User login

CMS sepsis measure a challenge to report

Hospitalists can champion sepsis-improvement efforts

In October 2015, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services implemented its first meaningful policy to attempt for addressing sepsis.

The condition – one of the leading causes of mortality among hospitalized patients – afflicts more than a million people each year in the United States, and between 15% and 30% of them die. Sepsis is one of the leading drivers of hospital readmissions, sending more patients back to the hospital than heart failure, pneumonia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.1

However, while providers seem to agree that time to address sepsis is past due, not everyone has embraced the Sepsis CMS Core Measure program, or SEP-1, as the means to best achieve it. This is, in part, because of discrepancies in how sepsis is defined, the burden of reporting, and what some consider to be arbitrary clinical requirements that may not correlate with better patient outcomes.

“Sepsis is indeed a critical public health problem, and it’s appropriate and valuable that Medicare and other policy makers are focusing on sepsis,” said Jeremy Kahn, MD, professor of critical care medicine and health policy and management at the University of Pittsburgh. “This was really the first approach at that … but at 85-pages long, it really is an enormous effort for hospitals to adhere to this measure.”

This is because of the tension between the “intense desire to improve sepsis outcomes” and the “incredible burden” of keeping up with the necessary documentation while also providing quality care, Dr. Kahn said.

In December 2017, Dr. Kahn helped lead a study published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine aimed at trying to understand hospital perceptions of SEP-1. Over the course of 29 interviews with randomly selected hospital quality leaders across the United States, including physicians and nurses, the results came as a surprise.2

“Generally, hospitals were very supportive of the concept, and there was no pushback on the idea that we should be measuring and reporting sepsis quality to CMS,” he said.

However, the research team found that respondents believed the program’s requirements with respect to treatment and documentation were complex and not always linked to patient-centered outcomes. Meeting the SEP-1 bundles consistently required hospitals to dedicate resources that not all may have, especially those in small, rural communities and those serving as urban safety nets.

Some, like emergency medicine physician Annahieta Kalantari, DO (who did not participate in the survey), feel that SEP-1 forces providers to practice “check-box” medicine and undermines successful efforts that don’t necessarily align with the CMS policy.

She arrived at her institution, Aria-Jefferson Health in Philadelphia, before CMS adopted SEP-1; at that time, she took note of the fact that the rate of sepsis mortalities in her hospital was, in her words, not great when compared with that at similar institutions. And then she helped do something about it.

“I thought, ‘We’re a Premier reporting hospital,’ so we did a gap analysis as to why and put together protocols for the hospital to follow with our sepsis patients, including a sepsis alert and a lot of education,” said Dr. Kalantari, associate program director for the emergency medicine residency program at Aria-Jefferson and a former chair of its sepsis management committee. “Before you knew it, mortalities were below benchmark.”

But once SEP-1 began, she said, the hospital was unable to check all of the boxes all of the time.

“We kept track, but we weren’t hitting all the bundles exactly within the periods of time recommended, but our mortalities were still amazing,” she said. “CMS basically picked definitions [for sepsis], and most of us don’t know what they’re basing them on because no one can agree on a definition anyway. Now they’re penalizing hospitals if they don’t hit the check marks in time, but we’d already demonstrated that our mortality and patient care was exceptional.”

She added: “I am extremely dissatisfied, as someone who provides frontline patient care, with how CMS is choosing to measure us.”

Dr. Kalantari wrote a piece in the Western Journal of Emergency Medicine in July 2017 in which she and coauthors outline the issues they take with SEP-1. They lay out the tension among the varied definitions of what sepsis is – and isn’t – and they also illuminate the apparent conflict between what CMS has officially defined and what evidence-based studies conducted since 2001 have suggested.3

In particular, CMS defines severe sepsis as an initial lactate above 2 mmol/L and septic shock as an initial lactate presentation of greater than 4 mmol/L. However, Dr. Kalantari and here coauthors argue in the paper that there is no standard definition of sepsis and that decades of attempts to achieve one have failed to reach consensus among providers. CMS, she said, fails to acknowledge this.

Defining sepsis

In fact, in 2016, another new definition of sepsis emerged by way of a 19-member task-force of experts: The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock, also called Sepsis-3.4 In March 2017, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign adopted this definition, which defined sepsis as a “life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection.”5

“I think the definition has always been a challenging part of sepsis,” said Kencee Graves, MD, a hospitalist at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. “The definitions came about for research purposes, so … they are not perfectly sensitive nor specific.”

However, Dr. Graves believes SEP-1 is a step in the right direction in that it brings awareness to sepsis and holds providers accountable. Several years ago, she and her colleague Devin Horton, MD, also a hospitalist at the University of Utah, embarked on a massive undertaking to address sepsis in their hospital. It was, at the time, lacking in “sepsis culture,” Dr. Horton said.

“One of the big things that motivated both of us was that we started doing chart review together and – it’s always easier with 20/20 hindsight – we were noticing that residents were missing the signs of sepsis,” Dr. Horton explained. “The clinical criteria would be there, but no one would say the word.” This is important, he said, because sepsis is time critical.

So the pair set out to create a cultural change by sharing data and collecting input from each service and unit, which relied heavily on nursing staff to perpetuate change. They created an early warning system in the medical record and worked with units to achieve flexibility in their criteria.

While the early warning system seemed helpful on the floor, SEP-1 adherence rates changed little in the emergency department. So Dr. Graves and Dr. Horton worked out an ED-specific process map that started at triage and was modeled after myocardial infarction STEMI protocols. From April through December 2016, the ED achieved between 29.5% adherence to the SEP-1 bundles, they said according to CMS abstractor data. After the change, between January and March 2017, the ED saw 52.2% adherence.

Dr. Kalantari would like to see CMS allow hospitals to evaluate and alter their processes more individually, with the required result being lower sepsis mortality. Hospitalists, said Dr. Kahn, are well poised to champion these sepsis improvement efforts.

“Hospitalists are uniquely positioned to lead in this area because they are a visible presence and a link between providers doing multidisciplinary acute care,” he said. “The other thing hospitalists can do is insist on rolling out approaches that are evidence based and not likely to cause harm by leading to over resuscitation, or ensuring patients are receiving central-line insertions only when needed.”

This is currently a moment for hospitals to innovate and provide meaningful feedback to CMS, which, he said, is listening.

“It’s a myth that CMS rolls out policy without listening to the clinical community, but what they want is constructive criticism, not just to hear ‘We’re not ready and we have to push this down the road,’ ” Dr. Kahn said. “The time is now in the era of accountability in health care.”

References

1. Sepsis. National Institute of General Medical Sciences. https://www.nigms.nih.gov/education/pages/factsheet_sepsis.aspx. Updated Sept 2017. Accessed Jan 4, 2018.

2. Barbash I et al. Hospital perceptions of Medicare’s sepsis quality reporting initiative. J Hosp Med. 2017;12;963-8.

3. Kalantari A et al. Sepsis Definitions: The search for gold and what CMS got wrong. West J Emerg Med. 2017 Aug;18(5):951-6.

4. Singer M et. al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016 Feb 23;315(8):801-10.

5. Rhodes A et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:304.

Hospitalists can champion sepsis-improvement efforts

Hospitalists can champion sepsis-improvement efforts

In October 2015, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services implemented its first meaningful policy to attempt for addressing sepsis.

The condition – one of the leading causes of mortality among hospitalized patients – afflicts more than a million people each year in the United States, and between 15% and 30% of them die. Sepsis is one of the leading drivers of hospital readmissions, sending more patients back to the hospital than heart failure, pneumonia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.1

However, while providers seem to agree that time to address sepsis is past due, not everyone has embraced the Sepsis CMS Core Measure program, or SEP-1, as the means to best achieve it. This is, in part, because of discrepancies in how sepsis is defined, the burden of reporting, and what some consider to be arbitrary clinical requirements that may not correlate with better patient outcomes.

“Sepsis is indeed a critical public health problem, and it’s appropriate and valuable that Medicare and other policy makers are focusing on sepsis,” said Jeremy Kahn, MD, professor of critical care medicine and health policy and management at the University of Pittsburgh. “This was really the first approach at that … but at 85-pages long, it really is an enormous effort for hospitals to adhere to this measure.”

