User login

Is COVID-19 accelerating progress toward high-value care?

As Rachna Rawal, MD, was donning her personal protective equipment (PPE), a process that has become deeply ingrained into her muscle memory, a nurse approached her to ask, “Hey, for Mr. Smith, any chance we can time these labs to be done together with his medication administration? We’ve been in and out of that room a few times already.”

As someone who embraces high-value care, this simple suggestion surprised her. What an easy strategy to minimize room entry with full PPE, lab testing, and patient interruptions. That same day, someone else asked, “Do we need overnight vitals?”

COVID-19 has forced hospitalists to reconsider almost every aspect of care. It feels like every decision we make including things we do routinely – labs, vital signs, imaging – needs to be reassessed to determine the actual benefit to the patient balanced against concerns about staff safety, dwindling PPE supplies, and medication reserves. We are all faced with frequently answering the question, “How will this intervention help the patient?” This question lies at the heart of delivering high-value care.

High-value care is providing the best care possible through efficient use of resources, achieving optimal results for each patient. While high-value care has become a prominent focus over the past decade, COVID-19’s high transmissibility without a cure – and associated scarcity of health care resources – have sparked additional discussions on the front lines about promoting patient outcomes while avoiding waste. Clinicians may not have realized that these were high-value care conversations.

The United States’ health care quality and cost crises, worsened in the face of the current pandemic, have been glaringly apparent for years. Our country is spending more money on health care than anywhere else in the world without desired improvements in patient outcomes. A 2019 JAMA study found that 25% of all health care spending, an estimated $760 to $935 billion, is considered waste, and a significant proportion of this waste is due to repetitive care, overuse and unnecessary care in the U.S.1

Examples of low-value care tests include ordering daily labs in stable medicine inpatients, routine urine electrolytes in acute kidney injury, and folate testing in anemia. The Choosing Wisely® national campaign, Journal of Hospital Medicine’s “Things We Do For No Reason,” and JAMA Internal Medicine’s “Teachable Moment” series have provided guidance on areas where common testing or interventions may not benefit patient outcomes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised questions related to other widely-utilized practices: Can medication times be readjusted to allow only one entry into the room? Will these labs or imaging studies actually change management? Are vital checks every 4 hours needed?

Why did it take the COVID-19 threat to our medical system to force many of us to have these discussions? Despite prior efforts to integrate high-value care into hospital practices, long-standing habits and deep-seeded culture are challenging to overcome. Once clinicians develop practice habits, these behaviors tend to persist throughout their careers.2 In many ways, COVID-19 was like hitting a “reset button” as health care professionals were forced to rapidly confront their deeply-ingrained hospital practices and habits. From new protocols for patient rounding to universal masking and social distancing to ground-breaking strategies like awake proning, the response to COVID-19 has represented an unprecedented rapid shift in practice. Previously, consequences of overuse were too downstream or too abstract for clinicians to see in real-time. However, now the ramifications of these choices hit closer to home with obvious potential consequences – like spreading a terrifying virus.

There are three interventions that hospitalists should consider implementing immediately in the COVID-19 era that accelerate us toward high-value care. Routine lab tests, imaging, and overnight vitals represent opportunities to provide patient-centered care while also remaining cognizant of resource utilization.

One area in hospital medicine that has proven challenging to significantly change practice has been routine daily labs. Patients on a general medical inpatient service who are clinically stable generally do not benefit from routine lab work.3 Avoiding these tests does not increase mortality or length of stay in clinically stable patients.3 However, despite this evidence, many patients with COVID-19 and other conditions experience lab draws that are not timed together and are done each morning out of “routine.” Choosing Wisely® recommendations from the Society of Hospital Medicine encourage clinicians to question routine lab work for COVID-19 patients and to consider batching them, if possible.3,4 In COVID-19 patients, the risks of not batching tests are magnified, both in terms of the patient-centered experience and for clinician safety. In essence, COVID-19 has pushed us to consider the elements of safety, PPE conservation and other factors, rather than making decisions based solely on their own comfort, convenience, or historical practice.

Clinicians are also reconsidering the necessity of imaging during the pandemic. The “Things We Do For No Reason” article on “Choosing Wisely® in the COVID-19 era” highlights this well.4 It is more important now than ever to decide whether the timing and type of imaging will change management for your patient. Questions to ask include: Can a portable x-ray be used to avoid patient travel and will that CT scan help your patient? A posterior-anterior/lateral x-ray can potentially provide more information depending on the clinical scenario. However, we now need to assess if that extra information is going to impact patient management. Downstream consequences of these decisions include not only risks to the patient but also infectious exposures for staff and others during patient travel.

Lastly, overnight vital sign checks are another intervention we should analyze through this high-value care lens. The Journal of Hospital Medicine released a “Things We Do For No Reason” article about minimizing overnight vitals to promote uninterrupted sleep at night.5 Deleterious effects of interrupting the sleep of our patients include delirium and patient dissatisfaction.5 Studies have shown the benefits of this approach, yet the shift away from routine overnight vitals has not yet widely occurred.

COVID-19 has pressed us to save PPE and minimize exposure risk; hence, some centers are coordinating the timing of vitals with medication administration times, when feasible. In the stable patient recovering from COVID-19, overnight vitals may not be necessary, particularly if remote monitoring is available. This accomplishes multiple goals: Providing high quality patient care, reducing resource utilization, and minimizing patient nighttime interruptions – all culminating in high-value care.

Even though the COVID-19 pandemic has brought unforeseen emotional, physical, and financial challenges for the health care system and its workers, there may be a silver lining. The pandemic has sparked high-value care discussions, and the urgency of the crisis may be instilling new practices in our daily work. This virus has indeed left a terrible wake of destruction, but may also be a nudge to permanently change our culture of overuse to help us shape the habits of all trainees during this tumultuous time. This experience will hopefully culminate in a culture in which clinicians routinely ask, “How will this intervention help the patient?”

Dr. Rawal is clinical assistant professor of medicine, University of Pittsburgh. Dr. Linker is assistant professor of medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Dr. Moriates is associate professor of internal medicine, Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin.

References

1. Shrank W et al. Waste in The US healthcare system. JAMA. 2019;322(15):1501-9.

2. Chen C et al. Spending patterns in region of residency training and subsequent expenditures for care provided by practicing physicians for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2385-93.

3. Eaton KP et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-9.

4. Cho H et al. Choosing Wisely in the COVID-19 Era: Preventing harm to healthcare workers. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(6):360-2.

5. Orlov N and Arora V. Things we do for no reason: Routine overnight vital sign checks. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):272-27.

As Rachna Rawal, MD, was donning her personal protective equipment (PPE), a process that has become deeply ingrained into her muscle memory, a nurse approached her to ask, “Hey, for Mr. Smith, any chance we can time these labs to be done together with his medication administration? We’ve been in and out of that room a few times already.”

As someone who embraces high-value care, this simple suggestion surprised her. What an easy strategy to minimize room entry with full PPE, lab testing, and patient interruptions. That same day, someone else asked, “Do we need overnight vitals?”

COVID-19 has forced hospitalists to reconsider almost every aspect of care. It feels like every decision we make including things we do routinely – labs, vital signs, imaging – needs to be reassessed to determine the actual benefit to the patient balanced against concerns about staff safety, dwindling PPE supplies, and medication reserves. We are all faced with frequently answering the question, “How will this intervention help the patient?” This question lies at the heart of delivering high-value care.

High-value care is providing the best care possible through efficient use of resources, achieving optimal results for each patient. While high-value care has become a prominent focus over the past decade, COVID-19’s high transmissibility without a cure – and associated scarcity of health care resources – have sparked additional discussions on the front lines about promoting patient outcomes while avoiding waste. Clinicians may not have realized that these were high-value care conversations.

