User login

It’s a gimmick

March 30 was National Doctor’s Day, which resulted in my getting all kinds of generic emails from pharmaceutical reps, market research places, insurance companies, and the two hospitals I’m on staff at.

They all had similar meaningless platitudes thanking me for what I do, reassuring me that I’m appreciated, that I make the world a better place, yadda yadda yadda. The hospital even said I could swing by the medical staff office and pick up an “appreciation bag,” which I’m told contained a T-shirt, bottle of hand sanitizer, and a few other trinkets.

Spare me.

I’m not looking for any of that. In fact, I really don’t care.

Wishing me a “Happy Doctors Day” after spending the other 364 days denying my claims, refusing to cover tests or medications for my patients who need them (I don’t order these things for the hell of it, you know), telling me that I’m bringing down your Press Ganey scores, complaining about the copay that I have no control over, yelling at my staff for doing their jobs ... is pretty damn hollow.

It’s kind of like Mother’s Day: If you’re a jackass to your mom most of the year, sending her flowers on a Sunday in May doesn’t make it all right.

People also seem to forget that, in a small practice, my awesome staff is an extension of myself. Mistreating them, then wishing me a “Happy Doctor’s Day,” is also worthless.

I still like what I do. All the hassles from insurance companies, various administrators, the occasional angry patient … after all these years, they put a dent in it, but I still have no regrets about the course I’ve chosen. They can’t take away the happiness I get from helping those who need me.

It’s a job I love that’s allowed me to support my family and work with two wonderful staff members I’d never have met otherwise.

And that’s all I need.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

March 30 was National Doctor’s Day, which resulted in my getting all kinds of generic emails from pharmaceutical reps, market research places, insurance companies, and the two hospitals I’m on staff at.

They all had similar meaningless platitudes thanking me for what I do, reassuring me that I’m appreciated, that I make the world a better place, yadda yadda yadda. The hospital even said I could swing by the medical staff office and pick up an “appreciation bag,” which I’m told contained a T-shirt, bottle of hand sanitizer, and a few other trinkets.

Spare me.

I’m not looking for any of that. In fact, I really don’t care.

Wishing me a “Happy Doctors Day” after spending the other 364 days denying my claims, refusing to cover tests or medications for my patients who need them (I don’t order these things for the hell of it, you know), telling me that I’m bringing down your Press Ganey scores, complaining about the copay that I have no control over, yelling at my staff for doing their jobs ... is pretty damn hollow.

It’s kind of like Mother’s Day: If you’re a jackass to your mom most of the year, sending her flowers on a Sunday in May doesn’t make it all right.

People also seem to forget that, in a small practice, my awesome staff is an extension of myself. Mistreating them, then wishing me a “Happy Doctor’s Day,” is also worthless.

I still like what I do. All the hassles from insurance companies, various administrators, the occasional angry patient … after all these years, they put a dent in it, but I still have no regrets about the course I’ve chosen. They can’t take away the happiness I get from helping those who need me.

It’s a job I love that’s allowed me to support my family and work with two wonderful staff members I’d never have met otherwise.

And that’s all I need.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

March 30 was National Doctor’s Day, which resulted in my getting all kinds of generic emails from pharmaceutical reps, market research places, insurance companies, and the two hospitals I’m on staff at.

They all had similar meaningless platitudes thanking me for what I do, reassuring me that I’m appreciated, that I make the world a better place, yadda yadda yadda. The hospital even said I could swing by the medical staff office and pick up an “appreciation bag,” which I’m told contained a T-shirt, bottle of hand sanitizer, and a few other trinkets.

Spare me.

I’m not looking for any of that. In fact, I really don’t care.

Wishing me a “Happy Doctors Day” after spending the other 364 days denying my claims, refusing to cover tests or medications for my patients who need them (I don’t order these things for the hell of it, you know), telling me that I’m bringing down your Press Ganey scores, complaining about the copay that I have no control over, yelling at my staff for doing their jobs ... is pretty damn hollow.

It’s kind of like Mother’s Day: If you’re a jackass to your mom most of the year, sending her flowers on a Sunday in May doesn’t make it all right.

People also seem to forget that, in a small practice, my awesome staff is an extension of myself. Mistreating them, then wishing me a “Happy Doctor’s Day,” is also worthless.

I still like what I do. All the hassles from insurance companies, various administrators, the occasional angry patient … after all these years, they put a dent in it, but I still have no regrets about the course I’ve chosen. They can’t take away the happiness I get from helping those who need me.

It’s a job I love that’s allowed me to support my family and work with two wonderful staff members I’d never have met otherwise.

And that’s all I need.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

How and why the language of medicine must change

The United States has never achieved a single high standard of medical care equity for all of its people, and the trend line does not appear favorable. The closest we have reached is basic Medicare (Parts A and B), military medicine, the Veterans Health Administration, and large nonprofit groups like Kaiser Permanente. It seems that the nature of we individualistic Americans is to always try to seek an advantage.

But even achieving equity in medical care would not ensure equity in health. The social determinants of health (income level, education, politics, government, geography, neighborhood, country of origin, language spoken, literacy, gender, and yes – race and ethnicity) have far more influence on health equity than does medical care.

Narratives can both reflect and influence culture. Considering the harmful effects of the current political divisiveness in the United States, the timing is ideal for our three leading medical and health education organizations – the American Medical Association, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – to publish a definitive position paper called “Advancing Health Equity: A Guide to Language, Narrative and Concepts.”

What’s in a word?

According to William Shakespeare, “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet” (Romeo and Juliet). Maybe. But if the word used were “thorn” or “thistle,” it just would not be the same.

Words comprise language and wield enormous power with human beings. Wars are fought over geographic boundaries often defined by the language spoken by the people: think 2022, Russian-speaking Ukrainians. Think Winston Churchill’s massive 1,500-page “A History of the English-Speaking Peoples.” Think about the political power of French in Quebec, Canada.

Thus, it should be no surprise that words, acronyms, and abbreviations become rallying cries for political activists of all stripes: PC, January 6, Woke, 1619, BLM, Critical Race Theory, 1776, Remember Pearl Harbor, Remember the Alamo, the Civil War or the War Between the States, the War for Southern Independence, the War of Northern Aggression, the War of the Rebellion, or simply “The Lost Cause.” How about Realpolitik?

Is “medical language” the language of the people or of the profession? Physicians must understand each other, and physicians also must communicate clearly with patients using words that convey neutral meanings and don’t interfere with objective understanding. Medical editors prefer the brevity of one or a few words to clearly convey meaning.

I consider this document from the AMA and AAMC to be both profound and profoundly important for the healing professions. The contributors frequently use words like “humility” as they describe their efforts and products, knowing full well that they (and their organizations) stand to be figuratively torn limb from limb by a host of critics – or worse, ignored and marginalized.

