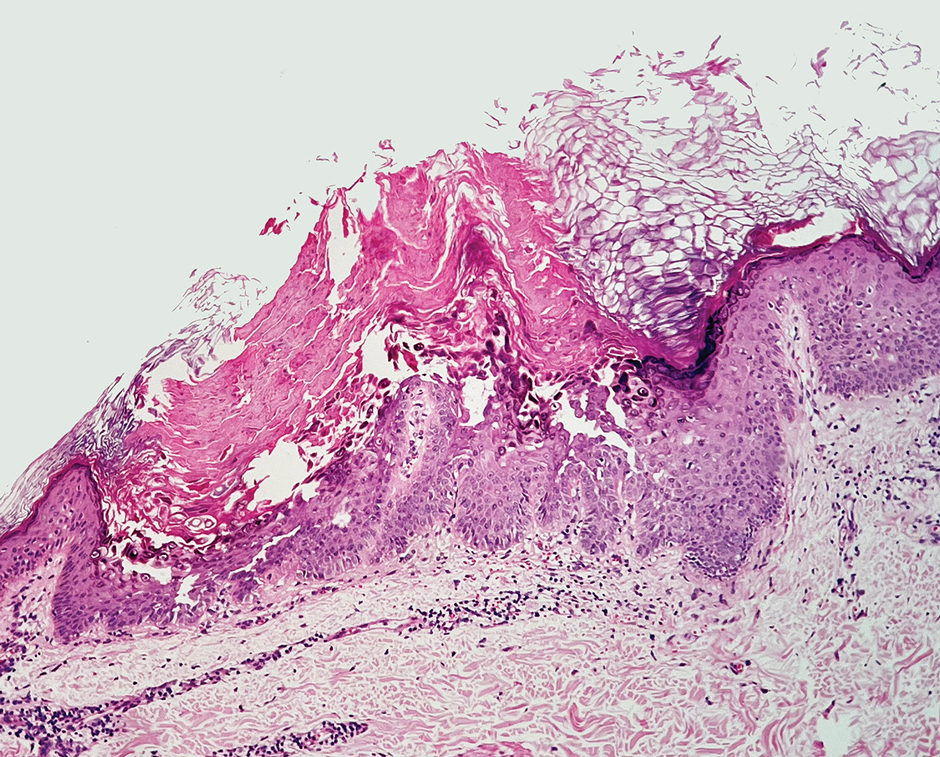

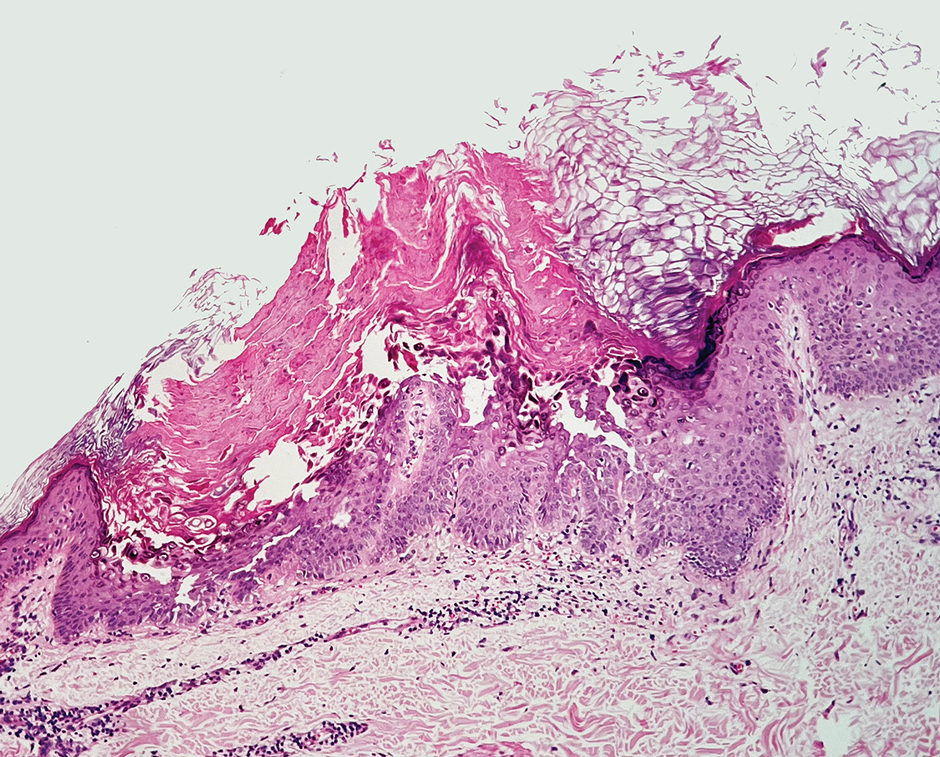

Patient 1—A 50-year-old man with a 6-month history of eczema and restrictive dietary intake was admitted to the hospital for septic shock attributed to a left foot infection of 5-days’ duration. The patient had experienced unintentional weight loss with severe protein-calorie malnutrition. His dietary history was notable for selective eating behaviors, intermittent meal skipping, and vegetarianism. Mucocutaneous examination by the dermatology consult team showed exfoliative dermatitis with angular cheilitis, corkscrew hairs on the legs (eFigure 1), and scattered purpura throughout the body. The differential diagnosis included eczema exacerbation, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma/Sézary syndrome, and malnutrition-related dermatosis. Punch biopsies of the left medial knee and right lateral arm revealed impetiginized, spongiotic, psoriasiform dermatitis with papillary dermal edema. The histologic changes were consistent with malnutrition-related dermatosis. Laboratory results included low vitamin C levels (0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.2-2.1 mg/dL]), undetectable zinc levels (<10 μg/dL [reference range ,60-130 μg/dL]), a low platelet count (21 kμ/L [reference range, 150-400 k/μL]),low albumin levels (0.9 mg/dL (13.0 g/dL [reference range, 14.0-17.4 g/dL]). The final diagnosis was exfoliative dermatitis due to eczema and multiple nutrient deficiencies (vitamin C and zinc). The patient was treated with vitamin C 500 mg/d and was started on mirtazapine to improve his appetite. Following a 3-month hospitalization, the patient was lost to follow-up after discharge.

