User login

Balancing clinical and supportive care at every step of the disease continuum

It seems it was just yesterday that we did our first “mutation analysis” to help guide us in our treatment of patients with a drug that was more likely to work than not. Of course, I am referring to estrogen-receptor/progesterone receptor (ER/PR) blocking therapy, and “yesterday” actually goes all the way back to the 1970s! When tamoxifen was first given to unselected metastatic breast cancer patients, the response rate was low, but when the study population was “enriched” with breast cancer patients who were ER/ PR-positive, the response rates improved and the outcomes were more favorable. So began the era of tumor markers and enriching patient populations, and the process now referred to as mutation analysis, which is becoming more broadly applicable to other tumors as well.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

It seems it was just yesterday that we did our first “mutation analysis” to help guide us in our treatment of patients with a drug that was more likely to work than not. Of course, I am referring to estrogen-receptor/progesterone receptor (ER/PR) blocking therapy, and “yesterday” actually goes all the way back to the 1970s! When tamoxifen was first given to unselected metastatic breast cancer patients, the response rate was low, but when the study population was “enriched” with breast cancer patients who were ER/ PR-positive, the response rates improved and the outcomes were more favorable. So began the era of tumor markers and enriching patient populations, and the process now referred to as mutation analysis, which is becoming more broadly applicable to other tumors as well.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

It seems it was just yesterday that we did our first “mutation analysis” to help guide us in our treatment of patients with a drug that was more likely to work than not. Of course, I am referring to estrogen-receptor/progesterone receptor (ER/PR) blocking therapy, and “yesterday” actually goes all the way back to the 1970s! When tamoxifen was first given to unselected metastatic breast cancer patients, the response rate was low, but when the study population was “enriched” with breast cancer patients who were ER/ PR-positive, the response rates improved and the outcomes were more favorable. So began the era of tumor markers and enriching patient populations, and the process now referred to as mutation analysis, which is becoming more broadly applicable to other tumors as well.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Pan-AKT inhibitor shrinks tumors in patients with AKT1 mutation

BOSTON – A novel pan-AKT inhibitor was associated in a phase 1 trial with tumor shrinkage in a large proportion of patients with solid tumors bearing a mutation in AKT1.

The investigational compound, labeled AZD5363, targets the AKT1 E17K mutation, which occurs in approximately 0.5% to 4% of many different types of solid tumors. In a phase I trial, 33 of 41 assessable patients with tumors bearing the mutation had regression of tumors, reported Dr. David M. Hyman, acting director of experimental therapeutics at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

“We believe this is the first clinical data suggesting that the AKT1 E17K mutations are targetable driver mutations in solid tumors,” he said at a briefing at the AACR/NCI/EORTC International Conference on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics.

Mutations in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway are frequently found in human cancers, and dysregulation of the pathway has been shown to drive tumor growth and survival of malignant cells.

“Although this pathway is among the most commonly activated in all human cancer, it is rarely activated by somatic mutation of AKT itself,” Dr. Hyman said. “When you see AKT mutations, they are almost always of a single allele at the 17 amino acid position, which is the E17K mutation. This is a mutation that has been extensively functionally classified, and behaves as a classic driver oncogene.”

The E17K mutation occurs in approximately 4% of breast cancers, 2% of bladder cancers, 1.5% of colorectal tumors, 1% each of cervical, ovarian, and prostate cancers, and 0.5% of lung adenocarcinomas.

AZD5363 is a catalytic inhibitor of all AKT isoforms 1, 2, and 3. In preclinical studies, it has been shown to inhibit tumor cell proliferation in vitro, and tumor growth in vivo in tumor xenograft models.

Dr. Hyman and colleagues reported on early results from one part of a four-part, phase I study of AZD5363 in adults with advanced solid tumors. Part D of the ongoing study focuses on patients with tumors bearing AKT1 mutations.

At present, 45 patients with E17K mutations have been treated with the agent, including 21 with estrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancer, four with triple-negative breast cancer, 14 with gynecological cancers, and eight with other tumor types.

As noted, of 41 patients with sufficient data for assessment, 33 had some degree of tumor regression, and of this group 12 met RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors) parameters for partial responses. Among patients assessable for response, 14 of 18 with ER-positive breast cancer had lesion shrinkage, and five of these patients had partial responses (3 confirmed and 2 unconfirmed).

Among patients with gynecological tumors, 9 of 11 had shrinkage of their target lesion, including 3 with confirmed partial responses. Two of these patients are still on study, with the longest follow-up at the time of data cutoff of 39.2 months

Among patients with 12 other tumor types (apocrine anal, triple-negative breast cancer, colon, lung, prostate, squamous anal, thyroid) 10 patients had demonstrated target lesion shrinkage, one had a confirmed partial response that is ongoing, and two had unconfirmed partial response, one of which is ongoing.

The investigators also used cell-free DNA (cfDNA) analysis to evaluate efficacy of AZD5363 during treatment, and found that declines in AKT1 cfDNA allele fractions were transient among non-responders, whereas declines persisting for 21 days or more correlated with both durable tumor regression and RECIST response (P = .0049).

Dr. Hyman noted that there were also preclinical signs that AZD5363 could lead to reactivation of ER signaling.

“It became a natural question to ask whether patients did better with a combination of ER-directed therapy and AKT-directed therapy,” he said.

To answer this question, the investigators offered sequential therapy to patients with ER-positive breast cancer who had previously had resistance to the ER degrader fulvestrant and who had progressed on AZD5363 monotherapy. Two patients were offered crossover to AZD5363 with fulvestrant, regardless of prior hormonal therapy.

One of the patients had disease progression while on the combination. The second patient, who had received 10 prior lines of therapy and had disease progression before starting on the combination at 120 days on treatment, had significant shrinkage of her breast lesion 6 weeks after starting on the combination, and liver lesions that had previously enhanced on imaging are no longer enhancing, and her cfDNA allele fractions have declined. She remains on the combination after more than 160 days.

“This was very convincing evidence to us of synergy between these two compounds,” he said.

Dr. Jean-Charles Soria, from the Institut Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France, who moderated the briefing, commented that “although this [mutation] is a rare situation, in the range of 2% to 3%, it’s certainly important, because 2% to 3% of breast cancer patients is a significant number, so this drug has legs,” he said.

The question yet to be settled, however, is the true duration of response, he added.

The study is sponsored by AstraZeneca. Dr. Hyman disclosed consulting for Atara Biotherapeutics. Dr. Soria reported having no disclosures.

BOSTON – A novel pan-AKT inhibitor was associated in a phase 1 trial with tumor shrinkage in a large proportion of patients with solid tumors bearing a mutation in AKT1.

The investigational compound, labeled AZD5363, targets the AKT1 E17K mutation, which occurs in approximately 0.5% to 4% of many different types of solid tumors. In a phase I trial, 33 of 41 assessable patients with tumors bearing the mutation had regression of tumors, reported Dr. David M. Hyman, acting director of experimental therapeutics at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

“We believe this is the first clinical data suggesting that the AKT1 E17K mutations are targetable driver mutations in solid tumors,” he said at a briefing at the AACR/NCI/EORTC International Conference on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics.

Mutations in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway are frequently found in human cancers, and dysregulation of the pathway has been shown to drive tumor growth and survival of malignant cells.

“Although this pathway is among the most commonly activated in all human cancer, it is rarely activated by somatic mutation of AKT itself,” Dr. Hyman said. “When you see AKT mutations, they are almost always of a single allele at the 17 amino acid position, which is the E17K mutation. This is a mutation that has been extensively functionally classified, and behaves as a classic driver oncogene.”

The E17K mutation occurs in approximately 4% of breast cancers, 2% of bladder cancers, 1.5% of colorectal tumors, 1% each of cervical, ovarian, and prostate cancers, and 0.5% of lung adenocarcinomas.

