User login

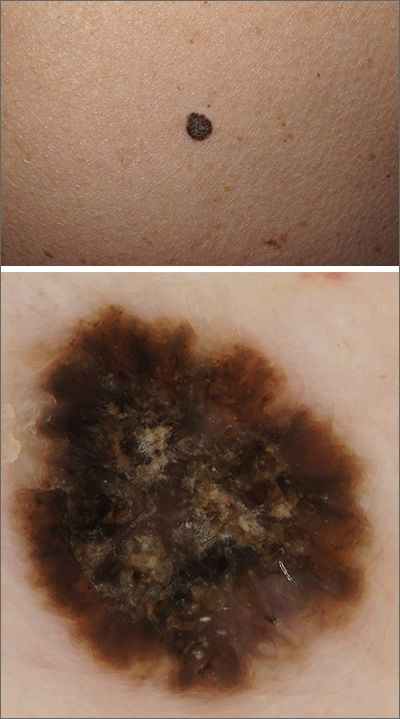

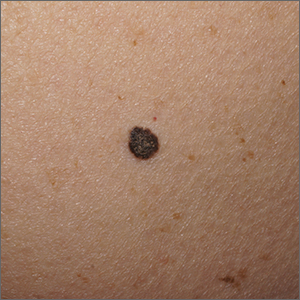

Black papule on the back

A solitary dark lesion on the back of an adult is worrisome for melanoma. A scoop-shave biopsy was ordered with the aim of achieving a 1- to 3-mm margin. The biopsy identified the lesion as a benign pigmented seborrheic keratosis (SK).

SKs are a group of common, keratinocyte neoplasms that can occur in large numbers on a patient. They may meet many of the ABCDE criteria (Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color [varying shades or deep black color], Diameter > 6 mm, or Evolving/changing) used to grossly identify potential melanomas. It is worth noting that not all dark-pigmented lesions arise from melanocytes. In this instance, the dark SK is made of keratinocytes that had accumulated melanin.

Dermoscopy usually helps distinguish SKs from melanocytic neoplasm, which would include nevi and melanoma. Melanocytic lesions (whether benign nevi or malignant melanoma) will display a pigment network, globules, streaks, homogeneous blue or tan color, or characteristic vascular findings. SKs, on the other hand, often demonstrate sharply demarcated borders, milia-like cysts or comedo-like openings, and hairpin vessels.

Both the clinical and dermoscopic photos in this case showed a sharply demarcated border, lack of network, and an absence of any vascular markings. The central scale crust did not exclude a melanocytic lesion and there were peripheral small black dots that could have been asymmetrical globules; however, the biopsy negated those clinical concerns.

Dermoscopy improves diagnostic specificity, but not perfectly. The number of benign lesions biopsied for every malignant lesion confirmed decreases from about 18 without dermoscopy to 8 or fewer for the most experienced dermoscopy practitioners.1 This case highlights one of many instances of a clinically and dermoscopically suspicious lesion that ultimately was benign.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Terushkin V, Warycha M, Levy M, et al. Analysis of the benign to malignant ratio of lesions biopsied by a general dermatologist before and after the adoption of dermoscopy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:343-344. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.12

A solitary dark lesion on the back of an adult is worrisome for melanoma. A scoop-shave biopsy was ordered with the aim of achieving a 1- to 3-mm margin. The biopsy identified the lesion as a benign pigmented seborrheic keratosis (SK).

SKs are a group of common, keratinocyte neoplasms that can occur in large numbers on a patient. They may meet many of the ABCDE criteria (Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color [varying shades or deep black color], Diameter > 6 mm, or Evolving/changing) used to grossly identify potential melanomas. It is worth noting that not all dark-pigmented lesions arise from melanocytes. In this instance, the dark SK is made of keratinocytes that had accumulated melanin.

Dermoscopy usually helps distinguish SKs from melanocytic neoplasm, which would include nevi and melanoma. Melanocytic lesions (whether benign nevi or malignant melanoma) will display a pigment network, globules, streaks, homogeneous blue or tan color, or characteristic vascular findings. SKs, on the other hand, often demonstrate sharply demarcated borders, milia-like cysts or comedo-like openings, and hairpin vessels.

Both the clinical and dermoscopic photos in this case showed a sharply demarcated border, lack of network, and an absence of any vascular markings. The central scale crust did not exclude a melanocytic lesion and there were peripheral small black dots that could have been asymmetrical globules; however, the biopsy negated those clinical concerns.

Dermoscopy improves diagnostic specificity, but not perfectly. The number of benign lesions biopsied for every malignant lesion confirmed decreases from about 18 without dermoscopy to 8 or fewer for the most experienced dermoscopy practitioners.1 This case highlights one of many instances of a clinically and dermoscopically suspicious lesion that ultimately was benign.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

A solitary dark lesion on the back of an adult is worrisome for melanoma. A scoop-shave biopsy was ordered with the aim of achieving a 1- to 3-mm margin. The biopsy identified the lesion as a benign pigmented seborrheic keratosis (SK).

SKs are a group of common, keratinocyte neoplasms that can occur in large numbers on a patient. They may meet many of the ABCDE criteria (Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color [varying shades or deep black color], Diameter > 6 mm, or Evolving/changing) used to grossly identify potential melanomas. It is worth noting that not all dark-pigmented lesions arise from melanocytes. In this instance, the dark SK is made of keratinocytes that had accumulated melanin.

Dermoscopy usually helps distinguish SKs from melanocytic neoplasm, which would include nevi and melanoma. Melanocytic lesions (whether benign nevi or malignant melanoma) will display a pigment network, globules, streaks, homogeneous blue or tan color, or characteristic vascular findings. SKs, on the other hand, often demonstrate sharply demarcated borders, milia-like cysts or comedo-like openings, and hairpin vessels.

Both the clinical and dermoscopic photos in this case showed a sharply demarcated border, lack of network, and an absence of any vascular markings. The central scale crust did not exclude a melanocytic lesion and there were peripheral small black dots that could have been asymmetrical globules; however, the biopsy negated those clinical concerns.

Dermoscopy improves diagnostic specificity, but not perfectly. The number of benign lesions biopsied for every malignant lesion confirmed decreases from about 18 without dermoscopy to 8 or fewer for the most experienced dermoscopy practitioners.1 This case highlights one of many instances of a clinically and dermoscopically suspicious lesion that ultimately was benign.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Terushkin V, Warycha M, Levy M, et al. Analysis of the benign to malignant ratio of lesions biopsied by a general dermatologist before and after the adoption of dermoscopy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:343-344. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.12

1. Terushkin V, Warycha M, Levy M, et al. Analysis of the benign to malignant ratio of lesions biopsied by a general dermatologist before and after the adoption of dermoscopy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:343-344. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.12

USPSTF: Continue gonorrhea, chlamydia screening in sexually active young women, teens

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) announced on Tuesday that it is standing by its 2014 recommendations that sexually active girls and young women be screened for chlamydia and gonorrhea. But the panel is not ready to provide guidance about screening males even amid an outbreak of gonorrhea infections among men who have sex with men (MSM).

“For men in general, there’s not enough evidence to determine whether screening will reduce the risk of complications or spreading infections to others,” said Marti Kubik, PhD, RN, in an interview. Dr. Kubik is a professor at the George Mason University School of Nursing, Fairfax, Va., and is a member of the task force. “We need further research so we will know how to make those recommendations,” she said.

The screening recommendations for chlamydia and gonorrhea were published Sept. 14 in the Journal of the American Medical Association. The guidance is identical to the panel’s 2014 recommendations. The task force recommends screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea in all sexually active females aged 24 years or younger and in sexually active women aged 25 and older if they are at higher risk because of factors such as new or multiple sex partners.

“We continue to see rising rates of these infections in spite of consistent screening recommendations,” Dr. Kubik said. “In 2019, the CDC recorded nearly 2 million cases of chlamydia and a half million cases of gonorrhea. The big clincher is that chlamydia and gonorrhea can occur without symptoms. It’s critical to screen if we’re going to prevent serious health complications.”

