User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Sepsis readmissions risk linked to residence in a poor neighborhoods

according to a study published in Critical Care Medicine.

The association between living in a disadvantaged neighborhood and 30-day readmission remained significant even after adjustment for “individual demographic variables, active tobacco use, length of index hospitalization, severity of acute and chronic morbidity, and place of initial discharge,” wrote Panagis Galiatsatos, MD, of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and colleagues.

“Our findings suggest the need for interventions that emphasize neighborhood-level socioeconomic variables in addition to individual-level efforts in an effort to promote and achieve health equity for patients who survive a hospitalization due to sepsis,” the authors wrote. “With a third of our cohort rehospitalized with infections, and other studies emphasizing that the most common readmission diagnosis was infection, attention toward both anticipating and attenuating the risk of infection in sepsis survivors, especially among those who live in higher risk neighborhoods, must be a priority for the prevention of readmissions.”

Although she did not find the study results surprising, Eva DuGoff, PhD, a senior managing consultant with the Berkeley Research Group and a visiting assistant professor at University of Maryland School of Public Health, College Park, said in an interview that she was impressed with how clinically rigorous the analysis was, both in confirming an accurate sepsis diagnosis and in using the more refined measure of the Area Deprivation Index (ADI) to assess neighborhood disadvantage.

“I think it makes sense that people who have less means and are in neighborhoods with fewer resources would run into more issues and would need to return to the hospital, above and beyond the clinical risk factors, such as smoking and chronic conditions,” said Dr. DuGoff, who studies health disparities but was not involved in this study.

Shayla N.M. Durfey MD, ScM, a pediatric resident at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., said in an interview she was similarly unsurprised by the findings.

“People who live in disadvantaged neighborhoods may have less access to walking spaces, healthy food, and safe housing and more exposure to poor air quality, toxic stress, and violence – any of which can negatively impact health or recovery from illness through stress responses, nutritional deficiencies, or comorbidities, such as reactive airway disease, obesity, hypertension, and diabetes,” said Dr. Durfey, who studies health disparities but was not involved in this study. “Our research has found these neighborhood-level factors often matter above and beyond individual social determinants of health.”

Dr. Galiatsatos and associates conducted a retrospective study in Baltimore that compared readmission rates in 2017 at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center among patients discharged after a hospitalization for sepsis, coded via ICD-10. They relied on the ADI to categorize the neighborhoods of patients’ residential addresses. The ADI rates various socioeconomic components, including income, education, employment, and housing characteristics, on a scale of 1-100 in geographic blocks, with higher score indicating a greater level of disadvantage.

Among 647 hospitalized patients with an ICD-10 code of sepsis who also met criteria for sepsis or septic shock per the Sepsis-3 definition, 17.9% were excluded from the analysis because they died or were transferred to hospice care. The other 531 patients had an average age of 61, and just under one-third (30.9%) were active smokers. Their average length of stay was 6.9 days, with a mean Charlson Comorbidity Index of 4.2 and a mean Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score of 4.9.

The average ADI for all the patients was 54.2, but the average score was 63 for the 22% of patients who were readmitted within 30 days of initial discharge, compared with an average 51.8 for patients not readmitted (P < .001).

Among those 117 readmitted, “39 patients had a reinfection, 68 had an exacerbation of their chronic conditions, and 10 were admitted for ‘concerning symptoms’ without a primary admitting diagnosis,” the investigators reported. Because “a third of our cohort was readmitted with an infection, it is possible that more disadvantaged neighborhoods created more challenges for a person’s immune system, which may be compromised after recovering from sepsis.”

Dr. DuGoff further noted that health literacy may be lower among people living in less advantaged neighborhoods.

“A number of studies suggest when patients leave the hospital, they’re not sure what they need to do. The language is complicated, and it’s hard to know what kind of medication to take when, and when you’re supposed to return to the doctor or the hospital,” Dr. DuGoff said. “Managing all of that can be pretty scary for people, particularly after a traumatic experience with sepsis at the hospital.”

Most patients had been discharged home (67.3%), but the 31.6% discharged to a skilled nursing facility had a greater likelihood of readmission, compared with those discharged home (P < .01); 1% were discharged to acute rehabilitation. The average length of stay during the index hospitalization was also greater for those readmitted (8.7 days) than for those not readmitted (6.4 days). The groups did not differ in terms of their acute organ dysfunction or severity of their comorbidities.

However, even after adjustment for these factors, “neighborhood disadvantage remained significantly associated with 30-day rehospitalization in patients who were discharged with sepsis,” the authors said. Specifically, each additional standard deviation greater in patients’ ADI was associated with increased risk of 30-day readmission (P < .001).

“Given that the ADI is a composite score, we cannot identify which component is the predominant driver of rehospitalizations for patients who survive sepsis,” the authors wrote. “However, all components that make up the index are intertwined, and policy efforts targeting one (i.e., unemployment) will likely impact others (i.e., housing).”

Dr. Durfey said that medical schools have not traditionally provided training related to management of social risk factors, although this is changing in more recent curricula. But the findings still have clinical relevance for practitioners.

“Certainly, the first step is awareness of where and how patients live and being mindful of how treatment plans may be impacted by social factors at both the individual and community levels,” Dr. Durfey said. “An important part of this is working in partnership with social workers and case managers. Importantly, clinicians can also partner with disadvantaged communities to advocate for improved conditions through policy change and act as expert witnesses to how neighborhood level factors impact health.”

Dr. DuGoff also wondered what implications these findings might have currently, with regards to COVID-19.

“People living in disadvantaged neighborhoods are already at higher risk for getting the disease, and this study raises really good questions about how we should be monitoring discharge now in anticipation of these types of issues,” she said.

The authors noted that their study is cross-sectional and cannot indicate causation, and the findings of a single urban institution may not be generalizable elsewhere. They also did not consider what interventions individual patients had during their index hospitalization that could have increased frailty.

The study did not note external funding. One coauthor of the study, Suchi Saria, PhD, reported receiving honoraria and travel reimbursement from two dozen biotechnology companies for keynotes and advisory board service; she also holds equity in Patient Ping and Bayesian Health. The other authors reported no industry disclosures. In addition to consulting for Berkeley Research Group, Dr. DuGoff has received a past honorarium from Zimmer Biomet. Dr. Durfey has no disclosures.

SOURCE: Galiatsatos P et al. Crit Care Med. 2020 Jun;48(6):808-14.

according to a study published in Critical Care Medicine.

The association between living in a disadvantaged neighborhood and 30-day readmission remained significant even after adjustment for “individual demographic variables, active tobacco use, length of index hospitalization, severity of acute and chronic morbidity, and place of initial discharge,” wrote Panagis Galiatsatos, MD, of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and colleagues.

“Our findings suggest the need for interventions that emphasize neighborhood-level socioeconomic variables in addition to individual-level efforts in an effort to promote and achieve health equity for patients who survive a hospitalization due to sepsis,” the authors wrote. “With a third of our cohort rehospitalized with infections, and other studies emphasizing that the most common readmission diagnosis was infection, attention toward both anticipating and attenuating the risk of infection in sepsis survivors, especially among those who live in higher risk neighborhoods, must be a priority for the prevention of readmissions.”

Although she did not find the study results surprising, Eva DuGoff, PhD, a senior managing consultant with the Berkeley Research Group and a visiting assistant professor at University of Maryland School of Public Health, College Park, said in an interview that she was impressed with how clinically rigorous the analysis was, both in confirming an accurate sepsis diagnosis and in using the more refined measure of the Area Deprivation Index (ADI) to assess neighborhood disadvantage.

“I think it makes sense that people who have less means and are in neighborhoods with fewer resources would run into more issues and would need to return to the hospital, above and beyond the clinical risk factors, such as smoking and chronic conditions,” said Dr. DuGoff, who studies health disparities but was not involved in this study.

Shayla N.M. Durfey MD, ScM, a pediatric resident at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., said in an interview she was similarly unsurprised by the findings.

