User login

Hard habit to break

“I love practicing medicine.”

The speaker was one of my patients. A distinguished, friendly, gentleman in his mid-to-late 70s, here to see me for a minor problem. He still practices medicine part time.

Since his neurologic issue was simple, we spent a fair amount of the time chatting. We’d both seen changes in medicine over time, he more than I, obviously.

Some good, some bad. Fancier toys, better drugs, more paperwork (even if it’s not all on paper anymore).

But we both still like what we do, and have no plans to give it up anytime soon.

Some doctors end up hating their jobs and leave the field. I understand that, and I don’t blame them. It’s not an easy one.

But I still enjoy the job. I look forward to seeing patients each day, turning over their cases, trying to figure them out, and doing what I can to help people.

I see that it is similar with attorneys. Maybe it’s part of the time and commitment you put into getting to a job that makes it hard to walk away as you get older. Or maybe (probably more likely) it’s some intrinsic part of the personality that drove you to get there.

I’m roughly two-thirds of the way through my career, but still don’t have any plans to close down. Granted, that’s practical – I have kids in college, a mortgage, and office overhead. My colleague across the desk can stop practicing whenever he wants, but gets satisfaction, validation, and enjoyment from doing the same job. At this point in his life that’s more important than the money.

I hope to someday feel that same way. I don’t want to always work the 80-90 hours a week I do now, but I can’t imagine not doing this, either.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

“I love practicing medicine.”

The speaker was one of my patients. A distinguished, friendly, gentleman in his mid-to-late 70s, here to see me for a minor problem. He still practices medicine part time.

Since his neurologic issue was simple, we spent a fair amount of the time chatting. We’d both seen changes in medicine over time, he more than I, obviously.

Some good, some bad. Fancier toys, better drugs, more paperwork (even if it’s not all on paper anymore).

But we both still like what we do, and have no plans to give it up anytime soon.

Some doctors end up hating their jobs and leave the field. I understand that, and I don’t blame them. It’s not an easy one.

But I still enjoy the job. I look forward to seeing patients each day, turning over their cases, trying to figure them out, and doing what I can to help people.

I see that it is similar with attorneys. Maybe it’s part of the time and commitment you put into getting to a job that makes it hard to walk away as you get older. Or maybe (probably more likely) it’s some intrinsic part of the personality that drove you to get there.

I’m roughly two-thirds of the way through my career, but still don’t have any plans to close down. Granted, that’s practical – I have kids in college, a mortgage, and office overhead. My colleague across the desk can stop practicing whenever he wants, but gets satisfaction, validation, and enjoyment from doing the same job. At this point in his life that’s more important than the money.

I hope to someday feel that same way. I don’t want to always work the 80-90 hours a week I do now, but I can’t imagine not doing this, either.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

“I love practicing medicine.”

The speaker was one of my patients. A distinguished, friendly, gentleman in his mid-to-late 70s, here to see me for a minor problem. He still practices medicine part time.

Since his neurologic issue was simple, we spent a fair amount of the time chatting. We’d both seen changes in medicine over time, he more than I, obviously.

Some good, some bad. Fancier toys, better drugs, more paperwork (even if it’s not all on paper anymore).

But we both still like what we do, and have no plans to give it up anytime soon.

Some doctors end up hating their jobs and leave the field. I understand that, and I don’t blame them. It’s not an easy one.

But I still enjoy the job. I look forward to seeing patients each day, turning over their cases, trying to figure them out, and doing what I can to help people.

I see that it is similar with attorneys. Maybe it’s part of the time and commitment you put into getting to a job that makes it hard to walk away as you get older. Or maybe (probably more likely) it’s some intrinsic part of the personality that drove you to get there.

I’m roughly two-thirds of the way through my career, but still don’t have any plans to close down. Granted, that’s practical – I have kids in college, a mortgage, and office overhead. My colleague across the desk can stop practicing whenever he wants, but gets satisfaction, validation, and enjoyment from doing the same job. At this point in his life that’s more important than the money.

I hope to someday feel that same way. I don’t want to always work the 80-90 hours a week I do now, but I can’t imagine not doing this, either.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Bored? Change the world or read a book

A weekend, for most of us in solo practice, doesn’t really signify time off from work. It just means we’re not seeing patients at the office.

There’s always business stuff to do (like payroll and paying bills), legal cases to review, the never-ending forms for a million things, and all the other stuff there never seems to be enough time to do on weekdays.

So this weekend I started attacking the pile after dinner on Friday and found myself done by Saturday afternoon. Which is rare, usually I spend the better part of a weekend at my desk.

And then, unexpectedly faced with an empty desk, I found myself wondering what to do.

Boredom is one of the odder human conditions. Certainly, there are more ways to waste time now than there ever have been. TV, Netflix, phone games, TikTok, books, just to name a few.

But do we always have to be entertained? Many great scientists have said that world-changing ideas have come to them when they weren’t working, such as while showering or riding to work. Leo Szilard was crossing a London street in 1933 when he suddenly saw how a nuclear chain reaction would be self-sustaining once initiated. (Fortunately, he wasn’t hit by a car in the process.)

But I’m not Szilard. So I rationalized a reason not to exercise and sat on the couch with a book.

The remarkable human brain doesn’t shut down easily. With nothing else to do, most other mammals tend to doze off. But not us. It’s always on, trying to think of the next goal, the next move, the next whatever.

Having nothing to do sounds like a great idea, until you have nothing to do. It may be fine for a few days, but after a while you realize there’s only so long you can stare at the waves or mountains before your mind turns back to “what’s next.”

This isn’t a bad thing. Being bored is probably constructive. Without realizing it we use it to form new ideas and start new plans.

Maybe this is why we’re here. The mind that keeps working is a powerful tool, driving us forward in all walks of life. Perhaps it’s this feature that pushed the development of intelligence further and led us to form civilizations.

Perhaps it’s the real reason we keep moving forward.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

A weekend, for most of us in solo practice, doesn’t really signify time off from work. It just means we’re not seeing patients at the office.

There’s always business stuff to do (like payroll and paying bills), legal cases to review, the never-ending forms for a million things, and all the other stuff there never seems to be enough time to do on weekdays.

So this weekend I started attacking the pile after dinner on Friday and found myself done by Saturday afternoon. Which is rare, usually I spend the better part of a weekend at my desk.

And then, unexpectedly faced with an empty desk, I found myself wondering what to do.

Boredom is one of the odder human conditions. Certainly, there are more ways to waste time now than there ever have been. TV, Netflix, phone games, TikTok, books, just to name a few.

But do we always have to be entertained? Many great scientists have said that world-changing ideas have come to them when they weren’t working, such as while showering or riding to work. Leo Szilard was crossing a London street in 1933 when he suddenly saw how a nuclear chain reaction would be self-sustaining once initiated. (Fortunately, he wasn’t hit by a car in the process.)

But I’m not Szilard. So I rationalized a reason not to exercise and sat on the couch with a book.

The remarkable human brain doesn’t shut down easily. With nothing else to do, most other mammals tend to doze off. But not us. It’s always on, trying to think of the next goal, the next move, the next whatever.

Having nothing to do sounds like a great idea, until you have nothing to do. It may be fine for a few days, but after a while you realize there’s only so long you can stare at the waves or mountains before your mind turns back to “what’s next.”

This isn’t a bad thing. Being bored is probably constructive. Without realizing it we use it to form new ideas and start new plans.

Maybe this is why we’re here. The mind that keeps working is a powerful tool, driving us forward in all walks of life. Perhaps it’s this feature that pushed the development of intelligence further and led us to form civilizations.

Perhaps it’s the real reason we keep moving forward.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

A weekend, for most of us in solo practice, doesn’t really signify time off from work. It just means we’re not seeing patients at the office.

There’s always business stuff to do (like payroll and paying bills), legal cases to review, the never-ending forms for a million things, and all the other stuff there never seems to be enough time to do on weekdays.

So this weekend I started attacking the pile after dinner on Friday and found myself done by Saturday afternoon. Which is rare, usually I spend the better part of a weekend at my desk.

And then, unexpectedly faced with an empty desk, I found myself wondering what to do.

Boredom is one of the odder human conditions. Certainly, there are more ways to waste time now than there ever have been. TV, Netflix, phone games, TikTok, books, just to name a few.

But do we always have to be entertained? Many great scientists have said that world-changing ideas have come to them when they weren’t working, such as while showering or riding to work. Leo Szilard was crossing a London street in 1933 when he suddenly saw how a nuclear chain reaction would be self-sustaining once initiated. (Fortunately, he wasn’t hit by a car in the process.)

But I’m not Szilard. So I rationalized a reason not to exercise and sat on the couch with a book.

The remarkable human brain doesn’t shut down easily. With nothing else to do, most other mammals tend to doze off. But not us. It’s always on, trying to think of the next goal, the next move, the next whatever.

