User login

Impact of NSAID Use on Bleeding Rates for Patients Taking Rivaroxaban or Apixaban

Impact of NSAID Use on Bleeding Rates for Patients Taking Rivaroxaban or Apixaban

Clinical practice has shifted from vitamin K antagonists to direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) for atrial fibrillation treatment due to their more favorable risk-benefit profile and less lifestyle modification required.1,2 However, the advantage of a lower bleeding risk with DOACs could be compromised by potentially problematic pharmacokinetic interactions like those conferred by antiplatelets or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).3,4 Treating a patient needing anticoagulation with a DOAC who has comorbidities may introduce unavoidable drug-drug interactions. This particularly happens with over-the-counter and prescription NSAIDs used for the management of pain and inflammatory conditions.5

NSAIDs primarily affect 2 cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme isomers, COX-1 and COX-2.6 COX-1 helps maintain gastrointestinal (GI) mucosa integrity and platelet aggregation processes, whereas COX-2 is engaged in pain signaling and inflammation mediation. COX-1 inhibition is associated with more bleeding-related adverse events (AEs), especially in the GI tract. COX-2 inhibition is thought to provide analgesia and anti-inflammatory properties without elevating bleeding risk. This premise is responsible for the preferential use of celecoxib, a COX-2 selective NSAID, which should confer a lower bleeding risk compared to nonselective NSAIDs such as ibuprofen and naproxen.7 NSAIDs have been documented as independent risk factors for bleeding. NSAID users are about 3 times as likely to develop GI AEs compared to nonNSAID users.8

Many clinicians aim to further mitigate NSAID-associated bleeding risk by coprescribing a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). PPIs provide gastroprotection against NSAID-induced mucosal injury and sequential complication of GI bleeding. In a multicenter randomized control trial, patients who received concomitant PPI therapy while undergoing chronic NSAID therapy—including nonselective and COX-2 selective NSAIDs—had a significantly lower risk of GI ulcer development (placebo, 17.0%; 20 mg esomeprazole, 5.2%; 40 mg esomeprazole, 4.6%).9 Current clinical guidelines for preventing NSAIDassociated bleeding complications recommend using a COX-2 selective NSAID in combination with PPI therapy for patients at high risk for GI-related bleeding, including the concomitant use of anticoagulants.10

There is evidence suggesting an increased bleeding risk with NSAIDs when used in combination with vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin.11,12 A systematic review of warfarin and concomitant NSAID use found an increased risk of overall bleeding with NSAID use in combination with warfarin (odds ratio 1.58; 95% CI, 1.18-2.12), compared to warfarin alone.12

Posthoc analyses of randomized clinical trials have also demonstrated an increased bleeding risk with oral anticoagulation and concomitant NSAID use.13,14 In the RE-LY trial, NSAID users on warfarin or dabigatran had a statistically significant increased risk of major bleeding compared to non-NSAID users (hazard ratio [HR] 1.68; 95% CI, 1.40- 2.02; P < .001).13 In the ARISTOTLE trial, patients on warfarin or apixaban who were incident NSAID users were found to have an increased risk of major bleeding (HR 1.61; 95% CI, 1.11-2.33) and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding (HR 1.70; 95% CI, 1.16- 2.48).14 These trials found a statistically significant increased bleeding risk associated with NSAID use, though the populations evaluated included patients taking warfarin and patients taking DOACs. These trials did not evaluate the bleeding risk of concomitant NSAID use among DOACs alone.

Evidence on NSAID-associated bleeding risk with DOACs is lacking in settings where the patient population, prescribing practices, and monitoring levels are variable. Within the Veterans Health Administration, clinical pharmacist practitioners (CPPs) in anticoagulation clinics oversee DOAC therapy management. CPPs monitor safety and efficacy of DOAC therapies through a population health management tool, the DOAC Dashboard.15 The DOAC Dashboard creates alerts for patients who may require an intervention based on certain clinical parameters, such as drug-drug interactions.16 Whenever a patient on a DOAC is prescribed an NSAID, an alert is generated on the DOAC Dashboard to flag the CPPs for the potential need for an intervention. If NSAID therapy remains clinically indicated, CPPs may recommend risk reduction strategies such as a COX-2 selective NSAID or coprescribing a PPI.10

The DOAC Dashboard provides an ideal setting for investigating the effects of NSAID use, NSAID selectivity, and PPI coprescribing on DOAC bleeding rates. With an increasing population of patients receiving anticoagulation therapy with a DOAC, more guidance regarding the bleeding risk of concomitant NSAID use with DOACs is needed. Studies evaluating the bleeding risk with concomitant NSAID use in patients on a DOAC alone are limited. This is the first study to date to compare bleeding risk with concomitant NSAID use between DOACs. This study provides information on bleeding risk with NSAID use among commonly prescribed DOACs, rivaroxaban and apixaban, and the potential impacts of current risk reduction strategies.

METHODS

This single-center retrospective cohort review was performed using the electronic health records (EHRs) of patients enrolled in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Mountain Home Healthcare System who received rivaroxaban or apixaban from December 2020 to December 2022. This study received approval from the East Tennessee State University/VA Institutional Review Board committee.

Patients were identified through the DOAC Dashboard, aged 21 to 100 years, and received rivaroxaban or apixaban at a therapeutic dose: rivaroxaban 10 to 20 mg daily or apixaban 2.5 to 5 mg twice daily. Patients were excluded if they were prescribed dual antiplatelet therapy, received rivaroxaban at dosing indicated for peripheral vascular disease, were undergoing dialysis, had evidence of moderate to severe hepatic impairment or any hepatic disease with coagulopathy, were undergoing chemotherapy or radiation, or had hematological conditions with predisposed bleeding risk. These patients were excluded to mitigate the potential confounding impact from nontherapeutic DOAC dosing strategies and conditions associated with an increased bleeding risk.

Eligible patients were stratified based on NSAID use. NSAID users were defined as patients prescribed an oral NSAID, including both acute and chronic courses, at any point during the study time frame while actively on a DOAC. Bleeding events were reviewed to evaluate rates between rivaroxaban and apixaban among NSAID and nonNSAID users. Identified NSAID users were further assessed for NSAID selectivity and PPI coprescribing as a subgroup analysis for the secondary assessment.

Data Collection

Baseline data were collected, including age, body mass index, anticoagulation indication, DOAC agent, DOAC dose, and DOAC total daily dose. Baseline serum creatinine levels, liver function tests, hemoglobin levels, and platelet counts were collected from the most recent data available immediately prior to the bleeding event, if applicable.

The DOAC Dashboard was reviewed for active and dismissed drug interaction alerts to identify patients taking rivaroxaban or apixaban who were prescribed an NSAID. Patients were categorized in the NSAID group if an interacting drug alert with an NSAID was reported during the study time frame. Data available through the interacting drug alerts on NSAID use were limited to the interacting drug name and date of the reported flag. Manual EHR review was required to confirm dates of NSAID therapy initiation and NSAID discontinuation, if applicable.

Data regarding concomitant antiplatelet use were obtained through review of the active and dismissed drug interaction alerts on the DOAC Dashboard. Concomitant antiplatelet use was defined as the prescribing of a single antiplatelet agent at any point while receiving DOAC therapy. Data on concomitant antiplatelets were collected regardless of NSAID status.

Data on coprescribed PPI therapy were obtained through manual EHR review of identified NSAID users. Coprescribed PPI therapy was defined as the prescribing of a PPI at any point during NSAID therapy. Data regarding PPI use among non-NSAID users were not collected because the secondary endpoint was designed to assess PPI use only among patients coprescribed a DOAC and NSAID.

Outcomes

Bleeding events were identified through an outcomes report generated by the DOAC Dashboard based on International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision diagnosis codes associated with a bleeding event. The outcomes report captures diagnoses from the outpatient and inpatient care settings. Reported bleeding events were limited to patients who received a DOAC at any point in the 6 months prior to the event and excluded patients with recent DOAC initiation within 7 days of the event, as these patients are not captured on the DOAC Dashboard.

All reported bleeding events were manually reviewed in the EHR and categorized as a major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleed, according to International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis criteria. Validated bleeding events were then crossreferenced with the interacting drug alerts report to identify events with potentially overlapping NSAID therapy at the time of the event. Overlapping NSAID therapy was defined as the prescribing of an NSAID at any point in the 6 months prior to the event. All events with potential overlapping NSAID therapies were manually reviewed for confirmation of NSAID status at the time of the event.

The primary endpoint was a composite of any bleeding event per International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis criteria. The secondary endpoint evaluated the potential impact of NSAID selectivity or PPI coprescribing on the bleeding rate among the NSAID user groups.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed consistent with the methods used in the ARISTOTLE and RE-LY trials. It was determined that a sample size of 504 patients, with ≥ 168 patients in each group, would provide 80% power using a 2-sided a of 0.05. HRs with 95% CIs and respective P values were calculated using a SPSS-adapted online calculator.