This is because of the tension between the “intense desire to improve sepsis outcomes” and the “incredible burden” of keeping up with the necessary documentation while also providing quality care, Dr. Kahn said.

In December 2017, Dr. Kahn helped lead a study published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine aimed at trying to understand hospital perceptions of SEP-1. Over the course of 29 interviews with randomly selected hospital quality leaders across the United States, including physicians and nurses, the results came as a surprise.2

“Generally, hospitals were very supportive of the concept, and there was no pushback on the idea that we should be measuring and reporting sepsis quality to CMS,” he said.

However, the research team found that respondents believed the program’s requirements with respect to treatment and documentation were complex and not always linked to patient-centered outcomes. Meeting the SEP-1 bundles consistently required hospitals to dedicate resources that not all may have, especially those in small, rural communities and those serving as urban safety nets.

Some, like emergency medicine physician Annahieta Kalantari, DO (who did not participate in the survey), feel that SEP-1 forces providers to practice “check-box” medicine and undermines successful efforts that don’t necessarily align with the CMS policy.

She arrived at her institution, Aria-Jefferson Health in Philadelphia, before CMS adopted SEP-1; at that time, she took note of the fact that the rate of sepsis mortalities in her hospital was, in her words, not great when compared with that at similar institutions. And then she helped do something about it.

“I thought, ‘We’re a Premier reporting hospital,’ so we did a gap analysis as to why and put together protocols for the hospital to follow with our sepsis patients, including a sepsis alert and a lot of education,” said Dr. Kalantari, associate program director for the emergency medicine residency program at Aria-Jefferson and a former chair of its sepsis management committee. “Before you knew it, mortalities were below benchmark.”

But once SEP-1 began, she said, the hospital was unable to check all of the boxes all of the time.

“We kept track, but we weren’t hitting all the bundles exactly within the periods of time recommended, but our mortalities were still amazing,” she said. “CMS basically picked definitions [for sepsis], and most of us don’t know what they’re basing them on because no one can agree on a definition anyway. Now they’re penalizing hospitals if they don’t hit the check marks in time, but we’d already demonstrated that our mortality and patient care was exceptional.”

She added: “I am extremely dissatisfied, as someone who provides frontline patient care, with how CMS is choosing to measure us.”

Dr. Kalantari wrote a piece in the Western Journal of Emergency Medicine in July 2017 in which she and coauthors outline the issues they take with SEP-1. They lay out the tension among the varied definitions of what sepsis is – and isn’t – and they also illuminate the apparent conflict between what CMS has officially defined and what evidence-based studies conducted since 2001 have suggested.3

In particular, CMS defines severe sepsis as an initial lactate above 2 mmol/L and septic shock as an initial lactate presentation of greater than 4 mmol/L. However, Dr. Kalantari and here coauthors argue in the paper that there is no standard definition of sepsis and that decades of attempts to achieve one have failed to reach consensus among providers. CMS, she said, fails to acknowledge this.

Defining sepsis

In fact, in 2016, another new definition of sepsis emerged by way of a 19-member task-force of experts: The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock, also called Sepsis-3.4 In March 2017, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign adopted this definition, which defined sepsis as a “life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection.”5

“I think the definition has always been a challenging part of sepsis,” said Kencee Graves, MD, a hospitalist at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. “The definitions came about for research purposes, so … they are not perfectly sensitive nor specific.”

However, Dr. Graves believes SEP-1 is a step in the right direction in that it brings awareness to sepsis and holds providers accountable. Several years ago, she and her colleague Devin Horton, MD, also a hospitalist at the University of Utah, embarked on a massive undertaking to address sepsis in their hospital. It was, at the time, lacking in “sepsis culture,” Dr. Horton said.

“One of the big things that motivated both of us was that we started doing chart review together and – it’s always easier with 20/20 hindsight – we were noticing that residents were missing the signs of sepsis,” Dr. Horton explained. “The clinical criteria would be there, but no one would say the word.” This is important, he said, because sepsis is time critical.

So the pair set out to create a cultural change by sharing data and collecting input from each service and unit, which relied heavily on nursing staff to perpetuate change. They created an early warning system in the medical record and worked with units to achieve flexibility in their criteria.

While the early warning system seemed helpful on the floor, SEP-1 adherence rates changed little in the emergency department. So Dr. Graves and Dr. Horton worked out an ED-specific process map that started at triage and was modeled after myocardial infarction STEMI protocols. From April through December 2016, the ED achieved between 29.5% adherence to the SEP-1 bundles, they said according to CMS abstractor data. After the change, between January and March 2017, the ED saw 52.2% adherence.

Dr. Kalantari would like to see CMS allow hospitals to evaluate and alter their processes more individually, with the required result being lower sepsis mortality. Hospitalists, said Dr. Kahn, are well poised to champion these sepsis improvement efforts.

“Hospitalists are uniquely positioned to lead in this area because they are a visible presence and a link between providers doing multidisciplinary acute care,” he said. “The other thing hospitalists can do is insist on rolling out approaches that are evidence based and not likely to cause harm by leading to over resuscitation, or ensuring patients are receiving central-line insertions only when needed.”

This is currently a moment for hospitals to innovate and provide meaningful feedback to CMS, which, he said, is listening.

“It’s a myth that CMS rolls out policy without listening to the clinical community, but what they want is constructive criticism, not just to hear ‘We’re not ready and we have to push this down the road,’ ” Dr. Kahn said. “The time is now in the era of accountability in health care.”

References

1. Sepsis. National Institute of General Medical Sciences. https://www.nigms.nih.gov/education/pages/factsheet_sepsis.aspx. Updated Sept 2017. Accessed Jan 4, 2018.

2. Barbash I et al. Hospital perceptions of Medicare’s sepsis quality reporting initiative. J Hosp Med. 2017;12;963-8.

3. Kalantari A et al. Sepsis Definitions: The search for gold and what CMS got wrong. West J Emerg Med. 2017 Aug;18(5):951-6.

4. Singer M et. al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016 Feb 23;315(8):801-10.

5. Rhodes A et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:304.

In October 2015, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services implemented its first meaningful policy to attempt for addressing sepsis.

The condition – one of the leading causes of mortality among hospitalized patients – afflicts more than a million people each year in the United States, and between 15% and 30% of them die. Sepsis is one of the leading drivers of hospital readmissions, sending more patients back to the hospital than heart failure, pneumonia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.1

However, while providers seem to agree that time to address sepsis is past due, not everyone has embraced the Sepsis CMS Core Measure program, or SEP-1, as the means to best achieve it. This is, in part, because of discrepancies in how sepsis is defined, the burden of reporting, and what some consider to be arbitrary clinical requirements that may not correlate with better patient outcomes.

“Sepsis is indeed a critical public health problem, and it’s appropriate and valuable that Medicare and other policy makers are focusing on sepsis,” said Jeremy Kahn, MD, professor of critical care medicine and health policy and management at the University of Pittsburgh. “This was really the first approach at that … but at 85-pages long, it really is an enormous effort for hospitals to adhere to this measure.”

This is because of the tension between the “intense desire to improve sepsis outcomes” and the “incredible burden” of keeping up with the necessary documentation while also providing quality care, Dr. Kahn said.

In December 2017, Dr. Kahn helped lead a study published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine aimed at trying to understand hospital perceptions of SEP-1. Over the course of 29 interviews with randomly selected hospital quality leaders across the United States, including physicians and nurses, the results came as a surprise.2

“Generally, hospitals were very supportive of the concept, and there was no pushback on the idea that we should be measuring and reporting sepsis quality to CMS,” he said.

However, the research team found that respondents believed the program’s requirements with respect to treatment and documentation were complex and not always linked to patient-centered outcomes. Meeting the SEP-1 bundles consistently required hospitals to dedicate resources that not all may have, especially those in small, rural communities and those serving as urban safety nets.