The report notes that chlamydia and gonorrhea may lead to pelvic inflammatory disease in women and to multiple complications in infants born to infected mothers. Men can develop urethritis and epididymitis. Both diseases can boost the risk for HIV infection and transmission.

“We want clinicians to review the new recommendation and feel confident about the evidence base that supports a need for us to be screening young women and older women who are at increased risk,” Dr. Kubik said. She noted that almost two-thirds of chlamydia cases and more than half of gonorrhea cases occur in men and women aged 15-24.

Unlike the CDC, which recommends annual chlamydia and gonorrhea screening in appropriate female patients, the task force provides no guidance on screening frequency. “We didn’t have the evidence base to make a recommendation about how often to screen,” Dr. Kubik said. “But recognizing that these often occur without symptoms, it’s reasonable for clinicians to screen patients whose sexual history reveals new or consistent risk factors.”

Philip A. Chan, MD, an associate professor at Brown University, Providence, R.I., who directs a sexually transmitted disease clinic, told this news organization that he found it frustrating that the task force didn’t make recommendations about screening of MSM. According to a commentary accompanying the new recommendations, the rate of gonorrhea in MSM – 5,166 cases per 100,000, or more than 5% – is at a historic high.

In contrast to the task force, the CDC recommends annual or more frequent testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia plus HIV and syphilis in sexually active MSM.

Dr. Chan noted that the task force’s guidance “tends to be the most evidence-based recommendations that exist. If the evidence isn’t there, they usually don’t make a recommendation.” Still, he said, “I would argue that there’s good evidence that in MSM, the risk for HIV acquisition warrants routine screening.”

Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, MPH, director of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, also noted the limits of the task force’s insistence on certain kinds of evidence. Dr. Marrazzo, who coauthored a commentary that accompanies the recommendations, said in an interview that the panel’s “reliance on randomized-controlled-trial-level evidence tends to limit its ability to evolve their recommendations in a way that could account for evolving epidemiology or advances in our understanding of pathophysiology of these infections.”

Dr. Chan noted that obstacles exist for patients even when screening recommendations are in place. Although insurers typically cover costs of chlamydia and gonorrhea screening tests, he said, the uninsured may have to pay $100 or more each.

The USPSTF is supported by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Kubik, Dr. Chan, and Dr. Marrazzo report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) announced on Tuesday that it is standing by its 2014 recommendations that sexually active girls and young women be screened for chlamydia and gonorrhea. But the panel is not ready to provide guidance about screening males even amid an outbreak of gonorrhea infections among men who have sex with men (MSM).

“For men in general, there’s not enough evidence to determine whether screening will reduce the risk of complications or spreading infections to others,” said Marti Kubik, PhD, RN, in an interview. Dr. Kubik is a professor at the George Mason University School of Nursing, Fairfax, Va., and is a member of the task force. “We need further research so we will know how to make those recommendations,” she said.

The screening recommendations for chlamydia and gonorrhea were published Sept. 14 in the Journal of the American Medical Association. The guidance is identical to the panel’s 2014 recommendations. The task force recommends screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea in all sexually active females aged 24 years or younger and in sexually active women aged 25 and older if they are at higher risk because of factors such as new or multiple sex partners.

“We continue to see rising rates of these infections in spite of consistent screening recommendations,” Dr. Kubik said. “In 2019, the CDC recorded nearly 2 million cases of chlamydia and a half million cases of gonorrhea. The big clincher is that chlamydia and gonorrhea can occur without symptoms. It’s critical to screen if we’re going to prevent serious health complications.”

The report notes that chlamydia and gonorrhea may lead to pelvic inflammatory disease in women and to multiple complications in infants born to infected mothers. Men can develop urethritis and epididymitis. Both diseases can boost the risk for HIV infection and transmission.

“We want clinicians to review the new recommendation and feel confident about the evidence base that supports a need for us to be screening young women and older women who are at increased risk,” Dr. Kubik said. She noted that almost two-thirds of chlamydia cases and more than half of gonorrhea cases occur in men and women aged 15-24.

Unlike the CDC, which recommends annual chlamydia and gonorrhea screening in appropriate female patients, the task force provides no guidance on screening frequency. “We didn’t have the evidence base to make a recommendation about how often to screen,” Dr. Kubik said. “But recognizing that these often occur without symptoms, it’s reasonable for clinicians to screen patients whose sexual history reveals new or consistent risk factors.”

Philip A. Chan, MD, an associate professor at Brown University, Providence, R.I., who directs a sexually transmitted disease clinic, told this news organization that he found it frustrating that the task force didn’t make recommendations about screening of MSM. According to a commentary accompanying the new recommendations, the rate of gonorrhea in MSM – 5,166 cases per 100,000, or more than 5% – is at a historic high.

In contrast to the task force, the CDC recommends annual or more frequent testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia plus HIV and syphilis in sexually active MSM.

Dr. Chan noted that the task force’s guidance “tends to be the most evidence-based recommendations that exist. If the evidence isn’t there, they usually don’t make a recommendation.” Still, he said, “I would argue that there’s good evidence that in MSM, the risk for HIV acquisition warrants routine screening.”

Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, MPH, director of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, also noted the limits of the task force’s insistence on certain kinds of evidence. Dr. Marrazzo, who coauthored a commentary that accompanies the recommendations, said in an interview that the panel’s “reliance on randomized-controlled-trial-level evidence tends to limit its ability to evolve their recommendations in a way that could account for evolving epidemiology or advances in our understanding of pathophysiology of these infections.”

Dr. Chan noted that obstacles exist for patients even when screening recommendations are in place. Although insurers typically cover costs of chlamydia and gonorrhea screening tests, he said, the uninsured may have to pay $100 or more each.

The USPSTF is supported by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Kubik, Dr. Chan, and Dr. Marrazzo report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) announced on Tuesday that it is standing by its 2014 recommendations that sexually active girls and young women be screened for chlamydia and gonorrhea. But the panel is not ready to provide guidance about screening males even amid an outbreak of gonorrhea infections among men who have sex with men (MSM).

“For men in general, there’s not enough evidence to determine whether screening will reduce the risk of complications or spreading infections to others,” said Marti Kubik, PhD, RN, in an interview. Dr. Kubik is a professor at the George Mason University School of Nursing, Fairfax, Va., and is a member of the task force. “We need further research so we will know how to make those recommendations,” she said.

The screening recommendations for chlamydia and gonorrhea were published Sept. 14 in the Journal of the American Medical Association. The guidance is identical to the panel’s 2014 recommendations. The task force recommends screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea in all sexually active females aged 24 years or younger and in sexually active women aged 25 and older if they are at higher risk because of factors such as new or multiple sex partners.

“We continue to see rising rates of these infections in spite of consistent screening recommendations,” Dr. Kubik said. “In 2019, the CDC recorded nearly 2 million cases of chlamydia and a half million cases of gonorrhea. The big clincher is that chlamydia and gonorrhea can occur without symptoms. It’s critical to screen if we’re going to prevent serious health complications.”

The report notes that chlamydia and gonorrhea may lead to pelvic inflammatory disease in women and to multiple complications in infants born to infected mothers. Men can develop urethritis and epididymitis. Both diseases can boost the risk for HIV infection and transmission.

“We want clinicians to review the new recommendation and feel confident about the evidence base that supports a need for us to be screening young women and older women who are at increased risk,” Dr. Kubik said. She noted that almost two-thirds of chlamydia cases and more than half of gonorrhea cases occur in men and women aged 15-24.

Unlike the CDC, which recommends annual chlamydia and gonorrhea screening in appropriate female patients, the task force provides no guidance on screening frequency. “We didn’t have the evidence base to make a recommendation about how often to screen,” Dr. Kubik said. “But recognizing that these often occur without symptoms, it’s reasonable for clinicians to screen patients whose sexual history reveals new or consistent risk factors.”

