User login

Duration of Adalimumab Therapy in Hidradenitis Suppurativa With and Without Oral Immunosuppressants

To the Editor:

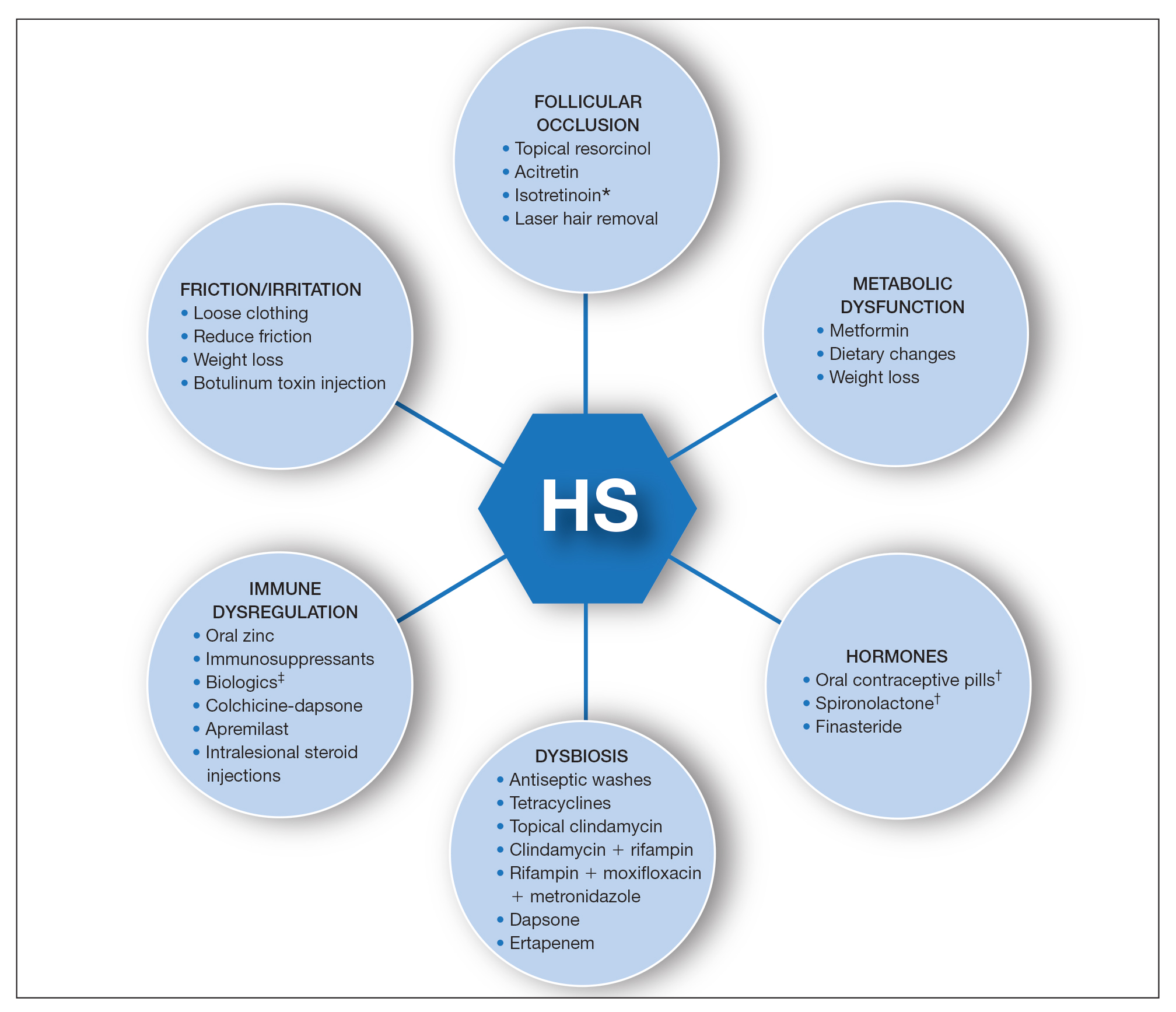

The tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor adalimumab is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). Although 50.6% of patients fulfilled Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response criteria with adalimumab at 12 weeks, many responders were not satisfied with their disease control, and secondary loss of Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response fulfillment occurred in 15.9% of patients within approximately 3 years.1 Without other US Food and Drug Administration–approved HS treatments, some dermatologists have combined adalimumab with methotrexate (MTX) and/or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) to attempt to increase the duration of satisfactory disease control while on adalimumab. Combining tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors with oral immunosuppressants is a well-established approach in psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease; however, to the best of our knowledge, this approach has not been studied for HS.2,3

To assess whether there is a role for combining adalimumab with MTX and/or MMF in the treatment of HS, we performed a single-institution retrospective chart review at the University of Connecticut Department of Dermatology to determine whether patients receiving combination therapy stayed on adalimumab longer than those who received adalimumab monotherapy. All patients receiving adalimumab for the treatment of HS with at least 1 follow-up visit 3 or more months after treatment initiation were included. Duration of treatment with adalimumab was defined as the length of time between initiation and termination of adalimumab, regardless of flares, adverse events, or addition of adjuvant therapy that occurred during this time span. Because standardized rating scales measuring the severity of HS at this time are not recorded routinely at our institution, treatment duration with adalimumab was used as a surrogate for measuring therapeutic success. Additionally, treatment duration is a meaningful end point, as patients with HS may require indefinite treatment. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were receiving adalimumab for the treatment of HS. Patients were excluded if they were lost to follow-up or had received adalimumab for less than 6 months, as data suggest that biologics do not reach peak effect for up to 6 months in HS.4

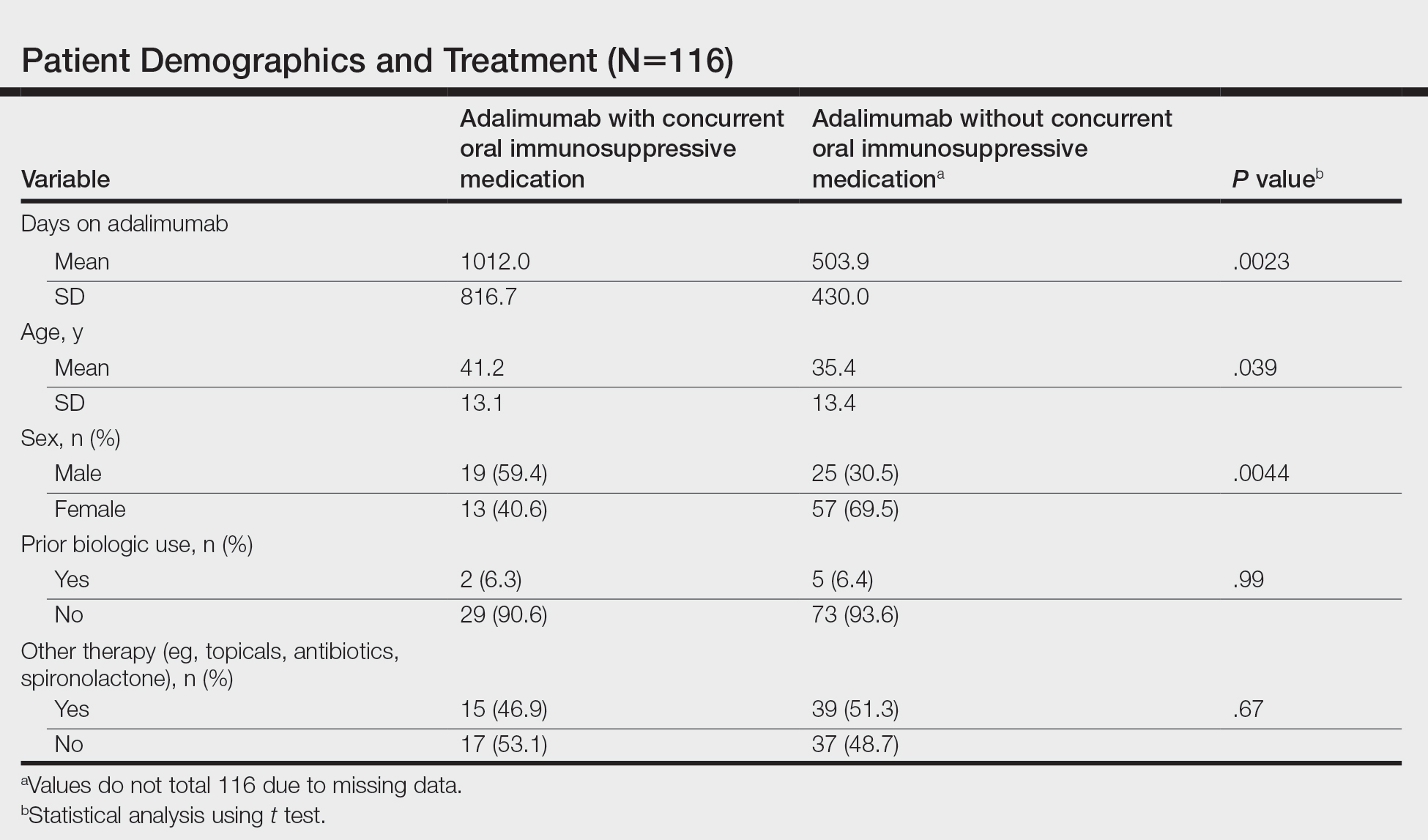

We identified 116 eligible patients with HS, 32 of whom received combination therapy. Five patients received 40 mg of adalimumab every other week, and 111 patients received 40 mg of adalimumab each week. Patients receiving oral immunosuppressants were more likely to be male and as likely to be biologic naïve compared to patients on monotherapy (Table). The average weekly dose of MTX was 14.63 mg, and the average daily dose of MMF was 1000 mg. The average number of days between starting adalimumab and starting an oral immunosuppressant was 114.5 (SD, 217; median, 0) days. Reasons for discontinuation of adalimumab included insufficient response, noncompliance, dislike of injections, adverse events, fear of adverse events, other medical issues unrelated to HS, and insurance coverage issues. Patients who ended treatment with adalimumab owing to insurance coverage issues were still included in our study because insurance coverage remains a major determinant of treatment choice in HS and is relevant to the dynamics of medical decision-making.

