User login

FDA grants priority review of acalabrutinib for second-line treatment of MCL

The Food and Drug Administration has granted a priority review for acalabrutinib, a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) who have received at least one prior therapy.

The new drug application is based on results from the phase 2 ACE-LY-004 trial, which evaluated the safety and efficacy of acalabrutinib in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL who had received at least one prior therapy.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted a priority review for acalabrutinib, a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) who have received at least one prior therapy.

The new drug application is based on results from the phase 2 ACE-LY-004 trial, which evaluated the safety and efficacy of acalabrutinib in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL who had received at least one prior therapy.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted a priority review for acalabrutinib, a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) who have received at least one prior therapy.

The new drug application is based on results from the phase 2 ACE-LY-004 trial, which evaluated the safety and efficacy of acalabrutinib in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL who had received at least one prior therapy.

Ibrutinib becomes first FDA-approved treatment for chronic GVHD

Ibrutinib (Imbruvica) added another notch on its indications belt with its Aug. 2 approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of adult patients with chronic graft versus host disease (cGVHD) after failure of one or more lines of systemic therapy.

The new indication makes ibrutinib the first FDA-approved therapy for the treatment of cGVHD, according to an FDA press release.

Ibrutinib’s other approved indications include chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma with 17p deletion, Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, marginal zone lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma, according to a press release from the FDA.

The recommended dose of ibrutinib for cGVHD is 420 mg (three 140 mg capsules once daily). Prescribing information is available on the FDA website.

Imbruvica is manufactured by Pharmacyclics.

mdales@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @maryjodales

Ibrutinib (Imbruvica) added another notch on its indications belt with its Aug. 2 approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of adult patients with chronic graft versus host disease (cGVHD) after failure of one or more lines of systemic therapy.

The new indication makes ibrutinib the first FDA-approved therapy for the treatment of cGVHD, according to an FDA press release.

Ibrutinib’s other approved indications include chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma with 17p deletion, Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, marginal zone lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma, according to a press release from the FDA.

The recommended dose of ibrutinib for cGVHD is 420 mg (three 140 mg capsules once daily). Prescribing information is available on the FDA website.

Imbruvica is manufactured by Pharmacyclics.

mdales@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @maryjodales

Ibrutinib (Imbruvica) added another notch on its indications belt with its Aug. 2 approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of adult patients with chronic graft versus host disease (cGVHD) after failure of one or more lines of systemic therapy.

The new indication makes ibrutinib the first FDA-approved therapy for the treatment of cGVHD, according to an FDA press release.

Ibrutinib’s other approved indications include chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma with 17p deletion, Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, marginal zone lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma, according to a press release from the FDA.

The recommended dose of ibrutinib for cGVHD is 420 mg (three 140 mg capsules once daily). Prescribing information is available on the FDA website.

Imbruvica is manufactured by Pharmacyclics.

mdales@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @maryjodales

Care of infants with ichthyosis requires ‘all hands on deck’

CHICAGO – The neonatal period and early infancy are especially critical for patients with ichthyosis, because compromised barrier function increases risk for morbidity and mortality.

“There are minimal data presently to guide management of patients with ichthyosis, making it a time of uncertainty,” Brittany Craiglow, MD, said at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology. “You’re going to want to get all hands on deck for the care of these patients. And don’t forget about the family – involve them in the care as much as possible. Reassure them; normalize their feelings, acknowledge them.”

There are six general phenotypes of ichthyosis that differ from the eventual “mature” phenotype and are associated with numerous genes: collodion baby, armor-like scale, exuberant vernix, erythroderma and scale, bullae and erosions, and generalized scale.

The collodion baby phenotype is characterized by a shiny parchment-like membrane that covers the baby’s body, ectropion, and fissures, and is commonly associated with autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis (ARCI). “About 10% of babies with ARCI are self healing, so they’ll go on to have largely normal skin,” Dr. Craiglow said. Guidelines for managing this phenotype can be found in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2012 Dec;67[6]:1362-74).

Armor-like scale is pathognomonic for harlequin ichthyosis. “This condition is associated with the highest mortality in the neonatal period,” she said. “In addition to the potential complications associated with other phenotypes, babies with harlequin ichthyosis can also have issues related to constriction of movement and flexibility and digital ischemia.” Tips for practical management of this phenotype were published online in the journal Pediatrics (2017 Jan;139[1]).

The exuberant vernix/cephalic hyperkeratosis phenotype generally appears in children with keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome (KID) and ichthyosis prematurity syndrome (IPS). Special considerations in KID include a hearing test and ophthalmology exam, while special considerations in IPS include respiratory compromise and atopic diathesis. Electron microscopy is diagnostic, characterized by curvilinear bodies in the granular layer.

The erythroderma and scale phenotype occurs most commonly in ARCI and Netherton syndrome. “Special considerations in Netherton syndrome include failure to thrive/growth failure,” Dr. Craiglow said. “Hair shaft abnormalities are usually present later, and nutritional support is really important.”

Bullae and erosions are hallmark signs of epidermolytic/superficial ichthyosis. On biopsy, epidermolytic hyperkeratosis is diagnostic for this phenotype. At the same time, cases with normal skin or xerosis are suggestive of X-linked ichthyosis, ichthyosis vulgaris, erythrokeratodermas, and Sjögren-Larsson syndrome.

Genetic testing for ichthyosis is generally readily available, Dr. Craiglow said. She advised clinicians to obtain a sample soon after birth to confirm the clinical diagnosis, assist with assessing prognosis, and enable genetic counseling. “It’s important to help identify those at risk for systemic complications,” she said. “Obtaining insurance coverage may be easier when sent during hospital admission.”

Babies with moderate to severe congenital ichthyosis are typically cared for in the neonatal ICU of a tertiary care center by a multidisciplinary team consisting of neonatology, dermatology, nursing, nutrition, and genetics, as well as ophthalmology, otolaryngology, orthopedics, plastic surgery, and spiritual/religious services in many cases. “These babies often have impaired thermoregulation,” Dr. Craiglow said. “They need to be in an isolette, generally with humidity somewhere between 50% and 70% – you don’t want it too high, because they can overheat. It’s also important to get them out of the isolette and into an open crib when they’re ready. That can help with bonding and has been shown to decrease hospital stay.”

Infection is a common culprit for morbidity and mortality. “In general, there are not a lot of data to guide our management; but generally, we don’t recommend prophylactic antibiotics,” Dr. Craiglow said. “Some people do surveillance cultures just to know what microbes are there in case there are signs of infection. Look for level of alertness, because they’re not always going to have a fever. Look for hemodynamic instability, irritability, or poor feeding, and have a low threshold to do your cultures and treat if necessary.”

Pain control is an imperative aspect of pain management.

“Typical newborn pain parameters of facial expression and extremity tone may be hard to interpret,” she said. “Look at heart rate, blood pressure, crying, level of arousal, and have a low threshold to treat for pain, especially prior to changing dressings. Acetaminophen and NSAIDs and even opioids in some cases might be indicated. Families want to know that pain is being adequately controlled.”

Retinoids are generally used in patients with harlequin ichthyosis. “In the United States, we generally use acitretin, but there is no liquid formulation, so you have to enlist help from a compounding pharmacy to mix a formulation of 0.5-0.1 mg/kg per day,” Dr. Craiglow said. “You want to start as soon as you can. Topical retinoids such as tazarotene are also an option.”

Resources that she recommends for parents include the Foundation for Ichthyosis and Related Skin Types, the Ichthyosis Support Group, and the European Network for Ichthyosis.

Dr. Craiglow reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – The neonatal period and early infancy are especially critical for patients with ichthyosis, because compromised barrier function increases risk for morbidity and mortality.

“There are minimal data presently to guide management of patients with ichthyosis, making it a time of uncertainty,” Brittany Craiglow, MD, said at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology. “You’re going to want to get all hands on deck for the care of these patients. And don’t forget about the family – involve them in the care as much as possible. Reassure them; normalize their feelings, acknowledge them.”

There are six general phenotypes of ichthyosis that differ from the eventual “mature” phenotype and are associated with numerous genes: collodion baby, armor-like scale, exuberant vernix, erythroderma and scale, bullae and erosions, and generalized scale.

