User login

When cold-induced vasospasm is the tip of the iceberg

For many patients, Raynaud symptoms are mild enough to not even mention to their primary care provider, and conversely, there is little reason for most clinicians to routinely inquire about such symptoms. So it may surprise some readers to read about the nuances of diagnosis and treatment discussed by Shapiro and Wigley in this issue of the Journal.

To a rheumatologist, Raynaud phenomenon, particularly of recent onset in an adult, raises the specter of an underlying systemic inflammatory disease. The phenomenon is not linked to a specific diagnosis; it is associated with lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, cryoglobulinemia, inflammatory myopathy, Sjögren syndrome, and, in its severe form, with the scleroderma syndromes. We focus on differentiating between these rheumatic disorders once we have discarded nonrheumatic causes such as atherosclerotic arterial disease, carcinoma, embolism, Buerger disease, medications, smoking, or thrombosis.

But rheumatologists are toward the bottom of the diagnostic funnel—we see these patients when an underlying disease is already suspected. The real challenge is for the primary care providers who first recognize the digital vasospasm on examination or are told of the symptoms by their patient. These clinicians need to know which initial reflexive actions are warranted and which can wait, for, as noted by Shapiro and Wigley, there are several options.

The first action is to try to determine the timeline, although Raynaud disease often has an insidious onset or the patient doesn’t recall the onset. New and sudden onset likely has a stronger association with an underlying disease. A focused physical examination should look for digital stigmata of ischemic damage; the presence of digital ulcers or healed digital pits indicates a possible vascular occlusive component in addition to the vascular spasm. This strongly suggests scleroderma or Buerger disease, as tissue damage doesn’t occur in (primary) Raynaud disease or generally even with Raynaud phenomenon associated with lupus or other rheumatic disorders. Sclerodactyly should be looked for: diffuse finger puffiness, skin-tightening, or early signs such as loss of the usual finger skin creases. Telangiectasia (not vascular spiders or cherry angiomata) should be searched for, particularly on the palms, face, and inner lips, as these vascular lesions are common in patients with limited scleroderma. Careful auscultation for basilar lung crackles should be done. Distal pulses should all be assessed, and bruits in the neck, abdomen and inguinal areas should be carefully sought.

Patients should be questioned about any symptom-associated reduction in exercise tolerance and particularly about trouble swallowing, “heartburn,” and symptoms of reflux. Although patients with Raynaud disease may have demonstrable esophageal dysmotility, the presence of significant, new, or worsened symptoms raises the concern of scleroderma. Patients should be asked about symptoms of malabsorption. Specific questioning should be directed at eliciting a history of joint stiffness and especially muscle weakness. The latter can be approached by inquiring about new or progressive difficulty in specific tasks such as walking up steps, brushing hair, and arising from low chairs or the toilet. Distinguishing muscle weakness from general fatigue is not always easy, but it is important.

Shapiro and Wigley discuss the extremely useful evaluation of nailfold capillaries, which can be done with a standard magnifier or ophthalmoscope. This is very valuable to help predict the development or current presence of a systemic rheumatic disease. But this is not a technique that most clinicians are familiar with. A potentially useful surrogate or adjunctive test, especially in the setting of new-onset Raynaud, is the antinuclear antibody (ANA) test; I prefer the immunofluorescent assay. While a positive test alone (with Raynaud) does not define the presence of any rheumatic disease, several older studies suggest that patients with a new onset of Raynaud phenomenon and a positive ANA test are more likely to develop a systemic autoimmune disorder than if the test is negative. Those who do so (and this is far from all) are most likely to have the disease manifest within a few years. Hence, if the ANA test is positive but the history, physical examination, and limited laboratory testing (complete blood cell count with differential, complete metabolic panel, creatine kinase, and urinalysis) are normal, it is reasonable to reexamine the patient in 3 months and then every 6 months for 2 to 3 years, repeating the focused history and physical examination. It is also reasonable at some point to refer these patients to a rheumatologist.

Since Raynaud phenomenon is common, and the associated severe rheumatic disorders associated with it are rare, it is easy to not recognize Raynaud phenomenon as a clue to the onset of a potentially severe systemic disease. Yet with a few simple questions, a focused examination, and minimal laboratory testing, patients who are more likely to harbor a systemic disease can usually be treated symptomatically if necessary, and appropriately triaged to observation or for subspecialty referral.

For many patients, Raynaud symptoms are mild enough to not even mention to their primary care provider, and conversely, there is little reason for most clinicians to routinely inquire about such symptoms. So it may surprise some readers to read about the nuances of diagnosis and treatment discussed by Shapiro and Wigley in this issue of the Journal.

To a rheumatologist, Raynaud phenomenon, particularly of recent onset in an adult, raises the specter of an underlying systemic inflammatory disease. The phenomenon is not linked to a specific diagnosis; it is associated with lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, cryoglobulinemia, inflammatory myopathy, Sjögren syndrome, and, in its severe form, with the scleroderma syndromes. We focus on differentiating between these rheumatic disorders once we have discarded nonrheumatic causes such as atherosclerotic arterial disease, carcinoma, embolism, Buerger disease, medications, smoking, or thrombosis.

But rheumatologists are toward the bottom of the diagnostic funnel—we see these patients when an underlying disease is already suspected. The real challenge is for the primary care providers who first recognize the digital vasospasm on examination or are told of the symptoms by their patient. These clinicians need to know which initial reflexive actions are warranted and which can wait, for, as noted by Shapiro and Wigley, there are several options.

The first action is to try to determine the timeline, although Raynaud disease often has an insidious onset or the patient doesn’t recall the onset. New and sudden onset likely has a stronger association with an underlying disease. A focused physical examination should look for digital stigmata of ischemic damage; the presence of digital ulcers or healed digital pits indicates a possible vascular occlusive component in addition to the vascular spasm. This strongly suggests scleroderma or Buerger disease, as tissue damage doesn’t occur in (primary) Raynaud disease or generally even with Raynaud phenomenon associated with lupus or other rheumatic disorders. Sclerodactyly should be looked for: diffuse finger puffiness, skin-tightening, or early signs such as loss of the usual finger skin creases. Telangiectasia (not vascular spiders or cherry angiomata) should be searched for, particularly on the palms, face, and inner lips, as these vascular lesions are common in patients with limited scleroderma. Careful auscultation for basilar lung crackles should be done. Distal pulses should all be assessed, and bruits in the neck, abdomen and inguinal areas should be carefully sought.

Patients should be questioned about any symptom-associated reduction in exercise tolerance and particularly about trouble swallowing, “heartburn,” and symptoms of reflux. Although patients with Raynaud disease may have demonstrable esophageal dysmotility, the presence of significant, new, or worsened symptoms raises the concern of scleroderma. Patients should be asked about symptoms of malabsorption. Specific questioning should be directed at eliciting a history of joint stiffness and especially muscle weakness. The latter can be approached by inquiring about new or progressive difficulty in specific tasks such as walking up steps, brushing hair, and arising from low chairs or the toilet. Distinguishing muscle weakness from general fatigue is not always easy, but it is important.

Shapiro and Wigley discuss the extremely useful evaluation of nailfold capillaries, which can be done with a standard magnifier or ophthalmoscope. This is very valuable to help predict the development or current presence of a systemic rheumatic disease. But this is not a technique that most clinicians are familiar with. A potentially useful surrogate or adjunctive test, especially in the setting of new-onset Raynaud, is the antinuclear antibody (ANA) test; I prefer the immunofluorescent assay. While a positive test alone (with Raynaud) does not define the presence of any rheumatic disease, several older studies suggest that patients with a new onset of Raynaud phenomenon and a positive ANA test are more likely to develop a systemic autoimmune disorder than if the test is negative. Those who do so (and this is far from all) are most likely to have the disease manifest within a few years. Hence, if the ANA test is positive but the history, physical examination, and limited laboratory testing (complete blood cell count with differential, complete metabolic panel, creatine kinase, and urinalysis) are normal, it is reasonable to reexamine the patient in 3 months and then every 6 months for 2 to 3 years, repeating the focused history and physical examination. It is also reasonable at some point to refer these patients to a rheumatologist.

Since Raynaud phenomenon is common, and the associated severe rheumatic disorders associated with it are rare, it is easy to not recognize Raynaud phenomenon as a clue to the onset of a potentially severe systemic disease. Yet with a few simple questions, a focused examination, and minimal laboratory testing, patients who are more likely to harbor a systemic disease can usually be treated symptomatically if necessary, and appropriately triaged to observation or for subspecialty referral.

For many patients, Raynaud symptoms are mild enough to not even mention to their primary care provider, and conversely, there is little reason for most clinicians to routinely inquire about such symptoms. So it may surprise some readers to read about the nuances of diagnosis and treatment discussed by Shapiro and Wigley in this issue of the Journal.

