User login

An appeal for equitable access to care for early pregnancy loss

Remarkable advances in care for early pregnancy loss (EPL) have occurred over the past several years. Misoprostol with mifepristone pretreatment is now the gold standard for medical management after recent research showed that this regimen improves both the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of medical management.1 Manual vacuum aspiration (MVA)’s portability, effectiveness, and safety ensure that providers can offer procedural EPL management in almost any clinical setting. Medication management and in-office uterine aspiration are two evidence-based options for EPL management that may increase access for the 25% of pregnant women who experience EPL. Unfortunately, many women do not have access to either option. Equitable access to early pregnancy loss management can be achieved by expanding access to mifepristone and office-based MVA.

However, access to mifepristone and initiating office-based MVA is challenging. Mifepristone is one of several medications regulated under the Food and Drug Administration’s Risk Evaluation and Management Strategies (REMS) program.2

The REMS guidelines restrict clinicians in prescribing and dispensing mifepristone, including the key provision that mifepristone may be dispensed only in clinics, medical offices, and hospitals. Clinicians cannot write a prescription for mifepristone for a patient to pick up at the pharmacy. Efforts are underway to roll back the REMS. Barriers to office-based MVA include time, culture shift among staff, gathering equipment, and creating protocols. Clinicians can improve access to EPL management in a variety of ways:

- MVA training: Ob.gyns. who lack training in MVA use can take advantage of several programs designed to teach the skill to clinicians, including programs such as Training, Education, and Advocacy in Miscarriage Management (TEAMM).3,4 MVA is easy to learn for ob.gyns. and procedural complications are uncommon. In the office setting, complications requiring transfer to a higher level of care are rare.5 With adequate training, whether during residency or afterward, ob.gyns. can learn to safely and effectively use MVA for procedural EPL management in the office and in the emergency department.

- Partnerships with pharmacists to reduce barriers to mifepristone: Ob.gyns. working in a variety of clinical settings, including independent clinics, critical access hospitals, community hospitals, and academic medical centers, have worked closely with on-site pharmacists to place mifepristone on their practice sites’ formularies.6 These ob.gyn.–pharmacist collaborations often require explanations to institutional Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committees of the benefits of mifepristone to patients, detailed indications for mifepristone’s use, and methods to secure mifepristone on site.

- Partnerships with emergency department and outpatient nursing and administration to promote MVA: Provision of MVA is ideal for safe, effective, and cost-efficient procedural EPL management in both the emergency department and outpatient setting. However, access to MVA in emergency rooms and outpatient clinical settings is suboptimal. Some clinicians push back against MVA use in the emergency department, citing fears that performing the procedure in the emergency department unnecessarily uses staff and resources reserved for patients with more critical illnesses. Ob.gyns. should also work with emergency medicine physicians and emergency department nursing staff and hospital administrators in explaining that MVA in the emergency room is patient centered and cost effective.

Interdisciplinary collaboration and training are two strategies that can increase access to mifepristone and MVA for EPL management. Use of mifepristone/misoprostol and office/emergency department MVA for treatment of EPL is patient centered, evidence based, feasible, highly effective, and timely. These two health care interventions are practical in almost any setting, including rural and other low-resource settings. By using these strategies to overcome the logistical and institutional challenges, ob.gyns. can help countless women with EPL gain access to the best EPL care.

Dr. Espey is chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Dr. Jackson is an obstetrician/gynecologist at Michigan State University in Flint. They have no disclosures to report.

References

1. Schreiber CA et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jun 7;378(23):2161-70.

2. Food and Drug Administration. Mifeprex (mifepristone) information.

3. The TEAMM (Training, Education, and Advocacy in Miscarriage Management) Project. Training interprofessional teams to manage miscarriage. Accessed March 15, 2021.

4. Quinley KE et al. Ann Emerg Med. 2019 Jul;72(1):86-92.

5. Milingos DS et al. BJOG. 2009 Aug;116(9):1268-71.

6. Calloway D et al. Contraception. 2021 Jul;104(1):24-8.

Remarkable advances in care for early pregnancy loss (EPL) have occurred over the past several years. Misoprostol with mifepristone pretreatment is now the gold standard for medical management after recent research showed that this regimen improves both the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of medical management.1 Manual vacuum aspiration (MVA)’s portability, effectiveness, and safety ensure that providers can offer procedural EPL management in almost any clinical setting. Medication management and in-office uterine aspiration are two evidence-based options for EPL management that may increase access for the 25% of pregnant women who experience EPL. Unfortunately, many women do not have access to either option. Equitable access to early pregnancy loss management can be achieved by expanding access to mifepristone and office-based MVA.

However, access to mifepristone and initiating office-based MVA is challenging. Mifepristone is one of several medications regulated under the Food and Drug Administration’s Risk Evaluation and Management Strategies (REMS) program.2

The REMS guidelines restrict clinicians in prescribing and dispensing mifepristone, including the key provision that mifepristone may be dispensed only in clinics, medical offices, and hospitals. Clinicians cannot write a prescription for mifepristone for a patient to pick up at the pharmacy. Efforts are underway to roll back the REMS. Barriers to office-based MVA include time, culture shift among staff, gathering equipment, and creating protocols. Clinicians can improve access to EPL management in a variety of ways:

- MVA training: Ob.gyns. who lack training in MVA use can take advantage of several programs designed to teach the skill to clinicians, including programs such as Training, Education, and Advocacy in Miscarriage Management (TEAMM).3,4 MVA is easy to learn for ob.gyns. and procedural complications are uncommon. In the office setting, complications requiring transfer to a higher level of care are rare.5 With adequate training, whether during residency or afterward, ob.gyns. can learn to safely and effectively use MVA for procedural EPL management in the office and in the emergency department.

- Partnerships with pharmacists to reduce barriers to mifepristone: Ob.gyns. working in a variety of clinical settings, including independent clinics, critical access hospitals, community hospitals, and academic medical centers, have worked closely with on-site pharmacists to place mifepristone on their practice sites’ formularies.6 These ob.gyn.–pharmacist collaborations often require explanations to institutional Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committees of the benefits of mifepristone to patients, detailed indications for mifepristone’s use, and methods to secure mifepristone on site.

- Partnerships with emergency department and outpatient nursing and administration to promote MVA: Provision of MVA is ideal for safe, effective, and cost-efficient procedural EPL management in both the emergency department and outpatient setting. However, access to MVA in emergency rooms and outpatient clinical settings is suboptimal. Some clinicians push back against MVA use in the emergency department, citing fears that performing the procedure in the emergency department unnecessarily uses staff and resources reserved for patients with more critical illnesses. Ob.gyns. should also work with emergency medicine physicians and emergency department nursing staff and hospital administrators in explaining that MVA in the emergency room is patient centered and cost effective.

Interdisciplinary collaboration and training are two strategies that can increase access to mifepristone and MVA for EPL management. Use of mifepristone/misoprostol and office/emergency department MVA for treatment of EPL is patient centered, evidence based, feasible, highly effective, and timely. These two health care interventions are practical in almost any setting, including rural and other low-resource settings. By using these strategies to overcome the logistical and institutional challenges, ob.gyns. can help countless women with EPL gain access to the best EPL care.

Dr. Espey is chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Dr. Jackson is an obstetrician/gynecologist at Michigan State University in Flint. They have no disclosures to report.

References

1. Schreiber CA et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jun 7;378(23):2161-70.

2. Food and Drug Administration. Mifeprex (mifepristone) information.

3. The TEAMM (Training, Education, and Advocacy in Miscarriage Management) Project. Training interprofessional teams to manage miscarriage. Accessed March 15, 2021.

4. Quinley KE et al. Ann Emerg Med. 2019 Jul;72(1):86-92.

5. Milingos DS et al. BJOG. 2009 Aug;116(9):1268-71.

6. Calloway D et al. Contraception. 2021 Jul;104(1):24-8.

Remarkable advances in care for early pregnancy loss (EPL) have occurred over the past several years. Misoprostol with mifepristone pretreatment is now the gold standard for medical management after recent research showed that this regimen improves both the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of medical management.1 Manual vacuum aspiration (MVA)’s portability, effectiveness, and safety ensure that providers can offer procedural EPL management in almost any clinical setting. Medication management and in-office uterine aspiration are two evidence-based options for EPL management that may increase access for the 25% of pregnant women who experience EPL. Unfortunately, many women do not have access to either option. Equitable access to early pregnancy loss management can be achieved by expanding access to mifepristone and office-based MVA.

However, access to mifepristone and initiating office-based MVA is challenging. Mifepristone is one of several medications regulated under the Food and Drug Administration’s Risk Evaluation and Management Strategies (REMS) program.2

The REMS guidelines restrict clinicians in prescribing and dispensing mifepristone, including the key provision that mifepristone may be dispensed only in clinics, medical offices, and hospitals. Clinicians cannot write a prescription for mifepristone for a patient to pick up at the pharmacy. Efforts are underway to roll back the REMS. Barriers to office-based MVA include time, culture shift among staff, gathering equipment, and creating protocols. Clinicians can improve access to EPL management in a variety of ways:

- MVA training: Ob.gyns. who lack training in MVA use can take advantage of several programs designed to teach the skill to clinicians, including programs such as Training, Education, and Advocacy in Miscarriage Management (TEAMM).3,4 MVA is easy to learn for ob.gyns. and procedural complications are uncommon. In the office setting, complications requiring transfer to a higher level of care are rare.5 With adequate training, whether during residency or afterward, ob.gyns. can learn to safely and effectively use MVA for procedural EPL management in the office and in the emergency department.

- Partnerships with pharmacists to reduce barriers to mifepristone: Ob.gyns. working in a variety of clinical settings, including independent clinics, critical access hospitals, community hospitals, and academic medical centers, have worked closely with on-site pharmacists to place mifepristone on their practice sites’ formularies.6 These ob.gyn.–pharmacist collaborations often require explanations to institutional Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committees of the benefits of mifepristone to patients, detailed indications for mifepristone’s use, and methods to secure mifepristone on site.