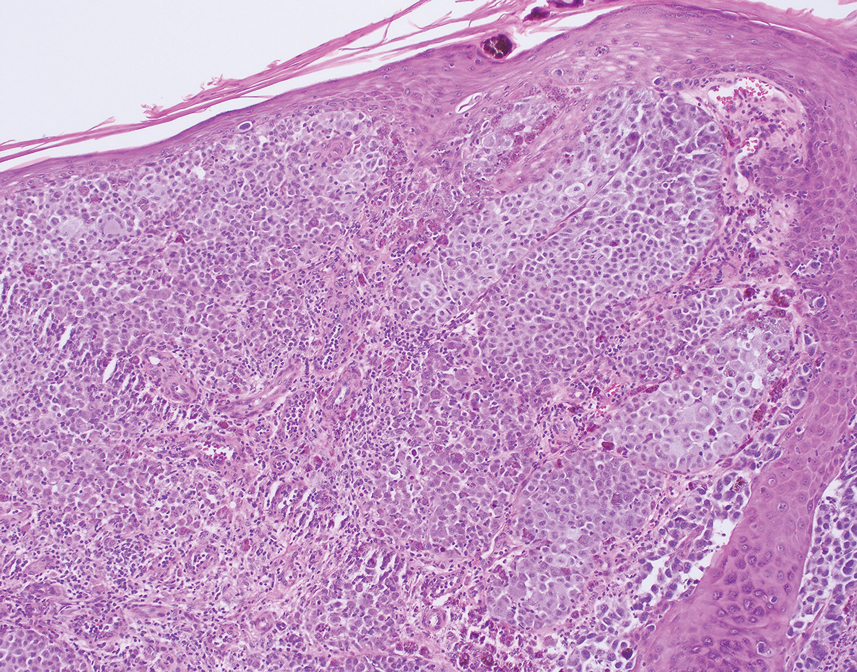

Patient 2—A 55-year-old woman with a history of multiple psychiatric disorders presented to the dermatology consult service with an asymptomatic purpuric eruption on the right antecubital fossa of 2 days’ duration that spread to the proximal thighs. Five days prior to presentation, she had received an allogeneic bone marrow transplant complicated by mucositis. She also reported a 4-month history of decreased appetite. At the current presentation, numerous acral, follicular based, purpuric macules and papules without associated corkscrew hairs were observed (eFigure 2). The differential diagnosis included a purpuric drug reaction, viral exanthem, acute graft-vs-host disease, neutrophilic dermatoses, and vitamin C deficiency–related dermatosis. Laboratory results revealed undetectable vitamin C levels (<0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.3-2.7 mg/dL]), a low platelet count (8 k/μL [reference range, 150-400 k/μL]), normal albumin levels (3.7 g/dL [reference range, 3.5-5.0 g/dL]), and low hemoglobin (7.8 g/dL [reference range, 14.0-17.4 g/dL]). Based on the histopathologic finding of subtle interface dermatitis with purpura from a punch biopsy of the right forearm, the eruption was attributed to scurvy. Although dermatology recommended supplementation with vitamin C 1000 mg/d, the decision was deferred by the primary team and the purpura improved without it—suggesting the purpura was only partly attributable to low vitamin C.

