User login

Kleptomania: 4 Tips for better diagnosis and treatment

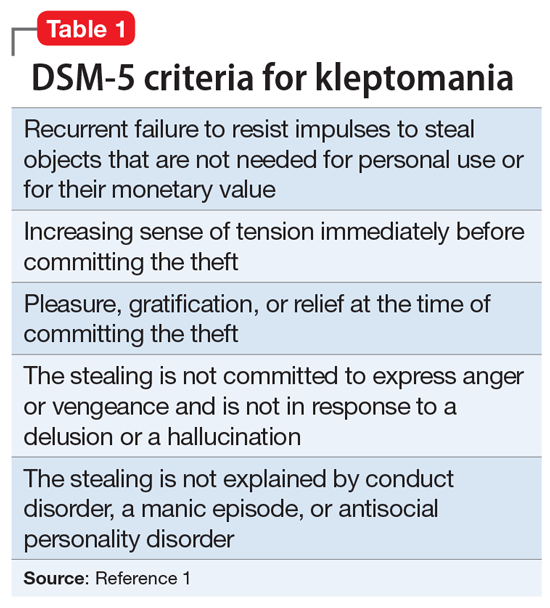

Kleptomania is characterized by a recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects that are not needed for personal use or their monetary value.1 It is a rare disorder; an estimated 0.3% to 0.6% of the general population meet DSM-5 criteria for kleptomania (Table 1).1 Kleptomania usually begins in early adolescence and is more common among females than males (3:1).1 Although DSM-5 does not outline how long symptoms need to be present for patients to meet the diagnostic criteria, the disorder may persist for years, even when patients face legal consequences.1

Due to the clinical ambiguities surrounding kleptomania, it remains one of psychiatry’s most poorly understood diagnoses2 and regularly goes undiagnosed and untreated. Here we provide 4 tips for better diagnosis and treatment of this condition.

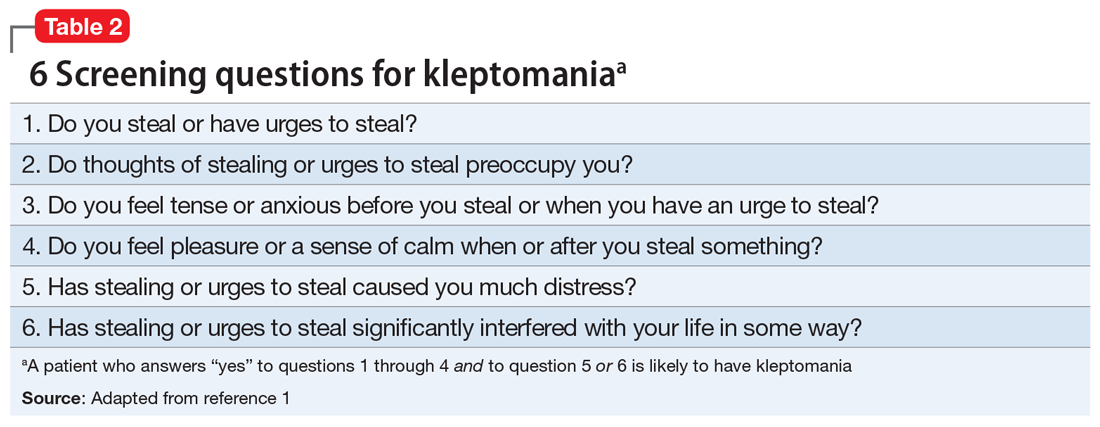

1. Screen for kleptomania in patients with other psychiatric disorders because kleptomania often is comorbid with other mental illnesses. Patients who present for evaluation of a mood disorder, substance use, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, impulse control disorders, conduct disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder should be screened for kleptomania.1,3,4 Patients with kleptomania often are reluctant to discuss their stealing because they may experience humiliation and guilt related to theft.1,4 Undiagnosed kleptomania can be fatal; a study of suicide attempts in 107 individuals with kleptomania found that 92% of the patients attributed their attempt specifically to kleptomania.5 Table 21 offers screening questions based on the DSM-5 criteria for kleptomania.

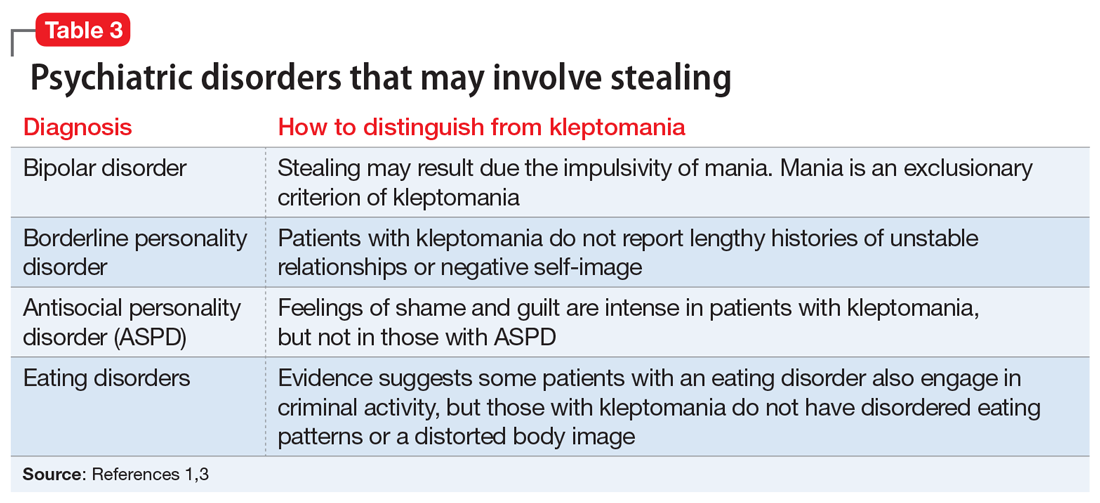

2. Distinguish kleptomania from other diagnoses that can include stealing. Because stealing can be a symptom of several other psychiatric disorders, misdiagnosis is fairly common.1 The differential can include bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and eating disorder. Table 31,3 describes how to differentiate these diagnoses from kleptomania.

3. Select an appropriate treatment. There are no FDA-approved medications for kleptomania, but some agents may help. In an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 25 patients with kleptomania who received naltrexone (50 to 150 mg/d) demonstrated significant reductions in stealing urges and behavior.6 Some evidence suggests a combination of pharmacologic and behavioral therapy (cognitive-behavioral therapy, covert sensitization, and systemic desensitization) may be the optimal treatment strategy for kleptomania.4

4. Monitor progress. After initiating treatment, use the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale7 (K-SAS) to determine treatment efficacy. The K-SAS is an 11-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the severity of kleptomania symptoms during the past week.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Goldman MJ. Kleptomania: making sense of the nonsensical. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:986-996.

3. Yao S, Kuja‐Halkola R, Thornton LM, et al. Risk of being convicted of theft and other crimes in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a prospective cohort study in a Swedish female population. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(9):1095-1103.

4. Grant JE, Kim SW. Clinical characteristics and associated psychopathology of 22 patients of kleptomania. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43(5):378-384.

5. Odlaug BL, Grant JE, Kim SW. Suicide attempts in 107 adolescents and adults with kleptomania. Arch Suicide Res. 2012;16(4):348-359.

6. Grant JE, Kim SW, Odlaug BL. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the opiate antagonist, naltrexone, in the treatment of kleptomania. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(7):600-606.

7. Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. Kleptomania: clinical characteristics and relationship to substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):291-295.

Kleptomania is characterized by a recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects that are not needed for personal use or their monetary value.1 It is a rare disorder; an estimated 0.3% to 0.6% of the general population meet DSM-5 criteria for kleptomania (Table 1).1 Kleptomania usually begins in early adolescence and is more common among females than males (3:1).1 Although DSM-5 does not outline how long symptoms need to be present for patients to meet the diagnostic criteria, the disorder may persist for years, even when patients face legal consequences.1

Due to the clinical ambiguities surrounding kleptomania, it remains one of psychiatry’s most poorly understood diagnoses2 and regularly goes undiagnosed and untreated. Here we provide 4 tips for better diagnosis and treatment of this condition.

1. Screen for kleptomania in patients with other psychiatric disorders because kleptomania often is comorbid with other mental illnesses. Patients who present for evaluation of a mood disorder, substance use, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, impulse control disorders, conduct disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder should be screened for kleptomania.1,3,4 Patients with kleptomania often are reluctant to discuss their stealing because they may experience humiliation and guilt related to theft.1,4 Undiagnosed kleptomania can be fatal; a study of suicide attempts in 107 individuals with kleptomania found that 92% of the patients attributed their attempt specifically to kleptomania.5 Table 21 offers screening questions based on the DSM-5 criteria for kleptomania.

2. Distinguish kleptomania from other diagnoses that can include stealing. Because stealing can be a symptom of several other psychiatric disorders, misdiagnosis is fairly common.1 The differential can include bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and eating disorder. Table 31,3 describes how to differentiate these diagnoses from kleptomania.

3. Select an appropriate treatment. There are no FDA-approved medications for kleptomania, but some agents may help. In an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 25 patients with kleptomania who received naltrexone (50 to 150 mg/d) demonstrated significant reductions in stealing urges and behavior.6 Some evidence suggests a combination of pharmacologic and behavioral therapy (cognitive-behavioral therapy, covert sensitization, and systemic desensitization) may be the optimal treatment strategy for kleptomania.4

4. Monitor progress. After initiating treatment, use the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale7 (K-SAS) to determine treatment efficacy. The K-SAS is an 11-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the severity of kleptomania symptoms during the past week.

Kleptomania is characterized by a recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects that are not needed for personal use or their monetary value.1 It is a rare disorder; an estimated 0.3% to 0.6% of the general population meet DSM-5 criteria for kleptomania (Table 1).1 Kleptomania usually begins in early adolescence and is more common among females than males (3:1).1 Although DSM-5 does not outline how long symptoms need to be present for patients to meet the diagnostic criteria, the disorder may persist for years, even when patients face legal consequences.1

Due to the clinical ambiguities surrounding kleptomania, it remains one of psychiatry’s most poorly understood diagnoses2 and regularly goes undiagnosed and untreated. Here we provide 4 tips for better diagnosis and treatment of this condition.

1. Screen for kleptomania in patients with other psychiatric disorders because kleptomania often is comorbid with other mental illnesses. Patients who present for evaluation of a mood disorder, substance use, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, impulse control disorders, conduct disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder should be screened for kleptomania.1,3,4 Patients with kleptomania often are reluctant to discuss their stealing because they may experience humiliation and guilt related to theft.1,4 Undiagnosed kleptomania can be fatal; a study of suicide attempts in 107 individuals with kleptomania found that 92% of the patients attributed their attempt specifically to kleptomania.5 Table 21 offers screening questions based on the DSM-5 criteria for kleptomania.