- Partnerships with emergency department and outpatient nursing and administration to promote MVA: Provision of MVA is ideal for safe, effective, and cost-efficient procedural EPL management in both the emergency department and outpatient setting. However, access to MVA in emergency rooms and outpatient clinical settings is suboptimal. Some clinicians push back against MVA use in the emergency department, citing fears that performing the procedure in the emergency department unnecessarily uses staff and resources reserved for patients with more critical illnesses. Ob.gyns. should also work with emergency medicine physicians and emergency department nursing staff and hospital administrators in explaining that MVA in the emergency room is patient centered and cost effective.

Interdisciplinary collaboration and training are two strategies that can increase access to mifepristone and MVA for EPL management. Use of mifepristone/misoprostol and office/emergency department MVA for treatment of EPL is patient centered, evidence based, feasible, highly effective, and timely. These two health care interventions are practical in almost any setting, including rural and other low-resource settings. By using these strategies to overcome the logistical and institutional challenges, ob.gyns. can help countless women with EPL gain access to the best EPL care.

Dr. Espey is chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Dr. Jackson is an obstetrician/gynecologist at Michigan State University in Flint. They have no disclosures to report.

References

1. Schreiber CA et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jun 7;378(23):2161-70.

2. Food and Drug Administration. Mifeprex (mifepristone) information.

3. The TEAMM (Training, Education, and Advocacy in Miscarriage Management) Project. Training interprofessional teams to manage miscarriage. Accessed March 15, 2021.

4. Quinley KE et al. Ann Emerg Med. 2019 Jul;72(1):86-92.

5. Milingos DS et al. BJOG. 2009 Aug;116(9):1268-71.

6. Calloway D et al. Contraception. 2021 Jul;104(1):24-8.

Authors’ response

My co-authors and I appreciate the excellent comments regarding our Photo Rounds column, “Foot rash and joint pain,” and would like to provide some additional detail.

After our patient’s 27-day hospital stay, he was admitted to a rehabilitation center for continued inpatient physical therapy for 14 days due to weakness and deconditioning. Following his discharge from the rehabilitation center, the patient was still confined to a wheelchair. He was prescribed an oral prednisone taper (as mentioned in our article) and celecoxib 200 mg bid and referred for outpatient physical therapy. At a follow-up appointment with the rheumatologist, he received adalimumab 80 mg followed by 40 mg every other week, which led to improvement in his range of motion and pain. Two months after outpatient physical therapy, the patient was lost to follow-up.

We agree with Dr. Hahn et al that many of these patients with chlamydia-associated ReA become “long-haulers.” In medicine—especially when rare diseases are considered—we must often make decisions without perfect science. The studies referenced by Dr. Hahn et al suggest that combinations of doxycycline and rifampin or azithromycin and rifampin may treat not only chlamydial infection, but ReA and associated cutaneous disease, as well.1,2 While these studies are small in size, larger studies may never be funded. We agree that combination therapy should be considered in this population of patients.

Hannah R. Badon, MD

Ross L. Pearlman, MD

Robert T. Brodell, MD

Jackson, MS

1. Carter JD, Valeriano J, Vasey FB. Doxycycline versus doxycycline and rifampin in undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy, with special reference to chlamydia-induced arthritis. A prospective, randomized 9-month comparison. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1973-1980.

2. Carter JD, Espinoza LR, Inman RD, et al. Combination antibiotics as a treatment for chronic Chlamydia-induced reactive arthritis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1298-1307. doi: 10.1002/art.27394

My co-authors and I appreciate the excellent comments regarding our Photo Rounds column, “Foot rash and joint pain,” and would like to provide some additional detail.

After our patient’s 27-day hospital stay, he was admitted to a rehabilitation center for continued inpatient physical therapy for 14 days due to weakness and deconditioning. Following his discharge from the rehabilitation center, the patient was still confined to a wheelchair. He was prescribed an oral prednisone taper (as mentioned in our article) and celecoxib 200 mg bid and referred for outpatient physical therapy. At a follow-up appointment with the rheumatologist, he received adalimumab 80 mg followed by 40 mg every other week, which led to improvement in his range of motion and pain. Two months after outpatient physical therapy, the patient was lost to follow-up.

We agree with Dr. Hahn et al that many of these patients with chlamydia-associated ReA become “long-haulers.” In medicine—especially when rare diseases are considered—we must often make decisions without perfect science. The studies referenced by Dr. Hahn et al suggest that combinations of doxycycline and rifampin or azithromycin and rifampin may treat not only chlamydial infection, but ReA and associated cutaneous disease, as well.1,2 While these studies are small in size, larger studies may never be funded. We agree that combination therapy should be considered in this population of patients.

Hannah R. Badon, MD

Ross L. Pearlman, MD

Robert T. Brodell, MD

Jackson, MS

My co-authors and I appreciate the excellent comments regarding our Photo Rounds column, “Foot rash and joint pain,” and would like to provide some additional detail.

After our patient’s 27-day hospital stay, he was admitted to a rehabilitation center for continued inpatient physical therapy for 14 days due to weakness and deconditioning. Following his discharge from the rehabilitation center, the patient was still confined to a wheelchair. He was prescribed an oral prednisone taper (as mentioned in our article) and celecoxib 200 mg bid and referred for outpatient physical therapy. At a follow-up appointment with the rheumatologist, he received adalimumab 80 mg followed by 40 mg every other week, which led to improvement in his range of motion and pain. Two months after outpatient physical therapy, the patient was lost to follow-up.

We agree with Dr. Hahn et al that many of these patients with chlamydia-associated ReA become “long-haulers.” In medicine—especially when rare diseases are considered—we must often make decisions without perfect science. The studies referenced by Dr. Hahn et al suggest that combinations of doxycycline and rifampin or azithromycin and rifampin may treat not only chlamydial infection, but ReA and associated cutaneous disease, as well.1,2 While these studies are small in size, larger studies may never be funded. We agree that combination therapy should be considered in this population of patients.

Hannah R. Badon, MD

Ross L. Pearlman, MD

Robert T. Brodell, MD

Jackson, MS

1. Carter JD, Valeriano J, Vasey FB. Doxycycline versus doxycycline and rifampin in undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy, with special reference to chlamydia-induced arthritis. A prospective, randomized 9-month comparison. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1973-1980.

2. Carter JD, Espinoza LR, Inman RD, et al. Combination antibiotics as a treatment for chronic Chlamydia-induced reactive arthritis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1298-1307. doi: 10.1002/art.27394

1. Carter JD, Valeriano J, Vasey FB. Doxycycline versus doxycycline and rifampin in undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy, with special reference to chlamydia-induced arthritis. A prospective, randomized 9-month comparison. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1973-1980.

2. Carter JD, Espinoza LR, Inman RD, et al. Combination antibiotics as a treatment for chronic Chlamydia-induced reactive arthritis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1298-1307. doi: 10.1002/art.27394

How best to treat “long-haulers” with reactive arthritis?

In the June Photo Rounds column, “Foot rash and joint pain” (J Fam Pract. 2021;70:249-251), Badon et al presented a case of chlamydia-associated reactive arthritis (ReA), formerly called Reiter syndrome, in a 21-year-old man following Chlamydia trachomatis urethritis. We would like to point out that, contrary to the conventional definition of ReA, in which the causative pathogen can’t be cultured from the affected joints,1 chlamydia-associated ReA is associated with evidence of chronic joint infection that, while not cultivable, can be confirmed by real-time polymerase chain reaction testing of metabolically active pathogens in synovial tissue and/or fluid.2

C trachomatis and C pneumoniae are the most frequent causative pathogens to elicit ReA.3 Short-course antibiotics and anti-inflammatory treatments can palliate ReA, but these treatments often do not provide a cure.3 Two controlled clinical trials demonstrated that chlamydia-associated ReA can be treated successfully with longer-term combination antibiotic therapy.4,5 ReA is usually diagnosed in the acute stage (first 6 months) and can become chronic in 30% of cases.6 It would be interesting to know the long-term treatment and outcome data for the case patient.

David L. Hahn, MD, MS

Alan P. Hudson, PhD

Charles Stratton, MD

Wilmore Webley, PhD

Judith Whittum-Hudson, PhD

1. Yu D, van Tubergenm A. Reactive arthritis. UpToDate. Updated 2021. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.uptodate.com/contents/reactive-arthritis

2. Gérard HC, Carter JD, Hudson AP. Chlamydia trachomatis is present and metabolically active during the remitting phase in synovial tissues from patients with chronic chlamydia-induced reactive arthritis. Am J Med Sci. 2013;346:22-25. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3182648740

3. Zeidler H, Hudson AP. New insights into chlamydia and arthritis. Promise of a cure? Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:637-644. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204110

4. Carter JD, Valeriano J, Vasey FB. Doxycycline versus doxycycline and rifampin in undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy, with special reference to chlamydia-induced arthritis. A prospective, randomized 9-month comparison. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1973-1980.

5. Carter JD, Espinoza LR, Inman RD, et al. Combination antibiotics as a treatment for chronic Chlamydia-induced reactive arthritis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1298-1307. doi: 10.1002/art.27394

6. Carter JD, Inman RD, Whittum-Hudson J, et al. Chlamydia and chronic arthritis. Ann Med. 2012;44:784-792. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2011.606830

In the June Photo Rounds column, “Foot rash and joint pain” (J Fam Pract. 2021;70:249-251), Badon et al presented a case of chlamydia-associated reactive arthritis (ReA), formerly called Reiter syndrome, in a 21-year-old man following Chlamydia trachomatis urethritis. We would like to point out that, contrary to the conventional definition of ReA, in which the causative pathogen can’t be cultured from the affected joints,1 chlamydia-associated ReA is associated with evidence of chronic joint infection that, while not cultivable, can be confirmed by real-time polymerase chain reaction testing of metabolically active pathogens in synovial tissue and/or fluid.2

C trachomatis and C pneumoniae are the most frequent causative pathogens to elicit ReA.3 Short-course antibiotics and anti-inflammatory treatments can palliate ReA, but these treatments often do not provide a cure.3 Two controlled clinical trials demonstrated that chlamydia-associated ReA can be treated successfully with longer-term combination antibiotic therapy.4,5 ReA is usually diagnosed in the acute stage (first 6 months) and can become chronic in 30% of cases.6 It would be interesting to know the long-term treatment and outcome data for the case patient.

