User login

Height is independent predictor of VTE

Taller individuals have an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), according to research published in Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics.

In a study of more than 2 million Swedish siblings, researchers found that height was an independent predictor of VTE, with the lowest VTE risk observed in the shortest participants.

The association between height and VTE was present in both men and women (all of whom had been pregnant).

“Height is not something we can do anything about,” noted study author Bengt Zöller, MD, PhD, of Lund University and Malmö University Hospital in Sweden.

“However, the height in the population has increased and continues increasing, which could be contributing to the fact that the incidence of thrombosis has increased.”

For this study, Dr Zöller and his colleagues analyzed 2 cohorts of Swedish individuals without a prior VTE.

There were 1,610,870 men who were followed from enrollment—1969 to 2010—until 2012.

And there were 1,093,342 women who were followed from their first pregnancy—1982 to 2012—until 2012.

The researchers identified sibling pairs so they could adjust their analysis for genetic and environmental factors that might impact VTE risk.

The team found the risk of VTE was 69% lower for the shortest women (<155 cm, <5′1″) than it was for the tallest women (≥185 cm, ≥6′).

The risk of VTE was 65% lower for the shortest men (<160 cm, <5′3″) than the tallest men (≥190 cm, ≥6′2″).

Dr Zöller said gravity may influence the association between height and VTE risk.

“It could just be that because taller individuals have longer leg veins, there is more surface area where problems can occur,” he said. “There is also more gravitational pressure in leg veins of taller persons that can increase the risk of blood flow slowing or temporarily stopping.”

It is worth noting that the researchers didn’t have access to data for childhood and parent lifestyle factors that might influence VTE risk, such as smoking, diet, and physical activity. In addition, the study consisted of Swedish people and may not be translatable to other populations.

Nevertheless, Dr Zöller said, “I think we should start to include height in [VTE] risk assessment, just as [we do] overweight, although formal studies are needed to determine exactly how height interacts with inherited blood disorders and other conditions.” ![]()

Taller individuals have an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), according to research published in Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics.

In a study of more than 2 million Swedish siblings, researchers found that height was an independent predictor of VTE, with the lowest VTE risk observed in the shortest participants.

The association between height and VTE was present in both men and women (all of whom had been pregnant).

“Height is not something we can do anything about,” noted study author Bengt Zöller, MD, PhD, of Lund University and Malmö University Hospital in Sweden.

“However, the height in the population has increased and continues increasing, which could be contributing to the fact that the incidence of thrombosis has increased.”

For this study, Dr Zöller and his colleagues analyzed 2 cohorts of Swedish individuals without a prior VTE.

There were 1,610,870 men who were followed from enrollment—1969 to 2010—until 2012.

And there were 1,093,342 women who were followed from their first pregnancy—1982 to 2012—until 2012.

The researchers identified sibling pairs so they could adjust their analysis for genetic and environmental factors that might impact VTE risk.

The team found the risk of VTE was 69% lower for the shortest women (<155 cm, <5′1″) than it was for the tallest women (≥185 cm, ≥6′).

The risk of VTE was 65% lower for the shortest men (<160 cm, <5′3″) than the tallest men (≥190 cm, ≥6′2″).

Dr Zöller said gravity may influence the association between height and VTE risk.

“It could just be that because taller individuals have longer leg veins, there is more surface area where problems can occur,” he said. “There is also more gravitational pressure in leg veins of taller persons that can increase the risk of blood flow slowing or temporarily stopping.”

It is worth noting that the researchers didn’t have access to data for childhood and parent lifestyle factors that might influence VTE risk, such as smoking, diet, and physical activity. In addition, the study consisted of Swedish people and may not be translatable to other populations.

Nevertheless, Dr Zöller said, “I think we should start to include height in [VTE] risk assessment, just as [we do] overweight, although formal studies are needed to determine exactly how height interacts with inherited blood disorders and other conditions.” ![]()

Taller individuals have an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), according to research published in Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics.

In a study of more than 2 million Swedish siblings, researchers found that height was an independent predictor of VTE, with the lowest VTE risk observed in the shortest participants.

The association between height and VTE was present in both men and women (all of whom had been pregnant).

“Height is not something we can do anything about,” noted study author Bengt Zöller, MD, PhD, of Lund University and Malmö University Hospital in Sweden.

“However, the height in the population has increased and continues increasing, which could be contributing to the fact that the incidence of thrombosis has increased.”

For this study, Dr Zöller and his colleagues analyzed 2 cohorts of Swedish individuals without a prior VTE.

There were 1,610,870 men who were followed from enrollment—1969 to 2010—until 2012.

And there were 1,093,342 women who were followed from their first pregnancy—1982 to 2012—until 2012.

The researchers identified sibling pairs so they could adjust their analysis for genetic and environmental factors that might impact VTE risk.

The team found the risk of VTE was 69% lower for the shortest women (<155 cm, <5′1″) than it was for the tallest women (≥185 cm, ≥6′).

The risk of VTE was 65% lower for the shortest men (<160 cm, <5′3″) than the tallest men (≥190 cm, ≥6′2″).

Dr Zöller said gravity may influence the association between height and VTE risk.

“It could just be that because taller individuals have longer leg veins, there is more surface area where problems can occur,” he said. “There is also more gravitational pressure in leg veins of taller persons that can increase the risk of blood flow slowing or temporarily stopping.”

It is worth noting that the researchers didn’t have access to data for childhood and parent lifestyle factors that might influence VTE risk, such as smoking, diet, and physical activity. In addition, the study consisted of Swedish people and may not be translatable to other populations.

Nevertheless, Dr Zöller said, “I think we should start to include height in [VTE] risk assessment, just as [we do] overweight, although formal studies are needed to determine exactly how height interacts with inherited blood disorders and other conditions.” ![]()

Anticoagulant prompts weight gain in mice

Researchers say they have discovered a novel role for heparin as a promoter of food intake and weight gain in animal models.

The team’s findings suggest heparin could be a potential target for drugs regulating appetite and weight control.

“In addition to its role as an anticoagulant, heparin, which is normally produced by the body, has been known to affect other biological functions,” said Yong Xu, MD, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas.

“In this study, we are among the first groups to investigate heparin’s potential role in regulating the body’s energy balance.”

Dr Xu and his colleagues described this study in Cell Reports.

“Our earlier studies showed that serum heparin levels in mice increased significantly during starvation,” said Dr Gang Shu, of South China Agricultural University in Guangzhou, China.

“These encouraged us to explore a potential role of heparin in feeding control.”

This exploration revealed that treatment with heparin increased food intake and body weight in male and female mice.

Then, the researchers found that heparin stimulates AgRP neurons located in the hypothalamus. This results in increased production of AgRP protein, a neuropeptide that stimulates food intake.

“We also demonstrated that heparin activates AgRP neurons by competing with insulin for binding to the insulin receptor,” Dr Shu said.

“Insulin and heparin have opposite effects on AgRP neurons,” Dr Xu noted. “Insulin treatment suppresses AgRP neuron firing of electrical impulses and expression of AgRP neuropeptides. We found that heparin competes with and prevents insulin from binding to insulin receptors on AgRP neurons.”

The researchers also found that, by competing for insulin receptor binding, heparin inhibits FoxO1 activity to promote AgRP release and feeding.

The team noted that FoxO1 has been shown to be highly expressed in AgRP neurons and to represent a key intracellular component of pathways integrating AgRP-mediated food intake and peripheral metabolic signals.