To a rheumatologist, Raynaud phenomenon, particularly of recent onset in an adult, raises the specter of an underlying systemic inflammatory disease. The phenomenon is not linked to a specific diagnosis; it is associated with lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, cryoglobulinemia, inflammatory myopathy, Sjögren syndrome, and, in its severe form, with the scleroderma syndromes. We focus on differentiating between these rheumatic disorders once we have discarded nonrheumatic causes such as atherosclerotic arterial disease, carcinoma, embolism, Buerger disease, medications, smoking, or thrombosis.

But rheumatologists are toward the bottom of the diagnostic funnel—we see these patients when an underlying disease is already suspected. The real challenge is for the primary care providers who first recognize the digital vasospasm on examination or are told of the symptoms by their patient. These clinicians need to know which initial reflexive actions are warranted and which can wait, for, as noted by Shapiro and Wigley, there are several options.

The first action is to try to determine the timeline, although Raynaud disease often has an insidious onset or the patient doesn’t recall the onset. New and sudden onset likely has a stronger association with an underlying disease. A focused physical examination should look for digital stigmata of ischemic damage; the presence of digital ulcers or healed digital pits indicates a possible vascular occlusive component in addition to the vascular spasm. This strongly suggests scleroderma or Buerger disease, as tissue damage doesn’t occur in (primary) Raynaud disease or generally even with Raynaud phenomenon associated with lupus or other rheumatic disorders. Sclerodactyly should be looked for: diffuse finger puffiness, skin-tightening, or early signs such as loss of the usual finger skin creases. Telangiectasia (not vascular spiders or cherry angiomata) should be searched for, particularly on the palms, face, and inner lips, as these vascular lesions are common in patients with limited scleroderma. Careful auscultation for basilar lung crackles should be done. Distal pulses should all be assessed, and bruits in the neck, abdomen and inguinal areas should be carefully sought.

Patients should be questioned about any symptom-associated reduction in exercise tolerance and particularly about trouble swallowing, “heartburn,” and symptoms of reflux. Although patients with Raynaud disease may have demonstrable esophageal dysmotility, the presence of significant, new, or worsened symptoms raises the concern of scleroderma. Patients should be asked about symptoms of malabsorption. Specific questioning should be directed at eliciting a history of joint stiffness and especially muscle weakness. The latter can be approached by inquiring about new or progressive difficulty in specific tasks such as walking up steps, brushing hair, and arising from low chairs or the toilet. Distinguishing muscle weakness from general fatigue is not always easy, but it is important.

Shapiro and Wigley discuss the extremely useful evaluation of nailfold capillaries, which can be done with a standard magnifier or ophthalmoscope. This is very valuable to help predict the development or current presence of a systemic rheumatic disease. But this is not a technique that most clinicians are familiar with. A potentially useful surrogate or adjunctive test, especially in the setting of new-onset Raynaud, is the antinuclear antibody (ANA) test; I prefer the immunofluorescent assay. While a positive test alone (with Raynaud) does not define the presence of any rheumatic disease, several older studies suggest that patients with a new onset of Raynaud phenomenon and a positive ANA test are more likely to develop a systemic autoimmune disorder than if the test is negative. Those who do so (and this is far from all) are most likely to have the disease manifest within a few years. Hence, if the ANA test is positive but the history, physical examination, and limited laboratory testing (complete blood cell count with differential, complete metabolic panel, creatine kinase, and urinalysis) are normal, it is reasonable to reexamine the patient in 3 months and then every 6 months for 2 to 3 years, repeating the focused history and physical examination. It is also reasonable at some point to refer these patients to a rheumatologist.

Since Raynaud phenomenon is common, and the associated severe rheumatic disorders associated with it are rare, it is easy to not recognize Raynaud phenomenon as a clue to the onset of a potentially severe systemic disease. Yet with a few simple questions, a focused examination, and minimal laboratory testing, patients who are more likely to harbor a systemic disease can usually be treated symptomatically if necessary, and appropriately triaged to observation or for subspecialty referral.

Liquid biopsy predicts checkpoint inhibitor response

The overall response rate to immune checkpoint inhibitors was 45% among cancer patients who had more than three variants of unknown significance in their circulating tumor DNA; among those with three or fewer, the response rate was 15%, according to a University of California, San Diego, investigation with 69 subjects.

Higher mutation burdens in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) also correlated with improved progression-free and overall survival across 20 cancer types, the investigators reported (Clin Cancer Res. 2017 Oct. 1. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1439).

Tumor mutation burdens can predict response to checkpoint inhibitors, but they are usually assessed by tissue biopsy, which is costly and invasive. The findings suggest that blood tests could replace tissue biopsies to green-light immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment.

“Our current results may be clinically exploitable. ... Liquid biopsies that assess blood-derived ctDNA are noninvasive, easily acquired, and inexpensive. The ctDNA derived from blood may also represent shed DNA from multiple metastatic sites, whereas tissue genomics reflects only the piece of tissue removed,” said investigators led by Yulian Khagi, MD, a hematology-oncology fellow at the university.

In a press statement, Dr. Khagi said “If verified by further studies, clinicians will be able to utilize the ... results of this simple blood test to make determinations about whether to use checkpoint inhibitor–based immune therapy in a variety of tumor types.”

The 69 patients were a median of 56 years old, and 43 (62.3%) were men. Melanoma, lung cancer, and head and neck cancer were the most common malignancies. The majority of patients had anti–PD-1 or PD-L1 monotherapy.

For most patients, blood samples were drawn a month or 2 before treatment. Next-generation sequencing (Guardant360) was done on ctDNA to detect alterations in cancer genes. Of the 69 patients, 20 (29%) had more than three variants of unknown significance (VUS); the rest had three or fewer.

The median overall survival was 15.3 months from the start of immunotherapy. For patients with three or fewer VUS, median overall survival was 10.72 months; for patients with more, median overall survival could not be calculated because more than half were alive at the study’s conclusion.

Median progression-fee survival was 2.07 months with three or fewer VUS, versus 3.84 months with more. The findings were statistically significant.

Similar results were found when all genomic alterations, not just VUS, were examined and dichotomized as six or more versus fewer than six.

“The number of genes assayed in our ctDNA analysis was only between 54 and 70. Unlike targeted NGS [next-generation sequencing] of tumor tissue, which often tests for hundreds of genes and allows a relatively accurate estimate of total mutational burden, targeted NGS of plasma ctDNA provides only a limited snapshot of the cancer genome. More extensive ctDNA gene panels merit investigation to determine if they increase the correlative value of our findings,” the investigators said.

The work was funded by the Joan and Irwin Jacobs Fund and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Khagi had no industry disclosures. Three authors reported financial ties to a number of companies, including Boehringer, Merck, Guardant, and Pfizer. The senior author has ownership interests in CureMatch.

The overall response rate to immune checkpoint inhibitors was 45% among cancer patients who had more than three variants of unknown significance in their circulating tumor DNA; among those with three or fewer, the response rate was 15%, according to a University of California, San Diego, investigation with 69 subjects.

Higher mutation burdens in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) also correlated with improved progression-free and overall survival across 20 cancer types, the investigators reported (Clin Cancer Res. 2017 Oct. 1. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1439).

Tumor mutation burdens can predict response to checkpoint inhibitors, but they are usually assessed by tissue biopsy, which is costly and invasive. The findings suggest that blood tests could replace tissue biopsies to green-light immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment.

“Our current results may be clinically exploitable. ... Liquid biopsies that assess blood-derived ctDNA are noninvasive, easily acquired, and inexpensive. The ctDNA derived from blood may also represent shed DNA from multiple metastatic sites, whereas tissue genomics reflects only the piece of tissue removed,” said investigators led by Yulian Khagi, MD, a hematology-oncology fellow at the university.

In a press statement, Dr. Khagi said “If verified by further studies, clinicians will be able to utilize the ... results of this simple blood test to make determinations about whether to use checkpoint inhibitor–based immune therapy in a variety of tumor types.”

The 69 patients were a median of 56 years old, and 43 (62.3%) were men. Melanoma, lung cancer, and head and neck cancer were the most common malignancies. The majority of patients had anti–PD-1 or PD-L1 monotherapy.

For most patients, blood samples were drawn a month or 2 before treatment. Next-generation sequencing (Guardant360) was done on ctDNA to detect alterations in cancer genes. Of the 69 patients, 20 (29%) had more than three variants of unknown significance (VUS); the rest had three or fewer.

