User login

Frailty Trends in an Older Veteran Subpopulation 1 Year Prior and Into the COVID-19 Pandemic Using CAN Scores

Frailty is an age-associated, nonspecific vulnerability to adverse health outcomes. Frailty can also be described as a complex of symptoms characterized by impaired stress tolerance due to a decline in the functionality of different organs.1 The prevalence of frailty varies widely depending on the method of measurement and the population studied.2-4 It is a nonconstant factor that increases with age. A deficit accumulation frailty index (FI) is one method used to measure frailty.5 This approach sees frailty as a multidimensional risk state measured by quantity rather than the nature of health concerns. A deficit accumulation FI does not require physical testing but correlates well with other phenotypic FIs.6 It is, however, time consuming, as ≥ 30 deficits need to be measured to offer greater stability to the frailty estimate.

Health care is seeing increasing utilization of big data analytics to derive predictive models and help with resource allocation. There are currently 2 existing automated tools to predict health care utilization and mortality at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA): the VA Frailty Index (VA-FI-10) and the Care Assessment Need (CAN). VA-FI-10 is an International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) update of the VA-FI that was created in March 2021. The VA-FI-10 is a claims-based frailty assessment tool using 31 health deficits. Calculating the VA-FI-10 requires defining an index date and lookback period (typically 3 years) relative to which it will be calculated.7

CAN is a set of risk-stratifying statistical models run on veterans receiving VA primary care services as part of a patient aligned care team (PACT) using electronic health record data.8 Each veteran is stratified based on the individual’s risks of hospitalization, death, and hospitalization or death. These 3 events are predicted for 90-day and 1-year time periods for a total of 6 distinct outcomes. CAN is currently on its third iteration (CAN 2.5) and scores range from 0 (low) to 99 (high). CAN scores are updated weekly. The 1-year hospitalization probabilities for all patients range from 0.8% to 93.1%. For patients with a CAN score of 50, the probability of being hospitalized within a year ranges from 4.5% to 5.2%, which increases to 32.2% to 36% for veterans with a CAN score of 95. The probability range widens significantly (32.2%-93.1%) for patients in the top 5 CAN scores (95-99).

CAN scores are a potential screening tool for frailty among older adults; they are generated automatically and provide acceptable diagnostic accuracy. Hence, the CAN score may be a useful tool for primary care practitioners for the detection of frailty in their patients. The CAN score has shown a moderate positive association with the FRAIL Scale.9,10 The population-based studies that have used the FI approach (differing FIs, depending on the data available) give robust results: People accumulate an average of 0.03 deficits per year after the age of 70 years.11 Interventions to delay or reverse frailty have not been clearly defined with heterogeneity in the definition of frailty and measurement of frailty outcomes.12,13 The prevalence of frailty in the veteran population is substantially higher than the prevalence in community populations with a similar age distribution. There is also mounting evidence that veterans accumulate deficits more rapidly than their civilian counterparts.14

COVID-19 was declared a pandemic in March 2020 and had many impacts on global health that were most marked in the first year. These included reductions in hospital visits for non-COVID-19 health concerns, a reduction in completed screening tests, an initial reduction in other infectious diseases (attributable to quarantines), and an increase or worsening of mental health concerns.15,16

We aimed to investigate whether frailty increased disproportionately in a subset of older veterans in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic when compared with the previous year using CAN scores. This single institution, longitudinal cohort study was determined to be exempt from institutional review board review but was approved by the Phoenix VA Health Care System (PVAHCS) Research and Development Committee.

Methods

The Office of Clinical Systems Development and Evaluation (CSDE–10E2A) produces a weekly CAN Score Report to help identify the highest-risk patients in a primary care panel or cohort. CAN scores range from 0 (lowest risk) to 99 (highest risk), indicating how likely a patient is to experience hospitalization or death compared with other VA patients. CAN scores are calculated with statistical prediction models that use data elements from the following Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) domains: demographics, health care utilization, laboratory tests, medical conditions, medications, and vital signs (eAppendix available online at 10.12788/fp.0385).

The CAN Score Report is generated weekly and stored on a CDW server. A patient will receive all 6 distinct CAN scores if they are: (1) assigned to a primary care PACT on the risk date; (2) a veteran; (3) not hospitalized in a VA facility on the risk date; and (4) alive as of the risk date. New to CAN 2.5 is that patients who meet criteria 1, 2, and 4 but are hospitalized in a VA facility on the risk date will receive CAN scores for the 1-year and 90-day mortality models.

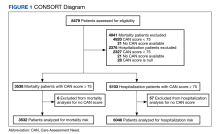

Utilizing VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VA HSR RES 13-457, US Department of Veterans Affairs [2008]), we obtained 2 lists of veterans aged 70 to 75 years on February 8, 2019, with a calculated CAN score of ≥ 75 for 1-year mortality and 1-year hospitalization on that date. A veteran with a CAN score of ≥ 75 is likely to be prefrail or frail.9,10 Veterans who did not have a corresponding calculated CAN score on February 7, 2020, and February 12, 2021, were excluded. COVID-19 was declared a public health emergency in the United States on January 31, 2020, and the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11, 2020.17 We picked February 7, 2020, within this time frame and without any other special significance. We picked additional CAN score calculation dates approximately 1 year prior and 1 year after this date. Veterans had to be alive on February 12, 2021, (the last date of the CAN score) to be included in the cohorts.

Statistical Analyses

The difference in CAN score from one year to the next was calculated for each patient. The difference between 2019 and 2020 was compared with the difference between 2020 to 2021 using a paired t test. Yearly CAN score values were analyzed using repeated measures analysis of variance. The number of patients that showed an increase in CAN score (ie, increased risk of either mortality or hospitalization within the year) or a decrease (lower risk) was compared using the χ2 test. IBM SPSS v26 and GraphPad Prism v18 were used for statistical analysis. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

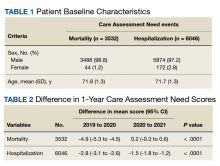

There were 3538 veterans at PVAHCS who met the inclusion criteria and had a 1-year mortality CAN score ≥ 75 on February 8, 2019.

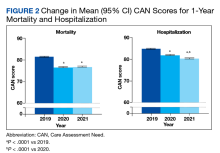

In the hospitalization group, there were 6046 veterans in the analysis; 57 veterans missing a 1-year hospitalization CAN score that were excluded. The mean age was 71.7 (1.3) years and included 5874 male (97.2%) and 172 female (2.8%) veterans. There was a decline in mean 1-year hospitalization CAN scores in our subset of frail older veterans by 2.8 (95% CI, -3.1 to -2.6) in the year preceding the COVID-19 pandemic. This mean decline slowed significantly to 1.5 (95% CI, -1.8 to -1.2; P < .0001) after the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Mean CAN scores for 1-year hospitalization were 84.6 (95% CI, 84.4 to 84.8), 81.8 (95% CI, 81.5 to 82.1), and 80.2 (95% CI, 79.9 to 80.6)

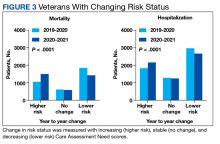

We also calculated the number of veterans with increasing, stable, and decreasing CAN scores across each of our defined periods in both the 1-year mortality and hospitalization groups.

A previous study used a 1-year combined hospitalization or mortality event CAN score as the most all-inclusive measure of frailty but determined that it was possible that 1 of the other 5 CAN risk measures could perform better in predicting frailty.10 We collected and presented data for 1-year mortality and hospitalization CAN scores. There were declines in pandemic-related US hospitalizations for illnesses not related to COVID-19 during the first few months of the pandemic.18 This may or may not have affected the 1-year hospitalization CAN score data; thus, we used the 1-year mortality CAN score data to predict frailty.

Discussion

We studied frailty trends in an older veteran subpopulation enrolled at the PVAHCS 1 year prior and into the COVID-19 pandemic using CAN scores. Frailty is a dynamic state. Previous frailty assessments aimed to identify patients at the highest risk of death. With the advent of advanced therapeutics for several diseases, the number of medical conditions that are now managed as chronic illnesses continues to grow. There is a role for repeated measures of frailty to try to identify frailty trends.19 These trends may assist us in resource allocation, identifying interventions that work and those that do not.

