User login

Anatomical liver resection surpasses nonanatomical resection for overall survival in HCC

Key clinical point: Overall survival at 3 and 5 years was significantly greater in HCC patients who underwent anatomical liver resection compared to those who had nonanatomical liver resection (hazard ratios 0.79 and 0.83, respectively).

Major finding: Patients who underwent anatomical liver resection showed significantly better recurrence-free survival at 1, 3, and 5 years compared to those who underwent nonanatomical liver resection (HR 0.79, 0.81, and 0.82, respectively); anatomical liver resection patients also showed improved recurrence-free survival in a subgroup analysis of tumors less than 5 cm in diameter.

Study details: The data come from a meta-analysis of 19 propensity score matching studies of hepatocellular carcinoma patients who underwent anatomical or nonanatomical liver resection.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Shin S and Kim T-S. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2021 Jun 30. doi: 10.14701/ahbps.EP-37.

Key clinical point: Overall survival at 3 and 5 years was significantly greater in HCC patients who underwent anatomical liver resection compared to those who had nonanatomical liver resection (hazard ratios 0.79 and 0.83, respectively).

Major finding: Patients who underwent anatomical liver resection showed significantly better recurrence-free survival at 1, 3, and 5 years compared to those who underwent nonanatomical liver resection (HR 0.79, 0.81, and 0.82, respectively); anatomical liver resection patients also showed improved recurrence-free survival in a subgroup analysis of tumors less than 5 cm in diameter.

Study details: The data come from a meta-analysis of 19 propensity score matching studies of hepatocellular carcinoma patients who underwent anatomical or nonanatomical liver resection.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Shin S and Kim T-S. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2021 Jun 30. doi: 10.14701/ahbps.EP-37.

Key clinical point: Overall survival at 3 and 5 years was significantly greater in HCC patients who underwent anatomical liver resection compared to those who had nonanatomical liver resection (hazard ratios 0.79 and 0.83, respectively).

Major finding: Patients who underwent anatomical liver resection showed significantly better recurrence-free survival at 1, 3, and 5 years compared to those who underwent nonanatomical liver resection (HR 0.79, 0.81, and 0.82, respectively); anatomical liver resection patients also showed improved recurrence-free survival in a subgroup analysis of tumors less than 5 cm in diameter.

Study details: The data come from a meta-analysis of 19 propensity score matching studies of hepatocellular carcinoma patients who underwent anatomical or nonanatomical liver resection.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Shin S and Kim T-S. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2021 Jun 30. doi: 10.14701/ahbps.EP-37.

Lenvatinib extends time to disease progression in HCC patients with portal vein tumor thrombus

Key clinical point: Hepatocellular carcinoma patients with PVTT who received lenvatinib had a significantly longer time to progression compared to those treated with sorafenib.

Major finding: The median time to progression was 4.7 months for HCC patients with PVTT who received lenvatinib, compared to 3.1 months for those treated with sorafenib (hazard ratio 0.55, P = .029). In addition, objective response rates were significantly higher in the lenvatinib group vs the sorafenib group (53.1% vs 25.0%).

Study details: The data come from an open-label, single-center, randomized trial of 64 adults with previous untreated hepatocellular carcinoma and portal vein tumor thrombus (PVTT). Patients received TACE plus lenvatinib or sorafenib.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Beijing Municipal Hospital Management Center Young Talent Training program. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Ding X et al. Cancer. 2021 Jul 8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33677.

Key clinical point: Hepatocellular carcinoma patients with PVTT who received lenvatinib had a significantly longer time to progression compared to those treated with sorafenib.

Major finding: The median time to progression was 4.7 months for HCC patients with PVTT who received lenvatinib, compared to 3.1 months for those treated with sorafenib (hazard ratio 0.55, P = .029). In addition, objective response rates were significantly higher in the lenvatinib group vs the sorafenib group (53.1% vs 25.0%).

Study details: The data come from an open-label, single-center, randomized trial of 64 adults with previous untreated hepatocellular carcinoma and portal vein tumor thrombus (PVTT). Patients received TACE plus lenvatinib or sorafenib.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Beijing Municipal Hospital Management Center Young Talent Training program. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Ding X et al. Cancer. 2021 Jul 8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33677.

Key clinical point: Hepatocellular carcinoma patients with PVTT who received lenvatinib had a significantly longer time to progression compared to those treated with sorafenib.

Major finding: The median time to progression was 4.7 months for HCC patients with PVTT who received lenvatinib, compared to 3.1 months for those treated with sorafenib (hazard ratio 0.55, P = .029). In addition, objective response rates were significantly higher in the lenvatinib group vs the sorafenib group (53.1% vs 25.0%).

Study details: The data come from an open-label, single-center, randomized trial of 64 adults with previous untreated hepatocellular carcinoma and portal vein tumor thrombus (PVTT). Patients received TACE plus lenvatinib or sorafenib.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Beijing Municipal Hospital Management Center Young Talent Training program. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Ding X et al. Cancer. 2021 Jul 8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33677.

A clarion call for regulating PBMs: Health care groups, states push back on legal challenges

Mark Nelson, PharmD, recalls the anguish when a major pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) moved all veteran patients with prostate cancer at his facility from an effective medication to a pricier alternative therapy. “All of these patients were stable on their therapy and were extremely distraught about their medications being changed,” said Dr. Nelson, CEO of Northwest Medical Specialties in Washington State. While there was no clinical reason to change the medication, “our oncologists had no choice other than to comply,” he said.

It’s unclear why a PBM would switch to a more expensive medication that has no additional clinical benefit, he continued. “Why upset so many veterans? For what reason? We were not given a reason despite our very vocal protest.”

Angus B. Worthing, MD, sees these scenarios unfold every day in his rheumatology practice in the Washington, D.C., area. “In my clinic with 25 doctors, we have three full-time people that only handle PBMs,” he said in an interview. He and others in the medical community, as well as many states, have been pushing back on what they see as efforts by PBMs to raise drug prices and collect the profits at the expense of patients.

PCMA’s challenges against PBM law

The Pharmaceutical Care Management Association (PCMA), a trade group that represents PBMs, has sued at least a half dozen states on their ability to regulate PBMs. However, a landmark case in late 2020 (Pharmaceutical Care Management Association v. Rutledge) set a new precedent. Reversing a lower appeals court decision, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in favor of allowing states to put in place fair regulation of these entities.

Dr. Worthing and others hope that the medical community and states can leverage this ruling in another lawsuit PCMA brought against North Dakota (PCMA v. Wehbi). PCMA filed this lawsuit in 2017, which challenges two statutes on PBM regulation. The group has issued similar legal challenges in Maine, the District of Columbia, Iowa, Oklahoma, and Arkansas with the Rutledge case.

“PBMs have become massive profit centers while (ironically) increasing patients’ out-of-pocket costs, interfering with doctor-patient relationships, and impairing patient access to appropriate treatment,” according to an amicus brief filed by The Alliance for Transparent & Affordable Prescriptions (ATAP), the Community Oncology Alliance (COA), and American Pharmacies, supporting North Dakota in the Wehbi case.

This is to ensure the case represents the voices of physicians, patients, nurses, and other stakeholders, and underscores PBM abuses, said Dr. Worthing, vice president of ATAP. He also serves as the American College of Rheumatology’s representative on ATAP’s Executive Committee.

PCMA did not respond to requests for comment. Its CEO and president, J.C. Scott, emphasizes that PBMs have a long track record of reducing drug costs for patients and plan sponsors. In 2021, PCMA released 21 policy solutions, a set of industry principles and a three-part policy platform, all with an aim to bring down costs and increase access to pharmaceutical care, according to the organization.

PCMA estimates that the strategies in its platform (updating Medicare Part D, accelerating value-based care, and eliminating anticompetitive ‘pay for delay’ agreements) would save the federal government a maximum of $398.7 billion over 10 years.

According to Wendy Hemmen, senior director with Texas Oncology in Dallas, PBMs do their own unique calculations to arrive at their cost reductions. “Essentially in a PBM, they use things that make their story. Numbers reported to plan sponsors and to the public are not audited and are usually in terms of percentages or a per member per month. Data points are moved around, dropped, or reclassified to make the story that the PBM needs to tell,” Ms. Hemmen said.

