User login

The first signs of elusive dysautonomia may appear on the skin

During the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, Adelaide A. Hebert, MD, defined dysautonomia as an umbrella term describing conditions that result in a malfunction of the autonomic nervous system. “This encompasses both the sympathetic and the parasympathetic components of the nervous system,” said Dr. Hebert, professor of dermatology and pediatrics, and chief of pediatric dermatology at the University of Texas, Houston. “Clinical findings may be neurometabolic, developmental, and/or degenerative,” representing a “whole constellation of issues” that physicians may encounter in practice, she noted. Of particular interest is postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), which affects between 1 million and 3 million people in the United States. Typical symptoms include lightheadedness, fainting, and a rapid increase in heartbeat after standing up from a seated position. Other conditions associated with dysautonomia include neurocardiogenic syncope and multiple system atrophy.

Dysautonomia can impact the brain, heart, mouth, blood vessels, eyes, immune cells, and bladder, as well as the skin. Patient presentations vary with symptoms that can range from mild to debilitating. The average time from symptom onset to diagnosis of dysautonomia is 7 years. “It is very difficult to put together these mysterious symptoms that patients have unless one really thinks about dysautonomia as a possible diagnosis,” Dr. Hebert said.

One of the common symptoms that she has seen in her clinical practice is joint hypermobility. “There is a known association between dysautonomia and hypermobile-type Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), and these patients often have hyperhidrosis,” she said. “So, keep in mind that you could see hypermobility, especially in those with EDS, with associated hyperhidrosis and dysautonomia.” Two key references that she recommends to clinicians when evaluating patients with possible dysautonomia are a study on postural tachycardia in hypermobile EDS, and an article on cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in hypermobile EDS.

The Beighton Scoring System, which measures joint mobility on a 9-point scale, involves assessment of the joint mobility of the knuckle of both pinky fingers, the base of both thumbs, the elbows, knees, and spine. An instructional video on how to perform a joint hypermobility assessment is available on the Ehler-Danlos Society website.

Literature review

In March 2021, Dr. Hebert and colleagues from other medical specialties published a summary of the literature on cutaneous manifestations in dysautonomia, with an emphasis on syndromes of orthostatic intolerance. “We had neurology, cardiology, along with dermatology involved in contributing the findings they had seen in the UTHealth McGovern Dysautonomia Center of Excellence as there was a dearth of literature that taught us about the cutaneous manifestations of orthostatic intolerance syndromes,” Dr. Hebert said.

One study included in the review showed that 23 out of 26 patients with POTS had at least one of the following cutaneous manifestations: flushing, Raynaud’s phenomenon, evanescent hyperemia, livedo reticularis, erythromelalgia, and hypo- or hyperhidrosis. “If you see a patient with any of these findings, you want to think about the possibility of dysautonomia,” she said, adding that urticaria can also be a finding.

To screen for dysautonomia, she advised, “ask patients if they have difficulty sitting or standing upright, if they have indigestion or other gastric symptoms, abnormal blood vessel functioning such as low or high blood pressure, increased or decreased sweating, changes in urinary frequency or urinary incontinence, or challenges with vision.”

If the patient answers yes to two or more of these questions, she said, consider a referral to neurology and/or cardiology or a center of excellence for further evaluation with tilt-table testing and other screening tools. She also recommended a review published in 2015 that describes the dermatological manifestations of postural tachycardia syndrome and includes illustrated cases.

One of Dr. Hebert’s future dermatology residents assembled a composite of data from the Dysautonomia Center of Excellence, and in the study, found that, compared with males, females with dysautonomia suffer more from excessive sweating, paleness of the face, pale extremities, swelling, cyanosis, cold intolerance, flushing, and hot flashes.

Dr. Hebert disclosed that she has been a consultant to and an adviser for several pharmaceutical companies.

During the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, Adelaide A. Hebert, MD, defined dysautonomia as an umbrella term describing conditions that result in a malfunction of the autonomic nervous system. “This encompasses both the sympathetic and the parasympathetic components of the nervous system,” said Dr. Hebert, professor of dermatology and pediatrics, and chief of pediatric dermatology at the University of Texas, Houston. “Clinical findings may be neurometabolic, developmental, and/or degenerative,” representing a “whole constellation of issues” that physicians may encounter in practice, she noted. Of particular interest is postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), which affects between 1 million and 3 million people in the United States. Typical symptoms include lightheadedness, fainting, and a rapid increase in heartbeat after standing up from a seated position. Other conditions associated with dysautonomia include neurocardiogenic syncope and multiple system atrophy.

Dysautonomia can impact the brain, heart, mouth, blood vessels, eyes, immune cells, and bladder, as well as the skin. Patient presentations vary with symptoms that can range from mild to debilitating. The average time from symptom onset to diagnosis of dysautonomia is 7 years. “It is very difficult to put together these mysterious symptoms that patients have unless one really thinks about dysautonomia as a possible diagnosis,” Dr. Hebert said.

One of the common symptoms that she has seen in her clinical practice is joint hypermobility. “There is a known association between dysautonomia and hypermobile-type Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), and these patients often have hyperhidrosis,” she said. “So, keep in mind that you could see hypermobility, especially in those with EDS, with associated hyperhidrosis and dysautonomia.” Two key references that she recommends to clinicians when evaluating patients with possible dysautonomia are a study on postural tachycardia in hypermobile EDS, and an article on cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in hypermobile EDS.

The Beighton Scoring System, which measures joint mobility on a 9-point scale, involves assessment of the joint mobility of the knuckle of both pinky fingers, the base of both thumbs, the elbows, knees, and spine. An instructional video on how to perform a joint hypermobility assessment is available on the Ehler-Danlos Society website.

Literature review

In March 2021, Dr. Hebert and colleagues from other medical specialties published a summary of the literature on cutaneous manifestations in dysautonomia, with an emphasis on syndromes of orthostatic intolerance. “We had neurology, cardiology, along with dermatology involved in contributing the findings they had seen in the UTHealth McGovern Dysautonomia Center of Excellence as there was a dearth of literature that taught us about the cutaneous manifestations of orthostatic intolerance syndromes,” Dr. Hebert said.

One study included in the review showed that 23 out of 26 patients with POTS had at least one of the following cutaneous manifestations: flushing, Raynaud’s phenomenon, evanescent hyperemia, livedo reticularis, erythromelalgia, and hypo- or hyperhidrosis. “If you see a patient with any of these findings, you want to think about the possibility of dysautonomia,” she said, adding that urticaria can also be a finding.

To screen for dysautonomia, she advised, “ask patients if they have difficulty sitting or standing upright, if they have indigestion or other gastric symptoms, abnormal blood vessel functioning such as low or high blood pressure, increased or decreased sweating, changes in urinary frequency or urinary incontinence, or challenges with vision.”

If the patient answers yes to two or more of these questions, she said, consider a referral to neurology and/or cardiology or a center of excellence for further evaluation with tilt-table testing and other screening tools. She also recommended a review published in 2015 that describes the dermatological manifestations of postural tachycardia syndrome and includes illustrated cases.

One of Dr. Hebert’s future dermatology residents assembled a composite of data from the Dysautonomia Center of Excellence, and in the study, found that, compared with males, females with dysautonomia suffer more from excessive sweating, paleness of the face, pale extremities, swelling, cyanosis, cold intolerance, flushing, and hot flashes.

Dr. Hebert disclosed that she has been a consultant to and an adviser for several pharmaceutical companies.

During the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, Adelaide A. Hebert, MD, defined dysautonomia as an umbrella term describing conditions that result in a malfunction of the autonomic nervous system. “This encompasses both the sympathetic and the parasympathetic components of the nervous system,” said Dr. Hebert, professor of dermatology and pediatrics, and chief of pediatric dermatology at the University of Texas, Houston. “Clinical findings may be neurometabolic, developmental, and/or degenerative,” representing a “whole constellation of issues” that physicians may encounter in practice, she noted. Of particular interest is postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), which affects between 1 million and 3 million people in the United States. Typical symptoms include lightheadedness, fainting, and a rapid increase in heartbeat after standing up from a seated position. Other conditions associated with dysautonomia include neurocardiogenic syncope and multiple system atrophy.

