User login

Cardiology News is an independent news source that provides cardiologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on cardiology and the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is the online destination and multimedia properties of Cardiology News, the independent news publication for cardiologists. Cardiology news is the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in cardiology as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

Early or delayed AFib ablation after heart failure hospitalization?

TOPLINE:

Among patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) hospitalized for worsening heart failure (HF), catheter (cath) ablation within 90 days of admission, compared with other times, is associated with reduced risk for all-cause mortality and HF-related mortality.

METHODOLOGY:

Cath ablation has become technically safer for patients with both AFib and HF, but the best timing for the ablation procedure after HF hospitalization has been unclear.

The study included 2,786 patients with HF who underwent cath ablation for AFib at 128 centers in the nationwide Japanese Registry of Acute Decompensated Heart Failure, were hospitalized with worsening HF, and survived at least 90 days after discharge.

The population included 103 individuals who underwent cath ablation within 90 days after admission; the remaining 2,683 participants served as the control group.

The researchers also looked at all-cause mortality 90 days after admission for HF in analysis of 83 early-ablation cases vs. 83 propensity-matched controls.

TAKEAWAY:

The early–cath ablation group was younger, predominantly male, had less history of prior HF hospitalizations, and greater incidence of paroxysmal AF, compared with the control group.

All-cause mortality was significantly lower in the early–cath ablation group than in the control group (hazard ratio, 0.38; 95% confidence interval, 0.24-0.60; P < .001) over a median of 4.1 years.

Risk reductions were similarly significant for secondary endpoints, including cardiovascular (CV) mortality and HF mortality.

In the matched cohort analysis (83 in both groups) all-cause mortality was significantly reduced for those in the early–cath ablation group, compared with the matched controls (HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.25-0.88; P = .014), with similarly significant risk reductions for CV mortality and HF mortality.

IN PRACTICE:

the report states. Early catheter ablation, as early as during the hospitalization for HF, “might be a way to stabilize HF and solve the problems associated with long hospitalization periods and polypharmacy.”

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Kazuo Sakamoto, MD, PhD, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan, and colleagues. It was published online July 19, 2023 in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

LIMITATIONS:

The early-ablation cohort was much smaller than the control group, and the analysis could not adjust for any variation in institutional characteristics, such as location and available equipment. Other unmeasured potential confounders include duration of AFib and patient lifestyle characteristics and success or failure of ablation.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Johnson & Johnson, the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, and Ministry of Health and Labor. Dr. Sakamoto reports no relevant conflicts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Among patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) hospitalized for worsening heart failure (HF), catheter (cath) ablation within 90 days of admission, compared with other times, is associated with reduced risk for all-cause mortality and HF-related mortality.

METHODOLOGY:

Cath ablation has become technically safer for patients with both AFib and HF, but the best timing for the ablation procedure after HF hospitalization has been unclear.

The study included 2,786 patients with HF who underwent cath ablation for AFib at 128 centers in the nationwide Japanese Registry of Acute Decompensated Heart Failure, were hospitalized with worsening HF, and survived at least 90 days after discharge.

The population included 103 individuals who underwent cath ablation within 90 days after admission; the remaining 2,683 participants served as the control group.

The researchers also looked at all-cause mortality 90 days after admission for HF in analysis of 83 early-ablation cases vs. 83 propensity-matched controls.

TAKEAWAY:

The early–cath ablation group was younger, predominantly male, had less history of prior HF hospitalizations, and greater incidence of paroxysmal AF, compared with the control group.

All-cause mortality was significantly lower in the early–cath ablation group than in the control group (hazard ratio, 0.38; 95% confidence interval, 0.24-0.60; P < .001) over a median of 4.1 years.

Risk reductions were similarly significant for secondary endpoints, including cardiovascular (CV) mortality and HF mortality.

In the matched cohort analysis (83 in both groups) all-cause mortality was significantly reduced for those in the early–cath ablation group, compared with the matched controls (HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.25-0.88; P = .014), with similarly significant risk reductions for CV mortality and HF mortality.

IN PRACTICE:

the report states. Early catheter ablation, as early as during the hospitalization for HF, “might be a way to stabilize HF and solve the problems associated with long hospitalization periods and polypharmacy.”

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Kazuo Sakamoto, MD, PhD, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan, and colleagues. It was published online July 19, 2023 in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

LIMITATIONS:

The early-ablation cohort was much smaller than the control group, and the analysis could not adjust for any variation in institutional characteristics, such as location and available equipment. Other unmeasured potential confounders include duration of AFib and patient lifestyle characteristics and success or failure of ablation.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Johnson & Johnson, the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, and Ministry of Health and Labor. Dr. Sakamoto reports no relevant conflicts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Among patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) hospitalized for worsening heart failure (HF), catheter (cath) ablation within 90 days of admission, compared with other times, is associated with reduced risk for all-cause mortality and HF-related mortality.

METHODOLOGY:

Cath ablation has become technically safer for patients with both AFib and HF, but the best timing for the ablation procedure after HF hospitalization has been unclear.

The study included 2,786 patients with HF who underwent cath ablation for AFib at 128 centers in the nationwide Japanese Registry of Acute Decompensated Heart Failure, were hospitalized with worsening HF, and survived at least 90 days after discharge.

The population included 103 individuals who underwent cath ablation within 90 days after admission; the remaining 2,683 participants served as the control group.

The researchers also looked at all-cause mortality 90 days after admission for HF in analysis of 83 early-ablation cases vs. 83 propensity-matched controls.

TAKEAWAY:

The early–cath ablation group was younger, predominantly male, had less history of prior HF hospitalizations, and greater incidence of paroxysmal AF, compared with the control group.

All-cause mortality was significantly lower in the early–cath ablation group than in the control group (hazard ratio, 0.38; 95% confidence interval, 0.24-0.60; P < .001) over a median of 4.1 years.

Risk reductions were similarly significant for secondary endpoints, including cardiovascular (CV) mortality and HF mortality.

In the matched cohort analysis (83 in both groups) all-cause mortality was significantly reduced for those in the early–cath ablation group, compared with the matched controls (HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.25-0.88; P = .014), with similarly significant risk reductions for CV mortality and HF mortality.

IN PRACTICE:

the report states. Early catheter ablation, as early as during the hospitalization for HF, “might be a way to stabilize HF and solve the problems associated with long hospitalization periods and polypharmacy.”

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Kazuo Sakamoto, MD, PhD, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan, and colleagues. It was published online July 19, 2023 in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

LIMITATIONS:

The early-ablation cohort was much smaller than the control group, and the analysis could not adjust for any variation in institutional characteristics, such as location and available equipment. Other unmeasured potential confounders include duration of AFib and patient lifestyle characteristics and success or failure of ablation.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Johnson & Johnson, the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, and Ministry of Health and Labor. Dr. Sakamoto reports no relevant conflicts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JACC: CLINICAL ELECTROPHYSIOLOGY

Time to end direct-to-consumer ads, says physician

One has to be living off the grid to not be bombarded with direct-to-consumer (DTC) pharmaceutical advertising. Since 1997, when the Food and Drug Administration eased restrictions on this prohibition and allowed pharmaceutical companies to promote prescription-only medications to the public, there has been a deluge of ads in magazines, on the Internet, and, most annoying, on commercial television.

These television ads are quite formulaic:

We are initially introduced to a number of highly functioning patients (typically actors) who are engaged in rewarding pursuits. A voiceover narration then presents the pharmaceutical to be promoted, suggesting (not so subtly) to consumers that taking the advertised drug will improve one’s disease outlook or quality of life such that they too, just like the actors in the minidrama, can lead such highly productive lives.

The potential best-case scenarios of these new treatments may be stated. There then follows a litany of side effects – some of them life threatening – warnings, and contraindications. We’re again treated to another 5 or 10 seconds of patients leading “the good life,” and almost all of the ads end with the narrator concluding: “Ask your doctor (sometimes ‘provider’) if _____ is right for you.”