The median overall survival was 15.3 months from the start of immunotherapy. For patients with three or fewer VUS, median overall survival was 10.72 months; for patients with more, median overall survival could not be calculated because more than half were alive at the study’s conclusion.

Median progression-fee survival was 2.07 months with three or fewer VUS, versus 3.84 months with more. The findings were statistically significant.

Similar results were found when all genomic alterations, not just VUS, were examined and dichotomized as six or more versus fewer than six.

“The number of genes assayed in our ctDNA analysis was only between 54 and 70. Unlike targeted NGS [next-generation sequencing] of tumor tissue, which often tests for hundreds of genes and allows a relatively accurate estimate of total mutational burden, targeted NGS of plasma ctDNA provides only a limited snapshot of the cancer genome. More extensive ctDNA gene panels merit investigation to determine if they increase the correlative value of our findings,” the investigators said.

The work was funded by the Joan and Irwin Jacobs Fund and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Khagi had no industry disclosures. Three authors reported financial ties to a number of companies, including Boehringer, Merck, Guardant, and Pfizer. The senior author has ownership interests in CureMatch.

The overall response rate to immune checkpoint inhibitors was 45% among cancer patients who had more than three variants of unknown significance in their circulating tumor DNA; among those with three or fewer, the response rate was 15%, according to a University of California, San Diego, investigation with 69 subjects.

Higher mutation burdens in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) also correlated with improved progression-free and overall survival across 20 cancer types, the investigators reported (Clin Cancer Res. 2017 Oct. 1. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1439).

Tumor mutation burdens can predict response to checkpoint inhibitors, but they are usually assessed by tissue biopsy, which is costly and invasive. The findings suggest that blood tests could replace tissue biopsies to green-light immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment.

“Our current results may be clinically exploitable. ... Liquid biopsies that assess blood-derived ctDNA are noninvasive, easily acquired, and inexpensive. The ctDNA derived from blood may also represent shed DNA from multiple metastatic sites, whereas tissue genomics reflects only the piece of tissue removed,” said investigators led by Yulian Khagi, MD, a hematology-oncology fellow at the university.

In a press statement, Dr. Khagi said “If verified by further studies, clinicians will be able to utilize the ... results of this simple blood test to make determinations about whether to use checkpoint inhibitor–based immune therapy in a variety of tumor types.”

The 69 patients were a median of 56 years old, and 43 (62.3%) were men. Melanoma, lung cancer, and head and neck cancer were the most common malignancies. The majority of patients had anti–PD-1 or PD-L1 monotherapy.

For most patients, blood samples were drawn a month or 2 before treatment. Next-generation sequencing (Guardant360) was done on ctDNA to detect alterations in cancer genes. Of the 69 patients, 20 (29%) had more than three variants of unknown significance (VUS); the rest had three or fewer.

The median overall survival was 15.3 months from the start of immunotherapy. For patients with three or fewer VUS, median overall survival was 10.72 months; for patients with more, median overall survival could not be calculated because more than half were alive at the study’s conclusion.

Median progression-fee survival was 2.07 months with three or fewer VUS, versus 3.84 months with more. The findings were statistically significant.

Similar results were found when all genomic alterations, not just VUS, were examined and dichotomized as six or more versus fewer than six.

“The number of genes assayed in our ctDNA analysis was only between 54 and 70. Unlike targeted NGS [next-generation sequencing] of tumor tissue, which often tests for hundreds of genes and allows a relatively accurate estimate of total mutational burden, targeted NGS of plasma ctDNA provides only a limited snapshot of the cancer genome. More extensive ctDNA gene panels merit investigation to determine if they increase the correlative value of our findings,” the investigators said.

The work was funded by the Joan and Irwin Jacobs Fund and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Khagi had no industry disclosures. Three authors reported financial ties to a number of companies, including Boehringer, Merck, Guardant, and Pfizer. The senior author has ownership interests in CureMatch.

FROM CLINICAL CANCER RESEARCH

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The overall response rate to immune checkpoint inhibitors was 45% among cancer patients who had more than three variants of unknown significance in their circulating tumor DNA; among those with three or fewer, the response rate was 15%.

Data source: Review of 69 cancer patients.

Disclosures: The work was funded by the Joan and Irwin Jacobs Fund and the National Cancer Institute. Three investigators reported financial ties to a number of companies, including Boehringer, Merck, Guardant, and Pfizer. The senior author has ownership interests in CureMatch.

Obesity: When to consider medication

Modest weight loss of 5% to 10% among patients who are overweight or obese can result in a clinically relevant reduction in cardiovascular (CV) disease risk.1 This amount of weight loss can increase insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue, liver, and muscle, and have a positive impact on blood sugar, blood pressure, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.1,2

All patients who are obese or overweight with increased CV risk should be counseled on diet, exercise, and other behavioral interventions.3 Weight loss secondary to lifestyle modification alone, however, leads to adaptive physiologic responses, which increase appetite and reduce energy expenditure.4-6

Pharmacotherapy can counteract this metabolic adaptation and lead to sustained weight loss. Antiobesity medication can be considered if a patient has a body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2 or ≥27 kg/m2 with obesity-related comorbidities such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, or obstructive sleep apnea.3,7

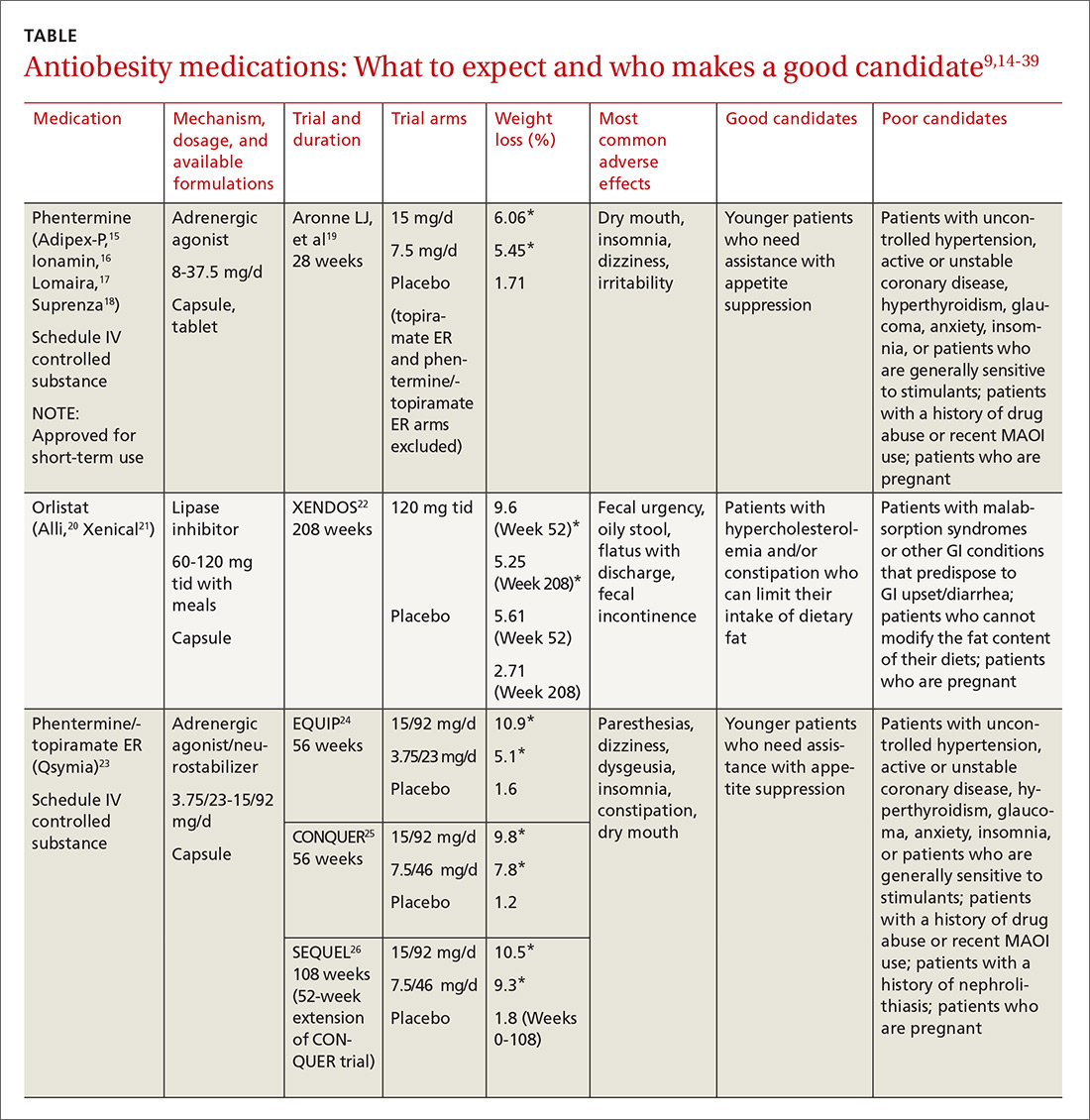

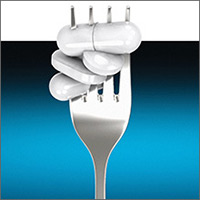

Until recently, there were few pharmacologic options approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the management of obesity. The mainstays of treatment were phentermine (Adipex-P, Ionamin, Suprenza) and orlistat (Alli, Xenical). Since 2012, however, 4 agents have been approved as adjuncts to a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity for long-term weight management.8,9 Phentermine/topiramate extended-release (ER) (Qsymia) and lorcaserin (Belviq) were approved in 2012,10,11 and naltrexone sustained release (SR)/bupropion SR (Contrave) and liraglutide 3 mg (Saxenda) were approved in 201412,13 (TABLE9,14-39). These medications have the potential to not only limit weight gain, but also promote weight loss and, thus, improve blood pressure, cholesterol, glucose, and insulin.40