Although this study was conducted in animals, the researchers believe its results have implications for patients. The research suggests heparin can affect how the body regulates appetite, so heparin might be a target for treating eating disorders. ![]()

Researchers say they have discovered a novel role for heparin as a promoter of food intake and weight gain in animal models.

The team’s findings suggest heparin could be a potential target for drugs regulating appetite and weight control.

“In addition to its role as an anticoagulant, heparin, which is normally produced by the body, has been known to affect other biological functions,” said Yong Xu, MD, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas.

“In this study, we are among the first groups to investigate heparin’s potential role in regulating the body’s energy balance.”

Dr Xu and his colleagues described this study in Cell Reports.

“Our earlier studies showed that serum heparin levels in mice increased significantly during starvation,” said Dr Gang Shu, of South China Agricultural University in Guangzhou, China.

“These encouraged us to explore a potential role of heparin in feeding control.”

This exploration revealed that treatment with heparin increased food intake and body weight in male and female mice.

Then, the researchers found that heparin stimulates AgRP neurons located in the hypothalamus. This results in increased production of AgRP protein, a neuropeptide that stimulates food intake.

“We also demonstrated that heparin activates AgRP neurons by competing with insulin for binding to the insulin receptor,” Dr Shu said.

“Insulin and heparin have opposite effects on AgRP neurons,” Dr Xu noted. “Insulin treatment suppresses AgRP neuron firing of electrical impulses and expression of AgRP neuropeptides. We found that heparin competes with and prevents insulin from binding to insulin receptors on AgRP neurons.”

The researchers also found that, by competing for insulin receptor binding, heparin inhibits FoxO1 activity to promote AgRP release and feeding.

The team noted that FoxO1 has been shown to be highly expressed in AgRP neurons and to represent a key intracellular component of pathways integrating AgRP-mediated food intake and peripheral metabolic signals.

Although this study was conducted in animals, the researchers believe its results have implications for patients. The research suggests heparin can affect how the body regulates appetite, so heparin might be a target for treating eating disorders. ![]()

Researchers say they have discovered a novel role for heparin as a promoter of food intake and weight gain in animal models.

The team’s findings suggest heparin could be a potential target for drugs regulating appetite and weight control.

“In addition to its role as an anticoagulant, heparin, which is normally produced by the body, has been known to affect other biological functions,” said Yong Xu, MD, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas.

“In this study, we are among the first groups to investigate heparin’s potential role in regulating the body’s energy balance.”

Dr Xu and his colleagues described this study in Cell Reports.

“Our earlier studies showed that serum heparin levels in mice increased significantly during starvation,” said Dr Gang Shu, of South China Agricultural University in Guangzhou, China.

“These encouraged us to explore a potential role of heparin in feeding control.”

This exploration revealed that treatment with heparin increased food intake and body weight in male and female mice.

Then, the researchers found that heparin stimulates AgRP neurons located in the hypothalamus. This results in increased production of AgRP protein, a neuropeptide that stimulates food intake.

“We also demonstrated that heparin activates AgRP neurons by competing with insulin for binding to the insulin receptor,” Dr Shu said.

“Insulin and heparin have opposite effects on AgRP neurons,” Dr Xu noted. “Insulin treatment suppresses AgRP neuron firing of electrical impulses and expression of AgRP neuropeptides. We found that heparin competes with and prevents insulin from binding to insulin receptors on AgRP neurons.”

The researchers also found that, by competing for insulin receptor binding, heparin inhibits FoxO1 activity to promote AgRP release and feeding.

The team noted that FoxO1 has been shown to be highly expressed in AgRP neurons and to represent a key intracellular component of pathways integrating AgRP-mediated food intake and peripheral metabolic signals.

Although this study was conducted in animals, the researchers believe its results have implications for patients. The research suggests heparin can affect how the body regulates appetite, so heparin might be a target for treating eating disorders. ![]()

How thyroid hormone affects RBC production

Physicians have long known that patients with an underactive thyroid tend to have anemia because thyroid hormone stimulates red blood cell (RBC) production.

Now, researchers say they have determined how this occurs.

Xiaofei Gao, PhD, of Westlake Institute for Advanced Study in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China, and his colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in PNAS.

The team began by studying the formation of human RBCs in culture. They wondered if something in the culture serum was essential for RBC maturation. So they ran the serum through a charcoal filter, which attracts and retains hydrophobic molecules.

Once filtered, the serum no longer supported RBC production. This validated the researchers’ theory that one of the hydrophobic molecules was key to RBC maturation.

In fact, the team found thyroid hormone was essential for the final step of RBC maturation.

When the researchers added thyroid hormone back to the serum, RBC progenitors once again started down the path to maturation.

If thyroid hormone was added at an earlier stage of development, the RBCs short-circuited their usual developmental processes and began turning into mature RBCs.

With further investigation, the researchers pinpointed the receptor inside maturing RBCs to which thyroid hormone binds—thyroid hormone receptor beta (TRβ).

From there, the team found that nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4), a protein necessary for thyroid hormone stimulation, works with TRβ to regulate RBC development.

Finally, experiments showed that TRβ agonists could stimulate RBC development and alleviate anemic symptoms in a mouse model of chronic anemia.

The researchers therefore believe this work could lead to new therapies for anemic patients, including those with an underactive thyroid. ![]()

Physicians have long known that patients with an underactive thyroid tend to have anemia because thyroid hormone stimulates red blood cell (RBC) production.

Now, researchers say they have determined how this occurs.

Xiaofei Gao, PhD, of Westlake Institute for Advanced Study in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China, and his colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in PNAS.

The team began by studying the formation of human RBCs in culture. They wondered if something in the culture serum was essential for RBC maturation. So they ran the serum through a charcoal filter, which attracts and retains hydrophobic molecules.

Once filtered, the serum no longer supported RBC production. This validated the researchers’ theory that one of the hydrophobic molecules was key to RBC maturation.

In fact, the team found thyroid hormone was essential for the final step of RBC maturation.

When the researchers added thyroid hormone back to the serum, RBC progenitors once again started down the path to maturation.

If thyroid hormone was added at an earlier stage of development, the RBCs short-circuited their usual developmental processes and began turning into mature RBCs.

With further investigation, the researchers pinpointed the receptor inside maturing RBCs to which thyroid hormone binds—thyroid hormone receptor beta (TRβ).

From there, the team found that nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4), a protein necessary for thyroid hormone stimulation, works with TRβ to regulate RBC development.

Finally, experiments showed that TRβ agonists could stimulate RBC development and alleviate anemic symptoms in a mouse model of chronic anemia.

The researchers therefore believe this work could lead to new therapies for anemic patients, including those with an underactive thyroid. ![]()

Physicians have long known that patients with an underactive thyroid tend to have anemia because thyroid hormone stimulates red blood cell (RBC) production.

Now, researchers say they have determined how this occurs.

Xiaofei Gao, PhD, of Westlake Institute for Advanced Study in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China, and his colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in PNAS.

The team began by studying the formation of human RBCs in culture. They wondered if something in the culture serum was essential for RBC maturation. So they ran the serum through a charcoal filter, which attracts and retains hydrophobic molecules.

Once filtered, the serum no longer supported RBC production. This validated the researchers’ theory that one of the hydrophobic molecules was key to RBC maturation.

In fact, the team found thyroid hormone was essential for the final step of RBC maturation.

When the researchers added thyroid hormone back to the serum, RBC progenitors once again started down the path to maturation.

If thyroid hormone was added at an earlier stage of development, the RBCs short-circuited their usual developmental processes and began turning into mature RBCs.

With further investigation, the researchers pinpointed the receptor inside maturing RBCs to which thyroid hormone binds—thyroid hormone receptor beta (TRβ).