Some studies have shown an overall declining lethality of frailty. This may reflect improvements in the care and management of chronic conditions, screening tests, and increased awareness of healthy lifestyles.20 Another study of frailty trajectories in a veteran population in the 5 years preceding death showed multiple trajectories (stable, gradually increasing, rapidly increasing, and recovering).19

The PACT is a primary care model implemented at VA medical centers in April 2010. It is a patient-centered medical home model (PCMH) with several components. The VA treats a population of socioeconomically vulnerable patients with complex chronic illness management needs. Some of the components of a PACT model relevant to our study include facilitated self-management support for veterans in between practitioner visits via care partners, peer-to-peer and transitional care programs, physical activity and diet programs, primary care mental health, integration between primary and specialty care, and telehealth.21 A previous study has shown that VA primary care clinics with the most PCMH components in place had greater improvements in several chronic disease quality measures than in clinics with a lower number of PCMH components.22

Limitations

Our study is limited by our older veteran population demographics. We chose only a subset of older veterans at a single VA center for this study and cannot extrapolate the results to all older frail veterans or community dwelling older adults. Robust individuals may also transition to prefrailty and frailty over longer periods; our study monitored frailty trends over 2 years.

CAN scores are not quality measures to improve upon. Allocation and utilization of additional resources may clinically benefit a patient but increase their CAN scores. Although our results are statistically significant, we are unable to make any conclusions about clinical significance.

Conclusions

Our study results indicate frailty as determined by 1-year mortality CAN scores significantly increased in a subset of older veterans during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic when compared with the previous year. Whether this change in frailty is temporary or long lasting remains to be seen. Automated CAN scores can be effectively utilized to monitor frailty trends in certain veteran populations over longer periods.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Phoenix Veterans Affairs Health Care System.

1. Rohrmann S. Epidemiology of frailty in older people. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1216:21-27. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-33330-0_3

2. Bandeen-Roche K, Seplaki CL, Huang J, et al. Frailty in older adults: a nationally representative profile in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(11):1427-1434. doi:10.1093/gerona/glv133

3. Siriwardhana DD, Hardoon S, Rait G, Weerasinghe MC, Walters KR. Prevalence of frailty and prefrailty among community-dwelling older adults in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e018195. Published 2018 Mar 1. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018195

4. Song X, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Prevalence and 10-year outcomes of frailty in older adults in relation to deficit accumulation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):681-687. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02764.x

5. Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(7):722-727. doi:10.1093/gerona/62.7.722

6. Buta BJ, Walston JD, Godino JG, et al. Frailty assessment instruments: Systematic characterization of the uses and contexts of highly-cited instruments. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;26:53-61. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2015.12.003

7. Cheng D, DuMontier C, Yildirim C, et al. Updating and validating the U.S. Veterans Affairs Frailty Index: transitioning From ICD-9 to ICD-10. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2021;76(7):1318-1325. doi:10.1093/gerona/glab071

8. Fihn SD, Francis J, Clancy C, et al. Insights from advanced analytics at the Veterans Health Administration. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(7):1203-1211. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0054

9. Ruiz JG, Priyadarshni S, Rahaman Z, et al. Validation of an automatically generated screening score for frailty: the care assessment need (CAN) score. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):106. doi:10.1186/s12877-018-0802-7

10. Ruiz JG, Rahaman Z, Dang S, Anam R, Valencia WM, Mintzer MJ. Association of the CAN score with the FRAIL scale in community dwelling older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018;30(10):1241-1245. doi:10.1007/s40520-018-0910-4

11. Ofori-Asenso R, Chin KL, Mazidi M, et al. Global incidence of frailty and prefrailty among community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e198398. Published 2019 Aug 2. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8398

12. Marcucci M, Damanti S, Germini F, et al. Interventions to prevent, delay or reverse frailty in older people: a journey towards clinical guidelines. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):193. Published 2019 Oct 29. doi:10.1186/s12916-019-1434-2

13. Travers J, Romero-Ortuno R, Bailey J, Cooney MT. Delaying and reversing frailty: a systematic review of primary care interventions. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(678):e61-e69. doi:10.3399/bjgp18X700241

14. Orkaby AR, Nussbaum L, Ho YL, et al. The burden of frailty among U.S. veterans and its association with mortality, 2002-2012. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74(8):1257-1264. doi:10.1093/gerona/gly232

15. Bakouny Z, Paciotti M, Schmidt AL, Lipsitz SR, Choueiri TK, Trinh QD. Cancer screening tests and cancer diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(3):458-460. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.7600

16. Steffen R, Lautenschlager S, Fehr J. Travel restrictions and lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic-impact on notified infectious diseases in Switzerland. J Travel Med. 2020;27(8):taaa180. doi:10.1093/jtm/taaa180

17. CDC Museum COVID-19 Timeline. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated March 15, 2023. Accessed May 12, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/covid19.html18. Nguyen JL, Benigno M, Malhotra D, et al. Pandemic-related declines in hospitalization for non-COVID-19-related illness in the United States from January through July 2020. PLoS One. 2022;17(1):e0262347. Published 2022 Jan 6. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0262347

19. Ward RE, Orkaby AR, Dumontier C, et al. Trajectories of frailty in the 5 years prior to death among U.S. veterans born 1927-1934. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2021;76(11):e347-e353. doi:10.1093/gerona/glab196

20. Bäckman K, Joas E, Falk H, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K, Skoog I. Changes in the lethality of frailty over 30 years: evidence from two cohorts of 70-year-olds in Gothenburg Sweden. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(7):945-950. doi:10.1093/gerona/glw160

21. Piette JD, Holtz B, Beard AJ, et al. Improving chronic illness care for veterans within the framework of the Patient-Centered Medical Home: experiences from the Ann Arbor Patient-Aligned Care Team Laboratory. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1(4):615-623. doi:10.1007/s13142-011-0065-8

22. Rosland AM, Nelson K, Sun H, et al. The patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(7):e263-e272. Published 2013 Jul 1.

Frailty is an age-associated, nonspecific vulnerability to adverse health outcomes. Frailty can also be described as a complex of symptoms characterized by impaired stress tolerance due to a decline in the functionality of different organs.1 The prevalence of frailty varies widely depending on the method of measurement and the population studied.2-4 It is a nonconstant factor that increases with age. A deficit accumulation frailty index (FI) is one method used to measure frailty.5 This approach sees frailty as a multidimensional risk state measured by quantity rather than the nature of health concerns. A deficit accumulation FI does not require physical testing but correlates well with other phenotypic FIs.6 It is, however, time consuming, as ≥ 30 deficits need to be measured to offer greater stability to the frailty estimate.

Health care is seeing increasing utilization of big data analytics to derive predictive models and help with resource allocation. There are currently 2 existing automated tools to predict health care utilization and mortality at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA): the VA Frailty Index (VA-FI-10) and the Care Assessment Need (CAN). VA-FI-10 is an International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) update of the VA-FI that was created in March 2021. The VA-FI-10 is a claims-based frailty assessment tool using 31 health deficits. Calculating the VA-FI-10 requires defining an index date and lookback period (typically 3 years) relative to which it will be calculated.7

CAN is a set of risk-stratifying statistical models run on veterans receiving VA primary care services as part of a patient aligned care team (PACT) using electronic health record data.8 Each veteran is stratified based on the individual’s risks of hospitalization, death, and hospitalization or death. These 3 events are predicted for 90-day and 1-year time periods for a total of 6 distinct outcomes. CAN is currently on its third iteration (CAN 2.5) and scores range from 0 (low) to 99 (high). CAN scores are updated weekly. The 1-year hospitalization probabilities for all patients range from 0.8% to 93.1%. For patients with a CAN score of 50, the probability of being hospitalized within a year ranges from 4.5% to 5.2%, which increases to 32.2% to 36% for veterans with a CAN score of 95. The probability range widens significantly (32.2%-93.1%) for patients in the top 5 CAN scores (95-99).