Amicus briefs dispute ERISA connection

North Dakota legislation prohibits PBMs from charging copays to patients that exceed the cost of a drug. It also prohibits gag clause provisions that restrict what pharmacists may discuss with patients. PBMs may charge fees based on performance metrics, but they must use nationally recognized metrics. Fees must be disclosed at the point of sale.

In its legal challenges, PCMA has asserted that state laws violate the preemption clause in the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). “Federal preemption allows employers flexibility to administer innovative benefit plans in an environment of increasing health care costs. The court’s decision in Rutledge v. PCMA will either uphold or threaten these federal protections,” PCMA asserted in a statement issued in March 2020.

ATAP’s amicus brief, and another one filed by 34 attorneys general that supports the North Dakota statute to regulate PBMs, counter that this isn’t the case.

“First, PBM regulation (in its common and standard form) does not reference ERISA itself. These laws leave all plans on equal footing; they do not single out ERISA plans for preferred or disfavored coverage, and they do not change the playing field for ERISA plans alone ... Second, PBM regulation does not have any prohibited connection with ERISA plans,” noted authors in the ATAP brief.

PCMA has also included Medicare preemption in its arguments against PBM regulation. This is meritless, wrote the state attorneys general. “Medicare preempts state laws only if a Medicare ‘standard’ particularly addresses the subject of state regulation. Because the challenged North Dakota laws do not dictate plan benefits or conflict with a Medicare standard, they are not preempted.”

The auctioning of medications

PBMs in theory could use their market power to drive down costs by extracting discounts from drug makers and pharmacies. In reality, they retain any price concessions and discounts for themselves, ATAP’s brief continued.

A system that PBMs have put into place, called step therapy, is essentially an auction for the preferred spot that will be authorized and covered, Dr. Worthing explained.

PBMs create formularies through this auction. The highest rebate to the PBM earns the top spot in the auction and becomes the preferred drug. “That highest bid gets paid for by passing the cost along to patients and insurance plans, and PBMs pocket the profits. This provides an incentive for pharmaceutical manufacturers to raise prices,” he said.

Dr. Worthing has seen these practices trickle down and affect his patients. “Frequently, the medication I prescribe based on what’s best for the patient based on their disease activity, values, and medical history is often not covered because a different drug or portfolio of drugs has earned the top spot in step therapy. This is an extremely frustrating and cumbersome process that not only delays access to treatments but also provides an incentive for higher drug prices,” he said.

There are other ways in which PBMs get in the way of care, said Ms. Hemmen, whose facility serves complex-care oncology patients.

“PBMs force scripts out of higher-quality pharmacies that preserve unfragmented care. They incentivize plan sponsors to put programs into place that take away patient choice, fragment care, and drive scripts to their own owned pharmacies,” she said.

Rutledge case sets precedent

In the Rutledge case, PCMA had challenged an Arkansas law that forbid PBMs from paying local pharmacies at a lower rate than what the pharmacies were reimbursed to fill prescriptions. Although the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with PCMA, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Arkansas in late 2020.

The appeals court also backed PCMA in PCMA v. Wehbi. However, the Supreme Court vacated this decision and remanded it back to the appeals court, asking for a reconsideration in wake of the outcome in Rutledge v. PCMA.

PCMA has argued that Rutledge was a narrow decision, limited to state laws that regulate PBM reimbursements, and that Rutledge has no bearing on North Dakota law.

While it’s unfortunate that PCMA is trying to delay implementation of sensible regulations, “a lot of us are happy that this issue is coming to light,” Dr. Worthing said. “As a rheumatologist and health policy advocate, exposing drug middlemen is the most important bipartisan issue in the country today because it gets at the core of making sure that sick people get access to the medications they need and reducing the budget of insurance carriers, hospitals, and the federal budget.”

The ATAP brief noted that 28 state attorneys general have filed suit against PBMs, “securing settlements compelling PBMs to correct deceptive trade practices.”

Many people at the state and local level were waiting for the Supreme Court to decide on Rutledge before enacting legislation and sensible regulations, and now they can go ahead and do it, said Dr. Worthing. “I expect to see this across the country as states look at budgets, and as patients bring personal stories to light. We look forward to states passing these kinds of laws to regulate PBMs.”

The ACR doesn’t anticipate a ruling in the Wehbi case until the spring of 2022.

Recent laws passed around PBMs and the pharmacy benefit are a good first step in holding PBMs accountable for quality of care and honoring patient choice, Ms. Hemmen said. The laws also begin to address the fiscal manipulations PBMs use to gain advantage and direct scripts to their own coffers, she added. However, this may not have enough teeth. “These state laws are coming from a provider perspective, and they don’t anticipate what PBMs will do in response. The PBMs are going to work around it.”

Mark Nelson, PharmD, recalls the anguish when a major pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) moved all veteran patients with prostate cancer at his facility from an effective medication to a pricier alternative therapy. “All of these patients were stable on their therapy and were extremely distraught about their medications being changed,” said Dr. Nelson, CEO of Northwest Medical Specialties in Washington State. While there was no clinical reason to change the medication, “our oncologists had no choice other than to comply,” he said.

It’s unclear why a PBM would switch to a more expensive medication that has no additional clinical benefit, he continued. “Why upset so many veterans? For what reason? We were not given a reason despite our very vocal protest.”

Angus B. Worthing, MD, sees these scenarios unfold every day in his rheumatology practice in the Washington, D.C., area. “In my clinic with 25 doctors, we have three full-time people that only handle PBMs,” he said in an interview. He and others in the medical community, as well as many states, have been pushing back on what they see as efforts by PBMs to raise drug prices and collect the profits at the expense of patients.

PCMA’s challenges against PBM law

The Pharmaceutical Care Management Association (PCMA), a trade group that represents PBMs, has sued at least a half dozen states on their ability to regulate PBMs. However, a landmark case in late 2020 (Pharmaceutical Care Management Association v. Rutledge) set a new precedent. Reversing a lower appeals court decision, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in favor of allowing states to put in place fair regulation of these entities.

Dr. Worthing and others hope that the medical community and states can leverage this ruling in another lawsuit PCMA brought against North Dakota (PCMA v. Wehbi). PCMA filed this lawsuit in 2017, which challenges two statutes on PBM regulation. The group has issued similar legal challenges in Maine, the District of Columbia, Iowa, Oklahoma, and Arkansas with the Rutledge case.

“PBMs have become massive profit centers while (ironically) increasing patients’ out-of-pocket costs, interfering with doctor-patient relationships, and impairing patient access to appropriate treatment,” according to an amicus brief filed by The Alliance for Transparent & Affordable Prescriptions (ATAP), the Community Oncology Alliance (COA), and American Pharmacies, supporting North Dakota in the Wehbi case.

This is to ensure the case represents the voices of physicians, patients, nurses, and other stakeholders, and underscores PBM abuses, said Dr. Worthing, vice president of ATAP. He also serves as the American College of Rheumatology’s representative on ATAP’s Executive Committee.

PCMA did not respond to requests for comment. Its CEO and president, J.C. Scott, emphasizes that PBMs have a long track record of reducing drug costs for patients and plan sponsors. In 2021, PCMA released 21 policy solutions, a set of industry principles and a three-part policy platform, all with an aim to bring down costs and increase access to pharmaceutical care, according to the organization.

PCMA estimates that the strategies in its platform (updating Medicare Part D, accelerating value-based care, and eliminating anticompetitive ‘pay for delay’ agreements) would save the federal government a maximum of $398.7 billion over 10 years.

According to Wendy Hemmen, senior director with Texas Oncology in Dallas, PBMs do their own unique calculations to arrive at their cost reductions. “Essentially in a PBM, they use things that make their story. Numbers reported to plan sponsors and to the public are not audited and are usually in terms of percentages or a per member per month. Data points are moved around, dropped, or reclassified to make the story that the PBM needs to tell,” Ms. Hemmen said.

Amicus briefs dispute ERISA connection

North Dakota legislation prohibits PBMs from charging copays to patients that exceed the cost of a drug. It also prohibits gag clause provisions that restrict what pharmacists may discuss with patients. PBMs may charge fees based on performance metrics, but they must use nationally recognized metrics. Fees must be disclosed at the point of sale.