David L. Hahn, MD, MS

Alan P. Hudson, PhD

Charles Stratton, MD

Wilmore Webley, PhD

Judith Whittum-Hudson, PhD

In the June Photo Rounds column, “Foot rash and joint pain” (J Fam Pract. 2021;70:249-251), Badon et al presented a case of chlamydia-associated reactive arthritis (ReA), formerly called Reiter syndrome, in a 21-year-old man following Chlamydia trachomatis urethritis. We would like to point out that, contrary to the conventional definition of ReA, in which the causative pathogen can’t be cultured from the affected joints,1 chlamydia-associated ReA is associated with evidence of chronic joint infection that, while not cultivable, can be confirmed by real-time polymerase chain reaction testing of metabolically active pathogens in synovial tissue and/or fluid.2

C trachomatis and C pneumoniae are the most frequent causative pathogens to elicit ReA.3 Short-course antibiotics and anti-inflammatory treatments can palliate ReA, but these treatments often do not provide a cure.3 Two controlled clinical trials demonstrated that chlamydia-associated ReA can be treated successfully with longer-term combination antibiotic therapy.4,5 ReA is usually diagnosed in the acute stage (first 6 months) and can become chronic in 30% of cases.6 It would be interesting to know the long-term treatment and outcome data for the case patient.

David L. Hahn, MD, MS

Alan P. Hudson, PhD

Charles Stratton, MD

Wilmore Webley, PhD

Judith Whittum-Hudson, PhD

1. Yu D, van Tubergenm A. Reactive arthritis. UpToDate. Updated 2021. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.uptodate.com/contents/reactive-arthritis

2. Gérard HC, Carter JD, Hudson AP. Chlamydia trachomatis is present and metabolically active during the remitting phase in synovial tissues from patients with chronic chlamydia-induced reactive arthritis. Am J Med Sci. 2013;346:22-25. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3182648740

3. Zeidler H, Hudson AP. New insights into chlamydia and arthritis. Promise of a cure? Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:637-644. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204110

4. Carter JD, Valeriano J, Vasey FB. Doxycycline versus doxycycline and rifampin in undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy, with special reference to chlamydia-induced arthritis. A prospective, randomized 9-month comparison. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1973-1980.

5. Carter JD, Espinoza LR, Inman RD, et al. Combination antibiotics as a treatment for chronic Chlamydia-induced reactive arthritis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1298-1307. doi: 10.1002/art.27394

6. Carter JD, Inman RD, Whittum-Hudson J, et al. Chlamydia and chronic arthritis. Ann Med. 2012;44:784-792. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2011.606830

1. Yu D, van Tubergenm A. Reactive arthritis. UpToDate. Updated 2021. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.uptodate.com/contents/reactive-arthritis

2. Gérard HC, Carter JD, Hudson AP. Chlamydia trachomatis is present and metabolically active during the remitting phase in synovial tissues from patients with chronic chlamydia-induced reactive arthritis. Am J Med Sci. 2013;346:22-25. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3182648740

3. Zeidler H, Hudson AP. New insights into chlamydia and arthritis. Promise of a cure? Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:637-644. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204110

4. Carter JD, Valeriano J, Vasey FB. Doxycycline versus doxycycline and rifampin in undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy, with special reference to chlamydia-induced arthritis. A prospective, randomized 9-month comparison. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1973-1980.

5. Carter JD, Espinoza LR, Inman RD, et al. Combination antibiotics as a treatment for chronic Chlamydia-induced reactive arthritis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1298-1307. doi: 10.1002/art.27394

6. Carter JD, Inman RD, Whittum-Hudson J, et al. Chlamydia and chronic arthritis. Ann Med. 2012;44:784-792. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2011.606830

Buprenorphine offers a way to rise from the ashes of addiction

One of the most rewarding aspects of being a physician is having a direct impact on alleviating patient suffering. On the other hand, one of the more difficult elements is a confrontational patient with unreasonable expectations or inappropriate demands. I have experienced both ends of the spectrum while engaging with patients who have opioid use disorder (OUD).

An untreated patient with OUD might provide an untruthful history, attempt to falsify exam findings, or even become threatening or abusive in an attempt to secure opiate pain medication. Managing a patient with OUD by providing buprenorphine treatment, however, is a completely different experience.

There is no controversy about the effectiveness of buprenorphine treatment for OUD. Patients seeking it are not looking for inappropriate care but rather a treatment that is established as an unequivocal standard with proven results for better treatment outcomes1-3 and reduced mortality.4 Personally, I’ve found offering buprenorphine treatment to be one of the most rewarding aspects of practicing medicine. It is a real joy to witness people turn their lives around with meaningful outcomes such as gainful employment, eradication of hepatitis C, reconciliation of broken relationships, resolution of legal troubles, and long-term sobriety. Being a part of lives that are practically resurrected from the ashes of addiction by prescribing medicine is indeed an exceptional experience.

On April 28, 2021, the Department of Health and Human Services provided notice for immediate action allowing for any DEA-licensed provider to obtain an X-waiver to treat 30 active patients without educational prerequisite or certification of behavioral health referral capacity.5 The X-waiver requirements were reduced, as outlined by SAMSHA,6 to a simple online notice of intent7 that can be completed in less than 5 minutes.

I encourage my colleagues to obtain the X-waiver by the simplified process, start prescribing buprenorphine, and be a part of the solution to the opioid epidemic. Of course, there will be struggles and lessons learned, but these can most certainly be eclipsed by a focus on the rewarding experience of restoring wholeness to the lives of many patients.

Aaron Newcomb, DO

Carbondale, IL

1. Norton BL, Beitin A, Glenn M, et al. Retention in buprenorphine treatment is associated with improved HCV care outcomes. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;75:38-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.01.015

2. Evans EA, Zhu Y, Yoo C, et al. Criminal justice outcomes over 5 years after randomization to buprenorphine-naloxone or methadone treatment for opioid use disorder. Addiction. 2019;114:1396-1404. doi: 10.1111/add.14620

3. Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, et al. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane. Published February 6, 2014. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.cochrane.org/CD002207/ADDICTN_buprenorphine-maintenance-versus-placebo-or-methadone-maintenance-for-opioid-dependence

4. Methadone and buprenorphine reduce risk of death after opioid overdose. National Institutes of Health. Published June 19, 2018. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/methadone-buprenorphine-reduce-risk-death-after-opioid-overdose

5. Practice Guidelines for the Administration of Buprenorphine for Treating Opioid Use Disorder. Department of Health and Human Services; 2021. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/04/28/2021-08961/practice-guidelines-for-the-administration-of-buprenorphine-for-treating-opioid-use-disorder

6. US Department of Health & Human Services. Become a buprenorphine waivered practitioner. SAMHSA. Updated May 14, 2021. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/become-buprenorphine-waivered-practitioner

7. Buprenorphine waiver notification. SAMHSA. Accessed August 10, 2021. https://buprenorphine.samhsa.gov/forms/select-practitioner-type.php

One of the most rewarding aspects of being a physician is having a direct impact on alleviating patient suffering. On the other hand, one of the more difficult elements is a confrontational patient with unreasonable expectations or inappropriate demands. I have experienced both ends of the spectrum while engaging with patients who have opioid use disorder (OUD).

An untreated patient with OUD might provide an untruthful history, attempt to falsify exam findings, or even become threatening or abusive in an attempt to secure opiate pain medication. Managing a patient with OUD by providing buprenorphine treatment, however, is a completely different experience.

There is no controversy about the effectiveness of buprenorphine treatment for OUD. Patients seeking it are not looking for inappropriate care but rather a treatment that is established as an unequivocal standard with proven results for better treatment outcomes1-3 and reduced mortality.4 Personally, I’ve found offering buprenorphine treatment to be one of the most rewarding aspects of practicing medicine. It is a real joy to witness people turn their lives around with meaningful outcomes such as gainful employment, eradication of hepatitis C, reconciliation of broken relationships, resolution of legal troubles, and long-term sobriety. Being a part of lives that are practically resurrected from the ashes of addiction by prescribing medicine is indeed an exceptional experience.

On April 28, 2021, the Department of Health and Human Services provided notice for immediate action allowing for any DEA-licensed provider to obtain an X-waiver to treat 30 active patients without educational prerequisite or certification of behavioral health referral capacity.5 The X-waiver requirements were reduced, as outlined by SAMSHA,6 to a simple online notice of intent7 that can be completed in less than 5 minutes.

I encourage my colleagues to obtain the X-waiver by the simplified process, start prescribing buprenorphine, and be a part of the solution to the opioid epidemic. Of course, there will be struggles and lessons learned, but these can most certainly be eclipsed by a focus on the rewarding experience of restoring wholeness to the lives of many patients.

Aaron Newcomb, DO

Carbondale, IL

One of the most rewarding aspects of being a physician is having a direct impact on alleviating patient suffering. On the other hand, one of the more difficult elements is a confrontational patient with unreasonable expectations or inappropriate demands. I have experienced both ends of the spectrum while engaging with patients who have opioid use disorder (OUD).

An untreated patient with OUD might provide an untruthful history, attempt to falsify exam findings, or even become threatening or abusive in an attempt to secure opiate pain medication. Managing a patient with OUD by providing buprenorphine treatment, however, is a completely different experience.

There is no controversy about the effectiveness of buprenorphine treatment for OUD. Patients seeking it are not looking for inappropriate care but rather a treatment that is established as an unequivocal standard with proven results for better treatment outcomes1-3 and reduced mortality.4 Personally, I’ve found offering buprenorphine treatment to be one of the most rewarding aspects of practicing medicine. It is a real joy to witness people turn their lives around with meaningful outcomes such as gainful employment, eradication of hepatitis C, reconciliation of broken relationships, resolution of legal troubles, and long-term sobriety. Being a part of lives that are practically resurrected from the ashes of addiction by prescribing medicine is indeed an exceptional experience.

On April 28, 2021, the Department of Health and Human Services provided notice for immediate action allowing for any DEA-licensed provider to obtain an X-waiver to treat 30 active patients without educational prerequisite or certification of behavioral health referral capacity.5 The X-waiver requirements were reduced, as outlined by SAMSHA,6 to a simple online notice of intent7 that can be completed in less than 5 minutes.