Having nothing to do sounds like a great idea, until you have nothing to do. It may be fine for a few days, but after a while you realize there’s only so long you can stare at the waves or mountains before your mind turns back to “what’s next.”

This isn’t a bad thing. Being bored is probably constructive. Without realizing it we use it to form new ideas and start new plans.

Maybe this is why we’re here. The mind that keeps working is a powerful tool, driving us forward in all walks of life. Perhaps it’s this feature that pushed the development of intelligence further and led us to form civilizations.

Perhaps it’s the real reason we keep moving forward.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Book Review: Quality improvement in mental health care

Sunil Khushalani and Antonio DePaolo,

“Transforming Mental Healthcare: Applying Performance Improvement Methods to Mental Healthcare”

(London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis, 2022)

Since the publication of our book, “Lean Behavioral Health: The Kings County Hospital Story” (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2014) almost a decade ago, “Transforming Mental Healthcare” is the first major book published about the use of a system for quality improvement across the health care continuum. That it has taken this long is probably surprising to those of us who have spent careers on trying to improve what is universally described as a system that is “broken” and in need of a major overhaul.

Every news cycle that reports mass violence typically spends a good bit of time talking about the failures of the mental health care system. One important lesson I learned when taking over the beleaguered Kings County (N.Y.) psychiatry service in 2009 (a department that has made extraordinary improvements over the years and is now exclaimed by the U.S. Department of Justice as “a model program”), is that the employees on the front line are often erroneously blamed for such failures.

The failure is systemic and usually starts at the top of the table of organization, not at the bottom. Dr. Khushalani and Dr. DePaolo have produced an excellent volume that should be purchased by every mental health care CEO and given “with thanks” to the local leaders overseeing the direct care of some of our nation’s most vulnerable patient populations.

The first part of “Transforming Mental Healthcare” provides an excellent overview of the current state of our mental health care system and its too numerous to name problems. This section could be a primer for all our legislators so their eyes can be opened to the failures on the ground that require their help in correcting. Many of the “failures” of our mental health care are societal failures – lack of affordable housing, access to care, reimbursement for care, gun access, etc. – and cannot be “fixed” by providers of care. Such problems are societal problems that call for societal and governmental solutions, and not only at the local level but from coast to coast.

The remainder of this easy to read and follow text provides many rich resources for the deliverers of mental health care. (e.g., plan-do-act, standard work, and A3 thinking).

The closing section focuses on leadership and culture – often overlooked to the detriment of any organization that doesn’t pay close attention to supporting both. Culture is cultivated and nourished by the organization’s leaders. Culture empowers staff to become problem solvers and agents of improvement. Empowered staff support and enrich their culture. Together a workplace that brings out the best of all its people is created, and burnout is held at bay.

“Transforming Mental Healthcare: Applying Performance Improvement Methods to Mental Healthcare” is a welcome and essential addition to the current morass, which is our mental health care delivery system, an oasis in the desert from which perhaps the lotus flower can emerge.

Dr. Merlino is emeritus professor of psychiatry, SUNY Downstate College of Medicine, Rhinebeck, N.Y., and formerly director of psychiatry at Kings County Hospital Center, Brooklyn, NY. He is the coauthor of “Lean Behavioral Health: The Kings County Hospital Story.” .

Sunil Khushalani and Antonio DePaolo,

“Transforming Mental Healthcare: Applying Performance Improvement Methods to Mental Healthcare”

(London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis, 2022)

Since the publication of our book, “Lean Behavioral Health: The Kings County Hospital Story” (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2014) almost a decade ago, “Transforming Mental Healthcare” is the first major book published about the use of a system for quality improvement across the health care continuum. That it has taken this long is probably surprising to those of us who have spent careers on trying to improve what is universally described as a system that is “broken” and in need of a major overhaul.

Every news cycle that reports mass violence typically spends a good bit of time talking about the failures of the mental health care system. One important lesson I learned when taking over the beleaguered Kings County (N.Y.) psychiatry service in 2009 (a department that has made extraordinary improvements over the years and is now exclaimed by the U.S. Department of Justice as “a model program”), is that the employees on the front line are often erroneously blamed for such failures.

The failure is systemic and usually starts at the top of the table of organization, not at the bottom. Dr. Khushalani and Dr. DePaolo have produced an excellent volume that should be purchased by every mental health care CEO and given “with thanks” to the local leaders overseeing the direct care of some of our nation’s most vulnerable patient populations.

The first part of “Transforming Mental Healthcare” provides an excellent overview of the current state of our mental health care system and its too numerous to name problems. This section could be a primer for all our legislators so their eyes can be opened to the failures on the ground that require their help in correcting. Many of the “failures” of our mental health care are societal failures – lack of affordable housing, access to care, reimbursement for care, gun access, etc. – and cannot be “fixed” by providers of care. Such problems are societal problems that call for societal and governmental solutions, and not only at the local level but from coast to coast.

The remainder of this easy to read and follow text provides many rich resources for the deliverers of mental health care. (e.g., plan-do-act, standard work, and A3 thinking).

The closing section focuses on leadership and culture – often overlooked to the detriment of any organization that doesn’t pay close attention to supporting both. Culture is cultivated and nourished by the organization’s leaders. Culture empowers staff to become problem solvers and agents of improvement. Empowered staff support and enrich their culture. Together a workplace that brings out the best of all its people is created, and burnout is held at bay.

“Transforming Mental Healthcare: Applying Performance Improvement Methods to Mental Healthcare” is a welcome and essential addition to the current morass, which is our mental health care delivery system, an oasis in the desert from which perhaps the lotus flower can emerge.

Dr. Merlino is emeritus professor of psychiatry, SUNY Downstate College of Medicine, Rhinebeck, N.Y., and formerly director of psychiatry at Kings County Hospital Center, Brooklyn, NY. He is the coauthor of “Lean Behavioral Health: The Kings County Hospital Story.” .

Sunil Khushalani and Antonio DePaolo,

“Transforming Mental Healthcare: Applying Performance Improvement Methods to Mental Healthcare”

(London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis, 2022)

Since the publication of our book, “Lean Behavioral Health: The Kings County Hospital Story” (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2014) almost a decade ago, “Transforming Mental Healthcare” is the first major book published about the use of a system for quality improvement across the health care continuum. That it has taken this long is probably surprising to those of us who have spent careers on trying to improve what is universally described as a system that is “broken” and in need of a major overhaul.

Every news cycle that reports mass violence typically spends a good bit of time talking about the failures of the mental health care system. One important lesson I learned when taking over the beleaguered Kings County (N.Y.) psychiatry service in 2009 (a department that has made extraordinary improvements over the years and is now exclaimed by the U.S. Department of Justice as “a model program”), is that the employees on the front line are often erroneously blamed for such failures.

The failure is systemic and usually starts at the top of the table of organization, not at the bottom. Dr. Khushalani and Dr. DePaolo have produced an excellent volume that should be purchased by every mental health care CEO and given “with thanks” to the local leaders overseeing the direct care of some of our nation’s most vulnerable patient populations.

The first part of “Transforming Mental Healthcare” provides an excellent overview of the current state of our mental health care system and its too numerous to name problems. This section could be a primer for all our legislators so their eyes can be opened to the failures on the ground that require their help in correcting. Many of the “failures” of our mental health care are societal failures – lack of affordable housing, access to care, reimbursement for care, gun access, etc. – and cannot be “fixed” by providers of care. Such problems are societal problems that call for societal and governmental solutions, and not only at the local level but from coast to coast.

The remainder of this easy to read and follow text provides many rich resources for the deliverers of mental health care. (e.g., plan-do-act, standard work, and A3 thinking).

The closing section focuses on leadership and culture – often overlooked to the detriment of any organization that doesn’t pay close attention to supporting both. Culture is cultivated and nourished by the organization’s leaders. Culture empowers staff to become problem solvers and agents of improvement. Empowered staff support and enrich their culture. Together a workplace that brings out the best of all its people is created, and burnout is held at bay.

“Transforming Mental Healthcare: Applying Performance Improvement Methods to Mental Healthcare” is a welcome and essential addition to the current morass, which is our mental health care delivery system, an oasis in the desert from which perhaps the lotus flower can emerge.

Dr. Merlino is emeritus professor of psychiatry, SUNY Downstate College of Medicine, Rhinebeck, N.Y., and formerly director of psychiatry at Kings County Hospital Center, Brooklyn, NY. He is the coauthor of “Lean Behavioral Health: The Kings County Hospital Story.” .

The toll of the unwanted pregnancy

In the wake of the Supreme Court’s June decision to repeal a federal right to abortion, many women will now be faced with the prospect of carrying an unwanted pregnancy to term.

One group of researchers has studied the fate of these women and their families for the last decade. Their findings show that women who were denied an abortion are worse off physically, mentally, and economically than those who underwent the procedure.