“People who live in disadvantaged neighborhoods may have less access to walking spaces, healthy food, and safe housing and more exposure to poor air quality, toxic stress, and violence – any of which can negatively impact health or recovery from illness through stress responses, nutritional deficiencies, or comorbidities, such as reactive airway disease, obesity, hypertension, and diabetes,” said Dr. Durfey, who studies health disparities but was not involved in this study. “Our research has found these neighborhood-level factors often matter above and beyond individual social determinants of health.”

Dr. Galiatsatos and associates conducted a retrospective study in Baltimore that compared readmission rates in 2017 at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center among patients discharged after a hospitalization for sepsis, coded via ICD-10. They relied on the ADI to categorize the neighborhoods of patients’ residential addresses. The ADI rates various socioeconomic components, including income, education, employment, and housing characteristics, on a scale of 1-100 in geographic blocks, with higher score indicating a greater level of disadvantage.

Among 647 hospitalized patients with an ICD-10 code of sepsis who also met criteria for sepsis or septic shock per the Sepsis-3 definition, 17.9% were excluded from the analysis because they died or were transferred to hospice care. The other 531 patients had an average age of 61, and just under one-third (30.9%) were active smokers. Their average length of stay was 6.9 days, with a mean Charlson Comorbidity Index of 4.2 and a mean Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score of 4.9.

The average ADI for all the patients was 54.2, but the average score was 63 for the 22% of patients who were readmitted within 30 days of initial discharge, compared with an average 51.8 for patients not readmitted (P < .001).

Among those 117 readmitted, “39 patients had a reinfection, 68 had an exacerbation of their chronic conditions, and 10 were admitted for ‘concerning symptoms’ without a primary admitting diagnosis,” the investigators reported. Because “a third of our cohort was readmitted with an infection, it is possible that more disadvantaged neighborhoods created more challenges for a person’s immune system, which may be compromised after recovering from sepsis.”

Dr. DuGoff further noted that health literacy may be lower among people living in less advantaged neighborhoods.

“A number of studies suggest when patients leave the hospital, they’re not sure what they need to do. The language is complicated, and it’s hard to know what kind of medication to take when, and when you’re supposed to return to the doctor or the hospital,” Dr. DuGoff said. “Managing all of that can be pretty scary for people, particularly after a traumatic experience with sepsis at the hospital.”

Most patients had been discharged home (67.3%), but the 31.6% discharged to a skilled nursing facility had a greater likelihood of readmission, compared with those discharged home (P < .01); 1% were discharged to acute rehabilitation. The average length of stay during the index hospitalization was also greater for those readmitted (8.7 days) than for those not readmitted (6.4 days). The groups did not differ in terms of their acute organ dysfunction or severity of their comorbidities.

However, even after adjustment for these factors, “neighborhood disadvantage remained significantly associated with 30-day rehospitalization in patients who were discharged with sepsis,” the authors said. Specifically, each additional standard deviation greater in patients’ ADI was associated with increased risk of 30-day readmission (P < .001).

“Given that the ADI is a composite score, we cannot identify which component is the predominant driver of rehospitalizations for patients who survive sepsis,” the authors wrote. “However, all components that make up the index are intertwined, and policy efforts targeting one (i.e., unemployment) will likely impact others (i.e., housing).”

Dr. Durfey said that medical schools have not traditionally provided training related to management of social risk factors, although this is changing in more recent curricula. But the findings still have clinical relevance for practitioners.

“Certainly, the first step is awareness of where and how patients live and being mindful of how treatment plans may be impacted by social factors at both the individual and community levels,” Dr. Durfey said. “An important part of this is working in partnership with social workers and case managers. Importantly, clinicians can also partner with disadvantaged communities to advocate for improved conditions through policy change and act as expert witnesses to how neighborhood level factors impact health.”

Dr. DuGoff also wondered what implications these findings might have currently, with regards to COVID-19.

“People living in disadvantaged neighborhoods are already at higher risk for getting the disease, and this study raises really good questions about how we should be monitoring discharge now in anticipation of these types of issues,” she said.

The authors noted that their study is cross-sectional and cannot indicate causation, and the findings of a single urban institution may not be generalizable elsewhere. They also did not consider what interventions individual patients had during their index hospitalization that could have increased frailty.

The study did not note external funding. One coauthor of the study, Suchi Saria, PhD, reported receiving honoraria and travel reimbursement from two dozen biotechnology companies for keynotes and advisory board service; she also holds equity in Patient Ping and Bayesian Health. The other authors reported no industry disclosures. In addition to consulting for Berkeley Research Group, Dr. DuGoff has received a past honorarium from Zimmer Biomet. Dr. Durfey has no disclosures.

SOURCE: Galiatsatos P et al. Crit Care Med. 2020 Jun;48(6):808-14.

according to a study published in Critical Care Medicine.

The association between living in a disadvantaged neighborhood and 30-day readmission remained significant even after adjustment for “individual demographic variables, active tobacco use, length of index hospitalization, severity of acute and chronic morbidity, and place of initial discharge,” wrote Panagis Galiatsatos, MD, of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and colleagues.

“Our findings suggest the need for interventions that emphasize neighborhood-level socioeconomic variables in addition to individual-level efforts in an effort to promote and achieve health equity for patients who survive a hospitalization due to sepsis,” the authors wrote. “With a third of our cohort rehospitalized with infections, and other studies emphasizing that the most common readmission diagnosis was infection, attention toward both anticipating and attenuating the risk of infection in sepsis survivors, especially among those who live in higher risk neighborhoods, must be a priority for the prevention of readmissions.”

Although she did not find the study results surprising, Eva DuGoff, PhD, a senior managing consultant with the Berkeley Research Group and a visiting assistant professor at University of Maryland School of Public Health, College Park, said in an interview that she was impressed with how clinically rigorous the analysis was, both in confirming an accurate sepsis diagnosis and in using the more refined measure of the Area Deprivation Index (ADI) to assess neighborhood disadvantage.

“I think it makes sense that people who have less means and are in neighborhoods with fewer resources would run into more issues and would need to return to the hospital, above and beyond the clinical risk factors, such as smoking and chronic conditions,” said Dr. DuGoff, who studies health disparities but was not involved in this study.

Shayla N.M. Durfey MD, ScM, a pediatric resident at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., said in an interview she was similarly unsurprised by the findings.

“People who live in disadvantaged neighborhoods may have less access to walking spaces, healthy food, and safe housing and more exposure to poor air quality, toxic stress, and violence – any of which can negatively impact health or recovery from illness through stress responses, nutritional deficiencies, or comorbidities, such as reactive airway disease, obesity, hypertension, and diabetes,” said Dr. Durfey, who studies health disparities but was not involved in this study. “Our research has found these neighborhood-level factors often matter above and beyond individual social determinants of health.”

Dr. Galiatsatos and associates conducted a retrospective study in Baltimore that compared readmission rates in 2017 at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center among patients discharged after a hospitalization for sepsis, coded via ICD-10. They relied on the ADI to categorize the neighborhoods of patients’ residential addresses. The ADI rates various socioeconomic components, including income, education, employment, and housing characteristics, on a scale of 1-100 in geographic blocks, with higher score indicating a greater level of disadvantage.

Among 647 hospitalized patients with an ICD-10 code of sepsis who also met criteria for sepsis or septic shock per the Sepsis-3 definition, 17.9% were excluded from the analysis because they died or were transferred to hospice care. The other 531 patients had an average age of 61, and just under one-third (30.9%) were active smokers. Their average length of stay was 6.9 days, with a mean Charlson Comorbidity Index of 4.2 and a mean Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score of 4.9.

The average ADI for all the patients was 54.2, but the average score was 63 for the 22% of patients who were readmitted within 30 days of initial discharge, compared with an average 51.8 for patients not readmitted (P < .001).

Among those 117 readmitted, “39 patients had a reinfection, 68 had an exacerbation of their chronic conditions, and 10 were admitted for ‘concerning symptoms’ without a primary admitting diagnosis,” the investigators reported. Because “a third of our cohort was readmitted with an infection, it is possible that more disadvantaged neighborhoods created more challenges for a person’s immune system, which may be compromised after recovering from sepsis.”

Dr. DuGoff further noted that health literacy may be lower among people living in less advantaged neighborhoods.

