User login

Perianal North American Blastomycosis

Cutaneous North American blastomycosis is a deep fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus that is endemic to the Great Lakes region as well as the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys where it thrives in moist acidic soil enriched with organic material.1,2 In humans, the annual incidence rate is estimated to be 0.6 cases per million,3 though it may be as high as 42 cases per 100,000 in endemic areas.4 Infection typically results from the inhalation of conidia and manifests as either acute or chronic pneumonia.5 Most patients with acute disease present with nonspecific flulike symptoms and a nonproductive cough.

Dissemination occurs in approximately 25% of cases,6 most commonly affecting the skin. Other potential sites of dissemination include bone, the genitourinary tract, and the central nervous system. Cutaneous lesions, which may be either verrucous or ulcerative plaques, often occur on or around orifices contiguous to the respiratory tract.7 Verrucous lesions tend to have an irregular shape with well-defined borders and surface crusting. Ulcerative lesions have heaped-up borders and often have an exudative base.8 The differential diagnosis of cutaneous North American blastomycosis lesions includes squamous cell carcinoma, giant keratoacanthoma, verrucae, basal cell carcinoma, scrofuloderma, lupus vulgaris, nocardiosis, syphilis, bromoderma, iododerma, granuloma inguinale, tuberculosis verrucosa cutis, mycetoma, and actinomycosis.7,8

Although periorificial cutaneous manifestations of disseminated blastomycosis are common, perianal lesions are rare. The differential diagnosis of perianal verrucous plaques includes condyloma acuminatum, squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, Buschke-Löwenstein tumor, actinomycosis, and localized fungal infections such as blastomycosis.9

Case Report

A 57-year-old man presented with a palpable perianal mass that produced small amounts of blood in his underwear and on toilet paper. The patient reported no history of hemorrhoids, anoreceptive intercourse, or sexually transmitted disease. Four months prior to presentation, he had a prolonged upper respiratory tract illness with a subjective fever and productive cough of 2 months’ duration. The patient described himself as an avid outdoorsman who worked at a summer resort and spent a great deal of time in the forests of central Wisconsin last autumn. Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated, firm, moist plaque with a verrucous surface that measured 3.5×2.7 cm and extended from the anal verge to the perianal skin (Figure 1).

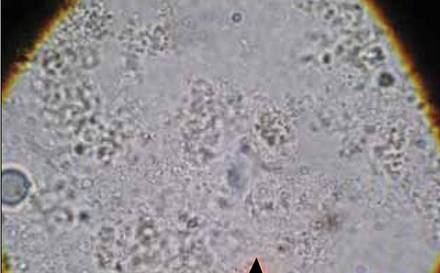

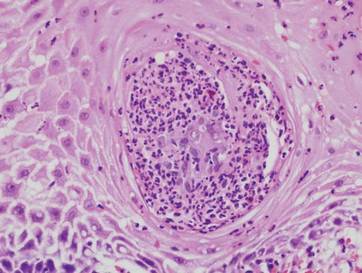

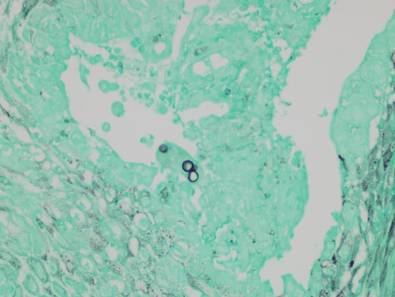

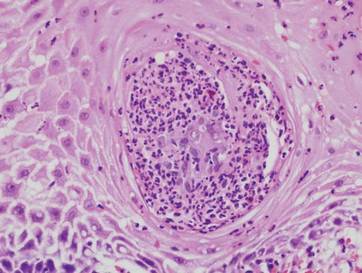

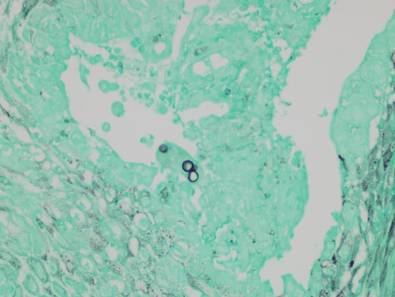

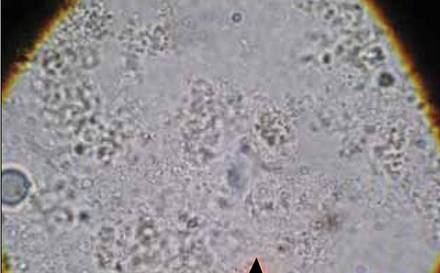

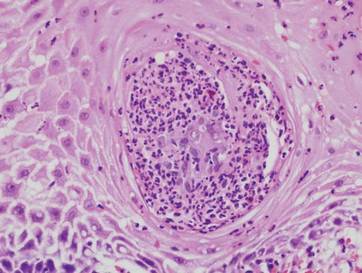

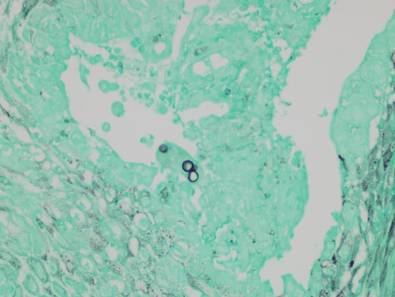

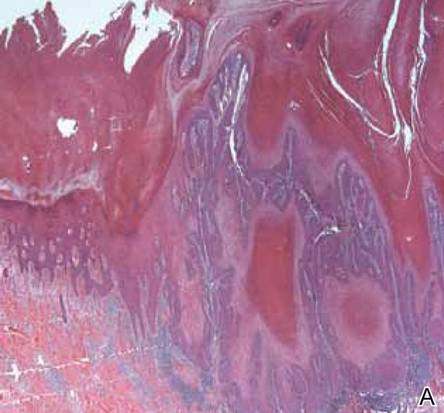

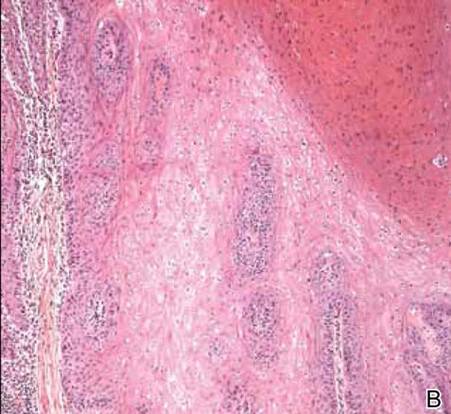

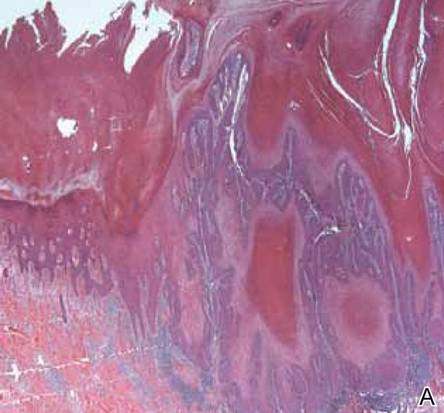

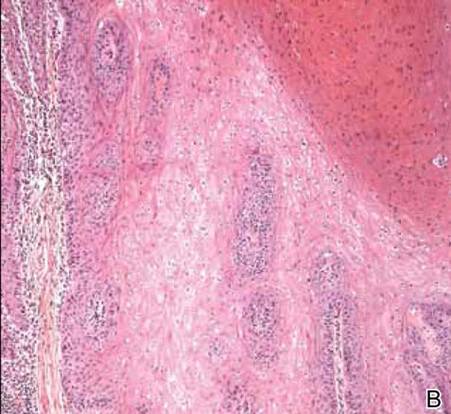

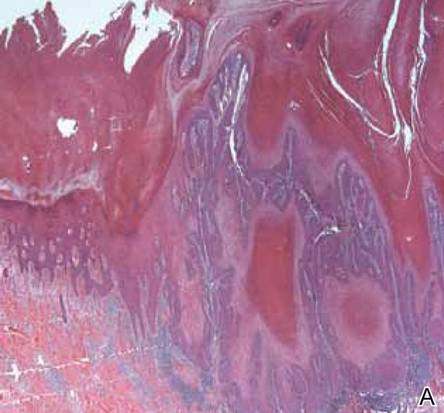

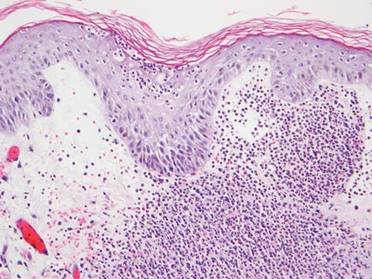

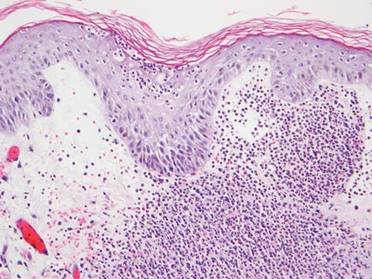

Potassium hydroxide preparation of a biopsy specimen (Figure 2), a punch biopsy of the lesion (Figure 3), and Gomori methenamine-silver staining (Figure 4) revealed scattered yeast spores, some demonstrating broad-based budding, with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, dermal neutrophils, and intraepithelial microabscesses. The patient’s urine was positive for Blastomyces antigen (1.04 ng/mL). Chest radiography demonstrated a localized infiltrate in the right hilum with possible mass effect. Computed tomography showed a consolidative opacity measuring 4.0×3.4 cm in the upper lobe of the right lung (Figure 5).

