User login

News and Views that Matter to Pediatricians

The leading independent newspaper covering news and commentary in pediatrics.

Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis Diagnosis

It’s wintertime, peak season for GAS pharyngitis, and you’d think that this far into the 21st century we would have a foolproof process for diagnosing which among the many patients with pharyngitis have true GAS pharyngitis. Thinking back to the 1980s, we have come a long way from simple throat cultures for detecting GAS, e.g., numerous point of care (POC) Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA), waved rapid antigen detection tests (RADT), and numerous highly sensitive molecular assays, e.g. nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT). But if you think the issues surrounding management of GAS pharyngitis have been solved by these newer tests, think again.

Several good reviews1-3 are excellent resources for those wishing a refresher on GAS diagnosis/management issues. They present nitty gritty details on comparative advantages/disadvantages of the many testing options while reminding us of the nuts and bolts of GAS pharyngitis. The following are a few nuggets from these articles.

Properly collected throat specimen. A quality throat specimen involves swabbing both tonsillar pillars plus posterior pharynx without touching tongue or inner cheeks. Two swab collections increase sensitivity by almost 10% compared with a single swab. Transport media is preferred if samples will not be cultured within 24 hours. Caveat: RADT testing of a transport media-diluted sample lowers sensitivity compared with direct swab use.

Reliable GAS detection. Commercially available tests in 2025 are well studied. Culture is considered a gold standard for detecting clinically relevant GAS by CDC.4 Culture has good sensitivity (estimated 80%-90% varying among studies and by quality of specimens) and 99% specificity but requires 16-24 hours for results. RADT solves the time-delay issues and has near 100% specificity but sensitivity used to be as low as 65%, hence the 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline recommendation for backup throat culture for negative tests.5 However, current RADT have sensitivities in the 85%-90% range.3,4 So a positive RADT reliably and quickly indicates GAS antigens are present. NAAT have the highest combined sensitivity and specificity, near 100% for each, and a positive reliably indicates GAS nucleic acids are present.

So why not simply always use NAAT? First, it’s a “be careful what you wish for” scenario. NAAT can, and do, detect dead remnants and colonizing GAS way more than culture.2,3 So NAAT are overly sensitive, adding an extra layer of interpretation difficulty, ie, as many as 20% of positive NAAT detections may be carriers or dead GAS. Second, NAAT often requires special instrumentation and kits are more expensive. That said, reimbursement is often higher for NAAT.

Choice based on accuracy in detecting GAS. If time delays were not a problem, culture would still seem the answer. If more rapid detection is needed, either RADT with culture back up or NAAT could be the answer. That said, consider that in the real world, throat cultures are less sensitive and RADT are less specific than indicated by some published data.6 So, the ideal answer, it seems, would be NAAT GAS detection coupled with a confirmatory biomarker of GAS infection. Such innate immune biomarkers may be on the horizon.3

But first, pretest screening. In 2025 what do we do with a positive result? Do we prescribe antibiotics? Do we think the detected GAS bacteria/antigens/nucleic acids represent the cause of the pharyngitis? Or did we just detect dead GAS or even a carrier, while a virus is the true cause? Challenges for this decision include most pharyngitis (up to 70%) being due to viruses, not GAS, plus up to 20% of GAS detections even by less sensitive culture or RADT can be carriers, plus an added 10%-20% of RADT and NAAT detections are dead GAS. Thus, with indiscriminate testing of all pharyngitis patients, the number of truly positive GAS detections that are actually “false positives” (GAS in some form is present but not causing pharyngitis) may be almost as high as for those representing true GAS pharyngitis.

