User login

Short Sleep Duration Is Associated With Greater Brain Atrophy

BOSTON—Compared with intermediate sleep duration, shorter sleep is associated with greater brain atrophy among community-dwelling older adults, according to a study presented at the 31st Annual Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies. Sleep duration appears to have no association with hippocampal volume, however.

More than 80% of older adults have sleep complaints, and research indicating an association between disturbed sleep and poor cognitive outcomes is accumulating. Sleep could be a crucial modifiable risk factor for cognitive outcomes, but few studies have examined the association between nonrespiratory sleep measures and brain volume, said Adam Spira, PhD, Associate Professor of Mental Health at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore.

Participants Underwent MRI and Actigraphy

Dr. Spira and his colleagues at the National Institute on Aging Intramural Research Program and Johns Hopkins University studied adults without dementia enrolled in the ongoing Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. To be eligible for the study, participants could not have cognitive impairment, functional limitations, or chronic medical conditions besides controlled hypertension.

Dr. Spira and colleagues examined the 183 participants for whom wrist actigraphy and MRI data from the same study visit were available. The sample’s mean age was 75. About 57% of the sample was female, and 28% were racial or ethnic minorities (mostly African American). Approximately 84% of the sample had 16 or more years of education.

Participants completed an average of 6.8 nights of actigraphy. The actigraph unit was worn on the nondominant wrist. The study’s primary actigraphy variables were total sleep time (TST), wake after sleep onset (WASO), and average wake bout length. Participants also underwent 3-T MRI, and the researchers’ main imaging variables were ventricular volume and hippocampal volume. Dr. Spira and colleagues adjusted their analyses for age, sex, education, race, depressive symptomatology, and the log of the intracranial volume.

Links Between Sleep and Brain Volumes

The population’s mean TST was 6.6 hours, and the investigators divided the TST data into tertiles. The mean TST for tertile 1 was 5.4 hours, the mean TST for tertile 2 was 6.6 hours, and the mean TST for tertile 3 was 7.7 hours. Mean WASO was 53 minutes, and mean wake bout length was 2.5 minutes.

Dr. Spira’s group found a statistically significant 0.17-unit increase in ventricular volume in tertile 1, compared with tertile 2. They also found a 0.12-unit increase in ventricular volume in tertile 3, compared with tertile 2, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. WASO was not associated with ventricular volume, but the investigators found a statistically significant 0.06-unit increase in ventricular volume for every standard deviation increase in average wake bout length.

There was no significant association between TST and hippocampal volume. Every standard deviation increase in WASO, however, was associated with decrease in hippocampal volume that was not statistically significant. Wake bout length was not associated with hippocampal volume.

Because it is a cross sectional study, the researchers cannot examine the temporal associations that would support the possibility of a causal effect of sleep on brain atrophy, said Dr. Spira. “It could also be that brain atrophy is linked to disturbed sleep,” he added. The investigators did not screen participants for sleep apnea or adjust the data for BMI.

The findings are consistent, however, with longitudinal results of studies with self-report measures of sleep duration or quality, and with cross sectional associations between actigraphic fragmentation indices and lower brain volumes.

“Longitudinal studies with larger samples are needed,” said Dr. Spira. “Ultimately, trials will be needed to examine the effects of optimizing sleep on cognitive and neuroimaging outcomes.”

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Branger P, Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Tomadesso C, et al. Relationships between sleep quality and brain volume, metabolism, and amyloid deposition in late adulthood. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;41:107-114.

Koo DL, Shin JH, Lim JS, et al. Changes in subcortical shape and cognitive function in patients with chronic insomnia. Sleep Med. 2017;35:23-26.

BOSTON—Compared with intermediate sleep duration, shorter sleep is associated with greater brain atrophy among community-dwelling older adults, according to a study presented at the 31st Annual Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies. Sleep duration appears to have no association with hippocampal volume, however.

More than 80% of older adults have sleep complaints, and research indicating an association between disturbed sleep and poor cognitive outcomes is accumulating. Sleep could be a crucial modifiable risk factor for cognitive outcomes, but few studies have examined the association between nonrespiratory sleep measures and brain volume, said Adam Spira, PhD, Associate Professor of Mental Health at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore.

Participants Underwent MRI and Actigraphy

Dr. Spira and his colleagues at the National Institute on Aging Intramural Research Program and Johns Hopkins University studied adults without dementia enrolled in the ongoing Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. To be eligible for the study, participants could not have cognitive impairment, functional limitations, or chronic medical conditions besides controlled hypertension.

Dr. Spira and colleagues examined the 183 participants for whom wrist actigraphy and MRI data from the same study visit were available. The sample’s mean age was 75. About 57% of the sample was female, and 28% were racial or ethnic minorities (mostly African American). Approximately 84% of the sample had 16 or more years of education.

Participants completed an average of 6.8 nights of actigraphy. The actigraph unit was worn on the nondominant wrist. The study’s primary actigraphy variables were total sleep time (TST), wake after sleep onset (WASO), and average wake bout length. Participants also underwent 3-T MRI, and the researchers’ main imaging variables were ventricular volume and hippocampal volume. Dr. Spira and colleagues adjusted their analyses for age, sex, education, race, depressive symptomatology, and the log of the intracranial volume.

Links Between Sleep and Brain Volumes

The population’s mean TST was 6.6 hours, and the investigators divided the TST data into tertiles. The mean TST for tertile 1 was 5.4 hours, the mean TST for tertile 2 was 6.6 hours, and the mean TST for tertile 3 was 7.7 hours. Mean WASO was 53 minutes, and mean wake bout length was 2.5 minutes.

Dr. Spira’s group found a statistically significant 0.17-unit increase in ventricular volume in tertile 1, compared with tertile 2. They also found a 0.12-unit increase in ventricular volume in tertile 3, compared with tertile 2, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. WASO was not associated with ventricular volume, but the investigators found a statistically significant 0.06-unit increase in ventricular volume for every standard deviation increase in average wake bout length.

There was no significant association between TST and hippocampal volume. Every standard deviation increase in WASO, however, was associated with decrease in hippocampal volume that was not statistically significant. Wake bout length was not associated with hippocampal volume.

Because it is a cross sectional study, the researchers cannot examine the temporal associations that would support the possibility of a causal effect of sleep on brain atrophy, said Dr. Spira. “It could also be that brain atrophy is linked to disturbed sleep,” he added. The investigators did not screen participants for sleep apnea or adjust the data for BMI.

The findings are consistent, however, with longitudinal results of studies with self-report measures of sleep duration or quality, and with cross sectional associations between actigraphic fragmentation indices and lower brain volumes.

“Longitudinal studies with larger samples are needed,” said Dr. Spira. “Ultimately, trials will be needed to examine the effects of optimizing sleep on cognitive and neuroimaging outcomes.”

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Branger P, Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Tomadesso C, et al. Relationships between sleep quality and brain volume, metabolism, and amyloid deposition in late adulthood. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;41:107-114.

Koo DL, Shin JH, Lim JS, et al. Changes in subcortical shape and cognitive function in patients with chronic insomnia. Sleep Med. 2017;35:23-26.

BOSTON—Compared with intermediate sleep duration, shorter sleep is associated with greater brain atrophy among community-dwelling older adults, according to a study presented at the 31st Annual Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies. Sleep duration appears to have no association with hippocampal volume, however.

More than 80% of older adults have sleep complaints, and research indicating an association between disturbed sleep and poor cognitive outcomes is accumulating. Sleep could be a crucial modifiable risk factor for cognitive outcomes, but few studies have examined the association between nonrespiratory sleep measures and brain volume, said Adam Spira, PhD, Associate Professor of Mental Health at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore.

Participants Underwent MRI and Actigraphy

Dr. Spira and his colleagues at the National Institute on Aging Intramural Research Program and Johns Hopkins University studied adults without dementia enrolled in the ongoing Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. To be eligible for the study, participants could not have cognitive impairment, functional limitations, or chronic medical conditions besides controlled hypertension.