CAN scores are a potential screening tool for frailty among older adults; they are generated automatically and provide acceptable diagnostic accuracy. Hence, the CAN score may be a useful tool for primary care practitioners for the detection of frailty in their patients. The CAN score has shown a moderate positive association with the FRAIL Scale.9,10 The population-based studies that have used the FI approach (differing FIs, depending on the data available) give robust results: People accumulate an average of 0.03 deficits per year after the age of 70 years.11 Interventions to delay or reverse frailty have not been clearly defined with heterogeneity in the definition of frailty and measurement of frailty outcomes.12,13 The prevalence of frailty in the veteran population is substantially higher than the prevalence in community populations with a similar age distribution. There is also mounting evidence that veterans accumulate deficits more rapidly than their civilian counterparts.14

COVID-19 was declared a pandemic in March 2020 and had many impacts on global health that were most marked in the first year. These included reductions in hospital visits for non-COVID-19 health concerns, a reduction in completed screening tests, an initial reduction in other infectious diseases (attributable to quarantines), and an increase or worsening of mental health concerns.15,16

We aimed to investigate whether frailty increased disproportionately in a subset of older veterans in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic when compared with the previous year using CAN scores. This single institution, longitudinal cohort study was determined to be exempt from institutional review board review but was approved by the Phoenix VA Health Care System (PVAHCS) Research and Development Committee.

Methods

The Office of Clinical Systems Development and Evaluation (CSDE–10E2A) produces a weekly CAN Score Report to help identify the highest-risk patients in a primary care panel or cohort. CAN scores range from 0 (lowest risk) to 99 (highest risk), indicating how likely a patient is to experience hospitalization or death compared with other VA patients. CAN scores are calculated with statistical prediction models that use data elements from the following Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) domains: demographics, health care utilization, laboratory tests, medical conditions, medications, and vital signs (eAppendix available online at 10.12788/fp.0385).

The CAN Score Report is generated weekly and stored on a CDW server. A patient will receive all 6 distinct CAN scores if they are: (1) assigned to a primary care PACT on the risk date; (2) a veteran; (3) not hospitalized in a VA facility on the risk date; and (4) alive as of the risk date. New to CAN 2.5 is that patients who meet criteria 1, 2, and 4 but are hospitalized in a VA facility on the risk date will receive CAN scores for the 1-year and 90-day mortality models.

Utilizing VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VA HSR RES 13-457, US Department of Veterans Affairs [2008]), we obtained 2 lists of veterans aged 70 to 75 years on February 8, 2019, with a calculated CAN score of ≥ 75 for 1-year mortality and 1-year hospitalization on that date. A veteran with a CAN score of ≥ 75 is likely to be prefrail or frail.9,10 Veterans who did not have a corresponding calculated CAN score on February 7, 2020, and February 12, 2021, were excluded. COVID-19 was declared a public health emergency in the United States on January 31, 2020, and the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11, 2020.17 We picked February 7, 2020, within this time frame and without any other special significance. We picked additional CAN score calculation dates approximately 1 year prior and 1 year after this date. Veterans had to be alive on February 12, 2021, (the last date of the CAN score) to be included in the cohorts.

Statistical Analyses

The difference in CAN score from one year to the next was calculated for each patient. The difference between 2019 and 2020 was compared with the difference between 2020 to 2021 using a paired t test. Yearly CAN score values were analyzed using repeated measures analysis of variance. The number of patients that showed an increase in CAN score (ie, increased risk of either mortality or hospitalization within the year) or a decrease (lower risk) was compared using the χ2 test. IBM SPSS v26 and GraphPad Prism v18 were used for statistical analysis. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

There were 3538 veterans at PVAHCS who met the inclusion criteria and had a 1-year mortality CAN score ≥ 75 on February 8, 2019.

In the hospitalization group, there were 6046 veterans in the analysis; 57 veterans missing a 1-year hospitalization CAN score that were excluded. The mean age was 71.7 (1.3) years and included 5874 male (97.2%) and 172 female (2.8%) veterans. There was a decline in mean 1-year hospitalization CAN scores in our subset of frail older veterans by 2.8 (95% CI, -3.1 to -2.6) in the year preceding the COVID-19 pandemic. This mean decline slowed significantly to 1.5 (95% CI, -1.8 to -1.2; P < .0001) after the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Mean CAN scores for 1-year hospitalization were 84.6 (95% CI, 84.4 to 84.8), 81.8 (95% CI, 81.5 to 82.1), and 80.2 (95% CI, 79.9 to 80.6)

We also calculated the number of veterans with increasing, stable, and decreasing CAN scores across each of our defined periods in both the 1-year mortality and hospitalization groups.

A previous study used a 1-year combined hospitalization or mortality event CAN score as the most all-inclusive measure of frailty but determined that it was possible that 1 of the other 5 CAN risk measures could perform better in predicting frailty.10 We collected and presented data for 1-year mortality and hospitalization CAN scores. There were declines in pandemic-related US hospitalizations for illnesses not related to COVID-19 during the first few months of the pandemic.18 This may or may not have affected the 1-year hospitalization CAN score data; thus, we used the 1-year mortality CAN score data to predict frailty.

Discussion

We studied frailty trends in an older veteran subpopulation enrolled at the PVAHCS 1 year prior and into the COVID-19 pandemic using CAN scores. Frailty is a dynamic state. Previous frailty assessments aimed to identify patients at the highest risk of death. With the advent of advanced therapeutics for several diseases, the number of medical conditions that are now managed as chronic illnesses continues to grow. There is a role for repeated measures of frailty to try to identify frailty trends.19 These trends may assist us in resource allocation, identifying interventions that work and those that do not.

Some studies have shown an overall declining lethality of frailty. This may reflect improvements in the care and management of chronic conditions, screening tests, and increased awareness of healthy lifestyles.20 Another study of frailty trajectories in a veteran population in the 5 years preceding death showed multiple trajectories (stable, gradually increasing, rapidly increasing, and recovering).19

The PACT is a primary care model implemented at VA medical centers in April 2010. It is a patient-centered medical home model (PCMH) with several components. The VA treats a population of socioeconomically vulnerable patients with complex chronic illness management needs. Some of the components of a PACT model relevant to our study include facilitated self-management support for veterans in between practitioner visits via care partners, peer-to-peer and transitional care programs, physical activity and diet programs, primary care mental health, integration between primary and specialty care, and telehealth.21 A previous study has shown that VA primary care clinics with the most PCMH components in place had greater improvements in several chronic disease quality measures than in clinics with a lower number of PCMH components.22

Limitations

Our study is limited by our older veteran population demographics. We chose only a subset of older veterans at a single VA center for this study and cannot extrapolate the results to all older frail veterans or community dwelling older adults. Robust individuals may also transition to prefrailty and frailty over longer periods; our study monitored frailty trends over 2 years.

CAN scores are not quality measures to improve upon. Allocation and utilization of additional resources may clinically benefit a patient but increase their CAN scores. Although our results are statistically significant, we are unable to make any conclusions about clinical significance.

Conclusions

Our study results indicate frailty as determined by 1-year mortality CAN scores significantly increased in a subset of older veterans during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic when compared with the previous year. Whether this change in frailty is temporary or long lasting remains to be seen. Automated CAN scores can be effectively utilized to monitor frailty trends in certain veteran populations over longer periods.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Phoenix Veterans Affairs Health Care System.

Frailty is an age-associated, nonspecific vulnerability to adverse health outcomes. Frailty can also be described as a complex of symptoms characterized by impaired stress tolerance due to a decline in the functionality of different organs.1 The prevalence of frailty varies widely depending on the method of measurement and the population studied.2-4 It is a nonconstant factor that increases with age. A deficit accumulation frailty index (FI) is one method used to measure frailty.5 This approach sees frailty as a multidimensional risk state measured by quantity rather than the nature of health concerns. A deficit accumulation FI does not require physical testing but correlates well with other phenotypic FIs.6 It is, however, time consuming, as ≥ 30 deficits need to be measured to offer greater stability to the frailty estimate.