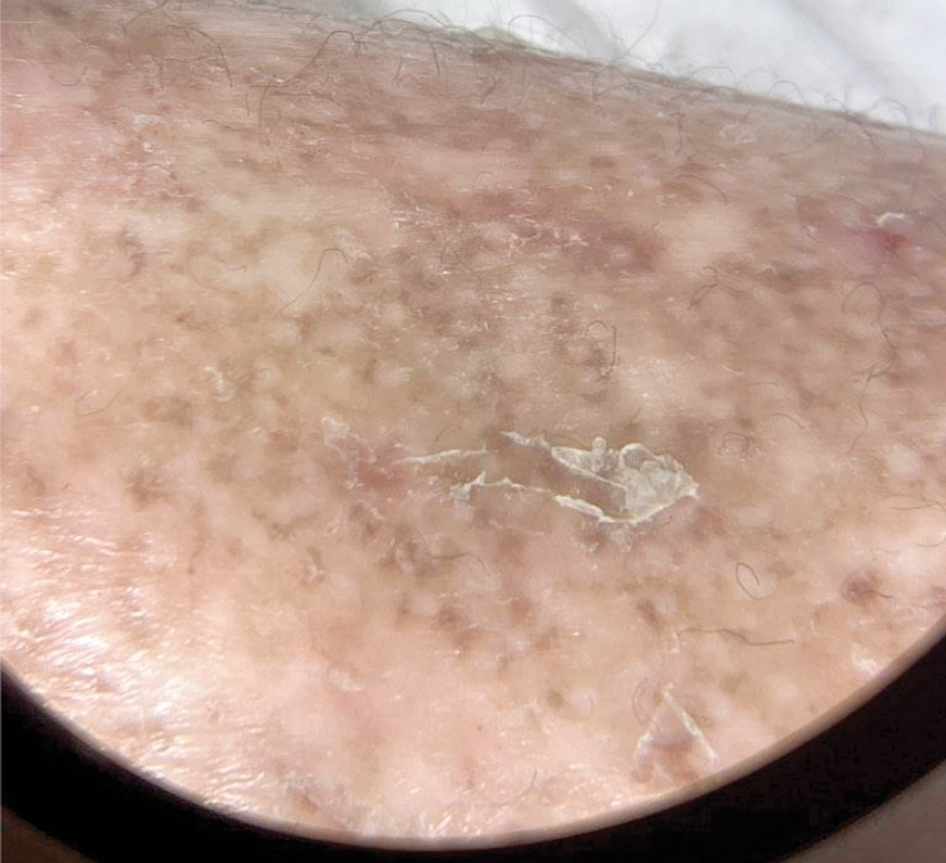

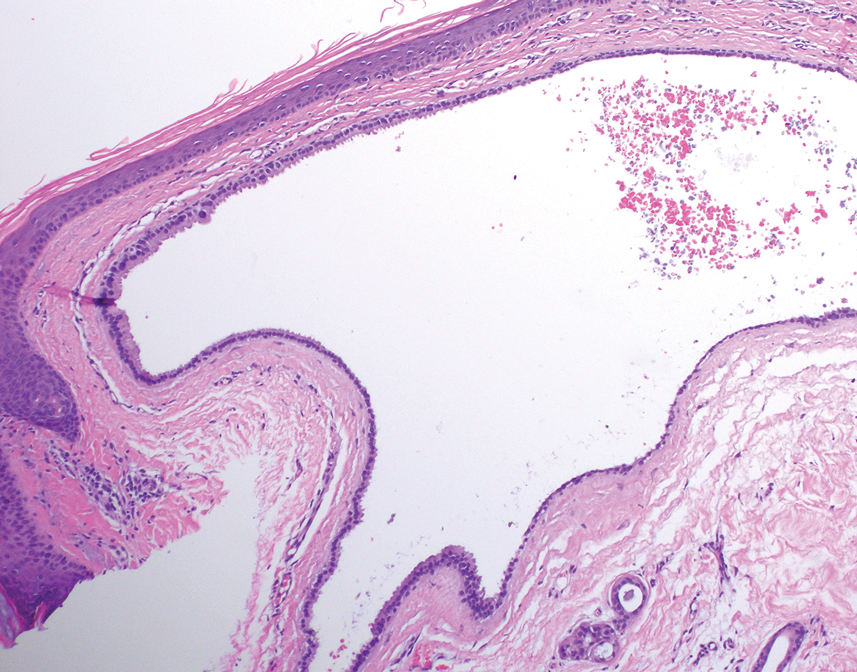

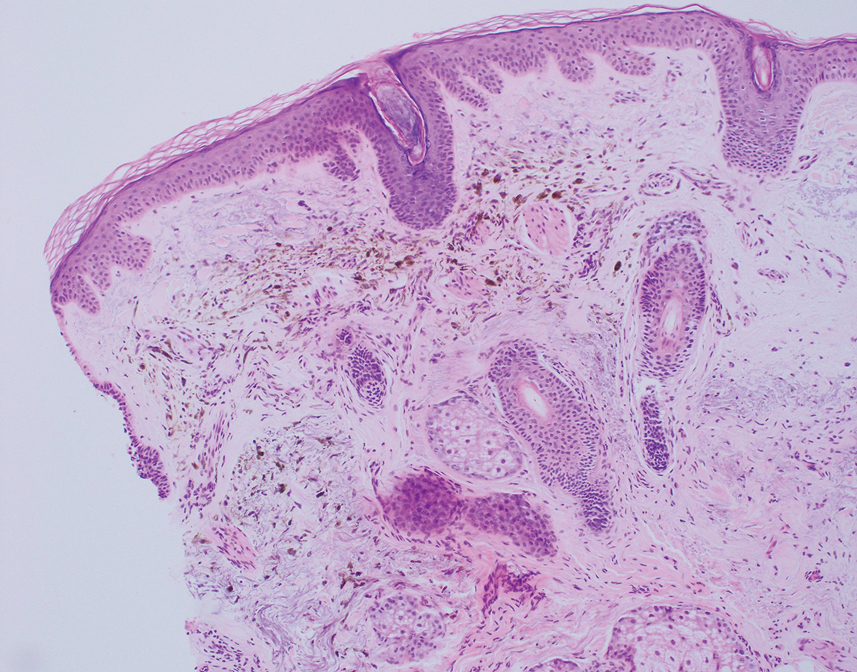

Patient 3—A 77-year-old woman with a history of low oral intake, a low body mass index (18.15 kg/m2 [reference range, 18.5-24.9]), vegetarianism, multiple psychiatric disorders, dementia, recent Clostridioides difficile colitis treated with meropenem, and recurrent idiopathic pancytopenia presented to the hospital with recurrent oral erosions and purpura of the legs for an unknown period. Physical examination by the dermatology consult team revealed superficial lip desquamation; erosions of the buccal mucosa with no involvement of the inner lip or gingiva; mild gingival hyperplasia (eFigure 3); and scaly, purpuric, follicular macules and papules on the legs. The arms and legs were devoid of hair. Laboratory results were notable for low vitamin C levels (0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.3-2.7 mg/dL]), a low platelet count (28 k/μL [reference range, 150-500 k/μL]), low albumin levels (2.9 g/dL [reference range, 3.5-5.0 g/dL]), and low hemoglobin (8.8 g/dL [reference range, 12.0-16.0 g/ dL]). A punch biopsy from the left thigh revealed pauci-inflammatory interface dermatitis with purpura. Based on the clinical and histologic findings, a final diagnosis of purpuric drug eruption (from the meropenem) and scurvy was made. Nutritional support included supplementation with vitamin C 1000 mg/d. The patient’s oral erosions and purpura gradually resolved with treatment throughout her 1.5-month hospitalization.

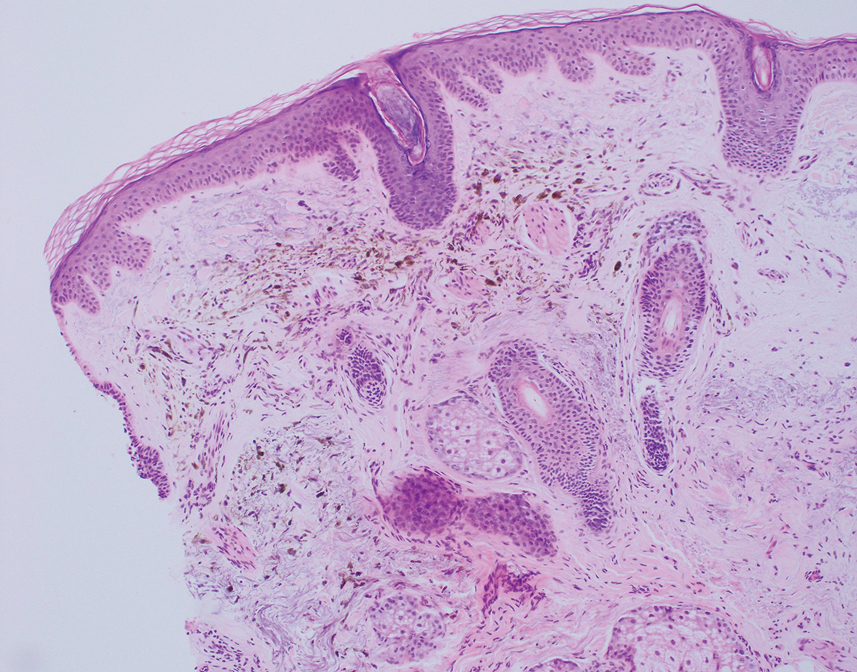

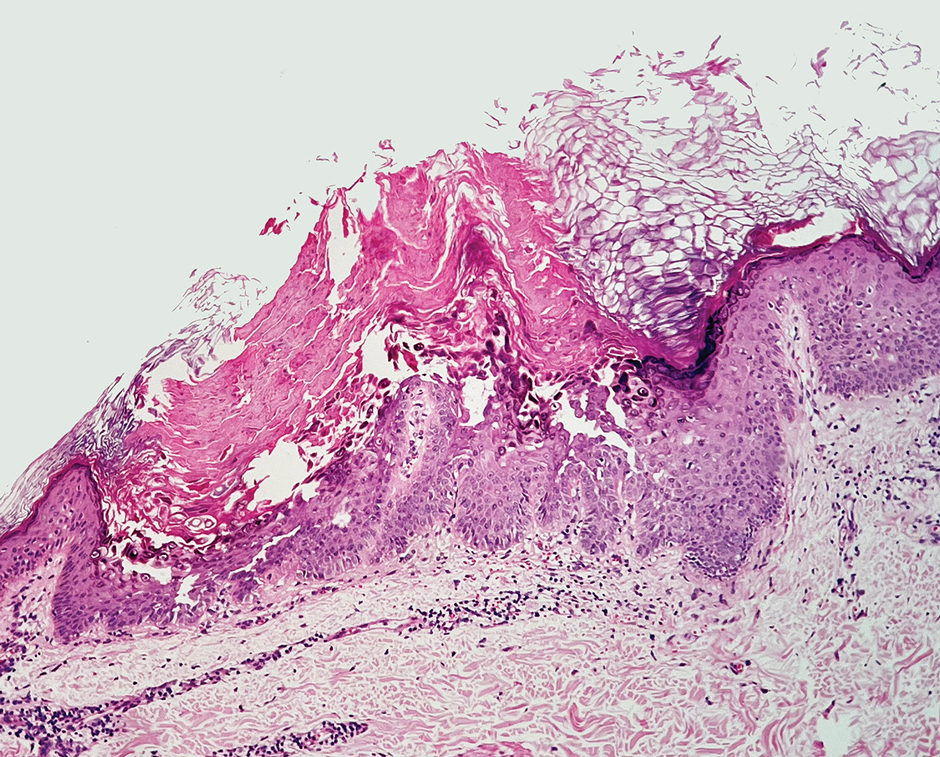

Patient 4—A 67-year-old woman with a history of extensive cardiovascular disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease without esophagitis, end-stage renal disease not requiring hemodialysis, and loss of appetite presented with a painful pruritic eruption on the legs with groin involvement of 2 months’ duration. The patient was admitted to the hospital for worsening mental status and weakness accompanied by dark stools, hematuria, and a productive cough with red-tinged sputum. Physical examination by the dermatology consult team showed a scaly, follicular, purpuric eruption affecting the acral and intertriginous sites (eFigure 4). The patient had sparse leg hair, making it difficult to assess for hair tortuosity. A punch biopsy of the left posterior knee revealed purpuric psoriasiform dermatitis, which was consistent with nutritional deficiency– associated dermatosis. Laboratory results included low vitamin C (<0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.3-2.7 mg/dL]), zinc, (58 μg/dL [reference range, 60-130 μg/dL]), and albumin levels (3.3 g/dL [reference range, 3.5-5.0 g/dL]) and a low platelet count (67 k/μL [reference range, 150- 500 k/μL]). The patient was started on supplementation with vitamin C 1000 mg/d with improvement of the purpura.