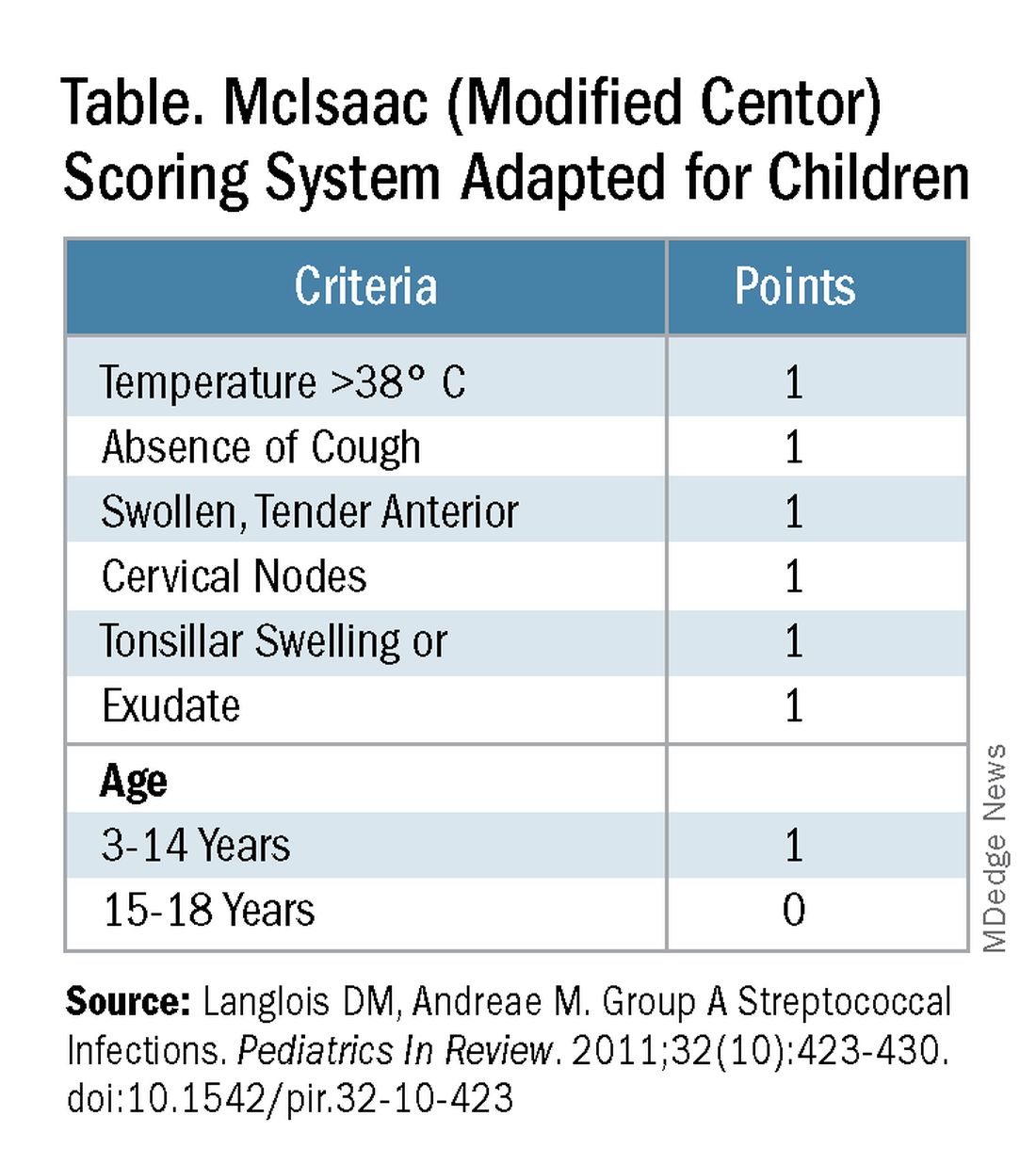

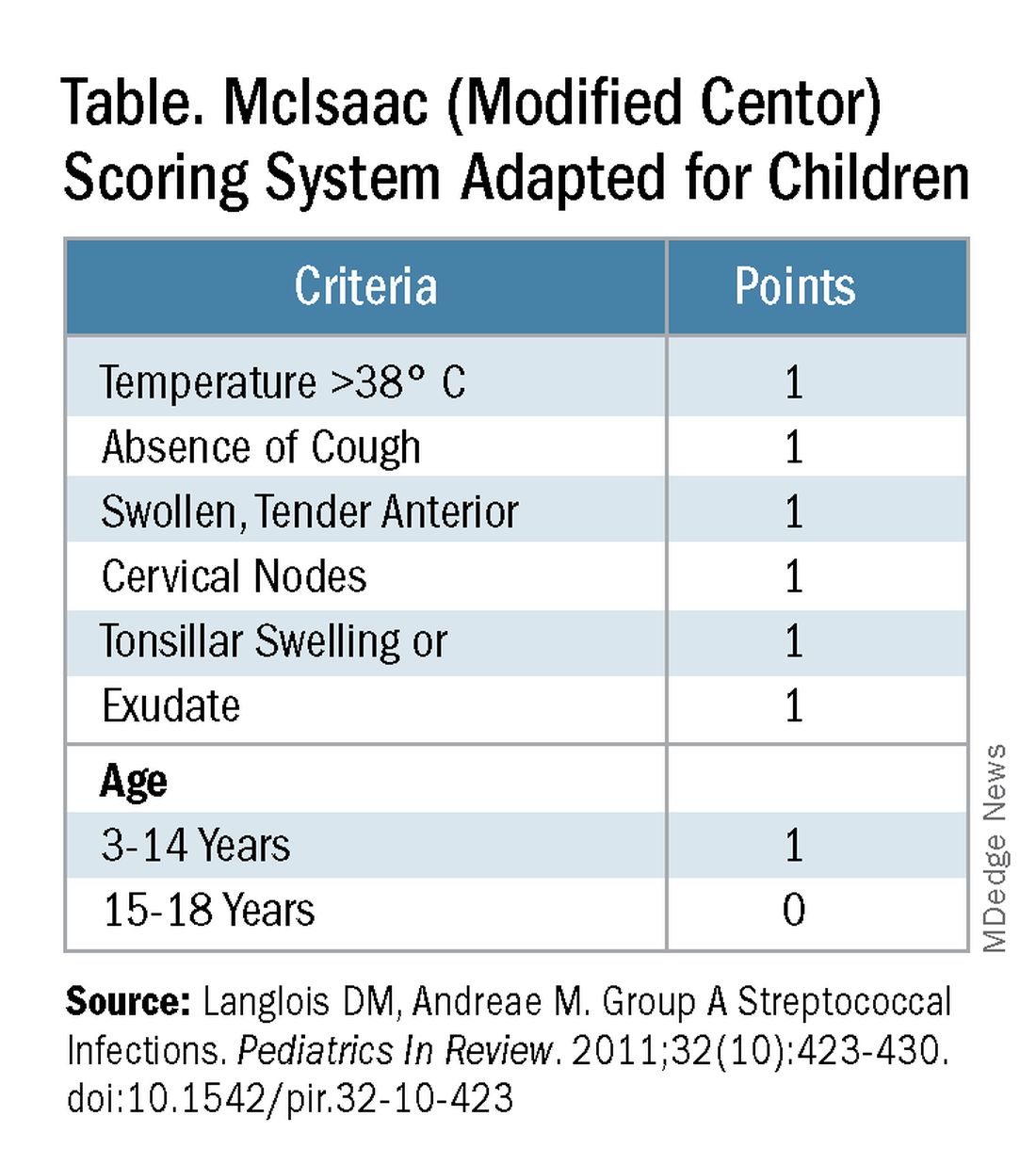

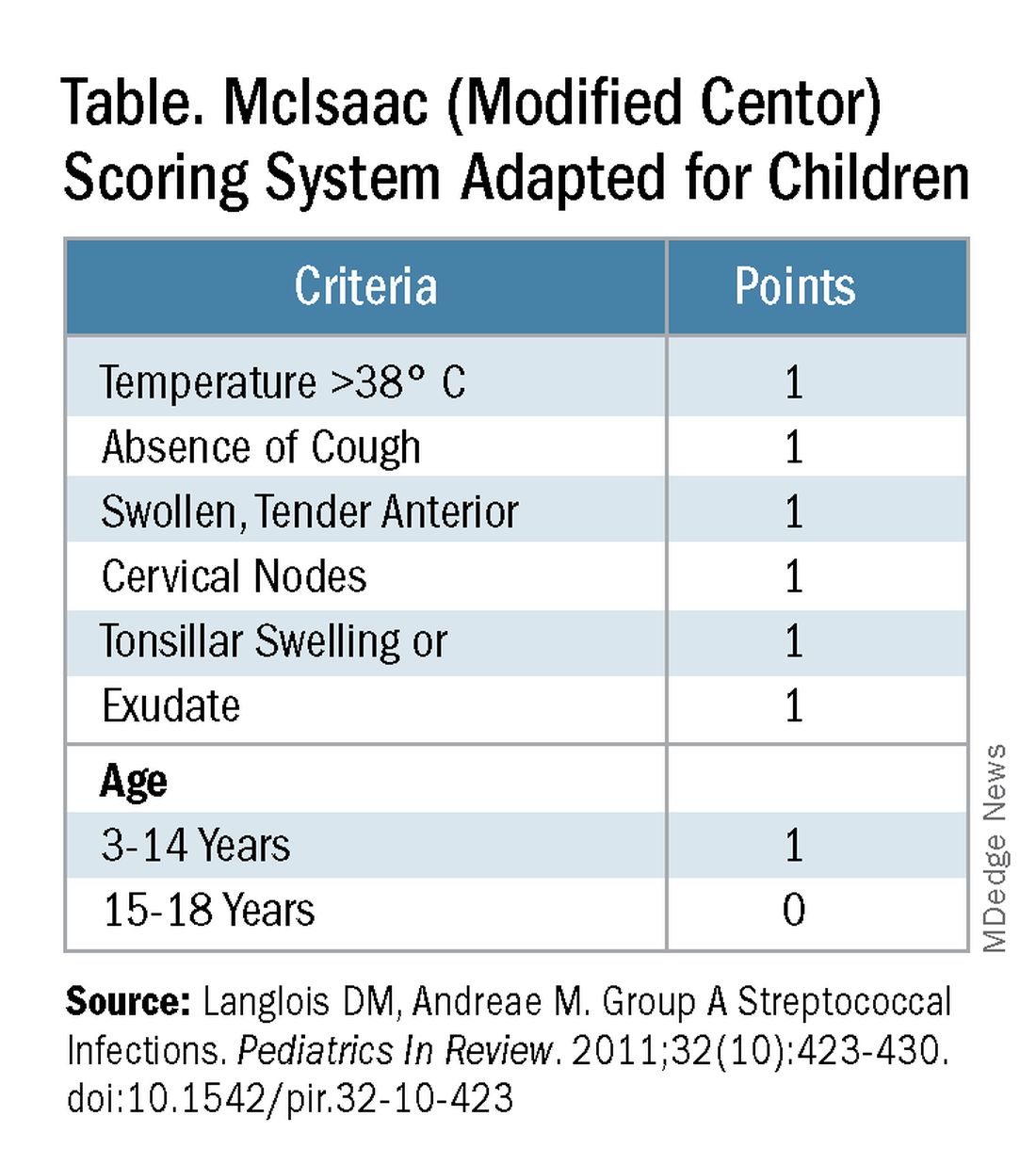

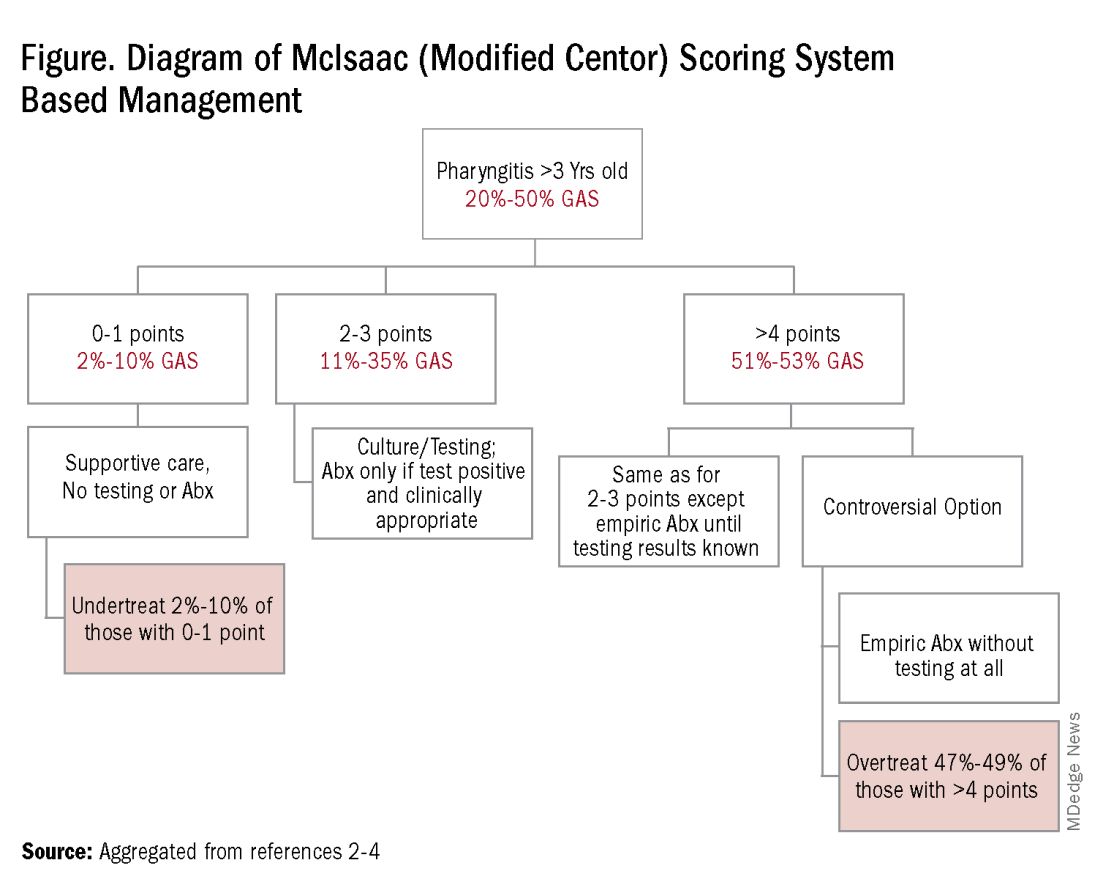

Some tool is needed to minimize testing patients who are likely to have viral pharyngitis to reduce test-positive/GAS-pharyngitis-negative scenarios. Pretest patient screening therefore is critical to increase the positive predictive value of positive GAS testing results. The history and physical can be helpful. In the simplest form of pretest screening, eliminate those younger than 3 years old* or those with viral type sign/symptoms, eg conjunctivitis, cough, coryza.7 This could cut “false” positives by as much as a half. More complete validated scoring systems are also available but remain imperfect. The most published is the McIsaac score (modified Centor score).3-5,8 (See Table and Figure.)

