User login

Tennessee’s Medicaid block grant proposal could have deep impacts

In late September, Gov. Bill Lee (R) submitted a draft proposal to the Trump administration requesting the government convert the federal share of the state’s Medicaid funding into a $7.9 billion lump sum.

Under the proposal, the federal spending cap would apply to currently eligible children and adults, patients covered based on disability, and currently eligible seniors, but not to newly eligible patients, prescription drugs, dually eligible enrollees, and reimbursement to disproportionate-share hospitals and critical access hospitals. The proposed block grant would increase on a per capita basis for new patients and would adjust annually for inflation.

Gov. Lee contends the block grant would allow for more efficiency in the state’s Medicaid program – called TennCare – and generate significant savings, which the state would split 50/50 with the federal government, according to the proposal.

“The traditional model of Medicaid financing is an outdated model of fundamentally misaligned incentives,” Gov. Lee said in the waiver request. “New models of Medicaid financing are needed that reward states for promoting value and health, not merely spending more money. Tennessee’s Medicaid block grant proposal represents a natural progression of the state’s history of nationally recognized innovation and financial management. It also ensures that TennCare members continue to receive high-quality, cost-effective care well into the future.”

Tennessee’s proposal aims to provide care to low-income recipients more efficiently, while breaking Medicaid’s “perverse dynamic” in which states seek to extract more money from the federal government, said Doug Badger, a visiting fellow in domestic policy studies at the conservative-leaning Heritage Foundation.

“The waiver would incentivize Tennessee to reduce federal spending while maintaining access to care,” Mr. Badger said in an interview. “It is an idea worth testing. Tennessee will have to convince federal officials that its proposal would maintain quality of care without increasing federal spending. If they clear those hurdles, the federal government should approve the waiver.”

However, Dan Hawkins, senior vice president for public policy and research at the nonpartisan National Association of Community Health Centers said the proposal contains some concerning omissions and extreme demands that could affect access to care. For instance, the waiver calls for complete exemption from federal Medicaid requirements, including managed care rules that ensure access and network adequacy protections, pregnancy care rules, requirements pertaining to the treatment of disabled adults and children, and early and periodic screening, diagnostic, and treatment (EPSDT) requirements. Under the waiver, the state would no longer be subject to federal oversight for its enrollment, coverage, or management decisions.

“The most shocking thing is that [Tennessee has] provided no estimate of impact on the population served, either in terms of their health or their ability to access care or the amount of money it would cost to serve them,” Mr. Hawkins said in an interview. “They are essentially saying, ‘Send [the block grant] to us and go away.’ ”

Without the federal protections, Tennessee could take any number of measures to reduce costs, adds Andy Schneider a research professor at Georgetown University and an analyst for Georgetown University Health Policy Institute’s Center for Children and Families, both in Washington. Mr. Schneider served as a senior advisor at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services under the Obama administration.

“What would the state do in a world where it no longer had to follow federal rules in contracting with risk-based managed care organizations [MCOs] and in a world where it wanted to save money?” Mr. Schneider said in an interview. “Well, without the federal protections, it could reduce its payments on behalf of enrolled beneficiaries to the MCOs, it could not require the MCOs to have adequate provider networks, not require the MCOs to describe what services they were or were not providing, it could eliminate appeals protections for beneficiaries. Just let your imagination run wild.”

It is uncertain whether the waiver will be approved. Mr. Hawkins noted that CMS leadership has expressed support for the notion of a block grant. In his 2020 fiscal year federal budget for example, President Trump proposed a number of changes to Medicaid, including the potential for state Medicaid block grants or per capita caps. The Office of Management and Budget, meanwhile, is currently preparing guidance for state governments on creating block grants for Medicaid.

“On the other hand, this proposal is so outrageous I have to believe that even the federal government, even CMS, would blanch and come back requiring some additional changes in return for approving the proposal,” Mr. Hawkins said.

Mr. Schneider believes if the block grant is approved, it will likely face immediate litigation.

“The Department of Health & Human Services does not have the authority to give the state a block grant, only Congress can do that,” said Mr. Schneider who recently blogged about the proposal. “The reason for that is that, as the state makes clear in its proposal, it wants to reimagine the traditional Medicaid financing arrangement. That traditional financing arrangement has been in place since 1965. The executive branch can’t [change] it. It simply does not have the authority.”

Mr. Badger emphasized there is no shortage of speculation about the impact of fixed Medicaid allotments. What is needed now, he said, is evidence.

“A well-designed demonstration project will yield that evidence,” he said. “The statute gives the [HHS] Secretary authority to authorize demonstrations precisely to replace speculation with data. The best way to assess the impact of a fixed allotment is to test it in the real world.”

Tennessee will hold public hearings about its proposal in early October and collect feedback through Oct. 18. A final proposal is expected in November.

In late September, Gov. Bill Lee (R) submitted a draft proposal to the Trump administration requesting the government convert the federal share of the state’s Medicaid funding into a $7.9 billion lump sum.

Under the proposal, the federal spending cap would apply to currently eligible children and adults, patients covered based on disability, and currently eligible seniors, but not to newly eligible patients, prescription drugs, dually eligible enrollees, and reimbursement to disproportionate-share hospitals and critical access hospitals. The proposed block grant would increase on a per capita basis for new patients and would adjust annually for inflation.

Gov. Lee contends the block grant would allow for more efficiency in the state’s Medicaid program – called TennCare – and generate significant savings, which the state would split 50/50 with the federal government, according to the proposal.

“The traditional model of Medicaid financing is an outdated model of fundamentally misaligned incentives,” Gov. Lee said in the waiver request. “New models of Medicaid financing are needed that reward states for promoting value and health, not merely spending more money. Tennessee’s Medicaid block grant proposal represents a natural progression of the state’s history of nationally recognized innovation and financial management. It also ensures that TennCare members continue to receive high-quality, cost-effective care well into the future.”

Tennessee’s proposal aims to provide care to low-income recipients more efficiently, while breaking Medicaid’s “perverse dynamic” in which states seek to extract more money from the federal government, said Doug Badger, a visiting fellow in domestic policy studies at the conservative-leaning Heritage Foundation.

“The waiver would incentivize Tennessee to reduce federal spending while maintaining access to care,” Mr. Badger said in an interview. “It is an idea worth testing. Tennessee will have to convince federal officials that its proposal would maintain quality of care without increasing federal spending. If they clear those hurdles, the federal government should approve the waiver.”

However, Dan Hawkins, senior vice president for public policy and research at the nonpartisan National Association of Community Health Centers said the proposal contains some concerning omissions and extreme demands that could affect access to care. For instance, the waiver calls for complete exemption from federal Medicaid requirements, including managed care rules that ensure access and network adequacy protections, pregnancy care rules, requirements pertaining to the treatment of disabled adults and children, and early and periodic screening, diagnostic, and treatment (EPSDT) requirements. Under the waiver, the state would no longer be subject to federal oversight for its enrollment, coverage, or management decisions.

“The most shocking thing is that [Tennessee has] provided no estimate of impact on the population served, either in terms of their health or their ability to access care or the amount of money it would cost to serve them,” Mr. Hawkins said in an interview. “They are essentially saying, ‘Send [the block grant] to us and go away.’ ”

Without the federal protections, Tennessee could take any number of measures to reduce costs, adds Andy Schneider a research professor at Georgetown University and an analyst for Georgetown University Health Policy Institute’s Center for Children and Families, both in Washington. Mr. Schneider served as a senior advisor at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services under the Obama administration.