Despite the growing obesity epidemic and the availability of several additional medications for chronic weight management, use of antiobesity pharmacotherapy has been limited. Barriers to use include inadequate training of health care professionals, poor insurance coverage for new agents, and low reimbursement for office visits to address weight.41

In addition, the number of obesity medicine specialists, while increasing, is still not sufficient. Therefore, it is imperative for other health care professionals—namely family practitioners—to be aware of the treatment options available to patients who are overweight or obese and to be adept at using them.

In this review, we present 4 cases that depict patients who could benefit from the addition of antiobesity pharmacotherapy to a comprehensive treatment plan that includes diet, physical activity, and behavioral modification.

[polldaddy:9840472]

CASE 1 Melissa C, a 27-year-old woman with obesity (BMI 33 kg/m2), hyperlipidemia, and migraine headaches, presents for weight management. Despite a calorie-reduced diet and 200 minutes per week of exercise for the past 6 months, she has been unable to lose weight. The only medications she’s taking are oral contraceptive pills and sumatriptan, as needed. She suffers from migraines 3 times a month and has no anxiety. Laboratory test results are normal with the exception of an elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level.

Which medication is an appropriate next step for Ms. C?

Discussion

When considering an antiobesity agent for any patient, there are 2 important questions to ask:

- Are there contraindications, drug-drug interactions, or undesirable adverse effects associated with this medication that could be problematic for the patient?

- Can this medication improve other symptoms or conditions the patient has?

In addition, see “Before prescribing antiobesity medication . . .”

SIDEBAR

Before prescribing antiobesity medication . . .Have a frank discussion with the patient and be sure to cover the following points:

- The rationale for pharmacologic treatment is to counteract adaptive physiologic responses, which increase appetite and reduce energy expenditure, in response to diet-induced weight loss.

- Antiobesity medication is only one component of a comprehensive treatment plan, which also includes diet, physical activity, and behavior modification.

- Antiobesity agents are intended for long-term use, as obesity is a chronic disease. If/when you stop the medication, there may be some weight regain, similar to an increase in blood pressure after discontinuing an antihypertensive agent.

- Because antiobesity medications improve many parameters including glucose/hemoglobin A1c, lipids, blood pressure, and waist circumference, it is possible that the addition of one antiobesity medication can reduce, or even eliminate, the need for several other medications.

Remember that many patients who present for obesity management have experienced weight bias. It is important to not be judgmental, but rather explain why obesity is a chronic disease. If patients understand the physiology of their condition, they will understand that their limited success with weight loss in the past is not just a matter of willpower. Lifestyle change and weight loss are extremely difficult, so it is important to provide encouragement and support for ongoing behavioral modification.

Phentermine/topiramate ER is a good first choice for this young patient with class I (BMI 30-34.9 kg/m2) obesity and migraines, as she can likely tolerate a stimulant and her migraines might improve with topiramate. Before starting the medication, ask about insomnia and nephrolithiasis in addition to anxiety and other contraindications (ie, glaucoma, hyperthyroidism, recent monoamine oxidase inhibitor use, or a known hypersensitivity or idiosyncrasy to sympathomimetic amines).23 The most common adverse events reported in phase III trials were dry mouth, paresthesia, and constipation.24-26

Not for pregnant women. Women of childbearing age must have a negative pregnancy test before starting phentermine/topiramate ER and every month while taking the medication. The FDA requires a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) to inform prescribers and patients about the increased risk of congenital malformation, specifically orofacial clefts, in infants exposed to topiramate during the first trimester of pregnancy.42 REMS focuses on the importance of pregnancy prevention, the consistent use of birth control, and the need to discontinue phentermine/topiramate ER immediately if pregnancy occurs.

Flexible dosing. Phentermine/topiramate ER is available in 4 dosages: phentermine 3.75 mg/topiramate 23 mg ER; phentermine 7.5 mg/topiramate 46 mg ER; phentermine 11.25 mg/topiramate 69 mg ER; and phentermine 15 mg/topiramate 92 mg ER. Gradual dose escalation minimizes risks and adverse events.23

Monitor patients frequently to evaluate for adverse effects and ensure adherence to diet, exercise, and lifestyle modifications. If weight loss is slower or less robust than expected, check for dietary indiscretion, as medications have limited efficacy without appropriate behavioral changes.

Discontinue phentermine/topiramate ER if the patient does not achieve 5% weight loss after 12 weeks on the maximum dose, as it is unlikely that she will achieve and sustain clinically meaningful weight loss with continued treatment.23 In this case, consider another agent with a different mechanism of action. Any of the other antiobesity medications could be appropriate for this patient.

CASE 2 Norman S, a 52-year-old overweight man (BMI 29 kg/m2) with type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, osteoarthritis, and glaucoma, has recently hit a plateau with his weight loss. He lost 45 pounds secondary to diet and exercise, but hasn’t been able to lose any more. He also struggles with constant hunger. His medications include metformin 1000 mg bid, atorvastatin 10 mg/d, and occasional acetaminophen/oxycodone for knee pain until he undergoes a left knee replacement. Laboratory values are normal except for a hemoglobin A1c of 7.2%.

Mr. S is afraid of needles and cannot tolerate stimulants due to anxiety. Which medication is an appropriate next step for this patient?

Discussion

Lorcaserin is a good choice for this patient who is overweight and has several weight-related comorbidities. He has worked hard to lose a significant number of pounds, and is now at high risk of regaining them. That’s because his appetite has increased with his new exercise regimen, but his energy expenditure has decreased secondary to metabolic adaptation.

Narrowing the field. Naltrexone SR/bupropion SR cannot be used because of his opioid use. Phentermine/topiramate ER is contraindicated for patients with glaucoma, and liraglutide 3 mg is not appropriate given the patient’s fear of needles.

He could try orlistat, especially if he struggles with constipation, but the gastrointestinal adverse effects are difficult for many patients to tolerate. While not an antiobesity medication, a sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor could be prescribed for his diabetes and may also promote weight loss.43

An appealing choice. The glucose-lowering effect of lorcaserin could provide an added benefit for the patient. The BLOOM-DM (Behavioral modification and lorcaserin for overweight and obesity management in diabetes mellitus) study reported a mean reduction in hemoglobin A1c of 0.9% in the treatment group compared with a 0.4% reduction in the placebo group,30 and the effect of lorcaserin on A1c appeared to be independent of weight loss.

Mechanism of action: Cause for concern? Although lorcaserin selectively binds to serotonin 5-HT2C receptors, the theoretical risk of cardiac valvulopathy was evaluated in phase III studies, as fenfluramine, a 5-HT2B-receptor agonist, was withdrawn from the US market in 1997 for this reason.44 Both the BLOOM (Behavioral modification and lorcaserin for overweight and obesity management) and BLOSSOM (Behavioral modification and lorcaserin second study for obesity management) studies found that lorcaserin did not increase the incidence of FDA-defined cardiac valvulopathy.28,29

Formulations/adverse effects. Lorcaserin is available in 2 formulations: 10-mg tablets, which are taken twice daily, or 20-mg XR tablets, which are taken once daily. Both are generally well tolerated.27,45 The most common adverse event reported in phase III trials was headache.28,30,43 Discontinue lorcaserin if the patient does not lose 5% of his initial weight after 12 weeks, as weight loss at this stage is a good predictor of longer-term success.46

Some patients don’t respond. Interestingly, a subset of patients do not respond to lorcaserin. The most likely explanation for different responses to the medication is that there are many causes of obesity, only some of which respond to 5-HT2C agonism. Currently, we do not perform pharmacogenomic testing before prescribing lorcaserin, but perhaps an inexpensive test to identify responders will be available in the future.