Philip A. Chan, MD, an associate professor at Brown University, Providence, R.I., who directs a sexually transmitted disease clinic, told this news organization that he found it frustrating that the task force didn’t make recommendations about screening of MSM. According to a commentary accompanying the new recommendations, the rate of gonorrhea in MSM – 5,166 cases per 100,000, or more than 5% – is at a historic high.

In contrast to the task force, the CDC recommends annual or more frequent testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia plus HIV and syphilis in sexually active MSM.

Dr. Chan noted that the task force’s guidance “tends to be the most evidence-based recommendations that exist. If the evidence isn’t there, they usually don’t make a recommendation.” Still, he said, “I would argue that there’s good evidence that in MSM, the risk for HIV acquisition warrants routine screening.”

Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, MPH, director of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, also noted the limits of the task force’s insistence on certain kinds of evidence. Dr. Marrazzo, who coauthored a commentary that accompanies the recommendations, said in an interview that the panel’s “reliance on randomized-controlled-trial-level evidence tends to limit its ability to evolve their recommendations in a way that could account for evolving epidemiology or advances in our understanding of pathophysiology of these infections.”

Dr. Chan noted that obstacles exist for patients even when screening recommendations are in place. Although insurers typically cover costs of chlamydia and gonorrhea screening tests, he said, the uninsured may have to pay $100 or more each.

The USPSTF is supported by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Kubik, Dr. Chan, and Dr. Marrazzo report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Candida auris transmission can be contained in postacute care settings

A new study from Orange County, California, shows how Candida auris, an emerging pathogen, was successfully identified and contained in long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs) and ventilator-capable skilled-nursing facilities (vSNFs).

Lead author Ellora Karmarkar, MD, MSc, formerly an epidemic intelligence service officer with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and currently with the California Department of Public Health, said in an interview that the prospective surveillance of urine cultures for C. auris was prompted by “seeing what was happening in New York, New Jersey, and Illinois [being] pretty alarming for a lot of the health officials in California, [who] know that LTACHs are high-risk facilities because they take care of really sick people. Some of those people are there for a very long time.”

Therefore, the study authors decided to focus their investigations there, rather than in acute care hospitals, which were believed to be at lower risk for C. auris outbreaks.

The Orange County Health Department, working with the California Department of Health and the CDC, asked labs to prospectively identify all Candida isolates in urines from LTACHs between September 2018 and February 2019. Normally, labs do not speciate Candida from nonsterile body sites.

Dan Diekema, MD, an epidemiologist and clinical microbiologist at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, who was not involved in the study, told this news organization, “Acute care hospitals really ought to be moving toward doing species identification of Candida from nonsterile sites if they really want to have a better chance of detecting this early.”

The OCHD also screened LTACH and vSNF patients with composite cultures from the axilla-groin or nasal swabs. Screening was undertaken because 5%-10% of colonized patients later develop invasive infections, and 30%-60% die.

The first bloodstream infection was detected in May 2019. Per the report, published online Sept. 7 in Annals of Internal Medicine, “As of 1 January 2020, of 182 patients, 22 (12%) died within 30 days of C. auris identification; 47 (26%) died within 90 days. One of 47 deaths was attributed to C. auris.” Whole-genome sequencing showed that the isolates were all closely related in clade III.

Experts conducted extensive education in infection control at the LTACHs, and communication among the LTACHs and between the long-term facilities and acute care hospitals was improved. As a result, receiving facilities accepting transfers began culturing their newly admitted patients and quickly identified 4 of 99 patients with C. auris who had no known history of colonization. By October 2019, the outbreak was contained in two facilities, down from the nine where C. auris was initially found.

Dr. Diekema noted, “The challenge, of course, for a new emerging MDRO [multidrug-resistant organism] like Candida auris, is that the initial approach, in general, has to be almost passive, when you have not seen the organism. ... Passive surveillance means that you just carefully monitor your clinical cultures, and the first time you detect the MDRO of concern, then you begin doing the point prevalence surveys. ... This [prospective] kind of approach is really good for how we should move forward with both initial detection and containment of MDRO spread.”

Many outbreak studies are confined to a particular institution. Authors of an accompanying editorial commented that this study “underlines the importance of proactive protocols for outbreak investigations and containment measures across the entirety of the health care network serving at-risk patients.”

In her research, Dr. Karmarkar observed that, “some of these facilities don’t have the same infrastructure and infection prevention and control that an acute care hospital might.”

She said in an interview that, “one of the challenges was that people were so focused on COVID that they forgot about the MDROs. ... Some of the things that we recommend to help control Candida auris are also excellent practices for every other organism including COVID care. ... What I appreciated about this investigation is that every facility that we went to was so open to learning, so happy to have us there. They’re very interested in learning about Candida auris and understanding what they could do to control it.”

While recent attention has been on the frightening levels of multidrug resistance in C. auris, Dr. Karmarkar concluded that the “central message in our investigation is that with the right effort, the right approach, and the right team this is an intervenable issue. It’s not inevitable if the attention is focused on it to pick it up early and then try to contain it.”

Dr. Karmarkar reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Diekema reports research funding from bioMerieux and consulting fees from Opgen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study from Orange County, California, shows how Candida auris, an emerging pathogen, was successfully identified and contained in long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs) and ventilator-capable skilled-nursing facilities (vSNFs).

Lead author Ellora Karmarkar, MD, MSc, formerly an epidemic intelligence service officer with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and currently with the California Department of Public Health, said in an interview that the prospective surveillance of urine cultures for C. auris was prompted by “seeing what was happening in New York, New Jersey, and Illinois [being] pretty alarming for a lot of the health officials in California, [who] know that LTACHs are high-risk facilities because they take care of really sick people. Some of those people are there for a very long time.”

Therefore, the study authors decided to focus their investigations there, rather than in acute care hospitals, which were believed to be at lower risk for C. auris outbreaks.

The Orange County Health Department, working with the California Department of Health and the CDC, asked labs to prospectively identify all Candida isolates in urines from LTACHs between September 2018 and February 2019. Normally, labs do not speciate Candida from nonsterile body sites.

Dan Diekema, MD, an epidemiologist and clinical microbiologist at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, who was not involved in the study, told this news organization, “Acute care hospitals really ought to be moving toward doing species identification of Candida from nonsterile sites if they really want to have a better chance of detecting this early.”

The OCHD also screened LTACH and vSNF patients with composite cultures from the axilla-groin or nasal swabs. Screening was undertaken because 5%-10% of colonized patients later develop invasive infections, and 30%-60% die.

The first bloodstream infection was detected in May 2019. Per the report, published online Sept. 7 in Annals of Internal Medicine, “As of 1 January 2020, of 182 patients, 22 (12%) died within 30 days of C. auris identification; 47 (26%) died within 90 days. One of 47 deaths was attributed to C. auris.” Whole-genome sequencing showed that the isolates were all closely related in clade III.

Experts conducted extensive education in infection control at the LTACHs, and communication among the LTACHs and between the long-term facilities and acute care hospitals was improved. As a result, receiving facilities accepting transfers began culturing their newly admitted patients and quickly identified 4 of 99 patients with C. auris who had no known history of colonization. By October 2019, the outbreak was contained in two facilities, down from the nine where C. auris was initially found.

Dr. Diekema noted, “The challenge, of course, for a new emerging MDRO [multidrug-resistant organism] like Candida auris, is that the initial approach, in general, has to be almost passive, when you have not seen the organism. ... Passive surveillance means that you just carefully monitor your clinical cultures, and the first time you detect the MDRO of concern, then you begin doing the point prevalence surveys. ... This [prospective] kind of approach is really good for how we should move forward with both initial detection and containment of MDRO spread.”

Many outbreak studies are confined to a particular institution. Authors of an accompanying editorial commented that this study “underlines the importance of proactive protocols for outbreak investigations and containment measures across the entirety of the health care network serving at-risk patients.”

