User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Low-risk TAVR loses ground at 2 years in PARTNER 3

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) continued to show superiority over surgical replacement in terms of the primary composite endpoint in low-surgical-risk patients at 2 years of follow-up in the landmark randomized PARTNER 3 trial, but the between-group differences favoring the transcatheter procedure in some key outcomes have narrowed considerably, Michael J. Mack, MD, reported in a video presentation of his research during the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation, which was presented online this year. ACC organizers chose to present parts of the meeting virtually after COVID-19 concerns caused them to cancel the meeting.

“On the basis of 1-year data, many physicians were counseling patients that TAVR outcomes were better than surgery. Now we see that the outcomes are roughly the same at 2 years,” said Dr. Mack, who is medical director of cardiothoracic surgery and chairman of the Baylor Scott & White The Heart Hospital – Plano (Tex.) Research Center.

PARTNER 3 randomized 1,000 patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis with a tricuspid valve and a very low mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk score of 1.9% to TAVR with the Sapien 3 valve or surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR). The 1-year results presented at ACC 2019 caused a huge stir, with the primary composite outcome of death, stroke, or cardiovascular rehospitalization occurring in 8.5% of TAVR patients and 15.6% of the SAVR group, representing a 48% relative risk reduction and a resounding win for TAVR (N Engl J Med. 2019 May 2;380:1695-705). At 2 years, the difference in the composite outcome remained statistically significant, but the gap had closed: 11.5% with TAVR and 17.4% with SAVR for a 37% relative risk reduction.

Moreover, the between-group difference in stroke, which at 1 year was significantly in favor of TAVR at 1.2% versus 3.3%, was no longer significant at 2 years, with rates of 2.4% versus 3.6%. Nor was the difference in mortality significant: 2.4% with TAVR, 3.2% with SAVR.

What was a statistically significant between-group difference at 2 years – and an eye-catching one at that – involved the cumulative incidence of valve thrombosis confirmed by CT or echocardiography: 2.6% in the TAVR arm, compared with 0.7% with SAVR, with most of these unwanted events coming in year 2.

The good news was there was no echocardiographic evidence of deterioration in valve structure or function in either study arm at 2 years. The mean gradients and aortic valve areas remained unchanged in both arms between 1 and 2 years, as did the frequency of mild or moderate paravalvular leak. Prospective follow-up will continue annually out to 10 years.

“I think it’s way too early to expect to see a signal, but I think it’s somewhat comforting at this point that there’s no signal of early structural valve deterioration,” Dr. Mack said.

Discussant Howard C. Hermann, MD, commented: “I guess the biggest concern in looking at the data is the increase in stroke and valve thrombosis, both numerically and relative to SAVR, between years 1 and 2.”

Dr. Mack offered a note of reassurance regarding the valve thrombosis findings: The rates he presented were based upon the now-outdated second Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC-2) definition, per study protocol. When he and his coinvestigators recalculated the valve thrombosis rates using the contemporary VARC-3 definition of valve deterioration and bioprosthetic valve failure, the incidence was very low and not significantly different in the two study arms, at roughly 1%.

Dr. Hermann, professor of medicine and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratories at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, had a question: As a clinician taking care of TAVR patients, what clinical or hemodynamic findings should prompt an imaging study looking for valve thrombus or deterioration that might prompt initiating oral anticoagulation?

“If there’s a change in hemodynamics, an increasing valve gradient, if there’s increasing paravalvular leak, or if there’s a change in symptoms, that should prompt an imaging study. Only with confirmation of valve thrombosis on an imaging study should anticoagulation be considered. Oral anticoagulation is not benign: Of the six clinical events associated with valve thrombosis in the study, two were related to anticoagulation,” Dr. Mack replied.

“Regarding whether patients should receive warfarin or a novel anticoagulant, I don’t think we have evidence that there’s benefit to anything other than warfarin at the current time,” he added.

Dr. Mack reported receiving research support from Edwards Lifesciences, the sponsor of PARTNER 3, as well as from Abbott, Gore, and Medtronic.

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) continued to show superiority over surgical replacement in terms of the primary composite endpoint in low-surgical-risk patients at 2 years of follow-up in the landmark randomized PARTNER 3 trial, but the between-group differences favoring the transcatheter procedure in some key outcomes have narrowed considerably, Michael J. Mack, MD, reported in a video presentation of his research during the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation, which was presented online this year. ACC organizers chose to present parts of the meeting virtually after COVID-19 concerns caused them to cancel the meeting.

“On the basis of 1-year data, many physicians were counseling patients that TAVR outcomes were better than surgery. Now we see that the outcomes are roughly the same at 2 years,” said Dr. Mack, who is medical director of cardiothoracic surgery and chairman of the Baylor Scott & White The Heart Hospital – Plano (Tex.) Research Center.

PARTNER 3 randomized 1,000 patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis with a tricuspid valve and a very low mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk score of 1.9% to TAVR with the Sapien 3 valve or surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR). The 1-year results presented at ACC 2019 caused a huge stir, with the primary composite outcome of death, stroke, or cardiovascular rehospitalization occurring in 8.5% of TAVR patients and 15.6% of the SAVR group, representing a 48% relative risk reduction and a resounding win for TAVR (N Engl J Med. 2019 May 2;380:1695-705). At 2 years, the difference in the composite outcome remained statistically significant, but the gap had closed: 11.5% with TAVR and 17.4% with SAVR for a 37% relative risk reduction.

Moreover, the between-group difference in stroke, which at 1 year was significantly in favor of TAVR at 1.2% versus 3.3%, was no longer significant at 2 years, with rates of 2.4% versus 3.6%. Nor was the difference in mortality significant: 2.4% with TAVR, 3.2% with SAVR.

What was a statistically significant between-group difference at 2 years – and an eye-catching one at that – involved the cumulative incidence of valve thrombosis confirmed by CT or echocardiography: 2.6% in the TAVR arm, compared with 0.7% with SAVR, with most of these unwanted events coming in year 2.

The good news was there was no echocardiographic evidence of deterioration in valve structure or function in either study arm at 2 years. The mean gradients and aortic valve areas remained unchanged in both arms between 1 and 2 years, as did the frequency of mild or moderate paravalvular leak. Prospective follow-up will continue annually out to 10 years.

“I think it’s way too early to expect to see a signal, but I think it’s somewhat comforting at this point that there’s no signal of early structural valve deterioration,” Dr. Mack said.

Discussant Howard C. Hermann, MD, commented: “I guess the biggest concern in looking at the data is the increase in stroke and valve thrombosis, both numerically and relative to SAVR, between years 1 and 2.”

Dr. Mack offered a note of reassurance regarding the valve thrombosis findings: The rates he presented were based upon the now-outdated second Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC-2) definition, per study protocol. When he and his coinvestigators recalculated the valve thrombosis rates using the contemporary VARC-3 definition of valve deterioration and bioprosthetic valve failure, the incidence was very low and not significantly different in the two study arms, at roughly 1%.

Dr. Hermann, professor of medicine and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratories at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, had a question: As a clinician taking care of TAVR patients, what clinical or hemodynamic findings should prompt an imaging study looking for valve thrombus or deterioration that might prompt initiating oral anticoagulation?

“If there’s a change in hemodynamics, an increasing valve gradient, if there’s increasing paravalvular leak, or if there’s a change in symptoms, that should prompt an imaging study. Only with confirmation of valve thrombosis on an imaging study should anticoagulation be considered. Oral anticoagulation is not benign: Of the six clinical events associated with valve thrombosis in the study, two were related to anticoagulation,” Dr. Mack replied.

“Regarding whether patients should receive warfarin or a novel anticoagulant, I don’t think we have evidence that there’s benefit to anything other than warfarin at the current time,” he added.

Dr. Mack reported receiving research support from Edwards Lifesciences, the sponsor of PARTNER 3, as well as from Abbott, Gore, and Medtronic.