The United States’ health care quality and cost crises, worsened in the face of the current pandemic, have been glaringly apparent for years. Our country is spending more money on health care than anywhere else in the world without desired improvements in patient outcomes. A 2019 JAMA study found that 25% of all health care spending, an estimated $760 to $935 billion, is considered waste, and a significant proportion of this waste is due to repetitive care, overuse and unnecessary care in the U.S.1

Examples of low-value care tests include ordering daily labs in stable medicine inpatients, routine urine electrolytes in acute kidney injury, and folate testing in anemia. The Choosing Wisely® national campaign, Journal of Hospital Medicine’s “Things We Do For No Reason,” and JAMA Internal Medicine’s “Teachable Moment” series have provided guidance on areas where common testing or interventions may not benefit patient outcomes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised questions related to other widely-utilized practices: Can medication times be readjusted to allow only one entry into the room? Will these labs or imaging studies actually change management? Are vital checks every 4 hours needed?

Why did it take the COVID-19 threat to our medical system to force many of us to have these discussions? Despite prior efforts to integrate high-value care into hospital practices, long-standing habits and deep-seeded culture are challenging to overcome. Once clinicians develop practice habits, these behaviors tend to persist throughout their careers.2 In many ways, COVID-19 was like hitting a “reset button” as health care professionals were forced to rapidly confront their deeply-ingrained hospital practices and habits. From new protocols for patient rounding to universal masking and social distancing to ground-breaking strategies like awake proning, the response to COVID-19 has represented an unprecedented rapid shift in practice. Previously, consequences of overuse were too downstream or too abstract for clinicians to see in real-time. However, now the ramifications of these choices hit closer to home with obvious potential consequences – like spreading a terrifying virus.

There are three interventions that hospitalists should consider implementing immediately in the COVID-19 era that accelerate us toward high-value care. Routine lab tests, imaging, and overnight vitals represent opportunities to provide patient-centered care while also remaining cognizant of resource utilization.

One area in hospital medicine that has proven challenging to significantly change practice has been routine daily labs. Patients on a general medical inpatient service who are clinically stable generally do not benefit from routine lab work.3 Avoiding these tests does not increase mortality or length of stay in clinically stable patients.3 However, despite this evidence, many patients with COVID-19 and other conditions experience lab draws that are not timed together and are done each morning out of “routine.” Choosing Wisely® recommendations from the Society of Hospital Medicine encourage clinicians to question routine lab work for COVID-19 patients and to consider batching them, if possible.3,4 In COVID-19 patients, the risks of not batching tests are magnified, both in terms of the patient-centered experience and for clinician safety. In essence, COVID-19 has pushed us to consider the elements of safety, PPE conservation and other factors, rather than making decisions based solely on their own comfort, convenience, or historical practice.

Clinicians are also reconsidering the necessity of imaging during the pandemic. The “Things We Do For No Reason” article on “Choosing Wisely® in the COVID-19 era” highlights this well.4 It is more important now than ever to decide whether the timing and type of imaging will change management for your patient. Questions to ask include: Can a portable x-ray be used to avoid patient travel and will that CT scan help your patient? A posterior-anterior/lateral x-ray can potentially provide more information depending on the clinical scenario. However, we now need to assess if that extra information is going to impact patient management. Downstream consequences of these decisions include not only risks to the patient but also infectious exposures for staff and others during patient travel.

Lastly, overnight vital sign checks are another intervention we should analyze through this high-value care lens. The Journal of Hospital Medicine released a “Things We Do For No Reason” article about minimizing overnight vitals to promote uninterrupted sleep at night.5 Deleterious effects of interrupting the sleep of our patients include delirium and patient dissatisfaction.5 Studies have shown the benefits of this approach, yet the shift away from routine overnight vitals has not yet widely occurred.

COVID-19 has pressed us to save PPE and minimize exposure risk; hence, some centers are coordinating the timing of vitals with medication administration times, when feasible. In the stable patient recovering from COVID-19, overnight vitals may not be necessary, particularly if remote monitoring is available. This accomplishes multiple goals: Providing high quality patient care, reducing resource utilization, and minimizing patient nighttime interruptions – all culminating in high-value care.

Even though the COVID-19 pandemic has brought unforeseen emotional, physical, and financial challenges for the health care system and its workers, there may be a silver lining. The pandemic has sparked high-value care discussions, and the urgency of the crisis may be instilling new practices in our daily work. This virus has indeed left a terrible wake of destruction, but may also be a nudge to permanently change our culture of overuse to help us shape the habits of all trainees during this tumultuous time. This experience will hopefully culminate in a culture in which clinicians routinely ask, “How will this intervention help the patient?”

Dr. Rawal is clinical assistant professor of medicine, University of Pittsburgh. Dr. Linker is assistant professor of medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Dr. Moriates is associate professor of internal medicine, Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin.

References

1. Shrank W et al. Waste in The US healthcare system. JAMA. 2019;322(15):1501-9.

2. Chen C et al. Spending patterns in region of residency training and subsequent expenditures for care provided by practicing physicians for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2385-93.

3. Eaton KP et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-9.

4. Cho H et al. Choosing Wisely in the COVID-19 Era: Preventing harm to healthcare workers. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(6):360-2.

5. Orlov N and Arora V. Things we do for no reason: Routine overnight vital sign checks. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):272-27.

As Rachna Rawal, MD, was donning her personal protective equipment (PPE), a process that has become deeply ingrained into her muscle memory, a nurse approached her to ask, “Hey, for Mr. Smith, any chance we can time these labs to be done together with his medication administration? We’ve been in and out of that room a few times already.”

As someone who embraces high-value care, this simple suggestion surprised her. What an easy strategy to minimize room entry with full PPE, lab testing, and patient interruptions. That same day, someone else asked, “Do we need overnight vitals?”

COVID-19 has forced hospitalists to reconsider almost every aspect of care. It feels like every decision we make including things we do routinely – labs, vital signs, imaging – needs to be reassessed to determine the actual benefit to the patient balanced against concerns about staff safety, dwindling PPE supplies, and medication reserves. We are all faced with frequently answering the question, “How will this intervention help the patient?” This question lies at the heart of delivering high-value care.

High-value care is providing the best care possible through efficient use of resources, achieving optimal results for each patient. While high-value care has become a prominent focus over the past decade, COVID-19’s high transmissibility without a cure – and associated scarcity of health care resources – have sparked additional discussions on the front lines about promoting patient outcomes while avoiding waste. Clinicians may not have realized that these were high-value care conversations.

The United States’ health care quality and cost crises, worsened in the face of the current pandemic, have been glaringly apparent for years. Our country is spending more money on health care than anywhere else in the world without desired improvements in patient outcomes. A 2019 JAMA study found that 25% of all health care spending, an estimated $760 to $935 billion, is considered waste, and a significant proportion of this waste is due to repetitive care, overuse and unnecessary care in the U.S.1

Examples of low-value care tests include ordering daily labs in stable medicine inpatients, routine urine electrolytes in acute kidney injury, and folate testing in anemia. The Choosing Wisely® national campaign, Journal of Hospital Medicine’s “Things We Do For No Reason,” and JAMA Internal Medicine’s “Teachable Moment” series have provided guidance on areas where common testing or interventions may not benefit patient outcomes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised questions related to other widely-utilized practices: Can medication times be readjusted to allow only one entry into the room? Will these labs or imaging studies actually change management? Are vital checks every 4 hours needed?