In her research, Dr. Karmarkar observed that, “some of these facilities don’t have the same infrastructure and infection prevention and control that an acute care hospital might.”

She said in an interview that, “one of the challenges was that people were so focused on COVID that they forgot about the MDROs. ... Some of the things that we recommend to help control Candida auris are also excellent practices for every other organism including COVID care. ... What I appreciated about this investigation is that every facility that we went to was so open to learning, so happy to have us there. They’re very interested in learning about Candida auris and understanding what they could do to control it.”

While recent attention has been on the frightening levels of multidrug resistance in C. auris, Dr. Karmarkar concluded that the “central message in our investigation is that with the right effort, the right approach, and the right team this is an intervenable issue. It’s not inevitable if the attention is focused on it to pick it up early and then try to contain it.”

Dr. Karmarkar reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Diekema reports research funding from bioMerieux and consulting fees from Opgen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study from Orange County, California, shows how Candida auris, an emerging pathogen, was successfully identified and contained in long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs) and ventilator-capable skilled-nursing facilities (vSNFs).

Lead author Ellora Karmarkar, MD, MSc, formerly an epidemic intelligence service officer with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and currently with the California Department of Public Health, said in an interview that the prospective surveillance of urine cultures for C. auris was prompted by “seeing what was happening in New York, New Jersey, and Illinois [being] pretty alarming for a lot of the health officials in California, [who] know that LTACHs are high-risk facilities because they take care of really sick people. Some of those people are there for a very long time.”

Therefore, the study authors decided to focus their investigations there, rather than in acute care hospitals, which were believed to be at lower risk for C. auris outbreaks.

The Orange County Health Department, working with the California Department of Health and the CDC, asked labs to prospectively identify all Candida isolates in urines from LTACHs between September 2018 and February 2019. Normally, labs do not speciate Candida from nonsterile body sites.

Dan Diekema, MD, an epidemiologist and clinical microbiologist at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, who was not involved in the study, told this news organization, “Acute care hospitals really ought to be moving toward doing species identification of Candida from nonsterile sites if they really want to have a better chance of detecting this early.”

The OCHD also screened LTACH and vSNF patients with composite cultures from the axilla-groin or nasal swabs. Screening was undertaken because 5%-10% of colonized patients later develop invasive infections, and 30%-60% die.

The first bloodstream infection was detected in May 2019. Per the report, published online Sept. 7 in Annals of Internal Medicine, “As of 1 January 2020, of 182 patients, 22 (12%) died within 30 days of C. auris identification; 47 (26%) died within 90 days. One of 47 deaths was attributed to C. auris.” Whole-genome sequencing showed that the isolates were all closely related in clade III.

Experts conducted extensive education in infection control at the LTACHs, and communication among the LTACHs and between the long-term facilities and acute care hospitals was improved. As a result, receiving facilities accepting transfers began culturing their newly admitted patients and quickly identified 4 of 99 patients with C. auris who had no known history of colonization. By October 2019, the outbreak was contained in two facilities, down from the nine where C. auris was initially found.

Dr. Diekema noted, “The challenge, of course, for a new emerging MDRO [multidrug-resistant organism] like Candida auris, is that the initial approach, in general, has to be almost passive, when you have not seen the organism. ... Passive surveillance means that you just carefully monitor your clinical cultures, and the first time you detect the MDRO of concern, then you begin doing the point prevalence surveys. ... This [prospective] kind of approach is really good for how we should move forward with both initial detection and containment of MDRO spread.”

Many outbreak studies are confined to a particular institution. Authors of an accompanying editorial commented that this study “underlines the importance of proactive protocols for outbreak investigations and containment measures across the entirety of the health care network serving at-risk patients.”

In her research, Dr. Karmarkar observed that, “some of these facilities don’t have the same infrastructure and infection prevention and control that an acute care hospital might.”

She said in an interview that, “one of the challenges was that people were so focused on COVID that they forgot about the MDROs. ... Some of the things that we recommend to help control Candida auris are also excellent practices for every other organism including COVID care. ... What I appreciated about this investigation is that every facility that we went to was so open to learning, so happy to have us there. They’re very interested in learning about Candida auris and understanding what they could do to control it.”

While recent attention has been on the frightening levels of multidrug resistance in C. auris, Dr. Karmarkar concluded that the “central message in our investigation is that with the right effort, the right approach, and the right team this is an intervenable issue. It’s not inevitable if the attention is focused on it to pick it up early and then try to contain it.”

Dr. Karmarkar reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Diekema reports research funding from bioMerieux and consulting fees from Opgen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

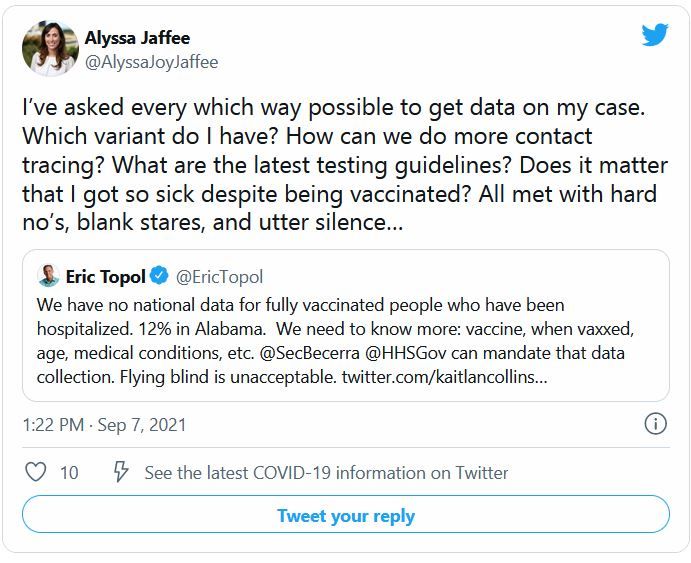

Why misinformation spreads

Over the past 16 months, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted not only our vulnerability to disease outbreaks but also our susceptibility to misinformation and the dangers of “fake news.”

In fact, COVID-19 is not a pandemic but rather a syndemic of viral disease and misinformation. In the current digital age, there is an abundance of information at our fingertips. This has resulted in a surplus of accurate as well as inaccurate information – information that is subject to the various biases we humans are subject to.

Our decision making and cognition are colored by our internal and external environmental biases, whether through our emotions, societal influences, or cues from the “machines” that are now such an omnipresent part of our lives.

Let’s break them down:

- Emotional bias: We’re only human, and our emotions often overwhelm objective judgment. Even when the evidence is of low quality, emotional attachments can deter us from rational thinking. This kind of bias can be rooted in personal experiences.

- Societal bias: Thoughts, opinions, or perspectives of peers are powerful forces that may influence our decisions and viewpoints. We can conceptualize our social networks as partisan circles and “echo chambers.” This bias is perhaps most evident in various online social media platforms.

- Machine bias: Our online platforms are laced with algorithms that tailor the content we see. Accordingly, the curated content we see (and, by extension, the less diverse content we view) may reinforce existing biases, such as confirmation bias.

- Although bias plays a significant role in decision making, we should also consider intuition versus deliberation – and whether the “gut” is a reliable source of information.

Intuition versus deliberation: The power of reasoning

The dual process theory suggests that thought may be categorized in two ways: System 1, referred to as rapid, intuitive, or automatic thinking (which may be a result of personal experience); and system 2, referred to as deliberate or controlled thinking (for example, reasoned thinking). System 1 versus system 2 may be conceptualized as fast versus slow thinking.

Let’s use the Cognitive Reflection Test to illustrate the dual process theory. This test measures the ability to reflect and deliberate on a question and to forgo an intuitive, rapid response. One of the questions asks: “A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?” A common answer is that the ball costs $0.10. However, the ball actually costs $0.05. The common response is a “gut” response, rather than an analytic or deliberate response.

