User login

Busting eczema treatment myths: applying the evidence

LAS VEGAS – In the treatment of eczema, the gap between evidence and practice can be broad.

Dermatologists who treat atopic dermatitis confront many challenges – patients may be severely atopic, have a hard time being compliant with therapies, and have frequent recurrences, Dr. Robert Sidbury said at the Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas dermatology seminar. “It just is not easy,” he said.

However, even for challenging patients, physicians should be mindful of evidence-supported treatments and be attentive to practice gaps, said Dr. Sidbury, chief of the division of dermatology at the University of Washington’s Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Though the field is rapidly changing, the American Academy of Dermatology has issued practice guidelines that can help guide clinical treatment decisions, said Dr. Sidbury, who helped develop the AAD guidelines. He noted that prescribers may eventually feel the pain of the practice gap if AMA-driven performance measures are enforced.

At the meeting, Dr. Sidbury discussed areas in which many clinicians may have a practice gap in the treatment of eczema. Topping the list of non–evidence-based eczema care are overuse of steroids, oral antibiotics, and nonsedating antihistamines.

Practice gap: Many clinicians believe that topical steroids are more effective for atopic dermatitis when used twice daily.

Reality: “Randomized, controlled trials and a systematic review suggest that there is no benefit to twice-daily use of steroids,” over once-daily use, Dr. Sidbury said, though he admitted that he’s having a hard time breaking his own longstanding practice habit of prescribing twice- rather than once-daily dosing of topical corticosteroids. He pointed out that Dr. Hywel Williams, the director of the University of Nottingham’s Center of Evidence-Based Dermatology, England, calls this the “lowest-hanging fruit” in terms of cost savings, safety, and convenience to patients.

Practice gap: Unnecessary skin cultures can lead to overuse of systemic antibiotics in atopic dermatitis.

Reality: Colonization with Staphylococcus aureus occurs in more than 90% of adults with atopic dermatitis, but the vast majority of these patients are not infected. “Except for bleach baths in concert with intranasal mupirocin, no topical antistaphylococcal treatment has been shown to be clinically helpful in patients with atopic dermatitis,” Dr. Sidbury said.

“How do we know when eczema is infected? We know it when we see it. You are best served by using your clinical gestalt,” he added. Eczematous skin presents along a continuum, ranging from erythema, scaling, and crusting, to a frankly purulent appearance with clear infection, and clinical presentation and judgment should guide treatment. Barring frank infection, the evidence doesn’t support use of systemic antibiotics (Br J Dermatol. 2010 Jul;163 [1]:12-26).

Practice gap: Many patients with atopic dermatitis receive nonsedating antihistamines for itching.

Reality: There is no evidence that nonsedating antihistamines are beneficial unless the patient has concurrent rhinoconjunctivitis, so data don’t support their use “for the actual itch of eczema,” Dr. Sidbury said. In fact, the AMA-sponsored Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement nearly passed an overuse measure that would have penalized the prescription of nonsedating antihistamines in this setting, he said.

Practice gap: Systemic immunomodulatory therapy is used for pediatric atopic dermatitis, despite the lack of data that provide clear guidance.

Reality: The landscape here is a little more complicated, according to Dr. Sidbury. Among the systemic immunosuppressants, cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate have the most evidence backing their use. However, there remains a lack of comparative studies and a lack of studies evaluating these therapies in the pediatric population, he said.

In general, Dr. Sidbury said that systemic therapy for atopic dermatitis is indicated only when control is inadequate despite truly optimized topical care, and the condition is having a “significant negative physical, psychological, or social impact” on the patient. Before beginning these potent systemic therapies, it’s important to assess that the patient and family are truly adherent to the topical treatment regime, and that adjunctive treatments like wet wraps and strict allergen avoidance are being followed. The Food and Drug Administration is beginning to include pediatric patients in clinical trials of systemic therapy for atopic dermatitis, so the quality of data should improve.

If systemic therapy is initiated, some clinical pearls can guide use, he said. Cyclosporine has the quickest onset of action and can be dosed at 3-6 mg/kg per day, divided into twice daily dosing. The maximum dose is 300 mg/day, and the microemulsion form is preferred. Overall, mycophenolate is the best-tolerated immunosuppressive. If methotrexate is chosen, it should be dosed at 0.2-0.7 mg/kg per week; liver function should be checked at 5-7 days after dosing, since methotrexate can cause a transient transaminitis. There are no standard recommendations to guide if or when to do liver biopsy recommendations in children receiving methotrexate. (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Aug;71[2]:327-49).

Practice gap: Eczema appointments may only last 10-20 minutes.

Reality: “Proper eczema education takes much longer,” Dr. Sidbury said. Among patients and clinicians, there is still “rampant misinformation,” with persistence of fundamental knowledge gaps. “Studies repeatedly validate the role of education” in providing optimal care for eczema sufferers and their families, he emphasized (Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015 Jan 23. doi: 10.1111/pai.12338).

How is a busy physician to integrate all of these recommendations into practice and make sure patients are getting proper education? “Don’t reinvent the wheel – Google it!” Dr. Sidbury said. Resources from the National Eczema Association, among others, can help guide care. Eczema action plans that can be downloaded provide a roadmap for shared decision making; food allergy clinical practice guidelines help patients avoid allergens, and patients can further their knowledge when directed to reputable websites like the National Eczema Association and resources like www.eczemacenter.org, at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego.

Dr. Sidbury disclosed that he was a site principal investigator for an Anacor Pharmaceuticals–sponsored trial of a new topical anti-inflammatory agent for allergic dermatitis, and that he is on the Scientific Advisory Committee of the National Eczema Association.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @karioakes

LAS VEGAS – In the treatment of eczema, the gap between evidence and practice can be broad.

Dermatologists who treat atopic dermatitis confront many challenges – patients may be severely atopic, have a hard time being compliant with therapies, and have frequent recurrences, Dr. Robert Sidbury said at the Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas dermatology seminar. “It just is not easy,” he said.

However, even for challenging patients, physicians should be mindful of evidence-supported treatments and be attentive to practice gaps, said Dr. Sidbury, chief of the division of dermatology at the University of Washington’s Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Though the field is rapidly changing, the American Academy of Dermatology has issued practice guidelines that can help guide clinical treatment decisions, said Dr. Sidbury, who helped develop the AAD guidelines. He noted that prescribers may eventually feel the pain of the practice gap if AMA-driven performance measures are enforced.

At the meeting, Dr. Sidbury discussed areas in which many clinicians may have a practice gap in the treatment of eczema. Topping the list of non–evidence-based eczema care are overuse of steroids, oral antibiotics, and nonsedating antihistamines.

Practice gap: Many clinicians believe that topical steroids are more effective for atopic dermatitis when used twice daily.

Reality: “Randomized, controlled trials and a systematic review suggest that there is no benefit to twice-daily use of steroids,” over once-daily use, Dr. Sidbury said, though he admitted that he’s having a hard time breaking his own longstanding practice habit of prescribing twice- rather than once-daily dosing of topical corticosteroids. He pointed out that Dr. Hywel Williams, the director of the University of Nottingham’s Center of Evidence-Based Dermatology, England, calls this the “lowest-hanging fruit” in terms of cost savings, safety, and convenience to patients.

Practice gap: Unnecessary skin cultures can lead to overuse of systemic antibiotics in atopic dermatitis.

Reality: Colonization with Staphylococcus aureus occurs in more than 90% of adults with atopic dermatitis, but the vast majority of these patients are not infected. “Except for bleach baths in concert with intranasal mupirocin, no topical antistaphylococcal treatment has been shown to be clinically helpful in patients with atopic dermatitis,” Dr. Sidbury said.

“How do we know when eczema is infected? We know it when we see it. You are best served by using your clinical gestalt,” he added. Eczematous skin presents along a continuum, ranging from erythema, scaling, and crusting, to a frankly purulent appearance with clear infection, and clinical presentation and judgment should guide treatment. Barring frank infection, the evidence doesn’t support use of systemic antibiotics (Br J Dermatol. 2010 Jul;163 [1]:12-26).

Practice gap: Many patients with atopic dermatitis receive nonsedating antihistamines for itching.