AZD5363 is a catalytic inhibitor of all AKT isoforms 1, 2, and 3. In preclinical studies, it has been shown to inhibit tumor cell proliferation in vitro, and tumor growth in vivo in tumor xenograft models.

Dr. Hyman and colleagues reported on early results from one part of a four-part, phase I study of AZD5363 in adults with advanced solid tumors. Part D of the ongoing study focuses on patients with tumors bearing AKT1 mutations.

At present, 45 patients with E17K mutations have been treated with the agent, including 21 with estrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancer, four with triple-negative breast cancer, 14 with gynecological cancers, and eight with other tumor types.

As noted, of 41 patients with sufficient data for assessment, 33 had some degree of tumor regression, and of this group 12 met RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors) parameters for partial responses. Among patients assessable for response, 14 of 18 with ER-positive breast cancer had lesion shrinkage, and five of these patients had partial responses (3 confirmed and 2 unconfirmed).

Among patients with gynecological tumors, 9 of 11 had shrinkage of their target lesion, including 3 with confirmed partial responses. Two of these patients are still on study, with the longest follow-up at the time of data cutoff of 39.2 months

Among patients with 12 other tumor types (apocrine anal, triple-negative breast cancer, colon, lung, prostate, squamous anal, thyroid) 10 patients had demonstrated target lesion shrinkage, one had a confirmed partial response that is ongoing, and two had unconfirmed partial response, one of which is ongoing.

The investigators also used cell-free DNA (cfDNA) analysis to evaluate efficacy of AZD5363 during treatment, and found that declines in AKT1 cfDNA allele fractions were transient among non-responders, whereas declines persisting for 21 days or more correlated with both durable tumor regression and RECIST response (P = .0049).

Dr. Hyman noted that there were also preclinical signs that AZD5363 could lead to reactivation of ER signaling.

“It became a natural question to ask whether patients did better with a combination of ER-directed therapy and AKT-directed therapy,” he said.

To answer this question, the investigators offered sequential therapy to patients with ER-positive breast cancer who had previously had resistance to the ER degrader fulvestrant and who had progressed on AZD5363 monotherapy. Two patients were offered crossover to AZD5363 with fulvestrant, regardless of prior hormonal therapy.

One of the patients had disease progression while on the combination. The second patient, who had received 10 prior lines of therapy and had disease progression before starting on the combination at 120 days on treatment, had significant shrinkage of her breast lesion 6 weeks after starting on the combination, and liver lesions that had previously enhanced on imaging are no longer enhancing, and her cfDNA allele fractions have declined. She remains on the combination after more than 160 days.

“This was very convincing evidence to us of synergy between these two compounds,” he said.

Dr. Jean-Charles Soria, from the Institut Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France, who moderated the briefing, commented that “although this [mutation] is a rare situation, in the range of 2% to 3%, it’s certainly important, because 2% to 3% of breast cancer patients is a significant number, so this drug has legs,” he said.

The question yet to be settled, however, is the true duration of response, he added.

The study is sponsored by AstraZeneca. Dr. Hyman disclosed consulting for Atara Biotherapeutics. Dr. Soria reported having no disclosures.

BOSTON – A novel pan-AKT inhibitor was associated in a phase 1 trial with tumor shrinkage in a large proportion of patients with solid tumors bearing a mutation in AKT1.

The investigational compound, labeled AZD5363, targets the AKT1 E17K mutation, which occurs in approximately 0.5% to 4% of many different types of solid tumors. In a phase I trial, 33 of 41 assessable patients with tumors bearing the mutation had regression of tumors, reported Dr. David M. Hyman, acting director of experimental therapeutics at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

“We believe this is the first clinical data suggesting that the AKT1 E17K mutations are targetable driver mutations in solid tumors,” he said at a briefing at the AACR/NCI/EORTC International Conference on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics.

Mutations in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway are frequently found in human cancers, and dysregulation of the pathway has been shown to drive tumor growth and survival of malignant cells.

“Although this pathway is among the most commonly activated in all human cancer, it is rarely activated by somatic mutation of AKT itself,” Dr. Hyman said. “When you see AKT mutations, they are almost always of a single allele at the 17 amino acid position, which is the E17K mutation. This is a mutation that has been extensively functionally classified, and behaves as a classic driver oncogene.”

The E17K mutation occurs in approximately 4% of breast cancers, 2% of bladder cancers, 1.5% of colorectal tumors, 1% each of cervical, ovarian, and prostate cancers, and 0.5% of lung adenocarcinomas.

AZD5363 is a catalytic inhibitor of all AKT isoforms 1, 2, and 3. In preclinical studies, it has been shown to inhibit tumor cell proliferation in vitro, and tumor growth in vivo in tumor xenograft models.

Dr. Hyman and colleagues reported on early results from one part of a four-part, phase I study of AZD5363 in adults with advanced solid tumors. Part D of the ongoing study focuses on patients with tumors bearing AKT1 mutations.

At present, 45 patients with E17K mutations have been treated with the agent, including 21 with estrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancer, four with triple-negative breast cancer, 14 with gynecological cancers, and eight with other tumor types.

As noted, of 41 patients with sufficient data for assessment, 33 had some degree of tumor regression, and of this group 12 met RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors) parameters for partial responses. Among patients assessable for response, 14 of 18 with ER-positive breast cancer had lesion shrinkage, and five of these patients had partial responses (3 confirmed and 2 unconfirmed).

Among patients with gynecological tumors, 9 of 11 had shrinkage of their target lesion, including 3 with confirmed partial responses. Two of these patients are still on study, with the longest follow-up at the time of data cutoff of 39.2 months

Among patients with 12 other tumor types (apocrine anal, triple-negative breast cancer, colon, lung, prostate, squamous anal, thyroid) 10 patients had demonstrated target lesion shrinkage, one had a confirmed partial response that is ongoing, and two had unconfirmed partial response, one of which is ongoing.

The investigators also used cell-free DNA (cfDNA) analysis to evaluate efficacy of AZD5363 during treatment, and found that declines in AKT1 cfDNA allele fractions were transient among non-responders, whereas declines persisting for 21 days or more correlated with both durable tumor regression and RECIST response (P = .0049).

Dr. Hyman noted that there were also preclinical signs that AZD5363 could lead to reactivation of ER signaling.

“It became a natural question to ask whether patients did better with a combination of ER-directed therapy and AKT-directed therapy,” he said.

To answer this question, the investigators offered sequential therapy to patients with ER-positive breast cancer who had previously had resistance to the ER degrader fulvestrant and who had progressed on AZD5363 monotherapy. Two patients were offered crossover to AZD5363 with fulvestrant, regardless of prior hormonal therapy.

One of the patients had disease progression while on the combination. The second patient, who had received 10 prior lines of therapy and had disease progression before starting on the combination at 120 days on treatment, had significant shrinkage of her breast lesion 6 weeks after starting on the combination, and liver lesions that had previously enhanced on imaging are no longer enhancing, and her cfDNA allele fractions have declined. She remains on the combination after more than 160 days.

“This was very convincing evidence to us of synergy between these two compounds,” he said.

Dr. Jean-Charles Soria, from the Institut Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France, who moderated the briefing, commented that “although this [mutation] is a rare situation, in the range of 2% to 3%, it’s certainly important, because 2% to 3% of breast cancer patients is a significant number, so this drug has legs,” he said.

The question yet to be settled, however, is the true duration of response, he added.

The study is sponsored by AstraZeneca. Dr. Hyman disclosed consulting for Atara Biotherapeutics. Dr. Soria reported having no disclosures.

Key clinical point: A novel pan-AKT inhibitor shrinks tumors in patients harboring a mutation in AKT1.

Major finding: Among patients assessable for response, 33 of 41 had tumor regression on AZD5363 monotherapy.

Data source: Phase I study in 45 patients with solid tumors carrying the AKT1 E17K mutation.

Disclosures: The study is sponsored by AstraZeneca. Dr. Hyman disclosed consulting for Atara Biotherapeutics. Dr. Soria reported having no disclosures.