Comment

Micronutrient deficiencies may be common in hospitalized patients due to an increased prevalence of predisposing risk factors including infection, malnutrition, malabsorptive conditions, psychiatric diseases, and chronic illnesses.3 Acute-phase response in hospitalized patients also has been strongly associated with decreased plasma vitamin C levels.4 This phenomenon is postulated to be due to the increase in ascorbic acid uptake by circulating granulocytes in acute disease5; however because low vitamin C levels during the acute-phase response may not always accurately reflect total body stores, other clinical features should be assessed. Previously reported social history risk factors include smoking, alcohol consumption, marijuana use, restrictive diets, vegetarianism, and living alone.6,7

The unifying clinical clues for scurvy in our 4 patients were a history of poor oral intake and purpura. While purpura is nonspecific and can appear after traumatic injury to the skin in elderly patients with photodamage and coagulation disorders, it also is associated with vitamin C deficiency, even with a normal platelet count, circulating von Willebrand factor levels, and prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time.8 This is because vitamin C is vital in forming the collagen and extracellular matrix. Specifically, it is a cofactor for lysine and proline hydroxylase enzymes needed for the á-helix crosslinks in collagen, which are essential for its structural integrity.9 Collagen is a structural protein that maintains the blood vessel walls, skin, and the basement membrane. A deficiency in vitamin C leads to impairment in collagen synthesis, and insufficient collagen results in compromised connective tissue, blood vessels, and hair strength, which may lead to purpura. All of our patients had thrombocytopenia, and similarly, consideration for scurvy in hospitalized patients with risk factors for micronutrient deficiency is a must. Additional findings such as a follicular-based pattern of the purpura, hair tortuosity, restrictive dietary history, histopathology reports consistent with nutritional dermatoses, serum vitamin C levels, and improvement with vitamin C supplementation are more specific for scurvy. All of these factors can assist the clinician in detecting and confirming these micronutrient deficiencies.

Although there are no established therapeutic guidelines for scurvy, the mainstay of treatment is vitamin C repletion, either orally or parenterally. In hospitalized patients, one suggested regimen is 1000 mg of intravenous ascorbic acid daily for 3 days, followed by further supplementation with a dose of 250 to 500 mg twice daily for 1 month as needed after discharge.10 Symptom improvement occurs about 72 hours after vitamin replacement.8 We recommended 500 to 1000 mg of daily vitamin C supplementation for our patients.

Final Thoughts

This case series highlights the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for scurvy in hospitalized patients presenting with purpura, especially in a follicular-based pattern, who have multiple medical comorbidities and risk factors for vitamin C deficiency. The manifestations of scurvy are heterogeneous, necessitating a comprehensive mucocutaneous examination. The diagnosis of scurvy requires correlation of the findings from the patient history, clinical examination, laboratory results, and histopathology.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Adult scurvy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999; 41:895-910.

- Marsh RL, Trinidad J, Shearer S, et al. Association between micronutrient deficiency dermatoses and clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1226-1228.

- Hoffman M, Micheletti RG, Shields BE. Nutritional dermatoses in the hospitalized patient. Cutis. 2020;105:296-302, 308, E1-E5.

- Fain O, Pariés J, Jacquart B, et al. Hypovitaminosis C in hospitalized patients. Eur J Intern Med. 2003;14:419-425.

- Moser U, Weber F. Uptake of ascorbic acid by human granulocytes. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 1984;54:47-53.

- Swanson AM, Hughey LC. Acute inpatient presentation of scurvy. Cutis. 2010;86:205-207.

- Christopher KL, Menachof KK, Fathi R. Scurvy masquerading as reactive arthritis. Cutis. 2019;103:E21-E23.

- Antonelli M, Burzo ML, Pecorini G, et al. Scurvy as cause of purpura in the XXI century: a review on this “ancient” disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22:4355-4358.

- Maxfield L, Daley SF, Crane JS. Vitamin C deficiency. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated November 12, 2023. Accessed September 6, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493187/

- Gandhi M, Elfeky O, Ertugrul H, et al. Scurvy: rediscovering a forgotten disease. Diseases. 2023;11:78.

Scurvy, caused by vitamin C or ascorbic acid deficiency, historically has been associated primarily with developing nations and famine; however, specific populations in industrialized nations remain at an increased risk, particularly individuals with a history of smoking, alcohol use, restrictive diet, poor oral intake, psychiatric disorders, dementia, bone marrow transplantation, gastroesophageal reflux disease, end-stage renal disease, and hospitalization.1 Micronutrient deficiency– associated dermatoses have been linked to poor clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients.2 In this case series, we report 4 hospitalized patients with scurvy, each presenting with unique comorbidities and risk factors for vitamin C deficiency (eTable).

Case Reports

Patient 1—A 50-year-old man with a 6-month history of eczema and restrictive dietary intake was admitted to the hospital for septic shock attributed to a left foot infection of 5-days’ duration. The patient had experienced unintentional weight loss with severe protein-calorie malnutrition. His dietary history was notable for selective eating behaviors, intermittent meal skipping, and vegetarianism. Mucocutaneous examination by the dermatology consult team showed exfoliative dermatitis with angular cheilitis, corkscrew hairs on the legs (eFigure 1), and scattered purpura throughout the body. The differential diagnosis included eczema exacerbation, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma/Sézary syndrome, and malnutrition-related dermatosis. Punch biopsies of the left medial knee and right lateral arm revealed impetiginized, spongiotic, psoriasiform dermatitis with papillary dermal edema. The histologic changes were consistent with malnutrition-related dermatosis. Laboratory results included low vitamin C levels (0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.2-2.1 mg/dL]), undetectable zinc levels (<10 μg/dL [reference range ,60-130 μg/dL]), a low platelet count (21 kμ/L [reference range, 150-400 k/μL]),low albumin levels (0.9 mg/dL (13.0 g/dL [reference range, 14.0-17.4 g/dL]). The final diagnosis was exfoliative dermatitis due to eczema and multiple nutrient deficiencies (vitamin C and zinc). The patient was treated with vitamin C 500 mg/d and was started on mirtazapine to improve his appetite. Following a 3-month hospitalization, the patient was lost to follow-up after discharge.

Patient 2—A 55-year-old woman with a history of multiple psychiatric disorders presented to the dermatology consult service with an asymptomatic purpuric eruption on the right antecubital fossa of 2 days’ duration that spread to the proximal thighs. Five days prior to presentation, she had received an allogeneic bone marrow transplant complicated by mucositis. She also reported a 4-month history of decreased appetite. At the current presentation, numerous acral, follicular based, purpuric macules and papules without associated corkscrew hairs were observed (eFigure 2). The differential diagnosis included a purpuric drug reaction, viral exanthem, acute graft-vs-host disease, neutrophilic dermatoses, and vitamin C deficiency–related dermatosis. Laboratory results revealed undetectable vitamin C levels (<0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.3-2.7 mg/dL]), a low platelet count (8 k/μL [reference range, 150-400 k/μL]), normal albumin levels (3.7 g/dL [reference range, 3.5-5.0 g/dL]), and low hemoglobin (7.8 g/dL [reference range, 14.0-17.4 g/dL]). Based on the histopathologic finding of subtle interface dermatitis with purpura from a punch biopsy of the right forearm, the eruption was attributed to scurvy. Although dermatology recommended supplementation with vitamin C 1000 mg/d, the decision was deferred by the primary team and the purpura improved without it—suggesting the purpura was only partly attributable to low vitamin C.

