User login

Possible Simeprevir/Sofosbuvir-Induced Hepatic Decompensation With Acute Kidney Failure

The emergence of hepatitis C (HCV) treatment regimens in the past 5 years has resulted in a major paradigm shift in the management of those infected with this virus. The 2011 approval of boceprevir and telaprevir was associated with a higher virologic response (50%-75%) and a shorter length of therapy depending on the patient population. Despite these gains, first generation direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) required multiple doses, had a higher pill burden with numerous drug interactions, and adverse effects (AEs). In addition, viral resistance limited the full use of the first generation DAAs for all genotypes.

Sofosbuvir, simeprevir, and ledipasvir-sofosbuvir (second generation DAAs) boast even higher (> 90%) sustained virologic response rates (SVR) and more tolerable AE profiles especially anemia, depression, and gastrointestinal symptoms compared with the first generation DAAs. At the time of treatment for this case study, sofosbuvir/ledipasvir was not commercially available. Sofosbuvir in combination with simeprevir with or without ribavirin was one of the preferred treatment options for chronic HCV.1

Unlike the first generation DAAs, which have been associated with a decline in renal function compared with conventional pegylated interferon and ribavirin, sofosbuvir is extensively renally eliminated by glomerular filtration and active tubular secretion as the metabolite GS-331007. On the other hand, simeprevir is hepatically metabolized.

A PubMed literature search for reports of “simeprevir-induced” or “sofosbuvir-induced with hepatic, renal failure, acute kidney injury” yielded only 1 published case of hepatic decompensation likely related to simeprevir, but no case report of simeprevir and sofosbuvir associated with hepatic decompensation and acute kidney injury.4 In this article, the authors describe a case of hepatic decompensation and acute kidney injury caused by simeprevir/sofosbuvir initiation for chronic HCV that required intensive care and dialysis.

Case Report

The patient was a 62-year-old African American man with chronic HCV, genotype 1b, TT IL28B, and 4,980,000 IU baseline viral load. He was treatment naïve with biopsy proven compensated cirrhosis, and Child-Turcotte-Pugh class A with a pretreatment model for end-stage liver disease score of 12. His past medical history included hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD) (baseline serum creatinine [SCr] 1.4-1.8 mg/dL), benign prostatic hypertrophy, depression, obesity (30.6 body mass index, 246 lb), and psoriasis. In addition, the patient was on the following maintenance medications: allopurinol, bupropion, diltiazem, sustained-release and immediate-release morphine, sennosides, and terazosin.

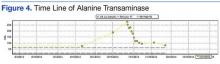

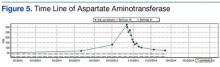

In September 2014, the patient was diagnosed with biopsy-confirmed hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) Barcelona clinic liver cancer stage B T3aN0M0 stage III. He was considered for transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), but treatment was withheld due to subsequent increase in liver function tests (LFTs) with total bilirubin (TB) 2.9 mg/dL, direct bilirubin (DB) 1.8 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase test (AST) 130 U/L, and alanine aminotransferase test (ALT) 188 U/L (baseline: TB 1.1 mg/dL, AST 69 U/L, and ALT 76 U/L). These results were thought to be the result of worsening hepatic function from untreated HCV, therefore, treatment was initiated.

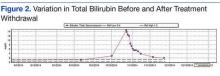

The patient was started on simeprevir 150 mg orally daily and sofosbuvir 400 mg orally daily with an estimated baseline creatinine clearance of 67 mL/min per Cockcroft-Gault equation.5 Two days after therapy initiation, the patient presented to the emergency department with the following symptoms: hiccups, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Laboratory results showed 10.85 mg/dL SCr and 91 mg/dL blood urea nitrogen (BUN), TB increased to 14.6 mg/dL with AST of 325 U/L and ALT 277 U/L. The patient reported no use of acetaminophen, alcohol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or other nephrotoxic agents.

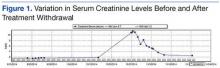

Upon admission, the patient was diagnosed with drug-induced hepatitis and acute kidney injury (AKI). Simeprevir/sofosbuvir was discontinued along with allopurinol, bupropion, lisinopril, and morphine. An abdominal ultrasound was negative for obstructive uropathy. The patient did not respond to fluid boluses. A nephrologist was consulted, and dialysis was initiated. The patient underwent dialysis for 3 days and his LFTs and SCr levels started trending downward (Figures 1 to 5).

The patient was discharged after 8 days. After 3 weeks, the SCr decreased to 2.29 mg/dL, BUN was 26 mg/dL, TB was 2 mg/dL, DB was 0.9 mg/dL, AST was 73 U/L, and ALT was 81 U/L. Weekly laboratory values continued to improve following discharge but did not return to baseline levels. The patient remained off HCV treatment.

Discussion

The patient had baseline CKD with SCr > 1.5 mg/dL; however, the significant decline in renal function and worsening hepatic function were thought to be the result of external factors. Although hepatorenal syndrome was considered, the authors suspected that the AKI and hepatic decompensation were related to simeprevir/sofosbuvir regimens due to their presumed relationship and probability analysis. Osinusi and colleagues noted a decline in renal function in a patient who received ledipasvir/sofosbuvir for 6 weeks in an open-label pilot study.6 Stine and colleagues also reported on cases of simeprevir-related hepatic decompensation.4

In this case, the authors employed the Naranjo algorithm adverse drug reaction probability scale to assess whether there was a causal relationship between this event and initiation of simeprevir/sofosbuvir regimen.7 The Naranjo score was 4, indicating a possible link between simeprevir/sofosbuvir initiation and hepatic decompensation and AKI. This case may be the first postmarketing report of significant hepatic decompensation and AKI related to simeprevir/sofosbuvir.

Unlike simeprevir, which undergoes extensive oxidative metabolism by CYP3A in the liver and has negligible renal clearance with < 1% of the dose recovered in the urine, sofosbuvir is extensively metabolized by the kidneys with an active metabolite, GS-331007, and about 80% of the dose is recovered in urine (78% as GS-331007; 3.5% as sofosbuvir).8,9 The potential for drug-drug interaction also was assessed because simeprevir is extensively metabolized by the hepatic cytochrome CYP34 system and possibly CYP2C8 and CYP2C19. Clinically significant interactions could have occurred with diltiazem and morphine, because the coadministration of these medications along with simeprevir, an inhibitor of P-glycoprotein (P-gp), and intestinal CYP3A4, may result in increased diltiazem and morphine plasma concentrations.

Of note, because sofosbuvir is a substrate of P-gp, it may have its serum concentration increased by simeprevir. Inducers and inhibitors of P-gp may alter the plasma concentration of sofosbuvir. The major metabolite, GS-331007, is not a substrate of P-gp. Drugs that induce P-gp may reduce the therapeutic effect of sofosbuvir; however, the FDA-labeling suggests that inhibitors of P-gp may be coadministered with sofosbuvir.

According to simeprevir prescribing information, drug interaction studies have demonstrated that moderate CYP3A4 inhibitors, such as diltiazem (although coadministration have not been studied), increased the maximum serum concentration (Cmax), minumum serum concentration (Cmin), and AUC of simeprevir.7 As a result, concurrent use of simeprevir with a moderate CYP3A4 inhibitors is not recommended. Morphine and simeprevir interaction also is possible via the P-gp inhibition of simeprevir. Morphine concentration may have increased and metabolites may have accumulated, leading to urinary retention and elevated creatinine. In addition, decreased oral intake and subsequent nausea/vomiting may have compounded the renal insult.

Conclusion

Given that updated HCV treatment guidelines include simeprevir/sofosbuvir as an alternative treatment option, clinicians should be aware of hepatic decompensation with markedly elevated bilirubin and AKI during simeprevir and sofosbuvir treatment. Careful consideration is needed prior to the initiation of simeprevir/sofosbuvir, particularly in patients with advanced liver disease or known HCC and baseline renal impairment.

1. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C: Initial Treatment of HCV. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America Website. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed February 8, 2016.

2. Mauss S, Hueppe D, Alshuth U. Renal impairment is frequent in chronic hepatitis C patient under triple therapy with telaprevir or boceprevir. Hepatology. 2014;59(1):46-48.

3. Virlogeux V, Pradat P, Bailly F, et al. Boceprevir and telaprevir-based triple therapy for chronic hepatitis C: virolgical efficacy and impact on kidney function and model for end-stage liver disease score. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21(9):e98-e107.

4. Stine JG, Intagliata N, Shah L, et al. Hepatic decompensation likely attributable to simeprevir in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(4):1031-1035.

5. Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16(1):31-41.

6. Osinusi A, Kohli A, Marti MM, et al. Re-treamtent of chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection after relapse: an open-label pilot study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(9):634-638.

7. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239-245.

8. Olysio (simeprevir) [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Therapeutics; 2014.

9. Sovaldi (sofosbuvir) [package insert]. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences, Inc; 2014.

The emergence of hepatitis C (HCV) treatment regimens in the past 5 years has resulted in a major paradigm shift in the management of those infected with this virus. The 2011 approval of boceprevir and telaprevir was associated with a higher virologic response (50%-75%) and a shorter length of therapy depending on the patient population. Despite these gains, first generation direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) required multiple doses, had a higher pill burden with numerous drug interactions, and adverse effects (AEs). In addition, viral resistance limited the full use of the first generation DAAs for all genotypes.