This example can be extrapolated to social media behavior, such as when individuals endorse beliefs and behaviors that may be far from the truth (for example, conspiracy ideation). It is not uncommon for individuals to rely on intuition, which may be incorrect, as a driving source of truth. Although one’s intuition can be correct, it’s important to be careful and to deliberate.

But would deliberate engagement lead to more politically valenced perspectives? One hypothesis posits that system 2 can lead to false claims and worsening discernment of truth. Another, and more popular, account of classical reasoning says that more thoughtful engagement (regardless of one’s political beliefs) is less susceptible to false news (for example, hyperpartisan news).

Additionally, having good literacy (political, scientific, or general) is important for discerning the truth, especially regarding events in which the information and/or claims of knowledge have been heavily manipulated.

Are believing and sharing the same?

Interestingly, believing in a headline and sharing it are not the same. A study that investigated the difference between the two found that although individuals were able to discern the validity of headlines, the veracity of those headlines was not a determining factor in sharing the story on social media.

It has been suggested that social media context may distract individuals from engaging in deliberate thinking that would enhance their ability to determine the accuracy of the content. The dissociation between truthfulness and sharing may be a result of the “attention economy,” which refers to user engagement of likes, comments, shares, and so forth. As such, social media behavior and content consumption may not necessarily reflect one’s beliefs and may be influenced by what others value.

To combat the spread of misinformation, it has been suggested that proactive interventions – “prebunking” or “inoculation” – are necessary. This idea is in accordance with the inoculation theory, which suggests that pre-exposure can confer resistance to challenge. This line of thinking is aligned with the use of vaccines to counter medical illnesses. Increasing awareness of individual vulnerability to manipulation and misinformation has also been proposed as a strategy to resist persuasion.

The age old tale of what others think of us versus what we believe to be true has existed long before the viral overtake of social media. The main difference today is that social media acts as a catalyst for pockets of misinformation. Although social media outlets are cracking down on “false news,” we must consider what criteria should be employed to identify false information. Should external bodies regulate our content consumption? We are certainly entering a gray zone of “wrong” versus “right.” With the overabundance of information available online, it may be the case of “them” versus “us” – that is, those who do not believe in the existence of misinformation versus those who do.

Leanna M. W. Lui, HBSc, completed an HBSc global health specialist degree at the University of Toronto, where she is now an MSc candidate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Over the past 16 months, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted not only our vulnerability to disease outbreaks but also our susceptibility to misinformation and the dangers of “fake news.”

In fact, COVID-19 is not a pandemic but rather a syndemic of viral disease and misinformation. In the current digital age, there is an abundance of information at our fingertips. This has resulted in a surplus of accurate as well as inaccurate information – information that is subject to the various biases we humans are subject to.

Our decision making and cognition are colored by our internal and external environmental biases, whether through our emotions, societal influences, or cues from the “machines” that are now such an omnipresent part of our lives.

Let’s break them down:

- Emotional bias: We’re only human, and our emotions often overwhelm objective judgment. Even when the evidence is of low quality, emotional attachments can deter us from rational thinking. This kind of bias can be rooted in personal experiences.

- Societal bias: Thoughts, opinions, or perspectives of peers are powerful forces that may influence our decisions and viewpoints. We can conceptualize our social networks as partisan circles and “echo chambers.” This bias is perhaps most evident in various online social media platforms.

- Machine bias: Our online platforms are laced with algorithms that tailor the content we see. Accordingly, the curated content we see (and, by extension, the less diverse content we view) may reinforce existing biases, such as confirmation bias.

- Although bias plays a significant role in decision making, we should also consider intuition versus deliberation – and whether the “gut” is a reliable source of information.

Intuition versus deliberation: The power of reasoning

The dual process theory suggests that thought may be categorized in two ways: System 1, referred to as rapid, intuitive, or automatic thinking (which may be a result of personal experience); and system 2, referred to as deliberate or controlled thinking (for example, reasoned thinking). System 1 versus system 2 may be conceptualized as fast versus slow thinking.

Let’s use the Cognitive Reflection Test to illustrate the dual process theory. This test measures the ability to reflect and deliberate on a question and to forgo an intuitive, rapid response. One of the questions asks: “A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?” A common answer is that the ball costs $0.10. However, the ball actually costs $0.05. The common response is a “gut” response, rather than an analytic or deliberate response.

This example can be extrapolated to social media behavior, such as when individuals endorse beliefs and behaviors that may be far from the truth (for example, conspiracy ideation). It is not uncommon for individuals to rely on intuition, which may be incorrect, as a driving source of truth. Although one’s intuition can be correct, it’s important to be careful and to deliberate.

But would deliberate engagement lead to more politically valenced perspectives? One hypothesis posits that system 2 can lead to false claims and worsening discernment of truth. Another, and more popular, account of classical reasoning says that more thoughtful engagement (regardless of one’s political beliefs) is less susceptible to false news (for example, hyperpartisan news).

Additionally, having good literacy (political, scientific, or general) is important for discerning the truth, especially regarding events in which the information and/or claims of knowledge have been heavily manipulated.

Are believing and sharing the same?

Interestingly, believing in a headline and sharing it are not the same. A study that investigated the difference between the two found that although individuals were able to discern the validity of headlines, the veracity of those headlines was not a determining factor in sharing the story on social media.

It has been suggested that social media context may distract individuals from engaging in deliberate thinking that would enhance their ability to determine the accuracy of the content. The dissociation between truthfulness and sharing may be a result of the “attention economy,” which refers to user engagement of likes, comments, shares, and so forth. As such, social media behavior and content consumption may not necessarily reflect one’s beliefs and may be influenced by what others value.

To combat the spread of misinformation, it has been suggested that proactive interventions – “prebunking” or “inoculation” – are necessary. This idea is in accordance with the inoculation theory, which suggests that pre-exposure can confer resistance to challenge. This line of thinking is aligned with the use of vaccines to counter medical illnesses. Increasing awareness of individual vulnerability to manipulation and misinformation has also been proposed as a strategy to resist persuasion.

The age old tale of what others think of us versus what we believe to be true has existed long before the viral overtake of social media. The main difference today is that social media acts as a catalyst for pockets of misinformation. Although social media outlets are cracking down on “false news,” we must consider what criteria should be employed to identify false information. Should external bodies regulate our content consumption? We are certainly entering a gray zone of “wrong” versus “right.” With the overabundance of information available online, it may be the case of “them” versus “us” – that is, those who do not believe in the existence of misinformation versus those who do.

Leanna M. W. Lui, HBSc, completed an HBSc global health specialist degree at the University of Toronto, where she is now an MSc candidate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Over the past 16 months, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted not only our vulnerability to disease outbreaks but also our susceptibility to misinformation and the dangers of “fake news.”

In fact, COVID-19 is not a pandemic but rather a syndemic of viral disease and misinformation. In the current digital age, there is an abundance of information at our fingertips. This has resulted in a surplus of accurate as well as inaccurate information – information that is subject to the various biases we humans are subject to.

Our decision making and cognition are colored by our internal and external environmental biases, whether through our emotions, societal influences, or cues from the “machines” that are now such an omnipresent part of our lives.

Let’s break them down:

- Emotional bias: We’re only human, and our emotions often overwhelm objective judgment. Even when the evidence is of low quality, emotional attachments can deter us from rational thinking. This kind of bias can be rooted in personal experiences.

- Societal bias: Thoughts, opinions, or perspectives of peers are powerful forces that may influence our decisions and viewpoints. We can conceptualize our social networks as partisan circles and “echo chambers.” This bias is perhaps most evident in various online social media platforms.

- Machine bias: Our online platforms are laced with algorithms that tailor the content we see. Accordingly, the curated content we see (and, by extension, the less diverse content we view) may reinforce existing biases, such as confirmation bias.

- Although bias plays a significant role in decision making, we should also consider intuition versus deliberation – and whether the “gut” is a reliable source of information.