|  |

The patient was diagnosed with cutaneous North American blastomycosis and prescribed a 6-month course of oral itraconazole 200 mg twice daily. At his 3-month follow-up visit, the perianal plaque hadalmost completely resolved (Figure 6). However, because the patient had increasing lower extremity edema, subjective hearing loss, and abnormal liver function tests, itraconazole treatment was discontinued and replaced with oral fluconazole 400 mg daily for the next 3 months. The right hilar mass had visibly improved on follow-up chest radiography 2 months after the patient started antifungal therapy with itraconazole and had resolved within another 3 months of treatment.

|

|

Comment

Cutaneous blastomycosis results most often from the hematogenous spread of B dermatitidis from the lungs and rarely from direct inoculation.5,10 Skin lesions tend to occur on exposed areas, such as the face, scalp, hands, wrists, feet, and ankles.7,11-13 Dissemination to the perianal skin is rare, though it has been reported in 2 other patients; both patients, similar to our patient, had evidence of pulmonary involvement at some point in their clinical course.9,14

Diagnosis is based on identification of B dermatitidis by microscopy or culture. Potassium hydroxide preparation of biopsy specimens typically shows broad-based budding yeast.13 Characteristic findings of histopathologic studies include pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperplasia, intraepidermal abscesses, and a dermal infiltrate of polymorphonuclear leukocytes.15 On fungal culture, B dermatitidis is slow growing and may require a 2- to 4-week incubation period. Serologic tests are available, but sensitivity is low, at 9%, 28%, and 77% for complement fixation, immunodiffusion, and enzyme immunoassay, respectively.16

Conclusion

North American blastomycosis should be considered in patients who have verrucous or ulcerative perianal lesions and have lived in or traveled to endemic regions, especially if they have recent or ongoing pulmonary symptoms. Potassium hydroxide preparation and fungal staining of biopsy specimens can aid in diagnosis.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation’s Office of Scientific Writing and Publication (Marshfield, Wisconsin) for editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

1. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Davis JP. Epidemiologic aspects of blastomycosis, the enigmatic systemic mycosis. Semin Respir Infect. 1986;1:29-39.

2. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Weeks RJ, et al. Isolation of Blastomyces dermatitidis in soil associated with a large outbreak of blastomycosis in Wisconsin. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:529-534.

3. Reingold AL, Lu XD, Plikaytis BD, et al. Systemic mycoses in the United States, 1980-1982. J Med Vet Mycol. 1986;24:433-436.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Blastomycosis—Wisconsin, 1986-1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1996;45:601-603.

5. Smith JA, Kauffman CA. Blastomycosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7:173-180.

6. Goldman M, Johnson PC, Sarosi GA. Fungal pneumonias. the endemic mycoses. Clin Chest Med. 1999;20:507-519.

7. Mercurio MG, Elewski BE. Cutaneous blastomycosis. Cutis. 1992;50:422-424.

8. Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-381.

9. Ricciardi R, Alavi K, Filice GA, et al. Blastomyces dermatitidis of the perianal skin: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:118-121.

10. Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis [published online ahead of print April 17, 2002]. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:e44-e49.

11. Kisso B, Mahmoud F, Thakkar JR. Blastomycosis presenting as recurrent tender cutaneous nodules. S D Med. 2006;59:255-259.

12. Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2010.

13. Mason AR, Cortes GY, Cook J, et al. Cutaneous blastomycosis: a diagnostic challenge. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:824-830.

14. Linn JE. Pseudo-epitheliomatous lesions of the perirectal tissue: report of a case of squamous epithelioma due to blastomycosis. South Med J. 1958;51:1101-1104.

15. Woofter MJ, Cripps DJ, Warner TF. Verrucous plaques on the face. North American blastomycosis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:547, 550.

16. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Kaufman L, et al. Serological tests for blastomycosis: assessments during a large point-source outbreak in Wisconsin. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:262-268.

Cutaneous North American blastomycosis is a deep fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus that is endemic to the Great Lakes region as well as the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys where it thrives in moist acidic soil enriched with organic material.1,2 In humans, the annual incidence rate is estimated to be 0.6 cases per million,3 though it may be as high as 42 cases per 100,000 in endemic areas.4 Infection typically results from the inhalation of conidia and manifests as either acute or chronic pneumonia.5 Most patients with acute disease present with nonspecific flulike symptoms and a nonproductive cough.

Dissemination occurs in approximately 25% of cases,6 most commonly affecting the skin. Other potential sites of dissemination include bone, the genitourinary tract, and the central nervous system. Cutaneous lesions, which may be either verrucous or ulcerative plaques, often occur on or around orifices contiguous to the respiratory tract.7 Verrucous lesions tend to have an irregular shape with well-defined borders and surface crusting. Ulcerative lesions have heaped-up borders and often have an exudative base.8 The differential diagnosis of cutaneous North American blastomycosis lesions includes squamous cell carcinoma, giant keratoacanthoma, verrucae, basal cell carcinoma, scrofuloderma, lupus vulgaris, nocardiosis, syphilis, bromoderma, iododerma, granuloma inguinale, tuberculosis verrucosa cutis, mycetoma, and actinomycosis.7,8

Although periorificial cutaneous manifestations of disseminated blastomycosis are common, perianal lesions are rare. The differential diagnosis of perianal verrucous plaques includes condyloma acuminatum, squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, Buschke-Löwenstein tumor, actinomycosis, and localized fungal infections such as blastomycosis.9

Case Report

A 57-year-old man presented with a palpable perianal mass that produced small amounts of blood in his underwear and on toilet paper. The patient reported no history of hemorrhoids, anoreceptive intercourse, or sexually transmitted disease. Four months prior to presentation, he had a prolonged upper respiratory tract illness with a subjective fever and productive cough of 2 months’ duration. The patient described himself as an avid outdoorsman who worked at a summer resort and spent a great deal of time in the forests of central Wisconsin last autumn. Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated, firm, moist plaque with a verrucous surface that measured 3.5×2.7 cm and extended from the anal verge to the perianal skin (Figure 1).

Potassium hydroxide preparation of a biopsy specimen (Figure 2), a punch biopsy of the lesion (Figure 3), and Gomori methenamine-silver staining (Figure 4) revealed scattered yeast spores, some demonstrating broad-based budding, with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, dermal neutrophils, and intraepithelial microabscesses. The patient’s urine was positive for Blastomyces antigen (1.04 ng/mL). Chest radiography demonstrated a localized infiltrate in the right hilum with possible mass effect. Computed tomography showed a consolidative opacity measuring 4.0×3.4 cm in the upper lobe of the right lung (Figure 5).

|  |

The patient was diagnosed with cutaneous North American blastomycosis and prescribed a 6-month course of oral itraconazole 200 mg twice daily. At his 3-month follow-up visit, the perianal plaque hadalmost completely resolved (Figure 6). However, because the patient had increasing lower extremity edema, subjective hearing loss, and abnormal liver function tests, itraconazole treatment was discontinued and replaced with oral fluconazole 400 mg daily for the next 3 months. The right hilar mass had visibly improved on follow-up chest radiography 2 months after the patient started antifungal therapy with itraconazole and had resolved within another 3 months of treatment.

|

|

Comment

Cutaneous blastomycosis results most often from the hematogenous spread of B dermatitidis from the lungs and rarely from direct inoculation.5,10 Skin lesions tend to occur on exposed areas, such as the face, scalp, hands, wrists, feet, and ankles.7,11-13 Dissemination to the perianal skin is rare, though it has been reported in 2 other patients; both patients, similar to our patient, had evidence of pulmonary involvement at some point in their clinical course.9,14

Diagnosis is based on identification of B dermatitidis by microscopy or culture. Potassium hydroxide preparation of biopsy specimens typically shows broad-based budding yeast.13 Characteristic findings of histopathologic studies include pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperplasia, intraepidermal abscesses, and a dermal infiltrate of polymorphonuclear leukocytes.15 On fungal culture, B dermatitidis is slow growing and may require a 2- to 4-week incubation period. Serologic tests are available, but sensitivity is low, at 9%, 28%, and 77% for complement fixation, immunodiffusion, and enzyme immunoassay, respectively.16

Conclusion

North American blastomycosis should be considered in patients who have verrucous or ulcerative perianal lesions and have lived in or traveled to endemic regions, especially if they have recent or ongoing pulmonary symptoms. Potassium hydroxide preparation and fungal staining of biopsy specimens can aid in diagnosis.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation’s Office of Scientific Writing and Publication (Marshfield, Wisconsin) for editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Cutaneous North American blastomycosis is a deep fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus that is endemic to the Great Lakes region as well as the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys where it thrives in moist acidic soil enriched with organic material.1,2 In humans, the annual incidence rate is estimated to be 0.6 cases per million,3 though it may be as high as 42 cases per 100,000 in endemic areas.4 Infection typically results from the inhalation of conidia and manifests as either acute or chronic pneumonia.5 Most patients with acute disease present with nonspecific flulike symptoms and a nonproductive cough.