CASE 3 Kathryn M, a 38-year-old woman with obesity (BMI 42 kg/m2), obstructive sleep apnea, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and depression, is eager to get better control over her weight. Her medications include lansoprazole 30 mg/d and a multivitamin. She reports constantly thinking about food and not being able to control her impulses to buy large quantities of unhealthy snacks. She is so preoccupied by thoughts of food that she has difficulty concentrating at work.

Ms. M smokes a quarter of a pack of cigarettes daily, but she is ready to quit. She views bariatric surgery as a “last resort” and has no anxiety, pain, or history of seizures. Which medication is appropriate for this patient?

Discussion

This patient with class III obesity (BMI ≥40 kg/m2) is eligible for bariatric surgery; however, she is not interested in pursuing it at this time. It is important to discuss all of her options before deciding on a treatment plan. For patients like Ms. M, who would benefit from more than modest weight loss, consider a multidisciplinary approach including lifestyle modifications, pharmacotherapy, devices (eg, an intragastric balloon), and/or surgery. You would need to make clear to Ms. M that she may still be eligible for insurance coverage for surgery if she changes her mind after pursuing other treatments as long as her BMI remains ≥35 kg/m2 with obesity-related comorbidities.

Naltrexone SR/bupropion SR is a good choice for Ms. M because she describes debilitating cravings and addictive behavior surrounding food. Patients taking naltrexone SR/bupropion SR in the Contrave Obesity Research (COR)-I and COR-II phase III trials experienced a reduced frequency of food cravings, reduced difficulty in resisting food cravings, and an increased ability to control eating compared with those assigned to placebo.32,33

Added benefits. Bupropion could also help Ms. M quit smoking and improve her mood, as it is FDA-approved for smoking cessation and depression. She denies anxiety and seizures, so bupropion is not contraindicated. Even if a patient denies a history of seizure, ask about any conditions that predispose to seizures, such as anorexia nervosa or bulimia or the abrupt discontinuation of alcohol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, or antiepileptic drugs.

Opioid use. Although the patient denies pain, ask about potential opioid use, as naltrexone is an opioid receptor antagonist. Patients should be informed that opioids may be ineffective if they are required unexpectedly (eg, for trauma) and that naltrexone SR/bupropion SR should be withheld for any planned surgical procedure potentially requiring opioid use.

Other options. While naltrexone SR/bupropion SR is the most appropriate choice for this patient because it addresses Ms. M’s problematic eating behaviors while potentially improving mood and assisting with smoking cessation, phentermine/topiramate ER, lorcaserin, and liraglutide 3 mg could also be used and should certainly be tried if naltrexone SR/bupropion SR does not produce the desired weight loss.

Adverse effects. Titrate naltrexone SR/bupropion SR slowly to the treatment dose to minimize risks and adverse events.31 The most common adverse effects reported in phase III trials were nausea, constipation, and headache.34,35,45,46 Discontinue naltrexone SR/bupropion SR if the patient does not achieve 5% weight loss at 16 weeks (after 12 weeks at the maintenance dose).31

CASE 4 William P, a 65-year-old man with obesity (BMI 39 kg/m2) who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery and who has type 2 diabetes, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, remains concerned about his weight. He lost 100 lbs following surgery and maintained his weight for 3 years, but then regained 30 lbs. He comes in for an office visit because he’s concerned about his increasing blood sugar and wants to prevent further weight gain. His medications include metformin 1000 mg bid, lisinopril 5 mg/d, carvedilol 12.5 mg bid, simvastatin 20 mg/d, and aspirin 81 mg/d. Laboratory test results are normal except for a hemoglobin A1c of 8%. He denies pancreatitis and a personal or family history of thyroid cancer.

Which medication is an appropriate next step for Mr. P?

Discussion

Pharmacotherapy is a great option for this patient, who is regaining weight following bariatric surgery. Phentermine/topiramate ER is the only medication that would be contraindicated because of his heart disease. Lorcaserin and naltrexone SR/bupropion SR could be considered, but liraglutide 3 mg is the most appropriate option, given his need for further glucose control.

Furthermore, the recent LEADER (Liraglutide effect and action in diabetes: evaluation of CV outcome results) trial reported a significant mortality benefit with liraglutide 1.8 mg/d among patients with type 2 diabetes and high CV risk.47 The study found that liraglutide was superior to placebo in reducing CV events.

Contraindications. Ask patients about a history of pancreatitis before starting liraglutide 3 mg given the possible increased risk. In addition, liraglutide is contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2. Thyroid C-cell tumors have been found in rodents given supratherapeutic doses of liraglutide;48 however, there is no evidence of liraglutide causing C-cell tumors in humans.

For patients taking a medication that can cause hypoglycemia, such as insulin or a sulfonylurea, monitor blood sugar and consider reducing the dose of that medication when starting liraglutide.

Administration and titration. Liraglutide is injected subcutaneously once daily. The dose is titrated up weekly to reduce gastrointestinal symptoms.36 The most common adverse effects reported in phase III trials were nausea, diarrhea, and constipation.37-39 Discontinue liraglutide 3 mg if the patient does not lose at least 4% of baseline body weight after 16 weeks.49

CORRESPONDENCE

Katherine H. Saunders, MD, DABOM, Comprehensive Weight Control Center, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, Weill Cornell Medicine, 1165 York Avenue, New York, NY 10065; kph2001@med.cornell.edu.

1. Wing RR, Lang W, Wadden TA, et al. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1481-1486.

2. Magkos F, Fraterrigo G, Yoshino J. Effects of moderate and subsequent progressive weight loss on metabolic function and adipose tissue biology in humans with obesity. Cell Metab. 2016;23:591-601.

3. Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2985-3023.

4. Sumithran P, Predergast LA, Delbridge E, et al. Long-term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1597-1604.

5. Greenway FL. Physiological adaptations to weight loss and factors favouring weight regain. Int J Obes (Lond). 2015;39:1188-1196.

6. Fothergill E, Guo J, Howard L, et al. Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after “The Biggest Loser” competition. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24:1612-1619.

7. Apovian CM, Aronne LJ, Bessesen DH, et al. Pharmacological management of obesity: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:342-362.

8. Saunders KH, Shukla AP, Igel LI, et al. Pharmacotherapy for obesity. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2016;45:521-538.

9. Saunders KH, Kumar RB, Igel LI, et al. Pharmacologic approaches to weight management: recent gains and shortfalls in combating obesity. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2016;18:36.

10. US Food and Drug Administration. Drug approval package. Qsymia. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2012/022580Orig1s000_qsymia_toc.cfm. Accessed August 28, 2017.

11. Arena Pharmaceuticals. Arena Pharmaceuticals and Eisai announce FDA approval of BELVIQ® (lorcaserin HCl) for chronic weight management in adults who are overweight with a comorbidity or obese. Available at: http://invest.arenapharm.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=687182. Accessed August 28, 2017.

12. Drugs.com. Contrave approval history. Available at: https://www.drugs.com/history/contrave.html. Accessed August 28, 2017.

13. US Food and Drug Administration. Drugs@FDA: FDA approved drug products. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=206321. Accessed August 28, 2017.

14. Igel LI, Kumar RB, Saunders KH, et al. Practical use of pharmacotherapy for obesity. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1765-1779.

15. Adipex-P package insert. Available at: http://www.iodine.com/drug/phentermine/fda-package-insert. Accessed August 28, 2017.

16. Ionamin package insert. Available at: http://druginserts.com/lib/rx/meds/ionamin/. Accessed August 28, 2017.

17. Lomaira package insert. Available at: https://www.lomaira.com/Prescribing_Information.pdf. Accessed August 28, 2017.

18. Suprenza package insert. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/202088s001lbl.pdf. Accessed August 28, 2017.

19. Aronne LJ, Wadden TA, Peterson C, et al. Evaluation of phentermine and topiramate versus phentermine/topiramate extended-release in obese adults. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21:2163-2171.

20. Alli package labeling. Available at: http://druginserts.com/lib/otc/meds/alli-1/. Accessed August 28, 2017.

21. Xenical package insert. Available at: https://www.gene.com/download/pdf/xenical_prescribing.pdf. Accessed August 28, 2017.

22. Torgerson JS, Hauptman J, Boldrin MN, et al. XENical in the prevention of Diabetes in Obese Subjects (XENDOS) study: a randomized study of orlistat as an adjunct to lifestyle changes for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in obese patients. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:155-161.

23. Qsymia package insert. Available at: https://www.qsymia.com/pdf/prescribing-information.pdf. Accessed August 28, 2017.

