User login

Rivaroxaban monitoring kit launched in Europe

Instrumentation Laboratory, a company that develops in vitro diagnostic instruments, has announced the commercialization of the HemosIL Rivaroxaban Testing Solution in Europe.

This testing kit consists of the HemosIL Liquid Anti-Xa Assay, Rivaroxaban Calibrators, and Rivaroxaban Controls, which can be used with ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing Systems to monitor patients taking the oral anticoagulant rivaroxaban (Xarelto).

The assay, calibrators, and controls are now CE IVD Marked under the European IVD Directive 98/79/EC.

This allows Instrumentation Laboratory to distribute the HemosIL Rivaroxaban Testing Solution in the European Union and other international territories.

Although monitoring is generally not required for patients on rivaroxaban, there are cases in which measuring rivaroxaban may be necessary.

This includes patients who present with bleeding, require reversal of anticoagulation, experience deteriorating renal function, or must undergo surgery or an invasive procedure and have taken rivaroxaban within 24 hours or longer if creatinine clearance is < 50 mL min-1.

Liquid Anti-Xa Assay

The HemosIL Liquid Anti-Xa kit is a one-stage chromogenic assay based on a synthetic chromogenic substrate and factor Xa inactivation. Rivaroxaban levels in patient plasma are measured automatically on an ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing System when this assay is calibrated with the HemosIL Rivaroxaban Calibrators.

The Anti-Xa Assay kit consists of:

- Factor Xa reagent: 5 x 2.5 mL vial of a liquid preparation containing purified bovine factor Xa (approximately 5.5 nkat/mL), Tris-Buffer, EDTA, dextran sulfate, sodium chloride, and bovine serum albumin.

- Chromogenic substrate: 5 x 3 mL vial of liquid chromogenic substrate S-2732 (approximately 1.2 mg/mL) and bulking agent.

Rivaroxaban Calibrators

The HemosIL Rivaroxaban Calibrators are intended for the calibration of the Liquid Anti-Xa Assay when testing for rivaroxaban on an ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing System.

Two levels of lyophilized calibrators prepared from human citrated plasma by means of a dedicated process at 2 different concentrations of rivaroxaban are used by the instrument to automatically prepare a calibration curve.

The Rivaroxaban Calibrator kit consists of:

- Rivaroxaban Calibrator 1: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing buffers and stabilizers.

- Rivaroxaban Calibrator 2: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing rivaroxaban, buffers, and stabilizers.

Rivaroxaban Controls

HemosIL Rivaroxaban Controls are intended for the quality control of the Liquid Anti-Xa Assay when testing for rivaroxaban on an ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing System.

Two levels of lyophilized controls are prepared from human citrated plasma by means of a dedicated process at 2 different concentrations of rivaroxaban. Use of both controls is recommended for a complete quality control program.

The Rivaroxaban Controls kit consists of:

- Rivaroxaban Low Control: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing rivaroxaban, stabilizers, and buffer solution.

- Rivaroxaban High Control: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing rivaroxaban, stabilizers, and buffer solution.

Instrumentation Laboratory, a company that develops in vitro diagnostic instruments, has announced the commercialization of the HemosIL Rivaroxaban Testing Solution in Europe.

This testing kit consists of the HemosIL Liquid Anti-Xa Assay, Rivaroxaban Calibrators, and Rivaroxaban Controls, which can be used with ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing Systems to monitor patients taking the oral anticoagulant rivaroxaban (Xarelto).

The assay, calibrators, and controls are now CE IVD Marked under the European IVD Directive 98/79/EC.

This allows Instrumentation Laboratory to distribute the HemosIL Rivaroxaban Testing Solution in the European Union and other international territories.

Although monitoring is generally not required for patients on rivaroxaban, there are cases in which measuring rivaroxaban may be necessary.

This includes patients who present with bleeding, require reversal of anticoagulation, experience deteriorating renal function, or must undergo surgery or an invasive procedure and have taken rivaroxaban within 24 hours or longer if creatinine clearance is < 50 mL min-1.

Liquid Anti-Xa Assay

The HemosIL Liquid Anti-Xa kit is a one-stage chromogenic assay based on a synthetic chromogenic substrate and factor Xa inactivation. Rivaroxaban levels in patient plasma are measured automatically on an ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing System when this assay is calibrated with the HemosIL Rivaroxaban Calibrators.

The Anti-Xa Assay kit consists of:

- Factor Xa reagent: 5 x 2.5 mL vial of a liquid preparation containing purified bovine factor Xa (approximately 5.5 nkat/mL), Tris-Buffer, EDTA, dextran sulfate, sodium chloride, and bovine serum albumin.

- Chromogenic substrate: 5 x 3 mL vial of liquid chromogenic substrate S-2732 (approximately 1.2 mg/mL) and bulking agent.

Rivaroxaban Calibrators

The HemosIL Rivaroxaban Calibrators are intended for the calibration of the Liquid Anti-Xa Assay when testing for rivaroxaban on an ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing System.

Two levels of lyophilized calibrators prepared from human citrated plasma by means of a dedicated process at 2 different concentrations of rivaroxaban are used by the instrument to automatically prepare a calibration curve.

The Rivaroxaban Calibrator kit consists of:

- Rivaroxaban Calibrator 1: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing buffers and stabilizers.

- Rivaroxaban Calibrator 2: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing rivaroxaban, buffers, and stabilizers.

Rivaroxaban Controls

HemosIL Rivaroxaban Controls are intended for the quality control of the Liquid Anti-Xa Assay when testing for rivaroxaban on an ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing System.

Two levels of lyophilized controls are prepared from human citrated plasma by means of a dedicated process at 2 different concentrations of rivaroxaban. Use of both controls is recommended for a complete quality control program.

The Rivaroxaban Controls kit consists of:

- Rivaroxaban Low Control: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing rivaroxaban, stabilizers, and buffer solution.

- Rivaroxaban High Control: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing rivaroxaban, stabilizers, and buffer solution.

Instrumentation Laboratory, a company that develops in vitro diagnostic instruments, has announced the commercialization of the HemosIL Rivaroxaban Testing Solution in Europe.

This testing kit consists of the HemosIL Liquid Anti-Xa Assay, Rivaroxaban Calibrators, and Rivaroxaban Controls, which can be used with ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing Systems to monitor patients taking the oral anticoagulant rivaroxaban (Xarelto).

The assay, calibrators, and controls are now CE IVD Marked under the European IVD Directive 98/79/EC.

This allows Instrumentation Laboratory to distribute the HemosIL Rivaroxaban Testing Solution in the European Union and other international territories.

Although monitoring is generally not required for patients on rivaroxaban, there are cases in which measuring rivaroxaban may be necessary.

This includes patients who present with bleeding, require reversal of anticoagulation, experience deteriorating renal function, or must undergo surgery or an invasive procedure and have taken rivaroxaban within 24 hours or longer if creatinine clearance is < 50 mL min-1.

Liquid Anti-Xa Assay

The HemosIL Liquid Anti-Xa kit is a one-stage chromogenic assay based on a synthetic chromogenic substrate and factor Xa inactivation. Rivaroxaban levels in patient plasma are measured automatically on an ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing System when this assay is calibrated with the HemosIL Rivaroxaban Calibrators.

The Anti-Xa Assay kit consists of:

- Factor Xa reagent: 5 x 2.5 mL vial of a liquid preparation containing purified bovine factor Xa (approximately 5.5 nkat/mL), Tris-Buffer, EDTA, dextran sulfate, sodium chloride, and bovine serum albumin.

- Chromogenic substrate: 5 x 3 mL vial of liquid chromogenic substrate S-2732 (approximately 1.2 mg/mL) and bulking agent.

Rivaroxaban Calibrators

The HemosIL Rivaroxaban Calibrators are intended for the calibration of the Liquid Anti-Xa Assay when testing for rivaroxaban on an ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing System.