Sofosbuvir, simeprevir, and ledipasvir-sofosbuvir (second generation DAAs) boast even higher (> 90%) sustained virologic response rates (SVR) and more tolerable AE profiles especially anemia, depression, and gastrointestinal symptoms compared with the first generation DAAs. At the time of treatment for this case study, sofosbuvir/ledipasvir was not commercially available. Sofosbuvir in combination with simeprevir with or without ribavirin was one of the preferred treatment options for chronic HCV.1

Unlike the first generation DAAs, which have been associated with a decline in renal function compared with conventional pegylated interferon and ribavirin, sofosbuvir is extensively renally eliminated by glomerular filtration and active tubular secretion as the metabolite GS-331007. On the other hand, simeprevir is hepatically metabolized.

A PubMed literature search for reports of “simeprevir-induced” or “sofosbuvir-induced with hepatic, renal failure, acute kidney injury” yielded only 1 published case of hepatic decompensation likely related to simeprevir, but no case report of simeprevir and sofosbuvir associated with hepatic decompensation and acute kidney injury.4 In this article, the authors describe a case of hepatic decompensation and acute kidney injury caused by simeprevir/sofosbuvir initiation for chronic HCV that required intensive care and dialysis.

Case Report

The patient was a 62-year-old African American man with chronic HCV, genotype 1b, TT IL28B, and 4,980,000 IU baseline viral load. He was treatment naïve with biopsy proven compensated cirrhosis, and Child-Turcotte-Pugh class A with a pretreatment model for end-stage liver disease score of 12. His past medical history included hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD) (baseline serum creatinine [SCr] 1.4-1.8 mg/dL), benign prostatic hypertrophy, depression, obesity (30.6 body mass index, 246 lb), and psoriasis. In addition, the patient was on the following maintenance medications: allopurinol, bupropion, diltiazem, sustained-release and immediate-release morphine, sennosides, and terazosin.

In September 2014, the patient was diagnosed with biopsy-confirmed hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) Barcelona clinic liver cancer stage B T3aN0M0 stage III. He was considered for transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), but treatment was withheld due to subsequent increase in liver function tests (LFTs) with total bilirubin (TB) 2.9 mg/dL, direct bilirubin (DB) 1.8 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase test (AST) 130 U/L, and alanine aminotransferase test (ALT) 188 U/L (baseline: TB 1.1 mg/dL, AST 69 U/L, and ALT 76 U/L). These results were thought to be the result of worsening hepatic function from untreated HCV, therefore, treatment was initiated.

The patient was started on simeprevir 150 mg orally daily and sofosbuvir 400 mg orally daily with an estimated baseline creatinine clearance of 67 mL/min per Cockcroft-Gault equation.5 Two days after therapy initiation, the patient presented to the emergency department with the following symptoms: hiccups, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Laboratory results showed 10.85 mg/dL SCr and 91 mg/dL blood urea nitrogen (BUN), TB increased to 14.6 mg/dL with AST of 325 U/L and ALT 277 U/L. The patient reported no use of acetaminophen, alcohol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or other nephrotoxic agents.

Upon admission, the patient was diagnosed with drug-induced hepatitis and acute kidney injury (AKI). Simeprevir/sofosbuvir was discontinued along with allopurinol, bupropion, lisinopril, and morphine. An abdominal ultrasound was negative for obstructive uropathy. The patient did not respond to fluid boluses. A nephrologist was consulted, and dialysis was initiated. The patient underwent dialysis for 3 days and his LFTs and SCr levels started trending downward (Figures 1 to 5).

The patient was discharged after 8 days. After 3 weeks, the SCr decreased to 2.29 mg/dL, BUN was 26 mg/dL, TB was 2 mg/dL, DB was 0.9 mg/dL, AST was 73 U/L, and ALT was 81 U/L. Weekly laboratory values continued to improve following discharge but did not return to baseline levels. The patient remained off HCV treatment.

Discussion

The patient had baseline CKD with SCr > 1.5 mg/dL; however, the significant decline in renal function and worsening hepatic function were thought to be the result of external factors. Although hepatorenal syndrome was considered, the authors suspected that the AKI and hepatic decompensation were related to simeprevir/sofosbuvir regimens due to their presumed relationship and probability analysis. Osinusi and colleagues noted a decline in renal function in a patient who received ledipasvir/sofosbuvir for 6 weeks in an open-label pilot study.6 Stine and colleagues also reported on cases of simeprevir-related hepatic decompensation.4

In this case, the authors employed the Naranjo algorithm adverse drug reaction probability scale to assess whether there was a causal relationship between this event and initiation of simeprevir/sofosbuvir regimen.7 The Naranjo score was 4, indicating a possible link between simeprevir/sofosbuvir initiation and hepatic decompensation and AKI. This case may be the first postmarketing report of significant hepatic decompensation and AKI related to simeprevir/sofosbuvir.

Unlike simeprevir, which undergoes extensive oxidative metabolism by CYP3A in the liver and has negligible renal clearance with < 1% of the dose recovered in the urine, sofosbuvir is extensively metabolized by the kidneys with an active metabolite, GS-331007, and about 80% of the dose is recovered in urine (78% as GS-331007; 3.5% as sofosbuvir).8,9 The potential for drug-drug interaction also was assessed because simeprevir is extensively metabolized by the hepatic cytochrome CYP34 system and possibly CYP2C8 and CYP2C19. Clinically significant interactions could have occurred with diltiazem and morphine, because the coadministration of these medications along with simeprevir, an inhibitor of P-glycoprotein (P-gp), and intestinal CYP3A4, may result in increased diltiazem and morphine plasma concentrations.

Of note, because sofosbuvir is a substrate of P-gp, it may have its serum concentration increased by simeprevir. Inducers and inhibitors of P-gp may alter the plasma concentration of sofosbuvir. The major metabolite, GS-331007, is not a substrate of P-gp. Drugs that induce P-gp may reduce the therapeutic effect of sofosbuvir; however, the FDA-labeling suggests that inhibitors of P-gp may be coadministered with sofosbuvir.

According to simeprevir prescribing information, drug interaction studies have demonstrated that moderate CYP3A4 inhibitors, such as diltiazem (although coadministration have not been studied), increased the maximum serum concentration (Cmax), minumum serum concentration (Cmin), and AUC of simeprevir.7 As a result, concurrent use of simeprevir with a moderate CYP3A4 inhibitors is not recommended. Morphine and simeprevir interaction also is possible via the P-gp inhibition of simeprevir. Morphine concentration may have increased and metabolites may have accumulated, leading to urinary retention and elevated creatinine. In addition, decreased oral intake and subsequent nausea/vomiting may have compounded the renal insult.

Conclusion

Given that updated HCV treatment guidelines include simeprevir/sofosbuvir as an alternative treatment option, clinicians should be aware of hepatic decompensation with markedly elevated bilirubin and AKI during simeprevir and sofosbuvir treatment. Careful consideration is needed prior to the initiation of simeprevir/sofosbuvir, particularly in patients with advanced liver disease or known HCC and baseline renal impairment.

The emergence of hepatitis C (HCV) treatment regimens in the past 5 years has resulted in a major paradigm shift in the management of those infected with this virus. The 2011 approval of boceprevir and telaprevir was associated with a higher virologic response (50%-75%) and a shorter length of therapy depending on the patient population. Despite these gains, first generation direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) required multiple doses, had a higher pill burden with numerous drug interactions, and adverse effects (AEs). In addition, viral resistance limited the full use of the first generation DAAs for all genotypes.

Sofosbuvir, simeprevir, and ledipasvir-sofosbuvir (second generation DAAs) boast even higher (> 90%) sustained virologic response rates (SVR) and more tolerable AE profiles especially anemia, depression, and gastrointestinal symptoms compared with the first generation DAAs. At the time of treatment for this case study, sofosbuvir/ledipasvir was not commercially available. Sofosbuvir in combination with simeprevir with or without ribavirin was one of the preferred treatment options for chronic HCV.1

Unlike the first generation DAAs, which have been associated with a decline in renal function compared with conventional pegylated interferon and ribavirin, sofosbuvir is extensively renally eliminated by glomerular filtration and active tubular secretion as the metabolite GS-331007. On the other hand, simeprevir is hepatically metabolized.

A PubMed literature search for reports of “simeprevir-induced” or “sofosbuvir-induced with hepatic, renal failure, acute kidney injury” yielded only 1 published case of hepatic decompensation likely related to simeprevir, but no case report of simeprevir and sofosbuvir associated with hepatic decompensation and acute kidney injury.4 In this article, the authors describe a case of hepatic decompensation and acute kidney injury caused by simeprevir/sofosbuvir initiation for chronic HCV that required intensive care and dialysis.