Health care is seeing increasing utilization of big data analytics to derive predictive models and help with resource allocation. There are currently 2 existing automated tools to predict health care utilization and mortality at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA): the VA Frailty Index (VA-FI-10) and the Care Assessment Need (CAN). VA-FI-10 is an International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) update of the VA-FI that was created in March 2021. The VA-FI-10 is a claims-based frailty assessment tool using 31 health deficits. Calculating the VA-FI-10 requires defining an index date and lookback period (typically 3 years) relative to which it will be calculated.7

CAN is a set of risk-stratifying statistical models run on veterans receiving VA primary care services as part of a patient aligned care team (PACT) using electronic health record data.8 Each veteran is stratified based on the individual’s risks of hospitalization, death, and hospitalization or death. These 3 events are predicted for 90-day and 1-year time periods for a total of 6 distinct outcomes. CAN is currently on its third iteration (CAN 2.5) and scores range from 0 (low) to 99 (high). CAN scores are updated weekly. The 1-year hospitalization probabilities for all patients range from 0.8% to 93.1%. For patients with a CAN score of 50, the probability of being hospitalized within a year ranges from 4.5% to 5.2%, which increases to 32.2% to 36% for veterans with a CAN score of 95. The probability range widens significantly (32.2%-93.1%) for patients in the top 5 CAN scores (95-99).

CAN scores are a potential screening tool for frailty among older adults; they are generated automatically and provide acceptable diagnostic accuracy. Hence, the CAN score may be a useful tool for primary care practitioners for the detection of frailty in their patients. The CAN score has shown a moderate positive association with the FRAIL Scale.9,10 The population-based studies that have used the FI approach (differing FIs, depending on the data available) give robust results: People accumulate an average of 0.03 deficits per year after the age of 70 years.11 Interventions to delay or reverse frailty have not been clearly defined with heterogeneity in the definition of frailty and measurement of frailty outcomes.12,13 The prevalence of frailty in the veteran population is substantially higher than the prevalence in community populations with a similar age distribution. There is also mounting evidence that veterans accumulate deficits more rapidly than their civilian counterparts.14

COVID-19 was declared a pandemic in March 2020 and had many impacts on global health that were most marked in the first year. These included reductions in hospital visits for non-COVID-19 health concerns, a reduction in completed screening tests, an initial reduction in other infectious diseases (attributable to quarantines), and an increase or worsening of mental health concerns.15,16

We aimed to investigate whether frailty increased disproportionately in a subset of older veterans in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic when compared with the previous year using CAN scores. This single institution, longitudinal cohort study was determined to be exempt from institutional review board review but was approved by the Phoenix VA Health Care System (PVAHCS) Research and Development Committee.

Methods

The Office of Clinical Systems Development and Evaluation (CSDE–10E2A) produces a weekly CAN Score Report to help identify the highest-risk patients in a primary care panel or cohort. CAN scores range from 0 (lowest risk) to 99 (highest risk), indicating how likely a patient is to experience hospitalization or death compared with other VA patients. CAN scores are calculated with statistical prediction models that use data elements from the following Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) domains: demographics, health care utilization, laboratory tests, medical conditions, medications, and vital signs (eAppendix available online at 10.12788/fp.0385).

The CAN Score Report is generated weekly and stored on a CDW server. A patient will receive all 6 distinct CAN scores if they are: (1) assigned to a primary care PACT on the risk date; (2) a veteran; (3) not hospitalized in a VA facility on the risk date; and (4) alive as of the risk date. New to CAN 2.5 is that patients who meet criteria 1, 2, and 4 but are hospitalized in a VA facility on the risk date will receive CAN scores for the 1-year and 90-day mortality models.

Utilizing VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VA HSR RES 13-457, US Department of Veterans Affairs [2008]), we obtained 2 lists of veterans aged 70 to 75 years on February 8, 2019, with a calculated CAN score of ≥ 75 for 1-year mortality and 1-year hospitalization on that date. A veteran with a CAN score of ≥ 75 is likely to be prefrail or frail.9,10 Veterans who did not have a corresponding calculated CAN score on February 7, 2020, and February 12, 2021, were excluded. COVID-19 was declared a public health emergency in the United States on January 31, 2020, and the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11, 2020.17 We picked February 7, 2020, within this time frame and without any other special significance. We picked additional CAN score calculation dates approximately 1 year prior and 1 year after this date. Veterans had to be alive on February 12, 2021, (the last date of the CAN score) to be included in the cohorts.

Statistical Analyses

The difference in CAN score from one year to the next was calculated for each patient. The difference between 2019 and 2020 was compared with the difference between 2020 to 2021 using a paired t test. Yearly CAN score values were analyzed using repeated measures analysis of variance. The number of patients that showed an increase in CAN score (ie, increased risk of either mortality or hospitalization within the year) or a decrease (lower risk) was compared using the χ2 test. IBM SPSS v26 and GraphPad Prism v18 were used for statistical analysis. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

There were 3538 veterans at PVAHCS who met the inclusion criteria and had a 1-year mortality CAN score ≥ 75 on February 8, 2019.

In the hospitalization group, there were 6046 veterans in the analysis; 57 veterans missing a 1-year hospitalization CAN score that were excluded. The mean age was 71.7 (1.3) years and included 5874 male (97.2%) and 172 female (2.8%) veterans. There was a decline in mean 1-year hospitalization CAN scores in our subset of frail older veterans by 2.8 (95% CI, -3.1 to -2.6) in the year preceding the COVID-19 pandemic. This mean decline slowed significantly to 1.5 (95% CI, -1.8 to -1.2; P < .0001) after the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Mean CAN scores for 1-year hospitalization were 84.6 (95% CI, 84.4 to 84.8), 81.8 (95% CI, 81.5 to 82.1), and 80.2 (95% CI, 79.9 to 80.6)

We also calculated the number of veterans with increasing, stable, and decreasing CAN scores across each of our defined periods in both the 1-year mortality and hospitalization groups.

A previous study used a 1-year combined hospitalization or mortality event CAN score as the most all-inclusive measure of frailty but determined that it was possible that 1 of the other 5 CAN risk measures could perform better in predicting frailty.10 We collected and presented data for 1-year mortality and hospitalization CAN scores. There were declines in pandemic-related US hospitalizations for illnesses not related to COVID-19 during the first few months of the pandemic.18 This may or may not have affected the 1-year hospitalization CAN score data; thus, we used the 1-year mortality CAN score data to predict frailty.

Discussion

We studied frailty trends in an older veteran subpopulation enrolled at the PVAHCS 1 year prior and into the COVID-19 pandemic using CAN scores. Frailty is a dynamic state. Previous frailty assessments aimed to identify patients at the highest risk of death. With the advent of advanced therapeutics for several diseases, the number of medical conditions that are now managed as chronic illnesses continues to grow. There is a role for repeated measures of frailty to try to identify frailty trends.19 These trends may assist us in resource allocation, identifying interventions that work and those that do not.

Some studies have shown an overall declining lethality of frailty. This may reflect improvements in the care and management of chronic conditions, screening tests, and increased awareness of healthy lifestyles.20 Another study of frailty trajectories in a veteran population in the 5 years preceding death showed multiple trajectories (stable, gradually increasing, rapidly increasing, and recovering).19

The PACT is a primary care model implemented at VA medical centers in April 2010. It is a patient-centered medical home model (PCMH) with several components. The VA treats a population of socioeconomically vulnerable patients with complex chronic illness management needs. Some of the components of a PACT model relevant to our study include facilitated self-management support for veterans in between practitioner visits via care partners, peer-to-peer and transitional care programs, physical activity and diet programs, primary care mental health, integration between primary and specialty care, and telehealth.21 A previous study has shown that VA primary care clinics with the most PCMH components in place had greater improvements in several chronic disease quality measures than in clinics with a lower number of PCMH components.22

Limitations

Our study is limited by our older veteran population demographics. We chose only a subset of older veterans at a single VA center for this study and cannot extrapolate the results to all older frail veterans or community dwelling older adults. Robust individuals may also transition to prefrailty and frailty over longer periods; our study monitored frailty trends over 2 years.

CAN scores are not quality measures to improve upon. Allocation and utilization of additional resources may clinically benefit a patient but increase their CAN scores. Although our results are statistically significant, we are unable to make any conclusions about clinical significance.