Statistical analysis was conducted on all patients inclusive of any reason for discontinuation to avoid bias in the calculation of treatment duration. Cox regression analysis was conducted for all independent variables and was noncontributory. Kaplan-Meier methodology was used to assess the duration of treatment of adalimumab with and without concomitant oral immunosuppressants, and quartile survival times were calculated. Quartile survival time is the time point after adalimumab initiation at which 25% of patients have discontinued adalimumab. We chose quartile survival time instead of average treatment duration to adequately power this study, given our small patient pool.

Although patients receiving adalimumab with oral immunosuppressants had a longer quartile treatment duration (450 days; 95% CI, 185-1800) than the group without oral immunosuppressants (360 days; 95% CI, 200-700), neither MTX nor MMF was shown to significantly prolong duration of therapy with adalimumab (log-rank test: P=.12). Additionally, patients receiving combination therapy were just as likely to discontinue adalimumab as those on monotherapy (χ2 test: P=.93). Patients who took both MTX and MMF at different times did show a statistically significant increase in adalimumab quartile treatment duration (1710 days; 95% CI, 1620 [upper limit not calculable]), but this is likely because these patients were kept on adalimumab while trialing adjunctive medications.

The results of our study indicate that MTX and MMF do not prolong duration of adalimumab therapy, which suggests that adalimumab combination therapy with MTX and MMF may not improve HS more than adalimumab alone, and/or partial responders to adalimumab monotherapy are unlikely to be converted to satisfactory responders with the addition of oral immunosuppressants. Limitations of our study include that it was retrospective, used treatment duration as a surrogate for objective efficacy measures, and relied on a single-institution data source. Additionally, owing to our small sample size, we were unable to account for certain potential confounders, including patient weight and insurance status. Future controlled prospective studies using objective end points are needed to further elucidate whether oral immunosuppressants have a role as an adjunct in the treatment of HS.

- Zouboulis CC, Okun MM, Prens EP, et al. Long-term adalimumab efficacy in patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: 3-year results of a phase 3 open-label extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:60-69.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.040

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057

- Sultan KS, Berkowitz JC, Khan S. Combination therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2017;8:103-113. doi:10.4292/wjgpt.v8.i2.103

- Prussick L, Rothstein B, Joshipura D, et al. Open-label, investigator-initiated, single-site exploratory trial evaluating secukinumab, an anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, for patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:609-611.

To the Editor:

The tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor adalimumab is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). Although 50.6% of patients fulfilled Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response criteria with adalimumab at 12 weeks, many responders were not satisfied with their disease control, and secondary loss of Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response fulfillment occurred in 15.9% of patients within approximately 3 years.1 Without other US Food and Drug Administration–approved HS treatments, some dermatologists have combined adalimumab with methotrexate (MTX) and/or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) to attempt to increase the duration of satisfactory disease control while on adalimumab. Combining tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors with oral immunosuppressants is a well-established approach in psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease; however, to the best of our knowledge, this approach has not been studied for HS.2,3

To assess whether there is a role for combining adalimumab with MTX and/or MMF in the treatment of HS, we performed a single-institution retrospective chart review at the University of Connecticut Department of Dermatology to determine whether patients receiving combination therapy stayed on adalimumab longer than those who received adalimumab monotherapy. All patients receiving adalimumab for the treatment of HS with at least 1 follow-up visit 3 or more months after treatment initiation were included. Duration of treatment with adalimumab was defined as the length of time between initiation and termination of adalimumab, regardless of flares, adverse events, or addition of adjuvant therapy that occurred during this time span. Because standardized rating scales measuring the severity of HS at this time are not recorded routinely at our institution, treatment duration with adalimumab was used as a surrogate for measuring therapeutic success. Additionally, treatment duration is a meaningful end point, as patients with HS may require indefinite treatment. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were receiving adalimumab for the treatment of HS. Patients were excluded if they were lost to follow-up or had received adalimumab for less than 6 months, as data suggest that biologics do not reach peak effect for up to 6 months in HS.4

We identified 116 eligible patients with HS, 32 of whom received combination therapy. Five patients received 40 mg of adalimumab every other week, and 111 patients received 40 mg of adalimumab each week. Patients receiving oral immunosuppressants were more likely to be male and as likely to be biologic naïve compared to patients on monotherapy (Table). The average weekly dose of MTX was 14.63 mg, and the average daily dose of MMF was 1000 mg. The average number of days between starting adalimumab and starting an oral immunosuppressant was 114.5 (SD, 217; median, 0) days. Reasons for discontinuation of adalimumab included insufficient response, noncompliance, dislike of injections, adverse events, fear of adverse events, other medical issues unrelated to HS, and insurance coverage issues. Patients who ended treatment with adalimumab owing to insurance coverage issues were still included in our study because insurance coverage remains a major determinant of treatment choice in HS and is relevant to the dynamics of medical decision-making.

Statistical analysis was conducted on all patients inclusive of any reason for discontinuation to avoid bias in the calculation of treatment duration. Cox regression analysis was conducted for all independent variables and was noncontributory. Kaplan-Meier methodology was used to assess the duration of treatment of adalimumab with and without concomitant oral immunosuppressants, and quartile survival times were calculated. Quartile survival time is the time point after adalimumab initiation at which 25% of patients have discontinued adalimumab. We chose quartile survival time instead of average treatment duration to adequately power this study, given our small patient pool.

Although patients receiving adalimumab with oral immunosuppressants had a longer quartile treatment duration (450 days; 95% CI, 185-1800) than the group without oral immunosuppressants (360 days; 95% CI, 200-700), neither MTX nor MMF was shown to significantly prolong duration of therapy with adalimumab (log-rank test: P=.12). Additionally, patients receiving combination therapy were just as likely to discontinue adalimumab as those on monotherapy (χ2 test: P=.93). Patients who took both MTX and MMF at different times did show a statistically significant increase in adalimumab quartile treatment duration (1710 days; 95% CI, 1620 [upper limit not calculable]), but this is likely because these patients were kept on adalimumab while trialing adjunctive medications.

The results of our study indicate that MTX and MMF do not prolong duration of adalimumab therapy, which suggests that adalimumab combination therapy with MTX and MMF may not improve HS more than adalimumab alone, and/or partial responders to adalimumab monotherapy are unlikely to be converted to satisfactory responders with the addition of oral immunosuppressants. Limitations of our study include that it was retrospective, used treatment duration as a surrogate for objective efficacy measures, and relied on a single-institution data source. Additionally, owing to our small sample size, we were unable to account for certain potential confounders, including patient weight and insurance status. Future controlled prospective studies using objective end points are needed to further elucidate whether oral immunosuppressants have a role as an adjunct in the treatment of HS.

To the Editor:

The tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor adalimumab is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). Although 50.6% of patients fulfilled Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response criteria with adalimumab at 12 weeks, many responders were not satisfied with their disease control, and secondary loss of Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response fulfillment occurred in 15.9% of patients within approximately 3 years.1 Without other US Food and Drug Administration–approved HS treatments, some dermatologists have combined adalimumab with methotrexate (MTX) and/or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) to attempt to increase the duration of satisfactory disease control while on adalimumab. Combining tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors with oral immunosuppressants is a well-established approach in psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease; however, to the best of our knowledge, this approach has not been studied for HS.2,3

To assess whether there is a role for combining adalimumab with MTX and/or MMF in the treatment of HS, we performed a single-institution retrospective chart review at the University of Connecticut Department of Dermatology to determine whether patients receiving combination therapy stayed on adalimumab longer than those who received adalimumab monotherapy. All patients receiving adalimumab for the treatment of HS with at least 1 follow-up visit 3 or more months after treatment initiation were included. Duration of treatment with adalimumab was defined as the length of time between initiation and termination of adalimumab, regardless of flares, adverse events, or addition of adjuvant therapy that occurred during this time span. Because standardized rating scales measuring the severity of HS at this time are not recorded routinely at our institution, treatment duration with adalimumab was used as a surrogate for measuring therapeutic success. Additionally, treatment duration is a meaningful end point, as patients with HS may require indefinite treatment. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were receiving adalimumab for the treatment of HS. Patients were excluded if they were lost to follow-up or had received adalimumab for less than 6 months, as data suggest that biologics do not reach peak effect for up to 6 months in HS.4

We identified 116 eligible patients with HS, 32 of whom received combination therapy. Five patients received 40 mg of adalimumab every other week, and 111 patients received 40 mg of adalimumab each week. Patients receiving oral immunosuppressants were more likely to be male and as likely to be biologic naïve compared to patients on monotherapy (Table). The average weekly dose of MTX was 14.63 mg, and the average daily dose of MMF was 1000 mg. The average number of days between starting adalimumab and starting an oral immunosuppressant was 114.5 (SD, 217; median, 0) days. Reasons for discontinuation of adalimumab included insufficient response, noncompliance, dislike of injections, adverse events, fear of adverse events, other medical issues unrelated to HS, and insurance coverage issues. Patients who ended treatment with adalimumab owing to insurance coverage issues were still included in our study because insurance coverage remains a major determinant of treatment choice in HS and is relevant to the dynamics of medical decision-making.

Statistical analysis was conducted on all patients inclusive of any reason for discontinuation to avoid bias in the calculation of treatment duration. Cox regression analysis was conducted for all independent variables and was noncontributory. Kaplan-Meier methodology was used to assess the duration of treatment of adalimumab with and without concomitant oral immunosuppressants, and quartile survival times were calculated. Quartile survival time is the time point after adalimumab initiation at which 25% of patients have discontinued adalimumab. We chose quartile survival time instead of average treatment duration to adequately power this study, given our small patient pool.

Although patients receiving adalimumab with oral immunosuppressants had a longer quartile treatment duration (450 days; 95% CI, 185-1800) than the group without oral immunosuppressants (360 days; 95% CI, 200-700), neither MTX nor MMF was shown to significantly prolong duration of therapy with adalimumab (log-rank test: P=.12). Additionally, patients receiving combination therapy were just as likely to discontinue adalimumab as those on monotherapy (χ2 test: P=.93). Patients who took both MTX and MMF at different times did show a statistically significant increase in adalimumab quartile treatment duration (1710 days; 95% CI, 1620 [upper limit not calculable]), but this is likely because these patients were kept on adalimumab while trialing adjunctive medications.