Reality: There is no evidence that nonsedating antihistamines are beneficial unless the patient has concurrent rhinoconjunctivitis, so data don’t support their use “for the actual itch of eczema,” Dr. Sidbury said. In fact, the AMA-sponsored Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement nearly passed an overuse measure that would have penalized the prescription of nonsedating antihistamines in this setting, he said.

Practice gap: Systemic immunomodulatory therapy is used for pediatric atopic dermatitis, despite the lack of data that provide clear guidance.

Reality: The landscape here is a little more complicated, according to Dr. Sidbury. Among the systemic immunosuppressants, cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate have the most evidence backing their use. However, there remains a lack of comparative studies and a lack of studies evaluating these therapies in the pediatric population, he said.

In general, Dr. Sidbury said that systemic therapy for atopic dermatitis is indicated only when control is inadequate despite truly optimized topical care, and the condition is having a “significant negative physical, psychological, or social impact” on the patient. Before beginning these potent systemic therapies, it’s important to assess that the patient and family are truly adherent to the topical treatment regime, and that adjunctive treatments like wet wraps and strict allergen avoidance are being followed. The Food and Drug Administration is beginning to include pediatric patients in clinical trials of systemic therapy for atopic dermatitis, so the quality of data should improve.

If systemic therapy is initiated, some clinical pearls can guide use, he said. Cyclosporine has the quickest onset of action and can be dosed at 3-6 mg/kg per day, divided into twice daily dosing. The maximum dose is 300 mg/day, and the microemulsion form is preferred. Overall, mycophenolate is the best-tolerated immunosuppressive. If methotrexate is chosen, it should be dosed at 0.2-0.7 mg/kg per week; liver function should be checked at 5-7 days after dosing, since methotrexate can cause a transient transaminitis. There are no standard recommendations to guide if or when to do liver biopsy recommendations in children receiving methotrexate. (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Aug;71[2]:327-49).

Practice gap: Eczema appointments may only last 10-20 minutes.

Reality: “Proper eczema education takes much longer,” Dr. Sidbury said. Among patients and clinicians, there is still “rampant misinformation,” with persistence of fundamental knowledge gaps. “Studies repeatedly validate the role of education” in providing optimal care for eczema sufferers and their families, he emphasized (Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015 Jan 23. doi: 10.1111/pai.12338).

How is a busy physician to integrate all of these recommendations into practice and make sure patients are getting proper education? “Don’t reinvent the wheel – Google it!” Dr. Sidbury said. Resources from the National Eczema Association, among others, can help guide care. Eczema action plans that can be downloaded provide a roadmap for shared decision making; food allergy clinical practice guidelines help patients avoid allergens, and patients can further their knowledge when directed to reputable websites like the National Eczema Association and resources like www.eczemacenter.org, at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego.

Dr. Sidbury disclosed that he was a site principal investigator for an Anacor Pharmaceuticals–sponsored trial of a new topical anti-inflammatory agent for allergic dermatitis, and that he is on the Scientific Advisory Committee of the National Eczema Association.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @karioakes

LAS VEGAS – In the treatment of eczema, the gap between evidence and practice can be broad.

Dermatologists who treat atopic dermatitis confront many challenges – patients may be severely atopic, have a hard time being compliant with therapies, and have frequent recurrences, Dr. Robert Sidbury said at the Skin Disease Education Foundation’s annual Las Vegas dermatology seminar. “It just is not easy,” he said.

However, even for challenging patients, physicians should be mindful of evidence-supported treatments and be attentive to practice gaps, said Dr. Sidbury, chief of the division of dermatology at the University of Washington’s Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Though the field is rapidly changing, the American Academy of Dermatology has issued practice guidelines that can help guide clinical treatment decisions, said Dr. Sidbury, who helped develop the AAD guidelines. He noted that prescribers may eventually feel the pain of the practice gap if AMA-driven performance measures are enforced.

At the meeting, Dr. Sidbury discussed areas in which many clinicians may have a practice gap in the treatment of eczema. Topping the list of non–evidence-based eczema care are overuse of steroids, oral antibiotics, and nonsedating antihistamines.

Practice gap: Many clinicians believe that topical steroids are more effective for atopic dermatitis when used twice daily.

Reality: “Randomized, controlled trials and a systematic review suggest that there is no benefit to twice-daily use of steroids,” over once-daily use, Dr. Sidbury said, though he admitted that he’s having a hard time breaking his own longstanding practice habit of prescribing twice- rather than once-daily dosing of topical corticosteroids. He pointed out that Dr. Hywel Williams, the director of the University of Nottingham’s Center of Evidence-Based Dermatology, England, calls this the “lowest-hanging fruit” in terms of cost savings, safety, and convenience to patients.

Practice gap: Unnecessary skin cultures can lead to overuse of systemic antibiotics in atopic dermatitis.

Reality: Colonization with Staphylococcus aureus occurs in more than 90% of adults with atopic dermatitis, but the vast majority of these patients are not infected. “Except for bleach baths in concert with intranasal mupirocin, no topical antistaphylococcal treatment has been shown to be clinically helpful in patients with atopic dermatitis,” Dr. Sidbury said.

“How do we know when eczema is infected? We know it when we see it. You are best served by using your clinical gestalt,” he added. Eczematous skin presents along a continuum, ranging from erythema, scaling, and crusting, to a frankly purulent appearance with clear infection, and clinical presentation and judgment should guide treatment. Barring frank infection, the evidence doesn’t support use of systemic antibiotics (Br J Dermatol. 2010 Jul;163 [1]:12-26).

Practice gap: Many patients with atopic dermatitis receive nonsedating antihistamines for itching.

Reality: There is no evidence that nonsedating antihistamines are beneficial unless the patient has concurrent rhinoconjunctivitis, so data don’t support their use “for the actual itch of eczema,” Dr. Sidbury said. In fact, the AMA-sponsored Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement nearly passed an overuse measure that would have penalized the prescription of nonsedating antihistamines in this setting, he said.

Practice gap: Systemic immunomodulatory therapy is used for pediatric atopic dermatitis, despite the lack of data that provide clear guidance.

Reality: The landscape here is a little more complicated, according to Dr. Sidbury. Among the systemic immunosuppressants, cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate have the most evidence backing their use. However, there remains a lack of comparative studies and a lack of studies evaluating these therapies in the pediatric population, he said.

In general, Dr. Sidbury said that systemic therapy for atopic dermatitis is indicated only when control is inadequate despite truly optimized topical care, and the condition is having a “significant negative physical, psychological, or social impact” on the patient. Before beginning these potent systemic therapies, it’s important to assess that the patient and family are truly adherent to the topical treatment regime, and that adjunctive treatments like wet wraps and strict allergen avoidance are being followed. The Food and Drug Administration is beginning to include pediatric patients in clinical trials of systemic therapy for atopic dermatitis, so the quality of data should improve.

If systemic therapy is initiated, some clinical pearls can guide use, he said. Cyclosporine has the quickest onset of action and can be dosed at 3-6 mg/kg per day, divided into twice daily dosing. The maximum dose is 300 mg/day, and the microemulsion form is preferred. Overall, mycophenolate is the best-tolerated immunosuppressive. If methotrexate is chosen, it should be dosed at 0.2-0.7 mg/kg per week; liver function should be checked at 5-7 days after dosing, since methotrexate can cause a transient transaminitis. There are no standard recommendations to guide if or when to do liver biopsy recommendations in children receiving methotrexate. (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Aug;71[2]:327-49).

Practice gap: Eczema appointments may only last 10-20 minutes.

Reality: “Proper eczema education takes much longer,” Dr. Sidbury said. Among patients and clinicians, there is still “rampant misinformation,” with persistence of fundamental knowledge gaps. “Studies repeatedly validate the role of education” in providing optimal care for eczema sufferers and their families, he emphasized (Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015 Jan 23. doi: 10.1111/pai.12338).

How is a busy physician to integrate all of these recommendations into practice and make sure patients are getting proper education? “Don’t reinvent the wheel – Google it!” Dr. Sidbury said. Resources from the National Eczema Association, among others, can help guide care. Eczema action plans that can be downloaded provide a roadmap for shared decision making; food allergy clinical practice guidelines help patients avoid allergens, and patients can further their knowledge when directed to reputable websites like the National Eczema Association and resources like www.eczemacenter.org, at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego.