Conclusions

Our study results indicate frailty as determined by 1-year mortality CAN scores significantly increased in a subset of older veterans during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic when compared with the previous year. Whether this change in frailty is temporary or long lasting remains to be seen. Automated CAN scores can be effectively utilized to monitor frailty trends in certain veteran populations over longer periods.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Phoenix Veterans Affairs Health Care System.

1. Rohrmann S. Epidemiology of frailty in older people. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1216:21-27. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-33330-0_3

2. Bandeen-Roche K, Seplaki CL, Huang J, et al. Frailty in older adults: a nationally representative profile in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(11):1427-1434. doi:10.1093/gerona/glv133

3. Siriwardhana DD, Hardoon S, Rait G, Weerasinghe MC, Walters KR. Prevalence of frailty and prefrailty among community-dwelling older adults in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e018195. Published 2018 Mar 1. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018195

4. Song X, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Prevalence and 10-year outcomes of frailty in older adults in relation to deficit accumulation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):681-687. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02764.x

5. Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(7):722-727. doi:10.1093/gerona/62.7.722

6. Buta BJ, Walston JD, Godino JG, et al. Frailty assessment instruments: Systematic characterization of the uses and contexts of highly-cited instruments. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;26:53-61. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2015.12.003

7. Cheng D, DuMontier C, Yildirim C, et al. Updating and validating the U.S. Veterans Affairs Frailty Index: transitioning From ICD-9 to ICD-10. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2021;76(7):1318-1325. doi:10.1093/gerona/glab071

8. Fihn SD, Francis J, Clancy C, et al. Insights from advanced analytics at the Veterans Health Administration. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(7):1203-1211. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0054

9. Ruiz JG, Priyadarshni S, Rahaman Z, et al. Validation of an automatically generated screening score for frailty: the care assessment need (CAN) score. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):106. doi:10.1186/s12877-018-0802-7

10. Ruiz JG, Rahaman Z, Dang S, Anam R, Valencia WM, Mintzer MJ. Association of the CAN score with the FRAIL scale in community dwelling older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018;30(10):1241-1245. doi:10.1007/s40520-018-0910-4

11. Ofori-Asenso R, Chin KL, Mazidi M, et al. Global incidence of frailty and prefrailty among community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e198398. Published 2019 Aug 2. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8398

12. Marcucci M, Damanti S, Germini F, et al. Interventions to prevent, delay or reverse frailty in older people: a journey towards clinical guidelines. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):193. Published 2019 Oct 29. doi:10.1186/s12916-019-1434-2

13. Travers J, Romero-Ortuno R, Bailey J, Cooney MT. Delaying and reversing frailty: a systematic review of primary care interventions. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(678):e61-e69. doi:10.3399/bjgp18X700241

14. Orkaby AR, Nussbaum L, Ho YL, et al. The burden of frailty among U.S. veterans and its association with mortality, 2002-2012. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74(8):1257-1264. doi:10.1093/gerona/gly232

15. Bakouny Z, Paciotti M, Schmidt AL, Lipsitz SR, Choueiri TK, Trinh QD. Cancer screening tests and cancer diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(3):458-460. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.7600

16. Steffen R, Lautenschlager S, Fehr J. Travel restrictions and lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic-impact on notified infectious diseases in Switzerland. J Travel Med. 2020;27(8):taaa180. doi:10.1093/jtm/taaa180

17. CDC Museum COVID-19 Timeline. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated March 15, 2023. Accessed May 12, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/covid19.html18. Nguyen JL, Benigno M, Malhotra D, et al. Pandemic-related declines in hospitalization for non-COVID-19-related illness in the United States from January through July 2020. PLoS One. 2022;17(1):e0262347. Published 2022 Jan 6. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0262347

19. Ward RE, Orkaby AR, Dumontier C, et al. Trajectories of frailty in the 5 years prior to death among U.S. veterans born 1927-1934. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2021;76(11):e347-e353. doi:10.1093/gerona/glab196

20. Bäckman K, Joas E, Falk H, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K, Skoog I. Changes in the lethality of frailty over 30 years: evidence from two cohorts of 70-year-olds in Gothenburg Sweden. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(7):945-950. doi:10.1093/gerona/glw160

21. Piette JD, Holtz B, Beard AJ, et al. Improving chronic illness care for veterans within the framework of the Patient-Centered Medical Home: experiences from the Ann Arbor Patient-Aligned Care Team Laboratory. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1(4):615-623. doi:10.1007/s13142-011-0065-8

22. Rosland AM, Nelson K, Sun H, et al. The patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(7):e263-e272. Published 2013 Jul 1.

1. Rohrmann S. Epidemiology of frailty in older people. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1216:21-27. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-33330-0_3

2. Bandeen-Roche K, Seplaki CL, Huang J, et al. Frailty in older adults: a nationally representative profile in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(11):1427-1434. doi:10.1093/gerona/glv133

3. Siriwardhana DD, Hardoon S, Rait G, Weerasinghe MC, Walters KR. Prevalence of frailty and prefrailty among community-dwelling older adults in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e018195. Published 2018 Mar 1. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018195

4. Song X, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Prevalence and 10-year outcomes of frailty in older adults in relation to deficit accumulation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):681-687. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02764.x

5. Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(7):722-727. doi:10.1093/gerona/62.7.722

6. Buta BJ, Walston JD, Godino JG, et al. Frailty assessment instruments: Systematic characterization of the uses and contexts of highly-cited instruments. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;26:53-61. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2015.12.003

7. Cheng D, DuMontier C, Yildirim C, et al. Updating and validating the U.S. Veterans Affairs Frailty Index: transitioning From ICD-9 to ICD-10. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2021;76(7):1318-1325. doi:10.1093/gerona/glab071

8. Fihn SD, Francis J, Clancy C, et al. Insights from advanced analytics at the Veterans Health Administration. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(7):1203-1211. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0054

9. Ruiz JG, Priyadarshni S, Rahaman Z, et al. Validation of an automatically generated screening score for frailty: the care assessment need (CAN) score. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):106. doi:10.1186/s12877-018-0802-7

10. Ruiz JG, Rahaman Z, Dang S, Anam R, Valencia WM, Mintzer MJ. Association of the CAN score with the FRAIL scale in community dwelling older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018;30(10):1241-1245. doi:10.1007/s40520-018-0910-4

11. Ofori-Asenso R, Chin KL, Mazidi M, et al. Global incidence of frailty and prefrailty among community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e198398. Published 2019 Aug 2. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8398

12. Marcucci M, Damanti S, Germini F, et al. Interventions to prevent, delay or reverse frailty in older people: a journey towards clinical guidelines. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):193. Published 2019 Oct 29. doi:10.1186/s12916-019-1434-2

13. Travers J, Romero-Ortuno R, Bailey J, Cooney MT. Delaying and reversing frailty: a systematic review of primary care interventions. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(678):e61-e69. doi:10.3399/bjgp18X700241

14. Orkaby AR, Nussbaum L, Ho YL, et al. The burden of frailty among U.S. veterans and its association with mortality, 2002-2012. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74(8):1257-1264. doi:10.1093/gerona/gly232

15. Bakouny Z, Paciotti M, Schmidt AL, Lipsitz SR, Choueiri TK, Trinh QD. Cancer screening tests and cancer diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(3):458-460. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.7600

16. Steffen R, Lautenschlager S, Fehr J. Travel restrictions and lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic-impact on notified infectious diseases in Switzerland. J Travel Med. 2020;27(8):taaa180. doi:10.1093/jtm/taaa180

17. CDC Museum COVID-19 Timeline. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated March 15, 2023. Accessed May 12, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/covid19.html18. Nguyen JL, Benigno M, Malhotra D, et al. Pandemic-related declines in hospitalization for non-COVID-19-related illness in the United States from January through July 2020. PLoS One. 2022;17(1):e0262347. Published 2022 Jan 6. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0262347

19. Ward RE, Orkaby AR, Dumontier C, et al. Trajectories of frailty in the 5 years prior to death among U.S. veterans born 1927-1934. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2021;76(11):e347-e353. doi:10.1093/gerona/glab196

20. Bäckman K, Joas E, Falk H, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K, Skoog I. Changes in the lethality of frailty over 30 years: evidence from two cohorts of 70-year-olds in Gothenburg Sweden. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(7):945-950. doi:10.1093/gerona/glw160

21. Piette JD, Holtz B, Beard AJ, et al. Improving chronic illness care for veterans within the framework of the Patient-Centered Medical Home: experiences from the Ann Arbor Patient-Aligned Care Team Laboratory. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1(4):615-623. doi:10.1007/s13142-011-0065-8

22. Rosland AM, Nelson K, Sun H, et al. The patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(7):e263-e272. Published 2013 Jul 1.