Patient 3—A 77-year-old woman with a history of low oral intake, a low body mass index (18.15 kg/m2 [reference range, 18.5-24.9]), vegetarianism, multiple psychiatric disorders, dementia, recent Clostridioides difficile colitis treated with meropenem, and recurrent idiopathic pancytopenia presented to the hospital with recurrent oral erosions and purpura of the legs for an unknown period. Physical examination by the dermatology consult team revealed superficial lip desquamation; erosions of the buccal mucosa with no involvement of the inner lip or gingiva; mild gingival hyperplasia (eFigure 3); and scaly, purpuric, follicular macules and papules on the legs. The arms and legs were devoid of hair. Laboratory results were notable for low vitamin C levels (0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.3-2.7 mg/dL]), a low platelet count (28 k/μL [reference range, 150-500 k/μL]), low albumin levels (2.9 g/dL [reference range, 3.5-5.0 g/dL]), and low hemoglobin (8.8 g/dL [reference range, 12.0-16.0 g/ dL]). A punch biopsy from the left thigh revealed pauci-inflammatory interface dermatitis with purpura. Based on the clinical and histologic findings, a final diagnosis of purpuric drug eruption (from the meropenem) and scurvy was made. Nutritional support included supplementation with vitamin C 1000 mg/d. The patient’s oral erosions and purpura gradually resolved with treatment throughout her 1.5-month hospitalization.

Patient 4—A 67-year-old woman with a history of extensive cardiovascular disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease without esophagitis, end-stage renal disease not requiring hemodialysis, and loss of appetite presented with a painful pruritic eruption on the legs with groin involvement of 2 months’ duration. The patient was admitted to the hospital for worsening mental status and weakness accompanied by dark stools, hematuria, and a productive cough with red-tinged sputum. Physical examination by the dermatology consult team showed a scaly, follicular, purpuric eruption affecting the acral and intertriginous sites (eFigure 4). The patient had sparse leg hair, making it difficult to assess for hair tortuosity. A punch biopsy of the left posterior knee revealed purpuric psoriasiform dermatitis, which was consistent with nutritional deficiency– associated dermatosis. Laboratory results included low vitamin C (<0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.3-2.7 mg/dL]), zinc, (58 μg/dL [reference range, 60-130 μg/dL]), and albumin levels (3.3 g/dL [reference range, 3.5-5.0 g/dL]) and a low platelet count (67 k/μL [reference range, 150- 500 k/μL]). The patient was started on supplementation with vitamin C 1000 mg/d with improvement of the purpura.

Comment

Micronutrient deficiencies may be common in hospitalized patients due to an increased prevalence of predisposing risk factors including infection, malnutrition, malabsorptive conditions, psychiatric diseases, and chronic illnesses.3 Acute-phase response in hospitalized patients also has been strongly associated with decreased plasma vitamin C levels.4 This phenomenon is postulated to be due to the increase in ascorbic acid uptake by circulating granulocytes in acute disease5; however because low vitamin C levels during the acute-phase response may not always accurately reflect total body stores, other clinical features should be assessed. Previously reported social history risk factors include smoking, alcohol consumption, marijuana use, restrictive diets, vegetarianism, and living alone.6,7

The unifying clinical clues for scurvy in our 4 patients were a history of poor oral intake and purpura. While purpura is nonspecific and can appear after traumatic injury to the skin in elderly patients with photodamage and coagulation disorders, it also is associated with vitamin C deficiency, even with a normal platelet count, circulating von Willebrand factor levels, and prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time.8 This is because vitamin C is vital in forming the collagen and extracellular matrix. Specifically, it is a cofactor for lysine and proline hydroxylase enzymes needed for the á-helix crosslinks in collagen, which are essential for its structural integrity.9 Collagen is a structural protein that maintains the blood vessel walls, skin, and the basement membrane. A deficiency in vitamin C leads to impairment in collagen synthesis, and insufficient collagen results in compromised connective tissue, blood vessels, and hair strength, which may lead to purpura. All of our patients had thrombocytopenia, and similarly, consideration for scurvy in hospitalized patients with risk factors for micronutrient deficiency is a must. Additional findings such as a follicular-based pattern of the purpura, hair tortuosity, restrictive dietary history, histopathology reports consistent with nutritional dermatoses, serum vitamin C levels, and improvement with vitamin C supplementation are more specific for scurvy. All of these factors can assist the clinician in detecting and confirming these micronutrient deficiencies.

Although there are no established therapeutic guidelines for scurvy, the mainstay of treatment is vitamin C repletion, either orally or parenterally. In hospitalized patients, one suggested regimen is 1000 mg of intravenous ascorbic acid daily for 3 days, followed by further supplementation with a dose of 250 to 500 mg twice daily for 1 month as needed after discharge.10 Symptom improvement occurs about 72 hours after vitamin replacement.8 We recommended 500 to 1000 mg of daily vitamin C supplementation for our patients.

Final Thoughts

This case series highlights the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for scurvy in hospitalized patients presenting with purpura, especially in a follicular-based pattern, who have multiple medical comorbidities and risk factors for vitamin C deficiency. The manifestations of scurvy are heterogeneous, necessitating a comprehensive mucocutaneous examination. The diagnosis of scurvy requires correlation of the findings from the patient history, clinical examination, laboratory results, and histopathology.

Scurvy, caused by vitamin C or ascorbic acid deficiency, historically has been associated primarily with developing nations and famine; however, specific populations in industrialized nations remain at an increased risk, particularly individuals with a history of smoking, alcohol use, restrictive diet, poor oral intake, psychiatric disorders, dementia, bone marrow transplantation, gastroesophageal reflux disease, end-stage renal disease, and hospitalization.1 Micronutrient deficiency– associated dermatoses have been linked to poor clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients.2 In this case series, we report 4 hospitalized patients with scurvy, each presenting with unique comorbidities and risk factors for vitamin C deficiency (eTable).

Case Reports

Patient 1—A 50-year-old man with a 6-month history of eczema and restrictive dietary intake was admitted to the hospital for septic shock attributed to a left foot infection of 5-days’ duration. The patient had experienced unintentional weight loss with severe protein-calorie malnutrition. His dietary history was notable for selective eating behaviors, intermittent meal skipping, and vegetarianism. Mucocutaneous examination by the dermatology consult team showed exfoliative dermatitis with angular cheilitis, corkscrew hairs on the legs (eFigure 1), and scattered purpura throughout the body. The differential diagnosis included eczema exacerbation, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma/Sézary syndrome, and malnutrition-related dermatosis. Punch biopsies of the left medial knee and right lateral arm revealed impetiginized, spongiotic, psoriasiform dermatitis with papillary dermal edema. The histologic changes were consistent with malnutrition-related dermatosis. Laboratory results included low vitamin C levels (0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.2-2.1 mg/dL]), undetectable zinc levels (<10 μg/dL [reference range ,60-130 μg/dL]), a low platelet count (21 kμ/L [reference range, 150-400 k/μL]),low albumin levels (0.9 mg/dL (13.0 g/dL [reference range, 14.0-17.4 g/dL]). The final diagnosis was exfoliative dermatitis due to eczema and multiple nutrient deficiencies (vitamin C and zinc). The patient was treated with vitamin C 500 mg/d and was started on mirtazapine to improve his appetite. Following a 3-month hospitalization, the patient was lost to follow-up after discharge.

Patient 2—A 55-year-old woman with a history of multiple psychiatric disorders presented to the dermatology consult service with an asymptomatic purpuric eruption on the right antecubital fossa of 2 days’ duration that spread to the proximal thighs. Five days prior to presentation, she had received an allogeneic bone marrow transplant complicated by mucositis. She also reported a 4-month history of decreased appetite. At the current presentation, numerous acral, follicular based, purpuric macules and papules without associated corkscrew hairs were observed (eFigure 2). The differential diagnosis included a purpuric drug reaction, viral exanthem, acute graft-vs-host disease, neutrophilic dermatoses, and vitamin C deficiency–related dermatosis. Laboratory results revealed undetectable vitamin C levels (<0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.3-2.7 mg/dL]), a low platelet count (8 k/μL [reference range, 150-400 k/μL]), normal albumin levels (3.7 g/dL [reference range, 3.5-5.0 g/dL]), and low hemoglobin (7.8 g/dL [reference range, 14.0-17.4 g/dL]). Based on the histopathologic finding of subtle interface dermatitis with purpura from a punch biopsy of the right forearm, the eruption was attributed to scurvy. Although dermatology recommended supplementation with vitamin C 1000 mg/d, the decision was deferred by the primary team and the purpura improved without it—suggesting the purpura was only partly attributable to low vitamin C.