“A number of studies suggest when patients leave the hospital, they’re not sure what they need to do. The language is complicated, and it’s hard to know what kind of medication to take when, and when you’re supposed to return to the doctor or the hospital,” Dr. DuGoff said. “Managing all of that can be pretty scary for people, particularly after a traumatic experience with sepsis at the hospital.”

Most patients had been discharged home (67.3%), but the 31.6% discharged to a skilled nursing facility had a greater likelihood of readmission, compared with those discharged home (P < .01); 1% were discharged to acute rehabilitation. The average length of stay during the index hospitalization was also greater for those readmitted (8.7 days) than for those not readmitted (6.4 days). The groups did not differ in terms of their acute organ dysfunction or severity of their comorbidities.

However, even after adjustment for these factors, “neighborhood disadvantage remained significantly associated with 30-day rehospitalization in patients who were discharged with sepsis,” the authors said. Specifically, each additional standard deviation greater in patients’ ADI was associated with increased risk of 30-day readmission (P < .001).

“Given that the ADI is a composite score, we cannot identify which component is the predominant driver of rehospitalizations for patients who survive sepsis,” the authors wrote. “However, all components that make up the index are intertwined, and policy efforts targeting one (i.e., unemployment) will likely impact others (i.e., housing).”

Dr. Durfey said that medical schools have not traditionally provided training related to management of social risk factors, although this is changing in more recent curricula. But the findings still have clinical relevance for practitioners.

“Certainly, the first step is awareness of where and how patients live and being mindful of how treatment plans may be impacted by social factors at both the individual and community levels,” Dr. Durfey said. “An important part of this is working in partnership with social workers and case managers. Importantly, clinicians can also partner with disadvantaged communities to advocate for improved conditions through policy change and act as expert witnesses to how neighborhood level factors impact health.”

Dr. DuGoff also wondered what implications these findings might have currently, with regards to COVID-19.

“People living in disadvantaged neighborhoods are already at higher risk for getting the disease, and this study raises really good questions about how we should be monitoring discharge now in anticipation of these types of issues,” she said.

The authors noted that their study is cross-sectional and cannot indicate causation, and the findings of a single urban institution may not be generalizable elsewhere. They also did not consider what interventions individual patients had during their index hospitalization that could have increased frailty.

The study did not note external funding. One coauthor of the study, Suchi Saria, PhD, reported receiving honoraria and travel reimbursement from two dozen biotechnology companies for keynotes and advisory board service; she also holds equity in Patient Ping and Bayesian Health. The other authors reported no industry disclosures. In addition to consulting for Berkeley Research Group, Dr. DuGoff has received a past honorarium from Zimmer Biomet. Dr. Durfey has no disclosures.

SOURCE: Galiatsatos P et al. Crit Care Med. 2020 Jun;48(6):808-14.

FROM CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE

Republican or Democrat, Americans vote for face masks

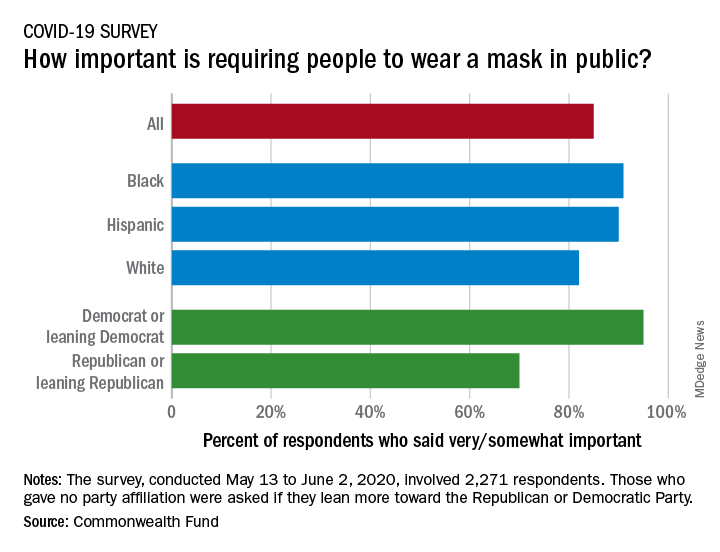

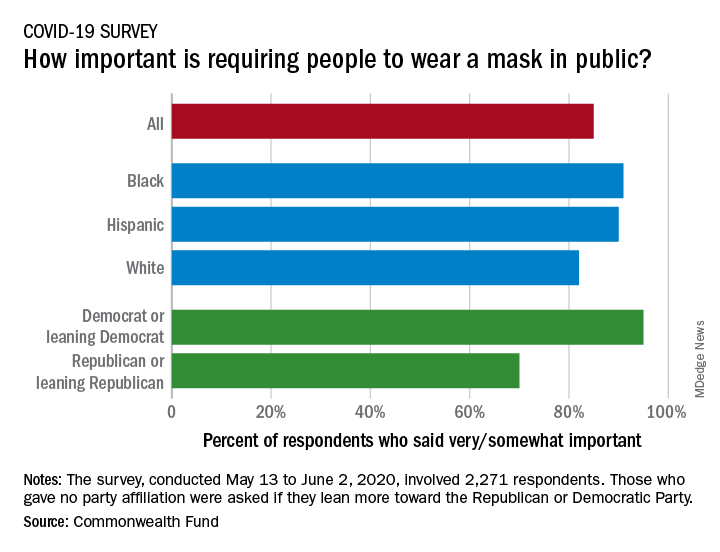

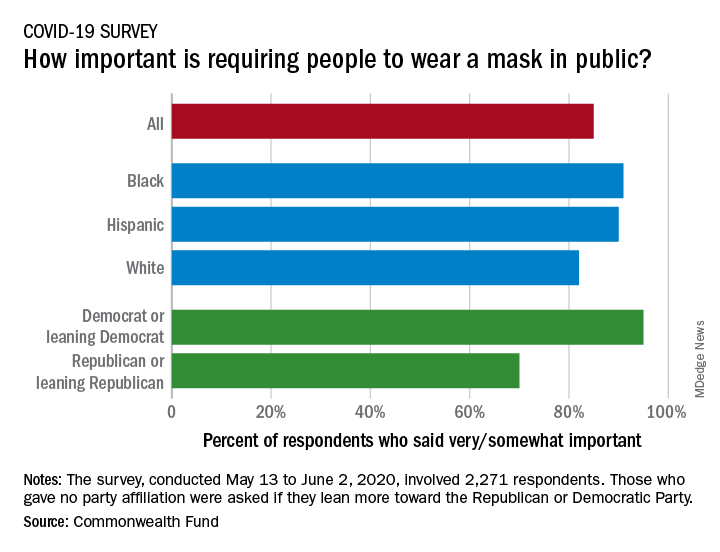

Most Americans support the required use of face masks in public, along with universal COVID-19 testing, to provide a safe work environment during the pandemic, according to a new report from the Commonwealth Fund.

Results of a recent survey show that 85% of adults believe that it is very or somewhat important to require everyone to wear a face mask “at work, when shopping, and on public transportation,” said Sara R. Collins, PhD, vice president for health care coverage and access at the fund, and associates.

In that survey, conducted from May 13 to June 2, 2020, and involving 2,271 respondents, regular COVID-19 testing for everyone was supported by 81% of the sample as way to ensure a safe work environment until a vaccine is available, the researchers said in the report.

Support on both issues was consistently high across both racial/ethnic and political lines. Mandatory mask use gained 91% support among black respondents, 90% in Hispanics, and 82% in whites. There was greater distance between the political parties, but 70% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents support mask use, compared with 95% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents, they said.

Regarding regular testing, 66% of Republicans and those leaning Republican said that it was very/somewhat important to ensure a safe work environment, as did 91% on the Democratic side. Hispanics offered the most support by race/ethnicity, with 90% saying that testing was very/somewhat important, compared with 86% of black respondents and 78% of white respondents, Dr. Collins and associates said.

Two-thirds of Republicans said that it was very/somewhat important for the government to trace the contacts of any person who tested positive for COVID-19, a sentiment shared by 91% of Democrats. That type of tracing was supported by 88% of blacks, 85% of Hispanics, and 79% of whites, based on the polling results.

