User login

Cardiology News is an independent news source that provides cardiologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on cardiology and the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is the online destination and multimedia properties of Cardiology News, the independent news publication for cardiologists. Cardiology news is the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in cardiology as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

Semaglutide win in HFpEF with obesity regardless of ejection fraction: STEP-HFpEF

CLEVELAND – independently of baseline left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

The finding comes from a prespecified secondary analysis of the STEP-HFpEF trial of more than 500 nondiabetic patients with obesity and HF with an initial LVEF of 45% or greater.

They suggest that for patients with the obesity phenotype of HFpEF, semaglutide (Wegovy) could potentially join SGLT2 inhibitors on the short list of meds with consistent treatment effects whether LVEF is mildly reduced, preserved, or in the normal range.

That would distinguish the drug, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, from mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), sacubitril-valsartan (Entresto), and other renin-angiotensin-system inhibitors (RASi), whose benefits tend to taper off with rising LVEF.

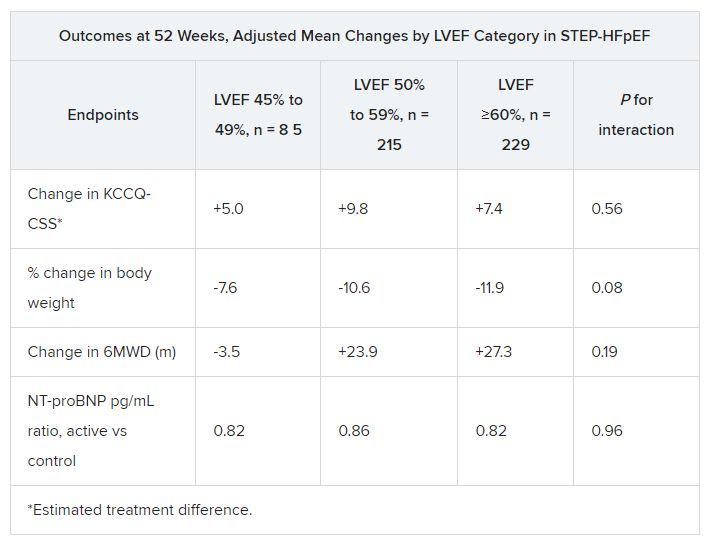

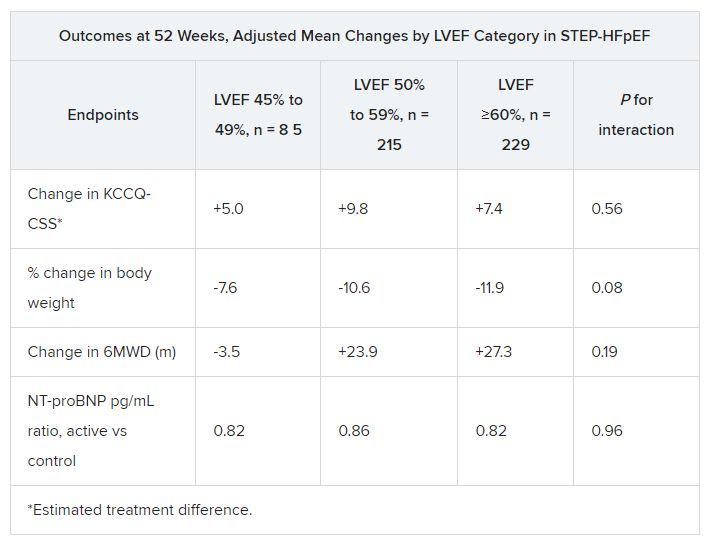

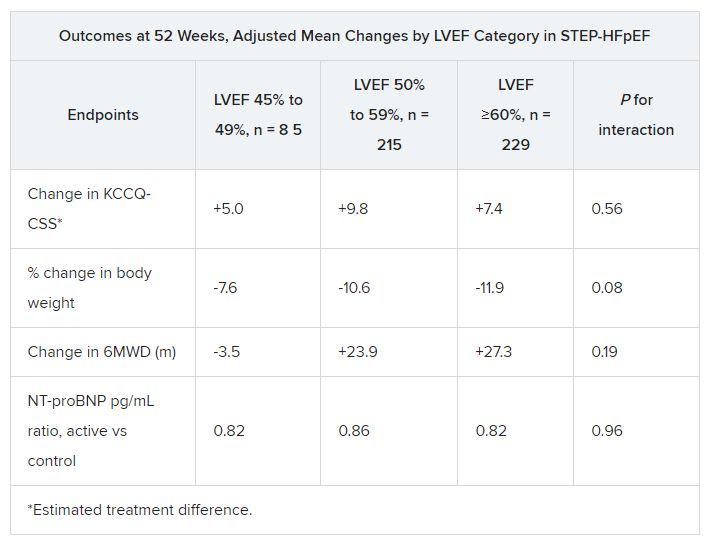

The patients assigned to semaglutide showed significant improvement in both primary endpoints – change in Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Clinical Summary Score (KCCQ-CSS) and change in body weight at 52 weeks – whether their baseline LVEF was 45%-49%, 50%-59%, or 60% or greater.

Results were similar for improvements in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and levels of NT-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and C-reactive protein, observed Javed Butler, MD, when presenting the analysis at the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America, Cleveland.

Dr. Butler, of Baylor Scott and White Research Institute, Dallas, and the University of Mississippi, Jackson, is also lead author of the study, which was published on the same day in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

In his presentation, Dr. Butler singled out the NT-proBNP finding as “very meaningful” with respect to understanding potential mechanisms of the drug effects observed in the trial.

For example, people with obesity tend to have lower than average natriuretic peptide levels that “actually go up a bit” when they lose weight, he observed. But in the trial, “we saw a reduction in NT-proBNP in spite of the weight loss,” regardless of LVEF category.

John McMurray, MD, University of Glasgow, the invited discussant for Dr. Butler’s presentation, agreed that it raises the question whether weight loss was the sole semaglutide effect responsible for the improvement in heart failure status and biomarkers. The accompanying NT-proBNP reductions – when the opposite might otherwise have been expected – may point to a possible mechanism of action that is “something more than just weight loss,” he said. “If that were the case, it becomes very important, because it means that this treatment might do good things in non-obese patients or might do good things in patients with other types of heart failure.”

‘Vital reassurance’

More definitive trials are needed “to clarify safety and efficacy of obesity-targeted therapeutics in HF across the ejection fraction spectrum,” according to an accompanying editorial).

Still, the STEP-HFpEF analysis “strengthens the role of GLP-1 [receptor agonists] to ameliorate health status” for patients with obesity and HF with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction, write Muthiah Vaduganathan, MD, MPH, and John W. Ostrominski, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

Its findings “provide vital reassurance” on semaglutide safety and efficacy in HF with below-normal LVEF and “tentatively support the existence of a more general, LVEF-independent, obesity-related HF phenotype capable of favorable modification with incretin-based therapies.”

The lack of heterogeneity in treatment effects across LVEF subgroups “is not surprising,” but “the findings reinforce that the benefits of this therapy in those meeting trial criteria do not vary by left ventricular ejection fraction,” Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center, said in an interview.

It remains unknown, however, “whether the improvement in health status, functional status, and reduced inflammation” will translate to reduced risk of cardiovascular death or HF hospitalization, said Dr. Fonarow, who isn’t connected to STEP-HFpEF.

It’s a question for future studies, he agreed, whether semaglutide would confer similar benefits for patients with obesity and HF with LVEF less than 45% or in non-obese HF patients.

Dr. McMurray proposed that future GLP-1 receptor agonist heart-failure trials should include non-obese patients to determine whether the effects seen in STEP-HFpEF were due to something more than weight loss. Trials in patients with obesity and HF with reduced LVEF would also be important.

“If it turns out just to be about weight loss, then we need to think about the alternatives,” including diet, exercise, and bariatric surgery but also, potentially, weight-loss drugs other than semaglutide, he said.

No heterogeneity by LVEF

STEP-HFpEF randomly assigned 529 patients free of diabetes with an LVEF greater than or equal to 45%, a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2, and NYHA functional status of 2-4 to either a placebo injection or 2.4-mg semaglutide subcutaneously once a week (the dose used for weight reduction) atop standard care.