RESULTS

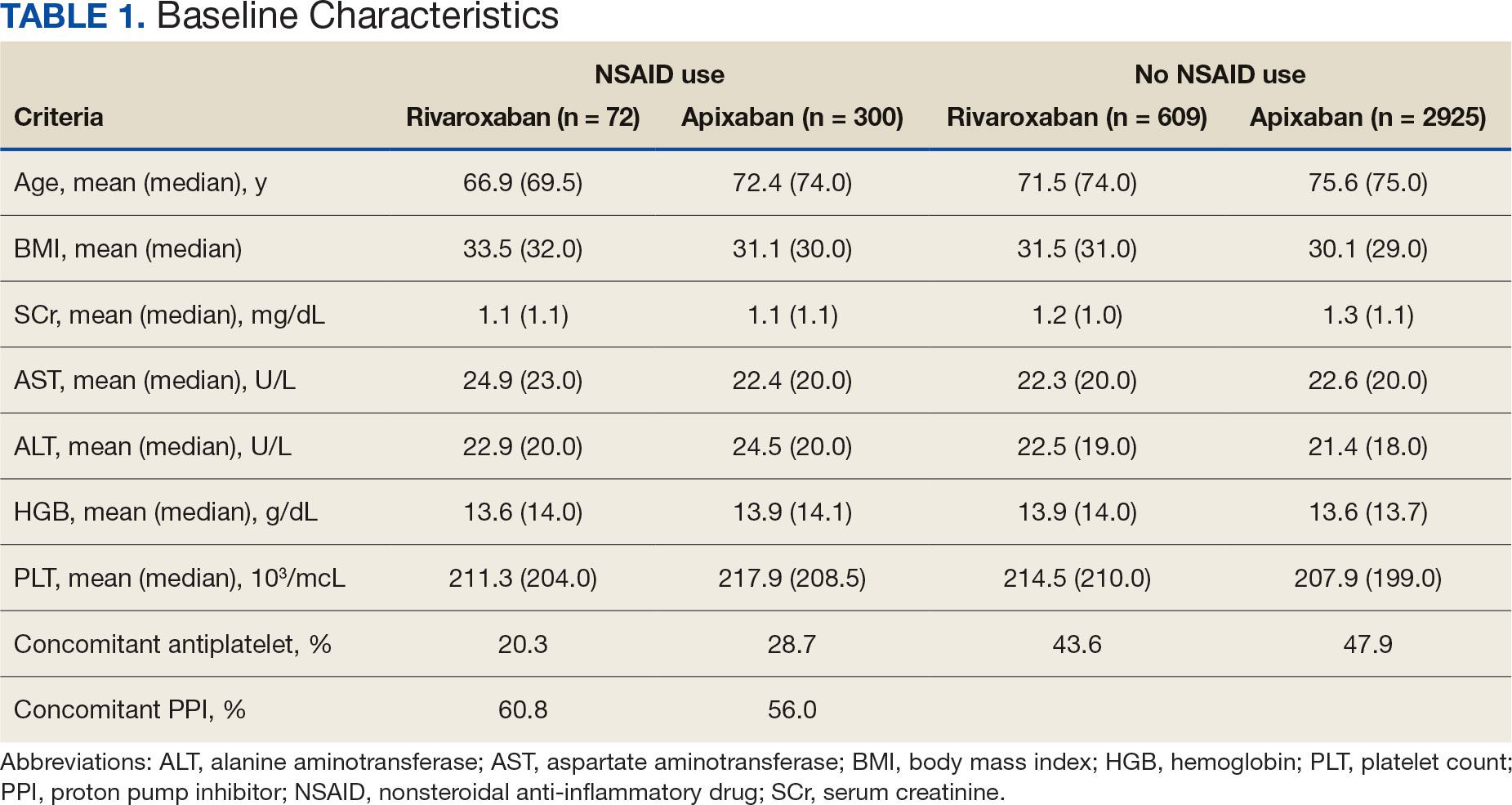

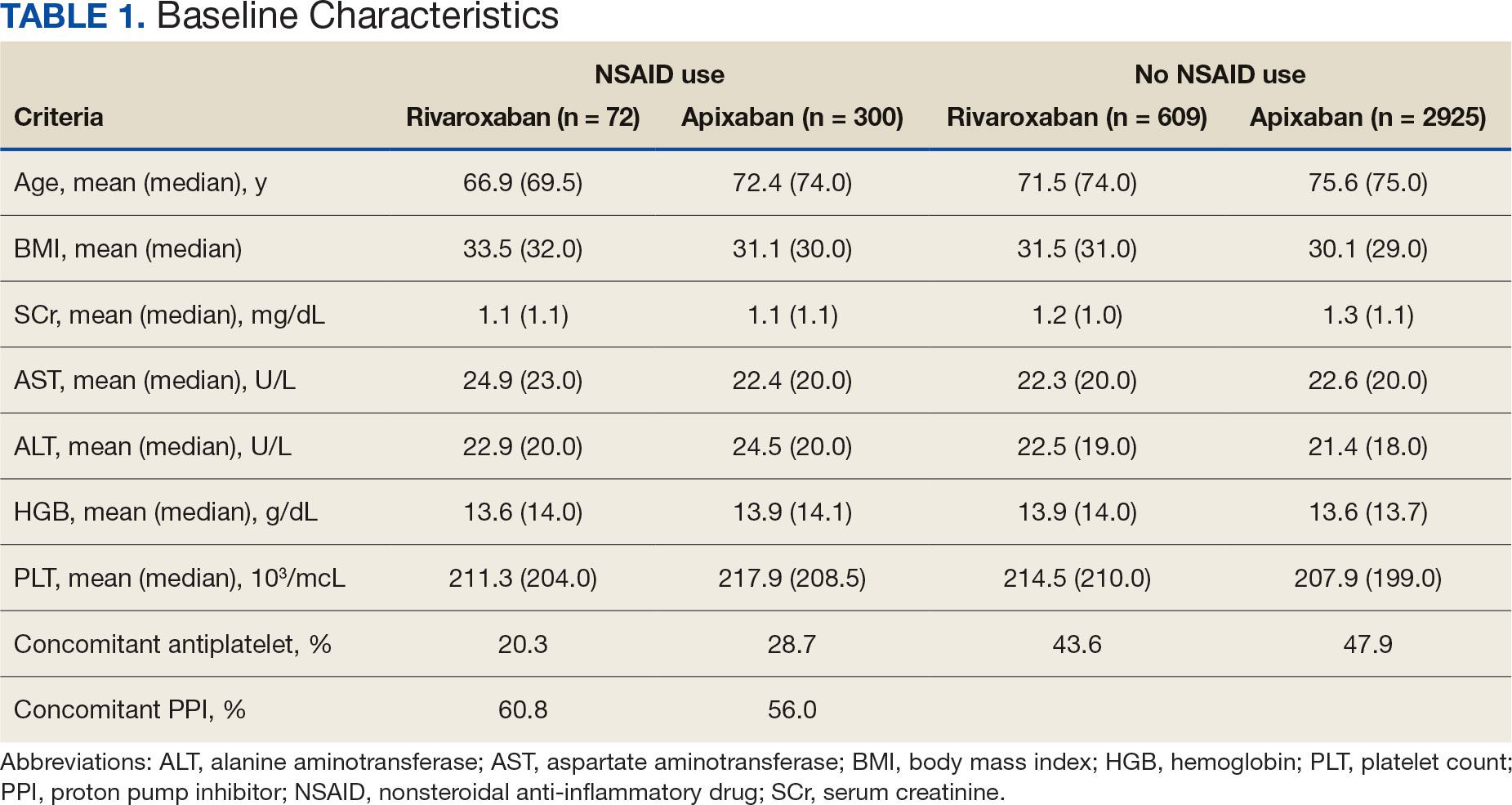

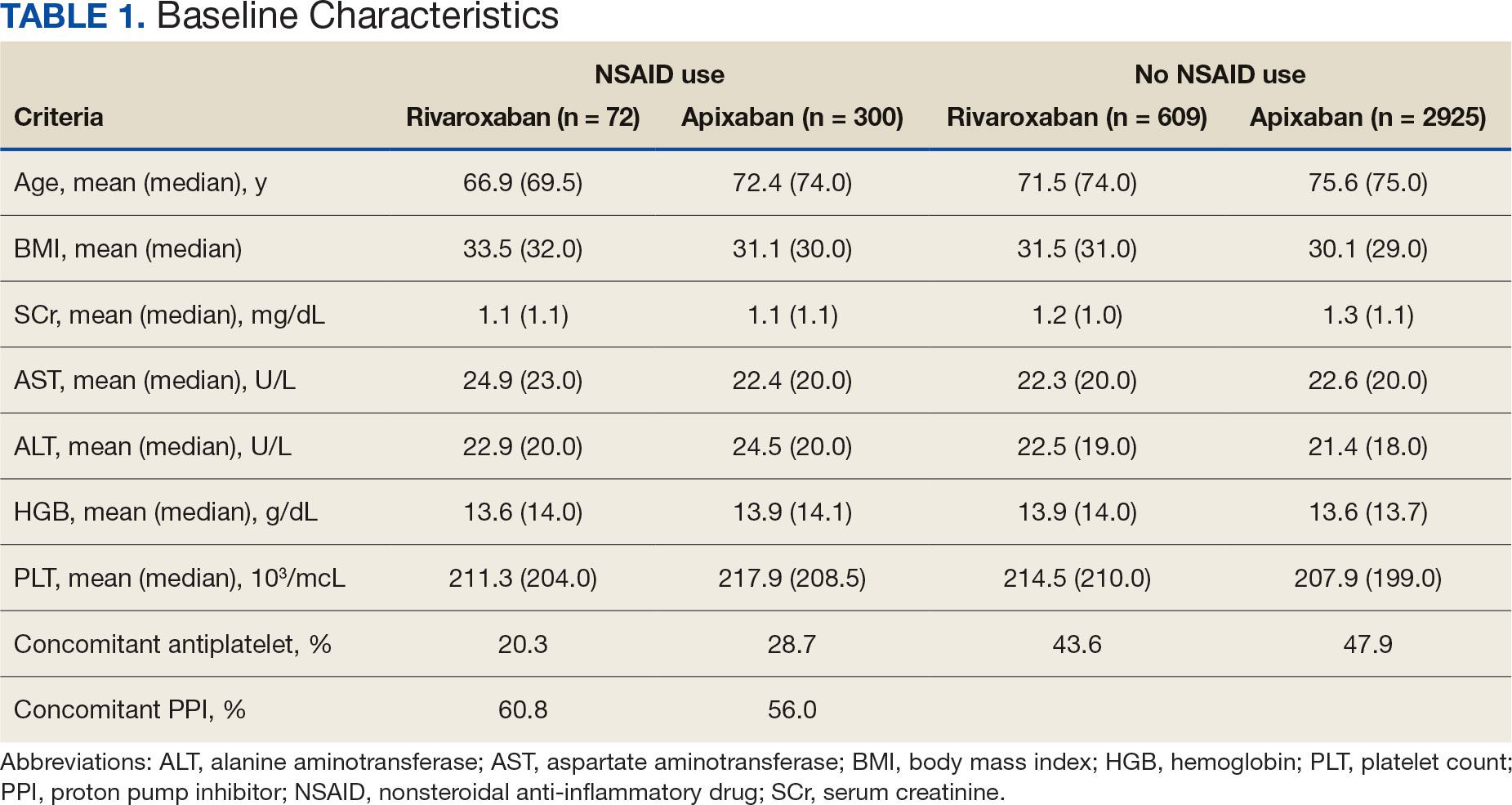

The DOAC Dashboard identified 681 patients on rivaroxaban and 3225 patients on apixaban; 72 patients on rivaroxaban (10.6%) and 300 patients on apixaban (9.3%) were NSAID users. The mean age of NSAID users was 66.9 years in the rivaroxaban group and 72.4 years in the apixaban group. The mean age of non-NSAID users was 71.5 years in the rivaroxaban group and 75.6 years in the apixaban group. No appreciable differences were observed among subgroups in body mass index, renal function, hepatic function, hemoglobin, or platelet counts, and no statistically significant differences were identified (Table 1). Antiplatelet agents identified included aspirin, clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor. Fifteen patients (20.3%) in the rivaroxaban group and 87 patients (28.7%) in the apixaban group had concomitant antiplatelet and NSAID use. Forty-five patients on rivaroxaban (60.8%) and 170 (55.9%) on apixaban were prescribed concomitant PPI and NSAID at baseline. Among non-NSAID users, there was concomitant antiplatelet use for 265 patients (43.6%) in the rivaroxaban group and 1401 patients (47.9%) in the apixaban group. Concomitant PPI use was identified among 63 patients (60.0%) taking selective NSAIDs and 182 (57.2%) taking nonselective NSAIDs.

