User login

Diabetes Report: The News Isn’t Good

According to the CDC’s recently released National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2014, an additional 3 million people developed diabetes between 2010 and 2012; but nearly 1 in 4 don’t know they have it. The report is based on 2012 data, which show that the number of people with diabetes rose from 26 million in 2010 to 29 million in 2012.

American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) are most affected: 16% of AI/ANs aged ≥ 20 years have diabetes, compared with 13% of non-Hispanic blacks, 13% of Hispanics, 9% of Asian Americans, and 8% of non-Hispanic whites. But even those figures don’t tell the whole story. For instance, among AI/AN adults, the rate of diabetes ranges from 6% among Alaska Natives to 24% among American Indians in southern Arizona. Among Hispanic adults, Puerto Ricans (15%) and Mexican Americans (14%) have the highest rates, compared with 9% of Cubans and Central and South Americans. Among Asian Americans, 13% of Asian Indians and 11% of Filipinos have diabetes, vs 4% of Chinese.

Moreover, 1 in 3 American adults has prediabetes—an estimated 86 million. Without weight loss and moderate physical activity, the CDC predicts as many as 30% of American adults will develop diabetes within 5 years.

Diabetes is a public health concern that affects all age groups. According to SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth, a multicenter study, during 2008 and 2009, an estimated 18,436 Americans aged < 20 years were newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes annually, and 5,089 were newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes annually.

The physical costs are high. In 2010, diabetes was the seventh leading cause of death in the U.S. and may even have been underreported—only about 35% to 40% of death certificates for people with diabetes listed diabetes anywhere on the certificate. In 2011, hypoglycemia was the first-listed diagnosis for about 282,000 emergency department (ED) visits, and 175,000 ED visits were for hyperglycemic crisis. In 2010, 2,361 adults aged ≥ 20 years died of hyperglycemic crisis. In 2003 to 2006, after adjusting for population age differences, deaths due to cardiovascular disease were nearly doubled among adults aged ≥ 18 years with diagnosed diabetes, compared with adults without diagnosed diabetes. In 2010, diabetes also increased the rates of heart attack and stroke (1.8-fold and 1.5-fold, respectively) and in 2011 was the primary cause of kidney failure in 44% of all new cases.

The costs of care are high, as well. The CDC estimates the total medical costs associated with diabetes and its related complications for 2012 at $245 billion, up from $174 billion in 2010. Average medical expenses among people with diagnosed diabetes ran 2.3 times higher than for people without diabetes.

The report’s estimates were derived from a variety of sources, including CDC, IHS, NIH, and the U.S. Census Bureau; and published studies, including the 2009-2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and the 2010-2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS).

According to the CDC’s recently released National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2014, an additional 3 million people developed diabetes between 2010 and 2012; but nearly 1 in 4 don’t know they have it. The report is based on 2012 data, which show that the number of people with diabetes rose from 26 million in 2010 to 29 million in 2012.

American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) are most affected: 16% of AI/ANs aged ≥ 20 years have diabetes, compared with 13% of non-Hispanic blacks, 13% of Hispanics, 9% of Asian Americans, and 8% of non-Hispanic whites. But even those figures don’t tell the whole story. For instance, among AI/AN adults, the rate of diabetes ranges from 6% among Alaska Natives to 24% among American Indians in southern Arizona. Among Hispanic adults, Puerto Ricans (15%) and Mexican Americans (14%) have the highest rates, compared with 9% of Cubans and Central and South Americans. Among Asian Americans, 13% of Asian Indians and 11% of Filipinos have diabetes, vs 4% of Chinese.

Moreover, 1 in 3 American adults has prediabetes—an estimated 86 million. Without weight loss and moderate physical activity, the CDC predicts as many as 30% of American adults will develop diabetes within 5 years.

Diabetes is a public health concern that affects all age groups. According to SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth, a multicenter study, during 2008 and 2009, an estimated 18,436 Americans aged < 20 years were newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes annually, and 5,089 were newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes annually.

The physical costs are high. In 2010, diabetes was the seventh leading cause of death in the U.S. and may even have been underreported—only about 35% to 40% of death certificates for people with diabetes listed diabetes anywhere on the certificate. In 2011, hypoglycemia was the first-listed diagnosis for about 282,000 emergency department (ED) visits, and 175,000 ED visits were for hyperglycemic crisis. In 2010, 2,361 adults aged ≥ 20 years died of hyperglycemic crisis. In 2003 to 2006, after adjusting for population age differences, deaths due to cardiovascular disease were nearly doubled among adults aged ≥ 18 years with diagnosed diabetes, compared with adults without diagnosed diabetes. In 2010, diabetes also increased the rates of heart attack and stroke (1.8-fold and 1.5-fold, respectively) and in 2011 was the primary cause of kidney failure in 44% of all new cases.

The costs of care are high, as well. The CDC estimates the total medical costs associated with diabetes and its related complications for 2012 at $245 billion, up from $174 billion in 2010. Average medical expenses among people with diagnosed diabetes ran 2.3 times higher than for people without diabetes.

The report’s estimates were derived from a variety of sources, including CDC, IHS, NIH, and the U.S. Census Bureau; and published studies, including the 2009-2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and the 2010-2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS).

According to the CDC’s recently released National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2014, an additional 3 million people developed diabetes between 2010 and 2012; but nearly 1 in 4 don’t know they have it. The report is based on 2012 data, which show that the number of people with diabetes rose from 26 million in 2010 to 29 million in 2012.

American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) are most affected: 16% of AI/ANs aged ≥ 20 years have diabetes, compared with 13% of non-Hispanic blacks, 13% of Hispanics, 9% of Asian Americans, and 8% of non-Hispanic whites. But even those figures don’t tell the whole story. For instance, among AI/AN adults, the rate of diabetes ranges from 6% among Alaska Natives to 24% among American Indians in southern Arizona. Among Hispanic adults, Puerto Ricans (15%) and Mexican Americans (14%) have the highest rates, compared with 9% of Cubans and Central and South Americans. Among Asian Americans, 13% of Asian Indians and 11% of Filipinos have diabetes, vs 4% of Chinese.

Moreover, 1 in 3 American adults has prediabetes—an estimated 86 million. Without weight loss and moderate physical activity, the CDC predicts as many as 30% of American adults will develop diabetes within 5 years.

Diabetes is a public health concern that affects all age groups. According to SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth, a multicenter study, during 2008 and 2009, an estimated 18,436 Americans aged < 20 years were newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes annually, and 5,089 were newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes annually.

The physical costs are high. In 2010, diabetes was the seventh leading cause of death in the U.S. and may even have been underreported—only about 35% to 40% of death certificates for people with diabetes listed diabetes anywhere on the certificate. In 2011, hypoglycemia was the first-listed diagnosis for about 282,000 emergency department (ED) visits, and 175,000 ED visits were for hyperglycemic crisis. In 2010, 2,361 adults aged ≥ 20 years died of hyperglycemic crisis. In 2003 to 2006, after adjusting for population age differences, deaths due to cardiovascular disease were nearly doubled among adults aged ≥ 18 years with diagnosed diabetes, compared with adults without diagnosed diabetes. In 2010, diabetes also increased the rates of heart attack and stroke (1.8-fold and 1.5-fold, respectively) and in 2011 was the primary cause of kidney failure in 44% of all new cases.

The costs of care are high, as well. The CDC estimates the total medical costs associated with diabetes and its related complications for 2012 at $245 billion, up from $174 billion in 2010. Average medical expenses among people with diagnosed diabetes ran 2.3 times higher than for people without diabetes.

The report’s estimates were derived from a variety of sources, including CDC, IHS, NIH, and the U.S. Census Bureau; and published studies, including the 2009-2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and the 2010-2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS).