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) continued to show superiority over surgical replacement in terms of the primary composite endpoint in low-surgical-risk patients at 2 years of follow-up in the landmark randomized PARTNER 3 trial, but the between-group differences favoring the transcatheter procedure in some key outcomes have narrowed considerably, Michael J. Mack, MD, reported in a video presentation of his research during the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation, which was presented online this year. ACC organizers chose to present parts of the meeting virtually after COVID-19 concerns caused them to cancel the meeting.

“On the basis of 1-year data, many physicians were counseling patients that TAVR outcomes were better than surgery. Now we see that the outcomes are roughly the same at 2 years,” said Dr. Mack, who is medical director of cardiothoracic surgery and chairman of the Baylor Scott & White The Heart Hospital – Plano (Tex.) Research Center.

PARTNER 3 randomized 1,000 patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis with a tricuspid valve and a very low mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk score of 1.9% to TAVR with the Sapien 3 valve or surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR). The 1-year results presented at ACC 2019 caused a huge stir, with the primary composite outcome of death, stroke, or cardiovascular rehospitalization occurring in 8.5% of TAVR patients and 15.6% of the SAVR group, representing a 48% relative risk reduction and a resounding win for TAVR (N Engl J Med. 2019 May 2;380:1695-705). At 2 years, the difference in the composite outcome remained statistically significant, but the gap had closed: 11.5% with TAVR and 17.4% with SAVR for a 37% relative risk reduction.

Moreover, the between-group difference in stroke, which at 1 year was significantly in favor of TAVR at 1.2% versus 3.3%, was no longer significant at 2 years, with rates of 2.4% versus 3.6%. Nor was the difference in mortality significant: 2.4% with TAVR, 3.2% with SAVR.

What was a statistically significant between-group difference at 2 years – and an eye-catching one at that – involved the cumulative incidence of valve thrombosis confirmed by CT or echocardiography: 2.6% in the TAVR arm, compared with 0.7% with SAVR, with most of these unwanted events coming in year 2.

The good news was there was no echocardiographic evidence of deterioration in valve structure or function in either study arm at 2 years. The mean gradients and aortic valve areas remained unchanged in both arms between 1 and 2 years, as did the frequency of mild or moderate paravalvular leak. Prospective follow-up will continue annually out to 10 years.

“I think it’s way too early to expect to see a signal, but I think it’s somewhat comforting at this point that there’s no signal of early structural valve deterioration,” Dr. Mack said.

Discussant Howard C. Hermann, MD, commented: “I guess the biggest concern in looking at the data is the increase in stroke and valve thrombosis, both numerically and relative to SAVR, between years 1 and 2.”

Dr. Mack offered a note of reassurance regarding the valve thrombosis findings: The rates he presented were based upon the now-outdated second Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC-2) definition, per study protocol. When he and his coinvestigators recalculated the valve thrombosis rates using the contemporary VARC-3 definition of valve deterioration and bioprosthetic valve failure, the incidence was very low and not significantly different in the two study arms, at roughly 1%.

Dr. Hermann, professor of medicine and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratories at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, had a question: As a clinician taking care of TAVR patients, what clinical or hemodynamic findings should prompt an imaging study looking for valve thrombus or deterioration that might prompt initiating oral anticoagulation?

“If there’s a change in hemodynamics, an increasing valve gradient, if there’s increasing paravalvular leak, or if there’s a change in symptoms, that should prompt an imaging study. Only with confirmation of valve thrombosis on an imaging study should anticoagulation be considered. Oral anticoagulation is not benign: Of the six clinical events associated with valve thrombosis in the study, two were related to anticoagulation,” Dr. Mack replied.

“Regarding whether patients should receive warfarin or a novel anticoagulant, I don’t think we have evidence that there’s benefit to anything other than warfarin at the current time,” he added.

Dr. Mack reported receiving research support from Edwards Lifesciences, the sponsor of PARTNER 3, as well as from Abbott, Gore, and Medtronic.

FROM ACC 2020

The 7 strategies of highly effective people facing the COVID-19 pandemic

A few weeks ago, I saw more than 60 responses to a post on Nextdoor.com entitled, “Toilet paper strategies?”

Asking for help is a great coping mechanism when one is struggling to find a strategy, even if it’s for toilet paper. What other kinds of coping strategies can help us through this historic and unprecedented time?

The late Stephen R. Covey, PhD, wrote about the coping strategies of highly effective people in his book, “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.”1 For, no matter how smart, perfect, or careful you may be, life will never be trouble free. When trouble comes, it’s important to have coping strategies that help you navigate through choppy waters. Whether you are a practitioner trying to help your patients or someone who wants to maximize their personal resilience during a worldwide pandemic, here are my conceptualizations of the seven top strategies highly effective people use when facing challenges.

Strategy #1: Begin with the end in mind

In 2007, this strategy helped me not only survive but thrive when I battled for my right to practice as a holistic psychiatrist against the Maryland Board of Physicians.2 From the first moment when I read the letter from the board, to the last when I read the administrative law judge’s dismissal, I turned to this strategy to help me cope with unrelenting stress.

I imagined myself remembering being the kind of person I wanted to be, wrote that script for myself, and created those memories for my future self. I wanted to remember myself as being brave, calm, strong, and grounded, so I behaved each day as if I were all of those things.

As Dr. Covey wrote, “ ‘Begin with the end in mind’ is based on the principle that all things are created twice. There’s a mental or first creation, and a physical or second creation to all things.” Imagine who you would like to remember yourself being a year or two down the road. Do you want to remember yourself showing good judgment and being positive and compassionate during this pandemic? Then, follow the script you’ve created in your mind and be that person now, knowing that you are forming memories for your future self. Your future self will look back at who you are right now with appreciation and satisfaction. Of course, this is a habit that you can apply to your entire life.

Strategy #2: Be proactive

Between the event and the outcome is you. You are the interpreter and transformer of the event, with the freedom to apply your will and intention on the event. Whether it is living through a pandemic or dealing with misplaced keys, every day you are revealing your nature through how you deal with life. To be proactive is different from being reactive. Within each of us there is a will, the drive, to rise above our difficult environments.

Dr. Covey wrote, “the ability to subordinate an impulse to a value is the essence of the proactive person.” A woman shared with me that she created an Excel spreadsheet with some of the things she plans to do with her free time while she stays in her NYC apartment. She doesn’t want to slip into a passive state and waste her time. That’s being proactive.

Strategy #3: Set proper priorities

Or, as Dr. Covey would say, “Put first things first.” During a pandemic, when the world seems to be precariously tilting at an angle, it’s easy to cling to outdated standards, expectations, and behavioral patterns. Doing so heightens our sense of regret, fear, and scarcity. Valuing gratitude will empower you to deal with financial loss differently because you can still remain grateful despite uncontrollable losses. We can choose “to have or to be” as psychoanalyst, Erich Fromm, PhD, would say.3 If your happiness is measured by how much money you have, then it would make sense that, when the amount shrinks, so does your happiness. However, if your happiness is a side effect of who you are, you will remain a mountain before the winds and tides of circumstance.

Strategy #4: Create a win/win mentality

This state of mind is built on character. Dr. Covey separates character into three categories: integrity, maturity, and abundance mentality. A lack of character resulted in the hoarding of toilet paper in many communities and the cry for help from Nextdoor.com. I noticed that, in the 60+ responses that included advice about using bidets, old towels, and even leaves, no one offered to share a bag of toilet paper. That’s because people experienced the fear of scarcity, in turn, causing the scarcity they feared.

During a pandemic, a highly effective person or company thinks beyond themselves to create a win/win scenario. At a grocery store in my neighborhood, a man stands at its entrance with a bottle of disinfectant spray in one hand for the shoppers and a sign on the sidewalk with guidelines for purchasing products to avoid hoarding. He tells you where the wipes are for the carts as you enter the store. People line up 6 feet apart, waiting to enter, to limit the number of shoppers inside the store, facilitating proper physical distancing. Instead of maximizing profits at the expense of everyone’s health and safety, the process is a win/win for everyone, from shoppers to employees.

Strategy #5: Develop empathy and understanding

Seeking to first understand and then be understood is one of the most powerful tools of effective people. In my holistic practice, every patient comes in with their own unique needs that evolve and transform over time. I must remain open, or I fail to deliver appropriately.