Dr. Spira and colleagues examined the 183 participants for whom wrist actigraphy and MRI data from the same study visit were available. The sample’s mean age was 75. About 57% of the sample was female, and 28% were racial or ethnic minorities (mostly African American). Approximately 84% of the sample had 16 or more years of education.

Participants completed an average of 6.8 nights of actigraphy. The actigraph unit was worn on the nondominant wrist. The study’s primary actigraphy variables were total sleep time (TST), wake after sleep onset (WASO), and average wake bout length. Participants also underwent 3-T MRI, and the researchers’ main imaging variables were ventricular volume and hippocampal volume. Dr. Spira and colleagues adjusted their analyses for age, sex, education, race, depressive symptomatology, and the log of the intracranial volume.

Links Between Sleep and Brain Volumes

The population’s mean TST was 6.6 hours, and the investigators divided the TST data into tertiles. The mean TST for tertile 1 was 5.4 hours, the mean TST for tertile 2 was 6.6 hours, and the mean TST for tertile 3 was 7.7 hours. Mean WASO was 53 minutes, and mean wake bout length was 2.5 minutes.

Dr. Spira’s group found a statistically significant 0.17-unit increase in ventricular volume in tertile 1, compared with tertile 2. They also found a 0.12-unit increase in ventricular volume in tertile 3, compared with tertile 2, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. WASO was not associated with ventricular volume, but the investigators found a statistically significant 0.06-unit increase in ventricular volume for every standard deviation increase in average wake bout length.

There was no significant association between TST and hippocampal volume. Every standard deviation increase in WASO, however, was associated with decrease in hippocampal volume that was not statistically significant. Wake bout length was not associated with hippocampal volume.

Because it is a cross sectional study, the researchers cannot examine the temporal associations that would support the possibility of a causal effect of sleep on brain atrophy, said Dr. Spira. “It could also be that brain atrophy is linked to disturbed sleep,” he added. The investigators did not screen participants for sleep apnea or adjust the data for BMI.

The findings are consistent, however, with longitudinal results of studies with self-report measures of sleep duration or quality, and with cross sectional associations between actigraphic fragmentation indices and lower brain volumes.

“Longitudinal studies with larger samples are needed,” said Dr. Spira. “Ultimately, trials will be needed to examine the effects of optimizing sleep on cognitive and neuroimaging outcomes.”

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Branger P, Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Tomadesso C, et al. Relationships between sleep quality and brain volume, metabolism, and amyloid deposition in late adulthood. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;41:107-114.

Koo DL, Shin JH, Lim JS, et al. Changes in subcortical shape and cognitive function in patients with chronic insomnia. Sleep Med. 2017;35:23-26.

Ex Vivo Confocal Microscopy in Clinical Practice: Report From the AAD Meeting

Depression Across the Spectrum of Mood Disorders: Advanced Strategies in Major Depressive Disorder and Bipolar Disorder

Mauricio Tohen, MD, DrPH, MBA

Professor and Chair

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

University of New Mexico School of Medicine

Albuquerque, New Mexico

Claudia Baldassano, MD

Associate Professor of Psychiatry

Department of Psychiatry

University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Vladimir Maletic, MD, MS

Clinical Professor of Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral Science

University of South Carolina School of Medicine

Greenville, South Carolina

Consulting Associate

Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Department of Psychiatry

Duke University

Durham, North Carolina

Click here to read the supplement

After reading, visit https://MERdepression.cvent.com to complete the posttest and evaluation for CME/CE credit.

Mauricio Tohen, MD, DrPH, MBA

Professor and Chair

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

University of New Mexico School of Medicine

Albuquerque, New Mexico

Claudia Baldassano, MD

Associate Professor of Psychiatry

Department of Psychiatry

University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Vladimir Maletic, MD, MS

Clinical Professor of Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral Science

University of South Carolina School of Medicine

Greenville, South Carolina

Consulting Associate

Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Department of Psychiatry

Duke University

Durham, North Carolina

Click here to read the supplement

After reading, visit https://MERdepression.cvent.com to complete the posttest and evaluation for CME/CE credit.

Mauricio Tohen, MD, DrPH, MBA

Professor and Chair

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

University of New Mexico School of Medicine

Albuquerque, New Mexico

Claudia Baldassano, MD

Associate Professor of Psychiatry

Department of Psychiatry

University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Vladimir Maletic, MD, MS

Clinical Professor of Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral Science

University of South Carolina School of Medicine

Greenville, South Carolina

Consulting Associate

Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Department of Psychiatry

Duke University

Durham, North Carolina

Click here to read the supplement

After reading, visit https://MERdepression.cvent.com to complete the posttest and evaluation for CME/CE credit.

Delay in delivery--mother and child die: $1.4M settlement

Delay in delivery--mother and child die: $1.4M settlement

ESTATE'S CLAIM:

The standard of care for placenta accreta requires delivery between 34 and 36 weeks of gestation. The mother died from a placental abruption and amniotic fluid embolism. Placenta accreta increases the risk of catastrophic hemorrhage. If delivery had occurred on January 14, both the mother and child would be alive.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The case settled before trial.

VERDICT:

A $1.425 million Georgia settlement was reached. The settlement amount was limited by a damages cap unique to the defendant hospital.

Placental abruption not detected: $6.2M settlement

At 24 weeks of gestation, a mother presented to the hospital with premature contractions that subsided after her arrival. She was discharged from the hospital. The woman gave birth in her bathtub several hours later. The baby was 10 weeks premature. He suffered profound brain damage and has significant physical defects.

PARENT'S CLAIM:

Neither the ObGyn nor the hospital staff appreciated that the mother was experiencing placental abruption. If diagnosed, treatment could have prevented fetal injury.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The case was settled prior to trial.

VERDICT:

A $6.2 million New York settlement was reached.

Child has brachial plexus injury: $2M award

A woman was admitted to the hospital for elective induction of labor. She gained a significant amount of weight while pregnant. During delivery, her family practitioner (FP) determined that vacuum extraction was needed but he was not qualified to use the device. An in-house ObGyn was called in to use the vacuum extractor. The FP delivered the baby's shoulders. The infant was born with a floppy right arm and later diagnosed with rupture injuries to the C-5 and C-6 vertebrae and permanent brachial plexus damage. She has limited range of motion in her right arm and shoulder.

PARENT'S CLAIM:

The FP was relatively inexperienced in labor and delivery. He should not have ordered vacuum extraction because of risk factors including the mother's small stature, her significant weight gain during pregnancy, the use of epidural anesthesia, and induction of labor. Using vacuum extraction increases the risk of shoulder dystocia.

The FP improperly applied excessive downward traction on the fetus causing the infant to sustain a brachial plexus injury.

The FP did not notify the parents of the child's injury immediately after birth; he told them about the injury just before discharge.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

There is no evidence in the medical records of a shoulder dystocia; "no shoulder dystocia" was charted shortly after delivery. No one in the delivery room testified to a delay in delivering the infant's shoulders. The mother's internal contractions caused the injury. The baby was not injured to the extent claimed.

VERDICT:

The ObGyn who used the vacuum extractor settled before the trial for $300,000. A $2 million Illinois verdict was returned against the FP.

Delay in treating infant in respiratory distress: $7.27M settlement

A child was delivered by a certified nurse midwife at a birthing center. At birth, the baby had a heart rate of 60 bpm and was in respiratory distress but there was no one at the clinic qualified to intubate the infant. Emergency personnel were called but the infant remained in respiratory distress for 8 minutes. The baby experienced birth asphyxia with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy resulting in severe cerebral palsy.

PARENT'S CLAIM:

The birthing center was poorly staffed and unprepared to treat an emergency situation.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The defendants denied all allegations of negligence. The case was settled during trial.

VERDICT:

A $7.27 million Pennsylvania settlement was reached.

Was the spinal block given at wrong level?