Americans spend more money on their prescriptions than do citizens of any other highly developed nation. I have personally heard from patients who get their prescriptions from other countries, where they are more affordable. These patients will also cut their pills in half or take a medication every other day instead of every day, to economize on drug costs.

Another “trick” they use to save money – and I have heard pharmacists and pharmaceutical reps themselves recommend this – is to ask for a higher dose of a medication, usually double, and then use a pill cutter to divide a tablet in half, thus making their prescription last twice as long. Why do Americans have to resort to such “workarounds”?

Many of the medications advertised are for relatively rare conditions, such as thyroid eye disease or myasthenia gravis (which affects up to about 60,000 patients in the United States). Why not spend these advertising dollars on programs to make drugs taken by the millions of Americans with common conditions (for example, hypertension, diabetes, heart failure) more affordable?

Very often the television ads contain medical jargon, such as: “If you have the EGFR mutation, or if your cancer is HER2 negative ...”

Do most patients truly understand what these terms mean? And what happens when a patient’s physician doesn’t prescribe a medication that a patient has seen on TV and asks for, or when the physician believes that a generic (nonadvertised) medication might work just as well? This creates conflict and potential discord, adversely affecting the doctor-patient relationship.

An oncologist colleague related to me that he often has to spend time correcting patients’ misperceptions of potential miracle cures offered by these ads, and that several patients have left his practice because he would not prescribe a drug they saw advertised.

Further, while these ads urge patients to try expensive “newest and latest” treatments, pharmacy benefit plans are working with health care insurance conglomerates to reduce costs of pharmaceuticals.

How does this juxtaposition of opposing forces make any sense?

It is time for us to put an end to DTC advertising, at least on television. It will require legislative action by our federal government to end this practice (legal, by the way, only in the United States and New Zealand), and hence the willingness of our politicians to get behind legislation to do so.

Just as a law was passed to prohibit tobacco advertising on television, so should a law be passed to regulate DTC pharmaceutical advertising.

The time to end DTC advertising has come!

Lloyd Alterman, MD, is a retired physician and chairman of the New Jersey Universal Healthcare Coalition. He disclosed having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One has to be living off the grid to not be bombarded with direct-to-consumer (DTC) pharmaceutical advertising. Since 1997, when the Food and Drug Administration eased restrictions on this prohibition and allowed pharmaceutical companies to promote prescription-only medications to the public, there has been a deluge of ads in magazines, on the Internet, and, most annoying, on commercial television.

These television ads are quite formulaic:

We are initially introduced to a number of highly functioning patients (typically actors) who are engaged in rewarding pursuits. A voiceover narration then presents the pharmaceutical to be promoted, suggesting (not so subtly) to consumers that taking the advertised drug will improve one’s disease outlook or quality of life such that they too, just like the actors in the minidrama, can lead such highly productive lives.

The potential best-case scenarios of these new treatments may be stated. There then follows a litany of side effects – some of them life threatening – warnings, and contraindications. We’re again treated to another 5 or 10 seconds of patients leading “the good life,” and almost all of the ads end with the narrator concluding: “Ask your doctor (sometimes ‘provider’) if _____ is right for you.”

Americans spend more money on their prescriptions than do citizens of any other highly developed nation. I have personally heard from patients who get their prescriptions from other countries, where they are more affordable. These patients will also cut their pills in half or take a medication every other day instead of every day, to economize on drug costs.

Another “trick” they use to save money – and I have heard pharmacists and pharmaceutical reps themselves recommend this – is to ask for a higher dose of a medication, usually double, and then use a pill cutter to divide a tablet in half, thus making their prescription last twice as long. Why do Americans have to resort to such “workarounds”?

Many of the medications advertised are for relatively rare conditions, such as thyroid eye disease or myasthenia gravis (which affects up to about 60,000 patients in the United States). Why not spend these advertising dollars on programs to make drugs taken by the millions of Americans with common conditions (for example, hypertension, diabetes, heart failure) more affordable?

Very often the television ads contain medical jargon, such as: “If you have the EGFR mutation, or if your cancer is HER2 negative ...”

Do most patients truly understand what these terms mean? And what happens when a patient’s physician doesn’t prescribe a medication that a patient has seen on TV and asks for, or when the physician believes that a generic (nonadvertised) medication might work just as well? This creates conflict and potential discord, adversely affecting the doctor-patient relationship.

An oncologist colleague related to me that he often has to spend time correcting patients’ misperceptions of potential miracle cures offered by these ads, and that several patients have left his practice because he would not prescribe a drug they saw advertised.

Further, while these ads urge patients to try expensive “newest and latest” treatments, pharmacy benefit plans are working with health care insurance conglomerates to reduce costs of pharmaceuticals.

How does this juxtaposition of opposing forces make any sense?

It is time for us to put an end to DTC advertising, at least on television. It will require legislative action by our federal government to end this practice (legal, by the way, only in the United States and New Zealand), and hence the willingness of our politicians to get behind legislation to do so.

Just as a law was passed to prohibit tobacco advertising on television, so should a law be passed to regulate DTC pharmaceutical advertising.

The time to end DTC advertising has come!

Lloyd Alterman, MD, is a retired physician and chairman of the New Jersey Universal Healthcare Coalition. He disclosed having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One has to be living off the grid to not be bombarded with direct-to-consumer (DTC) pharmaceutical advertising. Since 1997, when the Food and Drug Administration eased restrictions on this prohibition and allowed pharmaceutical companies to promote prescription-only medications to the public, there has been a deluge of ads in magazines, on the Internet, and, most annoying, on commercial television.

These television ads are quite formulaic:

We are initially introduced to a number of highly functioning patients (typically actors) who are engaged in rewarding pursuits. A voiceover narration then presents the pharmaceutical to be promoted, suggesting (not so subtly) to consumers that taking the advertised drug will improve one’s disease outlook or quality of life such that they too, just like the actors in the minidrama, can lead such highly productive lives.

The potential best-case scenarios of these new treatments may be stated. There then follows a litany of side effects – some of them life threatening – warnings, and contraindications. We’re again treated to another 5 or 10 seconds of patients leading “the good life,” and almost all of the ads end with the narrator concluding: “Ask your doctor (sometimes ‘provider’) if _____ is right for you.”

Americans spend more money on their prescriptions than do citizens of any other highly developed nation. I have personally heard from patients who get their prescriptions from other countries, where they are more affordable. These patients will also cut their pills in half or take a medication every other day instead of every day, to economize on drug costs.

Another “trick” they use to save money – and I have heard pharmacists and pharmaceutical reps themselves recommend this – is to ask for a higher dose of a medication, usually double, and then use a pill cutter to divide a tablet in half, thus making their prescription last twice as long. Why do Americans have to resort to such “workarounds”?

Many of the medications advertised are for relatively rare conditions, such as thyroid eye disease or myasthenia gravis (which affects up to about 60,000 patients in the United States). Why not spend these advertising dollars on programs to make drugs taken by the millions of Americans with common conditions (for example, hypertension, diabetes, heart failure) more affordable?

Very often the television ads contain medical jargon, such as: “If you have the EGFR mutation, or if your cancer is HER2 negative ...”

Do most patients truly understand what these terms mean? And what happens when a patient’s physician doesn’t prescribe a medication that a patient has seen on TV and asks for, or when the physician believes that a generic (nonadvertised) medication might work just as well? This creates conflict and potential discord, adversely affecting the doctor-patient relationship.

An oncologist colleague related to me that he often has to spend time correcting patients’ misperceptions of potential miracle cures offered by these ads, and that several patients have left his practice because he would not prescribe a drug they saw advertised.

Further, while these ads urge patients to try expensive “newest and latest” treatments, pharmacy benefit plans are working with health care insurance conglomerates to reduce costs of pharmaceuticals.

How does this juxtaposition of opposing forces make any sense?

It is time for us to put an end to DTC advertising, at least on television. It will require legislative action by our federal government to end this practice (legal, by the way, only in the United States and New Zealand), and hence the willingness of our politicians to get behind legislation to do so.