Some, like emergency medicine physician Annahieta Kalantari, DO (who did not participate in the survey), feel that SEP-1 forces providers to practice “check-box” medicine and undermines successful efforts that don’t necessarily align with the CMS policy.

She arrived at her institution, Aria-Jefferson Health in Philadelphia, before CMS adopted SEP-1; at that time, she took note of the fact that the rate of sepsis mortalities in her hospital was, in her words, not great when compared with that at similar institutions. And then she helped do something about it.

“I thought, ‘We’re a Premier reporting hospital,’ so we did a gap analysis as to why and put together protocols for the hospital to follow with our sepsis patients, including a sepsis alert and a lot of education,” said Dr. Kalantari, associate program director for the emergency medicine residency program at Aria-Jefferson and a former chair of its sepsis management committee. “Before you knew it, mortalities were below benchmark.”

But once SEP-1 began, she said, the hospital was unable to check all of the boxes all of the time.

“We kept track, but we weren’t hitting all the bundles exactly within the periods of time recommended, but our mortalities were still amazing,” she said. “CMS basically picked definitions [for sepsis], and most of us don’t know what they’re basing them on because no one can agree on a definition anyway. Now they’re penalizing hospitals if they don’t hit the check marks in time, but we’d already demonstrated that our mortality and patient care was exceptional.”

She added: “I am extremely dissatisfied, as someone who provides frontline patient care, with how CMS is choosing to measure us.”

Dr. Kalantari wrote a piece in the Western Journal of Emergency Medicine in July 2017 in which she and coauthors outline the issues they take with SEP-1. They lay out the tension among the varied definitions of what sepsis is – and isn’t – and they also illuminate the apparent conflict between what CMS has officially defined and what evidence-based studies conducted since 2001 have suggested.3

In particular, CMS defines severe sepsis as an initial lactate above 2 mmol/L and septic shock as an initial lactate presentation of greater than 4 mmol/L. However, Dr. Kalantari and here coauthors argue in the paper that there is no standard definition of sepsis and that decades of attempts to achieve one have failed to reach consensus among providers. CMS, she said, fails to acknowledge this.

Defining sepsis

In fact, in 2016, another new definition of sepsis emerged by way of a 19-member task-force of experts: The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock, also called Sepsis-3.4 In March 2017, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign adopted this definition, which defined sepsis as a “life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection.”5

“I think the definition has always been a challenging part of sepsis,” said Kencee Graves, MD, a hospitalist at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. “The definitions came about for research purposes, so … they are not perfectly sensitive nor specific.”

However, Dr. Graves believes SEP-1 is a step in the right direction in that it brings awareness to sepsis and holds providers accountable. Several years ago, she and her colleague Devin Horton, MD, also a hospitalist at the University of Utah, embarked on a massive undertaking to address sepsis in their hospital. It was, at the time, lacking in “sepsis culture,” Dr. Horton said.

“One of the big things that motivated both of us was that we started doing chart review together and – it’s always easier with 20/20 hindsight – we were noticing that residents were missing the signs of sepsis,” Dr. Horton explained. “The clinical criteria would be there, but no one would say the word.” This is important, he said, because sepsis is time critical.

So the pair set out to create a cultural change by sharing data and collecting input from each service and unit, which relied heavily on nursing staff to perpetuate change. They created an early warning system in the medical record and worked with units to achieve flexibility in their criteria.

While the early warning system seemed helpful on the floor, SEP-1 adherence rates changed little in the emergency department. So Dr. Graves and Dr. Horton worked out an ED-specific process map that started at triage and was modeled after myocardial infarction STEMI protocols. From April through December 2016, the ED achieved between 29.5% adherence to the SEP-1 bundles, they said according to CMS abstractor data. After the change, between January and March 2017, the ED saw 52.2% adherence.

Dr. Kalantari would like to see CMS allow hospitals to evaluate and alter their processes more individually, with the required result being lower sepsis mortality. Hospitalists, said Dr. Kahn, are well poised to champion these sepsis improvement efforts.

“Hospitalists are uniquely positioned to lead in this area because they are a visible presence and a link between providers doing multidisciplinary acute care,” he said. “The other thing hospitalists can do is insist on rolling out approaches that are evidence based and not likely to cause harm by leading to over resuscitation, or ensuring patients are receiving central-line insertions only when needed.”

This is currently a moment for hospitals to innovate and provide meaningful feedback to CMS, which, he said, is listening.

“It’s a myth that CMS rolls out policy without listening to the clinical community, but what they want is constructive criticism, not just to hear ‘We’re not ready and we have to push this down the road,’ ” Dr. Kahn said. “The time is now in the era of accountability in health care.”

References

1. Sepsis. National Institute of General Medical Sciences. https://www.nigms.nih.gov/education/pages/factsheet_sepsis.aspx. Updated Sept 2017. Accessed Jan 4, 2018.

2. Barbash I et al. Hospital perceptions of Medicare’s sepsis quality reporting initiative. J Hosp Med. 2017;12;963-8.

3. Kalantari A et al. Sepsis Definitions: The search for gold and what CMS got wrong. West J Emerg Med. 2017 Aug;18(5):951-6.

4. Singer M et. al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016 Feb 23;315(8):801-10.

5. Rhodes A et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:304.

CDC warns of hepatitis A outbreaks in injection drug users

From January 2017 to April 2018, more than 2,500 cases of hepatitis A infection associated with person-to-person transmission were reported to the CDC; of the 1,900 cases where risk factors are known, 68% were related to drug use, homelessness, or both. Various state responses caused a shortage in hepatitis A vaccine during this time, however, because of improvements in controlling outbreaks and an increased vaccine supply, the vaccine has become more available.

Usage of contaminated needles or other injection paraphernalia increase risk of hepatitis A infection, and transience, economic instability, limited health care access, distrust of public officials and public messages, and frequent lack of follow-up contact information in the population who regularly inject drugs make them difficult to reach with preventative services, such as vaccination, use of sterile injection equipment, and case management and contact tracing.

“These challenges make outbreaks among these groups difficult to control,” the CDC said in a statement.

The CDC recommends health departments ensure people who report drug use are vaccinated for hepatitis A, and consider programs to educate at-risk populations, as well as to provide vaccinations in places where at-risk populations may seek treatment. Health care providers should encourage patients who report drug use to be vaccinated for the disease.

For health care professionals, the CDC recommends considering a diagnosis of hepatitis A in any patient with jaundice and clinically compatible symptoms. The agency also recommends one dose of single-antigen hepatitis A vaccine or immune globulin within 2 weeks of exposure for unvaccinated patients who have been exposed to hepatitis A virus.

Find the full Health Advisory on the CDC website.

From January 2017 to April 2018, more than 2,500 cases of hepatitis A infection associated with person-to-person transmission were reported to the CDC; of the 1,900 cases where risk factors are known, 68% were related to drug use, homelessness, or both. Various state responses caused a shortage in hepatitis A vaccine during this time, however, because of improvements in controlling outbreaks and an increased vaccine supply, the vaccine has become more available.

Usage of contaminated needles or other injection paraphernalia increase risk of hepatitis A infection, and transience, economic instability, limited health care access, distrust of public officials and public messages, and frequent lack of follow-up contact information in the population who regularly inject drugs make them difficult to reach with preventative services, such as vaccination, use of sterile injection equipment, and case management and contact tracing.

“These challenges make outbreaks among these groups difficult to control,” the CDC said in a statement.

The CDC recommends health departments ensure people who report drug use are vaccinated for hepatitis A, and consider programs to educate at-risk populations, as well as to provide vaccinations in places where at-risk populations may seek treatment. Health care providers should encourage patients who report drug use to be vaccinated for the disease.

For health care professionals, the CDC recommends considering a diagnosis of hepatitis A in any patient with jaundice and clinically compatible symptoms. The agency also recommends one dose of single-antigen hepatitis A vaccine or immune globulin within 2 weeks of exposure for unvaccinated patients who have been exposed to hepatitis A virus.

Find the full Health Advisory on the CDC website.