A MOTHER WENT TO THE HOSPITAL in labor. Prior to cesarean delivery, she underwent an anesthetic spinal block administered by a CRNA. Initially, the patient reported pain shortly after the injection was performed until the block worked. The baby's delivery was uneventful.

In recovery a few hours later, the patient reported intense and uncontrollable pain in her legs. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a fluid pocket on her spinal cord at the L1-L2 level. The patient has permanent pain, numbness, and tingling in in both legs.

PATIENT'S CLAIM:

The CRNA failed to insert the spinal block needle in the proper location.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The CRNA contended that he complied with the standard of care. He claimed that the patient had an unusual spinal cord anatomy: it was tethered down to the L3-L4 level.

VERDICT:

A $509,152 Kentucky verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Delay in delivery--mother and child die: $1.4M settlement

ESTATE'S CLAIM:

The standard of care for placenta accreta requires delivery between 34 and 36 weeks of gestation. The mother died from a placental abruption and amniotic fluid embolism. Placenta accreta increases the risk of catastrophic hemorrhage. If delivery had occurred on January 14, both the mother and child would be alive.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The case settled before trial.

VERDICT:

A $1.425 million Georgia settlement was reached. The settlement amount was limited by a damages cap unique to the defendant hospital.

Placental abruption not detected: $6.2M settlement

At 24 weeks of gestation, a mother presented to the hospital with premature contractions that subsided after her arrival. She was discharged from the hospital. The woman gave birth in her bathtub several hours later. The baby was 10 weeks premature. He suffered profound brain damage and has significant physical defects.

PARENT'S CLAIM:

Neither the ObGyn nor the hospital staff appreciated that the mother was experiencing placental abruption. If diagnosed, treatment could have prevented fetal injury.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The case was settled prior to trial.

VERDICT:

A $6.2 million New York settlement was reached.

Child has brachial plexus injury: $2M award

A woman was admitted to the hospital for elective induction of labor. She gained a significant amount of weight while pregnant. During delivery, her family practitioner (FP) determined that vacuum extraction was needed but he was not qualified to use the device. An in-house ObGyn was called in to use the vacuum extractor. The FP delivered the baby's shoulders. The infant was born with a floppy right arm and later diagnosed with rupture injuries to the C-5 and C-6 vertebrae and permanent brachial plexus damage. She has limited range of motion in her right arm and shoulder.

PARENT'S CLAIM:

The FP was relatively inexperienced in labor and delivery. He should not have ordered vacuum extraction because of risk factors including the mother's small stature, her significant weight gain during pregnancy, the use of epidural anesthesia, and induction of labor. Using vacuum extraction increases the risk of shoulder dystocia.

The FP improperly applied excessive downward traction on the fetus causing the infant to sustain a brachial plexus injury.

The FP did not notify the parents of the child's injury immediately after birth; he told them about the injury just before discharge.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

There is no evidence in the medical records of a shoulder dystocia; "no shoulder dystocia" was charted shortly after delivery. No one in the delivery room testified to a delay in delivering the infant's shoulders. The mother's internal contractions caused the injury. The baby was not injured to the extent claimed.

VERDICT:

The ObGyn who used the vacuum extractor settled before the trial for $300,000. A $2 million Illinois verdict was returned against the FP.

Delay in treating infant in respiratory distress: $7.27M settlement

A child was delivered by a certified nurse midwife at a birthing center. At birth, the baby had a heart rate of 60 bpm and was in respiratory distress but there was no one at the clinic qualified to intubate the infant. Emergency personnel were called but the infant remained in respiratory distress for 8 minutes. The baby experienced birth asphyxia with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy resulting in severe cerebral palsy.

PARENT'S CLAIM:

The birthing center was poorly staffed and unprepared to treat an emergency situation.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The defendants denied all allegations of negligence. The case was settled during trial.

VERDICT:

A $7.27 million Pennsylvania settlement was reached.

Was the spinal block given at wrong level?

A MOTHER WENT TO THE HOSPITAL in labor. Prior to cesarean delivery, she underwent an anesthetic spinal block administered by a CRNA. Initially, the patient reported pain shortly after the injection was performed until the block worked. The baby's delivery was uneventful.

In recovery a few hours later, the patient reported intense and uncontrollable pain in her legs. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a fluid pocket on her spinal cord at the L1-L2 level. The patient has permanent pain, numbness, and tingling in in both legs.

PATIENT'S CLAIM:

The CRNA failed to insert the spinal block needle in the proper location.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The CRNA contended that he complied with the standard of care. He claimed that the patient had an unusual spinal cord anatomy: it was tethered down to the L3-L4 level.

VERDICT:

A $509,152 Kentucky verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Delay in delivery--mother and child die: $1.4M settlement

ESTATE'S CLAIM:

The standard of care for placenta accreta requires delivery between 34 and 36 weeks of gestation. The mother died from a placental abruption and amniotic fluid embolism. Placenta accreta increases the risk of catastrophic hemorrhage. If delivery had occurred on January 14, both the mother and child would be alive.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The case settled before trial.

VERDICT:

A $1.425 million Georgia settlement was reached. The settlement amount was limited by a damages cap unique to the defendant hospital.

Placental abruption not detected: $6.2M settlement

At 24 weeks of gestation, a mother presented to the hospital with premature contractions that subsided after her arrival. She was discharged from the hospital. The woman gave birth in her bathtub several hours later. The baby was 10 weeks premature. He suffered profound brain damage and has significant physical defects.

PARENT'S CLAIM:

Neither the ObGyn nor the hospital staff appreciated that the mother was experiencing placental abruption. If diagnosed, treatment could have prevented fetal injury.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The case was settled prior to trial.

VERDICT:

A $6.2 million New York settlement was reached.

Child has brachial plexus injury: $2M award

A woman was admitted to the hospital for elective induction of labor. She gained a significant amount of weight while pregnant. During delivery, her family practitioner (FP) determined that vacuum extraction was needed but he was not qualified to use the device. An in-house ObGyn was called in to use the vacuum extractor. The FP delivered the baby's shoulders. The infant was born with a floppy right arm and later diagnosed with rupture injuries to the C-5 and C-6 vertebrae and permanent brachial plexus damage. She has limited range of motion in her right arm and shoulder.

PARENT'S CLAIM:

The FP was relatively inexperienced in labor and delivery. He should not have ordered vacuum extraction because of risk factors including the mother's small stature, her significant weight gain during pregnancy, the use of epidural anesthesia, and induction of labor. Using vacuum extraction increases the risk of shoulder dystocia.

The FP improperly applied excessive downward traction on the fetus causing the infant to sustain a brachial plexus injury.

The FP did not notify the parents of the child's injury immediately after birth; he told them about the injury just before discharge.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

There is no evidence in the medical records of a shoulder dystocia; "no shoulder dystocia" was charted shortly after delivery. No one in the delivery room testified to a delay in delivering the infant's shoulders. The mother's internal contractions caused the injury. The baby was not injured to the extent claimed.

VERDICT:

The ObGyn who used the vacuum extractor settled before the trial for $300,000. A $2 million Illinois verdict was returned against the FP.

Delay in treating infant in respiratory distress: $7.27M settlement

A child was delivered by a certified nurse midwife at a birthing center. At birth, the baby had a heart rate of 60 bpm and was in respiratory distress but there was no one at the clinic qualified to intubate the infant. Emergency personnel were called but the infant remained in respiratory distress for 8 minutes. The baby experienced birth asphyxia with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy resulting in severe cerebral palsy.

PARENT'S CLAIM:

The birthing center was poorly staffed and unprepared to treat an emergency situation.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The defendants denied all allegations of negligence. The case was settled during trial.

VERDICT:

A $7.27 million Pennsylvania settlement was reached.

Was the spinal block given at wrong level?

A MOTHER WENT TO THE HOSPITAL in labor. Prior to cesarean delivery, she underwent an anesthetic spinal block administered by a CRNA. Initially, the patient reported pain shortly after the injection was performed until the block worked. The baby's delivery was uneventful.

