User login

PVd improved survival in lenalidomide-exposed myeloma

CHICAGO – For patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma previously exposed to lenalidomide, the combination of pomalidomide plus bortezomib and low‐dose dexamethasone (PVd) improved response and progression-free survival, results of the phase 3 OPTIMISMM trial showed.

Risk of disease progression or death was reduced by 39%, compared with bortezomib and low-dose dexamethasone alone (Vd), among patients in the trial, of whom approximately 70% were lenalidomide refractory, reported investigator Paul G. Richardson, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

The improvements in efficacy seen with the PVd regimen were more pronounced in patients with only one prior line of therapy, and overall, the safety profile of the triplet regimen was consistent with known toxicities of each individual agent, Dr. Richardson reported.

Together, those results “would seem to support the use of this triplet [therapy] in first relapse in patients with relapsed/refractory myeloma and prior exposure to lenalidomide,” he said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“This study, importantly, evaluated a clinically relevant patient population and a growing patient population who receive upfront lenalidomide and maintenance in that setting and for whom lenalidomide is no longer a viable treatment option,” Dr. Richardson added.

Lenalidomide has become a mainstay of upfront myeloma treatment, and the Food and Drug Administration recently gave approval to lenalidomide as maintenance after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Accordingly, it’s important to understand the benefits of triplet therapies in patients progressing on lenalidomide therapy and in whom lenalidomide is no longer a treatment option, Dr. Richardson said.

Pomalidomide, a potent oral immunomodulatory agent, is already approved for relapsed/refractory myeloma after two or more previous therapies that include lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor in patients who progress on or within 60 days of treatment.

In the OPTIMISMM trial, 559 patients who had received prior therapy, including at least two cycles of lenalidomide, were randomized to receive either PVd or Vd until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Median progression-free survival was 11.20 months for PVd versus 7.10 months for Vd (hazard ratio, 0.61; 95% confidence interval, 0.49-0.77; P less than .0001).

Progression-free survival results were “even more encouraging” in the subset of patients with only one prior line of therapy, Dr. Richardson said, reporting a median of 20.73 months for PVd versus 11.63 for Vd (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.36-0.82; P = .0027).

The overall response rate was 82.2% for PVd versus 50.0% for Vd (P less than .001). In patients with only one prior line of therapy, the overall response rate was 90.1% and 54.8% for PVd and Vd, respectively (P less than .001).

The progression-free survival advantage occurred regardless of whether patients were refractory to lenalidomide, Dr. Richardson added. Median progression-free survival for PVd versus Vd was 9.53 and 5.59 months, respectively, in the lenalidomide-refractory patients (P less than .001) and 22.01 versus 11.63 months in non–lenalidomide refractory patients (P less than .001).

The side effect profile of PVd was “very much as expected,” with more neutropenia seen with the PVd than with Vd, though rates of febrile neutropenia were low, Dr. Richardson said. Likewise, the rate of infection was higher in the triplet arm, but it was generally manageable, he added.

Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism rates were low in both arms, as were the rates of secondary primary malignancies. Analysis of minimal residual disease and quality of life are ongoing.

PVd could “arguably be now an important treatment platform for future directions in combination with other strategies,” Dr. Richardson said.

The study was supported by Celgene. Dr. Richardson reported advisory board work for Celgene, Novartis, Oncopeptides, Janssen, Amgen, and Takeda, and research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, and Takeda.

SOURCE: Richardson PG et al. ASCO 2018, Abstract 8001.

CHICAGO – For patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma previously exposed to lenalidomide, the combination of pomalidomide plus bortezomib and low‐dose dexamethasone (PVd) improved response and progression-free survival, results of the phase 3 OPTIMISMM trial showed.

Risk of disease progression or death was reduced by 39%, compared with bortezomib and low-dose dexamethasone alone (Vd), among patients in the trial, of whom approximately 70% were lenalidomide refractory, reported investigator Paul G. Richardson, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

The improvements in efficacy seen with the PVd regimen were more pronounced in patients with only one prior line of therapy, and overall, the safety profile of the triplet regimen was consistent with known toxicities of each individual agent, Dr. Richardson reported.

Together, those results “would seem to support the use of this triplet [therapy] in first relapse in patients with relapsed/refractory myeloma and prior exposure to lenalidomide,” he said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“This study, importantly, evaluated a clinically relevant patient population and a growing patient population who receive upfront lenalidomide and maintenance in that setting and for whom lenalidomide is no longer a viable treatment option,” Dr. Richardson added.

Lenalidomide has become a mainstay of upfront myeloma treatment, and the Food and Drug Administration recently gave approval to lenalidomide as maintenance after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Accordingly, it’s important to understand the benefits of triplet therapies in patients progressing on lenalidomide therapy and in whom lenalidomide is no longer a treatment option, Dr. Richardson said.

Pomalidomide, a potent oral immunomodulatory agent, is already approved for relapsed/refractory myeloma after two or more previous therapies that include lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor in patients who progress on or within 60 days of treatment.

In the OPTIMISMM trial, 559 patients who had received prior therapy, including at least two cycles of lenalidomide, were randomized to receive either PVd or Vd until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Median progression-free survival was 11.20 months for PVd versus 7.10 months for Vd (hazard ratio, 0.61; 95% confidence interval, 0.49-0.77; P less than .0001).

Progression-free survival results were “even more encouraging” in the subset of patients with only one prior line of therapy, Dr. Richardson said, reporting a median of 20.73 months for PVd versus 11.63 for Vd (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.36-0.82; P = .0027).

The overall response rate was 82.2% for PVd versus 50.0% for Vd (P less than .001). In patients with only one prior line of therapy, the overall response rate was 90.1% and 54.8% for PVd and Vd, respectively (P less than .001).

The progression-free survival advantage occurred regardless of whether patients were refractory to lenalidomide, Dr. Richardson added. Median progression-free survival for PVd versus Vd was 9.53 and 5.59 months, respectively, in the lenalidomide-refractory patients (P less than .001) and 22.01 versus 11.63 months in non–lenalidomide refractory patients (P less than .001).

The side effect profile of PVd was “very much as expected,” with more neutropenia seen with the PVd than with Vd, though rates of febrile neutropenia were low, Dr. Richardson said. Likewise, the rate of infection was higher in the triplet arm, but it was generally manageable, he added.

Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism rates were low in both arms, as were the rates of secondary primary malignancies. Analysis of minimal residual disease and quality of life are ongoing.

PVd could “arguably be now an important treatment platform for future directions in combination with other strategies,” Dr. Richardson said.

The study was supported by Celgene. Dr. Richardson reported advisory board work for Celgene, Novartis, Oncopeptides, Janssen, Amgen, and Takeda, and research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, and Takeda.

SOURCE: Richardson PG et al. ASCO 2018, Abstract 8001.

CHICAGO – For patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma previously exposed to lenalidomide, the combination of pomalidomide plus bortezomib and low‐dose dexamethasone (PVd) improved response and progression-free survival, results of the phase 3 OPTIMISMM trial showed.

Risk of disease progression or death was reduced by 39%, compared with bortezomib and low-dose dexamethasone alone (Vd), among patients in the trial, of whom approximately 70% were lenalidomide refractory, reported investigator Paul G. Richardson, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

The improvements in efficacy seen with the PVd regimen were more pronounced in patients with only one prior line of therapy, and overall, the safety profile of the triplet regimen was consistent with known toxicities of each individual agent, Dr. Richardson reported.

Together, those results “would seem to support the use of this triplet [therapy] in first relapse in patients with relapsed/refractory myeloma and prior exposure to lenalidomide,” he said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“This study, importantly, evaluated a clinically relevant patient population and a growing patient population who receive upfront lenalidomide and maintenance in that setting and for whom lenalidomide is no longer a viable treatment option,” Dr. Richardson added.

Lenalidomide has become a mainstay of upfront myeloma treatment, and the Food and Drug Administration recently gave approval to lenalidomide as maintenance after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Accordingly, it’s important to understand the benefits of triplet therapies in patients progressing on lenalidomide therapy and in whom lenalidomide is no longer a treatment option, Dr. Richardson said.

Pomalidomide, a potent oral immunomodulatory agent, is already approved for relapsed/refractory myeloma after two or more previous therapies that include lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor in patients who progress on or within 60 days of treatment.