From January 2017 to April 2018, more than 2,500 cases of hepatitis A infection associated with person-to-person transmission were reported to the CDC; of the 1,900 cases where risk factors are known, 68% were related to drug use, homelessness, or both. Various state responses caused a shortage in hepatitis A vaccine during this time, however, because of improvements in controlling outbreaks and an increased vaccine supply, the vaccine has become more available.

Usage of contaminated needles or other injection paraphernalia increase risk of hepatitis A infection, and transience, economic instability, limited health care access, distrust of public officials and public messages, and frequent lack of follow-up contact information in the population who regularly inject drugs make them difficult to reach with preventative services, such as vaccination, use of sterile injection equipment, and case management and contact tracing.

“These challenges make outbreaks among these groups difficult to control,” the CDC said in a statement.

The CDC recommends health departments ensure people who report drug use are vaccinated for hepatitis A, and consider programs to educate at-risk populations, as well as to provide vaccinations in places where at-risk populations may seek treatment. Health care providers should encourage patients who report drug use to be vaccinated for the disease.

For health care professionals, the CDC recommends considering a diagnosis of hepatitis A in any patient with jaundice and clinically compatible symptoms. The agency also recommends one dose of single-antigen hepatitis A vaccine or immune globulin within 2 weeks of exposure for unvaccinated patients who have been exposed to hepatitis A virus.

Find the full Health Advisory on the CDC website.

Malnourished U.S. inpatients often go untreated

WASHINGTON – Hospital staffs often fail to treat .

A retrospective review of more than 150,000 patients admitted during a single year at any center within a large, multicenter U.S. hospital system found that even when patients receive oral nutritional supplementation, there is often a substantial delay to its onset.

The data also suggested potential benefits from treating malnutrition with oral nutritional supplementation (ONS). Patients who received ONS had a 10% relative reduction in their rate of 30-day readmission, compared with malnourished patients who did not receive supplements after adjusting for several baseline demographic and clinical variables, Gerard Mullin, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week. His analysis also showed that every doubling of the time from hospital admission to an order for ONS significantly linked with a 6% rise in hospital length of stay.

The findings “highlight the importance of malnutrition screening on admission, starting a nutrition intervention as soon as malnutrition is confirmed, and treating with appropriate ONS,” said Dr. Mullin, a gastroenterologist at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore and director of the Celiac Disease Clinic. A standard formulation of Ensure was the ONS routinely used at the Johns Hopkins hospitals

“We’re missing malnutrition,” Dr. Mullin said in an interview. The hospital accreditation standards of the Joint Commission call for assessment of the nutritional status of hospitalized patients within 24 hours of admission (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2015 Oct;41[10]:469-73). Screening is “not uniformly done,” and when malnutrition is identified, the finding must usually pass through several layers of a hospital’s medico-bureaucratic process before treatment actually starts, he noted. Plus, there’s often dismissal of the importance of intervention. “It’s important to treat patients with ONS sooner than later,” he said.

Dr. Mullin and his associates studied hospital records for 153,161 people admitted to any of the Baltimore-area hospitals in the Johns Hopkins system during October 2016 through the end of September 2017. The hospital staff routinely assessed nutritional status of patients after admission with a two-question screen based on the Malnutrition Screening Tool (Nutrition. 1999 June;15[6]:458-64): Have you had unplanned weight loss of 10 pounds or more during the past 6 months? Have you had decreased oral intake over the past 5 days? This identified 30,284 (20%) who qualified as possibly malnourished by either criterion. The researchers also retrospectively applied a more detailed screen to the patient records using the criteria set by an international consensus guideline committee in 2010 (J Parenter Enteraal Nutr. 2010 Mar-Apr;34[2]:156-9). This identified 8,713 of the hospitalized patients (6%) as malnourished soon after admission. Despite these numbers a scant 274 patients among these 8,713 (3%) actually received ONS, Dr. Mullin reported. In addition, it took an average of 85 hours from the time of each malnourished patient’s admission to when the ONS order appeared in their record.

Dr. Mullin conceded that both the association his group found between treatment with ONS and a reduced rate of 30-day readmission to any of the hospitals in the Johns Hopkins system, and the association between a delay in the time to the start of ONS and length of stay may have been confounded by factors not accounted for in the adjustments they applied. But he maintained that the links are consistent with results from prior studies, and warrant running prospective, randomized studies to better document the impact of ONS on newly admitted patients identified as malnourished.

“We need more of these types of studies and interventional trials to show that ONS makes a difference,” Dr. Mullin said.

The study was sponsored by Abbott, which markets the oral nutritional supplement Ensure. Dr. Mullin had no additional disclosures.

mzoler@mdedge.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

SOURCE: Source: Mullin G et al. DDW 2018 presentation 883.

WASHINGTON – Hospital staffs often fail to treat .

A retrospective review of more than 150,000 patients admitted during a single year at any center within a large, multicenter U.S. hospital system found that even when patients receive oral nutritional supplementation, there is often a substantial delay to its onset.

The data also suggested potential benefits from treating malnutrition with oral nutritional supplementation (ONS). Patients who received ONS had a 10% relative reduction in their rate of 30-day readmission, compared with malnourished patients who did not receive supplements after adjusting for several baseline demographic and clinical variables, Gerard Mullin, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week. His analysis also showed that every doubling of the time from hospital admission to an order for ONS significantly linked with a 6% rise in hospital length of stay.

The findings “highlight the importance of malnutrition screening on admission, starting a nutrition intervention as soon as malnutrition is confirmed, and treating with appropriate ONS,” said Dr. Mullin, a gastroenterologist at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore and director of the Celiac Disease Clinic. A standard formulation of Ensure was the ONS routinely used at the Johns Hopkins hospitals

“We’re missing malnutrition,” Dr. Mullin said in an interview. The hospital accreditation standards of the Joint Commission call for assessment of the nutritional status of hospitalized patients within 24 hours of admission (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2015 Oct;41[10]:469-73). Screening is “not uniformly done,” and when malnutrition is identified, the finding must usually pass through several layers of a hospital’s medico-bureaucratic process before treatment actually starts, he noted. Plus, there’s often dismissal of the importance of intervention. “It’s important to treat patients with ONS sooner than later,” he said.

Dr. Mullin and his associates studied hospital records for 153,161 people admitted to any of the Baltimore-area hospitals in the Johns Hopkins system during October 2016 through the end of September 2017. The hospital staff routinely assessed nutritional status of patients after admission with a two-question screen based on the Malnutrition Screening Tool (Nutrition. 1999 June;15[6]:458-64): Have you had unplanned weight loss of 10 pounds or more during the past 6 months? Have you had decreased oral intake over the past 5 days? This identified 30,284 (20%) who qualified as possibly malnourished by either criterion. The researchers also retrospectively applied a more detailed screen to the patient records using the criteria set by an international consensus guideline committee in 2010 (J Parenter Enteraal Nutr. 2010 Mar-Apr;34[2]:156-9). This identified 8,713 of the hospitalized patients (6%) as malnourished soon after admission. Despite these numbers a scant 274 patients among these 8,713 (3%) actually received ONS, Dr. Mullin reported. In addition, it took an average of 85 hours from the time of each malnourished patient’s admission to when the ONS order appeared in their record.

Dr. Mullin conceded that both the association his group found between treatment with ONS and a reduced rate of 30-day readmission to any of the hospitals in the Johns Hopkins system, and the association between a delay in the time to the start of ONS and length of stay may have been confounded by factors not accounted for in the adjustments they applied. But he maintained that the links are consistent with results from prior studies, and warrant running prospective, randomized studies to better document the impact of ONS on newly admitted patients identified as malnourished.

“We need more of these types of studies and interventional trials to show that ONS makes a difference,” Dr. Mullin said.

The study was sponsored by Abbott, which markets the oral nutritional supplement Ensure. Dr. Mullin had no additional disclosures.

mzoler@mdedge.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

SOURCE: Source: Mullin G et al. DDW 2018 presentation 883.

WASHINGTON – Hospital staffs often fail to treat .

A retrospective review of more than 150,000 patients admitted during a single year at any center within a large, multicenter U.S. hospital system found that even when patients receive oral nutritional supplementation, there is often a substantial delay to its onset.