Learning to listen and then to clearly communicate ideas is essential to effective health care. During this time, it is critical that health care providers and political leaders first listen/understand and then communicate clearly to serve everyone in the best way possible.

In our brains, the frontal lobes (the adult in the room) manages our amygdala (the child in the room) when we get enough sleep, meditate, spend time in nature, exercise, and eat healthy food.4 Stress can interfere with the frontal lobe’s ability to maintain empathy, inhibit unhealthy impulses, and delay gratification. During the pandemic, we can help to shift from the stress response, or “fight-or-flight” response, driven by the sympathetic nervous system to a “rest-and-digest” response driven by the parasympathetic system through coherent breathing, taking slow, deep, relaxed breaths (6 seconds on inhalation and 6 seconds on exhalation). The vagus nerve connected to our diaphragm will help the heart return to a healthy rhythm.5

Strategy #6: Synergize and integrate

All of life is interdependent, each part no more or less important than any other. Is oxygen more important than hydrogen? Is H2O different from the oxygen and hydrogen atoms that make it?

During a pandemic, it’s important for us to appreciate each other’s contributions and work synergistically for the good of the whole. Our survival depends on valuing each other and our planet. This perspective informs the practice of physical distancing and staying home to minimize the spread of the virus and its impact on the health care system, regardless of whether an individual belongs in the high-risk group or not.

Many high-achieving people train in extremely competitive settings in which survival depends on individual performance rather than mutual cooperation. This training process encourages a disregard for others. Good leaders, however, understand that cooperation and mutual respect are essential to personal well-being.

Strategy #7: Practice self-care

There are five aspects of our lives that depend on our self-care: spiritual, mental, emotional, physical, and social. Unfortunately, many kind-hearted people are kinder to others than to themselves. There is really only one person who can truly take care of you properly, and that is yourself. In Seattle, where many suffered early in the pandemic, holistic psychiatrist David Kopacz, MD, is reminding people to nurture themselves in his post, “Nurture Yourself During the Pandemic: Try New Recipes!”6 Indeed, that is what many must do since eating out is not an option now. If you find yourself stuck at home with more time on your hands, take the opportunity to care for yourself. Ask yourself what you really need during this time, and make the effort to provide it to yourself.

After the pandemic is over, will you have grown from the experiences and become a better person from it? Despite our current circumstances, we can continue to grow as individuals and as a community, armed with strategies that can benefit all of us.

References

1. Covey SR. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1989.

2. Lee AW. Townsend Letter. 2009 Jun;311:22-3.

3. Fromm E. To Have or To Be? New York: Continuum International Publishing; 2005.

4. Rushlau K. Integrative Healthcare Symposium. 2020 Feb 21.

5. Gerbarg PL. Mind Body Practices for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Presentation at Integrative Medicine for Mental Health Conference. 2016 Sep.

6. Kopacz D. Nurture Yourself During the Pandemic: Try New Recipes! Being Fully Human. 2020 Mar 22.

Dr. Lee specializes in integrative and holistic psychiatry and has a private practice in Gaithersburg, Md. She has no disclosures.

A few weeks ago, I saw more than 60 responses to a post on Nextdoor.com entitled, “Toilet paper strategies?”

Asking for help is a great coping mechanism when one is struggling to find a strategy, even if it’s for toilet paper. What other kinds of coping strategies can help us through this historic and unprecedented time?

The late Stephen R. Covey, PhD, wrote about the coping strategies of highly effective people in his book, “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.”1 For, no matter how smart, perfect, or careful you may be, life will never be trouble free. When trouble comes, it’s important to have coping strategies that help you navigate through choppy waters. Whether you are a practitioner trying to help your patients or someone who wants to maximize their personal resilience during a worldwide pandemic, here are my conceptualizations of the seven top strategies highly effective people use when facing challenges.

Strategy #1: Begin with the end in mind

In 2007, this strategy helped me not only survive but thrive when I battled for my right to practice as a holistic psychiatrist against the Maryland Board of Physicians.2 From the first moment when I read the letter from the board, to the last when I read the administrative law judge’s dismissal, I turned to this strategy to help me cope with unrelenting stress.

I imagined myself remembering being the kind of person I wanted to be, wrote that script for myself, and created those memories for my future self. I wanted to remember myself as being brave, calm, strong, and grounded, so I behaved each day as if I were all of those things.

As Dr. Covey wrote, “ ‘Begin with the end in mind’ is based on the principle that all things are created twice. There’s a mental or first creation, and a physical or second creation to all things.” Imagine who you would like to remember yourself being a year or two down the road. Do you want to remember yourself showing good judgment and being positive and compassionate during this pandemic? Then, follow the script you’ve created in your mind and be that person now, knowing that you are forming memories for your future self. Your future self will look back at who you are right now with appreciation and satisfaction. Of course, this is a habit that you can apply to your entire life.

Strategy #2: Be proactive

Between the event and the outcome is you. You are the interpreter and transformer of the event, with the freedom to apply your will and intention on the event. Whether it is living through a pandemic or dealing with misplaced keys, every day you are revealing your nature through how you deal with life. To be proactive is different from being reactive. Within each of us there is a will, the drive, to rise above our difficult environments.

Dr. Covey wrote, “the ability to subordinate an impulse to a value is the essence of the proactive person.” A woman shared with me that she created an Excel spreadsheet with some of the things she plans to do with her free time while she stays in her NYC apartment. She doesn’t want to slip into a passive state and waste her time. That’s being proactive.

Strategy #3: Set proper priorities

Or, as Dr. Covey would say, “Put first things first.” During a pandemic, when the world seems to be precariously tilting at an angle, it’s easy to cling to outdated standards, expectations, and behavioral patterns. Doing so heightens our sense of regret, fear, and scarcity. Valuing gratitude will empower you to deal with financial loss differently because you can still remain grateful despite uncontrollable losses. We can choose “to have or to be” as psychoanalyst, Erich Fromm, PhD, would say.3 If your happiness is measured by how much money you have, then it would make sense that, when the amount shrinks, so does your happiness. However, if your happiness is a side effect of who you are, you will remain a mountain before the winds and tides of circumstance.

Strategy #4: Create a win/win mentality

This state of mind is built on character. Dr. Covey separates character into three categories: integrity, maturity, and abundance mentality. A lack of character resulted in the hoarding of toilet paper in many communities and the cry for help from Nextdoor.com. I noticed that, in the 60+ responses that included advice about using bidets, old towels, and even leaves, no one offered to share a bag of toilet paper. That’s because people experienced the fear of scarcity, in turn, causing the scarcity they feared.

During a pandemic, a highly effective person or company thinks beyond themselves to create a win/win scenario. At a grocery store in my neighborhood, a man stands at its entrance with a bottle of disinfectant spray in one hand for the shoppers and a sign on the sidewalk with guidelines for purchasing products to avoid hoarding. He tells you where the wipes are for the carts as you enter the store. People line up 6 feet apart, waiting to enter, to limit the number of shoppers inside the store, facilitating proper physical distancing. Instead of maximizing profits at the expense of everyone’s health and safety, the process is a win/win for everyone, from shoppers to employees.

Strategy #5: Develop empathy and understanding

Seeking to first understand and then be understood is one of the most powerful tools of effective people. In my holistic practice, every patient comes in with their own unique needs that evolve and transform over time. I must remain open, or I fail to deliver appropriately.

Learning to listen and then to clearly communicate ideas is essential to effective health care. During this time, it is critical that health care providers and political leaders first listen/understand and then communicate clearly to serve everyone in the best way possible.

In our brains, the frontal lobes (the adult in the room) manages our amygdala (the child in the room) when we get enough sleep, meditate, spend time in nature, exercise, and eat healthy food.4 Stress can interfere with the frontal lobe’s ability to maintain empathy, inhibit unhealthy impulses, and delay gratification. During the pandemic, we can help to shift from the stress response, or “fight-or-flight” response, driven by the sympathetic nervous system to a “rest-and-digest” response driven by the parasympathetic system through coherent breathing, taking slow, deep, relaxed breaths (6 seconds on inhalation and 6 seconds on exhalation). The vagus nerve connected to our diaphragm will help the heart return to a healthy rhythm.5

Strategy #6: Synergize and integrate

All of life is interdependent, each part no more or less important than any other. Is oxygen more important than hydrogen? Is H2O different from the oxygen and hydrogen atoms that make it?