Just as a law was passed to prohibit tobacco advertising on television, so should a law be passed to regulate DTC pharmaceutical advertising.

The time to end DTC advertising has come!

Lloyd Alterman, MD, is a retired physician and chairman of the New Jersey Universal Healthcare Coalition. He disclosed having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Daily statin cuts cardiovascular risk in HIV

BRISBANE, AUSTRALIA – that show pitavastatin therapy is associated with a significantly lower risk of cardiovascular events than placebo.

“There was a significant 35% lower risk of major adverse cardiovascular events after a median follow-up of 5.1 years “ said Steven Grinspoon, MD, from Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, who presented the final analysis of data from the REPRIEVE trial at the International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science.

The results were simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine. The primary endpoint of major adverse cardiovascular events included a composite of outcomes that included cardiovascular death, stroke, myocardial infarction, hospitalization for unstable angina, and transient ischemic attack among those treated with pitavastatin, compared with placebo (95% confidence interval, 0.48-0.90; P = .002).

The REPRIEVE trial was halted earlier this year for efficacy after an interim analysis pointed to a significantly lower rate of cardiovascular events in the treatment group.

The international double-blind, placebo-controlled trial randomly assigned 7,769 people with HIV infection, who were at low to moderate risk of cardiovascular disease, to either 4 mg daily of pitavastatin calcium or placebo.

The secondary outcome – a composite of major cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality – also showed a significant 21% reduction in risk with pitavastatin treatment, compared with placebo (95% CI, 0.65-0.96).

Cardiovascular events in HIV

HIV infection is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, Dr. Grinspoon pointed out, and those living with HIV have about double the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke, compared with the general population.

“There’s an unmet need for people living with HIV who have low to moderate traditional risk, for whom HIV is even considered a risk equivalent but for whom no primary prevention strategy has been tested in a large trial,” Dr. Grinspoon said during an interview.

Those enrolled in the study had a 10-year Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease risk score ranging from 2.1% to 7%, with a median of 4.5%. While LDL cholesterol levels at baseline ranged from 87 to 128 mg/dL, the study showed a similar reduction in cardiovascular risk regardless of LDL.

“These are types of people who, if they came to the doctor’s office right now before REPRIEVE, they would largely be told your risk score is not really making you eligible for a statin,” Dr. Grinspoon said.

He explained that what is most interesting about the reduction in risk is that it was nearly twice what would be expected with LDL lowering, based on what has previously been seen in statin trials in non–HIV-positive populations.

“I think the data are suggesting that it’s certainly in part due to the reduction in LDL – that is very important – but it’s also due to other factors beyond changes in LDL,” Dr. Grinspoon said. He speculated that the statin could be affecting anti-inflammatory and immune pathways, and that this could account for some of the reduction in cardiovascular risk, but “those data are cooking, and they’re being analyzed as we speak.”

In a substudy analysis of REPRIEVE, Markella Zanni, MD, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, focused on the women in the clinical trial.

Women’s risk

In REPRIEVE, 31.1% of the study population were women. Dr. Zanni and her team investigated whether there are differences in the way HIV affects the risk of developing atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in women, compared with men.

They found that women have both higher levels of inflammatory markers, such as interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and D-dimer, but a lower prevalence of coronary artery plaques than men.

“This finding represents an interesting paradox given that high levels of select inflammatory markers have been associated with coronary artery plaque, both among women living with HIV and among men living with HIV,” Dr. Zanni explained.

She says the researchers were hoping to further explore whether inflammation is fueling the increased risk for atherosclerotic disease, and particularly the higher risk evident in women living with HIV, compared with men.

“Women living with HIV should discuss with their treating clinicians heart risks and possible prevention strategies, including statin therapy coupled with healthy lifestyle changes addressing modifiable, traditional metabolic risk factors” she said.

Time for primary prevention?

All patients in the study were on antiretroviral therapy and investigators report that pitavastatin does not interact with these medications. The median CD4 cell count was 621 cells/mm3, and 87.5% of participants had an HIV viral load below the lower limit of quantification.

Participants were enrolled from 12 countries including the United States, Spain, Brazil, South Africa, and Thailand, and around two-thirds were non-White. Individuals of South Asian ethnicity showed the biggest reduction in cardiovascular risk with pitavastatin treatment.

There was a 74% higher rate of muscle pain and weakness in the pitavastatin group – affecting 91 people in the treatment arm and 53 in the placebo arm – but the majority were low grade. The rate of rhabdomyolysis of grade 3 or above was lower in the statin group, with three cases, compared with four cases in the placebo group.

Commenting on the findings, Laura Waters, MD, a genitourinary and HIV medicine consultant at Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust’s Mortimer Market Centre, said that, while HIV infection was considered a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, risk calculators don’t specifically adjust for HIV infection.

“Now that we’ve got effective HIV drugs and people can enjoy normal life expectancy, cardiovascular disease is a particular issue for people with HIV,” she said.

Dr. Waters, who was not involved with the study, suggested that people living with HIV should discuss the use of statins with their doctor, but she acknowledged there are some barriers to treatment in people living with HIV. “It’s another pill, and when it’s a borderline [decision] it is easy to say, ‘I have to think about it,’ ” she said, with the result that statin treatment is often deferred.

The REPRIEVE study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, Kowa Pharmaceuticals America, Gilead Sciences, and ViiV Healthcare. Dr. Grinspoon declared institutional grants from National Institutes of Health, Kowa Pharmaceuticals America, Gilead Sciences, and ViiV Healthcare and consultancies unrelated to the study. Dr. Zanni reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

BRISBANE, AUSTRALIA – that show pitavastatin therapy is associated with a significantly lower risk of cardiovascular events than placebo.

“There was a significant 35% lower risk of major adverse cardiovascular events after a median follow-up of 5.1 years “ said Steven Grinspoon, MD, from Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, who presented the final analysis of data from the REPRIEVE trial at the International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science.

The results were simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine. The primary endpoint of major adverse cardiovascular events included a composite of outcomes that included cardiovascular death, stroke, myocardial infarction, hospitalization for unstable angina, and transient ischemic attack among those treated with pitavastatin, compared with placebo (95% confidence interval, 0.48-0.90; P = .002).

The REPRIEVE trial was halted earlier this year for efficacy after an interim analysis pointed to a significantly lower rate of cardiovascular events in the treatment group.

The international double-blind, placebo-controlled trial randomly assigned 7,769 people with HIV infection, who were at low to moderate risk of cardiovascular disease, to either 4 mg daily of pitavastatin calcium or placebo.

The secondary outcome – a composite of major cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality – also showed a significant 21% reduction in risk with pitavastatin treatment, compared with placebo (95% CI, 0.65-0.96).

Cardiovascular events in HIV

HIV infection is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, Dr. Grinspoon pointed out, and those living with HIV have about double the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke, compared with the general population.

“There’s an unmet need for people living with HIV who have low to moderate traditional risk, for whom HIV is even considered a risk equivalent but for whom no primary prevention strategy has been tested in a large trial,” Dr. Grinspoon said during an interview.

Those enrolled in the study had a 10-year Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease risk score ranging from 2.1% to 7%, with a median of 4.5%. While LDL cholesterol levels at baseline ranged from 87 to 128 mg/dL, the study showed a similar reduction in cardiovascular risk regardless of LDL.

“These are types of people who, if they came to the doctor’s office right now before REPRIEVE, they would largely be told your risk score is not really making you eligible for a statin,” Dr. Grinspoon said.

He explained that what is most interesting about the reduction in risk is that it was nearly twice what would be expected with LDL lowering, based on what has previously been seen in statin trials in non–HIV-positive populations.

“I think the data are suggesting that it’s certainly in part due to the reduction in LDL – that is very important – but it’s also due to other factors beyond changes in LDL,” Dr. Grinspoon said. He speculated that the statin could be affecting anti-inflammatory and immune pathways, and that this could account for some of the reduction in cardiovascular risk, but “those data are cooking, and they’re being analyzed as we speak.”