The data also suggested potential benefits from treating malnutrition with oral nutritional supplementation (ONS). Patients who received ONS had a 10% relative reduction in their rate of 30-day readmission, compared with malnourished patients who did not receive supplements after adjusting for several baseline demographic and clinical variables, Gerard Mullin, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week. His analysis also showed that every doubling of the time from hospital admission to an order for ONS significantly linked with a 6% rise in hospital length of stay.

The findings “highlight the importance of malnutrition screening on admission, starting a nutrition intervention as soon as malnutrition is confirmed, and treating with appropriate ONS,” said Dr. Mullin, a gastroenterologist at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore and director of the Celiac Disease Clinic. A standard formulation of Ensure was the ONS routinely used at the Johns Hopkins hospitals

“We’re missing malnutrition,” Dr. Mullin said in an interview. The hospital accreditation standards of the Joint Commission call for assessment of the nutritional status of hospitalized patients within 24 hours of admission (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2015 Oct;41[10]:469-73). Screening is “not uniformly done,” and when malnutrition is identified, the finding must usually pass through several layers of a hospital’s medico-bureaucratic process before treatment actually starts, he noted. Plus, there’s often dismissal of the importance of intervention. “It’s important to treat patients with ONS sooner than later,” he said.

Dr. Mullin and his associates studied hospital records for 153,161 people admitted to any of the Baltimore-area hospitals in the Johns Hopkins system during October 2016 through the end of September 2017. The hospital staff routinely assessed nutritional status of patients after admission with a two-question screen based on the Malnutrition Screening Tool (Nutrition. 1999 June;15[6]:458-64): Have you had unplanned weight loss of 10 pounds or more during the past 6 months? Have you had decreased oral intake over the past 5 days? This identified 30,284 (20%) who qualified as possibly malnourished by either criterion. The researchers also retrospectively applied a more detailed screen to the patient records using the criteria set by an international consensus guideline committee in 2010 (J Parenter Enteraal Nutr. 2010 Mar-Apr;34[2]:156-9). This identified 8,713 of the hospitalized patients (6%) as malnourished soon after admission. Despite these numbers a scant 274 patients among these 8,713 (3%) actually received ONS, Dr. Mullin reported. In addition, it took an average of 85 hours from the time of each malnourished patient’s admission to when the ONS order appeared in their record.

Dr. Mullin conceded that both the association his group found between treatment with ONS and a reduced rate of 30-day readmission to any of the hospitals in the Johns Hopkins system, and the association between a delay in the time to the start of ONS and length of stay may have been confounded by factors not accounted for in the adjustments they applied. But he maintained that the links are consistent with results from prior studies, and warrant running prospective, randomized studies to better document the impact of ONS on newly admitted patients identified as malnourished.

“We need more of these types of studies and interventional trials to show that ONS makes a difference,” Dr. Mullin said.

The study was sponsored by Abbott, which markets the oral nutritional supplement Ensure. Dr. Mullin had no additional disclosures.

mzoler@mdedge.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

SOURCE: Source: Mullin G et al. DDW 2018 presentation 883.

REPORTING FROM DDW 2018

Key clinical point: Malnourished U.S. hospital inpatients often go untreated.

Major finding: Three percent of patients retrospectively identified as malnourished soon after hospital admission received oral nutritional supplementation.

Study details: Retrospective review of 153,161 patients admitted to a large U.S. hospital network during 2016-2017.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Abbott, which markets the oral nutritional supplement Ensure. Dr. Mullin had no additional disclosures.

Source: Mullin G et al. Digestive Disease Week presentation 883.

Education sessions upped COPD patients’ knowledge of their disease

A brief patient-directed education program delivered at the time of hospitalization for an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) improved disease-specific knowledge, according to results of a pilot randomized trial.

Patients who participated in education sessions had a significant improvement in their scores on the Bristol COPD Knowledge Questionnaire (BCKQ), compared with control patients who received no education, study investigators reported in the journal Chest.

“Early education may be a bridge to more active approaches and could provide an important contribution to self-management interventions post-AECOPD,” wrote first author Tania Janaudis-Ferreira, PhD, of the School of Physical and Occupational Therapy, McGill University, Montreal, and her co-authors.

In the study, patients admitted to a community hospital with an AECOPD were randomized to standard care plus brief education or standard care alone. The education consisted of two 30-minute sessions delivered by a physiotherapist, either in the hospital or at home up to 2 weeks after the admission.

Before and after the intervention period, participant knowledge was measured using both the BCKQ and the Lung Information Needs Questionnaire (LINQ).

A total of 31 patients participated, including 15 in the intervention group and 16 in the control group, although 3 patients in the control group did not complete the follow-up testing, investigators said in their report.

The mean change in BCKQ was 8 points for the educational intervention group, and 3.4 for the control group (P = 0.02). That result was in keeping with findings of a previous randomized study noting an 8.3-point change in BCKQ scores for COPD patients who received education in the primary care setting, Dr. Janaudis-Ferreira and co-authors said.

“The change itself is relatively modest, suggesting more frequent sessions might result in greater improvements,” they wrote. For example, they said, an 8-week educational intervention delivered in the context of pulmonary rehabilitation program in one study yielded a mean change of 18.3 points on the BCKQ in the intervention group.

By contrast, the investigators found no significant difference in LINQ score changes between the intervention and control groups (P = .8).

That may indicate that two 30-minute sessions were not sufficient to attend to patients’ learning needs, authors said, though it could also have been an issue with the instrument itself in the setting of this study.

“The majority of the questions in the LINQ ask whether or not a doctor or nurse has explained a specific question to the patient,” authors explained. “Since a physiotherapist delivered the program, had the wording been altered to include physiotherapists or a more general term for healthcare professionals, we may have seen a change in these results.”

Dr. Janaudis-Ferreira and co-authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose. The study was funded by a grant from the Canadian Respiratory Health Professionals, which did not have input in research or manuscript development.

SOURCE: Janaudis-Ferreira T, et al. Chest

A brief patient-directed education program delivered at the time of hospitalization for an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) improved disease-specific knowledge, according to results of a pilot randomized trial.

Patients who participated in education sessions had a significant improvement in their scores on the Bristol COPD Knowledge Questionnaire (BCKQ), compared with control patients who received no education, study investigators reported in the journal Chest.

“Early education may be a bridge to more active approaches and could provide an important contribution to self-management interventions post-AECOPD,” wrote first author Tania Janaudis-Ferreira, PhD, of the School of Physical and Occupational Therapy, McGill University, Montreal, and her co-authors.

In the study, patients admitted to a community hospital with an AECOPD were randomized to standard care plus brief education or standard care alone. The education consisted of two 30-minute sessions delivered by a physiotherapist, either in the hospital or at home up to 2 weeks after the admission.

Before and after the intervention period, participant knowledge was measured using both the BCKQ and the Lung Information Needs Questionnaire (LINQ).

A total of 31 patients participated, including 15 in the intervention group and 16 in the control group, although 3 patients in the control group did not complete the follow-up testing, investigators said in their report.

The mean change in BCKQ was 8 points for the educational intervention group, and 3.4 for the control group (P = 0.02). That result was in keeping with findings of a previous randomized study noting an 8.3-point change in BCKQ scores for COPD patients who received education in the primary care setting, Dr. Janaudis-Ferreira and co-authors said.

“The change itself is relatively modest, suggesting more frequent sessions might result in greater improvements,” they wrote. For example, they said, an 8-week educational intervention delivered in the context of pulmonary rehabilitation program in one study yielded a mean change of 18.3 points on the BCKQ in the intervention group.

By contrast, the investigators found no significant difference in LINQ score changes between the intervention and control groups (P = .8).

That may indicate that two 30-minute sessions were not sufficient to attend to patients’ learning needs, authors said, though it could also have been an issue with the instrument itself in the setting of this study.

“The majority of the questions in the LINQ ask whether or not a doctor or nurse has explained a specific question to the patient,” authors explained. “Since a physiotherapist delivered the program, had the wording been altered to include physiotherapists or a more general term for healthcare professionals, we may have seen a change in these results.”