“There has been much hypothesizing about harms from abortion without considering what the consequences are when someone wants an abortion and can’t get one,” said Diana Greene Foster, PhD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at University of California, San Francisco.

Dr. Foster leads the Turnaway Study, one of the first efforts to examine the physical and mental health effects of receiving or being denied abortions. The ongoing research also charts the economic and social outcomes of women and their families in either circumstance.

Dr. Foster and her colleagues have followed women through childbirth, examining their well-being through phone interviews months to years after the initial interviews.

The economic consequences of carrying an unwanted pregnancy are clear. Women who did not receive a wanted abortion were more likely to live under the poverty line and struggle to cover basic living expenses like food, housing, and transportation.

The physical toll is also significant.

A 2019 analysis from the Turnaway Study found that eight out of 1,132 participants died, two after delivery, during the five-year follow up period – a far greater proportion than what would be expected among women of reproductive age. The researchers also found that women who carry unwanted pregnancies have more comorbid conditions before and after delivery than other women.

Lauren J. Ralph, PhD, MPH, an epidemiologist and member of the Turnaway Study team, examined the physical well-being of women after delivering their unwanted pregnancies.

“They reported more chronic pain, more gestational hypertension, and were more likely to rate their health as fair or poor,” Dr. Ralph said. “Somewhat to our surprise, we also found that two women denied abortions died due to pregnancy-related causes. This is my biggest concern with the loss of abortion access, as all scientific evidence indicates we will see a rise in maternal deaths as a result.”

At least one preliminary study, released as a preprint and not yet peer reviewed, estimates that the number of women who will die each year from pregnancy complications will rise by 24%. For Black women, mortality could jump from 18% to 39% in every state, according to the researchers from the University of Colorado, Boulder.

State of denial

Regulations set in place at abortion clinics in each state individually determine who is able to obtain an abortion, dictated by a “gestational age limit” – how far along a woman is in her pregnancy from the end of her menstrual cycle. Some of the women from the Turnaway Study were unable to receive an abortion because of how far along they were. Others were granted the abortion because they were just under their state’s limit.

Before the latest Supreme Court ruling, this limit was 20 weeks in most states. Now, the cutoff can be as little as 6 weeks – before many women know they are pregnant – or zero weeks, under the most restrictive laws.

Over 70% of women who are denied an abortion carry the pregnancy to term, according to Dr. Foster’s analysis.

Interviews with nearly 1,000 women – in both the first and second trimester of pregnancy – in the Turnaway Study who sought abortions at 30 abortion clinics around the country revealed the main reasons for seeking the procedure were (a) not being able to afford a child; (b) the pregnancy coming at the wrong time in life; or (c) the partner involved not being suitable.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 59.7% of women seeking an abortion in the United States are already mothers. Having an unplanned child results in dramatically worse economic circumstances for their other children, who become nearly four times more likely to live below the poverty line than their peers. They also experience slower physical and mental development as a result of the arrival of the new sibling.

The latest efforts by states to ban abortion could make the situation much worse, said Liza Fuentes, DrPh, senior research scientist at the Guttmacher Institute. “We will need further research on what it means for women to be denied care in the context of the new restrictions,” Dr. Fuentes told this news organization.

Researchers cannot yet predict how many women will be unable to obtain an abortion in the coming months. But John Donahue, PhD, JD, an economist and professor of law at Stanford (Calif.) University, estimated that state laws would prevent roughly one-third of the 1 million abortions per year based on 2021 figures.

Dr. Ralph and her colleagues with the Turnaway Study know that restricting access to abortions will not make the need for abortions disappear. Rather, women will be forced to travel, potentially long distances at significant cost, for the procedure or will seek medication abortion by mail through virtual clinics.

But Dr. Ralph said she’s concerned about women who live in areas where telehealth abortions are banned, or who discover their pregnancies late, as medical abortions are only recommended for women who are 10 weeks pregnant or less.

“They may look to self-source the medications online or elsewhere, potentially putting themself at legal risk,” she said. “And, as my research has shown, others may turn to self-managing an abortion with herbs, other drugs or medications, or physical methods like hitting themselves in the abdomen; with this they put themselves at both legal and potentially medical risk.”

Constance Bohon, MD, an ob.gyn. in Washington, D.C., said further research should track what happens to women if they’re forced to leave a job to care for another child.

“Many of these women live paycheck to paycheck and cannot afford the cost of an additional child,” Dr. Bohon said. “They may also need to rely on social service agencies to help them find food and housing.”

Dr. Fuentes said she hopes the Turnaway Study will inspire other researchers to examine laws that outlaw abortion and the corresponding long-term effects on women.

“From a medical and a public health standpoint, these laws are unjust,” Dr. Fuentes said in an interview. “They’re not grounded in evidence, and they incur great costs not just to pregnant people but their families and their communities as well.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the wake of the Supreme Court’s June decision to repeal a federal right to abortion, many women will now be faced with the prospect of carrying an unwanted pregnancy to term.

One group of researchers has studied the fate of these women and their families for the last decade. Their findings show that women who were denied an abortion are worse off physically, mentally, and economically than those who underwent the procedure.

“There has been much hypothesizing about harms from abortion without considering what the consequences are when someone wants an abortion and can’t get one,” said Diana Greene Foster, PhD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at University of California, San Francisco.

Dr. Foster leads the Turnaway Study, one of the first efforts to examine the physical and mental health effects of receiving or being denied abortions. The ongoing research also charts the economic and social outcomes of women and their families in either circumstance.

Dr. Foster and her colleagues have followed women through childbirth, examining their well-being through phone interviews months to years after the initial interviews.

The economic consequences of carrying an unwanted pregnancy are clear. Women who did not receive a wanted abortion were more likely to live under the poverty line and struggle to cover basic living expenses like food, housing, and transportation.

The physical toll is also significant.

A 2019 analysis from the Turnaway Study found that eight out of 1,132 participants died, two after delivery, during the five-year follow up period – a far greater proportion than what would be expected among women of reproductive age. The researchers also found that women who carry unwanted pregnancies have more comorbid conditions before and after delivery than other women.

Lauren J. Ralph, PhD, MPH, an epidemiologist and member of the Turnaway Study team, examined the physical well-being of women after delivering their unwanted pregnancies.

“They reported more chronic pain, more gestational hypertension, and were more likely to rate their health as fair or poor,” Dr. Ralph said. “Somewhat to our surprise, we also found that two women denied abortions died due to pregnancy-related causes. This is my biggest concern with the loss of abortion access, as all scientific evidence indicates we will see a rise in maternal deaths as a result.”

At least one preliminary study, released as a preprint and not yet peer reviewed, estimates that the number of women who will die each year from pregnancy complications will rise by 24%. For Black women, mortality could jump from 18% to 39% in every state, according to the researchers from the University of Colorado, Boulder.

State of denial

Regulations set in place at abortion clinics in each state individually determine who is able to obtain an abortion, dictated by a “gestational age limit” – how far along a woman is in her pregnancy from the end of her menstrual cycle. Some of the women from the Turnaway Study were unable to receive an abortion because of how far along they were. Others were granted the abortion because they were just under their state’s limit.

Before the latest Supreme Court ruling, this limit was 20 weeks in most states. Now, the cutoff can be as little as 6 weeks – before many women know they are pregnant – or zero weeks, under the most restrictive laws.

Over 70% of women who are denied an abortion carry the pregnancy to term, according to Dr. Foster’s analysis.

Interviews with nearly 1,000 women – in both the first and second trimester of pregnancy – in the Turnaway Study who sought abortions at 30 abortion clinics around the country revealed the main reasons for seeking the procedure were (a) not being able to afford a child; (b) the pregnancy coming at the wrong time in life; or (c) the partner involved not being suitable.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 59.7% of women seeking an abortion in the United States are already mothers. Having an unplanned child results in dramatically worse economic circumstances for their other children, who become nearly four times more likely to live below the poverty line than their peers. They also experience slower physical and mental development as a result of the arrival of the new sibling.

The latest efforts by states to ban abortion could make the situation much worse, said Liza Fuentes, DrPh, senior research scientist at the Guttmacher Institute. “We will need further research on what it means for women to be denied care in the context of the new restrictions,” Dr. Fuentes told this news organization.

Researchers cannot yet predict how many women will be unable to obtain an abortion in the coming months. But John Donahue, PhD, JD, an economist and professor of law at Stanford (Calif.) University, estimated that state laws would prevent roughly one-third of the 1 million abortions per year based on 2021 figures.

Dr. Ralph and her colleagues with the Turnaway Study know that restricting access to abortions will not make the need for abortions disappear. Rather, women will be forced to travel, potentially long distances at significant cost, for the procedure or will seek medication abortion by mail through virtual clinics.

