User login

Re-excision unnecessary in moderately dysplastic nevi with positive margins

ORLANDO – Re-excisions are not needed when clinically excised moderately dysplastic nevi have positive histologic margins, based on results of a retrospective study of 438 patients who were treated at nine academic medical centers in the United States.

Not a single patient in the study developed melanoma at the excision site after an average follow-up of 6.9 years, and at least 3 years in all cases, said Elizabeth G. Berry, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, and Atlanta Veterans Administration Medical Center, one of the study investigators.

The finding “really has the potential to change how we manage these lesions. You don’t need to cut [these patients] again. You can watch them. Close observation with routine skin surveillance is reasonable,” Dr. Berry said at the International Investigative Dermatology meeting.

Routine skin exams are essential for patients with a history of dysplastic nevi as these patients are at risk for developing melanoma. Indeed, in this study, 100 patients (22.8%) subsequently developed melanomas at a site other than the location of their biopsy.

The study included 438 patients who had 467 biopsies that indicated incomplete excision of a moderately dysplastic nevus from 1990 to 2014. Patients were at least 18 years old and were an average of 47 years old. About half had a history of dysplastic nevi, and a third had a history of melanoma.

All of their biopsies for moderately dysplastic nevi had positive margins, but patients had no clinically apparent residual pigment at their excision sites. Lesions were equally as likely to be removed by shave and punch biopsies, and the majority of the nevi were located on the trunk. Complete excision was the intent in all cases.

To control for interobserver variability, the centers submitted a total of 40 slides for central dermatopathology review, which found agreement in 35 cases (87.8%). Two of the remaining five cases were downgraded to mild dysplasia, two were upgraded to severe, and one patient was upgraded to melanoma in situ, but hasn’t had a recurrence after 5 years of follow-up.

Controlling for age, sex, and family history, a patient history of dysplastic nevus prior to the biopsy doubled the risk of a subsequent melanoma (P = .017), and a history of melanoma increased it almost eightfold (P less than .001).

Knowing these risk factors, patients with a history of dysplastic nevi “need to have more frequent total body skin exams. What that frequency is, we don’t know,” Dr. Berry said.

The investigators reported they had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Kim CC et al. IID 2018, Abstract 571.

ORLANDO – Re-excisions are not needed when clinically excised moderately dysplastic nevi have positive histologic margins, based on results of a retrospective study of 438 patients who were treated at nine academic medical centers in the United States.

Not a single patient in the study developed melanoma at the excision site after an average follow-up of 6.9 years, and at least 3 years in all cases, said Elizabeth G. Berry, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, and Atlanta Veterans Administration Medical Center, one of the study investigators.

The finding “really has the potential to change how we manage these lesions. You don’t need to cut [these patients] again. You can watch them. Close observation with routine skin surveillance is reasonable,” Dr. Berry said at the International Investigative Dermatology meeting.

Routine skin exams are essential for patients with a history of dysplastic nevi as these patients are at risk for developing melanoma. Indeed, in this study, 100 patients (22.8%) subsequently developed melanomas at a site other than the location of their biopsy.

The study included 438 patients who had 467 biopsies that indicated incomplete excision of a moderately dysplastic nevus from 1990 to 2014. Patients were at least 18 years old and were an average of 47 years old. About half had a history of dysplastic nevi, and a third had a history of melanoma.

All of their biopsies for moderately dysplastic nevi had positive margins, but patients had no clinically apparent residual pigment at their excision sites. Lesions were equally as likely to be removed by shave and punch biopsies, and the majority of the nevi were located on the trunk. Complete excision was the intent in all cases.

To control for interobserver variability, the centers submitted a total of 40 slides for central dermatopathology review, which found agreement in 35 cases (87.8%). Two of the remaining five cases were downgraded to mild dysplasia, two were upgraded to severe, and one patient was upgraded to melanoma in situ, but hasn’t had a recurrence after 5 years of follow-up.

Controlling for age, sex, and family history, a patient history of dysplastic nevus prior to the biopsy doubled the risk of a subsequent melanoma (P = .017), and a history of melanoma increased it almost eightfold (P less than .001).

Knowing these risk factors, patients with a history of dysplastic nevi “need to have more frequent total body skin exams. What that frequency is, we don’t know,” Dr. Berry said.

The investigators reported they had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Kim CC et al. IID 2018, Abstract 571.

ORLANDO – Re-excisions are not needed when clinically excised moderately dysplastic nevi have positive histologic margins, based on results of a retrospective study of 438 patients who were treated at nine academic medical centers in the United States.

Not a single patient in the study developed melanoma at the excision site after an average follow-up of 6.9 years, and at least 3 years in all cases, said Elizabeth G. Berry, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, and Atlanta Veterans Administration Medical Center, one of the study investigators.

The finding “really has the potential to change how we manage these lesions. You don’t need to cut [these patients] again. You can watch them. Close observation with routine skin surveillance is reasonable,” Dr. Berry said at the International Investigative Dermatology meeting.

Routine skin exams are essential for patients with a history of dysplastic nevi as these patients are at risk for developing melanoma. Indeed, in this study, 100 patients (22.8%) subsequently developed melanomas at a site other than the location of their biopsy.

The study included 438 patients who had 467 biopsies that indicated incomplete excision of a moderately dysplastic nevus from 1990 to 2014. Patients were at least 18 years old and were an average of 47 years old. About half had a history of dysplastic nevi, and a third had a history of melanoma.

All of their biopsies for moderately dysplastic nevi had positive margins, but patients had no clinically apparent residual pigment at their excision sites. Lesions were equally as likely to be removed by shave and punch biopsies, and the majority of the nevi were located on the trunk. Complete excision was the intent in all cases.

To control for interobserver variability, the centers submitted a total of 40 slides for central dermatopathology review, which found agreement in 35 cases (87.8%). Two of the remaining five cases were downgraded to mild dysplasia, two were upgraded to severe, and one patient was upgraded to melanoma in situ, but hasn’t had a recurrence after 5 years of follow-up.

Controlling for age, sex, and family history, a patient history of dysplastic nevus prior to the biopsy doubled the risk of a subsequent melanoma (P = .017), and a history of melanoma increased it almost eightfold (P less than .001).

Knowing these risk factors, patients with a history of dysplastic nevi “need to have more frequent total body skin exams. What that frequency is, we don’t know,” Dr. Berry said.

The investigators reported they had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Kim CC et al. IID 2018, Abstract 571.

REPORTING FROM IID 2018

Is Napping Associated With Risk of Parkinson’s Disease?

Older men who nap for over an hour per day, as measured by actigraphy, may be more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease.

BALTIMORE—Older men who nap for more than an hour per day are more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease over 11 years of follow-up, compared with those who nap for less than an hour per day and do not have excessive daytime sleepiness, according to a study described at the 32nd Annual Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Self-reported daytime sleepiness alone was not associated with increased risk, said Yue Leng, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, San Francisco.

The findings suggest that objective measures of napping might be valuable preclinical markers of Parkinson’s disease.

The mechanism underlying the association is unclear. It is possible that the ongoing degeneration in brain regions involved in the 24-hour sleep–wake cycle leads to increased napping in people who later develop Parkinson’s disease, she said.

“Excessive daytime sleepiness and daytime napping are common in older adults, especially those with Parkinson’s disease,” Dr. Leng said. Whether excessive daytime sleepiness or napping precedes the development of Parkinson’s disease and may be risk factors is not well understood, however. “There is a lack of objectively measured naps and also a lack of longitudinal studies. In fact, we are unaware of any longitudinal studies that have used objectively measured napping in relation to Parkinson’s disease risk.”

To examine the longitudinal association between objectively measured napping duration and risk of Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Leng and colleagues analyzed data from the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study (MrOS), a large, longitudinal, multicenter study of community-dwelling older men. They excluded men with Parkinson’s disease at baseline. The analysis included data from more than 2,900 men who had napping and sleep measures at baseline between 2003 and 2005 and were followed up for development of Parkinson’s disease over 11 years.

The investigators used actigraphy to measure napping. Participants wore a sleep watch on the dominant wrist for at least five consecutive 24-hour periods. The researchers defined napping as having at least five consecutive minutes of inactivity outside of the main sleep period. They defined excessive daytime sleepiness as a score greater than 10 on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.

The researchers identified Parkinson’s disease using physician diagnosis or Parkinson’s disease medication use. Their analysis adjusted for age, BMI, smoking, physical activity, depression, comorbidities, global cognition scores, medication use, and nighttime sleep variables (ie, efficiency, duration, and apnea–hypopnea index).

“The highest risk was in those who reported daytime sleepiness and had objective napping for at least an hour per day,” Dr. Leng said. These participants had more than twice the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease, compared with a reference group that did not have daytime sleepiness and napped for less than one hour per day (odds ratio, 2.52).

Participants who napped for at least an hour per day but did not report excessive daytime sleepiness also had increased risk (odds ratio, 1.96).

