User login

The importance of studying the placenta

It makes logical, intellectual sense that the placenta, an organ that is so integrally involved in pregnancy, will be of such great importance to the well-being, sustenance, and growth and development of the fetus. After all, the placental compartment and fetal compartment have the same origin early in embryogenesis, and the placenta is the sole source of nutrients and oxygen for the fetus.

However, the placenta has been extraordinarily poorly understood. Much of medicine has regarded the placenta like the appendix – an organ that may be easily discarded. We know too little about its functions and its biology. We do not even know whether there is a minimum amount of placenta that’s necessary for fetal health.

Over the years, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has placed an emphasis on certain key areas of study through efforts such as the Human Genome Project, the BRAIN Initiative, and the Cancer Moonshot. Such efforts involve sustained, fundamental research and usually lead to significant findings and subsequent application of the findings.

It is exciting to know that the NIH has launched its Human Placenta Project in an effort to better understand the biology of the placenta and to elucidate its functions. The technology that is employed will play an adjunctive role.

Fortunately, over the years various investigators have studied the placenta using ultrasound, color Doppler technology, and other techniques, and have reported important findings. The work of pathologist Carolyn M. Salafia, MD, and others has called attention to the importance of the shape and vasculature of the placenta, as well as blood flow.

To bring us up to date, as the NIH’s Human Placenta Project proceeds, I have asked Dr. Salafia to provide us with a review discussion of our current knowledge and its implications. Dr. Salafia specializes in reproductive and developmental pathology and reviews thousands of placentas each year through her work with various hospitals and as head of the Placental Modulation Laboratory at the Institute for Basic Research in Developmental Disabilities in Staten Island, N.Y.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

It makes logical, intellectual sense that the placenta, an organ that is so integrally involved in pregnancy, will be of such great importance to the well-being, sustenance, and growth and development of the fetus. After all, the placental compartment and fetal compartment have the same origin early in embryogenesis, and the placenta is the sole source of nutrients and oxygen for the fetus.

However, the placenta has been extraordinarily poorly understood. Much of medicine has regarded the placenta like the appendix – an organ that may be easily discarded. We know too little about its functions and its biology. We do not even know whether there is a minimum amount of placenta that’s necessary for fetal health.

Over the years, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has placed an emphasis on certain key areas of study through efforts such as the Human Genome Project, the BRAIN Initiative, and the Cancer Moonshot. Such efforts involve sustained, fundamental research and usually lead to significant findings and subsequent application of the findings.

It is exciting to know that the NIH has launched its Human Placenta Project in an effort to better understand the biology of the placenta and to elucidate its functions. The technology that is employed will play an adjunctive role.

Fortunately, over the years various investigators have studied the placenta using ultrasound, color Doppler technology, and other techniques, and have reported important findings. The work of pathologist Carolyn M. Salafia, MD, and others has called attention to the importance of the shape and vasculature of the placenta, as well as blood flow.

To bring us up to date, as the NIH’s Human Placenta Project proceeds, I have asked Dr. Salafia to provide us with a review discussion of our current knowledge and its implications. Dr. Salafia specializes in reproductive and developmental pathology and reviews thousands of placentas each year through her work with various hospitals and as head of the Placental Modulation Laboratory at the Institute for Basic Research in Developmental Disabilities in Staten Island, N.Y.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

It makes logical, intellectual sense that the placenta, an organ that is so integrally involved in pregnancy, will be of such great importance to the well-being, sustenance, and growth and development of the fetus. After all, the placental compartment and fetal compartment have the same origin early in embryogenesis, and the placenta is the sole source of nutrients and oxygen for the fetus.

However, the placenta has been extraordinarily poorly understood. Much of medicine has regarded the placenta like the appendix – an organ that may be easily discarded. We know too little about its functions and its biology. We do not even know whether there is a minimum amount of placenta that’s necessary for fetal health.

Over the years, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has placed an emphasis on certain key areas of study through efforts such as the Human Genome Project, the BRAIN Initiative, and the Cancer Moonshot. Such efforts involve sustained, fundamental research and usually lead to significant findings and subsequent application of the findings.

It is exciting to know that the NIH has launched its Human Placenta Project in an effort to better understand the biology of the placenta and to elucidate its functions. The technology that is employed will play an adjunctive role.

Fortunately, over the years various investigators have studied the placenta using ultrasound, color Doppler technology, and other techniques, and have reported important findings. The work of pathologist Carolyn M. Salafia, MD, and others has called attention to the importance of the shape and vasculature of the placenta, as well as blood flow.

To bring us up to date, as the NIH’s Human Placenta Project proceeds, I have asked Dr. Salafia to provide us with a review discussion of our current knowledge and its implications. Dr. Salafia specializes in reproductive and developmental pathology and reviews thousands of placentas each year through her work with various hospitals and as head of the Placental Modulation Laboratory at the Institute for Basic Research in Developmental Disabilities in Staten Island, N.Y.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

The Power of Two: Revisiting PA Autonomy

PA autonomy is a hot topic lately—not just within the profession but also in the public press. Earlier this year, Forbes touted efforts to loosen “barriers” to PA practice.1 The American Academy of Physician Assistants has identified 10 federal regulations that impose “unnecessary barriers” to medical care provided by PAs; these include cumbersome countersignatures, unnecessary supervision, and ordering restrictions on everything from home care to diabetic shoes.2 Lifting these barriers makes sense amid a shortage of physicians and an influx of newly insured patients (for more on this topic, see here). But as we acquire greater autonomy, we must not lose sight of the relationship that our profession was founded on—and that makes it unique.

Many PAs aspire to be truly independent practitioners, and some already are (eg, in remote and rural areas). Those of us who practice more closely with physicians may be more apt to appreciate the PA-physician partnership. In my 12 years as a PA, I have partnered with more than 50 physicians in cardiology, internal medicine, gastroenterology, and surgical oncology. I have also had the opportunity to witness the dynamic of other PA-physician relationships. As with all relationships, there is a wide range in synergy, productivity, and trust. Some ill-fated relationships are toxic and nonproductive; those merit a swift exit. At the other end of the spectrum are star-crossed partnerships that radiate competence, creativity, and confidence. In between these two extremes are the majority of PA-physician duos, working it out day to day in a kaleidoscopic health care world. It is clear that the physicians and PAs who not only work hard individually, but also work well within their relationship, benefit the most—and so do their patients.

We surgical PAs have a privileged bond that forms at the operating table. It is not only essential, but empowering, to know what each surgeon is thinking about his or her patient as the case unfolds. In medicine, collaboration may not be as intimate as it is in surgery. Still, there is no substitute for knowing our physicians well. Are our treatment goals in sync with theirs? Are we saying the same things to our patients? When we differ (as we often do), how do we achieve respectful and creative dissention? Can we each do our own thing and still be a credible and productive team?

What exactly is PA autonomy? Our scope of practice is delegated by a supervising physician and is limited to the services for which the physician can provide adequate supervision. The terms of supervision vary by state and by practice. In some states, a PA can have multiple “substitute” supervisors, as long as someone keeps a current list. The primary physician supervisor may or may not be the one the PA works with most closely. Some supervisory relationships are merely paper ones, a de rigueur document for the licensing file. Whatever form it takes, supervision has legal and clinical implications that should be implicit to both parties.

If supervision changes drastically, and PA autonomy becomes a reality, the name of our profession would have to change. Physician associate has been proposed. But until we eliminate the word physician, we are still partners with the very profession from which we intend to secede. Certainly, we need to abolish the possessive physician’s (a semantic that rankles universally). Let us get rid of that annoying (and misleading) apostrophe once and for all.