Dr. Sidbury disclosed that he was a site principal investigator for an Anacor Pharmaceuticals–sponsored trial of a new topical anti-inflammatory agent for allergic dermatitis, and that he is on the Scientific Advisory Committee of the National Eczema Association.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF LAS VEGAS DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

EADV: Another promising topical for atopic dermatitis

COPENHAGEN – A novel topical nonsteroidal inhibitor of phosphodiesterase-4 showed a favorable efficacy to side effect ratio in a phase II study of adolescents and adults with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis, Dr. Jon M. Hanifin reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“For topical agents, I think a 30% improvement with few side effects is a desirable balance,” observed Dr. Hanifin of Oregon Health and Sciences University, Portland.

The investigational agent, known for now as OPA-15406, is formulated as a twice-daily ointment. It is highly selective for the phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) B subtype.

Dr. Hanifin noted that these are “exciting times” in the development of new topical therapies for atopic dermatitis (AD). In addition to the successful phase II study of OPA-15406 he presented, a highlight of the EADV congress was the strongly positive pivotal phase III data presented for crisaborole, another nonsteroidal topical PDE-4 inhibitor, albeit with a different mechanism of action.

For Dr. Hanifin these developments are particularly satisfying personally because 33 years ago as a young investigator – before the term ‘translational science’ had come into vogue – he and his research team made the seminal observation that increased phosphodiesterase activity is “a basic biochemical characteristic relevant to skin immunocellular regulation in atopic disease” (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1982 Dec;70[6]:452-7).

The 8-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind phase II OPA-15406 dose-ranging study included 121 patients, 70% with moderate AD, the rest with mild disease. About 20% were adolescents, the rest adults. Their mean baseline Eczema Area Severity Index (EASI) score was 9.5, with a self-reported pruritus score of 61 on a 0-100 scale. Participants were randomized to twice-daily application of OPA-15406 at 0.3% or 1% or the vehicle ointment as a control.

A significant treatment effect was seen within the first week. At 1 week, the mean EASI score was reduced by 31% from baseline in the 1% OPA-15406 group, 15% with the 0.3% formulation, and 6% with vehicle. The active treatment remained significantly more effective than vehicle throughout the 8-week period.

Another measure of efficacy – an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 (clear) or 1 along with at least a 2-point improvement on the 0-5 scale at week 4 – was met by 21% of patients on 1% OPA-15406, 15% on the 0.3% formulation, and 2.7% on vehicle. By the less stringent standard of an IGA of 0 or 1 plus at least a 1-point reduction at week 4, the success rates were 30%, 24%, and 10%.

Dr. Hanifin said the 1% formulation is the one likely to advance to phase III studies, given its superior efficacy. This was particularly evident with regard to itch. At the first evaluation, after just 1 week of treatment, pruritus scores showed a mean 30% reduction with 1% OPA-15406 versus no significant change in controls. He added that his clinical impression is that many patients experience a significant improvement in itching within the first 24 hours on the 1% formulation, an observation that deserves formal study.

Scores on the Dermatology Life Quality Index and Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index were significantly better in the active therapy arms than with vehicle as early as week 1.

The adverse events findings were “not very exciting,” according to the dermatologist. No treatment-related serious adverse events occurred. The two most common adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation – worsening AD and pruritus – occurred more often in the vehicle-treated controls.

Session cochair Dr. Jacek Szepietowski called the pruritus results particularly impressive.

“It’s very difficult to do successful clinical trials of topicals for atopic dermatitis because the vehicle alone, especially if it’s an ointment, can have favorable effects which increase over time both on EASI and pruritus,” commented Dr. Szepietowski, professor and head of the department of dermatology, venereology, and allergology at the Medical University of Wroclaw (Poland).

The study was sponsored by Otsuka Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Hanifin reported serving as a consultant to and paid investigator for the company.

COPENHAGEN – A novel topical nonsteroidal inhibitor of phosphodiesterase-4 showed a favorable efficacy to side effect ratio in a phase II study of adolescents and adults with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis, Dr. Jon M. Hanifin reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“For topical agents, I think a 30% improvement with few side effects is a desirable balance,” observed Dr. Hanifin of Oregon Health and Sciences University, Portland.

The investigational agent, known for now as OPA-15406, is formulated as a twice-daily ointment. It is highly selective for the phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) B subtype.

Dr. Hanifin noted that these are “exciting times” in the development of new topical therapies for atopic dermatitis (AD). In addition to the successful phase II study of OPA-15406 he presented, a highlight of the EADV congress was the strongly positive pivotal phase III data presented for crisaborole, another nonsteroidal topical PDE-4 inhibitor, albeit with a different mechanism of action.

For Dr. Hanifin these developments are particularly satisfying personally because 33 years ago as a young investigator – before the term ‘translational science’ had come into vogue – he and his research team made the seminal observation that increased phosphodiesterase activity is “a basic biochemical characteristic relevant to skin immunocellular regulation in atopic disease” (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1982 Dec;70[6]:452-7).

The 8-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind phase II OPA-15406 dose-ranging study included 121 patients, 70% with moderate AD, the rest with mild disease. About 20% were adolescents, the rest adults. Their mean baseline Eczema Area Severity Index (EASI) score was 9.5, with a self-reported pruritus score of 61 on a 0-100 scale. Participants were randomized to twice-daily application of OPA-15406 at 0.3% or 1% or the vehicle ointment as a control.

A significant treatment effect was seen within the first week. At 1 week, the mean EASI score was reduced by 31% from baseline in the 1% OPA-15406 group, 15% with the 0.3% formulation, and 6% with vehicle. The active treatment remained significantly more effective than vehicle throughout the 8-week period.

Another measure of efficacy – an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 (clear) or 1 along with at least a 2-point improvement on the 0-5 scale at week 4 – was met by 21% of patients on 1% OPA-15406, 15% on the 0.3% formulation, and 2.7% on vehicle. By the less stringent standard of an IGA of 0 or 1 plus at least a 1-point reduction at week 4, the success rates were 30%, 24%, and 10%.

Dr. Hanifin said the 1% formulation is the one likely to advance to phase III studies, given its superior efficacy. This was particularly evident with regard to itch. At the first evaluation, after just 1 week of treatment, pruritus scores showed a mean 30% reduction with 1% OPA-15406 versus no significant change in controls. He added that his clinical impression is that many patients experience a significant improvement in itching within the first 24 hours on the 1% formulation, an observation that deserves formal study.

Scores on the Dermatology Life Quality Index and Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index were significantly better in the active therapy arms than with vehicle as early as week 1.

The adverse events findings were “not very exciting,” according to the dermatologist. No treatment-related serious adverse events occurred. The two most common adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation – worsening AD and pruritus – occurred more often in the vehicle-treated controls.

Session cochair Dr. Jacek Szepietowski called the pruritus results particularly impressive.

“It’s very difficult to do successful clinical trials of topicals for atopic dermatitis because the vehicle alone, especially if it’s an ointment, can have favorable effects which increase over time both on EASI and pruritus,” commented Dr. Szepietowski, professor and head of the department of dermatology, venereology, and allergology at the Medical University of Wroclaw (Poland).

The study was sponsored by Otsuka Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Hanifin reported serving as a consultant to and paid investigator for the company.

COPENHAGEN – A novel topical nonsteroidal inhibitor of phosphodiesterase-4 showed a favorable efficacy to side effect ratio in a phase II study of adolescents and adults with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis, Dr. Jon M. Hanifin reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“For topical agents, I think a 30% improvement with few side effects is a desirable balance,” observed Dr. Hanifin of Oregon Health and Sciences University, Portland.

The investigational agent, known for now as OPA-15406, is formulated as a twice-daily ointment. It is highly selective for the phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) B subtype.

Dr. Hanifin noted that these are “exciting times” in the development of new topical therapies for atopic dermatitis (AD). In addition to the successful phase II study of OPA-15406 he presented, a highlight of the EADV congress was the strongly positive pivotal phase III data presented for crisaborole, another nonsteroidal topical PDE-4 inhibitor, albeit with a different mechanism of action.