Dissemination occurs in approximately 25% of cases,6 most commonly affecting the skin. Other potential sites of dissemination include bone, the genitourinary tract, and the central nervous system. Cutaneous lesions, which may be either verrucous or ulcerative plaques, often occur on or around orifices contiguous to the respiratory tract.7 Verrucous lesions tend to have an irregular shape with well-defined borders and surface crusting. Ulcerative lesions have heaped-up borders and often have an exudative base.8 The differential diagnosis of cutaneous North American blastomycosis lesions includes squamous cell carcinoma, giant keratoacanthoma, verrucae, basal cell carcinoma, scrofuloderma, lupus vulgaris, nocardiosis, syphilis, bromoderma, iododerma, granuloma inguinale, tuberculosis verrucosa cutis, mycetoma, and actinomycosis.7,8

Although periorificial cutaneous manifestations of disseminated blastomycosis are common, perianal lesions are rare. The differential diagnosis of perianal verrucous plaques includes condyloma acuminatum, squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, Buschke-Löwenstein tumor, actinomycosis, and localized fungal infections such as blastomycosis.9

Case Report

A 57-year-old man presented with a palpable perianal mass that produced small amounts of blood in his underwear and on toilet paper. The patient reported no history of hemorrhoids, anoreceptive intercourse, or sexually transmitted disease. Four months prior to presentation, he had a prolonged upper respiratory tract illness with a subjective fever and productive cough of 2 months’ duration. The patient described himself as an avid outdoorsman who worked at a summer resort and spent a great deal of time in the forests of central Wisconsin last autumn. Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated, firm, moist plaque with a verrucous surface that measured 3.5×2.7 cm and extended from the anal verge to the perianal skin (Figure 1).

Potassium hydroxide preparation of a biopsy specimen (Figure 2), a punch biopsy of the lesion (Figure 3), and Gomori methenamine-silver staining (Figure 4) revealed scattered yeast spores, some demonstrating broad-based budding, with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, dermal neutrophils, and intraepithelial microabscesses. The patient’s urine was positive for Blastomyces antigen (1.04 ng/mL). Chest radiography demonstrated a localized infiltrate in the right hilum with possible mass effect. Computed tomography showed a consolidative opacity measuring 4.0×3.4 cm in the upper lobe of the right lung (Figure 5).

|  |

The patient was diagnosed with cutaneous North American blastomycosis and prescribed a 6-month course of oral itraconazole 200 mg twice daily. At his 3-month follow-up visit, the perianal plaque hadalmost completely resolved (Figure 6). However, because the patient had increasing lower extremity edema, subjective hearing loss, and abnormal liver function tests, itraconazole treatment was discontinued and replaced with oral fluconazole 400 mg daily for the next 3 months. The right hilar mass had visibly improved on follow-up chest radiography 2 months after the patient started antifungal therapy with itraconazole and had resolved within another 3 months of treatment.

|

|

Comment

Cutaneous blastomycosis results most often from the hematogenous spread of B dermatitidis from the lungs and rarely from direct inoculation.5,10 Skin lesions tend to occur on exposed areas, such as the face, scalp, hands, wrists, feet, and ankles.7,11-13 Dissemination to the perianal skin is rare, though it has been reported in 2 other patients; both patients, similar to our patient, had evidence of pulmonary involvement at some point in their clinical course.9,14

Diagnosis is based on identification of B dermatitidis by microscopy or culture. Potassium hydroxide preparation of biopsy specimens typically shows broad-based budding yeast.13 Characteristic findings of histopathologic studies include pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperplasia, intraepidermal abscesses, and a dermal infiltrate of polymorphonuclear leukocytes.15 On fungal culture, B dermatitidis is slow growing and may require a 2- to 4-week incubation period. Serologic tests are available, but sensitivity is low, at 9%, 28%, and 77% for complement fixation, immunodiffusion, and enzyme immunoassay, respectively.16

Conclusion

North American blastomycosis should be considered in patients who have verrucous or ulcerative perianal lesions and have lived in or traveled to endemic regions, especially if they have recent or ongoing pulmonary symptoms. Potassium hydroxide preparation and fungal staining of biopsy specimens can aid in diagnosis.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation’s Office of Scientific Writing and Publication (Marshfield, Wisconsin) for editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

1. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Davis JP. Epidemiologic aspects of blastomycosis, the enigmatic systemic mycosis. Semin Respir Infect. 1986;1:29-39.

2. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Weeks RJ, et al. Isolation of Blastomyces dermatitidis in soil associated with a large outbreak of blastomycosis in Wisconsin. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:529-534.

3. Reingold AL, Lu XD, Plikaytis BD, et al. Systemic mycoses in the United States, 1980-1982. J Med Vet Mycol. 1986;24:433-436.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Blastomycosis—Wisconsin, 1986-1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1996;45:601-603.

5. Smith JA, Kauffman CA. Blastomycosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7:173-180.

6. Goldman M, Johnson PC, Sarosi GA. Fungal pneumonias. the endemic mycoses. Clin Chest Med. 1999;20:507-519.

7. Mercurio MG, Elewski BE. Cutaneous blastomycosis. Cutis. 1992;50:422-424.

8. Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-381.

9. Ricciardi R, Alavi K, Filice GA, et al. Blastomyces dermatitidis of the perianal skin: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:118-121.

10. Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis [published online ahead of print April 17, 2002]. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:e44-e49.

11. Kisso B, Mahmoud F, Thakkar JR. Blastomycosis presenting as recurrent tender cutaneous nodules. S D Med. 2006;59:255-259.

12. Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2010.

13. Mason AR, Cortes GY, Cook J, et al. Cutaneous blastomycosis: a diagnostic challenge. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:824-830.

14. Linn JE. Pseudo-epitheliomatous lesions of the perirectal tissue: report of a case of squamous epithelioma due to blastomycosis. South Med J. 1958;51:1101-1104.

15. Woofter MJ, Cripps DJ, Warner TF. Verrucous plaques on the face. North American blastomycosis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:547, 550.

16. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Kaufman L, et al. Serological tests for blastomycosis: assessments during a large point-source outbreak in Wisconsin. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:262-268.

1. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Davis JP. Epidemiologic aspects of blastomycosis, the enigmatic systemic mycosis. Semin Respir Infect. 1986;1:29-39.

2. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Weeks RJ, et al. Isolation of Blastomyces dermatitidis in soil associated with a large outbreak of blastomycosis in Wisconsin. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:529-534.

3. Reingold AL, Lu XD, Plikaytis BD, et al. Systemic mycoses in the United States, 1980-1982. J Med Vet Mycol. 1986;24:433-436.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Blastomycosis—Wisconsin, 1986-1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1996;45:601-603.

5. Smith JA, Kauffman CA. Blastomycosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7:173-180.

6. Goldman M, Johnson PC, Sarosi GA. Fungal pneumonias. the endemic mycoses. Clin Chest Med. 1999;20:507-519.

7. Mercurio MG, Elewski BE. Cutaneous blastomycosis. Cutis. 1992;50:422-424.

8. Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-381.

9. Ricciardi R, Alavi K, Filice GA, et al. Blastomyces dermatitidis of the perianal skin: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:118-121.

10. Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis [published online ahead of print April 17, 2002]. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:e44-e49.

11. Kisso B, Mahmoud F, Thakkar JR. Blastomycosis presenting as recurrent tender cutaneous nodules. S D Med. 2006;59:255-259.

12. Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2010.

13. Mason AR, Cortes GY, Cook J, et al. Cutaneous blastomycosis: a diagnostic challenge. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:824-830.

14. Linn JE. Pseudo-epitheliomatous lesions of the perirectal tissue: report of a case of squamous epithelioma due to blastomycosis. South Med J. 1958;51:1101-1104.

15. Woofter MJ, Cripps DJ, Warner TF. Verrucous plaques on the face. North American blastomycosis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:547, 550.

16. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Kaufman L, et al. Serological tests for blastomycosis: assessments during a large point-source outbreak in Wisconsin. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:262-268.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous North American blastomycosis usually occurs in a periorificial distribution.

- The perianal region should be included in the periorificial regions considered in North American blastomycosis infections.

From the Washington Office

Last month’s edition of this column ended by calling Fellows’ attention to a new Web-based tool developed by the ACS Division of Advocacy and Health Policy to assist them in avoiding significant penalties in Medicare physician payment. This new online tool was highlighted in an e-mail sent to Fellows on June 24, 2015.