“What would the state do in a world where it no longer had to follow federal rules in contracting with risk-based managed care organizations [MCOs] and in a world where it wanted to save money?” Mr. Schneider said in an interview. “Well, without the federal protections, it could reduce its payments on behalf of enrolled beneficiaries to the MCOs, it could not require the MCOs to have adequate provider networks, not require the MCOs to describe what services they were or were not providing, it could eliminate appeals protections for beneficiaries. Just let your imagination run wild.”

It is uncertain whether the waiver will be approved. Mr. Hawkins noted that CMS leadership has expressed support for the notion of a block grant. In his 2020 fiscal year federal budget for example, President Trump proposed a number of changes to Medicaid, including the potential for state Medicaid block grants or per capita caps. The Office of Management and Budget, meanwhile, is currently preparing guidance for state governments on creating block grants for Medicaid.

“On the other hand, this proposal is so outrageous I have to believe that even the federal government, even CMS, would blanch and come back requiring some additional changes in return for approving the proposal,” Mr. Hawkins said.

Mr. Schneider believes if the block grant is approved, it will likely face immediate litigation.

“The Department of Health & Human Services does not have the authority to give the state a block grant, only Congress can do that,” said Mr. Schneider who recently blogged about the proposal. “The reason for that is that, as the state makes clear in its proposal, it wants to reimagine the traditional Medicaid financing arrangement. That traditional financing arrangement has been in place since 1965. The executive branch can’t [change] it. It simply does not have the authority.”

Mr. Badger emphasized there is no shortage of speculation about the impact of fixed Medicaid allotments. What is needed now, he said, is evidence.

“A well-designed demonstration project will yield that evidence,” he said. “The statute gives the [HHS] Secretary authority to authorize demonstrations precisely to replace speculation with data. The best way to assess the impact of a fixed allotment is to test it in the real world.”

Tennessee will hold public hearings about its proposal in early October and collect feedback through Oct. 18. A final proposal is expected in November.

In late September, Gov. Bill Lee (R) submitted a draft proposal to the Trump administration requesting the government convert the federal share of the state’s Medicaid funding into a $7.9 billion lump sum.

Under the proposal, the federal spending cap would apply to currently eligible children and adults, patients covered based on disability, and currently eligible seniors, but not to newly eligible patients, prescription drugs, dually eligible enrollees, and reimbursement to disproportionate-share hospitals and critical access hospitals. The proposed block grant would increase on a per capita basis for new patients and would adjust annually for inflation.

Gov. Lee contends the block grant would allow for more efficiency in the state’s Medicaid program – called TennCare – and generate significant savings, which the state would split 50/50 with the federal government, according to the proposal.

“The traditional model of Medicaid financing is an outdated model of fundamentally misaligned incentives,” Gov. Lee said in the waiver request. “New models of Medicaid financing are needed that reward states for promoting value and health, not merely spending more money. Tennessee’s Medicaid block grant proposal represents a natural progression of the state’s history of nationally recognized innovation and financial management. It also ensures that TennCare members continue to receive high-quality, cost-effective care well into the future.”

Tennessee’s proposal aims to provide care to low-income recipients more efficiently, while breaking Medicaid’s “perverse dynamic” in which states seek to extract more money from the federal government, said Doug Badger, a visiting fellow in domestic policy studies at the conservative-leaning Heritage Foundation.

“The waiver would incentivize Tennessee to reduce federal spending while maintaining access to care,” Mr. Badger said in an interview. “It is an idea worth testing. Tennessee will have to convince federal officials that its proposal would maintain quality of care without increasing federal spending. If they clear those hurdles, the federal government should approve the waiver.”

However, Dan Hawkins, senior vice president for public policy and research at the nonpartisan National Association of Community Health Centers said the proposal contains some concerning omissions and extreme demands that could affect access to care. For instance, the waiver calls for complete exemption from federal Medicaid requirements, including managed care rules that ensure access and network adequacy protections, pregnancy care rules, requirements pertaining to the treatment of disabled adults and children, and early and periodic screening, diagnostic, and treatment (EPSDT) requirements. Under the waiver, the state would no longer be subject to federal oversight for its enrollment, coverage, or management decisions.

“The most shocking thing is that [Tennessee has] provided no estimate of impact on the population served, either in terms of their health or their ability to access care or the amount of money it would cost to serve them,” Mr. Hawkins said in an interview. “They are essentially saying, ‘Send [the block grant] to us and go away.’ ”

Without the federal protections, Tennessee could take any number of measures to reduce costs, adds Andy Schneider a research professor at Georgetown University and an analyst for Georgetown University Health Policy Institute’s Center for Children and Families, both in Washington. Mr. Schneider served as a senior advisor at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services under the Obama administration.

“What would the state do in a world where it no longer had to follow federal rules in contracting with risk-based managed care organizations [MCOs] and in a world where it wanted to save money?” Mr. Schneider said in an interview. “Well, without the federal protections, it could reduce its payments on behalf of enrolled beneficiaries to the MCOs, it could not require the MCOs to have adequate provider networks, not require the MCOs to describe what services they were or were not providing, it could eliminate appeals protections for beneficiaries. Just let your imagination run wild.”

It is uncertain whether the waiver will be approved. Mr. Hawkins noted that CMS leadership has expressed support for the notion of a block grant. In his 2020 fiscal year federal budget for example, President Trump proposed a number of changes to Medicaid, including the potential for state Medicaid block grants or per capita caps. The Office of Management and Budget, meanwhile, is currently preparing guidance for state governments on creating block grants for Medicaid.

“On the other hand, this proposal is so outrageous I have to believe that even the federal government, even CMS, would blanch and come back requiring some additional changes in return for approving the proposal,” Mr. Hawkins said.

Mr. Schneider believes if the block grant is approved, it will likely face immediate litigation.

“The Department of Health & Human Services does not have the authority to give the state a block grant, only Congress can do that,” said Mr. Schneider who recently blogged about the proposal. “The reason for that is that, as the state makes clear in its proposal, it wants to reimagine the traditional Medicaid financing arrangement. That traditional financing arrangement has been in place since 1965. The executive branch can’t [change] it. It simply does not have the authority.”

Mr. Badger emphasized there is no shortage of speculation about the impact of fixed Medicaid allotments. What is needed now, he said, is evidence.

“A well-designed demonstration project will yield that evidence,” he said. “The statute gives the [HHS] Secretary authority to authorize demonstrations precisely to replace speculation with data. The best way to assess the impact of a fixed allotment is to test it in the real world.”

Tennessee will hold public hearings about its proposal in early October and collect feedback through Oct. 18. A final proposal is expected in November.

AAFP Congress adopts resolutions on physician privileges, medical education, employee benefits

PHILADELPHIA –

Practice enhancement

Hospital privileges were a hot topic for the reference committee on practice enhancement.

Adopted Resolution No. 304 calls on AAFP to oppose health insurance companies “privileging physicians based solely on their hospital privileges and hospital credentials.” The new rule also resolves that AAFP engage major national health insurance companies to develop methods to credential physicians that do not depend on hospital privileges.

The Congress also adopted Substitute Resolution No. 305, which calls on the AAFP to collaborate with the Joint Commission and other appropriate entities to create policy stating that hospitals remove undue barriers and restriction of privileges to hospitals and intensive care units for qualified family physicians who practice hospital medicine.