Proper Inpatient Documentation, Coding Essential to Avoid a Medicare Audit

Several years ago we sent a CPT coding auditor 15 chart notes generated by each doctor in our group. Among each doctors’ 15 notes were at least one or two billed as initial hospital care, follow up, discharge, critical care, and so on. This coding expert returned a report showing that, out of all the notes reviewed, a significant portion were not billed at the correct level. Most of the incorrectly billed notes were judged to reflect “up-coding,” and a few were seen as “down-coded.”

This was distressing and hard to believe.

So I took the same set of notes and paid a second coding expert for an independent review. She didn’t know about the first audit but returned a report that showed a nearly identical portion of incorrectly coded notes.

Two independent audits showing nearly the same portion of notes coded incorrectly was alarming. But it was difficult for my partners and me to address, because the auditors didn’t agree on the correct code for many of the notes. In some cases, both flagged a note as incorrectly coded but didn’t agree on the correct code. For a number of the notes, one auditor said the visit was “up-coded,” while the other said it was “down-coded.” There was so little agreement between the two of them that we had a hard time coming up with any firm conclusions about what we should do to improve our performance.

If experts who think about coding all the time can’t agree on the right code for a given note, how can hospitalists be expected to code nearly all of our visits accurately?

RAC: Recovery Audit Contractor

Despite what I believe is poor inter-rater reliability among coding auditors, we need to work diligently to comply with coding guidelines. A 2003 Federal law mandated a program of Recovery Audit Contractors, or RAC for short, to find cases of “up-coding” or other overbilling and require the provider to repay any resulting loss.

A number of companies are in the business of conducting RAC audits (one of them, CGI, is the Canadian company blamed for the failed “Obamacare” exchange websites), and there is a reasonable chance one of these companies has reviewed some of your charges—or those of your hospitalist colleagues.

The RAC auditors review information about your charges, and if they determine that you up-coded or overbilled, they send a “demand letter” summarizing their findings, along with the amount of money they have determined you should pay back. (Theoretically, they could notify you of “under-coding,” so that you can be paid more for past work, but I haven’t yet come across an example of that.)

It is common to appeal the RAC findings, but that can be a long process, and many organizations decide to pay back all the money requested by the RAC as quickly as possible to avoid paying interest on a delayed payment if the appeal is unsuccessful. In the case of a successful appeal, the money previously refunded by the doctor would be returned.

Page 338 of the CMS Fiscal Year 2015 “Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees” says that “…about 50 percent of the estimated 43,000 appeals [of adverse RAC audit findings] were fully or partially overturned…” This could mean the RACs are a sort of loose cannon, accusing many providers of overbilling while knowing that some won’t bother to appeal because they don’t understand the process or because the dollar amount involved for a single provider is too small to justify the time and expense of conducting the appeal. In this way, a RAC audit is like the $15 rebate on the last electronic gadget you bought. The seller knows that many people, including me, will fail to do the work required to claim the rebate.

Accuracy Strategies

There are a number of ways to help your group ensure appropriate CPT coding and reduce the chance a RAC will ask for money back.

Education. There are many ways to help providers in your practice understand the elements of documentation and coding. Periodic training classes (e.g. during orientation and annually thereafter) are useful but may not be enough. For me, this is a little like learning a foreign language by going to a couple of classes. Instead, I think “immersion training” is more effective. That might mean a doctor spends a few minutes with a certified coder on most working days for a few weeks. For example, they could meet for 15 minutes near lunchtime and review how the doctor plans to bill visits made that morning. Lastly, consider targeted education for each doctor, based on any problems found in an audit of his/her coding.

Review coding patterns. As I wrote in my August 2007 column, there is value in ensuring that each doctor in the group can see how her coding pattern differs from the group as a whole or any individual in the group. That is, what portion of follow-up visits was billed at the lowest, middle, and highest levels? What about admissions, discharges, and so on? I provided a sample report in that same column.

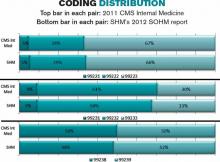

It also is worth taking the time to compare each doctor’s coding pattern to both the CMS Internal Medicine data and SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report. The accompanying figure shows the most current data sets available.

Keep in mind that the goal is not to simply ensure that your coding pattern matches these external data sets; knowing where yours differs from these sets can suggest where you might want to investigate further or seek additional education.

Coding audits. Having a certified coder audit your performance at least annually is a good idea. It can help uncover areas in which you’d benefit from further review and training, and if, heaven forbid, questions are ever raised about whether you’re intentionally up-coding (fraud), showing that you’re audited regularly could help demonstrate your efforts to code correctly. In the latter case, it is probably more valuable if the audit is done independently of your employer.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Several years ago we sent a CPT coding auditor 15 chart notes generated by each doctor in our group. Among each doctors’ 15 notes were at least one or two billed as initial hospital care, follow up, discharge, critical care, and so on. This coding expert returned a report showing that, out of all the notes reviewed, a significant portion were not billed at the correct level. Most of the incorrectly billed notes were judged to reflect “up-coding,” and a few were seen as “down-coded.”

This was distressing and hard to believe.

So I took the same set of notes and paid a second coding expert for an independent review. She didn’t know about the first audit but returned a report that showed a nearly identical portion of incorrectly coded notes.

Two independent audits showing nearly the same portion of notes coded incorrectly was alarming. But it was difficult for my partners and me to address, because the auditors didn’t agree on the correct code for many of the notes. In some cases, both flagged a note as incorrectly coded but didn’t agree on the correct code. For a number of the notes, one auditor said the visit was “up-coded,” while the other said it was “down-coded.” There was so little agreement between the two of them that we had a hard time coming up with any firm conclusions about what we should do to improve our performance.

If experts who think about coding all the time can’t agree on the right code for a given note, how can hospitalists be expected to code nearly all of our visits accurately?

RAC: Recovery Audit Contractor

Despite what I believe is poor inter-rater reliability among coding auditors, we need to work diligently to comply with coding guidelines. A 2003 Federal law mandated a program of Recovery Audit Contractors, or RAC for short, to find cases of “up-coding” or other overbilling and require the provider to repay any resulting loss.

A number of companies are in the business of conducting RAC audits (one of them, CGI, is the Canadian company blamed for the failed “Obamacare” exchange websites), and there is a reasonable chance one of these companies has reviewed some of your charges—or those of your hospitalist colleagues.

The RAC auditors review information about your charges, and if they determine that you up-coded or overbilled, they send a “demand letter” summarizing their findings, along with the amount of money they have determined you should pay back. (Theoretically, they could notify you of “under-coding,” so that you can be paid more for past work, but I haven’t yet come across an example of that.)

It is common to appeal the RAC findings, but that can be a long process, and many organizations decide to pay back all the money requested by the RAC as quickly as possible to avoid paying interest on a delayed payment if the appeal is unsuccessful. In the case of a successful appeal, the money previously refunded by the doctor would be returned.

Page 338 of the CMS Fiscal Year 2015 “Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees” says that “…about 50 percent of the estimated 43,000 appeals [of adverse RAC audit findings] were fully or partially overturned…” This could mean the RACs are a sort of loose cannon, accusing many providers of overbilling while knowing that some won’t bother to appeal because they don’t understand the process or because the dollar amount involved for a single provider is too small to justify the time and expense of conducting the appeal. In this way, a RAC audit is like the $15 rebate on the last electronic gadget you bought. The seller knows that many people, including me, will fail to do the work required to claim the rebate.

Accuracy Strategies

There are a number of ways to help your group ensure appropriate CPT coding and reduce the chance a RAC will ask for money back.