The collodion baby phenotype is characterized by a shiny parchment-like membrane that covers the baby’s body, ectropion, and fissures, and is commonly associated with autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis (ARCI). “About 10% of babies with ARCI are self healing, so they’ll go on to have largely normal skin,” Dr. Craiglow said. Guidelines for managing this phenotype can be found in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2012 Dec;67[6]:1362-74).

Armor-like scale is pathognomonic for harlequin ichthyosis. “This condition is associated with the highest mortality in the neonatal period,” she said. “In addition to the potential complications associated with other phenotypes, babies with harlequin ichthyosis can also have issues related to constriction of movement and flexibility and digital ischemia.” Tips for practical management of this phenotype were published online in the journal Pediatrics (2017 Jan;139[1]).

The exuberant vernix/cephalic hyperkeratosis phenotype generally appears in children with keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome (KID) and ichthyosis prematurity syndrome (IPS). Special considerations in KID include a hearing test and ophthalmology exam, while special considerations in IPS include respiratory compromise and atopic diathesis. Electron microscopy is diagnostic, characterized by curvilinear bodies in the granular layer.

The erythroderma and scale phenotype occurs most commonly in ARCI and Netherton syndrome. “Special considerations in Netherton syndrome include failure to thrive/growth failure,” Dr. Craiglow said. “Hair shaft abnormalities are usually present later, and nutritional support is really important.”

Bullae and erosions are hallmark signs of epidermolytic/superficial ichthyosis. On biopsy, epidermolytic hyperkeratosis is diagnostic for this phenotype. At the same time, cases with normal skin or xerosis are suggestive of X-linked ichthyosis, ichthyosis vulgaris, erythrokeratodermas, and Sjögren-Larsson syndrome.

Genetic testing for ichthyosis is generally readily available, Dr. Craiglow said. She advised clinicians to obtain a sample soon after birth to confirm the clinical diagnosis, assist with assessing prognosis, and enable genetic counseling. “It’s important to help identify those at risk for systemic complications,” she said. “Obtaining insurance coverage may be easier when sent during hospital admission.”

Babies with moderate to severe congenital ichthyosis are typically cared for in the neonatal ICU of a tertiary care center by a multidisciplinary team consisting of neonatology, dermatology, nursing, nutrition, and genetics, as well as ophthalmology, otolaryngology, orthopedics, plastic surgery, and spiritual/religious services in many cases. “These babies often have impaired thermoregulation,” Dr. Craiglow said. “They need to be in an isolette, generally with humidity somewhere between 50% and 70% – you don’t want it too high, because they can overheat. It’s also important to get them out of the isolette and into an open crib when they’re ready. That can help with bonding and has been shown to decrease hospital stay.”

Infection is a common culprit for morbidity and mortality. “In general, there are not a lot of data to guide our management; but generally, we don’t recommend prophylactic antibiotics,” Dr. Craiglow said. “Some people do surveillance cultures just to know what microbes are there in case there are signs of infection. Look for level of alertness, because they’re not always going to have a fever. Look for hemodynamic instability, irritability, or poor feeding, and have a low threshold to do your cultures and treat if necessary.”

Pain control is an imperative aspect of pain management.

“Typical newborn pain parameters of facial expression and extremity tone may be hard to interpret,” she said. “Look at heart rate, blood pressure, crying, level of arousal, and have a low threshold to treat for pain, especially prior to changing dressings. Acetaminophen and NSAIDs and even opioids in some cases might be indicated. Families want to know that pain is being adequately controlled.”

Retinoids are generally used in patients with harlequin ichthyosis. “In the United States, we generally use acitretin, but there is no liquid formulation, so you have to enlist help from a compounding pharmacy to mix a formulation of 0.5-0.1 mg/kg per day,” Dr. Craiglow said. “You want to start as soon as you can. Topical retinoids such as tazarotene are also an option.”

Resources that she recommends for parents include the Foundation for Ichthyosis and Related Skin Types, the Ichthyosis Support Group, and the European Network for Ichthyosis.

Dr. Craiglow reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – The neonatal period and early infancy are especially critical for patients with ichthyosis, because compromised barrier function increases risk for morbidity and mortality.

“There are minimal data presently to guide management of patients with ichthyosis, making it a time of uncertainty,” Brittany Craiglow, MD, said at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology. “You’re going to want to get all hands on deck for the care of these patients. And don’t forget about the family – involve them in the care as much as possible. Reassure them; normalize their feelings, acknowledge them.”

There are six general phenotypes of ichthyosis that differ from the eventual “mature” phenotype and are associated with numerous genes: collodion baby, armor-like scale, exuberant vernix, erythroderma and scale, bullae and erosions, and generalized scale.

The collodion baby phenotype is characterized by a shiny parchment-like membrane that covers the baby’s body, ectropion, and fissures, and is commonly associated with autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis (ARCI). “About 10% of babies with ARCI are self healing, so they’ll go on to have largely normal skin,” Dr. Craiglow said. Guidelines for managing this phenotype can be found in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2012 Dec;67[6]:1362-74).

Armor-like scale is pathognomonic for harlequin ichthyosis. “This condition is associated with the highest mortality in the neonatal period,” she said. “In addition to the potential complications associated with other phenotypes, babies with harlequin ichthyosis can also have issues related to constriction of movement and flexibility and digital ischemia.” Tips for practical management of this phenotype were published online in the journal Pediatrics (2017 Jan;139[1]).

The exuberant vernix/cephalic hyperkeratosis phenotype generally appears in children with keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome (KID) and ichthyosis prematurity syndrome (IPS). Special considerations in KID include a hearing test and ophthalmology exam, while special considerations in IPS include respiratory compromise and atopic diathesis. Electron microscopy is diagnostic, characterized by curvilinear bodies in the granular layer.

The erythroderma and scale phenotype occurs most commonly in ARCI and Netherton syndrome. “Special considerations in Netherton syndrome include failure to thrive/growth failure,” Dr. Craiglow said. “Hair shaft abnormalities are usually present later, and nutritional support is really important.”

Bullae and erosions are hallmark signs of epidermolytic/superficial ichthyosis. On biopsy, epidermolytic hyperkeratosis is diagnostic for this phenotype. At the same time, cases with normal skin or xerosis are suggestive of X-linked ichthyosis, ichthyosis vulgaris, erythrokeratodermas, and Sjögren-Larsson syndrome.

Genetic testing for ichthyosis is generally readily available, Dr. Craiglow said. She advised clinicians to obtain a sample soon after birth to confirm the clinical diagnosis, assist with assessing prognosis, and enable genetic counseling. “It’s important to help identify those at risk for systemic complications,” she said. “Obtaining insurance coverage may be easier when sent during hospital admission.”

Babies with moderate to severe congenital ichthyosis are typically cared for in the neonatal ICU of a tertiary care center by a multidisciplinary team consisting of neonatology, dermatology, nursing, nutrition, and genetics, as well as ophthalmology, otolaryngology, orthopedics, plastic surgery, and spiritual/religious services in many cases. “These babies often have impaired thermoregulation,” Dr. Craiglow said. “They need to be in an isolette, generally with humidity somewhere between 50% and 70% – you don’t want it too high, because they can overheat. It’s also important to get them out of the isolette and into an open crib when they’re ready. That can help with bonding and has been shown to decrease hospital stay.”

Infection is a common culprit for morbidity and mortality. “In general, there are not a lot of data to guide our management; but generally, we don’t recommend prophylactic antibiotics,” Dr. Craiglow said. “Some people do surveillance cultures just to know what microbes are there in case there are signs of infection. Look for level of alertness, because they’re not always going to have a fever. Look for hemodynamic instability, irritability, or poor feeding, and have a low threshold to do your cultures and treat if necessary.”

Pain control is an imperative aspect of pain management.

“Typical newborn pain parameters of facial expression and extremity tone may be hard to interpret,” she said. “Look at heart rate, blood pressure, crying, level of arousal, and have a low threshold to treat for pain, especially prior to changing dressings. Acetaminophen and NSAIDs and even opioids in some cases might be indicated. Families want to know that pain is being adequately controlled.”

Retinoids are generally used in patients with harlequin ichthyosis. “In the United States, we generally use acitretin, but there is no liquid formulation, so you have to enlist help from a compounding pharmacy to mix a formulation of 0.5-0.1 mg/kg per day,” Dr. Craiglow said. “You want to start as soon as you can. Topical retinoids such as tazarotene are also an option.”

