User login

What brought me back from the brink of suicide: A physician’s story

William Lynes, MD, had a flourishing medical practice and a fulfilling family life with three children when he first attempted suicide in 1999 at age 45. By 2003, depression and two more suicide attempts led to his early retirement.

In a session at the recent virtual American Psychiatric Association (APA) 2021 annual meeting, Dr. Lynes talked about the challenges of dealing with depression while managing the stresses of a career in medicine. The session in which he spoke was called, “The Suicidal Physician: Narratives From a Physician Who Survived and the Physician Widow of One Who Did Not.”

By writing and speaking about his experiences, he says, he has been able to retain his identity as a physician and avoid obsessive thoughts about suicide. He hopes conversations like these help other physicians feel less alone and enable them to push past stigmas to get the help they need. He suspects they do. More than 600 people joined the APA session, and Dr. Lynes received dozens of thankful messages afterward.

“I love medicine, but intrinsically, the practice of medicine is stressful, and you can’t get away,” said Dr. Lynes, a retired urologist in Temecula, Calif. “As far as feedback, it made me feel like it’s something I should continue to do.”

A way to heal

For Dr. Lynes, his “downward spiral into darkness” began with a series of catastrophic medical events starting in 1998, when he came home from a family vacation in Mexico feeling unwell. He didn’t bother to do anything about it – typical of a physician, he says. Then one night he woke up shaking with chills and fever. Soon he was in the hospital with respiratory failure from septic shock.

Dr. Lynes spent 6 weeks in the intensive care unit, including 4 weeks on a ventilator. He underwent a tracheostomy. He lost 40 pounds and experienced ICU-related delirium. It was a terrifying time, he said. When he tried to return to work 10 months later, he didn’t feel as though he could function normally.

Having once been a driven doctor who worked long hours, he now doubted himself and dreaded giving patients bad news. Spontaneously, he tried to take his own life.

Afterward, he concealed what had happened from everyone except his wife and managed to resume his practice. However, he was unable to regain the enthusiasm he had once had for his work. Although he had experienced depression before, this time it was unrelenting.

He sought help from a psychiatrist, received a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and began taking medication. Still, he struggled to fulfill his responsibilities. Then in April 2002, he had a snowboarding accident that caused multiple facial fractures and required five operations. When he returned to work this time, he felt like a failure but resisted asking colleagues for help.

A few months later, Dr. Lynes again attempted suicide, which led to another stay in the ICU and more time on a ventilator. Doctors told his family they didn’t think he would survive. When he recovered, he spent time as an inpatient in a psychiatric ward, where he received the first of a series of electroconvulsive therapy sessions. Compounding his anxiety and depression was the inability to come to terms with his life if he were not able to practice medicine.

The next fall, in September 2003, his third suicide attempt took place in his office on a weekend when no one was around. After locking the door, he looked at his reflection in the frame of his medical school diploma. The glass was cracked. “It was dark, it was black, it was cold,” he said. “I can remember seeing my reflection and thinking how disgusted I was.”

For years after that, Dr. Lynes struggled with his sense of self-worth. He hid from the medical system and dreaded doctors’ appointments. Finally in 2016, he found new meaning at a writing conference, where he met a fellow physician whose story was similar to his. She encouraged him to write about his experience. His essay was published in Annals of Internal Medicine that year. “Then I started speaking, and I feel like I’m a physician again,” he said. “That has really healed me quite a bit.”

Why physicians die by suicide

Working in health care can be extremely stressful, even in the best of times, said Michael Myers, MD, a psychiatrist at State University of New York, Brooklyn, and author of the book, “Why Physicians Die By Suicide: Lessons Learned From Their Families and Others Who Cared.”

Years of school and training culminate in a career in which demands are relentless. Societal expectations are high. Many doctors are perfectionists by nature, and physicians tend to feel intense pressure to compete for coveted positions.

Stress starts early in a medical career. A 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis of 183 studies from 43 countries showed that nearly 30% of medical students experienced symptoms of depression and that 11% reported suicidal thoughts, but only 15% sought help.

A 2015 review of 31 studies that involved residents showed that rates of depression remained close to 30% and that about three-quarters of trainees meet criteria for burnout, a type of emotional exhaustion and sense of inadequacy that can result from chronic stress at work.

The stress of medical training appears to be a direct cause of mental health struggles. Rates of depression are higher among those working to become physicians than among their peers of the same age, research shows. In addition, symptoms become more prevalent as people progress through their training.

The COVID-19 pandemic has added stress to an already stressful job. Of more than 2,300 physicians surveyed in August 2020 by the Physicians Foundation, a physicians advocacy organization, 50% indicated that they experienced excessive anger, tearfulness, or anxiety because of the way the pandemic affected their work; 30% felt hopeless or lacking purpose; and 8% had thoughts of self-harm related to the pandemic. Rates of burnout had risen from 40% in 2018 to 58%.

Those problems might be even more acute in places experiencing other types of crises. A 2020 study of 154 emergency department (ED) physicians in Libya, which is in the midst of a civil war, found that 65% were experiencing anxiety, 73% were showing signs of depression, and 68% felt emotionally exhausted.

Every story is different

It is unclear how common suicide is among physicians. One often-repeated estimate is that 300-400 physicians die by suicide each year, but no one is certain how that number was determined, said Dr. Myers, who organized the APA panel.

Studies on suicide are inconsistent, and trends are hard to pinpoint. Anecdotally, he has received just as many calls about physician suicides in the past year as he did before the pandemic started.

Every person is different, and so is every death. Sometimes, career problems have nothing to do with a physician’s suicide, Dr. Myers said. When job stress does play a role, factors are often varied and complex.

After a 35-year career as a double board certified ED physician, Matthew Seaman, MD, retired in January 2017. The same month, a patient filed a complaint against him with the Washington State medical board, which led to an investigation and a lawsuit.

The case was hard on Dr. Seaman, who had continued to work night shifts throughout his career and had won a Hero Award from the American Board of Emergency Medicine, said his wife, Linda Seaman, MD, a family practitioner in Yakima, Wash., who also spoke on the APA panel.

Dr. Seaman said that 2 years after the investigation started, her husband was growing increasingly depressed. In 2019, he testified in a deposition. She said the plaintiff’s attorney “tried every way he could to shame Matt, humiliate Matt, make him believe he was a very bad doctor.” Three days later, he died by suicide at age 62.

Looking back at the year leading up to her husband’s death, Dr. Seaman recognizes multiple obstacles that interfered with her husband’s ability to get help, including frustrating interactions with psychiatrists and the couple’s insurance company.

His identity and experience as a physician also played a role. A couple of months before he died, she tried unsuccessfully to reach his psychiatrist, whose office suggested he go to the ED. However, because he worked as an ED doctor in their small town, he wouldn’t go. Dr. Seaman suspects he was wary of the stigma.

Burnout likely set him up to cave in after decades of work on the front lines, she added. Working in the ED exposes providers to horrific, traumatic cases every day, she said. Physicians learn to suppress their own emotions to deal with what they encounter. Stuffing their feelings can lead to posttraumatic stress. “You just perform,” she said. “You learn to do that.”

A real gift

Whenever Dr. Myers hears stories about doctors who died by suicide or who have written about their mental health struggles to help others, he contacts them. One goal of his own writing and of the conference sessions he organizes is to make it easier for others to share their own stories.

“I tell them, first of all, their courage and honesty is a real gift, and they’re saving lives,” he said. “There are so many suffering doctors out there who think that they’re the only one.”

Public conversations such as those that occurred in the APA session also offer opportunities to share advice, including Dr. Myers’ recommendation that doctors be sure they have a primary care physician of their own.

Many don’t, he says, because they say they are too busy, they can treat their own symptoms, or they can self-refer to specialists when needed. But physicians don’t always recognize symptoms of depression in themselves, and when mental health problems arise, they may not seek help or treat themselves appropriately.

A primary care physician can be the first person to recognize a mental health problem and refer a patient for mental health care, said Dr. Myers, whose latest book, “Becoming a Doctors’ Doctor: A Memoir,” explores his experiences treating doctors with burnout and other mental health problems.

Whether they have a primary care doctor or not, he suggests that physicians talk to anyone they trust – a social worker, a religious leader, or a family member who can then help them find the right sort of care.

In the United States, around-the-clock help is available through the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255. A psychiatrist-run hotline specifically for physicians is available at 888-409-0141. “Reach out and get some help,” Dr. Myers said. “Just don’t do it alone.”

Dr. Lynes advocates setting boundaries between life and work. He has also benefited from writing about his experiences. A blog or a diary can help physicians process their feelings, he said. His 2016 essay marked a major turning point in his life, giving his life meaning in helping others.

“Since I wrote that article, I can’t tell you how much better I am,” he said. “Now, I’m not embarrassed to be around physicians. I actually consider myself a physician. I didn’t for many, many years. So, I’m doing pretty well.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

William Lynes, MD, had a flourishing medical practice and a fulfilling family life with three children when he first attempted suicide in 1999 at age 45. By 2003, depression and two more suicide attempts led to his early retirement.

In a session at the recent virtual American Psychiatric Association (APA) 2021 annual meeting, Dr. Lynes talked about the challenges of dealing with depression while managing the stresses of a career in medicine. The session in which he spoke was called, “The Suicidal Physician: Narratives From a Physician Who Survived and the Physician Widow of One Who Did Not.”

