User login

Three drug combinations represent next level for high-risk breast cancer

BRUSSELS – Now that dual combinations of targeted breast cancer drugs are standard treatment, researchers see up-front triple drug combinations as the next treatment frontier.

“Doublets are simply not enough,” Dejan Juric, MD, said at a breast cancer conference sponsored by the European Society of Medical Oncology. Triple-drug combinations offer the possibility of substantially-reduced rates of resistance development and the possibility of reducing dosages to improve tolerability.

One way to leverage the potential of a triple regimen is to target all three drugs at the same oncogenic pathway. “If we target a pathway with multiple drugs do we still need the maximally-tolerated dose of each? Clearly no,” said René Bernards, PhD, a professor at the Netherlands Cancer Institute in Amsterdam.

Dr. Bernards said he has as-yet unpublished evidence that individual-drug dosages can be cut when using a combination regimen that joins treatments targeted to the sequential signaling steps of Raf, MEK, and ERK in a key signaling cascade tied to the epidermal growth factor receptor (BBA Mol Cell Res. 2007 Aug;1773[8]:1263-84). “We now have drugs for all these [targets]. You can use 10% of the effective dose of each of these drugs and get complete inhibition of the pathway and not make cells resistant to these low-doses,” he declared.

Having drugs that work well together is critical, agreed Dr. Juric. “We need to keep searching for drugs where you can achieve nice inhibition by the triplet.” The goal is to “completely shut down a pathway,” he said. While “upfront combination is always superior to a sequential strategy, we hope that a new combination is not just more hits at the goal but a new quality.” The conventional concept of first-line, second-line, and third-line treatments is an “obstacle” to development of the most rational combinations.

A challenge when testing a triple regimen as first-line treatment is deciding which patients to target, as some hormone-receptor positive patients can do well on just an aromatase inhibitor.

“I don’t know which patients will do well on a single agent and who will need a combination,” said Dr. Juric. Given that uncertainty, his priorities are testing combination regimens that are both tolerable and cost effective. He also stressed the need to “better understand the tumor we are dealing with, using blood and biopsies, and use an adaptive approach” based on each tumor’s combination of characteristics.

As long as tolerability is possible, preclinical models suggest that the biggest impact from combination regimens comes in treatment naive patients. That would mean targeting patients with high-risk, estrogen–receptor positive breast cancer “where we know the risk continues for 20, 30 years and the long-term prognosis for relapse is very poor,” said Nicholas Turner, MD, a molecular oncologist at the Institute of Cancer Research and the Royal Marsden Hospital, both in London. “Perhaps a triple combination, if tolerable, would have the most potential to change the prognosis of these patients.”

Dr. Juric has been a consultant to Eisai, EMD, Novartis, and Serono. Dr. Bernards owns a portion of Agendia, a company that markets a breast cancer genetic test he codeveloped. Dr. Turner has received honoraria from Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BRUSSELS – Now that dual combinations of targeted breast cancer drugs are standard treatment, researchers see up-front triple drug combinations as the next treatment frontier.

“Doublets are simply not enough,” Dejan Juric, MD, said at a breast cancer conference sponsored by the European Society of Medical Oncology. Triple-drug combinations offer the possibility of substantially-reduced rates of resistance development and the possibility of reducing dosages to improve tolerability.

One way to leverage the potential of a triple regimen is to target all three drugs at the same oncogenic pathway. “If we target a pathway with multiple drugs do we still need the maximally-tolerated dose of each? Clearly no,” said René Bernards, PhD, a professor at the Netherlands Cancer Institute in Amsterdam.

Dr. Bernards said he has as-yet unpublished evidence that individual-drug dosages can be cut when using a combination regimen that joins treatments targeted to the sequential signaling steps of Raf, MEK, and ERK in a key signaling cascade tied to the epidermal growth factor receptor (BBA Mol Cell Res. 2007 Aug;1773[8]:1263-84). “We now have drugs for all these [targets]. You can use 10% of the effective dose of each of these drugs and get complete inhibition of the pathway and not make cells resistant to these low-doses,” he declared.

Having drugs that work well together is critical, agreed Dr. Juric. “We need to keep searching for drugs where you can achieve nice inhibition by the triplet.” The goal is to “completely shut down a pathway,” he said. While “upfront combination is always superior to a sequential strategy, we hope that a new combination is not just more hits at the goal but a new quality.” The conventional concept of first-line, second-line, and third-line treatments is an “obstacle” to development of the most rational combinations.

A challenge when testing a triple regimen as first-line treatment is deciding which patients to target, as some hormone-receptor positive patients can do well on just an aromatase inhibitor.

“I don’t know which patients will do well on a single agent and who will need a combination,” said Dr. Juric. Given that uncertainty, his priorities are testing combination regimens that are both tolerable and cost effective. He also stressed the need to “better understand the tumor we are dealing with, using blood and biopsies, and use an adaptive approach” based on each tumor’s combination of characteristics.

As long as tolerability is possible, preclinical models suggest that the biggest impact from combination regimens comes in treatment naive patients. That would mean targeting patients with high-risk, estrogen–receptor positive breast cancer “where we know the risk continues for 20, 30 years and the long-term prognosis for relapse is very poor,” said Nicholas Turner, MD, a molecular oncologist at the Institute of Cancer Research and the Royal Marsden Hospital, both in London. “Perhaps a triple combination, if tolerable, would have the most potential to change the prognosis of these patients.”

Dr. Juric has been a consultant to Eisai, EMD, Novartis, and Serono. Dr. Bernards owns a portion of Agendia, a company that markets a breast cancer genetic test he codeveloped. Dr. Turner has received honoraria from Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BRUSSELS – Now that dual combinations of targeted breast cancer drugs are standard treatment, researchers see up-front triple drug combinations as the next treatment frontier.

“Doublets are simply not enough,” Dejan Juric, MD, said at a breast cancer conference sponsored by the European Society of Medical Oncology. Triple-drug combinations offer the possibility of substantially-reduced rates of resistance development and the possibility of reducing dosages to improve tolerability.

One way to leverage the potential of a triple regimen is to target all three drugs at the same oncogenic pathway. “If we target a pathway with multiple drugs do we still need the maximally-tolerated dose of each? Clearly no,” said René Bernards, PhD, a professor at the Netherlands Cancer Institute in Amsterdam.

Dr. Bernards said he has as-yet unpublished evidence that individual-drug dosages can be cut when using a combination regimen that joins treatments targeted to the sequential signaling steps of Raf, MEK, and ERK in a key signaling cascade tied to the epidermal growth factor receptor (BBA Mol Cell Res. 2007 Aug;1773[8]:1263-84). “We now have drugs for all these [targets]. You can use 10% of the effective dose of each of these drugs and get complete inhibition of the pathway and not make cells resistant to these low-doses,” he declared.

Having drugs that work well together is critical, agreed Dr. Juric. “We need to keep searching for drugs where you can achieve nice inhibition by the triplet.” The goal is to “completely shut down a pathway,” he said. While “upfront combination is always superior to a sequential strategy, we hope that a new combination is not just more hits at the goal but a new quality.” The conventional concept of first-line, second-line, and third-line treatments is an “obstacle” to development of the most rational combinations.

A challenge when testing a triple regimen as first-line treatment is deciding which patients to target, as some hormone-receptor positive patients can do well on just an aromatase inhibitor.

“I don’t know which patients will do well on a single agent and who will need a combination,” said Dr. Juric. Given that uncertainty, his priorities are testing combination regimens that are both tolerable and cost effective. He also stressed the need to “better understand the tumor we are dealing with, using blood and biopsies, and use an adaptive approach” based on each tumor’s combination of characteristics.

As long as tolerability is possible, preclinical models suggest that the biggest impact from combination regimens comes in treatment naive patients. That would mean targeting patients with high-risk, estrogen–receptor positive breast cancer “where we know the risk continues for 20, 30 years and the long-term prognosis for relapse is very poor,” said Nicholas Turner, MD, a molecular oncologist at the Institute of Cancer Research and the Royal Marsden Hospital, both in London. “Perhaps a triple combination, if tolerable, would have the most potential to change the prognosis of these patients.”

