User login

Altha J. Stewart, MD, on the state of psychiatry

For this Psychiatry Leaders’ Perspectives, Awais Aftab, MD, interviewed Altha J. Stewart, MD. Dr. Stewart is Senior Associate Dean for Community Health Engagement at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC)–Memphis. She also serves as Chief of the Division of Social and Community Psychiatry and Director, Center for Health in Justice Involved Youth at UTHSC, where she manages community-based programs serving children impacted by trauma and mental illness and their families. In 2018, she was elected President of the American Psychiatric Association, the first African American individual elected in the 175-year history of the organization.

Dr. Aftab: Structural racism in academic and organized psychiatry is an issue that is close to your heart. What is your perspective on the current state of structural racism in American psychiatry, and what do you think we can do about it?

Dr. Stewart: That’s a good question to start with because I think the conversations that we need to have in academia in general and in academic psychiatry specifically really do frame the current issues that we are facing, whether we’re talking about eliminating health disparities or achieving mental health equity. Historically, from the very beginning these discussions have been structured in a racist manner. The early days of American psychiatry were very clearly directed towards maintaining a system that excluded large segments of the population of the time, since a particularly violent form of chattel slavery was being practiced in this country.

The mental health care system was primarily designed for the landowning white men of some standing in society, and so there was never any intent to do much in the way of providing quality humane service to people who were not part of that group. What we have today is a system that was designed for a racist societal structure, that was intended to perpetuate certain behaviors, policies, and practices that had at their core a racist framework. We have to acknowledge and start from this beginning point. This is not to blame anyone currently alive. These are larger structural problems. Before we can begin setting up strategic plans and other actions, we have to go back and acknowledge how we got here. We have to accept the responsibility for being here, and then we have to allow the conversations that need to happen to happen in a safe way, without further alienating people, or maligning and demeaning people who are for the most part well-intentioned but perhaps operating on automatic pilot in a system that is structurally racist.

Dr. Aftab: Do you think that the conversations that need to happen are taking place?

Dr. Stewart: Yes, I think they are beginning to happen. I do a fair number of talks and grand rounds, and what I discover when I meet with different academic departments and different groups is that most places now have a diversity committee, or the residents and students have assigned themselves as diversity leaders. They are really pushing to have these conversations, to insert these conversations into the training and education curricula. The structures in power are so deeply entrenched that many people, particularly younger people, are easily frustrated by the lack of forward motion. One of the things that seasoned leaders in psychiatry have to do is to help everyone understand that the movement forward might be glacial in the beginning, but any movement forward is good when it comes to this. The psychiatrists of my generation talked about cultural competence in psychiatry, but generations of today talk about structural competence. These are similar concepts, except that cultural competency worked within the traditional model, while structural competency recognizes that the system itself needs to change. I find this development very encouraging.

Dr. Aftab: What do you see as some of the strengths of our profession?

Continue to: Dr. Stewart

Dr. Stewart: I am a hopeful optimist when it comes to psychiatry. I have dedicated my professional life to psychiatry and specifically to community psychiatry. Throughout the time that I have practiced psychiatry, I have been encouraged that what we do as a medical specialty really does improve the quality of life for the people we serve. Situationally right now, we’re in a unique position because the COVID pandemic has laid open and then laid bare the whole issue of how we deal with psychological distress, whether it’s diagnosed mental illness or a natural, normal response to a catastrophic event. We are the experts in this. This is our sweet spot, our wheelhouse, whatever analogy you prefer. This is the moment where we assert our expertise as the leaders—not as service add-ons, not as followers, not as adjuncts, but as the leaders.

I am so impressed with the next generation of psychiatrists. They have a wonderful blend of pride and privilege at what they have been able to accomplish to get to the point where they are doctors and psychiatrists, but they have aligned that with a strong core sense of social justice, and they are moved by their responsibility to the people in the society around them.

Another strength of our profession is what we consider to be the “art” of psychiatry. That is, the way we marry the relational aspects of psychiatry with the biological, technical, and digital aspects to arrive at a happy collaboration that benefits people. It is our great skill to engage people, to interact with them therapeutically, to recognize and acknowledge the nonverbal cues. This skill will be even more important in the age of online mental health services. I’m an “old-school” therapist. I like that face-to-face interaction. I think it’s important to preserve that aspect of our practice, even as we move towards online services.

Dr. Aftab: Are there ways in which the status quo in psychiatry falls short of the ideal? What are our areas of relative weakness?

Dr. Stewart: I don’t think we can afford to remain in status quo, because we need to constantly think and rethink, evaluate and re-evaluate, assess things in the light of new information. Particularly if we’re talking about people who rely on public funding to get even the bare minimum services, status quo doesn’t cut it. It’s not good enough. I had a teacher during my residency, a child psychiatrist, who used to say, “Good, better, best. Never let it rest, until your good is better and your better is best.” Something about that has stuck with me. As my career progressed, I heard variations of it, including one from former Surgeon General of the United States David Satcher, who was not a psychiatrist, but pulled together the group that published the first Surgeon General’s report on mental health, followed by the Surgeon General’s report on mental health, culture, race, and ethnicity. He had the penetrating insight that risk factors are not to be accepted as predictive factors due to protective factors. If I am at risk for mental illness or a chronic medical condition based on my race or ethnicity or socioeconomic status or employment status, this does not mean that I am destined to experience that illness. In fact, we are not doing our job if we accept these outcomes as inevitable and make no attempt to change them. So, for me, if we accept the status quo, we give up on the message of “Good, better, best. Never let it rest, until your good is better and your better is best.”

Continue to: Dr. Aftab

Dr. Aftab: What is your perception of the threats that psychiatry faces or is likely to face in the future?

Dr. Stewart: Well, this is going to sound harsh, and I do hope that the readers do not feel that I intend it to be harsh. We get in our own way. I work in the public sector, for example, and the reality is that there aren’t enough psychiatrists to provide all the necessary psychiatric services for the people who need them. So many mental health clinics and practices employ other mental health professionals, whether they are psychologists or nurse practitioners or physician assistants with special training in mental health to provide those services. To have a blanket concern about anyone who is not an MD practicing in what is considered “our area” just begs the question that if we can’t do it and we don’t have enough psychiatrists to do it, should people just not get mental health treatment? Is that the solution? I don’t think so. I don’t think that’s what people want, either, but because of the energy that gets aroused around these issues, we lose sight of that end goal. I think the answer is that we must take leadership for ensuring that our colleagues are well-trained, maybe not as well-trained as physicians, but well-trained enough to provide good care working under our supervision.

Dr. Aftab: What do you envision for the future of psychiatry? What sort of opportunities lie ahead for us?

Dr. Stewart: I think we are moving naturally into the space of integrated or collaborative care. I think we’re going to have to acknowledge that going forward, the path to being a good psychiatrist means that we will also be consultants. Not just the consultation-liaison kind of consultant that we typically think of, but a consultant to the rest of medicine around shaping programs, addressing how we treat comorbid illness, looking at ways to minimize the morbidity and mortality associated with some of the chronic medical and mental diseases. We’re moving naturally in that direction. For some people, that must be frightening. All throughout medicine people are witnessing change, and we need to adapt. I would hope that the specialty that is designed to help others deal with change will figure out how to use those skills to help themselves deal with the changes that are coming!

For this Psychiatry Leaders’ Perspectives, Awais Aftab, MD, interviewed Altha J. Stewart, MD. Dr. Stewart is Senior Associate Dean for Community Health Engagement at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC)–Memphis. She also serves as Chief of the Division of Social and Community Psychiatry and Director, Center for Health in Justice Involved Youth at UTHSC, where she manages community-based programs serving children impacted by trauma and mental illness and their families. In 2018, she was elected President of the American Psychiatric Association, the first African American individual elected in the 175-year history of the organization.

Dr. Aftab: Structural racism in academic and organized psychiatry is an issue that is close to your heart. What is your perspective on the current state of structural racism in American psychiatry, and what do you think we can do about it?

Dr. Stewart: That’s a good question to start with because I think the conversations that we need to have in academia in general and in academic psychiatry specifically really do frame the current issues that we are facing, whether we’re talking about eliminating health disparities or achieving mental health equity. Historically, from the very beginning these discussions have been structured in a racist manner. The early days of American psychiatry were very clearly directed towards maintaining a system that excluded large segments of the population of the time, since a particularly violent form of chattel slavery was being practiced in this country.