Delegates requested amendments to a resolution that called on AAFP to oppose nonphysician health care professionals making credentialing or privileging decisions regarding family physicians and that the AAFP oppose the use of nonphysician health care professionals in providing consultations requested of other physicians. The Congress could not agree on a final wording of the resolution.

Douglas J. Gruenbacher, MD, a Kansas delegate who works in a small hospital, said, “We actually credential in our hospital radiologists, orthopedists ... urologists. Do I know what they know? So we have to have many of our nonphysician providers, our nurse practitioners, help us. ... Should they be independent? No, of course not, but they do play an important part of our team.”

Douglas W. Curran, MD, a delegate from Texas, said, “I think we continue to give away stuff without taking care of ourselves. I have seen it for 4 years and, as result, we have seen this expansion of second-class care for people. ... Those are huge decisions, especially thinking about who’s going to do what in our hospitals. That includes small hospitals; I practice in a small hospital. I get all of that.”

After much debate, the Congress voted in favor of referring two proposed amendments to the board.

The Congress also adopted an amended version of Substitute Resolution No. 303, which calls on AAFP to support insurance coverage of acupuncture for pain control when ordered by a licensed physician or licensed collaborating advanced clinician on their practice team.

Education

Multipronged Substitute Resolution No. 606 – adopted by the Congress – aims to address racial inequities in medical education. Specifically, it calls on AAFP to do the following:

- Instruct the Liaison Committee for Medical Education to add race to its existing Cultural Competence and Health Care Disparities section 7.6 of Functions and Structure of a Medical School: Standards for Accreditation of Medical Education Programs Leading to the MD Degree.

- Ask the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education to adopt an antiracism policy that includes corresponding curricular requirements,

- Develop and implement a policy on training in racism and implicit bias for officeholders and commission members.

- Take an active stance against racism when racist events occur within the medical community.

The Congress also adopted Resolution No. 611, which calls for the AAFP to encourage the expansion of clinical behavioral health fellowships for family medicine physicians.

The resolution received mixed testimony during the reference committee meeting, with those in favor of the resolution having cited the need for more education in behavioral health due to shortages in many communities. Opponents argued that completing the fellowship would not have added value in hospital privileging and insurance payment, because it would not lead physicians to earn a certificate of added qualification.

Delegates also passed Resolution 608, over the objections of the reference committee.

As adopted, the resolution calls for AAFP to express its concern that the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) Family Medicine Certification Longitudinal Assessment is the only alternative to 1-day-only certification exam, and for the AAFP to urge the ABFM to offer a longitudinal self-assessment process similar to the American Board of Obstetricians and Gynecologists self-assessment process to satisfy the cognitive component of ABFM’s continued certification requirement.

The Reference Committee on Education also referred several hotly debated resolutions back to the AAFP board of directors. No. 604 called on AAFP to support forgiving 1 year of federal medical student loans for every 2 years of full-time work in a primary care position, as well as tax credits for those working in rural or underserved areas.

Advocacy

The delegates also approved most of the recommendations of the reference committee on advocacy with little discussion.

Substitute Resolution No. 515, which was ultimately adopted with an amendment by the Congress, states that AAFP support policies that provide employees with reasonable benefits, including job security, wage replacement, and continued availability of health plan coverage in the event that leave by an employee becomes necessary for documented medical conditions, with protections for small businesses. Among the policies this resolution includes are the following:

- Medical leave for the employee, including pregnancy.

- Parental leave for the employee-parent, including leave for birth, adoption or foster care leading to adoption.

- Leave if medically appropriate to care for a member of the employee’s immediate family.

The Congress adopted several other resolutions recommended by the advocacy committee:

- Resolution No. 501, calling on AAFP to advocate for state-level adoption of the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact.

- Substitute Resolution No. 505, asking AAFP to request a National Coverage Determination for Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs to allow such programs to operate without physician supervision when an AED is immediately available, and the patient is attended by nursing staff currently trained in basic life support.

- Substitute Resolutions No. 506 and 507 to support and encourage the ability of parents to breastfeed in the workplace through its advocacy efforts, as well as promote the enforcements of current law.

- Resolution No. 508, to petition CMS, national health insurance companies, and pharmacy benefits managers to include all generic medications in a class within a health plan’s formulary and implement a system that informs the prescriber of all formulary alternatives to a medication when denying the same medication immediately upon denial, while also providing a mechanism to rapidly appeal the denial.

- Substitute Resolution No. 512, to petition the CMS to reevaluate its current policy on the time requirements for discharge summaries from hospitals and post-acute care facilities and specifically require such facilities to provide primary care physicians with discharge summaries within 7 days.

- Substitute Resolution No. 517, to unequivocally support the right of physicians to organize and bargain collectively.

- Substitute Resolution No. 519, to support legislation that decriminalizes people who are solicited for sex or sexual activities in exchange for money or goods, without supporting the legalization of the selling of sex, and advocate against legislation that decriminalizes sex-buying and third-parties who promote and/or profit from sex buying.

Some of the resolutions that incited many passionate responses during the reference committee on advocacy were not discussed during the Congress of Delegates meeting.

One of these asked the AAFP to oppose legislation of physician-patient decision making in child and adolescent gender-affirming care. Some in support of this resolution referred to this type of care as evidence-based medicine and said that legislators should be kept out of the exam room. Those opposed disagreed with classifying this type of care that way, noting that the long-term effects of some of the treatments are unknown.

During the reference committee, one opponent of the resolution, Lisa Gilbert, MD, claimed that gender-affirming care refers to blocking puberty, followed by cross-sex hormones,which would permanently sterilize the children. Dr. Gilbert, who identified herself as a member from Kansas speaking independently, added that if children have gone through puberty naturally, this would be a different discussion.

Kevin Wang, MD, an alternate delegate from Washington, who supported the resolution, noted that the rate of suicide in the transgender population is nine times that of the general population.

“I do want to emphasize that doing nothing does cause significant harm,” Dr. Wang said, The committee referred resolution No. 509 to the board for further clarification and study.

The merits of two other resolutions (No. 510 and No. 511), which called for the AAFP to no longer reject the use of “physician-assisted suicide” and “assisted suicide” and avoid the use of vague and euphemistic terms when referring to lethal medications prescribed with the intention of ending a patient’s life in statements and documents, also were heavily debated during the advocacy reference committee meeting. The committee recommended such resolutions be referred to the board for discussion.

The delegates approved the advocacy committee’s recommendations for Resolutions 509, 510, and 511.

PHILADELPHIA –

Practice enhancement

Hospital privileges were a hot topic for the reference committee on practice enhancement.

Adopted Resolution No. 304 calls on AAFP to oppose health insurance companies “privileging physicians based solely on their hospital privileges and hospital credentials.” The new rule also resolves that AAFP engage major national health insurance companies to develop methods to credential physicians that do not depend on hospital privileges.

The Congress also adopted Substitute Resolution No. 305, which calls on the AAFP to collaborate with the Joint Commission and other appropriate entities to create policy stating that hospitals remove undue barriers and restriction of privileges to hospitals and intensive care units for qualified family physicians who practice hospital medicine.

Delegates requested amendments to a resolution that called on AAFP to oppose nonphysician health care professionals making credentialing or privileging decisions regarding family physicians and that the AAFP oppose the use of nonphysician health care professionals in providing consultations requested of other physicians. The Congress could not agree on a final wording of the resolution.

Douglas J. Gruenbacher, MD, a Kansas delegate who works in a small hospital, said, “We actually credential in our hospital radiologists, orthopedists ... urologists. Do I know what they know? So we have to have many of our nonphysician providers, our nurse practitioners, help us. ... Should they be independent? No, of course not, but they do play an important part of our team.”