A total of 423 courses of NSAIDs were identified: 85 NSAID courses in the rivaroxaban group and 338 NSAID courses in the apixaban group. Most NSAID courses involved a nonselective NSAID in the rivaroxaban and apixaban NSAID user groups: 75.2% (n = 318) aggregately compared to 71.8% (n = 61) and 76.0% (n = 257) in the rivaroxaban and apixaban groups, respectively. The most frequent NSAID courses identified were meloxicam (26.7%; n = 113), celecoxib (24.8%; n = 105), ibuprofen (19.1%; n = 81), and naproxen (13.5%; n = 57). Data regarding NSAID therapy initiation and discontinuation dates were not readily available. As a result, the duration of NSAID courses was not captured.

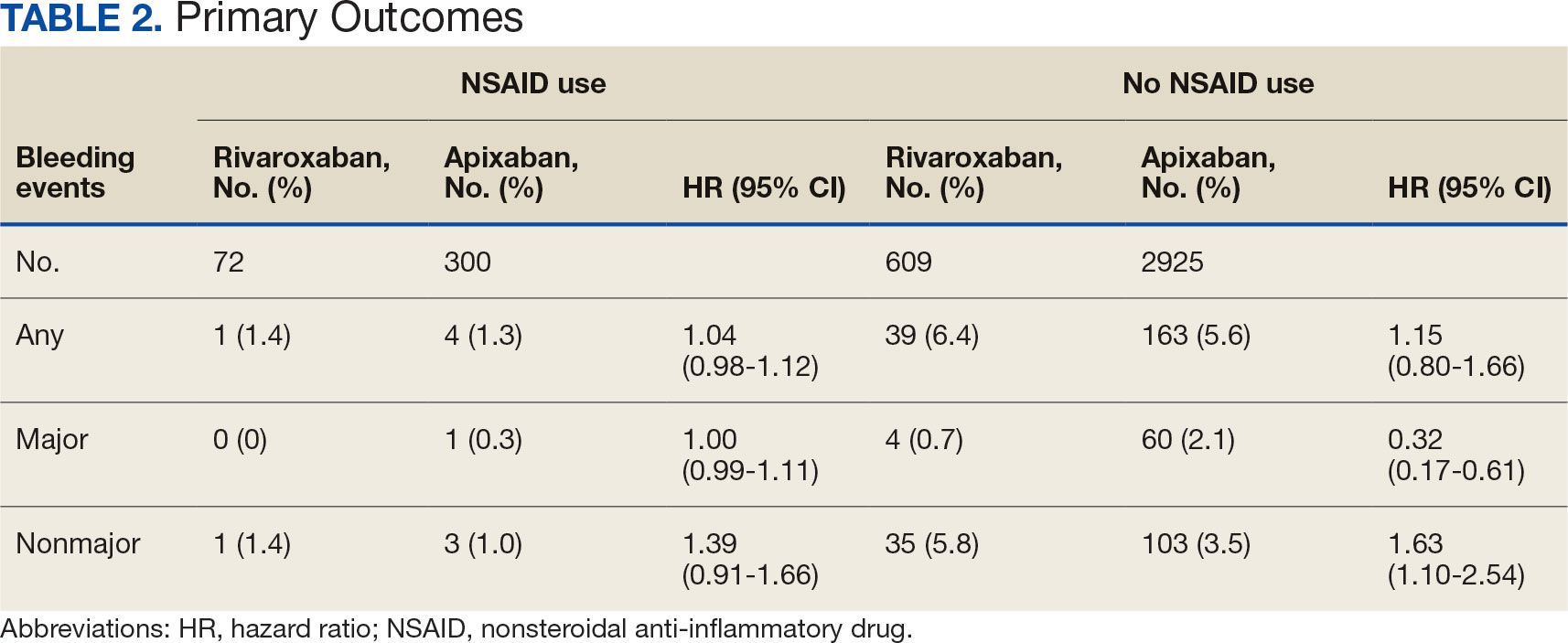

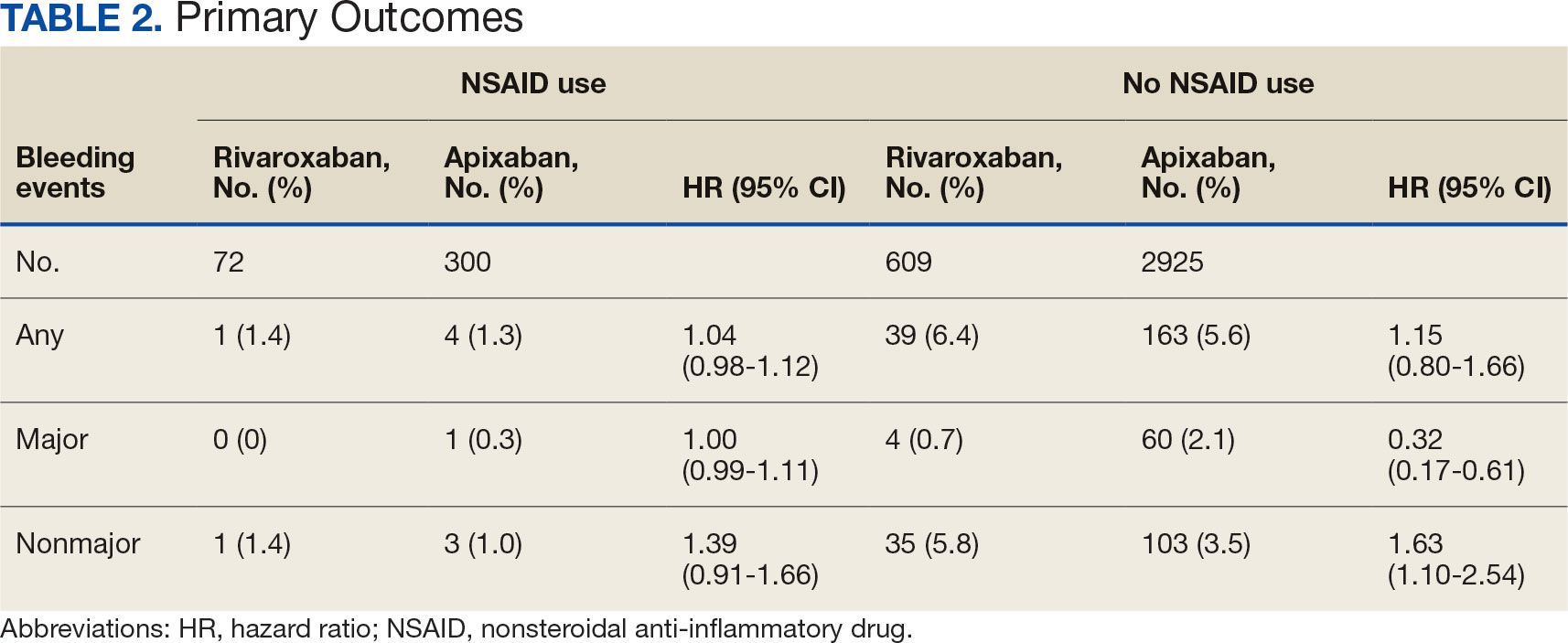

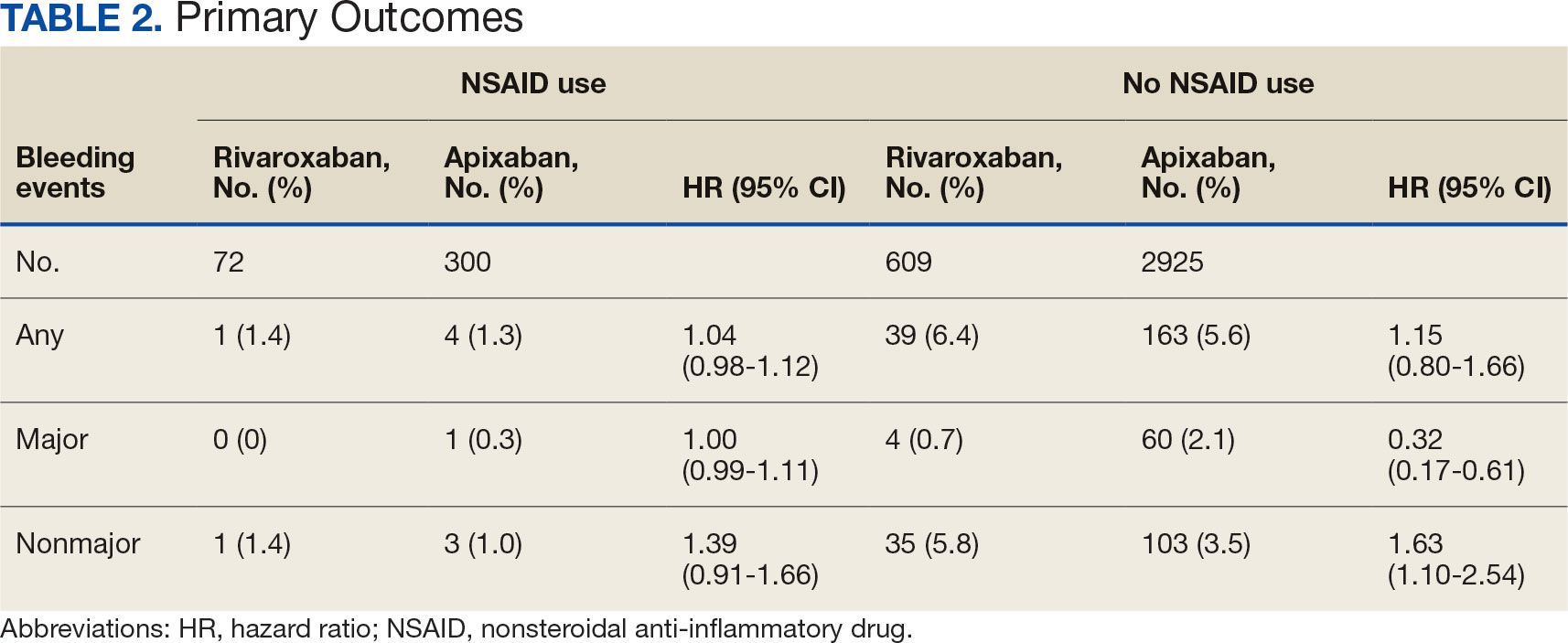

There was no statistically significant difference in bleeding rates between rivaroxaban and apixaban among NSAID users (HR 1.04; 95% CI, 0.98-1.12) or non-NSAID users (HR 1.15; 95% CI, 0.80-1.66) (Table 2). Apixaban non-NSAID users had a higher rate of major bleeds (HR 0.32; 95% CI, 0.17-0.61) while rivaroxaban non-NSAID users had a higher rate of clinically relevant nonmajor bleeds (HR 1.63; 95% CI, 1.10-2.54).