Resources that she recommends for parents include the Foundation for Ichthyosis and Related Skin Types, the Ichthyosis Support Group, and the European Network for Ichthyosis.

Dr. Craiglow reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT WCPD 2017

Manage headache separately from idiopathic intracranial hypertension

Headache in idiopathic intracranial hypertension appears to be clinically independent of raised intracranial pressure and may require a different treatment approach than simply lowering intracranial pressure, say the authors of a study published online July 28 in Headache.

The researchers looked at data from 165 patients with untreated idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) and mild vision loss, who were randomized to weight loss plus acetazolamide or placebo as part of the Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Treatment Trial.

In the 139 patients who had headaches at baseline, the researchers saw no significant correlation between lumbar puncture opening pressure – which was measured at baseline and 6 months – and Headache Impact Test-6 scores, or with the presence or absence of headache (Headache. 2017 Jul 28. doi: 10.1111/head.13153).

The study also failed to show any significant difference in headache outcomes between the acetazolamide and placebo groups at 6 months, although headaches in both groups improved overall during the course of the study.

“A substantial proportion of participants had severe headaches at 6 months, stressing the importance of incorporating other headache treatments,” the authors wrote. “These data support the view that additional treatments beyond those used to lower intracranial pressure are needed to treat the headaches associated with IIH.”

At baseline, participants with headache reported taking a range of symptomatic headache treatments including acetaminophen, ibuprofen, naproxen, and combination medications. Some also reported taking hydrocodone, tramadol, or combination formulations containing codeine.

More than one-third (37%) of the participants were assessed as overusing symptomatic pain medications, and 15 of these met the criteria for overuse of opioids or combination medications. Researchers noted that the mean Headache Impact Test-6 scores were significantly higher in those who were overusing medications, compared with those who weren’t.

The most common headache phenotype was migraine (52%), followed by tension-type headache (22%), probable migraine (16%), and probable tension-type headache (4%), with 7% unclassified.

Patients with headache also experienced associated symptoms such as photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, vomiting, visual loss or obscurations, diplopia, and dizziness.

The study was funded by the National Eye Institute. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Headache in idiopathic intracranial hypertension appears to be clinically independent of raised intracranial pressure and may require a different treatment approach than simply lowering intracranial pressure, say the authors of a study published online July 28 in Headache.

The researchers looked at data from 165 patients with untreated idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) and mild vision loss, who were randomized to weight loss plus acetazolamide or placebo as part of the Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Treatment Trial.

In the 139 patients who had headaches at baseline, the researchers saw no significant correlation between lumbar puncture opening pressure – which was measured at baseline and 6 months – and Headache Impact Test-6 scores, or with the presence or absence of headache (Headache. 2017 Jul 28. doi: 10.1111/head.13153).

The study also failed to show any significant difference in headache outcomes between the acetazolamide and placebo groups at 6 months, although headaches in both groups improved overall during the course of the study.

“A substantial proportion of participants had severe headaches at 6 months, stressing the importance of incorporating other headache treatments,” the authors wrote. “These data support the view that additional treatments beyond those used to lower intracranial pressure are needed to treat the headaches associated with IIH.”

At baseline, participants with headache reported taking a range of symptomatic headache treatments including acetaminophen, ibuprofen, naproxen, and combination medications. Some also reported taking hydrocodone, tramadol, or combination formulations containing codeine.

More than one-third (37%) of the participants were assessed as overusing symptomatic pain medications, and 15 of these met the criteria for overuse of opioids or combination medications. Researchers noted that the mean Headache Impact Test-6 scores were significantly higher in those who were overusing medications, compared with those who weren’t.

The most common headache phenotype was migraine (52%), followed by tension-type headache (22%), probable migraine (16%), and probable tension-type headache (4%), with 7% unclassified.

Patients with headache also experienced associated symptoms such as photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, vomiting, visual loss or obscurations, diplopia, and dizziness.

The study was funded by the National Eye Institute. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Headache in idiopathic intracranial hypertension appears to be clinically independent of raised intracranial pressure and may require a different treatment approach than simply lowering intracranial pressure, say the authors of a study published online July 28 in Headache.

The researchers looked at data from 165 patients with untreated idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) and mild vision loss, who were randomized to weight loss plus acetazolamide or placebo as part of the Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Treatment Trial.

In the 139 patients who had headaches at baseline, the researchers saw no significant correlation between lumbar puncture opening pressure – which was measured at baseline and 6 months – and Headache Impact Test-6 scores, or with the presence or absence of headache (Headache. 2017 Jul 28. doi: 10.1111/head.13153).

The study also failed to show any significant difference in headache outcomes between the acetazolamide and placebo groups at 6 months, although headaches in both groups improved overall during the course of the study.

“A substantial proportion of participants had severe headaches at 6 months, stressing the importance of incorporating other headache treatments,” the authors wrote. “These data support the view that additional treatments beyond those used to lower intracranial pressure are needed to treat the headaches associated with IIH.”

At baseline, participants with headache reported taking a range of symptomatic headache treatments including acetaminophen, ibuprofen, naproxen, and combination medications. Some also reported taking hydrocodone, tramadol, or combination formulations containing codeine.

More than one-third (37%) of the participants were assessed as overusing symptomatic pain medications, and 15 of these met the criteria for overuse of opioids or combination medications. Researchers noted that the mean Headache Impact Test-6 scores were significantly higher in those who were overusing medications, compared with those who weren’t.

The most common headache phenotype was migraine (52%), followed by tension-type headache (22%), probable migraine (16%), and probable tension-type headache (4%), with 7% unclassified.

Patients with headache also experienced associated symptoms such as photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, vomiting, visual loss or obscurations, diplopia, and dizziness.

The study was funded by the National Eye Institute. No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM HEADACHE

Key clinical point: and may require a different treatment approach.

Major finding: There were no significant differences in lumbar puncture opening pressure between patients with and without headache.

Data source: A subanalysis of 139 patients with headaches at baseline in addition to idiopathic intracranial hypertension and mild vision loss in the Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Treatment Trial.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Eye Institute. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Precise cause of pityriasis rosea remains elusive

CHICAGO – Pityriasis rosea was recognized as early as 1798, yet its precise cause remains elusive.

“We still don’t have a lot of information on it, because it’s self limited and it resolves,” John C. Browning, MD, said at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology. “There hasn’t been quite as much of a burning push for research into pityriasis rosea as there has been for pityriasis rubra pilaris, for instance.”

Classic pityriasis rosea (PR) is characterized by oval scaly, erythematous lesions on the trunk and extremities, sparing the face, scalp, palms, and soles, said Dr. Browning, a pediatric dermatologist who is chief of dermatology at the Children’s Hospital of San Antonio, Texas. The hallmark sign is a so-called herald patch, an oval, slightly scaly patch with a pale center, which usually appears on the trunk and remains isolated for about 2 weeks before the generalized papulosquamous eruption begins. This typically lasts for about 45 days but can range from 2 weeks to 5 months.

Symptoms of PR may include malaise, nausea, loss of appetite, headache, difficulty concentrating, irritability, gastrointestinal upset, upper respiratory symptoms, joint pain, lymph node swelling, sore throat, and low-grade fever. Pruritus is variable, both in frequency and in intensity, and can be exacerbated by topical medications. Some studies have found a higher female-to-male ratio, while other studies have shown no such association.

“Only 6% of PR cases have been reported in children under 10 years of age,” Dr. Browning said. “PR in dark-skinned children tends to have more facial involvement and a scaly appearance, compared with lighter-skinned children.”

Human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 and HHV 7, members of the Roseolovirus genus of HHVs, have been implicated in triggering PR. These viruses cause a primary infection and can establish latent infection with reactivation if altered immunity develops.

“That’s probably why we don’t see PR in younger children, because that’s when the primary infection is happening,” Dr. Browning said. “These viruses are commonly acquired during childhood, with adult seroprevalence in the range of 80%-90%. Latency occurs in monocytes, bone marrow progenitor cells, in salivary glands, the brain, and in the kidneys, so it’s pretty widespread.”

He added that controversy exists as to whether HHV 6 and 7 cause PR, because older diagnostic methods only detected the presence of HHV DNA, rather than viral load. “HHV reactivation, rather than primary infection, is more likely the cause of PR as supported by sporadic occurrence of PR, reduced contagiousness, age of PR onset, possible relapse during a limited span of time, and frequent occurrence after stress or immunosuppressive states such as pregnancy,” Dr. Browning said.