The survey, conducted for the Commonwealth Fund by the survey and market research firm SSRS, had a margin of error of ± 2.4 percentage points.

Most Americans support the required use of face masks in public, along with universal COVID-19 testing, to provide a safe work environment during the pandemic, according to a new report from the Commonwealth Fund.

Results of a recent survey show that 85% of adults believe that it is very or somewhat important to require everyone to wear a face mask “at work, when shopping, and on public transportation,” said Sara R. Collins, PhD, vice president for health care coverage and access at the fund, and associates.

In that survey, conducted from May 13 to June 2, 2020, and involving 2,271 respondents, regular COVID-19 testing for everyone was supported by 81% of the sample as way to ensure a safe work environment until a vaccine is available, the researchers said in the report.

Support on both issues was consistently high across both racial/ethnic and political lines. Mandatory mask use gained 91% support among black respondents, 90% in Hispanics, and 82% in whites. There was greater distance between the political parties, but 70% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents support mask use, compared with 95% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents, they said.

Regarding regular testing, 66% of Republicans and those leaning Republican said that it was very/somewhat important to ensure a safe work environment, as did 91% on the Democratic side. Hispanics offered the most support by race/ethnicity, with 90% saying that testing was very/somewhat important, compared with 86% of black respondents and 78% of white respondents, Dr. Collins and associates said.

Two-thirds of Republicans said that it was very/somewhat important for the government to trace the contacts of any person who tested positive for COVID-19, a sentiment shared by 91% of Democrats. That type of tracing was supported by 88% of blacks, 85% of Hispanics, and 79% of whites, based on the polling results.

The survey, conducted for the Commonwealth Fund by the survey and market research firm SSRS, had a margin of error of ± 2.4 percentage points.

Most Americans support the required use of face masks in public, along with universal COVID-19 testing, to provide a safe work environment during the pandemic, according to a new report from the Commonwealth Fund.

Results of a recent survey show that 85% of adults believe that it is very or somewhat important to require everyone to wear a face mask “at work, when shopping, and on public transportation,” said Sara R. Collins, PhD, vice president for health care coverage and access at the fund, and associates.

In that survey, conducted from May 13 to June 2, 2020, and involving 2,271 respondents, regular COVID-19 testing for everyone was supported by 81% of the sample as way to ensure a safe work environment until a vaccine is available, the researchers said in the report.

Support on both issues was consistently high across both racial/ethnic and political lines. Mandatory mask use gained 91% support among black respondents, 90% in Hispanics, and 82% in whites. There was greater distance between the political parties, but 70% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents support mask use, compared with 95% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents, they said.

Regarding regular testing, 66% of Republicans and those leaning Republican said that it was very/somewhat important to ensure a safe work environment, as did 91% on the Democratic side. Hispanics offered the most support by race/ethnicity, with 90% saying that testing was very/somewhat important, compared with 86% of black respondents and 78% of white respondents, Dr. Collins and associates said.

Two-thirds of Republicans said that it was very/somewhat important for the government to trace the contacts of any person who tested positive for COVID-19, a sentiment shared by 91% of Democrats. That type of tracing was supported by 88% of blacks, 85% of Hispanics, and 79% of whites, based on the polling results.

The survey, conducted for the Commonwealth Fund by the survey and market research firm SSRS, had a margin of error of ± 2.4 percentage points.

Three stages to COVID-19 brain damage, new review suggests

In stage 1, viral damage is limited to epithelial cells of the nose and mouth, and in stage 2 blood clots that form in the lungs may travel to the brain, leading to stroke. In stage 3, the virus crosses the blood-brain barrier and invades the brain.

“Our major take-home points are that patients with COVID-19 symptoms, such as shortness of breath, headache, or dizziness, may have neurological symptoms that, at the time of hospitalization, might not be noticed or prioritized, or whose neurological symptoms may become apparent only after they leave the hospital,” lead author Majid Fotuhi, MD, PhD, medical director of NeuroGrow Brain Fitness Center in McLean, Va., said.

“Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 should have a neurological evaluation and ideally a brain MRI before leaving the hospital; and, if there are abnormalities, they should follow up with a neurologist in 3-4 months,” said Dr. Fotuhi, who is also affiliate staff at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore.

The review was published online June 8 in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Wreaks CNS havoc

It has become “increasingly evident” that SARS-CoV-2 can cause neurologic manifestations, including anosmia, seizures, stroke, confusion, encephalopathy, and total paralysis, the authors wrote.

They noted that SARS-CoV-2 binds to ACE2, which facilitates the conversion of angiotensin II to angiotensin. After ACE2 has bound to respiratory epithelial cells and then to epithelial cells in blood vessels, SARS-CoV-2 triggers the formation of a “cytokine storm.”

These cytokines, in turn, increase vascular permeability, edema, and widespread inflammation, as well as triggering “hypercoagulation cascades,” which cause small and large blood clots that affect multiple organs.

If SARS-CoV-2 crosses the blood-brain barrier, directly entering the brain, it can contribute to demyelination or neurodegeneration.

“We very thoroughly reviewed the literature published between Jan. 1 and May 1, 2020, about neurological issues [in COVID-19] and what I found interesting is that so many neurological things can happen due to a virus which is so small,” said Dr. Fotuhi.

“This virus’ DNA has such limited information, and yet it can wreak havoc on our nervous system because it kicks off such a potent defense system in our body that damages our nervous system,” he said.

Three-stage classification

- Stage 1: The extent of SARS-CoV-2 binding to the ACE2 receptors is limited to the nasal and gustatory epithelial cells, with the cytokine storm remaining “low and controlled.” During this stage, patients may experience smell or taste impairments, but often recover without any interventions.

- Stage 2: A “robust immune response” is activated by the virus, leading to inflammation in the blood vessels, increased hypercoagulability factors, and the formation of blood clots in cerebral arteries and veins. The patient may therefore experience either large or small strokes. Additional stage 2 symptoms include fatigue, hemiplegia, sensory loss, , tetraplegia, , or ataxia.

- Stage 3: The cytokine storm in the blood vessels is so severe that it causes an “explosive inflammatory response” and penetrates the blood-brain barrier, leading to the entry of cytokines, blood components, and viral particles into the brain parenchyma and causing neuronal cell death and encephalitis. This stage can be characterized by seizures, confusion, , coma, loss of consciousness, or death.

“Patients in stage 3 are more likely to have long-term consequences, because there is evidence that the virus particles have actually penetrated the brain, and we know that SARS-CoV-2 can remain dormant in neurons for many years,” said Dr. Fotuhi.

“Studies of coronaviruses have shown a link between the viruses and the risk of multiple sclerosis or Parkinson’s disease even decades later,” he added.

“Based on several reports in recent months, between 36% to 55% of patients with COVID-19 that are hospitalized have some neurological symptoms, but if you don’t look for them, you won’t see them,” Dr. Fotuhi noted.

As a result, patients should be monitored over time after discharge, as they may develop cognitive dysfunction down the road.

Additionally, “it is imperative for patients [hospitalized with COVID-19] to get a baseline MRI before leaving the hospital so that we have a starting point for future evaluation and treatment,” said Dr. Fotuhi.

“The good news is that neurological manifestations of COVID-19 are treatable,” and “can improve with intensive training,” including lifestyle changes – such as a heart-healthy diet, regular physical activity, stress reduction, improved sleep, biofeedback, and brain rehabilitation, Dr. Fotuhi added.

Routine MRI not necessary

Kenneth Tyler, MD, chair of the department of neurology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, disagreed that all hospitalized patients with COVID-19 should routinely receive an MRI.

“Whenever you are using a piece of equipment on patients who are COVID-19 infected, you risk introducing the infection to uninfected patients,” he said. Instead, “the indication is in patients who develop unexplained neurological manifestations – altered mental status or focal seizures, for example – because in those cases, you do need to understand whether there are underlying structural abnormalities,” said Dr. Tyler, who was not involved in the review.