Two levels of lyophilized calibrators prepared from human citrated plasma by means of a dedicated process at 2 different concentrations of rivaroxaban are used by the instrument to automatically prepare a calibration curve.

The Rivaroxaban Calibrator kit consists of:

- Rivaroxaban Calibrator 1: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing buffers and stabilizers.

- Rivaroxaban Calibrator 2: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing rivaroxaban, buffers, and stabilizers.

Rivaroxaban Controls

HemosIL Rivaroxaban Controls are intended for the quality control of the Liquid Anti-Xa Assay when testing for rivaroxaban on an ACL TOP Hemostasis Testing System.

Two levels of lyophilized controls are prepared from human citrated plasma by means of a dedicated process at 2 different concentrations of rivaroxaban. Use of both controls is recommended for a complete quality control program.

The Rivaroxaban Controls kit consists of:

- Rivaroxaban Low Control: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing rivaroxaban, stabilizers, and buffer solution.

- Rivaroxaban High Control: 5 x 1 mL vials of a lyophilized human plasma containing rivaroxaban, stabilizers, and buffer solution.

Platform simplifies data analysis, team says

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Researchers say they have developed a user-friendly platform for analyzing transcriptomic and epigenomic sequencing data.

This platform, BioWardrobe, was designed to help biomedical researchers analyze data that might answer questions about diseases and basic biology.

“Although biologists can perform experiments and obtain the data, they often lack the programming expertise required to perform computational data analysis,” said Artem Barski, PhD, of the University of Cincinnati in Ohio.

“BioWardrobe aims to empower researchers by bridging this gap between data and knowledge.”

Dr Barski and Andrey Kartashov, also of the University of Cincinnati, described BioWardrobe in Genome Biology.

The pair said the recent proliferation of sequencing-based methods for analysis of gene expression, chromatin structure, and protein-DNA interactions has widened our horizons, but the volume of data obtained from sequencing requires computational data analysis.

Unfortunately, the bioinformatics and programming expertise required for this analysis may be absent in biomedical laboratories. And this can result in data inaccessibility or delays in applying modern sequencing-based technologies to pressing questions in basic and health-related research.

Dr Barski and Kartashov believe BioWardrobe can solve those problems by providing a “biologist-friendly” web interface.

BioWardrobe users can download data from institutional facilities or public databases, map reads, and visualize results on a genome browser. The platform also allows for differential gene expression and binding analysis, and it can create average tag-density profiles and heatmaps.

Dr Barski and Kartashov plan to continue improving BioWardrobe and continue using the platform in their own research on epigenetic regulation in the immune system, as well as in collaborative projects with other investigators. ![]()

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Researchers say they have developed a user-friendly platform for analyzing transcriptomic and epigenomic sequencing data.

This platform, BioWardrobe, was designed to help biomedical researchers analyze data that might answer questions about diseases and basic biology.

“Although biologists can perform experiments and obtain the data, they often lack the programming expertise required to perform computational data analysis,” said Artem Barski, PhD, of the University of Cincinnati in Ohio.

“BioWardrobe aims to empower researchers by bridging this gap between data and knowledge.”

Dr Barski and Andrey Kartashov, also of the University of Cincinnati, described BioWardrobe in Genome Biology.

The pair said the recent proliferation of sequencing-based methods for analysis of gene expression, chromatin structure, and protein-DNA interactions has widened our horizons, but the volume of data obtained from sequencing requires computational data analysis.

Unfortunately, the bioinformatics and programming expertise required for this analysis may be absent in biomedical laboratories. And this can result in data inaccessibility or delays in applying modern sequencing-based technologies to pressing questions in basic and health-related research.

Dr Barski and Kartashov believe BioWardrobe can solve those problems by providing a “biologist-friendly” web interface.

BioWardrobe users can download data from institutional facilities or public databases, map reads, and visualize results on a genome browser. The platform also allows for differential gene expression and binding analysis, and it can create average tag-density profiles and heatmaps.

Dr Barski and Kartashov plan to continue improving BioWardrobe and continue using the platform in their own research on epigenetic regulation in the immune system, as well as in collaborative projects with other investigators. ![]()

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Researchers say they have developed a user-friendly platform for analyzing transcriptomic and epigenomic sequencing data.

This platform, BioWardrobe, was designed to help biomedical researchers analyze data that might answer questions about diseases and basic biology.

“Although biologists can perform experiments and obtain the data, they often lack the programming expertise required to perform computational data analysis,” said Artem Barski, PhD, of the University of Cincinnati in Ohio.

“BioWardrobe aims to empower researchers by bridging this gap between data and knowledge.”

Dr Barski and Andrey Kartashov, also of the University of Cincinnati, described BioWardrobe in Genome Biology.

The pair said the recent proliferation of sequencing-based methods for analysis of gene expression, chromatin structure, and protein-DNA interactions has widened our horizons, but the volume of data obtained from sequencing requires computational data analysis.

Unfortunately, the bioinformatics and programming expertise required for this analysis may be absent in biomedical laboratories. And this can result in data inaccessibility or delays in applying modern sequencing-based technologies to pressing questions in basic and health-related research.

Dr Barski and Kartashov believe BioWardrobe can solve those problems by providing a “biologist-friendly” web interface.

BioWardrobe users can download data from institutional facilities or public databases, map reads, and visualize results on a genome browser. The platform also allows for differential gene expression and binding analysis, and it can create average tag-density profiles and heatmaps.

Dr Barski and Kartashov plan to continue improving BioWardrobe and continue using the platform in their own research on epigenetic regulation in the immune system, as well as in collaborative projects with other investigators. ![]()

Family-centered care in the NICU

Hospitals are slow to change, especially when changes – such as the inclusion of families in patient care – are not big money makers. Even so, in a competitive marketplace, hospitals are beginning to realize that patient and family satisfaction develops loyal customers.

When patients and families have a good experience, they are likely to return to the hospital and recommend the hospital to others. From a business perspective, it makes sense to develop family-oriented care in hospital specialty units such as the neonatal intensive care unit.

Involving families in the NICU also reduces the neonate’s length of stay (Nurs Adm Q. 2009 Jan-Mar;33[1]32-7).

COPE is a manualized intervention program comprising DVDs and a workbook.

The DVDs provide parents with educational information about the appearance and behavioral characteristics of their premature infants and about how they can participate in their infants’ care, meet their needs, enhance the quality of interaction with their infants, and facilitate their development.

The workbook skills-building activities assist parents in implementing the educational information (for example, learning how to read their infants’ awake states and stress cues, keeping track of important developmental milestones, determining what behaviors are helpful when their infants are stressed).

Parents listen to the COPE educational information on DVDs as they read it in their workbooks. The first intervention in COPE is delivered to the parents 2-4 days after the infant is admitted to the NICU. The second COPE intervention is delivered 2-4 days after the first intervention, and the third intervention is delivered to parents 1-4 days prior to the infant’s discharge from the NICU. Parents receive the fourth COPE intervention 1 week after the infant is discharged from the hospital. Each of the four DVDs has corresponding skills-building activities that parents complete after they listen to the educational information on the DVDs.

The problem

In NICUs, families are not the primary focus of care. To nursing staff, parents are an unknown factor. Parents may silence alarms or open cribs to touch the baby, not realizing that by doing so, they are dysregulating the neonate’s delicate environment. They see nurses moving things around, and so feel they should be able to do it, too. Parents come in many varieties. Some parents sit quietly and appear overwhelmed. Some parents behave erratically. Some parents may smell of alcohol or marijuana, putting everyone in the NICU on alert. Assessing and intervening with parents is helpful to nurses, reduces tension between nurse and parent, and ensures that the daily caring for the neonate is smooth and optimal. Nurses are eager to help with parents.

