User login

LGBTQ+ Youth Consult Questions remain over use of sex hormone therapy

“They Paused Puberty but Is There a Cost?”

“Bone Health: Puberty Blockers Not Fully Reversible.”

Headlines such as these from major national news outlets have begun to cast doubt on one of the medications used in treating gender-diverse adolescents and young adults. GnRH agonists, such as leuprorelin and triptorelin, were first approved by the Food and Drug Administration in the 1980s and have been used since then for a variety of medical indications. In the decades since, these medications have been successfully used with a generally favorable side effect profile.

GnRH agonists and puberty

In the treatment of precocious puberty, GnRH agonists are often started prior to the age of 7, depending on the age at which the affected patient begins showing signs of central puberty. These include breast development, scrotal enlargement, and so on. GnRH agonists typically are continued until age 10-12, depending on the patient and an informed discussion with the patient’s parents about optimal outcomes.1 Therefore, it is not uncommon to see these medications used for anywhere from 1 to 4 years, depending on the age at which precocious puberty started.

GnRH agonists are used in two populations of transgender individuals. The first group is those youths who have just started their natal, or biological, puberty. The medication is not started until the patient has biochemical or physical exam evidence that puberty has started. The medication is then continued until hormones are started. This is usually 2-3 years on average, depending on the age at which the medication was started. This is essentially comparable with cisgender youths who have taken these medications for precocious puberty. The second population of individuals who use GnRH agonists is transgender women who are also on estrogen therapy. In these women, the GnRH agonist is used for androgen (testosterone) suppression.

Concerns over bone health

One of the main concerns recently expressed about long-term use of GnRH agonists is their effect on bone density. Adolescence is a critical time for bone mineral density (BMD) accrual and this is driven by sex hormones. When GnRH agonists are used to delay puberty in transgender adolescents, this then delays the maturation of the adult skeleton until the GnRH agonist is stopped (and natal puberty resumes) or cross-sex hormones are started. In a recent multicenter study2 looking at baseline BMD of transgender youth at the time of GnRH agonist initiation, 30% of those assigned male at birth and 13% of those assigned female at birth had low bone mineral density for age (defined as a BMD z score of <–2). For those with low BMD, their physical activity scores were significantly lower than those with normal BMD. Thus, these adolescents require close follow-up, just like their cisgender peers.

There are currently no long-term data on the risk of developing fractures or osteoporosis in those individuals who were treated with GnRH agonists and then went on to start cross-sex hormone therapy. Some studies suggest that there is a risk that BMD does not recover after being on cross-sex hormones,3 while another study suggested that transgender men recover their BMD after being on testosterone.4 It is still unclear in that study why transgender women did not recover their BMD or why they were low at baseline. Interestingly, a 2012 study5 from Brazil showed that there was no difference in BMD for cisgender girls who had been off their GnRH agonist therapy for at least 3 years, as compared with their age-matched controls who had never been on GnRH agonist therapy. These conflicting data highlight the importance of long-term follow-up, as well as the need to include age-matched, cisgender control subjects, to better understand if there is truly a difference in transgender individuals or if today’s adolescents, in general, have low BMD.

Lingering questions

In summary, the use of GnRH agonists in transgender adolescents remains controversial because of the potential long-term effects on bone mineral density. However, this risk must be balanced against the risks of allowing natal puberty to progress in certain transgender individuals with the development of undesired secondary sex characteristics. More longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the long-term risks of osteoporosis and fractures in those who have undergone GnRH agonist therapy as part of their gender-affirming medical care, as well as any clinical interventions that might help mitigate this risk.

Dr. Cooper is assistant professor of pediatrics at UT Southwestern, Dallas, and an adolescent medicine specialist at Children’s Medical Center Dallas.

References

1. Harrington J et al. Treatment of precocious puberty. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-precocious-puberty.

2. Lee JY et al. J Endocr Soc. 2020;4(9):bvaa065. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvaa065.

3. Klink D et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(2):E270-5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2439.

4. Schagen SEE et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(12):e4252-e4263. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa604.

5. Alessandri SB et al. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2012;67(6):591-6. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2012(06)08.

“They Paused Puberty but Is There a Cost?”

“Bone Health: Puberty Blockers Not Fully Reversible.”

Headlines such as these from major national news outlets have begun to cast doubt on one of the medications used in treating gender-diverse adolescents and young adults. GnRH agonists, such as leuprorelin and triptorelin, were first approved by the Food and Drug Administration in the 1980s and have been used since then for a variety of medical indications. In the decades since, these medications have been successfully used with a generally favorable side effect profile.

GnRH agonists and puberty

In the treatment of precocious puberty, GnRH agonists are often started prior to the age of 7, depending on the age at which the affected patient begins showing signs of central puberty. These include breast development, scrotal enlargement, and so on. GnRH agonists typically are continued until age 10-12, depending on the patient and an informed discussion with the patient’s parents about optimal outcomes.1 Therefore, it is not uncommon to see these medications used for anywhere from 1 to 4 years, depending on the age at which precocious puberty started.

GnRH agonists are used in two populations of transgender individuals. The first group is those youths who have just started their natal, or biological, puberty. The medication is not started until the patient has biochemical or physical exam evidence that puberty has started. The medication is then continued until hormones are started. This is usually 2-3 years on average, depending on the age at which the medication was started. This is essentially comparable with cisgender youths who have taken these medications for precocious puberty. The second population of individuals who use GnRH agonists is transgender women who are also on estrogen therapy. In these women, the GnRH agonist is used for androgen (testosterone) suppression.

Concerns over bone health

One of the main concerns recently expressed about long-term use of GnRH agonists is their effect on bone density. Adolescence is a critical time for bone mineral density (BMD) accrual and this is driven by sex hormones. When GnRH agonists are used to delay puberty in transgender adolescents, this then delays the maturation of the adult skeleton until the GnRH agonist is stopped (and natal puberty resumes) or cross-sex hormones are started. In a recent multicenter study2 looking at baseline BMD of transgender youth at the time of GnRH agonist initiation, 30% of those assigned male at birth and 13% of those assigned female at birth had low bone mineral density for age (defined as a BMD z score of <–2). For those with low BMD, their physical activity scores were significantly lower than those with normal BMD. Thus, these adolescents require close follow-up, just like their cisgender peers.

There are currently no long-term data on the risk of developing fractures or osteoporosis in those individuals who were treated with GnRH agonists and then went on to start cross-sex hormone therapy. Some studies suggest that there is a risk that BMD does not recover after being on cross-sex hormones,3 while another study suggested that transgender men recover their BMD after being on testosterone.4 It is still unclear in that study why transgender women did not recover their BMD or why they were low at baseline. Interestingly, a 2012 study5 from Brazil showed that there was no difference in BMD for cisgender girls who had been off their GnRH agonist therapy for at least 3 years, as compared with their age-matched controls who had never been on GnRH agonist therapy. These conflicting data highlight the importance of long-term follow-up, as well as the need to include age-matched, cisgender control subjects, to better understand if there is truly a difference in transgender individuals or if today’s adolescents, in general, have low BMD.

Lingering questions

In summary, the use of GnRH agonists in transgender adolescents remains controversial because of the potential long-term effects on bone mineral density. However, this risk must be balanced against the risks of allowing natal puberty to progress in certain transgender individuals with the development of undesired secondary sex characteristics. More longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the long-term risks of osteoporosis and fractures in those who have undergone GnRH agonist therapy as part of their gender-affirming medical care, as well as any clinical interventions that might help mitigate this risk.

Dr. Cooper is assistant professor of pediatrics at UT Southwestern, Dallas, and an adolescent medicine specialist at Children’s Medical Center Dallas.

References

1. Harrington J et al. Treatment of precocious puberty. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-precocious-puberty.