Case Report

The patient was a 62-year-old African American man with chronic HCV, genotype 1b, TT IL28B, and 4,980,000 IU baseline viral load. He was treatment naïve with biopsy proven compensated cirrhosis, and Child-Turcotte-Pugh class A with a pretreatment model for end-stage liver disease score of 12. His past medical history included hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD) (baseline serum creatinine [SCr] 1.4-1.8 mg/dL), benign prostatic hypertrophy, depression, obesity (30.6 body mass index, 246 lb), and psoriasis. In addition, the patient was on the following maintenance medications: allopurinol, bupropion, diltiazem, sustained-release and immediate-release morphine, sennosides, and terazosin.

In September 2014, the patient was diagnosed with biopsy-confirmed hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) Barcelona clinic liver cancer stage B T3aN0M0 stage III. He was considered for transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), but treatment was withheld due to subsequent increase in liver function tests (LFTs) with total bilirubin (TB) 2.9 mg/dL, direct bilirubin (DB) 1.8 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase test (AST) 130 U/L, and alanine aminotransferase test (ALT) 188 U/L (baseline: TB 1.1 mg/dL, AST 69 U/L, and ALT 76 U/L). These results were thought to be the result of worsening hepatic function from untreated HCV, therefore, treatment was initiated.

The patient was started on simeprevir 150 mg orally daily and sofosbuvir 400 mg orally daily with an estimated baseline creatinine clearance of 67 mL/min per Cockcroft-Gault equation.5 Two days after therapy initiation, the patient presented to the emergency department with the following symptoms: hiccups, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Laboratory results showed 10.85 mg/dL SCr and 91 mg/dL blood urea nitrogen (BUN), TB increased to 14.6 mg/dL with AST of 325 U/L and ALT 277 U/L. The patient reported no use of acetaminophen, alcohol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or other nephrotoxic agents.

Upon admission, the patient was diagnosed with drug-induced hepatitis and acute kidney injury (AKI). Simeprevir/sofosbuvir was discontinued along with allopurinol, bupropion, lisinopril, and morphine. An abdominal ultrasound was negative for obstructive uropathy. The patient did not respond to fluid boluses. A nephrologist was consulted, and dialysis was initiated. The patient underwent dialysis for 3 days and his LFTs and SCr levels started trending downward (Figures 1 to 5).

The patient was discharged after 8 days. After 3 weeks, the SCr decreased to 2.29 mg/dL, BUN was 26 mg/dL, TB was 2 mg/dL, DB was 0.9 mg/dL, AST was 73 U/L, and ALT was 81 U/L. Weekly laboratory values continued to improve following discharge but did not return to baseline levels. The patient remained off HCV treatment.

Discussion

The patient had baseline CKD with SCr > 1.5 mg/dL; however, the significant decline in renal function and worsening hepatic function were thought to be the result of external factors. Although hepatorenal syndrome was considered, the authors suspected that the AKI and hepatic decompensation were related to simeprevir/sofosbuvir regimens due to their presumed relationship and probability analysis. Osinusi and colleagues noted a decline in renal function in a patient who received ledipasvir/sofosbuvir for 6 weeks in an open-label pilot study.6 Stine and colleagues also reported on cases of simeprevir-related hepatic decompensation.4

In this case, the authors employed the Naranjo algorithm adverse drug reaction probability scale to assess whether there was a causal relationship between this event and initiation of simeprevir/sofosbuvir regimen.7 The Naranjo score was 4, indicating a possible link between simeprevir/sofosbuvir initiation and hepatic decompensation and AKI. This case may be the first postmarketing report of significant hepatic decompensation and AKI related to simeprevir/sofosbuvir.

Unlike simeprevir, which undergoes extensive oxidative metabolism by CYP3A in the liver and has negligible renal clearance with < 1% of the dose recovered in the urine, sofosbuvir is extensively metabolized by the kidneys with an active metabolite, GS-331007, and about 80% of the dose is recovered in urine (78% as GS-331007; 3.5% as sofosbuvir).8,9 The potential for drug-drug interaction also was assessed because simeprevir is extensively metabolized by the hepatic cytochrome CYP34 system and possibly CYP2C8 and CYP2C19. Clinically significant interactions could have occurred with diltiazem and morphine, because the coadministration of these medications along with simeprevir, an inhibitor of P-glycoprotein (P-gp), and intestinal CYP3A4, may result in increased diltiazem and morphine plasma concentrations.

Of note, because sofosbuvir is a substrate of P-gp, it may have its serum concentration increased by simeprevir. Inducers and inhibitors of P-gp may alter the plasma concentration of sofosbuvir. The major metabolite, GS-331007, is not a substrate of P-gp. Drugs that induce P-gp may reduce the therapeutic effect of sofosbuvir; however, the FDA-labeling suggests that inhibitors of P-gp may be coadministered with sofosbuvir.

According to simeprevir prescribing information, drug interaction studies have demonstrated that moderate CYP3A4 inhibitors, such as diltiazem (although coadministration have not been studied), increased the maximum serum concentration (Cmax), minumum serum concentration (Cmin), and AUC of simeprevir.7 As a result, concurrent use of simeprevir with a moderate CYP3A4 inhibitors is not recommended. Morphine and simeprevir interaction also is possible via the P-gp inhibition of simeprevir. Morphine concentration may have increased and metabolites may have accumulated, leading to urinary retention and elevated creatinine. In addition, decreased oral intake and subsequent nausea/vomiting may have compounded the renal insult.

Conclusion

Given that updated HCV treatment guidelines include simeprevir/sofosbuvir as an alternative treatment option, clinicians should be aware of hepatic decompensation with markedly elevated bilirubin and AKI during simeprevir and sofosbuvir treatment. Careful consideration is needed prior to the initiation of simeprevir/sofosbuvir, particularly in patients with advanced liver disease or known HCC and baseline renal impairment.

1. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C: Initial Treatment of HCV. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America Website. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed February 8, 2016.

2. Mauss S, Hueppe D, Alshuth U. Renal impairment is frequent in chronic hepatitis C patient under triple therapy with telaprevir or boceprevir. Hepatology. 2014;59(1):46-48.

3. Virlogeux V, Pradat P, Bailly F, et al. Boceprevir and telaprevir-based triple therapy for chronic hepatitis C: virolgical efficacy and impact on kidney function and model for end-stage liver disease score. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21(9):e98-e107.

4. Stine JG, Intagliata N, Shah L, et al. Hepatic decompensation likely attributable to simeprevir in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(4):1031-1035.

5. Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16(1):31-41.

6. Osinusi A, Kohli A, Marti MM, et al. Re-treamtent of chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection after relapse: an open-label pilot study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(9):634-638.

7. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239-245.

8. Olysio (simeprevir) [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Therapeutics; 2014.

9. Sovaldi (sofosbuvir) [package insert]. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences, Inc; 2014.

1. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C: Initial Treatment of HCV. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America Website. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed February 8, 2016.

2. Mauss S, Hueppe D, Alshuth U. Renal impairment is frequent in chronic hepatitis C patient under triple therapy with telaprevir or boceprevir. Hepatology. 2014;59(1):46-48.

3. Virlogeux V, Pradat P, Bailly F, et al. Boceprevir and telaprevir-based triple therapy for chronic hepatitis C: virolgical efficacy and impact on kidney function and model for end-stage liver disease score. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21(9):e98-e107.

4. Stine JG, Intagliata N, Shah L, et al. Hepatic decompensation likely attributable to simeprevir in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(4):1031-1035.

5. Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16(1):31-41.

6. Osinusi A, Kohli A, Marti MM, et al. Re-treamtent of chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection after relapse: an open-label pilot study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(9):634-638.

7. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239-245.

8. Olysio (simeprevir) [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Therapeutics; 2014.

9. Sovaldi (sofosbuvir) [package insert]. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences, Inc; 2014.

Onychomatricoma: A Rare Case of Unguioblastic Fibroma of the Fingernail Associated With Trauma

Onychomatricoma (OM) is a rare benign neoplasm of the nail matrix. Even less common is its possible association with both trauma to the nail apparatus and onychomycosis. This case illustrates both of these findings.

Case Report

A 72-year-old white man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 26-year history of a thickened nail plate on the right third finger that had developed soon after a baseball injury. The patient reported that the nail was completely normal prior to the trauma. According to the patient, the distal aspect of the finger was directly hit by a baseball and subsequently was wrapped by the patient for a few weeks. The nail then turned black and eventually fell off. When the nail grew back, it appeared abnormal and in its current state. The patient stated the lesion was asymptomatic at the time of presentation.

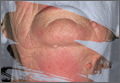

Physical examination revealed thickening, yellow discoloration, and transverse overcurvature of the nail plate on the right third finger with longitudinal ridging (Figure 1). A culture of the nail plate grew Chaetomium species. Application of topical clotrimazole for 3 months followed by a 6-week course of oral terbinafine produced no improvement. The patient then consented to a nail matrix incisional biopsy 6 months after initial presentation. After a digital nerve block was administered and a tourniquet of the proximal digit was applied, a nail avulsion was performed. Subsequently, a 3-mm punch biopsy was taken of the clinically apparent tumor in the nail matrix.