AHA: Candesartan protects against cardiotoxicity in breast cancer patients in PRADA

ORLANDO – Concomitant treatment with candesartan protects against the early decline in left ventricular ejection fraction associated with adjunct therapy for early breast cancer.

That was the key finding in the PRADA trial (PRevention of cArdiac Dysfunction during Adjuvant breast cancer therapy), the largest study to date looking at prevention of cardiac dysfunction in a breast cancer population.

Another important finding in PRADA was that unlike the angiotensin receptor blocker candesartan (Atacand), metoprolol, a beta blocker, didn’t prevent the early drop in LVEF commonly seen in breast cancer patients treated with anthracyclines and trastuzumab (Herceptin), even though both classes of heart medications are cornerstones of the treatment of ischemic and hypertensive cardiomyopathy, Dr. Geeta Gulati reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Although the cardiotoxicity of certain breast cancer treatments is widely recognized and has spawned the emerging field of cardio-oncology, the literature in this area is weak. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis identified only four published randomized studies evaluating the possible cardioprotective role for beta blockers and angiotensin antagonists in patients undergoing anthracycline-based chemotherapy (Postgrad Med J doi:10.1136/ postgradmedj-2015-133535). None of the studies was double-blind, all relied upon echocardiographic assessment of changes in LVEF rather than gold-standard cardiac MRI, and the study sizes were small -- just 18-45 breast cancer patients.

Most problematic of all, the studies employed a variety of different definitions of cardiotoxicity, noted Dr. Gulati of Akershus University Hospital in Lorenskog, Norway.

In contrast, PRADA was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, 2 by 2 factorial design, single-center trial, which included 120 patients with early breast cancer. Participants were randomized to candesartan at a starting dose of 8 mg and target dose of 32 mg/day, metoprolol starting at 25 mg with a target of 100 mg/day, or placebo after breast cancer surgery but before the start of anthracycline-containing chemotherapy.

The primary endpoint was change in LVEF from baseline to completion of adjuvant therapy, a period as short as 10 weeks and as long as 64 weeks depending upon whether a woman also underwent courses of trastuzumab, taxanes, and/or radiation therapy.

The overall decline in LVEF was 2.6% in the placebo group and 0.6% in the candesartan group, a significant difference. Metoprolol didn’t put a dent in the LVEF decline.

“Observational studies show early reduction in LVEF is associated with increased risk of developing heart failure later. So if a sustained, long-term effect of angiotensin inhibition can be confirmed in larger multicenter trials, preventive therapy may be indicated as standard care for breast cancer patients,” Dr. Gulati said.

Discussant Dr. Bonnie Ky of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, called PRADA an important study that moves the field of cardio-oncology forward, yet it’s also a trial that raises more questions than it answers.

PRADA certainly addresses a major problem: “The incidence of heart failure and cardiomyopathy increases over time in breast cancer patients exposed to anthracyclines and trastuzumab. Because patients are living longer because of cancer chemotherapy, their risk of dying of cardiovascular disease actually exceeds that of recurrent cancer in the long term,” she observed.

The study has three major limitations that prevent its findings being implemented in routine clinical practice at this time, Dr. Ky said. One is its relatively small size, even though it’s far bigger than any previous study. Another limitation is that this was an extremely low-cardiovascular-risk patient cohort: the baseline prevalence of diabetes was only 1.5%, fewer than 7% of patients had hypertension, and the baseline LVEF was 63%. That may be why no one developed a substantial decrement in LVEF or actual heart failure.

And since the incidence of cardiomyopathy following breast cancer therapy is known to climb over time, reaching a cumulative 12% at 6 years followup in trastuzumab-treated patients and 20% in those who receive both anthracyclines and trastuzumab (J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012 Sep 5;104(17):1293-305), the lack of extended followup time in PRADA is a significant shortcoming, she added.

The important questions raised by PRADA, Dr. Ky continued, include whether carvedilol or another beta blocker would have generated a positive result where metoprolol failed. Also, should the target population for prevention of cardiotoxicity be more narrowly focused on those at higher baseline cardiovascular risk? And bearing in mind that change in LVEF is a surrogate endpoint, what might be a more clinically meaningful and valid outcome measure? What’s the effect of carvedilol and other cardioprotective medications on cardiac biomarkers in breast cancer patients? And the most important questions of all, she said: What would be the effects of longer followup time and extended therapy?

“This study highlights for us in the field of cardio-oncology the critical need to develop a robust consensus definition of cardiotoxicity and a methodology to identify high cardiovascular risk patients,” she concluded.

PRADA was funded primarily by the University of Oslo and the Norwegian Cancer Society. Dr. Gulati reported having no financial conflicts of interest. Dr. Ky reported receiving a research grant from Pfizer and serving as a consultant to Bristol Myers Squibb.

ORLANDO – Concomitant treatment with candesartan protects against the early decline in left ventricular ejection fraction associated with adjunct therapy for early breast cancer.

That was the key finding in the PRADA trial (PRevention of cArdiac Dysfunction during Adjuvant breast cancer therapy), the largest study to date looking at prevention of cardiac dysfunction in a breast cancer population.

Another important finding in PRADA was that unlike the angiotensin receptor blocker candesartan (Atacand), metoprolol, a beta blocker, didn’t prevent the early drop in LVEF commonly seen in breast cancer patients treated with anthracyclines and trastuzumab (Herceptin), even though both classes of heart medications are cornerstones of the treatment of ischemic and hypertensive cardiomyopathy, Dr. Geeta Gulati reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Although the cardiotoxicity of certain breast cancer treatments is widely recognized and has spawned the emerging field of cardio-oncology, the literature in this area is weak. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis identified only four published randomized studies evaluating the possible cardioprotective role for beta blockers and angiotensin antagonists in patients undergoing anthracycline-based chemotherapy (Postgrad Med J doi:10.1136/ postgradmedj-2015-133535). None of the studies was double-blind, all relied upon echocardiographic assessment of changes in LVEF rather than gold-standard cardiac MRI, and the study sizes were small -- just 18-45 breast cancer patients.

Most problematic of all, the studies employed a variety of different definitions of cardiotoxicity, noted Dr. Gulati of Akershus University Hospital in Lorenskog, Norway.

In contrast, PRADA was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, 2 by 2 factorial design, single-center trial, which included 120 patients with early breast cancer. Participants were randomized to candesartan at a starting dose of 8 mg and target dose of 32 mg/day, metoprolol starting at 25 mg with a target of 100 mg/day, or placebo after breast cancer surgery but before the start of anthracycline-containing chemotherapy.

The primary endpoint was change in LVEF from baseline to completion of adjuvant therapy, a period as short as 10 weeks and as long as 64 weeks depending upon whether a woman also underwent courses of trastuzumab, taxanes, and/or radiation therapy.

The overall decline in LVEF was 2.6% in the placebo group and 0.6% in the candesartan group, a significant difference. Metoprolol didn’t put a dent in the LVEF decline.

“Observational studies show early reduction in LVEF is associated with increased risk of developing heart failure later. So if a sustained, long-term effect of angiotensin inhibition can be confirmed in larger multicenter trials, preventive therapy may be indicated as standard care for breast cancer patients,” Dr. Gulati said.

Discussant Dr. Bonnie Ky of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, called PRADA an important study that moves the field of cardio-oncology forward, yet it’s also a trial that raises more questions than it answers.

PRADA certainly addresses a major problem: “The incidence of heart failure and cardiomyopathy increases over time in breast cancer patients exposed to anthracyclines and trastuzumab. Because patients are living longer because of cancer chemotherapy, their risk of dying of cardiovascular disease actually exceeds that of recurrent cancer in the long term,” she observed.