The results of our study indicate that MTX and MMF do not prolong duration of adalimumab therapy, which suggests that adalimumab combination therapy with MTX and MMF may not improve HS more than adalimumab alone, and/or partial responders to adalimumab monotherapy are unlikely to be converted to satisfactory responders with the addition of oral immunosuppressants. Limitations of our study include that it was retrospective, used treatment duration as a surrogate for objective efficacy measures, and relied on a single-institution data source. Additionally, owing to our small sample size, we were unable to account for certain potential confounders, including patient weight and insurance status. Future controlled prospective studies using objective end points are needed to further elucidate whether oral immunosuppressants have a role as an adjunct in the treatment of HS.

- Zouboulis CC, Okun MM, Prens EP, et al. Long-term adalimumab efficacy in patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: 3-year results of a phase 3 open-label extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:60-69.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.040

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057

- Sultan KS, Berkowitz JC, Khan S. Combination therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2017;8:103-113. doi:10.4292/wjgpt.v8.i2.103

- Prussick L, Rothstein B, Joshipura D, et al. Open-label, investigator-initiated, single-site exploratory trial evaluating secukinumab, an anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, for patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:609-611.

- Zouboulis CC, Okun MM, Prens EP, et al. Long-term adalimumab efficacy in patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: 3-year results of a phase 3 open-label extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:60-69.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.040

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057

- Sultan KS, Berkowitz JC, Khan S. Combination therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2017;8:103-113. doi:10.4292/wjgpt.v8.i2.103

- Prussick L, Rothstein B, Joshipura D, et al. Open-label, investigator-initiated, single-site exploratory trial evaluating secukinumab, an anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, for patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:609-611.

Practice Points

- Adalimumab is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), yet many patients on adalimumab do not achieve satisfactory results. New treatment options are in demand for patients affected by HS.

- Although combining tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors with oral immunosuppressants such as methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil appears to be beneficial in treating other conditions such as psoriasis, these treatments may not have as great a benefit for patients with HS.

Cutaneous Manifestations and Clinical Disparities in Patients Without Housing

More than half a million individuals are without housing (NWH) on any given night in the United States, as estimated by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. 1 Lack of hygiene, increased risk of infection and infestation due to living conditions, and barriers to health care put these individuals at increased risk for disease. 2 Skin disease, including fungal infection and acne, are within the top 10 most prevalent diseases worldwide and can cause major psychologic impairment, yet dermatologic concerns and clinical outcomes in NWH patients have not been well characterized. 2-5 Further, because this vulnerable demographic tends to be underinsured, they frequently present to the emergency department (ED) for management of disease. 1,6 Survey of common concerns in NWH patients is of utility to consulting dermatologists and nondermatologist providers in the ED, who can familiarize themselves with management of diseases they are more likely to encounter. Few studies examine dermatologic conditions in the ED, and a thorough literature review indicates none have included homelessness as a variable. 6,7 Additionally, comparison with a matched control group of patients with housing (WH) is limited. 5,8 We present one of the largest comparisons of cutaneous disease in NWH vs WH patients in a single hospital system to elucidate the types of cutaneous disease that motivate patients to seek care, the location of skin disease, and differences in clinical care.

Methods

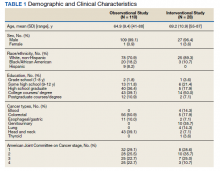

A retrospective medical record review of patients seen for an inclusive list of dermatologic diagnoses in the ED or while admitted at University Medical Center New Orleans, Louisiana (UMC), between January 1, 2018, and April 21, 2020, was conducted. This study was qualified as exempt from the institutional review board by Louisiana State University because it proposed zero risk to the patients and remained completely anonymous. Eight hundred forty-two total medical records were reviewed (NWH, 421; WH, 421)(Table 1). Patients with housing were matched based on self-identified race and ethnicity, sex, and age. Disease categories were constructed based on fundamental pathophysiology adapted from Dermatology9: infectious, noninfectious inflammatory, neoplasm, trauma and wounds, drug-related eruptions, vascular, pruritic, pigmented, bullous, neuropsychiatric, and other. Other included unspecified eruptions as well as miscellaneous lesions such as calluses. The current chief concern, anatomic location, and configuration were recorded, as well as biopsied lesions and outpatient referrals or inpatient consultations to dermatology or other specialties, including wound care, infectious disease, podiatry, and surgery. χ2 analysis was used to analyze significance of cutaneous categories, body location, and referrals. Groups smaller than 5 defaulted to the Fisher exact test.

Results

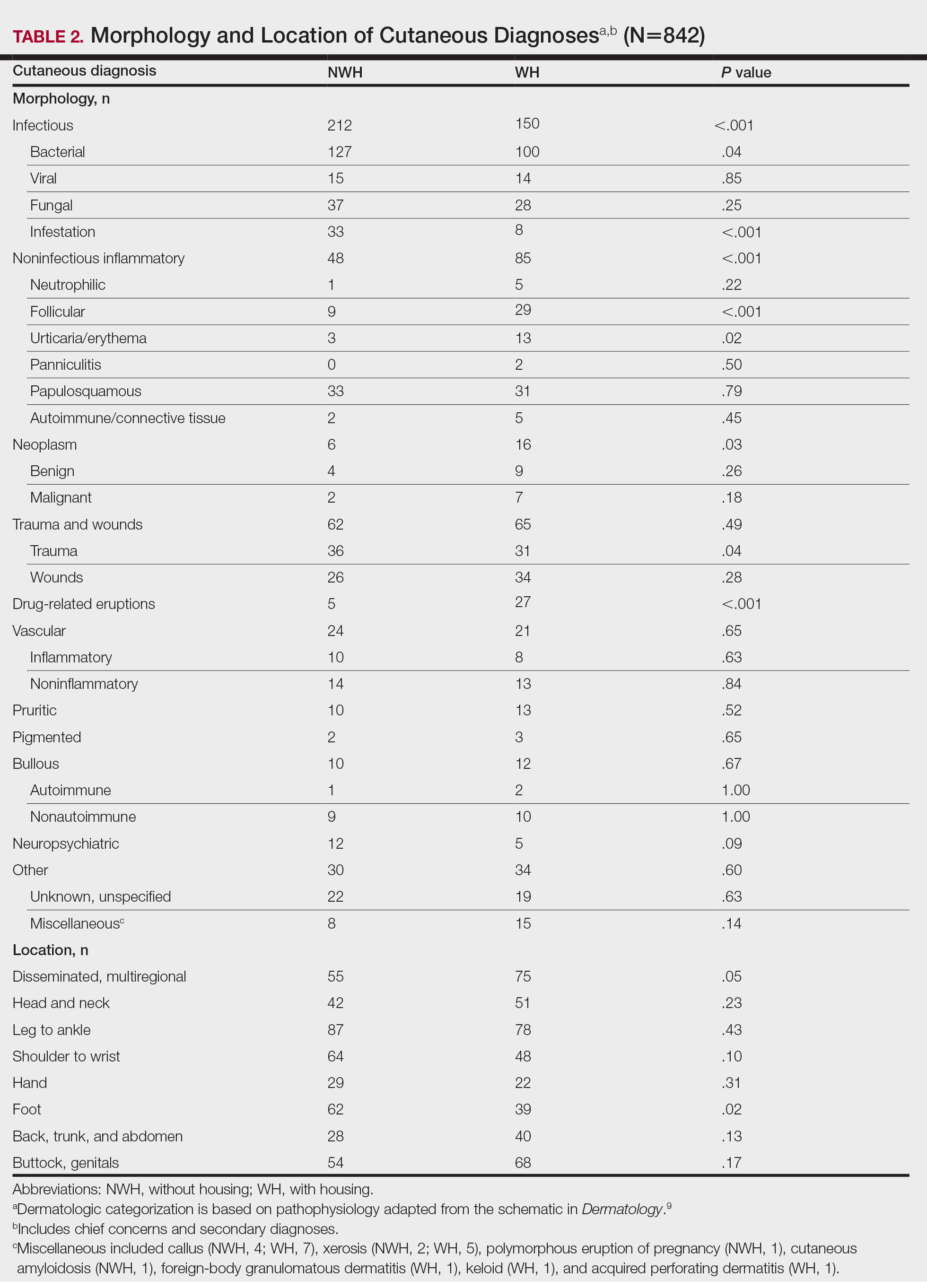

The total diagnoses (including both chief concerns and secondary diagnoses) are shown in Table 2. Chief concerns were more frequently cutaneous or dermatologic for WH (NWH, 209; WH, 307; P<.001). In both groups, cutaneous infectious etiologies were more likely to be a patient’s presenting chief concern (58% NWH, P=.002; 42% WH, P<.001). Noninfectious inflammatory etiologies and pigmented lesions were more likely to be secondary diagnoses with an unrelated noncutaneous concern; noninfectious inflammatory etiologies were only 16% of the total cutaneous chief concerns (11% NWH, P=.04; 20% WH, P=.03), and no pigmented lesions were chief concerns.

Infection was the most common chief concern, though NWH patients presented with significantly more infectious concerns (NWH, 212; WH, 150; P<.001), particularly infestations (NWH, 33; WH, 8; P<.001) and bacterial etiologies (NWH, 127; WH, 100; P=.04). The majority of bacterial etiologies were either an abscess or cellulitis (NWH, 106; WH, 83), though infected chronic wounds were categorized as bacterial infection when treated definitively as such (eg, in the case of sacral ulcers causing osteomyelitis)(NWH, 21; WH, 17). Of note, infectious etiology was associated with intravenous drug use (IVDU) in both NWH and WH patients. Of 184 NWH who reported IVDU, 127 had an infectious diagnosis (P<.001). Similarly, 43 of 56 total WH patients who reported IVDU had an infectious diagnosis (P<.001). Infestation (within the infectious category) included scabies (NWH, 20; WH, 3) and insect or arthropod bites (NWH, 12; WH, 5). Two NWH patients also presented with swelling of the lower extremities and were subsequently diagnosed with maggot infestations. Fungal and viral etiologies were not significantly increased in either group; however, NWH did have a higher incidence of tinea pedis (NWH, 14; WH, 4; P=.03).