Intuition versus deliberation: The power of reasoning

The dual process theory suggests that thought may be categorized in two ways: System 1, referred to as rapid, intuitive, or automatic thinking (which may be a result of personal experience); and system 2, referred to as deliberate or controlled thinking (for example, reasoned thinking). System 1 versus system 2 may be conceptualized as fast versus slow thinking.

Let’s use the Cognitive Reflection Test to illustrate the dual process theory. This test measures the ability to reflect and deliberate on a question and to forgo an intuitive, rapid response. One of the questions asks: “A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?” A common answer is that the ball costs $0.10. However, the ball actually costs $0.05. The common response is a “gut” response, rather than an analytic or deliberate response.

This example can be extrapolated to social media behavior, such as when individuals endorse beliefs and behaviors that may be far from the truth (for example, conspiracy ideation). It is not uncommon for individuals to rely on intuition, which may be incorrect, as a driving source of truth. Although one’s intuition can be correct, it’s important to be careful and to deliberate.

But would deliberate engagement lead to more politically valenced perspectives? One hypothesis posits that system 2 can lead to false claims and worsening discernment of truth. Another, and more popular, account of classical reasoning says that more thoughtful engagement (regardless of one’s political beliefs) is less susceptible to false news (for example, hyperpartisan news).

Additionally, having good literacy (political, scientific, or general) is important for discerning the truth, especially regarding events in which the information and/or claims of knowledge have been heavily manipulated.

Are believing and sharing the same?

Interestingly, believing in a headline and sharing it are not the same. A study that investigated the difference between the two found that although individuals were able to discern the validity of headlines, the veracity of those headlines was not a determining factor in sharing the story on social media.

It has been suggested that social media context may distract individuals from engaging in deliberate thinking that would enhance their ability to determine the accuracy of the content. The dissociation between truthfulness and sharing may be a result of the “attention economy,” which refers to user engagement of likes, comments, shares, and so forth. As such, social media behavior and content consumption may not necessarily reflect one’s beliefs and may be influenced by what others value.

To combat the spread of misinformation, it has been suggested that proactive interventions – “prebunking” or “inoculation” – are necessary. This idea is in accordance with the inoculation theory, which suggests that pre-exposure can confer resistance to challenge. This line of thinking is aligned with the use of vaccines to counter medical illnesses. Increasing awareness of individual vulnerability to manipulation and misinformation has also been proposed as a strategy to resist persuasion.

The age old tale of what others think of us versus what we believe to be true has existed long before the viral overtake of social media. The main difference today is that social media acts as a catalyst for pockets of misinformation. Although social media outlets are cracking down on “false news,” we must consider what criteria should be employed to identify false information. Should external bodies regulate our content consumption? We are certainly entering a gray zone of “wrong” versus “right.” With the overabundance of information available online, it may be the case of “them” versus “us” – that is, those who do not believe in the existence of misinformation versus those who do.

Leanna M. W. Lui, HBSc, completed an HBSc global health specialist degree at the University of Toronto, where she is now an MSc candidate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AGA Clinical Practice Update: Expert Review on IBD dysplasia surveillance, management

The American Gastroenterological Association recently published an expert review and clinical practice update addressing endoscopic surveillance and management of colorectal dysplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Because of practice-altering advances in therapy and surveillance over the past 2 decades, an updated approach is needed, according to authors led by Sanjay K. Murthy, MD, of Ottawa Hospital Research Institute and Fernando Velayos, MD, from Kaiser Permanente San Francisco Medical Center.

“Not long ago, notions of imperceptible CRC [colorectal cancer] development and urgent need for colectomy in the face of dysplasia dominated IBD practice,” the authors wrote in Gastroenterology. “However, improvements in disease management, as well as endoscopic technology and quality, have dramatically changed the way in which we conceptualize and manage IBD-related dysplasia over the past 20 years.”

Most notably, the authors called for a more conservative approach to sample collection and intervention.

“The practices of taking nontargeted biopsies and of referring patients for colectomy in the setting of low-grade or invisible dysplasia are being increasingly challenged in favor of ‘smart’ approaches that emphasize careful inspection and targeted sampling of visible and subtle lesions using newer technologies ... as well as endoscopic management of most lesions that appear endoscopically resectable,” the authors wrote. “Indeed, surgery is being increasingly reserved for lesions harboring strong risk factors for invasive cancer or when endoscopic clearance is not possible.”

The 14 best practice advice statements cover a variety of topics, including appropriate lesion terminology and characterization, endoscopy timing, and indications for biopsies, resection, and colectomy.

“The proposed conceptual model and best practice advice statements in this review are best used in conjunction with evolving literature and existing societal guidelines as part of a shared decision-making process,” the authors noted.

Lesion descriptions

First, the authors provided best practice advice for retirement of three older terms: “dysplasia-associated lesion or mass, adenoma-like mass, and flat dysplasia.” Instead, they advised sorting precancerous colorectal lesions into one of three categories: nonpolypoid (less than 2.5 mm tall), polypoid (at least 2.5 mm tall), or invisible (if detected by nontargeted biopsy).

According to the update, lesion descriptions should also include location, morphology, size, presence of ulceration, clarity of borders, presence within an area of past or current colitis, use of special visualization techniques, and perceived completeness of resection.

Surveillance timing

All patients with chronic IBD should undergo colonoscopy screening for dysplasia 8-10 years after diagnosis, the authors wrote. Subsequent colonoscopies should be performed every 1-5 years, depending on risk factors, such as family history of colorectal cancer and quality of prior surveillance exams.

Higher-risk patients may require colonoscopies earlier and more frequently, according to the update. Patients diagnosed with primary sclerosing cholangitis, for instance, should undergo immediate colonoscopy, while patients at high risk of dysplasia (such as those with prior CRC) should undergo annual pouch surveillance.

General principles and surveillance colonoscopy

“Conditions and practices for dysplasia detection should be optimized,” the authors wrote, “including control of inflammation, use of high-definition endoscopes, bowel preparation, careful washing and inspection of all colorectal mucosa, and targeted sampling of any suspicious mucosal irregularities.”

Endoscopists should consider use of dye spray chromoendoscopy, “particularly if a standard definition endoscope is used or if there is a history of dysplasia,” the authors wrote. Alternatively, virtual chromoendoscopy may be used in conjunction with high-definition endoscopy.

Biopsy, resection, and colectomy

According to the update, if chromoendoscopy is used, then biopsies should be targeted “where mucosal findings are suspicious for dysplasia or are inexplicably different from the surrounding mucosa.”

If chromoendoscopy isn’t used, then the authors advised clinicians to also perform nontargeted biopsies, ideally four per 10 cm of colon, in addition to targeted biopsies of suspicious areas.

When lesions are clearly demarcated and lack submucosal fibrosis or stigmata of invasive cancer, then endoscopic resection is preferred over biopsy. Following resection, mucosal biopsies are usually unnecessary, “unless there are concerns about resection completeness.”

“If the resectability of a lesion is in question, referral to a specialized endoscopist or inflammatory bowel disease center is suggested,” wrote the authors.

They noted that, if visible dysplasia is truly unresectable or if invisible multifocal/high-grade dysplasia is encountered, then colectomy should be performed.

IBD control

Finally, the authors emphasized the importance of adequately managing IBD activity to reduce dysplasia risk.

“Because CRC risk in IBD is primarily driven by inflammation, and available data do not demonstrate a clear independent chemopreventive effect of available agents, the focus of chemoprevention in IBD should be control of inflammation,” they wrote.

The expert review was commissioned and approved by the AGA Institute Clinical Practice Updates Committee and the AGA Governing Board. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

The American Gastroenterological Association recently published an expert review and clinical practice update addressing endoscopic surveillance and management of colorectal dysplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Because of practice-altering advances in therapy and surveillance over the past 2 decades, an updated approach is needed, according to authors led by Sanjay K. Murthy, MD, of Ottawa Hospital Research Institute and Fernando Velayos, MD, from Kaiser Permanente San Francisco Medical Center.