I encourage my colleagues to obtain the X-waiver by the simplified process, start prescribing buprenorphine, and be a part of the solution to the opioid epidemic. Of course, there will be struggles and lessons learned, but these can most certainly be eclipsed by a focus on the rewarding experience of restoring wholeness to the lives of many patients.

Aaron Newcomb, DO

Carbondale, IL

1. Norton BL, Beitin A, Glenn M, et al. Retention in buprenorphine treatment is associated with improved HCV care outcomes. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;75:38-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.01.015

2. Evans EA, Zhu Y, Yoo C, et al. Criminal justice outcomes over 5 years after randomization to buprenorphine-naloxone or methadone treatment for opioid use disorder. Addiction. 2019;114:1396-1404. doi: 10.1111/add.14620

3. Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, et al. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane. Published February 6, 2014. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.cochrane.org/CD002207/ADDICTN_buprenorphine-maintenance-versus-placebo-or-methadone-maintenance-for-opioid-dependence

4. Methadone and buprenorphine reduce risk of death after opioid overdose. National Institutes of Health. Published June 19, 2018. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/methadone-buprenorphine-reduce-risk-death-after-opioid-overdose

5. Practice Guidelines for the Administration of Buprenorphine for Treating Opioid Use Disorder. Department of Health and Human Services; 2021. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/04/28/2021-08961/practice-guidelines-for-the-administration-of-buprenorphine-for-treating-opioid-use-disorder

6. US Department of Health & Human Services. Become a buprenorphine waivered practitioner. SAMHSA. Updated May 14, 2021. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/become-buprenorphine-waivered-practitioner

7. Buprenorphine waiver notification. SAMHSA. Accessed August 10, 2021. https://buprenorphine.samhsa.gov/forms/select-practitioner-type.php

1. Norton BL, Beitin A, Glenn M, et al. Retention in buprenorphine treatment is associated with improved HCV care outcomes. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;75:38-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.01.015

2. Evans EA, Zhu Y, Yoo C, et al. Criminal justice outcomes over 5 years after randomization to buprenorphine-naloxone or methadone treatment for opioid use disorder. Addiction. 2019;114:1396-1404. doi: 10.1111/add.14620

3. Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, et al. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane. Published February 6, 2014. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.cochrane.org/CD002207/ADDICTN_buprenorphine-maintenance-versus-placebo-or-methadone-maintenance-for-opioid-dependence

4. Methadone and buprenorphine reduce risk of death after opioid overdose. National Institutes of Health. Published June 19, 2018. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/methadone-buprenorphine-reduce-risk-death-after-opioid-overdose

5. Practice Guidelines for the Administration of Buprenorphine for Treating Opioid Use Disorder. Department of Health and Human Services; 2021. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/04/28/2021-08961/practice-guidelines-for-the-administration-of-buprenorphine-for-treating-opioid-use-disorder

6. US Department of Health & Human Services. Become a buprenorphine waivered practitioner. SAMHSA. Updated May 14, 2021. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/become-buprenorphine-waivered-practitioner

7. Buprenorphine waiver notification. SAMHSA. Accessed August 10, 2021. https://buprenorphine.samhsa.gov/forms/select-practitioner-type.php

Smart watch glucose monitoring on the horizon

Earlier this year, technology news sites reported that the Apple Watch Series 7 and the Samsung Galaxy Watch 4 were going to have integrated optical sensors for checking interstitial fluid glucose levels with no blood sampling needed. By the summer, new articles indicated that the glucose sensing watches would not be released this year for either Apple or Samsung.

For now, the newest technology available for monitoring glucose is continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), which involves a tiny sensor being inserted under the skin. The sensor tests glucose every few minutes, and a transmitter wirelessly sends the information to a monitor, which may be part of an insulin pump or a separate device. Some CGMs send information directly to a smartphone or tablet, according to the National Institutes of Health.

In 1999 the Food and Drug Administration approved the first CGM, which was only approved for downloading 3 days of data at a doctor’s office. Interestingly, the first real-time CGM device for patients to use on their own was a watch, the Glucowatch Biographer. Because of irritation and other issues, that watch never caught on. In 2006 and 2008, Dexcom and then Abbott released the first real-time CGMs that allowed patients to frequently check their own blood sugars.1,2

How CGM has advanced diabetes management

The advent of CGM has advanced the field of diabetes management in many ways.

It has allowed patients to get real time feedback on how their behavior affects their blood sugar. The use of CGM along with the ensuing behavioral changes actually leads to a decrease in hemoglobin A1c, along with a lower risk of hypoglycemia. CGM has also resulted in patients having a better understanding of several aspects of glucose control, including glucose variability and nocturnal hypoglycemia.

Affordable, readily accessible CGM monitors that allow patients to intermittently use CGM have become available over the last 3 years.

In the United States alone, 34.2 million people have diabetes – nearly 1 in every 10 people. Many do not do self-monitoring of blood glucose and most do not use CGM. The current alternative to CGM – self monitoring of blood glucose – is cumbersome, and, since it requires regular finger sticks, is painful. Also, there is significant cost to each test strip that is used to self-monitor, and most insurance limits the number of times a day a patient can check their blood sugar. CGM used to be reserved only for patients who use multiple doses of insulin daily, and only began being approved for use for patients on basal insulin alone in June 2021.3

Most primary care doctors are just beginning to learn how to interpret CGM data.

Smart watch glucose monitoring predictions

When smart watch glucose monitoring arrives, it will suddenly change the playing field for patients with diabetes and their doctors alike.

We expect it to bring down the price of CGM and make it readily available to any patient who owns a smart watch with that function.

For doctors, the new technology will result in them suddenly being asked to advise their patients on how to use the data generated by watch-based CGM.

Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece. Dr. Persampiere is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health. You can contact them at fpnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Hirsh I. Introduction: History of Glucose Monitoring, in “Role of Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Diabetes Treatment.” American Diabetes Association. 2018.

2. Peters A. The Evidence Base for Continuous Glucose Monitoring, in “Role of Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Diabetes Treatment.” American Diabetes Association 2018.

3. “Medicare Loosening Restrictions for Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) Coverage,” Healthline. 2021 Jul 13.

Earlier this year, technology news sites reported that the Apple Watch Series 7 and the Samsung Galaxy Watch 4 were going to have integrated optical sensors for checking interstitial fluid glucose levels with no blood sampling needed. By the summer, new articles indicated that the glucose sensing watches would not be released this year for either Apple or Samsung.

For now, the newest technology available for monitoring glucose is continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), which involves a tiny sensor being inserted under the skin. The sensor tests glucose every few minutes, and a transmitter wirelessly sends the information to a monitor, which may be part of an insulin pump or a separate device. Some CGMs send information directly to a smartphone or tablet, according to the National Institutes of Health.

In 1999 the Food and Drug Administration approved the first CGM, which was only approved for downloading 3 days of data at a doctor’s office. Interestingly, the first real-time CGM device for patients to use on their own was a watch, the Glucowatch Biographer. Because of irritation and other issues, that watch never caught on. In 2006 and 2008, Dexcom and then Abbott released the first real-time CGMs that allowed patients to frequently check their own blood sugars.1,2

How CGM has advanced diabetes management

The advent of CGM has advanced the field of diabetes management in many ways.

It has allowed patients to get real time feedback on how their behavior affects their blood sugar. The use of CGM along with the ensuing behavioral changes actually leads to a decrease in hemoglobin A1c, along with a lower risk of hypoglycemia. CGM has also resulted in patients having a better understanding of several aspects of glucose control, including glucose variability and nocturnal hypoglycemia.

Affordable, readily accessible CGM monitors that allow patients to intermittently use CGM have become available over the last 3 years.

In the United States alone, 34.2 million people have diabetes – nearly 1 in every 10 people. Many do not do self-monitoring of blood glucose and most do not use CGM. The current alternative to CGM – self monitoring of blood glucose – is cumbersome, and, since it requires regular finger sticks, is painful. Also, there is significant cost to each test strip that is used to self-monitor, and most insurance limits the number of times a day a patient can check their blood sugar. CGM used to be reserved only for patients who use multiple doses of insulin daily, and only began being approved for use for patients on basal insulin alone in June 2021.3

Most primary care doctors are just beginning to learn how to interpret CGM data.

Smart watch glucose monitoring predictions

When smart watch glucose monitoring arrives, it will suddenly change the playing field for patients with diabetes and their doctors alike.

We expect it to bring down the price of CGM and make it readily available to any patient who owns a smart watch with that function.

For doctors, the new technology will result in them suddenly being asked to advise their patients on how to use the data generated by watch-based CGM.

Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece. Dr. Persampiere is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health. You can contact them at fpnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Hirsh I. Introduction: History of Glucose Monitoring, in “Role of Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Diabetes Treatment.” American Diabetes Association. 2018.

2. Peters A. The Evidence Base for Continuous Glucose Monitoring, in “Role of Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Diabetes Treatment.” American Diabetes Association 2018.

3. “Medicare Loosening Restrictions for Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) Coverage,” Healthline. 2021 Jul 13.

Earlier this year, technology news sites reported that the Apple Watch Series 7 and the Samsung Galaxy Watch 4 were going to have integrated optical sensors for checking interstitial fluid glucose levels with no blood sampling needed. By the summer, new articles indicated that the glucose sensing watches would not be released this year for either Apple or Samsung.

For now, the newest technology available for monitoring glucose is continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), which involves a tiny sensor being inserted under the skin. The sensor tests glucose every few minutes, and a transmitter wirelessly sends the information to a monitor, which may be part of an insulin pump or a separate device. Some CGMs send information directly to a smartphone or tablet, according to the National Institutes of Health.

In 1999 the Food and Drug Administration approved the first CGM, which was only approved for downloading 3 days of data at a doctor’s office. Interestingly, the first real-time CGM device for patients to use on their own was a watch, the Glucowatch Biographer. Because of irritation and other issues, that watch never caught on. In 2006 and 2008, Dexcom and then Abbott released the first real-time CGMs that allowed patients to frequently check their own blood sugars.1,2

How CGM has advanced diabetes management

The advent of CGM has advanced the field of diabetes management in many ways.

It has allowed patients to get real time feedback on how their behavior affects their blood sugar. The use of CGM along with the ensuing behavioral changes actually leads to a decrease in hemoglobin A1c, along with a lower risk of hypoglycemia. CGM has also resulted in patients having a better understanding of several aspects of glucose control, including glucose variability and nocturnal hypoglycemia.