The results indicate that objectively measured napping, rather than self-reported excessive daytime sleepiness, is important for Parkinson’s disease risk, Dr. Leng said.

Sensitivity analyses that excluded patients who developed Parkinson’s disease within two years after baseline and only included physician-confirmed cases of Parkinson’s disease had similar results.

Actigraphy is limited in its ability to differentiate between napping and inactivity, Dr. Leng noted. In addition, the results cannot be generalized to women and younger populations, she said.

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Leng Y, Goldman SM, Cawthon PM, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness, objective napping and 11-year risk of Parkinson’s disease in older men. Int J Epidemiol. 2018 Jun 4 [Epub ahead of print].

Older men who nap for over an hour per day, as measured by actigraphy, may be more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease.

Older men who nap for over an hour per day, as measured by actigraphy, may be more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease.

BALTIMORE—Older men who nap for more than an hour per day are more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease over 11 years of follow-up, compared with those who nap for less than an hour per day and do not have excessive daytime sleepiness, according to a study described at the 32nd Annual Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Self-reported daytime sleepiness alone was not associated with increased risk, said Yue Leng, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, San Francisco.

The findings suggest that objective measures of napping might be valuable preclinical markers of Parkinson’s disease.

The mechanism underlying the association is unclear. It is possible that the ongoing degeneration in brain regions involved in the 24-hour sleep–wake cycle leads to increased napping in people who later develop Parkinson’s disease, she said.

“Excessive daytime sleepiness and daytime napping are common in older adults, especially those with Parkinson’s disease,” Dr. Leng said. Whether excessive daytime sleepiness or napping precedes the development of Parkinson’s disease and may be risk factors is not well understood, however. “There is a lack of objectively measured naps and also a lack of longitudinal studies. In fact, we are unaware of any longitudinal studies that have used objectively measured napping in relation to Parkinson’s disease risk.”

To examine the longitudinal association between objectively measured napping duration and risk of Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Leng and colleagues analyzed data from the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study (MrOS), a large, longitudinal, multicenter study of community-dwelling older men. They excluded men with Parkinson’s disease at baseline. The analysis included data from more than 2,900 men who had napping and sleep measures at baseline between 2003 and 2005 and were followed up for development of Parkinson’s disease over 11 years.

The investigators used actigraphy to measure napping. Participants wore a sleep watch on the dominant wrist for at least five consecutive 24-hour periods. The researchers defined napping as having at least five consecutive minutes of inactivity outside of the main sleep period. They defined excessive daytime sleepiness as a score greater than 10 on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.

The researchers identified Parkinson’s disease using physician diagnosis or Parkinson’s disease medication use. Their analysis adjusted for age, BMI, smoking, physical activity, depression, comorbidities, global cognition scores, medication use, and nighttime sleep variables (ie, efficiency, duration, and apnea–hypopnea index).

“The highest risk was in those who reported daytime sleepiness and had objective napping for at least an hour per day,” Dr. Leng said. These participants had more than twice the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease, compared with a reference group that did not have daytime sleepiness and napped for less than one hour per day (odds ratio, 2.52).

Participants who napped for at least an hour per day but did not report excessive daytime sleepiness also had increased risk (odds ratio, 1.96).

The results indicate that objectively measured napping, rather than self-reported excessive daytime sleepiness, is important for Parkinson’s disease risk, Dr. Leng said.

Sensitivity analyses that excluded patients who developed Parkinson’s disease within two years after baseline and only included physician-confirmed cases of Parkinson’s disease had similar results.

Actigraphy is limited in its ability to differentiate between napping and inactivity, Dr. Leng noted. In addition, the results cannot be generalized to women and younger populations, she said.

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Leng Y, Goldman SM, Cawthon PM, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness, objective napping and 11-year risk of Parkinson’s disease in older men. Int J Epidemiol. 2018 Jun 4 [Epub ahead of print].

BALTIMORE—Older men who nap for more than an hour per day are more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease over 11 years of follow-up, compared with those who nap for less than an hour per day and do not have excessive daytime sleepiness, according to a study described at the 32nd Annual Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Self-reported daytime sleepiness alone was not associated with increased risk, said Yue Leng, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, San Francisco.

The findings suggest that objective measures of napping might be valuable preclinical markers of Parkinson’s disease.

The mechanism underlying the association is unclear. It is possible that the ongoing degeneration in brain regions involved in the 24-hour sleep–wake cycle leads to increased napping in people who later develop Parkinson’s disease, she said.

“Excessive daytime sleepiness and daytime napping are common in older adults, especially those with Parkinson’s disease,” Dr. Leng said. Whether excessive daytime sleepiness or napping precedes the development of Parkinson’s disease and may be risk factors is not well understood, however. “There is a lack of objectively measured naps and also a lack of longitudinal studies. In fact, we are unaware of any longitudinal studies that have used objectively measured napping in relation to Parkinson’s disease risk.”

To examine the longitudinal association between objectively measured napping duration and risk of Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Leng and colleagues analyzed data from the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study (MrOS), a large, longitudinal, multicenter study of community-dwelling older men. They excluded men with Parkinson’s disease at baseline. The analysis included data from more than 2,900 men who had napping and sleep measures at baseline between 2003 and 2005 and were followed up for development of Parkinson’s disease over 11 years.

The investigators used actigraphy to measure napping. Participants wore a sleep watch on the dominant wrist for at least five consecutive 24-hour periods. The researchers defined napping as having at least five consecutive minutes of inactivity outside of the main sleep period. They defined excessive daytime sleepiness as a score greater than 10 on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.

The researchers identified Parkinson’s disease using physician diagnosis or Parkinson’s disease medication use. Their analysis adjusted for age, BMI, smoking, physical activity, depression, comorbidities, global cognition scores, medication use, and nighttime sleep variables (ie, efficiency, duration, and apnea–hypopnea index).

“The highest risk was in those who reported daytime sleepiness and had objective napping for at least an hour per day,” Dr. Leng said. These participants had more than twice the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease, compared with a reference group that did not have daytime sleepiness and napped for less than one hour per day (odds ratio, 2.52).

Participants who napped for at least an hour per day but did not report excessive daytime sleepiness also had increased risk (odds ratio, 1.96).

The results indicate that objectively measured napping, rather than self-reported excessive daytime sleepiness, is important for Parkinson’s disease risk, Dr. Leng said.

Sensitivity analyses that excluded patients who developed Parkinson’s disease within two years after baseline and only included physician-confirmed cases of Parkinson’s disease had similar results.

Actigraphy is limited in its ability to differentiate between napping and inactivity, Dr. Leng noted. In addition, the results cannot be generalized to women and younger populations, she said.

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Leng Y, Goldman SM, Cawthon PM, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness, objective napping and 11-year risk of Parkinson’s disease in older men. Int J Epidemiol. 2018 Jun 4 [Epub ahead of print].

REM Sleep Behavior Disorder Predicts Rapid Motor and Cognitive Decline in Parkinson’s Disease

The disorder may have prognostic value only among patients with certain CSF results.

Among people with Parkinson’s disease, REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is associated with more rapid motor progression in patients with high levels of synuclein and dopaminergic pathology, according to research published online ahead of print August 8 in Neurology. RBD also indicates an increased risk of cognitive decline in patients with high degrees of synuclein and amyloid pathology.

“Our study is the first to link the predictive value of RBD symptoms to the presence of amyloid and synuclein pathology,” said Marios Politis, MD, PhD, Lily Safra Professor of Neurology and Neuroimaging, Consultant Neurologist, and the Director of the Neurodegeneration Imaging Group at King’s College London, and colleagues. “Measuring dopaminergic dysfunction and amyloid and synuclein burden in the screening of patients with RBD at an early stage of Parkinson’s disease, possibly even at the premotor phase of disease, could potentially identify the ones more likely to progress and develop dementia.”

The prevalence of RBD in patients with Parkinson’s disease ranges between 35% and 60%. Longitudinal data indicate that RBD is associated with faster development of cognitive decline and a greater risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Dr. Politis and colleagues examined the risk of motor progression and cognitive decline in patients with Parkinson’s disease and RBD who are untreated and at an early stage after disease onset.

The investigators selected 421 untreated patients with Parkinson’s disease and 196 healthy controls from the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative database for their analysis. Eligible participants presented for screening at less than two years after diagnosis. Patients underwent a [123I]FP-CIT SPECT scan, CSF assessment, 3-T MRI, and thorough clinical assessments.

Among participants with Parkinson’s disease, average age was about 61 at baseline. Approximately 66% of these participants were male, and their mean disease duration was about 6.6 years. Patients with RBD had poorer olfaction, a higher burden of nonmotor symptoms, and worse scores on neuropsychologic tests. Furthermore, patients with RBD had lower CSF amyloid β42 levels and higher ratios of total tau to amyloid β42, compared with patients without RBD.