During a pandemic, it’s important for us to appreciate each other’s contributions and work synergistically for the good of the whole. Our survival depends on valuing each other and our planet. This perspective informs the practice of physical distancing and staying home to minimize the spread of the virus and its impact on the health care system, regardless of whether an individual belongs in the high-risk group or not.

Many high-achieving people train in extremely competitive settings in which survival depends on individual performance rather than mutual cooperation. This training process encourages a disregard for others. Good leaders, however, understand that cooperation and mutual respect are essential to personal well-being.

Strategy #7: Practice self-care

There are five aspects of our lives that depend on our self-care: spiritual, mental, emotional, physical, and social. Unfortunately, many kind-hearted people are kinder to others than to themselves. There is really only one person who can truly take care of you properly, and that is yourself. In Seattle, where many suffered early in the pandemic, holistic psychiatrist David Kopacz, MD, is reminding people to nurture themselves in his post, “Nurture Yourself During the Pandemic: Try New Recipes!”6 Indeed, that is what many must do since eating out is not an option now. If you find yourself stuck at home with more time on your hands, take the opportunity to care for yourself. Ask yourself what you really need during this time, and make the effort to provide it to yourself.

After the pandemic is over, will you have grown from the experiences and become a better person from it? Despite our current circumstances, we can continue to grow as individuals and as a community, armed with strategies that can benefit all of us.

References

1. Covey SR. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1989.

2. Lee AW. Townsend Letter. 2009 Jun;311:22-3.

3. Fromm E. To Have or To Be? New York: Continuum International Publishing; 2005.

4. Rushlau K. Integrative Healthcare Symposium. 2020 Feb 21.

5. Gerbarg PL. Mind Body Practices for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Presentation at Integrative Medicine for Mental Health Conference. 2016 Sep.

6. Kopacz D. Nurture Yourself During the Pandemic: Try New Recipes! Being Fully Human. 2020 Mar 22.

Dr. Lee specializes in integrative and holistic psychiatry and has a private practice in Gaithersburg, Md. She has no disclosures.

A few weeks ago, I saw more than 60 responses to a post on Nextdoor.com entitled, “Toilet paper strategies?”

Asking for help is a great coping mechanism when one is struggling to find a strategy, even if it’s for toilet paper. What other kinds of coping strategies can help us through this historic and unprecedented time?

The late Stephen R. Covey, PhD, wrote about the coping strategies of highly effective people in his book, “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.”1 For, no matter how smart, perfect, or careful you may be, life will never be trouble free. When trouble comes, it’s important to have coping strategies that help you navigate through choppy waters. Whether you are a practitioner trying to help your patients or someone who wants to maximize their personal resilience during a worldwide pandemic, here are my conceptualizations of the seven top strategies highly effective people use when facing challenges.

Strategy #1: Begin with the end in mind

In 2007, this strategy helped me not only survive but thrive when I battled for my right to practice as a holistic psychiatrist against the Maryland Board of Physicians.2 From the first moment when I read the letter from the board, to the last when I read the administrative law judge’s dismissal, I turned to this strategy to help me cope with unrelenting stress.

I imagined myself remembering being the kind of person I wanted to be, wrote that script for myself, and created those memories for my future self. I wanted to remember myself as being brave, calm, strong, and grounded, so I behaved each day as if I were all of those things.

As Dr. Covey wrote, “ ‘Begin with the end in mind’ is based on the principle that all things are created twice. There’s a mental or first creation, and a physical or second creation to all things.” Imagine who you would like to remember yourself being a year or two down the road. Do you want to remember yourself showing good judgment and being positive and compassionate during this pandemic? Then, follow the script you’ve created in your mind and be that person now, knowing that you are forming memories for your future self. Your future self will look back at who you are right now with appreciation and satisfaction. Of course, this is a habit that you can apply to your entire life.

Strategy #2: Be proactive

Between the event and the outcome is you. You are the interpreter and transformer of the event, with the freedom to apply your will and intention on the event. Whether it is living through a pandemic or dealing with misplaced keys, every day you are revealing your nature through how you deal with life. To be proactive is different from being reactive. Within each of us there is a will, the drive, to rise above our difficult environments.

Dr. Covey wrote, “the ability to subordinate an impulse to a value is the essence of the proactive person.” A woman shared with me that she created an Excel spreadsheet with some of the things she plans to do with her free time while she stays in her NYC apartment. She doesn’t want to slip into a passive state and waste her time. That’s being proactive.

Strategy #3: Set proper priorities

Or, as Dr. Covey would say, “Put first things first.” During a pandemic, when the world seems to be precariously tilting at an angle, it’s easy to cling to outdated standards, expectations, and behavioral patterns. Doing so heightens our sense of regret, fear, and scarcity. Valuing gratitude will empower you to deal with financial loss differently because you can still remain grateful despite uncontrollable losses. We can choose “to have or to be” as psychoanalyst, Erich Fromm, PhD, would say.3 If your happiness is measured by how much money you have, then it would make sense that, when the amount shrinks, so does your happiness. However, if your happiness is a side effect of who you are, you will remain a mountain before the winds and tides of circumstance.

Strategy #4: Create a win/win mentality

This state of mind is built on character. Dr. Covey separates character into three categories: integrity, maturity, and abundance mentality. A lack of character resulted in the hoarding of toilet paper in many communities and the cry for help from Nextdoor.com. I noticed that, in the 60+ responses that included advice about using bidets, old towels, and even leaves, no one offered to share a bag of toilet paper. That’s because people experienced the fear of scarcity, in turn, causing the scarcity they feared.

During a pandemic, a highly effective person or company thinks beyond themselves to create a win/win scenario. At a grocery store in my neighborhood, a man stands at its entrance with a bottle of disinfectant spray in one hand for the shoppers and a sign on the sidewalk with guidelines for purchasing products to avoid hoarding. He tells you where the wipes are for the carts as you enter the store. People line up 6 feet apart, waiting to enter, to limit the number of shoppers inside the store, facilitating proper physical distancing. Instead of maximizing profits at the expense of everyone’s health and safety, the process is a win/win for everyone, from shoppers to employees.

Strategy #5: Develop empathy and understanding

Seeking to first understand and then be understood is one of the most powerful tools of effective people. In my holistic practice, every patient comes in with their own unique needs that evolve and transform over time. I must remain open, or I fail to deliver appropriately.

Learning to listen and then to clearly communicate ideas is essential to effective health care. During this time, it is critical that health care providers and political leaders first listen/understand and then communicate clearly to serve everyone in the best way possible.

In our brains, the frontal lobes (the adult in the room) manages our amygdala (the child in the room) when we get enough sleep, meditate, spend time in nature, exercise, and eat healthy food.4 Stress can interfere with the frontal lobe’s ability to maintain empathy, inhibit unhealthy impulses, and delay gratification. During the pandemic, we can help to shift from the stress response, or “fight-or-flight” response, driven by the sympathetic nervous system to a “rest-and-digest” response driven by the parasympathetic system through coherent breathing, taking slow, deep, relaxed breaths (6 seconds on inhalation and 6 seconds on exhalation). The vagus nerve connected to our diaphragm will help the heart return to a healthy rhythm.5

Strategy #6: Synergize and integrate

All of life is interdependent, each part no more or less important than any other. Is oxygen more important than hydrogen? Is H2O different from the oxygen and hydrogen atoms that make it?

During a pandemic, it’s important for us to appreciate each other’s contributions and work synergistically for the good of the whole. Our survival depends on valuing each other and our planet. This perspective informs the practice of physical distancing and staying home to minimize the spread of the virus and its impact on the health care system, regardless of whether an individual belongs in the high-risk group or not.

Many high-achieving people train in extremely competitive settings in which survival depends on individual performance rather than mutual cooperation. This training process encourages a disregard for others. Good leaders, however, understand that cooperation and mutual respect are essential to personal well-being.