Douglas W. Curran, MD, a delegate from Texas, said, “I think we continue to give away stuff without taking care of ourselves. I have seen it for 4 years and, as result, we have seen this expansion of second-class care for people. ... Those are huge decisions, especially thinking about who’s going to do what in our hospitals. That includes small hospitals; I practice in a small hospital. I get all of that.”

After much debate, the Congress voted in favor of referring two proposed amendments to the board.

The Congress also adopted an amended version of Substitute Resolution No. 303, which calls on AAFP to support insurance coverage of acupuncture for pain control when ordered by a licensed physician or licensed collaborating advanced clinician on their practice team.

Education

Multipronged Substitute Resolution No. 606 – adopted by the Congress – aims to address racial inequities in medical education. Specifically, it calls on AAFP to do the following:

- Instruct the Liaison Committee for Medical Education to add race to its existing Cultural Competence and Health Care Disparities section 7.6 of Functions and Structure of a Medical School: Standards for Accreditation of Medical Education Programs Leading to the MD Degree.

- Ask the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education to adopt an antiracism policy that includes corresponding curricular requirements,

- Develop and implement a policy on training in racism and implicit bias for officeholders and commission members.

- Take an active stance against racism when racist events occur within the medical community.

The Congress also adopted Resolution No. 611, which calls for the AAFP to encourage the expansion of clinical behavioral health fellowships for family medicine physicians.

The resolution received mixed testimony during the reference committee meeting, with those in favor of the resolution having cited the need for more education in behavioral health due to shortages in many communities. Opponents argued that completing the fellowship would not have added value in hospital privileging and insurance payment, because it would not lead physicians to earn a certificate of added qualification.

Delegates also passed Resolution 608, over the objections of the reference committee.

As adopted, the resolution calls for AAFP to express its concern that the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) Family Medicine Certification Longitudinal Assessment is the only alternative to 1-day-only certification exam, and for the AAFP to urge the ABFM to offer a longitudinal self-assessment process similar to the American Board of Obstetricians and Gynecologists self-assessment process to satisfy the cognitive component of ABFM’s continued certification requirement.

The Reference Committee on Education also referred several hotly debated resolutions back to the AAFP board of directors. No. 604 called on AAFP to support forgiving 1 year of federal medical student loans for every 2 years of full-time work in a primary care position, as well as tax credits for those working in rural or underserved areas.

Advocacy

The delegates also approved most of the recommendations of the reference committee on advocacy with little discussion.

Substitute Resolution No. 515, which was ultimately adopted with an amendment by the Congress, states that AAFP support policies that provide employees with reasonable benefits, including job security, wage replacement, and continued availability of health plan coverage in the event that leave by an employee becomes necessary for documented medical conditions, with protections for small businesses. Among the policies this resolution includes are the following:

- Medical leave for the employee, including pregnancy.

- Parental leave for the employee-parent, including leave for birth, adoption or foster care leading to adoption.

- Leave if medically appropriate to care for a member of the employee’s immediate family.

The Congress adopted several other resolutions recommended by the advocacy committee:

- Resolution No. 501, calling on AAFP to advocate for state-level adoption of the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact.

- Substitute Resolution No. 505, asking AAFP to request a National Coverage Determination for Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs to allow such programs to operate without physician supervision when an AED is immediately available, and the patient is attended by nursing staff currently trained in basic life support.

- Substitute Resolutions No. 506 and 507 to support and encourage the ability of parents to breastfeed in the workplace through its advocacy efforts, as well as promote the enforcements of current law.

- Resolution No. 508, to petition CMS, national health insurance companies, and pharmacy benefits managers to include all generic medications in a class within a health plan’s formulary and implement a system that informs the prescriber of all formulary alternatives to a medication when denying the same medication immediately upon denial, while also providing a mechanism to rapidly appeal the denial.

- Substitute Resolution No. 512, to petition the CMS to reevaluate its current policy on the time requirements for discharge summaries from hospitals and post-acute care facilities and specifically require such facilities to provide primary care physicians with discharge summaries within 7 days.

- Substitute Resolution No. 517, to unequivocally support the right of physicians to organize and bargain collectively.

- Substitute Resolution No. 519, to support legislation that decriminalizes people who are solicited for sex or sexual activities in exchange for money or goods, without supporting the legalization of the selling of sex, and advocate against legislation that decriminalizes sex-buying and third-parties who promote and/or profit from sex buying.

Some of the resolutions that incited many passionate responses during the reference committee on advocacy were not discussed during the Congress of Delegates meeting.

One of these asked the AAFP to oppose legislation of physician-patient decision making in child and adolescent gender-affirming care. Some in support of this resolution referred to this type of care as evidence-based medicine and said that legislators should be kept out of the exam room. Those opposed disagreed with classifying this type of care that way, noting that the long-term effects of some of the treatments are unknown.

During the reference committee, one opponent of the resolution, Lisa Gilbert, MD, claimed that gender-affirming care refers to blocking puberty, followed by cross-sex hormones,which would permanently sterilize the children. Dr. Gilbert, who identified herself as a member from Kansas speaking independently, added that if children have gone through puberty naturally, this would be a different discussion.

Kevin Wang, MD, an alternate delegate from Washington, who supported the resolution, noted that the rate of suicide in the transgender population is nine times that of the general population.

“I do want to emphasize that doing nothing does cause significant harm,” Dr. Wang said, The committee referred resolution No. 509 to the board for further clarification and study.

The merits of two other resolutions (No. 510 and No. 511), which called for the AAFP to no longer reject the use of “physician-assisted suicide” and “assisted suicide” and avoid the use of vague and euphemistic terms when referring to lethal medications prescribed with the intention of ending a patient’s life in statements and documents, also were heavily debated during the advocacy reference committee meeting. The committee recommended such resolutions be referred to the board for discussion.

The delegates approved the advocacy committee’s recommendations for Resolutions 509, 510, and 511.

PHILADELPHIA –

Practice enhancement

Hospital privileges were a hot topic for the reference committee on practice enhancement.

Adopted Resolution No. 304 calls on AAFP to oppose health insurance companies “privileging physicians based solely on their hospital privileges and hospital credentials.” The new rule also resolves that AAFP engage major national health insurance companies to develop methods to credential physicians that do not depend on hospital privileges.

The Congress also adopted Substitute Resolution No. 305, which calls on the AAFP to collaborate with the Joint Commission and other appropriate entities to create policy stating that hospitals remove undue barriers and restriction of privileges to hospitals and intensive care units for qualified family physicians who practice hospital medicine.

Delegates requested amendments to a resolution that called on AAFP to oppose nonphysician health care professionals making credentialing or privileging decisions regarding family physicians and that the AAFP oppose the use of nonphysician health care professionals in providing consultations requested of other physicians. The Congress could not agree on a final wording of the resolution.

Douglas J. Gruenbacher, MD, a Kansas delegate who works in a small hospital, said, “We actually credential in our hospital radiologists, orthopedists ... urologists. Do I know what they know? So we have to have many of our nonphysician providers, our nurse practitioners, help us. ... Should they be independent? No, of course not, but they do play an important part of our team.”

Douglas W. Curran, MD, a delegate from Texas, said, “I think we continue to give away stuff without taking care of ourselves. I have seen it for 4 years and, as result, we have seen this expansion of second-class care for people. ... Those are huge decisions, especially thinking about who’s going to do what in our hospitals. That includes small hospitals; I practice in a small hospital. I get all of that.”