Also commenting on the review, Vanja Douglas, MD, associate professor of clinical neurology, University of California, San Francisco, described the review as “thorough” and suggested it may “help us understand how to design observational studies to test whether the associations are due to severe respiratory illness or are specific to SARS-CoV-2 infection.”

Dr. Douglas, who was not involved in the review, added that it is “helpful in giving us a sense of which neurologic syndromes have been observed in COVID-19 patients, and therefore which patients neurologists may want to screen more carefully during the pandemic.”

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Fotuhi disclosed no relevant financial relationships. One coauthor reported receiving consulting fees as a member of the scientific advisory board for Brainreader and reports royalties for expert witness consultation in conjunction with Neurevolution. Dr. Tyler and Dr. Douglas disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In stage 1, viral damage is limited to epithelial cells of the nose and mouth, and in stage 2 blood clots that form in the lungs may travel to the brain, leading to stroke. In stage 3, the virus crosses the blood-brain barrier and invades the brain.

“Our major take-home points are that patients with COVID-19 symptoms, such as shortness of breath, headache, or dizziness, may have neurological symptoms that, at the time of hospitalization, might not be noticed or prioritized, or whose neurological symptoms may become apparent only after they leave the hospital,” lead author Majid Fotuhi, MD, PhD, medical director of NeuroGrow Brain Fitness Center in McLean, Va., said.

“Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 should have a neurological evaluation and ideally a brain MRI before leaving the hospital; and, if there are abnormalities, they should follow up with a neurologist in 3-4 months,” said Dr. Fotuhi, who is also affiliate staff at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore.

The review was published online June 8 in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Wreaks CNS havoc

It has become “increasingly evident” that SARS-CoV-2 can cause neurologic manifestations, including anosmia, seizures, stroke, confusion, encephalopathy, and total paralysis, the authors wrote.

They noted that SARS-CoV-2 binds to ACE2, which facilitates the conversion of angiotensin II to angiotensin. After ACE2 has bound to respiratory epithelial cells and then to epithelial cells in blood vessels, SARS-CoV-2 triggers the formation of a “cytokine storm.”

These cytokines, in turn, increase vascular permeability, edema, and widespread inflammation, as well as triggering “hypercoagulation cascades,” which cause small and large blood clots that affect multiple organs.

If SARS-CoV-2 crosses the blood-brain barrier, directly entering the brain, it can contribute to demyelination or neurodegeneration.

“We very thoroughly reviewed the literature published between Jan. 1 and May 1, 2020, about neurological issues [in COVID-19] and what I found interesting is that so many neurological things can happen due to a virus which is so small,” said Dr. Fotuhi.

“This virus’ DNA has such limited information, and yet it can wreak havoc on our nervous system because it kicks off such a potent defense system in our body that damages our nervous system,” he said.

Three-stage classification

- Stage 1: The extent of SARS-CoV-2 binding to the ACE2 receptors is limited to the nasal and gustatory epithelial cells, with the cytokine storm remaining “low and controlled.” During this stage, patients may experience smell or taste impairments, but often recover without any interventions.

- Stage 2: A “robust immune response” is activated by the virus, leading to inflammation in the blood vessels, increased hypercoagulability factors, and the formation of blood clots in cerebral arteries and veins. The patient may therefore experience either large or small strokes. Additional stage 2 symptoms include fatigue, hemiplegia, sensory loss, , tetraplegia, , or ataxia.

- Stage 3: The cytokine storm in the blood vessels is so severe that it causes an “explosive inflammatory response” and penetrates the blood-brain barrier, leading to the entry of cytokines, blood components, and viral particles into the brain parenchyma and causing neuronal cell death and encephalitis. This stage can be characterized by seizures, confusion, , coma, loss of consciousness, or death.

“Patients in stage 3 are more likely to have long-term consequences, because there is evidence that the virus particles have actually penetrated the brain, and we know that SARS-CoV-2 can remain dormant in neurons for many years,” said Dr. Fotuhi.

“Studies of coronaviruses have shown a link between the viruses and the risk of multiple sclerosis or Parkinson’s disease even decades later,” he added.

“Based on several reports in recent months, between 36% to 55% of patients with COVID-19 that are hospitalized have some neurological symptoms, but if you don’t look for them, you won’t see them,” Dr. Fotuhi noted.

As a result, patients should be monitored over time after discharge, as they may develop cognitive dysfunction down the road.

Additionally, “it is imperative for patients [hospitalized with COVID-19] to get a baseline MRI before leaving the hospital so that we have a starting point for future evaluation and treatment,” said Dr. Fotuhi.

“The good news is that neurological manifestations of COVID-19 are treatable,” and “can improve with intensive training,” including lifestyle changes – such as a heart-healthy diet, regular physical activity, stress reduction, improved sleep, biofeedback, and brain rehabilitation, Dr. Fotuhi added.

Routine MRI not necessary

Kenneth Tyler, MD, chair of the department of neurology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, disagreed that all hospitalized patients with COVID-19 should routinely receive an MRI.

“Whenever you are using a piece of equipment on patients who are COVID-19 infected, you risk introducing the infection to uninfected patients,” he said. Instead, “the indication is in patients who develop unexplained neurological manifestations – altered mental status or focal seizures, for example – because in those cases, you do need to understand whether there are underlying structural abnormalities,” said Dr. Tyler, who was not involved in the review.

Also commenting on the review, Vanja Douglas, MD, associate professor of clinical neurology, University of California, San Francisco, described the review as “thorough” and suggested it may “help us understand how to design observational studies to test whether the associations are due to severe respiratory illness or are specific to SARS-CoV-2 infection.”

Dr. Douglas, who was not involved in the review, added that it is “helpful in giving us a sense of which neurologic syndromes have been observed in COVID-19 patients, and therefore which patients neurologists may want to screen more carefully during the pandemic.”

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Fotuhi disclosed no relevant financial relationships. One coauthor reported receiving consulting fees as a member of the scientific advisory board for Brainreader and reports royalties for expert witness consultation in conjunction with Neurevolution. Dr. Tyler and Dr. Douglas disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In stage 1, viral damage is limited to epithelial cells of the nose and mouth, and in stage 2 blood clots that form in the lungs may travel to the brain, leading to stroke. In stage 3, the virus crosses the blood-brain barrier and invades the brain.

“Our major take-home points are that patients with COVID-19 symptoms, such as shortness of breath, headache, or dizziness, may have neurological symptoms that, at the time of hospitalization, might not be noticed or prioritized, or whose neurological symptoms may become apparent only after they leave the hospital,” lead author Majid Fotuhi, MD, PhD, medical director of NeuroGrow Brain Fitness Center in McLean, Va., said.

“Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 should have a neurological evaluation and ideally a brain MRI before leaving the hospital; and, if there are abnormalities, they should follow up with a neurologist in 3-4 months,” said Dr. Fotuhi, who is also affiliate staff at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore.

The review was published online June 8 in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Wreaks CNS havoc

It has become “increasingly evident” that SARS-CoV-2 can cause neurologic manifestations, including anosmia, seizures, stroke, confusion, encephalopathy, and total paralysis, the authors wrote.

They noted that SARS-CoV-2 binds to ACE2, which facilitates the conversion of angiotensin II to angiotensin. After ACE2 has bound to respiratory epithelial cells and then to epithelial cells in blood vessels, SARS-CoV-2 triggers the formation of a “cytokine storm.”

These cytokines, in turn, increase vascular permeability, edema, and widespread inflammation, as well as triggering “hypercoagulation cascades,” which cause small and large blood clots that affect multiple organs.

If SARS-CoV-2 crosses the blood-brain barrier, directly entering the brain, it can contribute to demyelination or neurodegeneration.

“We very thoroughly reviewed the literature published between Jan. 1 and May 1, 2020, about neurological issues [in COVID-19] and what I found interesting is that so many neurological things can happen due to a virus which is so small,” said Dr. Fotuhi.

“This virus’ DNA has such limited information, and yet it can wreak havoc on our nervous system because it kicks off such a potent defense system in our body that damages our nervous system,” he said.