Affordable, readily accessible CGM monitors that allow patients to intermittently use CGM have become available over the last 3 years.

In the United States alone, 34.2 million people have diabetes – nearly 1 in every 10 people. Many do not do self-monitoring of blood glucose and most do not use CGM. The current alternative to CGM – self monitoring of blood glucose – is cumbersome, and, since it requires regular finger sticks, is painful. Also, there is significant cost to each test strip that is used to self-monitor, and most insurance limits the number of times a day a patient can check their blood sugar. CGM used to be reserved only for patients who use multiple doses of insulin daily, and only began being approved for use for patients on basal insulin alone in June 2021.3

Most primary care doctors are just beginning to learn how to interpret CGM data.

Smart watch glucose monitoring predictions

When smart watch glucose monitoring arrives, it will suddenly change the playing field for patients with diabetes and their doctors alike.

We expect it to bring down the price of CGM and make it readily available to any patient who owns a smart watch with that function.

For doctors, the new technology will result in them suddenly being asked to advise their patients on how to use the data generated by watch-based CGM.

Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece. Dr. Persampiere is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health. You can contact them at fpnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Hirsh I. Introduction: History of Glucose Monitoring, in “Role of Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Diabetes Treatment.” American Diabetes Association. 2018.

2. Peters A. The Evidence Base for Continuous Glucose Monitoring, in “Role of Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Diabetes Treatment.” American Diabetes Association 2018.

3. “Medicare Loosening Restrictions for Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) Coverage,” Healthline. 2021 Jul 13.

Embedding diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice in hospital medicine

A road map for success

The language of equality in America’s founding was never truly embraced, resulting in a painful legacy of slavery, racial injustice, and gender inequality inherited by all generations. However, for as long as America has fallen short of this unfulfilled promise, individuals have dedicated their lives to the tireless work of correcting injustice. Although the process has been painstakingly slow, our nation has incrementally inched toward the promised vision of equality, and these efforts continue today. With increased attention to social justice movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, our collective social consciousness may be finally waking up to the systemic injustices embedded into our fundamental institutions.

Medicine is not immune to these injustices. Persistent underrepresentation of women and minorities remains in medical school faculty and the broader physician workforce, and the same inequities exist in hospital medicine.1-6 The report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) on diversity in medicine highlights the impact widespread implicit and explicit bias has on creating exclusionary environments, exemplified by research demonstrating lower promotion rates in non-White faculty.7-8 The report calls us, as physicians, to a broader mission: “Focusing solely on increasing compositional diversity along the academic continuum is insufficient. To effectively enact institutional change at academic medical centers ... leaders must focus their efforts on developing inclusive, equity-minded environments.”7

We have a clear moral imperative to correct these shortcomings for our profession and our patients. It is incumbent on our institutions and hospital medicine groups (HMGs) to embark on the necessary process of systemic institutional change to address inequality and justice within our field.

A road map for DEI and justice in hospital medicine

The policies and biases allowing these inequities to persist have existed for decades, and superficial efforts will not bring sufficient change. Our institutions require new building blocks from which the foundation of a wholly inclusive and equal system of practice can be constructed. Encouragingly, some institutions and HMGs have taken steps to modernize their practices. We offer examples and suggestions of concrete practices to begin this journey, organizing these efforts into three broad categories:

1. Recruitment and retention

2. Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

3. Community engagement and partnership.

Recruitment and retention

Improving equity and inclusion begins with recruitment. Search and hiring committees should be assembled intentionally, with gender balance, and ideally with diversity or equity experts invited to join. All members should receive unconscious bias training. For example, the University of Colorado utilizes a toolkit to ensure appropriate steps are followed in the recruitment process, including predetermined candidate selection criteria that are ranked in advance.

Job descriptions should be reviewed by a diversity expert, ensuring unbiased and ungendered language within written text. Advertisements should be wide-reaching, and the committee should consider asking applicants for a diversity statement. Interviews should include a variety of interviewers and interview types (e.g., 1:1, group, etc.). Letters of recommendation deserve special scrutiny; letters for women and minorities may be at risk of being shorter and less record focused, and may be subject to less professional respect, such as use of first names over honorifics or titles.