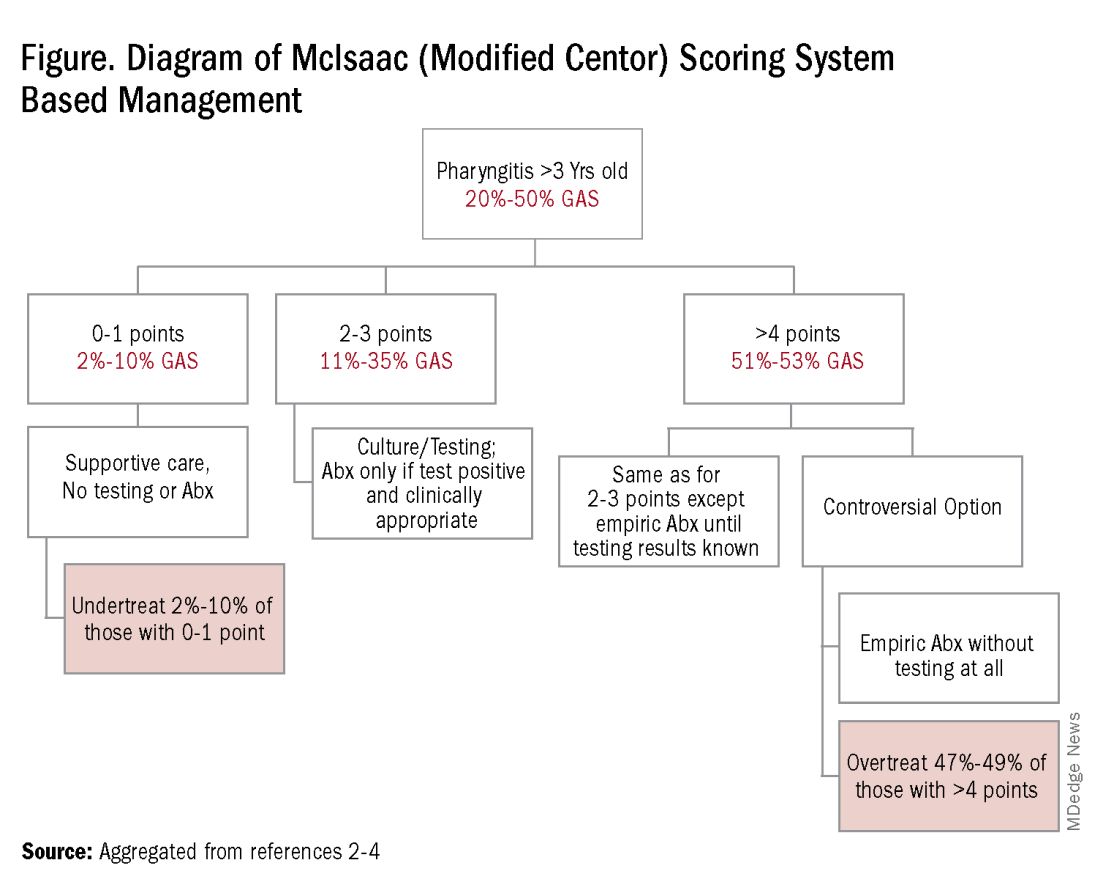

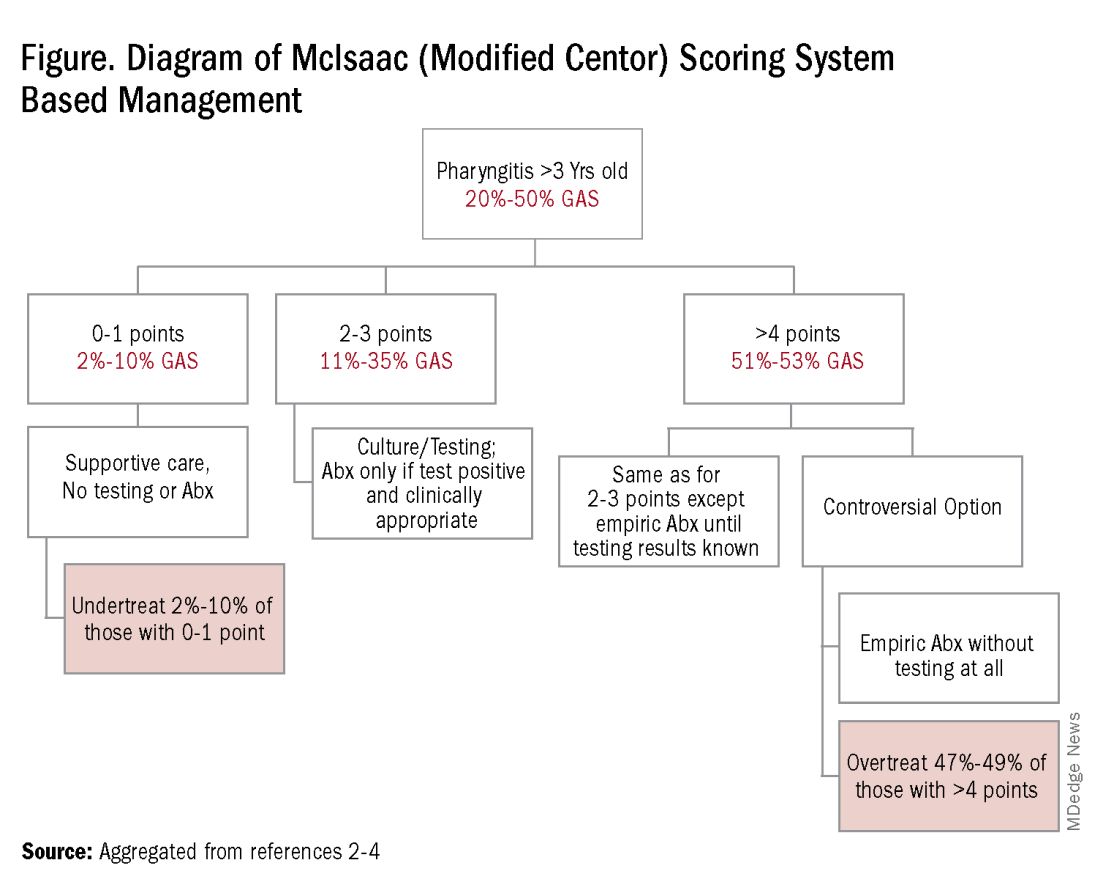

However, even with this validated scoring system, misdiagnoses and some antibiotic misuse will likely occur, particularly if the controversial option to treat a patient with a score above 4 without testing is used. For example, a 2004 study in patients older than 3 years old revealed that 45% with a score above 4 points did not have GAS pharyngitis. (McIsaac et al.) A 2012 study showed similar potential overdiagnosis from using the score without testing (45% with > 4 points did not have GAS pharyngitis). Of note, clinical scores of below 2 comprised up to 10% and would be neither tested nor treated. (Figure.)

Best clinical judgment. Regardless of the chosen test, we still need to interpret positive results, ie, use best clinical judgment. We know that even with pretest screening some positives tests will represent carriers or nonviable GAS. Yet true GAS pharyngitis needs antibiotic treatment to minimize nonpyogenic and pyogenic complications, plus reduce contagion/transmission risk and days of illness. Thus, we are forced to use best clinical judgment when considering if what could be GAS pharyngitis, particularly exudative pharyngitis, could actually be due to EBV, adenovirus, or gonococcus, each of which can mimic GAS findings. Differentiating these requires discussion beyond the scope of this article, but clues are often found in the history, the patient’s age, associated symptoms and distribution of tonsillopharyngeal exudate. Likewise Group C and G streptococcal pharyngitis can mimic GAS. Note: A comprehensive throat culture can identify these streptococci but requires a special order and likely a call to the laboratory.

Summary: The age-old problem persists, ie, differentiating the minority (~30%) of pharyngitis cases needing antibiotics from the majority that do not. We all wish to promptly treat true GAS pharyngitis; however our current tools remain imperfect. That said, we should strive to correctly diagnose/manage as many patients with pharyngitis as possible. I, for one, can’t wait until we get a validated biomarker that confirms GAS as the culprit in pharyngitis episodes. In the meantime, most providers likely have clinic or hospital approved pathways for managing GAS pharyngitis, many of which are at least in part based on data from sources for this discussion. If not, a firm foundation for creating one can be found in sources among the reference list below. Finally, if you think such pathways somehow interfere with patient flow, consider that a busy multi-provider private practice successfully integrated pretest screening and a pathway while maintaining patient flow and improving antibiotic stewardship.7

*Focal pharyngotonsillar GAS infection is rare in children younger than 3 years old, when GAS nasal passage infection may manifest as streptococcosis.9

Dr Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Missouri. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Bannerjee D, Selvarangan RS. The Evolution of Group A Streptococcus Pharyngitis Testing. Association for Diagnostics and Laboratory Medicine, 2018, Sep 1.

2. Cohen JF et al. Group A Streptococcus Pharyngitis in Children: New Perspectives on Rapid Diagnostic Testing and Antimicrobial Stewardship. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2024 Apr 24;13(4):250-256. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piae0223.

3. Boyanton Jr BL et al. Current Laboratory and Point-of-Care Pharyngitis Diagnostic Testing and Knowledge Gaps. J Infect Dis. 2024 Oct 23;230(Suppl 3):S182–S189. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiae415.

4. Group A Strep Infection. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024, Mar 1.

5. Shulman ST et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis: 2012 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2012 Nov 15;55(10):e86-102. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis629.

6. Rao A et al. Diagnosis and Antibiotic Treatment of Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis in Children in a Primary Care Setting: Impact of Point-of-Care Polymerase Chain Reaction. BMC Pediatr. 2019 Jan 16;19(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s12887-019-1393-y.

7. Norton LE et al. Improving Guideline-Based Streptococcal Pharyngitis Testing: A Quality Improvement Initiative. Pediatrics. 2018 Jul;142(1):e20172033. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2033.

8. MD+ Calc website. Centor Score (Modified/McIsaac) for Strep Pharyngitis.

9. Langlois DM, Andreae M. Group A Streptococcal Infections. Pediatr Rev. 2011 Oct;32(10):423-9; quiz 430. doi: 10.1542/pir.32-10-423.

It’s wintertime, peak season for GAS pharyngitis, and you’d think that this far into the 21st century we would have a foolproof process for diagnosing which among the many patients with pharyngitis have true GAS pharyngitis. Thinking back to the 1980s, we have come a long way from simple throat cultures for detecting GAS, e.g., numerous point of care (POC) Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA), waved rapid antigen detection tests (RADT), and numerous highly sensitive molecular assays, e.g. nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT). But if you think the issues surrounding management of GAS pharyngitis have been solved by these newer tests, think again.

Several good reviews1-3 are excellent resources for those wishing a refresher on GAS diagnosis/management issues. They present nitty gritty details on comparative advantages/disadvantages of the many testing options while reminding us of the nuts and bolts of GAS pharyngitis. The following are a few nuggets from these articles.

Properly collected throat specimen. A quality throat specimen involves swabbing both tonsillar pillars plus posterior pharynx without touching tongue or inner cheeks. Two swab collections increase sensitivity by almost 10% compared with a single swab. Transport media is preferred if samples will not be cultured within 24 hours. Caveat: RADT testing of a transport media-diluted sample lowers sensitivity compared with direct swab use.