But Dr. Ralph said she’s concerned about women who live in areas where telehealth abortions are banned, or who discover their pregnancies late, as medical abortions are only recommended for women who are 10 weeks pregnant or less.

“They may look to self-source the medications online or elsewhere, potentially putting themself at legal risk,” she said. “And, as my research has shown, others may turn to self-managing an abortion with herbs, other drugs or medications, or physical methods like hitting themselves in the abdomen; with this they put themselves at both legal and potentially medical risk.”

Constance Bohon, MD, an ob.gyn. in Washington, D.C., said further research should track what happens to women if they’re forced to leave a job to care for another child.

“Many of these women live paycheck to paycheck and cannot afford the cost of an additional child,” Dr. Bohon said. “They may also need to rely on social service agencies to help them find food and housing.”

Dr. Fuentes said she hopes the Turnaway Study will inspire other researchers to examine laws that outlaw abortion and the corresponding long-term effects on women.

“From a medical and a public health standpoint, these laws are unjust,” Dr. Fuentes said in an interview. “They’re not grounded in evidence, and they incur great costs not just to pregnant people but their families and their communities as well.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the wake of the Supreme Court’s June decision to repeal a federal right to abortion, many women will now be faced with the prospect of carrying an unwanted pregnancy to term.

One group of researchers has studied the fate of these women and their families for the last decade. Their findings show that women who were denied an abortion are worse off physically, mentally, and economically than those who underwent the procedure.

“There has been much hypothesizing about harms from abortion without considering what the consequences are when someone wants an abortion and can’t get one,” said Diana Greene Foster, PhD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at University of California, San Francisco.

Dr. Foster leads the Turnaway Study, one of the first efforts to examine the physical and mental health effects of receiving or being denied abortions. The ongoing research also charts the economic and social outcomes of women and their families in either circumstance.

Dr. Foster and her colleagues have followed women through childbirth, examining their well-being through phone interviews months to years after the initial interviews.

The economic consequences of carrying an unwanted pregnancy are clear. Women who did not receive a wanted abortion were more likely to live under the poverty line and struggle to cover basic living expenses like food, housing, and transportation.

The physical toll is also significant.

A 2019 analysis from the Turnaway Study found that eight out of 1,132 participants died, two after delivery, during the five-year follow up period – a far greater proportion than what would be expected among women of reproductive age. The researchers also found that women who carry unwanted pregnancies have more comorbid conditions before and after delivery than other women.

Lauren J. Ralph, PhD, MPH, an epidemiologist and member of the Turnaway Study team, examined the physical well-being of women after delivering their unwanted pregnancies.

“They reported more chronic pain, more gestational hypertension, and were more likely to rate their health as fair or poor,” Dr. Ralph said. “Somewhat to our surprise, we also found that two women denied abortions died due to pregnancy-related causes. This is my biggest concern with the loss of abortion access, as all scientific evidence indicates we will see a rise in maternal deaths as a result.”

At least one preliminary study, released as a preprint and not yet peer reviewed, estimates that the number of women who will die each year from pregnancy complications will rise by 24%. For Black women, mortality could jump from 18% to 39% in every state, according to the researchers from the University of Colorado, Boulder.

State of denial

Regulations set in place at abortion clinics in each state individually determine who is able to obtain an abortion, dictated by a “gestational age limit” – how far along a woman is in her pregnancy from the end of her menstrual cycle. Some of the women from the Turnaway Study were unable to receive an abortion because of how far along they were. Others were granted the abortion because they were just under their state’s limit.

Before the latest Supreme Court ruling, this limit was 20 weeks in most states. Now, the cutoff can be as little as 6 weeks – before many women know they are pregnant – or zero weeks, under the most restrictive laws.

Over 70% of women who are denied an abortion carry the pregnancy to term, according to Dr. Foster’s analysis.

Interviews with nearly 1,000 women – in both the first and second trimester of pregnancy – in the Turnaway Study who sought abortions at 30 abortion clinics around the country revealed the main reasons for seeking the procedure were (a) not being able to afford a child; (b) the pregnancy coming at the wrong time in life; or (c) the partner involved not being suitable.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 59.7% of women seeking an abortion in the United States are already mothers. Having an unplanned child results in dramatically worse economic circumstances for their other children, who become nearly four times more likely to live below the poverty line than their peers. They also experience slower physical and mental development as a result of the arrival of the new sibling.

The latest efforts by states to ban abortion could make the situation much worse, said Liza Fuentes, DrPh, senior research scientist at the Guttmacher Institute. “We will need further research on what it means for women to be denied care in the context of the new restrictions,” Dr. Fuentes told this news organization.

Researchers cannot yet predict how many women will be unable to obtain an abortion in the coming months. But John Donahue, PhD, JD, an economist and professor of law at Stanford (Calif.) University, estimated that state laws would prevent roughly one-third of the 1 million abortions per year based on 2021 figures.

Dr. Ralph and her colleagues with the Turnaway Study know that restricting access to abortions will not make the need for abortions disappear. Rather, women will be forced to travel, potentially long distances at significant cost, for the procedure or will seek medication abortion by mail through virtual clinics.

But Dr. Ralph said she’s concerned about women who live in areas where telehealth abortions are banned, or who discover their pregnancies late, as medical abortions are only recommended for women who are 10 weeks pregnant or less.

“They may look to self-source the medications online or elsewhere, potentially putting themself at legal risk,” she said. “And, as my research has shown, others may turn to self-managing an abortion with herbs, other drugs or medications, or physical methods like hitting themselves in the abdomen; with this they put themselves at both legal and potentially medical risk.”

Constance Bohon, MD, an ob.gyn. in Washington, D.C., said further research should track what happens to women if they’re forced to leave a job to care for another child.

“Many of these women live paycheck to paycheck and cannot afford the cost of an additional child,” Dr. Bohon said. “They may also need to rely on social service agencies to help them find food and housing.”

Dr. Fuentes said she hopes the Turnaway Study will inspire other researchers to examine laws that outlaw abortion and the corresponding long-term effects on women.

“From a medical and a public health standpoint, these laws are unjust,” Dr. Fuentes said in an interview. “They’re not grounded in evidence, and they incur great costs not just to pregnant people but their families and their communities as well.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physicians react: Compensation isn’t worth the hassles. What’s the solution?

How satisfied are physicians that they are fairly compensated for their dedication, skills, and time? That’s a subject that seems to steer many physicians to heated emotions and to a variety of issues with today’s medical field – not all of which directly affect their pay.

Medscape’s Physician Compensation Report 2022: “Incomes Gain, Pay Gaps Remain” generally shows encouraging trends. Physician income rose from a year earlier, when it stagnated as COVID-19 restrictions led patients to stay home and medical practices to cut hours or close. And for the first time in Medscape’s 11 years of reporting on physician compensation, average income rose for every medical specialty surveyed.

Heartening findings, right? Yet the tone of comments to the report was anything but peppy. One physician even complained his plumber earns more than he does.

A family physician lamented that he has “made less in the past 3 years, with more hassles and work” and he “can’t wait to retire next year.” Meanwhile, he complained, the U.S. health system is “the costliest, yet wasteful, with worse outcomes; reactive, not preventative; and has the costliest drugs and social issues.”

Do NPs and PAs encroach on your income?

The conversation about fair compensation launched some commenters into a discussion about competition from nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs). Some physicians expressed wariness at best, and anger at worst, about NPs and PAs evolving beyond traditional doctor support roles into certain direct patient support.

One-fourth of respondents in the compensation report said their income was negatively affected by competition from NPs, PAs, and other nonphysician providers. For example, with states like Arkansas expanding independent practice for certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs), one commenter complained, “we are no longer needed.”

Added another physician, “primary care, especially internal medicine, is just going away for doctors. We wasted, by all accounts, 4 full years of our working lives because NPs are ‘just as good.’ ”

Greater independence for NPs and PAs strengthens the hands of health insurers and “will end up hastening the demise of primary care as we have known it,” another reader predicted. Other physicians’ takes: “For the institution, it’s much cheaper to hire NPs than to hire doctors” and “overall, physician negotiating power will decrease in the future.”

Medicare reimbursement rates grate

Although 7 in 10 respondents in the compensation report said they would continue to accept new Medicare or Medicaid patients, comments reveal resentment about the practical need to work with Medicare and its resentment rates.

“An open question to Medicare: Are you doing the dumbest thing possible by paying low wages and giving huge administrative burdens for internal medicine on purpose?” one physician wrote. “Or are you really that short-sighted?”

Another reader cited an analysis from the American College of Surgeons of Medicare’s 1998 surgical CPT codes. If Medicare had left those codes alone beyond annual inflation adjustments, the study found, reimbursement rates by 2019 would be half of what they became.

Another way of looking at the code reimbursement increases is a 50% pay cut over 20 years for doctors and medical practices, that reader insisted. “The rising cost of employee wages, particularly of the last two-and-a-half years of COVID-19, combined with the effective pay cuts over the last 20 years, equals time to quit!”

Another commenter concurred. “In the 1990s, most full-time docs were making almost double what you see [in the report], and everything cost almost half of what it does now. So, MD purchasing power is between half and one-quarter of what it was in the early 1990s.”

Are self-pay models better?

Do physicians have a better chance at consistently fair income under a self-pay practice that avoids dealing with insurance companies?

One commenter hypothesized that psychiatrists once trailed internists in income but today earn more because many “quit working for insurance and went to a cash business 15 years ago.” Many family physicians did something similar by switching to a direct primary care model, he said.

This physician said he has done the same “with great results” for patients as well: shorter office visits, faster booking of appointments, no deductibles owed. Best of all, “I love practicing medicine again, and my patients love the great health care they receive.”

Another commenter agreed. “Two words: cash practice.” But another objected, “I guess only the very rich can afford to cover your business costs.”

Regardless of the payment model, another physician argued for private practice over employed positions. “Save on the bureaucratic expenses. Go back to private practice and get rid of electronic records.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

How satisfied are physicians that they are fairly compensated for their dedication, skills, and time? That’s a subject that seems to steer many physicians to heated emotions and to a variety of issues with today’s medical field – not all of which directly affect their pay.

Medscape’s Physician Compensation Report 2022: “Incomes Gain, Pay Gaps Remain” generally shows encouraging trends. Physician income rose from a year earlier, when it stagnated as COVID-19 restrictions led patients to stay home and medical practices to cut hours or close. And for the first time in Medscape’s 11 years of reporting on physician compensation, average income rose for every medical specialty surveyed.

Heartening findings, right? Yet the tone of comments to the report was anything but peppy. One physician even complained his plumber earns more than he does.

A family physician lamented that he has “made less in the past 3 years, with more hassles and work” and he “can’t wait to retire next year.” Meanwhile, he complained, the U.S. health system is “the costliest, yet wasteful, with worse outcomes; reactive, not preventative; and has the costliest drugs and social issues.”

Do NPs and PAs encroach on your income?

The conversation about fair compensation launched some commenters into a discussion about competition from nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs). Some physicians expressed wariness at best, and anger at worst, about NPs and PAs evolving beyond traditional doctor support roles into certain direct patient support.

One-fourth of respondents in the compensation report said their income was negatively affected by competition from NPs, PAs, and other nonphysician providers. For example, with states like Arkansas expanding independent practice for certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs), one commenter complained, “we are no longer needed.”

Added another physician, “primary care, especially internal medicine, is just going away for doctors. We wasted, by all accounts, 4 full years of our working lives because NPs are ‘just as good.’ ”

Greater independence for NPs and PAs strengthens the hands of health insurers and “will end up hastening the demise of primary care as we have known it,” another reader predicted. Other physicians’ takes: “For the institution, it’s much cheaper to hire NPs than to hire doctors” and “overall, physician negotiating power will decrease in the future.”

Medicare reimbursement rates grate

Although 7 in 10 respondents in the compensation report said they would continue to accept new Medicare or Medicaid patients, comments reveal resentment about the practical need to work with Medicare and its resentment rates.

“An open question to Medicare: Are you doing the dumbest thing possible by paying low wages and giving huge administrative burdens for internal medicine on purpose?” one physician wrote. “Or are you really that short-sighted?”

Another reader cited an analysis from the American College of Surgeons of Medicare’s 1998 surgical CPT codes. If Medicare had left those codes alone beyond annual inflation adjustments, the study found, reimbursement rates by 2019 would be half of what they became.

Another way of looking at the code reimbursement increases is a 50% pay cut over 20 years for doctors and medical practices, that reader insisted. “The rising cost of employee wages, particularly of the last two-and-a-half years of COVID-19, combined with the effective pay cuts over the last 20 years, equals time to quit!”

Another commenter concurred. “In the 1990s, most full-time docs were making almost double what you see [in the report], and everything cost almost half of what it does now. So, MD purchasing power is between half and one-quarter of what it was in the early 1990s.”

Are self-pay models better?

Do physicians have a better chance at consistently fair income under a self-pay practice that avoids dealing with insurance companies?

One commenter hypothesized that psychiatrists once trailed internists in income but today earn more because many “quit working for insurance and went to a cash business 15 years ago.” Many family physicians did something similar by switching to a direct primary care model, he said.

This physician said he has done the same “with great results” for patients as well: shorter office visits, faster booking of appointments, no deductibles owed. Best of all, “I love practicing medicine again, and my patients love the great health care they receive.”

Another commenter agreed. “Two words: cash practice.” But another objected, “I guess only the very rich can afford to cover your business costs.”

Regardless of the payment model, another physician argued for private practice over employed positions. “Save on the bureaucratic expenses. Go back to private practice and get rid of electronic records.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

How satisfied are physicians that they are fairly compensated for their dedication, skills, and time? That’s a subject that seems to steer many physicians to heated emotions and to a variety of issues with today’s medical field – not all of which directly affect their pay.

Medscape’s Physician Compensation Report 2022: “Incomes Gain, Pay Gaps Remain” generally shows encouraging trends. Physician income rose from a year earlier, when it stagnated as COVID-19 restrictions led patients to stay home and medical practices to cut hours or close. And for the first time in Medscape’s 11 years of reporting on physician compensation, average income rose for every medical specialty surveyed.

Heartening findings, right? Yet the tone of comments to the report was anything but peppy. One physician even complained his plumber earns more than he does.

A family physician lamented that he has “made less in the past 3 years, with more hassles and work” and he “can’t wait to retire next year.” Meanwhile, he complained, the U.S. health system is “the costliest, yet wasteful, with worse outcomes; reactive, not preventative; and has the costliest drugs and social issues.”

Do NPs and PAs encroach on your income?

The conversation about fair compensation launched some commenters into a discussion about competition from nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs). Some physicians expressed wariness at best, and anger at worst, about NPs and PAs evolving beyond traditional doctor support roles into certain direct patient support.

One-fourth of respondents in the compensation report said their income was negatively affected by competition from NPs, PAs, and other nonphysician providers. For example, with states like Arkansas expanding independent practice for certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs), one commenter complained, “we are no longer needed.”

Added another physician, “primary care, especially internal medicine, is just going away for doctors. We wasted, by all accounts, 4 full years of our working lives because NPs are ‘just as good.’ ”

Greater independence for NPs and PAs strengthens the hands of health insurers and “will end up hastening the demise of primary care as we have known it,” another reader predicted. Other physicians’ takes: “For the institution, it’s much cheaper to hire NPs than to hire doctors” and “overall, physician negotiating power will decrease in the future.”

Medicare reimbursement rates grate

Although 7 in 10 respondents in the compensation report said they would continue to accept new Medicare or Medicaid patients, comments reveal resentment about the practical need to work with Medicare and its resentment rates.

“An open question to Medicare: Are you doing the dumbest thing possible by paying low wages and giving huge administrative burdens for internal medicine on purpose?” one physician wrote. “Or are you really that short-sighted?”

Another reader cited an analysis from the American College of Surgeons of Medicare’s 1998 surgical CPT codes. If Medicare had left those codes alone beyond annual inflation adjustments, the study found, reimbursement rates by 2019 would be half of what they became.

Another way of looking at the code reimbursement increases is a 50% pay cut over 20 years for doctors and medical practices, that reader insisted. “The rising cost of employee wages, particularly of the last two-and-a-half years of COVID-19, combined with the effective pay cuts over the last 20 years, equals time to quit!”

Another commenter concurred. “In the 1990s, most full-time docs were making almost double what you see [in the report], and everything cost almost half of what it does now. So, MD purchasing power is between half and one-quarter of what it was in the early 1990s.”

Are self-pay models better?

Do physicians have a better chance at consistently fair income under a self-pay practice that avoids dealing with insurance companies?

One commenter hypothesized that psychiatrists once trailed internists in income but today earn more because many “quit working for insurance and went to a cash business 15 years ago.” Many family physicians did something similar by switching to a direct primary care model, he said.

This physician said he has done the same “with great results” for patients as well: shorter office visits, faster booking of appointments, no deductibles owed. Best of all, “I love practicing medicine again, and my patients love the great health care they receive.”

Another commenter agreed. “Two words: cash practice.” But another objected, “I guess only the very rich can afford to cover your business costs.”

Regardless of the payment model, another physician argued for private practice over employed positions. “Save on the bureaucratic expenses. Go back to private practice and get rid of electronic records.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

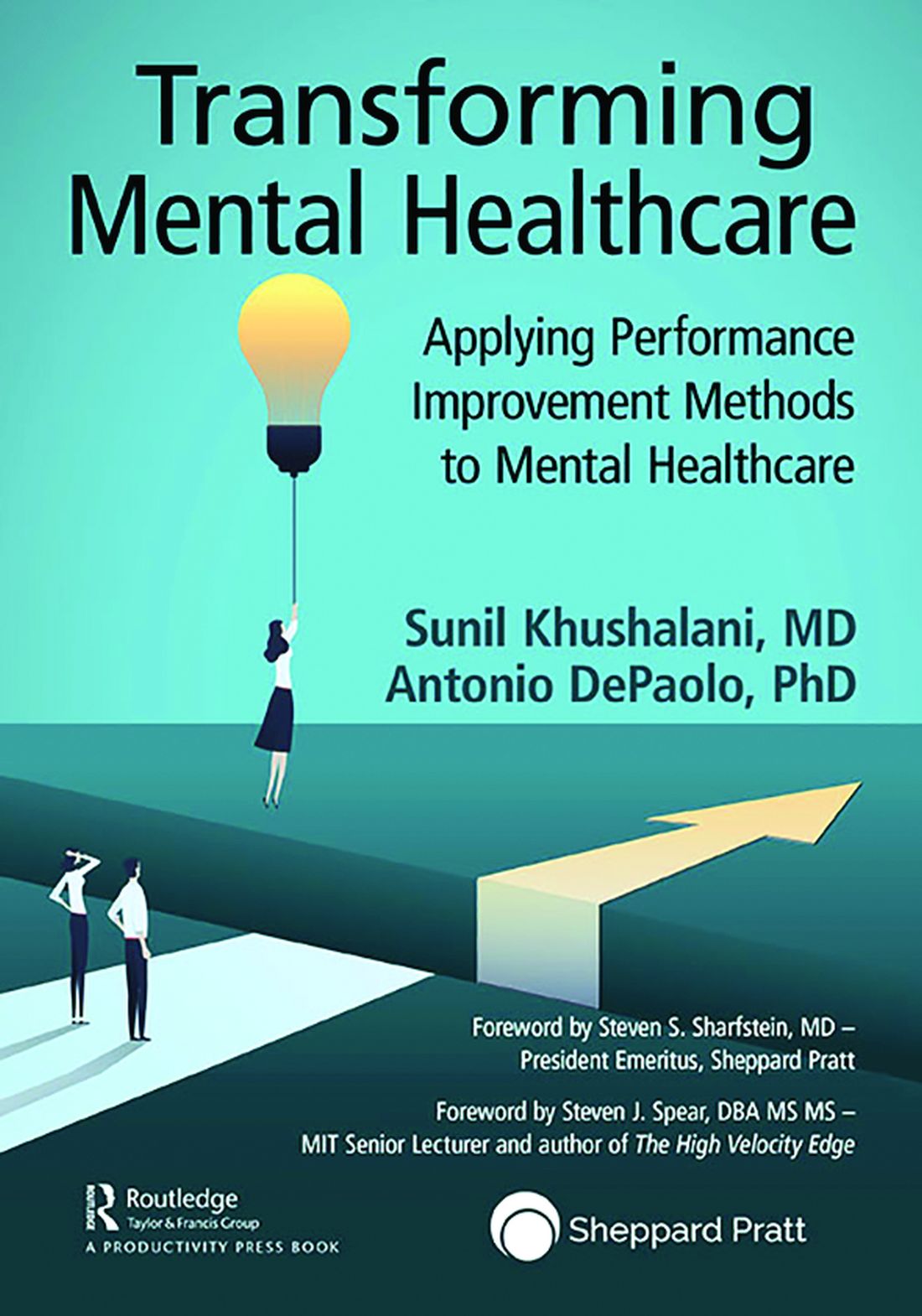

Pediatricians’ incomes rose faster than most specialties in 2021: Survey

In an unprecedented year when income increased for all specialties, pediatricians did better than most, according to a recent survey by Medscape.

. Medscape also noted that, for the first time in the 11 years it’s been conducting these physician compensation surveys, “all specialties have seen an increase in income.”

At least some of that positive news can be traced back to the reduced impact of COVID-19. “Compensation for most physicians is trending back up as demand for physicians accelerates. The market for physicians has done a complete 180 over just 7 or 8 months,” James Taylor of AMN Healthcare’s physician and leadership solutions division said in Medscape Pediatrician Compensation Report 2022.

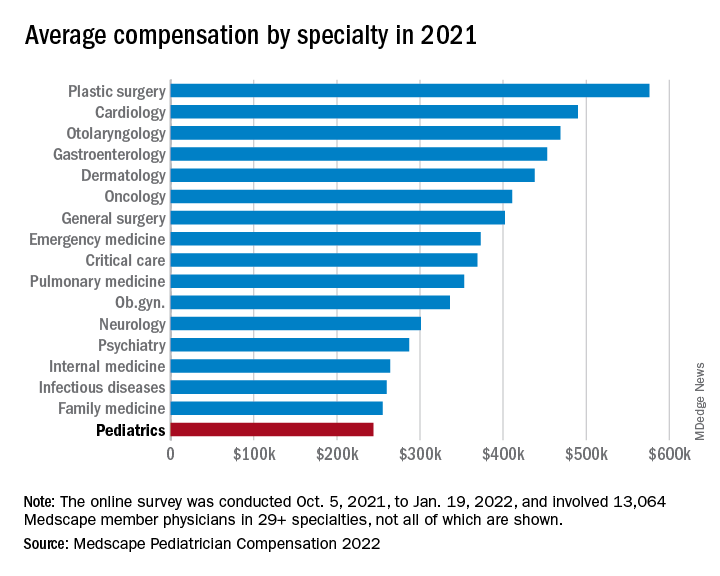

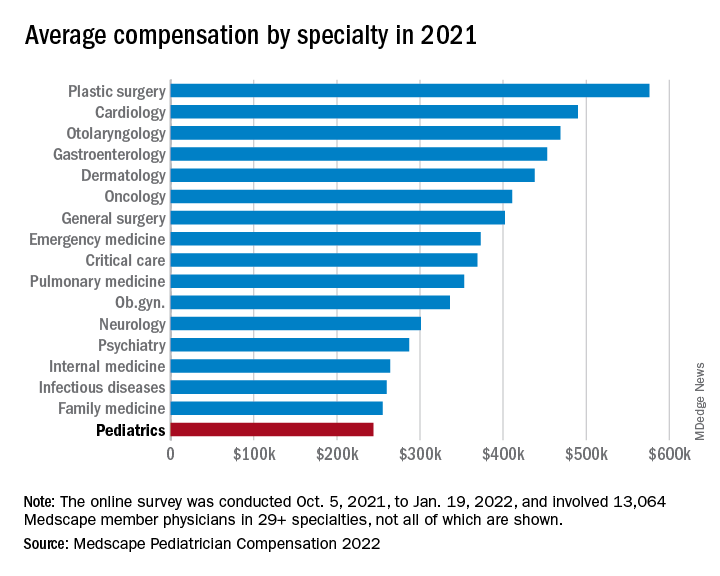

The 10% increase in pediatricians’ income, however, was not enough to reach the average for primary care physicians, $260,000, which was up by 7.4% over 2020. It was enough, though, to move pediatricians from the bottom of the earnings-by-specialty list, where they were last year, to next-to-last this year (public health/preventive medicine, with average earnings of $243,000 in 2021, is not shown in the graph).

The gender gap in earnings left male pediatricians’ income 26% higher than their female counterparts, slightly above the gap of 25% for primary care physicians and 24% for all physicians. For specialists, the gap was 31% in favor of men, based on data from 13,064 Medscape member physicians who participated in the survey, which was conducted online from Oct. 5, 2021, to Jan. 19, 2022. For the record, 57% of the pediatricians who responded were women.