Based on follow-up inquiries since received, I would like to delve deeper into the specifics of how to successfully participate in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) and hopefully assist Fellows in avoiding penalties of up to 9% in their Medicare physician payment in the year 2017 secondary to failure to successfully participate in the current law Medicare quality programs in the current calendar year of 2015.

Despite the much publicized, and laudable, permanent repeal of the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR), current law quality programs are still in effect. Medicare oversees several programs that offer physicians incentives for successful participation and/or penalties for failure to nonparticipation. These programs include the PQRS, the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VM) and the Electronic Health Record (EHR) Incentive Program, also known as the “EHR Meaningful Use program.”

Calendar year 2014 was the last year that physicians could earn incentives for some of these programs. Failure to participate in the Medicare quality programs leads to the potential for penalties that are applied 2 years after the performance period. Penalties in 2015 already are being assessed based on how successfully physicians participated in 2013. Thus, performance in 2015 will impact payment in 2017. Specifically, failure to participate in the programs in 2015 could result in a total penalty of 9% applied in 2017.

The College has developed resources to assist Fellows in being successful reporters. For most Fellows, the options found in the Surgeon Specific Registry (SSR) will be applicable. The SSR, formerly known as the ACS Case Log system, allows surgeons to track their cases and outcomes in a convenient and confidential manner. The SSR can also be utilized to comply with the regulatory requirements of submitting PQRS data as they have been approved to provide PQRS registry-based reporting for 2015. Use of the SSR is offered free of charge to ACS surgeon members and is available to nonmember surgeons for an annual fee.

The SSR offers a total of three options for surgeons to utilize to participate in PQRS reporting. Those options are: 1) General Surgery Measures Group; 2) Individual Measure reporting, which includes options for surgical specialties; and 3) Trauma Measures Option through the SSR’s Qualified Clinical Data Registry (QCDR). The deadline for submitting calendar year 2015 patient information in the SSR is January 31, 2016. The SSR will submit the PQRS data to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

For those surgeons for whom it could be applicable, the General Surgery Measures Group option is perhaps the least onerous in its requirements. Surgeons need report on a minimum of 20 patients, at least 11 of whom must be Medicare Part B patients. Should this option be selected, ALL seven of the included measures along with all nine risk factor variables must be reported for each of the 20 patients.

Surgeons may also choose to report individual measures data through the SSR. Those choosing this option are required to report on nine measures in three National Quality Strategy (NQS) categories, called “Domains.” One of the measures selected must further be designated as a “cross-cutting measure,” for example the documentation of current medications in the medical record, medication reconciliation, advanced care plan, or tobacco-use screening and cessation, as mentioned above. However, individual measures data must be entered for at least 50% of the provider’s Medicare Part B patients in order to be successful using this option. In order to assist one in determining whether this option is suitable for reporting, I would refer Fellows to the ACS website, www.facs.org/quality-programs/ssr/pqrs/options for a more expansive list of the individual measures, their “domains,” and whether or not they are designated as “cross-cutting.”

The SSR also provides the opportunity to leverage measures applicable to trauma surgery for successful PQRS reporting via the 2015 PQRS Trauma QCDR., which allow providers to submit non-PQRS measures, for example, measures not contained in the approved measure set or a measure that may be in the set but has substantive differences in the manner in which it is reported by the QCDR. The SSR Trauma QCDR includes 10 non-PQRS measures and one PQRS measure in this reporting option. Those choosing this option must report on 9 of the 11 designated measures, including 2 outcomes measures across three of the NQS domains. Reports must be completed on 50% of the surgeon’s Medicare Part B patients that meet the measurement requirements. One can also view the complete list of measures included in the Trauma Measures Option at the ACS website referenced above.

Lastly, for bariatric surgeons, the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program (MBSAQIP) has also been approved as a QCDR for PQRS for 2015 reporting. MBSAQIP participants have the opportunity to voluntarily elect that their QCDR quality measures be submitted for PQRS participation. Metabolic and bariatric surgeons will receive reports of their QCDR measure results such that they can track their results. MBSAQIP will submit approved QCDR measures on behalf of participants who elect to have such done on their behalf. Specifics on the approved MBSAQIP QCDR quality measures are available at www.facs.org/quality-programs/mbsaqip/resources/data-registry.

As always, ACS staff in both Washington and Chicago are available to answer questions and assist members in participating in the 2015 PQRS program:

• General PQRS questions: ACS Division of Advocacy and Health Policy, 202-337-6701 or QualityDC@facs.org.

• Specific SSR questions: ACS Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care, 312-202-5000 or ssr@facs.org.

• Information on MBSAQIP: ACS Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care, 312-202-5000 or rkrapikas@facs.org.

I highly encourage all Fellows to invest the time necessary to successfully participate in PQRS and thereby avoid penalties in their 2017 Medicare payment.

Until next month …

Dr. Bailey is a pediatric surgeon and Medical Director, Advocacy for the Division of Advocacy and Health Policy in the ACS offices in Washington.

Last month’s edition of this column ended by calling Fellows’ attention to a new Web-based tool developed by the ACS Division of Advocacy and Health Policy to assist them in avoiding significant penalties in Medicare physician payment. This new online tool was highlighted in an e-mail sent to Fellows on June 24, 2015.

Based on follow-up inquiries since received, I would like to delve deeper into the specifics of how to successfully participate in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) and hopefully assist Fellows in avoiding penalties of up to 9% in their Medicare physician payment in the year 2017 secondary to failure to successfully participate in the current law Medicare quality programs in the current calendar year of 2015.

Despite the much publicized, and laudable, permanent repeal of the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR), current law quality programs are still in effect. Medicare oversees several programs that offer physicians incentives for successful participation and/or penalties for failure to nonparticipation. These programs include the PQRS, the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VM) and the Electronic Health Record (EHR) Incentive Program, also known as the “EHR Meaningful Use program.”

Calendar year 2014 was the last year that physicians could earn incentives for some of these programs. Failure to participate in the Medicare quality programs leads to the potential for penalties that are applied 2 years after the performance period. Penalties in 2015 already are being assessed based on how successfully physicians participated in 2013. Thus, performance in 2015 will impact payment in 2017. Specifically, failure to participate in the programs in 2015 could result in a total penalty of 9% applied in 2017.

The College has developed resources to assist Fellows in being successful reporters. For most Fellows, the options found in the Surgeon Specific Registry (SSR) will be applicable. The SSR, formerly known as the ACS Case Log system, allows surgeons to track their cases and outcomes in a convenient and confidential manner. The SSR can also be utilized to comply with the regulatory requirements of submitting PQRS data as they have been approved to provide PQRS registry-based reporting for 2015. Use of the SSR is offered free of charge to ACS surgeon members and is available to nonmember surgeons for an annual fee.

The SSR offers a total of three options for surgeons to utilize to participate in PQRS reporting. Those options are: 1) General Surgery Measures Group; 2) Individual Measure reporting, which includes options for surgical specialties; and 3) Trauma Measures Option through the SSR’s Qualified Clinical Data Registry (QCDR). The deadline for submitting calendar year 2015 patient information in the SSR is January 31, 2016. The SSR will submit the PQRS data to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

For those surgeons for whom it could be applicable, the General Surgery Measures Group option is perhaps the least onerous in its requirements. Surgeons need report on a minimum of 20 patients, at least 11 of whom must be Medicare Part B patients. Should this option be selected, ALL seven of the included measures along with all nine risk factor variables must be reported for each of the 20 patients.

Surgeons may also choose to report individual measures data through the SSR. Those choosing this option are required to report on nine measures in three National Quality Strategy (NQS) categories, called “Domains.” One of the measures selected must further be designated as a “cross-cutting measure,” for example the documentation of current medications in the medical record, medication reconciliation, advanced care plan, or tobacco-use screening and cessation, as mentioned above. However, individual measures data must be entered for at least 50% of the provider’s Medicare Part B patients in order to be successful using this option. In order to assist one in determining whether this option is suitable for reporting, I would refer Fellows to the ACS website, www.facs.org/quality-programs/ssr/pqrs/options for a more expansive list of the individual measures, their “domains,” and whether or not they are designated as “cross-cutting.”

The SSR also provides the opportunity to leverage measures applicable to trauma surgery for successful PQRS reporting via the 2015 PQRS Trauma QCDR., which allow providers to submit non-PQRS measures, for example, measures not contained in the approved measure set or a measure that may be in the set but has substantive differences in the manner in which it is reported by the QCDR. The SSR Trauma QCDR includes 10 non-PQRS measures and one PQRS measure in this reporting option. Those choosing this option must report on 9 of the 11 designated measures, including 2 outcomes measures across three of the NQS domains. Reports must be completed on 50% of the surgeon’s Medicare Part B patients that meet the measurement requirements. One can also view the complete list of measures included in the Trauma Measures Option at the ACS website referenced above.

Lastly, for bariatric surgeons, the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program (MBSAQIP) has also been approved as a QCDR for PQRS for 2015 reporting. MBSAQIP participants have the opportunity to voluntarily elect that their QCDR quality measures be submitted for PQRS participation. Metabolic and bariatric surgeons will receive reports of their QCDR measure results such that they can track their results. MBSAQIP will submit approved QCDR measures on behalf of participants who elect to have such done on their behalf. Specifics on the approved MBSAQIP QCDR quality measures are available at www.facs.org/quality-programs/mbsaqip/resources/data-registry.