Classical presentations of PR are not clinically worrisome, but atypical cases could indicate other triggers, such as drug-induced PR. “This is typically more itchy, can have mucous membrane involvement, and you’re not going to see the herald patch,” he said. “It’s more likely to be confluent with no prodromal symptoms.” Agents that have been implicated in drug-induced PR include isotretinoin, terbinafine, and adalimumab.

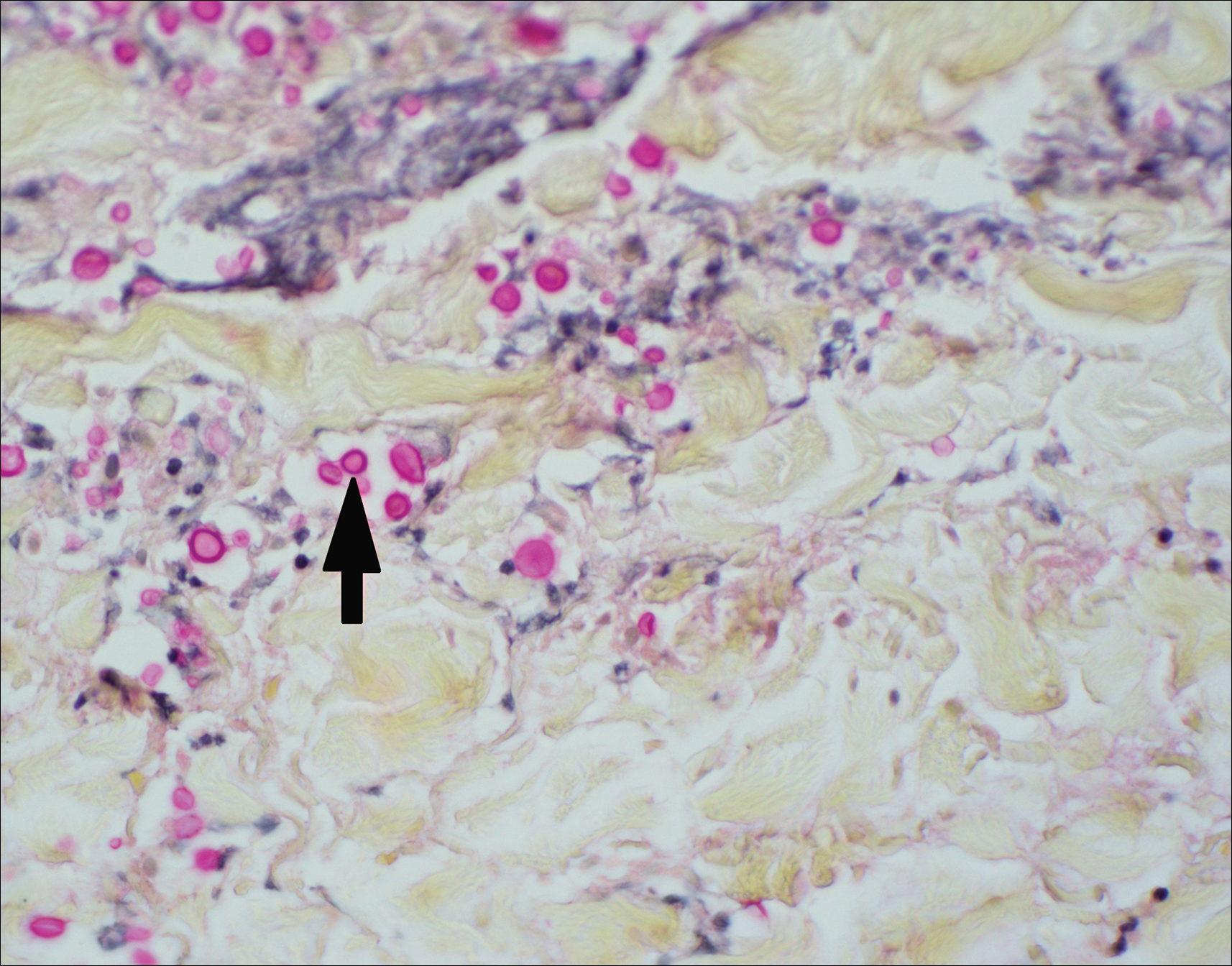

Other conditions that can trigger PR include secondary syphilis (characterized by involvement of the palms and soles, lymphadenopathy, and greater lesional infiltration); seborrheic dermatitis (characterized by greater involvement of the scalp and other hairy parts of the body); nummular eczema (more pruritic); and pityriasis lichenoides chronica, which involves more chronic and relapsing lesions. Histology of PR reveals focal parakeratosis in the epidermis in mounds with exocytosis of lymphocytes, variable spongiosis, mild acanthosis, and a thinned granular layer.

Dr. Browning noted that PR is more common in pregnancy. One study of 38 pregnant women with PR found that 13% miscarried before 16 weeks, compared with a normal miscarriage rate of 10% (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 May; 58[5 Suppl 1]:S78-83). “Neonatal hypotonia, weal motility, and hyporeactivity have been reported,” he said. “And with immunocompromised patients, you might see a longer, protracted course of PR.”

Although no treatment is recommended for classical cases of PR, Dr. Browning said that topical steroids “are widely employed because we all want to do something, especially if there’s some pruritus.” According to a position statement on the management of patients with PR, erythromycin has been reported to shorten the duration of rash and pruritus, but it can cause gastrointestinal disturbance (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016 Oct;30[10]:1670-81). Acyclovir has been reported to hasten clearance of PR in one placebo-controlled study, but PR has also been reported in another patient taking low doses of acyclovir. Phototherapy has also been found to be beneficial.

Dr. Browning reported having no financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – Pityriasis rosea was recognized as early as 1798, yet its precise cause remains elusive.

“We still don’t have a lot of information on it, because it’s self limited and it resolves,” John C. Browning, MD, said at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology. “There hasn’t been quite as much of a burning push for research into pityriasis rosea as there has been for pityriasis rubra pilaris, for instance.”

Classic pityriasis rosea (PR) is characterized by oval scaly, erythematous lesions on the trunk and extremities, sparing the face, scalp, palms, and soles, said Dr. Browning, a pediatric dermatologist who is chief of dermatology at the Children’s Hospital of San Antonio, Texas. The hallmark sign is a so-called herald patch, an oval, slightly scaly patch with a pale center, which usually appears on the trunk and remains isolated for about 2 weeks before the generalized papulosquamous eruption begins. This typically lasts for about 45 days but can range from 2 weeks to 5 months.

Symptoms of PR may include malaise, nausea, loss of appetite, headache, difficulty concentrating, irritability, gastrointestinal upset, upper respiratory symptoms, joint pain, lymph node swelling, sore throat, and low-grade fever. Pruritus is variable, both in frequency and in intensity, and can be exacerbated by topical medications. Some studies have found a higher female-to-male ratio, while other studies have shown no such association.

“Only 6% of PR cases have been reported in children under 10 years of age,” Dr. Browning said. “PR in dark-skinned children tends to have more facial involvement and a scaly appearance, compared with lighter-skinned children.”

Human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 and HHV 7, members of the Roseolovirus genus of HHVs, have been implicated in triggering PR. These viruses cause a primary infection and can establish latent infection with reactivation if altered immunity develops.

“That’s probably why we don’t see PR in younger children, because that’s when the primary infection is happening,” Dr. Browning said. “These viruses are commonly acquired during childhood, with adult seroprevalence in the range of 80%-90%. Latency occurs in monocytes, bone marrow progenitor cells, in salivary glands, the brain, and in the kidneys, so it’s pretty widespread.”

He added that controversy exists as to whether HHV 6 and 7 cause PR, because older diagnostic methods only detected the presence of HHV DNA, rather than viral load. “HHV reactivation, rather than primary infection, is more likely the cause of PR as supported by sporadic occurrence of PR, reduced contagiousness, age of PR onset, possible relapse during a limited span of time, and frequent occurrence after stress or immunosuppressive states such as pregnancy,” Dr. Browning said.

Classical presentations of PR are not clinically worrisome, but atypical cases could indicate other triggers, such as drug-induced PR. “This is typically more itchy, can have mucous membrane involvement, and you’re not going to see the herald patch,” he said. “It’s more likely to be confluent with no prodromal symptoms.” Agents that have been implicated in drug-induced PR include isotretinoin, terbinafine, and adalimumab.