Why did it take the COVID-19 threat to our medical system to force many of us to have these discussions? Despite prior efforts to integrate high-value care into hospital practices, long-standing habits and deep-seeded culture are challenging to overcome. Once clinicians develop practice habits, these behaviors tend to persist throughout their careers.2 In many ways, COVID-19 was like hitting a “reset button” as health care professionals were forced to rapidly confront their deeply-ingrained hospital practices and habits. From new protocols for patient rounding to universal masking and social distancing to ground-breaking strategies like awake proning, the response to COVID-19 has represented an unprecedented rapid shift in practice. Previously, consequences of overuse were too downstream or too abstract for clinicians to see in real-time. However, now the ramifications of these choices hit closer to home with obvious potential consequences – like spreading a terrifying virus.

There are three interventions that hospitalists should consider implementing immediately in the COVID-19 era that accelerate us toward high-value care. Routine lab tests, imaging, and overnight vitals represent opportunities to provide patient-centered care while also remaining cognizant of resource utilization.

One area in hospital medicine that has proven challenging to significantly change practice has been routine daily labs. Patients on a general medical inpatient service who are clinically stable generally do not benefit from routine lab work.3 Avoiding these tests does not increase mortality or length of stay in clinically stable patients.3 However, despite this evidence, many patients with COVID-19 and other conditions experience lab draws that are not timed together and are done each morning out of “routine.” Choosing Wisely® recommendations from the Society of Hospital Medicine encourage clinicians to question routine lab work for COVID-19 patients and to consider batching them, if possible.3,4 In COVID-19 patients, the risks of not batching tests are magnified, both in terms of the patient-centered experience and for clinician safety. In essence, COVID-19 has pushed us to consider the elements of safety, PPE conservation and other factors, rather than making decisions based solely on their own comfort, convenience, or historical practice.

Clinicians are also reconsidering the necessity of imaging during the pandemic. The “Things We Do For No Reason” article on “Choosing Wisely® in the COVID-19 era” highlights this well.4 It is more important now than ever to decide whether the timing and type of imaging will change management for your patient. Questions to ask include: Can a portable x-ray be used to avoid patient travel and will that CT scan help your patient? A posterior-anterior/lateral x-ray can potentially provide more information depending on the clinical scenario. However, we now need to assess if that extra information is going to impact patient management. Downstream consequences of these decisions include not only risks to the patient but also infectious exposures for staff and others during patient travel.

Lastly, overnight vital sign checks are another intervention we should analyze through this high-value care lens. The Journal of Hospital Medicine released a “Things We Do For No Reason” article about minimizing overnight vitals to promote uninterrupted sleep at night.5 Deleterious effects of interrupting the sleep of our patients include delirium and patient dissatisfaction.5 Studies have shown the benefits of this approach, yet the shift away from routine overnight vitals has not yet widely occurred.

COVID-19 has pressed us to save PPE and minimize exposure risk; hence, some centers are coordinating the timing of vitals with medication administration times, when feasible. In the stable patient recovering from COVID-19, overnight vitals may not be necessary, particularly if remote monitoring is available. This accomplishes multiple goals: Providing high quality patient care, reducing resource utilization, and minimizing patient nighttime interruptions – all culminating in high-value care.

Even though the COVID-19 pandemic has brought unforeseen emotional, physical, and financial challenges for the health care system and its workers, there may be a silver lining. The pandemic has sparked high-value care discussions, and the urgency of the crisis may be instilling new practices in our daily work. This virus has indeed left a terrible wake of destruction, but may also be a nudge to permanently change our culture of overuse to help us shape the habits of all trainees during this tumultuous time. This experience will hopefully culminate in a culture in which clinicians routinely ask, “How will this intervention help the patient?”

Dr. Rawal is clinical assistant professor of medicine, University of Pittsburgh. Dr. Linker is assistant professor of medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Dr. Moriates is associate professor of internal medicine, Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin.

References

1. Shrank W et al. Waste in The US healthcare system. JAMA. 2019;322(15):1501-9.

2. Chen C et al. Spending patterns in region of residency training and subsequent expenditures for care provided by practicing physicians for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2385-93.

3. Eaton KP et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-9.

4. Cho H et al. Choosing Wisely in the COVID-19 Era: Preventing harm to healthcare workers. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(6):360-2.

5. Orlov N and Arora V. Things we do for no reason: Routine overnight vital sign checks. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):272-27.

The journey from burnout to wellbeing

A check-in for you and your peers

COVID-19 did not discriminate when it came to the impact it imposed on our hospitalist community. As the nomenclature moves away from the negative connotations of ‘burnout’ to ‘wellbeing,’ the pandemic has taught us something important about being intentional about our personal health: we must secure our own oxygen masks before helping others.

In February 2020, the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Wellbeing Taskforce efforts quickly changed focus from addressing general wellbeing, to wellbeing during COVID-19. Our Taskforce was commissioned by SHM’s Board with a new charge: Address immediate and ongoing needs of well-being and resiliency support for hospitalists during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this essay, I will discuss how our SHM Wellbeing Taskforce approached the overall topic of wellbeing for hospitalists during the COVID-19 pandemic, including some of our Taskforce group experiences.

The Taskforce started with a framework to aide in cultivating open and authentic conversations within hospital medicine groups. Creating spaces for honest sharing around how providers are doing is a crucial first step to reducing stigma, building mutual support within a group, and elevating issues of wellbeing to the level where structural change can take place. The Taskforce established two objectives for normalizing and mitigating stressors we face as hospitalists during the COVID-19 pandemic:

- Provide a framework for hospitalists to take their own emotional pulse

- Provide an approach to reduce stigma of hospitalists who are suffering from pandemic stress

While a more typical approach to fix stress and burnout is using formal institutional interventions, we used the value and insight provided by SHM’s 7 Drivers of Burnout in Hospital Medicine to help guide the creation of SHM resources in addressing the severe emotional strain being felt across the country by hospitalists. The 7 Drivers support the idea that the social role peers and hospital leaders can make a crucial difference in mitigating stress and burnout. Two examples of social support come to mind from the Wellbeing Taskforce experience:

- Participate in your meetings. One example comes from a member of our group who had underestimated the “healing power” that our group meetings had provided to his psyche. The simple act of participating in our Taskforce meeting and being in the presence of our group had provided such a positive impact that he was better able to face the “death and misery” in his unit with a smile on his face.

- Share what is stressful. The second example of social support comes from an hour of Zoom-based facilitation meetings between the SHM’s Wellbeing Taskforce members and Chapter Leaders in late October. During our Taskforce debrief after the meeting, we came to realize the enormous burden of grief our peers were carrying as one hospitalist had lost a group colleague the previous week due to suicide. Our member who led this meeting was moved – as were we – at how this had impacted his small team, and he was reminded he was not alone.

To form meaningful relationships that foster support, there needs to be a space where people can safely come together at times that initially might feel awkward. After taking steps toward your peers, these conversations can become normalized and contribute to meaningful relationships, providing the opportunity for healthy exchanges on vulnerable topics like emotional and psychological wellbeing. A printable guide for this specific purpose (“HM COVID-19 Check-In Guide for Self and Peers”) was designed to help hospitalists move into safe and supportive conversations with each other. While it is difficult to place a value on the importance these types of conversations have on individual wellbeing, it is known that the quality of a positive work environment where people feel supported can moderate stress, morale, and depression. In other words, hospitalist groups can positively contribute to their social environment during stressful times by sharing meaningful and difficult experiences with one another.

Second, the Taskforce created a social media campaign to provide a public social space for sharing hospitalists’ COVID-19 experiences. We believed that sharing collective experiences with the theme of #YouAreNotAlone and a complementary social media campaign, SHM Cares, on SHM’s social media channels, would further connect the national hospitalist community and provide a different communication pathway to decrease a sense of isolation. This idea came from the second social support idea mentioned earlier to share what is stressful with others in a safe space. We understood that some hospitalists would be more comfortable sharing publicly their comments, photos, and videos in achieving a sense of hospitalist unity.