24. Allison DB, Gadde KM, Garvey WT, et al. Controlled-release phentermine/topiramate in severely obese adults: a randomized controlled trial (EQUIP). Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20:330-342.

25. Gadde KM, Allison DB, Ryan DH, et al. Effects of low-dose, controlled-release, phentermine plus topiramate combination on weight and associated comorbidities in overweight and obese adults (CONQUER): a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;377:1341-1352.

26. Garvey WT, Ryan DH, Look M, et al. Two-year sustained weight loss and metabolic benefits with controlled-release phentermine/topiramate in obese and overweight adults (SEQUEL): a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 extension study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:297-308.

27. Belviq package insert. Available at: https://www.belviq.com/-/media/Files/BelviqConsolidation/PDF/Belviq_Prescribing_information-pdf.PDF?la=en. Accessed August 28, 2017.

28. Smith SR, Weissman NJ, Anderson CM, et al. Multicenter, placebo-controlled trial of lorcaserin for weight management. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:245-256.

29. Fidler MC, Sanchez M, Raether B, et al. A one-year randomized trial of lorcaserin for weight loss in obese and overweight adults: the BLOSSOM trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:3067-3077.

30. O’Neil PM, Smith SR, Weissman NJ, et al. Randomized placebo controlled clinical trial of lorcaserin for weight loss in type 2 diabetes mellitus: the BLOOM-DM study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20:1426-1436.

31. Contrave package insert. Available at: https://contrave.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Contrave_PI.pdf. Accessed August 28, 2017.

32. Greenway FL, Fujioka K, Plodkowski RA, et al. Effect of naltrexone plus bupropion on weight loss in overweight and obese adults (COR-I): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376:595-605.

33. Apovian CM, Aronne L, Rubino D, et al. A randomized, phase 3 trial of naltrexone SR/bupropion SR on weight and obesity-related risk factors (COR-II). Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21:935-943.

34. Wadden TA, Foreyt JP, Foster GD, et al. Weight loss with naltrexone SR/bupropion SR combination therapy as an adjunct to behavior modification: the COR-BMOD trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011;19:110-120.

35. Hollander P, Gupta AK, Plodkowski R, et al. Effects of naltrexone sustained-release/bupropion sustained-release combination therapy on body weight and glycemic parameters in overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:4022-4029.

36. Saxenda package insert. Available at: http://www.novo-pi.com/saxenda.pdf. Accessed August 28, 2017.

37. Pi-Sunyer X, Astrup A, Fujioka K, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of 3.0 mg of liraglutide in weight management. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:11-22.

38. Davies MJ, Bergenstal R, Bode B, et al. Efficacy of liraglutide for weight loss among patients with type 2 diabetes: the SCALE Diabetes randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:687-699.

39. Wadden TA, Hollander P, Klein S, et al. Weight maintenance and additional weight loss with liraglutide after low-calorie-diet induced weight loss: the SCALE Maintenance randomized study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37:1443-1451.

40. Saunders KH, Igel LI, Aronne LJ. An update on naltrexone/bupropion extended-release in the treatment of obesity. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2016. [Epub ahead of print]

41. Thomas CE, Mauer EA, Shukla AP, et al. Low adoption of weight loss medications: a comparison of prescribing patterns of antiobesity pharmacotherapies and SGLT2s. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24:1955-1961.

42. Qsymia Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS). VIVUS, Inc. Available at: http://www.qsymiarems.com. Accessed January 16, 2017.

43. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empaglifozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2117-2128.

44. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA announces withdrawal fenfluramine and dexfenfluramine (Fen-Phen). Available at: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm179871.htm. Accessed August 28, 2017.

45. Belviq XR package insert. Available at: https://www.belviq.com/-/media/Files/BelviqConsolidation/PDF/belviqxr_prescribing_information-pdf.PDF?la=en. Accessed January 16, 2017.

46. Smith SR, O’Neil PM, Astrup A. Early weight loss while on lorcaserin, diet and exercise as a predictor of week 52 weight-loss outcomes. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22:2137-2146.

47. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311-322.

48. Madsen LW, Knauf JA, Gotfredsen C, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists and the thyroid: C-cell effects in mice are mediated via the GLP-1 receptor and not associated with RET activation. Endocrinology. 2012;153:1538-1547.

49. Fujioka K, O’Neil PM, Davies M, et al. Early weight loss with liraglutide 3.0 mg predicts 1-year weight loss and is associated with improvements in clinical markers. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24:2278-2288.

Modest weight loss of 5% to 10% among patients who are overweight or obese can result in a clinically relevant reduction in cardiovascular (CV) disease risk.1 This amount of weight loss can increase insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue, liver, and muscle, and have a positive impact on blood sugar, blood pressure, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.1,2

All patients who are obese or overweight with increased CV risk should be counseled on diet, exercise, and other behavioral interventions.3 Weight loss secondary to lifestyle modification alone, however, leads to adaptive physiologic responses, which increase appetite and reduce energy expenditure.4-6

Pharmacotherapy can counteract this metabolic adaptation and lead to sustained weight loss. Antiobesity medication can be considered if a patient has a body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2 or ≥27 kg/m2 with obesity-related comorbidities such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, or obstructive sleep apnea.3,7

Until recently, there were few pharmacologic options approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the management of obesity. The mainstays of treatment were phentermine (Adipex-P, Ionamin, Suprenza) and orlistat (Alli, Xenical). Since 2012, however, 4 agents have been approved as adjuncts to a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity for long-term weight management.8,9 Phentermine/topiramate extended-release (ER) (Qsymia) and lorcaserin (Belviq) were approved in 2012,10,11 and naltrexone sustained release (SR)/bupropion SR (Contrave) and liraglutide 3 mg (Saxenda) were approved in 201412,13 (TABLE9,14-39). These medications have the potential to not only limit weight gain, but also promote weight loss and, thus, improve blood pressure, cholesterol, glucose, and insulin.40

Despite the growing obesity epidemic and the availability of several additional medications for chronic weight management, use of antiobesity pharmacotherapy has been limited. Barriers to use include inadequate training of health care professionals, poor insurance coverage for new agents, and low reimbursement for office visits to address weight.41

In addition, the number of obesity medicine specialists, while increasing, is still not sufficient. Therefore, it is imperative for other health care professionals—namely family practitioners—to be aware of the treatment options available to patients who are overweight or obese and to be adept at using them.

In this review, we present 4 cases that depict patients who could benefit from the addition of antiobesity pharmacotherapy to a comprehensive treatment plan that includes diet, physical activity, and behavioral modification.

[polldaddy:9840472]

CASE 1 Melissa C, a 27-year-old woman with obesity (BMI 33 kg/m2), hyperlipidemia, and migraine headaches, presents for weight management. Despite a calorie-reduced diet and 200 minutes per week of exercise for the past 6 months, she has been unable to lose weight. The only medications she’s taking are oral contraceptive pills and sumatriptan, as needed. She suffers from migraines 3 times a month and has no anxiety. Laboratory test results are normal with the exception of an elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level.

Which medication is an appropriate next step for Ms. C?

Discussion

When considering an antiobesity agent for any patient, there are 2 important questions to ask:

- Are there contraindications, drug-drug interactions, or undesirable adverse effects associated with this medication that could be problematic for the patient?

- Can this medication improve other symptoms or conditions the patient has?

In addition, see “Before prescribing antiobesity medication . . .”

SIDEBAR

Before prescribing antiobesity medication . . .Have a frank discussion with the patient and be sure to cover the following points:

- The rationale for pharmacologic treatment is to counteract adaptive physiologic responses, which increase appetite and reduce energy expenditure, in response to diet-induced weight loss.

- Antiobesity medication is only one component of a comprehensive treatment plan, which also includes diet, physical activity, and behavior modification.

- Antiobesity agents are intended for long-term use, as obesity is a chronic disease. If/when you stop the medication, there may be some weight regain, similar to an increase in blood pressure after discontinuing an antihypertensive agent.

- Because antiobesity medications improve many parameters including glucose/hemoglobin A1c, lipids, blood pressure, and waist circumference, it is possible that the addition of one antiobesity medication can reduce, or even eliminate, the need for several other medications.

Remember that many patients who present for obesity management have experienced weight bias. It is important to not be judgmental, but rather explain why obesity is a chronic disease. If patients understand the physiology of their condition, they will understand that their limited success with weight loss in the past is not just a matter of willpower. Lifestyle change and weight loss are extremely difficult, so it is important to provide encouragement and support for ongoing behavioral modification.