“Not long ago, notions of imperceptible CRC [colorectal cancer] development and urgent need for colectomy in the face of dysplasia dominated IBD practice,” the authors wrote in Gastroenterology. “However, improvements in disease management, as well as endoscopic technology and quality, have dramatically changed the way in which we conceptualize and manage IBD-related dysplasia over the past 20 years.”

Most notably, the authors called for a more conservative approach to sample collection and intervention.

“The practices of taking nontargeted biopsies and of referring patients for colectomy in the setting of low-grade or invisible dysplasia are being increasingly challenged in favor of ‘smart’ approaches that emphasize careful inspection and targeted sampling of visible and subtle lesions using newer technologies ... as well as endoscopic management of most lesions that appear endoscopically resectable,” the authors wrote. “Indeed, surgery is being increasingly reserved for lesions harboring strong risk factors for invasive cancer or when endoscopic clearance is not possible.”

The 14 best practice advice statements cover a variety of topics, including appropriate lesion terminology and characterization, endoscopy timing, and indications for biopsies, resection, and colectomy.

“The proposed conceptual model and best practice advice statements in this review are best used in conjunction with evolving literature and existing societal guidelines as part of a shared decision-making process,” the authors noted.

Lesion descriptions

First, the authors provided best practice advice for retirement of three older terms: “dysplasia-associated lesion or mass, adenoma-like mass, and flat dysplasia.” Instead, they advised sorting precancerous colorectal lesions into one of three categories: nonpolypoid (less than 2.5 mm tall), polypoid (at least 2.5 mm tall), or invisible (if detected by nontargeted biopsy).

According to the update, lesion descriptions should also include location, morphology, size, presence of ulceration, clarity of borders, presence within an area of past or current colitis, use of special visualization techniques, and perceived completeness of resection.

Surveillance timing

All patients with chronic IBD should undergo colonoscopy screening for dysplasia 8-10 years after diagnosis, the authors wrote. Subsequent colonoscopies should be performed every 1-5 years, depending on risk factors, such as family history of colorectal cancer and quality of prior surveillance exams.

Higher-risk patients may require colonoscopies earlier and more frequently, according to the update. Patients diagnosed with primary sclerosing cholangitis, for instance, should undergo immediate colonoscopy, while patients at high risk of dysplasia (such as those with prior CRC) should undergo annual pouch surveillance.

General principles and surveillance colonoscopy

“Conditions and practices for dysplasia detection should be optimized,” the authors wrote, “including control of inflammation, use of high-definition endoscopes, bowel preparation, careful washing and inspection of all colorectal mucosa, and targeted sampling of any suspicious mucosal irregularities.”

Endoscopists should consider use of dye spray chromoendoscopy, “particularly if a standard definition endoscope is used or if there is a history of dysplasia,” the authors wrote. Alternatively, virtual chromoendoscopy may be used in conjunction with high-definition endoscopy.

Biopsy, resection, and colectomy

According to the update, if chromoendoscopy is used, then biopsies should be targeted “where mucosal findings are suspicious for dysplasia or are inexplicably different from the surrounding mucosa.”

If chromoendoscopy isn’t used, then the authors advised clinicians to also perform nontargeted biopsies, ideally four per 10 cm of colon, in addition to targeted biopsies of suspicious areas.

When lesions are clearly demarcated and lack submucosal fibrosis or stigmata of invasive cancer, then endoscopic resection is preferred over biopsy. Following resection, mucosal biopsies are usually unnecessary, “unless there are concerns about resection completeness.”

“If the resectability of a lesion is in question, referral to a specialized endoscopist or inflammatory bowel disease center is suggested,” wrote the authors.

They noted that, if visible dysplasia is truly unresectable or if invisible multifocal/high-grade dysplasia is encountered, then colectomy should be performed.

IBD control

Finally, the authors emphasized the importance of adequately managing IBD activity to reduce dysplasia risk.

“Because CRC risk in IBD is primarily driven by inflammation, and available data do not demonstrate a clear independent chemopreventive effect of available agents, the focus of chemoprevention in IBD should be control of inflammation,” they wrote.

The expert review was commissioned and approved by the AGA Institute Clinical Practice Updates Committee and the AGA Governing Board. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

The American Gastroenterological Association recently published an expert review and clinical practice update addressing endoscopic surveillance and management of colorectal dysplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Because of practice-altering advances in therapy and surveillance over the past 2 decades, an updated approach is needed, according to authors led by Sanjay K. Murthy, MD, of Ottawa Hospital Research Institute and Fernando Velayos, MD, from Kaiser Permanente San Francisco Medical Center.

“Not long ago, notions of imperceptible CRC [colorectal cancer] development and urgent need for colectomy in the face of dysplasia dominated IBD practice,” the authors wrote in Gastroenterology. “However, improvements in disease management, as well as endoscopic technology and quality, have dramatically changed the way in which we conceptualize and manage IBD-related dysplasia over the past 20 years.”

Most notably, the authors called for a more conservative approach to sample collection and intervention.

“The practices of taking nontargeted biopsies and of referring patients for colectomy in the setting of low-grade or invisible dysplasia are being increasingly challenged in favor of ‘smart’ approaches that emphasize careful inspection and targeted sampling of visible and subtle lesions using newer technologies ... as well as endoscopic management of most lesions that appear endoscopically resectable,” the authors wrote. “Indeed, surgery is being increasingly reserved for lesions harboring strong risk factors for invasive cancer or when endoscopic clearance is not possible.”

The 14 best practice advice statements cover a variety of topics, including appropriate lesion terminology and characterization, endoscopy timing, and indications for biopsies, resection, and colectomy.

“The proposed conceptual model and best practice advice statements in this review are best used in conjunction with evolving literature and existing societal guidelines as part of a shared decision-making process,” the authors noted.

Lesion descriptions

First, the authors provided best practice advice for retirement of three older terms: “dysplasia-associated lesion or mass, adenoma-like mass, and flat dysplasia.” Instead, they advised sorting precancerous colorectal lesions into one of three categories: nonpolypoid (less than 2.5 mm tall), polypoid (at least 2.5 mm tall), or invisible (if detected by nontargeted biopsy).

According to the update, lesion descriptions should also include location, morphology, size, presence of ulceration, clarity of borders, presence within an area of past or current colitis, use of special visualization techniques, and perceived completeness of resection.

Surveillance timing

All patients with chronic IBD should undergo colonoscopy screening for dysplasia 8-10 years after diagnosis, the authors wrote. Subsequent colonoscopies should be performed every 1-5 years, depending on risk factors, such as family history of colorectal cancer and quality of prior surveillance exams.

Higher-risk patients may require colonoscopies earlier and more frequently, according to the update. Patients diagnosed with primary sclerosing cholangitis, for instance, should undergo immediate colonoscopy, while patients at high risk of dysplasia (such as those with prior CRC) should undergo annual pouch surveillance.

General principles and surveillance colonoscopy

“Conditions and practices for dysplasia detection should be optimized,” the authors wrote, “including control of inflammation, use of high-definition endoscopes, bowel preparation, careful washing and inspection of all colorectal mucosa, and targeted sampling of any suspicious mucosal irregularities.”

Endoscopists should consider use of dye spray chromoendoscopy, “particularly if a standard definition endoscope is used or if there is a history of dysplasia,” the authors wrote. Alternatively, virtual chromoendoscopy may be used in conjunction with high-definition endoscopy.

Biopsy, resection, and colectomy

According to the update, if chromoendoscopy is used, then biopsies should be targeted “where mucosal findings are suspicious for dysplasia or are inexplicably different from the surrounding mucosa.”

If chromoendoscopy isn’t used, then the authors advised clinicians to also perform nontargeted biopsies, ideally four per 10 cm of colon, in addition to targeted biopsies of suspicious areas.

When lesions are clearly demarcated and lack submucosal fibrosis or stigmata of invasive cancer, then endoscopic resection is preferred over biopsy. Following resection, mucosal biopsies are usually unnecessary, “unless there are concerns about resection completeness.”