Reliable GAS detection. Commercially available tests in 2025 are well studied. Culture is considered a gold standard for detecting clinically relevant GAS by CDC.4 Culture has good sensitivity (estimated 80%-90% varying among studies and by quality of specimens) and 99% specificity but requires 16-24 hours for results. RADT solves the time-delay issues and has near 100% specificity but sensitivity used to be as low as 65%, hence the 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline recommendation for backup throat culture for negative tests.5 However, current RADT have sensitivities in the 85%-90% range.3,4 So a positive RADT reliably and quickly indicates GAS antigens are present. NAAT have the highest combined sensitivity and specificity, near 100% for each, and a positive reliably indicates GAS nucleic acids are present.

So why not simply always use NAAT? First, it’s a “be careful what you wish for” scenario. NAAT can, and do, detect dead remnants and colonizing GAS way more than culture.2,3 So NAAT are overly sensitive, adding an extra layer of interpretation difficulty, ie, as many as 20% of positive NAAT detections may be carriers or dead GAS. Second, NAAT often requires special instrumentation and kits are more expensive. That said, reimbursement is often higher for NAAT.

Choice based on accuracy in detecting GAS. If time delays were not a problem, culture would still seem the answer. If more rapid detection is needed, either RADT with culture back up or NAAT could be the answer. That said, consider that in the real world, throat cultures are less sensitive and RADT are less specific than indicated by some published data.6 So, the ideal answer, it seems, would be NAAT GAS detection coupled with a confirmatory biomarker of GAS infection. Such innate immune biomarkers may be on the horizon.3

But first, pretest screening. In 2025 what do we do with a positive result? Do we prescribe antibiotics? Do we think the detected GAS bacteria/antigens/nucleic acids represent the cause of the pharyngitis? Or did we just detect dead GAS or even a carrier, while a virus is the true cause? Challenges for this decision include most pharyngitis (up to 70%) being due to viruses, not GAS, plus up to 20% of GAS detections even by less sensitive culture or RADT can be carriers, plus an added 10%-20% of RADT and NAAT detections are dead GAS. Thus, with indiscriminate testing of all pharyngitis patients, the number of truly positive GAS detections that are actually “false positives” (GAS in some form is present but not causing pharyngitis) may be almost as high as for those representing true GAS pharyngitis.

Some tool is needed to minimize testing patients who are likely to have viral pharyngitis to reduce test-positive/GAS-pharyngitis-negative scenarios. Pretest patient screening therefore is critical to increase the positive predictive value of positive GAS testing results. The history and physical can be helpful. In the simplest form of pretest screening, eliminate those younger than 3 years old* or those with viral type sign/symptoms, eg conjunctivitis, cough, coryza.7 This could cut “false” positives by as much as a half. More complete validated scoring systems are also available but remain imperfect. The most published is the McIsaac score (modified Centor score).3-5,8 (See Table and Figure.)

However, even with this validated scoring system, misdiagnoses and some antibiotic misuse will likely occur, particularly if the controversial option to treat a patient with a score above 4 without testing is used. For example, a 2004 study in patients older than 3 years old revealed that 45% with a score above 4 points did not have GAS pharyngitis. (McIsaac et al.) A 2012 study showed similar potential overdiagnosis from using the score without testing (45% with > 4 points did not have GAS pharyngitis). Of note, clinical scores of below 2 comprised up to 10% and would be neither tested nor treated. (Figure.)

Best clinical judgment. Regardless of the chosen test, we still need to interpret positive results, ie, use best clinical judgment. We know that even with pretest screening some positives tests will represent carriers or nonviable GAS. Yet true GAS pharyngitis needs antibiotic treatment to minimize nonpyogenic and pyogenic complications, plus reduce contagion/transmission risk and days of illness. Thus, we are forced to use best clinical judgment when considering if what could be GAS pharyngitis, particularly exudative pharyngitis, could actually be due to EBV, adenovirus, or gonococcus, each of which can mimic GAS findings. Differentiating these requires discussion beyond the scope of this article, but clues are often found in the history, the patient’s age, associated symptoms and distribution of tonsillopharyngeal exudate. Likewise Group C and G streptococcal pharyngitis can mimic GAS. Note: A comprehensive throat culture can identify these streptococci but requires a special order and likely a call to the laboratory.

Summary: The age-old problem persists, ie, differentiating the minority (~30%) of pharyngitis cases needing antibiotics from the majority that do not. We all wish to promptly treat true GAS pharyngitis; however our current tools remain imperfect. That said, we should strive to correctly diagnose/manage as many patients with pharyngitis as possible. I, for one, can’t wait until we get a validated biomarker that confirms GAS as the culprit in pharyngitis episodes. In the meantime, most providers likely have clinic or hospital approved pathways for managing GAS pharyngitis, many of which are at least in part based on data from sources for this discussion. If not, a firm foundation for creating one can be found in sources among the reference list below. Finally, if you think such pathways somehow interfere with patient flow, consider that a busy multi-provider private practice successfully integrated pretest screening and a pathway while maintaining patient flow and improving antibiotic stewardship.7

*Focal pharyngotonsillar GAS infection is rare in children younger than 3 years old, when GAS nasal passage infection may manifest as streptococcosis.9

Dr Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Missouri. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Bannerjee D, Selvarangan RS. The Evolution of Group A Streptococcus Pharyngitis Testing. Association for Diagnostics and Laboratory Medicine, 2018, Sep 1.

2. Cohen JF et al. Group A Streptococcus Pharyngitis in Children: New Perspectives on Rapid Diagnostic Testing and Antimicrobial Stewardship. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2024 Apr 24;13(4):250-256. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piae0223.

3. Boyanton Jr BL et al. Current Laboratory and Point-of-Care Pharyngitis Diagnostic Testing and Knowledge Gaps. J Infect Dis. 2024 Oct 23;230(Suppl 3):S182–S189. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiae415.

4. Group A Strep Infection. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024, Mar 1.

5. Shulman ST et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis: 2012 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2012 Nov 15;55(10):e86-102. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis629.

6. Rao A et al. Diagnosis and Antibiotic Treatment of Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis in Children in a Primary Care Setting: Impact of Point-of-Care Polymerase Chain Reaction. BMC Pediatr. 2019 Jan 16;19(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s12887-019-1393-y.

7. Norton LE et al. Improving Guideline-Based Streptococcal Pharyngitis Testing: A Quality Improvement Initiative. Pediatrics. 2018 Jul;142(1):e20172033. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2033.

8. MD+ Calc website. Centor Score (Modified/McIsaac) for Strep Pharyngitis.

9. Langlois DM, Andreae M. Group A Streptococcal Infections. Pediatr Rev. 2011 Oct;32(10):423-9; quiz 430. doi: 10.1542/pir.32-10-423.

It’s wintertime, peak season for GAS pharyngitis, and you’d think that this far into the 21st century we would have a foolproof process for diagnosing which among the many patients with pharyngitis have true GAS pharyngitis. Thinking back to the 1980s, we have come a long way from simple throat cultures for detecting GAS, e.g., numerous point of care (POC) Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA), waved rapid antigen detection tests (RADT), and numerous highly sensitive molecular assays, e.g. nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT). But if you think the issues surrounding management of GAS pharyngitis have been solved by these newer tests, think again.

Several good reviews1-3 are excellent resources for those wishing a refresher on GAS diagnosis/management issues. They present nitty gritty details on comparative advantages/disadvantages of the many testing options while reminding us of the nuts and bolts of GAS pharyngitis. The following are a few nuggets from these articles.

Properly collected throat specimen. A quality throat specimen involves swabbing both tonsillar pillars plus posterior pharynx without touching tongue or inner cheeks. Two swab collections increase sensitivity by almost 10% compared with a single swab. Transport media is preferred if samples will not be cultured within 24 hours. Caveat: RADT testing of a transport media-diluted sample lowers sensitivity compared with direct swab use.

Reliable GAS detection. Commercially available tests in 2025 are well studied. Culture is considered a gold standard for detecting clinically relevant GAS by CDC.4 Culture has good sensitivity (estimated 80%-90% varying among studies and by quality of specimens) and 99% specificity but requires 16-24 hours for results. RADT solves the time-delay issues and has near 100% specificity but sensitivity used to be as low as 65%, hence the 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline recommendation for backup throat culture for negative tests.5 However, current RADT have sensitivities in the 85%-90% range.3,4 So a positive RADT reliably and quickly indicates GAS antigens are present. NAAT have the highest combined sensitivity and specificity, near 100% for each, and a positive reliably indicates GAS nucleic acids are present.

So why not simply always use NAAT? First, it’s a “be careful what you wish for” scenario. NAAT can, and do, detect dead remnants and colonizing GAS way more than culture.2,3 So NAAT are overly sensitive, adding an extra layer of interpretation difficulty, ie, as many as 20% of positive NAAT detections may be carriers or dead GAS. Second, NAAT often requires special instrumentation and kits are more expensive. That said, reimbursement is often higher for NAAT.

Choice based on accuracy in detecting GAS. If time delays were not a problem, culture would still seem the answer. If more rapid detection is needed, either RADT with culture back up or NAAT could be the answer. That said, consider that in the real world, throat cultures are less sensitive and RADT are less specific than indicated by some published data.6 So, the ideal answer, it seems, would be NAAT GAS detection coupled with a confirmatory biomarker of GAS infection. Such innate immune biomarkers may be on the horizon.3

But first, pretest screening. In 2025 what do we do with a positive result? Do we prescribe antibiotics? Do we think the detected GAS bacteria/antigens/nucleic acids represent the cause of the pharyngitis? Or did we just detect dead GAS or even a carrier, while a virus is the true cause? Challenges for this decision include most pharyngitis (up to 70%) being due to viruses, not GAS, plus up to 20% of GAS detections even by less sensitive culture or RADT can be carriers, plus an added 10%-20% of RADT and NAAT detections are dead GAS. Thus, with indiscriminate testing of all pharyngitis patients, the number of truly positive GAS detections that are actually “false positives” (GAS in some form is present but not causing pharyngitis) may be almost as high as for those representing true GAS pharyngitis.