After much debate, the Congress voted in favor of referring two proposed amendments to the board.

The Congress also adopted an amended version of Substitute Resolution No. 303, which calls on AAFP to support insurance coverage of acupuncture for pain control when ordered by a licensed physician or licensed collaborating advanced clinician on their practice team.

Education

Multipronged Substitute Resolution No. 606 – adopted by the Congress – aims to address racial inequities in medical education. Specifically, it calls on AAFP to do the following:

- Instruct the Liaison Committee for Medical Education to add race to its existing Cultural Competence and Health Care Disparities section 7.6 of Functions and Structure of a Medical School: Standards for Accreditation of Medical Education Programs Leading to the MD Degree.

- Ask the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education to adopt an antiracism policy that includes corresponding curricular requirements,

- Develop and implement a policy on training in racism and implicit bias for officeholders and commission members.

- Take an active stance against racism when racist events occur within the medical community.

The Congress also adopted Resolution No. 611, which calls for the AAFP to encourage the expansion of clinical behavioral health fellowships for family medicine physicians.

The resolution received mixed testimony during the reference committee meeting, with those in favor of the resolution having cited the need for more education in behavioral health due to shortages in many communities. Opponents argued that completing the fellowship would not have added value in hospital privileging and insurance payment, because it would not lead physicians to earn a certificate of added qualification.

Delegates also passed Resolution 608, over the objections of the reference committee.

As adopted, the resolution calls for AAFP to express its concern that the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) Family Medicine Certification Longitudinal Assessment is the only alternative to 1-day-only certification exam, and for the AAFP to urge the ABFM to offer a longitudinal self-assessment process similar to the American Board of Obstetricians and Gynecologists self-assessment process to satisfy the cognitive component of ABFM’s continued certification requirement.

The Reference Committee on Education also referred several hotly debated resolutions back to the AAFP board of directors. No. 604 called on AAFP to support forgiving 1 year of federal medical student loans for every 2 years of full-time work in a primary care position, as well as tax credits for those working in rural or underserved areas.

Advocacy

The delegates also approved most of the recommendations of the reference committee on advocacy with little discussion.

Substitute Resolution No. 515, which was ultimately adopted with an amendment by the Congress, states that AAFP support policies that provide employees with reasonable benefits, including job security, wage replacement, and continued availability of health plan coverage in the event that leave by an employee becomes necessary for documented medical conditions, with protections for small businesses. Among the policies this resolution includes are the following:

- Medical leave for the employee, including pregnancy.

- Parental leave for the employee-parent, including leave for birth, adoption or foster care leading to adoption.

- Leave if medically appropriate to care for a member of the employee’s immediate family.

The Congress adopted several other resolutions recommended by the advocacy committee:

- Resolution No. 501, calling on AAFP to advocate for state-level adoption of the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact.

- Substitute Resolution No. 505, asking AAFP to request a National Coverage Determination for Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs to allow such programs to operate without physician supervision when an AED is immediately available, and the patient is attended by nursing staff currently trained in basic life support.

- Substitute Resolutions No. 506 and 507 to support and encourage the ability of parents to breastfeed in the workplace through its advocacy efforts, as well as promote the enforcements of current law.

- Resolution No. 508, to petition CMS, national health insurance companies, and pharmacy benefits managers to include all generic medications in a class within a health plan’s formulary and implement a system that informs the prescriber of all formulary alternatives to a medication when denying the same medication immediately upon denial, while also providing a mechanism to rapidly appeal the denial.

- Substitute Resolution No. 512, to petition the CMS to reevaluate its current policy on the time requirements for discharge summaries from hospitals and post-acute care facilities and specifically require such facilities to provide primary care physicians with discharge summaries within 7 days.

- Substitute Resolution No. 517, to unequivocally support the right of physicians to organize and bargain collectively.

- Substitute Resolution No. 519, to support legislation that decriminalizes people who are solicited for sex or sexual activities in exchange for money or goods, without supporting the legalization of the selling of sex, and advocate against legislation that decriminalizes sex-buying and third-parties who promote and/or profit from sex buying.

Some of the resolutions that incited many passionate responses during the reference committee on advocacy were not discussed during the Congress of Delegates meeting.

One of these asked the AAFP to oppose legislation of physician-patient decision making in child and adolescent gender-affirming care. Some in support of this resolution referred to this type of care as evidence-based medicine and said that legislators should be kept out of the exam room. Those opposed disagreed with classifying this type of care that way, noting that the long-term effects of some of the treatments are unknown.

During the reference committee, one opponent of the resolution, Lisa Gilbert, MD, claimed that gender-affirming care refers to blocking puberty, followed by cross-sex hormones,which would permanently sterilize the children. Dr. Gilbert, who identified herself as a member from Kansas speaking independently, added that if children have gone through puberty naturally, this would be a different discussion.

Kevin Wang, MD, an alternate delegate from Washington, who supported the resolution, noted that the rate of suicide in the transgender population is nine times that of the general population.

“I do want to emphasize that doing nothing does cause significant harm,” Dr. Wang said, The committee referred resolution No. 509 to the board for further clarification and study.

The merits of two other resolutions (No. 510 and No. 511), which called for the AAFP to no longer reject the use of “physician-assisted suicide” and “assisted suicide” and avoid the use of vague and euphemistic terms when referring to lethal medications prescribed with the intention of ending a patient’s life in statements and documents, also were heavily debated during the advocacy reference committee meeting. The committee recommended such resolutions be referred to the board for discussion.

The delegates approved the advocacy committee’s recommendations for Resolutions 509, 510, and 511.

REPORTING FROM AAFP Congress

I have seen the future

Many patients have seen their long-term physicians retire. When I ask how they like their new doctors, they say: “She’s okay, I guess. Quite efficient. Seems thorough. But it’s not the same. It’s just business. Nothing personal.”

Sometimes you have to look backward to look forward. So it’s perhaps fitting that I glimpsed the future at my last colonoscopy.

In recent years, I’ve had such procedures at a local suburban surgicenter. Easy access, plenty of parking.

The woman who checks me in is all business. She scans my insurance cards and hands me a clipboard with a medical history form. Have I ever had cancer? A hernia? Am I pregnant? I wonder whether anyone reads these.

A different young woman brings me inside, the first of many new faces. Their roles are murky.

In a curtained cubby, yet another staff person asks me to pack my clothes in a plastic bag and put on a johnny. Then an older man enters, initiating furious multitasking. A different nursing assistant asks me to confirm my name and date of birth, then inserts an intravenous line in one arm, while the old doctor hands me an anesthesia consent form to sign with the other hand. I check many answers very fast, ignore the small-print boilerplate, and sign.

I am handed two more consent forms to sign, one from each side. The staff makes no pretense of explaining them or even telling me what they are for, and I make none of reading them.

They depart, replaced by still another person, who rolls me into the next room. He confirms my name and date of birth, and which procedure I am there for. The purpose of these multiple checks is clear, along with dispiriting depersonalization. One could mitigate this with some light banter, but no one bothers. No time.

My physician – whom I actually know – enters, says hello, and exchanges pleasantries. The last guy asks me to turn onto my left side. Intravenous sedation flows into my veins. The rest is silence.

Sometime later I wake up, greeted by another staff person. She asks if I am okay and offers me water or juice and saltines. Noting her Boston Red Sox sweatshirt, I say, “Great game last night,” but she does not know what I am talking about. She cares only for football and plans to fly to Nashville, Tenn., to watch her favorites.