Dysautonomia can impact the brain, heart, mouth, blood vessels, eyes, immune cells, and bladder, as well as the skin. Patient presentations vary with symptoms that can range from mild to debilitating. The average time from symptom onset to diagnosis of dysautonomia is 7 years. “It is very difficult to put together these mysterious symptoms that patients have unless one really thinks about dysautonomia as a possible diagnosis,” Dr. Hebert said.

One of the common symptoms that she has seen in her clinical practice is joint hypermobility. “There is a known association between dysautonomia and hypermobile-type Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), and these patients often have hyperhidrosis,” she said. “So, keep in mind that you could see hypermobility, especially in those with EDS, with associated hyperhidrosis and dysautonomia.” Two key references that she recommends to clinicians when evaluating patients with possible dysautonomia are a study on postural tachycardia in hypermobile EDS, and an article on cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in hypermobile EDS.

The Beighton Scoring System, which measures joint mobility on a 9-point scale, involves assessment of the joint mobility of the knuckle of both pinky fingers, the base of both thumbs, the elbows, knees, and spine. An instructional video on how to perform a joint hypermobility assessment is available on the Ehler-Danlos Society website.

Literature review

In March 2021, Dr. Hebert and colleagues from other medical specialties published a summary of the literature on cutaneous manifestations in dysautonomia, with an emphasis on syndromes of orthostatic intolerance. “We had neurology, cardiology, along with dermatology involved in contributing the findings they had seen in the UTHealth McGovern Dysautonomia Center of Excellence as there was a dearth of literature that taught us about the cutaneous manifestations of orthostatic intolerance syndromes,” Dr. Hebert said.

One study included in the review showed that 23 out of 26 patients with POTS had at least one of the following cutaneous manifestations: flushing, Raynaud’s phenomenon, evanescent hyperemia, livedo reticularis, erythromelalgia, and hypo- or hyperhidrosis. “If you see a patient with any of these findings, you want to think about the possibility of dysautonomia,” she said, adding that urticaria can also be a finding.

To screen for dysautonomia, she advised, “ask patients if they have difficulty sitting or standing upright, if they have indigestion or other gastric symptoms, abnormal blood vessel functioning such as low or high blood pressure, increased or decreased sweating, changes in urinary frequency or urinary incontinence, or challenges with vision.”

If the patient answers yes to two or more of these questions, she said, consider a referral to neurology and/or cardiology or a center of excellence for further evaluation with tilt-table testing and other screening tools. She also recommended a review published in 2015 that describes the dermatological manifestations of postural tachycardia syndrome and includes illustrated cases.

One of Dr. Hebert’s future dermatology residents assembled a composite of data from the Dysautonomia Center of Excellence, and in the study, found that, compared with males, females with dysautonomia suffer more from excessive sweating, paleness of the face, pale extremities, swelling, cyanosis, cold intolerance, flushing, and hot flashes.

Dr. Hebert disclosed that she has been a consultant to and an adviser for several pharmaceutical companies.

FROM SPD 2021

Dissolving pacemaker impressive in early research

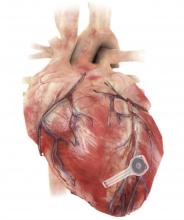

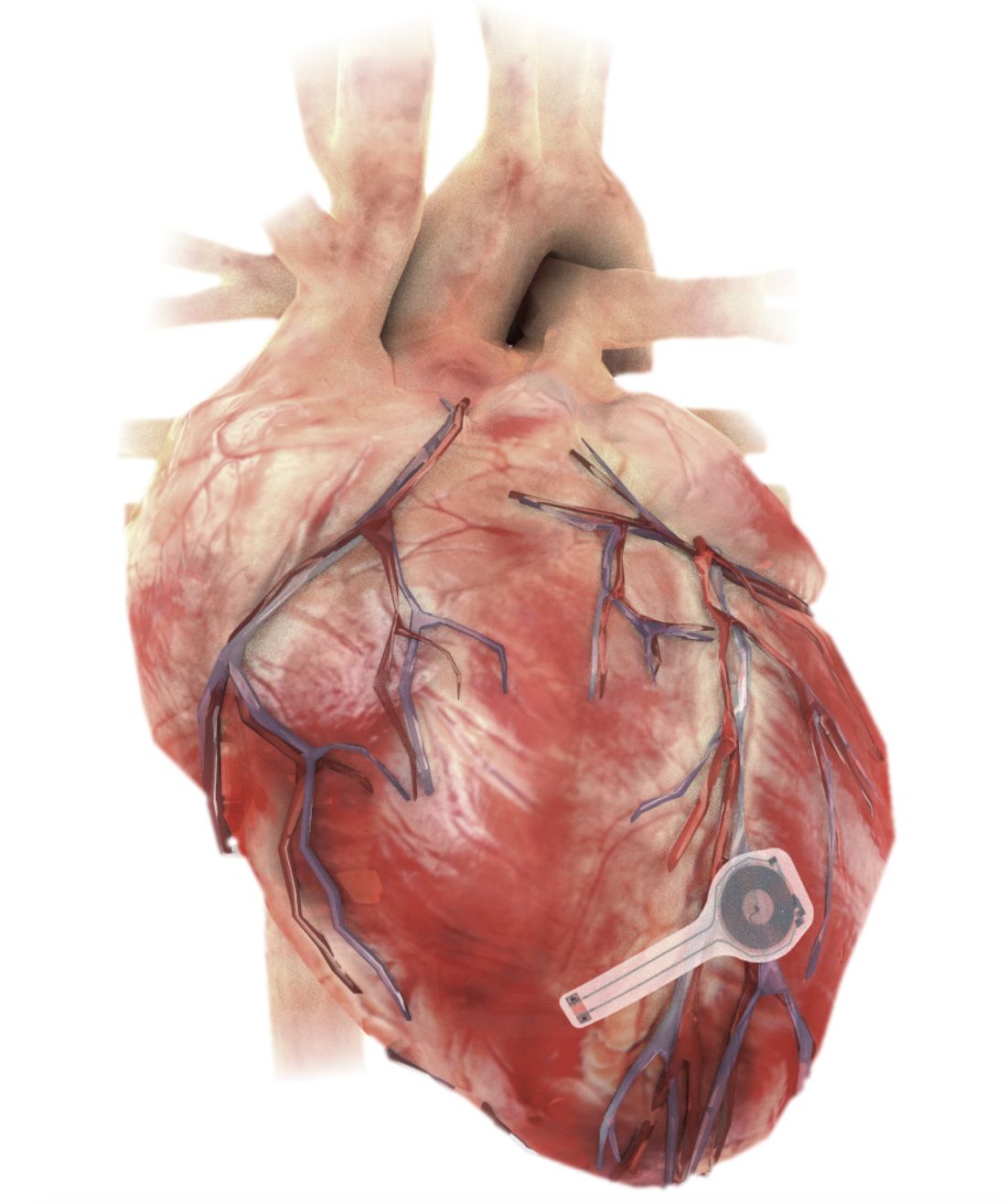

A fully implantable, bioresorbable pacemaker has been developed that’s capable of sustaining heart rhythms in animal and human donor hearts before disappearing over 5-7 weeks.

Temporary pacing devices are frequently used after cardiac surgery but rely on bulky external generators and transcutaneous pacing leads that run the risk of becoming infected or dislodged and can damage the heart when removed if they’re enveloped in fibrotic tissue.

The experimental device is thin, powered without leads or batteries, and made of water-soluble, biocompatible materials, thereby bypassing many of the disadvantages of conventional temporary pacing devices, according to John A. Rogers, PhD, who led the device’s development and directs the Querrey Simpson Institute for Bioelectronics at Northwestern University in Chicago.

“The total material load on the body is very minimal,” he said in an interview. “The amount of silicon and magnesium in a multivitamin tablet is about 3,000 times more than the amount of those materials in our electronics. So you can think of them as a very tiny vitamin pill, in a sense, but configured with electronic functionality.”

Dr. Rogers and his team have a reputation for innovation in bioelectronic medicine, having recently constructed transient wireless devices to accelerate neuroregeneration associated with damaged peripheral nerves, to monitor critically ill neonates, and to detect early signs and symptoms associated with COVID-19.