In its legal challenges, PCMA has asserted that state laws violate the preemption clause in the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). “Federal preemption allows employers flexibility to administer innovative benefit plans in an environment of increasing health care costs. The court’s decision in Rutledge v. PCMA will either uphold or threaten these federal protections,” PCMA asserted in a statement issued in March 2020.

ATAP’s amicus brief, and another one filed by 34 attorneys general that supports the North Dakota statute to regulate PBMs, counter that this isn’t the case.

“First, PBM regulation (in its common and standard form) does not reference ERISA itself. These laws leave all plans on equal footing; they do not single out ERISA plans for preferred or disfavored coverage, and they do not change the playing field for ERISA plans alone ... Second, PBM regulation does not have any prohibited connection with ERISA plans,” noted authors in the ATAP brief.

PCMA has also included Medicare preemption in its arguments against PBM regulation. This is meritless, wrote the state attorneys general. “Medicare preempts state laws only if a Medicare ‘standard’ particularly addresses the subject of state regulation. Because the challenged North Dakota laws do not dictate plan benefits or conflict with a Medicare standard, they are not preempted.”

The auctioning of medications

PBMs in theory could use their market power to drive down costs by extracting discounts from drug makers and pharmacies. In reality, they retain any price concessions and discounts for themselves, ATAP’s brief continued.

A system that PBMs have put into place, called step therapy, is essentially an auction for the preferred spot that will be authorized and covered, Dr. Worthing explained.

PBMs create formularies through this auction. The highest rebate to the PBM earns the top spot in the auction and becomes the preferred drug. “That highest bid gets paid for by passing the cost along to patients and insurance plans, and PBMs pocket the profits. This provides an incentive for pharmaceutical manufacturers to raise prices,” he said.

Dr. Worthing has seen these practices trickle down and affect his patients. “Frequently, the medication I prescribe based on what’s best for the patient based on their disease activity, values, and medical history is often not covered because a different drug or portfolio of drugs has earned the top spot in step therapy. This is an extremely frustrating and cumbersome process that not only delays access to treatments but also provides an incentive for higher drug prices,” he said.

There are other ways in which PBMs get in the way of care, said Ms. Hemmen, whose facility serves complex-care oncology patients.

“PBMs force scripts out of higher-quality pharmacies that preserve unfragmented care. They incentivize plan sponsors to put programs into place that take away patient choice, fragment care, and drive scripts to their own owned pharmacies,” she said.

Rutledge case sets precedent

In the Rutledge case, PCMA had challenged an Arkansas law that forbid PBMs from paying local pharmacies at a lower rate than what the pharmacies were reimbursed to fill prescriptions. Although the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with PCMA, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Arkansas in late 2020.

The appeals court also backed PCMA in PCMA v. Wehbi. However, the Supreme Court vacated this decision and remanded it back to the appeals court, asking for a reconsideration in wake of the outcome in Rutledge v. PCMA.

PCMA has argued that Rutledge was a narrow decision, limited to state laws that regulate PBM reimbursements, and that Rutledge has no bearing on North Dakota law.

While it’s unfortunate that PCMA is trying to delay implementation of sensible regulations, “a lot of us are happy that this issue is coming to light,” Dr. Worthing said. “As a rheumatologist and health policy advocate, exposing drug middlemen is the most important bipartisan issue in the country today because it gets at the core of making sure that sick people get access to the medications they need and reducing the budget of insurance carriers, hospitals, and the federal budget.”

The ATAP brief noted that 28 state attorneys general have filed suit against PBMs, “securing settlements compelling PBMs to correct deceptive trade practices.”

Many people at the state and local level were waiting for the Supreme Court to decide on Rutledge before enacting legislation and sensible regulations, and now they can go ahead and do it, said Dr. Worthing. “I expect to see this across the country as states look at budgets, and as patients bring personal stories to light. We look forward to states passing these kinds of laws to regulate PBMs.”

The ACR doesn’t anticipate a ruling in the Wehbi case until the spring of 2022.

Recent laws passed around PBMs and the pharmacy benefit are a good first step in holding PBMs accountable for quality of care and honoring patient choice, Ms. Hemmen said. The laws also begin to address the fiscal manipulations PBMs use to gain advantage and direct scripts to their own coffers, she added. However, this may not have enough teeth. “These state laws are coming from a provider perspective, and they don’t anticipate what PBMs will do in response. The PBMs are going to work around it.”

Mark Nelson, PharmD, recalls the anguish when a major pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) moved all veteran patients with prostate cancer at his facility from an effective medication to a pricier alternative therapy. “All of these patients were stable on their therapy and were extremely distraught about their medications being changed,” said Dr. Nelson, CEO of Northwest Medical Specialties in Washington State. While there was no clinical reason to change the medication, “our oncologists had no choice other than to comply,” he said.

It’s unclear why a PBM would switch to a more expensive medication that has no additional clinical benefit, he continued. “Why upset so many veterans? For what reason? We were not given a reason despite our very vocal protest.”

Angus B. Worthing, MD, sees these scenarios unfold every day in his rheumatology practice in the Washington, D.C., area. “In my clinic with 25 doctors, we have three full-time people that only handle PBMs,” he said in an interview. He and others in the medical community, as well as many states, have been pushing back on what they see as efforts by PBMs to raise drug prices and collect the profits at the expense of patients.

PCMA’s challenges against PBM law

The Pharmaceutical Care Management Association (PCMA), a trade group that represents PBMs, has sued at least a half dozen states on their ability to regulate PBMs. However, a landmark case in late 2020 (Pharmaceutical Care Management Association v. Rutledge) set a new precedent. Reversing a lower appeals court decision, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in favor of allowing states to put in place fair regulation of these entities.

Dr. Worthing and others hope that the medical community and states can leverage this ruling in another lawsuit PCMA brought against North Dakota (PCMA v. Wehbi). PCMA filed this lawsuit in 2017, which challenges two statutes on PBM regulation. The group has issued similar legal challenges in Maine, the District of Columbia, Iowa, Oklahoma, and Arkansas with the Rutledge case.

“PBMs have become massive profit centers while (ironically) increasing patients’ out-of-pocket costs, interfering with doctor-patient relationships, and impairing patient access to appropriate treatment,” according to an amicus brief filed by The Alliance for Transparent & Affordable Prescriptions (ATAP), the Community Oncology Alliance (COA), and American Pharmacies, supporting North Dakota in the Wehbi case.

This is to ensure the case represents the voices of physicians, patients, nurses, and other stakeholders, and underscores PBM abuses, said Dr. Worthing, vice president of ATAP. He also serves as the American College of Rheumatology’s representative on ATAP’s Executive Committee.

PCMA did not respond to requests for comment. Its CEO and president, J.C. Scott, emphasizes that PBMs have a long track record of reducing drug costs for patients and plan sponsors. In 2021, PCMA released 21 policy solutions, a set of industry principles and a three-part policy platform, all with an aim to bring down costs and increase access to pharmaceutical care, according to the organization.

PCMA estimates that the strategies in its platform (updating Medicare Part D, accelerating value-based care, and eliminating anticompetitive ‘pay for delay’ agreements) would save the federal government a maximum of $398.7 billion over 10 years.

According to Wendy Hemmen, senior director with Texas Oncology in Dallas, PBMs do their own unique calculations to arrive at their cost reductions. “Essentially in a PBM, they use things that make their story. Numbers reported to plan sponsors and to the public are not audited and are usually in terms of percentages or a per member per month. Data points are moved around, dropped, or reclassified to make the story that the PBM needs to tell,” Ms. Hemmen said.

Amicus briefs dispute ERISA connection

North Dakota legislation prohibits PBMs from charging copays to patients that exceed the cost of a drug. It also prohibits gag clause provisions that restrict what pharmacists may discuss with patients. PBMs may charge fees based on performance metrics, but they must use nationally recognized metrics. Fees must be disclosed at the point of sale.

In its legal challenges, PCMA has asserted that state laws violate the preemption clause in the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). “Federal preemption allows employers flexibility to administer innovative benefit plans in an environment of increasing health care costs. The court’s decision in Rutledge v. PCMA will either uphold or threaten these federal protections,” PCMA asserted in a statement issued in March 2020.

