User login

Five reasons sacubitril/valsartan should not be approved for HFpEF

In an ideal world, people could afford sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto), and clinicians would be allowed to prescribe it using clinical judgment as their guide. The imprimatur of an “[Food and Drug Administration]–labeled indication” would be unnecessary.

This is not our world. Guideline writers, third-party payers, and FDA regulators now play major roles in clinical decisions.

The angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor is approved for use in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). In December 2020, an FDA advisory committee voted 12-1 in support of a vaguely worded question: Does PARAGON-HF provide sufficient evidence to support any indication for the drug in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF)? The committee did not reach a consensus on what that indication should be.

Before I list five reasons why I hope the FDA does not approve the drug for any indication in patients with HFpEF, let’s review the seminal trial.

PARAGON-HF

PARAGON-HF randomly assigned slightly more than 4,800 patients with symptomatic HFpEF (left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] ≥45%) to sacubitril/valsartan or valsartan alone. The primary endpoint was total hospitalizations for heart failure (HHF) and death because of cardiovascular (CV) events.

Sacubitril/valsartan reduced the rate of the primary endpoint by 13% (rate ratio, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.75-1.01; P = .06). There were 894 primary endpoint events in the sacubitril/valsartan arm, compared with 1,009 events in the valsartan arm.

The lower rate of events in the sacubitril/valsartan arm was driven by fewer hospitalizations for heart failure. CV death was essentially the same in both arms (204 deaths in the sacubitril/valsartan group versus 212 deaths in the valsartan group).

A note on the patients: the investigators screened more than 10,000 patients and enrolled less than half of them. The mean age was 73 years; 52% of patients were women, but only 2% were Black. The mean LVEF was 57%; 95% of patients had hypertension and were receiving diuretics at baseline.

Now to the five reasons not to approve the drug for this indication.

1. Uncertainty of benefit in HFpEF

A P value for the primary endpoint greater than the threshold of .05 suggests some degree of uncertainty. A nice way of describing this uncertainty is with a Bayesian analysis. Whereas a P value tells you the chance of seeing these results if the drug has no benefit, the Bayesian approach tells you the chance of drug benefit given the trial results.

By email, James Brophy, MD, a senior scientist in the Centre for Outcomes Research and Evaluation at McGill University, Montreal, showed me a Bayesian calculation of PARAGON-HF. He estimated a 38% chance that sacubitril/valsartan had a clinically meaningful 15% reduction in the primary endpoint, a 3% chance that it worsens outcomes, and a 58% chance that it is essentially no better than valsartan.

The take-home is that, in PARAGON-HF, a best-case scenario involving select high-risk patients with run-in periods and trial-level follow-up, there is substantial uncertainty as to whether the drug is any better than a generic standard.

2. Modest effect size in PARAGON-HF

Let’s assume the benefit seen in PARAGON-HF is not caused by chance. Was the effect clinically significant?

For context, consider the large effect size that sacubitril/valsartan had versus enalapril for patients with HFrEF.

In PARADIGM-HF, sacubitril/valsartan led to a 20% reduction in the composite primary endpoint. Importantly, this included equal reductions in both HHF and CV death. All-cause death was also significantly reduced in the active arm.

Because patients with HFpEF have a similarly poor prognosis as those with HFrEF, a truly beneficial drug should reduce not only HHF but also CV death and overall death. The lack of effect on these “harder” endpoints in PARAGON-HF points to a far more modest effect size for sacubitril/valsartan in HFpEF.

What’s more, even the signal of reduced HHF in PARAGON-HF is tenuous. The PARAGON-HF authors chose total HHF, whereas previous trials in patients with HFpEF used first HHF as their primary endpoint. Had PARAGON-HF followed the methods of prior trials, first HHF would not have made statistical significance (hazard ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.79-1.04)

3. Subgroups not compelling

Proponents highlight the possibility that sacubitril/valsartan exerted a heterogenous effect in two subgroups.

In women, sacubitril/valsartan resulted in a 27% reduction in the primary endpoint (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.59-0.90), whereas men showed no significant difference (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.85-1.25). And the drug seemed to have little benefit over valsartan in patients with a median LVEF greater than 57%.

The problem with subgroups is that, if you look at enough of them, some can be positive on the basis of chance alone. For instance, patients enrolled in western Europe had an outsized benefit from sacubitril/valsartan, compared with patients from other areas.

FDA reviewers noted: “It is possible that the heterogeneity of treatment effect observed in the subgroups by gender and LVEF in PARAGON-HF is a chance finding.”

By email, clinical trial expert Sanjay Kaul, MD, from Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, expressed serious concern with the subgroup analyses in PARAGON-HF because the sex interaction was confined to HHF alone. There was no interaction for other outcomes, such as CV death, all-cause mortality, renal endpoints, blood pressure, or lowering of N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide.

Similarly, the interaction with ejection fraction was confined to total HHF; it was not seen with New York Heart Association class improvement, all-cause mortality, quality of life, renal endpoints, or time to first event.

Dr. Kaul also emphasized something cardiologists know well, “that ejection fraction is not a static variable and is expected to change during the course of the trial.” This point makes it hard to believe that a partially subjective measurement, such as LVEF, could be a precise modifier of benefit.

4. Approval would stop research

If the FDA approves sacubitril/valsartan for patients with HFpEF, there is a near-zero chance we will learn whether there are subsets of patients who benefit more or less from the drug.

It will be the defibrillator problem all over again. Namely, while the average effect of a defibrillator is to reduce mortality in patients with HFrEF, in approximately 9 of 10 patients the implanted device is never used. Efforts to find subgroups that are most likely to need (or not need) an implantable defibrillator have been impossible because industry has no incentive to fund trials that may narrow the number of patients who qualify for their product.

It will be the same with sacubitril/valsartan. This is not nefarious; it is merely a limitation of industry funding of trials.

5. Opportunity costs

The category of HFpEF is vast.

FDA approval – even for a subset of these patients – would have huge cost implications. I understand cost issues are considered outside the purview of the FDA, but health care spending isn’t infinite. Money spent covering this costly drug is money not available for other things.

Despite this nation’s wealth, we struggle to provide even basic care to large numbers of people. Approval of an expensive drug with no or modest benefit will only exacerbate these stark disparities.

Conclusion

Given our current system of health care delivery, my pragmatic answer is for the FDA to say no to sacubitril/valsartan for HFpEF.

If you believe the drug has outsized benefits in women or those with mild impairment of systolic function, the way to answer these questions is not with subgroup analyses from a trial that did not reach statistical significance in its primary endpoint, but with more randomized trials. Isn’t that what “exploratory” subgroups are for?

Holding off on an indication for HFpEF will force proponents to define a subset of patients who garner a clear and substantial benefit from sacubitril/valsartan.

Dr. Mandrola practices cardiac electrophysiology in Louisville, Ky., and is a writer and podcaster for Medscape. He espouses a conservative approach to medical practice. He participates in clinical research and writes often about the state of medical evidence. MDedge is part of the Medscape Professional Network.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In an ideal world, people could afford sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto), and clinicians would be allowed to prescribe it using clinical judgment as their guide. The imprimatur of an “[Food and Drug Administration]–labeled indication” would be unnecessary.

This is not our world. Guideline writers, third-party payers, and FDA regulators now play major roles in clinical decisions.

The angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor is approved for use in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). In December 2020, an FDA advisory committee voted 12-1 in support of a vaguely worded question: Does PARAGON-HF provide sufficient evidence to support any indication for the drug in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF)? The committee did not reach a consensus on what that indication should be.

Before I list five reasons why I hope the FDA does not approve the drug for any indication in patients with HFpEF, let’s review the seminal trial.

PARAGON-HF

PARAGON-HF randomly assigned slightly more than 4,800 patients with symptomatic HFpEF (left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] ≥45%) to sacubitril/valsartan or valsartan alone. The primary endpoint was total hospitalizations for heart failure (HHF) and death because of cardiovascular (CV) events.

Sacubitril/valsartan reduced the rate of the primary endpoint by 13% (rate ratio, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.75-1.01; P = .06). There were 894 primary endpoint events in the sacubitril/valsartan arm, compared with 1,009 events in the valsartan arm.

The lower rate of events in the sacubitril/valsartan arm was driven by fewer hospitalizations for heart failure. CV death was essentially the same in both arms (204 deaths in the sacubitril/valsartan group versus 212 deaths in the valsartan group).

A note on the patients: the investigators screened more than 10,000 patients and enrolled less than half of them. The mean age was 73 years; 52% of patients were women, but only 2% were Black. The mean LVEF was 57%; 95% of patients had hypertension and were receiving diuretics at baseline.

Now to the five reasons not to approve the drug for this indication.

1. Uncertainty of benefit in HFpEF

A P value for the primary endpoint greater than the threshold of .05 suggests some degree of uncertainty. A nice way of describing this uncertainty is with a Bayesian analysis. Whereas a P value tells you the chance of seeing these results if the drug has no benefit, the Bayesian approach tells you the chance of drug benefit given the trial results.

By email, James Brophy, MD, a senior scientist in the Centre for Outcomes Research and Evaluation at McGill University, Montreal, showed me a Bayesian calculation of PARAGON-HF. He estimated a 38% chance that sacubitril/valsartan had a clinically meaningful 15% reduction in the primary endpoint, a 3% chance that it worsens outcomes, and a 58% chance that it is essentially no better than valsartan.