In the OPTIMISMM trial, 559 patients who had received prior therapy, including at least two cycles of lenalidomide, were randomized to receive either PVd or Vd until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Median progression-free survival was 11.20 months for PVd versus 7.10 months for Vd (hazard ratio, 0.61; 95% confidence interval, 0.49-0.77; P less than .0001).

Progression-free survival results were “even more encouraging” in the subset of patients with only one prior line of therapy, Dr. Richardson said, reporting a median of 20.73 months for PVd versus 11.63 for Vd (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.36-0.82; P = .0027).

The overall response rate was 82.2% for PVd versus 50.0% for Vd (P less than .001). In patients with only one prior line of therapy, the overall response rate was 90.1% and 54.8% for PVd and Vd, respectively (P less than .001).

The progression-free survival advantage occurred regardless of whether patients were refractory to lenalidomide, Dr. Richardson added. Median progression-free survival for PVd versus Vd was 9.53 and 5.59 months, respectively, in the lenalidomide-refractory patients (P less than .001) and 22.01 versus 11.63 months in non–lenalidomide refractory patients (P less than .001).

The side effect profile of PVd was “very much as expected,” with more neutropenia seen with the PVd than with Vd, though rates of febrile neutropenia were low, Dr. Richardson said. Likewise, the rate of infection was higher in the triplet arm, but it was generally manageable, he added.

Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism rates were low in both arms, as were the rates of secondary primary malignancies. Analysis of minimal residual disease and quality of life are ongoing.

PVd could “arguably be now an important treatment platform for future directions in combination with other strategies,” Dr. Richardson said.

The study was supported by Celgene. Dr. Richardson reported advisory board work for Celgene, Novartis, Oncopeptides, Janssen, Amgen, and Takeda, and research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, and Takeda.

SOURCE: Richardson PG et al. ASCO 2018, Abstract 8001.

REPORTING FROM ASCO 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Risk of disease progression or death was reduced by 39% with pomalidomide plus bortezomib and low‐dose dexamethasone (PVd), compared with use of bortezomib and low-dose dexamethasone alone (Vd).

Study details: The phase 3 OPTIMISMM trial including 559 patients who had received prior therapy with at least two cycles of lenalidomide.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Celgene. Dr. Richardson reported advisory board work for Celgene, Novartis, Oncopeptides, Janssen, Amgen, and Takeda and research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, and Takeda.

Source: Richardson PG et al. ASCO 2018, Abstract 8001.

Screen sooner and more often for those with family history of CRC

WASHINGTON – The number of first- and second-degree relatives with colorectal cancer can increase an individual’s risk for CRC, which could require screening to be done more frequently.

“There have been multiple guidelines reported as to what should be done for these individuals,” Harminder Singh, MD, of the University of Manitoba and his associates stated. “However, for the most part, they have not systematically analyzed the data.” He went on to say that, “more importantly, there’s been no recent AGA [American Gastroenterological Association] or Canadian Association of Gastroenterology statement, which led the development of this guideline.”

To address this issue, Dr. Singh and his colleagues conducted a systematic review of 10 literature searches to answer the following five questions concerning colorectal risk and screening practices: What is the effect of a family history of CRC on an individual’s risk of CRC? What is the effect of a family history of adenoma on an individual’s risk of CRC? At what age should CRC screening begin? Which screening tests are optimal? What are the optimal testing intervals for people with a family history of CRC or adenoma?

These questions were developed via an iterative online platform and then further developed and voted on by a team of specialists. GRADE (Grading of Recommendation Assessment, Development and Evaluation) was used to assess the quality of evidence to support these questions.

Similarly, individuals with two or more first-degree relatives with CRC had a two- to fourfold increased risk of developing CRC, compared with the general population. The review also found that, of the 20 recommendation statements from the review panel, there was consensus about 19 of them.

Colorectal cancer screening is recommended for all individuals with a family history of CRC or documented adenoma. Similarly, colonoscopy is recommended as the preferred test for individuals at the highest risk– those with one or more affected first-degree relatives. Fecal immunochemistry tests are considered a viable alternative except in patients with two or more first-degree relatives.

If a patient is considered to have an elevated risk of CRC because of family history, then screening should begin when they are aged 10 years younger than when that first-degree relative was diagnosed, and a 5-year screening interval should be followed after that.

Dr. Singh pointed out that the age of the affected first-degree relative should be considered when weighing an individual’s related risk of developing CRC. For example, having an first-degree relative who is diagnosed after the age of 75 is not likely to elevate an individual’s risk of developing CRC. Individuals with one or more second-degree relatives with CRC or nonadvanced adenoma do not appear to have an elevated risk of developing CRC and should be screened according to average-risk guidelines.

Dr. Singh reported receiving funding for from Merck Canada.

SOURCE: Leddin D. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jun. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(18)31083-7.

WASHINGTON – The number of first- and second-degree relatives with colorectal cancer can increase an individual’s risk for CRC, which could require screening to be done more frequently.

“There have been multiple guidelines reported as to what should be done for these individuals,” Harminder Singh, MD, of the University of Manitoba and his associates stated. “However, for the most part, they have not systematically analyzed the data.” He went on to say that, “more importantly, there’s been no recent AGA [American Gastroenterological Association] or Canadian Association of Gastroenterology statement, which led the development of this guideline.”

To address this issue, Dr. Singh and his colleagues conducted a systematic review of 10 literature searches to answer the following five questions concerning colorectal risk and screening practices: What is the effect of a family history of CRC on an individual’s risk of CRC? What is the effect of a family history of adenoma on an individual’s risk of CRC? At what age should CRC screening begin? Which screening tests are optimal? What are the optimal testing intervals for people with a family history of CRC or adenoma?

These questions were developed via an iterative online platform and then further developed and voted on by a team of specialists. GRADE (Grading of Recommendation Assessment, Development and Evaluation) was used to assess the quality of evidence to support these questions.

Similarly, individuals with two or more first-degree relatives with CRC had a two- to fourfold increased risk of developing CRC, compared with the general population. The review also found that, of the 20 recommendation statements from the review panel, there was consensus about 19 of them.

Colorectal cancer screening is recommended for all individuals with a family history of CRC or documented adenoma. Similarly, colonoscopy is recommended as the preferred test for individuals at the highest risk– those with one or more affected first-degree relatives. Fecal immunochemistry tests are considered a viable alternative except in patients with two or more first-degree relatives.

If a patient is considered to have an elevated risk of CRC because of family history, then screening should begin when they are aged 10 years younger than when that first-degree relative was diagnosed, and a 5-year screening interval should be followed after that.

Dr. Singh pointed out that the age of the affected first-degree relative should be considered when weighing an individual’s related risk of developing CRC. For example, having an first-degree relative who is diagnosed after the age of 75 is not likely to elevate an individual’s risk of developing CRC. Individuals with one or more second-degree relatives with CRC or nonadvanced adenoma do not appear to have an elevated risk of developing CRC and should be screened according to average-risk guidelines.

Dr. Singh reported receiving funding for from Merck Canada.

SOURCE: Leddin D. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jun. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(18)31083-7.

WASHINGTON – The number of first- and second-degree relatives with colorectal cancer can increase an individual’s risk for CRC, which could require screening to be done more frequently.

“There have been multiple guidelines reported as to what should be done for these individuals,” Harminder Singh, MD, of the University of Manitoba and his associates stated. “However, for the most part, they have not systematically analyzed the data.” He went on to say that, “more importantly, there’s been no recent AGA [American Gastroenterological Association] or Canadian Association of Gastroenterology statement, which led the development of this guideline.”

To address this issue, Dr. Singh and his colleagues conducted a systematic review of 10 literature searches to answer the following five questions concerning colorectal risk and screening practices: What is the effect of a family history of CRC on an individual’s risk of CRC? What is the effect of a family history of adenoma on an individual’s risk of CRC? At what age should CRC screening begin? Which screening tests are optimal? What are the optimal testing intervals for people with a family history of CRC or adenoma?

These questions were developed via an iterative online platform and then further developed and voted on by a team of specialists. GRADE (Grading of Recommendation Assessment, Development and Evaluation) was used to assess the quality of evidence to support these questions.

Similarly, individuals with two or more first-degree relatives with CRC had a two- to fourfold increased risk of developing CRC, compared with the general population. The review also found that, of the 20 recommendation statements from the review panel, there was consensus about 19 of them.