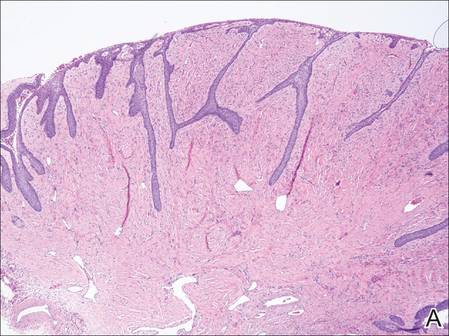

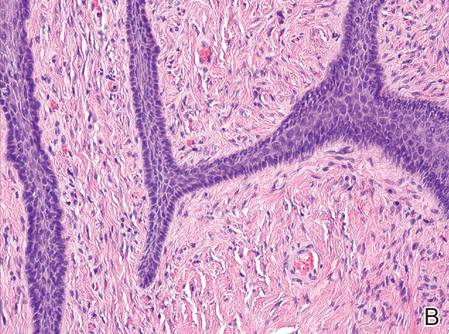

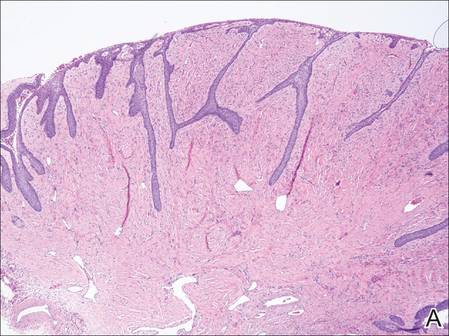

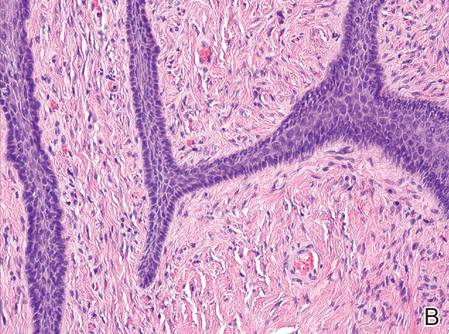

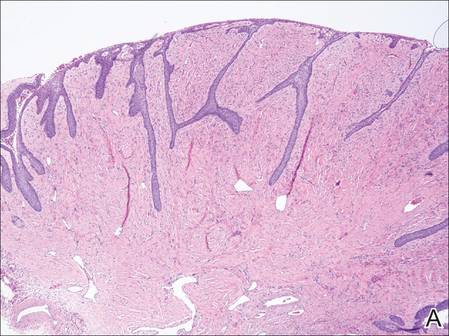

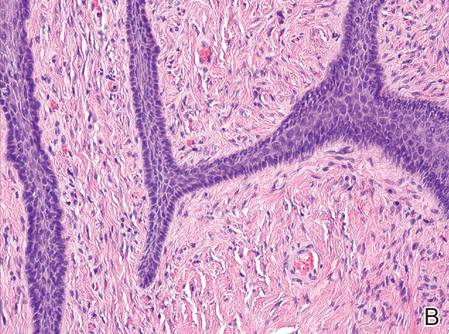

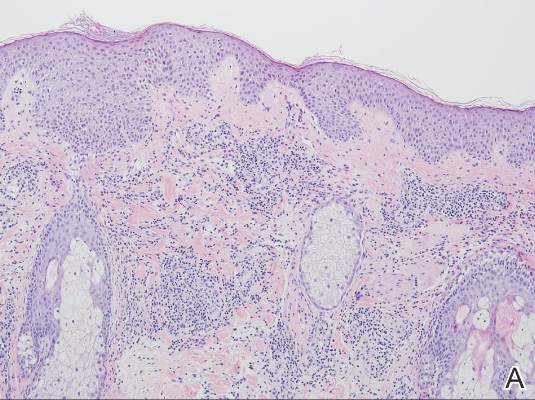

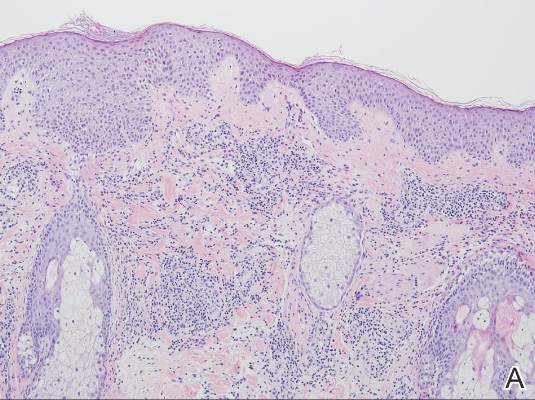

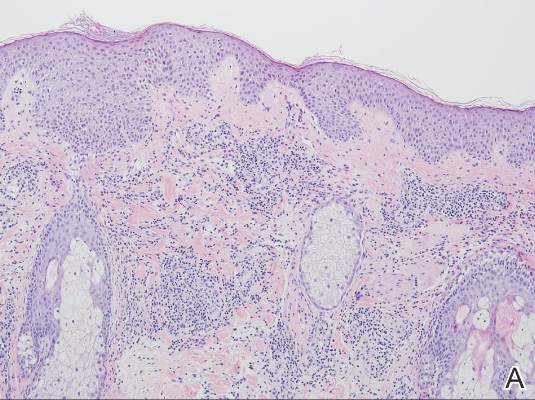

On microscopic examination of the removed tissue, a benign mixed epithelial and stromal proliferative lesion was noted. The basaloid epithelium, lacking a granular layer, arose from the surface epithelial layer and formed a reticulated pattern extending into the stromal component, which was moderately cellular with spindle to fusiform nuclei dissecting between collagen bundles arranged in parallel arrays (Figure 2). The stromal component predominated over the epithelial component in this neoplasm. The nail was preserved in formalin and underwent hematoxylin and eosin staining. It was thickened and grossly showed filiform fibrous projections extending into the nail plate. Histologically, the nail displayed prominent oval clear channels. Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal organisms.

A diagnosis of unguioblastic fibroma–type OM was made. After receiving the diagnosis, expected course, and treatment options, the patient was offered conservative surgical excision but preferred clinical monitoring. At his last visit (6 months after the biopsy), the nail plate distal to the biopsy site had thinning and improvement, while the nail plate distal to the matrix that was not removed continued to show thickening, yellow discoloration, overcurvature, and longitudinal ridging (Figure 3).

|  | |

Figure 2. The basaloid epithelium arose from the surface epithelial layer and formed a reticulated pattern extending into the stromal component (A)(H&E, original magnification ×2). At higher magnification, the stromal component was moderately cellular with spindle to fusiform nuclei dissecting between collagen bundles arranged in parallel arrays (B)(H&E, original magnification ×10). | ||

|

|

Comment

Onychomatricoma is a rare tumor originating from the nail matrix. The tumor was first described by Baran and Kint1 in 1992 using the term onychomatrixoma, but later the term onychomatricoma became more widely used.2 Onychomatricomas are more common in adults (mean age, 48 years) and white individuals with no gender predilection.3,4 Fingernail involvement is twice as common as toenail involvement.3 Onychomatricoma is the only tumor that actively produces a nail plate.4

Clinically, OM presents with yellow discoloration along the entire nail plate and proximal splinter hemorrhages. It has a tendency toward transverse overcurvature of the nail plate with prominent longitudinal ridging.4 Trauma has been associated in at least 3 cases reported in the literature, though the association was sometimes weak.3,4 Xanthonychia and onychodystrophy of the nail are common.3 Pterygium, melanonychia, nail bleeding, and cutaneous horns have been reported but are rare.3-5 The tumor typically is painless with no radiographic bone involvement.3 Onychomycosis can be present,3 which may either be a predisposing factor for the tumor or secondary due to the deformed nail plate.4

When the nail plate is avulsed and the proximal nail fold is turned back, the matrix tumor is exposed. This polypoid and filiform tumor has characteristic fingerlike fibrokeratogenous projections extending from the nail matrix into the nail plate.3

Histologically, the tumor is fibroepithelial or biphasic with stromal and epithelial components. It has a lobulated and papillary growth pattern with 2 distinct areas that correspond to 2 anatomic zones.3 The base of the tumor corresponds to the proximal anatomic zone, which begins at the root of the nail and extends to the cuticle. This area is composed of V-shaped keratinous zones similar to the normal matrix. If the nail is removed prior to excision, these areas can be avulsed, leaving clear clefts. The superficial aspect of the tumor corresponds to the distal anatomic zone, which is located in the region of the lunula. This area is composed of multiple digitate or fingerlike projections with a fibrous core and a thick matrical epithelial covering.3 These digitations extend into small cavities in the nail plate, which can be visualized as clear channels or woodwormlike holes in hematoxylin and eosin–stained specimens. A biphasic fibrous stroma also can be observed with the superficial dermis being cellular with fibrillary collagen and the deep dermis more hypocellular with thicker collagen bundles.3,4

An analysis of keratins in the nail matrix, bed, and isthmus showed that OM has the capacity to recapitulate the entire nail unit with differentiation toward the nail bed and isthmus.6 It appears that the mesenchymal component has an inductive effect that can lead to complete epithelial onychogenic differentiation.6

Due to the histological differences among the described cases of OM in the literature, a new classification based on the spectrum of epithelial to stromal ratio of stromal cellularity and the extent of nuclear pleomorphism was proposed in 2004.7 The prominent feature of the unguioblastoma type of OM is epithelial, while the cellular stroma is the prominent feature in the unguioblastic fibroma type. Atypical unguioblastic fibroma refers to a tumor with increased mitotic activity and nuclear pleomorphism among the stroma.7

Most OM tumors follow a benign clinical course; however, complete excision is advised to include the normal nail matrix proximal to the lesion, which may prevent recurrence and serves as a primary treatment.