The take-home is that, in PARAGON-HF, a best-case scenario involving select high-risk patients with run-in periods and trial-level follow-up, there is substantial uncertainty as to whether the drug is any better than a generic standard.

2. Modest effect size in PARAGON-HF

Let’s assume the benefit seen in PARAGON-HF is not caused by chance. Was the effect clinically significant?

For context, consider the large effect size that sacubitril/valsartan had versus enalapril for patients with HFrEF.

In PARADIGM-HF, sacubitril/valsartan led to a 20% reduction in the composite primary endpoint. Importantly, this included equal reductions in both HHF and CV death. All-cause death was also significantly reduced in the active arm.

Because patients with HFpEF have a similarly poor prognosis as those with HFrEF, a truly beneficial drug should reduce not only HHF but also CV death and overall death. The lack of effect on these “harder” endpoints in PARAGON-HF points to a far more modest effect size for sacubitril/valsartan in HFpEF.

What’s more, even the signal of reduced HHF in PARAGON-HF is tenuous. The PARAGON-HF authors chose total HHF, whereas previous trials in patients with HFpEF used first HHF as their primary endpoint. Had PARAGON-HF followed the methods of prior trials, first HHF would not have made statistical significance (hazard ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.79-1.04)

3. Subgroups not compelling

Proponents highlight the possibility that sacubitril/valsartan exerted a heterogenous effect in two subgroups.

In women, sacubitril/valsartan resulted in a 27% reduction in the primary endpoint (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.59-0.90), whereas men showed no significant difference (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.85-1.25). And the drug seemed to have little benefit over valsartan in patients with a median LVEF greater than 57%.

The problem with subgroups is that, if you look at enough of them, some can be positive on the basis of chance alone. For instance, patients enrolled in western Europe had an outsized benefit from sacubitril/valsartan, compared with patients from other areas.

FDA reviewers noted: “It is possible that the heterogeneity of treatment effect observed in the subgroups by gender and LVEF in PARAGON-HF is a chance finding.”

By email, clinical trial expert Sanjay Kaul, MD, from Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, expressed serious concern with the subgroup analyses in PARAGON-HF because the sex interaction was confined to HHF alone. There was no interaction for other outcomes, such as CV death, all-cause mortality, renal endpoints, blood pressure, or lowering of N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide.

Similarly, the interaction with ejection fraction was confined to total HHF; it was not seen with New York Heart Association class improvement, all-cause mortality, quality of life, renal endpoints, or time to first event.

Dr. Kaul also emphasized something cardiologists know well, “that ejection fraction is not a static variable and is expected to change during the course of the trial.” This point makes it hard to believe that a partially subjective measurement, such as LVEF, could be a precise modifier of benefit.

4. Approval would stop research

If the FDA approves sacubitril/valsartan for patients with HFpEF, there is a near-zero chance we will learn whether there are subsets of patients who benefit more or less from the drug.

It will be the defibrillator problem all over again. Namely, while the average effect of a defibrillator is to reduce mortality in patients with HFrEF, in approximately 9 of 10 patients the implanted device is never used. Efforts to find subgroups that are most likely to need (or not need) an implantable defibrillator have been impossible because industry has no incentive to fund trials that may narrow the number of patients who qualify for their product.

It will be the same with sacubitril/valsartan. This is not nefarious; it is merely a limitation of industry funding of trials.

5. Opportunity costs

The category of HFpEF is vast.

FDA approval – even for a subset of these patients – would have huge cost implications. I understand cost issues are considered outside the purview of the FDA, but health care spending isn’t infinite. Money spent covering this costly drug is money not available for other things.

Despite this nation’s wealth, we struggle to provide even basic care to large numbers of people. Approval of an expensive drug with no or modest benefit will only exacerbate these stark disparities.

Conclusion

Given our current system of health care delivery, my pragmatic answer is for the FDA to say no to sacubitril/valsartan for HFpEF.

If you believe the drug has outsized benefits in women or those with mild impairment of systolic function, the way to answer these questions is not with subgroup analyses from a trial that did not reach statistical significance in its primary endpoint, but with more randomized trials. Isn’t that what “exploratory” subgroups are for?

Holding off on an indication for HFpEF will force proponents to define a subset of patients who garner a clear and substantial benefit from sacubitril/valsartan.

Dr. Mandrola practices cardiac electrophysiology in Louisville, Ky., and is a writer and podcaster for Medscape. He espouses a conservative approach to medical practice. He participates in clinical research and writes often about the state of medical evidence. MDedge is part of the Medscape Professional Network.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In an ideal world, people could afford sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto), and clinicians would be allowed to prescribe it using clinical judgment as their guide. The imprimatur of an “[Food and Drug Administration]–labeled indication” would be unnecessary.

This is not our world. Guideline writers, third-party payers, and FDA regulators now play major roles in clinical decisions.

The angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor is approved for use in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). In December 2020, an FDA advisory committee voted 12-1 in support of a vaguely worded question: Does PARAGON-HF provide sufficient evidence to support any indication for the drug in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF)? The committee did not reach a consensus on what that indication should be.

Before I list five reasons why I hope the FDA does not approve the drug for any indication in patients with HFpEF, let’s review the seminal trial.

PARAGON-HF

PARAGON-HF randomly assigned slightly more than 4,800 patients with symptomatic HFpEF (left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] ≥45%) to sacubitril/valsartan or valsartan alone. The primary endpoint was total hospitalizations for heart failure (HHF) and death because of cardiovascular (CV) events.

Sacubitril/valsartan reduced the rate of the primary endpoint by 13% (rate ratio, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.75-1.01; P = .06). There were 894 primary endpoint events in the sacubitril/valsartan arm, compared with 1,009 events in the valsartan arm.

The lower rate of events in the sacubitril/valsartan arm was driven by fewer hospitalizations for heart failure. CV death was essentially the same in both arms (204 deaths in the sacubitril/valsartan group versus 212 deaths in the valsartan group).

A note on the patients: the investigators screened more than 10,000 patients and enrolled less than half of them. The mean age was 73 years; 52% of patients were women, but only 2% were Black. The mean LVEF was 57%; 95% of patients had hypertension and were receiving diuretics at baseline.

Now to the five reasons not to approve the drug for this indication.

1. Uncertainty of benefit in HFpEF

A P value for the primary endpoint greater than the threshold of .05 suggests some degree of uncertainty. A nice way of describing this uncertainty is with a Bayesian analysis. Whereas a P value tells you the chance of seeing these results if the drug has no benefit, the Bayesian approach tells you the chance of drug benefit given the trial results.

By email, James Brophy, MD, a senior scientist in the Centre for Outcomes Research and Evaluation at McGill University, Montreal, showed me a Bayesian calculation of PARAGON-HF. He estimated a 38% chance that sacubitril/valsartan had a clinically meaningful 15% reduction in the primary endpoint, a 3% chance that it worsens outcomes, and a 58% chance that it is essentially no better than valsartan.

The take-home is that, in PARAGON-HF, a best-case scenario involving select high-risk patients with run-in periods and trial-level follow-up, there is substantial uncertainty as to whether the drug is any better than a generic standard.

2. Modest effect size in PARAGON-HF

Let’s assume the benefit seen in PARAGON-HF is not caused by chance. Was the effect clinically significant?

For context, consider the large effect size that sacubitril/valsartan had versus enalapril for patients with HFrEF.

In PARADIGM-HF, sacubitril/valsartan led to a 20% reduction in the composite primary endpoint. Importantly, this included equal reductions in both HHF and CV death. All-cause death was also significantly reduced in the active arm.

Because patients with HFpEF have a similarly poor prognosis as those with HFrEF, a truly beneficial drug should reduce not only HHF but also CV death and overall death. The lack of effect on these “harder” endpoints in PARAGON-HF points to a far more modest effect size for sacubitril/valsartan in HFpEF.

What’s more, even the signal of reduced HHF in PARAGON-HF is tenuous. The PARAGON-HF authors chose total HHF, whereas previous trials in patients with HFpEF used first HHF as their primary endpoint. Had PARAGON-HF followed the methods of prior trials, first HHF would not have made statistical significance (hazard ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.79-1.04)

3. Subgroups not compelling

Proponents highlight the possibility that sacubitril/valsartan exerted a heterogenous effect in two subgroups.

In women, sacubitril/valsartan resulted in a 27% reduction in the primary endpoint (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.59-0.90), whereas men showed no significant difference (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.85-1.25). And the drug seemed to have little benefit over valsartan in patients with a median LVEF greater than 57%.

The problem with subgroups is that, if you look at enough of them, some can be positive on the basis of chance alone. For instance, patients enrolled in western Europe had an outsized benefit from sacubitril/valsartan, compared with patients from other areas.

FDA reviewers noted: “It is possible that the heterogeneity of treatment effect observed in the subgroups by gender and LVEF in PARAGON-HF is a chance finding.”

By email, clinical trial expert Sanjay Kaul, MD, from Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, expressed serious concern with the subgroup analyses in PARAGON-HF because the sex interaction was confined to HHF alone. There was no interaction for other outcomes, such as CV death, all-cause mortality, renal endpoints, blood pressure, or lowering of N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide.

Similarly, the interaction with ejection fraction was confined to total HHF; it was not seen with New York Heart Association class improvement, all-cause mortality, quality of life, renal endpoints, or time to first event.

Dr. Kaul also emphasized something cardiologists know well, “that ejection fraction is not a static variable and is expected to change during the course of the trial.” This point makes it hard to believe that a partially subjective measurement, such as LVEF, could be a precise modifier of benefit.