Phentermine/topiramate ER is a good first choice for this young patient with class I (BMI 30-34.9 kg/m2) obesity and migraines, as she can likely tolerate a stimulant and her migraines might improve with topiramate. Before starting the medication, ask about insomnia and nephrolithiasis in addition to anxiety and other contraindications (ie, glaucoma, hyperthyroidism, recent monoamine oxidase inhibitor use, or a known hypersensitivity or idiosyncrasy to sympathomimetic amines).23 The most common adverse events reported in phase III trials were dry mouth, paresthesia, and constipation.24-26

Not for pregnant women. Women of childbearing age must have a negative pregnancy test before starting phentermine/topiramate ER and every month while taking the medication. The FDA requires a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) to inform prescribers and patients about the increased risk of congenital malformation, specifically orofacial clefts, in infants exposed to topiramate during the first trimester of pregnancy.42 REMS focuses on the importance of pregnancy prevention, the consistent use of birth control, and the need to discontinue phentermine/topiramate ER immediately if pregnancy occurs.

Flexible dosing. Phentermine/topiramate ER is available in 4 dosages: phentermine 3.75 mg/topiramate 23 mg ER; phentermine 7.5 mg/topiramate 46 mg ER; phentermine 11.25 mg/topiramate 69 mg ER; and phentermine 15 mg/topiramate 92 mg ER. Gradual dose escalation minimizes risks and adverse events.23

Monitor patients frequently to evaluate for adverse effects and ensure adherence to diet, exercise, and lifestyle modifications. If weight loss is slower or less robust than expected, check for dietary indiscretion, as medications have limited efficacy without appropriate behavioral changes.

Discontinue phentermine/topiramate ER if the patient does not achieve 5% weight loss after 12 weeks on the maximum dose, as it is unlikely that she will achieve and sustain clinically meaningful weight loss with continued treatment.23 In this case, consider another agent with a different mechanism of action. Any of the other antiobesity medications could be appropriate for this patient.

CASE 2 Norman S, a 52-year-old overweight man (BMI 29 kg/m2) with type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, osteoarthritis, and glaucoma, has recently hit a plateau with his weight loss. He lost 45 pounds secondary to diet and exercise, but hasn’t been able to lose any more. He also struggles with constant hunger. His medications include metformin 1000 mg bid, atorvastatin 10 mg/d, and occasional acetaminophen/oxycodone for knee pain until he undergoes a left knee replacement. Laboratory values are normal except for a hemoglobin A1c of 7.2%.

Mr. S is afraid of needles and cannot tolerate stimulants due to anxiety. Which medication is an appropriate next step for this patient?

Discussion

Lorcaserin is a good choice for this patient who is overweight and has several weight-related comorbidities. He has worked hard to lose a significant number of pounds, and is now at high risk of regaining them. That’s because his appetite has increased with his new exercise regimen, but his energy expenditure has decreased secondary to metabolic adaptation.

Narrowing the field. Naltrexone SR/bupropion SR cannot be used because of his opioid use. Phentermine/topiramate ER is contraindicated for patients with glaucoma, and liraglutide 3 mg is not appropriate given the patient’s fear of needles.

He could try orlistat, especially if he struggles with constipation, but the gastrointestinal adverse effects are difficult for many patients to tolerate. While not an antiobesity medication, a sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor could be prescribed for his diabetes and may also promote weight loss.43

An appealing choice. The glucose-lowering effect of lorcaserin could provide an added benefit for the patient. The BLOOM-DM (Behavioral modification and lorcaserin for overweight and obesity management in diabetes mellitus) study reported a mean reduction in hemoglobin A1c of 0.9% in the treatment group compared with a 0.4% reduction in the placebo group,30 and the effect of lorcaserin on A1c appeared to be independent of weight loss.

Mechanism of action: Cause for concern? Although lorcaserin selectively binds to serotonin 5-HT2C receptors, the theoretical risk of cardiac valvulopathy was evaluated in phase III studies, as fenfluramine, a 5-HT2B-receptor agonist, was withdrawn from the US market in 1997 for this reason.44 Both the BLOOM (Behavioral modification and lorcaserin for overweight and obesity management) and BLOSSOM (Behavioral modification and lorcaserin second study for obesity management) studies found that lorcaserin did not increase the incidence of FDA-defined cardiac valvulopathy.28,29

Formulations/adverse effects. Lorcaserin is available in 2 formulations: 10-mg tablets, which are taken twice daily, or 20-mg XR tablets, which are taken once daily. Both are generally well tolerated.27,45 The most common adverse event reported in phase III trials was headache.28,30,43 Discontinue lorcaserin if the patient does not lose 5% of his initial weight after 12 weeks, as weight loss at this stage is a good predictor of longer-term success.46

Some patients don’t respond. Interestingly, a subset of patients do not respond to lorcaserin. The most likely explanation for different responses to the medication is that there are many causes of obesity, only some of which respond to 5-HT2C agonism. Currently, we do not perform pharmacogenomic testing before prescribing lorcaserin, but perhaps an inexpensive test to identify responders will be available in the future.

CASE 3 Kathryn M, a 38-year-old woman with obesity (BMI 42 kg/m2), obstructive sleep apnea, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and depression, is eager to get better control over her weight. Her medications include lansoprazole 30 mg/d and a multivitamin. She reports constantly thinking about food and not being able to control her impulses to buy large quantities of unhealthy snacks. She is so preoccupied by thoughts of food that she has difficulty concentrating at work.

Ms. M smokes a quarter of a pack of cigarettes daily, but she is ready to quit. She views bariatric surgery as a “last resort” and has no anxiety, pain, or history of seizures. Which medication is appropriate for this patient?

Discussion

This patient with class III obesity (BMI ≥40 kg/m2) is eligible for bariatric surgery; however, she is not interested in pursuing it at this time. It is important to discuss all of her options before deciding on a treatment plan. For patients like Ms. M, who would benefit from more than modest weight loss, consider a multidisciplinary approach including lifestyle modifications, pharmacotherapy, devices (eg, an intragastric balloon), and/or surgery. You would need to make clear to Ms. M that she may still be eligible for insurance coverage for surgery if she changes her mind after pursuing other treatments as long as her BMI remains ≥35 kg/m2 with obesity-related comorbidities.

Naltrexone SR/bupropion SR is a good choice for Ms. M because she describes debilitating cravings and addictive behavior surrounding food. Patients taking naltrexone SR/bupropion SR in the Contrave Obesity Research (COR)-I and COR-II phase III trials experienced a reduced frequency of food cravings, reduced difficulty in resisting food cravings, and an increased ability to control eating compared with those assigned to placebo.32,33

Added benefits. Bupropion could also help Ms. M quit smoking and improve her mood, as it is FDA-approved for smoking cessation and depression. She denies anxiety and seizures, so bupropion is not contraindicated. Even if a patient denies a history of seizure, ask about any conditions that predispose to seizures, such as anorexia nervosa or bulimia or the abrupt discontinuation of alcohol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, or antiepileptic drugs.

Opioid use. Although the patient denies pain, ask about potential opioid use, as naltrexone is an opioid receptor antagonist. Patients should be informed that opioids may be ineffective if they are required unexpectedly (eg, for trauma) and that naltrexone SR/bupropion SR should be withheld for any planned surgical procedure potentially requiring opioid use.

Other options. While naltrexone SR/bupropion SR is the most appropriate choice for this patient because it addresses Ms. M’s problematic eating behaviors while potentially improving mood and assisting with smoking cessation, phentermine/topiramate ER, lorcaserin, and liraglutide 3 mg could also be used and should certainly be tried if naltrexone SR/bupropion SR does not produce the desired weight loss.

Adverse effects. Titrate naltrexone SR/bupropion SR slowly to the treatment dose to minimize risks and adverse events.31 The most common adverse effects reported in phase III trials were nausea, constipation, and headache.34,35,45,46 Discontinue naltrexone SR/bupropion SR if the patient does not achieve 5% weight loss at 16 weeks (after 12 weeks at the maintenance dose).31

CASE 4 William P, a 65-year-old man with obesity (BMI 39 kg/m2) who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery and who has type 2 diabetes, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, remains concerned about his weight. He lost 100 lbs following surgery and maintained his weight for 3 years, but then regained 30 lbs. He comes in for an office visit because he’s concerned about his increasing blood sugar and wants to prevent further weight gain. His medications include metformin 1000 mg bid, lisinopril 5 mg/d, carvedilol 12.5 mg bid, simvastatin 20 mg/d, and aspirin 81 mg/d. Laboratory test results are normal except for a hemoglobin A1c of 8%. He denies pancreatitis and a personal or family history of thyroid cancer.

Which medication is an appropriate next step for Mr. P?