Shortly after Dr. Rogers joined Northwestern, Rishi Arora, MD, a cardiac electrophysiologist and professor of medicine at Northwestern, reached out to discuss how they could leverage wireless electronics for patients needing temporary pacing.

“It was a natural marriage,” Dr. Arora said in an interview. “Part of the reason to go into the heart was because the cardiology group here at Northwestern, especially on the electrophysiology side, has been very involved in translational research, and John also had a very strong collaboration before he came here with Igor Efimov, [PhD, of George Washington University, Washington], a giant in the field in terms of heart rhythm research.”

Dr. Arora noted that the incidence of temporary pacing after cardiac surgery is at least 10% but can reach 20%. Current devices work well in most patients, but temporary pacing with epicardial wires can cause complications and, typically, work well only for a few days after cardiac surgery. Clinically, though, several patients need postoperative pacing support for 1-2 weeks.

“So if something like this were available where you could tack it onto the surface and forget it for a week or 10 days or 2 weeks, you’d be doing those 20% of patients a huge service,” he said.

Bioresorbable scaffold déjà vu?

The philosophy of “leave nothing behind” is nothing new in cardiology, with bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) gaining initial support as a potential solution to neoatherosclerosis and late-stent thrombosis in permanent metal stents. Failure to show advantages, and safety concerns such as in-scaffold thrombosis, however, led Abbott to stop global sales of the first approved BVS and Boston Scientific to halt its BVS program in 2017.

The wireless pacemaker, however, is an electrical device, not a mechanical one, observed Dr. Rogers. “The fact that it’s not in the bloodstream greatly lowers risks and, as I mentioned before, everything is super thin, low-mass quantities of materials. So, I guess there’s a relationship there, but it’s different in a couple of very important ways.”

As Dr. Rogers, Dr. Arora, Dr. Efimov, and colleagues recently reported in Nature Biotechnology, the electronic part of the pacemaker contains three layers: A loop antenna with a bilayer tungsten-coated magnesium inductive coil, a radiofrequency PIN diode based on a monocrystalline silicon nanomembrane, and a poly (lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) dielectric interlayer.

The electronic components rest between two encapsulation layers of PLGA to isolate the active materials from the surrounding biofluids during implantation, and connect to a pair of flexible extension electrodes that deliver the electrical stimuli to a contact pad sutured onto the heart. The entire system is about 16 mm in width and 15 mm in length, and weighs in at about 0.3 g.

The pacemaker receives power and control commands through a wireless inductive power transfer – the same technology used in implanted medical devices, smartphones, and radio-frequency identification tags – between the receiver coil in the device and a wand-shaped, external transmission coil placed on top of or within a few inches of the heart.

“Right now we’re almost at 15 inches, which I think is a very respectable distance for this particular piece of hardware, and clinically very doable,” observed Dr. Arora.

Competing considerations

Testing thus far shows effective ventricular capture across a range of frequencies in mouse and rabbit hearts and successful pacing and activation of human cardiac tissue.

In vivo tests in dogs also suggest that the system can “achieve the power necessary for operation of bioresorbable pacemakers in adult human patients,” the authors say.

Electrodes placed on the dogs’ legs showed a change in ECG signals from a narrow QRS complex (consistent with a normal rate sinus rhythm of 350-400 bpm) to a widened QRS complex with a shortened R-R interval (consistent with a paced rhythm of 400-450 bpm) – indicating successful ventricular capture.

The device successfully paced the dogs through postoperative day 4 but couldn’t provide enough energy to capture the ventricular myocardium on day 5 and failed to pace the heart on day 6, even when transmitting voltages were increased from 1 Vpp to more than 10 Vpp.

Dr. Rogers pointed out that a transient device of theirs that uses very thin films of silica provides stable intracranial pressure monitoring for traumatic brain injury recovery for 3 weeks before dissolving. The problem with the polymers used as encapsulating layers in the pacemaker is that even if they haven’t completely dissolved, there’s a finite rate of water permeation through the film.

“It turns out that’s what’s become the limiting factor, rather than the chemistry of bioresorption,” he said. “So, what we’re seeing with these devices beginning to degrade electrically in terms of performance around 5-6 days is due to that water permeation.”

Although it is not part of the current study, there’s no reason thin silica layers couldn’t be incorporated into the pacemaker to make it less water permeable, Dr. Rogers said. Still, this will have to be weighed against the competing consideration of stable operating life.

The researchers specifically chose materials that would naturally bioresorb via hydrolysis and metabolic action in the body. PLGA degrades into glycolic and lactic acid, the tungsten-coated magnesium inductive coil into Wox and Mg(OH)2, and the silicon nanomembrane radiofrequency PIN diode into Si(OH)4.

CT imaging in rat models shows the device is enveloped in fibrotic tissue and completely decouples from the heart at 4 weeks, while images of explanted devices suggest the pacemaker largely dissolves within 3 weeks and the remaining residues disappear after 12 weeks.

The researchers have started an investigational device exemption process to allow the device to be used in clinical trials, and they plan to dig deeper into the potential for fragments to form at various stages of resorption, which some imaging suggests may occur.

“Because these devices are made out of pure materials and they’re in a heterogeneous environment, both mechanically and biomechanically, the devices don’t resorb in a perfectly uniform way and, as a result, at the tail end of the process you can end up with small fragments that eventually bioresorb, but before they’re gone, they are potentially mobile within the body cavity,” Dr. Rogers said.

“We feel that because the devices aren’t in the bloodstream, the risk associated with those fragments is probably manageable but at the same time, these are the sorts of details that must be thoroughly addressed before trials in humans,” he said, adding that one solution, if needed, would be to encapsulate the entire device in a thin bioresorbable hydrogel as a containment vehicle.

Dr. Arora said they hope the pacemaker “will make patients’ lives a lot easier in the postoperative setting but, even there, I think one must remember current pacing technology in this setting is actually very good. So there’s a word of caution not to get ahead of ourselves.”

Looking forward, the excitement of this approach is not only in the immediate postop setting but in the transvenous setting, he said. “If we can get to the point where we can actually do this transvenously, that opens up a huge window of opportunity because there we’re talking about post-TAVR [transcatheter aortic valve replacement], post–myocardial infarction, etc.”

Currently, temporary transvenous pacing can be quite unreliable because of a high risk of dislodgement and infection – much higher than for surgical pacing wires, he noted.

“In terms of translatability to larger numbers of patients, the value would be huge. But again, a lot needs to be done before we can get there. But if it can get to that point, then I think you have a real therapy that could potentially be transformative,” Dr. Arora said.

Dr. Rogers reported support from the Leducq Foundation projects RHYTHM and ROI-HL121270. Dr. Arora has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Coauthor disclosures are listed in the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A fully implantable, bioresorbable pacemaker has been developed that’s capable of sustaining heart rhythms in animal and human donor hearts before disappearing over 5-7 weeks.

Temporary pacing devices are frequently used after cardiac surgery but rely on bulky external generators and transcutaneous pacing leads that run the risk of becoming infected or dislodged and can damage the heart when removed if they’re enveloped in fibrotic tissue.

The experimental device is thin, powered without leads or batteries, and made of water-soluble, biocompatible materials, thereby bypassing many of the disadvantages of conventional temporary pacing devices, according to John A. Rogers, PhD, who led the device’s development and directs the Querrey Simpson Institute for Bioelectronics at Northwestern University in Chicago.

“The total material load on the body is very minimal,” he said in an interview. “The amount of silicon and magnesium in a multivitamin tablet is about 3,000 times more than the amount of those materials in our electronics. So you can think of them as a very tiny vitamin pill, in a sense, but configured with electronic functionality.”

Dr. Rogers and his team have a reputation for innovation in bioelectronic medicine, having recently constructed transient wireless devices to accelerate neuroregeneration associated with damaged peripheral nerves, to monitor critically ill neonates, and to detect early signs and symptoms associated with COVID-19.

Shortly after Dr. Rogers joined Northwestern, Rishi Arora, MD, a cardiac electrophysiologist and professor of medicine at Northwestern, reached out to discuss how they could leverage wireless electronics for patients needing temporary pacing.

“It was a natural marriage,” Dr. Arora said in an interview. “Part of the reason to go into the heart was because the cardiology group here at Northwestern, especially on the electrophysiology side, has been very involved in translational research, and John also had a very strong collaboration before he came here with Igor Efimov, [PhD, of George Washington University, Washington], a giant in the field in terms of heart rhythm research.”