Other conditions that can trigger PR include secondary syphilis (characterized by involvement of the palms and soles, lymphadenopathy, and greater lesional infiltration); seborrheic dermatitis (characterized by greater involvement of the scalp and other hairy parts of the body); nummular eczema (more pruritic); and pityriasis lichenoides chronica, which involves more chronic and relapsing lesions. Histology of PR reveals focal parakeratosis in the epidermis in mounds with exocytosis of lymphocytes, variable spongiosis, mild acanthosis, and a thinned granular layer.

Dr. Browning noted that PR is more common in pregnancy. One study of 38 pregnant women with PR found that 13% miscarried before 16 weeks, compared with a normal miscarriage rate of 10% (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 May; 58[5 Suppl 1]:S78-83). “Neonatal hypotonia, weal motility, and hyporeactivity have been reported,” he said. “And with immunocompromised patients, you might see a longer, protracted course of PR.”

Although no treatment is recommended for classical cases of PR, Dr. Browning said that topical steroids “are widely employed because we all want to do something, especially if there’s some pruritus.” According to a position statement on the management of patients with PR, erythromycin has been reported to shorten the duration of rash and pruritus, but it can cause gastrointestinal disturbance (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016 Oct;30[10]:1670-81). Acyclovir has been reported to hasten clearance of PR in one placebo-controlled study, but PR has also been reported in another patient taking low doses of acyclovir. Phototherapy has also been found to be beneficial.

Dr. Browning reported having no financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – Pityriasis rosea was recognized as early as 1798, yet its precise cause remains elusive.

“We still don’t have a lot of information on it, because it’s self limited and it resolves,” John C. Browning, MD, said at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology. “There hasn’t been quite as much of a burning push for research into pityriasis rosea as there has been for pityriasis rubra pilaris, for instance.”

Classic pityriasis rosea (PR) is characterized by oval scaly, erythematous lesions on the trunk and extremities, sparing the face, scalp, palms, and soles, said Dr. Browning, a pediatric dermatologist who is chief of dermatology at the Children’s Hospital of San Antonio, Texas. The hallmark sign is a so-called herald patch, an oval, slightly scaly patch with a pale center, which usually appears on the trunk and remains isolated for about 2 weeks before the generalized papulosquamous eruption begins. This typically lasts for about 45 days but can range from 2 weeks to 5 months.

Symptoms of PR may include malaise, nausea, loss of appetite, headache, difficulty concentrating, irritability, gastrointestinal upset, upper respiratory symptoms, joint pain, lymph node swelling, sore throat, and low-grade fever. Pruritus is variable, both in frequency and in intensity, and can be exacerbated by topical medications. Some studies have found a higher female-to-male ratio, while other studies have shown no such association.

“Only 6% of PR cases have been reported in children under 10 years of age,” Dr. Browning said. “PR in dark-skinned children tends to have more facial involvement and a scaly appearance, compared with lighter-skinned children.”

Human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 and HHV 7, members of the Roseolovirus genus of HHVs, have been implicated in triggering PR. These viruses cause a primary infection and can establish latent infection with reactivation if altered immunity develops.

“That’s probably why we don’t see PR in younger children, because that’s when the primary infection is happening,” Dr. Browning said. “These viruses are commonly acquired during childhood, with adult seroprevalence in the range of 80%-90%. Latency occurs in monocytes, bone marrow progenitor cells, in salivary glands, the brain, and in the kidneys, so it’s pretty widespread.”

He added that controversy exists as to whether HHV 6 and 7 cause PR, because older diagnostic methods only detected the presence of HHV DNA, rather than viral load. “HHV reactivation, rather than primary infection, is more likely the cause of PR as supported by sporadic occurrence of PR, reduced contagiousness, age of PR onset, possible relapse during a limited span of time, and frequent occurrence after stress or immunosuppressive states such as pregnancy,” Dr. Browning said.

Classical presentations of PR are not clinically worrisome, but atypical cases could indicate other triggers, such as drug-induced PR. “This is typically more itchy, can have mucous membrane involvement, and you’re not going to see the herald patch,” he said. “It’s more likely to be confluent with no prodromal symptoms.” Agents that have been implicated in drug-induced PR include isotretinoin, terbinafine, and adalimumab.

Other conditions that can trigger PR include secondary syphilis (characterized by involvement of the palms and soles, lymphadenopathy, and greater lesional infiltration); seborrheic dermatitis (characterized by greater involvement of the scalp and other hairy parts of the body); nummular eczema (more pruritic); and pityriasis lichenoides chronica, which involves more chronic and relapsing lesions. Histology of PR reveals focal parakeratosis in the epidermis in mounds with exocytosis of lymphocytes, variable spongiosis, mild acanthosis, and a thinned granular layer.

Dr. Browning noted that PR is more common in pregnancy. One study of 38 pregnant women with PR found that 13% miscarried before 16 weeks, compared with a normal miscarriage rate of 10% (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 May; 58[5 Suppl 1]:S78-83). “Neonatal hypotonia, weal motility, and hyporeactivity have been reported,” he said. “And with immunocompromised patients, you might see a longer, protracted course of PR.”

Although no treatment is recommended for classical cases of PR, Dr. Browning said that topical steroids “are widely employed because we all want to do something, especially if there’s some pruritus.” According to a position statement on the management of patients with PR, erythromycin has been reported to shorten the duration of rash and pruritus, but it can cause gastrointestinal disturbance (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016 Oct;30[10]:1670-81). Acyclovir has been reported to hasten clearance of PR in one placebo-controlled study, but PR has also been reported in another patient taking low doses of acyclovir. Phototherapy has also been found to be beneficial.

Dr. Browning reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCPD 2017

How Can Neurologists Help Manage Symptoms in Patients With ALS?

Prognosis and Multidisciplinary Care

ALS is a rare degenerative disorder of motor neurons of the cerebral cortex, brainstem, and spinal cord that results in progressive wasting and paralysis of voluntary muscles. The median age of onset is 55, and the disease has a slight male predominance. Fifty percent of patients with ALS die within three years of symptoms onset; 90% of patients die within five years. Patients with bulbar-onset ALS are more likely to die sooner. Riluzole is the only FDA-approved disease-modifying therapy for patients with ALS. Studies have indicated that this drug extends median survival by two to three months.

In addition, data suggest that multidisciplinary care improves quality of life and survival in patients with ALS. Traynor et al found that survival increased by 7.5 months among all patients in multidisciplinary clinics; patients with bulbar onset lived 9.5 months longer.

Managing Muscle Cramps

Recent studies suggest that muscle cramps occur in 85% of patients with ALS. Cramps can vary in severity and can be debilitating, said Dr. Weiss. Some patients can have as many as 50 cramps per day. Few efficacious treatments for managing this symptom of ALS are available. A recent trial showed that patients who received either 300 mg or 900 mg of mexiletine experienced significant declines in cramping.

Spasticity

It is common for patients with ALS to develop spasticity. Several therapies that may reduce spasticity include baclofen, tizanidine, diazepam, and botulinum toxin injections. The baclofen pump might be more helpful than these therapies for patients who have upper motor neuron dominance.

Sialorrhea

Sialorrhea occurs when patients are unable to clear extra saliva due to weakness in the oropharyngeal muscles. Doses of 600 mg to 1,200 mg of guaifenesin twice per day may be beneficial in managing sialorrhea. Other drying agents such as atropine drops and glycopyrrolate may also be efficacious. These drying agents may cause urinary retention in older patients, Dr. Weiss cautioned.

Amitriptyline can also help manage sialorrhea. It also improves sleep and reduces depression. Hyoscyamine, the transdermal scopolamine patch, and botulinum toxin injections into the submandibular glands may also be beneficial for patients. A suction machine or a mechanical in-exsufflator can also help manage this symptom of ALS.

Emotional Incontinence and Depression

Pseudobulbar affect, also known as emotional incontinence, affects as much as 50% of patients with ALS and is more common in bulbar ALS. This condition causes patients to have uncontrollable episodes of laughing and crying that are inconsistent with the patients’ mood. A randomized controlled trial found that dextromethorphan–quinidine was beneficial in managing these emotional symptoms. Other treatments include tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Reactive clinical depression occurs in 9% to 11% of patients with ALS. Once the ALS diagnosis is confirmed, patients should be counseled about their prognosis; their spouses and family members should also be offered counseling. Antidepressants such as tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors should be offered to all patients. These drugs may help to elevate mood, stimulate appetite, and improve sleep.