Strategy #7: Practice self-care

There are five aspects of our lives that depend on our self-care: spiritual, mental, emotional, physical, and social. Unfortunately, many kind-hearted people are kinder to others than to themselves. There is really only one person who can truly take care of you properly, and that is yourself. In Seattle, where many suffered early in the pandemic, holistic psychiatrist David Kopacz, MD, is reminding people to nurture themselves in his post, “Nurture Yourself During the Pandemic: Try New Recipes!”6 Indeed, that is what many must do since eating out is not an option now. If you find yourself stuck at home with more time on your hands, take the opportunity to care for yourself. Ask yourself what you really need during this time, and make the effort to provide it to yourself.

After the pandemic is over, will you have grown from the experiences and become a better person from it? Despite our current circumstances, we can continue to grow as individuals and as a community, armed with strategies that can benefit all of us.

References

1. Covey SR. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1989.

2. Lee AW. Townsend Letter. 2009 Jun;311:22-3.

3. Fromm E. To Have or To Be? New York: Continuum International Publishing; 2005.

4. Rushlau K. Integrative Healthcare Symposium. 2020 Feb 21.

5. Gerbarg PL. Mind Body Practices for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Presentation at Integrative Medicine for Mental Health Conference. 2016 Sep.

6. Kopacz D. Nurture Yourself During the Pandemic: Try New Recipes! Being Fully Human. 2020 Mar 22.

Dr. Lee specializes in integrative and holistic psychiatry and has a private practice in Gaithersburg, Md. She has no disclosures.

Almost 90% of COVID-19 admissions involve comorbidities

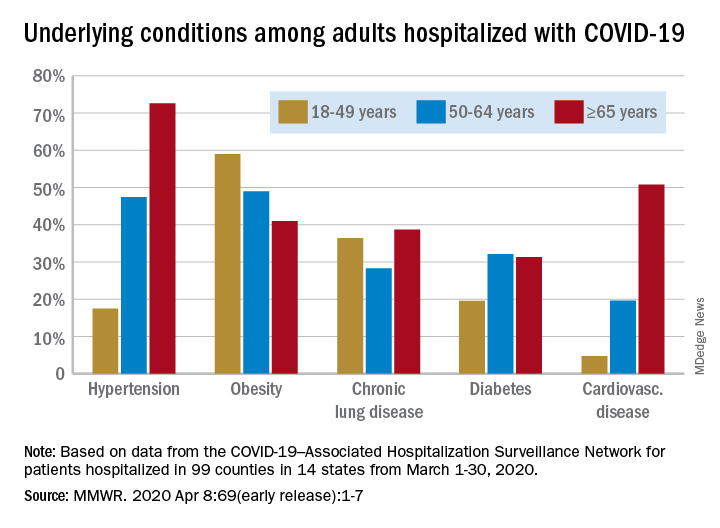

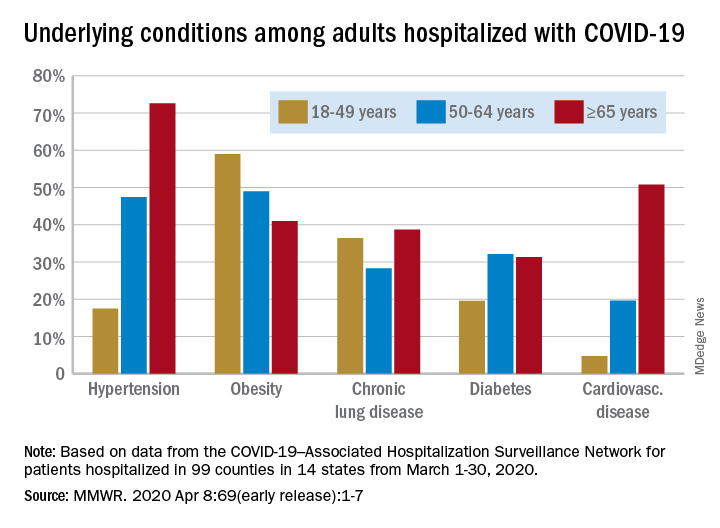

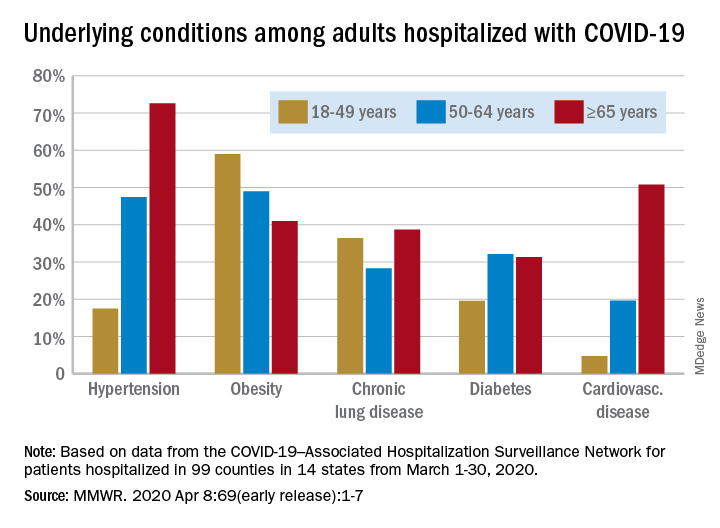

The hospitalization rate for COVID-19 is 4.6 per 100,000 population, and almost 90% of hospitalized patients have some type of underlying condition, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Data collected by the newly created COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET) put the exact prevalence of underlying conditions at 89.3% for patients hospitalized during March 1-30, 2020, Shikha Garg, MD, of the CDC’s COVID-NET team and associates wrote in the MMWR.

The hospitalization rate, based on COVID-NET data for March 1-28, increased with patient age. Those aged 65 years and older were admitted at a rate of 13.8 per 100,000, with 50- to 64-year-olds next at 7.4 per 100,000 and 18- to 49-year-olds at 2.5, they wrote.

The patients aged 65 years and older also were the most likely to have one or more underlying conditions, at 94.4%, compared with 86.4% of those aged 50-64 years and 85.4% of individuals who were aged 18-44 years, the investigators reported.

Hypertension was the most common comorbidity among the oldest patients, with a prevalence of 72.6%, followed by cardiovascular disease at 50.8% and obesity at 41%. In the two younger groups, obesity was the condition most often seen in COVID-19 patients, with prevalences of 49% in 50- to 64-year-olds and 59% in those aged 18-49, Dr. Garg and associates wrote.

“These findings underscore the importance of preventive measures (e.g., social distancing, respiratory hygiene, and wearing face coverings in public settings where social distancing measures are difficult to maintain) to protect older adults and persons with underlying medical conditions,” the investigators wrote.

COVID-NET surveillance includes laboratory-confirmed hospitalizations in 99 counties in 14 states: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Tennessee, and Utah. Those counties represent about 10% of the U.S. population.

SOURCE: Garg S et al. MMWR. 2020 Apr 8;69(early release):1-7.

The hospitalization rate for COVID-19 is 4.6 per 100,000 population, and almost 90% of hospitalized patients have some type of underlying condition, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Data collected by the newly created COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET) put the exact prevalence of underlying conditions at 89.3% for patients hospitalized during March 1-30, 2020, Shikha Garg, MD, of the CDC’s COVID-NET team and associates wrote in the MMWR.

The hospitalization rate, based on COVID-NET data for March 1-28, increased with patient age. Those aged 65 years and older were admitted at a rate of 13.8 per 100,000, with 50- to 64-year-olds next at 7.4 per 100,000 and 18- to 49-year-olds at 2.5, they wrote.

The patients aged 65 years and older also were the most likely to have one or more underlying conditions, at 94.4%, compared with 86.4% of those aged 50-64 years and 85.4% of individuals who were aged 18-44 years, the investigators reported.

Hypertension was the most common comorbidity among the oldest patients, with a prevalence of 72.6%, followed by cardiovascular disease at 50.8% and obesity at 41%. In the two younger groups, obesity was the condition most often seen in COVID-19 patients, with prevalences of 49% in 50- to 64-year-olds and 59% in those aged 18-49, Dr. Garg and associates wrote.