2. Distinguish kleptomania from other diagnoses that can include stealing. Because stealing can be a symptom of several other psychiatric disorders, misdiagnosis is fairly common.1 The differential can include bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and eating disorder. Table 31,3 describes how to differentiate these diagnoses from kleptomania.

3. Select an appropriate treatment. There are no FDA-approved medications for kleptomania, but some agents may help. In an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 25 patients with kleptomania who received naltrexone (50 to 150 mg/d) demonstrated significant reductions in stealing urges and behavior.6 Some evidence suggests a combination of pharmacologic and behavioral therapy (cognitive-behavioral therapy, covert sensitization, and systemic desensitization) may be the optimal treatment strategy for kleptomania.4

4. Monitor progress. After initiating treatment, use the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale7 (K-SAS) to determine treatment efficacy. The K-SAS is an 11-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the severity of kleptomania symptoms during the past week.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Goldman MJ. Kleptomania: making sense of the nonsensical. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:986-996.

3. Yao S, Kuja‐Halkola R, Thornton LM, et al. Risk of being convicted of theft and other crimes in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a prospective cohort study in a Swedish female population. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(9):1095-1103.

4. Grant JE, Kim SW. Clinical characteristics and associated psychopathology of 22 patients of kleptomania. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43(5):378-384.

5. Odlaug BL, Grant JE, Kim SW. Suicide attempts in 107 adolescents and adults with kleptomania. Arch Suicide Res. 2012;16(4):348-359.

6. Grant JE, Kim SW, Odlaug BL. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the opiate antagonist, naltrexone, in the treatment of kleptomania. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(7):600-606.

7. Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. Kleptomania: clinical characteristics and relationship to substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):291-295.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Goldman MJ. Kleptomania: making sense of the nonsensical. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:986-996.

3. Yao S, Kuja‐Halkola R, Thornton LM, et al. Risk of being convicted of theft and other crimes in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a prospective cohort study in a Swedish female population. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(9):1095-1103.

4. Grant JE, Kim SW. Clinical characteristics and associated psychopathology of 22 patients of kleptomania. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43(5):378-384.

5. Odlaug BL, Grant JE, Kim SW. Suicide attempts in 107 adolescents and adults with kleptomania. Arch Suicide Res. 2012;16(4):348-359.

6. Grant JE, Kim SW, Odlaug BL. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the opiate antagonist, naltrexone, in the treatment of kleptomania. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(7):600-606.

7. Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. Kleptomania: clinical characteristics and relationship to substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):291-295.

Improving your experience with electronic health records

The electronic health record (EHR) was introduced to improve how clinicians document patient information, contribute to medical research, and allow for medical records to be universally transferable.1 However, many clinicians find EHRs to be burdensome, time-consuming, and inefficient. Clinicians often spend multiple hours each day navigating their EHR system, which reduces the amount of time they spend interacting with patients and contributes to physician burnout.1-3 For example, in a study of 142 family medicine physicians, clinicians reported that they spent approximately 6 hours per work day interacting with their EHR.3

Clearly, the EHR needs a fundamental revision. In the meantime, how can we adapt to improve the situation? Here I suggest practical steps clinicians can take to improve their experience with their EHR system.4-8

Steps to take during patient visits

Because entering information into the EHR can be distracting, be prepared to multitask during each clinical encounter.1-7 Be ready to address pertinent inquiries and issues your patient raises, and provide instructions on therapies and interventions. Because interpersonal relations are important during clinical encounters, establish interaction with your patient by acknowledging them and maintaining frequent eye contact.7 Consider allowing your patient to view the EHR screen because doing so might increase his/her involvement in the visit.

So that you can pay closer attention to your patient, consider taking notes during the visit and entering the information into the EHR later. Consider improving your typing skills to increase the speed of your note-taking. Alternatively, using a voice-recognition recording tool to transcribe your notes via speech might help you spend less time on note-taking.3 Whenever possible, finish charting for one patient before meeting with the next because doing so will save time and help you to better remember details.7

In addition, lowering your overall stress might help reduce the burden of using the EHR.3-5 Adopt healthy behaviors, including good sleep, nutrition, exercise, and hobbies, and strive for balance in your routines. Attend to any personal medical or psychiatric conditions, and avoid misusing alcohol, medications, or other substances.

Optimize how your practice functions

With your clinical group and colleagues, create a comfortable environment, good patient-to-doctor interactions, and a smooth flow within the practice. Simplify registration. Ask patients to complete screening forms before an appointment; this information could be entered directly into their EHR.3 Consider using physician-extender staff and other personnel, such as scribes, to complete documentation into the EHR.3,8 This may help reduce burnout, create more time for clinical care, and improve face-to-face patient interactions.8 Employing scribes can allow doctors to be better able to directly attend to their patients while complying with record-keeping needs. Although scribes make charting easier, they are an additional expense, and must be trained.

Consider EHR training

EHR training sessions can teach you how to use your EHR system more efficiently.6 Such education may help boost confidence, aid documentation, and reduce the amount of time spent correcting coding errors. In a study of 3,500 physicians who underwent a 3-day intensive EHR training course, 85% to 98% reported having improved the quality, readability, and clinical accuracy of their documentation.6

Help shape future EHRs

Individual doctors and professional groups can promote EHR improvements through their state, regional, and/or national organizations and medical societies. These bodies should deliver EHR revision recommendations to government officials, who can craft laws and regulations, and can influence regulators and/or insurance companies. Clinicians also can communicate with EHR developers on ways to simplify the usability of these tools, such as reducing the amount of steps the EHR’s interface requires.5 With a more efficient EHR, we can better concentrate on patient care, which will reduce expenses and should yield better outcomes.

1. Ehrenfeld JM, Wonderer JP. Technology as friend or foe? Do electronic health records increase burnout? Curr Opin Anesthesiol. 2018;31(3):357-360.

2. Meigs SL, Solomon M. Electronic health record use a bitter pill for many physicians. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2016;13:1d.

3. Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, et al. Tethered to the EHR: primary care physician workload assessment using EHR event log data and time-motion observations. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):419-426.

4. Fogarty CT, Winters P, Farah S. Improving patient-centered communication while using an electronic health record: report from a curriculum evaluation. Int J Psych Med. 2016;51(4):379-389.

5. Guo U, Chen L, Mehta PH. Electronic health record innovations: helping physicians - one less click at a time. Health Inf Manag. 2017;46(3):140-144.

6. Robinson KE, Kersey JA. Novel electronic health record (EHR) education intervention in large healthcare organization improves quality, efficiency, time, and impact on burnout. Medicine. 2018;91(38):e123419. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012319.

7. Fogarty CT. Getting your notes done on time. Fam Pract Manag. 2016;23(2):40.

8. DeChant PF, Acs A, Rhee KB, et al. Effect of organization-directed workplace interventions on physician burnout: a systematic review. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2019;3(4):384-408.

The electronic health record (EHR) was introduced to improve how clinicians document patient information, contribute to medical research, and allow for medical records to be universally transferable.1 However, many clinicians find EHRs to be burdensome, time-consuming, and inefficient. Clinicians often spend multiple hours each day navigating their EHR system, which reduces the amount of time they spend interacting with patients and contributes to physician burnout.1-3 For example, in a study of 142 family medicine physicians, clinicians reported that they spent approximately 6 hours per work day interacting with their EHR.3

Clearly, the EHR needs a fundamental revision. In the meantime, how can we adapt to improve the situation? Here I suggest practical steps clinicians can take to improve their experience with their EHR system.4-8

Steps to take during patient visits

Because entering information into the EHR can be distracting, be prepared to multitask during each clinical encounter.1-7 Be ready to address pertinent inquiries and issues your patient raises, and provide instructions on therapies and interventions. Because interpersonal relations are important during clinical encounters, establish interaction with your patient by acknowledging them and maintaining frequent eye contact.7 Consider allowing your patient to view the EHR screen because doing so might increase his/her involvement in the visit.

So that you can pay closer attention to your patient, consider taking notes during the visit and entering the information into the EHR later. Consider improving your typing skills to increase the speed of your note-taking. Alternatively, using a voice-recognition recording tool to transcribe your notes via speech might help you spend less time on note-taking.3 Whenever possible, finish charting for one patient before meeting with the next because doing so will save time and help you to better remember details.7

In addition, lowering your overall stress might help reduce the burden of using the EHR.3-5 Adopt healthy behaviors, including good sleep, nutrition, exercise, and hobbies, and strive for balance in your routines. Attend to any personal medical or psychiatric conditions, and avoid misusing alcohol, medications, or other substances.

Optimize how your practice functions

With your clinical group and colleagues, create a comfortable environment, good patient-to-doctor interactions, and a smooth flow within the practice. Simplify registration. Ask patients to complete screening forms before an appointment; this information could be entered directly into their EHR.3 Consider using physician-extender staff and other personnel, such as scribes, to complete documentation into the EHR.3,8 This may help reduce burnout, create more time for clinical care, and improve face-to-face patient interactions.8 Employing scribes can allow doctors to be better able to directly attend to their patients while complying with record-keeping needs. Although scribes make charting easier, they are an additional expense, and must be trained.

Consider EHR training

EHR training sessions can teach you how to use your EHR system more efficiently.6 Such education may help boost confidence, aid documentation, and reduce the amount of time spent correcting coding errors. In a study of 3,500 physicians who underwent a 3-day intensive EHR training course, 85% to 98% reported having improved the quality, readability, and clinical accuracy of their documentation.6

Help shape future EHRs

Individual doctors and professional groups can promote EHR improvements through their state, regional, and/or national organizations and medical societies. These bodies should deliver EHR revision recommendations to government officials, who can craft laws and regulations, and can influence regulators and/or insurance companies. Clinicians also can communicate with EHR developers on ways to simplify the usability of these tools, such as reducing the amount of steps the EHR’s interface requires.5 With a more efficient EHR, we can better concentrate on patient care, which will reduce expenses and should yield better outcomes.