During 60 months of follow-up, RBD was associated with faster motor progression (hazard ratio [HR], 1.368) and cognitive decline (HR, 1.794). RBD predicted motor progression only in patients with Parkinson’s disease who had low α-synuclein levels and low [123I]FP-CIT uptake in the striatum (HR, 2.091). RBD predicted cognitive decline only in patients with Parkinson’s disease who had low amyloid β42 and low α-synuclein levels (HR, 2.810). RBD was not associated with cognitive decline or pathologic changes among healthy controls.

Parkinson’s disease with RBD “was previously suggested as a specific Parkinson’s disease phenotype associated with faster motor progression and characterized by reduced tremor, high frequency of falls, and a lower amplitude of response to medication dose,” said Dr. Politis and coauthors. “Our findings extend these observations and indicate that the Parkinson’s disease-RBD phenotype may vary in terms of progression of motor or cognitive symptoms, depending on underlying α-synuclein, amyloid β, and dopaminergic pathology."

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Pagano G, De Micco R, Yousaf T, et al. REM behavior disorder predicts motor progression and cognitive decline in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2018 Aug 8 [Epub ahead of print].

The disorder may have prognostic value only among patients with certain CSF results.

The disorder may have prognostic value only among patients with certain CSF results.

Among people with Parkinson’s disease, REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is associated with more rapid motor progression in patients with high levels of synuclein and dopaminergic pathology, according to research published online ahead of print August 8 in Neurology. RBD also indicates an increased risk of cognitive decline in patients with high degrees of synuclein and amyloid pathology.

“Our study is the first to link the predictive value of RBD symptoms to the presence of amyloid and synuclein pathology,” said Marios Politis, MD, PhD, Lily Safra Professor of Neurology and Neuroimaging, Consultant Neurologist, and the Director of the Neurodegeneration Imaging Group at King’s College London, and colleagues. “Measuring dopaminergic dysfunction and amyloid and synuclein burden in the screening of patients with RBD at an early stage of Parkinson’s disease, possibly even at the premotor phase of disease, could potentially identify the ones more likely to progress and develop dementia.”

The prevalence of RBD in patients with Parkinson’s disease ranges between 35% and 60%. Longitudinal data indicate that RBD is associated with faster development of cognitive decline and a greater risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Dr. Politis and colleagues examined the risk of motor progression and cognitive decline in patients with Parkinson’s disease and RBD who are untreated and at an early stage after disease onset.

The investigators selected 421 untreated patients with Parkinson’s disease and 196 healthy controls from the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative database for their analysis. Eligible participants presented for screening at less than two years after diagnosis. Patients underwent a [123I]FP-CIT SPECT scan, CSF assessment, 3-T MRI, and thorough clinical assessments.

Among participants with Parkinson’s disease, average age was about 61 at baseline. Approximately 66% of these participants were male, and their mean disease duration was about 6.6 years. Patients with RBD had poorer olfaction, a higher burden of nonmotor symptoms, and worse scores on neuropsychologic tests. Furthermore, patients with RBD had lower CSF amyloid β42 levels and higher ratios of total tau to amyloid β42, compared with patients without RBD.

During 60 months of follow-up, RBD was associated with faster motor progression (hazard ratio [HR], 1.368) and cognitive decline (HR, 1.794). RBD predicted motor progression only in patients with Parkinson’s disease who had low α-synuclein levels and low [123I]FP-CIT uptake in the striatum (HR, 2.091). RBD predicted cognitive decline only in patients with Parkinson’s disease who had low amyloid β42 and low α-synuclein levels (HR, 2.810). RBD was not associated with cognitive decline or pathologic changes among healthy controls.

Parkinson’s disease with RBD “was previously suggested as a specific Parkinson’s disease phenotype associated with faster motor progression and characterized by reduced tremor, high frequency of falls, and a lower amplitude of response to medication dose,” said Dr. Politis and coauthors. “Our findings extend these observations and indicate that the Parkinson’s disease-RBD phenotype may vary in terms of progression of motor or cognitive symptoms, depending on underlying α-synuclein, amyloid β, and dopaminergic pathology."

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Pagano G, De Micco R, Yousaf T, et al. REM behavior disorder predicts motor progression and cognitive decline in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2018 Aug 8 [Epub ahead of print].

Among people with Parkinson’s disease, REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is associated with more rapid motor progression in patients with high levels of synuclein and dopaminergic pathology, according to research published online ahead of print August 8 in Neurology. RBD also indicates an increased risk of cognitive decline in patients with high degrees of synuclein and amyloid pathology.

“Our study is the first to link the predictive value of RBD symptoms to the presence of amyloid and synuclein pathology,” said Marios Politis, MD, PhD, Lily Safra Professor of Neurology and Neuroimaging, Consultant Neurologist, and the Director of the Neurodegeneration Imaging Group at King’s College London, and colleagues. “Measuring dopaminergic dysfunction and amyloid and synuclein burden in the screening of patients with RBD at an early stage of Parkinson’s disease, possibly even at the premotor phase of disease, could potentially identify the ones more likely to progress and develop dementia.”

The prevalence of RBD in patients with Parkinson’s disease ranges between 35% and 60%. Longitudinal data indicate that RBD is associated with faster development of cognitive decline and a greater risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Dr. Politis and colleagues examined the risk of motor progression and cognitive decline in patients with Parkinson’s disease and RBD who are untreated and at an early stage after disease onset.

The investigators selected 421 untreated patients with Parkinson’s disease and 196 healthy controls from the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative database for their analysis. Eligible participants presented for screening at less than two years after diagnosis. Patients underwent a [123I]FP-CIT SPECT scan, CSF assessment, 3-T MRI, and thorough clinical assessments.

Among participants with Parkinson’s disease, average age was about 61 at baseline. Approximately 66% of these participants were male, and their mean disease duration was about 6.6 years. Patients with RBD had poorer olfaction, a higher burden of nonmotor symptoms, and worse scores on neuropsychologic tests. Furthermore, patients with RBD had lower CSF amyloid β42 levels and higher ratios of total tau to amyloid β42, compared with patients without RBD.

During 60 months of follow-up, RBD was associated with faster motor progression (hazard ratio [HR], 1.368) and cognitive decline (HR, 1.794). RBD predicted motor progression only in patients with Parkinson’s disease who had low α-synuclein levels and low [123I]FP-CIT uptake in the striatum (HR, 2.091). RBD predicted cognitive decline only in patients with Parkinson’s disease who had low amyloid β42 and low α-synuclein levels (HR, 2.810). RBD was not associated with cognitive decline or pathologic changes among healthy controls.

Parkinson’s disease with RBD “was previously suggested as a specific Parkinson’s disease phenotype associated with faster motor progression and characterized by reduced tremor, high frequency of falls, and a lower amplitude of response to medication dose,” said Dr. Politis and coauthors. “Our findings extend these observations and indicate that the Parkinson’s disease-RBD phenotype may vary in terms of progression of motor or cognitive symptoms, depending on underlying α-synuclein, amyloid β, and dopaminergic pathology."

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Pagano G, De Micco R, Yousaf T, et al. REM behavior disorder predicts motor progression and cognitive decline in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2018 Aug 8 [Epub ahead of print].

Multiday Seizure Cycles May Be Common

Tracking seizure cycles could facilitate personalized medicine and improve seizure reduction.

Multiday epileptic seizure cycles may occur in many individuals with epilepsy, according to a retrospective cohort study published online ahead of print September 12 in Lancet Neurology.

About 80% of patients in the study showed circadian modulation of their seizure rates, and more than 20% had strong circaseptan (ie, seven-day) rhythms, said Mark J. Cook, MD, a neurologist at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne, and colleagues.

The high prevalence of multiday seizure cycles could present an opportunity to improve treatment through the development of patient-specific chronotherapy (ie, the administration of medication when seizures are most likely). “Even without fully understanding the mechanisms of seizure cycles, temporal patterns can be incorporated into patient management plans,” said Dr. Cook.

The investigators based their study on two seizure datasets. One was a US cohort of 1,118 patients who reported at least 100 seizures through the SeizureTracker website or mobile app. The other was an Australian cohort of 12 patients with focal epilepsy who had at least 30 seizures recorded by an implanted electrocorticography device during follow-up that ranged between six months and three years.

In the US cohort, 86% of participants had at least one significant cycle in their seizure times, and 64% had more than one cycle. Most of the cycles (80%) were circadian, while 21% of people had significant circaseptan cycles in one analysis using the Hodges-Ajne test, a statistical method used to test for circular uniformity. “Many patients also showed some evidence of cycles lasting up to a month,” said the authors.

A confirmatory analysis using Monte Carlo simulation found that 7% of people, or 77 individuals, had significant circaseptan cycles. “The probability that 77 patients would randomly share a specific cycle is infinitesimal,” said the authors.