Impact of Pharmacist Interventions at an Outpatient US Coast Guard Clinic

The US Coast Guard (USCG) operates within the US Department of Homeland Security during times of peace and represents a force of > 55,000 active-duty service members (ADSMs), civilians, and reservists. ADSMs account for about 40,000 USCG personnel. The missions of the USCG include activities such as maritime law enforcement (drug interdiction), search and rescue, and defense readiness.1 Akin to other US Department of Defense (DoD) services, USCG ADSMs are required to maintain medical readiness to maximize operational success.

Whereas the DoD centralizes its health care services at military treatment facilities, USCG health care tends to be dispersed to smaller clinics and sickbays across large geographic areas. The USCG operates 42 clinics of varying sizes and medical capabilities, providing outpatient, dentistry, pharmacy, laboratory, radiology, physical therapy, optometry, and other health care services. Many ADSMs are evaluated by a USCG medical officer in these outpatient clinics, and ADSMs may choose to fill prescriptions at the in-house pharmacy if present at that clinic.

The USCG has 14 field pharmacists. In addition to the standard dispensing role at their respective clinics, USCG pharmacists provide regional oversight of pharmaceutical services for USCG units within their area of responsibility (AOR). Therefore, USCG pharmacists clinically, operationally, and logistically support these regional assets within their AOR while serving the traditional pharmacist role. USCG pharmacists have access to ADSM electronic health records (EHRs) when evaluating prescription orders, similar to other ambulatory care settings.

New recruits and accessions into the USCG are first screened for disqualifying health conditions, and ADSMs are required to maintain medical readiness throughout their careers.2 Therefore, this population tends to be younger and overall healthier compared with the general population. Equally important, medication errors or inappropriate prescribing in the ADSM group could negatively affect their duty status and mission readiness of the USCG in addition to exposing the ADSM to medication-related harms.

Duty status is an important and unique consideration in this population. ADSMs are expected to be deployable worldwide and physically and mentally capable of executing all duties associated with their position. Duty status implications and the perceived ability to stand watch are tied to an ADMS’s specialty, training, and unit role. Duty status is based on various frameworks like the USCG Medical Manual, Aeromedical Policy Letters, and other governing documents.3 Duty status determinations are initiated by privileged USCG medical practitioners and may be executed in consultation with relevant commands and other subject matter experts. An inappropriately dosed antibiotic prescription, for example, can extend the duration that an ADSM would be considered unfit for full duty due to prolonged illness. Accordingly, being on a limited duty status may negatively affect USCG total mission readiness as a whole. USCG pharmacists play a vital role in optimizing ADSMs’ medication therapies to ensure safety and efficacy.

Currently no published literature explores the number of medication interventions or the impact of those interventions made by USCG pharmacists. This study aimed to quantify the number, duty status impact, and replicability of medication interventions made by one pharmacist at the USCG Base Alameda clinic over 6 months.

Methods

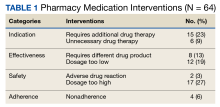

As part of a USCG quality improvement study, a pharmacist tracked all medication interventions on a spreadsheet at USCG Base Alameda clinic from July 1, 2021, to December 31, 2021. The study defined a medication intervention as a communication with the prescriber with the intention to change the medication, strength, dose, dosage form, quantity, or instructions. Each intervention was subcategorized as either a drug therapy problem (DTP) or a non-DTP intervention. Interventions were divided into 7 categories.

Each DTP intervention was evaluated in a retrospective chart review by a panel of USCG pharmacists to assess for duty status severity and replicability. For duty status severity, the panel reviewed the intervention after considering patient-specific factors and determined whether the original prescribing (had there not been an intervention) could have reasonably resulted in a change of duty status for the ADSM from a fit for full duty (FFFD) status to a different duty status (eg, fit for limited duty [FFLD]). This duty status review factored in potential impacts across multiple positions and billets, including aviators (pilots) and divers. In addition, the panel, whose members all have prior community pharmacy experience, assessed replicability by determining whether the same intervention could have reasonably been made in the absence of access to the patient EHR, as would be common in a community pharmacy setting.

Interventions without an identified DTP were considered non-DTP interventions. These interventions involved recommendations for a more cost-effective medication or a similar in stock therapeutic option to minimize delay of patient care. The spreadsheet also included the date, medication name, medication class, specific intervention made, outcome, and other descriptive comments.

Results

During the 6-month period, 1751 prescriptions were dispensed at USCG Base Alameda pharmacy with 116 interventions (7%).

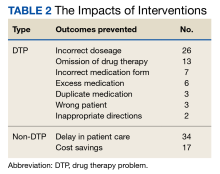

Among the DTP interventions, 26 (41%) dealt with an inappropriate dose, 13 (20%) were for medication omission, 7 (11%) for inappropriate dosage form, and 6 (9%) for excess medication (Table 2).

Discussion

This study is novel in examining the impact of a pharmacist’s medication interventions in a USCG ambulatory care practice setting. A PubMed literature search of the phrases “Coast Guard AND pharmacy” or “Coast Guard AND pharmacy AND intervention” yielded no results specific to pharmacy interventions in a USCG setting. However, the 2021 implementation of the enterprise-wide MHS GENESIS EHR may support additional tracking and analysis tools in the future.

Pharmacist interventions have been studied in diverse patient populations and practice settings, and most conclude that pharmacists make meaningful interventions at their respective organizations.4-7 Many of these studies were conducted at open-door health care systems, whereas USCG clinics serve ADSMs nearly exclusively. The ADSM population tends to be younger and healthier due to age requirements and medical accession and retention standards.

It is important to recognize the value of a USCG pharmacist in identifying and rectifying potential medication errors, particularly those that may affect the ability to stand duty for ADSMs. An example intervention includes changing the daily starting dose of citalopram from the ordered 30 mg to the intended 10 mg. Inappropriately prescribed medication regimens may increase the incidence of adverse effects or prolong duration to therapeutic efficacy, which impairs the ability to stand duty. There were 3 circumstances where the prescriber had ordered the medication for an incorrect ADSM that were rectified by the pharmacist. If left unchanged, these errors could negatively affect the ADSM’s overall health, well-being, and duty status.

The acceptance rate for interventions in this study was 96%. The literature suggests a highly variable acceptance rate of pharmacist interventions when examined across various practice settings, health systems, and geographic locations.8-10 This study’s comparatively high rate could be due to the pharmacist-prescriber relationships at USCG clinics. By virtue of colocatation and teamwork initiatives, the pharmacist has the opportunity to develop positive rapport with physicians, physician assistants, and other clinic staff.

Having access to EHRs allowed the pharmacist to make 18 of the DTP interventions. Chart access is not unique to the USCG and is common in other ambulatory care settings. Those 18 interventions, such as reconciling a prescription ordered as fluticasone/salmeterol but recorded in the EHR as “will prescribe montelukast,” were deemed possible because of EHR access. Such interventions could potentially be lost if ADSMs solely received their pharmaceutical care elsewhere.

USCG uses independent duty health services technicians (IDHSs) who practice in settings where a medical officer is not present, such as at smaller sickbays or aboard Coast Guard cutters. In this study, an IDHS had mistakenly created a medication order for the medical officer to sign for bupropion SR, when the ADSM had been taking and was intended to continue taking bupropion XL. This order was signed off by the medical officer, but this oversight was identified and corrected by the pharmacist before dispensing. This indicates that there is a vital educational role that the USCG pharmacist fulfills when working with health care team members within the AOR.