Dr. Juric has been a consultant to Eisai, EMD, Novartis, and Serono. Dr. Bernards owns a portion of Agendia, a company that markets a breast cancer genetic test he codeveloped. Dr. Turner has received honoraria from Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM IMPAKT 2017

Few states fully back HCV prevention, treatment

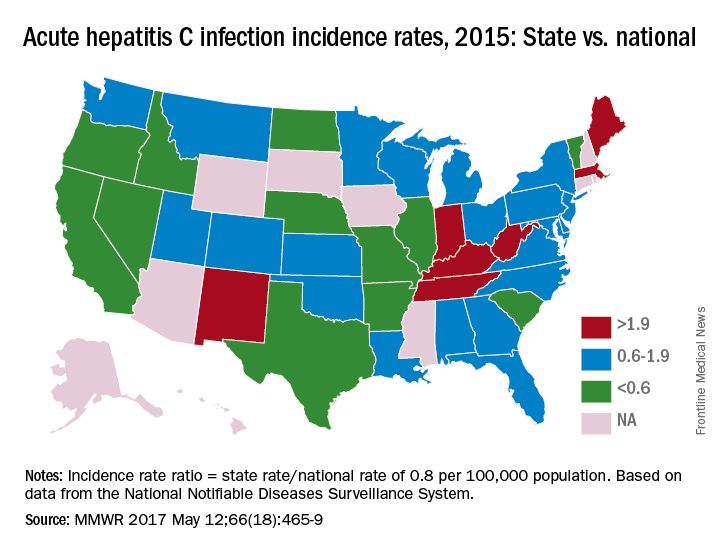

The prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) varies considerably by state, and the same can be said for the state laws and policies attempting to decrease that prevalence, according to an assessment by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2015, incidence of acute HCV infection exceeded the national average of 0.8 per 100,000 population in 17 states, including seven with rates that at least doubled it, the report noted. New HCV infections have increased in recent years despite curative therapies “and known preventive measures to interrupt transmission.”

The “most comprehensive” laws on prevention through clean needle access as of 2016 were found in Maine, Nevada, and Utah, with laws in 12 other states categorized as “more comprehensive” and 18 states falling into the “least comprehensive” category. On the Medicaid side of the equation, 16 states had permissive policies that did not require sobriety or required only screening and counseling before treatment, 24 states had restrictive policies that requited sobriety, and 10 states had no policy available, the report showed (MMWR. 2017 May 12:66[18]:465-9).

Only three states – Massachusetts, New Mexico, and Washington – had a comprehensive (all three were considered “more comprehensive”) set of prevention laws and a permissive treatment policy, the investigators said, while also noting that two of the three – Massachusetts and New Mexico – were among the states with acute HCV rates that were at least twice the national average.

“Although the costs of HCV therapies have raised budgetary issues for state Medicaid programs in the past, the costs of HCV treatment have declined in recent years, increasing the cost-effectiveness of treatment, particularly among persons who inject drugs and who might serve as an ongoing source of transmission to others,” the report concluded.

The analysis examined three types of laws on access to clean needles and syringes: authorization of exchange programs, the scope of drug paraphernalia laws, and retail sale of needles and syringes. Each law was assessed for five elements, including authorization of syringe exchange statewide or in selected jurisdictions and exemption of needles or syringes from the definition of drug paraphernalia.

For the accompanying map (see “Acute hepatitis C infection incidence rates, 2015: State vs. national”), each state’s acute HCV incidence rate for 2015 was divided by the national rate to determine the incidence rate ratio, with data unavailable for 10 states.

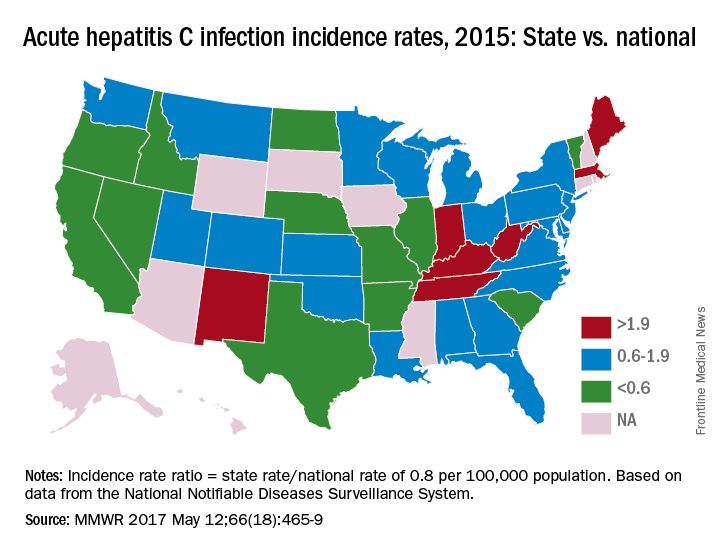

The prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) varies considerably by state, and the same can be said for the state laws and policies attempting to decrease that prevalence, according to an assessment by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2015, incidence of acute HCV infection exceeded the national average of 0.8 per 100,000 population in 17 states, including seven with rates that at least doubled it, the report noted. New HCV infections have increased in recent years despite curative therapies “and known preventive measures to interrupt transmission.”

The “most comprehensive” laws on prevention through clean needle access as of 2016 were found in Maine, Nevada, and Utah, with laws in 12 other states categorized as “more comprehensive” and 18 states falling into the “least comprehensive” category. On the Medicaid side of the equation, 16 states had permissive policies that did not require sobriety or required only screening and counseling before treatment, 24 states had restrictive policies that requited sobriety, and 10 states had no policy available, the report showed (MMWR. 2017 May 12:66[18]:465-9).

Only three states – Massachusetts, New Mexico, and Washington – had a comprehensive (all three were considered “more comprehensive”) set of prevention laws and a permissive treatment policy, the investigators said, while also noting that two of the three – Massachusetts and New Mexico – were among the states with acute HCV rates that were at least twice the national average.

“Although the costs of HCV therapies have raised budgetary issues for state Medicaid programs in the past, the costs of HCV treatment have declined in recent years, increasing the cost-effectiveness of treatment, particularly among persons who inject drugs and who might serve as an ongoing source of transmission to others,” the report concluded.

The analysis examined three types of laws on access to clean needles and syringes: authorization of exchange programs, the scope of drug paraphernalia laws, and retail sale of needles and syringes. Each law was assessed for five elements, including authorization of syringe exchange statewide or in selected jurisdictions and exemption of needles or syringes from the definition of drug paraphernalia.

For the accompanying map (see “Acute hepatitis C infection incidence rates, 2015: State vs. national”), each state’s acute HCV incidence rate for 2015 was divided by the national rate to determine the incidence rate ratio, with data unavailable for 10 states.

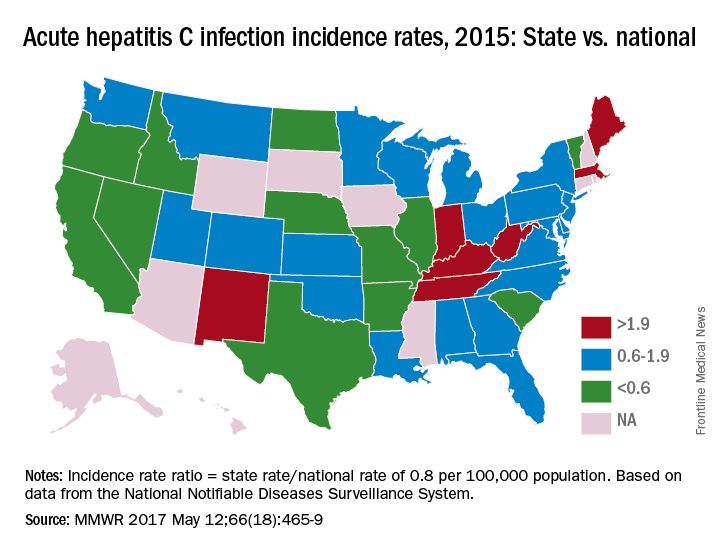

The prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) varies considerably by state, and the same can be said for the state laws and policies attempting to decrease that prevalence, according to an assessment by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2015, incidence of acute HCV infection exceeded the national average of 0.8 per 100,000 population in 17 states, including seven with rates that at least doubled it, the report noted. New HCV infections have increased in recent years despite curative therapies “and known preventive measures to interrupt transmission.”

The “most comprehensive” laws on prevention through clean needle access as of 2016 were found in Maine, Nevada, and Utah, with laws in 12 other states categorized as “more comprehensive” and 18 states falling into the “least comprehensive” category. On the Medicaid side of the equation, 16 states had permissive policies that did not require sobriety or required only screening and counseling before treatment, 24 states had restrictive policies that requited sobriety, and 10 states had no policy available, the report showed (MMWR. 2017 May 12:66[18]:465-9).