Conclusion

Onychomatricoma is a benign neoplasm of the nail matrix that may be triggered by trauma; however, due to the weak association, further observations and studies should be conducted to substantiate this possibility. Patients with the classic clinical presentation possibly may be spared a nail avulsion and biopsy. Onychomycosis occurs in the setting of OM, and culture and treatment are unlikely to change the appearance or course of this nail condition.

1. Baran R, Kint A. Onychomatrixoma. filamentous tufted tumour in the matrix of a funnel-shaped nail: a new entity (report of three cases). Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:510-515.

2. Haneke E, Franken J. Onychomatricoma. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21:984-987.

3. Gaertner EM, Gordon M, Reed T. Onychomatricoma: case report of an unusual subungual tumor with literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36(suppl 1):66-69.

4. Cañueto J, Santos-Briz Á, García JL, et al. Onychomatricoma: genome-wide analyses of a rare nail matrix tumor. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:573-578.

5. Perrin C, Baran R. Onychomatricoma with dorsalpterygium: pathogenic mechanisms in 3 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:990-994.

6. Perrin C, Langbein L, Schweizer J, et al. Onychomatricoma in the light of the microanatomy of the normal nail unit. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:131-139.

7. Ko CJ, Shi L, Barr RJ, et al. Unguioblastoma and unguioblastic fibroma—an expanded spectrum of onychomatricoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:307-311.

Onychomatricoma (OM) is a rare benign neoplasm of the nail matrix. Even less common is its possible association with both trauma to the nail apparatus and onychomycosis. This case illustrates both of these findings.

Case Report

A 72-year-old white man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 26-year history of a thickened nail plate on the right third finger that had developed soon after a baseball injury. The patient reported that the nail was completely normal prior to the trauma. According to the patient, the distal aspect of the finger was directly hit by a baseball and subsequently was wrapped by the patient for a few weeks. The nail then turned black and eventually fell off. When the nail grew back, it appeared abnormal and in its current state. The patient stated the lesion was asymptomatic at the time of presentation.

Physical examination revealed thickening, yellow discoloration, and transverse overcurvature of the nail plate on the right third finger with longitudinal ridging (Figure 1). A culture of the nail plate grew Chaetomium species. Application of topical clotrimazole for 3 months followed by a 6-week course of oral terbinafine produced no improvement. The patient then consented to a nail matrix incisional biopsy 6 months after initial presentation. After a digital nerve block was administered and a tourniquet of the proximal digit was applied, a nail avulsion was performed. Subsequently, a 3-mm punch biopsy was taken of the clinically apparent tumor in the nail matrix.

On microscopic examination of the removed tissue, a benign mixed epithelial and stromal proliferative lesion was noted. The basaloid epithelium, lacking a granular layer, arose from the surface epithelial layer and formed a reticulated pattern extending into the stromal component, which was moderately cellular with spindle to fusiform nuclei dissecting between collagen bundles arranged in parallel arrays (Figure 2). The stromal component predominated over the epithelial component in this neoplasm. The nail was preserved in formalin and underwent hematoxylin and eosin staining. It was thickened and grossly showed filiform fibrous projections extending into the nail plate. Histologically, the nail displayed prominent oval clear channels. Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal organisms.

A diagnosis of unguioblastic fibroma–type OM was made. After receiving the diagnosis, expected course, and treatment options, the patient was offered conservative surgical excision but preferred clinical monitoring. At his last visit (6 months after the biopsy), the nail plate distal to the biopsy site had thinning and improvement, while the nail plate distal to the matrix that was not removed continued to show thickening, yellow discoloration, overcurvature, and longitudinal ridging (Figure 3).

|  | |

Figure 2. The basaloid epithelium arose from the surface epithelial layer and formed a reticulated pattern extending into the stromal component (A)(H&E, original magnification ×2). At higher magnification, the stromal component was moderately cellular with spindle to fusiform nuclei dissecting between collagen bundles arranged in parallel arrays (B)(H&E, original magnification ×10). | ||

|

|

Comment

Onychomatricoma is a rare tumor originating from the nail matrix. The tumor was first described by Baran and Kint1 in 1992 using the term onychomatrixoma, but later the term onychomatricoma became more widely used.2 Onychomatricomas are more common in adults (mean age, 48 years) and white individuals with no gender predilection.3,4 Fingernail involvement is twice as common as toenail involvement.3 Onychomatricoma is the only tumor that actively produces a nail plate.4

Clinically, OM presents with yellow discoloration along the entire nail plate and proximal splinter hemorrhages. It has a tendency toward transverse overcurvature of the nail plate with prominent longitudinal ridging.4 Trauma has been associated in at least 3 cases reported in the literature, though the association was sometimes weak.3,4 Xanthonychia and onychodystrophy of the nail are common.3 Pterygium, melanonychia, nail bleeding, and cutaneous horns have been reported but are rare.3-5 The tumor typically is painless with no radiographic bone involvement.3 Onychomycosis can be present,3 which may either be a predisposing factor for the tumor or secondary due to the deformed nail plate.4

When the nail plate is avulsed and the proximal nail fold is turned back, the matrix tumor is exposed. This polypoid and filiform tumor has characteristic fingerlike fibrokeratogenous projections extending from the nail matrix into the nail plate.3

Histologically, the tumor is fibroepithelial or biphasic with stromal and epithelial components. It has a lobulated and papillary growth pattern with 2 distinct areas that correspond to 2 anatomic zones.3 The base of the tumor corresponds to the proximal anatomic zone, which begins at the root of the nail and extends to the cuticle. This area is composed of V-shaped keratinous zones similar to the normal matrix. If the nail is removed prior to excision, these areas can be avulsed, leaving clear clefts. The superficial aspect of the tumor corresponds to the distal anatomic zone, which is located in the region of the lunula. This area is composed of multiple digitate or fingerlike projections with a fibrous core and a thick matrical epithelial covering.3 These digitations extend into small cavities in the nail plate, which can be visualized as clear channels or woodwormlike holes in hematoxylin and eosin–stained specimens. A biphasic fibrous stroma also can be observed with the superficial dermis being cellular with fibrillary collagen and the deep dermis more hypocellular with thicker collagen bundles.3,4

An analysis of keratins in the nail matrix, bed, and isthmus showed that OM has the capacity to recapitulate the entire nail unit with differentiation toward the nail bed and isthmus.6 It appears that the mesenchymal component has an inductive effect that can lead to complete epithelial onychogenic differentiation.6

Due to the histological differences among the described cases of OM in the literature, a new classification based on the spectrum of epithelial to stromal ratio of stromal cellularity and the extent of nuclear pleomorphism was proposed in 2004.7 The prominent feature of the unguioblastoma type of OM is epithelial, while the cellular stroma is the prominent feature in the unguioblastic fibroma type. Atypical unguioblastic fibroma refers to a tumor with increased mitotic activity and nuclear pleomorphism among the stroma.7

Most OM tumors follow a benign clinical course; however, complete excision is advised to include the normal nail matrix proximal to the lesion, which may prevent recurrence and serves as a primary treatment.

Conclusion

Onychomatricoma is a benign neoplasm of the nail matrix that may be triggered by trauma; however, due to the weak association, further observations and studies should be conducted to substantiate this possibility. Patients with the classic clinical presentation possibly may be spared a nail avulsion and biopsy. Onychomycosis occurs in the setting of OM, and culture and treatment are unlikely to change the appearance or course of this nail condition.

Onychomatricoma (OM) is a rare benign neoplasm of the nail matrix. Even less common is its possible association with both trauma to the nail apparatus and onychomycosis. This case illustrates both of these findings.

Case Report

A 72-year-old white man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 26-year history of a thickened nail plate on the right third finger that had developed soon after a baseball injury. The patient reported that the nail was completely normal prior to the trauma. According to the patient, the distal aspect of the finger was directly hit by a baseball and subsequently was wrapped by the patient for a few weeks. The nail then turned black and eventually fell off. When the nail grew back, it appeared abnormal and in its current state. The patient stated the lesion was asymptomatic at the time of presentation.

