User login

Postmarket safety events common in FDA-approved drugs

New research suggests postmarket safety events are common for therapeutics approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Researchers evaluated more than 200 pharmaceuticals and biologics approved by the FDA from 2001 through 2010 and found that nearly a third of these products were affected by a postmarket safety event.

Most of the events were boxed warnings or safety communications, but there were a few products withdrawn from the market due to safety issues.

Joseph S. Ross, MD, of the Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, and his colleagues reported these findings in JAMA.

The researchers noted that most pivotal trials that form the basis for FDA approval enroll fewer than 1000 patients and have follow-up of 6 months or less.

Therefore, uncommon or long-term serious safety risks may only become evident after approval, when new therapeutics are used in larger patient populations and for longer periods of time.

With this in mind, Dr Ross and his colleagues examined postmarket safety events for all novel therapeutics approved by the FDA between January 2001 and December 2010 (followed-up through February 2017).

Safety events included withdrawals due to safety concerns, FDA issuance of incremental boxed warnings added in the postmarket period, and FDA issuance of safety communications.

From 2001 through 2010, the FDA approved 222 novel therapeutics—183 pharmaceuticals and 39 biologics.

During a median follow-up of 11.7 years, there were 123 postmarket safety events—3 withdrawals, 61 boxed warnings, and 59 safety communications.

“The fact that the FDA is issuing safety communications means it is doing a good job of following newly approved drugs and evaluating their safety up in the postmarket period,” Dr Ross said.

The 123 safety events identified affected 71 (32%) of the 222 therapeutics.

The median time from FDA approval to the first postmarket safety event was 4.2 years. And 31% of the therapeutics were still affected by a postmarket safety event at 10 years.

The researchers found that postmarket safety events were significantly more frequent in biologics (P=0.03), drugs used to treat psychiatric disease (P<0.001), products approved near their regulatory deadline (P=0.008), and therapeutics granted accelerated approval (P=0.02).

“[The accelerated approval finding] shows that there is the potential for compromising patient safety when drug evaluation is persistently sped up,” Dr Ross said.

On the other hand, the researchers also found that postmarket safety events were significantly less frequent in therapeutics the FDA reviewed in less than 200 days (P=0.02).

The researchers said these findings should be interpreted cautiously, but they can be used to inform ongoing surveillance efforts. ![]()

New research suggests postmarket safety events are common for therapeutics approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Researchers evaluated more than 200 pharmaceuticals and biologics approved by the FDA from 2001 through 2010 and found that nearly a third of these products were affected by a postmarket safety event.

Most of the events were boxed warnings or safety communications, but there were a few products withdrawn from the market due to safety issues.

Joseph S. Ross, MD, of the Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, and his colleagues reported these findings in JAMA.

The researchers noted that most pivotal trials that form the basis for FDA approval enroll fewer than 1000 patients and have follow-up of 6 months or less.

Therefore, uncommon or long-term serious safety risks may only become evident after approval, when new therapeutics are used in larger patient populations and for longer periods of time.

With this in mind, Dr Ross and his colleagues examined postmarket safety events for all novel therapeutics approved by the FDA between January 2001 and December 2010 (followed-up through February 2017).

Safety events included withdrawals due to safety concerns, FDA issuance of incremental boxed warnings added in the postmarket period, and FDA issuance of safety communications.

From 2001 through 2010, the FDA approved 222 novel therapeutics—183 pharmaceuticals and 39 biologics.

During a median follow-up of 11.7 years, there were 123 postmarket safety events—3 withdrawals, 61 boxed warnings, and 59 safety communications.

“The fact that the FDA is issuing safety communications means it is doing a good job of following newly approved drugs and evaluating their safety up in the postmarket period,” Dr Ross said.

The 123 safety events identified affected 71 (32%) of the 222 therapeutics.

The median time from FDA approval to the first postmarket safety event was 4.2 years. And 31% of the therapeutics were still affected by a postmarket safety event at 10 years.

The researchers found that postmarket safety events were significantly more frequent in biologics (P=0.03), drugs used to treat psychiatric disease (P<0.001), products approved near their regulatory deadline (P=0.008), and therapeutics granted accelerated approval (P=0.02).

“[The accelerated approval finding] shows that there is the potential for compromising patient safety when drug evaluation is persistently sped up,” Dr Ross said.

On the other hand, the researchers also found that postmarket safety events were significantly less frequent in therapeutics the FDA reviewed in less than 200 days (P=0.02).

The researchers said these findings should be interpreted cautiously, but they can be used to inform ongoing surveillance efforts. ![]()

New research suggests postmarket safety events are common for therapeutics approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Researchers evaluated more than 200 pharmaceuticals and biologics approved by the FDA from 2001 through 2010 and found that nearly a third of these products were affected by a postmarket safety event.

Most of the events were boxed warnings or safety communications, but there were a few products withdrawn from the market due to safety issues.

Joseph S. Ross, MD, of the Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, and his colleagues reported these findings in JAMA.

The researchers noted that most pivotal trials that form the basis for FDA approval enroll fewer than 1000 patients and have follow-up of 6 months or less.

Therefore, uncommon or long-term serious safety risks may only become evident after approval, when new therapeutics are used in larger patient populations and for longer periods of time.

With this in mind, Dr Ross and his colleagues examined postmarket safety events for all novel therapeutics approved by the FDA between January 2001 and December 2010 (followed-up through February 2017).

Safety events included withdrawals due to safety concerns, FDA issuance of incremental boxed warnings added in the postmarket period, and FDA issuance of safety communications.

From 2001 through 2010, the FDA approved 222 novel therapeutics—183 pharmaceuticals and 39 biologics.

During a median follow-up of 11.7 years, there were 123 postmarket safety events—3 withdrawals, 61 boxed warnings, and 59 safety communications.

“The fact that the FDA is issuing safety communications means it is doing a good job of following newly approved drugs and evaluating their safety up in the postmarket period,” Dr Ross said.

The 123 safety events identified affected 71 (32%) of the 222 therapeutics.

The median time from FDA approval to the first postmarket safety event was 4.2 years. And 31% of the therapeutics were still affected by a postmarket safety event at 10 years.

The researchers found that postmarket safety events were significantly more frequent in biologics (P=0.03), drugs used to treat psychiatric disease (P<0.001), products approved near their regulatory deadline (P=0.008), and therapeutics granted accelerated approval (P=0.02).

“[The accelerated approval finding] shows that there is the potential for compromising patient safety when drug evaluation is persistently sped up,” Dr Ross said.

On the other hand, the researchers also found that postmarket safety events were significantly less frequent in therapeutics the FDA reviewed in less than 200 days (P=0.02).

The researchers said these findings should be interpreted cautiously, but they can be used to inform ongoing surveillance efforts. ![]()

Endometriosis: From Identification to Management

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Staging endometriosis

- Medications for treating endometriosis

- Complications

Endometriosis is a gynecologic disorder characterized by the presence and growth of endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity (ie, endometrial implants), most commonly found on the ovaries. Although its pathophysiology is not completely understood, the disease is associated with dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and infertility.1,2 Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent disorder, predominantly affecting women of childbearing age. It occurs in 10% to 15% of the general female population, but prevalence is even higher (35% to 50%) among women who experience pelvic pain and/or infertility.1-4 Although endometriosis mainly affects women in their mid-to-late 20s, it can also manifest in adolescence.3,5 Nearly half of all adolescents with intractable dysmenorrhea are diagnosed with endometriosis.5

ETIOLOGY

The etiology of endometriosis, while not completely understood, is likely multifactorial. Factors that may influence its development include gene expression, tissue response to hormones, neuronal tissue involvement, lack of protective factors, inflammation, and cellular oxidative stress.6,7

Several theories regarding the etiology of endometriosis have been proposed; the most widely accepted is the transplantation theory, which suggests that endometriosis results from retrograde flow of menstrual tissue through the fallopian tubes. During menstruation, fragments of the endometrium are driven through the fallopian tubes and into the pelvic cavity, where they can implant onto the pelvic structures, leading to further growth and invasion.2,6,8 Women who have polymenorrhea, prolonged menses, and early menarche therefore have an increased risk for endometriosis.8 This theory does not account for the fact that although nearly 90% of women have some elements of retrograde menstrual flow, only a fraction of them develop endometriosis.6

Two other plausible explanations are the coelomic metaplasia and embryonic rest theories. In the coelomic metaplasia theory, the mesothelium (coelomic epithelium)—which encases the ovaries—invaginates into the ovaries and undergoes a metaplastic change to endometrial tissue. This could explain the development of endometriosis in patients with the congenital malformation Müllerian agenesis. In the embryonic rest theory, Müllerian remnants in the rectovaginal area, left behind by the Müllerian duct system, have the potential to differentiate into endometrial tissue.2,5,6,8

Another theory involving lymphatic or hematologic spread has been proposed, which would explain the presence of endometrial implants at sites distant from the uterus (eg, the pleural cavity and brain). However, this theory is not widely understood