As previously reported, those assigned to semaglutide showed significant improvements at 1 year in symptoms and in physical limitation, per changes in KCCQ-CSS, and weight loss, compared with the control group. Their exercise capacity, as measured by 6MWD, also improved.

The more weight patients lost while taking semaglutide, the better their KCCQ-CSS and 6MWD outcomes, a prior secondary analysis suggested. But the STEP-HFpEF researchers said weight loss did not appear to explain all of their gains, compared with usual care.

For the current analysis, the 263 patients assigned to receive semaglutide and 266 control patients were divided into three groups by baseline LVEF and compared for the same outcomes.

The semaglutide group, compared with control patients, also showed a significantly increased hierarchical composite win ratio, 1.72 (95% CI, 1.37-2.15; P < .001), that was consistent across LVEF categories and that accounted for all-cause mortality, HF events, KCCQ-CSS and 6MWD changes, and change in CRP.

Limitations make it hard to generalize the results, the authors caution. Well over 90% of the participants were White patients, for example, and the overall trial was not powered to show subgroup differences.

Given the many patients with HFpEF who have a cardiometabolic phenotype and are with overweight or obesity, write Dr. Butler and colleagues, their treatment approach “may ultimately include combination therapy with SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists, given their non-overlapping and complementary mechanisms of action.”

Dr. Fonarow noted that both MRAs and sacubitril-valsartan offer clinical benefits for patients with HF and LVEF “in the 41%-60% range” that are evident “across BMI categories.”

So it’s likely, he said, that those medications as well as SGLT2 inhibitors will be used along with GLP-1 receptor agonists for patients with HFpEF and obesity.

STEP-HFpEF was funded by Novo Nordisk. Dr. Butler and the other authors disclose consulting for many companies, a list of which can be found in the report. Dr. Fonarow reports consulting for multiple companies. Dr. McMurray discloses consulting for AstraZeneca. Dr. Ostrominski reports no relevant disclosures. Dr. Vaduganathan discloses receiving grant support, serving on advisory boards, or speaking for multiple companies and serving on committees for studies sponsored by AstraZeneca, Galmed, Novartis, Bayer AG, Occlutech, and Impulse Dynamics.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

CLEVELAND – independently of baseline left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

The finding comes from a prespecified secondary analysis of the STEP-HFpEF trial of more than 500 nondiabetic patients with obesity and HF with an initial LVEF of 45% or greater.

They suggest that for patients with the obesity phenotype of HFpEF, semaglutide (Wegovy) could potentially join SGLT2 inhibitors on the short list of meds with consistent treatment effects whether LVEF is mildly reduced, preserved, or in the normal range.

That would distinguish the drug, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, from mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), sacubitril-valsartan (Entresto), and other renin-angiotensin-system inhibitors (RASi), whose benefits tend to taper off with rising LVEF.

The patients assigned to semaglutide showed significant improvement in both primary endpoints – change in Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Clinical Summary Score (KCCQ-CSS) and change in body weight at 52 weeks – whether their baseline LVEF was 45%-49%, 50%-59%, or 60% or greater.

Results were similar for improvements in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and levels of NT-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and C-reactive protein, observed Javed Butler, MD, when presenting the analysis at the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America, Cleveland.

Dr. Butler, of Baylor Scott and White Research Institute, Dallas, and the University of Mississippi, Jackson, is also lead author of the study, which was published on the same day in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

In his presentation, Dr. Butler singled out the NT-proBNP finding as “very meaningful” with respect to understanding potential mechanisms of the drug effects observed in the trial.

For example, people with obesity tend to have lower than average natriuretic peptide levels that “actually go up a bit” when they lose weight, he observed. But in the trial, “we saw a reduction in NT-proBNP in spite of the weight loss,” regardless of LVEF category.

John McMurray, MD, University of Glasgow, the invited discussant for Dr. Butler’s presentation, agreed that it raises the question whether weight loss was the sole semaglutide effect responsible for the improvement in heart failure status and biomarkers. The accompanying NT-proBNP reductions – when the opposite might otherwise have been expected – may point to a possible mechanism of action that is “something more than just weight loss,” he said. “If that were the case, it becomes very important, because it means that this treatment might do good things in non-obese patients or might do good things in patients with other types of heart failure.”

‘Vital reassurance’

More definitive trials are needed “to clarify safety and efficacy of obesity-targeted therapeutics in HF across the ejection fraction spectrum,” according to an accompanying editorial).

Still, the STEP-HFpEF analysis “strengthens the role of GLP-1 [receptor agonists] to ameliorate health status” for patients with obesity and HF with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction, write Muthiah Vaduganathan, MD, MPH, and John W. Ostrominski, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

Its findings “provide vital reassurance” on semaglutide safety and efficacy in HF with below-normal LVEF and “tentatively support the existence of a more general, LVEF-independent, obesity-related HF phenotype capable of favorable modification with incretin-based therapies.”

The lack of heterogeneity in treatment effects across LVEF subgroups “is not surprising,” but “the findings reinforce that the benefits of this therapy in those meeting trial criteria do not vary by left ventricular ejection fraction,” Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center, said in an interview.

It remains unknown, however, “whether the improvement in health status, functional status, and reduced inflammation” will translate to reduced risk of cardiovascular death or HF hospitalization, said Dr. Fonarow, who isn’t connected to STEP-HFpEF.

It’s a question for future studies, he agreed, whether semaglutide would confer similar benefits for patients with obesity and HF with LVEF less than 45% or in non-obese HF patients.

Dr. McMurray proposed that future GLP-1 receptor agonist heart-failure trials should include non-obese patients to determine whether the effects seen in STEP-HFpEF were due to something more than weight loss. Trials in patients with obesity and HF with reduced LVEF would also be important.

“If it turns out just to be about weight loss, then we need to think about the alternatives,” including diet, exercise, and bariatric surgery but also, potentially, weight-loss drugs other than semaglutide, he said.

No heterogeneity by LVEF

STEP-HFpEF randomly assigned 529 patients free of diabetes with an LVEF greater than or equal to 45%, a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2, and NYHA functional status of 2-4 to either a placebo injection or 2.4-mg semaglutide subcutaneously once a week (the dose used for weight reduction) atop standard care.

As previously reported, those assigned to semaglutide showed significant improvements at 1 year in symptoms and in physical limitation, per changes in KCCQ-CSS, and weight loss, compared with the control group. Their exercise capacity, as measured by 6MWD, also improved.

The more weight patients lost while taking semaglutide, the better their KCCQ-CSS and 6MWD outcomes, a prior secondary analysis suggested. But the STEP-HFpEF researchers said weight loss did not appear to explain all of their gains, compared with usual care.

For the current analysis, the 263 patients assigned to receive semaglutide and 266 control patients were divided into three groups by baseline LVEF and compared for the same outcomes.

The semaglutide group, compared with control patients, also showed a significantly increased hierarchical composite win ratio, 1.72 (95% CI, 1.37-2.15; P < .001), that was consistent across LVEF categories and that accounted for all-cause mortality, HF events, KCCQ-CSS and 6MWD changes, and change in CRP.

Limitations make it hard to generalize the results, the authors caution. Well over 90% of the participants were White patients, for example, and the overall trial was not powered to show subgroup differences.

Given the many patients with HFpEF who have a cardiometabolic phenotype and are with overweight or obesity, write Dr. Butler and colleagues, their treatment approach “may ultimately include combination therapy with SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists, given their non-overlapping and complementary mechanisms of action.”

Dr. Fonarow noted that both MRAs and sacubitril-valsartan offer clinical benefits for patients with HF and LVEF “in the 41%-60% range” that are evident “across BMI categories.”

So it’s likely, he said, that those medications as well as SGLT2 inhibitors will be used along with GLP-1 receptor agonists for patients with HFpEF and obesity.