Patient 3—A 77-year-old woman with a history of low oral intake, a low body mass index (18.15 kg/m2 [reference range, 18.5-24.9]), vegetarianism, multiple psychiatric disorders, dementia, recent Clostridioides difficile colitis treated with meropenem, and recurrent idiopathic pancytopenia presented to the hospital with recurrent oral erosions and purpura of the legs for an unknown period. Physical examination by the dermatology consult team revealed superficial lip desquamation; erosions of the buccal mucosa with no involvement of the inner lip or gingiva; mild gingival hyperplasia (eFigure 3); and scaly, purpuric, follicular macules and papules on the legs. The arms and legs were devoid of hair. Laboratory results were notable for low vitamin C levels (0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.3-2.7 mg/dL]), a low platelet count (28 k/μL [reference range, 150-500 k/μL]), low albumin levels (2.9 g/dL [reference range, 3.5-5.0 g/dL]), and low hemoglobin (8.8 g/dL [reference range, 12.0-16.0 g/ dL]). A punch biopsy from the left thigh revealed pauci-inflammatory interface dermatitis with purpura. Based on the clinical and histologic findings, a final diagnosis of purpuric drug eruption (from the meropenem) and scurvy was made. Nutritional support included supplementation with vitamin C 1000 mg/d. The patient’s oral erosions and purpura gradually resolved with treatment throughout her 1.5-month hospitalization.

Patient 4—A 67-year-old woman with a history of extensive cardiovascular disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease without esophagitis, end-stage renal disease not requiring hemodialysis, and loss of appetite presented with a painful pruritic eruption on the legs with groin involvement of 2 months’ duration. The patient was admitted to the hospital for worsening mental status and weakness accompanied by dark stools, hematuria, and a productive cough with red-tinged sputum. Physical examination by the dermatology consult team showed a scaly, follicular, purpuric eruption affecting the acral and intertriginous sites (eFigure 4). The patient had sparse leg hair, making it difficult to assess for hair tortuosity. A punch biopsy of the left posterior knee revealed purpuric psoriasiform dermatitis, which was consistent with nutritional deficiency– associated dermatosis. Laboratory results included low vitamin C (<0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.3-2.7 mg/dL]), zinc, (58 μg/dL [reference range, 60-130 μg/dL]), and albumin levels (3.3 g/dL [reference range, 3.5-5.0 g/dL]) and a low platelet count (67 k/μL [reference range, 150- 500 k/μL]). The patient was started on supplementation with vitamin C 1000 mg/d with improvement of the purpura.

Comment

Micronutrient deficiencies may be common in hospitalized patients due to an increased prevalence of predisposing risk factors including infection, malnutrition, malabsorptive conditions, psychiatric diseases, and chronic illnesses.3 Acute-phase response in hospitalized patients also has been strongly associated with decreased plasma vitamin C levels.4 This phenomenon is postulated to be due to the increase in ascorbic acid uptake by circulating granulocytes in acute disease5; however because low vitamin C levels during the acute-phase response may not always accurately reflect total body stores, other clinical features should be assessed. Previously reported social history risk factors include smoking, alcohol consumption, marijuana use, restrictive diets, vegetarianism, and living alone.6,7

The unifying clinical clues for scurvy in our 4 patients were a history of poor oral intake and purpura. While purpura is nonspecific and can appear after traumatic injury to the skin in elderly patients with photodamage and coagulation disorders, it also is associated with vitamin C deficiency, even with a normal platelet count, circulating von Willebrand factor levels, and prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time.8 This is because vitamin C is vital in forming the collagen and extracellular matrix. Specifically, it is a cofactor for lysine and proline hydroxylase enzymes needed for the á-helix crosslinks in collagen, which are essential for its structural integrity.9 Collagen is a structural protein that maintains the blood vessel walls, skin, and the basement membrane. A deficiency in vitamin C leads to impairment in collagen synthesis, and insufficient collagen results in compromised connective tissue, blood vessels, and hair strength, which may lead to purpura. All of our patients had thrombocytopenia, and similarly, consideration for scurvy in hospitalized patients with risk factors for micronutrient deficiency is a must. Additional findings such as a follicular-based pattern of the purpura, hair tortuosity, restrictive dietary history, histopathology reports consistent with nutritional dermatoses, serum vitamin C levels, and improvement with vitamin C supplementation are more specific for scurvy. All of these factors can assist the clinician in detecting and confirming these micronutrient deficiencies.

Although there are no established therapeutic guidelines for scurvy, the mainstay of treatment is vitamin C repletion, either orally or parenterally. In hospitalized patients, one suggested regimen is 1000 mg of intravenous ascorbic acid daily for 3 days, followed by further supplementation with a dose of 250 to 500 mg twice daily for 1 month as needed after discharge.10 Symptom improvement occurs about 72 hours after vitamin replacement.8 We recommended 500 to 1000 mg of daily vitamin C supplementation for our patients.

Final Thoughts

This case series highlights the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for scurvy in hospitalized patients presenting with purpura, especially in a follicular-based pattern, who have multiple medical comorbidities and risk factors for vitamin C deficiency. The manifestations of scurvy are heterogeneous, necessitating a comprehensive mucocutaneous examination. The diagnosis of scurvy requires correlation of the findings from the patient history, clinical examination, laboratory results, and histopathology.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Adult scurvy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999; 41:895-910.

- Marsh RL, Trinidad J, Shearer S, et al. Association between micronutrient deficiency dermatoses and clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1226-1228.

- Hoffman M, Micheletti RG, Shields BE. Nutritional dermatoses in the hospitalized patient. Cutis. 2020;105:296-302, 308, E1-E5.

- Fain O, Pariés J, Jacquart B, et al. Hypovitaminosis C in hospitalized patients. Eur J Intern Med. 2003;14:419-425.

- Moser U, Weber F. Uptake of ascorbic acid by human granulocytes. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 1984;54:47-53.

- Swanson AM, Hughey LC. Acute inpatient presentation of scurvy. Cutis. 2010;86:205-207.

- Christopher KL, Menachof KK, Fathi R. Scurvy masquerading as reactive arthritis. Cutis. 2019;103:E21-E23.

- Antonelli M, Burzo ML, Pecorini G, et al. Scurvy as cause of purpura in the XXI century: a review on this “ancient” disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22:4355-4358.

- Maxfield L, Daley SF, Crane JS. Vitamin C deficiency. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated November 12, 2023. Accessed September 6, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493187/

- Gandhi M, Elfeky O, Ertugrul H, et al. Scurvy: rediscovering a forgotten disease. Diseases. 2023;11:78.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Adult scurvy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999; 41:895-910.

- Marsh RL, Trinidad J, Shearer S, et al. Association between micronutrient deficiency dermatoses and clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1226-1228.

- Hoffman M, Micheletti RG, Shields BE. Nutritional dermatoses in the hospitalized patient. Cutis. 2020;105:296-302, 308, E1-E5.

- Fain O, Pariés J, Jacquart B, et al. Hypovitaminosis C in hospitalized patients. Eur J Intern Med. 2003;14:419-425.

- Moser U, Weber F. Uptake of ascorbic acid by human granulocytes. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 1984;54:47-53.