The mental health care system was primarily designed for the landowning white men of some standing in society, and so there was never any intent to do much in the way of providing quality humane service to people who were not part of that group. What we have today is a system that was designed for a racist societal structure, that was intended to perpetuate certain behaviors, policies, and practices that had at their core a racist framework. We have to acknowledge and start from this beginning point. This is not to blame anyone currently alive. These are larger structural problems. Before we can begin setting up strategic plans and other actions, we have to go back and acknowledge how we got here. We have to accept the responsibility for being here, and then we have to allow the conversations that need to happen to happen in a safe way, without further alienating people, or maligning and demeaning people who are for the most part well-intentioned but perhaps operating on automatic pilot in a system that is structurally racist.

Dr. Aftab: Do you think that the conversations that need to happen are taking place?

Dr. Stewart: Yes, I think they are beginning to happen. I do a fair number of talks and grand rounds, and what I discover when I meet with different academic departments and different groups is that most places now have a diversity committee, or the residents and students have assigned themselves as diversity leaders. They are really pushing to have these conversations, to insert these conversations into the training and education curricula. The structures in power are so deeply entrenched that many people, particularly younger people, are easily frustrated by the lack of forward motion. One of the things that seasoned leaders in psychiatry have to do is to help everyone understand that the movement forward might be glacial in the beginning, but any movement forward is good when it comes to this. The psychiatrists of my generation talked about cultural competence in psychiatry, but generations of today talk about structural competence. These are similar concepts, except that cultural competency worked within the traditional model, while structural competency recognizes that the system itself needs to change. I find this development very encouraging.

Dr. Aftab: What do you see as some of the strengths of our profession?

Continue to: Dr. Stewart

Dr. Stewart: I am a hopeful optimist when it comes to psychiatry. I have dedicated my professional life to psychiatry and specifically to community psychiatry. Throughout the time that I have practiced psychiatry, I have been encouraged that what we do as a medical specialty really does improve the quality of life for the people we serve. Situationally right now, we’re in a unique position because the COVID pandemic has laid open and then laid bare the whole issue of how we deal with psychological distress, whether it’s diagnosed mental illness or a natural, normal response to a catastrophic event. We are the experts in this. This is our sweet spot, our wheelhouse, whatever analogy you prefer. This is the moment where we assert our expertise as the leaders—not as service add-ons, not as followers, not as adjuncts, but as the leaders.

I am so impressed with the next generation of psychiatrists. They have a wonderful blend of pride and privilege at what they have been able to accomplish to get to the point where they are doctors and psychiatrists, but they have aligned that with a strong core sense of social justice, and they are moved by their responsibility to the people in the society around them.

Another strength of our profession is what we consider to be the “art” of psychiatry. That is, the way we marry the relational aspects of psychiatry with the biological, technical, and digital aspects to arrive at a happy collaboration that benefits people. It is our great skill to engage people, to interact with them therapeutically, to recognize and acknowledge the nonverbal cues. This skill will be even more important in the age of online mental health services. I’m an “old-school” therapist. I like that face-to-face interaction. I think it’s important to preserve that aspect of our practice, even as we move towards online services.

Dr. Aftab: Are there ways in which the status quo in psychiatry falls short of the ideal? What are our areas of relative weakness?

Dr. Stewart: I don’t think we can afford to remain in status quo, because we need to constantly think and rethink, evaluate and re-evaluate, assess things in the light of new information. Particularly if we’re talking about people who rely on public funding to get even the bare minimum services, status quo doesn’t cut it. It’s not good enough. I had a teacher during my residency, a child psychiatrist, who used to say, “Good, better, best. Never let it rest, until your good is better and your better is best.” Something about that has stuck with me. As my career progressed, I heard variations of it, including one from former Surgeon General of the United States David Satcher, who was not a psychiatrist, but pulled together the group that published the first Surgeon General’s report on mental health, followed by the Surgeon General’s report on mental health, culture, race, and ethnicity. He had the penetrating insight that risk factors are not to be accepted as predictive factors due to protective factors. If I am at risk for mental illness or a chronic medical condition based on my race or ethnicity or socioeconomic status or employment status, this does not mean that I am destined to experience that illness. In fact, we are not doing our job if we accept these outcomes as inevitable and make no attempt to change them. So, for me, if we accept the status quo, we give up on the message of “Good, better, best. Never let it rest, until your good is better and your better is best.”

Continue to: Dr. Aftab

Dr. Aftab: What is your perception of the threats that psychiatry faces or is likely to face in the future?

Dr. Stewart: Well, this is going to sound harsh, and I do hope that the readers do not feel that I intend it to be harsh. We get in our own way. I work in the public sector, for example, and the reality is that there aren’t enough psychiatrists to provide all the necessary psychiatric services for the people who need them. So many mental health clinics and practices employ other mental health professionals, whether they are psychologists or nurse practitioners or physician assistants with special training in mental health to provide those services. To have a blanket concern about anyone who is not an MD practicing in what is considered “our area” just begs the question that if we can’t do it and we don’t have enough psychiatrists to do it, should people just not get mental health treatment? Is that the solution? I don’t think so. I don’t think that’s what people want, either, but because of the energy that gets aroused around these issues, we lose sight of that end goal. I think the answer is that we must take leadership for ensuring that our colleagues are well-trained, maybe not as well-trained as physicians, but well-trained enough to provide good care working under our supervision.

Dr. Aftab: What do you envision for the future of psychiatry? What sort of opportunities lie ahead for us?

Dr. Stewart: I think we are moving naturally into the space of integrated or collaborative care. I think we’re going to have to acknowledge that going forward, the path to being a good psychiatrist means that we will also be consultants. Not just the consultation-liaison kind of consultant that we typically think of, but a consultant to the rest of medicine around shaping programs, addressing how we treat comorbid illness, looking at ways to minimize the morbidity and mortality associated with some of the chronic medical and mental diseases. We’re moving naturally in that direction. For some people, that must be frightening. All throughout medicine people are witnessing change, and we need to adapt. I would hope that the specialty that is designed to help others deal with change will figure out how to use those skills to help themselves deal with the changes that are coming!

For this Psychiatry Leaders’ Perspectives, Awais Aftab, MD, interviewed Altha J. Stewart, MD. Dr. Stewart is Senior Associate Dean for Community Health Engagement at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC)–Memphis. She also serves as Chief of the Division of Social and Community Psychiatry and Director, Center for Health in Justice Involved Youth at UTHSC, where she manages community-based programs serving children impacted by trauma and mental illness and their families. In 2018, she was elected President of the American Psychiatric Association, the first African American individual elected in the 175-year history of the organization.

Dr. Aftab: Structural racism in academic and organized psychiatry is an issue that is close to your heart. What is your perspective on the current state of structural racism in American psychiatry, and what do you think we can do about it?

Dr. Stewart: That’s a good question to start with because I think the conversations that we need to have in academia in general and in academic psychiatry specifically really do frame the current issues that we are facing, whether we’re talking about eliminating health disparities or achieving mental health equity. Historically, from the very beginning these discussions have been structured in a racist manner. The early days of American psychiatry were very clearly directed towards maintaining a system that excluded large segments of the population of the time, since a particularly violent form of chattel slavery was being practiced in this country.

The mental health care system was primarily designed for the landowning white men of some standing in society, and so there was never any intent to do much in the way of providing quality humane service to people who were not part of that group. What we have today is a system that was designed for a racist societal structure, that was intended to perpetuate certain behaviors, policies, and practices that had at their core a racist framework. We have to acknowledge and start from this beginning point. This is not to blame anyone currently alive. These are larger structural problems. Before we can begin setting up strategic plans and other actions, we have to go back and acknowledge how we got here. We have to accept the responsibility for being here, and then we have to allow the conversations that need to happen to happen in a safe way, without further alienating people, or maligning and demeaning people who are for the most part well-intentioned but perhaps operating on automatic pilot in a system that is structurally racist.

Dr. Aftab: Do you think that the conversations that need to happen are taking place?

Dr. Stewart: Yes, I think they are beginning to happen. I do a fair number of talks and grand rounds, and what I discover when I meet with different academic departments and different groups is that most places now have a diversity committee, or the residents and students have assigned themselves as diversity leaders. They are really pushing to have these conversations, to insert these conversations into the training and education curricula. The structures in power are so deeply entrenched that many people, particularly younger people, are easily frustrated by the lack of forward motion. One of the things that seasoned leaders in psychiatry have to do is to help everyone understand that the movement forward might be glacial in the beginning, but any movement forward is good when it comes to this. The psychiatrists of my generation talked about cultural competence in psychiatry, but generations of today talk about structural competence. These are similar concepts, except that cultural competency worked within the traditional model, while structural competency recognizes that the system itself needs to change. I find this development very encouraging.