The two most recent hypotheses on endometriosis are associated with an abnormal immune system and a possible genetic predisposition. The peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis has different levels of prostanoids, cytokines, growth factors, and interleukins than that of women who do not have the condition. It is uncertain whether the relationship between peritoneal fluid changes and endometriosis is causal.6 A genetic correlation has been suggested, based on an increased prevalence of endometriosis in women with an affected first-degree relative; in a case-control study on family incidence of endometriosis, 5.9% to 9.6% of first-degree relatives and 1.3% of second-degree relatives were affected.9 The Oxford Endometriosis Gene (OXEGENE) study is currently investigating susceptible loci for endometriosis genes, which could provide a better understanding of the disease process.6

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The most common symptoms of endometriosis are dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility, but 20% to 25% of affected women are asymptomatic.4,10,11 Pelvic pain in women most often heralds onset of menses and worsens during menstruation.1 Other symptoms include back pain, dyschezia, dysuria, nausea, lethargy, and chronic fatigue.4,8,10

Endometriosis is concomitant with infertility; endometrial adhesions that attach to pelvic organs cause distortion of pelvic structures and impaired ovum release and pick-up, and are believed to reduce fecundity. Additionally, women with endometriosis have low ovarian reserve and low-quality oocytes.6,8 Altered chemical elements (ie, prostanoids, cytokines, growth factors, and interleukins) may also contribute to endometrial-related infertility; intrapelvic growth factors could affect the fallopian tubes or pelvic environment, and thus the oocytes in a similar fashion.6

In adolescents, endometriosis can present as cyclic or acyclic pain; severe dysmenorrhea; dysmenorrhea that responds poorly to medications (eg, oral contraceptive pills [OCPs] or NSAIDs); and prolonged menstruation with premenstrual spotting.1

The physical exam may reveal tender nodules in the posterior vaginal fornix; cervical motion tenderness; a fixed uterus, cervix, or adnexa; uterine motion tenderness; thickening, pain, tenderness, or nodularity of the uterosacral ligament; or tender adnexal masses due to endometriomas.8,10

PATHOLOGIC CHARACTERISTICS AND STAGING

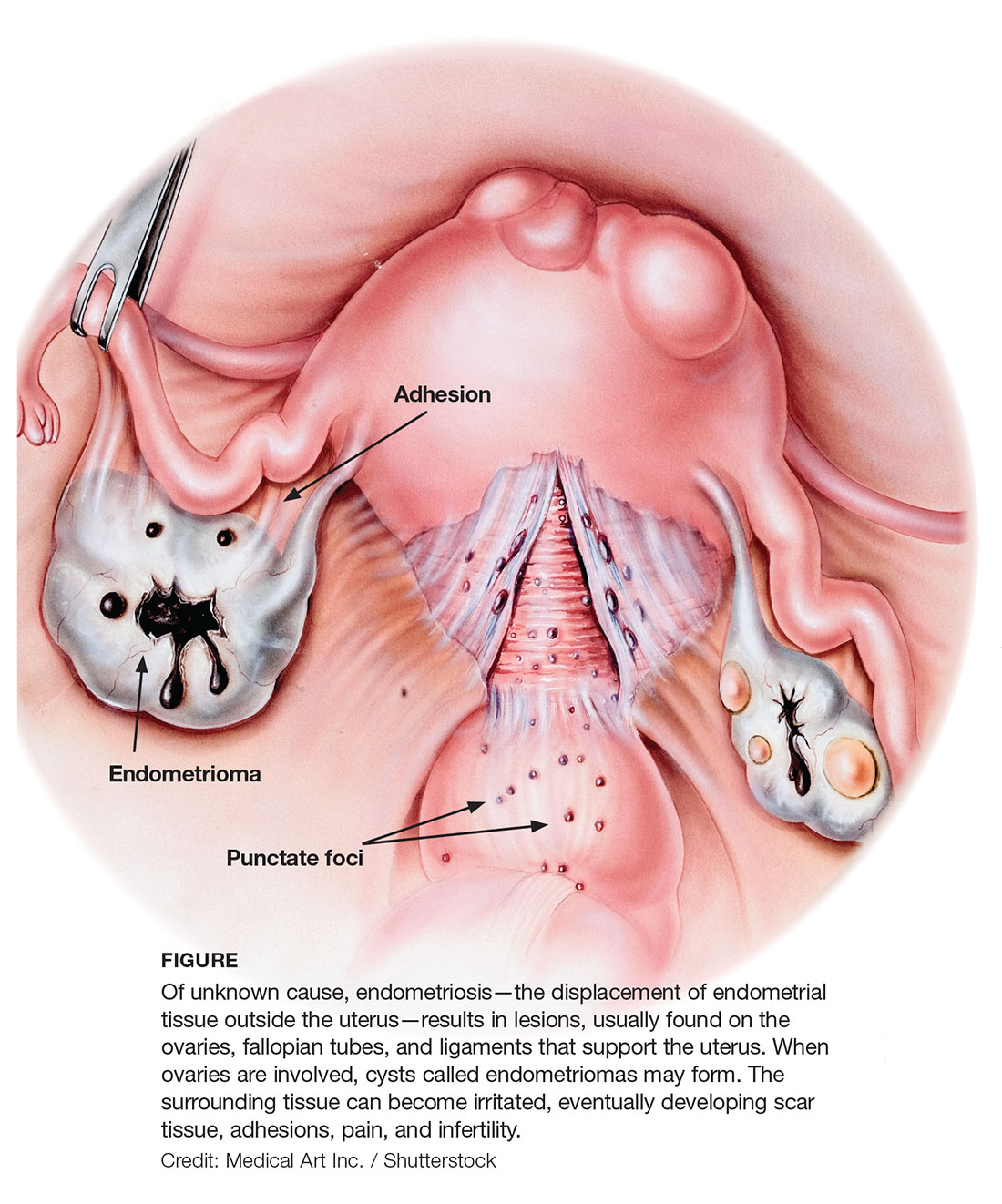

Gross pathology of endometriosis varies based on duration of disease and depth of implants or lesions. Implants range from punctate foci to small stellate patches that vary in color but typically measure less than 2 cm. They manifest most commonly in the ovaries, followed by the anterior and posterior cul-de-sac, posterior broad ligament, and uterosacral ligament. Implants can also be located on the uterus, fallopian tubes, sigmoid colon, ureter, small intestine, lungs, and brain (see Figure).3

Due to recurrent cyclic hemorrhage within a deep implant, endometriomas typically appear in the ovaries, entirely replacing normal ovarian tissue. Endometriomas are composed of dark, thick, degenerated blood products that result in a brown cyst—hence their designation as chocolate cysts. Microscopically, they are comprised of endometrial glands, stroma, and sometimes smooth muscle.3

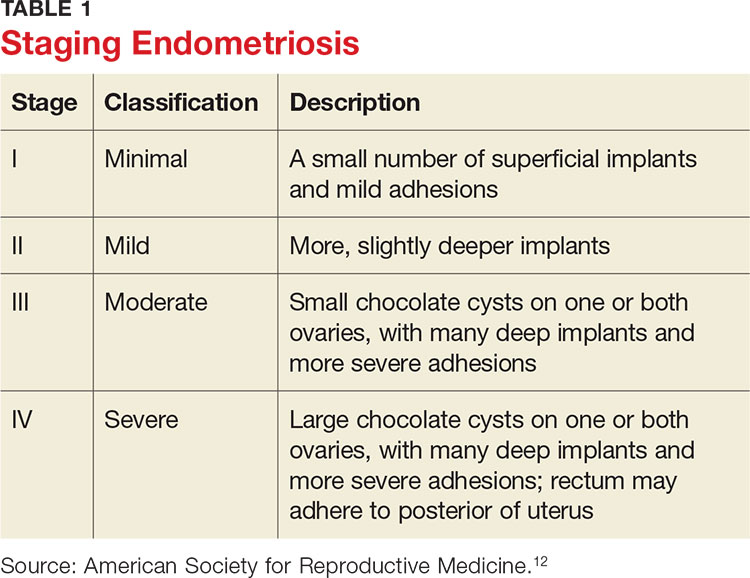

Staging of endometriosis is determined by the volume, depth, location, and size of the implants (see Table 1). It is important to note that staging does not necessarily reflect symptom severity.12

DIAGNOSIS

There are several approaches to the diagnostic evaluation of endometriosis, all of which should be guided by the clinical presentation and physical examination. Clinical characteristics can be nonspecific and highly variable, warranting more reliable diagnostic methods.

Laparoscopy is the diagnostic gold standard for endometriosis, and biopsy of implants revealing endometrial tissue is confirmatory. Less invasive diagnostic methods include ultrasound and MRI—but without confirmatory histologic sampling, these only yield a presumptive diagnosis.

With ultrasonography, a transvaginal approach should be taken. While endometriomas have a variety of presentations on ultrasound, most appear as a homogenous, hypoechoic, focal lesion within the ovary. MRI has greater specificity than ultrasound for diagnosis of endometriomas. However, “shading,” or loss of signal, within an endometrioma is a feature commonly found on MRI.3

Other tests that aid in the diagnosis, but are not definitive, include sedimentation rate and tumor marker CA-125. These are both commonly elevated in patients with endometriosis. Measurement of CA-125 is helpful for identifying patients with infertility and severe endometriosis, who would therefore benefit from early surgical intervention.8

TREATMENT

There is no permanent cure for endometriosis; treatment entails nonsurgical and surgical approaches to symptom resolution. Treatment is directed by the patient’s desire to maintain fertility.