Education. There are many ways to help providers in your practice understand the elements of documentation and coding. Periodic training classes (e.g. during orientation and annually thereafter) are useful but may not be enough. For me, this is a little like learning a foreign language by going to a couple of classes. Instead, I think “immersion training” is more effective. That might mean a doctor spends a few minutes with a certified coder on most working days for a few weeks. For example, they could meet for 15 minutes near lunchtime and review how the doctor plans to bill visits made that morning. Lastly, consider targeted education for each doctor, based on any problems found in an audit of his/her coding.

Review coding patterns. As I wrote in my August 2007 column, there is value in ensuring that each doctor in the group can see how her coding pattern differs from the group as a whole or any individual in the group. That is, what portion of follow-up visits was billed at the lowest, middle, and highest levels? What about admissions, discharges, and so on? I provided a sample report in that same column.

It also is worth taking the time to compare each doctor’s coding pattern to both the CMS Internal Medicine data and SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report. The accompanying figure shows the most current data sets available.

Keep in mind that the goal is not to simply ensure that your coding pattern matches these external data sets; knowing where yours differs from these sets can suggest where you might want to investigate further or seek additional education.

Coding audits. Having a certified coder audit your performance at least annually is a good idea. It can help uncover areas in which you’d benefit from further review and training, and if, heaven forbid, questions are ever raised about whether you’re intentionally up-coding (fraud), showing that you’re audited regularly could help demonstrate your efforts to code correctly. In the latter case, it is probably more valuable if the audit is done independently of your employer.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Several years ago we sent a CPT coding auditor 15 chart notes generated by each doctor in our group. Among each doctors’ 15 notes were at least one or two billed as initial hospital care, follow up, discharge, critical care, and so on. This coding expert returned a report showing that, out of all the notes reviewed, a significant portion were not billed at the correct level. Most of the incorrectly billed notes were judged to reflect “up-coding,” and a few were seen as “down-coded.”

This was distressing and hard to believe.

So I took the same set of notes and paid a second coding expert for an independent review. She didn’t know about the first audit but returned a report that showed a nearly identical portion of incorrectly coded notes.

Two independent audits showing nearly the same portion of notes coded incorrectly was alarming. But it was difficult for my partners and me to address, because the auditors didn’t agree on the correct code for many of the notes. In some cases, both flagged a note as incorrectly coded but didn’t agree on the correct code. For a number of the notes, one auditor said the visit was “up-coded,” while the other said it was “down-coded.” There was so little agreement between the two of them that we had a hard time coming up with any firm conclusions about what we should do to improve our performance.

If experts who think about coding all the time can’t agree on the right code for a given note, how can hospitalists be expected to code nearly all of our visits accurately?

RAC: Recovery Audit Contractor

Despite what I believe is poor inter-rater reliability among coding auditors, we need to work diligently to comply with coding guidelines. A 2003 Federal law mandated a program of Recovery Audit Contractors, or RAC for short, to find cases of “up-coding” or other overbilling and require the provider to repay any resulting loss.

A number of companies are in the business of conducting RAC audits (one of them, CGI, is the Canadian company blamed for the failed “Obamacare” exchange websites), and there is a reasonable chance one of these companies has reviewed some of your charges—or those of your hospitalist colleagues.

The RAC auditors review information about your charges, and if they determine that you up-coded or overbilled, they send a “demand letter” summarizing their findings, along with the amount of money they have determined you should pay back. (Theoretically, they could notify you of “under-coding,” so that you can be paid more for past work, but I haven’t yet come across an example of that.)

It is common to appeal the RAC findings, but that can be a long process, and many organizations decide to pay back all the money requested by the RAC as quickly as possible to avoid paying interest on a delayed payment if the appeal is unsuccessful. In the case of a successful appeal, the money previously refunded by the doctor would be returned.

Page 338 of the CMS Fiscal Year 2015 “Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees” says that “…about 50 percent of the estimated 43,000 appeals [of adverse RAC audit findings] were fully or partially overturned…” This could mean the RACs are a sort of loose cannon, accusing many providers of overbilling while knowing that some won’t bother to appeal because they don’t understand the process or because the dollar amount involved for a single provider is too small to justify the time and expense of conducting the appeal. In this way, a RAC audit is like the $15 rebate on the last electronic gadget you bought. The seller knows that many people, including me, will fail to do the work required to claim the rebate.

Accuracy Strategies

There are a number of ways to help your group ensure appropriate CPT coding and reduce the chance a RAC will ask for money back.

Education. There are many ways to help providers in your practice understand the elements of documentation and coding. Periodic training classes (e.g. during orientation and annually thereafter) are useful but may not be enough. For me, this is a little like learning a foreign language by going to a couple of classes. Instead, I think “immersion training” is more effective. That might mean a doctor spends a few minutes with a certified coder on most working days for a few weeks. For example, they could meet for 15 minutes near lunchtime and review how the doctor plans to bill visits made that morning. Lastly, consider targeted education for each doctor, based on any problems found in an audit of his/her coding.

Review coding patterns. As I wrote in my August 2007 column, there is value in ensuring that each doctor in the group can see how her coding pattern differs from the group as a whole or any individual in the group. That is, what portion of follow-up visits was billed at the lowest, middle, and highest levels? What about admissions, discharges, and so on? I provided a sample report in that same column.

It also is worth taking the time to compare each doctor’s coding pattern to both the CMS Internal Medicine data and SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report. The accompanying figure shows the most current data sets available.

Keep in mind that the goal is not to simply ensure that your coding pattern matches these external data sets; knowing where yours differs from these sets can suggest where you might want to investigate further or seek additional education.

Coding audits. Having a certified coder audit your performance at least annually is a good idea. It can help uncover areas in which you’d benefit from further review and training, and if, heaven forbid, questions are ever raised about whether you’re intentionally up-coding (fraud), showing that you’re audited regularly could help demonstrate your efforts to code correctly. In the latter case, it is probably more valuable if the audit is done independently of your employer.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Delay in ICD-10 Implementation to Impact Hospitalists, Physicians, Payers

On April 1, President Obama signed into law a bill that again delays a permanent fix of the sustainable growth rate formula, or SGR, the so-called “doc fix.” The bill also contained a surprise provision added by Congress to delay implementation of the switch from ICD-9 to ICD-10. The mandated conversion was supposed to take place by October 1 of this year; its delay will have a range of impacts on everyone from physicians to payers.

Hospitalists and others must weigh their options going forward, as many health systems and groups are already well on their way toward compliance with the 2014 deadline.

At this point, prevailing wisdom is that Congress added the delay as an appeasement to physician groups that would be unhappy about its failure to pass an SGR replacement, says Jeffrey Smith, senior director of federal affairs for CHIME, the College of Healthcare Information Management Executives.

“The appeasement, if in fact that was the motivation, was too little too late,” Smith says, adding Congress “caused a lot of unnecessary chaos.”

For instance, according to Modern Healthcare, executives at Catholic Health Initiatives had already invested millions of dollars updating software programs to handle the coding switch ahead of a new electronic health record system roll-out in 89 of its hospitals, which would not have been ready by the ICD-10 deadline.

“Anyone in the process has to circle the wagons again and reconsider their timelines,” Smith says. “The legislation has punished people trying to do the right thing.”

The transition to ICD-10 is a massive update to the 30-year-old ICD-9 codes, which no longer adequately reflect medical diagnoses, procedures, technology, and knowledge. There are five times more diagnosis codes and 21 times more procedural codes in ICD-10. It’s been on the table for at least a decade, and this was not the first delay.