More neoplasms (NWH, 6; WH, 16; P=.03), noninfectious inflammatory eruptions (NWH, 48; WH, 85; P<.001), and cutaneous drug eruptions (NWH, 5; WH, 27; P<.001) were reported in WH patients. There was no significant difference in benign vs malignant neoplastic processes between groups. More noninfectious inflammatory eruptions in WH were specifically driven by a markedly increased incidence of follicular (NWH, 9; WH, 29; P<.001) and urticarial/erythematous (NWH, 3; WH, 13; P=.02) lesions. Follicular etiologies included acne (NWH, 1; WH, 6; P=.12), folliculitis (NWH, 5; WH, 2; P=.45), hidradenitis suppurativa (NWH, 2; WH, 11; P=.02), and pilonidal and sebaceous cysts (NWH, 1; WH, 10; P=.01). Allergic urticaria dominated the urticarial/erythematous category (NWH, 3; WH, 11; P=.06), though there were 2 WH presentations of diffuse erythema and skin peeling.

Another substantial proportion of cutaneous etiologies were due to trauma or chronic wounds. Significantly more traumatic injuries presented in NWH patients vs WH patients (36 vs 31; P=.04). Trauma included human or dog bites (NWH, 5; WH, 4), sunburns (NWH, 3; WH, 0), other burns (NWH, 11; WH, 13), abrasions and lacerations (NWH, 16; WH, 3; P=.004), and foreign bodies (NWH, 1; WH, 1). Wounds consisted of chronic wounds such as those due to diabetes mellitus (foot ulcers) or immobility (sacral ulcers); numbers were similar between groups.

Looking at location, NWH patients had more pathology on the feet (NWH, 62; WH, 39; P=.02), whereas WH patients had more disseminated multiregional concerns (NWH, 55; WH, 75; P=.05). No one body location was notably more likely to warrant a chief concern.

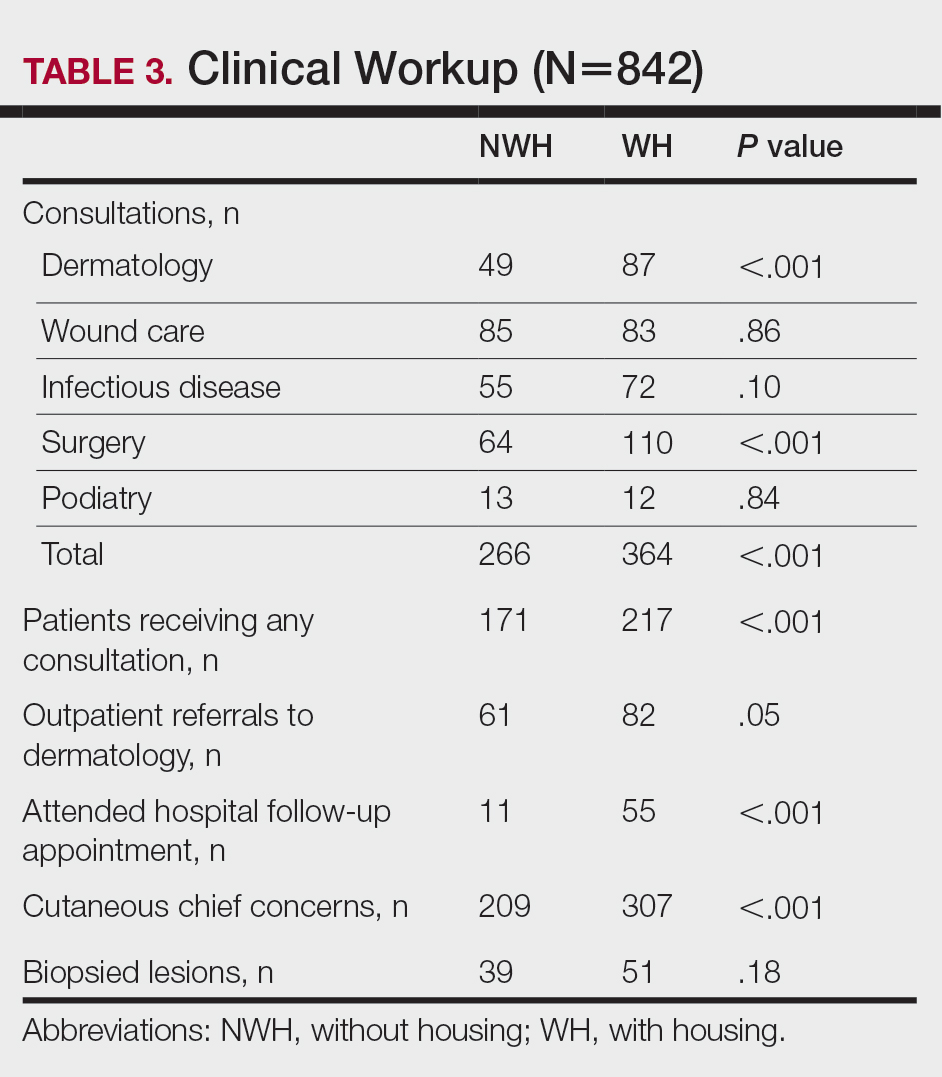

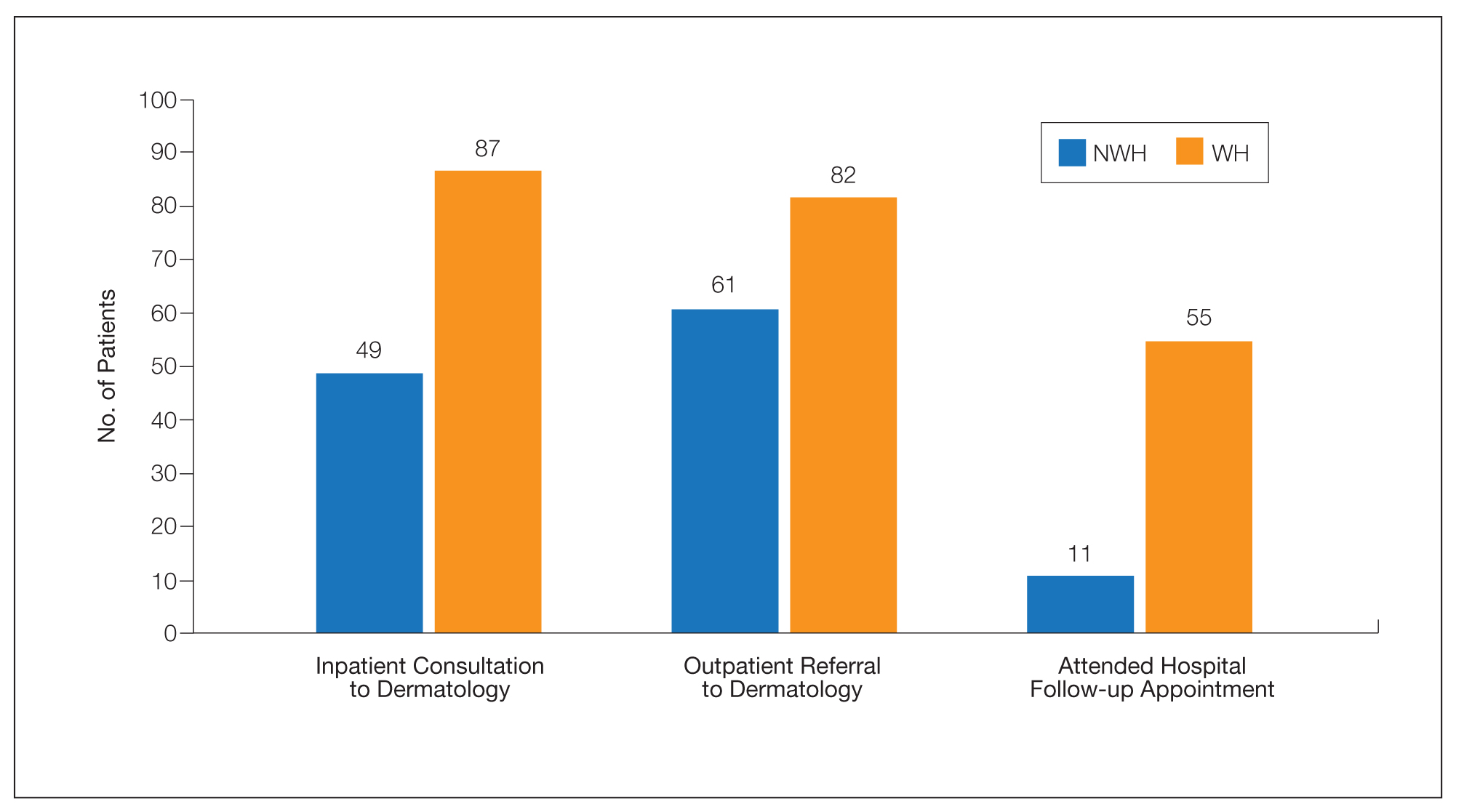

For clinical outcomes, more WH patients received a consultation of any kind (NWH, 171; WH, 217; P<.001), consultation to dermatology (NWH, 49; WH, 87; P<.001), and consultation to surgery (NWH, 64; WH, 110; P<.001)(Table 3 and Figure). More outpatient referrals to dermatology were made for WH patients (NWH, 61; WH, 82; P=.05). Notably, NWH patients presented for 80% fewer hospital follow-up appointments (NWH, 11; WH, 55; P<.001). It is essential to note that these findings were not affected by self-reported race or ethnicity. Results remained significant when broken into cohorts consisting of patients with and without skin of color.

Comment

Cutaneous Concerns in NWH Patients—Although cutaneous disease has been reported to disproportionately affect NWH patients,10 in our cohort, NWH patients had fewer cutaneous chief concerns than WH patients. However, without comparing with all patients entering the ED at UMC, we cannot make a statement on this claim. We do present a few reasons why NWH patients do not have more cutaneous concerns. First, they may wait to present with cutaneous disease until it becomes more severe (eg, until chronic wounds have progressed to infections). Second, as discussed in depth by Hollestein and Nijsten,3 dermatologic disease may be a major contributor to the overall count of disability-adjusted life years but may play a minor role in individual disability. Therefore, skin disease often is considered less important on an individual basis, despite substantial psychosocial burden, leading to further stigmatization of this vulnerable population and discouraged care-seeking behavior, particularly for noninfectious inflammatory eruptions, which were notably more present in WH individuals. Third, fewer dermatologic lesions were reported on NWH patients, which may explain why all 3 WH pigmented lesions were diagnosed after presentation with a noncutaneous concern (eg, headache, anemia, nausea).