Using our shared experiences, we identified three pillars for the final structure of the HM COVID-19 Check-In Guide for Self and Peers:

- Pillar 1. Recognize your issues. Recall our oxygen mask metaphor and this is what we mean by recognizing symptoms of new stressors (e.g., sleeplessness, irritability, forgetfulness).

- Pillar 2. Know what to say. A simple open-ended question about how the other person is working through the pandemic is an easy way to start a connection. We learned from a mental health perspective that it is unlikely that you could say anything to make a situation worse by offering a listening ear.

- Pillar 3. Check in with others. Listen to others without trying to fix the person or the situation. When appropriate, offer humorous reflections without diminishing the problem. Be a partner and commit to check in regularly with the other person.

Cultivating human connections outside of your immediate peer group can be valuable and offer additional perspective to stressful situations. For instance, one of my roles as a hospitalist administrator has been offering support by regularly listening as my physicians ‘talk out’ their day confidentially for as long as they needed. Offering open conversation in a safe and confidential way can have a healing effect. As one of my former hospitalists used to say, if issues are not addressed, they will “ooze out somewhere else.”

The HM COVID-19 Check-In Guide for Self and Peers and the SHM Cares social media campaign was the result of the Taskforce’s collective observations to help others normalize the feeling that ‘it’s OK not to be OK.’ Using the pandemic as context, the 7 Drivers of Hospitalist Burnout reminded us that the increased burnout issues we face will require continued attention past the pandemic. The value in cultivating human connections has never been more important. The SHM Wellbeing Taskforce is committed to provide continued resources. Checking in with others and listening to peers are all part of a personal wellbeing and resilience strategy. On behalf of the SHM Wellbeing Taskforce, we hope the information in this article will highlight the importance of continued attention to personal wellbeing during and after the pandemic.

Dr. Robinson received her PhD in organizational learning, performance and change from Colorado State University in 2019. Her dissertation topic was exploring hospitalist burnout, engagement, and social support. She is administrative director of inpatient medicine at St. Mary’s Medical Center in Grand Junction, Colo., a part of SCL Health. She has volunteered in numerous SHM committees, and currently serves on the SHM Wellbeing Taskforce.

A check-in for you and your peers

A check-in for you and your peers

COVID-19 did not discriminate when it came to the impact it imposed on our hospitalist community. As the nomenclature moves away from the negative connotations of ‘burnout’ to ‘wellbeing,’ the pandemic has taught us something important about being intentional about our personal health: we must secure our own oxygen masks before helping others.

In February 2020, the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Wellbeing Taskforce efforts quickly changed focus from addressing general wellbeing, to wellbeing during COVID-19. Our Taskforce was commissioned by SHM’s Board with a new charge: Address immediate and ongoing needs of well-being and resiliency support for hospitalists during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this essay, I will discuss how our SHM Wellbeing Taskforce approached the overall topic of wellbeing for hospitalists during the COVID-19 pandemic, including some of our Taskforce group experiences.

The Taskforce started with a framework to aide in cultivating open and authentic conversations within hospital medicine groups. Creating spaces for honest sharing around how providers are doing is a crucial first step to reducing stigma, building mutual support within a group, and elevating issues of wellbeing to the level where structural change can take place. The Taskforce established two objectives for normalizing and mitigating stressors we face as hospitalists during the COVID-19 pandemic:

- Provide a framework for hospitalists to take their own emotional pulse

- Provide an approach to reduce stigma of hospitalists who are suffering from pandemic stress

While a more typical approach to fix stress and burnout is using formal institutional interventions, we used the value and insight provided by SHM’s 7 Drivers of Burnout in Hospital Medicine to help guide the creation of SHM resources in addressing the severe emotional strain being felt across the country by hospitalists. The 7 Drivers support the idea that the social role peers and hospital leaders can make a crucial difference in mitigating stress and burnout. Two examples of social support come to mind from the Wellbeing Taskforce experience:

- Participate in your meetings. One example comes from a member of our group who had underestimated the “healing power” that our group meetings had provided to his psyche. The simple act of participating in our Taskforce meeting and being in the presence of our group had provided such a positive impact that he was better able to face the “death and misery” in his unit with a smile on his face.

- Share what is stressful. The second example of social support comes from an hour of Zoom-based facilitation meetings between the SHM’s Wellbeing Taskforce members and Chapter Leaders in late October. During our Taskforce debrief after the meeting, we came to realize the enormous burden of grief our peers were carrying as one hospitalist had lost a group colleague the previous week due to suicide. Our member who led this meeting was moved – as were we – at how this had impacted his small team, and he was reminded he was not alone.

To form meaningful relationships that foster support, there needs to be a space where people can safely come together at times that initially might feel awkward. After taking steps toward your peers, these conversations can become normalized and contribute to meaningful relationships, providing the opportunity for healthy exchanges on vulnerable topics like emotional and psychological wellbeing. A printable guide for this specific purpose (“HM COVID-19 Check-In Guide for Self and Peers”) was designed to help hospitalists move into safe and supportive conversations with each other. While it is difficult to place a value on the importance these types of conversations have on individual wellbeing, it is known that the quality of a positive work environment where people feel supported can moderate stress, morale, and depression. In other words, hospitalist groups can positively contribute to their social environment during stressful times by sharing meaningful and difficult experiences with one another.

Second, the Taskforce created a social media campaign to provide a public social space for sharing hospitalists’ COVID-19 experiences. We believed that sharing collective experiences with the theme of #YouAreNotAlone and a complementary social media campaign, SHM Cares, on SHM’s social media channels, would further connect the national hospitalist community and provide a different communication pathway to decrease a sense of isolation. This idea came from the second social support idea mentioned earlier to share what is stressful with others in a safe space. We understood that some hospitalists would be more comfortable sharing publicly their comments, photos, and videos in achieving a sense of hospitalist unity.

Using our shared experiences, we identified three pillars for the final structure of the HM COVID-19 Check-In Guide for Self and Peers:

- Pillar 1. Recognize your issues. Recall our oxygen mask metaphor and this is what we mean by recognizing symptoms of new stressors (e.g., sleeplessness, irritability, forgetfulness).

- Pillar 2. Know what to say. A simple open-ended question about how the other person is working through the pandemic is an easy way to start a connection. We learned from a mental health perspective that it is unlikely that you could say anything to make a situation worse by offering a listening ear.

- Pillar 3. Check in with others. Listen to others without trying to fix the person or the situation. When appropriate, offer humorous reflections without diminishing the problem. Be a partner and commit to check in regularly with the other person.

Cultivating human connections outside of your immediate peer group can be valuable and offer additional perspective to stressful situations. For instance, one of my roles as a hospitalist administrator has been offering support by regularly listening as my physicians ‘talk out’ their day confidentially for as long as they needed. Offering open conversation in a safe and confidential way can have a healing effect. As one of my former hospitalists used to say, if issues are not addressed, they will “ooze out somewhere else.”

The HM COVID-19 Check-In Guide for Self and Peers and the SHM Cares social media campaign was the result of the Taskforce’s collective observations to help others normalize the feeling that ‘it’s OK not to be OK.’ Using the pandemic as context, the 7 Drivers of Hospitalist Burnout reminded us that the increased burnout issues we face will require continued attention past the pandemic. The value in cultivating human connections has never been more important. The SHM Wellbeing Taskforce is committed to provide continued resources. Checking in with others and listening to peers are all part of a personal wellbeing and resilience strategy. On behalf of the SHM Wellbeing Taskforce, we hope the information in this article will highlight the importance of continued attention to personal wellbeing during and after the pandemic.