Physical examination revealed thickening, yellow discoloration, and transverse overcurvature of the nail plate on the right third finger with longitudinal ridging (Figure 1). A culture of the nail plate grew Chaetomium species. Application of topical clotrimazole for 3 months followed by a 6-week course of oral terbinafine produced no improvement. The patient then consented to a nail matrix incisional biopsy 6 months after initial presentation. After a digital nerve block was administered and a tourniquet of the proximal digit was applied, a nail avulsion was performed. Subsequently, a 3-mm punch biopsy was taken of the clinically apparent tumor in the nail matrix.

On microscopic examination of the removed tissue, a benign mixed epithelial and stromal proliferative lesion was noted. The basaloid epithelium, lacking a granular layer, arose from the surface epithelial layer and formed a reticulated pattern extending into the stromal component, which was moderately cellular with spindle to fusiform nuclei dissecting between collagen bundles arranged in parallel arrays (Figure 2). The stromal component predominated over the epithelial component in this neoplasm. The nail was preserved in formalin and underwent hematoxylin and eosin staining. It was thickened and grossly showed filiform fibrous projections extending into the nail plate. Histologically, the nail displayed prominent oval clear channels. Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal organisms.

A diagnosis of unguioblastic fibroma–type OM was made. After receiving the diagnosis, expected course, and treatment options, the patient was offered conservative surgical excision but preferred clinical monitoring. At his last visit (6 months after the biopsy), the nail plate distal to the biopsy site had thinning and improvement, while the nail plate distal to the matrix that was not removed continued to show thickening, yellow discoloration, overcurvature, and longitudinal ridging (Figure 3).

|  | |

Figure 2. The basaloid epithelium arose from the surface epithelial layer and formed a reticulated pattern extending into the stromal component (A)(H&E, original magnification ×2). At higher magnification, the stromal component was moderately cellular with spindle to fusiform nuclei dissecting between collagen bundles arranged in parallel arrays (B)(H&E, original magnification ×10). | ||

|

|

Comment

Onychomatricoma is a rare tumor originating from the nail matrix. The tumor was first described by Baran and Kint1 in 1992 using the term onychomatrixoma, but later the term onychomatricoma became more widely used.2 Onychomatricomas are more common in adults (mean age, 48 years) and white individuals with no gender predilection.3,4 Fingernail involvement is twice as common as toenail involvement.3 Onychomatricoma is the only tumor that actively produces a nail plate.4

Clinically, OM presents with yellow discoloration along the entire nail plate and proximal splinter hemorrhages. It has a tendency toward transverse overcurvature of the nail plate with prominent longitudinal ridging.4 Trauma has been associated in at least 3 cases reported in the literature, though the association was sometimes weak.3,4 Xanthonychia and onychodystrophy of the nail are common.3 Pterygium, melanonychia, nail bleeding, and cutaneous horns have been reported but are rare.3-5 The tumor typically is painless with no radiographic bone involvement.3 Onychomycosis can be present,3 which may either be a predisposing factor for the tumor or secondary due to the deformed nail plate.4

When the nail plate is avulsed and the proximal nail fold is turned back, the matrix tumor is exposed. This polypoid and filiform tumor has characteristic fingerlike fibrokeratogenous projections extending from the nail matrix into the nail plate.3

Histologically, the tumor is fibroepithelial or biphasic with stromal and epithelial components. It has a lobulated and papillary growth pattern with 2 distinct areas that correspond to 2 anatomic zones.3 The base of the tumor corresponds to the proximal anatomic zone, which begins at the root of the nail and extends to the cuticle. This area is composed of V-shaped keratinous zones similar to the normal matrix. If the nail is removed prior to excision, these areas can be avulsed, leaving clear clefts. The superficial aspect of the tumor corresponds to the distal anatomic zone, which is located in the region of the lunula. This area is composed of multiple digitate or fingerlike projections with a fibrous core and a thick matrical epithelial covering.3 These digitations extend into small cavities in the nail plate, which can be visualized as clear channels or woodwormlike holes in hematoxylin and eosin–stained specimens. A biphasic fibrous stroma also can be observed with the superficial dermis being cellular with fibrillary collagen and the deep dermis more hypocellular with thicker collagen bundles.3,4

An analysis of keratins in the nail matrix, bed, and isthmus showed that OM has the capacity to recapitulate the entire nail unit with differentiation toward the nail bed and isthmus.6 It appears that the mesenchymal component has an inductive effect that can lead to complete epithelial onychogenic differentiation.6

Due to the histological differences among the described cases of OM in the literature, a new classification based on the spectrum of epithelial to stromal ratio of stromal cellularity and the extent of nuclear pleomorphism was proposed in 2004.7 The prominent feature of the unguioblastoma type of OM is epithelial, while the cellular stroma is the prominent feature in the unguioblastic fibroma type. Atypical unguioblastic fibroma refers to a tumor with increased mitotic activity and nuclear pleomorphism among the stroma.7

Most OM tumors follow a benign clinical course; however, complete excision is advised to include the normal nail matrix proximal to the lesion, which may prevent recurrence and serves as a primary treatment.

Conclusion

Onychomatricoma is a benign neoplasm of the nail matrix that may be triggered by trauma; however, due to the weak association, further observations and studies should be conducted to substantiate this possibility. Patients with the classic clinical presentation possibly may be spared a nail avulsion and biopsy. Onychomycosis occurs in the setting of OM, and culture and treatment are unlikely to change the appearance or course of this nail condition.

1. Baran R, Kint A. Onychomatrixoma. filamentous tufted tumour in the matrix of a funnel-shaped nail: a new entity (report of three cases). Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:510-515.

2. Haneke E, Franken J. Onychomatricoma. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21:984-987.

3. Gaertner EM, Gordon M, Reed T. Onychomatricoma: case report of an unusual subungual tumor with literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36(suppl 1):66-69.

4. Cañueto J, Santos-Briz Á, García JL, et al. Onychomatricoma: genome-wide analyses of a rare nail matrix tumor. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:573-578.

5. Perrin C, Baran R. Onychomatricoma with dorsalpterygium: pathogenic mechanisms in 3 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:990-994.

6. Perrin C, Langbein L, Schweizer J, et al. Onychomatricoma in the light of the microanatomy of the normal nail unit. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:131-139.

7. Ko CJ, Shi L, Barr RJ, et al. Unguioblastoma and unguioblastic fibroma—an expanded spectrum of onychomatricoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:307-311.

1. Baran R, Kint A. Onychomatrixoma. filamentous tufted tumour in the matrix of a funnel-shaped nail: a new entity (report of three cases). Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:510-515.

2. Haneke E, Franken J. Onychomatricoma. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21:984-987.

3. Gaertner EM, Gordon M, Reed T. Onychomatricoma: case report of an unusual subungual tumor with literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36(suppl 1):66-69.

4. Cañueto J, Santos-Briz Á, García JL, et al. Onychomatricoma: genome-wide analyses of a rare nail matrix tumor. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:573-578.

5. Perrin C, Baran R. Onychomatricoma with dorsalpterygium: pathogenic mechanisms in 3 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:990-994.

6. Perrin C, Langbein L, Schweizer J, et al. Onychomatricoma in the light of the microanatomy of the normal nail unit. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:131-139.

7. Ko CJ, Shi L, Barr RJ, et al. Unguioblastoma and unguioblastic fibroma—an expanded spectrum of onychomatricoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:307-311.

Practice Points

- Onychomatricoma is a rare benign neoplasm of the nail matrix that actively produces a nail plate.

- Onychomatricoma should be in the differential diagnosis of a thickened discolored nail plate with transverse overcurvature.

- Onychomatricoma has been associated with onychomycosis and trauma to the nail apparatus.

Angioedema Following tPA Administration for Acute Cerebrovascular Accident

The use of thrombolytic medications for the treatment of acute ischemic cerebral infarctions has dynamically altered stroke care. However, there are both major and minor side effects associated with its use—most notably major bleeding, which led to strict inclusion and exclusion criteria governing the administration of this medication class. One less recognized but potentially serious complication is angioedema secondary to tissue plasminogen activator (tPA). Our case emphasizes the importance of early recognition of this clinical syndrome as it relates to airway compromise and potential respiratory failure in patients who are treated with tPA.

Case

A 70-year-old woman with a history of diabetes and hypertension and a remote history of breast cancer, nonhemiplegic migraines, and hypothyroidism presented to the ED with complaints of aphasia and right-sided paralysis, with onset 2 hours prior. Regarding the patient’s medication history, she had been taking lisinopril for hypertension.

Upon assessment, the patient was awake and alert and her vital signs were normal and stable, but she was aphasic, unable to accurately phonate, and was not able to move her right arm or leg against gravity. Her sensation appeared intact, and she had mild facial asymmetry with inability to raise the right corner of her mouth; her tongue had midline protrusion.

An emergent computed tomography (CT) scan of the head demonstrated mild brain atrophy and minimal low attenuation within the cerebral hemispheric white matter—most noticeably within the subcortical region of the left frontal lobe, consistent with small vessel ischemia. There was no evidence of acute intracranial hemorrhage, midline shift, or focal mass effect, and no convincing CT evidence for acute large vessel, cortical-based infarction.