STEP-HFpEF was funded by Novo Nordisk. Dr. Butler and the other authors disclose consulting for many companies, a list of which can be found in the report. Dr. Fonarow reports consulting for multiple companies. Dr. McMurray discloses consulting for AstraZeneca. Dr. Ostrominski reports no relevant disclosures. Dr. Vaduganathan discloses receiving grant support, serving on advisory boards, or speaking for multiple companies and serving on committees for studies sponsored by AstraZeneca, Galmed, Novartis, Bayer AG, Occlutech, and Impulse Dynamics.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

CLEVELAND – independently of baseline left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

The finding comes from a prespecified secondary analysis of the STEP-HFpEF trial of more than 500 nondiabetic patients with obesity and HF with an initial LVEF of 45% or greater.

They suggest that for patients with the obesity phenotype of HFpEF, semaglutide (Wegovy) could potentially join SGLT2 inhibitors on the short list of meds with consistent treatment effects whether LVEF is mildly reduced, preserved, or in the normal range.

That would distinguish the drug, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, from mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), sacubitril-valsartan (Entresto), and other renin-angiotensin-system inhibitors (RASi), whose benefits tend to taper off with rising LVEF.

The patients assigned to semaglutide showed significant improvement in both primary endpoints – change in Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Clinical Summary Score (KCCQ-CSS) and change in body weight at 52 weeks – whether their baseline LVEF was 45%-49%, 50%-59%, or 60% or greater.

Results were similar for improvements in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and levels of NT-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and C-reactive protein, observed Javed Butler, MD, when presenting the analysis at the annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America, Cleveland.

Dr. Butler, of Baylor Scott and White Research Institute, Dallas, and the University of Mississippi, Jackson, is also lead author of the study, which was published on the same day in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

In his presentation, Dr. Butler singled out the NT-proBNP finding as “very meaningful” with respect to understanding potential mechanisms of the drug effects observed in the trial.

For example, people with obesity tend to have lower than average natriuretic peptide levels that “actually go up a bit” when they lose weight, he observed. But in the trial, “we saw a reduction in NT-proBNP in spite of the weight loss,” regardless of LVEF category.

John McMurray, MD, University of Glasgow, the invited discussant for Dr. Butler’s presentation, agreed that it raises the question whether weight loss was the sole semaglutide effect responsible for the improvement in heart failure status and biomarkers. The accompanying NT-proBNP reductions – when the opposite might otherwise have been expected – may point to a possible mechanism of action that is “something more than just weight loss,” he said. “If that were the case, it becomes very important, because it means that this treatment might do good things in non-obese patients or might do good things in patients with other types of heart failure.”

‘Vital reassurance’

More definitive trials are needed “to clarify safety and efficacy of obesity-targeted therapeutics in HF across the ejection fraction spectrum,” according to an accompanying editorial).

Still, the STEP-HFpEF analysis “strengthens the role of GLP-1 [receptor agonists] to ameliorate health status” for patients with obesity and HF with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction, write Muthiah Vaduganathan, MD, MPH, and John W. Ostrominski, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

Its findings “provide vital reassurance” on semaglutide safety and efficacy in HF with below-normal LVEF and “tentatively support the existence of a more general, LVEF-independent, obesity-related HF phenotype capable of favorable modification with incretin-based therapies.”

The lack of heterogeneity in treatment effects across LVEF subgroups “is not surprising,” but “the findings reinforce that the benefits of this therapy in those meeting trial criteria do not vary by left ventricular ejection fraction,” Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center, said in an interview.

It remains unknown, however, “whether the improvement in health status, functional status, and reduced inflammation” will translate to reduced risk of cardiovascular death or HF hospitalization, said Dr. Fonarow, who isn’t connected to STEP-HFpEF.

It’s a question for future studies, he agreed, whether semaglutide would confer similar benefits for patients with obesity and HF with LVEF less than 45% or in non-obese HF patients.

Dr. McMurray proposed that future GLP-1 receptor agonist heart-failure trials should include non-obese patients to determine whether the effects seen in STEP-HFpEF were due to something more than weight loss. Trials in patients with obesity and HF with reduced LVEF would also be important.

“If it turns out just to be about weight loss, then we need to think about the alternatives,” including diet, exercise, and bariatric surgery but also, potentially, weight-loss drugs other than semaglutide, he said.

No heterogeneity by LVEF

STEP-HFpEF randomly assigned 529 patients free of diabetes with an LVEF greater than or equal to 45%, a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2, and NYHA functional status of 2-4 to either a placebo injection or 2.4-mg semaglutide subcutaneously once a week (the dose used for weight reduction) atop standard care.

As previously reported, those assigned to semaglutide showed significant improvements at 1 year in symptoms and in physical limitation, per changes in KCCQ-CSS, and weight loss, compared with the control group. Their exercise capacity, as measured by 6MWD, also improved.

The more weight patients lost while taking semaglutide, the better their KCCQ-CSS and 6MWD outcomes, a prior secondary analysis suggested. But the STEP-HFpEF researchers said weight loss did not appear to explain all of their gains, compared with usual care.

For the current analysis, the 263 patients assigned to receive semaglutide and 266 control patients were divided into three groups by baseline LVEF and compared for the same outcomes.

The semaglutide group, compared with control patients, also showed a significantly increased hierarchical composite win ratio, 1.72 (95% CI, 1.37-2.15; P < .001), that was consistent across LVEF categories and that accounted for all-cause mortality, HF events, KCCQ-CSS and 6MWD changes, and change in CRP.

Limitations make it hard to generalize the results, the authors caution. Well over 90% of the participants were White patients, for example, and the overall trial was not powered to show subgroup differences.

Given the many patients with HFpEF who have a cardiometabolic phenotype and are with overweight or obesity, write Dr. Butler and colleagues, their treatment approach “may ultimately include combination therapy with SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists, given their non-overlapping and complementary mechanisms of action.”

Dr. Fonarow noted that both MRAs and sacubitril-valsartan offer clinical benefits for patients with HF and LVEF “in the 41%-60% range” that are evident “across BMI categories.”

So it’s likely, he said, that those medications as well as SGLT2 inhibitors will be used along with GLP-1 receptor agonists for patients with HFpEF and obesity.

STEP-HFpEF was funded by Novo Nordisk. Dr. Butler and the other authors disclose consulting for many companies, a list of which can be found in the report. Dr. Fonarow reports consulting for multiple companies. Dr. McMurray discloses consulting for AstraZeneca. Dr. Ostrominski reports no relevant disclosures. Dr. Vaduganathan discloses receiving grant support, serving on advisory boards, or speaking for multiple companies and serving on committees for studies sponsored by AstraZeneca, Galmed, Novartis, Bayer AG, Occlutech, and Impulse Dynamics.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

AT HFSA 2023

Burnout in medical profession higher among women, younger clinicians

The poster child for a burned-out physician is a young woman practicing in primary care, according to a new study of more than 1,300 clinicians.

The study, published in JAMA Network Open. investigated patterns in physician burnout among 1,373 physicians at Massachusetts General Physicians Organization, a hospital-owned group practice. It assessed burnout in 3 years: 2017, 2019, and 2021.

Respondents were queried about their satisfaction with their career and compensation, as well as their well-being, administrative workload, and leadership and diversity.

Female physicians exhibited a higher burnout rate than male physicians (odds ratio, 1.47; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-2.12), while among primary care physicians (PCPs), the burnout rate was almost three times higher than among those in internal medicine (OR, 2.82; 95% CI, 1.76-4.50). Among physicians with 30 or more years of experience, the burnout rate was lower than among those with 10 years of experience or less (OR, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.13-0.35).

The fact that burnout disproportionately affects female physicians could reflect the additional household and family obligations women are often expected to handle, as well as their desire to form relationships with their patients, according to Timothy Hoff, PhD, a professor of management, healthcare systems, and health policy at Northeastern University, Boston.

“Female physicians tend to practice differently than their male counterparts,” said Dr. Hoff, who studies primary care. “They may focus more on the relational aspects of care, and that could lead to a higher rate of burnout.”

The study used the Maslach Burnout Inventory and three burnout subscales: exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced personal efficacy. The cohort was composed of 50% men, 67% White respondents, and 87% non-Hispanic respondents. A little over two-thirds of physicians had from 11 to 20 years of experience.