Many of us chose to become PAs to be extenders, rather than bearing ultimate responsibility. That is not to say that we are not willing to make decisions, take risks, or accept liability—that comes with the license and the territory. But in choosing to assist, we have deliberately chosen a dependent role. While physician assistant indeed implies a subordinate relationship, it is not necessarily a subservient one. There is plenty of room for both shared and separate decision-making, for specifically delegated or situational authority. The PA-physician relationship is built on mutual trust that is earned and reinforced on a daily basis. Decisional confidence and technical competence—not wimpy dependence—is the product of a dynamic PA-physician relationship.

As the health care market changes, we can and should afford ourselves every professional opportunity to work as salaried providers or to sign on as single contractors. There are many alternative PA-physician relationships, both legally and financially. If we so desire, we should pursue advanced degrees and specialty certifications and be compensated accordingly. However, multi-tasseled resumes should remain optional. They are costly and not within the reach of everyone, nor do they necessarily make a better PA.

In this new age of autonomy for advanced practice providers, some will say that only a dinosaur could have made these comments. If that is true, thank you for allowing me to wag my tail. The fact remains that PAs offer something unique. In an era of serious physician shortages, we offer patients the opportunity to have both a relationship with their internist, surgeon, or specialist and access to our own capable care and treatment. This is the “package deal” that, sadly, is in danger of becoming overlooked—if not extinct.

1. Japsen B. States remove barriers to physician assistants . Forbes. March 6, 2016. www.forbes.com/sites/brucejapsen/2016/03/06/states-remove-barriers-to-physician-assistants. Accessed September 13, 2016.

2. American Academy of Physician Assistants. Top ten federal laws & regulations imposing unnecessary barriers to medical care provided by PAs. www.aapa.org/workarea/downloadasset.aspx?id=6442450999. Accessed September 13, 2016.

PA autonomy is a hot topic lately—not just within the profession but also in the public press. Earlier this year, Forbes touted efforts to loosen “barriers” to PA practice.1 The American Academy of Physician Assistants has identified 10 federal regulations that impose “unnecessary barriers” to medical care provided by PAs; these include cumbersome countersignatures, unnecessary supervision, and ordering restrictions on everything from home care to diabetic shoes.2 Lifting these barriers makes sense amid a shortage of physicians and an influx of newly insured patients (for more on this topic, see here). But as we acquire greater autonomy, we must not lose sight of the relationship that our profession was founded on—and that makes it unique.

Many PAs aspire to be truly independent practitioners, and some already are (eg, in remote and rural areas). Those of us who practice more closely with physicians may be more apt to appreciate the PA-physician partnership. In my 12 years as a PA, I have partnered with more than 50 physicians in cardiology, internal medicine, gastroenterology, and surgical oncology. I have also had the opportunity to witness the dynamic of other PA-physician relationships. As with all relationships, there is a wide range in synergy, productivity, and trust. Some ill-fated relationships are toxic and nonproductive; those merit a swift exit. At the other end of the spectrum are star-crossed partnerships that radiate competence, creativity, and confidence. In between these two extremes are the majority of PA-physician duos, working it out day to day in a kaleidoscopic health care world. It is clear that the physicians and PAs who not only work hard individually, but also work well within their relationship, benefit the most—and so do their patients.

We surgical PAs have a privileged bond that forms at the operating table. It is not only essential, but empowering, to know what each surgeon is thinking about his or her patient as the case unfolds. In medicine, collaboration may not be as intimate as it is in surgery. Still, there is no substitute for knowing our physicians well. Are our treatment goals in sync with theirs? Are we saying the same things to our patients? When we differ (as we often do), how do we achieve respectful and creative dissention? Can we each do our own thing and still be a credible and productive team?

What exactly is PA autonomy? Our scope of practice is delegated by a supervising physician and is limited to the services for which the physician can provide adequate supervision. The terms of supervision vary by state and by practice. In some states, a PA can have multiple “substitute” supervisors, as long as someone keeps a current list. The primary physician supervisor may or may not be the one the PA works with most closely. Some supervisory relationships are merely paper ones, a de rigueur document for the licensing file. Whatever form it takes, supervision has legal and clinical implications that should be implicit to both parties.

If supervision changes drastically, and PA autonomy becomes a reality, the name of our profession would have to change. Physician associate has been proposed. But until we eliminate the word physician, we are still partners with the very profession from which we intend to secede. Certainly, we need to abolish the possessive physician’s (a semantic that rankles universally). Let us get rid of that annoying (and misleading) apostrophe once and for all.

Many of us chose to become PAs to be extenders, rather than bearing ultimate responsibility. That is not to say that we are not willing to make decisions, take risks, or accept liability—that comes with the license and the territory. But in choosing to assist, we have deliberately chosen a dependent role. While physician assistant indeed implies a subordinate relationship, it is not necessarily a subservient one. There is plenty of room for both shared and separate decision-making, for specifically delegated or situational authority. The PA-physician relationship is built on mutual trust that is earned and reinforced on a daily basis. Decisional confidence and technical competence—not wimpy dependence—is the product of a dynamic PA-physician relationship.

As the health care market changes, we can and should afford ourselves every professional opportunity to work as salaried providers or to sign on as single contractors. There are many alternative PA-physician relationships, both legally and financially. If we so desire, we should pursue advanced degrees and specialty certifications and be compensated accordingly. However, multi-tasseled resumes should remain optional. They are costly and not within the reach of everyone, nor do they necessarily make a better PA.

In this new age of autonomy for advanced practice providers, some will say that only a dinosaur could have made these comments. If that is true, thank you for allowing me to wag my tail. The fact remains that PAs offer something unique. In an era of serious physician shortages, we offer patients the opportunity to have both a relationship with their internist, surgeon, or specialist and access to our own capable care and treatment. This is the “package deal” that, sadly, is in danger of becoming overlooked—if not extinct.

PA autonomy is a hot topic lately—not just within the profession but also in the public press. Earlier this year, Forbes touted efforts to loosen “barriers” to PA practice.1 The American Academy of Physician Assistants has identified 10 federal regulations that impose “unnecessary barriers” to medical care provided by PAs; these include cumbersome countersignatures, unnecessary supervision, and ordering restrictions on everything from home care to diabetic shoes.2 Lifting these barriers makes sense amid a shortage of physicians and an influx of newly insured patients (for more on this topic, see here). But as we acquire greater autonomy, we must not lose sight of the relationship that our profession was founded on—and that makes it unique.

Many PAs aspire to be truly independent practitioners, and some already are (eg, in remote and rural areas). Those of us who practice more closely with physicians may be more apt to appreciate the PA-physician partnership. In my 12 years as a PA, I have partnered with more than 50 physicians in cardiology, internal medicine, gastroenterology, and surgical oncology. I have also had the opportunity to witness the dynamic of other PA-physician relationships. As with all relationships, there is a wide range in synergy, productivity, and trust. Some ill-fated relationships are toxic and nonproductive; those merit a swift exit. At the other end of the spectrum are star-crossed partnerships that radiate competence, creativity, and confidence. In between these two extremes are the majority of PA-physician duos, working it out day to day in a kaleidoscopic health care world. It is clear that the physicians and PAs who not only work hard individually, but also work well within their relationship, benefit the most—and so do their patients.

We surgical PAs have a privileged bond that forms at the operating table. It is not only essential, but empowering, to know what each surgeon is thinking about his or her patient as the case unfolds. In medicine, collaboration may not be as intimate as it is in surgery. Still, there is no substitute for knowing our physicians well. Are our treatment goals in sync with theirs? Are we saying the same things to our patients? When we differ (as we often do), how do we achieve respectful and creative dissention? Can we each do our own thing and still be a credible and productive team?