Curtains are closed, and I am asked to dress. Another assistant directs me to a chair, where I will await my ride home. Through I try to walk alone, she takes my arm. “We assist everyone,” she explains.

As the sedation wears off, I observe. All around me I see movement, brisk and purposeful. Staff members crisscross before me from all angles, striding from one task to another, from prep room A to cubby D, walking with or pushing patients from procedure room M to holding area 8H. No one I’ve just met recognizes me, or acknowledges having met me before.

At last, the final staff member approaches. She flashes a kind smile as she takes my arm to walk me to the door. I take this for a personal touch, until she explains that she must make sure I don’t fall and that I get into the right car. As we pass, no one in the waiting room, neither staff nor patients, takes any notice.

My wife is outside, idling in the correct car. She’s brought coffee and a chocolate croissant, which – almost – makes last night’s prep worthwhile. She confirms neither my name nor date of birth.

Altogether, I have been in and out in 90 minutes. In the car, I peruse the handout that had been given to me as I exited. Drinking my coffee, I read the postcare instructions and enjoy its full-color pictures. Seldom has my cecum looked more radiant.

In “The Checklist Manifesto,” Atul Gawande described the outcome improvement that systematized practice can achieve. Data analysis confirms the measurably superior efficacy of such a method.

As for me, I feel like output from one of today’s cataract factories: like a car just extruded from an automated wash, with a photo on its front seat of the shiny, Simonized hubcaps included with the premium service package.

Just business, though. Nothing personal.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Many patients have seen their long-term physicians retire. When I ask how they like their new doctors, they say: “She’s okay, I guess. Quite efficient. Seems thorough. But it’s not the same. It’s just business. Nothing personal.”

Sometimes you have to look backward to look forward. So it’s perhaps fitting that I glimpsed the future at my last colonoscopy.

In recent years, I’ve had such procedures at a local suburban surgicenter. Easy access, plenty of parking.

The woman who checks me in is all business. She scans my insurance cards and hands me a clipboard with a medical history form. Have I ever had cancer? A hernia? Am I pregnant? I wonder whether anyone reads these.

A different young woman brings me inside, the first of many new faces. Their roles are murky.

In a curtained cubby, yet another staff person asks me to pack my clothes in a plastic bag and put on a johnny. Then an older man enters, initiating furious multitasking. A different nursing assistant asks me to confirm my name and date of birth, then inserts an intravenous line in one arm, while the old doctor hands me an anesthesia consent form to sign with the other hand. I check many answers very fast, ignore the small-print boilerplate, and sign.

I am handed two more consent forms to sign, one from each side. The staff makes no pretense of explaining them or even telling me what they are for, and I make none of reading them.

They depart, replaced by still another person, who rolls me into the next room. He confirms my name and date of birth, and which procedure I am there for. The purpose of these multiple checks is clear, along with dispiriting depersonalization. One could mitigate this with some light banter, but no one bothers. No time.

My physician – whom I actually know – enters, says hello, and exchanges pleasantries. The last guy asks me to turn onto my left side. Intravenous sedation flows into my veins. The rest is silence.

Sometime later I wake up, greeted by another staff person. She asks if I am okay and offers me water or juice and saltines. Noting her Boston Red Sox sweatshirt, I say, “Great game last night,” but she does not know what I am talking about. She cares only for football and plans to fly to Nashville, Tenn., to watch her favorites.

Curtains are closed, and I am asked to dress. Another assistant directs me to a chair, where I will await my ride home. Through I try to walk alone, she takes my arm. “We assist everyone,” she explains.

As the sedation wears off, I observe. All around me I see movement, brisk and purposeful. Staff members crisscross before me from all angles, striding from one task to another, from prep room A to cubby D, walking with or pushing patients from procedure room M to holding area 8H. No one I’ve just met recognizes me, or acknowledges having met me before.

At last, the final staff member approaches. She flashes a kind smile as she takes my arm to walk me to the door. I take this for a personal touch, until she explains that she must make sure I don’t fall and that I get into the right car. As we pass, no one in the waiting room, neither staff nor patients, takes any notice.

My wife is outside, idling in the correct car. She’s brought coffee and a chocolate croissant, which – almost – makes last night’s prep worthwhile. She confirms neither my name nor date of birth.

Altogether, I have been in and out in 90 minutes. In the car, I peruse the handout that had been given to me as I exited. Drinking my coffee, I read the postcare instructions and enjoy its full-color pictures. Seldom has my cecum looked more radiant.

In “The Checklist Manifesto,” Atul Gawande described the outcome improvement that systematized practice can achieve. Data analysis confirms the measurably superior efficacy of such a method.

As for me, I feel like output from one of today’s cataract factories: like a car just extruded from an automated wash, with a photo on its front seat of the shiny, Simonized hubcaps included with the premium service package.

Just business, though. Nothing personal.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Many patients have seen their long-term physicians retire. When I ask how they like their new doctors, they say: “She’s okay, I guess. Quite efficient. Seems thorough. But it’s not the same. It’s just business. Nothing personal.”

Sometimes you have to look backward to look forward. So it’s perhaps fitting that I glimpsed the future at my last colonoscopy.

In recent years, I’ve had such procedures at a local suburban surgicenter. Easy access, plenty of parking.

The woman who checks me in is all business. She scans my insurance cards and hands me a clipboard with a medical history form. Have I ever had cancer? A hernia? Am I pregnant? I wonder whether anyone reads these.

A different young woman brings me inside, the first of many new faces. Their roles are murky.

In a curtained cubby, yet another staff person asks me to pack my clothes in a plastic bag and put on a johnny. Then an older man enters, initiating furious multitasking. A different nursing assistant asks me to confirm my name and date of birth, then inserts an intravenous line in one arm, while the old doctor hands me an anesthesia consent form to sign with the other hand. I check many answers very fast, ignore the small-print boilerplate, and sign.

I am handed two more consent forms to sign, one from each side. The staff makes no pretense of explaining them or even telling me what they are for, and I make none of reading them.

They depart, replaced by still another person, who rolls me into the next room. He confirms my name and date of birth, and which procedure I am there for. The purpose of these multiple checks is clear, along with dispiriting depersonalization. One could mitigate this with some light banter, but no one bothers. No time.

My physician – whom I actually know – enters, says hello, and exchanges pleasantries. The last guy asks me to turn onto my left side. Intravenous sedation flows into my veins. The rest is silence.

Sometime later I wake up, greeted by another staff person. She asks if I am okay and offers me water or juice and saltines. Noting her Boston Red Sox sweatshirt, I say, “Great game last night,” but she does not know what I am talking about. She cares only for football and plans to fly to Nashville, Tenn., to watch her favorites.

Curtains are closed, and I am asked to dress. Another assistant directs me to a chair, where I will await my ride home. Through I try to walk alone, she takes my arm. “We assist everyone,” she explains.

As the sedation wears off, I observe. All around me I see movement, brisk and purposeful. Staff members crisscross before me from all angles, striding from one task to another, from prep room A to cubby D, walking with or pushing patients from procedure room M to holding area 8H. No one I’ve just met recognizes me, or acknowledges having met me before.

At last, the final staff member approaches. She flashes a kind smile as she takes my arm to walk me to the door. I take this for a personal touch, until she explains that she must make sure I don’t fall and that I get into the right car. As we pass, no one in the waiting room, neither staff nor patients, takes any notice.

My wife is outside, idling in the correct car. She’s brought coffee and a chocolate croissant, which – almost – makes last night’s prep worthwhile. She confirms neither my name nor date of birth.