For Dr. Hanifin these developments are particularly satisfying personally because 33 years ago as a young investigator – before the term ‘translational science’ had come into vogue – he and his research team made the seminal observation that increased phosphodiesterase activity is “a basic biochemical characteristic relevant to skin immunocellular regulation in atopic disease” (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1982 Dec;70[6]:452-7).

The 8-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind phase II OPA-15406 dose-ranging study included 121 patients, 70% with moderate AD, the rest with mild disease. About 20% were adolescents, the rest adults. Their mean baseline Eczema Area Severity Index (EASI) score was 9.5, with a self-reported pruritus score of 61 on a 0-100 scale. Participants were randomized to twice-daily application of OPA-15406 at 0.3% or 1% or the vehicle ointment as a control.

A significant treatment effect was seen within the first week. At 1 week, the mean EASI score was reduced by 31% from baseline in the 1% OPA-15406 group, 15% with the 0.3% formulation, and 6% with vehicle. The active treatment remained significantly more effective than vehicle throughout the 8-week period.

Another measure of efficacy – an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 (clear) or 1 along with at least a 2-point improvement on the 0-5 scale at week 4 – was met by 21% of patients on 1% OPA-15406, 15% on the 0.3% formulation, and 2.7% on vehicle. By the less stringent standard of an IGA of 0 or 1 plus at least a 1-point reduction at week 4, the success rates were 30%, 24%, and 10%.

Dr. Hanifin said the 1% formulation is the one likely to advance to phase III studies, given its superior efficacy. This was particularly evident with regard to itch. At the first evaluation, after just 1 week of treatment, pruritus scores showed a mean 30% reduction with 1% OPA-15406 versus no significant change in controls. He added that his clinical impression is that many patients experience a significant improvement in itching within the first 24 hours on the 1% formulation, an observation that deserves formal study.

Scores on the Dermatology Life Quality Index and Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index were significantly better in the active therapy arms than with vehicle as early as week 1.

The adverse events findings were “not very exciting,” according to the dermatologist. No treatment-related serious adverse events occurred. The two most common adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation – worsening AD and pruritus – occurred more often in the vehicle-treated controls.

Session cochair Dr. Jacek Szepietowski called the pruritus results particularly impressive.

“It’s very difficult to do successful clinical trials of topicals for atopic dermatitis because the vehicle alone, especially if it’s an ointment, can have favorable effects which increase over time both on EASI and pruritus,” commented Dr. Szepietowski, professor and head of the department of dermatology, venereology, and allergology at the Medical University of Wroclaw (Poland).

The study was sponsored by Otsuka Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Hanifin reported serving as a consultant to and paid investigator for the company.

AT THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point: The pipeline for nonsteroidal topical therapies for pediatric and adult atopic dermatitis shows great promise.

Major finding: Atopic dermatitis patients showed a mean 31% reduction in Eczema Area Severity Index scores after 1 week on topical 1% OPA-15406 ointment, compared with a 6% decrease on vehicle alone.

Data source: This phase II multicenter, double-blind, 8-week randomized trial included 121 adolescents and adults with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Otsuka Pharmaceuticals. The presenter reported serving as a consultant and paid investigator for the company.

Dupilumab effective for atopic dermatitis

Dupilumab, an investigational monoclonal antibody directed against interleukin-4 and interleukin-13, was effective for treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adults, and higher doses were associated with better outcomes, according to Dr. Diamant Thaçi, and associates.

In the international, randomized, placebo-controlled study, 379 patients were split into six groups and treated for 16 weeks, receiving either 300 mg dupilumab once a week, 300 mg every 2 weeks, 200 mg every 2 weeks, 300 mg every 4 weeks, 100 mg every 4 weeks, or placebo.

Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores were most improved in the 300-mg-weekly group, with a reduction of 74%, followed by the 300-mg-every-2-weeks group with a 68% reduction. (Dupilumab is administered subcutaneously). EASI scores were similarly improved in the 200-mg-every-2-weeks and 300-mg-every-4-weeks groups, with reductions of 65% and 64%, respectively. The reduction was 45% in the 100-mg-every-4-weeks group and 18% in the placebo group.

Adverse events related to treatment were similar in both groups, with 80% of the placebo group and 81% of the dupilumab group reporting at least one adverse event. The most common side effect was nasopharyngitis, reported in 28% of the dupilumab group and in 26% of the placebo group.

“The emerging data with dupilumab in multiple atopic diseases provides the first compelling clinical data to support a single unifying hypothesis regarding the drivers of allergic and atopic diseases in general (i.e., that IL-4 and IL-13 are key drivers of signs and symptoms in these clinical settings), and suggests that their blockade might also be effective in other atopic settings,” the investigators concluded.

This was a dose-ranging phase IIb study. Results from phase III studies of dupilumab in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis that is not adequately controlled with topical atopic dermatitis medications are expected in the first half of 2016. Dupilumab is currently under clinical development and its safety and efficacy have not been fully evaluated by any regulatory authority, according to a press statement issued by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals and Sanofi, which are developing the drug.

Find the full study in the Lancet (doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[15]00388-8).

Dr. Thaçi is with the Comprehensive Center for Inflammation Medicine, at University Hospital Schleswig- Holstein, Campus Lübeck (Germany).

Dupilumab, an investigational monoclonal antibody directed against interleukin-4 and interleukin-13, was effective for treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adults, and higher doses were associated with better outcomes, according to Dr. Diamant Thaçi, and associates.

In the international, randomized, placebo-controlled study, 379 patients were split into six groups and treated for 16 weeks, receiving either 300 mg dupilumab once a week, 300 mg every 2 weeks, 200 mg every 2 weeks, 300 mg every 4 weeks, 100 mg every 4 weeks, or placebo.

Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores were most improved in the 300-mg-weekly group, with a reduction of 74%, followed by the 300-mg-every-2-weeks group with a 68% reduction. (Dupilumab is administered subcutaneously). EASI scores were similarly improved in the 200-mg-every-2-weeks and 300-mg-every-4-weeks groups, with reductions of 65% and 64%, respectively. The reduction was 45% in the 100-mg-every-4-weeks group and 18% in the placebo group.

Adverse events related to treatment were similar in both groups, with 80% of the placebo group and 81% of the dupilumab group reporting at least one adverse event. The most common side effect was nasopharyngitis, reported in 28% of the dupilumab group and in 26% of the placebo group.

“The emerging data with dupilumab in multiple atopic diseases provides the first compelling clinical data to support a single unifying hypothesis regarding the drivers of allergic and atopic diseases in general (i.e., that IL-4 and IL-13 are key drivers of signs and symptoms in these clinical settings), and suggests that their blockade might also be effective in other atopic settings,” the investigators concluded.

This was a dose-ranging phase IIb study. Results from phase III studies of dupilumab in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis that is not adequately controlled with topical atopic dermatitis medications are expected in the first half of 2016. Dupilumab is currently under clinical development and its safety and efficacy have not been fully evaluated by any regulatory authority, according to a press statement issued by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals and Sanofi, which are developing the drug.

Find the full study in the Lancet (doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[15]00388-8).

Dr. Thaçi is with the Comprehensive Center for Inflammation Medicine, at University Hospital Schleswig- Holstein, Campus Lübeck (Germany).

Dupilumab, an investigational monoclonal antibody directed against interleukin-4 and interleukin-13, was effective for treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adults, and higher doses were associated with better outcomes, according to Dr. Diamant Thaçi, and associates.

In the international, randomized, placebo-controlled study, 379 patients were split into six groups and treated for 16 weeks, receiving either 300 mg dupilumab once a week, 300 mg every 2 weeks, 200 mg every 2 weeks, 300 mg every 4 weeks, 100 mg every 4 weeks, or placebo.

Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores were most improved in the 300-mg-weekly group, with a reduction of 74%, followed by the 300-mg-every-2-weeks group with a 68% reduction. (Dupilumab is administered subcutaneously). EASI scores were similarly improved in the 200-mg-every-2-weeks and 300-mg-every-4-weeks groups, with reductions of 65% and 64%, respectively. The reduction was 45% in the 100-mg-every-4-weeks group and 18% in the placebo group.

Adverse events related to treatment were similar in both groups, with 80% of the placebo group and 81% of the dupilumab group reporting at least one adverse event. The most common side effect was nasopharyngitis, reported in 28% of the dupilumab group and in 26% of the placebo group.