What exactly is PA autonomy? Our scope of practice is delegated by a supervising physician and is limited to the services for which the physician can provide adequate supervision. The terms of supervision vary by state and by practice. In some states, a PA can have multiple “substitute” supervisors, as long as someone keeps a current list. The primary physician supervisor may or may not be the one the PA works with most closely. Some supervisory relationships are merely paper ones, a de rigueur document for the licensing file. Whatever form it takes, supervision has legal and clinical implications that should be implicit to both parties.

If supervision changes drastically, and PA autonomy becomes a reality, the name of our profession would have to change. Physician associate has been proposed. But until we eliminate the word physician, we are still partners with the very profession from which we intend to secede. Certainly, we need to abolish the possessive physician’s (a semantic that rankles universally). Let us get rid of that annoying (and misleading) apostrophe once and for all.

Many of us chose to become PAs to be extenders, rather than bearing ultimate responsibility. That is not to say that we are not willing to make decisions, take risks, or accept liability—that comes with the license and the territory. But in choosing to assist, we have deliberately chosen a dependent role. While physician assistant indeed implies a subordinate relationship, it is not necessarily a subservient one. There is plenty of room for both shared and separate decision-making, for specifically delegated or situational authority. The PA-physician relationship is built on mutual trust that is earned and reinforced on a daily basis. Decisional confidence and technical competence—not wimpy dependence—is the product of a dynamic PA-physician relationship.

As the health care market changes, we can and should afford ourselves every professional opportunity to work as salaried providers or to sign on as single contractors. There are many alternative PA-physician relationships, both legally and financially. If we so desire, we should pursue advanced degrees and specialty certifications and be compensated accordingly. However, multi-tasseled resumes should remain optional. They are costly and not within the reach of everyone, nor do they necessarily make a better PA.

In this new age of autonomy for advanced practice providers, some will say that only a dinosaur could have made these comments. If that is true, thank you for allowing me to wag my tail. The fact remains that PAs offer something unique. In an era of serious physician shortages, we offer patients the opportunity to have both a relationship with their internist, surgeon, or specialist and access to our own capable care and treatment. This is the “package deal” that, sadly, is in danger of becoming overlooked—if not extinct.

1. Japsen B. States remove barriers to physician assistants . Forbes. March 6, 2016. www.forbes.com/sites/brucejapsen/2016/03/06/states-remove-barriers-to-physician-assistants. Accessed September 13, 2016.

2. American Academy of Physician Assistants. Top ten federal laws & regulations imposing unnecessary barriers to medical care provided by PAs. www.aapa.org/workarea/downloadasset.aspx?id=6442450999. Accessed September 13, 2016.

1. Japsen B. States remove barriers to physician assistants . Forbes. March 6, 2016. www.forbes.com/sites/brucejapsen/2016/03/06/states-remove-barriers-to-physician-assistants. Accessed September 13, 2016.

2. American Academy of Physician Assistants. Top ten federal laws & regulations imposing unnecessary barriers to medical care provided by PAs. www.aapa.org/workarea/downloadasset.aspx?id=6442450999. Accessed September 13, 2016.

Why placental shape and vasculature matter

The intrauterine environment significantly influences not only fetal and infant health, but adult health risks as well. Yet current efforts in obstetrics to assess the environment and optimize fetal and long-term outcomes are based on diagnostics that focus on and measure fetal signs and symptoms. By and large, the current approach overlooks the placenta – the organ that serves as the principal regulator of fetal growth and health. If the fetus appears free of risk or complications, we assume the placenta must be “okay.”

Yet this isn’t always the case. By assuming the placenta is healthy and not observing and measuring its condition, we are too often too late to effectively alter fetal- and longer-term outcomes once fetal signs and symptoms appear.

Research in recent decades, and particularly in the past 10 years, has demonstrated that placental shape matters, that it’s linked to function, and that quantifying abnormalities in shape and growth can be a meaningful clinical tool for detecting and preventing disease early in pregnancy.

We now know, specifically, that abnormal shapes reflect alterations in placental vascular architecture that lead to reduced placental efficiency. We also now understand that placental weight or size may serve as a proxy for fetoplacental metabolism.

We have more research to do to further develop models, to collect more data, and to more fully understand the placental pathology that precedes detectable fetal and/or maternal disease. We also need to know whether the early detection of placental disease has sufficient positive predictive value to allow for safe and effective intervention.1

The National Institutes of Health is investing more than $40 million in its Human Placenta Project, which aims to develop new technologies to help researchers monitor the placenta in real time. Yet it is possible that the use of ultrasound and Doppler – technologies that we employ routinely and know are safe – may go a long way toward deepening our knowledge that will, in turn, hone our ability to identify early risks.

When I speak to fellow pathologists, my message is, “Let’s stop wasting data.” For ob.gyns., my message is twofold: First, appreciate the potential to predict and alter downstream fetal and/or maternal risks by observing and measuring the placenta. Second, be aware of the value of early in vivo placental images, as well as photographs, and more precise measures of delivered placentas.

Why shape matters

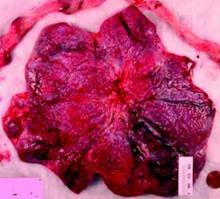

The “average” or “typical” placental shape is round or oval with a centrally inserted umbilical cord. In practice, we see a variety of surface shapes and cord insertion sites, with common variations such as bi- or multi-lobate shapes, or otherwise irregular shapes and cord insertions that are eccentric, marginal, or velamentous. Interestingly, many irregularly shaped placentas display symmetry and have regular, defined geometrical patterns, like snowflakes.2

We have long understood that the microscopic growth of the human placenta involves repeated vascular branching analogous to the roots of a tree. This vascular development, or “placental arborization,” reflects the health of the maternal environment and impacts fetal health.

It is only in recent years, however, that we’ve gained a much better understanding of the relationship of the vascular structure and the shape of the placenta, and an understanding of how early changes in the branching structure of the placenta’s vascular tree drive variation in mature placental shape.

By applying a well-accepted mathematical model for generating highly branched fractals (a model for random growth known in the mathematical physics world as diffusion limited aggregation, or DLA), we have reliably reproduced the variability in placental shapes and related these shapes to the structure of the underlying vascular tree.

When the model is run with unperturbed, random values of a branching growth parameter, we get round-oval fractal shapes. But when the growth parameter is perturbed at a single point in time – when a one-time, early change is introduced – arborization is negatively affected and we get irregular shapes.

The model’s output has explained and verified a clinically observed association between non-round, non-oval placental shapes and smaller newborn birth weight for given placental weight.

This association was evident in an analysis of data collected as part of the National Collaborative Perinatal Project (1959-1974), which included placental measures such as weight, shape, size, and thickness for more than 24,000 women. It also was apparent in an analysis of data and images collected as part of the Pregnancy, Infection, and Nutrition (PIN) Study, conducted in North Carolina.

One take-away from both of these studies has been that increased variability of placental shape is associated with lower placental functional efficiency. Moreover, in the University of North Carolina cohort, the impact of placental vascular pathology (either maternal uteroplacental or fetoplacental) on placental efficiency and function was shown to be dependent on shape. Only in the case of irregularly shaped chorionic plates did each of the two pathologies have a significant association with placental inefficiency.3

The realization that placental size (weight/mass/volume) may serve as a proxy for the fetoplacental basal metabolic rate came after it was shown that Kleiber’s law, which states that basal metabolic rate (BMR) is proportional to the body mass to the 3/4 power, can be applied to the newborn’s birth weight by substituting placental weight for BMR.