About 93% of those surveyed responded; by comparison, response rates were between 27% and 32% in previous analyses of physician burnout, the study authors say. They attribute this high participation rate to the fact that they compensated each participant with $850, more than is usually offered.

Hilton Gomes, MD, a partner at a concierge primary care practice in Miami – who has been practicing medicine for more than 15 years – said the increased rates of burnout among his younger colleagues are partly the result of a recent shift in what is considered the ideal work-life balance.

“Younger generations of doctors enter the profession with a strong desire for a better work-life balance. Unfortunately, medicine does not typically lend itself to achieving this balance,” he said.

Dr. Gomes recalled a time in medical school when he tried to visit his former pediatrician, who couldn’t be found at home.

“His wife informed me that he was tending to an urgent sick visit at the hospital, while his wife had to deal with their own grandson’s fracture being treated at urgent care,” Dr. Gomes said. “This illustrates, in my experience, how older generations of physicians accepted the demands of the profession as part of their commitment, and this often involved putting our own families second.”

Dr. Gomes, like many other PCPs who have converted to concierge medicine, previously worked at a practice where he saw nearly two dozen patients a day for a maximum of 15 minutes each.

“The structure of managed care often results in primary care physicians spending less time with patients and more time on paperwork, which is not the reason why physicians enter the field of medicine,” Dr. Gomes said.

Physicians are not alone in their feelings of physical and mental exhaustion. In the Medscape Physician Assistant Burnout Report 2023, 16% of respondents said the burnout they experienced was so severe that they were thinking of leaving medicine.

In 2022, PCP burnout cost the United States $260 million in excess health care expenditures. Burnout has also increased rates of physician suicide over the past 50 years and has led to a rise in medical errors.

Physicians say that programs that teach them to perform yoga and take deep breaths – which are offered by their employers – are not the solution.

“We sort of know what the realities of physician burnout are now; the imperative is to address it,” Dr. Hoff said. “We need studies that focus on the concepts of sustainability.”

The study was funded by the Massachusetts General Physicians Organization. A coauthor reports receiving a grant from the American Heart Association. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The poster child for a burned-out physician is a young woman practicing in primary care, according to a new study of more than 1,300 clinicians.

The study, published in JAMA Network Open. investigated patterns in physician burnout among 1,373 physicians at Massachusetts General Physicians Organization, a hospital-owned group practice. It assessed burnout in 3 years: 2017, 2019, and 2021.

Respondents were queried about their satisfaction with their career and compensation, as well as their well-being, administrative workload, and leadership and diversity.

Female physicians exhibited a higher burnout rate than male physicians (odds ratio, 1.47; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-2.12), while among primary care physicians (PCPs), the burnout rate was almost three times higher than among those in internal medicine (OR, 2.82; 95% CI, 1.76-4.50). Among physicians with 30 or more years of experience, the burnout rate was lower than among those with 10 years of experience or less (OR, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.13-0.35).

The fact that burnout disproportionately affects female physicians could reflect the additional household and family obligations women are often expected to handle, as well as their desire to form relationships with their patients, according to Timothy Hoff, PhD, a professor of management, healthcare systems, and health policy at Northeastern University, Boston.

“Female physicians tend to practice differently than their male counterparts,” said Dr. Hoff, who studies primary care. “They may focus more on the relational aspects of care, and that could lead to a higher rate of burnout.”

The study used the Maslach Burnout Inventory and three burnout subscales: exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced personal efficacy. The cohort was composed of 50% men, 67% White respondents, and 87% non-Hispanic respondents. A little over two-thirds of physicians had from 11 to 20 years of experience.

About 93% of those surveyed responded; by comparison, response rates were between 27% and 32% in previous analyses of physician burnout, the study authors say. They attribute this high participation rate to the fact that they compensated each participant with $850, more than is usually offered.

Hilton Gomes, MD, a partner at a concierge primary care practice in Miami – who has been practicing medicine for more than 15 years – said the increased rates of burnout among his younger colleagues are partly the result of a recent shift in what is considered the ideal work-life balance.

“Younger generations of doctors enter the profession with a strong desire for a better work-life balance. Unfortunately, medicine does not typically lend itself to achieving this balance,” he said.

Dr. Gomes recalled a time in medical school when he tried to visit his former pediatrician, who couldn’t be found at home.

“His wife informed me that he was tending to an urgent sick visit at the hospital, while his wife had to deal with their own grandson’s fracture being treated at urgent care,” Dr. Gomes said. “This illustrates, in my experience, how older generations of physicians accepted the demands of the profession as part of their commitment, and this often involved putting our own families second.”

Dr. Gomes, like many other PCPs who have converted to concierge medicine, previously worked at a practice where he saw nearly two dozen patients a day for a maximum of 15 minutes each.

“The structure of managed care often results in primary care physicians spending less time with patients and more time on paperwork, which is not the reason why physicians enter the field of medicine,” Dr. Gomes said.

Physicians are not alone in their feelings of physical and mental exhaustion. In the Medscape Physician Assistant Burnout Report 2023, 16% of respondents said the burnout they experienced was so severe that they were thinking of leaving medicine.

In 2022, PCP burnout cost the United States $260 million in excess health care expenditures. Burnout has also increased rates of physician suicide over the past 50 years and has led to a rise in medical errors.

Physicians say that programs that teach them to perform yoga and take deep breaths – which are offered by their employers – are not the solution.

“We sort of know what the realities of physician burnout are now; the imperative is to address it,” Dr. Hoff said. “We need studies that focus on the concepts of sustainability.”

The study was funded by the Massachusetts General Physicians Organization. A coauthor reports receiving a grant from the American Heart Association. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The poster child for a burned-out physician is a young woman practicing in primary care, according to a new study of more than 1,300 clinicians.

The study, published in JAMA Network Open. investigated patterns in physician burnout among 1,373 physicians at Massachusetts General Physicians Organization, a hospital-owned group practice. It assessed burnout in 3 years: 2017, 2019, and 2021.

Respondents were queried about their satisfaction with their career and compensation, as well as their well-being, administrative workload, and leadership and diversity.

Female physicians exhibited a higher burnout rate than male physicians (odds ratio, 1.47; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-2.12), while among primary care physicians (PCPs), the burnout rate was almost three times higher than among those in internal medicine (OR, 2.82; 95% CI, 1.76-4.50). Among physicians with 30 or more years of experience, the burnout rate was lower than among those with 10 years of experience or less (OR, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.13-0.35).

The fact that burnout disproportionately affects female physicians could reflect the additional household and family obligations women are often expected to handle, as well as their desire to form relationships with their patients, according to Timothy Hoff, PhD, a professor of management, healthcare systems, and health policy at Northeastern University, Boston.

“Female physicians tend to practice differently than their male counterparts,” said Dr. Hoff, who studies primary care. “They may focus more on the relational aspects of care, and that could lead to a higher rate of burnout.”

The study used the Maslach Burnout Inventory and three burnout subscales: exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced personal efficacy. The cohort was composed of 50% men, 67% White respondents, and 87% non-Hispanic respondents. A little over two-thirds of physicians had from 11 to 20 years of experience.

About 93% of those surveyed responded; by comparison, response rates were between 27% and 32% in previous analyses of physician burnout, the study authors say. They attribute this high participation rate to the fact that they compensated each participant with $850, more than is usually offered.

Hilton Gomes, MD, a partner at a concierge primary care practice in Miami – who has been practicing medicine for more than 15 years – said the increased rates of burnout among his younger colleagues are partly the result of a recent shift in what is considered the ideal work-life balance.

“Younger generations of doctors enter the profession with a strong desire for a better work-life balance. Unfortunately, medicine does not typically lend itself to achieving this balance,” he said.

Dr. Gomes recalled a time in medical school when he tried to visit his former pediatrician, who couldn’t be found at home.

“His wife informed me that he was tending to an urgent sick visit at the hospital, while his wife had to deal with their own grandson’s fracture being treated at urgent care,” Dr. Gomes said. “This illustrates, in my experience, how older generations of physicians accepted the demands of the profession as part of their commitment, and this often involved putting our own families second.”