In the Australian study, 11 of 12 patients had strong rhythms at 24 hours, one had a significant cycle of exactly one week, and two others had cycles of approximately one week.

“Some people had stronger rhythms at time scales longer than 24 hours, which suggests that circadian regulation was not necessarily the strongest modulating factor of epileptic activity,” said the investigators. The cause of longer seizure cycles remains unclear, though peak seizure times might be linked to varying stress levels, seasonal changes in sleep quality, or biologic cycles such as menstruation.

—Andrew D. Bowser

Suggested Reading

Karoly PJ, Goldenholz DM, Freestone DR, et al. Circadian and circaseptan rhythms in human epilepsy: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Sep 12 [Epub ahead of print].

Tracking seizure cycles could facilitate personalized medicine and improve seizure reduction.

Tracking seizure cycles could facilitate personalized medicine and improve seizure reduction.

Multiday epileptic seizure cycles may occur in many individuals with epilepsy, according to a retrospective cohort study published online ahead of print September 12 in Lancet Neurology.

About 80% of patients in the study showed circadian modulation of their seizure rates, and more than 20% had strong circaseptan (ie, seven-day) rhythms, said Mark J. Cook, MD, a neurologist at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne, and colleagues.

The high prevalence of multiday seizure cycles could present an opportunity to improve treatment through the development of patient-specific chronotherapy (ie, the administration of medication when seizures are most likely). “Even without fully understanding the mechanisms of seizure cycles, temporal patterns can be incorporated into patient management plans,” said Dr. Cook.

The investigators based their study on two seizure datasets. One was a US cohort of 1,118 patients who reported at least 100 seizures through the SeizureTracker website or mobile app. The other was an Australian cohort of 12 patients with focal epilepsy who had at least 30 seizures recorded by an implanted electrocorticography device during follow-up that ranged between six months and three years.

In the US cohort, 86% of participants had at least one significant cycle in their seizure times, and 64% had more than one cycle. Most of the cycles (80%) were circadian, while 21% of people had significant circaseptan cycles in one analysis using the Hodges-Ajne test, a statistical method used to test for circular uniformity. “Many patients also showed some evidence of cycles lasting up to a month,” said the authors.

A confirmatory analysis using Monte Carlo simulation found that 7% of people, or 77 individuals, had significant circaseptan cycles. “The probability that 77 patients would randomly share a specific cycle is infinitesimal,” said the authors.

In the Australian study, 11 of 12 patients had strong rhythms at 24 hours, one had a significant cycle of exactly one week, and two others had cycles of approximately one week.

“Some people had stronger rhythms at time scales longer than 24 hours, which suggests that circadian regulation was not necessarily the strongest modulating factor of epileptic activity,” said the investigators. The cause of longer seizure cycles remains unclear, though peak seizure times might be linked to varying stress levels, seasonal changes in sleep quality, or biologic cycles such as menstruation.

—Andrew D. Bowser

Suggested Reading

Karoly PJ, Goldenholz DM, Freestone DR, et al. Circadian and circaseptan rhythms in human epilepsy: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Sep 12 [Epub ahead of print].

Multiday epileptic seizure cycles may occur in many individuals with epilepsy, according to a retrospective cohort study published online ahead of print September 12 in Lancet Neurology.

About 80% of patients in the study showed circadian modulation of their seizure rates, and more than 20% had strong circaseptan (ie, seven-day) rhythms, said Mark J. Cook, MD, a neurologist at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne, and colleagues.

The high prevalence of multiday seizure cycles could present an opportunity to improve treatment through the development of patient-specific chronotherapy (ie, the administration of medication when seizures are most likely). “Even without fully understanding the mechanisms of seizure cycles, temporal patterns can be incorporated into patient management plans,” said Dr. Cook.

The investigators based their study on two seizure datasets. One was a US cohort of 1,118 patients who reported at least 100 seizures through the SeizureTracker website or mobile app. The other was an Australian cohort of 12 patients with focal epilepsy who had at least 30 seizures recorded by an implanted electrocorticography device during follow-up that ranged between six months and three years.

In the US cohort, 86% of participants had at least one significant cycle in their seizure times, and 64% had more than one cycle. Most of the cycles (80%) were circadian, while 21% of people had significant circaseptan cycles in one analysis using the Hodges-Ajne test, a statistical method used to test for circular uniformity. “Many patients also showed some evidence of cycles lasting up to a month,” said the authors.

A confirmatory analysis using Monte Carlo simulation found that 7% of people, or 77 individuals, had significant circaseptan cycles. “The probability that 77 patients would randomly share a specific cycle is infinitesimal,” said the authors.

In the Australian study, 11 of 12 patients had strong rhythms at 24 hours, one had a significant cycle of exactly one week, and two others had cycles of approximately one week.

“Some people had stronger rhythms at time scales longer than 24 hours, which suggests that circadian regulation was not necessarily the strongest modulating factor of epileptic activity,” said the investigators. The cause of longer seizure cycles remains unclear, though peak seizure times might be linked to varying stress levels, seasonal changes in sleep quality, or biologic cycles such as menstruation.

—Andrew D. Bowser

Suggested Reading

Karoly PJ, Goldenholz DM, Freestone DR, et al. Circadian and circaseptan rhythms in human epilepsy: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Sep 12 [Epub ahead of print].

Stroke Increases the Risk of All-Cause Dementia

Protecting the blood supply to the brain could reduce the risk of incident dementia.

Stroke is a strong independent risk factor for all-cause dementia, according to research published online ahead of print August 25 in Alzheimer’s & Dementia. Clinicians should incorporate stroke-prevention strategies into their health interventions to reduce patients’ risk of dementia, said the authors.

“Around a third of dementia cases are thought to be potentially preventable, though this estimate does not take into account the risk associated with stroke,” said David Llewellyn, PhD, Senior Research Fellow at University of Exeter Medical School in the United Kingdom. “Our findings indicate that this figure could be even higher and reinforce the importance of protecting the blood supply to the brain when attempting to reduce the global burden of dementia.”

Meta-Analysis of Previous Research

Stroke is a recognized risk factor for all-cause dementia, but no researchers had previously performed a meta-analysis to quantify the risk. Dr. Llewellyn and colleagues searched Medline, PsycINFO, and Embase databases for prospective studies that investigated the association between prevalent or incident stroke and incident all-cause dementia. They excluded studies that lacked a comparison group or that had a comparison group other than a stroke-free group. The investigators pooled adjusted estimates across studies using random effects meta-analysis and evaluated potential effect modifiers with meta-regression.

Dr. Llewellyn and colleagues identified 11,129 articles, 26 of which were eligible for analysis. They also included 16 studies from a previous systematic review and four studies identified through backward and forward citation searches. In all, 36 studies examined prevalent stroke (1.9 million participants), and 12 studies examined incident stroke (1.3 million participants). The studies were conducted in America, Europe, Asia, and Australia and included more than three million participants. Follow-up periods ranged from nine months to 25 years.

Stroke Affected Dementia Risk

When the researchers pooled results from 22 cohorts of participants who were cognitively normal at baseline, they found that those with prevalent stroke had a higher adjusted risk of incident dementia, compared with those without stroke (hazard ratio [HR], 1.69). Sensitivity analyses did not change the results significantly. Prevalent stroke was associated with a higher risk of incident dementia among men than among women. Sex explained 50.2% of heterogeneity between studies for prevalent stroke.

After combining the adjusted results from eight studies, Dr. Llewellyn and colleagues found that incident stroke more than doubled the risk of incident all-cause dementia, compared with no incident stroke (risk ratio [RR], 2.18). For a sensitivity analysis, the investigators excluded three studies that combined stroke with transient ischemic attack; this adjustment strengthened the association.

The study’s strengths include the investigators’ search of several major databases and their contacts with authors who provided relevant data. The analysis reflects the limitations of the original studies, however. These limitations include selective samples and differences in stroke assessment and dementia diagnosis criteria. In addition, dementia may develop years before it is diagnosed. “More detailed reporting of the interval between stroke occurrence and dementia diagnosis in future studies will help to better characterize the role of time since stroke in the risk of dementia,” said Dr. Llewellyn.

—Erik Greb

Kuz´ma E, Lourida I, Moore SF, et al. Stroke and dementia risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2018 Aug 25 [Epub ahead of print].

Protecting the blood supply to the brain could reduce the risk of incident dementia.

Protecting the blood supply to the brain could reduce the risk of incident dementia.

Stroke is a strong independent risk factor for all-cause dementia, according to research published online ahead of print August 25 in Alzheimer’s & Dementia. Clinicians should incorporate stroke-prevention strategies into their health interventions to reduce patients’ risk of dementia, said the authors.

“Around a third of dementia cases are thought to be potentially preventable, though this estimate does not take into account the risk associated with stroke,” said David Llewellyn, PhD, Senior Research Fellow at University of Exeter Medical School in the United Kingdom. “Our findings indicate that this figure could be even higher and reinforce the importance of protecting the blood supply to the brain when attempting to reduce the global burden of dementia.”