This fetal-placental version (placenta weight = .75 birth weight) of Kleiber’s law was validated through an analysis of the sets of placental measures and birth weights stored in the Collaborative Perinatal Project. It has implications for our ability to use ultrasound and Doppler measures to predict risk and to understand pathologic pregnancies, such as those complicated by diabetes or fetal growth restriction.

Research also has shed light on the timing of shape variants. We now know that abnormalities of placental surface shape result mainly from early influences – perturbations of placental growth that occur no later than mid-gestation – rather than from trophotropism (the placenta “grows where it can and does not grow where it can’t”) and passive uterine remodeling later in pregnancy, as has traditionally been believed.4

With respect to the umbilical cord, the location of cord insertion is independent of eventual disk shape, but is to a large degree determined by the end of the first trimester. In addition, cord insertion does influence and is correlated with chorionic vascular density and with disk thickness. Greater eccentricity of cord insertion appears to be linked to increased placental disk thickness, each of which is independently associated with reduced placental functional efficiency.5,6

We have worked with placentas from newborns in families with an older child diagnosed with autism and have found significant differences between these placentas and the placentas of low-risk newborns. In particular, we have measured a reduction in the number or chorionic surface vessel branch points of more than 40%.

Current implications

Irregularities in placental surface shape, disk thickness, and various descriptors of placental size may all be determined from ultrasound and Doppler imaging. We can also assess cord insertion and chorionic surface vessel distribution, track patterns and rates of placental growth, and use various placental measures to understand placental efficiency and to improve the specificity of placental histopathologic diagnoses.

At this point, our use of in vivo imaging of the placenta has mainly involved grayscale ultrasound, but with color or power Doppler and improved surface network tracing protocols, we could save the red and blue areas we visualize as a “shape” and assess the density of surface vessel branching, for instance, and the degree of uniformity in vessel distribution.

We currently have quantitative markers of placental shape and mathematical models to help us identify at-risk pregnancies. What we need are more data from early ultrasounds (from all pregnancies and not only complicated ones) and more comprehensive and precise models of placental growth and function. This will enable us to better identify preclinical fetoplacental pathophysiology and predict downstream risks.

In the meantime, the delivered placenta can be a valuable source of information – an extra dimension for looking back in time. With a paradigm shift toward more thorough pathologic analysis, the delivered placenta can provide unique insights into how placental growth evolved during the pregnancy.

Do not throw away the placenta, and do not just weigh it. Take a photograph, because even with a photograph we can assess vascular density, disk thickness, and other placental characteristics.

In the case of pregnancy complications or suboptimal outcomes, the knowledge we can gain from the delivered placenta can help the physician and patient to understand recurrence risks and to better target evaluation, monitoring, and management in the next pregnancy.

References

1. Am J Perinatol. 2016 Aug 4. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1586508.

2. Placenta. 2008 Sep;29(9):790-7.

3. Placenta. 2010 Nov;31(11):958-62.

4. Placenta. 2012 Mar;33(3):164-70.

5. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2011 Aug;2(4):205-11.

6. Placenta. 2009 Dec;30(12):1058-64.

Dr. Salafia leads the Placental Modulation Laboratory at New York State’s Institute for Basic Research in Developmental Disabilities, Staten Island, N.Y. She reported that she has no relevant financial disclosures.

The intrauterine environment significantly influences not only fetal and infant health, but adult health risks as well. Yet current efforts in obstetrics to assess the environment and optimize fetal and long-term outcomes are based on diagnostics that focus on and measure fetal signs and symptoms. By and large, the current approach overlooks the placenta – the organ that serves as the principal regulator of fetal growth and health. If the fetus appears free of risk or complications, we assume the placenta must be “okay.”

Yet this isn’t always the case. By assuming the placenta is healthy and not observing and measuring its condition, we are too often too late to effectively alter fetal- and longer-term outcomes once fetal signs and symptoms appear.

Research in recent decades, and particularly in the past 10 years, has demonstrated that placental shape matters, that it’s linked to function, and that quantifying abnormalities in shape and growth can be a meaningful clinical tool for detecting and preventing disease early in pregnancy.

We now know, specifically, that abnormal shapes reflect alterations in placental vascular architecture that lead to reduced placental efficiency. We also now understand that placental weight or size may serve as a proxy for fetoplacental metabolism.

We have more research to do to further develop models, to collect more data, and to more fully understand the placental pathology that precedes detectable fetal and/or maternal disease. We also need to know whether the early detection of placental disease has sufficient positive predictive value to allow for safe and effective intervention.1

The National Institutes of Health is investing more than $40 million in its Human Placenta Project, which aims to develop new technologies to help researchers monitor the placenta in real time. Yet it is possible that the use of ultrasound and Doppler – technologies that we employ routinely and know are safe – may go a long way toward deepening our knowledge that will, in turn, hone our ability to identify early risks.

When I speak to fellow pathologists, my message is, “Let’s stop wasting data.” For ob.gyns., my message is twofold: First, appreciate the potential to predict and alter downstream fetal and/or maternal risks by observing and measuring the placenta. Second, be aware of the value of early in vivo placental images, as well as photographs, and more precise measures of delivered placentas.

Why shape matters

The “average” or “typical” placental shape is round or oval with a centrally inserted umbilical cord. In practice, we see a variety of surface shapes and cord insertion sites, with common variations such as bi- or multi-lobate shapes, or otherwise irregular shapes and cord insertions that are eccentric, marginal, or velamentous. Interestingly, many irregularly shaped placentas display symmetry and have regular, defined geometrical patterns, like snowflakes.2

We have long understood that the microscopic growth of the human placenta involves repeated vascular branching analogous to the roots of a tree. This vascular development, or “placental arborization,” reflects the health of the maternal environment and impacts fetal health.

It is only in recent years, however, that we’ve gained a much better understanding of the relationship of the vascular structure and the shape of the placenta, and an understanding of how early changes in the branching structure of the placenta’s vascular tree drive variation in mature placental shape.

By applying a well-accepted mathematical model for generating highly branched fractals (a model for random growth known in the mathematical physics world as diffusion limited aggregation, or DLA), we have reliably reproduced the variability in placental shapes and related these shapes to the structure of the underlying vascular tree.

When the model is run with unperturbed, random values of a branching growth parameter, we get round-oval fractal shapes. But when the growth parameter is perturbed at a single point in time – when a one-time, early change is introduced – arborization is negatively affected and we get irregular shapes.

The model’s output has explained and verified a clinically observed association between non-round, non-oval placental shapes and smaller newborn birth weight for given placental weight.

This association was evident in an analysis of data collected as part of the National Collaborative Perinatal Project (1959-1974), which included placental measures such as weight, shape, size, and thickness for more than 24,000 women. It also was apparent in an analysis of data and images collected as part of the Pregnancy, Infection, and Nutrition (PIN) Study, conducted in North Carolina.

One take-away from both of these studies has been that increased variability of placental shape is associated with lower placental functional efficiency. Moreover, in the University of North Carolina cohort, the impact of placental vascular pathology (either maternal uteroplacental or fetoplacental) on placental efficiency and function was shown to be dependent on shape. Only in the case of irregularly shaped chorionic plates did each of the two pathologies have a significant association with placental inefficiency.3

The realization that placental size (weight/mass/volume) may serve as a proxy for the fetoplacental basal metabolic rate came after it was shown that Kleiber’s law, which states that basal metabolic rate (BMR) is proportional to the body mass to the 3/4 power, can be applied to the newborn’s birth weight by substituting placental weight for BMR.

This fetal-placental version (placenta weight = .75 birth weight) of Kleiber’s law was validated through an analysis of the sets of placental measures and birth weights stored in the Collaborative Perinatal Project. It has implications for our ability to use ultrasound and Doppler measures to predict risk and to understand pathologic pregnancies, such as those complicated by diabetes or fetal growth restriction.