Dr. Gomes, like many other PCPs who have converted to concierge medicine, previously worked at a practice where he saw nearly two dozen patients a day for a maximum of 15 minutes each.

“The structure of managed care often results in primary care physicians spending less time with patients and more time on paperwork, which is not the reason why physicians enter the field of medicine,” Dr. Gomes said.

Physicians are not alone in their feelings of physical and mental exhaustion. In the Medscape Physician Assistant Burnout Report 2023, 16% of respondents said the burnout they experienced was so severe that they were thinking of leaving medicine.

In 2022, PCP burnout cost the United States $260 million in excess health care expenditures. Burnout has also increased rates of physician suicide over the past 50 years and has led to a rise in medical errors.

Physicians say that programs that teach them to perform yoga and take deep breaths – which are offered by their employers – are not the solution.

“We sort of know what the realities of physician burnout are now; the imperative is to address it,” Dr. Hoff said. “We need studies that focus on the concepts of sustainability.”

The study was funded by the Massachusetts General Physicians Organization. A coauthor reports receiving a grant from the American Heart Association. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Home-based exercise benefits patients with PAD

TOPLINE:

Compared with supervised treadmill workouts at a gym, which is considered first-line therapy for walking impairment in lower extremity peripheral artery disease (PAD), exercising at home significantly improves 6-minute walking (6MW) distance, but not maximal treadmill walking distance, results of a new meta-analysis show.

METHODOLOGY:

- The analysis included five randomized clinical trials with a total of 719 participants, mean age 68.6 years, all led by researchers at Northwestern University, Chicago, that compared either supervised treadmill or home-based walking exercise with a nonexercise control group in people with PAD (defined as Ankle Brachial Index ≤ 0.90).

- All trials measured 6-minute walk (6MW) distance (walking as far as possible in 6 minutes), treadmill walking performance, and outcomes from the Walking Impairment Questionnaire (WIQ), which includes distance, walking speed, and stair-climbing domains, at baseline and at 6 months.

- Supervised treadmill exercise interventions included three individualized exercise sessions per week with an exercise physiologist at an exercise center, and home-based exercises involved walking near home 5 days per week, both for up to 50 minutes per session.

TAKEAWAY:

- After adjusting for study, age, sex, race, smoking, history of myocardial infarction, heart failure, and baseline 6MW distance, the study found both exercise interventions were better than nonexercise controls for 6MW distance.

- Compared with supervised treadmill exercise, home-based walking was associated with significantly improved mean 6MW distance (31.8 m vs. 55.6 m; adjusted between-group difference: −23.8 m; 95% confidence interval, −44.0 to −3.6; P = .021), and significantly improved WIQ walking speed score.

- However, home-based walking was associated with significantly less improvement in maximal treadmill walking distance, compared with supervised treadmill exercise (adjusted between-group difference: 132.5 m; 95% CI, 72.1-192.9; P < .001).

IN PRACTICE:

Home-based walking exercise “circumvents” barriers to accessing supervised exercise such as having to travel to a facility, said the authors, who noted the new data “demonstrated a large and consistent effect of home-based walking exercise on improved 6MW distance and also significantly improved the WIQ walking speed score, compared with supervised treadmill exercise.”

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Neela D. Thangada, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues. It was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Data were combined from different randomized clinical trials that were led by one investigative team, and reported comparisons were not prespecified. Comparisons between supervised and home-based exercise lacked statistical power for the WIQ distance and stair-climbing measures.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was sponsored by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Thangada reports no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for study coauthors can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Compared with supervised treadmill workouts at a gym, which is considered first-line therapy for walking impairment in lower extremity peripheral artery disease (PAD), exercising at home significantly improves 6-minute walking (6MW) distance, but not maximal treadmill walking distance, results of a new meta-analysis show.

METHODOLOGY:

- The analysis included five randomized clinical trials with a total of 719 participants, mean age 68.6 years, all led by researchers at Northwestern University, Chicago, that compared either supervised treadmill or home-based walking exercise with a nonexercise control group in people with PAD (defined as Ankle Brachial Index ≤ 0.90).

- All trials measured 6-minute walk (6MW) distance (walking as far as possible in 6 minutes), treadmill walking performance, and outcomes from the Walking Impairment Questionnaire (WIQ), which includes distance, walking speed, and stair-climbing domains, at baseline and at 6 months.

- Supervised treadmill exercise interventions included three individualized exercise sessions per week with an exercise physiologist at an exercise center, and home-based exercises involved walking near home 5 days per week, both for up to 50 minutes per session.

TAKEAWAY:

- After adjusting for study, age, sex, race, smoking, history of myocardial infarction, heart failure, and baseline 6MW distance, the study found both exercise interventions were better than nonexercise controls for 6MW distance.

- Compared with supervised treadmill exercise, home-based walking was associated with significantly improved mean 6MW distance (31.8 m vs. 55.6 m; adjusted between-group difference: −23.8 m; 95% confidence interval, −44.0 to −3.6; P = .021), and significantly improved WIQ walking speed score.

- However, home-based walking was associated with significantly less improvement in maximal treadmill walking distance, compared with supervised treadmill exercise (adjusted between-group difference: 132.5 m; 95% CI, 72.1-192.9; P < .001).

IN PRACTICE:

Home-based walking exercise “circumvents” barriers to accessing supervised exercise such as having to travel to a facility, said the authors, who noted the new data “demonstrated a large and consistent effect of home-based walking exercise on improved 6MW distance and also significantly improved the WIQ walking speed score, compared with supervised treadmill exercise.”

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Neela D. Thangada, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues. It was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Data were combined from different randomized clinical trials that were led by one investigative team, and reported comparisons were not prespecified. Comparisons between supervised and home-based exercise lacked statistical power for the WIQ distance and stair-climbing measures.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was sponsored by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Thangada reports no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for study coauthors can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Compared with supervised treadmill workouts at a gym, which is considered first-line therapy for walking impairment in lower extremity peripheral artery disease (PAD), exercising at home significantly improves 6-minute walking (6MW) distance, but not maximal treadmill walking distance, results of a new meta-analysis show.

METHODOLOGY:

- The analysis included five randomized clinical trials with a total of 719 participants, mean age 68.6 years, all led by researchers at Northwestern University, Chicago, that compared either supervised treadmill or home-based walking exercise with a nonexercise control group in people with PAD (defined as Ankle Brachial Index ≤ 0.90).

- All trials measured 6-minute walk (6MW) distance (walking as far as possible in 6 minutes), treadmill walking performance, and outcomes from the Walking Impairment Questionnaire (WIQ), which includes distance, walking speed, and stair-climbing domains, at baseline and at 6 months.

- Supervised treadmill exercise interventions included three individualized exercise sessions per week with an exercise physiologist at an exercise center, and home-based exercises involved walking near home 5 days per week, both for up to 50 minutes per session.

TAKEAWAY:

- After adjusting for study, age, sex, race, smoking, history of myocardial infarction, heart failure, and baseline 6MW distance, the study found both exercise interventions were better than nonexercise controls for 6MW distance.

- Compared with supervised treadmill exercise, home-based walking was associated with significantly improved mean 6MW distance (31.8 m vs. 55.6 m; adjusted between-group difference: −23.8 m; 95% confidence interval, −44.0 to −3.6; P = .021), and significantly improved WIQ walking speed score.

- However, home-based walking was associated with significantly less improvement in maximal treadmill walking distance, compared with supervised treadmill exercise (adjusted between-group difference: 132.5 m; 95% CI, 72.1-192.9; P < .001).

IN PRACTICE:

Home-based walking exercise “circumvents” barriers to accessing supervised exercise such as having to travel to a facility, said the authors, who noted the new data “demonstrated a large and consistent effect of home-based walking exercise on improved 6MW distance and also significantly improved the WIQ walking speed score, compared with supervised treadmill exercise.”