From there, the team found that nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4), a protein necessary for thyroid hormone stimulation, works with TRβ to regulate RBC development.

Finally, experiments showed that TRβ agonists could stimulate RBC development and alleviate anemic symptoms in a mouse model of chronic anemia.

The researchers therefore believe this work could lead to new therapies for anemic patients, including those with an underactive thyroid. ![]()

Postpartum depression screening in well-child care appears promising

, according to results of a study from the Netherlands.

“This promising finding warrants wider implementation of screening for postpartum depression,” said Dr. Angarath I. Van der Zee-van den Berg of the University of Twente, Enschede, the Netherlands, and associates.

Results showed significantly fewer mothers in the intervention group were depressed at 9 months post partum, compared with the CAU group (0.6% of 1,843 vs. 2.5% 1,246 for major depression), with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.28 (95% confidence interval, 0.12-0.63). The difference also was significant for minor and major depression, with 3.0% of the intervention group affected vs. 8.4% of the CAU group, and the adjusted odds ratio was 0.40 (95% confidence interval, 0.27-0.58). For parenting, anxiety symptoms, and mental health functioning, the intervention resulted in effect sizes ranging from 0.23 to 0.27.

“We found screening for postpartum depression to have a negligible effect on socioemotional development of the child with no former evidence to compare with,” Dr. Van der Zee-van den Berg and his associates said. “Attention for the mother-child interaction in the trajectory after screening may improve child outcomes; this evidently requires further study.”

To find out more information see Pediatrics (2017;140[4]:e20170110).

, according to results of a study from the Netherlands.

“This promising finding warrants wider implementation of screening for postpartum depression,” said Dr. Angarath I. Van der Zee-van den Berg of the University of Twente, Enschede, the Netherlands, and associates.

Results showed significantly fewer mothers in the intervention group were depressed at 9 months post partum, compared with the CAU group (0.6% of 1,843 vs. 2.5% 1,246 for major depression), with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.28 (95% confidence interval, 0.12-0.63). The difference also was significant for minor and major depression, with 3.0% of the intervention group affected vs. 8.4% of the CAU group, and the adjusted odds ratio was 0.40 (95% confidence interval, 0.27-0.58). For parenting, anxiety symptoms, and mental health functioning, the intervention resulted in effect sizes ranging from 0.23 to 0.27.

“We found screening for postpartum depression to have a negligible effect on socioemotional development of the child with no former evidence to compare with,” Dr. Van der Zee-van den Berg and his associates said. “Attention for the mother-child interaction in the trajectory after screening may improve child outcomes; this evidently requires further study.”

To find out more information see Pediatrics (2017;140[4]:e20170110).

, according to results of a study from the Netherlands.

“This promising finding warrants wider implementation of screening for postpartum depression,” said Dr. Angarath I. Van der Zee-van den Berg of the University of Twente, Enschede, the Netherlands, and associates.

Results showed significantly fewer mothers in the intervention group were depressed at 9 months post partum, compared with the CAU group (0.6% of 1,843 vs. 2.5% 1,246 for major depression), with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.28 (95% confidence interval, 0.12-0.63). The difference also was significant for minor and major depression, with 3.0% of the intervention group affected vs. 8.4% of the CAU group, and the adjusted odds ratio was 0.40 (95% confidence interval, 0.27-0.58). For parenting, anxiety symptoms, and mental health functioning, the intervention resulted in effect sizes ranging from 0.23 to 0.27.

“We found screening for postpartum depression to have a negligible effect on socioemotional development of the child with no former evidence to compare with,” Dr. Van der Zee-van den Berg and his associates said. “Attention for the mother-child interaction in the trajectory after screening may improve child outcomes; this evidently requires further study.”

To find out more information see Pediatrics (2017;140[4]:e20170110).

FROM PEDIATRICS

Behavioral Health: Using Rating Scales in a Clinical Setting

In the current health care environment, there is an increasing demand for objective assessment of disease states.1 This is particularly apparent in the realm of behavioral health, where documentation of outcomes lags that of other areas of medicine.

In 2012, the additional health care costs incurred by persons with mental health diagnoses were estimated to be $293 billion among commercially insured, Medicaid, and Medicare beneficiaries in the United States—a figure that is 273% higher than the cost for those without psychiatric diagnoses.2 Psychiatric and medical illnesses can be so tightly linked that accurate diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders becomes essential to control medical illnesses. It is not surprising that there is increased scrutiny to the ways in which behavioral health care can be objectively assessed and monitored, and payers such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services increasingly require objective documentation of disease state improvement for payment.3

Support for objective assessment of disease derives from the collaborative care model. This model is designed to better integrate mental health and primary care (among other practices) by establishing the Patient-Centered Medical Home and emphasizing screening and monitoring patient-reported outcomes over time to assess treatment response.4 This approach, which is endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association, is associated with significant improvements in outcomes compared with usual care.5 It tracks patient progress using validated clinical rating scales and other screening tools (eg, Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9] for depression), an approach that is analogous to how patients with type 2 diabetes are monitored by A1C lab tests.6 An extensive body of research supports the impact of this approach on treatment. A 2012 Cochrane review associated collaborative care with significant improvements in depression and anxiety outcomes compared with usual treatment.7

Despite these findings, a recent Kennedy Forum brief asserts that behavioral health is characterized by a "lack of systematic measurement to determine whether patients are responding to treatment."8 That same brief points to the many validated, easy-to-administer rating scales and screening tools that can reliably measure the frequency and severity of psychiatric symptoms over time, and likens the lack of their use to "treating high blood pressure without using a blood pressure cuff to measure if a patient's blood pressure is improving."8 In fact, it is estimated that only 18% of psychiatrists and 11% of psychologists use rating scales routinely.9,10 This lack of use denies clinicians important information that can help detect deterioration or lack of improvement in their patients; implementing these scales in primary care can help early detection of behavioral health problems.

Behavioral health is replete with rating scales and screening tools, and the number of competing scales can make choosing a measure difficult.1 Nonetheless, not all scales are appropriate for clinical use; many are designed for research, for instance, and are lengthy and difficult to administer.

Let's review a number of rating scales that are brief, useful, and easy to administer. A framework for the screening tools addressed in this article is available on the federally funded Center for Integrated Health Solutions website (www.integration.samhsa.gov). This site promotes the use of tools designed to assist in screening and monitoring for depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, substance use, and suicidality.11

QUALITY CRITERIA FOR RATING SCALES

The quality of a rating scale is determined by the following attributes.

Objectivity. The ability of a scale to obtain the same results, regardless of who administers, analyzes, or interprets it.

Reliability. The ability of a scale to convey consistent and reproducible information across time, patients, and raters.

Validity. The degree to which the scale measures what it is supposed to measure (eg, depressive symptoms). Sensitivity and specificity are measures of validity and provide additional information about the rating scale; namely, whether the scale can detect the presence of a disease (sensitivity) and whether it detects only that disease or condition and not another (specificity).

Establishment of norms. Whether a scale provides reference values for different clinical groups.

Practicability. The resources required to administer the assessment instrument in terms of time, staff, and material.12

In addition to meeting these quality criteria, selection of a scale can be based on whether it is self-rated or observer-rated. Advantages to self-rated scales, such as the PHQ-9, Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ), and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale, are their practicability—they are easy to administer and don't require much time—and their use in evaluating and raising awareness of subjective states.