The study has three major limitations that prevent its findings being implemented in routine clinical practice at this time, Dr. Ky said. One is its relatively small size, even though it’s far bigger than any previous study. Another limitation is that this was an extremely low-cardiovascular-risk patient cohort: the baseline prevalence of diabetes was only 1.5%, fewer than 7% of patients had hypertension, and the baseline LVEF was 63%. That may be why no one developed a substantial decrement in LVEF or actual heart failure.

And since the incidence of cardiomyopathy following breast cancer therapy is known to climb over time, reaching a cumulative 12% at 6 years followup in trastuzumab-treated patients and 20% in those who receive both anthracyclines and trastuzumab (J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012 Sep 5;104(17):1293-305), the lack of extended followup time in PRADA is a significant shortcoming, she added.

The important questions raised by PRADA, Dr. Ky continued, include whether carvedilol or another beta blocker would have generated a positive result where metoprolol failed. Also, should the target population for prevention of cardiotoxicity be more narrowly focused on those at higher baseline cardiovascular risk? And bearing in mind that change in LVEF is a surrogate endpoint, what might be a more clinically meaningful and valid outcome measure? What’s the effect of carvedilol and other cardioprotective medications on cardiac biomarkers in breast cancer patients? And the most important questions of all, she said: What would be the effects of longer followup time and extended therapy?

“This study highlights for us in the field of cardio-oncology the critical need to develop a robust consensus definition of cardiotoxicity and a methodology to identify high cardiovascular risk patients,” she concluded.

PRADA was funded primarily by the University of Oslo and the Norwegian Cancer Society. Dr. Gulati reported having no financial conflicts of interest. Dr. Ky reported receiving a research grant from Pfizer and serving as a consultant to Bristol Myers Squibb.

ORLANDO – Concomitant treatment with candesartan protects against the early decline in left ventricular ejection fraction associated with adjunct therapy for early breast cancer.

That was the key finding in the PRADA trial (PRevention of cArdiac Dysfunction during Adjuvant breast cancer therapy), the largest study to date looking at prevention of cardiac dysfunction in a breast cancer population.

Another important finding in PRADA was that unlike the angiotensin receptor blocker candesartan (Atacand), metoprolol, a beta blocker, didn’t prevent the early drop in LVEF commonly seen in breast cancer patients treated with anthracyclines and trastuzumab (Herceptin), even though both classes of heart medications are cornerstones of the treatment of ischemic and hypertensive cardiomyopathy, Dr. Geeta Gulati reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Although the cardiotoxicity of certain breast cancer treatments is widely recognized and has spawned the emerging field of cardio-oncology, the literature in this area is weak. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis identified only four published randomized studies evaluating the possible cardioprotective role for beta blockers and angiotensin antagonists in patients undergoing anthracycline-based chemotherapy (Postgrad Med J doi:10.1136/ postgradmedj-2015-133535). None of the studies was double-blind, all relied upon echocardiographic assessment of changes in LVEF rather than gold-standard cardiac MRI, and the study sizes were small -- just 18-45 breast cancer patients.

Most problematic of all, the studies employed a variety of different definitions of cardiotoxicity, noted Dr. Gulati of Akershus University Hospital in Lorenskog, Norway.

In contrast, PRADA was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, 2 by 2 factorial design, single-center trial, which included 120 patients with early breast cancer. Participants were randomized to candesartan at a starting dose of 8 mg and target dose of 32 mg/day, metoprolol starting at 25 mg with a target of 100 mg/day, or placebo after breast cancer surgery but before the start of anthracycline-containing chemotherapy.

The primary endpoint was change in LVEF from baseline to completion of adjuvant therapy, a period as short as 10 weeks and as long as 64 weeks depending upon whether a woman also underwent courses of trastuzumab, taxanes, and/or radiation therapy.

The overall decline in LVEF was 2.6% in the placebo group and 0.6% in the candesartan group, a significant difference. Metoprolol didn’t put a dent in the LVEF decline.

“Observational studies show early reduction in LVEF is associated with increased risk of developing heart failure later. So if a sustained, long-term effect of angiotensin inhibition can be confirmed in larger multicenter trials, preventive therapy may be indicated as standard care for breast cancer patients,” Dr. Gulati said.

Discussant Dr. Bonnie Ky of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, called PRADA an important study that moves the field of cardio-oncology forward, yet it’s also a trial that raises more questions than it answers.

PRADA certainly addresses a major problem: “The incidence of heart failure and cardiomyopathy increases over time in breast cancer patients exposed to anthracyclines and trastuzumab. Because patients are living longer because of cancer chemotherapy, their risk of dying of cardiovascular disease actually exceeds that of recurrent cancer in the long term,” she observed.

The study has three major limitations that prevent its findings being implemented in routine clinical practice at this time, Dr. Ky said. One is its relatively small size, even though it’s far bigger than any previous study. Another limitation is that this was an extremely low-cardiovascular-risk patient cohort: the baseline prevalence of diabetes was only 1.5%, fewer than 7% of patients had hypertension, and the baseline LVEF was 63%. That may be why no one developed a substantial decrement in LVEF or actual heart failure.

And since the incidence of cardiomyopathy following breast cancer therapy is known to climb over time, reaching a cumulative 12% at 6 years followup in trastuzumab-treated patients and 20% in those who receive both anthracyclines and trastuzumab (J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012 Sep 5;104(17):1293-305), the lack of extended followup time in PRADA is a significant shortcoming, she added.

The important questions raised by PRADA, Dr. Ky continued, include whether carvedilol or another beta blocker would have generated a positive result where metoprolol failed. Also, should the target population for prevention of cardiotoxicity be more narrowly focused on those at higher baseline cardiovascular risk? And bearing in mind that change in LVEF is a surrogate endpoint, what might be a more clinically meaningful and valid outcome measure? What’s the effect of carvedilol and other cardioprotective medications on cardiac biomarkers in breast cancer patients? And the most important questions of all, she said: What would be the effects of longer followup time and extended therapy?

“This study highlights for us in the field of cardio-oncology the critical need to develop a robust consensus definition of cardiotoxicity and a methodology to identify high cardiovascular risk patients,” she concluded.

PRADA was funded primarily by the University of Oslo and the Norwegian Cancer Society. Dr. Gulati reported having no financial conflicts of interest. Dr. Ky reported receiving a research grant from Pfizer and serving as a consultant to Bristol Myers Squibb.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Inroads are being made in the growing problem of breast cancer treatment-associated cardiomyopathy.

Major finding: The average 2.6% decline from baseline in breast cancer patients during adjuvant therapy with anthracyclines with or without trastuzumab was negated by concomitant candesartan but not by metoprolol.

Data source: The PRADA trial was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 2 by 2 factorial design study involving 120 patients undergoing adjuvant therapy for early breast cancer.

Disclosures: The primary sponsors of the study were the University of Oslo and the Norwegian Cancer Society. Additional support was provided by Abbott Diagnostic and AstraZeneca. The presenter reported no financial conflicts of interest.

Decision model shows prophylactic double mastectomy more costly to patients

CHICAGO – Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy is more expensive and provides a lower quality of life than unilateral mastectomy in younger women with sporadic breast cancer, a cost-effectiveness analysis shows.

“Unilateral mastectomy dominated contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in the treatment of unilateral, sporadic breast cancer,” Robert C. Keskey said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

Among these women without a family history of breast cancer, unilateral mastectomy (UM) with 20 years of routine surveillance cost an average of $5,583 less than contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM) ($13,703 vs. $19,286).

Women who chose UM also gained 0.21 quality adjusted life-years (QALYs), or about 2-3 months in perfect health (21.75 vs. 21.54).

Despite a decline in contralateral breast cancers, the national rate of CPM has risen from 9.7% to 24% in women 45 years of age or younger, due in part to the Angelina Jolie effect.

CPM reduces the risk of contralateral breast cancer by up to 95%, but has not been proven to provide a survival advantage and increases complications, Mr. Keskey of the University of Louisville (Ky.) said.

Discussant Dr. Judy Boughey of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., observed that this is the third model to tackle this important issue and that all three came up with different results and conclusions.