Dr. Janaudis-Ferreira and co-authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose. The study was funded by a grant from the Canadian Respiratory Health Professionals, which did not have input in research or manuscript development.

SOURCE: Janaudis-Ferreira T, et al. Chest

A brief patient-directed education program delivered at the time of hospitalization for an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) improved disease-specific knowledge, according to results of a pilot randomized trial.

Patients who participated in education sessions had a significant improvement in their scores on the Bristol COPD Knowledge Questionnaire (BCKQ), compared with control patients who received no education, study investigators reported in the journal Chest.

“Early education may be a bridge to more active approaches and could provide an important contribution to self-management interventions post-AECOPD,” wrote first author Tania Janaudis-Ferreira, PhD, of the School of Physical and Occupational Therapy, McGill University, Montreal, and her co-authors.

In the study, patients admitted to a community hospital with an AECOPD were randomized to standard care plus brief education or standard care alone. The education consisted of two 30-minute sessions delivered by a physiotherapist, either in the hospital or at home up to 2 weeks after the admission.

Before and after the intervention period, participant knowledge was measured using both the BCKQ and the Lung Information Needs Questionnaire (LINQ).

A total of 31 patients participated, including 15 in the intervention group and 16 in the control group, although 3 patients in the control group did not complete the follow-up testing, investigators said in their report.

The mean change in BCKQ was 8 points for the educational intervention group, and 3.4 for the control group (P = 0.02). That result was in keeping with findings of a previous randomized study noting an 8.3-point change in BCKQ scores for COPD patients who received education in the primary care setting, Dr. Janaudis-Ferreira and co-authors said.

“The change itself is relatively modest, suggesting more frequent sessions might result in greater improvements,” they wrote. For example, they said, an 8-week educational intervention delivered in the context of pulmonary rehabilitation program in one study yielded a mean change of 18.3 points on the BCKQ in the intervention group.

By contrast, the investigators found no significant difference in LINQ score changes between the intervention and control groups (P = .8).

That may indicate that two 30-minute sessions were not sufficient to attend to patients’ learning needs, authors said, though it could also have been an issue with the instrument itself in the setting of this study.

“The majority of the questions in the LINQ ask whether or not a doctor or nurse has explained a specific question to the patient,” authors explained. “Since a physiotherapist delivered the program, had the wording been altered to include physiotherapists or a more general term for healthcare professionals, we may have seen a change in these results.”

Dr. Janaudis-Ferreira and co-authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose. The study was funded by a grant from the Canadian Respiratory Health Professionals, which did not have input in research or manuscript development.

SOURCE: Janaudis-Ferreira T, et al. Chest

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point: Two 30-minute education sessions improved patients’ disease-specific knowledge for an acute exacerbation of COPD.

Major finding: Mean change on the Bristol COPD Knowledge Questionnaire (BCKQ) was 8 points for the educational intervention, and 3.4 for controls.

Study details: A pilot randomized controlled trial of 31 patients admitted to a community hospital.

Disclosures: Authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose. The study was funded by a grant from the Canadian Respiratory Health Professionals, which did not have input in research or manuscript development.

Source: Janaudis-Ferreira T, et al. Chest 2018 Jun 4.

Hospital-acquired conditions drop 8% since 2014, saving 8,000 lives and $3 billion

From 2014 to 2016, the rate of potentially deadly hospital-acquired conditions in the United States dropped by 8% – a change that translated into 350,000 fewer such conditions, 8,000 fewer inpatient deaths, and a national savings of almost $3 billion.

The preliminary new baseline rate for hospital-acquired conditions (HACs) is 90 per 1,000 discharges – down from 98 per 1,000 discharges at the end of 2014, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s new report, “AHRQ National Scorecard on Hospital-Acquired Conditions – Updated Baseline Rates and Preliminary Results 2014-2016.”

The largest improvements occurred in central line–associated bloodstream infections (down 31% from 2014), postoperative venous thromboembolism (21% decline), adverse drug events (15% decline), and pressure ulcers (10% decline). A new category, C. difficile infections, also showed a large decline over 2014 (11%).

These numbers build on earlier successes associated with a national goal set by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to reduce HACs by 20% by 2019. They should be hailed as proof that attention to prevention strategies can save lives and money, said Seema Verma, CMS administrator.

“Today’s results show that this is a tremendous accomplishment by America’s hospitals in delivering high-quality, affordable healthcare,” Ms. Verma said in a press statement. “CMS is committed to moving the healthcare system to one that improves quality and fosters innovation while reducing administrative burden and lowering costs. This work could not be accomplished without the concerted effort of our many hospital, patient, provider, private, and federal partners – all working together to ensure the best possible care by protecting patients from harm and making care safer.”

The numbers continue to go in the right direction, the report noted. Data reported in late 2016 found a 17% decline in HACs from 2010 to 2014. This equated to 2.1 million HACs, 87,000 fewer deaths, and a savings of $19.9 billion.

Much work remains to be done to achieve the stated 2019 goal, the report noted, but the rewards are great. Reaching the 20% reduction goal would secure a total decrease in the HAC rate from 98 to 78 per 1,000 discharges. This would result in 1.78 million fewer HAC in the years from 2015-2019. That decrease would ultimately save 53,000 lives and $19.1 billion over 5 years.

From 2014 to 2016, the rate of potentially deadly hospital-acquired conditions in the United States dropped by 8% – a change that translated into 350,000 fewer such conditions, 8,000 fewer inpatient deaths, and a national savings of almost $3 billion.

The preliminary new baseline rate for hospital-acquired conditions (HACs) is 90 per 1,000 discharges – down from 98 per 1,000 discharges at the end of 2014, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s new report, “AHRQ National Scorecard on Hospital-Acquired Conditions – Updated Baseline Rates and Preliminary Results 2014-2016.”

The largest improvements occurred in central line–associated bloodstream infections (down 31% from 2014), postoperative venous thromboembolism (21% decline), adverse drug events (15% decline), and pressure ulcers (10% decline). A new category, C. difficile infections, also showed a large decline over 2014 (11%).

These numbers build on earlier successes associated with a national goal set by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to reduce HACs by 20% by 2019. They should be hailed as proof that attention to prevention strategies can save lives and money, said Seema Verma, CMS administrator.

“Today’s results show that this is a tremendous accomplishment by America’s hospitals in delivering high-quality, affordable healthcare,” Ms. Verma said in a press statement. “CMS is committed to moving the healthcare system to one that improves quality and fosters innovation while reducing administrative burden and lowering costs. This work could not be accomplished without the concerted effort of our many hospital, patient, provider, private, and federal partners – all working together to ensure the best possible care by protecting patients from harm and making care safer.”

The numbers continue to go in the right direction, the report noted. Data reported in late 2016 found a 17% decline in HACs from 2010 to 2014. This equated to 2.1 million HACs, 87,000 fewer deaths, and a savings of $19.9 billion.

Much work remains to be done to achieve the stated 2019 goal, the report noted, but the rewards are great. Reaching the 20% reduction goal would secure a total decrease in the HAC rate from 98 to 78 per 1,000 discharges. This would result in 1.78 million fewer HAC in the years from 2015-2019. That decrease would ultimately save 53,000 lives and $19.1 billion over 5 years.

From 2014 to 2016, the rate of potentially deadly hospital-acquired conditions in the United States dropped by 8% – a change that translated into 350,000 fewer such conditions, 8,000 fewer inpatient deaths, and a national savings of almost $3 billion.

The preliminary new baseline rate for hospital-acquired conditions (HACs) is 90 per 1,000 discharges – down from 98 per 1,000 discharges at the end of 2014, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s new report, “AHRQ National Scorecard on Hospital-Acquired Conditions – Updated Baseline Rates and Preliminary Results 2014-2016.”

The largest improvements occurred in central line–associated bloodstream infections (down 31% from 2014), postoperative venous thromboembolism (21% decline), adverse drug events (15% decline), and pressure ulcers (10% decline). A new category, C. difficile infections, also showed a large decline over 2014 (11%).