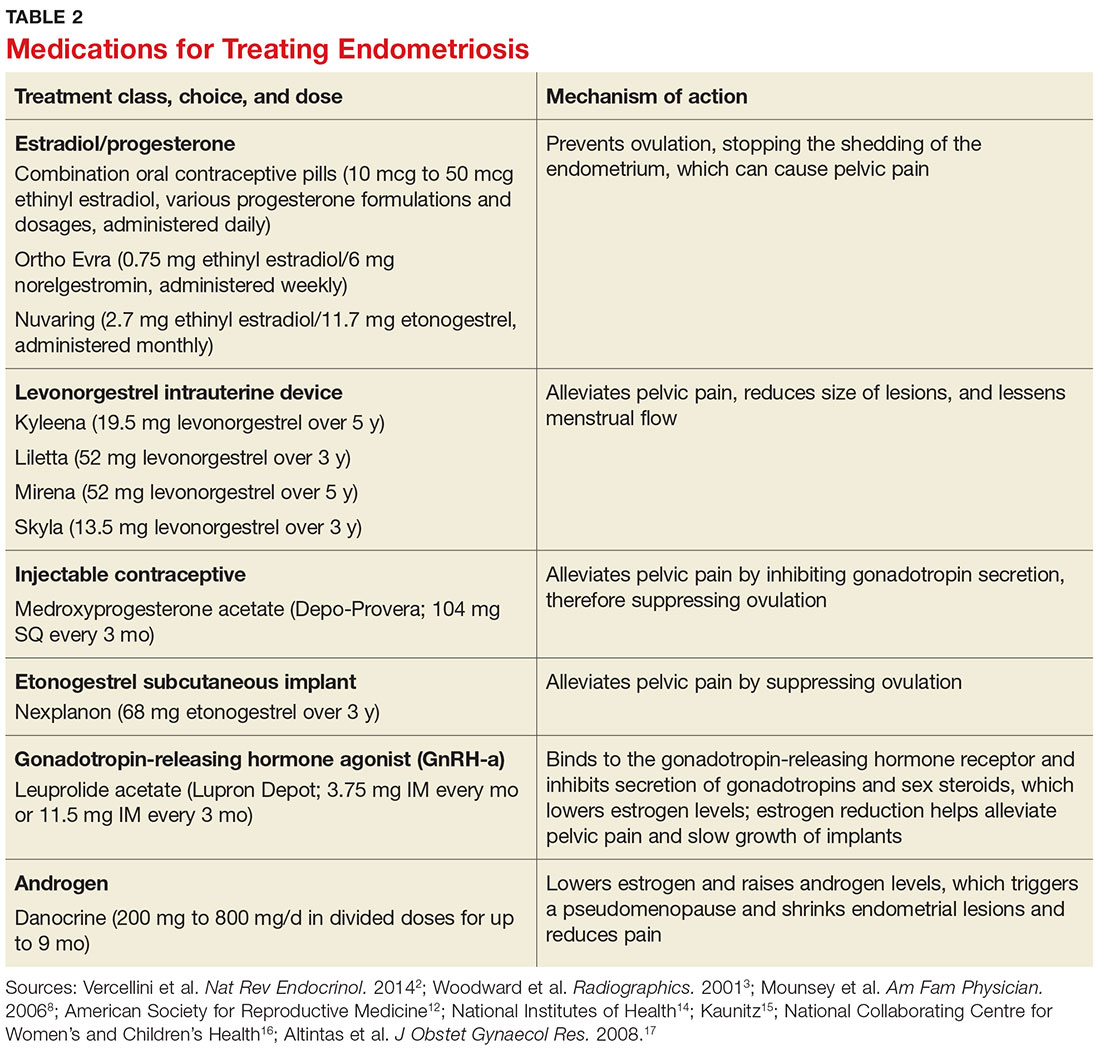

Conservative treatment of pelvic pain with NSAIDs is a common approach. Progestins are also used to treat pelvic pain; they create an acyclic, hypo-estrogenic environment by blocking ovarian estrogen secretion and subsequent endometrial cell proliferation. In addition to alleviating pain, progestins also prevent disease recurrence after surgery.2,13 Options include combination OCPs, levonorgestrel intrauterine devices, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and etonogestrel implants. Combination OCPs and medroxyprogesterone acetate are considered to be firstline treatment.8

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRH-a), such as leuprolide acetate, and androgenic agents, such as danocrine, are also indicated for relief of pain resulting from biopsy-confirmed endometriosis. Danocrine has been shown to ameliorate pain in up to 92% of patients.3,8 Other unconventional treatment modalities include aromatase inhibitors, selective estrogen receptor modulators, anti-inflammatory agents, and immunomodulators.2 For an outline of the medication choices and their mechanisms of action, see Table 2.

Surgery, or ablation of the implants, is another viable treatment option; it can be performed via laparoscopy or laparotomy. Although the success rate is high, implants recur in 28% of patients 18 months after surgery and in 40% of patients after nine years; 40% to 50% of patients have adhesion recurrence.3

Patients who have concomitant infertility can be treated with advanced reproductive techniques, including intrauterine insemination and ovarian hyperstimulation. The monthly fecundity rate with such techniques is 9% to 18%.3 Laparoscopic surgery with ablation of endometrial implants may increase fertility in patients with endometriosis.8

Hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy are definitive treatment options reserved for patients with intractable pain and those who do not wish to maintain fertility.3,8 Recurrent symptoms occur in 10% of patients 10 years after hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy, compared with 62% of those who have hysterectomy alone.8 Complete surgical removal of endometriomas, and ovary if affected, can reduce risk for epithelial ovarian cancer in the future.2

COMPLICATIONS

Adhesions are a common complication of endometriosis. Ultrasound can be used for diagnosis and to determine whether pelvic organs are fixed (ie, fixed retroverted uterus). MRI may also be used; adhesions appear as “speculated low-signal-intensity stranding that obscures organ interfaces.”3 Other suggestive findings on MRI include posterior displacement of the pelvic organs, elevation of the posterior vaginal fornix, hydrosalpinx, loculated fluid collections, and angulated bowel loops.3

Malignant transformation is rare, affecting fewer than 1% of patients with endometriosis. Most malignancies arise from ovarian endometriosis and can be related to unopposed estrogen therapy; they are typically large and have a solid component. The most common endometriosis-related malignant neoplasm is endometrioid carcinoma, followed by clear-cell carcinoma.3

CONCLUSION

Patients with endometriosis often present with complaints such as dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, and chronic pelvic pain, but surgical and histologic findings indicate that symptom severity does not necessarily equate to disease severity. Definitive diagnosis requires an invasive surgical procedure.

In the absence of a cure, endometriosis treatment focuses on symptom control and improvement in quality of life. Familiarity with the disease process and knowledge of treatment options will help health care providers achieve this goal for patients who experience the potentially life-altering effects of endometriosis.

1. Janssen EB, Rijkers AC, Hoppenbrouwers K, et al. Prevalence of endometriosis diagnosed by laparoscopy in adolescents with dysmenorrhea or chronic pelvic pain: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19(5):570-582.

2. Vercellini P, Viganò P, Somigliana E, Fedele L. Endometriosis: pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014; 10(5):261-275.

3. Woodward PJ, Sohaey R, Mezzetti TP. Endometriosis: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2001;21(1):193-216.

4. Bulletti C, Coccia ME, Battistoni S, Borini A. Endometriosis and infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2010;27(8):441-447.

5. Ahn SH, Monsanto SP, Miller C, et al. Pathophysiology and immune dysfunction in endometriosis. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2015:1-12.

6. Child TJ, Tan SL. Endometriosis: aetiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Drugs. 2001;61(12):1735-1750.

7. Farrell E, Garad R. Clinical update: endometriosis. Aust Nurs J. 2012;20(5):37-39.

8. Mounsey AL, Wilgus A, Slawson DC. Diagnosis and management of endometriosis. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(4):594-600.

9. Nouri K, Ott J, Krupitz B, et al. Family incidence of endometriosis in first-, second-, and third-degree relatives: case-control study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;8(85):1-7.

10. Riazi H, Tehranian N, Ziaei S, et al. Clinical diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis: a scoping review. BMC Women’s Health. 2015;15(39):1-12.

11. Acién P, Velasco I. Endometriosis: a disease that remains enigmatic. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:1-12.

12. American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Endometriosis: a guide for patients. www.conceive.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/ASRM-endometriosis.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2017.

13. Angioni S, Cofelice V, Pontis A, et al. New trends of progestins treatment of endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2014; 30(11):769-773.

14. National Institutes of Health. What are the treatments for endometriosis? www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/endometri/conditioninfo/Pages/treatment.aspx. Accessed April 19, 2017.

15. Kaunitz AM. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate for contraception. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/depot-medroxyprogesterone-acetate-for-contraception. Accessed April 19, 2017.

16. National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. Long-acting reversible contraception: the effective and appropriate use of long-acting reversible contraception. London, England: RCOG Press; 2005. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK51051/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK51051.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2017.