Infectious Cutaneous Diagnoses—The increased presentation of infectious etiologies, especially bacterial, is linked to the increased numbers of IVDUs reported in NWH individuals as well as increased exposure and decreased access to basic hygienic supplies. Intravenous drug use acted as an effect modifier of infectious etiology diagnoses, playing a major role in both NWH and WH cohorts. Although Black and Hispanic individuals as well as individuals with low socioeconomic status have increased proportions of skin cancer, there are inadequate data on the prevalence in NWH individuals.4 We found no increase in malignant dermatologic processes in NWH individuals; however, this may be secondary to inadequate screening with a total body skin examination.

Clinical Workup of NWH Patients—Because most NWH individuals present to the ED to receive care, their care compared with WH patients should be considered. In this cohort, WH patients received a less extensive clinical workup. They received almost half as many dermatologic consultations and fewer outpatient referrals to dermatology. Major communication barriers may affect NWH presentation to follow-up, which was drastically lower than WH individuals, as scheduling typically occurs well after discharge from the ED or inpatient unit. We suggest a few alterations to improve dermatologic care for NWH individuals:

• Consider inpatient consultation for serious dermatologic conditions—even if chronic—to improve disease control, considering that many barriers inhibit follow-up in clinic.

• Involve outreach teams, such as the Assertive Community Treatment teams, that assist individuals by delivering medicine for psychiatric disorders, conducting total-body skin examinations, assisting with wound care, providing basic skin barrier creams or medicaments, and carrying information regarding outpatient follow-up.

• Educate ED providers on the most common skin concerns, especially those that fall within the noninfectious inflammatory category, such as hidradenitis suppurativa, which could easily be misdiagnosed as an abscess.

Future Directions—Owing to limitations of a retrospective cohort study, we present several opportunities for further research on this vulnerable population. The severity of disease, especially infectious etiologies, should be graded to determine if NWH patients truly present later in the disease course. The duration and quality of housing for NWH patients could be categorized based on living conditions (eg, on the street vs in a shelter). Although the findings of our NWH cohort presenting to the ED at UMC provide helpful insight into dermatologic disease, these findings may be disparate from those conducted at other locations in the United States. University Medical Center provides care to mostly subsidized insurance plans in a racially diverse community. Improved outcomes for the NWH individuals living in New Orleans start with obtaining a greater understanding of their diseases and where disparities exist that can be bridged with better care.

Acknowledgment—The dataset generated during this study and used for analysis is not publicly available to protect public health information but is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384:1529-1540. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6

- Contag C, Lowenstein SE, Jain S, et al. Survey of symptomatic dermatologic disease in homeless patients at a shelter-based clinic. Our Dermatol Online. 2017;8:133-137. doi:10.7241/ourd.20172.37

- Hollestein LM, Nijsten T. An insight into the global burden of skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1499-1501. doi:10.1038/jid.2013.513

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Grossberg AL, Carranza D, Lamp K, et al. Dermatologic care in the homeless and underserved populations: observations from the Venice Family Clinic. Cutis. 2012;89:25-32.

- Mackelprang JL, Graves JM, Rivara FP. Homeless in America: injuries treated in US emergency departments, 2007-2011. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2014;21:289-297. doi:10.1038/jid.2014.371

- Chen CL, Fitzpatrick L, Kamel H. Who uses the emergency department for dermatologic care? a statewide analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:308-313. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.013

- Stratigos AJ, Stern R, Gonzalez E, et al. Prevalence of skin disease in a cohort of shelter-based homeless men. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:197-202. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70048-4

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Badiaga S, Menard A, Tissot Dupont H, et al. Prevalence of skin infections in sheltered homeless. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:382-386.

More than half a million individuals are without housing (NWH) on any given night in the United States, as estimated by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. 1 Lack of hygiene, increased risk of infection and infestation due to living conditions, and barriers to health care put these individuals at increased risk for disease. 2 Skin disease, including fungal infection and acne, are within the top 10 most prevalent diseases worldwide and can cause major psychologic impairment, yet dermatologic concerns and clinical outcomes in NWH patients have not been well characterized. 2-5 Further, because this vulnerable demographic tends to be underinsured, they frequently present to the emergency department (ED) for management of disease. 1,6 Survey of common concerns in NWH patients is of utility to consulting dermatologists and nondermatologist providers in the ED, who can familiarize themselves with management of diseases they are more likely to encounter. Few studies examine dermatologic conditions in the ED, and a thorough literature review indicates none have included homelessness as a variable. 6,7 Additionally, comparison with a matched control group of patients with housing (WH) is limited. 5,8 We present one of the largest comparisons of cutaneous disease in NWH vs WH patients in a single hospital system to elucidate the types of cutaneous disease that motivate patients to seek care, the location of skin disease, and differences in clinical care.

Methods

A retrospective medical record review of patients seen for an inclusive list of dermatologic diagnoses in the ED or while admitted at University Medical Center New Orleans, Louisiana (UMC), between January 1, 2018, and April 21, 2020, was conducted. This study was qualified as exempt from the institutional review board by Louisiana State University because it proposed zero risk to the patients and remained completely anonymous. Eight hundred forty-two total medical records were reviewed (NWH, 421; WH, 421)(Table 1). Patients with housing were matched based on self-identified race and ethnicity, sex, and age. Disease categories were constructed based on fundamental pathophysiology adapted from Dermatology9: infectious, noninfectious inflammatory, neoplasm, trauma and wounds, drug-related eruptions, vascular, pruritic, pigmented, bullous, neuropsychiatric, and other. Other included unspecified eruptions as well as miscellaneous lesions such as calluses. The current chief concern, anatomic location, and configuration were recorded, as well as biopsied lesions and outpatient referrals or inpatient consultations to dermatology or other specialties, including wound care, infectious disease, podiatry, and surgery. χ2 analysis was used to analyze significance of cutaneous categories, body location, and referrals. Groups smaller than 5 defaulted to the Fisher exact test.

Results

The total diagnoses (including both chief concerns and secondary diagnoses) are shown in Table 2. Chief concerns were more frequently cutaneous or dermatologic for WH (NWH, 209; WH, 307; P<.001). In both groups, cutaneous infectious etiologies were more likely to be a patient’s presenting chief concern (58% NWH, P=.002; 42% WH, P<.001). Noninfectious inflammatory etiologies and pigmented lesions were more likely to be secondary diagnoses with an unrelated noncutaneous concern; noninfectious inflammatory etiologies were only 16% of the total cutaneous chief concerns (11% NWH, P=.04; 20% WH, P=.03), and no pigmented lesions were chief concerns.

Infection was the most common chief concern, though NWH patients presented with significantly more infectious concerns (NWH, 212; WH, 150; P<.001), particularly infestations (NWH, 33; WH, 8; P<.001) and bacterial etiologies (NWH, 127; WH, 100; P=.04). The majority of bacterial etiologies were either an abscess or cellulitis (NWH, 106; WH, 83), though infected chronic wounds were categorized as bacterial infection when treated definitively as such (eg, in the case of sacral ulcers causing osteomyelitis)(NWH, 21; WH, 17). Of note, infectious etiology was associated with intravenous drug use (IVDU) in both NWH and WH patients. Of 184 NWH who reported IVDU, 127 had an infectious diagnosis (P<.001). Similarly, 43 of 56 total WH patients who reported IVDU had an infectious diagnosis (P<.001). Infestation (within the infectious category) included scabies (NWH, 20; WH, 3) and insect or arthropod bites (NWH, 12; WH, 5). Two NWH patients also presented with swelling of the lower extremities and were subsequently diagnosed with maggot infestations. Fungal and viral etiologies were not significantly increased in either group; however, NWH did have a higher incidence of tinea pedis (NWH, 14; WH, 4; P=.03).

More neoplasms (NWH, 6; WH, 16; P=.03), noninfectious inflammatory eruptions (NWH, 48; WH, 85; P<.001), and cutaneous drug eruptions (NWH, 5; WH, 27; P<.001) were reported in WH patients. There was no significant difference in benign vs malignant neoplastic processes between groups. More noninfectious inflammatory eruptions in WH were specifically driven by a markedly increased incidence of follicular (NWH, 9; WH, 29; P<.001) and urticarial/erythematous (NWH, 3; WH, 13; P=.02) lesions. Follicular etiologies included acne (NWH, 1; WH, 6; P=.12), folliculitis (NWH, 5; WH, 2; P=.45), hidradenitis suppurativa (NWH, 2; WH, 11; P=.02), and pilonidal and sebaceous cysts (NWH, 1; WH, 10; P=.01). Allergic urticaria dominated the urticarial/erythematous category (NWH, 3; WH, 11; P=.06), though there were 2 WH presentations of diffuse erythema and skin peeling.

Another substantial proportion of cutaneous etiologies were due to trauma or chronic wounds. Significantly more traumatic injuries presented in NWH patients vs WH patients (36 vs 31; P=.04). Trauma included human or dog bites (NWH, 5; WH, 4), sunburns (NWH, 3; WH, 0), other burns (NWH, 11; WH, 13), abrasions and lacerations (NWH, 16; WH, 3; P=.004), and foreign bodies (NWH, 1; WH, 1). Wounds consisted of chronic wounds such as those due to diabetes mellitus (foot ulcers) or immobility (sacral ulcers); numbers were similar between groups.

Looking at location, NWH patients had more pathology on the feet (NWH, 62; WH, 39; P=.02), whereas WH patients had more disseminated multiregional concerns (NWH, 55; WH, 75; P=.05). No one body location was notably more likely to warrant a chief concern.

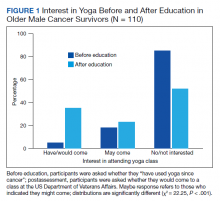

For clinical outcomes, more WH patients received a consultation of any kind (NWH, 171; WH, 217; P<.001), consultation to dermatology (NWH, 49; WH, 87; P<.001), and consultation to surgery (NWH, 64; WH, 110; P<.001)(Table 3 and Figure). More outpatient referrals to dermatology were made for WH patients (NWH, 61; WH, 82; P=.05). Notably, NWH patients presented for 80% fewer hospital follow-up appointments (NWH, 11; WH, 55; P<.001). It is essential to note that these findings were not affected by self-reported race or ethnicity. Results remained significant when broken into cohorts consisting of patients with and without skin of color.