Equally important to consider are the non-DTP interventions. In a military setting, minimizations of delay in care are a high priority. There were 34 instances where the pharmacist made an intervention to recommend a similar therapeutic medication that was in stock to ensure that the ADSM had timely access to the medication without the need for prior authorization. In the context of short-notice, mission-critical deployments that may last for multiple months, recognizing medication shortages or other inventory constraints and recommending therapeutic alternatives ensures that the USCG can maintain a ready posture for missions in addition to providing timely and quality patient care.

Saving about $1700 over 6 months is also important. While this was not explicitly evaluated in the study, prescribers may not be acutely aware of medication pricing. There are often significant price differences between different formulations of the same medication (eg, naproxen delayed-release vs tablets). Because USCG pharmacists are responsible for ordering medications and managing their regional budget within the AOR, they are best poised to make cost-savings recommendations. These interventions suggest that USCG pharmacists must continue to remain actively involved in the patient care team alongside physicians, physician assistants, nurses, and corpsmen. Throughout this setting and in so many others, patients’ health outcomes improve when pharmacists are more engaged in the pharmacotherapy care plan.

Limitations

Currently, the USCG does not publish ADSM demographic or health-related data, making it difficult to evaluate these interventions in the context of age, gender, or type of disease. Accordingly, potential directions for future research include how USCG pharmacists’ interventions are stratified by duty station and initial diagnosis. Such studies may support future models where USCG pharmacists are providing targeted education to prescribers based on disease or medication classes.

This analysis may have limited applicability to other practice settings even within USCG. Most USCG clinics have a limited number of medical officers; indeed, many have only one, and clinics with pharmacies typically have 1 to 5 medical officers aboard. USCG medical officers have a multitude of other duties, which may impact prescribing patterns and pharmacist interventions. Statistical analyses were limited by the dearth of baseline data or comparative literature. Finally, the assessment of DTP interventions’ impact did not use an official measurement tool like the US Department of Veterans Affairs’ Safety Assessment Code matrix.11 Instead, the study used the internal USCG pharmacist panel for the fitness for duty consideration as the main stratification of the DTP interventions’ duty status severity, because maintaining medical readiness is the top priority for a USCG clinic.

Conclusions

The multifaceted role of pharmacists in USCG clinics includes collaborating with the patient care team to make pharmacy interventions that have significant impacts on ADSMs’ wellness and the USCG mission. The ADSMs of this nation deserve quality medical care that translates into mission readiness, and the USCG pharmacy force stands ready to support that goal.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of CDR Christopher Janik, US Coast Guard Headquarters, and LCDR Darin Schneider, US Coast Guard D11 Regional Practice Manager, in the drafting of the manuscript.

1. US Coast Guard. Missions. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.uscg.mil/About/Missions

2. US Coast Guard. Coast Guard Medical Manual. Updated September 13, 2022. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://media.defense.gov/2022/Sep/14/2003076969/-1/-1/0/CIM_6000_1F.PDF

3. US Coast Guard. USCG Aeromedical Policy Letters. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.dcms.uscg.mil/Portals/10/CG-1/cg112/cg1121/docs/pdf/USCG_Aeromedical_Policy_Letters.pdf

4. Bedouch P, Sylvoz N, Charpiat B, et al. Trends in pharmacists’ medication order review in French hospitals from 2006 to 2009: analysis of pharmacists’ interventions from the Act-IP website observatory. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2015;40(1):32-40. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12214

5. Ooi PL, Zainal H, Lean QY, Ming LC, Ibrahim B. Pharmacists’ interventions on electronic prescriptions from various specialty wards in a Malaysian public hospital: a cross-sectional study. Pharmacy (Basel). 2021;9(4):161. Published 2021 Oct 1. doi:10.3390/pharmacy9040161

6. Alomi YA, El-Bahnasawi M, Kamran M, Shaweesh T, Alhaj S, Radwan RA. The clinical outcomes of pharmacist interventions at critical care services of private hospital in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia. PTB Report. 2019;5(1):16-19. doi:10.5530/ptb.2019.5.4

7. Garin N, Sole N, Lucas B, et al. Drug related problems in clinical practice: a cross-sectional study on their prevalence, risk factors and associated pharmaceutical interventions. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):883. Published 2021 Jan 13. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-80560-2

8. Zaal RJ, den Haak EW, Andrinopoulou ER, van Gelder T, Vulto AG, van den Bemt PMLA. Physicians’ acceptance of pharmacists’ interventions in daily hospital practice. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020;42(1):141-149. doi:10.1007/s11096-020-00970-0

9. Carson GL, Crosby K, Huxall GR, Brahm NC. Acceptance rates for pharmacist-initiated interventions in long-term care facilities. Inov Pharm. 2013;4(4):Article 135.

10. Bondesson A, Holmdahl L, Midlöv P, Höglund P, Andersson E, Eriksson T. Acceptance and importance of clinical pharmacists’ LIMM-based recommendations. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012;34(2):272-276. doi:10.1007/s11096-012-9609-3

11. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Safety assessment code (SAC) matrix. Updated June 3, 2015. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.patientsafety.va.gov/professionals/publications/matrix.asp

The US Coast Guard (USCG) operates within the US Department of Homeland Security during times of peace and represents a force of > 55,000 active-duty service members (ADSMs), civilians, and reservists. ADSMs account for about 40,000 USCG personnel. The missions of the USCG include activities such as maritime law enforcement (drug interdiction), search and rescue, and defense readiness.1 Akin to other US Department of Defense (DoD) services, USCG ADSMs are required to maintain medical readiness to maximize operational success.

Whereas the DoD centralizes its health care services at military treatment facilities, USCG health care tends to be dispersed to smaller clinics and sickbays across large geographic areas. The USCG operates 42 clinics of varying sizes and medical capabilities, providing outpatient, dentistry, pharmacy, laboratory, radiology, physical therapy, optometry, and other health care services. Many ADSMs are evaluated by a USCG medical officer in these outpatient clinics, and ADSMs may choose to fill prescriptions at the in-house pharmacy if present at that clinic.

The USCG has 14 field pharmacists. In addition to the standard dispensing role at their respective clinics, USCG pharmacists provide regional oversight of pharmaceutical services for USCG units within their area of responsibility (AOR). Therefore, USCG pharmacists clinically, operationally, and logistically support these regional assets within their AOR while serving the traditional pharmacist role. USCG pharmacists have access to ADSM electronic health records (EHRs) when evaluating prescription orders, similar to other ambulatory care settings.

New recruits and accessions into the USCG are first screened for disqualifying health conditions, and ADSMs are required to maintain medical readiness throughout their careers.2 Therefore, this population tends to be younger and overall healthier compared with the general population. Equally important, medication errors or inappropriate prescribing in the ADSM group could negatively affect their duty status and mission readiness of the USCG in addition to exposing the ADSM to medication-related harms.

Duty status is an important and unique consideration in this population. ADSMs are expected to be deployable worldwide and physically and mentally capable of executing all duties associated with their position. Duty status implications and the perceived ability to stand watch are tied to an ADMS’s specialty, training, and unit role. Duty status is based on various frameworks like the USCG Medical Manual, Aeromedical Policy Letters, and other governing documents.3 Duty status determinations are initiated by privileged USCG medical practitioners and may be executed in consultation with relevant commands and other subject matter experts. An inappropriately dosed antibiotic prescription, for example, can extend the duration that an ADSM would be considered unfit for full duty due to prolonged illness. Accordingly, being on a limited duty status may negatively affect USCG total mission readiness as a whole. USCG pharmacists play a vital role in optimizing ADSMs’ medication therapies to ensure safety and efficacy.

Currently no published literature explores the number of medication interventions or the impact of those interventions made by USCG pharmacists. This study aimed to quantify the number, duty status impact, and replicability of medication interventions made by one pharmacist at the USCG Base Alameda clinic over 6 months.

Methods

As part of a USCG quality improvement study, a pharmacist tracked all medication interventions on a spreadsheet at USCG Base Alameda clinic from July 1, 2021, to December 31, 2021. The study defined a medication intervention as a communication with the prescriber with the intention to change the medication, strength, dose, dosage form, quantity, or instructions. Each intervention was subcategorized as either a drug therapy problem (DTP) or a non-DTP intervention. Interventions were divided into 7 categories.