ATAP’s amicus brief, and another one filed by 34 attorneys general that supports the North Dakota statute to regulate PBMs, counter that this isn’t the case.

“First, PBM regulation (in its common and standard form) does not reference ERISA itself. These laws leave all plans on equal footing; they do not single out ERISA plans for preferred or disfavored coverage, and they do not change the playing field for ERISA plans alone ... Second, PBM regulation does not have any prohibited connection with ERISA plans,” noted authors in the ATAP brief.

PCMA has also included Medicare preemption in its arguments against PBM regulation. This is meritless, wrote the state attorneys general. “Medicare preempts state laws only if a Medicare ‘standard’ particularly addresses the subject of state regulation. Because the challenged North Dakota laws do not dictate plan benefits or conflict with a Medicare standard, they are not preempted.”

The auctioning of medications

PBMs in theory could use their market power to drive down costs by extracting discounts from drug makers and pharmacies. In reality, they retain any price concessions and discounts for themselves, ATAP’s brief continued.

A system that PBMs have put into place, called step therapy, is essentially an auction for the preferred spot that will be authorized and covered, Dr. Worthing explained.

PBMs create formularies through this auction. The highest rebate to the PBM earns the top spot in the auction and becomes the preferred drug. “That highest bid gets paid for by passing the cost along to patients and insurance plans, and PBMs pocket the profits. This provides an incentive for pharmaceutical manufacturers to raise prices,” he said.

Dr. Worthing has seen these practices trickle down and affect his patients. “Frequently, the medication I prescribe based on what’s best for the patient based on their disease activity, values, and medical history is often not covered because a different drug or portfolio of drugs has earned the top spot in step therapy. This is an extremely frustrating and cumbersome process that not only delays access to treatments but also provides an incentive for higher drug prices,” he said.

There are other ways in which PBMs get in the way of care, said Ms. Hemmen, whose facility serves complex-care oncology patients.

“PBMs force scripts out of higher-quality pharmacies that preserve unfragmented care. They incentivize plan sponsors to put programs into place that take away patient choice, fragment care, and drive scripts to their own owned pharmacies,” she said.

Rutledge case sets precedent

In the Rutledge case, PCMA had challenged an Arkansas law that forbid PBMs from paying local pharmacies at a lower rate than what the pharmacies were reimbursed to fill prescriptions. Although the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with PCMA, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Arkansas in late 2020.

The appeals court also backed PCMA in PCMA v. Wehbi. However, the Supreme Court vacated this decision and remanded it back to the appeals court, asking for a reconsideration in wake of the outcome in Rutledge v. PCMA.

PCMA has argued that Rutledge was a narrow decision, limited to state laws that regulate PBM reimbursements, and that Rutledge has no bearing on North Dakota law.

While it’s unfortunate that PCMA is trying to delay implementation of sensible regulations, “a lot of us are happy that this issue is coming to light,” Dr. Worthing said. “As a rheumatologist and health policy advocate, exposing drug middlemen is the most important bipartisan issue in the country today because it gets at the core of making sure that sick people get access to the medications they need and reducing the budget of insurance carriers, hospitals, and the federal budget.”

The ATAP brief noted that 28 state attorneys general have filed suit against PBMs, “securing settlements compelling PBMs to correct deceptive trade practices.”

Many people at the state and local level were waiting for the Supreme Court to decide on Rutledge before enacting legislation and sensible regulations, and now they can go ahead and do it, said Dr. Worthing. “I expect to see this across the country as states look at budgets, and as patients bring personal stories to light. We look forward to states passing these kinds of laws to regulate PBMs.”

The ACR doesn’t anticipate a ruling in the Wehbi case until the spring of 2022.

Recent laws passed around PBMs and the pharmacy benefit are a good first step in holding PBMs accountable for quality of care and honoring patient choice, Ms. Hemmen said. The laws also begin to address the fiscal manipulations PBMs use to gain advantage and direct scripts to their own coffers, she added. However, this may not have enough teeth. “These state laws are coming from a provider perspective, and they don’t anticipate what PBMs will do in response. The PBMs are going to work around it.”

Statin use shows dose-dependent reduction in the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis B patients

Key clinical point: Statin users had a consistent, significant, dose-dependent reduction in the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in a nested case-control study. Aspirin users showed some reduction in risk, but it was not dose dependent.

Major finding: In the nested case-control study, both statin use, and aspirin use were significantly associated with reduced HCC risk (odds ratio 0.34 and 0.92, respectively), but only statins showed a dose-dependent risk reduction.

Study details: The data come from a nationwide, nested case-control study with a cohort of 538 135 treatment-naïve, non-cirrhotic adults with chronic hepatitis B. The participants were identified from data gathered between 2005 and 2015 through the National Health Insurance Service in Korea. From this group, 6,539 HCC cases were matched to 26,156 controls.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Choi W-M et al. Liver Int. 2021. doi: 10.1111/liv.15011.

Key clinical point: Statin users had a consistent, significant, dose-dependent reduction in the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in a nested case-control study. Aspirin users showed some reduction in risk, but it was not dose dependent.

Major finding: In the nested case-control study, both statin use, and aspirin use were significantly associated with reduced HCC risk (odds ratio 0.34 and 0.92, respectively), but only statins showed a dose-dependent risk reduction.

Study details: The data come from a nationwide, nested case-control study with a cohort of 538 135 treatment-naïve, non-cirrhotic adults with chronic hepatitis B. The participants were identified from data gathered between 2005 and 2015 through the National Health Insurance Service in Korea. From this group, 6,539 HCC cases were matched to 26,156 controls.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Choi W-M et al. Liver Int. 2021. doi: 10.1111/liv.15011.

Key clinical point: Statin users had a consistent, significant, dose-dependent reduction in the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in a nested case-control study. Aspirin users showed some reduction in risk, but it was not dose dependent.

Major finding: In the nested case-control study, both statin use, and aspirin use were significantly associated with reduced HCC risk (odds ratio 0.34 and 0.92, respectively), but only statins showed a dose-dependent risk reduction.

Study details: The data come from a nationwide, nested case-control study with a cohort of 538 135 treatment-naïve, non-cirrhotic adults with chronic hepatitis B. The participants were identified from data gathered between 2005 and 2015 through the National Health Insurance Service in Korea. From this group, 6,539 HCC cases were matched to 26,156 controls.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Choi W-M et al. Liver Int. 2021. doi: 10.1111/liv.15011.

TARE beats systemic therapy for survival benefits in hepatocellular carcinoma with major vascular invasion

Key clinical point: Transarterial radioembolization (TARE) was associated with a significantly higher overall survival compared to systemic therapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma with major vascular invasion (HCC-MVI).

Major finding: In a propensity-score matched and landmark-time adjusted analysis, the median overall survival for HCC-MVI patients treated with TARE was 7.1 months, compared to 4.9 months for patients treated with systemic therapy. Target trial emulation of an additional 236 patients with HCC-MVI showed a similar advantage with TARE.

Study details: The data come from 1,514 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma with major vascular invasion (HCC-MVI) identified from the National Cancer Database for the period between 2010 and 2015.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Kwee SA et al. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2021 Jul 6. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2021.07.001.

Key clinical point: Transarterial radioembolization (TARE) was associated with a significantly higher overall survival compared to systemic therapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma with major vascular invasion (HCC-MVI).

Major finding: In a propensity-score matched and landmark-time adjusted analysis, the median overall survival for HCC-MVI patients treated with TARE was 7.1 months, compared to 4.9 months for patients treated with systemic therapy. Target trial emulation of an additional 236 patients with HCC-MVI showed a similar advantage with TARE.

Study details: The data come from 1,514 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma with major vascular invasion (HCC-MVI) identified from the National Cancer Database for the period between 2010 and 2015.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Kwee SA et al. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2021 Jul 6. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2021.07.001.

Key clinical point: Transarterial radioembolization (TARE) was associated with a significantly higher overall survival compared to systemic therapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma with major vascular invasion (HCC-MVI).