As always, ACS staff in both Washington and Chicago are available to answer questions and assist members in participating in the 2015 PQRS program:

• General PQRS questions: ACS Division of Advocacy and Health Policy, 202-337-6701 or QualityDC@facs.org.

• Specific SSR questions: ACS Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care, 312-202-5000 or ssr@facs.org.

• Information on MBSAQIP: ACS Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care, 312-202-5000 or rkrapikas@facs.org.

I highly encourage all Fellows to invest the time necessary to successfully participate in PQRS and thereby avoid penalties in their 2017 Medicare payment.

Until next month …

Dr. Bailey is a pediatric surgeon and Medical Director, Advocacy for the Division of Advocacy and Health Policy in the ACS offices in Washington.

Last month’s edition of this column ended by calling Fellows’ attention to a new Web-based tool developed by the ACS Division of Advocacy and Health Policy to assist them in avoiding significant penalties in Medicare physician payment. This new online tool was highlighted in an e-mail sent to Fellows on June 24, 2015.

Based on follow-up inquiries since received, I would like to delve deeper into the specifics of how to successfully participate in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) and hopefully assist Fellows in avoiding penalties of up to 9% in their Medicare physician payment in the year 2017 secondary to failure to successfully participate in the current law Medicare quality programs in the current calendar year of 2015.

Despite the much publicized, and laudable, permanent repeal of the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR), current law quality programs are still in effect. Medicare oversees several programs that offer physicians incentives for successful participation and/or penalties for failure to nonparticipation. These programs include the PQRS, the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VM) and the Electronic Health Record (EHR) Incentive Program, also known as the “EHR Meaningful Use program.”

Calendar year 2014 was the last year that physicians could earn incentives for some of these programs. Failure to participate in the Medicare quality programs leads to the potential for penalties that are applied 2 years after the performance period. Penalties in 2015 already are being assessed based on how successfully physicians participated in 2013. Thus, performance in 2015 will impact payment in 2017. Specifically, failure to participate in the programs in 2015 could result in a total penalty of 9% applied in 2017.

The College has developed resources to assist Fellows in being successful reporters. For most Fellows, the options found in the Surgeon Specific Registry (SSR) will be applicable. The SSR, formerly known as the ACS Case Log system, allows surgeons to track their cases and outcomes in a convenient and confidential manner. The SSR can also be utilized to comply with the regulatory requirements of submitting PQRS data as they have been approved to provide PQRS registry-based reporting for 2015. Use of the SSR is offered free of charge to ACS surgeon members and is available to nonmember surgeons for an annual fee.

The SSR offers a total of three options for surgeons to utilize to participate in PQRS reporting. Those options are: 1) General Surgery Measures Group; 2) Individual Measure reporting, which includes options for surgical specialties; and 3) Trauma Measures Option through the SSR’s Qualified Clinical Data Registry (QCDR). The deadline for submitting calendar year 2015 patient information in the SSR is January 31, 2016. The SSR will submit the PQRS data to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

For those surgeons for whom it could be applicable, the General Surgery Measures Group option is perhaps the least onerous in its requirements. Surgeons need report on a minimum of 20 patients, at least 11 of whom must be Medicare Part B patients. Should this option be selected, ALL seven of the included measures along with all nine risk factor variables must be reported for each of the 20 patients.

Surgeons may also choose to report individual measures data through the SSR. Those choosing this option are required to report on nine measures in three National Quality Strategy (NQS) categories, called “Domains.” One of the measures selected must further be designated as a “cross-cutting measure,” for example the documentation of current medications in the medical record, medication reconciliation, advanced care plan, or tobacco-use screening and cessation, as mentioned above. However, individual measures data must be entered for at least 50% of the provider’s Medicare Part B patients in order to be successful using this option. In order to assist one in determining whether this option is suitable for reporting, I would refer Fellows to the ACS website, www.facs.org/quality-programs/ssr/pqrs/options for a more expansive list of the individual measures, their “domains,” and whether or not they are designated as “cross-cutting.”

The SSR also provides the opportunity to leverage measures applicable to trauma surgery for successful PQRS reporting via the 2015 PQRS Trauma QCDR., which allow providers to submit non-PQRS measures, for example, measures not contained in the approved measure set or a measure that may be in the set but has substantive differences in the manner in which it is reported by the QCDR. The SSR Trauma QCDR includes 10 non-PQRS measures and one PQRS measure in this reporting option. Those choosing this option must report on 9 of the 11 designated measures, including 2 outcomes measures across three of the NQS domains. Reports must be completed on 50% of the surgeon’s Medicare Part B patients that meet the measurement requirements. One can also view the complete list of measures included in the Trauma Measures Option at the ACS website referenced above.

Lastly, for bariatric surgeons, the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program (MBSAQIP) has also been approved as a QCDR for PQRS for 2015 reporting. MBSAQIP participants have the opportunity to voluntarily elect that their QCDR quality measures be submitted for PQRS participation. Metabolic and bariatric surgeons will receive reports of their QCDR measure results such that they can track their results. MBSAQIP will submit approved QCDR measures on behalf of participants who elect to have such done on their behalf. Specifics on the approved MBSAQIP QCDR quality measures are available at www.facs.org/quality-programs/mbsaqip/resources/data-registry.

As always, ACS staff in both Washington and Chicago are available to answer questions and assist members in participating in the 2015 PQRS program:

• General PQRS questions: ACS Division of Advocacy and Health Policy, 202-337-6701 or QualityDC@facs.org.

• Specific SSR questions: ACS Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care, 312-202-5000 or ssr@facs.org.

• Information on MBSAQIP: ACS Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care, 312-202-5000 or rkrapikas@facs.org.

I highly encourage all Fellows to invest the time necessary to successfully participate in PQRS and thereby avoid penalties in their 2017 Medicare payment.

Until next month …

Dr. Bailey is a pediatric surgeon and Medical Director, Advocacy for the Division of Advocacy and Health Policy in the ACS offices in Washington.

The Rural Surgeon: The burden of transfer

I have been on both ends of the phone call. I began my career at a several-hundred bed community hospital in a town without a university medical center. We took all the local knife-and-gun club incidents, and whatever other surgical emergencies might arise, while receiving phone calls from nearly every point of the magnetic compass. It’s easy to recall the sagging feeling when you realize more serious work is coming in on the helicopter from Podunk, USA, and you’re not off call for another few hours. These memories linger as now I’m the one making the phone calls. When I state that I am the one, I mean the one and only; this is solo general surgery practice and I’m the only general surgeon in my county.

When I do speak with colleagues kind enough to accept our patients, I feel relieved. But the burden of transfer doesn’t travel away with the patient in the ambulance or on the airplane. There always seem to be questions or looks of concern lately, and I don’t just mean from other medical professionals. Maybe it is an Internet thing, but everyone is a critic these days. We are being watched by more than partners and employers, more than payers and agencies, more than our government bean counters. Families, allied health professionals, and even nonclinical staff all have opinions about which patients stay and which leaves our 14-bed, critical access hospital. Gods may have once walked these halls, but nowadays it’s just me!

Of course, any interested party can also criticize my decisions to keep any particular patient; why would anybody restrict their furrowed glare only to transfers? When we keep patients at the edge of our practice, or perform a procedure that is only done rarely locally, we incite more than just the volume debate on the ACS Communities. Goodness – my wife has heard about cases I have done via town chitter-chatter before I even get home!

How does one deal with being whipsawed? This phenomenon is defined in the business world as being subjected to two difficult situations or opposing pressures at the same time. If you transfer, you are criticized. The only thing that changes are the critics if you keep and care for that very same patient! For many rural colleagues, being whipsawed is on the short list of job dissatisfaction drivers; somewhere behind the heavyweight champ of being asked to be in two different places at the same time.

Transferring a patient rarely leads to the lasting criticism that keeping an ill patient locally can. Obviously keeping a patient extends the time period where others can knowingly shake their heads in disbelief. That extra time allows us to educate staff and others as to why a patient with more than simple hernia or appendicitis is being admitted to our little hospital. We can detail why this is a really good thing for everyone – including the patient!

So many of our locals are elderly, and when we keep one for serious surgical illness, so much goes into that decision besides just the patient’s age and comorbid conditions. Immediate family, friends, or existing social support all must be examined and understood. A significant number of geriatric couples are only “independent” together; send one off for surgery a hundred or more miles away and the remaining spouse suffers measurably. Sometimes there is no local family, as nuclear members live in neighboring states or even overseas. I’m always surprised when my patients have trouble even arranging rides to and from our facilities for the routine procedures we do regularly. I think to myself, what will they do when the inevitable happens?