Colorectal cancer screening is recommended for all individuals with a family history of CRC or documented adenoma. Similarly, colonoscopy is recommended as the preferred test for individuals at the highest risk– those with one or more affected first-degree relatives. Fecal immunochemistry tests are considered a viable alternative except in patients with two or more first-degree relatives.

If a patient is considered to have an elevated risk of CRC because of family history, then screening should begin when they are aged 10 years younger than when that first-degree relative was diagnosed, and a 5-year screening interval should be followed after that.

Dr. Singh pointed out that the age of the affected first-degree relative should be considered when weighing an individual’s related risk of developing CRC. For example, having an first-degree relative who is diagnosed after the age of 75 is not likely to elevate an individual’s risk of developing CRC. Individuals with one or more second-degree relatives with CRC or nonadvanced adenoma do not appear to have an elevated risk of developing CRC and should be screened according to average-risk guidelines.

Dr. Singh reported receiving funding for from Merck Canada.

SOURCE: Leddin D. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jun. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(18)31083-7.

REPORTING FROM DDW 2018

Key clinical point: Patients with 1 or more first-degree relative with CRC should be screened more often.

Major finding: Patients with one or more first-degree relatives with CRC or adenoma had a twofold greater risk of developing CRC, compared with those without a family history of these diseases.

Study details: A systematic review of 10 literature searches assessing risk of CRC in those with a family history of CRC.

Disclosures: Dr. Singh has received funding from Merck Canada.

Source: Leddin D. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jun. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(18)31083-7.

EULAR recommendations on steroids: ‘As necessary, but as little as possible’

AMSTERDAM – Glucocorticosteroids remain an important therapeutic option for many patients with rheumatic and nonrheumatic disease, but careful assessment of their relative benefits and risks needs to be considered when prescribing, according to an expert summary of currently available European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

From rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) to vasculitis, myositis, and even gout, steroids are widely used in the rheumatic diseases, said Frank Buttgereit, MD, during a final plenary session at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“These are strong-acting, rapidly acting, efficacious drugs,” observed Dr. Buttgereit, who is a professor in the department of rheumatology at Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin. While effective at reducing inflammation and providing immunosuppression, they are, of course, not without their well-known risks. Some of the well-documented risks he pointed out were the development of osteoporosis, myopathy, and edema; the disruption of lipid and carbohydrate metabolism; and the risk of developing glaucoma and cataracts.

“This leads to the question on how to optimize the use of these drugs,” Dr. Buttgereit said. “EULAR is constantly working to improve its guidelines,” and updating these in line with the available evidence, he added. “The bottom line is always give as much as necessary but as little as possible.”

Over the past few years, EULAR’s Glucocorticoid Task Force has been reviewing and updating recommendations on the use of these drugs and it has published several important documents clarifying their use in RA and in PMR. The task force has also published a viewpoint article on the long-term use of steroids, defining the conditions where an “acceptably low level of harm” might exist to enable their continued use. There have also been separate recommendations, published in 2010, on how to monitor these drugs (Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69[11]:1913-9).

Clarifying the role of steroids in rheumatoid arthritis

The latest (2016) EULAR recommendations on the use of glucocorticosteroids were published last year (Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76[6]:960-77) and included an important adjustment on when they should be initially used in RA, Dr. Buttgereit explained. Previous recommendations had said that steroids could be combined with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) but had suggested that they be used at a low dose. Now the wording has changed to focus on short-term use rather than dosing.

“Glucocorticoids can be given initially at different dosages, and using different routes of administration,” he said in a video interview at the EULAR Congress. The practice on what dose to give varies from country to country, he noted, so the recommendations are now being less prescriptive.

“We have made it clear that glucocorticoids should really be used only when initiating conventional synthetic DMARDs, but not necessarily if you switch to biologics or targeted synthetics because usually the onset of their actions is pretty fast,” Dr. Buttgereit said.

One thing that hasn’t changed is that steroid should be tapered down as “rapidly as clinically feasible” until, ideally, their full withdrawal. Although there are cases when that might not be possible, and their long-term use might be warranted. This is when you get into discussion about the benefit-to-risk ratio, he said.

Steroids for polymyalgia rheumatica

Steroids may be used as monotherapy in patients with PMR, Dr. Buttgereit observed, which is in contrast to other conditions such as RA. Although the evidence for use of steroids in PMR is limited, the EULAR Glucocorticoid Task Force and American College of Rheumatology recommended (Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74[10]:1799-807) using a starting dose of a prednisolone-equivalent dose between 12.5 and 25 mg/day, and if there is an improvement in few weeks, the dose can start to be reduced. Tapering should be rapid at first to bring the dose down to 10 mg/day and followed by a more gradual dose-reduction phase.

“So, you can see we are giving more or less precise recommendations on how to start, how to taper,” Dr. Buttgereit said.

Balancing long-term benefit vs. harm

Balancing the long-term benefits and risks of steroids in rheumatic disease was the focus of a EULAR viewpoint article published 3 years ago in 2015 (Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;75[6]:952-7).

Three main messages can be drawn out of this work, Dr. Buttgereit said.

First, treatment with steroids for 3-6 months is associated with more benefits than risks if doses of 5 mg/day or less are used. There is one important exception to this, however, and that is the use of steroids in patients with comorbid cardiovascular disease.

Second, using doses of 10 mg/day for long periods tips the balance toward more risks than benefits, and “this means you should avoid this.”

Third, doses of 5-10 mg/day may be appropriate, but there are certain patient factors that will influence the benefit-to-harm ratio that need to be considered. These include older age, smoking, high alcohol consumption, and poor nutrition. There are also factors that may help protect the patients from risk, such as early diagnosis, low disease activity, low cumulative dose of steroids, and a shorter duration of treatment.

“It’s not only the dose, it’s also the absence or presence of risk factors and/or preventive measures,” that’s important, Dr. Buttgereit said.

Dr. Buttgereit has received consultancy fees, honoraria, and/or travel expenses from Amgen, Horizon Pharma, Mundipharma, Roche, and Pfizer and grant or study support from Amgen, Mundipharma, and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Buttgereit F. EULAR 2018 Congress, Abstract SP160.

AMSTERDAM – Glucocorticosteroids remain an important therapeutic option for many patients with rheumatic and nonrheumatic disease, but careful assessment of their relative benefits and risks needs to be considered when prescribing, according to an expert summary of currently available European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

From rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) to vasculitis, myositis, and even gout, steroids are widely used in the rheumatic diseases, said Frank Buttgereit, MD, during a final plenary session at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“These are strong-acting, rapidly acting, efficacious drugs,” observed Dr. Buttgereit, who is a professor in the department of rheumatology at Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin. While effective at reducing inflammation and providing immunosuppression, they are, of course, not without their well-known risks. Some of the well-documented risks he pointed out were the development of osteoporosis, myopathy, and edema; the disruption of lipid and carbohydrate metabolism; and the risk of developing glaucoma and cataracts.

“This leads to the question on how to optimize the use of these drugs,” Dr. Buttgereit said. “EULAR is constantly working to improve its guidelines,” and updating these in line with the available evidence, he added. “The bottom line is always give as much as necessary but as little as possible.”

Over the past few years, EULAR’s Glucocorticoid Task Force has been reviewing and updating recommendations on the use of these drugs and it has published several important documents clarifying their use in RA and in PMR. The task force has also published a viewpoint article on the long-term use of steroids, defining the conditions where an “acceptably low level of harm” might exist to enable their continued use. There have also been separate recommendations, published in 2010, on how to monitor these drugs (Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69[11]:1913-9).

Clarifying the role of steroids in rheumatoid arthritis

The latest (2016) EULAR recommendations on the use of glucocorticosteroids were published last year (Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76[6]:960-77) and included an important adjustment on when they should be initially used in RA, Dr. Buttgereit explained. Previous recommendations had said that steroids could be combined with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) but had suggested that they be used at a low dose. Now the wording has changed to focus on short-term use rather than dosing.

“Glucocorticoids can be given initially at different dosages, and using different routes of administration,” he said in a video interview at the EULAR Congress. The practice on what dose to give varies from country to country, he noted, so the recommendations are now being less prescriptive.

“We have made it clear that glucocorticoids should really be used only when initiating conventional synthetic DMARDs, but not necessarily if you switch to biologics or targeted synthetics because usually the onset of their actions is pretty fast,” Dr. Buttgereit said.