Three-stage classification

- Stage 1: The extent of SARS-CoV-2 binding to the ACE2 receptors is limited to the nasal and gustatory epithelial cells, with the cytokine storm remaining “low and controlled.” During this stage, patients may experience smell or taste impairments, but often recover without any interventions.

- Stage 2: A “robust immune response” is activated by the virus, leading to inflammation in the blood vessels, increased hypercoagulability factors, and the formation of blood clots in cerebral arteries and veins. The patient may therefore experience either large or small strokes. Additional stage 2 symptoms include fatigue, hemiplegia, sensory loss, , tetraplegia, , or ataxia.

- Stage 3: The cytokine storm in the blood vessels is so severe that it causes an “explosive inflammatory response” and penetrates the blood-brain barrier, leading to the entry of cytokines, blood components, and viral particles into the brain parenchyma and causing neuronal cell death and encephalitis. This stage can be characterized by seizures, confusion, , coma, loss of consciousness, or death.

“Patients in stage 3 are more likely to have long-term consequences, because there is evidence that the virus particles have actually penetrated the brain, and we know that SARS-CoV-2 can remain dormant in neurons for many years,” said Dr. Fotuhi.

“Studies of coronaviruses have shown a link between the viruses and the risk of multiple sclerosis or Parkinson’s disease even decades later,” he added.

“Based on several reports in recent months, between 36% to 55% of patients with COVID-19 that are hospitalized have some neurological symptoms, but if you don’t look for them, you won’t see them,” Dr. Fotuhi noted.

As a result, patients should be monitored over time after discharge, as they may develop cognitive dysfunction down the road.

Additionally, “it is imperative for patients [hospitalized with COVID-19] to get a baseline MRI before leaving the hospital so that we have a starting point for future evaluation and treatment,” said Dr. Fotuhi.

“The good news is that neurological manifestations of COVID-19 are treatable,” and “can improve with intensive training,” including lifestyle changes – such as a heart-healthy diet, regular physical activity, stress reduction, improved sleep, biofeedback, and brain rehabilitation, Dr. Fotuhi added.

Routine MRI not necessary

Kenneth Tyler, MD, chair of the department of neurology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, disagreed that all hospitalized patients with COVID-19 should routinely receive an MRI.

“Whenever you are using a piece of equipment on patients who are COVID-19 infected, you risk introducing the infection to uninfected patients,” he said. Instead, “the indication is in patients who develop unexplained neurological manifestations – altered mental status or focal seizures, for example – because in those cases, you do need to understand whether there are underlying structural abnormalities,” said Dr. Tyler, who was not involved in the review.

Also commenting on the review, Vanja Douglas, MD, associate professor of clinical neurology, University of California, San Francisco, described the review as “thorough” and suggested it may “help us understand how to design observational studies to test whether the associations are due to severe respiratory illness or are specific to SARS-CoV-2 infection.”

Dr. Douglas, who was not involved in the review, added that it is “helpful in giving us a sense of which neurologic syndromes have been observed in COVID-19 patients, and therefore which patients neurologists may want to screen more carefully during the pandemic.”

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Fotuhi disclosed no relevant financial relationships. One coauthor reported receiving consulting fees as a member of the scientific advisory board for Brainreader and reports royalties for expert witness consultation in conjunction with Neurevolution. Dr. Tyler and Dr. Douglas disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Weight loss failures drive bariatric surgery regrets

Not all weight loss surgery patients “live happily ever after,” according to Daniel B. Jones, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston.

A 2014 study of 22 women who underwent weight loss surgery reported lower energy, worse quality of life, and persistent eating disorders, Dr. Jones said in a presentation at the virtual Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium by Global Academy for Medical Education.

However, postprocedure problems don’t always equal regrets, he said. “Although many women [in the 2014 study] reported negative thoughts and health issues after weight loss surgery, none of them said they regret undergoing the procedure,” he noted.

To further examine decision regret in patients who underwent gastric bypass and gastric banding, Dr. Jones participated in a study of patients’ attitudes 4 years after gastric bypass and gastric banding (Obes Surg. 2019;29:1624-31).

“Weight loss surgery is neither risk free nor universally effective, yet few studies have examined what proportion of patients regret having undergone weight loss surgery,” he noted.

Dr. Jones and colleagues interviewed patients at two weight loss surgery centers and used specific metrics and a multivariate analysis to examine associations among weight loss, quality of life, and decision regret.

A total of 205 Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) patients responded at 1 year after surgery: 181, 156, and 134 patients responded at 2, 3, and 4 years, respectively.

At 1 year, 2% reported regret and that they would not choose the surgery again, and by 4 years, 5% reported regret, based on overall regret scores greater than 50. In addition, 13% of patients at 1 year and 4 years reported that weight loss surgery caused “some” or “a lot” of negative effects.

The researchers also interviewed gastric band patients: 170, 157, 146, and 123 responded at years 1,2,3, and 4.

Overall, 8% of these patients expressed regret at 1 year, and 20% expressed regret at 4 years, said Dr. Jones.

“Almost 20% did not think they made the right decision,” he said.

Dr. Jones noted. An average weight loss of 7.4% of excess body weight was associated with regret scores greater than 50, while an average weight loss of 21.1% was associated with regret scores less than 50, he said.

In addition, poor sexual function, but not weight loss or other quality-of-life factors was significantly associated with regret among RYGB patients.

Many surgeons are performing sleeve gastrectomies, which appear to yield greater weight loss than gastric banding and fewer complications than gastric bypass, said Dr. Jones. His study did not include sleeve gastrectomies, but “I expect a sleeve gastrectomy to do pretty well in this analysis,” and to be associated with less patient regret, he said.

Overall, better patient education is key to improving patients’ experiences and reducing feelings of regret, said Dr. Jones.

“The better patients understand the difference between band, bypass, and sleeve preoperatively, the better we can set expectations,” he said. Dr. Jones’ institution has developed an app for laparoscopic sleeve that guides patients through the process from preop through postoperative stay, he noted.

Given the association between amount of weight lost and regret, “setting expectations is very important,” and could include not only written consent but also webinars, information sessions, and apps for patients in advance to help mitigate regrets after the procedure, Dr. Jones concluded.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Jones disclosed serving on the medical advisory board for Allurion.

Not all weight loss surgery patients “live happily ever after,” according to Daniel B. Jones, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston.

A 2014 study of 22 women who underwent weight loss surgery reported lower energy, worse quality of life, and persistent eating disorders, Dr. Jones said in a presentation at the virtual Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium by Global Academy for Medical Education.

However, postprocedure problems don’t always equal regrets, he said. “Although many women [in the 2014 study] reported negative thoughts and health issues after weight loss surgery, none of them said they regret undergoing the procedure,” he noted.

To further examine decision regret in patients who underwent gastric bypass and gastric banding, Dr. Jones participated in a study of patients’ attitudes 4 years after gastric bypass and gastric banding (Obes Surg. 2019;29:1624-31).

“Weight loss surgery is neither risk free nor universally effective, yet few studies have examined what proportion of patients regret having undergone weight loss surgery,” he noted.

Dr. Jones and colleagues interviewed patients at two weight loss surgery centers and used specific metrics and a multivariate analysis to examine associations among weight loss, quality of life, and decision regret.

A total of 205 Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) patients responded at 1 year after surgery: 181, 156, and 134 patients responded at 2, 3, and 4 years, respectively.

At 1 year, 2% reported regret and that they would not choose the surgery again, and by 4 years, 5% reported regret, based on overall regret scores greater than 50. In addition, 13% of patients at 1 year and 4 years reported that weight loss surgery caused “some” or “a lot” of negative effects.

The researchers also interviewed gastric band patients: 170, 157, 146, and 123 responded at years 1,2,3, and 4.

Overall, 8% of these patients expressed regret at 1 year, and 20% expressed regret at 4 years, said Dr. Jones.

“Almost 20% did not think they made the right decision,” he said.

Dr. Jones noted. An average weight loss of 7.4% of excess body weight was associated with regret scores greater than 50, while an average weight loss of 21.1% was associated with regret scores less than 50, he said.