By writing and speaking about his experiences, he says, he has been able to retain his identity as a physician and avoid obsessive thoughts about suicide. He hopes conversations like these help other physicians feel less alone and enable them to push past stigmas to get the help they need. He suspects they do. More than 600 people joined the APA session, and Dr. Lynes received dozens of thankful messages afterward.

“I love medicine, but intrinsically, the practice of medicine is stressful, and you can’t get away,” said Dr. Lynes, a retired urologist in Temecula, Calif. “As far as feedback, it made me feel like it’s something I should continue to do.”

A way to heal

For Dr. Lynes, his “downward spiral into darkness” began with a series of catastrophic medical events starting in 1998, when he came home from a family vacation in Mexico feeling unwell. He didn’t bother to do anything about it – typical of a physician, he says. Then one night he woke up shaking with chills and fever. Soon he was in the hospital with respiratory failure from septic shock.

Dr. Lynes spent 6 weeks in the intensive care unit, including 4 weeks on a ventilator. He underwent a tracheostomy. He lost 40 pounds and experienced ICU-related delirium. It was a terrifying time, he said. When he tried to return to work 10 months later, he didn’t feel as though he could function normally.

Having once been a driven doctor who worked long hours, he now doubted himself and dreaded giving patients bad news. Spontaneously, he tried to take his own life.

Afterward, he concealed what had happened from everyone except his wife and managed to resume his practice. However, he was unable to regain the enthusiasm he had once had for his work. Although he had experienced depression before, this time it was unrelenting.

He sought help from a psychiatrist, received a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and began taking medication. Still, he struggled to fulfill his responsibilities. Then in April 2002, he had a snowboarding accident that caused multiple facial fractures and required five operations. When he returned to work this time, he felt like a failure but resisted asking colleagues for help.

A few months later, Dr. Lynes again attempted suicide, which led to another stay in the ICU and more time on a ventilator. Doctors told his family they didn’t think he would survive. When he recovered, he spent time as an inpatient in a psychiatric ward, where he received the first of a series of electroconvulsive therapy sessions. Compounding his anxiety and depression was the inability to come to terms with his life if he were not able to practice medicine.

The next fall, in September 2003, his third suicide attempt took place in his office on a weekend when no one was around. After locking the door, he looked at his reflection in the frame of his medical school diploma. The glass was cracked. “It was dark, it was black, it was cold,” he said. “I can remember seeing my reflection and thinking how disgusted I was.”

For years after that, Dr. Lynes struggled with his sense of self-worth. He hid from the medical system and dreaded doctors’ appointments. Finally in 2016, he found new meaning at a writing conference, where he met a fellow physician whose story was similar to his. She encouraged him to write about his experience. His essay was published in Annals of Internal Medicine that year. “Then I started speaking, and I feel like I’m a physician again,” he said. “That has really healed me quite a bit.”

Why physicians die by suicide

Working in health care can be extremely stressful, even in the best of times, said Michael Myers, MD, a psychiatrist at State University of New York, Brooklyn, and author of the book, “Why Physicians Die By Suicide: Lessons Learned From Their Families and Others Who Cared.”

Years of school and training culminate in a career in which demands are relentless. Societal expectations are high. Many doctors are perfectionists by nature, and physicians tend to feel intense pressure to compete for coveted positions.

Stress starts early in a medical career. A 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis of 183 studies from 43 countries showed that nearly 30% of medical students experienced symptoms of depression and that 11% reported suicidal thoughts, but only 15% sought help.

A 2015 review of 31 studies that involved residents showed that rates of depression remained close to 30% and that about three-quarters of trainees meet criteria for burnout, a type of emotional exhaustion and sense of inadequacy that can result from chronic stress at work.

The stress of medical training appears to be a direct cause of mental health struggles. Rates of depression are higher among those working to become physicians than among their peers of the same age, research shows. In addition, symptoms become more prevalent as people progress through their training.

The COVID-19 pandemic has added stress to an already stressful job. Of more than 2,300 physicians surveyed in August 2020 by the Physicians Foundation, a physicians advocacy organization, 50% indicated that they experienced excessive anger, tearfulness, or anxiety because of the way the pandemic affected their work; 30% felt hopeless or lacking purpose; and 8% had thoughts of self-harm related to the pandemic. Rates of burnout had risen from 40% in 2018 to 58%.

Those problems might be even more acute in places experiencing other types of crises. A 2020 study of 154 emergency department (ED) physicians in Libya, which is in the midst of a civil war, found that 65% were experiencing anxiety, 73% were showing signs of depression, and 68% felt emotionally exhausted.

Every story is different

It is unclear how common suicide is among physicians. One often-repeated estimate is that 300-400 physicians die by suicide each year, but no one is certain how that number was determined, said Dr. Myers, who organized the APA panel.

Studies on suicide are inconsistent, and trends are hard to pinpoint. Anecdotally, he has received just as many calls about physician suicides in the past year as he did before the pandemic started.

Every person is different, and so is every death. Sometimes, career problems have nothing to do with a physician’s suicide, Dr. Myers said. When job stress does play a role, factors are often varied and complex.

After a 35-year career as a double board certified ED physician, Matthew Seaman, MD, retired in January 2017. The same month, a patient filed a complaint against him with the Washington State medical board, which led to an investigation and a lawsuit.

The case was hard on Dr. Seaman, who had continued to work night shifts throughout his career and had won a Hero Award from the American Board of Emergency Medicine, said his wife, Linda Seaman, MD, a family practitioner in Yakima, Wash., who also spoke on the APA panel.

Dr. Seaman said that 2 years after the investigation started, her husband was growing increasingly depressed. In 2019, he testified in a deposition. She said the plaintiff’s attorney “tried every way he could to shame Matt, humiliate Matt, make him believe he was a very bad doctor.” Three days later, he died by suicide at age 62.

Looking back at the year leading up to her husband’s death, Dr. Seaman recognizes multiple obstacles that interfered with her husband’s ability to get help, including frustrating interactions with psychiatrists and the couple’s insurance company.

His identity and experience as a physician also played a role. A couple of months before he died, she tried unsuccessfully to reach his psychiatrist, whose office suggested he go to the ED. However, because he worked as an ED doctor in their small town, he wouldn’t go. Dr. Seaman suspects he was wary of the stigma.

Burnout likely set him up to cave in after decades of work on the front lines, she added. Working in the ED exposes providers to horrific, traumatic cases every day, she said. Physicians learn to suppress their own emotions to deal with what they encounter. Stuffing their feelings can lead to posttraumatic stress. “You just perform,” she said. “You learn to do that.”

A real gift

Whenever Dr. Myers hears stories about doctors who died by suicide or who have written about their mental health struggles to help others, he contacts them. One goal of his own writing and of the conference sessions he organizes is to make it easier for others to share their own stories.

“I tell them, first of all, their courage and honesty is a real gift, and they’re saving lives,” he said. “There are so many suffering doctors out there who think that they’re the only one.”

Public conversations such as those that occurred in the APA session also offer opportunities to share advice, including Dr. Myers’ recommendation that doctors be sure they have a primary care physician of their own.

Many don’t, he says, because they say they are too busy, they can treat their own symptoms, or they can self-refer to specialists when needed. But physicians don’t always recognize symptoms of depression in themselves, and when mental health problems arise, they may not seek help or treat themselves appropriately.

A primary care physician can be the first person to recognize a mental health problem and refer a patient for mental health care, said Dr. Myers, whose latest book, “Becoming a Doctors’ Doctor: A Memoir,” explores his experiences treating doctors with burnout and other mental health problems.

Whether they have a primary care doctor or not, he suggests that physicians talk to anyone they trust – a social worker, a religious leader, or a family member who can then help them find the right sort of care.

In the United States, around-the-clock help is available through the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255. A psychiatrist-run hotline specifically for physicians is available at 888-409-0141. “Reach out and get some help,” Dr. Myers said. “Just don’t do it alone.”

Dr. Lynes advocates setting boundaries between life and work. He has also benefited from writing about his experiences. A blog or a diary can help physicians process their feelings, he said. His 2016 essay marked a major turning point in his life, giving his life meaning in helping others.

“Since I wrote that article, I can’t tell you how much better I am,” he said. “Now, I’m not embarrassed to be around physicians. I actually consider myself a physician. I didn’t for many, many years. So, I’m doing pretty well.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

William Lynes, MD, had a flourishing medical practice and a fulfilling family life with three children when he first attempted suicide in 1999 at age 45. By 2003, depression and two more suicide attempts led to his early retirement.

In a session at the recent virtual American Psychiatric Association (APA) 2021 annual meeting, Dr. Lynes talked about the challenges of dealing with depression while managing the stresses of a career in medicine. The session in which he spoke was called, “The Suicidal Physician: Narratives From a Physician Who Survived and the Physician Widow of One Who Did Not.”

By writing and speaking about his experiences, he says, he has been able to retain his identity as a physician and avoid obsessive thoughts about suicide. He hopes conversations like these help other physicians feel less alone and enable them to push past stigmas to get the help they need. He suspects they do. More than 600 people joined the APA session, and Dr. Lynes received dozens of thankful messages afterward.

“I love medicine, but intrinsically, the practice of medicine is stressful, and you can’t get away,” said Dr. Lynes, a retired urologist in Temecula, Calif. “As far as feedback, it made me feel like it’s something I should continue to do.”

A way to heal

For Dr. Lynes, his “downward spiral into darkness” began with a series of catastrophic medical events starting in 1998, when he came home from a family vacation in Mexico feeling unwell. He didn’t bother to do anything about it – typical of a physician, he says. Then one night he woke up shaking with chills and fever. Soon he was in the hospital with respiratory failure from septic shock.