Discussion

Pharmacotherapy is a great option for this patient, who is regaining weight following bariatric surgery. Phentermine/topiramate ER is the only medication that would be contraindicated because of his heart disease. Lorcaserin and naltrexone SR/bupropion SR could be considered, but liraglutide 3 mg is the most appropriate option, given his need for further glucose control.

Furthermore, the recent LEADER (Liraglutide effect and action in diabetes: evaluation of CV outcome results) trial reported a significant mortality benefit with liraglutide 1.8 mg/d among patients with type 2 diabetes and high CV risk.47 The study found that liraglutide was superior to placebo in reducing CV events.

Contraindications. Ask patients about a history of pancreatitis before starting liraglutide 3 mg given the possible increased risk. In addition, liraglutide is contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2. Thyroid C-cell tumors have been found in rodents given supratherapeutic doses of liraglutide;48 however, there is no evidence of liraglutide causing C-cell tumors in humans.

For patients taking a medication that can cause hypoglycemia, such as insulin or a sulfonylurea, monitor blood sugar and consider reducing the dose of that medication when starting liraglutide.

Administration and titration. Liraglutide is injected subcutaneously once daily. The dose is titrated up weekly to reduce gastrointestinal symptoms.36 The most common adverse effects reported in phase III trials were nausea, diarrhea, and constipation.37-39 Discontinue liraglutide 3 mg if the patient does not lose at least 4% of baseline body weight after 16 weeks.49

CORRESPONDENCE

Katherine H. Saunders, MD, DABOM, Comprehensive Weight Control Center, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, Weill Cornell Medicine, 1165 York Avenue, New York, NY 10065; kph2001@med.cornell.edu.

Modest weight loss of 5% to 10% among patients who are overweight or obese can result in a clinically relevant reduction in cardiovascular (CV) disease risk.1 This amount of weight loss can increase insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue, liver, and muscle, and have a positive impact on blood sugar, blood pressure, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.1,2

All patients who are obese or overweight with increased CV risk should be counseled on diet, exercise, and other behavioral interventions.3 Weight loss secondary to lifestyle modification alone, however, leads to adaptive physiologic responses, which increase appetite and reduce energy expenditure.4-6

Pharmacotherapy can counteract this metabolic adaptation and lead to sustained weight loss. Antiobesity medication can be considered if a patient has a body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2 or ≥27 kg/m2 with obesity-related comorbidities such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, or obstructive sleep apnea.3,7

Until recently, there were few pharmacologic options approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the management of obesity. The mainstays of treatment were phentermine (Adipex-P, Ionamin, Suprenza) and orlistat (Alli, Xenical). Since 2012, however, 4 agents have been approved as adjuncts to a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity for long-term weight management.8,9 Phentermine/topiramate extended-release (ER) (Qsymia) and lorcaserin (Belviq) were approved in 2012,10,11 and naltrexone sustained release (SR)/bupropion SR (Contrave) and liraglutide 3 mg (Saxenda) were approved in 201412,13 (TABLE9,14-39). These medications have the potential to not only limit weight gain, but also promote weight loss and, thus, improve blood pressure, cholesterol, glucose, and insulin.40

Despite the growing obesity epidemic and the availability of several additional medications for chronic weight management, use of antiobesity pharmacotherapy has been limited. Barriers to use include inadequate training of health care professionals, poor insurance coverage for new agents, and low reimbursement for office visits to address weight.41

In addition, the number of obesity medicine specialists, while increasing, is still not sufficient. Therefore, it is imperative for other health care professionals—namely family practitioners—to be aware of the treatment options available to patients who are overweight or obese and to be adept at using them.

In this review, we present 4 cases that depict patients who could benefit from the addition of antiobesity pharmacotherapy to a comprehensive treatment plan that includes diet, physical activity, and behavioral modification.

[polldaddy:9840472]

CASE 1 Melissa C, a 27-year-old woman with obesity (BMI 33 kg/m2), hyperlipidemia, and migraine headaches, presents for weight management. Despite a calorie-reduced diet and 200 minutes per week of exercise for the past 6 months, she has been unable to lose weight. The only medications she’s taking are oral contraceptive pills and sumatriptan, as needed. She suffers from migraines 3 times a month and has no anxiety. Laboratory test results are normal with the exception of an elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level.

Which medication is an appropriate next step for Ms. C?

Discussion

When considering an antiobesity agent for any patient, there are 2 important questions to ask:

- Are there contraindications, drug-drug interactions, or undesirable adverse effects associated with this medication that could be problematic for the patient?

- Can this medication improve other symptoms or conditions the patient has?

In addition, see “Before prescribing antiobesity medication . . .”

SIDEBAR

Before prescribing antiobesity medication . . .Have a frank discussion with the patient and be sure to cover the following points:

- The rationale for pharmacologic treatment is to counteract adaptive physiologic responses, which increase appetite and reduce energy expenditure, in response to diet-induced weight loss.

- Antiobesity medication is only one component of a comprehensive treatment plan, which also includes diet, physical activity, and behavior modification.

- Antiobesity agents are intended for long-term use, as obesity is a chronic disease. If/when you stop the medication, there may be some weight regain, similar to an increase in blood pressure after discontinuing an antihypertensive agent.

- Because antiobesity medications improve many parameters including glucose/hemoglobin A1c, lipids, blood pressure, and waist circumference, it is possible that the addition of one antiobesity medication can reduce, or even eliminate, the need for several other medications.

Remember that many patients who present for obesity management have experienced weight bias. It is important to not be judgmental, but rather explain why obesity is a chronic disease. If patients understand the physiology of their condition, they will understand that their limited success with weight loss in the past is not just a matter of willpower. Lifestyle change and weight loss are extremely difficult, so it is important to provide encouragement and support for ongoing behavioral modification.

Phentermine/topiramate ER is a good first choice for this young patient with class I (BMI 30-34.9 kg/m2) obesity and migraines, as she can likely tolerate a stimulant and her migraines might improve with topiramate. Before starting the medication, ask about insomnia and nephrolithiasis in addition to anxiety and other contraindications (ie, glaucoma, hyperthyroidism, recent monoamine oxidase inhibitor use, or a known hypersensitivity or idiosyncrasy to sympathomimetic amines).23 The most common adverse events reported in phase III trials were dry mouth, paresthesia, and constipation.24-26

Not for pregnant women. Women of childbearing age must have a negative pregnancy test before starting phentermine/topiramate ER and every month while taking the medication. The FDA requires a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) to inform prescribers and patients about the increased risk of congenital malformation, specifically orofacial clefts, in infants exposed to topiramate during the first trimester of pregnancy.42 REMS focuses on the importance of pregnancy prevention, the consistent use of birth control, and the need to discontinue phentermine/topiramate ER immediately if pregnancy occurs.

Flexible dosing. Phentermine/topiramate ER is available in 4 dosages: phentermine 3.75 mg/topiramate 23 mg ER; phentermine 7.5 mg/topiramate 46 mg ER; phentermine 11.25 mg/topiramate 69 mg ER; and phentermine 15 mg/topiramate 92 mg ER. Gradual dose escalation minimizes risks and adverse events.23

Monitor patients frequently to evaluate for adverse effects and ensure adherence to diet, exercise, and lifestyle modifications. If weight loss is slower or less robust than expected, check for dietary indiscretion, as medications have limited efficacy without appropriate behavioral changes.

Discontinue phentermine/topiramate ER if the patient does not achieve 5% weight loss after 12 weeks on the maximum dose, as it is unlikely that she will achieve and sustain clinically meaningful weight loss with continued treatment.23 In this case, consider another agent with a different mechanism of action. Any of the other antiobesity medications could be appropriate for this patient.

CASE 2 Norman S, a 52-year-old overweight man (BMI 29 kg/m2) with type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, osteoarthritis, and glaucoma, has recently hit a plateau with his weight loss. He lost 45 pounds secondary to diet and exercise, but hasn’t been able to lose any more. He also struggles with constant hunger. His medications include metformin 1000 mg bid, atorvastatin 10 mg/d, and occasional acetaminophen/oxycodone for knee pain until he undergoes a left knee replacement. Laboratory values are normal except for a hemoglobin A1c of 7.2%.

Mr. S is afraid of needles and cannot tolerate stimulants due to anxiety. Which medication is an appropriate next step for this patient?

Discussion

Lorcaserin is a good choice for this patient who is overweight and has several weight-related comorbidities. He has worked hard to lose a significant number of pounds, and is now at high risk of regaining them. That’s because his appetite has increased with his new exercise regimen, but his energy expenditure has decreased secondary to metabolic adaptation.

Narrowing the field. Naltrexone SR/bupropion SR cannot be used because of his opioid use. Phentermine/topiramate ER is contraindicated for patients with glaucoma, and liraglutide 3 mg is not appropriate given the patient’s fear of needles.