In a substudy analysis of REPRIEVE, Markella Zanni, MD, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, focused on the women in the clinical trial.

Women’s risk

In REPRIEVE, 31.1% of the study population were women. Dr. Zanni and her team investigated whether there are differences in the way HIV affects the risk of developing atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in women, compared with men.

They found that women have both higher levels of inflammatory markers, such as interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and D-dimer, but a lower prevalence of coronary artery plaques than men.

“This finding represents an interesting paradox given that high levels of select inflammatory markers have been associated with coronary artery plaque, both among women living with HIV and among men living with HIV,” Dr. Zanni explained.

She says the researchers were hoping to further explore whether inflammation is fueling the increased risk for atherosclerotic disease, and particularly the higher risk evident in women living with HIV, compared with men.

“Women living with HIV should discuss with their treating clinicians heart risks and possible prevention strategies, including statin therapy coupled with healthy lifestyle changes addressing modifiable, traditional metabolic risk factors” she said.

Time for primary prevention?

All patients in the study were on antiretroviral therapy and investigators report that pitavastatin does not interact with these medications. The median CD4 cell count was 621 cells/mm3, and 87.5% of participants had an HIV viral load below the lower limit of quantification.

Participants were enrolled from 12 countries including the United States, Spain, Brazil, South Africa, and Thailand, and around two-thirds were non-White. Individuals of South Asian ethnicity showed the biggest reduction in cardiovascular risk with pitavastatin treatment.

There was a 74% higher rate of muscle pain and weakness in the pitavastatin group – affecting 91 people in the treatment arm and 53 in the placebo arm – but the majority were low grade. The rate of rhabdomyolysis of grade 3 or above was lower in the statin group, with three cases, compared with four cases in the placebo group.

Commenting on the findings, Laura Waters, MD, a genitourinary and HIV medicine consultant at Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust’s Mortimer Market Centre, said that, while HIV infection was considered a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, risk calculators don’t specifically adjust for HIV infection.

“Now that we’ve got effective HIV drugs and people can enjoy normal life expectancy, cardiovascular disease is a particular issue for people with HIV,” she said.

Dr. Waters, who was not involved with the study, suggested that people living with HIV should discuss the use of statins with their doctor, but she acknowledged there are some barriers to treatment in people living with HIV. “It’s another pill, and when it’s a borderline [decision] it is easy to say, ‘I have to think about it,’ ” she said, with the result that statin treatment is often deferred.

The REPRIEVE study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, Kowa Pharmaceuticals America, Gilead Sciences, and ViiV Healthcare. Dr. Grinspoon declared institutional grants from National Institutes of Health, Kowa Pharmaceuticals America, Gilead Sciences, and ViiV Healthcare and consultancies unrelated to the study. Dr. Zanni reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

BRISBANE, AUSTRALIA – that show pitavastatin therapy is associated with a significantly lower risk of cardiovascular events than placebo.

“There was a significant 35% lower risk of major adverse cardiovascular events after a median follow-up of 5.1 years “ said Steven Grinspoon, MD, from Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, who presented the final analysis of data from the REPRIEVE trial at the International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science.

The results were simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine. The primary endpoint of major adverse cardiovascular events included a composite of outcomes that included cardiovascular death, stroke, myocardial infarction, hospitalization for unstable angina, and transient ischemic attack among those treated with pitavastatin, compared with placebo (95% confidence interval, 0.48-0.90; P = .002).

The REPRIEVE trial was halted earlier this year for efficacy after an interim analysis pointed to a significantly lower rate of cardiovascular events in the treatment group.

The international double-blind, placebo-controlled trial randomly assigned 7,769 people with HIV infection, who were at low to moderate risk of cardiovascular disease, to either 4 mg daily of pitavastatin calcium or placebo.

The secondary outcome – a composite of major cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality – also showed a significant 21% reduction in risk with pitavastatin treatment, compared with placebo (95% CI, 0.65-0.96).

Cardiovascular events in HIV

HIV infection is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, Dr. Grinspoon pointed out, and those living with HIV have about double the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke, compared with the general population.

“There’s an unmet need for people living with HIV who have low to moderate traditional risk, for whom HIV is even considered a risk equivalent but for whom no primary prevention strategy has been tested in a large trial,” Dr. Grinspoon said during an interview.

Those enrolled in the study had a 10-year Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease risk score ranging from 2.1% to 7%, with a median of 4.5%. While LDL cholesterol levels at baseline ranged from 87 to 128 mg/dL, the study showed a similar reduction in cardiovascular risk regardless of LDL.

“These are types of people who, if they came to the doctor’s office right now before REPRIEVE, they would largely be told your risk score is not really making you eligible for a statin,” Dr. Grinspoon said.

He explained that what is most interesting about the reduction in risk is that it was nearly twice what would be expected with LDL lowering, based on what has previously been seen in statin trials in non–HIV-positive populations.

“I think the data are suggesting that it’s certainly in part due to the reduction in LDL – that is very important – but it’s also due to other factors beyond changes in LDL,” Dr. Grinspoon said. He speculated that the statin could be affecting anti-inflammatory and immune pathways, and that this could account for some of the reduction in cardiovascular risk, but “those data are cooking, and they’re being analyzed as we speak.”

In a substudy analysis of REPRIEVE, Markella Zanni, MD, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, focused on the women in the clinical trial.

Women’s risk

In REPRIEVE, 31.1% of the study population were women. Dr. Zanni and her team investigated whether there are differences in the way HIV affects the risk of developing atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in women, compared with men.

They found that women have both higher levels of inflammatory markers, such as interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and D-dimer, but a lower prevalence of coronary artery plaques than men.

“This finding represents an interesting paradox given that high levels of select inflammatory markers have been associated with coronary artery plaque, both among women living with HIV and among men living with HIV,” Dr. Zanni explained.

She says the researchers were hoping to further explore whether inflammation is fueling the increased risk for atherosclerotic disease, and particularly the higher risk evident in women living with HIV, compared with men.

“Women living with HIV should discuss with their treating clinicians heart risks and possible prevention strategies, including statin therapy coupled with healthy lifestyle changes addressing modifiable, traditional metabolic risk factors” she said.

Time for primary prevention?

All patients in the study were on antiretroviral therapy and investigators report that pitavastatin does not interact with these medications. The median CD4 cell count was 621 cells/mm3, and 87.5% of participants had an HIV viral load below the lower limit of quantification.

Participants were enrolled from 12 countries including the United States, Spain, Brazil, South Africa, and Thailand, and around two-thirds were non-White. Individuals of South Asian ethnicity showed the biggest reduction in cardiovascular risk with pitavastatin treatment.

There was a 74% higher rate of muscle pain and weakness in the pitavastatin group – affecting 91 people in the treatment arm and 53 in the placebo arm – but the majority were low grade. The rate of rhabdomyolysis of grade 3 or above was lower in the statin group, with three cases, compared with four cases in the placebo group.

Commenting on the findings, Laura Waters, MD, a genitourinary and HIV medicine consultant at Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust’s Mortimer Market Centre, said that, while HIV infection was considered a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, risk calculators don’t specifically adjust for HIV infection.

“Now that we’ve got effective HIV drugs and people can enjoy normal life expectancy, cardiovascular disease is a particular issue for people with HIV,” she said.

Dr. Waters, who was not involved with the study, suggested that people living with HIV should discuss the use of statins with their doctor, but she acknowledged there are some barriers to treatment in people living with HIV. “It’s another pill, and when it’s a borderline [decision] it is easy to say, ‘I have to think about it,’ ” she said, with the result that statin treatment is often deferred.