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Neela D. Thangada, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues. It was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Data were combined from different randomized clinical trials that were led by one investigative team, and reported comparisons were not prespecified. Comparisons between supervised and home-based exercise lacked statistical power for the WIQ distance and stair-climbing measures.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was sponsored by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Thangada reports no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for study coauthors can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Lead pollutants as harmful to health as particulate matter

in a presentation to the World Bank. Their work was published in The Lancet Planetary Health.

As Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana report, the economic consequences of increased exposure to lead are already immense, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). The study was financed by the Korea Green Growth Trust Fund and the World Bank’s Pollution Management and Environmental Health Program.

Intellectual, cardiovascular effects

“It is a very important publication that affects all of us,” pediatrician Stephan Böse-O’Reilly, MD, of the Institute and Polyclinic for Occupational, Social, and Environmental Health at Ludwig Maximilian University Hospital in Munich, Germany, said in an interview. “The study, the results of which I think are very reliable, shows that elevated levels of lead in the blood have a much more drastic effect on children’s intelligence than we previously thought.”

It is well known that lead affects the antenatal and postnatal cognitive development of children, Dr. Böse-O’Reilly explained. But the extent of this effect has quite clearly been underestimated before now.

On the other hand, Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana’s work could prove that lead may lead to more cardiovascular diseases in adulthood. “We already knew that increased exposure to lead increased the risk of high blood pressure and, as a result, mortality,” said Dr. Böse-O’Reilly. “This study now very clearly shows that the risk of arteriosclerosis, for example, also increases through lead exposure.”

Figures from 2019

“For the first time, to our knowledge, we aimed to estimate the global burden and cost of IQ loss and cardiovascular disease mortality from lead exposure,” wrote Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana. For their calculations, the scientists used blood lead level estimates from the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2019.

They estimated IQ loss in children younger than 5 years using the internationally recognized blood lead level–IQ loss function. The researchers subsequently estimated the cost of this IQ loss based on the loss in lifetime income, presented as cost in U.S. dollars and percentage of gross domestic product (GDP).

Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana estimated cardiovascular deaths caused by lead exposure in adults aged 25 years or older using a model that captures the effects of lead exposure on cardiovascular disease mortality that is mediated through mechanisms other than hypertension.

Finally, they used the statistical life expectancy to estimate the welfare cost of premature mortality, also presented as cost in U.S. dollars and percentage of GDP. All estimates were calculated according to the World Bank income classification for 2019.

Millions of deaths

As reported by Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana, children younger than 5 years lost an estimated 765 million IQ points worldwide because of lead exposure in this period. In 2019, 5,545,000 adults died from cardiovascular diseases caused by lead exposure. The scientists recorded 729 million of the IQ points lost (95.3%) and 5,004,000 (90.2%) of the deaths as occurring in LMICs.

The IQ loss here was nearly 80% higher than a previous estimate, wrote Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana. The number of cardiovascular disease deaths they determined was six times higher than the GBD 2019 estimate.

“These are results with which the expert societies, especially the German Society of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine and the German Cardiac Society, and the corresponding professional associations need to concern themselves,” said Dr. Böse-O’Reilly.

Although blood lead concentrations have declined substantially since the phase-out of leaded gasoline, especially in Western countries, lead still represents a major health issue because it stays in the bones for decades.

European situation moderate

“We need a broad discussion on questions such as whether lead levels should be included in prophylactic assessments in certain age groups, what blood level is even tolerable, and in what situation medicinal therapy with chelating agents would possibly be appropriate,” said Dr. Böse-O’Reilly.

“Of course, we cannot answer these questions on the basis of one individual study,” he added. “However, the work in question definitely illustrates how dangerous lead can be and that we need further research into the actual burden and the best preventive measures.”

In this respect, the situation in Europe is still comparatively moderate. “Globally, lead exposure has risen in recent years,” said Dr. Böse-O’Reilly. According to an investigation by the Planet Earth Foundation, outside of the European Union, lead can increasingly be found in toys, spices, and cooking utensils, for example.

“Especially in lower-income countries, there is a lack of consumer protection or a good monitoring program like we have here in the EU,” said Dr. Böse-O’Reilly. In these countries, lead is sometimes added to spices by unscrupulous retailers to make the color more intense or to simply add to its weight to gain more profit.

Recycling lead-acid batteries or other electrical waste, often transferred to poorer countries, constitutes a large problem. “In general, children in Germany have a blood lead level of less than 1 mcg/dL,” explained Dr. Böse-O’Reilly. “In some regions of Indonesia, where these recycling factories are located, more than 50% of children have levels of more than 20 mcg/dL.”

Particulate matter

According to Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana, the global cost of increased lead exposure was around $6 trillion USD in 2019, which was equivalent to 6.9% of global GDP. About 77% of the cost ($4.62 trillion USD) comprised the welfare costs of cardiovascular disease mortality, and 23% ($1.38 trillion USD) comprised the present value of future income losses because of IQ loss in children.

“Our findings suggest that global lead exposure has health and economic costs on par with PM2.5 air pollution,” wrote the authors. This places lead as an environmental risk factor on par with particulate matter and above that of air pollution from solid fuels, ahead of unsafe drinking water, unhygienic sanitation, or insufficient handwashing.

“This finding is in contrast to that of GBD 2019, which ranked lead exposure as a distant fourth environmental risk factor, due to not accounting for IQ loss in children – other than idiopathic developmental intellectual disability in a small subset of children – and reporting a substantially lower estimate of adult cardiovascular disease mortality,” wrote Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana.

“A central implication for future research and policy is that LMICs bear an extraordinarily large share of the health and cost burden of lead exposure,” wrote the authors. Consequently, improved quality of blood lead level measurements and identification of sources containing lead are urgently needed there.

Improved recycling methods

Dr. Böse-O’Reilly would like an increased focus on children. “If children’s cognitive skills are lost, this of course has a long-term effect on a country’s economic position,” he said. “Precisely that which LMICs actually need for their development is being stripped from them.

“We should think long and hard about whether we really need to send so much of our electrical waste and so many old cars to poorer countries, where they are incorrectly recycled,” he warned. “We should at least give the LMICs the support necessary for them to be able to process lead-containing products in the future so that less lead makes it into the environment.

“Through these global cycles, we all contribute a lot toward the worldwide lead burden,” Dr. Böse-O’Reilly said. “In my opinion, the German Supply Chain Act is therefore definitely sensible. Not only does it protect our own economy, but it also protects the health of people in other countries.”

This article was translated from Medscape’s German Edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

in a presentation to the World Bank. Their work was published in The Lancet Planetary Health.

As Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana report, the economic consequences of increased exposure to lead are already immense, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). The study was financed by the Korea Green Growth Trust Fund and the World Bank’s Pollution Management and Environmental Health Program.

Intellectual, cardiovascular effects

“It is a very important publication that affects all of us,” pediatrician Stephan Böse-O’Reilly, MD, of the Institute and Polyclinic for Occupational, Social, and Environmental Health at Ludwig Maximilian University Hospital in Munich, Germany, said in an interview. “The study, the results of which I think are very reliable, shows that elevated levels of lead in the blood have a much more drastic effect on children’s intelligence than we previously thought.”

It is well known that lead affects the antenatal and postnatal cognitive development of children, Dr. Böse-O’Reilly explained. But the extent of this effect has quite clearly been underestimated before now.

On the other hand, Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana’s work could prove that lead may lead to more cardiovascular diseases in adulthood. “We already knew that increased exposure to lead increased the risk of high blood pressure and, as a result, mortality,” said Dr. Böse-O’Reilly. “This study now very clearly shows that the risk of arteriosclerosis, for example, also increases through lead exposure.”

Figures from 2019

“For the first time, to our knowledge, we aimed to estimate the global burden and cost of IQ loss and cardiovascular disease mortality from lead exposure,” wrote Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana. For their calculations, the scientists used blood lead level estimates from the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2019.

They estimated IQ loss in children younger than 5 years using the internationally recognized blood lead level–IQ loss function. The researchers subsequently estimated the cost of this IQ loss based on the loss in lifetime income, presented as cost in U.S. dollars and percentage of gross domestic product (GDP).

Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana estimated cardiovascular deaths caused by lead exposure in adults aged 25 years or older using a model that captures the effects of lead exposure on cardiovascular disease mortality that is mediated through mechanisms other than hypertension.

Finally, they used the statistical life expectancy to estimate the welfare cost of premature mortality, also presented as cost in U.S. dollars and percentage of GDP. All estimates were calculated according to the World Bank income classification for 2019.

Millions of deaths

As reported by Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana, children younger than 5 years lost an estimated 765 million IQ points worldwide because of lead exposure in this period. In 2019, 5,545,000 adults died from cardiovascular diseases caused by lead exposure. The scientists recorded 729 million of the IQ points lost (95.3%) and 5,004,000 (90.2%) of the deaths as occurring in LMICs.

The IQ loss here was nearly 80% higher than a previous estimate, wrote Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana. The number of cardiovascular disease deaths they determined was six times higher than the GBD 2019 estimate.

“These are results with which the expert societies, especially the German Society of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine and the German Cardiac Society, and the corresponding professional associations need to concern themselves,” said Dr. Böse-O’Reilly.

Although blood lead concentrations have declined substantially since the phase-out of leaded gasoline, especially in Western countries, lead still represents a major health issue because it stays in the bones for decades.

European situation moderate

“We need a broad discussion on questions such as whether lead levels should be included in prophylactic assessments in certain age groups, what blood level is even tolerable, and in what situation medicinal therapy with chelating agents would possibly be appropriate,” said Dr. Böse-O’Reilly.

“Of course, we cannot answer these questions on the basis of one individual study,” he added. “However, the work in question definitely illustrates how dangerous lead can be and that we need further research into the actual burden and the best preventive measures.”

In this respect, the situation in Europe is still comparatively moderate. “Globally, lead exposure has risen in recent years,” said Dr. Böse-O’Reilly. According to an investigation by the Planet Earth Foundation, outside of the European Union, lead can increasingly be found in toys, spices, and cooking utensils, for example.

“Especially in lower-income countries, there is a lack of consumer protection or a good monitoring program like we have here in the EU,” said Dr. Böse-O’Reilly. In these countries, lead is sometimes added to spices by unscrupulous retailers to make the color more intense or to simply add to its weight to gain more profit.

Recycling lead-acid batteries or other electrical waste, often transferred to poorer countries, constitutes a large problem. “In general, children in Germany have a blood lead level of less than 1 mcg/dL,” explained Dr. Böse-O’Reilly. “In some regions of Indonesia, where these recycling factories are located, more than 50% of children have levels of more than 20 mcg/dL.”

Particulate matter

According to Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana, the global cost of increased lead exposure was around $6 trillion USD in 2019, which was equivalent to 6.9% of global GDP. About 77% of the cost ($4.62 trillion USD) comprised the welfare costs of cardiovascular disease mortality, and 23% ($1.38 trillion USD) comprised the present value of future income losses because of IQ loss in children.

“Our findings suggest that global lead exposure has health and economic costs on par with PM2.5 air pollution,” wrote the authors. This places lead as an environmental risk factor on par with particulate matter and above that of air pollution from solid fuels, ahead of unsafe drinking water, unhygienic sanitation, or insufficient handwashing.

“This finding is in contrast to that of GBD 2019, which ranked lead exposure as a distant fourth environmental risk factor, due to not accounting for IQ loss in children – other than idiopathic developmental intellectual disability in a small subset of children – and reporting a substantially lower estimate of adult cardiovascular disease mortality,” wrote Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana.

“A central implication for future research and policy is that LMICs bear an extraordinarily large share of the health and cost burden of lead exposure,” wrote the authors. Consequently, improved quality of blood lead level measurements and identification of sources containing lead are urgently needed there.

Improved recycling methods

Dr. Böse-O’Reilly would like an increased focus on children. “If children’s cognitive skills are lost, this of course has a long-term effect on a country’s economic position,” he said. “Precisely that which LMICs actually need for their development is being stripped from them.

“We should think long and hard about whether we really need to send so much of our electrical waste and so many old cars to poorer countries, where they are incorrectly recycled,” he warned. “We should at least give the LMICs the support necessary for them to be able to process lead-containing products in the future so that less lead makes it into the environment.

“Through these global cycles, we all contribute a lot toward the worldwide lead burden,” Dr. Böse-O’Reilly said. “In my opinion, the German Supply Chain Act is therefore definitely sensible. Not only does it protect our own economy, but it also protects the health of people in other countries.”

This article was translated from Medscape’s German Edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

in a presentation to the World Bank. Their work was published in The Lancet Planetary Health.

As Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana report, the economic consequences of increased exposure to lead are already immense, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). The study was financed by the Korea Green Growth Trust Fund and the World Bank’s Pollution Management and Environmental Health Program.

Intellectual, cardiovascular effects

“It is a very important publication that affects all of us,” pediatrician Stephan Böse-O’Reilly, MD, of the Institute and Polyclinic for Occupational, Social, and Environmental Health at Ludwig Maximilian University Hospital in Munich, Germany, said in an interview. “The study, the results of which I think are very reliable, shows that elevated levels of lead in the blood have a much more drastic effect on children’s intelligence than we previously thought.”

It is well known that lead affects the antenatal and postnatal cognitive development of children, Dr. Böse-O’Reilly explained. But the extent of this effect has quite clearly been underestimated before now.

On the other hand, Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana’s work could prove that lead may lead to more cardiovascular diseases in adulthood. “We already knew that increased exposure to lead increased the risk of high blood pressure and, as a result, mortality,” said Dr. Böse-O’Reilly. “This study now very clearly shows that the risk of arteriosclerosis, for example, also increases through lead exposure.”

Figures from 2019

“For the first time, to our knowledge, we aimed to estimate the global burden and cost of IQ loss and cardiovascular disease mortality from lead exposure,” wrote Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana. For their calculations, the scientists used blood lead level estimates from the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2019.

They estimated IQ loss in children younger than 5 years using the internationally recognized blood lead level–IQ loss function. The researchers subsequently estimated the cost of this IQ loss based on the loss in lifetime income, presented as cost in U.S. dollars and percentage of gross domestic product (GDP).

Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana estimated cardiovascular deaths caused by lead exposure in adults aged 25 years or older using a model that captures the effects of lead exposure on cardiovascular disease mortality that is mediated through mechanisms other than hypertension.

Finally, they used the statistical life expectancy to estimate the welfare cost of premature mortality, also presented as cost in U.S. dollars and percentage of GDP. All estimates were calculated according to the World Bank income classification for 2019.

Millions of deaths

As reported by Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana, children younger than 5 years lost an estimated 765 million IQ points worldwide because of lead exposure in this period. In 2019, 5,545,000 adults died from cardiovascular diseases caused by lead exposure. The scientists recorded 729 million of the IQ points lost (95.3%) and 5,004,000 (90.2%) of the deaths as occurring in LMICs.

The IQ loss here was nearly 80% higher than a previous estimate, wrote Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana. The number of cardiovascular disease deaths they determined was six times higher than the GBD 2019 estimate.

“These are results with which the expert societies, especially the German Society of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine and the German Cardiac Society, and the corresponding professional associations need to concern themselves,” said Dr. Böse-O’Reilly.

Although blood lead concentrations have declined substantially since the phase-out of leaded gasoline, especially in Western countries, lead still represents a major health issue because it stays in the bones for decades.

European situation moderate

“We need a broad discussion on questions such as whether lead levels should be included in prophylactic assessments in certain age groups, what blood level is even tolerable, and in what situation medicinal therapy with chelating agents would possibly be appropriate,” said Dr. Böse-O’Reilly.

“Of course, we cannot answer these questions on the basis of one individual study,” he added. “However, the work in question definitely illustrates how dangerous lead can be and that we need further research into the actual burden and the best preventive measures.”

In this respect, the situation in Europe is still comparatively moderate. “Globally, lead exposure has risen in recent years,” said Dr. Böse-O’Reilly. According to an investigation by the Planet Earth Foundation, outside of the European Union, lead can increasingly be found in toys, spices, and cooking utensils, for example.