These numbers build on earlier successes associated with a national goal set by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to reduce HACs by 20% by 2019. They should be hailed as proof that attention to prevention strategies can save lives and money, said Seema Verma, CMS administrator.

“Today’s results show that this is a tremendous accomplishment by America’s hospitals in delivering high-quality, affordable healthcare,” Ms. Verma said in a press statement. “CMS is committed to moving the healthcare system to one that improves quality and fosters innovation while reducing administrative burden and lowering costs. This work could not be accomplished without the concerted effort of our many hospital, patient, provider, private, and federal partners – all working together to ensure the best possible care by protecting patients from harm and making care safer.”

The numbers continue to go in the right direction, the report noted. Data reported in late 2016 found a 17% decline in HACs from 2010 to 2014. This equated to 2.1 million HACs, 87,000 fewer deaths, and a savings of $19.9 billion.

Much work remains to be done to achieve the stated 2019 goal, the report noted, but the rewards are great. Reaching the 20% reduction goal would secure a total decrease in the HAC rate from 98 to 78 per 1,000 discharges. This would result in 1.78 million fewer HAC in the years from 2015-2019. That decrease would ultimately save 53,000 lives and $19.1 billion over 5 years.

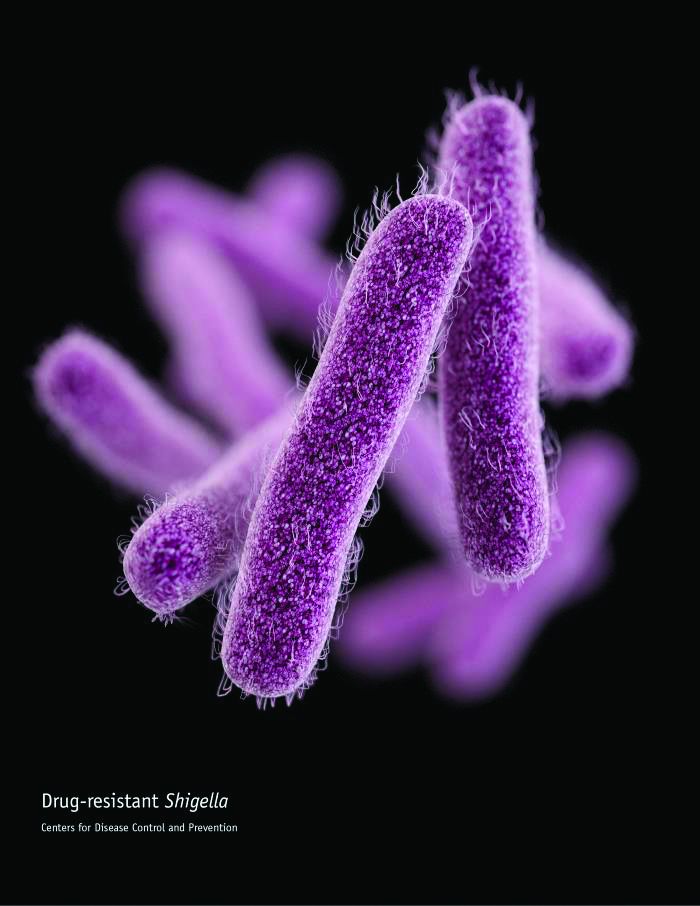

CDC concerned about multidrug-resistant Shigella

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have issued follow-up recommendations for managing and reporting Shigella infections because of concerns about increasing antibiotic resistance and the possibility of treatment failures.

Isolates with no resistance to quinolone antibiotics have ciprofloxacin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of less than 0.015 mcg/mL. However, the CDC has continued to identify isolates of Shigella that, while still within the susceptible range for the fluoroquinolone antibiotic ciprofloxacin (that is, having MIC values less than 1 mcg/mL), have MIC values for ciprofloxacin of 0.12-1.0 mcg/mL, thus appearing to harbor one or more resistance mechanisms. Furthermore, the CDC has identified an increasing number of isolates that have MIC values for azithromycin exceeding the epidemiologic cutoff value, which suggests some form of acquired resistance.

“CDC is particularly concerned about people who are at high risk for multidrug-resistant Shigella infections and are more likely to require antibiotic treatment, such as men who have sex with men, patients who are homeless, and immunocompromised patients. These patients often have more severe disease, prolonged shedding, and recurrent infections,” the recommendations stated.

More information can be found in the CDC’s Health Alert Network release.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have issued follow-up recommendations for managing and reporting Shigella infections because of concerns about increasing antibiotic resistance and the possibility of treatment failures.

Isolates with no resistance to quinolone antibiotics have ciprofloxacin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of less than 0.015 mcg/mL. However, the CDC has continued to identify isolates of Shigella that, while still within the susceptible range for the fluoroquinolone antibiotic ciprofloxacin (that is, having MIC values less than 1 mcg/mL), have MIC values for ciprofloxacin of 0.12-1.0 mcg/mL, thus appearing to harbor one or more resistance mechanisms. Furthermore, the CDC has identified an increasing number of isolates that have MIC values for azithromycin exceeding the epidemiologic cutoff value, which suggests some form of acquired resistance.

“CDC is particularly concerned about people who are at high risk for multidrug-resistant Shigella infections and are more likely to require antibiotic treatment, such as men who have sex with men, patients who are homeless, and immunocompromised patients. These patients often have more severe disease, prolonged shedding, and recurrent infections,” the recommendations stated.

More information can be found in the CDC’s Health Alert Network release.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have issued follow-up recommendations for managing and reporting Shigella infections because of concerns about increasing antibiotic resistance and the possibility of treatment failures.

Isolates with no resistance to quinolone antibiotics have ciprofloxacin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of less than 0.015 mcg/mL. However, the CDC has continued to identify isolates of Shigella that, while still within the susceptible range for the fluoroquinolone antibiotic ciprofloxacin (that is, having MIC values less than 1 mcg/mL), have MIC values for ciprofloxacin of 0.12-1.0 mcg/mL, thus appearing to harbor one or more resistance mechanisms. Furthermore, the CDC has identified an increasing number of isolates that have MIC values for azithromycin exceeding the epidemiologic cutoff value, which suggests some form of acquired resistance.

“CDC is particularly concerned about people who are at high risk for multidrug-resistant Shigella infections and are more likely to require antibiotic treatment, such as men who have sex with men, patients who are homeless, and immunocompromised patients. These patients often have more severe disease, prolonged shedding, and recurrent infections,” the recommendations stated.

More information can be found in the CDC’s Health Alert Network release.

A clinical pathway to standardize use of maintenance IV fluids

Clinical question

Can an evidence-based clinical pathway improve adherence to recent recommendations to use isotonic solutions for maintenance intravenous fluids in hospitalized children?

Background

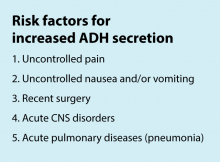

The traditional teaching regarding composition of maintenance intravenous fluids (IVF) in children has been based on the Holliday-Segar method.1 Since its publication in Pediatrics in 1957, concerns have been raised regarding the risk of iatrogenic hyponatremia caused by giving hypotonic fluids determined by this method,2 especially in patients with an elevated risk of increased antidiuretic hormone (ADH) secretion.3 Multiple recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have confirmed that isotonic IVF reduces the risk of hyponatremia in hospitalized children.4

Study design

Interrupted time series analysis before and after pathway implementation.

Setting

370-bed tertiary care free-standing children’s hospital.

Synopsis

A multidisciplinary team was assembled, comprising physicians and nurses in hospital medicine, general pediatrics, emergency medicine, and nephrology. After a systematic review of the recent literature, a clinical algorithm and web-based training module were developed. Faculty in general pediatrics, hospital medicine, and emergency medicine were required to complete the module, while medical and surgical residents were encouraged but not required to complete the module. A maintenance IVF order set was created and embedded into all order sets previously containing IVF orders and was also available in stand-alone form.