The REPRIEVE study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, Kowa Pharmaceuticals America, Gilead Sciences, and ViiV Healthcare. Dr. Grinspoon declared institutional grants from National Institutes of Health, Kowa Pharmaceuticals America, Gilead Sciences, and ViiV Healthcare and consultancies unrelated to the study. Dr. Zanni reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT IAS 2023

Same-session PCI rates ‘surprisingly high’

Stable patients who have a diagnostic cardiac catheterization for multivessel disease or two-vessel proximal left anterior descending disease often have percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in the same session, possibly without input from a multidisciplinary heart team, a new study suggests.

The study, a retrospective analysis of more than 8,000 catheterization procedures in New York State during 2018 and 2019, was published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

Among the stable patients with multivessel disease or left main (LM) disease who had PCI, 78.4% of PCIs were performed in the same session as their diagnostic catheterization procedure, known as ad hoc PCI, a “surprisingly high rate,” the authors wrote.

The 2011 clinical guidelines in place during the study period advised coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery as a class 1 recommendation for LM disease, whereas PCI is a lower-class recommendation (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:e44-e-122), they noted.

“Ad hoc PCI can be inadvisable when guidelines indicate that patients can realize better outcomes with CABG surgery,” lead study author Edward L. Hannan, PhD, MS, said in an interview. “The issue is that ad hoc PCI eliminates the opportunity for a multidisciplinary heart team to evaluate the patient.”

Dr. Hannan is principal investigator for the cardiac services program at the New York State Department of Health in Albany and distinguished professor emeritus at the University of Albany School of Public Health.

The researchers analyzed data from two mandatory New York State PCI and cardiac surgery registries, the Percutaneous Coronary Interventions Reporting System and the Cardiac Surgery Reporting System. A total of 91,146 patients had an index PCI from Dec. 1, 2017, to Nov. 30, 2019.

The study included patients who had two-vessel disease with proximal left anterior descending (PLAD) disease, three-vessel disease or unprotected LM disease. Exclusion criteria included a previous revascularization, among a host of other factors. The analysis also identified 10,122 patients who had coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery in addition to the 8,196 patients who had PCI.

The percentage for ad hoc PCI ranged from 58.7% for those with unprotected LM disease to 85.4% for patients with two-vessel PLAD. Among the patients who had PCI for three-vessel disease, 76.7% had an ad hoc PCI.

Selected subgroups had lower ad hoc PCI rates. When patients who had a myocardial infarction within 1-7 days were excluded, the ad hoc percentage decreased slightly to 77.2%. PCI patients with diabetes were also less likely to have ad hoc PCI (75.7% vs. 80.4%, P < .0001), as were patients with compromised left ventricular ejection fraction (< 35%; 64.6% vs. 80.5%, P < .0001).

When all revascularizations – PCI plus CABG – were taken into account, the rate of ad hoc PCIs was 35.1%. Rates were 63.9% for patients with two-vessel PLAD disease, 32.4% for those with three-vessel disease, and 11.5% for patients with unprotected LM disease.

One potential disadvantage of ad hoc PCI, the authors noted, is that it doesn’t allow time for a multidisciplinary heart team to evaluate the patient for a different treatment, such as CABG or medical therapy. “This multidisciplinary team can evaluate all the pros and cons of different approaches, such as PCI vs. CABG surgery in this case,” Dr. Hannan said.

The study findings imply a potential overutilization of PCI and a greater likelihood of forgoing a more appropriate intervention, he said, “given that we have chosen for the study groups of patients who in general benefit more with CABG surgery.”

The results also showed variability in ad hoc PCI rates among hospitals and physicians. “They are large enough to suggest that there is a fairly large variation across the state in the use of heart teams,” he said.

For unprotected LM disease, the risk adjusted rate for hospitals of ad hoc PCIs among all PCIs ranged from 25.6% in the lowest quartile to 93.7% in the highest. Physician rates of ad hoc PCIs for the same indication, which were ranked by tertile, ranged from 22% for the lowest to 84.3% for the highest (P < .001).

One strength of the study, Dr. Hannan said, is that it is a large population-based study that excluded groups for whom an ad hoc PCI would be appropriate, such as emergency patients. One limitation is that it did not account for legitimate reasons for ad hoc PCI, including contraindications for CABG surgery and patient refusal of CABG surgery.

In an invited editorial comment, James C. Blankenship, MD, and Krishna Patel, MD, wrote that this study shows that “past criticisms of ad hoc PCI have had seemingly little effect.”

“The article provides a striking example of a difference between guideline-directed practice and real-life practice,” Dr. Blankenship said in an interview. “Guideline recommendations for the heart team approach are well known by interventionalists, so the findings of this study do not reflect ignorance of cardiologists.” Dr. Blankenship, a cardiologist and professor of medicine at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, is a coauthor of the 2011 PCI guidelines.

It’s more likely the study findings “reflect unconscious biases and sincere beliefs of patients and interventionalists that PCI rather than CABG is in patients’ best interests,” Dr. Blankenship said.

He noted the variation in practice across hospitals and individuals suggests an opportunity for improvement. “If the guidelines are correct, then perhaps interventionalists should be held accountable for making sure the heart team approach is followed,” he said. “Alternatively, perhaps a modified approach that guarantees patient-centered decision making and is ethically acceptable could be identified.”

The study received funding from the New York State Department of Health. Dr. Hannan and Dr. Blankenship and Dr. Patel have no relevant disclosures.

Stable patients who have a diagnostic cardiac catheterization for multivessel disease or two-vessel proximal left anterior descending disease often have percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in the same session, possibly without input from a multidisciplinary heart team, a new study suggests.

The study, a retrospective analysis of more than 8,000 catheterization procedures in New York State during 2018 and 2019, was published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

Among the stable patients with multivessel disease or left main (LM) disease who had PCI, 78.4% of PCIs were performed in the same session as their diagnostic catheterization procedure, known as ad hoc PCI, a “surprisingly high rate,” the authors wrote.

The 2011 clinical guidelines in place during the study period advised coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery as a class 1 recommendation for LM disease, whereas PCI is a lower-class recommendation (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:e44-e-122), they noted.

“Ad hoc PCI can be inadvisable when guidelines indicate that patients can realize better outcomes with CABG surgery,” lead study author Edward L. Hannan, PhD, MS, said in an interview. “The issue is that ad hoc PCI eliminates the opportunity for a multidisciplinary heart team to evaluate the patient.”

Dr. Hannan is principal investigator for the cardiac services program at the New York State Department of Health in Albany and distinguished professor emeritus at the University of Albany School of Public Health.

The researchers analyzed data from two mandatory New York State PCI and cardiac surgery registries, the Percutaneous Coronary Interventions Reporting System and the Cardiac Surgery Reporting System. A total of 91,146 patients had an index PCI from Dec. 1, 2017, to Nov. 30, 2019.

The study included patients who had two-vessel disease with proximal left anterior descending (PLAD) disease, three-vessel disease or unprotected LM disease. Exclusion criteria included a previous revascularization, among a host of other factors. The analysis also identified 10,122 patients who had coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery in addition to the 8,196 patients who had PCI.

The percentage for ad hoc PCI ranged from 58.7% for those with unprotected LM disease to 85.4% for patients with two-vessel PLAD. Among the patients who had PCI for three-vessel disease, 76.7% had an ad hoc PCI.

Selected subgroups had lower ad hoc PCI rates. When patients who had a myocardial infarction within 1-7 days were excluded, the ad hoc percentage decreased slightly to 77.2%. PCI patients with diabetes were also less likely to have ad hoc PCI (75.7% vs. 80.4%, P < .0001), as were patients with compromised left ventricular ejection fraction (< 35%; 64.6% vs. 80.5%, P < .0001).

When all revascularizations – PCI plus CABG – were taken into account, the rate of ad hoc PCIs was 35.1%. Rates were 63.9% for patients with two-vessel PLAD disease, 32.4% for those with three-vessel disease, and 11.5% for patients with unprotected LM disease.

One potential disadvantage of ad hoc PCI, the authors noted, is that it doesn’t allow time for a multidisciplinary heart team to evaluate the patient for a different treatment, such as CABG or medical therapy. “This multidisciplinary team can evaluate all the pros and cons of different approaches, such as PCI vs. CABG surgery in this case,” Dr. Hannan said.