Dr. Lynes spent 6 weeks in the intensive care unit, including 4 weeks on a ventilator. He underwent a tracheostomy. He lost 40 pounds and experienced ICU-related delirium. It was a terrifying time, he said. When he tried to return to work 10 months later, he didn’t feel as though he could function normally.

Having once been a driven doctor who worked long hours, he now doubted himself and dreaded giving patients bad news. Spontaneously, he tried to take his own life.

Afterward, he concealed what had happened from everyone except his wife and managed to resume his practice. However, he was unable to regain the enthusiasm he had once had for his work. Although he had experienced depression before, this time it was unrelenting.

He sought help from a psychiatrist, received a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and began taking medication. Still, he struggled to fulfill his responsibilities. Then in April 2002, he had a snowboarding accident that caused multiple facial fractures and required five operations. When he returned to work this time, he felt like a failure but resisted asking colleagues for help.

A few months later, Dr. Lynes again attempted suicide, which led to another stay in the ICU and more time on a ventilator. Doctors told his family they didn’t think he would survive. When he recovered, he spent time as an inpatient in a psychiatric ward, where he received the first of a series of electroconvulsive therapy sessions. Compounding his anxiety and depression was the inability to come to terms with his life if he were not able to practice medicine.

The next fall, in September 2003, his third suicide attempt took place in his office on a weekend when no one was around. After locking the door, he looked at his reflection in the frame of his medical school diploma. The glass was cracked. “It was dark, it was black, it was cold,” he said. “I can remember seeing my reflection and thinking how disgusted I was.”

For years after that, Dr. Lynes struggled with his sense of self-worth. He hid from the medical system and dreaded doctors’ appointments. Finally in 2016, he found new meaning at a writing conference, where he met a fellow physician whose story was similar to his. She encouraged him to write about his experience. His essay was published in Annals of Internal Medicine that year. “Then I started speaking, and I feel like I’m a physician again,” he said. “That has really healed me quite a bit.”

Why physicians die by suicide

Working in health care can be extremely stressful, even in the best of times, said Michael Myers, MD, a psychiatrist at State University of New York, Brooklyn, and author of the book, “Why Physicians Die By Suicide: Lessons Learned From Their Families and Others Who Cared.”

Years of school and training culminate in a career in which demands are relentless. Societal expectations are high. Many doctors are perfectionists by nature, and physicians tend to feel intense pressure to compete for coveted positions.

Stress starts early in a medical career. A 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis of 183 studies from 43 countries showed that nearly 30% of medical students experienced symptoms of depression and that 11% reported suicidal thoughts, but only 15% sought help.

A 2015 review of 31 studies that involved residents showed that rates of depression remained close to 30% and that about three-quarters of trainees meet criteria for burnout, a type of emotional exhaustion and sense of inadequacy that can result from chronic stress at work.

The stress of medical training appears to be a direct cause of mental health struggles. Rates of depression are higher among those working to become physicians than among their peers of the same age, research shows. In addition, symptoms become more prevalent as people progress through their training.

The COVID-19 pandemic has added stress to an already stressful job. Of more than 2,300 physicians surveyed in August 2020 by the Physicians Foundation, a physicians advocacy organization, 50% indicated that they experienced excessive anger, tearfulness, or anxiety because of the way the pandemic affected their work; 30% felt hopeless or lacking purpose; and 8% had thoughts of self-harm related to the pandemic. Rates of burnout had risen from 40% in 2018 to 58%.

Those problems might be even more acute in places experiencing other types of crises. A 2020 study of 154 emergency department (ED) physicians in Libya, which is in the midst of a civil war, found that 65% were experiencing anxiety, 73% were showing signs of depression, and 68% felt emotionally exhausted.

Every story is different

It is unclear how common suicide is among physicians. One often-repeated estimate is that 300-400 physicians die by suicide each year, but no one is certain how that number was determined, said Dr. Myers, who organized the APA panel.

Studies on suicide are inconsistent, and trends are hard to pinpoint. Anecdotally, he has received just as many calls about physician suicides in the past year as he did before the pandemic started.

Every person is different, and so is every death. Sometimes, career problems have nothing to do with a physician’s suicide, Dr. Myers said. When job stress does play a role, factors are often varied and complex.

After a 35-year career as a double board certified ED physician, Matthew Seaman, MD, retired in January 2017. The same month, a patient filed a complaint against him with the Washington State medical board, which led to an investigation and a lawsuit.

The case was hard on Dr. Seaman, who had continued to work night shifts throughout his career and had won a Hero Award from the American Board of Emergency Medicine, said his wife, Linda Seaman, MD, a family practitioner in Yakima, Wash., who also spoke on the APA panel.

Dr. Seaman said that 2 years after the investigation started, her husband was growing increasingly depressed. In 2019, he testified in a deposition. She said the plaintiff’s attorney “tried every way he could to shame Matt, humiliate Matt, make him believe he was a very bad doctor.” Three days later, he died by suicide at age 62.

Looking back at the year leading up to her husband’s death, Dr. Seaman recognizes multiple obstacles that interfered with her husband’s ability to get help, including frustrating interactions with psychiatrists and the couple’s insurance company.

His identity and experience as a physician also played a role. A couple of months before he died, she tried unsuccessfully to reach his psychiatrist, whose office suggested he go to the ED. However, because he worked as an ED doctor in their small town, he wouldn’t go. Dr. Seaman suspects he was wary of the stigma.

Burnout likely set him up to cave in after decades of work on the front lines, she added. Working in the ED exposes providers to horrific, traumatic cases every day, she said. Physicians learn to suppress their own emotions to deal with what they encounter. Stuffing their feelings can lead to posttraumatic stress. “You just perform,” she said. “You learn to do that.”

A real gift

Whenever Dr. Myers hears stories about doctors who died by suicide or who have written about their mental health struggles to help others, he contacts them. One goal of his own writing and of the conference sessions he organizes is to make it easier for others to share their own stories.

“I tell them, first of all, their courage and honesty is a real gift, and they’re saving lives,” he said. “There are so many suffering doctors out there who think that they’re the only one.”

Public conversations such as those that occurred in the APA session also offer opportunities to share advice, including Dr. Myers’ recommendation that doctors be sure they have a primary care physician of their own.

Many don’t, he says, because they say they are too busy, they can treat their own symptoms, or they can self-refer to specialists when needed. But physicians don’t always recognize symptoms of depression in themselves, and when mental health problems arise, they may not seek help or treat themselves appropriately.

A primary care physician can be the first person to recognize a mental health problem and refer a patient for mental health care, said Dr. Myers, whose latest book, “Becoming a Doctors’ Doctor: A Memoir,” explores his experiences treating doctors with burnout and other mental health problems.

Whether they have a primary care doctor or not, he suggests that physicians talk to anyone they trust – a social worker, a religious leader, or a family member who can then help them find the right sort of care.

In the United States, around-the-clock help is available through the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255. A psychiatrist-run hotline specifically for physicians is available at 888-409-0141. “Reach out and get some help,” Dr. Myers said. “Just don’t do it alone.”

Dr. Lynes advocates setting boundaries between life and work. He has also benefited from writing about his experiences. A blog or a diary can help physicians process their feelings, he said. His 2016 essay marked a major turning point in his life, giving his life meaning in helping others.

“Since I wrote that article, I can’t tell you how much better I am,” he said. “Now, I’m not embarrassed to be around physicians. I actually consider myself a physician. I didn’t for many, many years. So, I’m doing pretty well.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

APA, AMA, others move to stop insurer from overturning mental health claims ruling

The American Psychiatric Association has joined with the American Medical Association and other medical societies to oppose United Behavioral Health’s (UBH) request that a court throw out a ruling that found the insurer unfairly denied tens of thousands of claims for mental health and substance use disorder services.

Wit v. United Behavioral Health, in litigation since 2014, is being closely watched by clinicians, patients, providers, and attorneys.

Reena Kapoor, MD, chair of the APA’s Committee on Judicial Action, said in an interview that the APA is hopeful that “whatever the court says about UBH should be applicable to all insurance companies that are providing employer-sponsored health benefits.”

In a friend of the court (amicus curiae) brief, the APA, AMA, the California Medical Association, Southern California Psychiatric Society, Northern California Psychiatric Society, Orange County Psychiatric Society, Central California Psychiatric Society, and San Diego Psychiatric Society argue that “despite the availability of professionally developed, evidence-based guidelines embodying generally accepted standards of care for mental health and substance use disorders, managed care organizations commonly base coverage decisions on internally developed ‘level of care guidelines’ that are inappropriately restrictive.”

The guidelines “may lead to denial of coverage for treatment that is recommended by a patient’s physician and even cut off coverage when treatment is already being delivered,” said the groups.

The U.S. Department of Labor also filed a brief in support of the plaintiffs who are suing UBH. Those individuals suffered injury when they were denied coverage, said the federal agency, which regulates employer-sponsored insurance plans.

California Attorney General Rob Bonta also made an amicus filing supporting the plaintiffs.

“When insurers limit access to this critical care, they leave Californians who need it feeling as if they have no other option than to try to cope alone,” said Mr. Bonta in a statement.

‘Discrimination must end’

Mr. Bonta said he agreed with a 2019 ruling by the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California that UBH had violated its fiduciary duties by wrongfully using its internally developed coverage determination guidelines and level of care guidelines to deny care.