Research also has shed light on the timing of shape variants. We now know that abnormalities of placental surface shape result mainly from early influences – perturbations of placental growth that occur no later than mid-gestation – rather than from trophotropism (the placenta “grows where it can and does not grow where it can’t”) and passive uterine remodeling later in pregnancy, as has traditionally been believed.4

With respect to the umbilical cord, the location of cord insertion is independent of eventual disk shape, but is to a large degree determined by the end of the first trimester. In addition, cord insertion does influence and is correlated with chorionic vascular density and with disk thickness. Greater eccentricity of cord insertion appears to be linked to increased placental disk thickness, each of which is independently associated with reduced placental functional efficiency.5,6

We have worked with placentas from newborns in families with an older child diagnosed with autism and have found significant differences between these placentas and the placentas of low-risk newborns. In particular, we have measured a reduction in the number or chorionic surface vessel branch points of more than 40%.

Current implications

Irregularities in placental surface shape, disk thickness, and various descriptors of placental size may all be determined from ultrasound and Doppler imaging. We can also assess cord insertion and chorionic surface vessel distribution, track patterns and rates of placental growth, and use various placental measures to understand placental efficiency and to improve the specificity of placental histopathologic diagnoses.

At this point, our use of in vivo imaging of the placenta has mainly involved grayscale ultrasound, but with color or power Doppler and improved surface network tracing protocols, we could save the red and blue areas we visualize as a “shape” and assess the density of surface vessel branching, for instance, and the degree of uniformity in vessel distribution.

We currently have quantitative markers of placental shape and mathematical models to help us identify at-risk pregnancies. What we need are more data from early ultrasounds (from all pregnancies and not only complicated ones) and more comprehensive and precise models of placental growth and function. This will enable us to better identify preclinical fetoplacental pathophysiology and predict downstream risks.

In the meantime, the delivered placenta can be a valuable source of information – an extra dimension for looking back in time. With a paradigm shift toward more thorough pathologic analysis, the delivered placenta can provide unique insights into how placental growth evolved during the pregnancy.

Do not throw away the placenta, and do not just weigh it. Take a photograph, because even with a photograph we can assess vascular density, disk thickness, and other placental characteristics.

In the case of pregnancy complications or suboptimal outcomes, the knowledge we can gain from the delivered placenta can help the physician and patient to understand recurrence risks and to better target evaluation, monitoring, and management in the next pregnancy.

References

1. Am J Perinatol. 2016 Aug 4. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1586508.

2. Placenta. 2008 Sep;29(9):790-7.

3. Placenta. 2010 Nov;31(11):958-62.

4. Placenta. 2012 Mar;33(3):164-70.

5. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2011 Aug;2(4):205-11.

6. Placenta. 2009 Dec;30(12):1058-64.

Dr. Salafia leads the Placental Modulation Laboratory at New York State’s Institute for Basic Research in Developmental Disabilities, Staten Island, N.Y. She reported that she has no relevant financial disclosures.

The intrauterine environment significantly influences not only fetal and infant health, but adult health risks as well. Yet current efforts in obstetrics to assess the environment and optimize fetal and long-term outcomes are based on diagnostics that focus on and measure fetal signs and symptoms. By and large, the current approach overlooks the placenta – the organ that serves as the principal regulator of fetal growth and health. If the fetus appears free of risk or complications, we assume the placenta must be “okay.”

Yet this isn’t always the case. By assuming the placenta is healthy and not observing and measuring its condition, we are too often too late to effectively alter fetal- and longer-term outcomes once fetal signs and symptoms appear.

Research in recent decades, and particularly in the past 10 years, has demonstrated that placental shape matters, that it’s linked to function, and that quantifying abnormalities in shape and growth can be a meaningful clinical tool for detecting and preventing disease early in pregnancy.

We now know, specifically, that abnormal shapes reflect alterations in placental vascular architecture that lead to reduced placental efficiency. We also now understand that placental weight or size may serve as a proxy for fetoplacental metabolism.

We have more research to do to further develop models, to collect more data, and to more fully understand the placental pathology that precedes detectable fetal and/or maternal disease. We also need to know whether the early detection of placental disease has sufficient positive predictive value to allow for safe and effective intervention.1

The National Institutes of Health is investing more than $40 million in its Human Placenta Project, which aims to develop new technologies to help researchers monitor the placenta in real time. Yet it is possible that the use of ultrasound and Doppler – technologies that we employ routinely and know are safe – may go a long way toward deepening our knowledge that will, in turn, hone our ability to identify early risks.

When I speak to fellow pathologists, my message is, “Let’s stop wasting data.” For ob.gyns., my message is twofold: First, appreciate the potential to predict and alter downstream fetal and/or maternal risks by observing and measuring the placenta. Second, be aware of the value of early in vivo placental images, as well as photographs, and more precise measures of delivered placentas.

Why shape matters

The “average” or “typical” placental shape is round or oval with a centrally inserted umbilical cord. In practice, we see a variety of surface shapes and cord insertion sites, with common variations such as bi- or multi-lobate shapes, or otherwise irregular shapes and cord insertions that are eccentric, marginal, or velamentous. Interestingly, many irregularly shaped placentas display symmetry and have regular, defined geometrical patterns, like snowflakes.2

We have long understood that the microscopic growth of the human placenta involves repeated vascular branching analogous to the roots of a tree. This vascular development, or “placental arborization,” reflects the health of the maternal environment and impacts fetal health.

It is only in recent years, however, that we’ve gained a much better understanding of the relationship of the vascular structure and the shape of the placenta, and an understanding of how early changes in the branching structure of the placenta’s vascular tree drive variation in mature placental shape.

By applying a well-accepted mathematical model for generating highly branched fractals (a model for random growth known in the mathematical physics world as diffusion limited aggregation, or DLA), we have reliably reproduced the variability in placental shapes and related these shapes to the structure of the underlying vascular tree.

When the model is run with unperturbed, random values of a branching growth parameter, we get round-oval fractal shapes. But when the growth parameter is perturbed at a single point in time – when a one-time, early change is introduced – arborization is negatively affected and we get irregular shapes.

The model’s output has explained and verified a clinically observed association between non-round, non-oval placental shapes and smaller newborn birth weight for given placental weight.

This association was evident in an analysis of data collected as part of the National Collaborative Perinatal Project (1959-1974), which included placental measures such as weight, shape, size, and thickness for more than 24,000 women. It also was apparent in an analysis of data and images collected as part of the Pregnancy, Infection, and Nutrition (PIN) Study, conducted in North Carolina.

One take-away from both of these studies has been that increased variability of placental shape is associated with lower placental functional efficiency. Moreover, in the University of North Carolina cohort, the impact of placental vascular pathology (either maternal uteroplacental or fetoplacental) on placental efficiency and function was shown to be dependent on shape. Only in the case of irregularly shaped chorionic plates did each of the two pathologies have a significant association with placental inefficiency.3

The realization that placental size (weight/mass/volume) may serve as a proxy for the fetoplacental basal metabolic rate came after it was shown that Kleiber’s law, which states that basal metabolic rate (BMR) is proportional to the body mass to the 3/4 power, can be applied to the newborn’s birth weight by substituting placental weight for BMR.

This fetal-placental version (placenta weight = .75 birth weight) of Kleiber’s law was validated through an analysis of the sets of placental measures and birth weights stored in the Collaborative Perinatal Project. It has implications for our ability to use ultrasound and Doppler measures to predict risk and to understand pathologic pregnancies, such as those complicated by diabetes or fetal growth restriction.