17. Altintas D, Kokcu A, Tosun M, Kandemir B. Comparison of the effects of cetrorelix, a GnRH antagonist, and leuprolide, a GnRH agonist, on experimental endometriosis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008;34(6):1014-1019.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Staging endometriosis

- Medications for treating endometriosis

- Complications

Endometriosis is a gynecologic disorder characterized by the presence and growth of endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity (ie, endometrial implants), most commonly found on the ovaries. Although its pathophysiology is not completely understood, the disease is associated with dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and infertility.1,2 Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent disorder, predominantly affecting women of childbearing age. It occurs in 10% to 15% of the general female population, but prevalence is even higher (35% to 50%) among women who experience pelvic pain and/or infertility.1-4 Although endometriosis mainly affects women in their mid-to-late 20s, it can also manifest in adolescence.3,5 Nearly half of all adolescents with intractable dysmenorrhea are diagnosed with endometriosis.5

ETIOLOGY

The etiology of endometriosis, while not completely understood, is likely multifactorial. Factors that may influence its development include gene expression, tissue response to hormones, neuronal tissue involvement, lack of protective factors, inflammation, and cellular oxidative stress.6,7

Several theories regarding the etiology of endometriosis have been proposed; the most widely accepted is the transplantation theory, which suggests that endometriosis results from retrograde flow of menstrual tissue through the fallopian tubes. During menstruation, fragments of the endometrium are driven through the fallopian tubes and into the pelvic cavity, where they can implant onto the pelvic structures, leading to further growth and invasion.2,6,8 Women who have polymenorrhea, prolonged menses, and early menarche therefore have an increased risk for endometriosis.8 This theory does not account for the fact that although nearly 90% of women have some elements of retrograde menstrual flow, only a fraction of them develop endometriosis.6

Two other plausible explanations are the coelomic metaplasia and embryonic rest theories. In the coelomic metaplasia theory, the mesothelium (coelomic epithelium)—which encases the ovaries—invaginates into the ovaries and undergoes a metaplastic change to endometrial tissue. This could explain the development of endometriosis in patients with the congenital malformation Müllerian agenesis. In the embryonic rest theory, Müllerian remnants in the rectovaginal area, left behind by the Müllerian duct system, have the potential to differentiate into endometrial tissue.2,5,6,8

Another theory involving lymphatic or hematologic spread has been proposed, which would explain the presence of endometrial implants at sites distant from the uterus (eg, the pleural cavity and brain). However, this theory is not widely understood

The two most recent hypotheses on endometriosis are associated with an abnormal immune system and a possible genetic predisposition. The peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis has different levels of prostanoids, cytokines, growth factors, and interleukins than that of women who do not have the condition. It is uncertain whether the relationship between peritoneal fluid changes and endometriosis is causal.6 A genetic correlation has been suggested, based on an increased prevalence of endometriosis in women with an affected first-degree relative; in a case-control study on family incidence of endometriosis, 5.9% to 9.6% of first-degree relatives and 1.3% of second-degree relatives were affected.9 The Oxford Endometriosis Gene (OXEGENE) study is currently investigating susceptible loci for endometriosis genes, which could provide a better understanding of the disease process.6

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The most common symptoms of endometriosis are dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility, but 20% to 25% of affected women are asymptomatic.4,10,11 Pelvic pain in women most often heralds onset of menses and worsens during menstruation.1 Other symptoms include back pain, dyschezia, dysuria, nausea, lethargy, and chronic fatigue.4,8,10

Endometriosis is concomitant with infertility; endometrial adhesions that attach to pelvic organs cause distortion of pelvic structures and impaired ovum release and pick-up, and are believed to reduce fecundity. Additionally, women with endometriosis have low ovarian reserve and low-quality oocytes.6,8 Altered chemical elements (ie, prostanoids, cytokines, growth factors, and interleukins) may also contribute to endometrial-related infertility; intrapelvic growth factors could affect the fallopian tubes or pelvic environment, and thus the oocytes in a similar fashion.6

In adolescents, endometriosis can present as cyclic or acyclic pain; severe dysmenorrhea; dysmenorrhea that responds poorly to medications (eg, oral contraceptive pills [OCPs] or NSAIDs); and prolonged menstruation with premenstrual spotting.1

The physical exam may reveal tender nodules in the posterior vaginal fornix; cervical motion tenderness; a fixed uterus, cervix, or adnexa; uterine motion tenderness; thickening, pain, tenderness, or nodularity of the uterosacral ligament; or tender adnexal masses due to endometriomas.8,10

PATHOLOGIC CHARACTERISTICS AND STAGING

Gross pathology of endometriosis varies based on duration of disease and depth of implants or lesions. Implants range from punctate foci to small stellate patches that vary in color but typically measure less than 2 cm. They manifest most commonly in the ovaries, followed by the anterior and posterior cul-de-sac, posterior broad ligament, and uterosacral ligament. Implants can also be located on the uterus, fallopian tubes, sigmoid colon, ureter, small intestine, lungs, and brain (see Figure).3

Due to recurrent cyclic hemorrhage within a deep implant, endometriomas typically appear in the ovaries, entirely replacing normal ovarian tissue. Endometriomas are composed of dark, thick, degenerated blood products that result in a brown cyst—hence their designation as chocolate cysts. Microscopically, they are comprised of endometrial glands, stroma, and sometimes smooth muscle.3

Staging of endometriosis is determined by the volume, depth, location, and size of the implants (see Table 1). It is important to note that staging does not necessarily reflect symptom severity.12

DIAGNOSIS

There are several approaches to the diagnostic evaluation of endometriosis, all of which should be guided by the clinical presentation and physical examination. Clinical characteristics can be nonspecific and highly variable, warranting more reliable diagnostic methods.

Laparoscopy is the diagnostic gold standard for endometriosis, and biopsy of implants revealing endometrial tissue is confirmatory. Less invasive diagnostic methods include ultrasound and MRI—but without confirmatory histologic sampling, these only yield a presumptive diagnosis.

With ultrasonography, a transvaginal approach should be taken. While endometriomas have a variety of presentations on ultrasound, most appear as a homogenous, hypoechoic, focal lesion within the ovary. MRI has greater specificity than ultrasound for diagnosis of endometriomas. However, “shading,” or loss of signal, within an endometrioma is a feature commonly found on MRI.3

Other tests that aid in the diagnosis, but are not definitive, include sedimentation rate and tumor marker CA-125. These are both commonly elevated in patients with endometriosis. Measurement of CA-125 is helpful for identifying patients with infertility and severe endometriosis, who would therefore benefit from early surgical intervention.8

TREATMENT

There is no permanent cure for endometriosis; treatment entails nonsurgical and surgical approaches to symptom resolution. Treatment is directed by the patient’s desire to maintain fertility.

Conservative treatment of pelvic pain with NSAIDs is a common approach. Progestins are also used to treat pelvic pain; they create an acyclic, hypo-estrogenic environment by blocking ovarian estrogen secretion and subsequent endometrial cell proliferation. In addition to alleviating pain, progestins also prevent disease recurrence after surgery.2,13 Options include combination OCPs, levonorgestrel intrauterine devices, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and etonogestrel implants. Combination OCPs and medroxyprogesterone acetate are considered to be firstline treatment.8

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRH-a), such as leuprolide acetate, and androgenic agents, such as danocrine, are also indicated for relief of pain resulting from biopsy-confirmed endometriosis. Danocrine has been shown to ameliorate pain in up to 92% of patients.3,8 Other unconventional treatment modalities include aromatase inhibitors, selective estrogen receptor modulators, anti-inflammatory agents, and immunomodulators.2 For an outline of the medication choices and their mechanisms of action, see Table 2.

Surgery, or ablation of the implants, is another viable treatment option; it can be performed via laparoscopy or laparotomy. Although the success rate is high, implants recur in 28% of patients 18 months after surgery and in 40% of patients after nine years; 40% to 50% of patients have adhesion recurrence.3

Patients who have concomitant infertility can be treated with advanced reproductive techniques, including intrauterine insemination and ovarian hyperstimulation. The monthly fecundity rate with such techniques is 9% to 18%.3 Laparoscopic surgery with ablation of endometrial implants may increase fertility in patients with endometriosis.8

Hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy are definitive treatment options reserved for patients with intractable pain and those who do not wish to maintain fertility.3,8 Recurrent symptoms occur in 10% of patients 10 years after hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy, compared with 62% of those who have hysterectomy alone.8 Complete surgical removal of endometriomas, and ovary if affected, can reduce risk for epithelial ovarian cancer in the future.2

COMPLICATIONS

Adhesions are a common complication of endometriosis. Ultrasound can be used for diagnosis and to determine whether pelvic organs are fixed (ie, fixed retroverted uterus). MRI may also be used; adhesions appear as “speculated low-signal-intensity stranding that obscures organ interfaces.”3 Other suggestive findings on MRI include posterior displacement of the pelvic organs, elevation of the posterior vaginal fornix, hydrosalpinx, loculated fluid collections, and angulated bowel loops.3

Malignant transformation is rare, affecting fewer than 1% of patients with endometriosis. Most malignancies arise from ovarian endometriosis and can be related to unopposed estrogen therapy; they are typically large and have a solid component. The most common endometriosis-related malignant neoplasm is endometrioid carcinoma, followed by clear-cell carcinoma.3

CONCLUSION

Patients with endometriosis often present with complaints such as dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, and chronic pelvic pain, but surgical and histologic findings indicate that symptom severity does not necessarily equate to disease severity. Definitive diagnosis requires an invasive surgical procedure.