In 2012, when fewer groups were on their way to compliance, CMS estimated that a one-year push-back of ICD-10 conversion could cost up to $306 million. With the latest delay, the American Health Information Management Association says CMS now estimates those costs between $1 billion and $6.6 billion.

However, according to the American Medical Association, which has actively lobbied to stop ICD-10 altogether, the costs of implementing ICD-10 range from $57,000 for small physician practices to as high as $8 million for large practices.

The increased number of codes, the increased number of characters per code, and the increased specificity require significant planning, training, software updates, and financial investments.

The Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) also pushed for ICD-10 delay, concerned that many groups would not be ready by Oct. 1. MGMA surveys showed as much, says Robert Tennant, senior policy advisor for MGMA.“We were concerned that if everyone has to flip the switch at the same time, there will be huge problems, as there were for healthcare.gov,” Tennant explains.

What MGMA would like to see is more thorough end-to-end testing and staggered roll-outs. Hospitals and health plans should be permitted to start using ICD-10 coding when they're ready, even if ahead of the next deadline, Tennant said. MGMA would also like to see a period of dual coding built in.

The ball is now in CMS' court.

“I think that CMS has within its power … the ability to embolden the industry to be more confident,” Smith says. “Even if it’s not going to require ICD-10 codes [by October 2014], hopefully they are still doing testing, still doing benchmarking, and by the time the deadline rolls around, it will touch every sector of the healthcare economy.”

Hospitalists, Smith says, should be more involved in the conversation going forward, to help maintain the momentum and preserve the investments made by their groups and institutions. Those not ready should push for compliance, rather than finding themselves in the same position a year from now.

Many of the hospital CIOs (chief information officers) he has talked to say that while they are stopping the car, they are keeping the engine running. Some will push for dual coding, even if only internally, because it’s proving to be a valuable tool in understanding their patient populations.

“It’s a frustrating time any time you have to kind of stop something with so much momentum, with hundreds of millions, if not billions, spent in advance of the conversion,” Smith says. “It does nothing to help care in this country to stay on ICD-9. Everybody understands those codes are completely exhausted, and the data we are getting out of it, while workable, is certainly not going to get us where we need to be in terms of transforming healthcare.”

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Madison, Wis.

On April 1, President Obama signed into law a bill that again delays a permanent fix of the sustainable growth rate formula, or SGR, the so-called “doc fix.” The bill also contained a surprise provision added by Congress to delay implementation of the switch from ICD-9 to ICD-10. The mandated conversion was supposed to take place by October 1 of this year; its delay will have a range of impacts on everyone from physicians to payers.

Hospitalists and others must weigh their options going forward, as many health systems and groups are already well on their way toward compliance with the 2014 deadline.

At this point, prevailing wisdom is that Congress added the delay as an appeasement to physician groups that would be unhappy about its failure to pass an SGR replacement, says Jeffrey Smith, senior director of federal affairs for CHIME, the College of Healthcare Information Management Executives.

“The appeasement, if in fact that was the motivation, was too little too late,” Smith says, adding Congress “caused a lot of unnecessary chaos.”

For instance, according to Modern Healthcare, executives at Catholic Health Initiatives had already invested millions of dollars updating software programs to handle the coding switch ahead of a new electronic health record system roll-out in 89 of its hospitals, which would not have been ready by the ICD-10 deadline.

“Anyone in the process has to circle the wagons again and reconsider their timelines,” Smith says. “The legislation has punished people trying to do the right thing.”

The transition to ICD-10 is a massive update to the 30-year-old ICD-9 codes, which no longer adequately reflect medical diagnoses, procedures, technology, and knowledge. There are five times more diagnosis codes and 21 times more procedural codes in ICD-10. It’s been on the table for at least a decade, and this was not the first delay.

In 2012, when fewer groups were on their way to compliance, CMS estimated that a one-year push-back of ICD-10 conversion could cost up to $306 million. With the latest delay, the American Health Information Management Association says CMS now estimates those costs between $1 billion and $6.6 billion.

However, according to the American Medical Association, which has actively lobbied to stop ICD-10 altogether, the costs of implementing ICD-10 range from $57,000 for small physician practices to as high as $8 million for large practices.

The increased number of codes, the increased number of characters per code, and the increased specificity require significant planning, training, software updates, and financial investments.

The Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) also pushed for ICD-10 delay, concerned that many groups would not be ready by Oct. 1. MGMA surveys showed as much, says Robert Tennant, senior policy advisor for MGMA.“We were concerned that if everyone has to flip the switch at the same time, there will be huge problems, as there were for healthcare.gov,” Tennant explains.

What MGMA would like to see is more thorough end-to-end testing and staggered roll-outs. Hospitals and health plans should be permitted to start using ICD-10 coding when they're ready, even if ahead of the next deadline, Tennant said. MGMA would also like to see a period of dual coding built in.

The ball is now in CMS' court.

“I think that CMS has within its power … the ability to embolden the industry to be more confident,” Smith says. “Even if it’s not going to require ICD-10 codes [by October 2014], hopefully they are still doing testing, still doing benchmarking, and by the time the deadline rolls around, it will touch every sector of the healthcare economy.”

Hospitalists, Smith says, should be more involved in the conversation going forward, to help maintain the momentum and preserve the investments made by their groups and institutions. Those not ready should push for compliance, rather than finding themselves in the same position a year from now.

Many of the hospital CIOs (chief information officers) he has talked to say that while they are stopping the car, they are keeping the engine running. Some will push for dual coding, even if only internally, because it’s proving to be a valuable tool in understanding their patient populations.

“It’s a frustrating time any time you have to kind of stop something with so much momentum, with hundreds of millions, if not billions, spent in advance of the conversion,” Smith says. “It does nothing to help care in this country to stay on ICD-9. Everybody understands those codes are completely exhausted, and the data we are getting out of it, while workable, is certainly not going to get us where we need to be in terms of transforming healthcare.”

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Madison, Wis.

On April 1, President Obama signed into law a bill that again delays a permanent fix of the sustainable growth rate formula, or SGR, the so-called “doc fix.” The bill also contained a surprise provision added by Congress to delay implementation of the switch from ICD-9 to ICD-10. The mandated conversion was supposed to take place by October 1 of this year; its delay will have a range of impacts on everyone from physicians to payers.

Hospitalists and others must weigh their options going forward, as many health systems and groups are already well on their way toward compliance with the 2014 deadline.

At this point, prevailing wisdom is that Congress added the delay as an appeasement to physician groups that would be unhappy about its failure to pass an SGR replacement, says Jeffrey Smith, senior director of federal affairs for CHIME, the College of Healthcare Information Management Executives.

“The appeasement, if in fact that was the motivation, was too little too late,” Smith says, adding Congress “caused a lot of unnecessary chaos.”

For instance, according to Modern Healthcare, executives at Catholic Health Initiatives had already invested millions of dollars updating software programs to handle the coding switch ahead of a new electronic health record system roll-out in 89 of its hospitals, which would not have been ready by the ICD-10 deadline.

“Anyone in the process has to circle the wagons again and reconsider their timelines,” Smith says. “The legislation has punished people trying to do the right thing.”

The transition to ICD-10 is a massive update to the 30-year-old ICD-9 codes, which no longer adequately reflect medical diagnoses, procedures, technology, and knowledge. There are five times more diagnosis codes and 21 times more procedural codes in ICD-10. It’s been on the table for at least a decade, and this was not the first delay.

In 2012, when fewer groups were on their way to compliance, CMS estimated that a one-year push-back of ICD-10 conversion could cost up to $306 million. With the latest delay, the American Health Information Management Association says CMS now estimates those costs between $1 billion and $6.6 billion.

However, according to the American Medical Association, which has actively lobbied to stop ICD-10 altogether, the costs of implementing ICD-10 range from $57,000 for small physician practices to as high as $8 million for large practices.