Inclusion criteria (“pathway eligible”) included being euvolemic and requiring IVF. Exclusion criteria included fluid status derangements, critical illness, severe serum sodium abnormalities (serum sodium ≥150 mEq/L or ≤130 mEq/L) use of TPN or ketogenic diet. In the order set, IVF composition was determined based on risk factors for increased ADH secretion. Inclusion of potassium in IVF was also determined by the pathway.

Over the 1-year study period, 11,602 pathway-eligible encounters in 10,287 patients were reviewed. Use of isotonic maintenance IVF increased significantly from 9.3% to 50.6%, while use of hypotonic fluids decreased from 94.2% to 56.6%. Use of potassium-containing IVF increased from 52.9% to 75.3%. Dysnatremia continued to occur due to hypotonic IVF use.

Bottom line

A combined clinical pathway and training module to standardize the composition of IVF is feasible, and results in increased use of isotonic and potassium-containing fluids.

Citation

Rooholamini S, Clifton H, Haaland W, et al. Outcomes of a clinical pathway to standardize use of maintenance intravenous fluids. Hosp Pediatr. 2017 Dec;7(12):703-9.

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist at Baystate Children’s Hospital in Springfield, Mass., and is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

References

1. Holliday MA et al. The maintenance need for water in parenteral fluid therapy. Pediatrics 1957;19:823-32.

2. Friedman JN et al. Comparison of isotonic and hypotonic intravenous maintenance fluids: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:445-51.

3. Fuchs J et al. Current Issues in Intravenous Fluid Use in Hospitalized Children. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2017;12:284-9.

4. McNab S et al. Isotonic versus hypotonic solutions for maintenance intravenous fluid administration in children. Cochrane Database. Syst Rev 2014:CD009457.

Clinical question

Can an evidence-based clinical pathway improve adherence to recent recommendations to use isotonic solutions for maintenance intravenous fluids in hospitalized children?

Background

The traditional teaching regarding composition of maintenance intravenous fluids (IVF) in children has been based on the Holliday-Segar method.1 Since its publication in Pediatrics in 1957, concerns have been raised regarding the risk of iatrogenic hyponatremia caused by giving hypotonic fluids determined by this method,2 especially in patients with an elevated risk of increased antidiuretic hormone (ADH) secretion.3 Multiple recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have confirmed that isotonic IVF reduces the risk of hyponatremia in hospitalized children.4

Study design

Interrupted time series analysis before and after pathway implementation.

Setting

370-bed tertiary care free-standing children’s hospital.

Synopsis

A multidisciplinary team was assembled, comprising physicians and nurses in hospital medicine, general pediatrics, emergency medicine, and nephrology. After a systematic review of the recent literature, a clinical algorithm and web-based training module were developed. Faculty in general pediatrics, hospital medicine, and emergency medicine were required to complete the module, while medical and surgical residents were encouraged but not required to complete the module. A maintenance IVF order set was created and embedded into all order sets previously containing IVF orders and was also available in stand-alone form.

Inclusion criteria (“pathway eligible”) included being euvolemic and requiring IVF. Exclusion criteria included fluid status derangements, critical illness, severe serum sodium abnormalities (serum sodium ≥150 mEq/L or ≤130 mEq/L) use of TPN or ketogenic diet. In the order set, IVF composition was determined based on risk factors for increased ADH secretion. Inclusion of potassium in IVF was also determined by the pathway.

Over the 1-year study period, 11,602 pathway-eligible encounters in 10,287 patients were reviewed. Use of isotonic maintenance IVF increased significantly from 9.3% to 50.6%, while use of hypotonic fluids decreased from 94.2% to 56.6%. Use of potassium-containing IVF increased from 52.9% to 75.3%. Dysnatremia continued to occur due to hypotonic IVF use.

Bottom line

A combined clinical pathway and training module to standardize the composition of IVF is feasible, and results in increased use of isotonic and potassium-containing fluids.

Citation

Rooholamini S, Clifton H, Haaland W, et al. Outcomes of a clinical pathway to standardize use of maintenance intravenous fluids. Hosp Pediatr. 2017 Dec;7(12):703-9.

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist at Baystate Children’s Hospital in Springfield, Mass., and is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

References

1. Holliday MA et al. The maintenance need for water in parenteral fluid therapy. Pediatrics 1957;19:823-32.

2. Friedman JN et al. Comparison of isotonic and hypotonic intravenous maintenance fluids: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:445-51.

3. Fuchs J et al. Current Issues in Intravenous Fluid Use in Hospitalized Children. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2017;12:284-9.

4. McNab S et al. Isotonic versus hypotonic solutions for maintenance intravenous fluid administration in children. Cochrane Database. Syst Rev 2014:CD009457.

Clinical question

Can an evidence-based clinical pathway improve adherence to recent recommendations to use isotonic solutions for maintenance intravenous fluids in hospitalized children?

Background

The traditional teaching regarding composition of maintenance intravenous fluids (IVF) in children has been based on the Holliday-Segar method.1 Since its publication in Pediatrics in 1957, concerns have been raised regarding the risk of iatrogenic hyponatremia caused by giving hypotonic fluids determined by this method,2 especially in patients with an elevated risk of increased antidiuretic hormone (ADH) secretion.3 Multiple recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have confirmed that isotonic IVF reduces the risk of hyponatremia in hospitalized children.4

Study design

Interrupted time series analysis before and after pathway implementation.

Setting

370-bed tertiary care free-standing children’s hospital.

Synopsis

A multidisciplinary team was assembled, comprising physicians and nurses in hospital medicine, general pediatrics, emergency medicine, and nephrology. After a systematic review of the recent literature, a clinical algorithm and web-based training module were developed. Faculty in general pediatrics, hospital medicine, and emergency medicine were required to complete the module, while medical and surgical residents were encouraged but not required to complete the module. A maintenance IVF order set was created and embedded into all order sets previously containing IVF orders and was also available in stand-alone form.

Inclusion criteria (“pathway eligible”) included being euvolemic and requiring IVF. Exclusion criteria included fluid status derangements, critical illness, severe serum sodium abnormalities (serum sodium ≥150 mEq/L or ≤130 mEq/L) use of TPN or ketogenic diet. In the order set, IVF composition was determined based on risk factors for increased ADH secretion. Inclusion of potassium in IVF was also determined by the pathway.

Over the 1-year study period, 11,602 pathway-eligible encounters in 10,287 patients were reviewed. Use of isotonic maintenance IVF increased significantly from 9.3% to 50.6%, while use of hypotonic fluids decreased from 94.2% to 56.6%. Use of potassium-containing IVF increased from 52.9% to 75.3%. Dysnatremia continued to occur due to hypotonic IVF use.

Bottom line

A combined clinical pathway and training module to standardize the composition of IVF is feasible, and results in increased use of isotonic and potassium-containing fluids.

Citation

Rooholamini S, Clifton H, Haaland W, et al. Outcomes of a clinical pathway to standardize use of maintenance intravenous fluids. Hosp Pediatr. 2017 Dec;7(12):703-9.

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist at Baystate Children’s Hospital in Springfield, Mass., and is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

References

1. Holliday MA et al. The maintenance need for water in parenteral fluid therapy. Pediatrics 1957;19:823-32.

2. Friedman JN et al. Comparison of isotonic and hypotonic intravenous maintenance fluids: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:445-51.

3. Fuchs J et al. Current Issues in Intravenous Fluid Use in Hospitalized Children. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2017;12:284-9.

4. McNab S et al. Isotonic versus hypotonic solutions for maintenance intravenous fluid administration in children. Cochrane Database. Syst Rev 2014:CD009457.

Trio of blood biomarkers elevated in children with LRTIs

TORONTO – While C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, and proadrenomedullin are associated with development of severe clinical outcomes in children with lower respiratory tract infections, proadrenomedullin is most strongly associated with disease severity, preliminary results from a prospective cohort study showed.

“Despite the fact that pneumonia guidelines call the site of care decision the most important decision in the management of pediatric pneumonia, no validated risk stratification tools exist for pediatric lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI),” lead study author Todd A. Florin, MD, said at the annual Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. “Biomarkers offer an objective means of classifying disease severity and clinical outcomes.”