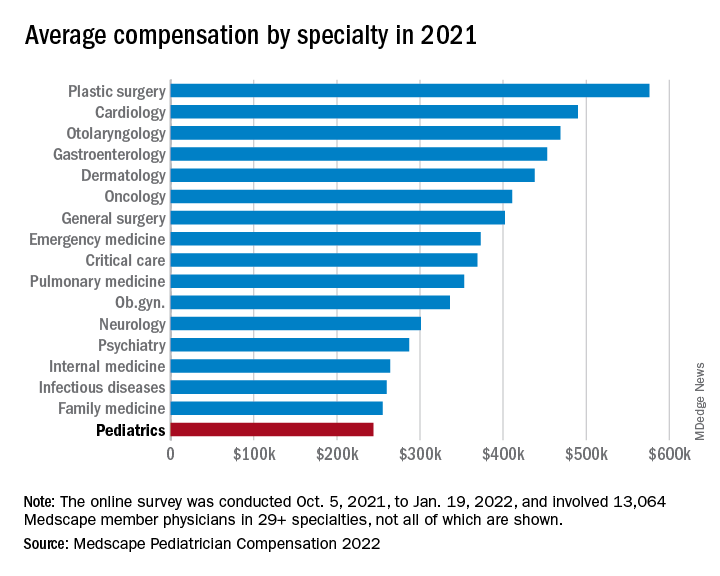

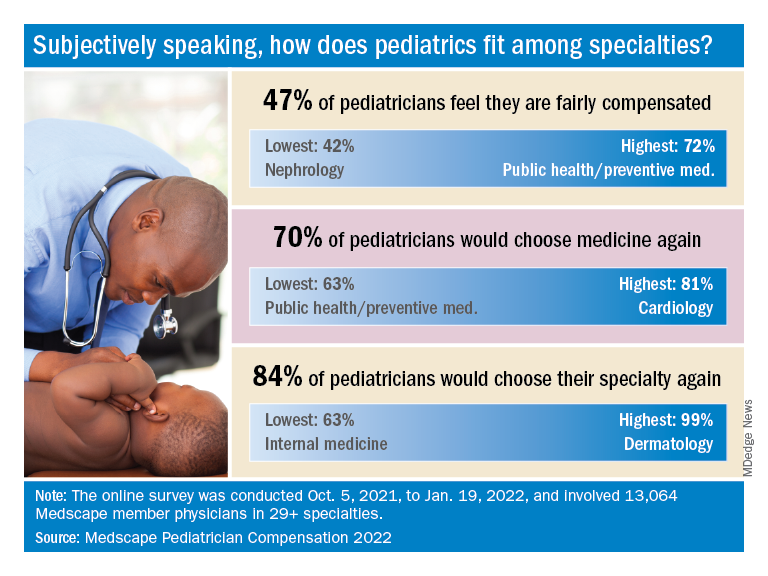

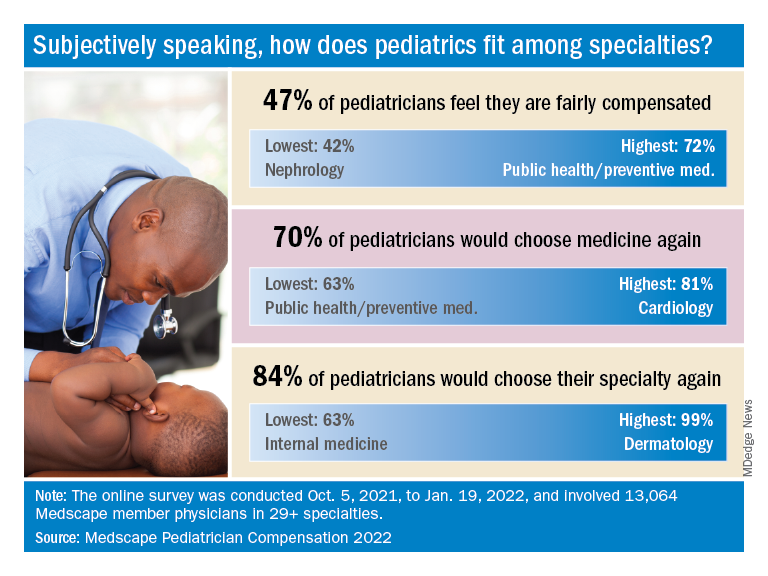

The gaps and low income averages were enough, it seems, to keep pediatricians fairly negative regarding their feelings on compensation. Only 47% think they were fairly compensated in 2021, higher only than diabetes/endocrinology and nephrology. Among the other primary care specialties, internal medicine and ob.gyn. were slightly higher at 49% and family medicine was 55% – still just middle of the pack, compared with public health/preventive medicine at 72%, Medscape said in the report.

Would you do it again?

Moving to the less-economic aspects of the survey, respondents also were asked if they would choose medicine again as a career. Once more pediatricians were low on the scale, as only 70% said that they would enter medicine again, down from 77% last year and lower than this year’s average of 73% average for all physicians.

When they were asked if they would choose pediatrics again as a specialty, the response was a bit more positive: 84% said yes. That middle-of-the-pack showing was well ahead of internal medicine (63%) and family medicine (68%), but well below dermatology (99%) and orthopedics (97%), which are “among the top groups in our survey year after year,” Medscape said.

Did the administrative challenges of medical practice have an effect on those answers? Pediatrician respondents said that they spend 14.9 hours per week on paperwork and administration, close to the average of 15.5 hours for all physicians. The internists, who are least likely to choose their original specialty again, spend 18.7 hours on paperwork each week, while dermatologists, the most likely to repeat their first choice, have just 11.9 hours of paperwork per week.

The exact number of pediatricians involved in the survey was not provided, but they made up about 8% of the total cohort, which works out to somewhere between 1,000 and 1,100 individuals. All respondents had to be practicing in the United States, and compensation was analyzed for full-time physicians only. The sampling error is ±0.86% at a 95% confidence level.

In an unprecedented year when income increased for all specialties, pediatricians did better than most, according to a recent survey by Medscape.

. Medscape also noted that, for the first time in the 11 years it’s been conducting these physician compensation surveys, “all specialties have seen an increase in income.”

At least some of that positive news can be traced back to the reduced impact of COVID-19. “Compensation for most physicians is trending back up as demand for physicians accelerates. The market for physicians has done a complete 180 over just 7 or 8 months,” James Taylor of AMN Healthcare’s physician and leadership solutions division said in Medscape Pediatrician Compensation Report 2022.

The 10% increase in pediatricians’ income, however, was not enough to reach the average for primary care physicians, $260,000, which was up by 7.4% over 2020. It was enough, though, to move pediatricians from the bottom of the earnings-by-specialty list, where they were last year, to next-to-last this year (public health/preventive medicine, with average earnings of $243,000 in 2021, is not shown in the graph).

The gender gap in earnings left male pediatricians’ income 26% higher than their female counterparts, slightly above the gap of 25% for primary care physicians and 24% for all physicians. For specialists, the gap was 31% in favor of men, based on data from 13,064 Medscape member physicians who participated in the survey, which was conducted online from Oct. 5, 2021, to Jan. 19, 2022. For the record, 57% of the pediatricians who responded were women.

The gaps and low income averages were enough, it seems, to keep pediatricians fairly negative regarding their feelings on compensation. Only 47% think they were fairly compensated in 2021, higher only than diabetes/endocrinology and nephrology. Among the other primary care specialties, internal medicine and ob.gyn. were slightly higher at 49% and family medicine was 55% – still just middle of the pack, compared with public health/preventive medicine at 72%, Medscape said in the report.

Would you do it again?

Moving to the less-economic aspects of the survey, respondents also were asked if they would choose medicine again as a career. Once more pediatricians were low on the scale, as only 70% said that they would enter medicine again, down from 77% last year and lower than this year’s average of 73% average for all physicians.

When they were asked if they would choose pediatrics again as a specialty, the response was a bit more positive: 84% said yes. That middle-of-the-pack showing was well ahead of internal medicine (63%) and family medicine (68%), but well below dermatology (99%) and orthopedics (97%), which are “among the top groups in our survey year after year,” Medscape said.

Did the administrative challenges of medical practice have an effect on those answers? Pediatrician respondents said that they spend 14.9 hours per week on paperwork and administration, close to the average of 15.5 hours for all physicians. The internists, who are least likely to choose their original specialty again, spend 18.7 hours on paperwork each week, while dermatologists, the most likely to repeat their first choice, have just 11.9 hours of paperwork per week.

The exact number of pediatricians involved in the survey was not provided, but they made up about 8% of the total cohort, which works out to somewhere between 1,000 and 1,100 individuals. All respondents had to be practicing in the United States, and compensation was analyzed for full-time physicians only. The sampling error is ±0.86% at a 95% confidence level.

In an unprecedented year when income increased for all specialties, pediatricians did better than most, according to a recent survey by Medscape.

. Medscape also noted that, for the first time in the 11 years it’s been conducting these physician compensation surveys, “all specialties have seen an increase in income.”

At least some of that positive news can be traced back to the reduced impact of COVID-19. “Compensation for most physicians is trending back up as demand for physicians accelerates. The market for physicians has done a complete 180 over just 7 or 8 months,” James Taylor of AMN Healthcare’s physician and leadership solutions division said in Medscape Pediatrician Compensation Report 2022.

The 10% increase in pediatricians’ income, however, was not enough to reach the average for primary care physicians, $260,000, which was up by 7.4% over 2020. It was enough, though, to move pediatricians from the bottom of the earnings-by-specialty list, where they were last year, to next-to-last this year (public health/preventive medicine, with average earnings of $243,000 in 2021, is not shown in the graph).

The gender gap in earnings left male pediatricians’ income 26% higher than their female counterparts, slightly above the gap of 25% for primary care physicians and 24% for all physicians. For specialists, the gap was 31% in favor of men, based on data from 13,064 Medscape member physicians who participated in the survey, which was conducted online from Oct. 5, 2021, to Jan. 19, 2022. For the record, 57% of the pediatricians who responded were women.