“This probably highlights that our models are highly dependent on the assumptions made and the costs that are involved in building the model,” she said.

The first model developed at the Mayo Clinic by Dr. Boughey and others, reported that CPM is cost effective for women younger than 70 years. However, it did not take into account reconstruction and complications (J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2993-3000), Mr. Keskey said during his talk.

The second model showed that CPM is cost saving, but provides a lower quality of life than UM in women younger than 50 years (Ann Surg Oncol. 2014 Jul;21:2209-17). This study only provided 10-year follow-up and overestimated reconstruction and complication rates, he said.

Dr. Boughey observed that the new model did not include symmetry, which was shown to be a big driver of CPM in a separate University of Michigan survey presented during the same session.

In addition, the quality-of-life assumptions used are the same as those in the second model, but significantly different from those in the Mayo model. In that analysis, if a patient felt that their quality of life was improved by a CPM, then the CPM was clearly cost effective, Dr. Boughey noted.

“So for a patient you see in the clinic who feels their quality of life is better with a CPM than without a CPM, does this model really apply?” she asked.

Mr. Keskey replied, “I think it still does in terms of the patient understanding what they’re going to face financially. It’s an important component of the puzzle. If they’re okay spending that money because they feel that either psychologically they are going to have a better quality of life or they feel their outcomes will be positive no matter what, then I think it’s important to understand this difference in cost and use that to make their decision.”

Study details

The investigators, led by Dr. Nicolas Ajkay, also of Louisville, created a decision tree using TreeAge Pro 2015 software to analyze the long-term costs of CPM vs. UM with routine surveillance in women aged 45 years and younger with sporadic breast cancer. The model included 16 event probabilities taken from the recent literature including complications with and without reconstruction, 5- and 10-year contralateral breast cancer risk, cancer stage, and hormone-receptor status.

Effectiveness was measured by QALYs taken from surveyed breast cancer patients. Medical costs were obtained from the 2014 Medicare physician fee schedule.

Because the physician fee schedule is not all inclusive, the investigators compared CPM and UM using costs from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), which contain total costs on hospital discharge after a procedure. When this was done, CPM cost an average of $15,425 more than UM and provided a lower quality of life, Mr. Keskey said.

The investigators also replaced yearly mammography in the unilateral mastectomy group with more expensive surveillance using breast magnetic resonance imaging. In this model, CPM actually saved about $300 ($19,286 vs. $19,560), but again provided a lower quality of life (21.54 vs. 21.75), he said. It resulted in a savings of $1,300 per QALY lost, which is not enough to be deemed cost effective.

“So even using a more expensive surveillance method, contralateral prophylactic mastectomy was still not cost effective,” Mr. Keskey said.

Finally, reconstruction rates were varied to see whether this would impact outcomes. The national reconstruction rate following unilateral mastectomy is about 28%, which resulted in a lifetime cost in the initial analysis model of about $13,703.

In order to make CPM less expensive than UM, the reconstruction rate following CPM would have to be dropped to 0% ($12,580) from the national rate of 75% ($19,286), he said. Further, even if the UM reconstruction rate was hiked to 100%, the lifetime costs associated with a unilateral mastectomy were cheaper at $19,275.

Limitations of the model include the subjective nature of QALYs, the cost-effectiveness analysis is a theoretical model, and its costs need to be validated against real-world numbers, Mr. Keskey said.

During a discussion of the study, however, an attendee expressed concern that the data will be used to deny insurance coverage for women seeking a prophylactic contralateral mastectomy.

The decision to undergo prophylactic mastectomy is very personal and needs to be individualized, despite the suggestion of increased cost and less quality of life in the study, according to senior author and colleague Dr. Nicolas Ajkay.

“For some patients, the thought of repeating breast cancer treatment, though a low probability, may be unacceptable; for others, imaging surveillance may not be a reasonable option; and a patient with preexisting breast asymmetry may consider bilateral mastectomy as a way to achieve symmetry and better cosmesis,” he said in an interview. “Our objective from the inception of the study, even before analyzing the results, was that this information could be part of a patient-physician discussion, never the main factor in the decision-making process.”

The authors and Dr. Boughey reported no conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy is more expensive and provides a lower quality of life than unilateral mastectomy in younger women with sporadic breast cancer, a cost-effectiveness analysis shows.

“Unilateral mastectomy dominated contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in the treatment of unilateral, sporadic breast cancer,” Robert C. Keskey said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

Among these women without a family history of breast cancer, unilateral mastectomy (UM) with 20 years of routine surveillance cost an average of $5,583 less than contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM) ($13,703 vs. $19,286).

Women who chose UM also gained 0.21 quality adjusted life-years (QALYs), or about 2-3 months in perfect health (21.75 vs. 21.54).

Despite a decline in contralateral breast cancers, the national rate of CPM has risen from 9.7% to 24% in women 45 years of age or younger, due in part to the Angelina Jolie effect.

CPM reduces the risk of contralateral breast cancer by up to 95%, but has not been proven to provide a survival advantage and increases complications, Mr. Keskey of the University of Louisville (Ky.) said.

Discussant Dr. Judy Boughey of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., observed that this is the third model to tackle this important issue and that all three came up with different results and conclusions.

“This probably highlights that our models are highly dependent on the assumptions made and the costs that are involved in building the model,” she said.

The first model developed at the Mayo Clinic by Dr. Boughey and others, reported that CPM is cost effective for women younger than 70 years. However, it did not take into account reconstruction and complications (J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2993-3000), Mr. Keskey said during his talk.

The second model showed that CPM is cost saving, but provides a lower quality of life than UM in women younger than 50 years (Ann Surg Oncol. 2014 Jul;21:2209-17). This study only provided 10-year follow-up and overestimated reconstruction and complication rates, he said.

Dr. Boughey observed that the new model did not include symmetry, which was shown to be a big driver of CPM in a separate University of Michigan survey presented during the same session.

In addition, the quality-of-life assumptions used are the same as those in the second model, but significantly different from those in the Mayo model. In that analysis, if a patient felt that their quality of life was improved by a CPM, then the CPM was clearly cost effective, Dr. Boughey noted.

“So for a patient you see in the clinic who feels their quality of life is better with a CPM than without a CPM, does this model really apply?” she asked.

Mr. Keskey replied, “I think it still does in terms of the patient understanding what they’re going to face financially. It’s an important component of the puzzle. If they’re okay spending that money because they feel that either psychologically they are going to have a better quality of life or they feel their outcomes will be positive no matter what, then I think it’s important to understand this difference in cost and use that to make their decision.”

Study details

The investigators, led by Dr. Nicolas Ajkay, also of Louisville, created a decision tree using TreeAge Pro 2015 software to analyze the long-term costs of CPM vs. UM with routine surveillance in women aged 45 years and younger with sporadic breast cancer. The model included 16 event probabilities taken from the recent literature including complications with and without reconstruction, 5- and 10-year contralateral breast cancer risk, cancer stage, and hormone-receptor status.

Effectiveness was measured by QALYs taken from surveyed breast cancer patients. Medical costs were obtained from the 2014 Medicare physician fee schedule.

Because the physician fee schedule is not all inclusive, the investigators compared CPM and UM using costs from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), which contain total costs on hospital discharge after a procedure. When this was done, CPM cost an average of $15,425 more than UM and provided a lower quality of life, Mr. Keskey said.

The investigators also replaced yearly mammography in the unilateral mastectomy group with more expensive surveillance using breast magnetic resonance imaging. In this model, CPM actually saved about $300 ($19,286 vs. $19,560), but again provided a lower quality of life (21.54 vs. 21.75), he said. It resulted in a savings of $1,300 per QALY lost, which is not enough to be deemed cost effective.

“So even using a more expensive surveillance method, contralateral prophylactic mastectomy was still not cost effective,” Mr. Keskey said.