Only three states – Massachusetts, New Mexico, and Washington – had a comprehensive (all three were considered “more comprehensive”) set of prevention laws and a permissive treatment policy, the investigators said, while also noting that two of the three – Massachusetts and New Mexico – were among the states with acute HCV rates that were at least twice the national average.

“Although the costs of HCV therapies have raised budgetary issues for state Medicaid programs in the past, the costs of HCV treatment have declined in recent years, increasing the cost-effectiveness of treatment, particularly among persons who inject drugs and who might serve as an ongoing source of transmission to others,” the report concluded.

The analysis examined three types of laws on access to clean needles and syringes: authorization of exchange programs, the scope of drug paraphernalia laws, and retail sale of needles and syringes. Each law was assessed for five elements, including authorization of syringe exchange statewide or in selected jurisdictions and exemption of needles or syringes from the definition of drug paraphernalia.

For the accompanying map (see “Acute hepatitis C infection incidence rates, 2015: State vs. national”), each state’s acute HCV incidence rate for 2015 was divided by the national rate to determine the incidence rate ratio, with data unavailable for 10 states.

FROM MMWR

Postcesarean outpatient opioid needs predicted by inpatient use

SAN DIEGO – The amount of pain medication a women requires in the hospital after a cesarean delivery was an accurate predictor of postdischarge needs, and could provide guidance to tailor home prescriptions, reducing the amount of unused opioids left after recovery, according to a new study.

Jenna Emerson, MD, and her colleagues also found that more than half of the opioid medications prescribed for home postcesarean use went untaken, and that one in five women used no opioid medication after leaving the hospital.

The prospective cohort study, one of two awarded the Donald F. Richardson Prize at the meeting, looked at how much opioid medication was used by women while they were inpatients, and also asked women to keep track of how much medication they used at home, to see if one could predict the other.

The pilot study enrolled 100 women who had a postdelivery inpatient stay of less than 8 days, who spoke English, and who had given birth to a live viable infant. The study’s statistical analysis looked for relationships not only between inpatient and outpatient use of opioids, but also between patient characteristics and level of opioid use in the hospital and at home.

A total of 76 women completed follow-up, said Dr. Emerson, who is a fourth-year ob.gyn. resident at Brown University, Providence, R.I. One patient was excluded because she was on high opioid doses for addiction treatment before delivery, and her postdelivery opioid requirements represented a clear outlier in the data.

The investigators used medical record data to determine opioid requirements as inpatients after cesarean delivery. For standardization of different strengths of opioids, use was expressed by using Mean Morphine Equivalents (MME). Baseline patient demographic characteristics and comorbidities were also obtained from medical record review.

Patients were asked to track their home opioid use for 2 weeks postdischarge, and also received a follow-up phone call at the end of their first 2 weeks at home.

Inpatient opioid use was divided into tertiles according to low (less than 40 MME), medium (41-70 MME), and high (greater than 70 MME) use. Overall, the group’s mean opioid use in the final 24 hours before discharge was 59 MME, an amount Dr. Emerson said was equivalent to about eight tablets of oxycodone/acetaminophen or 12 tablets of hydrocodone/acetaminophen.

Most patients (89%) went home with a prescription for oxycodone/acetaminophen, and the mean number of pills prescribed per patient was 35. For the original group of 100 patients, this meant that prescriptions were written for 3,150 oxycodone/acetaminophen tablets, 162 hydrocodone/acetaminophen tablets, and 139 oxycodone tablets.

Home use over the first 2 weeks postdischarge was a mean 126 MME, or the equivalent of about 17 oxycodone/acetaminophen tablets. A total of 39% of women reported they had used less than half of their opioid medication; 21% had used all or required more opioids, and 20% had used at least half of their opioids. One in five patients (20%) had not taken a single opioid tablet after discharge from the hospital, and only 2 of the 75 women were still using opioids at the time of the 2-week follow-up call, Dr. Emerson said.

This means there was a total of 1,538 tablets of unused prescription opioid medication left in the homes of the 75 women included in the final analysis, Dr. Emerson said.

When the investigators compared inpatient and outpatient opioid use, they found that 26 women (34.7%) had been in the lowest tertile of inpatient opioid use. These women also had the lowest mean MME at home, using 53 MME in the first 2 weeks post discharge. The middle tertile for inpatient use used a mean 111 MME at home, while the highest used 195 MME (analysis of variance P less than .001).

Higher outpatient opioid use was seen in patients with a history of psychiatric comorbidities (MME 172 vs. 103 for no psychiatric comorbidities; P = .046). Other factors associated with numerically higher use that did not reach statistical significance included breastfeeding status (MME 197 for no breastfeeding, 112 for breastfeeding; P = .068) and insurance status (MME 154 for public, 95 for private; P = .058).

Patients’ mean age was 30.3 years; 63% of participants were Caucasian, 5% were black, and 19% identified their ethnicity as Hispanic. Patients were about evenly divided between having public and private insurance, and most (72%) had some post-high school education. Just 5% had a prior history of drug use or abuse, and about half (49%) were having a repeat cesarean delivery. Three quarters were breastfeeding their infants.

Unused opioid prescriptions are a significant contributor to the pool of opioids available for diversion and recent work has shown that up to 23% of opioids prescribed are used for “nonmedical” purposes, Dr. Emerson said. Since cesarean deliveries are the most commonly performed major surgery in the United States, the opportunity to reduce the number of opioids available for diversion is significant, she said.

“Opioid prescription use after cesarean delivery should be tailored to patient needs,” she said, calling for larger studies to validate and expand on the findings.

Dr. Emerson reported having no outside sources of funding and no relevant financial disclosures.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

SAN DIEGO – The amount of pain medication a women requires in the hospital after a cesarean delivery was an accurate predictor of postdischarge needs, and could provide guidance to tailor home prescriptions, reducing the amount of unused opioids left after recovery, according to a new study.

Jenna Emerson, MD, and her colleagues also found that more than half of the opioid medications prescribed for home postcesarean use went untaken, and that one in five women used no opioid medication after leaving the hospital.

The prospective cohort study, one of two awarded the Donald F. Richardson Prize at the meeting, looked at how much opioid medication was used by women while they were inpatients, and also asked women to keep track of how much medication they used at home, to see if one could predict the other.

The pilot study enrolled 100 women who had a postdelivery inpatient stay of less than 8 days, who spoke English, and who had given birth to a live viable infant. The study’s statistical analysis looked for relationships not only between inpatient and outpatient use of opioids, but also between patient characteristics and level of opioid use in the hospital and at home.

A total of 76 women completed follow-up, said Dr. Emerson, who is a fourth-year ob.gyn. resident at Brown University, Providence, R.I. One patient was excluded because she was on high opioid doses for addiction treatment before delivery, and her postdelivery opioid requirements represented a clear outlier in the data.

The investigators used medical record data to determine opioid requirements as inpatients after cesarean delivery. For standardization of different strengths of opioids, use was expressed by using Mean Morphine Equivalents (MME). Baseline patient demographic characteristics and comorbidities were also obtained from medical record review.

Patients were asked to track their home opioid use for 2 weeks postdischarge, and also received a follow-up phone call at the end of their first 2 weeks at home.

Inpatient opioid use was divided into tertiles according to low (less than 40 MME), medium (41-70 MME), and high (greater than 70 MME) use. Overall, the group’s mean opioid use in the final 24 hours before discharge was 59 MME, an amount Dr. Emerson said was equivalent to about eight tablets of oxycodone/acetaminophen or 12 tablets of hydrocodone/acetaminophen.

Most patients (89%) went home with a prescription for oxycodone/acetaminophen, and the mean number of pills prescribed per patient was 35. For the original group of 100 patients, this meant that prescriptions were written for 3,150 oxycodone/acetaminophen tablets, 162 hydrocodone/acetaminophen tablets, and 139 oxycodone tablets.

Home use over the first 2 weeks postdischarge was a mean 126 MME, or the equivalent of about 17 oxycodone/acetaminophen tablets. A total of 39% of women reported they had used less than half of their opioid medication; 21% had used all or required more opioids, and 20% had used at least half of their opioids. One in five patients (20%) had not taken a single opioid tablet after discharge from the hospital, and only 2 of the 75 women were still using opioids at the time of the 2-week follow-up call, Dr. Emerson said.