One thing that hasn’t changed is that steroid should be tapered down as “rapidly as clinically feasible” until, ideally, their full withdrawal. Although there are cases when that might not be possible, and their long-term use might be warranted. This is when you get into discussion about the benefit-to-risk ratio, he said.

Steroids for polymyalgia rheumatica

Steroids may be used as monotherapy in patients with PMR, Dr. Buttgereit observed, which is in contrast to other conditions such as RA. Although the evidence for use of steroids in PMR is limited, the EULAR Glucocorticoid Task Force and American College of Rheumatology recommended (Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74[10]:1799-807) using a starting dose of a prednisolone-equivalent dose between 12.5 and 25 mg/day, and if there is an improvement in few weeks, the dose can start to be reduced. Tapering should be rapid at first to bring the dose down to 10 mg/day and followed by a more gradual dose-reduction phase.

“So, you can see we are giving more or less precise recommendations on how to start, how to taper,” Dr. Buttgereit said.

Balancing long-term benefit vs. harm

Balancing the long-term benefits and risks of steroids in rheumatic disease was the focus of a EULAR viewpoint article published 3 years ago in 2015 (Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;75[6]:952-7).

Three main messages can be drawn out of this work, Dr. Buttgereit said.

First, treatment with steroids for 3-6 months is associated with more benefits than risks if doses of 5 mg/day or less are used. There is one important exception to this, however, and that is the use of steroids in patients with comorbid cardiovascular disease.

Second, using doses of 10 mg/day for long periods tips the balance toward more risks than benefits, and “this means you should avoid this.”

Third, doses of 5-10 mg/day may be appropriate, but there are certain patient factors that will influence the benefit-to-harm ratio that need to be considered. These include older age, smoking, high alcohol consumption, and poor nutrition. There are also factors that may help protect the patients from risk, such as early diagnosis, low disease activity, low cumulative dose of steroids, and a shorter duration of treatment.

“It’s not only the dose, it’s also the absence or presence of risk factors and/or preventive measures,” that’s important, Dr. Buttgereit said.

Dr. Buttgereit has received consultancy fees, honoraria, and/or travel expenses from Amgen, Horizon Pharma, Mundipharma, Roche, and Pfizer and grant or study support from Amgen, Mundipharma, and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Buttgereit F. EULAR 2018 Congress, Abstract SP160.

AMSTERDAM – Glucocorticosteroids remain an important therapeutic option for many patients with rheumatic and nonrheumatic disease, but careful assessment of their relative benefits and risks needs to be considered when prescribing, according to an expert summary of currently available European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

From rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) to vasculitis, myositis, and even gout, steroids are widely used in the rheumatic diseases, said Frank Buttgereit, MD, during a final plenary session at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“These are strong-acting, rapidly acting, efficacious drugs,” observed Dr. Buttgereit, who is a professor in the department of rheumatology at Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin. While effective at reducing inflammation and providing immunosuppression, they are, of course, not without their well-known risks. Some of the well-documented risks he pointed out were the development of osteoporosis, myopathy, and edema; the disruption of lipid and carbohydrate metabolism; and the risk of developing glaucoma and cataracts.

“This leads to the question on how to optimize the use of these drugs,” Dr. Buttgereit said. “EULAR is constantly working to improve its guidelines,” and updating these in line with the available evidence, he added. “The bottom line is always give as much as necessary but as little as possible.”

Over the past few years, EULAR’s Glucocorticoid Task Force has been reviewing and updating recommendations on the use of these drugs and it has published several important documents clarifying their use in RA and in PMR. The task force has also published a viewpoint article on the long-term use of steroids, defining the conditions where an “acceptably low level of harm” might exist to enable their continued use. There have also been separate recommendations, published in 2010, on how to monitor these drugs (Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69[11]:1913-9).

Clarifying the role of steroids in rheumatoid arthritis

The latest (2016) EULAR recommendations on the use of glucocorticosteroids were published last year (Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76[6]:960-77) and included an important adjustment on when they should be initially used in RA, Dr. Buttgereit explained. Previous recommendations had said that steroids could be combined with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) but had suggested that they be used at a low dose. Now the wording has changed to focus on short-term use rather than dosing.

“Glucocorticoids can be given initially at different dosages, and using different routes of administration,” he said in a video interview at the EULAR Congress. The practice on what dose to give varies from country to country, he noted, so the recommendations are now being less prescriptive.

“We have made it clear that glucocorticoids should really be used only when initiating conventional synthetic DMARDs, but not necessarily if you switch to biologics or targeted synthetics because usually the onset of their actions is pretty fast,” Dr. Buttgereit said.

One thing that hasn’t changed is that steroid should be tapered down as “rapidly as clinically feasible” until, ideally, their full withdrawal. Although there are cases when that might not be possible, and their long-term use might be warranted. This is when you get into discussion about the benefit-to-risk ratio, he said.

Steroids for polymyalgia rheumatica

Steroids may be used as monotherapy in patients with PMR, Dr. Buttgereit observed, which is in contrast to other conditions such as RA. Although the evidence for use of steroids in PMR is limited, the EULAR Glucocorticoid Task Force and American College of Rheumatology recommended (Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74[10]:1799-807) using a starting dose of a prednisolone-equivalent dose between 12.5 and 25 mg/day, and if there is an improvement in few weeks, the dose can start to be reduced. Tapering should be rapid at first to bring the dose down to 10 mg/day and followed by a more gradual dose-reduction phase.

“So, you can see we are giving more or less precise recommendations on how to start, how to taper,” Dr. Buttgereit said.

Balancing long-term benefit vs. harm

Balancing the long-term benefits and risks of steroids in rheumatic disease was the focus of a EULAR viewpoint article published 3 years ago in 2015 (Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;75[6]:952-7).

Three main messages can be drawn out of this work, Dr. Buttgereit said.

First, treatment with steroids for 3-6 months is associated with more benefits than risks if doses of 5 mg/day or less are used. There is one important exception to this, however, and that is the use of steroids in patients with comorbid cardiovascular disease.

Second, using doses of 10 mg/day for long periods tips the balance toward more risks than benefits, and “this means you should avoid this.”

Third, doses of 5-10 mg/day may be appropriate, but there are certain patient factors that will influence the benefit-to-harm ratio that need to be considered. These include older age, smoking, high alcohol consumption, and poor nutrition. There are also factors that may help protect the patients from risk, such as early diagnosis, low disease activity, low cumulative dose of steroids, and a shorter duration of treatment.

“It’s not only the dose, it’s also the absence or presence of risk factors and/or preventive measures,” that’s important, Dr. Buttgereit said.

Dr. Buttgereit has received consultancy fees, honoraria, and/or travel expenses from Amgen, Horizon Pharma, Mundipharma, Roche, and Pfizer and grant or study support from Amgen, Mundipharma, and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Buttgereit F. EULAR 2018 Congress, Abstract SP160.

REPORTING FROM THE EULAR 2018 CONGRESS

Key clinical point: When dosing glucocorticoids, give as much as necessary but as little as possible.

Major finding:

Disclosures: Dr. Buttgereit has received consultancy fees, honoraria, and/or travel expenses from Amgen, Horizon Pharma, Mundipharma, Roche, and Pfizer and grant or study support from Amgen, Mundipharma, and Pfizer.

Source: Buttgereit F. EULAR 2018 Congress. Abstract SP160.

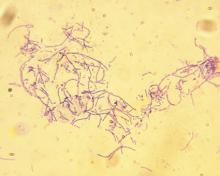

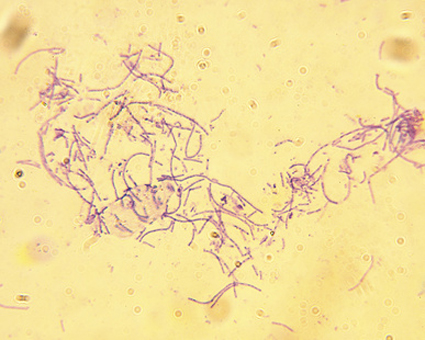

Anthrax vaccine recommendations updated in the event of a wide-area release

at their meeting.