Major finding: In a propensity-score matched and landmark-time adjusted analysis, the median overall survival for HCC-MVI patients treated with TARE was 7.1 months, compared to 4.9 months for patients treated with systemic therapy. Target trial emulation of an additional 236 patients with HCC-MVI showed a similar advantage with TARE.

Study details: The data come from 1,514 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma with major vascular invasion (HCC-MVI) identified from the National Cancer Database for the period between 2010 and 2015.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Kwee SA et al. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2021 Jul 6. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2021.07.001.

TARE extends health-related quality of life in HCC patients versus sorafenib

Key clinical point: Health-related quality of life was preserved longer in HCC patients treated with transarterial radioembolization (TARE) compared to those treated with sorafenib.

Major finding: The median time to deterioration in global health status was 3.9 months in TARE patients, vs 2.6 months in sorafenib patients. TARE patients also showed less deterioration in measures of physical functioning, role functioning, and social functioning compared to sorafenib patients.

Study details: The data come from 285 adults who were participants in a randomized trial of transarterial radioembolization (122 patients) or sorafenib (163 patients) for the treatment of locally advanced or inoperable HCC. Quality of life was assessed from the date of randomization until disease progression or study discontinuation, using the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 questionnaire.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. Lead author Dr. Pereira had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Pereira H et al. Eur J Cancer. 2021 Jul 6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.05.032.

Key clinical point: Health-related quality of life was preserved longer in HCC patients treated with transarterial radioembolization (TARE) compared to those treated with sorafenib.

Major finding: The median time to deterioration in global health status was 3.9 months in TARE patients, vs 2.6 months in sorafenib patients. TARE patients also showed less deterioration in measures of physical functioning, role functioning, and social functioning compared to sorafenib patients.

Study details: The data come from 285 adults who were participants in a randomized trial of transarterial radioembolization (122 patients) or sorafenib (163 patients) for the treatment of locally advanced or inoperable HCC. Quality of life was assessed from the date of randomization until disease progression or study discontinuation, using the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 questionnaire.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. Lead author Dr. Pereira had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Pereira H et al. Eur J Cancer. 2021 Jul 6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.05.032.

Key clinical point: Health-related quality of life was preserved longer in HCC patients treated with transarterial radioembolization (TARE) compared to those treated with sorafenib.

Major finding: The median time to deterioration in global health status was 3.9 months in TARE patients, vs 2.6 months in sorafenib patients. TARE patients also showed less deterioration in measures of physical functioning, role functioning, and social functioning compared to sorafenib patients.

Study details: The data come from 285 adults who were participants in a randomized trial of transarterial radioembolization (122 patients) or sorafenib (163 patients) for the treatment of locally advanced or inoperable HCC. Quality of life was assessed from the date of randomization until disease progression or study discontinuation, using the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 questionnaire.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. Lead author Dr. Pereira had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Pereira H et al. Eur J Cancer. 2021 Jul 6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.05.032.

Diabetes duration linked to increasing heart failure risk

In a multivariable analysis the rate of incident heart failure increased steadily and significantly as diabetes duration increased. Among the 168 study subjects (2% of the total study group) who had diabetes for at least 15 years, the subsequent incidence of heart failure was nearly threefold higher than among the 4,802 subjects (49%) who never had diabetes or prediabetes, reported Justin B. Echouffo-Tcheugui, MD, PhD, and coauthors in an article published in JACC Heart Failure.

People with prediabetes (32% of the study population) had a significant but modest increased rate of incident heart failure that was 16% higher than in control subjects who never developed diabetes. People with diabetes for durations of 0-4.9 years, 5.0-9.9 years, or 10-14.9 years, had steadily increasing relative incident heart failure rates of 29%, 97%, and 210%, respectively, compared with controls, reported Dr. Echouffo-Tcheugui, an endocrinologist at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore.

Similar rates of HFrEF and HFpEF

Among all 1,841 people in the dataset with diabetes for any length of time each additional 5 years of the disorder linked with a significant, relative 17% increase in the rate of incident heart failure. Incidence of heart failure rose even more sharply with added duration among those with a hemoglobin A1c of 7% or greater, compared with those with better glycemic control. And the rate of incident heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) roughly matched the rate of incident heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

The study dataset included 9,734 adults enrolled into the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, and during a median follow-up of 22.5 years they had nearly 2,000 episodes of either hospitalization or death secondary to incident heart failure. This included 617 (31%) events involving HFpEF, 495 events (25%) involving HFrEF, and 876 unclassified heart failure events.

The cohort averaged 63 years of age; 58% were women, 23% were Black, and 77% were White (the study design excluded people with other racial and ethnic backgrounds). The study design also excluded people with a history of heart failure or coronary artery disease, as well as those diagnosed with diabetes prior to age 18 resulting in a study group that presumably mostly had type 2 diabetes when diabetes was present. The report provided no data on the specific numbers of patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

“It’s not surprising that a longer duration of diabetes is associated with heart failure, but the etiology remains problematic,” commented Robert H. Eckel, MD, an endocrinologist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. “The impact of diabetes on incident heart failure is not well know, particularly duration of diabetes,” although disorders often found in patients with diabetes, such as hypertension and diabetic cardiomyopathy, likely have roles in causing heart failure, he said.

Diabetes duration may signal need for an SGLT2 inhibitor

“With emerging novel treatments like the SGLT2 [sodium-glucose cotransporter 2] inhibitors for preventing heart failure hospitalizations and deaths in patients with type 2 diabetes, this is a timely analysis,” Dr. Eckel said in an interview.

“There is no question that with increased duration of type 2 diabetes” the need for an agent from the SGLT2-inhibitor class increases. Although, because of the proven protection these drugs give against heart failure events and progression of chronic kidney disease, treatment with this drug class should start early in patients with type 2 diabetes, he added.

Dr. Echouffo-Tcheugui and his coauthors agreed, citing two important clinical take-aways from their findings:

First, interventions that delay the onset of diabetes may potentially reduce incident heart failure; second, patients with diabetes might benefit from cardioprotective treatments such as SGLT2 inhibitors, the report said.

“Our observations suggest the potential prognostic relevance of diabetes duration in assessing heart failure,” the authors wrote. Integrating diabetes duration into heart failure risk estimation in people with diabetes “could help refine the selection of high-risk individuals who may derive the greatest absolute benefit from aggressive cardioprotective therapies such as SGLT2 inhibitors.”

The analysis also identified several other demographic and clinical factors that influenced the relative effect of diabetes duration. Longer duration was linked with higher rates of incident heart failure in women compared with men, in Blacks compared with Whites, in people younger than 65 compared with older people, in people with an A1c of 7% or higher, and in those with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater.

The ARIC study and the analyses run by Dr. Echouffo-Tcheugui and his coauthors received no commercial funding. Dr. Echouffo-Tcheugui and Dr. Eckel had no relevant disclosures.

In a multivariable analysis the rate of incident heart failure increased steadily and significantly as diabetes duration increased. Among the 168 study subjects (2% of the total study group) who had diabetes for at least 15 years, the subsequent incidence of heart failure was nearly threefold higher than among the 4,802 subjects (49%) who never had diabetes or prediabetes, reported Justin B. Echouffo-Tcheugui, MD, PhD, and coauthors in an article published in JACC Heart Failure.

People with prediabetes (32% of the study population) had a significant but modest increased rate of incident heart failure that was 16% higher than in control subjects who never developed diabetes. People with diabetes for durations of 0-4.9 years, 5.0-9.9 years, or 10-14.9 years, had steadily increasing relative incident heart failure rates of 29%, 97%, and 210%, respectively, compared with controls, reported Dr. Echouffo-Tcheugui, an endocrinologist at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore.

Similar rates of HFrEF and HFpEF

Among all 1,841 people in the dataset with diabetes for any length of time each additional 5 years of the disorder linked with a significant, relative 17% increase in the rate of incident heart failure. Incidence of heart failure rose even more sharply with added duration among those with a hemoglobin A1c of 7% or greater, compared with those with better glycemic control. And the rate of incident heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) roughly matched the rate of incident heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

The study dataset included 9,734 adults enrolled into the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, and during a median follow-up of 22.5 years they had nearly 2,000 episodes of either hospitalization or death secondary to incident heart failure. This included 617 (31%) events involving HFpEF, 495 events (25%) involving HFrEF, and 876 unclassified heart failure events.