“If the resectability of a lesion is in question, referral to a specialized endoscopist or inflammatory bowel disease center is suggested,” wrote the authors.

They noted that, if visible dysplasia is truly unresectable or if invisible multifocal/high-grade dysplasia is encountered, then colectomy should be performed.

IBD control

Finally, the authors emphasized the importance of adequately managing IBD activity to reduce dysplasia risk.

“Because CRC risk in IBD is primarily driven by inflammation, and available data do not demonstrate a clear independent chemopreventive effect of available agents, the focus of chemoprevention in IBD should be control of inflammation,” they wrote.

The expert review was commissioned and approved by the AGA Institute Clinical Practice Updates Committee and the AGA Governing Board. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

A boy went to a COVID-swamped ER. He waited for hours. Then his appendix burst.

Seth was finally diagnosed with appendicitis more than six hours after arriving at Cleveland Clinic Martin Health North Hospital in late July. Around midnight, he was taken by ambulance to a sister hospital about a half-hour away that was better equipped to perform pediatric emergency surgery, his father said.

But by the time the doctor operated in the early morning hours, Seth’s appendix had burst – a potentially fatal complication.

They, too, need emergency care, but the sheer number of COVID-19 cases is crowding them out. Treatment has often been delayed as ERs scramble to find a bed that may be hundreds of miles away.

Some health officials now worry about looming ethical decisions. Last week, Idaho activated a “crisis standard of care,” which one official described as a “last resort.” It allows overwhelmed hospitals to ration care, including “in rare cases, ventilator (breathing machines) or intensive care unit (ICU) beds may need to be used for those who are most likely to survive, while patients who are not likely to survive may not be able to receive one,” the state’s website said.

The federal government’s latest data shows Alabama is at 100% of its intensive care unit capacity, with Texas, Georgia, Mississippi and Arkansas at more than 90% ICU capacity. Florida is just under 90%.

It’s the COVID-19 cases that are dominating. In Georgia, 62% of the ICU beds are now filled with just COVID-19 patients. In Texas, the percentage is nearly half.

To have so many ICU beds pressed into service for a single diagnosis is “unheard of,” said Dr. Hasan Kakli, an emergency room physician at Bellville Medical Center in Bellville, Texas, about an hour from Houston. “It’s approaching apocalyptic.”

In Texas, state data released Monday showed there were only 319 adult and 104 pediatric staffed ICU beds available across a state of 29 million people.

Hospitals need to hold some ICU beds for other patients, such as those recovering from major surgery or other critical conditions such as stroke, trauma or heart failure.

“This is not just a COVID issue,” said Dr. Normaliz Rodriguez, pediatric emergency physician at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg, Florida. “This is an everyone issue.”

While the latest hospital crisis echoes previous pandemic spikes, there are troubling differences this time around.

Before, localized COVID-19 hot spots led to bed shortages, but there were usually hospitals in the region not as affected that could accept a transfer.

Now, as the highly contagious delta variant envelops swaths of low-vaccination states all at once, it becomes harder to find nearby hospitals that are not slammed.

“Wait times can now be measured in days,” said Darrell Pile, CEO of the SouthEast Texas Regional Advisory Council, which helps coordinate patient transfers across a 25-county region.

Recently, Dr. Cedric Dark, a Houston emergency physician and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, said he saw a critically ill COVID-19 patient waiting in the emergency room for an ICU bed to open. The doctor worked eight hours, went home and came in the next day. The patient was still waiting.

Holding a seriously ill patient in an emergency room while waiting for an in-patient bed to open is known as boarding. The longer the wait, the more dangerous it can be for the patient, studies have found.

Not only do patients ultimately end up staying in the hospital or the ICU longer, some research suggests that long waits for a bed will worsen their condition and may increase the risk of in-hospital death.

That’s what happened last month in Texas.

On Aug. 21, around 11:30 a.m., Michelle Puget took her adult son, Daniel Wilkinson, to the Bellville Medical Center’s emergency room as a pain in his abdomen became unbearable. “Mama,” he said, “take me to the hospital.”

Wilkinson, a 46-year-old decorated Army veteran who did two tours of duty in Afghanistan, was ushered into an exam room about half an hour later. Kakli, the emergency room physician there, diagnosed gallstone pancreatitis, a serious but treatable condition that required a specialist to perform a surgical procedure and an ICU bed.

In other times, the transfer to a larger facility would be easy. But soon Kakli found himself on a frantic, six-hour quest to find a bed for his patient. Not only did he call hospitals across Texas, but he also tried Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma and Colorado. It was like throwing darts at a map and hoping to get lucky, he told ProPublica. But no one could or would take the transfer.

By 2:30 p.m., Wilkinson’s condition was deteriorating. Kakli told Puget to come back to the hospital. “I have to tell you,” she said he told her, “Your son is a very, very sick man. If he doesn’t get this procedure he will die.” She began to weep.

Two hours later, Wilkinson’s blood pressure was dropping, signaling his organs were failing, she said.

Kakli went on Facebook and posted an all-caps plea to physician groups around the nation: “GETTING REJECTED BY ALL HOSPITALS IN TEXAS DUE TO NO ICU BEDS. PLEASE HELP. MESSAGE ME IF YOU HAVE A BED. PATIENT IS IN ER NOW. I AM THE ER DOC. WILL FLY ANYWHERE.”

The doctor tried Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston for a second time. This time he found a bed.

Around 7 p.m., Wilkinson, still conscious but in grave condition, was flown by helicopter to the hospital. He was put in a medically induced coma. Through the night and into the next morning, medical teams worked to stabilize him enough to perform the procedure. They could not.

Doctors told his family the internal damage was catastrophic. “We made the decision we had to let him go,” Puget said.

Time of death: 1:37 p.m. Aug. 22 – 26 hours after he first arrived in the emergency room.

The story was first reported by CBS News. Kakli told ProPublica last week he still sometimes does the math in his head: It should have been 40 minutes from diagnosis in Bellville to transfer to the ICU in Houston. “If he had 40 minutes to wait instead of six hours, I strongly believe he would have had a different outcome.”

Another difference with the latest surge is how it’s affecting children.

Last year, schools were closed, and children were more protected because they were mostly isolated at home. In fact, children’s hospitals were often so empty during previous spikes they opened beds to adult patients.

Now, families are out more. Schools have reopened, some with mask mandates, some without. Vaccines are not yet available to those under 12. Suddenly the numbers of hospitalized children are on the rise, setting up the same type of competition for resources between young COVID-19 patients and those with other illnesses such as new onset diabetes, trauma, pneumonia or appendicitis.

Dr. Rafael Santiago, a pediatric emergency physician in Central Florida, said at Lakeland Regional Health Medical Center, the average number of children coming into the emergency room is around 130 per day. During the lockdown last spring, that number dropped to 33. Last month – “the busiest month ever” – the average daily number of children in the emergency room was 160.

Pediatric transfers are not yet as fraught as adult ones, Santiago said, but it does take more calls than it once did to secure a bed.

Seth Osborn, the 12-year-old whose appendix burst after a long wait, spent five days and four nights in the hospital as doctors pumped his body full of antibiotics to stave off infection from the rupture. The typical hospitalization for a routine appendectomy is about 24 hours.

The initial hospital bill for the stay came to more than $48,000, Nathaniel Osborn said. Although insurance paid for most of it, he said the family still borrowed against its house to cover the more than $5,000 in out-of-pocket costs so far.

While the hospital system where Seth was treated declined to comment about his case because of patient privacy laws, it did email a statement about the strain the pandemic is creating.

“Since July 2021, we have seen a tremendous spike in COVID-19 patients needing care and hospitalization. In mid-August, we saw the highest number of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 across the Cleveland Clinic Florida region, a total of 395 COVID-19 patients in four hospitals. Those hospitals have approximately 1,000 total beds,” the email to ProPublica said. “We strongly encourage vaccination. Approximately 90% of our patients hospitalized due to COVID-19 are unvaccinated.”