4. Approval would stop research

If the FDA approves sacubitril/valsartan for patients with HFpEF, there is a near-zero chance we will learn whether there are subsets of patients who benefit more or less from the drug.

It will be the defibrillator problem all over again. Namely, while the average effect of a defibrillator is to reduce mortality in patients with HFrEF, in approximately 9 of 10 patients the implanted device is never used. Efforts to find subgroups that are most likely to need (or not need) an implantable defibrillator have been impossible because industry has no incentive to fund trials that may narrow the number of patients who qualify for their product.

It will be the same with sacubitril/valsartan. This is not nefarious; it is merely a limitation of industry funding of trials.

5. Opportunity costs

The category of HFpEF is vast.

FDA approval – even for a subset of these patients – would have huge cost implications. I understand cost issues are considered outside the purview of the FDA, but health care spending isn’t infinite. Money spent covering this costly drug is money not available for other things.

Despite this nation’s wealth, we struggle to provide even basic care to large numbers of people. Approval of an expensive drug with no or modest benefit will only exacerbate these stark disparities.

Conclusion

Given our current system of health care delivery, my pragmatic answer is for the FDA to say no to sacubitril/valsartan for HFpEF.

If you believe the drug has outsized benefits in women or those with mild impairment of systolic function, the way to answer these questions is not with subgroup analyses from a trial that did not reach statistical significance in its primary endpoint, but with more randomized trials. Isn’t that what “exploratory” subgroups are for?

Holding off on an indication for HFpEF will force proponents to define a subset of patients who garner a clear and substantial benefit from sacubitril/valsartan.

Dr. Mandrola practices cardiac electrophysiology in Louisville, Ky., and is a writer and podcaster for Medscape. He espouses a conservative approach to medical practice. He participates in clinical research and writes often about the state of medical evidence. MDedge is part of the Medscape Professional Network.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Can ‘big’ be healthy? Yes – and no

While many people were committing to their New Year’s resolutions to lose weight, in January 2020 Cosmopolitan UK magazine released covers portraying 11 women of different shapes and sizes, with the headline, “This is healthy!” Each version of the cover features one or more of the 11 women wearing athletic gear and makeup, some of whom are caught mid-action – boxing, doing yoga, or simply rejoicing in being who they are. Seeing these, I was reminded of a patient I cared for as an intern.

Janet Spears (not her real name) was thin. Standing barely 5 feet 3 inches, she weighed 110 pounds. For those out there who think of size in terms of body mass index (BMI), it was about 20 kg/m2, solidly in the “normal” category. At the age of 62, despite this healthy BMI, she had so much plaque in her arteries that she needed surgery to improve blood flow to her foot.

Admittedly, whenever I had read about people with high cholesterol, type 2 diabetes, or atherosclerosis, I pictured bigger people. But when I met Ms. Spears, I realized that one’s health cannot necessarily be inferred from physical appearance.

As a bariatric surgeon board certified in obesity medicine, I’ve probably spent more time thinking and learning about obesity than most people – and yet I still didn’t know what to make of the Cosmopolitan covers.

I saw the reaction on Twitter before I saw the magazines themselves, and I quickly observed a number of people decrying the covers, suggesting that they promote obesity:

Multiple people suggested that this was inappropriate, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the fact that people with obesity are at risk for worse outcomes, compared with those without obesity. (As an aside, these comments suggest that people did not read the associated article, which is about fitness and body image more than it is about obesity.)

Does size reflect health?

Putting the pandemic aside for a moment, the question the magazine covers raise is whether physical appearance reflects health. That’s what got me thinking about Ms. Spears, who, though appearing healthy, was sick enough that she needed to have major surgery. This whole conversation hinges, of course, on one’s definition of health.

A common knee-jerk response, especially from physicians, would be to say that obesity is by definition unhealthy. Some researchers have suggested though that a segment of people with obesity fall into a category called metabolically healthy obesity, which is typically characterized by a limited set of data such as cholesterol, blood sugar, and blood pressure. Indeed, some people with obesity have normal values in those categories.

Being metabolically healthy, however, does not preclude other medical problems associated with obesity, including joint pain, cancer, and mood disorders, among other issues. So even those who have metabolically healthy obesity are not necessarily immune to the many other obesity-related conditions.

What about body positivity?

As I delved further into the conversation about these covers, I saw people embracing the idea of promoting different-sized bodies. With almost two thirds of the U.S. population having overweight or obesity, one might argue that it’s high time magazine covers and the media reflect the reality in our hometowns. Unrealistic images in the media are associated with negative self-image and disordered eating, so perhaps embracing the shapes of real people may help us all have healthier attitudes toward our bodies.

That said, this idea can be taken too far. The Health at Every Size movement, which some might consider to be the ultimate body-positivity movement, espouses the idea that size and health are completely unrelated. That crosses a line between what we know to be true – that, at a population level, higher weight is associated with more medical problems – and fake news.

Another idea to consider is fitness, as opposed to health. Fitness can be defined multiple ways, but if we consider it to be measured exercise capacity, those who are more fit have a longer life expectancy than those with lower fitness levels at a given BMI. While some feel that the Cosmopolitan covers promote obesity and are therefore irresponsible, it’s at least as likely that highlighting people with obesity being active may inspire others with obesity to do the same.