In recovery a few hours later, the patient reported intense and uncontrollable pain in her legs. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a fluid pocket on her spinal cord at the L1-L2 level. The patient has permanent pain, numbness, and tingling in in both legs.

PATIENT'S CLAIM:

The CRNA failed to insert the spinal block needle in the proper location.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The CRNA contended that he complied with the standard of care. He claimed that the patient had an unusual spinal cord anatomy: it was tethered down to the L3-L4 level.

VERDICT:

A $509,152 Kentucky verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Clinical Endpoints in PTCL: The Road Less Traveled

Release Date: August 1, 2017

Expiration Date: July 31, 2018

Note: This activity is no longer available for credit.

Agenda

Developing New Strategic Goals in PTCL (duration 27:00)

Andrei R. Shustov, MD

University of Washington School of Medicine

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center

Seattle, WA, USA

PTCL as a Rare Disease: A Case of Overall Survival (duration 19:00)

Owen A. O’Connor, MD, PhD

Columbia University Medical Center

The New York Presbyterian Hospital

New York, NY, USA

Why Might Response Rates Differ Between the East and West? (duration 17:00)

Kensei Tobinai, MD, PhD

National Cancer Center Hospital

Tokyo, Japan

Provided by:

Original activity supported by an educational grant from:

Spectrum Pharmaceuticals

Learning Objectives

At the end of the activity, participants should be able to:

- Explain why progression-free survival is important when treating patients with PTCL

- Determine when overall survival is possible

- Describe the challenges of using matched control analysis in PTCL clinical trials

- Discuss why different response rates to therapy for PTCL may be seen in Asian patients versus North American or European patients and define the possible contributing factors

Target Audience

Hematologists, oncologists, and other clinicians and scientists with an interest in T-cell lymphoma

Statement of Need

This activity explores clinical endpoints in PTCL, the importance of choosing the appropriate ones and the possibility of achieving them. Global and regional differences in PTCL are also explored as they relate to response rates. The presentations highlight the challenges physicians face in treating PTCL patients and recent developments are discussed to help practitioners evaluate the utility of these endpoints in choosing appropriate treatments to improve outcomes in their patients with PTCL.

FACULTY

Faculty

Andrei R. Shustov, MD

Disclosures: Consulting fee: Celgene; BMS

Owen O’Connor, MD, PhD

Disclosures: Consulting fees: Mundipharma; Celgene; Contracted Research: Mundipharma; Spectrum; Celgene; Seattle Genetics; TG Therapeutics; ADCT; Trillium

Kensei Tobinai, MD, PhD

Disclosures: Honoraria: Eisai; HUYA Bioscience International; Janssen; Mundipharma; Takeda; Zenyaku Kogyo; Contracted research: Abbvie; Celgene; Chugai Pharma; Eisai; GlaxoSmithKline; Janssen; Kyowa Hakko Kirin; Mundipharma; Ono Pharmaceutical; SERVIER; Takeda

Permissions

Andrei Shustov presentation

- Slide 7: PTCL Prognosis Is Indicative of Diverse Biology

- Reprinted with permission. © 2008 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slide 8: PTCL: Global Epidemiology

- Reprinted with permission. © 2008 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slide 9: PTCL: USA Epidemiology (top half)

- Reprinted with permission. © 2008 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slide 9: PTCL: USA Epidemiology (bottom half)

- Reprinted with permission. © 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slide 10: PTCL Prognosis: Histology x Race (USA)

- Reprinted with permission. © 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slide 12: PTCL Prognosis: Clinical Features (top right side)

- Reprinted with permission. © 2013 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slide 14: PTCL Prognosis: Molecular Classifiers (left side)

- Republished with permission of the American Society of Hematology, from Parilla Castellar ER, et al. Blood 2014;124:1473-1480

- Slide 14: PTCL Prognosis: Molecular Classifiers (right side)

- Republished with permission of the American Society of Hematology, from Iqbal J, et al. Blood 2014;123:2915-2923

- Slide 17: US Epidemiology of PTCL

- Reprinted with permission. © 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slides 18-19: Romidepsin in Relapsed/Refractory PTCL

- Reprinted with permission. © 2012 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slides 20-22, 25: Romidepsin in Elderly Patients

- Shustov A, et al. Romidepsin is effective and well tolerated in older patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma: analysis of two phase II trials. Leuk Lymphoma 2017 [Epub ahead of print]. Reprinted by permission of Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com

- Slides 27-28: Belinostat in Relapsed/Refractory PTCL

- Reprinted with permission. © 2015 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Kensei Tobinai presentation

- Slide 7: Overall Survival of ATL Pts in JCOG 9801

- Reprinted with permission. © 2007 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Disclaimer

The content and views presented in this educational activity are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Hemedicus, the supporter, or Frontline Medical Communications. This material is prepared based upon a review of multiple sources of information, but it is not exhaustive of the subject matter. Therefore, healthcare professionals and other individuals should review and consider other publications and materials on the subject matter before relying solely upon the information contained within this educational activity.

Release Date: August 1, 2017

Expiration Date: July 31, 2018

Note: This activity is no longer available for credit.

Agenda

Developing New Strategic Goals in PTCL (duration 27:00)

Andrei R. Shustov, MD

University of Washington School of Medicine

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center

Seattle, WA, USA

PTCL as a Rare Disease: A Case of Overall Survival (duration 19:00)

Owen A. O’Connor, MD, PhD

Columbia University Medical Center

The New York Presbyterian Hospital

New York, NY, USA

Why Might Response Rates Differ Between the East and West? (duration 17:00)

Kensei Tobinai, MD, PhD

National Cancer Center Hospital

Tokyo, Japan

Provided by:

Original activity supported by an educational grant from:

Spectrum Pharmaceuticals

Learning Objectives

At the end of the activity, participants should be able to:

- Explain why progression-free survival is important when treating patients with PTCL

- Determine when overall survival is possible

- Describe the challenges of using matched control analysis in PTCL clinical trials

- Discuss why different response rates to therapy for PTCL may be seen in Asian patients versus North American or European patients and define the possible contributing factors

Target Audience

Hematologists, oncologists, and other clinicians and scientists with an interest in T-cell lymphoma

Statement of Need

This activity explores clinical endpoints in PTCL, the importance of choosing the appropriate ones and the possibility of achieving them. Global and regional differences in PTCL are also explored as they relate to response rates. The presentations highlight the challenges physicians face in treating PTCL patients and recent developments are discussed to help practitioners evaluate the utility of these endpoints in choosing appropriate treatments to improve outcomes in their patients with PTCL.

FACULTY

Faculty

Andrei R. Shustov, MD

Disclosures: Consulting fee: Celgene; BMS

Owen O’Connor, MD, PhD

Disclosures: Consulting fees: Mundipharma; Celgene; Contracted Research: Mundipharma; Spectrum; Celgene; Seattle Genetics; TG Therapeutics; ADCT; Trillium

Kensei Tobinai, MD, PhD

Disclosures: Honoraria: Eisai; HUYA Bioscience International; Janssen; Mundipharma; Takeda; Zenyaku Kogyo; Contracted research: Abbvie; Celgene; Chugai Pharma; Eisai; GlaxoSmithKline; Janssen; Kyowa Hakko Kirin; Mundipharma; Ono Pharmaceutical; SERVIER; Takeda

Permissions

Andrei Shustov presentation

- Slide 7: PTCL Prognosis Is Indicative of Diverse Biology

- Reprinted with permission. © 2008 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slide 8: PTCL: Global Epidemiology

- Reprinted with permission. © 2008 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slide 9: PTCL: USA Epidemiology (top half)

- Reprinted with permission. © 2008 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slide 9: PTCL: USA Epidemiology (bottom half)

- Reprinted with permission. © 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slide 10: PTCL Prognosis: Histology x Race (USA)

- Reprinted with permission. © 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slide 12: PTCL Prognosis: Clinical Features (top right side)