2. Lee JY et al. J Endocr Soc. 2020;4(9):bvaa065. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvaa065.

3. Klink D et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(2):E270-5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2439.

4. Schagen SEE et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(12):e4252-e4263. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa604.

5. Alessandri SB et al. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2012;67(6):591-6. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2012(06)08.

“They Paused Puberty but Is There a Cost?”

“Bone Health: Puberty Blockers Not Fully Reversible.”

Headlines such as these from major national news outlets have begun to cast doubt on one of the medications used in treating gender-diverse adolescents and young adults. GnRH agonists, such as leuprorelin and triptorelin, were first approved by the Food and Drug Administration in the 1980s and have been used since then for a variety of medical indications. In the decades since, these medications have been successfully used with a generally favorable side effect profile.

GnRH agonists and puberty

In the treatment of precocious puberty, GnRH agonists are often started prior to the age of 7, depending on the age at which the affected patient begins showing signs of central puberty. These include breast development, scrotal enlargement, and so on. GnRH agonists typically are continued until age 10-12, depending on the patient and an informed discussion with the patient’s parents about optimal outcomes.1 Therefore, it is not uncommon to see these medications used for anywhere from 1 to 4 years, depending on the age at which precocious puberty started.

GnRH agonists are used in two populations of transgender individuals. The first group is those youths who have just started their natal, or biological, puberty. The medication is not started until the patient has biochemical or physical exam evidence that puberty has started. The medication is then continued until hormones are started. This is usually 2-3 years on average, depending on the age at which the medication was started. This is essentially comparable with cisgender youths who have taken these medications for precocious puberty. The second population of individuals who use GnRH agonists is transgender women who are also on estrogen therapy. In these women, the GnRH agonist is used for androgen (testosterone) suppression.

Concerns over bone health

One of the main concerns recently expressed about long-term use of GnRH agonists is their effect on bone density. Adolescence is a critical time for bone mineral density (BMD) accrual and this is driven by sex hormones. When GnRH agonists are used to delay puberty in transgender adolescents, this then delays the maturation of the adult skeleton until the GnRH agonist is stopped (and natal puberty resumes) or cross-sex hormones are started. In a recent multicenter study2 looking at baseline BMD of transgender youth at the time of GnRH agonist initiation, 30% of those assigned male at birth and 13% of those assigned female at birth had low bone mineral density for age (defined as a BMD z score of <–2). For those with low BMD, their physical activity scores were significantly lower than those with normal BMD. Thus, these adolescents require close follow-up, just like their cisgender peers.

There are currently no long-term data on the risk of developing fractures or osteoporosis in those individuals who were treated with GnRH agonists and then went on to start cross-sex hormone therapy. Some studies suggest that there is a risk that BMD does not recover after being on cross-sex hormones,3 while another study suggested that transgender men recover their BMD after being on testosterone.4 It is still unclear in that study why transgender women did not recover their BMD or why they were low at baseline. Interestingly, a 2012 study5 from Brazil showed that there was no difference in BMD for cisgender girls who had been off their GnRH agonist therapy for at least 3 years, as compared with their age-matched controls who had never been on GnRH agonist therapy. These conflicting data highlight the importance of long-term follow-up, as well as the need to include age-matched, cisgender control subjects, to better understand if there is truly a difference in transgender individuals or if today’s adolescents, in general, have low BMD.

Lingering questions

In summary, the use of GnRH agonists in transgender adolescents remains controversial because of the potential long-term effects on bone mineral density. However, this risk must be balanced against the risks of allowing natal puberty to progress in certain transgender individuals with the development of undesired secondary sex characteristics. More longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the long-term risks of osteoporosis and fractures in those who have undergone GnRH agonist therapy as part of their gender-affirming medical care, as well as any clinical interventions that might help mitigate this risk.

Dr. Cooper is assistant professor of pediatrics at UT Southwestern, Dallas, and an adolescent medicine specialist at Children’s Medical Center Dallas.

References

1. Harrington J et al. Treatment of precocious puberty. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-precocious-puberty.

2. Lee JY et al. J Endocr Soc. 2020;4(9):bvaa065. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvaa065.

3. Klink D et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(2):E270-5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2439.

4. Schagen SEE et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(12):e4252-e4263. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa604.

5. Alessandri SB et al. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2012;67(6):591-6. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2012(06)08.

Health care in America: Let that tapeworm grow

In my most recent column, “ ‘They All Laughed When I Spoke of Greedy Doctors,’ ” I attempted to provide a global understanding of some of the economic forces that have made American medicine what it is, how that happened, and why it is still happening.

I did not propose a fix. I have been proposing fixes for more than 30 years, on the pages of JAMA until 1999 and then for this news organization, most recently in 2019 with “Healthcare for All in a Land of Special Interests.”

Where you stand depends a lot on where you sit.

Is this good news or bad news? When William Hubbard was the dean of the University of Michigan School of Medicine in 1969, he said that “an academic medical center is the most efficient energy and resource trapping device that has ever been created” (personal communication, 1969).

To me as a faculty member of an academic medical center for many years, that was great news. We could grow faculty, erect buildings, take the best care of sick people, churn out research papers, mint new physicians and specialists, and get paid well in the process for doing “the Lord’s work.” What’s not to like? At that time, the proportion of the country’s gross national product expended for medical and health care was about 7%. And the predicted life span of an American at birth was 70.5 years.

Is this good news or bad news? In 2021, the proportion of our annual gross domestic product (GDP) consumed by health care was 18.3%, totaling $4.3 trillion, or $12,914 per person. For perspective, in 2021, the median income per capita was $37,638. Because quite a few Americans have very high incomes, the mean income per capita is much higher: $63,444. Predicted life span in 2021 was 76.4 years.

Thus, in a span of 53 years (1969-2022), only 5.9 years of life were gained per person born, for how many trillions of dollars expended? To me as a tax-paying citizen and payer of medical insurance premiums, that is bad news.

Is this good news or bad news? If we compare developed societies globally, our medical system does a whole lot of things very well indeed. But we spend a great deal more than any other country for health care and objectively achieve poorer outcomes. Thus, we are neither efficient nor effective. We keep a lot of workers very busy doing stuff, and they are generally well paid. As a worker, that’s good news; as a manager who values efficiency, it’s bad news indeed.

Is this good news or bad news? We’re the leader at finding money to pay people to do “health care work.” More Americans work in health care than any other field. In 2019, the United States employed some 21,000,000 people doing “health care and social assistance.” Among others, these occupations include physicians, dentists, dental hygienists and assistants, pharmacists, registered nurses, LVNs/LPNs, nursing aides, technologists and technicians, home health aides, respiratory therapists, occupational and speech therapists, social workers, childcare workers, and personal and home care aides. For a patient, parent, grandparent, and great-grandparent, it is good news to have all those folks available to take care of us when we need it.

So, while I have cringed at the frequent exposés from Roy Poses of what seem to me to be massive societal betrayals by American health care industry giants, it doesn’t have to be that way. Might it still be possible to do well while doing good?

A jobs program

Consider such common medical procedures as coronary artery stents or bypass grafts for stable angina (when optimal medical therapy is as good, or better than, and much less expensive); PSAs on asymptomatic men followed by unnecessary surgery for localized cancer; excess surgery for low back pain; and the jobs created by managing the people caught up in medical complications of the obesity epidemic.

Don’t forget the number of people employed simply to “follow the money” within our byzantine cockamamie medical billing system. In 2009, this prompted me to describe the bloated system as a “health care bubble” not unlike Enron, the submarket real estate financing debacle, or the dot-com boom and bust. I warned of the downside of bursting that bubble, particularly lost jobs.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) provided health insurance to some 35 million Americans who had been uninsured. It retarded health care inflation. But it did nothing to trim administrative costs or very high pay for nonclinical executives, or shareholder profits in those companies that were for-profit, or drug and device prices. Without the support of all those groups, the ACA would never have passed Congress. The ACA has clearly been a mixed blessing.