Our geography plays a serious role for those patients who don’t drive any appreciable distances. The mountains to our east are difficult to negotiate and west, well, you’ll get wet rather quickly. Going north and south on Highway 101 can be tricky during summer and dangerous any time in bad weather. I talk to some patients about sending them to Portland and I get looks in response like I’m proposing surgical care in some exotic foreign capital. Urban anxiety, traffic, and unfamiliarity with our largest metropolis make the 300-mile journey untenable for many of our patients; and the TV show isn’t helping our cause! Even cases that define themselves from the get-go as major university referrals return afterward and ask us to assume their postoperative care. Our patients often can’t make the trip to follow-up with the experts who provided their life-saving care.

Stretching our surgical muscles is obviously important for all ACS members. In bigger facilities you can see and sometimes scrub into fascinating cases in other subspecialties, or at least participate in discussions about such in the surgery lounge. I won’t attach a photo of the desk space that serves as my lounge, dictation station, bathroom, and locker. Let’s just say it’s probably not quite the same as many Fellows are used to.

For the rural solo practitioner, a bigger case, done perhaps with a medical student or just scrub technicians, may not be done as slickly as it would be by a surgical team approaching the same at the university. If the case can be done safely though, it pays dividends. After all, it could be tonight when a major car wreck happens, or a hemodynamically unstable abdominal sepsis case presents, and we are forced to do a serious case – perhaps surgery at the edge of my comfort zone or something we don’t do with frequency. Keeping some bigger cases makes those scenarios just a bit less scary.

I have been recruited as an advocate for our College, trying to influence those in our nation’s capital to reexamine the 96-hour rule as it applies to critical access hospitals. A phone call to my senior senator’s staff leads to a conference call and follow-up I remain involved with – a first in my professional career. One issue that resonated with D.C. staffers was recruiting my successor. How do we entice the young surgeon to a rural practice if all we do are lumps and bumps, appendectomies, and inguinal hernias? Regionalization of surgical care may be coming but that can’t excite our younger and future colleagues. In each of the last 2 years my third-year medical students parked here for their first rotation and got hustled into the OR to assist with emergency surgery. The enthusiasm was palpable and energizing, but one was a case that raised some eyebrows: pneumatosis intestinalis requiring two small bowel resections with anastomoses and an open abdomen in an elderly male. This fellow did great; I see him doing his grocery shopping these days. My perspective is that case enabled this year’s day 1 emergency, making the surgery safer here in rural America.

When we call to transfer a patient, please understand real thought and a piece of who we are as surgeons accompanies that patient. Transfer is very rarely a reflex action. Also, realize that not every case we keep is a weak fastball over the middle of the plate; sometimes we do real work here at the limit of our comfort zone, but we do so for myriad good reasons.

Dr. Levine is a general surgeon practicing in coastal southwestern Oregon. Despite growing up in Brooklyn and on Long Island in New York, he has been a practicing rural surgeon since 1999. Folks barely even notice the accent anymore!

I have been on both ends of the phone call. I began my career at a several-hundred bed community hospital in a town without a university medical center. We took all the local knife-and-gun club incidents, and whatever other surgical emergencies might arise, while receiving phone calls from nearly every point of the magnetic compass. It’s easy to recall the sagging feeling when you realize more serious work is coming in on the helicopter from Podunk, USA, and you’re not off call for another few hours. These memories linger as now I’m the one making the phone calls. When I state that I am the one, I mean the one and only; this is solo general surgery practice and I’m the only general surgeon in my county.

When I do speak with colleagues kind enough to accept our patients, I feel relieved. But the burden of transfer doesn’t travel away with the patient in the ambulance or on the airplane. There always seem to be questions or looks of concern lately, and I don’t just mean from other medical professionals. Maybe it is an Internet thing, but everyone is a critic these days. We are being watched by more than partners and employers, more than payers and agencies, more than our government bean counters. Families, allied health professionals, and even nonclinical staff all have opinions about which patients stay and which leaves our 14-bed, critical access hospital. Gods may have once walked these halls, but nowadays it’s just me!

Of course, any interested party can also criticize my decisions to keep any particular patient; why would anybody restrict their furrowed glare only to transfers? When we keep patients at the edge of our practice, or perform a procedure that is only done rarely locally, we incite more than just the volume debate on the ACS Communities. Goodness – my wife has heard about cases I have done via town chitter-chatter before I even get home!

How does one deal with being whipsawed? This phenomenon is defined in the business world as being subjected to two difficult situations or opposing pressures at the same time. If you transfer, you are criticized. The only thing that changes are the critics if you keep and care for that very same patient! For many rural colleagues, being whipsawed is on the short list of job dissatisfaction drivers; somewhere behind the heavyweight champ of being asked to be in two different places at the same time.

Transferring a patient rarely leads to the lasting criticism that keeping an ill patient locally can. Obviously keeping a patient extends the time period where others can knowingly shake their heads in disbelief. That extra time allows us to educate staff and others as to why a patient with more than simple hernia or appendicitis is being admitted to our little hospital. We can detail why this is a really good thing for everyone – including the patient!

So many of our locals are elderly, and when we keep one for serious surgical illness, so much goes into that decision besides just the patient’s age and comorbid conditions. Immediate family, friends, or existing social support all must be examined and understood. A significant number of geriatric couples are only “independent” together; send one off for surgery a hundred or more miles away and the remaining spouse suffers measurably. Sometimes there is no local family, as nuclear members live in neighboring states or even overseas. I’m always surprised when my patients have trouble even arranging rides to and from our facilities for the routine procedures we do regularly. I think to myself, what will they do when the inevitable happens?

Our geography plays a serious role for those patients who don’t drive any appreciable distances. The mountains to our east are difficult to negotiate and west, well, you’ll get wet rather quickly. Going north and south on Highway 101 can be tricky during summer and dangerous any time in bad weather. I talk to some patients about sending them to Portland and I get looks in response like I’m proposing surgical care in some exotic foreign capital. Urban anxiety, traffic, and unfamiliarity with our largest metropolis make the 300-mile journey untenable for many of our patients; and the TV show isn’t helping our cause! Even cases that define themselves from the get-go as major university referrals return afterward and ask us to assume their postoperative care. Our patients often can’t make the trip to follow-up with the experts who provided their life-saving care.

Stretching our surgical muscles is obviously important for all ACS members. In bigger facilities you can see and sometimes scrub into fascinating cases in other subspecialties, or at least participate in discussions about such in the surgery lounge. I won’t attach a photo of the desk space that serves as my lounge, dictation station, bathroom, and locker. Let’s just say it’s probably not quite the same as many Fellows are used to.

For the rural solo practitioner, a bigger case, done perhaps with a medical student or just scrub technicians, may not be done as slickly as it would be by a surgical team approaching the same at the university. If the case can be done safely though, it pays dividends. After all, it could be tonight when a major car wreck happens, or a hemodynamically unstable abdominal sepsis case presents, and we are forced to do a serious case – perhaps surgery at the edge of my comfort zone or something we don’t do with frequency. Keeping some bigger cases makes those scenarios just a bit less scary.

I have been recruited as an advocate for our College, trying to influence those in our nation’s capital to reexamine the 96-hour rule as it applies to critical access hospitals. A phone call to my senior senator’s staff leads to a conference call and follow-up I remain involved with – a first in my professional career. One issue that resonated with D.C. staffers was recruiting my successor. How do we entice the young surgeon to a rural practice if all we do are lumps and bumps, appendectomies, and inguinal hernias? Regionalization of surgical care may be coming but that can’t excite our younger and future colleagues. In each of the last 2 years my third-year medical students parked here for their first rotation and got hustled into the OR to assist with emergency surgery. The enthusiasm was palpable and energizing, but one was a case that raised some eyebrows: pneumatosis intestinalis requiring two small bowel resections with anastomoses and an open abdomen in an elderly male. This fellow did great; I see him doing his grocery shopping these days. My perspective is that case enabled this year’s day 1 emergency, making the surgery safer here in rural America.

When we call to transfer a patient, please understand real thought and a piece of who we are as surgeons accompanies that patient. Transfer is very rarely a reflex action. Also, realize that not every case we keep is a weak fastball over the middle of the plate; sometimes we do real work here at the limit of our comfort zone, but we do so for myriad good reasons.

Dr. Levine is a general surgeon practicing in coastal southwestern Oregon. Despite growing up in Brooklyn and on Long Island in New York, he has been a practicing rural surgeon since 1999. Folks barely even notice the accent anymore!

I have been on both ends of the phone call. I began my career at a several-hundred bed community hospital in a town without a university medical center. We took all the local knife-and-gun club incidents, and whatever other surgical emergencies might arise, while receiving phone calls from nearly every point of the magnetic compass. It’s easy to recall the sagging feeling when you realize more serious work is coming in on the helicopter from Podunk, USA, and you’re not off call for another few hours. These memories linger as now I’m the one making the phone calls. When I state that I am the one, I mean the one and only; this is solo general surgery practice and I’m the only general surgeon in my county.