Comment

Cutaneous Concerns in NWH Patients—Although cutaneous disease has been reported to disproportionately affect NWH patients,10 in our cohort, NWH patients had fewer cutaneous chief concerns than WH patients. However, without comparing with all patients entering the ED at UMC, we cannot make a statement on this claim. We do present a few reasons why NWH patients do not have more cutaneous concerns. First, they may wait to present with cutaneous disease until it becomes more severe (eg, until chronic wounds have progressed to infections). Second, as discussed in depth by Hollestein and Nijsten,3 dermatologic disease may be a major contributor to the overall count of disability-adjusted life years but may play a minor role in individual disability. Therefore, skin disease often is considered less important on an individual basis, despite substantial psychosocial burden, leading to further stigmatization of this vulnerable population and discouraged care-seeking behavior, particularly for noninfectious inflammatory eruptions, which were notably more present in WH individuals. Third, fewer dermatologic lesions were reported on NWH patients, which may explain why all 3 WH pigmented lesions were diagnosed after presentation with a noncutaneous concern (eg, headache, anemia, nausea).

Infectious Cutaneous Diagnoses—The increased presentation of infectious etiologies, especially bacterial, is linked to the increased numbers of IVDUs reported in NWH individuals as well as increased exposure and decreased access to basic hygienic supplies. Intravenous drug use acted as an effect modifier of infectious etiology diagnoses, playing a major role in both NWH and WH cohorts. Although Black and Hispanic individuals as well as individuals with low socioeconomic status have increased proportions of skin cancer, there are inadequate data on the prevalence in NWH individuals.4 We found no increase in malignant dermatologic processes in NWH individuals; however, this may be secondary to inadequate screening with a total body skin examination.

Clinical Workup of NWH Patients—Because most NWH individuals present to the ED to receive care, their care compared with WH patients should be considered. In this cohort, WH patients received a less extensive clinical workup. They received almost half as many dermatologic consultations and fewer outpatient referrals to dermatology. Major communication barriers may affect NWH presentation to follow-up, which was drastically lower than WH individuals, as scheduling typically occurs well after discharge from the ED or inpatient unit. We suggest a few alterations to improve dermatologic care for NWH individuals:

• Consider inpatient consultation for serious dermatologic conditions—even if chronic—to improve disease control, considering that many barriers inhibit follow-up in clinic.

• Involve outreach teams, such as the Assertive Community Treatment teams, that assist individuals by delivering medicine for psychiatric disorders, conducting total-body skin examinations, assisting with wound care, providing basic skin barrier creams or medicaments, and carrying information regarding outpatient follow-up.

• Educate ED providers on the most common skin concerns, especially those that fall within the noninfectious inflammatory category, such as hidradenitis suppurativa, which could easily be misdiagnosed as an abscess.

Future Directions—Owing to limitations of a retrospective cohort study, we present several opportunities for further research on this vulnerable population. The severity of disease, especially infectious etiologies, should be graded to determine if NWH patients truly present later in the disease course. The duration and quality of housing for NWH patients could be categorized based on living conditions (eg, on the street vs in a shelter). Although the findings of our NWH cohort presenting to the ED at UMC provide helpful insight into dermatologic disease, these findings may be disparate from those conducted at other locations in the United States. University Medical Center provides care to mostly subsidized insurance plans in a racially diverse community. Improved outcomes for the NWH individuals living in New Orleans start with obtaining a greater understanding of their diseases and where disparities exist that can be bridged with better care.

Acknowledgment—The dataset generated during this study and used for analysis is not publicly available to protect public health information but is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

More than half a million individuals are without housing (NWH) on any given night in the United States, as estimated by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. 1 Lack of hygiene, increased risk of infection and infestation due to living conditions, and barriers to health care put these individuals at increased risk for disease. 2 Skin disease, including fungal infection and acne, are within the top 10 most prevalent diseases worldwide and can cause major psychologic impairment, yet dermatologic concerns and clinical outcomes in NWH patients have not been well characterized. 2-5 Further, because this vulnerable demographic tends to be underinsured, they frequently present to the emergency department (ED) for management of disease. 1,6 Survey of common concerns in NWH patients is of utility to consulting dermatologists and nondermatologist providers in the ED, who can familiarize themselves with management of diseases they are more likely to encounter. Few studies examine dermatologic conditions in the ED, and a thorough literature review indicates none have included homelessness as a variable. 6,7 Additionally, comparison with a matched control group of patients with housing (WH) is limited. 5,8 We present one of the largest comparisons of cutaneous disease in NWH vs WH patients in a single hospital system to elucidate the types of cutaneous disease that motivate patients to seek care, the location of skin disease, and differences in clinical care.

Methods

A retrospective medical record review of patients seen for an inclusive list of dermatologic diagnoses in the ED or while admitted at University Medical Center New Orleans, Louisiana (UMC), between January 1, 2018, and April 21, 2020, was conducted. This study was qualified as exempt from the institutional review board by Louisiana State University because it proposed zero risk to the patients and remained completely anonymous. Eight hundred forty-two total medical records were reviewed (NWH, 421; WH, 421)(Table 1). Patients with housing were matched based on self-identified race and ethnicity, sex, and age. Disease categories were constructed based on fundamental pathophysiology adapted from Dermatology9: infectious, noninfectious inflammatory, neoplasm, trauma and wounds, drug-related eruptions, vascular, pruritic, pigmented, bullous, neuropsychiatric, and other. Other included unspecified eruptions as well as miscellaneous lesions such as calluses. The current chief concern, anatomic location, and configuration were recorded, as well as biopsied lesions and outpatient referrals or inpatient consultations to dermatology or other specialties, including wound care, infectious disease, podiatry, and surgery. χ2 analysis was used to analyze significance of cutaneous categories, body location, and referrals. Groups smaller than 5 defaulted to the Fisher exact test.

Results

The total diagnoses (including both chief concerns and secondary diagnoses) are shown in Table 2. Chief concerns were more frequently cutaneous or dermatologic for WH (NWH, 209; WH, 307; P<.001). In both groups, cutaneous infectious etiologies were more likely to be a patient’s presenting chief concern (58% NWH, P=.002; 42% WH, P<.001). Noninfectious inflammatory etiologies and pigmented lesions were more likely to be secondary diagnoses with an unrelated noncutaneous concern; noninfectious inflammatory etiologies were only 16% of the total cutaneous chief concerns (11% NWH, P=.04; 20% WH, P=.03), and no pigmented lesions were chief concerns.

Infection was the most common chief concern, though NWH patients presented with significantly more infectious concerns (NWH, 212; WH, 150; P<.001), particularly infestations (NWH, 33; WH, 8; P<.001) and bacterial etiologies (NWH, 127; WH, 100; P=.04). The majority of bacterial etiologies were either an abscess or cellulitis (NWH, 106; WH, 83), though infected chronic wounds were categorized as bacterial infection when treated definitively as such (eg, in the case of sacral ulcers causing osteomyelitis)(NWH, 21; WH, 17). Of note, infectious etiology was associated with intravenous drug use (IVDU) in both NWH and WH patients. Of 184 NWH who reported IVDU, 127 had an infectious diagnosis (P<.001). Similarly, 43 of 56 total WH patients who reported IVDU had an infectious diagnosis (P<.001). Infestation (within the infectious category) included scabies (NWH, 20; WH, 3) and insect or arthropod bites (NWH, 12; WH, 5). Two NWH patients also presented with swelling of the lower extremities and were subsequently diagnosed with maggot infestations. Fungal and viral etiologies were not significantly increased in either group; however, NWH did have a higher incidence of tinea pedis (NWH, 14; WH, 4; P=.03).

More neoplasms (NWH, 6; WH, 16; P=.03), noninfectious inflammatory eruptions (NWH, 48; WH, 85; P<.001), and cutaneous drug eruptions (NWH, 5; WH, 27; P<.001) were reported in WH patients. There was no significant difference in benign vs malignant neoplastic processes between groups. More noninfectious inflammatory eruptions in WH were specifically driven by a markedly increased incidence of follicular (NWH, 9; WH, 29; P<.001) and urticarial/erythematous (NWH, 3; WH, 13; P=.02) lesions. Follicular etiologies included acne (NWH, 1; WH, 6; P=.12), folliculitis (NWH, 5; WH, 2; P=.45), hidradenitis suppurativa (NWH, 2; WH, 11; P=.02), and pilonidal and sebaceous cysts (NWH, 1; WH, 10; P=.01). Allergic urticaria dominated the urticarial/erythematous category (NWH, 3; WH, 11; P=.06), though there were 2 WH presentations of diffuse erythema and skin peeling.

Another substantial proportion of cutaneous etiologies were due to trauma or chronic wounds. Significantly more traumatic injuries presented in NWH patients vs WH patients (36 vs 31; P=.04). Trauma included human or dog bites (NWH, 5; WH, 4), sunburns (NWH, 3; WH, 0), other burns (NWH, 11; WH, 13), abrasions and lacerations (NWH, 16; WH, 3; P=.004), and foreign bodies (NWH, 1; WH, 1). Wounds consisted of chronic wounds such as those due to diabetes mellitus (foot ulcers) or immobility (sacral ulcers); numbers were similar between groups.

Looking at location, NWH patients had more pathology on the feet (NWH, 62; WH, 39; P=.02), whereas WH patients had more disseminated multiregional concerns (NWH, 55; WH, 75; P=.05). No one body location was notably more likely to warrant a chief concern.

For clinical outcomes, more WH patients received a consultation of any kind (NWH, 171; WH, 217; P<.001), consultation to dermatology (NWH, 49; WH, 87; P<.001), and consultation to surgery (NWH, 64; WH, 110; P<.001)(Table 3 and Figure). More outpatient referrals to dermatology were made for WH patients (NWH, 61; WH, 82; P=.05). Notably, NWH patients presented for 80% fewer hospital follow-up appointments (NWH, 11; WH, 55; P<.001). It is essential to note that these findings were not affected by self-reported race or ethnicity. Results remained significant when broken into cohorts consisting of patients with and without skin of color.

Comment

Cutaneous Concerns in NWH Patients—Although cutaneous disease has been reported to disproportionately affect NWH patients,10 in our cohort, NWH patients had fewer cutaneous chief concerns than WH patients. However, without comparing with all patients entering the ED at UMC, we cannot make a statement on this claim. We do present a few reasons why NWH patients do not have more cutaneous concerns. First, they may wait to present with cutaneous disease until it becomes more severe (eg, until chronic wounds have progressed to infections). Second, as discussed in depth by Hollestein and Nijsten,3 dermatologic disease may be a major contributor to the overall count of disability-adjusted life years but may play a minor role in individual disability. Therefore, skin disease often is considered less important on an individual basis, despite substantial psychosocial burden, leading to further stigmatization of this vulnerable population and discouraged care-seeking behavior, particularly for noninfectious inflammatory eruptions, which were notably more present in WH individuals. Third, fewer dermatologic lesions were reported on NWH patients, which may explain why all 3 WH pigmented lesions were diagnosed after presentation with a noncutaneous concern (eg, headache, anemia, nausea).

