User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

When your medical error harmed a patient and you’re wracked with guilt

Peter Schwartz, MD, was chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at a hospital in Reading, Pa., in the mid-1990s when a young physician sought him out. The doctor, whom Dr. Schwartz regarded as talented and empathetic, was visibly shaken. The expectant mother they were caring for had just lost her unborn child.

“The doctor came into my office within an hour of the event and asked me to look at the case,” Dr. Schwartz recalled. “I could see that they had failed to recognize ominous changes in the fetal heart rate, and I faced the pain of having to tell them, ‘I think this could have been handled much better.’” Dr. Schwartz delivered the news as compassionately as he could, but a subsequent review confirmed his suspicion: The doctor had made a serious error.

“The doctor was devastated,” he said. “She got counseling and took time off, but in the end, she quit practicing medicine. She said, ‘If I keep practicing, something like that could happen again, and I don’t think I could handle it.’”

To err may be human, but in a health care setting, the harm can be catastrophic. that their feelings of guilt, shame, and self-doubt can lead to depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and even suicidal ideation. The trauma can be so profound that, in a now famous 2000 editorial in the British Medical Journal, Albert Wu, MD, gave the phenomenon a name: “second victim syndrome.”

Today, as quality improvement organizations and health systems work to address medical errors in a just and transparent way, they’re realizing that finding ways to help traumatized clinicians is integral to their efforts.

Are doctors really ‘second victims?’

Although the medical field is moving away from the term “second victim,” which patient advocates argue lacks a ring of accountability, the emotional trauma doctors and other clinicians endure is garnering increased attention. In the 2 decades since Dr. Wu wrote his editorial, research has shown that many types of adverse health care events can evoke traumatic responses. In fact, studies indicate that from 10.4% to 43.3% of health care workers may experience negative symptoms following an adverse event.

But for doctors – who have sworn an oath to do no harm – the emotional toll of having committed a serious medical error can be particularly burdensome and lingering. In a Dutch study involving more than 4,300 doctors and nurses, respondents who were involved in a patient safety incident that resulted in harm were nine times more likely to have negative symptoms lasting longer than 6 months than those who were involved in a near-miss experience.

“There’s a feeling of wanting to erase yourself,” says Danielle Ofri, MD, a New York internist and author of “When We Do Harm: A Doctor Confronts Medical Error.”

That emotional response can have a profound impact on the way medical errors are disclosed, investigated, and ultimately resolved, said Thomas Gallagher, MD, an internist and executive director of the Collaborative for Accountability and Improvement, a patient safety program at the University of Washington.

“When something goes wrong, as physicians, we don’t know what to do,” Dr. Gallagher says. “We feel awful, and often our human reflexes lead us astray. The doctor’s own emotions become barriers to addressing the situation.” For example, guilt and shame may lead doctors to try to hide or diminish their mistakes. Some doctors might try to shift blame, while others may feel so guilty they assume they were responsible for an outcome that was beyond their control.

Recognizing that clinicians’ responses to medical errors are inextricably tangled with how those events are addressed, a growing number of health systems are making clinician support a key element when dealing with medical errors.

Emotional first aid

Although it’s typical for physicians to feel isolated in the wake of errors, these experiences are far from unique. Research conducted by University of Missouri Health Care nurse scientist Susan Scott, RN, PhD, shows that just as most individuals experiencing grief pass through several distinct emotional stages, health care professionals who make errors go through emotional stages that may occur sequentially or concurrently.

An initial period of chaos is often followed by intrusive reflections, haunting re-enactments, and feelings of inadequacy. The doctor’s thinking moves from “How did that happen?” to “What did I miss?” to “What will people think about me?” As the error comes under scrutiny by quality improvement organizations, licensing boards, and/or lawyers, the doctor feels besieged. The doctor may want to reach out but is afraid to. According to Dr. Scott, only 15% of care providers ask for help.

Recognizing that physicians and other care providers rarely ask for support – or may not realize they need it – a growing number of health systems are implementing Communication and Resolution Programs (CRPs). Rather than respond to medical errors with a deny-and-defend mentality, CRPs emphasize transparency and accountability.

This approach, which the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has embraced and codified with its Communication and Optimal Resolution (CANDOR) toolkit, focuses on prompt incident reporting; communication with and support for patients, family members, and caregivers affected by the event; event analysis; quality improvement; and just resolution of the event, including apologies and financial compensation where appropriate.

The CANDOR toolkit, which includes a module entitled Care for the Caregiver, directs health systems to identify individuals and establish teams, led by representatives from patient safety and/or risk management, who can respond promptly to an event. After ensuring the patient is clinically stable and safe, the CANDOR process provides for immediate and ongoing emotional support to the patient, the family, and the caregiver.

“A lot of what CRPs are about is creating structures and processes that normalize an open and compassionate response to harm events in medicine,” says Dr. Gallagher, who estimates that between 400 and 500 health systems now have CRPs in place.

Wisdom through adversity

While clinicians experience many difficult and negative emotions in the wake of medical errors, how they move forward after the event varies markedly. Some, unable to come to terms with the trauma, may move to another institution or leave medicine entirely. Others, while occasionally reliving the trauma, learn to cope. For the most fortunate, enduring the trauma of a medical error can lead to growth, insight, and wisdom.

In an article published in the journal Academic Medicine, researchers asked 61 physicians who had made serious medical errors, “What helped you to cope positively?” Some of the most common responses – talking about their feelings with a peer, disclosing and apologizing for a mistake, and developing system changes to prevent additional errors – are baked into some health systems’ CRP programs. Other respondents said they dedicated themselves to learning from the mistake, becoming experts in a given field, or sharing what they learned from the experience through teaching.

Dr. Ofri said that after she made an error decades ago while managing a patient with diabetic ketoacidosis, her senior resident publicly berated her for it. The incident taught her a clinical lesson: Never remove an insulin drip without administering long-acting insulin. More importantly, the resident’s verbal thumping taught her about the corrosive effects of shame. Today, Dr. Ofri, who works in a teaching hospital, says that when meeting a new medical team, she begins by recounting her five biggest medical errors.

“I want them to come to me if they make a mistake,” she says. “I want to first make sure the patient is okay. But then I want to make sure the doctor is okay. I also want to know: What was it about the system that contributed to the error, and what can we do to prevent similar errors in the future?”

Acceptance and compassion

Time, experience, supportive peers, an understanding partner or spouse: all of these can help a doctor recover from the trauma of a mistake. “But they’re not an eraser,” Dr. Schwartz said.

Sometimes, doctors say, the path forward starts with acceptance.

Jan Bonhoeffer, MD, author of “Dare to Care: How to Survive and Thrive in Today’s Medical World,” tells a story about a mistake that transformed his life. In 2004, he was working in a busy London emergency department when an adolescent girl arrived complaining of breathing trouble. Dr. Bonhoeffer diagnosed her with asthma and discharged her with an inhaler. The next day, the girl was back in the hospital – this time in the ICU, intubated, and on a ventilator. Because he had failed to take an x-ray, Dr. Bonhoeffer missed the tumor growing in the girl’s chest.

Dr. Bonhoeffer was shattered by his error. “After that experience, I knew I wanted to make learning from my mistakes part of my daily practice,” he says. Now, at the end of each workday, Dr. Bonhoeffer takes an inventory of the day and reflects on all his actions, large and small, clinical and not. “I take a few minutes and think about everything I did and what I should have done differently,” he said. The daily practice can be humbling because it forces him to confront his errors, but it is also empowering, he said, “because the next day I get to make a different choice.”

Dr. Bonhoeffer added, “Doctors are fallible, and you have to be compassionate with yourself. Compassion isn’t sweet. It’s not motherhood and honey pies. It’s coming to terms with reality. It’s not a cure, but it’s healing.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Peter Schwartz, MD, was chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at a hospital in Reading, Pa., in the mid-1990s when a young physician sought him out. The doctor, whom Dr. Schwartz regarded as talented and empathetic, was visibly shaken. The expectant mother they were caring for had just lost her unborn child.