Respiratory Insufficiency and Falls

Respiratory insufficiency is one of the leading causes of death among patients with ALS. Patients with this condition may have morning headaches, vivid dreams and nightmares, frequent nocturnal arousals, fatigue, excessive daytime somnolence, and dyspnea on exertion. The American Academy of Neurology recommends that patients start noninvasive ventilation if their sniff nasal pressure is less than 40 cm, their maximal inspiratory pressure is less than –60 cm, or their forced vital capacity is less than 50%.

Bourke et al found that noninvasive ventilation was associated with improvement in quality of life and survival in patients with ALS. The median survival was increased by 205 days, and quality of life was maintained above 75% of baseline on the sleep apnea quality of life index score. In addition, patients who have a peak cough expiratory flow of less than 270 L/min should be offered a mechanical in-exsufflator suction device. If the patient does not tolerate noninvasive ventilation, then palliative medicine and hospice may be appropriate, said Dr. Weiss.

Evidence suggests that 2% of patients with ALS die from fall-related complications. Risk factors for falls in ALS include muscle weakness, deficits in gait or balance, and cognitive impairment. Assistive devices, wheelchairs, and physical therapy can help prevent falls. Some patients may need a brace to help stabilize their gait.

Managing Frontotemporal Dementia

Research suggests that 10% of patients with ALS develop frontotemporal dementia. Nearly 50% of these patients demonstrate behavioral changes such as apathy, disinhibition, and hostility. In addition, the incidence of frontotemporal dementia is higher in patients with familial ALS. The treatment of frontotemporal dementia remains symptomatic.

Observational studies have indicated that antidepressant medications, particularly serotonin reuptake inhibitors like sertraline, paroxetine, and trazadone, decrease disinhibition, anxiety, repetitive behaviors, and impulsivity. Although antipsychotic medications like quetiapine or olanzapine can limit agitation, they must be used cautiously, as they can cause extrapyramidal side effects. In addition, behavioral modification may also be helpful for problematic behavior. Finally, these patients

Dysphagia and Malnourishment

Between 16% and 55% of patients with ALS become malnourished because of dysphagia. This condition is characterized by difficulty with chewing and swallowing, nasal regurgitation, or coughing when drinking liquids. Nutritional status must be monitored every three months in patients with ALS, said Dr. Weiss. In addition, their BMI must be calculated and their weight measured. Paganoni et al found that the risk of death increased sevenfold in patients with ALS who had a BMI less than 18.5. Patients with ALS also need to be queried about the severity of choking, duration of meals, and caloric intake. A speech therapist should evaluate patients at every visit. Dietary changes might also be necessary and may include thickening liquids and preparing food that forms easily into a bolus.

As this disease progresses, patients may need a percutaneous gastrostomy (PEG) tube. According to the American Academy of Neurology practice guidelines, it is time to discuss PEG placement when a patient with ALS starts to lose weight. When a patient’s forced vital capacity is over 50%, the procedure can be done safely. When it is less than 50%, the procedure entails an increased risk of complications, including death.

Managing Dysarthria and Hospice

More than 95% of patients with ALS lose their ability to speak before they die. This condition, known as dysarthria, is difficult to treat. Almost all patients with bulbar-onset ALS and nearly 70% of patients with spinal-onset ALS develop dysarthria. Alternative augmentative communication devices and speech pathologists can be helpful. The Speakit application is a free speech-generating device available for the iPad, and a DynaVox device is a more costly augmentative and alternative communication tool. These devices help patients to communicate their needs and to stay connected to others.

As ALS advances, patients might require palliative medicine or hospice care. Before a patient reaches advanced stages of the disease, he or she should fill out a directive and Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment form, said Dr. Weiss. Patients must meet one of two criteria to receive Medicare reimbursement for hospice care. The first is a forced vital capacity of less than 30% with dyspnea at rest. The second is rapid progression of the disease with life-threatening complications (eg, infections) over 12 months or severe nutritional impairment over 12 months. Treatments for terminal dyspnea include morphine sulfate, oxygen, lorazepam, and chlorpromazine. These medications may depress respiratory drive, however, said Dr. Weiss.

Current Research and Recently Completed Trials

Smith et al found that dextromethorphan–quinidine may improve bulbar function. In addition, recent studies have found that diaphragmatic pacing, an FDA-approved technique, shortened the survival of patients with ALS by one year. An interanalysis found that patients using the diaphragmatic pacer died prematurely, compared with patients who had sham surgery in which electrodes were not implanted. Several phase II studies have suggested that tirasemtiv is substantially beneficial in decelerating slow vital capacity. Finally, a 24-week randomized controlled trial found that edaravone improved function in patients with definite or probable ALS. Edaravone was FDA-approved in May 2017.

—Erica Tricarico

Suggested Reading

Miller RG, Mitchell JD, Moore DH. Riluzole for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)/motor neuron disease (MND). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(3):CD001447.

Miller RG, Jackson CE, Kasarskis EJ, et al. Practice parameter update: the care of the patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: drug, nutritional, and respiratory therapies (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2009;73(15):1218-1226.

Paganoni S, Deng J, Jaffa M, et al. Body mass index, not dyslipidemia, is an independent predictor of survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 2011;44(1):20-24.

Shefner JM, Wolff AA, Meng L, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase IIb trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of tirasemtiv in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2016;17(5-6):426-435.

Smith R, Pioro E, Myers K, et al. Enhanced bulbar function in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: The nuedexta treatment trial. Neurotherapeutics. 2017 Jan 9 [Epub ahead of print].

Traynor BJ, Alexander M, Corr B, et al. Effect of multidisciplinary amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) clinic on ALS survival: a population based study, 1996-2000. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(9):1258-1261.

Weiss MD, Macklin EA, Simmons Z, et al. A randomized trial of mexiletine in ALS: Safety and effects on muscle cramps and progression. Neurology. 2016;86(16):1474-1481.

Prognosis and Multidisciplinary Care

ALS is a rare degenerative disorder of motor neurons of the cerebral cortex, brainstem, and spinal cord that results in progressive wasting and paralysis of voluntary muscles. The median age of onset is 55, and the disease has a slight male predominance. Fifty percent of patients with ALS die within three years of symptoms onset; 90% of patients die within five years. Patients with bulbar-onset ALS are more likely to die sooner. Riluzole is the only FDA-approved disease-modifying therapy for patients with ALS. Studies have indicated that this drug extends median survival by two to three months.

In addition, data suggest that multidisciplinary care improves quality of life and survival in patients with ALS. Traynor et al found that survival increased by 7.5 months among all patients in multidisciplinary clinics; patients with bulbar onset lived 9.5 months longer.

Managing Muscle Cramps

Recent studies suggest that muscle cramps occur in 85% of patients with ALS. Cramps can vary in severity and can be debilitating, said Dr. Weiss. Some patients can have as many as 50 cramps per day. Few efficacious treatments for managing this symptom of ALS are available. A recent trial showed that patients who received either 300 mg or 900 mg of mexiletine experienced significant declines in cramping.

Spasticity

It is common for patients with ALS to develop spasticity. Several therapies that may reduce spasticity include baclofen, tizanidine, diazepam, and botulinum toxin injections. The baclofen pump might be more helpful than these therapies for patients who have upper motor neuron dominance.

Sialorrhea

Sialorrhea occurs when patients are unable to clear extra saliva due to weakness in the oropharyngeal muscles. Doses of 600 mg to 1,200 mg of guaifenesin twice per day may be beneficial in managing sialorrhea. Other drying agents such as atropine drops and glycopyrrolate may also be efficacious. These drying agents may cause urinary retention in older patients, Dr. Weiss cautioned.

Amitriptyline can also help manage sialorrhea. It also improves sleep and reduces depression. Hyoscyamine, the transdermal scopolamine patch, and botulinum toxin injections into the submandibular glands may also be beneficial for patients. A suction machine or a mechanical in-exsufflator can also help manage this symptom of ALS.