“The emerging data with dupilumab in multiple atopic diseases provides the first compelling clinical data to support a single unifying hypothesis regarding the drivers of allergic and atopic diseases in general (i.e., that IL-4 and IL-13 are key drivers of signs and symptoms in these clinical settings), and suggests that their blockade might also be effective in other atopic settings,” the investigators concluded.

This was a dose-ranging phase IIb study. Results from phase III studies of dupilumab in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis that is not adequately controlled with topical atopic dermatitis medications are expected in the first half of 2016. Dupilumab is currently under clinical development and its safety and efficacy have not been fully evaluated by any regulatory authority, according to a press statement issued by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals and Sanofi, which are developing the drug.

Find the full study in the Lancet (doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[15]00388-8).

Dr. Thaçi is with the Comprehensive Center for Inflammation Medicine, at University Hospital Schleswig- Holstein, Campus Lübeck (Germany).

EADV: Novel topical crisaborole shines in atopic dermatitis

COPENHAGEN – The nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor crisaborole aced all Food and Drug Administration–required efficacy and safety endpoints as a topical treatment for atopic dermatitis, according to results from a pair of pivotal phase III randomized trials.

“This is a fairly rapidly effective treatment,” explained Dr. Mark G. Lebwohl, who presented the findings at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. “It has a favorable safety profile and has been studied in patients as young as 2 years of age. It may represent a new, safe, and efficacious treatment for patients 2 years of age and older with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis.”

Atopic dermatitis (AD) experts have long complained of a major unmet need for new, safe, and effective topical agents for AD, a condition that affects an estimated 18%-20% of children and 2%-10% of adults. Current treatment options all have drawbacks.

Topical steroids, long a treatment mainstay, are viewed by many parents with phobic mistrust of safety. And both FDA-approved topical calcineurin inhibitors carry black box warnings of possible cancer risk.

The two pivotal phase III studies, identical in design, included a total of 1,522 patients aged 2 years through adulthood with mild to moderate AD. Roughly 60% of patients had moderate disease, as defined by an Investigator’s Static Global Assessment (ISGA) score of 3 on a 0-4 scale; the other 40% had mild AD. The mean involved body surface area was 18%.

Participants were randomized two to one to crisaborole ointment 2% b.i.d. or vehicle for 28 days. Physicians assessed patients at baseline on day 1 of the study and again on days 8, 15, 22, 29, and 36. The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients on day 29 who had an ISGA of 0 or 1 – clear or almost clear – as well as at least a 2-point improvement from baseline on that scale.

In one of the trials, that endpoint was achieved in 32.8% of the crisaborole group, compared with 25.4% of controls.

“That 25% placebo response is actually fairly typical for atopic dermatitis studies,” according to Dr. Lebwohl, professor and chairman of the department of dermatology at Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York.

In the other study, 31.4% of the crisaborole group and 18% of controls achieved the primary endpoint. In both studies, the difference was statistically significant in favor of topical crisaborole.

There were two prespecified secondary endpoints. One was time to treatment success, as defined by clear or almost clear. A “striking” significant difference between the study arms appeared as early as the first assessment, just 1 week into the trial, Dr. Lebwohl observed.

The other secondary endpoint was the FDA’s former efficacy standard, which required being clear or almost clear without the additional need for at least a 2-point ISGA improvement. That endpoint was achieved by 51.7% and 48.5% of crisaborole-treated patients in the two studies, compared with 40.6% and 29.7% of controls. Again, both differences were statistically significant.

No treatment-related serious adverse events occurred in either study. Mild application-site pain was slightly more common in the crisaborole-treated patients. But the rate of study discontinuations because of adverse events was identical between the crisaborole and control groups, at 1.2%. No differences in laboratory values, ECGs, or vital signs were noted between the two groups.

Dr. Lebwohl explained that boron is an essential element in crisaborole. The boron stimulates an increase in cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels, which in turn results in a steep reduction in production of inflammatory cytokines, including interleukins-4, -2, and -31, as well as tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

One audience member asked if it’s possible that crisaborole acts systemically rather than topically, given that patients averaged 18% body surface area involvement, and such a large area of damaged skin could conceivably allow the topical agent ready access to the circulation.

Dr. Lebwohl replied that systemic absorption of the drug was minor. “If you break down the results into patients with very low body surface areas – the lowest was 5% – those patients improved as well. So, I think it would be unlikely that this was a systemic effect.”

Anacor, which is developing the drug as a treatment for AD and other skin diseases, plans to file for marketing approval during the first half of 2016.

Anacor sponsored the two pivotal phase III randomized trials. Dr. Lebwohl declared having no financial conflicts of interest, because all funds went directly to the medical center in which he practices.

COPENHAGEN – The nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor crisaborole aced all Food and Drug Administration–required efficacy and safety endpoints as a topical treatment for atopic dermatitis, according to results from a pair of pivotal phase III randomized trials.

“This is a fairly rapidly effective treatment,” explained Dr. Mark G. Lebwohl, who presented the findings at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. “It has a favorable safety profile and has been studied in patients as young as 2 years of age. It may represent a new, safe, and efficacious treatment for patients 2 years of age and older with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis.”

Atopic dermatitis (AD) experts have long complained of a major unmet need for new, safe, and effective topical agents for AD, a condition that affects an estimated 18%-20% of children and 2%-10% of adults. Current treatment options all have drawbacks.

Topical steroids, long a treatment mainstay, are viewed by many parents with phobic mistrust of safety. And both FDA-approved topical calcineurin inhibitors carry black box warnings of possible cancer risk.

The two pivotal phase III studies, identical in design, included a total of 1,522 patients aged 2 years through adulthood with mild to moderate AD. Roughly 60% of patients had moderate disease, as defined by an Investigator’s Static Global Assessment (ISGA) score of 3 on a 0-4 scale; the other 40% had mild AD. The mean involved body surface area was 18%.

Participants were randomized two to one to crisaborole ointment 2% b.i.d. or vehicle for 28 days. Physicians assessed patients at baseline on day 1 of the study and again on days 8, 15, 22, 29, and 36. The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients on day 29 who had an ISGA of 0 or 1 – clear or almost clear – as well as at least a 2-point improvement from baseline on that scale.

In one of the trials, that endpoint was achieved in 32.8% of the crisaborole group, compared with 25.4% of controls.

“That 25% placebo response is actually fairly typical for atopic dermatitis studies,” according to Dr. Lebwohl, professor and chairman of the department of dermatology at Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York.

In the other study, 31.4% of the crisaborole group and 18% of controls achieved the primary endpoint. In both studies, the difference was statistically significant in favor of topical crisaborole.

There were two prespecified secondary endpoints. One was time to treatment success, as defined by clear or almost clear. A “striking” significant difference between the study arms appeared as early as the first assessment, just 1 week into the trial, Dr. Lebwohl observed.

The other secondary endpoint was the FDA’s former efficacy standard, which required being clear or almost clear without the additional need for at least a 2-point ISGA improvement. That endpoint was achieved by 51.7% and 48.5% of crisaborole-treated patients in the two studies, compared with 40.6% and 29.7% of controls. Again, both differences were statistically significant.

No treatment-related serious adverse events occurred in either study. Mild application-site pain was slightly more common in the crisaborole-treated patients. But the rate of study discontinuations because of adverse events was identical between the crisaborole and control groups, at 1.2%. No differences in laboratory values, ECGs, or vital signs were noted between the two groups.

Dr. Lebwohl explained that boron is an essential element in crisaborole. The boron stimulates an increase in cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels, which in turn results in a steep reduction in production of inflammatory cytokines, including interleukins-4, -2, and -31, as well as tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

One audience member asked if it’s possible that crisaborole acts systemically rather than topically, given that patients averaged 18% body surface area involvement, and such a large area of damaged skin could conceivably allow the topical agent ready access to the circulation.

Dr. Lebwohl replied that systemic absorption of the drug was minor. “If you break down the results into patients with very low body surface areas – the lowest was 5% – those patients improved as well. So, I think it would be unlikely that this was a systemic effect.”

Anacor, which is developing the drug as a treatment for AD and other skin diseases, plans to file for marketing approval during the first half of 2016.

Anacor sponsored the two pivotal phase III randomized trials. Dr. Lebwohl declared having no financial conflicts of interest, because all funds went directly to the medical center in which he practices.