The recommendations to the committee sought to optimize the use of Anthrax Vaccine Adsorbed (AVA) in post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) in the event of a wide-area release of Bacillus anthracis spores. In this event, a mass vaccination effort would be undertaken, requiring expedited administration of AVA. ACIP now recommends that the intramuscular administration may be used over the traditional subcutaneous approach if there are any operational or logistical challenges that delay effective vaccination. Another recommendation from ACIP would allow two full doses or three half doses of AVA to be used to expand vaccine coverage for PEP in the event there is an inadequate vaccine supply. The committee also recommended that AbxPEP, an antimicrobial, be stopped 42 days after the first dose of AVA or 2 weeks after the last dose.

William A. Bower, MD, of the division of high-consequence pathogens and pathology at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the anthrax work group looked at three nonhuman primate studies and eight human immunogenicity and adverse event studies during the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE). All of the animal studies were used to predict human survival by vaccinating the nonhuman primates with AVA, then challenging them with B. anthracis. Using animal studies to predict human survival is common practice under the “animal rule.”

When Dr. Bower and the work group assessed the studies comparing intramuscular administration with subcutaneous administration of AVA, they rated the overall evidence as GRADE 2. However, they rated the adverse events data as GRADE 1.

Dr. Bower and his colleagues also reviewed dose-sparing studies to identify the feasibility of allowing two full doses or three half doses of AVA to be used to expand vaccine coverage for PEP in the event there is an inadequate vaccine supply. For these studies, the anthrax work group gave a GRADE score of 2.

The overall evidence score for microbial duration for PEP was judged to be GRADE 2.

“These forthcoming recommendations will be used by the CDC to inform state and local health departments to better prepare for an emergency response to a wide-area release of Bacillus anthracis spores,” said Dr. Bower.

The committee’s recommendations must be approved by the CDC’s director before they are considered official recommendations.

Dr. Bower did not report any relevant financial conflicts of interest.

at their meeting.

The recommendations to the committee sought to optimize the use of Anthrax Vaccine Adsorbed (AVA) in post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) in the event of a wide-area release of Bacillus anthracis spores. In this event, a mass vaccination effort would be undertaken, requiring expedited administration of AVA. ACIP now recommends that the intramuscular administration may be used over the traditional subcutaneous approach if there are any operational or logistical challenges that delay effective vaccination. Another recommendation from ACIP would allow two full doses or three half doses of AVA to be used to expand vaccine coverage for PEP in the event there is an inadequate vaccine supply. The committee also recommended that AbxPEP, an antimicrobial, be stopped 42 days after the first dose of AVA or 2 weeks after the last dose.

William A. Bower, MD, of the division of high-consequence pathogens and pathology at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the anthrax work group looked at three nonhuman primate studies and eight human immunogenicity and adverse event studies during the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE). All of the animal studies were used to predict human survival by vaccinating the nonhuman primates with AVA, then challenging them with B. anthracis. Using animal studies to predict human survival is common practice under the “animal rule.”

When Dr. Bower and the work group assessed the studies comparing intramuscular administration with subcutaneous administration of AVA, they rated the overall evidence as GRADE 2. However, they rated the adverse events data as GRADE 1.

Dr. Bower and his colleagues also reviewed dose-sparing studies to identify the feasibility of allowing two full doses or three half doses of AVA to be used to expand vaccine coverage for PEP in the event there is an inadequate vaccine supply. For these studies, the anthrax work group gave a GRADE score of 2.

The overall evidence score for microbial duration for PEP was judged to be GRADE 2.

“These forthcoming recommendations will be used by the CDC to inform state and local health departments to better prepare for an emergency response to a wide-area release of Bacillus anthracis spores,” said Dr. Bower.

The committee’s recommendations must be approved by the CDC’s director before they are considered official recommendations.

Dr. Bower did not report any relevant financial conflicts of interest.

at their meeting.

The recommendations to the committee sought to optimize the use of Anthrax Vaccine Adsorbed (AVA) in post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) in the event of a wide-area release of Bacillus anthracis spores. In this event, a mass vaccination effort would be undertaken, requiring expedited administration of AVA. ACIP now recommends that the intramuscular administration may be used over the traditional subcutaneous approach if there are any operational or logistical challenges that delay effective vaccination. Another recommendation from ACIP would allow two full doses or three half doses of AVA to be used to expand vaccine coverage for PEP in the event there is an inadequate vaccine supply. The committee also recommended that AbxPEP, an antimicrobial, be stopped 42 days after the first dose of AVA or 2 weeks after the last dose.

William A. Bower, MD, of the division of high-consequence pathogens and pathology at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the anthrax work group looked at three nonhuman primate studies and eight human immunogenicity and adverse event studies during the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE). All of the animal studies were used to predict human survival by vaccinating the nonhuman primates with AVA, then challenging them with B. anthracis. Using animal studies to predict human survival is common practice under the “animal rule.”

When Dr. Bower and the work group assessed the studies comparing intramuscular administration with subcutaneous administration of AVA, they rated the overall evidence as GRADE 2. However, they rated the adverse events data as GRADE 1.

Dr. Bower and his colleagues also reviewed dose-sparing studies to identify the feasibility of allowing two full doses or three half doses of AVA to be used to expand vaccine coverage for PEP in the event there is an inadequate vaccine supply. For these studies, the anthrax work group gave a GRADE score of 2.

The overall evidence score for microbial duration for PEP was judged to be GRADE 2.

“These forthcoming recommendations will be used by the CDC to inform state and local health departments to better prepare for an emergency response to a wide-area release of Bacillus anthracis spores,” said Dr. Bower.

The committee’s recommendations must be approved by the CDC’s director before they are considered official recommendations.

Dr. Bower did not report any relevant financial conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM AN ACIP MEETING

Voxelotor cut transfusions in compassionate use sickle cell cohort

WASHINGTON – An investigational drug for sickle cell disease (SCD) boosted hemoglobin levels while reducing hospitalizations and transfusion needs by approximately two-thirds in a small cohort of severely affected patients.

Lanetta Bronté, MD, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the Foundation for Sickle Cell Disease Research, reviewed the FDA’s requirements for allowing expanded access to an investigational drug. The key point, she said, is that expanded access may be granted “for treatment of patients with serious or immediately life-threatening diseases or conditions that lack therapeutic alternatives.” And, she said, the potential for benefit should outweigh potential risk of taking the investigational drug.

Current treatments don’t really address serious disease-related complications for patients with advanced SCD, she said. Furthermore, these patients will often be excluded from clinical trials of new SCD therapies.

Voxelotor is a novel small molecule that stabilizes the sickle hemoglobin molecule as a monomer in its high oxygen state. Thus, polymerization of the hemoglobin molecules is inhibited, which decreases the amount of red blood cell damage. Other beneficial effects of voxelotor include improved rheology and reduced hemolysis, as well as a boost to the oxygen-carrying capacity of the sickle hemoglobin molecules, Dr. Bronté explained.

For the seven patients in Dr. Bronté’s clinic who were granted expanded access to voxelator, the disease burden of their end-stage SCD was heavy. All participants had iron overload, five were receiving frequent transfusions, two required chronic oxygen supplementation, and four had severe fatigue. One patient had end-stage renal disease, and another had experienced multiple organ failure and prolonged hospitalizations.

None of the patients qualified for participation in ongoing clinical trials of voxelotor, said Dr. Bronté, who is president of the Foundation for Sickle Cell Disease Research. She also maintains a private practice in Hollywood, Fla.

The four women and three men, aged 22-67 years, were treated with voxelotor for a range of 6-17 months under the FDA’s Expanded Access Program. All patients saw rapid increases in serum hemoglobin, with increases of at least 1 g/dL in five of the seven. Across the participants, increases ranged from 0.5-5.4 g/dL at 24 weeks, up from baseline values of 5.2-7.8 g/dL.

One marker of clinical efficacy that Dr. Bronté and her coauthors examined was the number of hospitalizations for pain from vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs). In the 24 weeks before beginning voxelotor, participants had a summed total of 28 hospitalizations. In the first 24 weeks of treatment, there were a total of nine VOC-related hospitalizations among the participants, a 67% decrease.

The total number of red blood cell transfusions required by the study population declined by a similar proportion, from 33 during the 24 weeks before voxelotor treatment to 13 during the first 24 weeks of treatment, a decrease of 60%.

Individual patients saw improvements related to some of their most troublesome SCD complications, Dr. Bronté reported. All four patients whose oxygen saturation levels had been below 95% on room air saw oxygen saturations improve to 98%-99% on voxelotor. The two patients who had moderate or moderately severe depression, as assessed by the Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item, had minimal or no depression on retest after 24 weeks of voxelotor treatment.