- Reprinted with permission. © 2013 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slide 14: PTCL Prognosis: Molecular Classifiers (left side)

- Republished with permission of the American Society of Hematology, from Parilla Castellar ER, et al. Blood 2014;124:1473-1480

- Slide 14: PTCL Prognosis: Molecular Classifiers (right side)

- Republished with permission of the American Society of Hematology, from Iqbal J, et al. Blood 2014;123:2915-2923

- Slide 17: US Epidemiology of PTCL

- Reprinted with permission. © 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slides 18-19: Romidepsin in Relapsed/Refractory PTCL

- Reprinted with permission. © 2012 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slides 20-22, 25: Romidepsin in Elderly Patients

- Shustov A, et al. Romidepsin is effective and well tolerated in older patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma: analysis of two phase II trials. Leuk Lymphoma 2017 [Epub ahead of print]. Reprinted by permission of Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com

- Slides 27-28: Belinostat in Relapsed/Refractory PTCL

- Reprinted with permission. © 2015 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Kensei Tobinai presentation

- Slide 7: Overall Survival of ATL Pts in JCOG 9801

- Reprinted with permission. © 2007 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Disclaimer

The content and views presented in this educational activity are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Hemedicus, the supporter, or Frontline Medical Communications. This material is prepared based upon a review of multiple sources of information, but it is not exhaustive of the subject matter. Therefore, healthcare professionals and other individuals should review and consider other publications and materials on the subject matter before relying solely upon the information contained within this educational activity.

Release Date: August 1, 2017

Expiration Date: July 31, 2018

Note: This activity is no longer available for credit.

Agenda

Developing New Strategic Goals in PTCL (duration 27:00)

Andrei R. Shustov, MD

University of Washington School of Medicine

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center

Seattle, WA, USA

PTCL as a Rare Disease: A Case of Overall Survival (duration 19:00)

Owen A. O’Connor, MD, PhD

Columbia University Medical Center

The New York Presbyterian Hospital

New York, NY, USA

Why Might Response Rates Differ Between the East and West? (duration 17:00)

Kensei Tobinai, MD, PhD

National Cancer Center Hospital

Tokyo, Japan

Provided by:

Original activity supported by an educational grant from:

Spectrum Pharmaceuticals

Learning Objectives

At the end of the activity, participants should be able to:

- Explain why progression-free survival is important when treating patients with PTCL

- Determine when overall survival is possible

- Describe the challenges of using matched control analysis in PTCL clinical trials

- Discuss why different response rates to therapy for PTCL may be seen in Asian patients versus North American or European patients and define the possible contributing factors

Target Audience

Hematologists, oncologists, and other clinicians and scientists with an interest in T-cell lymphoma

Statement of Need

This activity explores clinical endpoints in PTCL, the importance of choosing the appropriate ones and the possibility of achieving them. Global and regional differences in PTCL are also explored as they relate to response rates. The presentations highlight the challenges physicians face in treating PTCL patients and recent developments are discussed to help practitioners evaluate the utility of these endpoints in choosing appropriate treatments to improve outcomes in their patients with PTCL.

FACULTY

Faculty

Andrei R. Shustov, MD

Disclosures: Consulting fee: Celgene; BMS

Owen O’Connor, MD, PhD

Disclosures: Consulting fees: Mundipharma; Celgene; Contracted Research: Mundipharma; Spectrum; Celgene; Seattle Genetics; TG Therapeutics; ADCT; Trillium

Kensei Tobinai, MD, PhD

Disclosures: Honoraria: Eisai; HUYA Bioscience International; Janssen; Mundipharma; Takeda; Zenyaku Kogyo; Contracted research: Abbvie; Celgene; Chugai Pharma; Eisai; GlaxoSmithKline; Janssen; Kyowa Hakko Kirin; Mundipharma; Ono Pharmaceutical; SERVIER; Takeda

Permissions

Andrei Shustov presentation

- Slide 7: PTCL Prognosis Is Indicative of Diverse Biology

- Reprinted with permission. © 2008 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slide 8: PTCL: Global Epidemiology

- Reprinted with permission. © 2008 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slide 9: PTCL: USA Epidemiology (top half)

- Reprinted with permission. © 2008 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slide 9: PTCL: USA Epidemiology (bottom half)

- Reprinted with permission. © 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slide 10: PTCL Prognosis: Histology x Race (USA)

- Reprinted with permission. © 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slide 12: PTCL Prognosis: Clinical Features (top right side)

- Reprinted with permission. © 2013 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slide 14: PTCL Prognosis: Molecular Classifiers (left side)

- Republished with permission of the American Society of Hematology, from Parilla Castellar ER, et al. Blood 2014;124:1473-1480

- Slide 14: PTCL Prognosis: Molecular Classifiers (right side)

- Republished with permission of the American Society of Hematology, from Iqbal J, et al. Blood 2014;123:2915-2923

- Slide 17: US Epidemiology of PTCL

- Reprinted with permission. © 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slides 18-19: Romidepsin in Relapsed/Refractory PTCL

- Reprinted with permission. © 2012 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

- Slides 20-22, 25: Romidepsin in Elderly Patients

- Shustov A, et al. Romidepsin is effective and well tolerated in older patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma: analysis of two phase II trials. Leuk Lymphoma 2017 [Epub ahead of print]. Reprinted by permission of Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com

- Slides 27-28: Belinostat in Relapsed/Refractory PTCL

- Reprinted with permission. © 2015 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Kensei Tobinai presentation

- Slide 7: Overall Survival of ATL Pts in JCOG 9801

- Reprinted with permission. © 2007 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

Disclaimer

The content and views presented in this educational activity are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Hemedicus, the supporter, or Frontline Medical Communications. This material is prepared based upon a review of multiple sources of information, but it is not exhaustive of the subject matter. Therefore, healthcare professionals and other individuals should review and consider other publications and materials on the subject matter before relying solely upon the information contained within this educational activity.

Risk of sexual dysfunction in diabetes is high, but treatments can help

SAN DIEGO –

This isn’t normal for men of that age, according to Hunter B. Wessells, MD.“It’s not just that they’re aging. It’s a 20-year acceleration of the aging process,” he said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

That’s not all. In some cases, men with diabetes may experience decreased libido that’s potentially caused by low testosterone, said Dr. Wessells, professor and Wilma Wise Nelson, Ole A. Nelson, and Mabel Wise Nelson Endowed Chair in Urology at the University of Washington, Seattle

Still, research findings offer useful insights into the frequency of sexual dysfunction in people with diabetes and the potential – and limitations – of available treatments, said Dr. Wessells.

In patients with well-controlled diabetes, “these conditions impact quality of life to a greater degree than complications like nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy,” he said in an interview. “Thus, treatment of urological symptoms can be a high-yield endeavor.”

In both sexes, Dr. Wessells said, diabetes can disrupt the mechanism of desire, arousal, and orgasm by affecting a long list of bodily functions such as central nervous system stimulation, hormone activity, autonomic and somatic nerve activity, and processing of calcium ions and nitric acid.

In men, diabetes boosts the risk of erectile dysfunction to a larger extent than do related conditions such as obesity, heart disease, and depression. “But they are interrelated,” he said. “The primary mechanisms include the metabolic effects of high glucose, autonomic nerve damage, and microvascular disease.”

Low testosterone levels also can cause problems in patients with diabetes, he said. “Type 2 diabetes has greater effects on testosterone than type 1. It is most closely linked to weight in the type 1 population and affects only a small percentage.”

A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of 145 studies with more than 88,000 subjects (average age 55.8 ± 7.9 years) suggests that ED was more common in type 2 diabetes (66.3%) than type 1 diabetes (37.5%) after statistical adjustment to account for publication bias (Diabet Med. 2017 Jul 18. doi: 10.1111/dme.13403).