If any large American constituency were ever serious about reducing the percentage of our GDP expended on health care, we have excellent ways to do that while improving the health and well-being of the American people. But remember, one person’s liability (unnecessary work) is another person’s asset (needed job).

The MBAization of medicine

Meanwhile, back at Dean Hubbard’s voracious academic medical center, the high intellect and driven nature of those who are attracted to medicine as a career has had other effects. The resulting organizations reflect not only the glorious calling of caring for the sick and the availability of lots of money to recruit and compensate leaders, but also the necessity to develop strong executive types who won’t be “eaten alive” by the high-powered workforce of demanding physicians and the surrounding environment.

Thus, it came as no great surprise that in its 2021 determination of America’s top 25 Best Large Employers, Forbes included five health care organizations and seven universities. Beating out such giants as NASA, Cisco, Microsoft, Netflix, and Google, the University of Alabama Birmingham Hospital was ranked first. Mayo Clinic and Yale University came in third and fifth, respectively, and at the other end of the list were Duke (23), MIT (24), and MD Anderson (25).

My goodness! Well done.

Yet, as a country attempting to be balanced, Warren Buffett’s descriptive entreaty on the 2021 failure of Haven, the Amazon-Chase-Berkshire Hathaway joint initiative, remains troubling. Calling upon Haven to change the U.S. health care system, Buffet said, “We learned a lot about the difficulty of changing around an industry that’s 17% of the GDP. We were fighting a tapeworm in the American economy, and the tapeworm won.” They had failed to tame the American health care cost beast.

I am on record as despising the “MBAization” of American medicine. Unfairly, I blamed a professional and technical discipline for what I considered misuse. I hereby repent and renounce my earlier condemnations.

Take it all over?

Here’s an idea: If you can’t beat them, join them.

Medical care is important, especially for acute illnesses and injuries, early cancer therapy, and many chronic conditions. But the real determinants of health writ large are social: wealth, education, housing, nutritious food, childcare, climate, clean air and water, meaningful employment, safety from violence, exercise schemes, vaccinations, and so on.

Why doesn’t the American medical-industrial complex simply bestow the label of “health care” on all health-related social determinants? Take it all over. Good “health care” jobs for everyone. Medical professionals will still be blamed for the low health quality and poor outcome scores, the main social determinants of health over which we have no control or influence.

Let that tapeworm grow to encompass all social determinants of health, and measure results by length and quality of life, national human happiness, and, of course, jobs. We can do it. Let that bubble glow. Party time.

And that’s the way it is. That’s my opinion.

George Lundberg, MD, is editor-in-chief at Cancer Commons, president of the Lundberg Institute, executive advisor at Cureus, and a clinical professor of pathology at Northwestern University. Previously, he served as editor-in-chief of JAMA (including 10 specialty journals), American Medical News, and Medscape.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In my most recent column, “ ‘They All Laughed When I Spoke of Greedy Doctors,’ ” I attempted to provide a global understanding of some of the economic forces that have made American medicine what it is, how that happened, and why it is still happening.

I did not propose a fix. I have been proposing fixes for more than 30 years, on the pages of JAMA until 1999 and then for this news organization, most recently in 2019 with “Healthcare for All in a Land of Special Interests.”

Where you stand depends a lot on where you sit.

Is this good news or bad news? When William Hubbard was the dean of the University of Michigan School of Medicine in 1969, he said that “an academic medical center is the most efficient energy and resource trapping device that has ever been created” (personal communication, 1969).

To me as a faculty member of an academic medical center for many years, that was great news. We could grow faculty, erect buildings, take the best care of sick people, churn out research papers, mint new physicians and specialists, and get paid well in the process for doing “the Lord’s work.” What’s not to like? At that time, the proportion of the country’s gross national product expended for medical and health care was about 7%. And the predicted life span of an American at birth was 70.5 years.

Is this good news or bad news? In 2021, the proportion of our annual gross domestic product (GDP) consumed by health care was 18.3%, totaling $4.3 trillion, or $12,914 per person. For perspective, in 2021, the median income per capita was $37,638. Because quite a few Americans have very high incomes, the mean income per capita is much higher: $63,444. Predicted life span in 2021 was 76.4 years.

Thus, in a span of 53 years (1969-2022), only 5.9 years of life were gained per person born, for how many trillions of dollars expended? To me as a tax-paying citizen and payer of medical insurance premiums, that is bad news.

Is this good news or bad news? If we compare developed societies globally, our medical system does a whole lot of things very well indeed. But we spend a great deal more than any other country for health care and objectively achieve poorer outcomes. Thus, we are neither efficient nor effective. We keep a lot of workers very busy doing stuff, and they are generally well paid. As a worker, that’s good news; as a manager who values efficiency, it’s bad news indeed.

Is this good news or bad news? We’re the leader at finding money to pay people to do “health care work.” More Americans work in health care than any other field. In 2019, the United States employed some 21,000,000 people doing “health care and social assistance.” Among others, these occupations include physicians, dentists, dental hygienists and assistants, pharmacists, registered nurses, LVNs/LPNs, nursing aides, technologists and technicians, home health aides, respiratory therapists, occupational and speech therapists, social workers, childcare workers, and personal and home care aides. For a patient, parent, grandparent, and great-grandparent, it is good news to have all those folks available to take care of us when we need it.

So, while I have cringed at the frequent exposés from Roy Poses of what seem to me to be massive societal betrayals by American health care industry giants, it doesn’t have to be that way. Might it still be possible to do well while doing good?

A jobs program

Consider such common medical procedures as coronary artery stents or bypass grafts for stable angina (when optimal medical therapy is as good, or better than, and much less expensive); PSAs on asymptomatic men followed by unnecessary surgery for localized cancer; excess surgery for low back pain; and the jobs created by managing the people caught up in medical complications of the obesity epidemic.

Don’t forget the number of people employed simply to “follow the money” within our byzantine cockamamie medical billing system. In 2009, this prompted me to describe the bloated system as a “health care bubble” not unlike Enron, the submarket real estate financing debacle, or the dot-com boom and bust. I warned of the downside of bursting that bubble, particularly lost jobs.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) provided health insurance to some 35 million Americans who had been uninsured. It retarded health care inflation. But it did nothing to trim administrative costs or very high pay for nonclinical executives, or shareholder profits in those companies that were for-profit, or drug and device prices. Without the support of all those groups, the ACA would never have passed Congress. The ACA has clearly been a mixed blessing.

If any large American constituency were ever serious about reducing the percentage of our GDP expended on health care, we have excellent ways to do that while improving the health and well-being of the American people. But remember, one person’s liability (unnecessary work) is another person’s asset (needed job).

The MBAization of medicine

Meanwhile, back at Dean Hubbard’s voracious academic medical center, the high intellect and driven nature of those who are attracted to medicine as a career has had other effects. The resulting organizations reflect not only the glorious calling of caring for the sick and the availability of lots of money to recruit and compensate leaders, but also the necessity to develop strong executive types who won’t be “eaten alive” by the high-powered workforce of demanding physicians and the surrounding environment.

Thus, it came as no great surprise that in its 2021 determination of America’s top 25 Best Large Employers, Forbes included five health care organizations and seven universities. Beating out such giants as NASA, Cisco, Microsoft, Netflix, and Google, the University of Alabama Birmingham Hospital was ranked first. Mayo Clinic and Yale University came in third and fifth, respectively, and at the other end of the list were Duke (23), MIT (24), and MD Anderson (25).