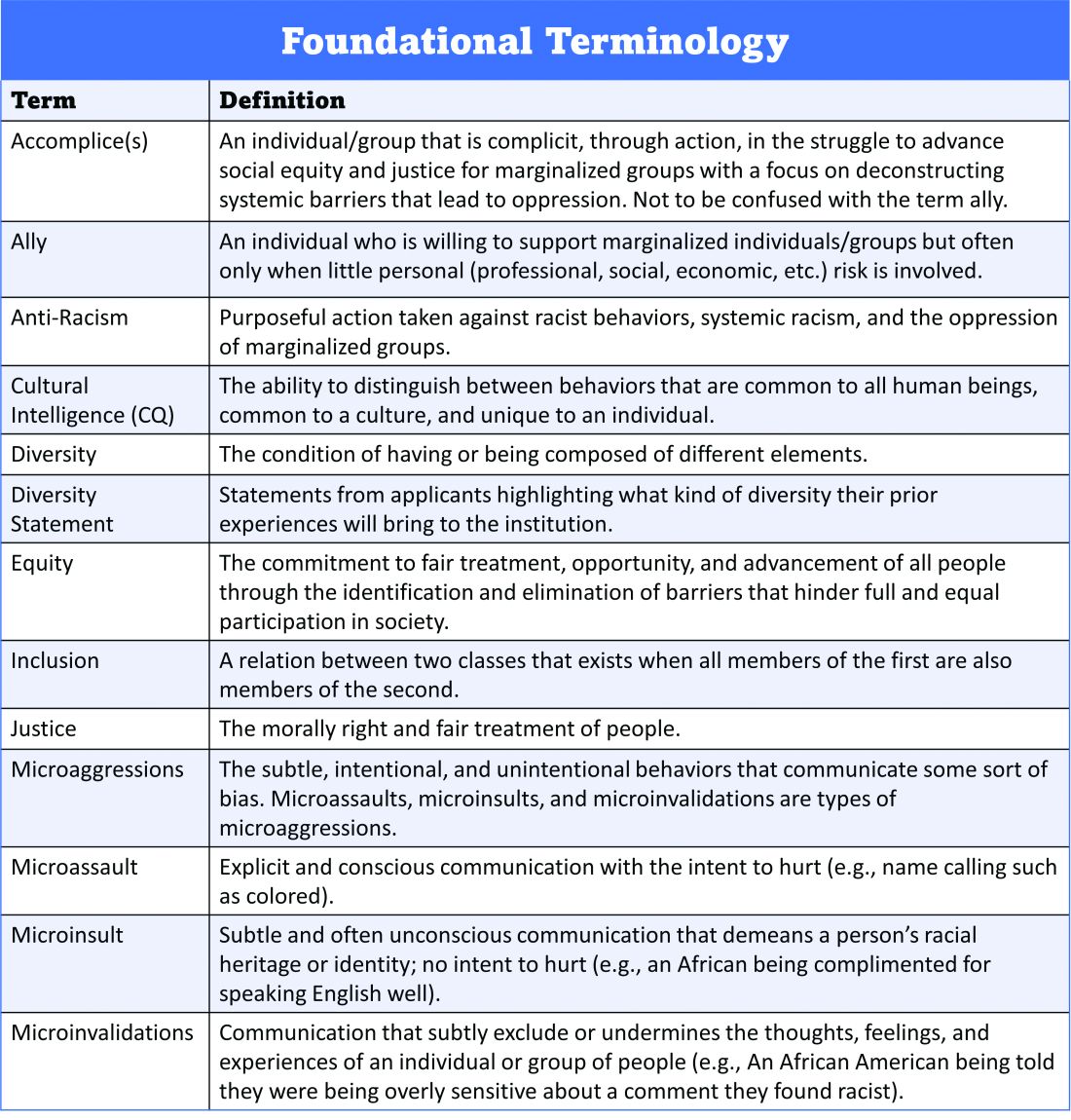

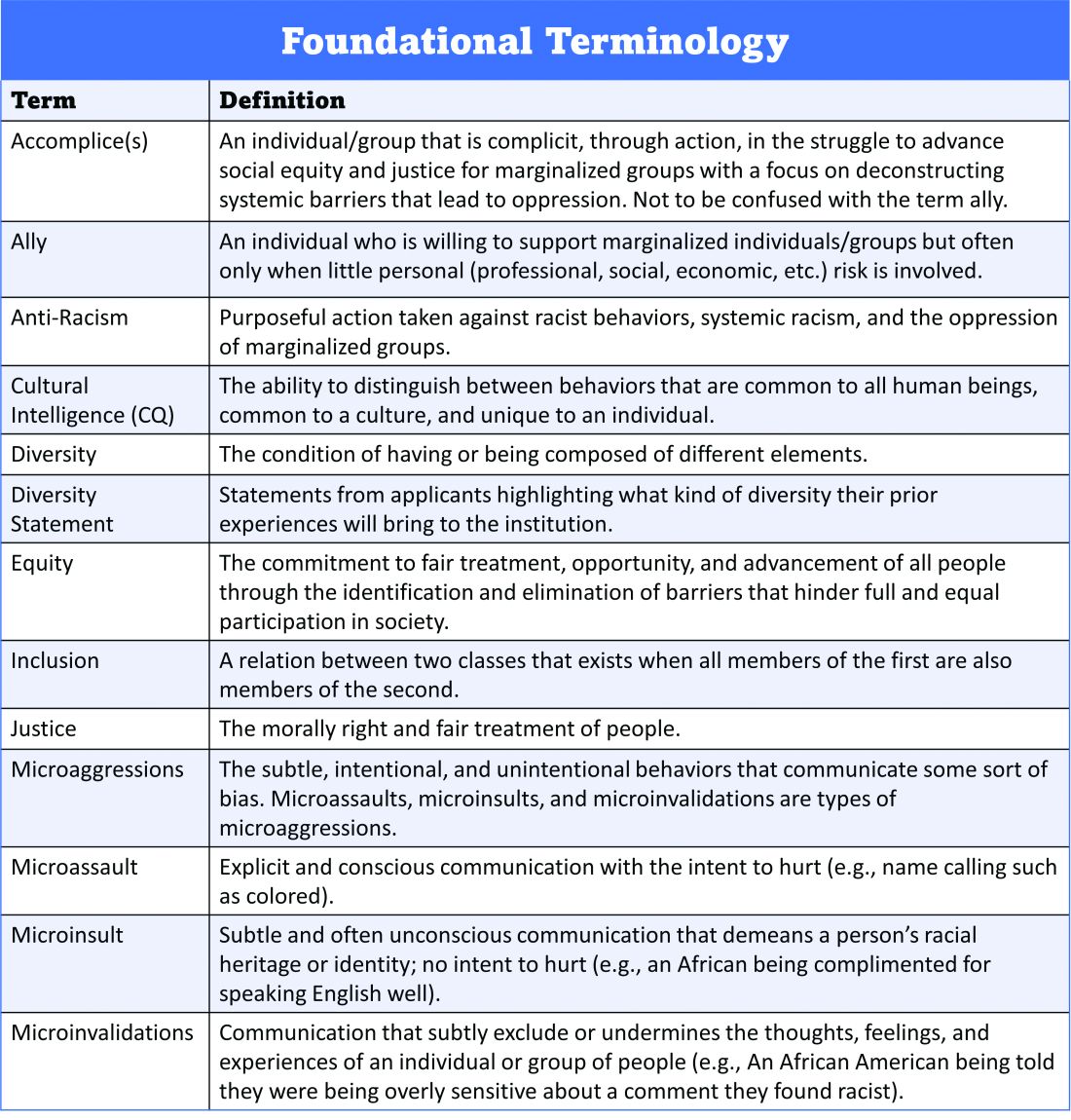

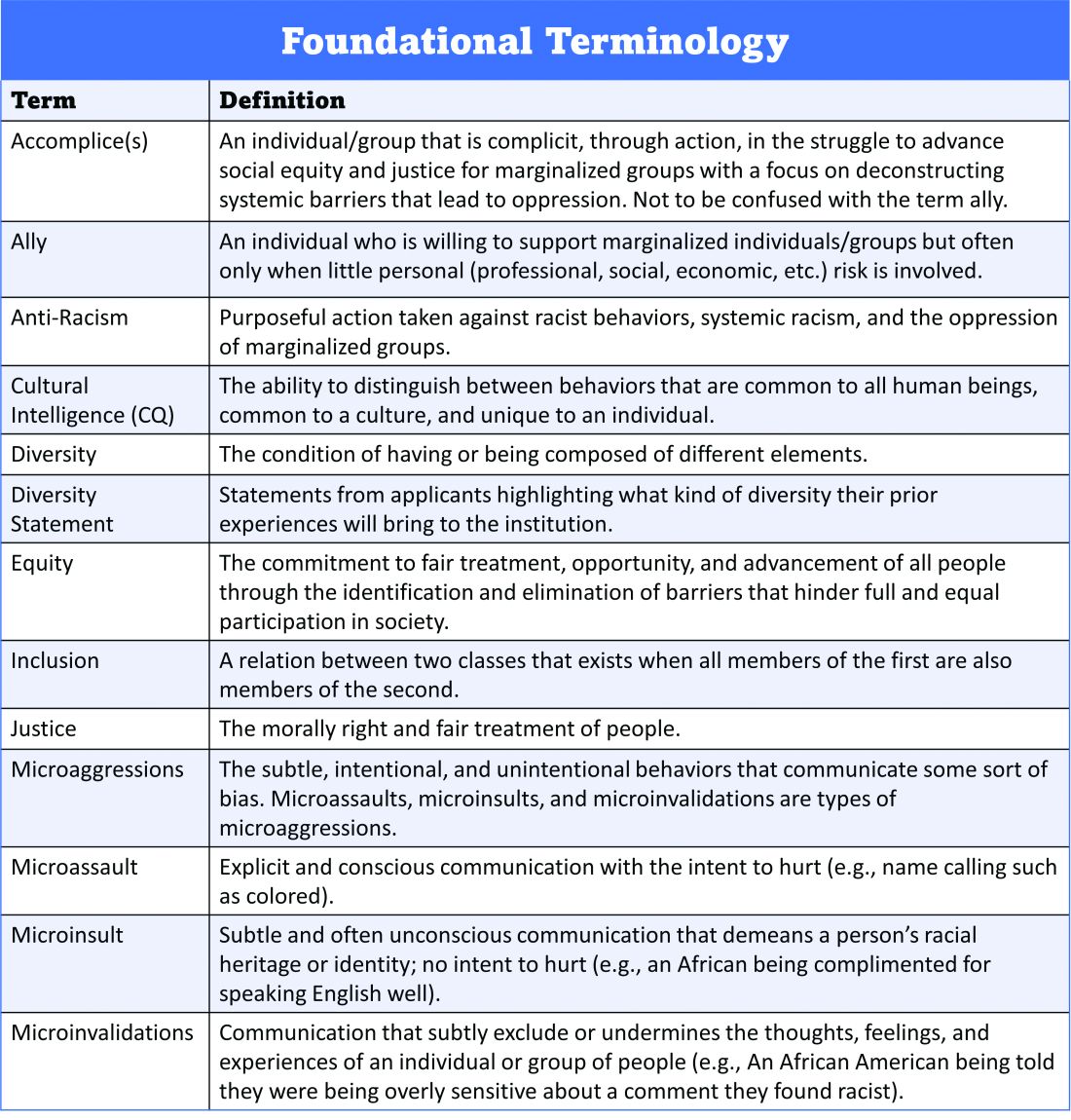

Once candidates are hired, institutions and HMGs should prioritize developing strategies to improve retention of a diverse workforce. This includes special attention to workplace culture, and thoughtfully striving for cultural intelligence within the group. Some examples may include developing affinity groups, such as underrepresented in medicine (UIM), women in medicine (WIM), or LGBTQ+ groups. Affinity groups provide a safe space for members and allies to support and uplift each other. Institutional and HMG leaders must educate themselves and their members on the importance of language (see table), and the more insidious forms of bias and discrimination that adversely affect workplace culture. Microinsults and microinvalidations, for example, can hurt and result in failure to recruit or turnover.

Conducting exit interviews when any hospitalist leaves is important to learn how to improve, but holding ‘stay’ interviews is mission critical. Stay interviews are an opportunity for HMG leaders to proactively understand why hospitalists stay, and what can be done to create more inclusive and equitable environments to retain them. This process creates psychological safety that brings challenges to the fore to be addressed, and spotlights best practices to be maintained and scaled.

Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

Women and minorities are known to be over-mentored and under-sponsored. Sponsorship is defined by Ayyala et al. as “active support by someone appropriately placed in the organization who has significant influence on decision making processes or structures and who is advocating for the career advancement of an individual and recommends them for leadership roles, awards, or high-profile speaking opportunities.”9 While the goal of mentorship is professional development, sponsorship emphasizes professional advancement. Deliberate steps to both mentor and then sponsor diverse hospitalists and future hospitalists (including trainees) are important to ensure equity.

More inclusive HMGs can be bolstered by prioritizing peer education on the professional imperative that we have a diverse workforce and equitable, just workplaces. Academic institutions may use existing structures such as grand rounds to provide education on these crucial topics, and all HMGs can host journal clubs and professional development sessions on leadership competencies that foster inclusion and equity. Sessions coordinated by women and minorities are also a form of justice, by helping overcome barriers to career advancement. Diverse faculty presenting in educational venues will result in content that is relevant to more audience members and will exemplify that leaders and experts are of all races, ethnicities, genders, ages, and abilities.

Groups should prioritize mentoring trainees and early-career hospitalists on scholarly projects that examine equity in opportunities of care, which signals that this science is valued as much as basic research. When used to demonstrate areas needing improvement, these projects can drive meaningful change. Even projects as straightforward as studying diversity in conference presenters, disparities in adherence to guidelines, or QI projects on how race is portrayed in the medical record can be powerful tools in advancing equity.

A key part of mentoring is training hospitalists and future hospitalists in how to be an upstander, as in how to intervene when a peer or patient is affected by bias, harassment, or discrimination. Receiving such training can prepare hospitalists for these nearly inevitable experiences and receiving training during usual work hours communicates that this is a valuable and necessary professional competency.

Community engagement and partnership

Institutions and HMGs should deliberately work to promote community engagement and partnership within their groups. Beyond promoting health equity, community engagement also fosters inclusivity by allowing community members to share their ideas and give recommendations to the institutions that serve them.

There is a growing body of literature that demonstrates how disadvantages by individual and neighborhood-level socioeconomic status (SES) contribute to disparities in specific disease conditions.10-11 Strategies to narrow the gap in SES disadvantages may help reduce race-related health disparities. Institutions that engage the community and develop programs to promote health equity can do so through bidirectional exchange of knowledge and mutual benefit.

An institution-specific example is Medicine for the Greater Good at Johns Hopkins. The founders of this program wrote, “health is not synonymous with medicine. To truly care for our patients and their communities, health care professionals must understand how to deliver equitable health care that meets the needs of the diverse populations we care for. The mission of Medicine for the Greater Good is to promote health and wellness beyond the confines of the hospital through an interactive and engaging partnership with the community ...” Community engagement also provides an opportunity for growing the cultural intelligence of institutions and HMGs.