The electronic health record (EHR) was introduced to improve how clinicians document patient information, contribute to medical research, and allow for medical records to be universally transferable.1 However, many clinicians find EHRs to be burdensome, time-consuming, and inefficient. Clinicians often spend multiple hours each day navigating their EHR system, which reduces the amount of time they spend interacting with patients and contributes to physician burnout.1-3 For example, in a study of 142 family medicine physicians, clinicians reported that they spent approximately 6 hours per work day interacting with their EHR.3

Clearly, the EHR needs a fundamental revision. In the meantime, how can we adapt to improve the situation? Here I suggest practical steps clinicians can take to improve their experience with their EHR system.4-8

Steps to take during patient visits

Because entering information into the EHR can be distracting, be prepared to multitask during each clinical encounter.1-7 Be ready to address pertinent inquiries and issues your patient raises, and provide instructions on therapies and interventions. Because interpersonal relations are important during clinical encounters, establish interaction with your patient by acknowledging them and maintaining frequent eye contact.7 Consider allowing your patient to view the EHR screen because doing so might increase his/her involvement in the visit.

So that you can pay closer attention to your patient, consider taking notes during the visit and entering the information into the EHR later. Consider improving your typing skills to increase the speed of your note-taking. Alternatively, using a voice-recognition recording tool to transcribe your notes via speech might help you spend less time on note-taking.3 Whenever possible, finish charting for one patient before meeting with the next because doing so will save time and help you to better remember details.7

In addition, lowering your overall stress might help reduce the burden of using the EHR.3-5 Adopt healthy behaviors, including good sleep, nutrition, exercise, and hobbies, and strive for balance in your routines. Attend to any personal medical or psychiatric conditions, and avoid misusing alcohol, medications, or other substances.

Optimize how your practice functions

With your clinical group and colleagues, create a comfortable environment, good patient-to-doctor interactions, and a smooth flow within the practice. Simplify registration. Ask patients to complete screening forms before an appointment; this information could be entered directly into their EHR.3 Consider using physician-extender staff and other personnel, such as scribes, to complete documentation into the EHR.3,8 This may help reduce burnout, create more time for clinical care, and improve face-to-face patient interactions.8 Employing scribes can allow doctors to be better able to directly attend to their patients while complying with record-keeping needs. Although scribes make charting easier, they are an additional expense, and must be trained.

Consider EHR training

EHR training sessions can teach you how to use your EHR system more efficiently.6 Such education may help boost confidence, aid documentation, and reduce the amount of time spent correcting coding errors. In a study of 3,500 physicians who underwent a 3-day intensive EHR training course, 85% to 98% reported having improved the quality, readability, and clinical accuracy of their documentation.6

Help shape future EHRs

Individual doctors and professional groups can promote EHR improvements through their state, regional, and/or national organizations and medical societies. These bodies should deliver EHR revision recommendations to government officials, who can craft laws and regulations, and can influence regulators and/or insurance companies. Clinicians also can communicate with EHR developers on ways to simplify the usability of these tools, such as reducing the amount of steps the EHR’s interface requires.5 With a more efficient EHR, we can better concentrate on patient care, which will reduce expenses and should yield better outcomes.

1. Ehrenfeld JM, Wonderer JP. Technology as friend or foe? Do electronic health records increase burnout? Curr Opin Anesthesiol. 2018;31(3):357-360.

2. Meigs SL, Solomon M. Electronic health record use a bitter pill for many physicians. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2016;13:1d.

3. Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, et al. Tethered to the EHR: primary care physician workload assessment using EHR event log data and time-motion observations. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):419-426.

4. Fogarty CT, Winters P, Farah S. Improving patient-centered communication while using an electronic health record: report from a curriculum evaluation. Int J Psych Med. 2016;51(4):379-389.

5. Guo U, Chen L, Mehta PH. Electronic health record innovations: helping physicians - one less click at a time. Health Inf Manag. 2017;46(3):140-144.

6. Robinson KE, Kersey JA. Novel electronic health record (EHR) education intervention in large healthcare organization improves quality, efficiency, time, and impact on burnout. Medicine. 2018;91(38):e123419. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012319.

7. Fogarty CT. Getting your notes done on time. Fam Pract Manag. 2016;23(2):40.

8. DeChant PF, Acs A, Rhee KB, et al. Effect of organization-directed workplace interventions on physician burnout: a systematic review. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2019;3(4):384-408.

1. Ehrenfeld JM, Wonderer JP. Technology as friend or foe? Do electronic health records increase burnout? Curr Opin Anesthesiol. 2018;31(3):357-360.

2. Meigs SL, Solomon M. Electronic health record use a bitter pill for many physicians. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2016;13:1d.

3. Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, et al. Tethered to the EHR: primary care physician workload assessment using EHR event log data and time-motion observations. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):419-426.

4. Fogarty CT, Winters P, Farah S. Improving patient-centered communication while using an electronic health record: report from a curriculum evaluation. Int J Psych Med. 2016;51(4):379-389.

5. Guo U, Chen L, Mehta PH. Electronic health record innovations: helping physicians - one less click at a time. Health Inf Manag. 2017;46(3):140-144.

6. Robinson KE, Kersey JA. Novel electronic health record (EHR) education intervention in large healthcare organization improves quality, efficiency, time, and impact on burnout. Medicine. 2018;91(38):e123419. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012319.

7. Fogarty CT. Getting your notes done on time. Fam Pract Manag. 2016;23(2):40.

8. DeChant PF, Acs A, Rhee KB, et al. Effect of organization-directed workplace interventions on physician burnout: a systematic review. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2019;3(4):384-408.

Eosinophilic esophagitis: Frequently asked questions (and answers) for the early-career gastroenterologist

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) has transformed over the past 3 decades from a rarely encountered entity to one of the most common causes of dysphagia in adults.1 Given the marked rise in prevalence, the early-career gastroenterologist will undoubtedly be involved with managing this disease.2 The typical presentation includes a young, atopic male presenting with dysphagia in the outpatient setting or, more acutely, with a food impaction when on call. As every fellow is keenly aware, the calls often come late at night as patients commonly have meat impactions while consuming dinner. Current management focuses on symptomatic, histologic, and endoscopic improvement with medication, dietary, and mechanical (i.e., dilation) modalities.

EoE is defined by the presence of esophageal dysfunction and esophageal eosinophilic inflammation with ≥15 eosinophils/high-powered field (eos/hpf) required for the diagnosis. With better understanding of the pathogenesis of EoE involving the complex interaction of environmental, host, and genetic factors, advancements have been made as it relates to the diagnostic criteria, endoscopic evaluation, and therapeutic options. In this article, we review the current management of adult patients with EoE and offer practical guidance to key questions for the young gastroenterologist as well as insights into future areas of interest.

What should I consider when diagnosing EoE?

Symptoms are central to the diagnosis and clinical presentation of EoE. In assessing symptoms, clinicians should be aware of adaptive “IMPACT” strategies patients often subconsciously develop in response to their chronic and progressive condition: Imbibing fluids with meals, modifying foods by cutting or pureeing, prolonging meal times, avoiding harder texture foods, chewing excessively, and turning away tablets/pills.3 Failure to query such adaptive behaviors may lead to an underestimation of disease activity and severity.

An important aspect to confirming the diagnosis of EoE is to exclude other causes of esophageal eosinophilia. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is known to cause esophageal eosinophilia and historically has been viewed as a distinct disease process. In fact, initial guidelines included lack of response to a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) trial or normal esophageal pH monitoring as diagnostic criteria.4 However, as experience was garnered, it became clear that PPI therapy was effective at improving inflammation in 30%-50% of patients with clinical presentations and histologic features consistent with EoE. As such, the concept of PPI–responsive esophageal eosinophilia (PPI-REE) was introduced in 2011.5 Further investigation then highlighted that PPI-REE and EoE had nearly identical clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features as well as eosinophil biomarker and gene expression profiles. Hence, recent international guidelines no longer necessitate a PPI trial to establish a diagnosis of EoE.6

The young gastroenterologist should also be mindful of other issues related to the initial diagnosis of EoE. EoE may present concomitantly with other disease entities including GERD, “extra-esophageal” eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases, concomitant IgE-mediated food allergy, hypereosinophilic syndromes, connective tissue disorders, autoimmune diseases, celiac disease, and inflammatory bowel disease.3 It has been speculated that some of these disorders share common aspects of genetic and environmental predisposing factors as well as shared pathogenesis. Careful history taking should include a full review of atopic conditions and GI-related symptoms and endoscopy should carefully inspect not only the esophagus, but also gastric and duodenal mucosa. The endoscopic features almost always reveal edema, rings, exudates, furrows, and strictures and can be assessed using the EoE Endoscopic Reference Scoring system (EREFS).7 EREFS allows for systematic identification of abnormalities that can inform decisions regarding treatment efficacy and decisions on the need for esophageal dilation. When the esophageal mucosa is evaluated for biopsies, furrows and exudates should be targeted, if present, and multiple biopsies (minimum of five to six) should be taken throughout the esophagus given the patchy nature of the disease.

How do I choose an initial therapy?