My goodness! Well done.

Yet, as a country attempting to be balanced, Warren Buffett’s descriptive entreaty on the 2021 failure of Haven, the Amazon-Chase-Berkshire Hathaway joint initiative, remains troubling. Calling upon Haven to change the U.S. health care system, Buffet said, “We learned a lot about the difficulty of changing around an industry that’s 17% of the GDP. We were fighting a tapeworm in the American economy, and the tapeworm won.” They had failed to tame the American health care cost beast.

I am on record as despising the “MBAization” of American medicine. Unfairly, I blamed a professional and technical discipline for what I considered misuse. I hereby repent and renounce my earlier condemnations.

Take it all over?

Here’s an idea: If you can’t beat them, join them.

Medical care is important, especially for acute illnesses and injuries, early cancer therapy, and many chronic conditions. But the real determinants of health writ large are social: wealth, education, housing, nutritious food, childcare, climate, clean air and water, meaningful employment, safety from violence, exercise schemes, vaccinations, and so on.

Why doesn’t the American medical-industrial complex simply bestow the label of “health care” on all health-related social determinants? Take it all over. Good “health care” jobs for everyone. Medical professionals will still be blamed for the low health quality and poor outcome scores, the main social determinants of health over which we have no control or influence.

Let that tapeworm grow to encompass all social determinants of health, and measure results by length and quality of life, national human happiness, and, of course, jobs. We can do it. Let that bubble glow. Party time.

And that’s the way it is. That’s my opinion.

George Lundberg, MD, is editor-in-chief at Cancer Commons, president of the Lundberg Institute, executive advisor at Cureus, and a clinical professor of pathology at Northwestern University. Previously, he served as editor-in-chief of JAMA (including 10 specialty journals), American Medical News, and Medscape.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In my most recent column, “ ‘They All Laughed When I Spoke of Greedy Doctors,’ ” I attempted to provide a global understanding of some of the economic forces that have made American medicine what it is, how that happened, and why it is still happening.

I did not propose a fix. I have been proposing fixes for more than 30 years, on the pages of JAMA until 1999 and then for this news organization, most recently in 2019 with “Healthcare for All in a Land of Special Interests.”

Where you stand depends a lot on where you sit.

Is this good news or bad news? When William Hubbard was the dean of the University of Michigan School of Medicine in 1969, he said that “an academic medical center is the most efficient energy and resource trapping device that has ever been created” (personal communication, 1969).

To me as a faculty member of an academic medical center for many years, that was great news. We could grow faculty, erect buildings, take the best care of sick people, churn out research papers, mint new physicians and specialists, and get paid well in the process for doing “the Lord’s work.” What’s not to like? At that time, the proportion of the country’s gross national product expended for medical and health care was about 7%. And the predicted life span of an American at birth was 70.5 years.

Is this good news or bad news? In 2021, the proportion of our annual gross domestic product (GDP) consumed by health care was 18.3%, totaling $4.3 trillion, or $12,914 per person. For perspective, in 2021, the median income per capita was $37,638. Because quite a few Americans have very high incomes, the mean income per capita is much higher: $63,444. Predicted life span in 2021 was 76.4 years.

Thus, in a span of 53 years (1969-2022), only 5.9 years of life were gained per person born, for how many trillions of dollars expended? To me as a tax-paying citizen and payer of medical insurance premiums, that is bad news.

Is this good news or bad news? If we compare developed societies globally, our medical system does a whole lot of things very well indeed. But we spend a great deal more than any other country for health care and objectively achieve poorer outcomes. Thus, we are neither efficient nor effective. We keep a lot of workers very busy doing stuff, and they are generally well paid. As a worker, that’s good news; as a manager who values efficiency, it’s bad news indeed.

Is this good news or bad news? We’re the leader at finding money to pay people to do “health care work.” More Americans work in health care than any other field. In 2019, the United States employed some 21,000,000 people doing “health care and social assistance.” Among others, these occupations include physicians, dentists, dental hygienists and assistants, pharmacists, registered nurses, LVNs/LPNs, nursing aides, technologists and technicians, home health aides, respiratory therapists, occupational and speech therapists, social workers, childcare workers, and personal and home care aides. For a patient, parent, grandparent, and great-grandparent, it is good news to have all those folks available to take care of us when we need it.

So, while I have cringed at the frequent exposés from Roy Poses of what seem to me to be massive societal betrayals by American health care industry giants, it doesn’t have to be that way. Might it still be possible to do well while doing good?

A jobs program

Consider such common medical procedures as coronary artery stents or bypass grafts for stable angina (when optimal medical therapy is as good, or better than, and much less expensive); PSAs on asymptomatic men followed by unnecessary surgery for localized cancer; excess surgery for low back pain; and the jobs created by managing the people caught up in medical complications of the obesity epidemic.

Don’t forget the number of people employed simply to “follow the money” within our byzantine cockamamie medical billing system. In 2009, this prompted me to describe the bloated system as a “health care bubble” not unlike Enron, the submarket real estate financing debacle, or the dot-com boom and bust. I warned of the downside of bursting that bubble, particularly lost jobs.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) provided health insurance to some 35 million Americans who had been uninsured. It retarded health care inflation. But it did nothing to trim administrative costs or very high pay for nonclinical executives, or shareholder profits in those companies that were for-profit, or drug and device prices. Without the support of all those groups, the ACA would never have passed Congress. The ACA has clearly been a mixed blessing.

If any large American constituency were ever serious about reducing the percentage of our GDP expended on health care, we have excellent ways to do that while improving the health and well-being of the American people. But remember, one person’s liability (unnecessary work) is another person’s asset (needed job).

The MBAization of medicine

Meanwhile, back at Dean Hubbard’s voracious academic medical center, the high intellect and driven nature of those who are attracted to medicine as a career has had other effects. The resulting organizations reflect not only the glorious calling of caring for the sick and the availability of lots of money to recruit and compensate leaders, but also the necessity to develop strong executive types who won’t be “eaten alive” by the high-powered workforce of demanding physicians and the surrounding environment.

Thus, it came as no great surprise that in its 2021 determination of America’s top 25 Best Large Employers, Forbes included five health care organizations and seven universities. Beating out such giants as NASA, Cisco, Microsoft, Netflix, and Google, the University of Alabama Birmingham Hospital was ranked first. Mayo Clinic and Yale University came in third and fifth, respectively, and at the other end of the list were Duke (23), MIT (24), and MD Anderson (25).

My goodness! Well done.

Yet, as a country attempting to be balanced, Warren Buffett’s descriptive entreaty on the 2021 failure of Haven, the Amazon-Chase-Berkshire Hathaway joint initiative, remains troubling. Calling upon Haven to change the U.S. health care system, Buffet said, “We learned a lot about the difficulty of changing around an industry that’s 17% of the GDP. We were fighting a tapeworm in the American economy, and the tapeworm won.” They had failed to tame the American health care cost beast.

I am on record as despising the “MBAization” of American medicine. Unfairly, I blamed a professional and technical discipline for what I considered misuse. I hereby repent and renounce my earlier condemnations.

Take it all over?

Here’s an idea: If you can’t beat them, join them.

Medical care is important, especially for acute illnesses and injuries, early cancer therapy, and many chronic conditions. But the real determinants of health writ large are social: wealth, education, housing, nutritious food, childcare, climate, clean air and water, meaningful employment, safety from violence, exercise schemes, vaccinations, and so on.

Why doesn’t the American medical-industrial complex simply bestow the label of “health care” on all health-related social determinants? Take it all over. Good “health care” jobs for everyone. Medical professionals will still be blamed for the low health quality and poor outcome scores, the main social determinants of health over which we have no control or influence.