Some tool is needed to minimize testing patients who are likely to have viral pharyngitis to reduce test-positive/GAS-pharyngitis-negative scenarios. Pretest patient screening therefore is critical to increase the positive predictive value of positive GAS testing results. The history and physical can be helpful. In the simplest form of pretest screening, eliminate those younger than 3 years old* or those with viral type sign/symptoms, eg conjunctivitis, cough, coryza.7 This could cut “false” positives by as much as a half. More complete validated scoring systems are also available but remain imperfect. The most published is the McIsaac score (modified Centor score).3-5,8 (See Table and Figure.)

However, even with this validated scoring system, misdiagnoses and some antibiotic misuse will likely occur, particularly if the controversial option to treat a patient with a score above 4 without testing is used. For example, a 2004 study in patients older than 3 years old revealed that 45% with a score above 4 points did not have GAS pharyngitis. (McIsaac et al.) A 2012 study showed similar potential overdiagnosis from using the score without testing (45% with > 4 points did not have GAS pharyngitis). Of note, clinical scores of below 2 comprised up to 10% and would be neither tested nor treated. (Figure.)

Best clinical judgment. Regardless of the chosen test, we still need to interpret positive results, ie, use best clinical judgment. We know that even with pretest screening some positives tests will represent carriers or nonviable GAS. Yet true GAS pharyngitis needs antibiotic treatment to minimize nonpyogenic and pyogenic complications, plus reduce contagion/transmission risk and days of illness. Thus, we are forced to use best clinical judgment when considering if what could be GAS pharyngitis, particularly exudative pharyngitis, could actually be due to EBV, adenovirus, or gonococcus, each of which can mimic GAS findings. Differentiating these requires discussion beyond the scope of this article, but clues are often found in the history, the patient’s age, associated symptoms and distribution of tonsillopharyngeal exudate. Likewise Group C and G streptococcal pharyngitis can mimic GAS. Note: A comprehensive throat culture can identify these streptococci but requires a special order and likely a call to the laboratory.

Summary: The age-old problem persists, ie, differentiating the minority (~30%) of pharyngitis cases needing antibiotics from the majority that do not. We all wish to promptly treat true GAS pharyngitis; however our current tools remain imperfect. That said, we should strive to correctly diagnose/manage as many patients with pharyngitis as possible. I, for one, can’t wait until we get a validated biomarker that confirms GAS as the culprit in pharyngitis episodes. In the meantime, most providers likely have clinic or hospital approved pathways for managing GAS pharyngitis, many of which are at least in part based on data from sources for this discussion. If not, a firm foundation for creating one can be found in sources among the reference list below. Finally, if you think such pathways somehow interfere with patient flow, consider that a busy multi-provider private practice successfully integrated pretest screening and a pathway while maintaining patient flow and improving antibiotic stewardship.7

*Focal pharyngotonsillar GAS infection is rare in children younger than 3 years old, when GAS nasal passage infection may manifest as streptococcosis.9

Dr Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Missouri. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Bannerjee D, Selvarangan RS. The Evolution of Group A Streptococcus Pharyngitis Testing. Association for Diagnostics and Laboratory Medicine, 2018, Sep 1.

2. Cohen JF et al. Group A Streptococcus Pharyngitis in Children: New Perspectives on Rapid Diagnostic Testing and Antimicrobial Stewardship. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2024 Apr 24;13(4):250-256. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piae0223.

3. Boyanton Jr BL et al. Current Laboratory and Point-of-Care Pharyngitis Diagnostic Testing and Knowledge Gaps. J Infect Dis. 2024 Oct 23;230(Suppl 3):S182–S189. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiae415.

4. Group A Strep Infection. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024, Mar 1.

5. Shulman ST et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis: 2012 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2012 Nov 15;55(10):e86-102. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis629.

6. Rao A et al. Diagnosis and Antibiotic Treatment of Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis in Children in a Primary Care Setting: Impact of Point-of-Care Polymerase Chain Reaction. BMC Pediatr. 2019 Jan 16;19(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s12887-019-1393-y.

7. Norton LE et al. Improving Guideline-Based Streptococcal Pharyngitis Testing: A Quality Improvement Initiative. Pediatrics. 2018 Jul;142(1):e20172033. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2033.

8. MD+ Calc website. Centor Score (Modified/McIsaac) for Strep Pharyngitis.

9. Langlois DM, Andreae M. Group A Streptococcal Infections. Pediatr Rev. 2011 Oct;32(10):423-9; quiz 430. doi: 10.1542/pir.32-10-423.

Crying Tolerance

Most of the papers I review merely validate a relationship that most of us, including the investigators, have already assumed based on common sense. However, every now and then I encounter a study whose findings clearly don’t support the researchers’ initial thesis. The most recent example of this unexpected finding is a paper designed to determine whether the sound of a crying infant would have an effect on a parent’s ability to accurately mix formula.

After a cursory reading of the investigators’ plan, most of us would have assumed from our own difficulties trying to accomplish something while our infant is crying that the crying would have a negative effect on our accuracy. Especially if it was a task that required careful measurement. However, when I skipped ahead to read the paper’s conclusion I was surprised that the investigators could found no significant negative relationship.

The explanation for this counterintuitive finding became readily apparent when I read the details of the study’s design more carefully. The investigators had chosen to use a generic recording of an infant crying, not the parent’s child nor even a live generic child on site.

No one enjoys listening to a child cry. It is certainly not a pleasant sound to the human ear. We seem to be hardwired to find it irritating. But, listening to our own child cry raises an entirely different suite of emotions, particularly if the child is close enough for us to intervene.

I’m not sure exactly what made the investigators choose a generic recording, but I suspect it was less expensive. Otherwise it would have required that the parents agree to subjecting their child to some stimulus that would have predictably induced the child to cry. Fortunately, the investigators were able to regroup in the wake of this lack of common sense in their experimental design and realized that, while their data failed to show a negative association with crying, it did provide an important message. Formula mixing errors, some with potentially harmful consequences, are far too common. In a commentary accompanying this paper, a pediatrician not involved in the study observes that, in our efforts to promote breastfeeding, we have given short shrift to teaching parents about accurate and safe formula preparation.

But, let’s return to the crying piece. Why is it so difficult for parents to tolerate their own crying infant? Common sense should tell us that we know our infant is helpless. The little child is totally reliant on us to for nutrition and protection from the ever-present environmental threats to its health and safety in the environment. In short, whether we are parents, daycare providers, or the mother’s boyfriend who has been left in charge, we are totally responsible for the life of that infant, at times a heavy burden.

That example of biologic variability is just one of the reasons why so many families find it difficult to set limits and follow through with consequences. When I have written about and spoken to parents in the office about discipline, I am happy if I can convince both parents to be on the same page (literally sometimes) in how they respond to their crying child.

Helping an infant learn to put itself to sleep is usually the first challenge that requires some agreement between parents on how long they can tolerate crying. Although allowing the infant to cry itself to sleep may be the best and most efficient strategy, it isn’t going to work when two parents and/or caregivers have widely different cry tolerances. In some situations these discrepancies can be managed by having the less tolerant parent temporarily move himself/herself to a location out of earshot. Something often easier said than accomplished.

At the heart of the solution is an acceptance by both parents that differing cry intolerances are not unusual and don’t imply that one partner is a better parent. As advisors we also must accept this reality and help the family find some other solution. Nothing is gained by allowing a disagreement between parents to make an already uncomfortable situation any worse.

While we don’t give out merit badges for it, being able to tolerate one’s own child crying for brief periods of time is a gift that can be helpful in certain situations. It is not a skill listed in the curriculum of most parenting classes, but learning more about what prompts babies to cry can be very helpful. This educational approach is exemplified by a Pediatrics Patient Page in a recent issue of JAMA Pediatrics. It’s rarely hunger and most often is sleep deprivation. It’s rarely the result of an undiscovered injury or medical condition, but may be a response to an overstimulating environment.

For those of us who are advisers, one of our responsibilities is to be alert to those few individuals whose intolerance to crying is so great that they are likely to injure the child or its mother to stop the crying. The simple question at an early well-child visit should be something like “How is everyone in the house when the child starts crying” might save a life. The stereotypic example is the young boyfriend of the mother, who may suspect that he is not the biologic father. However, any parent who is feeling insecure because of a financial situation, poor physical or mental health, or fatigue may lash out to achieve quiet. Crying is one of the realities of infancy. It is our job to help parents cope with it safely.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Most of the papers I review merely validate a relationship that most of us, including the investigators, have already assumed based on common sense. However, every now and then I encounter a study whose findings clearly don’t support the researchers’ initial thesis. The most recent example of this unexpected finding is a paper designed to determine whether the sound of a crying infant would have an effect on a parent’s ability to accurately mix formula.

After a cursory reading of the investigators’ plan, most of us would have assumed from our own difficulties trying to accomplish something while our infant is crying that the crying would have a negative effect on our accuracy. Especially if it was a task that required careful measurement. However, when I skipped ahead to read the paper’s conclusion I was surprised that the investigators could found no significant negative relationship.

The explanation for this counterintuitive finding became readily apparent when I read the details of the study’s design more carefully. The investigators had chosen to use a generic recording of an infant crying, not the parent’s child nor even a live generic child on site.

No one enjoys listening to a child cry. It is certainly not a pleasant sound to the human ear. We seem to be hardwired to find it irritating. But, listening to our own child cry raises an entirely different suite of emotions, particularly if the child is close enough for us to intervene.

I’m not sure exactly what made the investigators choose a generic recording, but I suspect it was less expensive. Otherwise it would have required that the parents agree to subjecting their child to some stimulus that would have predictably induced the child to cry. Fortunately, the investigators were able to regroup in the wake of this lack of common sense in their experimental design and realized that, while their data failed to show a negative association with crying, it did provide an important message. Formula mixing errors, some with potentially harmful consequences, are far too common. In a commentary accompanying this paper, a pediatrician not involved in the study observes that, in our efforts to promote breastfeeding, we have given short shrift to teaching parents about accurate and safe formula preparation.