“These findings underscore the importance of preventive measures (e.g., social distancing, respiratory hygiene, and wearing face coverings in public settings where social distancing measures are difficult to maintain) to protect older adults and persons with underlying medical conditions,” the investigators wrote.

COVID-NET surveillance includes laboratory-confirmed hospitalizations in 99 counties in 14 states: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Tennessee, and Utah. Those counties represent about 10% of the U.S. population.

SOURCE: Garg S et al. MMWR. 2020 Apr 8;69(early release):1-7.

The hospitalization rate for COVID-19 is 4.6 per 100,000 population, and almost 90% of hospitalized patients have some type of underlying condition, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Data collected by the newly created COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET) put the exact prevalence of underlying conditions at 89.3% for patients hospitalized during March 1-30, 2020, Shikha Garg, MD, of the CDC’s COVID-NET team and associates wrote in the MMWR.

The hospitalization rate, based on COVID-NET data for March 1-28, increased with patient age. Those aged 65 years and older were admitted at a rate of 13.8 per 100,000, with 50- to 64-year-olds next at 7.4 per 100,000 and 18- to 49-year-olds at 2.5, they wrote.

The patients aged 65 years and older also were the most likely to have one or more underlying conditions, at 94.4%, compared with 86.4% of those aged 50-64 years and 85.4% of individuals who were aged 18-44 years, the investigators reported.

Hypertension was the most common comorbidity among the oldest patients, with a prevalence of 72.6%, followed by cardiovascular disease at 50.8% and obesity at 41%. In the two younger groups, obesity was the condition most often seen in COVID-19 patients, with prevalences of 49% in 50- to 64-year-olds and 59% in those aged 18-49, Dr. Garg and associates wrote.

“These findings underscore the importance of preventive measures (e.g., social distancing, respiratory hygiene, and wearing face coverings in public settings where social distancing measures are difficult to maintain) to protect older adults and persons with underlying medical conditions,” the investigators wrote.

COVID-NET surveillance includes laboratory-confirmed hospitalizations in 99 counties in 14 states: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Tennessee, and Utah. Those counties represent about 10% of the U.S. population.

SOURCE: Garg S et al. MMWR. 2020 Apr 8;69(early release):1-7.

FROM THE MMWR

COVID 19: Psychiatric patients may be among the hardest hit

The COVID-19 pandemic represents a looming crisis for patients with severe mental illness (SMI) and the healthcare systems that serve them, one expert warns.

However, Benjamin Druss, MD, MPH, from Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health in Atlanta, Georgia, says there are strategies that can help minimize the risk of exposure and transmission of the virus in SMI patients.

In a viewpoint published online April 3 in JAMA Psychiatry, Druss, professor and chair in mental health, notes that “disasters disproportionately affect poor and vulnerable populations, and patients with serious mental illness may be among the hardest hit.”

In an interview with Medscape Medical News, Druss said patients with SMI have “a whole range of vulnerabilities” that put them at higher risk for COVID-19.

These include high rates of smoking, cardiovascular and lung disease, poverty, and homelessness. In fact, estimates show 25% of the US homeless population has a serious mental illness, said Druss.

“You have to keep an eye on these overlapping circles of vulnerable populations: those with disabilities in general and people with serious mental illness in particular; people who are poor; and people who have limited social networks,” he said.

Tailored Communication Vital

It’s important for patients with SMI to have up-to-date, accurate information about mitigating risk and knowing when to seek medical treatment for COVID-19, Druss noted.

Communication materials developed for the general population need to be tailored to address limited health literacy and challenges in implementing physical distancing recommendations, he said.

Patients with SMI also need support in maintaining healthy habits, including diet and physical activity, as well as self-management of chronic mental and physical health conditions, he added.

He noted that even in the face of current constraints on mental health care delivery, ensuring access to services is essential. The increased emphasis on caring for, and keeping in touch with, SMI patients through telepsychiatry is one effective way of addressing this issue, said Druss.

Since mental health clinicians are often the first responders for people with SMI, these professionals need training to recognize the signs and symptoms of COVID-19 and learn basic strategies to mitigate the spread of disease, not only for their patients but also for themselves, he added.

“Any given provider is going to be responsible for many, many patients, so keeping physically and mentally healthy will be vital.”

In order to ease the strain of COVID-19 on community mental health centers and psychiatric hospitals, which are at high risk for outbreaks and have limited capacity to treat medical illness, these institutions need contingency plans to detect and contain outbreaks if they occur.

“Careful planning and execution at multiple levels will be essential for minimizing the adverse outcomes of this pandemic for this vulnerable population,” Druss writes.

Voice of Experience

Commenting on the article for Medscape Medical News, Lloyd I. Sederer, MD, distinguished advisor for the New York State Office of Mental Health and adjunct professor at the Columbia School of Public Health in New York City, commended Druss for highlighting the need for more mental health services during the pandemic.

However, although Druss “has made some very good general statements,” these don’t really apply “in the wake of a real catastrophic event, which is what we’re having here,” Sederer said.

Sederer led Project Liberty, a massive mental health disaster response effort established in the wake of the Sept. 11 attacks in New York. Druss seems to infer that the mental health workforce is capable of expanding, but “what we learned is that the mental health system in this country is vastly undersupplied,” said Sederer.

During a disaster, the system “actually contracts” because clinics close and workforces are reduced. In this environment, some patients with a serious mental illness let their treatment “erode,” Sederer said.

While Druss called for clinics to have protocols for identifying and referring patients at risk for COVID-19, Sederer pointed out that “all the clinics are closed.”

However, he did note that many mental health clinics and hospitals are continuing to reach out to their vulnerable patients during this crisis.

On the 10th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, Sederer and colleagues published an article in Psychiatric Services that highlighted the “lessons learned” from the Project Liberty experience. One of the biggest lessons was the need for crisis counseling, which is “a recognized, proven intervention,” said Sederer.

Such an initiative involves trained outreach workers, identifying the untreated seriously mentally ill in the community, and “literally shepherding them to services,” he added.

In this current pandemic, it would be up to the federal government to mobilize such a crisis counseling initiative, Sederer explained.

Sederer noted that rapid relief groups like the Federal Emergency Management Agency do not cover mental health services. In order to be effective, disaster-related mental health services need to include funding for treatment, including focused therapies and medication.

Druss and Sederer have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The COVID-19 pandemic represents a looming crisis for patients with severe mental illness (SMI) and the healthcare systems that serve them, one expert warns.

However, Benjamin Druss, MD, MPH, from Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health in Atlanta, Georgia, says there are strategies that can help minimize the risk of exposure and transmission of the virus in SMI patients.

In a viewpoint published online April 3 in JAMA Psychiatry, Druss, professor and chair in mental health, notes that “disasters disproportionately affect poor and vulnerable populations, and patients with serious mental illness may be among the hardest hit.”

In an interview with Medscape Medical News, Druss said patients with SMI have “a whole range of vulnerabilities” that put them at higher risk for COVID-19.

These include high rates of smoking, cardiovascular and lung disease, poverty, and homelessness. In fact, estimates show 25% of the US homeless population has a serious mental illness, said Druss.

“You have to keep an eye on these overlapping circles of vulnerable populations: those with disabilities in general and people with serious mental illness in particular; people who are poor; and people who have limited social networks,” he said.

Tailored Communication Vital

It’s important for patients with SMI to have up-to-date, accurate information about mitigating risk and knowing when to seek medical treatment for COVID-19, Druss noted.

Communication materials developed for the general population need to be tailored to address limited health literacy and challenges in implementing physical distancing recommendations, he said.

Patients with SMI also need support in maintaining healthy habits, including diet and physical activity, as well as self-management of chronic mental and physical health conditions, he added.

He noted that even in the face of current constraints on mental health care delivery, ensuring access to services is essential. The increased emphasis on caring for, and keeping in touch with, SMI patients through telepsychiatry is one effective way of addressing this issue, said Druss.