However, reliability may be a concern, as some patients may lack insight or exaggerate or mask symptoms when completing such scales.13 Both observer- and self-rated scales can be used together to minimize bias, identify symptoms that might have been missed/not addressed in the clinical interview, and drive clinical decision-making. Both can also help patients communicate with their providers and make them feel more involved in clinical decision-making.8

ENDORSED RATING SCALES

The following scales have met many of the quality criteria described here and are endorsed by the government payer system. They can easily be incorporated into clinical practice and will provide useful clinical information that can assist in diagnosis and monitoring patient outcomes.

Patient Health Questionnaire

PHQ-9 is a nine-item self-report questionnaire that can help to detect depression and supplement a thorough mental health interview. It scores the nine DSM-IV criteria for depression on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). It is a public resource that is easy to find online, available without cost in several languages, and takes just a few minutes to complete.14

PHQ-9 has shown excellent test-retest reliability in screening for depression, and normative data on the instrument's use are available in various clinical populations.15 Research has shown that as PHQ-9 depression scores increase, functional status decreases, while depressive symptoms, sick days, and health care utilization increase.15 In one study, a PHQ-9 score of ≥ 10 had 88% sensitivity and specificity for detecting depression, with scores of 5, 10, 15, and 20 indicating mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression, respectively.16 In addition to its use as a screening tool, PHQ-9 is a responsive and reliable measure of depression treatment outcomes.17

Mood Disorder Questionnaire

MDQ is another brief, self-report questionnaire that is available online. It is designed to identify and monitor patients who are likely to meet diagnostic criteria for bipolar disorder.18,19

The first question on the MDQ asks if the patient has experienced any of 13 common mood and behavior symptoms. The second question asks if these symptoms have ever occurred at the same time, and the third asks the degree to which the patient finds the symptoms to be problematic. The remaining two questions provide additional clinical information, addressing family history of manic-depressive illness or bipolar disorder and whether a diagnosis of either disorder has been made.

The MDQ has shown validity in assessing bipolar disorder symptoms in a general population, although recent research suggests that imprecise recall bias may limit its reliability in detecting hypomanic episodes earlier in life.20,21 Nonetheless, its specificity of > 97% means that it will effectively screen out just about all true negatives.18

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale

The GAD-7 scale is a brief, self-administered questionnaire for screening and measuring severity of GAD.22 It asks patients to rate seven items that represent problems with general anxiety and scores each item on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Similar to the other measures, it is easily accessible online.

Research evidence supports the reliability and validity of GAD-7 as a measure of anxiety in the general population. Sensitivity and specificity are 89% and 82%, respectively. Normative data for age- and sex-specific subgroups support its use across age groups and in both males and females.23 The GAD-7 performs well for detecting and monitoring not only GAD but also panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder.24

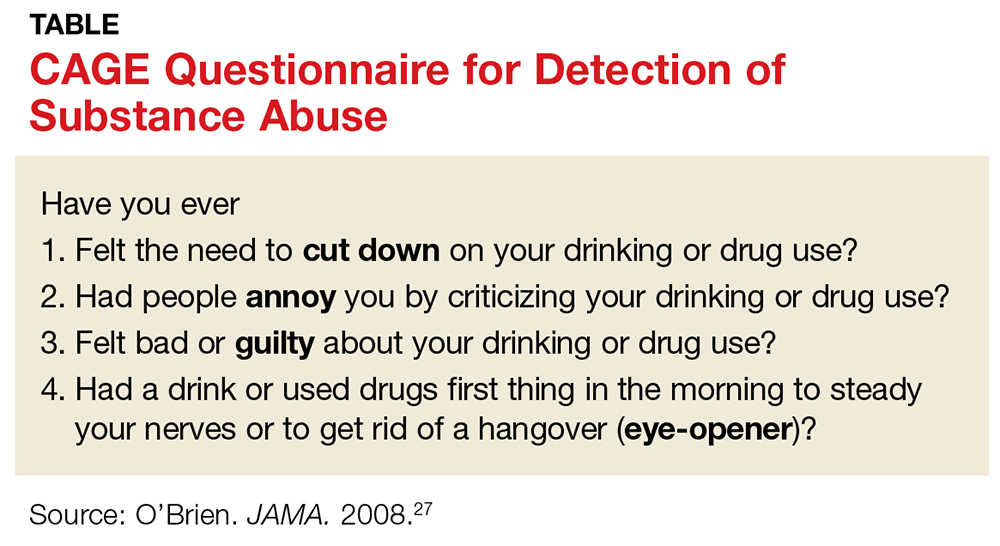

CAGE questionnaire for detection of substance use

The CAGE questionnaire is a widely used screening tool that was originally developed to detect alcohol abuse but has been adapted to assess other substance abuse.25,26 The omission of substance abuse from diagnostic consideration can have a major effect on quality of care, because substance abuse can be the underlying cause of other diseases. Therefore, routine administration of this instrument in clinical practice can lead to better understanding and monitoring of patient health.27

Similar to other instruments, CAGE is free and available online.27 It contains four simple questions, with 1 point assigned to each positive answer (see Table); the simple mnemonic makes the questions easy to remember and to administer in a clinical setting.

CAGE has demonstrated validity, with one study determining that scores ≥ 2 had a specificity and sensitivity of 76% and 93%, respectively, for identifying excessive drinking, and a specificity and sensitivity of 77% and 91%, respectively, for identifying alcohol abuse.28

Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)

C-SSRS was developed by researchers at Columbia University to assess the severity of and track changes over time in suicidal ideation and behavior. C-SSRS is two pages and takes only a few minutes to administer; however, it also may be completed as a self-report measure. The questions are phrased in an interview format, and while clinicians are encouraged to receive training prior to its administration, specific training in mental health is not required.

The "Lifetime/Recent" version allows practitioners to gather lifetime history of suicidality as well as any recent suicidal ideation and/or behavior, whereas the "Since Last Visit" version of the scale assesses suicidality in patients who have completed at least one Lifetime/Recent C-SSRS assessment. A truncated, six-item "Screener" version is typically used in emergency situations. A risk assessment can be added to either the Full or Screener version to summarize the answers from C-SSRS and document risk and protective factors.29

Several studies have found C-SSRS to be reliable and valid for identifying suicide risk in children and adults.30,31USA Today reported that an individual exhibiting even a single behavior identified by the scale is eight to 10 times more likely to complete suicide.32 In addition, the C-SSRS has helped reduce the suicide rate by 65% in one of the largest providers of community-based behavioral health care in the United States.32

USING SCALES TO AUGMENT CARE

Each of the scales described in this article can easily be incorporated into clinical practice. The information the scales provide can be used to track progression of symptoms and effectiveness of treatment. Although rating scales should never be used alone to establish a diagnosis or clinical treatment plan, they can and should be used to augment information from the clinician's assessment and follow-up interviews.5

1. McDowell I. Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

2. Kennedy Forum. Fixing behavioral health care in America: a national call for integrating and coordinating specialty behavioral health care with the medical system. http://thekennedyforum-dot-org.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/KennedyForum-BehavioralHealth_FINAL_3.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

3. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Behavioral health (BH) Clinical Quality Measures (CQMs) Program initiatives. www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/2012-09-27-behavioral-health-clinical-quality-measures-program-initiatives-public-forum.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

4. Unutzer J, Harbin H, Schoenbaum M. The collaborative care model: an approach for integrating physical and mental health care in Medicaid health homes. www.medicaid.gov/State-Resource-Center/Medicaid-State-Technical-Assistance/Health-Homes-Technical-Assistance/Downloads/HH-IRC-Collaborative-5-13.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

5. World Group On Psychiatric Evaluation; American Psychiatric Association Steering Committee On Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the psychiatric evaluation of adults. 2nd ed. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/psychevaladults.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

6. Melek S, Norris D, Paulus J. Economic Impact of Integrated Medical-Behavioral Healthcare: Implications for Psychiatry. Denver, CO: Milliman, Inc; 2014.

7. Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006525.

8. Kennedy Forum. Fixing behavioral health care in America: a national call for measurement-based care. www.thekennedyforum.org/a-national-call-for-measurement-based-care/. Accessed August 14, 2017.

9. Zimmerman M, McGlinchey JB. Why don't psychiatrists use scales to measure outcome when treating depressed patients? J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(12):1916-1919.

10. Hatfield D, McCullough L, Frantz SH, et al. Do we know when our clients get worse? An investigation of therapists' ability to detect negative client change. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2010;17(1):25-32.

11. SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Solutions. Screening tools. www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/screening-tools. Accessed August 14, 2017.

12. Moller HJ. Standardised rating scales in psychiatry: methodological basis, their possibilities and limitations and descriptions of important rating scales. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;10(1):6-26.

13. Sajatovic M, Ramirez LF. Rating Scales in Mental Health. 2nd ed. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp; 2003.

14. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/files/AssessmentTools/14-PHQ-9%20overview.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

15. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Rehab Measures Web site. www.rehabmeasures.org/Lists/RehabMeasures/DispForm.aspx?ID=954. Accessed August 14, 2017.

16. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613.

17. Löwe B, Unützer J, Callahan CM, et al. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Med Care. 2004;42(12):1194-1201.

18. Ketter TA. Strategies for monitoring outcomes in patients with bipolar disorder. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(suppl 1):10-16.

19. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire. University of Texas Medical Branch. www.dbsalliance.org/pdfs/MDQ.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

20. Hirschfeld RM, Holzer C, Calabrese JR, et al. Validity of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire: a general population study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):178-180.

21. Boschloo L, Nolen WA, Spijker AT, et al. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) for detecting (hypo) manic episodes: its validity and impact of recall bias. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(1):203-208.

22. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092-1097.

23. Lowe B, Decker O, Müller S, et al. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46(3):266-274.

24. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(5):317-325.

25. Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE Questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252(14):1905-1907.

26. CAGE substance abuse screening tool. Johns Hopkins Medicine. www.hopkinsmedicine.org/johns_hopkins_healthcare/downloads/cage%20substance%20screening%20tool.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

27. O'Brien CP. The CAGE questionnaire for detection of alcoholism: a remarkably useful but simple tool. JAMA. 2008;300(17):2054-2056.

28. Bernadt MW, Mumford J, Taylor C, et al. Comparison of questionnaire and laboratory tests in the detection of excessive drinking and alcoholism. Lancet. 1982;1(8267):325-328.

29. Columbia Suicide-Severity Rating Scale (CS-SRS). http://cssrs.columbia.edu/the-columbia-scale-c-ssrs/cssrs-for-communities-and-healthcare/#filter=.general-use.english. Accessed August 14, 2017.

30. Mundt JC, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, et al. Prediction of suicidal behavior in clinical research by lifetime suicidal ideation and behavior ascertained by the electronic Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(9):887-893.

31. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266-1277.

32. Esposito L. Suicide checklist spots people at highest risk. USA Today. http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/health/story/health/story/2011-11-09/Suicide-checklist-spots-peo ple-at-highest-risk/51135944/1. Accessed August 14, 2017.

In the current health care environment, there is an increasing demand for objective assessment of disease states.1 This is particularly apparent in the realm of behavioral health, where documentation of outcomes lags that of other areas of medicine.

In 2012, the additional health care costs incurred by persons with mental health diagnoses were estimated to be $293 billion among commercially insured, Medicaid, and Medicare beneficiaries in the United States—a figure that is 273% higher than the cost for those without psychiatric diagnoses.2 Psychiatric and medical illnesses can be so tightly linked that accurate diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders becomes essential to control medical illnesses. It is not surprising that there is increased scrutiny to the ways in which behavioral health care can be objectively assessed and monitored, and payers such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services increasingly require objective documentation of disease state improvement for payment.3

Support for objective assessment of disease derives from the collaborative care model. This model is designed to better integrate mental health and primary care (among other practices) by establishing the Patient-Centered Medical Home and emphasizing screening and monitoring patient-reported outcomes over time to assess treatment response.4 This approach, which is endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association, is associated with significant improvements in outcomes compared with usual care.5 It tracks patient progress using validated clinical rating scales and other screening tools (eg, Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9] for depression), an approach that is analogous to how patients with type 2 diabetes are monitored by A1C lab tests.6 An extensive body of research supports the impact of this approach on treatment. A 2012 Cochrane review associated collaborative care with significant improvements in depression and anxiety outcomes compared with usual treatment.7

Despite these findings, a recent Kennedy Forum brief asserts that behavioral health is characterized by a "lack of systematic measurement to determine whether patients are responding to treatment."8 That same brief points to the many validated, easy-to-administer rating scales and screening tools that can reliably measure the frequency and severity of psychiatric symptoms over time, and likens the lack of their use to "treating high blood pressure without using a blood pressure cuff to measure if a patient's blood pressure is improving."8 In fact, it is estimated that only 18% of psychiatrists and 11% of psychologists use rating scales routinely.9,10 This lack of use denies clinicians important information that can help detect deterioration or lack of improvement in their patients; implementing these scales in primary care can help early detection of behavioral health problems.

Behavioral health is replete with rating scales and screening tools, and the number of competing scales can make choosing a measure difficult.1 Nonetheless, not all scales are appropriate for clinical use; many are designed for research, for instance, and are lengthy and difficult to administer.

Let's review a number of rating scales that are brief, useful, and easy to administer. A framework for the screening tools addressed in this article is available on the federally funded Center for Integrated Health Solutions website (www.integration.samhsa.gov). This site promotes the use of tools designed to assist in screening and monitoring for depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, substance use, and suicidality.11

QUALITY CRITERIA FOR RATING SCALES

The quality of a rating scale is determined by the following attributes.

Objectivity. The ability of a scale to obtain the same results, regardless of who administers, analyzes, or interprets it.

Reliability. The ability of a scale to convey consistent and reproducible information across time, patients, and raters.

Validity. The degree to which the scale measures what it is supposed to measure (eg, depressive symptoms). Sensitivity and specificity are measures of validity and provide additional information about the rating scale; namely, whether the scale can detect the presence of a disease (sensitivity) and whether it detects only that disease or condition and not another (specificity).

Establishment of norms. Whether a scale provides reference values for different clinical groups.

Practicability. The resources required to administer the assessment instrument in terms of time, staff, and material.12

In addition to meeting these quality criteria, selection of a scale can be based on whether it is self-rated or observer-rated. Advantages to self-rated scales, such as the PHQ-9, Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ), and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale, are their practicability—they are easy to administer and don't require much time—and their use in evaluating and raising awareness of subjective states.

However, reliability may be a concern, as some patients may lack insight or exaggerate or mask symptoms when completing such scales.13 Both observer- and self-rated scales can be used together to minimize bias, identify symptoms that might have been missed/not addressed in the clinical interview, and drive clinical decision-making. Both can also help patients communicate with their providers and make them feel more involved in clinical decision-making.8

ENDORSED RATING SCALES

The following scales have met many of the quality criteria described here and are endorsed by the government payer system. They can easily be incorporated into clinical practice and will provide useful clinical information that can assist in diagnosis and monitoring patient outcomes.