The study findings imply a potential overutilization of PCI and a greater likelihood of forgoing a more appropriate intervention, he said, “given that we have chosen for the study groups of patients who in general benefit more with CABG surgery.”

The results also showed variability in ad hoc PCI rates among hospitals and physicians. “They are large enough to suggest that there is a fairly large variation across the state in the use of heart teams,” he said.

For unprotected LM disease, the risk adjusted rate for hospitals of ad hoc PCIs among all PCIs ranged from 25.6% in the lowest quartile to 93.7% in the highest. Physician rates of ad hoc PCIs for the same indication, which were ranked by tertile, ranged from 22% for the lowest to 84.3% for the highest (P < .001).

One strength of the study, Dr. Hannan said, is that it is a large population-based study that excluded groups for whom an ad hoc PCI would be appropriate, such as emergency patients. One limitation is that it did not account for legitimate reasons for ad hoc PCI, including contraindications for CABG surgery and patient refusal of CABG surgery.

In an invited editorial comment, James C. Blankenship, MD, and Krishna Patel, MD, wrote that this study shows that “past criticisms of ad hoc PCI have had seemingly little effect.”

“The article provides a striking example of a difference between guideline-directed practice and real-life practice,” Dr. Blankenship said in an interview. “Guideline recommendations for the heart team approach are well known by interventionalists, so the findings of this study do not reflect ignorance of cardiologists.” Dr. Blankenship, a cardiologist and professor of medicine at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, is a coauthor of the 2011 PCI guidelines.

It’s more likely the study findings “reflect unconscious biases and sincere beliefs of patients and interventionalists that PCI rather than CABG is in patients’ best interests,” Dr. Blankenship said.

He noted the variation in practice across hospitals and individuals suggests an opportunity for improvement. “If the guidelines are correct, then perhaps interventionalists should be held accountable for making sure the heart team approach is followed,” he said. “Alternatively, perhaps a modified approach that guarantees patient-centered decision making and is ethically acceptable could be identified.”

The study received funding from the New York State Department of Health. Dr. Hannan and Dr. Blankenship and Dr. Patel have no relevant disclosures.

Stable patients who have a diagnostic cardiac catheterization for multivessel disease or two-vessel proximal left anterior descending disease often have percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in the same session, possibly without input from a multidisciplinary heart team, a new study suggests.

The study, a retrospective analysis of more than 8,000 catheterization procedures in New York State during 2018 and 2019, was published in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

Among the stable patients with multivessel disease or left main (LM) disease who had PCI, 78.4% of PCIs were performed in the same session as their diagnostic catheterization procedure, known as ad hoc PCI, a “surprisingly high rate,” the authors wrote.

The 2011 clinical guidelines in place during the study period advised coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery as a class 1 recommendation for LM disease, whereas PCI is a lower-class recommendation (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:e44-e-122), they noted.

“Ad hoc PCI can be inadvisable when guidelines indicate that patients can realize better outcomes with CABG surgery,” lead study author Edward L. Hannan, PhD, MS, said in an interview. “The issue is that ad hoc PCI eliminates the opportunity for a multidisciplinary heart team to evaluate the patient.”

Dr. Hannan is principal investigator for the cardiac services program at the New York State Department of Health in Albany and distinguished professor emeritus at the University of Albany School of Public Health.

The researchers analyzed data from two mandatory New York State PCI and cardiac surgery registries, the Percutaneous Coronary Interventions Reporting System and the Cardiac Surgery Reporting System. A total of 91,146 patients had an index PCI from Dec. 1, 2017, to Nov. 30, 2019.

The study included patients who had two-vessel disease with proximal left anterior descending (PLAD) disease, three-vessel disease or unprotected LM disease. Exclusion criteria included a previous revascularization, among a host of other factors. The analysis also identified 10,122 patients who had coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery in addition to the 8,196 patients who had PCI.

The percentage for ad hoc PCI ranged from 58.7% for those with unprotected LM disease to 85.4% for patients with two-vessel PLAD. Among the patients who had PCI for three-vessel disease, 76.7% had an ad hoc PCI.

Selected subgroups had lower ad hoc PCI rates. When patients who had a myocardial infarction within 1-7 days were excluded, the ad hoc percentage decreased slightly to 77.2%. PCI patients with diabetes were also less likely to have ad hoc PCI (75.7% vs. 80.4%, P < .0001), as were patients with compromised left ventricular ejection fraction (< 35%; 64.6% vs. 80.5%, P < .0001).

When all revascularizations – PCI plus CABG – were taken into account, the rate of ad hoc PCIs was 35.1%. Rates were 63.9% for patients with two-vessel PLAD disease, 32.4% for those with three-vessel disease, and 11.5% for patients with unprotected LM disease.

One potential disadvantage of ad hoc PCI, the authors noted, is that it doesn’t allow time for a multidisciplinary heart team to evaluate the patient for a different treatment, such as CABG or medical therapy. “This multidisciplinary team can evaluate all the pros and cons of different approaches, such as PCI vs. CABG surgery in this case,” Dr. Hannan said.

The study findings imply a potential overutilization of PCI and a greater likelihood of forgoing a more appropriate intervention, he said, “given that we have chosen for the study groups of patients who in general benefit more with CABG surgery.”

The results also showed variability in ad hoc PCI rates among hospitals and physicians. “They are large enough to suggest that there is a fairly large variation across the state in the use of heart teams,” he said.

For unprotected LM disease, the risk adjusted rate for hospitals of ad hoc PCIs among all PCIs ranged from 25.6% in the lowest quartile to 93.7% in the highest. Physician rates of ad hoc PCIs for the same indication, which were ranked by tertile, ranged from 22% for the lowest to 84.3% for the highest (P < .001).

One strength of the study, Dr. Hannan said, is that it is a large population-based study that excluded groups for whom an ad hoc PCI would be appropriate, such as emergency patients. One limitation is that it did not account for legitimate reasons for ad hoc PCI, including contraindications for CABG surgery and patient refusal of CABG surgery.

In an invited editorial comment, James C. Blankenship, MD, and Krishna Patel, MD, wrote that this study shows that “past criticisms of ad hoc PCI have had seemingly little effect.”

“The article provides a striking example of a difference between guideline-directed practice and real-life practice,” Dr. Blankenship said in an interview. “Guideline recommendations for the heart team approach are well known by interventionalists, so the findings of this study do not reflect ignorance of cardiologists.” Dr. Blankenship, a cardiologist and professor of medicine at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, is a coauthor of the 2011 PCI guidelines.

It’s more likely the study findings “reflect unconscious biases and sincere beliefs of patients and interventionalists that PCI rather than CABG is in patients’ best interests,” Dr. Blankenship said.

He noted the variation in practice across hospitals and individuals suggests an opportunity for improvement. “If the guidelines are correct, then perhaps interventionalists should be held accountable for making sure the heart team approach is followed,” he said. “Alternatively, perhaps a modified approach that guarantees patient-centered decision making and is ethically acceptable could be identified.”

The study received funding from the New York State Department of Health. Dr. Hannan and Dr. Blankenship and Dr. Patel have no relevant disclosures.

FROM JACC; CARDIOVASCULAR INTERVENTIONS

Even exercise by ‘weekend warriors’ can cut CV risk

Moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) is a familiar and established approach to reducing cardiovascular (CV) risk, but it’s often believed that the exercise should be spread out across the week rather than concentrated within a couple of days.

A challenge to that view comes from an observational study of accelerometer-confirmed exercise in almost 90,000 people in their 60s. It suggests,

Researchers compared three patterns of MVPA in their subjects who wore accelerometers on their wrists for 1 week. Active WW subjects obtained at least 2.5 hours of exercise weekly, with at least half the amount completed over 1-2 days; “active regular” subjects achieved that exercise level but not mostly during 1 or 2 days; and those who were “inactive” fell short of 2.5 hours of exercise during the week. The group used a median exercise threshold of 3 hours, 50 minutes in a separate analysis.