Infectious Cutaneous Diagnoses—The increased presentation of infectious etiologies, especially bacterial, is linked to the increased numbers of IVDUs reported in NWH individuals as well as increased exposure and decreased access to basic hygienic supplies. Intravenous drug use acted as an effect modifier of infectious etiology diagnoses, playing a major role in both NWH and WH cohorts. Although Black and Hispanic individuals as well as individuals with low socioeconomic status have increased proportions of skin cancer, there are inadequate data on the prevalence in NWH individuals.4 We found no increase in malignant dermatologic processes in NWH individuals; however, this may be secondary to inadequate screening with a total body skin examination.

Clinical Workup of NWH Patients—Because most NWH individuals present to the ED to receive care, their care compared with WH patients should be considered. In this cohort, WH patients received a less extensive clinical workup. They received almost half as many dermatologic consultations and fewer outpatient referrals to dermatology. Major communication barriers may affect NWH presentation to follow-up, which was drastically lower than WH individuals, as scheduling typically occurs well after discharge from the ED or inpatient unit. We suggest a few alterations to improve dermatologic care for NWH individuals:

• Consider inpatient consultation for serious dermatologic conditions—even if chronic—to improve disease control, considering that many barriers inhibit follow-up in clinic.

• Involve outreach teams, such as the Assertive Community Treatment teams, that assist individuals by delivering medicine for psychiatric disorders, conducting total-body skin examinations, assisting with wound care, providing basic skin barrier creams or medicaments, and carrying information regarding outpatient follow-up.

• Educate ED providers on the most common skin concerns, especially those that fall within the noninfectious inflammatory category, such as hidradenitis suppurativa, which could easily be misdiagnosed as an abscess.

Future Directions—Owing to limitations of a retrospective cohort study, we present several opportunities for further research on this vulnerable population. The severity of disease, especially infectious etiologies, should be graded to determine if NWH patients truly present later in the disease course. The duration and quality of housing for NWH patients could be categorized based on living conditions (eg, on the street vs in a shelter). Although the findings of our NWH cohort presenting to the ED at UMC provide helpful insight into dermatologic disease, these findings may be disparate from those conducted at other locations in the United States. University Medical Center provides care to mostly subsidized insurance plans in a racially diverse community. Improved outcomes for the NWH individuals living in New Orleans start with obtaining a greater understanding of their diseases and where disparities exist that can be bridged with better care.

Acknowledgment—The dataset generated during this study and used for analysis is not publicly available to protect public health information but is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384:1529-1540. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6

- Contag C, Lowenstein SE, Jain S, et al. Survey of symptomatic dermatologic disease in homeless patients at a shelter-based clinic. Our Dermatol Online. 2017;8:133-137. doi:10.7241/ourd.20172.37

- Hollestein LM, Nijsten T. An insight into the global burden of skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1499-1501. doi:10.1038/jid.2013.513

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Grossberg AL, Carranza D, Lamp K, et al. Dermatologic care in the homeless and underserved populations: observations from the Venice Family Clinic. Cutis. 2012;89:25-32.

- Mackelprang JL, Graves JM, Rivara FP. Homeless in America: injuries treated in US emergency departments, 2007-2011. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2014;21:289-297. doi:10.1038/jid.2014.371

- Chen CL, Fitzpatrick L, Kamel H. Who uses the emergency department for dermatologic care? a statewide analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:308-313. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.013

- Stratigos AJ, Stern R, Gonzalez E, et al. Prevalence of skin disease in a cohort of shelter-based homeless men. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:197-202. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70048-4

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Badiaga S, Menard A, Tissot Dupont H, et al. Prevalence of skin infections in sheltered homeless. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:382-386.

- Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384:1529-1540. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6

- Contag C, Lowenstein SE, Jain S, et al. Survey of symptomatic dermatologic disease in homeless patients at a shelter-based clinic. Our Dermatol Online. 2017;8:133-137. doi:10.7241/ourd.20172.37

- Hollestein LM, Nijsten T. An insight into the global burden of skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1499-1501. doi:10.1038/jid.2013.513

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Grossberg AL, Carranza D, Lamp K, et al. Dermatologic care in the homeless and underserved populations: observations from the Venice Family Clinic. Cutis. 2012;89:25-32.

- Mackelprang JL, Graves JM, Rivara FP. Homeless in America: injuries treated in US emergency departments, 2007-2011. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2014;21:289-297. doi:10.1038/jid.2014.371

- Chen CL, Fitzpatrick L, Kamel H. Who uses the emergency department for dermatologic care? a statewide analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:308-313. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.013

- Stratigos AJ, Stern R, Gonzalez E, et al. Prevalence of skin disease in a cohort of shelter-based homeless men. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:197-202. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70048-4

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Badiaga S, Menard A, Tissot Dupont H, et al. Prevalence of skin infections in sheltered homeless. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:382-386.

Practice Points

- Dermatologic disease in patients without housing (NWH) is characterized by more infectious concerns and fewer follicular and urticarial noninfectious inflammatory eruptions compared with matched controls of those with housing.

- Patients with housing more frequently presented with cutaneous chief concerns and received more consultations while in the hospital.

- This study uncovered notable pathological and clinical differences in treating dermatologic conditions in NWH patients.

Comparison of Adverse Events With Vancomycin Diluted in Normal Saline vs Dextrose 5%

Vancomycin is a widely used IV antibiotic due to its broad-spectrum of activity, bactericidal nature, and low rates of resistance; however, adverse effects (AEs), including nephrotoxicity, are commonly associated with its use.1 The vancomycin therapeutic monitoring guidelines recognize the incidence of nephrotoxicity and suggest strategies for reducing the risk, including area under the curve/mean inhibitory concentration (AUC/MIC) monitoring rather than trough-only monitoring. Vancomycin-associated acute kidney injury (AKI) has been defined as an increase in serum creatinine (SCr) over a 48-hour period of ≥ 0.3 mg/dL or a percentage increase of ≥ 50%, which is consistent with the Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) guidelines.2,3 Vancomycin-associated AKI is a common AE, with its incidence reported in previous studies ranging from 10 to 20%.4,5

The most common crystalloid fluid administered to patients in the United States is 0.9% sodium chloride (NaCl), also known as normal saline (NS), and recent trials have explored its potential to cause AEs.6-8 Balanced crystalloid solutions, such as Plasma-Lyte and lactated Ringer’s solution (LR), contain buffering agents and lower concentrations of sodium and chloride compared with that of NS. Trials in the intensive care unit (ICU) and emergency department, such as the SMART-MED, SMART-SURG, and SALT-ED have reported a significantly lower rate of AKI when using balanced crystalloids compared with NS due to the concentration of sodium and chloride in NS being supraphysiologic to normal serum concentrations.6,7 Alternatively, the SPLIT trial evaluated the use of NS compared with Plasma-Lyte for ICU fluid therapy and did not find a statistically significant difference in AKI.8 Furthermore, some studies have reported increased risk for hyperchloremia when using NS compared with dextrose 5% in water (D5W) or balanced crystalloids, which can result in metabolic acidosis.6,7,9,10 These studies have shown how the choice of fluid can have a large effect on the incidence of AEs; bringing into question whether these effects could be additive when combined with the nephrotoxicity associated with vancomycin.6-9

Vancomycin is physically and chemically stable if diluted in D5W, NS, 5% dextrose in NS, LR, or 5% dextrose in LR.1 It is not known whether the selection of diluent has an effect on nephrotoxicity or other AEs of vancomycin therapy. Furthermore, clinicians may be unaware or unable to specify which diluent to use. There are currently no practice guidelines that favor one diluent over another for vancomycin; however, trials showing higher rates of AKI and hyperchloremia using NS for fluid resuscitation may indicate an increased potential for vancomycin-associated AKI when using NS as a diluent.6,7,9 This study was performed to evaluate whether the type of crystalloid used (D5W vs NS) can influence adverse outcomes for patients. While many factors may contribute to these AEs, the potential to reduce the risk of negative adverse outcomes for hospitalized patients is a significant area of exploration.

The primary outcome of this study was the incidence of AKI, defined using AKIN guidelines where the increase in SCr occurred at least 24 hours after starting vancomycin and within 36 hours of receiving the last vancomycin dose.3 AKI was staged using the AKIN guidelines (stage 1: increase in SCr of ≥ 0.3 mg/dL or by 50 to 99%; stage 2: increase in SCr by 100 to 199%; stage 3: increase in SCr by > 200%) based on changes in SCr from baseline during vancomycin therapy or within 36 hours of stopping vancomycin therapy.3 Secondary outcomes included the incidence of hyperglycemia, hyperchloremia, metabolic acidosis, hypernatremia, mortality in hospital, and mortality within 30 days from hospital discharge.

Methods

This single-center, retrospective study of veterans who received IV vancomycin within the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NF/SGVHS) in Gainesville, Florida, from July 1, 2015 to June 30, 2020, compared veterans who received vancomycin diluted in NS with those who received vancomycin diluted in D5W to assess for differences in AEs, including AKI, metabolic acidosis (serum bicarbonate level < 23 mmol/L), hyperchloremia (serum chloride levels > 108 mmol/L), hypernatremia (serum sodium > 145 mmol/L), and hyperglycemia (blood glucose > 180 mg/dL). The endpoint values were defined using the reference ranges determined by the local laboratory. At NF/SGVHS, vancomycin is diluted in D5W or NS based primarily on factors such as product availability and cost.

Study Criteria

Veterans were included if they received IV vancomycin between July 1, 2015 and June 30, 2020. The cohorts were grouped into those receiving vancomycin doses diluted in NS and those receiving vancomycin doses diluted in D5W. Veterans were excluded if they received < 80% of vancomycin doses diluted in their respective fluid, if they were on vancomycin for < 48 hours, or if they did not have laboratory results collected both before and after vancomycin therapy to assess a change. There were more patients receiving vancomycin in D5W, so a random sample was selected to have an equal size comparison group with those receiving NS. A sample size calculation was performed with an anticipated AKI incidence of 14%.5 To detect a 10% difference in the primary outcome with an α of 0.05 and 75% power, 226 patients (113 in each cohort) were needed for inclusion.