Emotional Incontinence and Depression

Pseudobulbar affect, also known as emotional incontinence, affects as much as 50% of patients with ALS and is more common in bulbar ALS. This condition causes patients to have uncontrollable episodes of laughing and crying that are inconsistent with the patients’ mood. A randomized controlled trial found that dextromethorphan–quinidine was beneficial in managing these emotional symptoms. Other treatments include tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Reactive clinical depression occurs in 9% to 11% of patients with ALS. Once the ALS diagnosis is confirmed, patients should be counseled about their prognosis; their spouses and family members should also be offered counseling. Antidepressants such as tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors should be offered to all patients. These drugs may help to elevate mood, stimulate appetite, and improve sleep.

Respiratory Insufficiency and Falls

Respiratory insufficiency is one of the leading causes of death among patients with ALS. Patients with this condition may have morning headaches, vivid dreams and nightmares, frequent nocturnal arousals, fatigue, excessive daytime somnolence, and dyspnea on exertion. The American Academy of Neurology recommends that patients start noninvasive ventilation if their sniff nasal pressure is less than 40 cm, their maximal inspiratory pressure is less than –60 cm, or their forced vital capacity is less than 50%.

Bourke et al found that noninvasive ventilation was associated with improvement in quality of life and survival in patients with ALS. The median survival was increased by 205 days, and quality of life was maintained above 75% of baseline on the sleep apnea quality of life index score. In addition, patients who have a peak cough expiratory flow of less than 270 L/min should be offered a mechanical in-exsufflator suction device. If the patient does not tolerate noninvasive ventilation, then palliative medicine and hospice may be appropriate, said Dr. Weiss.

Evidence suggests that 2% of patients with ALS die from fall-related complications. Risk factors for falls in ALS include muscle weakness, deficits in gait or balance, and cognitive impairment. Assistive devices, wheelchairs, and physical therapy can help prevent falls. Some patients may need a brace to help stabilize their gait.

Managing Frontotemporal Dementia

Research suggests that 10% of patients with ALS develop frontotemporal dementia. Nearly 50% of these patients demonstrate behavioral changes such as apathy, disinhibition, and hostility. In addition, the incidence of frontotemporal dementia is higher in patients with familial ALS. The treatment of frontotemporal dementia remains symptomatic.

Observational studies have indicated that antidepressant medications, particularly serotonin reuptake inhibitors like sertraline, paroxetine, and trazadone, decrease disinhibition, anxiety, repetitive behaviors, and impulsivity. Although antipsychotic medications like quetiapine or olanzapine can limit agitation, they must be used cautiously, as they can cause extrapyramidal side effects. In addition, behavioral modification may also be helpful for problematic behavior. Finally, these patients

Dysphagia and Malnourishment

Between 16% and 55% of patients with ALS become malnourished because of dysphagia. This condition is characterized by difficulty with chewing and swallowing, nasal regurgitation, or coughing when drinking liquids. Nutritional status must be monitored every three months in patients with ALS, said Dr. Weiss. In addition, their BMI must be calculated and their weight measured. Paganoni et al found that the risk of death increased sevenfold in patients with ALS who had a BMI less than 18.5. Patients with ALS also need to be queried about the severity of choking, duration of meals, and caloric intake. A speech therapist should evaluate patients at every visit. Dietary changes might also be necessary and may include thickening liquids and preparing food that forms easily into a bolus.

As this disease progresses, patients may need a percutaneous gastrostomy (PEG) tube. According to the American Academy of Neurology practice guidelines, it is time to discuss PEG placement when a patient with ALS starts to lose weight. When a patient’s forced vital capacity is over 50%, the procedure can be done safely. When it is less than 50%, the procedure entails an increased risk of complications, including death.

Managing Dysarthria and Hospice

More than 95% of patients with ALS lose their ability to speak before they die. This condition, known as dysarthria, is difficult to treat. Almost all patients with bulbar-onset ALS and nearly 70% of patients with spinal-onset ALS develop dysarthria. Alternative augmentative communication devices and speech pathologists can be helpful. The Speakit application is a free speech-generating device available for the iPad, and a DynaVox device is a more costly augmentative and alternative communication tool. These devices help patients to communicate their needs and to stay connected to others.

As ALS advances, patients might require palliative medicine or hospice care. Before a patient reaches advanced stages of the disease, he or she should fill out a directive and Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment form, said Dr. Weiss. Patients must meet one of two criteria to receive Medicare reimbursement for hospice care. The first is a forced vital capacity of less than 30% with dyspnea at rest. The second is rapid progression of the disease with life-threatening complications (eg, infections) over 12 months or severe nutritional impairment over 12 months. Treatments for terminal dyspnea include morphine sulfate, oxygen, lorazepam, and chlorpromazine. These medications may depress respiratory drive, however, said Dr. Weiss.

Current Research and Recently Completed Trials

Smith et al found that dextromethorphan–quinidine may improve bulbar function. In addition, recent studies have found that diaphragmatic pacing, an FDA-approved technique, shortened the survival of patients with ALS by one year. An interanalysis found that patients using the diaphragmatic pacer died prematurely, compared with patients who had sham surgery in which electrodes were not implanted. Several phase II studies have suggested that tirasemtiv is substantially beneficial in decelerating slow vital capacity. Finally, a 24-week randomized controlled trial found that edaravone improved function in patients with definite or probable ALS. Edaravone was FDA-approved in May 2017.

—Erica Tricarico

Suggested Reading

Miller RG, Mitchell JD, Moore DH. Riluzole for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)/motor neuron disease (MND). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(3):CD001447.

Miller RG, Jackson CE, Kasarskis EJ, et al. Practice parameter update: the care of the patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: drug, nutritional, and respiratory therapies (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2009;73(15):1218-1226.

Paganoni S, Deng J, Jaffa M, et al. Body mass index, not dyslipidemia, is an independent predictor of survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 2011;44(1):20-24.

Shefner JM, Wolff AA, Meng L, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase IIb trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of tirasemtiv in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2016;17(5-6):426-435.

Smith R, Pioro E, Myers K, et al. Enhanced bulbar function in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: The nuedexta treatment trial. Neurotherapeutics. 2017 Jan 9 [Epub ahead of print].

Traynor BJ, Alexander M, Corr B, et al. Effect of multidisciplinary amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) clinic on ALS survival: a population based study, 1996-2000. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(9):1258-1261.

Weiss MD, Macklin EA, Simmons Z, et al. A randomized trial of mexiletine in ALS: Safety and effects on muscle cramps and progression. Neurology. 2016;86(16):1474-1481.

Prognosis and Multidisciplinary Care

ALS is a rare degenerative disorder of motor neurons of the cerebral cortex, brainstem, and spinal cord that results in progressive wasting and paralysis of voluntary muscles. The median age of onset is 55, and the disease has a slight male predominance. Fifty percent of patients with ALS die within three years of symptoms onset; 90% of patients die within five years. Patients with bulbar-onset ALS are more likely to die sooner. Riluzole is the only FDA-approved disease-modifying therapy for patients with ALS. Studies have indicated that this drug extends median survival by two to three months.

In addition, data suggest that multidisciplinary care improves quality of life and survival in patients with ALS. Traynor et al found that survival increased by 7.5 months among all patients in multidisciplinary clinics; patients with bulbar onset lived 9.5 months longer.

Managing Muscle Cramps

Recent studies suggest that muscle cramps occur in 85% of patients with ALS. Cramps can vary in severity and can be debilitating, said Dr. Weiss. Some patients can have as many as 50 cramps per day. Few efficacious treatments for managing this symptom of ALS are available. A recent trial showed that patients who received either 300 mg or 900 mg of mexiletine experienced significant declines in cramping.

Spasticity

It is common for patients with ALS to develop spasticity. Several therapies that may reduce spasticity include baclofen, tizanidine, diazepam, and botulinum toxin injections. The baclofen pump might be more helpful than these therapies for patients who have upper motor neuron dominance.

Sialorrhea

Sialorrhea occurs when patients are unable to clear extra saliva due to weakness in the oropharyngeal muscles. Doses of 600 mg to 1,200 mg of guaifenesin twice per day may be beneficial in managing sialorrhea. Other drying agents such as atropine drops and glycopyrrolate may also be efficacious. These drying agents may cause urinary retention in older patients, Dr. Weiss cautioned.

Amitriptyline can also help manage sialorrhea. It also improves sleep and reduces depression. Hyoscyamine, the transdermal scopolamine patch, and botulinum toxin injections into the submandibular glands may also be beneficial for patients. A suction machine or a mechanical in-exsufflator can also help manage this symptom of ALS.