This means there was a total of 1,538 tablets of unused prescription opioid medication left in the homes of the 75 women included in the final analysis, Dr. Emerson said.

When the investigators compared inpatient and outpatient opioid use, they found that 26 women (34.7%) had been in the lowest tertile of inpatient opioid use. These women also had the lowest mean MME at home, using 53 MME in the first 2 weeks post discharge. The middle tertile for inpatient use used a mean 111 MME at home, while the highest used 195 MME (analysis of variance P less than .001).

Higher outpatient opioid use was seen in patients with a history of psychiatric comorbidities (MME 172 vs. 103 for no psychiatric comorbidities; P = .046). Other factors associated with numerically higher use that did not reach statistical significance included breastfeeding status (MME 197 for no breastfeeding, 112 for breastfeeding; P = .068) and insurance status (MME 154 for public, 95 for private; P = .058).

Patients’ mean age was 30.3 years; 63% of participants were Caucasian, 5% were black, and 19% identified their ethnicity as Hispanic. Patients were about evenly divided between having public and private insurance, and most (72%) had some post-high school education. Just 5% had a prior history of drug use or abuse, and about half (49%) were having a repeat cesarean delivery. Three quarters were breastfeeding their infants.

Unused opioid prescriptions are a significant contributor to the pool of opioids available for diversion and recent work has shown that up to 23% of opioids prescribed are used for “nonmedical” purposes, Dr. Emerson said. Since cesarean deliveries are the most commonly performed major surgery in the United States, the opportunity to reduce the number of opioids available for diversion is significant, she said.

“Opioid prescription use after cesarean delivery should be tailored to patient needs,” she said, calling for larger studies to validate and expand on the findings.

Dr. Emerson reported having no outside sources of funding and no relevant financial disclosures.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

SAN DIEGO – The amount of pain medication a women requires in the hospital after a cesarean delivery was an accurate predictor of postdischarge needs, and could provide guidance to tailor home prescriptions, reducing the amount of unused opioids left after recovery, according to a new study.

Jenna Emerson, MD, and her colleagues also found that more than half of the opioid medications prescribed for home postcesarean use went untaken, and that one in five women used no opioid medication after leaving the hospital.

The prospective cohort study, one of two awarded the Donald F. Richardson Prize at the meeting, looked at how much opioid medication was used by women while they were inpatients, and also asked women to keep track of how much medication they used at home, to see if one could predict the other.

The pilot study enrolled 100 women who had a postdelivery inpatient stay of less than 8 days, who spoke English, and who had given birth to a live viable infant. The study’s statistical analysis looked for relationships not only between inpatient and outpatient use of opioids, but also between patient characteristics and level of opioid use in the hospital and at home.

A total of 76 women completed follow-up, said Dr. Emerson, who is a fourth-year ob.gyn. resident at Brown University, Providence, R.I. One patient was excluded because she was on high opioid doses for addiction treatment before delivery, and her postdelivery opioid requirements represented a clear outlier in the data.

The investigators used medical record data to determine opioid requirements as inpatients after cesarean delivery. For standardization of different strengths of opioids, use was expressed by using Mean Morphine Equivalents (MME). Baseline patient demographic characteristics and comorbidities were also obtained from medical record review.

Patients were asked to track their home opioid use for 2 weeks postdischarge, and also received a follow-up phone call at the end of their first 2 weeks at home.

Inpatient opioid use was divided into tertiles according to low (less than 40 MME), medium (41-70 MME), and high (greater than 70 MME) use. Overall, the group’s mean opioid use in the final 24 hours before discharge was 59 MME, an amount Dr. Emerson said was equivalent to about eight tablets of oxycodone/acetaminophen or 12 tablets of hydrocodone/acetaminophen.

Most patients (89%) went home with a prescription for oxycodone/acetaminophen, and the mean number of pills prescribed per patient was 35. For the original group of 100 patients, this meant that prescriptions were written for 3,150 oxycodone/acetaminophen tablets, 162 hydrocodone/acetaminophen tablets, and 139 oxycodone tablets.

Home use over the first 2 weeks postdischarge was a mean 126 MME, or the equivalent of about 17 oxycodone/acetaminophen tablets. A total of 39% of women reported they had used less than half of their opioid medication; 21% had used all or required more opioids, and 20% had used at least half of their opioids. One in five patients (20%) had not taken a single opioid tablet after discharge from the hospital, and only 2 of the 75 women were still using opioids at the time of the 2-week follow-up call, Dr. Emerson said.

This means there was a total of 1,538 tablets of unused prescription opioid medication left in the homes of the 75 women included in the final analysis, Dr. Emerson said.

When the investigators compared inpatient and outpatient opioid use, they found that 26 women (34.7%) had been in the lowest tertile of inpatient opioid use. These women also had the lowest mean MME at home, using 53 MME in the first 2 weeks post discharge. The middle tertile for inpatient use used a mean 111 MME at home, while the highest used 195 MME (analysis of variance P less than .001).

Higher outpatient opioid use was seen in patients with a history of psychiatric comorbidities (MME 172 vs. 103 for no psychiatric comorbidities; P = .046). Other factors associated with numerically higher use that did not reach statistical significance included breastfeeding status (MME 197 for no breastfeeding, 112 for breastfeeding; P = .068) and insurance status (MME 154 for public, 95 for private; P = .058).

Patients’ mean age was 30.3 years; 63% of participants were Caucasian, 5% were black, and 19% identified their ethnicity as Hispanic. Patients were about evenly divided between having public and private insurance, and most (72%) had some post-high school education. Just 5% had a prior history of drug use or abuse, and about half (49%) were having a repeat cesarean delivery. Three quarters were breastfeeding their infants.

Unused opioid prescriptions are a significant contributor to the pool of opioids available for diversion and recent work has shown that up to 23% of opioids prescribed are used for “nonmedical” purposes, Dr. Emerson said. Since cesarean deliveries are the most commonly performed major surgery in the United States, the opportunity to reduce the number of opioids available for diversion is significant, she said.

“Opioid prescription use after cesarean delivery should be tailored to patient needs,” she said, calling for larger studies to validate and expand on the findings.

Dr. Emerson reported having no outside sources of funding and no relevant financial disclosures.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

AT ACOG 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Inpatient opioid use by tertile was highly associated with outpatient opioid use by tertile (P less than .001).

Data source: A prospective cohort study of 75 women with cesarean deliveries of live viable infants.

Disclosures: The study authors reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

Sneak Peek: Journal of Hospital Medicine

BACKGROUND: Antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) have been advocated to improve antimicrobial utilization, but program implementation is variable.

OBJECTIVE: To determine associations of ASPs with facility characteristics and inpatient antimicrobial utilization measures in the Veterans Affairs (VA) system in 2012.

SETTING: All 130 VA facilities with acute care services.

RESULTS: Variables associated with at least three favorable changes in antimicrobial utilization included presence of postgraduate physician/pharmacy training programs, number of antimicrobial-specific order sets, frequency of systematic de-escalation review, presence of pharmacists and/or infectious diseases (ID) attendings on acute care ward teams, and formal ID training of the lead ASP pharmacist. Variables associated with two unfavorable measures included bed size, the level of engagement with VA Antimicrobial Stewardship Task Force online resources, and utilization of antimicrobial stop orders.

CONCLUSIONS: Formalization of ASP processes and presence of pharmacy and ID expertise are associated with favorable utilization. Systematic de-escalation review and order set establishment may be high-yield interventions.

Also in JHM

High prevalence of inappropriate benzodiazepine and sedative hypnotic prescriptions among hospitalized older adults

AUTHORS: Elisabeth Anna Pek, MD, Andrew Remfry, MD, Ciara Pendrith, MSc, Chris Fan-Lun, BScPhm, R. Sacha Bhatia, MD, and Christine Soong, MD, MSc, SFHM

Incidence, predictors, and outcomes of hospital-acquired anemia

AUTHORS: Anil N. Makam, MD, MAS, Oanh K. Nguyen, MD, MAS, Christopher Clark, MPA, and Ethan A. Halm, MD, MPH

Association between radiologic incidental findings and resource utilization in patients admitted with chest pain in an urban medical center

AUTHORS: Venkat P. Gundareddy, MD, MPH, SFHM, Nisa M. Maruthur, MD, MHS, Abednego Chibungu, MD, Preetam Bollampally, MD, Regina Landis, MS, abd Shaker M. Eid, MD, MBA

Clinical utility of routine CBC testing in patients with community-acquired pneumonia

AUTHORS: Neelaysh Vukkadala, BS, and Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, SFHM

Overuse of troponin? A comprehensive evaluation of testing in a large hospital system

AUTHORS: Gibbs Wilson, MD, Kyler Barkley, MD, Kipp Slicker, DO, Robert Kowal, MD, PhD, Brandon Pope, PhD, and Jeffrey Michel, MD

BACKGROUND: Antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) have been advocated to improve antimicrobial utilization, but program implementation is variable.