Voxelotor was generally well tolerated at a 900-mg once-daily oral dose. One patient developed grade 2 diarrhea after increasing the dose to 1,500 mg, but symptoms resolved after returning to the 900-mg dose. Another patient had transient mild diarrhea on 900 mg of voxelotor; the symptoms resolved without changing or stopping the drug, Dr. Bronté said. There were no serious treatment-related adverse events.

Among this seriously ill population, two patients died after beginning voxelotor treatment, but both deaths were judged to be unrelated to the treatment. Dr. Bronté reported that the two deceased patients, one of whom was on voxelotor for 16 months and the other for 7 months, did experience reduced transfusion needs and reduced VOC-related hospitalizations while on the drug, experiences that were similar to the surviving members of the cohort.

“Voxelotor administered via compassionate use demonstrated large improvements in anemia and hemolysis, including in patients with lower baseline hemoglobin than studied in clinical trials to date,” Dr. Bronté said.

Taken together with clinical improvements and improved patient-focused outcomes among a severely affected population, “these data … support ongoing investigation in controlled clinical trials to confirm the benefits of voxelotor in a broad range of patients with SCD,” she said.

The study was supported by Global Blood Therapeutics, the manufacturer of voxelotor. Dr. Bronté reported having no other conflicts of interest.

WASHINGTON – An investigational drug for sickle cell disease (SCD) boosted hemoglobin levels while reducing hospitalizations and transfusion needs by approximately two-thirds in a small cohort of severely affected patients.

Lanetta Bronté, MD, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the Foundation for Sickle Cell Disease Research, reviewed the FDA’s requirements for allowing expanded access to an investigational drug. The key point, she said, is that expanded access may be granted “for treatment of patients with serious or immediately life-threatening diseases or conditions that lack therapeutic alternatives.” And, she said, the potential for benefit should outweigh potential risk of taking the investigational drug.

Current treatments don’t really address serious disease-related complications for patients with advanced SCD, she said. Furthermore, these patients will often be excluded from clinical trials of new SCD therapies.

Voxelotor is a novel small molecule that stabilizes the sickle hemoglobin molecule as a monomer in its high oxygen state. Thus, polymerization of the hemoglobin molecules is inhibited, which decreases the amount of red blood cell damage. Other beneficial effects of voxelotor include improved rheology and reduced hemolysis, as well as a boost to the oxygen-carrying capacity of the sickle hemoglobin molecules, Dr. Bronté explained.

For the seven patients in Dr. Bronté’s clinic who were granted expanded access to voxelator, the disease burden of their end-stage SCD was heavy. All participants had iron overload, five were receiving frequent transfusions, two required chronic oxygen supplementation, and four had severe fatigue. One patient had end-stage renal disease, and another had experienced multiple organ failure and prolonged hospitalizations.

None of the patients qualified for participation in ongoing clinical trials of voxelotor, said Dr. Bronté, who is president of the Foundation for Sickle Cell Disease Research. She also maintains a private practice in Hollywood, Fla.

The four women and three men, aged 22-67 years, were treated with voxelotor for a range of 6-17 months under the FDA’s Expanded Access Program. All patients saw rapid increases in serum hemoglobin, with increases of at least 1 g/dL in five of the seven. Across the participants, increases ranged from 0.5-5.4 g/dL at 24 weeks, up from baseline values of 5.2-7.8 g/dL.

One marker of clinical efficacy that Dr. Bronté and her coauthors examined was the number of hospitalizations for pain from vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs). In the 24 weeks before beginning voxelotor, participants had a summed total of 28 hospitalizations. In the first 24 weeks of treatment, there were a total of nine VOC-related hospitalizations among the participants, a 67% decrease.

The total number of red blood cell transfusions required by the study population declined by a similar proportion, from 33 during the 24 weeks before voxelotor treatment to 13 during the first 24 weeks of treatment, a decrease of 60%.

Individual patients saw improvements related to some of their most troublesome SCD complications, Dr. Bronté reported. All four patients whose oxygen saturation levels had been below 95% on room air saw oxygen saturations improve to 98%-99% on voxelotor. The two patients who had moderate or moderately severe depression, as assessed by the Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item, had minimal or no depression on retest after 24 weeks of voxelotor treatment.

Voxelotor was generally well tolerated at a 900-mg once-daily oral dose. One patient developed grade 2 diarrhea after increasing the dose to 1,500 mg, but symptoms resolved after returning to the 900-mg dose. Another patient had transient mild diarrhea on 900 mg of voxelotor; the symptoms resolved without changing or stopping the drug, Dr. Bronté said. There were no serious treatment-related adverse events.

Among this seriously ill population, two patients died after beginning voxelotor treatment, but both deaths were judged to be unrelated to the treatment. Dr. Bronté reported that the two deceased patients, one of whom was on voxelotor for 16 months and the other for 7 months, did experience reduced transfusion needs and reduced VOC-related hospitalizations while on the drug, experiences that were similar to the surviving members of the cohort.

“Voxelotor administered via compassionate use demonstrated large improvements in anemia and hemolysis, including in patients with lower baseline hemoglobin than studied in clinical trials to date,” Dr. Bronté said.

Taken together with clinical improvements and improved patient-focused outcomes among a severely affected population, “these data … support ongoing investigation in controlled clinical trials to confirm the benefits of voxelotor in a broad range of patients with SCD,” she said.

The study was supported by Global Blood Therapeutics, the manufacturer of voxelotor. Dr. Bronté reported having no other conflicts of interest.

WASHINGTON – An investigational drug for sickle cell disease (SCD) boosted hemoglobin levels while reducing hospitalizations and transfusion needs by approximately two-thirds in a small cohort of severely affected patients.

Lanetta Bronté, MD, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the Foundation for Sickle Cell Disease Research, reviewed the FDA’s requirements for allowing expanded access to an investigational drug. The key point, she said, is that expanded access may be granted “for treatment of patients with serious or immediately life-threatening diseases or conditions that lack therapeutic alternatives.” And, she said, the potential for benefit should outweigh potential risk of taking the investigational drug.

Current treatments don’t really address serious disease-related complications for patients with advanced SCD, she said. Furthermore, these patients will often be excluded from clinical trials of new SCD therapies.

Voxelotor is a novel small molecule that stabilizes the sickle hemoglobin molecule as a monomer in its high oxygen state. Thus, polymerization of the hemoglobin molecules is inhibited, which decreases the amount of red blood cell damage. Other beneficial effects of voxelotor include improved rheology and reduced hemolysis, as well as a boost to the oxygen-carrying capacity of the sickle hemoglobin molecules, Dr. Bronté explained.

For the seven patients in Dr. Bronté’s clinic who were granted expanded access to voxelator, the disease burden of their end-stage SCD was heavy. All participants had iron overload, five were receiving frequent transfusions, two required chronic oxygen supplementation, and four had severe fatigue. One patient had end-stage renal disease, and another had experienced multiple organ failure and prolonged hospitalizations.

None of the patients qualified for participation in ongoing clinical trials of voxelotor, said Dr. Bronté, who is president of the Foundation for Sickle Cell Disease Research. She also maintains a private practice in Hollywood, Fla.

The four women and three men, aged 22-67 years, were treated with voxelotor for a range of 6-17 months under the FDA’s Expanded Access Program. All patients saw rapid increases in serum hemoglobin, with increases of at least 1 g/dL in five of the seven. Across the participants, increases ranged from 0.5-5.4 g/dL at 24 weeks, up from baseline values of 5.2-7.8 g/dL.

One marker of clinical efficacy that Dr. Bronté and her coauthors examined was the number of hospitalizations for pain from vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs). In the 24 weeks before beginning voxelotor, participants had a summed total of 28 hospitalizations. In the first 24 weeks of treatment, there were a total of nine VOC-related hospitalizations among the participants, a 67% decrease.

The total number of red blood cell transfusions required by the study population declined by a similar proportion, from 33 during the 24 weeks before voxelotor treatment to 13 during the first 24 weeks of treatment, a decrease of 60%.

Individual patients saw improvements related to some of their most troublesome SCD complications, Dr. Bronté reported. All four patients whose oxygen saturation levels had been below 95% on room air saw oxygen saturations improve to 98%-99% on voxelotor. The two patients who had moderate or moderately severe depression, as assessed by the Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item, had minimal or no depression on retest after 24 weeks of voxelotor treatment.