Dr. Arora noted that the incidence of temporary pacing after cardiac surgery is at least 10% but can reach 20%. Current devices work well in most patients, but temporary pacing with epicardial wires can cause complications and, typically, work well only for a few days after cardiac surgery. Clinically, though, several patients need postoperative pacing support for 1-2 weeks.

“So if something like this were available where you could tack it onto the surface and forget it for a week or 10 days or 2 weeks, you’d be doing those 20% of patients a huge service,” he said.

Bioresorbable scaffold déjà vu?

The philosophy of “leave nothing behind” is nothing new in cardiology, with bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) gaining initial support as a potential solution to neoatherosclerosis and late-stent thrombosis in permanent metal stents. Failure to show advantages, and safety concerns such as in-scaffold thrombosis, however, led Abbott to stop global sales of the first approved BVS and Boston Scientific to halt its BVS program in 2017.

The wireless pacemaker, however, is an electrical device, not a mechanical one, observed Dr. Rogers. “The fact that it’s not in the bloodstream greatly lowers risks and, as I mentioned before, everything is super thin, low-mass quantities of materials. So, I guess there’s a relationship there, but it’s different in a couple of very important ways.”

As Dr. Rogers, Dr. Arora, Dr. Efimov, and colleagues recently reported in Nature Biotechnology, the electronic part of the pacemaker contains three layers: A loop antenna with a bilayer tungsten-coated magnesium inductive coil, a radiofrequency PIN diode based on a monocrystalline silicon nanomembrane, and a poly (lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) dielectric interlayer.

The electronic components rest between two encapsulation layers of PLGA to isolate the active materials from the surrounding biofluids during implantation, and connect to a pair of flexible extension electrodes that deliver the electrical stimuli to a contact pad sutured onto the heart. The entire system is about 16 mm in width and 15 mm in length, and weighs in at about 0.3 g.

The pacemaker receives power and control commands through a wireless inductive power transfer – the same technology used in implanted medical devices, smartphones, and radio-frequency identification tags – between the receiver coil in the device and a wand-shaped, external transmission coil placed on top of or within a few inches of the heart.

“Right now we’re almost at 15 inches, which I think is a very respectable distance for this particular piece of hardware, and clinically very doable,” observed Dr. Arora.

Competing considerations

Testing thus far shows effective ventricular capture across a range of frequencies in mouse and rabbit hearts and successful pacing and activation of human cardiac tissue.

In vivo tests in dogs also suggest that the system can “achieve the power necessary for operation of bioresorbable pacemakers in adult human patients,” the authors say.

Electrodes placed on the dogs’ legs showed a change in ECG signals from a narrow QRS complex (consistent with a normal rate sinus rhythm of 350-400 bpm) to a widened QRS complex with a shortened R-R interval (consistent with a paced rhythm of 400-450 bpm) – indicating successful ventricular capture.

The device successfully paced the dogs through postoperative day 4 but couldn’t provide enough energy to capture the ventricular myocardium on day 5 and failed to pace the heart on day 6, even when transmitting voltages were increased from 1 Vpp to more than 10 Vpp.

Dr. Rogers pointed out that a transient device of theirs that uses very thin films of silica provides stable intracranial pressure monitoring for traumatic brain injury recovery for 3 weeks before dissolving. The problem with the polymers used as encapsulating layers in the pacemaker is that even if they haven’t completely dissolved, there’s a finite rate of water permeation through the film.

“It turns out that’s what’s become the limiting factor, rather than the chemistry of bioresorption,” he said. “So, what we’re seeing with these devices beginning to degrade electrically in terms of performance around 5-6 days is due to that water permeation.”

Although it is not part of the current study, there’s no reason thin silica layers couldn’t be incorporated into the pacemaker to make it less water permeable, Dr. Rogers said. Still, this will have to be weighed against the competing consideration of stable operating life.

The researchers specifically chose materials that would naturally bioresorb via hydrolysis and metabolic action in the body. PLGA degrades into glycolic and lactic acid, the tungsten-coated magnesium inductive coil into Wox and Mg(OH)2, and the silicon nanomembrane radiofrequency PIN diode into Si(OH)4.

CT imaging in rat models shows the device is enveloped in fibrotic tissue and completely decouples from the heart at 4 weeks, while images of explanted devices suggest the pacemaker largely dissolves within 3 weeks and the remaining residues disappear after 12 weeks.

The researchers have started an investigational device exemption process to allow the device to be used in clinical trials, and they plan to dig deeper into the potential for fragments to form at various stages of resorption, which some imaging suggests may occur.

“Because these devices are made out of pure materials and they’re in a heterogeneous environment, both mechanically and biomechanically, the devices don’t resorb in a perfectly uniform way and, as a result, at the tail end of the process you can end up with small fragments that eventually bioresorb, but before they’re gone, they are potentially mobile within the body cavity,” Dr. Rogers said.

“We feel that because the devices aren’t in the bloodstream, the risk associated with those fragments is probably manageable but at the same time, these are the sorts of details that must be thoroughly addressed before trials in humans,” he said, adding that one solution, if needed, would be to encapsulate the entire device in a thin bioresorbable hydrogel as a containment vehicle.

Dr. Arora said they hope the pacemaker “will make patients’ lives a lot easier in the postoperative setting but, even there, I think one must remember current pacing technology in this setting is actually very good. So there’s a word of caution not to get ahead of ourselves.”

Looking forward, the excitement of this approach is not only in the immediate postop setting but in the transvenous setting, he said. “If we can get to the point where we can actually do this transvenously, that opens up a huge window of opportunity because there we’re talking about post-TAVR [transcatheter aortic valve replacement], post–myocardial infarction, etc.”

Currently, temporary transvenous pacing can be quite unreliable because of a high risk of dislodgement and infection – much higher than for surgical pacing wires, he noted.

“In terms of translatability to larger numbers of patients, the value would be huge. But again, a lot needs to be done before we can get there. But if it can get to that point, then I think you have a real therapy that could potentially be transformative,” Dr. Arora said.

Dr. Rogers reported support from the Leducq Foundation projects RHYTHM and ROI-HL121270. Dr. Arora has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Coauthor disclosures are listed in the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A fully implantable, bioresorbable pacemaker has been developed that’s capable of sustaining heart rhythms in animal and human donor hearts before disappearing over 5-7 weeks.

Temporary pacing devices are frequently used after cardiac surgery but rely on bulky external generators and transcutaneous pacing leads that run the risk of becoming infected or dislodged and can damage the heart when removed if they’re enveloped in fibrotic tissue.

The experimental device is thin, powered without leads or batteries, and made of water-soluble, biocompatible materials, thereby bypassing many of the disadvantages of conventional temporary pacing devices, according to John A. Rogers, PhD, who led the device’s development and directs the Querrey Simpson Institute for Bioelectronics at Northwestern University in Chicago.

“The total material load on the body is very minimal,” he said in an interview. “The amount of silicon and magnesium in a multivitamin tablet is about 3,000 times more than the amount of those materials in our electronics. So you can think of them as a very tiny vitamin pill, in a sense, but configured with electronic functionality.”

Dr. Rogers and his team have a reputation for innovation in bioelectronic medicine, having recently constructed transient wireless devices to accelerate neuroregeneration associated with damaged peripheral nerves, to monitor critically ill neonates, and to detect early signs and symptoms associated with COVID-19.

Shortly after Dr. Rogers joined Northwestern, Rishi Arora, MD, a cardiac electrophysiologist and professor of medicine at Northwestern, reached out to discuss how they could leverage wireless electronics for patients needing temporary pacing.

“It was a natural marriage,” Dr. Arora said in an interview. “Part of the reason to go into the heart was because the cardiology group here at Northwestern, especially on the electrophysiology side, has been very involved in translational research, and John also had a very strong collaboration before he came here with Igor Efimov, [PhD, of George Washington University, Washington], a giant in the field in terms of heart rhythm research.”

Dr. Arora noted that the incidence of temporary pacing after cardiac surgery is at least 10% but can reach 20%. Current devices work well in most patients, but temporary pacing with epicardial wires can cause complications and, typically, work well only for a few days after cardiac surgery. Clinically, though, several patients need postoperative pacing support for 1-2 weeks.