Since mental health clinicians are often the first responders for people with SMI, these professionals need training to recognize the signs and symptoms of COVID-19 and learn basic strategies to mitigate the spread of disease, not only for their patients but also for themselves, he added.

“Any given provider is going to be responsible for many, many patients, so keeping physically and mentally healthy will be vital.”

In order to ease the strain of COVID-19 on community mental health centers and psychiatric hospitals, which are at high risk for outbreaks and have limited capacity to treat medical illness, these institutions need contingency plans to detect and contain outbreaks if they occur.

“Careful planning and execution at multiple levels will be essential for minimizing the adverse outcomes of this pandemic for this vulnerable population,” Druss writes.

Voice of Experience

Commenting on the article for Medscape Medical News, Lloyd I. Sederer, MD, distinguished advisor for the New York State Office of Mental Health and adjunct professor at the Columbia School of Public Health in New York City, commended Druss for highlighting the need for more mental health services during the pandemic.

However, although Druss “has made some very good general statements,” these don’t really apply “in the wake of a real catastrophic event, which is what we’re having here,” Sederer said.

Sederer led Project Liberty, a massive mental health disaster response effort established in the wake of the Sept. 11 attacks in New York. Druss seems to infer that the mental health workforce is capable of expanding, but “what we learned is that the mental health system in this country is vastly undersupplied,” said Sederer.

During a disaster, the system “actually contracts” because clinics close and workforces are reduced. In this environment, some patients with a serious mental illness let their treatment “erode,” Sederer said.

While Druss called for clinics to have protocols for identifying and referring patients at risk for COVID-19, Sederer pointed out that “all the clinics are closed.”

However, he did note that many mental health clinics and hospitals are continuing to reach out to their vulnerable patients during this crisis.

On the 10th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, Sederer and colleagues published an article in Psychiatric Services that highlighted the “lessons learned” from the Project Liberty experience. One of the biggest lessons was the need for crisis counseling, which is “a recognized, proven intervention,” said Sederer.

Such an initiative involves trained outreach workers, identifying the untreated seriously mentally ill in the community, and “literally shepherding them to services,” he added.

In this current pandemic, it would be up to the federal government to mobilize such a crisis counseling initiative, Sederer explained.

Sederer noted that rapid relief groups like the Federal Emergency Management Agency do not cover mental health services. In order to be effective, disaster-related mental health services need to include funding for treatment, including focused therapies and medication.

Druss and Sederer have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The COVID-19 pandemic represents a looming crisis for patients with severe mental illness (SMI) and the healthcare systems that serve them, one expert warns.

However, Benjamin Druss, MD, MPH, from Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health in Atlanta, Georgia, says there are strategies that can help minimize the risk of exposure and transmission of the virus in SMI patients.

In a viewpoint published online April 3 in JAMA Psychiatry, Druss, professor and chair in mental health, notes that “disasters disproportionately affect poor and vulnerable populations, and patients with serious mental illness may be among the hardest hit.”

In an interview with Medscape Medical News, Druss said patients with SMI have “a whole range of vulnerabilities” that put them at higher risk for COVID-19.

These include high rates of smoking, cardiovascular and lung disease, poverty, and homelessness. In fact, estimates show 25% of the US homeless population has a serious mental illness, said Druss.

“You have to keep an eye on these overlapping circles of vulnerable populations: those with disabilities in general and people with serious mental illness in particular; people who are poor; and people who have limited social networks,” he said.

Tailored Communication Vital

It’s important for patients with SMI to have up-to-date, accurate information about mitigating risk and knowing when to seek medical treatment for COVID-19, Druss noted.

Communication materials developed for the general population need to be tailored to address limited health literacy and challenges in implementing physical distancing recommendations, he said.

Patients with SMI also need support in maintaining healthy habits, including diet and physical activity, as well as self-management of chronic mental and physical health conditions, he added.

He noted that even in the face of current constraints on mental health care delivery, ensuring access to services is essential. The increased emphasis on caring for, and keeping in touch with, SMI patients through telepsychiatry is one effective way of addressing this issue, said Druss.

Since mental health clinicians are often the first responders for people with SMI, these professionals need training to recognize the signs and symptoms of COVID-19 and learn basic strategies to mitigate the spread of disease, not only for their patients but also for themselves, he added.

“Any given provider is going to be responsible for many, many patients, so keeping physically and mentally healthy will be vital.”

In order to ease the strain of COVID-19 on community mental health centers and psychiatric hospitals, which are at high risk for outbreaks and have limited capacity to treat medical illness, these institutions need contingency plans to detect and contain outbreaks if they occur.

“Careful planning and execution at multiple levels will be essential for minimizing the adverse outcomes of this pandemic for this vulnerable population,” Druss writes.

Voice of Experience

Commenting on the article for Medscape Medical News, Lloyd I. Sederer, MD, distinguished advisor for the New York State Office of Mental Health and adjunct professor at the Columbia School of Public Health in New York City, commended Druss for highlighting the need for more mental health services during the pandemic.

However, although Druss “has made some very good general statements,” these don’t really apply “in the wake of a real catastrophic event, which is what we’re having here,” Sederer said.

Sederer led Project Liberty, a massive mental health disaster response effort established in the wake of the Sept. 11 attacks in New York. Druss seems to infer that the mental health workforce is capable of expanding, but “what we learned is that the mental health system in this country is vastly undersupplied,” said Sederer.

During a disaster, the system “actually contracts” because clinics close and workforces are reduced. In this environment, some patients with a serious mental illness let their treatment “erode,” Sederer said.

While Druss called for clinics to have protocols for identifying and referring patients at risk for COVID-19, Sederer pointed out that “all the clinics are closed.”

However, he did note that many mental health clinics and hospitals are continuing to reach out to their vulnerable patients during this crisis.

On the 10th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, Sederer and colleagues published an article in Psychiatric Services that highlighted the “lessons learned” from the Project Liberty experience. One of the biggest lessons was the need for crisis counseling, which is “a recognized, proven intervention,” said Sederer.

Such an initiative involves trained outreach workers, identifying the untreated seriously mentally ill in the community, and “literally shepherding them to services,” he added.

In this current pandemic, it would be up to the federal government to mobilize such a crisis counseling initiative, Sederer explained.

Sederer noted that rapid relief groups like the Federal Emergency Management Agency do not cover mental health services. In order to be effective, disaster-related mental health services need to include funding for treatment, including focused therapies and medication.

Druss and Sederer have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Crisis counseling, not therapy, is what’s needed in the wake of COVID-19

In the wake of the attacks on the World Trade Center, the public mental health system in the New York City area mounted the largest mental health disaster response in history. I was New York City’s mental health commissioner at the time. We called the initiative Project Liberty and over 3 years obtained $137 million in funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to support it.

Through Project Liberty, New York established the Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program (CCP). And it didn’t take us long to realize that what affected people need following a disaster is not necessarily psychotherapy, as might be expected, but in fact crisis counseling, or helping impacted individuals and their families regain control of their anxieties and effectively respond to an immediate disaster. This proved true not only after 9/11 but also after other recent disasters, including hurricanes Katrina and Sandy. The mental health system must now step up again to assuage fears and anxieties—both individual and collective—around the rapidly spreading COVID-19 pandemic.

So, what is crisis counseling?

A person’s usual adaptive, problem-solving capabilities are often compromised after a disaster, but they are there, and if accessed, they can help those afflicted with mental symptoms following a crisis to mentally endure. thereby making it a different approach from traditional psychotherapy.

The five key concepts in crisis counseling are:

- It is strength-based, which means its foundation is rooted in the assumption that resilience and competence are innate human qualities.

- Crisis counseling also employs anonymity. Impacted individuals should not be diagnosed or labeled. As a result, there are no resulting medical records.

- The approach is outreach-oriented, in which counselors provide services out in the community rather than in traditional mental health settings. This occurs primarily in homes, community centers, and settings, as well as in disaster shelters.

- It is culturally attuned, whereby all staff appreciate and respect a community’s cultural beliefs, values, and primary language.

- It is aimed at supporting, not replacing, existing community support systems (eg, a crisis counselor supports but does not organize, deliver, or manage community recovery activities).