Dr. Aftab: What do you see as some of the strengths of our profession?

Continue to: Dr. Stewart

Dr. Stewart: I am a hopeful optimist when it comes to psychiatry. I have dedicated my professional life to psychiatry and specifically to community psychiatry. Throughout the time that I have practiced psychiatry, I have been encouraged that what we do as a medical specialty really does improve the quality of life for the people we serve. Situationally right now, we’re in a unique position because the COVID pandemic has laid open and then laid bare the whole issue of how we deal with psychological distress, whether it’s diagnosed mental illness or a natural, normal response to a catastrophic event. We are the experts in this. This is our sweet spot, our wheelhouse, whatever analogy you prefer. This is the moment where we assert our expertise as the leaders—not as service add-ons, not as followers, not as adjuncts, but as the leaders.

I am so impressed with the next generation of psychiatrists. They have a wonderful blend of pride and privilege at what they have been able to accomplish to get to the point where they are doctors and psychiatrists, but they have aligned that with a strong core sense of social justice, and they are moved by their responsibility to the people in the society around them.

Another strength of our profession is what we consider to be the “art” of psychiatry. That is, the way we marry the relational aspects of psychiatry with the biological, technical, and digital aspects to arrive at a happy collaboration that benefits people. It is our great skill to engage people, to interact with them therapeutically, to recognize and acknowledge the nonverbal cues. This skill will be even more important in the age of online mental health services. I’m an “old-school” therapist. I like that face-to-face interaction. I think it’s important to preserve that aspect of our practice, even as we move towards online services.

Dr. Aftab: Are there ways in which the status quo in psychiatry falls short of the ideal? What are our areas of relative weakness?

Dr. Stewart: I don’t think we can afford to remain in status quo, because we need to constantly think and rethink, evaluate and re-evaluate, assess things in the light of new information. Particularly if we’re talking about people who rely on public funding to get even the bare minimum services, status quo doesn’t cut it. It’s not good enough. I had a teacher during my residency, a child psychiatrist, who used to say, “Good, better, best. Never let it rest, until your good is better and your better is best.” Something about that has stuck with me. As my career progressed, I heard variations of it, including one from former Surgeon General of the United States David Satcher, who was not a psychiatrist, but pulled together the group that published the first Surgeon General’s report on mental health, followed by the Surgeon General’s report on mental health, culture, race, and ethnicity. He had the penetrating insight that risk factors are not to be accepted as predictive factors due to protective factors. If I am at risk for mental illness or a chronic medical condition based on my race or ethnicity or socioeconomic status or employment status, this does not mean that I am destined to experience that illness. In fact, we are not doing our job if we accept these outcomes as inevitable and make no attempt to change them. So, for me, if we accept the status quo, we give up on the message of “Good, better, best. Never let it rest, until your good is better and your better is best.”

Continue to: Dr. Aftab

Dr. Aftab: What is your perception of the threats that psychiatry faces or is likely to face in the future?

Dr. Stewart: Well, this is going to sound harsh, and I do hope that the readers do not feel that I intend it to be harsh. We get in our own way. I work in the public sector, for example, and the reality is that there aren’t enough psychiatrists to provide all the necessary psychiatric services for the people who need them. So many mental health clinics and practices employ other mental health professionals, whether they are psychologists or nurse practitioners or physician assistants with special training in mental health to provide those services. To have a blanket concern about anyone who is not an MD practicing in what is considered “our area” just begs the question that if we can’t do it and we don’t have enough psychiatrists to do it, should people just not get mental health treatment? Is that the solution? I don’t think so. I don’t think that’s what people want, either, but because of the energy that gets aroused around these issues, we lose sight of that end goal. I think the answer is that we must take leadership for ensuring that our colleagues are well-trained, maybe not as well-trained as physicians, but well-trained enough to provide good care working under our supervision.

Dr. Aftab: What do you envision for the future of psychiatry? What sort of opportunities lie ahead for us?

Dr. Stewart: I think we are moving naturally into the space of integrated or collaborative care. I think we’re going to have to acknowledge that going forward, the path to being a good psychiatrist means that we will also be consultants. Not just the consultation-liaison kind of consultant that we typically think of, but a consultant to the rest of medicine around shaping programs, addressing how we treat comorbid illness, looking at ways to minimize the morbidity and mortality associated with some of the chronic medical and mental diseases. We’re moving naturally in that direction. For some people, that must be frightening. All throughout medicine people are witnessing change, and we need to adapt. I would hope that the specialty that is designed to help others deal with change will figure out how to use those skills to help themselves deal with the changes that are coming!

Lithium and kidney disease: Understand the risks

Lithium is one of the most widely used mood stabilizers and is considered a first-line treatment for bipolar disorder because of its proven antimanic and prophylactic effects.1 This medication also can reduce the risk of suicide in patients with bipolar disorder.2 However, it has a narrow therapeutic index. While lithium has many reversible adverse effects—such as tremors, gastrointestinal disturbance, and thyroid dysfunction—its perceived irreversible nephrotoxic effects makes some clinicians hesitant to prescribe it.3,4 In this article, we describe the relationship between lithium and nephrotoxicity, explain the apparent contradiction in published research regarding this topic, and offer suggestions for how to determine whether you should continue treatment with lithium for a patient who develops renal changes.

A lithium dilemma

Many psychiatrists have faced the dilemma of whether to discontinue lithium upon the appearance of glomerular renal changes and risk exposing patients to relapse or suicide, or to continue prescribing lithium and risk development of end stage renal disease (ESRD). Discontinuing lithium is not associated with the reversal of renal changes and kidney recovery,5 and exposes patients to psychiatric risks, such as mood recurrence and increased risk of suicide.6 Switching from lithium to another mood stabilizer is associated with a host of adverse effects, including diabetes mellitus and weight gain, and mood stabilizer use is not associated with reduced renal risk in patients with bipolar disorder.5 For example, Markowitz et al6 evaluated 24 patients with renal insufficiency after an average of 13.6 years of chronic lithium treatment. Despite stopping lithium, 8 patients out of the 19 available for follow-up (42%) developed ESRD.6 This study also found that serum creatinine levels >2.5 mg/dL are a predictor of progression to ESRD.6

Discontinuing lithium is associated with high rates of mood recurrence (60% to 70%), especially for patients who had been stable on lithium for years.7,8 If lithium is tapered slowly, the risk of mood recurrence may drop to approximately 42% over the subsequent 18 months, but this is nearly 3-fold greater than the risk of mood recurrence in patients with good response to valproate who are switched to another mood stabilizer (16.7%, c2 = 4.3, P = .048),9 which suggests that stopping lithium is particularly problematic. Considering the lifetime consequences of bipolar illness, for most patients who have been receiving lithium for a long time, the recommendation is to continue lithium.10,11

The reasons for conflicting evidence

Many studies indicate that there is either no statistically significant association or a very low association between lithium and developing ESRD,12-16 while others suggest that long-term lithium treatment increases the risk of chronic nephropathy to a clinically relevant degree (note that these arguments are not mutually exclusive).6,17-22 Much of this confusion has to do with not making a distinction between renal tubular dysfunction, which occurs early and in approximately one-half of patients treated with lithium,23 and glomerular dysfunction, which occurs late and is associated with reductions in glomerular filtration and ESRD.24 Adding to the confusion is that even without lithium, the rate of renal disease in patients with mood disorders is 2- to 3-fold higher than that of the general population.25 Lithium treatment is associated with a rate that is higher still,25-27 but this effect is erroneously exaggerated in studies that examined patients treated with lithium without comparison to a mood-disorder control group.