In the absence of a cure, endometriosis treatment focuses on symptom control and improvement in quality of life. Familiarity with the disease process and knowledge of treatment options will help health care providers achieve this goal for patients who experience the potentially life-altering effects of endometriosis.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Staging endometriosis

- Medications for treating endometriosis

- Complications

Endometriosis is a gynecologic disorder characterized by the presence and growth of endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity (ie, endometrial implants), most commonly found on the ovaries. Although its pathophysiology is not completely understood, the disease is associated with dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and infertility.1,2 Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent disorder, predominantly affecting women of childbearing age. It occurs in 10% to 15% of the general female population, but prevalence is even higher (35% to 50%) among women who experience pelvic pain and/or infertility.1-4 Although endometriosis mainly affects women in their mid-to-late 20s, it can also manifest in adolescence.3,5 Nearly half of all adolescents with intractable dysmenorrhea are diagnosed with endometriosis.5

ETIOLOGY

The etiology of endometriosis, while not completely understood, is likely multifactorial. Factors that may influence its development include gene expression, tissue response to hormones, neuronal tissue involvement, lack of protective factors, inflammation, and cellular oxidative stress.6,7

Several theories regarding the etiology of endometriosis have been proposed; the most widely accepted is the transplantation theory, which suggests that endometriosis results from retrograde flow of menstrual tissue through the fallopian tubes. During menstruation, fragments of the endometrium are driven through the fallopian tubes and into the pelvic cavity, where they can implant onto the pelvic structures, leading to further growth and invasion.2,6,8 Women who have polymenorrhea, prolonged menses, and early menarche therefore have an increased risk for endometriosis.8 This theory does not account for the fact that although nearly 90% of women have some elements of retrograde menstrual flow, only a fraction of them develop endometriosis.6

Two other plausible explanations are the coelomic metaplasia and embryonic rest theories. In the coelomic metaplasia theory, the mesothelium (coelomic epithelium)—which encases the ovaries—invaginates into the ovaries and undergoes a metaplastic change to endometrial tissue. This could explain the development of endometriosis in patients with the congenital malformation Müllerian agenesis. In the embryonic rest theory, Müllerian remnants in the rectovaginal area, left behind by the Müllerian duct system, have the potential to differentiate into endometrial tissue.2,5,6,8

Another theory involving lymphatic or hematologic spread has been proposed, which would explain the presence of endometrial implants at sites distant from the uterus (eg, the pleural cavity and brain). However, this theory is not widely understood

The two most recent hypotheses on endometriosis are associated with an abnormal immune system and a possible genetic predisposition. The peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis has different levels of prostanoids, cytokines, growth factors, and interleukins than that of women who do not have the condition. It is uncertain whether the relationship between peritoneal fluid changes and endometriosis is causal.6 A genetic correlation has been suggested, based on an increased prevalence of endometriosis in women with an affected first-degree relative; in a case-control study on family incidence of endometriosis, 5.9% to 9.6% of first-degree relatives and 1.3% of second-degree relatives were affected.9 The Oxford Endometriosis Gene (OXEGENE) study is currently investigating susceptible loci for endometriosis genes, which could provide a better understanding of the disease process.6

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The most common symptoms of endometriosis are dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility, but 20% to 25% of affected women are asymptomatic.4,10,11 Pelvic pain in women most often heralds onset of menses and worsens during menstruation.1 Other symptoms include back pain, dyschezia, dysuria, nausea, lethargy, and chronic fatigue.4,8,10

Endometriosis is concomitant with infertility; endometrial adhesions that attach to pelvic organs cause distortion of pelvic structures and impaired ovum release and pick-up, and are believed to reduce fecundity. Additionally, women with endometriosis have low ovarian reserve and low-quality oocytes.6,8 Altered chemical elements (ie, prostanoids, cytokines, growth factors, and interleukins) may also contribute to endometrial-related infertility; intrapelvic growth factors could affect the fallopian tubes or pelvic environment, and thus the oocytes in a similar fashion.6

In adolescents, endometriosis can present as cyclic or acyclic pain; severe dysmenorrhea; dysmenorrhea that responds poorly to medications (eg, oral contraceptive pills [OCPs] or NSAIDs); and prolonged menstruation with premenstrual spotting.1

The physical exam may reveal tender nodules in the posterior vaginal fornix; cervical motion tenderness; a fixed uterus, cervix, or adnexa; uterine motion tenderness; thickening, pain, tenderness, or nodularity of the uterosacral ligament; or tender adnexal masses due to endometriomas.8,10

PATHOLOGIC CHARACTERISTICS AND STAGING

Gross pathology of endometriosis varies based on duration of disease and depth of implants or lesions. Implants range from punctate foci to small stellate patches that vary in color but typically measure less than 2 cm. They manifest most commonly in the ovaries, followed by the anterior and posterior cul-de-sac, posterior broad ligament, and uterosacral ligament. Implants can also be located on the uterus, fallopian tubes, sigmoid colon, ureter, small intestine, lungs, and brain (see Figure).3

Due to recurrent cyclic hemorrhage within a deep implant, endometriomas typically appear in the ovaries, entirely replacing normal ovarian tissue. Endometriomas are composed of dark, thick, degenerated blood products that result in a brown cyst—hence their designation as chocolate cysts. Microscopically, they are comprised of endometrial glands, stroma, and sometimes smooth muscle.3

Staging of endometriosis is determined by the volume, depth, location, and size of the implants (see Table 1). It is important to note that staging does not necessarily reflect symptom severity.12

DIAGNOSIS

There are several approaches to the diagnostic evaluation of endometriosis, all of which should be guided by the clinical presentation and physical examination. Clinical characteristics can be nonspecific and highly variable, warranting more reliable diagnostic methods.

Laparoscopy is the diagnostic gold standard for endometriosis, and biopsy of implants revealing endometrial tissue is confirmatory. Less invasive diagnostic methods include ultrasound and MRI—but without confirmatory histologic sampling, these only yield a presumptive diagnosis.

With ultrasonography, a transvaginal approach should be taken. While endometriomas have a variety of presentations on ultrasound, most appear as a homogenous, hypoechoic, focal lesion within the ovary. MRI has greater specificity than ultrasound for diagnosis of endometriomas. However, “shading,” or loss of signal, within an endometrioma is a feature commonly found on MRI.3

Other tests that aid in the diagnosis, but are not definitive, include sedimentation rate and tumor marker CA-125. These are both commonly elevated in patients with endometriosis. Measurement of CA-125 is helpful for identifying patients with infertility and severe endometriosis, who would therefore benefit from early surgical intervention.8

TREATMENT

There is no permanent cure for endometriosis; treatment entails nonsurgical and surgical approaches to symptom resolution. Treatment is directed by the patient’s desire to maintain fertility.

Conservative treatment of pelvic pain with NSAIDs is a common approach. Progestins are also used to treat pelvic pain; they create an acyclic, hypo-estrogenic environment by blocking ovarian estrogen secretion and subsequent endometrial cell proliferation. In addition to alleviating pain, progestins also prevent disease recurrence after surgery.2,13 Options include combination OCPs, levonorgestrel intrauterine devices, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and etonogestrel implants. Combination OCPs and medroxyprogesterone acetate are considered to be firstline treatment.8

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRH-a), such as leuprolide acetate, and androgenic agents, such as danocrine, are also indicated for relief of pain resulting from biopsy-confirmed endometriosis. Danocrine has been shown to ameliorate pain in up to 92% of patients.3,8 Other unconventional treatment modalities include aromatase inhibitors, selective estrogen receptor modulators, anti-inflammatory agents, and immunomodulators.2 For an outline of the medication choices and their mechanisms of action, see Table 2.

Surgery, or ablation of the implants, is another viable treatment option; it can be performed via laparoscopy or laparotomy. Although the success rate is high, implants recur in 28% of patients 18 months after surgery and in 40% of patients after nine years; 40% to 50% of patients have adhesion recurrence.3

Patients who have concomitant infertility can be treated with advanced reproductive techniques, including intrauterine insemination and ovarian hyperstimulation. The monthly fecundity rate with such techniques is 9% to 18%.3 Laparoscopic surgery with ablation of endometrial implants may increase fertility in patients with endometriosis.8

Hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy are definitive treatment options reserved for patients with intractable pain and those who do not wish to maintain fertility.3,8 Recurrent symptoms occur in 10% of patients 10 years after hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy, compared with 62% of those who have hysterectomy alone.8 Complete surgical removal of endometriomas, and ovary if affected, can reduce risk for epithelial ovarian cancer in the future.2

COMPLICATIONS

Adhesions are a common complication of endometriosis. Ultrasound can be used for diagnosis and to determine whether pelvic organs are fixed (ie, fixed retroverted uterus). MRI may also be used; adhesions appear as “speculated low-signal-intensity stranding that obscures organ interfaces.”3 Other suggestive findings on MRI include posterior displacement of the pelvic organs, elevation of the posterior vaginal fornix, hydrosalpinx, loculated fluid collections, and angulated bowel loops.3

Malignant transformation is rare, affecting fewer than 1% of patients with endometriosis. Most malignancies arise from ovarian endometriosis and can be related to unopposed estrogen therapy; they are typically large and have a solid component. The most common endometriosis-related malignant neoplasm is endometrioid carcinoma, followed by clear-cell carcinoma.3

CONCLUSION

Patients with endometriosis often present with complaints such as dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, and chronic pelvic pain, but surgical and histologic findings indicate that symptom severity does not necessarily equate to disease severity. Definitive diagnosis requires an invasive surgical procedure.