A smaller analysis found that men with diabetes had almost four times the odds (odd ratio = 3.62) of ED compared with healthy controls (Diabet Med. 2017 Jul 18. doi: 10.1111/dme.13403). Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors – such as sildenafil, vardenafil, and tadalafil – are one option for men with diabetes and ED, Dr. Wessells said. “They work pretty well, but men with diabetes tend to have more severe ED. They’re going to get better, but will they get better enough to be normal? That’s the question.”

A 2007 Cochrane Library analysis found that men with diabetes and ED gained from PDE5 inhibitors overall (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jan 24[1]:CD002187. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002187.pub3).

“They’re not going to do as well as the general population,” Dr. Wessells said, “but we should try these as first-line agents in absence of things like severe unstable cardiovascular disease and other risk factors.”

Second-line therapies, typically offered by urologists, include penile prostheses and injection therapy, he said. A 2014 analysis of previous research found that men with diabetes were “more than 50% more likely to be prescribed secondary ED treatments over the 2-year observation period, and more than twice as likely to undergo penile prosthesis surgery” (Int J Impot Res. 2014 May-Jun;26[3]:112-5).

As for women, a 2009 study found that of 424 sexually active women with type 1 diabetes (97% of whom were white), 35% showed signs of female sexual dysfunction (FSD). Of those with FSD, problems included loss of libido (57%); problems with orgasm (51%), lubrication (47%), and/or arousal (38%); and pain (21%) (Diabetes Care. 2009 May;32[5]:780-5).

Only one drug, flibanserin (Addyi), is approved for FSD in the United States. Its impact on patients with diabetes is unknown, Dr. Wessells said, and the drug has the potential for significant adverse events.

The good news: Research is providing insight into which men and women are more likely to develop sexual dysfunction, Dr. Wessells said.

Age is important in both genders. For women, depression and being married appear to be risk factors, he said. “This needs more exploration to help us understand how to intervene.”

And in men, he said, ED is linked to jumps in hemoglobin A1c, while men on intensive glycemic therapy have a lower risk.

“Maybe we can find out who needs to be targeted for earlier intervention,” he said. This is especially important for men because ED becomes more likely to be irreversible after just a few years, he said.

Dr. Wessells reports no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO –

This isn’t normal for men of that age, according to Hunter B. Wessells, MD.“It’s not just that they’re aging. It’s a 20-year acceleration of the aging process,” he said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

That’s not all. In some cases, men with diabetes may experience decreased libido that’s potentially caused by low testosterone, said Dr. Wessells, professor and Wilma Wise Nelson, Ole A. Nelson, and Mabel Wise Nelson Endowed Chair in Urology at the University of Washington, Seattle

Still, research findings offer useful insights into the frequency of sexual dysfunction in people with diabetes and the potential – and limitations – of available treatments, said Dr. Wessells.

In patients with well-controlled diabetes, “these conditions impact quality of life to a greater degree than complications like nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy,” he said in an interview. “Thus, treatment of urological symptoms can be a high-yield endeavor.”

In both sexes, Dr. Wessells said, diabetes can disrupt the mechanism of desire, arousal, and orgasm by affecting a long list of bodily functions such as central nervous system stimulation, hormone activity, autonomic and somatic nerve activity, and processing of calcium ions and nitric acid.

In men, diabetes boosts the risk of erectile dysfunction to a larger extent than do related conditions such as obesity, heart disease, and depression. “But they are interrelated,” he said. “The primary mechanisms include the metabolic effects of high glucose, autonomic nerve damage, and microvascular disease.”

Low testosterone levels also can cause problems in patients with diabetes, he said. “Type 2 diabetes has greater effects on testosterone than type 1. It is most closely linked to weight in the type 1 population and affects only a small percentage.”

A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of 145 studies with more than 88,000 subjects (average age 55.8 ± 7.9 years) suggests that ED was more common in type 2 diabetes (66.3%) than type 1 diabetes (37.5%) after statistical adjustment to account for publication bias (Diabet Med. 2017 Jul 18. doi: 10.1111/dme.13403).

A smaller analysis found that men with diabetes had almost four times the odds (odd ratio = 3.62) of ED compared with healthy controls (Diabet Med. 2017 Jul 18. doi: 10.1111/dme.13403). Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors – such as sildenafil, vardenafil, and tadalafil – are one option for men with diabetes and ED, Dr. Wessells said. “They work pretty well, but men with diabetes tend to have more severe ED. They’re going to get better, but will they get better enough to be normal? That’s the question.”

A 2007 Cochrane Library analysis found that men with diabetes and ED gained from PDE5 inhibitors overall (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jan 24[1]:CD002187. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002187.pub3).

“They’re not going to do as well as the general population,” Dr. Wessells said, “but we should try these as first-line agents in absence of things like severe unstable cardiovascular disease and other risk factors.”

Second-line therapies, typically offered by urologists, include penile prostheses and injection therapy, he said. A 2014 analysis of previous research found that men with diabetes were “more than 50% more likely to be prescribed secondary ED treatments over the 2-year observation period, and more than twice as likely to undergo penile prosthesis surgery” (Int J Impot Res. 2014 May-Jun;26[3]:112-5).

As for women, a 2009 study found that of 424 sexually active women with type 1 diabetes (97% of whom were white), 35% showed signs of female sexual dysfunction (FSD). Of those with FSD, problems included loss of libido (57%); problems with orgasm (51%), lubrication (47%), and/or arousal (38%); and pain (21%) (Diabetes Care. 2009 May;32[5]:780-5).

Only one drug, flibanserin (Addyi), is approved for FSD in the United States. Its impact on patients with diabetes is unknown, Dr. Wessells said, and the drug has the potential for significant adverse events.

The good news: Research is providing insight into which men and women are more likely to develop sexual dysfunction, Dr. Wessells said.

Age is important in both genders. For women, depression and being married appear to be risk factors, he said. “This needs more exploration to help us understand how to intervene.”

And in men, he said, ED is linked to jumps in hemoglobin A1c, while men on intensive glycemic therapy have a lower risk.

“Maybe we can find out who needs to be targeted for earlier intervention,” he said. This is especially important for men because ED becomes more likely to be irreversible after just a few years, he said.

Dr. Wessells reports no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO –

This isn’t normal for men of that age, according to Hunter B. Wessells, MD.“It’s not just that they’re aging. It’s a 20-year acceleration of the aging process,” he said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

That’s not all. In some cases, men with diabetes may experience decreased libido that’s potentially caused by low testosterone, said Dr. Wessells, professor and Wilma Wise Nelson, Ole A. Nelson, and Mabel Wise Nelson Endowed Chair in Urology at the University of Washington, Seattle

Still, research findings offer useful insights into the frequency of sexual dysfunction in people with diabetes and the potential – and limitations – of available treatments, said Dr. Wessells.

In patients with well-controlled diabetes, “these conditions impact quality of life to a greater degree than complications like nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy,” he said in an interview. “Thus, treatment of urological symptoms can be a high-yield endeavor.”

In both sexes, Dr. Wessells said, diabetes can disrupt the mechanism of desire, arousal, and orgasm by affecting a long list of bodily functions such as central nervous system stimulation, hormone activity, autonomic and somatic nerve activity, and processing of calcium ions and nitric acid.

In men, diabetes boosts the risk of erectile dysfunction to a larger extent than do related conditions such as obesity, heart disease, and depression. “But they are interrelated,” he said. “The primary mechanisms include the metabolic effects of high glucose, autonomic nerve damage, and microvascular disease.”

Low testosterone levels also can cause problems in patients with diabetes, he said. “Type 2 diabetes has greater effects on testosterone than type 1. It is most closely linked to weight in the type 1 population and affects only a small percentage.”

A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of 145 studies with more than 88,000 subjects (average age 55.8 ± 7.9 years) suggests that ED was more common in type 2 diabetes (66.3%) than type 1 diabetes (37.5%) after statistical adjustment to account for publication bias (Diabet Med. 2017 Jul 18. doi: 10.1111/dme.13403).