Renal tubular dysfunction presents as diabetes insipidus with polyuria and polydipsia, which is related to a reduced ability to concentrate the urine.28 Reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR) as a consequence of lithium treatment occurs in 15% of patients23 and represents approximately 0.22% of patients on dialysis.18 Lithium-related reduction in GFR is a slowly progressive process that typically requires >20 years of lithium use to result in ESRD.18 While some decline in GFR may be seen within 1 year after starting lithium, the average age of patients who develop ESRD is 65 years.6 Interestingly, short-term animal studies have suggested that lithium may have antiproteinuric, protective, and pro-reparative effects in acute kidney injury.29

Anatomical anomalies in lithium-related glomerular dysfunction

In a study conducted before improved imaging technology was developed, Markowitz et al6 used renal biopsy to evaluate lithium-related nephropathy in 24 patients.6 Findings revealed chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis in all patients, along with a wide range of abnormalities, including tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis interspersed with microcyst formation arising from distal tubules or collecting ducts.6 Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) was found in 50% of patients. This might have been a result of nephron loss and compensatory hypertrophy of surviving nephrons, which suggests that FSGS is possibly a post-adaptive effect (rather than a direct damaging effect) of lithium on the glomerulus. The most noticeable finding was the appearance of microcysts in 62.5% of patients.6 It is important to note that these biopsy techniques sampled a relatively small fraction of the kidney volume, and that microcysts might have been more prevalent.

Recently, noninvasive imaging techniques have been used to detect microcysts in patients developing lithium-related nephropathy. While ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) can detect renal microcysts, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), specifically the half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo T2-weighted and gadolinium-enhanced (FISP three-dimensional MR angiographic) sequence, is the best noninvasive technology to demonstrate the presence of renal microcysts of a diameter of 1 to 2 mm.30 Ultrasound is sometimes difficult to utilize because while classic cysts appear as anechoic, lithium-induced microcysts may have the appearance of small echogenic foci.31,32 When evaluated by CT, renal microcysts may appear as hypodense lesions.

Continue to: Recent small studies...

Recent small studies have shown that MRI can detect renal microcysts in approximately 100% of patients who are receiving chronic lithium treatment and have renal insufficiency. One MRI study found renal microcysts in all 16 patients.33 In another MRI study of 4 patients, all were positive for renal microcysts.34 The relationship between MRI findings and renal function impairment in patients receiving long-term lithium therapy is still not clear; however, 1 study that examined 35 patients who received lithium reported that the number of cysts is generally related to the duration of lithium therapy.35 Thus, microcysts seem to present long before the elevation in creatinine, and nearly always present in patients with some glomerular dysfunction.

Cystic renal lesions have a wide variety of differential diagnoses, including simple renal cysts; glomerulocystic kidney disease; medullary cystic kidney disease and acquired cystic kidney disease; and multicystic dysplastic kidney and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.36 In patients who have a long history of lithium use, lithium-related nephrotoxicity should be added to the differential diagnosis. The ubiquitous presence of renal microcysts and their relationship to duration of lithium exposure and renal function suggest that they may be intimately related to lithium-related ESRD.37

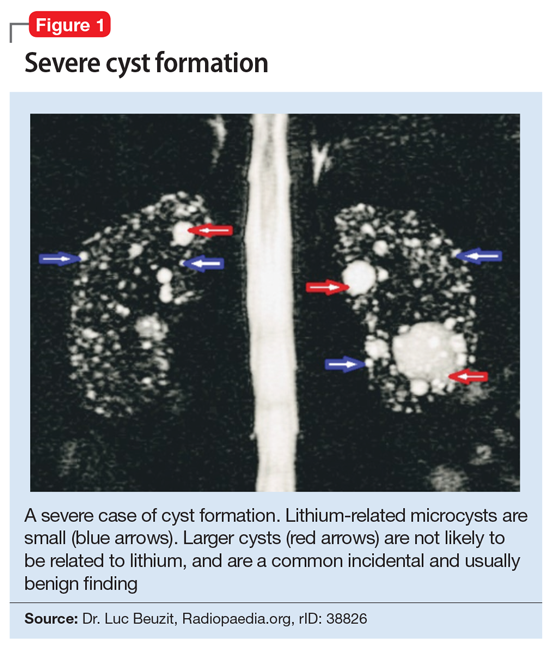

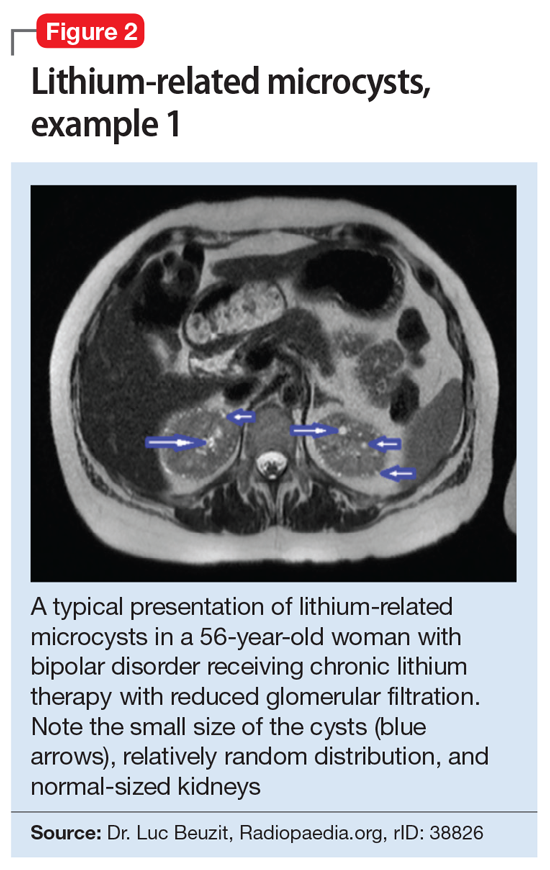

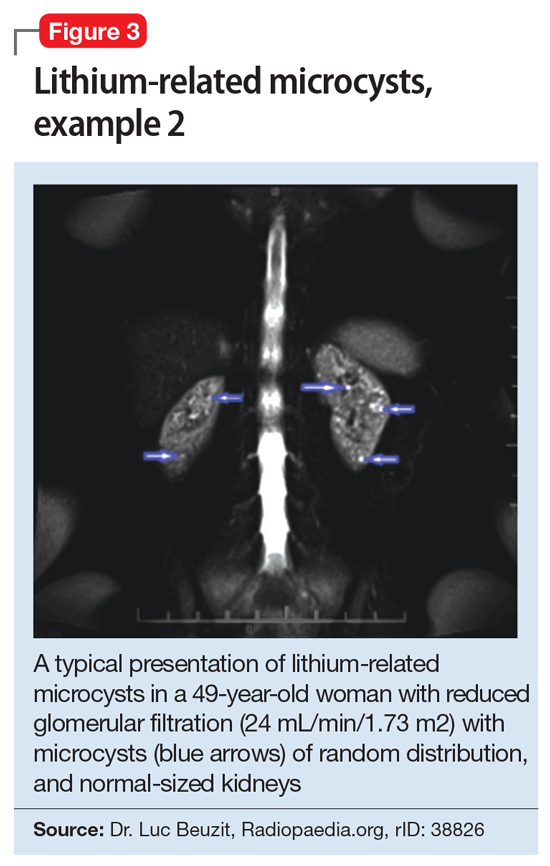

This association appears to be sufficiently reliable and clinicians can use T2-weighted MRI to determine if renal dysfunction is related to lithium. Lithium-related renal microcysts are visualized as multiple bilateral hyperintense foci with a diameter of 1 to 3 mm that involve both the cortex and medulla, tend to be symmetrically distributed throughout the kidney, and are associated with normal-sized kidneys.33,36 Large cysts are unlikely to be related to lithium; only microcysts are associated with lithium treatment. For examples of how these cysts appear on MRI, see Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3. The exact mechanism of lithium-related nephrotoxicity is unclear, but may be related to the mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway or GSK-3beta (glycogen synthase kinase-3beta) (Box6,37-44).

Box 1

The exact mechanism of lithium-related nephrotoxicity is unclear. The mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway is an intracellular signaling pathway important in controlling cell proliferation and cell growth via the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1). Researchers have hypothesized that the mTOR pathway may be responsible for lithium-induced microcysts.38 One study found that mTOR signaling is activated in the renal collecting ducts of mice that received long-term lithium.38 After the same mice received rapamycin (sirolimus), an allosteric inhibitor of mTOR, lithium-induced proliferation of medullary collecting duct cells (microcysts) was reversed.38

Additionally, GSK-3beta (glycogen synthase kinase-3beta), which is expressed in the adult kidney and is a target for lithium, appears to have a role in this pathology. GSK-3beta is involved in multiple biologic processes, including immunomodulation, embryologic development, and tissue injury and repair. It has the ability to promote apoptosis and inhibit proliferation.39 At therapeutic levels, lithium can inhibit GSK-3beta activity by phosphorylation of the serine 9 residue pGSK-3beta-s9.40 This action is believed to play a role in lithium’s neuroprotective properties, specifically through inhibiting the proapoptotic effects of GSK-3beta.41,42 Ironically, this antiapoptotic mechanism of lithium may be associated with its renal adverse effects.