Research also has shed light on the timing of shape variants. We now know that abnormalities of placental surface shape result mainly from early influences – perturbations of placental growth that occur no later than mid-gestation – rather than from trophotropism (the placenta “grows where it can and does not grow where it can’t”) and passive uterine remodeling later in pregnancy, as has traditionally been believed.4

With respect to the umbilical cord, the location of cord insertion is independent of eventual disk shape, but is to a large degree determined by the end of the first trimester. In addition, cord insertion does influence and is correlated with chorionic vascular density and with disk thickness. Greater eccentricity of cord insertion appears to be linked to increased placental disk thickness, each of which is independently associated with reduced placental functional efficiency.5,6

We have worked with placentas from newborns in families with an older child diagnosed with autism and have found significant differences between these placentas and the placentas of low-risk newborns. In particular, we have measured a reduction in the number or chorionic surface vessel branch points of more than 40%.

Current implications

Irregularities in placental surface shape, disk thickness, and various descriptors of placental size may all be determined from ultrasound and Doppler imaging. We can also assess cord insertion and chorionic surface vessel distribution, track patterns and rates of placental growth, and use various placental measures to understand placental efficiency and to improve the specificity of placental histopathologic diagnoses.

At this point, our use of in vivo imaging of the placenta has mainly involved grayscale ultrasound, but with color or power Doppler and improved surface network tracing protocols, we could save the red and blue areas we visualize as a “shape” and assess the density of surface vessel branching, for instance, and the degree of uniformity in vessel distribution.

We currently have quantitative markers of placental shape and mathematical models to help us identify at-risk pregnancies. What we need are more data from early ultrasounds (from all pregnancies and not only complicated ones) and more comprehensive and precise models of placental growth and function. This will enable us to better identify preclinical fetoplacental pathophysiology and predict downstream risks.

In the meantime, the delivered placenta can be a valuable source of information – an extra dimension for looking back in time. With a paradigm shift toward more thorough pathologic analysis, the delivered placenta can provide unique insights into how placental growth evolved during the pregnancy.

Do not throw away the placenta, and do not just weigh it. Take a photograph, because even with a photograph we can assess vascular density, disk thickness, and other placental characteristics.

In the case of pregnancy complications or suboptimal outcomes, the knowledge we can gain from the delivered placenta can help the physician and patient to understand recurrence risks and to better target evaluation, monitoring, and management in the next pregnancy.

References

1. Am J Perinatol. 2016 Aug 4. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1586508.

2. Placenta. 2008 Sep;29(9):790-7.

3. Placenta. 2010 Nov;31(11):958-62.

4. Placenta. 2012 Mar;33(3):164-70.

5. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2011 Aug;2(4):205-11.

6. Placenta. 2009 Dec;30(12):1058-64.

Dr. Salafia leads the Placental Modulation Laboratory at New York State’s Institute for Basic Research in Developmental Disabilities, Staten Island, N.Y. She reported that she has no relevant financial disclosures.

Compete and Solve Clinical Cases with Human Diagnosis Project

SHM recently partnered with the Human Diagnosis Project. Human Dx is the world’s first open diagnostic system, which aims to understand the fundamental data structure of diagnosis and, in the future, considerably impact the cost of, access to, and effectiveness of healthcare globally.

Human Dx’s Global Morning Reports feature weekly case competitions of differential diagnoses and clinical reasoning skills. Each day, attendings, fellows, residents, and medical students have the opportunity to solve the best cases from around the world from the prior day and submit cases for the next day. This partnership with SHM provides a unique, interactive learning platform with cases tailored to hospitalists.

The rules are simple:

- Increase your “Impact” by creating and solving cases online.

- Creating cases creates more “Impact” than solving cases.

The team and individual with the most “Impact” each week win. Sign up today and test your skills in hospital medicine diagnostics at www.humandx.org/shm/.

SHM recently partnered with the Human Diagnosis Project. Human Dx is the world’s first open diagnostic system, which aims to understand the fundamental data structure of diagnosis and, in the future, considerably impact the cost of, access to, and effectiveness of healthcare globally.

Human Dx’s Global Morning Reports feature weekly case competitions of differential diagnoses and clinical reasoning skills. Each day, attendings, fellows, residents, and medical students have the opportunity to solve the best cases from around the world from the prior day and submit cases for the next day. This partnership with SHM provides a unique, interactive learning platform with cases tailored to hospitalists.

The rules are simple:

- Increase your “Impact” by creating and solving cases online.

- Creating cases creates more “Impact” than solving cases.

The team and individual with the most “Impact” each week win. Sign up today and test your skills in hospital medicine diagnostics at www.humandx.org/shm/.

SHM recently partnered with the Human Diagnosis Project. Human Dx is the world’s first open diagnostic system, which aims to understand the fundamental data structure of diagnosis and, in the future, considerably impact the cost of, access to, and effectiveness of healthcare globally.

Human Dx’s Global Morning Reports feature weekly case competitions of differential diagnoses and clinical reasoning skills. Each day, attendings, fellows, residents, and medical students have the opportunity to solve the best cases from around the world from the prior day and submit cases for the next day. This partnership with SHM provides a unique, interactive learning platform with cases tailored to hospitalists.

The rules are simple:

- Increase your “Impact” by creating and solving cases online.

- Creating cases creates more “Impact” than solving cases.

The team and individual with the most “Impact” each week win. Sign up today and test your skills in hospital medicine diagnostics at www.humandx.org/shm/.

2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report Now Available

- The percentage of the hospital’s total patient volume (for the population the group serves, i.e., adult versus children versus both) that the hospital medicine group (HMG) was responsible for caring for

- The presence of medical hospitalists within the HMG focusing their practice on a specific medical subspecialty, such as critical care, neurology, or oncology

- The value of CME allowances for hospitalists

- The utilization of prolonged service codes by hospitalists

- Charge capture methodologies being used by HMGs

- For academic HMGs, the dollar amount of financial support provided for non-clinical work

Order your copy now and improve your practice today at www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

- The percentage of the hospital’s total patient volume (for the population the group serves, i.e., adult versus children versus both) that the hospital medicine group (HMG) was responsible for caring for

- The presence of medical hospitalists within the HMG focusing their practice on a specific medical subspecialty, such as critical care, neurology, or oncology

- The value of CME allowances for hospitalists

- The utilization of prolonged service codes by hospitalists

- Charge capture methodologies being used by HMGs

- For academic HMGs, the dollar amount of financial support provided for non-clinical work

Order your copy now and improve your practice today at www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

- The percentage of the hospital’s total patient volume (for the population the group serves, i.e., adult versus children versus both) that the hospital medicine group (HMG) was responsible for caring for

- The presence of medical hospitalists within the HMG focusing their practice on a specific medical subspecialty, such as critical care, neurology, or oncology

- The value of CME allowances for hospitalists

- The utilization of prolonged service codes by hospitalists

- Charge capture methodologies being used by HMGs

- For academic HMGs, the dollar amount of financial support provided for non-clinical work

Order your copy now and improve your practice today at www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

Factor IX therapy approved in Japan

Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) has approved albutrepenonacog alfa (Idelvion) to treat and prevent bleeding in children and adults with hemophilia B.

Albutrepenonacog alfa is a fusion protein linking recombinant coagulation factor IX with recombinant albumin.

The product is now approved for use as routine prophylaxis, for on-demand control of bleeding, and for perioperative management of bleeding.

Albutrepenonacog alfa is being developed by CSL Behring.

The company says the product is the first and only hemophilia B therapy with up to 14-day dosing intervals.

According to CSL Behring, albutrepenonacog alfa can deliver high-level protection from bleeds by maintaining factor IX activity levels at an average of 20% in patients treated prophylactically every 7 days and an average of 12% in patients treated prophylactically every 14 days.