The cohort averaged 63 years of age; 58% were women, 23% were Black, and 77% were White (the study design excluded people with other racial and ethnic backgrounds). The study design also excluded people with a history of heart failure or coronary artery disease, as well as those diagnosed with diabetes prior to age 18 resulting in a study group that presumably mostly had type 2 diabetes when diabetes was present. The report provided no data on the specific numbers of patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

“It’s not surprising that a longer duration of diabetes is associated with heart failure, but the etiology remains problematic,” commented Robert H. Eckel, MD, an endocrinologist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. “The impact of diabetes on incident heart failure is not well know, particularly duration of diabetes,” although disorders often found in patients with diabetes, such as hypertension and diabetic cardiomyopathy, likely have roles in causing heart failure, he said.

Diabetes duration may signal need for an SGLT2 inhibitor

“With emerging novel treatments like the SGLT2 [sodium-glucose cotransporter 2] inhibitors for preventing heart failure hospitalizations and deaths in patients with type 2 diabetes, this is a timely analysis,” Dr. Eckel said in an interview.

“There is no question that with increased duration of type 2 diabetes” the need for an agent from the SGLT2-inhibitor class increases. Although, because of the proven protection these drugs give against heart failure events and progression of chronic kidney disease, treatment with this drug class should start early in patients with type 2 diabetes, he added.

Dr. Echouffo-Tcheugui and his coauthors agreed, citing two important clinical take-aways from their findings:

First, interventions that delay the onset of diabetes may potentially reduce incident heart failure; second, patients with diabetes might benefit from cardioprotective treatments such as SGLT2 inhibitors, the report said.

“Our observations suggest the potential prognostic relevance of diabetes duration in assessing heart failure,” the authors wrote. Integrating diabetes duration into heart failure risk estimation in people with diabetes “could help refine the selection of high-risk individuals who may derive the greatest absolute benefit from aggressive cardioprotective therapies such as SGLT2 inhibitors.”

The analysis also identified several other demographic and clinical factors that influenced the relative effect of diabetes duration. Longer duration was linked with higher rates of incident heart failure in women compared with men, in Blacks compared with Whites, in people younger than 65 compared with older people, in people with an A1c of 7% or higher, and in those with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater.

The ARIC study and the analyses run by Dr. Echouffo-Tcheugui and his coauthors received no commercial funding. Dr. Echouffo-Tcheugui and Dr. Eckel had no relevant disclosures.

In a multivariable analysis the rate of incident heart failure increased steadily and significantly as diabetes duration increased. Among the 168 study subjects (2% of the total study group) who had diabetes for at least 15 years, the subsequent incidence of heart failure was nearly threefold higher than among the 4,802 subjects (49%) who never had diabetes or prediabetes, reported Justin B. Echouffo-Tcheugui, MD, PhD, and coauthors in an article published in JACC Heart Failure.

People with prediabetes (32% of the study population) had a significant but modest increased rate of incident heart failure that was 16% higher than in control subjects who never developed diabetes. People with diabetes for durations of 0-4.9 years, 5.0-9.9 years, or 10-14.9 years, had steadily increasing relative incident heart failure rates of 29%, 97%, and 210%, respectively, compared with controls, reported Dr. Echouffo-Tcheugui, an endocrinologist at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore.

Similar rates of HFrEF and HFpEF

Among all 1,841 people in the dataset with diabetes for any length of time each additional 5 years of the disorder linked with a significant, relative 17% increase in the rate of incident heart failure. Incidence of heart failure rose even more sharply with added duration among those with a hemoglobin A1c of 7% or greater, compared with those with better glycemic control. And the rate of incident heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) roughly matched the rate of incident heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

The study dataset included 9,734 adults enrolled into the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, and during a median follow-up of 22.5 years they had nearly 2,000 episodes of either hospitalization or death secondary to incident heart failure. This included 617 (31%) events involving HFpEF, 495 events (25%) involving HFrEF, and 876 unclassified heart failure events.

The cohort averaged 63 years of age; 58% were women, 23% were Black, and 77% were White (the study design excluded people with other racial and ethnic backgrounds). The study design also excluded people with a history of heart failure or coronary artery disease, as well as those diagnosed with diabetes prior to age 18 resulting in a study group that presumably mostly had type 2 diabetes when diabetes was present. The report provided no data on the specific numbers of patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

“It’s not surprising that a longer duration of diabetes is associated with heart failure, but the etiology remains problematic,” commented Robert H. Eckel, MD, an endocrinologist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. “The impact of diabetes on incident heart failure is not well know, particularly duration of diabetes,” although disorders often found in patients with diabetes, such as hypertension and diabetic cardiomyopathy, likely have roles in causing heart failure, he said.

Diabetes duration may signal need for an SGLT2 inhibitor

“With emerging novel treatments like the SGLT2 [sodium-glucose cotransporter 2] inhibitors for preventing heart failure hospitalizations and deaths in patients with type 2 diabetes, this is a timely analysis,” Dr. Eckel said in an interview.

“There is no question that with increased duration of type 2 diabetes” the need for an agent from the SGLT2-inhibitor class increases. Although, because of the proven protection these drugs give against heart failure events and progression of chronic kidney disease, treatment with this drug class should start early in patients with type 2 diabetes, he added.

Dr. Echouffo-Tcheugui and his coauthors agreed, citing two important clinical take-aways from their findings:

First, interventions that delay the onset of diabetes may potentially reduce incident heart failure; second, patients with diabetes might benefit from cardioprotective treatments such as SGLT2 inhibitors, the report said.

“Our observations suggest the potential prognostic relevance of diabetes duration in assessing heart failure,” the authors wrote. Integrating diabetes duration into heart failure risk estimation in people with diabetes “could help refine the selection of high-risk individuals who may derive the greatest absolute benefit from aggressive cardioprotective therapies such as SGLT2 inhibitors.”

The analysis also identified several other demographic and clinical factors that influenced the relative effect of diabetes duration. Longer duration was linked with higher rates of incident heart failure in women compared with men, in Blacks compared with Whites, in people younger than 65 compared with older people, in people with an A1c of 7% or higher, and in those with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater.

The ARIC study and the analyses run by Dr. Echouffo-Tcheugui and his coauthors received no commercial funding. Dr. Echouffo-Tcheugui and Dr. Eckel had no relevant disclosures.