Altogether, I have been in and out in 90 minutes. In the car, I peruse the handout that had been given to me as I exited. Drinking my coffee, I read the postcare instructions and enjoy its full-color pictures. Seldom has my cecum looked more radiant.

In “The Checklist Manifesto,” Atul Gawande described the outcome improvement that systematized practice can achieve. Data analysis confirms the measurably superior efficacy of such a method.

As for me, I feel like output from one of today’s cataract factories: like a car just extruded from an automated wash, with a photo on its front seat of the shiny, Simonized hubcaps included with the premium service package.

Just business, though. Nothing personal.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Advancing Order Set Design

In the current health care environment, hospitals are constantly challenged to improve quality metrics and deliver better health care outcomes. One means to achieving quality improvement is through the use of order sets, groups of related orders that a health care provider (HCP) can place with either a few keystrokes or mouse clicks.1

Historically, design of order sets has largely focused on clicking checkboxes containing evidence-based practices. According to Bates and colleagues and the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, incorporating evidence-based medicine (EBM) into order sets is not by itself sufficient.2,3Execution of proper design coupled with simplicity and provider efficiency is paramount to HCP buy-in, increased likelihood of order set adherence, and to potentially better outcomes.

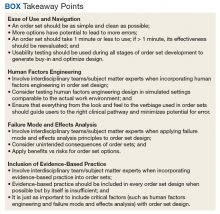

In this article, we outline advancements in order set design. These improvements increase provider efficiency and ease of use; incorporate human factors engineering (HFE); apply failure mode and effects analysis; and include EBM.

Methods

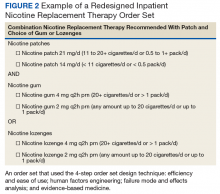

An inpatient nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) order was developed as part of a multifaceted solution to improve tobacco cessation care at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVH) in Tampa, Florida, a complexity level 1a facility. This NRT order set used the 4-step order set design framework the authors’ developed (for additional information about the NRT order set, contact the authors). We distinguish order set design technique between 2 different inpatient NRT order sets. The first order set in the comparison (Figure 1) is an inpatient NRT order set of unknown origin—it is common for US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical facilities to share order sets and other resources. The second order set (Figure 2) is an inpatient NRT order set we designed using our 4-step process for comparison in this article. No institutional review board approval was required as this work met criteria for operational improvement activities exempt from ethics review.

Justin Iannello, DO, MBA, was the team leader and developer of the 4-step order set design technique. The intervention team consisted of 4 internal medicine physicians with expertise in quality improvement and patient safety: 1 certified professional in patient safety and certified as a Lean Six Sigma Black Belt; 2 physicians certified as Lean Six Sigma Black Belts; and 1 physician certified as a Lean Six Sigma Green Belt. Two inpatient clinical pharmacists and 1 quality management specialist also were involved in its development.

Development of a new NRT order set was felt to be an integral part of the tobacco cessation care delivery process. An NRT order set perceived by users as value-added required a solution that merged EBM with standardization and applied quality improvement principles. The result was an approach to order set design that focused on 4 key questions: Is the order set efficient and easy to use/navigate? Is human factors engineering incorporated? Is failure mode and effects analysis applied? Are evidence-based practices included?

Ease of Use and Navigation

Implementing an order set that is efficient and easy to use or navigate seems straightforward but can be difficult to execute. Figure 1 shows many detailed options consisting of different combinations of nicotine patches, lozenges, and gum. Also included are oral tobacco cessation options (bupropion and varenicline). Although more options may seem better, confusion about appropriate medication selection can occur.

According to Heath and Heath, too many options can result in lack of action.4 For example, Heath and Heath discuss a food store that offered 6 free samples of different jams on one day and 24 jams the following day. The customers who sampled 6 different types of jam were 10 times more likely to buy jam. The authors concluded that the more options available, the more difficulty a potential buyer has in deciding on a course of action.4

In clinical situations where a HCP is using an order set, the number of options can mean the difference between use vs avoidance if the choices are overwhelming. HCPs process layers of detail every day when creating differential diagnoses and treatment plans. While that level of detail is necessary clinically, that same level of detail included in orders sets can create challenges for HCPs.

Figure 2 advances the order set in Figure 1 by providing a simpler and cleaner design, so HCPs can more easily review and process the information. This order set design minimizes the number of options available to help users make the right decision, focusing on value for the appropriate setting and audience. In other words, order sets should not be a “one size fits all” approach.

Order sets should be tailored to the appropriate clinical setting (eg, inpatient acute care, outpatient clinic setting, etc) and HCP (eg, hospitalist, tobacco cessation specialist, etc). We are comparing NRT order sets designed for HCPs who do not routinely prescribe oral tobacco cessation products in the inpatient setting. When possible, autogenerated bundle orders should also be used according to evidence-based recommendations (such as nicotine patch tapers) for ease of use and further simplification of order sets.

Finally, usability testing known as “evaluating a product or service by testing it with representative users” helps further refine an order set.5Usability testing should be applied during all phases of order set development with end user(s) as it helps identify problems with order set design prior to implementation. By applying usability testing, the order set becomes more meaningful and valued by the user.

Human Factors Engineering

HFE is “the study of all the factors that make it easier to do the work in the right way.”6 HFE seeks to identify, align, and apply processes for people and the world within which they live and work to promote safe and efficient practices, especially in relation to the technology and physical design features in their work environment.6

The average American adult makes about 35,000 decisions per day.7 Thus, there is potential for error at any moment. Design that does not take HFE into account can be dangerous. For example, when tube feed and IV line connectors look similar and are compatible, patients may inadvertently receive food administered directly into their bloodstream.8

HFE can and should be applied to order sets. Everything from the look, feel, and verbiage of an order set affects potential outcomes. For example, consider the impact even seemingly minor modifications can have on outcomes simply by guiding users in a different way: Figure 1 provides NRT options based on cigarette use per day, whereas Figure 2 conveys pack use per day in relation to the equivalent number of cigarettes used daily. These differences may seem small; however, it helps guide users to the right choice when considering that health care providers have been historically trained on social history gathering that emphasizes packs per day and pack-years.

Failure Mode and Effects Analysis

Failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA) is “a structured way to identify and address potential problems, or failures and their resulting effects on the system or process before an adverse event occurs.”9 The benefit of an order set must be weighed against the risk during development. FMEA should be applied during order set design to assess and limit risk just as with any other clinical care process.

FMEA examines both level of risk and frequency of risk occurrence associated with a new proposed process. For example, let’s evaluate an order set designed for pain control after surgery that consists of multiple high-risk opioids along with antihistamine medications for as-needed itch relief (a non-life-threatening adverse event (AE) of opioids well known by the medical community). An interdisciplinary FMEA team consisting of subject matter experts may examine how the process should flow in step-by-step detail and then discuss the benefit of a process and risk for potential error. A FMEA team would then analyze what could go wrong with each part of the process and assign a level of risk and risk frequency for various steps in the process, and then decide that certain steps should be modified or eliminated. Perhaps after FMEA, a facility might conclude that the risk of serious complications is high when you combine opioid use with antihistamine medications. The facility could decide to remove antihistamine medications from an order set if it is determined that risks outweigh benefits. While a root cause analysis might identify the cause of an AE after order set use, these situations can be prevented with FMEA.