Voxelotor was generally well tolerated at a 900-mg once-daily oral dose. One patient developed grade 2 diarrhea after increasing the dose to 1,500 mg, but symptoms resolved after returning to the 900-mg dose. Another patient had transient mild diarrhea on 900 mg of voxelotor; the symptoms resolved without changing or stopping the drug, Dr. Bronté said. There were no serious treatment-related adverse events.

Among this seriously ill population, two patients died after beginning voxelotor treatment, but both deaths were judged to be unrelated to the treatment. Dr. Bronté reported that the two deceased patients, one of whom was on voxelotor for 16 months and the other for 7 months, did experience reduced transfusion needs and reduced VOC-related hospitalizations while on the drug, experiences that were similar to the surviving members of the cohort.

“Voxelotor administered via compassionate use demonstrated large improvements in anemia and hemolysis, including in patients with lower baseline hemoglobin than studied in clinical trials to date,” Dr. Bronté said.

Taken together with clinical improvements and improved patient-focused outcomes among a severely affected population, “these data … support ongoing investigation in controlled clinical trials to confirm the benefits of voxelotor in a broad range of patients with SCD,” she said.

The study was supported by Global Blood Therapeutics, the manufacturer of voxelotor. Dr. Bronté reported having no other conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM FSCDR 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Transfusion requirements were cut by 60% in the first 24 weeks on voxelotor.

Study details: Open label case series of seven patients with end-stage SCD at a single center.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Global Blood Therapeutics, which manufactures voxelotor. Dr. Bronté reported having no other conflicts of interest.

In JIA, etanercept associated with lower uveitis risk compared with methotrexate

AMSTERDAM – Etanercept does not appear to increase the risk of uveitis relative to methotrexate in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), according to a large retrospective cohort study presented at the EULAR 2018 Congress.

“When we added in a fully adjusted hazard ratio, it showed a lower risk in the development of uveitis in patients on etanercept [compared with methotrexate],” reported Rebecca Davies, a research assistant at the University of Manchester (England).

These data were characterized as reassuring for JIA patients being considered for etanercept, but Ms. Davies was cautious about suggesting that etanercept has a protective effect. Even though hazard ratios were calculated with propensity-adjusted Cox regression analyses, Ms. Davies believes the best interpretation of these data is that etanercept therapy is not likely to contribute significantly to the risk of uveitis.

The substantial differences between the comparator groups provide one reason to refrain from speculating that etanercept is protective against uveitis. The risk of uveitis is greater both in younger patients and in the first year after diagnosis. Patients in the etanercept group were older than patients in the methotrexate group and they started etanercept a longer time after the JIA diagnosis.

“The initiation of etanercept later in the disease may mean that more of these patients had already passed through the window of greatest risk,” Ms. Davies explained.

The data for this study were drawn from a British Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology cohort registry. Confined to patients first starting as opposed to restarting therapy, 1,009 patients initiating etanercept were compared to 508 patients initiating methotrexate.

In addition to an older age (11 vs. 9 years) and disease duration at start of therapy (3 vs. 1 years), a lower proportion of patients in the etanercept group had a persistent oligoarthritis subtype (5% vs. 17%). During follow-up, there were 15 cases (0.15%) of uveitis in the etanercept group and 18 (3.5%) in the methotrexate group.

The crude incidence of uveitis was 0.6 per 100 patient-years for etanercept versus 2.4 per 100 patient-years for methotrexate, according to Ms. Davies. After adjustment for a broad number of variables, including age, gender, disease scores, disease duration, baseline steroid use, and the presence of comorbidities, there was still a 70% lower risk of uveitis among those treated with etanercept (hazard ratio 0.30; 95% confidence interval, 0.1-0.9).

The low relative rate of uveitis after starting etanercept is discordant with several previous studies, according to Ms. Davies. In two retrospective studies conducted in the United States and one in Canada, etanercept treatment was associated with higher rates of uveitis than other tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. In a German study, etanercept was associated with a higher risk of uveitis than that of methotrexate.

Although a highly effective anti-inflammatory agent such as etanercept might be expected to have a protective effect against uveitis, at least relative to methotrexate, Ms. Davies suggested that the previous reports of potential causal association and the limitations of this retrospective analysis require a more cautious interpretation.

“It is possible that those considered to be at high risk of developing uveitis were kept away from etanercept,” said Ms. Davis, providing one of several explanations why skepticism is needed in regard to assuming uveitis protection from etanercept.

With up to 1 in 10 patients with JIA eventually developing sight-threatening uveitis, risk management is a priority, according to Ms. Davies. Current guidelines in the United Kingdom call for an ophthalmologist consult within 6 weeks of a diagnosis. Although several risk factors for uveitis have been published, the goal of this study was to determine whether exposure to etanercept is among these risks. According to Ms. Davies, these data suggest that this is not the case, but prospective studies comparing etanercept to other biologics would be particularly helpful in determining which therapy is most appropriate in order to reduce uveitis risk.

SOURCE: EULAR 2018 Congress. Abstract OP0351.

AMSTERDAM – Etanercept does not appear to increase the risk of uveitis relative to methotrexate in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), according to a large retrospective cohort study presented at the EULAR 2018 Congress.

“When we added in a fully adjusted hazard ratio, it showed a lower risk in the development of uveitis in patients on etanercept [compared with methotrexate],” reported Rebecca Davies, a research assistant at the University of Manchester (England).

These data were characterized as reassuring for JIA patients being considered for etanercept, but Ms. Davies was cautious about suggesting that etanercept has a protective effect. Even though hazard ratios were calculated with propensity-adjusted Cox regression analyses, Ms. Davies believes the best interpretation of these data is that etanercept therapy is not likely to contribute significantly to the risk of uveitis.

The substantial differences between the comparator groups provide one reason to refrain from speculating that etanercept is protective against uveitis. The risk of uveitis is greater both in younger patients and in the first year after diagnosis. Patients in the etanercept group were older than patients in the methotrexate group and they started etanercept a longer time after the JIA diagnosis.

“The initiation of etanercept later in the disease may mean that more of these patients had already passed through the window of greatest risk,” Ms. Davies explained.

The data for this study were drawn from a British Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology cohort registry. Confined to patients first starting as opposed to restarting therapy, 1,009 patients initiating etanercept were compared to 508 patients initiating methotrexate.

In addition to an older age (11 vs. 9 years) and disease duration at start of therapy (3 vs. 1 years), a lower proportion of patients in the etanercept group had a persistent oligoarthritis subtype (5% vs. 17%). During follow-up, there were 15 cases (0.15%) of uveitis in the etanercept group and 18 (3.5%) in the methotrexate group.

The crude incidence of uveitis was 0.6 per 100 patient-years for etanercept versus 2.4 per 100 patient-years for methotrexate, according to Ms. Davies. After adjustment for a broad number of variables, including age, gender, disease scores, disease duration, baseline steroid use, and the presence of comorbidities, there was still a 70% lower risk of uveitis among those treated with etanercept (hazard ratio 0.30; 95% confidence interval, 0.1-0.9).

The low relative rate of uveitis after starting etanercept is discordant with several previous studies, according to Ms. Davies. In two retrospective studies conducted in the United States and one in Canada, etanercept treatment was associated with higher rates of uveitis than other tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. In a German study, etanercept was associated with a higher risk of uveitis than that of methotrexate.

Although a highly effective anti-inflammatory agent such as etanercept might be expected to have a protective effect against uveitis, at least relative to methotrexate, Ms. Davies suggested that the previous reports of potential causal association and the limitations of this retrospective analysis require a more cautious interpretation.

“It is possible that those considered to be at high risk of developing uveitis were kept away from etanercept,” said Ms. Davis, providing one of several explanations why skepticism is needed in regard to assuming uveitis protection from etanercept.

With up to 1 in 10 patients with JIA eventually developing sight-threatening uveitis, risk management is a priority, according to Ms. Davies. Current guidelines in the United Kingdom call for an ophthalmologist consult within 6 weeks of a diagnosis. Although several risk factors for uveitis have been published, the goal of this study was to determine whether exposure to etanercept is among these risks. According to Ms. Davies, these data suggest that this is not the case, but prospective studies comparing etanercept to other biologics would be particularly helpful in determining which therapy is most appropriate in order to reduce uveitis risk.