Dr. Robinson received her PhD in organizational learning, performance and change from Colorado State University in 2019. Her dissertation topic was exploring hospitalist burnout, engagement, and social support. She is administrative director of inpatient medicine at St. Mary’s Medical Center in Grand Junction, Colo., a part of SCL Health. She has volunteered in numerous SHM committees, and currently serves on the SHM Wellbeing Taskforce.

COVID-19 did not discriminate when it came to the impact it imposed on our hospitalist community. As the nomenclature moves away from the negative connotations of ‘burnout’ to ‘wellbeing,’ the pandemic has taught us something important about being intentional about our personal health: we must secure our own oxygen masks before helping others.

In February 2020, the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Wellbeing Taskforce efforts quickly changed focus from addressing general wellbeing, to wellbeing during COVID-19. Our Taskforce was commissioned by SHM’s Board with a new charge: Address immediate and ongoing needs of well-being and resiliency support for hospitalists during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this essay, I will discuss how our SHM Wellbeing Taskforce approached the overall topic of wellbeing for hospitalists during the COVID-19 pandemic, including some of our Taskforce group experiences.

The Taskforce started with a framework to aide in cultivating open and authentic conversations within hospital medicine groups. Creating spaces for honest sharing around how providers are doing is a crucial first step to reducing stigma, building mutual support within a group, and elevating issues of wellbeing to the level where structural change can take place. The Taskforce established two objectives for normalizing and mitigating stressors we face as hospitalists during the COVID-19 pandemic:

- Provide a framework for hospitalists to take their own emotional pulse

- Provide an approach to reduce stigma of hospitalists who are suffering from pandemic stress

While a more typical approach to fix stress and burnout is using formal institutional interventions, we used the value and insight provided by SHM’s 7 Drivers of Burnout in Hospital Medicine to help guide the creation of SHM resources in addressing the severe emotional strain being felt across the country by hospitalists. The 7 Drivers support the idea that the social role peers and hospital leaders can make a crucial difference in mitigating stress and burnout. Two examples of social support come to mind from the Wellbeing Taskforce experience:

- Participate in your meetings. One example comes from a member of our group who had underestimated the “healing power” that our group meetings had provided to his psyche. The simple act of participating in our Taskforce meeting and being in the presence of our group had provided such a positive impact that he was better able to face the “death and misery” in his unit with a smile on his face.

- Share what is stressful. The second example of social support comes from an hour of Zoom-based facilitation meetings between the SHM’s Wellbeing Taskforce members and Chapter Leaders in late October. During our Taskforce debrief after the meeting, we came to realize the enormous burden of grief our peers were carrying as one hospitalist had lost a group colleague the previous week due to suicide. Our member who led this meeting was moved – as were we – at how this had impacted his small team, and he was reminded he was not alone.

To form meaningful relationships that foster support, there needs to be a space where people can safely come together at times that initially might feel awkward. After taking steps toward your peers, these conversations can become normalized and contribute to meaningful relationships, providing the opportunity for healthy exchanges on vulnerable topics like emotional and psychological wellbeing. A printable guide for this specific purpose (“HM COVID-19 Check-In Guide for Self and Peers”) was designed to help hospitalists move into safe and supportive conversations with each other. While it is difficult to place a value on the importance these types of conversations have on individual wellbeing, it is known that the quality of a positive work environment where people feel supported can moderate stress, morale, and depression. In other words, hospitalist groups can positively contribute to their social environment during stressful times by sharing meaningful and difficult experiences with one another.

Second, the Taskforce created a social media campaign to provide a public social space for sharing hospitalists’ COVID-19 experiences. We believed that sharing collective experiences with the theme of #YouAreNotAlone and a complementary social media campaign, SHM Cares, on SHM’s social media channels, would further connect the national hospitalist community and provide a different communication pathway to decrease a sense of isolation. This idea came from the second social support idea mentioned earlier to share what is stressful with others in a safe space. We understood that some hospitalists would be more comfortable sharing publicly their comments, photos, and videos in achieving a sense of hospitalist unity.

Using our shared experiences, we identified three pillars for the final structure of the HM COVID-19 Check-In Guide for Self and Peers:

- Pillar 1. Recognize your issues. Recall our oxygen mask metaphor and this is what we mean by recognizing symptoms of new stressors (e.g., sleeplessness, irritability, forgetfulness).

- Pillar 2. Know what to say. A simple open-ended question about how the other person is working through the pandemic is an easy way to start a connection. We learned from a mental health perspective that it is unlikely that you could say anything to make a situation worse by offering a listening ear.

- Pillar 3. Check in with others. Listen to others without trying to fix the person or the situation. When appropriate, offer humorous reflections without diminishing the problem. Be a partner and commit to check in regularly with the other person.

Cultivating human connections outside of your immediate peer group can be valuable and offer additional perspective to stressful situations. For instance, one of my roles as a hospitalist administrator has been offering support by regularly listening as my physicians ‘talk out’ their day confidentially for as long as they needed. Offering open conversation in a safe and confidential way can have a healing effect. As one of my former hospitalists used to say, if issues are not addressed, they will “ooze out somewhere else.”

The HM COVID-19 Check-In Guide for Self and Peers and the SHM Cares social media campaign was the result of the Taskforce’s collective observations to help others normalize the feeling that ‘it’s OK not to be OK.’ Using the pandemic as context, the 7 Drivers of Hospitalist Burnout reminded us that the increased burnout issues we face will require continued attention past the pandemic. The value in cultivating human connections has never been more important. The SHM Wellbeing Taskforce is committed to provide continued resources. Checking in with others and listening to peers are all part of a personal wellbeing and resilience strategy. On behalf of the SHM Wellbeing Taskforce, we hope the information in this article will highlight the importance of continued attention to personal wellbeing during and after the pandemic.

Dr. Robinson received her PhD in organizational learning, performance and change from Colorado State University in 2019. Her dissertation topic was exploring hospitalist burnout, engagement, and social support. She is administrative director of inpatient medicine at St. Mary’s Medical Center in Grand Junction, Colo., a part of SCL Health. She has volunteered in numerous SHM committees, and currently serves on the SHM Wellbeing Taskforce.

Nature or nurture in primary care?

Does the name Bruce Lipton sound familiar to you? Until a few years ago the only bell that it rang with me was that I had a high school classmate named Bruce Lipton. I recall that his father owned the local grocery store and he was one of the most prolific pranksters in a class with a long history of prank playing. If the name dredges up any associations for you it may because you have heard of a PhD biologist who has written and lectured extensively on epigenetics. You may have even read his most widely published book, “The Biology of Belief.” It turns out the Epigenetics Guy and my high school prankster classmate are one and the same.

After decades of separation – he is in California and I’m here in Maine – we have reconnected via Zoom mini reunions that our class has organized to combat the isolation that has descended on us with the pandemic. While I haven’t read his books, I have watched and listened to some of his podcasts and lectures. The devilish twinkle in his eye in the 1950s and 1960s has provided the scaffolding on which he has built a charismatic and persuasive presentation style.

Bruce was no dummy in school but his early career as a cell biologist doing research in stem-cell function was a surprise to all of us. But then high school reunions are often full of surprises and should serve as good reminders of the danger of profiling and pigeon-holing adolescents.

Professor Lipton’s take on epigenetics boils down to the notion that our genome should merely be considered a blueprint and not the final determinant of who we are and what illnesses befall us. His research and observations suggest to him that there are an uncountable number extragenomic factors, including environmental conditions and our belief systems, that can influence how that blueprint is read and the resulting expression of the genes we have inherited.