The sample size for the secondary endpoint consisted of bleeding events that were confirmed to have had an overlapping NSAID prescribed at the time of the event. For this secondary assessment, there was 1 rivaroxaban NSAID user bleeding event and 4 apixaban NSAID user bleeding events. For the rivaroxaban NSAID user bleeding event, the NSAID was nonselective and a PPI was not coprescribed. For the apixaban NSAID user bleeding events, 2 NSAIDs were nonselective and 2 were selective. All patients with apixaban and NSAID bleeding events had a coprescribed PPI. There was no clinically significant difference in the bleeding rates observed for NSAID selectivity or PPI coprescribing among the NSAID user subgroups.

DISCUSSION

This study found that there was no statistically significant difference for bleeding rates of major and nonmajor bleeding events between rivaroxaban and apixaban among NSAID users and non-NSAID users. This study did not identify a clinically significant impact on bleeding rates from NSAID selectivity or PPI coprescribing among the NSAID users.

There were notable but not statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics observed between the NSAID and non-NSAID user groups. On average, the rivaroxaban and apixaban NSAID users were younger compared with those not taking NSAIDs. NSAIDs, specifically nonselective NSAIDs, are recognized as potentially inappropriate medications for older adults given that this population is at an increased risk for GI ulcer development and/or GI bleeding.17 The non-NSAID user group likely consisted of older patients compared to the NSAID user group as clinicians may avoid prescribing NSAIDs to older adults regardless of concomitant DOAC therapy.

In addition to having an older patient population, non-NSAID users were more frequently prescribed a concomitant antiplatelet when compared with NSAID users. This prescribing pattern may be due to clinicians avoiding the use of NSAIDs in patients receiving DOAC therapy in combination with antiplatelet therapy, as these patients have been found to have an increased bleeding rate compared to DOAC therapy alone.18

Non-NSAID users had an overall higher bleeding rate for both major and nonmajor bleeding events. Based on this observation, it could be hypothesized that antiplatelet agents have a higher risk of bleeding in comparison to NSAIDs. In a subanalysis of the EXPAND study evaluating risk factors of major bleeding in patients receiving rivaroxaban, concomitant use of antiplatelet agents demonstrated a statistically significant increased risk of bleeding (HR 1.6; 95% CI, 1.2-2.3; P = .003) while concomitant use of NSAIDs did not (HR 0.8; 95% CI, 0.3-2.2; P = .67).19

In assessing PPI status at baseline, a majority of both rivaroxaban and apixaban NSAID users were coprescribed a PPI. This trend aligns with current clinical guideline recommendations for the prescribing of PPI therapy for GI protection in high-risk patients, such as those on DOAC therapy and concomitant NSAID therapy.10 Given the high proportion of NSAID users coprescribed a PPI at baseline, it may be possible that the true incidence of NSAID-associated bleeding events was higher than what this study found. This observation may reflect the impact from timely implementation of risk mitigation strategies by CPPs in the anticoagulation clinic. However, this study was not constructed to assess the efficacy of PPI use in this manner.

It is important to note the patients included in this study were followed by a pharmacist in an anticoagulation clinic using the DOAC Dashboard.15 This population management tool allows CPPs to make proactive interventions when a patient taking a DOAC receives an NSAID prescription, such as recommending the coprescribing of a PPI or use of a selective NSAID.10,16 These standards of care may have contributed to an overall reduced bleeding rate among the NSAID user group and may not be reflective of private practice.

The planned analysis of this study was modeled after the posthoc analysis of the RE-LY and ARISTOTLE trials. Both trials demonstrated an increased risk of bleeding with oral anticoagulation, including DOAC and warfarin, in combination with NSAID use. However, both trials found that NSAID use in patients treated with a DOAC was not independently associated with increased bleeding events compared with warfarin.13,14 The results of this study are comparable to the RE-LY and ARISTOTLE findings that NSAID use among patients treated with rivaroxaban or apixaban did not demonstrate a statistically significant increased bleeding risk.

Studies of NSAID use in combination with DOAC therapy have been limited to patient populations consisting of both DOAC and warfarin. Evidence from these trials outlines the increased bleeding risk associated with NSAID use in combination with oral anticoagulation; however, these patient populations include those on a DOAC and warfarin.13,14,19,20 Given the limited evidence on NSAID use among DOACs alone, it is assumed NSAID use in combination with DOACs has a similar risk of bleeding as warfarin use. This may cause clinicians to automatically exclude NSAID therapy as a treatment option for patients on a DOAC who are otherwise clinically appropriate candidates, such as those with underlying inflammatory conditions. Avoiding NSAID therapy in this patient population may lead to suboptimal pain management and increase the risk of patient harm from methods such as inappropriate opioid therapy prescribing.

DOAC therapy should not be a universal limitation to the use of NSAIDs. Although the risk of bleeding with NSAID therapy is always present, deliberate NSAID prescribing in addition to the timely implementation of risk mitigation strategies may provide an avenue for safe NSAID prescribing in patients receiving a DOAC. A population health-based approach to DOAC management, such as the DOAC Dashboard, appears to be effective at preventing patient harm when NSAIDs are prescribed in conjunction with DOACs.

Limitations

The DOAC Dashboard has been shown to be effective and efficient at monitoring DOAC therapy from a population-based approach.16 Reports generated through the DOAC Dashboard provide convenient access to patient data which allows for timely interventions; however, there are limits to its use for data collection. All the data elements necessary to properly assess bleeding risk with validated tools, such as HAS-BLED (hypertension, abnormal renal/liver function, stroke, bleeding history or predisposition, labile international normalized ratio, elderly, drugs/ alcohol concomitantly), are not available on DOAC Dashboard reports. Due to this constraint, bleeding risk assessments were not conducted at baseline and this study was unable to include risk modeling. Additionally, data elements like initiation and discontinuation dates and duration of therapies were not readily available. As a result, this study was unable to incorporate time as a data point.

This was a retrospective study that relied on manual review of chart documentation to verify bleeding events, but data obtained through the DOAC Dashboard were transferred directly from the EHR.15 Bleeding events available for evaluation were restricted to those that occurred at a VA facility. Additionally, the sample size within the rivaroxaban NSAID user group did not reach the predefined sample size required to reach power and may have been too small to detect a difference if one did exist. The secondary assessment had a low sample size of NSAID user bleeding events, making it difficult to fully assess its impact on NSAID selectivity and PPI coprescribing on bleeding rates. All courses of NSAIDs were equally valued regardless of the dose or therapy duration; however, this is consistent with how NSAID use was defined in the RE-LY and ARISTOTLE trials.

CONCLUSIONS

This retrospective cohort review found no statistically significant difference in the composite bleeding rates between rivaroxaban and apixaban among NSAID users and non-NSAID users. Moreover, there was no clinically significant impact observed for bleeding rates in regard to NSAID selectivity and PPI coprescribing among NSAID users. However, coprescribing of PPI therapy to patients on a DOAC who are clinically indicated for an NSAID may reduce the risk of bleeding. Population health management tools, such as the DOAC Dashboard, may also allow clinicians to safely prescribe NSAIDs to patients on a DOAC. Further large-scale observational studies are needed to quantify the real-world risk of bleeding with concomitant NSAID use among DOACs alone and to evaluate the impact from NSAID selectivity or PPI coprescribing.

- Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):955-962. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62343-0

- Ageno W, Gallus AS, Wittkowsky A, Crowther M, Hylek EM, Palareti G. Oral anticoagulant therapy: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e44S-e88S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2292

- Eikelboom J, Merli G. Bleeding with direct oral anticoagulants vs warfarin: clinical experience. Am J Med. 2016;129(11S):S33-S40. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.06.003

- Vranckx P, Valgimigli M, Heidbuchel H. The significance of drug-drug and drug-food interactions of oral anticoagulation. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2018;7(1):55-61. doi:10.15420/aer.2017.50.1

- Davis JS, Lee HY, Kim J, et al. Use of non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs in US adults: changes over time and by demographic. Open Heart. 2017;4(1):e000550. doi:10.1136/openhrt-2016-000550

- Schafer AI. Effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs on platelet function and systemic hemostasis. J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;35(3):209-219. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1995.tb04050.x

- Al-Saeed A. Gastrointestinal and cardiovascular risk of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Oman Med J. 2011;26(6):385-391. doi:10.5001/omj.2011.101

- Gabriel SE, Jaakkimainen L, Bombardier C. Risk for serious gastrointestinal complications related to use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115(10):787-796. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-115-10-787

- Scheiman JM, Yeomans ND, Talley NJ, et al. Prevention of ulcers by esomeprazole in at-risk patients using non-selective NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(4):701-710. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00499.x

- Freedberg DE, Kim LS, Yang YX. The risks and benefits of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: expert review and best practice advice from the American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(4):706-715. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.031

- Lamberts M, Lip GYH, Hansen ML, et al. Relation of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to serious bleeding and thromboembolism risk in patients with atrial fibrillation receiving antithrombotic therapy: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(10):690-698. doi:10.7326/M13-1581

- Villa Zapata L, Hansten PD, Panic J, et al. Risk of bleeding with exposure to warfarin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(7):1066-1074. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1710592

- Kent AP, Brueckmann M, Fraessdorf M, et al. Concomitant oral anticoagulant and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(3):255-267. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.063

- Dalgaard F, Mulder H, Wojdyla DM, et al. Patients with atrial fibrillation taking nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and oral anticoagulants in the ARISTOTLE Trial. Circulation. 2020;141(1):10-20. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041296

- Allen AL, Lucas J, Parra D, et al. Shifting the paradigm: a population health approach to the management of direct oral anticoagulants. J Am Heart Asssoc. 2021;10(24):e022758. doi:10.1161/JAHA.121.022758

- . Valencia D, Spoutz P, Stoppi J, et al. Impact of a direct oral anticoagulant population management tool on anticoagulation therapy monitoring in clinical practice. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;53(8):806-811. doi:10.1177/1060028019835843

- By the 2023 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2023 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(7):2052-2081. doi:10.1111/jgs.18372

- Kumar S, Danik SB, Altman RK, et al. Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants and antiplatelet therapy for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation. Cardiol Rev. 2016;24(5):218-223. doi:10.1097/CRD.0000000000000088

- Sakuma I, Uchiyama S, Atarashi H, et al. Clinical risk factors of stroke and major bleeding in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation under rivaroxaban: the EXPAND study sub-analysis. Heart Vessels. 2019;34(11):1839-1851. doi:10.1007/s00380-019-01425-x

- Davidson BL, Verheijen S, Lensing AWA, et al. Bleeding risk of patients with acute venous thromboembolism taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or aspirin. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(6):947-953. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.946

Clinical practice has shifted from vitamin K antagonists to direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) for atrial fibrillation treatment due to their more favorable risk-benefit profile and less lifestyle modification required.1,2 However, the advantage of a lower bleeding risk with DOACs could be compromised by potentially problematic pharmacokinetic interactions like those conferred by antiplatelets or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).3,4 Treating a patient needing anticoagulation with a DOAC who has comorbidities may introduce unavoidable drug-drug interactions. This particularly happens with over-the-counter and prescription NSAIDs used for the management of pain and inflammatory conditions.5