A smaller analysis found that men with diabetes had almost four times the odds (odd ratio = 3.62) of ED compared with healthy controls (Diabet Med. 2017 Jul 18. doi: 10.1111/dme.13403). Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors – such as sildenafil, vardenafil, and tadalafil – are one option for men with diabetes and ED, Dr. Wessells said. “They work pretty well, but men with diabetes tend to have more severe ED. They’re going to get better, but will they get better enough to be normal? That’s the question.”

A 2007 Cochrane Library analysis found that men with diabetes and ED gained from PDE5 inhibitors overall (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jan 24[1]:CD002187. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002187.pub3).

“They’re not going to do as well as the general population,” Dr. Wessells said, “but we should try these as first-line agents in absence of things like severe unstable cardiovascular disease and other risk factors.”

Second-line therapies, typically offered by urologists, include penile prostheses and injection therapy, he said. A 2014 analysis of previous research found that men with diabetes were “more than 50% more likely to be prescribed secondary ED treatments over the 2-year observation period, and more than twice as likely to undergo penile prosthesis surgery” (Int J Impot Res. 2014 May-Jun;26[3]:112-5).

As for women, a 2009 study found that of 424 sexually active women with type 1 diabetes (97% of whom were white), 35% showed signs of female sexual dysfunction (FSD). Of those with FSD, problems included loss of libido (57%); problems with orgasm (51%), lubrication (47%), and/or arousal (38%); and pain (21%) (Diabetes Care. 2009 May;32[5]:780-5).

Only one drug, flibanserin (Addyi), is approved for FSD in the United States. Its impact on patients with diabetes is unknown, Dr. Wessells said, and the drug has the potential for significant adverse events.

The good news: Research is providing insight into which men and women are more likely to develop sexual dysfunction, Dr. Wessells said.

Age is important in both genders. For women, depression and being married appear to be risk factors, he said. “This needs more exploration to help us understand how to intervene.”

And in men, he said, ED is linked to jumps in hemoglobin A1c, while men on intensive glycemic therapy have a lower risk.

“Maybe we can find out who needs to be targeted for earlier intervention,” he said. This is especially important for men because ED becomes more likely to be irreversible after just a few years, he said.

Dr. Wessells reports no relevant disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

David Henry's JCSO podcast, July-August 2017

For the July-August issue of the Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology, the Editor-in-Chief, Dr David Henry, discusses a recap by Howard Burris, MD, of the top presentations at this year’s annual meeting of the American Society for Clinical Oncology, and a selection of articles on some of the key findings reported at the meeting. A number of articles, in keeping with the journal mission of delivering content that can inform or change daily practice in the community setting, provide ‘how-to’ clinical and supportive advice. They include an outline by Thomas J Smith of Johns Hopkins University of how to initiate goals-of-care conversations with patients and their family members; a review of managing polycythemia vera in the community oncology setting; a New Therapies feature on how immunotherapies are shaping the treatment of hematologic malignancies; and research articles on using Onodera’s Prognostic Nutritional Index to predict wound complications in patients with soft tissue sarcoma, and bone remodeling associated with CTLA-4 inhibition. A third research article assesses a multidisciplinary survivorship program in a group of predominantly Hispanic women with breast cancer. Also in the line-up for discussion are Case Reports, one on managing high-grade pleomorphic sarcoma in a patient with colon metastasis and another on intramedullary spinal cord and leptomeningeal metastases presenting as cauda equina syndrome in a patient with melanoma.

Listen to the podcast below.

For the July-August issue of the Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology, the Editor-in-Chief, Dr David Henry, discusses a recap by Howard Burris, MD, of the top presentations at this year’s annual meeting of the American Society for Clinical Oncology, and a selection of articles on some of the key findings reported at the meeting. A number of articles, in keeping with the journal mission of delivering content that can inform or change daily practice in the community setting, provide ‘how-to’ clinical and supportive advice. They include an outline by Thomas J Smith of Johns Hopkins University of how to initiate goals-of-care conversations with patients and their family members; a review of managing polycythemia vera in the community oncology setting; a New Therapies feature on how immunotherapies are shaping the treatment of hematologic malignancies; and research articles on using Onodera’s Prognostic Nutritional Index to predict wound complications in patients with soft tissue sarcoma, and bone remodeling associated with CTLA-4 inhibition. A third research article assesses a multidisciplinary survivorship program in a group of predominantly Hispanic women with breast cancer. Also in the line-up for discussion are Case Reports, one on managing high-grade pleomorphic sarcoma in a patient with colon metastasis and another on intramedullary spinal cord and leptomeningeal metastases presenting as cauda equina syndrome in a patient with melanoma.

Listen to the podcast below.

For the July-August issue of the Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology, the Editor-in-Chief, Dr David Henry, discusses a recap by Howard Burris, MD, of the top presentations at this year’s annual meeting of the American Society for Clinical Oncology, and a selection of articles on some of the key findings reported at the meeting. A number of articles, in keeping with the journal mission of delivering content that can inform or change daily practice in the community setting, provide ‘how-to’ clinical and supportive advice. They include an outline by Thomas J Smith of Johns Hopkins University of how to initiate goals-of-care conversations with patients and their family members; a review of managing polycythemia vera in the community oncology setting; a New Therapies feature on how immunotherapies are shaping the treatment of hematologic malignancies; and research articles on using Onodera’s Prognostic Nutritional Index to predict wound complications in patients with soft tissue sarcoma, and bone remodeling associated with CTLA-4 inhibition. A third research article assesses a multidisciplinary survivorship program in a group of predominantly Hispanic women with breast cancer. Also in the line-up for discussion are Case Reports, one on managing high-grade pleomorphic sarcoma in a patient with colon metastasis and another on intramedullary spinal cord and leptomeningeal metastases presenting as cauda equina syndrome in a patient with melanoma.

Listen to the podcast below.

2017 Update on contraception

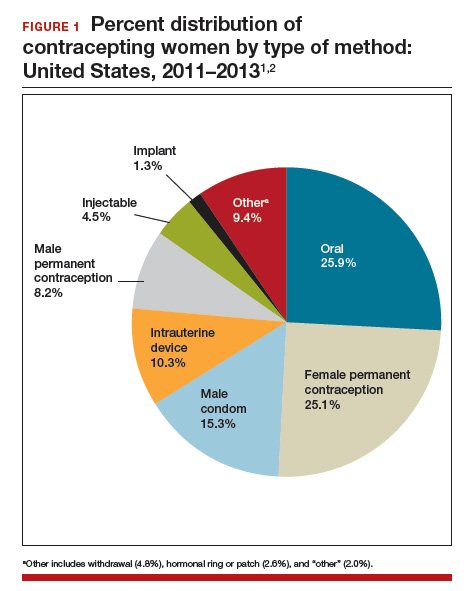

According to the most recent data (2011–2013), 62% of women of childbearing age (15–44 years) use some method of contraception. Of these “contracepting” women, about 25% reported relying on permanent contraception, making it one of the most common methods of contraception used by women in the United States (FIGURE 1).1,2 Women either can choose to have a permanent contraception procedure performed immediately postpartum, which occurs after approximately 9% of all hospital deliveries in the United States,3 or at a time separate from pregnancy.

The most common methods of permanent contraception include partial salpingectomy at the time of cesarean delivery or within 24 hours after vaginal delivery and laparoscopic occlusive procedures at a time unrelated to the postpartum period.3 Hysteroscopic occlusion of the tubal ostia is a newer option, introduced in 2002; its worldwide use is concentrated in the United States, which accounts for 80% of sales based on revenue.4

Historically, for procedures remote from pregnancy, the laparoscopic approach evolved with less sophisticated laparoscopic equipment and limited visualization, which resulted in efficiency and safety being the primary goals of the procedure.5 Accordingly, rapid occlusive procedures were commonplace. However, advancement of laparoscopic technology related to insufflation systems, surgical equipment, and video capabilities did not change this practice.