In addition, poor sexual function, but not weight loss or other quality-of-life factors was significantly associated with regret among RYGB patients.

Many surgeons are performing sleeve gastrectomies, which appear to yield greater weight loss than gastric banding and fewer complications than gastric bypass, said Dr. Jones. His study did not include sleeve gastrectomies, but “I expect a sleeve gastrectomy to do pretty well in this analysis,” and to be associated with less patient regret, he said.

Overall, better patient education is key to improving patients’ experiences and reducing feelings of regret, said Dr. Jones.

“The better patients understand the difference between band, bypass, and sleeve preoperatively, the better we can set expectations,” he said. Dr. Jones’ institution has developed an app for laparoscopic sleeve that guides patients through the process from preop through postoperative stay, he noted.

Given the association between amount of weight lost and regret, “setting expectations is very important,” and could include not only written consent but also webinars, information sessions, and apps for patients in advance to help mitigate regrets after the procedure, Dr. Jones concluded.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Jones disclosed serving on the medical advisory board for Allurion.

Not all weight loss surgery patients “live happily ever after,” according to Daniel B. Jones, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston.

A 2014 study of 22 women who underwent weight loss surgery reported lower energy, worse quality of life, and persistent eating disorders, Dr. Jones said in a presentation at the virtual Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium by Global Academy for Medical Education.

However, postprocedure problems don’t always equal regrets, he said. “Although many women [in the 2014 study] reported negative thoughts and health issues after weight loss surgery, none of them said they regret undergoing the procedure,” he noted.

To further examine decision regret in patients who underwent gastric bypass and gastric banding, Dr. Jones participated in a study of patients’ attitudes 4 years after gastric bypass and gastric banding (Obes Surg. 2019;29:1624-31).

“Weight loss surgery is neither risk free nor universally effective, yet few studies have examined what proportion of patients regret having undergone weight loss surgery,” he noted.

Dr. Jones and colleagues interviewed patients at two weight loss surgery centers and used specific metrics and a multivariate analysis to examine associations among weight loss, quality of life, and decision regret.

A total of 205 Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) patients responded at 1 year after surgery: 181, 156, and 134 patients responded at 2, 3, and 4 years, respectively.

At 1 year, 2% reported regret and that they would not choose the surgery again, and by 4 years, 5% reported regret, based on overall regret scores greater than 50. In addition, 13% of patients at 1 year and 4 years reported that weight loss surgery caused “some” or “a lot” of negative effects.

The researchers also interviewed gastric band patients: 170, 157, 146, and 123 responded at years 1,2,3, and 4.

Overall, 8% of these patients expressed regret at 1 year, and 20% expressed regret at 4 years, said Dr. Jones.

“Almost 20% did not think they made the right decision,” he said.

Dr. Jones noted. An average weight loss of 7.4% of excess body weight was associated with regret scores greater than 50, while an average weight loss of 21.1% was associated with regret scores less than 50, he said.

In addition, poor sexual function, but not weight loss or other quality-of-life factors was significantly associated with regret among RYGB patients.

Many surgeons are performing sleeve gastrectomies, which appear to yield greater weight loss than gastric banding and fewer complications than gastric bypass, said Dr. Jones. His study did not include sleeve gastrectomies, but “I expect a sleeve gastrectomy to do pretty well in this analysis,” and to be associated with less patient regret, he said.

Overall, better patient education is key to improving patients’ experiences and reducing feelings of regret, said Dr. Jones.

“The better patients understand the difference between band, bypass, and sleeve preoperatively, the better we can set expectations,” he said. Dr. Jones’ institution has developed an app for laparoscopic sleeve that guides patients through the process from preop through postoperative stay, he noted.

Given the association between amount of weight lost and regret, “setting expectations is very important,” and could include not only written consent but also webinars, information sessions, and apps for patients in advance to help mitigate regrets after the procedure, Dr. Jones concluded.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Dr. Jones disclosed serving on the medical advisory board for Allurion.

FROM MISS

Daily Recap: Docs are good at saving money; SARS-CoV-2 vaccine trials advance

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

Many physicians live within their means and save

Although about two of five physicians report a net worth of between $1 million and $5 million, about half report that they are living at or below their means, according to the latest Medscape Physician Debt and Net Worth Report 2020.

Net worth figures varied greatly by specialty. Among specialists, orthopedists were most likely (at 19%) to top the $5 million level, followed by plastic surgeons and gastroenterologists (both at 16%). Conversely, 46% of family physicians and 44% of pediatricians reported that their net worth was under $500,000. Gender gaps were also apparent in the data, especially at the highest levels. Twice as many male physicians (10%) as their female counterparts (5%) had a net worth of more than $5 million.

Asked about saving habits, 43% of physicians reported they live below their means. Just 7% said they live above their means. How do they save money? Survey respondents reported putting bonus money into an investment account, putting extra money toward paying down the mortgage, and bringing lunch to work everyday.

The survey responses on salary, debt, and net worth from more than 17,000 physicians spanning 30 specialties were collected prior to Feb. 11, before COVID-19 was declared a pandemic. Read more.

Phase 3 COVID-19 vaccine trials launching in July

There are now 120 Investigational New Drug applications to the Food and Drug Administration for a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, and researchers at more than 70 companies across the globe are interested in making a vaccine, according to Paul A. Offit, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

“The good news is that the new coronavirus is relatively stable,” Dr. Offit said during the virtual Pediatric Dermatology 2020: Best Practices and Innovations Conference. “Although it is a single-stranded RNA virus, it does mutate to some extent, but it doesn’t look like it’s going to mutate away from the vaccine. So, this is not going to be like influenza virus, where you must give a vaccine every year. I think we can make a vaccine that will last for several years. And we know the protein we’re interested in. We’re interested in antibodies directed against the spike glycoprotein, which is abundantly present on the surface of the virus. We know that if we make an antibody response to that protein, we can therefore prevent infection.” Read more.

FDA approves in-home breast cancer treatment

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a combination of subcutaneous breast cancer treatments that could be administered at home, following completion of chemotherapy.

The agency gave the green light to pertuzumab (Perjeta, Genentech/Roche), trastuzumab (Herceptin, Genentech/Roche) and hyaluronidase (Phesgo, Genentech/Roche), administered subcutaneously rather than intravenously, for the treatment of early and metastatic HER2-positive breast cancers.

Phesgo is initially used in combination with chemotherapy at an infusion center but could continue to be administered in a patient’s home by a qualified health care professional once chemotherapy is complete. Read more.

Could a visual tool aid migraine management?

A new visual tool aims to streamline patient-clinician communication about risk factors for progression from episodic to chronic migraines.

The tool is still just a prototype, but it could eventually synthesize patient responses to an integrated questionnaire and produce a chart illustrating where the patient stands with respect to a range of modifiable risk factors from depression to insomnia.

Physicians must see patients in short appointment periods, making it difficult to communicate all of the risk factors and behavioral characteristics that can contribute to risk of progression. “If you have a patient and you’re able to look at a visualization tool quickly and say: ‘Okay, my patient really is having insomnia and sleep issues,’ you can focus the session talking about sleep, cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia, and all the things we can help patients with,” lead researcher Ami Cuneo, MD, who is a headache fellow at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview.

Dr. Cuneo presented a poster describing the concept at the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society. Read more.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

Many physicians live within their means and save

Although about two of five physicians report a net worth of between $1 million and $5 million, about half report that they are living at or below their means, according to the latest Medscape Physician Debt and Net Worth Report 2020.

Net worth figures varied greatly by specialty. Among specialists, orthopedists were most likely (at 19%) to top the $5 million level, followed by plastic surgeons and gastroenterologists (both at 16%). Conversely, 46% of family physicians and 44% of pediatricians reported that their net worth was under $500,000. Gender gaps were also apparent in the data, especially at the highest levels. Twice as many male physicians (10%) as their female counterparts (5%) had a net worth of more than $5 million.

Asked about saving habits, 43% of physicians reported they live below their means. Just 7% said they live above their means. How do they save money? Survey respondents reported putting bonus money into an investment account, putting extra money toward paying down the mortgage, and bringing lunch to work everyday.