Albutrepenonacog alfa has also been approved in Canada, the European Union, Switzerland, and the US.

Phase 3 trial

The MHLW approved albutrepenonacog alfa based on results of the PROLONG-9FP clinical development program. PROLONG-9FP includes phase 1, 2, and 3 studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of albutrepenonacog alfa in adults and children (ages 1 to 61) with hemophilia B.

Data from the phase 3 study were published in Blood. The study included 63 previously treated male patients with severe hemophilia B. They had a mean age of 33 (range, 12 to 61).

The patients were divided into 2 groups. Group 1 (n=40) received routine prophylaxis with albutrepenonacog alfa once every 7 days for 26 weeks, followed by a 7-, 10-, or 14-day prophylaxis regimen for a mean of 50, 38, or 51 weeks, respectively.

Group 2 received on-demand treatment with albutrepenonacog alfa for bleeding episodes for 26 weeks (n=23) and then switched to a 7-day prophylaxis regimen for a mean of 45 weeks (n=19).

The median annualized bleeding rate (ABR) was 2.0 in the prophylaxis arm (group 1) and 23.5 in the on-demand treatment arm (group 2). The median spontaneous ABRs were 0.0 and 17.0, respectively.

For patients in group 2, there was a significant reduction in median ABRs when patients switched from on-demand treatment to prophylaxis—19.22 and 1.58, respectively (P<0.0001). And there was a significant reduction in median spontaneous ABRs—15.43 and 0.00, respectively (P<0.0001).

Overall, 98.6% of bleeding episodes were treated successfully, including 93.6% that were treated with a single injection of albutrepenonacog alfa.

None of the patients developed inhibitors or experienced thromboembolic events, anaphylaxis, or life-threatening adverse events (AEs).

There were 347 treatment-emergent AEs reported in 54 (85.7%) patients. The most common were nasopharyngitis (25.4%), headache (23.8%), arthralgia (4.3%), and influenza (11.1%).

Eleven mild/moderate AEs in 5 patients (7.9%) were considered possibly related to albutrepenonacog alfa. Two patients discontinued treatment due to AEs—1 with hypersensitivity and 1 with headache. ![]()

Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) has approved albutrepenonacog alfa (Idelvion) to treat and prevent bleeding in children and adults with hemophilia B.

Albutrepenonacog alfa is a fusion protein linking recombinant coagulation factor IX with recombinant albumin.

The product is now approved for use as routine prophylaxis, for on-demand control of bleeding, and for perioperative management of bleeding.

Albutrepenonacog alfa is being developed by CSL Behring.

The company says the product is the first and only hemophilia B therapy with up to 14-day dosing intervals.

According to CSL Behring, albutrepenonacog alfa can deliver high-level protection from bleeds by maintaining factor IX activity levels at an average of 20% in patients treated prophylactically every 7 days and an average of 12% in patients treated prophylactically every 14 days.

Albutrepenonacog alfa has also been approved in Canada, the European Union, Switzerland, and the US.

Phase 3 trial

The MHLW approved albutrepenonacog alfa based on results of the PROLONG-9FP clinical development program. PROLONG-9FP includes phase 1, 2, and 3 studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of albutrepenonacog alfa in adults and children (ages 1 to 61) with hemophilia B.

Data from the phase 3 study were published in Blood. The study included 63 previously treated male patients with severe hemophilia B. They had a mean age of 33 (range, 12 to 61).

The patients were divided into 2 groups. Group 1 (n=40) received routine prophylaxis with albutrepenonacog alfa once every 7 days for 26 weeks, followed by a 7-, 10-, or 14-day prophylaxis regimen for a mean of 50, 38, or 51 weeks, respectively.

Group 2 received on-demand treatment with albutrepenonacog alfa for bleeding episodes for 26 weeks (n=23) and then switched to a 7-day prophylaxis regimen for a mean of 45 weeks (n=19).

The median annualized bleeding rate (ABR) was 2.0 in the prophylaxis arm (group 1) and 23.5 in the on-demand treatment arm (group 2). The median spontaneous ABRs were 0.0 and 17.0, respectively.

For patients in group 2, there was a significant reduction in median ABRs when patients switched from on-demand treatment to prophylaxis—19.22 and 1.58, respectively (P<0.0001). And there was a significant reduction in median spontaneous ABRs—15.43 and 0.00, respectively (P<0.0001).

Overall, 98.6% of bleeding episodes were treated successfully, including 93.6% that were treated with a single injection of albutrepenonacog alfa.

None of the patients developed inhibitors or experienced thromboembolic events, anaphylaxis, or life-threatening adverse events (AEs).

There were 347 treatment-emergent AEs reported in 54 (85.7%) patients. The most common were nasopharyngitis (25.4%), headache (23.8%), arthralgia (4.3%), and influenza (11.1%).

Eleven mild/moderate AEs in 5 patients (7.9%) were considered possibly related to albutrepenonacog alfa. Two patients discontinued treatment due to AEs—1 with hypersensitivity and 1 with headache. ![]()

Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) has approved albutrepenonacog alfa (Idelvion) to treat and prevent bleeding in children and adults with hemophilia B.

Albutrepenonacog alfa is a fusion protein linking recombinant coagulation factor IX with recombinant albumin.

The product is now approved for use as routine prophylaxis, for on-demand control of bleeding, and for perioperative management of bleeding.

Albutrepenonacog alfa is being developed by CSL Behring.

The company says the product is the first and only hemophilia B therapy with up to 14-day dosing intervals.

According to CSL Behring, albutrepenonacog alfa can deliver high-level protection from bleeds by maintaining factor IX activity levels at an average of 20% in patients treated prophylactically every 7 days and an average of 12% in patients treated prophylactically every 14 days.

Albutrepenonacog alfa has also been approved in Canada, the European Union, Switzerland, and the US.

Phase 3 trial

The MHLW approved albutrepenonacog alfa based on results of the PROLONG-9FP clinical development program. PROLONG-9FP includes phase 1, 2, and 3 studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of albutrepenonacog alfa in adults and children (ages 1 to 61) with hemophilia B.

Data from the phase 3 study were published in Blood. The study included 63 previously treated male patients with severe hemophilia B. They had a mean age of 33 (range, 12 to 61).

The patients were divided into 2 groups. Group 1 (n=40) received routine prophylaxis with albutrepenonacog alfa once every 7 days for 26 weeks, followed by a 7-, 10-, or 14-day prophylaxis regimen for a mean of 50, 38, or 51 weeks, respectively.

Group 2 received on-demand treatment with albutrepenonacog alfa for bleeding episodes for 26 weeks (n=23) and then switched to a 7-day prophylaxis regimen for a mean of 45 weeks (n=19).

The median annualized bleeding rate (ABR) was 2.0 in the prophylaxis arm (group 1) and 23.5 in the on-demand treatment arm (group 2). The median spontaneous ABRs were 0.0 and 17.0, respectively.

For patients in group 2, there was a significant reduction in median ABRs when patients switched from on-demand treatment to prophylaxis—19.22 and 1.58, respectively (P<0.0001). And there was a significant reduction in median spontaneous ABRs—15.43 and 0.00, respectively (P<0.0001).

Overall, 98.6% of bleeding episodes were treated successfully, including 93.6% that were treated with a single injection of albutrepenonacog alfa.

None of the patients developed inhibitors or experienced thromboembolic events, anaphylaxis, or life-threatening adverse events (AEs).

There were 347 treatment-emergent AEs reported in 54 (85.7%) patients. The most common were nasopharyngitis (25.4%), headache (23.8%), arthralgia (4.3%), and influenza (11.1%).