“The doctor came into my office within an hour of the event and asked me to look at the case,” Dr. Schwartz recalled. “I could see that they had failed to recognize ominous changes in the fetal heart rate, and I faced the pain of having to tell them, ‘I think this could have been handled much better.’” Dr. Schwartz delivered the news as compassionately as he could, but a subsequent review confirmed his suspicion: The doctor had made a serious error.

“The doctor was devastated,” he said. “She got counseling and took time off, but in the end, she quit practicing medicine. She said, ‘If I keep practicing, something like that could happen again, and I don’t think I could handle it.’”

To err may be human, but in a health care setting, the harm can be catastrophic. that their feelings of guilt, shame, and self-doubt can lead to depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and even suicidal ideation. The trauma can be so profound that, in a now famous 2000 editorial in the British Medical Journal, Albert Wu, MD, gave the phenomenon a name: “second victim syndrome.”

Today, as quality improvement organizations and health systems work to address medical errors in a just and transparent way, they’re realizing that finding ways to help traumatized clinicians is integral to their efforts.

Are doctors really ‘second victims?’

Although the medical field is moving away from the term “second victim,” which patient advocates argue lacks a ring of accountability, the emotional trauma doctors and other clinicians endure is garnering increased attention. In the 2 decades since Dr. Wu wrote his editorial, research has shown that many types of adverse health care events can evoke traumatic responses. In fact, studies indicate that from 10.4% to 43.3% of health care workers may experience negative symptoms following an adverse event.

But for doctors – who have sworn an oath to do no harm – the emotional toll of having committed a serious medical error can be particularly burdensome and lingering. In a Dutch study involving more than 4,300 doctors and nurses, respondents who were involved in a patient safety incident that resulted in harm were nine times more likely to have negative symptoms lasting longer than 6 months than those who were involved in a near-miss experience.

“There’s a feeling of wanting to erase yourself,” says Danielle Ofri, MD, a New York internist and author of “When We Do Harm: A Doctor Confronts Medical Error.”

That emotional response can have a profound impact on the way medical errors are disclosed, investigated, and ultimately resolved, said Thomas Gallagher, MD, an internist and executive director of the Collaborative for Accountability and Improvement, a patient safety program at the University of Washington.

“When something goes wrong, as physicians, we don’t know what to do,” Dr. Gallagher says. “We feel awful, and often our human reflexes lead us astray. The doctor’s own emotions become barriers to addressing the situation.” For example, guilt and shame may lead doctors to try to hide or diminish their mistakes. Some doctors might try to shift blame, while others may feel so guilty they assume they were responsible for an outcome that was beyond their control.

Recognizing that clinicians’ responses to medical errors are inextricably tangled with how those events are addressed, a growing number of health systems are making clinician support a key element when dealing with medical errors.

Emotional first aid

Although it’s typical for physicians to feel isolated in the wake of errors, these experiences are far from unique. Research conducted by University of Missouri Health Care nurse scientist Susan Scott, RN, PhD, shows that just as most individuals experiencing grief pass through several distinct emotional stages, health care professionals who make errors go through emotional stages that may occur sequentially or concurrently.

An initial period of chaos is often followed by intrusive reflections, haunting re-enactments, and feelings of inadequacy. The doctor’s thinking moves from “How did that happen?” to “What did I miss?” to “What will people think about me?” As the error comes under scrutiny by quality improvement organizations, licensing boards, and/or lawyers, the doctor feels besieged. The doctor may want to reach out but is afraid to. According to Dr. Scott, only 15% of care providers ask for help.

Recognizing that physicians and other care providers rarely ask for support – or may not realize they need it – a growing number of health systems are implementing Communication and Resolution Programs (CRPs). Rather than respond to medical errors with a deny-and-defend mentality, CRPs emphasize transparency and accountability.

This approach, which the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has embraced and codified with its Communication and Optimal Resolution (CANDOR) toolkit, focuses on prompt incident reporting; communication with and support for patients, family members, and caregivers affected by the event; event analysis; quality improvement; and just resolution of the event, including apologies and financial compensation where appropriate.

The CANDOR toolkit, which includes a module entitled Care for the Caregiver, directs health systems to identify individuals and establish teams, led by representatives from patient safety and/or risk management, who can respond promptly to an event. After ensuring the patient is clinically stable and safe, the CANDOR process provides for immediate and ongoing emotional support to the patient, the family, and the caregiver.

“A lot of what CRPs are about is creating structures and processes that normalize an open and compassionate response to harm events in medicine,” says Dr. Gallagher, who estimates that between 400 and 500 health systems now have CRPs in place.

Wisdom through adversity

While clinicians experience many difficult and negative emotions in the wake of medical errors, how they move forward after the event varies markedly. Some, unable to come to terms with the trauma, may move to another institution or leave medicine entirely. Others, while occasionally reliving the trauma, learn to cope. For the most fortunate, enduring the trauma of a medical error can lead to growth, insight, and wisdom.

In an article published in the journal Academic Medicine, researchers asked 61 physicians who had made serious medical errors, “What helped you to cope positively?” Some of the most common responses – talking about their feelings with a peer, disclosing and apologizing for a mistake, and developing system changes to prevent additional errors – are baked into some health systems’ CRP programs. Other respondents said they dedicated themselves to learning from the mistake, becoming experts in a given field, or sharing what they learned from the experience through teaching.

Dr. Ofri said that after she made an error decades ago while managing a patient with diabetic ketoacidosis, her senior resident publicly berated her for it. The incident taught her a clinical lesson: Never remove an insulin drip without administering long-acting insulin. More importantly, the resident’s verbal thumping taught her about the corrosive effects of shame. Today, Dr. Ofri, who works in a teaching hospital, says that when meeting a new medical team, she begins by recounting her five biggest medical errors.

“I want them to come to me if they make a mistake,” she says. “I want to first make sure the patient is okay. But then I want to make sure the doctor is okay. I also want to know: What was it about the system that contributed to the error, and what can we do to prevent similar errors in the future?”

Acceptance and compassion

Time, experience, supportive peers, an understanding partner or spouse: all of these can help a doctor recover from the trauma of a mistake. “But they’re not an eraser,” Dr. Schwartz said.

Sometimes, doctors say, the path forward starts with acceptance.

Jan Bonhoeffer, MD, author of “Dare to Care: How to Survive and Thrive in Today’s Medical World,” tells a story about a mistake that transformed his life. In 2004, he was working in a busy London emergency department when an adolescent girl arrived complaining of breathing trouble. Dr. Bonhoeffer diagnosed her with asthma and discharged her with an inhaler. The next day, the girl was back in the hospital – this time in the ICU, intubated, and on a ventilator. Because he had failed to take an x-ray, Dr. Bonhoeffer missed the tumor growing in the girl’s chest.

Dr. Bonhoeffer was shattered by his error. “After that experience, I knew I wanted to make learning from my mistakes part of my daily practice,” he says. Now, at the end of each workday, Dr. Bonhoeffer takes an inventory of the day and reflects on all his actions, large and small, clinical and not. “I take a few minutes and think about everything I did and what I should have done differently,” he said. The daily practice can be humbling because it forces him to confront his errors, but it is also empowering, he said, “because the next day I get to make a different choice.”

Dr. Bonhoeffer added, “Doctors are fallible, and you have to be compassionate with yourself. Compassion isn’t sweet. It’s not motherhood and honey pies. It’s coming to terms with reality. It’s not a cure, but it’s healing.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Peter Schwartz, MD, was chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at a hospital in Reading, Pa., in the mid-1990s when a young physician sought him out. The doctor, whom Dr. Schwartz regarded as talented and empathetic, was visibly shaken. The expectant mother they were caring for had just lost her unborn child.

“The doctor came into my office within an hour of the event and asked me to look at the case,” Dr. Schwartz recalled. “I could see that they had failed to recognize ominous changes in the fetal heart rate, and I faced the pain of having to tell them, ‘I think this could have been handled much better.’” Dr. Schwartz delivered the news as compassionately as he could, but a subsequent review confirmed his suspicion: The doctor had made a serious error.