COPENHAGEN – The nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor crisaborole aced all Food and Drug Administration–required efficacy and safety endpoints as a topical treatment for atopic dermatitis, according to results from a pair of pivotal phase III randomized trials.

“This is a fairly rapidly effective treatment,” explained Dr. Mark G. Lebwohl, who presented the findings at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. “It has a favorable safety profile and has been studied in patients as young as 2 years of age. It may represent a new, safe, and efficacious treatment for patients 2 years of age and older with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis.”

Atopic dermatitis (AD) experts have long complained of a major unmet need for new, safe, and effective topical agents for AD, a condition that affects an estimated 18%-20% of children and 2%-10% of adults. Current treatment options all have drawbacks.

Topical steroids, long a treatment mainstay, are viewed by many parents with phobic mistrust of safety. And both FDA-approved topical calcineurin inhibitors carry black box warnings of possible cancer risk.

The two pivotal phase III studies, identical in design, included a total of 1,522 patients aged 2 years through adulthood with mild to moderate AD. Roughly 60% of patients had moderate disease, as defined by an Investigator’s Static Global Assessment (ISGA) score of 3 on a 0-4 scale; the other 40% had mild AD. The mean involved body surface area was 18%.

Participants were randomized two to one to crisaborole ointment 2% b.i.d. or vehicle for 28 days. Physicians assessed patients at baseline on day 1 of the study and again on days 8, 15, 22, 29, and 36. The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients on day 29 who had an ISGA of 0 or 1 – clear or almost clear – as well as at least a 2-point improvement from baseline on that scale.

In one of the trials, that endpoint was achieved in 32.8% of the crisaborole group, compared with 25.4% of controls.

“That 25% placebo response is actually fairly typical for atopic dermatitis studies,” according to Dr. Lebwohl, professor and chairman of the department of dermatology at Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York.

In the other study, 31.4% of the crisaborole group and 18% of controls achieved the primary endpoint. In both studies, the difference was statistically significant in favor of topical crisaborole.

There were two prespecified secondary endpoints. One was time to treatment success, as defined by clear or almost clear. A “striking” significant difference between the study arms appeared as early as the first assessment, just 1 week into the trial, Dr. Lebwohl observed.

The other secondary endpoint was the FDA’s former efficacy standard, which required being clear or almost clear without the additional need for at least a 2-point ISGA improvement. That endpoint was achieved by 51.7% and 48.5% of crisaborole-treated patients in the two studies, compared with 40.6% and 29.7% of controls. Again, both differences were statistically significant.

No treatment-related serious adverse events occurred in either study. Mild application-site pain was slightly more common in the crisaborole-treated patients. But the rate of study discontinuations because of adverse events was identical between the crisaborole and control groups, at 1.2%. No differences in laboratory values, ECGs, or vital signs were noted between the two groups.

Dr. Lebwohl explained that boron is an essential element in crisaborole. The boron stimulates an increase in cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels, which in turn results in a steep reduction in production of inflammatory cytokines, including interleukins-4, -2, and -31, as well as tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

One audience member asked if it’s possible that crisaborole acts systemically rather than topically, given that patients averaged 18% body surface area involvement, and such a large area of damaged skin could conceivably allow the topical agent ready access to the circulation.

Dr. Lebwohl replied that systemic absorption of the drug was minor. “If you break down the results into patients with very low body surface areas – the lowest was 5% – those patients improved as well. So, I think it would be unlikely that this was a systemic effect.”

Anacor, which is developing the drug as a treatment for AD and other skin diseases, plans to file for marketing approval during the first half of 2016.

Anacor sponsored the two pivotal phase III randomized trials. Dr. Lebwohl declared having no financial conflicts of interest, because all funds went directly to the medical center in which he practices.

AT THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Crisaborole topical ointment 2% b.i.d. appeared to be a safe and effective treatment for mild to moderate atopic dermatitis in children and adults.

Major finding: The primary combined efficacy endpoint was met by 32.8% and 31.4% of crisaborole-treated patients in two randomized trials, compared with 25.4% and 18% of vehicle-treated patients.

Data source: The two identically designed pivotal phase III clinical trials included 759 patients and 763 patients aged 2 years through adulthood with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis.

Disclosures: Anacor sponsored the two pivotal phase III randomized trials. Dr. Lebwohl declared having no financial conflicts of interest, because all funds went directly to the medical center in which he practices.

EADV: Atopic dermatitis boosts MI risk

COPENHAGEN – Adults with atopic dermatitis are at significantly increased risk of acute MI compared with the general population, according to a Danish national population-based case-control study.

Indeed, Danish adults with atopic dermatitis (AD) were at a 1.67-fold increased risk for an MI in a Cox regression analysis adjusted for age, gender, education level, and cardiovascular risk factors, Dr. Jette Lindorff Riis reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“The associated MI risk is comparable to that of Danish patients with psoriasis, another inflammatory skin disease, which has been associated with increased cardiovascular risk,” said Dr. Riis of Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital.

Her study included all 5,278 Danish adult AD patients who met the study enrollment criteria: born in 1900-1983, received a hospital discharge diagnosis of AD during 1977-2012, and had at least one additional hospital inpatient or outpatient visit for AD during follow-up. Three-quarters of patients were born in 1960-1983, the rest earlier. The follow-up period began at the time of hospital diagnosis of AD and continued to the time of MI, death, or the end of 2012.

The requirement that participants had to be diagnosed as having AD by a hospital-based physician, in most cases a dermatologist, and that they had to have a second hospital encounter for AD was created to minimize the likelihood of misdiagnosis, a not uncommon occurrence in the primary care setting, she explained.

Each of the 5,278 adults with AD was matched based upon age and gender with 10 controls. Follow-up was accomplished through linkages between Denmark’s comprehensive cradle-to-grave population-wide registries.

During a maximum follow-up of 35 years, the AD patients were at a 1.67-fold greater risk than that of controls after adjustment for potential confounders, including standard cardiovascular risk factors, stroke, and the use of antihypertensive, lipid-lowering, and antidiabetic medications.

The Danish registry data do not contain specific information about patients’ AD disease severity, so as a crude proxy the investigators looked at the number of hospital inpatient or outpatient visits for AD. They found that patients with 2-4 visits had an adjusted 1.31-fold increased risk of acute MI compared with controls, those with 5-9 visits had a 1.83-fold increased risk, and those with 10 or more hospital encounters for AD during follow-up had a 2.42-fold increased risk.

When Dr. Riis and coinvestigators compared adult Danes with AD to a Danish national cohort of psoriasis patients, they found the AD patients were at an adjusted 15% increased risk of MI, a nonsignificant difference. That’s an important finding, since a link between psoriasis and increased cardiovascular risk was first reported nearly a decade ago and has since been confirmed in multiple studies. Given that AD is quite common among adults – various studies have reported prevalence rates of 2%-10% – and that the skin disease appears to boost the risk of what is already the No. 1 cause of mortality in developed countries, the new findings have major implications for clinical practice.

“We might have to think more about cardiovascular risk factor reduction on a daily basis in order to take good care of our atopic dermatitis patients,” Dr. Riis observed.

The Danish study is the latest in a very recent flurry of research pointing for the first time to increased cardiovascular risk in adult AD. Earlier this year investigators at Northwestern University, Chicago, reported finding that adult atopic dermatitis patients have increased levels of cardiovascular risk factors (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 Mar;135[3]:721-8.e6), and even more recently they reported increased rates of coronary artery disease and MI in adults with self-reported AD in analyses of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and the 2010 and 2012 Health Interview Survey (Allergy. 2015 Oct;70[10]:1300-8).

Moreover, earlier this year, Dr. Riis’ colleagues at Aarhus reported a significantly increased rate of asymptomatic coronary artery stenosis in AD patients compared with controls (Am J Med. 2015 Jun 18. pii: S0002-9343[15]00545-8).

Dr. Riis said she’s eager to see studies evaluating whether systemic treatments for AD, which dampen systemic inflammation, also curb the elevated acute MI risk.