FROM JACC HEART FAILURE

Hand ulceration

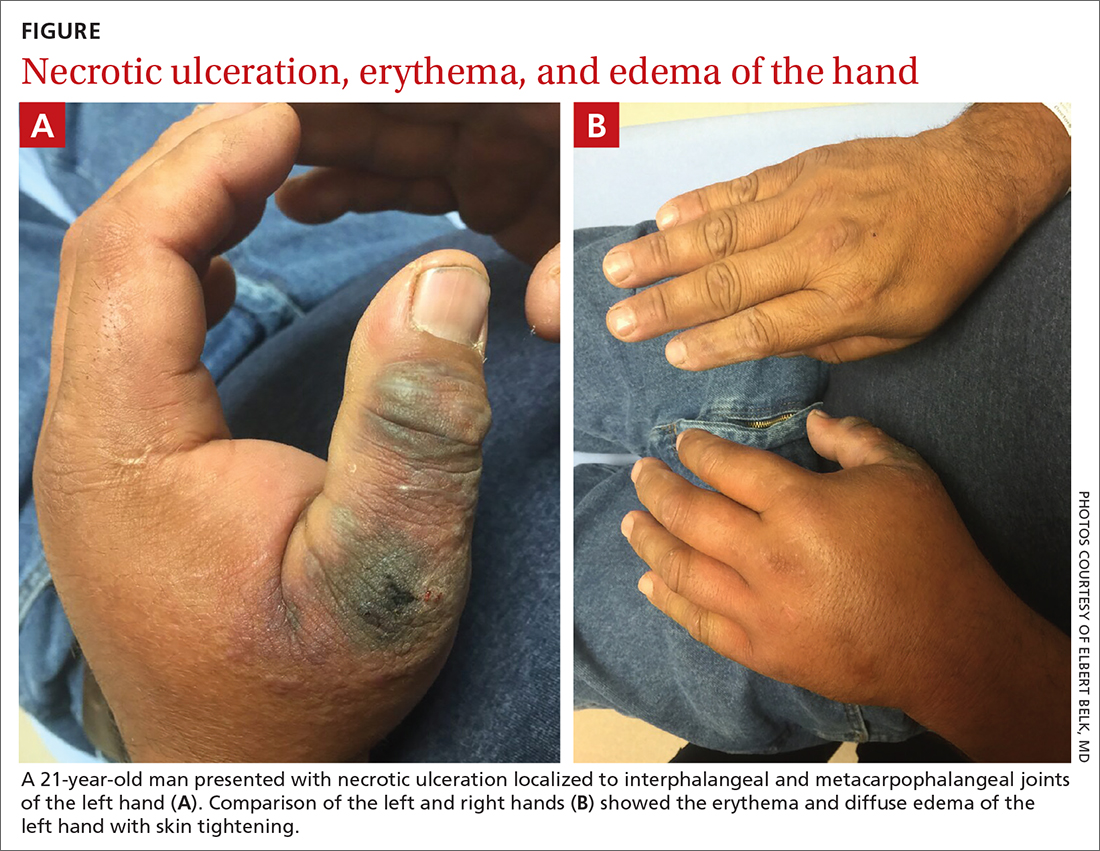

A 45-year-old man presented to a south Texas emergency department with a red, tender, edematous left hand. Earlier that day, he had been working in an oil field when his hand suddenly began to hurt.

On physical exam, puncture wounds were visible at the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb and the interphalangeal joint, dorsal aspect; the area was surrounded by necrotic black tissue (FIGURE). Additionally, erythema with extensive edema extended distally to the proximal interphalangeal joints of each digit. Upon palpation, the area was warm, firm, and tender, with the edema tracking proximally to his mid-forearm.

The patient had a temperature of 99.5 °F; his other vital signs were normal. His past medical history included hypertension.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Cellulitis, compartment syndrome by scorpion sting

Based on the necrotic puncture wounds, unilateral distribution of the swelling, and the patient’s acknowledgement that he’d seen a scorpion in his work environment prior to symptom onset, he was given a diagnosis of cellulitis with secondary compartment syndrome following a scorpion sting.

A geographic problem

In the United States, there are approximately 17,000 reported cases of scorpion stings every year, with fewer than 11 related deaths reported between 1999 and 2014.1 These cases tend to follow a geographic distribution along the American Southwest, with the highest incidence occurring in Arizona, followed by Texas; the majority of cases occur during the summer months.1

The most clinically relevant scorpion in the United States is the Centruroides sculpturatus, also known as the Arizona bark scorpion.2Centruroides spp can be recognized by a slender, yellow to light brown or tan body measuring 1.3 cm to 7.6 cm in length. There is a tubercule at the base of the stringer, a defining characteristic of the species.3

Urgent care is necessary for more severe symptoms

The most common complaint following a scorpion sting tends to be pain (88.7%), followed by numbness, edema, and erythema.1 Other signs and symptoms include muscle spasms, hypertension, and salivation. Symptoms can persist for 10 to 48 hours. Cardiovascular collapse and disseminated intravascular coagulation are 2 potentially fatal complications of a scorpion sting.

The diagnosis is made clinically based on history and physical exam findings; a complete blood count, coagulation panel, and creatine kinase and amylase/lipase bloodwork may be ordered to assess for end-organ complications. Local serious complications, such as compartment syndrome, should be urgently referred for surgical management.

Continue to: Signs of compartment syndrome...

Signs of compartment syndrome include tense, swollen compartments and pain with passive stretching of muscles within the compartment. Rapid progression of symptoms, as seen in this case, is also a red flag.

Differential diagnosis includes necrotizing fasciitis

The differential diagnosis includes uncomplicated cellulitis, as well as necrotizing fasciitis and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) cellulitis.

Necrotizing fasciitis. The lack of subcutaneous crackles and pain that is out of proportion to touch, as well as relatively normal vital signs, ruled out a diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis in this case.

Community-acquired MRSA is seen with purulent cellulitis. However, this patient had no purulent discharge.

Antivenom is only needed for severe cases

Treatment is primarily supportive; all patients should have the wound thoroughly cleaned, and pain can be controlled using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or opioid therapy.2 Tetanus prophylaxis should be given. The Centruroides antivenom, Anascorp, should be considered for patients with severe symptoms, including loss of muscle control, roving or abnormal eye movements, slurred speech, respiratory distress, excessive salivation, frothing at the mouth, and vomiting.4 In most cases, local poison control centers should be consulted for advice on management and to answer questions about antivenom availability.

Our patient was admitted to the hospital and an urgent surgery consult was obtained. The surgeon performed a fasciotomy to treat the compartment syndrome, and the patient survived without loss of his hand or arm.

1. Kang AM, Brooks DE. Nationwide scorpion exposures reported to US poison control centers from 2005 to 2015. J Med Toxicol. 2017;13:158-165. doi: 10.1007/s13181-016-0594-0

2. Barish RA, Arnold T. Scorpion Stings. Merck Manual. Updated April 2020. Accessed June 26, 2021. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/injuries-poisoning/bites-and-stings/scorpion-stings

3. González-Santillán E, Possani LD. North American scorpion species of public health importance with reappraisal of historical epidemiology. Acta Trop. 2018;187:264-274. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.08.002

4. Anascorp. Package insert. Accredo Health Group, Inc; 2011.

A 45-year-old man presented to a south Texas emergency department with a red, tender, edematous left hand. Earlier that day, he had been working in an oil field when his hand suddenly began to hurt.

On physical exam, puncture wounds were visible at the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb and the interphalangeal joint, dorsal aspect; the area was surrounded by necrotic black tissue (FIGURE). Additionally, erythema with extensive edema extended distally to the proximal interphalangeal joints of each digit. Upon palpation, the area was warm, firm, and tender, with the edema tracking proximally to his mid-forearm.

The patient had a temperature of 99.5 °F; his other vital signs were normal. His past medical history included hypertension.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Cellulitis, compartment syndrome by scorpion sting

Based on the necrotic puncture wounds, unilateral distribution of the swelling, and the patient’s acknowledgement that he’d seen a scorpion in his work environment prior to symptom onset, he was given a diagnosis of cellulitis with secondary compartment syndrome following a scorpion sting.

A geographic problem

In the United States, there are approximately 17,000 reported cases of scorpion stings every year, with fewer than 11 related deaths reported between 1999 and 2014.1 These cases tend to follow a geographic distribution along the American Southwest, with the highest incidence occurring in Arizona, followed by Texas; the majority of cases occur during the summer months.1

The most clinically relevant scorpion in the United States is the Centruroides sculpturatus, also known as the Arizona bark scorpion.2Centruroides spp can be recognized by a slender, yellow to light brown or tan body measuring 1.3 cm to 7.6 cm in length. There is a tubercule at the base of the stringer, a defining characteristic of the species.3

Urgent care is necessary for more severe symptoms

The most common complaint following a scorpion sting tends to be pain (88.7%), followed by numbness, edema, and erythema.1 Other signs and symptoms include muscle spasms, hypertension, and salivation. Symptoms can persist for 10 to 48 hours. Cardiovascular collapse and disseminated intravascular coagulation are 2 potentially fatal complications of a scorpion sting.

The diagnosis is made clinically based on history and physical exam findings; a complete blood count, coagulation panel, and creatine kinase and amylase/lipase bloodwork may be ordered to assess for end-organ complications. Local serious complications, such as compartment syndrome, should be urgently referred for surgical management.

Continue to: Signs of compartment syndrome...

Signs of compartment syndrome include tense, swollen compartments and pain with passive stretching of muscles within the compartment. Rapid progression of symptoms, as seen in this case, is also a red flag.

Differential diagnosis includes necrotizing fasciitis

The differential diagnosis includes uncomplicated cellulitis, as well as necrotizing fasciitis and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) cellulitis.