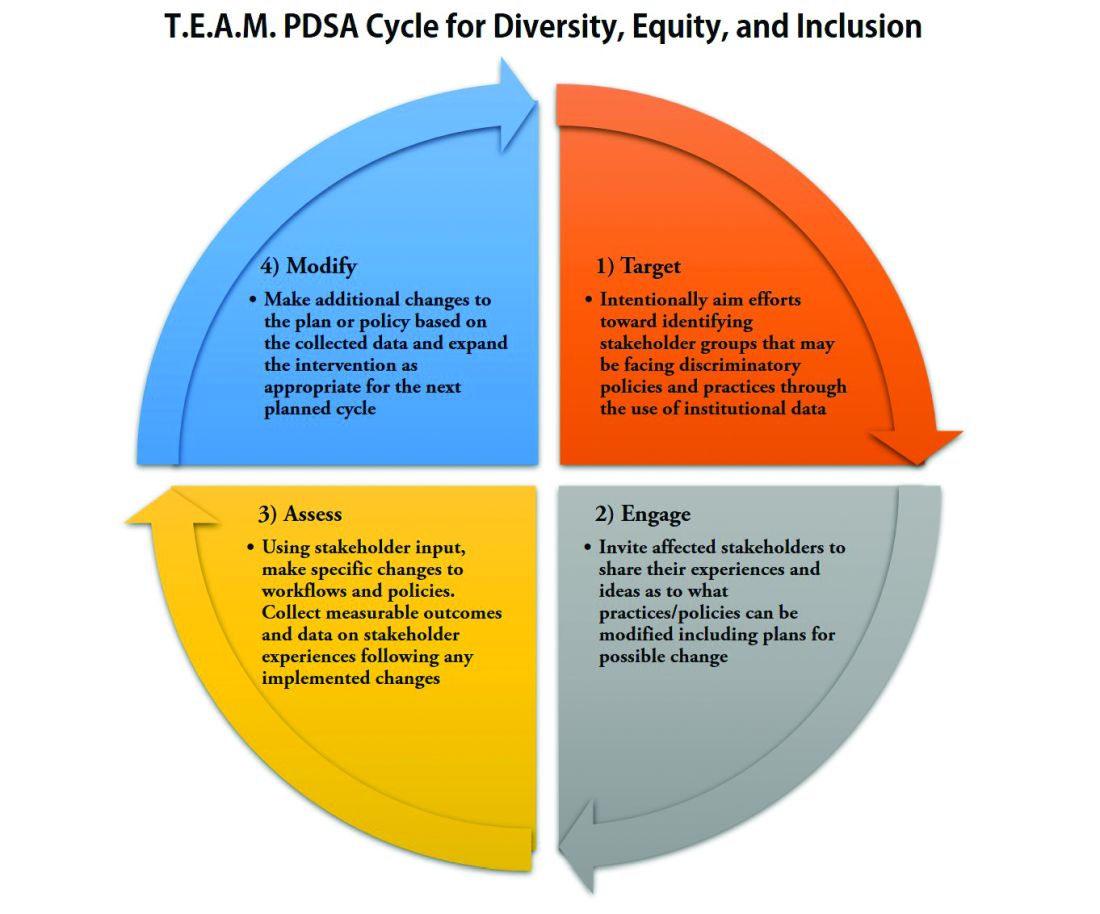

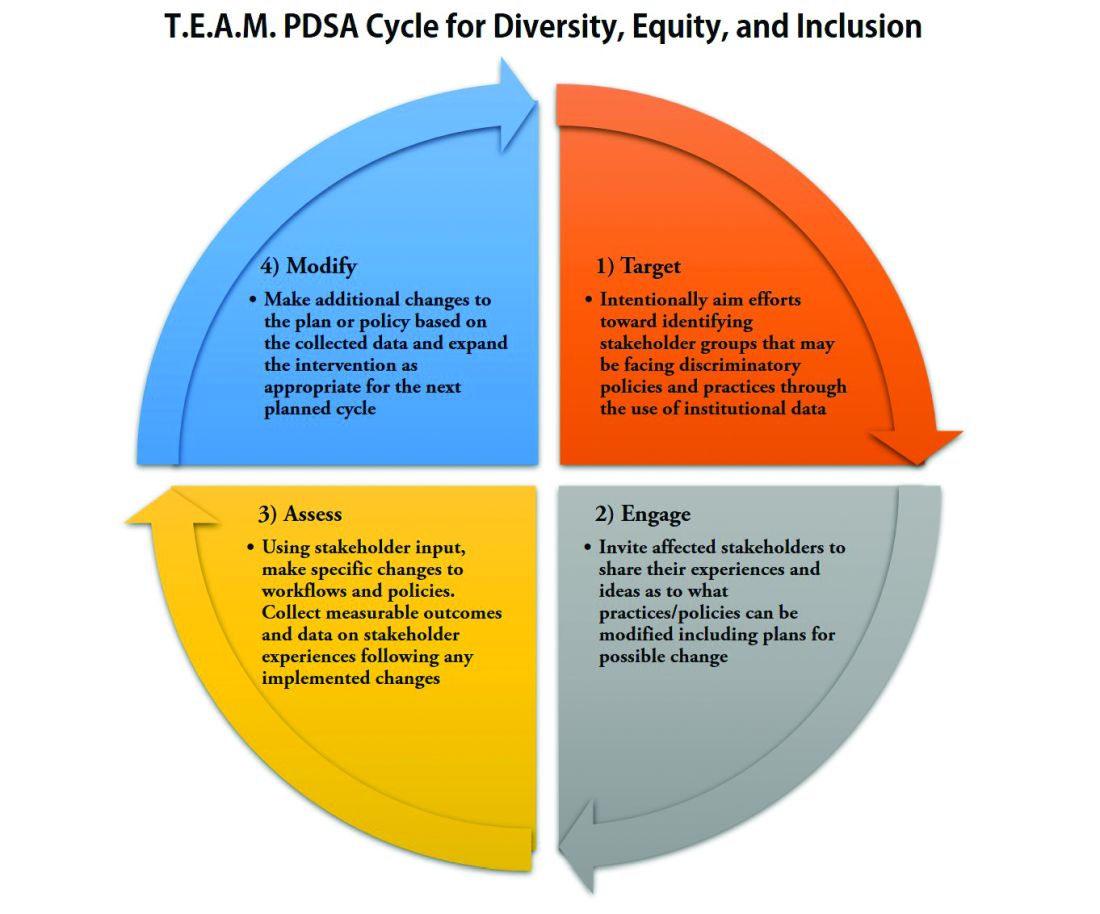

Tools for advancing comprehensive change – Repurposing PDSA cycles

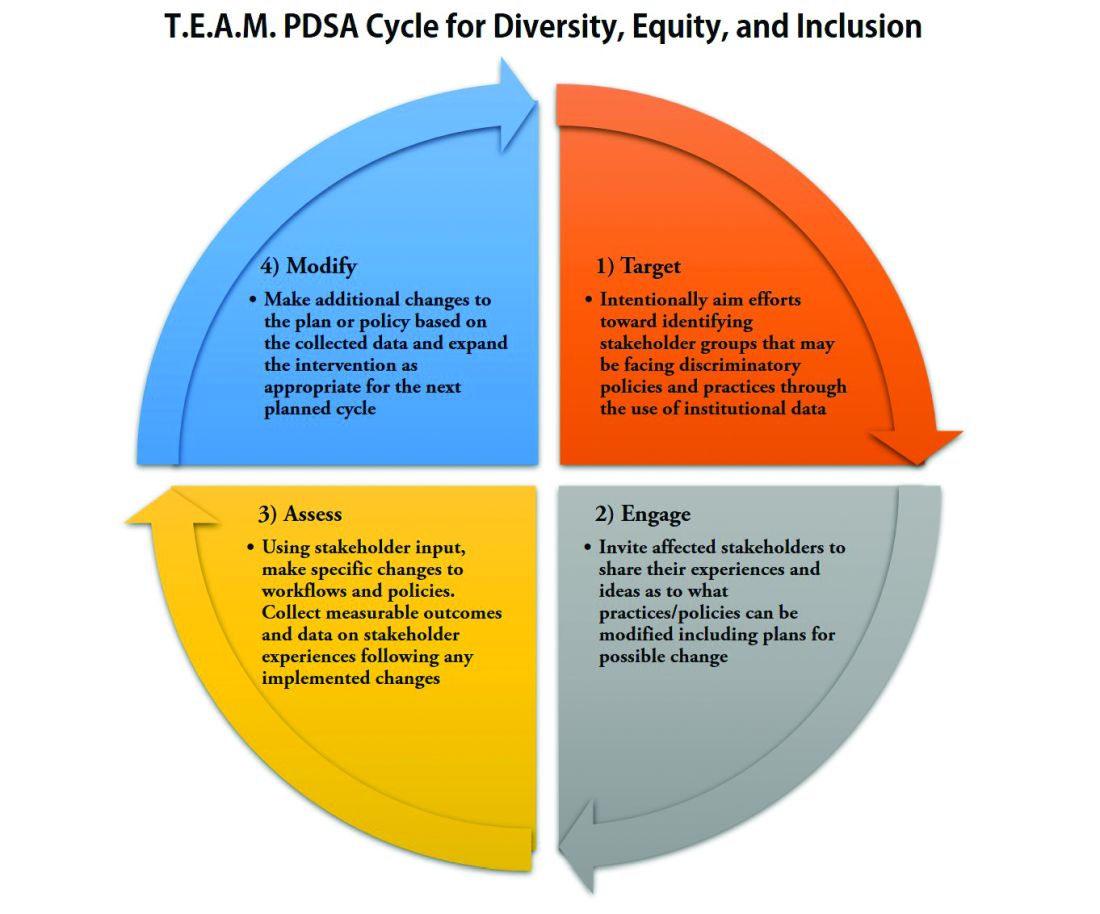

Whether institutions and HMGs are at the beginning of their journey or further along in the work of reducing disparities, having a systematic approach for implementing and refining policies and procedures can cultivate more inclusive and equitable environments. Thankfully, hospitalists are already equipped with the fundamental tools needed to advance change across their institutions – QI processes in the form of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles.

They allow a continuous cycle of successful incremental change based on direct evidence and experience. Any efforts to deconstruct systematic bias within our organizations must also be a continual process. Our female colleagues and colleagues of color need our institutions to engage unceasingly to bring about the equality they deserve. To that end, PDSA cycles are an apt tool to utilize in this work as they can naturally function in a never-ending process of improvement.

With PDSA as a model, we envision a cycle with steps that are intentionally purposed to fit the needs of equitable institutional change: Target-Engage-Assess-Modify. As highlighted (see graphic), these modifications ensure that stakeholders (i.e., those that unequal practices and policies affect the most) are engaged early and remain involved throughout the cycle.

As hospitalists, we have significant work ahead to ensure that we develop and maintain a diverse, equitable and inclusive workforce. This work to bring change will not be easy and will require a considerable investment of time and resources. However, with the strategies and tools that we have outlined, our institutions and HMGs can start the change needed in our profession for our patients and the workforce. In doing so, we can all be accomplices in the fight to achieve racial and gender equity, and social justice.