Emotional Incontinence and Depression

Pseudobulbar affect, also known as emotional incontinence, affects as much as 50% of patients with ALS and is more common in bulbar ALS. This condition causes patients to have uncontrollable episodes of laughing and crying that are inconsistent with the patients’ mood. A randomized controlled trial found that dextromethorphan–quinidine was beneficial in managing these emotional symptoms. Other treatments include tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Reactive clinical depression occurs in 9% to 11% of patients with ALS. Once the ALS diagnosis is confirmed, patients should be counseled about their prognosis; their spouses and family members should also be offered counseling. Antidepressants such as tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors should be offered to all patients. These drugs may help to elevate mood, stimulate appetite, and improve sleep.

Respiratory Insufficiency and Falls

Respiratory insufficiency is one of the leading causes of death among patients with ALS. Patients with this condition may have morning headaches, vivid dreams and nightmares, frequent nocturnal arousals, fatigue, excessive daytime somnolence, and dyspnea on exertion. The American Academy of Neurology recommends that patients start noninvasive ventilation if their sniff nasal pressure is less than 40 cm, their maximal inspiratory pressure is less than –60 cm, or their forced vital capacity is less than 50%.

Bourke et al found that noninvasive ventilation was associated with improvement in quality of life and survival in patients with ALS. The median survival was increased by 205 days, and quality of life was maintained above 75% of baseline on the sleep apnea quality of life index score. In addition, patients who have a peak cough expiratory flow of less than 270 L/min should be offered a mechanical in-exsufflator suction device. If the patient does not tolerate noninvasive ventilation, then palliative medicine and hospice may be appropriate, said Dr. Weiss.

Evidence suggests that 2% of patients with ALS die from fall-related complications. Risk factors for falls in ALS include muscle weakness, deficits in gait or balance, and cognitive impairment. Assistive devices, wheelchairs, and physical therapy can help prevent falls. Some patients may need a brace to help stabilize their gait.

Managing Frontotemporal Dementia

Research suggests that 10% of patients with ALS develop frontotemporal dementia. Nearly 50% of these patients demonstrate behavioral changes such as apathy, disinhibition, and hostility. In addition, the incidence of frontotemporal dementia is higher in patients with familial ALS. The treatment of frontotemporal dementia remains symptomatic.

Observational studies have indicated that antidepressant medications, particularly serotonin reuptake inhibitors like sertraline, paroxetine, and trazadone, decrease disinhibition, anxiety, repetitive behaviors, and impulsivity. Although antipsychotic medications like quetiapine or olanzapine can limit agitation, they must be used cautiously, as they can cause extrapyramidal side effects. In addition, behavioral modification may also be helpful for problematic behavior. Finally, these patients

Dysphagia and Malnourishment

Between 16% and 55% of patients with ALS become malnourished because of dysphagia. This condition is characterized by difficulty with chewing and swallowing, nasal regurgitation, or coughing when drinking liquids. Nutritional status must be monitored every three months in patients with ALS, said Dr. Weiss. In addition, their BMI must be calculated and their weight measured. Paganoni et al found that the risk of death increased sevenfold in patients with ALS who had a BMI less than 18.5. Patients with ALS also need to be queried about the severity of choking, duration of meals, and caloric intake. A speech therapist should evaluate patients at every visit. Dietary changes might also be necessary and may include thickening liquids and preparing food that forms easily into a bolus.

As this disease progresses, patients may need a percutaneous gastrostomy (PEG) tube. According to the American Academy of Neurology practice guidelines, it is time to discuss PEG placement when a patient with ALS starts to lose weight. When a patient’s forced vital capacity is over 50%, the procedure can be done safely. When it is less than 50%, the procedure entails an increased risk of complications, including death.

Managing Dysarthria and Hospice

More than 95% of patients with ALS lose their ability to speak before they die. This condition, known as dysarthria, is difficult to treat. Almost all patients with bulbar-onset ALS and nearly 70% of patients with spinal-onset ALS develop dysarthria. Alternative augmentative communication devices and speech pathologists can be helpful. The Speakit application is a free speech-generating device available for the iPad, and a DynaVox device is a more costly augmentative and alternative communication tool. These devices help patients to communicate their needs and to stay connected to others.

As ALS advances, patients might require palliative medicine or hospice care. Before a patient reaches advanced stages of the disease, he or she should fill out a directive and Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment form, said Dr. Weiss. Patients must meet one of two criteria to receive Medicare reimbursement for hospice care. The first is a forced vital capacity of less than 30% with dyspnea at rest. The second is rapid progression of the disease with life-threatening complications (eg, infections) over 12 months or severe nutritional impairment over 12 months. Treatments for terminal dyspnea include morphine sulfate, oxygen, lorazepam, and chlorpromazine. These medications may depress respiratory drive, however, said Dr. Weiss.

Current Research and Recently Completed Trials

Smith et al found that dextromethorphan–quinidine may improve bulbar function. In addition, recent studies have found that diaphragmatic pacing, an FDA-approved technique, shortened the survival of patients with ALS by one year. An interanalysis found that patients using the diaphragmatic pacer died prematurely, compared with patients who had sham surgery in which electrodes were not implanted. Several phase II studies have suggested that tirasemtiv is substantially beneficial in decelerating slow vital capacity. Finally, a 24-week randomized controlled trial found that edaravone improved function in patients with definite or probable ALS. Edaravone was FDA-approved in May 2017.

—Erica Tricarico

Suggested Reading

Miller RG, Mitchell JD, Moore DH. Riluzole for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)/motor neuron disease (MND). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(3):CD001447.

Miller RG, Jackson CE, Kasarskis EJ, et al. Practice parameter update: the care of the patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: drug, nutritional, and respiratory therapies (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2009;73(15):1218-1226.

Paganoni S, Deng J, Jaffa M, et al. Body mass index, not dyslipidemia, is an independent predictor of survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 2011;44(1):20-24.

Shefner JM, Wolff AA, Meng L, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase IIb trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of tirasemtiv in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2016;17(5-6):426-435.

Smith R, Pioro E, Myers K, et al. Enhanced bulbar function in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: The nuedexta treatment trial. Neurotherapeutics. 2017 Jan 9 [Epub ahead of print].

Traynor BJ, Alexander M, Corr B, et al. Effect of multidisciplinary amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) clinic on ALS survival: a population based study, 1996-2000. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(9):1258-1261.

Weiss MD, Macklin EA, Simmons Z, et al. A randomized trial of mexiletine in ALS: Safety and effects on muscle cramps and progression. Neurology. 2016;86(16):1474-1481.

One-third of sunscreens fall short of AAD recommendations

Sunscreens sold by two major retailers in the United States in 2017 are more adherent to the American Academy of Dermatology recommendations for sun protection than in 2014, but approximately 35% still do not meet the AAD criteria, according to results of a new study.

The results are based on data from a review of 472 products, available for sale on-line, a follow-up to a 2014 study that examined the proportion of sunscreen products that met three AAD recommendations: a sun protection factor of 30 or higher, broad-spectrum coverage, and 40-80 minutes of water resistance. In the 2014 study, almost 35% of sunscreens sold at Walmart and 41% of sunscreens sold at Walgreens met all three recommendations (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71[5]:1011-2).

Overall, about 65% of Walmart products and 73% of Walgreens products met all three recommendations, a significant increase from 2014 (P less than .01). When the products were broken down by recommendation, more than 90% in 2017 offered broad-spectrum coverage, and more than 75% offered 40-80 minutes of water resistance, representing significant increases from 2014(J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Aug;77[2]:377-9).

The proportion of products with SPF 30 or higher “remained stable, possibly because there were already many to begin with,” noted the authors, who found that 82% of the Walmart products and 86% of the Walgreens products had an SPF of at least 30.

Of the 31 products with tanning and bronzing on their primary display, however, only 6 met the three AAD criteria for sun protection; these findings were similar to the findings in 2014.

“Our study demonstrates that sunscreens available at major retailers more closely adhere to AAD guidelines in 2017 than in 2014, but there remains room for improvement,” they said, pointing out that almost 35% of products sold at Walmart, the largest U.S. retailer, did not meet all three recommendations and that “tanning and bronzing products continue to fail to meet AAD criteria.”

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Sunscreens sold by two major retailers in the United States in 2017 are more adherent to the American Academy of Dermatology recommendations for sun protection than in 2014, but approximately 35% still do not meet the AAD criteria, according to results of a new study.