The gaps and low income averages were enough, it seems, to keep pediatricians fairly negative regarding their feelings on compensation. Only 47% think they were fairly compensated in 2021, higher only than diabetes/endocrinology and nephrology. Among the other primary care specialties, internal medicine and ob.gyn. were slightly higher at 49% and family medicine was 55% – still just middle of the pack, compared with public health/preventive medicine at 72%, Medscape said in the report.

Would you do it again?

Moving to the less-economic aspects of the survey, respondents also were asked if they would choose medicine again as a career. Once more pediatricians were low on the scale, as only 70% said that they would enter medicine again, down from 77% last year and lower than this year’s average of 73% average for all physicians.

When they were asked if they would choose pediatrics again as a specialty, the response was a bit more positive: 84% said yes. That middle-of-the-pack showing was well ahead of internal medicine (63%) and family medicine (68%), but well below dermatology (99%) and orthopedics (97%), which are “among the top groups in our survey year after year,” Medscape said.

Did the administrative challenges of medical practice have an effect on those answers? Pediatrician respondents said that they spend 14.9 hours per week on paperwork and administration, close to the average of 15.5 hours for all physicians. The internists, who are least likely to choose their original specialty again, spend 18.7 hours on paperwork each week, while dermatologists, the most likely to repeat their first choice, have just 11.9 hours of paperwork per week.

The exact number of pediatricians involved in the survey was not provided, but they made up about 8% of the total cohort, which works out to somewhere between 1,000 and 1,100 individuals. All respondents had to be practicing in the United States, and compensation was analyzed for full-time physicians only. The sampling error is ±0.86% at a 95% confidence level.

How much health insurers pay for almost everything is about to go public

perhaps helping answer a question that has long dogged those who buy insurance: Are we getting the best deal we can?

As of July 1, health insurers and self-insured employers must post on websites just about every price they’ve negotiated with providers for health care services, item by item. About the only thing excluded are the prices paid for prescription drugs, except those administered in hospitals or doctors’ offices.

The federally required data release could affect future prices or even how employers contract for health care. Many will see for the first time how well their insurers are doing, compared with others.

The new rules are far broader than those that went into effect in 2021 requiring hospitals to post their negotiated rates for the public to see. Now insurers must post the amounts paid for “every physician in network, every hospital, every surgery center, every nursing facility,” said Jeffrey Leibach, a partner at the consulting firm Guidehouse.

“When you start doing the math, you’re talking trillions of records,” he said. The fines the federal government could impose for noncompliance are also heftier than the penalties that hospitals face.

Federal officials learned from the hospital experience and gave insurers more direction on what was expected, said Mr. Leibach. Insurers or self-insured employers could be fined as much as $100 a day for each violation, for each affected enrollee if they fail to provide the data.

“Get your calculator out: All of a sudden you are in the millions pretty fast,” Mr. Leibach said.

Determined consumers, especially those with high-deductible health plans, may try to dig in right away and use the data to try comparing what they will have to pay at different hospitals, clinics, or doctor offices for specific services.

But each database’s enormous size may mean that most people “will find it very hard to use the data in a nuanced way,” said Katherine Baicker, dean of the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy.

At least at first.

Entrepreneurs are expected to quickly translate the information into more user-friendly formats so it can be incorporated into new or existing services that estimate costs for patients. And starting Jan. 1, the rules require insurers to provide online tools that will help people get up-front cost estimates for about 500 so-called “shoppable” services, meaning medical care they can schedule ahead of time.

Once those things happen, “you’ll at least have the options in front of you,” said Chris Severn, CEO of Turquoise Health, an online company that has posted price information made available under the rules for hospitals, although many hospitals have yet to comply.

With the addition of the insurers’ data, sites like his will be able to drill down further into cost variation from one place to another or among insurers.

“If you’re going to get an x-ray, you will be able to see that you can do it for $250 at this hospital, $75 at the imaging center down the road, or your specialist can do it in office for $25,” he said.

Everyone will know everyone else’s business: for example, how much insurers Aetna and Humana pay the same surgery center for a knee replacement.

The requirements stem from the Affordable Care Act and a 2019 executive order by then-President Donald Trump.

“These plans are supposed to be acting on behalf of employers in negotiating good rates, and the little insight we have on that shows it has not happened,” said Elizabeth Mitchell, president and CEO of the Purchaser Business Group on Health, an affiliation of employers who offer job-based health benefits to workers. “I do believe the dynamics are going to change.”

Other observers are more circumspect.

“Maybe at best this will reduce the wide variance of prices out there,” said Zack Cooper, director of health policy at the Yale University Institution for Social and Policy Studies, New Haven, Conn. “But it won’t be unleashing a consumer revolution.”

Still, the biggest value of the July data release may well be to shed light on how successful insurers have been at negotiating prices. It comes on the heels of research that has shown tremendous variation in what is paid for health care. A recent study by Rand, for example, shows that employers that offer job-based insurance plans paid, on average, 224% more than Medicare for the same services.

Tens of thousands of employers who buy insurance coverage for their workers will get this more-complete pricing picture – and may not like what they see.

“What we’re learning from the hospital data is that insurers are really bad at negotiating,” said Gerard Anderson, a professor in the department of health policy at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg, Baltimore, citing research that found that negotiated rates for hospital care can be higher than what the facilities accept from patients who are not using insurance and are paying cash.

That could add to the frustration that Ms. Mitchell and others say employers have with the current health insurance system. More might try to contract with providers directly, only using insurance companies for claims processing.

Other employers may bring their insurers back to the bargaining table.

“For the first time, an employer will be able to go to an insurance company and say: ‘You have not negotiated a good-enough deal, and we know that because we can see the same provider has negotiated a better deal with another company,’ ” said James Gelfand, president of the ERISA Industry Committee, a trade group of self-insured employers.

If that happens, he added, “patients will be able to save money.”

That’s not necessarily a given, however.

Because this kind of public release of pricing data hasn’t been tried widely in health care before, how it will affect future spending remains uncertain. If insurers are pushed back to the bargaining table or providers see where they stand relative to their peers, prices could drop. However, some providers could raise their prices if they see they are charging less than their peers.

“Downward pressure may not be a given,” said Kelley Schultz, vice president of commercial policy for AHIP, the industry’s trade lobby.

Ms. Baicker said that, even after the data is out, rates will continue to be heavily influenced by local conditions, such as the size of an insurer or employer – providers often give bigger discounts, for example, to the insurers or self-insured employers that can send them the most patients. The number of hospitals in a region also matters – if an area has only one, for instance, that usually means the facility can demand higher rates.

Another unknown: Will insurers meet the deadline and provide usable data?

Ms. Schultz, at AHIP, said the industry is well on the way, partly because the original deadline was extended by 6 months. She expects insurers to do better than the hospital industry. “We saw a lot of hospitals that just decided not to post files or make them difficult to find,” she said.

So far, more than 300 noncompliant hospitals received warning letters from the government. But they could face fines of $300 a day fines for failing to comply, which is less than what insurers potentially face, although the federal government has recently upped the ante to up to $5,500 a day for the largest facilities.

Even after the pricing data is public, “I don’t think things will change overnight,” said Mr. Leibach. “Patients are still going to make care decisions based on their doctors and referrals, a lot of reasons other than price.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

perhaps helping answer a question that has long dogged those who buy insurance: Are we getting the best deal we can?

As of July 1, health insurers and self-insured employers must post on websites just about every price they’ve negotiated with providers for health care services, item by item. About the only thing excluded are the prices paid for prescription drugs, except those administered in hospitals or doctors’ offices.

The federally required data release could affect future prices or even how employers contract for health care. Many will see for the first time how well their insurers are doing, compared with others.

The new rules are far broader than those that went into effect in 2021 requiring hospitals to post their negotiated rates for the public to see. Now insurers must post the amounts paid for “every physician in network, every hospital, every surgery center, every nursing facility,” said Jeffrey Leibach, a partner at the consulting firm Guidehouse.

“When you start doing the math, you’re talking trillions of records,” he said. The fines the federal government could impose for noncompliance are also heftier than the penalties that hospitals face.

Federal officials learned from the hospital experience and gave insurers more direction on what was expected, said Mr. Leibach. Insurers or self-insured employers could be fined as much as $100 a day for each violation, for each affected enrollee if they fail to provide the data.

“Get your calculator out: All of a sudden you are in the millions pretty fast,” Mr. Leibach said.

Determined consumers, especially those with high-deductible health plans, may try to dig in right away and use the data to try comparing what they will have to pay at different hospitals, clinics, or doctor offices for specific services.

But each database’s enormous size may mean that most people “will find it very hard to use the data in a nuanced way,” said Katherine Baicker, dean of the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy.

At least at first.