NSAIDs primarily affect 2 cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme isomers, COX-1 and COX-2.6 COX-1 helps maintain gastrointestinal (GI) mucosa integrity and platelet aggregation processes, whereas COX-2 is engaged in pain signaling and inflammation mediation. COX-1 inhibition is associated with more bleeding-related adverse events (AEs), especially in the GI tract. COX-2 inhibition is thought to provide analgesia and anti-inflammatory properties without elevating bleeding risk. This premise is responsible for the preferential use of celecoxib, a COX-2 selective NSAID, which should confer a lower bleeding risk compared to nonselective NSAIDs such as ibuprofen and naproxen.7 NSAIDs have been documented as independent risk factors for bleeding. NSAID users are about 3 times as likely to develop GI AEs compared to nonNSAID users.8

Many clinicians aim to further mitigate NSAID-associated bleeding risk by coprescribing a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). PPIs provide gastroprotection against NSAID-induced mucosal injury and sequential complication of GI bleeding. In a multicenter randomized control trial, patients who received concomitant PPI therapy while undergoing chronic NSAID therapy—including nonselective and COX-2 selective NSAIDs—had a significantly lower risk of GI ulcer development (placebo, 17.0%; 20 mg esomeprazole, 5.2%; 40 mg esomeprazole, 4.6%).9 Current clinical guidelines for preventing NSAIDassociated bleeding complications recommend using a COX-2 selective NSAID in combination with PPI therapy for patients at high risk for GI-related bleeding, including the concomitant use of anticoagulants.10

There is evidence suggesting an increased bleeding risk with NSAIDs when used in combination with vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin.11,12 A systematic review of warfarin and concomitant NSAID use found an increased risk of overall bleeding with NSAID use in combination with warfarin (odds ratio 1.58; 95% CI, 1.18-2.12), compared to warfarin alone.12

Posthoc analyses of randomized clinical trials have also demonstrated an increased bleeding risk with oral anticoagulation and concomitant NSAID use.13,14 In the RE-LY trial, NSAID users on warfarin or dabigatran had a statistically significant increased risk of major bleeding compared to non-NSAID users (hazard ratio [HR] 1.68; 95% CI, 1.40- 2.02; P < .001).13 In the ARISTOTLE trial, patients on warfarin or apixaban who were incident NSAID users were found to have an increased risk of major bleeding (HR 1.61; 95% CI, 1.11-2.33) and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding (HR 1.70; 95% CI, 1.16- 2.48).14 These trials found a statistically significant increased bleeding risk associated with NSAID use, though the populations evaluated included patients taking warfarin and patients taking DOACs. These trials did not evaluate the bleeding risk of concomitant NSAID use among DOACs alone.

Evidence on NSAID-associated bleeding risk with DOACs is lacking in settings where the patient population, prescribing practices, and monitoring levels are variable. Within the Veterans Health Administration, clinical pharmacist practitioners (CPPs) in anticoagulation clinics oversee DOAC therapy management. CPPs monitor safety and efficacy of DOAC therapies through a population health management tool, the DOAC Dashboard.15 The DOAC Dashboard creates alerts for patients who may require an intervention based on certain clinical parameters, such as drug-drug interactions.16 Whenever a patient on a DOAC is prescribed an NSAID, an alert is generated on the DOAC Dashboard to flag the CPPs for the potential need for an intervention. If NSAID therapy remains clinically indicated, CPPs may recommend risk reduction strategies such as a COX-2 selective NSAID or coprescribing a PPI.10

The DOAC Dashboard provides an ideal setting for investigating the effects of NSAID use, NSAID selectivity, and PPI coprescribing on DOAC bleeding rates. With an increasing population of patients receiving anticoagulation therapy with a DOAC, more guidance regarding the bleeding risk of concomitant NSAID use with DOACs is needed. Studies evaluating the bleeding risk with concomitant NSAID use in patients on a DOAC alone are limited. This is the first study to date to compare bleeding risk with concomitant NSAID use between DOACs. This study provides information on bleeding risk with NSAID use among commonly prescribed DOACs, rivaroxaban and apixaban, and the potential impacts of current risk reduction strategies.

METHODS

This single-center retrospective cohort review was performed using the electronic health records (EHRs) of patients enrolled in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Mountain Home Healthcare System who received rivaroxaban or apixaban from December 2020 to December 2022. This study received approval from the East Tennessee State University/VA Institutional Review Board committee.

Patients were identified through the DOAC Dashboard, aged 21 to 100 years, and received rivaroxaban or apixaban at a therapeutic dose: rivaroxaban 10 to 20 mg daily or apixaban 2.5 to 5 mg twice daily. Patients were excluded if they were prescribed dual antiplatelet therapy, received rivaroxaban at dosing indicated for peripheral vascular disease, were undergoing dialysis, had evidence of moderate to severe hepatic impairment or any hepatic disease with coagulopathy, were undergoing chemotherapy or radiation, or had hematological conditions with predisposed bleeding risk. These patients were excluded to mitigate the potential confounding impact from nontherapeutic DOAC dosing strategies and conditions associated with an increased bleeding risk.

Eligible patients were stratified based on NSAID use. NSAID users were defined as patients prescribed an oral NSAID, including both acute and chronic courses, at any point during the study time frame while actively on a DOAC. Bleeding events were reviewed to evaluate rates between rivaroxaban and apixaban among NSAID and nonNSAID users. Identified NSAID users were further assessed for NSAID selectivity and PPI coprescribing as a subgroup analysis for the secondary assessment.

Data Collection

Baseline data were collected, including age, body mass index, anticoagulation indication, DOAC agent, DOAC dose, and DOAC total daily dose. Baseline serum creatinine levels, liver function tests, hemoglobin levels, and platelet counts were collected from the most recent data available immediately prior to the bleeding event, if applicable.

The DOAC Dashboard was reviewed for active and dismissed drug interaction alerts to identify patients taking rivaroxaban or apixaban who were prescribed an NSAID. Patients were categorized in the NSAID group if an interacting drug alert with an NSAID was reported during the study time frame. Data available through the interacting drug alerts on NSAID use were limited to the interacting drug name and date of the reported flag. Manual EHR review was required to confirm dates of NSAID therapy initiation and NSAID discontinuation, if applicable.

Data regarding concomitant antiplatelet use were obtained through review of the active and dismissed drug interaction alerts on the DOAC Dashboard. Concomitant antiplatelet use was defined as the prescribing of a single antiplatelet agent at any point while receiving DOAC therapy. Data on concomitant antiplatelets were collected regardless of NSAID status.

Data on coprescribed PPI therapy were obtained through manual EHR review of identified NSAID users. Coprescribed PPI therapy was defined as the prescribing of a PPI at any point during NSAID therapy. Data regarding PPI use among non-NSAID users were not collected because the secondary endpoint was designed to assess PPI use only among patients coprescribed a DOAC and NSAID.

Outcomes

Bleeding events were identified through an outcomes report generated by the DOAC Dashboard based on International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision diagnosis codes associated with a bleeding event. The outcomes report captures diagnoses from the outpatient and inpatient care settings. Reported bleeding events were limited to patients who received a DOAC at any point in the 6 months prior to the event and excluded patients with recent DOAC initiation within 7 days of the event, as these patients are not captured on the DOAC Dashboard.

All reported bleeding events were manually reviewed in the EHR and categorized as a major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleed, according to International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis criteria. Validated bleeding events were then crossreferenced with the interacting drug alerts report to identify events with potentially overlapping NSAID therapy at the time of the event. Overlapping NSAID therapy was defined as the prescribing of an NSAID at any point in the 6 months prior to the event. All events with potential overlapping NSAID therapies were manually reviewed for confirmation of NSAID status at the time of the event.

The primary endpoint was a composite of any bleeding event per International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis criteria. The secondary endpoint evaluated the potential impact of NSAID selectivity or PPI coprescribing on the bleeding rate among the NSAID user groups.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed consistent with the methods used in the ARISTOTLE and RE-LY trials. It was determined that a sample size of 504 patients, with ≥ 168 patients in each group, would provide 80% power using a 2-sided a of 0.05. HRs with 95% CIs and respective P values were calculated using a SPSS-adapted online calculator.

RESULTS

The DOAC Dashboard identified 681 patients on rivaroxaban and 3225 patients on apixaban; 72 patients on rivaroxaban (10.6%) and 300 patients on apixaban (9.3%) were NSAID users. The mean age of NSAID users was 66.9 years in the rivaroxaban group and 72.4 years in the apixaban group. The mean age of non-NSAID users was 71.5 years in the rivaroxaban group and 75.6 years in the apixaban group. No appreciable differences were observed among subgroups in body mass index, renal function, hepatic function, hemoglobin, or platelet counts, and no statistically significant differences were identified (Table 1). Antiplatelet agents identified included aspirin, clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor. Fifteen patients (20.3%) in the rivaroxaban group and 87 patients (28.7%) in the apixaban group had concomitant antiplatelet and NSAID use. Forty-five patients on rivaroxaban (60.8%) and 170 (55.9%) on apixaban were prescribed concomitant PPI and NSAID at baseline. Among non-NSAID users, there was concomitant antiplatelet use for 265 patients (43.6%) in the rivaroxaban group and 1401 patients (47.9%) in the apixaban group. Concomitant PPI use was identified among 63 patients (60.0%) taking selective NSAIDs and 182 (57.2%) taking nonselective NSAIDs.

A total of 423 courses of NSAIDs were identified: 85 NSAID courses in the rivaroxaban group and 338 NSAID courses in the apixaban group. Most NSAID courses involved a nonselective NSAID in the rivaroxaban and apixaban NSAID user groups: 75.2% (n = 318) aggregately compared to 71.8% (n = 61) and 76.0% (n = 257) in the rivaroxaban and apixaban groups, respectively. The most frequent NSAID courses identified were meloxicam (26.7%; n = 113), celecoxib (24.8%; n = 105), ibuprofen (19.1%; n = 81), and naproxen (13.5%; n = 57). Data regarding NSAID therapy initiation and discontinuation dates were not readily available. As a result, the duration of NSAID courses was not captured.

There was no statistically significant difference in bleeding rates between rivaroxaban and apixaban among NSAID users (HR 1.04; 95% CI, 0.98-1.12) or non-NSAID users (HR 1.15; 95% CI, 0.80-1.66) (Table 2). Apixaban non-NSAID users had a higher rate of major bleeds (HR 0.32; 95% CI, 0.17-0.61) while rivaroxaban non-NSAID users had a higher rate of clinically relevant nonmajor bleeds (HR 1.63; 95% CI, 1.10-2.54).