But, let’s return to the crying piece. Why is it so difficult for parents to tolerate their own crying infant? Common sense should tell us that we know our infant is helpless. The little child is totally reliant on us to for nutrition and protection from the ever-present environmental threats to its health and safety in the environment. In short, whether we are parents, daycare providers, or the mother’s boyfriend who has been left in charge, we are totally responsible for the life of that infant, at times a heavy burden.

That example of biologic variability is just one of the reasons why so many families find it difficult to set limits and follow through with consequences. When I have written about and spoken to parents in the office about discipline, I am happy if I can convince both parents to be on the same page (literally sometimes) in how they respond to their crying child.

Helping an infant learn to put itself to sleep is usually the first challenge that requires some agreement between parents on how long they can tolerate crying. Although allowing the infant to cry itself to sleep may be the best and most efficient strategy, it isn’t going to work when two parents and/or caregivers have widely different cry tolerances. In some situations these discrepancies can be managed by having the less tolerant parent temporarily move himself/herself to a location out of earshot. Something often easier said than accomplished.

At the heart of the solution is an acceptance by both parents that differing cry intolerances are not unusual and don’t imply that one partner is a better parent. As advisors we also must accept this reality and help the family find some other solution. Nothing is gained by allowing a disagreement between parents to make an already uncomfortable situation any worse.

While we don’t give out merit badges for it, being able to tolerate one’s own child crying for brief periods of time is a gift that can be helpful in certain situations. It is not a skill listed in the curriculum of most parenting classes, but learning more about what prompts babies to cry can be very helpful. This educational approach is exemplified by a Pediatrics Patient Page in a recent issue of JAMA Pediatrics. It’s rarely hunger and most often is sleep deprivation. It’s rarely the result of an undiscovered injury or medical condition, but may be a response to an overstimulating environment.

For those of us who are advisers, one of our responsibilities is to be alert to those few individuals whose intolerance to crying is so great that they are likely to injure the child or its mother to stop the crying. The simple question at an early well-child visit should be something like “How is everyone in the house when the child starts crying” might save a life. The stereotypic example is the young boyfriend of the mother, who may suspect that he is not the biologic father. However, any parent who is feeling insecure because of a financial situation, poor physical or mental health, or fatigue may lash out to achieve quiet. Crying is one of the realities of infancy. It is our job to help parents cope with it safely.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Most of the papers I review merely validate a relationship that most of us, including the investigators, have already assumed based on common sense. However, every now and then I encounter a study whose findings clearly don’t support the researchers’ initial thesis. The most recent example of this unexpected finding is a paper designed to determine whether the sound of a crying infant would have an effect on a parent’s ability to accurately mix formula.

After a cursory reading of the investigators’ plan, most of us would have assumed from our own difficulties trying to accomplish something while our infant is crying that the crying would have a negative effect on our accuracy. Especially if it was a task that required careful measurement. However, when I skipped ahead to read the paper’s conclusion I was surprised that the investigators could found no significant negative relationship.

The explanation for this counterintuitive finding became readily apparent when I read the details of the study’s design more carefully. The investigators had chosen to use a generic recording of an infant crying, not the parent’s child nor even a live generic child on site.

No one enjoys listening to a child cry. It is certainly not a pleasant sound to the human ear. We seem to be hardwired to find it irritating. But, listening to our own child cry raises an entirely different suite of emotions, particularly if the child is close enough for us to intervene.

I’m not sure exactly what made the investigators choose a generic recording, but I suspect it was less expensive. Otherwise it would have required that the parents agree to subjecting their child to some stimulus that would have predictably induced the child to cry. Fortunately, the investigators were able to regroup in the wake of this lack of common sense in their experimental design and realized that, while their data failed to show a negative association with crying, it did provide an important message. Formula mixing errors, some with potentially harmful consequences, are far too common. In a commentary accompanying this paper, a pediatrician not involved in the study observes that, in our efforts to promote breastfeeding, we have given short shrift to teaching parents about accurate and safe formula preparation.

But, let’s return to the crying piece. Why is it so difficult for parents to tolerate their own crying infant? Common sense should tell us that we know our infant is helpless. The little child is totally reliant on us to for nutrition and protection from the ever-present environmental threats to its health and safety in the environment. In short, whether we are parents, daycare providers, or the mother’s boyfriend who has been left in charge, we are totally responsible for the life of that infant, at times a heavy burden.

That example of biologic variability is just one of the reasons why so many families find it difficult to set limits and follow through with consequences. When I have written about and spoken to parents in the office about discipline, I am happy if I can convince both parents to be on the same page (literally sometimes) in how they respond to their crying child.

Helping an infant learn to put itself to sleep is usually the first challenge that requires some agreement between parents on how long they can tolerate crying. Although allowing the infant to cry itself to sleep may be the best and most efficient strategy, it isn’t going to work when two parents and/or caregivers have widely different cry tolerances. In some situations these discrepancies can be managed by having the less tolerant parent temporarily move himself/herself to a location out of earshot. Something often easier said than accomplished.

At the heart of the solution is an acceptance by both parents that differing cry intolerances are not unusual and don’t imply that one partner is a better parent. As advisors we also must accept this reality and help the family find some other solution. Nothing is gained by allowing a disagreement between parents to make an already uncomfortable situation any worse.

While we don’t give out merit badges for it, being able to tolerate one’s own child crying for brief periods of time is a gift that can be helpful in certain situations. It is not a skill listed in the curriculum of most parenting classes, but learning more about what prompts babies to cry can be very helpful. This educational approach is exemplified by a Pediatrics Patient Page in a recent issue of JAMA Pediatrics. It’s rarely hunger and most often is sleep deprivation. It’s rarely the result of an undiscovered injury or medical condition, but may be a response to an overstimulating environment.

For those of us who are advisers, one of our responsibilities is to be alert to those few individuals whose intolerance to crying is so great that they are likely to injure the child or its mother to stop the crying. The simple question at an early well-child visit should be something like “How is everyone in the house when the child starts crying” might save a life. The stereotypic example is the young boyfriend of the mother, who may suspect that he is not the biologic father. However, any parent who is feeling insecure because of a financial situation, poor physical or mental health, or fatigue may lash out to achieve quiet. Crying is one of the realities of infancy. It is our job to help parents cope with it safely.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Online CBT for Patients with AD: Self-Guided vs. Clinician-Guided Intervention Compared

TOPLINE:

A brief on the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM).

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a single-blind randomized clinical noninferiority trial at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden, enrolling 168 adults with AD (mean age, 39 years; 84.5% women) from November 2022 to April 2023.

- Participants were randomly assigned to either a 12-week self-guided online CBT intervention (n = 86) without clinician support or a comprehensive 12-week clinician-guided online CBT program (n = 82).

- The primary outcome was the change in POEM score from baseline; reduction of 4 or more points was considered a response, and the predefined noninferiority margin was 3 points.

TAKEAWAY:

- The clinician-guided group improved by 4.20 points on POEM, while the self-guided group improved by 4.60 points, with an estimated mean difference in change of 0.36 points, which was below noninferiority margin.

- Clinicians spent a mean of 36 minutes on treatment guidance and an additional 14 minutes on assessments in the clinician-guided group, whereas they spent only 15.8 minutes on assessments in the self-guided group.

- Both groups demonstrated significant improvements in quality of life, sleep, depressive mood, pruritus, and stress, with no serious adverse events being reported.

- Completion rates were higher in the self-guided group with 81% of participants completing five or more modules, compared with 67% in the clinician-guided group.

IN PRACTICE:

“Overall, the findings support a self-guided intervention as a noninferior and cost-effective alternative to a previously evaluated clinician-guided treatment,” the authors wrote. “Because psychological interventions are rare in dermatological care, this study is an important step toward implementation of CBT for people with AD. The effectiveness of CBT interventions in primary and dermatological specialist care should be investigated.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Dorian Kern, PhD, Division of Psychology, Karolinska Institutet, and was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

High data loss for secondary measurements could affect interpretation of these results. The study relied solely on self-reported measures. The predominance of women participants and the Swedish-language requirement may have limited participation from migrant populations, which could hinder the broader implementation of the study’s findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the Swedish Ministry of Health and Social Affairs. Kern reported receiving grants from the Swedish Ministry of Health and Social Affairs during the conduct of the study. Other authors also reported authorships and royalties, personal fees, grants, or held stocks in DahliaQomit.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

A brief on the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM).

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a single-blind randomized clinical noninferiority trial at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden, enrolling 168 adults with AD (mean age, 39 years; 84.5% women) from November 2022 to April 2023.

- Participants were randomly assigned to either a 12-week self-guided online CBT intervention (n = 86) without clinician support or a comprehensive 12-week clinician-guided online CBT program (n = 82).

- The primary outcome was the change in POEM score from baseline; reduction of 4 or more points was considered a response, and the predefined noninferiority margin was 3 points.

TAKEAWAY:

- The clinician-guided group improved by 4.20 points on POEM, while the self-guided group improved by 4.60 points, with an estimated mean difference in change of 0.36 points, which was below noninferiority margin.

- Clinicians spent a mean of 36 minutes on treatment guidance and an additional 14 minutes on assessments in the clinician-guided group, whereas they spent only 15.8 minutes on assessments in the self-guided group.

- Both groups demonstrated significant improvements in quality of life, sleep, depressive mood, pruritus, and stress, with no serious adverse events being reported.

- Completion rates were higher in the self-guided group with 81% of participants completing five or more modules, compared with 67% in the clinician-guided group.