“The doctor was devastated,” he said. “She got counseling and took time off, but in the end, she quit practicing medicine. She said, ‘If I keep practicing, something like that could happen again, and I don’t think I could handle it.’”

To err may be human, but in a health care setting, the harm can be catastrophic. that their feelings of guilt, shame, and self-doubt can lead to depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and even suicidal ideation. The trauma can be so profound that, in a now famous 2000 editorial in the British Medical Journal, Albert Wu, MD, gave the phenomenon a name: “second victim syndrome.”

Today, as quality improvement organizations and health systems work to address medical errors in a just and transparent way, they’re realizing that finding ways to help traumatized clinicians is integral to their efforts.

Are doctors really ‘second victims?’

Although the medical field is moving away from the term “second victim,” which patient advocates argue lacks a ring of accountability, the emotional trauma doctors and other clinicians endure is garnering increased attention. In the 2 decades since Dr. Wu wrote his editorial, research has shown that many types of adverse health care events can evoke traumatic responses. In fact, studies indicate that from 10.4% to 43.3% of health care workers may experience negative symptoms following an adverse event.

But for doctors – who have sworn an oath to do no harm – the emotional toll of having committed a serious medical error can be particularly burdensome and lingering. In a Dutch study involving more than 4,300 doctors and nurses, respondents who were involved in a patient safety incident that resulted in harm were nine times more likely to have negative symptoms lasting longer than 6 months than those who were involved in a near-miss experience.

“There’s a feeling of wanting to erase yourself,” says Danielle Ofri, MD, a New York internist and author of “When We Do Harm: A Doctor Confronts Medical Error.”

That emotional response can have a profound impact on the way medical errors are disclosed, investigated, and ultimately resolved, said Thomas Gallagher, MD, an internist and executive director of the Collaborative for Accountability and Improvement, a patient safety program at the University of Washington.

“When something goes wrong, as physicians, we don’t know what to do,” Dr. Gallagher says. “We feel awful, and often our human reflexes lead us astray. The doctor’s own emotions become barriers to addressing the situation.” For example, guilt and shame may lead doctors to try to hide or diminish their mistakes. Some doctors might try to shift blame, while others may feel so guilty they assume they were responsible for an outcome that was beyond their control.

Recognizing that clinicians’ responses to medical errors are inextricably tangled with how those events are addressed, a growing number of health systems are making clinician support a key element when dealing with medical errors.

Emotional first aid

Although it’s typical for physicians to feel isolated in the wake of errors, these experiences are far from unique. Research conducted by University of Missouri Health Care nurse scientist Susan Scott, RN, PhD, shows that just as most individuals experiencing grief pass through several distinct emotional stages, health care professionals who make errors go through emotional stages that may occur sequentially or concurrently.

An initial period of chaos is often followed by intrusive reflections, haunting re-enactments, and feelings of inadequacy. The doctor’s thinking moves from “How did that happen?” to “What did I miss?” to “What will people think about me?” As the error comes under scrutiny by quality improvement organizations, licensing boards, and/or lawyers, the doctor feels besieged. The doctor may want to reach out but is afraid to. According to Dr. Scott, only 15% of care providers ask for help.

Recognizing that physicians and other care providers rarely ask for support – or may not realize they need it – a growing number of health systems are implementing Communication and Resolution Programs (CRPs). Rather than respond to medical errors with a deny-and-defend mentality, CRPs emphasize transparency and accountability.

This approach, which the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has embraced and codified with its Communication and Optimal Resolution (CANDOR) toolkit, focuses on prompt incident reporting; communication with and support for patients, family members, and caregivers affected by the event; event analysis; quality improvement; and just resolution of the event, including apologies and financial compensation where appropriate.

The CANDOR toolkit, which includes a module entitled Care for the Caregiver, directs health systems to identify individuals and establish teams, led by representatives from patient safety and/or risk management, who can respond promptly to an event. After ensuring the patient is clinically stable and safe, the CANDOR process provides for immediate and ongoing emotional support to the patient, the family, and the caregiver.

“A lot of what CRPs are about is creating structures and processes that normalize an open and compassionate response to harm events in medicine,” says Dr. Gallagher, who estimates that between 400 and 500 health systems now have CRPs in place.

Wisdom through adversity

While clinicians experience many difficult and negative emotions in the wake of medical errors, how they move forward after the event varies markedly. Some, unable to come to terms with the trauma, may move to another institution or leave medicine entirely. Others, while occasionally reliving the trauma, learn to cope. For the most fortunate, enduring the trauma of a medical error can lead to growth, insight, and wisdom.

In an article published in the journal Academic Medicine, researchers asked 61 physicians who had made serious medical errors, “What helped you to cope positively?” Some of the most common responses – talking about their feelings with a peer, disclosing and apologizing for a mistake, and developing system changes to prevent additional errors – are baked into some health systems’ CRP programs. Other respondents said they dedicated themselves to learning from the mistake, becoming experts in a given field, or sharing what they learned from the experience through teaching.

Dr. Ofri said that after she made an error decades ago while managing a patient with diabetic ketoacidosis, her senior resident publicly berated her for it. The incident taught her a clinical lesson: Never remove an insulin drip without administering long-acting insulin. More importantly, the resident’s verbal thumping taught her about the corrosive effects of shame. Today, Dr. Ofri, who works in a teaching hospital, says that when meeting a new medical team, she begins by recounting her five biggest medical errors.

“I want them to come to me if they make a mistake,” she says. “I want to first make sure the patient is okay. But then I want to make sure the doctor is okay. I also want to know: What was it about the system that contributed to the error, and what can we do to prevent similar errors in the future?”

Acceptance and compassion

Time, experience, supportive peers, an understanding partner or spouse: all of these can help a doctor recover from the trauma of a mistake. “But they’re not an eraser,” Dr. Schwartz said.

Sometimes, doctors say, the path forward starts with acceptance.

Jan Bonhoeffer, MD, author of “Dare to Care: How to Survive and Thrive in Today’s Medical World,” tells a story about a mistake that transformed his life. In 2004, he was working in a busy London emergency department when an adolescent girl arrived complaining of breathing trouble. Dr. Bonhoeffer diagnosed her with asthma and discharged her with an inhaler. The next day, the girl was back in the hospital – this time in the ICU, intubated, and on a ventilator. Because he had failed to take an x-ray, Dr. Bonhoeffer missed the tumor growing in the girl’s chest.

Dr. Bonhoeffer was shattered by his error. “After that experience, I knew I wanted to make learning from my mistakes part of my daily practice,” he says. Now, at the end of each workday, Dr. Bonhoeffer takes an inventory of the day and reflects on all his actions, large and small, clinical and not. “I take a few minutes and think about everything I did and what I should have done differently,” he said. The daily practice can be humbling because it forces him to confront his errors, but it is also empowering, he said, “because the next day I get to make a different choice.”

Dr. Bonhoeffer added, “Doctors are fallible, and you have to be compassionate with yourself. Compassion isn’t sweet. It’s not motherhood and honey pies. It’s coming to terms with reality. It’s not a cure, but it’s healing.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Tiny hitchhikers like to ride in the trunk

Junk (germs) in the trunk

It’s been a long drive, and you’ve got a long way to go. You pull into a rest stop to use the bathroom and get some food. Quick, which order do you do those things in?

If you’re not a crazy person, you’d use the bathroom and then get your food. Who would bring food into a dirty bathroom? That’s kind of gross. Most people would take care of business, grab food, then get back in the car, eating along the way. Unfortunately, if you’re searching for a sanitary eating environment, your car may not actually be much better than that bathroom, according to new research from Aston University in Birmingham, England.

Let’s start off with the good news. The steering wheels of the five used cars that were swabbed for bacteria were pretty clean. Definitely cleaner than either of the toilet seats analyzed, likely thanks to increased usage of sanitizer, courtesy of the current pandemic. It’s easy to wipe down the steering wheel. Things break down, though, once we look elsewhere. The interiors of the five cars all contained just as much, if not more, bacteria than the toilet seats, with fecal matter commonly appearing on the driver’s seat.