At face value, Bruce’s basic premise falls very close to some of the conclusions I have toyed with in an attempt to explain what I have observed doing primary care pediatrics. For example, I have trouble blaming the meteoric rise of the ADHD phenomenon on a genetic mutation. I suspect there are likely to be extragenomic forces coming into play, such as sleep deprivation and changing child-rearing practices. In my Oct. 9, 2020, Letters from Maine column I referred to a Swedish twins study that suggested children from a family with a strong history of depression were more likely to develop depression when raised in an adopted family that experienced domestic turmoil. His philosophy also fits with my sense that I have more control over my own health outcomes than many other people.

However, Professor Lipton and I part company (just philosophically that is) when he slips into hyperbole and applies what he terms as the New Biology too broadly. He may be correct that the revolutionary changes which came in the wake of Watson and Crick’s double helix discovery have resulted in a view of pathophysiology that is overly focused on what we are learning about our genome. On the other hand it is refreshing to hear someone with his charismatic and persuasive skills question the status quo.

If you haven’t listened to what he has to say I urge you to browse the Internet and sample some of his talks. I am sure you will find what he has to say stimulating. I doubt you will buy his whole package but I suspect you may find some bits you can agree with.

It still boils down to the old nature versus nurture argument. He’s all in for nurture. I’m still more comfortable straddling the fence.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Does the name Bruce Lipton sound familiar to you? Until a few years ago the only bell that it rang with me was that I had a high school classmate named Bruce Lipton. I recall that his father owned the local grocery store and he was one of the most prolific pranksters in a class with a long history of prank playing. If the name dredges up any associations for you it may because you have heard of a PhD biologist who has written and lectured extensively on epigenetics. You may have even read his most widely published book, “The Biology of Belief.” It turns out the Epigenetics Guy and my high school prankster classmate are one and the same.

After decades of separation – he is in California and I’m here in Maine – we have reconnected via Zoom mini reunions that our class has organized to combat the isolation that has descended on us with the pandemic. While I haven’t read his books, I have watched and listened to some of his podcasts and lectures. The devilish twinkle in his eye in the 1950s and 1960s has provided the scaffolding on which he has built a charismatic and persuasive presentation style.

Bruce was no dummy in school but his early career as a cell biologist doing research in stem-cell function was a surprise to all of us. But then high school reunions are often full of surprises and should serve as good reminders of the danger of profiling and pigeon-holing adolescents.

Professor Lipton’s take on epigenetics boils down to the notion that our genome should merely be considered a blueprint and not the final determinant of who we are and what illnesses befall us. His research and observations suggest to him that there are an uncountable number extragenomic factors, including environmental conditions and our belief systems, that can influence how that blueprint is read and the resulting expression of the genes we have inherited.

At face value, Bruce’s basic premise falls very close to some of the conclusions I have toyed with in an attempt to explain what I have observed doing primary care pediatrics. For example, I have trouble blaming the meteoric rise of the ADHD phenomenon on a genetic mutation. I suspect there are likely to be extragenomic forces coming into play, such as sleep deprivation and changing child-rearing practices. In my Oct. 9, 2020, Letters from Maine column I referred to a Swedish twins study that suggested children from a family with a strong history of depression were more likely to develop depression when raised in an adopted family that experienced domestic turmoil. His philosophy also fits with my sense that I have more control over my own health outcomes than many other people.

However, Professor Lipton and I part company (just philosophically that is) when he slips into hyperbole and applies what he terms as the New Biology too broadly. He may be correct that the revolutionary changes which came in the wake of Watson and Crick’s double helix discovery have resulted in a view of pathophysiology that is overly focused on what we are learning about our genome. On the other hand it is refreshing to hear someone with his charismatic and persuasive skills question the status quo.

If you haven’t listened to what he has to say I urge you to browse the Internet and sample some of his talks. I am sure you will find what he has to say stimulating. I doubt you will buy his whole package but I suspect you may find some bits you can agree with.

It still boils down to the old nature versus nurture argument. He’s all in for nurture. I’m still more comfortable straddling the fence.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Does the name Bruce Lipton sound familiar to you? Until a few years ago the only bell that it rang with me was that I had a high school classmate named Bruce Lipton. I recall that his father owned the local grocery store and he was one of the most prolific pranksters in a class with a long history of prank playing. If the name dredges up any associations for you it may because you have heard of a PhD biologist who has written and lectured extensively on epigenetics. You may have even read his most widely published book, “The Biology of Belief.” It turns out the Epigenetics Guy and my high school prankster classmate are one and the same.

After decades of separation – he is in California and I’m here in Maine – we have reconnected via Zoom mini reunions that our class has organized to combat the isolation that has descended on us with the pandemic. While I haven’t read his books, I have watched and listened to some of his podcasts and lectures. The devilish twinkle in his eye in the 1950s and 1960s has provided the scaffolding on which he has built a charismatic and persuasive presentation style.

Bruce was no dummy in school but his early career as a cell biologist doing research in stem-cell function was a surprise to all of us. But then high school reunions are often full of surprises and should serve as good reminders of the danger of profiling and pigeon-holing adolescents.

Professor Lipton’s take on epigenetics boils down to the notion that our genome should merely be considered a blueprint and not the final determinant of who we are and what illnesses befall us. His research and observations suggest to him that there are an uncountable number extragenomic factors, including environmental conditions and our belief systems, that can influence how that blueprint is read and the resulting expression of the genes we have inherited.

At face value, Bruce’s basic premise falls very close to some of the conclusions I have toyed with in an attempt to explain what I have observed doing primary care pediatrics. For example, I have trouble blaming the meteoric rise of the ADHD phenomenon on a genetic mutation. I suspect there are likely to be extragenomic forces coming into play, such as sleep deprivation and changing child-rearing practices. In my Oct. 9, 2020, Letters from Maine column I referred to a Swedish twins study that suggested children from a family with a strong history of depression were more likely to develop depression when raised in an adopted family that experienced domestic turmoil. His philosophy also fits with my sense that I have more control over my own health outcomes than many other people.

However, Professor Lipton and I part company (just philosophically that is) when he slips into hyperbole and applies what he terms as the New Biology too broadly. He may be correct that the revolutionary changes which came in the wake of Watson and Crick’s double helix discovery have resulted in a view of pathophysiology that is overly focused on what we are learning about our genome. On the other hand it is refreshing to hear someone with his charismatic and persuasive skills question the status quo.

If you haven’t listened to what he has to say I urge you to browse the Internet and sample some of his talks. I am sure you will find what he has to say stimulating. I doubt you will buy his whole package but I suspect you may find some bits you can agree with.

It still boils down to the old nature versus nurture argument. He’s all in for nurture. I’m still more comfortable straddling the fence.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