Researchers have proposed that lithium enters distal nephron segments, inhibiting GSK-3beta and disrupting the balance between proliferative and apoptotic signals. The appearance of microcysts may be related to lithium’s antiapoptotic effect. In patients who received chronic treatment with lithium, their kidneys displayed multiple cortical microcysts immunopositive for GSK-3beta.43 Lithium may prevent the clearance of older renal tubular cells that would typically have been removed by normal apoptotic processes.37 As more of these tubular cells accumulate, they invaginate and form a cyst.37 As cysts accumulate during 20 years of treatment, the volume that the cysts occupy within the normal-sized and unyielding renal capsule displaces and injures otherwise healthy renal tissue, in a process similar to injury due to hydrocephalus in the brain.37

Interestingly, if the antiapoptotic mechanism of lithium-induced microcysts is true, it is possible that mood stabilizers that also have antiapoptotic properties (such as valproic acid) would also increase the risk of renal microcysts.44 This may underlie the observation that nearly one-half of patients continue to experience progression of renal disease after discontinuing lithium.6

Take-home points

In patients receiving chronic lithium treatment, it can take 20 years to produce a significant reduction in GFR. Switching patients who respond to lithium to other mood-stabilizing agents is associated with a significantly increased risk for mood recurrence and adverse consequences from the alternate medication. Because ESRD may occur more frequently in patients with mood disorders than in the general population, renal disease may be misattributed to lithium use. In approximately one-half of patients, renal disease will continue to progress after discontinuing lithium, which essentially eliminates the benefit of switching medications. This means that the decision to switch a patient who has responded well to lithium treatment for a decade or more to an alternate agent to avoid progression to ESRD may be associated with a very high potential cost but limited benefit.

One solution might be to more accurately identify patients with lithium-related glomerular disease, so that the potential benefit of switching may outweigh potential harm. The presence of renal microcysts on MRI of the kidney may be used to provide some of that reassurance. On renal biopsy, >60% of patients will have documented microcysts, and on MRI, it may approach 100%. The presence of microcysts provides potential evidence that reduced glomerular function is related to lithium. However, the absence of renal microcysts may not be as instructive—a negative MRI of the kidneys may not be sufficient evidence to rule out lithium as the culprit.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Lithium is an effective treatment for bipolar disorder, but its perceived irreversible nephrotoxic effects make some clinicians hesitant to prescribe it. Discontinuing lithium or switching to another medication also carries risks. For most patients who have been receiving lithium for a long time, the recommendation is to obtain a renal MRI and to cautiously continue lithium if the patient does not have microcysts.

Related Resources

- Hayes JF, Osborn DPJ, Francis E, et al. Prediction of individuals at high risk of chronic kidney disease during treatment with lithium for bipolar disorder. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-01964-z

- Pelekanos M, Foo K. A resident’s guide to lithium. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(4):e3-e7. doi:10.12788/cp.0113

Drug Brand Names

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Sirolimus • Rapamune

Valproate • Depacon

1. Severus E, Bauer M, Geddes J. Efficacy and effectiveness of lithium in the long-term treatment of bipolar disorders: an update 2018. Pharamacopsychiatry. 2018;51(5):173-176.

2. Smith KA, Cipriani A. Lithium and suicide in mood disorders: updated meta-review of the scientific literature. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19(7):575-586.

3. El-Mallakh RS. Lithium: actions and mechanisms. Progress in Psychiatry Series, 50. American Psychiatric Press; 1996.

4. Gitlin M. Why is not lithium prescribed more often? Here are the reasons. J Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 2016, 29:293-297.

5. Kessing LV, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Andersen PK, et al. Continuation of lithium after a diagnosis of chronic kidney disease. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;136(6):615-622.

6. Markowitz GS, Radhakrishnan J, Kambham N, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity: a progressive combined glomerular and tubulointerstitial nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11(8):1439-1448.

7. Faedda GL, Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, et al. Outcome after rapid vs gradual discontinuation of lithium treatment in bipolar disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(6):448-455.

8. Yazici O, Kora K, Polat A, et al. Controlled lithium discontinuation in bipolar patients with good response to long-term lithium prophylaxis. J Affect Disord. 2004;80(2-3):269-271.

9. Rosso G, Solia F, Albert U, et al. Affective recurrences in bipolar disorder after switching from lithium to valproate or vice versa: a series of 57 cases. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;37(2):278-281.

10. Werneke U, Ott M, Renberg ES, et al. A decision analysis of long-term lithium treatment and the risk of renal failure. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;126(3):186-197.

11. Sani G, Perugi G, Tondo L. Treatment of bipolar disorder in a lifetime perspective: is lithium still the best choice? Clin Drug Investig. 2017;37(8):713-727.

12. Vestergaard P, Amdisen A. Lithium treatment and kidney function: a follow-up study of 237 patients in long-term treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1981;63(4):333-345.

13. Walker RG, Bennett WM, Davies BM, et al. Structural and functional effects of long-term lithium therapy. Kidney Int Suppl. 1982;11:S13-S19.

14. Coskunol H, Vahip S, Mees ED, et al. Renal side-effects of long-term lithium treatment. J Affect Disord. 1997;43(1):5-10.

15. Paul R, Minay J, Cardwell C, et al. Meta-analysis of the effects of lithium usage on serum creatinine levels. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(10):1425-1431.

16. McKnight RF, Adida M, Budge K, et al. Lithium toxicity profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9817):721-728.

17. Turan T, Esel E, Tokgöz B, et al. Effects of short- and long-term lithium treatment on kidney functioning in patients with bipolar mood disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26(3):561-565.

18. Presne C, Fakhouri F, Noël LH, et al. Lithium-induced nephropathy: rate of progression and prognostic factors. Kidney Int. 2003;64(2):585-592.

19. McCann SM, Daly J, Kelly CB. The impact of long-term lithium treatment on renal function in an outpatient population. Ulster Med J. 2008;77(2):102-105.

20. Kripalani M, Shawcross J, Reilly J, et al. Lithium and chronic kidney disease. BMJ. 2009;339:b2452. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2452

21. Bendz H, Schön S, Attman PO, et al. Renal failure occurs in chronic lithium treatment but is uncommon. Kidney Int. 2010;77(3):219-224. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.433

22. Aiff H, Attman PO, Aurell M, et al. The impact of modern treatment principles may have eliminated lithium-induced renal failure. J Psychopharmacol. 2014; 28(2):151-154.

23. Boton R, Gaviria M, Batlle DC. Prevalence, pathogenesis, and treatment of renal dysfunction associated with chronic lithium therapy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1987;10(5):329-345.

24. Bocchetta A, Ardau R, Fanni T, et al. Renal function during long-term lithium treatment: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. BMC Med. 2015, 21;13:12. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0249-4

25. Tredget J, Kirov A, Kirov G. Effects of chronic lithium treatment on renal function. J Affect Disord. 2010;126(3):436-440.

26. Adam WR, Schweitzer I, Walker BG. Trade-off between the benefits of lithium treatment and the risk of chronic kidney disease. Nephrology. 2012,17(8):776-779.

27. Azab AN, Shnaider A, Osher Y, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2015;3(1):1-9.

28. Trepiccione F, Christensen BM. Lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: new clinical and experimental findings. J Nephrol. 2010;23 Suppl 16:S43-S48.

29. Gong R, Wang P, Dworkin L. What we need to know about the effect of lithium on the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;311(6):F1168-F1171. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00145.2016

30. Golshayan D, Nseir G, Venetz JP, et al. MR imaging as a specific diagnostic tool for bilateral microcysts in chronic lithium nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2012;81(6):601. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.449

31. Di Salvo DN, Park J, Laing FC. Lithium nephropathy: Unique sonographic findings. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31(4):637-644.

32. Jon´czyk-Potoczna K, Abramowicz M, Chłopocka-Woz´niak M, et al. Renal sonography in bipolar patients on long-term lithium treatment. J Clin Ultrasound. 2016;44(6):354-359.

33. Farres MT, Ronco P, Saadoun D, et al. Chronic lithium nephropathy: MR imaging for diagnosis. Radiol. 2003;229(2):570-574.