In the absence of a cure, endometriosis treatment focuses on symptom control and improvement in quality of life. Familiarity with the disease process and knowledge of treatment options will help health care providers achieve this goal for patients who experience the potentially life-altering effects of endometriosis.

1. Janssen EB, Rijkers AC, Hoppenbrouwers K, et al. Prevalence of endometriosis diagnosed by laparoscopy in adolescents with dysmenorrhea or chronic pelvic pain: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19(5):570-582.

2. Vercellini P, Viganò P, Somigliana E, Fedele L. Endometriosis: pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014; 10(5):261-275.

3. Woodward PJ, Sohaey R, Mezzetti TP. Endometriosis: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2001;21(1):193-216.

4. Bulletti C, Coccia ME, Battistoni S, Borini A. Endometriosis and infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2010;27(8):441-447.

5. Ahn SH, Monsanto SP, Miller C, et al. Pathophysiology and immune dysfunction in endometriosis. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2015:1-12.

6. Child TJ, Tan SL. Endometriosis: aetiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Drugs. 2001;61(12):1735-1750.

7. Farrell E, Garad R. Clinical update: endometriosis. Aust Nurs J. 2012;20(5):37-39.

8. Mounsey AL, Wilgus A, Slawson DC. Diagnosis and management of endometriosis. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(4):594-600.

9. Nouri K, Ott J, Krupitz B, et al. Family incidence of endometriosis in first-, second-, and third-degree relatives: case-control study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;8(85):1-7.

10. Riazi H, Tehranian N, Ziaei S, et al. Clinical diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis: a scoping review. BMC Women’s Health. 2015;15(39):1-12.

11. Acién P, Velasco I. Endometriosis: a disease that remains enigmatic. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:1-12.

12. American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Endometriosis: a guide for patients. www.conceive.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/ASRM-endometriosis.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2017.

13. Angioni S, Cofelice V, Pontis A, et al. New trends of progestins treatment of endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2014; 30(11):769-773.

14. National Institutes of Health. What are the treatments for endometriosis? www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/endometri/conditioninfo/Pages/treatment.aspx. Accessed April 19, 2017.

15. Kaunitz AM. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate for contraception. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/depot-medroxyprogesterone-acetate-for-contraception. Accessed April 19, 2017.

16. National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. Long-acting reversible contraception: the effective and appropriate use of long-acting reversible contraception. London, England: RCOG Press; 2005. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK51051/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK51051.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2017.

17. Altintas D, Kokcu A, Tosun M, Kandemir B. Comparison of the effects of cetrorelix, a GnRH antagonist, and leuprolide, a GnRH agonist, on experimental endometriosis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008;34(6):1014-1019.

1. Janssen EB, Rijkers AC, Hoppenbrouwers K, et al. Prevalence of endometriosis diagnosed by laparoscopy in adolescents with dysmenorrhea or chronic pelvic pain: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19(5):570-582.

2. Vercellini P, Viganò P, Somigliana E, Fedele L. Endometriosis: pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014; 10(5):261-275.

3. Woodward PJ, Sohaey R, Mezzetti TP. Endometriosis: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2001;21(1):193-216.

4. Bulletti C, Coccia ME, Battistoni S, Borini A. Endometriosis and infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2010;27(8):441-447.

5. Ahn SH, Monsanto SP, Miller C, et al. Pathophysiology and immune dysfunction in endometriosis. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2015:1-12.

6. Child TJ, Tan SL. Endometriosis: aetiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Drugs. 2001;61(12):1735-1750.

7. Farrell E, Garad R. Clinical update: endometriosis. Aust Nurs J. 2012;20(5):37-39.

8. Mounsey AL, Wilgus A, Slawson DC. Diagnosis and management of endometriosis. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(4):594-600.

9. Nouri K, Ott J, Krupitz B, et al. Family incidence of endometriosis in first-, second-, and third-degree relatives: case-control study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;8(85):1-7.

10. Riazi H, Tehranian N, Ziaei S, et al. Clinical diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis: a scoping review. BMC Women’s Health. 2015;15(39):1-12.

11. Acién P, Velasco I. Endometriosis: a disease that remains enigmatic. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:1-12.

12. American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Endometriosis: a guide for patients. www.conceive.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/ASRM-endometriosis.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2017.

13. Angioni S, Cofelice V, Pontis A, et al. New trends of progestins treatment of endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2014; 30(11):769-773.

14. National Institutes of Health. What are the treatments for endometriosis? www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/endometri/conditioninfo/Pages/treatment.aspx. Accessed April 19, 2017.

15. Kaunitz AM. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate for contraception. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/depot-medroxyprogesterone-acetate-for-contraception. Accessed April 19, 2017.

16. National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. Long-acting reversible contraception: the effective and appropriate use of long-acting reversible contraception. London, England: RCOG Press; 2005. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK51051/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK51051.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2017.

17. Altintas D, Kokcu A, Tosun M, Kandemir B. Comparison of the effects of cetrorelix, a GnRH antagonist, and leuprolide, a GnRH agonist, on experimental endometriosis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008;34(6):1014-1019.

Lower-dose aluminum hydroxide–adjuvanted polio vaccine noninferior to standard IPV

Aluminum hydroxide–adjuvanted vaccines with reduced doses of inactivated polio vaccine (IPV-Al) were noninferior to standard inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) in a large trial in the Dominican Republic, said Luis Rivera, MD, of the Hospital Maternidad Nuestra Señora de la Altagracia, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, and his associates.

If these findings are replicated in phase III trials and regulatory approval follows, such vaccines could be low-cost replacements for standard IPV and oral poliovirus vaccines in low-resource countries, the study authors suggested.

In this phase II, blinded, randomized trial with three investigational IPV-Al groups and one IPV group, the vaccines were given at 6 weeks, 10 weeks, 14 weeks, and 18 weeks to 823 infants who had not previously received any polio vaccination. The three new IPV-Al vaccines all proved to be noninferior to IPV for poliovirus types 1, 2, and 3.

For 1/10 IPV-Al, the seroconversion rates for the different poliovirus types were 98.5% (type 1), 94.6% (type 2), and 99.5% (type 3), compared with 100% (type 1), 98.5% (type 2), and 100% (type 3) for IPV.

This and the results from other studies “have paved the way for further clinical investigations of IPV-Al in phase III trials,” Dr. Rivera and his associates wrote.

“The low frequency of adverse events in this phase II trial suggests that a safety evaluation is not necessarily justified,” they concluded.

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation funded the study. The authors had no disclosures.

Read more in the Lancet Infectious Diseases (2017 Apr 25. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30177-9).

Aluminum hydroxide–adjuvanted vaccines with reduced doses of inactivated polio vaccine (IPV-Al) were noninferior to standard inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) in a large trial in the Dominican Republic, said Luis Rivera, MD, of the Hospital Maternidad Nuestra Señora de la Altagracia, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, and his associates.

If these findings are replicated in phase III trials and regulatory approval follows, such vaccines could be low-cost replacements for standard IPV and oral poliovirus vaccines in low-resource countries, the study authors suggested.

In this phase II, blinded, randomized trial with three investigational IPV-Al groups and one IPV group, the vaccines were given at 6 weeks, 10 weeks, 14 weeks, and 18 weeks to 823 infants who had not previously received any polio vaccination. The three new IPV-Al vaccines all proved to be noninferior to IPV for poliovirus types 1, 2, and 3.

For 1/10 IPV-Al, the seroconversion rates for the different poliovirus types were 98.5% (type 1), 94.6% (type 2), and 99.5% (type 3), compared with 100% (type 1), 98.5% (type 2), and 100% (type 3) for IPV.

This and the results from other studies “have paved the way for further clinical investigations of IPV-Al in phase III trials,” Dr. Rivera and his associates wrote.

“The low frequency of adverse events in this phase II trial suggests that a safety evaluation is not necessarily justified,” they concluded.

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation funded the study. The authors had no disclosures.

Read more in the Lancet Infectious Diseases (2017 Apr 25. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30177-9).

Aluminum hydroxide–adjuvanted vaccines with reduced doses of inactivated polio vaccine (IPV-Al) were noninferior to standard inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) in a large trial in the Dominican Republic, said Luis Rivera, MD, of the Hospital Maternidad Nuestra Señora de la Altagracia, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, and his associates.

If these findings are replicated in phase III trials and regulatory approval follows, such vaccines could be low-cost replacements for standard IPV and oral poliovirus vaccines in low-resource countries, the study authors suggested.

In this phase II, blinded, randomized trial with three investigational IPV-Al groups and one IPV group, the vaccines were given at 6 weeks, 10 weeks, 14 weeks, and 18 weeks to 823 infants who had not previously received any polio vaccination. The three new IPV-Al vaccines all proved to be noninferior to IPV for poliovirus types 1, 2, and 3.

For 1/10 IPV-Al, the seroconversion rates for the different poliovirus types were 98.5% (type 1), 94.6% (type 2), and 99.5% (type 3), compared with 100% (type 1), 98.5% (type 2), and 100% (type 3) for IPV.

This and the results from other studies “have paved the way for further clinical investigations of IPV-Al in phase III trials,” Dr. Rivera and his associates wrote.