“So if something like this were available where you could tack it onto the surface and forget it for a week or 10 days or 2 weeks, you’d be doing those 20% of patients a huge service,” he said.

Bioresorbable scaffold déjà vu?

The philosophy of “leave nothing behind” is nothing new in cardiology, with bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) gaining initial support as a potential solution to neoatherosclerosis and late-stent thrombosis in permanent metal stents. Failure to show advantages, and safety concerns such as in-scaffold thrombosis, however, led Abbott to stop global sales of the first approved BVS and Boston Scientific to halt its BVS program in 2017.

The wireless pacemaker, however, is an electrical device, not a mechanical one, observed Dr. Rogers. “The fact that it’s not in the bloodstream greatly lowers risks and, as I mentioned before, everything is super thin, low-mass quantities of materials. So, I guess there’s a relationship there, but it’s different in a couple of very important ways.”

As Dr. Rogers, Dr. Arora, Dr. Efimov, and colleagues recently reported in Nature Biotechnology, the electronic part of the pacemaker contains three layers: A loop antenna with a bilayer tungsten-coated magnesium inductive coil, a radiofrequency PIN diode based on a monocrystalline silicon nanomembrane, and a poly (lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) dielectric interlayer.

The electronic components rest between two encapsulation layers of PLGA to isolate the active materials from the surrounding biofluids during implantation, and connect to a pair of flexible extension electrodes that deliver the electrical stimuli to a contact pad sutured onto the heart. The entire system is about 16 mm in width and 15 mm in length, and weighs in at about 0.3 g.

The pacemaker receives power and control commands through a wireless inductive power transfer – the same technology used in implanted medical devices, smartphones, and radio-frequency identification tags – between the receiver coil in the device and a wand-shaped, external transmission coil placed on top of or within a few inches of the heart.

“Right now we’re almost at 15 inches, which I think is a very respectable distance for this particular piece of hardware, and clinically very doable,” observed Dr. Arora.

Competing considerations

Testing thus far shows effective ventricular capture across a range of frequencies in mouse and rabbit hearts and successful pacing and activation of human cardiac tissue.

In vivo tests in dogs also suggest that the system can “achieve the power necessary for operation of bioresorbable pacemakers in adult human patients,” the authors say.

Electrodes placed on the dogs’ legs showed a change in ECG signals from a narrow QRS complex (consistent with a normal rate sinus rhythm of 350-400 bpm) to a widened QRS complex with a shortened R-R interval (consistent with a paced rhythm of 400-450 bpm) – indicating successful ventricular capture.

The device successfully paced the dogs through postoperative day 4 but couldn’t provide enough energy to capture the ventricular myocardium on day 5 and failed to pace the heart on day 6, even when transmitting voltages were increased from 1 Vpp to more than 10 Vpp.

Dr. Rogers pointed out that a transient device of theirs that uses very thin films of silica provides stable intracranial pressure monitoring for traumatic brain injury recovery for 3 weeks before dissolving. The problem with the polymers used as encapsulating layers in the pacemaker is that even if they haven’t completely dissolved, there’s a finite rate of water permeation through the film.

“It turns out that’s what’s become the limiting factor, rather than the chemistry of bioresorption,” he said. “So, what we’re seeing with these devices beginning to degrade electrically in terms of performance around 5-6 days is due to that water permeation.”

Although it is not part of the current study, there’s no reason thin silica layers couldn’t be incorporated into the pacemaker to make it less water permeable, Dr. Rogers said. Still, this will have to be weighed against the competing consideration of stable operating life.

The researchers specifically chose materials that would naturally bioresorb via hydrolysis and metabolic action in the body. PLGA degrades into glycolic and lactic acid, the tungsten-coated magnesium inductive coil into Wox and Mg(OH)2, and the silicon nanomembrane radiofrequency PIN diode into Si(OH)4.

CT imaging in rat models shows the device is enveloped in fibrotic tissue and completely decouples from the heart at 4 weeks, while images of explanted devices suggest the pacemaker largely dissolves within 3 weeks and the remaining residues disappear after 12 weeks.

The researchers have started an investigational device exemption process to allow the device to be used in clinical trials, and they plan to dig deeper into the potential for fragments to form at various stages of resorption, which some imaging suggests may occur.

“Because these devices are made out of pure materials and they’re in a heterogeneous environment, both mechanically and biomechanically, the devices don’t resorb in a perfectly uniform way and, as a result, at the tail end of the process you can end up with small fragments that eventually bioresorb, but before they’re gone, they are potentially mobile within the body cavity,” Dr. Rogers said.

“We feel that because the devices aren’t in the bloodstream, the risk associated with those fragments is probably manageable but at the same time, these are the sorts of details that must be thoroughly addressed before trials in humans,” he said, adding that one solution, if needed, would be to encapsulate the entire device in a thin bioresorbable hydrogel as a containment vehicle.

Dr. Arora said they hope the pacemaker “will make patients’ lives a lot easier in the postoperative setting but, even there, I think one must remember current pacing technology in this setting is actually very good. So there’s a word of caution not to get ahead of ourselves.”

Looking forward, the excitement of this approach is not only in the immediate postop setting but in the transvenous setting, he said. “If we can get to the point where we can actually do this transvenously, that opens up a huge window of opportunity because there we’re talking about post-TAVR [transcatheter aortic valve replacement], post–myocardial infarction, etc.”

Currently, temporary transvenous pacing can be quite unreliable because of a high risk of dislodgement and infection – much higher than for surgical pacing wires, he noted.

“In terms of translatability to larger numbers of patients, the value would be huge. But again, a lot needs to be done before we can get there. But if it can get to that point, then I think you have a real therapy that could potentially be transformative,” Dr. Arora said.

Dr. Rogers reported support from the Leducq Foundation projects RHYTHM and ROI-HL121270. Dr. Arora has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Coauthor disclosures are listed in the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Aspirin efficacious and safe for VTE prophylaxis in total hip and knee replacement

Background: Most patients undergoing total hip replacement (THR) and total knee replacement (TKR) require anticoagulant therapy to reduce venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk. Compared with injectable low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), warfarin, and newer oral agents, aspirin is easily administered, inexpensive, and well tolerated and requires no monitoring. There are observational data to support aspirin as VTE prophylaxis after THR and TKR. However, high-quality randomized, clinical trials (RCT) in favor of aspirin have been limited. Recently, a large RCT (n = 3,224) that compared aspirin to rivaroxaban after THR and TKR has been published that supports aspirin use for VTE prophylaxis.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Seven studies from North America, four from Asia, and two from Europe.

Synopsis: In a meta-analysis comprising 13 RCT including 6,060 participants (2,969 aspirin and 3,091 comparator), there was no statistically significant difference in the risk of venous thromboembolism (including deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism) when comparing aspirin with other anticoagulants (LMWH, rivaroxaban) in patients undergoing THR and TKR. Also, there were no differences in the risk of adverse events, such as bleeding, wound complications, MI, and death, when aspirin was compared with other anticoagulants.

This systematic review and meta-analysis included trials from around the world, including the most recent and largest in this area. However, because of the heterogeneity and high risk of bias encountered in most RCTs included in this analysis, additional large, well-designed RCTs are needed to validate findings of this review.

Bottom line: Findings of the current meta-analysis support the use of aspirin for VTE prophylaxis after THR and TKR, in line with the 2012 recommendations of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Citation: Matharu GS et al. Clinical effectiveness and safety of aspirin for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after total hip and knee replacement. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Feb 3;180(3):376-84.

Dr. Mehta is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Most patients undergoing total hip replacement (THR) and total knee replacement (TKR) require anticoagulant therapy to reduce venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk. Compared with injectable low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), warfarin, and newer oral agents, aspirin is easily administered, inexpensive, and well tolerated and requires no monitoring. There are observational data to support aspirin as VTE prophylaxis after THR and TKR. However, high-quality randomized, clinical trials (RCT) in favor of aspirin have been limited. Recently, a large RCT (n = 3,224) that compared aspirin to rivaroxaban after THR and TKR has been published that supports aspirin use for VTE prophylaxis.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Seven studies from North America, four from Asia, and two from Europe.