The car interiors were less than sanitary, but they paled in comparison with the real winner here: the trunk. In each of the five cars, bacteria levels there far exceeded those in the toilets, and included everyone’s favorites – Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus.

So, snacking on a bag of chips as you drive along is probably okay, but the food that popped out of its bag and spent the last 5 minutes rolling around the back? Perhaps less okay. You may want to wash it. Or burn it. Or torch the entire car for good measure like we’re about to do. Next time we’ll buy a car without poop in it.

Shut the lid when you flush

Maybe you’ve never thought about this, but it’s actually extremely important to shut the toilet lid when you flush. Just think of all those germs flying around from the force of the flush. Is your toothbrush anywhere near the toilet? Ew. Those pesky little bacteria and viruses are everywhere, and we know we can’t really escape them, but we should really do our best once we’re made aware of where to find them.

It seems like a no-brainer these days since we’ve all been really focused on cleanliness during the pandemic, but according to a poll in the United Kingdom, 55% of the 2,000 participants said they don’t put the lid down while flushing.

The OnePoll survey commissioned by Harpic, a company that makes toilet-cleaning products, also advised that toilet water isn’t even completely clean after flushed several times and can still be contaminated with many germs. Company researchers took specialized pictures of flushing toilets and they looked like tiny little Fourth of July fireworks shows, minus the sparklers. The pictures proved that droplets can go all over the place, including on bathroom users.

“There has never been a more important time to take extra care around our homes, although the risks associated with germ spread in unhygienic bathrooms are high, the solution to keeping them clean is simple,” a Harpic researcher said. Since other studies have shown that coronavirus can be found in feces, it’s become increasingly important to keep ourselves and others safe. Fireworks are pretty, but not when they come out of your toilet.

The latest in MRI fashion

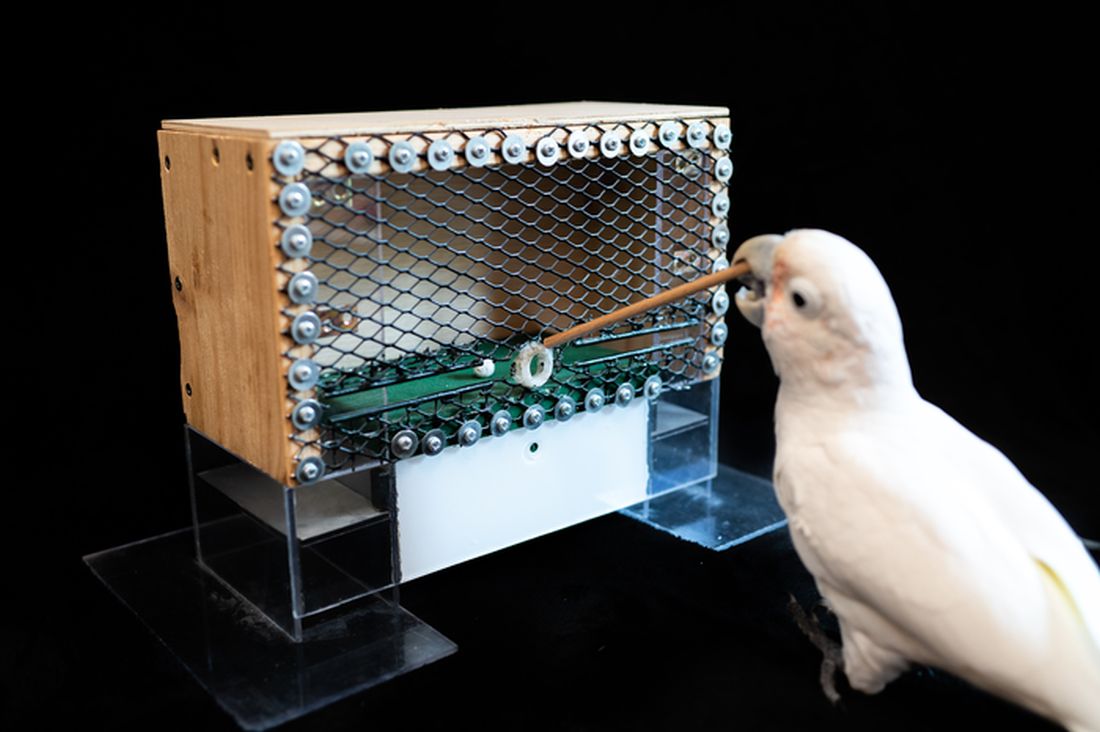

Do you see that photo just below? Looks like something you could buy at the Lego store, right? Well, it’s not. Nor is it the proverbial thinking cap come to life.

(Did someone just say “come to life”? That reminds us of our favorite scene from Frosty the Snowman.)

Anywaaay, about the photo. That funny-looking chapeau is what we in the science business call a metamaterial.

Nope, metamaterials have nothing to do with Facebook parent company Meta. We checked. According to a statement from Boston University, they are engineered structures “created from small unit cells that might be unspectacular alone, but when grouped together in a precise way, get new superpowers not found in nature.”

Superpowers, eh? Who doesn’t want superpowers? Even if they come with a funny hat.

The unit cells, known as resonators, are just plastic tubes wrapped in copper wiring, but when they are grouped in an array and precisely arranged into a helmet, they can channel the magnetic field of the MRI machine during a scan. In theory, that would create “crisper images that can be captured at twice the normal speed,” Xin Zhang, PhD, and her team at BU’s Photonics Center explained in the university statement.

In the future, the metamaterial device could “be used in conjunction with cheaper low-field MRI machines to make the technology more widely available, particularly in the developing world,” they suggested. Or, like so many other superpowers, it could fall into the wrong hands. Like those of Lex Luthor. Or Mark Zuckerberg. Or Frosty the Snowman.

The highway of the mind

How fast can you think on your feet? Well, according to a recently published study, it could be a legitimate measure of intelligence. Here’s the science.

Researchers from the University of Würzburg in Germany and Indiana University have suggested that a person’s intelligence score measures the ability, based on certain neuronal networks and their communication structures, to switch between resting state and different task states.

The investigators set up a study to observe almost 800 people while they completed seven tasks. By monitoring brain activity with functional magnetic resonance imaging, the teams found that subjects who had higher intelligence scores required “less adjustment when switching between different cognitive states,” they said in a separate statement.

It comes down to the network architecture of their brains.

Kirsten Hilger, PhD, head of the German group, described it in terms of highways. The resting state of the brain is normal traffic. It’s always moving. Holiday traffic is the task. The ability to handle the increased flow of commuters is a function of the highway infrastructure. The better the infrastructure, the higher the intelligence.

So the next time you’re stuck in traffic, think how efficient your brain would be with such a task. The quicker, the better.

Junk (germs) in the trunk

It’s been a long drive, and you’ve got a long way to go. You pull into a rest stop to use the bathroom and get some food. Quick, which order do you do those things in?

If you’re not a crazy person, you’d use the bathroom and then get your food. Who would bring food into a dirty bathroom? That’s kind of gross. Most people would take care of business, grab food, then get back in the car, eating along the way. Unfortunately, if you’re searching for a sanitary eating environment, your car may not actually be much better than that bathroom, according to new research from Aston University in Birmingham, England.

Let’s start off with the good news. The steering wheels of the five used cars that were swabbed for bacteria were pretty clean. Definitely cleaner than either of the toilet seats analyzed, likely thanks to increased usage of sanitizer, courtesy of the current pandemic. It’s easy to wipe down the steering wheel. Things break down, though, once we look elsewhere. The interiors of the five cars all contained just as much, if not more, bacteria than the toilet seats, with fecal matter commonly appearing on the driver’s seat.

The car interiors were less than sanitary, but they paled in comparison with the real winner here: the trunk. In each of the five cars, bacteria levels there far exceeded those in the toilets, and included everyone’s favorites – Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus.