Finally, reconstruction rates were varied to see whether this would impact outcomes. The national reconstruction rate following unilateral mastectomy is about 28%, which resulted in a lifetime cost in the initial analysis model of about $13,703.

In order to make CPM less expensive than UM, the reconstruction rate following CPM would have to be dropped to 0% ($12,580) from the national rate of 75% ($19,286), he said. Further, even if the UM reconstruction rate was hiked to 100%, the lifetime costs associated with a unilateral mastectomy were cheaper at $19,275.

Limitations of the model include the subjective nature of QALYs, the cost-effectiveness analysis is a theoretical model, and its costs need to be validated against real-world numbers, Mr. Keskey said.

During a discussion of the study, however, an attendee expressed concern that the data will be used to deny insurance coverage for women seeking a prophylactic contralateral mastectomy.

The decision to undergo prophylactic mastectomy is very personal and needs to be individualized, despite the suggestion of increased cost and less quality of life in the study, according to senior author and colleague Dr. Nicolas Ajkay.

“For some patients, the thought of repeating breast cancer treatment, though a low probability, may be unacceptable; for others, imaging surveillance may not be a reasonable option; and a patient with preexisting breast asymmetry may consider bilateral mastectomy as a way to achieve symmetry and better cosmesis,” he said in an interview. “Our objective from the inception of the study, even before analyzing the results, was that this information could be part of a patient-physician discussion, never the main factor in the decision-making process.”

The authors and Dr. Boughey reported no conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy is more expensive and provides a lower quality of life than unilateral mastectomy in younger women with sporadic breast cancer, a cost-effectiveness analysis shows.

“Unilateral mastectomy dominated contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in the treatment of unilateral, sporadic breast cancer,” Robert C. Keskey said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

Among these women without a family history of breast cancer, unilateral mastectomy (UM) with 20 years of routine surveillance cost an average of $5,583 less than contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM) ($13,703 vs. $19,286).

Women who chose UM also gained 0.21 quality adjusted life-years (QALYs), or about 2-3 months in perfect health (21.75 vs. 21.54).

Despite a decline in contralateral breast cancers, the national rate of CPM has risen from 9.7% to 24% in women 45 years of age or younger, due in part to the Angelina Jolie effect.

CPM reduces the risk of contralateral breast cancer by up to 95%, but has not been proven to provide a survival advantage and increases complications, Mr. Keskey of the University of Louisville (Ky.) said.

Discussant Dr. Judy Boughey of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., observed that this is the third model to tackle this important issue and that all three came up with different results and conclusions.

“This probably highlights that our models are highly dependent on the assumptions made and the costs that are involved in building the model,” she said.

The first model developed at the Mayo Clinic by Dr. Boughey and others, reported that CPM is cost effective for women younger than 70 years. However, it did not take into account reconstruction and complications (J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2993-3000), Mr. Keskey said during his talk.

The second model showed that CPM is cost saving, but provides a lower quality of life than UM in women younger than 50 years (Ann Surg Oncol. 2014 Jul;21:2209-17). This study only provided 10-year follow-up and overestimated reconstruction and complication rates, he said.

Dr. Boughey observed that the new model did not include symmetry, which was shown to be a big driver of CPM in a separate University of Michigan survey presented during the same session.

In addition, the quality-of-life assumptions used are the same as those in the second model, but significantly different from those in the Mayo model. In that analysis, if a patient felt that their quality of life was improved by a CPM, then the CPM was clearly cost effective, Dr. Boughey noted.

“So for a patient you see in the clinic who feels their quality of life is better with a CPM than without a CPM, does this model really apply?” she asked.

Mr. Keskey replied, “I think it still does in terms of the patient understanding what they’re going to face financially. It’s an important component of the puzzle. If they’re okay spending that money because they feel that either psychologically they are going to have a better quality of life or they feel their outcomes will be positive no matter what, then I think it’s important to understand this difference in cost and use that to make their decision.”

Study details

The investigators, led by Dr. Nicolas Ajkay, also of Louisville, created a decision tree using TreeAge Pro 2015 software to analyze the long-term costs of CPM vs. UM with routine surveillance in women aged 45 years and younger with sporadic breast cancer. The model included 16 event probabilities taken from the recent literature including complications with and without reconstruction, 5- and 10-year contralateral breast cancer risk, cancer stage, and hormone-receptor status.

Effectiveness was measured by QALYs taken from surveyed breast cancer patients. Medical costs were obtained from the 2014 Medicare physician fee schedule.

Because the physician fee schedule is not all inclusive, the investigators compared CPM and UM using costs from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), which contain total costs on hospital discharge after a procedure. When this was done, CPM cost an average of $15,425 more than UM and provided a lower quality of life, Mr. Keskey said.

The investigators also replaced yearly mammography in the unilateral mastectomy group with more expensive surveillance using breast magnetic resonance imaging. In this model, CPM actually saved about $300 ($19,286 vs. $19,560), but again provided a lower quality of life (21.54 vs. 21.75), he said. It resulted in a savings of $1,300 per QALY lost, which is not enough to be deemed cost effective.

“So even using a more expensive surveillance method, contralateral prophylactic mastectomy was still not cost effective,” Mr. Keskey said.

Finally, reconstruction rates were varied to see whether this would impact outcomes. The national reconstruction rate following unilateral mastectomy is about 28%, which resulted in a lifetime cost in the initial analysis model of about $13,703.

In order to make CPM less expensive than UM, the reconstruction rate following CPM would have to be dropped to 0% ($12,580) from the national rate of 75% ($19,286), he said. Further, even if the UM reconstruction rate was hiked to 100%, the lifetime costs associated with a unilateral mastectomy were cheaper at $19,275.

Limitations of the model include the subjective nature of QALYs, the cost-effectiveness analysis is a theoretical model, and its costs need to be validated against real-world numbers, Mr. Keskey said.

During a discussion of the study, however, an attendee expressed concern that the data will be used to deny insurance coverage for women seeking a prophylactic contralateral mastectomy.

The decision to undergo prophylactic mastectomy is very personal and needs to be individualized, despite the suggestion of increased cost and less quality of life in the study, according to senior author and colleague Dr. Nicolas Ajkay.

“For some patients, the thought of repeating breast cancer treatment, though a low probability, may be unacceptable; for others, imaging surveillance may not be a reasonable option; and a patient with preexisting breast asymmetry may consider bilateral mastectomy as a way to achieve symmetry and better cosmesis,” he said in an interview. “Our objective from the inception of the study, even before analyzing the results, was that this information could be part of a patient-physician discussion, never the main factor in the decision-making process.”

The authors and Dr. Boughey reported no conflicts of interest.

AT THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Unilateral mastectomy costs less and provides better quality of life than contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in younger women with sporadic breast cancer.

Major finding: Unilateral mastectomy with routine surveillance cost on average $5,583 less than prophylactic contralateral mastectomy.

Data source: Cost-effectiveness analysis of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy.

Disclosures: The authors and Dr. Boughey reported no conflicts of interest.

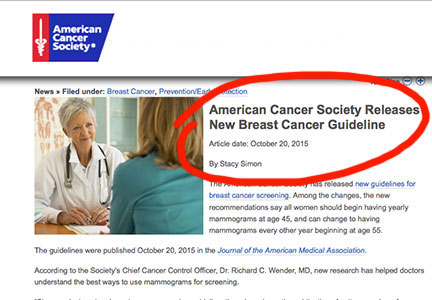

ACOG plans consensus conference on uniform guidelines for breast cancer screening

The Susan G. Komen Foundation estimates that 84% of breast cancers are found through mammography.1 Clearly, the value of mammography is proven. But controversy and confusion abound on how much mammography, and beginning at what age, is best for women.

Currently, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), the American Cancer Society (ACS), and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) all have differing recommendations about mammography and about the importance of clinical breast examinations. These inconsistencies largely are due to different interpretations of the same data, not the data itself, and tend to center on how harm is defined and measured. Importantly, these differences can wreak havoc on our patients’ confidence in our counsel and decision making, and can complicate women’s access to screening. Under the Affordable Care Act, women are guaranteed coverage of annual mammograms, but new USPSTF recommendations, due out soon, may undermine that guarantee.