Synopsis: In a meta-analysis comprising 13 RCT including 6,060 participants (2,969 aspirin and 3,091 comparator), there was no statistically significant difference in the risk of venous thromboembolism (including deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism) when comparing aspirin with other anticoagulants (LMWH, rivaroxaban) in patients undergoing THR and TKR. Also, there were no differences in the risk of adverse events, such as bleeding, wound complications, MI, and death, when aspirin was compared with other anticoagulants.

This systematic review and meta-analysis included trials from around the world, including the most recent and largest in this area. However, because of the heterogeneity and high risk of bias encountered in most RCTs included in this analysis, additional large, well-designed RCTs are needed to validate findings of this review.

Bottom line: Findings of the current meta-analysis support the use of aspirin for VTE prophylaxis after THR and TKR, in line with the 2012 recommendations of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Citation: Matharu GS et al. Clinical effectiveness and safety of aspirin for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after total hip and knee replacement. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Feb 3;180(3):376-84.

Dr. Mehta is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Most patients undergoing total hip replacement (THR) and total knee replacement (TKR) require anticoagulant therapy to reduce venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk. Compared with injectable low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), warfarin, and newer oral agents, aspirin is easily administered, inexpensive, and well tolerated and requires no monitoring. There are observational data to support aspirin as VTE prophylaxis after THR and TKR. However, high-quality randomized, clinical trials (RCT) in favor of aspirin have been limited. Recently, a large RCT (n = 3,224) that compared aspirin to rivaroxaban after THR and TKR has been published that supports aspirin use for VTE prophylaxis.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Seven studies from North America, four from Asia, and two from Europe.

Synopsis: In a meta-analysis comprising 13 RCT including 6,060 participants (2,969 aspirin and 3,091 comparator), there was no statistically significant difference in the risk of venous thromboembolism (including deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism) when comparing aspirin with other anticoagulants (LMWH, rivaroxaban) in patients undergoing THR and TKR. Also, there were no differences in the risk of adverse events, such as bleeding, wound complications, MI, and death, when aspirin was compared with other anticoagulants.

This systematic review and meta-analysis included trials from around the world, including the most recent and largest in this area. However, because of the heterogeneity and high risk of bias encountered in most RCTs included in this analysis, additional large, well-designed RCTs are needed to validate findings of this review.

Bottom line: Findings of the current meta-analysis support the use of aspirin for VTE prophylaxis after THR and TKR, in line with the 2012 recommendations of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Citation: Matharu GS et al. Clinical effectiveness and safety of aspirin for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after total hip and knee replacement. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Feb 3;180(3):376-84.

Dr. Mehta is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

CDC panel updates info on rare side effect after J&J vaccine

Despite recent reports of Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine,

The company also presented new data suggesting that the shots generate strong immune responses against circulating variants and that antibodies generated by the vaccine stay elevated for at least 8 months.

Members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) did not vote, but discussed and affirmed their support for recent decisions by the Food and Drug Administration and CDC to update patient information about the very low risk of GBS that appears to be associated with the vaccine, but to continue offering the vaccine to people in the United States.

The Johnson & Johnson shot has been a minor player in the U.S. vaccination campaign, accounting for less than 4% of all vaccine doses given in this country. Still, the single-dose inoculation, which doesn’t require ultra-cold storage, has been important for reaching people in rural areas, through mobile clinics, at colleges and primary care offices, and in vulnerable populations – those who are incarcerated or homeless.

The FDA says it has received reports of 100 cases of GBS after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in its Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System database through the end of June. The cases are still under investigation.

To date, more than 12 million doses of the vaccine have been administered, making the rate of GBS 8.1 cases for every million doses administered.

Although it is still extremely rare, that’s above the expected background rate of GBS of 1.6 cases for every million people, said Grace Lee, MD, a Stanford, Calif., pediatrician who chairs the ACIP’s Vaccine Safety Technical Work Group.

So far, most GBS cases (61%) have been among men. The midpoint age of the cases was 57 years. The average time to onset was 14 days, and 98% of cases occurred within 42 days of the shot. Facial paralysis has been associated with an estimated 30%-50% of cases. One person, who had heart failure, high blood pressure, and diabetes, has died.

Still, the benefits of the vaccine far outweigh its risks. For every million doses given to people over age 50, the vaccine prevents nearly 7,500 COVID-19 hospitalizations and nearly 100 deaths in women, and more than 13,000 COVID-19 hospitalizations and more than 2,400 deaths in men.

Rates of GBS after the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna were around 1 case for every 1 million doses given, which is not above the rate that would be expected without vaccination.

The link to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine prompted the FDA to add a warning to the vaccine’s patient safety information on July 12.

Also in July, the European Medicines Agency recommended a similar warning for the product information of the AstraZeneca vaccine Vaxzevria, which relies on similar technology.

Good against variants

Johnson & Johnson also presented new information showing its vaccine maintained high levels of neutralizing antibodies against four of the so-called “variants of concern” – Alpha, Gamma, Beta, and Delta. The protection generated by the vaccine lasted for at least 8 months after the shot, the company said.

“We’re still learning about the duration of protection and the breadth of coverage against this evolving variant landscape for each of the authorized vaccines,” said Mathai Mammen, MD, PhD, global head of research and development at Janssen, the company that makes the vaccine for J&J.

The company also said that its vaccine generated very strong T-cell responses. T cells destroy infected cells and, along with antibodies, are an important part of the body’s immune response.

Antibody levels and T-cell responses are markers for immunity. Measuring these levels isn’t the same as proving that shots can fend off an infection.

It’s still unclear exactly which component of the immune response is most important for fighting off COVID-19.

Dr. Mammen said the companies are still gathering that clinical data, and would present it soon.

“We will have a better view of the clinical efficacy in the coming weeks,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite recent reports of Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine,

The company also presented new data suggesting that the shots generate strong immune responses against circulating variants and that antibodies generated by the vaccine stay elevated for at least 8 months.

Members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) did not vote, but discussed and affirmed their support for recent decisions by the Food and Drug Administration and CDC to update patient information about the very low risk of GBS that appears to be associated with the vaccine, but to continue offering the vaccine to people in the United States.

The Johnson & Johnson shot has been a minor player in the U.S. vaccination campaign, accounting for less than 4% of all vaccine doses given in this country. Still, the single-dose inoculation, which doesn’t require ultra-cold storage, has been important for reaching people in rural areas, through mobile clinics, at colleges and primary care offices, and in vulnerable populations – those who are incarcerated or homeless.

The FDA says it has received reports of 100 cases of GBS after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in its Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System database through the end of June. The cases are still under investigation.

To date, more than 12 million doses of the vaccine have been administered, making the rate of GBS 8.1 cases for every million doses administered.

Although it is still extremely rare, that’s above the expected background rate of GBS of 1.6 cases for every million people, said Grace Lee, MD, a Stanford, Calif., pediatrician who chairs the ACIP’s Vaccine Safety Technical Work Group.

So far, most GBS cases (61%) have been among men. The midpoint age of the cases was 57 years. The average time to onset was 14 days, and 98% of cases occurred within 42 days of the shot. Facial paralysis has been associated with an estimated 30%-50% of cases. One person, who had heart failure, high blood pressure, and diabetes, has died.

Still, the benefits of the vaccine far outweigh its risks. For every million doses given to people over age 50, the vaccine prevents nearly 7,500 COVID-19 hospitalizations and nearly 100 deaths in women, and more than 13,000 COVID-19 hospitalizations and more than 2,400 deaths in men.

Rates of GBS after the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna were around 1 case for every 1 million doses given, which is not above the rate that would be expected without vaccination.

The link to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine prompted the FDA to add a warning to the vaccine’s patient safety information on July 12.

Also in July, the European Medicines Agency recommended a similar warning for the product information of the AstraZeneca vaccine Vaxzevria, which relies on similar technology.

Good against variants

Johnson & Johnson also presented new information showing its vaccine maintained high levels of neutralizing antibodies against four of the so-called “variants of concern” – Alpha, Gamma, Beta, and Delta. The protection generated by the vaccine lasted for at least 8 months after the shot, the company said.