Let that tapeworm grow to encompass all social determinants of health, and measure results by length and quality of life, national human happiness, and, of course, jobs. We can do it. Let that bubble glow. Party time.

And that’s the way it is. That’s my opinion.

George Lundberg, MD, is editor-in-chief at Cancer Commons, president of the Lundberg Institute, executive advisor at Cureus, and a clinical professor of pathology at Northwestern University. Previously, he served as editor-in-chief of JAMA (including 10 specialty journals), American Medical News, and Medscape.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A 50-year-old White male presented with a 4- to 5-year history of progressively growing violaceous lesions on his left lower extremity

with scarce T-cells, classically presenting as rapidly progressive, plum-colored lesions on the lower extremities.1,2 CBCLs, with PCDLBCL-LT accounting for 4%, make up the minority of cutaneous lymphomas in the Western world.1-3 The leg type variant, typically demonstrating a female predominance and median age of onset in the 70s, is clinically aggressive and associated with a poorer prognosis, increased recurrence rate, and 40%-60% 5-year survival rate.1-5

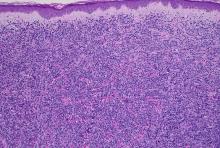

Histologically, this variant demonstrates a diffuse sheet-like growth of enlarged atypical B-cells distinctively separated from the epidermis by a prominent grenz zone. Classic PCDLBCL-LT immunophenotype includes B-cell markers CD20 and IgM; triple expressor phenotype indicating c-MYC, BCL-2, and BCL-6 positivity; as well as CD10 negativity, lack of BCL-2 rearrangement, and presence of a positive MYD-88 molecular result.

Other characteristic histopathological findings include positivity for post-germinal markers IRF4/MUM-1 and FOXP-1, positivity for additional B-cell markers, including CD79 and PAX5, and negativity of t(14;18) (q32;21).1,3-5

This case is of significant interest as it falls within the approximately 10% of PCDLBCL-LT cases demonstrating weak to negative MUM-1 staining, in addition to its presentation in a younger male individual.

While MUM-1 positivity is common in this subtype, its presence, or lack thereof, should not be looked at in isolation when evaluating diagnostic criteria, nor has it been shown to have a statistically significant effect on survival rate – in contrast to factors like lesion location on the leg versus non-leg lesions, multiple lesions at diagnosis, and dissemination to other sites.2,6

PCDLBCL-LT can uncommonly present in non-leg locations and only 10% depict associated B-symptoms, such as fatigue, night sweats, weight loss, or lymphadenopathy.2,6 First-line treatment is with the R-CHOP chemotherapy regimen – consisting of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone – although radiotherapy is sometimes considered in patients with a single small lesion.1,2

Because of possible cutaneous involvement beyond the legs, common lack of systemic symptoms, and variable immunophenotypes, this case of MUM-1 negative PCDLBCL-LT highlights the importance of a clinicopathological approach to differentiate the subtypes of CBCLs, allowing for proper and individualized stratification of risk, prognosis, and treatment.

This case was submitted and written by Marlee Hill, BS, Michael Franzetti, MD, Jeffrey McBride, MD, and Allison Hood, MD, of the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City. They also provided the photos. Donna Bilu Martin, MD, edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Willemze R et al. Blood. 2019;133(16):1703-14.

2. Willemze R et al. Blood. 2005;105(10):3768-85.

3. Sukswai N et al. Pathology. 2020;52(1):53-67.

4. Hristov AC. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136(8):876-81.

5. Sokol L et al. Cancer Control. 2012;19(3):236-44.

6. Grange F et al. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(9):1144-50.

with scarce T-cells, classically presenting as rapidly progressive, plum-colored lesions on the lower extremities.1,2 CBCLs, with PCDLBCL-LT accounting for 4%, make up the minority of cutaneous lymphomas in the Western world.1-3 The leg type variant, typically demonstrating a female predominance and median age of onset in the 70s, is clinically aggressive and associated with a poorer prognosis, increased recurrence rate, and 40%-60% 5-year survival rate.1-5

Histologically, this variant demonstrates a diffuse sheet-like growth of enlarged atypical B-cells distinctively separated from the epidermis by a prominent grenz zone. Classic PCDLBCL-LT immunophenotype includes B-cell markers CD20 and IgM; triple expressor phenotype indicating c-MYC, BCL-2, and BCL-6 positivity; as well as CD10 negativity, lack of BCL-2 rearrangement, and presence of a positive MYD-88 molecular result.

Other characteristic histopathological findings include positivity for post-germinal markers IRF4/MUM-1 and FOXP-1, positivity for additional B-cell markers, including CD79 and PAX5, and negativity of t(14;18) (q32;21).1,3-5

This case is of significant interest as it falls within the approximately 10% of PCDLBCL-LT cases demonstrating weak to negative MUM-1 staining, in addition to its presentation in a younger male individual.

While MUM-1 positivity is common in this subtype, its presence, or lack thereof, should not be looked at in isolation when evaluating diagnostic criteria, nor has it been shown to have a statistically significant effect on survival rate – in contrast to factors like lesion location on the leg versus non-leg lesions, multiple lesions at diagnosis, and dissemination to other sites.2,6

PCDLBCL-LT can uncommonly present in non-leg locations and only 10% depict associated B-symptoms, such as fatigue, night sweats, weight loss, or lymphadenopathy.2,6 First-line treatment is with the R-CHOP chemotherapy regimen – consisting of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone – although radiotherapy is sometimes considered in patients with a single small lesion.1,2

Because of possible cutaneous involvement beyond the legs, common lack of systemic symptoms, and variable immunophenotypes, this case of MUM-1 negative PCDLBCL-LT highlights the importance of a clinicopathological approach to differentiate the subtypes of CBCLs, allowing for proper and individualized stratification of risk, prognosis, and treatment.

This case was submitted and written by Marlee Hill, BS, Michael Franzetti, MD, Jeffrey McBride, MD, and Allison Hood, MD, of the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City. They also provided the photos. Donna Bilu Martin, MD, edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Willemze R et al. Blood. 2019;133(16):1703-14.

2. Willemze R et al. Blood. 2005;105(10):3768-85.

3. Sukswai N et al. Pathology. 2020;52(1):53-67.

4. Hristov AC. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136(8):876-81.

5. Sokol L et al. Cancer Control. 2012;19(3):236-44.

6. Grange F et al. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(9):1144-50.

with scarce T-cells, classically presenting as rapidly progressive, plum-colored lesions on the lower extremities.1,2 CBCLs, with PCDLBCL-LT accounting for 4%, make up the minority of cutaneous lymphomas in the Western world.1-3 The leg type variant, typically demonstrating a female predominance and median age of onset in the 70s, is clinically aggressive and associated with a poorer prognosis, increased recurrence rate, and 40%-60% 5-year survival rate.1-5

Histologically, this variant demonstrates a diffuse sheet-like growth of enlarged atypical B-cells distinctively separated from the epidermis by a prominent grenz zone. Classic PCDLBCL-LT immunophenotype includes B-cell markers CD20 and IgM; triple expressor phenotype indicating c-MYC, BCL-2, and BCL-6 positivity; as well as CD10 negativity, lack of BCL-2 rearrangement, and presence of a positive MYD-88 molecular result.

Other characteristic histopathological findings include positivity for post-germinal markers IRF4/MUM-1 and FOXP-1, positivity for additional B-cell markers, including CD79 and PAX5, and negativity of t(14;18) (q32;21).1,3-5

This case is of significant interest as it falls within the approximately 10% of PCDLBCL-LT cases demonstrating weak to negative MUM-1 staining, in addition to its presentation in a younger male individual.