Dr. Delapenha and Dr. Kisuule are based in the department of internal medicine, division of hospital medicine, at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Dr. Martin is based in the department of medicine, section of hospital medicine at the University of Chicago. Dr. Barrett is a hospitalist in the department of internal medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

References

1. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019: Figure 19. Percentage of physicians by sex, 2018. AAMC website.

2. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 16. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by sex and race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

3. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 15. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

4. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 6. Percentage of acceptees to U.S. medical schools by race/ethnicity (alone), academic year 2018-2019. AAMC website.

5. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019 Figure 18. Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

6. Herzke C et al. Gender issues in academic hospital medicine: A national survey of hospitalist leaders. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1641-6.

7. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Fostering diversity and inclusion. AAMC website.

8. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Executive summary. AAMC website.

9. Ayyala MS et al. Mentorship is not enough: Exploring sponsorship and its role in career advancement in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2019;94(1):94-100.

10. Ejike OC et al. Contribution of individual and neighborhood factors to racial disparities in respiratory outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021 Apr 15;203(8):987-97.

11. Galiatsatos P et al. The effect of community socioeconomic status on sepsis-attributable mortality. J Crit Care. 2018 Aug;46:129-33.

A road map for success

A road map for success

The language of equality in America’s founding was never truly embraced, resulting in a painful legacy of slavery, racial injustice, and gender inequality inherited by all generations. However, for as long as America has fallen short of this unfulfilled promise, individuals have dedicated their lives to the tireless work of correcting injustice. Although the process has been painstakingly slow, our nation has incrementally inched toward the promised vision of equality, and these efforts continue today. With increased attention to social justice movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, our collective social consciousness may be finally waking up to the systemic injustices embedded into our fundamental institutions.

Medicine is not immune to these injustices. Persistent underrepresentation of women and minorities remains in medical school faculty and the broader physician workforce, and the same inequities exist in hospital medicine.1-6 The report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) on diversity in medicine highlights the impact widespread implicit and explicit bias has on creating exclusionary environments, exemplified by research demonstrating lower promotion rates in non-White faculty.7-8 The report calls us, as physicians, to a broader mission: “Focusing solely on increasing compositional diversity along the academic continuum is insufficient. To effectively enact institutional change at academic medical centers ... leaders must focus their efforts on developing inclusive, equity-minded environments.”7

We have a clear moral imperative to correct these shortcomings for our profession and our patients. It is incumbent on our institutions and hospital medicine groups (HMGs) to embark on the necessary process of systemic institutional change to address inequality and justice within our field.

A road map for DEI and justice in hospital medicine

The policies and biases allowing these inequities to persist have existed for decades, and superficial efforts will not bring sufficient change. Our institutions require new building blocks from which the foundation of a wholly inclusive and equal system of practice can be constructed. Encouragingly, some institutions and HMGs have taken steps to modernize their practices. We offer examples and suggestions of concrete practices to begin this journey, organizing these efforts into three broad categories:

1. Recruitment and retention

2. Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

3. Community engagement and partnership.

Recruitment and retention

Improving equity and inclusion begins with recruitment. Search and hiring committees should be assembled intentionally, with gender balance, and ideally with diversity or equity experts invited to join. All members should receive unconscious bias training. For example, the University of Colorado utilizes a toolkit to ensure appropriate steps are followed in the recruitment process, including predetermined candidate selection criteria that are ranked in advance.

Job descriptions should be reviewed by a diversity expert, ensuring unbiased and ungendered language within written text. Advertisements should be wide-reaching, and the committee should consider asking applicants for a diversity statement. Interviews should include a variety of interviewers and interview types (e.g., 1:1, group, etc.). Letters of recommendation deserve special scrutiny; letters for women and minorities may be at risk of being shorter and less record focused, and may be subject to less professional respect, such as use of first names over honorifics or titles.

Once candidates are hired, institutions and HMGs should prioritize developing strategies to improve retention of a diverse workforce. This includes special attention to workplace culture, and thoughtfully striving for cultural intelligence within the group. Some examples may include developing affinity groups, such as underrepresented in medicine (UIM), women in medicine (WIM), or LGBTQ+ groups. Affinity groups provide a safe space for members and allies to support and uplift each other. Institutional and HMG leaders must educate themselves and their members on the importance of language (see table), and the more insidious forms of bias and discrimination that adversely affect workplace culture. Microinsults and microinvalidations, for example, can hurt and result in failure to recruit or turnover.

Conducting exit interviews when any hospitalist leaves is important to learn how to improve, but holding ‘stay’ interviews is mission critical. Stay interviews are an opportunity for HMG leaders to proactively understand why hospitalists stay, and what can be done to create more inclusive and equitable environments to retain them. This process creates psychological safety that brings challenges to the fore to be addressed, and spotlights best practices to be maintained and scaled.

Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

Women and minorities are known to be over-mentored and under-sponsored. Sponsorship is defined by Ayyala et al. as “active support by someone appropriately placed in the organization who has significant influence on decision making processes or structures and who is advocating for the career advancement of an individual and recommends them for leadership roles, awards, or high-profile speaking opportunities.”9 While the goal of mentorship is professional development, sponsorship emphasizes professional advancement. Deliberate steps to both mentor and then sponsor diverse hospitalists and future hospitalists (including trainees) are important to ensure equity.

More inclusive HMGs can be bolstered by prioritizing peer education on the professional imperative that we have a diverse workforce and equitable, just workplaces. Academic institutions may use existing structures such as grand rounds to provide education on these crucial topics, and all HMGs can host journal clubs and professional development sessions on leadership competencies that foster inclusion and equity. Sessions coordinated by women and minorities are also a form of justice, by helping overcome barriers to career advancement. Diverse faculty presenting in educational venues will result in content that is relevant to more audience members and will exemplify that leaders and experts are of all races, ethnicities, genders, ages, and abilities.

Groups should prioritize mentoring trainees and early-career hospitalists on scholarly projects that examine equity in opportunities of care, which signals that this science is valued as much as basic research. When used to demonstrate areas needing improvement, these projects can drive meaningful change. Even projects as straightforward as studying diversity in conference presenters, disparities in adherence to guidelines, or QI projects on how race is portrayed in the medical record can be powerful tools in advancing equity.

A key part of mentoring is training hospitalists and future hospitalists in how to be an upstander, as in how to intervene when a peer or patient is affected by bias, harassment, or discrimination. Receiving such training can prepare hospitalists for these nearly inevitable experiences and receiving training during usual work hours communicates that this is a valuable and necessary professional competency.

Community engagement and partnership

Institutions and HMGs should deliberately work to promote community engagement and partnership within their groups. Beyond promoting health equity, community engagement also fosters inclusivity by allowing community members to share their ideas and give recommendations to the institutions that serve them.

There is a growing body of literature that demonstrates how disadvantages by individual and neighborhood-level socioeconomic status (SES) contribute to disparities in specific disease conditions.10-11 Strategies to narrow the gap in SES disadvantages may help reduce race-related health disparities. Institutions that engage the community and develop programs to promote health equity can do so through bidirectional exchange of knowledge and mutual benefit.

An institution-specific example is Medicine for the Greater Good at Johns Hopkins. The founders of this program wrote, “health is not synonymous with medicine. To truly care for our patients and their communities, health care professionals must understand how to deliver equitable health care that meets the needs of the diverse populations we care for. The mission of Medicine for the Greater Good is to promote health and wellness beyond the confines of the hospital through an interactive and engaging partnership with the community ...” Community engagement also provides an opportunity for growing the cultural intelligence of institutions and HMGs.

Tools for advancing comprehensive change – Repurposing PDSA cycles

Whether institutions and HMGs are at the beginning of their journey or further along in the work of reducing disparities, having a systematic approach for implementing and refining policies and procedures can cultivate more inclusive and equitable environments. Thankfully, hospitalists are already equipped with the fundamental tools needed to advance change across their institutions – QI processes in the form of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles.

They allow a continuous cycle of successful incremental change based on direct evidence and experience. Any efforts to deconstruct systematic bias within our organizations must also be a continual process. Our female colleagues and colleagues of color need our institutions to engage unceasingly to bring about the equality they deserve. To that end, PDSA cycles are an apt tool to utilize in this work as they can naturally function in a never-ending process of improvement.

With PDSA as a model, we envision a cycle with steps that are intentionally purposed to fit the needs of equitable institutional change: Target-Engage-Assess-Modify. As highlighted (see graphic), these modifications ensure that stakeholders (i.e., those that unequal practices and policies affect the most) are engaged early and remain involved throughout the cycle.

As hospitalists, we have significant work ahead to ensure that we develop and maintain a diverse, equitable and inclusive workforce. This work to bring change will not be easy and will require a considerable investment of time and resources. However, with the strategies and tools that we have outlined, our institutions and HMGs can start the change needed in our profession for our patients and the workforce. In doing so, we can all be accomplices in the fight to achieve racial and gender equity, and social justice.

Dr. Delapenha and Dr. Kisuule are based in the department of internal medicine, division of hospital medicine, at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Dr. Martin is based in the department of medicine, section of hospital medicine at the University of Chicago. Dr. Barrett is a hospitalist in the department of internal medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

References

1. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019: Figure 19. Percentage of physicians by sex, 2018. AAMC website.

2. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 16. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by sex and race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

3. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 15. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

4. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 6. Percentage of acceptees to U.S. medical schools by race/ethnicity (alone), academic year 2018-2019. AAMC website.

5. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019 Figure 18. Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

6. Herzke C et al. Gender issues in academic hospital medicine: A national survey of hospitalist leaders. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1641-6.

7. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Fostering diversity and inclusion. AAMC website.

8. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Executive summary. AAMC website.

9. Ayyala MS et al. Mentorship is not enough: Exploring sponsorship and its role in career advancement in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2019;94(1):94-100.

10. Ejike OC et al. Contribution of individual and neighborhood factors to racial disparities in respiratory outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021 Apr 15;203(8):987-97.

11. Galiatsatos P et al. The effect of community socioeconomic status on sepsis-attributable mortality. J Crit Care. 2018 Aug;46:129-33.