Nursing perspective

From the nurses’ perspective, the parents are not the patient! Nurses have not been trained to assess and manage distressed parents. Nurses can provide basic education about the baby’s medical condition but do not have time to explain the details that overanxious parents might demand. The nurses recognize that some parents are under severe stress and do not want to leave the bedside, even to care for their own needs. The nurses recognize that some parents have their own health conditions but are unsure how to approach this issue. Nurses welcome education about how to intervene and how to refer parents to appropriate resources.

Parental perspective

Parents are distressed and uncertain about the fate of their newborns. There is an immediate need to gain as much information as possible about the baby’s medical condition and to understand what the nurses are “doing to our baby.” There may be concern that the nurse seems more bonded to the baby than the parents. There may be a lack of understanding of when the babies can be handled and what and when they can be fed. There is significant emotional distress about “not being able to take the baby home.” Parents may want to assign blame or may feel overwhelmed with guilt. For families with poor coping skills, fear and anger may predominate and can be directed at the nurses – an immediate and ever available target. Generally, parents want to be included as much as possible in the care of their children.

Postpartum disorders in the NICU

It is expected that having a baby in the NICU is stressful. However, a meta-analysis of 38 studies of stress in parents of preterm infants, compared with term infants, found that parents of preterm children experience only slightly more stress than do parents of term children. There is decreasing parental stress from the 1980s onward, probably because of the increased quality of care for preterm infants. These studies included 3,025 parents of preterm and low-birth-weight infants (PLoS One 2013;8[2]:e54992).

Over the long term, the psychological functioning of NICU parents is no different from that of control parents. A prospective randomized controlled study defined psychological distress as meeting one or more of the following criteria: any psychiatric diagnosis on the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview at 2 years; Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale score more than 12.5 at 2 years; Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale score more than 11.0 at 2 years, receiving treatment with antidepressants/psychotherapy/counseling over the previous 15 months (Psychosomatics 2014;55[6]:613-20).

In the short term, NICU parents are at risk for postpartum depression (PPD) with the resultant difficulty in establishing good attachment with their babies. The prevalence of PPD in mothers of term newborns is 10%-15%, compared with 28%-70% among NICU mothers (Int J Womens Health. 2014;2014[6]:975-87).

Fathers are known as the forgotten parents and experience a high prevalence of depressive symptoms. Fathers of term newborns experience depression at rates of 2%-10%, but rates of up to 60% have been reported in NICU fathers (Adv Neonatal Care. 2010 Aug;10[4]:200-3).

Prevention of psychiatric illness in family members

The NICU environment is often dimly lighted, and improving lighting prevents depression in NICU mothers. A 3-week bright-light therapy intervention improved the sleep and health outcomes of NICU mothers, who experienced less morning fatigue and depressive symptoms, and improved quality of life, compared with the control group (Biol Res Nurs. 2013 Oct;15[4] 398-406). An architect on our team is designing “quiet spaces” for parents and creating more ambient light and daylighting in our NICU.

For parents who do not want to leave the NICU, mobile computer terminals can bring education to the bedside. For parents who can leave the bedside, family educational interventions are well received (Adv Neonatal Care. 2013 Apr;13[2]:115-26).

In current practice, in our labor and delivery suite and in many NICUs, mothers are screened for postpartum depression via the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Br J Psychiatry 1987 Jun;150[6]:782-6). If mothers score over 13, they are referred for further assessment. Treatment often consists of referral for individual intervention for the mother (usually sertraline and disclosures/instructions about breastfeeding, as well as supportive psychotherapy).

What does family-centered care look like?

A family perspective supports the screening of both parents, using the EPDS. This can occur on admission of the baby to the NICU and at 2-week intervals thereafter and again at discharge (J Perinatol 2013 Oct;33[10]748-53). Ideally, family functioning also can be assessed, and if needed, intervention can be offered to the whole family system.

Family screening occurs in other pediatric medical settings. High-risk families can be identified with the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT) (Acta Oncol. 2015 May;54[5]:574-80).

The PAT is a brief parent self-report composed of items that assess risk associated with the child, family, and broader systems. It is currently used at 50 sites in 28 states in the United States. The PAT has been translated into Spanish, Columbian Spanish, Dutch, Brazilian Portuguese, Hebrew, Greek, Polish, Italian, Japanese, Chinese, and Korean, and is used internationally. English adaptations for Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and Singapore also are available. It has been modified for use in NICUs.

The screening enables health care providers to refer families to the appropriate service: support groups (low risk), psychoeducation (medium risk), or intensive outpatient services (high risk). This stratification allows for the appropriate use of services.

Likewise, family interventions can be thought about in tiers, similar to the risk stratification of the PAT. Tier 1 is a universal educational intervention for all parents, tier 2 parents have higher needs, and tier 3 parents need immediate intervention. The following descriptions show how this might work in practice.

Family intervention: Tier 1

•All families can be given educational material about the mental health needs of parents with a newborn in the NICU. Ideally, this material can be provided through handouts, references for further reading, and through websites accessed in the NICU. For parents who are willing to leave the NICU, they can attend support groups.

•All parents can be screened at initial contact in the NICU and then on discharge from the NICU. If the neonate stays an extended time, the parents can be screened at 2-week intervals. A high score on the EPDS screen indicates an immediate need to refer a parent. A family assessment tool, such as the PAT, can identify high-risk families for immediate referral.

•NICU nursing staff can actively address coparenting struggles. Our NICU nurses provide formal letters between nurses and parents to establish the parameters of the care of the baby, and provide direction for coparenting.

Family intervention: Tier 2

Parents identified on the PAT as having higher needs can be enrolled in psychoeducational groups, led by staff members who have behavioral health training and experience.

Family intervention: Tier 3

These parents are identified on the PAT as high risk and need significant health care services. The NICU social worker can actively work on consultation with addiction medicine, mental health, or social services.

In summary, a family approach in the NICU improves nurse-parent interactions. A focus on coparenting sets the stage for cooperation, trust, and better family outcomes. Some basic training in systems concepts and family dynamics can provide NICU staff with basic clinical skills to provide psychoeducation. Adequate screening can triage high-risk parents appropriately. For NICUs that want to implement a psychoeducational program, Melnyk’s COPE program is an evidenced-based program that is well worth implementation.

Dr. Heru is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Colorado Denver, Aurora. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (New York: Routledge, 2013). She thanks other members of the NICU team at the University of Colorado Hospital: Christy Math, Katherine Perica, and John J. White.

Hospitals are slow to change, especially when changes – such as the inclusion of families in patient care – are not big money makers. Even so, in a competitive marketplace, hospitals are beginning to realize that patient and family satisfaction develops loyal customers.

When patients and families have a good experience, they are likely to return to the hospital and recommend the hospital to others. From a business perspective, it makes sense to develop family-oriented care in hospital specialty units such as the neonatal intensive care unit.

Involving families in the NICU also reduces the neonate’s length of stay (Nurs Adm Q. 2009 Jan-Mar;33[1]32-7).

COPE is a manualized intervention program comprising DVDs and a workbook.

The DVDs provide parents with educational information about the appearance and behavioral characteristics of their premature infants and about how they can participate in their infants’ care, meet their needs, enhance the quality of interaction with their infants, and facilitate their development.

The workbook skills-building activities assist parents in implementing the educational information (for example, learning how to read their infants’ awake states and stress cues, keeping track of important developmental milestones, determining what behaviors are helpful when their infants are stressed).

Parents listen to the COPE educational information on DVDs as they read it in their workbooks. The first intervention in COPE is delivered to the parents 2-4 days after the infant is admitted to the NICU. The second COPE intervention is delivered 2-4 days after the first intervention, and the third intervention is delivered to parents 1-4 days prior to the infant’s discharge from the NICU. Parents receive the fourth COPE intervention 1 week after the infant is discharged from the hospital. Each of the four DVDs has corresponding skills-building activities that parents complete after they listen to the educational information on the DVDs.