34. Roque A, Herédia V, Ramalho M, et al. MR findings of lithium-related kidney disease: preliminary observations in four patients. Abdom Imaging. 2012;37(1):140-146.

35. Farshchian N, Farnia V, Aghaiani M, et al. MRI findings and renal function in patients on long-term lithium therapy. Eur Psychiatry. 2013; 28(Sl):1. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(13)77306-1

36. Wood CG 3rd, Stromberg LJ 3rd, Harmath CB, et al. CT and MR imaging for evaluation of cystic renal lesions and diseases. Radiographics. 2015;35(1):125-141.

37. Khan M, El-Mallakh RS. Renal microcysts and lithium. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2015;50(3):290-298.

38. Gao Y, Romero-Aleshire MJ, Cai Q, et al. Rapamycin inhibition of mTORC1 reverses lithium-induced proliferation of renal collecting duct cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;305(8):1201-1208.

39. Pap M, Cooper GM. Role of glycogen synthase kinase-3 in the phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt cell survival pathway. J Biol Chem. 1998:273(32):19929-19932.

40. Stambolic V, Ruel L, Woodgett JR. Lithium inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity and mimics wingless signalling in intact cells. Curr Biol. 1996;6(12):1664-1668.

41. Rao R. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 regulation of urinary concentrating ability. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2012;21(5):541-546.

42. Diniz BS, Machado Vieira R, Forlenza OV. Lithium and neuroprotection: translational evidence and implications for the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:493-500. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S33086

43. Kjaersgaard G, Madsen K, Marcussen N, et al. Tissue injury after lithium treatment in human and rat postnatal kidney involves glycogen synthase kinase-3β-positive epithelium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302(4):455-465.

44. Zhang C, Zhu J, Zhang J, et al. Neuroprotective and anti-apoptotic effects of valproic acid on adult rat cerebral cortex through ERK and Akt signaling pathway at acute phase of traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2014;1555:1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.01.051

Lithium is one of the most widely used mood stabilizers and is considered a first-line treatment for bipolar disorder because of its proven antimanic and prophylactic effects.1 This medication also can reduce the risk of suicide in patients with bipolar disorder.2 However, it has a narrow therapeutic index. While lithium has many reversible adverse effects—such as tremors, gastrointestinal disturbance, and thyroid dysfunction—its perceived irreversible nephrotoxic effects makes some clinicians hesitant to prescribe it.3,4 In this article, we describe the relationship between lithium and nephrotoxicity, explain the apparent contradiction in published research regarding this topic, and offer suggestions for how to determine whether you should continue treatment with lithium for a patient who develops renal changes.

A lithium dilemma

Many psychiatrists have faced the dilemma of whether to discontinue lithium upon the appearance of glomerular renal changes and risk exposing patients to relapse or suicide, or to continue prescribing lithium and risk development of end stage renal disease (ESRD). Discontinuing lithium is not associated with the reversal of renal changes and kidney recovery,5 and exposes patients to psychiatric risks, such as mood recurrence and increased risk of suicide.6 Switching from lithium to another mood stabilizer is associated with a host of adverse effects, including diabetes mellitus and weight gain, and mood stabilizer use is not associated with reduced renal risk in patients with bipolar disorder.5 For example, Markowitz et al6 evaluated 24 patients with renal insufficiency after an average of 13.6 years of chronic lithium treatment. Despite stopping lithium, 8 patients out of the 19 available for follow-up (42%) developed ESRD.6 This study also found that serum creatinine levels >2.5 mg/dL are a predictor of progression to ESRD.6

Discontinuing lithium is associated with high rates of mood recurrence (60% to 70%), especially for patients who had been stable on lithium for years.7,8 If lithium is tapered slowly, the risk of mood recurrence may drop to approximately 42% over the subsequent 18 months, but this is nearly 3-fold greater than the risk of mood recurrence in patients with good response to valproate who are switched to another mood stabilizer (16.7%, c2 = 4.3, P = .048),9 which suggests that stopping lithium is particularly problematic. Considering the lifetime consequences of bipolar illness, for most patients who have been receiving lithium for a long time, the recommendation is to continue lithium.10,11

The reasons for conflicting evidence

Many studies indicate that there is either no statistically significant association or a very low association between lithium and developing ESRD,12-16 while others suggest that long-term lithium treatment increases the risk of chronic nephropathy to a clinically relevant degree (note that these arguments are not mutually exclusive).6,17-22 Much of this confusion has to do with not making a distinction between renal tubular dysfunction, which occurs early and in approximately one-half of patients treated with lithium,23 and glomerular dysfunction, which occurs late and is associated with reductions in glomerular filtration and ESRD.24 Adding to the confusion is that even without lithium, the rate of renal disease in patients with mood disorders is 2- to 3-fold higher than that of the general population.25 Lithium treatment is associated with a rate that is higher still,25-27 but this effect is erroneously exaggerated in studies that examined patients treated with lithium without comparison to a mood-disorder control group.

Renal tubular dysfunction presents as diabetes insipidus with polyuria and polydipsia, which is related to a reduced ability to concentrate the urine.28 Reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR) as a consequence of lithium treatment occurs in 15% of patients23 and represents approximately 0.22% of patients on dialysis.18 Lithium-related reduction in GFR is a slowly progressive process that typically requires >20 years of lithium use to result in ESRD.18 While some decline in GFR may be seen within 1 year after starting lithium, the average age of patients who develop ESRD is 65 years.6 Interestingly, short-term animal studies have suggested that lithium may have antiproteinuric, protective, and pro-reparative effects in acute kidney injury.29

Anatomical anomalies in lithium-related glomerular dysfunction

In a study conducted before improved imaging technology was developed, Markowitz et al6 used renal biopsy to evaluate lithium-related nephropathy in 24 patients.6 Findings revealed chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis in all patients, along with a wide range of abnormalities, including tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis interspersed with microcyst formation arising from distal tubules or collecting ducts.6 Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) was found in 50% of patients. This might have been a result of nephron loss and compensatory hypertrophy of surviving nephrons, which suggests that FSGS is possibly a post-adaptive effect (rather than a direct damaging effect) of lithium on the glomerulus. The most noticeable finding was the appearance of microcysts in 62.5% of patients.6 It is important to note that these biopsy techniques sampled a relatively small fraction of the kidney volume, and that microcysts might have been more prevalent.

Recently, noninvasive imaging techniques have been used to detect microcysts in patients developing lithium-related nephropathy. While ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) can detect renal microcysts, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), specifically the half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo T2-weighted and gadolinium-enhanced (FISP three-dimensional MR angiographic) sequence, is the best noninvasive technology to demonstrate the presence of renal microcysts of a diameter of 1 to 2 mm.30 Ultrasound is sometimes difficult to utilize because while classic cysts appear as anechoic, lithium-induced microcysts may have the appearance of small echogenic foci.31,32 When evaluated by CT, renal microcysts may appear as hypodense lesions.

Continue to: Recent small studies...

Recent small studies have shown that MRI can detect renal microcysts in approximately 100% of patients who are receiving chronic lithium treatment and have renal insufficiency. One MRI study found renal microcysts in all 16 patients.33 In another MRI study of 4 patients, all were positive for renal microcysts.34 The relationship between MRI findings and renal function impairment in patients receiving long-term lithium therapy is still not clear; however, 1 study that examined 35 patients who received lithium reported that the number of cysts is generally related to the duration of lithium therapy.35 Thus, microcysts seem to present long before the elevation in creatinine, and nearly always present in patients with some glomerular dysfunction.

Cystic renal lesions have a wide variety of differential diagnoses, including simple renal cysts; glomerulocystic kidney disease; medullary cystic kidney disease and acquired cystic kidney disease; and multicystic dysplastic kidney and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.36 In patients who have a long history of lithium use, lithium-related nephrotoxicity should be added to the differential diagnosis. The ubiquitous presence of renal microcysts and their relationship to duration of lithium exposure and renal function suggest that they may be intimately related to lithium-related ESRD.37

This association appears to be sufficiently reliable and clinicians can use T2-weighted MRI to determine if renal dysfunction is related to lithium. Lithium-related renal microcysts are visualized as multiple bilateral hyperintense foci with a diameter of 1 to 3 mm that involve both the cortex and medulla, tend to be symmetrically distributed throughout the kidney, and are associated with normal-sized kidneys.33,36 Large cysts are unlikely to be related to lithium; only microcysts are associated with lithium treatment. For examples of how these cysts appear on MRI, see Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3. The exact mechanism of lithium-related nephrotoxicity is unclear, but may be related to the mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway or GSK-3beta (glycogen synthase kinase-3beta) (Box6,37-44).