Meta-Analysis of Previous Research

Stroke is a recognized risk factor for all-cause dementia, but no researchers had previously performed a meta-analysis to quantify the risk. Dr. Llewellyn and colleagues searched Medline, PsycINFO, and Embase databases for prospective studies that investigated the association between prevalent or incident stroke and incident all-cause dementia. They excluded studies that lacked a comparison group or that had a comparison group other than a stroke-free group. The investigators pooled adjusted estimates across studies using random effects meta-analysis and evaluated potential effect modifiers with meta-regression.

Dr. Llewellyn and colleagues identified 11,129 articles, 26 of which were eligible for analysis. They also included 16 studies from a previous systematic review and four studies identified through backward and forward citation searches. In all, 36 studies examined prevalent stroke (1.9 million participants), and 12 studies examined incident stroke (1.3 million participants). The studies were conducted in America, Europe, Asia, and Australia and included more than three million participants. Follow-up periods ranged from nine months to 25 years.

Stroke Affected Dementia Risk

When the researchers pooled results from 22 cohorts of participants who were cognitively normal at baseline, they found that those with prevalent stroke had a higher adjusted risk of incident dementia, compared with those without stroke (hazard ratio [HR], 1.69). Sensitivity analyses did not change the results significantly. Prevalent stroke was associated with a higher risk of incident dementia among men than among women. Sex explained 50.2% of heterogeneity between studies for prevalent stroke.

After combining the adjusted results from eight studies, Dr. Llewellyn and colleagues found that incident stroke more than doubled the risk of incident all-cause dementia, compared with no incident stroke (risk ratio [RR], 2.18). For a sensitivity analysis, the investigators excluded three studies that combined stroke with transient ischemic attack; this adjustment strengthened the association.

The study’s strengths include the investigators’ search of several major databases and their contacts with authors who provided relevant data. The analysis reflects the limitations of the original studies, however. These limitations include selective samples and differences in stroke assessment and dementia diagnosis criteria. In addition, dementia may develop years before it is diagnosed. “More detailed reporting of the interval between stroke occurrence and dementia diagnosis in future studies will help to better characterize the role of time since stroke in the risk of dementia,” said Dr. Llewellyn.

—Erik Greb

Kuz´ma E, Lourida I, Moore SF, et al. Stroke and dementia risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2018 Aug 25 [Epub ahead of print].

Stroke is a strong independent risk factor for all-cause dementia, according to research published online ahead of print August 25 in Alzheimer’s & Dementia. Clinicians should incorporate stroke-prevention strategies into their health interventions to reduce patients’ risk of dementia, said the authors.

“Around a third of dementia cases are thought to be potentially preventable, though this estimate does not take into account the risk associated with stroke,” said David Llewellyn, PhD, Senior Research Fellow at University of Exeter Medical School in the United Kingdom. “Our findings indicate that this figure could be even higher and reinforce the importance of protecting the blood supply to the brain when attempting to reduce the global burden of dementia.”

Meta-Analysis of Previous Research

Stroke is a recognized risk factor for all-cause dementia, but no researchers had previously performed a meta-analysis to quantify the risk. Dr. Llewellyn and colleagues searched Medline, PsycINFO, and Embase databases for prospective studies that investigated the association between prevalent or incident stroke and incident all-cause dementia. They excluded studies that lacked a comparison group or that had a comparison group other than a stroke-free group. The investigators pooled adjusted estimates across studies using random effects meta-analysis and evaluated potential effect modifiers with meta-regression.

Dr. Llewellyn and colleagues identified 11,129 articles, 26 of which were eligible for analysis. They also included 16 studies from a previous systematic review and four studies identified through backward and forward citation searches. In all, 36 studies examined prevalent stroke (1.9 million participants), and 12 studies examined incident stroke (1.3 million participants). The studies were conducted in America, Europe, Asia, and Australia and included more than three million participants. Follow-up periods ranged from nine months to 25 years.

Stroke Affected Dementia Risk

When the researchers pooled results from 22 cohorts of participants who were cognitively normal at baseline, they found that those with prevalent stroke had a higher adjusted risk of incident dementia, compared with those without stroke (hazard ratio [HR], 1.69). Sensitivity analyses did not change the results significantly. Prevalent stroke was associated with a higher risk of incident dementia among men than among women. Sex explained 50.2% of heterogeneity between studies for prevalent stroke.

After combining the adjusted results from eight studies, Dr. Llewellyn and colleagues found that incident stroke more than doubled the risk of incident all-cause dementia, compared with no incident stroke (risk ratio [RR], 2.18). For a sensitivity analysis, the investigators excluded three studies that combined stroke with transient ischemic attack; this adjustment strengthened the association.

The study’s strengths include the investigators’ search of several major databases and their contacts with authors who provided relevant data. The analysis reflects the limitations of the original studies, however. These limitations include selective samples and differences in stroke assessment and dementia diagnosis criteria. In addition, dementia may develop years before it is diagnosed. “More detailed reporting of the interval between stroke occurrence and dementia diagnosis in future studies will help to better characterize the role of time since stroke in the risk of dementia,” said Dr. Llewellyn.

—Erik Greb

Kuz´ma E, Lourida I, Moore SF, et al. Stroke and dementia risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2018 Aug 25 [Epub ahead of print].

Adult-Onset Still Disease: Persistent Pruritic Papular Rash With Unique Histopathologic Findings