Patient Health Questionnaire

PHQ-9 is a nine-item self-report questionnaire that can help to detect depression and supplement a thorough mental health interview. It scores the nine DSM-IV criteria for depression on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). It is a public resource that is easy to find online, available without cost in several languages, and takes just a few minutes to complete.14

PHQ-9 has shown excellent test-retest reliability in screening for depression, and normative data on the instrument's use are available in various clinical populations.15 Research has shown that as PHQ-9 depression scores increase, functional status decreases, while depressive symptoms, sick days, and health care utilization increase.15 In one study, a PHQ-9 score of ≥ 10 had 88% sensitivity and specificity for detecting depression, with scores of 5, 10, 15, and 20 indicating mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression, respectively.16 In addition to its use as a screening tool, PHQ-9 is a responsive and reliable measure of depression treatment outcomes.17

Mood Disorder Questionnaire

MDQ is another brief, self-report questionnaire that is available online. It is designed to identify and monitor patients who are likely to meet diagnostic criteria for bipolar disorder.18,19

The first question on the MDQ asks if the patient has experienced any of 13 common mood and behavior symptoms. The second question asks if these symptoms have ever occurred at the same time, and the third asks the degree to which the patient finds the symptoms to be problematic. The remaining two questions provide additional clinical information, addressing family history of manic-depressive illness or bipolar disorder and whether a diagnosis of either disorder has been made.

The MDQ has shown validity in assessing bipolar disorder symptoms in a general population, although recent research suggests that imprecise recall bias may limit its reliability in detecting hypomanic episodes earlier in life.20,21 Nonetheless, its specificity of > 97% means that it will effectively screen out just about all true negatives.18

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale

The GAD-7 scale is a brief, self-administered questionnaire for screening and measuring severity of GAD.22 It asks patients to rate seven items that represent problems with general anxiety and scores each item on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Similar to the other measures, it is easily accessible online.

Research evidence supports the reliability and validity of GAD-7 as a measure of anxiety in the general population. Sensitivity and specificity are 89% and 82%, respectively. Normative data for age- and sex-specific subgroups support its use across age groups and in both males and females.23 The GAD-7 performs well for detecting and monitoring not only GAD but also panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder.24

CAGE questionnaire for detection of substance use

The CAGE questionnaire is a widely used screening tool that was originally developed to detect alcohol abuse but has been adapted to assess other substance abuse.25,26 The omission of substance abuse from diagnostic consideration can have a major effect on quality of care, because substance abuse can be the underlying cause of other diseases. Therefore, routine administration of this instrument in clinical practice can lead to better understanding and monitoring of patient health.27

Similar to other instruments, CAGE is free and available online.27 It contains four simple questions, with 1 point assigned to each positive answer (see Table); the simple mnemonic makes the questions easy to remember and to administer in a clinical setting.

CAGE has demonstrated validity, with one study determining that scores ≥ 2 had a specificity and sensitivity of 76% and 93%, respectively, for identifying excessive drinking, and a specificity and sensitivity of 77% and 91%, respectively, for identifying alcohol abuse.28

Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)

C-SSRS was developed by researchers at Columbia University to assess the severity of and track changes over time in suicidal ideation and behavior. C-SSRS is two pages and takes only a few minutes to administer; however, it also may be completed as a self-report measure. The questions are phrased in an interview format, and while clinicians are encouraged to receive training prior to its administration, specific training in mental health is not required.

The "Lifetime/Recent" version allows practitioners to gather lifetime history of suicidality as well as any recent suicidal ideation and/or behavior, whereas the "Since Last Visit" version of the scale assesses suicidality in patients who have completed at least one Lifetime/Recent C-SSRS assessment. A truncated, six-item "Screener" version is typically used in emergency situations. A risk assessment can be added to either the Full or Screener version to summarize the answers from C-SSRS and document risk and protective factors.29

Several studies have found C-SSRS to be reliable and valid for identifying suicide risk in children and adults.30,31USA Today reported that an individual exhibiting even a single behavior identified by the scale is eight to 10 times more likely to complete suicide.32 In addition, the C-SSRS has helped reduce the suicide rate by 65% in one of the largest providers of community-based behavioral health care in the United States.32

USING SCALES TO AUGMENT CARE

Each of the scales described in this article can easily be incorporated into clinical practice. The information the scales provide can be used to track progression of symptoms and effectiveness of treatment. Although rating scales should never be used alone to establish a diagnosis or clinical treatment plan, they can and should be used to augment information from the clinician's assessment and follow-up interviews.5

In the current health care environment, there is an increasing demand for objective assessment of disease states.1 This is particularly apparent in the realm of behavioral health, where documentation of outcomes lags that of other areas of medicine.

In 2012, the additional health care costs incurred by persons with mental health diagnoses were estimated to be $293 billion among commercially insured, Medicaid, and Medicare beneficiaries in the United States—a figure that is 273% higher than the cost for those without psychiatric diagnoses.2 Psychiatric and medical illnesses can be so tightly linked that accurate diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders becomes essential to control medical illnesses. It is not surprising that there is increased scrutiny to the ways in which behavioral health care can be objectively assessed and monitored, and payers such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services increasingly require objective documentation of disease state improvement for payment.3

Support for objective assessment of disease derives from the collaborative care model. This model is designed to better integrate mental health and primary care (among other practices) by establishing the Patient-Centered Medical Home and emphasizing screening and monitoring patient-reported outcomes over time to assess treatment response.4 This approach, which is endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association, is associated with significant improvements in outcomes compared with usual care.5 It tracks patient progress using validated clinical rating scales and other screening tools (eg, Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9] for depression), an approach that is analogous to how patients with type 2 diabetes are monitored by A1C lab tests.6 An extensive body of research supports the impact of this approach on treatment. A 2012 Cochrane review associated collaborative care with significant improvements in depression and anxiety outcomes compared with usual treatment.7

Despite these findings, a recent Kennedy Forum brief asserts that behavioral health is characterized by a "lack of systematic measurement to determine whether patients are responding to treatment."8 That same brief points to the many validated, easy-to-administer rating scales and screening tools that can reliably measure the frequency and severity of psychiatric symptoms over time, and likens the lack of their use to "treating high blood pressure without using a blood pressure cuff to measure if a patient's blood pressure is improving."8 In fact, it is estimated that only 18% of psychiatrists and 11% of psychologists use rating scales routinely.9,10 This lack of use denies clinicians important information that can help detect deterioration or lack of improvement in their patients; implementing these scales in primary care can help early detection of behavioral health problems.

Behavioral health is replete with rating scales and screening tools, and the number of competing scales can make choosing a measure difficult.1 Nonetheless, not all scales are appropriate for clinical use; many are designed for research, for instance, and are lengthy and difficult to administer.

Let's review a number of rating scales that are brief, useful, and easy to administer. A framework for the screening tools addressed in this article is available on the federally funded Center for Integrated Health Solutions website (www.integration.samhsa.gov). This site promotes the use of tools designed to assist in screening and monitoring for depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, substance use, and suicidality.11

QUALITY CRITERIA FOR RATING SCALES

The quality of a rating scale is determined by the following attributes.

Objectivity. The ability of a scale to obtain the same results, regardless of who administers, analyzes, or interprets it.

Reliability. The ability of a scale to convey consistent and reproducible information across time, patients, and raters.

Validity. The degree to which the scale measures what it is supposed to measure (eg, depressive symptoms). Sensitivity and specificity are measures of validity and provide additional information about the rating scale; namely, whether the scale can detect the presence of a disease (sensitivity) and whether it detects only that disease or condition and not another (specificity).

Establishment of norms. Whether a scale provides reference values for different clinical groups.