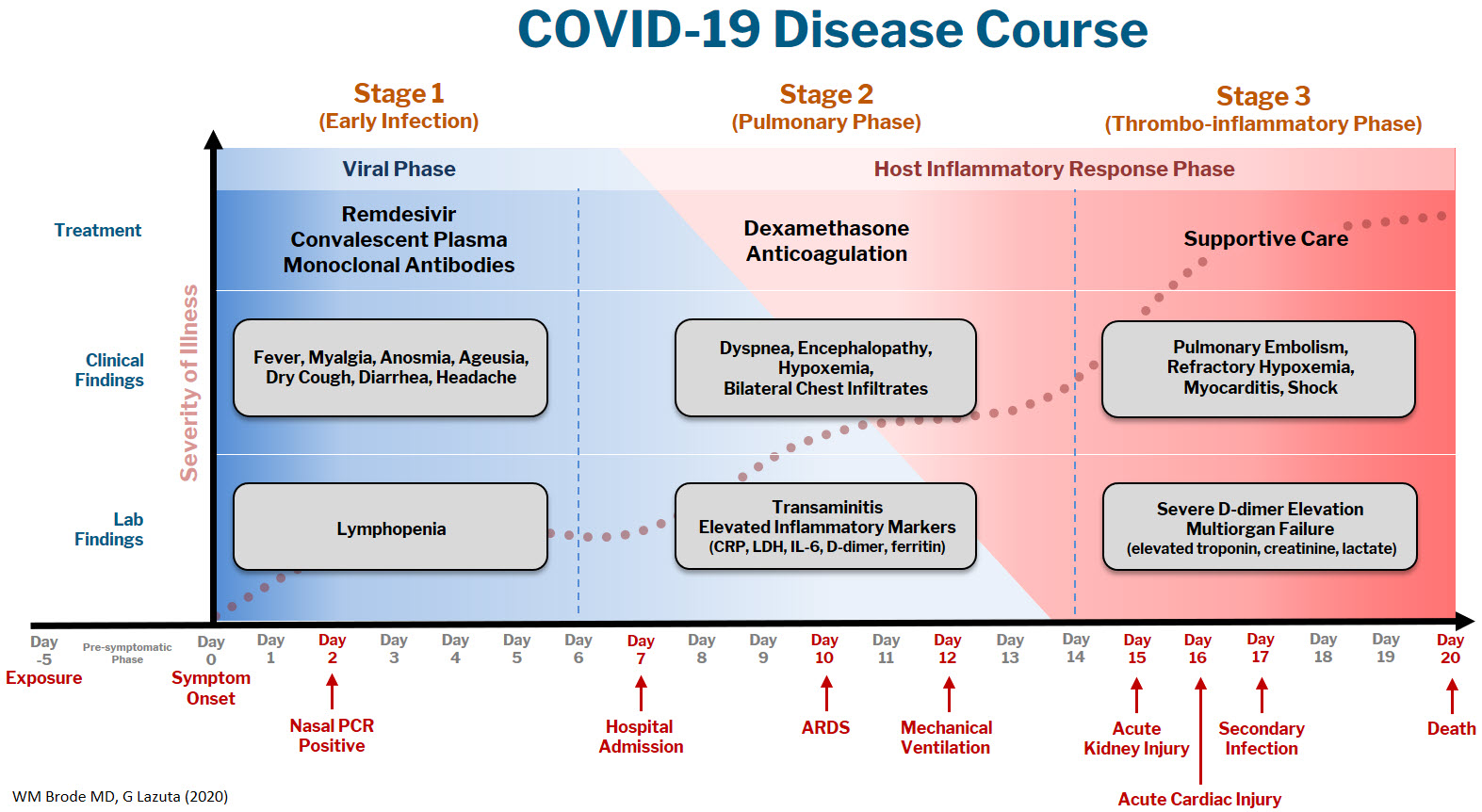

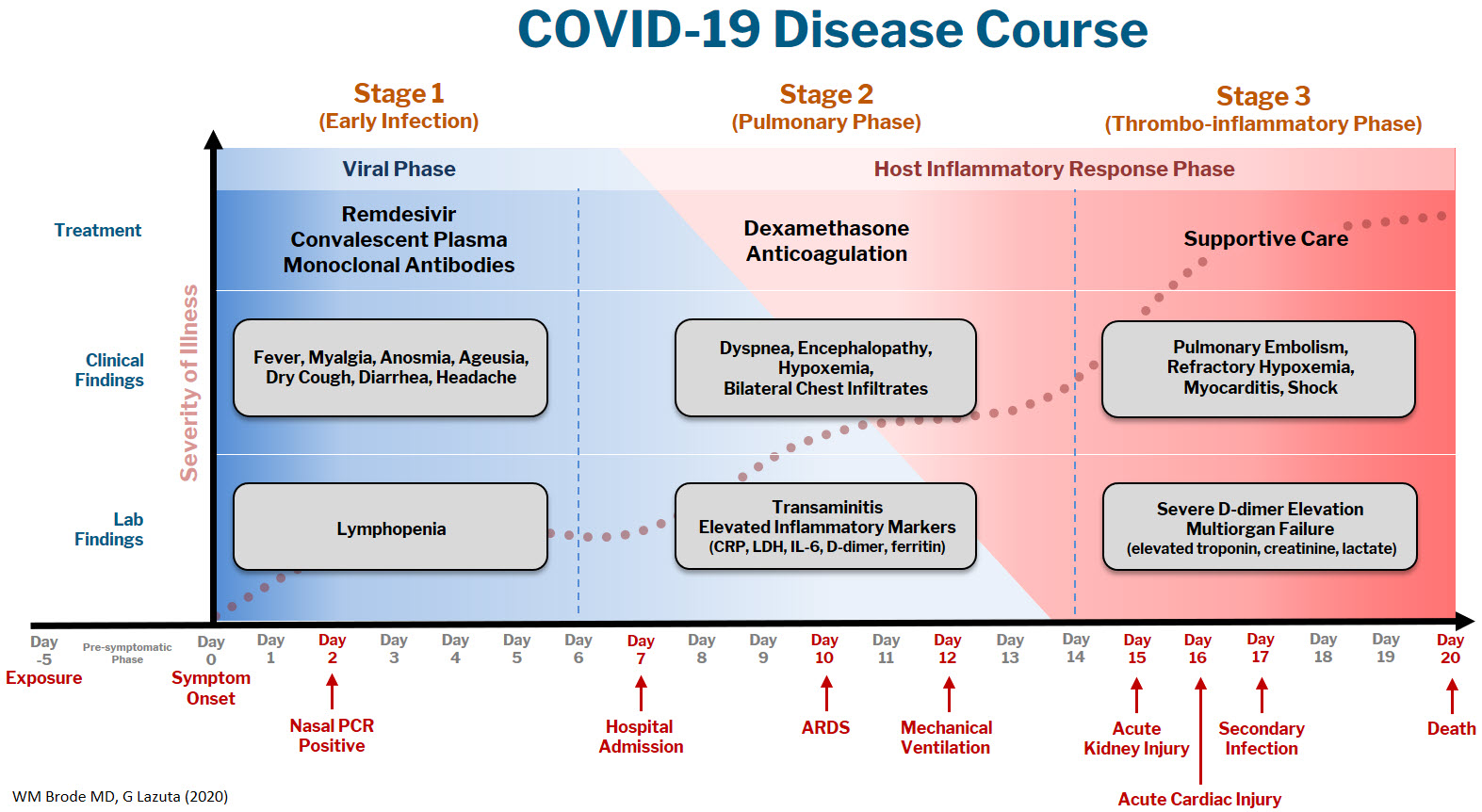

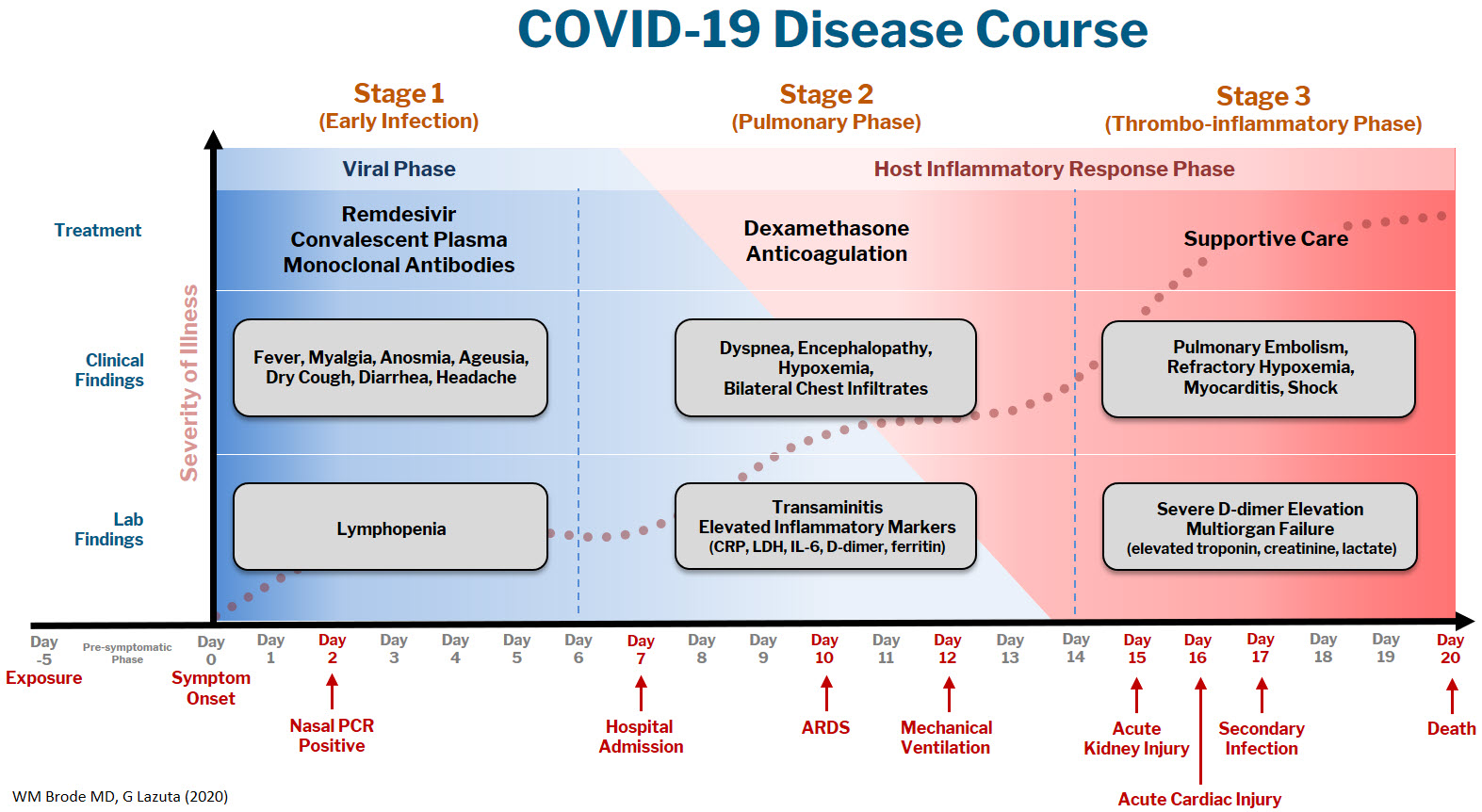

Now let’s bring the pandemic back into the picture. As much as we all wish that it was over, with uncontrolled spread in every state and record numbers of people dying, COVID-19 is still very much a part of our reality. Having obesity increases the risk of having a severe case of COVID-19 if infected. Patients with obesity are also more likely than those without obesity to be hospitalized, require intensive care, and die with COVID-19.

Guiding the conversation

Pandemic or not, the truth is that obesity is related to multiple medical problems. That does not mean that every person with obesity has medical problems. The musician Lizzo, for example, is someone with obesity who considers herself to be healthy. She posts images and videos of working out and shares her personal fitness routine with her millions of fans. As a physician, I worry about the medical conditions – metabolic or otherwise – that someone like her may develop. But I love how she embraces who she is while striving to be healthier.

Most of the critical comments I have seen about the Cosmopolitan covers have, at best, bordered on fat shaming; others are solidly in that category. And the vitriol aimed at the larger models is despicable. It seems that conversations about obesity often vacillate from one extreme (fat shaming) to the other (extreme body positivity).

Although it may not sell magazines, I would love to see more nuanced, fact-based discussions, both in the media and in our clinics. We can start by acknowledging the fact that people of different sizes can be healthy. The truth is that we can’t tell very much about a person’s health from their outward appearance, and we should probably stop trying to make such inferences.

Assessment of health is most accurately judged by each person with their medical team, not by observers who use media images as part of their own propaganda machine, pushing one extreme view or another. As physicians, we have the opportunity and the responsibility to support our patients in the pursuit of health, without shame or judgment. Maybe that’s a New Year’s resolution worth committing to.

Arghavan Salles, MD, PhD, is a bariatric surgeon.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While many people were committing to their New Year’s resolutions to lose weight, in January 2020 Cosmopolitan UK magazine released covers portraying 11 women of different shapes and sizes, with the headline, “This is healthy!” Each version of the cover features one or more of the 11 women wearing athletic gear and makeup, some of whom are caught mid-action – boxing, doing yoga, or simply rejoicing in being who they are. Seeing these, I was reminded of a patient I cared for as an intern.

Janet Spears (not her real name) was thin. Standing barely 5 feet 3 inches, she weighed 110 pounds. For those out there who think of size in terms of body mass index (BMI), it was about 20 kg/m2, solidly in the “normal” category. At the age of 62, despite this healthy BMI, she had so much plaque in her arteries that she needed surgery to improve blood flow to her foot.