“We’re still learning about the duration of protection and the breadth of coverage against this evolving variant landscape for each of the authorized vaccines,” said Mathai Mammen, MD, PhD, global head of research and development at Janssen, the company that makes the vaccine for J&J.

The company also said that its vaccine generated very strong T-cell responses. T cells destroy infected cells and, along with antibodies, are an important part of the body’s immune response.

Antibody levels and T-cell responses are markers for immunity. Measuring these levels isn’t the same as proving that shots can fend off an infection.

It’s still unclear exactly which component of the immune response is most important for fighting off COVID-19.

Dr. Mammen said the companies are still gathering that clinical data, and would present it soon.

“We will have a better view of the clinical efficacy in the coming weeks,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite recent reports of Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine,

The company also presented new data suggesting that the shots generate strong immune responses against circulating variants and that antibodies generated by the vaccine stay elevated for at least 8 months.

Members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) did not vote, but discussed and affirmed their support for recent decisions by the Food and Drug Administration and CDC to update patient information about the very low risk of GBS that appears to be associated with the vaccine, but to continue offering the vaccine to people in the United States.

The Johnson & Johnson shot has been a minor player in the U.S. vaccination campaign, accounting for less than 4% of all vaccine doses given in this country. Still, the single-dose inoculation, which doesn’t require ultra-cold storage, has been important for reaching people in rural areas, through mobile clinics, at colleges and primary care offices, and in vulnerable populations – those who are incarcerated or homeless.

The FDA says it has received reports of 100 cases of GBS after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in its Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System database through the end of June. The cases are still under investigation.

To date, more than 12 million doses of the vaccine have been administered, making the rate of GBS 8.1 cases for every million doses administered.

Although it is still extremely rare, that’s above the expected background rate of GBS of 1.6 cases for every million people, said Grace Lee, MD, a Stanford, Calif., pediatrician who chairs the ACIP’s Vaccine Safety Technical Work Group.

So far, most GBS cases (61%) have been among men. The midpoint age of the cases was 57 years. The average time to onset was 14 days, and 98% of cases occurred within 42 days of the shot. Facial paralysis has been associated with an estimated 30%-50% of cases. One person, who had heart failure, high blood pressure, and diabetes, has died.

Still, the benefits of the vaccine far outweigh its risks. For every million doses given to people over age 50, the vaccine prevents nearly 7,500 COVID-19 hospitalizations and nearly 100 deaths in women, and more than 13,000 COVID-19 hospitalizations and more than 2,400 deaths in men.

Rates of GBS after the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna were around 1 case for every 1 million doses given, which is not above the rate that would be expected without vaccination.

The link to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine prompted the FDA to add a warning to the vaccine’s patient safety information on July 12.

Also in July, the European Medicines Agency recommended a similar warning for the product information of the AstraZeneca vaccine Vaxzevria, which relies on similar technology.

Good against variants

Johnson & Johnson also presented new information showing its vaccine maintained high levels of neutralizing antibodies against four of the so-called “variants of concern” – Alpha, Gamma, Beta, and Delta. The protection generated by the vaccine lasted for at least 8 months after the shot, the company said.

“We’re still learning about the duration of protection and the breadth of coverage against this evolving variant landscape for each of the authorized vaccines,” said Mathai Mammen, MD, PhD, global head of research and development at Janssen, the company that makes the vaccine for J&J.

The company also said that its vaccine generated very strong T-cell responses. T cells destroy infected cells and, along with antibodies, are an important part of the body’s immune response.

Antibody levels and T-cell responses are markers for immunity. Measuring these levels isn’t the same as proving that shots can fend off an infection.

It’s still unclear exactly which component of the immune response is most important for fighting off COVID-19.

Dr. Mammen said the companies are still gathering that clinical data, and would present it soon.

“We will have a better view of the clinical efficacy in the coming weeks,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Exploring your fishpond: Steps toward managing anxiety in the age of COVID

COVID-19’s ever-changing trajectory has led to a notable rise in anxiety-related disorders in the United States. The average share of U.S. adults reporting symptoms of anxiety and or depressive disorder rose from 11% in 2019 to more than 41% in January 2021, according to a report from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

With the arrival of vaccines, Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, MD, MPH, chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center, has noticed a shift in patients’ fears and concerns. In an interview, she explained how anxiety in patients has evolved along with the pandemic. She also offered strategies for gaining control, engaging with community, and managing anxiety.

Question: When you see patients at this point in the pandemic, what do you ask them?

Answer: I ask them how the pandemic has affected them. Responses have changed over time. In the beginning, I saw a lot of fear, dread of the unknown, a lot of frustration about being in lockdown. As the vaccines have come in and taken hold, there is both a sense of relief, but still a lot of anxiety. Part of that is we’re getting different messages and very much changing messages over time. Then there’s the people who are unvaccinated, and we’re also seeing the Delta variant taking hold in the rest of the world. There’s a lot of anxiety, fear, and some depression, although that’s gotten better with the vaccine.

Q: How do we distinguish between reasonable or rational anxiety and excessive or irrational anxiety?

A: There’s not a bright line between them. What’s rational for one person is not rational for another. What we’ve seen is a spectrum. A rational anxiety is: “I’m not ready to go to a party.” Irrational represents all these crazy theories that are made up, such as putting a microchip into your arm with the vaccine so that the government can track you.

Q: How do you talk to these people thinking irrational thoughts?

A: You must listen to them and not just shut them down. Work with them. Many people with irrational thoughts, or believe in conspiracy theories, may not want to go near a psychiatrist. But there’s also the patients in the psychiatric ward who believe COVID doesn’t exist and there’s government plots. Like any other delusional material, we work with this by talking to these patients and using medication as appropriate.

Q: Do you support prescribing medication for those patients who continue to experience anxiety that is irrational?

A: Patients based in inpatient psychiatry are usually delusional. The medication we usually prescribe for these patients is antipsychotics. If it’s an outpatient who’s anxious about COVID, but has rational anxiety, we usually use antidepressants or antianxiety agents such as Zoloft, Paxil, or Lexapro.

Q: What other strategies can psychiatrists share with patients?

A: What I’ve seen throughout COVID is often an overwhelming sense of dread and inability to control the situation. I tell patients to do things they can control. You can go out and get exercise. Especially during the winter, I recommend that people take a walk and get some sunshine.

It also helps with anxiety to reach out and help someone else. Is there a neighbor you’re concerned about? By and large, this is something many communities have done well. The challenge is we’ve been avoiding each other physically for a long time. So, some of the standard ways of helping each other out, like volunteering at a food bank, have been a little problematic. But there are ways to have minimal people on staff to reduce exposure.

One thing I recommend with any type of anxiety is to learn how to control your breathing. Take breaths through the nose several times a day and teach yourself how to slow down. Another thing that helps many people is contact with animals – especially horses, dogs, and cats. You may not be able to adopt an animal, but you could work at a rescue shelter or other facilities. People can benefit from the nonverbal cues of an animal. A friend of mine got a shelter cat. It sleeps with her and licks her when she feels anxious.

Meditation and yoga are also useful. This is not for everyone, but it’s a way to turn down the level of “buzz” or anxiety. Don’t overdo it on caffeine or other things that increase anxiety. I would stay away from illicit drugs, as they increase anxiety.

Q: What do you say to patients to give them a sense of hope?

A: A lot of people aren’t ready to return to normal; they want to keep the social isolation, the masks, the working from home. We need to show patients what they have control over to minimize their own risk. For example, if they want to wear a mask, then they should wear one. Patients also really like the option of telehealth appointments.

Another way to cope is to identify what’s better about the way things are now and concentrate on those improvements. Here in Maryland, the traffic is so much better in the morning than it once was. There are things I don’t miss, like going to the airport and waiting 5 hours for a flight.

Q: What advice can you give psychiatrists who are experiencing anxiety?

A: We must manage our own anxiety so we can help our patients. Strategies I’ve mentioned are also helpful to psychiatrists or other health care professionals (such as) taking a walk, getting exercise, controlling what you can control. For me, it’s getting dressed, going to work, seeing patients. Having a daily structure, a routine, is important. Many people struggled with this at first. They were working from home and didn’t get much done; they did too much videogaming. It helps to set regular appointments if you’re working from home.