Box 1

The exact mechanism of lithium-related nephrotoxicity is unclear. The mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway is an intracellular signaling pathway important in controlling cell proliferation and cell growth via the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1). Researchers have hypothesized that the mTOR pathway may be responsible for lithium-induced microcysts.38 One study found that mTOR signaling is activated in the renal collecting ducts of mice that received long-term lithium.38 After the same mice received rapamycin (sirolimus), an allosteric inhibitor of mTOR, lithium-induced proliferation of medullary collecting duct cells (microcysts) was reversed.38

Additionally, GSK-3beta (glycogen synthase kinase-3beta), which is expressed in the adult kidney and is a target for lithium, appears to have a role in this pathology. GSK-3beta is involved in multiple biologic processes, including immunomodulation, embryologic development, and tissue injury and repair. It has the ability to promote apoptosis and inhibit proliferation.39 At therapeutic levels, lithium can inhibit GSK-3beta activity by phosphorylation of the serine 9 residue pGSK-3beta-s9.40 This action is believed to play a role in lithium’s neuroprotective properties, specifically through inhibiting the proapoptotic effects of GSK-3beta.41,42 Ironically, this antiapoptotic mechanism of lithium may be associated with its renal adverse effects.

Researchers have proposed that lithium enters distal nephron segments, inhibiting GSK-3beta and disrupting the balance between proliferative and apoptotic signals. The appearance of microcysts may be related to lithium’s antiapoptotic effect. In patients who received chronic treatment with lithium, their kidneys displayed multiple cortical microcysts immunopositive for GSK-3beta.43 Lithium may prevent the clearance of older renal tubular cells that would typically have been removed by normal apoptotic processes.37 As more of these tubular cells accumulate, they invaginate and form a cyst.37 As cysts accumulate during 20 years of treatment, the volume that the cysts occupy within the normal-sized and unyielding renal capsule displaces and injures otherwise healthy renal tissue, in a process similar to injury due to hydrocephalus in the brain.37

Interestingly, if the antiapoptotic mechanism of lithium-induced microcysts is true, it is possible that mood stabilizers that also have antiapoptotic properties (such as valproic acid) would also increase the risk of renal microcysts.44 This may underlie the observation that nearly one-half of patients continue to experience progression of renal disease after discontinuing lithium.6

Take-home points

In patients receiving chronic lithium treatment, it can take 20 years to produce a significant reduction in GFR. Switching patients who respond to lithium to other mood-stabilizing agents is associated with a significantly increased risk for mood recurrence and adverse consequences from the alternate medication. Because ESRD may occur more frequently in patients with mood disorders than in the general population, renal disease may be misattributed to lithium use. In approximately one-half of patients, renal disease will continue to progress after discontinuing lithium, which essentially eliminates the benefit of switching medications. This means that the decision to switch a patient who has responded well to lithium treatment for a decade or more to an alternate agent to avoid progression to ESRD may be associated with a very high potential cost but limited benefit.

One solution might be to more accurately identify patients with lithium-related glomerular disease, so that the potential benefit of switching may outweigh potential harm. The presence of renal microcysts on MRI of the kidney may be used to provide some of that reassurance. On renal biopsy, >60% of patients will have documented microcysts, and on MRI, it may approach 100%. The presence of microcysts provides potential evidence that reduced glomerular function is related to lithium. However, the absence of renal microcysts may not be as instructive—a negative MRI of the kidneys may not be sufficient evidence to rule out lithium as the culprit.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Lithium is an effective treatment for bipolar disorder, but its perceived irreversible nephrotoxic effects make some clinicians hesitant to prescribe it. Discontinuing lithium or switching to another medication also carries risks. For most patients who have been receiving lithium for a long time, the recommendation is to obtain a renal MRI and to cautiously continue lithium if the patient does not have microcysts.

Related Resources

- Hayes JF, Osborn DPJ, Francis E, et al. Prediction of individuals at high risk of chronic kidney disease during treatment with lithium for bipolar disorder. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-01964-z

- Pelekanos M, Foo K. A resident’s guide to lithium. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(4):e3-e7. doi:10.12788/cp.0113

Drug Brand Names

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Sirolimus • Rapamune

Valproate • Depacon

Lithium is one of the most widely used mood stabilizers and is considered a first-line treatment for bipolar disorder because of its proven antimanic and prophylactic effects.1 This medication also can reduce the risk of suicide in patients with bipolar disorder.2 However, it has a narrow therapeutic index. While lithium has many reversible adverse effects—such as tremors, gastrointestinal disturbance, and thyroid dysfunction—its perceived irreversible nephrotoxic effects makes some clinicians hesitant to prescribe it.3,4 In this article, we describe the relationship between lithium and nephrotoxicity, explain the apparent contradiction in published research regarding this topic, and offer suggestions for how to determine whether you should continue treatment with lithium for a patient who develops renal changes.

A lithium dilemma

Many psychiatrists have faced the dilemma of whether to discontinue lithium upon the appearance of glomerular renal changes and risk exposing patients to relapse or suicide, or to continue prescribing lithium and risk development of end stage renal disease (ESRD). Discontinuing lithium is not associated with the reversal of renal changes and kidney recovery,5 and exposes patients to psychiatric risks, such as mood recurrence and increased risk of suicide.6 Switching from lithium to another mood stabilizer is associated with a host of adverse effects, including diabetes mellitus and weight gain, and mood stabilizer use is not associated with reduced renal risk in patients with bipolar disorder.5 For example, Markowitz et al6 evaluated 24 patients with renal insufficiency after an average of 13.6 years of chronic lithium treatment. Despite stopping lithium, 8 patients out of the 19 available for follow-up (42%) developed ESRD.6 This study also found that serum creatinine levels >2.5 mg/dL are a predictor of progression to ESRD.6

Discontinuing lithium is associated with high rates of mood recurrence (60% to 70%), especially for patients who had been stable on lithium for years.7,8 If lithium is tapered slowly, the risk of mood recurrence may drop to approximately 42% over the subsequent 18 months, but this is nearly 3-fold greater than the risk of mood recurrence in patients with good response to valproate who are switched to another mood stabilizer (16.7%, c2 = 4.3, P = .048),9 which suggests that stopping lithium is particularly problematic. Considering the lifetime consequences of bipolar illness, for most patients who have been receiving lithium for a long time, the recommendation is to continue lithium.10,11

The reasons for conflicting evidence

Many studies indicate that there is either no statistically significant association or a very low association between lithium and developing ESRD,12-16 while others suggest that long-term lithium treatment increases the risk of chronic nephropathy to a clinically relevant degree (note that these arguments are not mutually exclusive).6,17-22 Much of this confusion has to do with not making a distinction between renal tubular dysfunction, which occurs early and in approximately one-half of patients treated with lithium,23 and glomerular dysfunction, which occurs late and is associated with reductions in glomerular filtration and ESRD.24 Adding to the confusion is that even without lithium, the rate of renal disease in patients with mood disorders is 2- to 3-fold higher than that of the general population.25 Lithium treatment is associated with a rate that is higher still,25-27 but this effect is erroneously exaggerated in studies that examined patients treated with lithium without comparison to a mood-disorder control group.

Renal tubular dysfunction presents as diabetes insipidus with polyuria and polydipsia, which is related to a reduced ability to concentrate the urine.28 Reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR) as a consequence of lithium treatment occurs in 15% of patients23 and represents approximately 0.22% of patients on dialysis.18 Lithium-related reduction in GFR is a slowly progressive process that typically requires >20 years of lithium use to result in ESRD.18 While some decline in GFR may be seen within 1 year after starting lithium, the average age of patients who develop ESRD is 65 years.6 Interestingly, short-term animal studies have suggested that lithium may have antiproteinuric, protective, and pro-reparative effects in acute kidney injury.29

Anatomical anomalies in lithium-related glomerular dysfunction

In a study conducted before improved imaging technology was developed, Markowitz et al6 used renal biopsy to evaluate lithium-related nephropathy in 24 patients.6 Findings revealed chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis in all patients, along with a wide range of abnormalities, including tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis interspersed with microcyst formation arising from distal tubules or collecting ducts.6 Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) was found in 50% of patients. This might have been a result of nephron loss and compensatory hypertrophy of surviving nephrons, which suggests that FSGS is possibly a post-adaptive effect (rather than a direct damaging effect) of lithium on the glomerulus. The most noticeable finding was the appearance of microcysts in 62.5% of patients.6 It is important to note that these biopsy techniques sampled a relatively small fraction of the kidney volume, and that microcysts might have been more prevalent.

Recently, noninvasive imaging techniques have been used to detect microcysts in patients developing lithium-related nephropathy. While ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) can detect renal microcysts, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), specifically the half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo T2-weighted and gadolinium-enhanced (FISP three-dimensional MR angiographic) sequence, is the best noninvasive technology to demonstrate the presence of renal microcysts of a diameter of 1 to 2 mm.30 Ultrasound is sometimes difficult to utilize because while classic cysts appear as anechoic, lithium-induced microcysts may have the appearance of small echogenic foci.31,32 When evaluated by CT, renal microcysts may appear as hypodense lesions.

Continue to: Recent small studies...

Recent small studies have shown that MRI can detect renal microcysts in approximately 100% of patients who are receiving chronic lithium treatment and have renal insufficiency. One MRI study found renal microcysts in all 16 patients.33 In another MRI study of 4 patients, all were positive for renal microcysts.34 The relationship between MRI findings and renal function impairment in patients receiving long-term lithium therapy is still not clear; however, 1 study that examined 35 patients who received lithium reported that the number of cysts is generally related to the duration of lithium therapy.35 Thus, microcysts seem to present long before the elevation in creatinine, and nearly always present in patients with some glomerular dysfunction.

Cystic renal lesions have a wide variety of differential diagnoses, including simple renal cysts; glomerulocystic kidney disease; medullary cystic kidney disease and acquired cystic kidney disease; and multicystic dysplastic kidney and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.36 In patients who have a long history of lithium use, lithium-related nephrotoxicity should be added to the differential diagnosis. The ubiquitous presence of renal microcysts and their relationship to duration of lithium exposure and renal function suggest that they may be intimately related to lithium-related ESRD.37

This association appears to be sufficiently reliable and clinicians can use T2-weighted MRI to determine if renal dysfunction is related to lithium. Lithium-related renal microcysts are visualized as multiple bilateral hyperintense foci with a diameter of 1 to 3 mm that involve both the cortex and medulla, tend to be symmetrically distributed throughout the kidney, and are associated with normal-sized kidneys.33,36 Large cysts are unlikely to be related to lithium; only microcysts are associated with lithium treatment. For examples of how these cysts appear on MRI, see Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3. The exact mechanism of lithium-related nephrotoxicity is unclear, but may be related to the mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway or GSK-3beta (glycogen synthase kinase-3beta) (Box6,37-44).

Box 1

The exact mechanism of lithium-related nephrotoxicity is unclear. The mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway is an intracellular signaling pathway important in controlling cell proliferation and cell growth via the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1). Researchers have hypothesized that the mTOR pathway may be responsible for lithium-induced microcysts.38 One study found that mTOR signaling is activated in the renal collecting ducts of mice that received long-term lithium.38 After the same mice received rapamycin (sirolimus), an allosteric inhibitor of mTOR, lithium-induced proliferation of medullary collecting duct cells (microcysts) was reversed.38

Additionally, GSK-3beta (glycogen synthase kinase-3beta), which is expressed in the adult kidney and is a target for lithium, appears to have a role in this pathology. GSK-3beta is involved in multiple biologic processes, including immunomodulation, embryologic development, and tissue injury and repair. It has the ability to promote apoptosis and inhibit proliferation.39 At therapeutic levels, lithium can inhibit GSK-3beta activity by phosphorylation of the serine 9 residue pGSK-3beta-s9.40 This action is believed to play a role in lithium’s neuroprotective properties, specifically through inhibiting the proapoptotic effects of GSK-3beta.41,42 Ironically, this antiapoptotic mechanism of lithium may be associated with its renal adverse effects.

Researchers have proposed that lithium enters distal nephron segments, inhibiting GSK-3beta and disrupting the balance between proliferative and apoptotic signals. The appearance of microcysts may be related to lithium’s antiapoptotic effect. In patients who received chronic treatment with lithium, their kidneys displayed multiple cortical microcysts immunopositive for GSK-3beta.43 Lithium may prevent the clearance of older renal tubular cells that would typically have been removed by normal apoptotic processes.37 As more of these tubular cells accumulate, they invaginate and form a cyst.37 As cysts accumulate during 20 years of treatment, the volume that the cysts occupy within the normal-sized and unyielding renal capsule displaces and injures otherwise healthy renal tissue, in a process similar to injury due to hydrocephalus in the brain.37

Interestingly, if the antiapoptotic mechanism of lithium-induced microcysts is true, it is possible that mood stabilizers that also have antiapoptotic properties (such as valproic acid) would also increase the risk of renal microcysts.44 This may underlie the observation that nearly one-half of patients continue to experience progression of renal disease after discontinuing lithium.6

Take-home points

In patients receiving chronic lithium treatment, it can take 20 years to produce a significant reduction in GFR. Switching patients who respond to lithium to other mood-stabilizing agents is associated with a significantly increased risk for mood recurrence and adverse consequences from the alternate medication. Because ESRD may occur more frequently in patients with mood disorders than in the general population, renal disease may be misattributed to lithium use. In approximately one-half of patients, renal disease will continue to progress after discontinuing lithium, which essentially eliminates the benefit of switching medications. This means that the decision to switch a patient who has responded well to lithium treatment for a decade or more to an alternate agent to avoid progression to ESRD may be associated with a very high potential cost but limited benefit.

One solution might be to more accurately identify patients with lithium-related glomerular disease, so that the potential benefit of switching may outweigh potential harm. The presence of renal microcysts on MRI of the kidney may be used to provide some of that reassurance. On renal biopsy, >60% of patients will have documented microcysts, and on MRI, it may approach 100%. The presence of microcysts provides potential evidence that reduced glomerular function is related to lithium. However, the absence of renal microcysts may not be as instructive—a negative MRI of the kidneys may not be sufficient evidence to rule out lithium as the culprit.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Lithium is an effective treatment for bipolar disorder, but its perceived irreversible nephrotoxic effects make some clinicians hesitant to prescribe it. Discontinuing lithium or switching to another medication also carries risks. For most patients who have been receiving lithium for a long time, the recommendation is to obtain a renal MRI and to cautiously continue lithium if the patient does not have microcysts.

Related Resources

- Hayes JF, Osborn DPJ, Francis E, et al. Prediction of individuals at high risk of chronic kidney disease during treatment with lithium for bipolar disorder. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-01964-z

- Pelekanos M, Foo K. A resident’s guide to lithium. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(4):e3-e7. doi:10.12788/cp.0113

Drug Brand Names

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Sirolimus • Rapamune

Valproate • Depacon

1. Severus E, Bauer M, Geddes J. Efficacy and effectiveness of lithium in the long-term treatment of bipolar disorders: an update 2018. Pharamacopsychiatry. 2018;51(5):173-176.

2. Smith KA, Cipriani A. Lithium and suicide in mood disorders: updated meta-review of the scientific literature. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19(7):575-586.

3. El-Mallakh RS. Lithium: actions and mechanisms. Progress in Psychiatry Series, 50. American Psychiatric Press; 1996.

4. Gitlin M. Why is not lithium prescribed more often? Here are the reasons. J Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 2016, 29:293-297.

5. Kessing LV, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Andersen PK, et al. Continuation of lithium after a diagnosis of chronic kidney disease. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;136(6):615-622.

6. Markowitz GS, Radhakrishnan J, Kambham N, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity: a progressive combined glomerular and tubulointerstitial nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11(8):1439-1448.

7. Faedda GL, Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, et al. Outcome after rapid vs gradual discontinuation of lithium treatment in bipolar disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(6):448-455.

8. Yazici O, Kora K, Polat A, et al. Controlled lithium discontinuation in bipolar patients with good response to long-term lithium prophylaxis. J Affect Disord. 2004;80(2-3):269-271.

9. Rosso G, Solia F, Albert U, et al. Affective recurrences in bipolar disorder after switching from lithium to valproate or vice versa: a series of 57 cases. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;37(2):278-281.

10. Werneke U, Ott M, Renberg ES, et al. A decision analysis of long-term lithium treatment and the risk of renal failure. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;126(3):186-197.