The increased number of codes, the increased number of characters per code, and the increased specificity require significant planning, training, software updates, and financial investments.

The Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) also pushed for ICD-10 delay, concerned that many groups would not be ready by Oct. 1. MGMA surveys showed as much, says Robert Tennant, senior policy advisor for MGMA.“We were concerned that if everyone has to flip the switch at the same time, there will be huge problems, as there were for healthcare.gov,” Tennant explains.

What MGMA would like to see is more thorough end-to-end testing and staggered roll-outs. Hospitals and health plans should be permitted to start using ICD-10 coding when they're ready, even if ahead of the next deadline, Tennant said. MGMA would also like to see a period of dual coding built in.

The ball is now in CMS' court.

“I think that CMS has within its power … the ability to embolden the industry to be more confident,” Smith says. “Even if it’s not going to require ICD-10 codes [by October 2014], hopefully they are still doing testing, still doing benchmarking, and by the time the deadline rolls around, it will touch every sector of the healthcare economy.”

Hospitalists, Smith says, should be more involved in the conversation going forward, to help maintain the momentum and preserve the investments made by their groups and institutions. Those not ready should push for compliance, rather than finding themselves in the same position a year from now.

Many of the hospital CIOs (chief information officers) he has talked to say that while they are stopping the car, they are keeping the engine running. Some will push for dual coding, even if only internally, because it’s proving to be a valuable tool in understanding their patient populations.

“It’s a frustrating time any time you have to kind of stop something with so much momentum, with hundreds of millions, if not billions, spent in advance of the conversion,” Smith says. “It does nothing to help care in this country to stay on ICD-9. Everybody understands those codes are completely exhausted, and the data we are getting out of it, while workable, is certainly not going to get us where we need to be in terms of transforming healthcare.”

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Madison, Wis.

Medicare Rule Change Raises Stakes for Hospital Discharge Planning

When she presents information to hospitalists about the little-known revision to Medicare’s condition of participation for discharge planning by hospitals, most hospitalists have no idea what Amy Boutwell, MD, MPP, is talking about. Even hospitalists who are active in their institutions’ efforts to improve transitions of care out of the hospital setting are unaware of the change, which was published in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Transmittal 87 and became effective July 19, 2013.

“I just don’t hear hospital professionals talking about it,” says Dr. Boutwell, a hospitalist at Newton-Wellesley Hospital and president of Collaborative Healthcare Strategies in Lexington, Mass. “When I say, ‘There are new rules of the road for discharge planning and evaluation,’ many are not aware of it.”

The revised condition states that the hospital must have a discharge planning process that applies to all patients—not just Medicare beneficiaries. Not every patient needs to have a written discharge plan—although this is recommended—but all patients should be screened and, if indicated, evaluated at an early stage of their hospitalization for risk of adverse post-discharge outcomes. Observation patients are not included in this requirement.

The discharge plan is different from a discharge summary document, which must be completed by the inpatient attending physician, not the hospital, and is not directly addressed in the regulation. The regulation does address the need for transfer of essential information to the next provider of care and says the hospital should have a written policy and procedure in place for discharge planning. The policy and procedure should be developed with input from medical staff and approved by the hospital’s governing body.

Any hospitalist participating with a hospital QI team involved in Project BOOST is helping their hospital comply with this condition of participation.

—Mark Williams, MD, FACP, SFHM, principal investigator of SHM’s Project BOOST

Transmittal 87 represents the first major update of the discharge planning regulation (Standard 482.43) and accompanying interpretive guidelines in more than a decade, Dr. Boutwell says. It consolidates and reorganizes 24 “tags” of regulatory language down to 13 and contains blue advisory boxes recommending best practices in discharge planning, drawn from the suggestions of a technical expert panel convened by CMS.

That panel included many of the country’s recognized thought leaders on improving care transitions, such as Mark Williams, MD, FACP, SFHM, principal investigator of SHM’s Project BOOST; Eric Coleman, MD, MPH, head of the University of Colorado’s division of health care policy and research and creator of the widely-adopted Care Transitions Program (caretransitions.org), and Dr. Boutwell, co-founder of the STAAR initiative (www.ihi.org/engage/Initiatives/completed/STAAR).

The new condition raises baseline expectations for discharge planning and elevates care transitions efforts from a quality improvement issue to the realm of regulatory compliance, Dr. Boutwell says.

“This goes way beyond case review,” she adds. “It represents an evolution from discharge planning case by case to a system for improving transitions of care [for the hospital]. I’m impressed.”

The recommendations are consistent with best practices promoted by Project BOOST, STAAR, Project RED [Re-Engineered Discharge], and other national quality initiatives for improving care transitions.

“Any hospitalist participating with a hospital QI team involved in Project BOOST is helping their hospital comply with this condition of participation,” Dr. Williams says.

In the Byzantine structure of federal regulations, Medicare’s conditions of participation are the regulations providers must meet in order to participate in the Medicare program and bill for their services. Condition-level citations, if not resolved, can cause hospitals to be decertified from Medicare. The accompanying interpretive guidelines, with survey protocols, are the playbook to help state auditors and providers know how to interpret and apply the language of the regulations. The suggestions and examples of best practices contained in the new condition are not required of hospitals but, if followed, could increase their likelihood of achieving better patient outcomes and staying in compliance with the regulations on surveys.

“If hospitals were to actually implement all of the CMS advisory practice recommendations contained in this 35-page document, they’d be in really good shape for effectively managing transitions of care,” says Teresa L. Hamblin, RN, MS, a CMS consultant with Joint Commission Resources. “The government has provided robust practice recommendations that are a model for what hospitals can do. I’d advise doing your best to implement these recommendations. Check your current processes using this detailed document for reference.”

Discharge planning starts at admission, Hamblin says. If the hospitalist assumes that responsibility, it becomes easier to leave a paper trail in the patient’s chart. Other important lessons for hospitalists include participation in a multidisciplinary approach to discharge planning (i.e., interdisciplinary rounding) and development of policies and procedures in this area.

“If the hospital has not elected to do a discharge plan on every patient, request this for your own patients and recommend it as a policy,” Hamblin says. “Go the extra mile, making follow-up appointments for your patients, filling prescriptions in house, and calling the patient 24 to 72 hours after discharge.”

Weekend coverage, when case managers typically are not present, is a particular challenge in care transitions.

“Encourage your hospital to provide reliable weekend coverage for discharge planning. Involve the nurses,” Hamblin says. “Anything the hospitalist can do to help the hospital close this gap is important.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

When she presents information to hospitalists about the little-known revision to Medicare’s condition of participation for discharge planning by hospitals, most hospitalists have no idea what Amy Boutwell, MD, MPP, is talking about. Even hospitalists who are active in their institutions’ efforts to improve transitions of care out of the hospital setting are unaware of the change, which was published in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Transmittal 87 and became effective July 19, 2013.

“I just don’t hear hospital professionals talking about it,” says Dr. Boutwell, a hospitalist at Newton-Wellesley Hospital and president of Collaborative Healthcare Strategies in Lexington, Mass. “When I say, ‘There are new rules of the road for discharge planning and evaluation,’ many are not aware of it.”

The revised condition states that the hospital must have a discharge planning process that applies to all patients—not just Medicare beneficiaries. Not every patient needs to have a written discharge plan—although this is recommended—but all patients should be screened and, if indicated, evaluated at an early stage of their hospitalization for risk of adverse post-discharge outcomes. Observation patients are not included in this requirement.