The survey responses on salary, debt, and net worth from more than 17,000 physicians spanning 30 specialties were collected prior to Feb. 11, before COVID-19 was declared a pandemic. Read more.

Phase 3 COVID-19 vaccine trials launching in July

There are now 120 Investigational New Drug applications to the Food and Drug Administration for a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, and researchers at more than 70 companies across the globe are interested in making a vaccine, according to Paul A. Offit, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

“The good news is that the new coronavirus is relatively stable,” Dr. Offit said during the virtual Pediatric Dermatology 2020: Best Practices and Innovations Conference. “Although it is a single-stranded RNA virus, it does mutate to some extent, but it doesn’t look like it’s going to mutate away from the vaccine. So, this is not going to be like influenza virus, where you must give a vaccine every year. I think we can make a vaccine that will last for several years. And we know the protein we’re interested in. We’re interested in antibodies directed against the spike glycoprotein, which is abundantly present on the surface of the virus. We know that if we make an antibody response to that protein, we can therefore prevent infection.” Read more.

FDA approves in-home breast cancer treatment

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a combination of subcutaneous breast cancer treatments that could be administered at home, following completion of chemotherapy.

The agency gave the green light to pertuzumab (Perjeta, Genentech/Roche), trastuzumab (Herceptin, Genentech/Roche) and hyaluronidase (Phesgo, Genentech/Roche), administered subcutaneously rather than intravenously, for the treatment of early and metastatic HER2-positive breast cancers.

Phesgo is initially used in combination with chemotherapy at an infusion center but could continue to be administered in a patient’s home by a qualified health care professional once chemotherapy is complete. Read more.

Could a visual tool aid migraine management?

A new visual tool aims to streamline patient-clinician communication about risk factors for progression from episodic to chronic migraines.

The tool is still just a prototype, but it could eventually synthesize patient responses to an integrated questionnaire and produce a chart illustrating where the patient stands with respect to a range of modifiable risk factors from depression to insomnia.

Physicians must see patients in short appointment periods, making it difficult to communicate all of the risk factors and behavioral characteristics that can contribute to risk of progression. “If you have a patient and you’re able to look at a visualization tool quickly and say: ‘Okay, my patient really is having insomnia and sleep issues,’ you can focus the session talking about sleep, cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia, and all the things we can help patients with,” lead researcher Ami Cuneo, MD, who is a headache fellow at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview.

Dr. Cuneo presented a poster describing the concept at the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society. Read more.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

Many physicians live within their means and save

Although about two of five physicians report a net worth of between $1 million and $5 million, about half report that they are living at or below their means, according to the latest Medscape Physician Debt and Net Worth Report 2020.

Net worth figures varied greatly by specialty. Among specialists, orthopedists were most likely (at 19%) to top the $5 million level, followed by plastic surgeons and gastroenterologists (both at 16%). Conversely, 46% of family physicians and 44% of pediatricians reported that their net worth was under $500,000. Gender gaps were also apparent in the data, especially at the highest levels. Twice as many male physicians (10%) as their female counterparts (5%) had a net worth of more than $5 million.

Asked about saving habits, 43% of physicians reported they live below their means. Just 7% said they live above their means. How do they save money? Survey respondents reported putting bonus money into an investment account, putting extra money toward paying down the mortgage, and bringing lunch to work everyday.

The survey responses on salary, debt, and net worth from more than 17,000 physicians spanning 30 specialties were collected prior to Feb. 11, before COVID-19 was declared a pandemic. Read more.

Phase 3 COVID-19 vaccine trials launching in July

There are now 120 Investigational New Drug applications to the Food and Drug Administration for a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, and researchers at more than 70 companies across the globe are interested in making a vaccine, according to Paul A. Offit, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

“The good news is that the new coronavirus is relatively stable,” Dr. Offit said during the virtual Pediatric Dermatology 2020: Best Practices and Innovations Conference. “Although it is a single-stranded RNA virus, it does mutate to some extent, but it doesn’t look like it’s going to mutate away from the vaccine. So, this is not going to be like influenza virus, where you must give a vaccine every year. I think we can make a vaccine that will last for several years. And we know the protein we’re interested in. We’re interested in antibodies directed against the spike glycoprotein, which is abundantly present on the surface of the virus. We know that if we make an antibody response to that protein, we can therefore prevent infection.” Read more.

FDA approves in-home breast cancer treatment

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a combination of subcutaneous breast cancer treatments that could be administered at home, following completion of chemotherapy.

The agency gave the green light to pertuzumab (Perjeta, Genentech/Roche), trastuzumab (Herceptin, Genentech/Roche) and hyaluronidase (Phesgo, Genentech/Roche), administered subcutaneously rather than intravenously, for the treatment of early and metastatic HER2-positive breast cancers.

Phesgo is initially used in combination with chemotherapy at an infusion center but could continue to be administered in a patient’s home by a qualified health care professional once chemotherapy is complete. Read more.

Could a visual tool aid migraine management?

A new visual tool aims to streamline patient-clinician communication about risk factors for progression from episodic to chronic migraines.

The tool is still just a prototype, but it could eventually synthesize patient responses to an integrated questionnaire and produce a chart illustrating where the patient stands with respect to a range of modifiable risk factors from depression to insomnia.

Physicians must see patients in short appointment periods, making it difficult to communicate all of the risk factors and behavioral characteristics that can contribute to risk of progression. “If you have a patient and you’re able to look at a visualization tool quickly and say: ‘Okay, my patient really is having insomnia and sleep issues,’ you can focus the session talking about sleep, cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia, and all the things we can help patients with,” lead researcher Ami Cuneo, MD, who is a headache fellow at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview.

Dr. Cuneo presented a poster describing the concept at the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society. Read more.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Managing pain expectations is key to enhanced recovery

Planning for reduced use of opioids in pain management involves identifying appropriate patients and managing their expectations, according to according to Timothy E. Miller, MB, ChB, FRCA, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., who is president of the American Society for Enhanced Recovery.

, he said in a presentation at the virtual Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium sponsored by Global Academy for Medical Education.

Dr. Miller shared a treatment algorithm for achieving optimal analgesia in patients after colorectal surgery that combines intravenous or oral analgesia with local anesthetics and additional nonopioid options. The algorithm involves choosing NSAIDs, acetaminophen, or gabapentin for IV/oral use. In addition, options for local anesthetic include with a choice of single-shot transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block.

Careful patient selection is key to an opioid-free or opioid reduced anesthetic strategy, Dr. Miller said. The appropriate patients have “no chronic opioids, no anxiety, and the desire to avoid opioid side effects,” he said.

Opioid-free or opioid-reduced strategies include realigning patient expectations to prepare for pain at a level of 2-4 on a scale of 10 as “expected and reasonable,” he said. Patients given no opioids or reduced opioids may report cramping after laparoscopic surgery, as well as shoulder pain that is referred from the CO2 bubble under the diaphragm, he said. However, opioids don’t treat the shoulder pain well, and “walking or changing position usually relieves this pain,” and it usually resolves within 24 hours, Dr. Miller noted. “Just letting the patient know what is expected in terms of pain relief in their recovery is hugely important,” he said.

The optimal analgesia after surgery is a plan that combines optimized patient comfort with the fastest functional recovery and the fewest side effects, he emphasized.

Optimized patient comfort includes optimal pain ratings at rest and with movement, a decreasing impact of pain on emotion, function, and sleep disruption, and an improvement in the patient experience, he said. The fastest functional recovery is defined as a return to drinking liquids, eating solid foods, performing activities of daily living, and maintaining normal bladder, bowel, and cognitive function. Side effects to be considered in analgesia included nausea, vomiting, sedation, ileus, itching, dizziness, and delirium, he said.

In an unpublished study, Dr. Miller and colleagues eliminated opioids intraoperatively in a series of 56 cases of laparoscopic cholecystectomy and found significantly less opioids needed in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU). In addition, opioid-free patients had significantly shorter length of stay in the PACU, he said. “We are writing this up for publication and looking into doing larger studies,” Dr. Miller said.

Questions include whether the opioid-free technique translates more broadly, he said.