OBJECTIVE: To determine associations of ASPs with facility characteristics and inpatient antimicrobial utilization measures in the Veterans Affairs (VA) system in 2012.

SETTING: All 130 VA facilities with acute care services.

RESULTS: Variables associated with at least three favorable changes in antimicrobial utilization included presence of postgraduate physician/pharmacy training programs, number of antimicrobial-specific order sets, frequency of systematic de-escalation review, presence of pharmacists and/or infectious diseases (ID) attendings on acute care ward teams, and formal ID training of the lead ASP pharmacist. Variables associated with two unfavorable measures included bed size, the level of engagement with VA Antimicrobial Stewardship Task Force online resources, and utilization of antimicrobial stop orders.

CONCLUSIONS: Formalization of ASP processes and presence of pharmacy and ID expertise are associated with favorable utilization. Systematic de-escalation review and order set establishment may be high-yield interventions.

Also in JHM

High prevalence of inappropriate benzodiazepine and sedative hypnotic prescriptions among hospitalized older adults

AUTHORS: Elisabeth Anna Pek, MD, Andrew Remfry, MD, Ciara Pendrith, MSc, Chris Fan-Lun, BScPhm, R. Sacha Bhatia, MD, and Christine Soong, MD, MSc, SFHM

Incidence, predictors, and outcomes of hospital-acquired anemia

AUTHORS: Anil N. Makam, MD, MAS, Oanh K. Nguyen, MD, MAS, Christopher Clark, MPA, and Ethan A. Halm, MD, MPH

Association between radiologic incidental findings and resource utilization in patients admitted with chest pain in an urban medical center

AUTHORS: Venkat P. Gundareddy, MD, MPH, SFHM, Nisa M. Maruthur, MD, MHS, Abednego Chibungu, MD, Preetam Bollampally, MD, Regina Landis, MS, abd Shaker M. Eid, MD, MBA

Clinical utility of routine CBC testing in patients with community-acquired pneumonia

AUTHORS: Neelaysh Vukkadala, BS, and Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, SFHM

Overuse of troponin? A comprehensive evaluation of testing in a large hospital system

AUTHORS: Gibbs Wilson, MD, Kyler Barkley, MD, Kipp Slicker, DO, Robert Kowal, MD, PhD, Brandon Pope, PhD, and Jeffrey Michel, MD

BACKGROUND: Antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) have been advocated to improve antimicrobial utilization, but program implementation is variable.

OBJECTIVE: To determine associations of ASPs with facility characteristics and inpatient antimicrobial utilization measures in the Veterans Affairs (VA) system in 2012.

SETTING: All 130 VA facilities with acute care services.

RESULTS: Variables associated with at least three favorable changes in antimicrobial utilization included presence of postgraduate physician/pharmacy training programs, number of antimicrobial-specific order sets, frequency of systematic de-escalation review, presence of pharmacists and/or infectious diseases (ID) attendings on acute care ward teams, and formal ID training of the lead ASP pharmacist. Variables associated with two unfavorable measures included bed size, the level of engagement with VA Antimicrobial Stewardship Task Force online resources, and utilization of antimicrobial stop orders.

CONCLUSIONS: Formalization of ASP processes and presence of pharmacy and ID expertise are associated with favorable utilization. Systematic de-escalation review and order set establishment may be high-yield interventions.

Also in JHM

High prevalence of inappropriate benzodiazepine and sedative hypnotic prescriptions among hospitalized older adults

AUTHORS: Elisabeth Anna Pek, MD, Andrew Remfry, MD, Ciara Pendrith, MSc, Chris Fan-Lun, BScPhm, R. Sacha Bhatia, MD, and Christine Soong, MD, MSc, SFHM

Incidence, predictors, and outcomes of hospital-acquired anemia

AUTHORS: Anil N. Makam, MD, MAS, Oanh K. Nguyen, MD, MAS, Christopher Clark, MPA, and Ethan A. Halm, MD, MPH

Association between radiologic incidental findings and resource utilization in patients admitted with chest pain in an urban medical center

AUTHORS: Venkat P. Gundareddy, MD, MPH, SFHM, Nisa M. Maruthur, MD, MHS, Abednego Chibungu, MD, Preetam Bollampally, MD, Regina Landis, MS, abd Shaker M. Eid, MD, MBA

Clinical utility of routine CBC testing in patients with community-acquired pneumonia

AUTHORS: Neelaysh Vukkadala, BS, and Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, SFHM

Overuse of troponin? A comprehensive evaluation of testing in a large hospital system

AUTHORS: Gibbs Wilson, MD, Kyler Barkley, MD, Kipp Slicker, DO, Robert Kowal, MD, PhD, Brandon Pope, PhD, and Jeffrey Michel, MD

Women less likely to be diagnosed with sleep disorders

Women are less likely to be diagnosed with and treated for sleep-disordered breathing, despite having symptoms similar to those of men, a Swedish study showed.

In a survey of 10,854 subjects, 14% of women reported being diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), compared with 25% of men (P less than .001), and 9% of women reported having any OSA treatment, compared with 16% of men (Sleep Med. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2017.02.032).

Underdiagnosis of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) in women may have dire consequences, as symptoms, specifically snoring and excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), correlate with increased risk for hypertension and diabetes, regardless of gender, according to Eva Lindberg, PhD, professor in the department of medical sciences, respiratory, allergy, and sleep research at Uppsala (Sweden) University, and her colleagues.

The mean age of the patients at baseline was 41 years. Mean body mass index was 25.4 kg/m2 for men and 24 kg/m2 for women.

On initial testing, approximately three times the percentage of men reported having issues with snoring and no EDS, compared with women (19% vs. 6% respectively), while more women reported the opposite, EDS but no snoring (19% vs. 11%). A slightly larger percentage of men reported having both symptoms (7.3% vs. 4.5%).

Investigators hypothesized the disparity between women and men reporting problems with snoring may be caused by gender expectations.

“It is more probable that SDB is still assumed to be a condition associated predominantly with men, and women feel ashamed of reporting these symptoms and seeking medical advice,” said Dr. Lindberg and her coinvestigators. These gender expectations may “contribute to females being less inclined to seek medical advice due to SDB symptoms.”

In a follow-up survey conducted 11 years after the initial one, doctors found 1,716 and 319 patients had received a new diagnosis for hypertension and diabetes, respectively.

While incidence was greater in men than in women for both (hypertension: 18.6% vs. 15.8% [P less than .001] and 3.6 vs. 2.4% [P less than .001], respectively), the investigators found “after adjusting for BMI and snoring at baseline, none of these gender differences remained significant.”

Physicians’ perception of SDB is partially responsible for the number of women who go undiagnosed, according to the researchers. Because SDB is considered to occur predominantly in males, doctors may overlook symptoms in female patients that would otherwise be a cause for further testing, they noted.

“[Even] among health professionals, SDB is still usually attributed to a male population, and female patients are therefore less frequently asked about the cardinal symptoms of snoring and sleepiness and do not therefore undergo sleep recordings. ... Also, among patients with obesity hypoventilation syndrome, females are generally diagnosed when the disease is more advanced and significantly more frequently develop acute disease before achieving treatment,” the investigators wrote.

“[Even] among health professionals, SDB is still usually attributed to a male population and female patients are therefore less frequently asked about the cardinal symptoms of snoring and sleepiness and do not therefore undergo sleep recordings ... Also, among patients with obesity hypoventilation syndrome, females are generally diagnosed when the disease is more advanced and significantly more frequently develop acute disease before achieving treatment,” the investigators claimed.

Dr. Lindberg and her team suggested engaging female patients more frequently about SDB symptoms, as well as referring patients with positive symptoms to participate in a sleep study.

The current study was limited by the nature of the data, which were self-reported. Patients were not surveyed via the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.

The study was funded by grants from the Norwegian Research Council, the Icelandic Research Council, Aarhus University, the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation, and the Estonian Science Foundation.

The investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @eaztweets

Women are less likely to be diagnosed with and treated for sleep-disordered breathing, despite having symptoms similar to those of men, a Swedish study showed.

In a survey of 10,854 subjects, 14% of women reported being diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), compared with 25% of men (P less than .001), and 9% of women reported having any OSA treatment, compared with 16% of men (Sleep Med. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2017.02.032).

Underdiagnosis of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) in women may have dire consequences, as symptoms, specifically snoring and excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), correlate with increased risk for hypertension and diabetes, regardless of gender, according to Eva Lindberg, PhD, professor in the department of medical sciences, respiratory, allergy, and sleep research at Uppsala (Sweden) University, and her colleagues.

The mean age of the patients at baseline was 41 years. Mean body mass index was 25.4 kg/m2 for men and 24 kg/m2 for women.

On initial testing, approximately three times the percentage of men reported having issues with snoring and no EDS, compared with women (19% vs. 6% respectively), while more women reported the opposite, EDS but no snoring (19% vs. 11%). A slightly larger percentage of men reported having both symptoms (7.3% vs. 4.5%).

Investigators hypothesized the disparity between women and men reporting problems with snoring may be caused by gender expectations.

“It is more probable that SDB is still assumed to be a condition associated predominantly with men, and women feel ashamed of reporting these symptoms and seeking medical advice,” said Dr. Lindberg and her coinvestigators. These gender expectations may “contribute to females being less inclined to seek medical advice due to SDB symptoms.”

In a follow-up survey conducted 11 years after the initial one, doctors found 1,716 and 319 patients had received a new diagnosis for hypertension and diabetes, respectively.

While incidence was greater in men than in women for both (hypertension: 18.6% vs. 15.8% [P less than .001] and 3.6 vs. 2.4% [P less than .001], respectively), the investigators found “after adjusting for BMI and snoring at baseline, none of these gender differences remained significant.”

Physicians’ perception of SDB is partially responsible for the number of women who go undiagnosed, according to the researchers. Because SDB is considered to occur predominantly in males, doctors may overlook symptoms in female patients that would otherwise be a cause for further testing, they noted.

“[Even] among health professionals, SDB is still usually attributed to a male population, and female patients are therefore less frequently asked about the cardinal symptoms of snoring and sleepiness and do not therefore undergo sleep recordings. ... Also, among patients with obesity hypoventilation syndrome, females are generally diagnosed when the disease is more advanced and significantly more frequently develop acute disease before achieving treatment,” the investigators wrote.

“[Even] among health professionals, SDB is still usually attributed to a male population and female patients are therefore less frequently asked about the cardinal symptoms of snoring and sleepiness and do not therefore undergo sleep recordings ... Also, among patients with obesity hypoventilation syndrome, females are generally diagnosed when the disease is more advanced and significantly more frequently develop acute disease before achieving treatment,” the investigators claimed.

Dr. Lindberg and her team suggested engaging female patients more frequently about SDB symptoms, as well as referring patients with positive symptoms to participate in a sleep study.

The current study was limited by the nature of the data, which were self-reported. Patients were not surveyed via the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.

The study was funded by grants from the Norwegian Research Council, the Icelandic Research Council, Aarhus University, the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation, and the Estonian Science Foundation.

The investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @eaztweets

Women are less likely to be diagnosed with and treated for sleep-disordered breathing, despite having symptoms similar to those of men, a Swedish study showed.

In a survey of 10,854 subjects, 14% of women reported being diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), compared with 25% of men (P less than .001), and 9% of women reported having any OSA treatment, compared with 16% of men (Sleep Med. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2017.02.032).

Underdiagnosis of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) in women may have dire consequences, as symptoms, specifically snoring and excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), correlate with increased risk for hypertension and diabetes, regardless of gender, according to Eva Lindberg, PhD, professor in the department of medical sciences, respiratory, allergy, and sleep research at Uppsala (Sweden) University, and her colleagues.

The mean age of the patients at baseline was 41 years. Mean body mass index was 25.4 kg/m2 for men and 24 kg/m2 for women.

On initial testing, approximately three times the percentage of men reported having issues with snoring and no EDS, compared with women (19% vs. 6% respectively), while more women reported the opposite, EDS but no snoring (19% vs. 11%). A slightly larger percentage of men reported having both symptoms (7.3% vs. 4.5%).

Investigators hypothesized the disparity between women and men reporting problems with snoring may be caused by gender expectations.

“It is more probable that SDB is still assumed to be a condition associated predominantly with men, and women feel ashamed of reporting these symptoms and seeking medical advice,” said Dr. Lindberg and her coinvestigators. These gender expectations may “contribute to females being less inclined to seek medical advice due to SDB symptoms.”

In a follow-up survey conducted 11 years after the initial one, doctors found 1,716 and 319 patients had received a new diagnosis for hypertension and diabetes, respectively.

While incidence was greater in men than in women for both (hypertension: 18.6% vs. 15.8% [P less than .001] and 3.6 vs. 2.4% [P less than .001], respectively), the investigators found “after adjusting for BMI and snoring at baseline, none of these gender differences remained significant.”

Physicians’ perception of SDB is partially responsible for the number of women who go undiagnosed, according to the researchers. Because SDB is considered to occur predominantly in males, doctors may overlook symptoms in female patients that would otherwise be a cause for further testing, they noted.

“[Even] among health professionals, SDB is still usually attributed to a male population, and female patients are therefore less frequently asked about the cardinal symptoms of snoring and sleepiness and do not therefore undergo sleep recordings. ... Also, among patients with obesity hypoventilation syndrome, females are generally diagnosed when the disease is more advanced and significantly more frequently develop acute disease before achieving treatment,” the investigators wrote.

“[Even] among health professionals, SDB is still usually attributed to a male population and female patients are therefore less frequently asked about the cardinal symptoms of snoring and sleepiness and do not therefore undergo sleep recordings ... Also, among patients with obesity hypoventilation syndrome, females are generally diagnosed when the disease is more advanced and significantly more frequently develop acute disease before achieving treatment,” the investigators claimed.

Dr. Lindberg and her team suggested engaging female patients more frequently about SDB symptoms, as well as referring patients with positive symptoms to participate in a sleep study.

The current study was limited by the nature of the data, which were self-reported. Patients were not surveyed via the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.

The study was funded by grants from the Norwegian Research Council, the Icelandic Research Council, Aarhus University, the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation, and the Estonian Science Foundation.

The investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @eaztweets

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Women were less likely than were men to be diagnosed with sleep apnea (14% vs. 25%, P = .001) or given treatment for any kind of sleep disordered breathing (9% vs. 16%, P = .01).

Data source: Survey of 10,854 subjects: 4,962 men and 5,892 women, gathered from the European Community Respiratory Health Survey with subsequent follow-up.

Disclosures: The study was funded by grants from the Norwegian Research Council, the Icelandic Research Council, Aarhus University, the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation, and the Estonian Science Foundation. The investigators report no relevant financial disclosures.

Oncology treatment errors: Emerging data shed light on risk factors, prevention

ORLANDO – Accumulating evidence is helping researchers better understand why errors occur during the delivery of cancer treatment and how to prevent them. Findings from a trio of studies were reported at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Identifying causes of incidents in radiation therapy

In the first study, Greg D. Judy, MD, a radiation oncology resident at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and his colleagues retrospectively reviewed records in their institution’s reporting system, called Good Catch, to identify near-miss incidents (ones that didn’t reach the patient) and safety incidents (ones that did) among patients undergoing radiation therapy from October 2014 through April 2016.

Multivariate analysis showed that patients had a significantly higher risk of near-miss or safety incidents if they had stage T2 disease (odds ratio, 3.3), were being treated for cancer involving the head and neck (5.2), or were receiving image-guided intensity-modulated radiation therapy (3.0) or daily imaging as part of their treatment (7.0), Dr. Judy reported.

“Head and neck site and image-guided IMRT [intensity-modulated radiation therapy] are complex entities: They have multiple steps in both the planning and delivery phase,” he said. “Daily imaging as well. It’s a much more complex process to do daily imaging for setup verification than it is to do once-a-week or even once-every-2-weeks setup verification.”

On the other hand, it was unclear why T2 stage was a risk factor. “We kind of hypothesized that it might be more of the disease site that really drives this, as you can have HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer which usually has lower T stages and more advanced nodal stages, but even then, that’s a head and neck site and we usually use image-guided IMRT, which are both very complex entities,” he said. The most common root causes for the incidents were issues related to documentation and scheduling (29% each), followed by issues related to communication (22%), technical treatment planning (14%), and technical treatment delivery (6%).