The discharge plan is different from a discharge summary document, which must be completed by the inpatient attending physician, not the hospital, and is not directly addressed in the regulation. The regulation does address the need for transfer of essential information to the next provider of care and says the hospital should have a written policy and procedure in place for discharge planning. The policy and procedure should be developed with input from medical staff and approved by the hospital’s governing body.

Any hospitalist participating with a hospital QI team involved in Project BOOST is helping their hospital comply with this condition of participation.

—Mark Williams, MD, FACP, SFHM, principal investigator of SHM’s Project BOOST

Transmittal 87 represents the first major update of the discharge planning regulation (Standard 482.43) and accompanying interpretive guidelines in more than a decade, Dr. Boutwell says. It consolidates and reorganizes 24 “tags” of regulatory language down to 13 and contains blue advisory boxes recommending best practices in discharge planning, drawn from the suggestions of a technical expert panel convened by CMS.

That panel included many of the country’s recognized thought leaders on improving care transitions, such as Mark Williams, MD, FACP, SFHM, principal investigator of SHM’s Project BOOST; Eric Coleman, MD, MPH, head of the University of Colorado’s division of health care policy and research and creator of the widely-adopted Care Transitions Program (caretransitions.org), and Dr. Boutwell, co-founder of the STAAR initiative (www.ihi.org/engage/Initiatives/completed/STAAR).

The new condition raises baseline expectations for discharge planning and elevates care transitions efforts from a quality improvement issue to the realm of regulatory compliance, Dr. Boutwell says.

“This goes way beyond case review,” she adds. “It represents an evolution from discharge planning case by case to a system for improving transitions of care [for the hospital]. I’m impressed.”

The recommendations are consistent with best practices promoted by Project BOOST, STAAR, Project RED [Re-Engineered Discharge], and other national quality initiatives for improving care transitions.

“Any hospitalist participating with a hospital QI team involved in Project BOOST is helping their hospital comply with this condition of participation,” Dr. Williams says.

In the Byzantine structure of federal regulations, Medicare’s conditions of participation are the regulations providers must meet in order to participate in the Medicare program and bill for their services. Condition-level citations, if not resolved, can cause hospitals to be decertified from Medicare. The accompanying interpretive guidelines, with survey protocols, are the playbook to help state auditors and providers know how to interpret and apply the language of the regulations. The suggestions and examples of best practices contained in the new condition are not required of hospitals but, if followed, could increase their likelihood of achieving better patient outcomes and staying in compliance with the regulations on surveys.

“If hospitals were to actually implement all of the CMS advisory practice recommendations contained in this 35-page document, they’d be in really good shape for effectively managing transitions of care,” says Teresa L. Hamblin, RN, MS, a CMS consultant with Joint Commission Resources. “The government has provided robust practice recommendations that are a model for what hospitals can do. I’d advise doing your best to implement these recommendations. Check your current processes using this detailed document for reference.”

Discharge planning starts at admission, Hamblin says. If the hospitalist assumes that responsibility, it becomes easier to leave a paper trail in the patient’s chart. Other important lessons for hospitalists include participation in a multidisciplinary approach to discharge planning (i.e., interdisciplinary rounding) and development of policies and procedures in this area.

“If the hospital has not elected to do a discharge plan on every patient, request this for your own patients and recommend it as a policy,” Hamblin says. “Go the extra mile, making follow-up appointments for your patients, filling prescriptions in house, and calling the patient 24 to 72 hours after discharge.”

Weekend coverage, when case managers typically are not present, is a particular challenge in care transitions.

“Encourage your hospital to provide reliable weekend coverage for discharge planning. Involve the nurses,” Hamblin says. “Anything the hospitalist can do to help the hospital close this gap is important.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

When she presents information to hospitalists about the little-known revision to Medicare’s condition of participation for discharge planning by hospitals, most hospitalists have no idea what Amy Boutwell, MD, MPP, is talking about. Even hospitalists who are active in their institutions’ efforts to improve transitions of care out of the hospital setting are unaware of the change, which was published in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Transmittal 87 and became effective July 19, 2013.

“I just don’t hear hospital professionals talking about it,” says Dr. Boutwell, a hospitalist at Newton-Wellesley Hospital and president of Collaborative Healthcare Strategies in Lexington, Mass. “When I say, ‘There are new rules of the road for discharge planning and evaluation,’ many are not aware of it.”

The revised condition states that the hospital must have a discharge planning process that applies to all patients—not just Medicare beneficiaries. Not every patient needs to have a written discharge plan—although this is recommended—but all patients should be screened and, if indicated, evaluated at an early stage of their hospitalization for risk of adverse post-discharge outcomes. Observation patients are not included in this requirement.

The discharge plan is different from a discharge summary document, which must be completed by the inpatient attending physician, not the hospital, and is not directly addressed in the regulation. The regulation does address the need for transfer of essential information to the next provider of care and says the hospital should have a written policy and procedure in place for discharge planning. The policy and procedure should be developed with input from medical staff and approved by the hospital’s governing body.

Any hospitalist participating with a hospital QI team involved in Project BOOST is helping their hospital comply with this condition of participation.

—Mark Williams, MD, FACP, SFHM, principal investigator of SHM’s Project BOOST

Transmittal 87 represents the first major update of the discharge planning regulation (Standard 482.43) and accompanying interpretive guidelines in more than a decade, Dr. Boutwell says. It consolidates and reorganizes 24 “tags” of regulatory language down to 13 and contains blue advisory boxes recommending best practices in discharge planning, drawn from the suggestions of a technical expert panel convened by CMS.

That panel included many of the country’s recognized thought leaders on improving care transitions, such as Mark Williams, MD, FACP, SFHM, principal investigator of SHM’s Project BOOST; Eric Coleman, MD, MPH, head of the University of Colorado’s division of health care policy and research and creator of the widely-adopted Care Transitions Program (caretransitions.org), and Dr. Boutwell, co-founder of the STAAR initiative (www.ihi.org/engage/Initiatives/completed/STAAR).

The new condition raises baseline expectations for discharge planning and elevates care transitions efforts from a quality improvement issue to the realm of regulatory compliance, Dr. Boutwell says.

“This goes way beyond case review,” she adds. “It represents an evolution from discharge planning case by case to a system for improving transitions of care [for the hospital]. I’m impressed.”

The recommendations are consistent with best practices promoted by Project BOOST, STAAR, Project RED [Re-Engineered Discharge], and other national quality initiatives for improving care transitions.

“Any hospitalist participating with a hospital QI team involved in Project BOOST is helping their hospital comply with this condition of participation,” Dr. Williams says.

In the Byzantine structure of federal regulations, Medicare’s conditions of participation are the regulations providers must meet in order to participate in the Medicare program and bill for their services. Condition-level citations, if not resolved, can cause hospitals to be decertified from Medicare. The accompanying interpretive guidelines, with survey protocols, are the playbook to help state auditors and providers know how to interpret and apply the language of the regulations. The suggestions and examples of best practices contained in the new condition are not required of hospitals but, if followed, could increase their likelihood of achieving better patient outcomes and staying in compliance with the regulations on surveys.

“If hospitals were to actually implement all of the CMS advisory practice recommendations contained in this 35-page document, they’d be in really good shape for effectively managing transitions of care,” says Teresa L. Hamblin, RN, MS, a CMS consultant with Joint Commission Resources. “The government has provided robust practice recommendations that are a model for what hospitals can do. I’d advise doing your best to implement these recommendations. Check your current processes using this detailed document for reference.”

Discharge planning starts at admission, Hamblin says. If the hospitalist assumes that responsibility, it becomes easier to leave a paper trail in the patient’s chart. Other important lessons for hospitalists include participation in a multidisciplinary approach to discharge planning (i.e., interdisciplinary rounding) and development of policies and procedures in this area.