The problem

In NICUs, families are not the primary focus of care. To nursing staff, parents are an unknown factor. Parents may silence alarms or open cribs to touch the baby, not realizing that by doing so, they are dysregulating the neonate’s delicate environment. They see nurses moving things around, and so feel they should be able to do it, too. Parents come in many varieties. Some parents sit quietly and appear overwhelmed. Some parents behave erratically. Some parents may smell of alcohol or marijuana, putting everyone in the NICU on alert. Assessing and intervening with parents is helpful to nurses, reduces tension between nurse and parent, and ensures that the daily caring for the neonate is smooth and optimal. Nurses are eager to help with parents.

Nursing perspective

From the nurses’ perspective, the parents are not the patient! Nurses have not been trained to assess and manage distressed parents. Nurses can provide basic education about the baby’s medical condition but do not have time to explain the details that overanxious parents might demand. The nurses recognize that some parents are under severe stress and do not want to leave the bedside, even to care for their own needs. The nurses recognize that some parents have their own health conditions but are unsure how to approach this issue. Nurses welcome education about how to intervene and how to refer parents to appropriate resources.

Parental perspective

Parents are distressed and uncertain about the fate of their newborns. There is an immediate need to gain as much information as possible about the baby’s medical condition and to understand what the nurses are “doing to our baby.” There may be concern that the nurse seems more bonded to the baby than the parents. There may be a lack of understanding of when the babies can be handled and what and when they can be fed. There is significant emotional distress about “not being able to take the baby home.” Parents may want to assign blame or may feel overwhelmed with guilt. For families with poor coping skills, fear and anger may predominate and can be directed at the nurses – an immediate and ever available target. Generally, parents want to be included as much as possible in the care of their children.

Postpartum disorders in the NICU

It is expected that having a baby in the NICU is stressful. However, a meta-analysis of 38 studies of stress in parents of preterm infants, compared with term infants, found that parents of preterm children experience only slightly more stress than do parents of term children. There is decreasing parental stress from the 1980s onward, probably because of the increased quality of care for preterm infants. These studies included 3,025 parents of preterm and low-birth-weight infants (PLoS One 2013;8[2]:e54992).

Over the long term, the psychological functioning of NICU parents is no different from that of control parents. A prospective randomized controlled study defined psychological distress as meeting one or more of the following criteria: any psychiatric diagnosis on the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview at 2 years; Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale score more than 12.5 at 2 years; Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale score more than 11.0 at 2 years, receiving treatment with antidepressants/psychotherapy/counseling over the previous 15 months (Psychosomatics 2014;55[6]:613-20).

In the short term, NICU parents are at risk for postpartum depression (PPD) with the resultant difficulty in establishing good attachment with their babies. The prevalence of PPD in mothers of term newborns is 10%-15%, compared with 28%-70% among NICU mothers (Int J Womens Health. 2014;2014[6]:975-87).

Fathers are known as the forgotten parents and experience a high prevalence of depressive symptoms. Fathers of term newborns experience depression at rates of 2%-10%, but rates of up to 60% have been reported in NICU fathers (Adv Neonatal Care. 2010 Aug;10[4]:200-3).

Prevention of psychiatric illness in family members

The NICU environment is often dimly lighted, and improving lighting prevents depression in NICU mothers. A 3-week bright-light therapy intervention improved the sleep and health outcomes of NICU mothers, who experienced less morning fatigue and depressive symptoms, and improved quality of life, compared with the control group (Biol Res Nurs. 2013 Oct;15[4] 398-406). An architect on our team is designing “quiet spaces” for parents and creating more ambient light and daylighting in our NICU.

For parents who do not want to leave the NICU, mobile computer terminals can bring education to the bedside. For parents who can leave the bedside, family educational interventions are well received (Adv Neonatal Care. 2013 Apr;13[2]:115-26).

In current practice, in our labor and delivery suite and in many NICUs, mothers are screened for postpartum depression via the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Br J Psychiatry 1987 Jun;150[6]:782-6). If mothers score over 13, they are referred for further assessment. Treatment often consists of referral for individual intervention for the mother (usually sertraline and disclosures/instructions about breastfeeding, as well as supportive psychotherapy).

What does family-centered care look like?

A family perspective supports the screening of both parents, using the EPDS. This can occur on admission of the baby to the NICU and at 2-week intervals thereafter and again at discharge (J Perinatol 2013 Oct;33[10]748-53). Ideally, family functioning also can be assessed, and if needed, intervention can be offered to the whole family system.

Family screening occurs in other pediatric medical settings. High-risk families can be identified with the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT) (Acta Oncol. 2015 May;54[5]:574-80).

The PAT is a brief parent self-report composed of items that assess risk associated with the child, family, and broader systems. It is currently used at 50 sites in 28 states in the United States. The PAT has been translated into Spanish, Columbian Spanish, Dutch, Brazilian Portuguese, Hebrew, Greek, Polish, Italian, Japanese, Chinese, and Korean, and is used internationally. English adaptations for Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and Singapore also are available. It has been modified for use in NICUs.

The screening enables health care providers to refer families to the appropriate service: support groups (low risk), psychoeducation (medium risk), or intensive outpatient services (high risk). This stratification allows for the appropriate use of services.

Likewise, family interventions can be thought about in tiers, similar to the risk stratification of the PAT. Tier 1 is a universal educational intervention for all parents, tier 2 parents have higher needs, and tier 3 parents need immediate intervention. The following descriptions show how this might work in practice.

Family intervention: Tier 1

•All families can be given educational material about the mental health needs of parents with a newborn in the NICU. Ideally, this material can be provided through handouts, references for further reading, and through websites accessed in the NICU. For parents who are willing to leave the NICU, they can attend support groups.

•All parents can be screened at initial contact in the NICU and then on discharge from the NICU. If the neonate stays an extended time, the parents can be screened at 2-week intervals. A high score on the EPDS screen indicates an immediate need to refer a parent. A family assessment tool, such as the PAT, can identify high-risk families for immediate referral.

•NICU nursing staff can actively address coparenting struggles. Our NICU nurses provide formal letters between nurses and parents to establish the parameters of the care of the baby, and provide direction for coparenting.

Family intervention: Tier 2

Parents identified on the PAT as having higher needs can be enrolled in psychoeducational groups, led by staff members who have behavioral health training and experience.

Family intervention: Tier 3

These parents are identified on the PAT as high risk and need significant health care services. The NICU social worker can actively work on consultation with addiction medicine, mental health, or social services.

In summary, a family approach in the NICU improves nurse-parent interactions. A focus on coparenting sets the stage for cooperation, trust, and better family outcomes. Some basic training in systems concepts and family dynamics can provide NICU staff with basic clinical skills to provide psychoeducation. Adequate screening can triage high-risk parents appropriately. For NICUs that want to implement a psychoeducational program, Melnyk’s COPE program is an evidenced-based program that is well worth implementation.

Dr. Heru is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Colorado Denver, Aurora. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (New York: Routledge, 2013). She thanks other members of the NICU team at the University of Colorado Hospital: Christy Math, Katherine Perica, and John J. White.

Hospitals are slow to change, especially when changes – such as the inclusion of families in patient care – are not big money makers. Even so, in a competitive marketplace, hospitals are beginning to realize that patient and family satisfaction develops loyal customers.

When patients and families have a good experience, they are likely to return to the hospital and recommend the hospital to others. From a business perspective, it makes sense to develop family-oriented care in hospital specialty units such as the neonatal intensive care unit.

Involving families in the NICU also reduces the neonate’s length of stay (Nurs Adm Q. 2009 Jan-Mar;33[1]32-7).

COPE is a manualized intervention program comprising DVDs and a workbook.

The DVDs provide parents with educational information about the appearance and behavioral characteristics of their premature infants and about how they can participate in their infants’ care, meet their needs, enhance the quality of interaction with their infants, and facilitate their development.

The workbook skills-building activities assist parents in implementing the educational information (for example, learning how to read their infants’ awake states and stress cues, keeping track of important developmental milestones, determining what behaviors are helpful when their infants are stressed).

Parents listen to the COPE educational information on DVDs as they read it in their workbooks. The first intervention in COPE is delivered to the parents 2-4 days after the infant is admitted to the NICU. The second COPE intervention is delivered 2-4 days after the first intervention, and the third intervention is delivered to parents 1-4 days prior to the infant’s discharge from the NICU. Parents receive the fourth COPE intervention 1 week after the infant is discharged from the hospital. Each of the four DVDs has corresponding skills-building activities that parents complete after they listen to the educational information on the DVDs.

The problem

In NICUs, families are not the primary focus of care. To nursing staff, parents are an unknown factor. Parents may silence alarms or open cribs to touch the baby, not realizing that by doing so, they are dysregulating the neonate’s delicate environment. They see nurses moving things around, and so feel they should be able to do it, too. Parents come in many varieties. Some parents sit quietly and appear overwhelmed. Some parents behave erratically. Some parents may smell of alcohol or marijuana, putting everyone in the NICU on alert. Assessing and intervening with parents is helpful to nurses, reduces tension between nurse and parent, and ensures that the daily caring for the neonate is smooth and optimal. Nurses are eager to help with parents.

Nursing perspective

From the nurses’ perspective, the parents are not the patient! Nurses have not been trained to assess and manage distressed parents. Nurses can provide basic education about the baby’s medical condition but do not have time to explain the details that overanxious parents might demand. The nurses recognize that some parents are under severe stress and do not want to leave the bedside, even to care for their own needs. The nurses recognize that some parents have their own health conditions but are unsure how to approach this issue. Nurses welcome education about how to intervene and how to refer parents to appropriate resources.

Parental perspective

Parents are distressed and uncertain about the fate of their newborns. There is an immediate need to gain as much information as possible about the baby’s medical condition and to understand what the nurses are “doing to our baby.” There may be concern that the nurse seems more bonded to the baby than the parents. There may be a lack of understanding of when the babies can be handled and what and when they can be fed. There is significant emotional distress about “not being able to take the baby home.” Parents may want to assign blame or may feel overwhelmed with guilt. For families with poor coping skills, fear and anger may predominate and can be directed at the nurses – an immediate and ever available target. Generally, parents want to be included as much as possible in the care of their children.

Postpartum disorders in the NICU

It is expected that having a baby in the NICU is stressful. However, a meta-analysis of 38 studies of stress in parents of preterm infants, compared with term infants, found that parents of preterm children experience only slightly more stress than do parents of term children. There is decreasing parental stress from the 1980s onward, probably because of the increased quality of care for preterm infants. These studies included 3,025 parents of preterm and low-birth-weight infants (PLoS One 2013;8[2]:e54992).

Over the long term, the psychological functioning of NICU parents is no different from that of control parents. A prospective randomized controlled study defined psychological distress as meeting one or more of the following criteria: any psychiatric diagnosis on the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview at 2 years; Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale score more than 12.5 at 2 years; Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale score more than 11.0 at 2 years, receiving treatment with antidepressants/psychotherapy/counseling over the previous 15 months (Psychosomatics 2014;55[6]:613-20).

In the short term, NICU parents are at risk for postpartum depression (PPD) with the resultant difficulty in establishing good attachment with their babies. The prevalence of PPD in mothers of term newborns is 10%-15%, compared with 28%-70% among NICU mothers (Int J Womens Health. 2014;2014[6]:975-87).

Fathers are known as the forgotten parents and experience a high prevalence of depressive symptoms. Fathers of term newborns experience depression at rates of 2%-10%, but rates of up to 60% have been reported in NICU fathers (Adv Neonatal Care. 2010 Aug;10[4]:200-3).

Prevention of psychiatric illness in family members

The NICU environment is often dimly lighted, and improving lighting prevents depression in NICU mothers. A 3-week bright-light therapy intervention improved the sleep and health outcomes of NICU mothers, who experienced less morning fatigue and depressive symptoms, and improved quality of life, compared with the control group (Biol Res Nurs. 2013 Oct;15[4] 398-406). An architect on our team is designing “quiet spaces” for parents and creating more ambient light and daylighting in our NICU.

For parents who do not want to leave the NICU, mobile computer terminals can bring education to the bedside. For parents who can leave the bedside, family educational interventions are well received (Adv Neonatal Care. 2013 Apr;13[2]:115-26).

In current practice, in our labor and delivery suite and in many NICUs, mothers are screened for postpartum depression via the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Br J Psychiatry 1987 Jun;150[6]:782-6). If mothers score over 13, they are referred for further assessment. Treatment often consists of referral for individual intervention for the mother (usually sertraline and disclosures/instructions about breastfeeding, as well as supportive psychotherapy).

What does family-centered care look like?

A family perspective supports the screening of both parents, using the EPDS. This can occur on admission of the baby to the NICU and at 2-week intervals thereafter and again at discharge (J Perinatol 2013 Oct;33[10]748-53). Ideally, family functioning also can be assessed, and if needed, intervention can be offered to the whole family system.

Family screening occurs in other pediatric medical settings. High-risk families can be identified with the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT) (Acta Oncol. 2015 May;54[5]:574-80).

The PAT is a brief parent self-report composed of items that assess risk associated with the child, family, and broader systems. It is currently used at 50 sites in 28 states in the United States. The PAT has been translated into Spanish, Columbian Spanish, Dutch, Brazilian Portuguese, Hebrew, Greek, Polish, Italian, Japanese, Chinese, and Korean, and is used internationally. English adaptations for Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and Singapore also are available. It has been modified for use in NICUs.

The screening enables health care providers to refer families to the appropriate service: support groups (low risk), psychoeducation (medium risk), or intensive outpatient services (high risk). This stratification allows for the appropriate use of services.

Likewise, family interventions can be thought about in tiers, similar to the risk stratification of the PAT. Tier 1 is a universal educational intervention for all parents, tier 2 parents have higher needs, and tier 3 parents need immediate intervention. The following descriptions show how this might work in practice.

Family intervention: Tier 1

•All families can be given educational material about the mental health needs of parents with a newborn in the NICU. Ideally, this material can be provided through handouts, references for further reading, and through websites accessed in the NICU. For parents who are willing to leave the NICU, they can attend support groups.

•All parents can be screened at initial contact in the NICU and then on discharge from the NICU. If the neonate stays an extended time, the parents can be screened at 2-week intervals. A high score on the EPDS screen indicates an immediate need to refer a parent. A family assessment tool, such as the PAT, can identify high-risk families for immediate referral.

•NICU nursing staff can actively address coparenting struggles. Our NICU nurses provide formal letters between nurses and parents to establish the parameters of the care of the baby, and provide direction for coparenting.

Family intervention: Tier 2

Parents identified on the PAT as having higher needs can be enrolled in psychoeducational groups, led by staff members who have behavioral health training and experience.

Family intervention: Tier 3

These parents are identified on the PAT as high risk and need significant health care services. The NICU social worker can actively work on consultation with addiction medicine, mental health, or social services.

In summary, a family approach in the NICU improves nurse-parent interactions. A focus on coparenting sets the stage for cooperation, trust, and better family outcomes. Some basic training in systems concepts and family dynamics can provide NICU staff with basic clinical skills to provide psychoeducation. Adequate screening can triage high-risk parents appropriately. For NICUs that want to implement a psychoeducational program, Melnyk’s COPE program is an evidenced-based program that is well worth implementation.

Dr. Heru is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Colorado Denver, Aurora. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (New York: Routledge, 2013). She thanks other members of the NICU team at the University of Colorado Hospital: Christy Math, Katherine Perica, and John J. White.