So, snacking on a bag of chips as you drive along is probably okay, but the food that popped out of its bag and spent the last 5 minutes rolling around the back? Perhaps less okay. You may want to wash it. Or burn it. Or torch the entire car for good measure like we’re about to do. Next time we’ll buy a car without poop in it.

Shut the lid when you flush

Maybe you’ve never thought about this, but it’s actually extremely important to shut the toilet lid when you flush. Just think of all those germs flying around from the force of the flush. Is your toothbrush anywhere near the toilet? Ew. Those pesky little bacteria and viruses are everywhere, and we know we can’t really escape them, but we should really do our best once we’re made aware of where to find them.

It seems like a no-brainer these days since we’ve all been really focused on cleanliness during the pandemic, but according to a poll in the United Kingdom, 55% of the 2,000 participants said they don’t put the lid down while flushing.

The OnePoll survey commissioned by Harpic, a company that makes toilet-cleaning products, also advised that toilet water isn’t even completely clean after flushed several times and can still be contaminated with many germs. Company researchers took specialized pictures of flushing toilets and they looked like tiny little Fourth of July fireworks shows, minus the sparklers. The pictures proved that droplets can go all over the place, including on bathroom users.

“There has never been a more important time to take extra care around our homes, although the risks associated with germ spread in unhygienic bathrooms are high, the solution to keeping them clean is simple,” a Harpic researcher said. Since other studies have shown that coronavirus can be found in feces, it’s become increasingly important to keep ourselves and others safe. Fireworks are pretty, but not when they come out of your toilet.

The latest in MRI fashion

Do you see that photo just below? Looks like something you could buy at the Lego store, right? Well, it’s not. Nor is it the proverbial thinking cap come to life.

(Did someone just say “come to life”? That reminds us of our favorite scene from Frosty the Snowman.)

Anywaaay, about the photo. That funny-looking chapeau is what we in the science business call a metamaterial.

Nope, metamaterials have nothing to do with Facebook parent company Meta. We checked. According to a statement from Boston University, they are engineered structures “created from small unit cells that might be unspectacular alone, but when grouped together in a precise way, get new superpowers not found in nature.”

Superpowers, eh? Who doesn’t want superpowers? Even if they come with a funny hat.

The unit cells, known as resonators, are just plastic tubes wrapped in copper wiring, but when they are grouped in an array and precisely arranged into a helmet, they can channel the magnetic field of the MRI machine during a scan. In theory, that would create “crisper images that can be captured at twice the normal speed,” Xin Zhang, PhD, and her team at BU’s Photonics Center explained in the university statement.

In the future, the metamaterial device could “be used in conjunction with cheaper low-field MRI machines to make the technology more widely available, particularly in the developing world,” they suggested. Or, like so many other superpowers, it could fall into the wrong hands. Like those of Lex Luthor. Or Mark Zuckerberg. Or Frosty the Snowman.

The highway of the mind

How fast can you think on your feet? Well, according to a recently published study, it could be a legitimate measure of intelligence. Here’s the science.

Researchers from the University of Würzburg in Germany and Indiana University have suggested that a person’s intelligence score measures the ability, based on certain neuronal networks and their communication structures, to switch between resting state and different task states.

The investigators set up a study to observe almost 800 people while they completed seven tasks. By monitoring brain activity with functional magnetic resonance imaging, the teams found that subjects who had higher intelligence scores required “less adjustment when switching between different cognitive states,” they said in a separate statement.

It comes down to the network architecture of their brains.

Kirsten Hilger, PhD, head of the German group, described it in terms of highways. The resting state of the brain is normal traffic. It’s always moving. Holiday traffic is the task. The ability to handle the increased flow of commuters is a function of the highway infrastructure. The better the infrastructure, the higher the intelligence.

So the next time you’re stuck in traffic, think how efficient your brain would be with such a task. The quicker, the better.

Junk (germs) in the trunk

It’s been a long drive, and you’ve got a long way to go. You pull into a rest stop to use the bathroom and get some food. Quick, which order do you do those things in?

If you’re not a crazy person, you’d use the bathroom and then get your food. Who would bring food into a dirty bathroom? That’s kind of gross. Most people would take care of business, grab food, then get back in the car, eating along the way. Unfortunately, if you’re searching for a sanitary eating environment, your car may not actually be much better than that bathroom, according to new research from Aston University in Birmingham, England.

Let’s start off with the good news. The steering wheels of the five used cars that were swabbed for bacteria were pretty clean. Definitely cleaner than either of the toilet seats analyzed, likely thanks to increased usage of sanitizer, courtesy of the current pandemic. It’s easy to wipe down the steering wheel. Things break down, though, once we look elsewhere. The interiors of the five cars all contained just as much, if not more, bacteria than the toilet seats, with fecal matter commonly appearing on the driver’s seat.

The car interiors were less than sanitary, but they paled in comparison with the real winner here: the trunk. In each of the five cars, bacteria levels there far exceeded those in the toilets, and included everyone’s favorites – Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus.

So, snacking on a bag of chips as you drive along is probably okay, but the food that popped out of its bag and spent the last 5 minutes rolling around the back? Perhaps less okay. You may want to wash it. Or burn it. Or torch the entire car for good measure like we’re about to do. Next time we’ll buy a car without poop in it.

Shut the lid when you flush

Maybe you’ve never thought about this, but it’s actually extremely important to shut the toilet lid when you flush. Just think of all those germs flying around from the force of the flush. Is your toothbrush anywhere near the toilet? Ew. Those pesky little bacteria and viruses are everywhere, and we know we can’t really escape them, but we should really do our best once we’re made aware of where to find them.

It seems like a no-brainer these days since we’ve all been really focused on cleanliness during the pandemic, but according to a poll in the United Kingdom, 55% of the 2,000 participants said they don’t put the lid down while flushing.

The OnePoll survey commissioned by Harpic, a company that makes toilet-cleaning products, also advised that toilet water isn’t even completely clean after flushed several times and can still be contaminated with many germs. Company researchers took specialized pictures of flushing toilets and they looked like tiny little Fourth of July fireworks shows, minus the sparklers. The pictures proved that droplets can go all over the place, including on bathroom users.

“There has never been a more important time to take extra care around our homes, although the risks associated with germ spread in unhygienic bathrooms are high, the solution to keeping them clean is simple,” a Harpic researcher said. Since other studies have shown that coronavirus can be found in feces, it’s become increasingly important to keep ourselves and others safe. Fireworks are pretty, but not when they come out of your toilet.

The latest in MRI fashion

Do you see that photo just below? Looks like something you could buy at the Lego store, right? Well, it’s not. Nor is it the proverbial thinking cap come to life.

(Did someone just say “come to life”? That reminds us of our favorite scene from Frosty the Snowman.)

Anywaaay, about the photo. That funny-looking chapeau is what we in the science business call a metamaterial.

Nope, metamaterials have nothing to do with Facebook parent company Meta. We checked. According to a statement from Boston University, they are engineered structures “created from small unit cells that might be unspectacular alone, but when grouped together in a precise way, get new superpowers not found in nature.”

Superpowers, eh? Who doesn’t want superpowers? Even if they come with a funny hat.

The unit cells, known as resonators, are just plastic tubes wrapped in copper wiring, but when they are grouped in an array and precisely arranged into a helmet, they can channel the magnetic field of the MRI machine during a scan. In theory, that would create “crisper images that can be captured at twice the normal speed,” Xin Zhang, PhD, and her team at BU’s Photonics Center explained in the university statement.

In the future, the metamaterial device could “be used in conjunction with cheaper low-field MRI machines to make the technology more widely available, particularly in the developing world,” they suggested. Or, like so many other superpowers, it could fall into the wrong hands. Like those of Lex Luthor. Or Mark Zuckerberg. Or Frosty the Snowman.

The highway of the mind

How fast can you think on your feet? Well, according to a recently published study, it could be a legitimate measure of intelligence. Here’s the science.

Researchers from the University of Würzburg in Germany and Indiana University have suggested that a person’s intelligence score measures the ability, based on certain neuronal networks and their communication structures, to switch between resting state and different task states.

The investigators set up a study to observe almost 800 people while they completed seven tasks. By monitoring brain activity with functional magnetic resonance imaging, the teams found that subjects who had higher intelligence scores required “less adjustment when switching between different cognitive states,” they said in a separate statement.

It comes down to the network architecture of their brains.

Kirsten Hilger, PhD, head of the German group, described it in terms of highways. The resting state of the brain is normal traffic. It’s always moving. Holiday traffic is the task. The ability to handle the increased flow of commuters is a function of the highway infrastructure. The better the infrastructure, the higher the intelligence.

So the next time you’re stuck in traffic, think how efficient your brain would be with such a task. The quicker, the better.

Ear tubes not recommended for recurrent AOM without effusion, ENTs maintain

A practice guideline update from the ENT community on tympanostomy tubes in children reaffirms that tube insertion should not be considered in cases of otitis media with effusion (OME) lasting less than 3 months, or in children with recurrent acute otitis media (AOM) without middle ear effusion at the time of assessment for the procedure.

New in the update from the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation (AAO-HNSF) is a strong recommendation for timely follow-up after surgery and recommendations against both routine use of prophylactic antibiotic ear drops after surgery and the initial use of long-term tubes except when there are specific reasons for doing so.

The update also expands the list of risk factors that place children with OME at increased risk of developmental difficulties – and often in need of timely ear tube placement – to include intellectual disability, learning disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

“Most of what we said in the 2013 [original] guideline was good and still valid ... and [important for] pediatricians, who are the key players” in managing otitis media, Jesse Hackell, MD, one of two general pediatricians who served on the Academy’s guideline update committee, said in an interview.

OME spontaneously clears up to 90% of the time within 3 months, said Dr. Hackell, of Pomona (New York) Pediatrics, and chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine.

The updated guideline, for children 6 months to 12 years, reaffirms a recommendation that tube insertion be offered to children with “bilateral OME for 3 months or longer AND documented hearing difficulties.”

It also reaffirms “options” (a lesser quality of evidence) that in the absence of hearing difficulties, surgery may be performed for children with chronic OME (3 months or longer) in one or both ears if 1) they are at increased risk of developmental difficulties from OME or 2) effusion is likely contributing to balance problems, poor school performance, behavioral problems, ear discomfort, or reduced quality of life.

Children with chronic OME who do not undergo surgery should be reevaluated at 3- to 6-month intervals and monitored until effusion is no longer present, significant hearing loss is detected, or structural abnormalities of the tympanic membrane or middle ear are detected, the update again recommends.

Tympanostomy tube placement is the most common ambulatory surgery performed on children in the United States, the guideline authors say. In 2014, about 9% of children had undergone the surgery, they wrote, noting also that “tubes were placed in 25%-30% of children with frequent ear infections.”

Recurrent AOM

The AAO-HNSF guidance regarding tympanostomy tubes for OME is similar overall to management guidance issued by the AAP in its clinical practice guideline on OME.

The organizations differ, however, on their guidance for tube insertion for recurrent AOM. In its 2013 clinical practice guideline on AOM, the AAP recommends that clinicians may offer tube insertion for recurrent AOM, with no mention of the presence or absence of persistent fluid as a consideration.

According to the AAO-HNSF update, grade A evidence, including some research published since its original 2013 guideline, has shown little benefit to tube insertion in reducing the incidence of AOM in otherwise healthy children who don’t have middle ear effusion.

One study published in 2019 assessed outcomes after watchful waiting and found that only one-third of 123 children eventually went on to tympanostomy tube placement, noted Richard M. Rosenfeld, MD, distinguished professor and chairman of otolaryngology at SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University in Brooklyn, N.Y., and lead author of the original and updated guidelines.

In practice, “the real question [for the ENT] is the future. If the ears are perfectly clear, will tubes really reduce the frequency of infections going forward?” Dr. Rosenfeld said in an interview. “All the evidence seems to say no, it doesn’t make much of a difference.”

Dr. Hackell said he’s confident that the question “is settled enough.” While there “could be stronger research and higher quality studies, the evidence is still pretty good to suggest you gain little to no benefit with tubes when you’re dealing with recurrent AOM without effusion,” he said.

Asked to comment on the ENT update and its guidance on tympanostomy tubes for children with recurrent AOM, an AAP spokesperson said the “issue is under review” and that the AAP did not currently have a statement.

At-risk children

The AAO-HNSF update renews a recommendation to evaluate children with either recurrent AOM or OME of any duration for increased risk for speech, language, or learning problems from OME because of baseline factors (sensory, physical, cognitive, or behavioral).

When OME becomes chronic – or when a tympanogram gives a flat-line reading – OME is likely to persist, and families of at-risk children especially should be encouraged to pursue tube placement, Dr. Rosenfeld said.

Despite prior guidance to this effect, he said, ear tubes are being underutilized in at-risk children, with effusion being missed in primary care and with ENTs not expediting tube placement upon referral.

“These children have learning issues, cognitive issues, developmental issues,” he said in the interview. “It’s a population that does very poorly with ears full of fluid ... and despite guidance suggesting these children should be prioritized with tubes, it doesn’t seem to be happening enough.”

Formulating guidelines for at-risk children is challenging because they are often excluded from trials, Dr. Rosenfeld said, which limits evidence about the benefits of tubes and limits the strength of recommendations.

The addition of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, intellectual disability, and learning disorder to the list of risk factors is notable, Dr. Hackell said. (The list includes autism spectrum disorder, developmental delay, and suspected or confirmed speech and language delay or disorder.)

“We know that kids with ADHD take in and process information a little differently ... it may be harder to get their attention with auditory stimulation,” he said. “So anything that would impact the taking in of information even for a short period of time increases their risk.”

Surgical practice

ENTs are advised in the new guidance to use long-term tubes and perioperative antibiotic ear drops more judiciously. “Long-term tubes have a role, but there are some doctors who routinely use them, even for a first-time surgery,” said Dr. Rosenfeld.

Overuse of long-term tubes results in a higher incidence of tympanic membrane perforation, chronic drainage, and other complications, as well as greater need for long-term follow-up. “There needs to be a reason – something to justify the need for prolonged ventilation,” he said.

Perioperative antibiotic ear drops are often administered during surgery and then prescribed routinely for all children afterward, but research has shown that saline irrigation during surgery and a single application of antibiotic/steroid drops is similarly efficacious in preventing otorrhea, the guideline says. Antibiotic ear drops are also “expensive,” noted Dr. Hackell. “There’s not enough benefit to justify it.”

The update also more explicitly advises selective use of adenoidectomy. A new option says that clinicians may perform the procedure as an adjunct to tube insertion for children 4 years or older to potentially reduce the future incidence of recurrent OME or the need for repeat surgery.

However, in younger children, it should not be offered unless there are symptoms directly related to adenoid infection or nasal obstruction. “Under 4 years, there’s no primary benefit for the ears,” said Dr. Rosenfeld.

Follow-up with the surgeon after tympanostomy tube insertion should occur within 3 months to assess outcomes and educate the family, the update strongly recommends.

And pediatricians should know, Dr. Hackell notes, that clinical evidence continues to show that earplugs and other water precautions are not routinely needed for children who have tubes in place. A good approach, the guideline says, is to “first avoid water precautions and instead reserve them for children with recurrent or persistent tympanostomy tube otorrhea.”

Asked to comment on the guideline update, Tim Joos, MD, MPH, who practices combined internal medicine/pediatrics in Seattle and is an editorial advisory board member of Pediatric News, noted the inclusion of patient information sheets with frequently asked questions – resources that can be useful for guiding parents through what’s often a shared decision-making process.

Neither Dr. Rosenfeld nor Dr. Hackell reported any disclosures. Other members of the guideline update committee reported various book royalties, consulting fees, and other disclosures. Dr. Joos reported he has no connections to the guideline authors.

A practice guideline update from the ENT community on tympanostomy tubes in children reaffirms that tube insertion should not be considered in cases of otitis media with effusion (OME) lasting less than 3 months, or in children with recurrent acute otitis media (AOM) without middle ear effusion at the time of assessment for the procedure.