“Especially in lower-income countries, there is a lack of consumer protection or a good monitoring program like we have here in the EU,” said Dr. Böse-O’Reilly. In these countries, lead is sometimes added to spices by unscrupulous retailers to make the color more intense or to simply add to its weight to gain more profit.

Recycling lead-acid batteries or other electrical waste, often transferred to poorer countries, constitutes a large problem. “In general, children in Germany have a blood lead level of less than 1 mcg/dL,” explained Dr. Böse-O’Reilly. “In some regions of Indonesia, where these recycling factories are located, more than 50% of children have levels of more than 20 mcg/dL.”

Particulate matter

According to Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana, the global cost of increased lead exposure was around $6 trillion USD in 2019, which was equivalent to 6.9% of global GDP. About 77% of the cost ($4.62 trillion USD) comprised the welfare costs of cardiovascular disease mortality, and 23% ($1.38 trillion USD) comprised the present value of future income losses because of IQ loss in children.

“Our findings suggest that global lead exposure has health and economic costs on par with PM2.5 air pollution,” wrote the authors. This places lead as an environmental risk factor on par with particulate matter and above that of air pollution from solid fuels, ahead of unsafe drinking water, unhygienic sanitation, or insufficient handwashing.

“This finding is in contrast to that of GBD 2019, which ranked lead exposure as a distant fourth environmental risk factor, due to not accounting for IQ loss in children – other than idiopathic developmental intellectual disability in a small subset of children – and reporting a substantially lower estimate of adult cardiovascular disease mortality,” wrote Mr. Larsen and Mr. Sánchez-Triana.

“A central implication for future research and policy is that LMICs bear an extraordinarily large share of the health and cost burden of lead exposure,” wrote the authors. Consequently, improved quality of blood lead level measurements and identification of sources containing lead are urgently needed there.

Improved recycling methods

Dr. Böse-O’Reilly would like an increased focus on children. “If children’s cognitive skills are lost, this of course has a long-term effect on a country’s economic position,” he said. “Precisely that which LMICs actually need for their development is being stripped from them.

“We should think long and hard about whether we really need to send so much of our electrical waste and so many old cars to poorer countries, where they are incorrectly recycled,” he warned. “We should at least give the LMICs the support necessary for them to be able to process lead-containing products in the future so that less lead makes it into the environment.

“Through these global cycles, we all contribute a lot toward the worldwide lead burden,” Dr. Böse-O’Reilly said. “In my opinion, the German Supply Chain Act is therefore definitely sensible. Not only does it protect our own economy, but it also protects the health of people in other countries.”

This article was translated from Medscape’s German Edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE LANCET PLANETARY HEALTH

Depression tied to higher all-cause and cardiovascular mortality

In a large prospective study, a graded higher risk of all-cause mortality and mortality from cardiovascular disease (CVD) and ischemic heart disease (IHD) emerged in adults with moderate to severe depressive symptoms, compared with those with no such symptoms.

Participants with mild depressive symptoms had a 35%-49% higher risk of all-cause and CVD mortality, respectively, while for those with moderate to severe depressive symptoms, the risk of all-cause, CVD, and IHD mortality was 62%, 79%, and 121% higher, respectively.

“This information highlights the importance for clinicians to identify patients with depressive symptoms and help them engage in treatment,” lead author Zefeng Zhang, MD, PhD, of the division for heart disease and stroke prevention at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, said in an interview.

The study appears in JAMA Network Open.

A nonclassic risk factor for CVD death

This graded positive association between depressive symptoms and CVD death was observed in data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005-2018, which were linked with the National Death Index through 2019 for adults aged 20 and older. Data analysis occurred from March 1 to May 26, 2023. According to the authors, their analyses extend findings from previous research by assessing these associations in a large, diverse, and nationally representative sample. Using more nuanced CVD-related causes of death, depressive symptoms emerged as a nontraditional risk factor for CVD mortality.

The study

In a total cohort of 23,694, about half male, mean overall age 44.7 years, prevalences of mild and moderate to severe depression were 14.9% and 7.2%, respectively, with depressive symptoms assessed by the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire asking about symptoms over the past 2 weeks.

Adults with depression had significantly lower CV health scores in six of the American Heart Association Life’s Essential 8 metrics for heart health. For all-cause mortality, hazard ratios were 1.35 (95% confidence interval, 1.07-1.72) for mild depressive symptoms vs. none and 1.62 (95% CI, 1.24-2.12) for moderate to severe depressive symptoms vs. none.

The corresponding hazard ratios were 1.49 (95% CI, 1.11-2.0) and 1.79 (95% CI,1.22-2.62) for CVD mortality and 0.96 (95% CI, 0.58-1.60) and 2.21 (95% CI, 1.24-3.91) for IHD death, with associations largely consistent across subgroups.

At the highest severity of depressive symptoms (almost daily for past 2 weeks), feeling tired or having little energy, poor appetite or overeating, and having little interest in doing things were significantly associated with all-cause and CVD mortality after adjusting for potential confounders.

Approximately 11%-16% of the positive associations could be explained by lifestyle factors such as excess alcohol consumption, overeating, and inactivity as per the AHA’s Life’s Essential 8 metrics.

“Taken together with the body of literature on associations between depression and CVD mortality, these findings can support public health efforts to develop a comprehensive, nationwide strategy to improve well-being, including both mental and cardiovascular health,” Dr. Zhang and associates wrote.

This research was funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

In a large prospective study, a graded higher risk of all-cause mortality and mortality from cardiovascular disease (CVD) and ischemic heart disease (IHD) emerged in adults with moderate to severe depressive symptoms, compared with those with no such symptoms.

Participants with mild depressive symptoms had a 35%-49% higher risk of all-cause and CVD mortality, respectively, while for those with moderate to severe depressive symptoms, the risk of all-cause, CVD, and IHD mortality was 62%, 79%, and 121% higher, respectively.

“This information highlights the importance for clinicians to identify patients with depressive symptoms and help them engage in treatment,” lead author Zefeng Zhang, MD, PhD, of the division for heart disease and stroke prevention at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, said in an interview.

The study appears in JAMA Network Open.

A nonclassic risk factor for CVD death

This graded positive association between depressive symptoms and CVD death was observed in data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005-2018, which were linked with the National Death Index through 2019 for adults aged 20 and older. Data analysis occurred from March 1 to May 26, 2023. According to the authors, their analyses extend findings from previous research by assessing these associations in a large, diverse, and nationally representative sample. Using more nuanced CVD-related causes of death, depressive symptoms emerged as a nontraditional risk factor for CVD mortality.

The study

In a total cohort of 23,694, about half male, mean overall age 44.7 years, prevalences of mild and moderate to severe depression were 14.9% and 7.2%, respectively, with depressive symptoms assessed by the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire asking about symptoms over the past 2 weeks.

Adults with depression had significantly lower CV health scores in six of the American Heart Association Life’s Essential 8 metrics for heart health. For all-cause mortality, hazard ratios were 1.35 (95% confidence interval, 1.07-1.72) for mild depressive symptoms vs. none and 1.62 (95% CI, 1.24-2.12) for moderate to severe depressive symptoms vs. none.

The corresponding hazard ratios were 1.49 (95% CI, 1.11-2.0) and 1.79 (95% CI,1.22-2.62) for CVD mortality and 0.96 (95% CI, 0.58-1.60) and 2.21 (95% CI, 1.24-3.91) for IHD death, with associations largely consistent across subgroups.

At the highest severity of depressive symptoms (almost daily for past 2 weeks), feeling tired or having little energy, poor appetite or overeating, and having little interest in doing things were significantly associated with all-cause and CVD mortality after adjusting for potential confounders.

Approximately 11%-16% of the positive associations could be explained by lifestyle factors such as excess alcohol consumption, overeating, and inactivity as per the AHA’s Life’s Essential 8 metrics.

“Taken together with the body of literature on associations between depression and CVD mortality, these findings can support public health efforts to develop a comprehensive, nationwide strategy to improve well-being, including both mental and cardiovascular health,” Dr. Zhang and associates wrote.