Admittedly, whenever I had read about people with high cholesterol, type 2 diabetes, or atherosclerosis, I pictured bigger people. But when I met Ms. Spears, I realized that one’s health cannot necessarily be inferred from physical appearance.

As a bariatric surgeon board certified in obesity medicine, I’ve probably spent more time thinking and learning about obesity than most people – and yet I still didn’t know what to make of the Cosmopolitan covers.

I saw the reaction on Twitter before I saw the magazines themselves, and I quickly observed a number of people decrying the covers, suggesting that they promote obesity:

Multiple people suggested that this was inappropriate, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the fact that people with obesity are at risk for worse outcomes, compared with those without obesity. (As an aside, these comments suggest that people did not read the associated article, which is about fitness and body image more than it is about obesity.)

Does size reflect health?

Putting the pandemic aside for a moment, the question the magazine covers raise is whether physical appearance reflects health. That’s what got me thinking about Ms. Spears, who, though appearing healthy, was sick enough that she needed to have major surgery. This whole conversation hinges, of course, on one’s definition of health.

A common knee-jerk response, especially from physicians, would be to say that obesity is by definition unhealthy. Some researchers have suggested though that a segment of people with obesity fall into a category called metabolically healthy obesity, which is typically characterized by a limited set of data such as cholesterol, blood sugar, and blood pressure. Indeed, some people with obesity have normal values in those categories.

Being metabolically healthy, however, does not preclude other medical problems associated with obesity, including joint pain, cancer, and mood disorders, among other issues. So even those who have metabolically healthy obesity are not necessarily immune to the many other obesity-related conditions.

What about body positivity?

As I delved further into the conversation about these covers, I saw people embracing the idea of promoting different-sized bodies. With almost two thirds of the U.S. population having overweight or obesity, one might argue that it’s high time magazine covers and the media reflect the reality in our hometowns. Unrealistic images in the media are associated with negative self-image and disordered eating, so perhaps embracing the shapes of real people may help us all have healthier attitudes toward our bodies.

That said, this idea can be taken too far. The Health at Every Size movement, which some might consider to be the ultimate body-positivity movement, espouses the idea that size and health are completely unrelated. That crosses a line between what we know to be true – that, at a population level, higher weight is associated with more medical problems – and fake news.

Another idea to consider is fitness, as opposed to health. Fitness can be defined multiple ways, but if we consider it to be measured exercise capacity, those who are more fit have a longer life expectancy than those with lower fitness levels at a given BMI. While some feel that the Cosmopolitan covers promote obesity and are therefore irresponsible, it’s at least as likely that highlighting people with obesity being active may inspire others with obesity to do the same.

Now let’s bring the pandemic back into the picture. As much as we all wish that it was over, with uncontrolled spread in every state and record numbers of people dying, COVID-19 is still very much a part of our reality. Having obesity increases the risk of having a severe case of COVID-19 if infected. Patients with obesity are also more likely than those without obesity to be hospitalized, require intensive care, and die with COVID-19.

Guiding the conversation

Pandemic or not, the truth is that obesity is related to multiple medical problems. That does not mean that every person with obesity has medical problems. The musician Lizzo, for example, is someone with obesity who considers herself to be healthy. She posts images and videos of working out and shares her personal fitness routine with her millions of fans. As a physician, I worry about the medical conditions – metabolic or otherwise – that someone like her may develop. But I love how she embraces who she is while striving to be healthier.

Most of the critical comments I have seen about the Cosmopolitan covers have, at best, bordered on fat shaming; others are solidly in that category. And the vitriol aimed at the larger models is despicable. It seems that conversations about obesity often vacillate from one extreme (fat shaming) to the other (extreme body positivity).

Although it may not sell magazines, I would love to see more nuanced, fact-based discussions, both in the media and in our clinics. We can start by acknowledging the fact that people of different sizes can be healthy. The truth is that we can’t tell very much about a person’s health from their outward appearance, and we should probably stop trying to make such inferences.

Assessment of health is most accurately judged by each person with their medical team, not by observers who use media images as part of their own propaganda machine, pushing one extreme view or another. As physicians, we have the opportunity and the responsibility to support our patients in the pursuit of health, without shame or judgment. Maybe that’s a New Year’s resolution worth committing to.

Arghavan Salles, MD, PhD, is a bariatric surgeon.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While many people were committing to their New Year’s resolutions to lose weight, in January 2020 Cosmopolitan UK magazine released covers portraying 11 women of different shapes and sizes, with the headline, “This is healthy!” Each version of the cover features one or more of the 11 women wearing athletic gear and makeup, some of whom are caught mid-action – boxing, doing yoga, or simply rejoicing in being who they are. Seeing these, I was reminded of a patient I cared for as an intern.

Janet Spears (not her real name) was thin. Standing barely 5 feet 3 inches, she weighed 110 pounds. For those out there who think of size in terms of body mass index (BMI), it was about 20 kg/m2, solidly in the “normal” category. At the age of 62, despite this healthy BMI, she had so much plaque in her arteries that she needed surgery to improve blood flow to her foot.

Admittedly, whenever I had read about people with high cholesterol, type 2 diabetes, or atherosclerosis, I pictured bigger people. But when I met Ms. Spears, I realized that one’s health cannot necessarily be inferred from physical appearance.

As a bariatric surgeon board certified in obesity medicine, I’ve probably spent more time thinking and learning about obesity than most people – and yet I still didn’t know what to make of the Cosmopolitan covers.

I saw the reaction on Twitter before I saw the magazines themselves, and I quickly observed a number of people decrying the covers, suggesting that they promote obesity:

Multiple people suggested that this was inappropriate, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the fact that people with obesity are at risk for worse outcomes, compared with those without obesity. (As an aside, these comments suggest that people did not read the associated article, which is about fitness and body image more than it is about obesity.)

Does size reflect health?

Putting the pandemic aside for a moment, the question the magazine covers raise is whether physical appearance reflects health. That’s what got me thinking about Ms. Spears, who, though appearing healthy, was sick enough that she needed to have major surgery. This whole conversation hinges, of course, on one’s definition of health.

A common knee-jerk response, especially from physicians, would be to say that obesity is by definition unhealthy. Some researchers have suggested though that a segment of people with obesity fall into a category called metabolically healthy obesity, which is typically characterized by a limited set of data such as cholesterol, blood sugar, and blood pressure. Indeed, some people with obesity have normal values in those categories.

Being metabolically healthy, however, does not preclude other medical problems associated with obesity, including joint pain, cancer, and mood disorders, among other issues. So even those who have metabolically healthy obesity are not necessarily immune to the many other obesity-related conditions.

What about body positivity?

As I delved further into the conversation about these covers, I saw people embracing the idea of promoting different-sized bodies. With almost two thirds of the U.S. population having overweight or obesity, one might argue that it’s high time magazine covers and the media reflect the reality in our hometowns. Unrealistic images in the media are associated with negative self-image and disordered eating, so perhaps embracing the shapes of real people may help us all have healthier attitudes toward our bodies.

That said, this idea can be taken too far. The Health at Every Size movement, which some might consider to be the ultimate body-positivity movement, espouses the idea that size and health are completely unrelated. That crosses a line between what we know to be true – that, at a population level, higher weight is associated with more medical problems – and fake news.

Another idea to consider is fitness, as opposed to health. Fitness can be defined multiple ways, but if we consider it to be measured exercise capacity, those who are more fit have a longer life expectancy than those with lower fitness levels at a given BMI. While some feel that the Cosmopolitan covers promote obesity and are therefore irresponsible, it’s at least as likely that highlighting people with obesity being active may inspire others with obesity to do the same.

Now let’s bring the pandemic back into the picture. As much as we all wish that it was over, with uncontrolled spread in every state and record numbers of people dying, COVID-19 is still very much a part of our reality. Having obesity increases the risk of having a severe case of COVID-19 if infected. Patients with obesity are also more likely than those without obesity to be hospitalized, require intensive care, and die with COVID-19.

Guiding the conversation

Pandemic or not, the truth is that obesity is related to multiple medical problems. That does not mean that every person with obesity has medical problems. The musician Lizzo, for example, is someone with obesity who considers herself to be healthy. She posts images and videos of working out and shares her personal fitness routine with her millions of fans. As a physician, I worry about the medical conditions – metabolic or otherwise – that someone like her may develop. But I love how she embraces who she is while striving to be healthier.

Most of the critical comments I have seen about the Cosmopolitan covers have, at best, bordered on fat shaming; others are solidly in that category. And the vitriol aimed at the larger models is despicable. It seems that conversations about obesity often vacillate from one extreme (fat shaming) to the other (extreme body positivity).

Although it may not sell magazines, I would love to see more nuanced, fact-based discussions, both in the media and in our clinics. We can start by acknowledging the fact that people of different sizes can be healthy. The truth is that we can’t tell very much about a person’s health from their outward appearance, and we should probably stop trying to make such inferences.

Assessment of health is most accurately judged by each person with their medical team, not by observers who use media images as part of their own propaganda machine, pushing one extreme view or another. As physicians, we have the opportunity and the responsibility to support our patients in the pursuit of health, without shame or judgment. Maybe that’s a New Year’s resolution worth committing to.

Arghavan Salles, MD, PhD, is a bariatric surgeon.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Intraoperative rupture of ovarian cancer: Does it worsen outcomes?