“If the hospital has not elected to do a discharge plan on every patient, request this for your own patients and recommend it as a policy,” Hamblin says. “Go the extra mile, making follow-up appointments for your patients, filling prescriptions in house, and calling the patient 24 to 72 hours after discharge.”

Weekend coverage, when case managers typically are not present, is a particular challenge in care transitions.

“Encourage your hospital to provide reliable weekend coverage for discharge planning. Involve the nurses,” Hamblin says. “Anything the hospitalist can do to help the hospital close this gap is important.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

SGR Reform, ICD-10 Implementation Delays Frustrate Hospitalists, Physicians

Congress has once again delayed implementation of draconian Medicare cuts tied to the sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula. It was the 17th temporary patch applied to the ailing physician reimbursement program, so the decision caused little surprise.

But with the same legislation—the Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014—being used to delay the long-awaited debut of ICD-10, many hospitalists and physicians couldn’t help but wonder whether billing and coding would now be as much of a political football as the SGR fix.1

The upshot: It doesn’t seem that way.

“I think it’s two separate issues,” says Phyllis “PJ” Floyd, RN, BSN, MBA, NE-BC, CCA, director of health information services and clinical documentation improvement at Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) in Charleston, S.C. “The fact that it was all in one bill, I don’t know that it was well thought out as much as it was, ‘Let’s put the ICD-10 in here at the same time.’

“It was just a few sentences, and then it wasn’t even brought up in the discussion on the floor.”

Four policy wonks interviewed by The Hospitalist concurred that while tying the ICD-10 delay to the SGR issue was an unexpected and frustrating development, the coding system likely will be implemented in the relative short term. Meanwhile, a long-term resolution of the SGR dilemma remains much more elusive.

“For about 12 hours, I felt relief about the ICD-10 [being delayed], and then I just realized, it’s still coming, presumably,” says John Nelson, MD, MHM, a co-founder and past president of SHM and medical director of the hospitalist practice at Overlake Hospital Medical Center in Bellevue, Wash. “[It’s] like a patient who needs surgery and finds out it’s canceled for the day and he’ll have it tomorrow. Well, that’s good for right now, but [he] still has to face this eventually.”

“Doc-Pay” Fix Near?

Congress’ recent decision to delay both an SGR fix and the ICD-10 are troubling to some hospitalists and others for different reasons.

The SGR extension through this year’s end means that physicians do not face a 24% cut to physician payments under Medicare. SHM has long lobbied against temporary patches to the SGR, repeatedly backing legislation that would once and for all scrap the formula and replace it with something sustainable.

The SGR formula was first crafted in 1997, but the now often-delayed cuts were a byproduct of the federal sequester that was included in the Budget Control Act of 2011. At the time, the massive reduction to Medicare payments was tied to political brinksmanship over the country’s debt ceiling. The cuts were implemented as a doomsday scenario that was never likely to actually happen, but despite negotiations over the past three years, no long-term compromise can be found. Paying for the reform remains the main stumbling block.

“I think, this year, Congress was as close as it’s been in a long time to enacting a serious fix, aided by the agreement of major professional societies like the American College of Physicians and American College of Surgeons,” says David Howard, PhD, an associate professor in the department of health policy and management at the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University in Atlanta. “They were all on board with this solution. ... Who knows, maybe if the economic situation continues to improve [and] tax revenues continue to go up...that will create a more favorable environment for compromise.”

Dr. Howard adds that while Congress might be close to a solution in theory, agreement on how to offset the roughly $100 billion in costs “is just very difficult.” That is why the healthcare professor is pessimistic that a long-term fix is truly at hand.

“The places where Congress might have looked for savings to offset the cost of the doc fix, such as hospital reimbursement rates or payment rates to Medicare Advantage plans—those are exactly the areas that the Affordable Care Act is targeting to pay for insurance expansion,” Dr. Howard adds. “So those areas of savings are not going to be available to offset the cost of the doc fix.”

ICD-10 Delays “Unfair”

The medical coding conundrum presents a different set of issues. The delay in transitioning healthcare providers from the ICD-9 medical coding classification system to the more complicated ICD-10 means the upgraded system is now against an Oct. 1, 2015, deadline. This comes after the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) already pushed back the original implementation date for ICD-10 by one year.

SHM Public Policy Committee member Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, says he thinks most doctors are content with the delay, particularly in light of some estimates that show that only about 20% of physicians “have actually initiated the ICD-10 transition.” But he also notes that it’s unfair to the health systems that have prepared for ICD-10.

“ICD-9 has a little more than 14,000 diagnostic codes and nearly 4,000 procedural codes. That is to be contrasted to ICD-10, which has more than 68,000 diagnostic codes ... and over 72,000 procedural codes,” Dr. Lenchus says. “So, it is not surprising that many take solace in the delay.”

–Dr. Lenchus

Dr. Nelson says the level of frustration for hospitalists is growing; however, the level of disruption for hospitals and health systems is reaching a boiling point.

“Of course, in some places, hospitalists may be the physician lead on ICD-10 efforts, so [they are] very much wrapped up in the problem of ‘What do we do now?’”

The answer, at least to the Coalition for ICD-10, a group of medical/technology trade groups, is to fight to ensure that the delays go no further. In an April letter to CMS Administrator Marilyn Tavenner, the coalition made that case, noting that in 2012, “CMS estimated the cost to the healthcare industry of a one-year delay to be as much as $6.6 billion, or approximately 30% of the $22 billion that CMS estimated had been invested or budgeted for ICD-10 implementation.”2

The letter went on to explain that the disruption and cost will grow each time the ICD-10 deadline is pushed.

“Furthermore, as CMS stated in 2012, implementation costs will continue to increase considerably with every year of a delay,” according to the letter. “The lost opportunity costs of failing to move to a more effective code set also continue to climb every year.”

Stay Engaged, Switch Gears

One of Floyd’s biggest concerns is that the ICD-10 implementation delays will affect physician engagement. The hospitalist groups at MUSC began training for ICD-10 in January 2013; however, the preparation and training were geared toward a 2014 implementation.

“You have to switch gears a little bit,” she says. “What we plan to do now is begin to do heavy auditing, and then from those audits we can give real-time feedback on what we’re doing well and what we’re not doing well. So I think that will be a method for engagement.”

She urges hospitalists, practice leaders, and informatics professionals to discuss ICD-10 not as a theoretical application, but as one tied to reimbursement that will have major impact in the years ahead. To that end, the American Health Information Management Association highlights the fact that the new coding system will result in higher-quality data that can improve performance measures, provide “increased sensitivity” to reimbursement methodologies, and help with stronger public health surveillance.3

“A lot of physicians see this as a hospital issue, and I think that’s why they shy away,” Floyd says. “Now there are some physicians who are interested in how well the hospital does, but the other piece is that it does affect things like [reduced] risk of mortality [and] comparison of data worldwide—those are things that we just have to continue to reiterate … and give them real examples.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Govtrack. H.R. 4302: Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014. https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/113/hr4302. Accessed June 5, 2014.

- Coalition for ICD. Letter to CMS Administrator Tavenner, April 11, 2014. http://coalitionforicd10.wordpress.com/2014/03/26/letter-from-the-coalition-for-icd-10. Accessed June 5, 2014.

- American Health Information Management Association. ICD-10-CM/PCS Transition: Planning and Preparation Checklist. http://journal.ahima.org/wp-content/uploads/ICD10-checklist.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2014.

Congress has once again delayed implementation of draconian Medicare cuts tied to the sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula. It was the 17th temporary patch applied to the ailing physician reimbursement program, so the decision caused little surprise.