Recent literature has suggested that complete fallopian tube removal provides additional benefits. With increasing knowledge about the origin of ovarian cancer, as well as increasing data to support the hypothesis that complete tubal excision results in increased ovarian cancer protection when compared with occlusive or partial salpingectomies, both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)6 and the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO)7 recommend discussing bilateral total salpingectomy with patients desiring permanent contraception. Although occlusive procedures decrease a woman’s lifetime risk of ovarian cancer by 24% to 34%,8,9 total salpingectomy likely reduces this risk by 49% to 65%.10,11

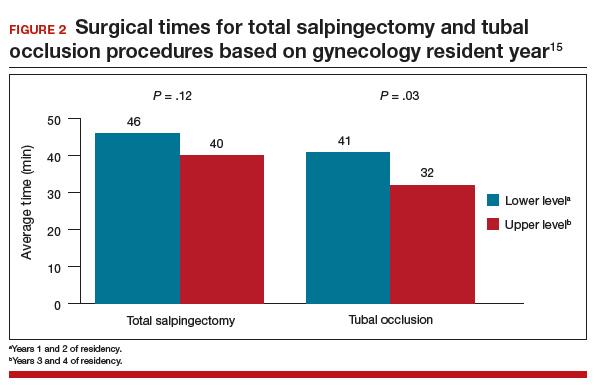

With this new evidence, McAlpine and colleagues initiated an educational campaign, targeting all ObGyns in British Columbia, which outlined the role of the fallopian tube in ovarian cancer and urged the consideration of total salpingectomy for permanent contraception in place of occlusive or partial salpingectomy procedures. They found that this one-time targeted education increased the use of total salpingectomy for permanent contraception from 0.5% at 2 years before the intervention to 33.3% by 2 years afterwards.12 On average, laparoscopic bilateral salpingectomy took 10 minutes longer to complete than occlusive procedures. Most importantly, they found no significant differences in complication rates, including hospital readmissions or blood transfusions.

Although our community can be applauded for the rapid uptake of concomitant bilateral salpingectomy at the time of benign hysterectomy,12,13 offering total salpingectomy for permanent contraception is far from common practice. Similarly, while multiple studies have been published to support the practice of opportunistic salpingectomy at the time of hysterectomy, little has been published about the use of bilateral salpingectomy for permanent contraception until this past year.

In this article, we review some of the first publications to focus specifically on the feasibility and safety profile of performing either immediate postpartum total salpingectomy or interval total salpingectomy in women desiring permanent contraception.

Family Planning experts are now strongly discouraging the use of terms like “sterilization,” “permanent sterilization,” and “tubal ligation” due to sterilization abuses that affected vulnerable and marginalized populations in the United States during the early-to mid-20th century.

In 1907, Indiana was the first state to enact a eugenics-based permanent sterilization law, which initiated an aggressive eugenics movement across the United States. This movement lasted for approximately 70 years and resulted in the sterilization of more than 60,000 women, men, and children against their will or without their knowledge. One of the major contributors to this movement was the state of California, which sterilized more than 20,000 women, men, and children.

They defined sterilization as a prophylactic measure that could simultaneously defend public health, preserve precious fiscal resources, and mitigate menace of the “unfit and feebleminded.” The US eugenics movement even inspired Hitler and the Nazi eugenics movement in Germany.

Because of these reproductive rights atrocities, a large counter movement to protect the rights of women, men, and children resulted in the creation of the Medicaid permanent sterilization consents that we still use today. Although some experts question whether the current Medicaid protective policy should be reevaluated, many are focused on the use of less offensive language when discussing the topic.

Current recommendations are to use the phrase “permanent contraception” or simply refer to the procedure name (salpingectomy, vasectomy, tubal occlusion, etc.) to move away from the connection to the eugenics movement.

Read about a total salpingectomy at delivery

Total salpingectomy: A viable option for permanent contraception after vaginal or at cesarean delivery

Shinar S, Blecher Y, Alpern S, et al. Total bilateral salpingectomy versus partial bilateral salpingectomy for permanent sterilization during cesarean delivery. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295(5):1185-1189.

Danis RB, Della Badia CR, Richard SD. Postpartum permanent sterilization: could bilateral salpingectomy replace bilateral tubal ligation? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23(6):928-932.

Shinar and colleagues presented a retrospective case series that included women undergoing permanent contraception procedures during cesarean delivery at a single tertiary medical center. The authors evaluated outcomes before and after a global hospital policy changed the preferred permanent contraception procedure from partial to total salpingectomy.

Details of the Shinar technique and outcomes

Of the 149 women included, 99 underwent partial salpingectomy via the modified Pomeroy technique and 50 underwent total salpingectomy using an electrothermal bipolar tissue-sealing instrument (Ligasure). The authors found no difference in operative times and similar rates of complications. Composite adverse outcomes, defined as surgery duration greater than 45 minutes, hemoglobin decline greater than 1.2 g/dL, need for blood transfusion, prolonged hospitalization, ICU admission, or re-laparotomy, were comparable and were reported as 30.3% and 36.0% in the partial and total salpingectomy groups, respectively, (P = .57).One major complication occurred in the total salpingectomy cohort; postoperatively the patient had hemodynamic instability and was found to have hemoperitoneum requiring exploratory laparotomy. Significant bleeding from the bilateral mesosalpinges was discovered, presumably directly related to the total salpingectomy.

Related article:

Hysteroscopic tubal occlusion: How new product labeling can be a resource for patient counseling

Details of Danis et al

Intuitively, performing salpingectomy at the time of cesarean delivery does not seem as significant a change in practice as would performing salpingectomy through a small periumbilical incision after vaginal delivery. However, Danis and colleagues did just that; they published a retrospective case series of total salpingectomy performed within 24 hours after a vaginal delivery at an urban, academic institution. They included all women admitted for full-term vaginal deliveries who desired permanent contraception, with no exclusion criteria related to body mass index (BMI). The authors reported on 80 women, including 64 (80%) who underwent partial salpingectomy via the modified Pomeroy or Parkland technique and 16 (20%) who underwent total salpingectomy. Most women had a BMI of less than 30 kg/m2; less than 15% of the women in each group had a BMI greater than 40 kg/m2.

The technique for total salpingectomy involved a 2- to 3-cm vertical incision at the level of the umbilicus, elevation of the entire fallopian tube with 2 Babcock clamps, followed by the development of 2 to 3 windows with monopolar electrocautery in the mesosalpinx and subsequent suture ligation with polyglactin 910 (Vicryl, Ethicon).

Major findings included slightly longer operative time in the total salpingectomy compared with the partial salpingectomy group (a finding consistent with other studies12,14,15) and no difference in complication rates. The average (SD) surgical time in the partial salpingectomy group was 59 (16) minutes, compared with 71 (6) minutes in the total salpingectomy group (P = .003). The authors reported 4 (6.3%) complications in the partial salpingectomy group--ileus, excessive bleeding from mesosalpinx, and incisional site hematoma--and no complications in the total salpingectomy group (P = .58).

These 2 studies, although small retrospective case series, demonstrate the feasibility of performing total salpingectomies with minimal operative time differences when compared with more traditional partial salpingectomy procedures. The re-laparotomy complication noted in the Shinar series cannot be dismissed, as this is a major morbidity, but it also should not dictate the conversation.

Overall, the need for blood transfusion or unintended major surgery after permanent contraception procedures is rare. In the U.S. Collaborative Review of Sterilization study, none of the 282 women who had a permanent contraception procedure performed via laparotomy experienced either of these outcomes.16 Only 1 of the 9,475 women (0.01%) having a laparoscopic procedure in this study required blood transfusion and 14 (0.15%) required reoperation secondary to a procedure complication.17 The complication reported in the Shinar study reminds us that the technique for salpingectomy in the postpartum period, whether partial or total, should be considered carefully, being mindful of the anatomical changes that occur in pregnancy.

While larger studies should be performed to confirm these initial findings, these 2 articles provide the reassurance that many providers may need before beginning to offer total salpingectomy procedures in the immediate postpartum period.