Intact removal of an ovarian cyst is a well-established gynecologic surgical principle because ovarian cancer is definitively diagnosed only in retrospect (after ovarian extraction) and intraoperative cyst rupture upstages an otherwise nonmetastatic cancer to stage IC. This lumps cancers that are ruptured during surgical extraction together with those that have spontaneously ruptured or have surface excrescences. The theoretical rationale for this “lumping” is that contact between malignant cells from the ruptured cyst may take hold on peritoneal surfaces resulting in development of metastases. To offset this theoretical risk, it has been recommended that all stage IC ovarian cancer is treated with chemotherapy, whereas low-grade stage IA and IB cancers generally are not. No conscientious surgeon wants their surgical intervention to be the cause of a patient needing toxic chemotherapy. But is the contact between malignant cyst fluid and the peritoneum truly as bad as a spontaneous breach of the surface of the tumor? Or is cyst rupture a confounder for other adverse prognostic features, such as histologic cell type and dense pelvic attachments? If ovarian cyst rupture is an independent risk factor for patients with stage I ovarian cancer, strategies should be employed to avoid this occurrence, and we should understand how to counsel and treat patients in whom this has occurred.

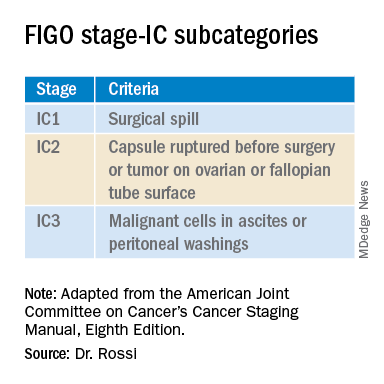

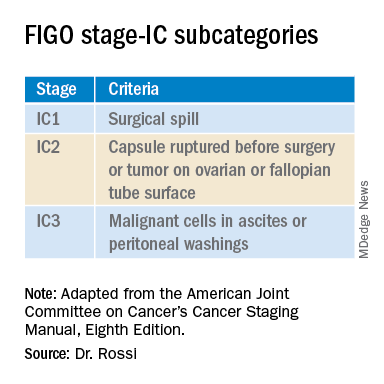

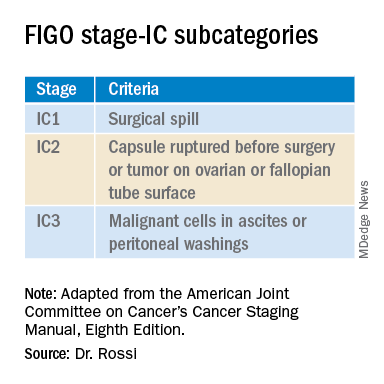

In 2017 the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging of epithelial ovarian cancer subcategorized stage IC. This group encompasses women with contact between malignant cells and the peritoneum in the absence of other extraovarian disease. The table includes these distinct groupings. Stage IC1 includes patients in whom intraoperative spill occurred. Stage IC2 includes women with preoperative cyst rupture, and or microscopic or macroscopic surface involvement because the data support that these cases carry a poorer prognosis, compared with those with intraoperative rupture (IC1).1 The final subcategory, IC3, includes women who have washings (obtained at the onset of surgery, prior to manipulation of the tumor) that were positive for malignant cells, denoting preexisting contact between the tumor and peritoneum and a phenotypically more aggressive tumor.

The clinical significance of ovarian cancer capsule rupture has been evaluated in multiple studies with some mixed results.1 Consistently, it is reported that preoperative rupture, surface or capsular involvement, and preexisting peritoneal circulation of metastatic cells all portend a poorer prognosis; however, it is less clear that iatrogenic surgical rupture has the same deleterious association. In a large retrospective series from Japan, the authors evaluated 15,163 cases of stage I ovarian cancer and identified 7,227 cases of iatrogenic (intraoperative) cyst rupture.2 These cases were significantly more likely to occur among clear cell cancers, and were more likely to occur in younger patients. Worse prognosis was associated with cell type (clear cell cancers), but non–clear cell cancers (such as serous, mucinous, and endometrioid) did not have a higher hazard ratio for death when intraoperative rupture occurred. But why would intraoperative cyst rupture result in worse prognosis for only one histologic cell type? The authors hypothesized that perhaps rupture was more likely to occur during extraction of these clear cell tumors because they were associated with dense adhesions from associated endometriosis, and perhaps an adverse biologic phenomenon associated with infiltrative endometriosis is driving the behavior of this cancer.

The Japanese study also looked at the effect of chemotherapy on these same patients’ outcomes. Interestingly, the addition of chemotherapy did not improve survival for the patients with stage IC1 cancers, which was in contrast to the improved survival seen when chemotherapy was given to those with spontaneous rupture or ovarian surface involvement (IC2, IC3). These data support differentiating the subgroups of stage IC cancer in treatment decision-making, and suggest that adjuvant chemotherapy might be avoided for patients with nonclear cell stage IC1 ovarian cancer. While the outcomes are worse for patients with ruptured clear cell cancers, current therapeutic options for clear cell cancers are limited because of their known resistance to traditional agents, and outcomes for women with clear cell cancer can be worse across all stages.

While cyst rupture may not always negatively affect prognosis, the goal of surgery remains an intact removal, which influences decisions regarding surgical approach. Most adnexal masses are removed via minimally invasive surgery (MIS). MIS is associated with benefits of morbidity and cost, and therefore should be considered wherever feasible. However, MIS is associated with an increased risk of ovarian cyst rupture, likely because of the rigid instrumentation used when approaching a curved structure, in addition to the disparity in size of the pathology, compared with the extraction site incision.3 When weighing the benefits and risks of different surgical approaches, it is important to gauge the probability of malignancy. Not all complex ovarian masses associated with elevations in tumor markers are malignant, and certainly most that are associated with normal tumor markers are not. If the preoperative clinical data suggest that the mass is more likely to be malignant (e.g., mostly solid, vascular tumors with very elevated tumor markers), consideration might be made to abandoning a purely minimally invasive approach to a hand-assisted MIS or laparotomy approach. However, it would seem that abandoning an MIS approach to remove every ovarian cyst is unwise given that there is clear patient benefit with MIS and, as discussed above, most cases of iatrogenic malignant cyst rupture are unavoidable even with laparotomy, and do not necessarily independently portend poorer survival or mandate chemotherapy.

Surgeons should be both nuanced and flexible and apply some basic rules of thumb when approaching the diagnostically uncertain adnexal mass. Peritoneal washings should be obtained at the commencement of the case to discriminate those cases of true stage IC3. The peritoneum parallel to the ovarian vessel should be extensively opened to a level above the pelvic brim. In order to do this, the physiological attachments between the sigmoid colon or cecum and the suspensory ligament of the ovary may need to be carefully mobilized. This allows for retroperitoneal identification of the ureter and skeletonization of the ovarian vessels at least 2 cm proximal to their insertion into the ovary and avoidance of contact with the ovary itself (which may have a fragile capsule) or incomplete ovarian resection. If the ovary remains invested close to the sidewall or colonic structures and the appropriate peritoneal and retroperitoneal mobilization has not occurred, the surgeon may unavoidably rupture the ovarian cyst as they try to “hug” the ovary with their bites of tissue in an attempt to avoid visceral injury. There is little role for an ovarian cystectomy in a postmenopausal woman undergoing surgery for a complex adnexal mass, particularly if she has elevated tumor markers, because the process of performing ovarian cystectomy commonly invokes cyst rupture or fragmentation. Ovarian cystectomy should be reserved for premenopausal women with adnexal masses at low suspicion for malignancy. If the adnexa appears densely adherent to adjacent structures – for example, associated with infiltrative endometriosis – consideration for laparotomy or a hand-assisted approach may be necessary; in such cases, even open surgery can result in cyst rupture, and the morbidity of conversion to laparotomy should be weighed for individual cases.

Finally, retrieval of the ovarian specimen should occur intact without morcellation. There should be no uncontained morcellation of adnexal structures during retrieval of even normal-appearing ovaries. The preferred retrieval method is to place the adnexa in an appropriately sized retrieval bag, after which contained morcellation or drainage can occur to facilitate removal through a laparoscopic incision. Contained morcellation is very difficult for large solid masses through a laparoscopic port site; in these cases, extension of the incision may be necessary.

While operative spill of an ovarian cancer does upstage nonmetastatic ovarian cancer, it is unclear that, in most cases, this is independently associated with worse prognosis, and chemotherapy may not always be of added value. However, best surgical practice should always include strategies to minimize the chance of rupture when approaching adnexal masses, particularly those at highest likelihood of malignancy.

References

1. Kim HS et al. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013 Mar 39(3):279-89.

2. Matsuo K et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Nov;134(5):1017-26.

3. Matsuo K et al. JAMA Oncol. 2020 Jul 1;6(7):1110-3.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Intact removal of an ovarian cyst is a well-established gynecologic surgical principle because ovarian cancer is definitively diagnosed only in retrospect (after ovarian extraction) and intraoperative cyst rupture upstages an otherwise nonmetastatic cancer to stage IC. This lumps cancers that are ruptured during surgical extraction together with those that have spontaneously ruptured or have surface excrescences. The theoretical rationale for this “lumping” is that contact between malignant cells from the ruptured cyst may take hold on peritoneal surfaces resulting in development of metastases. To offset this theoretical risk, it has been recommended that all stage IC ovarian cancer is treated with chemotherapy, whereas low-grade stage IA and IB cancers generally are not. No conscientious surgeon wants their surgical intervention to be the cause of a patient needing toxic chemotherapy. But is the contact between malignant cyst fluid and the peritoneum truly as bad as a spontaneous breach of the surface of the tumor? Or is cyst rupture a confounder for other adverse prognostic features, such as histologic cell type and dense pelvic attachments? If ovarian cyst rupture is an independent risk factor for patients with stage I ovarian cancer, strategies should be employed to avoid this occurrence, and we should understand how to counsel and treat patients in whom this has occurred.