The sample size for the secondary endpoint consisted of bleeding events that were confirmed to have had an overlapping NSAID prescribed at the time of the event. For this secondary assessment, there was 1 rivaroxaban NSAID user bleeding event and 4 apixaban NSAID user bleeding events. For the rivaroxaban NSAID user bleeding event, the NSAID was nonselective and a PPI was not coprescribed. For the apixaban NSAID user bleeding events, 2 NSAIDs were nonselective and 2 were selective. All patients with apixaban and NSAID bleeding events had a coprescribed PPI. There was no clinically significant difference in the bleeding rates observed for NSAID selectivity or PPI coprescribing among the NSAID user subgroups.

DISCUSSION

This study found that there was no statistically significant difference for bleeding rates of major and nonmajor bleeding events between rivaroxaban and apixaban among NSAID users and non-NSAID users. This study did not identify a clinically significant impact on bleeding rates from NSAID selectivity or PPI coprescribing among the NSAID users.

There were notable but not statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics observed between the NSAID and non-NSAID user groups. On average, the rivaroxaban and apixaban NSAID users were younger compared with those not taking NSAIDs. NSAIDs, specifically nonselective NSAIDs, are recognized as potentially inappropriate medications for older adults given that this population is at an increased risk for GI ulcer development and/or GI bleeding.17 The non-NSAID user group likely consisted of older patients compared to the NSAID user group as clinicians may avoid prescribing NSAIDs to older adults regardless of concomitant DOAC therapy.

In addition to having an older patient population, non-NSAID users were more frequently prescribed a concomitant antiplatelet when compared with NSAID users. This prescribing pattern may be due to clinicians avoiding the use of NSAIDs in patients receiving DOAC therapy in combination with antiplatelet therapy, as these patients have been found to have an increased bleeding rate compared to DOAC therapy alone.18

Non-NSAID users had an overall higher bleeding rate for both major and nonmajor bleeding events. Based on this observation, it could be hypothesized that antiplatelet agents have a higher risk of bleeding in comparison to NSAIDs. In a subanalysis of the EXPAND study evaluating risk factors of major bleeding in patients receiving rivaroxaban, concomitant use of antiplatelet agents demonstrated a statistically significant increased risk of bleeding (HR 1.6; 95% CI, 1.2-2.3; P = .003) while concomitant use of NSAIDs did not (HR 0.8; 95% CI, 0.3-2.2; P = .67).19

In assessing PPI status at baseline, a majority of both rivaroxaban and apixaban NSAID users were coprescribed a PPI. This trend aligns with current clinical guideline recommendations for the prescribing of PPI therapy for GI protection in high-risk patients, such as those on DOAC therapy and concomitant NSAID therapy.10 Given the high proportion of NSAID users coprescribed a PPI at baseline, it may be possible that the true incidence of NSAID-associated bleeding events was higher than what this study found. This observation may reflect the impact from timely implementation of risk mitigation strategies by CPPs in the anticoagulation clinic. However, this study was not constructed to assess the efficacy of PPI use in this manner.

It is important to note the patients included in this study were followed by a pharmacist in an anticoagulation clinic using the DOAC Dashboard.15 This population management tool allows CPPs to make proactive interventions when a patient taking a DOAC receives an NSAID prescription, such as recommending the coprescribing of a PPI or use of a selective NSAID.10,16 These standards of care may have contributed to an overall reduced bleeding rate among the NSAID user group and may not be reflective of private practice.

The planned analysis of this study was modeled after the posthoc analysis of the RE-LY and ARISTOTLE trials. Both trials demonstrated an increased risk of bleeding with oral anticoagulation, including DOAC and warfarin, in combination with NSAID use. However, both trials found that NSAID use in patients treated with a DOAC was not independently associated with increased bleeding events compared with warfarin.13,14 The results of this study are comparable to the RE-LY and ARISTOTLE findings that NSAID use among patients treated with rivaroxaban or apixaban did not demonstrate a statistically significant increased bleeding risk.

Studies of NSAID use in combination with DOAC therapy have been limited to patient populations consisting of both DOAC and warfarin. Evidence from these trials outlines the increased bleeding risk associated with NSAID use in combination with oral anticoagulation; however, these patient populations include those on a DOAC and warfarin.13,14,19,20 Given the limited evidence on NSAID use among DOACs alone, it is assumed NSAID use in combination with DOACs has a similar risk of bleeding as warfarin use. This may cause clinicians to automatically exclude NSAID therapy as a treatment option for patients on a DOAC who are otherwise clinically appropriate candidates, such as those with underlying inflammatory conditions. Avoiding NSAID therapy in this patient population may lead to suboptimal pain management and increase the risk of patient harm from methods such as inappropriate opioid therapy prescribing.

DOAC therapy should not be a universal limitation to the use of NSAIDs. Although the risk of bleeding with NSAID therapy is always present, deliberate NSAID prescribing in addition to the timely implementation of risk mitigation strategies may provide an avenue for safe NSAID prescribing in patients receiving a DOAC. A population health-based approach to DOAC management, such as the DOAC Dashboard, appears to be effective at preventing patient harm when NSAIDs are prescribed in conjunction with DOACs.

Limitations

The DOAC Dashboard has been shown to be effective and efficient at monitoring DOAC therapy from a population-based approach.16 Reports generated through the DOAC Dashboard provide convenient access to patient data which allows for timely interventions; however, there are limits to its use for data collection. All the data elements necessary to properly assess bleeding risk with validated tools, such as HAS-BLED (hypertension, abnormal renal/liver function, stroke, bleeding history or predisposition, labile international normalized ratio, elderly, drugs/ alcohol concomitantly), are not available on DOAC Dashboard reports. Due to this constraint, bleeding risk assessments were not conducted at baseline and this study was unable to include risk modeling. Additionally, data elements like initiation and discontinuation dates and duration of therapies were not readily available. As a result, this study was unable to incorporate time as a data point.

This was a retrospective study that relied on manual review of chart documentation to verify bleeding events, but data obtained through the DOAC Dashboard were transferred directly from the EHR.15 Bleeding events available for evaluation were restricted to those that occurred at a VA facility. Additionally, the sample size within the rivaroxaban NSAID user group did not reach the predefined sample size required to reach power and may have been too small to detect a difference if one did exist. The secondary assessment had a low sample size of NSAID user bleeding events, making it difficult to fully assess its impact on NSAID selectivity and PPI coprescribing on bleeding rates. All courses of NSAIDs were equally valued regardless of the dose or therapy duration; however, this is consistent with how NSAID use was defined in the RE-LY and ARISTOTLE trials.

CONCLUSIONS

This retrospective cohort review found no statistically significant difference in the composite bleeding rates between rivaroxaban and apixaban among NSAID users and non-NSAID users. Moreover, there was no clinically significant impact observed for bleeding rates in regard to NSAID selectivity and PPI coprescribing among NSAID users. However, coprescribing of PPI therapy to patients on a DOAC who are clinically indicated for an NSAID may reduce the risk of bleeding. Population health management tools, such as the DOAC Dashboard, may also allow clinicians to safely prescribe NSAIDs to patients on a DOAC. Further large-scale observational studies are needed to quantify the real-world risk of bleeding with concomitant NSAID use among DOACs alone and to evaluate the impact from NSAID selectivity or PPI coprescribing.

Clinical practice has shifted from vitamin K antagonists to direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) for atrial fibrillation treatment due to their more favorable risk-benefit profile and less lifestyle modification required.1,2 However, the advantage of a lower bleeding risk with DOACs could be compromised by potentially problematic pharmacokinetic interactions like those conferred by antiplatelets or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).3,4 Treating a patient needing anticoagulation with a DOAC who has comorbidities may introduce unavoidable drug-drug interactions. This particularly happens with over-the-counter and prescription NSAIDs used for the management of pain and inflammatory conditions.5

NSAIDs primarily affect 2 cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme isomers, COX-1 and COX-2.6 COX-1 helps maintain gastrointestinal (GI) mucosa integrity and platelet aggregation processes, whereas COX-2 is engaged in pain signaling and inflammation mediation. COX-1 inhibition is associated with more bleeding-related adverse events (AEs), especially in the GI tract. COX-2 inhibition is thought to provide analgesia and anti-inflammatory properties without elevating bleeding risk. This premise is responsible for the preferential use of celecoxib, a COX-2 selective NSAID, which should confer a lower bleeding risk compared to nonselective NSAIDs such as ibuprofen and naproxen.7 NSAIDs have been documented as independent risk factors for bleeding. NSAID users are about 3 times as likely to develop GI AEs compared to nonNSAID users.8

Many clinicians aim to further mitigate NSAID-associated bleeding risk by coprescribing a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). PPIs provide gastroprotection against NSAID-induced mucosal injury and sequential complication of GI bleeding. In a multicenter randomized control trial, patients who received concomitant PPI therapy while undergoing chronic NSAID therapy—including nonselective and COX-2 selective NSAIDs—had a significantly lower risk of GI ulcer development (placebo, 17.0%; 20 mg esomeprazole, 5.2%; 40 mg esomeprazole, 4.6%).9 Current clinical guidelines for preventing NSAIDassociated bleeding complications recommend using a COX-2 selective NSAID in combination with PPI therapy for patients at high risk for GI-related bleeding, including the concomitant use of anticoagulants.10

There is evidence suggesting an increased bleeding risk with NSAIDs when used in combination with vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin.11,12 A systematic review of warfarin and concomitant NSAID use found an increased risk of overall bleeding with NSAID use in combination with warfarin (odds ratio 1.58; 95% CI, 1.18-2.12), compared to warfarin alone.12

Posthoc analyses of randomized clinical trials have also demonstrated an increased bleeding risk with oral anticoagulation and concomitant NSAID use.13,14 In the RE-LY trial, NSAID users on warfarin or dabigatran had a statistically significant increased risk of major bleeding compared to non-NSAID users (hazard ratio [HR] 1.68; 95% CI, 1.40- 2.02; P < .001).13 In the ARISTOTLE trial, patients on warfarin or apixaban who were incident NSAID users were found to have an increased risk of major bleeding (HR 1.61; 95% CI, 1.11-2.33) and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding (HR 1.70; 95% CI, 1.16- 2.48).14 These trials found a statistically significant increased bleeding risk associated with NSAID use, though the populations evaluated included patients taking warfarin and patients taking DOACs. These trials did not evaluate the bleeding risk of concomitant NSAID use among DOACs alone.

Evidence on NSAID-associated bleeding risk with DOACs is lacking in settings where the patient population, prescribing practices, and monitoring levels are variable. Within the Veterans Health Administration, clinical pharmacist practitioners (CPPs) in anticoagulation clinics oversee DOAC therapy management. CPPs monitor safety and efficacy of DOAC therapies through a population health management tool, the DOAC Dashboard.15 The DOAC Dashboard creates alerts for patients who may require an intervention based on certain clinical parameters, such as drug-drug interactions.16 Whenever a patient on a DOAC is prescribed an NSAID, an alert is generated on the DOAC Dashboard to flag the CPPs for the potential need for an intervention. If NSAID therapy remains clinically indicated, CPPs may recommend risk reduction strategies such as a COX-2 selective NSAID or coprescribing a PPI.10

The DOAC Dashboard provides an ideal setting for investigating the effects of NSAID use, NSAID selectivity, and PPI coprescribing on DOAC bleeding rates. With an increasing population of patients receiving anticoagulation therapy with a DOAC, more guidance regarding the bleeding risk of concomitant NSAID use with DOACs is needed. Studies evaluating the bleeding risk with concomitant NSAID use in patients on a DOAC alone are limited. This is the first study to date to compare bleeding risk with concomitant NSAID use between DOACs. This study provides information on bleeding risk with NSAID use among commonly prescribed DOACs, rivaroxaban and apixaban, and the potential impacts of current risk reduction strategies.