Audience comments centered around the issue of whether the Danish results apply to the many less-severe cases of adult AD that never necessitate a trip to the hospital. Are those patients also at increased risk of MI? Dr. Riis said that remains an unanswered question, given that the investigators couldn’t find a reliable indicator of disease severity in the databases. They tried using systemic therapy as a proxy, but it turned out too few AD patients used systemic agents to be able to draw conclusions, which suggests the study population wasn’t at the extreme end of the AD severity spectrum.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, conducted free of commercial support.

COPENHAGEN – Adults with atopic dermatitis are at significantly increased risk of acute MI compared with the general population, according to a Danish national population-based case-control study.

Indeed, Danish adults with atopic dermatitis (AD) were at a 1.67-fold increased risk for an MI in a Cox regression analysis adjusted for age, gender, education level, and cardiovascular risk factors, Dr. Jette Lindorff Riis reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“The associated MI risk is comparable to that of Danish patients with psoriasis, another inflammatory skin disease, which has been associated with increased cardiovascular risk,” said Dr. Riis of Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital.

Her study included all 5,278 Danish adult AD patients who met the study enrollment criteria: born in 1900-1983, received a hospital discharge diagnosis of AD during 1977-2012, and had at least one additional hospital inpatient or outpatient visit for AD during follow-up. Three-quarters of patients were born in 1960-1983, the rest earlier. The follow-up period began at the time of hospital diagnosis of AD and continued to the time of MI, death, or the end of 2012.

The requirement that participants had to be diagnosed as having AD by a hospital-based physician, in most cases a dermatologist, and that they had to have a second hospital encounter for AD was created to minimize the likelihood of misdiagnosis, a not uncommon occurrence in the primary care setting, she explained.

Each of the 5,278 adults with AD was matched based upon age and gender with 10 controls. Follow-up was accomplished through linkages between Denmark’s comprehensive cradle-to-grave population-wide registries.

During a maximum follow-up of 35 years, the AD patients were at a 1.67-fold greater risk than that of controls after adjustment for potential confounders, including standard cardiovascular risk factors, stroke, and the use of antihypertensive, lipid-lowering, and antidiabetic medications.

The Danish registry data do not contain specific information about patients’ AD disease severity, so as a crude proxy the investigators looked at the number of hospital inpatient or outpatient visits for AD. They found that patients with 2-4 visits had an adjusted 1.31-fold increased risk of acute MI compared with controls, those with 5-9 visits had a 1.83-fold increased risk, and those with 10 or more hospital encounters for AD during follow-up had a 2.42-fold increased risk.

When Dr. Riis and coinvestigators compared adult Danes with AD to a Danish national cohort of psoriasis patients, they found the AD patients were at an adjusted 15% increased risk of MI, a nonsignificant difference. That’s an important finding, since a link between psoriasis and increased cardiovascular risk was first reported nearly a decade ago and has since been confirmed in multiple studies. Given that AD is quite common among adults – various studies have reported prevalence rates of 2%-10% – and that the skin disease appears to boost the risk of what is already the No. 1 cause of mortality in developed countries, the new findings have major implications for clinical practice.

“We might have to think more about cardiovascular risk factor reduction on a daily basis in order to take good care of our atopic dermatitis patients,” Dr. Riis observed.

The Danish study is the latest in a very recent flurry of research pointing for the first time to increased cardiovascular risk in adult AD. Earlier this year investigators at Northwestern University, Chicago, reported finding that adult atopic dermatitis patients have increased levels of cardiovascular risk factors (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 Mar;135[3]:721-8.e6), and even more recently they reported increased rates of coronary artery disease and MI in adults with self-reported AD in analyses of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and the 2010 and 2012 Health Interview Survey (Allergy. 2015 Oct;70[10]:1300-8).

Moreover, earlier this year, Dr. Riis’ colleagues at Aarhus reported a significantly increased rate of asymptomatic coronary artery stenosis in AD patients compared with controls (Am J Med. 2015 Jun 18. pii: S0002-9343[15]00545-8).

Dr. Riis said she’s eager to see studies evaluating whether systemic treatments for AD, which dampen systemic inflammation, also curb the elevated acute MI risk.

Audience comments centered around the issue of whether the Danish results apply to the many less-severe cases of adult AD that never necessitate a trip to the hospital. Are those patients also at increased risk of MI? Dr. Riis said that remains an unanswered question, given that the investigators couldn’t find a reliable indicator of disease severity in the databases. They tried using systemic therapy as a proxy, but it turned out too few AD patients used systemic agents to be able to draw conclusions, which suggests the study population wasn’t at the extreme end of the AD severity spectrum.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, conducted free of commercial support.

COPENHAGEN – Adults with atopic dermatitis are at significantly increased risk of acute MI compared with the general population, according to a Danish national population-based case-control study.

Indeed, Danish adults with atopic dermatitis (AD) were at a 1.67-fold increased risk for an MI in a Cox regression analysis adjusted for age, gender, education level, and cardiovascular risk factors, Dr. Jette Lindorff Riis reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“The associated MI risk is comparable to that of Danish patients with psoriasis, another inflammatory skin disease, which has been associated with increased cardiovascular risk,” said Dr. Riis of Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital.

Her study included all 5,278 Danish adult AD patients who met the study enrollment criteria: born in 1900-1983, received a hospital discharge diagnosis of AD during 1977-2012, and had at least one additional hospital inpatient or outpatient visit for AD during follow-up. Three-quarters of patients were born in 1960-1983, the rest earlier. The follow-up period began at the time of hospital diagnosis of AD and continued to the time of MI, death, or the end of 2012.

The requirement that participants had to be diagnosed as having AD by a hospital-based physician, in most cases a dermatologist, and that they had to have a second hospital encounter for AD was created to minimize the likelihood of misdiagnosis, a not uncommon occurrence in the primary care setting, she explained.

Each of the 5,278 adults with AD was matched based upon age and gender with 10 controls. Follow-up was accomplished through linkages between Denmark’s comprehensive cradle-to-grave population-wide registries.

During a maximum follow-up of 35 years, the AD patients were at a 1.67-fold greater risk than that of controls after adjustment for potential confounders, including standard cardiovascular risk factors, stroke, and the use of antihypertensive, lipid-lowering, and antidiabetic medications.

The Danish registry data do not contain specific information about patients’ AD disease severity, so as a crude proxy the investigators looked at the number of hospital inpatient or outpatient visits for AD. They found that patients with 2-4 visits had an adjusted 1.31-fold increased risk of acute MI compared with controls, those with 5-9 visits had a 1.83-fold increased risk, and those with 10 or more hospital encounters for AD during follow-up had a 2.42-fold increased risk.

When Dr. Riis and coinvestigators compared adult Danes with AD to a Danish national cohort of psoriasis patients, they found the AD patients were at an adjusted 15% increased risk of MI, a nonsignificant difference. That’s an important finding, since a link between psoriasis and increased cardiovascular risk was first reported nearly a decade ago and has since been confirmed in multiple studies. Given that AD is quite common among adults – various studies have reported prevalence rates of 2%-10% – and that the skin disease appears to boost the risk of what is already the No. 1 cause of mortality in developed countries, the new findings have major implications for clinical practice.

“We might have to think more about cardiovascular risk factor reduction on a daily basis in order to take good care of our atopic dermatitis patients,” Dr. Riis observed.

The Danish study is the latest in a very recent flurry of research pointing for the first time to increased cardiovascular risk in adult AD. Earlier this year investigators at Northwestern University, Chicago, reported finding that adult atopic dermatitis patients have increased levels of cardiovascular risk factors (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 Mar;135[3]:721-8.e6), and even more recently they reported increased rates of coronary artery disease and MI in adults with self-reported AD in analyses of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and the 2010 and 2012 Health Interview Survey (Allergy. 2015 Oct;70[10]:1300-8).

Moreover, earlier this year, Dr. Riis’ colleagues at Aarhus reported a significantly increased rate of asymptomatic coronary artery stenosis in AD patients compared with controls (Am J Med. 2015 Jun 18. pii: S0002-9343[15]00545-8).

Dr. Riis said she’s eager to see studies evaluating whether systemic treatments for AD, which dampen systemic inflammation, also curb the elevated acute MI risk.