In 2017 the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging of epithelial ovarian cancer subcategorized stage IC. This group encompasses women with contact between malignant cells and the peritoneum in the absence of other extraovarian disease. The table includes these distinct groupings. Stage IC1 includes patients in whom intraoperative spill occurred. Stage IC2 includes women with preoperative cyst rupture, and or microscopic or macroscopic surface involvement because the data support that these cases carry a poorer prognosis, compared with those with intraoperative rupture (IC1).1 The final subcategory, IC3, includes women who have washings (obtained at the onset of surgery, prior to manipulation of the tumor) that were positive for malignant cells, denoting preexisting contact between the tumor and peritoneum and a phenotypically more aggressive tumor.

The clinical significance of ovarian cancer capsule rupture has been evaluated in multiple studies with some mixed results.1 Consistently, it is reported that preoperative rupture, surface or capsular involvement, and preexisting peritoneal circulation of metastatic cells all portend a poorer prognosis; however, it is less clear that iatrogenic surgical rupture has the same deleterious association. In a large retrospective series from Japan, the authors evaluated 15,163 cases of stage I ovarian cancer and identified 7,227 cases of iatrogenic (intraoperative) cyst rupture.2 These cases were significantly more likely to occur among clear cell cancers, and were more likely to occur in younger patients. Worse prognosis was associated with cell type (clear cell cancers), but non–clear cell cancers (such as serous, mucinous, and endometrioid) did not have a higher hazard ratio for death when intraoperative rupture occurred. But why would intraoperative cyst rupture result in worse prognosis for only one histologic cell type? The authors hypothesized that perhaps rupture was more likely to occur during extraction of these clear cell tumors because they were associated with dense adhesions from associated endometriosis, and perhaps an adverse biologic phenomenon associated with infiltrative endometriosis is driving the behavior of this cancer.

The Japanese study also looked at the effect of chemotherapy on these same patients’ outcomes. Interestingly, the addition of chemotherapy did not improve survival for the patients with stage IC1 cancers, which was in contrast to the improved survival seen when chemotherapy was given to those with spontaneous rupture or ovarian surface involvement (IC2, IC3). These data support differentiating the subgroups of stage IC cancer in treatment decision-making, and suggest that adjuvant chemotherapy might be avoided for patients with nonclear cell stage IC1 ovarian cancer. While the outcomes are worse for patients with ruptured clear cell cancers, current therapeutic options for clear cell cancers are limited because of their known resistance to traditional agents, and outcomes for women with clear cell cancer can be worse across all stages.

While cyst rupture may not always negatively affect prognosis, the goal of surgery remains an intact removal, which influences decisions regarding surgical approach. Most adnexal masses are removed via minimally invasive surgery (MIS). MIS is associated with benefits of morbidity and cost, and therefore should be considered wherever feasible. However, MIS is associated with an increased risk of ovarian cyst rupture, likely because of the rigid instrumentation used when approaching a curved structure, in addition to the disparity in size of the pathology, compared with the extraction site incision.3 When weighing the benefits and risks of different surgical approaches, it is important to gauge the probability of malignancy. Not all complex ovarian masses associated with elevations in tumor markers are malignant, and certainly most that are associated with normal tumor markers are not. If the preoperative clinical data suggest that the mass is more likely to be malignant (e.g., mostly solid, vascular tumors with very elevated tumor markers), consideration might be made to abandoning a purely minimally invasive approach to a hand-assisted MIS or laparotomy approach. However, it would seem that abandoning an MIS approach to remove every ovarian cyst is unwise given that there is clear patient benefit with MIS and, as discussed above, most cases of iatrogenic malignant cyst rupture are unavoidable even with laparotomy, and do not necessarily independently portend poorer survival or mandate chemotherapy.

Surgeons should be both nuanced and flexible and apply some basic rules of thumb when approaching the diagnostically uncertain adnexal mass. Peritoneal washings should be obtained at the commencement of the case to discriminate those cases of true stage IC3. The peritoneum parallel to the ovarian vessel should be extensively opened to a level above the pelvic brim. In order to do this, the physiological attachments between the sigmoid colon or cecum and the suspensory ligament of the ovary may need to be carefully mobilized. This allows for retroperitoneal identification of the ureter and skeletonization of the ovarian vessels at least 2 cm proximal to their insertion into the ovary and avoidance of contact with the ovary itself (which may have a fragile capsule) or incomplete ovarian resection. If the ovary remains invested close to the sidewall or colonic structures and the appropriate peritoneal and retroperitoneal mobilization has not occurred, the surgeon may unavoidably rupture the ovarian cyst as they try to “hug” the ovary with their bites of tissue in an attempt to avoid visceral injury. There is little role for an ovarian cystectomy in a postmenopausal woman undergoing surgery for a complex adnexal mass, particularly if she has elevated tumor markers, because the process of performing ovarian cystectomy commonly invokes cyst rupture or fragmentation. Ovarian cystectomy should be reserved for premenopausal women with adnexal masses at low suspicion for malignancy. If the adnexa appears densely adherent to adjacent structures – for example, associated with infiltrative endometriosis – consideration for laparotomy or a hand-assisted approach may be necessary; in such cases, even open surgery can result in cyst rupture, and the morbidity of conversion to laparotomy should be weighed for individual cases.

Finally, retrieval of the ovarian specimen should occur intact without morcellation. There should be no uncontained morcellation of adnexal structures during retrieval of even normal-appearing ovaries. The preferred retrieval method is to place the adnexa in an appropriately sized retrieval bag, after which contained morcellation or drainage can occur to facilitate removal through a laparoscopic incision. Contained morcellation is very difficult for large solid masses through a laparoscopic port site; in these cases, extension of the incision may be necessary.

While operative spill of an ovarian cancer does upstage nonmetastatic ovarian cancer, it is unclear that, in most cases, this is independently associated with worse prognosis, and chemotherapy may not always be of added value. However, best surgical practice should always include strategies to minimize the chance of rupture when approaching adnexal masses, particularly those at highest likelihood of malignancy.

References

1. Kim HS et al. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013 Mar 39(3):279-89.

2. Matsuo K et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Nov;134(5):1017-26.

3. Matsuo K et al. JAMA Oncol. 2020 Jul 1;6(7):1110-3.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Intact removal of an ovarian cyst is a well-established gynecologic surgical principle because ovarian cancer is definitively diagnosed only in retrospect (after ovarian extraction) and intraoperative cyst rupture upstages an otherwise nonmetastatic cancer to stage IC. This lumps cancers that are ruptured during surgical extraction together with those that have spontaneously ruptured or have surface excrescences. The theoretical rationale for this “lumping” is that contact between malignant cells from the ruptured cyst may take hold on peritoneal surfaces resulting in development of metastases. To offset this theoretical risk, it has been recommended that all stage IC ovarian cancer is treated with chemotherapy, whereas low-grade stage IA and IB cancers generally are not. No conscientious surgeon wants their surgical intervention to be the cause of a patient needing toxic chemotherapy. But is the contact between malignant cyst fluid and the peritoneum truly as bad as a spontaneous breach of the surface of the tumor? Or is cyst rupture a confounder for other adverse prognostic features, such as histologic cell type and dense pelvic attachments? If ovarian cyst rupture is an independent risk factor for patients with stage I ovarian cancer, strategies should be employed to avoid this occurrence, and we should understand how to counsel and treat patients in whom this has occurred.

In 2017 the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging of epithelial ovarian cancer subcategorized stage IC. This group encompasses women with contact between malignant cells and the peritoneum in the absence of other extraovarian disease. The table includes these distinct groupings. Stage IC1 includes patients in whom intraoperative spill occurred. Stage IC2 includes women with preoperative cyst rupture, and or microscopic or macroscopic surface involvement because the data support that these cases carry a poorer prognosis, compared with those with intraoperative rupture (IC1).1 The final subcategory, IC3, includes women who have washings (obtained at the onset of surgery, prior to manipulation of the tumor) that were positive for malignant cells, denoting preexisting contact between the tumor and peritoneum and a phenotypically more aggressive tumor.

The clinical significance of ovarian cancer capsule rupture has been evaluated in multiple studies with some mixed results.1 Consistently, it is reported that preoperative rupture, surface or capsular involvement, and preexisting peritoneal circulation of metastatic cells all portend a poorer prognosis; however, it is less clear that iatrogenic surgical rupture has the same deleterious association. In a large retrospective series from Japan, the authors evaluated 15,163 cases of stage I ovarian cancer and identified 7,227 cases of iatrogenic (intraoperative) cyst rupture.2 These cases were significantly more likely to occur among clear cell cancers, and were more likely to occur in younger patients. Worse prognosis was associated with cell type (clear cell cancers), but non–clear cell cancers (such as serous, mucinous, and endometrioid) did not have a higher hazard ratio for death when intraoperative rupture occurred. But why would intraoperative cyst rupture result in worse prognosis for only one histologic cell type? The authors hypothesized that perhaps rupture was more likely to occur during extraction of these clear cell tumors because they were associated with dense adhesions from associated endometriosis, and perhaps an adverse biologic phenomenon associated with infiltrative endometriosis is driving the behavior of this cancer.