Practicability. The resources required to administer the assessment instrument in terms of time, staff, and material.12

In addition to meeting these quality criteria, selection of a scale can be based on whether it is self-rated or observer-rated. Advantages to self-rated scales, such as the PHQ-9, Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ), and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale, are their practicability—they are easy to administer and don't require much time—and their use in evaluating and raising awareness of subjective states.

However, reliability may be a concern, as some patients may lack insight or exaggerate or mask symptoms when completing such scales.13 Both observer- and self-rated scales can be used together to minimize bias, identify symptoms that might have been missed/not addressed in the clinical interview, and drive clinical decision-making. Both can also help patients communicate with their providers and make them feel more involved in clinical decision-making.8

ENDORSED RATING SCALES

The following scales have met many of the quality criteria described here and are endorsed by the government payer system. They can easily be incorporated into clinical practice and will provide useful clinical information that can assist in diagnosis and monitoring patient outcomes.

Patient Health Questionnaire

PHQ-9 is a nine-item self-report questionnaire that can help to detect depression and supplement a thorough mental health interview. It scores the nine DSM-IV criteria for depression on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). It is a public resource that is easy to find online, available without cost in several languages, and takes just a few minutes to complete.14

PHQ-9 has shown excellent test-retest reliability in screening for depression, and normative data on the instrument's use are available in various clinical populations.15 Research has shown that as PHQ-9 depression scores increase, functional status decreases, while depressive symptoms, sick days, and health care utilization increase.15 In one study, a PHQ-9 score of ≥ 10 had 88% sensitivity and specificity for detecting depression, with scores of 5, 10, 15, and 20 indicating mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression, respectively.16 In addition to its use as a screening tool, PHQ-9 is a responsive and reliable measure of depression treatment outcomes.17

Mood Disorder Questionnaire

MDQ is another brief, self-report questionnaire that is available online. It is designed to identify and monitor patients who are likely to meet diagnostic criteria for bipolar disorder.18,19

The first question on the MDQ asks if the patient has experienced any of 13 common mood and behavior symptoms. The second question asks if these symptoms have ever occurred at the same time, and the third asks the degree to which the patient finds the symptoms to be problematic. The remaining two questions provide additional clinical information, addressing family history of manic-depressive illness or bipolar disorder and whether a diagnosis of either disorder has been made.

The MDQ has shown validity in assessing bipolar disorder symptoms in a general population, although recent research suggests that imprecise recall bias may limit its reliability in detecting hypomanic episodes earlier in life.20,21 Nonetheless, its specificity of > 97% means that it will effectively screen out just about all true negatives.18

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale

The GAD-7 scale is a brief, self-administered questionnaire for screening and measuring severity of GAD.22 It asks patients to rate seven items that represent problems with general anxiety and scores each item on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Similar to the other measures, it is easily accessible online.

Research evidence supports the reliability and validity of GAD-7 as a measure of anxiety in the general population. Sensitivity and specificity are 89% and 82%, respectively. Normative data for age- and sex-specific subgroups support its use across age groups and in both males and females.23 The GAD-7 performs well for detecting and monitoring not only GAD but also panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder.24

CAGE questionnaire for detection of substance use

The CAGE questionnaire is a widely used screening tool that was originally developed to detect alcohol abuse but has been adapted to assess other substance abuse.25,26 The omission of substance abuse from diagnostic consideration can have a major effect on quality of care, because substance abuse can be the underlying cause of other diseases. Therefore, routine administration of this instrument in clinical practice can lead to better understanding and monitoring of patient health.27

Similar to other instruments, CAGE is free and available online.27 It contains four simple questions, with 1 point assigned to each positive answer (see Table); the simple mnemonic makes the questions easy to remember and to administer in a clinical setting.

CAGE has demonstrated validity, with one study determining that scores ≥ 2 had a specificity and sensitivity of 76% and 93%, respectively, for identifying excessive drinking, and a specificity and sensitivity of 77% and 91%, respectively, for identifying alcohol abuse.28

Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)

C-SSRS was developed by researchers at Columbia University to assess the severity of and track changes over time in suicidal ideation and behavior. C-SSRS is two pages and takes only a few minutes to administer; however, it also may be completed as a self-report measure. The questions are phrased in an interview format, and while clinicians are encouraged to receive training prior to its administration, specific training in mental health is not required.

The "Lifetime/Recent" version allows practitioners to gather lifetime history of suicidality as well as any recent suicidal ideation and/or behavior, whereas the "Since Last Visit" version of the scale assesses suicidality in patients who have completed at least one Lifetime/Recent C-SSRS assessment. A truncated, six-item "Screener" version is typically used in emergency situations. A risk assessment can be added to either the Full or Screener version to summarize the answers from C-SSRS and document risk and protective factors.29

Several studies have found C-SSRS to be reliable and valid for identifying suicide risk in children and adults.30,31USA Today reported that an individual exhibiting even a single behavior identified by the scale is eight to 10 times more likely to complete suicide.32 In addition, the C-SSRS has helped reduce the suicide rate by 65% in one of the largest providers of community-based behavioral health care in the United States.32

USING SCALES TO AUGMENT CARE

Each of the scales described in this article can easily be incorporated into clinical practice. The information the scales provide can be used to track progression of symptoms and effectiveness of treatment. Although rating scales should never be used alone to establish a diagnosis or clinical treatment plan, they can and should be used to augment information from the clinician's assessment and follow-up interviews.5

1. McDowell I. Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

2. Kennedy Forum. Fixing behavioral health care in America: a national call for integrating and coordinating specialty behavioral health care with the medical system. http://thekennedyforum-dot-org.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/KennedyForum-BehavioralHealth_FINAL_3.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

3. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Behavioral health (BH) Clinical Quality Measures (CQMs) Program initiatives. www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/2012-09-27-behavioral-health-clinical-quality-measures-program-initiatives-public-forum.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

4. Unutzer J, Harbin H, Schoenbaum M. The collaborative care model: an approach for integrating physical and mental health care in Medicaid health homes. www.medicaid.gov/State-Resource-Center/Medicaid-State-Technical-Assistance/Health-Homes-Technical-Assistance/Downloads/HH-IRC-Collaborative-5-13.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

5. World Group On Psychiatric Evaluation; American Psychiatric Association Steering Committee On Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the psychiatric evaluation of adults. 2nd ed. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/psychevaladults.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

6. Melek S, Norris D, Paulus J. Economic Impact of Integrated Medical-Behavioral Healthcare: Implications for Psychiatry. Denver, CO: Milliman, Inc; 2014.

7. Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006525.

8. Kennedy Forum. Fixing behavioral health care in America: a national call for measurement-based care. www.thekennedyforum.org/a-national-call-for-measurement-based-care/. Accessed August 14, 2017.

9. Zimmerman M, McGlinchey JB. Why don't psychiatrists use scales to measure outcome when treating depressed patients? J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(12):1916-1919.

10. Hatfield D, McCullough L, Frantz SH, et al. Do we know when our clients get worse? An investigation of therapists' ability to detect negative client change. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2010;17(1):25-32.

11. SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Solutions. Screening tools. www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/screening-tools. Accessed August 14, 2017.

12. Moller HJ. Standardised rating scales in psychiatry: methodological basis, their possibilities and limitations and descriptions of important rating scales. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;10(1):6-26.

13. Sajatovic M, Ramirez LF. Rating Scales in Mental Health. 2nd ed. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp; 2003.

14. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/files/AssessmentTools/14-PHQ-9%20overview.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

15. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Rehab Measures Web site. www.rehabmeasures.org/Lists/RehabMeasures/DispForm.aspx?ID=954. Accessed August 14, 2017.

16. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613.

17. Löwe B, Unützer J, Callahan CM, et al. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Med Care. 2004;42(12):1194-1201.

18. Ketter TA. Strategies for monitoring outcomes in patients with bipolar disorder. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(suppl 1):10-16.

19. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire. University of Texas Medical Branch. www.dbsalliance.org/pdfs/MDQ.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

20. Hirschfeld RM, Holzer C, Calabrese JR, et al. Validity of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire: a general population study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):178-180.

21. Boschloo L, Nolen WA, Spijker AT, et al. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) for detecting (hypo) manic episodes: its validity and impact of recall bias. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(1):203-208.

22. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092-1097.

23. Lowe B, Decker O, Müller S, et al. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46(3):266-274.

24. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(5):317-325.

25. Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE Questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252(14):1905-1907.

26. CAGE substance abuse screening tool. Johns Hopkins Medicine. www.hopkinsmedicine.org/johns_hopkins_healthcare/downloads/cage%20substance%20screening%20tool.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

27. O'Brien CP. The CAGE questionnaire for detection of alcoholism: a remarkably useful but simple tool. JAMA. 2008;300(17):2054-2056.

28. Bernadt MW, Mumford J, Taylor C, et al. Comparison of questionnaire and laboratory tests in the detection of excessive drinking and alcoholism. Lancet. 1982;1(8267):325-328.

29. Columbia Suicide-Severity Rating Scale (CS-SRS). http://cssrs.columbia.edu/the-columbia-scale-c-ssrs/cssrs-for-communities-and-healthcare/#filter=.general-use.english. Accessed August 14, 2017.

30. Mundt JC, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, et al. Prediction of suicidal behavior in clinical research by lifetime suicidal ideation and behavior ascertained by the electronic Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(9):887-893.

31. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266-1277.

32. Esposito L. Suicide checklist spots people at highest risk. USA Today. http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/health/story/health/story/2011-11-09/Suicide-checklist-spots-peo ple-at-highest-risk/51135944/1. Accessed August 14, 2017.

1. McDowell I. Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

2. Kennedy Forum. Fixing behavioral health care in America: a national call for integrating and coordinating specialty behavioral health care with the medical system. http://thekennedyforum-dot-org.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/KennedyForum-BehavioralHealth_FINAL_3.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

3. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Behavioral health (BH) Clinical Quality Measures (CQMs) Program initiatives. www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/2012-09-27-behavioral-health-clinical-quality-measures-program-initiatives-public-forum.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

4. Unutzer J, Harbin H, Schoenbaum M. The collaborative care model: an approach for integrating physical and mental health care in Medicaid health homes. www.medicaid.gov/State-Resource-Center/Medicaid-State-Technical-Assistance/Health-Homes-Technical-Assistance/Downloads/HH-IRC-Collaborative-5-13.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

5. World Group On Psychiatric Evaluation; American Psychiatric Association Steering Committee On Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the psychiatric evaluation of adults. 2nd ed. http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/psychevaladults.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

6. Melek S, Norris D, Paulus J. Economic Impact of Integrated Medical-Behavioral Healthcare: Implications for Psychiatry. Denver, CO: Milliman, Inc; 2014.

7. Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD006525.

8. Kennedy Forum. Fixing behavioral health care in America: a national call for measurement-based care. www.thekennedyforum.org/a-national-call-for-measurement-based-care/. Accessed August 14, 2017.

9. Zimmerman M, McGlinchey JB. Why don't psychiatrists use scales to measure outcome when treating depressed patients? J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(12):1916-1919.

10. Hatfield D, McCullough L, Frantz SH, et al. Do we know when our clients get worse? An investigation of therapists' ability to detect negative client change. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2010;17(1):25-32.

11. SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Solutions. Screening tools. www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/screening-tools. Accessed August 14, 2017.

12. Moller HJ. Standardised rating scales in psychiatry: methodological basis, their possibilities and limitations and descriptions of important rating scales. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;10(1):6-26.

13. Sajatovic M, Ramirez LF. Rating Scales in Mental Health. 2nd ed. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp; 2003.

14. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/files/AssessmentTools/14-PHQ-9%20overview.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

15. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Rehab Measures Web site. www.rehabmeasures.org/Lists/RehabMeasures/DispForm.aspx?ID=954. Accessed August 14, 2017.

16. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613.

17. Löwe B, Unützer J, Callahan CM, et al. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Med Care. 2004;42(12):1194-1201.

18. Ketter TA. Strategies for monitoring outcomes in patients with bipolar disorder. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(suppl 1):10-16.

19. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire. University of Texas Medical Branch. www.dbsalliance.org/pdfs/MDQ.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

20. Hirschfeld RM, Holzer C, Calabrese JR, et al. Validity of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire: a general population study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):178-180.

21. Boschloo L, Nolen WA, Spijker AT, et al. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) for detecting (hypo) manic episodes: its validity and impact of recall bias. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(1):203-208.

22. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092-1097.

23. Lowe B, Decker O, Müller S, et al. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46(3):266-274.

24. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(5):317-325.

25. Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE Questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252(14):1905-1907.

26. CAGE substance abuse screening tool. Johns Hopkins Medicine. www.hopkinsmedicine.org/johns_hopkins_healthcare/downloads/cage%20substance%20screening%20tool.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

27. O'Brien CP. The CAGE questionnaire for detection of alcoholism: a remarkably useful but simple tool. JAMA. 2008;300(17):2054-2056.

28. Bernadt MW, Mumford J, Taylor C, et al. Comparison of questionnaire and laboratory tests in the detection of excessive drinking and alcoholism. Lancet. 1982;1(8267):325-328.

29. Columbia Suicide-Severity Rating Scale (CS-SRS). http://cssrs.columbia.edu/the-columbia-scale-c-ssrs/cssrs-for-communities-and-healthcare/#filter=.general-use.english. Accessed August 14, 2017.

30. Mundt JC, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, et al. Prediction of suicidal behavior in clinical research by lifetime suicidal ideation and behavior ascertained by the electronic Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(9):887-893.

31. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266-1277.

32. Esposito L. Suicide checklist spots people at highest risk. USA Today. http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/health/story/health/story/2011-11-09/Suicide-checklist-spots-peo ple-at-highest-risk/51135944/1. Accessed August 14, 2017.

Prenatal antidepressant use linked to psychiatric illness in offspring

Antidepressant use before and during pregnancy may be associated with an increased risk of psychiatric disorders in offspring, according to the results of a population-based cohort study published Sept. 7 in the BMJ.

There have been contradictory findings in the literature about whether in utero exposure to SSRIs is associated with autism spectrum disorder and ADHD. “However, these studies did not investigate the overall risk of psychiatric disorders, which is important because differentiating between overlapping symptoms and diagnosing specific disorders are challenging in children and adolescents,” Xiaoqin Liu, MD, PhD, of Aarhus University in Denmark, and her coauthors wrote (BMJ 2017;358:j3668. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3668).

Participants were categorized into four groups based on maternal use of antidepressants; unexposed, antidepressant discontinuation (if the mother had used in the 2 years before but not during pregnancy), antidepressant continuation (if the use happened in the 2 years before pregnancy and during it), and new users (if antidepressant use happened only during pregnancy).

The study found that children whose mothers used antidepressants both in the 2 years before pregnancy and during pregnancy had a 27% higher incidence of any psychiatric disorder, compared with children whose mothers had used antidepressants but discontinued them before becoming pregnant (95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.38).