Crisis counselors are required to be licensed psychologists or have obtained a bachelor’s degree or higher in psychology, human services, or another health-related field. In other words, crisis counseling draws on a broad, though related, group of individuals. Before deployment into a disaster area, an applicant must complete the FEMA Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training, which is offered in the disaster area by the FEMA-funded CCP.

Crisis counselors provide trustworthy and actionable information about the disaster at hand and where to turn for resources and assistance. They assist with emotional support. And they aim to educate individuals, families, and communities about how to be resilient.

Crisis counseling, however, may not suffice for everyone impacted. We know that a person’s severity of response to a crisis is highly associated with the intensity and duration of exposure to the disaster (especially when it is life-threatening) and/or the degree of a person’s serious loss (of a loved one, home, job, health). We also know that previous trauma (eg, from childhood, domestic violence, or forced immigration) also predicts the gravity of the response to a current crisis. Which is why crisis counselors also are taught to identify those experiencing significant and persistent mental health and addiction problems because they need to be assisted, literally, in obtaining professional treatment.

Only in recent years has trauma been a recognized driver of stress, distress, and mental and addictive disorders. Until relatively recently, skill with, and access to, crisis counseling—and trauma-informed care—was rare among New York’s large and talented mental health professional community. Few had been trained in it in graduate school or practiced it because New York had been spared a disaster on par with 9/11. Following the attacks, Project Liberty’s programs served nearly 1.5 million affected individuals of very diverse ages, races, cultural backgrounds, and socioeconomic status. Their levels of “psychological distress,” the term we used and measured, ranged from low to very high.

The coronavirus pandemic now presents us with a tragically similar, catastrophic moment. The human consequences we face—psychologically, economically, and socially—are just beginning. But this time, the need is not just in New York but throughout our country.

We humans are resilient. We can bend the arc of crisis toward the light, to recovering our existing but overwhelmed capabilities. We can achieve this in a variety of ways. We can practice self-care. This isn’t an act of selfishness but is rather like putting on your own oxygen mask before trying to help your friend or loved one do the same. We can stay connected to the people we care about. We can eat well, get sufficient sleep, take a walk.

Identifying and pursuing practical goals is also important, like obtaining food, housing that is safe and reliable, transportation to where you need to go, and drawing upon financial and other resources that are issued in a disaster area. We can practice positive thinking and recall how we’ve mastered our troubles in the past; we can remind ourselves that “this too will pass.” Crises create an unusually opportune time for change and self-discovery. As Churchill said to the British people in the darkest moments of the start of World War II, “Never give up.”

Worthy of its own itemization are spiritual beliefs, faith—that however we think about a higher power (religious or secular), that power is on our side. Faith can comfort and sustain hope, particularly at a time when doubt about ourselves and humanity is triggered by disaster.

Maya Angelou’s words remind us at this moment of disaster: “...let us try to help before we have to offer therapy. That is to say, let’s see if we can’t prevent being ill by trying to offer a love of prevention before illness.”

Dr. Sederer is the former chief medical officer for the New York State Office of Mental Health and an adjunct professor in the Department of Epidemiology at the Columbia University School of Public Health. His latest book is The Addiction Solution: Treating Our Dependence on Opioids and Other Drugs.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the wake of the attacks on the World Trade Center, the public mental health system in the New York City area mounted the largest mental health disaster response in history. I was New York City’s mental health commissioner at the time. We called the initiative Project Liberty and over 3 years obtained $137 million in funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to support it.

Through Project Liberty, New York established the Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program (CCP). And it didn’t take us long to realize that what affected people need following a disaster is not necessarily psychotherapy, as might be expected, but in fact crisis counseling, or helping impacted individuals and their families regain control of their anxieties and effectively respond to an immediate disaster. This proved true not only after 9/11 but also after other recent disasters, including hurricanes Katrina and Sandy. The mental health system must now step up again to assuage fears and anxieties—both individual and collective—around the rapidly spreading COVID-19 pandemic.

So, what is crisis counseling?

A person’s usual adaptive, problem-solving capabilities are often compromised after a disaster, but they are there, and if accessed, they can help those afflicted with mental symptoms following a crisis to mentally endure. thereby making it a different approach from traditional psychotherapy.

The five key concepts in crisis counseling are:

- It is strength-based, which means its foundation is rooted in the assumption that resilience and competence are innate human qualities.

- Crisis counseling also employs anonymity. Impacted individuals should not be diagnosed or labeled. As a result, there are no resulting medical records.

- The approach is outreach-oriented, in which counselors provide services out in the community rather than in traditional mental health settings. This occurs primarily in homes, community centers, and settings, as well as in disaster shelters.

- It is culturally attuned, whereby all staff appreciate and respect a community’s cultural beliefs, values, and primary language.

- It is aimed at supporting, not replacing, existing community support systems (eg, a crisis counselor supports but does not organize, deliver, or manage community recovery activities).

Crisis counselors are required to be licensed psychologists or have obtained a bachelor’s degree or higher in psychology, human services, or another health-related field. In other words, crisis counseling draws on a broad, though related, group of individuals. Before deployment into a disaster area, an applicant must complete the FEMA Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training, which is offered in the disaster area by the FEMA-funded CCP.

Crisis counselors provide trustworthy and actionable information about the disaster at hand and where to turn for resources and assistance. They assist with emotional support. And they aim to educate individuals, families, and communities about how to be resilient.

Crisis counseling, however, may not suffice for everyone impacted. We know that a person’s severity of response to a crisis is highly associated with the intensity and duration of exposure to the disaster (especially when it is life-threatening) and/or the degree of a person’s serious loss (of a loved one, home, job, health). We also know that previous trauma (eg, from childhood, domestic violence, or forced immigration) also predicts the gravity of the response to a current crisis. Which is why crisis counselors also are taught to identify those experiencing significant and persistent mental health and addiction problems because they need to be assisted, literally, in obtaining professional treatment.

Only in recent years has trauma been a recognized driver of stress, distress, and mental and addictive disorders. Until relatively recently, skill with, and access to, crisis counseling—and trauma-informed care—was rare among New York’s large and talented mental health professional community. Few had been trained in it in graduate school or practiced it because New York had been spared a disaster on par with 9/11. Following the attacks, Project Liberty’s programs served nearly 1.5 million affected individuals of very diverse ages, races, cultural backgrounds, and socioeconomic status. Their levels of “psychological distress,” the term we used and measured, ranged from low to very high.

The coronavirus pandemic now presents us with a tragically similar, catastrophic moment. The human consequences we face—psychologically, economically, and socially—are just beginning. But this time, the need is not just in New York but throughout our country.

We humans are resilient. We can bend the arc of crisis toward the light, to recovering our existing but overwhelmed capabilities. We can achieve this in a variety of ways. We can practice self-care. This isn’t an act of selfishness but is rather like putting on your own oxygen mask before trying to help your friend or loved one do the same. We can stay connected to the people we care about. We can eat well, get sufficient sleep, take a walk.

Identifying and pursuing practical goals is also important, like obtaining food, housing that is safe and reliable, transportation to where you need to go, and drawing upon financial and other resources that are issued in a disaster area. We can practice positive thinking and recall how we’ve mastered our troubles in the past; we can remind ourselves that “this too will pass.” Crises create an unusually opportune time for change and self-discovery. As Churchill said to the British people in the darkest moments of the start of World War II, “Never give up.”

Worthy of its own itemization are spiritual beliefs, faith—that however we think about a higher power (religious or secular), that power is on our side. Faith can comfort and sustain hope, particularly at a time when doubt about ourselves and humanity is triggered by disaster.

Maya Angelou’s words remind us at this moment of disaster: “...let us try to help before we have to offer therapy. That is to say, let’s see if we can’t prevent being ill by trying to offer a love of prevention before illness.”

Dr. Sederer is the former chief medical officer for the New York State Office of Mental Health and an adjunct professor in the Department of Epidemiology at the Columbia University School of Public Health. His latest book is The Addiction Solution: Treating Our Dependence on Opioids and Other Drugs.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.