- Swanson AM, Hughey LC. Acute inpatient presentation of scurvy. Cutis. 2010;86:205-207.

- Christopher KL, Menachof KK, Fathi R. Scurvy masquerading as reactive arthritis. Cutis. 2019;103:E21-E23.

- Antonelli M, Burzo ML, Pecorini G, et al. Scurvy as cause of purpura in the XXI century: a review on this “ancient” disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22:4355-4358.

- Maxfield L, Daley SF, Crane JS. Vitamin C deficiency. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated November 12, 2023. Accessed September 6, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493187/

- Gandhi M, Elfeky O, Ertugrul H, et al. Scurvy: rediscovering a forgotten disease. Diseases. 2023;11:78.

Scurvy in Hospitalized Patients

Scurvy in Hospitalized Patients

PRACTICE POINTS

- Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for vitamin C deficiency/scurvy in hospitalized patients with purpura who have multiple medical comorbidities and risk factors.

- A low platelet count may mask underlying vitamin C deficiency, and patients may have concurrent deficiencies in other nutrients such as zinc.

Comparing the Quality of Patient Guidance on Dermatologic Care Generated by ChatGPT vs Reddit

Comparing the Quality of Patient Guidance on Dermatologic Care Generated by ChatGPT vs Reddit

To the Editor:

Online resources that are convenient and affordable play a crucial role in mitigating health inequality and improving patient access to health care information; however, the benefits are limited by the quality of information available, as medical misinformation can lead to patients engaging in harmful practices, making dangerous decisions, and even avoiding safe and effective treatments. In this study, we aimed to assess and compare the quality of patient guidance on dermatologic care generated by ChatGPT vs Reddit based on accuracy, appropriateness, and safety. It is essential to assess the quality and reliability of online health information to support patients in making informed decisions about their health.

The emergence and advancement of artificial intelligence and large language models such as ChatGPT present a new method for patients to access health care advice. ChatGPT can engage in conversation by accessing information from existing publicly available data on the internet, including books and websites, up to the year 2023 and providing humanlike responses with context.1 ChatGPT’s access to a breadth of online evidence-based literature ensures the dissemination of quality information that is quick and without inherent bias, offering the potential to more closely align with health care professionals. ChatGPT’s use in dermatology by patients has shown efficacy, with a 98.87% approval rate by dermatologists scoring its ability to recommend appropriate medication for common dermatologic conditions.2 However, ChatGPT has limitations when providing health care advice and has been observed to misunderstand health care standards, lack personalization, and offer incorrect references; currently, the latest publicly available version (ChatGPT 3.5) also is unable to analyze clinical images.3,4

Reddit is an online social media forum that allows users to post questions and photographs to which anyone can reply and offer advice. Patients may find comfort in online communities where they can connect with others facing similar challenges related to their diagnosis. Within these communities, the responses often share users’ own lived experiences and offer support based on what has and has not worked for them. Prior research found that users intentionally seeking health information via Reddit are likely to implement the advice they receive even without verification of its credibility, suggesting a trust and receptibility to ideas offered on the platform.5 Furthermore, a study analyzing the dermatologic content of 17 dermatology related subreddits that had 1000 or more subscribers found that 70.6% of posts fell under the category of “seeking health/cosmetic advice.”6 Reddit users thus are vulnerable to receiving advice based on personal bias and exposing their health information to the public.

We hypothesized that ChatGPT would provide users with guidance that was more closely aligned with typical dermatologists’ advice due to its thorough analysis and compilation of diverse sources and recommendations available on the internet. We expected Reddit to yield recommendations of lesser quality and a diminished safety score, primarily due to the absence of credibility-vetting mechanisms and the influence of personal biases within the advice shared.

User-submitted posts to large dermatologic community Reddit forums representing a few of the most common skin conditions (r/eczema, r/acne, r/Folliculitis, r/SebDerm, r/Hidradenitis, r/keratosis, and r/Psoriasis) were retrospectively reviewed from January 2024 to March 2024. The most popular posts that did not include photographs were included in our study. Posts with photographs were excluded, as clinical images were not able to be uploaded to the publicly available ChatGPT 3.5. We collected real user questions about common skin conditions from Reddit forums and then asked ChatGPT to answer those same questions. We compared ChatGPT’s responses to the most upvoted Reddit comments to see how they matched up (eTable).