Each DTP intervention was evaluated in a retrospective chart review by a panel of USCG pharmacists to assess for duty status severity and replicability. For duty status severity, the panel reviewed the intervention after considering patient-specific factors and determined whether the original prescribing (had there not been an intervention) could have reasonably resulted in a change of duty status for the ADSM from a fit for full duty (FFFD) status to a different duty status (eg, fit for limited duty [FFLD]). This duty status review factored in potential impacts across multiple positions and billets, including aviators (pilots) and divers. In addition, the panel, whose members all have prior community pharmacy experience, assessed replicability by determining whether the same intervention could have reasonably been made in the absence of access to the patient EHR, as would be common in a community pharmacy setting.

Interventions without an identified DTP were considered non-DTP interventions. These interventions involved recommendations for a more cost-effective medication or a similar in stock therapeutic option to minimize delay of patient care. The spreadsheet also included the date, medication name, medication class, specific intervention made, outcome, and other descriptive comments.

Results

During the 6-month period, 1751 prescriptions were dispensed at USCG Base Alameda pharmacy with 116 interventions (7%).

Among the DTP interventions, 26 (41%) dealt with an inappropriate dose, 13 (20%) were for medication omission, 7 (11%) for inappropriate dosage form, and 6 (9%) for excess medication (Table 2).

Discussion

This study is novel in examining the impact of a pharmacist’s medication interventions in a USCG ambulatory care practice setting. A PubMed literature search of the phrases “Coast Guard AND pharmacy” or “Coast Guard AND pharmacy AND intervention” yielded no results specific to pharmacy interventions in a USCG setting. However, the 2021 implementation of the enterprise-wide MHS GENESIS EHR may support additional tracking and analysis tools in the future.

Pharmacist interventions have been studied in diverse patient populations and practice settings, and most conclude that pharmacists make meaningful interventions at their respective organizations.4-7 Many of these studies were conducted at open-door health care systems, whereas USCG clinics serve ADSMs nearly exclusively. The ADSM population tends to be younger and healthier due to age requirements and medical accession and retention standards.

It is important to recognize the value of a USCG pharmacist in identifying and rectifying potential medication errors, particularly those that may affect the ability to stand duty for ADSMs. An example intervention includes changing the daily starting dose of citalopram from the ordered 30 mg to the intended 10 mg. Inappropriately prescribed medication regimens may increase the incidence of adverse effects or prolong duration to therapeutic efficacy, which impairs the ability to stand duty. There were 3 circumstances where the prescriber had ordered the medication for an incorrect ADSM that were rectified by the pharmacist. If left unchanged, these errors could negatively affect the ADSM’s overall health, well-being, and duty status.

The acceptance rate for interventions in this study was 96%. The literature suggests a highly variable acceptance rate of pharmacist interventions when examined across various practice settings, health systems, and geographic locations.8-10 This study’s comparatively high rate could be due to the pharmacist-prescriber relationships at USCG clinics. By virtue of colocatation and teamwork initiatives, the pharmacist has the opportunity to develop positive rapport with physicians, physician assistants, and other clinic staff.

Having access to EHRs allowed the pharmacist to make 18 of the DTP interventions. Chart access is not unique to the USCG and is common in other ambulatory care settings. Those 18 interventions, such as reconciling a prescription ordered as fluticasone/salmeterol but recorded in the EHR as “will prescribe montelukast,” were deemed possible because of EHR access. Such interventions could potentially be lost if ADSMs solely received their pharmaceutical care elsewhere.

USCG uses independent duty health services technicians (IDHSs) who practice in settings where a medical officer is not present, such as at smaller sickbays or aboard Coast Guard cutters. In this study, an IDHS had mistakenly created a medication order for the medical officer to sign for bupropion SR, when the ADSM had been taking and was intended to continue taking bupropion XL. This order was signed off by the medical officer, but this oversight was identified and corrected by the pharmacist before dispensing. This indicates that there is a vital educational role that the USCG pharmacist fulfills when working with health care team members within the AOR.

Equally important to consider are the non-DTP interventions. In a military setting, minimizations of delay in care are a high priority. There were 34 instances where the pharmacist made an intervention to recommend a similar therapeutic medication that was in stock to ensure that the ADSM had timely access to the medication without the need for prior authorization. In the context of short-notice, mission-critical deployments that may last for multiple months, recognizing medication shortages or other inventory constraints and recommending therapeutic alternatives ensures that the USCG can maintain a ready posture for missions in addition to providing timely and quality patient care.

Saving about $1700 over 6 months is also important. While this was not explicitly evaluated in the study, prescribers may not be acutely aware of medication pricing. There are often significant price differences between different formulations of the same medication (eg, naproxen delayed-release vs tablets). Because USCG pharmacists are responsible for ordering medications and managing their regional budget within the AOR, they are best poised to make cost-savings recommendations. These interventions suggest that USCG pharmacists must continue to remain actively involved in the patient care team alongside physicians, physician assistants, nurses, and corpsmen. Throughout this setting and in so many others, patients’ health outcomes improve when pharmacists are more engaged in the pharmacotherapy care plan.

Limitations

Currently, the USCG does not publish ADSM demographic or health-related data, making it difficult to evaluate these interventions in the context of age, gender, or type of disease. Accordingly, potential directions for future research include how USCG pharmacists’ interventions are stratified by duty station and initial diagnosis. Such studies may support future models where USCG pharmacists are providing targeted education to prescribers based on disease or medication classes.

This analysis may have limited applicability to other practice settings even within USCG. Most USCG clinics have a limited number of medical officers; indeed, many have only one, and clinics with pharmacies typically have 1 to 5 medical officers aboard. USCG medical officers have a multitude of other duties, which may impact prescribing patterns and pharmacist interventions. Statistical analyses were limited by the dearth of baseline data or comparative literature. Finally, the assessment of DTP interventions’ impact did not use an official measurement tool like the US Department of Veterans Affairs’ Safety Assessment Code matrix.11 Instead, the study used the internal USCG pharmacist panel for the fitness for duty consideration as the main stratification of the DTP interventions’ duty status severity, because maintaining medical readiness is the top priority for a USCG clinic.

Conclusions

The multifaceted role of pharmacists in USCG clinics includes collaborating with the patient care team to make pharmacy interventions that have significant impacts on ADSMs’ wellness and the USCG mission. The ADSMs of this nation deserve quality medical care that translates into mission readiness, and the USCG pharmacy force stands ready to support that goal.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of CDR Christopher Janik, US Coast Guard Headquarters, and LCDR Darin Schneider, US Coast Guard D11 Regional Practice Manager, in the drafting of the manuscript.

The US Coast Guard (USCG) operates within the US Department of Homeland Security during times of peace and represents a force of > 55,000 active-duty service members (ADSMs), civilians, and reservists. ADSMs account for about 40,000 USCG personnel. The missions of the USCG include activities such as maritime law enforcement (drug interdiction), search and rescue, and defense readiness.1 Akin to other US Department of Defense (DoD) services, USCG ADSMs are required to maintain medical readiness to maximize operational success.

Whereas the DoD centralizes its health care services at military treatment facilities, USCG health care tends to be dispersed to smaller clinics and sickbays across large geographic areas. The USCG operates 42 clinics of varying sizes and medical capabilities, providing outpatient, dentistry, pharmacy, laboratory, radiology, physical therapy, optometry, and other health care services. Many ADSMs are evaluated by a USCG medical officer in these outpatient clinics, and ADSMs may choose to fill prescriptions at the in-house pharmacy if present at that clinic.

The USCG has 14 field pharmacists. In addition to the standard dispensing role at their respective clinics, USCG pharmacists provide regional oversight of pharmaceutical services for USCG units within their area of responsibility (AOR). Therefore, USCG pharmacists clinically, operationally, and logistically support these regional assets within their AOR while serving the traditional pharmacist role. USCG pharmacists have access to ADSM electronic health records (EHRs) when evaluating prescription orders, similar to other ambulatory care settings.