When applying FMEA to Figure 1, while bupropion is known as an evidence-based oral tobacco cessation option, there is the possibility that bupropion could be inadvertently prescribed from the order set in a hospitalized patient with alcohol withdrawal and withdrawal seizure history. These potentially dangerous situations can be avoided with FMEA. Thus, although bupropion may be evidence-based for NRT, decisions regarding order set design using EBM alone are insufficient.

The practitioner must consider possible unintended consequences within order sets and target treatment options to the appropriate setting and audience. Although Figure 1 may appear to be more inclusive, the interdisciplinary committee designing the inpatient NRT order set felt there was heightened risk with introducing bupropion in Figure 1 and decided the risk would be lowered by removing bupropion from the redesigned NRT order set (Figure 2). In addition to the goal of balancing availability of NRT options with acceptable risk, Figure 2 also focused on building an NRT order set most applicable to the inpatient setting.

Including Evidence-Based Practices

EBM has become a routine part of clinical decision making. Therefore, including EBM in order set design is vital. EBM for NRT has demonstrated that combination therapy is more effective than is monotherapy to help tobacco users quit. Incremental doses of NRT are recommended for patients who use tobacco more frequently.10

As shown in Figures 1 and 2, both order set designs incorporate EBM for NRT. Although the importance of implementing EBM is evident, critical factors, such as HFE and FMEA make a difference with well-designed order sets.

Results

The 4-step order set design technique was used during development of an inpatient NRT order set at the JAHVH. Results for the inpatient Joint Commission Tobacco Treatment Measures were obtained from the Veterans Health Administration quality metric reporting system known as Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning (SAIL). SAIL performance measure outcomes, which include the inpatient Joint Commission Tobacco Treatment Measures, are derived from chart reviews conducted by the External Peer Review Program. Outcomes demonstrated that TOB-2 and TOB-3 (2 inpatient Joint Commission Tobacco Treatment Measures) known as tob20 and tob40, respectively, within SAIL improved by more than 300% after development of an NRT order set using the 4-step order set design framework along with implementation of a multifaceted tobacco cessation care delivery system at JAHVH.

Discussion

While the overall tobacco cessation care delivery system contributed to improved outcomes with the inpatient Joint Commission Tobacco Treatment Measures at JAHVH, the NRT order set was a cornerstone of the design. Although using our order set design technique does not necessarily guarantee successful outcomes, we believe using the 4-step order set design process increases the value of order sets and has potential to improve quality outcomes.

Limitations

Although improved outcomes following implementation of our NRT order set suggest correlation, causation cannot be proven. Also while the NRT order set is believed to have helped tremendously with outcomes, the entire tobacco cessation care delivery system at JAHVH contributed to the results. In addition, the inpatient Joint Commission Tobacco Treatment Measures help improve processes for tobacco cessation care. However, we are uncertain whether the results of our improvement efforts helped patients stop tobacco use. Further studies are needed to determine impact on population health. Finally, our results were based on improvement work done at a single center. Further studies are necessary to see whether results are reproducible.

Conclusion

There was significant improvement with the inpatient Joint Commission Tobacco Treatment Measures outcomes following development of a tobacco cessation care delivery system that included design of an inpatient NRT order set using a 4-step process we developed. This 4-step structure includes emphasis on efficiency and ease of use; human factors engineering; failure mode and effects analysis; and incorporation of evidence-based medicine (Box.) Postimplementation results showed improvement of the inpatient Joint Commission Tobacco Treatment Measures by greater than 3-fold at a single hospital.

The next steps for this initiative include testing the 4-step order set design process in multiple clinical settings to determine the effectiveness of this approach in other areas of clinical care.

1. Order set. http://clinfowiki.org/wiki/index.php/Order_set. Updated October 15, 2015. Accessed August 30, 2019.

2. Bates DW, Kuperman GJ, Wang S, et al. Ten commandments for effective clinical decision support: making the practice of evidence-based medicine a reality. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10(6):523-530.

3. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Guidelines for standard order sets. https://www.ismp.org/tools/guidelines/standardordersets.pdf. Published January 12, 2010. Accessed August 30, 2019.

4. Heath C, Heath D. Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard. New York, NY: Crown Business; 2010:50-51.

5. US Department of Health and Human Services. Usability testing. https://www.usability.gov/how-to-and-tools/methods/usability-testing.html. Accessed August 30, 2019.

6. World Health Organization. What is human factors and why is it important to patient safety? www.who.int/patientsafety/education/curriculum/who_mc_topic-2.pdf. Accessed August 30, 2019.

7. Sollisch J. The cure for decision fatigue. Wall Street Journal. June 10, 2016. https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-cure-for-decision-fatigue-1465596928. Accessed August 30, 2019.

8. ECRI Institute. Implementing the ENFit initiative for preventing enteral tubing misconnections. https://www.ecri.org/components/HDJournal/Pages/ENFit-for-Preventing-Enteral-Tubing-Misconnections.aspx. Published March 29, 2017. Accessed August 30, 2019.

9. Guidance for performing failure mode and effects analysis with performance improvement projects. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/QAPI/downloads/GuidanceForFMEA.pdf. Accessed August 30, 2019.

10. Diefanbach LJ, Smith PO, Nashelsky JM, Lindbloom E. What is the most effective nicotine replacement therapy? J Fam Pract. 2003;52(6):492-497.

In the current health care environment, hospitals are constantly challenged to improve quality metrics and deliver better health care outcomes. One means to achieving quality improvement is through the use of order sets, groups of related orders that a health care provider (HCP) can place with either a few keystrokes or mouse clicks.1

Historically, design of order sets has largely focused on clicking checkboxes containing evidence-based practices. According to Bates and colleagues and the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, incorporating evidence-based medicine (EBM) into order sets is not by itself sufficient.2,3Execution of proper design coupled with simplicity and provider efficiency is paramount to HCP buy-in, increased likelihood of order set adherence, and to potentially better outcomes.

In this article, we outline advancements in order set design. These improvements increase provider efficiency and ease of use; incorporate human factors engineering (HFE); apply failure mode and effects analysis; and include EBM.

Methods

An inpatient nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) order was developed as part of a multifaceted solution to improve tobacco cessation care at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVH) in Tampa, Florida, a complexity level 1a facility. This NRT order set used the 4-step order set design framework the authors’ developed (for additional information about the NRT order set, contact the authors). We distinguish order set design technique between 2 different inpatient NRT order sets. The first order set in the comparison (Figure 1) is an inpatient NRT order set of unknown origin—it is common for US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical facilities to share order sets and other resources. The second order set (Figure 2) is an inpatient NRT order set we designed using our 4-step process for comparison in this article. No institutional review board approval was required as this work met criteria for operational improvement activities exempt from ethics review.

Justin Iannello, DO, MBA, was the team leader and developer of the 4-step order set design technique. The intervention team consisted of 4 internal medicine physicians with expertise in quality improvement and patient safety: 1 certified professional in patient safety and certified as a Lean Six Sigma Black Belt; 2 physicians certified as Lean Six Sigma Black Belts; and 1 physician certified as a Lean Six Sigma Green Belt. Two inpatient clinical pharmacists and 1 quality management specialist also were involved in its development.

Development of a new NRT order set was felt to be an integral part of the tobacco cessation care delivery process. An NRT order set perceived by users as value-added required a solution that merged EBM with standardization and applied quality improvement principles. The result was an approach to order set design that focused on 4 key questions: Is the order set efficient and easy to use/navigate? Is human factors engineering incorporated? Is failure mode and effects analysis applied? Are evidence-based practices included?

Ease of Use and Navigation