The Japanese study also looked at the effect of chemotherapy on these same patients’ outcomes. Interestingly, the addition of chemotherapy did not improve survival for the patients with stage IC1 cancers, which was in contrast to the improved survival seen when chemotherapy was given to those with spontaneous rupture or ovarian surface involvement (IC2, IC3). These data support differentiating the subgroups of stage IC cancer in treatment decision-making, and suggest that adjuvant chemotherapy might be avoided for patients with nonclear cell stage IC1 ovarian cancer. While the outcomes are worse for patients with ruptured clear cell cancers, current therapeutic options for clear cell cancers are limited because of their known resistance to traditional agents, and outcomes for women with clear cell cancer can be worse across all stages.

While cyst rupture may not always negatively affect prognosis, the goal of surgery remains an intact removal, which influences decisions regarding surgical approach. Most adnexal masses are removed via minimally invasive surgery (MIS). MIS is associated with benefits of morbidity and cost, and therefore should be considered wherever feasible. However, MIS is associated with an increased risk of ovarian cyst rupture, likely because of the rigid instrumentation used when approaching a curved structure, in addition to the disparity in size of the pathology, compared with the extraction site incision.3 When weighing the benefits and risks of different surgical approaches, it is important to gauge the probability of malignancy. Not all complex ovarian masses associated with elevations in tumor markers are malignant, and certainly most that are associated with normal tumor markers are not. If the preoperative clinical data suggest that the mass is more likely to be malignant (e.g., mostly solid, vascular tumors with very elevated tumor markers), consideration might be made to abandoning a purely minimally invasive approach to a hand-assisted MIS or laparotomy approach. However, it would seem that abandoning an MIS approach to remove every ovarian cyst is unwise given that there is clear patient benefit with MIS and, as discussed above, most cases of iatrogenic malignant cyst rupture are unavoidable even with laparotomy, and do not necessarily independently portend poorer survival or mandate chemotherapy.

Surgeons should be both nuanced and flexible and apply some basic rules of thumb when approaching the diagnostically uncertain adnexal mass. Peritoneal washings should be obtained at the commencement of the case to discriminate those cases of true stage IC3. The peritoneum parallel to the ovarian vessel should be extensively opened to a level above the pelvic brim. In order to do this, the physiological attachments between the sigmoid colon or cecum and the suspensory ligament of the ovary may need to be carefully mobilized. This allows for retroperitoneal identification of the ureter and skeletonization of the ovarian vessels at least 2 cm proximal to their insertion into the ovary and avoidance of contact with the ovary itself (which may have a fragile capsule) or incomplete ovarian resection. If the ovary remains invested close to the sidewall or colonic structures and the appropriate peritoneal and retroperitoneal mobilization has not occurred, the surgeon may unavoidably rupture the ovarian cyst as they try to “hug” the ovary with their bites of tissue in an attempt to avoid visceral injury. There is little role for an ovarian cystectomy in a postmenopausal woman undergoing surgery for a complex adnexal mass, particularly if she has elevated tumor markers, because the process of performing ovarian cystectomy commonly invokes cyst rupture or fragmentation. Ovarian cystectomy should be reserved for premenopausal women with adnexal masses at low suspicion for malignancy. If the adnexa appears densely adherent to adjacent structures – for example, associated with infiltrative endometriosis – consideration for laparotomy or a hand-assisted approach may be necessary; in such cases, even open surgery can result in cyst rupture, and the morbidity of conversion to laparotomy should be weighed for individual cases.

Finally, retrieval of the ovarian specimen should occur intact without morcellation. There should be no uncontained morcellation of adnexal structures during retrieval of even normal-appearing ovaries. The preferred retrieval method is to place the adnexa in an appropriately sized retrieval bag, after which contained morcellation or drainage can occur to facilitate removal through a laparoscopic incision. Contained morcellation is very difficult for large solid masses through a laparoscopic port site; in these cases, extension of the incision may be necessary.

While operative spill of an ovarian cancer does upstage nonmetastatic ovarian cancer, it is unclear that, in most cases, this is independently associated with worse prognosis, and chemotherapy may not always be of added value. However, best surgical practice should always include strategies to minimize the chance of rupture when approaching adnexal masses, particularly those at highest likelihood of malignancy.

References

1. Kim HS et al. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013 Mar 39(3):279-89.

2. Matsuo K et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Nov;134(5):1017-26.

3. Matsuo K et al. JAMA Oncol. 2020 Jul 1;6(7):1110-3.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

ctDNA outperforms CEA in colorectal cancer

Despite standard blood monitoring and routine imaging, patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) tend to have multiple, incurable metastases when relapse occurs.

A new study indicates that postsurgical circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) testing may improve our ability to predict relapse in patients with stage I-III CRC.

ctDNA testing outperformed carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) testing in predicting relapse-free survival, and ctDNA was detected about 8 months prior to relapse detection via CT.

Tenna V. Henriksen, of Aarhus University in Denmark, presented these results at the 2021 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium (abstract 11).

The multi-institutional study included 260 patients with CRC – 4 with stage I disease, 90 with stage II, and 166 with stage III disease.

Patients were monitored with plasma ctDNA testing within 2 months of primary surgery. Some patients were monitored with follow-up ctDNA sampling every 3 months for an additional 3 years.

Individual tumors and matched germline DNA were interrogated with whole-exome sequencing, and somatic single nucleotide variants were identified. Personalized multiplex PCR assays were developed to track tumor-specific single nucleotide variants via the Signatera® ctDNA assay.

The researchers retrospectively assessed ctDNA’s performance in:

- Stratifying the postoperative risk of relapse.

- Quantifying the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients who had or did not have ctDNA in plasma.

- Efficiently detecting relapse, in comparison with standard surveillance tests.

Surveillance CT scans were performed at 12 and 36 months but not at the frequency recommended in NCCN guidelines.

In all, 165 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy. The decision to give chemotherapy was made on a clinical basis by treating physicians who were blinded to the results of ctDNA testing.

Results

Of the 260 patients analyzed, 48 relapsed. The median follow-up was 28.4 months overall and 29.9 months in the nonrelapse cases.

The researchers assessed postoperative ctDNA status prior to adjuvant chemotherapy in 218 patients and after adjuvant chemotherapy in 108 patients.

In the prechemotherapy group, 20 patients were ctDNA positive, and 80% of them relapsed. In contrast, 13% of the 198 ctDNA-negative patients relapsed. The hazard ratio (HR) for relapse-free survival was 11 (95% confidence interval, 5.9-21; P < .0001).

After adjuvant chemotherapy, 12.5% of the ctDNA-negative patients relapsed, compared with 83.3% of the ctDNA-positive patients. The HR for relapse-free survival was 12 (95% CI, 4.9-27; P < .0001).

Results from longitudinal ctDNA testing in 202 patients suggested that serial sampling is more useful than sampling at a single point in time. The recurrence rate was 3.4% among patients who remained persistently ctDNA negative, compared with 89.3% in patients who were ctDNA positive. The HR for relapse-free survival was 51 (95% CI, 20-125; P < .0001).

In a subgroup of 29 patients with clinical recurrence detected by CT imaging, ctDNA detection occurred a median of 8.1 months earlier than radiologic relapse.

Among the 197 patients who had serial CEA and ctDNA measurements, longitudinal CEA testing correlated with relapse-free survival (HR, 4.9; 95% CI, 3.2-15, P < .0001) but not nearly as well as ctDNA testing (HR, 95.7; 95% CI, 28-322, P < .0001) in a univariable analysis.

In a multivariable analysis, the HR for relapse-free survival was 1.8 (95% CI, 0.77-4.0; P = .184) for longitudinal CEA and 80.55 (95% CI, 23.1-281; P < .0001) for longitudinal ctDNA.

“[W]hen we pit them against each other in a multivariable analysis, we can see that all the predictive power is in the ctDNA samples,” Ms. Henriksen said. “This indicates that ctDNA is a stronger biomarker compared to CEA, at least with relapse-free survival.”

Availability is not actionability

Study discussant Michael J. Overman, MD, of MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, acknowledged that this research substantiates the ability of postoperative ctDNA detection to risk stratify patients with stage III CRC, the predominant stage of participants in the study.

The current results reinforce the researchers’ previously published work (JAMA Oncol. 2019;5[8]:1124-31) and affirm similar findings by other groups (JAMA Oncol. 2019;5[12]:1710-17 and JAMA Oncol. 2019;5[8]:1118-23).

However, Dr. Overman cautioned that “availability is not the same as actionability.”

He also said the “tumor-informed mutation” approach utilized in the Signatera assay differs from the simpler “panel-based” approach, which is also undergoing clinical testing and offers the additional opportunity to test potentially actionable epigenetic targets such as DNA methylation.

Furthermore, the practicality of integrating the tumor-informed mutation approach into the time constraints required in clinical practice was not evaluated in the current analysis.

Dr. Overman pointed out that 16 of the 20 ctDNA-positive patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy sustained a recurrence, so the chemotherapy benefit was lower than expected.

Finally, although ctDNA outperformed CEA in detecting relapse, the greatest impact of ctDNA is its potential to inform the clinician’s decision to escalate and deescalate treatment with impact on survival – a potential that remains unfulfilled.

Next steps

Ms. Henriksen closed her presentation with the perspective that, for serial ctDNA monitoring to be implemented in clinical settings, testing in randomized clinical trials will be needed.