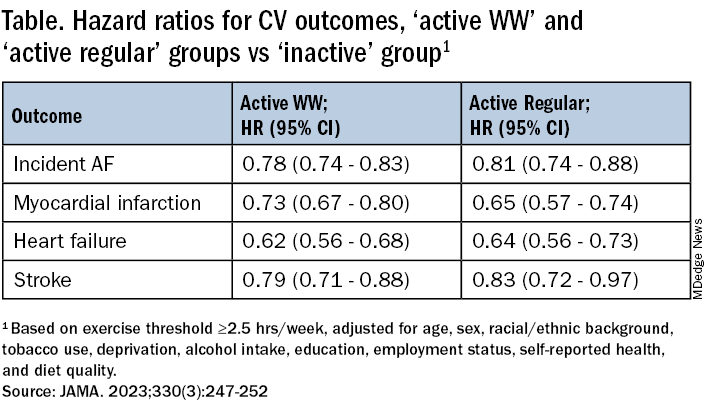

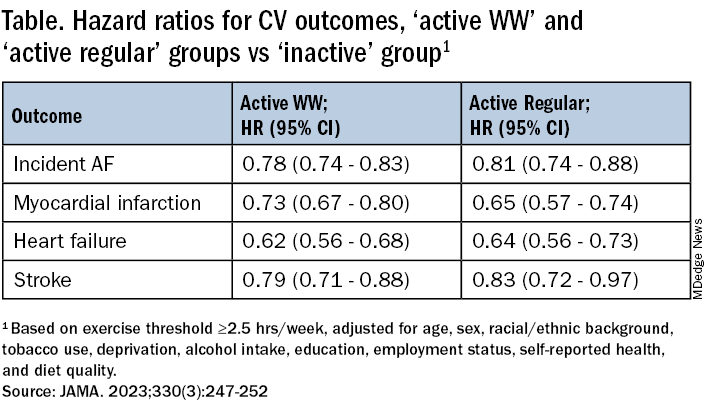

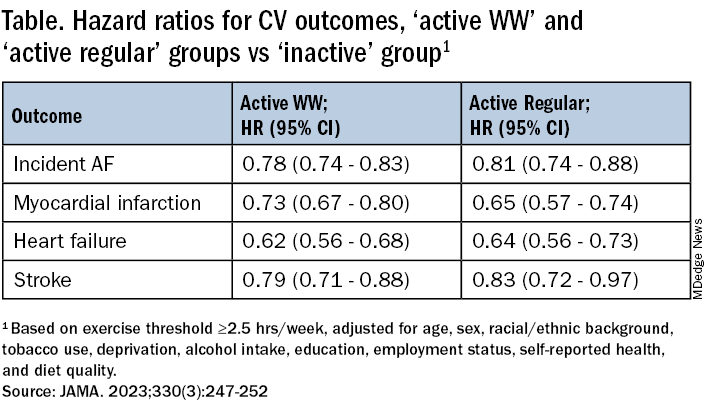

The “active” groups, compared with inactive subjects, achieved similar and significant reductions in risk for incident atrial fibrillation (AF), myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and heart failure (HF) over a median follow-up of 6.3 years at both weekly exercise thresholds, the group reported.

“The take-home [message] is that efforts to optimize activity, even if concentrated within just a day or 2 each week, should be expected to result in improved cardiovascular risk profiles,” lead author Shaan Khurshid, MD, MPH, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

The study was published online in JAMA.

The research “provides novel data on patterns of physical activity accumulation and the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases,” observed Peter Katzmarzyk, PhD, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, La., in an interview. He was not involved with the research. Its “marked strengths,” he noted, include a large sample population and “use of accelerometers to measure physical activity levels and patterns.”

Moreover, Dr. Katzmarzyk said, its findings are “important” for showing that physical activity “can be accumulated throughout the week in different ways, which opens up more options for busy people to get their physical activity in.”

Current guidelines from the World Health Organization and the American Heart Association recommend at least 150 minutes of MVPA weekly to lower risk for cardiovascular disease and death, but do not specify an optimal exercise time frame. The U.K. National Health Service recommends MVPA daily or spread evenly over perhaps 4-5 days.

“The weekend warrior pattern has been studied previously, but typically relying on self-reported data, which may be biased, or [in studies] too small to look at specific cardiovascular outcomes,” Dr. Khurshid explained.

In the UK Biobank database, he said, “We saw the opportunity to leverage the largest sample of measured activity to date” to address the question of whether exercise time pattern “affects specific major cardiovascular diseases differently,” Dr. Khurshid said

The primary analysis assessed exercise amount in a week based on the guideline-recommended threshold of at least 2.5 hours; a 3-hour, 50-minutes threshold was used in a secondary analysis. The group assessed multiple thresholds because optimal MVPS levels derived from wrist-based accelerometers are “unclear,” he said.

The sample consisted of 89,573 participants with a mean age 62; slightly more than half (56%) were women. Based on the weekly MVPA threshold of 2.5 hours , the WW, active regular, and inactive groups made up 42.2%, 24%, and 33.7% of the population, respectively.

Compared with the inactive group, the two active groups both showed significant risk reductions for the four clinical outcomes, to similar degrees, in multivariate analysis. The results were similar at the 230-minute weekly exercise threshold for incident AF, MI, and HF but not for stroke.

The findings were similarly consistent at the 3-hour, 50-minutes median threshold, although stroke differences were no longer significant.

Patients should be encouraged to exercise at recommended levels, “and should not be discouraged if, for whatever reasons, they are able to focus exercise within only 1 or a few days of the week,” said Dr. Khurshid. “Our findings suggest that it is the volume of activity, rather than the pattern, that matters most.”

The report notes several limitations of the study, including the exercise observation period limited to 1 week and that participants could have modified their behavior during the observation period. Also, the participants were almost all White, so the results may not be generalizable to other populations.

Clinicians should familiarize themselves with the “full range of recommendations” presented in the “Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd Edition” “and personalize prescriptions by setting achievable physical activity goals” based on age, physical abilities, and activity levels, states an accompanying editorial from Dr. Katzmarzyk and John M. Jakicic, PhD, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City.

Although MVPA at the recommended level of at least 2.5 hours per week will certainly be beneficial, they write, “the public health message should also clearly convey that every minute counts, especially among the three-quarters of U.S. adults who do not achieve that goal.”

Dr. Khurshid reported no relevant financial relationships; disclosures for the other authors are in the original article. Dr. Katzmarzyk reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Jakicic discloses receiving personal fees from Wondr Health, WW International (formerly Weight Watchers), and Educational Initiatives and grants from Epitomee Medical.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) is a familiar and established approach to reducing cardiovascular (CV) risk, but it’s often believed that the exercise should be spread out across the week rather than concentrated within a couple of days.

A challenge to that view comes from an observational study of accelerometer-confirmed exercise in almost 90,000 people in their 60s. It suggests,

Researchers compared three patterns of MVPA in their subjects who wore accelerometers on their wrists for 1 week. Active WW subjects obtained at least 2.5 hours of exercise weekly, with at least half the amount completed over 1-2 days; “active regular” subjects achieved that exercise level but not mostly during 1 or 2 days; and those who were “inactive” fell short of 2.5 hours of exercise during the week. The group used a median exercise threshold of 3 hours, 50 minutes in a separate analysis.

The “active” groups, compared with inactive subjects, achieved similar and significant reductions in risk for incident atrial fibrillation (AF), myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and heart failure (HF) over a median follow-up of 6.3 years at both weekly exercise thresholds, the group reported.

“The take-home [message] is that efforts to optimize activity, even if concentrated within just a day or 2 each week, should be expected to result in improved cardiovascular risk profiles,” lead author Shaan Khurshid, MD, MPH, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

The study was published online in JAMA.