SOURCE: EULAR 2018 Congress. Abstract OP0351.

AMSTERDAM – Etanercept does not appear to increase the risk of uveitis relative to methotrexate in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), according to a large retrospective cohort study presented at the EULAR 2018 Congress.

“When we added in a fully adjusted hazard ratio, it showed a lower risk in the development of uveitis in patients on etanercept [compared with methotrexate],” reported Rebecca Davies, a research assistant at the University of Manchester (England).

These data were characterized as reassuring for JIA patients being considered for etanercept, but Ms. Davies was cautious about suggesting that etanercept has a protective effect. Even though hazard ratios were calculated with propensity-adjusted Cox regression analyses, Ms. Davies believes the best interpretation of these data is that etanercept therapy is not likely to contribute significantly to the risk of uveitis.

The substantial differences between the comparator groups provide one reason to refrain from speculating that etanercept is protective against uveitis. The risk of uveitis is greater both in younger patients and in the first year after diagnosis. Patients in the etanercept group were older than patients in the methotrexate group and they started etanercept a longer time after the JIA diagnosis.

“The initiation of etanercept later in the disease may mean that more of these patients had already passed through the window of greatest risk,” Ms. Davies explained.

The data for this study were drawn from a British Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology cohort registry. Confined to patients first starting as opposed to restarting therapy, 1,009 patients initiating etanercept were compared to 508 patients initiating methotrexate.

In addition to an older age (11 vs. 9 years) and disease duration at start of therapy (3 vs. 1 years), a lower proportion of patients in the etanercept group had a persistent oligoarthritis subtype (5% vs. 17%). During follow-up, there were 15 cases (0.15%) of uveitis in the etanercept group and 18 (3.5%) in the methotrexate group.

The crude incidence of uveitis was 0.6 per 100 patient-years for etanercept versus 2.4 per 100 patient-years for methotrexate, according to Ms. Davies. After adjustment for a broad number of variables, including age, gender, disease scores, disease duration, baseline steroid use, and the presence of comorbidities, there was still a 70% lower risk of uveitis among those treated with etanercept (hazard ratio 0.30; 95% confidence interval, 0.1-0.9).

The low relative rate of uveitis after starting etanercept is discordant with several previous studies, according to Ms. Davies. In two retrospective studies conducted in the United States and one in Canada, etanercept treatment was associated with higher rates of uveitis than other tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. In a German study, etanercept was associated with a higher risk of uveitis than that of methotrexate.

Although a highly effective anti-inflammatory agent such as etanercept might be expected to have a protective effect against uveitis, at least relative to methotrexate, Ms. Davies suggested that the previous reports of potential causal association and the limitations of this retrospective analysis require a more cautious interpretation.

“It is possible that those considered to be at high risk of developing uveitis were kept away from etanercept,” said Ms. Davis, providing one of several explanations why skepticism is needed in regard to assuming uveitis protection from etanercept.

With up to 1 in 10 patients with JIA eventually developing sight-threatening uveitis, risk management is a priority, according to Ms. Davies. Current guidelines in the United Kingdom call for an ophthalmologist consult within 6 weeks of a diagnosis. Although several risk factors for uveitis have been published, the goal of this study was to determine whether exposure to etanercept is among these risks. According to Ms. Davies, these data suggest that this is not the case, but prospective studies comparing etanercept to other biologics would be particularly helpful in determining which therapy is most appropriate in order to reduce uveitis risk.

SOURCE: EULAR 2018 Congress. Abstract OP0351.

REPORTING FROM THE EULAR 2018 CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In children on new medication, the incidence of uveitis per 100 patients was 0.6 for etanercept and 2.4 for methotrexate.

Study details: Retrospective cohort registry.

Disclosures: The study was not funded by industry. Ms. Davies reports no potential conflicts of interest.

Source: EULAR 2018 Congress. Abstract OP0351.

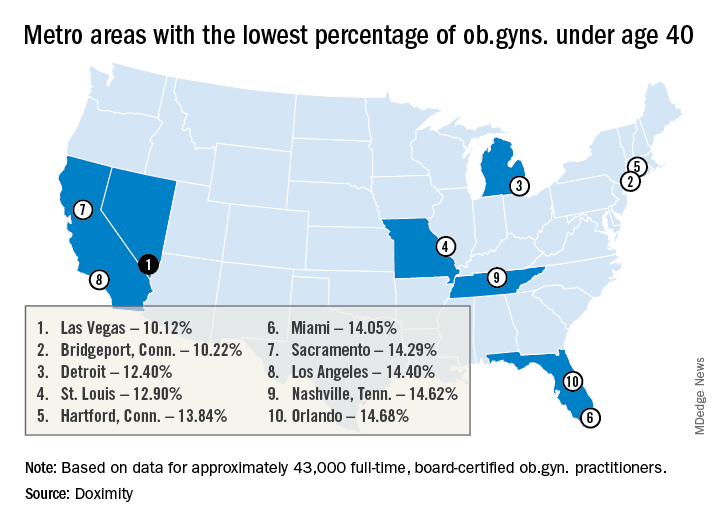

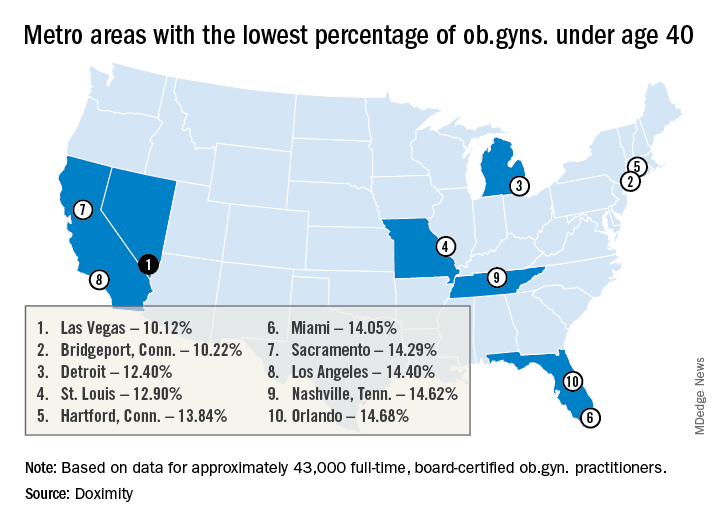

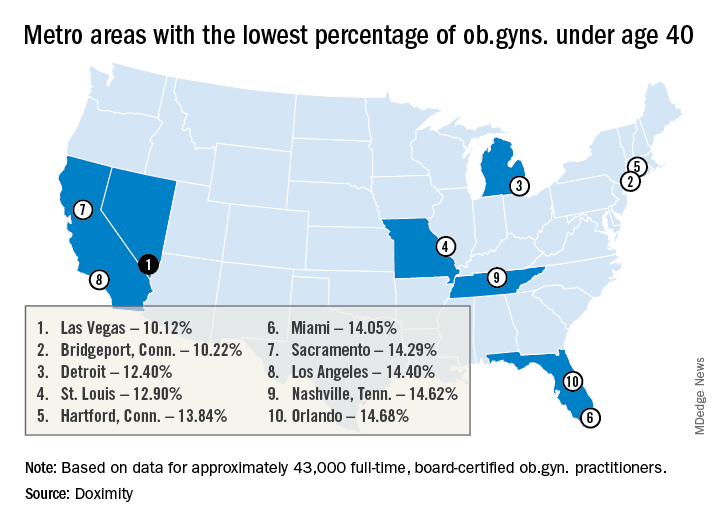

Ob.gyn. workforce shortage looms

The average age of ob.gyns. is rising across the country, signaling physician shortages that are projected to worsen over the next several decades. The pinch may be felt especially in areas with high birth rates and few younger ob.gyns., according to a report from Doximity.

Doximity’s geographic projections paint a fine-grained picture in agreement with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ projections of a national shortfall of up to 8,800 ob.gyns. by 2020, with the deficit of ob.gyns. potentially climbing to 22,000 by 2050.

Pittsburgh and Bridgeport, Conn. top the list of metropolitan areas with the oldest average age of practicing ob.gyns., with average ages of 52.32 and 52.12 years, respectively. Las Vegas, Detroit, Miami, Los Angeles, New York, Boston, and Chicago all also made the top 15 cities in this list.