Pre-COVID, many of us got a lot out of our professional meetings. We saw friends there. Now they’re either canceled or we’re doing them virtually, which isn’t the same thing. I think our profession could do a better job of reaching out to each other. We’re used to seeing each other once or twice a year at conventions. I’ve since found it hard to reach out to my colleagues via email. And everyone is tired of Zoom.

If they’re local, ask them to do a safe outdoor activity, a happy hour, a walk. If they’re not, maybe engage with them through a postcard or a phone call.

My colleagues and I go for walks at lunch. There’s a fishpond nearby and we talk to the fish and get a little silly. We sometimes take fish nets with us. People ask what the fish nets are for and we’ll say, “we’re chasing COVID away.”

Dr. Ritchie reported no conflicts of interest.

COVID-19’s ever-changing trajectory has led to a notable rise in anxiety-related disorders in the United States. The average share of U.S. adults reporting symptoms of anxiety and or depressive disorder rose from 11% in 2019 to more than 41% in January 2021, according to a report from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

With the arrival of vaccines, Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, MD, MPH, chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center, has noticed a shift in patients’ fears and concerns. In an interview, she explained how anxiety in patients has evolved along with the pandemic. She also offered strategies for gaining control, engaging with community, and managing anxiety.

Question: When you see patients at this point in the pandemic, what do you ask them?

Answer: I ask them how the pandemic has affected them. Responses have changed over time. In the beginning, I saw a lot of fear, dread of the unknown, a lot of frustration about being in lockdown. As the vaccines have come in and taken hold, there is both a sense of relief, but still a lot of anxiety. Part of that is we’re getting different messages and very much changing messages over time. Then there’s the people who are unvaccinated, and we’re also seeing the Delta variant taking hold in the rest of the world. There’s a lot of anxiety, fear, and some depression, although that’s gotten better with the vaccine.

Q: How do we distinguish between reasonable or rational anxiety and excessive or irrational anxiety?

A: There’s not a bright line between them. What’s rational for one person is not rational for another. What we’ve seen is a spectrum. A rational anxiety is: “I’m not ready to go to a party.” Irrational represents all these crazy theories that are made up, such as putting a microchip into your arm with the vaccine so that the government can track you.

Q: How do you talk to these people thinking irrational thoughts?

A: You must listen to them and not just shut them down. Work with them. Many people with irrational thoughts, or believe in conspiracy theories, may not want to go near a psychiatrist. But there’s also the patients in the psychiatric ward who believe COVID doesn’t exist and there’s government plots. Like any other delusional material, we work with this by talking to these patients and using medication as appropriate.

Q: Do you support prescribing medication for those patients who continue to experience anxiety that is irrational?

A: Patients based in inpatient psychiatry are usually delusional. The medication we usually prescribe for these patients is antipsychotics. If it’s an outpatient who’s anxious about COVID, but has rational anxiety, we usually use antidepressants or antianxiety agents such as Zoloft, Paxil, or Lexapro.

Q: What other strategies can psychiatrists share with patients?

A: What I’ve seen throughout COVID is often an overwhelming sense of dread and inability to control the situation. I tell patients to do things they can control. You can go out and get exercise. Especially during the winter, I recommend that people take a walk and get some sunshine.

It also helps with anxiety to reach out and help someone else. Is there a neighbor you’re concerned about? By and large, this is something many communities have done well. The challenge is we’ve been avoiding each other physically for a long time. So, some of the standard ways of helping each other out, like volunteering at a food bank, have been a little problematic. But there are ways to have minimal people on staff to reduce exposure.

One thing I recommend with any type of anxiety is to learn how to control your breathing. Take breaths through the nose several times a day and teach yourself how to slow down. Another thing that helps many people is contact with animals – especially horses, dogs, and cats. You may not be able to adopt an animal, but you could work at a rescue shelter or other facilities. People can benefit from the nonverbal cues of an animal. A friend of mine got a shelter cat. It sleeps with her and licks her when she feels anxious.

Meditation and yoga are also useful. This is not for everyone, but it’s a way to turn down the level of “buzz” or anxiety. Don’t overdo it on caffeine or other things that increase anxiety. I would stay away from illicit drugs, as they increase anxiety.

Q: What do you say to patients to give them a sense of hope?

A: A lot of people aren’t ready to return to normal; they want to keep the social isolation, the masks, the working from home. We need to show patients what they have control over to minimize their own risk. For example, if they want to wear a mask, then they should wear one. Patients also really like the option of telehealth appointments.

Another way to cope is to identify what’s better about the way things are now and concentrate on those improvements. Here in Maryland, the traffic is so much better in the morning than it once was. There are things I don’t miss, like going to the airport and waiting 5 hours for a flight.

Q: What advice can you give psychiatrists who are experiencing anxiety?

A: We must manage our own anxiety so we can help our patients. Strategies I’ve mentioned are also helpful to psychiatrists or other health care professionals (such as) taking a walk, getting exercise, controlling what you can control. For me, it’s getting dressed, going to work, seeing patients. Having a daily structure, a routine, is important. Many people struggled with this at first. They were working from home and didn’t get much done; they did too much videogaming. It helps to set regular appointments if you’re working from home.

Pre-COVID, many of us got a lot out of our professional meetings. We saw friends there. Now they’re either canceled or we’re doing them virtually, which isn’t the same thing. I think our profession could do a better job of reaching out to each other. We’re used to seeing each other once or twice a year at conventions. I’ve since found it hard to reach out to my colleagues via email. And everyone is tired of Zoom.

If they’re local, ask them to do a safe outdoor activity, a happy hour, a walk. If they’re not, maybe engage with them through a postcard or a phone call.

My colleagues and I go for walks at lunch. There’s a fishpond nearby and we talk to the fish and get a little silly. We sometimes take fish nets with us. People ask what the fish nets are for and we’ll say, “we’re chasing COVID away.”

Dr. Ritchie reported no conflicts of interest.

COVID-19’s ever-changing trajectory has led to a notable rise in anxiety-related disorders in the United States. The average share of U.S. adults reporting symptoms of anxiety and or depressive disorder rose from 11% in 2019 to more than 41% in January 2021, according to a report from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

With the arrival of vaccines, Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, MD, MPH, chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center, has noticed a shift in patients’ fears and concerns. In an interview, she explained how anxiety in patients has evolved along with the pandemic. She also offered strategies for gaining control, engaging with community, and managing anxiety.

Question: When you see patients at this point in the pandemic, what do you ask them?

Answer: I ask them how the pandemic has affected them. Responses have changed over time. In the beginning, I saw a lot of fear, dread of the unknown, a lot of frustration about being in lockdown. As the vaccines have come in and taken hold, there is both a sense of relief, but still a lot of anxiety. Part of that is we’re getting different messages and very much changing messages over time. Then there’s the people who are unvaccinated, and we’re also seeing the Delta variant taking hold in the rest of the world. There’s a lot of anxiety, fear, and some depression, although that’s gotten better with the vaccine.

Q: How do we distinguish between reasonable or rational anxiety and excessive or irrational anxiety?

A: There’s not a bright line between them. What’s rational for one person is not rational for another. What we’ve seen is a spectrum. A rational anxiety is: “I’m not ready to go to a party.” Irrational represents all these crazy theories that are made up, such as putting a microchip into your arm with the vaccine so that the government can track you.

Q: How do you talk to these people thinking irrational thoughts?

A: You must listen to them and not just shut them down. Work with them. Many people with irrational thoughts, or believe in conspiracy theories, may not want to go near a psychiatrist. But there’s also the patients in the psychiatric ward who believe COVID doesn’t exist and there’s government plots. Like any other delusional material, we work with this by talking to these patients and using medication as appropriate.

Q: Do you support prescribing medication for those patients who continue to experience anxiety that is irrational?

A: Patients based in inpatient psychiatry are usually delusional. The medication we usually prescribe for these patients is antipsychotics. If it’s an outpatient who’s anxious about COVID, but has rational anxiety, we usually use antidepressants or antianxiety agents such as Zoloft, Paxil, or Lexapro.

Q: What other strategies can psychiatrists share with patients?

A: What I’ve seen throughout COVID is often an overwhelming sense of dread and inability to control the situation. I tell patients to do things they can control. You can go out and get exercise. Especially during the winter, I recommend that people take a walk and get some sunshine.