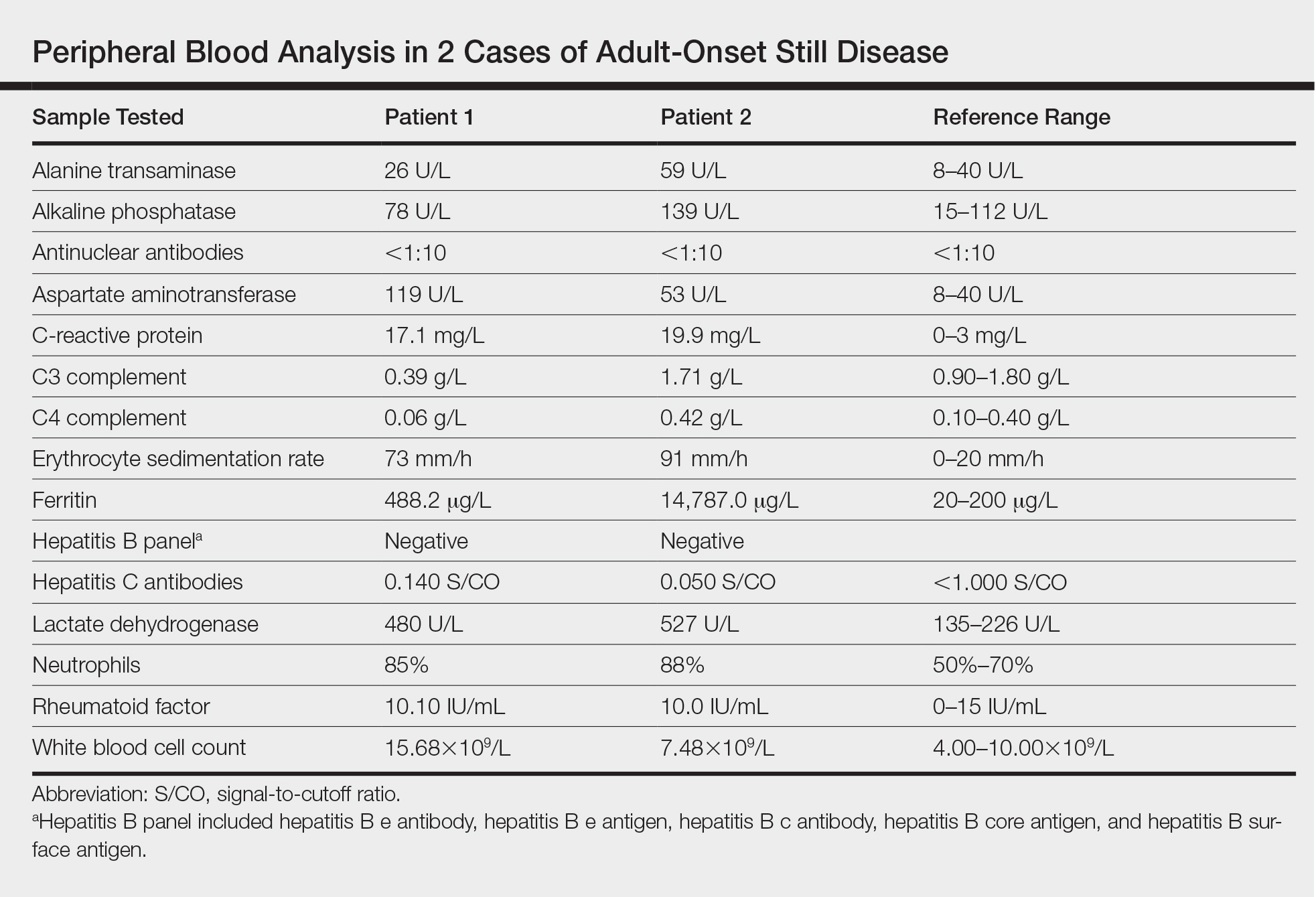

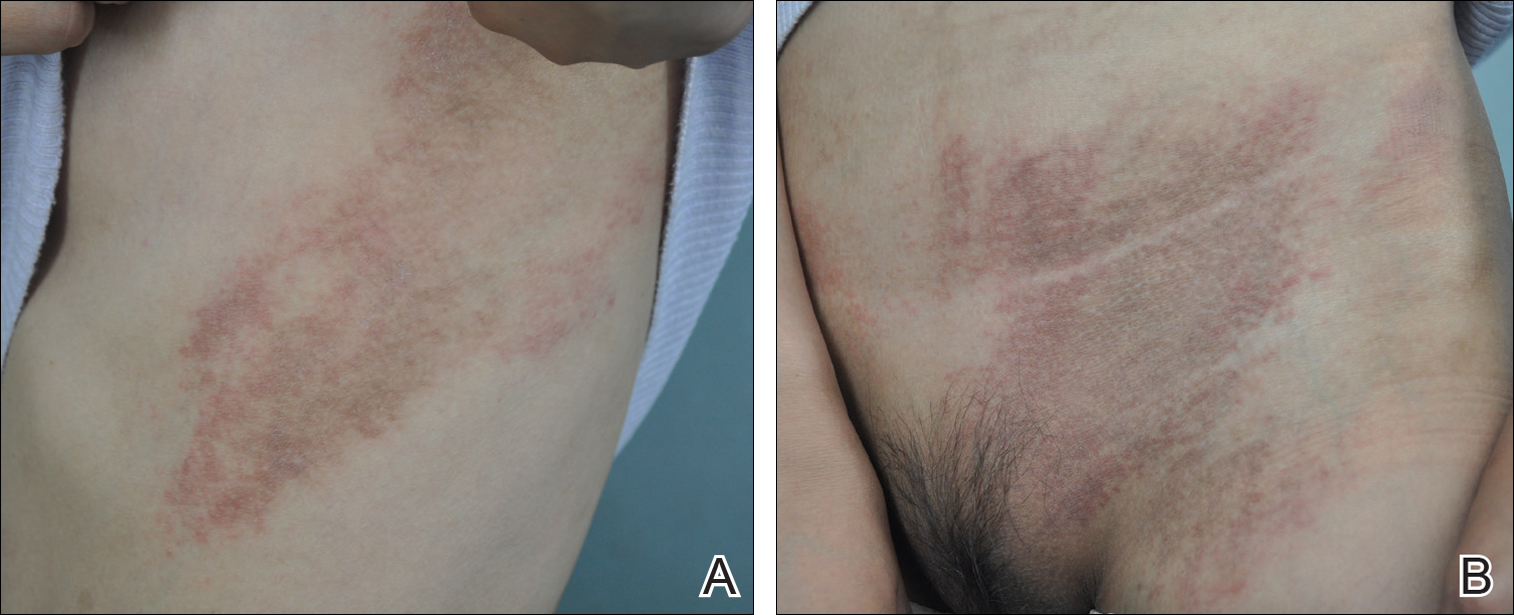

Adult-onset Still disease (AOSD) is a systemic inflammatory condition that clinically manifests as spiking fevers, arthralgia, evanescent skin rash, and lymphadenopathy. 1 The most commonly used criteria for diagnosing AOSD are the Yamaguchi criteria. 2 The major criteria include high fever for more than 1 week, arthralgia for more than 2 weeks, leukocytosis, and an evanescent skin rash. The minor criteria consist of sore throat, lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly, liver dysfunction, and negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies. Classically, the skin rash is described as an evanescent, salmon-colored erythema involving the extremities. Nevertheless, unusual cutaneous eruptions have been reported in AOSD, including persistent pruritic papules and plaques. 3 Importantly, this atypical rash demonstrates specific histologic findings that are not found on routine histopathology of a typical evanescent rash. We describe 2 patients with this atypical cutaneous eruption along with the unique histopathologic findings of AOSD.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 23-year-old Chinese woman presented with periodic fevers, persistent rash, and joint pain of 2 years’ duration. Her medical history included splenectomy for hepatosplenomegaly as well as evaluation by hematology for lymphadenopathy; a cervical lymph node biopsy showed lymphoid and follicular hyperplasia.

Twenty days later, the patient was referred to the dermatology department for evaluation of the persistent rash. The patient described a history of flushing of the face, severe joint pain in both arms and legs, aching muscles, and persistent sore throat. The patient did not report any history of drug ingestion. Physical examination revealed a fever (temperature, 39.2°C); swollen nontender lymph nodes in the neck, axillae, and groin; and salmon-colored and hyperpigmented patches and thin plaques over the neck, chest, abdomen, and arms (Figure 1). A splenectomy scar also was noted. Peripheral blood was collected for laboratory analyses, which revealed transaminitis and moderate hyperferritinemia (Table). An autoimmune panel was negative for rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. The patient was admitted to the hospital, and a skin biopsy was performed. Histology showed superficial dyskeratotic keratinocytes and sparse perivascular infiltration of neutrophils in the upper dermis (Figure 2).

The patient was diagnosed with AOSD based on fulfillment of the Yamaguchi criteria.2 She was treated with methylprednisolone 60 mg daily and was discharged 14 days later. At 16-month follow-up, the patient demonstrated complete resolution of symptoms with a maintenance dose of prednisolone (7.5 mg daily).

Patient 2

A 23-year-old black woman presented to the emergency department 3 months postpartum with recurrent high fevers, worsening joint pain, and persistent itchy rash of 2 months’ duration. The patient had no history of travel, autoimmune disease, or sick contacts. She occasionally took aspirin for joint pain. Physical examination revealed a fever (temperature, 39.1°C) along with hyperpigmented patches and thin scaly hyperpigmented papules coalescing into a poorly demarcated V-shaped plaque on the upper back and posterior neck, extending to the chest in a shawl-like distribution (Figure 3). Submental lymphadenopathy was present. The spleen was not palpable.

Peripheral blood was collected for laboratory analysis and demonstrated transaminitis and a markedly high ferritin level (Table). An autoimmune panel was negative for rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Skin biopsy was performed and demonstrated many necrotic keratinocytes, singly and in aggregates, distributed from the spinous layer to the stratum corneum. A neutrophilic infiltrate was present in the papillary dermis (Figure 4).

The patient met the Yamaguchi criteria and was subsequently diagnosed with AOSD. She was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone 20 mg every 8 hours and was discharged 1 week later on oral prednisone 60 mg daily to be tapered over a period of months. At 2-week follow-up, the patient continued to experience rash and joint pain; oral methotrexate 10 mg weekly was added to her regimen, as well as vitamin D, calcium, and folic acid supplementation. At the next 2-week follow-up the patient noted improvement in the rash as well as the joint pain, but both still persisted. Prednisone was decreased to 50 mg daily and methotrexate was increased to 15 mg weekly. The patient continued to show improvement over the subsequent 3 months, during which prednisone was tapered to 10 mg daily and methotrexate was increased to 20 mg weekly. The patient showed resolution of symptoms at 3-month follow-up on this regimen, with plans to continue the prednisone taper and maintain methotrexate dosing.

Comment

Adult-onset Still disease is a systemic inflammatory condition that clinically manifests as spiking fevers, arthralgia, salmon-pink evanescent erythema, and lymphadenopathy.2 The condition also can cause liver dysfunction, splenomegaly, pericarditis, pleuritis, renal dysfunction, and a reactive hemophagocytic syndrome.1 Furthermore, one review of the literature described an association with delayed-onset malignancy.4 Early diagnosis is important yet challenging, as AOSD is a diagnosis of exclusion. The Yamaguchi criteria are the most widely used method of diagnosis and demonstrate more than 90% sensitivity.In addition to the Yamaguchi criteria, marked hyperferritinemia is characteristic of AOSD and can act as an indicator of disease activity.5 Interestingly, both of our patients had elevated ferritin levels, with patient 2 showing marked elevation (Table). In both patients, all major criteria were fulfilled, except the typical skin rash.

The skin rash in AOSD, classically consisting of an evanescent, salmon-pink erythema predominantly involving the extremities, has been observed in up to 87% of AOSD patients.5 The histology of the typical evanescent rash is nonspecific, characterized by a relatively sparse, perivascular, mixed inflammatory infiltrate. Notably, other skin manifestations may be found in patients with AOSD.1,2,5-16 Persistent pruritic papules and plaques are the most commonly reported nonclassical rash, presenting as erythematous, slightly scaly papules and plaques with a linear configuration typically on the trunk.2 Both of our patients presented with this atypical eruption. Importantly, the histopathology of this unique rash displays distinctive features, which can aid in early diagnosis. Findings include dyskeratotic keratinocytes in the cornified layers as well as in the epidermis, and a sparse neutrophilic and/or lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis without vasculitis. These findings were evident in both histopathologic studies of our patients (Figures 2 and 4). Although not present in our patients, dermal mucin deposition has been demonstrated in some reports.1,13,15

A 2015 review of the literature yielded 30 cases of AOSD with pruritic persistent papules and plaques.4 The study confirmed a linear, erythematous or brown rash on the back and neck in the majority of cases. Histologic findings were congruent with those reported in our 2 cases: necrotic keratinocytes in the upper epidermis with a neutrophilic infiltrate in the upper dermis without vasculitis. Most patients showed rapid resolution of the rash and symptoms with the use of prednisone, prednisolone, or intravenous pulsed methylprednisolone. Interestingly, a range of presentations were noted, including prurigo pigmentosalike urticarial papules; lichenoid papules; and dermatographismlike, dermatomyositislike, and lichen amyloidosis–like rashes.4 In our report, patient 2 presented with a rash in a dermat-omyositislike shawl distribution. It has been suggested that patients with dermatomyositislike rashes require more potent immunotherapy as compared to patients with other rash morphologies.4 The need for methotrexate in addition to a prednisone taper in the clinical course of patient 2 lends further support to this observation.

Conclusion

A clinically and pathologically distinct form of cutaneous disease—AOSD with persistent pruritic papules and plaques—was observed in our 2 patients. These histopathologic findings facilitated timely diagnosis in both patients. A range of clinical morphologies may exist in AOSD, an awareness of which is paramount. Adult-onset Still disease should be included in the differential diagnosis of a dermatomyositislike presentation in a shawl distribution. Prompt diagnosis is essential to ensure adequate therapy.

- Yamamoto T. Cutaneous manifestations associated with adult-onset Still’s disease: important diagnostic values. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:2233-2237.

- Yamaguchi M, Ohta A, Tsunematsu T, et al. Preliminary criteria for classification of adult Still’s disease. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:424-431.

- Lee JY, Yang CC, Hsu MM. Histopathology of persistent papules and plaques in adult-onset Still’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:1003-1008.

- Sun NZ, Brezinski EA, Berliner J, et al. Updates in adult-onset Still disease: atypical cutaneous manifestations and associates with delayed malignancy [published online June 6, 2015]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:294-303.

- Schwarz-Eywill M, Heilig B, Bauer H, et al. Evaluation of serum ferritin as a marker for adult Still’s disease activity. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51:683-685.

- Ohta A, Yamaguchi M, Tsunematsu T, et al. Adult Still’s disease: a multicenter survey of Japanese patients. J Rheumatol. 1990;17:1058-1063.

- Kaur S, Bambery P, Dhar S. Persistent dermal plaque lesions in adult onset Still’s disease. Dermatology. 1994;188:241-242.

- Lübbe J, Hofer M, Chavaz P, et al. Adult onset Still’s disease with persistent plaques. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:710-713.

- Suzuki K, Kimura Y, Aoki M, et al. Persistent plaques and linear pigmentation in adult-onset Still’s disease. Dermatology. 2001;202:333-335.

- Fujii K, Konishi K, Kanno Y, et al. Persistent generalized erythema in adult-onset Still’s disease. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:824-825.

- Thien Huong NT, Pitche P, Minh Hoa T, et al. Persistent pigmented plaques in adult-onset Still’s disease. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2005;132:693-696.

- Lee JY, Yang CC, Hsu MM. Histopathology of persistent papules and plaques in adult-onset Still’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:1003-1008.

- Wolgamot G, Yoo J, Hurst S, et al. Unique histopathologic findings in a patient with adult-onset Still’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;49:194-196.

- Fortna RR, Gudjonsson JE, Seidel G, et al. Persistent pruritic papules and plaques: a characteristic histopathologic presentation seen in a subset of patients with adult-onset and juvenile Still’s disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:932-937.

- Yang CC, Lee JY, Liu MF, et al. Adult-onset Still’s disease with persistent skin eruption and fatal respiratory failure in a Taiwanese woman. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:593-594.

- Azeck AG, Littlewood SM. Adult-onset Still’s disease with atypical cutaneous features. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:360-363.

Adult-onset Still disease (AOSD) is a systemic inflammatory condition that clinically manifests as spiking fevers, arthralgia, evanescent skin rash, and lymphadenopathy. 1 The most commonly used criteria for diagnosing AOSD are the Yamaguchi criteria. 2 The major criteria include high fever for more than 1 week, arthralgia for more than 2 weeks, leukocytosis, and an evanescent skin rash. The minor criteria consist of sore throat, lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly, liver dysfunction, and negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies. Classically, the skin rash is described as an evanescent, salmon-colored erythema involving the extremities. Nevertheless, unusual cutaneous eruptions have been reported in AOSD, including persistent pruritic papules and plaques. 3 Importantly, this atypical rash demonstrates specific histologic findings that are not found on routine histopathology of a typical evanescent rash. We describe 2 patients with this atypical cutaneous eruption along with the unique histopathologic findings of AOSD.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 23-year-old Chinese woman presented with periodic fevers, persistent rash, and joint pain of 2 years’ duration. Her medical history included splenectomy for hepatosplenomegaly as well as evaluation by hematology for lymphadenopathy; a cervical lymph node biopsy showed lymphoid and follicular hyperplasia.

Twenty days later, the patient was referred to the dermatology department for evaluation of the persistent rash. The patient described a history of flushing of the face, severe joint pain in both arms and legs, aching muscles, and persistent sore throat. The patient did not report any history of drug ingestion. Physical examination revealed a fever (temperature, 39.2°C); swollen nontender lymph nodes in the neck, axillae, and groin; and salmon-colored and hyperpigmented patches and thin plaques over the neck, chest, abdomen, and arms (Figure 1). A splenectomy scar also was noted. Peripheral blood was collected for laboratory analyses, which revealed transaminitis and moderate hyperferritinemia (Table). An autoimmune panel was negative for rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. The patient was admitted to the hospital, and a skin biopsy was performed. Histology showed superficial dyskeratotic keratinocytes and sparse perivascular infiltration of neutrophils in the upper dermis (Figure 2).

The patient was diagnosed with AOSD based on fulfillment of the Yamaguchi criteria.2 She was treated with methylprednisolone 60 mg daily and was discharged 14 days later. At 16-month follow-up, the patient demonstrated complete resolution of symptoms with a maintenance dose of prednisolone (7.5 mg daily).

Patient 2

A 23-year-old black woman presented to the emergency department 3 months postpartum with recurrent high fevers, worsening joint pain, and persistent itchy rash of 2 months’ duration. The patient had no history of travel, autoimmune disease, or sick contacts. She occasionally took aspirin for joint pain. Physical examination revealed a fever (temperature, 39.1°C) along with hyperpigmented patches and thin scaly hyperpigmented papules coalescing into a poorly demarcated V-shaped plaque on the upper back and posterior neck, extending to the chest in a shawl-like distribution (Figure 3). Submental lymphadenopathy was present. The spleen was not palpable.

Peripheral blood was collected for laboratory analysis and demonstrated transaminitis and a markedly high ferritin level (Table). An autoimmune panel was negative for rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Skin biopsy was performed and demonstrated many necrotic keratinocytes, singly and in aggregates, distributed from the spinous layer to the stratum corneum. A neutrophilic infiltrate was present in the papillary dermis (Figure 4).

The patient met the Yamaguchi criteria and was subsequently diagnosed with AOSD. She was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone 20 mg every 8 hours and was discharged 1 week later on oral prednisone 60 mg daily to be tapered over a period of months. At 2-week follow-up, the patient continued to experience rash and joint pain; oral methotrexate 10 mg weekly was added to her regimen, as well as vitamin D, calcium, and folic acid supplementation. At the next 2-week follow-up the patient noted improvement in the rash as well as the joint pain, but both still persisted. Prednisone was decreased to 50 mg daily and methotrexate was increased to 15 mg weekly. The patient continued to show improvement over the subsequent 3 months, during which prednisone was tapered to 10 mg daily and methotrexate was increased to 20 mg weekly. The patient showed resolution of symptoms at 3-month follow-up on this regimen, with plans to continue the prednisone taper and maintain methotrexate dosing.

Comment

Adult-onset Still disease is a systemic inflammatory condition that clinically manifests as spiking fevers, arthralgia, salmon-pink evanescent erythema, and lymphadenopathy.2 The condition also can cause liver dysfunction, splenomegaly, pericarditis, pleuritis, renal dysfunction, and a reactive hemophagocytic syndrome.1 Furthermore, one review of the literature described an association with delayed-onset malignancy.4 Early diagnosis is important yet challenging, as AOSD is a diagnosis of exclusion. The Yamaguchi criteria are the most widely used method of diagnosis and demonstrate more than 90% sensitivity.In addition to the Yamaguchi criteria, marked hyperferritinemia is characteristic of AOSD and can act as an indicator of disease activity.5 Interestingly, both of our patients had elevated ferritin levels, with patient 2 showing marked elevation (Table). In both patients, all major criteria were fulfilled, except the typical skin rash.

The skin rash in AOSD, classically consisting of an evanescent, salmon-pink erythema predominantly involving the extremities, has been observed in up to 87% of AOSD patients.5 The histology of the typical evanescent rash is nonspecific, characterized by a relatively sparse, perivascular, mixed inflammatory infiltrate. Notably, other skin manifestations may be found in patients with AOSD.1,2,5-16 Persistent pruritic papules and plaques are the most commonly reported nonclassical rash, presenting as erythematous, slightly scaly papules and plaques with a linear configuration typically on the trunk.2 Both of our patients presented with this atypical eruption. Importantly, the histopathology of this unique rash displays distinctive features, which can aid in early diagnosis. Findings include dyskeratotic keratinocytes in the cornified layers as well as in the epidermis, and a sparse neutrophilic and/or lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis without vasculitis. These findings were evident in both histopathologic studies of our patients (Figures 2 and 4). Although not present in our patients, dermal mucin deposition has been demonstrated in some reports.1,13,15

A 2015 review of the literature yielded 30 cases of AOSD with pruritic persistent papules and plaques.4 The study confirmed a linear, erythematous or brown rash on the back and neck in the majority of cases. Histologic findings were congruent with those reported in our 2 cases: necrotic keratinocytes in the upper epidermis with a neutrophilic infiltrate in the upper dermis without vasculitis. Most patients showed rapid resolution of the rash and symptoms with the use of prednisone, prednisolone, or intravenous pulsed methylprednisolone. Interestingly, a range of presentations were noted, including prurigo pigmentosalike urticarial papules; lichenoid papules; and dermatographismlike, dermatomyositislike, and lichen amyloidosis–like rashes.4 In our report, patient 2 presented with a rash in a dermat-omyositislike shawl distribution. It has been suggested that patients with dermatomyositislike rashes require more potent immunotherapy as compared to patients with other rash morphologies.4 The need for methotrexate in addition to a prednisone taper in the clinical course of patient 2 lends further support to this observation.

Conclusion

A clinically and pathologically distinct form of cutaneous disease—AOSD with persistent pruritic papules and plaques—was observed in our 2 patients. These histopathologic findings facilitated timely diagnosis in both patients. A range of clinical morphologies may exist in AOSD, an awareness of which is paramount. Adult-onset Still disease should be included in the differential diagnosis of a dermatomyositislike presentation in a shawl distribution. Prompt diagnosis is essential to ensure adequate therapy.

Adult-onset Still disease (AOSD) is a systemic inflammatory condition that clinically manifests as spiking fevers, arthralgia, evanescent skin rash, and lymphadenopathy. 1 The most commonly used criteria for diagnosing AOSD are the Yamaguchi criteria. 2 The major criteria include high fever for more than 1 week, arthralgia for more than 2 weeks, leukocytosis, and an evanescent skin rash. The minor criteria consist of sore throat, lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly, liver dysfunction, and negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies. Classically, the skin rash is described as an evanescent, salmon-colored erythema involving the extremities. Nevertheless, unusual cutaneous eruptions have been reported in AOSD, including persistent pruritic papules and plaques. 3 Importantly, this atypical rash demonstrates specific histologic findings that are not found on routine histopathology of a typical evanescent rash. We describe 2 patients with this atypical cutaneous eruption along with the unique histopathologic findings of AOSD.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 23-year-old Chinese woman presented with periodic fevers, persistent rash, and joint pain of 2 years’ duration. Her medical history included splenectomy for hepatosplenomegaly as well as evaluation by hematology for lymphadenopathy; a cervical lymph node biopsy showed lymphoid and follicular hyperplasia.

Twenty days later, the patient was referred to the dermatology department for evaluation of the persistent rash. The patient described a history of flushing of the face, severe joint pain in both arms and legs, aching muscles, and persistent sore throat. The patient did not report any history of drug ingestion. Physical examination revealed a fever (temperature, 39.2°C); swollen nontender lymph nodes in the neck, axillae, and groin; and salmon-colored and hyperpigmented patches and thin plaques over the neck, chest, abdomen, and arms (Figure 1). A splenectomy scar also was noted. Peripheral blood was collected for laboratory analyses, which revealed transaminitis and moderate hyperferritinemia (Table). An autoimmune panel was negative for rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. The patient was admitted to the hospital, and a skin biopsy was performed. Histology showed superficial dyskeratotic keratinocytes and sparse perivascular infiltration of neutrophils in the upper dermis (Figure 2).

The patient was diagnosed with AOSD based on fulfillment of the Yamaguchi criteria.2 She was treated with methylprednisolone 60 mg daily and was discharged 14 days later. At 16-month follow-up, the patient demonstrated complete resolution of symptoms with a maintenance dose of prednisolone (7.5 mg daily).

Patient 2

A 23-year-old black woman presented to the emergency department 3 months postpartum with recurrent high fevers, worsening joint pain, and persistent itchy rash of 2 months’ duration. The patient had no history of travel, autoimmune disease, or sick contacts. She occasionally took aspirin for joint pain. Physical examination revealed a fever (temperature, 39.1°C) along with hyperpigmented patches and thin scaly hyperpigmented papules coalescing into a poorly demarcated V-shaped plaque on the upper back and posterior neck, extending to the chest in a shawl-like distribution (Figure 3). Submental lymphadenopathy was present. The spleen was not palpable.

Peripheral blood was collected for laboratory analysis and demonstrated transaminitis and a markedly high ferritin level (Table). An autoimmune panel was negative for rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Skin biopsy was performed and demonstrated many necrotic keratinocytes, singly and in aggregates, distributed from the spinous layer to the stratum corneum. A neutrophilic infiltrate was present in the papillary dermis (Figure 4).

The patient met the Yamaguchi criteria and was subsequently diagnosed with AOSD. She was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone 20 mg every 8 hours and was discharged 1 week later on oral prednisone 60 mg daily to be tapered over a period of months. At 2-week follow-up, the patient continued to experience rash and joint pain; oral methotrexate 10 mg weekly was added to her regimen, as well as vitamin D, calcium, and folic acid supplementation. At the next 2-week follow-up the patient noted improvement in the rash as well as the joint pain, but both still persisted. Prednisone was decreased to 50 mg daily and methotrexate was increased to 15 mg weekly. The patient continued to show improvement over the subsequent 3 months, during which prednisone was tapered to 10 mg daily and methotrexate was increased to 20 mg weekly. The patient showed resolution of symptoms at 3-month follow-up on this regimen, with plans to continue the prednisone taper and maintain methotrexate dosing.

Comment

Adult-onset Still disease is a systemic inflammatory condition that clinically manifests as spiking fevers, arthralgia, salmon-pink evanescent erythema, and lymphadenopathy.2 The condition also can cause liver dysfunction, splenomegaly, pericarditis, pleuritis, renal dysfunction, and a reactive hemophagocytic syndrome.1 Furthermore, one review of the literature described an association with delayed-onset malignancy.4 Early diagnosis is important yet challenging, as AOSD is a diagnosis of exclusion. The Yamaguchi criteria are the most widely used method of diagnosis and demonstrate more than 90% sensitivity.In addition to the Yamaguchi criteria, marked hyperferritinemia is characteristic of AOSD and can act as an indicator of disease activity.5 Interestingly, both of our patients had elevated ferritin levels, with patient 2 showing marked elevation (Table). In both patients, all major criteria were fulfilled, except the typical skin rash.

The skin rash in AOSD, classically consisting of an evanescent, salmon-pink erythema predominantly involving the extremities, has been observed in up to 87% of AOSD patients.5 The histology of the typical evanescent rash is nonspecific, characterized by a relatively sparse, perivascular, mixed inflammatory infiltrate. Notably, other skin manifestations may be found in patients with AOSD.1,2,5-16 Persistent pruritic papules and plaques are the most commonly reported nonclassical rash, presenting as erythematous, slightly scaly papules and plaques with a linear configuration typically on the trunk.2 Both of our patients presented with this atypical eruption. Importantly, the histopathology of this unique rash displays distinctive features, which can aid in early diagnosis. Findings include dyskeratotic keratinocytes in the cornified layers as well as in the epidermis, and a sparse neutrophilic and/or lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis without vasculitis. These findings were evident in both histopathologic studies of our patients (Figures 2 and 4). Although not present in our patients, dermal mucin deposition has been demonstrated in some reports.1,13,15