The patient was determined to be an appropriate candidate for tPA, and was consented in the usual fashion. Within 15 minutes of administration of intravenous (IV) tPA, her symptoms improved, the aphasia resolved, and she was able to lift her right arm and leg against gravity and verbally communicate. Approximately 30 minutes following the resolution of her neurological symptoms, however, the patient was noted to have bleeding around a tooth socket, which was controlled with gauze and pressure. She subsequently began to complain of swelling on her right inferior lip without acute airway compromise. Over the next 10 to 15 minutes, she began to develop tongue swelling and feelings of dyspnea without wheezing.

The patient’s airway was reassessed and was classified as a Mallampati class IV. Anesthesia services were consulted for an emergent, awake intubation for airway protection. She was medicated with midazolam IV, as well as atomized lidocaine and lidocaine gargle for local anesthesia. The patient was successfully intubated awake using a flexible fiber optic technique. She was admitted to the medical intensive care unit for further monitoring, where she was treated with IV methylprednisolone, famotidine, and diphenhydramine. She was extubated the following day, had a relatively uncomplicated hospital course, and was discharged on hospital day 5 with improvement in her speech and right-sided weakness.

Discussion

The risk of angioedema associated with tPA administration has been previously described, with an estimated rate of 1.3 to 5.1%.1-3 Studies have shown the risk of developing angioedema is significantly increased in the setting of concomitant use of an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I); CT studies have also shown evidence of frontal and insular ischemia, with an odds radio of 13.6 and 9.1, respectively.2 Our patient was on lisinopril and had early signs of ischemia in the frontal lobe on initial CT scan, which likely increased her risk for angioedema.

How tPA Can Trigger Angioedema

The development of angioedema after administration of tPA has a well-described biochemical basis. Angioedema has been linked to the local vasodilatory effects of bradykinin, mast cell degranulation, and histamine release from activation of the complement pathway.4 Tissue plasminogen activator may trigger both of these pathways. It is a serine protease that cleaves plasminogen to plasmin; the plasmin in turn cleaves fibrin, resulting in the desired thrombolytic effects.5 Plasmin can cause mast cell degranulation through conversion of C3 to C3a and through activation of the complement pathway through conversion of C1 to C1a.6

Studies have shown tPA to have low antigenicity, and activation of this pathway is most likely secondary to direct proteolytic effects as opposed to antibody complexes.7 In a study by Bennett et al,6 tPA was shown to significantly increase C3a, C4a, and C5a serum levels when given in the setting of myocardial infarction (MI). It has also been shown to activate and increase serum kallikrein, which cleaves high-molecular weight kininogen to bradykinin, a potent vasodilator.8,9

Since bradykinin is broken down by several enzymes, including ACE, degradation is therefore delayed in patients on ACE-I.10 The alternate pathway for bradykinin degradation in the absence of ACE may also result in formation of des-Arg bradykinin, another similar active metabolite that mimics the effects of bradykinins.9 The formation of bradykinin through the proteolytic effects of tPA, in combination with the delayed breakdown in patient’s taking an ACE-I, likely plays a significant role in the development of angioedema.

In addition to the direct proteolytic effect of tPA resulting in angioedema, the underlying ischemic insult may also predispose patients to angioedema. As was the case with our patient, angioedema preferentially affects the ipsilateral side of the patient’s deficit.2,11,12 Theories suggest this is due to the lack of autonomic compensatory responses in the setting of ischemic insult.2 Interestingly, the development of angioedema in relation to the use of recombinant-tPA (eg, alteplase) in the setting of MI has not been as well described and may be related to the effect of central nervous system insult.3

Treatment

Although hemorrhagic complications of tPA therapy for cerebrovascular accident are well known, the risk for angioedema as a complication is less recognized. In most cases, angioedema is transient, and very few patients require aggressive support.3,12 Treatments that have previously been described include antihistamines and steroids.1,11,13 Epinephrine has been reported in one case study as an adjunct treatment of tPA-induced angioedema; however, it was given in combination with steroids and antihistimines.14 Therefore, caution should be taken regarding the use of epinephrine in this setting as there may be a theoretical precipitation of intracranial hypertension or hemorrhage.2

Given the likely significant role of the bradykinin-mediated pathway in tPA-induced angioedema, the true efficacy of these agents is unknown. Our patient had significant labial and lingual involvement, and given the concern for impending airway compromise, fiber optic intubation was performed. The decision to intubate and the technique employed must be carefully considered as a failed airway and need for a surgical airway is a concerning prospect in the setting of fibrinolytics. Successful cricothyroidotomy without significant complications has been described in the setting of streptokinase-induced angioedema when given for MI.15

Conclusion

The use of tPA for the treatment of ischemic stroke has been increasing over the last decade.16,17 Given the high prevalence of ACE-I use in patients who are also at risk for ischemic stroke, physicians administering tPA must be aware of the risk of tPA-associated angioedema. Patients with a known history of angioedema or anaphylaxis to tPA should be counseled on these risks and should not be given this medication, but rather considered for potential endovascular or mechanical clot retrieval therapy if they meet inclusion criteria for its use.

1. Hill MD, Barber PA, Takahashi J, Demchuk AM, Feasby TE, Buchan AM. Anaphylactoid reactions and angioedema during alteplase treatment of acute ischemic stroke. CMAJ. 2000;162(9):1281-1284.

2. Hill MD, Lye T, Moss H, et al. Hemi-orolingual angioedema and ACE inhibition after alteplase treatment of stroke. Neurology. 2003;60(9):1525-1527.

3. Hill MD, Buchan AM; Canadian Alteplase for Stroke Effectiveness Study (CASES) Investigators. Thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke: results of the Canadian Alteplase for Stroke Effectiveness Study. CMAJ. 2005;172(10):1307-1312.

4. Lewis LM. Angioedema: etiology, pathophysiology, current and emerging therapies. J Emerg Med. 2013;45(5):789-796.

5. Loscalzo J, Braunwald E. Tissue plasminogen activator. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(14):935-931.

6. Bennett WR, Yawn DH, Migliore PJ, et al. Activation of the complement system by recombinant tissue plasminogen activator. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987;10(3):627-632.

7. Reed BR, Chen AB, Tanswell P, et al. Low incidence of antibodies to recombinant human tissue-type plasminogen activator in treated patients. Thromb Haemost. 1990;64(2):276-280.

8. Hoffmeister HM, Szabo S, Kastner C, et al. Thrombolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction: comparison of procoagulant effects of streptokinase and alteplase regimens with focus on the kallikrein system and plasmin. Circulation. 1998;98(23):2527-2533.

9. Molinaro G, Gervais N, Adam A. Biochemical basis of angioedema associated with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator treatment: an in vitro experimental approach. Stroke. 2002;33(6):1712-1716.

10. Bezalel S, Mahlab-Guri K, Asher I, Werner B, Sthoeger ZM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema. Am J Med. 2015;128(2):120-125.

11. Pancioli A, Brott T, Donaldson V, Miller R. Asymmetric angioneurotic edema associated with thrombolysis for acute stroke. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30(2):227-229.

12. Correia AS, Matias G, Calado S, Lourenço A, Viana-Baptista M. Orolingual angiodema associated with alteplase treatment of acute stroke: a reappraisal. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24(1):31-40.

13. Maertins M, Wol R, Swider M. Angioedema after administration of tPA for ischemic stroke: case report. Air Med J. 2011;30(5):276-278.

14. Fugate JE, Kalimullah EA, Wijdicks EF. Angioedema after tPA: what neurointensivists should know. Neurocrit Care. 2012;16(3):440-443.

15. Walls RM, Pollack CV Jr. Successful cricothyrotomy after thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a report of two cases. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35(2):188-191.

16. Lichtman JH, Watanabe E, Allen NB, Jones SB, Dostal J, Goldstein LB. Hospital arrival time and intravenous t-PA use in US Academic Medical Centers, 2001-2004. Stroke. 2009;40(12):3845-3850.

17. Schwamm LH, Ali SF, Reeves MJ, et al. Temporal trends in patient characteristics and treatment with intravenous thrombolysis among acute ischemic stroke patients at Get With the Guidelines-Stroke hospitals. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(5):543-549.

The use of thrombolytic medications for the treatment of acute ischemic cerebral infarctions has dynamically altered stroke care. However, there are both major and minor side effects associated with its use—most notably major bleeding, which led to strict inclusion and exclusion criteria governing the administration of this medication class. One less recognized but potentially serious complication is angioedema secondary to tissue plasminogen activator (tPA). Our case emphasizes the importance of early recognition of this clinical syndrome as it relates to airway compromise and potential respiratory failure in patients who are treated with tPA.

Case

A 70-year-old woman with a history of diabetes and hypertension and a remote history of breast cancer, nonhemiplegic migraines, and hypothyroidism presented to the ED with complaints of aphasia and right-sided paralysis, with onset 2 hours prior. Regarding the patient’s medication history, she had been taking lisinopril for hypertension.

Upon assessment, the patient was awake and alert and her vital signs were normal and stable, but she was aphasic, unable to accurately phonate, and was not able to move her right arm or leg against gravity. Her sensation appeared intact, and she had mild facial asymmetry with inability to raise the right corner of her mouth; her tongue had midline protrusion.