Data were collected using the Data Access Request Tracker tool through the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Informatics and Computing Infrastructure. Data collected included demographics, laboratory data at baseline and during vancomycin therapy, characteristics of antibiotic therapy, and mortality data. Of note, all laboratory values assessed in this study were obtained while the veteran was receiving vancomycin or within 36 hours of receiving the last vancomycin dose to appropriately assess any changes.

Statistical analysis of categorical data were analyzed using a χ2 test on the GraphPad online program. This study received institutional review board approval from the University of Florida and was conducted in accordance with protections for human subjects.

Results

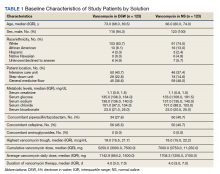

A total of 792 veterans received IV vancomycin NF/SGVHS in the defined study period. Of these, 381 veterans were excluded, including having < 80% of doses in a single solution (213 veterans), receiving IV vancomycin for < 48 hours (149 veterans), and not having necessary laboratory data available to assess a change in kidney function (19 veterans). An additional 165 veterans were randomly excluded from the D5W cohort in order to have an equal comparison group to the NS cohort; therefore, a total of 246 veterans were included in the final assessment (123 veterans in each cohort). The median patient age was 73 years (IQR, 68.0, 80.5) in the D5W group and 66 years (IQR, 60.0, 74.0) in the NS group; 83.7% of veterans in the D5W group and 74% veterans in the NS group were white; 94.3% of the D5W group and 100% of the NS group were male (Table 1).

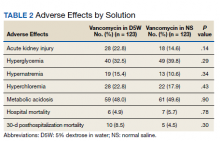

The percentage of AKI in the D5W group was 22.8% compared with 14.6% in the NS group (P = .14), and all cases were classified as stage 1 AKI. Baseline cases of hyperglycemia, hypernatremia, hyperchloremia, or metabolic acidosis were not included in the reported rates of each in order to determine a change during vancomycin therapy (Table 2).

The percentage of patients with hyperglycemia in the D5W group was 32.5% compared with 39.8% in the NS group (P = .29). The percentage of patients with hypernatremia in the D5W group was 15.4% compared with 10.6% in the NS group (P = .34). The percentage of patients with hyperchloremia in the D5W group was 22.8% compared with 17.9% in the NS group (P = .43). The percentage of patients with metabolic acidosis in the D5W group was 48.0% compared with 49.6% in the NS group (P = .90).

There were no significant differences in either in-hospital or posthospital mortality between the D5W and NS groups (in-hospital: 4.9% vs 5.7%, respectively; P = .78; 30-day posthospitalization: 8.5% vs 4.5%, respectively; P = .30).

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study comparing the AEs of vancomycin diluted in NS and vancomycin diluted with D5W showed no statistically significant differences in the incidence of AKI or any metabolic AEs. Although these results did not show an association between the incidence of AEs and the dilution fluid for vancomycin, other factors may contribute to the overall incidence of AEs. Factors such as cumulative vancomycin dose, duration of therapy, and presence of concomitant nephrotoxins have been known to increase the incidence of AKI and may have a greater impact on this incidence than the fluid used in administering the vancomycin.

These results specifically the incidence of AKI were not consistent with previous trials evaluating the AEs of NS. Based on previous trials, we expected the vancomycin in the NS cohort to have a significantly higher incidence of hypernatremia, hyperchloremia, and AKI. Our results may indicate that the volume of crystalloid received played a greater role on the incidence of AEs. Our study assessed the effect of a diluent for one IV medication that may have been only a few hundred milliliters of fluid per day. The total volume of IV fluid received from vancomycin was not assessed; thus, it is not known how the volume of fluid may have impacted the results.

One consideration with this study is the method used for monitoring vancomycin levels. Most of the patients included in this study were admitted prior to the release of the updated vancomycin guidelines, which advocated for the transition from traditional trough-only monitoring to AUC/MIC. In September 2019, NF/SGVHS ICUs made the transition to this new method of monitoring with a hospital-wide transition following the study end date. The D5W group had a slightly higher percentage of patients admitted to the ICU, thus were more likely to be monitored using AUC/MIC during this period. Literature has shown the AUC/MIC method of monitoring can result in a decreased daily dose, decreased trough levels, and decreased incidence of nephrotoxicity.11-14 Although the method for monitoring vancomycin has the potential to affect the incidence of AKI, the majority of patients were monitored using the traditional trough-only method with similar trough levels reported in both groups.

Limitations

This study is limited by its retrospective nature, the potential introduction of biases, and the inability to control for confounders that may have influenced the incidence of AEs. Potential confounders present in this study included the use of concomitant nephrotoxic medications, vancomycin dose, and underlying conditions, as these could have impacted the overall incidence of AEs.

The combination of piperacillin/tazobactam plus vancomycin has commonly been associated with an increased risk of nephrotoxicity. Previous studies have identified this nephrotoxic combination to have a significantly increased risk of AKI compared with vancomycin alone or when used in combination with alternative antibiotics such as cefepime or meropenem.15,16 In our study, there was a higher percentage of patients in the NS group with concomitant piperacillin/tazobactam, so this difference between the groups may have influenced the incidence of AKI. Nephrotoxic medications other than antibiotics were not assessed in this study; however, these also could have impacted our results significantly. While the vancomycin duration of therapy and highest trough levels were similar between groups, the NS group had a larger average daily dose and overall cumulative dose. Studies have identified the risk of nephrotoxicity increases with a vancomycin daily dose of 4 g, troughs > 15 mg/mL, and a duration of therapy > 7 days.15,16 In our study, the daily doses in both groups were < 4 g, so it is likely the average daily vancomycin dose had little impact on the incidence of AKI.

Another potential confounder identified was assessment of underlying conditions in the patients. Due to the limitations associated with the data extraction method, we could not assess for underlying conditions that may have impacted the results. Notably, the potential nephrotoxicity of NS has mostly been shown in critically ill patients. Therefore, the mixed acutely ill patient sample in this study may have been less likely to develop AKI from NS compared with an exclusively critically ill patient sample.

Selection bias and information bias are common with observational studies. In our study, selection bias may have been present since prospective randomization of patient samples was not possible. Since all data were extracted from the medical health record, information bias may have been present with the potential to impact the results. Due to the single-center nature of this study with a predominantly older, white male veteran patient sample, generalizability to other patient populations may be limited. We would expect the results of this study to be similar among other patient populations of a similar age and demographic; however, the external validity of this study may be weak among other populations. Although this study included enough patients based on sample size estimate, a larger sample size could have allowed for detection of smaller differences between groups and decreased the chance for type II error.

Conclusions

Overall, the results of this study do not suggest that the crystalloid used to dilute IV vancomycin is associated with differences in nephrotoxicity or other relevant AEs. Future studies evaluating the potential for AEs from medication diluent are warranted and would benefit from a prospective, randomized design. Further studies are both necessary and crucial for enhancing the quality of care to minimize the rates of AEs of commonly used medications.

Acknowledgment

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System in Gainesville, Florida.

1. Vancomycin hydrochloride intravenous injection, pharmacy bulk package. Package insert. Schaumburg, IL: APP Pharmaceuticals, LLC; 2011.

2. Rybak MJ, Le J, Lodise TP, et al. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin for serious methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: a revised consensus guideline and review by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am J Health-System Pharm. 2020;77(11):835-864. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxaa036

3. Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, et al; Acute Kidney Injury Network. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11(2):R31. doi:10.1186/cc5713

4. Elaysi S, Khalili H, Dashti-Khavidaki S, Mohammadpour A. Vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity: mechanism, incidence, risk factors and special populations–a literature review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68(9):1243-1255. doi:10.1007/s00228-012-1259-9

5. Gyamlani G, Potukuchi PK, Thomas F, et al. Vancomycin-associated acute kidney injury in a large veteran population. Am J Nephrol. 2019;49(2):133-142. doi:10.1159/000496484

6. Semler MW, Self WH, Wanderer JB, et al; SMART Investigators and the Pragmatic Critical Care Research Group. Balanced crystalloids versus saline in critically ill adults. N Engl Med. 2018;378(9):829-839. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1711584

7. Self WH, Semler MW, Wanderer JP, et al; SMART Investigators and the Pragmatic Critical Care Research Group. Balanced crystalloids versus saline in noncritically ill adults. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(20):819-828. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1804294

8. Young P, Bailey M, Beasley R, et al; SPLIT Investigators; ANZICS CTG. Effect of a buffered crystalloid solution vs saline on acute kidney injury among patients in the intensive care unit: the SPLIT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015;314(16):1701-1710. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.12334

9. Magee CA, Bastin ML, Bastin T, et al. Insidious harm of medication diluents as a contributor to cumulative volume and hyperchloremia: a prospective, open-label, sequential period pilot study. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(8):1217-1223. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000003191

10. Adeva-Andany MM, Fernández-Fernández C, Mouriño-Bayolo D, Castro-Quintela E, Domínguez-Montero A. Sodium bicarbonate therapy in patients with metabolic acidosis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:627673. doi:10.1155/2014/627673

11. Mcgrady KA, Benton M, Tart S, Bowers R. Evaluation of traditional vancomycin dosing versus utilizing an electronic AUC/MIC dosing program. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2020;18(3):2024. doi:10.18549/PharmPract.2020.3.2024

12. Clark L, Skrupky LP, Servais R, Brummitt CF, Dilworth TJ. Examining the relationship between vancomycin area under the concentration time curve and serum trough levels in adults with presumed or documented staphylococcal infections. Ther Drug Monit. 2019;41(4):483-488. doi:10.1097/FTD.0000000000000622

13. Neely MN, Kato L, Youn G, et al. Prospective trial on the use of trough concentration versus area under the curve to determine therapeutic vancomycin dosing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(2):e02042-17. doi:10.1128/AAC.02042-17

14. Aljefri DM, Avedissian SN, Youn G, et al. Vancomycin area under the curve and acute kidney injury: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69(11):1881-1887. doi:10.1128/AAC.02042-17

15. Molina KC, Barletta JF, Hall ST, Yazdani C, Huang V. The risk of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients receiving concomitant vancomycin with piperacillin-tazobactam or cefepime. J Intensive Care Med. 2019;35(12):1434-1438. doi:10.1177/0885066619828290