When I do speak with colleagues kind enough to accept our patients, I feel relieved. But the burden of transfer doesn’t travel away with the patient in the ambulance or on the airplane. There always seem to be questions or looks of concern lately, and I don’t just mean from other medical professionals. Maybe it is an Internet thing, but everyone is a critic these days. We are being watched by more than partners and employers, more than payers and agencies, more than our government bean counters. Families, allied health professionals, and even nonclinical staff all have opinions about which patients stay and which leaves our 14-bed, critical access hospital. Gods may have once walked these halls, but nowadays it’s just me!

Of course, any interested party can also criticize my decisions to keep any particular patient; why would anybody restrict their furrowed glare only to transfers? When we keep patients at the edge of our practice, or perform a procedure that is only done rarely locally, we incite more than just the volume debate on the ACS Communities. Goodness – my wife has heard about cases I have done via town chitter-chatter before I even get home!

How does one deal with being whipsawed? This phenomenon is defined in the business world as being subjected to two difficult situations or opposing pressures at the same time. If you transfer, you are criticized. The only thing that changes are the critics if you keep and care for that very same patient! For many rural colleagues, being whipsawed is on the short list of job dissatisfaction drivers; somewhere behind the heavyweight champ of being asked to be in two different places at the same time.

Transferring a patient rarely leads to the lasting criticism that keeping an ill patient locally can. Obviously keeping a patient extends the time period where others can knowingly shake their heads in disbelief. That extra time allows us to educate staff and others as to why a patient with more than simple hernia or appendicitis is being admitted to our little hospital. We can detail why this is a really good thing for everyone – including the patient!

So many of our locals are elderly, and when we keep one for serious surgical illness, so much goes into that decision besides just the patient’s age and comorbid conditions. Immediate family, friends, or existing social support all must be examined and understood. A significant number of geriatric couples are only “independent” together; send one off for surgery a hundred or more miles away and the remaining spouse suffers measurably. Sometimes there is no local family, as nuclear members live in neighboring states or even overseas. I’m always surprised when my patients have trouble even arranging rides to and from our facilities for the routine procedures we do regularly. I think to myself, what will they do when the inevitable happens?

Our geography plays a serious role for those patients who don’t drive any appreciable distances. The mountains to our east are difficult to negotiate and west, well, you’ll get wet rather quickly. Going north and south on Highway 101 can be tricky during summer and dangerous any time in bad weather. I talk to some patients about sending them to Portland and I get looks in response like I’m proposing surgical care in some exotic foreign capital. Urban anxiety, traffic, and unfamiliarity with our largest metropolis make the 300-mile journey untenable for many of our patients; and the TV show isn’t helping our cause! Even cases that define themselves from the get-go as major university referrals return afterward and ask us to assume their postoperative care. Our patients often can’t make the trip to follow-up with the experts who provided their life-saving care.

Stretching our surgical muscles is obviously important for all ACS members. In bigger facilities you can see and sometimes scrub into fascinating cases in other subspecialties, or at least participate in discussions about such in the surgery lounge. I won’t attach a photo of the desk space that serves as my lounge, dictation station, bathroom, and locker. Let’s just say it’s probably not quite the same as many Fellows are used to.

For the rural solo practitioner, a bigger case, done perhaps with a medical student or just scrub technicians, may not be done as slickly as it would be by a surgical team approaching the same at the university. If the case can be done safely though, it pays dividends. After all, it could be tonight when a major car wreck happens, or a hemodynamically unstable abdominal sepsis case presents, and we are forced to do a serious case – perhaps surgery at the edge of my comfort zone or something we don’t do with frequency. Keeping some bigger cases makes those scenarios just a bit less scary.

I have been recruited as an advocate for our College, trying to influence those in our nation’s capital to reexamine the 96-hour rule as it applies to critical access hospitals. A phone call to my senior senator’s staff leads to a conference call and follow-up I remain involved with – a first in my professional career. One issue that resonated with D.C. staffers was recruiting my successor. How do we entice the young surgeon to a rural practice if all we do are lumps and bumps, appendectomies, and inguinal hernias? Regionalization of surgical care may be coming but that can’t excite our younger and future colleagues. In each of the last 2 years my third-year medical students parked here for their first rotation and got hustled into the OR to assist with emergency surgery. The enthusiasm was palpable and energizing, but one was a case that raised some eyebrows: pneumatosis intestinalis requiring two small bowel resections with anastomoses and an open abdomen in an elderly male. This fellow did great; I see him doing his grocery shopping these days. My perspective is that case enabled this year’s day 1 emergency, making the surgery safer here in rural America.

When we call to transfer a patient, please understand real thought and a piece of who we are as surgeons accompanies that patient. Transfer is very rarely a reflex action. Also, realize that not every case we keep is a weak fastball over the middle of the plate; sometimes we do real work here at the limit of our comfort zone, but we do so for myriad good reasons.

Dr. Levine is a general surgeon practicing in coastal southwestern Oregon. Despite growing up in Brooklyn and on Long Island in New York, he has been a practicing rural surgeon since 1999. Folks barely even notice the accent anymore!

Verrucous Carcinoma on the Lower Extremities

To the Editor:

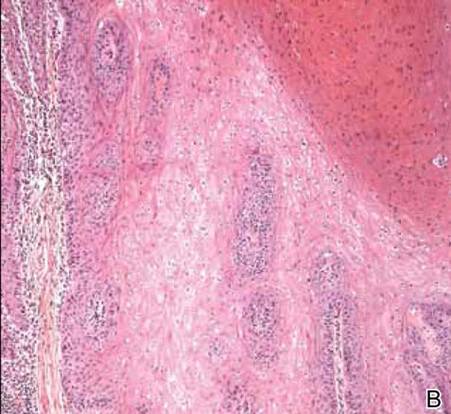

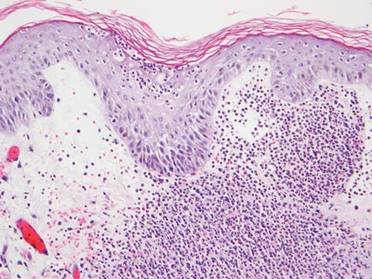

A 38-year-old black man presented with a slowly enlarging growth on the left thigh of 7 years’ duration. The lesion would occasionally scrape off but always recurred. He reported that the tumor developed in the area of a prior nevus. He reported no direct trauma to the area, chronic inflammation, or similar lesions elsewhere. His medical history included gastroesophageal reflux disease and inactive sarcoidosis. Physical examination revealed a 3×3×1-cm exophytic, hyperkeratotic, erythematous nodule with surrounding stellate and branching hyperpigmentation on the anterior aspect of the thigh (Figure 1). Pathologic examination demonstrated hyperkeratosis with an endophytic proliferation of mildly atypical keratinocytes with broad blunted rete ridges (Figure 2). Complete excision of the lesion was performed.

A 33-year-old black man presented with a rapidly growing lesion on the right fifth toe of 3 months’ duration. The patient originally believed the initial small papule was a corn, and after attempts to shave it down with a razor blade, the lesion grew rapidly into a large painful tumor. He reported no prior trauma to the area or history of a similar lesion. Physical examination revealed a 2×2×0.5-cm hyperkeratotic, papillated, hard nodule with a heaped-up border and no ulceration or drainage (Figure 3). A shave biopsy of the lesion was obtained. Microscopic examination revealed hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and papillomatosis with deep extension of mildly atypical keratinocytes into the dermis. Small toe amputation was performed by an orthopedic surgeon.

|

Verrucous carcinoma, first described by Ackerman1 in 1948, is an uncommon, low-grade, well-differentiated variant of squamous cell carcinoma. It presents as a slow-growing, bulky, exophytic tumor with a broad base. The tumor can ulcerate or present with surface sinus tracts that drain foul-smelling material. Typically, the tumor occurs in the fifth to sixth decades of life, with men outnumbering women by a ratio of 5.3 to 1.2 The prevalence of verrucous carcinoma in black individuals is unknown. A review of nonmelanoma skin cancers in skin of color identifies squamous cell carcinoma as the most common cutaneous carcinoma but does not report on the rare verrucous variant.3

Verrucous carcinoma is found in a variety of mucosal and skin surfaces. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity, found most commonly on the buccal mucosa, is known as florid oral papillomatosis or Ackerman carcinoma. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma is referred to as carcinoma cuniculatum or epithelioma cuniculatum and is predominantly located on the plantar surface of the foot. It is less commonly reported on the palm, scalp, face, extremities, and back. Verrucous carcinoma found in the anogenital area is referred to as the Buschke-Löwenstein tumor.4

Histologically, the lesion shows minimal cytologic atypia. Topped by an undulating keratinized mass, the deep margin of the tumor advances as a broad bulbous projection, compressing the underlying connective tissue in a bulldozing manner. Typically there also are keratin-filled sinuses and intraepidermal microabscesses.1

Human papillomavirus types 6, 11, 16, and 18 may be involved in the induction of the tumor. Human papillomavirus types 6 and 11 are frequently associated with the Buschke-Löwenstein tumor,2,4 while carcinoma cuniculatum is most commonly associated with human papillomavirus 16.5-7 In several cases of verrucous carcinoma, the tumor was reported to arise from preexisting lesions with chronic inflammation, such as a chronic ulcer, inflamed cyst, or burn scar.2 Ackerman carcinoma has been associated with the use of snuff, chewing tobacco, and betel nuts.