On October 20, ACOG responded to the ACS’ new recommendations on breast cancer screening by emphasizing our continued advice that women should begin annual mammography screening at age 40, along with a clinical breast exam.2

Consensus conference plansIn an effort to address widespread confusion among patients, health care professionals, and payers, ACOG is convening a consensus conference in January 2016, with the goal of arriving at a consistent set of guidelines that can be agreed to, implemented clinically across the country, and hopefully adopted by insurers, as well. Major organizations and providers of women’s health care, including ACS, will gather to evaluate and interpret the data in greater detail and to consider the available data in the broader context of patient care.

Without doubt, guidelines and recommendations will need to evolve as new evidence emerges, but our hope is that scientific and medical organizations can look at the same evidence and speak with one voice on what is best for women’s health. Our patients would benefit from that alone.

ACOG’s recommendations, summarized

- Clinical breast examination every year for women aged 19 and older.

- Screening mammography every year for women aged 40 and older.

- Breast self-awareness has the potential to detect palpable breast cancer and can be recommended.2

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Susan G. Komen Web site. Accuracy of mammograms. http://ww5.komen.org/BreastCancer/AccuracyofMammograms.html. Updated June 26, 2015. Accessed October 30, 2015.

- ACOG Statement on Revised American Cancer Society Recommendations on Breast Cancer Screening. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Web site. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Statements/2015/ACOG-Statement-on-Recommendations-on-Breast-Cancer-Screening. Published October 20, 2015. Accessed October 30, 2015.

The Susan G. Komen Foundation estimates that 84% of breast cancers are found through mammography.1 Clearly, the value of mammography is proven. But controversy and confusion abound on how much mammography, and beginning at what age, is best for women.

Currently, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), the American Cancer Society (ACS), and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) all have differing recommendations about mammography and about the importance of clinical breast examinations. These inconsistencies largely are due to different interpretations of the same data, not the data itself, and tend to center on how harm is defined and measured. Importantly, these differences can wreak havoc on our patients’ confidence in our counsel and decision making, and can complicate women’s access to screening. Under the Affordable Care Act, women are guaranteed coverage of annual mammograms, but new USPSTF recommendations, due out soon, may undermine that guarantee.

On October 20, ACOG responded to the ACS’ new recommendations on breast cancer screening by emphasizing our continued advice that women should begin annual mammography screening at age 40, along with a clinical breast exam.2

Consensus conference plansIn an effort to address widespread confusion among patients, health care professionals, and payers, ACOG is convening a consensus conference in January 2016, with the goal of arriving at a consistent set of guidelines that can be agreed to, implemented clinically across the country, and hopefully adopted by insurers, as well. Major organizations and providers of women’s health care, including ACS, will gather to evaluate and interpret the data in greater detail and to consider the available data in the broader context of patient care.

Without doubt, guidelines and recommendations will need to evolve as new evidence emerges, but our hope is that scientific and medical organizations can look at the same evidence and speak with one voice on what is best for women’s health. Our patients would benefit from that alone.

ACOG’s recommendations, summarized

- Clinical breast examination every year for women aged 19 and older.

- Screening mammography every year for women aged 40 and older.

- Breast self-awareness has the potential to detect palpable breast cancer and can be recommended.2

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The Susan G. Komen Foundation estimates that 84% of breast cancers are found through mammography.1 Clearly, the value of mammography is proven. But controversy and confusion abound on how much mammography, and beginning at what age, is best for women.

Currently, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), the American Cancer Society (ACS), and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) all have differing recommendations about mammography and about the importance of clinical breast examinations. These inconsistencies largely are due to different interpretations of the same data, not the data itself, and tend to center on how harm is defined and measured. Importantly, these differences can wreak havoc on our patients’ confidence in our counsel and decision making, and can complicate women’s access to screening. Under the Affordable Care Act, women are guaranteed coverage of annual mammograms, but new USPSTF recommendations, due out soon, may undermine that guarantee.

On October 20, ACOG responded to the ACS’ new recommendations on breast cancer screening by emphasizing our continued advice that women should begin annual mammography screening at age 40, along with a clinical breast exam.2

Consensus conference plansIn an effort to address widespread confusion among patients, health care professionals, and payers, ACOG is convening a consensus conference in January 2016, with the goal of arriving at a consistent set of guidelines that can be agreed to, implemented clinically across the country, and hopefully adopted by insurers, as well. Major organizations and providers of women’s health care, including ACS, will gather to evaluate and interpret the data in greater detail and to consider the available data in the broader context of patient care.

Without doubt, guidelines and recommendations will need to evolve as new evidence emerges, but our hope is that scientific and medical organizations can look at the same evidence and speak with one voice on what is best for women’s health. Our patients would benefit from that alone.

ACOG’s recommendations, summarized

- Clinical breast examination every year for women aged 19 and older.

- Screening mammography every year for women aged 40 and older.

- Breast self-awareness has the potential to detect palpable breast cancer and can be recommended.2

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Susan G. Komen Web site. Accuracy of mammograms. http://ww5.komen.org/BreastCancer/AccuracyofMammograms.html. Updated June 26, 2015. Accessed October 30, 2015.

- ACOG Statement on Revised American Cancer Society Recommendations on Breast Cancer Screening. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Web site. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Statements/2015/ACOG-Statement-on-Recommendations-on-Breast-Cancer-Screening. Published October 20, 2015. Accessed October 30, 2015.

- Susan G. Komen Web site. Accuracy of mammograms. http://ww5.komen.org/BreastCancer/AccuracyofMammograms.html. Updated June 26, 2015. Accessed October 30, 2015.

- ACOG Statement on Revised American Cancer Society Recommendations on Breast Cancer Screening. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Web site. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Statements/2015/ACOG-Statement-on-Recommendations-on-Breast-Cancer-Screening. Published October 20, 2015. Accessed October 30, 2015.

Adjuvant Systemic Therapy for Early-Stage Breast Cancer

Over the past 20 years, substantial progress has been achieved in our understanding of breast cancer and in breast cancer treatment, with mortality from breast cancer declining by more than 25% over this time. This progress has been characterized by a greater understanding of the molecular biology of breast cancer, rational drug design, development of agents with specific cellular targets and pathways, development of better prognostic and predictive multigene assays, and marked improvements in supportive care.

To read the full article in PDF:

Over the past 20 years, substantial progress has been achieved in our understanding of breast cancer and in breast cancer treatment, with mortality from breast cancer declining by more than 25% over this time. This progress has been characterized by a greater understanding of the molecular biology of breast cancer, rational drug design, development of agents with specific cellular targets and pathways, development of better prognostic and predictive multigene assays, and marked improvements in supportive care.

To read the full article in PDF:

Over the past 20 years, substantial progress has been achieved in our understanding of breast cancer and in breast cancer treatment, with mortality from breast cancer declining by more than 25% over this time. This progress has been characterized by a greater understanding of the molecular biology of breast cancer, rational drug design, development of agents with specific cellular targets and pathways, development of better prognostic and predictive multigene assays, and marked improvements in supportive care.

To read the full article in PDF:

How to individualize cancer risk reduction after a diagnosis of DCIS

A recent study reported in JAMA Oncology evaluated 10-year and 20-year breast cancer–specific mortality following diagnosis and treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries.1 The study included cases of pure DCIS (without lobular carcinoma in situ or microinvasion) diagnosed from 1988 to 2011 among women younger than age 70. It evaluated variables including age, race, income, type of surgery, radiation, subsequent diagnoses of invasive primary breast cancer, and, when applicable, cause of death.