OpenNotes: Transparency in health care

Transparency, until recently, was rarely associated with health care. Not anymore. For better and sometimes worse, there is a revolutionary movement toward transparency in all facets of health care: transparency of costs, outcomes, quality, service, and reputation. Full transparency has now come to medical records in the form of OpenNotes. This is a patient-centered initiative that allows patients full access to their charts, including all their doctors’ notes.

Patients have always had the right to see their records. Ordinarily though, they would be required to go to the medical records office, fill out paperwork, and request copies of their charts. They’d have to supply a reason and usually pay a fee. OpenNotes changes that. Open patient charts are free and easy to access, usually digitally. OpenNotes programs are still rare, and before we go any further, it’s important to examine what we’ve learned about them.

In 2010, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania, and Harborview Medical Center in Seattle invited 105 primary care physicians to open their notes to nearly 14,000 patients. The results were overwhelmingly (and to me, surprisingly) positive: More than 85% of patients accessed their notes at least once. Nearly 100% of patients wanted the program to continue. Patients reported a better understanding of their medical issues, better medication adherence, increased adoption of healthy habits, and less anxiety about their health. I would have expected more confusion and anxiety among the patients.

What about the physicians? According to the initiative, whereas 1 in 3 patients thought they should have unfettered access to their physicians’ notes, only 1 in 10 physicians did. That’s understandable. The physicians in the pilot shared many of the same concerns you and I have, namely that OpenNotes would lead to an increased workload to explain esoteric notes to patients and to allay anxieties.

Yet, this extra workload didn’t occur. Only 3% of physicians reported spending more time answering patients’ questions. One-fifth did report that they changed the language they used when writing notes, primarily to avoid offending patients. Every physician in the initiative said he or she would continue using OpenNotes. Surprised? So was I.

Even the usually conservative SERMO physician audience responded in an unexpected manner. According to a poll conducted this June, SERMO asked 2,300 physicians if patients should have access to their medical records (including MD notes). Forty-nine percent said “only on a case-by-case basis,” 34% said “yes, always,” and 17% said “no, never.”

So, are OpenNotes a success? Let’s take a closer look at some of the challenges: First, we physicians use language that will confuse patients at best and lead them to incorrect conclusions at worst. “Acne necrotica?” Sounds like a case of medieval pimples, but actually it’s pretty harmless. Or consider, “Differential diagnosis includes neuroendocrine tumor.” It doesn’t mean you have it, but some patients will believe they do. Will we have to dumb down our charts then to appease them? Won’t this degrade note quality, one of the primary objectives we are trying to avoid? It’s unclear.

The purpose of a patient note is to inform other providers and to remind ourselves of the critical information needed to care for a patient. It must be pithy and honest. It often reflects our inchoate thoughts as much as our diagnoses. It must also include the sundry requirements we know and love that are needed only to bill for the visit. These are not characteristics that make for a good patient read.

Indeed, the benefits of transparency are not limitless. In some instances, more transparency is worse. Imagine if all your emails and texts were transparent to everyone. Or if everything you’ve ever said about your mother-in-law were viewable by her. That would clearly be a case of bad transparency. Not sharing everything doesn’t mean we are dishonest or duplicitous. It means we are civil. It doesn’t mean we don’t care; it means we do care. We care about our friends and family. We care about our patients and the best way to make them well.

Unless we make it clear to patients that the notes they are viewing are not written for them, I’m worried simply opening charts could damage the doctor-patient relationship as much as it fosters it. Interestingly, there are companies trying to build a technical solution for this conundrum. Others are advocating for standardization of pathology and lab reports that are patient friendly. I’ll research these topics and let you know what I find out in a future column.

Perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised by the positive results from the OpenNotes initiative. After all, for the last several years, I have given patients their actual pathology report for every biopsy I’ve done (which numbers in the many thousands). I have had fewer than five follow-up questions from patients that I can remember. Pretty much all were legitimate, as I recall, including a wrong site error in a report.

Today, more than 5 million patients have access to their providers’ notes on OpenNotes. That number will grow. Our biggest risk is to not be involved. “Just say no” didn’t work for Nancy Reagan; it won’t do our cause any good either.

Dr. Benabio is a partner physician in the department of dermatology of the Southern California Permanente Group in San Diego, and a volunteer clinical assistant professor at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Benabio is @dermdoc on Twitter.

Transparency, until recently, was rarely associated with health care. Not anymore. For better and sometimes worse, there is a revolutionary movement toward transparency in all facets of health care: transparency of costs, outcomes, quality, service, and reputation. Full transparency has now come to medical records in the form of OpenNotes. This is a patient-centered initiative that allows patients full access to their charts, including all their doctors’ notes.

Patients have always had the right to see their records. Ordinarily though, they would be required to go to the medical records office, fill out paperwork, and request copies of their charts. They’d have to supply a reason and usually pay a fee. OpenNotes changes that. Open patient charts are free and easy to access, usually digitally. OpenNotes programs are still rare, and before we go any further, it’s important to examine what we’ve learned about them.

In 2010, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania, and Harborview Medical Center in Seattle invited 105 primary care physicians to open their notes to nearly 14,000 patients. The results were overwhelmingly (and to me, surprisingly) positive: More than 85% of patients accessed their notes at least once. Nearly 100% of patients wanted the program to continue. Patients reported a better understanding of their medical issues, better medication adherence, increased adoption of healthy habits, and less anxiety about their health. I would have expected more confusion and anxiety among the patients.

What about the physicians? According to the initiative, whereas 1 in 3 patients thought they should have unfettered access to their physicians’ notes, only 1 in 10 physicians did. That’s understandable. The physicians in the pilot shared many of the same concerns you and I have, namely that OpenNotes would lead to an increased workload to explain esoteric notes to patients and to allay anxieties.

Yet, this extra workload didn’t occur. Only 3% of physicians reported spending more time answering patients’ questions. One-fifth did report that they changed the language they used when writing notes, primarily to avoid offending patients. Every physician in the initiative said he or she would continue using OpenNotes. Surprised? So was I.

Even the usually conservative SERMO physician audience responded in an unexpected manner. According to a poll conducted this June, SERMO asked 2,300 physicians if patients should have access to their medical records (including MD notes). Forty-nine percent said “only on a case-by-case basis,” 34% said “yes, always,” and 17% said “no, never.”

So, are OpenNotes a success? Let’s take a closer look at some of the challenges: First, we physicians use language that will confuse patients at best and lead them to incorrect conclusions at worst. “Acne necrotica?” Sounds like a case of medieval pimples, but actually it’s pretty harmless. Or consider, “Differential diagnosis includes neuroendocrine tumor.” It doesn’t mean you have it, but some patients will believe they do. Will we have to dumb down our charts then to appease them? Won’t this degrade note quality, one of the primary objectives we are trying to avoid? It’s unclear.

The purpose of a patient note is to inform other providers and to remind ourselves of the critical information needed to care for a patient. It must be pithy and honest. It often reflects our inchoate thoughts as much as our diagnoses. It must also include the sundry requirements we know and love that are needed only to bill for the visit. These are not characteristics that make for a good patient read.

Indeed, the benefits of transparency are not limitless. In some instances, more transparency is worse. Imagine if all your emails and texts were transparent to everyone. Or if everything you’ve ever said about your mother-in-law were viewable by her. That would clearly be a case of bad transparency. Not sharing everything doesn’t mean we are dishonest or duplicitous. It means we are civil. It doesn’t mean we don’t care; it means we do care. We care about our friends and family. We care about our patients and the best way to make them well.

Unless we make it clear to patients that the notes they are viewing are not written for them, I’m worried simply opening charts could damage the doctor-patient relationship as much as it fosters it. Interestingly, there are companies trying to build a technical solution for this conundrum. Others are advocating for standardization of pathology and lab reports that are patient friendly. I’ll research these topics and let you know what I find out in a future column.

Perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised by the positive results from the OpenNotes initiative. After all, for the last several years, I have given patients their actual pathology report for every biopsy I’ve done (which numbers in the many thousands). I have had fewer than five follow-up questions from patients that I can remember. Pretty much all were legitimate, as I recall, including a wrong site error in a report.

Today, more than 5 million patients have access to their providers’ notes on OpenNotes. That number will grow. Our biggest risk is to not be involved. “Just say no” didn’t work for Nancy Reagan; it won’t do our cause any good either.

Dr. Benabio is a partner physician in the department of dermatology of the Southern California Permanente Group in San Diego, and a volunteer clinical assistant professor at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Benabio is @dermdoc on Twitter.

Transparency, until recently, was rarely associated with health care. Not anymore. For better and sometimes worse, there is a revolutionary movement toward transparency in all facets of health care: transparency of costs, outcomes, quality, service, and reputation. Full transparency has now come to medical records in the form of OpenNotes. This is a patient-centered initiative that allows patients full access to their charts, including all their doctors’ notes.

Patients have always had the right to see their records. Ordinarily though, they would be required to go to the medical records office, fill out paperwork, and request copies of their charts. They’d have to supply a reason and usually pay a fee. OpenNotes changes that. Open patient charts are free and easy to access, usually digitally. OpenNotes programs are still rare, and before we go any further, it’s important to examine what we’ve learned about them.

In 2010, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania, and Harborview Medical Center in Seattle invited 105 primary care physicians to open their notes to nearly 14,000 patients. The results were overwhelmingly (and to me, surprisingly) positive: More than 85% of patients accessed their notes at least once. Nearly 100% of patients wanted the program to continue. Patients reported a better understanding of their medical issues, better medication adherence, increased adoption of healthy habits, and less anxiety about their health. I would have expected more confusion and anxiety among the patients.

What about the physicians? According to the initiative, whereas 1 in 3 patients thought they should have unfettered access to their physicians’ notes, only 1 in 10 physicians did. That’s understandable. The physicians in the pilot shared many of the same concerns you and I have, namely that OpenNotes would lead to an increased workload to explain esoteric notes to patients and to allay anxieties.

Yet, this extra workload didn’t occur. Only 3% of physicians reported spending more time answering patients’ questions. One-fifth did report that they changed the language they used when writing notes, primarily to avoid offending patients. Every physician in the initiative said he or she would continue using OpenNotes. Surprised? So was I.

Even the usually conservative SERMO physician audience responded in an unexpected manner. According to a poll conducted this June, SERMO asked 2,300 physicians if patients should have access to their medical records (including MD notes). Forty-nine percent said “only on a case-by-case basis,” 34% said “yes, always,” and 17% said “no, never.”

So, are OpenNotes a success? Let’s take a closer look at some of the challenges: First, we physicians use language that will confuse patients at best and lead them to incorrect conclusions at worst. “Acne necrotica?” Sounds like a case of medieval pimples, but actually it’s pretty harmless. Or consider, “Differential diagnosis includes neuroendocrine tumor.” It doesn’t mean you have it, but some patients will believe they do. Will we have to dumb down our charts then to appease them? Won’t this degrade note quality, one of the primary objectives we are trying to avoid? It’s unclear.

The purpose of a patient note is to inform other providers and to remind ourselves of the critical information needed to care for a patient. It must be pithy and honest. It often reflects our inchoate thoughts as much as our diagnoses. It must also include the sundry requirements we know and love that are needed only to bill for the visit. These are not characteristics that make for a good patient read.

Indeed, the benefits of transparency are not limitless. In some instances, more transparency is worse. Imagine if all your emails and texts were transparent to everyone. Or if everything you’ve ever said about your mother-in-law were viewable by her. That would clearly be a case of bad transparency. Not sharing everything doesn’t mean we are dishonest or duplicitous. It means we are civil. It doesn’t mean we don’t care; it means we do care. We care about our friends and family. We care about our patients and the best way to make them well.

Unless we make it clear to patients that the notes they are viewing are not written for them, I’m worried simply opening charts could damage the doctor-patient relationship as much as it fosters it. Interestingly, there are companies trying to build a technical solution for this conundrum. Others are advocating for standardization of pathology and lab reports that are patient friendly. I’ll research these topics and let you know what I find out in a future column.

Perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised by the positive results from the OpenNotes initiative. After all, for the last several years, I have given patients their actual pathology report for every biopsy I’ve done (which numbers in the many thousands). I have had fewer than five follow-up questions from patients that I can remember. Pretty much all were legitimate, as I recall, including a wrong site error in a report.

Today, more than 5 million patients have access to their providers’ notes on OpenNotes. That number will grow. Our biggest risk is to not be involved. “Just say no” didn’t work for Nancy Reagan; it won’t do our cause any good either.

Dr. Benabio is a partner physician in the department of dermatology of the Southern California Permanente Group in San Diego, and a volunteer clinical assistant professor at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Benabio is @dermdoc on Twitter.

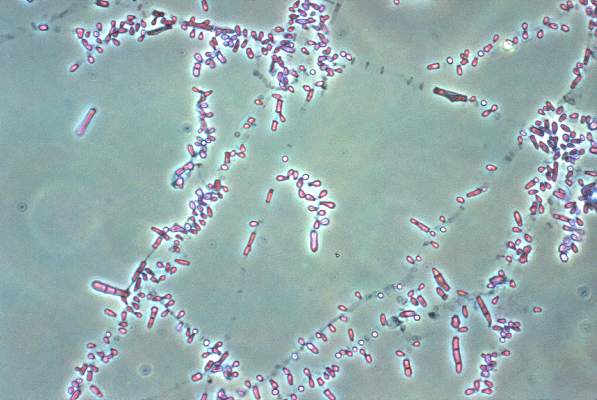

Fungal foot infections risk secondary infection in diabetic patients

VANCOUVER – Fungal foot infections in diabetic patients are often ignored and are far more than a cosmetic problem.

In patients with diabetes, tinea pedis and onychomycosis triple the likelihood of secondary bacterial infections including gram-negative intertrigo, cellulitis, and osteomyelitis. Further, they boost up to fivefold the risk of life- and limb-threatening gangrene, Dr. Manuela Papini said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Her own work (G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013 Dec;148(6):603-8), as well as that of others, indicates tinea pedis and onychomycosis in diabetic patients often goes undiagnosed, ignored, or inadequately treated.

In her own experience, four out of five diabetic patients with a fungal foot infection are unaware of it, she said. Moreover, half of those with a diagnosed fungal foot infection remain untreated or insufficiently treated, added Dr. Papini, a dermatologist at the University of Perugia (Italy).

Fungal infections of the foot are three times more common among diabetic individuals than the general population. The reasons for this disparity included impaired peripheral circulation, an immunocompromised state, autonomic neuropathy, and the inability to maintain good foot hygiene because of obesity, impaired vision, or advanced age.

The causative organisms of fungal infections in diabetic patients are the same as those seen in the general population. So are the recommended first-line treatments. But treatment response is generally poor – much worse than in nondiabetics. Adherence to antifungal medication also is a real problem in diabetic patients, due in large part to the high prevalence of comorbid conditions and resultant polypharmacy.

“Most diabetic patients say their large pill burden is an issue, and they think onychomycosis is the least important of their problems,” she explained.

Photodynamic therapy and laser treatments show promise, but the supporting data aren’t yet sufficient to warrant their introduction into clinical practice, according to Dr. Papini.

As for contemporary therapy, she noted that the British Association of Dermatologists, in its current onychomycosis treatment guidelines, reserves its A-strength recommendations for two oral drugs given daily for 12 weeks: terbinafine and itraconazole, although itraconazole can alternatively be used as pulse therapy for 3-6 months. Topical therapies are advised only for superficial white onychomycosis and early distal lateral subungual onychomycosis (Br J Dermatol. 2014 Nov;171(5):937-58).