“The low frequency of adverse events in this phase II trial suggests that a safety evaluation is not necessarily justified,” they concluded.

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation funded the study. The authors had no disclosures.

Read more in the Lancet Infectious Diseases (2017 Apr 25. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30177-9).

FROM THE LANCET INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Consider strongyloidiasis before giving oral steroids

SYDNEY – Think twice before prescribing oral steroids for patients who have urticarial dermatitis, diarrhea, and cough, especially if they have lived in or recently traveled to tropical areas, Ian McCrossin, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Australasian College of Dermatologists.

Strongyloides stercoralis, or threadworm, infection can flare dramatically when patients take oral steroids. “You get thousands of worms, and they punch their way through the bowel wall and take the bowel organisms with them; that’s when you get septicaemia,” Dr. McCrossin, a dermatologist from Liverpool Hospital, Sydney, said in an interview.

Dr. McCrossin cited an Australian study that found a strongyloides infection was present in 11.6% of 309 Vietnam veterans living in South Australia.

Risk factors for Strongyloides hyperinfection include compromised immunity, human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1, alcohol use disorder, malnutrition, and oral steroid use. Mortality rates from the resulting sepsis are as high as 87%, Dr. McCrossin said.

IgG ELISA is a reliable test for established strongyloidiasis, but is less effective for recent infection, hyperinfection, and in patients who are immunosuppressed. Eosinophilia has a poor predictive value. Light microscopy of stool samples may require evaluation of multiple stool samples unless the patient had hyperinfection.

Treatment generally consists of ivermectin, 200 mcg/kg orally for 1-2 days. Follow-up stool exams should be performed 2-4 weeks after treatment to confirm clearance of infection. In those patients with hyperinfections, ivermectin 200 mcg/kg orally is given daily until stool and/or sputum exams are negative for 2 weeks.

Dr. McCrossin declared no conflicts of interest.

SYDNEY – Think twice before prescribing oral steroids for patients who have urticarial dermatitis, diarrhea, and cough, especially if they have lived in or recently traveled to tropical areas, Ian McCrossin, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Australasian College of Dermatologists.

Strongyloides stercoralis, or threadworm, infection can flare dramatically when patients take oral steroids. “You get thousands of worms, and they punch their way through the bowel wall and take the bowel organisms with them; that’s when you get septicaemia,” Dr. McCrossin, a dermatologist from Liverpool Hospital, Sydney, said in an interview.

Dr. McCrossin cited an Australian study that found a strongyloides infection was present in 11.6% of 309 Vietnam veterans living in South Australia.

Risk factors for Strongyloides hyperinfection include compromised immunity, human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1, alcohol use disorder, malnutrition, and oral steroid use. Mortality rates from the resulting sepsis are as high as 87%, Dr. McCrossin said.

IgG ELISA is a reliable test for established strongyloidiasis, but is less effective for recent infection, hyperinfection, and in patients who are immunosuppressed. Eosinophilia has a poor predictive value. Light microscopy of stool samples may require evaluation of multiple stool samples unless the patient had hyperinfection.

Treatment generally consists of ivermectin, 200 mcg/kg orally for 1-2 days. Follow-up stool exams should be performed 2-4 weeks after treatment to confirm clearance of infection. In those patients with hyperinfections, ivermectin 200 mcg/kg orally is given daily until stool and/or sputum exams are negative for 2 weeks.

Dr. McCrossin declared no conflicts of interest.

SYDNEY – Think twice before prescribing oral steroids for patients who have urticarial dermatitis, diarrhea, and cough, especially if they have lived in or recently traveled to tropical areas, Ian McCrossin, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Australasian College of Dermatologists.

Strongyloides stercoralis, or threadworm, infection can flare dramatically when patients take oral steroids. “You get thousands of worms, and they punch their way through the bowel wall and take the bowel organisms with them; that’s when you get septicaemia,” Dr. McCrossin, a dermatologist from Liverpool Hospital, Sydney, said in an interview.

Dr. McCrossin cited an Australian study that found a strongyloides infection was present in 11.6% of 309 Vietnam veterans living in South Australia.

Risk factors for Strongyloides hyperinfection include compromised immunity, human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1, alcohol use disorder, malnutrition, and oral steroid use. Mortality rates from the resulting sepsis are as high as 87%, Dr. McCrossin said.

IgG ELISA is a reliable test for established strongyloidiasis, but is less effective for recent infection, hyperinfection, and in patients who are immunosuppressed. Eosinophilia has a poor predictive value. Light microscopy of stool samples may require evaluation of multiple stool samples unless the patient had hyperinfection.

Treatment generally consists of ivermectin, 200 mcg/kg orally for 1-2 days. Follow-up stool exams should be performed 2-4 weeks after treatment to confirm clearance of infection. In those patients with hyperinfections, ivermectin 200 mcg/kg orally is given daily until stool and/or sputum exams are negative for 2 weeks.

Dr. McCrossin declared no conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT ACDASM 2017

Cutaneous manifestations can signify severe systemic disease in ANCA-associated vasculitis

PORTLAND, ORE. – Clinicians who treat or diagnose ANCA-associated vasculitis should watch for a variety of skin lesions, which can signify severe systemic manifestations of disease, according to the results of a cross-sectional study of 1,184 patients from 130 centers worldwide.

Among patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) or eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), the presence of skin lesions approximately doubled the likelihood of renal, pulmonary, neurologic, or other severe systemic manifestations of ANCA-associated vasculitis (hazard ratios, 2.0; P less than .03).

This cohort is part of the Diagnostic and Classification Criteria in Vasculitis Study (DCVAS), which aims to develop classification and diagnostic criteria for primary systemic vasculitis. Fully 35% of patients had cutaneous manifestations of ANCA-associated vasculitis, including 47% of those with EGPA, 34% of those with GPA, and 28% of those with microscopic polyangiitis (MPA).

Petechiae/purpura were the most common cutaneous manifestations of all three subtypes, affecting 15% of the overall cohort, 21% of patients with EGPA, 16% of those with GPA, and 9% of those with MPA (P less than .01 for differences among groups). Petechiae/purpura did not more accurately predict systemic disease than other cutaneous findings, and skin lesions were not significantly associated with severe systemic disease in patients with MPA (HR, 0.63; 95% confidence interval, 0.35-1.14; P = .13), the investigators reported.

Besides petechiae/purpura, patients with EGPA most often presented with allergic and nonspecific cutaneous manifestations, such as pruritus (13% of patients), urticaria (8%), and maculopapular rash (8%), they said. In contrast, patients with GPA most often had painful skin lesions (10%) or maculopapular rash (7%), while those with MPA were more likely to have livedo reticularis or racemosa (7%).

Study participants tended to be in their mid-50s to mid-60s at diagnosis, about 48% were male, and most were Northern European, Southern European, or American whites, while 28% of those with MPA were Han Chinese, of another Chinese ethnicity, or Japanese.

“This study demonstrates that skin lesions are quite common and varied in granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis,” the investigators concluded.

Funders included the American College of Rheumatology, the European League Against Rheumatism, the Vasculitis Foundation, and the Dermatology Foundation. Dr. Micheletti had no conflicts of interest.

PORTLAND, ORE. – Clinicians who treat or diagnose ANCA-associated vasculitis should watch for a variety of skin lesions, which can signify severe systemic manifestations of disease, according to the results of a cross-sectional study of 1,184 patients from 130 centers worldwide.

Among patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) or eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), the presence of skin lesions approximately doubled the likelihood of renal, pulmonary, neurologic, or other severe systemic manifestations of ANCA-associated vasculitis (hazard ratios, 2.0; P less than .03).

This cohort is part of the Diagnostic and Classification Criteria in Vasculitis Study (DCVAS), which aims to develop classification and diagnostic criteria for primary systemic vasculitis. Fully 35% of patients had cutaneous manifestations of ANCA-associated vasculitis, including 47% of those with EGPA, 34% of those with GPA, and 28% of those with microscopic polyangiitis (MPA).

Petechiae/purpura were the most common cutaneous manifestations of all three subtypes, affecting 15% of the overall cohort, 21% of patients with EGPA, 16% of those with GPA, and 9% of those with MPA (P less than .01 for differences among groups). Petechiae/purpura did not more accurately predict systemic disease than other cutaneous findings, and skin lesions were not significantly associated with severe systemic disease in patients with MPA (HR, 0.63; 95% confidence interval, 0.35-1.14; P = .13), the investigators reported.

Besides petechiae/purpura, patients with EGPA most often presented with allergic and nonspecific cutaneous manifestations, such as pruritus (13% of patients), urticaria (8%), and maculopapular rash (8%), they said. In contrast, patients with GPA most often had painful skin lesions (10%) or maculopapular rash (7%), while those with MPA were more likely to have livedo reticularis or racemosa (7%).

Study participants tended to be in their mid-50s to mid-60s at diagnosis, about 48% were male, and most were Northern European, Southern European, or American whites, while 28% of those with MPA were Han Chinese, of another Chinese ethnicity, or Japanese.

“This study demonstrates that skin lesions are quite common and varied in granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis,” the investigators concluded.

Funders included the American College of Rheumatology, the European League Against Rheumatism, the Vasculitis Foundation, and the Dermatology Foundation. Dr. Micheletti had no conflicts of interest.