IN PRACTICE:

“Overall, the findings support a self-guided intervention as a noninferior and cost-effective alternative to a previously evaluated clinician-guided treatment,” the authors wrote. “Because psychological interventions are rare in dermatological care, this study is an important step toward implementation of CBT for people with AD. The effectiveness of CBT interventions in primary and dermatological specialist care should be investigated.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Dorian Kern, PhD, Division of Psychology, Karolinska Institutet, and was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

High data loss for secondary measurements could affect interpretation of these results. The study relied solely on self-reported measures. The predominance of women participants and the Swedish-language requirement may have limited participation from migrant populations, which could hinder the broader implementation of the study’s findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the Swedish Ministry of Health and Social Affairs. Kern reported receiving grants from the Swedish Ministry of Health and Social Affairs during the conduct of the study. Other authors also reported authorships and royalties, personal fees, grants, or held stocks in DahliaQomit.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

A brief on the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM).

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a single-blind randomized clinical noninferiority trial at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden, enrolling 168 adults with AD (mean age, 39 years; 84.5% women) from November 2022 to April 2023.

- Participants were randomly assigned to either a 12-week self-guided online CBT intervention (n = 86) without clinician support or a comprehensive 12-week clinician-guided online CBT program (n = 82).

- The primary outcome was the change in POEM score from baseline; reduction of 4 or more points was considered a response, and the predefined noninferiority margin was 3 points.

TAKEAWAY:

- The clinician-guided group improved by 4.20 points on POEM, while the self-guided group improved by 4.60 points, with an estimated mean difference in change of 0.36 points, which was below noninferiority margin.

- Clinicians spent a mean of 36 minutes on treatment guidance and an additional 14 minutes on assessments in the clinician-guided group, whereas they spent only 15.8 minutes on assessments in the self-guided group.

- Both groups demonstrated significant improvements in quality of life, sleep, depressive mood, pruritus, and stress, with no serious adverse events being reported.

- Completion rates were higher in the self-guided group with 81% of participants completing five or more modules, compared with 67% in the clinician-guided group.

IN PRACTICE:

“Overall, the findings support a self-guided intervention as a noninferior and cost-effective alternative to a previously evaluated clinician-guided treatment,” the authors wrote. “Because psychological interventions are rare in dermatological care, this study is an important step toward implementation of CBT for people with AD. The effectiveness of CBT interventions in primary and dermatological specialist care should be investigated.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Dorian Kern, PhD, Division of Psychology, Karolinska Institutet, and was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

High data loss for secondary measurements could affect interpretation of these results. The study relied solely on self-reported measures. The predominance of women participants and the Swedish-language requirement may have limited participation from migrant populations, which could hinder the broader implementation of the study’s findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the Swedish Ministry of Health and Social Affairs. Kern reported receiving grants from the Swedish Ministry of Health and Social Affairs during the conduct of the study. Other authors also reported authorships and royalties, personal fees, grants, or held stocks in DahliaQomit.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Central Line Skin Reactions in Children: Survey Addresses Treatment Protocols in Use

TOPLINE:

A and reported varying management approaches.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers developed and administered a 14-item Qualtrics survey to 107 dermatologists providing pediatric inpatient care through the Society for Pediatric Dermatology’s Inpatient Dermatology Section and Section Chief email lists.

- A total of 35 dermatologists (33%) from multiple institutions responded to the survey; most respondents (94%) specialized in pediatric dermatology.

- Researchers assessed management of CLD-associated adverse skin reactions.

TAKEAWAY:

- All respondents reported receiving CLD-related consults, but 66% indicated there was no personal or institutional standardized approach for managing CLD-associated skin reactions.

- Respondents said most reactions were in children aged 1-12 years (19 or 76% of 25 respondents) compared with those aged < 1 year (3 or 12% of 25 respondents).

- Management strategies included switching to alternative products, applying topical corticosteroids, and performing patch testing for allergies.

IN PRACTICE:

“Insights derived from this study, including variation in clinician familiarity with reaction patterns, underscore the necessity of a standardized protocol for classifying and managing cutaneous CLD reactions in pediatric patients,” the authors wrote. “Further investigation is needed to better characterize CLD-associated allergic CD [contact dermatitis], irritant CD, and skin infections, as well as at-risk populations, to better inform clinical approaches,” they added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Carly Mulinda, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, and was published online on December 16 in Pediatric Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors noted variable respondent awareness of institutional CLD and potential recency bias as key limitations of the study.

DISCLOSURES:

Study funding source was not declared. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

A and reported varying management approaches.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers developed and administered a 14-item Qualtrics survey to 107 dermatologists providing pediatric inpatient care through the Society for Pediatric Dermatology’s Inpatient Dermatology Section and Section Chief email lists.

- A total of 35 dermatologists (33%) from multiple institutions responded to the survey; most respondents (94%) specialized in pediatric dermatology.

- Researchers assessed management of CLD-associated adverse skin reactions.

TAKEAWAY:

- All respondents reported receiving CLD-related consults, but 66% indicated there was no personal or institutional standardized approach for managing CLD-associated skin reactions.

- Respondents said most reactions were in children aged 1-12 years (19 or 76% of 25 respondents) compared with those aged < 1 year (3 or 12% of 25 respondents).

- Management strategies included switching to alternative products, applying topical corticosteroids, and performing patch testing for allergies.

IN PRACTICE:

“Insights derived from this study, including variation in clinician familiarity with reaction patterns, underscore the necessity of a standardized protocol for classifying and managing cutaneous CLD reactions in pediatric patients,” the authors wrote. “Further investigation is needed to better characterize CLD-associated allergic CD [contact dermatitis], irritant CD, and skin infections, as well as at-risk populations, to better inform clinical approaches,” they added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Carly Mulinda, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, and was published online on December 16 in Pediatric Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors noted variable respondent awareness of institutional CLD and potential recency bias as key limitations of the study.

DISCLOSURES:

Study funding source was not declared. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

A and reported varying management approaches.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers developed and administered a 14-item Qualtrics survey to 107 dermatologists providing pediatric inpatient care through the Society for Pediatric Dermatology’s Inpatient Dermatology Section and Section Chief email lists.

- A total of 35 dermatologists (33%) from multiple institutions responded to the survey; most respondents (94%) specialized in pediatric dermatology.

- Researchers assessed management of CLD-associated adverse skin reactions.

TAKEAWAY:

- All respondents reported receiving CLD-related consults, but 66% indicated there was no personal or institutional standardized approach for managing CLD-associated skin reactions.

- Respondents said most reactions were in children aged 1-12 years (19 or 76% of 25 respondents) compared with those aged < 1 year (3 or 12% of 25 respondents).

- Management strategies included switching to alternative products, applying topical corticosteroids, and performing patch testing for allergies.

IN PRACTICE:

“Insights derived from this study, including variation in clinician familiarity with reaction patterns, underscore the necessity of a standardized protocol for classifying and managing cutaneous CLD reactions in pediatric patients,” the authors wrote. “Further investigation is needed to better characterize CLD-associated allergic CD [contact dermatitis], irritant CD, and skin infections, as well as at-risk populations, to better inform clinical approaches,” they added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Carly Mulinda, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, and was published online on December 16 in Pediatric Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors noted variable respondent awareness of institutional CLD and potential recency bias as key limitations of the study.

DISCLOSURES:

Study funding source was not declared. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Brain Changes in Youth Who Use Substances: Cause or Effect?

A widely accepted assumption in the addiction field is that neuroanatomical changes observed in young people who use alcohol or other substances are largely the consequence of exposure to these substances.

But a new study suggests that neuroanatomical features in children, including greater whole brain and cortical volumes, are evident before exposure to any substances.

The investigators, led by Alex P. Miller, PhD, assistant professor, Department of Psychiatry, Indiana University, Indianapolis, noted that the findings add to a growing body of work that suggests

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Neuroanatomy a Predisposing Risk Factor?

Earlier research showed that substance use is associated with lower gray matter volume, thinner cortex, and less white matter integrity. While it has been widely thought that these changes were induced by the use of alcohol or illicit drugs, recent longitudinal and genetic studies suggest that the neuroanatomical changes may also be predisposing risk factors for substance use.

To better understand the issue, investigators analyzed data on 9804 children (mean baseline age, 9.9 years; 53% men; 76% White) at 22 US sites enrolled in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study that’s examining brain and behavioral development from middle childhood to young adulthood.

The researchers collected information on the use of alcohol, nicotine, cannabis, and other illicit substances from in-person interviews at baseline and years 1, 2, and 3, as well as interim phone interviews at 6, 18, and 30 months. MRI scans provided extensive brain structural data, including global and regional cortical volume, thickness, surface area, sulcal depth, and subcortical volume.

Of the total, 3460 participants (35%) initiated substance use before age 15, with 90% reporting alcohol use initiation. There was considerable overlap between initiation of alcohol, nicotine, and cannabis.

The researchers tested whether baseline neuroanatomical variability was associated with any substance use initiation before or up to 3 years following initial neuroimaging scans. Study covariates included baseline age, sex, pubertal status, familial relationship (eg, sibling or twin), and prenatal substance exposures. Researchers didn’t control for sociodemographic characteristics as these could influence associations.

Significant Brain Differences

Compared with no substance use initiation, any substance use initiation was associated with larger global neuroanatomical indices, including whole brain (beta = 0.05; P = 2.80 × 10–8), total intracranial (beta = 0.04; P = 3.49 × 10−6), cortical (beta = 0.05; P = 4.31 × 10–8), and subcortical volumes (beta = 0.05; P = 4.39 × 10–8), as well as greater total cortical surface area (beta = 0.04; P = 6.05 × 10–7).

The direction of associations between cortical thickness and substance use initiation was regionally specific; any substance use initiation was characterized by thinner cortex in all frontal regions (eg, rostral middle frontal gyrus, beta = −0.03; P = 6.99 × 10–6), but thicker cortex in all other lobes. It was also associated with larger regional brain volumes, deeper regional sulci, and differences in regional cortical surface area.

The authors noted total cortical thickness peaks at age 1.7 years and steadily declines throughout life. By contrast, subcortical volumes peak at 14.4 years of age and generally remain stable before steep later life declines.

Secondary analyses compared initiation of the three most commonly used substances in early adolescence (alcohol, nicotine, and cannabis) with no substance use.