But with the same legislation—the Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014—being used to delay the long-awaited debut of ICD-10, many hospitalists and physicians couldn’t help but wonder whether billing and coding would now be as much of a political football as the SGR fix.1

The upshot: It doesn’t seem that way.

“I think it’s two separate issues,” says Phyllis “PJ” Floyd, RN, BSN, MBA, NE-BC, CCA, director of health information services and clinical documentation improvement at Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) in Charleston, S.C. “The fact that it was all in one bill, I don’t know that it was well thought out as much as it was, ‘Let’s put the ICD-10 in here at the same time.’

“It was just a few sentences, and then it wasn’t even brought up in the discussion on the floor.”

Four policy wonks interviewed by The Hospitalist concurred that while tying the ICD-10 delay to the SGR issue was an unexpected and frustrating development, the coding system likely will be implemented in the relative short term. Meanwhile, a long-term resolution of the SGR dilemma remains much more elusive.

“For about 12 hours, I felt relief about the ICD-10 [being delayed], and then I just realized, it’s still coming, presumably,” says John Nelson, MD, MHM, a co-founder and past president of SHM and medical director of the hospitalist practice at Overlake Hospital Medical Center in Bellevue, Wash. “[It’s] like a patient who needs surgery and finds out it’s canceled for the day and he’ll have it tomorrow. Well, that’s good for right now, but [he] still has to face this eventually.”

“Doc-Pay” Fix Near?

Congress’ recent decision to delay both an SGR fix and the ICD-10 are troubling to some hospitalists and others for different reasons.

The SGR extension through this year’s end means that physicians do not face a 24% cut to physician payments under Medicare. SHM has long lobbied against temporary patches to the SGR, repeatedly backing legislation that would once and for all scrap the formula and replace it with something sustainable.

The SGR formula was first crafted in 1997, but the now often-delayed cuts were a byproduct of the federal sequester that was included in the Budget Control Act of 2011. At the time, the massive reduction to Medicare payments was tied to political brinksmanship over the country’s debt ceiling. The cuts were implemented as a doomsday scenario that was never likely to actually happen, but despite negotiations over the past three years, no long-term compromise can be found. Paying for the reform remains the main stumbling block.

“I think, this year, Congress was as close as it’s been in a long time to enacting a serious fix, aided by the agreement of major professional societies like the American College of Physicians and American College of Surgeons,” says David Howard, PhD, an associate professor in the department of health policy and management at the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University in Atlanta. “They were all on board with this solution. ... Who knows, maybe if the economic situation continues to improve [and] tax revenues continue to go up...that will create a more favorable environment for compromise.”

Dr. Howard adds that while Congress might be close to a solution in theory, agreement on how to offset the roughly $100 billion in costs “is just very difficult.” That is why the healthcare professor is pessimistic that a long-term fix is truly at hand.

“The places where Congress might have looked for savings to offset the cost of the doc fix, such as hospital reimbursement rates or payment rates to Medicare Advantage plans—those are exactly the areas that the Affordable Care Act is targeting to pay for insurance expansion,” Dr. Howard adds. “So those areas of savings are not going to be available to offset the cost of the doc fix.”

ICD-10 Delays “Unfair”

The medical coding conundrum presents a different set of issues. The delay in transitioning healthcare providers from the ICD-9 medical coding classification system to the more complicated ICD-10 means the upgraded system is now against an Oct. 1, 2015, deadline. This comes after the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) already pushed back the original implementation date for ICD-10 by one year.

SHM Public Policy Committee member Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, says he thinks most doctors are content with the delay, particularly in light of some estimates that show that only about 20% of physicians “have actually initiated the ICD-10 transition.” But he also notes that it’s unfair to the health systems that have prepared for ICD-10.

“ICD-9 has a little more than 14,000 diagnostic codes and nearly 4,000 procedural codes. That is to be contrasted to ICD-10, which has more than 68,000 diagnostic codes ... and over 72,000 procedural codes,” Dr. Lenchus says. “So, it is not surprising that many take solace in the delay.”

–Dr. Lenchus

Dr. Nelson says the level of frustration for hospitalists is growing; however, the level of disruption for hospitals and health systems is reaching a boiling point.

“Of course, in some places, hospitalists may be the physician lead on ICD-10 efforts, so [they are] very much wrapped up in the problem of ‘What do we do now?’”

The answer, at least to the Coalition for ICD-10, a group of medical/technology trade groups, is to fight to ensure that the delays go no further. In an April letter to CMS Administrator Marilyn Tavenner, the coalition made that case, noting that in 2012, “CMS estimated the cost to the healthcare industry of a one-year delay to be as much as $6.6 billion, or approximately 30% of the $22 billion that CMS estimated had been invested or budgeted for ICD-10 implementation.”2

The letter went on to explain that the disruption and cost will grow each time the ICD-10 deadline is pushed.

“Furthermore, as CMS stated in 2012, implementation costs will continue to increase considerably with every year of a delay,” according to the letter. “The lost opportunity costs of failing to move to a more effective code set also continue to climb every year.”

Stay Engaged, Switch Gears

One of Floyd’s biggest concerns is that the ICD-10 implementation delays will affect physician engagement. The hospitalist groups at MUSC began training for ICD-10 in January 2013; however, the preparation and training were geared toward a 2014 implementation.

“You have to switch gears a little bit,” she says. “What we plan to do now is begin to do heavy auditing, and then from those audits we can give real-time feedback on what we’re doing well and what we’re not doing well. So I think that will be a method for engagement.”

She urges hospitalists, practice leaders, and informatics professionals to discuss ICD-10 not as a theoretical application, but as one tied to reimbursement that will have major impact in the years ahead. To that end, the American Health Information Management Association highlights the fact that the new coding system will result in higher-quality data that can improve performance measures, provide “increased sensitivity” to reimbursement methodologies, and help with stronger public health surveillance.3

“A lot of physicians see this as a hospital issue, and I think that’s why they shy away,” Floyd says. “Now there are some physicians who are interested in how well the hospital does, but the other piece is that it does affect things like [reduced] risk of mortality [and] comparison of data worldwide—those are things that we just have to continue to reiterate … and give them real examples.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Govtrack. H.R. 4302: Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014. https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/113/hr4302. Accessed June 5, 2014.

- Coalition for ICD. Letter to CMS Administrator Tavenner, April 11, 2014. http://coalitionforicd10.wordpress.com/2014/03/26/letter-from-the-coalition-for-icd-10. Accessed June 5, 2014.

- American Health Information Management Association. ICD-10-CM/PCS Transition: Planning and Preparation Checklist. http://journal.ahima.org/wp-content/uploads/ICD10-checklist.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2014.

Congress has once again delayed implementation of draconian Medicare cuts tied to the sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula. It was the 17th temporary patch applied to the ailing physician reimbursement program, so the decision caused little surprise.

But with the same legislation—the Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014—being used to delay the long-awaited debut of ICD-10, many hospitalists and physicians couldn’t help but wonder whether billing and coding would now be as much of a political football as the SGR fix.1

The upshot: It doesn’t seem that way.

“I think it’s two separate issues,” says Phyllis “PJ” Floyd, RN, BSN, MBA, NE-BC, CCA, director of health information services and clinical documentation improvement at Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) in Charleston, S.C. “The fact that it was all in one bill, I don’t know that it was well thought out as much as it was, ‘Let’s put the ICD-10 in here at the same time.’

“It was just a few sentences, and then it wasn’t even brought up in the discussion on the floor.”

Four policy wonks interviewed by The Hospitalist concurred that while tying the ICD-10 delay to the SGR issue was an unexpected and frustrating development, the coding system likely will be implemented in the relative short term. Meanwhile, a long-term resolution of the SGR dilemma remains much more elusive.