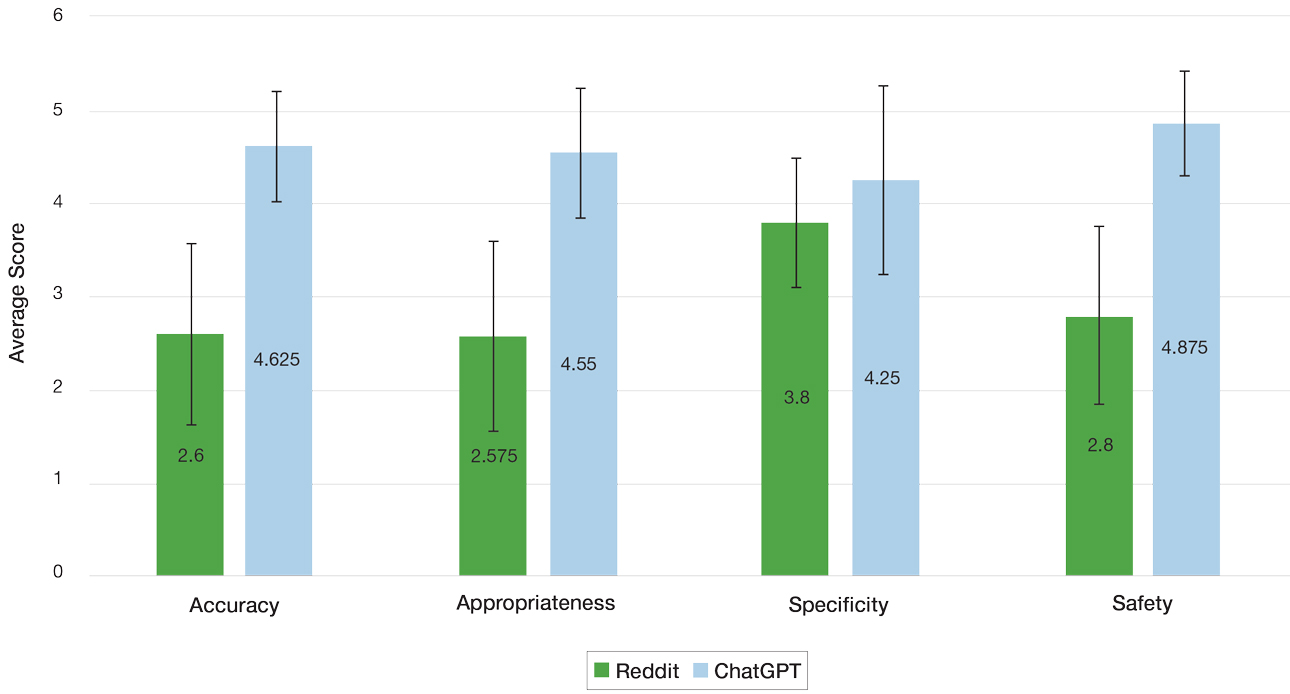

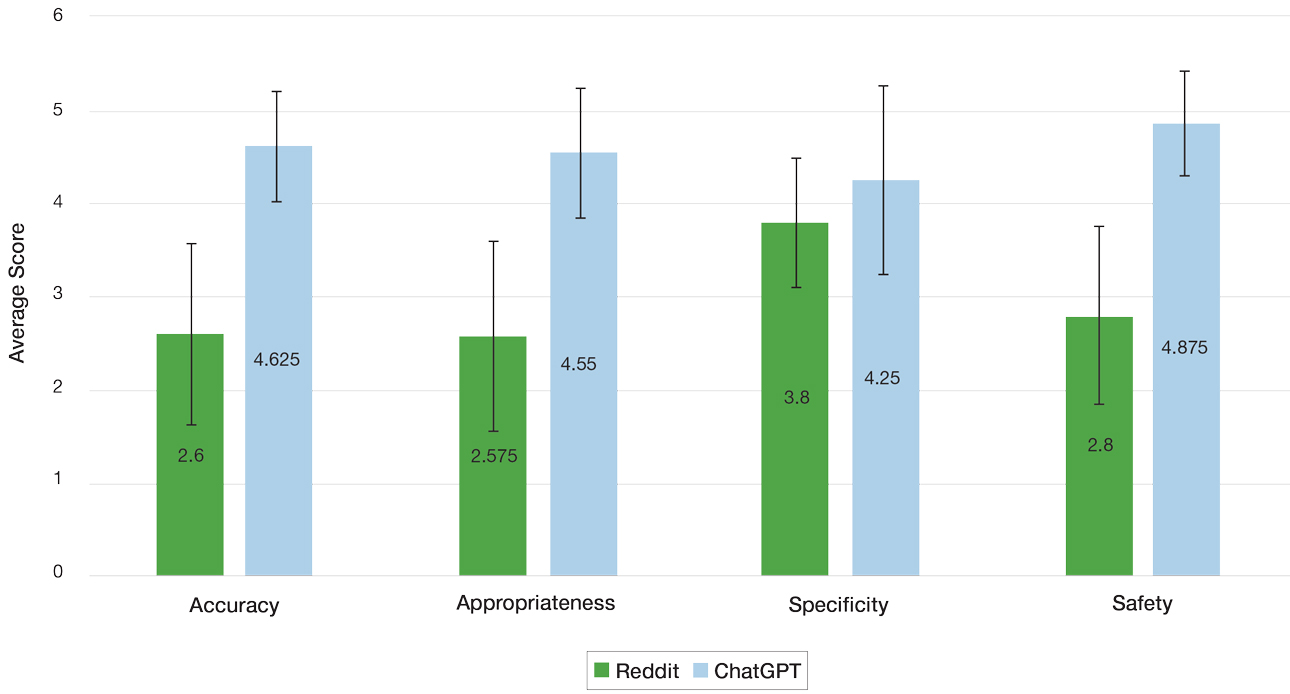

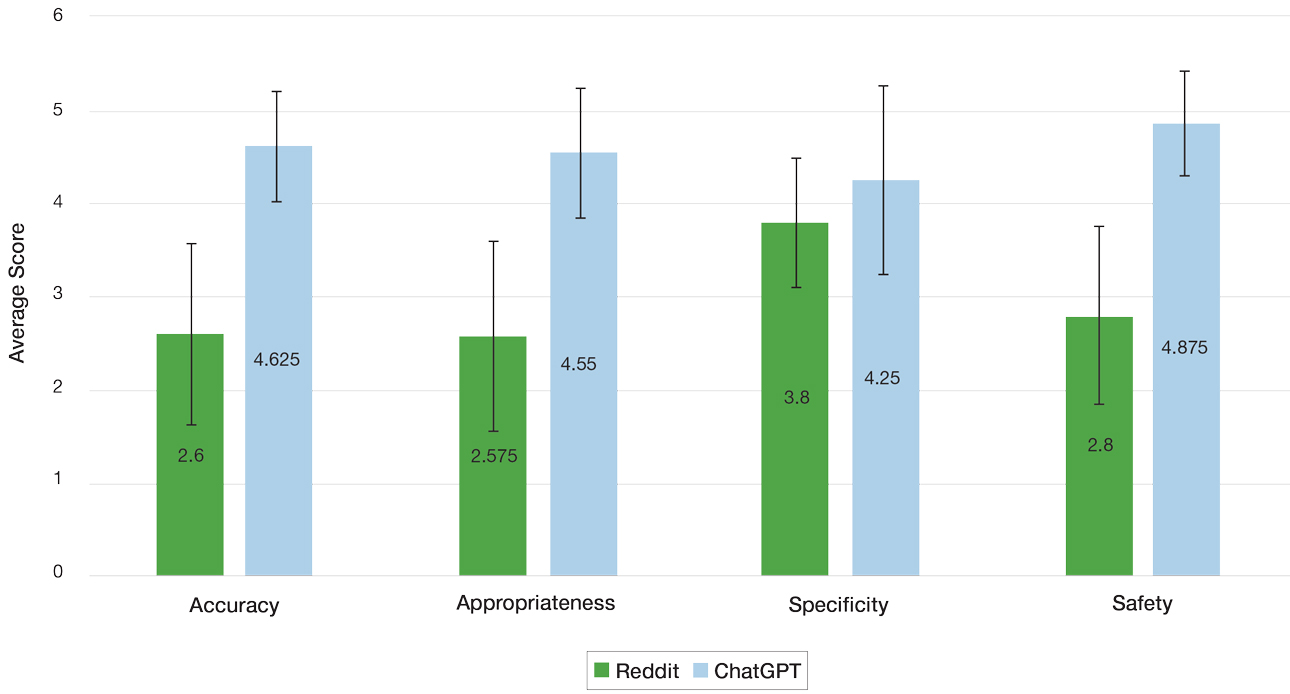

Each ChatGPT response and the top-rated Reddit comment were independently evaluated by a board certified dermatologist (S.A.) and a dermatology resident (A.H.K.). The quality of the ChatGPT and Reddit responses were determined by scoring the accuracy, appropriateness, safety consideration, and specificity on a 5-point Likert scale (1=low, 5=high). The 2 evaluators’ mean scores for each of the 4 categories were calculated based on adequate interrater reliability, which was tested using Cohen’s κ coefficient. Related-samples sign tests were used to compare ChatGPT and Reddit responses for each of the 4 categories. Analysis was completed using SPSS statistics software version 29.0 (IBM). The evaluators also were asked to provide qualitative feedback on the strengths and weaknesses of each response.

Our retrospective review yielded 20 total questions: 5 (25%) on atopic dermatitis, 4 (20%) on acne, 4 (20%) on hidradenitis suppurativa, 4 (20%) on psoriasis, 1 (5%) on folliculitis, 1 (5%) on keratosis pilaris, and 1 (5%) on seborrheic dermatitis. The number of posts was limited to 20 due to the extensive time required for grading each response. These 20 questions were selected from a larger pool of eligible posts based on factors such as clarity and relevance to common skin conditions. With regard to the types of questions that were asked, 6 (30%) were related to general management of a diagnosis, 5 (25%) were on treatment recommendations for symptom relief, 3 (15%) were on optimal utilization of current treatment regimens, 2 (10%) were on prescription side effects, 2 (10%) were on diagnosis presentation, 1 (5%) was on potential triggers of the diagnosis, and 1 (5%) was on natural treatment recommendations.

Mean (SD) evaluator scores for accuracy were significantly higher among ChatGPT responses compared with Reddit (4.63 [0.60] vs 2.60 [0.98])(P<.001). ChatGPT responses also were significantly higher for appropriateness compared with Reddit (4.55 [0.71] vs 2.58 [1.02])(P<.001) and safety consideration (4.88 [0.56] vs 2.80[0.97])(P <.001). There was no significant difference in mean specificity scores between ChatGPT and Reddit (4.25[1.02] vs 3.80 [0.70])(P=.096)(Figure).