The court also found that UBH’s medically necessary criteria meant that only “acute” episodes would be covered. Instead, said the court last November, chronic and comorbid conditions should always be treated, according to Maureen Gammon and Kathleen Rosenow of Willis Towers Watson, a risk advisor.

In November, the same Northern California District Court ruled on the remedies it would require of United, including that the insurer reprocess more than 67,000 claims. UBH was also barred indefinitely from using any of its guidelines to make coverage determinations. Instead, it was ordered to make determinations “consistent with generally accepted standards of care,” and consistent with state laws.

The District Court denied a request by UBH to put a hold on the claims reprocessing until it appealed the overall case. But the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in February granted that request.

Then, in March, United appealed the District Court’s overall ruling, claiming that the plaintiffs had not proven harm.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce has filed a brief in support of United, agreeing with its arguments.

However, the APA and other clinician groups said there is no question of harm.

“Failure to provide appropriate levels of care for treatment of mental illness and substance use disorders leads to relapse, overdose, transmission of infectious diseases, and death,” said APA CEO and Medical Director Saul Levin, MD, MPA, in a statement.

APA President Vivian Pender, MD, said guidelines that “are overly focused on stabilizing acute symptoms of mental health and substance use disorders” are not treating the underlying disease. “When the injury is physical, insurers treat the underlying disease and not just the symptoms. Discrimination against patients with mental illness must end,” she said.

No court has ever recognized the type of claims reprocessing ordered by the District Court judge, said attorneys Nathaniel Cohen and Joseph Laska of Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, in an analysis of the case.

Mr. Cohen and Mr. Laska write. “Practitioners, health plans, and health insurers would be wise to track UBH’s long-awaited appeal to the Ninth Circuit.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The American Psychiatric Association has joined with the American Medical Association and other medical societies to oppose United Behavioral Health’s (UBH) request that a court throw out a ruling that found the insurer unfairly denied tens of thousands of claims for mental health and substance use disorder services.

Wit v. United Behavioral Health, in litigation since 2014, is being closely watched by clinicians, patients, providers, and attorneys.

Reena Kapoor, MD, chair of the APA’s Committee on Judicial Action, said in an interview that the APA is hopeful that “whatever the court says about UBH should be applicable to all insurance companies that are providing employer-sponsored health benefits.”

In a friend of the court (amicus curiae) brief, the APA, AMA, the California Medical Association, Southern California Psychiatric Society, Northern California Psychiatric Society, Orange County Psychiatric Society, Central California Psychiatric Society, and San Diego Psychiatric Society argue that “despite the availability of professionally developed, evidence-based guidelines embodying generally accepted standards of care for mental health and substance use disorders, managed care organizations commonly base coverage decisions on internally developed ‘level of care guidelines’ that are inappropriately restrictive.”

The guidelines “may lead to denial of coverage for treatment that is recommended by a patient’s physician and even cut off coverage when treatment is already being delivered,” said the groups.

The U.S. Department of Labor also filed a brief in support of the plaintiffs who are suing UBH. Those individuals suffered injury when they were denied coverage, said the federal agency, which regulates employer-sponsored insurance plans.

California Attorney General Rob Bonta also made an amicus filing supporting the plaintiffs.

“When insurers limit access to this critical care, they leave Californians who need it feeling as if they have no other option than to try to cope alone,” said Mr. Bonta in a statement.

‘Discrimination must end’

Mr. Bonta said he agreed with a 2019 ruling by the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California that UBH had violated its fiduciary duties by wrongfully using its internally developed coverage determination guidelines and level of care guidelines to deny care.

The court also found that UBH’s medically necessary criteria meant that only “acute” episodes would be covered. Instead, said the court last November, chronic and comorbid conditions should always be treated, according to Maureen Gammon and Kathleen Rosenow of Willis Towers Watson, a risk advisor.

In November, the same Northern California District Court ruled on the remedies it would require of United, including that the insurer reprocess more than 67,000 claims. UBH was also barred indefinitely from using any of its guidelines to make coverage determinations. Instead, it was ordered to make determinations “consistent with generally accepted standards of care,” and consistent with state laws.

The District Court denied a request by UBH to put a hold on the claims reprocessing until it appealed the overall case. But the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in February granted that request.

Then, in March, United appealed the District Court’s overall ruling, claiming that the plaintiffs had not proven harm.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce has filed a brief in support of United, agreeing with its arguments.

However, the APA and other clinician groups said there is no question of harm.

“Failure to provide appropriate levels of care for treatment of mental illness and substance use disorders leads to relapse, overdose, transmission of infectious diseases, and death,” said APA CEO and Medical Director Saul Levin, MD, MPA, in a statement.

APA President Vivian Pender, MD, said guidelines that “are overly focused on stabilizing acute symptoms of mental health and substance use disorders” are not treating the underlying disease. “When the injury is physical, insurers treat the underlying disease and not just the symptoms. Discrimination against patients with mental illness must end,” she said.

No court has ever recognized the type of claims reprocessing ordered by the District Court judge, said attorneys Nathaniel Cohen and Joseph Laska of Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, in an analysis of the case.

Mr. Cohen and Mr. Laska write. “Practitioners, health plans, and health insurers would be wise to track UBH’s long-awaited appeal to the Ninth Circuit.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The American Psychiatric Association has joined with the American Medical Association and other medical societies to oppose United Behavioral Health’s (UBH) request that a court throw out a ruling that found the insurer unfairly denied tens of thousands of claims for mental health and substance use disorder services.

Wit v. United Behavioral Health, in litigation since 2014, is being closely watched by clinicians, patients, providers, and attorneys.

Reena Kapoor, MD, chair of the APA’s Committee on Judicial Action, said in an interview that the APA is hopeful that “whatever the court says about UBH should be applicable to all insurance companies that are providing employer-sponsored health benefits.”

In a friend of the court (amicus curiae) brief, the APA, AMA, the California Medical Association, Southern California Psychiatric Society, Northern California Psychiatric Society, Orange County Psychiatric Society, Central California Psychiatric Society, and San Diego Psychiatric Society argue that “despite the availability of professionally developed, evidence-based guidelines embodying generally accepted standards of care for mental health and substance use disorders, managed care organizations commonly base coverage decisions on internally developed ‘level of care guidelines’ that are inappropriately restrictive.”

The guidelines “may lead to denial of coverage for treatment that is recommended by a patient’s physician and even cut off coverage when treatment is already being delivered,” said the groups.

The U.S. Department of Labor also filed a brief in support of the plaintiffs who are suing UBH. Those individuals suffered injury when they were denied coverage, said the federal agency, which regulates employer-sponsored insurance plans.

California Attorney General Rob Bonta also made an amicus filing supporting the plaintiffs.

“When insurers limit access to this critical care, they leave Californians who need it feeling as if they have no other option than to try to cope alone,” said Mr. Bonta in a statement.

‘Discrimination must end’

Mr. Bonta said he agreed with a 2019 ruling by the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California that UBH had violated its fiduciary duties by wrongfully using its internally developed coverage determination guidelines and level of care guidelines to deny care.

The court also found that UBH’s medically necessary criteria meant that only “acute” episodes would be covered. Instead, said the court last November, chronic and comorbid conditions should always be treated, according to Maureen Gammon and Kathleen Rosenow of Willis Towers Watson, a risk advisor.

In November, the same Northern California District Court ruled on the remedies it would require of United, including that the insurer reprocess more than 67,000 claims. UBH was also barred indefinitely from using any of its guidelines to make coverage determinations. Instead, it was ordered to make determinations “consistent with generally accepted standards of care,” and consistent with state laws.

The District Court denied a request by UBH to put a hold on the claims reprocessing until it appealed the overall case. But the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in February granted that request.

Then, in March, United appealed the District Court’s overall ruling, claiming that the plaintiffs had not proven harm.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce has filed a brief in support of United, agreeing with its arguments.

However, the APA and other clinician groups said there is no question of harm.

“Failure to provide appropriate levels of care for treatment of mental illness and substance use disorders leads to relapse, overdose, transmission of infectious diseases, and death,” said APA CEO and Medical Director Saul Levin, MD, MPA, in a statement.

APA President Vivian Pender, MD, said guidelines that “are overly focused on stabilizing acute symptoms of mental health and substance use disorders” are not treating the underlying disease. “When the injury is physical, insurers treat the underlying disease and not just the symptoms. Discrimination against patients with mental illness must end,” she said.

No court has ever recognized the type of claims reprocessing ordered by the District Court judge, said attorneys Nathaniel Cohen and Joseph Laska of Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, in an analysis of the case.

Mr. Cohen and Mr. Laska write. “Practitioners, health plans, and health insurers would be wise to track UBH’s long-awaited appeal to the Ninth Circuit.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

No-cancel culture: How telehealth is making it easier to keep that therapy session

When the COVID-19 pandemic forced behavioral health providers to stop seeing patients in person and instead hold therapy sessions remotely, the switch produced an unintended, positive consequence: Fewer patients skipped appointments.

That had long been a problem in mental health care. Some outpatient programs previously had no-show rates as high as 60%, according to several studies.

Only 9% of psychiatrists reported that all patients kept their appointments before the pandemic, according to an American Psychiatric Association report. Once providers switched to telepsychiatry, that number increased to 32%.

Not only that, but providers and patients say teletherapy has largely been an effective lifeline for people struggling with anxiety, depression, and other psychological issues during an extraordinarily difficult time, even though it created a new set of challenges.

Many providers say they plan to continue offering teletherapy after the pandemic. Some states are making permanent the temporary pandemic rules that allow providers to be reimbursed at the same rates as for in-person visits, which is welcome news to practitioners who take patients’ insurance.

“We are in a mental health crisis right now, so more people are struggling and may be more open to accessing services,” said psychologist Allison Dempsey, PhD, associate professor at University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. “It’s much easier to connect from your living room.”

The problem for patients who didn’t show up was often as simple as a canceled ride, said Jody Long, a clinical social worker who studied the 60% rate of no-shows or late cancellations at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center psychiatric clinic in Memphis.

But sometimes it was the health problem itself. Mr. Long remembers seeing a first-time patient drive around the parking lot and then exit. The patient later called and told Mr. Long, “I just could not get out of the car; please forgive me and reschedule me.”

Mr. Long, now an assistant professor at Jacksonville (Ala.) State University, said that incident changed his perspective. “I realized when you’re having panic attacks or anxiety attacks or suffering from major depressive disorder, it’s hard,” he said. “It’s like you have built up these walls for protection and then all of a sudden you’re having to let these walls down.”

Absences strain providers whose bosses set billing and productivity expectations and those in private practice who lose billable hours, said Dr. Dempsey, who directs a program to provide mental health care for families of babies with serious medical complications. Psychotherapists often overbooked patients with the expectation that some would not show up.

Now Dr. Dempsey and colleagues no longer need to overbook. When patients don’t show up, staffers can sometimes contact a patient right away and hold the session. Other times, they can reschedule them for later that day or a different day.

And telepsychiatry performs as well as, if not better than, face-to-face delivery of mental health services, according to a World Journal of Psychiatry review of 452 studies.

Virtual visits can also save patients money, because they might not need to travel, take time off work, or pay for child care, said Jay Shore, MD, MPH, chairperson of the American Psychiatric Association’s telepsychiatry committee and a psychiatrist at the University of Colorado.

Dr. Shore started examining the potential of video conferencing to reach rural patients in the late ’90s and concluded that patients and providers can virtually build rapport, which he said is fundamental for effective therapy and medicine management.

But before the pandemic, almost 64% of psychiatrists had never used telehealth, according to the psychiatric association. Amid widespread skepticism, providers then had to do “10 years of implementations in 10 days,” said Dr. Shore, who has consulted with Dr. Dempsey and other providers.

Dr. Dempsey and colleagues faced a steep learning curve. She said she recently held a video therapy session with a mother who “seemed very out of it” before disappearing from the screen while her baby was crying.

She wondered if the patient’s exit was related to the stress of new motherhood or “something more concerning,” like addiction. She thinks she might have better understood the woman’s condition had they been in the same room. The patient called Dr. Dempsey’s team that night and told them she had relapsed into drug use and been taken to the emergency room. The mental health providers directed her to a treatment program, Dr. Dempsey said.

“We spent a lot of time reviewing what happened with that case and thinking about what we need to do differently,” Dr. Dempsey said.

Providers now routinely ask for the name of someone to call if they lose a connection and can no longer reach the patient.

In another session, Dr. Dempsey noticed that a patient seemed guarded and saw her partner hovering in the background. She said she worried about the possibility of domestic violence or “some other form of controlling behavior.”

In such cases, Dr. Dempsey called after the appointments or sent the patients secure messages to their online health portal. She asked if they felt safe and suggested they talk in person.

Such inability to maintain privacy remains a concern.

In a Walmart parking lot recently, psychologist Kristy Keefe, PsyD, of Western Illinois University, Macomb, heard a patient talking with her therapist from her car. Dr. Keefe said she wondered if the patient “had no other safe place to go to.”

To avoid that scenario, Dr. Keefe does 30-minute consultations with patients before their first telehealth appointment. She asks if they have space to talk where no one can overhear them and makes sure they have sufficient internet access and know how to use video conferencing.

To ensure that she, too, was prepared, Dr. Keefe upgraded her WiFi router, purchased two white-noise machines to drown out her conversations, and placed a stop sign on her door during appointments so her 5-year-old son knew she was seeing patients.

Dr. Keefe concluded that audio alone sometimes works better than video, which often lags. Over the phone, she and her psychology students “got really sensitive to tone fluctuations” in a patient’s voice and were better able to “pick up the emotion” than with video conferencing.

With those telehealth visits, her 20% no-show rate evaporated.

Kate Barnes, a 29-year-old middle school teacher in Fayetteville, Ark., who struggles with anxiety and depression, also has found visits easier by phone than by Zoom, because she doesn’t feel like a spotlight is on her.

“I can focus more on what I want to say,” she said.

In one of Dr. Keefe’s video sessions, though, a patient reached out, touched the camera and started to cry as she said how appreciative she was that someone was there, Dr. Keefe recalled.

“I am so very thankful that they had something in this terrible time of loss and trauma and isolation,” said Dr. Keefe.

Demand for mental health services will likely continue even after the lifting of all COVID restrictions. according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau and the National Health Interview Survey.

“That is not going to go away with snapping our fingers,” Dr. Dempsey said.

After the pandemic, Dr. Shore said, providers should review data from the past year and determine when virtual care or in-person care is more effective. He also said the health care industry needs to work to bridge the digital divide that exists because of lack of access to devices and broadband internet.

Even though Ms. Barnes said she did not see teletherapy as less effective than in-person therapy, she would like to return to seeing her therapist in person.

“When you are in person with someone, you can pick up on their body language better,” she said. “It’s a lot harder over a video call to do that.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

When the COVID-19 pandemic forced behavioral health providers to stop seeing patients in person and instead hold therapy sessions remotely, the switch produced an unintended, positive consequence: Fewer patients skipped appointments.

That had long been a problem in mental health care. Some outpatient programs previously had no-show rates as high as 60%, according to several studies.

Only 9% of psychiatrists reported that all patients kept their appointments before the pandemic, according to an American Psychiatric Association report. Once providers switched to telepsychiatry, that number increased to 32%.

Not only that, but providers and patients say teletherapy has largely been an effective lifeline for people struggling with anxiety, depression, and other psychological issues during an extraordinarily difficult time, even though it created a new set of challenges.

Many providers say they plan to continue offering teletherapy after the pandemic. Some states are making permanent the temporary pandemic rules that allow providers to be reimbursed at the same rates as for in-person visits, which is welcome news to practitioners who take patients’ insurance.

“We are in a mental health crisis right now, so more people are struggling and may be more open to accessing services,” said psychologist Allison Dempsey, PhD, associate professor at University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. “It’s much easier to connect from your living room.”

The problem for patients who didn’t show up was often as simple as a canceled ride, said Jody Long, a clinical social worker who studied the 60% rate of no-shows or late cancellations at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center psychiatric clinic in Memphis.

But sometimes it was the health problem itself. Mr. Long remembers seeing a first-time patient drive around the parking lot and then exit. The patient later called and told Mr. Long, “I just could not get out of the car; please forgive me and reschedule me.”

Mr. Long, now an assistant professor at Jacksonville (Ala.) State University, said that incident changed his perspective. “I realized when you’re having panic attacks or anxiety attacks or suffering from major depressive disorder, it’s hard,” he said. “It’s like you have built up these walls for protection and then all of a sudden you’re having to let these walls down.”

Absences strain providers whose bosses set billing and productivity expectations and those in private practice who lose billable hours, said Dr. Dempsey, who directs a program to provide mental health care for families of babies with serious medical complications. Psychotherapists often overbooked patients with the expectation that some would not show up.

Now Dr. Dempsey and colleagues no longer need to overbook. When patients don’t show up, staffers can sometimes contact a patient right away and hold the session. Other times, they can reschedule them for later that day or a different day.

And telepsychiatry performs as well as, if not better than, face-to-face delivery of mental health services, according to a World Journal of Psychiatry review of 452 studies.

Virtual visits can also save patients money, because they might not need to travel, take time off work, or pay for child care, said Jay Shore, MD, MPH, chairperson of the American Psychiatric Association’s telepsychiatry committee and a psychiatrist at the University of Colorado.

Dr. Shore started examining the potential of video conferencing to reach rural patients in the late ’90s and concluded that patients and providers can virtually build rapport, which he said is fundamental for effective therapy and medicine management.

But before the pandemic, almost 64% of psychiatrists had never used telehealth, according to the psychiatric association. Amid widespread skepticism, providers then had to do “10 years of implementations in 10 days,” said Dr. Shore, who has consulted with Dr. Dempsey and other providers.

Dr. Dempsey and colleagues faced a steep learning curve. She said she recently held a video therapy session with a mother who “seemed very out of it” before disappearing from the screen while her baby was crying.

She wondered if the patient’s exit was related to the stress of new motherhood or “something more concerning,” like addiction. She thinks she might have better understood the woman’s condition had they been in the same room. The patient called Dr. Dempsey’s team that night and told them she had relapsed into drug use and been taken to the emergency room. The mental health providers directed her to a treatment program, Dr. Dempsey said.

“We spent a lot of time reviewing what happened with that case and thinking about what we need to do differently,” Dr. Dempsey said.

Providers now routinely ask for the name of someone to call if they lose a connection and can no longer reach the patient.

In another session, Dr. Dempsey noticed that a patient seemed guarded and saw her partner hovering in the background. She said she worried about the possibility of domestic violence or “some other form of controlling behavior.”

In such cases, Dr. Dempsey called after the appointments or sent the patients secure messages to their online health portal. She asked if they felt safe and suggested they talk in person.

Such inability to maintain privacy remains a concern.

In a Walmart parking lot recently, psychologist Kristy Keefe, PsyD, of Western Illinois University, Macomb, heard a patient talking with her therapist from her car. Dr. Keefe said she wondered if the patient “had no other safe place to go to.”

To avoid that scenario, Dr. Keefe does 30-minute consultations with patients before their first telehealth appointment. She asks if they have space to talk where no one can overhear them and makes sure they have sufficient internet access and know how to use video conferencing.

To ensure that she, too, was prepared, Dr. Keefe upgraded her WiFi router, purchased two white-noise machines to drown out her conversations, and placed a stop sign on her door during appointments so her 5-year-old son knew she was seeing patients.

Dr. Keefe concluded that audio alone sometimes works better than video, which often lags. Over the phone, she and her psychology students “got really sensitive to tone fluctuations” in a patient’s voice and were better able to “pick up the emotion” than with video conferencing.

With those telehealth visits, her 20% no-show rate evaporated.

Kate Barnes, a 29-year-old middle school teacher in Fayetteville, Ark., who struggles with anxiety and depression, also has found visits easier by phone than by Zoom, because she doesn’t feel like a spotlight is on her.

“I can focus more on what I want to say,” she said.

In one of Dr. Keefe’s video sessions, though, a patient reached out, touched the camera and started to cry as she said how appreciative she was that someone was there, Dr. Keefe recalled.

“I am so very thankful that they had something in this terrible time of loss and trauma and isolation,” said Dr. Keefe.

Demand for mental health services will likely continue even after the lifting of all COVID restrictions. according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau and the National Health Interview Survey.

“That is not going to go away with snapping our fingers,” Dr. Dempsey said.

After the pandemic, Dr. Shore said, providers should review data from the past year and determine when virtual care or in-person care is more effective. He also said the health care industry needs to work to bridge the digital divide that exists because of lack of access to devices and broadband internet.

Even though Ms. Barnes said she did not see teletherapy as less effective than in-person therapy, she would like to return to seeing her therapist in person.

“When you are in person with someone, you can pick up on their body language better,” she said. “It’s a lot harder over a video call to do that.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

When the COVID-19 pandemic forced behavioral health providers to stop seeing patients in person and instead hold therapy sessions remotely, the switch produced an unintended, positive consequence: Fewer patients skipped appointments.

That had long been a problem in mental health care. Some outpatient programs previously had no-show rates as high as 60%, according to several studies.

Only 9% of psychiatrists reported that all patients kept their appointments before the pandemic, according to an American Psychiatric Association report. Once providers switched to telepsychiatry, that number increased to 32%.

Not only that, but providers and patients say teletherapy has largely been an effective lifeline for people struggling with anxiety, depression, and other psychological issues during an extraordinarily difficult time, even though it created a new set of challenges.

Many providers say they plan to continue offering teletherapy after the pandemic. Some states are making permanent the temporary pandemic rules that allow providers to be reimbursed at the same rates as for in-person visits, which is welcome news to practitioners who take patients’ insurance.

“We are in a mental health crisis right now, so more people are struggling and may be more open to accessing services,” said psychologist Allison Dempsey, PhD, associate professor at University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. “It’s much easier to connect from your living room.”

The problem for patients who didn’t show up was often as simple as a canceled ride, said Jody Long, a clinical social worker who studied the 60% rate of no-shows or late cancellations at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center psychiatric clinic in Memphis.

But sometimes it was the health problem itself. Mr. Long remembers seeing a first-time patient drive around the parking lot and then exit. The patient later called and told Mr. Long, “I just could not get out of the car; please forgive me and reschedule me.”

Mr. Long, now an assistant professor at Jacksonville (Ala.) State University, said that incident changed his perspective. “I realized when you’re having panic attacks or anxiety attacks or suffering from major depressive disorder, it’s hard,” he said. “It’s like you have built up these walls for protection and then all of a sudden you’re having to let these walls down.”

Absences strain providers whose bosses set billing and productivity expectations and those in private practice who lose billable hours, said Dr. Dempsey, who directs a program to provide mental health care for families of babies with serious medical complications. Psychotherapists often overbooked patients with the expectation that some would not show up.

Now Dr. Dempsey and colleagues no longer need to overbook. When patients don’t show up, staffers can sometimes contact a patient right away and hold the session. Other times, they can reschedule them for later that day or a different day.

And telepsychiatry performs as well as, if not better than, face-to-face delivery of mental health services, according to a World Journal of Psychiatry review of 452 studies.

Virtual visits can also save patients money, because they might not need to travel, take time off work, or pay for child care, said Jay Shore, MD, MPH, chairperson of the American Psychiatric Association’s telepsychiatry committee and a psychiatrist at the University of Colorado.

Dr. Shore started examining the potential of video conferencing to reach rural patients in the late ’90s and concluded that patients and providers can virtually build rapport, which he said is fundamental for effective therapy and medicine management.

But before the pandemic, almost 64% of psychiatrists had never used telehealth, according to the psychiatric association. Amid widespread skepticism, providers then had to do “10 years of implementations in 10 days,” said Dr. Shore, who has consulted with Dr. Dempsey and other providers.

Dr. Dempsey and colleagues faced a steep learning curve. She said she recently held a video therapy session with a mother who “seemed very out of it” before disappearing from the screen while her baby was crying.

She wondered if the patient’s exit was related to the stress of new motherhood or “something more concerning,” like addiction. She thinks she might have better understood the woman’s condition had they been in the same room. The patient called Dr. Dempsey’s team that night and told them she had relapsed into drug use and been taken to the emergency room. The mental health providers directed her to a treatment program, Dr. Dempsey said.

“We spent a lot of time reviewing what happened with that case and thinking about what we need to do differently,” Dr. Dempsey said.

Providers now routinely ask for the name of someone to call if they lose a connection and can no longer reach the patient.

In another session, Dr. Dempsey noticed that a patient seemed guarded and saw her partner hovering in the background. She said she worried about the possibility of domestic violence or “some other form of controlling behavior.”

In such cases, Dr. Dempsey called after the appointments or sent the patients secure messages to their online health portal. She asked if they felt safe and suggested they talk in person.

Such inability to maintain privacy remains a concern.

In a Walmart parking lot recently, psychologist Kristy Keefe, PsyD, of Western Illinois University, Macomb, heard a patient talking with her therapist from her car. Dr. Keefe said she wondered if the patient “had no other safe place to go to.”

To avoid that scenario, Dr. Keefe does 30-minute consultations with patients before their first telehealth appointment. She asks if they have space to talk where no one can overhear them and makes sure they have sufficient internet access and know how to use video conferencing.

To ensure that she, too, was prepared, Dr. Keefe upgraded her WiFi router, purchased two white-noise machines to drown out her conversations, and placed a stop sign on her door during appointments so her 5-year-old son knew she was seeing patients.

Dr. Keefe concluded that audio alone sometimes works better than video, which often lags. Over the phone, she and her psychology students “got really sensitive to tone fluctuations” in a patient’s voice and were better able to “pick up the emotion” than with video conferencing.

With those telehealth visits, her 20% no-show rate evaporated.

Kate Barnes, a 29-year-old middle school teacher in Fayetteville, Ark., who struggles with anxiety and depression, also has found visits easier by phone than by Zoom, because she doesn’t feel like a spotlight is on her.

“I can focus more on what I want to say,” she said.

In one of Dr. Keefe’s video sessions, though, a patient reached out, touched the camera and started to cry as she said how appreciative she was that someone was there, Dr. Keefe recalled.

“I am so very thankful that they had something in this terrible time of loss and trauma and isolation,” said Dr. Keefe.

Demand for mental health services will likely continue even after the lifting of all COVID restrictions. according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau and the National Health Interview Survey.

“That is not going to go away with snapping our fingers,” Dr. Dempsey said.

After the pandemic, Dr. Shore said, providers should review data from the past year and determine when virtual care or in-person care is more effective. He also said the health care industry needs to work to bridge the digital divide that exists because of lack of access to devices and broadband internet.

Even though Ms. Barnes said she did not see teletherapy as less effective than in-person therapy, she would like to return to seeing her therapist in person.

“When you are in person with someone, you can pick up on their body language better,” she said. “It’s a lot harder over a video call to do that.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

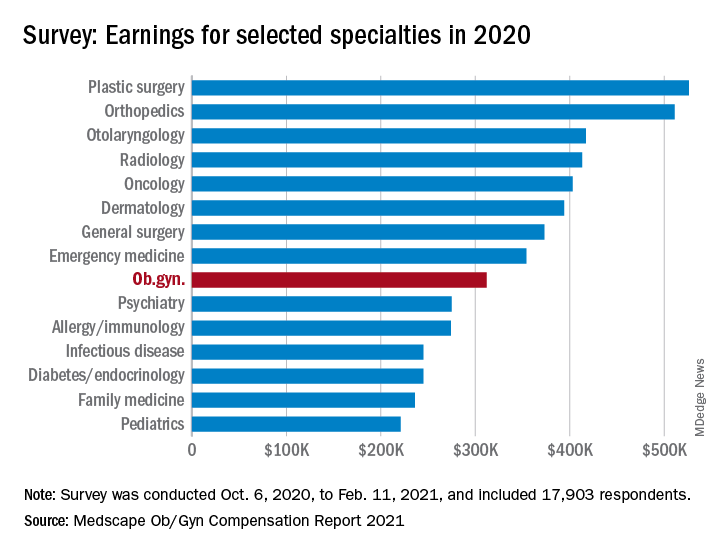

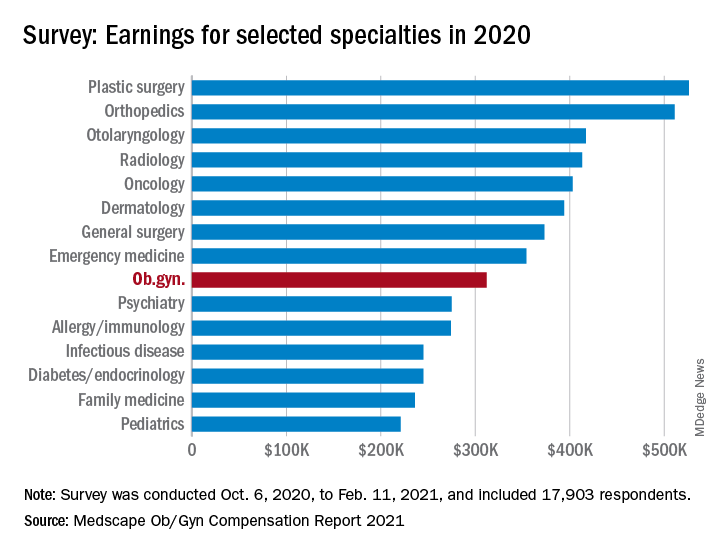

Cardiologists’ pay increases, despite COVID-19 impacts

Despite the huge challenges of COVID-19, including a drop in patient visits, cardiologists reported an average increase in income in 2020 and remain among the top earners in medicine, according to the 2021 Medscape Cardiologist Compensation Report.

Although 46% of cardiologists reported some decline in compensation, average cardiologist income was $459,000 in 2020 – up from $438,000 in 2019.

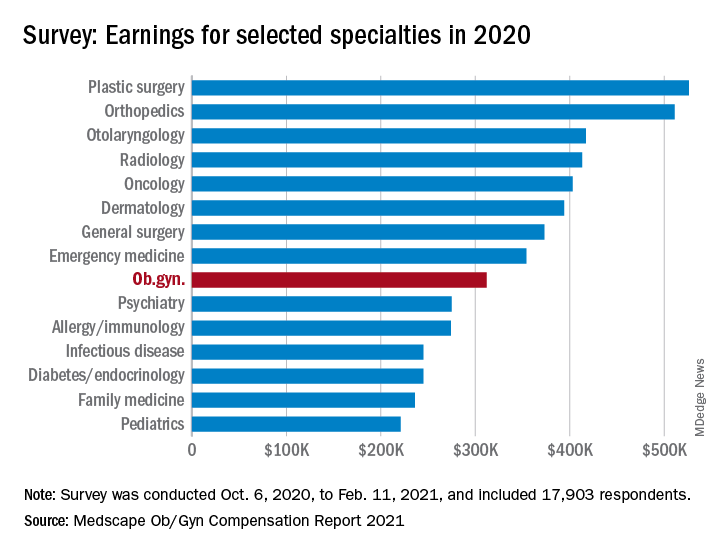

Cardiologist pay is the third highest of all specialties in the overall 2021 Medscape Physician Compensation Report, which covers U.S. physicians as a whole and almost 18,000 physicians in 29 specialties.

Only plastic surgeons ($526,000) and orthopedists ($511,000) earned more than cardiologists in 2020.

On average among cardiologists, self-employment yields a somewhat higher paycheck than does being employed ($477,000 vs. $450,000).

Just like in last year’s report, nearly two-thirds (61%) of cardiologists overall say they feel fairly compensated.

The average incentive bonus payment for cardiologists in 2020 was 14% of total salary, about the same as last year. Two-thirds of cardiologists who earn an incentive bonus achieve more than three-quarters of their potential annual payment, up from 55% the prior year.

COVID challenges and the road back

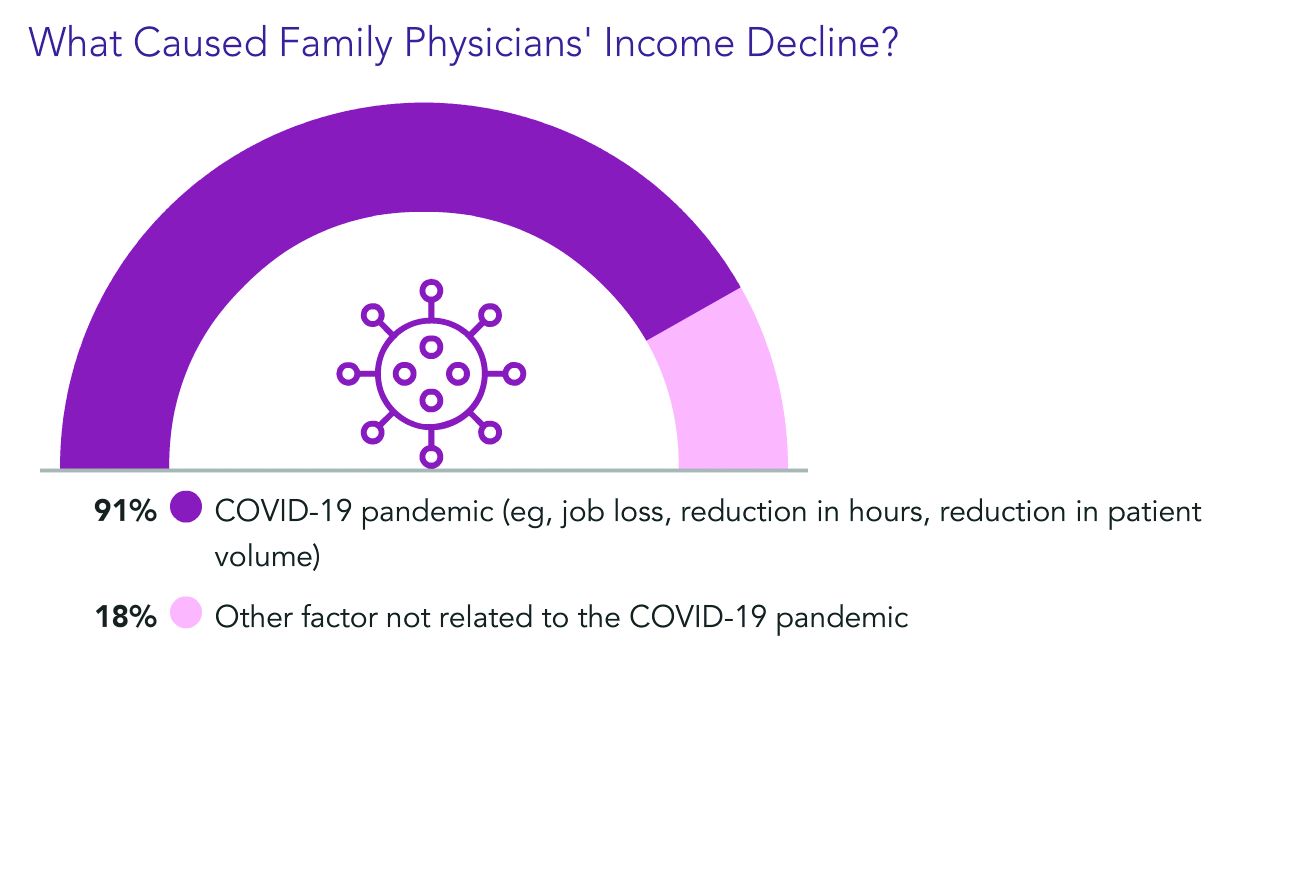

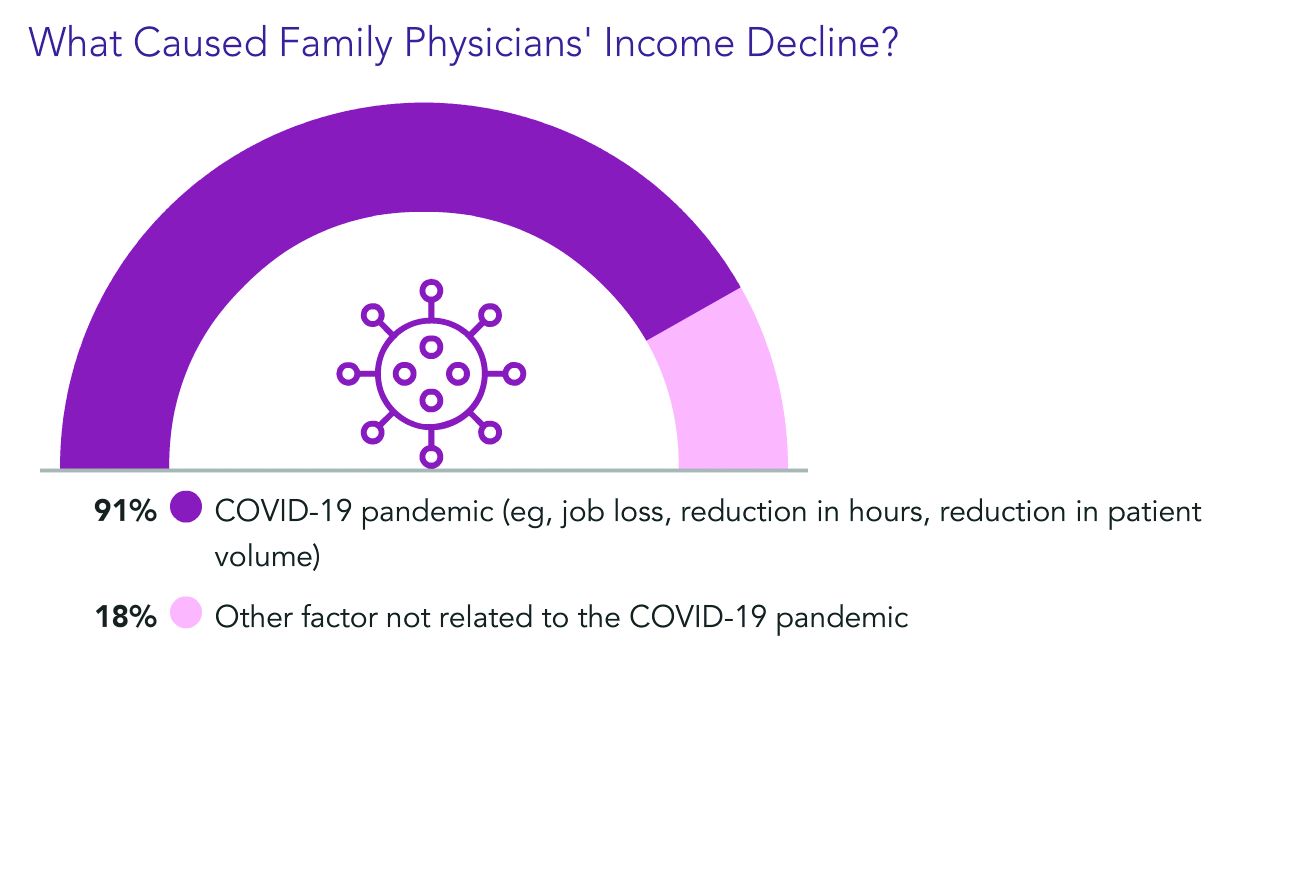

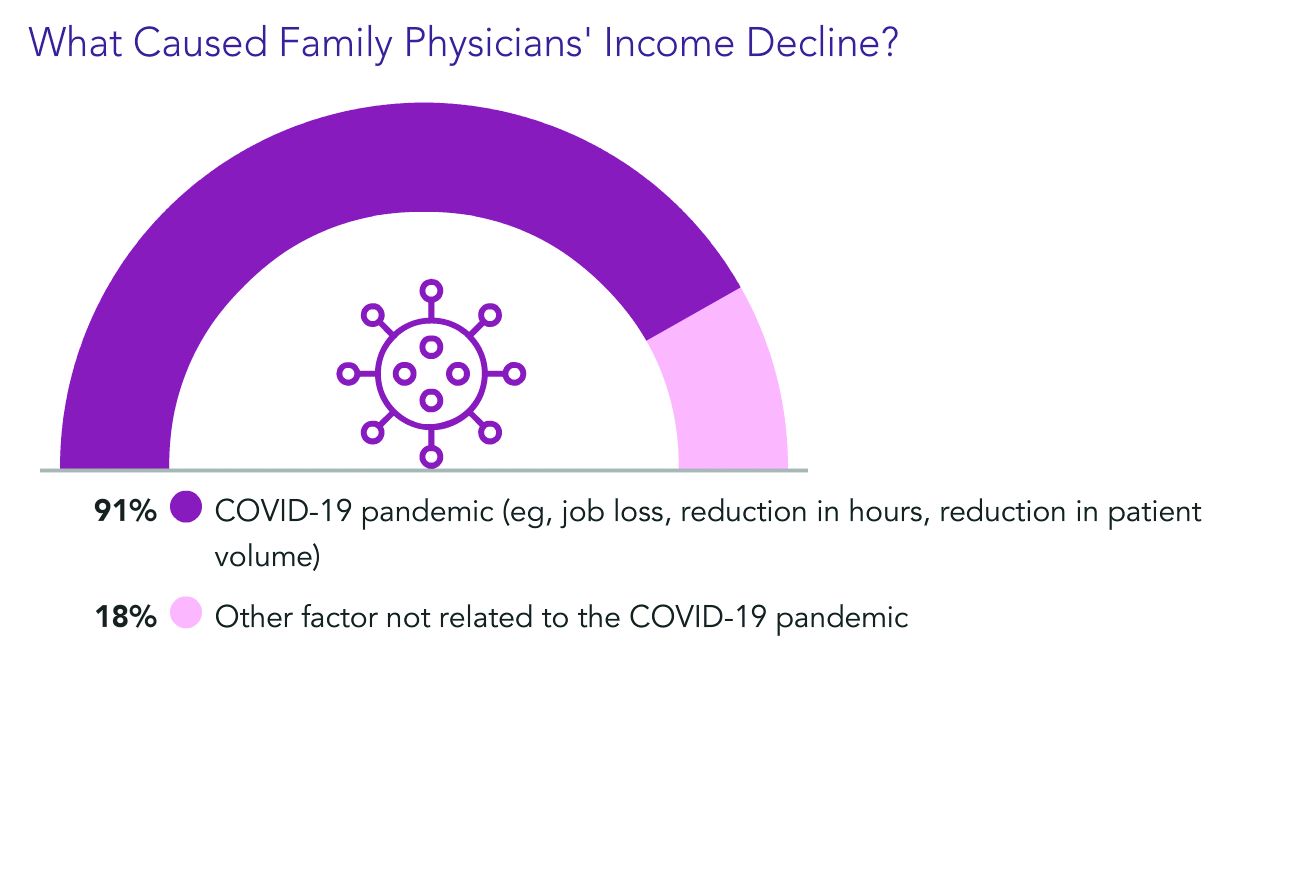

The vast majority (92%) of cardiologists who saw a drop in income last year cited COVID-related issues such as job loss, working fewer hours, and seeing fewer patients.

Close to half (48%) of cardiologists who suffered financial or practice-related ill effects as a result of the pandemic expect their income to return to normal this year; 38% believe it will take 2 to 3 years. Notably, 45% of physicians overall said the pandemic did not cause them financial or practice-related harm.

Physician work hours generally declined for at least some time during the pandemic – and some physicians were furloughed – but most are now working about the same number of hours they did prior to COVID-19.

Cardiologists are back working an average of 57 hours per week. Perhaps not surprising, intensivists, infectious disease physicians, and public health/preventive medicine physicians are pulling longer hours now, about 6 or 7 more per week than before.

Although working about the same number of hours per week now as they did before the pandemic, physicians overall are typically seeing fewer patients because of time spent on medical office safety protocols, answering COVID-19–related questions and other factors.

Cardiologists are seeing an average decline in weekly patient visits of about 6% – from 77 to 72 patients. Pediatricians are experiencing the largest average declines – from 78 patients per week prior to 64 now, an 18% drop.

Among self-employed cardiologists, 43% believe that a drop in patient volume of up to one-quarter is permanent.

Most cardiologists remain happy at work

Despite COVID-19 and other professional challenges, most cardiologists (and physicians overall) continue to find their work rewarding.

Cardiologists say the most rewarding aspect of their profession is “being good at what I do/finding answers and diagnoses” (27%), followed by relationships with and gratitude from patients (26%), making the world a better place (23%) and making good money at a job they like (12%). A few cited pride in their profession (6%) and teaching (2%). These figures are in line with last year’s responses.

The most challenging part of practicing cardiology is having so many rules and regulations (22%), followed by having to work long hours (16%), working with electronic health records (13%), trouble getting fair reimbursement (11%), danger/risk associated with treating COVID-19 patients (11%), dealing with difficult patients (8%) and worry about being sued (7%).

Bureaucratic tasks continue to be a burden for physicians in all specialties. On average, cardiologists spend 17.4 hours per week on paperwork and administration, similar to last year (16.9 hours per week) and to physicians overall (16.3 hours).

Despite the challenges, 86% of cardiologists said they would choose medicine again, and 92% would choose cardiology again, about the same as last year.

Most cardiologists (83%) plan to keep Medicare and/or Medicaid patients; only 1% say they won’t take new Medicare or Medicaid patients; and 16% are undecided.

Thirty-nine percent of cardiologists plan to participate in the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) in 2021.

“The stakes of the Quality Payment Program – the program that incorporates MIPS – are high, with a 9% penalty applied to all Medicare reimbursement for failure to participate,” said Elizabeth Woodcock, MBA, CPC, president of physician practice consulting firm Woodcock & Associates, Atlanta.

“With margins already slim, most physicians can’t afford this massive penalty. It makes sense to protect your revenue by complying with at least the bare minimum,” she noted.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite the huge challenges of COVID-19, including a drop in patient visits, cardiologists reported an average increase in income in 2020 and remain among the top earners in medicine, according to the 2021 Medscape Cardiologist Compensation Report.

Although 46% of cardiologists reported some decline in compensation, average cardiologist income was $459,000 in 2020 – up from $438,000 in 2019.

Cardiologist pay is the third highest of all specialties in the overall 2021 Medscape Physician Compensation Report, which covers U.S. physicians as a whole and almost 18,000 physicians in 29 specialties.

Only plastic surgeons ($526,000) and orthopedists ($511,000) earned more than cardiologists in 2020.

On average among cardiologists, self-employment yields a somewhat higher paycheck than does being employed ($477,000 vs. $450,000).

Just like in last year’s report, nearly two-thirds (61%) of cardiologists overall say they feel fairly compensated.