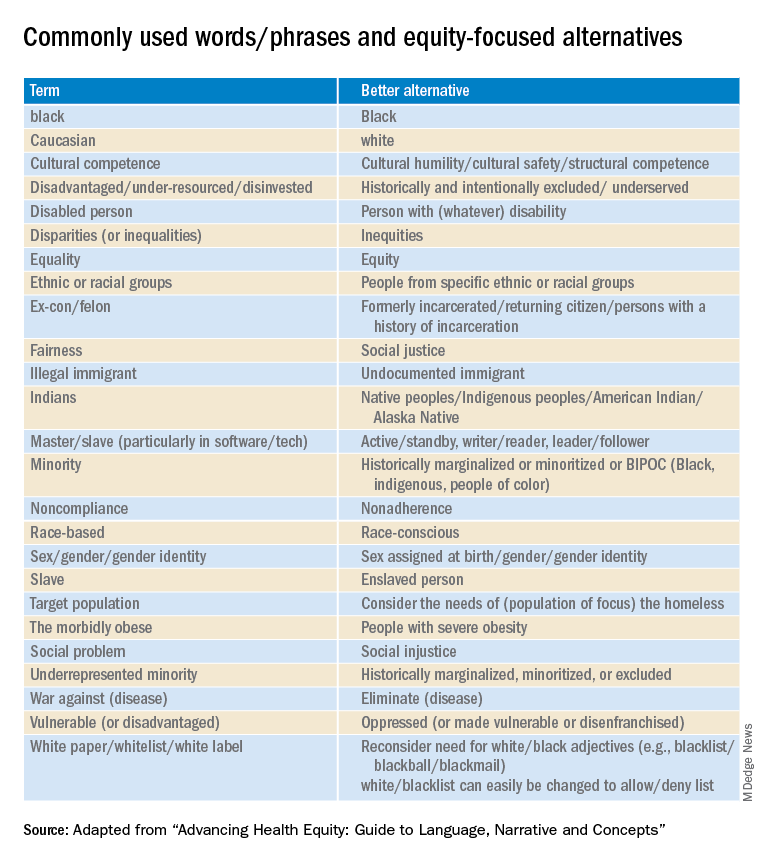

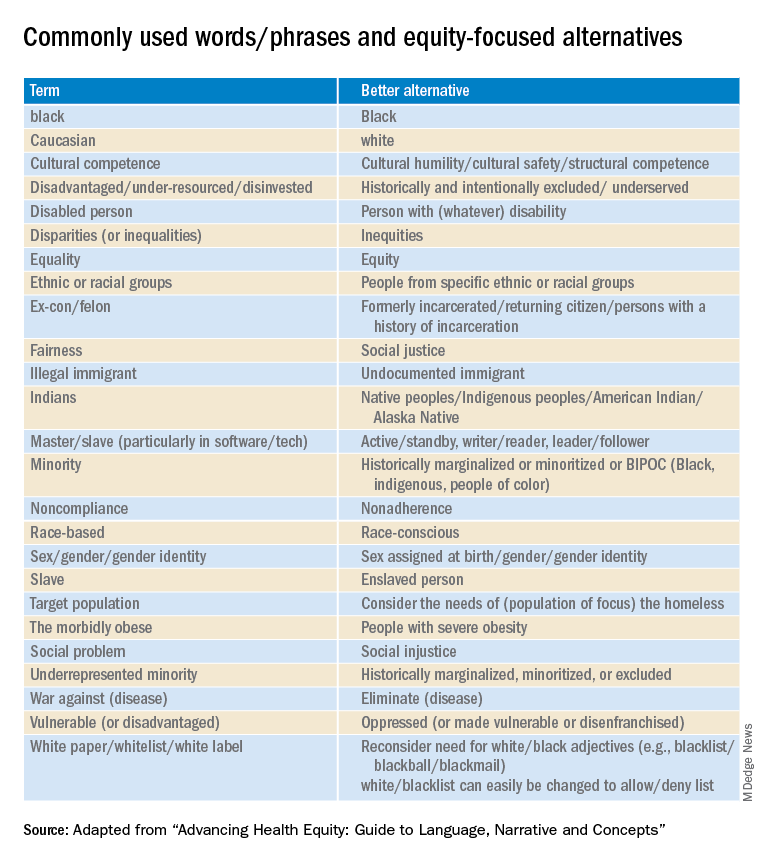

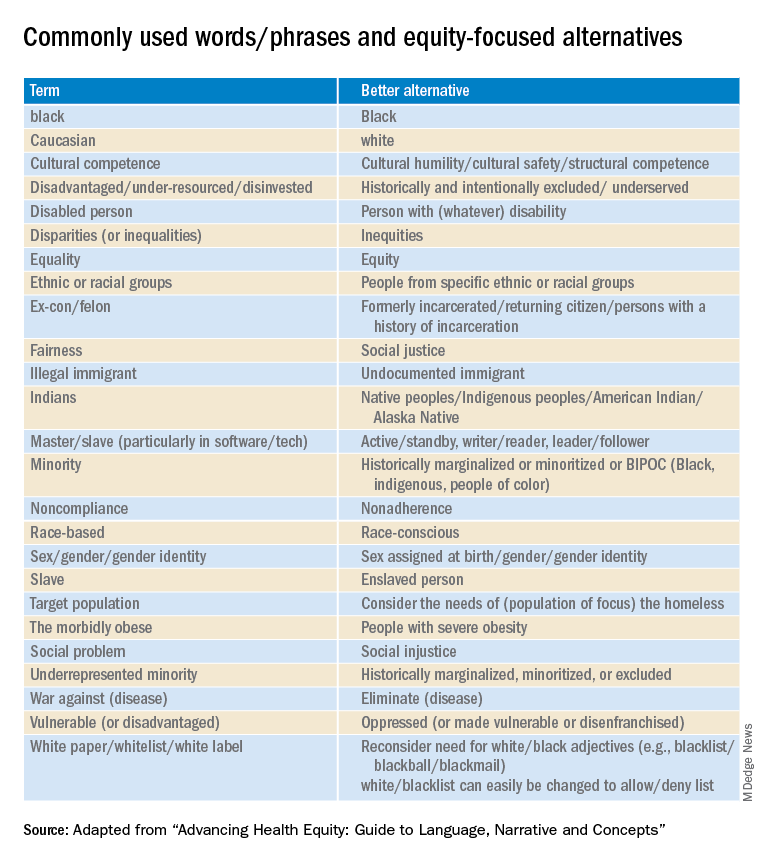

Part 1 of the Health Equity Guide is titled “Language for promoting health equity.”(the reader is referred to the Health Equity Guide for the reasoning and explanations for all).

Part 2 of the Health Equity Guide is called “Why narratives matter.” It includes features of dominant narratives; a substantial section on the narrative of race and the narrative of individualism; the purpose of a health equity–based narrative; how to change the narrative; and how to see and think critically through dialogue.

Part 3 of the Health Equity Guide is a glossary of 138 key terms such as “class,” “discrimination,” “gender dysphoria,” “non-White,” “racial capitalism,” and “structural competency.”

The CDC also has a toolkit for inclusive communication, the “Health Equity Guiding Principles for Inclusive Communication.”

The substantive message of the Health Equity Guide could affect what you say, write, and do (even how you think) every day as well as how those with whom you interact view you. It can affect the entire communication milieu in which you live, whether or not you like it. Read it seriously, as though your professional life depended on it. It may.

Dr. Lundberg is consulting professor of health research policy and pathology at Stanford (Calif.) University. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The United States has never achieved a single high standard of medical care equity for all of its people, and the trend line does not appear favorable. The closest we have reached is basic Medicare (Parts A and B), military medicine, the Veterans Health Administration, and large nonprofit groups like Kaiser Permanente. It seems that the nature of we individualistic Americans is to always try to seek an advantage.

But even achieving equity in medical care would not ensure equity in health. The social determinants of health (income level, education, politics, government, geography, neighborhood, country of origin, language spoken, literacy, gender, and yes – race and ethnicity) have far more influence on health equity than does medical care.

Narratives can both reflect and influence culture. Considering the harmful effects of the current political divisiveness in the United States, the timing is ideal for our three leading medical and health education organizations – the American Medical Association, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – to publish a definitive position paper called “Advancing Health Equity: A Guide to Language, Narrative and Concepts.”

What’s in a word?

According to William Shakespeare, “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet” (Romeo and Juliet). Maybe. But if the word used were “thorn” or “thistle,” it just would not be the same.

Words comprise language and wield enormous power with human beings. Wars are fought over geographic boundaries often defined by the language spoken by the people: think 2022, Russian-speaking Ukrainians. Think Winston Churchill’s massive 1,500-page “A History of the English-Speaking Peoples.” Think about the political power of French in Quebec, Canada.

Thus, it should be no surprise that words, acronyms, and abbreviations become rallying cries for political activists of all stripes: PC, January 6, Woke, 1619, BLM, Critical Race Theory, 1776, Remember Pearl Harbor, Remember the Alamo, the Civil War or the War Between the States, the War for Southern Independence, the War of Northern Aggression, the War of the Rebellion, or simply “The Lost Cause.” How about Realpolitik?

Is “medical language” the language of the people or of the profession? Physicians must understand each other, and physicians also must communicate clearly with patients using words that convey neutral meanings and don’t interfere with objective understanding. Medical editors prefer the brevity of one or a few words to clearly convey meaning.

I consider this document from the AMA and AAMC to be both profound and profoundly important for the healing professions. The contributors frequently use words like “humility” as they describe their efforts and products, knowing full well that they (and their organizations) stand to be figuratively torn limb from limb by a host of critics – or worse, ignored and marginalized.

Part 1 of the Health Equity Guide is titled “Language for promoting health equity.”(the reader is referred to the Health Equity Guide for the reasoning and explanations for all).

Part 2 of the Health Equity Guide is called “Why narratives matter.” It includes features of dominant narratives; a substantial section on the narrative of race and the narrative of individualism; the purpose of a health equity–based narrative; how to change the narrative; and how to see and think critically through dialogue.

Part 3 of the Health Equity Guide is a glossary of 138 key terms such as “class,” “discrimination,” “gender dysphoria,” “non-White,” “racial capitalism,” and “structural competency.”

The CDC also has a toolkit for inclusive communication, the “Health Equity Guiding Principles for Inclusive Communication.”

The substantive message of the Health Equity Guide could affect what you say, write, and do (even how you think) every day as well as how those with whom you interact view you. It can affect the entire communication milieu in which you live, whether or not you like it. Read it seriously, as though your professional life depended on it. It may.

Dr. Lundberg is consulting professor of health research policy and pathology at Stanford (Calif.) University. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The United States has never achieved a single high standard of medical care equity for all of its people, and the trend line does not appear favorable. The closest we have reached is basic Medicare (Parts A and B), military medicine, the Veterans Health Administration, and large nonprofit groups like Kaiser Permanente. It seems that the nature of we individualistic Americans is to always try to seek an advantage.

But even achieving equity in medical care would not ensure equity in health. The social determinants of health (income level, education, politics, government, geography, neighborhood, country of origin, language spoken, literacy, gender, and yes – race and ethnicity) have far more influence on health equity than does medical care.

Narratives can both reflect and influence culture. Considering the harmful effects of the current political divisiveness in the United States, the timing is ideal for our three leading medical and health education organizations – the American Medical Association, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – to publish a definitive position paper called “Advancing Health Equity: A Guide to Language, Narrative and Concepts.”

What’s in a word?

According to William Shakespeare, “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet” (Romeo and Juliet). Maybe. But if the word used were “thorn” or “thistle,” it just would not be the same.

Words comprise language and wield enormous power with human beings. Wars are fought over geographic boundaries often defined by the language spoken by the people: think 2022, Russian-speaking Ukrainians. Think Winston Churchill’s massive 1,500-page “A History of the English-Speaking Peoples.” Think about the political power of French in Quebec, Canada.

Thus, it should be no surprise that words, acronyms, and abbreviations become rallying cries for political activists of all stripes: PC, January 6, Woke, 1619, BLM, Critical Race Theory, 1776, Remember Pearl Harbor, Remember the Alamo, the Civil War or the War Between the States, the War for Southern Independence, the War of Northern Aggression, the War of the Rebellion, or simply “The Lost Cause.” How about Realpolitik?

Is “medical language” the language of the people or of the profession? Physicians must understand each other, and physicians also must communicate clearly with patients using words that convey neutral meanings and don’t interfere with objective understanding. Medical editors prefer the brevity of one or a few words to clearly convey meaning.

I consider this document from the AMA and AAMC to be both profound and profoundly important for the healing professions. The contributors frequently use words like “humility” as they describe their efforts and products, knowing full well that they (and their organizations) stand to be figuratively torn limb from limb by a host of critics – or worse, ignored and marginalized.

Part 1 of the Health Equity Guide is titled “Language for promoting health equity.”(the reader is referred to the Health Equity Guide for the reasoning and explanations for all).

Part 2 of the Health Equity Guide is called “Why narratives matter.” It includes features of dominant narratives; a substantial section on the narrative of race and the narrative of individualism; the purpose of a health equity–based narrative; how to change the narrative; and how to see and think critically through dialogue.

Part 3 of the Health Equity Guide is a glossary of 138 key terms such as “class,” “discrimination,” “gender dysphoria,” “non-White,” “racial capitalism,” and “structural competency.”

The CDC also has a toolkit for inclusive communication, the “Health Equity Guiding Principles for Inclusive Communication.”

The substantive message of the Health Equity Guide could affect what you say, write, and do (even how you think) every day as well as how those with whom you interact view you. It can affect the entire communication milieu in which you live, whether or not you like it. Read it seriously, as though your professional life depended on it. It may.

Dr. Lundberg is consulting professor of health research policy and pathology at Stanford (Calif.) University. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A little-known offshoot of hem/onc opens pathway for professional development

Only a small number of pediatric hematologist oncologists and even fewer of our adult counterparts feel comfortable evaluating and treating vascular anomalies.

While admittedly rare, these conditions are still common enough that clinicians in many disciplines encounter them. Hematologist/oncologists are most likely to see vascular malformations, which often present as mass lesions. Complications of these disorders occur across the hematology-oncology spectrum and include clots, pulmonary emboli, cancer predisposition, and an array of functional and psychosocial disorders.

Vascular anomalies are broadly categorized as vascular tumors or malformations. The tumors include hemangiomas, locally aggressive lesions, and true cancers. Malformations can be isolated disorders of one or more blood vessel types (veins, arteries, capillaries or lymphatics), or they can be one part of syndromic disorders. Lymphedema also falls under the heading of vascular anomalies. To make the terminology less confusing, in 2018 the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies refined its classification scheme.

Vascular malformations are thought to be congenital. Although some are obvious at birth, others aren’t apparent until adulthood. In most cases, they grow with a child and may do so disproportionately at puberty and with pregnancies. The fact that vascular malformations persist into adulthood is one reason why their care should be integral to medical hematology-oncology.

Although the cause of a vascular malformation is not always known, a wide range of genetic mutations thought to be pathogenic have been reported. These mutations are usually somatic (only within the involved tissues, not in the blood or germ cells and therefore, not heritable) and tend to cluster in the VEGF-PIK3CA and RAS-MAP signaling pathways.

These genes and pathways will be familiar to any oncologist who cares for patients with solid tumors, notably breast cancer or melanoma. However, unlike the clonal expansion seen in cancers, most vascular malformations will express pathogenic mutations in less than 20% of vascular endothelium within a malformation.

Since 2008, medical management has been limited to sirolimus (rapamycin), a mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, which can be effective even when mTOR mutations aren’t apparent. In a seminal phase 2 trial of 57 patients with complex vascular anomalies who were aged 0-29 years, 47 patients had a partial response, 3 patients had stable disease, and 7 patients had progressive disease. None had complete responses. These data highlight the need for more effective treatments.

Recently, vascular anomalists have begun to repurpose drugs from adult oncology that specifically target pathogenic mutations. Some studies underway include Novartis’ international Alpelisib (Piqray) clinical trial for adults and children with PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndromes (NCT04589650) and Merck’s follow-up study of the AKT inhibitor miransertib for PROS and Proteus syndrome. Doses tend to be lower than those used to treat cancers. To date, these have been generally well-tolerated, with sometimes striking but preliminary evidence of efficacy.

During the past 2 years, symposia on vascular anomalies at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology have launched what we are hoping is just the start of a broader discussion. In 2020, Fran Blei, MD, chaired Vascular Anomalies 101: Case-Based Discussion on the Diagnosis, Treatment and Lifelong Care of These Patients, and in 2021, Adrienne Hammill, MD, PhD, and Dr. Raj Kasthuri, MBBS, MD, chaired a more specialized symposium: Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT): A Practical Guide to Management.

Dr. Blatt is in the division of pediatric hematology oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Only a small number of pediatric hematologist oncologists and even fewer of our adult counterparts feel comfortable evaluating and treating vascular anomalies.

While admittedly rare, these conditions are still common enough that clinicians in many disciplines encounter them. Hematologist/oncologists are most likely to see vascular malformations, which often present as mass lesions. Complications of these disorders occur across the hematology-oncology spectrum and include clots, pulmonary emboli, cancer predisposition, and an array of functional and psychosocial disorders.

Vascular anomalies are broadly categorized as vascular tumors or malformations. The tumors include hemangiomas, locally aggressive lesions, and true cancers. Malformations can be isolated disorders of one or more blood vessel types (veins, arteries, capillaries or lymphatics), or they can be one part of syndromic disorders. Lymphedema also falls under the heading of vascular anomalies. To make the terminology less confusing, in 2018 the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies refined its classification scheme.

Vascular malformations are thought to be congenital. Although some are obvious at birth, others aren’t apparent until adulthood. In most cases, they grow with a child and may do so disproportionately at puberty and with pregnancies. The fact that vascular malformations persist into adulthood is one reason why their care should be integral to medical hematology-oncology.

Although the cause of a vascular malformation is not always known, a wide range of genetic mutations thought to be pathogenic have been reported. These mutations are usually somatic (only within the involved tissues, not in the blood or germ cells and therefore, not heritable) and tend to cluster in the VEGF-PIK3CA and RAS-MAP signaling pathways.

These genes and pathways will be familiar to any oncologist who cares for patients with solid tumors, notably breast cancer or melanoma. However, unlike the clonal expansion seen in cancers, most vascular malformations will express pathogenic mutations in less than 20% of vascular endothelium within a malformation.

Since 2008, medical management has been limited to sirolimus (rapamycin), a mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, which can be effective even when mTOR mutations aren’t apparent. In a seminal phase 2 trial of 57 patients with complex vascular anomalies who were aged 0-29 years, 47 patients had a partial response, 3 patients had stable disease, and 7 patients had progressive disease. None had complete responses. These data highlight the need for more effective treatments.

Recently, vascular anomalists have begun to repurpose drugs from adult oncology that specifically target pathogenic mutations. Some studies underway include Novartis’ international Alpelisib (Piqray) clinical trial for adults and children with PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndromes (NCT04589650) and Merck’s follow-up study of the AKT inhibitor miransertib for PROS and Proteus syndrome. Doses tend to be lower than those used to treat cancers. To date, these have been generally well-tolerated, with sometimes striking but preliminary evidence of efficacy.

During the past 2 years, symposia on vascular anomalies at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology have launched what we are hoping is just the start of a broader discussion. In 2020, Fran Blei, MD, chaired Vascular Anomalies 101: Case-Based Discussion on the Diagnosis, Treatment and Lifelong Care of These Patients, and in 2021, Adrienne Hammill, MD, PhD, and Dr. Raj Kasthuri, MBBS, MD, chaired a more specialized symposium: Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT): A Practical Guide to Management.

Dr. Blatt is in the division of pediatric hematology oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Only a small number of pediatric hematologist oncologists and even fewer of our adult counterparts feel comfortable evaluating and treating vascular anomalies.

While admittedly rare, these conditions are still common enough that clinicians in many disciplines encounter them. Hematologist/oncologists are most likely to see vascular malformations, which often present as mass lesions. Complications of these disorders occur across the hematology-oncology spectrum and include clots, pulmonary emboli, cancer predisposition, and an array of functional and psychosocial disorders.

Vascular anomalies are broadly categorized as vascular tumors or malformations. The tumors include hemangiomas, locally aggressive lesions, and true cancers. Malformations can be isolated disorders of one or more blood vessel types (veins, arteries, capillaries or lymphatics), or they can be one part of syndromic disorders. Lymphedema also falls under the heading of vascular anomalies. To make the terminology less confusing, in 2018 the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies refined its classification scheme.

Vascular malformations are thought to be congenital. Although some are obvious at birth, others aren’t apparent until adulthood. In most cases, they grow with a child and may do so disproportionately at puberty and with pregnancies. The fact that vascular malformations persist into adulthood is one reason why their care should be integral to medical hematology-oncology.

Although the cause of a vascular malformation is not always known, a wide range of genetic mutations thought to be pathogenic have been reported. These mutations are usually somatic (only within the involved tissues, not in the blood or germ cells and therefore, not heritable) and tend to cluster in the VEGF-PIK3CA and RAS-MAP signaling pathways.

These genes and pathways will be familiar to any oncologist who cares for patients with solid tumors, notably breast cancer or melanoma. However, unlike the clonal expansion seen in cancers, most vascular malformations will express pathogenic mutations in less than 20% of vascular endothelium within a malformation.

Since 2008, medical management has been limited to sirolimus (rapamycin), a mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, which can be effective even when mTOR mutations aren’t apparent. In a seminal phase 2 trial of 57 patients with complex vascular anomalies who were aged 0-29 years, 47 patients had a partial response, 3 patients had stable disease, and 7 patients had progressive disease. None had complete responses. These data highlight the need for more effective treatments.

Recently, vascular anomalists have begun to repurpose drugs from adult oncology that specifically target pathogenic mutations. Some studies underway include Novartis’ international Alpelisib (Piqray) clinical trial for adults and children with PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndromes (NCT04589650) and Merck’s follow-up study of the AKT inhibitor miransertib for PROS and Proteus syndrome. Doses tend to be lower than those used to treat cancers. To date, these have been generally well-tolerated, with sometimes striking but preliminary evidence of efficacy.

During the past 2 years, symposia on vascular anomalies at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology have launched what we are hoping is just the start of a broader discussion. In 2020, Fran Blei, MD, chaired Vascular Anomalies 101: Case-Based Discussion on the Diagnosis, Treatment and Lifelong Care of These Patients, and in 2021, Adrienne Hammill, MD, PhD, and Dr. Raj Kasthuri, MBBS, MD, chaired a more specialized symposium: Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT): A Practical Guide to Management.

Dr. Blatt is in the division of pediatric hematology oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Psychiatrist’s license revoked after alleged sexual assaults

after giving them ketamine and that he had an affair with the sister of another patient.

In its decision, the board stated that the psychiatrist, Cuyler Burns Goodwin, DO, committed gross negligence, violated ethical standards, departed from the standard of care, and was guilty of sexual misconduct.

“Even if one were to believe respondent’s denial of sexual assaults on Patient B and Patient C, his overall course of conduct in committing multiple other ethical violations and violations of the Medical Practice Act in connection with Patient A’s Sister, Patient B, and Patient C; his attitude toward and lack of insight into his offenses; and his lack of candor at hearing demonstrate that revocation of respondent’s license is required for protection of the public,” the board wrote in its March 8 order.

The board seeks to recover almost $65,000 in costs for the investigation, including for legal fees and expert testimony. The psychiatrist is not currently facing any criminal charges.

Family-run business

Dr. Goodwin received his medical license in 2013 and opened Sequoia Mind Health, a practice in Santa Rosa, Calif., soon after completing his residency at the University of California San Francisco, according to the board.

The allegations leading to the revocation of his license occurred at the Sequoia Mind Health practice, a family-run business that employed Dr. Goodwin’s mother as the office manager, his wife as the sole registered nurse, and his sister who worked reception for a time. Dr. Goodwin closed the practice in October 2019.

Until 2020, he worked as an emergency services psychiatrist for Sonoma County Behavioral Health. Other positions included stints at John George Psychiatric Pavilion in San Leandro, at Mendocino County Jail from 2018 to 2021, and at Lake County Jail from 2020 to 2021.

Since closing his practice, he also worked as a psychiatrist for Redwood Quality Management Company in Ukiah, Calif.

The board notified Dr. Goodwin in November 2020 that it was opening an investigation into his conduct.

Affair with patient’s sister

Patient A came to Dr. Goodwin in 2017 as an uninsured, homebound, 24-year-old with schizophrenia. He had not received previous mental health treatment and was entirely dependent on his family because of the severity of his symptoms.

Dr. Goodwin agreed to make home visits to provide medication management and psychotherapy and was paid in cash by the patient’s sister, who was a point of contact for the family.

The sister and Dr. Goodwin developed a friendship and, after commiserating about their troubled marriages, began a sexual relationship in 2018 and decided they would divorce their spouses and marry each other.

However, in November 2018, the sister became pregnant and, at her request, Dr. Goodwin prescribed misoprostol to induce an abortion. The affair and the abortion were later discovered by the sister’s family, who agreed to not file a complaint with the medical board in exchange for Dr. Goodwin’s agreeing to cease communications with the sister.

Nevertheless, the two continued the affair and in February 2019 the patient’s father and mother each separately complained to the medical board. The sister also sent a letter to the board urging against disciplinary action – but later acknowledged that the letter was prepared by Dr. Goodwin.

The family removed Patient A from Dr. Goodwin’s care in 2019. The sister’s relationship with Patient A and her family was damaged; she subsequently divorced her husband and moved out of state. She later told the board she regretted the relationship and knew it was wrong.

When Dr. Goodwin was initially interviewed in 2019 by the medical board, he refused to discuss the relationship or the misoprostol prescription. Then, at a later hearing, he said he did not see anything wrong with the relationship and did not believe it affected the care of Patient A.

The medical board’s expert witness said Dr. Goodwin’s behavior “showed he either had no knowledge of ethical boundaries or chose to ignore them, showing poor judgment and ‘cluelessness’ about the potential adverse effects of having a sexual relationship with Sister, which had the significant potential to compromise Patient A’s treatment.”

Sexual assault

Patient B came to Dr. Goodwin in 2017 to help taper her anxiety and depression medications. She informed him she had experienced multiple sexual assaults. He helped her taper off the drugs within a month and then hired her to work part-time at the practice’s reception desk.

After her symptoms worsened again after a traumatic event, Dr. Goodwin recommended the use of ketamine. Patient B received five ketamine treatments in a month with only Dr. Goodwin present in the room.

During one of those treatments he asked her questions about her sex life. Another night in the office he asked her to have a glass of wine with him and then allegedly sexually assaulted her.

Patient B soon quit the job via text, telling him his behavior was inappropriate. She told Dr. Goodwin she would not say anything about the assault but asked for a letter of recommendation for another job. Dr. Goodwin texted back that she was “100% right,” and he would give her a great recommendation, which he later did.

A year later, in 2019, Pamela Albro, PhD, a psychologist who provided therapy at Sequoia Mind Health, contacted Patient B to ask why she quit.

When Patient B told her about the assault, the therapist asked to share her name with Patient C, who had a similar experience. Patient B agreed and then submitted a police report and a complaint to the medical board in March 2019.

Dr. Goodwin denied Patient B’s allegations and “offered evasive and non-credible testimony” about Patient B’s text messages, the board said.

Another patient-employee

Patient C attended Dr. Goodwin’s clinic in May 2017 after a suicide attempt that required hospitalization. She told Dr. Goodwin she had experienced sexual trauma and assault in the past. Dr. Goodwin referred Patient C to Dr. Albro for therapy, managed her medications himself, and hired her to work at the clinic’s reception desk, even though she was still a patient.

Patient C worked 32 hours a week and took on other duties that included assisting in the administration of transcranial magnetic stimulation to clinic patients.

In late 2017, Dr. Goodwin recommended ketamine for Patient C and she received seven treatments from December 2017 through April 2019. There were no records of vital signs monitoring during the treatments, and Dr. Goodwin’s wife was present for only two sessions.

During the first treatment, where Patient C said she was feeling “out of it,” Dr. Goodwin allegedly sexually assaulted her.

Because of the ketamine, she told the medical board she was unable to speak or yell but said, “I screamed in my head.” After Dr. Goodwin left the room, she said she felt afraid, ashamed, and wanted to go home. Dr. Goodwin walked her to the lobby where her husband was waiting.

The patient did not tell her husband about the assault because she said she felt ashamed, and said she did not report Dr. Goodwin because it was not safe.

Disciplinary hearing

Patient C continued to work for Dr. Goodwin, calling it a confusing time in her life. She later learned about the affair with Patient A’s sister and about Patient B’s experience and resigned from the clinic in July 2019.

She still did not discuss the assault until early 2021 when the board contacted her again. She confided to her primary care physician, who noted that her PTSD symptoms had worsened.

Dr. Goodwin said in the disciplinary hearing that hiring Patient B and Patient C was “boundary crossing,” but he denied allegations of asking inappropriate questions or of sexual assault. The board, however, characterized the testimony of Patient B and Patient C as credible.

All of Dr. Goodwin’s other employers said at his disciplinary hearing that they believed he was a good psychiatrist and that they had never seen any unprofessional behavior.

The revocation of Dr. Goodwin’s license will be effective as of April 7. Dr. Goodwin’s attorney, Marvin H. Firestone, MD, JD, told this news organization he had “no comment” on the medical board’s decision or about his client.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

after giving them ketamine and that he had an affair with the sister of another patient.

In its decision, the board stated that the psychiatrist, Cuyler Burns Goodwin, DO, committed gross negligence, violated ethical standards, departed from the standard of care, and was guilty of sexual misconduct.

“Even if one were to believe respondent’s denial of sexual assaults on Patient B and Patient C, his overall course of conduct in committing multiple other ethical violations and violations of the Medical Practice Act in connection with Patient A’s Sister, Patient B, and Patient C; his attitude toward and lack of insight into his offenses; and his lack of candor at hearing demonstrate that revocation of respondent’s license is required for protection of the public,” the board wrote in its March 8 order.

The board seeks to recover almost $65,000 in costs for the investigation, including for legal fees and expert testimony. The psychiatrist is not currently facing any criminal charges.

Family-run business

Dr. Goodwin received his medical license in 2013 and opened Sequoia Mind Health, a practice in Santa Rosa, Calif., soon after completing his residency at the University of California San Francisco, according to the board.

The allegations leading to the revocation of his license occurred at the Sequoia Mind Health practice, a family-run business that employed Dr. Goodwin’s mother as the office manager, his wife as the sole registered nurse, and his sister who worked reception for a time. Dr. Goodwin closed the practice in October 2019.

Until 2020, he worked as an emergency services psychiatrist for Sonoma County Behavioral Health. Other positions included stints at John George Psychiatric Pavilion in San Leandro, at Mendocino County Jail from 2018 to 2021, and at Lake County Jail from 2020 to 2021.

Since closing his practice, he also worked as a psychiatrist for Redwood Quality Management Company in Ukiah, Calif.

The board notified Dr. Goodwin in November 2020 that it was opening an investigation into his conduct.

Affair with patient’s sister

Patient A came to Dr. Goodwin in 2017 as an uninsured, homebound, 24-year-old with schizophrenia. He had not received previous mental health treatment and was entirely dependent on his family because of the severity of his symptoms.

Dr. Goodwin agreed to make home visits to provide medication management and psychotherapy and was paid in cash by the patient’s sister, who was a point of contact for the family.

The sister and Dr. Goodwin developed a friendship and, after commiserating about their troubled marriages, began a sexual relationship in 2018 and decided they would divorce their spouses and marry each other.

However, in November 2018, the sister became pregnant and, at her request, Dr. Goodwin prescribed misoprostol to induce an abortion. The affair and the abortion were later discovered by the sister’s family, who agreed to not file a complaint with the medical board in exchange for Dr. Goodwin’s agreeing to cease communications with the sister.

Nevertheless, the two continued the affair and in February 2019 the patient’s father and mother each separately complained to the medical board. The sister also sent a letter to the board urging against disciplinary action – but later acknowledged that the letter was prepared by Dr. Goodwin.

The family removed Patient A from Dr. Goodwin’s care in 2019. The sister’s relationship with Patient A and her family was damaged; she subsequently divorced her husband and moved out of state. She later told the board she regretted the relationship and knew it was wrong.

When Dr. Goodwin was initially interviewed in 2019 by the medical board, he refused to discuss the relationship or the misoprostol prescription. Then, at a later hearing, he said he did not see anything wrong with the relationship and did not believe it affected the care of Patient A.

The medical board’s expert witness said Dr. Goodwin’s behavior “showed he either had no knowledge of ethical boundaries or chose to ignore them, showing poor judgment and ‘cluelessness’ about the potential adverse effects of having a sexual relationship with Sister, which had the significant potential to compromise Patient A’s treatment.”

Sexual assault

Patient B came to Dr. Goodwin in 2017 to help taper her anxiety and depression medications. She informed him she had experienced multiple sexual assaults. He helped her taper off the drugs within a month and then hired her to work part-time at the practice’s reception desk.

After her symptoms worsened again after a traumatic event, Dr. Goodwin recommended the use of ketamine. Patient B received five ketamine treatments in a month with only Dr. Goodwin present in the room.

During one of those treatments he asked her questions about her sex life. Another night in the office he asked her to have a glass of wine with him and then allegedly sexually assaulted her.

Patient B soon quit the job via text, telling him his behavior was inappropriate. She told Dr. Goodwin she would not say anything about the assault but asked for a letter of recommendation for another job. Dr. Goodwin texted back that she was “100% right,” and he would give her a great recommendation, which he later did.

A year later, in 2019, Pamela Albro, PhD, a psychologist who provided therapy at Sequoia Mind Health, contacted Patient B to ask why she quit.

When Patient B told her about the assault, the therapist asked to share her name with Patient C, who had a similar experience. Patient B agreed and then submitted a police report and a complaint to the medical board in March 2019.

Dr. Goodwin denied Patient B’s allegations and “offered evasive and non-credible testimony” about Patient B’s text messages, the board said.

Another patient-employee

Patient C attended Dr. Goodwin’s clinic in May 2017 after a suicide attempt that required hospitalization. She told Dr. Goodwin she had experienced sexual trauma and assault in the past. Dr. Goodwin referred Patient C to Dr. Albro for therapy, managed her medications himself, and hired her to work at the clinic’s reception desk, even though she was still a patient.

Patient C worked 32 hours a week and took on other duties that included assisting in the administration of transcranial magnetic stimulation to clinic patients.

In late 2017, Dr. Goodwin recommended ketamine for Patient C and she received seven treatments from December 2017 through April 2019. There were no records of vital signs monitoring during the treatments, and Dr. Goodwin’s wife was present for only two sessions.

During the first treatment, where Patient C said she was feeling “out of it,” Dr. Goodwin allegedly sexually assaulted her.

Because of the ketamine, she told the medical board she was unable to speak or yell but said, “I screamed in my head.” After Dr. Goodwin left the room, she said she felt afraid, ashamed, and wanted to go home. Dr. Goodwin walked her to the lobby where her husband was waiting.

The patient did not tell her husband about the assault because she said she felt ashamed, and said she did not report Dr. Goodwin because it was not safe.

Disciplinary hearing

Patient C continued to work for Dr. Goodwin, calling it a confusing time in her life. She later learned about the affair with Patient A’s sister and about Patient B’s experience and resigned from the clinic in July 2019.

She still did not discuss the assault until early 2021 when the board contacted her again. She confided to her primary care physician, who noted that her PTSD symptoms had worsened.

Dr. Goodwin said in the disciplinary hearing that hiring Patient B and Patient C was “boundary crossing,” but he denied allegations of asking inappropriate questions or of sexual assault. The board, however, characterized the testimony of Patient B and Patient C as credible.

All of Dr. Goodwin’s other employers said at his disciplinary hearing that they believed he was a good psychiatrist and that they had never seen any unprofessional behavior.

The revocation of Dr. Goodwin’s license will be effective as of April 7. Dr. Goodwin’s attorney, Marvin H. Firestone, MD, JD, told this news organization he had “no comment” on the medical board’s decision or about his client.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

after giving them ketamine and that he had an affair with the sister of another patient.

In its decision, the board stated that the psychiatrist, Cuyler Burns Goodwin, DO, committed gross negligence, violated ethical standards, departed from the standard of care, and was guilty of sexual misconduct.

“Even if one were to believe respondent’s denial of sexual assaults on Patient B and Patient C, his overall course of conduct in committing multiple other ethical violations and violations of the Medical Practice Act in connection with Patient A’s Sister, Patient B, and Patient C; his attitude toward and lack of insight into his offenses; and his lack of candor at hearing demonstrate that revocation of respondent’s license is required for protection of the public,” the board wrote in its March 8 order.

The board seeks to recover almost $65,000 in costs for the investigation, including for legal fees and expert testimony. The psychiatrist is not currently facing any criminal charges.

Family-run business

Dr. Goodwin received his medical license in 2013 and opened Sequoia Mind Health, a practice in Santa Rosa, Calif., soon after completing his residency at the University of California San Francisco, according to the board.

The allegations leading to the revocation of his license occurred at the Sequoia Mind Health practice, a family-run business that employed Dr. Goodwin’s mother as the office manager, his wife as the sole registered nurse, and his sister who worked reception for a time. Dr. Goodwin closed the practice in October 2019.

Until 2020, he worked as an emergency services psychiatrist for Sonoma County Behavioral Health. Other positions included stints at John George Psychiatric Pavilion in San Leandro, at Mendocino County Jail from 2018 to 2021, and at Lake County Jail from 2020 to 2021.

Since closing his practice, he also worked as a psychiatrist for Redwood Quality Management Company in Ukiah, Calif.

The board notified Dr. Goodwin in November 2020 that it was opening an investigation into his conduct.

Affair with patient’s sister

Patient A came to Dr. Goodwin in 2017 as an uninsured, homebound, 24-year-old with schizophrenia. He had not received previous mental health treatment and was entirely dependent on his family because of the severity of his symptoms.

Dr. Goodwin agreed to make home visits to provide medication management and psychotherapy and was paid in cash by the patient’s sister, who was a point of contact for the family.

The sister and Dr. Goodwin developed a friendship and, after commiserating about their troubled marriages, began a sexual relationship in 2018 and decided they would divorce their spouses and marry each other.

However, in November 2018, the sister became pregnant and, at her request, Dr. Goodwin prescribed misoprostol to induce an abortion. The affair and the abortion were later discovered by the sister’s family, who agreed to not file a complaint with the medical board in exchange for Dr. Goodwin’s agreeing to cease communications with the sister.

Nevertheless, the two continued the affair and in February 2019 the patient’s father and mother each separately complained to the medical board. The sister also sent a letter to the board urging against disciplinary action – but later acknowledged that the letter was prepared by Dr. Goodwin.

The family removed Patient A from Dr. Goodwin’s care in 2019. The sister’s relationship with Patient A and her family was damaged; she subsequently divorced her husband and moved out of state. She later told the board she regretted the relationship and knew it was wrong.

When Dr. Goodwin was initially interviewed in 2019 by the medical board, he refused to discuss the relationship or the misoprostol prescription. Then, at a later hearing, he said he did not see anything wrong with the relationship and did not believe it affected the care of Patient A.

The medical board’s expert witness said Dr. Goodwin’s behavior “showed he either had no knowledge of ethical boundaries or chose to ignore them, showing poor judgment and ‘cluelessness’ about the potential adverse effects of having a sexual relationship with Sister, which had the significant potential to compromise Patient A’s treatment.”

Sexual assault

Patient B came to Dr. Goodwin in 2017 to help taper her anxiety and depression medications. She informed him she had experienced multiple sexual assaults. He helped her taper off the drugs within a month and then hired her to work part-time at the practice’s reception desk.

After her symptoms worsened again after a traumatic event, Dr. Goodwin recommended the use of ketamine. Patient B received five ketamine treatments in a month with only Dr. Goodwin present in the room.

During one of those treatments he asked her questions about her sex life. Another night in the office he asked her to have a glass of wine with him and then allegedly sexually assaulted her.

Patient B soon quit the job via text, telling him his behavior was inappropriate. She told Dr. Goodwin she would not say anything about the assault but asked for a letter of recommendation for another job. Dr. Goodwin texted back that she was “100% right,” and he would give her a great recommendation, which he later did.

A year later, in 2019, Pamela Albro, PhD, a psychologist who provided therapy at Sequoia Mind Health, contacted Patient B to ask why she quit.

When Patient B told her about the assault, the therapist asked to share her name with Patient C, who had a similar experience. Patient B agreed and then submitted a police report and a complaint to the medical board in March 2019.

Dr. Goodwin denied Patient B’s allegations and “offered evasive and non-credible testimony” about Patient B’s text messages, the board said.

Another patient-employee

Patient C attended Dr. Goodwin’s clinic in May 2017 after a suicide attempt that required hospitalization. She told Dr. Goodwin she had experienced sexual trauma and assault in the past. Dr. Goodwin referred Patient C to Dr. Albro for therapy, managed her medications himself, and hired her to work at the clinic’s reception desk, even though she was still a patient.

Patient C worked 32 hours a week and took on other duties that included assisting in the administration of transcranial magnetic stimulation to clinic patients.

In late 2017, Dr. Goodwin recommended ketamine for Patient C and she received seven treatments from December 2017 through April 2019. There were no records of vital signs monitoring during the treatments, and Dr. Goodwin’s wife was present for only two sessions.

During the first treatment, where Patient C said she was feeling “out of it,” Dr. Goodwin allegedly sexually assaulted her.

Because of the ketamine, she told the medical board she was unable to speak or yell but said, “I screamed in my head.” After Dr. Goodwin left the room, she said she felt afraid, ashamed, and wanted to go home. Dr. Goodwin walked her to the lobby where her husband was waiting.

The patient did not tell her husband about the assault because she said she felt ashamed, and said she did not report Dr. Goodwin because it was not safe.

Disciplinary hearing

Patient C continued to work for Dr. Goodwin, calling it a confusing time in her life. She later learned about the affair with Patient A’s sister and about Patient B’s experience and resigned from the clinic in July 2019.

She still did not discuss the assault until early 2021 when the board contacted her again. She confided to her primary care physician, who noted that her PTSD symptoms had worsened.

Dr. Goodwin said in the disciplinary hearing that hiring Patient B and Patient C was “boundary crossing,” but he denied allegations of asking inappropriate questions or of sexual assault. The board, however, characterized the testimony of Patient B and Patient C as credible.

All of Dr. Goodwin’s other employers said at his disciplinary hearing that they believed he was a good psychiatrist and that they had never seen any unprofessional behavior.

The revocation of Dr. Goodwin’s license will be effective as of April 7. Dr. Goodwin’s attorney, Marvin H. Firestone, MD, JD, told this news organization he had “no comment” on the medical board’s decision or about his client.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

You’re not on a ‘best doctor’ list – does it matter?

Thousands of doctors get a shout out every year when they make the “Top Doctor” lists in various magazines. Some may be your colleagues or competitors. Should you be concerned if you’re not on the list?

Best Doctor lists are clearly popular with readers and make money for the magazines. They can also bring in patient revenue for doctors and their employers who promote them in news releases and on their websites.

For doctors on some of the top lists, the recognition can bring not only patients, but national or international visibility.

While the dollar value is hard to come by, some doctors say that these lists have attracted new patients to their practice.

Sarah St. Louis, MD, a physician manager of Associates in Urogynecology, is one of Orlando Style magazine’s Doctors of the Year and Orlando Family Magazine’s Top Doctors.

Several new patients have told her that they read about her in the magazines’ Top Doctor lists. “Urogynecology is not a well-known specialty – it’s a helpful way to get the word out about the women’s health specialty and what I do,” said Dr. St. Louis, an early career physician who started her practice in 2017.

The additional patient revenue has been worth the cost of displaying her profile in Orlando Style, which was about $800 for a half-page spread with her photo.

Top Doctor lists also work well for specialty practices whose patients can self-refer, such as plastic surgery, dermatology, orthopedics, gastroenterology, and geriatric medicine, said Andrea Eliscu, RN, founder and president of Medical Marketing in Orlando.

Being in a competitive market also matters. If a practice is the only one in town, those doctors may not need the publicity as much as doctors in an urban practice that faces stiff competition.

How do doctors get on these lists?

In most cases, doctors have to be nominated by their peers, a process that some say is flawed because it may shut out doctors who are less popular or well-connected.

Forty-eight regional magazines, including Chicago magazine and Philadelphia Magazine , partner with Castle Connolly to use their online Top Doctor database of more than 61,000 physicians in every major metropolitan area, said Steve Leibforth, managing director of Castle Connolly’s Top Doctors.

The company says it sends annual surveys to tens of thousands of practicing doctors asking them to nominate colleagues in their specialty. The nominated doctors are vetted by Castle Connolly’s physician-led research team on several criteria including professional qualifications, education, hospital and faculty appointments, research leadership, professional reputation and disciplinary history, and outcomes data when available, said Mr. Leibforth.

Washingtonian magazine says it sends annual online surveys to 13,500 physicians in the DC metro area asking them to nominate one colleague in their specialty. The top vote-getters in each of 39 categories are designated Top Doctors.

Orlando Family Magazine says its annual Top Doctor selections are based on reader polls and doctor nominations.

Consumers’ Research Council of America uses a point system based on each year the doctor has been in practice, education and continuing education, board certification, and membership in professional medical societies.

Doctors have many ways to promote that they’re listed as a “top” doctor. Dr. St. Louis takes advantage of the magazine’s free reprints, which she puts in her waiting room.

Others buy plaques to hang up in their waiting rooms or offices and announce the distinction on their websites, blogs, or social media. “They have to maximize the magazine distinction or it’s worthless,” said Ms. Eliscu.

Employers also like to spread the word when their doctors make it on “Top Doctor” lists.

“With Emory physicians making up nearly 50 percent of the list, that’s more than any other health system in Atlanta,” said an Emory University press release after nearly half of the university’s doctors made the Top Doctors list in Atlanta magazine.

Patients may be impressed: What about your peers?

Dr. St. Louis said that making some of these lists is less impressive than having a peer-reviewed journal article or receiving professional awards.

“Just because a physician is listed in a magazine as a ‘top doctor’ does not mean they are the best. There are far more medical, clinical, and scientific points to consider than just a pretty picture in a style magazine,” she said.

Wanda Filer, MD, MBA, who practiced family medicine until last year when she became chief medical officer for VaxCare in Orlando, said she ignores the many congratulatory letters in the mail announcing that she’s made one list or another.

“I don’t put much credence in the lists. I get notifications fairly often, and to me it always looks like they’re trying to sell a plaque. I’d rather let my work speak for itself.”

Arlen Meyers, MD, MBA, president and CEO of the Society of Physician Entrepreneurs and a paid strategic adviser to RYTE, a data-driven site for “best doctors” and “best hospitals,” said he received several of these “top doctor” awards when he was a professor of otolaryngology at the University of Colorado.

He has been critical of these awards for some time. “These doctor beauty pageants may be good for business but have little value for patients.”

He would like to see a new approach that is driven by data and what patients value. “If I have a lump in my thyroid, I want to know the best doctor to treat me based on outcomes data.”

He said a good rating system would include a data-driven approach based on treatment outcomes, publicly available data, price transparency, and patient values.

Whether a physician feels honored to be named a top physician or sees little value in it, most doctors are aware of the list’s marketing value for their practices and many choose to make use of it.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Thousands of doctors get a shout out every year when they make the “Top Doctor” lists in various magazines. Some may be your colleagues or competitors. Should you be concerned if you’re not on the list?

Best Doctor lists are clearly popular with readers and make money for the magazines. They can also bring in patient revenue for doctors and their employers who promote them in news releases and on their websites.

For doctors on some of the top lists, the recognition can bring not only patients, but national or international visibility.

While the dollar value is hard to come by, some doctors say that these lists have attracted new patients to their practice.

Sarah St. Louis, MD, a physician manager of Associates in Urogynecology, is one of Orlando Style magazine’s Doctors of the Year and Orlando Family Magazine’s Top Doctors.

Several new patients have told her that they read about her in the magazines’ Top Doctor lists. “Urogynecology is not a well-known specialty – it’s a helpful way to get the word out about the women’s health specialty and what I do,” said Dr. St. Louis, an early career physician who started her practice in 2017.

The additional patient revenue has been worth the cost of displaying her profile in Orlando Style, which was about $800 for a half-page spread with her photo.

Top Doctor lists also work well for specialty practices whose patients can self-refer, such as plastic surgery, dermatology, orthopedics, gastroenterology, and geriatric medicine, said Andrea Eliscu, RN, founder and president of Medical Marketing in Orlando.

Being in a competitive market also matters. If a practice is the only one in town, those doctors may not need the publicity as much as doctors in an urban practice that faces stiff competition.

How do doctors get on these lists?

In most cases, doctors have to be nominated by their peers, a process that some say is flawed because it may shut out doctors who are less popular or well-connected.

Forty-eight regional magazines, including Chicago magazine and Philadelphia Magazine , partner with Castle Connolly to use their online Top Doctor database of more than 61,000 physicians in every major metropolitan area, said Steve Leibforth, managing director of Castle Connolly’s Top Doctors.

The company says it sends annual surveys to tens of thousands of practicing doctors asking them to nominate colleagues in their specialty. The nominated doctors are vetted by Castle Connolly’s physician-led research team on several criteria including professional qualifications, education, hospital and faculty appointments, research leadership, professional reputation and disciplinary history, and outcomes data when available, said Mr. Leibforth.

Washingtonian magazine says it sends annual online surveys to 13,500 physicians in the DC metro area asking them to nominate one colleague in their specialty. The top vote-getters in each of 39 categories are designated Top Doctors.

Orlando Family Magazine says its annual Top Doctor selections are based on reader polls and doctor nominations.

Consumers’ Research Council of America uses a point system based on each year the doctor has been in practice, education and continuing education, board certification, and membership in professional medical societies.

Doctors have many ways to promote that they’re listed as a “top” doctor. Dr. St. Louis takes advantage of the magazine’s free reprints, which she puts in her waiting room.

Others buy plaques to hang up in their waiting rooms or offices and announce the distinction on their websites, blogs, or social media. “They have to maximize the magazine distinction or it’s worthless,” said Ms. Eliscu.

Employers also like to spread the word when their doctors make it on “Top Doctor” lists.

“With Emory physicians making up nearly 50 percent of the list, that’s more than any other health system in Atlanta,” said an Emory University press release after nearly half of the university’s doctors made the Top Doctors list in Atlanta magazine.

Patients may be impressed: What about your peers?

Dr. St. Louis said that making some of these lists is less impressive than having a peer-reviewed journal article or receiving professional awards.

“Just because a physician is listed in a magazine as a ‘top doctor’ does not mean they are the best. There are far more medical, clinical, and scientific points to consider than just a pretty picture in a style magazine,” she said.

Wanda Filer, MD, MBA, who practiced family medicine until last year when she became chief medical officer for VaxCare in Orlando, said she ignores the many congratulatory letters in the mail announcing that she’s made one list or another.

“I don’t put much credence in the lists. I get notifications fairly often, and to me it always looks like they’re trying to sell a plaque. I’d rather let my work speak for itself.”

Arlen Meyers, MD, MBA, president and CEO of the Society of Physician Entrepreneurs and a paid strategic adviser to RYTE, a data-driven site for “best doctors” and “best hospitals,” said he received several of these “top doctor” awards when he was a professor of otolaryngology at the University of Colorado.

He has been critical of these awards for some time. “These doctor beauty pageants may be good for business but have little value for patients.”

He would like to see a new approach that is driven by data and what patients value. “If I have a lump in my thyroid, I want to know the best doctor to treat me based on outcomes data.”

He said a good rating system would include a data-driven approach based on treatment outcomes, publicly available data, price transparency, and patient values.

Whether a physician feels honored to be named a top physician or sees little value in it, most doctors are aware of the list’s marketing value for their practices and many choose to make use of it.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Thousands of doctors get a shout out every year when they make the “Top Doctor” lists in various magazines. Some may be your colleagues or competitors. Should you be concerned if you’re not on the list?

Best Doctor lists are clearly popular with readers and make money for the magazines. They can also bring in patient revenue for doctors and their employers who promote them in news releases and on their websites.

For doctors on some of the top lists, the recognition can bring not only patients, but national or international visibility.

While the dollar value is hard to come by, some doctors say that these lists have attracted new patients to their practice.

Sarah St. Louis, MD, a physician manager of Associates in Urogynecology, is one of Orlando Style magazine’s Doctors of the Year and Orlando Family Magazine’s Top Doctors.

Several new patients have told her that they read about her in the magazines’ Top Doctor lists. “Urogynecology is not a well-known specialty – it’s a helpful way to get the word out about the women’s health specialty and what I do,” said Dr. St. Louis, an early career physician who started her practice in 2017.

The additional patient revenue has been worth the cost of displaying her profile in Orlando Style, which was about $800 for a half-page spread with her photo.

Top Doctor lists also work well for specialty practices whose patients can self-refer, such as plastic surgery, dermatology, orthopedics, gastroenterology, and geriatric medicine, said Andrea Eliscu, RN, founder and president of Medical Marketing in Orlando.

Being in a competitive market also matters. If a practice is the only one in town, those doctors may not need the publicity as much as doctors in an urban practice that faces stiff competition.

How do doctors get on these lists?

In most cases, doctors have to be nominated by their peers, a process that some say is flawed because it may shut out doctors who are less popular or well-connected.

Forty-eight regional magazines, including Chicago magazine and Philadelphia Magazine , partner with Castle Connolly to use their online Top Doctor database of more than 61,000 physicians in every major metropolitan area, said Steve Leibforth, managing director of Castle Connolly’s Top Doctors.

The company says it sends annual surveys to tens of thousands of practicing doctors asking them to nominate colleagues in their specialty. The nominated doctors are vetted by Castle Connolly’s physician-led research team on several criteria including professional qualifications, education, hospital and faculty appointments, research leadership, professional reputation and disciplinary history, and outcomes data when available, said Mr. Leibforth.

Washingtonian magazine says it sends annual online surveys to 13,500 physicians in the DC metro area asking them to nominate one colleague in their specialty. The top vote-getters in each of 39 categories are designated Top Doctors.

Orlando Family Magazine says its annual Top Doctor selections are based on reader polls and doctor nominations.

Consumers’ Research Council of America uses a point system based on each year the doctor has been in practice, education and continuing education, board certification, and membership in professional medical societies.

Doctors have many ways to promote that they’re listed as a “top” doctor. Dr. St. Louis takes advantage of the magazine’s free reprints, which she puts in her waiting room.

Others buy plaques to hang up in their waiting rooms or offices and announce the distinction on their websites, blogs, or social media. “They have to maximize the magazine distinction or it’s worthless,” said Ms. Eliscu.

Employers also like to spread the word when their doctors make it on “Top Doctor” lists.

“With Emory physicians making up nearly 50 percent of the list, that’s more than any other health system in Atlanta,” said an Emory University press release after nearly half of the university’s doctors made the Top Doctors list in Atlanta magazine.

Patients may be impressed: What about your peers?

Dr. St. Louis said that making some of these lists is less impressive than having a peer-reviewed journal article or receiving professional awards.

“Just because a physician is listed in a magazine as a ‘top doctor’ does not mean they are the best. There are far more medical, clinical, and scientific points to consider than just a pretty picture in a style magazine,” she said.

Wanda Filer, MD, MBA, who practiced family medicine until last year when she became chief medical officer for VaxCare in Orlando, said she ignores the many congratulatory letters in the mail announcing that she’s made one list or another.

“I don’t put much credence in the lists. I get notifications fairly often, and to me it always looks like they’re trying to sell a plaque. I’d rather let my work speak for itself.”

Arlen Meyers, MD, MBA, president and CEO of the Society of Physician Entrepreneurs and a paid strategic adviser to RYTE, a data-driven site for “best doctors” and “best hospitals,” said he received several of these “top doctor” awards when he was a professor of otolaryngology at the University of Colorado.

He has been critical of these awards for some time. “These doctor beauty pageants may be good for business but have little value for patients.”

He would like to see a new approach that is driven by data and what patients value. “If I have a lump in my thyroid, I want to know the best doctor to treat me based on outcomes data.”

He said a good rating system would include a data-driven approach based on treatment outcomes, publicly available data, price transparency, and patient values.

Whether a physician feels honored to be named a top physician or sees little value in it, most doctors are aware of the list’s marketing value for their practices and many choose to make use of it.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Will we ever outgrow the Goldwater rule?

Since it appeared in the first edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Principles of Medical Ethics in 1973, the “Goldwater rule” – often referred to in terms of where in the APA’s guideline it can be found, Section 7.3 – has placed a stringent prohibition on psychiatrists offering professional opinions about public figures “unless he or she has conducted an examination and has been granted proper authorization for such a statement.”1

Some psychiatrists experienced the restrictive nature of Section 7.3 more acutely perhaps than ever during the Trump presidency. This spurred numerous articles criticizing the guideline as an outdated “gag rule”2 that harms the public image of psychiatry.3 Some psychiatrists violated the rule to warn the public of the dangers of a president with “incipient dementia”4 occupying the most powerful position on earth.

Following President Trump’s exit from the White House, the alarm bells surrounding his presidency have quieted. Criticisms of the Goldwater rule, on the other hand, have persisted. Many of these criticisms now call for the rule to be refined, allowing for psychiatrists to give their professional opinions about public figures, but with certain guidelines on how to do so.5 Few have yet to make a sober case for the outright abolition of Section 7.3.6

Self-regulating and internal policing are important factors in the continued independence of the medical profession, and we should continue to hold each other to high professional standards. That being said, do psychiatrists need training wheels to prevent us from devolving into unprofessional social commentators? Other medical specialties do not see the need to implement a rule preventing their colleagues from expressing expertise in fear of embarrassment. Do we not have faith in our ability to conduct ourselves professionally? Is the Goldwater rule an admission of a juvenile lack of self-control within our field?

Not only do other medical specialties not forcibly handhold their members in public settings, but other “providers” in the realm of mental health likewise do not implement such strict self-restraints. Psychiatry staying silent on the matter of public figures leaves a void filled by other, arguably less qualified, individuals. Subsequently, the public discord risks being flooded with pseudoscientific pontification and distorted views of psychiatric illness. The cycle of speculating on the mental fitness of the president has outlived President Trump, with concerns about Joe Biden’s incoherence and waning cognition.7 Therein is an important argument to be made for the public duty of psychiatrists, with their greater expertise and clinical acumen, to weigh in on matters of societal importance in an attempt to dispel dangerous misconceptions.

Practical limitations are often raised and serve as the cornerstone for the Goldwater rule. Specifically, the limitation being that a psychiatrist cannot provide a professional opinion about an individual without a proper in-person evaluation. The psychiatric interview could be considered the most in-depth and comprehensive evaluation in all of medicine. Even so, is a trained psychiatrist presented with grandiosity, flight-of-ideas, and pressured speech unable to comment on the possibility of mania without a lengthy and comprehensive evaluation? How much disorganization of behavior and dialogue does one need to observe to recognize psychosis? For the experienced psychiatrist, many of these behavioral hallmarks are akin to an ST elevation on an EKG representing a heart attack.

When considering less extreme examples of mental affliction, such as depression and anxiety, many signs – including demeanor, motor activity, manner of speaking, and other aspects of behavior – are apparent to the perceptive psychiatrist without needing an extensive interview that dives into the depths of a person’s social history and childhood. After all, our own criteria for depression and mania do not require the presence of social stressors or childhood trauma. Even personality disorders can be reasonably postulated when a person behaves in a particular fashion. The recognition of transitional objects, items used to provide psychological comfort, including the “teddy bear sign” are common and scientifically studied methods to recognize personality disorder.8