New in the update from the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation (AAO-HNSF) is a strong recommendation for timely follow-up after surgery and recommendations against both routine use of prophylactic antibiotic ear drops after surgery and the initial use of long-term tubes except when there are specific reasons for doing so.

The update also expands the list of risk factors that place children with OME at increased risk of developmental difficulties – and often in need of timely ear tube placement – to include intellectual disability, learning disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

“Most of what we said in the 2013 [original] guideline was good and still valid ... and [important for] pediatricians, who are the key players” in managing otitis media, Jesse Hackell, MD, one of two general pediatricians who served on the Academy’s guideline update committee, said in an interview.

OME spontaneously clears up to 90% of the time within 3 months, said Dr. Hackell, of Pomona (New York) Pediatrics, and chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine.

The updated guideline, for children 6 months to 12 years, reaffirms a recommendation that tube insertion be offered to children with “bilateral OME for 3 months or longer AND documented hearing difficulties.”

It also reaffirms “options” (a lesser quality of evidence) that in the absence of hearing difficulties, surgery may be performed for children with chronic OME (3 months or longer) in one or both ears if 1) they are at increased risk of developmental difficulties from OME or 2) effusion is likely contributing to balance problems, poor school performance, behavioral problems, ear discomfort, or reduced quality of life.

Children with chronic OME who do not undergo surgery should be reevaluated at 3- to 6-month intervals and monitored until effusion is no longer present, significant hearing loss is detected, or structural abnormalities of the tympanic membrane or middle ear are detected, the update again recommends.

Tympanostomy tube placement is the most common ambulatory surgery performed on children in the United States, the guideline authors say. In 2014, about 9% of children had undergone the surgery, they wrote, noting also that “tubes were placed in 25%-30% of children with frequent ear infections.”

Recurrent AOM

The AAO-HNSF guidance regarding tympanostomy tubes for OME is similar overall to management guidance issued by the AAP in its clinical practice guideline on OME.

The organizations differ, however, on their guidance for tube insertion for recurrent AOM. In its 2013 clinical practice guideline on AOM, the AAP recommends that clinicians may offer tube insertion for recurrent AOM, with no mention of the presence or absence of persistent fluid as a consideration.

According to the AAO-HNSF update, grade A evidence, including some research published since its original 2013 guideline, has shown little benefit to tube insertion in reducing the incidence of AOM in otherwise healthy children who don’t have middle ear effusion.

One study published in 2019 assessed outcomes after watchful waiting and found that only one-third of 123 children eventually went on to tympanostomy tube placement, noted Richard M. Rosenfeld, MD, distinguished professor and chairman of otolaryngology at SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University in Brooklyn, N.Y., and lead author of the original and updated guidelines.

In practice, “the real question [for the ENT] is the future. If the ears are perfectly clear, will tubes really reduce the frequency of infections going forward?” Dr. Rosenfeld said in an interview. “All the evidence seems to say no, it doesn’t make much of a difference.”

Dr. Hackell said he’s confident that the question “is settled enough.” While there “could be stronger research and higher quality studies, the evidence is still pretty good to suggest you gain little to no benefit with tubes when you’re dealing with recurrent AOM without effusion,” he said.

Asked to comment on the ENT update and its guidance on tympanostomy tubes for children with recurrent AOM, an AAP spokesperson said the “issue is under review” and that the AAP did not currently have a statement.

At-risk children

The AAO-HNSF update renews a recommendation to evaluate children with either recurrent AOM or OME of any duration for increased risk for speech, language, or learning problems from OME because of baseline factors (sensory, physical, cognitive, or behavioral).

When OME becomes chronic – or when a tympanogram gives a flat-line reading – OME is likely to persist, and families of at-risk children especially should be encouraged to pursue tube placement, Dr. Rosenfeld said.

Despite prior guidance to this effect, he said, ear tubes are being underutilized in at-risk children, with effusion being missed in primary care and with ENTs not expediting tube placement upon referral.

“These children have learning issues, cognitive issues, developmental issues,” he said in the interview. “It’s a population that does very poorly with ears full of fluid ... and despite guidance suggesting these children should be prioritized with tubes, it doesn’t seem to be happening enough.”

Formulating guidelines for at-risk children is challenging because they are often excluded from trials, Dr. Rosenfeld said, which limits evidence about the benefits of tubes and limits the strength of recommendations.

The addition of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, intellectual disability, and learning disorder to the list of risk factors is notable, Dr. Hackell said. (The list includes autism spectrum disorder, developmental delay, and suspected or confirmed speech and language delay or disorder.)

“We know that kids with ADHD take in and process information a little differently ... it may be harder to get their attention with auditory stimulation,” he said. “So anything that would impact the taking in of information even for a short period of time increases their risk.”

Surgical practice

ENTs are advised in the new guidance to use long-term tubes and perioperative antibiotic ear drops more judiciously. “Long-term tubes have a role, but there are some doctors who routinely use them, even for a first-time surgery,” said Dr. Rosenfeld.

Overuse of long-term tubes results in a higher incidence of tympanic membrane perforation, chronic drainage, and other complications, as well as greater need for long-term follow-up. “There needs to be a reason – something to justify the need for prolonged ventilation,” he said.

Perioperative antibiotic ear drops are often administered during surgery and then prescribed routinely for all children afterward, but research has shown that saline irrigation during surgery and a single application of antibiotic/steroid drops is similarly efficacious in preventing otorrhea, the guideline says. Antibiotic ear drops are also “expensive,” noted Dr. Hackell. “There’s not enough benefit to justify it.”

The update also more explicitly advises selective use of adenoidectomy. A new option says that clinicians may perform the procedure as an adjunct to tube insertion for children 4 years or older to potentially reduce the future incidence of recurrent OME or the need for repeat surgery.

However, in younger children, it should not be offered unless there are symptoms directly related to adenoid infection or nasal obstruction. “Under 4 years, there’s no primary benefit for the ears,” said Dr. Rosenfeld.

Follow-up with the surgeon after tympanostomy tube insertion should occur within 3 months to assess outcomes and educate the family, the update strongly recommends.

And pediatricians should know, Dr. Hackell notes, that clinical evidence continues to show that earplugs and other water precautions are not routinely needed for children who have tubes in place. A good approach, the guideline says, is to “first avoid water precautions and instead reserve them for children with recurrent or persistent tympanostomy tube otorrhea.”

Asked to comment on the guideline update, Tim Joos, MD, MPH, who practices combined internal medicine/pediatrics in Seattle and is an editorial advisory board member of Pediatric News, noted the inclusion of patient information sheets with frequently asked questions – resources that can be useful for guiding parents through what’s often a shared decision-making process.

Neither Dr. Rosenfeld nor Dr. Hackell reported any disclosures. Other members of the guideline update committee reported various book royalties, consulting fees, and other disclosures. Dr. Joos reported he has no connections to the guideline authors.

A practice guideline update from the ENT community on tympanostomy tubes in children reaffirms that tube insertion should not be considered in cases of otitis media with effusion (OME) lasting less than 3 months, or in children with recurrent acute otitis media (AOM) without middle ear effusion at the time of assessment for the procedure.

New in the update from the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation (AAO-HNSF) is a strong recommendation for timely follow-up after surgery and recommendations against both routine use of prophylactic antibiotic ear drops after surgery and the initial use of long-term tubes except when there are specific reasons for doing so.

The update also expands the list of risk factors that place children with OME at increased risk of developmental difficulties – and often in need of timely ear tube placement – to include intellectual disability, learning disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

“Most of what we said in the 2013 [original] guideline was good and still valid ... and [important for] pediatricians, who are the key players” in managing otitis media, Jesse Hackell, MD, one of two general pediatricians who served on the Academy’s guideline update committee, said in an interview.

OME spontaneously clears up to 90% of the time within 3 months, said Dr. Hackell, of Pomona (New York) Pediatrics, and chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine.