Audience comments centered around the issue of whether the Danish results apply to the many less-severe cases of adult AD that never necessitate a trip to the hospital. Are those patients also at increased risk of MI? Dr. Riis said that remains an unanswered question, given that the investigators couldn’t find a reliable indicator of disease severity in the databases. They tried using systemic therapy as a proxy, but it turned out too few AD patients used systemic agents to be able to draw conclusions, which suggests the study population wasn’t at the extreme end of the AD severity spectrum.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, conducted free of commercial support.

AT THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Like psoriasis patients, adults with atopic dermatitis appear to be at increased risk for acute MI.

Major finding: Adults with atopic dermatitis were at an adjusted 1.67-fold increased risk of acute MI compared with matched controls after researchers controlled for potential confounders.

Data source: This Danish national case-control study of 5,278 adult atopic dermatitis patients and 52,780 matched controls followed for up to 35 years.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

Occupational Contact Dermatitis From Carbapenems

To the Editor:

Contact sensitivity to drugs that are systemically administered can occur among health care workers.1 We report the case of a 28-year-old nurse who developed eczema on the dorsal aspect of the hand (Figure 1A) and the face (Figure 1B) in the workplace. The nurse was working in the hematology department where she usually handled and administered antibiotics such as imipenem, ertapenem, piperacillin, vancomycin, anidulafungin, teicoplanin, and ciprofloxacin. She was moved to a different department where she did not have contact with the suspicious drugs and the dermatitis completely resolved.

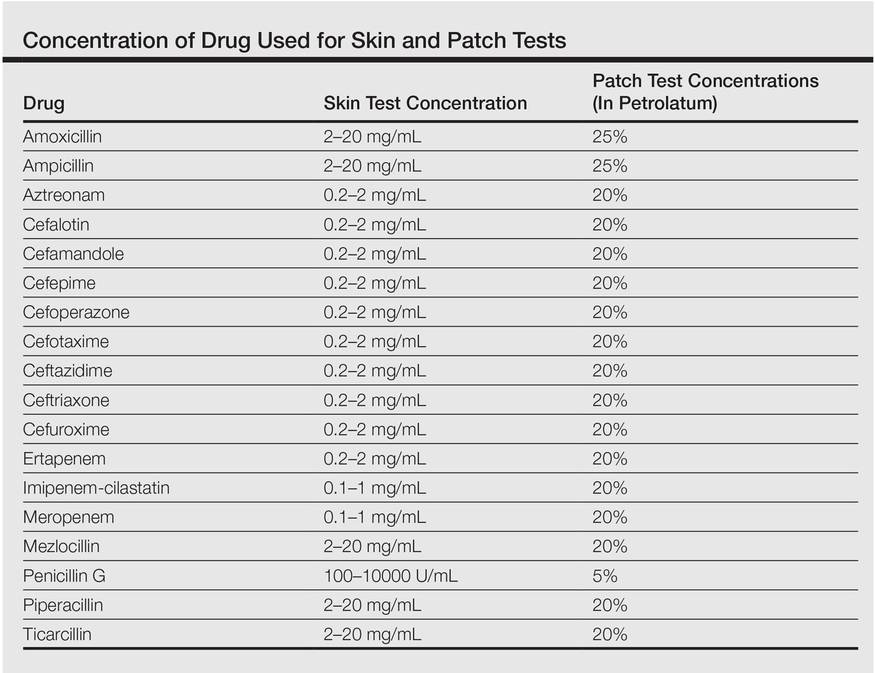

One month after the resolution of the eczema she was referred to our allergy department for an allergological evaluation. A dermatologic evaluation was made and a skin biopsy was performed from a lesional area of the left hand. The patient underwent delayed skin test and patch tests with many β-lactam compounds including penicilloyl polylysine, minor determinant mixture, penicillin G, penicillin V, ampicillin, amoxicillin, bacampicillin, piperacillin, mezlocillin and ticarcillin, imipenem-cilastatin, aztreonam, meropenem, ertapenem, and cephalosporins (eg, cephalexin, cefaclor, cefalotin, cefadroxil, cephradine, cefuroxime, ceftriaxone, cefixime, cefoperazone, cefamandole, ceftazidime, cefotaxime). Undiluted solutions of commercial drugs (parenteral drugs when available were used) were used for skin prick test, and if negative, they were tested intradermally as described by Schiavino et al.2 The concentrations used for the skin test and for the patch test are reported in the Table. Histamine (10 mg/mL) and saline were employed as positive and negative controls, respectively. Immediate reactions of at least 3 mm greater in diameter compared to the control for the skin prick test and 5 mm greater for intradermal tests were considered positive. Immediate-type skin tests were read after 20 minutes and also after 48 hours should any delayed reaction occur. An infiltrated erythema with a diameter greater than 5 mm was considered a delayed positive reaction.

Patch tests were applied to the interscapular region using acrylate adhesive strips with small plates. They were evaluated at 48 and 72 hours. Positivity was assessed according to the indications of the European Network for Drug Allergy.3 Patch tests were carried out using the same drugs as the skin test. All drugs were mixed in petrolatum at 25% wt/wt for ampicillin and amoxicillin, 5% for penicillin G, and 20% for the other drugs as recommended by Schiavino et al.2 We also performed patch tests with ertapenem in 20 healthy controls.

A skin biopsy from lesional skin showed a perivascular infiltrate of the upper dermis with spongiosis of the lesional area similar to eczema. Patch tests and intradermal tests were positive for ertapenem after 48 hours (Figure 2). Imipenem-cilastatin, ampicillin, piperacillin, mezlocillin, and meropenem showed a positive reaction for patch tests. We concluded that the patient had delayed hypersensitivity to carbapenems (ertapenem, imipenem-cilastatin, and meropenem) and semisynthetic penicillins (piperacillin, mezlocillin, and ampicillin).

Drug sensitization in nurses and in health care workers can occur. Natural and semisynthetic penicillin can cause allergic contact dermatitis in health care workers. We report a case of occupational allergy to ertapenem, which is a 1-β-methyl-carbapenem that is administered as a single agent. It is highly active in vitro against bacteria that are generally associated with community-acquired and mixed aerobic and anaerobic infections.4 Occupational contact allergy to other carbapenems such as meropenem also was reported.5 The contact sensitization potential of imipenem has been confirmed in the guinea pig.6 Carbapenems have a bicyclic nucleus composed by a β-lactam ring with an associated 5-membered ring. In our patient, patch tests for ertapenem, imipenem, and meropenem were positive. Although the cross-reactivity between imipenem and penicillin has been demonstrated,2 data on the cross-reactivity between the carbapenems are not strong. Bauer et al7 reported a case of an allergy to imipenem-cilastatin that tolerated treatment with meropenem, but our case showed a complete cross-reactivity between carbapenems. Patch tests for ampicillin, mezlocillin, and piperacillin also were positive; therefore, it can be hypothesized that in our patient, the β-lactam ring was the main epitope recognized by T lymphocytes. Gielen and Goossens1 reported in a study on work-related dermatitis that the most common sensitizers were antibiotics such as penicillins, cephalosporins, and aminoglycosides.

Health care workers should protect their hands with gloves during the preparation of drugs because they have the risk for developing an occupational contact allergy. Detailed allergological and dermatological evaluation is mandatory to confirm or exclude occupational contact allergy.

- Gielen K, Goossens A. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis from drugs in healthcare workers. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;45:273-279.

- Schiavino D, Nucera E, Lombardo C, et al. Cross-reactivity and tolerability of imipenem in patients with delayed-type, cell-mediated hypersensitivity to beta-lactams. Allergy. 2009;64:1644-1648.

- Romano A, Blanca M, Torres MJ, et al. Diagnosis of nonimmediate reactions to beta-lactam antibiotics. Allergy. 2004;59:1153-1160.

- Teppler H, Gesser RM, Friedland IR, et al. Safety and tolerability of ertapenem. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;53(suppl 2):75-81.

- Yesudian PD, King CM. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis from meropenem. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;45:53.

- Nagakura N, Souma S, Shimizu T, et al. Comparison of cross-reactivities of imipenem and other beta-lactam antibiotics by delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction in guinea pigs. Chem Pharm Bull. 1991;39:765-768.

- Bauer SL, Wall GC, Skoglund K, et al. Lack of cross-reactivity to meropenem in a patient with an allergy to imipenem-cilastatin. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:173-175.

To the Editor: