User login

Rethinking your journey to work every day

Burnout is seldom the result of a single factor. It is more often a tragic case of death by a thousand cuts: a balky user-unfriendly electronic medical record system, administrative pressure to see more patients and the resulting frustration of not being able to provide the care you feel they deserve, an overemphasis on documentation or you won’t get paid, the dark cloud of malpractice always overhead, and of course the difficult balance between family responsibilities and work. It often boils down to feeling that there aren’t enough hours in the day to get everything done and still have time to recharge your physical and psychological batteries.

A recent report in the Harvard Business School newsletter, Working Knowledge (“Commuting Hurts Productivity and Your Best Talent Suffers Most.” Lane Lambert. 2021 Mar 30) describes an interesting study by Andy Wu, assistant professor of business administration, in which he discovered that, for every 10 kilometers of commuting distance, there was a decrease in the productivity of high-tech inventors as measured by the number of patents registered by their companies. The quality of their inventions declined even more (7%) for each additional 10 kilometers of commute.

You might question the relevance of these findings with your work in an outpatient clinic, but a conscientious physician is also an inventor and a creator. Every patient, even those with what sounds like a routine complaint, presents a novel collection of management challenges. The best physicians treat their profession as an art and must be invent solutions on the fly.

There is abundant evidence that commuting also can have a negative effect on the physical and mental health of workers. (“The astonishing human potential wasted on commutes.” The Washington Post .Christopher Ingraham. 2016 Feb 25). Watching my father walk into the house after an hour-long train ride out of the city and listening to him grumble created an image that influenced every decision I made about where my wife and I would live and work.

Did I benefit from the luxury of growing up in a small suburban community? Of course I did and I shall be forever grateful for the sacrifice my father made to allow that to happen. But, I promised myself that, while I would make sacrifices for my family, a long or unpleasant commute was not going to be on that list. For a few years I tolerated a 10- to 12-minute car commute (three stoplights) but asked to dissolve the partnership because even that 9-mile ride was too much for me and instead spent the bulk of my 40-year career a 10-minute bike ride from my office and the two hospitals. It meant we didn’t have a view of the ocean or a gentleman’s farm but we had an extra hour together as a family and I arrived at work and at home happy.

The pandemic has been a wake-up call for many of the fortunate folks who have found that they can work from home, eliminating what may have been a time-gobbling commute that was creating more stress than they may have realized. Even if telemedicine continues to maintain some postpandemic presence, I suspect that most physicians will continue to be faced with the challenge of traveling to an office or hospital.

If work is losing some of its luster and/or you are arriving home grumpy from a long day in the office, it is easy to blame an insensitive office administrator or the clunky electronic medical record system ... they deserve it. But, it may be the journey and not just the destination that is the contributing to the problem. I realize that rethinking the decision about where one lives can be painful and the options may be limited. However, I hope that at least some of you can rethink the role your journey is playing in your life.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Burnout is seldom the result of a single factor. It is more often a tragic case of death by a thousand cuts: a balky user-unfriendly electronic medical record system, administrative pressure to see more patients and the resulting frustration of not being able to provide the care you feel they deserve, an overemphasis on documentation or you won’t get paid, the dark cloud of malpractice always overhead, and of course the difficult balance between family responsibilities and work. It often boils down to feeling that there aren’t enough hours in the day to get everything done and still have time to recharge your physical and psychological batteries.

A recent report in the Harvard Business School newsletter, Working Knowledge (“Commuting Hurts Productivity and Your Best Talent Suffers Most.” Lane Lambert. 2021 Mar 30) describes an interesting study by Andy Wu, assistant professor of business administration, in which he discovered that, for every 10 kilometers of commuting distance, there was a decrease in the productivity of high-tech inventors as measured by the number of patents registered by their companies. The quality of their inventions declined even more (7%) for each additional 10 kilometers of commute.

You might question the relevance of these findings with your work in an outpatient clinic, but a conscientious physician is also an inventor and a creator. Every patient, even those with what sounds like a routine complaint, presents a novel collection of management challenges. The best physicians treat their profession as an art and must be invent solutions on the fly.

There is abundant evidence that commuting also can have a negative effect on the physical and mental health of workers. (“The astonishing human potential wasted on commutes.” The Washington Post .Christopher Ingraham. 2016 Feb 25). Watching my father walk into the house after an hour-long train ride out of the city and listening to him grumble created an image that influenced every decision I made about where my wife and I would live and work.

Did I benefit from the luxury of growing up in a small suburban community? Of course I did and I shall be forever grateful for the sacrifice my father made to allow that to happen. But, I promised myself that, while I would make sacrifices for my family, a long or unpleasant commute was not going to be on that list. For a few years I tolerated a 10- to 12-minute car commute (three stoplights) but asked to dissolve the partnership because even that 9-mile ride was too much for me and instead spent the bulk of my 40-year career a 10-minute bike ride from my office and the two hospitals. It meant we didn’t have a view of the ocean or a gentleman’s farm but we had an extra hour together as a family and I arrived at work and at home happy.

The pandemic has been a wake-up call for many of the fortunate folks who have found that they can work from home, eliminating what may have been a time-gobbling commute that was creating more stress than they may have realized. Even if telemedicine continues to maintain some postpandemic presence, I suspect that most physicians will continue to be faced with the challenge of traveling to an office or hospital.

If work is losing some of its luster and/or you are arriving home grumpy from a long day in the office, it is easy to blame an insensitive office administrator or the clunky electronic medical record system ... they deserve it. But, it may be the journey and not just the destination that is the contributing to the problem. I realize that rethinking the decision about where one lives can be painful and the options may be limited. However, I hope that at least some of you can rethink the role your journey is playing in your life.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Burnout is seldom the result of a single factor. It is more often a tragic case of death by a thousand cuts: a balky user-unfriendly electronic medical record system, administrative pressure to see more patients and the resulting frustration of not being able to provide the care you feel they deserve, an overemphasis on documentation or you won’t get paid, the dark cloud of malpractice always overhead, and of course the difficult balance between family responsibilities and work. It often boils down to feeling that there aren’t enough hours in the day to get everything done and still have time to recharge your physical and psychological batteries.

A recent report in the Harvard Business School newsletter, Working Knowledge (“Commuting Hurts Productivity and Your Best Talent Suffers Most.” Lane Lambert. 2021 Mar 30) describes an interesting study by Andy Wu, assistant professor of business administration, in which he discovered that, for every 10 kilometers of commuting distance, there was a decrease in the productivity of high-tech inventors as measured by the number of patents registered by their companies. The quality of their inventions declined even more (7%) for each additional 10 kilometers of commute.

You might question the relevance of these findings with your work in an outpatient clinic, but a conscientious physician is also an inventor and a creator. Every patient, even those with what sounds like a routine complaint, presents a novel collection of management challenges. The best physicians treat their profession as an art and must be invent solutions on the fly.

There is abundant evidence that commuting also can have a negative effect on the physical and mental health of workers. (“The astonishing human potential wasted on commutes.” The Washington Post .Christopher Ingraham. 2016 Feb 25). Watching my father walk into the house after an hour-long train ride out of the city and listening to him grumble created an image that influenced every decision I made about where my wife and I would live and work.

Did I benefit from the luxury of growing up in a small suburban community? Of course I did and I shall be forever grateful for the sacrifice my father made to allow that to happen. But, I promised myself that, while I would make sacrifices for my family, a long or unpleasant commute was not going to be on that list. For a few years I tolerated a 10- to 12-minute car commute (three stoplights) but asked to dissolve the partnership because even that 9-mile ride was too much for me and instead spent the bulk of my 40-year career a 10-minute bike ride from my office and the two hospitals. It meant we didn’t have a view of the ocean or a gentleman’s farm but we had an extra hour together as a family and I arrived at work and at home happy.

The pandemic has been a wake-up call for many of the fortunate folks who have found that they can work from home, eliminating what may have been a time-gobbling commute that was creating more stress than they may have realized. Even if telemedicine continues to maintain some postpandemic presence, I suspect that most physicians will continue to be faced with the challenge of traveling to an office or hospital.

If work is losing some of its luster and/or you are arriving home grumpy from a long day in the office, it is easy to blame an insensitive office administrator or the clunky electronic medical record system ... they deserve it. But, it may be the journey and not just the destination that is the contributing to the problem. I realize that rethinking the decision about where one lives can be painful and the options may be limited. However, I hope that at least some of you can rethink the role your journey is playing in your life.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Sealing the envelope

Mike died last week.

He was a long-retired doc, in his mid-90s. One of my favorite patients to just chat with about nothing in particular. I learned more from him about restoring old grandfather clocks than I ever dreamed I’d know.

After receiving the sad news, I sat down, as I often do, to write a letter to his family. After 23 years I have a pretty standard idea of what I want to say, but it still always takes some thought.

Sealing the envelopes on these letters always seems to be more than just paperwork. There’s a symbolism to it, that I’m closing out my relationship, sometimes of 10-20 years, with the person involved.

Some patients become friends after a time. It’s a matter of chemistry. I don’t socialize with them outside my office, but still enjoy seeing them and talking about nonmedical stuff in the space around clinical questions and answers. They’re the ones it’s hardest to say goodbye to.

I’ll miss my 2-3 visits a year with Mike. We swapped medical war stories, family anecdotes, and the occasional tip about clock restoration that I’ll probably never use (but who knows, he didn’t start until after he retired).

Closing the envelope comes with the realization that I won’t be seeing him again. I don’t go to patient funerals, as I believe those are for families and close friends, and so writing the letter is the closest I’ll get to saying goodbye.

Medicine, and how we practice, is focused on what we do for the patient – which is what it should be.

But lost in the shuffle sometimes is realizing what the patient does for us. That’s also important, but harder to quantify. And sometimes we don’t realize it until we seal the envelope.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Mike died last week.

He was a long-retired doc, in his mid-90s. One of my favorite patients to just chat with about nothing in particular. I learned more from him about restoring old grandfather clocks than I ever dreamed I’d know.

After receiving the sad news, I sat down, as I often do, to write a letter to his family. After 23 years I have a pretty standard idea of what I want to say, but it still always takes some thought.

Sealing the envelopes on these letters always seems to be more than just paperwork. There’s a symbolism to it, that I’m closing out my relationship, sometimes of 10-20 years, with the person involved.

Some patients become friends after a time. It’s a matter of chemistry. I don’t socialize with them outside my office, but still enjoy seeing them and talking about nonmedical stuff in the space around clinical questions and answers. They’re the ones it’s hardest to say goodbye to.

I’ll miss my 2-3 visits a year with Mike. We swapped medical war stories, family anecdotes, and the occasional tip about clock restoration that I’ll probably never use (but who knows, he didn’t start until after he retired).

Closing the envelope comes with the realization that I won’t be seeing him again. I don’t go to patient funerals, as I believe those are for families and close friends, and so writing the letter is the closest I’ll get to saying goodbye.

Medicine, and how we practice, is focused on what we do for the patient – which is what it should be.

But lost in the shuffle sometimes is realizing what the patient does for us. That’s also important, but harder to quantify. And sometimes we don’t realize it until we seal the envelope.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Mike died last week.

He was a long-retired doc, in his mid-90s. One of my favorite patients to just chat with about nothing in particular. I learned more from him about restoring old grandfather clocks than I ever dreamed I’d know.

After receiving the sad news, I sat down, as I often do, to write a letter to his family. After 23 years I have a pretty standard idea of what I want to say, but it still always takes some thought.

Sealing the envelopes on these letters always seems to be more than just paperwork. There’s a symbolism to it, that I’m closing out my relationship, sometimes of 10-20 years, with the person involved.

Some patients become friends after a time. It’s a matter of chemistry. I don’t socialize with them outside my office, but still enjoy seeing them and talking about nonmedical stuff in the space around clinical questions and answers. They’re the ones it’s hardest to say goodbye to.

I’ll miss my 2-3 visits a year with Mike. We swapped medical war stories, family anecdotes, and the occasional tip about clock restoration that I’ll probably never use (but who knows, he didn’t start until after he retired).

Closing the envelope comes with the realization that I won’t be seeing him again. I don’t go to patient funerals, as I believe those are for families and close friends, and so writing the letter is the closest I’ll get to saying goodbye.

Medicine, and how we practice, is focused on what we do for the patient – which is what it should be.

But lost in the shuffle sometimes is realizing what the patient does for us. That’s also important, but harder to quantify. And sometimes we don’t realize it until we seal the envelope.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Garbage out: How much trash does a Mohs surgery practice produce?

left behind after surgical procedures. Their findings: Just two physicians – a surgeon and a surgical fellow – manage to produce nearly a ton of noncontaminated surgical waste annually even though they only see patients twice a week.

“While our emissions as Mohs surgeons are relatively small compared to other types of surgeries, we still emit a notable amount of greenhouse gases compared to nonmedical fields. Mohs surgeons tend to produce the most noncontaminated waste versus other categories, and that’s the category that could be most recyclable,” said Mohs surgeon Simon S. Yoo, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, who presented the results at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

Dr. Yoo, who spoke in an interview, said the coronavirus pandemic spurred the waste analysis. “In the past year, there seemed to be many questions as to the environmental causes and impacts of the pandemic,” he said. “We decided to investigate the environmental impact of Mohs surgery.”

He and surgical fellow Alvin Li, MD, analyzed all waste produced by their clinic over a 3-week period when 106 procedures were performed. They discovered that the surgeries produced 25.8 kg of biohazardous waste (29%), 2.2 kg of packaging waste (3%), 56.4 kg of noncontaminated waste (63%), and 7.5 kg of sharps waste (8%).

“The majority of the waste we produced was noncontaminated and possibly recyclable,” Dr. Yoo said. “However, most of this waste and its packaging did not have clear recycling instructions and presented a significant barrier to recycling by our staff.”

The study authors extrapolated the waste amount to annual totals of 413.5 kg of biohazardous waste, 34.9 kg of packaging waste, 902.3 kg of noncontaminated waste, and 119.9 kg of sharps waste. That adds up to 1,471 kg. The total of noncontaminated waste is the equivalent of nearly 2,000 pounds – a ton.

Dr. Yoo and Dr. Li estimate that the waste produced annual emissions equal to 6.5 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent. They estimate that the amount of emissions produced by Mohs surgeons nationally each year is 7,592 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent, equal to emissions produced by 19 million miles of passenger automobile travel.

Still, Dr. Yoo said, Mohs surgeries appear to produce fewer emissions than some other operations. “We estimate that an individual Mohs procedure generates around 10 kg of carbon dioxide equivalent whereas a single hysterectomy generates about 380 kg; much of this is due to the use of volatile anesthetics.”

Environmental protection advocate Mary Maloney, MD, professor of medicine and director of dermatologic surgery at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, urged colleagues to launch a similar waste-weighing project in their own clinics. “I challenge dermatologists to take a bag of your daily plastic waste and weigh it,” she said. “We’ll all be astounded by how much we throw away each day. Until you do that experiment yourself, you’ll have a hard time getting your arms around how much plastic we’re using.”

Dr. Maloney, a member of the American Academy of Dermatology Expert Resource Group for Climate Change and Environmental Issues, urged colleagues to consider strategies to reduce plastic use specifically. “Look at everything you use and see if there’s a nonplastic equivalent,” she said. Even reducing the use of plastic writing pens can make a difference, she said, as can cutting back on syringes and revising procedures so gloves don’t have to be changed as often.

No study funding was reported. Dr. Yoo and Dr. Maloney report no disclosures.

left behind after surgical procedures. Their findings: Just two physicians – a surgeon and a surgical fellow – manage to produce nearly a ton of noncontaminated surgical waste annually even though they only see patients twice a week.

“While our emissions as Mohs surgeons are relatively small compared to other types of surgeries, we still emit a notable amount of greenhouse gases compared to nonmedical fields. Mohs surgeons tend to produce the most noncontaminated waste versus other categories, and that’s the category that could be most recyclable,” said Mohs surgeon Simon S. Yoo, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, who presented the results at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

Dr. Yoo, who spoke in an interview, said the coronavirus pandemic spurred the waste analysis. “In the past year, there seemed to be many questions as to the environmental causes and impacts of the pandemic,” he said. “We decided to investigate the environmental impact of Mohs surgery.”

He and surgical fellow Alvin Li, MD, analyzed all waste produced by their clinic over a 3-week period when 106 procedures were performed. They discovered that the surgeries produced 25.8 kg of biohazardous waste (29%), 2.2 kg of packaging waste (3%), 56.4 kg of noncontaminated waste (63%), and 7.5 kg of sharps waste (8%).

“The majority of the waste we produced was noncontaminated and possibly recyclable,” Dr. Yoo said. “However, most of this waste and its packaging did not have clear recycling instructions and presented a significant barrier to recycling by our staff.”

The study authors extrapolated the waste amount to annual totals of 413.5 kg of biohazardous waste, 34.9 kg of packaging waste, 902.3 kg of noncontaminated waste, and 119.9 kg of sharps waste. That adds up to 1,471 kg. The total of noncontaminated waste is the equivalent of nearly 2,000 pounds – a ton.

Dr. Yoo and Dr. Li estimate that the waste produced annual emissions equal to 6.5 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent. They estimate that the amount of emissions produced by Mohs surgeons nationally each year is 7,592 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent, equal to emissions produced by 19 million miles of passenger automobile travel.

Still, Dr. Yoo said, Mohs surgeries appear to produce fewer emissions than some other operations. “We estimate that an individual Mohs procedure generates around 10 kg of carbon dioxide equivalent whereas a single hysterectomy generates about 380 kg; much of this is due to the use of volatile anesthetics.”

Environmental protection advocate Mary Maloney, MD, professor of medicine and director of dermatologic surgery at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, urged colleagues to launch a similar waste-weighing project in their own clinics. “I challenge dermatologists to take a bag of your daily plastic waste and weigh it,” she said. “We’ll all be astounded by how much we throw away each day. Until you do that experiment yourself, you’ll have a hard time getting your arms around how much plastic we’re using.”

Dr. Maloney, a member of the American Academy of Dermatology Expert Resource Group for Climate Change and Environmental Issues, urged colleagues to consider strategies to reduce plastic use specifically. “Look at everything you use and see if there’s a nonplastic equivalent,” she said. Even reducing the use of plastic writing pens can make a difference, she said, as can cutting back on syringes and revising procedures so gloves don’t have to be changed as often.

No study funding was reported. Dr. Yoo and Dr. Maloney report no disclosures.

left behind after surgical procedures. Their findings: Just two physicians – a surgeon and a surgical fellow – manage to produce nearly a ton of noncontaminated surgical waste annually even though they only see patients twice a week.

“While our emissions as Mohs surgeons are relatively small compared to other types of surgeries, we still emit a notable amount of greenhouse gases compared to nonmedical fields. Mohs surgeons tend to produce the most noncontaminated waste versus other categories, and that’s the category that could be most recyclable,” said Mohs surgeon Simon S. Yoo, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, who presented the results at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

Dr. Yoo, who spoke in an interview, said the coronavirus pandemic spurred the waste analysis. “In the past year, there seemed to be many questions as to the environmental causes and impacts of the pandemic,” he said. “We decided to investigate the environmental impact of Mohs surgery.”

He and surgical fellow Alvin Li, MD, analyzed all waste produced by their clinic over a 3-week period when 106 procedures were performed. They discovered that the surgeries produced 25.8 kg of biohazardous waste (29%), 2.2 kg of packaging waste (3%), 56.4 kg of noncontaminated waste (63%), and 7.5 kg of sharps waste (8%).

“The majority of the waste we produced was noncontaminated and possibly recyclable,” Dr. Yoo said. “However, most of this waste and its packaging did not have clear recycling instructions and presented a significant barrier to recycling by our staff.”

The study authors extrapolated the waste amount to annual totals of 413.5 kg of biohazardous waste, 34.9 kg of packaging waste, 902.3 kg of noncontaminated waste, and 119.9 kg of sharps waste. That adds up to 1,471 kg. The total of noncontaminated waste is the equivalent of nearly 2,000 pounds – a ton.

Dr. Yoo and Dr. Li estimate that the waste produced annual emissions equal to 6.5 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent. They estimate that the amount of emissions produced by Mohs surgeons nationally each year is 7,592 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent, equal to emissions produced by 19 million miles of passenger automobile travel.

Still, Dr. Yoo said, Mohs surgeries appear to produce fewer emissions than some other operations. “We estimate that an individual Mohs procedure generates around 10 kg of carbon dioxide equivalent whereas a single hysterectomy generates about 380 kg; much of this is due to the use of volatile anesthetics.”

Environmental protection advocate Mary Maloney, MD, professor of medicine and director of dermatologic surgery at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, urged colleagues to launch a similar waste-weighing project in their own clinics. “I challenge dermatologists to take a bag of your daily plastic waste and weigh it,” she said. “We’ll all be astounded by how much we throw away each day. Until you do that experiment yourself, you’ll have a hard time getting your arms around how much plastic we’re using.”

Dr. Maloney, a member of the American Academy of Dermatology Expert Resource Group for Climate Change and Environmental Issues, urged colleagues to consider strategies to reduce plastic use specifically. “Look at everything you use and see if there’s a nonplastic equivalent,” she said. Even reducing the use of plastic writing pens can make a difference, she said, as can cutting back on syringes and revising procedures so gloves don’t have to be changed as often.

No study funding was reported. Dr. Yoo and Dr. Maloney report no disclosures.

FROM THE ACMS ANNUAL MEETING

Dermatologists took 2020’s income drop in stride

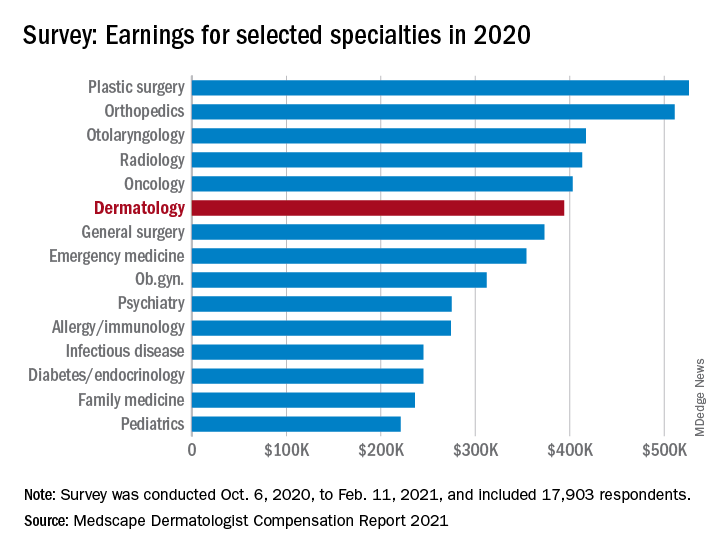

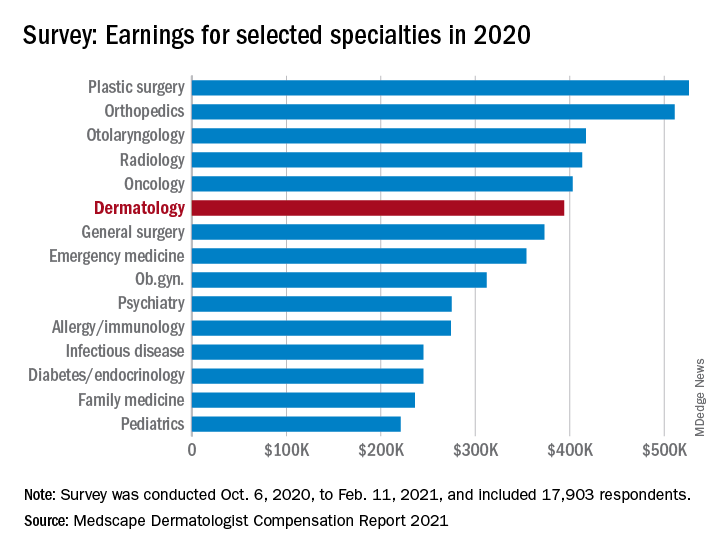

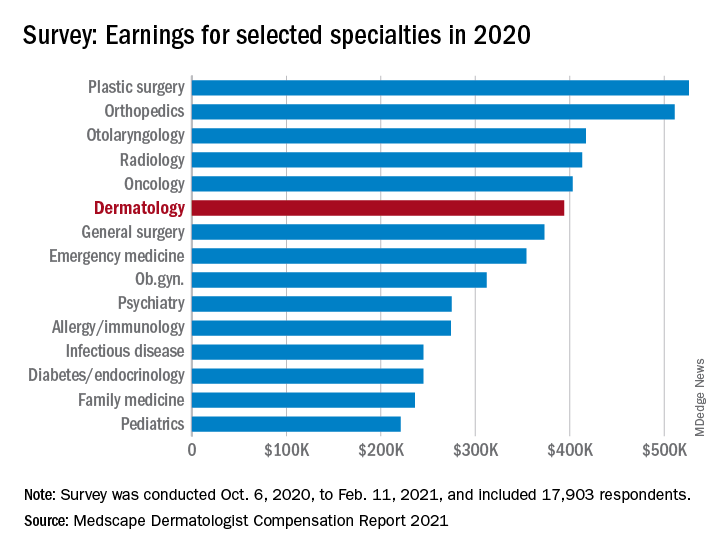

The numbers look like this: Average income was $394,000 in 2020, compared with $411,000 in 2019 – a drop of 4.1% – but 67% of dermatologists said they felt fairly compensated in 2020, compared with 65% in 2019, Medscape said in its 2021 Dermatologist Compensation Report. Only 3 of the 29 participating specialties had a more favorable reaction: oncology (79%), psychiatry (69%), and plastic surgery (68%).

“Most dermatologists who saw a drop in income cited COVID-19–related issues, such as job loss, fewer hours, and fewer patients,” Keith L. Martin wrote in the annual report, while also noting that 45% of dermatologist respondents “said that the pandemic did not cause them financial or practice-related harm.”

For the dermatologists who did see such negative effects, just over half (54%) said that they expect income to return to pre–COVID-19 levels in the next year, while 31% believe it will take 2-3 years and 12% said that their income would never return to normal. For all specialists included in the survey, the corresponding numbers were 42%, 41%, and 12%, with primary care physicians coming in at 39%, 43%, and 10%, the report said.

Among all participating specialties, plastic surgeons reported the highest average earnings at $526,000, with orthopedists ($511,000) and cardiologists ($459,000) next. Pediatricians had not just the lowest average income ($221,000) for 2020, but also the largest decline in patients seen per week (18%), according to the results of the survey, which was conducted from Oct. 6, 2020, to Feb. 11, 2021, and involved 17,903 physicians.

Dermatologists also experienced a larger-than-average decline (16%) in patient traffic – only the pediatricians had a larger drop – as their weekly patient count fell from 141 before the pandemic to the current 119. Despite that drop, though, average hours worked per week remained at 45, as time is now being spent on office safety protocols and other issues involving COVID-19, Medscape pointed out.

Dermatologists also spent more time on paperwork and administration in 2020 than in 2019: 14.6 hours per week versus 13.2 hours. Their 2020 average, however, was still lower than that of all physicians, 16.3 hours, and much lower than that of the infectious disease physicians, who topped the survey with an average of 24.2 hours per week, the Medscape data show.

One area where dermatologists did lead the survey was in their commitment to their specialty: 96% said they would choose dermatology again if given the chance, which was equaled by orthopedics and oncology, Medscape said.

The numbers look like this: Average income was $394,000 in 2020, compared with $411,000 in 2019 – a drop of 4.1% – but 67% of dermatologists said they felt fairly compensated in 2020, compared with 65% in 2019, Medscape said in its 2021 Dermatologist Compensation Report. Only 3 of the 29 participating specialties had a more favorable reaction: oncology (79%), psychiatry (69%), and plastic surgery (68%).

“Most dermatologists who saw a drop in income cited COVID-19–related issues, such as job loss, fewer hours, and fewer patients,” Keith L. Martin wrote in the annual report, while also noting that 45% of dermatologist respondents “said that the pandemic did not cause them financial or practice-related harm.”

For the dermatologists who did see such negative effects, just over half (54%) said that they expect income to return to pre–COVID-19 levels in the next year, while 31% believe it will take 2-3 years and 12% said that their income would never return to normal. For all specialists included in the survey, the corresponding numbers were 42%, 41%, and 12%, with primary care physicians coming in at 39%, 43%, and 10%, the report said.

Among all participating specialties, plastic surgeons reported the highest average earnings at $526,000, with orthopedists ($511,000) and cardiologists ($459,000) next. Pediatricians had not just the lowest average income ($221,000) for 2020, but also the largest decline in patients seen per week (18%), according to the results of the survey, which was conducted from Oct. 6, 2020, to Feb. 11, 2021, and involved 17,903 physicians.

Dermatologists also experienced a larger-than-average decline (16%) in patient traffic – only the pediatricians had a larger drop – as their weekly patient count fell from 141 before the pandemic to the current 119. Despite that drop, though, average hours worked per week remained at 45, as time is now being spent on office safety protocols and other issues involving COVID-19, Medscape pointed out.

Dermatologists also spent more time on paperwork and administration in 2020 than in 2019: 14.6 hours per week versus 13.2 hours. Their 2020 average, however, was still lower than that of all physicians, 16.3 hours, and much lower than that of the infectious disease physicians, who topped the survey with an average of 24.2 hours per week, the Medscape data show.

One area where dermatologists did lead the survey was in their commitment to their specialty: 96% said they would choose dermatology again if given the chance, which was equaled by orthopedics and oncology, Medscape said.

The numbers look like this: Average income was $394,000 in 2020, compared with $411,000 in 2019 – a drop of 4.1% – but 67% of dermatologists said they felt fairly compensated in 2020, compared with 65% in 2019, Medscape said in its 2021 Dermatologist Compensation Report. Only 3 of the 29 participating specialties had a more favorable reaction: oncology (79%), psychiatry (69%), and plastic surgery (68%).

“Most dermatologists who saw a drop in income cited COVID-19–related issues, such as job loss, fewer hours, and fewer patients,” Keith L. Martin wrote in the annual report, while also noting that 45% of dermatologist respondents “said that the pandemic did not cause them financial or practice-related harm.”

For the dermatologists who did see such negative effects, just over half (54%) said that they expect income to return to pre–COVID-19 levels in the next year, while 31% believe it will take 2-3 years and 12% said that their income would never return to normal. For all specialists included in the survey, the corresponding numbers were 42%, 41%, and 12%, with primary care physicians coming in at 39%, 43%, and 10%, the report said.

Among all participating specialties, plastic surgeons reported the highest average earnings at $526,000, with orthopedists ($511,000) and cardiologists ($459,000) next. Pediatricians had not just the lowest average income ($221,000) for 2020, but also the largest decline in patients seen per week (18%), according to the results of the survey, which was conducted from Oct. 6, 2020, to Feb. 11, 2021, and involved 17,903 physicians.

Dermatologists also experienced a larger-than-average decline (16%) in patient traffic – only the pediatricians had a larger drop – as their weekly patient count fell from 141 before the pandemic to the current 119. Despite that drop, though, average hours worked per week remained at 45, as time is now being spent on office safety protocols and other issues involving COVID-19, Medscape pointed out.

Dermatologists also spent more time on paperwork and administration in 2020 than in 2019: 14.6 hours per week versus 13.2 hours. Their 2020 average, however, was still lower than that of all physicians, 16.3 hours, and much lower than that of the infectious disease physicians, who topped the survey with an average of 24.2 hours per week, the Medscape data show.

One area where dermatologists did lead the survey was in their commitment to their specialty: 96% said they would choose dermatology again if given the chance, which was equaled by orthopedics and oncology, Medscape said.

New Editor in Chief: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH

With another long winter officially in the rearview mirror and spring sunshine displaying new signs of life outdoors, I am excited to share some of the changes happening inside the offices of the Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management (JCOM). It is my pleasure to introduce Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, as the journal’s new physician Editor in Chief. Dr. Barkoudah’s extensive experience in education and his work to improve patient outcomes will be assets to JCOM.

Specializing in both internal medicine and hospital medicine, Dr. Barkoudah is the Associate Director of the Hospital Medicine Unit and a Medical Director in the Department of Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He is also Assistant Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School, where he led the school’s international education efforts.

Dr. Barkoudah serves patients with a range of complex clinical disorders, managing their care and seeking innovative treatment options. His research interest is in health care outcomes as well as clinical trials of therapeutic interventions. Dr. Barkoudah also serves on numerous clinical innovation committees at Brigham Health and national task forces.

Dr. Barkoudah is an active member of several professional societies including the American College of Physicians, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Heart Association, Massachusetts Medical Society, among others. He was the Institutional Administration Fellow of the Safety and Quality Fellowship Program at the Institution for Healthcare Improvement.

On behalf of the JCOM Editorial Review Board, I want to extend a special thank you to outgoing editor Lori Tishler, MD, MPH. Dr. Tishler’s impact on the journal cannot be overstated, and we are indebted to the time and expertise she shared with the journal during her tenure.

—Eric Seger

With another long winter officially in the rearview mirror and spring sunshine displaying new signs of life outdoors, I am excited to share some of the changes happening inside the offices of the Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management (JCOM). It is my pleasure to introduce Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, as the journal’s new physician Editor in Chief. Dr. Barkoudah’s extensive experience in education and his work to improve patient outcomes will be assets to JCOM.

Specializing in both internal medicine and hospital medicine, Dr. Barkoudah is the Associate Director of the Hospital Medicine Unit and a Medical Director in the Department of Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He is also Assistant Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School, where he led the school’s international education efforts.

Dr. Barkoudah serves patients with a range of complex clinical disorders, managing their care and seeking innovative treatment options. His research interest is in health care outcomes as well as clinical trials of therapeutic interventions. Dr. Barkoudah also serves on numerous clinical innovation committees at Brigham Health and national task forces.

Dr. Barkoudah is an active member of several professional societies including the American College of Physicians, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Heart Association, Massachusetts Medical Society, among others. He was the Institutional Administration Fellow of the Safety and Quality Fellowship Program at the Institution for Healthcare Improvement.

On behalf of the JCOM Editorial Review Board, I want to extend a special thank you to outgoing editor Lori Tishler, MD, MPH. Dr. Tishler’s impact on the journal cannot be overstated, and we are indebted to the time and expertise she shared with the journal during her tenure.

—Eric Seger

With another long winter officially in the rearview mirror and spring sunshine displaying new signs of life outdoors, I am excited to share some of the changes happening inside the offices of the Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management (JCOM). It is my pleasure to introduce Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH, as the journal’s new physician Editor in Chief. Dr. Barkoudah’s extensive experience in education and his work to improve patient outcomes will be assets to JCOM.

Specializing in both internal medicine and hospital medicine, Dr. Barkoudah is the Associate Director of the Hospital Medicine Unit and a Medical Director in the Department of Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He is also Assistant Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School, where he led the school’s international education efforts.

Dr. Barkoudah serves patients with a range of complex clinical disorders, managing their care and seeking innovative treatment options. His research interest is in health care outcomes as well as clinical trials of therapeutic interventions. Dr. Barkoudah also serves on numerous clinical innovation committees at Brigham Health and national task forces.

Dr. Barkoudah is an active member of several professional societies including the American College of Physicians, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Heart Association, Massachusetts Medical Society, among others. He was the Institutional Administration Fellow of the Safety and Quality Fellowship Program at the Institution for Healthcare Improvement.

On behalf of the JCOM Editorial Review Board, I want to extend a special thank you to outgoing editor Lori Tishler, MD, MPH. Dr. Tishler’s impact on the journal cannot be overstated, and we are indebted to the time and expertise she shared with the journal during her tenure.

—Eric Seger

Impact of Hospitalist Programs on Perceived Care Quality, Interprofessional Collaboration, and Communication: Lessons from Implementation of 3 Hospital Medicine Programs in Canada

From the Fraser Health Authority, Surrey, BC, Canada (Drs. Yousefi and Paletta), and Catalyst Consulting Inc., Vancouver, BC, Canada (Elayne McIvor).

Objective: Despite the ongoing growth in the number of hospitalist programs in Canada, their impact on the quality of interprofessional communication, teamwork, and staff satisfaction is not well known. This study aimed to evaluate perceptions of frontline care providers and hospital managers about the impact of the implementation of 3 new hospitalist services on care quality, teamwork, and interprofessional communication.

Design: We used an online survey and semistructured interviews to evaluate respondents’ views on quality of interprofessional communication and collaboration, impact of the new services on quality of care, and overall staff satisfaction with the new inpatient care model.

Setting: Integrated Regional Health Authority in British Columbia, Canada.

Participants: Participants included hospital administrators, frontline care providers (across a range of professions), and hospital and community-based physicians.

Results: The majority of respondents reported high levels of satisfaction with their new hospital medicine services. They identified improvements in interprofessional collaboration and communication between hospitalists and other professionals, which were attributed to enhanced onsite presence of physicians. They also perceived improvements in quality of care and efficiency. On the other hand, they identified a number of challenges with the change process, and raised concerns about the impact of patient handoffs on care quality and efficiency.

Conclusion: Across 3 very different acute care settings, the implementation of a hospitalist service was widely perceived to have resulted in improved teamwork, quality of care, and interprofessional communication.

Keywords: hospital medicine; hospitalist; teamwork; interprofessional collaboration.

Over the past 2 decades, the hospitalist model has become prevalent in Canada and internationally.1 Hospitalist care has been associated with improvements in efficiency and quality of care.2-6 However, less is known about its impact on the quality of interprofessional communication, teamwork, and staff satisfaction. In a 2012 study of a specialized orthopedic facility in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), Ontario, Webster et al found a pervasive perception among interviewees that the addition of a hospitalist resulted in improved patient safety, expedited transfers, enhanced communication with Primary Care Providers (PCPs), and better continuity of care.7 They also identified enhanced collaboration among providers since the addition of the hospitalist to the care team. In another study of 5 community hospitals in the GTA, Conn et al8 found that staff on General Internal Medicine wards where hospitalists worked described superior interprofessional collaboration, deeper interpersonal relationships between physicians and other care team members, and a higher sense of “team-based care.”

Fraser Health Authority (FH) is an integrated regional health system with one of the largest regional Hospital Medicine (HM) networks in Canada.9 Over the past 2 decades, FH has implemented a number of HM services in its acute care facilities across a range of small and large community and academic hospitals. More recently, 3 hospitalist services were implemented over a 2-year period: new HM services in a tertiary referral center (Site A, July 2016) and a small community hospital (Site B, December 2016), and reintroduction of a hospitalist service in a medium-sized community hospital (Site C, January 2017). This provided a unique opportunity to assess the impact of the implementation of the hospitalist model across a range of facilities. The main objectives of this evaluation were to understand the level of physician, nursing, allied staff, and hospital administration satisfaction with the new hospitalist model, as well as the perceived impact of the service on efficiency and quality of care. As such, FH engaged an external consultant (EM) to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the introduction of its latest HM services.

Methods

Setting

Hospital medicine services are currently available in 10 of 12 acute care facilities within the FH system. The 3 sites described in this evaluation constitute the most recent sites where a hospitalist service was implemented.

Site A is a 272-bed tertiary referral center situated in a rapidly growing community. At the time of our evaluation, 21 Full Time Equivalent (FTE) hospitalists cared for an average of 126 patients, which constituted the majority of adult medical patients. Each day, 8 individuals rounded on admitted patients (average individual census: 16) with another person providing in-house, evening, and overnight coverage. An additional flexible shift during the early afternoon helped with Emergency Department (ED) admissions.

Site B is small, 45-bed community hospital in a semi-rural community. The hospitalist service began in December 2016, with 4 FTE hospitalists caring for an average of 28 patients daily. This constituted 2 hospitalists rounding daily on admitted patients, with on-call coverage provided from home.

Site C is a 188-bed community hospital with a hospitalist service initially introduced in 2005. In 2016, the program was disbanded and the site moved back to a primarily community-based model, in which family physicians in the community were invited to assume the care of hospitalized patients. However, the hospitalist program had to be reintroduced in January 2017 due to poor uptake among PCPs in the community. At the time of evaluation, 19 FTE hospitalists (with 7 hospitalists working daily) provided most responsible physician care to a daily census of 116 patients (average individual census: 16). The program also covered ED admissions in-house until midnight, with overnight call provided from home.

Approach

We adopted a utilization-focused evaluation approach to guide our investigation. In this approach, the assessment is deliberately planned and conducted in a way that it maximizes the likelihood that findings would be used by the organization to inform learning, adaptations, and decision-making.11 To enable this, the evaluator identified the primary intended recipients and engaged them at the start of the evaluation process to understand the main intended uses of the project. Moreover, the evaluator ensured that these intended uses of the evaluation guided all other decisions made throughout the process.

We collected data using an online survey of the staff at the 3 facilities, complemented by a series of semistructured qualitative interviews with FH administrators and frontline providers.

Online survey

We conducted an open online survey of a broad range of stakeholders who worked in the 3 facilities. To develop the questionnaire, we searched our department’s archives for previous surveys conducted from 2001 to 2005. We also interviewed the regional HM program management team to identify priority areas and reached out to the local leadership of the 3 acute care facilities for their input and support of the project. We refined the survey through several iterations, seeking input from experts in the FH Department of Evaluation and Research. The final questionnaire contained 10 items, including a mix of closed- and open-ended questions (Appendix A).

To reach the target audience, we collaborated with each hospital’s local leadership as well as the Divisions of Family Practice (DFP) that support local community PCPs in each hospital community.10 Existing email lists were compiled to create a master electronic survey distribution list. The initial invitation and 3 subsequent reminders were disseminated to the following target groups: hospital physicians (both hospitalists and nonhospitalists), PCPs, nursing and other allied professionals, administrators, and DFP leadership.

The survey consent form, background information, questions, and online platform (SimpleSurvey, Montreal, QC) were approved by FH’s Privacy Department. All respondents were required to provide their consent and able to withdraw at any time. Survey responses were kept anonymous and confidential, with results captured automatically into a spreadsheet by the survey platform. As an incentive for participation, respondents had the opportunity to win 1 of 3 $100 Visa gift cards. Personal contact information provided for the prize draw was collected in a separate survey that could not link back to respondents’ answers. The survey was trialed several times by the evaluation team to address any technical challenges before dissemination to the targeted participants.

Qualitative interviews

We conducted semistructured interviews with a purposive sample of FH administrators and frontline providers (Appendix B). The interview questions broadly mirrored the survey but allowed for more in-depth exploration of constructs. Interviewees were recruited through email invitations to selected senior and mid-level local and regional administrators, asking interviewees to refer our team to other contacts, and inviting survey respondents to voluntarily participate in a follow-up interview. One of the authors (EM), a Credentialed Evaluator, conducted all the one-time interviews either in-person at the individual participant’s workplace or by telephone. She did not have pre-existing relationships with any of the interviewees. Interviews were recorded and transcribed for analysis. Interviewees were required to consent to participate and understood that they could withdraw at any point. They were not offered incentives to participate. Interviews were carried out until thematic saturation was reached.

Analysis

A content analysis approach was employed for all qualitative data, which included open-ended responses from the online survey and interview transcripts. One of the authors (EM) conducted the analysis. The following steps were followed in the inductive content analysis process: repeated reading of the raw data, generation of initial thematic codes, organizing and sorting codes into categories (ie, main vs subcategories), coding of all data, quantifying codes, and interpreting themes. When responding to open-ended questions, respondents often provided multiple answers per question. Each of the respondents’ answers were coded. In alignment with the inductive nature of the analysis process, themes emerged organically from the data rather than the researchers using preconceived theories and categories to code the text. This was achieved by postponing the review of relevant literature on the topic until after the analysis was complete and using an external evaluation consultant (with no prior relationship to FH and limited theoretical knowledge of the topic matter) to analyze the data. Descriptive statistics were run on quantitative data in SPSS (v.24, IBM, Armonk, NY). For survey responses to be included in the analysis, the respondents needed to indicate which site they worked at and were required to answer at least 1 other survey question. One interviewee was excluded from the analysis since they were not familiar with the hospitalist model at their site.

Ethics approval

The evaluation protocol was reviewed by FH Department of Evaluation and Research and was deemed exempt from formal research ethics review.

Results

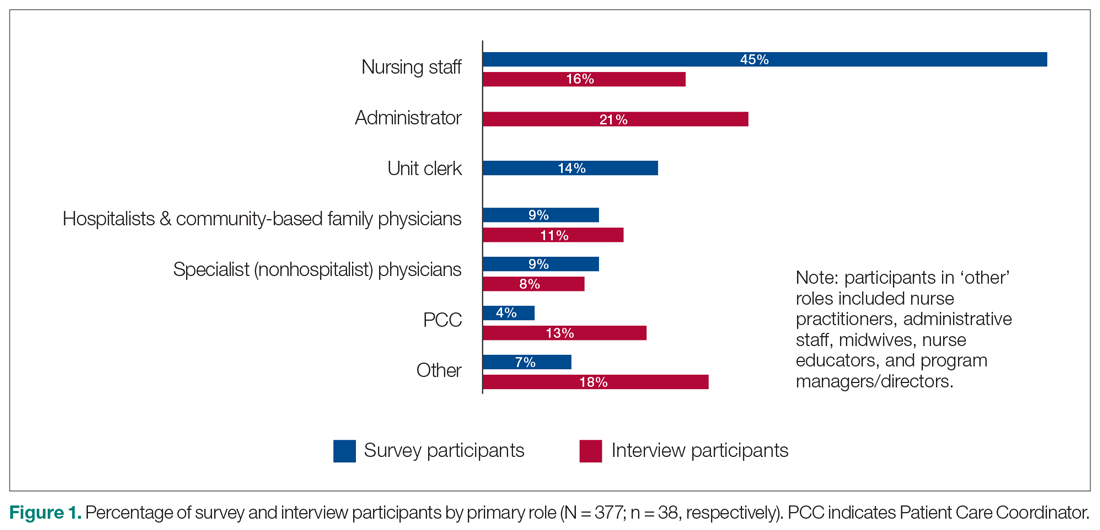

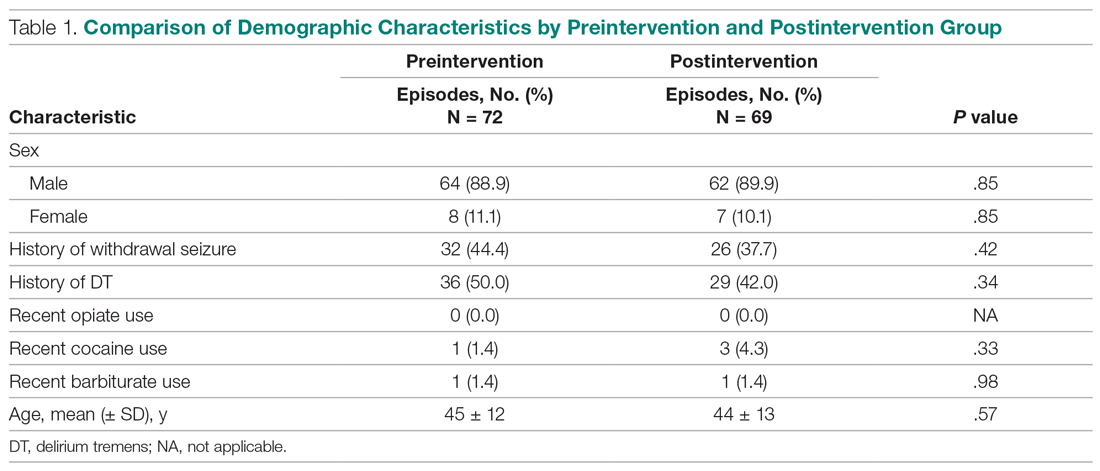

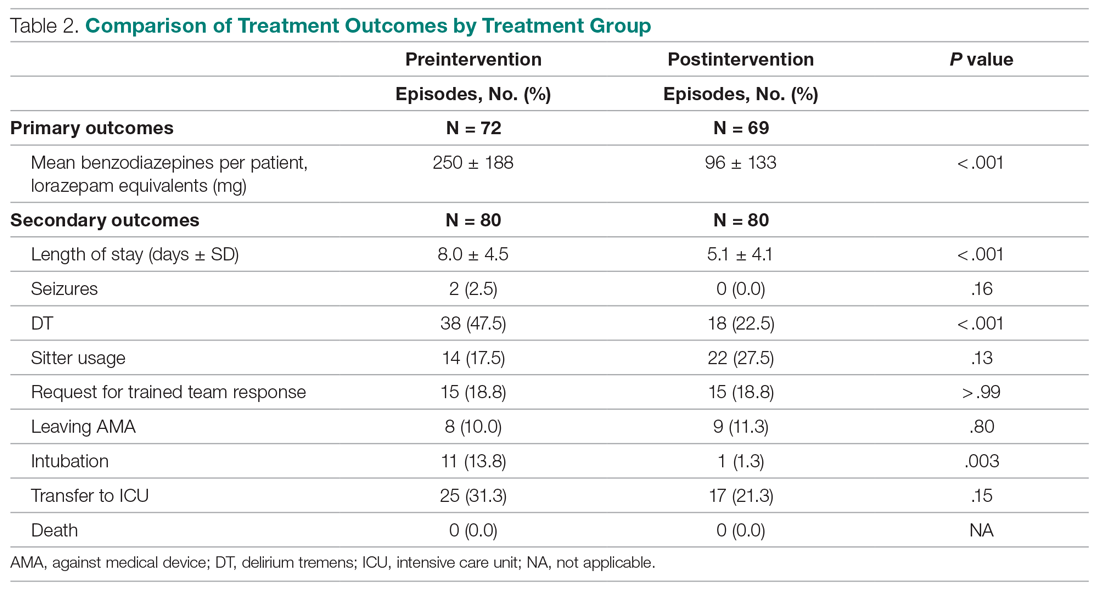

A total of 377 individuals responded to the online survey between January 8 and February 28, 2018 (response rate 14%). The distribution of respondents generally reflected the size of the respective acute care facilities. Compared to the overall sampled population, fewer nurses participated in the survey (45% vs 64%) while the rate of participation for Unit Clerks (14% vs 16%) and allied professionals (12% vs 16%) were similar.

Out of the 45 people approached for an interview, a total of 38 were conducted from January 3 to March 5, 2018 (response rate 84%). The interviews lasted an average of 42 minutes. Interviewees represented a range of administrative and health professional roles (Figure 1). Some interviewees held multiple positions.

Satisfaction with HM service

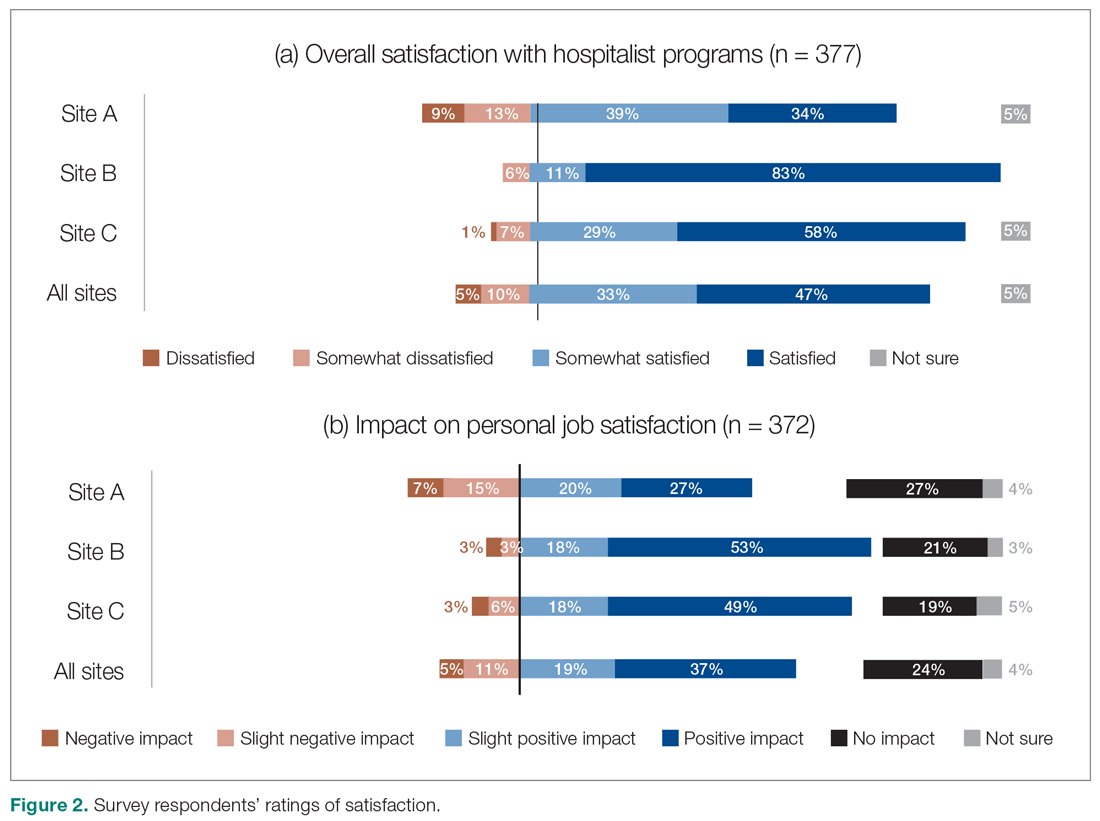

Across all sites, survey respondents reported high levels of satisfaction with their respective HM services and identified positive impacts on their job satisfaction (Figure 2). Almost all interviewees similarly expressed high satisfaction levels with their HM services (95%; n = 36).

Perceptions of HM service performance

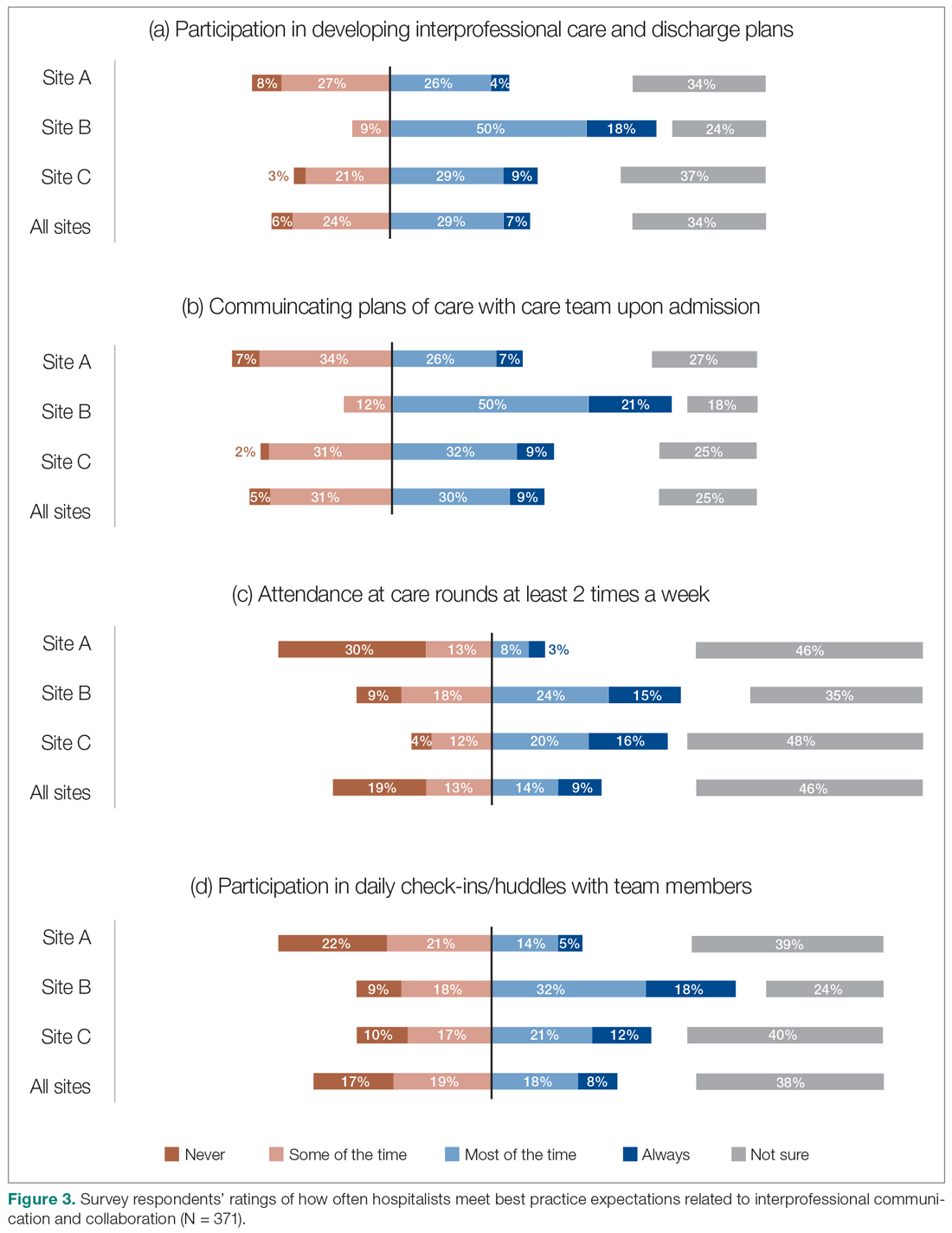

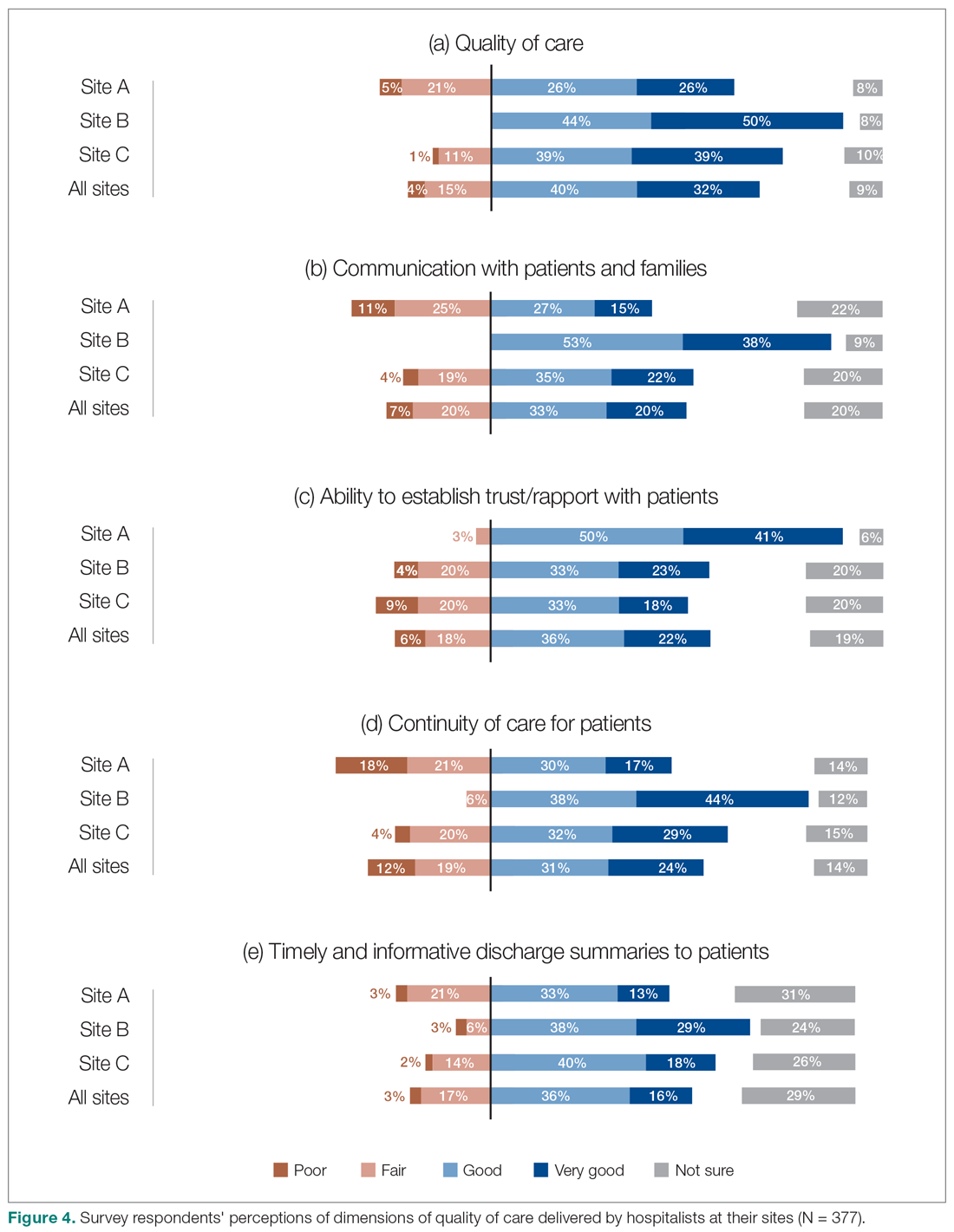

Survey respondents rated the strength of hospitalists’ interprofessional communication and collaboration with other physicians and with care teams. Roughly two-thirds reported that overall hospitalist communication was “good” or “very good.” We also asked participants to rate the frequency at which hospitalists met best practice expectations related to interprofessional teamwork. Across all sites, similar proportions of respondents (23% to 39%) reported that these best practices were met “most of the time” or “always” (Figure 3). Survey questions also assessed perceptions of respondents about the quality and safety of care provided by hospitalists (Figure 4).

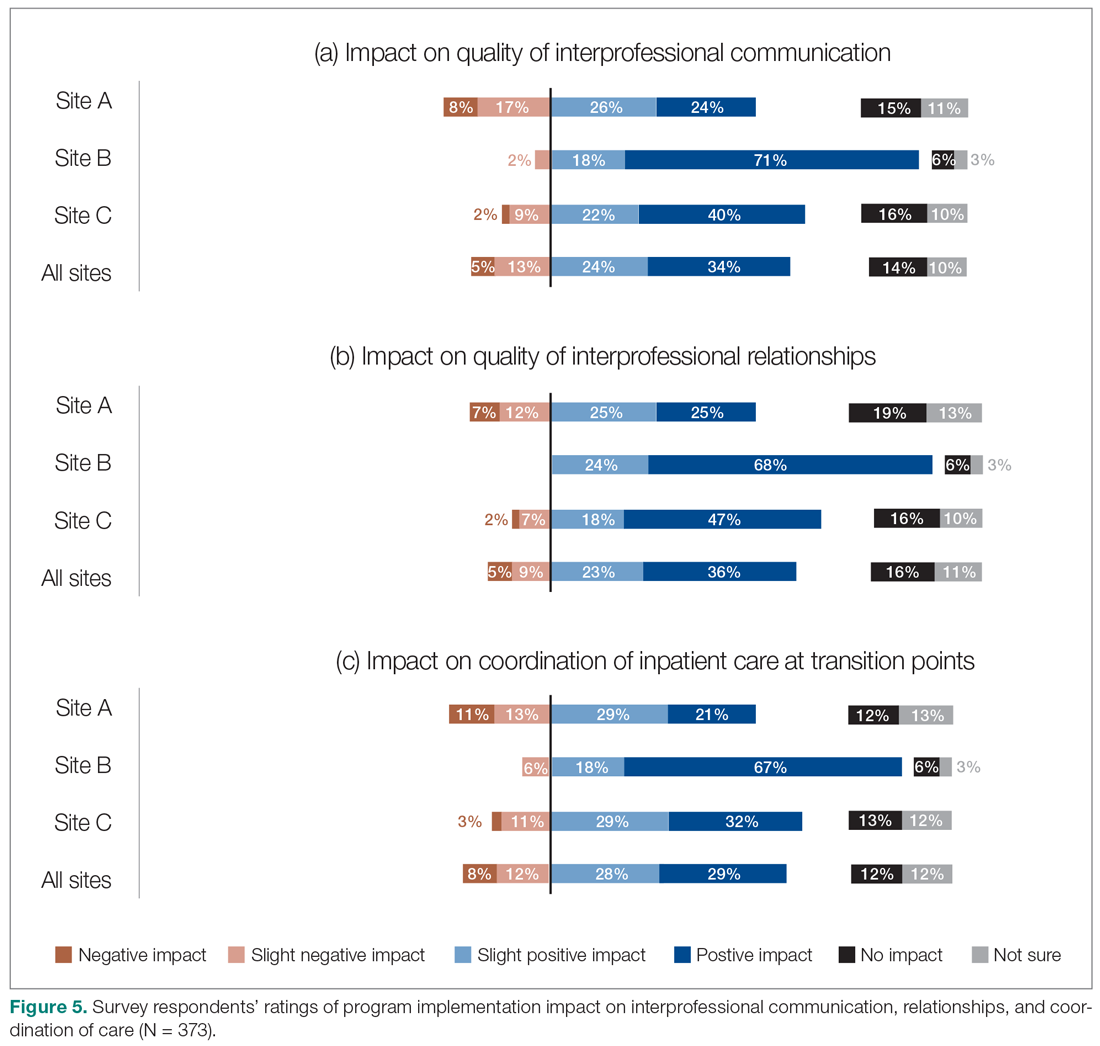

Perceptions of the impact of the HM service postimplementation

The majority of survey respondents reported improvements in the quality of communication, professional relationships, and coordination of inpatient care at transition points after the implementation of the HM service (Figure 5). This was also reflected in interviews, where some indicated that it was easier to communicate with hospitalists due to their on-site presence, accessibility, and 24/7 availability (n = 21). They also described improved collaboration within the care teams (n = 7), and easier communication with hospitalists because they were approachable, willing, and receptive (n = 4).

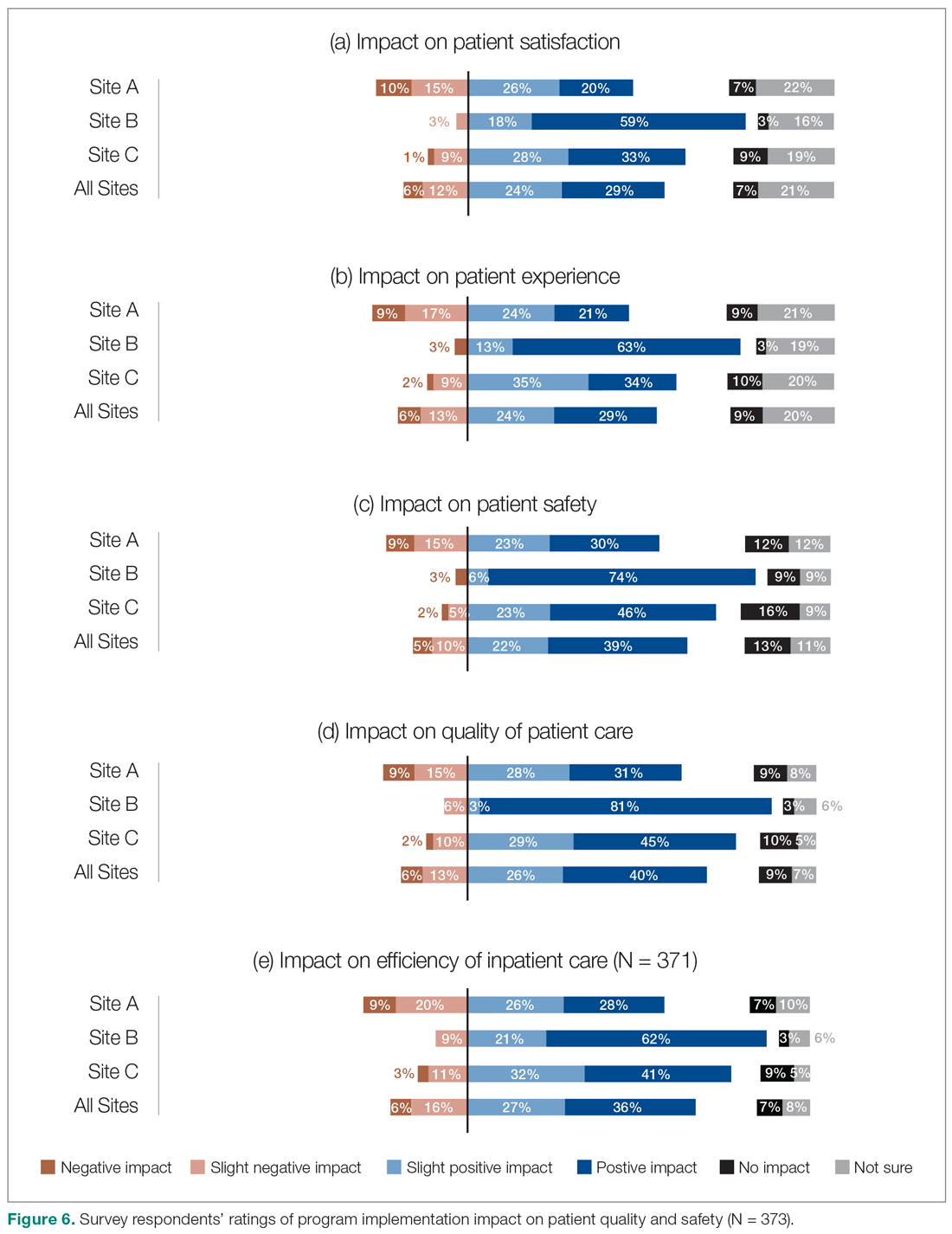

We also asked the survey respondents to assess the impact of the new hospitalist model on different dimensions of care quality, including patient satisfaction, patient experience, efficiency, and overall quality of care (Figure 6). Findings were comparable across these dimensions, with roughly 50-60% of respondents noting positive changes compared to before the implementation of the programs. However, most interviewees identified both positive and negative effects in these areas. Positive impacts included hospitalist on-site presence leading to better accessibility and timeliness of care (n = 5), hospitalists providing continuity to patients/families by working for weeklong rotations (n = 6), hospitalists being particularly skilled at managing complex clinical presentations (n = 2), and hospitalists being able to spend more time with patients (n = 2). On the other hand, some interviewees noted that patients and families did not like seeing multiple doctors due to frequent handoffs between hospitalists (n = 12). They also raised concerns that hospitalists did not know patients’ histories or had relationships with them, potentially leading to longer length of stay and unnecessary investigations (n = 8).

Site-to-site ratings of satisfaction and performance

Survey respondents’ satisfaction and performance ratings varied substantially site-to-site. Across all areas assessed, ratings were consistently highest at Site B (the smallest institution in our evaluation and the most recent addition to the HM network in the health authority). These differences were statistically significant across all survey questions asked.

Discussion

Findings from this study provide insight into the experiences of frontline health care professionals and administrators with the implementation of new HM services across a range of small to large acute care facilities. They indicate that the majority of respondents reported high levels of satisfaction with their hospitalist services. Most also indicated that the service had resulted in improvements compared to prior inpatient care models.

Over half of the survey respondents, and the majority of interviewees, reported a positive impact on interprofessional communication and collaboration. This was largely attributed to enhanced accessibility and availability of hospitalists:

- "Being on-site lends itself to better communication because they’re accessible. Hospitalists always answer the phone, but the general practitioners (GP) don’t always since they may be with other patients." (Dietician, Site A)

- "A big strength is that we have physician presence on the unit all day during scheduled hours, which makes us more accessible to nurses and more able to follow up on patients that we have concerns about." (Physician Leader, Site B)

However, the ratings dropped substantially when they were asked to assess adherence to specific best practices of such communication and collaboration, such as participation in daily check-ins or attendance at team care rounds (Figure 3). Interdisciplinary clinical rounds have been identified as a tool to improve the effectiveness of care teams.12 A number of elements have been identified as key components of effective rounds.13 Bedside rounds have also been found to enhance communication and teamwork.14,15 In our study, the discrepancy between overall high levels of satisfaction with hospitalists’ communication/collaboration despite low scores on participation in more concrete activities may illustrate the importance of informal and ad hoc opportunities for interactions between hospitalists and other care providers that result from the enhanced presence of hospitalists on care units.8 Outside of formal rounds, hospitalists have the ability to interact with other care providers throughout their shifts. Prior studies have shown that hospitalists spend a significant portion of their time communicating with other care team members throughout their workdays.16 At the same time, the amount of time spent on communication should be balanced against the need for provision of direct care at the bedside. Future research should aim to identify the right balance between these competing priorities, and to understand the nature and quality of the communication between various care providers.

We also aimed to understand the perceptions of study participants about the impact of the HM service on quality of care. Survey participants not only expressed reasonable satisfaction with various aspects of hospitalists’ performance, but also described a positive impact on care quality after the implementation of their new services. This was also reflected in the interviews:

- "The clinical knowledge of the new hospitalists is far better. Some are internal medicine trained, so they bring better knowledge and skills. I feel comfortable that they can take patients and manage them. I wasn’t always comfortable with doing that in the past." (Emergency Physician, Site C)

- "Hospitalists are really familiar with acute care and how it works. They’ve become more familiar with the discharge planning system and thus know more about the resources available. And even something as simple as knowing which forms to use." (Dietician, Site A)

It must be noted that these observations should ideally be corroborated through a robust before-after analysis of various quality measures. While such an analysis was beyond the scope of our current project, we have previously demonstrated that across our network (including the 3 sites included in our evaluation) hospitalist care is associated with lower mortality and readmission rates.4 Our findings appear to confirm previous suggestions that hospitalists’ dedicated focus on inpatient care may allow them to develop enhanced skills in the management of common conditions in the acute care setting17 which can be perceived to be of value to other hospital-based care providers.

The issue of frequent handover among hospitalists was the most commonly identified challenge by both survey respondents and interviewees:

- "They’re very reluctant to discharge patients if it’s their first day with the patient. Even if the previous hospitalist said they were ready for discharge, the new doc wants to run all of their own tests before they feel comfortable. Maybe it’s a trust issue between hospitalists when they hand patients over. It’s also being personally liable for patients if you discharge them." (Patient Care Coordinator, Site A)

- "Communication is an issue. There’s lots of turnover in hospitalists. Relationships were closer with GPs because we had so much more interaction with particular individuals." (Hospitalist Physician Leader, Site A)

It must be noted that we conducted our evaluation in a relatively short time span (within 2 years) after the 3 services were implemented. Developing trust among a large number of hospitalists newly recruited to these programs can take time and may be a factor that can explain the reluctance of some to discharge patients after handoffs. However, concerns about discontinuity of care inherent in the hospitalist model are not new.18,19 Better continuity has been associated with higher probability of patient discharges20 and improved outcomes.21 To address this challenge, the hospitalist community has focused on defining the core competencies associated with high quality handovers,22 and deliberate efforts to improve the quality of handoffs through quality improvement methodologies.23 Our study participants similarly identified these measures as potential solutions. Despite this, addressing hospitalist continuity of care remains a pressing challenge for the broader hospitalist community.24

Our evaluation has a number of methodological limitations. First, the survey response rate was only 14%, which raises questions about nonresponse bias and the representativeness of the findings to the larger population of interest. While the distribution of respondents was largely similar to the overall sampled population, a number of factors may have impacted our response rate. For example, we were only able to distribute our survey to health care providers’ institutional email addresses. Moreover, while we provided incentives for participation and sent out a number of reminders, we solely relied on one communication modality (ie, electronic communication) and did not utilize other methods (such as posters, reminder at meetings, in-person invitations). Second, while the survey included a number of open-ended questions, many of these responses were at times brief and difficult to interpret and were not included in the analysis. Third, all data collected were self-reported. For example, we could not corroborate comments about participation in interdisciplinary rounds by objective measures such as attendance records or direct observation. Self-report data is subjective in nature and is vulnerable to a range of biases, such as social desirability bias.25 Finally, patient satisfaction and experience with hospitalist care were not assessed by patients themselves. Ideally, standardized cross-site indicators should validate our patient-related results.

As mentioned above, hospitalist performance ratings varied substantially from site-to-site and were consistently higher at Site B (a small community hospital in a semi-rural area), followed by Site C (a medium-sized community hospital) and Site A (a tertiary referral center). The variability in program ratings and perceived hospitalist impacts between sites could be due to a variety of factors, such as the degree of change between the past and current models at each site, differences in hospitalist hiring processes, hospital size and culture, and differences in service design and operations. It may also be related to the timing of the introduction of the HM service, as Site B was the most recent site where the service was established. As such, there may be an element of recall bias behind the observed discrepancies. This highlights the importance of local context on respondent perceptions and suggests that our results may not be generalizable to other institutions with different attributes and characteristics.

Conclusion

Findings from this study have demonstrated that the recent hospitalist services in our health system have improved overall levels of interprofessional communication and teamwork, as well as perceptions of care quality among the majority of participants who reported high levels of satisfaction with their programs. Our findings further highlight the issue of frequent handovers among hospitalists as a pressing and ongoing challenge.

Corresponding Author: Vandad Yousefi, MD, CCFP, Past Regional Department Head – Hospital Medicine, Fraser Health Authority, Central City Tower, Suite 400, 13450 – 102nd Ave, Surrey, BC V3T 0H1; vandad.yousefi@fraserhealth.ca.

Financial disclosures: This project was funded by the Fraser Health Authority, which provided the funding for hiring of the external consultant to design, implement, and analyze the results of the evaluation program in collaboration with the Regional Hospitalist Program at Fraser Health.

1. Yousefi V, Wilton D. Re-designing Hospital Care: Learning from the Experience of Hospital Medicine in Canada. Journal of Global Health Care Systems. 2011;1(3).

2. White HL. Assessing the Prevalence, Penetration and Performance of Hospital Physicians in Ontario: Implications for the Quality and Efficiency of Inpatient Care. Doctoral Thesis; 2016.

3. Yousefi V, Chong CA. Does implementation of a hospitalist program in a Canadian community hospital improve measures of quality of care and utilization? An observational comparative analysis of hospitalists vs. traditional care providers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:204.

4. Yousefi V, Hejazi S, Lam A. Impact of Hospitalists on Care Outcomes in a Large Integrated Health System in British Columbia. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management. 2020;27(2):59-72.

5. Salim SA, Elmaraezy A, Pamarthy A, et al. Impact of hospitalists on the efficiency of inpatient care and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2019;9(2):121-134.

6. Peterson MC. A systematic review of outcomes and quality measures in adult patients cared for by hospitalists vs nonhospitalists. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2009;84(3):248-254.

7. Webster F, Bremner S, Jackson M, et al. The impact of a hospitalist on role boundaries in an orthopedic environment. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2012;5:249-256.

8. Gotlib Conn L, Reeves S, Dainty K, et al. Interprofessional communication with hospitalist and consultant physicians in general internal medicine: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012; 12:437.

9. About Fraser Health. Fraser Health Authority. Updated 2018. Accessed January 30, 2019. https://www.fraserhealth.ca/about-us/about-fraser-health#.XFJrl9JKiUk

10. Divisions of Family Practice. Accessed May 2, 2020. https://www.divisionsbc.ca/provincial/about-us

11. Patton MQ. Essentials of Utilization-Focused Evaluation. 2012. Sage Publications, Inc; 2011.

12. Buljac-Samardzic M, Doekhie KD, van Wijngaarden JDH. Interventions to improve team effectiveness within health care: a systematic review of the past decade. Hum Resour Health. 2020;18(1):2.

13. Verhaegh KJ, Seller-Boersma A, Simons R, et al. An exploratory study of healthcare professionals’ perceptions of interprofessional communication and collaboration. J Interprof Care. 2017;31(3):397-400.

14. O’Leary KJ, Johnson JK, Manojlovich M, et al. Redesigning systems to improve teamwork and quality for hospitalized patients (RESET): study protocol evaluating the effect of mentored implementation to redesign clinical microsystems. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):293.

15. Stein J, Payne C, Methvin A, et al. Reorganizing a hospital ward as an accountable care unit. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(1):36-40.

16. Yousefi V. How Canadian hospitalists spend their time - A work-sampling study within a hospital medicine program in Ontario. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management. 2011;18(4):159.

17. Marinella MA: Hospitalists-Where They Came from, Who They Are, and What They Do. Hosp Physician. 2002;38(5):32-36.

18. Wachter RM. An introduction to the hospitalist model. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(4 Pt 2):338-342.

19. Wachter RM, Goldman L. The hospitalist movement 5 years later. JAMA. 2002;287(4):487-494.

20. van Walraven C. The Influence of Inpatient Physician Continuity on Hospital Discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(9):1709-1714.

21. Goodwin JS, Li S, Kuo YF. Association of the Work Schedules of Hospitalists With Patient Outcomes of Hospitalization. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(2):215-222.

22. Nichani S, Fitterman N, Lukela M, Crocker J, the Society of Hospital Medicine, Patient Handoff. 2017 Hospital Medicine Revised Core Competencies. J Hosp Med. 2017;4:S74.

23. Lo HY, Mullan PC, Lye C, et al. A QI initiative: implementing a patient handoff checklist for pediatric hospitalist attendings. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5(1):u212920.w5661.

24. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 - The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011.

25. Grimm, P. Social Desirability Bias. In: Sheth J, Malhotra N, eds. Wiley International Encyclopedia of Marketing. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2010.

From the Fraser Health Authority, Surrey, BC, Canada (Drs. Yousefi and Paletta), and Catalyst Consulting Inc., Vancouver, BC, Canada (Elayne McIvor).

Objective: Despite the ongoing growth in the number of hospitalist programs in Canada, their impact on the quality of interprofessional communication, teamwork, and staff satisfaction is not well known. This study aimed to evaluate perceptions of frontline care providers and hospital managers about the impact of the implementation of 3 new hospitalist services on care quality, teamwork, and interprofessional communication.

Design: We used an online survey and semistructured interviews to evaluate respondents’ views on quality of interprofessional communication and collaboration, impact of the new services on quality of care, and overall staff satisfaction with the new inpatient care model.

Setting: Integrated Regional Health Authority in British Columbia, Canada.

Participants: Participants included hospital administrators, frontline care providers (across a range of professions), and hospital and community-based physicians.

Results: The majority of respondents reported high levels of satisfaction with their new hospital medicine services. They identified improvements in interprofessional collaboration and communication between hospitalists and other professionals, which were attributed to enhanced onsite presence of physicians. They also perceived improvements in quality of care and efficiency. On the other hand, they identified a number of challenges with the change process, and raised concerns about the impact of patient handoffs on care quality and efficiency.

Conclusion: Across 3 very different acute care settings, the implementation of a hospitalist service was widely perceived to have resulted in improved teamwork, quality of care, and interprofessional communication.

Keywords: hospital medicine; hospitalist; teamwork; interprofessional collaboration.

Over the past 2 decades, the hospitalist model has become prevalent in Canada and internationally.1 Hospitalist care has been associated with improvements in efficiency and quality of care.2-6 However, less is known about its impact on the quality of interprofessional communication, teamwork, and staff satisfaction. In a 2012 study of a specialized orthopedic facility in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), Ontario, Webster et al found a pervasive perception among interviewees that the addition of a hospitalist resulted in improved patient safety, expedited transfers, enhanced communication with Primary Care Providers (PCPs), and better continuity of care.7 They also identified enhanced collaboration among providers since the addition of the hospitalist to the care team. In another study of 5 community hospitals in the GTA, Conn et al8 found that staff on General Internal Medicine wards where hospitalists worked described superior interprofessional collaboration, deeper interpersonal relationships between physicians and other care team members, and a higher sense of “team-based care.”

Fraser Health Authority (FH) is an integrated regional health system with one of the largest regional Hospital Medicine (HM) networks in Canada.9 Over the past 2 decades, FH has implemented a number of HM services in its acute care facilities across a range of small and large community and academic hospitals. More recently, 3 hospitalist services were implemented over a 2-year period: new HM services in a tertiary referral center (Site A, July 2016) and a small community hospital (Site B, December 2016), and reintroduction of a hospitalist service in a medium-sized community hospital (Site C, January 2017). This provided a unique opportunity to assess the impact of the implementation of the hospitalist model across a range of facilities. The main objectives of this evaluation were to understand the level of physician, nursing, allied staff, and hospital administration satisfaction with the new hospitalist model, as well as the perceived impact of the service on efficiency and quality of care. As such, FH engaged an external consultant (EM) to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the introduction of its latest HM services.

Methods

Setting

Hospital medicine services are currently available in 10 of 12 acute care facilities within the FH system. The 3 sites described in this evaluation constitute the most recent sites where a hospitalist service was implemented.

Site A is a 272-bed tertiary referral center situated in a rapidly growing community. At the time of our evaluation, 21 Full Time Equivalent (FTE) hospitalists cared for an average of 126 patients, which constituted the majority of adult medical patients. Each day, 8 individuals rounded on admitted patients (average individual census: 16) with another person providing in-house, evening, and overnight coverage. An additional flexible shift during the early afternoon helped with Emergency Department (ED) admissions.

Site B is small, 45-bed community hospital in a semi-rural community. The hospitalist service began in December 2016, with 4 FTE hospitalists caring for an average of 28 patients daily. This constituted 2 hospitalists rounding daily on admitted patients, with on-call coverage provided from home.

Site C is a 188-bed community hospital with a hospitalist service initially introduced in 2005. In 2016, the program was disbanded and the site moved back to a primarily community-based model, in which family physicians in the community were invited to assume the care of hospitalized patients. However, the hospitalist program had to be reintroduced in January 2017 due to poor uptake among PCPs in the community. At the time of evaluation, 19 FTE hospitalists (with 7 hospitalists working daily) provided most responsible physician care to a daily census of 116 patients (average individual census: 16). The program also covered ED admissions in-house until midnight, with overnight call provided from home.

Approach

We adopted a utilization-focused evaluation approach to guide our investigation. In this approach, the assessment is deliberately planned and conducted in a way that it maximizes the likelihood that findings would be used by the organization to inform learning, adaptations, and decision-making.11 To enable this, the evaluator identified the primary intended recipients and engaged them at the start of the evaluation process to understand the main intended uses of the project. Moreover, the evaluator ensured that these intended uses of the evaluation guided all other decisions made throughout the process.

We collected data using an online survey of the staff at the 3 facilities, complemented by a series of semistructured qualitative interviews with FH administrators and frontline providers.

Online survey

We conducted an open online survey of a broad range of stakeholders who worked in the 3 facilities. To develop the questionnaire, we searched our department’s archives for previous surveys conducted from 2001 to 2005. We also interviewed the regional HM program management team to identify priority areas and reached out to the local leadership of the 3 acute care facilities for their input and support of the project. We refined the survey through several iterations, seeking input from experts in the FH Department of Evaluation and Research. The final questionnaire contained 10 items, including a mix of closed- and open-ended questions (Appendix A).