Necrotizing fasciitis. The lack of subcutaneous crackles and pain that is out of proportion to touch, as well as relatively normal vital signs, ruled out a diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis in this case.

Community-acquired MRSA is seen with purulent cellulitis. However, this patient had no purulent discharge.

Antivenom is only needed for severe cases

Treatment is primarily supportive; all patients should have the wound thoroughly cleaned, and pain can be controlled using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or opioid therapy.2 Tetanus prophylaxis should be given. The Centruroides antivenom, Anascorp, should be considered for patients with severe symptoms, including loss of muscle control, roving or abnormal eye movements, slurred speech, respiratory distress, excessive salivation, frothing at the mouth, and vomiting.4 In most cases, local poison control centers should be consulted for advice on management and to answer questions about antivenom availability.

Our patient was admitted to the hospital and an urgent surgery consult was obtained. The surgeon performed a fasciotomy to treat the compartment syndrome, and the patient survived without loss of his hand or arm.

A 45-year-old man presented to a south Texas emergency department with a red, tender, edematous left hand. Earlier that day, he had been working in an oil field when his hand suddenly began to hurt.

On physical exam, puncture wounds were visible at the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb and the interphalangeal joint, dorsal aspect; the area was surrounded by necrotic black tissue (FIGURE). Additionally, erythema with extensive edema extended distally to the proximal interphalangeal joints of each digit. Upon palpation, the area was warm, firm, and tender, with the edema tracking proximally to his mid-forearm.

The patient had a temperature of 99.5 °F; his other vital signs were normal. His past medical history included hypertension.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Cellulitis, compartment syndrome by scorpion sting

Based on the necrotic puncture wounds, unilateral distribution of the swelling, and the patient’s acknowledgement that he’d seen a scorpion in his work environment prior to symptom onset, he was given a diagnosis of cellulitis with secondary compartment syndrome following a scorpion sting.

A geographic problem

In the United States, there are approximately 17,000 reported cases of scorpion stings every year, with fewer than 11 related deaths reported between 1999 and 2014.1 These cases tend to follow a geographic distribution along the American Southwest, with the highest incidence occurring in Arizona, followed by Texas; the majority of cases occur during the summer months.1

The most clinically relevant scorpion in the United States is the Centruroides sculpturatus, also known as the Arizona bark scorpion.2Centruroides spp can be recognized by a slender, yellow to light brown or tan body measuring 1.3 cm to 7.6 cm in length. There is a tubercule at the base of the stringer, a defining characteristic of the species.3

Urgent care is necessary for more severe symptoms

The most common complaint following a scorpion sting tends to be pain (88.7%), followed by numbness, edema, and erythema.1 Other signs and symptoms include muscle spasms, hypertension, and salivation. Symptoms can persist for 10 to 48 hours. Cardiovascular collapse and disseminated intravascular coagulation are 2 potentially fatal complications of a scorpion sting.

The diagnosis is made clinically based on history and physical exam findings; a complete blood count, coagulation panel, and creatine kinase and amylase/lipase bloodwork may be ordered to assess for end-organ complications. Local serious complications, such as compartment syndrome, should be urgently referred for surgical management.

Continue to: Signs of compartment syndrome...

Signs of compartment syndrome include tense, swollen compartments and pain with passive stretching of muscles within the compartment. Rapid progression of symptoms, as seen in this case, is also a red flag.

Differential diagnosis includes necrotizing fasciitis

The differential diagnosis includes uncomplicated cellulitis, as well as necrotizing fasciitis and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) cellulitis.

Necrotizing fasciitis. The lack of subcutaneous crackles and pain that is out of proportion to touch, as well as relatively normal vital signs, ruled out a diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis in this case.

Community-acquired MRSA is seen with purulent cellulitis. However, this patient had no purulent discharge.

Antivenom is only needed for severe cases

Treatment is primarily supportive; all patients should have the wound thoroughly cleaned, and pain can be controlled using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or opioid therapy.2 Tetanus prophylaxis should be given. The Centruroides antivenom, Anascorp, should be considered for patients with severe symptoms, including loss of muscle control, roving or abnormal eye movements, slurred speech, respiratory distress, excessive salivation, frothing at the mouth, and vomiting.4 In most cases, local poison control centers should be consulted for advice on management and to answer questions about antivenom availability.

Our patient was admitted to the hospital and an urgent surgery consult was obtained. The surgeon performed a fasciotomy to treat the compartment syndrome, and the patient survived without loss of his hand or arm.

1. Kang AM, Brooks DE. Nationwide scorpion exposures reported to US poison control centers from 2005 to 2015. J Med Toxicol. 2017;13:158-165. doi: 10.1007/s13181-016-0594-0

2. Barish RA, Arnold T. Scorpion Stings. Merck Manual. Updated April 2020. Accessed June 26, 2021. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/injuries-poisoning/bites-and-stings/scorpion-stings

3. González-Santillán E, Possani LD. North American scorpion species of public health importance with reappraisal of historical epidemiology. Acta Trop. 2018;187:264-274. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.08.002

4. Anascorp. Package insert. Accredo Health Group, Inc; 2011.

1. Kang AM, Brooks DE. Nationwide scorpion exposures reported to US poison control centers from 2005 to 2015. J Med Toxicol. 2017;13:158-165. doi: 10.1007/s13181-016-0594-0

2. Barish RA, Arnold T. Scorpion Stings. Merck Manual. Updated April 2020. Accessed June 26, 2021. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/injuries-poisoning/bites-and-stings/scorpion-stings

3. González-Santillán E, Possani LD. North American scorpion species of public health importance with reappraisal of historical epidemiology. Acta Trop. 2018;187:264-274. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.08.002

4. Anascorp. Package insert. Accredo Health Group, Inc; 2011.

Moving patients beyond injury and back to work

This month, JFP tackles a topic—work disability—that might, at first, seem a bit outside our usual wheelhouse of clinical review articles. Work disability is, however, a very important topic. The authors point out that “... primary care clinicians are asked to provide guidance about work activities in nearly 10% of their patient encounters; however, 25% of those clinicians thought they had little influence over work disability outcomes.” This statement suggests that we need to learn more about managing work-related disability and how to influence patients’ outcomes in a positive manner.

I suspect that we tend to be pessimistic about our ability to influence patient outcomes because we are uncertain about the best course of action. The authors of this article provide excellent information about how we can—and should—help ill and injured patients return to work.

As I read the article, I reflected on my own experience providing patients with advice about returning to work. Two points, in particular, struck a chord with me.

1. Many factors in the process are beyond our control. The physician’s role in helping patients return to work after an injury or illness is limited. The authors remind us that there are many patient and employer factors that are beyond our control and that influence patients’ successful return to work. Patient factors include motivation, mental health, and job satisfaction. Employer factors include job flexibility and disability benefits and policies. And of course, there are system factors that include laws governing work-related disability.

2. Our role, while limited, is important. By putting forth a positive attitude toward recovery and providing encouragement to patients, we can facilitate an earlier return to work.

I am cognizant of the pivotal role we can play with back injuries, a frequent cause of work disability. A great deal of excellent research over the past 20 years guides us regarding treatment and prognosis. Most back injuries are due to musculoskeletal injury and improve quickly during the first week, no matter what the therapy. By steering these patients clear of narcotics, telling them to remain as physically active as their pain will allow, and letting them know they will recover, we can pave the way for an early return to work.

Let us all take full advantage, then, of these important conversations with our patients. Armed with the strategies in this month’s article, we can increase the likelihood of our patients’ success.

This month, JFP tackles a topic—work disability—that might, at first, seem a bit outside our usual wheelhouse of clinical review articles. Work disability is, however, a very important topic. The authors point out that “... primary care clinicians are asked to provide guidance about work activities in nearly 10% of their patient encounters; however, 25% of those clinicians thought they had little influence over work disability outcomes.” This statement suggests that we need to learn more about managing work-related disability and how to influence patients’ outcomes in a positive manner.

I suspect that we tend to be pessimistic about our ability to influence patient outcomes because we are uncertain about the best course of action. The authors of this article provide excellent information about how we can—and should—help ill and injured patients return to work.

As I read the article, I reflected on my own experience providing patients with advice about returning to work. Two points, in particular, struck a chord with me.