METHODS

This single-center retrospective cohort review was performed using the electronic health records (EHRs) of patients enrolled in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Mountain Home Healthcare System who received rivaroxaban or apixaban from December 2020 to December 2022. This study received approval from the East Tennessee State University/VA Institutional Review Board committee.

Patients were identified through the DOAC Dashboard, aged 21 to 100 years, and received rivaroxaban or apixaban at a therapeutic dose: rivaroxaban 10 to 20 mg daily or apixaban 2.5 to 5 mg twice daily. Patients were excluded if they were prescribed dual antiplatelet therapy, received rivaroxaban at dosing indicated for peripheral vascular disease, were undergoing dialysis, had evidence of moderate to severe hepatic impairment or any hepatic disease with coagulopathy, were undergoing chemotherapy or radiation, or had hematological conditions with predisposed bleeding risk. These patients were excluded to mitigate the potential confounding impact from nontherapeutic DOAC dosing strategies and conditions associated with an increased bleeding risk.

Eligible patients were stratified based on NSAID use. NSAID users were defined as patients prescribed an oral NSAID, including both acute and chronic courses, at any point during the study time frame while actively on a DOAC. Bleeding events were reviewed to evaluate rates between rivaroxaban and apixaban among NSAID and nonNSAID users. Identified NSAID users were further assessed for NSAID selectivity and PPI coprescribing as a subgroup analysis for the secondary assessment.

Data Collection

Baseline data were collected, including age, body mass index, anticoagulation indication, DOAC agent, DOAC dose, and DOAC total daily dose. Baseline serum creatinine levels, liver function tests, hemoglobin levels, and platelet counts were collected from the most recent data available immediately prior to the bleeding event, if applicable.

The DOAC Dashboard was reviewed for active and dismissed drug interaction alerts to identify patients taking rivaroxaban or apixaban who were prescribed an NSAID. Patients were categorized in the NSAID group if an interacting drug alert with an NSAID was reported during the study time frame. Data available through the interacting drug alerts on NSAID use were limited to the interacting drug name and date of the reported flag. Manual EHR review was required to confirm dates of NSAID therapy initiation and NSAID discontinuation, if applicable.

Data regarding concomitant antiplatelet use were obtained through review of the active and dismissed drug interaction alerts on the DOAC Dashboard. Concomitant antiplatelet use was defined as the prescribing of a single antiplatelet agent at any point while receiving DOAC therapy. Data on concomitant antiplatelets were collected regardless of NSAID status.

Data on coprescribed PPI therapy were obtained through manual EHR review of identified NSAID users. Coprescribed PPI therapy was defined as the prescribing of a PPI at any point during NSAID therapy. Data regarding PPI use among non-NSAID users were not collected because the secondary endpoint was designed to assess PPI use only among patients coprescribed a DOAC and NSAID.

Outcomes

Bleeding events were identified through an outcomes report generated by the DOAC Dashboard based on International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision diagnosis codes associated with a bleeding event. The outcomes report captures diagnoses from the outpatient and inpatient care settings. Reported bleeding events were limited to patients who received a DOAC at any point in the 6 months prior to the event and excluded patients with recent DOAC initiation within 7 days of the event, as these patients are not captured on the DOAC Dashboard.

All reported bleeding events were manually reviewed in the EHR and categorized as a major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleed, according to International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis criteria. Validated bleeding events were then crossreferenced with the interacting drug alerts report to identify events with potentially overlapping NSAID therapy at the time of the event. Overlapping NSAID therapy was defined as the prescribing of an NSAID at any point in the 6 months prior to the event. All events with potential overlapping NSAID therapies were manually reviewed for confirmation of NSAID status at the time of the event.

The primary endpoint was a composite of any bleeding event per International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis criteria. The secondary endpoint evaluated the potential impact of NSAID selectivity or PPI coprescribing on the bleeding rate among the NSAID user groups.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed consistent with the methods used in the ARISTOTLE and RE-LY trials. It was determined that a sample size of 504 patients, with ≥ 168 patients in each group, would provide 80% power using a 2-sided a of 0.05. HRs with 95% CIs and respective P values were calculated using a SPSS-adapted online calculator.

RESULTS

The DOAC Dashboard identified 681 patients on rivaroxaban and 3225 patients on apixaban; 72 patients on rivaroxaban (10.6%) and 300 patients on apixaban (9.3%) were NSAID users. The mean age of NSAID users was 66.9 years in the rivaroxaban group and 72.4 years in the apixaban group. The mean age of non-NSAID users was 71.5 years in the rivaroxaban group and 75.6 years in the apixaban group. No appreciable differences were observed among subgroups in body mass index, renal function, hepatic function, hemoglobin, or platelet counts, and no statistically significant differences were identified (Table 1). Antiplatelet agents identified included aspirin, clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor. Fifteen patients (20.3%) in the rivaroxaban group and 87 patients (28.7%) in the apixaban group had concomitant antiplatelet and NSAID use. Forty-five patients on rivaroxaban (60.8%) and 170 (55.9%) on apixaban were prescribed concomitant PPI and NSAID at baseline. Among non-NSAID users, there was concomitant antiplatelet use for 265 patients (43.6%) in the rivaroxaban group and 1401 patients (47.9%) in the apixaban group. Concomitant PPI use was identified among 63 patients (60.0%) taking selective NSAIDs and 182 (57.2%) taking nonselective NSAIDs.

A total of 423 courses of NSAIDs were identified: 85 NSAID courses in the rivaroxaban group and 338 NSAID courses in the apixaban group. Most NSAID courses involved a nonselective NSAID in the rivaroxaban and apixaban NSAID user groups: 75.2% (n = 318) aggregately compared to 71.8% (n = 61) and 76.0% (n = 257) in the rivaroxaban and apixaban groups, respectively. The most frequent NSAID courses identified were meloxicam (26.7%; n = 113), celecoxib (24.8%; n = 105), ibuprofen (19.1%; n = 81), and naproxen (13.5%; n = 57). Data regarding NSAID therapy initiation and discontinuation dates were not readily available. As a result, the duration of NSAID courses was not captured.

There was no statistically significant difference in bleeding rates between rivaroxaban and apixaban among NSAID users (HR 1.04; 95% CI, 0.98-1.12) or non-NSAID users (HR 1.15; 95% CI, 0.80-1.66) (Table 2). Apixaban non-NSAID users had a higher rate of major bleeds (HR 0.32; 95% CI, 0.17-0.61) while rivaroxaban non-NSAID users had a higher rate of clinically relevant nonmajor bleeds (HR 1.63; 95% CI, 1.10-2.54).

The sample size for the secondary endpoint consisted of bleeding events that were confirmed to have had an overlapping NSAID prescribed at the time of the event. For this secondary assessment, there was 1 rivaroxaban NSAID user bleeding event and 4 apixaban NSAID user bleeding events. For the rivaroxaban NSAID user bleeding event, the NSAID was nonselective and a PPI was not coprescribed. For the apixaban NSAID user bleeding events, 2 NSAIDs were nonselective and 2 were selective. All patients with apixaban and NSAID bleeding events had a coprescribed PPI. There was no clinically significant difference in the bleeding rates observed for NSAID selectivity or PPI coprescribing among the NSAID user subgroups.

DISCUSSION

This study found that there was no statistically significant difference for bleeding rates of major and nonmajor bleeding events between rivaroxaban and apixaban among NSAID users and non-NSAID users. This study did not identify a clinically significant impact on bleeding rates from NSAID selectivity or PPI coprescribing among the NSAID users.

There were notable but not statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics observed between the NSAID and non-NSAID user groups. On average, the rivaroxaban and apixaban NSAID users were younger compared with those not taking NSAIDs. NSAIDs, specifically nonselective NSAIDs, are recognized as potentially inappropriate medications for older adults given that this population is at an increased risk for GI ulcer development and/or GI bleeding.17 The non-NSAID user group likely consisted of older patients compared to the NSAID user group as clinicians may avoid prescribing NSAIDs to older adults regardless of concomitant DOAC therapy.

In addition to having an older patient population, non-NSAID users were more frequently prescribed a concomitant antiplatelet when compared with NSAID users. This prescribing pattern may be due to clinicians avoiding the use of NSAIDs in patients receiving DOAC therapy in combination with antiplatelet therapy, as these patients have been found to have an increased bleeding rate compared to DOAC therapy alone.18

Non-NSAID users had an overall higher bleeding rate for both major and nonmajor bleeding events. Based on this observation, it could be hypothesized that antiplatelet agents have a higher risk of bleeding in comparison to NSAIDs. In a subanalysis of the EXPAND study evaluating risk factors of major bleeding in patients receiving rivaroxaban, concomitant use of antiplatelet agents demonstrated a statistically significant increased risk of bleeding (HR 1.6; 95% CI, 1.2-2.3; P = .003) while concomitant use of NSAIDs did not (HR 0.8; 95% CI, 0.3-2.2; P = .67).19

In assessing PPI status at baseline, a majority of both rivaroxaban and apixaban NSAID users were coprescribed a PPI. This trend aligns with current clinical guideline recommendations for the prescribing of PPI therapy for GI protection in high-risk patients, such as those on DOAC therapy and concomitant NSAID therapy.10 Given the high proportion of NSAID users coprescribed a PPI at baseline, it may be possible that the true incidence of NSAID-associated bleeding events was higher than what this study found. This observation may reflect the impact from timely implementation of risk mitigation strategies by CPPs in the anticoagulation clinic. However, this study was not constructed to assess the efficacy of PPI use in this manner.

It is important to note the patients included in this study were followed by a pharmacist in an anticoagulation clinic using the DOAC Dashboard.15 This population management tool allows CPPs to make proactive interventions when a patient taking a DOAC receives an NSAID prescription, such as recommending the coprescribing of a PPI or use of a selective NSAID.10,16 These standards of care may have contributed to an overall reduced bleeding rate among the NSAID user group and may not be reflective of private practice.

The planned analysis of this study was modeled after the posthoc analysis of the RE-LY and ARISTOTLE trials. Both trials demonstrated an increased risk of bleeding with oral anticoagulation, including DOAC and warfarin, in combination with NSAID use. However, both trials found that NSAID use in patients treated with a DOAC was not independently associated with increased bleeding events compared with warfarin.13,14 The results of this study are comparable to the RE-LY and ARISTOTLE findings that NSAID use among patients treated with rivaroxaban or apixaban did not demonstrate a statistically significant increased bleeding risk.