PORTLAND, ORE. – Clinicians who treat or diagnose ANCA-associated vasculitis should watch for a variety of skin lesions, which can signify severe systemic manifestations of disease, according to the results of a cross-sectional study of 1,184 patients from 130 centers worldwide.

Among patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) or eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), the presence of skin lesions approximately doubled the likelihood of renal, pulmonary, neurologic, or other severe systemic manifestations of ANCA-associated vasculitis (hazard ratios, 2.0; P less than .03).

This cohort is part of the Diagnostic and Classification Criteria in Vasculitis Study (DCVAS), which aims to develop classification and diagnostic criteria for primary systemic vasculitis. Fully 35% of patients had cutaneous manifestations of ANCA-associated vasculitis, including 47% of those with EGPA, 34% of those with GPA, and 28% of those with microscopic polyangiitis (MPA).

Petechiae/purpura were the most common cutaneous manifestations of all three subtypes, affecting 15% of the overall cohort, 21% of patients with EGPA, 16% of those with GPA, and 9% of those with MPA (P less than .01 for differences among groups). Petechiae/purpura did not more accurately predict systemic disease than other cutaneous findings, and skin lesions were not significantly associated with severe systemic disease in patients with MPA (HR, 0.63; 95% confidence interval, 0.35-1.14; P = .13), the investigators reported.

Besides petechiae/purpura, patients with EGPA most often presented with allergic and nonspecific cutaneous manifestations, such as pruritus (13% of patients), urticaria (8%), and maculopapular rash (8%), they said. In contrast, patients with GPA most often had painful skin lesions (10%) or maculopapular rash (7%), while those with MPA were more likely to have livedo reticularis or racemosa (7%).

Study participants tended to be in their mid-50s to mid-60s at diagnosis, about 48% were male, and most were Northern European, Southern European, or American whites, while 28% of those with MPA were Han Chinese, of another Chinese ethnicity, or Japanese.

“This study demonstrates that skin lesions are quite common and varied in granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis,” the investigators concluded.

Funders included the American College of Rheumatology, the European League Against Rheumatism, the Vasculitis Foundation, and the Dermatology Foundation. Dr. Micheletti had no conflicts of interest.

AT SID 2017

Key clinical point: Skin lesions can be a red flag for severe systemic disease in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis.

Major finding: Among patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis or eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, the presence of skin lesions approximately doubled the likelihood of renal, pulmonary, neurologic, or other severe systemic manifestations of ANCA-associated vasculitis (HR, 2.0, P less than .03). The hazard ratio was not elevated in patients with microscopic polyangiitis.

Data source: A cross-sectional study of 1,184 patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis from 130 centers worldwide.

Disclosures: Funders included the American College of Rheumatology, the European League Against Rheumatism, the Vasculitis Foundation, and the Dermatology Foundation. Dr. Micheletti had no conflicts of interest.

Why Is Skin Cancer Mortality Higher in Patients With Skin of Color?

FDA approves avelumab for advanced urothelial carcinoma

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to avelumab for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma whose disease progressed during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy or within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant platinum-containing chemotherapy.

Approval was based on a confirmed overall response rate (ORR) of 16.1% in 26 patients who had been followed for at least 6 months in a single-arm, multicenter study that enrolled 242 patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma whose disease progressed following platinum-containing neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy. The ORR was 13.3% among 30 patients who had been followed for at least 13 weeks. Median time to response was 2.0 months (range 1.3-11.0). The median response duration had not been reached in patients followed for at least 13 weeks or at least 6 months, but ranged from 1.4+ to 17.4+ months in both groups, the FDA said in a statement.

Serious adverse reactions, including urinary tract infection/urosepsis, abdominal pain, musculoskeletal pain, creatinine increased/renal failure, dehydration, hematuria/urinary tract hemorrhage, intestinal obstruction/small intestinal obstruction, and pyrexia, were reported in 41% of patients, causing death in 6% of patients. The most common adverse reactions were infusion-related reaction, musculoskeletal pain, nausea, decreased appetite, and urinary tract infection.

The FDA recommended an intravenous infusion of 10 mg/kg over 60 minutes every 2 weeks, and premedication with an antihistamine and acetaminophen prior to the first four infusions of avelumab.

Full prescribing information is available here.

The drug is being marketed as Bavencio by EMD Serono.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to avelumab for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma whose disease progressed during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy or within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant platinum-containing chemotherapy.

Approval was based on a confirmed overall response rate (ORR) of 16.1% in 26 patients who had been followed for at least 6 months in a single-arm, multicenter study that enrolled 242 patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma whose disease progressed following platinum-containing neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy. The ORR was 13.3% among 30 patients who had been followed for at least 13 weeks. Median time to response was 2.0 months (range 1.3-11.0). The median response duration had not been reached in patients followed for at least 13 weeks or at least 6 months, but ranged from 1.4+ to 17.4+ months in both groups, the FDA said in a statement.

Serious adverse reactions, including urinary tract infection/urosepsis, abdominal pain, musculoskeletal pain, creatinine increased/renal failure, dehydration, hematuria/urinary tract hemorrhage, intestinal obstruction/small intestinal obstruction, and pyrexia, were reported in 41% of patients, causing death in 6% of patients. The most common adverse reactions were infusion-related reaction, musculoskeletal pain, nausea, decreased appetite, and urinary tract infection.

The FDA recommended an intravenous infusion of 10 mg/kg over 60 minutes every 2 weeks, and premedication with an antihistamine and acetaminophen prior to the first four infusions of avelumab.

Full prescribing information is available here.

The drug is being marketed as Bavencio by EMD Serono.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to avelumab for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma whose disease progressed during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy or within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant platinum-containing chemotherapy.

Approval was based on a confirmed overall response rate (ORR) of 16.1% in 26 patients who had been followed for at least 6 months in a single-arm, multicenter study that enrolled 242 patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma whose disease progressed following platinum-containing neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy. The ORR was 13.3% among 30 patients who had been followed for at least 13 weeks. Median time to response was 2.0 months (range 1.3-11.0). The median response duration had not been reached in patients followed for at least 13 weeks or at least 6 months, but ranged from 1.4+ to 17.4+ months in both groups, the FDA said in a statement.

Serious adverse reactions, including urinary tract infection/urosepsis, abdominal pain, musculoskeletal pain, creatinine increased/renal failure, dehydration, hematuria/urinary tract hemorrhage, intestinal obstruction/small intestinal obstruction, and pyrexia, were reported in 41% of patients, causing death in 6% of patients. The most common adverse reactions were infusion-related reaction, musculoskeletal pain, nausea, decreased appetite, and urinary tract infection.

The FDA recommended an intravenous infusion of 10 mg/kg over 60 minutes every 2 weeks, and premedication with an antihistamine and acetaminophen prior to the first four infusions of avelumab.

Full prescribing information is available here.

The drug is being marketed as Bavencio by EMD Serono.

Dalbavancin proves highly effective in osteomyelitis

VIENNA – Two infusions of the long-acting lipoglycopeptide antibiotic dalbavancin showed a favorable clinical benefit for treatment of adult osteomyelitis in a phase II study.

Dalbavancin (Dalvance) showed positive results while avoiding the complexities of standard therapies that require longer, more frequent dosing, Urania Rappo, MD, said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.

Dalbavancin already is approved for acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections, and its long terminal half-life of 14 days and high bone penetration made it a natural candidate for evaluation in the treatment of osteomyelitis, said Dr. Rappo, director of clinical development (anti-infectives) at Allergan, which markets the drug and sponsored the study.

Dalbavancin is a glycopeptide antibiotic with a lipid tail that prolongs its half-life, compared with other drugs in this category, such as vancomycin and teicoplanin, to which it is structurally related. It is highly potent against gram-positive bacterial infections, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

The drug’s MIC90 for S. aureus is 0.06 mcg/mL; vancomycin’s, in comparison, is 1 mcg/mL. A 2015 bone penetration study found that the bone level 12 hours after a 1,000-mg infusion was 6.3 mcg/g. This remained elevated for 14 days; the concentration at 2 weeks was 4 mcg/g (Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015 Apr;59[4]:1849-55).

“The mean bone-to-plasma penetration ratio was 13%, and drug levels in bone were very similar to free drug levels in serum, so we expect that much of this is free drug in the bone, available for antimicrobial activity,” Dr. Rappo noted. “It’s not only long lasting, but highly potent, meaning we need less drug to kill the infecting organism.”

Dalbavancin was administered as two 1,500-mg IV infusions, 1 week apart in Dr. Rappo’s randomized, open-label, phase II study – the first clinical trial to examine the drug’s effect in osteomyelitis in adults. The study is ongoing; she presented interim results on 68 patients, 59 of whom took dalbavancin. The nine patients in the standard-of-care arm were treated according to the investigator’s clinical judgment. Vancomycin was the most commonly employed therapy. Three patients received vancomycin infusions for 4 weeks. Four received a regimen of 4-16 days of intravenous vancomycin followed by intravenous linezolid or levofloxacin to complete a 4- to 6-week course of therapy. Adjunctive aztreonam was permitted for presumed coinfection with a gram-negative pathogen and a switch to oral antibiotic for gram-negative coverage was allowed after clinical improvement.