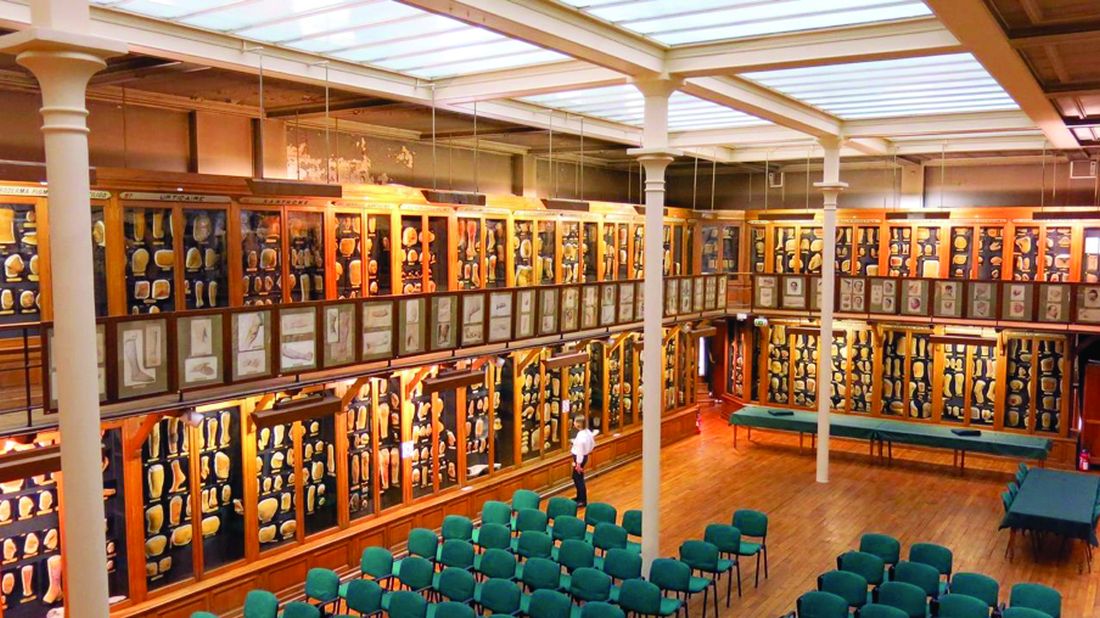

The Blitz and COVID-19

Lessons from history for hospitalists

The Blitz was a Nazi bombing campaign targeting London. It was designed to break the spirit of the British. Knowing London would be the centerpiece of the campaign, the British rather hastily established several psychiatric hospitals for the expected panic in the streets. However, despite 9 months of bombing, 43,000 civilians killed and 139,000 more wounded, the predicted chaos in the streets did not manifest. Civilians continued to work, industry continued to churn, and eventually, Hitler’s eye turned east toward Russia.

The surprising lack of pandemonium in London inspired Dr. John T. MacCurdy, who chronicled his findings in a book The Structure of Morale, more recently popularized in Malcolm Gladwell’s David and Goliath. A brief summary of Dr. MacCurdy’s theory divides the targeted Londoners into the following categories:

- Direct hit

- Near miss

- Remote miss

The direct hit group was defined as those killed by the bombing. However, As Dr. MacCurdy stated, “The morale of the community depends on the reaction of the survivors…Put this way, the fact is obvious, corpses do not run about spreading panic.”

A near miss were those for whom wounds were inflicted or loved ones were killed. This group felt the real repercussions of the bombing. However, with 139,000 wounded out of a city of 8 million people, they were a small minority.

The majority of Londoners, then, fit into the third group – the remote miss. These people faced a serious fear, but survived, often totally unscathed. The process of facing that fear without having panicked or having been harmed, then, led to “a feeling of excitement with a flavour of invulnerability.”

Therefore, rather than a city of millions running in fear in the streets, requiring military presence to control the chaos, London became a city of people who felt themselves, perhaps, invincible.

A similar threat passed through the world in the first several months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Hospitals were expected to be overrun, and ethics committees convened to discuss allocation of scarce ventilators. However, due, at least in part, to the impressive efforts of the populace of the United States, the majority of civilians did not feel the burden of this frightening disease. Certainly, in a few places, hospitals were overwhelmed, and resources were unavailable due to sheer numbers. These places saw those who suffered direct hits with the highest frequency. However, a disease with an infection fatality ratio recently estimated at 0.5-1%, with a relatively high rate of asymptomatic disease, led to a large majority of people who experienced the first wave of COVID-19 in the United States as a remote miss. COVID-19’s flattened first peak gave much of the population a sense of relief, and, perhaps, a “flavour of invulnerability.”

An anonymous, but concerned, household contact wrote The New York Times and illustrated perfectly the invulnerable feelings of a remote miss:

“I’m doing my best to avoid social contact, along with two other members of my household. We have sufficient supplies for a month. Despite that, one member insists on going out for trivial reasons, such as not liking the kind of apples we have. He’s 92. I’ve tried explaining and cajoling, using graphs and anecdotes to make the danger to all of us seem ‘real.’ It doesn’t take. His risk of death is many times greater than mine, and he’s poking holes in a lifeboat we all have to rely on. What is the correct path?”

American culture expects certainty from science. Therein lies the problem with a new disease no medical provider or researcher had seen prior to November 2019. Action was required in the effort to slow the spread with little to no data as a guide. Therefore, messages that seemed contradictory reached the public. “A mask less than N-95 grade will not protect you,” evolved to, “everyone should wear a homemade cloth mask.” As the pandemic evolved and data was gathered, new recommendations were presented. Unfortunately, such well-meaning and necessary changes led to confusion, mistrust, and conspiracy theories.

Psychologists have weighed in regarding other aspects of our culture that allow for the flourishing of misinformation. A photograph even loosely related to the information presented has been shown to increase the initial sense of trustworthiness. Simple repetition can also make a point seem more trustworthy. As social media pushes the daily deluge of information (with pictures!) to new heights, it is a small wonder misinformation remains in circulation.

Medicine’s response

The science of COVID-19 carries phenomenal uncertainties, but the psychology of those who have suffered direct hits or near misses are the daily bedside challenge of all physicians, but particularly of hospitalists. We live at the front lines of disease – as one colleague put it to me, “we are the watchers on the wall.” Though we do not yet have our hoped-for, evidence-based treatment for this virus, we are familiar with acute illness. We know the rapid change of health to disease, and we know the chronically ill who suffer exacerbations of such illness. Supporting patients and their loved ones through those times is our daily practice.

On the other hand, those who have experienced only remote misses remain vulnerable in this pandemic, despite their feelings of invincibility. Those that feel invincible may be the least interested in our advice. This, too, is no strange position for a physician. We have tools to reach patients who do not reach out to us. Traditional media outlets have been saturated with headlines and talking points about this disease. Physicians who have taken to social media have been met with appreciation in some situations, but ignored, doubted, or shunned in others. In May 2020, NBC News reported an ED doctor’s attempt to dispel some COVID myths on social media. Unfortunately, his remarks were summarily dismissed. Through the frustration, we persevere.

Out of the many responsible authorities who help battle misinformation, the World Health Organization’s mythbusting website (www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public/myth-busters) directly confronts many incorrect circulating ideas. My personal favorite at the time of this writing is: “Being able to hold your breath for 10 seconds or more without coughing or feeling discomfort DOES NOT mean you are free from COVID-19.”

For the policy and communication side of medicine in the midst of this pandemic, I will not claim to have a silver bullet. There are many intelligent, policy-minded people who are working on that very problem. However, as individual practitioners and as individual citizens, I can see two powerful tools that may help us move forward.

1) Confidence and humility: We live in a world of uncertainty, and we struggle against that every day. This pandemic has put our uncertainty clearly on display. However, we may also be confident in providing the best currently known care, even while holding the humility that what we know will likely change. Before COVID-19, we have all seen patients who received multiple different answers from multiple different providers. When I am willing to admit my uncertainty, I have witnessed patients’ skepticism transform into assuming an active role in their care.

For those who have suffered a direct hit or a near miss, honest conversations are vital to build a trusting physician-patient relationship. For the remote miss group, speaking candidly about our uncertainty displays our authenticity and helps combat conspiracy-type theories of ulterior motives. This becomes all the more crucial when new technologies are being deployed – for instance, a September 2020 CBS News survey showed only 21% of Americans planned to get a COVID-19 vaccine “as soon as possible.”

2) Insight into our driving emotions: While the near miss patients are likely ready to continue prevention measures, the remote miss group is often more difficult. When we do have the opportunity to discuss actions to impede the virus’ spread with the remote miss group, understanding their potentially unrecognized motivations helps with that conversation. I have shared the story of the London Blitz and the remote miss and seen people connect the dots with their own emotions. Effective counseling – expecting the feelings of invulnerability amongst the remote miss group – can support endurance with prevention measures amongst that group and help flatten the curve.