Findings for alcohol largely mirrored those for any substance use. However, the study uncovered additional significant associations, including greater left lateral occipital volume and bilateral para-hippocampal gyri cortical thickness and less bilateral superior frontal gyri cortical thickness.

Nicotine use was associated with lower right superior frontal gyrus volume and deeper left lateral orbitofrontal cortex sulci. And cannabis use was associated with thinner left precentral gyrus and lower right inferior parietal gyrus and right caudate volumes.

The authors noted results for nicotine and cannabis may not have had adequate statistical power, and small effects suggest these findings aren’t clinically informative for individuals. However, they wrote, “They do inform and challenge current theoretical models of addiction.”

Associations Precede Substance Use

A post hoc analysis further challenges current models of addiction. When researchers looked only at the 1203 youth who initiated substance use after the baseline neuroimaging session, they found most associations preceded substance use.

“That regional associations may precede substance use initiation, including less cortical thickness in the right rostral middle frontal gyrus, challenges predominant interpretations that these associations arise largely due to neurotoxic consequences of exposure and increases the plausibility that these features may, at least partially, reflect markers of predispositional risk,” wrote the authors.

A study limitation was that unmeasured confounders and undetected systemic differences in missing data may have influenced associations. Sociodemographic, environmental, and genetic variables that were not included as covariates are likely associated with both neuroanatomical variability and substance use initiation and may moderate associations between them, said the authors.

The ABCD Study provides “a robust and large database of longitudinal data” that goes beyond previous neuroimaging research “to understand the bidirectional relationship between brain structure and substance use,” Miller said in a press release.

“The hope is that these types of studies, in conjunction with other data on environmental exposures and genetic risk, could help change how we think about the development of substance use disorders and inform more accurate models of addiction moving forward,” Miller said.

Reevaluating Causal Assumptions

In an accompanying editorial, Felix Pichardo, MA, and Sylia Wilson, PhD, from the Institute of Child Development, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, suggested that it may be time to “reevaluate the causal assumptions that underlie brain disease models of addiction” and the mechanisms by which it develops, persists, and becomes harmful.

Neurotoxic effects of substances are central to current brain disease models of addiction, wrote Pichardo and Wilson. “Substance exposure is thought to affect cortical and subcortical regions that support interrelated systems, resulting in desensitization of reward-related processing, increased stress that prompts cravings, negative emotions when cravings are unsated, and weakening of cognitive control abilities that leads to repeated returns to use.”

The editorial writers praised the ABCD Study for its large sample size for providing a level of precision, statistical accuracy, and ability to identify both larger and smaller effects, which are critical for addiction research.

Unlike most addiction research that relies on cross-sectional designs, the current study used longitudinal assessments, which is another of its strengths, they noted.

“Longitudinal study designs like in the ABCD Study are fundamental for establishing temporal ordering across constructs, which is important because establishing temporal precedence is a key step in determining causal links and underlying mechanisms.”

The inclusion of several genetically informative components, such as the family study design, nested twin subsamples, and DNA collection, “allows researchers to extend beyond temporal precedence toward increased causal inference and identification of mechanisms,” they added.

The study received support from the National Institutes of Health. The study authors and editorial writers had no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A widely accepted assumption in the addiction field is that neuroanatomical changes observed in young people who use alcohol or other substances are largely the consequence of exposure to these substances.

But a new study suggests that neuroanatomical features in children, including greater whole brain and cortical volumes, are evident before exposure to any substances.

The investigators, led by Alex P. Miller, PhD, assistant professor, Department of Psychiatry, Indiana University, Indianapolis, noted that the findings add to a growing body of work that suggests

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Neuroanatomy a Predisposing Risk Factor?

Earlier research showed that substance use is associated with lower gray matter volume, thinner cortex, and less white matter integrity. While it has been widely thought that these changes were induced by the use of alcohol or illicit drugs, recent longitudinal and genetic studies suggest that the neuroanatomical changes may also be predisposing risk factors for substance use.

To better understand the issue, investigators analyzed data on 9804 children (mean baseline age, 9.9 years; 53% men; 76% White) at 22 US sites enrolled in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study that’s examining brain and behavioral development from middle childhood to young adulthood.

The researchers collected information on the use of alcohol, nicotine, cannabis, and other illicit substances from in-person interviews at baseline and years 1, 2, and 3, as well as interim phone interviews at 6, 18, and 30 months. MRI scans provided extensive brain structural data, including global and regional cortical volume, thickness, surface area, sulcal depth, and subcortical volume.

Of the total, 3460 participants (35%) initiated substance use before age 15, with 90% reporting alcohol use initiation. There was considerable overlap between initiation of alcohol, nicotine, and cannabis.

The researchers tested whether baseline neuroanatomical variability was associated with any substance use initiation before or up to 3 years following initial neuroimaging scans. Study covariates included baseline age, sex, pubertal status, familial relationship (eg, sibling or twin), and prenatal substance exposures. Researchers didn’t control for sociodemographic characteristics as these could influence associations.

Significant Brain Differences

Compared with no substance use initiation, any substance use initiation was associated with larger global neuroanatomical indices, including whole brain (beta = 0.05; P = 2.80 × 10–8), total intracranial (beta = 0.04; P = 3.49 × 10−6), cortical (beta = 0.05; P = 4.31 × 10–8), and subcortical volumes (beta = 0.05; P = 4.39 × 10–8), as well as greater total cortical surface area (beta = 0.04; P = 6.05 × 10–7).

The direction of associations between cortical thickness and substance use initiation was regionally specific; any substance use initiation was characterized by thinner cortex in all frontal regions (eg, rostral middle frontal gyrus, beta = −0.03; P = 6.99 × 10–6), but thicker cortex in all other lobes. It was also associated with larger regional brain volumes, deeper regional sulci, and differences in regional cortical surface area.

The authors noted total cortical thickness peaks at age 1.7 years and steadily declines throughout life. By contrast, subcortical volumes peak at 14.4 years of age and generally remain stable before steep later life declines.

Secondary analyses compared initiation of the three most commonly used substances in early adolescence (alcohol, nicotine, and cannabis) with no substance use.

Findings for alcohol largely mirrored those for any substance use. However, the study uncovered additional significant associations, including greater left lateral occipital volume and bilateral para-hippocampal gyri cortical thickness and less bilateral superior frontal gyri cortical thickness.

Nicotine use was associated with lower right superior frontal gyrus volume and deeper left lateral orbitofrontal cortex sulci. And cannabis use was associated with thinner left precentral gyrus and lower right inferior parietal gyrus and right caudate volumes.

The authors noted results for nicotine and cannabis may not have had adequate statistical power, and small effects suggest these findings aren’t clinically informative for individuals. However, they wrote, “They do inform and challenge current theoretical models of addiction.”

Associations Precede Substance Use

A post hoc analysis further challenges current models of addiction. When researchers looked only at the 1203 youth who initiated substance use after the baseline neuroimaging session, they found most associations preceded substance use.

“That regional associations may precede substance use initiation, including less cortical thickness in the right rostral middle frontal gyrus, challenges predominant interpretations that these associations arise largely due to neurotoxic consequences of exposure and increases the plausibility that these features may, at least partially, reflect markers of predispositional risk,” wrote the authors.

A study limitation was that unmeasured confounders and undetected systemic differences in missing data may have influenced associations. Sociodemographic, environmental, and genetic variables that were not included as covariates are likely associated with both neuroanatomical variability and substance use initiation and may moderate associations between them, said the authors.

The ABCD Study provides “a robust and large database of longitudinal data” that goes beyond previous neuroimaging research “to understand the bidirectional relationship between brain structure and substance use,” Miller said in a press release.

“The hope is that these types of studies, in conjunction with other data on environmental exposures and genetic risk, could help change how we think about the development of substance use disorders and inform more accurate models of addiction moving forward,” Miller said.

Reevaluating Causal Assumptions

In an accompanying editorial, Felix Pichardo, MA, and Sylia Wilson, PhD, from the Institute of Child Development, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, suggested that it may be time to “reevaluate the causal assumptions that underlie brain disease models of addiction” and the mechanisms by which it develops, persists, and becomes harmful.

Neurotoxic effects of substances are central to current brain disease models of addiction, wrote Pichardo and Wilson. “Substance exposure is thought to affect cortical and subcortical regions that support interrelated systems, resulting in desensitization of reward-related processing, increased stress that prompts cravings, negative emotions when cravings are unsated, and weakening of cognitive control abilities that leads to repeated returns to use.”

The editorial writers praised the ABCD Study for its large sample size for providing a level of precision, statistical accuracy, and ability to identify both larger and smaller effects, which are critical for addiction research.

Unlike most addiction research that relies on cross-sectional designs, the current study used longitudinal assessments, which is another of its strengths, they noted.

“Longitudinal study designs like in the ABCD Study are fundamental for establishing temporal ordering across constructs, which is important because establishing temporal precedence is a key step in determining causal links and underlying mechanisms.”

The inclusion of several genetically informative components, such as the family study design, nested twin subsamples, and DNA collection, “allows researchers to extend beyond temporal precedence toward increased causal inference and identification of mechanisms,” they added.

The study received support from the National Institutes of Health. The study authors and editorial writers had no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A widely accepted assumption in the addiction field is that neuroanatomical changes observed in young people who use alcohol or other substances are largely the consequence of exposure to these substances.

But a new study suggests that neuroanatomical features in children, including greater whole brain and cortical volumes, are evident before exposure to any substances.

The investigators, led by Alex P. Miller, PhD, assistant professor, Department of Psychiatry, Indiana University, Indianapolis, noted that the findings add to a growing body of work that suggests

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Neuroanatomy a Predisposing Risk Factor?

Earlier research showed that substance use is associated with lower gray matter volume, thinner cortex, and less white matter integrity. While it has been widely thought that these changes were induced by the use of alcohol or illicit drugs, recent longitudinal and genetic studies suggest that the neuroanatomical changes may also be predisposing risk factors for substance use.