Incidents having a communication root cause were more likely than were others to affect patients (P less than .001), and those having a technical treatment delivery root cause were more likely to have higher severity (P = .005).

“Like some other studies, we found really the key factor was the complexity of the treatment plan and complexity of the overall process that is the real driving factor. This is important to understand because it promotes the idea of developing a more dedicated and robust QA system for complex cases,” said Dr. Judy. “It also highlights the importance of a strong reporting system to support a safety culture, as well as promote the continuous learning improvements within a department.”

The national Radiation Oncology Incident Learning System (RO-ILS) has been developed by the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO). “This is gaining membership very rapidly, and it’s good because it facilitates cooperative research and also safety standards for our field,” he maintained.

“I’ll argue that they did that for a variety of reasons,” he elaborated. “Strong and effective leadership by Dr. Larry Marks, who’s really created a departmental culture of safety in which people can feel free to speak up. They have this wonderful Good Catch program in place. And they have these simulation review huddles ... where people feel free to talk about what happened yesterday or today that may be relevant moving forward.”

As for the national RO-ILS initiative, “I would look out to the audience and say, why is it that we don’t have such a program in medical oncology?” Dr. Jacobson said. “It’s probably time for us to do this,” he maintained.

Reducing chemotherapy errors in pediatric oncology

In the second study, Brian D. Weiss, MD, associate director of safety and compliance at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and his colleagues studied the impact of a safety initiative to prevent chemotherapy errors at their large urban pediatric academic center (J Clin Oncol 35, 2017 [suppl 8S; abstract 37]).

“Pediatric chemotherapy protocols are different from adult protocols. We dose based on age or weight or body surface area, and that can change within a protocol. You have to do adjustments every time they gain weight or grow some, which is different than for adult protocols,” he explained. “We have parents administering chemo at home. And the protocols most patients are on are very complicated, but there is no standardized format, so it makes crucial information for dose adjustments difficult to find.”

The team successively implemented about half a dozen interventions, such as dedicated chemotherapy safety zones where staff were not to be disturbed while checking orders and ear protectors as a visual deterrent to interruptions; a new chemotherapy registered nurse role with a detailed list of responsibilities; an event-reporting system to supplement the center’s error-reporting system and capture events not reaching the patient (near-miss events); and a daily chemotherapy huddle to discuss errors in a nonpunitive setting and review upcoming chemotherapy for readiness.

In the 6 years after the start of the initiative, 105,187 chemotherapy doses were administered at the center and 998 errors occurred, including 250 errors that reached the patient, according to results reported at the symposium and recently published (J Oncol Pract. 2017 April;13:e329-e336).

At the 22-month mark, the rate of chemotherapy errors reaching the patient had fallen from 3.8 in 1,000 doses at baseline to 1.9 in 1,000 doses. The reduction has since persisted for more than 4 years and translates to an estimated 155 fewer predicted errors reaching the patient because of the initiative.

“The errors that reached the patient were more often administration and dispensing errors,” Dr. Weiss said. “About two-thirds of those errors that didn’t reach the patient – because they got caught by the pharmacists and the nurses – were prescription errors.

“Our chemotherapy huddle has certainly increased our reporting of errors. We also now use it for patients on clinical trials ... any patient getting PK [pharmacokinetics] or PD [pharmacodynamics] sampled within the next 24 hours is reviewed at that meeting. And our missed samples have gone down significantly,” he noted. “It’s allowed us to manage our bed space better because now everybody knows who’s definitely coming in the next day and who’s maybe coming in the next day.”

“We are a large urban academic pediatric medical center. Some of these things may seem difficult to translate [to smaller facilities], but I’m not sure they are,” concluded Dr. Weiss.

Dr. Jacobson, the discussant, noted that the initiative was in keeping with this health system’s longstanding “obsessive” focus on patient safety and commended its rigorousness in, for example, setting clear goals, focusing on key drivers [processes] needed for change, and selecting a good outcome metric.

“This is very successful project,” he said. The success can be attributed to “strong and effective organization and leadership, building a culture of safety at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, and an important predefined measurement program and methodology.”

Building chemotherapy regimens more accurately

In the third study, a team led by Andrea Crespo, BSc, BScPhm, BCOP, an oncology pharmacist and member of the Systemic Treatment Team at Cancer Care Ontario, Toronto, studied errors introduced when chemotherapy regimens were moved from publications into orders used by centers in the province (J Clin Oncol. 35, 2017 [suppl 8S; abstract 51]).

Nearly all outpatient intravenous systemic treatment visits in Ontario are supported by a Systemic Treatment Computerized Prescriber Order Entry (ST-CPOE) system, she noted. Such systems can reduce error rates but are not foolproof.

She and her colleagues asked all Ontario treatment centers to review their active chemotherapy regimens. Data were analyzed to determine whether the regimens were built as intended with respect to their component drugs and doses, leading to identification of any unintentional discrepancies with the original regimen.

A total of 33 centers performed the review, and the median number of regimens reviewed was 375 per center, Ms. Crespo reported.

Unintentional discrepancies in regimens were found at 27% of centers. The total number reported was 369 discrepancies, with a range from 2 to 198 per center.

All of the nine centers where discrepancies were found participated in the provincial ST-CPOE system, and most had for at least 20 years. Furthermore, eight of them used a team of at least two pharmacists and one oncologist to build their regimens. “So you can see that discrepancies occurred despite a fairly rigorous regimen-build process and many years of experience with the system,” she said.

Of the 369 total discrepancies, 41% were related to alignment with the Systemic Treatment Quality-Based Program regimen, and 32% were regimens flagged to be inactivated because of outdated information, new standards, or lack of use.

A detailed analysis of the remaining 27%, or 101 unintentional discrepancies, showed that the majority were due to missing information (35.6%) or missing drugs (13.9%), incorrect doses (10.9%), and incorrect or missing schedules (10.9%). Potential to cause harm was mild for 55%, moderate for 28%, and none for 17%.

“Corrective action has been taken to address the discrepancies identified,” said Ms. Crespo.

Only 6% of the 33 centers reported having an established regimen review and maintenance process in place before the study, but all now have such a process. In addition, some centers that did not find any regimen discrepancies nonetheless reported adding quality improvement activities, such as changes in the ways regimens were built and documented, and revising regimen names to facilitate accurate selection.

In discussing the study, Dr. Jacobson noted the low proportion of centers having an established process at baseline to ensure appropriate regimen maintenance and updates. “You might want to think to yourselves, the medical oncologists in the group, whether your center has such a process in place,” he proposed.

It is not yet known whether the project has met its goal of improving the quality and accuracy of oncology regimens in Ontario, he maintained. “We are going to have to invite [Ms. Crespo] back in a year or two to see whether that turns out to be true.” On the other hand, “clearly what they have achieved was the ability to measure the variance between what was intended and what was actually built.”

Chief among the reasons for success, again, “was a strong and effective leadership and organizational structure, not at the department level or hospital level, but across the entire province through Cancer Care Ontario,” Dr. Jacobson said. “It’s clear that they have a focus on quality and patient safety, and this measurement program that they have put in place turned out to be useful.”

Dr. Judy, Dr. Weiss, and Ms. Crespo disclosed that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Accumulating evidence is helping researchers better understand why errors occur during the delivery of cancer treatment and how to prevent them. Findings from a trio of studies were reported at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Identifying causes of incidents in radiation therapy

In the first study, Greg D. Judy, MD, a radiation oncology resident at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and his colleagues retrospectively reviewed records in their institution’s reporting system, called Good Catch, to identify near-miss incidents (ones that didn’t reach the patient) and safety incidents (ones that did) among patients undergoing radiation therapy from October 2014 through April 2016.

Multivariate analysis showed that patients had a significantly higher risk of near-miss or safety incidents if they had stage T2 disease (odds ratio, 3.3), were being treated for cancer involving the head and neck (5.2), or were receiving image-guided intensity-modulated radiation therapy (3.0) or daily imaging as part of their treatment (7.0), Dr. Judy reported.

“Head and neck site and image-guided IMRT [intensity-modulated radiation therapy] are complex entities: They have multiple steps in both the planning and delivery phase,” he said. “Daily imaging as well. It’s a much more complex process to do daily imaging for setup verification than it is to do once-a-week or even once-every-2-weeks setup verification.”