While MUM-1 positivity is common in this subtype, its presence, or lack thereof, should not be looked at in isolation when evaluating diagnostic criteria, nor has it been shown to have a statistically significant effect on survival rate – in contrast to factors like lesion location on the leg versus non-leg lesions, multiple lesions at diagnosis, and dissemination to other sites.2,6

PCDLBCL-LT can uncommonly present in non-leg locations and only 10% depict associated B-symptoms, such as fatigue, night sweats, weight loss, or lymphadenopathy.2,6 First-line treatment is with the R-CHOP chemotherapy regimen – consisting of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone – although radiotherapy is sometimes considered in patients with a single small lesion.1,2

Because of possible cutaneous involvement beyond the legs, common lack of systemic symptoms, and variable immunophenotypes, this case of MUM-1 negative PCDLBCL-LT highlights the importance of a clinicopathological approach to differentiate the subtypes of CBCLs, allowing for proper and individualized stratification of risk, prognosis, and treatment.

This case was submitted and written by Marlee Hill, BS, Michael Franzetti, MD, Jeffrey McBride, MD, and Allison Hood, MD, of the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City. They also provided the photos. Donna Bilu Martin, MD, edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Willemze R et al. Blood. 2019;133(16):1703-14.

2. Willemze R et al. Blood. 2005;105(10):3768-85.

3. Sukswai N et al. Pathology. 2020;52(1):53-67.

4. Hristov AC. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136(8):876-81.

5. Sokol L et al. Cancer Control. 2012;19(3):236-44.

6. Grange F et al. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(9):1144-50.

There was no cervical, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy.

Why 9 is not too young for the HPV vaccine

For Sonja O’Leary, MD, higher rates of vaccination against human papillomavirus came with the flip of a switch.

Dr. O’Leary, the interim director of service for outpatient pediatric services at Denver Health and Hospital Authority, and her colleagues saw rates of HPV and other childhood immunizations drop during the COVID-19 pandemic and decided to act. Their health system, which includes 28 federally qualified health centers, offers vaccines at any inpatient or outpatient visit based on alerts from their electronic health record.

“It was actually really simple; it was really just changing our best-practice alert,” Dr. O’Leary said. Beginning in May 2021, and after notifying clinic staff of the impending change, DHHA dropped the alert for first dose of HPV from age 11 to 9.

The approach worked. Compared with the first 5 months of 2021, the percentage of children aged 9-13 years with an in-person visit who received at least one dose of HPV vaccine between June 2021 and August 2022 rose from 30.3% to 42.8% – a 41% increase. The share who received two doses by age 13 years more than doubled, from 19.3% to 42.7%, Dr. O’Leary said.

Frustrated efforts

Although those figures might seem to make an iron-clad case for earlier vaccinations against HPV – which is responsible for nearly 35,000 cases of cancer annually – factors beyond statistics have frustrated efforts to increase acceptance of the shots.

Data published in 2022 from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 89.6% of teens aged 13-17 years received at least one dose of tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine, and 89% got one or more doses of meningococcal conjugate vaccine. However, only 76.9% had received one or more doses of HPV vaccine. The rate of receiving both doses needed for full protection was much lower (61.7%).

Both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Cancer Society now endorse the strategy of offering HPV vaccine as early as age 9, which avoids the need for multiple shots at a single visit and results in more kids getting both doses. In a recent study that surveyed primary care professionals who see pediatric patients, 21% were already offering HPV vaccine at age 9, and another 48% were willing to try the approach.

What was the most common objection to the earlier age? Nearly three-quarters of clinicians said they felt that parents weren’t ready to talk about HPV vaccination yet.

Noel Brewer, PhD, one of the authors of the survey study, wondered why clinicians feel the need to bring up sex at all. “Providers should never be talking about sex when they are talking about vaccine, because that’s not the point,” said Dr. Brewer, the distinguished professor in public health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He pointed out that providers don’t talk about the route of transmission for any other vaccine.

Dr. Brewer led a randomized controlled trial that trained pediatric clinicians in the “announcement” strategy, in which the clinician announces the vaccines that are due at that visit. If the parent hesitates, the clinician then probes further to identify and address their concerns and provides more information. If the parent is still not convinced, the clinician notes the discussion in the chart and tries again at the next visit.

The strategy was effective: Intervention clinics had a 5.4% higher rate of HPV vaccination coverage than control clinics after six months. Dr. Brewer and his colleagues have trained over 1,700 providers in the technique since 2020.

A cancer – not STI – vaccine

Although DHHA hasn’t participated in Dr. Brewer’s training, Dr. O’Leary and her colleagues take a similar approach of simply stating which vaccines the child should receive that day. And they talk about HPV as a cancer vaccine instead of one to prevent a sexually transmitted infection.

In her experience, this emphasis changes the conversation. Dr. O’Leary described a typical comment from parents as, “Oh, of course I would give my child a vaccine that could prevent cancer.”

Ana Rodriguez, MD, MPH, an obstetrician, became interested in raising rates of vaccination against HPV after watching too many women battle a preventable cancer. She worked for several years in the Rio Grande Valley along the U.S. border with Mexico, an impoverished rural area with poor access to health care and high rates of HPV infection.

“I would treat women very young – not even 30 years of age – already fighting advanced precancerous lesions secondary to HPV,” said Dr. Rodriguez, an associate professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

In 2016, when Texas ranked 47th in the nation for rates of up-to-date HPV vaccination, Dr. Rodriguez helped launch a community-based educational campaign in four rural counties in the Rio Grande Valley using social media, radio, and in-person meetings with school PTA members and members of school boards to educate staff and parents about the need for vaccination against the infection.

In 2019, the team began offering the vaccine to children ages 9-12 years at back-to-school events, progress report nights, and other school events, pivoting to outdoor events using a mobile vaccine van after COVID-19 struck. They recently published a study showing that 73.6% of students who received their first dose of vaccine at age 11 or younger completed the series, compared with only 45.1% of children who got their first dose at age 12 or older.

Dr. Rodriguez encountered parents who felt 9 or 10 years old was too young because their children were not going to be sexually active anytime soon. Her response was to describe HPV as a tool to prevent cancer, telling parents, “If you vaccinate your kids young enough, they will be protected for life.”

Lifetime protection is another point in favor of giving HPV vaccine prior to Tdap and MenACWY. The response to the two-dose series of HPV in preadolescents is robust and long-lasting, with no downside to giving it a few years earlier. In contrast, immunity to MenACWY wanes after a few years, so the immunization must be given before children enter high school, when their risk for meningitis increases.

The annual toll of deaths in the United States from meningococcus, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis typically totals less than 100, whereas cancer deaths attributable to HPV infection number in the thousands each year. And that may be the best reason for attempting new strategies to help HPV vaccination rates catch up to the rest of the preteen vaccines.

Dr. Brewer’s work was supported by the Gillings School of Global Public Health, the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of North Carolina, and from training grants from the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Brewer has received research funding from Merck, Pfizer, and GSK and served as a paid advisor for Merck. Dr. O’Leary reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Rodriguez received a grant from the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas, and the study was supported by the Institute for Translational Sciences at the University of Texas Medical Branch.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For Sonja O’Leary, MD, higher rates of vaccination against human papillomavirus came with the flip of a switch.

Dr. O’Leary, the interim director of service for outpatient pediatric services at Denver Health and Hospital Authority, and her colleagues saw rates of HPV and other childhood immunizations drop during the COVID-19 pandemic and decided to act. Their health system, which includes 28 federally qualified health centers, offers vaccines at any inpatient or outpatient visit based on alerts from their electronic health record.

“It was actually really simple; it was really just changing our best-practice alert,” Dr. O’Leary said. Beginning in May 2021, and after notifying clinic staff of the impending change, DHHA dropped the alert for first dose of HPV from age 11 to 9.