Studies of NSAID use in combination with DOAC therapy have been limited to patient populations consisting of both DOAC and warfarin. Evidence from these trials outlines the increased bleeding risk associated with NSAID use in combination with oral anticoagulation; however, these patient populations include those on a DOAC and warfarin.13,14,19,20 Given the limited evidence on NSAID use among DOACs alone, it is assumed NSAID use in combination with DOACs has a similar risk of bleeding as warfarin use. This may cause clinicians to automatically exclude NSAID therapy as a treatment option for patients on a DOAC who are otherwise clinically appropriate candidates, such as those with underlying inflammatory conditions. Avoiding NSAID therapy in this patient population may lead to suboptimal pain management and increase the risk of patient harm from methods such as inappropriate opioid therapy prescribing.

DOAC therapy should not be a universal limitation to the use of NSAIDs. Although the risk of bleeding with NSAID therapy is always present, deliberate NSAID prescribing in addition to the timely implementation of risk mitigation strategies may provide an avenue for safe NSAID prescribing in patients receiving a DOAC. A population health-based approach to DOAC management, such as the DOAC Dashboard, appears to be effective at preventing patient harm when NSAIDs are prescribed in conjunction with DOACs.

Limitations

The DOAC Dashboard has been shown to be effective and efficient at monitoring DOAC therapy from a population-based approach.16 Reports generated through the DOAC Dashboard provide convenient access to patient data which allows for timely interventions; however, there are limits to its use for data collection. All the data elements necessary to properly assess bleeding risk with validated tools, such as HAS-BLED (hypertension, abnormal renal/liver function, stroke, bleeding history or predisposition, labile international normalized ratio, elderly, drugs/ alcohol concomitantly), are not available on DOAC Dashboard reports. Due to this constraint, bleeding risk assessments were not conducted at baseline and this study was unable to include risk modeling. Additionally, data elements like initiation and discontinuation dates and duration of therapies were not readily available. As a result, this study was unable to incorporate time as a data point.

This was a retrospective study that relied on manual review of chart documentation to verify bleeding events, but data obtained through the DOAC Dashboard were transferred directly from the EHR.15 Bleeding events available for evaluation were restricted to those that occurred at a VA facility. Additionally, the sample size within the rivaroxaban NSAID user group did not reach the predefined sample size required to reach power and may have been too small to detect a difference if one did exist. The secondary assessment had a low sample size of NSAID user bleeding events, making it difficult to fully assess its impact on NSAID selectivity and PPI coprescribing on bleeding rates. All courses of NSAIDs were equally valued regardless of the dose or therapy duration; however, this is consistent with how NSAID use was defined in the RE-LY and ARISTOTLE trials.

CONCLUSIONS

This retrospective cohort review found no statistically significant difference in the composite bleeding rates between rivaroxaban and apixaban among NSAID users and non-NSAID users. Moreover, there was no clinically significant impact observed for bleeding rates in regard to NSAID selectivity and PPI coprescribing among NSAID users. However, coprescribing of PPI therapy to patients on a DOAC who are clinically indicated for an NSAID may reduce the risk of bleeding. Population health management tools, such as the DOAC Dashboard, may also allow clinicians to safely prescribe NSAIDs to patients on a DOAC. Further large-scale observational studies are needed to quantify the real-world risk of bleeding with concomitant NSAID use among DOACs alone and to evaluate the impact from NSAID selectivity or PPI coprescribing.

- Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):955-962. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62343-0

- Ageno W, Gallus AS, Wittkowsky A, Crowther M, Hylek EM, Palareti G. Oral anticoagulant therapy: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e44S-e88S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2292

- Eikelboom J, Merli G. Bleeding with direct oral anticoagulants vs warfarin: clinical experience. Am J Med. 2016;129(11S):S33-S40. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.06.003

- Vranckx P, Valgimigli M, Heidbuchel H. The significance of drug-drug and drug-food interactions of oral anticoagulation. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2018;7(1):55-61. doi:10.15420/aer.2017.50.1

- Davis JS, Lee HY, Kim J, et al. Use of non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs in US adults: changes over time and by demographic. Open Heart. 2017;4(1):e000550. doi:10.1136/openhrt-2016-000550

- Schafer AI. Effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs on platelet function and systemic hemostasis. J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;35(3):209-219. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1995.tb04050.x

- Al-Saeed A. Gastrointestinal and cardiovascular risk of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Oman Med J. 2011;26(6):385-391. doi:10.5001/omj.2011.101

- Gabriel SE, Jaakkimainen L, Bombardier C. Risk for serious gastrointestinal complications related to use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115(10):787-796. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-115-10-787

- Scheiman JM, Yeomans ND, Talley NJ, et al. Prevention of ulcers by esomeprazole in at-risk patients using non-selective NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(4):701-710. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00499.x

- Freedberg DE, Kim LS, Yang YX. The risks and benefits of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: expert review and best practice advice from the American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(4):706-715. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.031

- Lamberts M, Lip GYH, Hansen ML, et al. Relation of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to serious bleeding and thromboembolism risk in patients with atrial fibrillation receiving antithrombotic therapy: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(10):690-698. doi:10.7326/M13-1581

- Villa Zapata L, Hansten PD, Panic J, et al. Risk of bleeding with exposure to warfarin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(7):1066-1074. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1710592

- Kent AP, Brueckmann M, Fraessdorf M, et al. Concomitant oral anticoagulant and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(3):255-267. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.063

- Dalgaard F, Mulder H, Wojdyla DM, et al. Patients with atrial fibrillation taking nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and oral anticoagulants in the ARISTOTLE Trial. Circulation. 2020;141(1):10-20. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041296

- Allen AL, Lucas J, Parra D, et al. Shifting the paradigm: a population health approach to the management of direct oral anticoagulants. J Am Heart Asssoc. 2021;10(24):e022758. doi:10.1161/JAHA.121.022758

- . Valencia D, Spoutz P, Stoppi J, et al. Impact of a direct oral anticoagulant population management tool on anticoagulation therapy monitoring in clinical practice. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;53(8):806-811. doi:10.1177/1060028019835843

- By the 2023 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2023 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(7):2052-2081. doi:10.1111/jgs.18372

- Kumar S, Danik SB, Altman RK, et al. Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants and antiplatelet therapy for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation. Cardiol Rev. 2016;24(5):218-223. doi:10.1097/CRD.0000000000000088

- Sakuma I, Uchiyama S, Atarashi H, et al. Clinical risk factors of stroke and major bleeding in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation under rivaroxaban: the EXPAND study sub-analysis. Heart Vessels. 2019;34(11):1839-1851. doi:10.1007/s00380-019-01425-x

- Davidson BL, Verheijen S, Lensing AWA, et al. Bleeding risk of patients with acute venous thromboembolism taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or aspirin. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(6):947-953. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.946

- Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):955-962. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62343-0

- Ageno W, Gallus AS, Wittkowsky A, Crowther M, Hylek EM, Palareti G. Oral anticoagulant therapy: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e44S-e88S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2292

- Eikelboom J, Merli G. Bleeding with direct oral anticoagulants vs warfarin: clinical experience. Am J Med. 2016;129(11S):S33-S40. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.06.003

- Vranckx P, Valgimigli M, Heidbuchel H. The significance of drug-drug and drug-food interactions of oral anticoagulation. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2018;7(1):55-61. doi:10.15420/aer.2017.50.1

- Davis JS, Lee HY, Kim J, et al. Use of non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs in US adults: changes over time and by demographic. Open Heart. 2017;4(1):e000550. doi:10.1136/openhrt-2016-000550

- Schafer AI. Effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs on platelet function and systemic hemostasis. J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;35(3):209-219. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1995.tb04050.x

- Al-Saeed A. Gastrointestinal and cardiovascular risk of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Oman Med J. 2011;26(6):385-391. doi:10.5001/omj.2011.101

- Gabriel SE, Jaakkimainen L, Bombardier C. Risk for serious gastrointestinal complications related to use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115(10):787-796. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-115-10-787

- Scheiman JM, Yeomans ND, Talley NJ, et al. Prevention of ulcers by esomeprazole in at-risk patients using non-selective NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(4):701-710. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00499.x

- Freedberg DE, Kim LS, Yang YX. The risks and benefits of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: expert review and best practice advice from the American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(4):706-715. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.031

- Lamberts M, Lip GYH, Hansen ML, et al. Relation of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to serious bleeding and thromboembolism risk in patients with atrial fibrillation receiving antithrombotic therapy: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(10):690-698. doi:10.7326/M13-1581

- Villa Zapata L, Hansten PD, Panic J, et al. Risk of bleeding with exposure to warfarin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(7):1066-1074. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1710592

- Kent AP, Brueckmann M, Fraessdorf M, et al. Concomitant oral anticoagulant and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(3):255-267. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.063

- Dalgaard F, Mulder H, Wojdyla DM, et al. Patients with atrial fibrillation taking nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and oral anticoagulants in the ARISTOTLE Trial. Circulation. 2020;141(1):10-20. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041296

- Allen AL, Lucas J, Parra D, et al. Shifting the paradigm: a population health approach to the management of direct oral anticoagulants. J Am Heart Asssoc. 2021;10(24):e022758. doi:10.1161/JAHA.121.022758

- . Valencia D, Spoutz P, Stoppi J, et al. Impact of a direct oral anticoagulant population management tool on anticoagulation therapy monitoring in clinical practice. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;53(8):806-811. doi:10.1177/1060028019835843

- By the 2023 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2023 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(7):2052-2081. doi:10.1111/jgs.18372

- Kumar S, Danik SB, Altman RK, et al. Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants and antiplatelet therapy for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation. Cardiol Rev. 2016;24(5):218-223. doi:10.1097/CRD.0000000000000088

- Sakuma I, Uchiyama S, Atarashi H, et al. Clinical risk factors of stroke and major bleeding in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation under rivaroxaban: the EXPAND study sub-analysis. Heart Vessels. 2019;34(11):1839-1851. doi:10.1007/s00380-019-01425-x

- Davidson BL, Verheijen S, Lensing AWA, et al. Bleeding risk of patients with acute venous thromboembolism taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or aspirin. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(6):947-953. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.946

Impact of NSAID Use on Bleeding Rates for Patients Taking Rivaroxaban or Apixaban

Impact of NSAID Use on Bleeding Rates for Patients Taking Rivaroxaban or Apixaban

Study Finds Association Between Statins and Glaucoma

Adults with high cholesterol taking statins may have a significantly higher risk of developing glaucoma than those not taking the cholesterol-lowering drugs, an observational study of a large research database found.

The study, published in Ophthalmology Glaucoma, analyzed electronic health records of 79,742 adults with hyperlipidemia in the All of Us Research Program database from 2017 to 2022. The repository is maintained by the National Institutes of Health and provides data for research into precision medicine.