An emergent computed tomography (CT) scan of the head demonstrated mild brain atrophy and minimal low attenuation within the cerebral hemispheric white matter—most noticeably within the subcortical region of the left frontal lobe, consistent with small vessel ischemia. There was no evidence of acute intracranial hemorrhage, midline shift, or focal mass effect, and no convincing CT evidence for acute large vessel, cortical-based infarction.

The patient was determined to be an appropriate candidate for tPA, and was consented in the usual fashion. Within 15 minutes of administration of intravenous (IV) tPA, her symptoms improved, the aphasia resolved, and she was able to lift her right arm and leg against gravity and verbally communicate. Approximately 30 minutes following the resolution of her neurological symptoms, however, the patient was noted to have bleeding around a tooth socket, which was controlled with gauze and pressure. She subsequently began to complain of swelling on her right inferior lip without acute airway compromise. Over the next 10 to 15 minutes, she began to develop tongue swelling and feelings of dyspnea without wheezing.

The patient’s airway was reassessed and was classified as a Mallampati class IV. Anesthesia services were consulted for an emergent, awake intubation for airway protection. She was medicated with midazolam IV, as well as atomized lidocaine and lidocaine gargle for local anesthesia. The patient was successfully intubated awake using a flexible fiber optic technique. She was admitted to the medical intensive care unit for further monitoring, where she was treated with IV methylprednisolone, famotidine, and diphenhydramine. She was extubated the following day, had a relatively uncomplicated hospital course, and was discharged on hospital day 5 with improvement in her speech and right-sided weakness.

Discussion

The risk of angioedema associated with tPA administration has been previously described, with an estimated rate of 1.3 to 5.1%.1-3 Studies have shown the risk of developing angioedema is significantly increased in the setting of concomitant use of an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I); CT studies have also shown evidence of frontal and insular ischemia, with an odds radio of 13.6 and 9.1, respectively.2 Our patient was on lisinopril and had early signs of ischemia in the frontal lobe on initial CT scan, which likely increased her risk for angioedema.

How tPA Can Trigger Angioedema

The development of angioedema after administration of tPA has a well-described biochemical basis. Angioedema has been linked to the local vasodilatory effects of bradykinin, mast cell degranulation, and histamine release from activation of the complement pathway.4 Tissue plasminogen activator may trigger both of these pathways. It is a serine protease that cleaves plasminogen to plasmin; the plasmin in turn cleaves fibrin, resulting in the desired thrombolytic effects.5 Plasmin can cause mast cell degranulation through conversion of C3 to C3a and through activation of the complement pathway through conversion of C1 to C1a.6

Studies have shown tPA to have low antigenicity, and activation of this pathway is most likely secondary to direct proteolytic effects as opposed to antibody complexes.7 In a study by Bennett et al,6 tPA was shown to significantly increase C3a, C4a, and C5a serum levels when given in the setting of myocardial infarction (MI). It has also been shown to activate and increase serum kallikrein, which cleaves high-molecular weight kininogen to bradykinin, a potent vasodilator.8,9

Since bradykinin is broken down by several enzymes, including ACE, degradation is therefore delayed in patients on ACE-I.10 The alternate pathway for bradykinin degradation in the absence of ACE may also result in formation of des-Arg bradykinin, another similar active metabolite that mimics the effects of bradykinins.9 The formation of bradykinin through the proteolytic effects of tPA, in combination with the delayed breakdown in patient’s taking an ACE-I, likely plays a significant role in the development of angioedema.

In addition to the direct proteolytic effect of tPA resulting in angioedema, the underlying ischemic insult may also predispose patients to angioedema. As was the case with our patient, angioedema preferentially affects the ipsilateral side of the patient’s deficit.2,11,12 Theories suggest this is due to the lack of autonomic compensatory responses in the setting of ischemic insult.2 Interestingly, the development of angioedema in relation to the use of recombinant-tPA (eg, alteplase) in the setting of MI has not been as well described and may be related to the effect of central nervous system insult.3

Treatment

Although hemorrhagic complications of tPA therapy for cerebrovascular accident are well known, the risk for angioedema as a complication is less recognized. In most cases, angioedema is transient, and very few patients require aggressive support.3,12 Treatments that have previously been described include antihistamines and steroids.1,11,13 Epinephrine has been reported in one case study as an adjunct treatment of tPA-induced angioedema; however, it was given in combination with steroids and antihistimines.14 Therefore, caution should be taken regarding the use of epinephrine in this setting as there may be a theoretical precipitation of intracranial hypertension or hemorrhage.2

Given the likely significant role of the bradykinin-mediated pathway in tPA-induced angioedema, the true efficacy of these agents is unknown. Our patient had significant labial and lingual involvement, and given the concern for impending airway compromise, fiber optic intubation was performed. The decision to intubate and the technique employed must be carefully considered as a failed airway and need for a surgical airway is a concerning prospect in the setting of fibrinolytics. Successful cricothyroidotomy without significant complications has been described in the setting of streptokinase-induced angioedema when given for MI.15

Conclusion

The use of tPA for the treatment of ischemic stroke has been increasing over the last decade.16,17 Given the high prevalence of ACE-I use in patients who are also at risk for ischemic stroke, physicians administering tPA must be aware of the risk of tPA-associated angioedema. Patients with a known history of angioedema or anaphylaxis to tPA should be counseled on these risks and should not be given this medication, but rather considered for potential endovascular or mechanical clot retrieval therapy if they meet inclusion criteria for its use.

The use of thrombolytic medications for the treatment of acute ischemic cerebral infarctions has dynamically altered stroke care. However, there are both major and minor side effects associated with its use—most notably major bleeding, which led to strict inclusion and exclusion criteria governing the administration of this medication class. One less recognized but potentially serious complication is angioedema secondary to tissue plasminogen activator (tPA). Our case emphasizes the importance of early recognition of this clinical syndrome as it relates to airway compromise and potential respiratory failure in patients who are treated with tPA.

Case

A 70-year-old woman with a history of diabetes and hypertension and a remote history of breast cancer, nonhemiplegic migraines, and hypothyroidism presented to the ED with complaints of aphasia and right-sided paralysis, with onset 2 hours prior. Regarding the patient’s medication history, she had been taking lisinopril for hypertension.

Upon assessment, the patient was awake and alert and her vital signs were normal and stable, but she was aphasic, unable to accurately phonate, and was not able to move her right arm or leg against gravity. Her sensation appeared intact, and she had mild facial asymmetry with inability to raise the right corner of her mouth; her tongue had midline protrusion.

An emergent computed tomography (CT) scan of the head demonstrated mild brain atrophy and minimal low attenuation within the cerebral hemispheric white matter—most noticeably within the subcortical region of the left frontal lobe, consistent with small vessel ischemia. There was no evidence of acute intracranial hemorrhage, midline shift, or focal mass effect, and no convincing CT evidence for acute large vessel, cortical-based infarction.

The patient was determined to be an appropriate candidate for tPA, and was consented in the usual fashion. Within 15 minutes of administration of intravenous (IV) tPA, her symptoms improved, the aphasia resolved, and she was able to lift her right arm and leg against gravity and verbally communicate. Approximately 30 minutes following the resolution of her neurological symptoms, however, the patient was noted to have bleeding around a tooth socket, which was controlled with gauze and pressure. She subsequently began to complain of swelling on her right inferior lip without acute airway compromise. Over the next 10 to 15 minutes, she began to develop tongue swelling and feelings of dyspnea without wheezing.

The patient’s airway was reassessed and was classified as a Mallampati class IV. Anesthesia services were consulted for an emergent, awake intubation for airway protection. She was medicated with midazolam IV, as well as atomized lidocaine and lidocaine gargle for local anesthesia. The patient was successfully intubated awake using a flexible fiber optic technique. She was admitted to the medical intensive care unit for further monitoring, where she was treated with IV methylprednisolone, famotidine, and diphenhydramine. She was extubated the following day, had a relatively uncomplicated hospital course, and was discharged on hospital day 5 with improvement in her speech and right-sided weakness.

Discussion

The risk of angioedema associated with tPA administration has been previously described, with an estimated rate of 1.3 to 5.1%.1-3 Studies have shown the risk of developing angioedema is significantly increased in the setting of concomitant use of an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I); CT studies have also shown evidence of frontal and insular ischemia, with an odds radio of 13.6 and 9.1, respectively.2 Our patient was on lisinopril and had early signs of ischemia in the frontal lobe on initial CT scan, which likely increased her risk for angioedema.

How tPA Can Trigger Angioedema

The development of angioedema after administration of tPA has a well-described biochemical basis. Angioedema has been linked to the local vasodilatory effects of bradykinin, mast cell degranulation, and histamine release from activation of the complement pathway.4 Tissue plasminogen activator may trigger both of these pathways. It is a serine protease that cleaves plasminogen to plasmin; the plasmin in turn cleaves fibrin, resulting in the desired thrombolytic effects.5 Plasmin can cause mast cell degranulation through conversion of C3 to C3a and through activation of the complement pathway through conversion of C1 to C1a.6