The approach worked. Compared with the first 5 months of 2021, the percentage of children aged 9-13 years with an in-person visit who received at least one dose of HPV vaccine between June 2021 and August 2022 rose from 30.3% to 42.8% – a 41% increase. The share who received two doses by age 13 years more than doubled, from 19.3% to 42.7%, Dr. O’Leary said.

Frustrated efforts

Although those figures might seem to make an iron-clad case for earlier vaccinations against HPV – which is responsible for nearly 35,000 cases of cancer annually – factors beyond statistics have frustrated efforts to increase acceptance of the shots.

Data published in 2022 from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 89.6% of teens aged 13-17 years received at least one dose of tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine, and 89% got one or more doses of meningococcal conjugate vaccine. However, only 76.9% had received one or more doses of HPV vaccine. The rate of receiving both doses needed for full protection was much lower (61.7%).

Both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Cancer Society now endorse the strategy of offering HPV vaccine as early as age 9, which avoids the need for multiple shots at a single visit and results in more kids getting both doses. In a recent study that surveyed primary care professionals who see pediatric patients, 21% were already offering HPV vaccine at age 9, and another 48% were willing to try the approach.

What was the most common objection to the earlier age? Nearly three-quarters of clinicians said they felt that parents weren’t ready to talk about HPV vaccination yet.

Noel Brewer, PhD, one of the authors of the survey study, wondered why clinicians feel the need to bring up sex at all. “Providers should never be talking about sex when they are talking about vaccine, because that’s not the point,” said Dr. Brewer, the distinguished professor in public health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He pointed out that providers don’t talk about the route of transmission for any other vaccine.

Dr. Brewer led a randomized controlled trial that trained pediatric clinicians in the “announcement” strategy, in which the clinician announces the vaccines that are due at that visit. If the parent hesitates, the clinician then probes further to identify and address their concerns and provides more information. If the parent is still not convinced, the clinician notes the discussion in the chart and tries again at the next visit.

The strategy was effective: Intervention clinics had a 5.4% higher rate of HPV vaccination coverage than control clinics after six months. Dr. Brewer and his colleagues have trained over 1,700 providers in the technique since 2020.

A cancer – not STI – vaccine

Although DHHA hasn’t participated in Dr. Brewer’s training, Dr. O’Leary and her colleagues take a similar approach of simply stating which vaccines the child should receive that day. And they talk about HPV as a cancer vaccine instead of one to prevent a sexually transmitted infection.

In her experience, this emphasis changes the conversation. Dr. O’Leary described a typical comment from parents as, “Oh, of course I would give my child a vaccine that could prevent cancer.”

Ana Rodriguez, MD, MPH, an obstetrician, became interested in raising rates of vaccination against HPV after watching too many women battle a preventable cancer. She worked for several years in the Rio Grande Valley along the U.S. border with Mexico, an impoverished rural area with poor access to health care and high rates of HPV infection.

“I would treat women very young – not even 30 years of age – already fighting advanced precancerous lesions secondary to HPV,” said Dr. Rodriguez, an associate professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

In 2016, when Texas ranked 47th in the nation for rates of up-to-date HPV vaccination, Dr. Rodriguez helped launch a community-based educational campaign in four rural counties in the Rio Grande Valley using social media, radio, and in-person meetings with school PTA members and members of school boards to educate staff and parents about the need for vaccination against the infection.

In 2019, the team began offering the vaccine to children ages 9-12 years at back-to-school events, progress report nights, and other school events, pivoting to outdoor events using a mobile vaccine van after COVID-19 struck. They recently published a study showing that 73.6% of students who received their first dose of vaccine at age 11 or younger completed the series, compared with only 45.1% of children who got their first dose at age 12 or older.

Dr. Rodriguez encountered parents who felt 9 or 10 years old was too young because their children were not going to be sexually active anytime soon. Her response was to describe HPV as a tool to prevent cancer, telling parents, “If you vaccinate your kids young enough, they will be protected for life.”

Lifetime protection is another point in favor of giving HPV vaccine prior to Tdap and MenACWY. The response to the two-dose series of HPV in preadolescents is robust and long-lasting, with no downside to giving it a few years earlier. In contrast, immunity to MenACWY wanes after a few years, so the immunization must be given before children enter high school, when their risk for meningitis increases.

The annual toll of deaths in the United States from meningococcus, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis typically totals less than 100, whereas cancer deaths attributable to HPV infection number in the thousands each year. And that may be the best reason for attempting new strategies to help HPV vaccination rates catch up to the rest of the preteen vaccines.

Dr. Brewer’s work was supported by the Gillings School of Global Public Health, the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of North Carolina, and from training grants from the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Brewer has received research funding from Merck, Pfizer, and GSK and served as a paid advisor for Merck. Dr. O’Leary reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Rodriguez received a grant from the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas, and the study was supported by the Institute for Translational Sciences at the University of Texas Medical Branch.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For Sonja O’Leary, MD, higher rates of vaccination against human papillomavirus came with the flip of a switch.

Dr. O’Leary, the interim director of service for outpatient pediatric services at Denver Health and Hospital Authority, and her colleagues saw rates of HPV and other childhood immunizations drop during the COVID-19 pandemic and decided to act. Their health system, which includes 28 federally qualified health centers, offers vaccines at any inpatient or outpatient visit based on alerts from their electronic health record.

“It was actually really simple; it was really just changing our best-practice alert,” Dr. O’Leary said. Beginning in May 2021, and after notifying clinic staff of the impending change, DHHA dropped the alert for first dose of HPV from age 11 to 9.

The approach worked. Compared with the first 5 months of 2021, the percentage of children aged 9-13 years with an in-person visit who received at least one dose of HPV vaccine between June 2021 and August 2022 rose from 30.3% to 42.8% – a 41% increase. The share who received two doses by age 13 years more than doubled, from 19.3% to 42.7%, Dr. O’Leary said.

Frustrated efforts

Although those figures might seem to make an iron-clad case for earlier vaccinations against HPV – which is responsible for nearly 35,000 cases of cancer annually – factors beyond statistics have frustrated efforts to increase acceptance of the shots.

Data published in 2022 from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 89.6% of teens aged 13-17 years received at least one dose of tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine, and 89% got one or more doses of meningococcal conjugate vaccine. However, only 76.9% had received one or more doses of HPV vaccine. The rate of receiving both doses needed for full protection was much lower (61.7%).

Both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Cancer Society now endorse the strategy of offering HPV vaccine as early as age 9, which avoids the need for multiple shots at a single visit and results in more kids getting both doses. In a recent study that surveyed primary care professionals who see pediatric patients, 21% were already offering HPV vaccine at age 9, and another 48% were willing to try the approach.

What was the most common objection to the earlier age? Nearly three-quarters of clinicians said they felt that parents weren’t ready to talk about HPV vaccination yet.

Noel Brewer, PhD, one of the authors of the survey study, wondered why clinicians feel the need to bring up sex at all. “Providers should never be talking about sex when they are talking about vaccine, because that’s not the point,” said Dr. Brewer, the distinguished professor in public health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He pointed out that providers don’t talk about the route of transmission for any other vaccine.

Dr. Brewer led a randomized controlled trial that trained pediatric clinicians in the “announcement” strategy, in which the clinician announces the vaccines that are due at that visit. If the parent hesitates, the clinician then probes further to identify and address their concerns and provides more information. If the parent is still not convinced, the clinician notes the discussion in the chart and tries again at the next visit.

The strategy was effective: Intervention clinics had a 5.4% higher rate of HPV vaccination coverage than control clinics after six months. Dr. Brewer and his colleagues have trained over 1,700 providers in the technique since 2020.