The updated guideline, for children 6 months to 12 years, reaffirms a recommendation that tube insertion be offered to children with “bilateral OME for 3 months or longer AND documented hearing difficulties.”

It also reaffirms “options” (a lesser quality of evidence) that in the absence of hearing difficulties, surgery may be performed for children with chronic OME (3 months or longer) in one or both ears if 1) they are at increased risk of developmental difficulties from OME or 2) effusion is likely contributing to balance problems, poor school performance, behavioral problems, ear discomfort, or reduced quality of life.

Children with chronic OME who do not undergo surgery should be reevaluated at 3- to 6-month intervals and monitored until effusion is no longer present, significant hearing loss is detected, or structural abnormalities of the tympanic membrane or middle ear are detected, the update again recommends.

Tympanostomy tube placement is the most common ambulatory surgery performed on children in the United States, the guideline authors say. In 2014, about 9% of children had undergone the surgery, they wrote, noting also that “tubes were placed in 25%-30% of children with frequent ear infections.”

Recurrent AOM

The AAO-HNSF guidance regarding tympanostomy tubes for OME is similar overall to management guidance issued by the AAP in its clinical practice guideline on OME.

The organizations differ, however, on their guidance for tube insertion for recurrent AOM. In its 2013 clinical practice guideline on AOM, the AAP recommends that clinicians may offer tube insertion for recurrent AOM, with no mention of the presence or absence of persistent fluid as a consideration.

According to the AAO-HNSF update, grade A evidence, including some research published since its original 2013 guideline, has shown little benefit to tube insertion in reducing the incidence of AOM in otherwise healthy children who don’t have middle ear effusion.

One study published in 2019 assessed outcomes after watchful waiting and found that only one-third of 123 children eventually went on to tympanostomy tube placement, noted Richard M. Rosenfeld, MD, distinguished professor and chairman of otolaryngology at SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University in Brooklyn, N.Y., and lead author of the original and updated guidelines.

In practice, “the real question [for the ENT] is the future. If the ears are perfectly clear, will tubes really reduce the frequency of infections going forward?” Dr. Rosenfeld said in an interview. “All the evidence seems to say no, it doesn’t make much of a difference.”

Dr. Hackell said he’s confident that the question “is settled enough.” While there “could be stronger research and higher quality studies, the evidence is still pretty good to suggest you gain little to no benefit with tubes when you’re dealing with recurrent AOM without effusion,” he said.

Asked to comment on the ENT update and its guidance on tympanostomy tubes for children with recurrent AOM, an AAP spokesperson said the “issue is under review” and that the AAP did not currently have a statement.

At-risk children

The AAO-HNSF update renews a recommendation to evaluate children with either recurrent AOM or OME of any duration for increased risk for speech, language, or learning problems from OME because of baseline factors (sensory, physical, cognitive, or behavioral).

When OME becomes chronic – or when a tympanogram gives a flat-line reading – OME is likely to persist, and families of at-risk children especially should be encouraged to pursue tube placement, Dr. Rosenfeld said.

Despite prior guidance to this effect, he said, ear tubes are being underutilized in at-risk children, with effusion being missed in primary care and with ENTs not expediting tube placement upon referral.

“These children have learning issues, cognitive issues, developmental issues,” he said in the interview. “It’s a population that does very poorly with ears full of fluid ... and despite guidance suggesting these children should be prioritized with tubes, it doesn’t seem to be happening enough.”

Formulating guidelines for at-risk children is challenging because they are often excluded from trials, Dr. Rosenfeld said, which limits evidence about the benefits of tubes and limits the strength of recommendations.

The addition of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, intellectual disability, and learning disorder to the list of risk factors is notable, Dr. Hackell said. (The list includes autism spectrum disorder, developmental delay, and suspected or confirmed speech and language delay or disorder.)

“We know that kids with ADHD take in and process information a little differently ... it may be harder to get their attention with auditory stimulation,” he said. “So anything that would impact the taking in of information even for a short period of time increases their risk.”

Surgical practice

ENTs are advised in the new guidance to use long-term tubes and perioperative antibiotic ear drops more judiciously. “Long-term tubes have a role, but there are some doctors who routinely use them, even for a first-time surgery,” said Dr. Rosenfeld.

Overuse of long-term tubes results in a higher incidence of tympanic membrane perforation, chronic drainage, and other complications, as well as greater need for long-term follow-up. “There needs to be a reason – something to justify the need for prolonged ventilation,” he said.

Perioperative antibiotic ear drops are often administered during surgery and then prescribed routinely for all children afterward, but research has shown that saline irrigation during surgery and a single application of antibiotic/steroid drops is similarly efficacious in preventing otorrhea, the guideline says. Antibiotic ear drops are also “expensive,” noted Dr. Hackell. “There’s not enough benefit to justify it.”

The update also more explicitly advises selective use of adenoidectomy. A new option says that clinicians may perform the procedure as an adjunct to tube insertion for children 4 years or older to potentially reduce the future incidence of recurrent OME or the need for repeat surgery.

However, in younger children, it should not be offered unless there are symptoms directly related to adenoid infection or nasal obstruction. “Under 4 years, there’s no primary benefit for the ears,” said Dr. Rosenfeld.

Follow-up with the surgeon after tympanostomy tube insertion should occur within 3 months to assess outcomes and educate the family, the update strongly recommends.

And pediatricians should know, Dr. Hackell notes, that clinical evidence continues to show that earplugs and other water precautions are not routinely needed for children who have tubes in place. A good approach, the guideline says, is to “first avoid water precautions and instead reserve them for children with recurrent or persistent tympanostomy tube otorrhea.”

Asked to comment on the guideline update, Tim Joos, MD, MPH, who practices combined internal medicine/pediatrics in Seattle and is an editorial advisory board member of Pediatric News, noted the inclusion of patient information sheets with frequently asked questions – resources that can be useful for guiding parents through what’s often a shared decision-making process.

Neither Dr. Rosenfeld nor Dr. Hackell reported any disclosures. Other members of the guideline update committee reported various book royalties, consulting fees, and other disclosures. Dr. Joos reported he has no connections to the guideline authors.

FROM OTOLARYNGOLOGY HEAD AND NECK SURGERY

Organ transplantation: Unvaccinated need not apply

I agree with most advice given by the affable TV character Ted Lasso. “Every choice is a chance,” he said. Pandemic-era physicians must now consider whether a politically motivated choice to decline COVID-19 vaccination should negatively affect the chance to receive an organ donation.

And in confronting these choices, we have a chance to educate the public on the complexities of the organ allocation process.

A well-informed patient’s personal choice should be honored, even if clinicians disagree, if it does not affect the well-being of others. For example, I once had a patient in acute leukemic crisis who declined blood products because she was a Jehovah’s Witness. She died. Her choice affected her longevity only.

Compare that decision with awarding an organ to an individual who has declined readily available protection of that organ. Weigh that choice against the fact that said protection is against an infectious disease that has killed over 5.5 million worldwide.

Some institutions stand strong, others hedge their bets

Admirably, Loyola University Health System understands that difference. They published a firm stand on transplant candidacy and COVID-19 vaccination status in the Journal of Heart and Lung Transplant. Daniel Dilling, MD, medical director of the lung transplantation program , and Mark Kuczewski, PhD, a professor of medical ethics at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill., wrote that: “We believe that requiring vaccination against COVID-19 should not be controversial when we focus strictly on established frameworks and practices surrounding eligibility for wait-listing to receive a solid organ transplant.”

The Cleveland Clinic apparently agrees. In October 2021, they denied a liver transplant to Michelle Vitullo of Ohio, whose daughter had been deemed “a perfect match.” Her daughter, also unvaccinated, stated: “Being denied for a nonmedical reason for someone’s beliefs that are different to yours, I mean that’s not how that should be.”

But vaccination status is a medical reason, given well-established data regarding increased mortality among the immunosuppressed. Ms. Vitullo then said: “We are trying to get to UPMC [University of Pittsburgh Medical Center] as they don’t require a vaccination.”