Overall mortality rate was 3.3%

Mean follow-up was 7.5 years, with a 20-year breast cancer–specific mortality rate of 3.3% overall. Mortality was higher among young women diagnosed before the age of 35 years (7.8% vs 3.2%), and among black women (7.0% vs 3.0% for white women). The risk of dying from breast cancer was 18 times higher for women who developed subsequent ipsilateral invasive breast cancer. Mortality also was related to adverse DCIS characteristics such as grade, size, comedo-necrosis, and lack of an estrogen receptor.

Among patients who underwent lumpectomy, the addition of radiation reduced the risk of subsequent ipsilateral invasive breast cancer at 10 years (2.5% vs 4.9%; P<.001). However, radiation did not improve the 10-year rate of breast cancer mortality (0.8% for women who had lumpectomy with radiation, 0.9% for women who had lumpectomy alone, and 1.3% for women with unilateral mastectomy).

The prevention of ipsilateral invasive recurrence with radiation did not reduce mortality rates, as more than 50% of the women who died of breast cancer did not have an ipsilateral invasive recurrence prior to their death.

How these findings fit

into the larger picture

The findings of this landmark study confirm earlier reports, which showed that radiation after lumpectomy can reduce local recurrence but does not improve survival.2

Likewise, mastectomy, when compared with lumpectomy, offers no survival benefit and does not represent appropriate therapy for most women with small, unifocal DCIS.3

DCIS itself is not a life-threatening condition and has been described as a precursor lesion that, over 10 to 40 years, can lead to the development of invasive disease (FIGURE).4,5 High-grade DCIS tends to lead to high-grade invasive ductal carcinoma, and low-grade DCIS may develop into low-grade invasive disease.6

The increasing prevalence of screening mammography means that more small in situ lesions are being identified in US women. Unlike colonoscopy, which can prevent colon cancer by removing colon polyps, mammography with subsequent surgical treatment of DCIS has not reduced the incidence of invasive breast cancer.7This finding leads us to question whether all DCIS should be considered a precursor lesion. This well publicized study is generating controversy regarding overdiagnosis and overtreatment of DCIS.

Limitations of this study

The majority of patients in the SEER registry underwent surgical treatment of DCIS with or without radiation and had a survival rate of more than 97%. Because there was no untreated control group, this study does not allow us to draw any inferences on the role of expectant management of DCIS.

Although it is often declined by patients, tamoxifen reduces the risk of ipsilateral and contralateral invasive and in situ breast cancer. Regrettably, information on the use of adjuvant hormonal therapy after an initial diagnosis of DCIS was not included in this analysis.

Why did death from invasive

cancer sometimes follow a

diagnosis of DCIS?

Several factors could have contributed to the 3% mortality rate from invasive breast cancer among women in this large study of DCIS. For one, it is challenging for pathologists to perform comprehensive tissue sampling of mastectomy specimens—or even large lumpectomy specimens. Accordingly, occult microinvasive disease could be missed.8,9 As a result, occult invasive disease could go untreated, which could have contributed to the breast cancer mortality observed in this study.

Recommendations for practice

How can we better predict the behavior of DCIS and tailor treatment based on the biological behavior of each patient’s disease?

Individualize therapy. The likelihood of local invasive breast cancer recurrence should be estimated for each patient based on the size and grade of her disease. Furthermore, genetic profiling of DCIS has been developed with the Oncotype DX test (Genomic Health) multigene assay. This test can be performed on pathology specimens and has been shown to estimate the risk of in situ and invasive in-breast recurrence in patients who have undergone margin-negative lumpectomy for DCIS and who prefer to avoid radiation but are willing to take tamoxifen.10

Counsel precisely and accurately. Beyond such testing, we should focus on what is important to our patients in explaining the diagnosis:

- Our patients want to know that they are going to survive. Explain that DCIS is not a life-threatening cancer but a significant risk factor and is fully treatable with a long-term survival rate of 97%.

- Do not omit surgery. Follow-up surgical excision is still recommended after a core needle biopsy diagnosis of DCIS, as there is a 25% risk of finding invasive disease upon surgical excision.11,12 In our opinion, surgical excision represents the standard of care for DCIS, as some lesions may harbor invasive breast cancer.

- Explain the pros and cons of radiation to the patient once surgical excision has confirmed the diagnosis of pure DCIS. If the patient’s goal is to avoid any recurrence, then radiation can be useful and is particularly appropriate for women with high-grade, large, and estrogen-receptor–negative DCIS. However, patients in this setting need to recognize that radiation will not improve their already excellent rate of survival. For many patients, any recurrence, whether it’s DCIS or invasive disease, can be a devastating emotional event. But even in patients who experience a recurrence, early detection and treatment portend a very good outcome.

- Be aware of the fear of chemotherapy. Avoiding chemotherapy is a paramount (and understandable) desire for many women diagnosed with breast cancer. Women who choose radiation reduce their likelihood of invasive recurrence and potentially avoid the need for chemotherapy in the future.

- Know when mastectomy is indicated. Multicentric extensive DCIS is still an indication for mastectomy. The safety of avoiding mastectomy in this setting needs to be assessed by randomized trials. It may be safe for some women with DCIS, such as elderly patients with low-grade lesions, to undergo lumpectomy to rule out underlying invasive disease and be treated with endocrine therapy and observation, with or without radiation therapy. The issue of multiple re-excisions for close margins is also being re-evaluated.

Informed and shared

decision making is key

DCIS is an increasingly common and usually non–life-threatening condition. Radical surgery such as bilateral mastectomy for small unifocal DCIS is excessive and will not improve a patient’s outcome. As a prominent breast surgeon has written:

We must balance the small risk of breast cancer recurrence after lumpectomy for DCIS with patients’ quality of life concerns. This goal is best accomplished by using an informed and shared decision-making strategy to help our patients make sound decisions regarding DCIS.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Narod SA, Iqbal J, Giannakeas V, et al. Breast cancer mortality after a diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(7):888–896.

- Wapnir IL, Dignam JJ, Fisher B, et al. Long-term outcomes of invasive ipsilateral breast tumor recurrences after lumpectomy in NSABP B-17 and B-24 randomized clinical trials for DCIS. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(6):478–488.

- Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1233–1241.

- Page D, Rogers L, Schuyler P, et al. The natural history of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. In: Silverstein MJ, Recht A, Lagios M, eds. Ductal Carcinoma in Situ of the Breast. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002:17–21.

- Sanders M, Schuyler P, Dupont W, Page D. The natural history of low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast in women treated by biopsy only revealed over 30 years of long-term follow-up. Cancer. 2005;103(12):2481–2484.

- Burstein HJ, Plyak K, Wong JS, et al. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(14):1430–1441.

- Lin C, Moore D, DeMichelle A, et al. The majority of locally advanced breast cancers are interval cancer [Abstract 1503]. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27.

- Lagios M, Westdahl P, Margolin F, Rose M. Duct carcinoma in situ: relationship of extend of noninvasive disease to the frequency of occult invasion, multicentricity, lymph node metastases, and short-term treatment failures. Cancer. 1982;50(7):1309–1314.

- Schuh M, Nemoto T, Penetrante R, et al. Intraductal carcinoma: analysis of presentation, pathologic findings, and outcome of disease. Arch Surg. 1986;121(11):1303–1307.

- Solin LJ, Gray R, Baehner FL, et al. A multigene expression assay to predict local recurrence risk for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(10):701–710.

- Bruening W, Schoelles K, Treadwell J, et al. Comparative effectiveness of core needle and open surgical biopsy for the diagnosis of breast lesions. Rockville, MD: Prepared by ECRI Institute for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality under contract No. 290-02-0019; Comparative Effectiveness Review; September 2008.

- Brennan ME, Turner RM, Ciatto S, et al. Ductal carcinoma in situ at core-needle biopsy: meta-analysis of underestimation and predictors of invasive breast cancer. Radiology. 2011;260(1):119–128.

- Morrow M, Winograd JM, Freer PE, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 8-2013: a 48-year-old woman with carcinoma in situ of the breast. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(11):1046–1053.