A cancer – not STI – vaccine

Although DHHA hasn’t participated in Dr. Brewer’s training, Dr. O’Leary and her colleagues take a similar approach of simply stating which vaccines the child should receive that day. And they talk about HPV as a cancer vaccine instead of one to prevent a sexually transmitted infection.

In her experience, this emphasis changes the conversation. Dr. O’Leary described a typical comment from parents as, “Oh, of course I would give my child a vaccine that could prevent cancer.”

Ana Rodriguez, MD, MPH, an obstetrician, became interested in raising rates of vaccination against HPV after watching too many women battle a preventable cancer. She worked for several years in the Rio Grande Valley along the U.S. border with Mexico, an impoverished rural area with poor access to health care and high rates of HPV infection.

“I would treat women very young – not even 30 years of age – already fighting advanced precancerous lesions secondary to HPV,” said Dr. Rodriguez, an associate professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

In 2016, when Texas ranked 47th in the nation for rates of up-to-date HPV vaccination, Dr. Rodriguez helped launch a community-based educational campaign in four rural counties in the Rio Grande Valley using social media, radio, and in-person meetings with school PTA members and members of school boards to educate staff and parents about the need for vaccination against the infection.

In 2019, the team began offering the vaccine to children ages 9-12 years at back-to-school events, progress report nights, and other school events, pivoting to outdoor events using a mobile vaccine van after COVID-19 struck. They recently published a study showing that 73.6% of students who received their first dose of vaccine at age 11 or younger completed the series, compared with only 45.1% of children who got their first dose at age 12 or older.

Dr. Rodriguez encountered parents who felt 9 or 10 years old was too young because their children were not going to be sexually active anytime soon. Her response was to describe HPV as a tool to prevent cancer, telling parents, “If you vaccinate your kids young enough, they will be protected for life.”

Lifetime protection is another point in favor of giving HPV vaccine prior to Tdap and MenACWY. The response to the two-dose series of HPV in preadolescents is robust and long-lasting, with no downside to giving it a few years earlier. In contrast, immunity to MenACWY wanes after a few years, so the immunization must be given before children enter high school, when their risk for meningitis increases.

The annual toll of deaths in the United States from meningococcus, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis typically totals less than 100, whereas cancer deaths attributable to HPV infection number in the thousands each year. And that may be the best reason for attempting new strategies to help HPV vaccination rates catch up to the rest of the preteen vaccines.

Dr. Brewer’s work was supported by the Gillings School of Global Public Health, the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of North Carolina, and from training grants from the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Brewer has received research funding from Merck, Pfizer, and GSK and served as a paid advisor for Merck. Dr. O’Leary reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Rodriguez received a grant from the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas, and the study was supported by the Institute for Translational Sciences at the University of Texas Medical Branch.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New colorectal cancer data reveal troubling trends

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains the second most common cause of cancer-related death in the United States. Although the past several decades have seen significantly greater emphasis on screening and disease prevention for CRC, it has also become increasingly apparent that the age profile and associated risks for this cancer are rapidly changing.

Evidence of this can be found in recently released CRC statistics from the American Cancer Society, which are updated every 3 years using population-based cancer registries.

The incidence in CRC has shown a progressive decline over the past 4 decades. However, whereas in the 2000s there was an average decline of approximately 3%-4% annually, it slowed to 1% per year between 2011 and 2019. This effect is in part because of the trends among younger individuals (< 55 years), in whom the incidence of CRC has increased by 9% over the past 25 years.

The incidence of regional-stage disease also increased by 2%-3% per year for those younger than 65 years, with an additional increase in the incidence of more advanced/distant disease by 0.5%-3% per year. The latter finding represents a reversal of earlier trends observed for staged disease in the decade from 1995 to 2005.

These recent statistics reveal other notable changes that occurred in parallel with the increased incidence of younger-onset CRC. There was a significant shift to left-sided tumors, with a 4% increase in rectal cancers in the decades spanning 1995–2019.

Although the overall mortality declined 2% from 2011 to 2020, the reverse was seen in patients younger than 50 years, in whom there was an increase by 0.5%-3% annually.

Available incidence and mortality data for the current year are understandably lacking, as there is a 2- to 4-year lag for data collection and assimilation, and there have also been methodological changes for tracking and projections. Nonetheless, 2023 projections estimate that there will be 153,020 new cases in the United States, with 19,550 (13%) to occur in those younger than 50 years and 33% in those aged 50-64 years. Overall, 43% of cases are projected to occur in those aged 45-49 years, which is noteworthy given that these ages are now included in the most current CRC screening recommendations.

Further underscoring the risks posed by earlier-onset trends is the projection of 52,550 CRC-related deaths in 2023, with 7% estimated to occur in those younger than 50 years.

What’s behind the trend toward younger onset?

The specific factors contributing to increasing rates of CRC in younger individuals are not well known, but there are several plausible explanations. Notable possible contributing factors reported in the literature include obesity, smoking, alcohol, diet, and microbial changes, among other demographic variables. Exposure to high-fructose corn syrup, sugar-sweetened beverages, and processed meats has also recently received attention as contributing dietary risk factors.

The shifting trends toward the onset of CRC among younger patients are now clearly established, with approximately 20% of new cases occurring in those in their early 50s or younger and a higher rate of left-sided tumor development. Unfortunately, these shifts are also associated with a more advanced stage of disease.

There are unique clinical challenges when it comes to identifying younger-onset CRC. A low level of suspicion among primary care providers that their younger patients may have CRC can result in delays in their receiving clinically appropriate diagnostic testing (particularly for overt or occult bleeding/iron deficiency). Younger patients may also be less likely to know about or adhere to new recommendations that they undergo screening.

The landscape for age-related CRC is changing. Although there are many obstacles for implementing new practices, these recent findings from the ACS also highlight a clear path for improvement.

David A. Johnson, MD, is professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, and a past president of the American College of Gastroenterology.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains the second most common cause of cancer-related death in the United States. Although the past several decades have seen significantly greater emphasis on screening and disease prevention for CRC, it has also become increasingly apparent that the age profile and associated risks for this cancer are rapidly changing.

Evidence of this can be found in recently released CRC statistics from the American Cancer Society, which are updated every 3 years using population-based cancer registries.

The incidence in CRC has shown a progressive decline over the past 4 decades. However, whereas in the 2000s there was an average decline of approximately 3%-4% annually, it slowed to 1% per year between 2011 and 2019. This effect is in part because of the trends among younger individuals (< 55 years), in whom the incidence of CRC has increased by 9% over the past 25 years.

The incidence of regional-stage disease also increased by 2%-3% per year for those younger than 65 years, with an additional increase in the incidence of more advanced/distant disease by 0.5%-3% per year. The latter finding represents a reversal of earlier trends observed for staged disease in the decade from 1995 to 2005.

These recent statistics reveal other notable changes that occurred in parallel with the increased incidence of younger-onset CRC. There was a significant shift to left-sided tumors, with a 4% increase in rectal cancers in the decades spanning 1995–2019.

Although the overall mortality declined 2% from 2011 to 2020, the reverse was seen in patients younger than 50 years, in whom there was an increase by 0.5%-3% annually.

Available incidence and mortality data for the current year are understandably lacking, as there is a 2- to 4-year lag for data collection and assimilation, and there have also been methodological changes for tracking and projections. Nonetheless, 2023 projections estimate that there will be 153,020 new cases in the United States, with 19,550 (13%) to occur in those younger than 50 years and 33% in those aged 50-64 years. Overall, 43% of cases are projected to occur in those aged 45-49 years, which is noteworthy given that these ages are now included in the most current CRC screening recommendations.

Further underscoring the risks posed by earlier-onset trends is the projection of 52,550 CRC-related deaths in 2023, with 7% estimated to occur in those younger than 50 years.