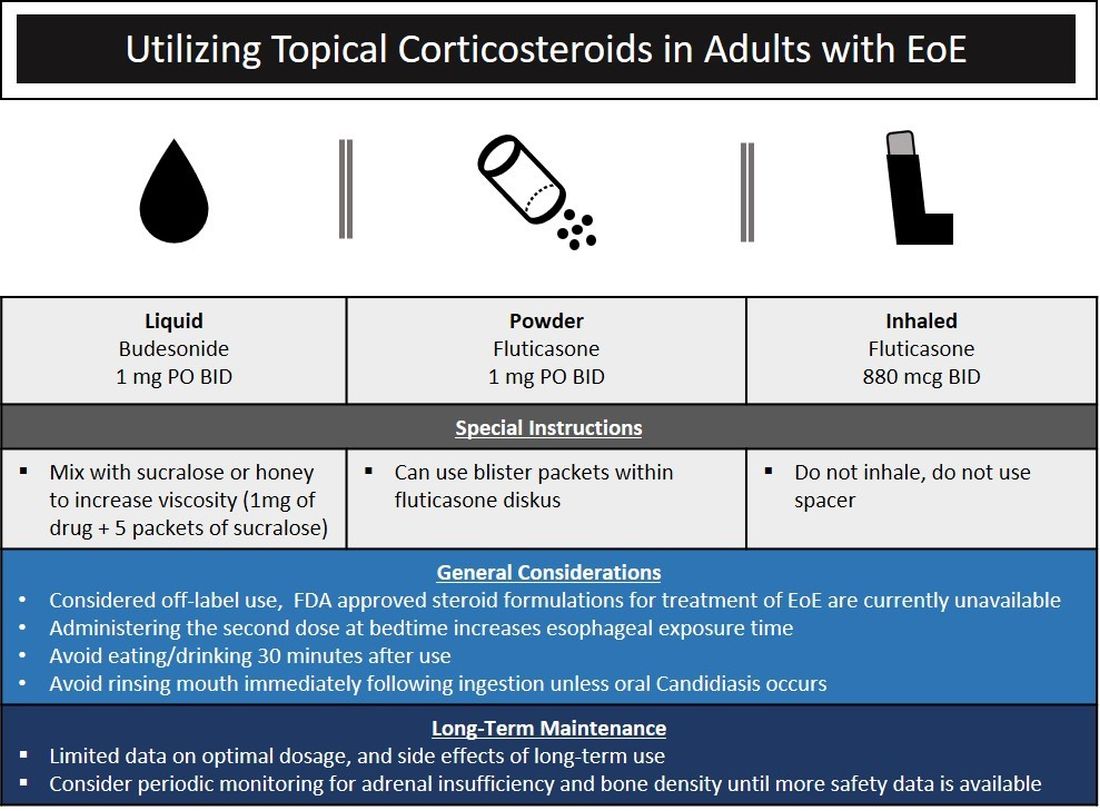

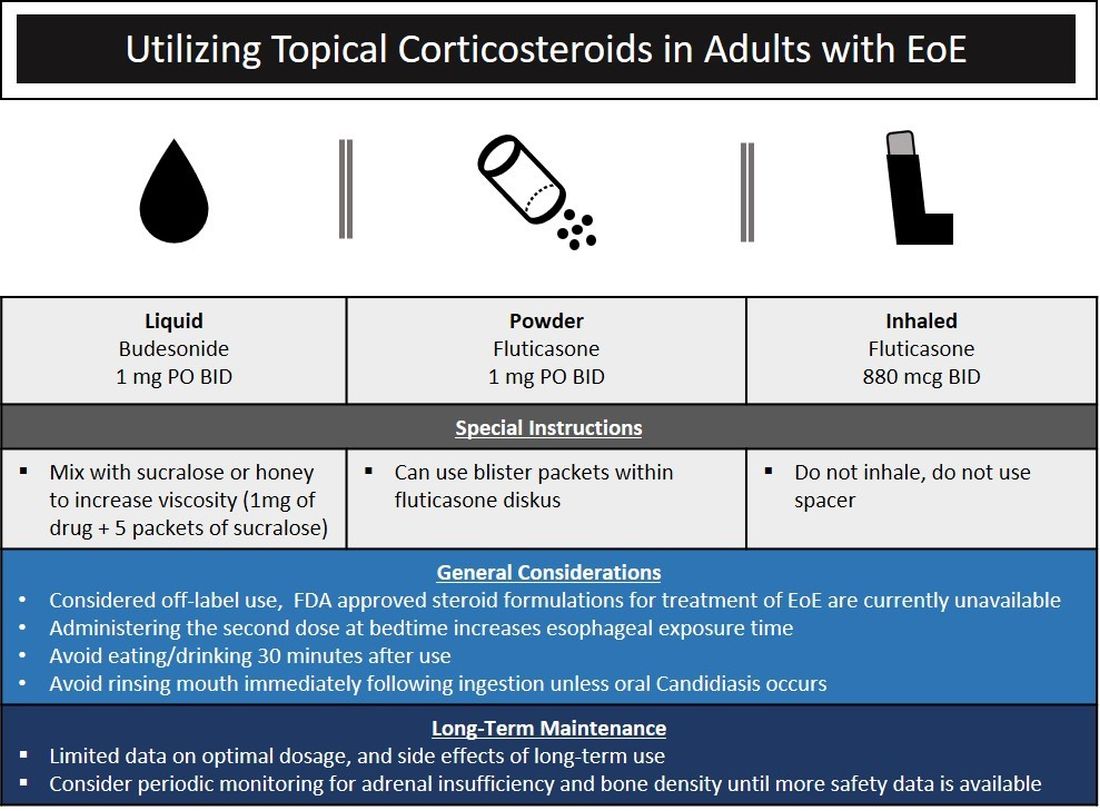

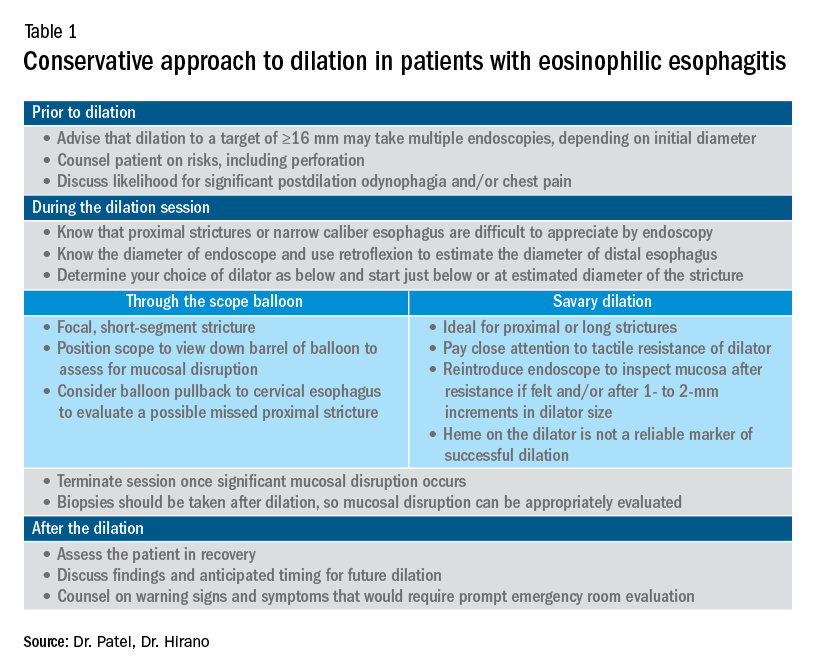

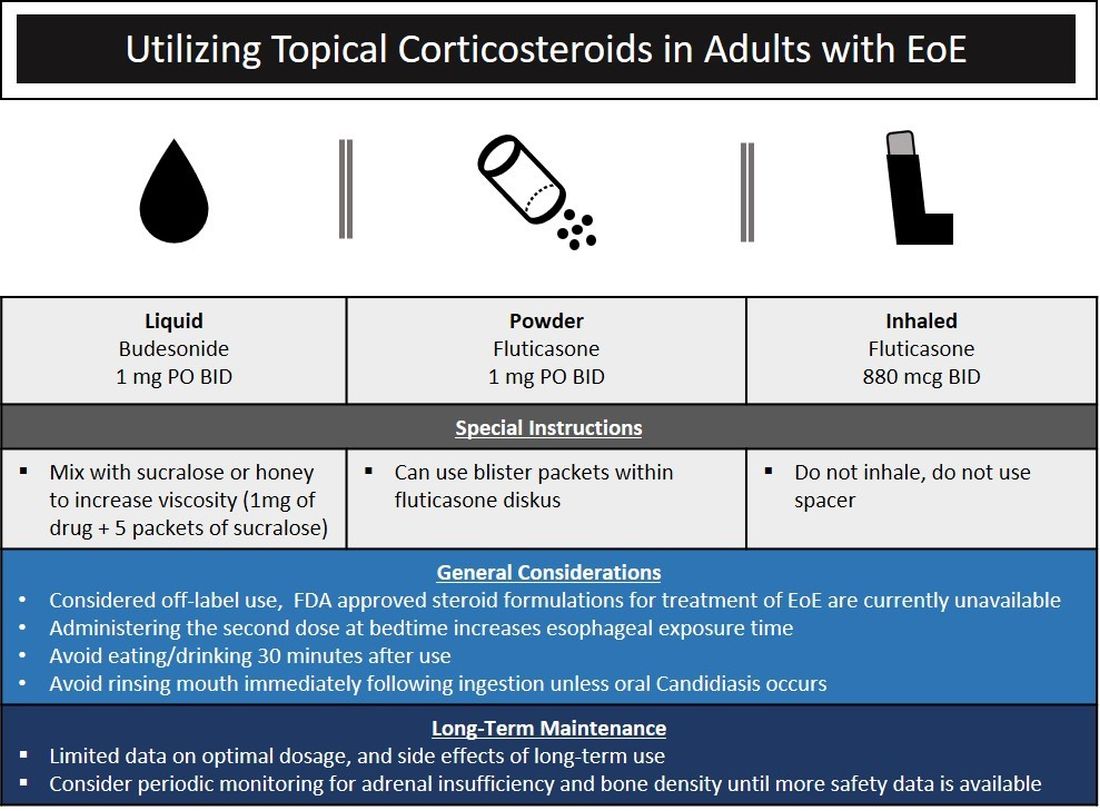

The choice of initial therapy considers patient preferences, medication availability, disease severity, impact on quality of life, and need for repeated endoscopies. While there are many novel agents currently being investigated in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials, the current mainstays of treatment include PPI therapy, topical steroids, dietary therapy, and dilation. Of note, there have been no head-to-head trials comparing these different modalities. A recent systematic review reported that PPIs can induce histologic remission in 42% of patients.8 The ease of use and availability of PPI therapy make this an attractive first choice for patients. Pooled estimates show that topical steroids can induce remission in 66% of patients.8 It is important to note that there is currently no Food and Drug Administration–approved formulation of steroids for the treatment of EoE. As such, there are several practical aspects to consider when instructing patients to use agents not designed for esophageal delivery (Figure 1).

Source: Dr. Patel, Dr. Hirano

Lack of insurance coverage for topical steroids can make cost of a prescription a deterrent to use. While topical steroids are well tolerated, concerns for candidiasis and adrenal insufficiency are being monitored in prospective, long-term clinical trials. Concomitant use of steroids with PPI would be appropriate for EoE patients with coexisting GERD (severe heartburn, erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus). In addition, we often combine steroids with PPI therapy for EoE patients who demonstrate a convincing but incomplete response to PPI monotherapy (i.e., reduction of baseline inflammation from 75 eos/hpf to 20 eos/hpf).

Diet therapy is a popular choice for management of EoE by patients, given the ability to remove food triggers that initiate the immune dysregulation and to avoid chronic medication use. Three dietary options have been described including an elemental, amino acid–based diet which eliminates all common food allergens, allergy testing–directed elimination diet, and an empiric elimination diet. Though elemental diets have shown the most efficacy, practical aspects of implementing, maintaining, and identifying triggers restrict their adoption by most patients and clinicians.9 Allergy-directed elimination diets, where allergens are eliminated based on office-based allergy testing, initially seemed promising, though studies have shown limited histologic remission, compared with other diet therapies as well as the inability to identify true food triggers. Advancement of office-based testing to identify food triggers is needed to streamline this dietary approach. In the adult patient, the empiric elimination diet remains an attractive choice of the available dietary therapies. In this dietary approach, which has shown efficacy in both children and adults, the most common food allergens (milk, wheat, soy, egg, nuts, and seafood) are eliminated.9

How do I make dietary therapy work in clinical practice?

Before dietary therapy is initiated, it is important that your practice is situated to support this approach and that patients fully understand the process. A multidisciplinary approach optimizes dietary therapy. Dietitians provide expert guidance on eliminating trigger foods, maintaining nutrition, and avoiding inadvertent cross-contamination. Patient questions may include the safety of consumption of non–cow-based cheese/milk, alcoholic beverages, wheat alternatives, and restaurant food. Allergists address concerns for a concomitant IgE food allergy based on a clinical history or previous testing. Patients should be informed that identifying a food trigger often takes several months and multiple endoscopies. Clinicians should be aware of potential food cost and accessibility issues as well as the reported, albeit uncommon, development of de novo IgE-mediated food allergy during reintroduction. Timing of diet therapy is also a factor in success. Patients should avoid starting diets during major holidays, family celebrations, college years, and busy travel months.

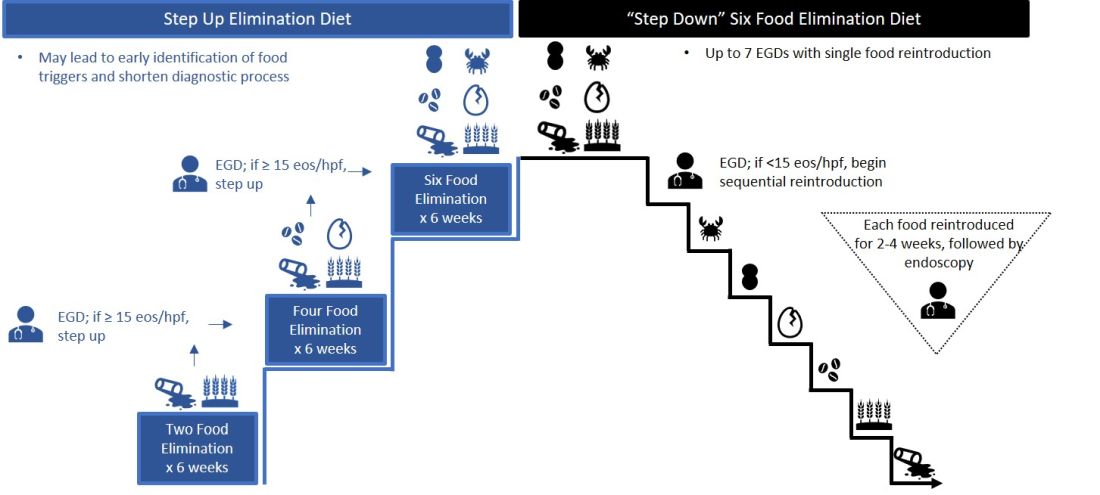

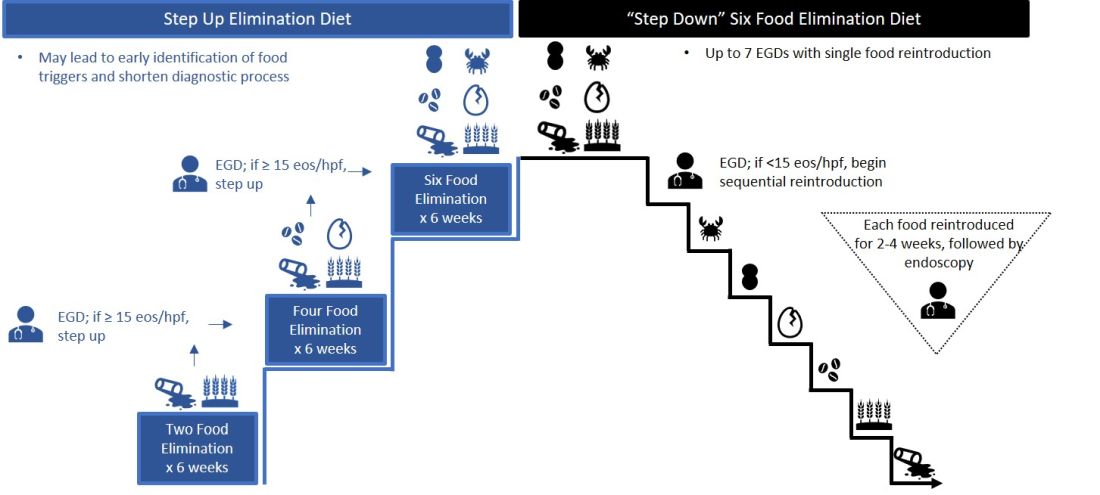

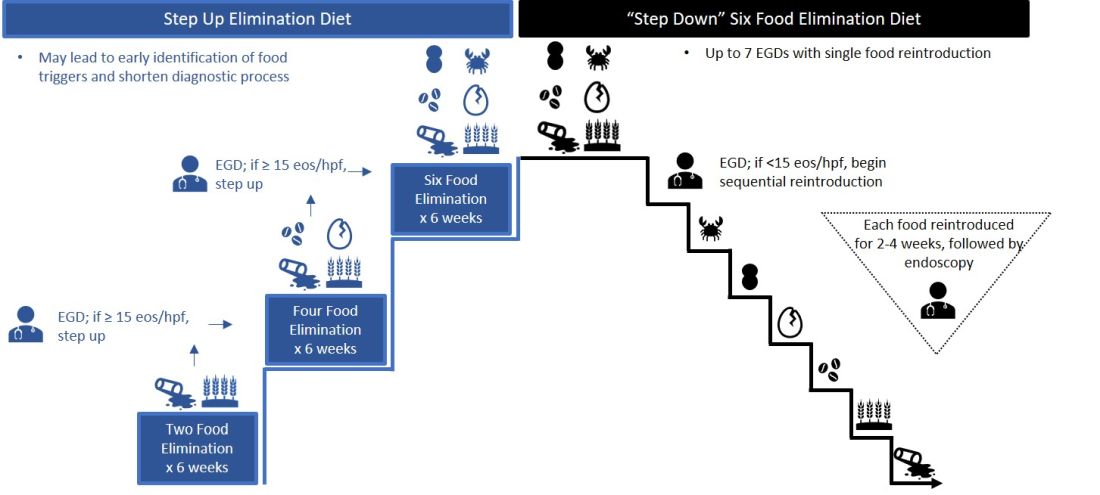

Particularly empiric elimination diets, frequently used in adults, several approaches have been described (Figure 2).

Source: Dr. Patel, Dr. Hirano

Initially, a step-down approach was described, with patients pursuing a six-food elimination diet (SFED), which eliminates the six most common triggers: milk, wheat, soy/legumes, egg, nuts, and seafood. Once in histologic remission, patients then systematically reintroduce foods in order to identify a causative trigger. Given that many patients have only one or two identified food triggers, other approaches were created including a single-food elimination diet eliminating milk, the two-food elimination diet (TFED) eliminating milk and wheat, and the four-food elimination diet (FFED) eliminating milk, wheat, soy/legumes, and eggs. A novel step-up approach has also now been described where patients start with the TFED and progress to the FFED and then potentially SFED based on histologic response.10 This approach has the potential to more readily identify triggers, decrease diagnostic time, and reduce endoscopic interventions. There are pros and cons to each elimination diet approach that should be discussed with patients. Many patients may find a one- or two-food elimination diet more feasible than a full SFED.

What should I consider when performing dilation?

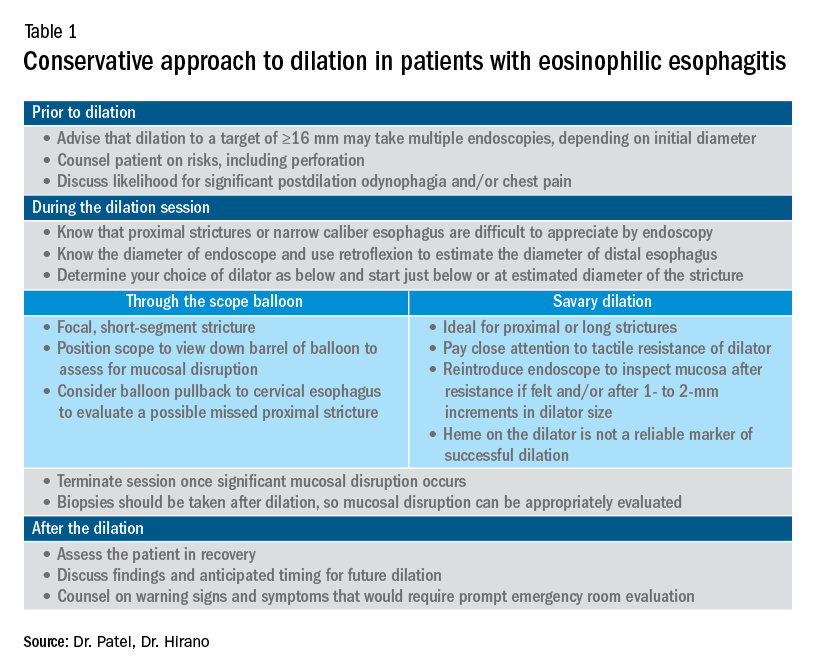

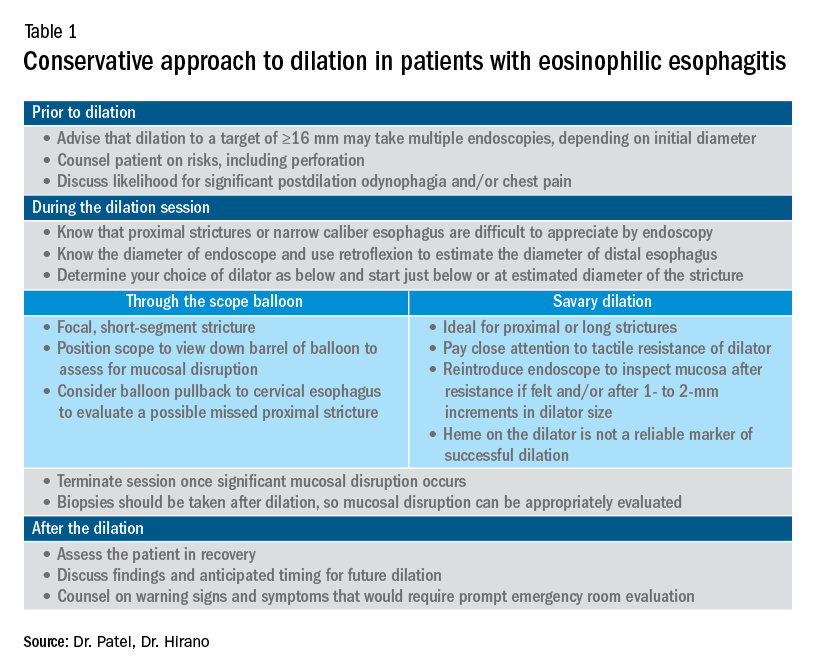

Esophageal dilation is frequently used to address the fibrostenotic complications of EoE that do not as readily respond to PPI, steroid, or diet therapy. The majority of patients note symptomatic improvement following dilation, though dilation alone does not address the inflammatory component of disease.8 With a conservative approach, the complication rates of esophageal dilation in EoE are similar to that of benign, esophageal strictures. Endoscopists should be aware that endoscopy alone can miss strictures and consider both practical and technical aspects when performing dilations (Table 1).11,12

When should an allergist be consulted?

The role of the allergist in the management of patients with EoE varies by patient and practice. IgE serologic or skin testing have limited accuracy in identifying food triggers for EoE. Nevertheless, the majority of patients with EoE have an atopic condition which may include asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, or IgE-mediated food allergy. Although EoE is thought to primarily occur from an immune response to ingested oral allergens, aeroallergens may exacerbate disease as evidenced by the seasonal variation in EoE symptoms in some patients. The allergist provides treatment for these “extraesophageal” atopic conditions which may, in turn, have synergistic effects on the treatment of EoE. Furthermore, allergists may prescribe biologic therapies that are FDA approved for the treatment of atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis. While not approved for EoE, several of these agents have shown efficacy in phase 2 clinical trials in EoE. In some practice settings, allergists primarily manage EoE patients with the assistance of gastroenterologists for periodic endoscopic activity assessment.

What are the key aspects of maintenance therapy?

The goals of treatment focus on symptomatic, histologic, and endoscopic improvement, and the prevention of future or ongoing fibrostenotic complications.2 Because of the adaptive eating behaviors discussed above, symptom response may not reliably correlate with histologic and/or endoscopic improvement. Moreover, dysphagia is related to strictures that often do not resolve in spite of resolution of mucosal inflammation. As such, histology and endoscopy are more objective and reliable targets of a successful response to therapy. Though studies have used variable esophageal density levels for response, using a cutoff of <15 eos/hpf as a therapeutic endpoint is reasonable for both initial response to therapy and long-term monitoring.13 We advocate for standardization of reporting endoscopic findings to better track change over time using the EREFS scoring system.7 While inflammatory features improve, the fibrostenotic features may persist despite improvement in histology. Dilation is often performed in these situations, especially for symptomatic individuals.

During clinical follow-up, the frequency of monitoring as it relates to symptom and endoscopic assessment is not well defined. It is reasonable to repeat endoscopic intervention following changes in therapy (i.e., reduction in steroid dosing or reintroduction of putative food triggers) or in symptoms.13 It is unclear if patients benefit from repeated endoscopies at set intervals without symptom change and after histologic response has been confirmed. In our practice, endoscopies are often considered on an annual basis. This interval is increased for patients with demonstrated stability of disease.

For patients who opt for dietary therapy and have one or two food triggers identified, long-term maintenance therapy can be straightforward with ongoing food avoidance. Limited data exist regarding long-term effectiveness of dietary therapy but loss of initial response has been reported that is often attributed to problems with adherence. Use of “diet holidays” or “planned cheats” to allow for intermittent consumption of trigger foods, often under the cover of short-term use of steroids, may improve the long-term feasibility of diet approaches.

In the recent American Gastroenterological Association guidelines, continuation of swallowed, topical steroids is recommended following remission with short-term treatment. The recurrence of both symptoms and inflammation following medication withdrawal supports this practice. Furthermore, natural history studies demonstrate progression of esophageal strictures with untreated disease.

There are no clear guidelines for long-term dosage and use of PPI or topical steroid therapy. Our practice is to down-titrate the dose of PPI or steroid following remission with short-term therapy, often starting with a reduction from twice a day to daily dosing. Although topical steroid therapy has fewer side effects, compared with systemic steroids, patients should be aware of the potential for adrenal suppression especially in an atopic population who may be exposed to multiple forms of topical steroids. Shared decision-making between patients and providers is recommended to determine comfort level with long-term use of prescription medications and dosage.

What’s on the horizon?

Several areas of development are underway to better assess and manage EoE. Novel histologic scoring tools now assess characteristics on pathology beyond eosinophil density, office-based testing modalities have been developed to assess inflammatory activity and thereby obviate the need for endoscopy, new technology can provide measures of esophageal remodeling and provide assessment of disease severity, and several biologic agents are being studied that target specific allergic mediators of the immune response in EoE.3,14-18 These novel tools, technologies, and therapies will undoubtedly change the management approach to EoE. Referral of patients into ongoing clinical trials will help inform advances in the field.

Conclusion

As an increasingly prevalent disease with a high degree of upper GI morbidity, EoE has transitioned from a rare entity to a commonly encountered disease. The new gastroenterologist will confront both straightforward as well as complex patients with EoE, and we offer several practical aspects on management. In the years ahead, the care of patients with EoE will continue to evolve to a more streamlined, effective, and personalized approach.

References

1. Kidambi T et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4335-41.

2. Dellon ES et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:319-32 e3.

3. Hirano I et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:840-51.

4. Furuta GT et al. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342-63.

5. Liacouras CA et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3-20 e6; quiz 1-2.

6. Dellon ES et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1022-33 e10.

7. Hirano I et al. Gut. 2013;62:489-95.

8. Rank MA et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1789-810 e15.

9. Arias A et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1639-48.

10. Molina-Infante J et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:1365-72.

11. Gentile N et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:1333-40.

12. Hirano I. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:601-6.

13. Hirano I et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1776-86.

14. Collins MH et al. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1-8.

15. Furuta GT et al. Gut. 2013;62:1395-405.

16. Katzka DA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:77-83 e2.

17. Kwiatek MA et al. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:82-90.

18. Nicodeme F et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1101-7 e1.

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) has transformed over the past 3 decades from a rarely encountered entity to one of the most common causes of dysphagia in adults.1 Given the marked rise in prevalence, the early-career gastroenterologist will undoubtedly be involved with managing this disease.2 The typical presentation includes a young, atopic male presenting with dysphagia in the outpatient setting or, more acutely, with a food impaction when on call. As every fellow is keenly aware, the calls often come late at night as patients commonly have meat impactions while consuming dinner. Current management focuses on symptomatic, histologic, and endoscopic improvement with medication, dietary, and mechanical (i.e., dilation) modalities.

EoE is defined by the presence of esophageal dysfunction and esophageal eosinophilic inflammation with ≥15 eosinophils/high-powered field (eos/hpf) required for the diagnosis. With better understanding of the pathogenesis of EoE involving the complex interaction of environmental, host, and genetic factors, advancements have been made as it relates to the diagnostic criteria, endoscopic evaluation, and therapeutic options. In this article, we review the current management of adult patients with EoE and offer practical guidance to key questions for the young gastroenterologist as well as insights into future areas of interest.

What should I consider when diagnosing EoE?

Symptoms are central to the diagnosis and clinical presentation of EoE. In assessing symptoms, clinicians should be aware of adaptive “IMPACT” strategies patients often subconsciously develop in response to their chronic and progressive condition: Imbibing fluids with meals, modifying foods by cutting or pureeing, prolonging meal times, avoiding harder texture foods, chewing excessively, and turning away tablets/pills.3 Failure to query such adaptive behaviors may lead to an underestimation of disease activity and severity.

An important aspect to confirming the diagnosis of EoE is to exclude other causes of esophageal eosinophilia. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is known to cause esophageal eosinophilia and historically has been viewed as a distinct disease process. In fact, initial guidelines included lack of response to a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) trial or normal esophageal pH monitoring as diagnostic criteria.4 However, as experience was garnered, it became clear that PPI therapy was effective at improving inflammation in 30%-50% of patients with clinical presentations and histologic features consistent with EoE. As such, the concept of PPI–responsive esophageal eosinophilia (PPI-REE) was introduced in 2011.5 Further investigation then highlighted that PPI-REE and EoE had nearly identical clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features as well as eosinophil biomarker and gene expression profiles. Hence, recent international guidelines no longer necessitate a PPI trial to establish a diagnosis of EoE.6

The young gastroenterologist should also be mindful of other issues related to the initial diagnosis of EoE. EoE may present concomitantly with other disease entities including GERD, “extra-esophageal” eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases, concomitant IgE-mediated food allergy, hypereosinophilic syndromes, connective tissue disorders, autoimmune diseases, celiac disease, and inflammatory bowel disease.3 It has been speculated that some of these disorders share common aspects of genetic and environmental predisposing factors as well as shared pathogenesis. Careful history taking should include a full review of atopic conditions and GI-related symptoms and endoscopy should carefully inspect not only the esophagus, but also gastric and duodenal mucosa. The endoscopic features almost always reveal edema, rings, exudates, furrows, and strictures and can be assessed using the EoE Endoscopic Reference Scoring system (EREFS).7 EREFS allows for systematic identification of abnormalities that can inform decisions regarding treatment efficacy and decisions on the need for esophageal dilation. When the esophageal mucosa is evaluated for biopsies, furrows and exudates should be targeted, if present, and multiple biopsies (minimum of five to six) should be taken throughout the esophagus given the patchy nature of the disease.

How do I choose an initial therapy?

The choice of initial therapy considers patient preferences, medication availability, disease severity, impact on quality of life, and need for repeated endoscopies. While there are many novel agents currently being investigated in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials, the current mainstays of treatment include PPI therapy, topical steroids, dietary therapy, and dilation. Of note, there have been no head-to-head trials comparing these different modalities. A recent systematic review reported that PPIs can induce histologic remission in 42% of patients.8 The ease of use and availability of PPI therapy make this an attractive first choice for patients. Pooled estimates show that topical steroids can induce remission in 66% of patients.8 It is important to note that there is currently no Food and Drug Administration–approved formulation of steroids for the treatment of EoE. As such, there are several practical aspects to consider when instructing patients to use agents not designed for esophageal delivery (Figure 1).

Source: Dr. Patel, Dr. Hirano

Lack of insurance coverage for topical steroids can make cost of a prescription a deterrent to use. While topical steroids are well tolerated, concerns for candidiasis and adrenal insufficiency are being monitored in prospective, long-term clinical trials. Concomitant use of steroids with PPI would be appropriate for EoE patients with coexisting GERD (severe heartburn, erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus). In addition, we often combine steroids with PPI therapy for EoE patients who demonstrate a convincing but incomplete response to PPI monotherapy (i.e., reduction of baseline inflammation from 75 eos/hpf to 20 eos/hpf).

Diet therapy is a popular choice for management of EoE by patients, given the ability to remove food triggers that initiate the immune dysregulation and to avoid chronic medication use. Three dietary options have been described including an elemental, amino acid–based diet which eliminates all common food allergens, allergy testing–directed elimination diet, and an empiric elimination diet. Though elemental diets have shown the most efficacy, practical aspects of implementing, maintaining, and identifying triggers restrict their adoption by most patients and clinicians.9 Allergy-directed elimination diets, where allergens are eliminated based on office-based allergy testing, initially seemed promising, though studies have shown limited histologic remission, compared with other diet therapies as well as the inability to identify true food triggers. Advancement of office-based testing to identify food triggers is needed to streamline this dietary approach. In the adult patient, the empiric elimination diet remains an attractive choice of the available dietary therapies. In this dietary approach, which has shown efficacy in both children and adults, the most common food allergens (milk, wheat, soy, egg, nuts, and seafood) are eliminated.9

How do I make dietary therapy work in clinical practice?

Before dietary therapy is initiated, it is important that your practice is situated to support this approach and that patients fully understand the process. A multidisciplinary approach optimizes dietary therapy. Dietitians provide expert guidance on eliminating trigger foods, maintaining nutrition, and avoiding inadvertent cross-contamination. Patient questions may include the safety of consumption of non–cow-based cheese/milk, alcoholic beverages, wheat alternatives, and restaurant food. Allergists address concerns for a concomitant IgE food allergy based on a clinical history or previous testing. Patients should be informed that identifying a food trigger often takes several months and multiple endoscopies. Clinicians should be aware of potential food cost and accessibility issues as well as the reported, albeit uncommon, development of de novo IgE-mediated food allergy during reintroduction. Timing of diet therapy is also a factor in success. Patients should avoid starting diets during major holidays, family celebrations, college years, and busy travel months.

Particularly empiric elimination diets, frequently used in adults, several approaches have been described (Figure 2).

Source: Dr. Patel, Dr. Hirano

Initially, a step-down approach was described, with patients pursuing a six-food elimination diet (SFED), which eliminates the six most common triggers: milk, wheat, soy/legumes, egg, nuts, and seafood. Once in histologic remission, patients then systematically reintroduce foods in order to identify a causative trigger. Given that many patients have only one or two identified food triggers, other approaches were created including a single-food elimination diet eliminating milk, the two-food elimination diet (TFED) eliminating milk and wheat, and the four-food elimination diet (FFED) eliminating milk, wheat, soy/legumes, and eggs. A novel step-up approach has also now been described where patients start with the TFED and progress to the FFED and then potentially SFED based on histologic response.10 This approach has the potential to more readily identify triggers, decrease diagnostic time, and reduce endoscopic interventions. There are pros and cons to each elimination diet approach that should be discussed with patients. Many patients may find a one- or two-food elimination diet more feasible than a full SFED.

What should I consider when performing dilation?

Esophageal dilation is frequently used to address the fibrostenotic complications of EoE that do not as readily respond to PPI, steroid, or diet therapy. The majority of patients note symptomatic improvement following dilation, though dilation alone does not address the inflammatory component of disease.8 With a conservative approach, the complication rates of esophageal dilation in EoE are similar to that of benign, esophageal strictures. Endoscopists should be aware that endoscopy alone can miss strictures and consider both practical and technical aspects when performing dilations (Table 1).11,12

When should an allergist be consulted?

The role of the allergist in the management of patients with EoE varies by patient and practice. IgE serologic or skin testing have limited accuracy in identifying food triggers for EoE. Nevertheless, the majority of patients with EoE have an atopic condition which may include asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, or IgE-mediated food allergy. Although EoE is thought to primarily occur from an immune response to ingested oral allergens, aeroallergens may exacerbate disease as evidenced by the seasonal variation in EoE symptoms in some patients. The allergist provides treatment for these “extraesophageal” atopic conditions which may, in turn, have synergistic effects on the treatment of EoE. Furthermore, allergists may prescribe biologic therapies that are FDA approved for the treatment of atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis. While not approved for EoE, several of these agents have shown efficacy in phase 2 clinical trials in EoE. In some practice settings, allergists primarily manage EoE patients with the assistance of gastroenterologists for periodic endoscopic activity assessment.

What are the key aspects of maintenance therapy?

The goals of treatment focus on symptomatic, histologic, and endoscopic improvement, and the prevention of future or ongoing fibrostenotic complications.2 Because of the adaptive eating behaviors discussed above, symptom response may not reliably correlate with histologic and/or endoscopic improvement. Moreover, dysphagia is related to strictures that often do not resolve in spite of resolution of mucosal inflammation. As such, histology and endoscopy are more objective and reliable targets of a successful response to therapy. Though studies have used variable esophageal density levels for response, using a cutoff of <15 eos/hpf as a therapeutic endpoint is reasonable for both initial response to therapy and long-term monitoring.13 We advocate for standardization of reporting endoscopic findings to better track change over time using the EREFS scoring system.7 While inflammatory features improve, the fibrostenotic features may persist despite improvement in histology. Dilation is often performed in these situations, especially for symptomatic individuals.

During clinical follow-up, the frequency of monitoring as it relates to symptom and endoscopic assessment is not well defined. It is reasonable to repeat endoscopic intervention following changes in therapy (i.e., reduction in steroid dosing or reintroduction of putative food triggers) or in symptoms.13 It is unclear if patients benefit from repeated endoscopies at set intervals without symptom change and after histologic response has been confirmed. In our practice, endoscopies are often considered on an annual basis. This interval is increased for patients with demonstrated stability of disease.

For patients who opt for dietary therapy and have one or two food triggers identified, long-term maintenance therapy can be straightforward with ongoing food avoidance. Limited data exist regarding long-term effectiveness of dietary therapy but loss of initial response has been reported that is often attributed to problems with adherence. Use of “diet holidays” or “planned cheats” to allow for intermittent consumption of trigger foods, often under the cover of short-term use of steroids, may improve the long-term feasibility of diet approaches.

In the recent American Gastroenterological Association guidelines, continuation of swallowed, topical steroids is recommended following remission with short-term treatment. The recurrence of both symptoms and inflammation following medication withdrawal supports this practice. Furthermore, natural history studies demonstrate progression of esophageal strictures with untreated disease.

There are no clear guidelines for long-term dosage and use of PPI or topical steroid therapy. Our practice is to down-titrate the dose of PPI or steroid following remission with short-term therapy, often starting with a reduction from twice a day to daily dosing. Although topical steroid therapy has fewer side effects, compared with systemic steroids, patients should be aware of the potential for adrenal suppression especially in an atopic population who may be exposed to multiple forms of topical steroids. Shared decision-making between patients and providers is recommended to determine comfort level with long-term use of prescription medications and dosage.

What’s on the horizon?

Several areas of development are underway to better assess and manage EoE. Novel histologic scoring tools now assess characteristics on pathology beyond eosinophil density, office-based testing modalities have been developed to assess inflammatory activity and thereby obviate the need for endoscopy, new technology can provide measures of esophageal remodeling and provide assessment of disease severity, and several biologic agents are being studied that target specific allergic mediators of the immune response in EoE.3,14-18 These novel tools, technologies, and therapies will undoubtedly change the management approach to EoE. Referral of patients into ongoing clinical trials will help inform advances in the field.

Conclusion

As an increasingly prevalent disease with a high degree of upper GI morbidity, EoE has transitioned from a rare entity to a commonly encountered disease. The new gastroenterologist will confront both straightforward as well as complex patients with EoE, and we offer several practical aspects on management. In the years ahead, the care of patients with EoE will continue to evolve to a more streamlined, effective, and personalized approach.

References

1. Kidambi T et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4335-41.

2. Dellon ES et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:319-32 e3.

3. Hirano I et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:840-51.

4. Furuta GT et al. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342-63.

5. Liacouras CA et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3-20 e6; quiz 1-2.

6. Dellon ES et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1022-33 e10.

7. Hirano I et al. Gut. 2013;62:489-95.

8. Rank MA et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1789-810 e15.

9. Arias A et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1639-48.

10. Molina-Infante J et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:1365-72.

11. Gentile N et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:1333-40.

12. Hirano I. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:601-6.

13. Hirano I et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1776-86.

14. Collins MH et al. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1-8.

15. Furuta GT et al. Gut. 2013;62:1395-405.

16. Katzka DA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:77-83 e2.

17. Kwiatek MA et al. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:82-90.

18. Nicodeme F et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1101-7 e1.

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) has transformed over the past 3 decades from a rarely encountered entity to one of the most common causes of dysphagia in adults.1 Given the marked rise in prevalence, the early-career gastroenterologist will undoubtedly be involved with managing this disease.2 The typical presentation includes a young, atopic male presenting with dysphagia in the outpatient setting or, more acutely, with a food impaction when on call. As every fellow is keenly aware, the calls often come late at night as patients commonly have meat impactions while consuming dinner. Current management focuses on symptomatic, histologic, and endoscopic improvement with medication, dietary, and mechanical (i.e., dilation) modalities.

EoE is defined by the presence of esophageal dysfunction and esophageal eosinophilic inflammation with ≥15 eosinophils/high-powered field (eos/hpf) required for the diagnosis. With better understanding of the pathogenesis of EoE involving the complex interaction of environmental, host, and genetic factors, advancements have been made as it relates to the diagnostic criteria, endoscopic evaluation, and therapeutic options. In this article, we review the current management of adult patients with EoE and offer practical guidance to key questions for the young gastroenterologist as well as insights into future areas of interest.

What should I consider when diagnosing EoE?

Symptoms are central to the diagnosis and clinical presentation of EoE. In assessing symptoms, clinicians should be aware of adaptive “IMPACT” strategies patients often subconsciously develop in response to their chronic and progressive condition: Imbibing fluids with meals, modifying foods by cutting or pureeing, prolonging meal times, avoiding harder texture foods, chewing excessively, and turning away tablets/pills.3 Failure to query such adaptive behaviors may lead to an underestimation of disease activity and severity.

An important aspect to confirming the diagnosis of EoE is to exclude other causes of esophageal eosinophilia. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is known to cause esophageal eosinophilia and historically has been viewed as a distinct disease process. In fact, initial guidelines included lack of response to a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) trial or normal esophageal pH monitoring as diagnostic criteria.4 However, as experience was garnered, it became clear that PPI therapy was effective at improving inflammation in 30%-50% of patients with clinical presentations and histologic features consistent with EoE. As such, the concept of PPI–responsive esophageal eosinophilia (PPI-REE) was introduced in 2011.5 Further investigation then highlighted that PPI-REE and EoE had nearly identical clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features as well as eosinophil biomarker and gene expression profiles. Hence, recent international guidelines no longer necessitate a PPI trial to establish a diagnosis of EoE.6

The young gastroenterologist should also be mindful of other issues related to the initial diagnosis of EoE. EoE may present concomitantly with other disease entities including GERD, “extra-esophageal” eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases, concomitant IgE-mediated food allergy, hypereosinophilic syndromes, connective tissue disorders, autoimmune diseases, celiac disease, and inflammatory bowel disease.3 It has been speculated that some of these disorders share common aspects of genetic and environmental predisposing factors as well as shared pathogenesis. Careful history taking should include a full review of atopic conditions and GI-related symptoms and endoscopy should carefully inspect not only the esophagus, but also gastric and duodenal mucosa. The endoscopic features almost always reveal edema, rings, exudates, furrows, and strictures and can be assessed using the EoE Endoscopic Reference Scoring system (EREFS).7 EREFS allows for systematic identification of abnormalities that can inform decisions regarding treatment efficacy and decisions on the need for esophageal dilation. When the esophageal mucosa is evaluated for biopsies, furrows and exudates should be targeted, if present, and multiple biopsies (minimum of five to six) should be taken throughout the esophagus given the patchy nature of the disease.

How do I choose an initial therapy?

The choice of initial therapy considers patient preferences, medication availability, disease severity, impact on quality of life, and need for repeated endoscopies. While there are many novel agents currently being investigated in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials, the current mainstays of treatment include PPI therapy, topical steroids, dietary therapy, and dilation. Of note, there have been no head-to-head trials comparing these different modalities. A recent systematic review reported that PPIs can induce histologic remission in 42% of patients.8 The ease of use and availability of PPI therapy make this an attractive first choice for patients. Pooled estimates show that topical steroids can induce remission in 66% of patients.8 It is important to note that there is currently no Food and Drug Administration–approved formulation of steroids for the treatment of EoE. As such, there are several practical aspects to consider when instructing patients to use agents not designed for esophageal delivery (Figure 1).

Source: Dr. Patel, Dr. Hirano

Lack of insurance coverage for topical steroids can make cost of a prescription a deterrent to use. While topical steroids are well tolerated, concerns for candidiasis and adrenal insufficiency are being monitored in prospective, long-term clinical trials. Concomitant use of steroids with PPI would be appropriate for EoE patients with coexisting GERD (severe heartburn, erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus). In addition, we often combine steroids with PPI therapy for EoE patients who demonstrate a convincing but incomplete response to PPI monotherapy (i.e., reduction of baseline inflammation from 75 eos/hpf to 20 eos/hpf).

Diet therapy is a popular choice for management of EoE by patients, given the ability to remove food triggers that initiate the immune dysregulation and to avoid chronic medication use. Three dietary options have been described including an elemental, amino acid–based diet which eliminates all common food allergens, allergy testing–directed elimination diet, and an empiric elimination diet. Though elemental diets have shown the most efficacy, practical aspects of implementing, maintaining, and identifying triggers restrict their adoption by most patients and clinicians.9 Allergy-directed elimination diets, where allergens are eliminated based on office-based allergy testing, initially seemed promising, though studies have shown limited histologic remission, compared with other diet therapies as well as the inability to identify true food triggers. Advancement of office-based testing to identify food triggers is needed to streamline this dietary approach. In the adult patient, the empiric elimination diet remains an attractive choice of the available dietary therapies. In this dietary approach, which has shown efficacy in both children and adults, the most common food allergens (milk, wheat, soy, egg, nuts, and seafood) are eliminated.9

How do I make dietary therapy work in clinical practice?

Before dietary therapy is initiated, it is important that your practice is situated to support this approach and that patients fully understand the process. A multidisciplinary approach optimizes dietary therapy. Dietitians provide expert guidance on eliminating trigger foods, maintaining nutrition, and avoiding inadvertent cross-contamination. Patient questions may include the safety of consumption of non–cow-based cheese/milk, alcoholic beverages, wheat alternatives, and restaurant food. Allergists address concerns for a concomitant IgE food allergy based on a clinical history or previous testing. Patients should be informed that identifying a food trigger often takes several months and multiple endoscopies. Clinicians should be aware of potential food cost and accessibility issues as well as the reported, albeit uncommon, development of de novo IgE-mediated food allergy during reintroduction. Timing of diet therapy is also a factor in success. Patients should avoid starting diets during major holidays, family celebrations, college years, and busy travel months.

Particularly empiric elimination diets, frequently used in adults, several approaches have been described (Figure 2).

Source: Dr. Patel, Dr. Hirano

Initially, a step-down approach was described, with patients pursuing a six-food elimination diet (SFED), which eliminates the six most common triggers: milk, wheat, soy/legumes, egg, nuts, and seafood. Once in histologic remission, patients then systematically reintroduce foods in order to identify a causative trigger. Given that many patients have only one or two identified food triggers, other approaches were created including a single-food elimination diet eliminating milk, the two-food elimination diet (TFED) eliminating milk and wheat, and the four-food elimination diet (FFED) eliminating milk, wheat, soy/legumes, and eggs. A novel step-up approach has also now been described where patients start with the TFED and progress to the FFED and then potentially SFED based on histologic response.10 This approach has the potential to more readily identify triggers, decrease diagnostic time, and reduce endoscopic interventions. There are pros and cons to each elimination diet approach that should be discussed with patients. Many patients may find a one- or two-food elimination diet more feasible than a full SFED.

What should I consider when performing dilation?

Esophageal dilation is frequently used to address the fibrostenotic complications of EoE that do not as readily respond to PPI, steroid, or diet therapy. The majority of patients note symptomatic improvement following dilation, though dilation alone does not address the inflammatory component of disease.8 With a conservative approach, the complication rates of esophageal dilation in EoE are similar to that of benign, esophageal strictures. Endoscopists should be aware that endoscopy alone can miss strictures and consider both practical and technical aspects when performing dilations (Table 1).11,12

When should an allergist be consulted?

The role of the allergist in the management of patients with EoE varies by patient and practice. IgE serologic or skin testing have limited accuracy in identifying food triggers for EoE. Nevertheless, the majority of patients with EoE have an atopic condition which may include asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, or IgE-mediated food allergy. Although EoE is thought to primarily occur from an immune response to ingested oral allergens, aeroallergens may exacerbate disease as evidenced by the seasonal variation in EoE symptoms in some patients. The allergist provides treatment for these “extraesophageal” atopic conditions which may, in turn, have synergistic effects on the treatment of EoE. Furthermore, allergists may prescribe biologic therapies that are FDA approved for the treatment of atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis. While not approved for EoE, several of these agents have shown efficacy in phase 2 clinical trials in EoE. In some practice settings, allergists primarily manage EoE patients with the assistance of gastroenterologists for periodic endoscopic activity assessment.

What are the key aspects of maintenance therapy?

The goals of treatment focus on symptomatic, histologic, and endoscopic improvement, and the prevention of future or ongoing fibrostenotic complications.2 Because of the adaptive eating behaviors discussed above, symptom response may not reliably correlate with histologic and/or endoscopic improvement. Moreover, dysphagia is related to strictures that often do not resolve in spite of resolution of mucosal inflammation. As such, histology and endoscopy are more objective and reliable targets of a successful response to therapy. Though studies have used variable esophageal density levels for response, using a cutoff of <15 eos/hpf as a therapeutic endpoint is reasonable for both initial response to therapy and long-term monitoring.13 We advocate for standardization of reporting endoscopic findings to better track change over time using the EREFS scoring system.7 While inflammatory features improve, the fibrostenotic features may persist despite improvement in histology. Dilation is often performed in these situations, especially for symptomatic individuals.

During clinical follow-up, the frequency of monitoring as it relates to symptom and endoscopic assessment is not well defined. It is reasonable to repeat endoscopic intervention following changes in therapy (i.e., reduction in steroid dosing or reintroduction of putative food triggers) or in symptoms.13 It is unclear if patients benefit from repeated endoscopies at set intervals without symptom change and after histologic response has been confirmed. In our practice, endoscopies are often considered on an annual basis. This interval is increased for patients with demonstrated stability of disease.

For patients who opt for dietary therapy and have one or two food triggers identified, long-term maintenance therapy can be straightforward with ongoing food avoidance. Limited data exist regarding long-term effectiveness of dietary therapy but loss of initial response has been reported that is often attributed to problems with adherence. Use of “diet holidays” or “planned cheats” to allow for intermittent consumption of trigger foods, often under the cover of short-term use of steroids, may improve the long-term feasibility of diet approaches.

In the recent American Gastroenterological Association guidelines, continuation of swallowed, topical steroids is recommended following remission with short-term treatment. The recurrence of both symptoms and inflammation following medication withdrawal supports this practice. Furthermore, natural history studies demonstrate progression of esophageal strictures with untreated disease.

There are no clear guidelines for long-term dosage and use of PPI or topical steroid therapy. Our practice is to down-titrate the dose of PPI or steroid following remission with short-term therapy, often starting with a reduction from twice a day to daily dosing. Although topical steroid therapy has fewer side effects, compared with systemic steroids, patients should be aware of the potential for adrenal suppression especially in an atopic population who may be exposed to multiple forms of topical steroids. Shared decision-making between patients and providers is recommended to determine comfort level with long-term use of prescription medications and dosage.

What’s on the horizon?

Several areas of development are underway to better assess and manage EoE. Novel histologic scoring tools now assess characteristics on pathology beyond eosinophil density, office-based testing modalities have been developed to assess inflammatory activity and thereby obviate the need for endoscopy, new technology can provide measures of esophageal remodeling and provide assessment of disease severity, and several biologic agents are being studied that target specific allergic mediators of the immune response in EoE.3,14-18 These novel tools, technologies, and therapies will undoubtedly change the management approach to EoE. Referral of patients into ongoing clinical trials will help inform advances in the field.

Conclusion

As an increasingly prevalent disease with a high degree of upper GI morbidity, EoE has transitioned from a rare entity to a commonly encountered disease. The new gastroenterologist will confront both straightforward as well as complex patients with EoE, and we offer several practical aspects on management. In the years ahead, the care of patients with EoE will continue to evolve to a more streamlined, effective, and personalized approach.

References

1. Kidambi T et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4335-41.

2. Dellon ES et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:319-32 e3.

3. Hirano I et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:840-51.