On the other hand, it was unclear why T2 stage was a risk factor. “We kind of hypothesized that it might be more of the disease site that really drives this, as you can have HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer which usually has lower T stages and more advanced nodal stages, but even then, that’s a head and neck site and we usually use image-guided IMRT, which are both very complex entities,” he said. The most common root causes for the incidents were issues related to documentation and scheduling (29% each), followed by issues related to communication (22%), technical treatment planning (14%), and technical treatment delivery (6%).

Incidents having a communication root cause were more likely than were others to affect patients (P less than .001), and those having a technical treatment delivery root cause were more likely to have higher severity (P = .005).

“Like some other studies, we found really the key factor was the complexity of the treatment plan and complexity of the overall process that is the real driving factor. This is important to understand because it promotes the idea of developing a more dedicated and robust QA system for complex cases,” said Dr. Judy. “It also highlights the importance of a strong reporting system to support a safety culture, as well as promote the continuous learning improvements within a department.”

The national Radiation Oncology Incident Learning System (RO-ILS) has been developed by the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO). “This is gaining membership very rapidly, and it’s good because it facilitates cooperative research and also safety standards for our field,” he maintained.

“I’ll argue that they did that for a variety of reasons,” he elaborated. “Strong and effective leadership by Dr. Larry Marks, who’s really created a departmental culture of safety in which people can feel free to speak up. They have this wonderful Good Catch program in place. And they have these simulation review huddles ... where people feel free to talk about what happened yesterday or today that may be relevant moving forward.”

As for the national RO-ILS initiative, “I would look out to the audience and say, why is it that we don’t have such a program in medical oncology?” Dr. Jacobson said. “It’s probably time for us to do this,” he maintained.

Reducing chemotherapy errors in pediatric oncology

In the second study, Brian D. Weiss, MD, associate director of safety and compliance at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and his colleagues studied the impact of a safety initiative to prevent chemotherapy errors at their large urban pediatric academic center (J Clin Oncol 35, 2017 [suppl 8S; abstract 37]).

“Pediatric chemotherapy protocols are different from adult protocols. We dose based on age or weight or body surface area, and that can change within a protocol. You have to do adjustments every time they gain weight or grow some, which is different than for adult protocols,” he explained. “We have parents administering chemo at home. And the protocols most patients are on are very complicated, but there is no standardized format, so it makes crucial information for dose adjustments difficult to find.”

The team successively implemented about half a dozen interventions, such as dedicated chemotherapy safety zones where staff were not to be disturbed while checking orders and ear protectors as a visual deterrent to interruptions; a new chemotherapy registered nurse role with a detailed list of responsibilities; an event-reporting system to supplement the center’s error-reporting system and capture events not reaching the patient (near-miss events); and a daily chemotherapy huddle to discuss errors in a nonpunitive setting and review upcoming chemotherapy for readiness.

In the 6 years after the start of the initiative, 105,187 chemotherapy doses were administered at the center and 998 errors occurred, including 250 errors that reached the patient, according to results reported at the symposium and recently published (J Oncol Pract. 2017 April;13:e329-e336).

At the 22-month mark, the rate of chemotherapy errors reaching the patient had fallen from 3.8 in 1,000 doses at baseline to 1.9 in 1,000 doses. The reduction has since persisted for more than 4 years and translates to an estimated 155 fewer predicted errors reaching the patient because of the initiative.

“The errors that reached the patient were more often administration and dispensing errors,” Dr. Weiss said. “About two-thirds of those errors that didn’t reach the patient – because they got caught by the pharmacists and the nurses – were prescription errors.

“Our chemotherapy huddle has certainly increased our reporting of errors. We also now use it for patients on clinical trials ... any patient getting PK [pharmacokinetics] or PD [pharmacodynamics] sampled within the next 24 hours is reviewed at that meeting. And our missed samples have gone down significantly,” he noted. “It’s allowed us to manage our bed space better because now everybody knows who’s definitely coming in the next day and who’s maybe coming in the next day.”

“We are a large urban academic pediatric medical center. Some of these things may seem difficult to translate [to smaller facilities], but I’m not sure they are,” concluded Dr. Weiss.

Dr. Jacobson, the discussant, noted that the initiative was in keeping with this health system’s longstanding “obsessive” focus on patient safety and commended its rigorousness in, for example, setting clear goals, focusing on key drivers [processes] needed for change, and selecting a good outcome metric.

“This is very successful project,” he said. The success can be attributed to “strong and effective organization and leadership, building a culture of safety at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, and an important predefined measurement program and methodology.”

Building chemotherapy regimens more accurately

In the third study, a team led by Andrea Crespo, BSc, BScPhm, BCOP, an oncology pharmacist and member of the Systemic Treatment Team at Cancer Care Ontario, Toronto, studied errors introduced when chemotherapy regimens were moved from publications into orders used by centers in the province (J Clin Oncol. 35, 2017 [suppl 8S; abstract 51]).

Nearly all outpatient intravenous systemic treatment visits in Ontario are supported by a Systemic Treatment Computerized Prescriber Order Entry (ST-CPOE) system, she noted. Such systems can reduce error rates but are not foolproof.

She and her colleagues asked all Ontario treatment centers to review their active chemotherapy regimens. Data were analyzed to determine whether the regimens were built as intended with respect to their component drugs and doses, leading to identification of any unintentional discrepancies with the original regimen.

A total of 33 centers performed the review, and the median number of regimens reviewed was 375 per center, Ms. Crespo reported.

Unintentional discrepancies in regimens were found at 27% of centers. The total number reported was 369 discrepancies, with a range from 2 to 198 per center.

All of the nine centers where discrepancies were found participated in the provincial ST-CPOE system, and most had for at least 20 years. Furthermore, eight of them used a team of at least two pharmacists and one oncologist to build their regimens. “So you can see that discrepancies occurred despite a fairly rigorous regimen-build process and many years of experience with the system,” she said.

Of the 369 total discrepancies, 41% were related to alignment with the Systemic Treatment Quality-Based Program regimen, and 32% were regimens flagged to be inactivated because of outdated information, new standards, or lack of use.

A detailed analysis of the remaining 27%, or 101 unintentional discrepancies, showed that the majority were due to missing information (35.6%) or missing drugs (13.9%), incorrect doses (10.9%), and incorrect or missing schedules (10.9%). Potential to cause harm was mild for 55%, moderate for 28%, and none for 17%.

“Corrective action has been taken to address the discrepancies identified,” said Ms. Crespo.

Only 6% of the 33 centers reported having an established regimen review and maintenance process in place before the study, but all now have such a process. In addition, some centers that did not find any regimen discrepancies nonetheless reported adding quality improvement activities, such as changes in the ways regimens were built and documented, and revising regimen names to facilitate accurate selection.

In discussing the study, Dr. Jacobson noted the low proportion of centers having an established process at baseline to ensure appropriate regimen maintenance and updates. “You might want to think to yourselves, the medical oncologists in the group, whether your center has such a process in place,” he proposed.

It is not yet known whether the project has met its goal of improving the quality and accuracy of oncology regimens in Ontario, he maintained. “We are going to have to invite [Ms. Crespo] back in a year or two to see whether that turns out to be true.” On the other hand, “clearly what they have achieved was the ability to measure the variance between what was intended and what was actually built.”

Chief among the reasons for success, again, “was a strong and effective leadership and organizational structure, not at the department level or hospital level, but across the entire province through Cancer Care Ontario,” Dr. Jacobson said. “It’s clear that they have a focus on quality and patient safety, and this measurement program that they have put in place turned out to be useful.”

Dr. Judy, Dr. Weiss, and Ms. Crespo disclosed that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – Accumulating evidence is helping researchers better understand why errors occur during the delivery of cancer treatment and how to prevent them. Findings from a trio of studies were reported at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Identifying causes of incidents in radiation therapy

In the first study, Greg D. Judy, MD, a radiation oncology resident at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and his colleagues retrospectively reviewed records in their institution’s reporting system, called Good Catch, to identify near-miss incidents (ones that didn’t reach the patient) and safety incidents (ones that did) among patients undergoing radiation therapy from October 2014 through April 2016.

Multivariate analysis showed that patients had a significantly higher risk of near-miss or safety incidents if they had stage T2 disease (odds ratio, 3.3), were being treated for cancer involving the head and neck (5.2), or were receiving image-guided intensity-modulated radiation therapy (3.0) or daily imaging as part of their treatment (7.0), Dr. Judy reported.