A systematic review of the published literature on treatment of diabetic fungal foot infections concluded that there is good evidence that oral terbinafine is as safe and effective as itraconazole for treating onychomycosis. The authors, however, found that there is no evidence to guide treatment of tinea pedis in the diabetic population (J Foot Ankle Res. 2011 Dec 4;4:26).

In the nondiabetic population, the first-line treatment for tinea pedis is typically a topical antifungal. A good option in diabetic patients is luliconazole (Luzu), which is active against Trichophyton rubrum – the most common causative organism – and has the advantage of simplicity: the regimen is once-daily treatment for 2 weeks, much shorter than for many other topical antifungals, Dr. Papini observed.

Until new and better treatments come along, she continued, the key to preventing relapse of fungal foot infections in diabetic patients is to choose the simplest and most effective therapy, stress to patients the importance of completing the treatment course, and provide instruction in self-inspection and disinfection of shoes and socks.

Dr. Papini reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

VANCOUVER – Fungal foot infections in diabetic patients are often ignored and are far more than a cosmetic problem.

In patients with diabetes, tinea pedis and onychomycosis triple the likelihood of secondary bacterial infections including gram-negative intertrigo, cellulitis, and osteomyelitis. Further, they boost up to fivefold the risk of life- and limb-threatening gangrene, Dr. Manuela Papini said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Her own work (G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013 Dec;148(6):603-8), as well as that of others, indicates tinea pedis and onychomycosis in diabetic patients often goes undiagnosed, ignored, or inadequately treated.

In her own experience, four out of five diabetic patients with a fungal foot infection are unaware of it, she said. Moreover, half of those with a diagnosed fungal foot infection remain untreated or insufficiently treated, added Dr. Papini, a dermatologist at the University of Perugia (Italy).

Fungal infections of the foot are three times more common among diabetic individuals than the general population. The reasons for this disparity included impaired peripheral circulation, an immunocompromised state, autonomic neuropathy, and the inability to maintain good foot hygiene because of obesity, impaired vision, or advanced age.

The causative organisms of fungal infections in diabetic patients are the same as those seen in the general population. So are the recommended first-line treatments. But treatment response is generally poor – much worse than in nondiabetics. Adherence to antifungal medication also is a real problem in diabetic patients, due in large part to the high prevalence of comorbid conditions and resultant polypharmacy.

“Most diabetic patients say their large pill burden is an issue, and they think onychomycosis is the least important of their problems,” she explained.

Photodynamic therapy and laser treatments show promise, but the supporting data aren’t yet sufficient to warrant their introduction into clinical practice, according to Dr. Papini.

As for contemporary therapy, she noted that the British Association of Dermatologists, in its current onychomycosis treatment guidelines, reserves its A-strength recommendations for two oral drugs given daily for 12 weeks: terbinafine and itraconazole, although itraconazole can alternatively be used as pulse therapy for 3-6 months. Topical therapies are advised only for superficial white onychomycosis and early distal lateral subungual onychomycosis (Br J Dermatol. 2014 Nov;171(5):937-58).

A systematic review of the published literature on treatment of diabetic fungal foot infections concluded that there is good evidence that oral terbinafine is as safe and effective as itraconazole for treating onychomycosis. The authors, however, found that there is no evidence to guide treatment of tinea pedis in the diabetic population (J Foot Ankle Res. 2011 Dec 4;4:26).

In the nondiabetic population, the first-line treatment for tinea pedis is typically a topical antifungal. A good option in diabetic patients is luliconazole (Luzu), which is active against Trichophyton rubrum – the most common causative organism – and has the advantage of simplicity: the regimen is once-daily treatment for 2 weeks, much shorter than for many other topical antifungals, Dr. Papini observed.

Until new and better treatments come along, she continued, the key to preventing relapse of fungal foot infections in diabetic patients is to choose the simplest and most effective therapy, stress to patients the importance of completing the treatment course, and provide instruction in self-inspection and disinfection of shoes and socks.

Dr. Papini reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

VANCOUVER – Fungal foot infections in diabetic patients are often ignored and are far more than a cosmetic problem.

In patients with diabetes, tinea pedis and onychomycosis triple the likelihood of secondary bacterial infections including gram-negative intertrigo, cellulitis, and osteomyelitis. Further, they boost up to fivefold the risk of life- and limb-threatening gangrene, Dr. Manuela Papini said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Her own work (G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013 Dec;148(6):603-8), as well as that of others, indicates tinea pedis and onychomycosis in diabetic patients often goes undiagnosed, ignored, or inadequately treated.

In her own experience, four out of five diabetic patients with a fungal foot infection are unaware of it, she said. Moreover, half of those with a diagnosed fungal foot infection remain untreated or insufficiently treated, added Dr. Papini, a dermatologist at the University of Perugia (Italy).

Fungal infections of the foot are three times more common among diabetic individuals than the general population. The reasons for this disparity included impaired peripheral circulation, an immunocompromised state, autonomic neuropathy, and the inability to maintain good foot hygiene because of obesity, impaired vision, or advanced age.

The causative organisms of fungal infections in diabetic patients are the same as those seen in the general population. So are the recommended first-line treatments. But treatment response is generally poor – much worse than in nondiabetics. Adherence to antifungal medication also is a real problem in diabetic patients, due in large part to the high prevalence of comorbid conditions and resultant polypharmacy.

“Most diabetic patients say their large pill burden is an issue, and they think onychomycosis is the least important of their problems,” she explained.

Photodynamic therapy and laser treatments show promise, but the supporting data aren’t yet sufficient to warrant their introduction into clinical practice, according to Dr. Papini.

As for contemporary therapy, she noted that the British Association of Dermatologists, in its current onychomycosis treatment guidelines, reserves its A-strength recommendations for two oral drugs given daily for 12 weeks: terbinafine and itraconazole, although itraconazole can alternatively be used as pulse therapy for 3-6 months. Topical therapies are advised only for superficial white onychomycosis and early distal lateral subungual onychomycosis (Br J Dermatol. 2014 Nov;171(5):937-58).

A systematic review of the published literature on treatment of diabetic fungal foot infections concluded that there is good evidence that oral terbinafine is as safe and effective as itraconazole for treating onychomycosis. The authors, however, found that there is no evidence to guide treatment of tinea pedis in the diabetic population (J Foot Ankle Res. 2011 Dec 4;4:26).

In the nondiabetic population, the first-line treatment for tinea pedis is typically a topical antifungal. A good option in diabetic patients is luliconazole (Luzu), which is active against Trichophyton rubrum – the most common causative organism – and has the advantage of simplicity: the regimen is once-daily treatment for 2 weeks, much shorter than for many other topical antifungals, Dr. Papini observed.

Until new and better treatments come along, she continued, the key to preventing relapse of fungal foot infections in diabetic patients is to choose the simplest and most effective therapy, stress to patients the importance of completing the treatment course, and provide instruction in self-inspection and disinfection of shoes and socks.

Dr. Papini reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCD 2015

One dollar and forty-two cents

No good deed goes unpunished.

We froze Myrna’s keratosis off her forehead. Gratis, of course.

This was followed by repeated calls from Myrna: the spot was red, it was painful, it wasn’t healing right.

So we mailed her an envelope filled with cream to help heal the skin. Although we used our regular postage meter, somehow Myrna got the package with $1.42 postage due.

Not going to work.

Myrna called to complain. Then she drove over and walked into the office, but we weren’t there. Then she called again and left a message. “I’m coming in this afternoon,” she said. “I expect to pick up my $1.42.”

Really.

Later that morning, Stephanie came by for a skin check. Because Stephanie is catering manager at a downtown ultra-upscale hotel, I knew she would both appreciate the tale of $1.42 and be able to top it. Everyone in her field can fill several books of client encounters no one could make up.

When I asked her to share some stories, Stephanie did not disappoint.

“Sure,” she said. “People plan lavish weddings, no expense spared. But when they send gift baskets, we have to charge $3.50 each to pay the livery people who deliver them. That they object to.