Eleven mild/moderate AEs in 5 patients (7.9%) were considered possibly related to albutrepenonacog alfa. Two patients discontinued treatment due to AEs—1 with hypersensitivity and 1 with headache. ![]()

Seven days of antibiotics sufficient for most hospital-acquired pneumonia

A 1-week course of antibiotics is sufficient for most hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia, regardless of the microbial etiology of the infection, according to an updated Clinical Practice Guidelines for managing adults with these disorders.

In addition, every hospital should develop its own antibiogram to align clinicians’ choice of treatments with the local distribution of likely pathogens and their antimicrobial susceptibilities. Both of these recommendations, as well as others that are also new to the updated guidelines, are intended to minimize patient exposure to unnecessary antibiotics and reduce antibiotic resistance, said Andre C. Kalil, MD, and Mark L. Metersky, MD, cochairs of the guidelines panel of 18 experts in infectious diseases, pulmonary medicine, critical care medicine, laboratory medicine, microbiology, pharmacology, and guideline methodology.

The guidelines, an update of the last version issued in 2005 and developed jointly by representatives of the Infectious Disease Society of America (including Dr. Kalil) and the American Thoracic Society (including Dr. Metersky), are intended for use by all clinicians who care for patients at risk for hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) or ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), including surgeons, anesthesiologists, and hospitalists as well as specialists in infectious diseases, pulmonary diseases, and critical care. The guidelines no longer use the concept of health care–associated pneumonia (HCAP), chiefly because new evidence shows that designation is too general: HCAP patients are not at high risk for multidrug-resistant organisms simply because of their contact with the health care system, the guidelines panel wrote (Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 1;63[5]:e61-e111).

The IDSA/ATS Guidelines strongly recommend short-course (1-week) antibiotic therapy instead of longer courses for both HAP and VAP and assert that antibiotic doses should be de-escalated rather than fixed. It advises that serum procalcitonin level plus clinical criteria, not just clinical criteria alone, should be used to guide antibiotic discontinuation, and suggests that the Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score not be used to guide discontinuation.

The guidelines also address empiric treatments when MRSA is suspected and give detailed guidance for selecting antibiotics once the causative organism is identified, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing gram-negative bacilli, Acinetobacter species, and pathogens resistant to carbapenem.

The guidelines include numerous other recommendations concerning the diagnosis of HAP and VAP, the optimal initial treatments, the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic optimization of antibiotic therapies, and the use of inhaled antibiotics. All the recommendations “are a compromise between the competing goals of providing early appropriate antibiotic coverage and avoiding superfluous treatment that may lead to adverse drug effects, Clostridium difficile infections, antibiotic resistance, and increased costs,” the guidelines panel noted.

The full-text guidelines, including details about the panel’s methodology in reviewing the current literature and the summaries of evidence that support each recommendation, is available free on the Clinical Infectious Diseases website.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society provided financial and administrative support to develop the guidelines. No industry funding was permitted. Dr. Kalil reported having no potential conflicts of interest; Dr. Metersky reported ties to Aradigm, Gilead, Pfizer, Bayer, and their associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

A 1-week course of antibiotics is sufficient for most hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia, regardless of the microbial etiology of the infection, according to an updated Clinical Practice Guidelines for managing adults with these disorders.

In addition, every hospital should develop its own antibiogram to align clinicians’ choice of treatments with the local distribution of likely pathogens and their antimicrobial susceptibilities. Both of these recommendations, as well as others that are also new to the updated guidelines, are intended to minimize patient exposure to unnecessary antibiotics and reduce antibiotic resistance, said Andre C. Kalil, MD, and Mark L. Metersky, MD, cochairs of the guidelines panel of 18 experts in infectious diseases, pulmonary medicine, critical care medicine, laboratory medicine, microbiology, pharmacology, and guideline methodology.

The guidelines, an update of the last version issued in 2005 and developed jointly by representatives of the Infectious Disease Society of America (including Dr. Kalil) and the American Thoracic Society (including Dr. Metersky), are intended for use by all clinicians who care for patients at risk for hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) or ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), including surgeons, anesthesiologists, and hospitalists as well as specialists in infectious diseases, pulmonary diseases, and critical care. The guidelines no longer use the concept of health care–associated pneumonia (HCAP), chiefly because new evidence shows that designation is too general: HCAP patients are not at high risk for multidrug-resistant organisms simply because of their contact with the health care system, the guidelines panel wrote (Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 1;63[5]:e61-e111).

The IDSA/ATS Guidelines strongly recommend short-course (1-week) antibiotic therapy instead of longer courses for both HAP and VAP and assert that antibiotic doses should be de-escalated rather than fixed. It advises that serum procalcitonin level plus clinical criteria, not just clinical criteria alone, should be used to guide antibiotic discontinuation, and suggests that the Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score not be used to guide discontinuation.

The guidelines also address empiric treatments when MRSA is suspected and give detailed guidance for selecting antibiotics once the causative organism is identified, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing gram-negative bacilli, Acinetobacter species, and pathogens resistant to carbapenem.

The guidelines include numerous other recommendations concerning the diagnosis of HAP and VAP, the optimal initial treatments, the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic optimization of antibiotic therapies, and the use of inhaled antibiotics. All the recommendations “are a compromise between the competing goals of providing early appropriate antibiotic coverage and avoiding superfluous treatment that may lead to adverse drug effects, Clostridium difficile infections, antibiotic resistance, and increased costs,” the guidelines panel noted.

The full-text guidelines, including details about the panel’s methodology in reviewing the current literature and the summaries of evidence that support each recommendation, is available free on the Clinical Infectious Diseases website.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society provided financial and administrative support to develop the guidelines. No industry funding was permitted. Dr. Kalil reported having no potential conflicts of interest; Dr. Metersky reported ties to Aradigm, Gilead, Pfizer, Bayer, and their associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

A 1-week course of antibiotics is sufficient for most hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia, regardless of the microbial etiology of the infection, according to an updated Clinical Practice Guidelines for managing adults with these disorders.

In addition, every hospital should develop its own antibiogram to align clinicians’ choice of treatments with the local distribution of likely pathogens and their antimicrobial susceptibilities. Both of these recommendations, as well as others that are also new to the updated guidelines, are intended to minimize patient exposure to unnecessary antibiotics and reduce antibiotic resistance, said Andre C. Kalil, MD, and Mark L. Metersky, MD, cochairs of the guidelines panel of 18 experts in infectious diseases, pulmonary medicine, critical care medicine, laboratory medicine, microbiology, pharmacology, and guideline methodology.

The guidelines, an update of the last version issued in 2005 and developed jointly by representatives of the Infectious Disease Society of America (including Dr. Kalil) and the American Thoracic Society (including Dr. Metersky), are intended for use by all clinicians who care for patients at risk for hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) or ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), including surgeons, anesthesiologists, and hospitalists as well as specialists in infectious diseases, pulmonary diseases, and critical care. The guidelines no longer use the concept of health care–associated pneumonia (HCAP), chiefly because new evidence shows that designation is too general: HCAP patients are not at high risk for multidrug-resistant organisms simply because of their contact with the health care system, the guidelines panel wrote (Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 1;63[5]:e61-e111).

The IDSA/ATS Guidelines strongly recommend short-course (1-week) antibiotic therapy instead of longer courses for both HAP and VAP and assert that antibiotic doses should be de-escalated rather than fixed. It advises that serum procalcitonin level plus clinical criteria, not just clinical criteria alone, should be used to guide antibiotic discontinuation, and suggests that the Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score not be used to guide discontinuation.

The guidelines also address empiric treatments when MRSA is suspected and give detailed guidance for selecting antibiotics once the causative organism is identified, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing gram-negative bacilli, Acinetobacter species, and pathogens resistant to carbapenem.