Communicating our strengths, transparently discussing our weaknesses, and better understanding underlying emotions for ourselves and our patients may help save lives. As physicians, that is our daily practice, unchanged even as medicine takes center stage in our national conversation.

Dr. Walthall completed his internal medicine residency at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, SC. After residency, he joined the faculty at MUSC in the Division of Hospital Medicine. He is also interested in systems-based care and has taken on the role of physician advisor. This essay appeared first on The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

Lessons from history for hospitalists

Lessons from history for hospitalists

The Blitz was a Nazi bombing campaign targeting London. It was designed to break the spirit of the British. Knowing London would be the centerpiece of the campaign, the British rather hastily established several psychiatric hospitals for the expected panic in the streets. However, despite 9 months of bombing, 43,000 civilians killed and 139,000 more wounded, the predicted chaos in the streets did not manifest. Civilians continued to work, industry continued to churn, and eventually, Hitler’s eye turned east toward Russia.

The surprising lack of pandemonium in London inspired Dr. John T. MacCurdy, who chronicled his findings in a book The Structure of Morale, more recently popularized in Malcolm Gladwell’s David and Goliath. A brief summary of Dr. MacCurdy’s theory divides the targeted Londoners into the following categories:

- Direct hit

- Near miss

- Remote miss

The direct hit group was defined as those killed by the bombing. However, As Dr. MacCurdy stated, “The morale of the community depends on the reaction of the survivors…Put this way, the fact is obvious, corpses do not run about spreading panic.”

A near miss were those for whom wounds were inflicted or loved ones were killed. This group felt the real repercussions of the bombing. However, with 139,000 wounded out of a city of 8 million people, they were a small minority.

The majority of Londoners, then, fit into the third group – the remote miss. These people faced a serious fear, but survived, often totally unscathed. The process of facing that fear without having panicked or having been harmed, then, led to “a feeling of excitement with a flavour of invulnerability.”

Therefore, rather than a city of millions running in fear in the streets, requiring military presence to control the chaos, London became a city of people who felt themselves, perhaps, invincible.

A similar threat passed through the world in the first several months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Hospitals were expected to be overrun, and ethics committees convened to discuss allocation of scarce ventilators. However, due, at least in part, to the impressive efforts of the populace of the United States, the majority of civilians did not feel the burden of this frightening disease. Certainly, in a few places, hospitals were overwhelmed, and resources were unavailable due to sheer numbers. These places saw those who suffered direct hits with the highest frequency. However, a disease with an infection fatality ratio recently estimated at 0.5-1%, with a relatively high rate of asymptomatic disease, led to a large majority of people who experienced the first wave of COVID-19 in the United States as a remote miss. COVID-19’s flattened first peak gave much of the population a sense of relief, and, perhaps, a “flavour of invulnerability.”

An anonymous, but concerned, household contact wrote The New York Times and illustrated perfectly the invulnerable feelings of a remote miss:

“I’m doing my best to avoid social contact, along with two other members of my household. We have sufficient supplies for a month. Despite that, one member insists on going out for trivial reasons, such as not liking the kind of apples we have. He’s 92. I’ve tried explaining and cajoling, using graphs and anecdotes to make the danger to all of us seem ‘real.’ It doesn’t take. His risk of death is many times greater than mine, and he’s poking holes in a lifeboat we all have to rely on. What is the correct path?”

American culture expects certainty from science. Therein lies the problem with a new disease no medical provider or researcher had seen prior to November 2019. Action was required in the effort to slow the spread with little to no data as a guide. Therefore, messages that seemed contradictory reached the public. “A mask less than N-95 grade will not protect you,” evolved to, “everyone should wear a homemade cloth mask.” As the pandemic evolved and data was gathered, new recommendations were presented. Unfortunately, such well-meaning and necessary changes led to confusion, mistrust, and conspiracy theories.

Psychologists have weighed in regarding other aspects of our culture that allow for the flourishing of misinformation. A photograph even loosely related to the information presented has been shown to increase the initial sense of trustworthiness. Simple repetition can also make a point seem more trustworthy. As social media pushes the daily deluge of information (with pictures!) to new heights, it is a small wonder misinformation remains in circulation.

Medicine’s response

The science of COVID-19 carries phenomenal uncertainties, but the psychology of those who have suffered direct hits or near misses are the daily bedside challenge of all physicians, but particularly of hospitalists. We live at the front lines of disease – as one colleague put it to me, “we are the watchers on the wall.” Though we do not yet have our hoped-for, evidence-based treatment for this virus, we are familiar with acute illness. We know the rapid change of health to disease, and we know the chronically ill who suffer exacerbations of such illness. Supporting patients and their loved ones through those times is our daily practice.

On the other hand, those who have experienced only remote misses remain vulnerable in this pandemic, despite their feelings of invincibility. Those that feel invincible may be the least interested in our advice. This, too, is no strange position for a physician. We have tools to reach patients who do not reach out to us. Traditional media outlets have been saturated with headlines and talking points about this disease. Physicians who have taken to social media have been met with appreciation in some situations, but ignored, doubted, or shunned in others. In May 2020, NBC News reported an ED doctor’s attempt to dispel some COVID myths on social media. Unfortunately, his remarks were summarily dismissed. Through the frustration, we persevere.

Out of the many responsible authorities who help battle misinformation, the World Health Organization’s mythbusting website (www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public/myth-busters) directly confronts many incorrect circulating ideas. My personal favorite at the time of this writing is: “Being able to hold your breath for 10 seconds or more without coughing or feeling discomfort DOES NOT mean you are free from COVID-19.”

For the policy and communication side of medicine in the midst of this pandemic, I will not claim to have a silver bullet. There are many intelligent, policy-minded people who are working on that very problem. However, as individual practitioners and as individual citizens, I can see two powerful tools that may help us move forward.

1) Confidence and humility: We live in a world of uncertainty, and we struggle against that every day. This pandemic has put our uncertainty clearly on display. However, we may also be confident in providing the best currently known care, even while holding the humility that what we know will likely change. Before COVID-19, we have all seen patients who received multiple different answers from multiple different providers. When I am willing to admit my uncertainty, I have witnessed patients’ skepticism transform into assuming an active role in their care.

For those who have suffered a direct hit or a near miss, honest conversations are vital to build a trusting physician-patient relationship. For the remote miss group, speaking candidly about our uncertainty displays our authenticity and helps combat conspiracy-type theories of ulterior motives. This becomes all the more crucial when new technologies are being deployed – for instance, a September 2020 CBS News survey showed only 21% of Americans planned to get a COVID-19 vaccine “as soon as possible.”

2) Insight into our driving emotions: While the near miss patients are likely ready to continue prevention measures, the remote miss group is often more difficult. When we do have the opportunity to discuss actions to impede the virus’ spread with the remote miss group, understanding their potentially unrecognized motivations helps with that conversation. I have shared the story of the London Blitz and the remote miss and seen people connect the dots with their own emotions. Effective counseling – expecting the feelings of invulnerability amongst the remote miss group – can support endurance with prevention measures amongst that group and help flatten the curve.

Communicating our strengths, transparently discussing our weaknesses, and better understanding underlying emotions for ourselves and our patients may help save lives. As physicians, that is our daily practice, unchanged even as medicine takes center stage in our national conversation.

Dr. Walthall completed his internal medicine residency at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, SC. After residency, he joined the faculty at MUSC in the Division of Hospital Medicine. He is also interested in systems-based care and has taken on the role of physician advisor. This essay appeared first on The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.