The research “provides novel data on patterns of physical activity accumulation and the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases,” observed Peter Katzmarzyk, PhD, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, La., in an interview. He was not involved with the research. Its “marked strengths,” he noted, include a large sample population and “use of accelerometers to measure physical activity levels and patterns.”

Moreover, Dr. Katzmarzyk said, its findings are “important” for showing that physical activity “can be accumulated throughout the week in different ways, which opens up more options for busy people to get their physical activity in.”

Current guidelines from the World Health Organization and the American Heart Association recommend at least 150 minutes of MVPA weekly to lower risk for cardiovascular disease and death, but do not specify an optimal exercise time frame. The U.K. National Health Service recommends MVPA daily or spread evenly over perhaps 4-5 days.

“The weekend warrior pattern has been studied previously, but typically relying on self-reported data, which may be biased, or [in studies] too small to look at specific cardiovascular outcomes,” Dr. Khurshid explained.

In the UK Biobank database, he said, “We saw the opportunity to leverage the largest sample of measured activity to date” to address the question of whether exercise time pattern “affects specific major cardiovascular diseases differently,” Dr. Khurshid said

The primary analysis assessed exercise amount in a week based on the guideline-recommended threshold of at least 2.5 hours; a 3-hour, 50-minutes threshold was used in a secondary analysis. The group assessed multiple thresholds because optimal MVPS levels derived from wrist-based accelerometers are “unclear,” he said.

The sample consisted of 89,573 participants with a mean age 62; slightly more than half (56%) were women. Based on the weekly MVPA threshold of 2.5 hours , the WW, active regular, and inactive groups made up 42.2%, 24%, and 33.7% of the population, respectively.

Compared with the inactive group, the two active groups both showed significant risk reductions for the four clinical outcomes, to similar degrees, in multivariate analysis. The results were similar at the 230-minute weekly exercise threshold for incident AF, MI, and HF but not for stroke.

The findings were similarly consistent at the 3-hour, 50-minutes median threshold, although stroke differences were no longer significant.

Patients should be encouraged to exercise at recommended levels, “and should not be discouraged if, for whatever reasons, they are able to focus exercise within only 1 or a few days of the week,” said Dr. Khurshid. “Our findings suggest that it is the volume of activity, rather than the pattern, that matters most.”

The report notes several limitations of the study, including the exercise observation period limited to 1 week and that participants could have modified their behavior during the observation period. Also, the participants were almost all White, so the results may not be generalizable to other populations.

Clinicians should familiarize themselves with the “full range of recommendations” presented in the “Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd Edition” “and personalize prescriptions by setting achievable physical activity goals” based on age, physical abilities, and activity levels, states an accompanying editorial from Dr. Katzmarzyk and John M. Jakicic, PhD, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City.

Although MVPA at the recommended level of at least 2.5 hours per week will certainly be beneficial, they write, “the public health message should also clearly convey that every minute counts, especially among the three-quarters of U.S. adults who do not achieve that goal.”

Dr. Khurshid reported no relevant financial relationships; disclosures for the other authors are in the original article. Dr. Katzmarzyk reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Jakicic discloses receiving personal fees from Wondr Health, WW International (formerly Weight Watchers), and Educational Initiatives and grants from Epitomee Medical.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) is a familiar and established approach to reducing cardiovascular (CV) risk, but it’s often believed that the exercise should be spread out across the week rather than concentrated within a couple of days.

A challenge to that view comes from an observational study of accelerometer-confirmed exercise in almost 90,000 people in their 60s. It suggests,

Researchers compared three patterns of MVPA in their subjects who wore accelerometers on their wrists for 1 week. Active WW subjects obtained at least 2.5 hours of exercise weekly, with at least half the amount completed over 1-2 days; “active regular” subjects achieved that exercise level but not mostly during 1 or 2 days; and those who were “inactive” fell short of 2.5 hours of exercise during the week. The group used a median exercise threshold of 3 hours, 50 minutes in a separate analysis.

The “active” groups, compared with inactive subjects, achieved similar and significant reductions in risk for incident atrial fibrillation (AF), myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and heart failure (HF) over a median follow-up of 6.3 years at both weekly exercise thresholds, the group reported.

“The take-home [message] is that efforts to optimize activity, even if concentrated within just a day or 2 each week, should be expected to result in improved cardiovascular risk profiles,” lead author Shaan Khurshid, MD, MPH, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

The study was published online in JAMA.

The research “provides novel data on patterns of physical activity accumulation and the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases,” observed Peter Katzmarzyk, PhD, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, La., in an interview. He was not involved with the research. Its “marked strengths,” he noted, include a large sample population and “use of accelerometers to measure physical activity levels and patterns.”

Moreover, Dr. Katzmarzyk said, its findings are “important” for showing that physical activity “can be accumulated throughout the week in different ways, which opens up more options for busy people to get their physical activity in.”

Current guidelines from the World Health Organization and the American Heart Association recommend at least 150 minutes of MVPA weekly to lower risk for cardiovascular disease and death, but do not specify an optimal exercise time frame. The U.K. National Health Service recommends MVPA daily or spread evenly over perhaps 4-5 days.

“The weekend warrior pattern has been studied previously, but typically relying on self-reported data, which may be biased, or [in studies] too small to look at specific cardiovascular outcomes,” Dr. Khurshid explained.

In the UK Biobank database, he said, “We saw the opportunity to leverage the largest sample of measured activity to date” to address the question of whether exercise time pattern “affects specific major cardiovascular diseases differently,” Dr. Khurshid said

The primary analysis assessed exercise amount in a week based on the guideline-recommended threshold of at least 2.5 hours; a 3-hour, 50-minutes threshold was used in a secondary analysis. The group assessed multiple thresholds because optimal MVPS levels derived from wrist-based accelerometers are “unclear,” he said.

The sample consisted of 89,573 participants with a mean age 62; slightly more than half (56%) were women. Based on the weekly MVPA threshold of 2.5 hours , the WW, active regular, and inactive groups made up 42.2%, 24%, and 33.7% of the population, respectively.

Compared with the inactive group, the two active groups both showed significant risk reductions for the four clinical outcomes, to similar degrees, in multivariate analysis. The results were similar at the 230-minute weekly exercise threshold for incident AF, MI, and HF but not for stroke.

The findings were similarly consistent at the 3-hour, 50-minutes median threshold, although stroke differences were no longer significant.

Patients should be encouraged to exercise at recommended levels, “and should not be discouraged if, for whatever reasons, they are able to focus exercise within only 1 or a few days of the week,” said Dr. Khurshid. “Our findings suggest that it is the volume of activity, rather than the pattern, that matters most.”

The report notes several limitations of the study, including the exercise observation period limited to 1 week and that participants could have modified their behavior during the observation period. Also, the participants were almost all White, so the results may not be generalizable to other populations.

Clinicians should familiarize themselves with the “full range of recommendations” presented in the “Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd Edition” “and personalize prescriptions by setting achievable physical activity goals” based on age, physical abilities, and activity levels, states an accompanying editorial from Dr. Katzmarzyk and John M. Jakicic, PhD, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City.

Although MVPA at the recommended level of at least 2.5 hours per week will certainly be beneficial, they write, “the public health message should also clearly convey that every minute counts, especially among the three-quarters of U.S. adults who do not achieve that goal.”

Dr. Khurshid reported no relevant financial relationships; disclosures for the other authors are in the original article. Dr. Katzmarzyk reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Jakicic discloses receiving personal fees from Wondr Health, WW International (formerly Weight Watchers), and Educational Initiatives and grants from Epitomee Medical.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA

Rising patient costs tied to private equity ownership

The report was a collaboration of University of California, Berkeley, staff and researchers from two nonprofits, the American Antitrust Institute and the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. It provides “convincing evidence that incentives to put profits before patients have grown stronger with an increase in private equity ownership of physician practices,” lead author Richard Scheffler, PhD, of UC Berkeley said in a statement.

The report also noted that private equity acquisitions of physician groups have risen sixfold in just a decade, increasing from 75 deals in 2012 to 484 deals in 2021.