Morbidity and mortality from verrucous carcinoma arises from local invasion and infiltration into adjacent bone. The tumor rarely metastasizes, with regional lymph nodes being the only reported site of metastasis.8 The treatment of cutaneous verrucous carcinoma is complete surgical excision. Mohs micrographic surgery is preferred because it minimizes recurrence risk.4 Radiation therapy is contraindicated because it has been reported to cause the tumor to become more aggressive.9,10 Although local recurrence may occur, the prognosis is usually favorable.

1. Ackerman LV. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery. 1948;23:670-678.

2. Kao GF, Graham JH, Helwig EB. Carcinoma cuniculatum (verrucous carcinoma of the skin). a clinicopathologic study of 46 cases with ultrastructural observations. Cancer. 1982;49:2395-2403.

3. Jackson BA. Nonmelanoma skin cancer in persons of color. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:93-95.

4. Schwartz RA. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-21; quiz 22-24.

5. Assaf C, Steinhoff M, Petrov I, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the axilla: case report and review. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:199-204.

6. Schell BJ, Rosen T, Rády P, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the foot associated with human papillomavirus type 16. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:49-55.

7. Miyamoto T, Sasaoka R, Hagari Y, et al. Association of cutaneous verrucous carcinoma with human papillomavirus type 16. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:168-169.

8. Walvekar RR, Chaukar DA, Deshpande MS, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity: a clinical and pathological study of 101 cases [published online ahead of print July 11, 2008]. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:47-51.

9. Perez CA, Krans FT, Evans JC, et al. Anaplastic transformation in verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity after radiation therapy. Radiology. 1966;86:108-115.

10. Proffett SD, Spooner TR, Kosek JC. Origin of undifferentiated neoplasm from verrucous epidermal carcinoma of oral cavity following irradiation. Cancer. 1970;26:389-393.

To the Editor:

A 38-year-old black man presented with a slowly enlarging growth on the left thigh of 7 years’ duration. The lesion would occasionally scrape off but always recurred. He reported that the tumor developed in the area of a prior nevus. He reported no direct trauma to the area, chronic inflammation, or similar lesions elsewhere. His medical history included gastroesophageal reflux disease and inactive sarcoidosis. Physical examination revealed a 3×3×1-cm exophytic, hyperkeratotic, erythematous nodule with surrounding stellate and branching hyperpigmentation on the anterior aspect of the thigh (Figure 1). Pathologic examination demonstrated hyperkeratosis with an endophytic proliferation of mildly atypical keratinocytes with broad blunted rete ridges (Figure 2). Complete excision of the lesion was performed.

A 33-year-old black man presented with a rapidly growing lesion on the right fifth toe of 3 months’ duration. The patient originally believed the initial small papule was a corn, and after attempts to shave it down with a razor blade, the lesion grew rapidly into a large painful tumor. He reported no prior trauma to the area or history of a similar lesion. Physical examination revealed a 2×2×0.5-cm hyperkeratotic, papillated, hard nodule with a heaped-up border and no ulceration or drainage (Figure 3). A shave biopsy of the lesion was obtained. Microscopic examination revealed hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and papillomatosis with deep extension of mildly atypical keratinocytes into the dermis. Small toe amputation was performed by an orthopedic surgeon.

|

Verrucous carcinoma, first described by Ackerman1 in 1948, is an uncommon, low-grade, well-differentiated variant of squamous cell carcinoma. It presents as a slow-growing, bulky, exophytic tumor with a broad base. The tumor can ulcerate or present with surface sinus tracts that drain foul-smelling material. Typically, the tumor occurs in the fifth to sixth decades of life, with men outnumbering women by a ratio of 5.3 to 1.2 The prevalence of verrucous carcinoma in black individuals is unknown. A review of nonmelanoma skin cancers in skin of color identifies squamous cell carcinoma as the most common cutaneous carcinoma but does not report on the rare verrucous variant.3

Verrucous carcinoma is found in a variety of mucosal and skin surfaces. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity, found most commonly on the buccal mucosa, is known as florid oral papillomatosis or Ackerman carcinoma. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma is referred to as carcinoma cuniculatum or epithelioma cuniculatum and is predominantly located on the plantar surface of the foot. It is less commonly reported on the palm, scalp, face, extremities, and back. Verrucous carcinoma found in the anogenital area is referred to as the Buschke-Löwenstein tumor.4

Histologically, the lesion shows minimal cytologic atypia. Topped by an undulating keratinized mass, the deep margin of the tumor advances as a broad bulbous projection, compressing the underlying connective tissue in a bulldozing manner. Typically there also are keratin-filled sinuses and intraepidermal microabscesses.1

Human papillomavirus types 6, 11, 16, and 18 may be involved in the induction of the tumor. Human papillomavirus types 6 and 11 are frequently associated with the Buschke-Löwenstein tumor,2,4 while carcinoma cuniculatum is most commonly associated with human papillomavirus 16.5-7 In several cases of verrucous carcinoma, the tumor was reported to arise from preexisting lesions with chronic inflammation, such as a chronic ulcer, inflamed cyst, or burn scar.2 Ackerman carcinoma has been associated with the use of snuff, chewing tobacco, and betel nuts.

Morbidity and mortality from verrucous carcinoma arises from local invasion and infiltration into adjacent bone. The tumor rarely metastasizes, with regional lymph nodes being the only reported site of metastasis.8 The treatment of cutaneous verrucous carcinoma is complete surgical excision. Mohs micrographic surgery is preferred because it minimizes recurrence risk.4 Radiation therapy is contraindicated because it has been reported to cause the tumor to become more aggressive.9,10 Although local recurrence may occur, the prognosis is usually favorable.

To the Editor:

A 38-year-old black man presented with a slowly enlarging growth on the left thigh of 7 years’ duration. The lesion would occasionally scrape off but always recurred. He reported that the tumor developed in the area of a prior nevus. He reported no direct trauma to the area, chronic inflammation, or similar lesions elsewhere. His medical history included gastroesophageal reflux disease and inactive sarcoidosis. Physical examination revealed a 3×3×1-cm exophytic, hyperkeratotic, erythematous nodule with surrounding stellate and branching hyperpigmentation on the anterior aspect of the thigh (Figure 1). Pathologic examination demonstrated hyperkeratosis with an endophytic proliferation of mildly atypical keratinocytes with broad blunted rete ridges (Figure 2). Complete excision of the lesion was performed.

A 33-year-old black man presented with a rapidly growing lesion on the right fifth toe of 3 months’ duration. The patient originally believed the initial small papule was a corn, and after attempts to shave it down with a razor blade, the lesion grew rapidly into a large painful tumor. He reported no prior trauma to the area or history of a similar lesion. Physical examination revealed a 2×2×0.5-cm hyperkeratotic, papillated, hard nodule with a heaped-up border and no ulceration or drainage (Figure 3). A shave biopsy of the lesion was obtained. Microscopic examination revealed hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and papillomatosis with deep extension of mildly atypical keratinocytes into the dermis. Small toe amputation was performed by an orthopedic surgeon.

|

Verrucous carcinoma, first described by Ackerman1 in 1948, is an uncommon, low-grade, well-differentiated variant of squamous cell carcinoma. It presents as a slow-growing, bulky, exophytic tumor with a broad base. The tumor can ulcerate or present with surface sinus tracts that drain foul-smelling material. Typically, the tumor occurs in the fifth to sixth decades of life, with men outnumbering women by a ratio of 5.3 to 1.2 The prevalence of verrucous carcinoma in black individuals is unknown. A review of nonmelanoma skin cancers in skin of color identifies squamous cell carcinoma as the most common cutaneous carcinoma but does not report on the rare verrucous variant.3

Verrucous carcinoma is found in a variety of mucosal and skin surfaces. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity, found most commonly on the buccal mucosa, is known as florid oral papillomatosis or Ackerman carcinoma. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma is referred to as carcinoma cuniculatum or epithelioma cuniculatum and is predominantly located on the plantar surface of the foot. It is less commonly reported on the palm, scalp, face, extremities, and back. Verrucous carcinoma found in the anogenital area is referred to as the Buschke-Löwenstein tumor.4

Histologically, the lesion shows minimal cytologic atypia. Topped by an undulating keratinized mass, the deep margin of the tumor advances as a broad bulbous projection, compressing the underlying connective tissue in a bulldozing manner. Typically there also are keratin-filled sinuses and intraepidermal microabscesses.1

Human papillomavirus types 6, 11, 16, and 18 may be involved in the induction of the tumor. Human papillomavirus types 6 and 11 are frequently associated with the Buschke-Löwenstein tumor,2,4 while carcinoma cuniculatum is most commonly associated with human papillomavirus 16.5-7 In several cases of verrucous carcinoma, the tumor was reported to arise from preexisting lesions with chronic inflammation, such as a chronic ulcer, inflamed cyst, or burn scar.2 Ackerman carcinoma has been associated with the use of snuff, chewing tobacco, and betel nuts.